User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

VIDEO: Compassionate care, decriminalization crucial to mitigating addiction epidemic

SAN DIEGO – Health care providers need to practice compassionate care to achieve the best results when managing patients who are dealing with opioid addiction, according to a panel of experts who spoke at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

Caring “compassionately is not enabling, [it’s] doing the right thing by the patient,” explained Chwen-Yuen Angie Chen, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University. “You can practice compassionate care if you have a knowledge base. Knowledge is extremely powerful and enables you to follow evidence-based medicine, which is truly compassionate care.”

Dr. Chen spoke at length about addiction medicine during a press conference outlining the ACP’s new position paper on preventing and treating substance abuse, where she was joined by ACP President Nitin S. Damle, MD, and ACP Board of Regents Chair Thomas G. Tape, MD. All three emphasized the need for decriminalization and destigmatization of opioid abuse, and they called on physicians to guide patients through resources and compassionate care to help them overcome the affliction.

“We know that we need to either taper, detoxify, or reduce opioid dosing. We know that we ought not to coprescribe with sedatives. We know that, if you need addiction treatment, you get referred, and you don’t just get cut off,” explained Dr. Chen.

In a video interview, Dr. Chen talked about the key take-home messages of the position paper, and she explained other aspects of substance abuse that requires provider’s awareness.

Dr. Chen did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN DIEGO – Health care providers need to practice compassionate care to achieve the best results when managing patients who are dealing with opioid addiction, according to a panel of experts who spoke at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

Caring “compassionately is not enabling, [it’s] doing the right thing by the patient,” explained Chwen-Yuen Angie Chen, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University. “You can practice compassionate care if you have a knowledge base. Knowledge is extremely powerful and enables you to follow evidence-based medicine, which is truly compassionate care.”

Dr. Chen spoke at length about addiction medicine during a press conference outlining the ACP’s new position paper on preventing and treating substance abuse, where she was joined by ACP President Nitin S. Damle, MD, and ACP Board of Regents Chair Thomas G. Tape, MD. All three emphasized the need for decriminalization and destigmatization of opioid abuse, and they called on physicians to guide patients through resources and compassionate care to help them overcome the affliction.

“We know that we need to either taper, detoxify, or reduce opioid dosing. We know that we ought not to coprescribe with sedatives. We know that, if you need addiction treatment, you get referred, and you don’t just get cut off,” explained Dr. Chen.

In a video interview, Dr. Chen talked about the key take-home messages of the position paper, and she explained other aspects of substance abuse that requires provider’s awareness.

Dr. Chen did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN DIEGO – Health care providers need to practice compassionate care to achieve the best results when managing patients who are dealing with opioid addiction, according to a panel of experts who spoke at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

Caring “compassionately is not enabling, [it’s] doing the right thing by the patient,” explained Chwen-Yuen Angie Chen, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University. “You can practice compassionate care if you have a knowledge base. Knowledge is extremely powerful and enables you to follow evidence-based medicine, which is truly compassionate care.”

Dr. Chen spoke at length about addiction medicine during a press conference outlining the ACP’s new position paper on preventing and treating substance abuse, where she was joined by ACP President Nitin S. Damle, MD, and ACP Board of Regents Chair Thomas G. Tape, MD. All three emphasized the need for decriminalization and destigmatization of opioid abuse, and they called on physicians to guide patients through resources and compassionate care to help them overcome the affliction.

“We know that we need to either taper, detoxify, or reduce opioid dosing. We know that we ought not to coprescribe with sedatives. We know that, if you need addiction treatment, you get referred, and you don’t just get cut off,” explained Dr. Chen.

In a video interview, Dr. Chen talked about the key take-home messages of the position paper, and she explained other aspects of substance abuse that requires provider’s awareness.

Dr. Chen did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT ACP INTERNAL MEDICINE

Robot-assisted surgery can be a pain

It’s early days for research on the physical impact of robot-assisted surgery on operators. But a study of surgeons who regularly do this kind of work suggests that surgical robots can be the cause of workplace injuries, despite their reputation for good ergonomic design and low stress on surgeon hands, wrists, backs, and necks

More than half (236) of 432 surveyed surgeons with at least 10 robotic surgeries annually reported physical discomfort associated with robotics consoles, according to a study out of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Most participants were male (71%) and averaged 48 years of age; their specialties comprised gynecology (68%), urology (20%), general surgery (8%), and others (3%).

Of the 432 participants, they reported physical discomfort in the following areas: fingers, 78%; necks, 74%; upper backs, 53%; and 43%, 34%, and 33% in the lower backs, eyes, and wrists, respectively.

Most of those who responded to the survey (80.8%) performed surgery with the da Vinci Si as their primary robotic system, with the rest using a different iteration of the da Vinci system.

Dr. Lee and his colleagues estimate the high rates of reported discomfort in fingers and necks are because of the structure of the robotics console.

“Due to the absence of tactile feedback at the master controller of the surgeon console, some robotic surgeons might close their fingers excessively when holding objects with instruments,” researchers said. “During the performance of suturing and knot-tying tasks, surgeons must squeeze their grip to hold a needle in place because there is no locking mechanism, which is present with open and laparoscopic needle holders.”

Researchers credit high rates of neck pain to the console as well, which “requires [surgeons] to maintain their neck position in a fixed place for extended period of time.”

While the rate of physical discomfort was 56%, participants rated the ergonomic functions of the console an average of 4 out of 5, with 5 being the highest score.

In contrast, surgeons gave low ratings to the communications systems used by the surgeon and the in-room supporting OR staff – an average of 2.87 out of 5 – noting an urgency for system updates.

Overall, researchers found that surgeons with high confidence in their ergonomic console settings were more likely to feel confident in the use of robotics in their surgical procedures and less likely to report physical discomfort. This finding led researchers to conclude the importance of surgeons new to robot-assisted surgery to receive education in ergonomic settings.

“Formal robotic surgery training programs should include this crucially important knowledge about optimal ergonomic guidelines so that any surgeon starting their training in robotic surgery would have the knowledge to maintain sound body posture and to minimize any physical strains while acquiring the best skill set,” according to Dr. Lee and his associates.

This study was limited by the self-reported data, which could create possible reporting bias, as well as by a small sample size. Since surgeons conducted more than one type of surgery annually, researchers found it difficult to identify what had caused the physical symptoms with complete confidence.

Researchers declared no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @EAZTweets

It’s early days for research on the physical impact of robot-assisted surgery on operators. But a study of surgeons who regularly do this kind of work suggests that surgical robots can be the cause of workplace injuries, despite their reputation for good ergonomic design and low stress on surgeon hands, wrists, backs, and necks

More than half (236) of 432 surveyed surgeons with at least 10 robotic surgeries annually reported physical discomfort associated with robotics consoles, according to a study out of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Most participants were male (71%) and averaged 48 years of age; their specialties comprised gynecology (68%), urology (20%), general surgery (8%), and others (3%).

Of the 432 participants, they reported physical discomfort in the following areas: fingers, 78%; necks, 74%; upper backs, 53%; and 43%, 34%, and 33% in the lower backs, eyes, and wrists, respectively.

Most of those who responded to the survey (80.8%) performed surgery with the da Vinci Si as their primary robotic system, with the rest using a different iteration of the da Vinci system.

Dr. Lee and his colleagues estimate the high rates of reported discomfort in fingers and necks are because of the structure of the robotics console.

“Due to the absence of tactile feedback at the master controller of the surgeon console, some robotic surgeons might close their fingers excessively when holding objects with instruments,” researchers said. “During the performance of suturing and knot-tying tasks, surgeons must squeeze their grip to hold a needle in place because there is no locking mechanism, which is present with open and laparoscopic needle holders.”

Researchers credit high rates of neck pain to the console as well, which “requires [surgeons] to maintain their neck position in a fixed place for extended period of time.”

While the rate of physical discomfort was 56%, participants rated the ergonomic functions of the console an average of 4 out of 5, with 5 being the highest score.

In contrast, surgeons gave low ratings to the communications systems used by the surgeon and the in-room supporting OR staff – an average of 2.87 out of 5 – noting an urgency for system updates.

