User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

New guideline outlines management of hip fractures in elderly patients

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons’ new guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of hip fractures in elderly patients targets problem areas such as postoperative delirium and pain management.

The clinical practice guideline, “Management of Hip Fractures in the Elderly,” addresses hip fractures in patients age 65 years and older and offers recommendations on issues such as the timing of surgery and the use of vitamin D.

The AAOS also hopes the guideline will expose gaps in the body of research literature that should be addressed in future studies. The guideline has been endorsed by the American Geriatrics Society, the U.S. Bone and Joint Initiative, the Orthopaedic Trauma Association, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and the Hip Society.

The guideline’s recommendations include:

• Regional analgesia should be used to improve preoperative pain control in patients with hip fracture.

• MRI should be the advanced imaging of choice for diagnosis of presumed hip fracture not apparent on initial radiographs.

• Hip fracture surgery should be performed within 48 hours of admission.

• An interdisciplinary care program should be utilized for patients with mild to moderate dementia who have sustained a hip fracture.

• Supplemental vitamin D and calcium should be given to patients following hip fracture surgery.

• Patients should be evaluated and treated for osteoporosis after sustaining a hip fracture.

To read the entire guideline document, click here: www.aaos.org/research/guidelines/HipFxGuideline.pdf.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons’ new guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of hip fractures in elderly patients targets problem areas such as postoperative delirium and pain management.

The clinical practice guideline, “Management of Hip Fractures in the Elderly,” addresses hip fractures in patients age 65 years and older and offers recommendations on issues such as the timing of surgery and the use of vitamin D.

The AAOS also hopes the guideline will expose gaps in the body of research literature that should be addressed in future studies. The guideline has been endorsed by the American Geriatrics Society, the U.S. Bone and Joint Initiative, the Orthopaedic Trauma Association, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and the Hip Society.

The guideline’s recommendations include:

• Regional analgesia should be used to improve preoperative pain control in patients with hip fracture.

• MRI should be the advanced imaging of choice for diagnosis of presumed hip fracture not apparent on initial radiographs.

• Hip fracture surgery should be performed within 48 hours of admission.

• An interdisciplinary care program should be utilized for patients with mild to moderate dementia who have sustained a hip fracture.

• Supplemental vitamin D and calcium should be given to patients following hip fracture surgery.

• Patients should be evaluated and treated for osteoporosis after sustaining a hip fracture.

To read the entire guideline document, click here: www.aaos.org/research/guidelines/HipFxGuideline.pdf.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons’ new guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of hip fractures in elderly patients targets problem areas such as postoperative delirium and pain management.

The clinical practice guideline, “Management of Hip Fractures in the Elderly,” addresses hip fractures in patients age 65 years and older and offers recommendations on issues such as the timing of surgery and the use of vitamin D.

The AAOS also hopes the guideline will expose gaps in the body of research literature that should be addressed in future studies. The guideline has been endorsed by the American Geriatrics Society, the U.S. Bone and Joint Initiative, the Orthopaedic Trauma Association, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and the Hip Society.

The guideline’s recommendations include:

• Regional analgesia should be used to improve preoperative pain control in patients with hip fracture.

• MRI should be the advanced imaging of choice for diagnosis of presumed hip fracture not apparent on initial radiographs.

• Hip fracture surgery should be performed within 48 hours of admission.

• An interdisciplinary care program should be utilized for patients with mild to moderate dementia who have sustained a hip fracture.

• Supplemental vitamin D and calcium should be given to patients following hip fracture surgery.

• Patients should be evaluated and treated for osteoporosis after sustaining a hip fracture.

To read the entire guideline document, click here: www.aaos.org/research/guidelines/HipFxGuideline.pdf.

Extended anticoagulant therapy reduced risk of VTE recurrence

Apixaban was the safest anticoagulant used for extended treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE), according to a network meta-analysis of more than 11.000 patients.

While several anticoagulants significantly reduced the risk of VTE recurrence compared to placebo, only apixaban also did not increase bleeding risk significantly more than placebo. In fact, all active therapies except aspirin increased the risk of composite bleeding by 2-4 times compared to apixaban (2.5 mg), according to Diana M. Sobieraj, Pharm.D., of the University of Connecticut, and her colleagues.

In addition to apixaban (2.5 mg and 5 mg), the other anticoagulants that significantly reduced the risk of VTE recurrence compared to placebo were dabigatran, rivaroxaban, idraparinux, and vitamin K antagonists (VKAs). Of these drugs, idraparinux was least effective and VKAs were most effective at reducing the risk of a recurring VTE,

All of the anticoagulants other than idraparinux significantly reduced VTE risk more than aspirin did, ranging from a 73% reduction, with either apixaban (2.5 mg) or rivaroxaban, to an 80% reduced risk with VKAs.

Whether anticoagulation therapy should be extended for patients with VTE beyond 3 months remains a topic of debate, but results of the analysis “provide additional justification for” doing so, “primarily in patients with unprovoked proximal [VTE] with low to moderate bleeding risk,” the researchers reported.

Find the full study in Thrombosis Research (doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2015.02.032)

Apixaban was the safest anticoagulant used for extended treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE), according to a network meta-analysis of more than 11.000 patients.

While several anticoagulants significantly reduced the risk of VTE recurrence compared to placebo, only apixaban also did not increase bleeding risk significantly more than placebo. In fact, all active therapies except aspirin increased the risk of composite bleeding by 2-4 times compared to apixaban (2.5 mg), according to Diana M. Sobieraj, Pharm.D., of the University of Connecticut, and her colleagues.

In addition to apixaban (2.5 mg and 5 mg), the other anticoagulants that significantly reduced the risk of VTE recurrence compared to placebo were dabigatran, rivaroxaban, idraparinux, and vitamin K antagonists (VKAs). Of these drugs, idraparinux was least effective and VKAs were most effective at reducing the risk of a recurring VTE,

All of the anticoagulants other than idraparinux significantly reduced VTE risk more than aspirin did, ranging from a 73% reduction, with either apixaban (2.5 mg) or rivaroxaban, to an 80% reduced risk with VKAs.

Whether anticoagulation therapy should be extended for patients with VTE beyond 3 months remains a topic of debate, but results of the analysis “provide additional justification for” doing so, “primarily in patients with unprovoked proximal [VTE] with low to moderate bleeding risk,” the researchers reported.

Find the full study in Thrombosis Research (doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2015.02.032)

Apixaban was the safest anticoagulant used for extended treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE), according to a network meta-analysis of more than 11.000 patients.

While several anticoagulants significantly reduced the risk of VTE recurrence compared to placebo, only apixaban also did not increase bleeding risk significantly more than placebo. In fact, all active therapies except aspirin increased the risk of composite bleeding by 2-4 times compared to apixaban (2.5 mg), according to Diana M. Sobieraj, Pharm.D., of the University of Connecticut, and her colleagues.

In addition to apixaban (2.5 mg and 5 mg), the other anticoagulants that significantly reduced the risk of VTE recurrence compared to placebo were dabigatran, rivaroxaban, idraparinux, and vitamin K antagonists (VKAs). Of these drugs, idraparinux was least effective and VKAs were most effective at reducing the risk of a recurring VTE,

All of the anticoagulants other than idraparinux significantly reduced VTE risk more than aspirin did, ranging from a 73% reduction, with either apixaban (2.5 mg) or rivaroxaban, to an 80% reduced risk with VKAs.

Whether anticoagulation therapy should be extended for patients with VTE beyond 3 months remains a topic of debate, but results of the analysis “provide additional justification for” doing so, “primarily in patients with unprovoked proximal [VTE] with low to moderate bleeding risk,” the researchers reported.

Find the full study in Thrombosis Research (doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2015.02.032)

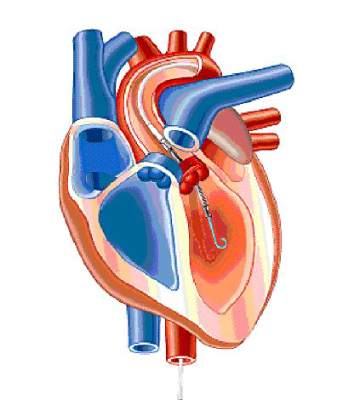

FDA approves miniature heart pump for use during high risk PCI

A miniature heart pump has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration to “help certain patients maintain stable heart function and circulation during certain high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention (HRPCI) procedures,” the agency has announced.

