User login

E-cigs surpass smoked tobacco in U.S. teens; marijuana use among ‘highest’ worldwide

Nearly a fifth of American high school seniors have used e-cigarettes recently, although tobacco smoking in this population is at an all-time low, according to the annual Monitoring the Future survey released Dec. 16.

“About 4% of 12th graders use e-cigarettes alone. They’ve never smoked a regular cigarette in their life,” Richard A. Miech, Ph.D., of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, one of the lead researchers on the study, said during a press conference held by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. This was the first year that data on e-cigarette use in teens were collected for the Monitoring the Future survey of drug, tobacco, and alcohol use in adolescents in 8th, 10th, and 12th grade. The survey has been conducted every year since 1975 by the University of Michigan and funded by NIDA.

Just over 17% of 12th graders reported past-month use of e-cigarettes. For 10th graders, the number was 16%, and for 8th graders it was nearly 9%. Daily cigarette smoking has decreased by half in the past 5 years across all age groups surveyed, with the largest decline being from just over 6% to about 3% in 10th graders.

Whether the decline in tobacco smoking correlates directly with the rise in e-cigarettes is unknown, NIDA director Dr. Nora Volkow said during the teleconference.

Particularly troubling, according to Dr. Miech, is that the 4% of 12th graders who reported using e-cigarettes exclusively tended to be college bound, a cohort he said typically does not use tobacco.

What actual harm e-cigarettes pose to youth, and whether they lead to other drug use are still open questions, according to Dr. Volkow.

“We can’t do a randomized, controlled trial of teens and give them e-cigarettes to see if they progress to harder drugs,” Dr. Miech said. “The best we can do is follow them as they age.”

Marijuana use among teens is steady and prevalent across all three age groups, according to the survey. More than a third of 12th graders (35%) reported past-year use of marijuana; nearly 6% reported daily use. “This constitutes one of the highest rates seen in any student population world wide,” said Dr. Volkow.

Similar to last year’s rates, 7% of eighth graders, 17% of 10th graders, and just over 21% of 12th graders reported smoking marijuana in the previous month.

The steady rates of marijuana use came as a welcome surprise, said Dr. Volkow, considering recent changes to marijuana laws at the state level and the way those changes might impact perception of marijuana use. In fact, there was a change across the entire study population in the perceived danger posed by marijuana, down from 27% 5 years ago to 16% this year.

In states with medical marijuana laws, 40% of 12th graders who reported using marijuana in the past year said they had used edible marijuana products, compared with 26% of seniors who lived in states without such legislation.

Whether digested versus smoked cannabinoids pose greater health risks to teens “is relatively new for us,” Dr. Volkow said, noting that there are little data on how quickly cannabinoids consumed orally may enter the bloodstream. “When you smoke a drug, it gets into the brain very rapidly, and that is associated with stronger rewarding affects and more addictiveness, but it also is associated with better control of how much you ingest.”

“It’s pretty obvious when people are smoking a joint – the feedback is quick,” said Dr. Lloyd D. Johnston, lead investigator for Monitoring the Future, also of the University of Michigan. Ingested marijuana is different and variable, he noted, both in the amount of marijuana consumed and in the time it takes for the drug to take effect. “I think it’s considerably more dangerous.”Understanding the bioavailability and the pharmacokinetics of edible marijuana is a pressing research concern at NIDA, Dr. Volkow said.

Nonmedical use of prescription drugs is down overall among survey respondents. Nonmedical use of Vicodin declined from 9.7% 5 years ago to 4.5% this year. For oxycontin, nonmedical use declined from 4.8% to 3.3%.

Alcohol use, particularly binge drinking in 12th graders, also is losing popularity. At its peak in 1998, 31.5% of 12th graders reported binge drinking; less than 20% did so in 2014. A decline in the use of synthetic marijuana (also known as K2/Spice) was also noted, down from nearly 8% in 12th graders to just under 6%. Heroin, crack cocaine, and methamphetamine use remained low and relatively unchanged from last year.

“Over all, this is good news,” said Dr. Volkow.

Monitoring the Future is unusual in that the data, gathered from nearly 42,000 U.S. students at 377 public and private schools across the country, are reported in the same year they are gathered.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Nearly a fifth of American high school seniors have used e-cigarettes recently, although tobacco smoking in this population is at an all-time low, according to the annual Monitoring the Future survey released Dec. 16.

“About 4% of 12th graders use e-cigarettes alone. They’ve never smoked a regular cigarette in their life,” Richard A. Miech, Ph.D., of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, one of the lead researchers on the study, said during a press conference held by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. This was the first year that data on e-cigarette use in teens were collected for the Monitoring the Future survey of drug, tobacco, and alcohol use in adolescents in 8th, 10th, and 12th grade. The survey has been conducted every year since 1975 by the University of Michigan and funded by NIDA.

Just over 17% of 12th graders reported past-month use of e-cigarettes. For 10th graders, the number was 16%, and for 8th graders it was nearly 9%. Daily cigarette smoking has decreased by half in the past 5 years across all age groups surveyed, with the largest decline being from just over 6% to about 3% in 10th graders.

Whether the decline in tobacco smoking correlates directly with the rise in e-cigarettes is unknown, NIDA director Dr. Nora Volkow said during the teleconference.

Particularly troubling, according to Dr. Miech, is that the 4% of 12th graders who reported using e-cigarettes exclusively tended to be college bound, a cohort he said typically does not use tobacco.

What actual harm e-cigarettes pose to youth, and whether they lead to other drug use are still open questions, according to Dr. Volkow.

“We can’t do a randomized, controlled trial of teens and give them e-cigarettes to see if they progress to harder drugs,” Dr. Miech said. “The best we can do is follow them as they age.”

Marijuana use among teens is steady and prevalent across all three age groups, according to the survey. More than a third of 12th graders (35%) reported past-year use of marijuana; nearly 6% reported daily use. “This constitutes one of the highest rates seen in any student population world wide,” said Dr. Volkow.

Similar to last year’s rates, 7% of eighth graders, 17% of 10th graders, and just over 21% of 12th graders reported smoking marijuana in the previous month.

The steady rates of marijuana use came as a welcome surprise, said Dr. Volkow, considering recent changes to marijuana laws at the state level and the way those changes might impact perception of marijuana use. In fact, there was a change across the entire study population in the perceived danger posed by marijuana, down from 27% 5 years ago to 16% this year.

In states with medical marijuana laws, 40% of 12th graders who reported using marijuana in the past year said they had used edible marijuana products, compared with 26% of seniors who lived in states without such legislation.

Whether digested versus smoked cannabinoids pose greater health risks to teens “is relatively new for us,” Dr. Volkow said, noting that there are little data on how quickly cannabinoids consumed orally may enter the bloodstream. “When you smoke a drug, it gets into the brain very rapidly, and that is associated with stronger rewarding affects and more addictiveness, but it also is associated with better control of how much you ingest.”

“It’s pretty obvious when people are smoking a joint – the feedback is quick,” said Dr. Lloyd D. Johnston, lead investigator for Monitoring the Future, also of the University of Michigan. Ingested marijuana is different and variable, he noted, both in the amount of marijuana consumed and in the time it takes for the drug to take effect. “I think it’s considerably more dangerous.”Understanding the bioavailability and the pharmacokinetics of edible marijuana is a pressing research concern at NIDA, Dr. Volkow said.

Nonmedical use of prescription drugs is down overall among survey respondents. Nonmedical use of Vicodin declined from 9.7% 5 years ago to 4.5% this year. For oxycontin, nonmedical use declined from 4.8% to 3.3%.

Alcohol use, particularly binge drinking in 12th graders, also is losing popularity. At its peak in 1998, 31.5% of 12th graders reported binge drinking; less than 20% did so in 2014. A decline in the use of synthetic marijuana (also known as K2/Spice) was also noted, down from nearly 8% in 12th graders to just under 6%. Heroin, crack cocaine, and methamphetamine use remained low and relatively unchanged from last year.

“Over all, this is good news,” said Dr. Volkow.

Monitoring the Future is unusual in that the data, gathered from nearly 42,000 U.S. students at 377 public and private schools across the country, are reported in the same year they are gathered.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Nearly a fifth of American high school seniors have used e-cigarettes recently, although tobacco smoking in this population is at an all-time low, according to the annual Monitoring the Future survey released Dec. 16.

