User login

Dapagliflozin meets primary endpoint in the DAPA-HF trial

The SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga) successfully met the primary endpoint of the phase 3 DAPA-HF trial in patients with heart failure, according to a press release from AstraZeneca.

DAPA-HF is an international, multicenter, parallel group, randomized, double-blind trial in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction with or without type 2 diabetes. Patients in the study received either 10 mg dapagliflozin or placebo, and the primary outcome was time to a worsening heart failure event or to cardiovascular death. Patients who received dapagliflozin had a statistically significant reduction in incidence of cardiovascular death and an increase in time to a heart failure event.

The adverse events reported for dapagliflozin in DAPA-HF matched the established safety profile for the drug, AstraZeneca noted in the press release.

“The benefits of dapagliflozin in DAPA-HF are very impressive, with a substantial reduction in the primary composite outcome of cardiovascular death or hospital admission. We hope these exciting new findings will ultimately help reduce the terrible burden of disease caused by heart failure and help improve outcomes for our patients,” said John McMurray, MD, of the Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences at the University of Glasgow.

Another dapagliflozin trial, called DELIVER, is focused on 4,700 patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction randomized to dapagliflozin (Farxiga) or placebo. That is due to be completed next year.

The full results from DAPA-HF will be presented at a later date.

The SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga) successfully met the primary endpoint of the phase 3 DAPA-HF trial in patients with heart failure, according to a press release from AstraZeneca.

DAPA-HF is an international, multicenter, parallel group, randomized, double-blind trial in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction with or without type 2 diabetes. Patients in the study received either 10 mg dapagliflozin or placebo, and the primary outcome was time to a worsening heart failure event or to cardiovascular death. Patients who received dapagliflozin had a statistically significant reduction in incidence of cardiovascular death and an increase in time to a heart failure event.

The adverse events reported for dapagliflozin in DAPA-HF matched the established safety profile for the drug, AstraZeneca noted in the press release.

“The benefits of dapagliflozin in DAPA-HF are very impressive, with a substantial reduction in the primary composite outcome of cardiovascular death or hospital admission. We hope these exciting new findings will ultimately help reduce the terrible burden of disease caused by heart failure and help improve outcomes for our patients,” said John McMurray, MD, of the Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences at the University of Glasgow.

Another dapagliflozin trial, called DELIVER, is focused on 4,700 patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction randomized to dapagliflozin (Farxiga) or placebo. That is due to be completed next year.

The full results from DAPA-HF will be presented at a later date.

The SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga) successfully met the primary endpoint of the phase 3 DAPA-HF trial in patients with heart failure, according to a press release from AstraZeneca.

DAPA-HF is an international, multicenter, parallel group, randomized, double-blind trial in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction with or without type 2 diabetes. Patients in the study received either 10 mg dapagliflozin or placebo, and the primary outcome was time to a worsening heart failure event or to cardiovascular death. Patients who received dapagliflozin had a statistically significant reduction in incidence of cardiovascular death and an increase in time to a heart failure event.

The adverse events reported for dapagliflozin in DAPA-HF matched the established safety profile for the drug, AstraZeneca noted in the press release.

“The benefits of dapagliflozin in DAPA-HF are very impressive, with a substantial reduction in the primary composite outcome of cardiovascular death or hospital admission. We hope these exciting new findings will ultimately help reduce the terrible burden of disease caused by heart failure and help improve outcomes for our patients,” said John McMurray, MD, of the Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences at the University of Glasgow.

Another dapagliflozin trial, called DELIVER, is focused on 4,700 patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction randomized to dapagliflozin (Farxiga) or placebo. That is due to be completed next year.

The full results from DAPA-HF will be presented at a later date.

Diabetes effect in heart failure varies by phenotype

Type 2 diabetes is a risk factor for heart failure and a common comorbidity in heart failure patients. New results from a large cohort study in Asia show that, for people with heart failure, having diabetes is associated with changes to the structure of the heart, lower quality of life, more readmissions to hospital, and higher risk of death.

Jonathan Yap, MBBS, MPH, of the National Heart Centre in Singapore, and colleagues, looked at data from a cohort enrolling 6,167 heart failure patients in 11 Asian countries for the prospective ASIAN-HF (Asian Sudden

Cardiac Death in Heart Failure) registry. The researchers identified 5,028 patients with heart failure and reduced left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF; 22% women), of whom 40% had type 2 diabetes. They also looked at 1,139 patients in the registry with heart failure and preserved LVEF (51% women), of whom 45% had type 2 disease. Controls without heart failure (n = 985; 9% with diabetes) from the SHOP (Singapore Heart Failure Outcomes and Phenotypes) study were included in the analysis, which was published August 21 in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

For both heart failure phenotypes, diabetes was associated with left ventricular hypertrophy, but there was no similar association in patients without diabetes. Dr. Yap and his colleagues reported differences in cardiac remodeling based on heart failure phenotype: The reduced LVEF patients had more eccentric hypertrophy, or dilation, of the left ventricular chamber, whereas the preserved LVEF patients had more concentric hypertrophy, or thickening, of the left ventricular wall.

The researchers also reported that patients with diabetes had lower health-related quality of life scores in both heart failure groups, compared with patients without diabetes, although those in the latter group with preserved LVEF did significantly worse on some quality of life measures. Patients with diabetes had more heart failure rehospitalizations (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.27; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.54; P = .014) and higher 1-year rates of a combined measure of all-cause mortality and hospitalization for heart failure (aHR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.05-1.41; P = .011). No differences were seen between phenotypes for these outcomes.

Dr. Yap and colleagues noted that this was the first large, multinational study investigating diabetes and heart failure in Asia and that “no prior studies have concomitantly included both HF types or controls without HF from the same population.” They listed among the study’s limitations a lack of uniform screening for diabetes that may have resulted in under-identification of diabetics in the cohort.

The Singapore government, the Biomedical Research Council, Boston Scientific, and Bayer sponsored the study. One coauthor disclosed receiving pharmaceutical industry support.

Source: Yap J et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019 Aug. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013114.

Type 2 diabetes is a risk factor for heart failure and a common comorbidity in heart failure patients. New results from a large cohort study in Asia show that, for people with heart failure, having diabetes is associated with changes to the structure of the heart, lower quality of life, more readmissions to hospital, and higher risk of death.

Jonathan Yap, MBBS, MPH, of the National Heart Centre in Singapore, and colleagues, looked at data from a cohort enrolling 6,167 heart failure patients in 11 Asian countries for the prospective ASIAN-HF (Asian Sudden

Cardiac Death in Heart Failure) registry. The researchers identified 5,028 patients with heart failure and reduced left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF; 22% women), of whom 40% had type 2 diabetes. They also looked at 1,139 patients in the registry with heart failure and preserved LVEF (51% women), of whom 45% had type 2 disease. Controls without heart failure (n = 985; 9% with diabetes) from the SHOP (Singapore Heart Failure Outcomes and Phenotypes) study were included in the analysis, which was published August 21 in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

For both heart failure phenotypes, diabetes was associated with left ventricular hypertrophy, but there was no similar association in patients without diabetes. Dr. Yap and his colleagues reported differences in cardiac remodeling based on heart failure phenotype: The reduced LVEF patients had more eccentric hypertrophy, or dilation, of the left ventricular chamber, whereas the preserved LVEF patients had more concentric hypertrophy, or thickening, of the left ventricular wall.

The researchers also reported that patients with diabetes had lower health-related quality of life scores in both heart failure groups, compared with patients without diabetes, although those in the latter group with preserved LVEF did significantly worse on some quality of life measures. Patients with diabetes had more heart failure rehospitalizations (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.27; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.54; P = .014) and higher 1-year rates of a combined measure of all-cause mortality and hospitalization for heart failure (aHR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.05-1.41; P = .011). No differences were seen between phenotypes for these outcomes.

Dr. Yap and colleagues noted that this was the first large, multinational study investigating diabetes and heart failure in Asia and that “no prior studies have concomitantly included both HF types or controls without HF from the same population.” They listed among the study’s limitations a lack of uniform screening for diabetes that may have resulted in under-identification of diabetics in the cohort.

The Singapore government, the Biomedical Research Council, Boston Scientific, and Bayer sponsored the study. One coauthor disclosed receiving pharmaceutical industry support.

Source: Yap J et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019 Aug. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013114.

