User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

Fresh Press: ACS Surgery News April digital issue is available

The April issue of ACS Surgery News is available online. Use the mobile app to download or view as a pdf.

This month’s issue features a story on an underrecognized problem among surgeons: chronic pain in the hands, neck, and back due to long hours of operating. In a related story, the AAOS has issued guidelines on, and rated the strength of, evidence for treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome.

Don’t miss the commentary from Dr. Layton F. Rikkers, Editor-in-Chief of ACS Surgery News, on the value of input from the quiet or introverted members of a team, and how to elicit their participation.

The April issue of ACS Surgery News is available online. Use the mobile app to download or view as a pdf.

This month’s issue features a story on an underrecognized problem among surgeons: chronic pain in the hands, neck, and back due to long hours of operating. In a related story, the AAOS has issued guidelines on, and rated the strength of, evidence for treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome.

Don’t miss the commentary from Dr. Layton F. Rikkers, Editor-in-Chief of ACS Surgery News, on the value of input from the quiet or introverted members of a team, and how to elicit their participation.

The April issue of ACS Surgery News is available online. Use the mobile app to download or view as a pdf.

This month’s issue features a story on an underrecognized problem among surgeons: chronic pain in the hands, neck, and back due to long hours of operating. In a related story, the AAOS has issued guidelines on, and rated the strength of, evidence for treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome.

Don’t miss the commentary from Dr. Layton F. Rikkers, Editor-in-Chief of ACS Surgery News, on the value of input from the quiet or introverted members of a team, and how to elicit their participation.

UnitedHealth Group leaving most ACA marketplaces

UnitedHealth Group will not sell policies next year in most of the health insurance marketplaces created by the Affordable Care Act, CEO Stephen Helmsley announced during an April 19 earnings call.

“Next year, we will remain in only a handful of states, and we will not carry financial exposure from exchanges into 2017,” Mr. Helmsley said, citing the company’s inability to offset the “shorter-term, higher-risk” population covered by the ACA exchange plans with large enough risk pools.

Mr. Helmsley did not say in which state marketplaces UnitedHealth Group (UHG) will continue to offer coverage.

Areas that could be hardest hit by the UHG withdrawal include Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Nebraska, North Carolina, and Tennessee, according to an analysis from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

For now, the decision by UHG is not likely to impact the average benchmark premium by more than a 1% increase, according to the analysis. That’s because the insurer was less likely than its competitors to offer lower-cost silver plans; when silver plans were offered, they were offered at or very near to the competitors’ prices. However, in states where the withdrawal of UHG means that two or fewer insurers are participating in the marketplace, benchmark premiums could rise substantially, according to the study.

The long-term effect of the UHG exit from most marketplaces is not clear, according to Kaiser’s analysts. “In areas with limited insurer participation, the remaining plans after a United exit may have more market power relative to providers, but in the absence of insurer competition, those savings may not be passed along to consumers,” they wrote.

ACA measures such as rate reviews and medical loss ratio provisions could mitigate adverse effects on consumers in these markets, giving regulators the power to force insurers to issue rebates if premiums outstrip the cost of care.

The insurer’s decision is simply evidence that typical market forces are in play, according to Jonathan Gold, a spokesperson for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

“As with any new market, we expect changes and adjustments in the early years with issuers both entering and exiting states,” Mr. Gold said in an interview. The UHG decision was not unexpected, as company officials said they were contemplating the move last November.

“We have full confidence, based on data, that the marketplaces will continue to thrive for years ahead,” he said, noting that in 2016, 39 insurers exited the marketplace, while 40 entered.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

UnitedHealth Group will not sell policies next year in most of the health insurance marketplaces created by the Affordable Care Act, CEO Stephen Helmsley announced during an April 19 earnings call.

“Next year, we will remain in only a handful of states, and we will not carry financial exposure from exchanges into 2017,” Mr. Helmsley said, citing the company’s inability to offset the “shorter-term, higher-risk” population covered by the ACA exchange plans with large enough risk pools.

Mr. Helmsley did not say in which state marketplaces UnitedHealth Group (UHG) will continue to offer coverage.

Areas that could be hardest hit by the UHG withdrawal include Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Nebraska, North Carolina, and Tennessee, according to an analysis from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

For now, the decision by UHG is not likely to impact the average benchmark premium by more than a 1% increase, according to the analysis. That’s because the insurer was less likely than its competitors to offer lower-cost silver plans; when silver plans were offered, they were offered at or very near to the competitors’ prices. However, in states where the withdrawal of UHG means that two or fewer insurers are participating in the marketplace, benchmark premiums could rise substantially, according to the study.

The long-term effect of the UHG exit from most marketplaces is not clear, according to Kaiser’s analysts. “In areas with limited insurer participation, the remaining plans after a United exit may have more market power relative to providers, but in the absence of insurer competition, those savings may not be passed along to consumers,” they wrote.

ACA measures such as rate reviews and medical loss ratio provisions could mitigate adverse effects on consumers in these markets, giving regulators the power to force insurers to issue rebates if premiums outstrip the cost of care.

The insurer’s decision is simply evidence that typical market forces are in play, according to Jonathan Gold, a spokesperson for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

“As with any new market, we expect changes and adjustments in the early years with issuers both entering and exiting states,” Mr. Gold said in an interview. The UHG decision was not unexpected, as company officials said they were contemplating the move last November.

“We have full confidence, based on data, that the marketplaces will continue to thrive for years ahead,” he said, noting that in 2016, 39 insurers exited the marketplace, while 40 entered.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

UnitedHealth Group will not sell policies next year in most of the health insurance marketplaces created by the Affordable Care Act, CEO Stephen Helmsley announced during an April 19 earnings call.

“Next year, we will remain in only a handful of states, and we will not carry financial exposure from exchanges into 2017,” Mr. Helmsley said, citing the company’s inability to offset the “shorter-term, higher-risk” population covered by the ACA exchange plans with large enough risk pools.

Mr. Helmsley did not say in which state marketplaces UnitedHealth Group (UHG) will continue to offer coverage.

Areas that could be hardest hit by the UHG withdrawal include Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Nebraska, North Carolina, and Tennessee, according to an analysis from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

For now, the decision by UHG is not likely to impact the average benchmark premium by more than a 1% increase, according to the analysis. That’s because the insurer was less likely than its competitors to offer lower-cost silver plans; when silver plans were offered, they were offered at or very near to the competitors’ prices. However, in states where the withdrawal of UHG means that two or fewer insurers are participating in the marketplace, benchmark premiums could rise substantially, according to the study.

The long-term effect of the UHG exit from most marketplaces is not clear, according to Kaiser’s analysts. “In areas with limited insurer participation, the remaining plans after a United exit may have more market power relative to providers, but in the absence of insurer competition, those savings may not be passed along to consumers,” they wrote.

ACA measures such as rate reviews and medical loss ratio provisions could mitigate adverse effects on consumers in these markets, giving regulators the power to force insurers to issue rebates if premiums outstrip the cost of care.

The insurer’s decision is simply evidence that typical market forces are in play, according to Jonathan Gold, a spokesperson for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

“As with any new market, we expect changes and adjustments in the early years with issuers both entering and exiting states,” Mr. Gold said in an interview. The UHG decision was not unexpected, as company officials said they were contemplating the move last November.

“We have full confidence, based on data, that the marketplaces will continue to thrive for years ahead,” he said, noting that in 2016, 39 insurers exited the marketplace, while 40 entered.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

STAMPEDE: Metabolic surgery bests medical therapy long term

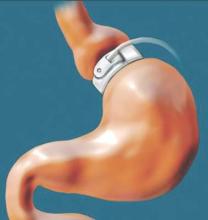

CHICAGO – The superiority of metabolic surgery over intensive medical therapy for achieving glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes was largely maintained at the final 5-year follow-up evaluation in the randomized, controlled STAMPEDE trial.

