User login

Open AAA repair mortality rates doubled for very-low-volume surgeons

NEW YORK – If New York State is representative, the risk of bad outcomes in patients undergoing open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (OAR) or carotid endarterectomy (CEA), including death in the case of OAR, is about double when performed by very low- versus higher-volume surgeons, according to data presented at a symposium on vascular and endovascular issues sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

“What should we do to fix the problem? We could require surgeons to track their outcomes in quality improvement registry,” suggested Jack L. Cronenwett, MD, professor of surgery, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H.

The outcomes were evaluated from inpatient data gathered from patients undergoing OAR or CEA in an all-payer database involving every hospital discharge in New York State. Surgeons were defined as very-low-volume for a given procedure if they averaged one or less per year, though the results held true if very-low-volume was defined as less than three cases per year, according to Dr. Cronenwett.

The database had outcomes on 8,781 OAR procedures and 68,896 CEA procedures performed from 2000 to 2014.

Of the 614 surgeons who performed one or more OARs over this period, 318 (51.8%) were defined as low-volume surgeons. Despite their substantial representation, they performed just 7.6% of the procedures.

When outcomes from procedures performed by very-low-volume surgeons were compared to those done by higher-volume surgeons, the mortality rates without adjustments were nearly double (6.7% vs. 3.5%; P less than .001). Procedures performed by low-volume surgeons were associated with far higher rates of sepsis or shock (5.7% vs. 3.7%; P = .008), and patients treated by low-volume surgeons were more likely to spend 9 or more days in the hospital (39.3% vs. 30.1%; P less than .001).

When fully adjusted for other variables, “low-volume surgeons had twofold higher odds [OR 2.09] of postoperative death,” Dr. Cronenwett reported.

Of the 1,071 surgeons who performed CEA over this period, 512 (47.8%) were low-volume. They performed 1.3% of the procedures.

Mortality and sepsis or shock following CEA were less than 1% in procedures performed by either low- or higher-volume surgeons without significant differences. However, procedures performed by low-volume surgeons were associated with a three-times higher rate of myocardial infarction (1.5% vs. 0.5%; P less than .001) and a 65% higher rate of stroke (3.5% vs. 2.1%; P = .003).

In addition, patients who underwent CEA performed by a low-volume surgeon had a significantly higher rate of 30-day readmission (11.5% vs. 8.5%; P = .002) and a significantly longer median length of stay (2 days vs. 1 day; P less than .001) than did those treated by a higher-volume surgeon.

Whether OAR or CEA, patients treated by a low-volume surgeon were more likely to have Medicaid coverage. The fact that procedures by low-volume surgeons were more likely to be performed in New York City than other areas of the state suggest that access to care was not a variable, according to Dr. Cronenwett.

Surgeon volume was calculated in this study by dividing the total number of OAR or CEA procedures performed by the number of years that the surgeon was in practice in New York State. Surgeons were classified as vascular surgeons if 75% or more of their surgical practice involved vascular procedures, cardiac surgeons if more than 20% of their surgical practice involved cardiac procedures, and general surgeons if they did not meet either of these criteria.

Of OAR procedures were done by a higher-volume surgeon, approximately 65% were by vascular specialists, 5% were by cardiac specialists, and the remaining were by general surgeons.

Of OAR procedures were done by a low-volume surgeon, approximately 25% were by vascular surgeons, 20% were by cardiac surgeons, and the remaining were by general surgeons. For CEA, there was a somewhat greater representation of general surgeons in both categories, but the patterns were similar.

Dr. Cronenwett argued that more rigorous steps should be taken to ensure that those with proven skills perform OAR and CEA and that open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair should be performed only by high-volume surgeons and hospitals. He suggested there are a variety of incentives or disincentives that could help, but he stressed the importance of tracking results and making them available to referring physicians and to patients.

“Some of the low-volume surgeons are probably not tracking their results so are not even aware of these bad outcomes,” he added.

Dr. Cronenwett reported that he had no relevant disclosures.

NEW YORK – If New York State is representative, the risk of bad outcomes in patients undergoing open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (OAR) or carotid endarterectomy (CEA), including death in the case of OAR, is about double when performed by very low- versus higher-volume surgeons, according to data presented at a symposium on vascular and endovascular issues sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

“What should we do to fix the problem? We could require surgeons to track their outcomes in quality improvement registry,” suggested Jack L. Cronenwett, MD, professor of surgery, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H.

The outcomes were evaluated from inpatient data gathered from patients undergoing OAR or CEA in an all-payer database involving every hospital discharge in New York State. Surgeons were defined as very-low-volume for a given procedure if they averaged one or less per year, though the results held true if very-low-volume was defined as less than three cases per year, according to Dr. Cronenwett.

The database had outcomes on 8,781 OAR procedures and 68,896 CEA procedures performed from 2000 to 2014.

Of the 614 surgeons who performed one or more OARs over this period, 318 (51.8%) were defined as low-volume surgeons. Despite their substantial representation, they performed just 7.6% of the procedures.

When outcomes from procedures performed by very-low-volume surgeons were compared to those done by higher-volume surgeons, the mortality rates without adjustments were nearly double (6.7% vs. 3.5%; P less than .001). Procedures performed by low-volume surgeons were associated with far higher rates of sepsis or shock (5.7% vs. 3.7%; P = .008), and patients treated by low-volume surgeons were more likely to spend 9 or more days in the hospital (39.3% vs. 30.1%; P less than .001).

When fully adjusted for other variables, “low-volume surgeons had twofold higher odds [OR 2.09] of postoperative death,” Dr. Cronenwett reported.

Of the 1,071 surgeons who performed CEA over this period, 512 (47.8%) were low-volume. They performed 1.3% of the procedures.

Mortality and sepsis or shock following CEA were less than 1% in procedures performed by either low- or higher-volume surgeons without significant differences. However, procedures performed by low-volume surgeons were associated with a three-times higher rate of myocardial infarction (1.5% vs. 0.5%; P less than .001) and a 65% higher rate of stroke (3.5% vs. 2.1%; P = .003).

In addition, patients who underwent CEA performed by a low-volume surgeon had a significantly higher rate of 30-day readmission (11.5% vs. 8.5%; P = .002) and a significantly longer median length of stay (2 days vs. 1 day; P less than .001) than did those treated by a higher-volume surgeon.

Whether OAR or CEA, patients treated by a low-volume surgeon were more likely to have Medicaid coverage. The fact that procedures by low-volume surgeons were more likely to be performed in New York City than other areas of the state suggest that access to care was not a variable, according to Dr. Cronenwett.

Surgeon volume was calculated in this study by dividing the total number of OAR or CEA procedures performed by the number of years that the surgeon was in practice in New York State. Surgeons were classified as vascular surgeons if 75% or more of their surgical practice involved vascular procedures, cardiac surgeons if more than 20% of their surgical practice involved cardiac procedures, and general surgeons if they did not meet either of these criteria.

Of OAR procedures were done by a higher-volume surgeon, approximately 65% were by vascular specialists, 5% were by cardiac specialists, and the remaining were by general surgeons.

Of OAR procedures were done by a low-volume surgeon, approximately 25% were by vascular surgeons, 20% were by cardiac surgeons, and the remaining were by general surgeons. For CEA, there was a somewhat greater representation of general surgeons in both categories, but the patterns were similar.

Dr. Cronenwett argued that more rigorous steps should be taken to ensure that those with proven skills perform OAR and CEA and that open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair should be performed only by high-volume surgeons and hospitals. He suggested there are a variety of incentives or disincentives that could help, but he stressed the importance of tracking results and making them available to referring physicians and to patients.

“Some of the low-volume surgeons are probably not tracking their results so are not even aware of these bad outcomes,” he added.

Dr. Cronenwett reported that he had no relevant disclosures.

NEW YORK – If New York State is representative, the risk of bad outcomes in patients undergoing open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (OAR) or carotid endarterectomy (CEA), including death in the case of OAR, is about double when performed by very low- versus higher-volume surgeons, according to data presented at a symposium on vascular and endovascular issues sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

“What should we do to fix the problem? We could require surgeons to track their outcomes in quality improvement registry,” suggested Jack L. Cronenwett, MD, professor of surgery, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H.