Type 2 diabetes is a risk factor for heart failure and a common comorbidity in heart failure patients. New results from a large cohort study in Asia show that, for people with heart failure, having diabetes is associated with changes to the structure of the heart, lower quality of life, more readmissions to hospital, and higher risk of death.

Jonathan Yap, MBBS, MPH, of the National Heart Centre in Singapore, and colleagues, looked at data from a cohort enrolling 6,167 heart failure patients in 11 Asian countries for the prospective ASIAN-HF (Asian Sudden

Cardiac Death in Heart Failure) registry. The researchers identified 5,028 patients with heart failure and reduced left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF; 22% women), of whom 40% had type 2 diabetes. They also looked at 1,139 patients in the registry with heart failure and preserved LVEF (51% women), of whom 45% had type 2 disease. Controls without heart failure (n = 985; 9% with diabetes) from the SHOP (Singapore Heart Failure Outcomes and Phenotypes) study were included in the analysis, which was published August 21 in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

For both heart failure phenotypes, diabetes was associated with left ventricular hypertrophy, but there was no similar association in patients without diabetes. Dr. Yap and his colleagues reported differences in cardiac remodeling based on heart failure phenotype: The reduced LVEF patients had more eccentric hypertrophy, or dilation, of the left ventricular chamber, whereas the preserved LVEF patients had more concentric hypertrophy, or thickening, of the left ventricular wall.

The researchers also reported that patients with diabetes had lower health-related quality of life scores in both heart failure groups, compared with patients without diabetes, although those in the latter group with preserved LVEF did significantly worse on some quality of life measures. Patients with diabetes had more heart failure rehospitalizations (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.27; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.54; P = .014) and higher 1-year rates of a combined measure of all-cause mortality and hospitalization for heart failure (aHR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.05-1.41; P = .011). No differences were seen between phenotypes for these outcomes.

Dr. Yap and colleagues noted that this was the first large, multinational study investigating diabetes and heart failure in Asia and that “no prior studies have concomitantly included both HF types or controls without HF from the same population.” They listed among the study’s limitations a lack of uniform screening for diabetes that may have resulted in under-identification of diabetics in the cohort.

The Singapore government, the Biomedical Research Council, Boston Scientific, and Bayer sponsored the study. One coauthor disclosed receiving pharmaceutical industry support.

Source: Yap J et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019 Aug. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013114.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION

Key clinical point: Patients with heart failure and type 2 diabetes have smaller left ventricular ejection fractions, poorer quality of life, and increased risk for all-cause and cardiovascular death and hospitalization for heart failure.

Major finding: Heart failure with comorbid type 2 diabetes is associated with cardiac remodeling, worse clinical outcomes, and higher risk for hospitalization; type of heart failure may have a role.

Study details: A prospective, multicenter cohort of 6,167 patients with heart failure in the ASIAN-HF (Asian Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure) registry enrolled in 11 Asian countries and 965 community-based controls without heart failure recruited as part of the control arm of the SHOP (Singapore Heart Failure Outcomes and Phenotypes) study.

Disclosures: The Singapore government, the Biomedical Research Council, Boston Scientific, and Bayer sponsored the study. One coauthor disclosed receiving pharmaceutical industry support.

Source: Yap J et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019 Aug. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013114.

Diabetes targets remain elusive for patients

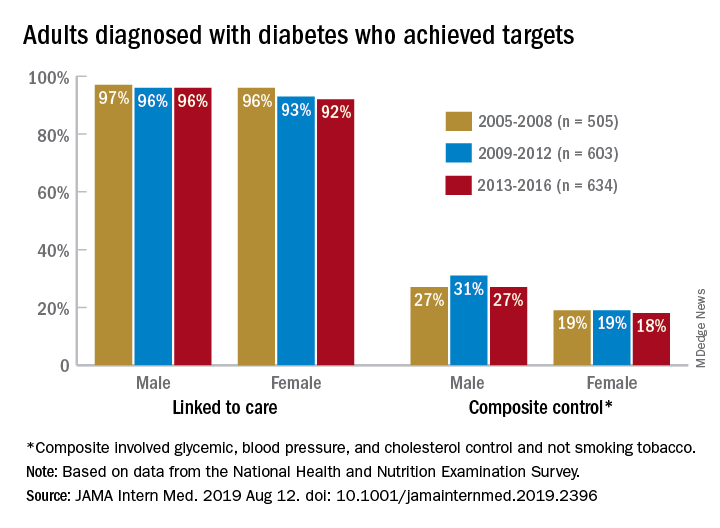

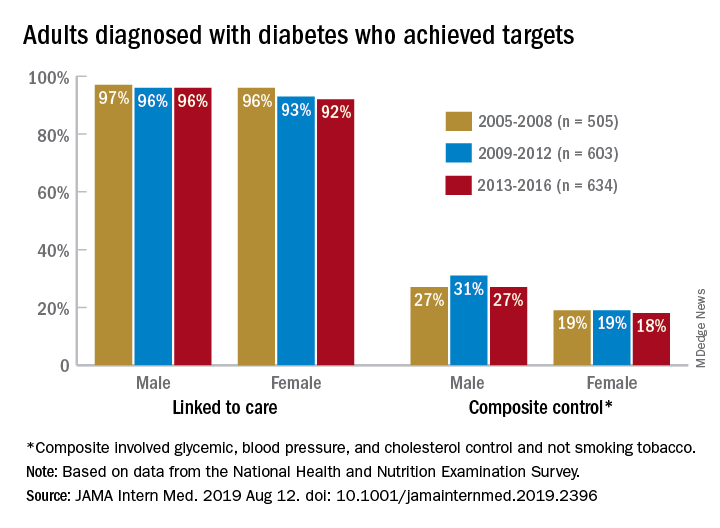

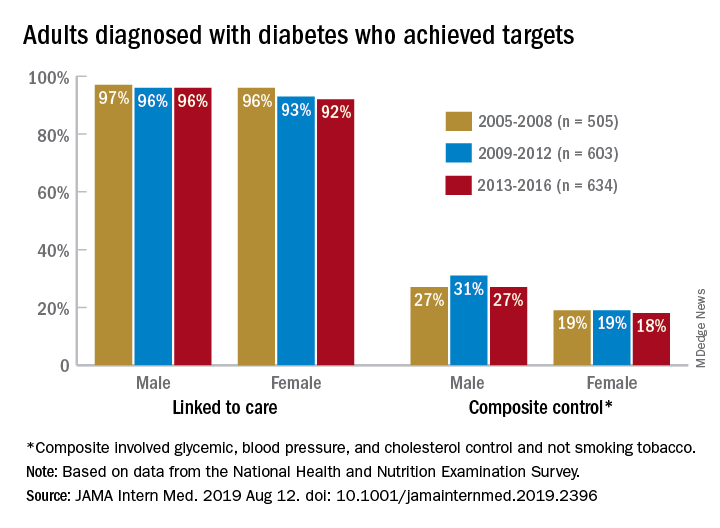

Some things never change: In 2005, most adults with diabetes missed their treatment targets. In 2016, most adults with diabetes missed their treatment targets. And during that time, from 2005 to 2016, around 96% of men and 94% of women were linked to care.

“Fewer than one in four American adults with diagnosed diabetes achieve a controlled level of blood sugar, blood pressure, and cholesterol, and do not smoke tobacco. Our results suggest that, despite major advances in diabetes drug discovery and movement to develop innovative care delivery models over the past two decades, achievement of diabetes care targets has not improved in the United States since 2005,” Pooyan Kazemian, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in a written statement.

During 2013-2016, only 23% of adults with diabetes met a combined composite target of glycemic (HbA1c below a liberal personalized level), blood pressure (less than 140/90 mm Hg), and cholesterol (LDL cholesterol level less than 100 mg/dL) control, as well as not smoking tobacco, Dr. Kazemian and associates reported in JAMA Internal Medicine. The corresponding figures were 25% (2009-2012) and 23% (2005-2008) for the two earlier time periods covered in the study,

The investigators used data for 1,742 nonpregnant adults from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey to evaluate the diabetes care cascade, which they defined as “diagnosis, linkage to care, achievement of individual treatment targets, and a composite of all individual targets.”

In 2013-2016, 94% of those diagnosed were linked to care, 64% met their HbA1c target, 70% achieved blood pressure control, 57% met the cholesterol target, and 85% were nonsmokers. When targets were combined, 41% achieved blood pressure and cholesterol control, and 25% met the glycemic, blood pressure, and cholesterol targets, they said.