The 150 subjects, who had “fairly severe diabetes” with an average disease duration of 8 years, were randomized to receive intensive medical therapy alone, or intensive medical therapy with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery or sleeve gastrectomy surgery. The primary endpoint of hemoglobin A1c less than 6% was achieved in 5%, 29%, and 23% of patients in the groups, respectively. The difference was statistically significant in favor of both types of surgery, Dr. Philip Raymond Schauer reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Furthermore, patients in the surgery groups fared better than those in the intensive medical therapy group on several other measures, including disease remission (defied as HbA1c less than 6% without diabetes medication), HbA1c less than 7% (the American Diabetes Association target for therapy), change in fasting plasma glucose from baseline, and changes in high- and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, said Dr. Schauer, director of the Cleveland Clinic Bariatric and Metabolic Institute.

Patients in the surgery groups also experienced a significantly greater reduction in the use of antihypertensive medications and lipid-lowering agents, he added.

The “very dramatic drop” in HbA1c seen early on in the surgical patients was, for the most part, sustained out to 5 years, he said.

The results for both surgeries were significantly better than those for intensive medical therapy, but the results with gastric bypass were more effective at 5 years than were those for sleeve gastrectomy, he added, noting that the surgery patients had better quality of life, compared with the intensive medical therapy patients.

As for adverse events in the surgery groups, no perioperative deaths occurred, and while there were some surgical complications, none resulted in long-term disability, Dr. Schauer said.

Anemia was more common in the surgery patients, but was fairly mild. The most common complication was weight gain in 20% of patients, and the overall reoperation rate was 7%.

Of note, patients in the study had body mass index ranging from 27 to 43 kg/m2, and those with BMI less than 35 had similar benefits as those with more severe obesity. This is important, as many insurance companies won’t cover metabolic surgery for patients with BMI less than 35, he explained.

These findings represent the longest follow-up to date comparing the efficacy of the two most common metabolic surgery procedures with medical treatment of type 2 diabetes for maintaining glycemic control or reducing end-organ complications. Three-year outcomes of STAMPEDE (Surgical Treatment and Medications Potentially Eradicate Diabetes Efficiently) were reported in 2014 (N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2002-13).

The participants ranged in age from 20 to 60 years. The average HbA1c was about 9%, the average BMI was 36, and most were on at least three antidiabetic medications at baseline. Half were on insulin.

The findings are important, because of the roughly 25 million Americans with type 2 diabetes, only about half have good glycemic control on their current medical treatment strategies, Dr. Schauer said.

Though limited by the single-center study design, the STAMPEDE findings show that metabolic surgery is more effective long term than intensive medical therapy in patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes and should be considered a treatment option in this population, he concluded, adding that multicenter studies would be helpful for determining the generalizability of the findings.

Dr. Schauer reported receiving consulting fees/honoraria from Ethicon Endosurgery and The Medicines Company, and having ownership interest in Surgical Excellence.

CHICAGO – The superiority of metabolic surgery over intensive medical therapy for achieving glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes was largely maintained at the final 5-year follow-up evaluation in the randomized, controlled STAMPEDE trial.

The 150 subjects, who had “fairly severe diabetes” with an average disease duration of 8 years, were randomized to receive intensive medical therapy alone, or intensive medical therapy with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery or sleeve gastrectomy surgery. The primary endpoint of hemoglobin A1c less than 6% was achieved in 5%, 29%, and 23% of patients in the groups, respectively. The difference was statistically significant in favor of both types of surgery, Dr. Philip Raymond Schauer reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Furthermore, patients in the surgery groups fared better than those in the intensive medical therapy group on several other measures, including disease remission (defied as HbA1c less than 6% without diabetes medication), HbA1c less than 7% (the American Diabetes Association target for therapy), change in fasting plasma glucose from baseline, and changes in high- and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, said Dr. Schauer, director of the Cleveland Clinic Bariatric and Metabolic Institute.

Patients in the surgery groups also experienced a significantly greater reduction in the use of antihypertensive medications and lipid-lowering agents, he added.

The “very dramatic drop” in HbA1c seen early on in the surgical patients was, for the most part, sustained out to 5 years, he said.

The results for both surgeries were significantly better than those for intensive medical therapy, but the results with gastric bypass were more effective at 5 years than were those for sleeve gastrectomy, he added, noting that the surgery patients had better quality of life, compared with the intensive medical therapy patients.

As for adverse events in the surgery groups, no perioperative deaths occurred, and while there were some surgical complications, none resulted in long-term disability, Dr. Schauer said.

Anemia was more common in the surgery patients, but was fairly mild. The most common complication was weight gain in 20% of patients, and the overall reoperation rate was 7%.

Of note, patients in the study had body mass index ranging from 27 to 43 kg/m2, and those with BMI less than 35 had similar benefits as those with more severe obesity. This is important, as many insurance companies won’t cover metabolic surgery for patients with BMI less than 35, he explained.

These findings represent the longest follow-up to date comparing the efficacy of the two most common metabolic surgery procedures with medical treatment of type 2 diabetes for maintaining glycemic control or reducing end-organ complications. Three-year outcomes of STAMPEDE (Surgical Treatment and Medications Potentially Eradicate Diabetes Efficiently) were reported in 2014 (N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2002-13).

The participants ranged in age from 20 to 60 years. The average HbA1c was about 9%, the average BMI was 36, and most were on at least three antidiabetic medications at baseline. Half were on insulin.

The findings are important, because of the roughly 25 million Americans with type 2 diabetes, only about half have good glycemic control on their current medical treatment strategies, Dr. Schauer said.

Though limited by the single-center study design, the STAMPEDE findings show that metabolic surgery is more effective long term than intensive medical therapy in patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes and should be considered a treatment option in this population, he concluded, adding that multicenter studies would be helpful for determining the generalizability of the findings.

Dr. Schauer reported receiving consulting fees/honoraria from Ethicon Endosurgery and The Medicines Company, and having ownership interest in Surgical Excellence.

CHICAGO – The superiority of metabolic surgery over intensive medical therapy for achieving glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes was largely maintained at the final 5-year follow-up evaluation in the randomized, controlled STAMPEDE trial.

The 150 subjects, who had “fairly severe diabetes” with an average disease duration of 8 years, were randomized to receive intensive medical therapy alone, or intensive medical therapy with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery or sleeve gastrectomy surgery. The primary endpoint of hemoglobin A1c less than 6% was achieved in 5%, 29%, and 23% of patients in the groups, respectively. The difference was statistically significant in favor of both types of surgery, Dr. Philip Raymond Schauer reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Furthermore, patients in the surgery groups fared better than those in the intensive medical therapy group on several other measures, including disease remission (defied as HbA1c less than 6% without diabetes medication), HbA1c less than 7% (the American Diabetes Association target for therapy), change in fasting plasma glucose from baseline, and changes in high- and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, said Dr. Schauer, director of the Cleveland Clinic Bariatric and Metabolic Institute.

Patients in the surgery groups also experienced a significantly greater reduction in the use of antihypertensive medications and lipid-lowering agents, he added.

The “very dramatic drop” in HbA1c seen early on in the surgical patients was, for the most part, sustained out to 5 years, he said.

The results for both surgeries were significantly better than those for intensive medical therapy, but the results with gastric bypass were more effective at 5 years than were those for sleeve gastrectomy, he added, noting that the surgery patients had better quality of life, compared with the intensive medical therapy patients.

As for adverse events in the surgery groups, no perioperative deaths occurred, and while there were some surgical complications, none resulted in long-term disability, Dr. Schauer said.

Anemia was more common in the surgery patients, but was fairly mild. The most common complication was weight gain in 20% of patients, and the overall reoperation rate was 7%.