The Impella 2.5 System, manufactured by Abiomed, is “intended for temporary use by patients with severe symptomatic CAD [coronary artery disease] and diminished (but stable) heart function who are undergoing HRPCI but are not candidates for surgical coronary bypass treatment,” according to the FDA’s statement.

“Use of the Impella 2.5 System is intended to prevent episodes of unstable heart function, including unstable blood pressure and poor circulation, in patients who are at high risk for its occurrence,” Dr. William Maisel, acting director of the Office of Device Evaluation in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the statement.

Approval was based on the PROTECT II study and observational data from the USpella Registry.

“The overall data provided evidence that, for patients with severe CAD and diminished heart function, the temporary circulatory support provided by the Impella 2.5 System during an HRPCI procedure may allow a longer and more thorough procedure by preventing episodes of hemodynamic instability ... due to temporary abnormalities in heart function,” the FDA statement said. In addition, “fewer later adverse events” such as the need for repeat HRPCI procedures, “may occur in patients undergoing HRPCI with the pump compared to patients undergoing HRPCI with an intra-aortic balloon pump,” according to the FDA.

The FDA statement also noted that the system can be used as an alternative to the intra-aortic balloon pump “without significantly increasing the safety risks of the HRPCI procedure.”

As a postmarketing requirement, the manufacturer will conduct a single arm study of the device in high-risk PCI patients, according to the company’s statement announcing approval.

The wording of the approved indication is as follows, according to Abiomed: “The Impella 2.5 is a temporary (less than or equal to 6 hours) ventricular support device indicated for use during high-risk PCI performed in elective or urgent hemodynamically stable patients with severe coronary artery disease and depressed left ventricular ejection fraction, when a heart team, including a cardiac surgeon, has determined high-risk PCI is the appropriate therapeutic option. Use of the Impella 2.5 in these patients may prevent hemodynamic instability that may occur during planned temporary coronary occlusions and may reduce peri- and postprocedural adverse events.”

A miniature heart pump has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration to “help certain patients maintain stable heart function and circulation during certain high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention (HRPCI) procedures,” the agency has announced.

The Impella 2.5 System, manufactured by Abiomed, is “intended for temporary use by patients with severe symptomatic CAD [coronary artery disease] and diminished (but stable) heart function who are undergoing HRPCI but are not candidates for surgical coronary bypass treatment,” according to the FDA’s statement.

“Use of the Impella 2.5 System is intended to prevent episodes of unstable heart function, including unstable blood pressure and poor circulation, in patients who are at high risk for its occurrence,” Dr. William Maisel, acting director of the Office of Device Evaluation in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the statement.

Approval was based on the PROTECT II study and observational data from the USpella Registry.

“The overall data provided evidence that, for patients with severe CAD and diminished heart function, the temporary circulatory support provided by the Impella 2.5 System during an HRPCI procedure may allow a longer and more thorough procedure by preventing episodes of hemodynamic instability ... due to temporary abnormalities in heart function,” the FDA statement said. In addition, “fewer later adverse events” such as the need for repeat HRPCI procedures, “may occur in patients undergoing HRPCI with the pump compared to patients undergoing HRPCI with an intra-aortic balloon pump,” according to the FDA.

The FDA statement also noted that the system can be used as an alternative to the intra-aortic balloon pump “without significantly increasing the safety risks of the HRPCI procedure.”

As a postmarketing requirement, the manufacturer will conduct a single arm study of the device in high-risk PCI patients, according to the company’s statement announcing approval.

The wording of the approved indication is as follows, according to Abiomed: “The Impella 2.5 is a temporary (less than or equal to 6 hours) ventricular support device indicated for use during high-risk PCI performed in elective or urgent hemodynamically stable patients with severe coronary artery disease and depressed left ventricular ejection fraction, when a heart team, including a cardiac surgeon, has determined high-risk PCI is the appropriate therapeutic option. Use of the Impella 2.5 in these patients may prevent hemodynamic instability that may occur during planned temporary coronary occlusions and may reduce peri- and postprocedural adverse events.”

A miniature heart pump has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration to “help certain patients maintain stable heart function and circulation during certain high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention (HRPCI) procedures,” the agency has announced.

The Impella 2.5 System, manufactured by Abiomed, is “intended for temporary use by patients with severe symptomatic CAD [coronary artery disease] and diminished (but stable) heart function who are undergoing HRPCI but are not candidates for surgical coronary bypass treatment,” according to the FDA’s statement.

“Use of the Impella 2.5 System is intended to prevent episodes of unstable heart function, including unstable blood pressure and poor circulation, in patients who are at high risk for its occurrence,” Dr. William Maisel, acting director of the Office of Device Evaluation in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the statement.

Approval was based on the PROTECT II study and observational data from the USpella Registry.

“The overall data provided evidence that, for patients with severe CAD and diminished heart function, the temporary circulatory support provided by the Impella 2.5 System during an HRPCI procedure may allow a longer and more thorough procedure by preventing episodes of hemodynamic instability ... due to temporary abnormalities in heart function,” the FDA statement said. In addition, “fewer later adverse events” such as the need for repeat HRPCI procedures, “may occur in patients undergoing HRPCI with the pump compared to patients undergoing HRPCI with an intra-aortic balloon pump,” according to the FDA.

The FDA statement also noted that the system can be used as an alternative to the intra-aortic balloon pump “without significantly increasing the safety risks of the HRPCI procedure.”

As a postmarketing requirement, the manufacturer will conduct a single arm study of the device in high-risk PCI patients, according to the company’s statement announcing approval.

The wording of the approved indication is as follows, according to Abiomed: “The Impella 2.5 is a temporary (less than or equal to 6 hours) ventricular support device indicated for use during high-risk PCI performed in elective or urgent hemodynamically stable patients with severe coronary artery disease and depressed left ventricular ejection fraction, when a heart team, including a cardiac surgeon, has determined high-risk PCI is the appropriate therapeutic option. Use of the Impella 2.5 in these patients may prevent hemodynamic instability that may occur during planned temporary coronary occlusions and may reduce peri- and postprocedural adverse events.”

Study: No value in sending hernia sac specimens for routine pathology

Pathologic evaluations of hernia sac specimens from adult patients did not alter clinical management, and cost a medical center more than $75,000 over 4 years, according to a study published online in the American Journal of Surgery.

“The results from our study indicate that ‘routine’ evaluation of hernia sac specimens is likely neither indicated nor cost effective,” said Dr. Patrick Chesley of Madigan Army Medical Center, Fort Lewis, Wash., and his associates. “The rarity of changes in diagnosis and treatment from routine pathologic examination of a hernia sac does not justify this practice, and indicates that it may be omitted except in unique circumstances.”

The practice of sending hernia sac specimens for pathologic evaluation dates to 1926, when the American College of Surgeons Minimum Standard for Hospitals stated that all tissues removed during surgery should be examined and the results reported. The Joint Commission reiterated that recommendation in 1998, stating in its Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Pathology and Clinical Laboratory Services that ‘‘specimens removed during surgery need to be evaluated for gross and microscopic abnormalities before a final diagnosis can be made.”

But the literature offers little support for the recommendation regarding hernia sac specimens, and institutions are starting to question the practice, Dr. Chesley and his associates wrote (Am. J. Surg. 2015 Feb. 12 [doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.12.019]).

In one study, for example, pathologists reviewed 1,020 hernia sac specimens and found that only one had yielded an unexpected result – an atypical lipoma that did not affect patient management. Another study reviewed more than 2,000 hernia repairs and found that only 34% cases underwent pathologic review, with no resulting changes in treatment or management of any case.