Overall, researchers found that surgeons with high confidence in their ergonomic console settings were more likely to feel confident in the use of robotics in their surgical procedures and less likely to report physical discomfort. This finding led researchers to conclude the importance of surgeons new to robot-assisted surgery to receive education in ergonomic settings.

“Formal robotic surgery training programs should include this crucially important knowledge about optimal ergonomic guidelines so that any surgeon starting their training in robotic surgery would have the knowledge to maintain sound body posture and to minimize any physical strains while acquiring the best skill set,” according to Dr. Lee and his associates.

This study was limited by the self-reported data, which could create possible reporting bias, as well as by a small sample size. Since surgeons conducted more than one type of surgery annually, researchers found it difficult to identify what had caused the physical symptoms with complete confidence.

Researchers declared no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @EAZTweets

It’s early days for research on the physical impact of robot-assisted surgery on operators. But a study of surgeons who regularly do this kind of work suggests that surgical robots can be the cause of workplace injuries, despite their reputation for good ergonomic design and low stress on surgeon hands, wrists, backs, and necks

More than half (236) of 432 surveyed surgeons with at least 10 robotic surgeries annually reported physical discomfort associated with robotics consoles, according to a study out of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Most participants were male (71%) and averaged 48 years of age; their specialties comprised gynecology (68%), urology (20%), general surgery (8%), and others (3%).

Of the 432 participants, they reported physical discomfort in the following areas: fingers, 78%; necks, 74%; upper backs, 53%; and 43%, 34%, and 33% in the lower backs, eyes, and wrists, respectively.

Most of those who responded to the survey (80.8%) performed surgery with the da Vinci Si as their primary robotic system, with the rest using a different iteration of the da Vinci system.

Dr. Lee and his colleagues estimate the high rates of reported discomfort in fingers and necks are because of the structure of the robotics console.

“Due to the absence of tactile feedback at the master controller of the surgeon console, some robotic surgeons might close their fingers excessively when holding objects with instruments,” researchers said. “During the performance of suturing and knot-tying tasks, surgeons must squeeze their grip to hold a needle in place because there is no locking mechanism, which is present with open and laparoscopic needle holders.”

Researchers credit high rates of neck pain to the console as well, which “requires [surgeons] to maintain their neck position in a fixed place for extended period of time.”

While the rate of physical discomfort was 56%, participants rated the ergonomic functions of the console an average of 4 out of 5, with 5 being the highest score.

In contrast, surgeons gave low ratings to the communications systems used by the surgeon and the in-room supporting OR staff – an average of 2.87 out of 5 – noting an urgency for system updates.

Overall, researchers found that surgeons with high confidence in their ergonomic console settings were more likely to feel confident in the use of robotics in their surgical procedures and less likely to report physical discomfort. This finding led researchers to conclude the importance of surgeons new to robot-assisted surgery to receive education in ergonomic settings.

“Formal robotic surgery training programs should include this crucially important knowledge about optimal ergonomic guidelines so that any surgeon starting their training in robotic surgery would have the knowledge to maintain sound body posture and to minimize any physical strains while acquiring the best skill set,” according to Dr. Lee and his associates.

This study was limited by the self-reported data, which could create possible reporting bias, as well as by a small sample size. Since surgeons conducted more than one type of surgery annually, researchers found it difficult to identify what had caused the physical symptoms with complete confidence.

Researchers declared no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @EAZTweets

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of 432 participating surgeons, 236 (56.1%) reported having physical discomfort during or after using the surgical robot.

Data source: A 20-question, self-reporting survey disseminated to surgeons via email, analyzed using logistic regression.

Disclosures: Researchers declared no relevant financial disclosures.

Do you attend a patient’s funeral?

I’ve never been to a patient’s funeral, though I know plenty of other doctors who have.

I suppose this is a highly personal decision. Some feel they should go out of respect to the patient, or if they had a particularly strong or longstanding relationship with them.

Part of it is feeling like an outsider. To me, funerals are a chance for loved ones and close friends to say their goodbyes. I generally try to keep a professional distance. It makes the job easier.

Another is simply a reluctance to take time off from the office. Even though someone I cared for is gone, that person is not the only one that I see. I have to continue caring for the patients who still need me.

There’s also an aspect of fear. Family members who don’t know you well may see your presence as a sign of guilt that you did something wrong. Or, in the irrational nature of grief and anger, become belligerent, accusing you of incompetence. These sorts of confrontations can never end well for either side.

All of us are facing death sooner or later. As physicians, our job is to prolong and improve quality of life as best we can, knowing that inevitably we’ll lose. When that happens, the most we can ever ask is that we did our best. And that we continue to care for those who still depend on us.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

[polldaddy:9711658]

I’ve never been to a patient’s funeral, though I know plenty of other doctors who have.

I suppose this is a highly personal decision. Some feel they should go out of respect to the patient, or if they had a particularly strong or longstanding relationship with them.

Part of it is feeling like an outsider. To me, funerals are a chance for loved ones and close friends to say their goodbyes. I generally try to keep a professional distance. It makes the job easier.

Another is simply a reluctance to take time off from the office. Even though someone I cared for is gone, that person is not the only one that I see. I have to continue caring for the patients who still need me.

There’s also an aspect of fear. Family members who don’t know you well may see your presence as a sign of guilt that you did something wrong. Or, in the irrational nature of grief and anger, become belligerent, accusing you of incompetence. These sorts of confrontations can never end well for either side.

All of us are facing death sooner or later. As physicians, our job is to prolong and improve quality of life as best we can, knowing that inevitably we’ll lose. When that happens, the most we can ever ask is that we did our best. And that we continue to care for those who still depend on us.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

[polldaddy:9711658]

I’ve never been to a patient’s funeral, though I know plenty of other doctors who have.

I suppose this is a highly personal decision. Some feel they should go out of respect to the patient, or if they had a particularly strong or longstanding relationship with them.

Part of it is feeling like an outsider. To me, funerals are a chance for loved ones and close friends to say their goodbyes. I generally try to keep a professional distance. It makes the job easier.

Another is simply a reluctance to take time off from the office. Even though someone I cared for is gone, that person is not the only one that I see. I have to continue caring for the patients who still need me.

There’s also an aspect of fear. Family members who don’t know you well may see your presence as a sign of guilt that you did something wrong. Or, in the irrational nature of grief and anger, become belligerent, accusing you of incompetence. These sorts of confrontations can never end well for either side.

All of us are facing death sooner or later. As physicians, our job is to prolong and improve quality of life as best we can, knowing that inevitably we’ll lose. When that happens, the most we can ever ask is that we did our best. And that we continue to care for those who still depend on us.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

[polldaddy:9711658]

Safe to avoid sentinel node biopsy in some breast cancer patients

SEATTLE – Sentinel lymph node biopsy is widely used in patients with early-stage breast cancer for staging the axilla, but it can be safely omitted in some patients, according to new research presented at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium.

In women aged 70 years and older with hormone receptor (HR)–positive invasive breast cancer, the risk of nodal involvement is 14%-15%, which adds support to the premise that sentinel lymph node surgery could be avoided in many of the women deemed to be low risk.

The Choosing Wisely campaign was initiated to reduce excess cost and expenditures in health care. The Society of Surgical Oncology recently released five Choosing Wisely guidelines that included specific tests or procedures commonly ordered but not always necessary in surgical oncology, explained study author Jessemae Welsh, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. One of the recommendations was to avoid routine sentinel node biopsy in clinically node-negative women over age 70 years with hormone receptor–positive invasive breast cancer.

“Their rationale is that hormone therapy is the standard of care in these women and sentinel node surgery has shown no impact on local regional recurrence or breast cancer mortality,” said Dr. Welsh. “Therefore it would be safe to treat this population without any axillary node staging.”

She noted that the average 70-year-old woman may live another 14-16 years. “So the question is, how should we be applying the Choosing Wisely guidelines?”

Dr. Welsh and her colleagues evaluated the factors that might be impacting nodal positivity in this population, and in particular, they looked at T stage and tumor grade.

They used two large databases to identify all women over the age of 70 years with HR+ cN0 invasive disease in the institutional breast surgery database (IBSD, 2008-2016) from the Mayo Clinic and the National Cancer Database (NCDB, 2004-2013).