Of note, patients in the study had body mass index ranging from 27 to 43 kg/m2, and those with BMI less than 35 had similar benefits as those with more severe obesity. This is important, as many insurance companies won’t cover metabolic surgery for patients with BMI less than 35, he explained.

These findings represent the longest follow-up to date comparing the efficacy of the two most common metabolic surgery procedures with medical treatment of type 2 diabetes for maintaining glycemic control or reducing end-organ complications. Three-year outcomes of STAMPEDE (Surgical Treatment and Medications Potentially Eradicate Diabetes Efficiently) were reported in 2014 (N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2002-13).

The participants ranged in age from 20 to 60 years. The average HbA1c was about 9%, the average BMI was 36, and most were on at least three antidiabetic medications at baseline. Half were on insulin.

The findings are important, because of the roughly 25 million Americans with type 2 diabetes, only about half have good glycemic control on their current medical treatment strategies, Dr. Schauer said.

Though limited by the single-center study design, the STAMPEDE findings show that metabolic surgery is more effective long term than intensive medical therapy in patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes and should be considered a treatment option in this population, he concluded, adding that multicenter studies would be helpful for determining the generalizability of the findings.

Dr. Schauer reported receiving consulting fees/honoraria from Ethicon Endosurgery and The Medicines Company, and having ownership interest in Surgical Excellence.

AT ACC 16

Key clinical point: The superiority of metabolic surgery over intensive medical therapy for achieving glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes in the randomized, controlled STAMPEDE persisted at the final 5-year follow-up evaluation.

Major finding: The primary endpoint of HbA1c less than 6% was achieved in 5%, 29%, and 23% of patients in the medication and medication plus Roux-en-Y or sleeve gastrectomy groups, respectively.

Data source: The randomized, controlled STAMPEDE trial in 150 subjects.

Disclosures: Dr. Schauer reported receiving consulting fees/honoraria from Ethicon Endosurgery and The Medicines Company, and having ownership interest in Surgical Excellence.

Apply now for the 2016 Claude H. Organ, Jr., MD, FACS, Traveling Fellowship

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) is now accepting applications for the 2016 Claude H. Organ, Jr., MD, FACS, Traveling Fellowship. The deadline for all application materials is June 1.

The family and friends of the late Dr. Organ established an endowment through the ACS Foundation to provide funding for this fellowship, which is awarded annually to an outstanding young surgeon from the Society of Black Academic Surgeons, the Association of Women Surgeons, or the Surgical Section of the National Medical Association. The fellowship, in the amount of $5,000, enables a U.S. or Canadian Fellow or Associate Fellow younger than age 45 who is a member of one of these societies to attend an educational meeting or participate in an extended visit to an institution of his or her choice, tailored to his or her research interests.

Past awardees have used their fellowships to develop their careers in creative ways. The most recent fellow, Kathie-Ann Joseph, MD, MPH, FACS, associate professor of surgery, New York University School of Medicine, and chief of surgery, Bellevue Hospital Center, New York, NY, is researching how health care systems work in a major metropolitan area, with a focus on the ways that large hospitals systems manage care for underserved women.

The full requirements for the Claude H. Organ, Jr., MD, FACS, Traveling Fellowship are posted at facs.org/member-services/scholarships/special/organ. The 2016 awardee will be informed of the College’s decision by August 2016. Questions and application materials should be submitted to the attention of Kate Early, ACS Scholarships Administrator, at [email protected].

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) is now accepting applications for the 2016 Claude H. Organ, Jr., MD, FACS, Traveling Fellowship. The deadline for all application materials is June 1.

The family and friends of the late Dr. Organ established an endowment through the ACS Foundation to provide funding for this fellowship, which is awarded annually to an outstanding young surgeon from the Society of Black Academic Surgeons, the Association of Women Surgeons, or the Surgical Section of the National Medical Association. The fellowship, in the amount of $5,000, enables a U.S. or Canadian Fellow or Associate Fellow younger than age 45 who is a member of one of these societies to attend an educational meeting or participate in an extended visit to an institution of his or her choice, tailored to his or her research interests.

Past awardees have used their fellowships to develop their careers in creative ways. The most recent fellow, Kathie-Ann Joseph, MD, MPH, FACS, associate professor of surgery, New York University School of Medicine, and chief of surgery, Bellevue Hospital Center, New York, NY, is researching how health care systems work in a major metropolitan area, with a focus on the ways that large hospitals systems manage care for underserved women.

The full requirements for the Claude H. Organ, Jr., MD, FACS, Traveling Fellowship are posted at facs.org/member-services/scholarships/special/organ. The 2016 awardee will be informed of the College’s decision by August 2016. Questions and application materials should be submitted to the attention of Kate Early, ACS Scholarships Administrator, at [email protected].

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) is now accepting applications for the 2016 Claude H. Organ, Jr., MD, FACS, Traveling Fellowship. The deadline for all application materials is June 1.

The family and friends of the late Dr. Organ established an endowment through the ACS Foundation to provide funding for this fellowship, which is awarded annually to an outstanding young surgeon from the Society of Black Academic Surgeons, the Association of Women Surgeons, or the Surgical Section of the National Medical Association. The fellowship, in the amount of $5,000, enables a U.S. or Canadian Fellow or Associate Fellow younger than age 45 who is a member of one of these societies to attend an educational meeting or participate in an extended visit to an institution of his or her choice, tailored to his or her research interests.

Past awardees have used their fellowships to develop their careers in creative ways. The most recent fellow, Kathie-Ann Joseph, MD, MPH, FACS, associate professor of surgery, New York University School of Medicine, and chief of surgery, Bellevue Hospital Center, New York, NY, is researching how health care systems work in a major metropolitan area, with a focus on the ways that large hospitals systems manage care for underserved women.

The full requirements for the Claude H. Organ, Jr., MD, FACS, Traveling Fellowship are posted at facs.org/member-services/scholarships/special/organ. The 2016 awardee will be informed of the College’s decision by August 2016. Questions and application materials should be submitted to the attention of Kate Early, ACS Scholarships Administrator, at [email protected].

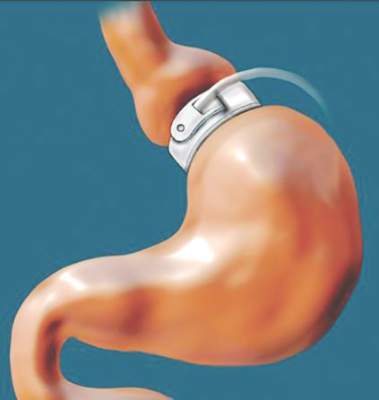

Earlier bariatric surgery may improve cardiovascular outcomes

CHICAGO – Sooner may be better than later when it comes to the timing of bariatric surgery in patients with morbid obesity.

Of 828 patients with body mass index of at least 35 kg/m2 who underwent laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding performed by a single surgeon and were followed for up to 11 years (mean of 10 years), 423 were aged 45 years or younger, and 405 were over age 45 years at the time of surgery. A comparison of outcomes between the two age groups showed that older age at the time of surgery was an independent predictor of cardiovascular events (hazard ratio, 1.8), Maharaj Singh, Ph.D., a biostatistician at the Aurora Research Institute, Milwaukee, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Despite a similar reduction in body weight after gastric banding surgery, the older patients experienced more cardiovascular events: myocardial infarction occurred in 0.2% and 1.7% of patients in the younger and older age groups, respectively, pulmonary embolism occurred in 0.7% and 4.3%, congestive heart failure occurred in 2.8% and 7.8%, and stroke occurred in 3.7% and 7.6%, Dr. Singh said.

“Although the older group had more comorbidities, these were accounted for by multivariate analysis and age over 45 years remained an independent predictor of poor cardiovascular outcomes,” senior coauthor Dr. Arshad Jahangir, professor of medicine at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said in an interview.