“About 4% of 12th graders use e-cigarettes alone. They’ve never smoked a regular cigarette in their life,” Richard A. Miech, Ph.D., of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, one of the lead researchers on the study, said during a press conference held by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. This was the first year that data on e-cigarette use in teens were collected for the Monitoring the Future survey of drug, tobacco, and alcohol use in adolescents in 8th, 10th, and 12th grade. The survey has been conducted every year since 1975 by the University of Michigan and funded by NIDA.

Just over 17% of 12th graders reported past-month use of e-cigarettes. For 10th graders, the number was 16%, and for 8th graders it was nearly 9%. Daily cigarette smoking has decreased by half in the past 5 years across all age groups surveyed, with the largest decline being from just over 6% to about 3% in 10th graders.

Whether the decline in tobacco smoking correlates directly with the rise in e-cigarettes is unknown, NIDA director Dr. Nora Volkow said during the teleconference.

Particularly troubling, according to Dr. Miech, is that the 4% of 12th graders who reported using e-cigarettes exclusively tended to be college bound, a cohort he said typically does not use tobacco.

What actual harm e-cigarettes pose to youth, and whether they lead to other drug use are still open questions, according to Dr. Volkow.

“We can’t do a randomized, controlled trial of teens and give them e-cigarettes to see if they progress to harder drugs,” Dr. Miech said. “The best we can do is follow them as they age.”

Marijuana use among teens is steady and prevalent across all three age groups, according to the survey. More than a third of 12th graders (35%) reported past-year use of marijuana; nearly 6% reported daily use. “This constitutes one of the highest rates seen in any student population world wide,” said Dr. Volkow.

Similar to last year’s rates, 7% of eighth graders, 17% of 10th graders, and just over 21% of 12th graders reported smoking marijuana in the previous month.

The steady rates of marijuana use came as a welcome surprise, said Dr. Volkow, considering recent changes to marijuana laws at the state level and the way those changes might impact perception of marijuana use. In fact, there was a change across the entire study population in the perceived danger posed by marijuana, down from 27% 5 years ago to 16% this year.

In states with medical marijuana laws, 40% of 12th graders who reported using marijuana in the past year said they had used edible marijuana products, compared with 26% of seniors who lived in states without such legislation.

Whether digested versus smoked cannabinoids pose greater health risks to teens “is relatively new for us,” Dr. Volkow said, noting that there are little data on how quickly cannabinoids consumed orally may enter the bloodstream. “When you smoke a drug, it gets into the brain very rapidly, and that is associated with stronger rewarding affects and more addictiveness, but it also is associated with better control of how much you ingest.”

“It’s pretty obvious when people are smoking a joint – the feedback is quick,” said Dr. Lloyd D. Johnston, lead investigator for Monitoring the Future, also of the University of Michigan. Ingested marijuana is different and variable, he noted, both in the amount of marijuana consumed and in the time it takes for the drug to take effect. “I think it’s considerably more dangerous.”Understanding the bioavailability and the pharmacokinetics of edible marijuana is a pressing research concern at NIDA, Dr. Volkow said.

Nonmedical use of prescription drugs is down overall among survey respondents. Nonmedical use of Vicodin declined from 9.7% 5 years ago to 4.5% this year. For oxycontin, nonmedical use declined from 4.8% to 3.3%.

Alcohol use, particularly binge drinking in 12th graders, also is losing popularity. At its peak in 1998, 31.5% of 12th graders reported binge drinking; less than 20% did so in 2014. A decline in the use of synthetic marijuana (also known as K2/Spice) was also noted, down from nearly 8% in 12th graders to just under 6%. Heroin, crack cocaine, and methamphetamine use remained low and relatively unchanged from last year.

“Over all, this is good news,” said Dr. Volkow.

Monitoring the Future is unusual in that the data, gathered from nearly 42,000 U.S. students at 377 public and private schools across the country, are reported in the same year they are gathered.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

FROM NIDA

Key clinical point: Drug use prevention efforts aimed at adolescents appear to have impact, but little is known about effects of e-cigarette use.

Major finding: Nearly one-fifth of U.S. high school seniors have used e-cigarettes this year, and 6% of high school seniors smoke marijuana daily.

Data source: Survey conducted in 2014 of 41,551 teens from 377 public and private schools across the U.S.

Disclosures: Monitoring the Future is supported by grant DA001411 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The investigators report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Case Studies in Toxicology: An Amazonian Herb Goes Mainstream

Case

A 23-year-old Hispanic woman with no past medical history is brought to the ED for the second time in one day. On her first presentation, which was for a fever and a headache, meningitis was excluded with normal laboratory tests that included a lumbar puncture. She was administered acetaminophen for fever and pain control, and was discharged with a diagnosis of viral illness. On this second visit, 10 hours after being discharged, she presented because her family noted convulsions that began 3 hours after taking an herbal headache remedy given to her by a naturopath.

The patient arrived to the ED with a persistent seizure that terminated following administration of 2 mg of lorazepam. Her initial vital signs were: blood pressure, 115/51 mm Hg; heart rate, 121 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 24 breaths/minute; temperature, 97.6oF. Oxygen (O2) saturation was 100% with 2 L of O2 administered via nasal cannula. Her neurological examination was significant for a depressed mental status, pupils that were 6 mm and minimally reactive, clonus, and hyperreflexia. Repeat laboratory evaluation found a leukocytosis of 22.0 x 103/µL, serum bicarbonate of 9 mEq/L, and an anion gap of 22 with a normal serum lactate.

What is the differential diagnosis of this patient?

The history of medicinal plant ingestion raises the possibility of a toxicologic etiology. However, because the patient took the “medication” to treat another disorder, a search for an alternate cause should be performed. The differential diagnosis of a toxin-induced seizure is broad and includes pharmaceuticals (eg, tramadol, antihistamines), which may be surreptitiously added to herbal medication to assure efficacy. Plants associated with seizures include those containing antimuscarinic tropane alkaloids such as Jimsonweed (though a rare side effect from this plant product) or the water hemlock (Cicuta maculata). Contaminants of the plant itself may include pesticides such as organophosphates.

Although unlikely in a 21 year old, withdrawal from benzodiazepines, ethanol, baclofen, or gamma hydroxybutyrate are other possible etiologies. In addition to pharmaceutical and plant-derived causes, carbon monoxide poisoning should be a consideration in any patient with headache and flu-like illness.

This patient also presented with a constellation of other findings that included hyperreflexia, clonus, tachycardia, and altered mental status. Together these signs are expected in patients with serotonin toxicity (also referred to as serotonin syndrome), neuroleptic malignant syndrome, exogenous thyrotoxicosis, and lithium poisoning.

Case Continuation

The naturopathic practitioner arrived at the ED concerned about the patient, informing the ED team that she had given the patient 2 ounces of ayahuasca tea.

What is ayahuasca? What is the mechanism by which it exerts toxic effects?

Ayahuasca is a plant-derived psychotropic beverage that is used for religious purposes by members of two Brazilian churches—Centro Espírita Beneficente União do Vegetal (UDV) and Santo Daime. The ayahuasca beverage consists of two pharmacologically active compounds that together, but not individually, are psychoactive. The desired active effects for church participants include hallucinations, and vomiting to bring about a “religious purge.”1

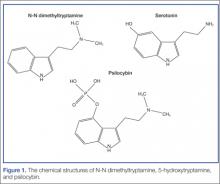

Ayahuasca is prepared by combining two plants indigenous to the Amazon Basin area: Banisteriopsis caapi and either Psychotria viridis or Diplopterys cabrerana. B caapi contains the β-carboline alkaloids harmine, harmaline, and tetrahydroharmine. These alkaloids act as reversible inhibitors of the monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A) enzyme. The bark and stems of B caapi are boiled along with either P viridis or D cabrerana, both of which contain the potent hallucinogen N-N dimethyltryptamine (DMT).2 Normally, DMT is not active orally because it is enzymatically metabolized by MAO-A. However, when taken in the presence of the B caapi-derived MAO-A–inhibiting harmine alkaloids, DMT reaches the systemic circulation and produces its clinical effects.3

What are the clinical findings of serotonin toxicity?

