User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

ACOG taking steps to increase vaginal hysterectomy rates

ORLANDO – The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists is taking steps intended to reverse the declining rates of vaginal hysterectomy, the preferred procedure for benign indications, according to an outline of plans presented at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

The immediate focus is on building skills both during and after training programs, said Dr. Sandra A. Carson, ACOG’s vice president for education. She reported that overall rates of hysterectomies have been declining over the past decade, but the decline has been especially steep for vaginal procedures. This has an adverse impact on training.

“Data show that over the past 10 years, residents have performed on average 8 fewer hysterectomies, but the average number of vaginal hysterectomies has been essentially halved to 17 or 18 over 4 years of residency training,” said Dr. Carson, who made her remarks as part of the invited TeLinde lecture.

This rate of vaginal hysterectomies during training is generally considered to be insufficient to provide training graduates with the confidence to perform them in routine practice, she said.

The vaginal approach has long been identified by ACOG as the preferred route of hysterectomy for benign disease because of evidence of better outcomes and fewer complications. In an ACOG committee opinion #444 entitled “Choosing the Route of Hysterectomy for Benign Disease” (reaffirmed in 2011), laparoscopic, abdominal, and robotic procedures were characterized as alternatives when vaginal hysterectomy is not feasible (Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;114:1156-8).

“We know that vaginal hysterectomy overall is better for women, so we need to get honest with ourselves about doing something about the trends,” she said at the SGS meeting, jointly sponsored by the American College of Surgeons.

Of strategies to reverse the trend, training is key, said Dr. Carson. This has led ACOG to develop several programs, including a CME-accredited surgical skills training module that includes objectives, instruction, information on how to construct a low-cost simulator, and an assessment tool. There is also a program available designed to help teachers teach vaginal hysterectomy.

ACOG also is developing a task force of teachers for mentoring. The goal is to advise surgeons who have learned the techniques of vaginal hysterectomy but may not yet have the confidence to perform them on their own. Ten experts already have volunteered to serve on the task force, and several training programs have expressed interest in receiving this form of support, Dr. Carson said.

However, she acknowledged several potential obstacles for widespread implementation of the task force that require resolution, such as providing credentialing, liability insurance, and reimbursement for advisers. ACOG has been active in considering solutions for each of these, such as using operating room cameras that would allow advisers to participate remotely.

In addition to training, however, Dr. Carson reported that ACOG is looking at strategies to align incentives that would encourage vaginal hysterectomies. This could include convincing third-party payers to provide greater reimbursement for an approach that may be less costly than alternatives, particularly robotic hysterectomy.

“We all need to decide that this is the right thing for women, but if you want to do this, we want to help you,” Dr. Carson told the audience of gynecologic surgeons.

Concern about the declining rates of vaginal hysterectomy is not new, said Dr. Ernest G. Lockrow, professor and vice chairman obstetrics and gynecology, Uniformed Services University of the Health Services, Bethesda, Md. In an interview, he suggested that there has long been hand-wringing about how to halt the decline in the approach. What is new, according to Dr. Lockrow, is the ACOG commitment for change.

“Based on what we heard today, it appears that ACOG is getting a little more serious about doing something about this issue,” Dr. Lockrow said. He is not certain how effective the strategies outlined by Dr. Carson will be in turning around current trends, “but I think we are seeing some steps in the right direction.”

Dr. Carson reported no relevant financial disclosures

ORLANDO – The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists is taking steps intended to reverse the declining rates of vaginal hysterectomy, the preferred procedure for benign indications, according to an outline of plans presented at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

The immediate focus is on building skills both during and after training programs, said Dr. Sandra A. Carson, ACOG’s vice president for education. She reported that overall rates of hysterectomies have been declining over the past decade, but the decline has been especially steep for vaginal procedures. This has an adverse impact on training.

“Data show that over the past 10 years, residents have performed on average 8 fewer hysterectomies, but the average number of vaginal hysterectomies has been essentially halved to 17 or 18 over 4 years of residency training,” said Dr. Carson, who made her remarks as part of the invited TeLinde lecture.

This rate of vaginal hysterectomies during training is generally considered to be insufficient to provide training graduates with the confidence to perform them in routine practice, she said.

The vaginal approach has long been identified by ACOG as the preferred route of hysterectomy for benign disease because of evidence of better outcomes and fewer complications. In an ACOG committee opinion #444 entitled “Choosing the Route of Hysterectomy for Benign Disease” (reaffirmed in 2011), laparoscopic, abdominal, and robotic procedures were characterized as alternatives when vaginal hysterectomy is not feasible (Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;114:1156-8).

“We know that vaginal hysterectomy overall is better for women, so we need to get honest with ourselves about doing something about the trends,” she said at the SGS meeting, jointly sponsored by the American College of Surgeons.

Of strategies to reverse the trend, training is key, said Dr. Carson. This has led ACOG to develop several programs, including a CME-accredited surgical skills training module that includes objectives, instruction, information on how to construct a low-cost simulator, and an assessment tool. There is also a program available designed to help teachers teach vaginal hysterectomy.

ACOG also is developing a task force of teachers for mentoring. The goal is to advise surgeons who have learned the techniques of vaginal hysterectomy but may not yet have the confidence to perform them on their own. Ten experts already have volunteered to serve on the task force, and several training programs have expressed interest in receiving this form of support, Dr. Carson said.

However, she acknowledged several potential obstacles for widespread implementation of the task force that require resolution, such as providing credentialing, liability insurance, and reimbursement for advisers. ACOG has been active in considering solutions for each of these, such as using operating room cameras that would allow advisers to participate remotely.

In addition to training, however, Dr. Carson reported that ACOG is looking at strategies to align incentives that would encourage vaginal hysterectomies. This could include convincing third-party payers to provide greater reimbursement for an approach that may be less costly than alternatives, particularly robotic hysterectomy.

“We all need to decide that this is the right thing for women, but if you want to do this, we want to help you,” Dr. Carson told the audience of gynecologic surgeons.

Concern about the declining rates of vaginal hysterectomy is not new, said Dr. Ernest G. Lockrow, professor and vice chairman obstetrics and gynecology, Uniformed Services University of the Health Services, Bethesda, Md. In an interview, he suggested that there has long been hand-wringing about how to halt the decline in the approach. What is new, according to Dr. Lockrow, is the ACOG commitment for change.

“Based on what we heard today, it appears that ACOG is getting a little more serious about doing something about this issue,” Dr. Lockrow said. He is not certain how effective the strategies outlined by Dr. Carson will be in turning around current trends, “but I think we are seeing some steps in the right direction.”

Dr. Carson reported no relevant financial disclosures

ORLANDO – The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists is taking steps intended to reverse the declining rates of vaginal hysterectomy, the preferred procedure for benign indications, according to an outline of plans presented at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

The immediate focus is on building skills both during and after training programs, said Dr. Sandra A. Carson, ACOG’s vice president for education. She reported that overall rates of hysterectomies have been declining over the past decade, but the decline has been especially steep for vaginal procedures. This has an adverse impact on training.

“Data show that over the past 10 years, residents have performed on average 8 fewer hysterectomies, but the average number of vaginal hysterectomies has been essentially halved to 17 or 18 over 4 years of residency training,” said Dr. Carson, who made her remarks as part of the invited TeLinde lecture.

This rate of vaginal hysterectomies during training is generally considered to be insufficient to provide training graduates with the confidence to perform them in routine practice, she said.

The vaginal approach has long been identified by ACOG as the preferred route of hysterectomy for benign disease because of evidence of better outcomes and fewer complications. In an ACOG committee opinion #444 entitled “Choosing the Route of Hysterectomy for Benign Disease” (reaffirmed in 2011), laparoscopic, abdominal, and robotic procedures were characterized as alternatives when vaginal hysterectomy is not feasible (Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;114:1156-8).

“We know that vaginal hysterectomy overall is better for women, so we need to get honest with ourselves about doing something about the trends,” she said at the SGS meeting, jointly sponsored by the American College of Surgeons.