“We found that none of the U.S. diabetes care variables improved from 2005 to 2016,” Dr. Kazemian and associates noted. Women were less likely than men to meet their treatment goals (see graph) over the course of the study, as were adults aged 18-44 years and black and Hispanic individuals.

“Recent advances in [treatments for diabetes] have not effectively reached the populations at risk and may indicate an immediate need for better approaches to the delivery of diabetes care, including a continued focus on reaching underserved populations with persistent disparities in care,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the Boston Area Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center and Massachusetts General Hospital. One investigator reported that her husband has equity in Apolo1bio. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Kazemian P et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 12. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2396.

Some things never change: In 2005, most adults with diabetes missed their treatment targets. In 2016, most adults with diabetes missed their treatment targets. And during that time, from 2005 to 2016, around 96% of men and 94% of women were linked to care.

“Fewer than one in four American adults with diagnosed diabetes achieve a controlled level of blood sugar, blood pressure, and cholesterol, and do not smoke tobacco. Our results suggest that, despite major advances in diabetes drug discovery and movement to develop innovative care delivery models over the past two decades, achievement of diabetes care targets has not improved in the United States since 2005,” Pooyan Kazemian, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in a written statement.

During 2013-2016, only 23% of adults with diabetes met a combined composite target of glycemic (HbA1c below a liberal personalized level), blood pressure (less than 140/90 mm Hg), and cholesterol (LDL cholesterol level less than 100 mg/dL) control, as well as not smoking tobacco, Dr. Kazemian and associates reported in JAMA Internal Medicine. The corresponding figures were 25% (2009-2012) and 23% (2005-2008) for the two earlier time periods covered in the study,

The investigators used data for 1,742 nonpregnant adults from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey to evaluate the diabetes care cascade, which they defined as “diagnosis, linkage to care, achievement of individual treatment targets, and a composite of all individual targets.”

In 2013-2016, 94% of those diagnosed were linked to care, 64% met their HbA1c target, 70% achieved blood pressure control, 57% met the cholesterol target, and 85% were nonsmokers. When targets were combined, 41% achieved blood pressure and cholesterol control, and 25% met the glycemic, blood pressure, and cholesterol targets, they said.

“We found that none of the U.S. diabetes care variables improved from 2005 to 2016,” Dr. Kazemian and associates noted. Women were less likely than men to meet their treatment goals (see graph) over the course of the study, as were adults aged 18-44 years and black and Hispanic individuals.

“Recent advances in [treatments for diabetes] have not effectively reached the populations at risk and may indicate an immediate need for better approaches to the delivery of diabetes care, including a continued focus on reaching underserved populations with persistent disparities in care,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the Boston Area Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center and Massachusetts General Hospital. One investigator reported that her husband has equity in Apolo1bio. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Kazemian P et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 12. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2396.

Some things never change: In 2005, most adults with diabetes missed their treatment targets. In 2016, most adults with diabetes missed their treatment targets. And during that time, from 2005 to 2016, around 96% of men and 94% of women were linked to care.

“Fewer than one in four American adults with diagnosed diabetes achieve a controlled level of blood sugar, blood pressure, and cholesterol, and do not smoke tobacco. Our results suggest that, despite major advances in diabetes drug discovery and movement to develop innovative care delivery models over the past two decades, achievement of diabetes care targets has not improved in the United States since 2005,” Pooyan Kazemian, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in a written statement.

During 2013-2016, only 23% of adults with diabetes met a combined composite target of glycemic (HbA1c below a liberal personalized level), blood pressure (less than 140/90 mm Hg), and cholesterol (LDL cholesterol level less than 100 mg/dL) control, as well as not smoking tobacco, Dr. Kazemian and associates reported in JAMA Internal Medicine. The corresponding figures were 25% (2009-2012) and 23% (2005-2008) for the two earlier time periods covered in the study,

The investigators used data for 1,742 nonpregnant adults from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey to evaluate the diabetes care cascade, which they defined as “diagnosis, linkage to care, achievement of individual treatment targets, and a composite of all individual targets.”

In 2013-2016, 94% of those diagnosed were linked to care, 64% met their HbA1c target, 70% achieved blood pressure control, 57% met the cholesterol target, and 85% were nonsmokers. When targets were combined, 41% achieved blood pressure and cholesterol control, and 25% met the glycemic, blood pressure, and cholesterol targets, they said.

“We found that none of the U.S. diabetes care variables improved from 2005 to 2016,” Dr. Kazemian and associates noted. Women were less likely than men to meet their treatment goals (see graph) over the course of the study, as were adults aged 18-44 years and black and Hispanic individuals.

“Recent advances in [treatments for diabetes] have not effectively reached the populations at risk and may indicate an immediate need for better approaches to the delivery of diabetes care, including a continued focus on reaching underserved populations with persistent disparities in care,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the Boston Area Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center and Massachusetts General Hospital. One investigator reported that her husband has equity in Apolo1bio. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Kazemian P et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 12. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2396.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Diabetic neuropathy: Often silent, often dangerous

SAN DIEGO – Neuropathy can blur the seriousness of injuries, especially in patients with diabetes, and that can lead to severe consequences such as falls, foot ulcers, gangrene, and amputations, said Lucia M. Novak, MSN, ANP-BC, BC-ADM, CDTC, in a presentation on assessing and treating neuropathies at the Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit, sponsored by Global Academy for Medical Education.

As many as half of the cases of diabetic neuropathy may have no symptoms, and more than two-thirds of cases of diabetic neuropathy, even some with obvious symptoms, are ignored or missed by clinicians, said Ms. Novak, director of the Riverside Diabetes Center and adjunct assistant professor at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, both in Bethesda, Md.

At the same time, she said, diabetic neuropathy is very common. It affects an estimated 10%-15% of newly diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes, 50% of patients with type 2 disease after 10 years, and as many as 30% of patients with prediabetes.

The condition is less common in type 1 diabetes, affecting an estimated 20% of patients after 20 years, she said.

“All we can do in our patients with type 2 diabetes and diabetic neuropathy, is to slow down the progression, although improving glycemic control can prevent it in type 1,” she said, citing findings suggesting that

A 2012 report analyzed research into the effect of glycemic control on neuropathy in diabetes and found a pair of studies that reported a 60%-70% reduction of risk in patients with type 1 diabetes who received regular insulin dosing. However, the evidence for type 2 diabetes was not as definitive, and analysis of findings from eight randomized, controlled trials in patients with type 2 diabetes supported a relatively small reduction in the development of neuropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes who were receiving enhanced glycemic control (Lancet Neurol. 2012;11[6]:521-34).

Ms. Novak focused mainly on peripheral neuropathy, which is believed to account for 50%-75% of all neuropathy in patients with diabetes. She emphasized the importance of screening because it is crucial for preventing foot ulcers, which affect more than a third of patients with diabetes over their lifetimes.

She recommended following the American Diabetes Association’s 2017 position statement on diabetic neuropathy (Diabetes Care. 2017;40[1]:136-54), beginning with performing a visual examination of the feet at every visit.

Comprehensive screening

In patients with type 1 diabetes, there should be an annual comprehensive screening beginning within 5 years of diagnosis. Patients with type 2 disease should be screened at diagnosis and then annually, as outlined in the ADA statement.

The comprehensive exam involves using tools, such as tuning forks and monofilaments, to test sensation. Different tools are required to test both small and large fibers in the foot, Ms. Novak said, and doing both kinds of testing greatly increases the likelihood of detecting neuropathy.

Check for pulse, bone deformities, dry skin

In addition, “you’ll be feeling for their pulses, looking for bony deformities, and looking at anything is going on between the toes [to make sure] the skin is intact,” she said.

Patients with diabetic neuropathy often have dry skin, she said, so make sure they’re moisturizing. “Look at the condition of their shoes,” she added, “which will tell you how they walk.”

Ill-fitting shoes are a common cause of foot ulcers, said Ms. Novak, who noted that some patients refuse to wear unattractive diabetic shoes and prefer to wear more fashionable – and dangerous – tight-fitting shoes.

Treatment options

Glycemic control makes a difference, especially for patients with type 1, as does control of risk factors, such as obesity. But diabetic neuropathy cannot be reversed.

Pain can be managed with a range of medications. “We can’t cure the neuropathy, we can at least help patients with the symptoms so that they can have a good night’s sleep,” she said.