The rates of patients who were node positive (pN+) were based on those who had undergone axillary surgery.

The researchers then stratified patients by clinical T stage and tumor grade to compare risk of pN+ across strata.

Of 705 selected patients in the IBSD, 191 or 14.3% were pN+ and a similar rate was observed in the NCDB; 15.2% (19,607/129,216). Tumor grade and clinical T stage were associated with pN+.

“The overall rates were about 14% for both databases, and when we stratified this by T stage, we could see increasing node positivity with increasing T stage,” said Dr. Welsh.

In similar fashion, the researchers observed comparable increases when they stratified it by grade. “Increasing grades were associated with increasing rates, especially for grade 2 and higher,” said Dr. Welsh.

When the two factors were combined, the researchers were able to define low-risk criteria as clinical T1a-b, grade 1-2 or clinical T1c, grade 1. The low-risk group accounted for 54.3% (IBSD) and 43.2% (NCDB) of patients, and pN+ rates within this group were 7.6% (IBSD) and 7.4% (NCDB).

Patients outside of this subcohort had pN+ rates of 22.4% (IBSD) and 23.0% (NCDB), which extrapolated to a relative risk of 2.95 (95% CI: 1.97-4.42) and 3.11 (95% CI: 2.99-3.23), respectively (each P less than .001).

“Women in the high-risk group had three times the risk of node positivity as the low-risk group,” she said. “Based on our data, we can say that for grade 1 T1a-c we can omit sentinel node surgery, and also for grade 2 T1 a-b.”

But for grade 3, T2 or higher, or any grade 2 Tc tumors, clinicians should continue to consider sentinel node surgery, taking into account individual patient factors.

The investigator had no disclosures.

Are there patients older than 70 years of age who have a low risk of nodal metastasis and/or even if they had nodal metastasis, could be adequately treated with anti-hormones?

If the answer is “yes,” then sentinel node sampling can be avoided in these patients. This study identified a group with a low risk for nodal metastasis. Even though it may be difficult to estimate tumor size preoperatively for lobular cancers, this is less of a problem for ductal cancers. Another approach is to use molecular profiling to determine which patients may “skip” sentinel node biopsy. Molecular profiling can identify patients who will have an excellent outcome with adjuvant anti-hormones even in the presence of nodal metastases.

Maureen Chung, MD, FACS, is medical director of the breast care program at Southcoast Health, North Dartmouth, Mass.

Are there patients older than 70 years of age who have a low risk of nodal metastasis and/or even if they had nodal metastasis, could be adequately treated with anti-hormones?

If the answer is “yes,” then sentinel node sampling can be avoided in these patients. This study identified a group with a low risk for nodal metastasis. Even though it may be difficult to estimate tumor size preoperatively for lobular cancers, this is less of a problem for ductal cancers. Another approach is to use molecular profiling to determine which patients may “skip” sentinel node biopsy. Molecular profiling can identify patients who will have an excellent outcome with adjuvant anti-hormones even in the presence of nodal metastases.

Maureen Chung, MD, FACS, is medical director of the breast care program at Southcoast Health, North Dartmouth, Mass.

Are there patients older than 70 years of age who have a low risk of nodal metastasis and/or even if they had nodal metastasis, could be adequately treated with anti-hormones?

If the answer is “yes,” then sentinel node sampling can be avoided in these patients. This study identified a group with a low risk for nodal metastasis. Even though it may be difficult to estimate tumor size preoperatively for lobular cancers, this is less of a problem for ductal cancers. Another approach is to use molecular profiling to determine which patients may “skip” sentinel node biopsy. Molecular profiling can identify patients who will have an excellent outcome with adjuvant anti-hormones even in the presence of nodal metastases.

Maureen Chung, MD, FACS, is medical director of the breast care program at Southcoast Health, North Dartmouth, Mass.

SEATTLE – Sentinel lymph node biopsy is widely used in patients with early-stage breast cancer for staging the axilla, but it can be safely omitted in some patients, according to new research presented at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium.

In women aged 70 years and older with hormone receptor (HR)–positive invasive breast cancer, the risk of nodal involvement is 14%-15%, which adds support to the premise that sentinel lymph node surgery could be avoided in many of the women deemed to be low risk.

The Choosing Wisely campaign was initiated to reduce excess cost and expenditures in health care. The Society of Surgical Oncology recently released five Choosing Wisely guidelines that included specific tests or procedures commonly ordered but not always necessary in surgical oncology, explained study author Jessemae Welsh, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. One of the recommendations was to avoid routine sentinel node biopsy in clinically node-negative women over age 70 years with hormone receptor–positive invasive breast cancer.

“Their rationale is that hormone therapy is the standard of care in these women and sentinel node surgery has shown no impact on local regional recurrence or breast cancer mortality,” said Dr. Welsh. “Therefore it would be safe to treat this population without any axillary node staging.”

She noted that the average 70-year-old woman may live another 14-16 years. “So the question is, how should we be applying the Choosing Wisely guidelines?”

Dr. Welsh and her colleagues evaluated the factors that might be impacting nodal positivity in this population, and in particular, they looked at T stage and tumor grade.

They used two large databases to identify all women over the age of 70 years with HR+ cN0 invasive disease in the institutional breast surgery database (IBSD, 2008-2016) from the Mayo Clinic and the National Cancer Database (NCDB, 2004-2013).

The rates of patients who were node positive (pN+) were based on those who had undergone axillary surgery.

The researchers then stratified patients by clinical T stage and tumor grade to compare risk of pN+ across strata.

Of 705 selected patients in the IBSD, 191 or 14.3% were pN+ and a similar rate was observed in the NCDB; 15.2% (19,607/129,216). Tumor grade and clinical T stage were associated with pN+.

“The overall rates were about 14% for both databases, and when we stratified this by T stage, we could see increasing node positivity with increasing T stage,” said Dr. Welsh.

In similar fashion, the researchers observed comparable increases when they stratified it by grade. “Increasing grades were associated with increasing rates, especially for grade 2 and higher,” said Dr. Welsh.

When the two factors were combined, the researchers were able to define low-risk criteria as clinical T1a-b, grade 1-2 or clinical T1c, grade 1. The low-risk group accounted for 54.3% (IBSD) and 43.2% (NCDB) of patients, and pN+ rates within this group were 7.6% (IBSD) and 7.4% (NCDB).

Patients outside of this subcohort had pN+ rates of 22.4% (IBSD) and 23.0% (NCDB), which extrapolated to a relative risk of 2.95 (95% CI: 1.97-4.42) and 3.11 (95% CI: 2.99-3.23), respectively (each P less than .001).

“Women in the high-risk group had three times the risk of node positivity as the low-risk group,” she said. “Based on our data, we can say that for grade 1 T1a-c we can omit sentinel node surgery, and also for grade 2 T1 a-b.”

But for grade 3, T2 or higher, or any grade 2 Tc tumors, clinicians should continue to consider sentinel node surgery, taking into account individual patient factors.

The investigator had no disclosures.

SEATTLE – Sentinel lymph node biopsy is widely used in patients with early-stage breast cancer for staging the axilla, but it can be safely omitted in some patients, according to new research presented at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium.

In women aged 70 years and older with hormone receptor (HR)–positive invasive breast cancer, the risk of nodal involvement is 14%-15%, which adds support to the premise that sentinel lymph node surgery could be avoided in many of the women deemed to be low risk.

The Choosing Wisely campaign was initiated to reduce excess cost and expenditures in health care. The Society of Surgical Oncology recently released five Choosing Wisely guidelines that included specific tests or procedures commonly ordered but not always necessary in surgical oncology, explained study author Jessemae Welsh, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. One of the recommendations was to avoid routine sentinel node biopsy in clinically node-negative women over age 70 years with hormone receptor–positive invasive breast cancer.

“Their rationale is that hormone therapy is the standard of care in these women and sentinel node surgery has shown no impact on local regional recurrence or breast cancer mortality,” said Dr. Welsh. “Therefore it would be safe to treat this population without any axillary node staging.”

She noted that the average 70-year-old woman may live another 14-16 years. “So the question is, how should we be applying the Choosing Wisely guidelines?”

