User login

Aspirin alone preferred antithrombotic strategy after TAVI

Aspirin alone after transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) significantly reduced bleeding, compared with aspirin plus clopidogrel, without increasing thromboembolic events, in the latest results from the POPular TAVI study.

“Physicians can easily and safely reduce rate of bleeding by omitting clopidogrel after TAVI,” lead author, Jorn Brouwer, MD, St Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, the Netherlands, said.

“Aspirin alone should be used in patients undergoing TAVI who are not on oral anticoagulants and have not recently undergone coronary stenting,” he concluded.

Senior author, Jurriën ten Berg, MD, PhD, also from St Antonius Hospital, said in an interview: “I think we can say for TAVI patients, when it comes to antithrombotic therapy, less is definitely more.”

“This is a major change to clinical practice, with current guidelines recommending 3-6 months of dual antiplatelet therapy after a TAVI procedure,” he added. “We expected that these guidelines will change after our results.”

These latest results from POPular TAVI were presented at the virtual European Society of Cardiology Congress 2020 and simultaneously published online in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial was conducted in two cohorts of patients undergoing TAVI. The results from cohort B – in patients who were already taking an anticoagulant for another indication – were reported earlier this year and showed no benefit of adding clopidogrel and an increase in bleeding. Now the current results in cohort A – patients undergoing TAVI who do not have an established indication for long-term anticoagulation – show similar results, with aspirin alone preferred over aspirin plus clopidogrel.

Dr. ten Berg explained that the recommendation for dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) was adopted mainly because this has been shown to be beneficial in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stenting; it was thought the same benefits would be seen in TAVI, which also uses a stent-based delivery system.

“However, TAVI patients are a different population – they are generally much older than PCI patients, with an average age of 80 plus, and they have many more comorbidities, so they are much higher bleeding risk,” Dr. ten Berg explained. “In addition, the catheters used for TAVI are larger than those used for PCI, forcing the femoral route to be employed, and both of these factors increases bleeding risk.”

“We saw that, in the trial, patients on dual antiplatelet therapy had a much greater rate of major bleeding and the addition of clopidogrel did not reduce the risk of major thrombotic events,” such as stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), or cardiovascular (CV) death.

Given that the TAVI procedure is associated with an increase in stroke in the immediate few days after the procedure, it would seem logical that increased antiplatelet therapy would be beneficial in reducing this, Dr. ten Berg noted.

“But this is not what we are seeing,” he said. “The stroke incidence was similar in the two groups in POPular TAVI. This suggests that the strokes may not be platelet mediated. They might be caused by another mechanism, such as dislodgement of calcium from the valve or tissue from the aorta.”

For the current part of the study, 690 patients who were undergoing TAVI and did not have an indication for long-term anticoagulation were randomly assigned to receive aspirin alone or aspirin plus clopidogrel for 3 months.

The two primary outcomes were all bleeding (including minor, major, and life-threatening or disabling bleeding) and non–procedure-related bleeding over a period of 12 months. Most bleeding at the TAVI puncture site was counted as not procedure related.

Results showed that a bleeding event occurred in 15.1% of patients receiving aspirin alone and 26.6% of those receiving aspirin plus clopidogrel (risk ratio, 0.57; P = .001). Non–procedure-related bleeding occurred 15.1% of patients receiving aspirin alone vs 24.9% of those receiving aspirin plus clopidogrel (risk ratio, 0.61; P = .005). Major, life-threatening, or disabling bleeding occurred in 5.1% of the aspirin-alone group versus 10.8% of those in the aspirin plus clopidogrel group.

Two secondary outcomes included thromboembolic events. The secondary composite one endpoint of death from cardiovascular causes, non–procedure-related bleeding, stroke, or MI at 1 year occurred in 23.0% of those receiving aspirin alone and in 31.1% of those receiving aspirin plus clopidogrel (difference, −8.2 percentage points; P for noninferiority < .001; risk ratio, 0.74; P for superiority = .04).

The secondary composite two endpoint of death from cardiovascular causes, ischemic stroke, or MI at 1 year occurred in 9.7% of the aspirin-alone group versus 9.9% of the dual-antiplatelet group (difference, −0.2 percentage points; P for noninferiority = .004; risk ratio, 0.98; P for superiority = .93).

Dr. ten Berg pointed out that the trial was not strictly powered to look at thrombotic events, but he added: “There was no hint of an increase in the aspirin-alone group and there was quite a high event rate, so we should have seen something if it was there.”

The group has also performed a meta-analysis of these results, with some previous smaller studies also comparing aspirin and DAPT in TAVI which again showed no reduction in thrombotic events with dual-antiplatelet therapy.

Dr. ten Berg noted that the trial included all-comer TAVI patients. “The overall risk was quite a low [STS score, 2.5]. This is a reflection of the typical TAVI patient we are seeing but I would say our results apply to patients of all risk.”

Simplifies and clarifies

Discussant of the trial at the ESC Hotline session, Anna Sonia Petronio, MD, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Pisana, Pisa, Italy, said, “This was an excellent and essential study that simplifies and clarifies aspects of TAVI treatment and needs to change the guidelines.”

“These results will have a large impact on clinical practice in this elderly population,” she said. But she added that more data are needed for younger patients and more complicated cases, such as valve-in-valve and bicuspid valves.

Commenting on the results, Robert Bonow, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, said, “The optimal antithrombotic management of patients undergoing TAVI who do not otherwise have an indication for anticoagulation [such as atrial fibrillation] has been uncertain and debatable. Aspirin plus clopidogrel for 3-6 months has been the standard, based on the experience with coronary stents.”

“Thus, the current results of cohort A of the POPular TAVI trial showing significant reduction in bleeding events with aspirin alone compared to DAPT for 3 months, with no difference in ischemic events, are important observations,” he said. “It is noteworthy that most of the bleeding events occurred in the first 30 days.

“This is a relatively small randomized trial, so whether these results will be practice changing will depend on confirmation by additional studies, but it is reassuring to know that patients at higher risk for bleeding would appear to do well with low-dose aspirin alone after TAVI,” Dr. Bonow added.

“These results complete the circle in terms of antithrombotic therapy after TAVI,” commented Michael Reardon, MD, Houston Methodist DeBakey Heart & Vascular Institute, Texas.

“I would add two caveats: First is that most of the difference in the primary endpoint occurs in the first month and levels out between the groups after that,” Dr. Reardon said. “Second is that this does not address the issue of leaflet thickening and immobility.”

Ashish Pershad, MD, Banner – University Medicine Heart Institute, Phoenix, added: “This trial answers a very important question and shows dual-antiplatelet therapy is hazardous in TAVI patients. Clopidogrel is not needed.”

Dr. Pershad says he still wonders about patients who receive very small valves who may have a higher risk for valve-induced thrombosis. “While there were some of these patients in the trial, the numbers were small, so we need more data on this group,” he commented.

“But for bread-and-butter TAVI, aspirin alone is the best choice, and the previous results showed, for patients already taking oral anticoagulation, no additional antithrombotic therapy is required,” Dr. Pershad concluded. “This is a big deal and will change the way we treat patients.”

The POPular trial was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development. Brouwer reports no disclosures.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Aspirin alone after transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) significantly reduced bleeding, compared with aspirin plus clopidogrel, without increasing thromboembolic events, in the latest results from the POPular TAVI study.

“Physicians can easily and safely reduce rate of bleeding by omitting clopidogrel after TAVI,” lead author, Jorn Brouwer, MD, St Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, the Netherlands, said.

“Aspirin alone should be used in patients undergoing TAVI who are not on oral anticoagulants and have not recently undergone coronary stenting,” he concluded.

Senior author, Jurriën ten Berg, MD, PhD, also from St Antonius Hospital, said in an interview: “I think we can say for TAVI patients, when it comes to antithrombotic therapy, less is definitely more.”

“This is a major change to clinical practice, with current guidelines recommending 3-6 months of dual antiplatelet therapy after a TAVI procedure,” he added. “We expected that these guidelines will change after our results.”

These latest results from POPular TAVI were presented at the virtual European Society of Cardiology Congress 2020 and simultaneously published online in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial was conducted in two cohorts of patients undergoing TAVI. The results from cohort B – in patients who were already taking an anticoagulant for another indication – were reported earlier this year and showed no benefit of adding clopidogrel and an increase in bleeding. Now the current results in cohort A – patients undergoing TAVI who do not have an established indication for long-term anticoagulation – show similar results, with aspirin alone preferred over aspirin plus clopidogrel.