Ms. Novak also suggested passing on the following snippets of advice to patients:

- Do not walk barefoot.

- Check your feet every day.

- Moisturize your skin, and always dry thoroughly between your toes.

- Seek medical attention if your nails cut into your skin or you develop a callus or areas of redness/warmth.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Ms. Novak reported relationships with Nova Nordisk, Sanofi, Janssen, and AstraZeneca.

SAN DIEGO – Neuropathy can blur the seriousness of injuries, especially in patients with diabetes, and that can lead to severe consequences such as falls, foot ulcers, gangrene, and amputations, said Lucia M. Novak, MSN, ANP-BC, BC-ADM, CDTC, in a presentation on assessing and treating neuropathies at the Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit, sponsored by Global Academy for Medical Education.

As many as half of the cases of diabetic neuropathy may have no symptoms, and more than two-thirds of cases of diabetic neuropathy, even some with obvious symptoms, are ignored or missed by clinicians, said Ms. Novak, director of the Riverside Diabetes Center and adjunct assistant professor at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, both in Bethesda, Md.

At the same time, she said, diabetic neuropathy is very common. It affects an estimated 10%-15% of newly diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes, 50% of patients with type 2 disease after 10 years, and as many as 30% of patients with prediabetes.

The condition is less common in type 1 diabetes, affecting an estimated 20% of patients after 20 years, she said.

“All we can do in our patients with type 2 diabetes and diabetic neuropathy, is to slow down the progression, although improving glycemic control can prevent it in type 1,” she said, citing findings suggesting that

A 2012 report analyzed research into the effect of glycemic control on neuropathy in diabetes and found a pair of studies that reported a 60%-70% reduction of risk in patients with type 1 diabetes who received regular insulin dosing. However, the evidence for type 2 diabetes was not as definitive, and analysis of findings from eight randomized, controlled trials in patients with type 2 diabetes supported a relatively small reduction in the development of neuropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes who were receiving enhanced glycemic control (Lancet Neurol. 2012;11[6]:521-34).

Ms. Novak focused mainly on peripheral neuropathy, which is believed to account for 50%-75% of all neuropathy in patients with diabetes. She emphasized the importance of screening because it is crucial for preventing foot ulcers, which affect more than a third of patients with diabetes over their lifetimes.

She recommended following the American Diabetes Association’s 2017 position statement on diabetic neuropathy (Diabetes Care. 2017;40[1]:136-54), beginning with performing a visual examination of the feet at every visit.

Comprehensive screening

In patients with type 1 diabetes, there should be an annual comprehensive screening beginning within 5 years of diagnosis. Patients with type 2 disease should be screened at diagnosis and then annually, as outlined in the ADA statement.

The comprehensive exam involves using tools, such as tuning forks and monofilaments, to test sensation. Different tools are required to test both small and large fibers in the foot, Ms. Novak said, and doing both kinds of testing greatly increases the likelihood of detecting neuropathy.

Check for pulse, bone deformities, dry skin

In addition, “you’ll be feeling for their pulses, looking for bony deformities, and looking at anything is going on between the toes [to make sure] the skin is intact,” she said.

Patients with diabetic neuropathy often have dry skin, she said, so make sure they’re moisturizing. “Look at the condition of their shoes,” she added, “which will tell you how they walk.”

Ill-fitting shoes are a common cause of foot ulcers, said Ms. Novak, who noted that some patients refuse to wear unattractive diabetic shoes and prefer to wear more fashionable – and dangerous – tight-fitting shoes.

Treatment options

Glycemic control makes a difference, especially for patients with type 1, as does control of risk factors, such as obesity. But diabetic neuropathy cannot be reversed.

Pain can be managed with a range of medications. “We can’t cure the neuropathy, we can at least help patients with the symptoms so that they can have a good night’s sleep,” she said.

Ms. Novak also suggested passing on the following snippets of advice to patients:

- Do not walk barefoot.

- Check your feet every day.

- Moisturize your skin, and always dry thoroughly between your toes.

- Seek medical attention if your nails cut into your skin or you develop a callus or areas of redness/warmth.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Ms. Novak reported relationships with Nova Nordisk, Sanofi, Janssen, and AstraZeneca.

SAN DIEGO – Neuropathy can blur the seriousness of injuries, especially in patients with diabetes, and that can lead to severe consequences such as falls, foot ulcers, gangrene, and amputations, said Lucia M. Novak, MSN, ANP-BC, BC-ADM, CDTC, in a presentation on assessing and treating neuropathies at the Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit, sponsored by Global Academy for Medical Education.

As many as half of the cases of diabetic neuropathy may have no symptoms, and more than two-thirds of cases of diabetic neuropathy, even some with obvious symptoms, are ignored or missed by clinicians, said Ms. Novak, director of the Riverside Diabetes Center and adjunct assistant professor at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, both in Bethesda, Md.

At the same time, she said, diabetic neuropathy is very common. It affects an estimated 10%-15% of newly diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes, 50% of patients with type 2 disease after 10 years, and as many as 30% of patients with prediabetes.

The condition is less common in type 1 diabetes, affecting an estimated 20% of patients after 20 years, she said.

“All we can do in our patients with type 2 diabetes and diabetic neuropathy, is to slow down the progression, although improving glycemic control can prevent it in type 1,” she said, citing findings suggesting that

A 2012 report analyzed research into the effect of glycemic control on neuropathy in diabetes and found a pair of studies that reported a 60%-70% reduction of risk in patients with type 1 diabetes who received regular insulin dosing. However, the evidence for type 2 diabetes was not as definitive, and analysis of findings from eight randomized, controlled trials in patients with type 2 diabetes supported a relatively small reduction in the development of neuropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes who were receiving enhanced glycemic control (Lancet Neurol. 2012;11[6]:521-34).

Ms. Novak focused mainly on peripheral neuropathy, which is believed to account for 50%-75% of all neuropathy in patients with diabetes. She emphasized the importance of screening because it is crucial for preventing foot ulcers, which affect more than a third of patients with diabetes over their lifetimes.

She recommended following the American Diabetes Association’s 2017 position statement on diabetic neuropathy (Diabetes Care. 2017;40[1]:136-54), beginning with performing a visual examination of the feet at every visit.

Comprehensive screening

In patients with type 1 diabetes, there should be an annual comprehensive screening beginning within 5 years of diagnosis. Patients with type 2 disease should be screened at diagnosis and then annually, as outlined in the ADA statement.

The comprehensive exam involves using tools, such as tuning forks and monofilaments, to test sensation. Different tools are required to test both small and large fibers in the foot, Ms. Novak said, and doing both kinds of testing greatly increases the likelihood of detecting neuropathy.

Check for pulse, bone deformities, dry skin

In addition, “you’ll be feeling for their pulses, looking for bony deformities, and looking at anything is going on between the toes [to make sure] the skin is intact,” she said.

Patients with diabetic neuropathy often have dry skin, she said, so make sure they’re moisturizing. “Look at the condition of their shoes,” she added, “which will tell you how they walk.”

Ill-fitting shoes are a common cause of foot ulcers, said Ms. Novak, who noted that some patients refuse to wear unattractive diabetic shoes and prefer to wear more fashionable – and dangerous – tight-fitting shoes.

Treatment options

Glycemic control makes a difference, especially for patients with type 1, as does control of risk factors, such as obesity. But diabetic neuropathy cannot be reversed.

Pain can be managed with a range of medications. “We can’t cure the neuropathy, we can at least help patients with the symptoms so that they can have a good night’s sleep,” she said.

Ms. Novak also suggested passing on the following snippets of advice to patients:

- Do not walk barefoot.

- Check your feet every day.

- Moisturize your skin, and always dry thoroughly between your toes.

- Seek medical attention if your nails cut into your skin or you develop a callus or areas of redness/warmth.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Ms. Novak reported relationships with Nova Nordisk, Sanofi, Janssen, and AstraZeneca.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM MEDS 2019

Diagnosing and managing diabetes and depression

SAN DIEGO – Nearly 350 years ago, British physician Thomas Willis wrote that diabetes seemed often to occur in patients who were experiencing “significant life stress, sadness, or long sorrow.” That, according to Ellen D. Mandel, DMH, MPA, MS, PA-C, RDN, CDE, a clinical professor at Pace University in New York City, was an important insight into the link between mind and body in patients with diabetes.