Dr. Welsh and her colleagues evaluated the factors that might be impacting nodal positivity in this population, and in particular, they looked at T stage and tumor grade.

They used two large databases to identify all women over the age of 70 years with HR+ cN0 invasive disease in the institutional breast surgery database (IBSD, 2008-2016) from the Mayo Clinic and the National Cancer Database (NCDB, 2004-2013).

The rates of patients who were node positive (pN+) were based on those who had undergone axillary surgery.

The researchers then stratified patients by clinical T stage and tumor grade to compare risk of pN+ across strata.

Of 705 selected patients in the IBSD, 191 or 14.3% were pN+ and a similar rate was observed in the NCDB; 15.2% (19,607/129,216). Tumor grade and clinical T stage were associated with pN+.

“The overall rates were about 14% for both databases, and when we stratified this by T stage, we could see increasing node positivity with increasing T stage,” said Dr. Welsh.

In similar fashion, the researchers observed comparable increases when they stratified it by grade. “Increasing grades were associated with increasing rates, especially for grade 2 and higher,” said Dr. Welsh.

When the two factors were combined, the researchers were able to define low-risk criteria as clinical T1a-b, grade 1-2 or clinical T1c, grade 1. The low-risk group accounted for 54.3% (IBSD) and 43.2% (NCDB) of patients, and pN+ rates within this group were 7.6% (IBSD) and 7.4% (NCDB).

Patients outside of this subcohort had pN+ rates of 22.4% (IBSD) and 23.0% (NCDB), which extrapolated to a relative risk of 2.95 (95% CI: 1.97-4.42) and 3.11 (95% CI: 2.99-3.23), respectively (each P less than .001).

“Women in the high-risk group had three times the risk of node positivity as the low-risk group,” she said. “Based on our data, we can say that for grade 1 T1a-c we can omit sentinel node surgery, and also for grade 2 T1 a-b.”

But for grade 3, T2 or higher, or any grade 2 Tc tumors, clinicians should continue to consider sentinel node surgery, taking into account individual patient factors.

The investigator had no disclosures.

Key clinical point: Sentinel node biopsy can be safely avoided in certain populations of breast cancer patients.

Major finding: In women 70 years and older with hormone receptor (HR)–positive invasive breast cancer who are at low risk, sentinel node surgery can safely be avoided.

Data source: Two large databases of more than 150,000 women, from the Mayo Clinic and the National Cancer Database.

Disclosures: There was no funding source disclosed. The author had no disclosures.

Robot-assisted surgery: Twice the price

HOUSTON – Robot-assisted operations for inguinal hernia repair (IHR) and cholecystectomy have grown steadily in recent years, but these procedures can be done equally well by traditional operations at a fraction of the cost, according to a study from Geisinger Medical Center in Pennsylvania.

Ellen Vogels, DO, of Geisinger, reported results of a study of 1,248 cholecystectomies and 723 initial IHRs from 2007 to 2016. The cholecystectomies were done via robot-assisted surgery or laparoscopy in the hospital or via laparoscopy in an ambulatory surgery center (ASC). The IHRs were done robotically, open, or laparoscopically in the hospital, or open or laparoscopically in an ASC.

Dr. Vogels quoted statistics from the ECRI Institute that showed robotic surgery procedures have increased 178% between 2009 and 2014, and the two procedures the group studied are the most frequently performed robotic procedures.

Within the Geisinger system, the study found a 3:1 cost disparity for IHR: $6,292 total cost for hospital-based robotic surgery vs. $3,421 for ASC-based laparoscopy IHR and $1,853 for ASC-based open repair. For cholecystectomy, the disparity isn’t as wide – it’s 2:1 – but is still significant: Total costs for hospital-based robotic surgery are $6,057 vs. $3,443 for ASC-based cholecystectomy and $3,270 for hospital-based laparoscopic cholecystectomy (the study did not include any open cholecystectomies).

Total costs not only include costs for the procedure but also all related pre- and postoperative care. The cost analysis did not account for the cost of the robot, including maintenance contracts, or costs for laparoscopic instruments. Variable costs also ranged from about $3,000 for robotic IHR to $942 for ASC open repair – which means the lowest per-procedure cost for the latter was around $900.

“Translating this into the fact that cholecystectomies and inguinal hernia repairs are the most often performed general surgery procedures, ambulatory surgery centers can save over $60 billion over the next 10 years in just overhead costs as well as increased efficiency,” Dr. Vogels said.

The study also found access issues depending on where patients had their operations. “As far as service and access in our institution alone, we found that patients going to the main hospital spent as much as two times longer getting these procedures done as compared to the ambulatory surgery centers,” Dr. Vogels said.

Robotic procedures also required longer operative times, the study found – an average of 109 minutes for IHR vs. about an hour for ASC procedures and hospital-based open surgery (but averaging 78 minutes for in-hospital laparoscopy); and 73 minutes for robotic cholecystectomy, 60 minutes for hospital laparoscopy, and 45 minutes for ASC laparoscopy.

Robotic session moderator Dmitry Oleynikov, MD, FACS, of the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, asked Dr. Vogels if putting a robotic platform in an ambulatory surgery setting would make it more cost effective.

That’s not practical from a cost or efficiency perspective, she said.

“When you look at the cost of the ASCs, specifically in the hernia group, the lowest-cost hernia repair is about $800; with the robot it’s going to be significantly higher than that, up to three times higher than that,” Dr. Vogels replied. “Then you’re also changing all those simple ambulatory surgery procedures to more involved robotic procedures, so it’s hard to justify doing that in the ASC.”

Dr. Vogels and her coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – Robot-assisted operations for inguinal hernia repair (IHR) and cholecystectomy have grown steadily in recent years, but these procedures can be done equally well by traditional operations at a fraction of the cost, according to a study from Geisinger Medical Center in Pennsylvania.

Ellen Vogels, DO, of Geisinger, reported results of a study of 1,248 cholecystectomies and 723 initial IHRs from 2007 to 2016. The cholecystectomies were done via robot-assisted surgery or laparoscopy in the hospital or via laparoscopy in an ambulatory surgery center (ASC). The IHRs were done robotically, open, or laparoscopically in the hospital, or open or laparoscopically in an ASC.

Dr. Vogels quoted statistics from the ECRI Institute that showed robotic surgery procedures have increased 178% between 2009 and 2014, and the two procedures the group studied are the most frequently performed robotic procedures.

Within the Geisinger system, the study found a 3:1 cost disparity for IHR: $6,292 total cost for hospital-based robotic surgery vs. $3,421 for ASC-based laparoscopy IHR and $1,853 for ASC-based open repair. For cholecystectomy, the disparity isn’t as wide – it’s 2:1 – but is still significant: Total costs for hospital-based robotic surgery are $6,057 vs. $3,443 for ASC-based cholecystectomy and $3,270 for hospital-based laparoscopic cholecystectomy (the study did not include any open cholecystectomies).

Total costs not only include costs for the procedure but also all related pre- and postoperative care. The cost analysis did not account for the cost of the robot, including maintenance contracts, or costs for laparoscopic instruments. Variable costs also ranged from about $3,000 for robotic IHR to $942 for ASC open repair – which means the lowest per-procedure cost for the latter was around $900.

“Translating this into the fact that cholecystectomies and inguinal hernia repairs are the most often performed general surgery procedures, ambulatory surgery centers can save over $60 billion over the next 10 years in just overhead costs as well as increased efficiency,” Dr. Vogels said.

The study also found access issues depending on where patients had their operations. “As far as service and access in our institution alone, we found that patients going to the main hospital spent as much as two times longer getting these procedures done as compared to the ambulatory surgery centers,” Dr. Vogels said.

Robotic procedures also required longer operative times, the study found – an average of 109 minutes for IHR vs. about an hour for ASC procedures and hospital-based open surgery (but averaging 78 minutes for in-hospital laparoscopy); and 73 minutes for robotic cholecystectomy, 60 minutes for hospital laparoscopy, and 45 minutes for ASC laparoscopy.

Robotic session moderator Dmitry Oleynikov, MD, FACS, of the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, asked Dr. Vogels if putting a robotic platform in an ambulatory surgery setting would make it more cost effective.

That’s not practical from a cost or efficiency perspective, she said.