Dr. ten Berg explained that the recommendation for dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) was adopted mainly because this has been shown to be beneficial in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stenting; it was thought the same benefits would be seen in TAVI, which also uses a stent-based delivery system.

“However, TAVI patients are a different population – they are generally much older than PCI patients, with an average age of 80 plus, and they have many more comorbidities, so they are much higher bleeding risk,” Dr. ten Berg explained. “In addition, the catheters used for TAVI are larger than those used for PCI, forcing the femoral route to be employed, and both of these factors increases bleeding risk.”

“We saw that, in the trial, patients on dual antiplatelet therapy had a much greater rate of major bleeding and the addition of clopidogrel did not reduce the risk of major thrombotic events,” such as stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), or cardiovascular (CV) death.

Given that the TAVI procedure is associated with an increase in stroke in the immediate few days after the procedure, it would seem logical that increased antiplatelet therapy would be beneficial in reducing this, Dr. ten Berg noted.

“But this is not what we are seeing,” he said. “The stroke incidence was similar in the two groups in POPular TAVI. This suggests that the strokes may not be platelet mediated. They might be caused by another mechanism, such as dislodgement of calcium from the valve or tissue from the aorta.”

For the current part of the study, 690 patients who were undergoing TAVI and did not have an indication for long-term anticoagulation were randomly assigned to receive aspirin alone or aspirin plus clopidogrel for 3 months.

The two primary outcomes were all bleeding (including minor, major, and life-threatening or disabling bleeding) and non–procedure-related bleeding over a period of 12 months. Most bleeding at the TAVI puncture site was counted as not procedure related.

Results showed that a bleeding event occurred in 15.1% of patients receiving aspirin alone and 26.6% of those receiving aspirin plus clopidogrel (risk ratio, 0.57; P = .001). Non–procedure-related bleeding occurred 15.1% of patients receiving aspirin alone vs 24.9% of those receiving aspirin plus clopidogrel (risk ratio, 0.61; P = .005). Major, life-threatening, or disabling bleeding occurred in 5.1% of the aspirin-alone group versus 10.8% of those in the aspirin plus clopidogrel group.

Two secondary outcomes included thromboembolic events. The secondary composite one endpoint of death from cardiovascular causes, non–procedure-related bleeding, stroke, or MI at 1 year occurred in 23.0% of those receiving aspirin alone and in 31.1% of those receiving aspirin plus clopidogrel (difference, −8.2 percentage points; P for noninferiority < .001; risk ratio, 0.74; P for superiority = .04).

The secondary composite two endpoint of death from cardiovascular causes, ischemic stroke, or MI at 1 year occurred in 9.7% of the aspirin-alone group versus 9.9% of the dual-antiplatelet group (difference, −0.2 percentage points; P for noninferiority = .004; risk ratio, 0.98; P for superiority = .93).

Dr. ten Berg pointed out that the trial was not strictly powered to look at thrombotic events, but he added: “There was no hint of an increase in the aspirin-alone group and there was quite a high event rate, so we should have seen something if it was there.”

The group has also performed a meta-analysis of these results, with some previous smaller studies also comparing aspirin and DAPT in TAVI which again showed no reduction in thrombotic events with dual-antiplatelet therapy.

Dr. ten Berg noted that the trial included all-comer TAVI patients. “The overall risk was quite a low [STS score, 2.5]. This is a reflection of the typical TAVI patient we are seeing but I would say our results apply to patients of all risk.”

Simplifies and clarifies

Discussant of the trial at the ESC Hotline session, Anna Sonia Petronio, MD, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Pisana, Pisa, Italy, said, “This was an excellent and essential study that simplifies and clarifies aspects of TAVI treatment and needs to change the guidelines.”

“These results will have a large impact on clinical practice in this elderly population,” she said. But she added that more data are needed for younger patients and more complicated cases, such as valve-in-valve and bicuspid valves.

Commenting on the results, Robert Bonow, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, said, “The optimal antithrombotic management of patients undergoing TAVI who do not otherwise have an indication for anticoagulation [such as atrial fibrillation] has been uncertain and debatable. Aspirin plus clopidogrel for 3-6 months has been the standard, based on the experience with coronary stents.”

“Thus, the current results of cohort A of the POPular TAVI trial showing significant reduction in bleeding events with aspirin alone compared to DAPT for 3 months, with no difference in ischemic events, are important observations,” he said. “It is noteworthy that most of the bleeding events occurred in the first 30 days.

“This is a relatively small randomized trial, so whether these results will be practice changing will depend on confirmation by additional studies, but it is reassuring to know that patients at higher risk for bleeding would appear to do well with low-dose aspirin alone after TAVI,” Dr. Bonow added.

“These results complete the circle in terms of antithrombotic therapy after TAVI,” commented Michael Reardon, MD, Houston Methodist DeBakey Heart & Vascular Institute, Texas.

“I would add two caveats: First is that most of the difference in the primary endpoint occurs in the first month and levels out between the groups after that,” Dr. Reardon said. “Second is that this does not address the issue of leaflet thickening and immobility.”

Ashish Pershad, MD, Banner – University Medicine Heart Institute, Phoenix, added: “This trial answers a very important question and shows dual-antiplatelet therapy is hazardous in TAVI patients. Clopidogrel is not needed.”

Dr. Pershad says he still wonders about patients who receive very small valves who may have a higher risk for valve-induced thrombosis. “While there were some of these patients in the trial, the numbers were small, so we need more data on this group,” he commented.

“But for bread-and-butter TAVI, aspirin alone is the best choice, and the previous results showed, for patients already taking oral anticoagulation, no additional antithrombotic therapy is required,” Dr. Pershad concluded. “This is a big deal and will change the way we treat patients.”

The POPular trial was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development. Brouwer reports no disclosures.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Aspirin alone after transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) significantly reduced bleeding, compared with aspirin plus clopidogrel, without increasing thromboembolic events, in the latest results from the POPular TAVI study.

“Physicians can easily and safely reduce rate of bleeding by omitting clopidogrel after TAVI,” lead author, Jorn Brouwer, MD, St Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, the Netherlands, said.

“Aspirin alone should be used in patients undergoing TAVI who are not on oral anticoagulants and have not recently undergone coronary stenting,” he concluded.

Senior author, Jurriën ten Berg, MD, PhD, also from St Antonius Hospital, said in an interview: “I think we can say for TAVI patients, when it comes to antithrombotic therapy, less is definitely more.”

“This is a major change to clinical practice, with current guidelines recommending 3-6 months of dual antiplatelet therapy after a TAVI procedure,” he added. “We expected that these guidelines will change after our results.”

These latest results from POPular TAVI were presented at the virtual European Society of Cardiology Congress 2020 and simultaneously published online in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial was conducted in two cohorts of patients undergoing TAVI. The results from cohort B – in patients who were already taking an anticoagulant for another indication – were reported earlier this year and showed no benefit of adding clopidogrel and an increase in bleeding. Now the current results in cohort A – patients undergoing TAVI who do not have an established indication for long-term anticoagulation – show similar results, with aspirin alone preferred over aspirin plus clopidogrel.

Dr. ten Berg explained that the recommendation for dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) was adopted mainly because this has been shown to be beneficial in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stenting; it was thought the same benefits would be seen in TAVI, which also uses a stent-based delivery system.

“However, TAVI patients are a different population – they are generally much older than PCI patients, with an average age of 80 plus, and they have many more comorbidities, so they are much higher bleeding risk,” Dr. ten Berg explained. “In addition, the catheters used for TAVI are larger than those used for PCI, forcing the femoral route to be employed, and both of these factors increases bleeding risk.”

“We saw that, in the trial, patients on dual antiplatelet therapy had a much greater rate of major bleeding and the addition of clopidogrel did not reduce the risk of major thrombotic events,” such as stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), or cardiovascular (CV) death.

Given that the TAVI procedure is associated with an increase in stroke in the immediate few days after the procedure, it would seem logical that increased antiplatelet therapy would be beneficial in reducing this, Dr. ten Berg noted.

“But this is not what we are seeing,” he said. “The stroke incidence was similar in the two groups in POPular TAVI. This suggests that the strokes may not be platelet mediated. They might be caused by another mechanism, such as dislodgement of calcium from the valve or tissue from the aorta.”

For the current part of the study, 690 patients who were undergoing TAVI and did not have an indication for long-term anticoagulation were randomly assigned to receive aspirin alone or aspirin plus clopidogrel for 3 months.