For their study, Dr. Chesley and his coinvestigators retrospectively reviewed operative reports and medical records for 1,216 inguinal, incisional, umbilical, and ventral hernia repairs, all of which occurred at a single medical center between 2007 and 2011. More than half (55.4%) of cases were inguinal hernia repairs, 21.5% were umbilical, 11.4% were incisional, and 11.7% were ventral. In 20% of cases, surgeons sent hernia sac specimens for pathologic evaluation. Of these, 96% were selected for routine examination and 4% were selected because of concerns about possible gross abnormalities, the researchers said. Regardless of the reason for pathologic evaluation, none of the 246 examinations produced findings that reportedly altered clinical management, they said. Furthermore, pathologic evaluations cost patients about $300 to $350 each, for a total bill of more than $75,000 during the course of the study.

“These data reflect previous results from the pediatric surgical literature, and support the notion that routine pathologic evaluation of hernia sac specimens is not indicated,” the researchers concluded. But the recommendation should only apply to routine pathologic examinations, and surgeons should continue to treat abnormal intraoperative findings during hernia repair as indications for pathologic evaluation at their own discretion, they said.

Because the study was retrospective, the researchers could not ensure completeness of the data, they said. They also lacked a standardized method for reporting the reasons for specimen collection.

They reported no funding sources and declared no conflicts of interest.

Pathologic evaluations of hernia sac specimens from adult patients did not alter clinical management, and cost a medical center more than $75,000 over 4 years, according to a study published online in the American Journal of Surgery.

“The results from our study indicate that ‘routine’ evaluation of hernia sac specimens is likely neither indicated nor cost effective,” said Dr. Patrick Chesley of Madigan Army Medical Center, Fort Lewis, Wash., and his associates. “The rarity of changes in diagnosis and treatment from routine pathologic examination of a hernia sac does not justify this practice, and indicates that it may be omitted except in unique circumstances.”

The practice of sending hernia sac specimens for pathologic evaluation dates to 1926, when the American College of Surgeons Minimum Standard for Hospitals stated that all tissues removed during surgery should be examined and the results reported. The Joint Commission reiterated that recommendation in 1998, stating in its Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Pathology and Clinical Laboratory Services that ‘‘specimens removed during surgery need to be evaluated for gross and microscopic abnormalities before a final diagnosis can be made.”

But the literature offers little support for the recommendation regarding hernia sac specimens, and institutions are starting to question the practice, Dr. Chesley and his associates wrote (Am. J. Surg. 2015 Feb. 12 [doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.12.019]).

In one study, for example, pathologists reviewed 1,020 hernia sac specimens and found that only one had yielded an unexpected result – an atypical lipoma that did not affect patient management. Another study reviewed more than 2,000 hernia repairs and found that only 34% cases underwent pathologic review, with no resulting changes in treatment or management of any case.

For their study, Dr. Chesley and his coinvestigators retrospectively reviewed operative reports and medical records for 1,216 inguinal, incisional, umbilical, and ventral hernia repairs, all of which occurred at a single medical center between 2007 and 2011. More than half (55.4%) of cases were inguinal hernia repairs, 21.5% were umbilical, 11.4% were incisional, and 11.7% were ventral. In 20% of cases, surgeons sent hernia sac specimens for pathologic evaluation. Of these, 96% were selected for routine examination and 4% were selected because of concerns about possible gross abnormalities, the researchers said. Regardless of the reason for pathologic evaluation, none of the 246 examinations produced findings that reportedly altered clinical management, they said. Furthermore, pathologic evaluations cost patients about $300 to $350 each, for a total bill of more than $75,000 during the course of the study.

“These data reflect previous results from the pediatric surgical literature, and support the notion that routine pathologic evaluation of hernia sac specimens is not indicated,” the researchers concluded. But the recommendation should only apply to routine pathologic examinations, and surgeons should continue to treat abnormal intraoperative findings during hernia repair as indications for pathologic evaluation at their own discretion, they said.

Because the study was retrospective, the researchers could not ensure completeness of the data, they said. They also lacked a standardized method for reporting the reasons for specimen collection.

They reported no funding sources and declared no conflicts of interest.

Pathologic evaluations of hernia sac specimens from adult patients did not alter clinical management, and cost a medical center more than $75,000 over 4 years, according to a study published online in the American Journal of Surgery.

“The results from our study indicate that ‘routine’ evaluation of hernia sac specimens is likely neither indicated nor cost effective,” said Dr. Patrick Chesley of Madigan Army Medical Center, Fort Lewis, Wash., and his associates. “The rarity of changes in diagnosis and treatment from routine pathologic examination of a hernia sac does not justify this practice, and indicates that it may be omitted except in unique circumstances.”

The practice of sending hernia sac specimens for pathologic evaluation dates to 1926, when the American College of Surgeons Minimum Standard for Hospitals stated that all tissues removed during surgery should be examined and the results reported. The Joint Commission reiterated that recommendation in 1998, stating in its Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Pathology and Clinical Laboratory Services that ‘‘specimens removed during surgery need to be evaluated for gross and microscopic abnormalities before a final diagnosis can be made.”

But the literature offers little support for the recommendation regarding hernia sac specimens, and institutions are starting to question the practice, Dr. Chesley and his associates wrote (Am. J. Surg. 2015 Feb. 12 [doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.12.019]).

In one study, for example, pathologists reviewed 1,020 hernia sac specimens and found that only one had yielded an unexpected result – an atypical lipoma that did not affect patient management. Another study reviewed more than 2,000 hernia repairs and found that only 34% cases underwent pathologic review, with no resulting changes in treatment or management of any case.

For their study, Dr. Chesley and his coinvestigators retrospectively reviewed operative reports and medical records for 1,216 inguinal, incisional, umbilical, and ventral hernia repairs, all of which occurred at a single medical center between 2007 and 2011. More than half (55.4%) of cases were inguinal hernia repairs, 21.5% were umbilical, 11.4% were incisional, and 11.7% were ventral. In 20% of cases, surgeons sent hernia sac specimens for pathologic evaluation. Of these, 96% were selected for routine examination and 4% were selected because of concerns about possible gross abnormalities, the researchers said. Regardless of the reason for pathologic evaluation, none of the 246 examinations produced findings that reportedly altered clinical management, they said. Furthermore, pathologic evaluations cost patients about $300 to $350 each, for a total bill of more than $75,000 during the course of the study.

“These data reflect previous results from the pediatric surgical literature, and support the notion that routine pathologic evaluation of hernia sac specimens is not indicated,” the researchers concluded. But the recommendation should only apply to routine pathologic examinations, and surgeons should continue to treat abnormal intraoperative findings during hernia repair as indications for pathologic evaluation at their own discretion, they said.

Because the study was retrospective, the researchers could not ensure completeness of the data, they said. They also lacked a standardized method for reporting the reasons for specimen collection.

They reported no funding sources and declared no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SURGERY

Key clinical point: Pathologic examination of hernia sac specimens can be omitted except in unique cases.

Major finding: Pathologic evaluation yielded no information that changed clinical management.

Data source: Four-year, single-center retrospective analysis of hernia sac specimens from 246 adults.

Disclosures: The investigators reported no funding sources and declared no conflicts of interest.

