User login

Weight-loss drug options expand, but beware cardiac risk

LOS ANGELES – Newer medications are much more powerful, but they come with cautions – insurer coverage can be a hurdle, and there are significant gaps in knowledge about their risks for patients with heart disease, Ken Fujioka, MD, told colleagues at the annual scientific and clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

Dr. Fujioka, of Scripps Clinic in San Diego, shared some tips with his peers about using medications to reduce weight.

Diabetes drugs help, but may need a boost

Metformin can reduce weight by as much as 3%, Dr. Fujioka said. And there may be another benefit related to long-term weight loss maintenance, he said, citing a 15-year study of overweight or obese patients at high risk for diabetes who either received metformin, underwent an intensive lifestyle intervention, or took a placebo. Of the participants with weight loss of at least 5% after the first year, those originally assigned to receive metformin had the greatest weight loss during years 6-15. Older age, the amount of weight initially lost, and continued used of metformin were predictors of long-term weight loss maintenance, according to the researchers (Ann Intern Med. 2019 Apr 23. doi: 10.7326/M18-1605).

There are other options among diabetes drugs. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors – a class of drugs that includes canagliflozin (Invokana), dapagliflozin (Farxiga), and empagliflozin (Jardiance) – have a striking effect on weight loss, Dr. Fujioka said. They can cause 300 calories to be flushed out in the urine each day. But that typically doesn’t translate into weight loss of more than 20 pounds, he said, because the body doesn’t fully adjust to fewer calories.

“The patients begin to eat more,” he said. “They have to take in more calories to make up for [the loss]. They’re not consciously trying to do this. It’s a metabolic adaptation, so 2%-3% [weight loss] is about all you’ll get. You won’t get 10% or 20%.”

To drive up weight loss, Dr. Fujioka recommended adding the glucagonlike peptide–1 [GLP1] receptor diabetes drug exenatide (Byetta; Bydureon) or the appetite suppressant phentermine (Adipex-p; Lomaira) to an SGLT2 inhibitor. Recent studies have shown that the drug combinations have a greater impact on weight loss than when taken separately (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016 Dec;4[12]:1004-16; Diabetes Care. 2017 May;40[5]:632-9).

In regard to phentermine, which acts similarly to amphetamine, Dr. Fujioka advised colleagues to be aware that “15 mg or less is really safe, but you drive pulse and heart rate beyond that.”

Consider insurance coverage and other factors

Often, insurers will pay for GLP1-receptor and SGLT2-inhibitor medications in patients with diabetes, even if their hemoglobin A1c is in the healthy range, Dr. Fujioka said, but they’ll balk at paying for specific weight-loss medications, although that can vary by the region of the country. He added that cash discount cards are available for several weight-loss drugs.

Newer weight-loss drugs ...

Dr. Fujioka highlighted a quartet of weight-loss drugs that have been approved in recent years.

- Lorcaserin (Belviq), a selective serotonin 2C receptor agonist, has shown unique benefits in patients with diabetes. A large, multinational, randomized controlled trial found that the drug reduced the risk for incident diabetes, induced remission of hyperglycemia, and reduced the risk of microvascular complications in obese and overweight patients (Lancet. 2018 Nov 24;392[10161]:2269-79).

- Phentermine/topiramate (Qsymia), a combination of an antiseizure medication (topiramate) and an appetite suppressant (phentermine). A 2014 study found that the drug, together with lifestyle modification, effectively promoted weight loss and improved glycemic control in obese or overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (Diabetes Care. 2014 Dec;37[12]:3309-16).

- Naltrexone/bupropion (Contrave), a combination of an addiction drug (naltrexone) and an antidepressant (bupropion). Findings from a 2013 study reported that the drug “in overweight/obese patients with type 2 diabetes induced weight loss... was associated with improvements in glycemic control and select cardiovascular risk factors and was generally well tolerated with a safety profile similar to that in patients without diabetes.” (Diabetes Care. 2013 Dec;36[12]:4022-9).

- Liraglutide, an injectable GLP1 agonist that has been approved for diabetes (Victoza) and weight loss (Saxenda). Dr. Fujioka was coauthor for a study in which the findings suggested that the drug could prevent prediabetes from turning into diabetes. (Lancet. 2017 Apr 8;389[10077]:1399-409).

... but watch out for safety in patients with heart disease

Two of the newer weight-loss drugs are OK to prescribe for diabetic patients with heart disease, Dr. Fujioka said, but two are not, because no cardiac safety trials have been completed for them.

Liraglutide (at a dose of 3.0 mg) is considered safe based on previous data (Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018 Mar;20[3]:734-9), Dr. Fujioka said. Likewise, findings from a trial with lorcaserin in which 12,000 overweight or obese patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or multiple cardiovascular risk factors received either lorcaserin (10 mg twice daily) or placebo, suggested that lorcaserin helped sustain weight loss without a higher rate of major cardiovascular events compared with placebo (N Engl J Med. 2018 Sep 20;379[12]:1107-17).However, no such cardiac safety trials have been completed for naltrexone/bupropion or phentermine/topiramate, said Dr. Fujioka. As a result, he said he could not recommend either of them for patients with high-risk cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Fujioka disclosed relationships of various types with Novo Nordisk, Eisai, Gelesis, KVK Tech, Amgen, Sunovion, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Janssen Global Services.

LOS ANGELES – Newer medications are much more powerful, but they come with cautions – insurer coverage can be a hurdle, and there are significant gaps in knowledge about their risks for patients with heart disease, Ken Fujioka, MD, told colleagues at the annual scientific and clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

Dr. Fujioka, of Scripps Clinic in San Diego, shared some tips with his peers about using medications to reduce weight.

Diabetes drugs help, but may need a boost

Metformin can reduce weight by as much as 3%, Dr. Fujioka said. And there may be another benefit related to long-term weight loss maintenance, he said, citing a 15-year study of overweight or obese patients at high risk for diabetes who either received metformin, underwent an intensive lifestyle intervention, or took a placebo. Of the participants with weight loss of at least 5% after the first year, those originally assigned to receive metformin had the greatest weight loss during years 6-15. Older age, the amount of weight initially lost, and continued used of metformin were predictors of long-term weight loss maintenance, according to the researchers (Ann Intern Med. 2019 Apr 23. doi: 10.7326/M18-1605).

There are other options among diabetes drugs. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors – a class of drugs that includes canagliflozin (Invokana), dapagliflozin (Farxiga), and empagliflozin (Jardiance) – have a striking effect on weight loss, Dr. Fujioka said. They can cause 300 calories to be flushed out in the urine each day. But that typically doesn’t translate into weight loss of more than 20 pounds, he said, because the body doesn’t fully adjust to fewer calories.

“The patients begin to eat more,” he said. “They have to take in more calories to make up for [the loss]. They’re not consciously trying to do this. It’s a metabolic adaptation, so 2%-3% [weight loss] is about all you’ll get. You won’t get 10% or 20%.”

To drive up weight loss, Dr. Fujioka recommended adding the glucagonlike peptide–1 [GLP1] receptor diabetes drug exenatide (Byetta; Bydureon) or the appetite suppressant phentermine (Adipex-p; Lomaira) to an SGLT2 inhibitor. Recent studies have shown that the drug combinations have a greater impact on weight loss than when taken separately (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016 Dec;4[12]:1004-16; Diabetes Care. 2017 May;40[5]:632-9).

In regard to phentermine, which acts similarly to amphetamine, Dr. Fujioka advised colleagues to be aware that “15 mg or less is really safe, but you drive pulse and heart rate beyond that.”

Consider insurance coverage and other factors

Often, insurers will pay for GLP1-receptor and SGLT2-inhibitor medications in patients with diabetes, even if their hemoglobin A1c is in the healthy range, Dr. Fujioka said, but they’ll balk at paying for specific weight-loss medications, although that can vary by the region of the country. He added that cash discount cards are available for several weight-loss drugs.

Newer weight-loss drugs ...

Dr. Fujioka highlighted a quartet of weight-loss drugs that have been approved in recent years.

- Lorcaserin (Belviq), a selective serotonin 2C receptor agonist, has shown unique benefits in patients with diabetes. A large, multinational, randomized controlled trial found that the drug reduced the risk for incident diabetes, induced remission of hyperglycemia, and reduced the risk of microvascular complications in obese and overweight patients (Lancet. 2018 Nov 24;392[10161]:2269-79).