“When you look at the cost of the ASCs, specifically in the hernia group, the lowest-cost hernia repair is about $800; with the robot it’s going to be significantly higher than that, up to three times higher than that,” Dr. Vogels replied. “Then you’re also changing all those simple ambulatory surgery procedures to more involved robotic procedures, so it’s hard to justify doing that in the ASC.”

Dr. Vogels and her coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – Robot-assisted operations for inguinal hernia repair (IHR) and cholecystectomy have grown steadily in recent years, but these procedures can be done equally well by traditional operations at a fraction of the cost, according to a study from Geisinger Medical Center in Pennsylvania.

Ellen Vogels, DO, of Geisinger, reported results of a study of 1,248 cholecystectomies and 723 initial IHRs from 2007 to 2016. The cholecystectomies were done via robot-assisted surgery or laparoscopy in the hospital or via laparoscopy in an ambulatory surgery center (ASC). The IHRs were done robotically, open, or laparoscopically in the hospital, or open or laparoscopically in an ASC.

Dr. Vogels quoted statistics from the ECRI Institute that showed robotic surgery procedures have increased 178% between 2009 and 2014, and the two procedures the group studied are the most frequently performed robotic procedures.

Within the Geisinger system, the study found a 3:1 cost disparity for IHR: $6,292 total cost for hospital-based robotic surgery vs. $3,421 for ASC-based laparoscopy IHR and $1,853 for ASC-based open repair. For cholecystectomy, the disparity isn’t as wide – it’s 2:1 – but is still significant: Total costs for hospital-based robotic surgery are $6,057 vs. $3,443 for ASC-based cholecystectomy and $3,270 for hospital-based laparoscopic cholecystectomy (the study did not include any open cholecystectomies).

Total costs not only include costs for the procedure but also all related pre- and postoperative care. The cost analysis did not account for the cost of the robot, including maintenance contracts, or costs for laparoscopic instruments. Variable costs also ranged from about $3,000 for robotic IHR to $942 for ASC open repair – which means the lowest per-procedure cost for the latter was around $900.

“Translating this into the fact that cholecystectomies and inguinal hernia repairs are the most often performed general surgery procedures, ambulatory surgery centers can save over $60 billion over the next 10 years in just overhead costs as well as increased efficiency,” Dr. Vogels said.

The study also found access issues depending on where patients had their operations. “As far as service and access in our institution alone, we found that patients going to the main hospital spent as much as two times longer getting these procedures done as compared to the ambulatory surgery centers,” Dr. Vogels said.

Robotic procedures also required longer operative times, the study found – an average of 109 minutes for IHR vs. about an hour for ASC procedures and hospital-based open surgery (but averaging 78 minutes for in-hospital laparoscopy); and 73 minutes for robotic cholecystectomy, 60 minutes for hospital laparoscopy, and 45 minutes for ASC laparoscopy.

Robotic session moderator Dmitry Oleynikov, MD, FACS, of the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, asked Dr. Vogels if putting a robotic platform in an ambulatory surgery setting would make it more cost effective.

That’s not practical from a cost or efficiency perspective, she said.

“When you look at the cost of the ASCs, specifically in the hernia group, the lowest-cost hernia repair is about $800; with the robot it’s going to be significantly higher than that, up to three times higher than that,” Dr. Vogels replied. “Then you’re also changing all those simple ambulatory surgery procedures to more involved robotic procedures, so it’s hard to justify doing that in the ASC.”

Dr. Vogels and her coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT SAGES 2017

Key clinical point: Outcomes for robot-assisted inguinal hernia repair and cholecystectomy are similar to those for outpatient open and laparoscopic procedures.

Major finding: Robotic IHR costs up to three times more than open outpatient surgery, and robotic cholecystectomy costs twice as much as outpatient surgery.

Data source: Study of 1,971 in-hospital robotic, laparoscopic, and open procedures, and outpatient laparoscopic and open operations done from 2007 to 2016 at Geisinger Medical Center.

Disclosures: Dr. Vogels and coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

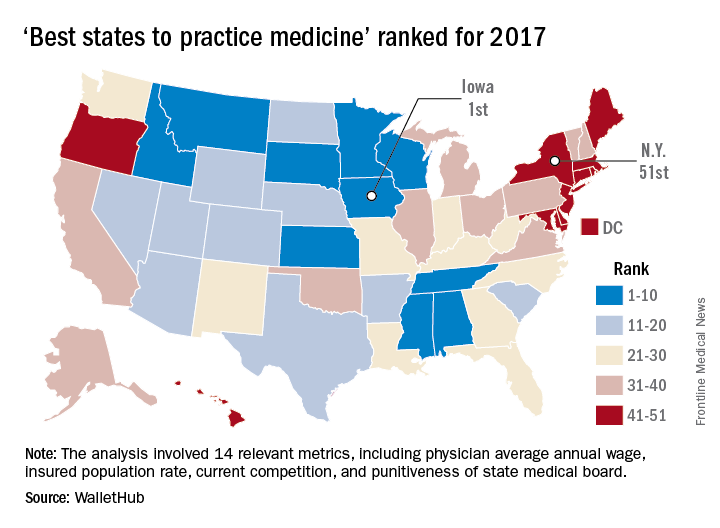

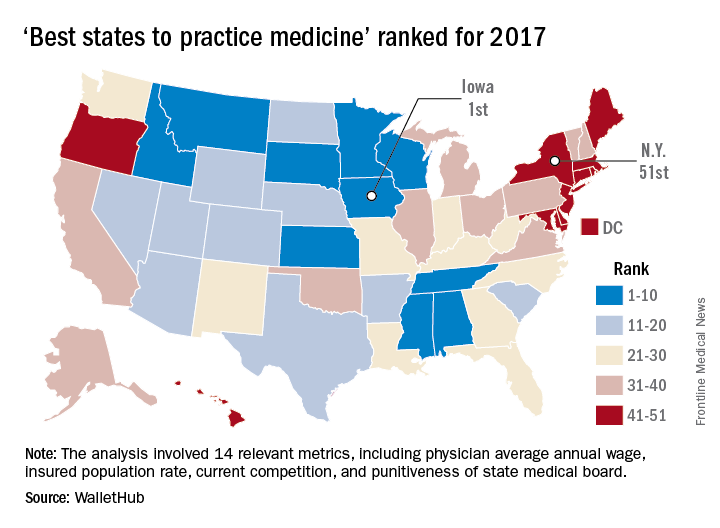

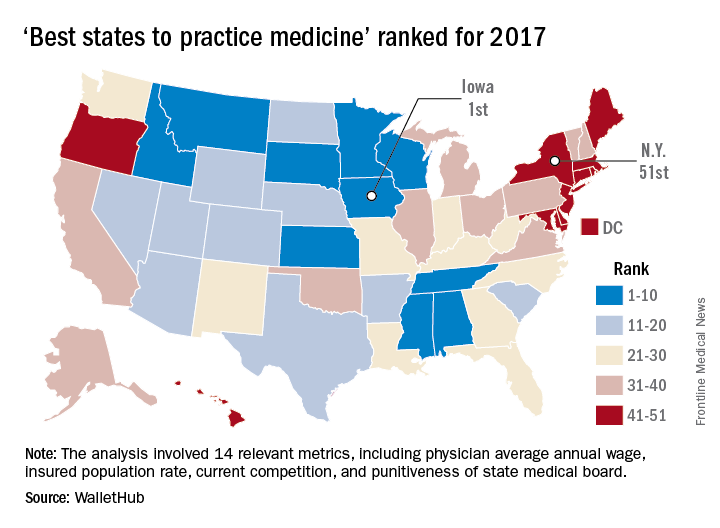

Moving or starting a practice? Consider Iowa

The federal government may or may not believe in global warming, but when it comes to states’ medical practice climates, Iowa trumps them all, according to the personal finance website WalletHub.

The Hawkeye State came out on top of WalletHub’s list of the Best States to Practice Medicine for 2017 with 68.7 out of a possible 100 points, while New York finished 51st (Washington, D.C., was 50th) with 28.5 points. Minnesota is the second-best state for physicians, followed by Idaho, Wisconsin, and Kansas. The rest of the bottom five included New Jersey at 49th, Maryland at 48th, and Rhode Island at 47th, WalletHub reported.