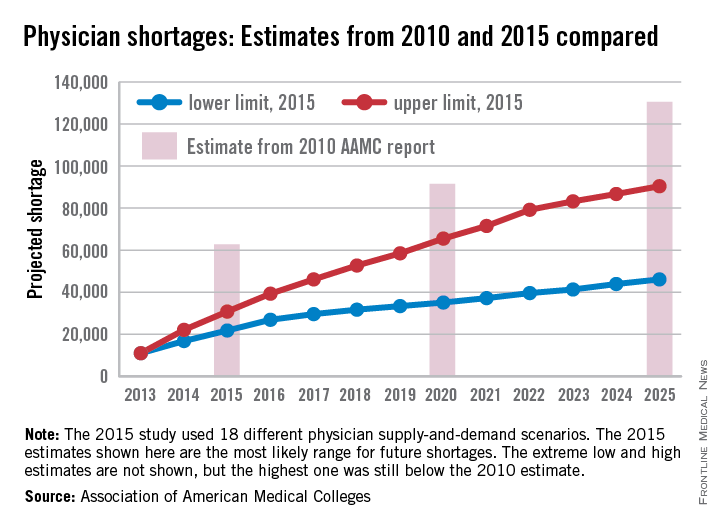

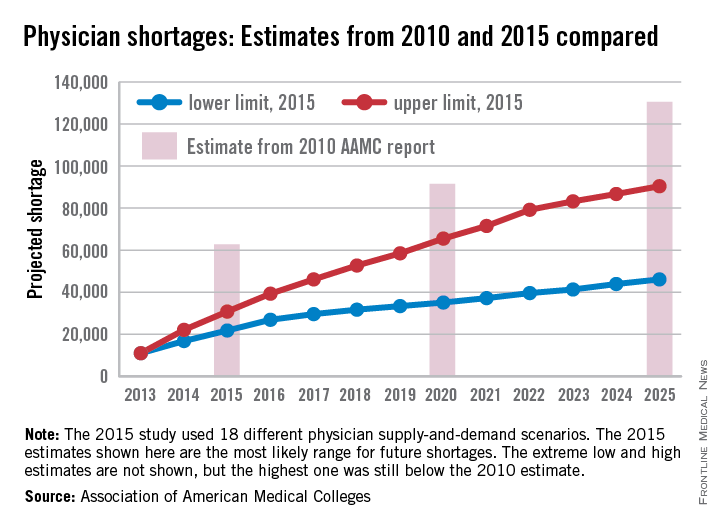

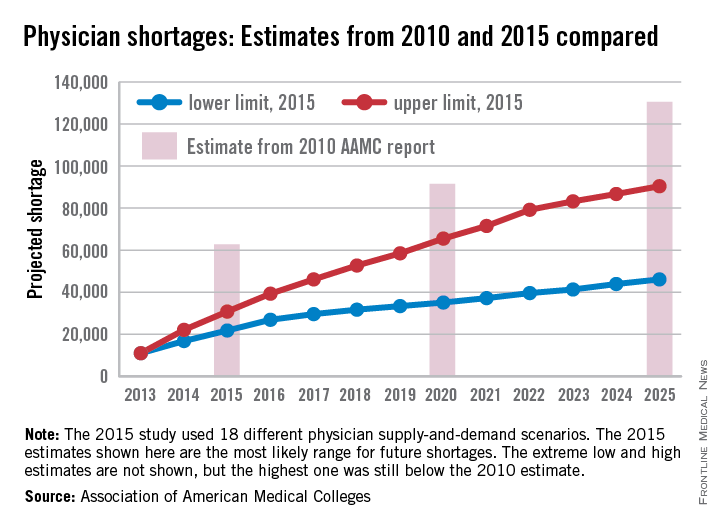

Future physician shortages could be smaller than originally forecast

The Association of American Medical Colleges, after taking another look into its crystal ball of supply and demand, reported that the future will have smaller shortages of physicians than it forecast in 2010.

All of the scenarios analyzed in the new AAMC study suggest “that demand for physicians in 2025 will exceed supply by 46,100 to 90,400.” In a 2010 study, the AAMC projected a shortage of 130,600 physicians by 2025.

The differences between the estimates are the result of several factors: the Census Bureau reduced its population projections for 2025 by 10.2 million people, the number of medical school graduates has risen from 27,000 to 29,000 a year, the number of physician extenders is increasing, and new assumptions were made involving the current shortage of psychiatrists that affected future levels of care delivery, the AAMC said.

The new study also included a scenario featuring full implementation of the Affordable Care Act, which is expected to account for 2% of the projected increase in physician demand. That effect will be most noticeable in the surgical specialties, which could see a 3.2% increase in demand as a result of ACA implementation, the report said.

The Association of American Medical Colleges, after taking another look into its crystal ball of supply and demand, reported that the future will have smaller shortages of physicians than it forecast in 2010.

All of the scenarios analyzed in the new AAMC study suggest “that demand for physicians in 2025 will exceed supply by 46,100 to 90,400.” In a 2010 study, the AAMC projected a shortage of 130,600 physicians by 2025.

The differences between the estimates are the result of several factors: the Census Bureau reduced its population projections for 2025 by 10.2 million people, the number of medical school graduates has risen from 27,000 to 29,000 a year, the number of physician extenders is increasing, and new assumptions were made involving the current shortage of psychiatrists that affected future levels of care delivery, the AAMC said.

The new study also included a scenario featuring full implementation of the Affordable Care Act, which is expected to account for 2% of the projected increase in physician demand. That effect will be most noticeable in the surgical specialties, which could see a 3.2% increase in demand as a result of ACA implementation, the report said.

The Association of American Medical Colleges, after taking another look into its crystal ball of supply and demand, reported that the future will have smaller shortages of physicians than it forecast in 2010.

All of the scenarios analyzed in the new AAMC study suggest “that demand for physicians in 2025 will exceed supply by 46,100 to 90,400.” In a 2010 study, the AAMC projected a shortage of 130,600 physicians by 2025.

The differences between the estimates are the result of several factors: the Census Bureau reduced its population projections for 2025 by 10.2 million people, the number of medical school graduates has risen from 27,000 to 29,000 a year, the number of physician extenders is increasing, and new assumptions were made involving the current shortage of psychiatrists that affected future levels of care delivery, the AAMC said.

The new study also included a scenario featuring full implementation of the Affordable Care Act, which is expected to account for 2% of the projected increase in physician demand. That effect will be most noticeable in the surgical specialties, which could see a 3.2% increase in demand as a result of ACA implementation, the report said.

New bill consolidates SGR fix, CHIP reauthorization

Bipartisan lawmakers have introduced a bill that would repeal the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) formula, this time with language that would reauthorize the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) for 2 years.

Leaders on the House Energy and Commerce and House Ways and Means committees on March 24 announced H.R. 2, the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act. The proposal builds on H.R. 1470, the SGR Repeal and Medicare Provider Payment Modernization Act – reintroduced March 19 – by extending CHIP funding through fiscal 2017. Funding for the program expires in September. The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act also includes 2-year reauthorization of the Community Health Centers program, the National Health Service Corps, and the Teaching Health Centers program, all of which would expire in 2015.

The changes would be paid for by income-related premium adjustments for Medicare parts B and D, Medigap reforms, an increase of levy authority on payments to Medicare providers with delinquent tax debt, adjustments to inpatient hospital payment rates, a delay of Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) changes until 2018, and a 1% market basket update for post–acute care providers.

The payment proposals of the bill reflect a working framework released by committee members March 20. A vote on the SGR package is expected this week.

The bill culminates years of efforts by lawmakers and stakeholders and will strengthen Medicare over the long term, according to Energy and Commerce Committee Chairman Fred Upton (R-Mich.).

“We can see the light at the end of the SGR tunnel – finally,” Rep. Upton said in a statement. “This responsible legislative package reflects years of bipartisan work, is a good deal for seniors, and a good deal for children, too. It’s time to put a stop once and for all to the repeated SGR crises and start to put Medicare on a stronger path forward for our seniors.”

The committee’s ranking member, Rep. Frank Pallone (D-N.J.) agreed.

“Finally, after a decade of trying, we have a bipartisan bill that will permanently repeal the flawed SGR and move Medicare to a health care system based on quality and efficiency, that is good for seniors and doctors alike,” Rep. Pallone said.

“As with any bipartisan effort, this legislation reflects give and take on both sides. However, we have come to a balanced compromise that will end uncertainty in the system, extend CHIP, fund Community Health Centers, and make permanent the Qualifying Individual (QI) program that helps low income seniors pay their Medicare premiums,” he added.

In addition to repealing the SGR, the final bill includes a 0.5% pay increase per year for the next 5 years; consolidates existing quality programs into a single value-based performance program; incentivizes physicians to use alternate payment models that focus on care coordination and preventive care; and pushes for more transparency of Medicare data for physicians, providers, and patients.

The latest bill comes a week before the current SGR patch expires on March 31. Without legislative action, physicians will see a 21% cut in Medicare pay.

Bipartisan lawmakers have introduced a bill that would repeal the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) formula, this time with language that would reauthorize the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) for 2 years.

Leaders on the House Energy and Commerce and House Ways and Means committees on March 24 announced H.R. 2, the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act. The proposal builds on H.R. 1470, the SGR Repeal and Medicare Provider Payment Modernization Act – reintroduced March 19 – by extending CHIP funding through fiscal 2017. Funding for the program expires in September. The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act also includes 2-year reauthorization of the Community Health Centers program, the National Health Service Corps, and the Teaching Health Centers program, all of which would expire in 2015.

