User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

Feds delay online enrollment in small business exchange for 1 year

Small employers seeking health insurance through the Affordable Care Act’s small business marketplace will have to wait another year to enroll online.

Officials at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced on Nov. 27 that online enrollment would be delayed until November 2014, though enrollment will continue through paper applications. Employers will also be able to sign up for insurance through insurance brokers or agents, and directly through health plans.

The administration delayed the Small Business Health Options Program (SHOP) Marketplace to prioritize fixes to healthcare.gov, the tech-plagued federal marketplace used by individuals purchasing insurance, according to Julie Bataille, director of CMS’ Office of Communications.

The SHOP Marketplace allows small businesses with 50 or fewer full-time-equivalent employees to choose health plan options. For 2014, employers will only be able to select one plan.

Businesses with 50 or fewer employees are not required to offer insurance under the Affordable Care Act, though their employees must have coverage in place by March 31, 2014, in order to avoid a penalty under the health law.

In the meantime, federal health officials said they are still "on track" to meet their self-imposed deadline of Nov. 30 for getting healthcare.gov working well for the vast majority of users. By the end of November, healthcare.gov will be able to handle about 50,000 users at one time and more than 800,000 over the course of a day. But officials also stressed that Nov. 30 does not represent a relaunch of the website.

"It is not a magical date," Ms. Bataille said.

Small employers seeking health insurance through the Affordable Care Act’s small business marketplace will have to wait another year to enroll online.

Officials at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced on Nov. 27 that online enrollment would be delayed until November 2014, though enrollment will continue through paper applications. Employers will also be able to sign up for insurance through insurance brokers or agents, and directly through health plans.

The administration delayed the Small Business Health Options Program (SHOP) Marketplace to prioritize fixes to healthcare.gov, the tech-plagued federal marketplace used by individuals purchasing insurance, according to Julie Bataille, director of CMS’ Office of Communications.

The SHOP Marketplace allows small businesses with 50 or fewer full-time-equivalent employees to choose health plan options. For 2014, employers will only be able to select one plan.

Businesses with 50 or fewer employees are not required to offer insurance under the Affordable Care Act, though their employees must have coverage in place by March 31, 2014, in order to avoid a penalty under the health law.

In the meantime, federal health officials said they are still "on track" to meet their self-imposed deadline of Nov. 30 for getting healthcare.gov working well for the vast majority of users. By the end of November, healthcare.gov will be able to handle about 50,000 users at one time and more than 800,000 over the course of a day. But officials also stressed that Nov. 30 does not represent a relaunch of the website.

"It is not a magical date," Ms. Bataille said.

Small employers seeking health insurance through the Affordable Care Act’s small business marketplace will have to wait another year to enroll online.

Officials at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced on Nov. 27 that online enrollment would be delayed until November 2014, though enrollment will continue through paper applications. Employers will also be able to sign up for insurance through insurance brokers or agents, and directly through health plans.

The administration delayed the Small Business Health Options Program (SHOP) Marketplace to prioritize fixes to healthcare.gov, the tech-plagued federal marketplace used by individuals purchasing insurance, according to Julie Bataille, director of CMS’ Office of Communications.

The SHOP Marketplace allows small businesses with 50 or fewer full-time-equivalent employees to choose health plan options. For 2014, employers will only be able to select one plan.

Businesses with 50 or fewer employees are not required to offer insurance under the Affordable Care Act, though their employees must have coverage in place by March 31, 2014, in order to avoid a penalty under the health law.

In the meantime, federal health officials said they are still "on track" to meet their self-imposed deadline of Nov. 30 for getting healthcare.gov working well for the vast majority of users. By the end of November, healthcare.gov will be able to handle about 50,000 users at one time and more than 800,000 over the course of a day. But officials also stressed that Nov. 30 does not represent a relaunch of the website.

"It is not a magical date," Ms. Bataille said.

Gastric bypass associated with reversal of aging process

ATLANTA – Gastric bypass was associated with the lengthening of telomeres, an indication that surgical weight loss may reverse aging in obese patients.

The most significant changes in telomere length occurred in patients with biomarkers indicative of higher levels of preoperative inflammation and cholesterol, according to findings presented by bariatric surgeon John Morton at this year’s Obesity Week.

"Telomeres are unique markers for aging and are linked to chronic diseases and things like smoking and depression," Dr. Morton said in an interview. "There are a lot of things that can potentially affect telomeres, but there aren’t a lot of things that can affect them in a positive sense."

Dr. Morton and his colleagues at Stanford (Calif.) University measured the baseline telomere length, weight, C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, cholesterol levels, and fasting insulin levels in 51 gastric bypass surgery patients (77% female, average age 49 years). The group’s mean body mass index was 44 kg/m2. The measurements were taken again at 3, 6, and 12 months. Telomere length was determined using quantitative polymerase chain reaction testing.

In all patients, excess body weight loss at 12 months averaged 71%; CRP levels, indicative of inflammation, dropped an average of more than 60%. Fasting insulin levels decreased from 24 uIU/mL at baseline to 6 uIU/mL when measured 1 year after surgery. These results were consistent with those of previous studies, but this study was the first to correlate such changes with the body’s biomarkers for aging, telomeres, Dr. Morton said.

Unexpected results

Telomere length did not change significantly across the cohort, but when analyzed according to CRP and LDL levels, significant changes in telomere length were found in patients whose levels of both were higher at baseline (P = .0387 and P = .005). In those whose baseline CRP was high, there also was a significant positive correlation between telomere lengthening and weight loss (P = .0498) and increases in HDL cholesterol level (P = .0176).

The results were somewhat unexpected. "The thing that surprised me the most was that if there were going to be changes, then they should be across the board," said Dr. Morton. "But where it really made a difference was in those who had [high levels of markers of] inflammation. It was a pretty specific result in a pretty specific population."

At least one other longitudinal study has shown the impact of nonsurgical intervention, namely a change in diet, on the length of telomeres (PLoS One 2013;8:e62781[doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062781]), but Dr. Morton said the study, which emphasized eating less red meat and more fish, fresh vegetables, and olive oil did not demonstrate results that were notably different from his findings.

"One thing that study’s diet, the Mediterranean Diet, is known to do is to raise HDL," said Dr. Morton. "In our study we also saw a correlation between telomere lengthening and increases in HDL. That’s really hard to do. There aren’t a lot of medicines that can really affect the ‘good’ cholesterol."

‘Unique ability’ of gastric bypass

The study did not examine the relationship between telomeres and other kinds of surgical interventions for weight loss, but Dr. Morton said future studies on bariatric procedures such as the sleeve gastrectomy need to be conducted before they can be equated with bypass.

"Gastric bypass has a unique affect on inflammation that is independent of the other operations," said Dr. Morton, referring to data he presented earlier this year at the American College of Surgeons annual meeting, discussing the relationship between bypass and diabetes. "We have shown that C-reactive protein decreases more with gastric bypass than with other operations."

That of all the surgical interventions, gastric bypass has the greatest impact on diabetes, independent of weight loss, points to future research on inflammation, said Dr. Morton. "People are starting to think that type 2 diabetes is not just a burned-out pancreas, but that a lot of inflammation is involved."

Calling bariatric surgery a "platform for investigation" that can help [us] understand the connection between inflammation and the processes of disease in the general population, not just those with obesity, Dr. Morton said, "I think the future will elucidate some of those processes, and will come up with different interventions such as drugs."

Dr. Morton said he did not have any relevant financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Gastric bypass was associated with the lengthening of telomeres, an indication that surgical weight loss may reverse aging in obese patients.

The most significant changes in telomere length occurred in patients with biomarkers indicative of higher levels of preoperative inflammation and cholesterol, according to findings presented by bariatric surgeon John Morton at this year’s Obesity Week.

"Telomeres are unique markers for aging and are linked to chronic diseases and things like smoking and depression," Dr. Morton said in an interview. "There are a lot of things that can potentially affect telomeres, but there aren’t a lot of things that can affect them in a positive sense."