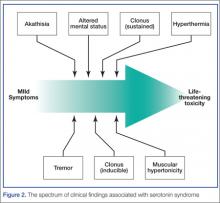

Serotonin toxicity is a collection of clinical findings that fall under three main categories: autonomic hyperactivity, altered mental status, and muscle rigidity.5 The autonomic findings may include tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, shivering, diaphoresis, or mydriasis. Altered mental status ranges from mild agitation and hypervigilance to agitated delirium to obtundation. Other neurological findings may include tremor, myoclonus, hyperreflexia, or seizures. The onset of these signs is rapid, usually occurring within minutes after exposure to one or more serotonergic compounds. Although rare, severe serotonin toxicity may be associated with hypotension and shock, leading to death.4

The diagnosis of serotonin toxicity is based on the history and physical examination of the patient. Diagnostic criteria that have been suggested include the following: (1) a recent addition or increase in a known serotonergic agent; (2) absence of other possible etiologies; (3) no recent increase or addition of a neuroleptic agent (suggesting neuroleptic malignant syndrome); and/or (4) at least 3 of the following symptoms—mental status changes, myoclonus, agitation, hyperreflexia, diaphoresis, shivering, tremor, diarrhea, incoordination, fever5 (Figure 2).

How should this patient be managed?

The management of serotonin toxicity is primarily supportive with aggressive control of hyperthermia and autonomic instability. The precipitating xenobiotic agent should be immediately discontinued. In general, treatment with intravenous fluids, cooling measures, benzodiazepines, and a nonspecific 5-HT antagonist such as cyproheptadine should greatly improve the patient’s clinical status. Patients with severe toxicity may require induced paralysis and intubation.4 It is not clear in this case if the serotonin hyperactivation was due to the DMT (5-HT2A is associated with serotonin toxicity) or another serotonergic agent (eg, dextromethorphan from a cough and cold preparation) in combination with the MAO-inhibiting harmine alkaloids.

What is the availability of ayahuasca in the United States? How is it used in its nonherbal form?

...[Ayahuasca] is currently available in the United States and is legal for use by members of the UDV and Santo Daime churches. Many clinicians are becoming increasingly familiar with this herbal preparation since the recreational use of ayahuasca is gaining popularity in the United States. Internet fora with information on how to safely use ayahuasca, such as avoiding aged cheeses, are becoming more prevalent.7 A recent article in the New York Times described an ayahuasca gathering in Brooklyn, New York, where participants use the herb in a communal fashion.8 This herbal product is also associated with the Hollywood social scene and has received celebrity endorsements.8

The National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that the number of people in the United States who have used DMT has gone up almost every year since 2006, from an estimated 688,000 in 2006 to 1,475,000 in 2012.9 When used alone (not as ayahuasca), DMT is almost exclusively insufflated as a nasal snuff, bypassing hepatic elimination. It has an onset of around 45 seconds and a duration of 5 to 10 minutes. Insufflating DMT was historically referred to as a “businessman’s trip” because users were able to have a brief hallucinogenic experience on a lunch break and recover rapidly to perform their normal work.10

International law declares that DMT is an illegal substance and its importation is banned. However, its use for religious purposes, as is allowed for mescaline found in peyote, remains controversial.7 The UDV brought suit in United States federal court to prevent interference with the church’s use of ayahuasca during religious ceremonies based on the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. This act states that the government should not cause substantial imposition on religious practices in the absence of a compelling government interest. The court sided with the UDV, finding that the government had not sufficiently proved the alleged health risks posed by ayahuasca and could not show a substantial risk that the drug would be abused recreationally.11 Thus it is currently available in the United States and is legal for use by members of the UDV and Santo Daime churches.

Ayahuasca is not regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration. Many different types of preparations with different ingredients as well as different concentrations may exist, and clinical variability should be expected. Understanding that ayahuasca is capable of inhibiting MAO is important in order to avoid foods and medications, such as dextromethorphan, that may trigger adverse effects.

Case Conclusion

The patient’s hospital course was complicated by an additional seizure 12 hours after her initial presentation. By 36 hours she was back to her baseline mental status with a normal neurological examination.

Dr Fil is a senior fellow in medical toxicology at North Shore University Hospital, Manhasset, New York. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Gable RS. Risk assessment of ritual use of oral dimethyltryptamine (DMT) and harmala alkaloids. Addiction. 2007;102(1):24-34.

- Riba J, McIlhenny EH, Valle M, Bouso JC, Barker SA. Metabolism and Disposition of N,N-dimethyltryptamine and harmala alkaloids after oral administration of ayahuasca. Drug Test Anal. 2012;4(7-8):610-616.

- Riba J, Valle M, Urbano G, Yritia M, Morte A, Barbanoj MJ. Human Pharmacology of Ayahuasca: Subjective and Cardiovascular Effects, Monoamine Metabolite Excretion and Pharmacokinetics. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306(1):73-83

- Boyer EW, Shannon M. The serotonin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11);1112-1120.

- Sternbach H. The serotonin syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(6):6;705-713.

- Dunkley EJ, Isbister GK, Sibbritt D, Dawson AH, Whyte IM. The Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria: simple and accurate diagnostic decision rules for serotonin toxicity. QJM. 2003;96(9):635-642.

- Erowid. Ayahuasca Vault. https://www.erowid.org/chemicals/ayahuasca/ayahuasca.shtml. Accessed November 25, 2014.

- Morris B. Ayahuasca: a strong cup of tea. New York Times. June 13, 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/15/fashion/ayahuasca-a-strong-cup-of-tea.html. Accessed November 25, 2014.

- Quintanilla D. DMT: Hallucinogenic Drug Used in Shamanic Rituals Goes Mainstream. 10 Dec 2013. Available: http://www.opposingviews.com/i/health/dmt-hallucinogenic-drug-used-shamanic-rituals-goes-mainstream. Last accessed 11/14/14.

- Haroz R, Greenberg MI. Emerging drugs of abuse. Med Clin North Am. 2005;89(6):1259-1276.

- Gonzales v. O Centro Espirita Beneficente Uniao do Vegetal, 546 US 418 (2006). Available at http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=7036734975431570669&hl=en&as_sdt=6&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr. Accessed November 25, 2014.

Case

A 23-year-old Hispanic woman with no past medical history is brought to the ED for the second time in one day. On her first presentation, which was for a fever and a headache, meningitis was excluded with normal laboratory tests that included a lumbar puncture. She was administered acetaminophen for fever and pain control, and was discharged with a diagnosis of viral illness. On this second visit, 10 hours after being discharged, she presented because her family noted convulsions that began 3 hours after taking an herbal headache remedy given to her by a naturopath.

The patient arrived to the ED with a persistent seizure that terminated following administration of 2 mg of lorazepam. Her initial vital signs were: blood pressure, 115/51 mm Hg; heart rate, 121 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 24 breaths/minute; temperature, 97.6oF. Oxygen (O2) saturation was 100% with 2 L of O2 administered via nasal cannula. Her neurological examination was significant for a depressed mental status, pupils that were 6 mm and minimally reactive, clonus, and hyperreflexia. Repeat laboratory evaluation found a leukocytosis of 22.0 x 103/µL, serum bicarbonate of 9 mEq/L, and an anion gap of 22 with a normal serum lactate.

What is the differential diagnosis of this patient?

The history of medicinal plant ingestion raises the possibility of a toxicologic etiology. However, because the patient took the “medication” to treat another disorder, a search for an alternate cause should be performed. The differential diagnosis of a toxin-induced seizure is broad and includes pharmaceuticals (eg, tramadol, antihistamines), which may be surreptitiously added to herbal medication to assure efficacy. Plants associated with seizures include those containing antimuscarinic tropane alkaloids such as Jimsonweed (though a rare side effect from this plant product) or the water hemlock (Cicuta maculata). Contaminants of the plant itself may include pesticides such as organophosphates.

Although unlikely in a 21 year old, withdrawal from benzodiazepines, ethanol, baclofen, or gamma hydroxybutyrate are other possible etiologies. In addition to pharmaceutical and plant-derived causes, carbon monoxide poisoning should be a consideration in any patient with headache and flu-like illness.

This patient also presented with a constellation of other findings that included hyperreflexia, clonus, tachycardia, and altered mental status. Together these signs are expected in patients with serotonin toxicity (also referred to as serotonin syndrome), neuroleptic malignant syndrome, exogenous thyrotoxicosis, and lithium poisoning.

Case Continuation

The naturopathic practitioner arrived at the ED concerned about the patient, informing the ED team that she had given the patient 2 ounces of ayahuasca tea.