The two primary outcomes were all bleeding (including minor, major, and life-threatening or disabling bleeding) and non–procedure-related bleeding over a period of 12 months. Most bleeding at the TAVI puncture site was counted as not procedure related.

Results showed that a bleeding event occurred in 15.1% of patients receiving aspirin alone and 26.6% of those receiving aspirin plus clopidogrel (risk ratio, 0.57; P = .001). Non–procedure-related bleeding occurred 15.1% of patients receiving aspirin alone vs 24.9% of those receiving aspirin plus clopidogrel (risk ratio, 0.61; P = .005). Major, life-threatening, or disabling bleeding occurred in 5.1% of the aspirin-alone group versus 10.8% of those in the aspirin plus clopidogrel group.

Two secondary outcomes included thromboembolic events. The secondary composite one endpoint of death from cardiovascular causes, non–procedure-related bleeding, stroke, or MI at 1 year occurred in 23.0% of those receiving aspirin alone and in 31.1% of those receiving aspirin plus clopidogrel (difference, −8.2 percentage points; P for noninferiority < .001; risk ratio, 0.74; P for superiority = .04).

The secondary composite two endpoint of death from cardiovascular causes, ischemic stroke, or MI at 1 year occurred in 9.7% of the aspirin-alone group versus 9.9% of the dual-antiplatelet group (difference, −0.2 percentage points; P for noninferiority = .004; risk ratio, 0.98; P for superiority = .93).

Dr. ten Berg pointed out that the trial was not strictly powered to look at thrombotic events, but he added: “There was no hint of an increase in the aspirin-alone group and there was quite a high event rate, so we should have seen something if it was there.”

The group has also performed a meta-analysis of these results, with some previous smaller studies also comparing aspirin and DAPT in TAVI which again showed no reduction in thrombotic events with dual-antiplatelet therapy.

Dr. ten Berg noted that the trial included all-comer TAVI patients. “The overall risk was quite a low [STS score, 2.5]. This is a reflection of the typical TAVI patient we are seeing but I would say our results apply to patients of all risk.”

Simplifies and clarifies

Discussant of the trial at the ESC Hotline session, Anna Sonia Petronio, MD, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Pisana, Pisa, Italy, said, “This was an excellent and essential study that simplifies and clarifies aspects of TAVI treatment and needs to change the guidelines.”

“These results will have a large impact on clinical practice in this elderly population,” she said. But she added that more data are needed for younger patients and more complicated cases, such as valve-in-valve and bicuspid valves.

Commenting on the results, Robert Bonow, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, said, “The optimal antithrombotic management of patients undergoing TAVI who do not otherwise have an indication for anticoagulation [such as atrial fibrillation] has been uncertain and debatable. Aspirin plus clopidogrel for 3-6 months has been the standard, based on the experience with coronary stents.”

“Thus, the current results of cohort A of the POPular TAVI trial showing significant reduction in bleeding events with aspirin alone compared to DAPT for 3 months, with no difference in ischemic events, are important observations,” he said. “It is noteworthy that most of the bleeding events occurred in the first 30 days.

“This is a relatively small randomized trial, so whether these results will be practice changing will depend on confirmation by additional studies, but it is reassuring to know that patients at higher risk for bleeding would appear to do well with low-dose aspirin alone after TAVI,” Dr. Bonow added.

“These results complete the circle in terms of antithrombotic therapy after TAVI,” commented Michael Reardon, MD, Houston Methodist DeBakey Heart & Vascular Institute, Texas.

“I would add two caveats: First is that most of the difference in the primary endpoint occurs in the first month and levels out between the groups after that,” Dr. Reardon said. “Second is that this does not address the issue of leaflet thickening and immobility.”

Ashish Pershad, MD, Banner – University Medicine Heart Institute, Phoenix, added: “This trial answers a very important question and shows dual-antiplatelet therapy is hazardous in TAVI patients. Clopidogrel is not needed.”

Dr. Pershad says he still wonders about patients who receive very small valves who may have a higher risk for valve-induced thrombosis. “While there were some of these patients in the trial, the numbers were small, so we need more data on this group,” he commented.

“But for bread-and-butter TAVI, aspirin alone is the best choice, and the previous results showed, for patients already taking oral anticoagulation, no additional antithrombotic therapy is required,” Dr. Pershad concluded. “This is a big deal and will change the way we treat patients.”

The POPular trial was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development. Brouwer reports no disclosures.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Report touts PFO closure in divers; experts disagree

A new report recommends the surgical closure of patent foramen ovale (PFO) in high-risk divers, but physicians in the United States urged caution about widespread use of the procedure in this population.

“PFO closure is recommended in divers with a high-grade PFO, with a history of unprovoked decompression sickness [DCS], or at the diver’s preference. Besides protection from DCS, PFO closure also offers the diver life-long protection from PFO-associated stroke,” write the authors of an analysis of the DIVE-PFO Registry.

The investigators, led by Jakub Honêk, MD, PhD, of Motol

Over a mean of about 7 years, the divers who underwent catheter-based PFO closure had no unprovoked decompression sickness (DCS), while the condition occurred in 11% of those who hadn’t had the procedure, according to the report, a research letter published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.Decompression sickness, also known as the bends, can occur as gas bubbles pass through the circulatory system as divers ascend. In divers with PFO, which affects about 25% of the population, the bubbles can bypass filtration in the lungs and cause strokes, said neurologist David Thaler, MD, PhD, of Tufts Medical Center, Boston.

PFO closure via surgery is one option for divers with PFO, but there’s debate over whether the procedure should be widespread. For the new research letter, researchers prospectively tracked 748 divers in the DIVE-PFO (Decompression Illness Prevention in Divers with a Patent Foramen Ovale) registry during 2006-2018. Twenty-two percent had high-grade PFO.

In divers with PFO of grade 3 or above, procedures were performed if patients had a history of DCS or if they couldn’t adapt to conservative diving recommendations. The researchers said this population included commercial divers.

The groups that did or didn’t undergo surgery were similar in age (40.0 and 37.3 years, respectively, P = 0.079), and sex (78.2% and 79.6% male, respectively, P = 0.893), but differed in number of new dives (30,684 vs. 25,328, respectively, P < 0.001,), ). They were tracked for a mean of 7.1 years and 6.5 years, respectively.

It’s not clear whether the divers who underwent the closure procedure had fewer DCSs because they were more cautious about dive safety than the other diver group. The research letter doesn’t mention whether strokes occurred in divers in the two groups.

The study authors write that the results are consistent with previous findings that “PFO closure eliminates arterial gas emboli, “PFO is a major risk factor for unprovoked DCS,” and “PFO closure is a safe procedure with a very low complication rate.”

In interviews, physicians who are familiar with diver safety questioned the value of the findings and said medical professionals shouldn’t change practice.

Not so fast, experts say

Dr. Thaler, the Tufts Medical Center neurologist, questioned why the report explored a link between PFO and DCS. Overall, he said, the findings are too incomplete to inform practice. Anesthesiologist Richard Moon, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., also questioned the study’s examination of DCS. “Most DCS cases are uncorrelated with PFO. It is only serious cases, a minority, that could conceivably be related to PFO, and even then, many serious cases that occur in divers with PFO are unrelated to it.” He added that “numerous divers with mild DCS ... have been mistakenly evaluated for PFO. Such practice is unsubstantiated by data.”

Should more closures be performed in this population? “I would be hesitant to make the recommended closures in divers,” said cardiologist David C. Peritz, MD, of Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H. “There are probably other ways that you can decrease your chances of getting decompression illness and make your dives more safe.”

Cardiologist Clifford J. Kavinsky, MD, PhD, of Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, said the closure procedure is “relatively safe” when performed by experienced surgeons. He noted that it is “only approved to prevent recurrent ischemic stroke in patients predominantly between the ages of 18 and 60 years who have experienced a cortical stroke presumed to be of embolic nature and for which no obvious cause can be found.”

As for high-risk divers, he said PFO closures “can be considered, but the data as yet are not strong enough to strongly recommend it.”

The Czech Republic’s Ministry of Health funded the study. The authors report no relevant disclosures. Dr. Thaler, Dr. Kavinsky, Dr. Moon and Dr. Peritz report no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Honěk J et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Sep 1;76(9):1149-50.

A new report recommends the surgical closure of patent foramen ovale (PFO) in high-risk divers, but physicians in the United States urged caution about widespread use of the procedure in this population.

“PFO closure is recommended in divers with a high-grade PFO, with a history of unprovoked decompression sickness [DCS], or at the diver’s preference. Besides protection from DCS, PFO closure also offers the diver life-long protection from PFO-associated stroke,” write the authors of an analysis of the DIVE-PFO Registry.