Dr. Morton and his colleagues at Stanford (Calif.) University measured the baseline telomere length, weight, C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, cholesterol levels, and fasting insulin levels in 51 gastric bypass surgery patients (77% female, average age 49 years). The group’s mean body mass index was 44 kg/m2. The measurements were taken again at 3, 6, and 12 months. Telomere length was determined using quantitative polymerase chain reaction testing.

In all patients, excess body weight loss at 12 months averaged 71%; CRP levels, indicative of inflammation, dropped an average of more than 60%. Fasting insulin levels decreased from 24 uIU/mL at baseline to 6 uIU/mL when measured 1 year after surgery. These results were consistent with those of previous studies, but this study was the first to correlate such changes with the body’s biomarkers for aging, telomeres, Dr. Morton said.

Unexpected results

Telomere length did not change significantly across the cohort, but when analyzed according to CRP and LDL levels, significant changes in telomere length were found in patients whose levels of both were higher at baseline (P = .0387 and P = .005). In those whose baseline CRP was high, there also was a significant positive correlation between telomere lengthening and weight loss (P = .0498) and increases in HDL cholesterol level (P = .0176).

The results were somewhat unexpected. "The thing that surprised me the most was that if there were going to be changes, then they should be across the board," said Dr. Morton. "But where it really made a difference was in those who had [high levels of markers of] inflammation. It was a pretty specific result in a pretty specific population."

At least one other longitudinal study has shown the impact of nonsurgical intervention, namely a change in diet, on the length of telomeres (PLoS One 2013;8:e62781[doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062781]), but Dr. Morton said the study, which emphasized eating less red meat and more fish, fresh vegetables, and olive oil did not demonstrate results that were notably different from his findings.

"One thing that study’s diet, the Mediterranean Diet, is known to do is to raise HDL," said Dr. Morton. "In our study we also saw a correlation between telomere lengthening and increases in HDL. That’s really hard to do. There aren’t a lot of medicines that can really affect the ‘good’ cholesterol."

‘Unique ability’ of gastric bypass

The study did not examine the relationship between telomeres and other kinds of surgical interventions for weight loss, but Dr. Morton said future studies on bariatric procedures such as the sleeve gastrectomy need to be conducted before they can be equated with bypass.

"Gastric bypass has a unique affect on inflammation that is independent of the other operations," said Dr. Morton, referring to data he presented earlier this year at the American College of Surgeons annual meeting, discussing the relationship between bypass and diabetes. "We have shown that C-reactive protein decreases more with gastric bypass than with other operations."

That of all the surgical interventions, gastric bypass has the greatest impact on diabetes, independent of weight loss, points to future research on inflammation, said Dr. Morton. "People are starting to think that type 2 diabetes is not just a burned-out pancreas, but that a lot of inflammation is involved."

Calling bariatric surgery a "platform for investigation" that can help [us] understand the connection between inflammation and the processes of disease in the general population, not just those with obesity, Dr. Morton said, "I think the future will elucidate some of those processes, and will come up with different interventions such as drugs."

Dr. Morton said he did not have any relevant financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Gastric bypass was associated with the lengthening of telomeres, an indication that surgical weight loss may reverse aging in obese patients.

The most significant changes in telomere length occurred in patients with biomarkers indicative of higher levels of preoperative inflammation and cholesterol, according to findings presented by bariatric surgeon John Morton at this year’s Obesity Week.

"Telomeres are unique markers for aging and are linked to chronic diseases and things like smoking and depression," Dr. Morton said in an interview. "There are a lot of things that can potentially affect telomeres, but there aren’t a lot of things that can affect them in a positive sense."

Dr. Morton and his colleagues at Stanford (Calif.) University measured the baseline telomere length, weight, C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, cholesterol levels, and fasting insulin levels in 51 gastric bypass surgery patients (77% female, average age 49 years). The group’s mean body mass index was 44 kg/m2. The measurements were taken again at 3, 6, and 12 months. Telomere length was determined using quantitative polymerase chain reaction testing.

In all patients, excess body weight loss at 12 months averaged 71%; CRP levels, indicative of inflammation, dropped an average of more than 60%. Fasting insulin levels decreased from 24 uIU/mL at baseline to 6 uIU/mL when measured 1 year after surgery. These results were consistent with those of previous studies, but this study was the first to correlate such changes with the body’s biomarkers for aging, telomeres, Dr. Morton said.

Unexpected results

Telomere length did not change significantly across the cohort, but when analyzed according to CRP and LDL levels, significant changes in telomere length were found in patients whose levels of both were higher at baseline (P = .0387 and P = .005). In those whose baseline CRP was high, there also was a significant positive correlation between telomere lengthening and weight loss (P = .0498) and increases in HDL cholesterol level (P = .0176).

The results were somewhat unexpected. "The thing that surprised me the most was that if there were going to be changes, then they should be across the board," said Dr. Morton. "But where it really made a difference was in those who had [high levels of markers of] inflammation. It was a pretty specific result in a pretty specific population."

At least one other longitudinal study has shown the impact of nonsurgical intervention, namely a change in diet, on the length of telomeres (PLoS One 2013;8:e62781[doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062781]), but Dr. Morton said the study, which emphasized eating less red meat and more fish, fresh vegetables, and olive oil did not demonstrate results that were notably different from his findings.

"One thing that study’s diet, the Mediterranean Diet, is known to do is to raise HDL," said Dr. Morton. "In our study we also saw a correlation between telomere lengthening and increases in HDL. That’s really hard to do. There aren’t a lot of medicines that can really affect the ‘good’ cholesterol."

‘Unique ability’ of gastric bypass

The study did not examine the relationship between telomeres and other kinds of surgical interventions for weight loss, but Dr. Morton said future studies on bariatric procedures such as the sleeve gastrectomy need to be conducted before they can be equated with bypass.

"Gastric bypass has a unique affect on inflammation that is independent of the other operations," said Dr. Morton, referring to data he presented earlier this year at the American College of Surgeons annual meeting, discussing the relationship between bypass and diabetes. "We have shown that C-reactive protein decreases more with gastric bypass than with other operations."

That of all the surgical interventions, gastric bypass has the greatest impact on diabetes, independent of weight loss, points to future research on inflammation, said Dr. Morton. "People are starting to think that type 2 diabetes is not just a burned-out pancreas, but that a lot of inflammation is involved."

Calling bariatric surgery a "platform for investigation" that can help [us] understand the connection between inflammation and the processes of disease in the general population, not just those with obesity, Dr. Morton said, "I think the future will elucidate some of those processes, and will come up with different interventions such as drugs."

Dr. Morton said he did not have any relevant financial disclosures.

AT OBESITY WEEK

Major finding: Significant increases in telomere length were observed after gastric bypass in individuals with high baseline CRP or LDL cholesterol levels (P = .0387 and P = .005, respectively); weight loss and increased levels of HDL cholesterol were positively correlated with telomere length in patients with high baseline CRP (P = .0498 and P = .0176).

Data source: A prospective study of 51 gastric bypass patients (77% female) whose telomere lengths, LDL, and CRP levels were measured at baseline and at 3,6, and 12 months.

Disclosures: Dr. Morton said he did not have any relevant financial disclosures.

Simple intensity-modulated radiotherapy improves breast cancer cosmesis

Dose homogeneity with intensity-modulated radiotherapy reduced the risk of skin telangiectasia, resulting in superior overall cosmesis for early breast cancer patients in a 5-year single-center trial.

"This study should act as an evidence-based lever for change for radiotherapy centers that have yet to implement breast IMRT (intensity-modulated radiotherapy)," wrote Dr. Mukesh B. Mukesh of Cambridge (England) University Hospitals National Health Service Foundation Trust, and colleagues.