What is ayahuasca? What is the mechanism by which it exerts toxic effects?

Ayahuasca is a plant-derived psychotropic beverage that is used for religious purposes by members of two Brazilian churches—Centro Espírita Beneficente União do Vegetal (UDV) and Santo Daime. The ayahuasca beverage consists of two pharmacologically active compounds that together, but not individually, are psychoactive. The desired active effects for church participants include hallucinations, and vomiting to bring about a “religious purge.”1

Ayahuasca is prepared by combining two plants indigenous to the Amazon Basin area: Banisteriopsis caapi and either Psychotria viridis or Diplopterys cabrerana. B caapi contains the β-carboline alkaloids harmine, harmaline, and tetrahydroharmine. These alkaloids act as reversible inhibitors of the monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A) enzyme. The bark and stems of B caapi are boiled along with either P viridis or D cabrerana, both of which contain the potent hallucinogen N-N dimethyltryptamine (DMT).2 Normally, DMT is not active orally because it is enzymatically metabolized by MAO-A. However, when taken in the presence of the B caapi-derived MAO-A–inhibiting harmine alkaloids, DMT reaches the systemic circulation and produces its clinical effects.3

What are the clinical findings of serotonin toxicity?

Serotonin toxicity is a collection of clinical findings that fall under three main categories: autonomic hyperactivity, altered mental status, and muscle rigidity.5 The autonomic findings may include tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, shivering, diaphoresis, or mydriasis. Altered mental status ranges from mild agitation and hypervigilance to agitated delirium to obtundation. Other neurological findings may include tremor, myoclonus, hyperreflexia, or seizures. The onset of these signs is rapid, usually occurring within minutes after exposure to one or more serotonergic compounds. Although rare, severe serotonin toxicity may be associated with hypotension and shock, leading to death.4

The diagnosis of serotonin toxicity is based on the history and physical examination of the patient. Diagnostic criteria that have been suggested include the following: (1) a recent addition or increase in a known serotonergic agent; (2) absence of other possible etiologies; (3) no recent increase or addition of a neuroleptic agent (suggesting neuroleptic malignant syndrome); and/or (4) at least 3 of the following symptoms—mental status changes, myoclonus, agitation, hyperreflexia, diaphoresis, shivering, tremor, diarrhea, incoordination, fever5 (Figure 2).

How should this patient be managed?

The management of serotonin toxicity is primarily supportive with aggressive control of hyperthermia and autonomic instability. The precipitating xenobiotic agent should be immediately discontinued. In general, treatment with intravenous fluids, cooling measures, benzodiazepines, and a nonspecific 5-HT antagonist such as cyproheptadine should greatly improve the patient’s clinical status. Patients with severe toxicity may require induced paralysis and intubation.4 It is not clear in this case if the serotonin hyperactivation was due to the DMT (5-HT2A is associated with serotonin toxicity) or another serotonergic agent (eg, dextromethorphan from a cough and cold preparation) in combination with the MAO-inhibiting harmine alkaloids.

What is the availability of ayahuasca in the United States? How is it used in its nonherbal form?

...[Ayahuasca] is currently available in the United States and is legal for use by members of the UDV and Santo Daime churches. Many clinicians are becoming increasingly familiar with this herbal preparation since the recreational use of ayahuasca is gaining popularity in the United States. Internet fora with information on how to safely use ayahuasca, such as avoiding aged cheeses, are becoming more prevalent.7 A recent article in the New York Times described an ayahuasca gathering in Brooklyn, New York, where participants use the herb in a communal fashion.8 This herbal product is also associated with the Hollywood social scene and has received celebrity endorsements.8

The National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that the number of people in the United States who have used DMT has gone up almost every year since 2006, from an estimated 688,000 in 2006 to 1,475,000 in 2012.9 When used alone (not as ayahuasca), DMT is almost exclusively insufflated as a nasal snuff, bypassing hepatic elimination. It has an onset of around 45 seconds and a duration of 5 to 10 minutes. Insufflating DMT was historically referred to as a “businessman’s trip” because users were able to have a brief hallucinogenic experience on a lunch break and recover rapidly to perform their normal work.10

International law declares that DMT is an illegal substance and its importation is banned. However, its use for religious purposes, as is allowed for mescaline found in peyote, remains controversial.7 The UDV brought suit in United States federal court to prevent interference with the church’s use of ayahuasca during religious ceremonies based on the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. This act states that the government should not cause substantial imposition on religious practices in the absence of a compelling government interest. The court sided with the UDV, finding that the government had not sufficiently proved the alleged health risks posed by ayahuasca and could not show a substantial risk that the drug would be abused recreationally.11 Thus it is currently available in the United States and is legal for use by members of the UDV and Santo Daime churches.

Ayahuasca is not regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration. Many different types of preparations with different ingredients as well as different concentrations may exist, and clinical variability should be expected. Understanding that ayahuasca is capable of inhibiting MAO is important in order to avoid foods and medications, such as dextromethorphan, that may trigger adverse effects.

Case Conclusion

The patient’s hospital course was complicated by an additional seizure 12 hours after her initial presentation. By 36 hours she was back to her baseline mental status with a normal neurological examination.

Dr Fil is a senior fellow in medical toxicology at North Shore University Hospital, Manhasset, New York. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

Case

A 23-year-old Hispanic woman with no past medical history is brought to the ED for the second time in one day. On her first presentation, which was for a fever and a headache, meningitis was excluded with normal laboratory tests that included a lumbar puncture. She was administered acetaminophen for fever and pain control, and was discharged with a diagnosis of viral illness. On this second visit, 10 hours after being discharged, she presented because her family noted convulsions that began 3 hours after taking an herbal headache remedy given to her by a naturopath.

The patient arrived to the ED with a persistent seizure that terminated following administration of 2 mg of lorazepam. Her initial vital signs were: blood pressure, 115/51 mm Hg; heart rate, 121 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 24 breaths/minute; temperature, 97.6oF. Oxygen (O2) saturation was 100% with 2 L of O2 administered via nasal cannula. Her neurological examination was significant for a depressed mental status, pupils that were 6 mm and minimally reactive, clonus, and hyperreflexia. Repeat laboratory evaluation found a leukocytosis of 22.0 x 103/µL, serum bicarbonate of 9 mEq/L, and an anion gap of 22 with a normal serum lactate.

What is the differential diagnosis of this patient?

The history of medicinal plant ingestion raises the possibility of a toxicologic etiology. However, because the patient took the “medication” to treat another disorder, a search for an alternate cause should be performed. The differential diagnosis of a toxin-induced seizure is broad and includes pharmaceuticals (eg, tramadol, antihistamines), which may be surreptitiously added to herbal medication to assure efficacy. Plants associated with seizures include those containing antimuscarinic tropane alkaloids such as Jimsonweed (though a rare side effect from this plant product) or the water hemlock (Cicuta maculata). Contaminants of the plant itself may include pesticides such as organophosphates.

Although unlikely in a 21 year old, withdrawal from benzodiazepines, ethanol, baclofen, or gamma hydroxybutyrate are other possible etiologies. In addition to pharmaceutical and plant-derived causes, carbon monoxide poisoning should be a consideration in any patient with headache and flu-like illness.

This patient also presented with a constellation of other findings that included hyperreflexia, clonus, tachycardia, and altered mental status. Together these signs are expected in patients with serotonin toxicity (also referred to as serotonin syndrome), neuroleptic malignant syndrome, exogenous thyrotoxicosis, and lithium poisoning.

Case Continuation

The naturopathic practitioner arrived at the ED concerned about the patient, informing the ED team that she had given the patient 2 ounces of ayahuasca tea.

What is ayahuasca? What is the mechanism by which it exerts toxic effects?