WalletHub compared the 50 states and Washington using 14 different metrics across two broad categories: “opportunity and competition” (70 points) and “medical environment” (30 points). Metrics included physicians’ average annual wage (adjusted for cost of living), hospitals per capita, quality of public hospital system, and annual malpractice liability insurance rate.

The federal government may or may not believe in global warming, but when it comes to states’ medical practice climates, Iowa trumps them all, according to the personal finance website WalletHub.

The Hawkeye State came out on top of WalletHub’s list of the Best States to Practice Medicine for 2017 with 68.7 out of a possible 100 points, while New York finished 51st (Washington, D.C., was 50th) with 28.5 points. Minnesota is the second-best state for physicians, followed by Idaho, Wisconsin, and Kansas. The rest of the bottom five included New Jersey at 49th, Maryland at 48th, and Rhode Island at 47th, WalletHub reported.

WalletHub compared the 50 states and Washington using 14 different metrics across two broad categories: “opportunity and competition” (70 points) and “medical environment” (30 points). Metrics included physicians’ average annual wage (adjusted for cost of living), hospitals per capita, quality of public hospital system, and annual malpractice liability insurance rate.

The federal government may or may not believe in global warming, but when it comes to states’ medical practice climates, Iowa trumps them all, according to the personal finance website WalletHub.

The Hawkeye State came out on top of WalletHub’s list of the Best States to Practice Medicine for 2017 with 68.7 out of a possible 100 points, while New York finished 51st (Washington, D.C., was 50th) with 28.5 points. Minnesota is the second-best state for physicians, followed by Idaho, Wisconsin, and Kansas. The rest of the bottom five included New Jersey at 49th, Maryland at 48th, and Rhode Island at 47th, WalletHub reported.

WalletHub compared the 50 states and Washington using 14 different metrics across two broad categories: “opportunity and competition” (70 points) and “medical environment” (30 points). Metrics included physicians’ average annual wage (adjusted for cost of living), hospitals per capita, quality of public hospital system, and annual malpractice liability insurance rate.

Associate Fellows: Apply now for ACS Fellowship

Associate Fellows who are interested in pursuing the next level of membership and who meet the criteria for Fellowship are encouraged to start the application process now.

Applications for American College of Surgeons (ACS) Fellowship for induction at the 2018 Clinical Congress in Boston, MA, are due December 1, 2017.

ACS Fellowship is granted to physicians who devote their practice entirely to surgical services and who agree to practice in accordance with the College’s professional and ethical standards.

The College’s Fellowship Pledge and Statements on Principles, found on the ACS website at facs.org, outline the ACS standards of practice. All ACS Fellows and applicants for Fellowship are expected to adhere to these standards.

Surgeons voluntarily submit applications for Fellowship, thereby inviting an evaluation of their practice by their peers. In evaluating the eligibility of Fellowship applicants, the College investigates each applicant’s entire surgical practice. Applicants for Fellowship are required to provide to the appointed committees of the College all information deemed necessary for the investigation and evaluation of their surgical practice.

It is our intention that all Associate Fellows consider applying for Fellowship within the first six years of their surgical practice. To encourage that transition, Associate Fellowship is limited to surgeons who have been in practice less than six years.

Requirements

The basic requirements for Domestic (U.S. and Canada) Fellowship are as follows:

• Certification by an appropriate American Board of Medical Specialties surgical specialty board, an American Osteopathic Association surgical specialty board, or the Royal College of Surgeons in Canada

• One year of surgical practice after the completion of all formal training (including fellowships)

• A current appointment at a primary hospital with no reportable action pending

A full list of the domestic requirements can be accessed at facs.org/member-services/join/fellows. The list of requirements for International Fellowship is online at facs.org/member-services/join/international.

Associate Fellows who are current with their membership dues may apply online for free by visiting facs.org/member-services/join and clicking on the link for either Fellow or International Fellow. You will need your log-in information to access the application. If you do not have your log-in information, contact the College’s Member Services staff at 800-293-9623 or via e-mail at [email protected].

The application requests basic information regarding licensure, certification, education, and hospital affiliations. Applicants also are asked to provide the names of five Fellows of the College, preferably from their current practice location, to serve as references. Applicants do not need to request letters of recommendation; simply list the names in your application, and the College staff will contact your references.

If you need assistance finding ACS Fellows in your area, go to facs.org and click on the “Find a Surgeon” button.

When your application is processed, you will receive an e-mail notification providing details about the application timeline along with a request for your surgical case list.

All Fellowship applicants are required to participate in a personal interview by an ACS committee in their local area. Exceptions are made for military applicants. Following the interview, you will receive notification by July 15 of the action taken on your application. Approved applicants are designated as Initiates to be inducted as Fellows during the Convocation Ceremony at the Clinical Congress.

Contact Member Services with questions at any time throughout the application process. We look forward to you becoming a Fellow of the American College of Surgeons.

Associate Fellows who are interested in pursuing the next level of membership and who meet the criteria for Fellowship are encouraged to start the application process now.

Applications for American College of Surgeons (ACS) Fellowship for induction at the 2018 Clinical Congress in Boston, MA, are due December 1, 2017.

ACS Fellowship is granted to physicians who devote their practice entirely to surgical services and who agree to practice in accordance with the College’s professional and ethical standards.

The College’s Fellowship Pledge and Statements on Principles, found on the ACS website at facs.org, outline the ACS standards of practice. All ACS Fellows and applicants for Fellowship are expected to adhere to these standards.

Surgeons voluntarily submit applications for Fellowship, thereby inviting an evaluation of their practice by their peers. In evaluating the eligibility of Fellowship applicants, the College investigates each applicant’s entire surgical practice. Applicants for Fellowship are required to provide to the appointed committees of the College all information deemed necessary for the investigation and evaluation of their surgical practice.

It is our intention that all Associate Fellows consider applying for Fellowship within the first six years of their surgical practice. To encourage that transition, Associate Fellowship is limited to surgeons who have been in practice less than six years.

Requirements

The basic requirements for Domestic (U.S. and Canada) Fellowship are as follows:

• Certification by an appropriate American Board of Medical Specialties surgical specialty board, an American Osteopathic Association surgical specialty board, or the Royal College of Surgeons in Canada

• One year of surgical practice after the completion of all formal training (including fellowships)

• A current appointment at a primary hospital with no reportable action pending

A full list of the domestic requirements can be accessed at facs.org/member-services/join/fellows. The list of requirements for International Fellowship is online at facs.org/member-services/join/international.

Associate Fellows who are current with their membership dues may apply online for free by visiting facs.org/member-services/join and clicking on the link for either Fellow or International Fellow. You will need your log-in information to access the application. If you do not have your log-in information, contact the College’s Member Services staff at 800-293-9623 or via e-mail at [email protected].

The application requests basic information regarding licensure, certification, education, and hospital affiliations. Applicants also are asked to provide the names of five Fellows of the College, preferably from their current practice location, to serve as references. Applicants do not need to request letters of recommendation; simply list the names in your application, and the College staff will contact your references.

If you need assistance finding ACS Fellows in your area, go to facs.org and click on the “Find a Surgeon” button.

When your application is processed, you will receive an e-mail notification providing details about the application timeline along with a request for your surgical case list.

All Fellowship applicants are required to participate in a personal interview by an ACS committee in their local area. Exceptions are made for military applicants. Following the interview, you will receive notification by July 15 of the action taken on your application. Approved applicants are designated as Initiates to be inducted as Fellows during the Convocation Ceremony at the Clinical Congress.

Contact Member Services with questions at any time throughout the application process. We look forward to you becoming a Fellow of the American College of Surgeons.

Associate Fellows who are interested in pursuing the next level of membership and who meet the criteria for Fellowship are encouraged to start the application process now.

Applications for American College of Surgeons (ACS) Fellowship for induction at the 2018 Clinical Congress in Boston, MA, are due December 1, 2017.

ACS Fellowship is granted to physicians who devote their practice entirely to surgical services and who agree to practice in accordance with the College’s professional and ethical standards.