- Phentermine/topiramate (Qsymia), a combination of an antiseizure medication (topiramate) and an appetite suppressant (phentermine). A 2014 study found that the drug, together with lifestyle modification, effectively promoted weight loss and improved glycemic control in obese or overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (Diabetes Care. 2014 Dec;37[12]:3309-16).

- Naltrexone/bupropion (Contrave), a combination of an addiction drug (naltrexone) and an antidepressant (bupropion). Findings from a 2013 study reported that the drug “in overweight/obese patients with type 2 diabetes induced weight loss... was associated with improvements in glycemic control and select cardiovascular risk factors and was generally well tolerated with a safety profile similar to that in patients without diabetes.” (Diabetes Care. 2013 Dec;36[12]:4022-9).

- Liraglutide, an injectable GLP1 agonist that has been approved for diabetes (Victoza) and weight loss (Saxenda). Dr. Fujioka was coauthor for a study in which the findings suggested that the drug could prevent prediabetes from turning into diabetes. (Lancet. 2017 Apr 8;389[10077]:1399-409).

... but watch out for safety in patients with heart disease

Two of the newer weight-loss drugs are OK to prescribe for diabetic patients with heart disease, Dr. Fujioka said, but two are not, because no cardiac safety trials have been completed for them.

Liraglutide (at a dose of 3.0 mg) is considered safe based on previous data (Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018 Mar;20[3]:734-9), Dr. Fujioka said. Likewise, findings from a trial with lorcaserin in which 12,000 overweight or obese patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or multiple cardiovascular risk factors received either lorcaserin (10 mg twice daily) or placebo, suggested that lorcaserin helped sustain weight loss without a higher rate of major cardiovascular events compared with placebo (N Engl J Med. 2018 Sep 20;379[12]:1107-17).However, no such cardiac safety trials have been completed for naltrexone/bupropion or phentermine/topiramate, said Dr. Fujioka. As a result, he said he could not recommend either of them for patients with high-risk cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Fujioka disclosed relationships of various types with Novo Nordisk, Eisai, Gelesis, KVK Tech, Amgen, Sunovion, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Janssen Global Services.

LOS ANGELES – Newer medications are much more powerful, but they come with cautions – insurer coverage can be a hurdle, and there are significant gaps in knowledge about their risks for patients with heart disease, Ken Fujioka, MD, told colleagues at the annual scientific and clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

Dr. Fujioka, of Scripps Clinic in San Diego, shared some tips with his peers about using medications to reduce weight.

Diabetes drugs help, but may need a boost

Metformin can reduce weight by as much as 3%, Dr. Fujioka said. And there may be another benefit related to long-term weight loss maintenance, he said, citing a 15-year study of overweight or obese patients at high risk for diabetes who either received metformin, underwent an intensive lifestyle intervention, or took a placebo. Of the participants with weight loss of at least 5% after the first year, those originally assigned to receive metformin had the greatest weight loss during years 6-15. Older age, the amount of weight initially lost, and continued used of metformin were predictors of long-term weight loss maintenance, according to the researchers (Ann Intern Med. 2019 Apr 23. doi: 10.7326/M18-1605).

There are other options among diabetes drugs. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors – a class of drugs that includes canagliflozin (Invokana), dapagliflozin (Farxiga), and empagliflozin (Jardiance) – have a striking effect on weight loss, Dr. Fujioka said. They can cause 300 calories to be flushed out in the urine each day. But that typically doesn’t translate into weight loss of more than 20 pounds, he said, because the body doesn’t fully adjust to fewer calories.

“The patients begin to eat more,” he said. “They have to take in more calories to make up for [the loss]. They’re not consciously trying to do this. It’s a metabolic adaptation, so 2%-3% [weight loss] is about all you’ll get. You won’t get 10% or 20%.”

To drive up weight loss, Dr. Fujioka recommended adding the glucagonlike peptide–1 [GLP1] receptor diabetes drug exenatide (Byetta; Bydureon) or the appetite suppressant phentermine (Adipex-p; Lomaira) to an SGLT2 inhibitor. Recent studies have shown that the drug combinations have a greater impact on weight loss than when taken separately (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016 Dec;4[12]:1004-16; Diabetes Care. 2017 May;40[5]:632-9).

In regard to phentermine, which acts similarly to amphetamine, Dr. Fujioka advised colleagues to be aware that “15 mg or less is really safe, but you drive pulse and heart rate beyond that.”

Consider insurance coverage and other factors

Often, insurers will pay for GLP1-receptor and SGLT2-inhibitor medications in patients with diabetes, even if their hemoglobin A1c is in the healthy range, Dr. Fujioka said, but they’ll balk at paying for specific weight-loss medications, although that can vary by the region of the country. He added that cash discount cards are available for several weight-loss drugs.

Newer weight-loss drugs ...

Dr. Fujioka highlighted a quartet of weight-loss drugs that have been approved in recent years.

- Lorcaserin (Belviq), a selective serotonin 2C receptor agonist, has shown unique benefits in patients with diabetes. A large, multinational, randomized controlled trial found that the drug reduced the risk for incident diabetes, induced remission of hyperglycemia, and reduced the risk of microvascular complications in obese and overweight patients (Lancet. 2018 Nov 24;392[10161]:2269-79).

- Phentermine/topiramate (Qsymia), a combination of an antiseizure medication (topiramate) and an appetite suppressant (phentermine). A 2014 study found that the drug, together with lifestyle modification, effectively promoted weight loss and improved glycemic control in obese or overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (Diabetes Care. 2014 Dec;37[12]:3309-16).

- Naltrexone/bupropion (Contrave), a combination of an addiction drug (naltrexone) and an antidepressant (bupropion). Findings from a 2013 study reported that the drug “in overweight/obese patients with type 2 diabetes induced weight loss... was associated with improvements in glycemic control and select cardiovascular risk factors and was generally well tolerated with a safety profile similar to that in patients without diabetes.” (Diabetes Care. 2013 Dec;36[12]:4022-9).

- Liraglutide, an injectable GLP1 agonist that has been approved for diabetes (Victoza) and weight loss (Saxenda). Dr. Fujioka was coauthor for a study in which the findings suggested that the drug could prevent prediabetes from turning into diabetes. (Lancet. 2017 Apr 8;389[10077]:1399-409).

... but watch out for safety in patients with heart disease

Two of the newer weight-loss drugs are OK to prescribe for diabetic patients with heart disease, Dr. Fujioka said, but two are not, because no cardiac safety trials have been completed for them.

Liraglutide (at a dose of 3.0 mg) is considered safe based on previous data (Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018 Mar;20[3]:734-9), Dr. Fujioka said. Likewise, findings from a trial with lorcaserin in which 12,000 overweight or obese patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or multiple cardiovascular risk factors received either lorcaserin (10 mg twice daily) or placebo, suggested that lorcaserin helped sustain weight loss without a higher rate of major cardiovascular events compared with placebo (N Engl J Med. 2018 Sep 20;379[12]:1107-17).However, no such cardiac safety trials have been completed for naltrexone/bupropion or phentermine/topiramate, said Dr. Fujioka. As a result, he said he could not recommend either of them for patients with high-risk cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Fujioka disclosed relationships of various types with Novo Nordisk, Eisai, Gelesis, KVK Tech, Amgen, Sunovion, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Janssen Global Services.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AACE 2019

New adventures of an old device: Clinic delivers cortisol via the insulin pump

LOS ANGELES – The venerable insulin pump is being repurposed: A Detroit-area endocrinology

“We’ve seen amazing results,” said endocrinologist Opada Alzohaili, MD, MBA, of Wayne State University, Detroit, coauthor of a study released at the annual scientific and clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

Dr. Alzohaili said he and his colleagues developed the approach to manage patients who are “so sick that they go to the hospital 10-12 times a year.” Oral medication just did not control their disorder.

“Most of the time, we end up way overdosing them [on oral medication] just to prevent them from going to the hospital in adrenal crisis,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Alzohaili said his clinic has tested delivering hydrocortisone via insulin pump in about 20 patients. The report presented at the conference focused on six patients who had failed oral hydrocortisone treatment for adrenal insufficiency. Testing showed that all had malabsorption of the drug.

The patients underwent training in how to use and adjust the pump, which allows dosing adjustments in increments of 1 mg. They learned how to adjust their doses based on their situation, Dr. Alzohaili said.

According to the report, the average number of adrenal crises in the patients over a 6-month period fell from a mean of 2.3 before baseline to 0.5 after treatment began. The maximum dose of hydrocortisone dose fell by 38%, while the average mean weight of patients rose from 182 pounds to 199 pounds.