The Cambridge Breast IMRT Trial randomized 1,145 women with early breast cancer to receive either standard radiotherapy or simple intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), which uses additional irradiation fields to smooth out the dose to the target area.

In the multivariate analysis, significantly fewer patients in the IMRT arm had suboptimal overall cosmesis (OR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.44 to 0.98; P = .038) and skin telangiectasia (OR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.34 to 0.95; P = .031), according to data published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology (doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.49.7842). However the two groups did not significantly differ based on photographically assessed breast shrinkage, clinically assessed edema, tumor bed induration or pigmentation, according to the researchers.

Also, there was no statistically significant difference in 5-year locoregional recurrence and overall survival rates.

Surgical cosmesis had a significant impact on outcomes, as patients with moderate to poor baseline surgical cosmesis were more likely to have suboptimal final cosmesis (OR, 8.15; 95% CI, 6.09 to 10.92; P < .001), tumor bed induration (OR, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.44 to 2.26; P < .001), and photographically assessed breast shrinkage (OR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.21 to 1.96; P < .001).

Factors such as large breast volume and tumor bed boost were also associated with an increased risk of suboptimal overall cosmesis. Older patients, and those with postoperative breast infections, large breast volume, and tumor bed boost, were also more likely to develop skin telangiectasia.

The patients enrolled in the study all had operable unilateral, histologically confirmed invasive breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ requiring radiotherapy after breast-conservation surgery.

All patients were assigned a standard radiotherapy plan. Those with satisfactory dose homogeneity were not randomly assigned but treated with standard radiotherapy and followed up as if randomly assigned, while those whose plan had significant dose inhomogeneity (defined as > or = 2 cm3 volume receiving greater than 107% of the prescribed dose) were randomized between standard radiotherapy (control arm) and simple IMRT.

There were a significant number of patient withdrawals at the 5-year analysis due to factors such as travel difficulties, social issues, and personal choice, and cancer-related factors.

The researchers declared having no conflicts of interest.

Dose homogeneity with intensity-modulated radiotherapy reduced the risk of skin telangiectasia, resulting in superior overall cosmesis for early breast cancer patients in a 5-year single-center trial.

"This study should act as an evidence-based lever for change for radiotherapy centers that have yet to implement breast IMRT (intensity-modulated radiotherapy)," wrote Dr. Mukesh B. Mukesh of Cambridge (England) University Hospitals National Health Service Foundation Trust, and colleagues.

The Cambridge Breast IMRT Trial randomized 1,145 women with early breast cancer to receive either standard radiotherapy or simple intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), which uses additional irradiation fields to smooth out the dose to the target area.

In the multivariate analysis, significantly fewer patients in the IMRT arm had suboptimal overall cosmesis (OR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.44 to 0.98; P = .038) and skin telangiectasia (OR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.34 to 0.95; P = .031), according to data published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology (doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.49.7842). However the two groups did not significantly differ based on photographically assessed breast shrinkage, clinically assessed edema, tumor bed induration or pigmentation, according to the researchers.

Also, there was no statistically significant difference in 5-year locoregional recurrence and overall survival rates.

Surgical cosmesis had a significant impact on outcomes, as patients with moderate to poor baseline surgical cosmesis were more likely to have suboptimal final cosmesis (OR, 8.15; 95% CI, 6.09 to 10.92; P < .001), tumor bed induration (OR, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.44 to 2.26; P < .001), and photographically assessed breast shrinkage (OR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.21 to 1.96; P < .001).

Factors such as large breast volume and tumor bed boost were also associated with an increased risk of suboptimal overall cosmesis. Older patients, and those with postoperative breast infections, large breast volume, and tumor bed boost, were also more likely to develop skin telangiectasia.

The patients enrolled in the study all had operable unilateral, histologically confirmed invasive breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ requiring radiotherapy after breast-conservation surgery.

All patients were assigned a standard radiotherapy plan. Those with satisfactory dose homogeneity were not randomly assigned but treated with standard radiotherapy and followed up as if randomly assigned, while those whose plan had significant dose inhomogeneity (defined as > or = 2 cm3 volume receiving greater than 107% of the prescribed dose) were randomized between standard radiotherapy (control arm) and simple IMRT.

There were a significant number of patient withdrawals at the 5-year analysis due to factors such as travel difficulties, social issues, and personal choice, and cancer-related factors.

The researchers declared having no conflicts of interest.

Dose homogeneity with intensity-modulated radiotherapy reduced the risk of skin telangiectasia, resulting in superior overall cosmesis for early breast cancer patients in a 5-year single-center trial.

"This study should act as an evidence-based lever for change for radiotherapy centers that have yet to implement breast IMRT (intensity-modulated radiotherapy)," wrote Dr. Mukesh B. Mukesh of Cambridge (England) University Hospitals National Health Service Foundation Trust, and colleagues.

The Cambridge Breast IMRT Trial randomized 1,145 women with early breast cancer to receive either standard radiotherapy or simple intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), which uses additional irradiation fields to smooth out the dose to the target area.

In the multivariate analysis, significantly fewer patients in the IMRT arm had suboptimal overall cosmesis (OR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.44 to 0.98; P = .038) and skin telangiectasia (OR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.34 to 0.95; P = .031), according to data published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology (doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.49.7842). However the two groups did not significantly differ based on photographically assessed breast shrinkage, clinically assessed edema, tumor bed induration or pigmentation, according to the researchers.

Also, there was no statistically significant difference in 5-year locoregional recurrence and overall survival rates.

Surgical cosmesis had a significant impact on outcomes, as patients with moderate to poor baseline surgical cosmesis were more likely to have suboptimal final cosmesis (OR, 8.15; 95% CI, 6.09 to 10.92; P < .001), tumor bed induration (OR, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.44 to 2.26; P < .001), and photographically assessed breast shrinkage (OR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.21 to 1.96; P < .001).

Factors such as large breast volume and tumor bed boost were also associated with an increased risk of suboptimal overall cosmesis. Older patients, and those with postoperative breast infections, large breast volume, and tumor bed boost, were also more likely to develop skin telangiectasia.

The patients enrolled in the study all had operable unilateral, histologically confirmed invasive breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ requiring radiotherapy after breast-conservation surgery.

All patients were assigned a standard radiotherapy plan. Those with satisfactory dose homogeneity were not randomly assigned but treated with standard radiotherapy and followed up as if randomly assigned, while those whose plan had significant dose inhomogeneity (defined as > or = 2 cm3 volume receiving greater than 107% of the prescribed dose) were randomized between standard radiotherapy (control arm) and simple IMRT.

There were a significant number of patient withdrawals at the 5-year analysis due to factors such as travel difficulties, social issues, and personal choice, and cancer-related factors.

The researchers declared having no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Major finding: Significantly fewer patients in the IMRT arm had suboptimal overall cosmesis (OR, 0.65; 95%CI, 0.44 to 0.98; P = .038) and skin telangiectasia (OR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.34 to 0.95; P = .031).

Data source: Single-center randomized controlled trial of 1,145 patients with early breast cancer.

Disclosures: Dr. Mukesh had no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ready or not? Most ICUs not as prepared for disaster as they think

CHICAGO – When Superstorm Sandy was done barreling across New York City and the surrounding coast 14 months ago, flooding streets and knocking out power to millions, Dr. Laura Evans, director of the medical intensive care unit at Bellevue Hospital along the East River in Manhattan, emerged weary and wiser.