The outcomes were evaluated from inpatient data gathered from patients undergoing OAR or CEA in an all-payer database involving every hospital discharge in New York State. Surgeons were defined as very-low-volume for a given procedure if they averaged one or less per year, though the results held true if very-low-volume was defined as less than three cases per year, according to Dr. Cronenwett.

The database had outcomes on 8,781 OAR procedures and 68,896 CEA procedures performed from 2000 to 2014.

Of the 614 surgeons who performed one or more OARs over this period, 318 (51.8%) were defined as low-volume surgeons. Despite their substantial representation, they performed just 7.6% of the procedures.

When outcomes from procedures performed by very-low-volume surgeons were compared to those done by higher-volume surgeons, the mortality rates without adjustments were nearly double (6.7% vs. 3.5%; P less than .001). Procedures performed by low-volume surgeons were associated with far higher rates of sepsis or shock (5.7% vs. 3.7%; P = .008), and patients treated by low-volume surgeons were more likely to spend 9 or more days in the hospital (39.3% vs. 30.1%; P less than .001).

When fully adjusted for other variables, “low-volume surgeons had twofold higher odds [OR 2.09] of postoperative death,” Dr. Cronenwett reported.

Of the 1,071 surgeons who performed CEA over this period, 512 (47.8%) were low-volume. They performed 1.3% of the procedures.

Mortality and sepsis or shock following CEA were less than 1% in procedures performed by either low- or higher-volume surgeons without significant differences. However, procedures performed by low-volume surgeons were associated with a three-times higher rate of myocardial infarction (1.5% vs. 0.5%; P less than .001) and a 65% higher rate of stroke (3.5% vs. 2.1%; P = .003).

In addition, patients who underwent CEA performed by a low-volume surgeon had a significantly higher rate of 30-day readmission (11.5% vs. 8.5%; P = .002) and a significantly longer median length of stay (2 days vs. 1 day; P less than .001) than did those treated by a higher-volume surgeon.

Whether OAR or CEA, patients treated by a low-volume surgeon were more likely to have Medicaid coverage. The fact that procedures by low-volume surgeons were more likely to be performed in New York City than other areas of the state suggest that access to care was not a variable, according to Dr. Cronenwett.

Surgeon volume was calculated in this study by dividing the total number of OAR or CEA procedures performed by the number of years that the surgeon was in practice in New York State. Surgeons were classified as vascular surgeons if 75% or more of their surgical practice involved vascular procedures, cardiac surgeons if more than 20% of their surgical practice involved cardiac procedures, and general surgeons if they did not meet either of these criteria.

Of OAR procedures were done by a higher-volume surgeon, approximately 65% were by vascular specialists, 5% were by cardiac specialists, and the remaining were by general surgeons.

Of OAR procedures were done by a low-volume surgeon, approximately 25% were by vascular surgeons, 20% were by cardiac surgeons, and the remaining were by general surgeons. For CEA, there was a somewhat greater representation of general surgeons in both categories, but the patterns were similar.

Dr. Cronenwett argued that more rigorous steps should be taken to ensure that those with proven skills perform OAR and CEA and that open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair should be performed only by high-volume surgeons and hospitals. He suggested there are a variety of incentives or disincentives that could help, but he stressed the importance of tracking results and making them available to referring physicians and to patients.

“Some of the low-volume surgeons are probably not tracking their results so are not even aware of these bad outcomes,” he added.

Dr. Cronenwett reported that he had no relevant disclosures.

REPORTING FROM VEITHSYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In-hospital mortality is approximately double (OR 2.09; P less than .001) for very low-volume relative to high-volume surgeon.

Study details: Retrospective database review.

Disclosures: Dr. Cronenwett reports no conflicts of interest.

Source: Cronenwett JL et al. 2018; 45th VEITHsymposium.

Leg ulceration guidelines expected to soon include endovascular ablation

NEW YORK – Guidelines for the management of leg ulcerations will be changed to accommodate the results of the Early Venous Reflux Ablation trial, according to this video interview with the senior author, Alun H Davies, DSc, professor of vascular surgery, Imperial College, London.

In this video interview, conducted at a symposium on vascular and endovascular issues sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Dr. Davies recaps the major results of the study, which associated immediate endovascular ablation (early intervention) with significantly faster healing than did compression therapy with ablation, considered only after 6 months (delayed intervention).

These data have been published (N Engl J Med 2018 May 31;378:2105-14), but Dr. Davies focused in this interview on the cost efficacy of early intervention with endovascular ablation. In the United Kingdom, where the study was conducted, the data support the cost efficacy, but Dr. Davies predicted even greater savings in the United States because of the expense of frequent wound care visits.

Based on data from a randomized trial, he expects guidelines, including those in the United States, to be revised to list early endovascular ablation as a 1b or 1A recommendation, thereby establishing this intervention as a standard.

If follow-up after 3 years confirms a lower rate of recurrence, an advantage previously shown for open surgery relative to compression healing, the case for early endovascular intervention will be even stronger, according to Dr. Davies.

NEW YORK – Guidelines for the management of leg ulcerations will be changed to accommodate the results of the Early Venous Reflux Ablation trial, according to this video interview with the senior author, Alun H Davies, DSc, professor of vascular surgery, Imperial College, London.

In this video interview, conducted at a symposium on vascular and endovascular issues sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Dr. Davies recaps the major results of the study, which associated immediate endovascular ablation (early intervention) with significantly faster healing than did compression therapy with ablation, considered only after 6 months (delayed intervention).

These data have been published (N Engl J Med 2018 May 31;378:2105-14), but Dr. Davies focused in this interview on the cost efficacy of early intervention with endovascular ablation. In the United Kingdom, where the study was conducted, the data support the cost efficacy, but Dr. Davies predicted even greater savings in the United States because of the expense of frequent wound care visits.

Based on data from a randomized trial, he expects guidelines, including those in the United States, to be revised to list early endovascular ablation as a 1b or 1A recommendation, thereby establishing this intervention as a standard.

If follow-up after 3 years confirms a lower rate of recurrence, an advantage previously shown for open surgery relative to compression healing, the case for early endovascular intervention will be even stronger, according to Dr. Davies.

NEW YORK – Guidelines for the management of leg ulcerations will be changed to accommodate the results of the Early Venous Reflux Ablation trial, according to this video interview with the senior author, Alun H Davies, DSc, professor of vascular surgery, Imperial College, London.

In this video interview, conducted at a symposium on vascular and endovascular issues sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Dr. Davies recaps the major results of the study, which associated immediate endovascular ablation (early intervention) with significantly faster healing than did compression therapy with ablation, considered only after 6 months (delayed intervention).

These data have been published (N Engl J Med 2018 May 31;378:2105-14), but Dr. Davies focused in this interview on the cost efficacy of early intervention with endovascular ablation. In the United Kingdom, where the study was conducted, the data support the cost efficacy, but Dr. Davies predicted even greater savings in the United States because of the expense of frequent wound care visits.

Based on data from a randomized trial, he expects guidelines, including those in the United States, to be revised to list early endovascular ablation as a 1b or 1A recommendation, thereby establishing this intervention as a standard.

If follow-up after 3 years confirms a lower rate of recurrence, an advantage previously shown for open surgery relative to compression healing, the case for early endovascular intervention will be even stronger, according to Dr. Davies.

REPORTING FROM VEITHSYMPOSIUM

SVS guidelines address scope of practice concerns

NEW YORK – Vascular surgeons are the only specialty qualified to treat all vascular disorders with open surgery and/or endovascular treatment, including the thoracic aorta, according to the updated “Guidelines for hospital privileges in vascular surgery and endovascular interventions: Recommendations of the Society for Vascular Surgery.”

The guidelines, published in May’s Journal of Vascular Surgery, were last updated in 2008, said Keith D. Calligaro, MD, who spoke on their importance and potential benefits to vascular surgeons during his presentation at the VEITHsymposium.