Of strategies to reverse the trend, training is key, said Dr. Carson. This has led ACOG to develop several programs, including a CME-accredited surgical skills training module that includes objectives, instruction, information on how to construct a low-cost simulator, and an assessment tool. There is also a program available designed to help teachers teach vaginal hysterectomy.

ACOG also is developing a task force of teachers for mentoring. The goal is to advise surgeons who have learned the techniques of vaginal hysterectomy but may not yet have the confidence to perform them on their own. Ten experts already have volunteered to serve on the task force, and several training programs have expressed interest in receiving this form of support, Dr. Carson said.

However, she acknowledged several potential obstacles for widespread implementation of the task force that require resolution, such as providing credentialing, liability insurance, and reimbursement for advisers. ACOG has been active in considering solutions for each of these, such as using operating room cameras that would allow advisers to participate remotely.

In addition to training, however, Dr. Carson reported that ACOG is looking at strategies to align incentives that would encourage vaginal hysterectomies. This could include convincing third-party payers to provide greater reimbursement for an approach that may be less costly than alternatives, particularly robotic hysterectomy.

“We all need to decide that this is the right thing for women, but if you want to do this, we want to help you,” Dr. Carson told the audience of gynecologic surgeons.

Concern about the declining rates of vaginal hysterectomy is not new, said Dr. Ernest G. Lockrow, professor and vice chairman obstetrics and gynecology, Uniformed Services University of the Health Services, Bethesda, Md. In an interview, he suggested that there has long been hand-wringing about how to halt the decline in the approach. What is new, according to Dr. Lockrow, is the ACOG commitment for change.

“Based on what we heard today, it appears that ACOG is getting a little more serious about doing something about this issue,” Dr. Lockrow said. He is not certain how effective the strategies outlined by Dr. Carson will be in turning around current trends, “but I think we are seeing some steps in the right direction.”

Dr. Carson reported no relevant financial disclosures

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SGS 2015

Avoid voriconazole in transplant patients at risk for skin cancer

SAN FRANCISCO – Voriconazole increased the risk of squamous cell carcinoma by 73% in a review of 455 lung transplant patients at the University of California, San Francisco.

The increase was for any exposure to the drug after transplant (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.73; P = .03). The investigators also found that each additional 30-day exposure at 200 mg of voriconazole twice daily increased the risk of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) by 3.0% (HR, 1.03; P < .001). The results were adjusted for age at transplant, sex, and race. Overall, SCC risk was highest among white men aged 50 years or older at the time of transplant.

Although voriconazole did protect against posttransplant Aspergillus colonization (aHR, 0.50; P < .001), it did not reduce the risk of invasive aspergillosis. The drug reduced all-cause mortality only among colonized subjects (aHR, 0.34; P = .03), and offered no mortality benefit among those who were not colonized.

There was no difference in all-cause mortality between patients who had any exposure to voriconazole and those who did not, “but we actually found a 2% increased risk of death for each 1 month on the medication. Patients who weren’t colonized were the ones contributing to this increased risk of death,” said lead investigator Matthew Mansh, now a medical student at Stanford (Calif.) University.

There was no increased risk of SCC with alternative antifungals, including inhaled amphotericin and posaconazole. These alternatives should be considered instead of voriconazole in people at higher risk for skin cancer after lung transplants, according to the study, Mr. Mansh noted.

Voriconazole, which is widely used for antifungal prophylaxis after solid organ transplants, has been linked to skin cancer. The reason for the carcinogenic effect is not known; researchers are working to unravel the molecular mechanisms.

“Physicians should be cautious when using voriconazole in the care of transplant recipients. If you see a patient who is developing phototoxicity” with voriconazole, “and if they don’t have evidence of Aspergillus colonization, you may want to limit exposure to high doses of this drug or suggest an alternative,” Mr. Mansh said.

“We have now demonstrated that the alternatives “don’t carry this increased risk of cutaneous SCC,” Mr. Mansh said at the American Academy of Dermatology annual meeting.

The mean age of the study patients at transplant was 52 years, and the majority of patients were white; slightly more than half were men. Most had bilateral lung transplants, with pulmonary fibrosis at the leading indication.

Voriconazole was used in 85% of the patients for an average of 10 months. A quarter of voriconazole patients developed SCC within 5 years of transplant, and 43% within 10 years. Among patients who did not receive the drug, 15% developed SCC within 5 years of transplant, and 28% developed SCC within 10 years of transplant.

“The benefit of voriconazole in terms of death was limited to patients with evidence of Aspergillus colonization, and it wasn’t dose dependent. Patients who had a higher cumulative exposure did not get more benefit,” Mr. Mansh said.

Mr. Mansh had no relevant disclosures.

|

Dr. Paul T. Nghiem |

This is a carefully done study with a practical message: voriconazole patients are at a prolonged increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma. If patients develop phototoxicity or are fair-skinned, have sun damage, a history of squamous cell carcinoma or other risk factors, I think it’s highly appropriate to suggest an alternative. The alternatives are not at all associated with phototoxicity or squamous cell carcinoma.

Dr. Paul T. Nghiem moderated the late-breaker presentation in which the study was presented and is a professor of dermatology at the University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Nghiem had no disclosures related to the study.

|

Dr. Paul T. Nghiem |

This is a carefully done study with a practical message: voriconazole patients are at a prolonged increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma. If patients develop phototoxicity or are fair-skinned, have sun damage, a history of squamous cell carcinoma or other risk factors, I think it’s highly appropriate to suggest an alternative. The alternatives are not at all associated with phototoxicity or squamous cell carcinoma.

Dr. Paul T. Nghiem moderated the late-breaker presentation in which the study was presented and is a professor of dermatology at the University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Nghiem had no disclosures related to the study.

|

Dr. Paul T. Nghiem |

This is a carefully done study with a practical message: voriconazole patients are at a prolonged increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma. If patients develop phototoxicity or are fair-skinned, have sun damage, a history of squamous cell carcinoma or other risk factors, I think it’s highly appropriate to suggest an alternative. The alternatives are not at all associated with phototoxicity or squamous cell carcinoma.

Dr. Paul T. Nghiem moderated the late-breaker presentation in which the study was presented and is a professor of dermatology at the University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Nghiem had no disclosures related to the study.

SAN FRANCISCO – Voriconazole increased the risk of squamous cell carcinoma by 73% in a review of 455 lung transplant patients at the University of California, San Francisco.

The increase was for any exposure to the drug after transplant (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.73; P = .03). The investigators also found that each additional 30-day exposure at 200 mg of voriconazole twice daily increased the risk of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) by 3.0% (HR, 1.03; P < .001). The results were adjusted for age at transplant, sex, and race. Overall, SCC risk was highest among white men aged 50 years or older at the time of transplant.

Although voriconazole did protect against posttransplant Aspergillus colonization (aHR, 0.50; P < .001), it did not reduce the risk of invasive aspergillosis. The drug reduced all-cause mortality only among colonized subjects (aHR, 0.34; P = .03), and offered no mortality benefit among those who were not colonized.

There was no difference in all-cause mortality between patients who had any exposure to voriconazole and those who did not, “but we actually found a 2% increased risk of death for each 1 month on the medication. Patients who weren’t colonized were the ones contributing to this increased risk of death,” said lead investigator Matthew Mansh, now a medical student at Stanford (Calif.) University.

There was no increased risk of SCC with alternative antifungals, including inhaled amphotericin and posaconazole. These alternatives should be considered instead of voriconazole in people at higher risk for skin cancer after lung transplants, according to the study, Mr. Mansh noted.

Voriconazole, which is widely used for antifungal prophylaxis after solid organ transplants, has been linked to skin cancer. The reason for the carcinogenic effect is not known; researchers are working to unravel the molecular mechanisms.

“Physicians should be cautious when using voriconazole in the care of transplant recipients. If you see a patient who is developing phototoxicity” with voriconazole, “and if they don’t have evidence of Aspergillus colonization, you may want to limit exposure to high doses of this drug or suggest an alternative,” Mr. Mansh said.

“We have now demonstrated that the alternatives “don’t carry this increased risk of cutaneous SCC,” Mr. Mansh said at the American Academy of Dermatology annual meeting.