Ayahuasca is a plant-derived psychotropic beverage that is used for religious purposes by members of two Brazilian churches—Centro Espírita Beneficente União do Vegetal (UDV) and Santo Daime. The ayahuasca beverage consists of two pharmacologically active compounds that together, but not individually, are psychoactive. The desired active effects for church participants include hallucinations, and vomiting to bring about a “religious purge.”1

Ayahuasca is prepared by combining two plants indigenous to the Amazon Basin area: Banisteriopsis caapi and either Psychotria viridis or Diplopterys cabrerana. B caapi contains the β-carboline alkaloids harmine, harmaline, and tetrahydroharmine. These alkaloids act as reversible inhibitors of the monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A) enzyme. The bark and stems of B caapi are boiled along with either P viridis or D cabrerana, both of which contain the potent hallucinogen N-N dimethyltryptamine (DMT).2 Normally, DMT is not active orally because it is enzymatically metabolized by MAO-A. However, when taken in the presence of the B caapi-derived MAO-A–inhibiting harmine alkaloids, DMT reaches the systemic circulation and produces its clinical effects.3

What are the clinical findings of serotonin toxicity?

Serotonin toxicity is a collection of clinical findings that fall under three main categories: autonomic hyperactivity, altered mental status, and muscle rigidity.5 The autonomic findings may include tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, shivering, diaphoresis, or mydriasis. Altered mental status ranges from mild agitation and hypervigilance to agitated delirium to obtundation. Other neurological findings may include tremor, myoclonus, hyperreflexia, or seizures. The onset of these signs is rapid, usually occurring within minutes after exposure to one or more serotonergic compounds. Although rare, severe serotonin toxicity may be associated with hypotension and shock, leading to death.4

The diagnosis of serotonin toxicity is based on the history and physical examination of the patient. Diagnostic criteria that have been suggested include the following: (1) a recent addition or increase in a known serotonergic agent; (2) absence of other possible etiologies; (3) no recent increase or addition of a neuroleptic agent (suggesting neuroleptic malignant syndrome); and/or (4) at least 3 of the following symptoms—mental status changes, myoclonus, agitation, hyperreflexia, diaphoresis, shivering, tremor, diarrhea, incoordination, fever5 (Figure 2).

How should this patient be managed?

The management of serotonin toxicity is primarily supportive with aggressive control of hyperthermia and autonomic instability. The precipitating xenobiotic agent should be immediately discontinued. In general, treatment with intravenous fluids, cooling measures, benzodiazepines, and a nonspecific 5-HT antagonist such as cyproheptadine should greatly improve the patient’s clinical status. Patients with severe toxicity may require induced paralysis and intubation.4 It is not clear in this case if the serotonin hyperactivation was due to the DMT (5-HT2A is associated with serotonin toxicity) or another serotonergic agent (eg, dextromethorphan from a cough and cold preparation) in combination with the MAO-inhibiting harmine alkaloids.

What is the availability of ayahuasca in the United States? How is it used in its nonherbal form?

...[Ayahuasca] is currently available in the United States and is legal for use by members of the UDV and Santo Daime churches. Many clinicians are becoming increasingly familiar with this herbal preparation since the recreational use of ayahuasca is gaining popularity in the United States. Internet fora with information on how to safely use ayahuasca, such as avoiding aged cheeses, are becoming more prevalent.7 A recent article in the New York Times described an ayahuasca gathering in Brooklyn, New York, where participants use the herb in a communal fashion.8 This herbal product is also associated with the Hollywood social scene and has received celebrity endorsements.8

The National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that the number of people in the United States who have used DMT has gone up almost every year since 2006, from an estimated 688,000 in 2006 to 1,475,000 in 2012.9 When used alone (not as ayahuasca), DMT is almost exclusively insufflated as a nasal snuff, bypassing hepatic elimination. It has an onset of around 45 seconds and a duration of 5 to 10 minutes. Insufflating DMT was historically referred to as a “businessman’s trip” because users were able to have a brief hallucinogenic experience on a lunch break and recover rapidly to perform their normal work.10

International law declares that DMT is an illegal substance and its importation is banned. However, its use for religious purposes, as is allowed for mescaline found in peyote, remains controversial.7 The UDV brought suit in United States federal court to prevent interference with the church’s use of ayahuasca during religious ceremonies based on the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. This act states that the government should not cause substantial imposition on religious practices in the absence of a compelling government interest. The court sided with the UDV, finding that the government had not sufficiently proved the alleged health risks posed by ayahuasca and could not show a substantial risk that the drug would be abused recreationally.11 Thus it is currently available in the United States and is legal for use by members of the UDV and Santo Daime churches.

Ayahuasca is not regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration. Many different types of preparations with different ingredients as well as different concentrations may exist, and clinical variability should be expected. Understanding that ayahuasca is capable of inhibiting MAO is important in order to avoid foods and medications, such as dextromethorphan, that may trigger adverse effects.

Case Conclusion

The patient’s hospital course was complicated by an additional seizure 12 hours after her initial presentation. By 36 hours she was back to her baseline mental status with a normal neurological examination.

Dr Fil is a senior fellow in medical toxicology at North Shore University Hospital, Manhasset, New York. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Gable RS. Risk assessment of ritual use of oral dimethyltryptamine (DMT) and harmala alkaloids. Addiction. 2007;102(1):24-34.

- Riba J, McIlhenny EH, Valle M, Bouso JC, Barker SA. Metabolism and Disposition of N,N-dimethyltryptamine and harmala alkaloids after oral administration of ayahuasca. Drug Test Anal. 2012;4(7-8):610-616.

- Riba J, Valle M, Urbano G, Yritia M, Morte A, Barbanoj MJ. Human Pharmacology of Ayahuasca: Subjective and Cardiovascular Effects, Monoamine Metabolite Excretion and Pharmacokinetics. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306(1):73-83

- Boyer EW, Shannon M. The serotonin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11);1112-1120.

- Sternbach H. The serotonin syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(6):6;705-713.

- Dunkley EJ, Isbister GK, Sibbritt D, Dawson AH, Whyte IM. The Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria: simple and accurate diagnostic decision rules for serotonin toxicity. QJM. 2003;96(9):635-642.

- Erowid. Ayahuasca Vault. https://www.erowid.org/chemicals/ayahuasca/ayahuasca.shtml. Accessed November 25, 2014.

- Morris B. Ayahuasca: a strong cup of tea. New York Times. June 13, 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/15/fashion/ayahuasca-a-strong-cup-of-tea.html. Accessed November 25, 2014.

- Quintanilla D. DMT: Hallucinogenic Drug Used in Shamanic Rituals Goes Mainstream. 10 Dec 2013. Available: http://www.opposingviews.com/i/health/dmt-hallucinogenic-drug-used-shamanic-rituals-goes-mainstream. Last accessed 11/14/14.

- Haroz R, Greenberg MI. Emerging drugs of abuse. Med Clin North Am. 2005;89(6):1259-1276.

- Gonzales v. O Centro Espirita Beneficente Uniao do Vegetal, 546 US 418 (2006). Available at http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=7036734975431570669&hl=en&as_sdt=6&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr. Accessed November 25, 2014.

- Gable RS. Risk assessment of ritual use of oral dimethyltryptamine (DMT) and harmala alkaloids. Addiction. 2007;102(1):24-34.

- Riba J, McIlhenny EH, Valle M, Bouso JC, Barker SA. Metabolism and Disposition of N,N-dimethyltryptamine and harmala alkaloids after oral administration of ayahuasca. Drug Test Anal. 2012;4(7-8):610-616.

- Riba J, Valle M, Urbano G, Yritia M, Morte A, Barbanoj MJ. Human Pharmacology of Ayahuasca: Subjective and Cardiovascular Effects, Monoamine Metabolite Excretion and Pharmacokinetics. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306(1):73-83

- Boyer EW, Shannon M. The serotonin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11);1112-1120.

- Sternbach H. The serotonin syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(6):6;705-713.

- Dunkley EJ, Isbister GK, Sibbritt D, Dawson AH, Whyte IM. The Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria: simple and accurate diagnostic decision rules for serotonin toxicity. QJM. 2003;96(9):635-642.

- Erowid. Ayahuasca Vault. https://www.erowid.org/chemicals/ayahuasca/ayahuasca.shtml. Accessed November 25, 2014.

- Morris B. Ayahuasca: a strong cup of tea. New York Times. June 13, 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/15/fashion/ayahuasca-a-strong-cup-of-tea.html. Accessed November 25, 2014.

- Quintanilla D. DMT: Hallucinogenic Drug Used in Shamanic Rituals Goes Mainstream. 10 Dec 2013. Available: http://www.opposingviews.com/i/health/dmt-hallucinogenic-drug-used-shamanic-rituals-goes-mainstream. Last accessed 11/14/14.

- Haroz R, Greenberg MI. Emerging drugs of abuse. Med Clin North Am. 2005;89(6):1259-1276.