The thoracic aorta component of the guidelines addresses scope of practice concerns between vascular and thoracic surgeons, said Dr. Calligaro, who is a clinical professor of surgery, University of Pennsylvania, and chief of vascular surgery and endovascular therapy at Pennsylvania Hospital, both in Philadelphia.

The guidelines relied on training requirements to provide some of the data to define vascular surgeons and privileges. The open vascular surgery training requirements still are defined by the Residency Review Committee for surgery, and those requirements include 250 major open vascular cases during training, including 30 open abdominal operations, 25 carotid, 45 peripheral open surgery cases, and 10 complex vascular surgeries, said Dr. Calligaro. “In terms of endovascular treatment, the training requirements are over 100 diagnostic caths and over 80 therapeutic interventions, and during training you would have had to have done more than 20 EVARs [endovascular aneurysm repairs].” That number jumped up from five EVARs in the previous guidelines.

Ultimately, “the SVS is basically saying ‘you need to be a vascular surgeon to perform vascular surgery,’ and you need have to have completed an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–accredited vascular residency.

“So if you are a general surgeon or a heart surgeon and you go to a new hospital and say ‘I want to do vascular,’ the vascular surgeon at that institution can refer to this document and say ‘no, the SVS is saying [the surgeon doesn’t] have the training.’ And I think that’s a pretty gutsy and important call,” said Dr. Calligaro.

It is a different case for endovascular surgery, he said. In this case, the requirement is to have completed an ACGME-accredited program in either vascular surgery, interventional radiology, or interventional cardiology to indicate the appropriate level of training. But SVS agreed with the recommendation by the American College of Cardiology that cardiologists not only had to complete 1 year of coronary interventions but also 1 year of peripheral intervention training, as well.

“So if you are at your hospital and have a cardiologist who is starting to do peripheral vascular stuff, now at least you can wave part of this document and say ‘Hey, look, the most important vascular society in the country is saying that, unless this individual had a year of peripheral training, this cardiologist should not be allowed to do endovascular peripheral interventions,’ ” Dr. Calligaro said.

SOURCE: Calligaro KD et al. J Vasc Surg. 2018 May;67(5):1337-44.

NEW YORK – Vascular surgeons are the only specialty qualified to treat all vascular disorders with open surgery and/or endovascular treatment, including the thoracic aorta, according to the updated “Guidelines for hospital privileges in vascular surgery and endovascular interventions: Recommendations of the Society for Vascular Surgery.”

The guidelines, published in May’s Journal of Vascular Surgery, were last updated in 2008, said Keith D. Calligaro, MD, who spoke on their importance and potential benefits to vascular surgeons during his presentation at the VEITHsymposium.

The thoracic aorta component of the guidelines addresses scope of practice concerns between vascular and thoracic surgeons, said Dr. Calligaro, who is a clinical professor of surgery, University of Pennsylvania, and chief of vascular surgery and endovascular therapy at Pennsylvania Hospital, both in Philadelphia.

The guidelines relied on training requirements to provide some of the data to define vascular surgeons and privileges. The open vascular surgery training requirements still are defined by the Residency Review Committee for surgery, and those requirements include 250 major open vascular cases during training, including 30 open abdominal operations, 25 carotid, 45 peripheral open surgery cases, and 10 complex vascular surgeries, said Dr. Calligaro. “In terms of endovascular treatment, the training requirements are over 100 diagnostic caths and over 80 therapeutic interventions, and during training you would have had to have done more than 20 EVARs [endovascular aneurysm repairs].” That number jumped up from five EVARs in the previous guidelines.

Ultimately, “the SVS is basically saying ‘you need to be a vascular surgeon to perform vascular surgery,’ and you need have to have completed an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–accredited vascular residency.

“So if you are a general surgeon or a heart surgeon and you go to a new hospital and say ‘I want to do vascular,’ the vascular surgeon at that institution can refer to this document and say ‘no, the SVS is saying [the surgeon doesn’t] have the training.’ And I think that’s a pretty gutsy and important call,” said Dr. Calligaro.

It is a different case for endovascular surgery, he said. In this case, the requirement is to have completed an ACGME-accredited program in either vascular surgery, interventional radiology, or interventional cardiology to indicate the appropriate level of training. But SVS agreed with the recommendation by the American College of Cardiology that cardiologists not only had to complete 1 year of coronary interventions but also 1 year of peripheral intervention training, as well.

“So if you are at your hospital and have a cardiologist who is starting to do peripheral vascular stuff, now at least you can wave part of this document and say ‘Hey, look, the most important vascular society in the country is saying that, unless this individual had a year of peripheral training, this cardiologist should not be allowed to do endovascular peripheral interventions,’ ” Dr. Calligaro said.

SOURCE: Calligaro KD et al. J Vasc Surg. 2018 May;67(5):1337-44.

NEW YORK – Vascular surgeons are the only specialty qualified to treat all vascular disorders with open surgery and/or endovascular treatment, including the thoracic aorta, according to the updated “Guidelines for hospital privileges in vascular surgery and endovascular interventions: Recommendations of the Society for Vascular Surgery.”

The guidelines, published in May’s Journal of Vascular Surgery, were last updated in 2008, said Keith D. Calligaro, MD, who spoke on their importance and potential benefits to vascular surgeons during his presentation at the VEITHsymposium.

The thoracic aorta component of the guidelines addresses scope of practice concerns between vascular and thoracic surgeons, said Dr. Calligaro, who is a clinical professor of surgery, University of Pennsylvania, and chief of vascular surgery and endovascular therapy at Pennsylvania Hospital, both in Philadelphia.

The guidelines relied on training requirements to provide some of the data to define vascular surgeons and privileges. The open vascular surgery training requirements still are defined by the Residency Review Committee for surgery, and those requirements include 250 major open vascular cases during training, including 30 open abdominal operations, 25 carotid, 45 peripheral open surgery cases, and 10 complex vascular surgeries, said Dr. Calligaro. “In terms of endovascular treatment, the training requirements are over 100 diagnostic caths and over 80 therapeutic interventions, and during training you would have had to have done more than 20 EVARs [endovascular aneurysm repairs].” That number jumped up from five EVARs in the previous guidelines.

Ultimately, “the SVS is basically saying ‘you need to be a vascular surgeon to perform vascular surgery,’ and you need have to have completed an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–accredited vascular residency.

“So if you are a general surgeon or a heart surgeon and you go to a new hospital and say ‘I want to do vascular,’ the vascular surgeon at that institution can refer to this document and say ‘no, the SVS is saying [the surgeon doesn’t] have the training.’ And I think that’s a pretty gutsy and important call,” said Dr. Calligaro.

It is a different case for endovascular surgery, he said. In this case, the requirement is to have completed an ACGME-accredited program in either vascular surgery, interventional radiology, or interventional cardiology to indicate the appropriate level of training. But SVS agreed with the recommendation by the American College of Cardiology that cardiologists not only had to complete 1 year of coronary interventions but also 1 year of peripheral intervention training, as well.

“So if you are at your hospital and have a cardiologist who is starting to do peripheral vascular stuff, now at least you can wave part of this document and say ‘Hey, look, the most important vascular society in the country is saying that, unless this individual had a year of peripheral training, this cardiologist should not be allowed to do endovascular peripheral interventions,’ ” Dr. Calligaro said.

SOURCE: Calligaro KD et al. J Vasc Surg. 2018 May;67(5):1337-44.

REPORTING FROM THE VEITHSYMPOSIUM

VQI-VVR registry data eyed for guiding development of ethical standards

NEW YORK – Registry data can be used to craft guidance for determining the appropriateness of procedures at vein centers, based on data presented by Thomas W. Wakefield, MD at the 2018 Veith Symposium.

The Vascular Quality Initiative Varicose Vein Registry (VQI-VVR), initiated in 2014 by the Society for Vascular Surgery in conjunction with the American Venous Forum, captures procedures that are performed in vein centers, office-based practices, and ambulatory or inpatient settings. The VVR looks at ablation and phlebectomy techniques and captures data including patient demographics, history, procedure data, plus early and late office-based and patient-reported follow-up in order to benchmark and improve outcomes and develop best practices and to help meet vein center certification requirements. The VVR includes 39 centers and more than 23,000 procedures.