The mean age of the study patients at transplant was 52 years, and the majority of patients were white; slightly more than half were men. Most had bilateral lung transplants, with pulmonary fibrosis at the leading indication.

Voriconazole was used in 85% of the patients for an average of 10 months. A quarter of voriconazole patients developed SCC within 5 years of transplant, and 43% within 10 years. Among patients who did not receive the drug, 15% developed SCC within 5 years of transplant, and 28% developed SCC within 10 years of transplant.

“The benefit of voriconazole in terms of death was limited to patients with evidence of Aspergillus colonization, and it wasn’t dose dependent. Patients who had a higher cumulative exposure did not get more benefit,” Mr. Mansh said.

Mr. Mansh had no relevant disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Voriconazole increased the risk of squamous cell carcinoma by 73% in a review of 455 lung transplant patients at the University of California, San Francisco.

The increase was for any exposure to the drug after transplant (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.73; P = .03). The investigators also found that each additional 30-day exposure at 200 mg of voriconazole twice daily increased the risk of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) by 3.0% (HR, 1.03; P < .001). The results were adjusted for age at transplant, sex, and race. Overall, SCC risk was highest among white men aged 50 years or older at the time of transplant.

Although voriconazole did protect against posttransplant Aspergillus colonization (aHR, 0.50; P < .001), it did not reduce the risk of invasive aspergillosis. The drug reduced all-cause mortality only among colonized subjects (aHR, 0.34; P = .03), and offered no mortality benefit among those who were not colonized.

There was no difference in all-cause mortality between patients who had any exposure to voriconazole and those who did not, “but we actually found a 2% increased risk of death for each 1 month on the medication. Patients who weren’t colonized were the ones contributing to this increased risk of death,” said lead investigator Matthew Mansh, now a medical student at Stanford (Calif.) University.

There was no increased risk of SCC with alternative antifungals, including inhaled amphotericin and posaconazole. These alternatives should be considered instead of voriconazole in people at higher risk for skin cancer after lung transplants, according to the study, Mr. Mansh noted.

Voriconazole, which is widely used for antifungal prophylaxis after solid organ transplants, has been linked to skin cancer. The reason for the carcinogenic effect is not known; researchers are working to unravel the molecular mechanisms.

“Physicians should be cautious when using voriconazole in the care of transplant recipients. If you see a patient who is developing phototoxicity” with voriconazole, “and if they don’t have evidence of Aspergillus colonization, you may want to limit exposure to high doses of this drug or suggest an alternative,” Mr. Mansh said.

“We have now demonstrated that the alternatives “don’t carry this increased risk of cutaneous SCC,” Mr. Mansh said at the American Academy of Dermatology annual meeting.

The mean age of the study patients at transplant was 52 years, and the majority of patients were white; slightly more than half were men. Most had bilateral lung transplants, with pulmonary fibrosis at the leading indication.

Voriconazole was used in 85% of the patients for an average of 10 months. A quarter of voriconazole patients developed SCC within 5 years of transplant, and 43% within 10 years. Among patients who did not receive the drug, 15% developed SCC within 5 years of transplant, and 28% developed SCC within 10 years of transplant.

“The benefit of voriconazole in terms of death was limited to patients with evidence of Aspergillus colonization, and it wasn’t dose dependent. Patients who had a higher cumulative exposure did not get more benefit,” Mr. Mansh said.

Mr. Mansh had no relevant disclosures.

AT AAD 2015

Key clinical point: Use an alternative antifungal after lung transplant in white men aged 50 years and older.

Major finding: Exposure to voriconazole increased the risk of squamous cell carcinoma by 73% after lung transplant (aHR, 1.73; P = .03); each additional 30‐day exposure at 200 mg twice daily increased the risk by 3.0% (HR 1.03; P < .001).

Data source: Retrospective cohort study of 455 lung transplant patients

Disclosures: The lead investigator had no relevant disclosures.

Medicare is stingy in first year of doctor bonuses

Dr. Michael Kitchell initially welcomed the federal government’s new quality incentives for doctors. His medical group in Iowa has always scored better than most in the quality reports that Medicare has provided doctors in recent years, he said.

But when the government launched a new payment system that will soon apply to all physicians who accept Medicare, Dr. Kitchell’s McFarland Clinic in Ames didn’t win a bonus. In fact, there are few winners: Out of 1,010 large physician groups that the government evaluated, just 14 are getting payment increases this year, according to Medicare. Losers also are scarce. Only 11 groups will be getting reductions for low quality or high spending.

“We performed well, but not enough for the bonus,” said Dr. Kitchell, a neurologist. “My sense of disappointment here is really significant. Why even bother?”

Within 3 years, the Obama administration wants quality of care to be considered in allocating $9 of every $10 Medicare pays directly to providers to treat the elderly and disabled. One part of that effort is well underway: revising hospital payments based on excess readmissions, patient satisfaction, and other quality measures. Expanding this approach to physicians is touchier, as many are suspicious of the government judging them and reluctant to share performance metrics that Medicare requests.

“Without having any indication that this is improving patient care, they just keep piling on additional requirements,” said Dr. Mark Donnell, an anesthesiologist in Silver City, N.M. Dr. Donnell said he only reports a third of the quality measures he is expected to. “So much of what’s done in medicine is only done to meet the requirements,” he said.

The new financial incentive for doctors, called a physician value-based payment modifier, allows the federal government to boost or lower the amount it reimburses doctors based on how they score on quality measures and how much their patients cost Medicare. How doctors rate this year will determine payments for more than 900,000 physicians by 2017.

Medicare is easing doctors into the program, applying it this year only to medical groups with at least 100 health professionals, including doctors, nurses, speech-language pathologists, and occupational therapists. Next year, the program expands Medicare to groups of 10 or more health professionals. In 2017, all remaining doctors who take Medicare – along with about 360,000 other health professionals – will be included. By early in the next decade, 9% of the payments Medicare makes to doctors and other professionals would be at risk under a bill that the House of Representatives passed in March.

The quality metrics used to judge doctors vary by specialty. One test looks at how consistently doctors keep an accurate list of all the drugs patients were taking. Others track the rate of complications after cataract surgery or whether patients received recommended treatments for particular cancers.

There are more than 250 quality measures. Groups and doctors must report a selection – generally nine, which they choose – or else be automatically penalized. This year, 319 large medical groups are having their reimbursements reduced by 1% because they did not meet Medicare’s reporting standards.

Physicians who do report their quality data fear the measures are sometimes misguided, usually a hassle and may encourage doctors to avoid poorer and sicker patients, who tend to have more trouble controlling asthma or staying on antidepressants, for instance.

Dr. Leanne Chrisman-Khawam, a family physician in Cleveland, said many of her patients have difficulty just getting to follow-up appointments, since they must take two or three buses. She said those battling obesity or diabetes are less likely to reform their diets to emphasize fresh foods, which are expensive and less available in poor neighborhoods. “You’re going to link that physician’s payment to that life?” she asked.

Dr. Hamilton Lempert, an emergency physician in Cincinnati, criticized one measure that requires him to track how often he follows up with patients with high blood pressure.

“Most everyone’s blood pressure is elevated in the emergency department because they’re anxious,” Dr. Lempert said. Another metric encourages testing the heart’s electrical impulses in patients with nontraumatic chest pain, which Lempert said has led emergency rooms to give priority to these cases over more serious ones.

“It’s just very frustrating, the things we have to do to jump through the hoops,” he said.

In the first year that doctors are affected by the program, they can choose to forgo bonuses or penalties based on their performance. After that, the program is mandatory. This year, 564 groups opted out, but even if all of them had been included, only 3% would have gotten increases and 38% would have seen lower payments, mostly for not satisfactorily reporting quality measures, Medicare data show.

Smaller groups and solo practitioners are even less likely to report quality to the government. “The participation rates, even though it’s mandated, are just really low,” said Dr. Alyna Chien, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School. It’s “a level of analytics that just is not typically built into a doctor’s office.”