- Gonzales v. O Centro Espirita Beneficente Uniao do Vegetal, 546 US 418 (2006). Available at http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=7036734975431570669&hl=en&as_sdt=6&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr. Accessed November 25, 2014.

Case Studies in Toxicology: Sippin’ on Some “Sizzurp”

Case

A 19-year-old man was found unresponsive by his girlfriend. They both attended a party the previous night where a number of people were drinking alcohol and cough syrup to get “high.” When emergency medical technicians arrived at the patient’s house, they administered naloxone, which somewhat improved the patient’s level of consciousness; oxygen was also delivered via facemask.

Upon arrival to the ED, the patient complained of hearing loss and tinnitus. His initial vital signs were: blood pressure, 99/60 mm Hg; heart rate, 110 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/minute; temperature, 96.8°F. Oxygen saturation was 80% on room air. On examination, he was lethargic but responsive to voice and oriented to time, place, and person. His pupils were pinpoint; his hearing was decreased bilaterally; his breathing was shallow, with rales audible at both lung bases; his bowel sounds were hypoactive; and his skin was warm and moist. The rest of the examination was otherwise unremarkable.

What cough and cold products are commonly abused with the intent to get high?

Hundreds of nonprescription pharmaceutical products—each with the potential for misuse or abuse—are available to consumers in retail stores and online. These products can be classified by expected clinical effect, which helps clinicians with the diagnosis and management of these patients (Table).

Of the antitussive products currently available over the counter (OTC), those that contain dextromethorphan have the widest abuse potential. Referred to as “dex,” “DMX,” or “tuss,” this drug is widely abused among adolescents and young adults due to its easy availability. In therapeutic doses, dextromethorphan suppresses cough via the medullary cough center. Ingesting dextromethorphan at higher doses, a practice referred to as “Robo tripping,” can produce hallucinations and a dissociative state marked by alterations in consciousness and impaired motor control. Dextromethorphan is a structural analog of ketamine and phencyclidine, which accounts for their similar clinical effects.

Codeine

Codeine is another drug added to various cough medications for its antitussive properties. An opioid, it acts centrally to suppress cough and has mild analgesic properties. It is available only by prescription in the United States, but can be purchased as an OTC product in other countries. Recently, it has come into the media spotlight as the starting product to make “Krokodil” (see Emerg Med. 2014;46[2]:76-78).

Case Continuation

While undergoing his workup in the ED, the patient became increasingly lethargic with persistent hypoxia. Although initially

responsive to naloxone, his respirations became more labored, requiring intubation. Prior to intubation and while awake, the patient mentioned that he was drinking “sizzurp” the evening prior. He denied the use of other drugs or of having any suicidal intent. A postintubation chest X-ray revealed a left-sided retrocardiac infiltrate consistent with aspiration pneumonitis.

What is sizzurp?

Sizzurp is a slang term used to describe a beverage that is most frequently comprised of fruit-flavored soda, codeine/promethazine hydrochloride cough syrup (CPHCS), and hard candy (classically a Jolly Rancher).1 This combination is ingested by the user with the intent of achieving a unique high—attributable to the combined effects of codeine, an opioid, and promethazine, an antihistamine (with antipsychotic properties). According to user reports, CPHCS induces a deep sense of euphoria, relaxation, and a slowed sense of time.2 Additional slang terms used to describe this product include “lean,” “purple drank,” “purp,” “drank,” “syrup,” “barre,” and “Texas tea.”

According to one source, purple drank originated in Houston, Texas around the 1960s, when blues musicians would combine dextromethorphan with beer.3 Over time, the recipe was modified, and by the 1980s, when purple drank was adopted by hip-hop musicians from the same Houston neighborhoods, the name sizzurp took hold.

In the 1990s, one Houston-based hiphop artist, DJ Screw, developed a genre of music called “chopped and screwed,” inspired by the CPHCS high and notable for its slowed-down tempo that fit the sedation and decreased motor activity induced by the drug. As chopped and screwed music became popularized, so too did the recreational use of CPHCS. In 2000, “Sippin’ on Some Sizzurp,” a hit song by southern hip-hop group Three Six Mafia, introduced CPHCS to more mainstream hip-hop audiences.

Despite the CPHCS-related deaths of a number of hip-hop musicians, including DJ Screw, as well as the arrests of professional

football players linked to abusing the drug, CPHCS continues to be glorified by a number of hip-hop and pop musicians.

Unfortunately, media attention of these events often has the paradoxical effect of promoting use among adolescents and young adults, and CPHCS has become a drug of choice for black adolescents in many Texas communities.4 However, one study attempting to define a purple drank user profile among college students at a large public university in the southeastern United States revealed that use was most prevalent among urban male youth primarily from Hispanic, Native American, and white ethnic backgrounds—challenging the notion that it is confined to the black community.5

Although CPHCS is only available by prescription in the United States, its widespread abuse suggests easy access to this drug. In April 2014, Actavis, the pharmaceutical company that produces a promethazine/codeine product known as the “champagne of sizzurp,” made a bold decision to cease all production and sales of the product in direct response to the widespread media attention and glamorization of CPHCS. In its announcement, the company cited its “commitment to being a partner in the fight against prescription-drug abuse.”6 Despite Actavis’ cessation of manufacturing CPHC, at least four other companies continue to sell similar formulations.

What are the dangers of CPHCS use?

The effects produced by CPHCS are described as euphoric, which may be attributable to both codeine and promethazine. Codeine, or 3-methyl morphine, is an inactive opioid agonist and prodrug that requires metabolic activation via O-demethylation to morphine by CYP2D6. Onset of action occurs 30 to 45 minutes after ingestion, while peak effects are reached within 1 to 2 hours and last approximately 4 to 6 hours.7 Since approximately 5% to 7% of the white population lack CPY2D6 function, these individuals will experience no analgesic or euphoric effects from codeine.8 However, ultra-rapid CYP2D6 metabolizers can produce significant and potentially life-threatening concentrations of morphine.

Adverse effects of recreational codeine use are similar to that of any opioid and include central nervous system (CNS) depression, miosis, and hypoactive bowel sounds, with severe toxicity marked by coma, respiratory depression, hypotension, bradycardia, and/or death due to respiratory arrest. Aspiration pneumonitis and rhabdomyolysis are complications of impaired airway protection and prolonged immobility. Opioid-induced ototoxicity, resulting in either temporary or permanent hearing loss, is a rare complication, described largely in case reports.9 (See Emerg Med. 2012;44[11]:4-6).

Promethazine hydrochloride contributes to the unique effects experienced by the recreational user and likely acts synergistically with codeine to augment CNS depression. Both a histamine H1-receptor antagonist and the muscarinic dopamine (D2)-receptor antagonist promethazine is included in prescription cough syrups to produce its antihistamine, antiemetic, and sedative properties.7 It is well absorbed from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract with more limited oral bioavailability due to the first-pass effect. Onset of action occurs within 20 minutes of administration, and the duration of effect is approximately 4 to 6 hours. Adverse effects of promethazine include variable CNS effects, from obtundation to agitated delirium, and are often accompanied by anticholinergic effects such as hyperthermia, dry flushed skin, mydriasis, hypoactive bowel sounds, and urinary retention. Neurological manifestations, likely mediated by dopamine blockade, include muscle rigidity, athetosis, hyperreflexia, and other upper motor neuron signs. Severe toxicity can produce coma, respiratory depression, seizure, and/or death.

What are the treatment strategies?

Management of patients with CPHCS toxicity, as with all poisoned patients, begins with rapid evaluation and stabilization of the airway, breathing, and circulation. The benefits of GI decontamination are likely to be outweighed by the risks engendered by CNS depression. While supportive care is the mainstay, targeted therapies may include naloxone for the treatment of opioid-induced respiratory depression and physostigmine, when contraindications have been ruled out, for the reversal of the anticholinergic toxidrome.

Conclusion

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit where he was treated for aspiration pneumonitis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, rhabdomyolysis, and acute renal failure. His hearing loss and tinnitus resolved. He was extubated on hospital day 9 and discharged from the hospital on day 14.

Dr Laskowski is a medical toxicology fellow in the department of emergency medicine at New York University Langone Medical Center. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Sizzurp. Urban Dictionary Web site. http://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=sizzurp. Accessed October 15, 2014.