“As clinicians, we should be worried about mental illness in our patients with diabetes,” Dr. Mandel, a physician assistant educator, said during a presentation at the Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit by Global Academy for Medical Education.

In particular, she said, – and vice versa.

Dr. Mandel pointed to findings suggesting that 11% of patients with diabetes show signs of clinical depression, which is higher than in the general population, with many more believed to have subclinical depression (Diabetes Care. 2015;38[4]:551-60).

Anxiety can be a key factor in trying to understand how diabetes might contribute to depression. “Diabetes is a very stressful condition ... [and patients] may be fatigued and exhausted.” On top of that, they have to make nutrition changes, or at least pay attention to their diet and overall care, all of which can have a cumulatively negative impact on patient well-being.

Conversely, depression can contribute to diabetes. “They kind of go hand in hand,” she said, pointing to depression’s ability to disrupt appetite, diminish energy, and boost levels of cortisol.

Among the findings that provide evidence of a link between diabetes and depression are those from a study in which investigators estimated that for every 1-point increase in depression symptoms, the risk of diabetes will go up by as much as 5% (Clin Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018 Jan 4. doi: 10.1186/s40842-017-0052-1). Moreover, a 2013 review linked the combination of diabetes and depression to an adjusted 1.5-fold increase in risk of all-cause death (PLoS One. 2013 Mar 5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057058).

Dr. Mandel offered these tips about diagnosing depression in patients with diabetes and helping them feel comfortable:

- Put yourself in the patient’s shoes. “One of the biggest barriers to referring patients to diabetic education is that they don’t want to have to admit to a group that they have diabetes. They keep it to themselves, to their own detriment. In addition, there’s a lot of worry about insurance.” Patients with diabetes often have self-esteem issues and financial or insurance challenges, all of which need to be factored in when working with them, Dr. Mandel said.

- Ask questions and use screening tools. Two simple questions are helpful in starting a conversation and gathering useful information: Over the past 2 weeks, have you often been bothered by [having] little interest or pleasure in doing things? What about being bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless? If the patient answers “yes” to either of these questions, it will be a positive screen, and two “no” answers will be a negative screen. With the “yes” responses, one should follow-up with a screening tool – typically, the one approved by your institution. Dr. Mandel also highlighted the Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale (PHQ-9), which is available online, or the brief, two-item Diabetes Distress Scale (DDS2) questionnaire.

- Keep your own language in mind. “The way you communicate with your patients can elevate their feeling about themselves or destroy how they feel about themselves,” Dr. Mandel said. “We’re trying to stop calling people with diabetes ‘diabetics.’ People don’t want to be labeled like that. Don’t blame yourself if you use this language, but work to make the changes,” Dr. Mandel suggested.

- Watch out for other forms of bias. Beware of unconsciously stereotyping your patients. “It affects how people relate to you, how they adhere to your suggestions, and how much they’ll trust [and confide in] you, which can have clinical implications,” Dr. Mandel said.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Mandel has no disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Nearly 350 years ago, British physician Thomas Willis wrote that diabetes seemed often to occur in patients who were experiencing “significant life stress, sadness, or long sorrow.” That, according to Ellen D. Mandel, DMH, MPA, MS, PA-C, RDN, CDE, a clinical professor at Pace University in New York City, was an important insight into the link between mind and body in patients with diabetes.

“As clinicians, we should be worried about mental illness in our patients with diabetes,” Dr. Mandel, a physician assistant educator, said during a presentation at the Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit by Global Academy for Medical Education.

In particular, she said, – and vice versa.

Dr. Mandel pointed to findings suggesting that 11% of patients with diabetes show signs of clinical depression, which is higher than in the general population, with many more believed to have subclinical depression (Diabetes Care. 2015;38[4]:551-60).

Anxiety can be a key factor in trying to understand how diabetes might contribute to depression. “Diabetes is a very stressful condition ... [and patients] may be fatigued and exhausted.” On top of that, they have to make nutrition changes, or at least pay attention to their diet and overall care, all of which can have a cumulatively negative impact on patient well-being.

Conversely, depression can contribute to diabetes. “They kind of go hand in hand,” she said, pointing to depression’s ability to disrupt appetite, diminish energy, and boost levels of cortisol.

Among the findings that provide evidence of a link between diabetes and depression are those from a study in which investigators estimated that for every 1-point increase in depression symptoms, the risk of diabetes will go up by as much as 5% (Clin Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018 Jan 4. doi: 10.1186/s40842-017-0052-1). Moreover, a 2013 review linked the combination of diabetes and depression to an adjusted 1.5-fold increase in risk of all-cause death (PLoS One. 2013 Mar 5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057058).

Dr. Mandel offered these tips about diagnosing depression in patients with diabetes and helping them feel comfortable:

- Put yourself in the patient’s shoes. “One of the biggest barriers to referring patients to diabetic education is that they don’t want to have to admit to a group that they have diabetes. They keep it to themselves, to their own detriment. In addition, there’s a lot of worry about insurance.” Patients with diabetes often have self-esteem issues and financial or insurance challenges, all of which need to be factored in when working with them, Dr. Mandel said.

- Ask questions and use screening tools. Two simple questions are helpful in starting a conversation and gathering useful information: Over the past 2 weeks, have you often been bothered by [having] little interest or pleasure in doing things? What about being bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless? If the patient answers “yes” to either of these questions, it will be a positive screen, and two “no” answers will be a negative screen. With the “yes” responses, one should follow-up with a screening tool – typically, the one approved by your institution. Dr. Mandel also highlighted the Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale (PHQ-9), which is available online, or the brief, two-item Diabetes Distress Scale (DDS2) questionnaire.

- Keep your own language in mind. “The way you communicate with your patients can elevate their feeling about themselves or destroy how they feel about themselves,” Dr. Mandel said. “We’re trying to stop calling people with diabetes ‘diabetics.’ People don’t want to be labeled like that. Don’t blame yourself if you use this language, but work to make the changes,” Dr. Mandel suggested.

- Watch out for other forms of bias. Beware of unconsciously stereotyping your patients. “It affects how people relate to you, how they adhere to your suggestions, and how much they’ll trust [and confide in] you, which can have clinical implications,” Dr. Mandel said.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Mandel has no disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Nearly 350 years ago, British physician Thomas Willis wrote that diabetes seemed often to occur in patients who were experiencing “significant life stress, sadness, or long sorrow.” That, according to Ellen D. Mandel, DMH, MPA, MS, PA-C, RDN, CDE, a clinical professor at Pace University in New York City, was an important insight into the link between mind and body in patients with diabetes.

“As clinicians, we should be worried about mental illness in our patients with diabetes,” Dr. Mandel, a physician assistant educator, said during a presentation at the Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit by Global Academy for Medical Education.

In particular, she said, – and vice versa.

Dr. Mandel pointed to findings suggesting that 11% of patients with diabetes show signs of clinical depression, which is higher than in the general population, with many more believed to have subclinical depression (Diabetes Care. 2015;38[4]:551-60).

Anxiety can be a key factor in trying to understand how diabetes might contribute to depression. “Diabetes is a very stressful condition ... [and patients] may be fatigued and exhausted.” On top of that, they have to make nutrition changes, or at least pay attention to their diet and overall care, all of which can have a cumulatively negative impact on patient well-being.

Conversely, depression can contribute to diabetes. “They kind of go hand in hand,” she said, pointing to depression’s ability to disrupt appetite, diminish energy, and boost levels of cortisol.

Among the findings that provide evidence of a link between diabetes and depression are those from a study in which investigators estimated that for every 1-point increase in depression symptoms, the risk of diabetes will go up by as much as 5% (Clin Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018 Jan 4. doi: 10.1186/s40842-017-0052-1). Moreover, a 2013 review linked the combination of diabetes and depression to an adjusted 1.5-fold increase in risk of all-cause death (PLoS One. 2013 Mar 5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057058).

Dr. Mandel offered these tips about diagnosing depression in patients with diabetes and helping them feel comfortable:

- Put yourself in the patient’s shoes. “One of the biggest barriers to referring patients to diabetic education is that they don’t want to have to admit to a group that they have diabetes. They keep it to themselves, to their own detriment. In addition, there’s a lot of worry about insurance.” Patients with diabetes often have self-esteem issues and financial or insurance challenges, all of which need to be factored in when working with them, Dr. Mandel said.