Dr. Lisa Bielamowicz, chief medical officer of The Advisory Board, a consulting group, predicted more doctors will start reporting their quality scores when the prospect of fines is greater. “They are not going to motivate until it is absolutely necessary,” she said. “If you look at these small practices, a lot of them just run on a shoestring.”

This year’s assessments of big groups were based on patients seen in 2013. A total of $11 million of the $1.2 billion Medicare pays doctors is being given out as bonuses, which translates to a 5% payment increase for those 14 groups getting payment increases this year. That money came from low performers and those that did not report quality measures to Medicare’s satisfaction; they are losing up to 1%.

The exact amount any of these groups lose will depend on the number and nature of the services they provide over the year. This year, 268 medical groups were exempted because at least one of their doctors was participating in one of the government’s experiments in providing care differently.

Officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services declined to be interviewed about the program but said in a prepared statement that they have been providing all doctors with reports showing their quality and costs. “We hope that this information will provide meaningful and actionable information to physicians so that they may improve the coordination and integration of the health care provided to beneficiaries,” the statement said.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a nonprofit national health policy news service. KHN’s coverage of aging and long-term-care issues is supported in part by a grant from The SCAN Foundation.

Dr. Michael Kitchell initially welcomed the federal government’s new quality incentives for doctors. His medical group in Iowa has always scored better than most in the quality reports that Medicare has provided doctors in recent years, he said.

But when the government launched a new payment system that will soon apply to all physicians who accept Medicare, Dr. Kitchell’s McFarland Clinic in Ames didn’t win a bonus. In fact, there are few winners: Out of 1,010 large physician groups that the government evaluated, just 14 are getting payment increases this year, according to Medicare. Losers also are scarce. Only 11 groups will be getting reductions for low quality or high spending.

“We performed well, but not enough for the bonus,” said Dr. Kitchell, a neurologist. “My sense of disappointment here is really significant. Why even bother?”

Within 3 years, the Obama administration wants quality of care to be considered in allocating $9 of every $10 Medicare pays directly to providers to treat the elderly and disabled. One part of that effort is well underway: revising hospital payments based on excess readmissions, patient satisfaction, and other quality measures. Expanding this approach to physicians is touchier, as many are suspicious of the government judging them and reluctant to share performance metrics that Medicare requests.

“Without having any indication that this is improving patient care, they just keep piling on additional requirements,” said Dr. Mark Donnell, an anesthesiologist in Silver City, N.M. Dr. Donnell said he only reports a third of the quality measures he is expected to. “So much of what’s done in medicine is only done to meet the requirements,” he said.

The new financial incentive for doctors, called a physician value-based payment modifier, allows the federal government to boost or lower the amount it reimburses doctors based on how they score on quality measures and how much their patients cost Medicare. How doctors rate this year will determine payments for more than 900,000 physicians by 2017.

Medicare is easing doctors into the program, applying it this year only to medical groups with at least 100 health professionals, including doctors, nurses, speech-language pathologists, and occupational therapists. Next year, the program expands Medicare to groups of 10 or more health professionals. In 2017, all remaining doctors who take Medicare – along with about 360,000 other health professionals – will be included. By early in the next decade, 9% of the payments Medicare makes to doctors and other professionals would be at risk under a bill that the House of Representatives passed in March.

The quality metrics used to judge doctors vary by specialty. One test looks at how consistently doctors keep an accurate list of all the drugs patients were taking. Others track the rate of complications after cataract surgery or whether patients received recommended treatments for particular cancers.

There are more than 250 quality measures. Groups and doctors must report a selection – generally nine, which they choose – or else be automatically penalized. This year, 319 large medical groups are having their reimbursements reduced by 1% because they did not meet Medicare’s reporting standards.

Physicians who do report their quality data fear the measures are sometimes misguided, usually a hassle and may encourage doctors to avoid poorer and sicker patients, who tend to have more trouble controlling asthma or staying on antidepressants, for instance.

Dr. Leanne Chrisman-Khawam, a family physician in Cleveland, said many of her patients have difficulty just getting to follow-up appointments, since they must take two or three buses. She said those battling obesity or diabetes are less likely to reform their diets to emphasize fresh foods, which are expensive and less available in poor neighborhoods. “You’re going to link that physician’s payment to that life?” she asked.

Dr. Hamilton Lempert, an emergency physician in Cincinnati, criticized one measure that requires him to track how often he follows up with patients with high blood pressure.

“Most everyone’s blood pressure is elevated in the emergency department because they’re anxious,” Dr. Lempert said. Another metric encourages testing the heart’s electrical impulses in patients with nontraumatic chest pain, which Lempert said has led emergency rooms to give priority to these cases over more serious ones.

“It’s just very frustrating, the things we have to do to jump through the hoops,” he said.

In the first year that doctors are affected by the program, they can choose to forgo bonuses or penalties based on their performance. After that, the program is mandatory. This year, 564 groups opted out, but even if all of them had been included, only 3% would have gotten increases and 38% would have seen lower payments, mostly for not satisfactorily reporting quality measures, Medicare data show.

Smaller groups and solo practitioners are even less likely to report quality to the government. “The participation rates, even though it’s mandated, are just really low,” said Dr. Alyna Chien, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School. It’s “a level of analytics that just is not typically built into a doctor’s office.”

Dr. Lisa Bielamowicz, chief medical officer of The Advisory Board, a consulting group, predicted more doctors will start reporting their quality scores when the prospect of fines is greater. “They are not going to motivate until it is absolutely necessary,” she said. “If you look at these small practices, a lot of them just run on a shoestring.”

This year’s assessments of big groups were based on patients seen in 2013. A total of $11 million of the $1.2 billion Medicare pays doctors is being given out as bonuses, which translates to a 5% payment increase for those 14 groups getting payment increases this year. That money came from low performers and those that did not report quality measures to Medicare’s satisfaction; they are losing up to 1%.

The exact amount any of these groups lose will depend on the number and nature of the services they provide over the year. This year, 268 medical groups were exempted because at least one of their doctors was participating in one of the government’s experiments in providing care differently.

Officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services declined to be interviewed about the program but said in a prepared statement that they have been providing all doctors with reports showing their quality and costs. “We hope that this information will provide meaningful and actionable information to physicians so that they may improve the coordination and integration of the health care provided to beneficiaries,” the statement said.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a nonprofit national health policy news service. KHN’s coverage of aging and long-term-care issues is supported in part by a grant from The SCAN Foundation.

Dr. Michael Kitchell initially welcomed the federal government’s new quality incentives for doctors. His medical group in Iowa has always scored better than most in the quality reports that Medicare has provided doctors in recent years, he said.

But when the government launched a new payment system that will soon apply to all physicians who accept Medicare, Dr. Kitchell’s McFarland Clinic in Ames didn’t win a bonus. In fact, there are few winners: Out of 1,010 large physician groups that the government evaluated, just 14 are getting payment increases this year, according to Medicare. Losers also are scarce. Only 11 groups will be getting reductions for low quality or high spending.

“We performed well, but not enough for the bonus,” said Dr. Kitchell, a neurologist. “My sense of disappointment here is really significant. Why even bother?”

Within 3 years, the Obama administration wants quality of care to be considered in allocating $9 of every $10 Medicare pays directly to providers to treat the elderly and disabled. One part of that effort is well underway: revising hospital payments based on excess readmissions, patient satisfaction, and other quality measures. Expanding this approach to physicians is touchier, as many are suspicious of the government judging them and reluctant to share performance metrics that Medicare requests.

“Without having any indication that this is improving patient care, they just keep piling on additional requirements,” said Dr. Mark Donnell, an anesthesiologist in Silver City, N.M. Dr. Donnell said he only reports a third of the quality measures he is expected to. “So much of what’s done in medicine is only done to meet the requirements,” he said.

The new financial incentive for doctors, called a physician value-based payment modifier, allows the federal government to boost or lower the amount it reimburses doctors based on how they score on quality measures and how much their patients cost Medicare. How doctors rate this year will determine payments for more than 900,000 physicians by 2017.