The investigators, led by Jakub Honêk, MD, PhD, of Motol

Over a mean of about 7 years, the divers who underwent catheter-based PFO closure had no unprovoked decompression sickness (DCS), while the condition occurred in 11% of those who hadn’t had the procedure, according to the report, a research letter published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.Decompression sickness, also known as the bends, can occur as gas bubbles pass through the circulatory system as divers ascend. In divers with PFO, which affects about 25% of the population, the bubbles can bypass filtration in the lungs and cause strokes, said neurologist David Thaler, MD, PhD, of Tufts Medical Center, Boston.

PFO closure via surgery is one option for divers with PFO, but there’s debate over whether the procedure should be widespread. For the new research letter, researchers prospectively tracked 748 divers in the DIVE-PFO (Decompression Illness Prevention in Divers with a Patent Foramen Ovale) registry during 2006-2018. Twenty-two percent had high-grade PFO.

In divers with PFO of grade 3 or above, procedures were performed if patients had a history of DCS or if they couldn’t adapt to conservative diving recommendations. The researchers said this population included commercial divers.

The groups that did or didn’t undergo surgery were similar in age (40.0 and 37.3 years, respectively, P = 0.079), and sex (78.2% and 79.6% male, respectively, P = 0.893), but differed in number of new dives (30,684 vs. 25,328, respectively, P < 0.001,), ). They were tracked for a mean of 7.1 years and 6.5 years, respectively.

It’s not clear whether the divers who underwent the closure procedure had fewer DCSs because they were more cautious about dive safety than the other diver group. The research letter doesn’t mention whether strokes occurred in divers in the two groups.

The study authors write that the results are consistent with previous findings that “PFO closure eliminates arterial gas emboli, “PFO is a major risk factor for unprovoked DCS,” and “PFO closure is a safe procedure with a very low complication rate.”

In interviews, physicians who are familiar with diver safety questioned the value of the findings and said medical professionals shouldn’t change practice.

Not so fast, experts say

Dr. Thaler, the Tufts Medical Center neurologist, questioned why the report explored a link between PFO and DCS. Overall, he said, the findings are too incomplete to inform practice. Anesthesiologist Richard Moon, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., also questioned the study’s examination of DCS. “Most DCS cases are uncorrelated with PFO. It is only serious cases, a minority, that could conceivably be related to PFO, and even then, many serious cases that occur in divers with PFO are unrelated to it.” He added that “numerous divers with mild DCS ... have been mistakenly evaluated for PFO. Such practice is unsubstantiated by data.”

Should more closures be performed in this population? “I would be hesitant to make the recommended closures in divers,” said cardiologist David C. Peritz, MD, of Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H. “There are probably other ways that you can decrease your chances of getting decompression illness and make your dives more safe.”

Cardiologist Clifford J. Kavinsky, MD, PhD, of Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, said the closure procedure is “relatively safe” when performed by experienced surgeons. He noted that it is “only approved to prevent recurrent ischemic stroke in patients predominantly between the ages of 18 and 60 years who have experienced a cortical stroke presumed to be of embolic nature and for which no obvious cause can be found.”

As for high-risk divers, he said PFO closures “can be considered, but the data as yet are not strong enough to strongly recommend it.”

The Czech Republic’s Ministry of Health funded the study. The authors report no relevant disclosures. Dr. Thaler, Dr. Kavinsky, Dr. Moon and Dr. Peritz report no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Honěk J et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Sep 1;76(9):1149-50.

A new report recommends the surgical closure of patent foramen ovale (PFO) in high-risk divers, but physicians in the United States urged caution about widespread use of the procedure in this population.

“PFO closure is recommended in divers with a high-grade PFO, with a history of unprovoked decompression sickness [DCS], or at the diver’s preference. Besides protection from DCS, PFO closure also offers the diver life-long protection from PFO-associated stroke,” write the authors of an analysis of the DIVE-PFO Registry.

The investigators, led by Jakub Honêk, MD, PhD, of Motol

Over a mean of about 7 years, the divers who underwent catheter-based PFO closure had no unprovoked decompression sickness (DCS), while the condition occurred in 11% of those who hadn’t had the procedure, according to the report, a research letter published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.Decompression sickness, also known as the bends, can occur as gas bubbles pass through the circulatory system as divers ascend. In divers with PFO, which affects about 25% of the population, the bubbles can bypass filtration in the lungs and cause strokes, said neurologist David Thaler, MD, PhD, of Tufts Medical Center, Boston.

PFO closure via surgery is one option for divers with PFO, but there’s debate over whether the procedure should be widespread. For the new research letter, researchers prospectively tracked 748 divers in the DIVE-PFO (Decompression Illness Prevention in Divers with a Patent Foramen Ovale) registry during 2006-2018. Twenty-two percent had high-grade PFO.

In divers with PFO of grade 3 or above, procedures were performed if patients had a history of DCS or if they couldn’t adapt to conservative diving recommendations. The researchers said this population included commercial divers.

The groups that did or didn’t undergo surgery were similar in age (40.0 and 37.3 years, respectively, P = 0.079), and sex (78.2% and 79.6% male, respectively, P = 0.893), but differed in number of new dives (30,684 vs. 25,328, respectively, P < 0.001,), ). They were tracked for a mean of 7.1 years and 6.5 years, respectively.

It’s not clear whether the divers who underwent the closure procedure had fewer DCSs because they were more cautious about dive safety than the other diver group. The research letter doesn’t mention whether strokes occurred in divers in the two groups.

The study authors write that the results are consistent with previous findings that “PFO closure eliminates arterial gas emboli, “PFO is a major risk factor for unprovoked DCS,” and “PFO closure is a safe procedure with a very low complication rate.”

In interviews, physicians who are familiar with diver safety questioned the value of the findings and said medical professionals shouldn’t change practice.

Not so fast, experts say

Dr. Thaler, the Tufts Medical Center neurologist, questioned why the report explored a link between PFO and DCS. Overall, he said, the findings are too incomplete to inform practice. Anesthesiologist Richard Moon, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., also questioned the study’s examination of DCS. “Most DCS cases are uncorrelated with PFO. It is only serious cases, a minority, that could conceivably be related to PFO, and even then, many serious cases that occur in divers with PFO are unrelated to it.” He added that “numerous divers with mild DCS ... have been mistakenly evaluated for PFO. Such practice is unsubstantiated by data.”

Should more closures be performed in this population? “I would be hesitant to make the recommended closures in divers,” said cardiologist David C. Peritz, MD, of Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H. “There are probably other ways that you can decrease your chances of getting decompression illness and make your dives more safe.”

Cardiologist Clifford J. Kavinsky, MD, PhD, of Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, said the closure procedure is “relatively safe” when performed by experienced surgeons. He noted that it is “only approved to prevent recurrent ischemic stroke in patients predominantly between the ages of 18 and 60 years who have experienced a cortical stroke presumed to be of embolic nature and for which no obvious cause can be found.”

As for high-risk divers, he said PFO closures “can be considered, but the data as yet are not strong enough to strongly recommend it.”

The Czech Republic’s Ministry of Health funded the study. The authors report no relevant disclosures. Dr. Thaler, Dr. Kavinsky, Dr. Moon and Dr. Peritz report no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Honěk J et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Sep 1;76(9):1149-50.

FROM JACC

Hypertension often goes undertreated in patients with a history of stroke

A new study of hypertension treatment trends found that “To our knowledge, the present study is the first to analyze and report national antihypertensive medication trends exclusively among individuals with a history of stroke in the United States,” wrote Daniel Santos, MD, and Mandip S. Dhamoon, MD, DrPH, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Their study was published in JAMA Neurology.

To examine blood pressure control and treatment trends among stroke survivors, the researchers examined more than a decade of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The cross-sectional survey is conducted in 2-year cycles; the authors analyzed the results from 2005 to 2016 and uncovered a total of 4,971,136 eligible individuals with a history of both stroke and hypertension.

The mean age of the study population was 67.1 (95% confidence interval, 66.1-68.1), and 2,790,518 (56.1%) were women. Their mean blood pressure was 134/68 mm Hg (95% CI, 133/67–136/69), and the average number of antihypertensive medications they were taking was 1.8 (95% CI, 1.7-1.9). Of the 4,971,136 analyzed individuals, 4,721,409 (95%) were aware of their hypertension diagnosis yet more than 10% of that group had not previously been prescribed an antihypertensive medication.