In addition, the mean dose of hydrocortisone decreased with the use of the pump delivery system, from 85.8 mg with oral treatment to 32.4 mg on pump therapy, and the mean level of cortisol increased from 11.8 mcg/dL with oral treatment to 12.3 mcg/dL on pump therapy.

The researchers said that the pump provides better delivery of the medication compared with the oral route, and that the patients experienced fewer interactions with other medications.

Some patients developed skin reactions to the pump, but those adverse events were resolved by changing the pump’s location on the body and by using hypoallergenic needles, Dr. Alzohaili said.

There were fewer cases of clogging with the pumps than is normally seen when they’re used with insulin, he added.

As for expense, Dr. Alzohaili said the pumps cost thousands of dollars and supplies can cost between $100 and $150 a month. In the first couple of cases, patients paid for the treatment themselves, he said, but in later cases, insurers were willing to pay for the treatment once they learned about the results.

Other researchers have successfully used insulin pumps to deliver hydrocortisone to small numbers of patients with adrenal insufficiency, including British and U.S. teams that reported positive results in 2015 and 2018, respectively.

The next step, Dr. Alzohaili said, is to attract the interest of insulin pump manufacturers by using the treatment in more patients. “I’ve spoken to CEOs, but none of them is interested in using cortisol in their pumps,” he said. “If you don’t have the company supporting the research, it becomes difficult for it to become standard of care. So I’m trying to build awareness [of its use] and the number of patients [who use the pump].”

Dr. Alzohaili reported no financial conflicts of interest or disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – The venerable insulin pump is being repurposed: A Detroit-area endocrinology

“We’ve seen amazing results,” said endocrinologist Opada Alzohaili, MD, MBA, of Wayne State University, Detroit, coauthor of a study released at the annual scientific and clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

Dr. Alzohaili said he and his colleagues developed the approach to manage patients who are “so sick that they go to the hospital 10-12 times a year.” Oral medication just did not control their disorder.

“Most of the time, we end up way overdosing them [on oral medication] just to prevent them from going to the hospital in adrenal crisis,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Alzohaili said his clinic has tested delivering hydrocortisone via insulin pump in about 20 patients. The report presented at the conference focused on six patients who had failed oral hydrocortisone treatment for adrenal insufficiency. Testing showed that all had malabsorption of the drug.

The patients underwent training in how to use and adjust the pump, which allows dosing adjustments in increments of 1 mg. They learned how to adjust their doses based on their situation, Dr. Alzohaili said.

According to the report, the average number of adrenal crises in the patients over a 6-month period fell from a mean of 2.3 before baseline to 0.5 after treatment began. The maximum dose of hydrocortisone dose fell by 38%, while the average mean weight of patients rose from 182 pounds to 199 pounds.

In addition, the mean dose of hydrocortisone decreased with the use of the pump delivery system, from 85.8 mg with oral treatment to 32.4 mg on pump therapy, and the mean level of cortisol increased from 11.8 mcg/dL with oral treatment to 12.3 mcg/dL on pump therapy.

The researchers said that the pump provides better delivery of the medication compared with the oral route, and that the patients experienced fewer interactions with other medications.

Some patients developed skin reactions to the pump, but those adverse events were resolved by changing the pump’s location on the body and by using hypoallergenic needles, Dr. Alzohaili said.

There were fewer cases of clogging with the pumps than is normally seen when they’re used with insulin, he added.

As for expense, Dr. Alzohaili said the pumps cost thousands of dollars and supplies can cost between $100 and $150 a month. In the first couple of cases, patients paid for the treatment themselves, he said, but in later cases, insurers were willing to pay for the treatment once they learned about the results.

Other researchers have successfully used insulin pumps to deliver hydrocortisone to small numbers of patients with adrenal insufficiency, including British and U.S. teams that reported positive results in 2015 and 2018, respectively.

The next step, Dr. Alzohaili said, is to attract the interest of insulin pump manufacturers by using the treatment in more patients. “I’ve spoken to CEOs, but none of them is interested in using cortisol in their pumps,” he said. “If you don’t have the company supporting the research, it becomes difficult for it to become standard of care. So I’m trying to build awareness [of its use] and the number of patients [who use the pump].”

Dr. Alzohaili reported no financial conflicts of interest or disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – The venerable insulin pump is being repurposed: A Detroit-area endocrinology

“We’ve seen amazing results,” said endocrinologist Opada Alzohaili, MD, MBA, of Wayne State University, Detroit, coauthor of a study released at the annual scientific and clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

Dr. Alzohaili said he and his colleagues developed the approach to manage patients who are “so sick that they go to the hospital 10-12 times a year.” Oral medication just did not control their disorder.

“Most of the time, we end up way overdosing them [on oral medication] just to prevent them from going to the hospital in adrenal crisis,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Alzohaili said his clinic has tested delivering hydrocortisone via insulin pump in about 20 patients. The report presented at the conference focused on six patients who had failed oral hydrocortisone treatment for adrenal insufficiency. Testing showed that all had malabsorption of the drug.

The patients underwent training in how to use and adjust the pump, which allows dosing adjustments in increments of 1 mg. They learned how to adjust their doses based on their situation, Dr. Alzohaili said.

According to the report, the average number of adrenal crises in the patients over a 6-month period fell from a mean of 2.3 before baseline to 0.5 after treatment began. The maximum dose of hydrocortisone dose fell by 38%, while the average mean weight of patients rose from 182 pounds to 199 pounds.

In addition, the mean dose of hydrocortisone decreased with the use of the pump delivery system, from 85.8 mg with oral treatment to 32.4 mg on pump therapy, and the mean level of cortisol increased from 11.8 mcg/dL with oral treatment to 12.3 mcg/dL on pump therapy.

The researchers said that the pump provides better delivery of the medication compared with the oral route, and that the patients experienced fewer interactions with other medications.

Some patients developed skin reactions to the pump, but those adverse events were resolved by changing the pump’s location on the body and by using hypoallergenic needles, Dr. Alzohaili said.

There were fewer cases of clogging with the pumps than is normally seen when they’re used with insulin, he added.

As for expense, Dr. Alzohaili said the pumps cost thousands of dollars and supplies can cost between $100 and $150 a month. In the first couple of cases, patients paid for the treatment themselves, he said, but in later cases, insurers were willing to pay for the treatment once they learned about the results.

Other researchers have successfully used insulin pumps to deliver hydrocortisone to small numbers of patients with adrenal insufficiency, including British and U.S. teams that reported positive results in 2015 and 2018, respectively.

The next step, Dr. Alzohaili said, is to attract the interest of insulin pump manufacturers by using the treatment in more patients. “I’ve spoken to CEOs, but none of them is interested in using cortisol in their pumps,” he said. “If you don’t have the company supporting the research, it becomes difficult for it to become standard of care. So I’m trying to build awareness [of its use] and the number of patients [who use the pump].”

Dr. Alzohaili reported no financial conflicts of interest or disclosures.

REPORTING FROM AACE 2019

Liraglutide seems safe, effective in children already on metformin

The addition of liraglutide to metformin shows significantly improved glycemic control in children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes, compared with metformin alone, according to data presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting in Baltimore.

The phase 3 study, which was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine, involved 134 patients aged 10-17 years with type 2 diabetes who were managing their diabetes with diet and exercise, metformin, or insulin.

Participants were randomized either to subcutaneous liraglutide – dose-escalated up to 1.8 mg/day, depending on efficacy and side effects – or placebo for 52 weeks. The first 26 weeks were double blind and the second 26 weeks were an open-label extension period.

At 26 weeks, mean glycated hemoglobin levels in the liraglutide group had decreased by 0.64 percentage points from baseline, but in the placebo group they had increased by 0.42 percentage points, representing a treatment difference of –1.06 percentage points (P less than .001). By week 52, the treatment difference between the two groups had increased to –1.30 percentage points.

William V. Tamborlane, MD, from the department of pediatrics at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his coauthors wrote that metformin is the approved drug of choice for pediatric patients with type 2 diabetes, and that insulin currently is the only approved option for those who do not have an adequate response to metformin monotherapy.

“This discrepancy in available treatments for youth as compared with adults persists because of a lack of successfully completed trials needed for approval of new drugs for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in children since a trial of metformin was completed in 1999,” they wrote.

The study showed that significantly more patients in the liraglutide group (63.7%) achieved glycated hemoglobin levels below 7%, compared with 36.5% of patients in the placebo group. Fasting plasma glucose levels were decreased in the liraglutide group at both 26 and 52 weeks, but had increased in the placebo group.