- Ask questions and use screening tools. Two simple questions are helpful in starting a conversation and gathering useful information: Over the past 2 weeks, have you often been bothered by [having] little interest or pleasure in doing things? What about being bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless? If the patient answers “yes” to either of these questions, it will be a positive screen, and two “no” answers will be a negative screen. With the “yes” responses, one should follow-up with a screening tool – typically, the one approved by your institution. Dr. Mandel also highlighted the Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale (PHQ-9), which is available online, or the brief, two-item Diabetes Distress Scale (DDS2) questionnaire.

- Keep your own language in mind. “The way you communicate with your patients can elevate their feeling about themselves or destroy how they feel about themselves,” Dr. Mandel said. “We’re trying to stop calling people with diabetes ‘diabetics.’ People don’t want to be labeled like that. Don’t blame yourself if you use this language, but work to make the changes,” Dr. Mandel suggested.

- Watch out for other forms of bias. Beware of unconsciously stereotyping your patients. “It affects how people relate to you, how they adhere to your suggestions, and how much they’ll trust [and confide in] you, which can have clinical implications,” Dr. Mandel said.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Mandel has no disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM MEDS 2019

Oral semaglutide monotherapy delivers HbA1c improvements in type 2 diabetes

Oral semaglutide monotherapy was superior to placebo for improving glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels at all doses tested in adults with type 2 diabetes who had been previously insufficiently managed with diet and exercise, according to findings from a global, randomized trial.

The drug also showed dose-dependent weight loss, with a statistically significant effect on body weight, compared with placebo, at higher doses.

To date, the glucagon-like peptide–1 receptor agonist has been available as weekly subcutaneous shots for patients with type 2 diabetes, and in that form they have been shown to be effective in reducing HbA1c, inducing weight loss, and lowering the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with cardiovascular disease or those who are at high risk for it, wrote Vanita R. Aroda, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues. The report is in Diabetes Care.

The novel oral semaglutide tablet is designed to enhance medication absorption, and the pharmacokinetics and dosage were established in phase 2 studies, they noted.

In the phase 3 Peptide Innovation for Early Diabetes Treatment 1 (PIONEER 1) study, Dr. Aroda and colleagues randomized 703 adults with type 2 diabetes to receive either 3 mg, 7 mg, or 14 mg of oral semaglutide daily, or placebo. The average age of the patients was 55 years, about half were women, and the average baseline HbA1c was 8.0% (64 mmol/mol). The primary endpoint was change in HbA1c level from baseline to week 26, and the secondary endpoint was change in body weight over the same period.

After 26 weeks of once-daily treatment, patients in semaglutide group showed significant reductions in HbA1c from baseline with all three doses: –0.6% (3 mg), –0.9% (7 mg), and –1.1% (14 mg), with P less than .001 for all, based on an intention-to-treat analysis. Similar results occurred using an on-treatment analysis, with differences of –0.7%, –1.2%, and –1.4%, respectively, for the three doses.

In addition, patients in all dose groups achieved the secondary endpoint of reduction in body weight, compared with placebo, from baseline to 26 weeks based on both types of analyses. “Significantly more patients achieved body weight loss of at least 5% with oral semaglutide at 7 mg and 14 mg, compared with placebo,” Dr. Aroda and colleagues wrote (intention-to-treat: –0.1 for 3 mg daily [P = .87], –0.9 for 7 mg [P = .09], –2.3 for 14 mg [P less than .001]; and on-treatment: –0.2 for 3 mg [P = .71], –1.0 for 7 mg [P = .01], –2.6 for 14 mg [P less than .001]).

The overall incidence of adverse events and serious adverse events was similar in the treatment and placebo groups, with the most frequent being nausea and diarrhea. No deaths occurred among patients on the medication.

The findings were limited by several factors, including a patient population that had a relatively short duration of diabetes (mean, 3.5 years) and that the oral semaglutide was used as first-line monotherapy, without first using metformin, the researchers noted. However, oral semaglutide “achieved clinically meaningful and superior glucose lowering,” compared with placebo, at all three doses, they wrote.

“Ongoing additional studies in the PIONEER program will further define the effect when used in combination with other glucose-lowering therapies and in other populations of interest, such as those with high cardiovascular risk or renal impairment,” they emphasized

Novo Nordisk funded the study. The lead author disclosed relationships with Novo Nordisk, and several coauthors disclosed relationships with or employment by the company.

SOURCE: Aroda VR et al. Diabetes Care. 2019 Jul. doi: 10.2337/dc19-0749.

Oral semaglutide monotherapy was superior to placebo for improving glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels at all doses tested in adults with type 2 diabetes who had been previously insufficiently managed with diet and exercise, according to findings from a global, randomized trial.

The drug also showed dose-dependent weight loss, with a statistically significant effect on body weight, compared with placebo, at higher doses.

To date, the glucagon-like peptide–1 receptor agonist has been available as weekly subcutaneous shots for patients with type 2 diabetes, and in that form they have been shown to be effective in reducing HbA1c, inducing weight loss, and lowering the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with cardiovascular disease or those who are at high risk for it, wrote Vanita R. Aroda, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues. The report is in Diabetes Care.

The novel oral semaglutide tablet is designed to enhance medication absorption, and the pharmacokinetics and dosage were established in phase 2 studies, they noted.

In the phase 3 Peptide Innovation for Early Diabetes Treatment 1 (PIONEER 1) study, Dr. Aroda and colleagues randomized 703 adults with type 2 diabetes to receive either 3 mg, 7 mg, or 14 mg of oral semaglutide daily, or placebo. The average age of the patients was 55 years, about half were women, and the average baseline HbA1c was 8.0% (64 mmol/mol). The primary endpoint was change in HbA1c level from baseline to week 26, and the secondary endpoint was change in body weight over the same period.

After 26 weeks of once-daily treatment, patients in semaglutide group showed significant reductions in HbA1c from baseline with all three doses: –0.6% (3 mg), –0.9% (7 mg), and –1.1% (14 mg), with P less than .001 for all, based on an intention-to-treat analysis. Similar results occurred using an on-treatment analysis, with differences of –0.7%, –1.2%, and –1.4%, respectively, for the three doses.

In addition, patients in all dose groups achieved the secondary endpoint of reduction in body weight, compared with placebo, from baseline to 26 weeks based on both types of analyses. “Significantly more patients achieved body weight loss of at least 5% with oral semaglutide at 7 mg and 14 mg, compared with placebo,” Dr. Aroda and colleagues wrote (intention-to-treat: –0.1 for 3 mg daily [P = .87], –0.9 for 7 mg [P = .09], –2.3 for 14 mg [P less than .001]; and on-treatment: –0.2 for 3 mg [P = .71], –1.0 for 7 mg [P = .01], –2.6 for 14 mg [P less than .001]).

The overall incidence of adverse events and serious adverse events was similar in the treatment and placebo groups, with the most frequent being nausea and diarrhea. No deaths occurred among patients on the medication.

The findings were limited by several factors, including a patient population that had a relatively short duration of diabetes (mean, 3.5 years) and that the oral semaglutide was used as first-line monotherapy, without first using metformin, the researchers noted. However, oral semaglutide “achieved clinically meaningful and superior glucose lowering,” compared with placebo, at all three doses, they wrote.

“Ongoing additional studies in the PIONEER program will further define the effect when used in combination with other glucose-lowering therapies and in other populations of interest, such as those with high cardiovascular risk or renal impairment,” they emphasized

Novo Nordisk funded the study. The lead author disclosed relationships with Novo Nordisk, and several coauthors disclosed relationships with or employment by the company.

SOURCE: Aroda VR et al. Diabetes Care. 2019 Jul. doi: 10.2337/dc19-0749.

Oral semaglutide monotherapy was superior to placebo for improving glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels at all doses tested in adults with type 2 diabetes who had been previously insufficiently managed with diet and exercise, according to findings from a global, randomized trial.

The drug also showed dose-dependent weight loss, with a statistically significant effect on body weight, compared with placebo, at higher doses.

To date, the glucagon-like peptide–1 receptor agonist has been available as weekly subcutaneous shots for patients with type 2 diabetes, and in that form they have been shown to be effective in reducing HbA1c, inducing weight loss, and lowering the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with cardiovascular disease or those who are at high risk for it, wrote Vanita R. Aroda, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues. The report is in Diabetes Care.

The novel oral semaglutide tablet is designed to enhance medication absorption, and the pharmacokinetics and dosage were established in phase 2 studies, they noted.