More than 37% (n = 1,846,470) of the participants had uncontrolled high blood pressure upon examination (95% CI, 33.5%-40.8%), and 15.3% (95% CI, 12.5%-18.0%) were not taking any medication for it at all. The most commonly used antihypertensive medications included ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (59.2%; 95% CI, 54.9%-63.4%), beta-blockers (43.8%; 95% CI, 40.3%-47.3%), diuretics (41.6%; 95% CI, 37.3%-45.9%) and calcium-channel blockers (31.5%; 95% CI, 28.2%-34.8%).* Roughly 57% of the sample was taking more than one antihypertensive medication (95% CI, 52.8%-60.6%) while 28% (95% CI, 24.6%-31.5%) were taking only one.

Continued surveillance is key

“All the studies that have ever been done show that hypertension is inadequately treated,” Louis Caplan, MD, of Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, both in Boston, said in an interview. “One of the reasons is that it can be hard to get some of the patients to seek treatment, particularly Black Americans. Also, a lot of the medicines to treat high blood pressure have side effects, so many patients don’t want to take the pills.

“Treating hypertension really requires continued surveillance,” he added. “It’s not one visit where the doctor gives you a pill. It’s taking the pill, following your blood pressure, and seeing if it works. If it doesn’t, then maybe you change the dose, get another pill, and are followed once again. That doesn’t happen as often as it should.”

In regard to next steps, Dr. Caplan urged that hypertension “be evaluated more seriously. Even as home blood pressure kits and monitoring become increasingly available, many doctors are still going by a casual blood pressure test in the office, which doesn’t tell you how serious the problem is. There needs to be more use of technology and more conditioning of patients to monitor their own blood pressure as a guide, and then we go from there.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including the NHANES’s reliance on self-reporting a history of stroke and the inability to distinguish between subtypes of stroke. In addition, they noted that many antihypertensive medications have uses beyond treating hypertension, which introduces “another confounding factor to medication trends.”

The authors and Dr. Caplan reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Santos D et al. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Jul 27. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2499.

Correction, 8/20/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the confidence interval for diuretics.

A new study of hypertension treatment trends found that “To our knowledge, the present study is the first to analyze and report national antihypertensive medication trends exclusively among individuals with a history of stroke in the United States,” wrote Daniel Santos, MD, and Mandip S. Dhamoon, MD, DrPH, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Their study was published in JAMA Neurology.

To examine blood pressure control and treatment trends among stroke survivors, the researchers examined more than a decade of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The cross-sectional survey is conducted in 2-year cycles; the authors analyzed the results from 2005 to 2016 and uncovered a total of 4,971,136 eligible individuals with a history of both stroke and hypertension.

The mean age of the study population was 67.1 (95% confidence interval, 66.1-68.1), and 2,790,518 (56.1%) were women. Their mean blood pressure was 134/68 mm Hg (95% CI, 133/67–136/69), and the average number of antihypertensive medications they were taking was 1.8 (95% CI, 1.7-1.9). Of the 4,971,136 analyzed individuals, 4,721,409 (95%) were aware of their hypertension diagnosis yet more than 10% of that group had not previously been prescribed an antihypertensive medication.

More than 37% (n = 1,846,470) of the participants had uncontrolled high blood pressure upon examination (95% CI, 33.5%-40.8%), and 15.3% (95% CI, 12.5%-18.0%) were not taking any medication for it at all. The most commonly used antihypertensive medications included ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (59.2%; 95% CI, 54.9%-63.4%), beta-blockers (43.8%; 95% CI, 40.3%-47.3%), diuretics (41.6%; 95% CI, 37.3%-45.9%) and calcium-channel blockers (31.5%; 95% CI, 28.2%-34.8%).* Roughly 57% of the sample was taking more than one antihypertensive medication (95% CI, 52.8%-60.6%) while 28% (95% CI, 24.6%-31.5%) were taking only one.

Continued surveillance is key

“All the studies that have ever been done show that hypertension is inadequately treated,” Louis Caplan, MD, of Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, both in Boston, said in an interview. “One of the reasons is that it can be hard to get some of the patients to seek treatment, particularly Black Americans. Also, a lot of the medicines to treat high blood pressure have side effects, so many patients don’t want to take the pills.

“Treating hypertension really requires continued surveillance,” he added. “It’s not one visit where the doctor gives you a pill. It’s taking the pill, following your blood pressure, and seeing if it works. If it doesn’t, then maybe you change the dose, get another pill, and are followed once again. That doesn’t happen as often as it should.”

In regard to next steps, Dr. Caplan urged that hypertension “be evaluated more seriously. Even as home blood pressure kits and monitoring become increasingly available, many doctors are still going by a casual blood pressure test in the office, which doesn’t tell you how serious the problem is. There needs to be more use of technology and more conditioning of patients to monitor their own blood pressure as a guide, and then we go from there.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including the NHANES’s reliance on self-reporting a history of stroke and the inability to distinguish between subtypes of stroke. In addition, they noted that many antihypertensive medications have uses beyond treating hypertension, which introduces “another confounding factor to medication trends.”

The authors and Dr. Caplan reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Santos D et al. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Jul 27. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2499.

Correction, 8/20/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the confidence interval for diuretics.

A new study of hypertension treatment trends found that “To our knowledge, the present study is the first to analyze and report national antihypertensive medication trends exclusively among individuals with a history of stroke in the United States,” wrote Daniel Santos, MD, and Mandip S. Dhamoon, MD, DrPH, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Their study was published in JAMA Neurology.

To examine blood pressure control and treatment trends among stroke survivors, the researchers examined more than a decade of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The cross-sectional survey is conducted in 2-year cycles; the authors analyzed the results from 2005 to 2016 and uncovered a total of 4,971,136 eligible individuals with a history of both stroke and hypertension.

The mean age of the study population was 67.1 (95% confidence interval, 66.1-68.1), and 2,790,518 (56.1%) were women. Their mean blood pressure was 134/68 mm Hg (95% CI, 133/67–136/69), and the average number of antihypertensive medications they were taking was 1.8 (95% CI, 1.7-1.9). Of the 4,971,136 analyzed individuals, 4,721,409 (95%) were aware of their hypertension diagnosis yet more than 10% of that group had not previously been prescribed an antihypertensive medication.

More than 37% (n = 1,846,470) of the participants had uncontrolled high blood pressure upon examination (95% CI, 33.5%-40.8%), and 15.3% (95% CI, 12.5%-18.0%) were not taking any medication for it at all. The most commonly used antihypertensive medications included ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (59.2%; 95% CI, 54.9%-63.4%), beta-blockers (43.8%; 95% CI, 40.3%-47.3%), diuretics (41.6%; 95% CI, 37.3%-45.9%) and calcium-channel blockers (31.5%; 95% CI, 28.2%-34.8%).* Roughly 57% of the sample was taking more than one antihypertensive medication (95% CI, 52.8%-60.6%) while 28% (95% CI, 24.6%-31.5%) were taking only one.

Continued surveillance is key

“All the studies that have ever been done show that hypertension is inadequately treated,” Louis Caplan, MD, of Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, both in Boston, said in an interview. “One of the reasons is that it can be hard to get some of the patients to seek treatment, particularly Black Americans. Also, a lot of the medicines to treat high blood pressure have side effects, so many patients don’t want to take the pills.

“Treating hypertension really requires continued surveillance,” he added. “It’s not one visit where the doctor gives you a pill. It’s taking the pill, following your blood pressure, and seeing if it works. If it doesn’t, then maybe you change the dose, get another pill, and are followed once again. That doesn’t happen as often as it should.”

In regard to next steps, Dr. Caplan urged that hypertension “be evaluated more seriously. Even as home blood pressure kits and monitoring become increasingly available, many doctors are still going by a casual blood pressure test in the office, which doesn’t tell you how serious the problem is. There needs to be more use of technology and more conditioning of patients to monitor their own blood pressure as a guide, and then we go from there.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including the NHANES’s reliance on self-reporting a history of stroke and the inability to distinguish between subtypes of stroke. In addition, they noted that many antihypertensive medications have uses beyond treating hypertension, which introduces “another confounding factor to medication trends.”

The authors and Dr. Caplan reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Santos D et al. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Jul 27. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2499.