Other independent predictors of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in the study were sleep apnea (hazard ratio, 4), history of hypertension (HR, 1.9), and depression, (HR, 1.8), Dr. Jahangir said.

“Gender, race, and diabetes mellitus did not independently predict cardiovascular events,” he said.

Weight loss after bariatric surgery has been shown to reduce the risk of adverse cardiovascular events, but it has remained unclear whether the reduction in risk varies based on age at the time of surgery, he said.

The current findings suggest that the effects of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding–induced weight loss on cardiovascular outcomes are greater in patients who undergo the surgery at a younger age, he said, adding that the findings also “raise important questions about whether better control of sleep apnea, hypertension, and depression could help further reduce cardiovascular events in morbidly obese individuals undergoing bariatric surgery and should be addressed in a prospective study of these patients.”

The authors reported having no disclosures.

CHICAGO – Sooner may be better than later when it comes to the timing of bariatric surgery in patients with morbid obesity.

Of 828 patients with body mass index of at least 35 kg/m2 who underwent laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding performed by a single surgeon and were followed for up to 11 years (mean of 10 years), 423 were aged 45 years or younger, and 405 were over age 45 years at the time of surgery. A comparison of outcomes between the two age groups showed that older age at the time of surgery was an independent predictor of cardiovascular events (hazard ratio, 1.8), Maharaj Singh, Ph.D., a biostatistician at the Aurora Research Institute, Milwaukee, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Despite a similar reduction in body weight after gastric banding surgery, the older patients experienced more cardiovascular events: myocardial infarction occurred in 0.2% and 1.7% of patients in the younger and older age groups, respectively, pulmonary embolism occurred in 0.7% and 4.3%, congestive heart failure occurred in 2.8% and 7.8%, and stroke occurred in 3.7% and 7.6%, Dr. Singh said.

“Although the older group had more comorbidities, these were accounted for by multivariate analysis and age over 45 years remained an independent predictor of poor cardiovascular outcomes,” senior coauthor Dr. Arshad Jahangir, professor of medicine at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said in an interview.

Other independent predictors of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in the study were sleep apnea (hazard ratio, 4), history of hypertension (HR, 1.9), and depression, (HR, 1.8), Dr. Jahangir said.

“Gender, race, and diabetes mellitus did not independently predict cardiovascular events,” he said.

Weight loss after bariatric surgery has been shown to reduce the risk of adverse cardiovascular events, but it has remained unclear whether the reduction in risk varies based on age at the time of surgery, he said.

The current findings suggest that the effects of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding–induced weight loss on cardiovascular outcomes are greater in patients who undergo the surgery at a younger age, he said, adding that the findings also “raise important questions about whether better control of sleep apnea, hypertension, and depression could help further reduce cardiovascular events in morbidly obese individuals undergoing bariatric surgery and should be addressed in a prospective study of these patients.”

The authors reported having no disclosures.

CHICAGO – Sooner may be better than later when it comes to the timing of bariatric surgery in patients with morbid obesity.

Of 828 patients with body mass index of at least 35 kg/m2 who underwent laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding performed by a single surgeon and were followed for up to 11 years (mean of 10 years), 423 were aged 45 years or younger, and 405 were over age 45 years at the time of surgery. A comparison of outcomes between the two age groups showed that older age at the time of surgery was an independent predictor of cardiovascular events (hazard ratio, 1.8), Maharaj Singh, Ph.D., a biostatistician at the Aurora Research Institute, Milwaukee, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Despite a similar reduction in body weight after gastric banding surgery, the older patients experienced more cardiovascular events: myocardial infarction occurred in 0.2% and 1.7% of patients in the younger and older age groups, respectively, pulmonary embolism occurred in 0.7% and 4.3%, congestive heart failure occurred in 2.8% and 7.8%, and stroke occurred in 3.7% and 7.6%, Dr. Singh said.

“Although the older group had more comorbidities, these were accounted for by multivariate analysis and age over 45 years remained an independent predictor of poor cardiovascular outcomes,” senior coauthor Dr. Arshad Jahangir, professor of medicine at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said in an interview.

Other independent predictors of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in the study were sleep apnea (hazard ratio, 4), history of hypertension (HR, 1.9), and depression, (HR, 1.8), Dr. Jahangir said.

“Gender, race, and diabetes mellitus did not independently predict cardiovascular events,” he said.

Weight loss after bariatric surgery has been shown to reduce the risk of adverse cardiovascular events, but it has remained unclear whether the reduction in risk varies based on age at the time of surgery, he said.

The current findings suggest that the effects of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding–induced weight loss on cardiovascular outcomes are greater in patients who undergo the surgery at a younger age, he said, adding that the findings also “raise important questions about whether better control of sleep apnea, hypertension, and depression could help further reduce cardiovascular events in morbidly obese individuals undergoing bariatric surgery and should be addressed in a prospective study of these patients.”

The authors reported having no disclosures.

AT ACC 16

Key clinical point: Morbidly obese patients who underwent bariatric surgery before age 45 years had a reduced risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes vs. those aged 45 or older at the time of surgery, despite similar weight loss.

Major finding: Older vs. younger age at the time of surgery was an independent predictor of cardiovascular events (hazard ratio, 1.8).

Data source: A review of outcomes in 828 laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding patients.

Disclosures: The authors reported having no disclosures.

Dispensing with expert testimony

Question: When a doctor could not find a dislodged biopsy guide wire, he abandoned his search after informing the patient of his intention to retrieve it at a later date. Two months later, he was successful in locating and removing the foreign body, but the patient alleged she suffered pain and anxiety in the interim. She filed a negligence lawsuit and, based on the “obvious” nature of her injuries, called no expert witness to testify on her behalf.

Which of the following choices is best?

A. Expert testimony is always needed to establish the applicable standard of care in medical negligence lawsuits.

B. Although a plaintiff is not qualified to expound on medical matters, he/she can offer evidence from learned treatises and medical texts.

C. The jury is the one who determines whether a plaintiff can invoke either the res ipsa loquitur doctrine or the “common knowledge” rule to obviate the need for an expert witness.

D. This patient will likely win her case.

E. All are incorrect.

Answer: E. It is well-established law that the question of negligence must be decided by reference to relevant medical standards of care for which the plaintiff carries the burden of proving through expert medical testimony. Only a professional, duly qualified by the court as an expert witness, is allowed to offer medical testimony – whereas the plaintiff typically will be disqualified from playing this role because of the complexity of issues involved.

However, under either the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur (“the thing speaks for itself”) or the “common knowledge” rule, a court (i.e., the judge) may allow the jury to infer negligence in the absence of expert testimony.

The res doctrine is invoked where there is only circumstantial but no direct evidence, and three conditions are met: 1) The injury would not have occurred in the absence of someone’s negligence; 2) the plaintiff was not at fault; and 3) the defendant had total control of the instrumentality that led to the injury.

The closely related “common knowledge” rule relies on the everyday knowledge and experience of the layperson to identify plain and obvious negligent conduct, which then allows the judge to waive the expert requirement.

The two principles are frequently used interchangeably, ultimately favoring the plaintiff by dispensing with the difficult and expensive task of securing a qualified expert willing to testify against a doctor defendant.

The best example of res in action is the surgeon who inadvertently leaves behind a sponge or instrument inside a body cavity. Other successfully litigated examples include a cardiac arrest in the operating room, hypoxia in the recovery room, burns to the buttock, gangrene after the accidental injection of penicillin into an artery, air trapped subcutaneously from a displaced needle, and a pierced eyeball during a procedure.

A particularly well-known example is Ybarra v. Spangard, in which the patient developed shoulder injuries during an appendectomy.1 The Supreme Court of California felt it was appropriate to place the burden on the operating room defendants to explain how the patient, unconscious under general anesthesia throughout the procedure, sustained the shoulder injury.