The changes would be paid for by income-related premium adjustments for Medicare parts B and D, Medigap reforms, an increase of levy authority on payments to Medicare providers with delinquent tax debt, adjustments to inpatient hospital payment rates, a delay of Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) changes until 2018, and a 1% market basket update for post–acute care providers.

The payment proposals of the bill reflect a working framework released by committee members March 20. A vote on the SGR package is expected this week.

The bill culminates years of efforts by lawmakers and stakeholders and will strengthen Medicare over the long term, according to Energy and Commerce Committee Chairman Fred Upton (R-Mich.).

“We can see the light at the end of the SGR tunnel – finally,” Rep. Upton said in a statement. “This responsible legislative package reflects years of bipartisan work, is a good deal for seniors, and a good deal for children, too. It’s time to put a stop once and for all to the repeated SGR crises and start to put Medicare on a stronger path forward for our seniors.”

The committee’s ranking member, Rep. Frank Pallone (D-N.J.) agreed.

“Finally, after a decade of trying, we have a bipartisan bill that will permanently repeal the flawed SGR and move Medicare to a health care system based on quality and efficiency, that is good for seniors and doctors alike,” Rep. Pallone said.

“As with any bipartisan effort, this legislation reflects give and take on both sides. However, we have come to a balanced compromise that will end uncertainty in the system, extend CHIP, fund Community Health Centers, and make permanent the Qualifying Individual (QI) program that helps low income seniors pay their Medicare premiums,” he added.

In addition to repealing the SGR, the final bill includes a 0.5% pay increase per year for the next 5 years; consolidates existing quality programs into a single value-based performance program; incentivizes physicians to use alternate payment models that focus on care coordination and preventive care; and pushes for more transparency of Medicare data for physicians, providers, and patients.

The latest bill comes a week before the current SGR patch expires on March 31. Without legislative action, physicians will see a 21% cut in Medicare pay.

Bipartisan lawmakers have introduced a bill that would repeal the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) formula, this time with language that would reauthorize the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) for 2 years.

Leaders on the House Energy and Commerce and House Ways and Means committees on March 24 announced H.R. 2, the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act. The proposal builds on H.R. 1470, the SGR Repeal and Medicare Provider Payment Modernization Act – reintroduced March 19 – by extending CHIP funding through fiscal 2017. Funding for the program expires in September. The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act also includes 2-year reauthorization of the Community Health Centers program, the National Health Service Corps, and the Teaching Health Centers program, all of which would expire in 2015.

The changes would be paid for by income-related premium adjustments for Medicare parts B and D, Medigap reforms, an increase of levy authority on payments to Medicare providers with delinquent tax debt, adjustments to inpatient hospital payment rates, a delay of Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) changes until 2018, and a 1% market basket update for post–acute care providers.

The payment proposals of the bill reflect a working framework released by committee members March 20. A vote on the SGR package is expected this week.

The bill culminates years of efforts by lawmakers and stakeholders and will strengthen Medicare over the long term, according to Energy and Commerce Committee Chairman Fred Upton (R-Mich.).

“We can see the light at the end of the SGR tunnel – finally,” Rep. Upton said in a statement. “This responsible legislative package reflects years of bipartisan work, is a good deal for seniors, and a good deal for children, too. It’s time to put a stop once and for all to the repeated SGR crises and start to put Medicare on a stronger path forward for our seniors.”

The committee’s ranking member, Rep. Frank Pallone (D-N.J.) agreed.

“Finally, after a decade of trying, we have a bipartisan bill that will permanently repeal the flawed SGR and move Medicare to a health care system based on quality and efficiency, that is good for seniors and doctors alike,” Rep. Pallone said.

“As with any bipartisan effort, this legislation reflects give and take on both sides. However, we have come to a balanced compromise that will end uncertainty in the system, extend CHIP, fund Community Health Centers, and make permanent the Qualifying Individual (QI) program that helps low income seniors pay their Medicare premiums,” he added.

In addition to repealing the SGR, the final bill includes a 0.5% pay increase per year for the next 5 years; consolidates existing quality programs into a single value-based performance program; incentivizes physicians to use alternate payment models that focus on care coordination and preventive care; and pushes for more transparency of Medicare data for physicians, providers, and patients.

The latest bill comes a week before the current SGR patch expires on March 31. Without legislative action, physicians will see a 21% cut in Medicare pay.

VIDEO: Data support switching to transradial PCI access

SAN DIEGO – Cardiologists should switch from transfemoral to transradial access in acute coronary syndrome patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, given the reduced mortality rates associated with the transradial approach in the MATRIX study and other studies, Dr. Cindy L. Grines said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Because U.S. interventionalists are “under the clock” when treating patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction, “many physicians have been unwilling to risk having a difficult transradial case that would take too much time,” explained Dr. Grines, an interventional cardiologist at the Detroit Medical Center.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

For that and other reasons, American interventionalists have been “slow adopters” of the transradial approach, currently using it for about 20% of PCIs, compared with a worldwide rate of about 70%.

It may take instituting incentives to get U.S. cardiologists to change their practice, Dr. Grines suggested in an interview. That could involve increased reimbursement for PCIs done transradially, an increased allowance on acceptable door-to-balloon times for STEMI patients treated transradially, or imposition of new standards for quality assurance that mandate use of transradial in a certain percentage of PCI cases, she said.

The MATRIX study included a second, independent, prespecified analysis that compared outcomes in patients randomized to treatment with two different antithrombin drugs, either bivalirudin (Angiomax) or unfractionated heparin.

That part of the study showed that while treatment with either of the two drugs resulted in no statistically significant difference in the study’s two primary endpoints, treatment with bivalirudin led to statistically significant reductions in all-cause death and cardiovascular death, as well as in major bleeding events, compared with patients treated with unfractionated heparin (Lancet 2015 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60292-6]).

Although bivalirudin has generally been the more commonly used antithrombin drug in this clinical setting by U.S. interventionalists in recent years, results reported last year from the HEAT-PCI trial (Lancet 2014;384:1849-58) that showed better outcomes with unfractionated heparin have led to reduced use of bivalirudin, Dr. Grines said.

The new results from MATRIX coupled with results from other trials that compared those drugs can make clinicians “more confident about the benefit of bivalirudin,” she said.

Dr. Grines has been a consultant to and received honoraria from the Medicines Company, which markets Angiomax, and from Abbott Vascular, Merck, and the Volcano Group.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

SAN DIEGO – Cardiologists should switch from transfemoral to transradial access in acute coronary syndrome patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, given the reduced mortality rates associated with the transradial approach in the MATRIX study and other studies, Dr. Cindy L. Grines said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Because U.S. interventionalists are “under the clock” when treating patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction, “many physicians have been unwilling to risk having a difficult transradial case that would take too much time,” explained Dr. Grines, an interventional cardiologist at the Detroit Medical Center.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

For that and other reasons, American interventionalists have been “slow adopters” of the transradial approach, currently using it for about 20% of PCIs, compared with a worldwide rate of about 70%.

It may take instituting incentives to get U.S. cardiologists to change their practice, Dr. Grines suggested in an interview. That could involve increased reimbursement for PCIs done transradially, an increased allowance on acceptable door-to-balloon times for STEMI patients treated transradially, or imposition of new standards for quality assurance that mandate use of transradial in a certain percentage of PCI cases, she said.

The MATRIX study included a second, independent, prespecified analysis that compared outcomes in patients randomized to treatment with two different antithrombin drugs, either bivalirudin (Angiomax) or unfractionated heparin.

That part of the study showed that while treatment with either of the two drugs resulted in no statistically significant difference in the study’s two primary endpoints, treatment with bivalirudin led to statistically significant reductions in all-cause death and cardiovascular death, as well as in major bleeding events, compared with patients treated with unfractionated heparin (Lancet 2015 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60292-6]).

Although bivalirudin has generally been the more commonly used antithrombin drug in this clinical setting by U.S. interventionalists in recent years, results reported last year from the HEAT-PCI trial (Lancet 2014;384:1849-58) that showed better outcomes with unfractionated heparin have led to reduced use of bivalirudin, Dr. Grines said.