- Jodeine. Sippin’ purple drank: an experience with promethazine with codeine & cannabis. Erowid Web site. https://www.erowid.org/experiences/exp.php?ID=54165. Accessed October 15, 2014.

- Fergusen G. Sizzurp. KCRW Radio Web site. http://www.kcrw.com/news-culture/shows/good-food/butter-carving-the-last-supper-sizzurp-cheftestants. March 23, 2013. Accessed October 15, 2014.

- Elwood WN. Sticky business: patterns of procurement and misuse of prescription cough syrup in Houston. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2001;33(2):121-133.

- Agnich LE, Stogner JM, Miller BL, Marcum CD. Purple drank prevalence and characteristics of misusers of codeine cough syrup mixtures. Addict Behav. 2013;38(9):2445-2449.

- Hlavaty C. Drug company cites abuse, pop culture hype in ending cough syrup production. Houston Chronicle. April 24, 2014. http://blog.chron.com/thetexican/2014/04/drug-company-cites-abuse-pop-culture-hype-in-ending-cough-syrup-production/. Accessed October 15, 2014.

- Burns JM, Boyer EW. Antitussives and substance abuse. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2013;4:75-82.

- Nelson LS, Olsen D. Opioids. In: Nelson LS, Lewin NA, Howland MA, Hoffman RS, Goldfrank LR, Flomenbaum NE, eds. Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies. 9th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2011:559-578.

- Freeman SR, Bray ME, Amos CS, Gibson WP. The association of codeine, macrocytosis and bilateral sudden or rapidly progressive profound sensorineural deafness. Acta Otolaryngol. 2009;129(1):1061-1066.

Case

A 19-year-old man was found unresponsive by his girlfriend. They both attended a party the previous night where a number of people were drinking alcohol and cough syrup to get “high.” When emergency medical technicians arrived at the patient’s house, they administered naloxone, which somewhat improved the patient’s level of consciousness; oxygen was also delivered via facemask.

Upon arrival to the ED, the patient complained of hearing loss and tinnitus. His initial vital signs were: blood pressure, 99/60 mm Hg; heart rate, 110 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/minute; temperature, 96.8°F. Oxygen saturation was 80% on room air. On examination, he was lethargic but responsive to voice and oriented to time, place, and person. His pupils were pinpoint; his hearing was decreased bilaterally; his breathing was shallow, with rales audible at both lung bases; his bowel sounds were hypoactive; and his skin was warm and moist. The rest of the examination was otherwise unremarkable.

What cough and cold products are commonly abused with the intent to get high?

Hundreds of nonprescription pharmaceutical products—each with the potential for misuse or abuse—are available to consumers in retail stores and online. These products can be classified by expected clinical effect, which helps clinicians with the diagnosis and management of these patients (Table).

Of the antitussive products currently available over the counter (OTC), those that contain dextromethorphan have the widest abuse potential. Referred to as “dex,” “DMX,” or “tuss,” this drug is widely abused among adolescents and young adults due to its easy availability. In therapeutic doses, dextromethorphan suppresses cough via the medullary cough center. Ingesting dextromethorphan at higher doses, a practice referred to as “Robo tripping,” can produce hallucinations and a dissociative state marked by alterations in consciousness and impaired motor control. Dextromethorphan is a structural analog of ketamine and phencyclidine, which accounts for their similar clinical effects.

Codeine

Codeine is another drug added to various cough medications for its antitussive properties. An opioid, it acts centrally to suppress cough and has mild analgesic properties. It is available only by prescription in the United States, but can be purchased as an OTC product in other countries. Recently, it has come into the media spotlight as the starting product to make “Krokodil” (see Emerg Med. 2014;46[2]:76-78).

Case Continuation

While undergoing his workup in the ED, the patient became increasingly lethargic with persistent hypoxia. Although initially

responsive to naloxone, his respirations became more labored, requiring intubation. Prior to intubation and while awake, the patient mentioned that he was drinking “sizzurp” the evening prior. He denied the use of other drugs or of having any suicidal intent. A postintubation chest X-ray revealed a left-sided retrocardiac infiltrate consistent with aspiration pneumonitis.

What is sizzurp?

Sizzurp is a slang term used to describe a beverage that is most frequently comprised of fruit-flavored soda, codeine/promethazine hydrochloride cough syrup (CPHCS), and hard candy (classically a Jolly Rancher).1 This combination is ingested by the user with the intent of achieving a unique high—attributable to the combined effects of codeine, an opioid, and promethazine, an antihistamine (with antipsychotic properties). According to user reports, CPHCS induces a deep sense of euphoria, relaxation, and a slowed sense of time.2 Additional slang terms used to describe this product include “lean,” “purple drank,” “purp,” “drank,” “syrup,” “barre,” and “Texas tea.”

According to one source, purple drank originated in Houston, Texas around the 1960s, when blues musicians would combine dextromethorphan with beer.3 Over time, the recipe was modified, and by the 1980s, when purple drank was adopted by hip-hop musicians from the same Houston neighborhoods, the name sizzurp took hold.

In the 1990s, one Houston-based hiphop artist, DJ Screw, developed a genre of music called “chopped and screwed,” inspired by the CPHCS high and notable for its slowed-down tempo that fit the sedation and decreased motor activity induced by the drug. As chopped and screwed music became popularized, so too did the recreational use of CPHCS. In 2000, “Sippin’ on Some Sizzurp,” a hit song by southern hip-hop group Three Six Mafia, introduced CPHCS to more mainstream hip-hop audiences.

Despite the CPHCS-related deaths of a number of hip-hop musicians, including DJ Screw, as well as the arrests of professional

football players linked to abusing the drug, CPHCS continues to be glorified by a number of hip-hop and pop musicians.

Unfortunately, media attention of these events often has the paradoxical effect of promoting use among adolescents and young adults, and CPHCS has become a drug of choice for black adolescents in many Texas communities.4 However, one study attempting to define a purple drank user profile among college students at a large public university in the southeastern United States revealed that use was most prevalent among urban male youth primarily from Hispanic, Native American, and white ethnic backgrounds—challenging the notion that it is confined to the black community.5

Although CPHCS is only available by prescription in the United States, its widespread abuse suggests easy access to this drug. In April 2014, Actavis, the pharmaceutical company that produces a promethazine/codeine product known as the “champagne of sizzurp,” made a bold decision to cease all production and sales of the product in direct response to the widespread media attention and glamorization of CPHCS. In its announcement, the company cited its “commitment to being a partner in the fight against prescription-drug abuse.”6 Despite Actavis’ cessation of manufacturing CPHC, at least four other companies continue to sell similar formulations.

What are the dangers of CPHCS use?

The effects produced by CPHCS are described as euphoric, which may be attributable to both codeine and promethazine. Codeine, or 3-methyl morphine, is an inactive opioid agonist and prodrug that requires metabolic activation via O-demethylation to morphine by CYP2D6. Onset of action occurs 30 to 45 minutes after ingestion, while peak effects are reached within 1 to 2 hours and last approximately 4 to 6 hours.7 Since approximately 5% to 7% of the white population lack CPY2D6 function, these individuals will experience no analgesic or euphoric effects from codeine.8 However, ultra-rapid CYP2D6 metabolizers can produce significant and potentially life-threatening concentrations of morphine.

Adverse effects of recreational codeine use are similar to that of any opioid and include central nervous system (CNS) depression, miosis, and hypoactive bowel sounds, with severe toxicity marked by coma, respiratory depression, hypotension, bradycardia, and/or death due to respiratory arrest. Aspiration pneumonitis and rhabdomyolysis are complications of impaired airway protection and prolonged immobility. Opioid-induced ototoxicity, resulting in either temporary or permanent hearing loss, is a rare complication, described largely in case reports.9 (See Emerg Med. 2012;44[11]:4-6).

Promethazine hydrochloride contributes to the unique effects experienced by the recreational user and likely acts synergistically with codeine to augment CNS depression. Both a histamine H1-receptor antagonist and the muscarinic dopamine (D2)-receptor antagonist promethazine is included in prescription cough syrups to produce its antihistamine, antiemetic, and sedative properties.7 It is well absorbed from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract with more limited oral bioavailability due to the first-pass effect. Onset of action occurs within 20 minutes of administration, and the duration of effect is approximately 4 to 6 hours. Adverse effects of promethazine include variable CNS effects, from obtundation to agitated delirium, and are often accompanied by anticholinergic effects such as hyperthermia, dry flushed skin, mydriasis, hypoactive bowel sounds, and urinary retention. Neurological manifestations, likely mediated by dopamine blockade, include muscle rigidity, athetosis, hyperreflexia, and other upper motor neuron signs. Severe toxicity can produce coma, respiratory depression, seizure, and/or death.