The scenario provided in the opening question is taken from a 2013 New York case, James v. Wormuth, in which the plaintiff relied on the res doctrine.2 The defendant doctor had left a guide wire in the plaintiff’s chest following a biopsy and was unable to locate it after a 20-minute search. However, he was able to retrieve the wire 2 months later under C-arm imaging.

The plaintiff sued the doctor for pain and anxiety, but did not call any expert witness, relying instead on the “foreign object” basis for invoking the res doctrine. The lower court ruled for the doctor, and the court of appeals affirmed.

It reasoned that the object was left behind deliberately, not unintentionally, and that under the circumstances of the case, an expert witness was needed to set out the applicable standard of care, without which a jury could not determine whether the doctor’s professional judgment breached the requisite standard. The court also ruled that the plaintiff failed to satisfy the “exclusive control” requirement of the res doctrine, because several other individuals participated to an extent in the medical procedure.

Hawaii’s case of Barbee v. Queen’s Medical Center is illustrative of the “common knowledge” rule.3 Mr. Barbee, age 75 years, underwent laparoscopic nephrectomy for a malignancy. Massive bleeding complicated his postoperative course, the hemoglobin falling into the 3 range, and he required emergent reoperation. Over the next 18 months, the patient progressively deteriorated, eventually requiring dialysis and dying from a stroke and intestinal volvulus.

Notwithstanding an initial jury verdict in favor of the plaintiff’s children, awarding each of the three children $365,000, the defendants filed a so-called JNOV motion (current term is “judgment as a matter of law”) to negate the jury verdict, on the basis that the plaintiffs failed to present competent expert testimony at trial to prove causation.

The plaintiffs countered that the cause of death was within the realm of common knowledge, thus no expert was necessary. They asserted that “any lay person can easily grasp the concept that a person dies from losing so much blood that multiple organs fail to perform their functions.” Mr. Barbee’s death thus was not “of such a technical nature that lay persons are incompetent to draw their own conclusions from facts presented without aid.”

Hawaii’s Intermediate Court of Appeals disagreed with the plaintiffs, holding that although “Hawaii does recognize a ‘common knowledge’ exception to the requirement that a plaintiff must introduce expert medical testimony on causation … this exception is rare in application.” The court asserted that the causal link between any alleged negligence and Mr. Barbee’s death 17 months later is not within the realm of common knowledge.

It reasoned that the long-term effects of internal bleeding are not so widely known as to be analogous to leaving a sponge within a patient or removing the wrong limb during an amputation. Moreover, Mr. Barbee had a long history of preexisting conditions, including hypertension, diabetes, and cancer. He also suffered numerous and serious postoperative medical conditions, including a stroke and surgery to remove part of his intestine, which had become gangrenous.

Thus, the role that preexisting conditions and/or the subsequent complications of this type played in Mr. Barbee’s death was not within the knowledge of the average layperson.

The “common knowledge” rule is aligned with, though not identical to, the res doctrine, but courts are known to conflate the two legal principles, often using them interchangeably.4

Strictly speaking, the “common knowledge” waiver comes into play where direct evidence of negligent conduct lies within the realm of everyday lay knowledge that the physician had deviated from common practice. It may or may not address the causation issue.

On the other hand, res is successfully invoked when, despite no direct evidence of negligence and causation, the circumstances surrounding the injury are such that the plaintiff’s case can go to the jury without expert testimony.

References

1. Ybarra v. Spangard, 154 P.2d 687 (Cal. 1944).

2. James v. Wormuth, 997 N.E.2d 133 (N.Y. 2013).

3. Barbee v. Queen’s Medical Center, 119 Haw 136 (2008).

4. Spinner, Amanda E. Common Ignorance: Medical Malpractice Law and the Misconceived Application of the “Common Knowledge” and “Res Ipsa Loquitur” Doctrines.” Touro Law Review: Vol. 31: No. 3, Article 15. Available at http://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol31/iss3/15.

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, and currently directs the St. Francis International Center for Healthcare Ethics in Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the articles in this series are adapted from the author’s 2006 book, “Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk,” and his 2012 Halsbury treatise, “Medical Negligence and Professional Misconduct.” For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Question: When a doctor could not find a dislodged biopsy guide wire, he abandoned his search after informing the patient of his intention to retrieve it at a later date. Two months later, he was successful in locating and removing the foreign body, but the patient alleged she suffered pain and anxiety in the interim. She filed a negligence lawsuit and, based on the “obvious” nature of her injuries, called no expert witness to testify on her behalf.

Which of the following choices is best?

A. Expert testimony is always needed to establish the applicable standard of care in medical negligence lawsuits.

B. Although a plaintiff is not qualified to expound on medical matters, he/she can offer evidence from learned treatises and medical texts.

C. The jury is the one who determines whether a plaintiff can invoke either the res ipsa loquitur doctrine or the “common knowledge” rule to obviate the need for an expert witness.

D. This patient will likely win her case.

E. All are incorrect.

Answer: E. It is well-established law that the question of negligence must be decided by reference to relevant medical standards of care for which the plaintiff carries the burden of proving through expert medical testimony. Only a professional, duly qualified by the court as an expert witness, is allowed to offer medical testimony – whereas the plaintiff typically will be disqualified from playing this role because of the complexity of issues involved.

However, under either the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur (“the thing speaks for itself”) or the “common knowledge” rule, a court (i.e., the judge) may allow the jury to infer negligence in the absence of expert testimony.

The res doctrine is invoked where there is only circumstantial but no direct evidence, and three conditions are met: 1) The injury would not have occurred in the absence of someone’s negligence; 2) the plaintiff was not at fault; and 3) the defendant had total control of the instrumentality that led to the injury.

The closely related “common knowledge” rule relies on the everyday knowledge and experience of the layperson to identify plain and obvious negligent conduct, which then allows the judge to waive the expert requirement.

The two principles are frequently used interchangeably, ultimately favoring the plaintiff by dispensing with the difficult and expensive task of securing a qualified expert willing to testify against a doctor defendant.

The best example of res in action is the surgeon who inadvertently leaves behind a sponge or instrument inside a body cavity. Other successfully litigated examples include a cardiac arrest in the operating room, hypoxia in the recovery room, burns to the buttock, gangrene after the accidental injection of penicillin into an artery, air trapped subcutaneously from a displaced needle, and a pierced eyeball during a procedure.

A particularly well-known example is Ybarra v. Spangard, in which the patient developed shoulder injuries during an appendectomy.1 The Supreme Court of California felt it was appropriate to place the burden on the operating room defendants to explain how the patient, unconscious under general anesthesia throughout the procedure, sustained the shoulder injury.

The scenario provided in the opening question is taken from a 2013 New York case, James v. Wormuth, in which the plaintiff relied on the res doctrine.2 The defendant doctor had left a guide wire in the plaintiff’s chest following a biopsy and was unable to locate it after a 20-minute search. However, he was able to retrieve the wire 2 months later under C-arm imaging.

The plaintiff sued the doctor for pain and anxiety, but did not call any expert witness, relying instead on the “foreign object” basis for invoking the res doctrine. The lower court ruled for the doctor, and the court of appeals affirmed.

It reasoned that the object was left behind deliberately, not unintentionally, and that under the circumstances of the case, an expert witness was needed to set out the applicable standard of care, without which a jury could not determine whether the doctor’s professional judgment breached the requisite standard. The court also ruled that the plaintiff failed to satisfy the “exclusive control” requirement of the res doctrine, because several other individuals participated to an extent in the medical procedure.

Hawaii’s case of Barbee v. Queen’s Medical Center is illustrative of the “common knowledge” rule.3 Mr. Barbee, age 75 years, underwent laparoscopic nephrectomy for a malignancy. Massive bleeding complicated his postoperative course, the hemoglobin falling into the 3 range, and he required emergent reoperation. Over the next 18 months, the patient progressively deteriorated, eventually requiring dialysis and dying from a stroke and intestinal volvulus.