Dr. Wakefield, who heads the VVR, used this registry as a means to illustrate how VQIs could be used to establish whether “the expected health benefit exceeds the expected negative consequences by a sufficiently wide margin that the procedure is worth doing.” This can be considered to be “appropriateness, which is part of ethical treatment.” Dr. Wakefield is the Stanley Professor of Vascular Surgery at the University of Michigan and section head, vascular surgery, University of Michigan Cardiovascular Center, Ann Arbor.

Data from the VQI registry (of which the VVR is a component) are now being used to generate appropriateness reports, said Dr. Wakefield.

The VQI represents a large comprehensive database of long-term data to define appropriate care. In addition, the VQI infrastructure is already geared to producing these reports both at a center and at a surgeon level. One disadvantage of the VVR registry, however, is low participation – only the 39 centers – and that it doesn’t capture cosmetic procedures and lesser (C1) disease. Further, it’s “likely the VQI participants are the ‘good actors,’ ” he added.

Targets for appropriateness include the proportion of patients undergoing ablation C2 or C4 disease or greater, the mean number of ablations per patient, the mean number of ablations per limb, and the proportion of perforated ablations for greater than C4 disease. Plotting out the data for these procedures at the center level can be assessed against current thinking on best practices in the various areas. For example, “the mean number of ablations per patient has been suggested at 1.8 to be about the right number,” and he used the graph of the center performance in this area to show that most of the centers were below this objective.

In an even more appropriate example of how this kind of data could be used to determine appropriateness, Dr. Wakefield described how perforated ablations should be performed for greater than C4 disease, but not for C2 disease. He described how, according to the actual data in the registry, there have been 870 total perforated treatments recorded, 38% for C2 disease, and of these 332 procedures, almost half of these were performed at one center only, with two other centers reporting 30 such procedures. “So clearly there are three centers that are doing perforated ablations for patients that are outside the guidelines,” Dr. Wakefield pointed out.

In future, payer demand is likely to demand that each treating physician provide evidence of the appropriateness of procedures performed, as well as appropriate patient selection and adherence to best practices, and good outcomes, which is part of what a society-based registry such as the VVR can provide.

“I believe the VQI-VVR is well-positioned to meet these needs. And if we ask the question ‘can VQI be used as a benchmark for setting ethical standards,’ I think it can certainly be used to help set appropriate standards, and since appropriateness is one part of ethical standards, I believe it has a role,” he concluded.

Dr. Wakefield reported that he had no disclosures.

NEW YORK – Registry data can be used to craft guidance for determining the appropriateness of procedures at vein centers, based on data presented by Thomas W. Wakefield, MD at the 2018 Veith Symposium.

The Vascular Quality Initiative Varicose Vein Registry (VQI-VVR), initiated in 2014 by the Society for Vascular Surgery in conjunction with the American Venous Forum, captures procedures that are performed in vein centers, office-based practices, and ambulatory or inpatient settings. The VVR looks at ablation and phlebectomy techniques and captures data including patient demographics, history, procedure data, plus early and late office-based and patient-reported follow-up in order to benchmark and improve outcomes and develop best practices and to help meet vein center certification requirements. The VVR includes 39 centers and more than 23,000 procedures.

Dr. Wakefield, who heads the VVR, used this registry as a means to illustrate how VQIs could be used to establish whether “the expected health benefit exceeds the expected negative consequences by a sufficiently wide margin that the procedure is worth doing.” This can be considered to be “appropriateness, which is part of ethical treatment.” Dr. Wakefield is the Stanley Professor of Vascular Surgery at the University of Michigan and section head, vascular surgery, University of Michigan Cardiovascular Center, Ann Arbor.

Data from the VQI registry (of which the VVR is a component) are now being used to generate appropriateness reports, said Dr. Wakefield.

The VQI represents a large comprehensive database of long-term data to define appropriate care. In addition, the VQI infrastructure is already geared to producing these reports both at a center and at a surgeon level. One disadvantage of the VVR registry, however, is low participation – only the 39 centers – and that it doesn’t capture cosmetic procedures and lesser (C1) disease. Further, it’s “likely the VQI participants are the ‘good actors,’ ” he added.

Targets for appropriateness include the proportion of patients undergoing ablation C2 or C4 disease or greater, the mean number of ablations per patient, the mean number of ablations per limb, and the proportion of perforated ablations for greater than C4 disease. Plotting out the data for these procedures at the center level can be assessed against current thinking on best practices in the various areas. For example, “the mean number of ablations per patient has been suggested at 1.8 to be about the right number,” and he used the graph of the center performance in this area to show that most of the centers were below this objective.

In an even more appropriate example of how this kind of data could be used to determine appropriateness, Dr. Wakefield described how perforated ablations should be performed for greater than C4 disease, but not for C2 disease. He described how, according to the actual data in the registry, there have been 870 total perforated treatments recorded, 38% for C2 disease, and of these 332 procedures, almost half of these were performed at one center only, with two other centers reporting 30 such procedures. “So clearly there are three centers that are doing perforated ablations for patients that are outside the guidelines,” Dr. Wakefield pointed out.

In future, payer demand is likely to demand that each treating physician provide evidence of the appropriateness of procedures performed, as well as appropriate patient selection and adherence to best practices, and good outcomes, which is part of what a society-based registry such as the VVR can provide.

“I believe the VQI-VVR is well-positioned to meet these needs. And if we ask the question ‘can VQI be used as a benchmark for setting ethical standards,’ I think it can certainly be used to help set appropriate standards, and since appropriateness is one part of ethical standards, I believe it has a role,” he concluded.

Dr. Wakefield reported that he had no disclosures.

NEW YORK – Registry data can be used to craft guidance for determining the appropriateness of procedures at vein centers, based on data presented by Thomas W. Wakefield, MD at the 2018 Veith Symposium.

The Vascular Quality Initiative Varicose Vein Registry (VQI-VVR), initiated in 2014 by the Society for Vascular Surgery in conjunction with the American Venous Forum, captures procedures that are performed in vein centers, office-based practices, and ambulatory or inpatient settings. The VVR looks at ablation and phlebectomy techniques and captures data including patient demographics, history, procedure data, plus early and late office-based and patient-reported follow-up in order to benchmark and improve outcomes and develop best practices and to help meet vein center certification requirements. The VVR includes 39 centers and more than 23,000 procedures.

Dr. Wakefield, who heads the VVR, used this registry as a means to illustrate how VQIs could be used to establish whether “the expected health benefit exceeds the expected negative consequences by a sufficiently wide margin that the procedure is worth doing.” This can be considered to be “appropriateness, which is part of ethical treatment.” Dr. Wakefield is the Stanley Professor of Vascular Surgery at the University of Michigan and section head, vascular surgery, University of Michigan Cardiovascular Center, Ann Arbor.

Data from the VQI registry (of which the VVR is a component) are now being used to generate appropriateness reports, said Dr. Wakefield.

The VQI represents a large comprehensive database of long-term data to define appropriate care. In addition, the VQI infrastructure is already geared to producing these reports both at a center and at a surgeon level. One disadvantage of the VVR registry, however, is low participation – only the 39 centers – and that it doesn’t capture cosmetic procedures and lesser (C1) disease. Further, it’s “likely the VQI participants are the ‘good actors,’ ” he added.

Targets for appropriateness include the proportion of patients undergoing ablation C2 or C4 disease or greater, the mean number of ablations per patient, the mean number of ablations per limb, and the proportion of perforated ablations for greater than C4 disease. Plotting out the data for these procedures at the center level can be assessed against current thinking on best practices in the various areas. For example, “the mean number of ablations per patient has been suggested at 1.8 to be about the right number,” and he used the graph of the center performance in this area to show that most of the centers were below this objective.

In an even more appropriate example of how this kind of data could be used to determine appropriateness, Dr. Wakefield described how perforated ablations should be performed for greater than C4 disease, but not for C2 disease. He described how, according to the actual data in the registry, there have been 870 total perforated treatments recorded, 38% for C2 disease, and of these 332 procedures, almost half of these were performed at one center only, with two other centers reporting 30 such procedures. “So clearly there are three centers that are doing perforated ablations for patients that are outside the guidelines,” Dr. Wakefield pointed out.