The College’s Fellowship Pledge and Statements on Principles, found on the ACS website at facs.org, outline the ACS standards of practice. All ACS Fellows and applicants for Fellowship are expected to adhere to these standards.

Surgeons voluntarily submit applications for Fellowship, thereby inviting an evaluation of their practice by their peers. In evaluating the eligibility of Fellowship applicants, the College investigates each applicant’s entire surgical practice. Applicants for Fellowship are required to provide to the appointed committees of the College all information deemed necessary for the investigation and evaluation of their surgical practice.

It is our intention that all Associate Fellows consider applying for Fellowship within the first six years of their surgical practice. To encourage that transition, Associate Fellowship is limited to surgeons who have been in practice less than six years.

Requirements

The basic requirements for Domestic (U.S. and Canada) Fellowship are as follows:

• Certification by an appropriate American Board of Medical Specialties surgical specialty board, an American Osteopathic Association surgical specialty board, or the Royal College of Surgeons in Canada

• One year of surgical practice after the completion of all formal training (including fellowships)

• A current appointment at a primary hospital with no reportable action pending

A full list of the domestic requirements can be accessed at facs.org/member-services/join/fellows. The list of requirements for International Fellowship is online at facs.org/member-services/join/international.

Associate Fellows who are current with their membership dues may apply online for free by visiting facs.org/member-services/join and clicking on the link for either Fellow or International Fellow. You will need your log-in information to access the application. If you do not have your log-in information, contact the College’s Member Services staff at 800-293-9623 or via e-mail at [email protected].

The application requests basic information regarding licensure, certification, education, and hospital affiliations. Applicants also are asked to provide the names of five Fellows of the College, preferably from their current practice location, to serve as references. Applicants do not need to request letters of recommendation; simply list the names in your application, and the College staff will contact your references.

If you need assistance finding ACS Fellows in your area, go to facs.org and click on the “Find a Surgeon” button.

When your application is processed, you will receive an e-mail notification providing details about the application timeline along with a request for your surgical case list.

All Fellowship applicants are required to participate in a personal interview by an ACS committee in their local area. Exceptions are made for military applicants. Following the interview, you will receive notification by July 15 of the action taken on your application. Approved applicants are designated as Initiates to be inducted as Fellows during the Convocation Ceremony at the Clinical Congress.

Contact Member Services with questions at any time throughout the application process. We look forward to you becoming a Fellow of the American College of Surgeons.

Rate of heroin use in U.S. soars, especially among white individuals

Rates of heroin use and heroin use disorder rose dramatically between 2001-2002 and 2012-2013, and the trend was greatest among the white population. The rise among white individuals could be tied to the opioid epidemic, because nonmedical opioid also rose disproportionately in that group, according to research published online March 29.

The findings come from an analysis of 43,093 people who responded to the 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), and 36,309 respondents to the 2012-2013 NESARC-III.

In addition, Dr. Martins and her associates found a significant rise in the number of white heroin users who had started nonmedical prescription opioid (NMPO) use before heroin (35.83% to 52.83%; P =.01). In contrast, the percentage of nonwhite individuals who started off with NMPO use dropped from 44.12% to 26.20% (P = .04).

The increase in heroin use was larger among individuals at less than 100% of the poverty level (0.44% to 2.42%; P less than .001), as well as among people with education levels of less than high school (heroin use, 0.41% to 2.01%; P = .03; heroin use disorder, 0.24% to 0.87%; P = .08) and among those with no more than high school education (heroin use, 0.39% to 2.15%; P =.003; heroin use disorder, 0.29% to 1.11%; P = .003). The absolute values of the findings may be inexact, because the methods of the two surveys differed slightly. In addition, the investigators did not include homeless and incarcerated individuals.

Based on their analysis, Dr. Martins and her associates offered strategies aimed at addressing the crisis. “To curb the heroin epidemic, particularly among younger adults, collective prevention and intervention efforts may be most effective,” they wrote. “Promising examples include expansion of access to medication-assisted treatment (including methadone hydrochloride, buprenorphine hydrochloride, or injectable naltrexone hydrochloride), educational programs in schools and community settings, overdose prevention training in concert with comprehensive naloxone hydrochloride distribution programs, and consistent use of prescription drug–monitoring programs that implement best practices by prescribers.”

NESARC and NESARC-III were funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The authors received funding from several sources, including the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the New York State Psychiatric Institute, and the J. William Fulbright and the Colciencias doctoral scholarships. One of the study authors, Deborah S. Hasin, PhD, was a principal investigator on a study that was funded by InVentiv Health Consulting, which pool funds from nine pharmaceutical companies.

Opioid misuse can be prevented by the medical community with a change in prescribing practices aimed at limiting the supply of prescription opioids, Bertha K. Madras, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Mar 29. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0163). Also, medical training “should include awareness of the risks posed by high opioid doses, immediate-release formulations, use combined with alcohol and/or benzodiazepines, history of overdoses, and other factors,” she wrote.

The United States has more than 14,000 drug treatment programs, but many are staffed with clinicians who are not licensed. One way to foster comprehensive services would be to develop an integrated medical and behavioral treatment system that would be supervised by a physician and substance abuse specialist. “Resources, training, and workforce issues are a concern, but the benefits of integrated health care and behavioral treatment conceivably outweigh the risks of maintaining the status quo,” she wrote.

Dr. Madras is affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School in Boston, and McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass. She also serves on the scientific advisory board of RiverMend Health and consults for Guidepoint.

Opioid misuse can be prevented by the medical community with a change in prescribing practices aimed at limiting the supply of prescription opioids, Bertha K. Madras, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Mar 29. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0163). Also, medical training “should include awareness of the risks posed by high opioid doses, immediate-release formulations, use combined with alcohol and/or benzodiazepines, history of overdoses, and other factors,” she wrote.

The United States has more than 14,000 drug treatment programs, but many are staffed with clinicians who are not licensed. One way to foster comprehensive services would be to develop an integrated medical and behavioral treatment system that would be supervised by a physician and substance abuse specialist. “Resources, training, and workforce issues are a concern, but the benefits of integrated health care and behavioral treatment conceivably outweigh the risks of maintaining the status quo,” she wrote.

Dr. Madras is affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School in Boston, and McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass. She also serves on the scientific advisory board of RiverMend Health and consults for Guidepoint.

Opioid misuse can be prevented by the medical community with a change in prescribing practices aimed at limiting the supply of prescription opioids, Bertha K. Madras, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Mar 29. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0163). Also, medical training “should include awareness of the risks posed by high opioid doses, immediate-release formulations, use combined with alcohol and/or benzodiazepines, history of overdoses, and other factors,” she wrote.

The United States has more than 14,000 drug treatment programs, but many are staffed with clinicians who are not licensed. One way to foster comprehensive services would be to develop an integrated medical and behavioral treatment system that would be supervised by a physician and substance abuse specialist. “Resources, training, and workforce issues are a concern, but the benefits of integrated health care and behavioral treatment conceivably outweigh the risks of maintaining the status quo,” she wrote.

Dr. Madras is affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School in Boston, and McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass. She also serves on the scientific advisory board of RiverMend Health and consults for Guidepoint.

Rates of heroin use and heroin use disorder rose dramatically between 2001-2002 and 2012-2013, and the trend was greatest among the white population. The rise among white individuals could be tied to the opioid epidemic, because nonmedical opioid also rose disproportionately in that group, according to research published online March 29.

The findings come from an analysis of 43,093 people who responded to the 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), and 36,309 respondents to the 2012-2013 NESARC-III.

In addition, Dr. Martins and her associates found a significant rise in the number of white heroin users who had started nonmedical prescription opioid (NMPO) use before heroin (35.83% to 52.83%; P =.01). In contrast, the percentage of nonwhite individuals who started off with NMPO use dropped from 44.12% to 26.20% (P = .04).

The increase in heroin use was larger among individuals at less than 100% of the poverty level (0.44% to 2.42%; P less than .001), as well as among people with education levels of less than high school (heroin use, 0.41% to 2.01%; P = .03; heroin use disorder, 0.24% to 0.87%; P = .08) and among those with no more than high school education (heroin use, 0.39% to 2.15%; P =.003; heroin use disorder, 0.29% to 1.11%; P = .003). The absolute values of the findings may be inexact, because the methods of the two surveys differed slightly. In addition, the investigators did not include homeless and incarcerated individuals.