Notwithstanding an initial jury verdict in favor of the plaintiff’s children, awarding each of the three children $365,000, the defendants filed a so-called JNOV motion (current term is “judgment as a matter of law”) to negate the jury verdict, on the basis that the plaintiffs failed to present competent expert testimony at trial to prove causation.

The plaintiffs countered that the cause of death was within the realm of common knowledge, thus no expert was necessary. They asserted that “any lay person can easily grasp the concept that a person dies from losing so much blood that multiple organs fail to perform their functions.” Mr. Barbee’s death thus was not “of such a technical nature that lay persons are incompetent to draw their own conclusions from facts presented without aid.”

Hawaii’s Intermediate Court of Appeals disagreed with the plaintiffs, holding that although “Hawaii does recognize a ‘common knowledge’ exception to the requirement that a plaintiff must introduce expert medical testimony on causation … this exception is rare in application.” The court asserted that the causal link between any alleged negligence and Mr. Barbee’s death 17 months later is not within the realm of common knowledge.

It reasoned that the long-term effects of internal bleeding are not so widely known as to be analogous to leaving a sponge within a patient or removing the wrong limb during an amputation. Moreover, Mr. Barbee had a long history of preexisting conditions, including hypertension, diabetes, and cancer. He also suffered numerous and serious postoperative medical conditions, including a stroke and surgery to remove part of his intestine, which had become gangrenous.

Thus, the role that preexisting conditions and/or the subsequent complications of this type played in Mr. Barbee’s death was not within the knowledge of the average layperson.

The “common knowledge” rule is aligned with, though not identical to, the res doctrine, but courts are known to conflate the two legal principles, often using them interchangeably.4

Strictly speaking, the “common knowledge” waiver comes into play where direct evidence of negligent conduct lies within the realm of everyday lay knowledge that the physician had deviated from common practice. It may or may not address the causation issue.

On the other hand, res is successfully invoked when, despite no direct evidence of negligence and causation, the circumstances surrounding the injury are such that the plaintiff’s case can go to the jury without expert testimony.

References

1. Ybarra v. Spangard, 154 P.2d 687 (Cal. 1944).

2. James v. Wormuth, 997 N.E.2d 133 (N.Y. 2013).

3. Barbee v. Queen’s Medical Center, 119 Haw 136 (2008).

4. Spinner, Amanda E. Common Ignorance: Medical Malpractice Law and the Misconceived Application of the “Common Knowledge” and “Res Ipsa Loquitur” Doctrines.” Touro Law Review: Vol. 31: No. 3, Article 15. Available at http://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol31/iss3/15.

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, and currently directs the St. Francis International Center for Healthcare Ethics in Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the articles in this series are adapted from the author’s 2006 book, “Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk,” and his 2012 Halsbury treatise, “Medical Negligence and Professional Misconduct.” For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Question: When a doctor could not find a dislodged biopsy guide wire, he abandoned his search after informing the patient of his intention to retrieve it at a later date. Two months later, he was successful in locating and removing the foreign body, but the patient alleged she suffered pain and anxiety in the interim. She filed a negligence lawsuit and, based on the “obvious” nature of her injuries, called no expert witness to testify on her behalf.

Which of the following choices is best?

A. Expert testimony is always needed to establish the applicable standard of care in medical negligence lawsuits.

B. Although a plaintiff is not qualified to expound on medical matters, he/she can offer evidence from learned treatises and medical texts.

C. The jury is the one who determines whether a plaintiff can invoke either the res ipsa loquitur doctrine or the “common knowledge” rule to obviate the need for an expert witness.

D. This patient will likely win her case.

E. All are incorrect.

Answer: E. It is well-established law that the question of negligence must be decided by reference to relevant medical standards of care for which the plaintiff carries the burden of proving through expert medical testimony. Only a professional, duly qualified by the court as an expert witness, is allowed to offer medical testimony – whereas the plaintiff typically will be disqualified from playing this role because of the complexity of issues involved.

However, under either the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur (“the thing speaks for itself”) or the “common knowledge” rule, a court (i.e., the judge) may allow the jury to infer negligence in the absence of expert testimony.

The res doctrine is invoked where there is only circumstantial but no direct evidence, and three conditions are met: 1) The injury would not have occurred in the absence of someone’s negligence; 2) the plaintiff was not at fault; and 3) the defendant had total control of the instrumentality that led to the injury.

The closely related “common knowledge” rule relies on the everyday knowledge and experience of the layperson to identify plain and obvious negligent conduct, which then allows the judge to waive the expert requirement.

The two principles are frequently used interchangeably, ultimately favoring the plaintiff by dispensing with the difficult and expensive task of securing a qualified expert willing to testify against a doctor defendant.

The best example of res in action is the surgeon who inadvertently leaves behind a sponge or instrument inside a body cavity. Other successfully litigated examples include a cardiac arrest in the operating room, hypoxia in the recovery room, burns to the buttock, gangrene after the accidental injection of penicillin into an artery, air trapped subcutaneously from a displaced needle, and a pierced eyeball during a procedure.

A particularly well-known example is Ybarra v. Spangard, in which the patient developed shoulder injuries during an appendectomy.1 The Supreme Court of California felt it was appropriate to place the burden on the operating room defendants to explain how the patient, unconscious under general anesthesia throughout the procedure, sustained the shoulder injury.

The scenario provided in the opening question is taken from a 2013 New York case, James v. Wormuth, in which the plaintiff relied on the res doctrine.2 The defendant doctor had left a guide wire in the plaintiff’s chest following a biopsy and was unable to locate it after a 20-minute search. However, he was able to retrieve the wire 2 months later under C-arm imaging.

The plaintiff sued the doctor for pain and anxiety, but did not call any expert witness, relying instead on the “foreign object” basis for invoking the res doctrine. The lower court ruled for the doctor, and the court of appeals affirmed.

It reasoned that the object was left behind deliberately, not unintentionally, and that under the circumstances of the case, an expert witness was needed to set out the applicable standard of care, without which a jury could not determine whether the doctor’s professional judgment breached the requisite standard. The court also ruled that the plaintiff failed to satisfy the “exclusive control” requirement of the res doctrine, because several other individuals participated to an extent in the medical procedure.

Hawaii’s case of Barbee v. Queen’s Medical Center is illustrative of the “common knowledge” rule.3 Mr. Barbee, age 75 years, underwent laparoscopic nephrectomy for a malignancy. Massive bleeding complicated his postoperative course, the hemoglobin falling into the 3 range, and he required emergent reoperation. Over the next 18 months, the patient progressively deteriorated, eventually requiring dialysis and dying from a stroke and intestinal volvulus.

Notwithstanding an initial jury verdict in favor of the plaintiff’s children, awarding each of the three children $365,000, the defendants filed a so-called JNOV motion (current term is “judgment as a matter of law”) to negate the jury verdict, on the basis that the plaintiffs failed to present competent expert testimony at trial to prove causation.

The plaintiffs countered that the cause of death was within the realm of common knowledge, thus no expert was necessary. They asserted that “any lay person can easily grasp the concept that a person dies from losing so much blood that multiple organs fail to perform their functions.” Mr. Barbee’s death thus was not “of such a technical nature that lay persons are incompetent to draw their own conclusions from facts presented without aid.”

Hawaii’s Intermediate Court of Appeals disagreed with the plaintiffs, holding that although “Hawaii does recognize a ‘common knowledge’ exception to the requirement that a plaintiff must introduce expert medical testimony on causation … this exception is rare in application.” The court asserted that the causal link between any alleged negligence and Mr. Barbee’s death 17 months later is not within the realm of common knowledge.