Medicare is easing doctors into the program, applying it this year only to medical groups with at least 100 health professionals, including doctors, nurses, speech-language pathologists, and occupational therapists. Next year, the program expands Medicare to groups of 10 or more health professionals. In 2017, all remaining doctors who take Medicare – along with about 360,000 other health professionals – will be included. By early in the next decade, 9% of the payments Medicare makes to doctors and other professionals would be at risk under a bill that the House of Representatives passed in March.

The quality metrics used to judge doctors vary by specialty. One test looks at how consistently doctors keep an accurate list of all the drugs patients were taking. Others track the rate of complications after cataract surgery or whether patients received recommended treatments for particular cancers.

There are more than 250 quality measures. Groups and doctors must report a selection – generally nine, which they choose – or else be automatically penalized. This year, 319 large medical groups are having their reimbursements reduced by 1% because they did not meet Medicare’s reporting standards.

Physicians who do report their quality data fear the measures are sometimes misguided, usually a hassle and may encourage doctors to avoid poorer and sicker patients, who tend to have more trouble controlling asthma or staying on antidepressants, for instance.

Dr. Leanne Chrisman-Khawam, a family physician in Cleveland, said many of her patients have difficulty just getting to follow-up appointments, since they must take two or three buses. She said those battling obesity or diabetes are less likely to reform their diets to emphasize fresh foods, which are expensive and less available in poor neighborhoods. “You’re going to link that physician’s payment to that life?” she asked.

Dr. Hamilton Lempert, an emergency physician in Cincinnati, criticized one measure that requires him to track how often he follows up with patients with high blood pressure.

“Most everyone’s blood pressure is elevated in the emergency department because they’re anxious,” Dr. Lempert said. Another metric encourages testing the heart’s electrical impulses in patients with nontraumatic chest pain, which Lempert said has led emergency rooms to give priority to these cases over more serious ones.

“It’s just very frustrating, the things we have to do to jump through the hoops,” he said.

In the first year that doctors are affected by the program, they can choose to forgo bonuses or penalties based on their performance. After that, the program is mandatory. This year, 564 groups opted out, but even if all of them had been included, only 3% would have gotten increases and 38% would have seen lower payments, mostly for not satisfactorily reporting quality measures, Medicare data show.

Smaller groups and solo practitioners are even less likely to report quality to the government. “The participation rates, even though it’s mandated, are just really low,” said Dr. Alyna Chien, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School. It’s “a level of analytics that just is not typically built into a doctor’s office.”

Dr. Lisa Bielamowicz, chief medical officer of The Advisory Board, a consulting group, predicted more doctors will start reporting their quality scores when the prospect of fines is greater. “They are not going to motivate until it is absolutely necessary,” she said. “If you look at these small practices, a lot of them just run on a shoestring.”

This year’s assessments of big groups were based on patients seen in 2013. A total of $11 million of the $1.2 billion Medicare pays doctors is being given out as bonuses, which translates to a 5% payment increase for those 14 groups getting payment increases this year. That money came from low performers and those that did not report quality measures to Medicare’s satisfaction; they are losing up to 1%.

The exact amount any of these groups lose will depend on the number and nature of the services they provide over the year. This year, 268 medical groups were exempted because at least one of their doctors was participating in one of the government’s experiments in providing care differently.

Officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services declined to be interviewed about the program but said in a prepared statement that they have been providing all doctors with reports showing their quality and costs. “We hope that this information will provide meaningful and actionable information to physicians so that they may improve the coordination and integration of the health care provided to beneficiaries,” the statement said.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a nonprofit national health policy news service. KHN’s coverage of aging and long-term-care issues is supported in part by a grant from The SCAN Foundation.

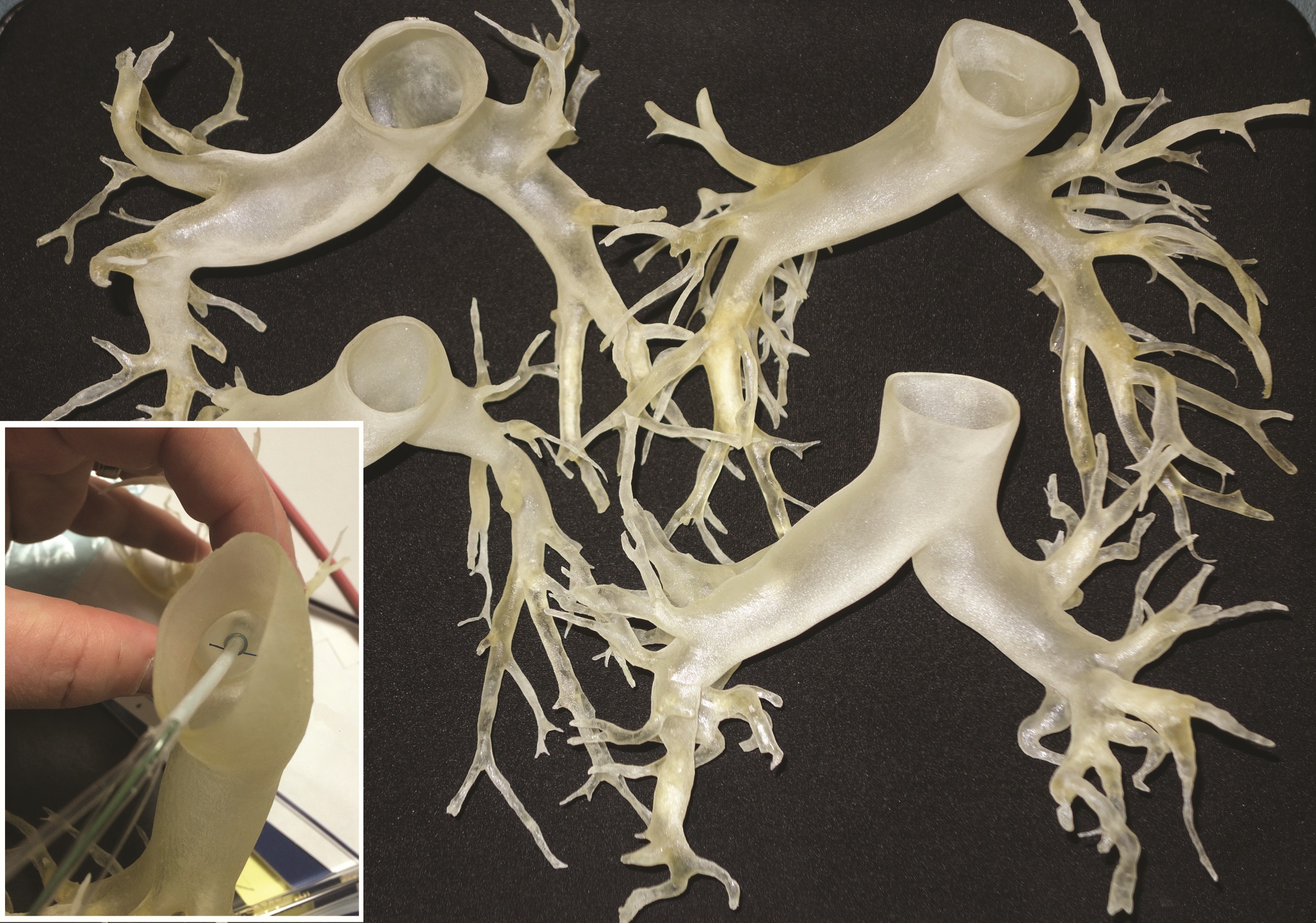

Disruptive medicine: 3-D printing revolution

The emergence of 3-D printing is beginning to look like a case of ‘disruptive medicine.’ Exploratory research in this area is ongoing in cardiology and orthopaedic and plastic surgery, and the experimental applications multiply daily.

Currently, 3-D printed models are being used for simulation training, preprocedural planning, development of personalized surgical equipment, and in a few cases, temporary structures for insertion in patients. As 3-D printers become cheaper, costs for their use in medicine are expected to decline

This rapidly developing technology is being applied in cardiothoracic surgery. The 3-D printing technology was used to construct flexible 3-D models of 10 human patient pulmonary arteries as part of a project to develop a new delivery catheter for regional lung chemotherapy.