Although the number of reported adverse events were similar between the two groups, there were significantly more reports of gastrointestinal adverse events – particularly nausea – in patients taking liraglutide, compared with those on placebo.

However, the study did not show a difference between liraglutide and placebo in lowering body mass index, although mean body weight decreases – which were seen in both groups – were maintained at week 52 only in the liraglutide group. The authors suggested this might be owing to the relatively small number of patients enrolled in the study and that some of the children were still growing.

Novo Nordisk, which manufactures liraglutide, supported the study. Twelve authors reported grants or support from Novo Nordisk in relation to the trial. Three authors were employees of Novo Nordisk. Eight authors reported unrelated grants and fees from Novo Nordisk and other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Tamborlane WV et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Apr 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903822.

The addition of liraglutide to metformin shows significantly improved glycemic control in children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes, compared with metformin alone, according to data presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting in Baltimore.

The phase 3 study, which was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine, involved 134 patients aged 10-17 years with type 2 diabetes who were managing their diabetes with diet and exercise, metformin, or insulin.

Participants were randomized either to subcutaneous liraglutide – dose-escalated up to 1.8 mg/day, depending on efficacy and side effects – or placebo for 52 weeks. The first 26 weeks were double blind and the second 26 weeks were an open-label extension period.

At 26 weeks, mean glycated hemoglobin levels in the liraglutide group had decreased by 0.64 percentage points from baseline, but in the placebo group they had increased by 0.42 percentage points, representing a treatment difference of –1.06 percentage points (P less than .001). By week 52, the treatment difference between the two groups had increased to –1.30 percentage points.

William V. Tamborlane, MD, from the department of pediatrics at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his coauthors wrote that metformin is the approved drug of choice for pediatric patients with type 2 diabetes, and that insulin currently is the only approved option for those who do not have an adequate response to metformin monotherapy.

“This discrepancy in available treatments for youth as compared with adults persists because of a lack of successfully completed trials needed for approval of new drugs for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in children since a trial of metformin was completed in 1999,” they wrote.

The study showed that significantly more patients in the liraglutide group (63.7%) achieved glycated hemoglobin levels below 7%, compared with 36.5% of patients in the placebo group. Fasting plasma glucose levels were decreased in the liraglutide group at both 26 and 52 weeks, but had increased in the placebo group.

Although the number of reported adverse events were similar between the two groups, there were significantly more reports of gastrointestinal adverse events – particularly nausea – in patients taking liraglutide, compared with those on placebo.

However, the study did not show a difference between liraglutide and placebo in lowering body mass index, although mean body weight decreases – which were seen in both groups – were maintained at week 52 only in the liraglutide group. The authors suggested this might be owing to the relatively small number of patients enrolled in the study and that some of the children were still growing.

Novo Nordisk, which manufactures liraglutide, supported the study. Twelve authors reported grants or support from Novo Nordisk in relation to the trial. Three authors were employees of Novo Nordisk. Eight authors reported unrelated grants and fees from Novo Nordisk and other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Tamborlane WV et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Apr 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903822.

The addition of liraglutide to metformin shows significantly improved glycemic control in children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes, compared with metformin alone, according to data presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting in Baltimore.

The phase 3 study, which was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine, involved 134 patients aged 10-17 years with type 2 diabetes who were managing their diabetes with diet and exercise, metformin, or insulin.

Participants were randomized either to subcutaneous liraglutide – dose-escalated up to 1.8 mg/day, depending on efficacy and side effects – or placebo for 52 weeks. The first 26 weeks were double blind and the second 26 weeks were an open-label extension period.

At 26 weeks, mean glycated hemoglobin levels in the liraglutide group had decreased by 0.64 percentage points from baseline, but in the placebo group they had increased by 0.42 percentage points, representing a treatment difference of –1.06 percentage points (P less than .001). By week 52, the treatment difference between the two groups had increased to –1.30 percentage points.

William V. Tamborlane, MD, from the department of pediatrics at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his coauthors wrote that metformin is the approved drug of choice for pediatric patients with type 2 diabetes, and that insulin currently is the only approved option for those who do not have an adequate response to metformin monotherapy.

“This discrepancy in available treatments for youth as compared with adults persists because of a lack of successfully completed trials needed for approval of new drugs for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in children since a trial of metformin was completed in 1999,” they wrote.

The study showed that significantly more patients in the liraglutide group (63.7%) achieved glycated hemoglobin levels below 7%, compared with 36.5% of patients in the placebo group. Fasting plasma glucose levels were decreased in the liraglutide group at both 26 and 52 weeks, but had increased in the placebo group.

Although the number of reported adverse events were similar between the two groups, there were significantly more reports of gastrointestinal adverse events – particularly nausea – in patients taking liraglutide, compared with those on placebo.

However, the study did not show a difference between liraglutide and placebo in lowering body mass index, although mean body weight decreases – which were seen in both groups – were maintained at week 52 only in the liraglutide group. The authors suggested this might be owing to the relatively small number of patients enrolled in the study and that some of the children were still growing.

Novo Nordisk, which manufactures liraglutide, supported the study. Twelve authors reported grants or support from Novo Nordisk in relation to the trial. Three authors were employees of Novo Nordisk. Eight authors reported unrelated grants and fees from Novo Nordisk and other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Tamborlane WV et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Apr 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903822.

FROM PAS 2019

Type 2 diabetes bumps up short-term risk for bone fracture

LOS ANGELES – results from a large community-based study have shown.

“Osteoporotic fractures are a significant public health burden, causing high morbidity, mortality, and associated health care costs,” Elizabeth J. Samelson, PhD, said in an interview in advance of the annual scientific and clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. “Risk of fractures are higher in patients with type 2 diabetes. Further, outcomes are worse in type 2 diabetes patients, with greater frequency of complications following a fracture.”

Given the projected increase in type 2 diabetes in the U.S. population, Dr. Samelson, an associate scientist at the Marcus Institute for Aging Research at Hebrew SeniorLife and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues set out to evaluate the short- and long-term risks of bone fractures associated with the disease. They drew from 2,105 women and 1,130 men who participated in the Framingham Original and Offspring Cohorts and whose baseline osteoporosis visit was around 1990. Type 2 diabetes was defined as having a fasting plasma glucose of greater than 125 mg/dL or being on treatment for the disease. Incident fractures excluded finger, toe, skull, face, and pathologic fractures, and the researchers used repeated measures analyses to estimate hazard ratios for the association between type 2 diabetes, type 2 diabetes medication use, and type 2 diabetes duration and incident fracture, adjusted for age, sex, height, and weight.

The mean age of the study participants was 67 years, and the mean follow-up was 9 years. The prevalence of type 2 diabetes in women and men was 7% and 13%, respectively, and 63% and 51% of those were on medication for the disease. The mean duration of diabetes was 8 years.

Dr. Samelson and colleagues found that the cumulative incidence of fracture was 37% in women with type 2 diabetes and 30% in those without the disease. Meanwhile, the cumulative incidence of fracture was 11% in men with type 2 diabetes and 16% in those without the disease. The researchers also found that type 2 diabetes was associated with 1-year fracture risk in women (hazard ratio, 2.23), but not in men.

In the entire study population, longer duration of type 2 diabetes increased the 2-year fracture risk (HR, 1.28), as did the use of any type 2 diabetes medication (HR, 1.70). The researchers observed no statistically significant differences between type 2 diabetes and long-term incidence of fracture.

“Previous studies have contributed to understanding the higher incidence of fractures and worse outcomes in type 2 diabetes, [but] the current study demonstrated that patients [with type 2 diabetes] have 50% to 100% higher short-term [1- to 2-year] risk of fracture independent of clinical risk factors, whereas long-term [10-year] risk of fracture was similar in [patients with] type 2 diabetes and those who do not have [the disease],” Dr. Samelson said. “The current study has some inherent limitations of observational studies, including a lack of definitive determination of causality and that the results are not generalizable to patients with similar demographics. The study, however, is robust in the availability of detailed clinical information, which allows for control of multiple confounding variables.”

Dr. Samelson reported having no financial disclosures. Coauthors Setareh Williams, PhD, and Rich Weiss, MD, are employees and shareholders of Radius Health Inc.

LOS ANGELES – results from a large community-based study have shown.

“Osteoporotic fractures are a significant public health burden, causing high morbidity, mortality, and associated health care costs,” Elizabeth J. Samelson, PhD, said in an interview in advance of the annual scientific and clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. “Risk of fractures are higher in patients with type 2 diabetes. Further, outcomes are worse in type 2 diabetes patients, with greater frequency of complications following a fracture.”