It reasoned that the long-term effects of internal bleeding are not so widely known as to be analogous to leaving a sponge within a patient or removing the wrong limb during an amputation. Moreover, Mr. Barbee had a long history of preexisting conditions, including hypertension, diabetes, and cancer. He also suffered numerous and serious postoperative medical conditions, including a stroke and surgery to remove part of his intestine, which had become gangrenous.

Thus, the role that preexisting conditions and/or the subsequent complications of this type played in Mr. Barbee’s death was not within the knowledge of the average layperson.

The “common knowledge” rule is aligned with, though not identical to, the res doctrine, but courts are known to conflate the two legal principles, often using them interchangeably.4

Strictly speaking, the “common knowledge” waiver comes into play where direct evidence of negligent conduct lies within the realm of everyday lay knowledge that the physician had deviated from common practice. It may or may not address the causation issue.

On the other hand, res is successfully invoked when, despite no direct evidence of negligence and causation, the circumstances surrounding the injury are such that the plaintiff’s case can go to the jury without expert testimony.

References

1. Ybarra v. Spangard, 154 P.2d 687 (Cal. 1944).

2. James v. Wormuth, 997 N.E.2d 133 (N.Y. 2013).

3. Barbee v. Queen’s Medical Center, 119 Haw 136 (2008).

4. Spinner, Amanda E. Common Ignorance: Medical Malpractice Law and the Misconceived Application of the “Common Knowledge” and “Res Ipsa Loquitur” Doctrines.” Touro Law Review: Vol. 31: No. 3, Article 15. Available at http://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol31/iss3/15.

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, and currently directs the St. Francis International Center for Healthcare Ethics in Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the articles in this series are adapted from the author’s 2006 book, “Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk,” and his 2012 Halsbury treatise, “Medical Negligence and Professional Misconduct.” For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

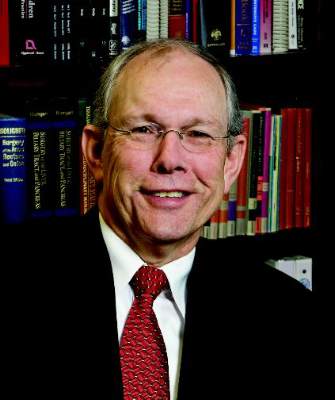

The Power of Quiet

In his insightful book “The Wisdom of Crowds” (New York: Anchor Books, 2004), James Surowiecke makes the convincing argument that many heads are wiser than one, even if that one is the sole expert regarding the subject under discussion. As long as the decision-making group is diverse, with each individual being allowed to come to an independent conclusion, this tenet appears to hold, whether the group is estimating the number of jelly beans in a jar or resolving a difficult issue. The message is clear: As a leader your leadership will be more effective if you solicit input from all members of your group, including those who may be reluctant to offer it.

In another excellent book, “Quiet” (New York: Crown Publishers, 2012), Susan Cain posits that, from early in the 20th century on, despite the considerable value it has to offer, introversion has become a “second-class personality trait.” Although highly valued earlier in our history, the thoughtful, introspective temperament was replaced by the aggressive, decisive character as the ideal.

Cain delves deeply into the substantial differences between extroverts and introverts, acknowledging that there are many gradations between the extremes. Extroverts tend to be loquacious and are seldom hesitant to offer their opinions on complex, difficult issues, even when their understanding of them is limited. They don’t always think before speaking and are less skilled listeners than introverts. They prefer to come to decisions rapidly, sometimes with incomplete data, and are much more decisive than introverts.

Introverts, on the other hand, prefer to listen rather than talk and to thoroughly vet an issue before reaching a decision. When they do, they are uncomfortable expressing it in a group setting. They prefer to work alone rather than in groups and, because of their thoughtful approach, their solutions to problems may be more innovative and sound than the shoot-from-the-hip, rapid answers that extroverts frequently propose. They abhor conflict and are likely to remain silent during controversy. In sum, although more difficult to elicit, obtaining input from the quiet members of the group is very worthwhile.

Often the most timely and ideal resolution is reached by balanced contributions from both personality types, the decision-making extroverts and the more thoughtful but reticent introverts. In fact, some of the best team members are those who are not on either extreme of the extrovert-introvert scale. But considering the fact that one-third to one-half of Americans are introverts (I suspect the fraction is a bit less among surgeons) and hesitant to offer their opinions in a group setting, how is this to be accomplished?

First, as a leader, you need to be sensitive to the fact that the introverts in your group are likely out of their comfort zone during communal meetings. It may even be embarrassing for them if they are called upon to offer their advice or opinion. To some degree this reluctance can be overcome by a leader who always attempts to reach consensus by valuing everyone’s opinion. Even the arrangement of the meeting room is important. The ideal is for all participants to be situated around a table rather than facing an imposing leader at the front of the room. This “leveling of the play field” emphasizes equality, de-emphasizes hierarchy, and encourages all to participate. The least likely to contribute can often be nudged from their quiet solitude by gentle urging from the leader with a statement such as: “Joe, I know you have a thoughtful perspective on this. Can you share it with the group?”

However, even the best-run meeting may not result in satisfactory resolution of difficult issues. In my experience, even those toward the extrovert end of the spectrum may be hesitant to offer their honest opinion in a meeting if it is in conflict with that of the leader. It is not uncommon to come to a consensus resolution of a controversial issue in a group meeting only to find out from hallway chatter that many disagree with the agreement reached. It is essential that the leader have access to this hallway chatter. This can be accomplished by way of confidantes who have the trust of both the troops and the leader.

During my years of leadership, a useful and productive technique I fostered to prompt input from introverts and honest assessments from all was to visit individual offices after the busy work day had quieted down, usually after 5 p.m. Meeting with individual faculty in their offices rather than in mine lent an informality to the conversation that could not be duplicated in the office of the chairman. In these one-on-one encounters, I found that even my relatively quiet faculty members felt comfortable in expressing their views regarding controversial issues facing our department. These informal chats also allowed me to become aware of problems they were facing in their professional and personal lives. They were great opportunities for mentoring and bonding as well. When these individual discussions precede what is anticipated to be a contentious group meeting, the likelihood of a successful conclusion is significantly enhanced.

Although my leadership experience was confined within the walls of academe, I believe these principles apply to anyone invited to lead a group in virtually any setting. Individual meetings are not an efficient way to lead, but they may provide a more effective and, in some cases, more rapid means of reaching consensus than innumerable group meetings with follow-up emails. When the group is too large to conference with everyone individually, one-on-one meetings with several key players may achieve the same result. During the process, don’t forget the quiet ones. They sometimes contribute the best and most innovative solutions to complex problems. There is power in quiet.

Dr. Rikkers is Editor in Chief of ACS Surgery News.

In his insightful book “The Wisdom of Crowds” (New York: Anchor Books, 2004), James Surowiecke makes the convincing argument that many heads are wiser than one, even if that one is the sole expert regarding the subject under discussion. As long as the decision-making group is diverse, with each individual being allowed to come to an independent conclusion, this tenet appears to hold, whether the group is estimating the number of jelly beans in a jar or resolving a difficult issue. The message is clear: As a leader your leadership will be more effective if you solicit input from all members of your group, including those who may be reluctant to offer it.

In another excellent book, “Quiet” (New York: Crown Publishers, 2012), Susan Cain posits that, from early in the 20th century on, despite the considerable value it has to offer, introversion has become a “second-class personality trait.” Although highly valued earlier in our history, the thoughtful, introspective temperament was replaced by the aggressive, decisive character as the ideal.

Cain delves deeply into the substantial differences between extroverts and introverts, acknowledging that there are many gradations between the extremes. Extroverts tend to be loquacious and are seldom hesitant to offer their opinions on complex, difficult issues, even when their understanding of them is limited. They don’t always think before speaking and are less skilled listeners than introverts. They prefer to come to decisions rapidly, sometimes with incomplete data, and are much more decisive than introverts.