In future, payer demand is likely to demand that each treating physician provide evidence of the appropriateness of procedures performed, as well as appropriate patient selection and adherence to best practices, and good outcomes, which is part of what a society-based registry such as the VVR can provide.

“I believe the VQI-VVR is well-positioned to meet these needs. And if we ask the question ‘can VQI be used as a benchmark for setting ethical standards,’ I think it can certainly be used to help set appropriate standards, and since appropriateness is one part of ethical standards, I believe it has a role,” he concluded.

Dr. Wakefield reported that he had no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM THE 2018 VEITH SYMPOSIUM

Growing the pool of academic vascular surgeons

NEW YORK – Strategies for growing the pool of academic vascular surgeons might help avert the expected scarcity of physicians in this specialty, according to Peter K. Henke, MD, a professor of vascular surgery at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Dr. Henke recounted in a video interview key messages he delivered at a symposium on vascular and endovascular issues sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. He argued for going back to basics to enlist residents and fellows completing their training to stay in the specialty and consider an academic position.

Many of these steps are known, such as verifying that mentors are available to encourage skill acquisition and providing adequate time to achieve an acceptable balance of research and clinical work.

However, a successful program would not solely focus on luring young and promising junior faculty, he said. A supportive atmosphere requires collaboration and support to flow both up and down the ranks of seniority where everyone benefits.As an example, he singled out midlevel faculty as vulnerable when programs are not developed to ensure support is equally distributed. He explained that midlevel faculty members denied the encouragement available to surgeons just initiating their career can feel abandoned when they are skilled but not yet leaders in their program.

The Society of Vascular Surgery is pursing several initiatives to address the projected shortage within this specialty, according to Dr. Henke, but he argues that leaders of academic programs have a role to play in helping make the specialty attractive, particularly for those considering an academic career.

NEW YORK – Strategies for growing the pool of academic vascular surgeons might help avert the expected scarcity of physicians in this specialty, according to Peter K. Henke, MD, a professor of vascular surgery at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Dr. Henke recounted in a video interview key messages he delivered at a symposium on vascular and endovascular issues sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. He argued for going back to basics to enlist residents and fellows completing their training to stay in the specialty and consider an academic position.

Many of these steps are known, such as verifying that mentors are available to encourage skill acquisition and providing adequate time to achieve an acceptable balance of research and clinical work.

However, a successful program would not solely focus on luring young and promising junior faculty, he said. A supportive atmosphere requires collaboration and support to flow both up and down the ranks of seniority where everyone benefits.As an example, he singled out midlevel faculty as vulnerable when programs are not developed to ensure support is equally distributed. He explained that midlevel faculty members denied the encouragement available to surgeons just initiating their career can feel abandoned when they are skilled but not yet leaders in their program.

The Society of Vascular Surgery is pursing several initiatives to address the projected shortage within this specialty, according to Dr. Henke, but he argues that leaders of academic programs have a role to play in helping make the specialty attractive, particularly for those considering an academic career.

NEW YORK – Strategies for growing the pool of academic vascular surgeons might help avert the expected scarcity of physicians in this specialty, according to Peter K. Henke, MD, a professor of vascular surgery at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Dr. Henke recounted in a video interview key messages he delivered at a symposium on vascular and endovascular issues sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. He argued for going back to basics to enlist residents and fellows completing their training to stay in the specialty and consider an academic position.

Many of these steps are known, such as verifying that mentors are available to encourage skill acquisition and providing adequate time to achieve an acceptable balance of research and clinical work.

However, a successful program would not solely focus on luring young and promising junior faculty, he said. A supportive atmosphere requires collaboration and support to flow both up and down the ranks of seniority where everyone benefits.As an example, he singled out midlevel faculty as vulnerable when programs are not developed to ensure support is equally distributed. He explained that midlevel faculty members denied the encouragement available to surgeons just initiating their career can feel abandoned when they are skilled but not yet leaders in their program.

The Society of Vascular Surgery is pursing several initiatives to address the projected shortage within this specialty, according to Dr. Henke, but he argues that leaders of academic programs have a role to play in helping make the specialty attractive, particularly for those considering an academic career.

REPORTING FROM VEITHSYMPOSIUM

Drug-coated balloon advantage persists in femoral artery disease

NEW YORK – John Laird, MD, of the Adventist Heart Institute, St. Helena, Calif., presented the data at a symposium on vascular and endovascular issues sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

The data were drawn from the IN.PACT trial. In this trial, 331 patients were randomized to a paclitaxel-coated DCB device or standard percutaneous balloon angioplasty (PCBA), Dr. Laird explained.

The 5-year results are consistent with those previously reported at 1, 2, and 3 years. According to Dr. Laird, DCB continues to show an advantage for major outcomes over PCBA, and adverse events remain low.

Three DCB devices now available in the United States for dilatation of narrowed SFA. Although all have been associated with a reduced risk of target lesion revascularization relative to standard PCBA, the long-term follow-up presented from IN.PACT by Dr. Laird are the first to document 5-year outcomes.

In a video interview, Dr. Laird reported that there have been no thrombotic events since the 3-year results were presented.

Overall, he explains that the long-term outcomes provide additional confirmation that DCB is a safe procedure that reduces the need for stenting in SFA occlusions. Although he believes there might be clinically significant differences between available DCB devices, he concludes that DCB can be considered the first-line therapy for treating occluded femoral-popliteal arteries.

NEW YORK – John Laird, MD, of the Adventist Heart Institute, St. Helena, Calif., presented the data at a symposium on vascular and endovascular issues sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

The data were drawn from the IN.PACT trial. In this trial, 331 patients were randomized to a paclitaxel-coated DCB device or standard percutaneous balloon angioplasty (PCBA), Dr. Laird explained.

The 5-year results are consistent with those previously reported at 1, 2, and 3 years. According to Dr. Laird, DCB continues to show an advantage for major outcomes over PCBA, and adverse events remain low.

Three DCB devices now available in the United States for dilatation of narrowed SFA. Although all have been associated with a reduced risk of target lesion revascularization relative to standard PCBA, the long-term follow-up presented from IN.PACT by Dr. Laird are the first to document 5-year outcomes.

In a video interview, Dr. Laird reported that there have been no thrombotic events since the 3-year results were presented.

Overall, he explains that the long-term outcomes provide additional confirmation that DCB is a safe procedure that reduces the need for stenting in SFA occlusions. Although he believes there might be clinically significant differences between available DCB devices, he concludes that DCB can be considered the first-line therapy for treating occluded femoral-popliteal arteries.

NEW YORK – John Laird, MD, of the Adventist Heart Institute, St. Helena, Calif., presented the data at a symposium on vascular and endovascular issues sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

The data were drawn from the IN.PACT trial. In this trial, 331 patients were randomized to a paclitaxel-coated DCB device or standard percutaneous balloon angioplasty (PCBA), Dr. Laird explained.

The 5-year results are consistent with those previously reported at 1, 2, and 3 years. According to Dr. Laird, DCB continues to show an advantage for major outcomes over PCBA, and adverse events remain low.

Three DCB devices now available in the United States for dilatation of narrowed SFA. Although all have been associated with a reduced risk of target lesion revascularization relative to standard PCBA, the long-term follow-up presented from IN.PACT by Dr. Laird are the first to document 5-year outcomes.

In a video interview, Dr. Laird reported that there have been no thrombotic events since the 3-year results were presented.

Overall, he explains that the long-term outcomes provide additional confirmation that DCB is a safe procedure that reduces the need for stenting in SFA occlusions. Although he believes there might be clinically significant differences between available DCB devices, he concludes that DCB can be considered the first-line therapy for treating occluded femoral-popliteal arteries.

REPORTING FROM VEITHSYMPOSIUM

What are the barriers to solving the upcoming vascular surgeon shortage?