Given the projected increase in type 2 diabetes in the U.S. population, Dr. Samelson, an associate scientist at the Marcus Institute for Aging Research at Hebrew SeniorLife and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues set out to evaluate the short- and long-term risks of bone fractures associated with the disease. They drew from 2,105 women and 1,130 men who participated in the Framingham Original and Offspring Cohorts and whose baseline osteoporosis visit was around 1990. Type 2 diabetes was defined as having a fasting plasma glucose of greater than 125 mg/dL or being on treatment for the disease. Incident fractures excluded finger, toe, skull, face, and pathologic fractures, and the researchers used repeated measures analyses to estimate hazard ratios for the association between type 2 diabetes, type 2 diabetes medication use, and type 2 diabetes duration and incident fracture, adjusted for age, sex, height, and weight.

The mean age of the study participants was 67 years, and the mean follow-up was 9 years. The prevalence of type 2 diabetes in women and men was 7% and 13%, respectively, and 63% and 51% of those were on medication for the disease. The mean duration of diabetes was 8 years.

Dr. Samelson and colleagues found that the cumulative incidence of fracture was 37% in women with type 2 diabetes and 30% in those without the disease. Meanwhile, the cumulative incidence of fracture was 11% in men with type 2 diabetes and 16% in those without the disease. The researchers also found that type 2 diabetes was associated with 1-year fracture risk in women (hazard ratio, 2.23), but not in men.

In the entire study population, longer duration of type 2 diabetes increased the 2-year fracture risk (HR, 1.28), as did the use of any type 2 diabetes medication (HR, 1.70). The researchers observed no statistically significant differences between type 2 diabetes and long-term incidence of fracture.

“Previous studies have contributed to understanding the higher incidence of fractures and worse outcomes in type 2 diabetes, [but] the current study demonstrated that patients [with type 2 diabetes] have 50% to 100% higher short-term [1- to 2-year] risk of fracture independent of clinical risk factors, whereas long-term [10-year] risk of fracture was similar in [patients with] type 2 diabetes and those who do not have [the disease],” Dr. Samelson said. “The current study has some inherent limitations of observational studies, including a lack of definitive determination of causality and that the results are not generalizable to patients with similar demographics. The study, however, is robust in the availability of detailed clinical information, which allows for control of multiple confounding variables.”

Dr. Samelson reported having no financial disclosures. Coauthors Setareh Williams, PhD, and Rich Weiss, MD, are employees and shareholders of Radius Health Inc.

LOS ANGELES – results from a large community-based study have shown.

“Osteoporotic fractures are a significant public health burden, causing high morbidity, mortality, and associated health care costs,” Elizabeth J. Samelson, PhD, said in an interview in advance of the annual scientific and clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. “Risk of fractures are higher in patients with type 2 diabetes. Further, outcomes are worse in type 2 diabetes patients, with greater frequency of complications following a fracture.”

Given the projected increase in type 2 diabetes in the U.S. population, Dr. Samelson, an associate scientist at the Marcus Institute for Aging Research at Hebrew SeniorLife and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues set out to evaluate the short- and long-term risks of bone fractures associated with the disease. They drew from 2,105 women and 1,130 men who participated in the Framingham Original and Offspring Cohorts and whose baseline osteoporosis visit was around 1990. Type 2 diabetes was defined as having a fasting plasma glucose of greater than 125 mg/dL or being on treatment for the disease. Incident fractures excluded finger, toe, skull, face, and pathologic fractures, and the researchers used repeated measures analyses to estimate hazard ratios for the association between type 2 diabetes, type 2 diabetes medication use, and type 2 diabetes duration and incident fracture, adjusted for age, sex, height, and weight.

The mean age of the study participants was 67 years, and the mean follow-up was 9 years. The prevalence of type 2 diabetes in women and men was 7% and 13%, respectively, and 63% and 51% of those were on medication for the disease. The mean duration of diabetes was 8 years.

Dr. Samelson and colleagues found that the cumulative incidence of fracture was 37% in women with type 2 diabetes and 30% in those without the disease. Meanwhile, the cumulative incidence of fracture was 11% in men with type 2 diabetes and 16% in those without the disease. The researchers also found that type 2 diabetes was associated with 1-year fracture risk in women (hazard ratio, 2.23), but not in men.

In the entire study population, longer duration of type 2 diabetes increased the 2-year fracture risk (HR, 1.28), as did the use of any type 2 diabetes medication (HR, 1.70). The researchers observed no statistically significant differences between type 2 diabetes and long-term incidence of fracture.

“Previous studies have contributed to understanding the higher incidence of fractures and worse outcomes in type 2 diabetes, [but] the current study demonstrated that patients [with type 2 diabetes] have 50% to 100% higher short-term [1- to 2-year] risk of fracture independent of clinical risk factors, whereas long-term [10-year] risk of fracture was similar in [patients with] type 2 diabetes and those who do not have [the disease],” Dr. Samelson said. “The current study has some inherent limitations of observational studies, including a lack of definitive determination of causality and that the results are not generalizable to patients with similar demographics. The study, however, is robust in the availability of detailed clinical information, which allows for control of multiple confounding variables.”

Dr. Samelson reported having no financial disclosures. Coauthors Setareh Williams, PhD, and Rich Weiss, MD, are employees and shareholders of Radius Health Inc.

REPORTING FROM AACE 2019

Gastric outlet obstruction: A red flag, potentially manageable

A 72-year-old woman presents to the emergency department with progressive nausea and vomiting. One week earlier, she developed early satiety and nausea with vomiting after eating solid food. Three days later her symptoms progressed, and she became unable to take anything by mouth. The patient also experienced a 40-lb weight loss in the previous 3 months. She denies symptoms of abdominal pain, hematemesis, or melena. Her medical history includes cholecystectomy and type 2 diabetes mellitus, diagnosed 1 year ago. She has no family history of gastrointestinal malignancy. She says she smoked 1 pack a day in her 20s. She does not consume alcohol.

On physical examination, she is normotensive with a heart rate of 105 beats per minute. The oral mucosa is dry, and the abdomen is mildly distended and tender to palpation in the epigastrium. Laboratory evaluation reveals hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis.

Computed tomography (CT) reveals a mass 3 cm by 4 cm in the pancreatic head. The mass has invaded the medial wall of the duodenum, with obstruction of the pancreatic and common bile ducts and extension into and occlusion of the superior mesenteric vein, with soft-tissue expansion around the superior mesenteric artery. CT also reveals retained stomach contents and an air-fluid level consistent with gastric outlet obstruction.

INTRINSIC OR EXTRINSIC BLOCKAGE

Gastric outlet obstruction, also called pyloric obstruction, is caused by intrinsic or extrinsic mechanical blockage of gastric emptying, generally in the distal stomach, pyloric channel, or duodenum, with associated symptoms of nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and early satiety. It is encountered in both the clinic and the hospital.

Here, we review the causes, diagnosis, and management of this disorder.

BENIGN AND MALIGNANT CAUSES

In a retrospective study of 76 patients hospitalized with gastric outlet obstruction between 2006 and 2015 at our institution,2 29 cases (38%) were due to malignancy and 47 (62%) were due to benign causes. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma accounted for 13 cases (17%), while gastric adenocarcinoma accounted for 5 cases (7%); less common malignant causes were cholangiocarcinoma, cancer of the ampulla of Vater, duodenal adenocarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and metastatic disease. Of the benign causes, the most common were peptic ulcer disease (13 cases, 17%) and postoperative strictures or adhesions (11 cases, 14%).

These numbers reflect general trends around the world.

Less gastric cancer, more pancreatic cancer

The last several decades have seen a trend toward more cases due to cancer and fewer due to benign causes.3–14

In earlier studies in both developed and developing countries, gastric adenocarcinoma was the most common malignant cause of gastric outlet obstruction. Since then, it has become less common in Western countries, although it remains more common in Asia and Africa.7–14 This trend likely reflects environmental factors, including decreased prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection, a major risk factor for gastric cancer, in Western countries.15–17

At the same time, pancreatic cancer is on the rise,16 and up to 20% of patients with pancreatic cancer develop gastric outlet obstruction.18 In a prospective observational study of 108 patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction undergoing endoscopic stenting, pancreatic cancer was by far the most common malignancy, occurring in 54% of patients, followed by gastric cancer in 13%.19

Less peptic ulcer disease, but still common

Peptic ulcer disease used to account for up to 90% of cases of gastric outlet obstruction, and it is still the most common benign cause.