The new results from MATRIX coupled with results from other trials that compared those drugs can make clinicians “more confident about the benefit of bivalirudin,” she said.

Dr. Grines has been a consultant to and received honoraria from the Medicines Company, which markets Angiomax, and from Abbott Vascular, Merck, and the Volcano Group.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

SAN DIEGO – Cardiologists should switch from transfemoral to transradial access in acute coronary syndrome patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, given the reduced mortality rates associated with the transradial approach in the MATRIX study and other studies, Dr. Cindy L. Grines said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Because U.S. interventionalists are “under the clock” when treating patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction, “many physicians have been unwilling to risk having a difficult transradial case that would take too much time,” explained Dr. Grines, an interventional cardiologist at the Detroit Medical Center.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

For that and other reasons, American interventionalists have been “slow adopters” of the transradial approach, currently using it for about 20% of PCIs, compared with a worldwide rate of about 70%.

It may take instituting incentives to get U.S. cardiologists to change their practice, Dr. Grines suggested in an interview. That could involve increased reimbursement for PCIs done transradially, an increased allowance on acceptable door-to-balloon times for STEMI patients treated transradially, or imposition of new standards for quality assurance that mandate use of transradial in a certain percentage of PCI cases, she said.

The MATRIX study included a second, independent, prespecified analysis that compared outcomes in patients randomized to treatment with two different antithrombin drugs, either bivalirudin (Angiomax) or unfractionated heparin.

That part of the study showed that while treatment with either of the two drugs resulted in no statistically significant difference in the study’s two primary endpoints, treatment with bivalirudin led to statistically significant reductions in all-cause death and cardiovascular death, as well as in major bleeding events, compared with patients treated with unfractionated heparin (Lancet 2015 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60292-6]).

Although bivalirudin has generally been the more commonly used antithrombin drug in this clinical setting by U.S. interventionalists in recent years, results reported last year from the HEAT-PCI trial (Lancet 2014;384:1849-58) that showed better outcomes with unfractionated heparin have led to reduced use of bivalirudin, Dr. Grines said.

The new results from MATRIX coupled with results from other trials that compared those drugs can make clinicians “more confident about the benefit of bivalirudin,” she said.

Dr. Grines has been a consultant to and received honoraria from the Medicines Company, which markets Angiomax, and from Abbott Vascular, Merck, and the Volcano Group.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ACC 15

Commentary: Critical care bed management: Can we do better?

Is it possible to give the best critical care while spending less money and resources doing it? Can we reduce waste while improving quality in a so-called lean approach to critical care? I believe that we have too many critical care beds, and we fill some of those beds with patients who can be taken care of at less intense levels of care—which are also less expensive.

Most work that is done to improve critical care looks at the quality of care. This is an area where a lot of data are accumulating. Take septic shock, for example. In the recently published ProCESS trial (The ProCESS Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2014. 370[18]:1683), the 60-day in-hospital mortality for septic shock was 18.2% to 21.0%. A lot of institutions (including mine) are struggling to get their septic shock mortality rate under 30%. Although some people critique the ProCESS trial mortality rate on patient selection, most of us try to figure out how to duplicate that lower rate. We do this in areas other than septic shock. If we are comparable in whatever quality statistic, we applaud our success. If we aren’t comparable, we look at ways to improve, often based on what was done in that particular study.

How big of a financial burden is our critical care spending? According to an analysis of critical care beds by Halpern and colleagues (Crit Care Med. 2004;32[6]:1254), the number of hospital beds decreased 26.4% between 1985 and 2000, and the absolute number of critical care beds increased 26.2% (quantitated at 67,357 adult beds in 2007 per SCCM.org, www.sccm.org/Communications/Pages/CriticalCareStats.aspx). Critical care beds cost $2,674 per day in 2000, up from $1,185 (our CFOs tell us it is more like $3,500 to $4,000 per day now). They represented 13.3% of hospital costs, 4.2% of national health expenditures (NHE), and 0.56% of gross domestic product (GDP). There are 55,000 critically ill patients cared for each day in the United States, representing 5 million ICU patients per year. This is an enormous expenditure of money and it is growing.

Another interesting observation by Halpern and colleagues (Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1254) was that critical care beds were only at 65% occupancy. This reflects my own experience where we operate at a 70% average ICU bed occupancy. We have created a larger financial burden with the fixed costs of one-third more ICU beds than we actually use. Some bed availability is desirable, but how much is too much? Are we doing the best job to give quality care and spend money wisely? Can we be more efficient in the throughput of patients and in their care? Admission criteria should be part of any unit, designed to place all patients who need ICU care appropriately in the ICU and exclude those whose care can be managed at a lesser level of intensity and cost. Discharge criteria, care protocols (e.g., wake up and wean), checklists, and daily attention to the usual parameters (e.g., DVT prophylaxis) are essential for high-quality but efficient care. Done 24/7, we can maximize efficiency and quality with a minimum of ICU readmissions. Throughput is part of every physician’s job description. The physician who wants one more day for his or her patient in the ICU simply because the nurse has fewer patients misses a number of points. Why would anyone want more exposure to resistant organisms, more noise, more awakenings, and less sleep, just to name a few? Keeping that non-ICU patient in the ICU bed might even delay the transfer of another patient coming from the ED, where we know they often don’t get good ICU care.

Are the beds filled only with what we intensivists would consider legitimate ICU patients, defined by both generally accepted (endotracheal tube in place) and individually specified criteria (unit specific related to other unit capabilities)? That would impact cost. An interesting article by Gooch and Kahn (JAMA. 2014; 311[6]:567) discussed the demand elasticity of the ICU. They considered the changes in case mix of patients between days of high and low bed availability. They contended that when ICU beds were available, there was an increase in patients who were unlikely to benefit from ICU admission. This group included a population of patients likely to survive and whose illness severity was low and a population of patients who were unlikely to survive and had a high illness severity. In other words, admissions expand to fill the staff-able beds. If this is true, it is another area where better management could lower costs without reducing the quality of care.

What if bed availability truly is reduced, often by a lack of critical care nursing staff if not physical beds? Here the answer is unclear. Town (Crit Care Med. 2014;42[9]:2037) looked at ICU readmission rates and the odds of having a cardiac arrest on the ward related to bed availability. Five ICUs with 63 beds total were examined. As ICU bed availability decreased, the odds of patients who were discharged from the ICU being readmitted to the ICU went up. Also, the odds of patients having a cardiac arrest on the ward increased when medical (not total) ICU beds were less available. In 2013, Wagner and colleagues (Ann Intern Med. 2013;159[7]:447) looked at 155 ICUs with 200,730 patients discharged from ICUs to hospital floors from 2001 to 2008. They examined what they call the strain metrics. These included the standardized ICU census, the proportion of new admissions, and the average predicted probability of death of the other patients in the ICU on the days of ICU discharge. When the strain metrics increased, ICU patients had shorter ICU length of stay and ICU readmission odds went up. They didn’t, however, see an increased odds of death, a reduced odds of being discharged home, or a longer total hospital LOS. In a third study reported in 2008 in the Annals of Internal Medicine by Howell and colleagues (Ann Intern Med. 2008;149[11]:804), an innovative method of bed management was described. Because of an overcrowded ED and a high ambulance diversion rate, hospitalists implemented a system of bed control that was based on knowledge of ICU beds and ED congestion and flow. Bed assignments were better controlled by twice-daily ICU rounds and regular visits to the ED: throughput for admitted patients decreased by 98 minutes and time on diversion decreased significantly.

Mery and Kahn reported in 2013 (Crit Care. 2013;17[3]:315) that when ICU bed availability was reduced, there was a reduction in the likelihood of ICU admission within 2 hours of a medical emergency team (MET) activation. What is interesting about this study done in three hospitals in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, is that there was an increased likelihood that the patient goals of care changed to comfort care when there was no bed availability, compared with two ICU beds being available. Even more interesting is that hospital mortality did not vary significantly by ICU bed availability: More patients were moved to palliative care yet no more people died. Perhaps a lack of ICU beds expedited appropriateness of care.