NEW YORK – Increasing the number of 0+5 integrated vascular surgery residency programs would help to alleviate a projected shortage of vascular surgeons, according to William D. Jordan, Jr., MD, professor of surgery, Emory University, Atlanta.*

“Ultimately the question is whether the workforce pipeline is large enough,” Dr. Jordan said at a symposium on vascular and endovascular issues sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. “When you consider that there are little more than 600 vascular trainees right now, and almost 600 planned retirements over the next 5 years, the answer to the question is no. Our workforce pipeline is not big enough.”

Dr. Jordan pointed out that, in addition, if one considers the current geographic distribution of vascular surgeons across the country, and go with the new standard that 1.4 surgeons are needed per 100,000 population, there is not a single state in the country that matches up to that goal. “So we are clearly going to have a shortage,” he commented. The only way to fill that shortage is to produce more vascular surgeons. But how does the change to a 0+5 residency program model impact that need?

In a survey conducted by the Association of Program Directors in Vascular Surgery in 2016, regarding challenges as perceived by the trainees, the top two concerns expressed were regarding competing specialties and physician burnout. Statistics bear out the concern regarding competing specialties, for example, there is an increase of 85% in interventional cardiology trainees being produced and a nearly 50% increase in interventional radiology trainees. However, in vascular, it is only 18%. With regard to the goals of those vascular trainees, 90% indicated that they wanted to be attached to some academic or teaching environment. “They don’t want to be the lone wolf out there,” Dr. Jordan said, and this is from concerns regarding workload, mentorship, and camaraderie, as well as regulatory and administrative obligations that are steadily increasing and can be handled more easily in a large institution. This will not fill the need for vascular surgeons in community hospitals, creating a shortage of distribution as well as actual numbers.

One key problem with current training is the fact that the new form of student comes with almost no real surgical skills and there is a dearth of vascular surgery cases available to fully accommodate many of them throughout their training career. This is a problem exacerbated by some residency review committees, which are loathe to give vascular surgery cases to new trainees.

Integrated vascular surgery residency programs have grown and there is a substantially greater interest in them, receiving even more applicants than orthopedics or neurosurgery. U.S. interest exceeds the number of 0+5 positions available. One way to deal with the projected 31% deficit in vascular surgeons by 2025 would thus be to increase the number of these training positions. The financial accommodations to do this would be large, but perhaps the creation of an independent vascular surgery specialty board would facilitate dealing with that issue, he concluded.

Dr. Jordan reported no disclosures relevant to his talk.

Correction, 11/19/18: An earlier version of this article misidentified the speaker in the session. The speaker was William D. Jordan, Jr., MD.

NEW YORK – Increasing the number of 0+5 integrated vascular surgery residency programs would help to alleviate a projected shortage of vascular surgeons, according to William D. Jordan, Jr., MD, professor of surgery, Emory University, Atlanta.*

“Ultimately the question is whether the workforce pipeline is large enough,” Dr. Jordan said at a symposium on vascular and endovascular issues sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. “When you consider that there are little more than 600 vascular trainees right now, and almost 600 planned retirements over the next 5 years, the answer to the question is no. Our workforce pipeline is not big enough.”

Dr. Jordan pointed out that, in addition, if one considers the current geographic distribution of vascular surgeons across the country, and go with the new standard that 1.4 surgeons are needed per 100,000 population, there is not a single state in the country that matches up to that goal. “So we are clearly going to have a shortage,” he commented. The only way to fill that shortage is to produce more vascular surgeons. But how does the change to a 0+5 residency program model impact that need?

In a survey conducted by the Association of Program Directors in Vascular Surgery in 2016, regarding challenges as perceived by the trainees, the top two concerns expressed were regarding competing specialties and physician burnout. Statistics bear out the concern regarding competing specialties, for example, there is an increase of 85% in interventional cardiology trainees being produced and a nearly 50% increase in interventional radiology trainees. However, in vascular, it is only 18%. With regard to the goals of those vascular trainees, 90% indicated that they wanted to be attached to some academic or teaching environment. “They don’t want to be the lone wolf out there,” Dr. Jordan said, and this is from concerns regarding workload, mentorship, and camaraderie, as well as regulatory and administrative obligations that are steadily increasing and can be handled more easily in a large institution. This will not fill the need for vascular surgeons in community hospitals, creating a shortage of distribution as well as actual numbers.

One key problem with current training is the fact that the new form of student comes with almost no real surgical skills and there is a dearth of vascular surgery cases available to fully accommodate many of them throughout their training career. This is a problem exacerbated by some residency review committees, which are loathe to give vascular surgery cases to new trainees.

Integrated vascular surgery residency programs have grown and there is a substantially greater interest in them, receiving even more applicants than orthopedics or neurosurgery. U.S. interest exceeds the number of 0+5 positions available. One way to deal with the projected 31% deficit in vascular surgeons by 2025 would thus be to increase the number of these training positions. The financial accommodations to do this would be large, but perhaps the creation of an independent vascular surgery specialty board would facilitate dealing with that issue, he concluded.

Dr. Jordan reported no disclosures relevant to his talk.

Correction, 11/19/18: An earlier version of this article misidentified the speaker in the session. The speaker was William D. Jordan, Jr., MD.

NEW YORK – Increasing the number of 0+5 integrated vascular surgery residency programs would help to alleviate a projected shortage of vascular surgeons, according to William D. Jordan, Jr., MD, professor of surgery, Emory University, Atlanta.*

“Ultimately the question is whether the workforce pipeline is large enough,” Dr. Jordan said at a symposium on vascular and endovascular issues sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. “When you consider that there are little more than 600 vascular trainees right now, and almost 600 planned retirements over the next 5 years, the answer to the question is no. Our workforce pipeline is not big enough.”

Dr. Jordan pointed out that, in addition, if one considers the current geographic distribution of vascular surgeons across the country, and go with the new standard that 1.4 surgeons are needed per 100,000 population, there is not a single state in the country that matches up to that goal. “So we are clearly going to have a shortage,” he commented. The only way to fill that shortage is to produce more vascular surgeons. But how does the change to a 0+5 residency program model impact that need?

In a survey conducted by the Association of Program Directors in Vascular Surgery in 2016, regarding challenges as perceived by the trainees, the top two concerns expressed were regarding competing specialties and physician burnout. Statistics bear out the concern regarding competing specialties, for example, there is an increase of 85% in interventional cardiology trainees being produced and a nearly 50% increase in interventional radiology trainees. However, in vascular, it is only 18%. With regard to the goals of those vascular trainees, 90% indicated that they wanted to be attached to some academic or teaching environment. “They don’t want to be the lone wolf out there,” Dr. Jordan said, and this is from concerns regarding workload, mentorship, and camaraderie, as well as regulatory and administrative obligations that are steadily increasing and can be handled more easily in a large institution. This will not fill the need for vascular surgeons in community hospitals, creating a shortage of distribution as well as actual numbers.

One key problem with current training is the fact that the new form of student comes with almost no real surgical skills and there is a dearth of vascular surgery cases available to fully accommodate many of them throughout their training career. This is a problem exacerbated by some residency review committees, which are loathe to give vascular surgery cases to new trainees.

Integrated vascular surgery residency programs have grown and there is a substantially greater interest in them, receiving even more applicants than orthopedics or neurosurgery. U.S. interest exceeds the number of 0+5 positions available. One way to deal with the projected 31% deficit in vascular surgeons by 2025 would thus be to increase the number of these training positions. The financial accommodations to do this would be large, but perhaps the creation of an independent vascular surgery specialty board would facilitate dealing with that issue, he concluded.

Dr. Jordan reported no disclosures relevant to his talk.

Correction, 11/19/18: An earlier version of this article misidentified the speaker in the session. The speaker was William D. Jordan, Jr., MD.

REPORTING FROM THE VEITHSYMPOSIUM

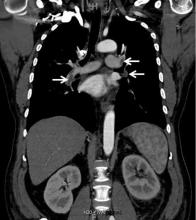

A bovine arch predicts worse outcomes with type B aortic dissections

NEW YORK – The presence of a bovine arch predicts higher mortality in patients with a type B aortic dissection (TBAD), according to a study presented by Jan S. Brunkwall, MD, at a symposium on vascular and endovascular issues sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

The bovine arch is a congenital interruption in the evolution of the arch, and is a misnomer because it does not actually reflect the arch branching pattern found in cattle. It represents the most common variation of the aortic arch, with a prevalence of 1%-41%, depending on the literature, according to a study published by Dr. Brunkwall, chairman of the department of vascular and endovascular surgery at the University of Cologne (Germany), and his colleagues (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2018; 55:385-391).