At one point, the ICU faced the real possibility of having just a handful of working power outlets to serve dozens of patients, and the number of crucial decisions to be made rose along with the water level. "Prior to the storm, disaster preparedness was not a core interest of mine, and it’s something I hope never to repeat," Dr. Evans told attendees at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

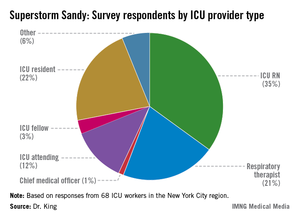

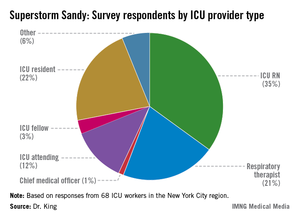

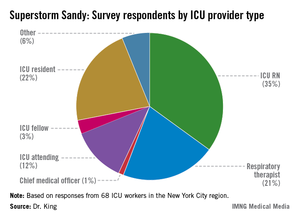

In a recent survey, ICU practitioners who endured havoc caused by Sandy in the New York City region reported having had little to no training in emergency evacuation care. "When I look at these data, I think there is a mismatch in terms of our self-perception of readiness compared to what patients actually require in an evacuation. It’s in stark contrast to the checklist we use every single day to put in a central venous catheter," said Dr. Mary Alice King, who presented her research as a copanelist with Dr. Evans. Dr. King is medical director of the pediatric trauma ICU at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle.

Contingency for loss of power

The nation’s oldest public hospital, Bellevue is adjacent to New York’s tidal East River. The river’s high tide the evening of Oct. 29, 2012, coincided with the arrival of the storm’s surge, and within minutes the hospital’s basement was inundated with 10 million gallons of seawater. And then the main power went out, taking with it the use of 32 elevators, the entire voice-over-Internet-protocol phone system, and the electronic medical records system, Dr. Evans said. The flood also knocked out the hospital’s ability to connect to its Internet servers. "We had very impaired means of communication," Dr. Evans said.

Survey data presented by Dr. King underscored that loss of power affects ICU functions in virtually all ways. The number one tool Dr. King’s survey respondents said they’d depended on most during their disaster response was their flashlights (24%); meanwhile, the top two items the respondents said they wished they’d had on hand were reliable phones, since, as at Bellevue, many of their phones were powered by voice-over-Internet protocols which, for most, went down with power outages; and backup electricity sources such as generators.

Leadership plan

Of the 68 survey respondents, 34% of whom were in evacuation leadership roles, Dr. King said only 23% admitted to having felt ill prepared to manage the pressure and details necessary to safely evacuate their patients. "As nonemergency department hospital providers, we receive little to no training on how to evacuate patients," said Dr. King.

In Bellevue’s case, Dr. Evans said that there was a leadership contingency already in place because of the hospital’s having been prepared the year before, when Hurricane Irene muscled its way up the Northeast’s Atlantic coast, also causing flooding and wind damage, though on a far smaller scare. "We had an ad hoc committee," said Dr. Evans. "Although we didn’t know exactly who would be on it because we didn’t know who would be there during the storm, we knew we would have medical, nursing, and ethical leaders to make resource allocation decisions." Most important about the leadership committee’s makeup, she said, was that ultimately, "none of us were directly involved in patient care, so none of us had the responsibility for being advocates. We wanted the attending physicians to be able to advocate for their patients."

The committee discerned that if backup generators failed, the ICU would have only six power outlets to depend on for its almost 60 patients. "The question was, whom would they be allocated for out of the 56 patients?

"Our responsibility was to make the wisest decisions about allocating a scarce resource," Dr. Evans said.

Practice the plan

Dry runs matter. "Forty-seven percent of survey respondents said that patient triage criteria were determined at the time of [the storm]," and a third of those surveyed said they weren’t aware of any triage criteria, Dr. King said.

And once plans are made, "it’s important to drill them," emphasized Dr. King’s copresenter Dr. Colin Grissom, associate medical director of the shock trauma ICU at Intermountain Medical Center, Murray, Utah. Superstorm Sandy, for all its havoc, came with some notice – the weather forecast. However, he pointed out that typically disasters happen without warning: "More than half of all hospital evacuations occur as a result of an internal event such as a fire or an intruder."

Also important to consider, said Dr. King, is that neonatal and pediatric ICUs have different evacuation needs from adult ones. "Regions should consider stockpiling neonatal transport ventilators and circuits," she said. "They should also consider designating pediatric disaster receiving hospitals, similar to burn disaster receiving hospitals."

Ethical considerations

At Bellevue, Dr. Evans said the hospital’s leadership planned patient triage according to influenza pandemic guidelines issued by the provincial government of Ontario, Canada, and the New York State Taskforce on Life and the Law guidelines for ventilator allocation during a public health disaster.

"We knew that if the disaster went very badly, we would be met with much criticism," said Dr. Evans, who joked that she was up nights worried about seeing her name skewered in local headlines: "I kept wondering, ‘What rhymes with Evans?’ "

Using the two sets of guidelines, both heavily oriented toward allocating ventilators, said Dr. Evans, "we did what we thought was ethical and fair. We made the best decisions we could."

The Ontario guidelines, she said, are predicated on Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores. Just as the ad hoc committee determined that of the 56 patients in the census, there were "far more folks in the red (highest priority) and yellow (immediate priority) group than we had power outlets," the group received word that the protective housing around the generator fuel pumps had failed, and total loss of power was anticipated in 2 hours.

The committee reconfigured and, among other contingencies, began assigning coverage of two providers each to the bedside of every ventilated patient, and preparing nurses to count drops per minute of continuous medication.

The ‘bucket brigade’

Although the intensivists who’d participated in Superstorm Sandy evacuations said they felt most frustrated by the lack of communication during the event, 57% said that teamwork had been essential to the success of the evacuations.

"We work as teams in our units. That is something I think we bring as a real strength to ICU evacuations," said Dr. King.

And so it was at Bellevue.

"Due to the heroics of a lot of staff and volunteers, we did not have to execute this plan," said Dr. Evans. Instead, the "Bellevue bucket brigade," using 5-gallon jugs, formed a relay team stretching from the ground floor outside where the fuel tanks were, up to the 13th, where the backup generators were located. "The fuel tank up on the 13th floor was only accessible by stepladder, so someone had to climb up there and pour the fuel through a funnel," said Dr. Evans. "But because of this, we never lost backup power, and we successfully evacuated our hospital without complications to our patients."

Individualized plan key to success

While leadership and communication were essential, said Dr. Evans, she concluded that thinking through how existing guidelines can help was also key, but did not go far enough. "Unfortunately, no document can provide for all contingencies. Complete reliance on any [guidelines] is not good. You have to think about how you would individualize things to your own facility."

The survey was sponsored by the ACCP and conducted by Dr. King as part of her role on the ACCP’s mass critical care task force evacuation panel, which will issue a consensus on the topic sometime in early 2014.

Dr. Evans, Dr. King, and Dr. Grissom reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Ten keys to ICU evacuation plan

When not under immediate threat

1) Create transport and other agreements with other facilities in region, including triage criteria.

2) Detail ICU evacuation plan, including vertical evacuation plan; simulate so all parties are familiar with their role, including those involved in patient transport.

3) Designate critical care leadership.

During imminent threat

4) Request assistance from regional facilities and appropriate agencies.

5) Ensure power and transportation resources are operable and in place.

6) Prioritize patients for evacuation.

During evacuation

7) Triage patients.

8) Include all patient information with patient.

9) Transport patients.

10) Track patients and all equipment.

Source: Dr. Colin Grissom

*This story has been updated 11/26/13

Dr. W. Michael Alberts, FCCP, comments: To paraphrase an old saying about insurance, "disaster preparedness is not needed until it is." Those health care facilities that have a clear documented plan and have drilled on the specifics are very pleased that they devoted time and effort when disaster strikes. While – knock on wood – the Moffitt Cancer Center here in Tampa has not needed our "Disaster Management Plan" (or as we in Florida say "Hurricane Management Plan") this year, it is only a matter of time and we’ll be ready when the need arises.

We urge you to review your plan before you need it.

Dr. W. Michael Alberts is chief medical officer, Moffitt Cancer Center, and professor of oncology and medicine at the University of South Florida, Tampa.