In 1990, gastric outlet obstruction was estimated to occur in 5% to 10% of all hospital admissions for ulcer-related complications, accounting for 2,000 operations annually.20,21 Gastric outlet obstruction now occurs in fewer than 5% of patients with duodenal ulcer disease and fewer than 2% of patients with gastric ulcer disease.22

Peptic ulcer disease remains an important cause of obstruction in countries with poor access to acid-suppressing drugs.23

Gastric outlet obstruction occurs in both acute and chronic peptic ulcer disease. In acute peptic ulcer disease, tissue inflammation and edema result in mechanical obstruction. Chronic peptic ulcer disease results in tissue scarring and fibrosis with strictures.20

Environmental factors, including improved diet, hygiene, physical activity, and the decreased prevalence of H pylori infection, also contribute to the decreased prevalence of peptic ulcer disease and its complications, including gastric outlet obstruction.3 The continued occurrence of peptic ulcer disease is associated with widespread use of low-dose aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), the most common causes of peptic ulcer disease in Western countries.24,25

Other nonmalignant causes of gastric outlet obstruction are diverse and less common. They include caustic ingestion, postsurgical strictures, benign tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, Crohn disease, and pancreatic disorders including acute pancreatitis, pancreatic pseudocyst, chronic pancreatitis, and annular pancreas. Intramural duodenal hematoma may cause obstruction after blunt abdominal trauma, endoscopic biopsy, or gastrostomy tube migration, especially in the setting of a bleeding disorder or anticoagulation.26

Tuberculosis should be suspected in countries in which it is common.7 In a prospective study of 64 patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction in India,27 16 (25%) had corrosive injury, 16 (25%) had tuberculosis, and 15 (23%) had peptic ulcer disease. Compared with patients with corrosive injury and peptic ulcer disease, patients with gastroduodenal tuberculosis had the best outcomes with appropriate treatment.

Other reported causes include Bouveret syndrome (an impacted gallstone in the proximal duodenum), phytobezoar, diaphragmatic hernia, gastric volvulus, and Ladd bands (peritoneal bands associated with intestinal malrotation).7,28,29

PRESENTING SYMPTOMS

Symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction include nausea, nonbilious vomiting, epigastric pain, early satiety, abdominal distention, and weight loss.

In our patients, the most common presenting symptoms were nausea and vomiting (80%), followed by abdominal pain (72%); weight loss (15%), abdominal distention (15%), and early satiety (9%) were less common.2

Patients with gastric outlet obstruction secondary to malignancy generally present with a shorter duration of symptoms than those with peptic ulcer disease and are more likely to be older.8,13 Other conditions with an acute onset of symptoms include gastric polyp prolapse, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube migration, gastric volvulus, and gallstone impaction.

Patients with gastric outlet obstruction associated with peptic ulcer disease generally have a long-standing history of symptoms, including dyspepsia and weight loss over several years.4

SIGNS ON EXAMINATION

On examination, look for signs of chronic gastric obstruction and its consequences, such as malnutrition, cachexia, volume depletion, and dental erosions.

A succussion splash may suggest gastric outlet obstruction. This is elicited by rocking the patient back and forth by the hips or abdomen while listening over the stomach for a splash, which may be heard without a stethoscope. The test is considered positive if present 3 or more hours after drinking fluids and suggests retention of gastric materials.30,31

In thin individuals, chronic gastric outlet obstruction makes the stomach dilate and hypertrophy, which may be evident by a palpably thickened stomach with visible gastric peristalsis.4

Other notable findings on physical examination may include a palpable abdominal mass, epigastric pain, or an abnormality suggestive of metastatic gastric cancer, such as an enlarged left supraclavicular lymph node (Virchow node) or periumbilical lymph node (Sister Mary Joseph nodule). The Virchow node is at the junction of the thoracic duct and the left subclavian vein where the lymphatic circulation from the body drains into the systemic circulation, and it may be the first sign of gastric cancer.32 Sister Mary Joseph nodule (named after a surgical assistant to Dr. William James Mayo) refers to a palpable mass at the umbilicus, generally resulting from metastasis of an abdominal malignancy.33

SIGNS ON FURTHER STUDIES

Laboratory evaluation may show signs of poor oral intake and electrolyte abnormalities secondary to chronic nausea, vomiting, and dehydration, including hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis and hypokalemia.

The underlying cause of gastric outlet obstruction has major implications for treatment and prognosis and cannot be differentiated by clinical presentation alone.1,9 Diagnosis is based on clinical features and radiologic or endoscopic evaluation consistent with gastric outlet obstruction.

Plain radiography may reveal an enlarged gastric bubble, and contrast studies may be useful to determine whether the obstruction is partial or complete, depending on whether the contrast passes into the small bowel.

Upper endoscopy is often needed to establish the diagnosis and cause. Emptying the stomach with a nasogastric tube is recommended before endoscopy to minimize the risk of aspiration during the procedure, and endotracheal intubation should be considered for airway protection.34 Findings of gastric outlet obstruction on upper endoscopy include retained food and liquid. Endoscopic biopsy is important to differentiate between benign and malignant causes. For patients with malignancy, endoscopic ultrasonography is useful for diagnosis via tissue sampling with fine-needle aspiration and locoregional staging.35

A strategy. Most patients whose clinical presentation suggests gastric outlet obstruction require cross-sectional radiologic imaging, upper endoscopy, or both.36 CT is the preferred imaging study to evaluate for intestinal obstruction.36,37 Patients with suspected complete obstruction or perforation should undergo CT before upper endoscopy. Oral contrast may interfere with endoscopy and should be avoided if endoscopy is planned. Additionally, giving oral contrast may worsen patient discomfort and increase the risk of nausea, vomiting, and aspiration.36,37

Following radiographic evaluation, upper endoscopy can be performed after gastric decompression to identify the location and extent of the obstruction and to potentially provide a definitive diagnosis with biopsy.36

DIFFERENTIATE FROM GASTROPARESIS

Gastroparesis is a chronic neuromuscular disorder characterized by delayed gastric emptying without mechanical obstruction.38 The most common causes are diabetes, surgery, and idiopathy. Other causes include viral infection, connective tissue diseases, ischemia, infiltrative disorders, radiation, neurologic disorders, and paraneoplastic syndromes.39,40

Gastric outlet obstruction and gastroparesis share clinical symptoms including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, early satiety, and weight loss and are important to differentiate.36,38 Although abdominal pain may be present in both gastric outlet obstruction and gastroparesis, in gastroparesis it tends not to be the dominant symptom.40

Gastric scintigraphy is most commonly used to objectively quantify delayed gastric emptying.39 Upper endoscopy is imperative to exclude mechanical obstruction.39

MANAGEMENT

Initially, patients with signs and symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction should be given:

- Nothing by mouth (NPO)

- Intravenous fluids to correct volume depletion and electrolyte abnormalities

- A nasogastric tube for gastric decompression and symptom relief if symptoms persist despite being NPO

- A parenteral proton pump inhibitor, regardless of the cause of obstruction, to decrease gastric secretions41

- Medications for pain and nausea, if needed.

Definitive treatment of gastric outlet obstruction depends on the underlying cause, whether benign or malignant.

Management of benign gastric outlet obstruction

Symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction resolve spontaneously in about half of cases caused by acute peptic ulcer disease, as acute inflammation resolves.9,22

Endoscopic dilation is an important option in patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction, including peptic ulcer disease. Peptic ulcer disease-induced gastric outlet obstruction can be safely treated with endoscopic balloon dilation. This treatment almost always relieves symptoms immediately; however, the long-term response has varied from 16% to 100%, and patients may require more than 1 dilation procedure.25,42,43 The need for 2 or more dilation procedures may predict need for surgery.44 Gastric outlet obstruction after caustic ingestion or endoscopic submucosal dissection may also respond to endoscopic balloon dilation.36

Eradication of H pylori may be effective and lead to complete resolution of symptoms in patients with gastric outlet obstruction due to this infection.45–47

NSAIDs should be discontinued in patients with peptic ulcer disease and gastric outlet obstruction. These drugs damage the gastrointestinal mucosa by inhibiting cyclo-oxygenase (COX) enzymes and decreasing synthesis of prostaglandins, which are important for mucosal defense.48 Patients may be unaware of NSAIDs contained in over-the-counter medications and may have difficulty discontinuing NSAIDs taken for pain.49

These drugs are an important cause of refractory peptic ulcer disease and can be detected by platelet COX activity testing, although this test is not widely available. In a study of patients with peptic ulcer disease without definite NSAID use or H pylori infection, up to one-third had evidence of surreptitious NSAID use as detected by platelet COX activity testing.50 In another study,51 platelet COX activity testing discovered over 20% more aspirin users than clinical history alone.