Correction, 8/20/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the confidence interval for diuretics.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

COVID-19 fears would keep most Hispanics with stroke, MI symptoms home

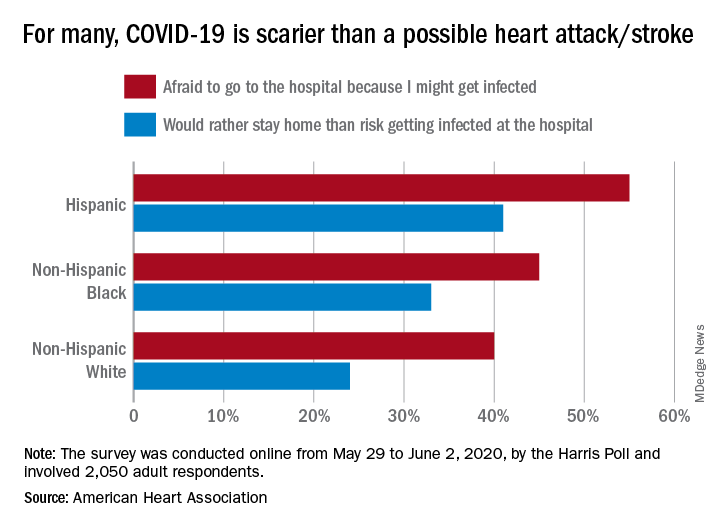

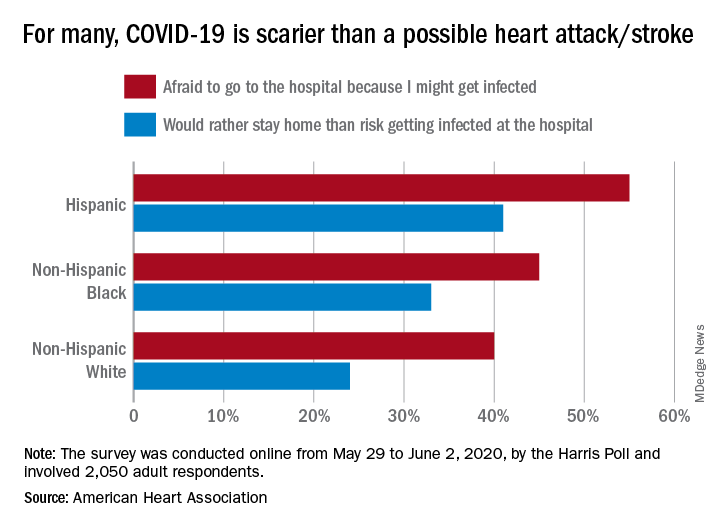

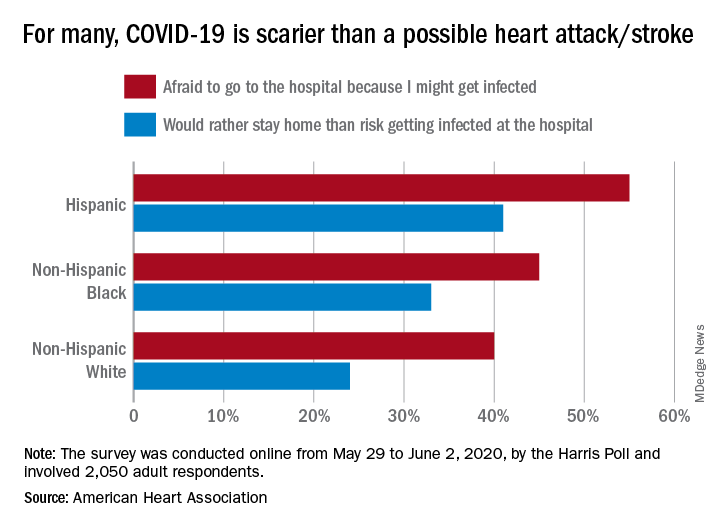

More than half of Hispanic adults would be afraid to go to a hospital for a possible heart attack or stroke because they might get infected with SARS-CoV-2, according to a new survey from the American Heart Association.

Compared with Hispanic respondents, 55% of whom said they feared COVID-19, significantly fewer Blacks (45%) and Whites (40%) would be scared to go to the hospital if they thought they were having a heart attack or stroke, the AHA said based on the survey of 2,050 adults, which was conducted May 29 to June 2, 2020, by the Harris Poll.

Hispanics also were significantly more likely to stay home if they thought they were experiencing a heart attack or stroke (41%), rather than risk getting infected at the hospital, than were Blacks (33%), who were significantly more likely than Whites (24%) to stay home, the AHA reported.

White respondents, on the other hand, were the most likely to believe (89%) that a hospital would give them the same quality of care provided to everyone else. Hispanics and Blacks had significantly lower rates, at 78% and 74%, respectively, the AHA noted.

These findings are “yet another challenge for Black and Hispanic communities, who are more likely to have underlying health conditions such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes and dying of COVID-19 at disproportionately high rates,” Rafael Ortiz, MD, American Heart Association volunteer medical expert and chief of neuro-endovascular surgery at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, said in the AHA statement.

The survey was performed in conjunction with the AHA’s “Don’t Die of Doubt” campaign, which “reminds Americans, especially in Hispanic and Black communities, that the hospital remains the safest place to be if experiencing symptoms of a heart attack or a stroke.”

Among all the survey respondents, 57% said they would feel better if hospitals treated COVID-19 patients in a separate area. A number of other possible precautions ranked lower in helping them feel better:

- Screen all visitors, patients, and staff for COVID-19 symptoms when they enter the hospital: 39%.

- Require all patients, visitors, and staff to wear masks: 30%.

- Put increased cleaning protocols in place to disinfect multiple times per day: 23%.

- “Nothing would make me feel comfortable”: 6%.

Despite all the concerns about the risk of coronavirus infection, however, most Americans (77%) still believe that hospitals are the safest place to be in the event of a medical emergency, and 84% said that hospitals are prepared to safely treat emergencies that are not related to the pandemic, the AHA reported.

“Health care professionals know what to do even when things seem chaotic, and emergency departments have made plans behind the scenes to keep patients and healthcare workers safe even during a pandemic,” Dr. Ortiz pointed out.

More than half of Hispanic adults would be afraid to go to a hospital for a possible heart attack or stroke because they might get infected with SARS-CoV-2, according to a new survey from the American Heart Association.

Compared with Hispanic respondents, 55% of whom said they feared COVID-19, significantly fewer Blacks (45%) and Whites (40%) would be scared to go to the hospital if they thought they were having a heart attack or stroke, the AHA said based on the survey of 2,050 adults, which was conducted May 29 to June 2, 2020, by the Harris Poll.

Hispanics also were significantly more likely to stay home if they thought they were experiencing a heart attack or stroke (41%), rather than risk getting infected at the hospital, than were Blacks (33%), who were significantly more likely than Whites (24%) to stay home, the AHA reported.

White respondents, on the other hand, were the most likely to believe (89%) that a hospital would give them the same quality of care provided to everyone else. Hispanics and Blacks had significantly lower rates, at 78% and 74%, respectively, the AHA noted.

These findings are “yet another challenge for Black and Hispanic communities, who are more likely to have underlying health conditions such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes and dying of COVID-19 at disproportionately high rates,” Rafael Ortiz, MD, American Heart Association volunteer medical expert and chief of neuro-endovascular surgery at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, said in the AHA statement.

The survey was performed in conjunction with the AHA’s “Don’t Die of Doubt” campaign, which “reminds Americans, especially in Hispanic and Black communities, that the hospital remains the safest place to be if experiencing symptoms of a heart attack or a stroke.”

Among all the survey respondents, 57% said they would feel better if hospitals treated COVID-19 patients in a separate area. A number of other possible precautions ranked lower in helping them feel better:

- Screen all visitors, patients, and staff for COVID-19 symptoms when they enter the hospital: 39%.

- Require all patients, visitors, and staff to wear masks: 30%.

- Put increased cleaning protocols in place to disinfect multiple times per day: 23%.

- “Nothing would make me feel comfortable”: 6%.

Despite all the concerns about the risk of coronavirus infection, however, most Americans (77%) still believe that hospitals are the safest place to be in the event of a medical emergency, and 84% said that hospitals are prepared to safely treat emergencies that are not related to the pandemic, the AHA reported.

“Health care professionals know what to do even when things seem chaotic, and emergency departments have made plans behind the scenes to keep patients and healthcare workers safe even during a pandemic,” Dr. Ortiz pointed out.

More than half of Hispanic adults would be afraid to go to a hospital for a possible heart attack or stroke because they might get infected with SARS-CoV-2, according to a new survey from the American Heart Association.