In order to assess the effect of the bovine arch on survival, Dr. Brunkwall and his colleagues performed a retrospective cohort analysis of patients with TBAD admitted at two centers. CT angiograms (CTAs) of patients referred because of aortic dissection were also reevaluated with regard to the presence of a bovine arch.

A total of 154 patients with TBAD and 168 with type A aortic dissection were assessed, and 110 oncologic patients who had undergone a chest CTA for disease staging during the study period acted as a control group.

There was an overall prevalence of 17.6% for bovine arch variants, with no statistical difference in prevalence between patients with a dissection and those in the control group, or between patients with a type A or type B dissection. However, mortality was 34.5% in patients with TBAD who had a bovine arch versus 16% in patients without a bovine arch. This was a significant difference (P =.04), according to Dr. Brunkwall.

Multivariate analysis showed that the presence of a bovine arch with TBAD was an independent predictor of mortality. “The reason for the high mortality cannot be explained by our data,” said Dr. Brunkwall, “but there has been a suggestion that the shear stress is different and higher in patients with a bovine arch leading to a stiffer aorta and more endothelial damage.”

Dr. Brunkwall reported that he had no disclosures.

NEW YORK – The presence of a bovine arch predicts higher mortality in patients with a type B aortic dissection (TBAD), according to a study presented by Jan S. Brunkwall, MD, at a symposium on vascular and endovascular issues sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

The bovine arch is a congenital interruption in the evolution of the arch, and is a misnomer because it does not actually reflect the arch branching pattern found in cattle. It represents the most common variation of the aortic arch, with a prevalence of 1%-41%, depending on the literature, according to a study published by Dr. Brunkwall, chairman of the department of vascular and endovascular surgery at the University of Cologne (Germany), and his colleagues (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2018; 55:385-391).

In order to assess the effect of the bovine arch on survival, Dr. Brunkwall and his colleagues performed a retrospective cohort analysis of patients with TBAD admitted at two centers. CT angiograms (CTAs) of patients referred because of aortic dissection were also reevaluated with regard to the presence of a bovine arch.

A total of 154 patients with TBAD and 168 with type A aortic dissection were assessed, and 110 oncologic patients who had undergone a chest CTA for disease staging during the study period acted as a control group.

There was an overall prevalence of 17.6% for bovine arch variants, with no statistical difference in prevalence between patients with a dissection and those in the control group, or between patients with a type A or type B dissection. However, mortality was 34.5% in patients with TBAD who had a bovine arch versus 16% in patients without a bovine arch. This was a significant difference (P =.04), according to Dr. Brunkwall.

Multivariate analysis showed that the presence of a bovine arch with TBAD was an independent predictor of mortality. “The reason for the high mortality cannot be explained by our data,” said Dr. Brunkwall, “but there has been a suggestion that the shear stress is different and higher in patients with a bovine arch leading to a stiffer aorta and more endothelial damage.”

Dr. Brunkwall reported that he had no disclosures.

NEW YORK – The presence of a bovine arch predicts higher mortality in patients with a type B aortic dissection (TBAD), according to a study presented by Jan S. Brunkwall, MD, at a symposium on vascular and endovascular issues sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

The bovine arch is a congenital interruption in the evolution of the arch, and is a misnomer because it does not actually reflect the arch branching pattern found in cattle. It represents the most common variation of the aortic arch, with a prevalence of 1%-41%, depending on the literature, according to a study published by Dr. Brunkwall, chairman of the department of vascular and endovascular surgery at the University of Cologne (Germany), and his colleagues (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2018; 55:385-391).

In order to assess the effect of the bovine arch on survival, Dr. Brunkwall and his colleagues performed a retrospective cohort analysis of patients with TBAD admitted at two centers. CT angiograms (CTAs) of patients referred because of aortic dissection were also reevaluated with regard to the presence of a bovine arch.

A total of 154 patients with TBAD and 168 with type A aortic dissection were assessed, and 110 oncologic patients who had undergone a chest CTA for disease staging during the study period acted as a control group.

There was an overall prevalence of 17.6% for bovine arch variants, with no statistical difference in prevalence between patients with a dissection and those in the control group, or between patients with a type A or type B dissection. However, mortality was 34.5% in patients with TBAD who had a bovine arch versus 16% in patients without a bovine arch. This was a significant difference (P =.04), according to Dr. Brunkwall.

Multivariate analysis showed that the presence of a bovine arch with TBAD was an independent predictor of mortality. “The reason for the high mortality cannot be explained by our data,” said Dr. Brunkwall, “but there has been a suggestion that the shear stress is different and higher in patients with a bovine arch leading to a stiffer aorta and more endothelial damage.”

Dr. Brunkwall reported that he had no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM VEITHSYMPOSIUM

Renal vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

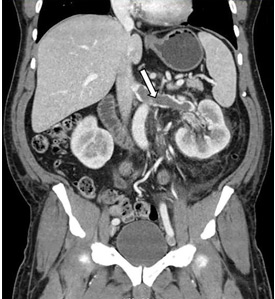

A 49-year-old man developed nephrotic-range proteinuria (urine protein–creatinine ratio 4.1 g/g), and primary membranous nephropathy was diagnosed by kidney biopsy. He declined therapy apart from angiotensin receptor blockade.

Five months after undergoing the biopsy, he presented to the emergency room with marked dyspnea, cough, and epigastric discomfort. His blood pressure was 160/100 mm Hg, heart rate 95 beats/minute, and oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry 97% at rest on ambient air, decreasing to 92% with ambulation.

Initial laboratory testing results were as follows:

- Sodium 135 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.9 mmol/L (3.7–5.1)

- Chloride 104 mmol/L (97–105)

- Bicarbonate 21 mmol/L (22–30)

- Blood urea nitrogen 14 mg/dL (9–24)

- Serum creatinine 1.1 mg/dL (0.73–1.22)

- Albumin 2.1 g/dL (3.4–4.9).

Urinalysis revealed the following:

- 5 red blood cells per high-power field, compared with 1 to 2 previously

- 3+ proteinuria

- Urine protein–creatinine ratio 11 g/g

- No glucosuria.

Electrocardiography revealed normal sinus rhythm without ischemic changes. Chest radiography did not show consolidation.

At 7 months after the thrombotic event, there was no evidence of residual renal vein thrombosis on magnetic resonance venography, and at 14 months his serum creatinine level was 0.9 mg/dL, albumin 4.0 g/dL, and urine protein–creatinine ratio 0.8 g/g.

RENAL VEIN THROMBOSIS: RISK FACTORS AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Severe hypoalbuminemia in the setting of nephrotic syndrome due to membranous nephropathy is associated with the highest risk of venous thromboembolic events, with renal vein thrombus being the classic complication.1 Venous thromboembolic events also occur in other nephrotic syndromes, albeit at a lower frequency.2

Venous thromboembolic events are estimated to occur in 7% to 33% of patients with membranous glomerulopathy, with albumin levels less than 2.8 g/dL considered a notable risk factor.1,2

While often a chronic complication, acute renal vein thrombosis may present with flank pain and hematuria.3 In our patient, the dramatic increase in proteinuria and possibly the increase in hematuria suggested renal vein thrombosis. Proximal tubular dysfunction, such as glucosuria, can be seen on occasion.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Screening asymptomatic patients for renal vein thrombosis is not recommended, and the decision to start prophylactic anticoagulation must be individualized.4

Although renal venography historically was the gold standard test to diagnose renal vein thrombosis, it has been replaced by noninvasive imaging such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance venography.