In the phase 3 Peptide Innovation for Early Diabetes Treatment 1 (PIONEER 1) study, Dr. Aroda and colleagues randomized 703 adults with type 2 diabetes to receive either 3 mg, 7 mg, or 14 mg of oral semaglutide daily, or placebo. The average age of the patients was 55 years, about half were women, and the average baseline HbA1c was 8.0% (64 mmol/mol). The primary endpoint was change in HbA1c level from baseline to week 26, and the secondary endpoint was change in body weight over the same period.

After 26 weeks of once-daily treatment, patients in semaglutide group showed significant reductions in HbA1c from baseline with all three doses: –0.6% (3 mg), –0.9% (7 mg), and –1.1% (14 mg), with P less than .001 for all, based on an intention-to-treat analysis. Similar results occurred using an on-treatment analysis, with differences of –0.7%, –1.2%, and –1.4%, respectively, for the three doses.

In addition, patients in all dose groups achieved the secondary endpoint of reduction in body weight, compared with placebo, from baseline to 26 weeks based on both types of analyses. “Significantly more patients achieved body weight loss of at least 5% with oral semaglutide at 7 mg and 14 mg, compared with placebo,” Dr. Aroda and colleagues wrote (intention-to-treat: –0.1 for 3 mg daily [P = .87], –0.9 for 7 mg [P = .09], –2.3 for 14 mg [P less than .001]; and on-treatment: –0.2 for 3 mg [P = .71], –1.0 for 7 mg [P = .01], –2.6 for 14 mg [P less than .001]).

The overall incidence of adverse events and serious adverse events was similar in the treatment and placebo groups, with the most frequent being nausea and diarrhea. No deaths occurred among patients on the medication.

The findings were limited by several factors, including a patient population that had a relatively short duration of diabetes (mean, 3.5 years) and that the oral semaglutide was used as first-line monotherapy, without first using metformin, the researchers noted. However, oral semaglutide “achieved clinically meaningful and superior glucose lowering,” compared with placebo, at all three doses, they wrote.

“Ongoing additional studies in the PIONEER program will further define the effect when used in combination with other glucose-lowering therapies and in other populations of interest, such as those with high cardiovascular risk or renal impairment,” they emphasized

Novo Nordisk funded the study. The lead author disclosed relationships with Novo Nordisk, and several coauthors disclosed relationships with or employment by the company.

SOURCE: Aroda VR et al. Diabetes Care. 2019 Jul. doi: 10.2337/dc19-0749.

FROM DIABETES CARE

Mediterranean diet tied to improved cognition in type 2 diabetes

People with type 2 diabetes whose diet followed a “Mediterranean” pattern – high in vegetables, legumes, fish, and unsaturated fats – saw global cognitive improvements over a 2-year period, compared with individuals with different eating patterns, even if the latter incorporated healthy dietary features. In addition, effective glycemic control seemed to have a role in sustaining the benefits associated with the Mediterranean-type diet.

Adults without type 2 diabetes, meanwhile, did not see the cognitive improvements associated with a Mediterranean diet, suggesting that the pathways linking diet to cognition may be different for individuals with and without diabetes, according to Josiemer Mattei, PhD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston and colleagues.

The investigators used data from the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study, a longitudinal cohort of about 1,499 adults aged 45-75 years who lived in Boston and identified as Puerto Rican, for their research, which was published in Diabetes Care.

At baseline, participants were administered a questionnaire to capture their eating patterns. Four diet-quality scores – Mediterranean Diet Score, Healthy Eating Index, Alternate Healthy Eating Index, and DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) were analyzed. The participants were also screened for diabetes, and nearly 40% of them were found to have type 2 diabetes at baseline (74% uncontrolled). They underwent a battery of cognitive tests, including the Mini-Mental State Exam and tests for verbal fluency, executive function, word recognition, and figure copying. The study endpoints included 2-year change in global cognitive function as well as executive and memory function. At 2 years, data was available for 913 participants.

Among participants with type 2 diabetes, greater adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet was significantly associated with a higher positive change at the 2-year follow-up in global cognitive function score (0.027 [SD, 0.011]; P = .016), the Mini-Mental State Exam, and other individual tests. The association was significant for those who were under glycemic control at baseline and who remained stable or improved over 2 years, but not for those with poor or worsening glycemic control.

“The Mediterranean diet explained as much or more of the variability in predicting changes in cognitive function in our study as did age, especially for participants with type 2 diabetes under glycemic control. ... This dietary pattern may provide more cognitive benefits [in this patient group] than other modifiable and nonmodifiable factors,” the authors wrote in their analysis. They stressed that a Mediterranean dietary pattern can be realized through foods and dishes that are already standard in many Puerto Rican households.

In participants who did not have diabetes, improvement in memory function measures was seen in association with a Mediterranean diet, but also with adherence to other eating patterns that are deemed healthy. That suggests that for this subgroup, any evidence-based healthy diet – not just the Mediterranean diet – may have some benefits for memory function.

“Dietary recommendations for cognitive health may need to be tailored for individuals with versus without type 2 diabetes,” the authors concluded.

Dr. Mattei and colleagues acknowledged as a limitation of their study its observational design.

The study received funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institute on Aging; and Harvard University. The authors reported no financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mattei et al. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(8):1372-9.

People with type 2 diabetes whose diet followed a “Mediterranean” pattern – high in vegetables, legumes, fish, and unsaturated fats – saw global cognitive improvements over a 2-year period, compared with individuals with different eating patterns, even if the latter incorporated healthy dietary features. In addition, effective glycemic control seemed to have a role in sustaining the benefits associated with the Mediterranean-type diet.

Adults without type 2 diabetes, meanwhile, did not see the cognitive improvements associated with a Mediterranean diet, suggesting that the pathways linking diet to cognition may be different for individuals with and without diabetes, according to Josiemer Mattei, PhD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston and colleagues.

The investigators used data from the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study, a longitudinal cohort of about 1,499 adults aged 45-75 years who lived in Boston and identified as Puerto Rican, for their research, which was published in Diabetes Care.

At baseline, participants were administered a questionnaire to capture their eating patterns. Four diet-quality scores – Mediterranean Diet Score, Healthy Eating Index, Alternate Healthy Eating Index, and DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) were analyzed. The participants were also screened for diabetes, and nearly 40% of them were found to have type 2 diabetes at baseline (74% uncontrolled). They underwent a battery of cognitive tests, including the Mini-Mental State Exam and tests for verbal fluency, executive function, word recognition, and figure copying. The study endpoints included 2-year change in global cognitive function as well as executive and memory function. At 2 years, data was available for 913 participants.

Among participants with type 2 diabetes, greater adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet was significantly associated with a higher positive change at the 2-year follow-up in global cognitive function score (0.027 [SD, 0.011]; P = .016), the Mini-Mental State Exam, and other individual tests. The association was significant for those who were under glycemic control at baseline and who remained stable or improved over 2 years, but not for those with poor or worsening glycemic control.

“The Mediterranean diet explained as much or more of the variability in predicting changes in cognitive function in our study as did age, especially for participants with type 2 diabetes under glycemic control. ... This dietary pattern may provide more cognitive benefits [in this patient group] than other modifiable and nonmodifiable factors,” the authors wrote in their analysis. They stressed that a Mediterranean dietary pattern can be realized through foods and dishes that are already standard in many Puerto Rican households.

In participants who did not have diabetes, improvement in memory function measures was seen in association with a Mediterranean diet, but also with adherence to other eating patterns that are deemed healthy. That suggests that for this subgroup, any evidence-based healthy diet – not just the Mediterranean diet – may have some benefits for memory function.

“Dietary recommendations for cognitive health may need to be tailored for individuals with versus without type 2 diabetes,” the authors concluded.

Dr. Mattei and colleagues acknowledged as a limitation of their study its observational design.

The study received funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institute on Aging; and Harvard University. The authors reported no financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mattei et al. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(8):1372-9.

People with type 2 diabetes whose diet followed a “Mediterranean” pattern – high in vegetables, legumes, fish, and unsaturated fats – saw global cognitive improvements over a 2-year period, compared with individuals with different eating patterns, even if the latter incorporated healthy dietary features. In addition, effective glycemic control seemed to have a role in sustaining the benefits associated with the Mediterranean-type diet.

Adults without type 2 diabetes, meanwhile, did not see the cognitive improvements associated with a Mediterranean diet, suggesting that the pathways linking diet to cognition may be different for individuals with and without diabetes, according to Josiemer Mattei, PhD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston and colleagues.