Computed tomography and CT angiography in combination with software-driven segmentation techniques were used for generation and adjustment of 3-D polygon mesh to form reconstructed models of the pulmonary arteries. The reconstructed models were exported as stereolithographic data sets and further processed, according to Sergei N. Kurenov of the department of thoracic surgery, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, N.Y., and his colleagues.

How the process works

In this process, producing the anatomical pulmonary artery models required a series of steps: data acquisition from the patient CT digital data, 3-D visualization and segmentation, surface rendering and creating a 3-D polygon mesh, geometrical surface preparation – simplification, refinement, and geometry fixing, and the hollowing of an existing volume to “thicken” the walls.

Three contrast CT data sets with a 0.625-mm, 1-mm, and 2-mm slice thickness were gathered for each patient.

The scans were processed using commercial software packages. Because of the high variability of curvature and embedding in complex anatomical scenes with other vessels interference, the pulmary artery segmentation using the software tools required a clear understanding of the patient’s anatomy, which took 4-8 hours for the experienced operator, according to the researchers.

After further computer processing of the virtual reconstructed pulmonary model, it was sent to the 3-D printer, which used a rubberlike material that is elastic and semitransparent, behaving similarly to polyurethane.

The 10 unique models were successfully created with no print failures, although the original plan of using a 1-mm mural thickness proved too fragile, so the entire group was printed with a 1.5-mm wall. The design process took 8 hours from CT image to stereolithographic model, and printing required an overall total of 97 hours, according to the report published online in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery [doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.12.059].

Accurate models of individual patients’ anatomy

The physical measurements of the model were accurate for clinical purposes, with the 95% confidence levels for the 10 models demonstrating equivalence. Anatomic measurements using this process could be useful for general pulmonary artery catheter design, according to the authors. These measurements showed sufficient similarity for a design to be created that would be effective for most patients, although this finding would have to be validated with a larger sample of patients.

“While many of the measurements could have been made with software analysis of the 3-D files, some measurements were greatly facilitated by bending the model and aligning the physical catheter. These measurements represent distance beyond which a catheter might cause damage,” they added.

Biological 3-D printing of organs

Gut is a perfect beginning project for 3-D printing, Dr. John Geibel said at the 2015 American Gastroenterological Association Tech Summit, which was sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology. It has a very simple shape – just a long hollow tube. Epithelial cells grow and turn over very quickly, suggesting that a length of artificial intestine could be grown relatively quickly. And although intestine is composed of a number of distinct layers, a 3-D bioprinter would have no trouble laying down concentric circles of each one to recreate their natural morphology.

“It will take time. It will take planning. But this is going to happen,” said Dr. Geibel of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

To create a length of intestine, the print heads of a bioprinter would be loaded with cells from all of the gut layers – the serosa, the different muscle strata, the mucosa. Each would be laid down in its respective anatomic ring, supported all around by a hydrogel. The print sequence would be repeated over and over until the required length of intestine was created. From then, Dr. Geibel said, it would be only a matter of days before the cells knit themselves together so well that the gel could be dissolved and the new tissue ready for transplant.

Liver would likely be the next organ up for printing, with the ultimate goal of creating fully transplantable organs. The need is enormous, and can’t be overstated. Patients who need a new liver wait an average of 4 years before they receive one.

The liver is much more complicated than a length of gut. It is cellularly complex and highly vascularized. But liver-printing is already a reality. Bioprinted “3-D liver-in-a-dish,” created by San Diego–based Organovo, has function, if not form. The cells work together; they grow, divide, and secrete bile acids. However, they exist as a formless, nonvascular blob.

As it stands (or rather, lies) now, bioprinted liver is a perfect preclinical model – perfectly replicating how the liver would respond to drugs without any of the messy adverse events that hurt patients. But it needs some backbone, or more accurately, some matrix, in order to morph again and grow into a complete organ. A liver-shaped collagen matrix could provide the necessary frame for cells to grow in and around; tunnels through it would form pathways for a similarly engineered vasculature.

The project to create 3-D models of pulmonary arteries is one of many ongoing efforts in this field. “Going forward, this technology competes with virtual educational media for health care professionals, trainees, and patients. Complex anatomy can be visualized easily on a scale model at the operating table (rather than by manipulating a nonsterile pointing device on a computer). The [pulmonary arteries] we printed could be used in a relatively low-cost lifelike [video-assisted thoracoscopic] lobectomy trainer,” the authors stated, while acknowledging the current issue of cost and time.

Printing services were funded by an unrestricted grant from Incodema3D, which employs Dan Sammons, one of the authors of the study. The other authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

“Disruptive medicine: 3-D printing revolution” reports on an important new technology well worth surgeons’ attention. The basic process reported is a simple, but in many ways, revolutionary approach to manufacturing or assembly. 3-D printing is an additive manufacturing process, exactly the opposite from the usual subtractive process. As an example, a block of steel might be milled, drilled and machined into an engine block in a series of processes to remove material from the original piece of steel, a subtractive process.

3-D printing is an additive manufacturing process whereby materials (metal, plastic, other) are layered together to make a complex three-dimensional solid object. Working from a CAD file, material is laid down in successive layers until the entire object is created. Each layer deposited can be imagined as a thinly sliced horizontal cross-section of the eventual object. As such, 3-D printing is really a stack of 2-D prints. The technique was invented by Charles Hull in 1986 and is revolutionizing prototyping and, in some cases, manufacturing. Applications have included prototyping, metal casting, architectural design and building, and in 3-D design and visualization: this application is well-demonstrated in the medical application of pulmonary artery reconstruction outlined in this article. In this case, complex anatomy can be easily visualized on a solid full-scale model of the pulmonary vasculature, and treatment plans more easily formulated and even modeled.

An extensive, thoughtful discussion of medical 3-D printing can be found in the November 24, 2014 The New Yorker article entitled “Print Thyself: How 3-D printing is revolutionizing medicine.” Other medical applications described include 3-D reconstruction in complex craniofacial repairs, modeling of abnormalities in the tracheobronchial tree to design surgical strategies to manage airway stenosis, and in reconstructive modeling for complex traumatic injuries in bone and soft tissue.

Beyond such applications, concepts have evolved to areas of 3-D printing using mixtures of cells and matrix as an approach to the engineering and additive assembly of complex tissues, and even organs. Thus, functional organs might someday be produced; a massive step beyond simple prototyping.

As in many areas of science and technology, the field moves quickly. The March 20, 2015 issue of Science published a report on “Continuous liquid interface production (CLIP) of 3D objects.” This true 3-D printing process is up to 100 times faster than current technologies and is compatible with producing objects from soft elastic materials, ceramics and biologics! More to come…

Thomas M. Krummel, MD, FACS, is the Emile Holman Professor and Chair, Department of Surgery at Stanford University and the Co-Director, Biodesign Innovation Program at Stanford. He is also a member of the Board of Directors of the Fogarty Institute for Innovation.

“Disruptive medicine: 3-D printing revolution” reports on an important new technology well worth surgeons’ attention. The basic process reported is a simple, but in many ways, revolutionary approach to manufacturing or assembly. 3-D printing is an additive manufacturing process, exactly the opposite from the usual subtractive process. As an example, a block of steel might be milled, drilled and machined into an engine block in a series of processes to remove material from the original piece of steel, a subtractive process.

3-D printing is an additive manufacturing process whereby materials (metal, plastic, other) are layered together to make a complex three-dimensional solid object. Working from a CAD file, material is laid down in successive layers until the entire object is created. Each layer deposited can be imagined as a thinly sliced horizontal cross-section of the eventual object. As such, 3-D printing is really a stack of 2-D prints. The technique was invented by Charles Hull in 1986 and is revolutionizing prototyping and, in some cases, manufacturing. Applications have included prototyping, metal casting, architectural design and building, and in 3-D design and visualization: this application is well-demonstrated in the medical application of pulmonary artery reconstruction outlined in this article. In this case, complex anatomy can be easily visualized on a solid full-scale model of the pulmonary vasculature, and treatment plans more easily formulated and even modeled.