While anticoagulation remains the treatment of choice, catheter-directed thrombectomy or surgical thrombectomy can be considered for some patients with acute renal vein thrombosis.5

- Couser WG. Primary membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 12(6):983–997. doi:10.2215/CJN.11761116

- Barbour SJ, Greenwald A, Djurdjev O, et al. Disease-specific risk of venous thromboembolic events is increased in idiopathic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 2012; 81(2):190–195. doi:10.1038/ki.2011.312

- Lionaki S, Derebail VK, Hogan SL, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7(1):43–51. doi:10.2215/CJN.04250511

- Lee T, Biddle AK, Lionaki S, et al. Personalized prophylactic anticoagulation decision analysis in patients with membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int 2014; 85(6):1412–1420. doi:10.1038/ki.2013.476

- Jaar BG, Kim HS, Samaniego MD, Lund GB, Atta MG. Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy: a new approach in the treatment of acute renal-vein thrombosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002; 17(6):1122–1125. pmid:12032209

A 49-year-old man developed nephrotic-range proteinuria (urine protein–creatinine ratio 4.1 g/g), and primary membranous nephropathy was diagnosed by kidney biopsy. He declined therapy apart from angiotensin receptor blockade.

Five months after undergoing the biopsy, he presented to the emergency room with marked dyspnea, cough, and epigastric discomfort. His blood pressure was 160/100 mm Hg, heart rate 95 beats/minute, and oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry 97% at rest on ambient air, decreasing to 92% with ambulation.

Initial laboratory testing results were as follows:

- Sodium 135 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.9 mmol/L (3.7–5.1)

- Chloride 104 mmol/L (97–105)

- Bicarbonate 21 mmol/L (22–30)

- Blood urea nitrogen 14 mg/dL (9–24)

- Serum creatinine 1.1 mg/dL (0.73–1.22)

- Albumin 2.1 g/dL (3.4–4.9).

Urinalysis revealed the following:

- 5 red blood cells per high-power field, compared with 1 to 2 previously

- 3+ proteinuria

- Urine protein–creatinine ratio 11 g/g

- No glucosuria.

Electrocardiography revealed normal sinus rhythm without ischemic changes. Chest radiography did not show consolidation.

At 7 months after the thrombotic event, there was no evidence of residual renal vein thrombosis on magnetic resonance venography, and at 14 months his serum creatinine level was 0.9 mg/dL, albumin 4.0 g/dL, and urine protein–creatinine ratio 0.8 g/g.

RENAL VEIN THROMBOSIS: RISK FACTORS AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Severe hypoalbuminemia in the setting of nephrotic syndrome due to membranous nephropathy is associated with the highest risk of venous thromboembolic events, with renal vein thrombus being the classic complication.1 Venous thromboembolic events also occur in other nephrotic syndromes, albeit at a lower frequency.2

Venous thromboembolic events are estimated to occur in 7% to 33% of patients with membranous glomerulopathy, with albumin levels less than 2.8 g/dL considered a notable risk factor.1,2

While often a chronic complication, acute renal vein thrombosis may present with flank pain and hematuria.3 In our patient, the dramatic increase in proteinuria and possibly the increase in hematuria suggested renal vein thrombosis. Proximal tubular dysfunction, such as glucosuria, can be seen on occasion.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Screening asymptomatic patients for renal vein thrombosis is not recommended, and the decision to start prophylactic anticoagulation must be individualized.4

Although renal venography historically was the gold standard test to diagnose renal vein thrombosis, it has been replaced by noninvasive imaging such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance venography.

While anticoagulation remains the treatment of choice, catheter-directed thrombectomy or surgical thrombectomy can be considered for some patients with acute renal vein thrombosis.5

A 49-year-old man developed nephrotic-range proteinuria (urine protein–creatinine ratio 4.1 g/g), and primary membranous nephropathy was diagnosed by kidney biopsy. He declined therapy apart from angiotensin receptor blockade.

Five months after undergoing the biopsy, he presented to the emergency room with marked dyspnea, cough, and epigastric discomfort. His blood pressure was 160/100 mm Hg, heart rate 95 beats/minute, and oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry 97% at rest on ambient air, decreasing to 92% with ambulation.

Initial laboratory testing results were as follows:

- Sodium 135 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.9 mmol/L (3.7–5.1)

- Chloride 104 mmol/L (97–105)

- Bicarbonate 21 mmol/L (22–30)

- Blood urea nitrogen 14 mg/dL (9–24)

- Serum creatinine 1.1 mg/dL (0.73–1.22)

- Albumin 2.1 g/dL (3.4–4.9).

Urinalysis revealed the following:

- 5 red blood cells per high-power field, compared with 1 to 2 previously

- 3+ proteinuria

- Urine protein–creatinine ratio 11 g/g

- No glucosuria.

Electrocardiography revealed normal sinus rhythm without ischemic changes. Chest radiography did not show consolidation.

At 7 months after the thrombotic event, there was no evidence of residual renal vein thrombosis on magnetic resonance venography, and at 14 months his serum creatinine level was 0.9 mg/dL, albumin 4.0 g/dL, and urine protein–creatinine ratio 0.8 g/g.

RENAL VEIN THROMBOSIS: RISK FACTORS AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Severe hypoalbuminemia in the setting of nephrotic syndrome due to membranous nephropathy is associated with the highest risk of venous thromboembolic events, with renal vein thrombus being the classic complication.1 Venous thromboembolic events also occur in other nephrotic syndromes, albeit at a lower frequency.2

Venous thromboembolic events are estimated to occur in 7% to 33% of patients with membranous glomerulopathy, with albumin levels less than 2.8 g/dL considered a notable risk factor.1,2

While often a chronic complication, acute renal vein thrombosis may present with flank pain and hematuria.3 In our patient, the dramatic increase in proteinuria and possibly the increase in hematuria suggested renal vein thrombosis. Proximal tubular dysfunction, such as glucosuria, can be seen on occasion.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Screening asymptomatic patients for renal vein thrombosis is not recommended, and the decision to start prophylactic anticoagulation must be individualized.4

Although renal venography historically was the gold standard test to diagnose renal vein thrombosis, it has been replaced by noninvasive imaging such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance venography.

While anticoagulation remains the treatment of choice, catheter-directed thrombectomy or surgical thrombectomy can be considered for some patients with acute renal vein thrombosis.5

- Couser WG. Primary membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 12(6):983–997. doi:10.2215/CJN.11761116

- Barbour SJ, Greenwald A, Djurdjev O, et al. Disease-specific risk of venous thromboembolic events is increased in idiopathic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 2012; 81(2):190–195. doi:10.1038/ki.2011.312

- Lionaki S, Derebail VK, Hogan SL, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7(1):43–51. doi:10.2215/CJN.04250511

- Lee T, Biddle AK, Lionaki S, et al. Personalized prophylactic anticoagulation decision analysis in patients with membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int 2014; 85(6):1412–1420. doi:10.1038/ki.2013.476

- Jaar BG, Kim HS, Samaniego MD, Lund GB, Atta MG. Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy: a new approach in the treatment of acute renal-vein thrombosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002; 17(6):1122–1125. pmid:12032209

- Couser WG. Primary membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 12(6):983–997. doi:10.2215/CJN.11761116

- Barbour SJ, Greenwald A, Djurdjev O, et al. Disease-specific risk of venous thromboembolic events is increased in idiopathic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 2012; 81(2):190–195. doi:10.1038/ki.2011.312

- Lionaki S, Derebail VK, Hogan SL, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7(1):43–51. doi:10.2215/CJN.04250511

- Lee T, Biddle AK, Lionaki S, et al. Personalized prophylactic anticoagulation decision analysis in patients with membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int 2014; 85(6):1412–1420. doi:10.1038/ki.2013.476

- Jaar BG, Kim HS, Samaniego MD, Lund GB, Atta MG. Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy: a new approach in the treatment of acute renal-vein thrombosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002; 17(6):1122–1125. pmid:12032209

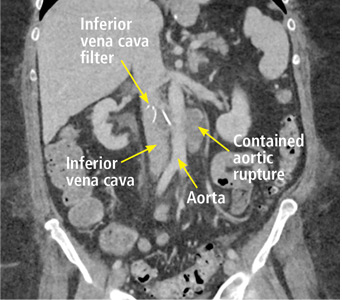

Back pain as a sign of inferior vena cava filter complications