What are the treatment strategies?

Management of patients with CPHCS toxicity, as with all poisoned patients, begins with rapid evaluation and stabilization of the airway, breathing, and circulation. The benefits of GI decontamination are likely to be outweighed by the risks engendered by CNS depression. While supportive care is the mainstay, targeted therapies may include naloxone for the treatment of opioid-induced respiratory depression and physostigmine, when contraindications have been ruled out, for the reversal of the anticholinergic toxidrome.

Conclusion

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit where he was treated for aspiration pneumonitis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, rhabdomyolysis, and acute renal failure. His hearing loss and tinnitus resolved. He was extubated on hospital day 9 and discharged from the hospital on day 14.

Dr Laskowski is a medical toxicology fellow in the department of emergency medicine at New York University Langone Medical Center. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

Case

A 19-year-old man was found unresponsive by his girlfriend. They both attended a party the previous night where a number of people were drinking alcohol and cough syrup to get “high.” When emergency medical technicians arrived at the patient’s house, they administered naloxone, which somewhat improved the patient’s level of consciousness; oxygen was also delivered via facemask.

Upon arrival to the ED, the patient complained of hearing loss and tinnitus. His initial vital signs were: blood pressure, 99/60 mm Hg; heart rate, 110 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/minute; temperature, 96.8°F. Oxygen saturation was 80% on room air. On examination, he was lethargic but responsive to voice and oriented to time, place, and person. His pupils were pinpoint; his hearing was decreased bilaterally; his breathing was shallow, with rales audible at both lung bases; his bowel sounds were hypoactive; and his skin was warm and moist. The rest of the examination was otherwise unremarkable.

What cough and cold products are commonly abused with the intent to get high?

Hundreds of nonprescription pharmaceutical products—each with the potential for misuse or abuse—are available to consumers in retail stores and online. These products can be classified by expected clinical effect, which helps clinicians with the diagnosis and management of these patients (Table).

Of the antitussive products currently available over the counter (OTC), those that contain dextromethorphan have the widest abuse potential. Referred to as “dex,” “DMX,” or “tuss,” this drug is widely abused among adolescents and young adults due to its easy availability. In therapeutic doses, dextromethorphan suppresses cough via the medullary cough center. Ingesting dextromethorphan at higher doses, a practice referred to as “Robo tripping,” can produce hallucinations and a dissociative state marked by alterations in consciousness and impaired motor control. Dextromethorphan is a structural analog of ketamine and phencyclidine, which accounts for their similar clinical effects.

Codeine

Codeine is another drug added to various cough medications for its antitussive properties. An opioid, it acts centrally to suppress cough and has mild analgesic properties. It is available only by prescription in the United States, but can be purchased as an OTC product in other countries. Recently, it has come into the media spotlight as the starting product to make “Krokodil” (see Emerg Med. 2014;46[2]:76-78).

Case Continuation

While undergoing his workup in the ED, the patient became increasingly lethargic with persistent hypoxia. Although initially

responsive to naloxone, his respirations became more labored, requiring intubation. Prior to intubation and while awake, the patient mentioned that he was drinking “sizzurp” the evening prior. He denied the use of other drugs or of having any suicidal intent. A postintubation chest X-ray revealed a left-sided retrocardiac infiltrate consistent with aspiration pneumonitis.

What is sizzurp?

Sizzurp is a slang term used to describe a beverage that is most frequently comprised of fruit-flavored soda, codeine/promethazine hydrochloride cough syrup (CPHCS), and hard candy (classically a Jolly Rancher).1 This combination is ingested by the user with the intent of achieving a unique high—attributable to the combined effects of codeine, an opioid, and promethazine, an antihistamine (with antipsychotic properties). According to user reports, CPHCS induces a deep sense of euphoria, relaxation, and a slowed sense of time.2 Additional slang terms used to describe this product include “lean,” “purple drank,” “purp,” “drank,” “syrup,” “barre,” and “Texas tea.”

According to one source, purple drank originated in Houston, Texas around the 1960s, when blues musicians would combine dextromethorphan with beer.3 Over time, the recipe was modified, and by the 1980s, when purple drank was adopted by hip-hop musicians from the same Houston neighborhoods, the name sizzurp took hold.

In the 1990s, one Houston-based hiphop artist, DJ Screw, developed a genre of music called “chopped and screwed,” inspired by the CPHCS high and notable for its slowed-down tempo that fit the sedation and decreased motor activity induced by the drug. As chopped and screwed music became popularized, so too did the recreational use of CPHCS. In 2000, “Sippin’ on Some Sizzurp,” a hit song by southern hip-hop group Three Six Mafia, introduced CPHCS to more mainstream hip-hop audiences.

Despite the CPHCS-related deaths of a number of hip-hop musicians, including DJ Screw, as well as the arrests of professional

football players linked to abusing the drug, CPHCS continues to be glorified by a number of hip-hop and pop musicians.

Unfortunately, media attention of these events often has the paradoxical effect of promoting use among adolescents and young adults, and CPHCS has become a drug of choice for black adolescents in many Texas communities.4 However, one study attempting to define a purple drank user profile among college students at a large public university in the southeastern United States revealed that use was most prevalent among urban male youth primarily from Hispanic, Native American, and white ethnic backgrounds—challenging the notion that it is confined to the black community.5

Although CPHCS is only available by prescription in the United States, its widespread abuse suggests easy access to this drug. In April 2014, Actavis, the pharmaceutical company that produces a promethazine/codeine product known as the “champagne of sizzurp,” made a bold decision to cease all production and sales of the product in direct response to the widespread media attention and glamorization of CPHCS. In its announcement, the company cited its “commitment to being a partner in the fight against prescription-drug abuse.”6 Despite Actavis’ cessation of manufacturing CPHC, at least four other companies continue to sell similar formulations.

What are the dangers of CPHCS use?

The effects produced by CPHCS are described as euphoric, which may be attributable to both codeine and promethazine. Codeine, or 3-methyl morphine, is an inactive opioid agonist and prodrug that requires metabolic activation via O-demethylation to morphine by CYP2D6. Onset of action occurs 30 to 45 minutes after ingestion, while peak effects are reached within 1 to 2 hours and last approximately 4 to 6 hours.7 Since approximately 5% to 7% of the white population lack CPY2D6 function, these individuals will experience no analgesic or euphoric effects from codeine.8 However, ultra-rapid CYP2D6 metabolizers can produce significant and potentially life-threatening concentrations of morphine.

Adverse effects of recreational codeine use are similar to that of any opioid and include central nervous system (CNS) depression, miosis, and hypoactive bowel sounds, with severe toxicity marked by coma, respiratory depression, hypotension, bradycardia, and/or death due to respiratory arrest. Aspiration pneumonitis and rhabdomyolysis are complications of impaired airway protection and prolonged immobility. Opioid-induced ototoxicity, resulting in either temporary or permanent hearing loss, is a rare complication, described largely in case reports.9 (See Emerg Med. 2012;44[11]:4-6).

Promethazine hydrochloride contributes to the unique effects experienced by the recreational user and likely acts synergistically with codeine to augment CNS depression. Both a histamine H1-receptor antagonist and the muscarinic dopamine (D2)-receptor antagonist promethazine is included in prescription cough syrups to produce its antihistamine, antiemetic, and sedative properties.7 It is well absorbed from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract with more limited oral bioavailability due to the first-pass effect. Onset of action occurs within 20 minutes of administration, and the duration of effect is approximately 4 to 6 hours. Adverse effects of promethazine include variable CNS effects, from obtundation to agitated delirium, and are often accompanied by anticholinergic effects such as hyperthermia, dry flushed skin, mydriasis, hypoactive bowel sounds, and urinary retention. Neurological manifestations, likely mediated by dopamine blockade, include muscle rigidity, athetosis, hyperreflexia, and other upper motor neuron signs. Severe toxicity can produce coma, respiratory depression, seizure, and/or death.

What are the treatment strategies?