To summarize, we have more patients in critical care beds where we spend ever-increasing amounts of our health-care dollars, but we seem to have more critical care beds than we need. We still have patients in our ICUs who would be better cared for elsewhere in our institutions. We can perform more cost-effective throughput when we are pressed to do so and usually we can do it safely.

I contend that the next improvement in lean ICU medicine will be better management tools. Comprehensive checklists have helped me where computer solutions have yet to be developed. I am working to create hardware/software management solutions that will make my job more cost-effective and provide a sustainable process for what comes after me.

Dr. Waxman is associate professor of medicine, KU School of Medicine, Kansas City, Kan.; medical director, Medical Surgical ICU/PCU, Research Medical Center; and adjunct professor, Rockhurst University, Helzberg School of Management, Kansas City, Mo.

What is the ideal number of ICU beds for any given hospital? Which criteria should be used to determine who gets those beds? Who is the best gatekeeper to equitably allow admission to the ICU? And is there an app for that? The “right” answers to these questions vary depending on who is providing you with the answer key.

Dr. Mike Waxman begins to unravel these complex issues and challenges us to do more with less. The data are clear that the ratio of ICU beds to general ward beds in U.S. hospitals is markedly increased, compared with other developed countries – and that we fill those beds with patients of lower acuity. Our epidemiology colleagues have made several other troubling observations of late: ICU admissions are growing fastest in patients aged 85 and older; most admissions from the ED are for symptoms – think chest pain or shortness of breath – that can signal a life-threatening condition but are more likely due to other problems; and the utilization of advanced imaging prior to ICU transfer has more than doubled in recent years. These findings suggest that factors such as changing demographics and medical-legal concerns are working against our “lean” approach to ICU care.

Equally troubling, many patients and non-ICU clinicians now view the hospital’s general ward vs. ICU bed designation on par with an airline gate agent’s coach vs. business class seat assignment. Through their eyes, patients receive more attention (2:1 nurse staffing and 24/7 in-house coverage anyone?) and more monitoring (Ah, I see you have the machine that goes “ping”) behind the velvet ropes of the ICU. Lost from their view, buried deep in the bowels of the electronic medical record, is the fact that three times as many dollars are spent on their care without any incremental benefit. Sadly, many cost-conscious intensivists who attempt to use evidence-based criteria for ICU triage are steamrolled into submission by such misinformed clinicians and/or administrators under the misplaced auspices of patient safety. Hopefully innovators such as Dr. Waxman will succeed in moving the needle and transform our JICU (just-in-case unit) beds back to ICU beds.

Dr. Lee E. Morrow, FCCP, is professor of medicine and professor of pharmacy at Creighton University, Omaha, Neb.

What is the ideal number of ICU beds for any given hospital? Which criteria should be used to determine who gets those beds? Who is the best gatekeeper to equitably allow admission to the ICU? And is there an app for that? The “right” answers to these questions vary depending on who is providing you with the answer key.

Dr. Mike Waxman begins to unravel these complex issues and challenges us to do more with less. The data are clear that the ratio of ICU beds to general ward beds in U.S. hospitals is markedly increased, compared with other developed countries – and that we fill those beds with patients of lower acuity. Our epidemiology colleagues have made several other troubling observations of late: ICU admissions are growing fastest in patients aged 85 and older; most admissions from the ED are for symptoms – think chest pain or shortness of breath – that can signal a life-threatening condition but are more likely due to other problems; and the utilization of advanced imaging prior to ICU transfer has more than doubled in recent years. These findings suggest that factors such as changing demographics and medical-legal concerns are working against our “lean” approach to ICU care.

Equally troubling, many patients and non-ICU clinicians now view the hospital’s general ward vs. ICU bed designation on par with an airline gate agent’s coach vs. business class seat assignment. Through their eyes, patients receive more attention (2:1 nurse staffing and 24/7 in-house coverage anyone?) and more monitoring (Ah, I see you have the machine that goes “ping”) behind the velvet ropes of the ICU. Lost from their view, buried deep in the bowels of the electronic medical record, is the fact that three times as many dollars are spent on their care without any incremental benefit. Sadly, many cost-conscious intensivists who attempt to use evidence-based criteria for ICU triage are steamrolled into submission by such misinformed clinicians and/or administrators under the misplaced auspices of patient safety. Hopefully innovators such as Dr. Waxman will succeed in moving the needle and transform our JICU (just-in-case unit) beds back to ICU beds.

Dr. Lee E. Morrow, FCCP, is professor of medicine and professor of pharmacy at Creighton University, Omaha, Neb.

What is the ideal number of ICU beds for any given hospital? Which criteria should be used to determine who gets those beds? Who is the best gatekeeper to equitably allow admission to the ICU? And is there an app for that? The “right” answers to these questions vary depending on who is providing you with the answer key.

Dr. Mike Waxman begins to unravel these complex issues and challenges us to do more with less. The data are clear that the ratio of ICU beds to general ward beds in U.S. hospitals is markedly increased, compared with other developed countries – and that we fill those beds with patients of lower acuity. Our epidemiology colleagues have made several other troubling observations of late: ICU admissions are growing fastest in patients aged 85 and older; most admissions from the ED are for symptoms – think chest pain or shortness of breath – that can signal a life-threatening condition but are more likely due to other problems; and the utilization of advanced imaging prior to ICU transfer has more than doubled in recent years. These findings suggest that factors such as changing demographics and medical-legal concerns are working against our “lean” approach to ICU care.

Equally troubling, many patients and non-ICU clinicians now view the hospital’s general ward vs. ICU bed designation on par with an airline gate agent’s coach vs. business class seat assignment. Through their eyes, patients receive more attention (2:1 nurse staffing and 24/7 in-house coverage anyone?) and more monitoring (Ah, I see you have the machine that goes “ping”) behind the velvet ropes of the ICU. Lost from their view, buried deep in the bowels of the electronic medical record, is the fact that three times as many dollars are spent on their care without any incremental benefit. Sadly, many cost-conscious intensivists who attempt to use evidence-based criteria for ICU triage are steamrolled into submission by such misinformed clinicians and/or administrators under the misplaced auspices of patient safety. Hopefully innovators such as Dr. Waxman will succeed in moving the needle and transform our JICU (just-in-case unit) beds back to ICU beds.

Dr. Lee E. Morrow, FCCP, is professor of medicine and professor of pharmacy at Creighton University, Omaha, Neb.

Is it possible to give the best critical care while spending less money and resources doing it? Can we reduce waste while improving quality in a so-called lean approach to critical care? I believe that we have too many critical care beds, and we fill some of those beds with patients who can be taken care of at less intense levels of care—which are also less expensive.

Most work that is done to improve critical care looks at the quality of care. This is an area where a lot of data are accumulating. Take septic shock, for example. In the recently published ProCESS trial (The ProCESS Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2014. 370[18]:1683), the 60-day in-hospital mortality for septic shock was 18.2% to 21.0%. A lot of institutions (including mine) are struggling to get their septic shock mortality rate under 30%. Although some people critique the ProCESS trial mortality rate on patient selection, most of us try to figure out how to duplicate that lower rate. We do this in areas other than septic shock. If we are comparable in whatever quality statistic, we applaud our success. If we aren’t comparable, we look at ways to improve, often based on what was done in that particular study.

How big of a financial burden is our critical care spending? According to an analysis of critical care beds by Halpern and colleagues (Crit Care Med. 2004;32[6]:1254), the number of hospital beds decreased 26.4% between 1985 and 2000, and the absolute number of critical care beds increased 26.2% (quantitated at 67,357 adult beds in 2007 per SCCM.org, www.sccm.org/Communications/Pages/CriticalCareStats.aspx). Critical care beds cost $2,674 per day in 2000, up from $1,185 (our CFOs tell us it is more like $3,500 to $4,000 per day now). They represented 13.3% of hospital costs, 4.2% of national health expenditures (NHE), and 0.56% of gross domestic product (GDP). There are 55,000 critically ill patients cared for each day in the United States, representing 5 million ICU patients per year. This is an enormous expenditure of money and it is growing.