Dr. W. Michael Alberts, FCCP, comments: To paraphrase an old saying about insurance, "disaster preparedness is not needed until it is." Those health care facilities that have a clear documented plan and have drilled on the specifics are very pleased that they devoted time and effort when disaster strikes. While – knock on wood – the Moffitt Cancer Center here in Tampa has not needed our "Disaster Management Plan" (or as we in Florida say "Hurricane Management Plan") this year, it is only a matter of time and we’ll be ready when the need arises.

We urge you to review your plan before you need it.

Dr. W. Michael Alberts is chief medical officer, Moffitt Cancer Center, and professor of oncology and medicine at the University of South Florida, Tampa.

Dr. W. Michael Alberts, FCCP, comments: To paraphrase an old saying about insurance, "disaster preparedness is not needed until it is." Those health care facilities that have a clear documented plan and have drilled on the specifics are very pleased that they devoted time and effort when disaster strikes. While – knock on wood – the Moffitt Cancer Center here in Tampa has not needed our "Disaster Management Plan" (or as we in Florida say "Hurricane Management Plan") this year, it is only a matter of time and we’ll be ready when the need arises.

We urge you to review your plan before you need it.

Dr. W. Michael Alberts is chief medical officer, Moffitt Cancer Center, and professor of oncology and medicine at the University of South Florida, Tampa.

CHICAGO – When Superstorm Sandy was done barreling across New York City and the surrounding coast 14 months ago, flooding streets and knocking out power to millions, Dr. Laura Evans, director of the medical intensive care unit at Bellevue Hospital along the East River in Manhattan, emerged weary and wiser.

At one point, the ICU faced the real possibility of having just a handful of working power outlets to serve dozens of patients, and the number of crucial decisions to be made rose along with the water level. "Prior to the storm, disaster preparedness was not a core interest of mine, and it’s something I hope never to repeat," Dr. Evans told attendees at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

In a recent survey, ICU practitioners who endured havoc caused by Sandy in the New York City region reported having had little to no training in emergency evacuation care. "When I look at these data, I think there is a mismatch in terms of our self-perception of readiness compared to what patients actually require in an evacuation. It’s in stark contrast to the checklist we use every single day to put in a central venous catheter," said Dr. Mary Alice King, who presented her research as a copanelist with Dr. Evans. Dr. King is medical director of the pediatric trauma ICU at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle.

Contingency for loss of power

The nation’s oldest public hospital, Bellevue is adjacent to New York’s tidal East River. The river’s high tide the evening of Oct. 29, 2012, coincided with the arrival of the storm’s surge, and within minutes the hospital’s basement was inundated with 10 million gallons of seawater. And then the main power went out, taking with it the use of 32 elevators, the entire voice-over-Internet-protocol phone system, and the electronic medical records system, Dr. Evans said. The flood also knocked out the hospital’s ability to connect to its Internet servers. "We had very impaired means of communication," Dr. Evans said.

Survey data presented by Dr. King underscored that loss of power affects ICU functions in virtually all ways. The number one tool Dr. King’s survey respondents said they’d depended on most during their disaster response was their flashlights (24%); meanwhile, the top two items the respondents said they wished they’d had on hand were reliable phones, since, as at Bellevue, many of their phones were powered by voice-over-Internet protocols which, for most, went down with power outages; and backup electricity sources such as generators.

Leadership plan

Of the 68 survey respondents, 34% of whom were in evacuation leadership roles, Dr. King said only 23% admitted to having felt ill prepared to manage the pressure and details necessary to safely evacuate their patients. "As nonemergency department hospital providers, we receive little to no training on how to evacuate patients," said Dr. King.

In Bellevue’s case, Dr. Evans said that there was a leadership contingency already in place because of the hospital’s having been prepared the year before, when Hurricane Irene muscled its way up the Northeast’s Atlantic coast, also causing flooding and wind damage, though on a far smaller scare. "We had an ad hoc committee," said Dr. Evans. "Although we didn’t know exactly who would be on it because we didn’t know who would be there during the storm, we knew we would have medical, nursing, and ethical leaders to make resource allocation decisions." Most important about the leadership committee’s makeup, she said, was that ultimately, "none of us were directly involved in patient care, so none of us had the responsibility for being advocates. We wanted the attending physicians to be able to advocate for their patients."

The committee discerned that if backup generators failed, the ICU would have only six power outlets to depend on for its almost 60 patients. "The question was, whom would they be allocated for out of the 56 patients?

"Our responsibility was to make the wisest decisions about allocating a scarce resource," Dr. Evans said.

Practice the plan

Dry runs matter. "Forty-seven percent of survey respondents said that patient triage criteria were determined at the time of [the storm]," and a third of those surveyed said they weren’t aware of any triage criteria, Dr. King said.

And once plans are made, "it’s important to drill them," emphasized Dr. King’s copresenter Dr. Colin Grissom, associate medical director of the shock trauma ICU at Intermountain Medical Center, Murray, Utah. Superstorm Sandy, for all its havoc, came with some notice – the weather forecast. However, he pointed out that typically disasters happen without warning: "More than half of all hospital evacuations occur as a result of an internal event such as a fire or an intruder."

Also important to consider, said Dr. King, is that neonatal and pediatric ICUs have different evacuation needs from adult ones. "Regions should consider stockpiling neonatal transport ventilators and circuits," she said. "They should also consider designating pediatric disaster receiving hospitals, similar to burn disaster receiving hospitals."

Ethical considerations

At Bellevue, Dr. Evans said the hospital’s leadership planned patient triage according to influenza pandemic guidelines issued by the provincial government of Ontario, Canada, and the New York State Taskforce on Life and the Law guidelines for ventilator allocation during a public health disaster.

"We knew that if the disaster went very badly, we would be met with much criticism," said Dr. Evans, who joked that she was up nights worried about seeing her name skewered in local headlines: "I kept wondering, ‘What rhymes with Evans?’ "

Using the two sets of guidelines, both heavily oriented toward allocating ventilators, said Dr. Evans, "we did what we thought was ethical and fair. We made the best decisions we could."

The Ontario guidelines, she said, are predicated on Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores. Just as the ad hoc committee determined that of the 56 patients in the census, there were "far more folks in the red (highest priority) and yellow (immediate priority) group than we had power outlets," the group received word that the protective housing around the generator fuel pumps had failed, and total loss of power was anticipated in 2 hours.

The committee reconfigured and, among other contingencies, began assigning coverage of two providers each to the bedside of every ventilated patient, and preparing nurses to count drops per minute of continuous medication.

The ‘bucket brigade’

Although the intensivists who’d participated in Superstorm Sandy evacuations said they felt most frustrated by the lack of communication during the event, 57% said that teamwork had been essential to the success of the evacuations.

"We work as teams in our units. That is something I think we bring as a real strength to ICU evacuations," said Dr. King.

And so it was at Bellevue.

"Due to the heroics of a lot of staff and volunteers, we did not have to execute this plan," said Dr. Evans. Instead, the "Bellevue bucket brigade," using 5-gallon jugs, formed a relay team stretching from the ground floor outside where the fuel tanks were, up to the 13th, where the backup generators were located. "The fuel tank up on the 13th floor was only accessible by stepladder, so someone had to climb up there and pour the fuel through a funnel," said Dr. Evans. "But because of this, we never lost backup power, and we successfully evacuated our hospital without complications to our patients."

Individualized plan key to success

While leadership and communication were essential, said Dr. Evans, she concluded that thinking through how existing guidelines can help was also key, but did not go far enough. "Unfortunately, no document can provide for all contingencies. Complete reliance on any [guidelines] is not good. You have to think about how you would individualize things to your own facility."

The survey was sponsored by the ACCP and conducted by Dr. King as part of her role on the ACCP’s mass critical care task force evacuation panel, which will issue a consensus on the topic sometime in early 2014.

Dr. Evans, Dr. King, and Dr. Grissom reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Ten keys to ICU evacuation plan

When not under immediate threat

1) Create transport and other agreements with other facilities in region, including triage criteria.