Introverts, on the other hand, prefer to listen rather than talk and to thoroughly vet an issue before reaching a decision. When they do, they are uncomfortable expressing it in a group setting. They prefer to work alone rather than in groups and, because of their thoughtful approach, their solutions to problems may be more innovative and sound than the shoot-from-the-hip, rapid answers that extroverts frequently propose. They abhor conflict and are likely to remain silent during controversy. In sum, although more difficult to elicit, obtaining input from the quiet members of the group is very worthwhile.

Often the most timely and ideal resolution is reached by balanced contributions from both personality types, the decision-making extroverts and the more thoughtful but reticent introverts. In fact, some of the best team members are those who are not on either extreme of the extrovert-introvert scale. But considering the fact that one-third to one-half of Americans are introverts (I suspect the fraction is a bit less among surgeons) and hesitant to offer their opinions in a group setting, how is this to be accomplished?

First, as a leader, you need to be sensitive to the fact that the introverts in your group are likely out of their comfort zone during communal meetings. It may even be embarrassing for them if they are called upon to offer their advice or opinion. To some degree this reluctance can be overcome by a leader who always attempts to reach consensus by valuing everyone’s opinion. Even the arrangement of the meeting room is important. The ideal is for all participants to be situated around a table rather than facing an imposing leader at the front of the room. This “leveling of the play field” emphasizes equality, de-emphasizes hierarchy, and encourages all to participate. The least likely to contribute can often be nudged from their quiet solitude by gentle urging from the leader with a statement such as: “Joe, I know you have a thoughtful perspective on this. Can you share it with the group?”

However, even the best-run meeting may not result in satisfactory resolution of difficult issues. In my experience, even those toward the extrovert end of the spectrum may be hesitant to offer their honest opinion in a meeting if it is in conflict with that of the leader. It is not uncommon to come to a consensus resolution of a controversial issue in a group meeting only to find out from hallway chatter that many disagree with the agreement reached. It is essential that the leader have access to this hallway chatter. This can be accomplished by way of confidantes who have the trust of both the troops and the leader.

During my years of leadership, a useful and productive technique I fostered to prompt input from introverts and honest assessments from all was to visit individual offices after the busy work day had quieted down, usually after 5 p.m. Meeting with individual faculty in their offices rather than in mine lent an informality to the conversation that could not be duplicated in the office of the chairman. In these one-on-one encounters, I found that even my relatively quiet faculty members felt comfortable in expressing their views regarding controversial issues facing our department. These informal chats also allowed me to become aware of problems they were facing in their professional and personal lives. They were great opportunities for mentoring and bonding as well. When these individual discussions precede what is anticipated to be a contentious group meeting, the likelihood of a successful conclusion is significantly enhanced.

Although my leadership experience was confined within the walls of academe, I believe these principles apply to anyone invited to lead a group in virtually any setting. Individual meetings are not an efficient way to lead, but they may provide a more effective and, in some cases, more rapid means of reaching consensus than innumerable group meetings with follow-up emails. When the group is too large to conference with everyone individually, one-on-one meetings with several key players may achieve the same result. During the process, don’t forget the quiet ones. They sometimes contribute the best and most innovative solutions to complex problems. There is power in quiet.

Dr. Rikkers is Editor in Chief of ACS Surgery News.

In his insightful book “The Wisdom of Crowds” (New York: Anchor Books, 2004), James Surowiecke makes the convincing argument that many heads are wiser than one, even if that one is the sole expert regarding the subject under discussion. As long as the decision-making group is diverse, with each individual being allowed to come to an independent conclusion, this tenet appears to hold, whether the group is estimating the number of jelly beans in a jar or resolving a difficult issue. The message is clear: As a leader your leadership will be more effective if you solicit input from all members of your group, including those who may be reluctant to offer it.

In another excellent book, “Quiet” (New York: Crown Publishers, 2012), Susan Cain posits that, from early in the 20th century on, despite the considerable value it has to offer, introversion has become a “second-class personality trait.” Although highly valued earlier in our history, the thoughtful, introspective temperament was replaced by the aggressive, decisive character as the ideal.

Cain delves deeply into the substantial differences between extroverts and introverts, acknowledging that there are many gradations between the extremes. Extroverts tend to be loquacious and are seldom hesitant to offer their opinions on complex, difficult issues, even when their understanding of them is limited. They don’t always think before speaking and are less skilled listeners than introverts. They prefer to come to decisions rapidly, sometimes with incomplete data, and are much more decisive than introverts.

Introverts, on the other hand, prefer to listen rather than talk and to thoroughly vet an issue before reaching a decision. When they do, they are uncomfortable expressing it in a group setting. They prefer to work alone rather than in groups and, because of their thoughtful approach, their solutions to problems may be more innovative and sound than the shoot-from-the-hip, rapid answers that extroverts frequently propose. They abhor conflict and are likely to remain silent during controversy. In sum, although more difficult to elicit, obtaining input from the quiet members of the group is very worthwhile.

Often the most timely and ideal resolution is reached by balanced contributions from both personality types, the decision-making extroverts and the more thoughtful but reticent introverts. In fact, some of the best team members are those who are not on either extreme of the extrovert-introvert scale. But considering the fact that one-third to one-half of Americans are introverts (I suspect the fraction is a bit less among surgeons) and hesitant to offer their opinions in a group setting, how is this to be accomplished?

First, as a leader, you need to be sensitive to the fact that the introverts in your group are likely out of their comfort zone during communal meetings. It may even be embarrassing for them if they are called upon to offer their advice or opinion. To some degree this reluctance can be overcome by a leader who always attempts to reach consensus by valuing everyone’s opinion. Even the arrangement of the meeting room is important. The ideal is for all participants to be situated around a table rather than facing an imposing leader at the front of the room. This “leveling of the play field” emphasizes equality, de-emphasizes hierarchy, and encourages all to participate. The least likely to contribute can often be nudged from their quiet solitude by gentle urging from the leader with a statement such as: “Joe, I know you have a thoughtful perspective on this. Can you share it with the group?”

However, even the best-run meeting may not result in satisfactory resolution of difficult issues. In my experience, even those toward the extrovert end of the spectrum may be hesitant to offer their honest opinion in a meeting if it is in conflict with that of the leader. It is not uncommon to come to a consensus resolution of a controversial issue in a group meeting only to find out from hallway chatter that many disagree with the agreement reached. It is essential that the leader have access to this hallway chatter. This can be accomplished by way of confidantes who have the trust of both the troops and the leader.

During my years of leadership, a useful and productive technique I fostered to prompt input from introverts and honest assessments from all was to visit individual offices after the busy work day had quieted down, usually after 5 p.m. Meeting with individual faculty in their offices rather than in mine lent an informality to the conversation that could not be duplicated in the office of the chairman. In these one-on-one encounters, I found that even my relatively quiet faculty members felt comfortable in expressing their views regarding controversial issues facing our department. These informal chats also allowed me to become aware of problems they were facing in their professional and personal lives. They were great opportunities for mentoring and bonding as well. When these individual discussions precede what is anticipated to be a contentious group meeting, the likelihood of a successful conclusion is significantly enhanced.

Although my leadership experience was confined within the walls of academe, I believe these principles apply to anyone invited to lead a group in virtually any setting. Individual meetings are not an efficient way to lead, but they may provide a more effective and, in some cases, more rapid means of reaching consensus than innumerable group meetings with follow-up emails. When the group is too large to conference with everyone individually, one-on-one meetings with several key players may achieve the same result. During the process, don’t forget the quiet ones. They sometimes contribute the best and most innovative solutions to complex problems. There is power in quiet.

Dr. Rikkers is Editor in Chief of ACS Surgery News.

From the Washington Office: A guide to in-district meetings with your representatives and senators