Another interesting observation by Halpern and colleagues (Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1254) was that critical care beds were only at 65% occupancy. This reflects my own experience where we operate at a 70% average ICU bed occupancy. We have created a larger financial burden with the fixed costs of one-third more ICU beds than we actually use. Some bed availability is desirable, but how much is too much? Are we doing the best job to give quality care and spend money wisely? Can we be more efficient in the throughput of patients and in their care? Admission criteria should be part of any unit, designed to place all patients who need ICU care appropriately in the ICU and exclude those whose care can be managed at a lesser level of intensity and cost. Discharge criteria, care protocols (e.g., wake up and wean), checklists, and daily attention to the usual parameters (e.g., DVT prophylaxis) are essential for high-quality but efficient care. Done 24/7, we can maximize efficiency and quality with a minimum of ICU readmissions. Throughput is part of every physician’s job description. The physician who wants one more day for his or her patient in the ICU simply because the nurse has fewer patients misses a number of points. Why would anyone want more exposure to resistant organisms, more noise, more awakenings, and less sleep, just to name a few? Keeping that non-ICU patient in the ICU bed might even delay the transfer of another patient coming from the ED, where we know they often don’t get good ICU care.

Are the beds filled only with what we intensivists would consider legitimate ICU patients, defined by both generally accepted (endotracheal tube in place) and individually specified criteria (unit specific related to other unit capabilities)? That would impact cost. An interesting article by Gooch and Kahn (JAMA. 2014; 311[6]:567) discussed the demand elasticity of the ICU. They considered the changes in case mix of patients between days of high and low bed availability. They contended that when ICU beds were available, there was an increase in patients who were unlikely to benefit from ICU admission. This group included a population of patients likely to survive and whose illness severity was low and a population of patients who were unlikely to survive and had a high illness severity. In other words, admissions expand to fill the staff-able beds. If this is true, it is another area where better management could lower costs without reducing the quality of care.

What if bed availability truly is reduced, often by a lack of critical care nursing staff if not physical beds? Here the answer is unclear. Town (Crit Care Med. 2014;42[9]:2037) looked at ICU readmission rates and the odds of having a cardiac arrest on the ward related to bed availability. Five ICUs with 63 beds total were examined. As ICU bed availability decreased, the odds of patients who were discharged from the ICU being readmitted to the ICU went up. Also, the odds of patients having a cardiac arrest on the ward increased when medical (not total) ICU beds were less available. In 2013, Wagner and colleagues (Ann Intern Med. 2013;159[7]:447) looked at 155 ICUs with 200,730 patients discharged from ICUs to hospital floors from 2001 to 2008. They examined what they call the strain metrics. These included the standardized ICU census, the proportion of new admissions, and the average predicted probability of death of the other patients in the ICU on the days of ICU discharge. When the strain metrics increased, ICU patients had shorter ICU length of stay and ICU readmission odds went up. They didn’t, however, see an increased odds of death, a reduced odds of being discharged home, or a longer total hospital LOS. In a third study reported in 2008 in the Annals of Internal Medicine by Howell and colleagues (Ann Intern Med. 2008;149[11]:804), an innovative method of bed management was described. Because of an overcrowded ED and a high ambulance diversion rate, hospitalists implemented a system of bed control that was based on knowledge of ICU beds and ED congestion and flow. Bed assignments were better controlled by twice-daily ICU rounds and regular visits to the ED: throughput for admitted patients decreased by 98 minutes and time on diversion decreased significantly.

Mery and Kahn reported in 2013 (Crit Care. 2013;17[3]:315) that when ICU bed availability was reduced, there was a reduction in the likelihood of ICU admission within 2 hours of a medical emergency team (MET) activation. What is interesting about this study done in three hospitals in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, is that there was an increased likelihood that the patient goals of care changed to comfort care when there was no bed availability, compared with two ICU beds being available. Even more interesting is that hospital mortality did not vary significantly by ICU bed availability: More patients were moved to palliative care yet no more people died. Perhaps a lack of ICU beds expedited appropriateness of care.

To summarize, we have more patients in critical care beds where we spend ever-increasing amounts of our health-care dollars, but we seem to have more critical care beds than we need. We still have patients in our ICUs who would be better cared for elsewhere in our institutions. We can perform more cost-effective throughput when we are pressed to do so and usually we can do it safely.

I contend that the next improvement in lean ICU medicine will be better management tools. Comprehensive checklists have helped me where computer solutions have yet to be developed. I am working to create hardware/software management solutions that will make my job more cost-effective and provide a sustainable process for what comes after me.

Dr. Waxman is associate professor of medicine, KU School of Medicine, Kansas City, Kan.; medical director, Medical Surgical ICU/PCU, Research Medical Center; and adjunct professor, Rockhurst University, Helzberg School of Management, Kansas City, Mo.

Is it possible to give the best critical care while spending less money and resources doing it? Can we reduce waste while improving quality in a so-called lean approach to critical care? I believe that we have too many critical care beds, and we fill some of those beds with patients who can be taken care of at less intense levels of care—which are also less expensive.

Most work that is done to improve critical care looks at the quality of care. This is an area where a lot of data are accumulating. Take septic shock, for example. In the recently published ProCESS trial (The ProCESS Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2014. 370[18]:1683), the 60-day in-hospital mortality for septic shock was 18.2% to 21.0%. A lot of institutions (including mine) are struggling to get their septic shock mortality rate under 30%. Although some people critique the ProCESS trial mortality rate on patient selection, most of us try to figure out how to duplicate that lower rate. We do this in areas other than septic shock. If we are comparable in whatever quality statistic, we applaud our success. If we aren’t comparable, we look at ways to improve, often based on what was done in that particular study.

How big of a financial burden is our critical care spending? According to an analysis of critical care beds by Halpern and colleagues (Crit Care Med. 2004;32[6]:1254), the number of hospital beds decreased 26.4% between 1985 and 2000, and the absolute number of critical care beds increased 26.2% (quantitated at 67,357 adult beds in 2007 per SCCM.org, www.sccm.org/Communications/Pages/CriticalCareStats.aspx). Critical care beds cost $2,674 per day in 2000, up from $1,185 (our CFOs tell us it is more like $3,500 to $4,000 per day now). They represented 13.3% of hospital costs, 4.2% of national health expenditures (NHE), and 0.56% of gross domestic product (GDP). There are 55,000 critically ill patients cared for each day in the United States, representing 5 million ICU patients per year. This is an enormous expenditure of money and it is growing.

Another interesting observation by Halpern and colleagues (Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1254) was that critical care beds were only at 65% occupancy. This reflects my own experience where we operate at a 70% average ICU bed occupancy. We have created a larger financial burden with the fixed costs of one-third more ICU beds than we actually use. Some bed availability is desirable, but how much is too much? Are we doing the best job to give quality care and spend money wisely? Can we be more efficient in the throughput of patients and in their care? Admission criteria should be part of any unit, designed to place all patients who need ICU care appropriately in the ICU and exclude those whose care can be managed at a lesser level of intensity and cost. Discharge criteria, care protocols (e.g., wake up and wean), checklists, and daily attention to the usual parameters (e.g., DVT prophylaxis) are essential for high-quality but efficient care. Done 24/7, we can maximize efficiency and quality with a minimum of ICU readmissions. Throughput is part of every physician’s job description. The physician who wants one more day for his or her patient in the ICU simply because the nurse has fewer patients misses a number of points. Why would anyone want more exposure to resistant organisms, more noise, more awakenings, and less sleep, just to name a few? Keeping that non-ICU patient in the ICU bed might even delay the transfer of another patient coming from the ED, where we know they often don’t get good ICU care.

Are the beds filled only with what we intensivists would consider legitimate ICU patients, defined by both generally accepted (endotracheal tube in place) and individually specified criteria (unit specific related to other unit capabilities)? That would impact cost. An interesting article by Gooch and Kahn (JAMA. 2014; 311[6]:567) discussed the demand elasticity of the ICU. They considered the changes in case mix of patients between days of high and low bed availability. They contended that when ICU beds were available, there was an increase in patients who were unlikely to benefit from ICU admission. This group included a population of patients likely to survive and whose illness severity was low and a population of patients who were unlikely to survive and had a high illness severity. In other words, admissions expand to fill the staff-able beds. If this is true, it is another area where better management could lower costs without reducing the quality of care.