2) Detail ICU evacuation plan, including vertical evacuation plan; simulate so all parties are familiar with their role, including those involved in patient transport.

3) Designate critical care leadership.

During imminent threat

4) Request assistance from regional facilities and appropriate agencies.

5) Ensure power and transportation resources are operable and in place.

6) Prioritize patients for evacuation.

During evacuation

7) Triage patients.

8) Include all patient information with patient.

9) Transport patients.

10) Track patients and all equipment.

Source: Dr. Colin Grissom

*This story has been updated 11/26/13

CHICAGO – When Superstorm Sandy was done barreling across New York City and the surrounding coast 14 months ago, flooding streets and knocking out power to millions, Dr. Laura Evans, director of the medical intensive care unit at Bellevue Hospital along the East River in Manhattan, emerged weary and wiser.

At one point, the ICU faced the real possibility of having just a handful of working power outlets to serve dozens of patients, and the number of crucial decisions to be made rose along with the water level. "Prior to the storm, disaster preparedness was not a core interest of mine, and it’s something I hope never to repeat," Dr. Evans told attendees at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

In a recent survey, ICU practitioners who endured havoc caused by Sandy in the New York City region reported having had little to no training in emergency evacuation care. "When I look at these data, I think there is a mismatch in terms of our self-perception of readiness compared to what patients actually require in an evacuation. It’s in stark contrast to the checklist we use every single day to put in a central venous catheter," said Dr. Mary Alice King, who presented her research as a copanelist with Dr. Evans. Dr. King is medical director of the pediatric trauma ICU at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle.

Contingency for loss of power

The nation’s oldest public hospital, Bellevue is adjacent to New York’s tidal East River. The river’s high tide the evening of Oct. 29, 2012, coincided with the arrival of the storm’s surge, and within minutes the hospital’s basement was inundated with 10 million gallons of seawater. And then the main power went out, taking with it the use of 32 elevators, the entire voice-over-Internet-protocol phone system, and the electronic medical records system, Dr. Evans said. The flood also knocked out the hospital’s ability to connect to its Internet servers. "We had very impaired means of communication," Dr. Evans said.

Survey data presented by Dr. King underscored that loss of power affects ICU functions in virtually all ways. The number one tool Dr. King’s survey respondents said they’d depended on most during their disaster response was their flashlights (24%); meanwhile, the top two items the respondents said they wished they’d had on hand were reliable phones, since, as at Bellevue, many of their phones were powered by voice-over-Internet protocols which, for most, went down with power outages; and backup electricity sources such as generators.

Leadership plan

Of the 68 survey respondents, 34% of whom were in evacuation leadership roles, Dr. King said only 23% admitted to having felt ill prepared to manage the pressure and details necessary to safely evacuate their patients. "As nonemergency department hospital providers, we receive little to no training on how to evacuate patients," said Dr. King.

In Bellevue’s case, Dr. Evans said that there was a leadership contingency already in place because of the hospital’s having been prepared the year before, when Hurricane Irene muscled its way up the Northeast’s Atlantic coast, also causing flooding and wind damage, though on a far smaller scare. "We had an ad hoc committee," said Dr. Evans. "Although we didn’t know exactly who would be on it because we didn’t know who would be there during the storm, we knew we would have medical, nursing, and ethical leaders to make resource allocation decisions." Most important about the leadership committee’s makeup, she said, was that ultimately, "none of us were directly involved in patient care, so none of us had the responsibility for being advocates. We wanted the attending physicians to be able to advocate for their patients."

The committee discerned that if backup generators failed, the ICU would have only six power outlets to depend on for its almost 60 patients. "The question was, whom would they be allocated for out of the 56 patients?

"Our responsibility was to make the wisest decisions about allocating a scarce resource," Dr. Evans said.

Practice the plan

Dry runs matter. "Forty-seven percent of survey respondents said that patient triage criteria were determined at the time of [the storm]," and a third of those surveyed said they weren’t aware of any triage criteria, Dr. King said.

And once plans are made, "it’s important to drill them," emphasized Dr. King’s copresenter Dr. Colin Grissom, associate medical director of the shock trauma ICU at Intermountain Medical Center, Murray, Utah. Superstorm Sandy, for all its havoc, came with some notice – the weather forecast. However, he pointed out that typically disasters happen without warning: "More than half of all hospital evacuations occur as a result of an internal event such as a fire or an intruder."

Also important to consider, said Dr. King, is that neonatal and pediatric ICUs have different evacuation needs from adult ones. "Regions should consider stockpiling neonatal transport ventilators and circuits," she said. "They should also consider designating pediatric disaster receiving hospitals, similar to burn disaster receiving hospitals."

Ethical considerations

At Bellevue, Dr. Evans said the hospital’s leadership planned patient triage according to influenza pandemic guidelines issued by the provincial government of Ontario, Canada, and the New York State Taskforce on Life and the Law guidelines for ventilator allocation during a public health disaster.

"We knew that if the disaster went very badly, we would be met with much criticism," said Dr. Evans, who joked that she was up nights worried about seeing her name skewered in local headlines: "I kept wondering, ‘What rhymes with Evans?’ "

Using the two sets of guidelines, both heavily oriented toward allocating ventilators, said Dr. Evans, "we did what we thought was ethical and fair. We made the best decisions we could."

The Ontario guidelines, she said, are predicated on Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores. Just as the ad hoc committee determined that of the 56 patients in the census, there were "far more folks in the red (highest priority) and yellow (immediate priority) group than we had power outlets," the group received word that the protective housing around the generator fuel pumps had failed, and total loss of power was anticipated in 2 hours.

The committee reconfigured and, among other contingencies, began assigning coverage of two providers each to the bedside of every ventilated patient, and preparing nurses to count drops per minute of continuous medication.

The ‘bucket brigade’

Although the intensivists who’d participated in Superstorm Sandy evacuations said they felt most frustrated by the lack of communication during the event, 57% said that teamwork had been essential to the success of the evacuations.

"We work as teams in our units. That is something I think we bring as a real strength to ICU evacuations," said Dr. King.

And so it was at Bellevue.

"Due to the heroics of a lot of staff and volunteers, we did not have to execute this plan," said Dr. Evans. Instead, the "Bellevue bucket brigade," using 5-gallon jugs, formed a relay team stretching from the ground floor outside where the fuel tanks were, up to the 13th, where the backup generators were located. "The fuel tank up on the 13th floor was only accessible by stepladder, so someone had to climb up there and pour the fuel through a funnel," said Dr. Evans. "But because of this, we never lost backup power, and we successfully evacuated our hospital without complications to our patients."

Individualized plan key to success

While leadership and communication were essential, said Dr. Evans, she concluded that thinking through how existing guidelines can help was also key, but did not go far enough. "Unfortunately, no document can provide for all contingencies. Complete reliance on any [guidelines] is not good. You have to think about how you would individualize things to your own facility."

The survey was sponsored by the ACCP and conducted by Dr. King as part of her role on the ACCP’s mass critical care task force evacuation panel, which will issue a consensus on the topic sometime in early 2014.

Dr. Evans, Dr. King, and Dr. Grissom reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Ten keys to ICU evacuation plan

When not under immediate threat

1) Create transport and other agreements with other facilities in region, including triage criteria.

2) Detail ICU evacuation plan, including vertical evacuation plan; simulate so all parties are familiar with their role, including those involved in patient transport.

3) Designate critical care leadership.

During imminent threat

4) Request assistance from regional facilities and appropriate agencies.

5) Ensure power and transportation resources are operable and in place.

6) Prioritize patients for evacuation.

During evacuation

7) Triage patients.

8) Include all patient information with patient.

9) Transport patients.

10) Track patients and all equipment.

Source: Dr. Colin Grissom

*This story has been updated 11/26/13

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM CHEST 2013

Major finding: Although 78% of ICU staff had never performed a vertical ICU evacuation drill, only 23% admitted to feeling "inadequately trained" during Superstorm Sandy evacuations.