An extensive, thoughtful discussion of medical 3-D printing can be found in the November 24, 2014 The New Yorker article entitled “Print Thyself: How 3-D printing is revolutionizing medicine.” Other medical applications described include 3-D reconstruction in complex craniofacial repairs, modeling of abnormalities in the tracheobronchial tree to design surgical strategies to manage airway stenosis, and in reconstructive modeling for complex traumatic injuries in bone and soft tissue.

Beyond such applications, concepts have evolved to areas of 3-D printing using mixtures of cells and matrix as an approach to the engineering and additive assembly of complex tissues, and even organs. Thus, functional organs might someday be produced; a massive step beyond simple prototyping.

As in many areas of science and technology, the field moves quickly. The March 20, 2015 issue of Science published a report on “Continuous liquid interface production (CLIP) of 3D objects.” This true 3-D printing process is up to 100 times faster than current technologies and is compatible with producing objects from soft elastic materials, ceramics and biologics! More to come…

Thomas M. Krummel, MD, FACS, is the Emile Holman Professor and Chair, Department of Surgery at Stanford University and the Co-Director, Biodesign Innovation Program at Stanford. He is also a member of the Board of Directors of the Fogarty Institute for Innovation.

“Disruptive medicine: 3-D printing revolution” reports on an important new technology well worth surgeons’ attention. The basic process reported is a simple, but in many ways, revolutionary approach to manufacturing or assembly. 3-D printing is an additive manufacturing process, exactly the opposite from the usual subtractive process. As an example, a block of steel might be milled, drilled and machined into an engine block in a series of processes to remove material from the original piece of steel, a subtractive process.

3-D printing is an additive manufacturing process whereby materials (metal, plastic, other) are layered together to make a complex three-dimensional solid object. Working from a CAD file, material is laid down in successive layers until the entire object is created. Each layer deposited can be imagined as a thinly sliced horizontal cross-section of the eventual object. As such, 3-D printing is really a stack of 2-D prints. The technique was invented by Charles Hull in 1986 and is revolutionizing prototyping and, in some cases, manufacturing. Applications have included prototyping, metal casting, architectural design and building, and in 3-D design and visualization: this application is well-demonstrated in the medical application of pulmonary artery reconstruction outlined in this article. In this case, complex anatomy can be easily visualized on a solid full-scale model of the pulmonary vasculature, and treatment plans more easily formulated and even modeled.

An extensive, thoughtful discussion of medical 3-D printing can be found in the November 24, 2014 The New Yorker article entitled “Print Thyself: How 3-D printing is revolutionizing medicine.” Other medical applications described include 3-D reconstruction in complex craniofacial repairs, modeling of abnormalities in the tracheobronchial tree to design surgical strategies to manage airway stenosis, and in reconstructive modeling for complex traumatic injuries in bone and soft tissue.

Beyond such applications, concepts have evolved to areas of 3-D printing using mixtures of cells and matrix as an approach to the engineering and additive assembly of complex tissues, and even organs. Thus, functional organs might someday be produced; a massive step beyond simple prototyping.

As in many areas of science and technology, the field moves quickly. The March 20, 2015 issue of Science published a report on “Continuous liquid interface production (CLIP) of 3D objects.” This true 3-D printing process is up to 100 times faster than current technologies and is compatible with producing objects from soft elastic materials, ceramics and biologics! More to come…

Thomas M. Krummel, MD, FACS, is the Emile Holman Professor and Chair, Department of Surgery at Stanford University and the Co-Director, Biodesign Innovation Program at Stanford. He is also a member of the Board of Directors of the Fogarty Institute for Innovation.

The emergence of 3-D printing is beginning to look like a case of ‘disruptive medicine.’ Exploratory research in this area is ongoing in cardiology and orthopaedic and plastic surgery, and the experimental applications multiply daily.

Currently, 3-D printed models are being used for simulation training, preprocedural planning, development of personalized surgical equipment, and in a few cases, temporary structures for insertion in patients. As 3-D printers become cheaper, costs for their use in medicine are expected to decline

This rapidly developing technology is being applied in cardiothoracic surgery. The 3-D printing technology was used to construct flexible 3-D models of 10 human patient pulmonary arteries as part of a project to develop a new delivery catheter for regional lung chemotherapy.

Computed tomography and CT angiography in combination with software-driven segmentation techniques were used for generation and adjustment of 3-D polygon mesh to form reconstructed models of the pulmonary arteries. The reconstructed models were exported as stereolithographic data sets and further processed, according to Sergei N. Kurenov of the department of thoracic surgery, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, N.Y., and his colleagues.

How the process works

In this process, producing the anatomical pulmonary artery models required a series of steps: data acquisition from the patient CT digital data, 3-D visualization and segmentation, surface rendering and creating a 3-D polygon mesh, geometrical surface preparation – simplification, refinement, and geometry fixing, and the hollowing of an existing volume to “thicken” the walls.

Three contrast CT data sets with a 0.625-mm, 1-mm, and 2-mm slice thickness were gathered for each patient.

The scans were processed using commercial software packages. Because of the high variability of curvature and embedding in complex anatomical scenes with other vessels interference, the pulmary artery segmentation using the software tools required a clear understanding of the patient’s anatomy, which took 4-8 hours for the experienced operator, according to the researchers.

After further computer processing of the virtual reconstructed pulmonary model, it was sent to the 3-D printer, which used a rubberlike material that is elastic and semitransparent, behaving similarly to polyurethane.

The 10 unique models were successfully created with no print failures, although the original plan of using a 1-mm mural thickness proved too fragile, so the entire group was printed with a 1.5-mm wall. The design process took 8 hours from CT image to stereolithographic model, and printing required an overall total of 97 hours, according to the report published online in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery [doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.12.059].

Accurate models of individual patients’ anatomy

The physical measurements of the model were accurate for clinical purposes, with the 95% confidence levels for the 10 models demonstrating equivalence. Anatomic measurements using this process could be useful for general pulmonary artery catheter design, according to the authors. These measurements showed sufficient similarity for a design to be created that would be effective for most patients, although this finding would have to be validated with a larger sample of patients.

“While many of the measurements could have been made with software analysis of the 3-D files, some measurements were greatly facilitated by bending the model and aligning the physical catheter. These measurements represent distance beyond which a catheter might cause damage,” they added.

Biological 3-D printing of organs

Gut is a perfect beginning project for 3-D printing, Dr. John Geibel said at the 2015 American Gastroenterological Association Tech Summit, which was sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology. It has a very simple shape – just a long hollow tube. Epithelial cells grow and turn over very quickly, suggesting that a length of artificial intestine could be grown relatively quickly. And although intestine is composed of a number of distinct layers, a 3-D bioprinter would have no trouble laying down concentric circles of each one to recreate their natural morphology.

“It will take time. It will take planning. But this is going to happen,” said Dr. Geibel of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

To create a length of intestine, the print heads of a bioprinter would be loaded with cells from all of the gut layers – the serosa, the different muscle strata, the mucosa. Each would be laid down in its respective anatomic ring, supported all around by a hydrogel. The print sequence would be repeated over and over until the required length of intestine was created. From then, Dr. Geibel said, it would be only a matter of days before the cells knit themselves together so well that the gel could be dissolved and the new tissue ready for transplant.

Liver would likely be the next organ up for printing, with the ultimate goal of creating fully transplantable organs. The need is enormous, and can’t be overstated. Patients who need a new liver wait an average of 4 years before they receive one.

The liver is much more complicated than a length of gut. It is cellularly complex and highly vascularized. But liver-printing is already a reality. Bioprinted “3-D liver-in-a-dish,” created by San Diego–based Organovo, has function, if not form. The cells work together; they grow, divide, and secrete bile acids. However, they exist as a formless, nonvascular blob.

As it stands (or rather, lies) now, bioprinted liver is a perfect preclinical model – perfectly replicating how the liver would respond to drugs without any of the messy adverse events that hurt patients. But it needs some backbone, or more accurately, some matrix, in order to morph again and grow into a complete organ. A liver-shaped collagen matrix could provide the necessary frame for cells to grow in and around; tunnels through it would form pathways for a similarly engineered vasculature.