Based on their analysis, Dr. Martins and her associates offered strategies aimed at addressing the crisis. “To curb the heroin epidemic, particularly among younger adults, collective prevention and intervention efforts may be most effective,” they wrote. “Promising examples include expansion of access to medication-assisted treatment (including methadone hydrochloride, buprenorphine hydrochloride, or injectable naltrexone hydrochloride), educational programs in schools and community settings, overdose prevention training in concert with comprehensive naloxone hydrochloride distribution programs, and consistent use of prescription drug–monitoring programs that implement best practices by prescribers.”

NESARC and NESARC-III were funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The authors received funding from several sources, including the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the New York State Psychiatric Institute, and the J. William Fulbright and the Colciencias doctoral scholarships. One of the study authors, Deborah S. Hasin, PhD, was a principal investigator on a study that was funded by InVentiv Health Consulting, which pool funds from nine pharmaceutical companies.

Rates of heroin use and heroin use disorder rose dramatically between 2001-2002 and 2012-2013, and the trend was greatest among the white population. The rise among white individuals could be tied to the opioid epidemic, because nonmedical opioid also rose disproportionately in that group, according to research published online March 29.

The findings come from an analysis of 43,093 people who responded to the 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), and 36,309 respondents to the 2012-2013 NESARC-III.

In addition, Dr. Martins and her associates found a significant rise in the number of white heroin users who had started nonmedical prescription opioid (NMPO) use before heroin (35.83% to 52.83%; P =.01). In contrast, the percentage of nonwhite individuals who started off with NMPO use dropped from 44.12% to 26.20% (P = .04).

The increase in heroin use was larger among individuals at less than 100% of the poverty level (0.44% to 2.42%; P less than .001), as well as among people with education levels of less than high school (heroin use, 0.41% to 2.01%; P = .03; heroin use disorder, 0.24% to 0.87%; P = .08) and among those with no more than high school education (heroin use, 0.39% to 2.15%; P =.003; heroin use disorder, 0.29% to 1.11%; P = .003). The absolute values of the findings may be inexact, because the methods of the two surveys differed slightly. In addition, the investigators did not include homeless and incarcerated individuals.

Based on their analysis, Dr. Martins and her associates offered strategies aimed at addressing the crisis. “To curb the heroin epidemic, particularly among younger adults, collective prevention and intervention efforts may be most effective,” they wrote. “Promising examples include expansion of access to medication-assisted treatment (including methadone hydrochloride, buprenorphine hydrochloride, or injectable naltrexone hydrochloride), educational programs in schools and community settings, overdose prevention training in concert with comprehensive naloxone hydrochloride distribution programs, and consistent use of prescription drug–monitoring programs that implement best practices by prescribers.”

NESARC and NESARC-III were funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The authors received funding from several sources, including the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the New York State Psychiatric Institute, and the J. William Fulbright and the Colciencias doctoral scholarships. One of the study authors, Deborah S. Hasin, PhD, was a principal investigator on a study that was funded by InVentiv Health Consulting, which pool funds from nine pharmaceutical companies.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

Key clinical point: Campaigns are needed to educate the public about harms tied to heroin use, and access should be expanded to populations at risk for both heroin use and heroin use disorder.

Major finding: Rates of lifetime heroin use rose from 0.33% to 1.61%.

Data source: Retrospective analysis of 43,093 respondents to the 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), and 36,309 respondents to the 2012-2013 NESARC-III.

Disclosures: NESARC and NESARC-III were funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The authors received funding from several sources, including the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the New York State Psychiatric Institute, and the J. William Fulbright and the Colciencias doctoral scholarships. One of the study authors, Deborah S. Hasin, PhD, was a principal investigator on a study that was funded by InVentiv Health Consulting, which pools funds from nine pharmaceutical companies.

Dr. Henri Ford Accorded Honorary Fellowship in RCSEng

Henri R. Ford, MD, MHA, FACS, FAAP, vice-president and surgeon-in-chief, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles; professor of surgery and vice-dean for medical education, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California; and member of the American College of Surgeons Board of Regents, was accorded Honorary Fellowship in the Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCSEng) on March 7 in London, U.K.

A world-renowned Haitian-American surgeon, Dr. Ford played a prominent role in organizing and leading medical teams in response to the catastrophic 2010 earthquake in Haiti. Born in Haiti, Dr. Ford regularly returns to his native country to teach, lead operating teams, and assist in developing surgical systems, which the island nation historically has lacked. His accomplishments there are myriad. For example, in May 2015, Dr. Ford led a team of health care professionals that made history by completing the first separation of conjoined twins in Haiti. (Read more about the operation at www.cbsnews.com/news/more-than-just-a-surgery-conjoined-twins-separated-in-haiti/.)

Dr. Ford and his family fled Haiti’s oppressive regime and came to the U.S. when he was 13 years old. He received his medical degree from Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, and trained in general surgery at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY. He completed his pediatric surgical training at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, PA. Prior to joining Children’s Hospital Los Angeles in 2005, Dr. Ford was professor and chief, division of pediatric surgery, and surgeon-in-chief, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh and the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

Su-Anna Boddy, MS, FRCS, council member for the RCSEng, introduced Dr. Ford at the ceremony and spoke of his accomplishments, and Clare Marx, CBE, DL, PRCS, RCSEng president, formally awarded him the honor.

Henri R. Ford, MD, MHA, FACS, FAAP, vice-president and surgeon-in-chief, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles; professor of surgery and vice-dean for medical education, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California; and member of the American College of Surgeons Board of Regents, was accorded Honorary Fellowship in the Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCSEng) on March 7 in London, U.K.

A world-renowned Haitian-American surgeon, Dr. Ford played a prominent role in organizing and leading medical teams in response to the catastrophic 2010 earthquake in Haiti. Born in Haiti, Dr. Ford regularly returns to his native country to teach, lead operating teams, and assist in developing surgical systems, which the island nation historically has lacked. His accomplishments there are myriad. For example, in May 2015, Dr. Ford led a team of health care professionals that made history by completing the first separation of conjoined twins in Haiti. (Read more about the operation at www.cbsnews.com/news/more-than-just-a-surgery-conjoined-twins-separated-in-haiti/.)

Dr. Ford and his family fled Haiti’s oppressive regime and came to the U.S. when he was 13 years old. He received his medical degree from Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, and trained in general surgery at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY. He completed his pediatric surgical training at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, PA. Prior to joining Children’s Hospital Los Angeles in 2005, Dr. Ford was professor and chief, division of pediatric surgery, and surgeon-in-chief, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh and the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

Su-Anna Boddy, MS, FRCS, council member for the RCSEng, introduced Dr. Ford at the ceremony and spoke of his accomplishments, and Clare Marx, CBE, DL, PRCS, RCSEng president, formally awarded him the honor.

Henri R. Ford, MD, MHA, FACS, FAAP, vice-president and surgeon-in-chief, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles; professor of surgery and vice-dean for medical education, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California; and member of the American College of Surgeons Board of Regents, was accorded Honorary Fellowship in the Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCSEng) on March 7 in London, U.K.

A world-renowned Haitian-American surgeon, Dr. Ford played a prominent role in organizing and leading medical teams in response to the catastrophic 2010 earthquake in Haiti. Born in Haiti, Dr. Ford regularly returns to his native country to teach, lead operating teams, and assist in developing surgical systems, which the island nation historically has lacked. His accomplishments there are myriad. For example, in May 2015, Dr. Ford led a team of health care professionals that made history by completing the first separation of conjoined twins in Haiti. (Read more about the operation at www.cbsnews.com/news/more-than-just-a-surgery-conjoined-twins-separated-in-haiti/.)

Dr. Ford and his family fled Haiti’s oppressive regime and came to the U.S. when he was 13 years old. He received his medical degree from Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, and trained in general surgery at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY. He completed his pediatric surgical training at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, PA. Prior to joining Children’s Hospital Los Angeles in 2005, Dr. Ford was professor and chief, division of pediatric surgery, and surgeon-in-chief, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh and the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.