Data source: Survey of 68 ICU workers in the New York City region, all of whom worked through Superstorm Sandy.

Disclosures: Dr. Evans, Dr. King, and Dr. Grissom reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Electrocautery incision of lymph nodes improved biopsy yield

Endobronchial ultrasound–guided biopsies made after an electrocautery incision to the lymph node improved biopsy yields from 39% to 71% in 38 nodes, according to a small study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians meeting.

"Because it is not always possible to pass biopsy forceps through defects in the lymph node – the literature indicates a failure rate of between 10% and 29% – we developed a novel technique," said presenter Dr. Kyle Bramley of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The technique employs EBUS, and involves passing an electrocautery knife activated at 40 W through the working channel of the scope in order to make an incision in the bronchial wall and enlarge the defect in the lymph node. This facilitates passage of the forceps into the node so that a larger biopsy sample can be obtained.

To test their technique, Dr. Bramley and his colleagues designed a prospective observational cohort study at a single tertiary academic medical center. Twenty patients (mean age, 68 years), including 11 women, who were undergoing EBUS were enrolled. An associated lung mass was present in 14 (70%) of the participants; 6 (30%) had isolated lymphadenopathy. One patient had prior lymphoma, and two others had prior lung cancer.

The researchers evaluated 68 nodes in all; 19 patients had nodes greater than 9 mm. Cautery was only used when initial attempts failed to biopsy nodes 9 mm or larger using EBUS-guided miniforceps of 1.2 mm.

The average node size biopsied using EBUS-transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) was 5.7 mm. The average forceps-biopsied node was 15.8 mm.

In all, 23 nodes were biopsied successfully on the first pass using EBUS-TBNA only. The biopsies yielded diagnostic material such as lymphocytes, malignancy, or granulomas in 15 of these nodes.

Of the 15 nodes that required cautery, 12 yielded diagnostic material, and 3 had no diagnostic material.

The overall yield increased from 39% (15 out of 38) without cautery to 71% (27 out of 38) when cautery was used.

Notably, four patients had clinically relevant discrepancies between their cytologies and histopathologies. "In all four, TBNA provided a definitive diagnosis," said Dr. Bramley. "The forceps provided fibroconnective tissue or necrotic debris."

These results did not negate the efficacy of the cautery technique, according to Dr. Bramley. "We think we had a forceps issue ... the 1.2 mm are flexible, but they were unable to push all the way through a tough lymph node capsule."

Dr. Bramley also said that other factors, including the operator learning curve, the smaller size of the nodes the investigators attempted to biopsy, and the "nonideal" population they were studying, contributed to these results.

He and his colleagues have since adjusted the procedure to make cauterization routine and to include a 1.9-mm transbronchial biopsy forceps needle, "which, incidentally, is a lot less expensive than the larger forceps we’d been using," he said.

Although more study is needed, Dr. Bramley said he and his team believed that this technique would be appropriate for future use in isolated mediastinal lymphadenopathy, especially with a low suspicion of non–small cell lung carcinoma; evaluation of lymphoma; and clinical trials requiring core biopsy.

Dr. Bramley had no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Frank Podbielski, FCCP, comments: The authors have again proven that a larger pathology specimen obtained at the time of biopsy significantly improves diagnostic accuracy, especially in the setting of mediastinal nodes that are difficult to access and thus require an electrocautery incision through the airway in concert with EBUS guidance.

Dr. Francis J. Podbielski leads the Lung Cancer Program at Jordan Hospital in Plymouth, Mass.

Dr. Frank Podbielski, FCCP, comments: The authors have again proven that a larger pathology specimen obtained at the time of biopsy significantly improves diagnostic accuracy, especially in the setting of mediastinal nodes that are difficult to access and thus require an electrocautery incision through the airway in concert with EBUS guidance.

Dr. Francis J. Podbielski leads the Lung Cancer Program at Jordan Hospital in Plymouth, Mass.

Dr. Frank Podbielski, FCCP, comments: The authors have again proven that a larger pathology specimen obtained at the time of biopsy significantly improves diagnostic accuracy, especially in the setting of mediastinal nodes that are difficult to access and thus require an electrocautery incision through the airway in concert with EBUS guidance.

Dr. Francis J. Podbielski leads the Lung Cancer Program at Jordan Hospital in Plymouth, Mass.

Endobronchial ultrasound–guided biopsies made after an electrocautery incision to the lymph node improved biopsy yields from 39% to 71% in 38 nodes, according to a small study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians meeting.

"Because it is not always possible to pass biopsy forceps through defects in the lymph node – the literature indicates a failure rate of between 10% and 29% – we developed a novel technique," said presenter Dr. Kyle Bramley of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The technique employs EBUS, and involves passing an electrocautery knife activated at 40 W through the working channel of the scope in order to make an incision in the bronchial wall and enlarge the defect in the lymph node. This facilitates passage of the forceps into the node so that a larger biopsy sample can be obtained.

To test their technique, Dr. Bramley and his colleagues designed a prospective observational cohort study at a single tertiary academic medical center. Twenty patients (mean age, 68 years), including 11 women, who were undergoing EBUS were enrolled. An associated lung mass was present in 14 (70%) of the participants; 6 (30%) had isolated lymphadenopathy. One patient had prior lymphoma, and two others had prior lung cancer.

The researchers evaluated 68 nodes in all; 19 patients had nodes greater than 9 mm. Cautery was only used when initial attempts failed to biopsy nodes 9 mm or larger using EBUS-guided miniforceps of 1.2 mm.

The average node size biopsied using EBUS-transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) was 5.7 mm. The average forceps-biopsied node was 15.8 mm.

In all, 23 nodes were biopsied successfully on the first pass using EBUS-TBNA only. The biopsies yielded diagnostic material such as lymphocytes, malignancy, or granulomas in 15 of these nodes.

Of the 15 nodes that required cautery, 12 yielded diagnostic material, and 3 had no diagnostic material.

The overall yield increased from 39% (15 out of 38) without cautery to 71% (27 out of 38) when cautery was used.

Notably, four patients had clinically relevant discrepancies between their cytologies and histopathologies. "In all four, TBNA provided a definitive diagnosis," said Dr. Bramley. "The forceps provided fibroconnective tissue or necrotic debris."

These results did not negate the efficacy of the cautery technique, according to Dr. Bramley. "We think we had a forceps issue ... the 1.2 mm are flexible, but they were unable to push all the way through a tough lymph node capsule."

Dr. Bramley also said that other factors, including the operator learning curve, the smaller size of the nodes the investigators attempted to biopsy, and the "nonideal" population they were studying, contributed to these results.

He and his colleagues have since adjusted the procedure to make cauterization routine and to include a 1.9-mm transbronchial biopsy forceps needle, "which, incidentally, is a lot less expensive than the larger forceps we’d been using," he said.

Although more study is needed, Dr. Bramley said he and his team believed that this technique would be appropriate for future use in isolated mediastinal lymphadenopathy, especially with a low suspicion of non–small cell lung carcinoma; evaluation of lymphoma; and clinical trials requiring core biopsy.

Dr. Bramley had no relevant disclosures.

Endobronchial ultrasound–guided biopsies made after an electrocautery incision to the lymph node improved biopsy yields from 39% to 71% in 38 nodes, according to a small study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians meeting.

"Because it is not always possible to pass biopsy forceps through defects in the lymph node – the literature indicates a failure rate of between 10% and 29% – we developed a novel technique," said presenter Dr. Kyle Bramley of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The technique employs EBUS, and involves passing an electrocautery knife activated at 40 W through the working channel of the scope in order to make an incision in the bronchial wall and enlarge the defect in the lymph node. This facilitates passage of the forceps into the node so that a larger biopsy sample can be obtained.