The investigators used data from the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study, a longitudinal cohort of about 1,499 adults aged 45-75 years who lived in Boston and identified as Puerto Rican, for their research, which was published in Diabetes Care.

At baseline, participants were administered a questionnaire to capture their eating patterns. Four diet-quality scores – Mediterranean Diet Score, Healthy Eating Index, Alternate Healthy Eating Index, and DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) were analyzed. The participants were also screened for diabetes, and nearly 40% of them were found to have type 2 diabetes at baseline (74% uncontrolled). They underwent a battery of cognitive tests, including the Mini-Mental State Exam and tests for verbal fluency, executive function, word recognition, and figure copying. The study endpoints included 2-year change in global cognitive function as well as executive and memory function. At 2 years, data was available for 913 participants.

Among participants with type 2 diabetes, greater adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet was significantly associated with a higher positive change at the 2-year follow-up in global cognitive function score (0.027 [SD, 0.011]; P = .016), the Mini-Mental State Exam, and other individual tests. The association was significant for those who were under glycemic control at baseline and who remained stable or improved over 2 years, but not for those with poor or worsening glycemic control.

“The Mediterranean diet explained as much or more of the variability in predicting changes in cognitive function in our study as did age, especially for participants with type 2 diabetes under glycemic control. ... This dietary pattern may provide more cognitive benefits [in this patient group] than other modifiable and nonmodifiable factors,” the authors wrote in their analysis. They stressed that a Mediterranean dietary pattern can be realized through foods and dishes that are already standard in many Puerto Rican households.

In participants who did not have diabetes, improvement in memory function measures was seen in association with a Mediterranean diet, but also with adherence to other eating patterns that are deemed healthy. That suggests that for this subgroup, any evidence-based healthy diet – not just the Mediterranean diet – may have some benefits for memory function.

“Dietary recommendations for cognitive health may need to be tailored for individuals with versus without type 2 diabetes,” the authors concluded.

Dr. Mattei and colleagues acknowledged as a limitation of their study its observational design.

The study received funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institute on Aging; and Harvard University. The authors reported no financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mattei et al. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(8):1372-9.

FROM DIABETES CARE

Perils of ‘type’-casting: When adult-onset diabetes isn’t what you think it is

SAN DIEGO – We all know about type 1 and type 2 diabetes. But when an adult patient comes in with symptoms suggestive of diabetes, it is never a good idea to assume it’s either one or the other. In fact, said physician assistant Ji Hyun “CJ” Chun, PA-C, MPAS, BC-ADM, there are plenty of other possibilities from cancer, to monogenetic diabetes, to a condition informally known as type 1.5.

“In most cases, it will be type 1 or type 2, but don’t default everything,” Mr. Chun said at the Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit by Global Academy for Medical Education.

He offered the following advice on the diagnosis of adult-onset diabetes:

- Don’t forget the 5% ... and the other 5%. In adults, an estimated 90% of cases of diabetes are type 2, but 5% are type 1 and another 5% are secondary to other conditions, said Mr. Chun, who is based at OptumCare Medical Group, Laguna Niguel, Calif., and has served as president of the American Society of Endocrine PAs. In the past, age seemed to be an important tool for diagnosis, because younger patients typically had type 1 diabetes and older patients typically had type 2, he said. But age alone is no longer useful for diagnosis. Cases of type 2 diabetes are much more common in children these days because of the prevalence of obesity in that population, and an estimated 60% of cases of type 1 disease are diagnosed after the age of 20. In fact, patients may develop type 1 into their 30s, 40s, or 50s, he said, depending on the severity of their autoimmunity.

- Keep ‘type 1.5’ in mind. Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA), also known as type 1.5, is a slowly developing subtype of type 1 diabetes, Mr. Chun said. There is reason to suspect LADA in lean patients, those younger than 50, and those with personal or family histories of autoimmunity, Mr. Chun said.

- Consider monogenetic diabetes. Many conditions can cause secondary diabetes, among them, monogenetic diabetes, which is caused by a single genetic mutation, whereas type 1 and type 2 diabetes are caused by multiple mutations. Monogenetic diabetes causes an estimated 1%-2% of diabetes cases, said Mr. Chun. Research findings have suggested that it is most likely to be misdiagnosed in younger adults, and that patients may go many years without receiving a correct diagnosis. Maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) is a kind of monogenetic diabetes and typically occurs before the age of 25. There are many subtypes, of which one – MODY 2 – requires no treatment at all. In those patients, said Mr. Chun, “you do nothing. You leave them alone.” It is important to keep in mind that the genetic testing for MODY is expensive, Mr Chun cautioned. Some labs charge between $5,000 and $7,000 for panels, so “look for labs that perform cheaper tests,” he advised, adding that he has found a lab that charges just $250.

- Watch out for cancer. There is a long list of other possible causes of secondary diabetes, including Cushing’s syndrome, hyperthyroidism, hemochromatosis (iron overload), and pancreatic cancer. Mr. Chun said he has lost three patients to pancreatic cancer, while two other patients did well. “Keep in mind that these cases aren’t that common, but they’re there.” He suggested that pancreatic cancer should be considered in patients with rapid onset or worsening of diabetes without known cause, abnormal weight loss, abnormal liver/biliary studies, and jaundice.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Mr. Chun disclosed that he is on the AstraZeneca speakers bureau and the Sanofi advisory board.

SAN DIEGO – We all know about type 1 and type 2 diabetes. But when an adult patient comes in with symptoms suggestive of diabetes, it is never a good idea to assume it’s either one or the other. In fact, said physician assistant Ji Hyun “CJ” Chun, PA-C, MPAS, BC-ADM, there are plenty of other possibilities from cancer, to monogenetic diabetes, to a condition informally known as type 1.5.

“In most cases, it will be type 1 or type 2, but don’t default everything,” Mr. Chun said at the Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit by Global Academy for Medical Education.

He offered the following advice on the diagnosis of adult-onset diabetes:

- Don’t forget the 5% ... and the other 5%. In adults, an estimated 90% of cases of diabetes are type 2, but 5% are type 1 and another 5% are secondary to other conditions, said Mr. Chun, who is based at OptumCare Medical Group, Laguna Niguel, Calif., and has served as president of the American Society of Endocrine PAs. In the past, age seemed to be an important tool for diagnosis, because younger patients typically had type 1 diabetes and older patients typically had type 2, he said. But age alone is no longer useful for diagnosis. Cases of type 2 diabetes are much more common in children these days because of the prevalence of obesity in that population, and an estimated 60% of cases of type 1 disease are diagnosed after the age of 20. In fact, patients may develop type 1 into their 30s, 40s, or 50s, he said, depending on the severity of their autoimmunity.

- Keep ‘type 1.5’ in mind. Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA), also known as type 1.5, is a slowly developing subtype of type 1 diabetes, Mr. Chun said. There is reason to suspect LADA in lean patients, those younger than 50, and those with personal or family histories of autoimmunity, Mr. Chun said.

- Consider monogenetic diabetes. Many conditions can cause secondary diabetes, among them, monogenetic diabetes, which is caused by a single genetic mutation, whereas type 1 and type 2 diabetes are caused by multiple mutations. Monogenetic diabetes causes an estimated 1%-2% of diabetes cases, said Mr. Chun. Research findings have suggested that it is most likely to be misdiagnosed in younger adults, and that patients may go many years without receiving a correct diagnosis. Maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) is a kind of monogenetic diabetes and typically occurs before the age of 25. There are many subtypes, of which one – MODY 2 – requires no treatment at all. In those patients, said Mr. Chun, “you do nothing. You leave them alone.” It is important to keep in mind that the genetic testing for MODY is expensive, Mr Chun cautioned. Some labs charge between $5,000 and $7,000 for panels, so “look for labs that perform cheaper tests,” he advised, adding that he has found a lab that charges just $250.

- Watch out for cancer. There is a long list of other possible causes of secondary diabetes, including Cushing’s syndrome, hyperthyroidism, hemochromatosis (iron overload), and pancreatic cancer. Mr. Chun said he has lost three patients to pancreatic cancer, while two other patients did well. “Keep in mind that these cases aren’t that common, but they’re there.” He suggested that pancreatic cancer should be considered in patients with rapid onset or worsening of diabetes without known cause, abnormal weight loss, abnormal liver/biliary studies, and jaundice.