Surgery for patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction is used only when medical management and endoscopic dilation fail. Ideally, surgery should relieve the obstruction and target the underlying cause, such as peptic ulcer disease. Laparoscopic surgery is generally preferred to open surgery because patients can resume oral intake sooner, have a shorter hospital stay, and have less intraoperative blood loss.52 The simplest surgical procedure to relieve obstruction is laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy.

Patients with gastric outlet obstruction and peptic ulcer disease warrant laparoscopic vagotomy and antrectomy or distal gastrectomy. This removes the obstruction and the stimulus for gastric secretion.53 An alternative is vagotomy with a drainage procedure (pyloroplasty or gastrojejunostomy), which has a similar postoperative course and reduction in gastric acid secretion compared with antrectomy or distal gastrectomy.53,54

Daily proton pump inhibitors can be used for patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction not associated with peptic ulcer disease or risk factors; for such cases, vagotomy is not required.

Management of malignant gastric outlet obstruction

Patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction may have intractable nausea and abdominal pain secondary to retention of gastric contents. The major goal of therapy is to improve symptoms and restore tolerance of an oral diet. The short-term prognosis of malignant gastric outlet obstruction is poor, with a median survival of 3 to 4 months, as these patients often have unresectable disease.55

Surgical bypass used to be the standard of care for palliation of malignant gastric obstruction, but that was before endoscopic stenting was developed.

Endoscopic stenting allows patients to resume oral intake and get out of the hospital sooner with fewer complications than with open surgical bypass. It may be a more appropriate option for palliation of symptoms in patients with malignant obstruction who have a poor prognosis and prefer a less invasive intervention.55,56

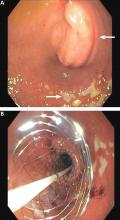

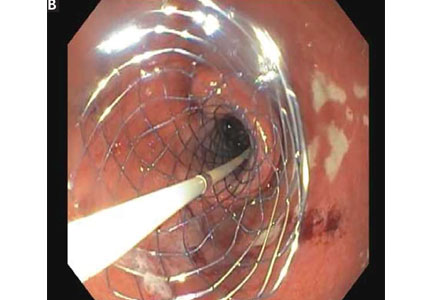

Endoscopic duodenal stenting of malignant gastric outlet obstruction has a success rate of greater than 90%, and most patients can tolerate a mechanical soft diet afterward.34 The procedure is usually performed with a 9-cm or 12-cm self-expanding duodenal stent, 22 mm in diameter, placed over a guide wire under endoscopic and fluoroscopic guidance (Figure 2). The stent is placed by removing the outer catheter, with distal-to-proximal stent deployment.

Patients who also have biliary obstruction may require biliary stent placement, which is generally performed before duodenal stenting. For patients with an endoscopic stent who develop biliary obstruction, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography can be attempted with placement of a biliary stent; however, these patients may require biliary drain placement by percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography or by endoscopic ultrasonographically guided transduodenal or transgastric biliary drainage.

From 20% to 30% of patients require repeated endoscopic stent placement, although most patients die within several months after stenting.34 Surgical options for patients who do not respond to endoscopic stenting include open or laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy.55

Laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy may provide better long-term outcomes than duodenal stenting for patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction and a life expectancy longer than a few months.

A 2017 retrospective study of 155 patients with gastric outlet obstruction secondary to unresectable gastric cancer suggested that those who underwent laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy had better oral intake, better tolerance of chemotherapy, and longer overall survival than those who underwent duodenal stenting. Postsurgical complications were more common in the laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy group (16%) than in the duodenal stenting group (0%).57

In most of the studies comparing endoscopic stenting with surgery, the surgery was open gastrojejunostomy; there are limited data directly comparing stenting with laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy.55 Endoscopic stenting is estimated to be significantly less costly than surgery, with a median cost of $12,000 less than gastrojejunostomy.58 As an alternative to enteral stenting and surgical gastrojejunostomy, ultrasonography-guided endoscopic gastrojejunostomy or gastroenterostomy with placement of a lumen-apposing metal stent is emerging as a third treatment option and is under active investigation.59

Patients with malignancy that is potentially curable by resection should undergo surgical evaluation before consideration of endoscopic stenting. For patients who are not candidates for surgery or endoscopic stenting, a percutaneous gastrostomy tube can be considered for gastric decompression and symptom relief.

CASE CONCLUDED

The patient underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy with endoscopic ultrasonography for evaluation of her pancreatic mass. Before the procedure, she was intubated to minimize the risk of aspiration due to persistent nausea and retained gastric contents. A large submucosal mass was found in the duodenal bulb. Endoscopic ultrasonography showed a mass within the pancreatic head with pancreatic duct obstruction. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy was performed, and pathology study revealed pancreatic adenocarcinoma. The patient underwent stenting with a 22-mm by 12-cm WallFlex stent (Boston Scientific), which led to resolution of nausea and advancement to a mechanical soft diet on hospital discharge.

She was scheduled for follow-up in the outpatient clinic for treatment of pancreatic cancer.

- Johnson CD. Gastric outlet obstruction malignant until proved otherwise. Am J Gastroenterol 1995; 90(10):1740. pmid:7572886

- Koop AH, Palmer WC, Mareth K, Burton MC, Bowman A, Stancampiano F. Tu1335 - Pancreatic cancer most common cause of malignant gastric outlet obstruction at a tertiary referral center: a 10 year retrospective study [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2018; 154(6, suppl 1):S-1343.

- Hall R, Royston C, Bardhan KD. The scars of time: the disappearance of peptic ulcer-related pyloric stenosis through the 20th century. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2014; 44(3):201–208. doi:10.4997/JRCPE.2014.303

- Kreel L, Ellis H. Pyloric stenosis in adults: a clinical and radiological study of 100 consecutive patients. Gut 1965; 6(3):253–261. pmid:18668780

- Shone DN, Nikoomanesh P, Smith-Meek MM, Bender JS. Malignancy is the most common cause of gastric outlet obstruction in the era of H2 blockers. Am J Gastroenterol 1995; 90(10):1769–1770. pmid:7572891

- Ellis H. The diagnosis of benign and malignant pyloric obstruction. Clin Oncol 1976; 2(1):11–15. pmid:1277618

- Samad A, Khanzada TW, Shoukat I. Gastric outlet obstruction: change in etiology. Pak J Surg 2007; 23(1):29–32.

- Chowdhury A, Dhali GK, Banerjee PK. Etiology of gastric outlet obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91(8):1679. pmid:8759707

- Johnson CD, Ellis H. Gastric outlet obstruction now predicts malignancy. Br J Surg 1990; 77(9):1023–1024. pmid:2207566

- Misra SP, Dwivedi M, Misra V. Malignancy is the most common cause of gastric outlet obstruction even in a developing country. Endoscopy 1998; 30(5):484–486. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1001313

- Essoun SD, Dakubo JCB. Update of aetiological patterns of adult gastric outlet obstruction in Accra, Ghana. Int J Clin Med 2014; 5(17):1059–1064. doi:10.4236/ijcm.2014.517136

- Jaka H, Mchembe MD, Rambau PF, Chalya PL. Gastric outlet obstruction at Bugando Medical Centre in Northwestern Tanzania: a prospective review of 184 cases. BMC Surg 2013; 13:41. doi:10.1186/1471-2482-13-41

- Sukumar V, Ravindran C, Prasad RV. Demographic and etiological patterns of gastric outlet obstruction in Kerala, South India. N Am J Med Sci 2015; 7(9):403–406. doi:10.4103/1947-2714.166220

- Yoursef M, Mirza MR, Khan S. Gastric outlet obstruction. Pak J Surg 2005; 10(4):48–50.

- Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015; 136(5):E359–E386. doi:10.1002/ijc.29210

- Parkin DM, Stjernsward J, Muir CS. Estimates of the worldwide frequency of twelve major cancers. Bull World Health Organ 1984; 62(2):163–182. pmid:6610488

- Karimi P, Islami F, Anandasabapathy S, Freedman ND, Kamangar F. Gastric cancer: descriptive epidemiology, risk factors, screening, and prevention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014; 23(5):700–713. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1057

- Jeurnink SM, Steyerberg EW, van Hooft JE, et al; Dutch SUSTENT Study Group. Surgical gastrojejunostomy or endoscopic stent placement for the palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruction (SUSTENT) study): a multicenter randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 71(3):490–499. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2009.09.042

- Tringali A, Didden P, Repici A, et al. Endoscopic treatment of malignant gastric and duodenal strictures: a prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 79(1):66–75. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2013.06.032

- Malfertheiner P, Chan FK, McColl KE. Peptic ulcer disease. Lancet 2009; 374(9699):1449–1461. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60938-7

- Gibson JB, Behrman SW, Fabian TC, Britt LG. Gastric outlet obstruction resulting from peptic ulcer disease requiring surgical intervention is infrequently associated with Helicobacter pylori infection. J Am Coll Surg 2000; 191(1):32–37. pmid:10898181

- Kochhar R, Kochhar S. Endoscopic balloon dilation for benign gastric outlet obstruction in adults. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 2(1):29–35. doi:10.4253/wjge.v2.i1.29

- Kotisso R. Gastric outlet obstruction in Northwestern Ethiopia. East Cent Afr J Surg 2000; 5(2):25-29.

- Hamzaoui L, Bouassida M, Ben Mansour I, et al. Balloon dilatation in patients with gastric outlet obstruction related to peptic ulcer disease. Arab J Gastroenterol 2015; 16(3–4):121–124. doi:10.1016/j.ajg.2015.07.004

- Najm WI. Peptic ulcer disease. Prim Care 2011; 38(3):383–394. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2011.05.001

- Veloso N, Amaro P, Ferreira M, Romaozinho JM, Sofia C. Acute pancreatitis associated with a nontraumatic, intramural duodenal hematoma. Endoscopy 2013; 45(suppl 2):E51–E52. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1325969

- Maharshi S, Puri AS, Sachdeva S, Kumar A, Dalal A, Gupta M. Aetiological spectrum of benign gastric outlet obstruction in India: new trends. Trop Doct 2016; 46(4):186–191. doi:10.1177/0049475515626032

- Sala MA, Ligabo AN, de Arruda MC, Indiani JM, Nacif MS. Intestinal malrotation associated with duodenal obstruction secondary to Ladd’s bands. Radiol Bras 2016; 49(4):271–272. doi:10.1590/0100-3984.2015.0106

- Alibegovic E, Kurtcehajic A, Hujdurovic A, Mujagic S, Alibegovic J, Kurtcehajic D. Bouveret syndrome or gallstone ileus. Am J Med 2018; 131(4):e175. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.10.044

- Lau JY, Chung SC, Sung JJ, et al. Through-the-scope balloon dilation for pyloric stenosis: long-term results. Gastrointest Endosc 1996; 43(2 Pt 1):98–101. pmid:8635729

- Ray K, Snowden C, Khatri K, McFall M. Gastric outlet obstruction from a caecal volvulus, herniated through epiploic foramen: a case report. BMJ Case Rep 2009; pii:bcr05.2009.1880. doi:10.1136/bcr.05.2009.1880

- Baumgart DC, Fischer A. Virchow’s node. Lancet 2007; 370(9598):1568. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61661-4

- Dar IH, Kamili MA, Dar SH, Kuchaai FA. Sister Mary Joseph nodule—a case report with review of literature. J Res Med Sci 2009; 14(6):385–387. pmid:21772912

- Tang SJ. Endoscopic stent placement for gastric outlet obstruction. Video Journal and Encyclopedia of GI Endoscopy 2013; 1(1):133–136.

- Valero M, Robles-Medranda C. Endoscopic ultrasound in oncology: an update of clinical applications in the gastrointestinal tract. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 9(6):243–254.

- ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Fukami N, Anderson MA, Khan K, et al. The role of endoscopy in gastroduodenal obstruction and gastroparesis. Gastrointest Endosc 2011; 74(1):13–21. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2010.12.003

- Ros PR, Huprich JE. ACR appropriateness criteria on suspected small-bowel obstruction. J Am Coll Radiol 2006; 3(11):838–841. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2006.09.018

- Pasricha PJ, Parkman HP. Gastroparesis: definitions and diagnosis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2015; 44(1):1–7. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2014.11.001

- Stein B, Everhart KK, Lacy BE. Gastroparesis: a review of current diagnosis and treatment options. J Clin Gastroenterol 2015; 49(7):550–558. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000320

- Camilleri M, Parkman HP, Shafi MA, Abell TL, Gerson L; American College of Gastroenterology. Clinical guideline: management of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108(1):18–37.

- Gursoy O, Memis D, Sut N. Effect of proton pump inhibitors on gastric juice volume, gastric pH and gastric intramucosal pH in critically ill patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Drug Investig 2008; 28(12):777–782. doi:10.2165/0044011-200828120-00005

- Kuwada SK, Alexander GL. Long-term outcome of endoscopic dilation of nonmalignant pyloric stenosis. Gastrointest Endosc 1995; 41(1):15–17. pmid:7698619

- Kochhar R, Sethy PK, Nagi B, Wig JD. Endoscopic balloon dilatation of benign gastric outlet obstruction. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 19(4):418–422. pmid:15012779

- Perng CL, Lin HJ, Lo WC, Lai CR, Guo WS, Lee SD. Characteristics of patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction requiring surgery after endoscopic balloon dilation. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91(5):987–990. pmid:8633593

- Taskin V, Gurer I, Ozyilkan E, Sare M, Hilmioglu F. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on peptic ulcer disease complicated with outlet obstruction. Helicobacter 2000; 5(1):38–40. pmid:10672050

- de Boer WA, Driessen WM. Resolution of gastric outlet obstruction after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. J Clin Gastroenterol 1995; 21(4):329–330. pmid:8583113

- Tursi A, Cammarota G, Papa A, Montalto M, Fedeli G, Gasbarrini G. Helicobacter pylori eradication helps resolve pyloric and duodenal stenosis. J Clin Gastroenterol 1996; 23(2):157–158. pmid:8877648

- Schmassmann A. Mechanisms of ulcer healing and effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med 1998; 104(3A):43S–51S; discussion 79S–80S. pmid:9572320

- Kim HU. Diagnostic and treatment approaches for refractory peptic ulcers. Clin Endosc 2015; 48(4):285–290. doi:10.5946/ce.2015.48.4.285

- Ong TZ, Hawkey CJ, Ho KY. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use is a significant cause of peptic ulcer disease in a tertiary hospital in Singapore: a prospective study. J Clin Gastroenterol 2006; 40(9):795–800. doi:10.1097/01.mcg.0000225610.41105.7f

- Lanas A, Sekar MC, Hirschowitz BI. Objective evidence of aspirin use in both ulcer and nonulcer upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology 1992; 103(3):862–869. pmid:1499936

- Zhang LP, Tabrizian P, Nguyen S, Telem D, Divino C. Laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy for the treatment of gastric outlet obstruction. JSLS 2011; 15(2):169–173. doi:10.4293/108680811X13022985132074

- Lagoo J, Pappas TN, Perez A. A relic or still relevant: the narrowing role for vagotomy in the treatment of peptic ulcer disease. Am J Surg 2014; 207(1):120–126. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.02.012

- Csendes A, Maluenda F, Braghetto I, Schutte H, Burdiles P, Diaz JC. Prospective randomized study comparing three surgical techniques for the treatment of gastric outlet obstruction secondary to duodenal ulcer. Am J Surg 1993; 166(1):45–49. pmid:8101050

- Ly J, O’Grady G, Mittal A, Plank L, Windsor JA. A systematic review of methods to palliate malignant gastric outlet obstruction. Surg Endosc 2010; 24(2):290–297. doi:10.1007/s00464-009-0577-1

- Goldberg EM. Palliative treatment of gastric outlet obstruction in terminal patients: SEMS. Stent every malignant stricture! Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 79(1):76–78. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2013.07.056

- Min SH, Son SY, Jung DH, et al. Laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy versus duodenal stenting in unresectable gastric cancer with gastric outlet obstruction. Ann Surg Treat Res 2017; 93(3):130–136. doi:10.4174/astr.2017.93.3.130

- Roy A, Kim M, Christein J, Varadarajulu S. Stenting versus gastrojejunostomy for management of malignant gastric outlet obstruction: comparison of clinical outcomes and costs. Surg Endosc 2012; 26(11):3114–119. doi:10.1007/s00464-012-2301-9

- Amin S, Sethi A. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastrojejunostomy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2017; 27(4):707–713. doi:10.1016/j.giec.2017.06.009