The project to create 3-D models of pulmonary arteries is one of many ongoing efforts in this field. “Going forward, this technology competes with virtual educational media for health care professionals, trainees, and patients. Complex anatomy can be visualized easily on a scale model at the operating table (rather than by manipulating a nonsterile pointing device on a computer). The [pulmonary arteries] we printed could be used in a relatively low-cost lifelike [video-assisted thoracoscopic] lobectomy trainer,” the authors stated, while acknowledging the current issue of cost and time.

Printing services were funded by an unrestricted grant from Incodema3D, which employs Dan Sammons, one of the authors of the study. The other authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

The emergence of 3-D printing is beginning to look like a case of ‘disruptive medicine.’ Exploratory research in this area is ongoing in cardiology and orthopaedic and plastic surgery, and the experimental applications multiply daily.

Currently, 3-D printed models are being used for simulation training, preprocedural planning, development of personalized surgical equipment, and in a few cases, temporary structures for insertion in patients. As 3-D printers become cheaper, costs for their use in medicine are expected to decline

This rapidly developing technology is being applied in cardiothoracic surgery. The 3-D printing technology was used to construct flexible 3-D models of 10 human patient pulmonary arteries as part of a project to develop a new delivery catheter for regional lung chemotherapy.

Computed tomography and CT angiography in combination with software-driven segmentation techniques were used for generation and adjustment of 3-D polygon mesh to form reconstructed models of the pulmonary arteries. The reconstructed models were exported as stereolithographic data sets and further processed, according to Sergei N. Kurenov of the department of thoracic surgery, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, N.Y., and his colleagues.

How the process works

In this process, producing the anatomical pulmonary artery models required a series of steps: data acquisition from the patient CT digital data, 3-D visualization and segmentation, surface rendering and creating a 3-D polygon mesh, geometrical surface preparation – simplification, refinement, and geometry fixing, and the hollowing of an existing volume to “thicken” the walls.

Three contrast CT data sets with a 0.625-mm, 1-mm, and 2-mm slice thickness were gathered for each patient.

The scans were processed using commercial software packages. Because of the high variability of curvature and embedding in complex anatomical scenes with other vessels interference, the pulmary artery segmentation using the software tools required a clear understanding of the patient’s anatomy, which took 4-8 hours for the experienced operator, according to the researchers.

After further computer processing of the virtual reconstructed pulmonary model, it was sent to the 3-D printer, which used a rubberlike material that is elastic and semitransparent, behaving similarly to polyurethane.

The 10 unique models were successfully created with no print failures, although the original plan of using a 1-mm mural thickness proved too fragile, so the entire group was printed with a 1.5-mm wall. The design process took 8 hours from CT image to stereolithographic model, and printing required an overall total of 97 hours, according to the report published online in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery [doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.12.059].

Accurate models of individual patients’ anatomy

The physical measurements of the model were accurate for clinical purposes, with the 95% confidence levels for the 10 models demonstrating equivalence. Anatomic measurements using this process could be useful for general pulmonary artery catheter design, according to the authors. These measurements showed sufficient similarity for a design to be created that would be effective for most patients, although this finding would have to be validated with a larger sample of patients.

“While many of the measurements could have been made with software analysis of the 3-D files, some measurements were greatly facilitated by bending the model and aligning the physical catheter. These measurements represent distance beyond which a catheter might cause damage,” they added.

Biological 3-D printing of organs

Gut is a perfect beginning project for 3-D printing, Dr. John Geibel said at the 2015 American Gastroenterological Association Tech Summit, which was sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology. It has a very simple shape – just a long hollow tube. Epithelial cells grow and turn over very quickly, suggesting that a length of artificial intestine could be grown relatively quickly. And although intestine is composed of a number of distinct layers, a 3-D bioprinter would have no trouble laying down concentric circles of each one to recreate their natural morphology.

“It will take time. It will take planning. But this is going to happen,” said Dr. Geibel of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

To create a length of intestine, the print heads of a bioprinter would be loaded with cells from all of the gut layers – the serosa, the different muscle strata, the mucosa. Each would be laid down in its respective anatomic ring, supported all around by a hydrogel. The print sequence would be repeated over and over until the required length of intestine was created. From then, Dr. Geibel said, it would be only a matter of days before the cells knit themselves together so well that the gel could be dissolved and the new tissue ready for transplant.

Liver would likely be the next organ up for printing, with the ultimate goal of creating fully transplantable organs. The need is enormous, and can’t be overstated. Patients who need a new liver wait an average of 4 years before they receive one.

The liver is much more complicated than a length of gut. It is cellularly complex and highly vascularized. But liver-printing is already a reality. Bioprinted “3-D liver-in-a-dish,” created by San Diego–based Organovo, has function, if not form. The cells work together; they grow, divide, and secrete bile acids. However, they exist as a formless, nonvascular blob.

As it stands (or rather, lies) now, bioprinted liver is a perfect preclinical model – perfectly replicating how the liver would respond to drugs without any of the messy adverse events that hurt patients. But it needs some backbone, or more accurately, some matrix, in order to morph again and grow into a complete organ. A liver-shaped collagen matrix could provide the necessary frame for cells to grow in and around; tunnels through it would form pathways for a similarly engineered vasculature.

The project to create 3-D models of pulmonary arteries is one of many ongoing efforts in this field. “Going forward, this technology competes with virtual educational media for health care professionals, trainees, and patients. Complex anatomy can be visualized easily on a scale model at the operating table (rather than by manipulating a nonsterile pointing device on a computer). The [pulmonary arteries] we printed could be used in a relatively low-cost lifelike [video-assisted thoracoscopic] lobectomy trainer,” the authors stated, while acknowledging the current issue of cost and time.

Printing services were funded by an unrestricted grant from Incodema3D, which employs Dan Sammons, one of the authors of the study. The other authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

Palliative surgery eases pain at end of life

HOUSTON – Palliative surgery can alleviate pain and improve the quality of life for patients dying from advanced cancers, without compromising performance status, a study showed.

Among 202 patients with stage III or IV cancers who underwent surgery with palliation as the goal, pain scores were significantly improved after surgery, while Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) scores remained unchanged, said Dr. Anne Falor, a surgical oncology fellow at City of Hope in Duarte, Calif.

“Surgical oncology has not been historically involved in palliative care. If a patient is deemed unresectable, his or her treatment is often the purview of medical or radiation oncology,” she said at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium.

But for patients who are likely to have prolonged disease-free intervals, palliative surgery can be performed with low morbidity, she said.

Dr. Falor and her colleagues reviewed their center’s experience with palliative surgery in 2011, during which time 202 patients with a predicted 5-year survival of less than 5% underwent a total of 247 palliative procedures.

The patients had malignancies at various sites, including the large intestine, lung, stomach, breast, prostate, lymph nodes, esophagus, pancreas, and ovaries.

The primary indications for the procedure included dysphagia, pain/wound problems, dyspnea, nausea and vomiting, and dysuria.

Most of the patients (83%) had a single procedure, but 13% had two operations, 4% had three operations, 1% had four procedures, and 0.4% had five or more interventions.

The majority of procedures performed were endoscopic interventions characterized as minor in nature, followed by minor genitourinary and thoracic interventions, although a nearly equal proportion of thoracic interventions (about 28%) were major procedures such as diverting ostomy.

When the investigators looked at 30-day outcomes following palliative surgery, they found that only 13% of patients needed an urgent care visit, 2% required a triage call, 22% were readmitted, and 60% had an institutional supportive care referral.

Total 30-day morbidity of any kind was seen in 37% of patients; 15% of patients died within 30 days of surgery.

Looking at quality of life outcomes, the investigators found no differences in the percentage of patients with KPS scores from 80 to 100 between the presurgery and postsurgery periods (78% and 70%, respectively, P = ns).

There were significant improvements, however, in pain scores, which dropped by a mean of 1.2 points from the preoperative period to discharge (P < .0001), and decreased by 0.6 points before surgery to the first follow-up visit (P = .0037).

Dr. Falor said that it’s important for patients and their care team to have a discussion regarding expectations for surgery and the goals of care.

The study was internally funded. Dr. Falor reported having no conflicts of interest.