To test their technique, Dr. Bramley and his colleagues designed a prospective observational cohort study at a single tertiary academic medical center. Twenty patients (mean age, 68 years), including 11 women, who were undergoing EBUS were enrolled. An associated lung mass was present in 14 (70%) of the participants; 6 (30%) had isolated lymphadenopathy. One patient had prior lymphoma, and two others had prior lung cancer.

The researchers evaluated 68 nodes in all; 19 patients had nodes greater than 9 mm. Cautery was only used when initial attempts failed to biopsy nodes 9 mm or larger using EBUS-guided miniforceps of 1.2 mm.

The average node size biopsied using EBUS-transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) was 5.7 mm. The average forceps-biopsied node was 15.8 mm.

In all, 23 nodes were biopsied successfully on the first pass using EBUS-TBNA only. The biopsies yielded diagnostic material such as lymphocytes, malignancy, or granulomas in 15 of these nodes.

Of the 15 nodes that required cautery, 12 yielded diagnostic material, and 3 had no diagnostic material.

The overall yield increased from 39% (15 out of 38) without cautery to 71% (27 out of 38) when cautery was used.

Notably, four patients had clinically relevant discrepancies between their cytologies and histopathologies. "In all four, TBNA provided a definitive diagnosis," said Dr. Bramley. "The forceps provided fibroconnective tissue or necrotic debris."

These results did not negate the efficacy of the cautery technique, according to Dr. Bramley. "We think we had a forceps issue ... the 1.2 mm are flexible, but they were unable to push all the way through a tough lymph node capsule."

Dr. Bramley also said that other factors, including the operator learning curve, the smaller size of the nodes the investigators attempted to biopsy, and the "nonideal" population they were studying, contributed to these results.

He and his colleagues have since adjusted the procedure to make cauterization routine and to include a 1.9-mm transbronchial biopsy forceps needle, "which, incidentally, is a lot less expensive than the larger forceps we’d been using," he said.

Although more study is needed, Dr. Bramley said he and his team believed that this technique would be appropriate for future use in isolated mediastinal lymphadenopathy, especially with a low suspicion of non–small cell lung carcinoma; evaluation of lymphoma; and clinical trials requiring core biopsy.

Dr. Bramley had no relevant disclosures.

Major finding: EBUS-guided lymph node biopsies made after electrocautery incision improved biopsy yields from 39% to 71% in 38 lymph nodes.

Data source: Prospective observational cohort study of 20 patients at a single tertiary academic medical center.

Disclosures: Dr. Bramley had no relevant disclosures.

VIDEO: Genetic profiling transforms cancer treatment trials

Many newly designed cancer-treatment trials are incorporating detailed genetic analyses in their prospective design. A consequence is that the trials need to screen and include large numbers of patients to allow for statistically meaningful data to result.

Watch our exclusive interview here:

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Many newly designed cancer-treatment trials are incorporating detailed genetic analyses in their prospective design. A consequence is that the trials need to screen and include large numbers of patients to allow for statistically meaningful data to result.

Watch our exclusive interview here:

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Many newly designed cancer-treatment trials are incorporating detailed genetic analyses in their prospective design. A consequence is that the trials need to screen and include large numbers of patients to allow for statistically meaningful data to result.

Watch our exclusive interview here:

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Genetic profiling transforms cancer treatment trials

BRUSSELS – The ballooning list of genetic markers linked with various cancers is spawning a radical shift in the design of oncology treatment trials.

These days, the trend is to incorporate detailed genetic analysis into the trials, so that once the results are in, researchers can try to correlate treatment responses or failures with variations in each tumor’s genetic profile.

Leaders in the field say that, ideally, the tumor of every single patient now entering a cancer treatment trial should undergo a baseline genetic analysis, either using a large panel of targeted genetic markers or full-genome sequencing – although they acknowledge that, for the time being, complete sequencing provides much more information than can be used practically.

This changing paradigm of cancer treatment trial design comes with a major, built-in limitation that seems solvable only by dramatically increasing the scope of patients enrolled in trials: Each mutational cancer "driver" seems specific for just a few percent of patients. That means making statistically meaningful correlations among the responses of patients to various drugs and their tumors’ genetic profiles requires sifting through thousands of patients, far more than usually enroll in treatment trials today.

"The big challenge is to identify the mutations or genetic alterations that help inform the results of clinical trials. There are a lot of potential genetic markers, but very few have been validated. Tumors are being sequenced, and we find lots of mutations; but we don’t yet know what to do with most of this information," said Dr. Francisco J. Esteva, professor of medicine and director of the breast medical oncology program at New York University in an interview during a meeting on markers in cancer.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

"Finding ‘actionable’ mutations is very complicated because of next-generation sequencing," Dr. Esteva added. "We have some very good inhibitor drugs" aimed at certain mutations that can be highly effective in selected patients, "but when we give these drugs to larger populations of patients, the drugs may not work."

Even though a tumor may carry a genetic mutation identified as a cancer driver and thus an effective target for drug treatment in some patients, the mutation may not be the most important driver in other patients.

"Trying to find the mutations or other genetic changes that can be effective targets for treatment sounds simple, but it’s really not so simple," noted Dr. Esteva, an organizer of the meeting, sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, and the National Cancer Institute.

"We’ve been in an era where we looked at one genetic marker at a time. Now it’s pretty clear that this approach will not move us forward fast enough," said Dr. Lisa A. Carey, professor and medical director of the breast center at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, and another organizer of the meeting.

"Looking at a full genetic profile of the tumor has great appeal but is also more complicated," Dr. Carey explained. "Today, we have a limited portfolio of genetic markers with known clinical significance and a limited portfolio of drugs. We’ve had some huge success stories [with targeted therapy], but it’s not simple, and it is far from solved."

"Finding a target in a patient’s tumor and having an agent that inhibits the target does not imply clinical benefit," said Dr. Shivaani Kummar, head of early clinical trials development in the division of cancer treatment and diagnosis of the National Cancer Institute.

The enormous volume of genetic information now available from next-generation sequencing, which can supply data on hundreds or even potentially thousands of individual genes for a relatively affordable price, "is affecting trial design, leading to ‘umbrella’ designs that use a variety of genetic markers and panels of several drugs," said Dr. Robert L. Becker Jr., a chief medical officer at the Center for Devices and Radiological Health of the Food and Drug Administration.

"Is the current model for development of diagnostic markers and drugs sustainable?’" Dr. Becker asked. "Next-generation sequencing is different, because it can query an almost unlimited number of analytes in a single assay."

At the meeting, a series of researchers from the United States and Europe described and discussed several recently designed drug treatment trials prospectively structured to collect wide-ranging genetic data from the tumors of enrolled patients.

One example is the MATCH (Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice) trial, expected to start in 2014 with a goal of enrolling about 1,000 patients with solid tumors that have progressed following initial treatment with at least one drug. The investigators will use targeted mutations or amplifications as well as whole exome sequencing to try to better assign patients to their next regimen, said Dr. Kummar.

"It’s a new paradigm of trial design for cancer," said Dr. Esteva. "Going forward, all major drug trials should be designed" to include genetic analyses.

But the MATCH trial, as well as several others outlined at the meeting, will require casting large nets to find adequate numbers of appropriate patients to enroll.

"It’s a small subset of patients with each type of mutation, so getting the sample size required to get information about treatments will require a community effort," said Dr. Esteva. "It’s very important to have a lot of patients to get meaningful results." Progressing from studies with relatively small numbers of patients at academic centers to the larger populations of patients treated by community oncologists "will be one of the biggest challenges," he said.

Incorporating routine genetic analyses into trials and into routine practice also raises other issues, Dr. Carey noted. "Does the tumor evolve during treatment, so that what was found with testing at baseline is no longer the disease being treated?"

Once genetic profiling of tumors becomes routine, another challenge will be efficiently and reliably alerting physicians and patients when a genetic marker that had no known clinical consequence when it was first found in a patient’s tumor is subsequently discovered to be effectively treated with a targeted drug, she said.