Compared with Hispanic respondents, 55% of whom said they feared COVID-19, significantly fewer Blacks (45%) and Whites (40%) would be scared to go to the hospital if they thought they were having a heart attack or stroke, the AHA said based on the survey of 2,050 adults, which was conducted May 29 to June 2, 2020, by the Harris Poll.

Hispanics also were significantly more likely to stay home if they thought they were experiencing a heart attack or stroke (41%), rather than risk getting infected at the hospital, than were Blacks (33%), who were significantly more likely than Whites (24%) to stay home, the AHA reported.

White respondents, on the other hand, were the most likely to believe (89%) that a hospital would give them the same quality of care provided to everyone else. Hispanics and Blacks had significantly lower rates, at 78% and 74%, respectively, the AHA noted.

These findings are “yet another challenge for Black and Hispanic communities, who are more likely to have underlying health conditions such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes and dying of COVID-19 at disproportionately high rates,” Rafael Ortiz, MD, American Heart Association volunteer medical expert and chief of neuro-endovascular surgery at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, said in the AHA statement.

The survey was performed in conjunction with the AHA’s “Don’t Die of Doubt” campaign, which “reminds Americans, especially in Hispanic and Black communities, that the hospital remains the safest place to be if experiencing symptoms of a heart attack or a stroke.”

Among all the survey respondents, 57% said they would feel better if hospitals treated COVID-19 patients in a separate area. A number of other possible precautions ranked lower in helping them feel better:

- Screen all visitors, patients, and staff for COVID-19 symptoms when they enter the hospital: 39%.

- Require all patients, visitors, and staff to wear masks: 30%.

- Put increased cleaning protocols in place to disinfect multiple times per day: 23%.

- “Nothing would make me feel comfortable”: 6%.

Despite all the concerns about the risk of coronavirus infection, however, most Americans (77%) still believe that hospitals are the safest place to be in the event of a medical emergency, and 84% said that hospitals are prepared to safely treat emergencies that are not related to the pandemic, the AHA reported.

“Health care professionals know what to do even when things seem chaotic, and emergency departments have made plans behind the scenes to keep patients and healthcare workers safe even during a pandemic,” Dr. Ortiz pointed out.

New oral anticoagulants drive ACC consensus on bleeding

Patients on oral anticoagulants who experience a bleeding event may be able to discontinue therapy if certain circumstances apply, according to updated guidance from the American College of Cardiology.

The emergence of direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs) to prevent venous thromboembolism and the introduction of new reversal strategies for factor Xa inhibitors prompted the creation of an Expert Consensus Decision Pathway to update the version from 2017, according to the ACC. Expert consensus decision pathways (ECDPs) are a component of the solution sets issued by the ACC to “address key questions facing care teams and attempt to provide practical guidance to be applied at the point of care.”

In an ECDP published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, the writing committee members developed treatment algorithms for managing bleeding in patients on DOACs and vitamin K antagonists (VKAs).

Bleeding was classified as major or nonmajor, with major defined as “bleeding that is associated with hemodynamic compromise, occurs in an anatomically critical site, requires transfusion of at least 2 units of packed red blood cells [RBCs]), or results in a hemoglobin drop greater than 2 g/dL. All other types of bleeding were classified as nonmajor.

The document includes a graphic algorithm for assessing bleed severity and managing major versus nonmajor bleeding, and a separate graphic describes considerations for reversal and use of hemostatic agents according to whether the patient is taking a VKA (warfarin and other coumarins), a direct thrombin inhibitor (dabigatran), the factor Xa inhibitors apixaban and rivaroxaban, or the factor Xa inhibitors betrixaban and edoxaban.

Another algorithm outlines whether to discontinue, delay, or restart anticoagulation. Considerations for restarting anticoagulation include whether the patient is pregnant, awaiting an invasive procedure, not able to receive medication by mouth, has a high risk of rebleeding, or is being bridged back to a vitamin K antagonist with high thrombotic risk.

In most cases of GI bleeding, for example, current data support restarting oral anticoagulants once hemostasis is achieved, but patients who experience intracranial hemorrhage should delay restarting any anticoagulation for at least 4 weeks if they are without high thrombotic risk, according to the document.

The report also recommends clinician-patient discussion before resuming anticoagulation, ideally with time allowed for patients to develop questions. Discussions should include the signs of bleeding, assessment of risk for a thromboembolic event, and the benefits of anticoagulation.

“The proliferation of oral anticoagulants (warfarin and DOACs) and growing indications for their use prompted the need for guidance on the management of these drugs,” said Gordon F. Tomaselli, MD, chair of the writing committee, in an interview. “This document provides guidance on management at the time of a bleeding complication. This includes acute management, starting and stopping drugs, and use of reversal agents,” he said. “This of course will be a dynamic document as the list of these drugs and their antidotes expand,” he noted.

“The biggest change from the previous guidelines are twofold: an update on laboratory assessment to monitor drug levels and use of reversal agents,” while the acute management strategies have otherwise remained similar to previous documents, said Dr. Tomaselli.

Dr. Tomaselli said that he was not surprised by the biological aspects of recent research while developing the statement. However, “the extent of the use of multiple anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents was a bit surprising and complicates therapy with each of the agents,” he noted.

The way the pathways are presented may make them challenging to follow in clinical practice, said Dr. Tomaselli. “The pathways are described linearly and in practice often many things have to happen at once,” he said. “The other main issue may be limitations in the availability of some of the newer reversal agents,” he added.

“The complication of bleeding is difficult to avoid,” said Dr. Tomaselli, and for future research, “the focus needs to continue to refine the indications for anticoagulation and appropriate use with other drugs that predispose to bleeding. We also need better methods and testing to monitor drugs levels and the effect on coagulation,” he said.

In accordance with the ACC Solution Set Oversight Committee, the writing committee members, including Dr. Tomaselli, had no relevant relationships with industry to disclose.

SOURCE: Tomaselli GF et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.053.

Patients on oral anticoagulants who experience a bleeding event may be able to discontinue therapy if certain circumstances apply, according to updated guidance from the American College of Cardiology.

The emergence of direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs) to prevent venous thromboembolism and the introduction of new reversal strategies for factor Xa inhibitors prompted the creation of an Expert Consensus Decision Pathway to update the version from 2017, according to the ACC. Expert consensus decision pathways (ECDPs) are a component of the solution sets issued by the ACC to “address key questions facing care teams and attempt to provide practical guidance to be applied at the point of care.”

In an ECDP published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, the writing committee members developed treatment algorithms for managing bleeding in patients on DOACs and vitamin K antagonists (VKAs).

Bleeding was classified as major or nonmajor, with major defined as “bleeding that is associated with hemodynamic compromise, occurs in an anatomically critical site, requires transfusion of at least 2 units of packed red blood cells [RBCs]), or results in a hemoglobin drop greater than 2 g/dL. All other types of bleeding were classified as nonmajor.

The document includes a graphic algorithm for assessing bleed severity and managing major versus nonmajor bleeding, and a separate graphic describes considerations for reversal and use of hemostatic agents according to whether the patient is taking a VKA (warfarin and other coumarins), a direct thrombin inhibitor (dabigatran), the factor Xa inhibitors apixaban and rivaroxaban, or the factor Xa inhibitors betrixaban and edoxaban.

Another algorithm outlines whether to discontinue, delay, or restart anticoagulation. Considerations for restarting anticoagulation include whether the patient is pregnant, awaiting an invasive procedure, not able to receive medication by mouth, has a high risk of rebleeding, or is being bridged back to a vitamin K antagonist with high thrombotic risk.

In most cases of GI bleeding, for example, current data support restarting oral anticoagulants once hemostasis is achieved, but patients who experience intracranial hemorrhage should delay restarting any anticoagulation for at least 4 weeks if they are without high thrombotic risk, according to the document.

The report also recommends clinician-patient discussion before resuming anticoagulation, ideally with time allowed for patients to develop questions. Discussions should include the signs of bleeding, assessment of risk for a thromboembolic event, and the benefits of anticoagulation.

“The proliferation of oral anticoagulants (warfarin and DOACs) and growing indications for their use prompted the need for guidance on the management of these drugs,” said Gordon F. Tomaselli, MD, chair of the writing committee, in an interview. “This document provides guidance on management at the time of a bleeding complication. This includes acute management, starting and stopping drugs, and use of reversal agents,” he said. “This of course will be a dynamic document as the list of these drugs and their antidotes expand,” he noted.

“The biggest change from the previous guidelines are twofold: an update on laboratory assessment to monitor drug levels and use of reversal agents,” while the acute management strategies have otherwise remained similar to previous documents, said Dr. Tomaselli.

Dr. Tomaselli said that he was not surprised by the biological aspects of recent research while developing the statement. However, “the extent of the use of multiple anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents was a bit surprising and complicates therapy with each of the agents,” he noted.

The way the pathways are presented may make them challenging to follow in clinical practice, said Dr. Tomaselli. “The pathways are described linearly and in practice often many things have to happen at once,” he said. “The other main issue may be limitations in the availability of some of the newer reversal agents,” he added.

“The complication of bleeding is difficult to avoid,” said Dr. Tomaselli, and for future research, “the focus needs to continue to refine the indications for anticoagulation and appropriate use with other drugs that predispose to bleeding. We also need better methods and testing to monitor drugs levels and the effect on coagulation,” he said.

In accordance with the ACC Solution Set Oversight Committee, the writing committee members, including Dr. Tomaselli, had no relevant relationships with industry to disclose.

SOURCE: Tomaselli GF et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.053.

Patients on oral anticoagulants who experience a bleeding event may be able to discontinue therapy if certain circumstances apply, according to updated guidance from the American College of Cardiology.

The emergence of direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs) to prevent venous thromboembolism and the introduction of new reversal strategies for factor Xa inhibitors prompted the creation of an Expert Consensus Decision Pathway to update the version from 2017, according to the ACC. Expert consensus decision pathways (ECDPs) are a component of the solution sets issued by the ACC to “address key questions facing care teams and attempt to provide practical guidance to be applied at the point of care.”

In an ECDP published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, the writing committee members developed treatment algorithms for managing bleeding in patients on DOACs and vitamin K antagonists (VKAs).

Bleeding was classified as major or nonmajor, with major defined as “bleeding that is associated with hemodynamic compromise, occurs in an anatomically critical site, requires transfusion of at least 2 units of packed red blood cells [RBCs]), or results in a hemoglobin drop greater than 2 g/dL. All other types of bleeding were classified as nonmajor.

The document includes a graphic algorithm for assessing bleed severity and managing major versus nonmajor bleeding, and a separate graphic describes considerations for reversal and use of hemostatic agents according to whether the patient is taking a VKA (warfarin and other coumarins), a direct thrombin inhibitor (dabigatran), the factor Xa inhibitors apixaban and rivaroxaban, or the factor Xa inhibitors betrixaban and edoxaban.

Another algorithm outlines whether to discontinue, delay, or restart anticoagulation. Considerations for restarting anticoagulation include whether the patient is pregnant, awaiting an invasive procedure, not able to receive medication by mouth, has a high risk of rebleeding, or is being bridged back to a vitamin K antagonist with high thrombotic risk.

In most cases of GI bleeding, for example, current data support restarting oral anticoagulants once hemostasis is achieved, but patients who experience intracranial hemorrhage should delay restarting any anticoagulation for at least 4 weeks if they are without high thrombotic risk, according to the document.

The report also recommends clinician-patient discussion before resuming anticoagulation, ideally with time allowed for patients to develop questions. Discussions should include the signs of bleeding, assessment of risk for a thromboembolic event, and the benefits of anticoagulation.

“The proliferation of oral anticoagulants (warfarin and DOACs) and growing indications for their use prompted the need for guidance on the management of these drugs,” said Gordon F. Tomaselli, MD, chair of the writing committee, in an interview. “This document provides guidance on management at the time of a bleeding complication. This includes acute management, starting and stopping drugs, and use of reversal agents,” he said. “This of course will be a dynamic document as the list of these drugs and their antidotes expand,” he noted.

“The biggest change from the previous guidelines are twofold: an update on laboratory assessment to monitor drug levels and use of reversal agents,” while the acute management strategies have otherwise remained similar to previous documents, said Dr. Tomaselli.

Dr. Tomaselli said that he was not surprised by the biological aspects of recent research while developing the statement. However, “the extent of the use of multiple anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents was a bit surprising and complicates therapy with each of the agents,” he noted.

The way the pathways are presented may make them challenging to follow in clinical practice, said Dr. Tomaselli. “The pathways are described linearly and in practice often many things have to happen at once,” he said. “The other main issue may be limitations in the availability of some of the newer reversal agents,” he added.

“The complication of bleeding is difficult to avoid,” said Dr. Tomaselli, and for future research, “the focus needs to continue to refine the indications for anticoagulation and appropriate use with other drugs that predispose to bleeding. We also need better methods and testing to monitor drugs levels and the effect on coagulation,” he said.

In accordance with the ACC Solution Set Oversight Committee, the writing committee members, including Dr. Tomaselli, had no relevant relationships with industry to disclose.

SOURCE: Tomaselli GF et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.053.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Ticagrelor/aspirin combo: Fewer repeat strokes and deaths, but more bleeds

, new data show. However, severe bleeding was more common in the ticagrelor/aspirin group than in the aspirin-only group.

“We found that ticagrelor plus aspirin reduced the risk of stroke or death, compared to aspirin alone in patients presenting acutely with stroke or TIA,” reported lead author S. Claiborne Johnston, MD, PhD, dean and vice president for medical affairs, Dell Medical School, the University of Texas, Austin.

Although the combination also increased the risk for major hemorrhage, that increase was small and would not overwhelm the benefit, he said.

The study was published online July 16 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Attractive properties

“Lots of patients have stroke in the days to weeks after first presenting with a stroke or TIA,” said Dr. Johnston, who is also the Frank and Charmaine Denius Distinguished Dean’s Chair at Dell Medical School. “Aspirin has been the standard of care but is only partially effective. Clopidogrel plus aspirin is another option that has recently been proven, [but] ticagrelor has attractive properties as an antiplatelet agent and works synergistically with aspirin,” he added.

Ticagrelor is a direct-acting antiplatelet agent that does not depend on metabolic activation and that “reversibly binds” and inhibits the P2Y12 receptor on platelets. Previous research has evaluated clopidogrel and aspirin for the secondary prevention of ischemic stroke or TIA. In an earlier trial, ticagrelor was no better than aspirin in preventing these subsequent events. However, the investigators noted that the combination of the two drugs has not been well studied.

The randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial involved 11,016 patients at 414 sites in 28 countries. Patients who had experienced mild to moderate acute noncardioembolic ischemic stroke (mean age, 65 years; 39% women; roughly 54% White) were randomly assigned to receive either ticagrelor plus aspirin (n = 5,523) or aspirin alone (n = 5,493) for 30 days. Of these patients, 91% had sustained a stroke, and 9% had sustained a TIA.

Thirty days was chosen as the treatment period because the risk for subsequent stroke tends to occur mainly in the first month after an acute ischemic stroke or TIA. The primary outcome was “a composite of stroke or death in a time-to-first-event analysis from randomization to 30 days of follow-up.” For the study, “stroke” encompassed ischemic, hemorrhagic, or stroke of undetermined type, and “death” included deaths of all causes. Secondary outcomes included first subsequent ischemic stroke and disability (defined as a score of >1 on the Rankin Scale).

Almost all patients (99.5%) were taking aspirin during the treatment period, and most were also taking an antihypertensive and a statin (74% and 83%, respectively).

Patients in the ticagrelor/aspirin group had fewer primary-outcome events in comparison with those in the aspirin-only group (303 patients [5.5%] vs. 362 patients [6.6%]; hazard ratio, 0.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.71-0.96; P = 0.02). Incidence of subsequent ischemic stroke were similarly lower in the ticagrelor/aspirin group in comparison with the aspirin-only group (276 patients [5.0%] vs. 345 patients [6.3%]; HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.68-0.93; P = .004).

On the other hand, there was no significant difference between the groups in the incidence of overall disability (23.8% of the patients in the ticagrelor/aspirin group and in 24.1% of the patients in the aspirin group; odds ratio, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.89-1.07; P = .61).

There were differences between the groups in severe bleeding, which occurred in 28 patients (0.5%) in the ticagrelor/aspirin group and in seven patients (0.15) in the ticagrelor group (HR, 3.99; 95% CI, 1.74-9.14; P = .001). Moreover, more patients in the ticagrelor/aspirin group experienced a composite of intracranial hemorrhage or fatal bleeding compared with the aspirin-only group (0.4% vs 0.1%). Fatal bleeding occurred in 0.2% of patients in the ticagrelor/aspirin group versus 0.1% of patients in the aspirin group. More patients in the ticagrelor-aspirin group permanently discontinued the treatment because of bleeding than in the aspirin-only group (2.8% vs. 0.6%).