User login

Comparison of Anterior and Posterior Corticosteroid Injections for Pain Relief and Functional Improvement in Shoulder Impingement Syndrome

Take-Home Points

When conservative treatments for SIS do not resolve symptoms, inflammation and pain can be reduced with use of subacromial CSI.

Both anterior CSI and posterior CSI significantly improved pain and function for up to 6 months

CSI combined with structured PT produced significant improvement in pain and function in patients with SIS, regardless of injection route used.

Clinical response to CSI may not depend on injection accuracy.

Clinicians should rely on their clinical acumen when selecting injection routes, as anterior and posterior are both beneficial.

Shoulder pain, a common clinical problem, occurs in 7% to 34% of the general population and in 21% of people older than 70 years.1Subacromial impingement refers to shoulder pain resulting from mechanical impingement of the rotator cuff underneath the coracoacromial arch between the acromion and the humeral head.2,3 Subacromial impingement syndrome (SIS) is the most common cause of shoulder pain, resulting in significant functional deficits and disability.3

Treatment options for SIS include conservative modalities such as use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, physical therapy (PT), and subacromial corticosteroid injections (CSIs). Studies have found short- and long-term improvement in pain, function, and range of motion after CSI.4-8 Subacromial CSI can be administered through an anterior or a posterior route.4,9 There have been several studies of the accuracy of anterior and posterior CSIs,10-12 with 2 studies finding similar accuracy for these routes.10,11 However, there may be a sex difference: In women, a posterior route may be less accurate than an anterior or a lateral route.12

Although the accuracy of anterior and posterior routes has been studied, their effect on clinical outcomes has not. We conducted a study to understand the effects of anterior and posterior CSIs on SIS. As one of the accuracy studies suggested anterior CSI is more accurate—the anterior route was theorized to provide easier access to the subacromial space12—we hypothesized patients treated with anterior CSI would have superior clinical outcomes 6 months after injection.12,13

Materials and Methods

Study Participants and Randomization

After this study received Institutional Review Board approval, patients with shoulder pain of more than 3 months’ duration and consistent with SIS were screened for inclusion. Eligible patients had pain in the anterior biceps and over the top of the shoulder with overhead activities as well as one or more clinical findings on physical examination: Hawkins-Kennedy sign, Neer sign, painful arc, and infraspinatus pain (pain with external rotation).

Patients were excluded if their history included prior subacromial CSI, adhesive capsulitis (inability to passively abduct shoulder to 90° with scapular stabilization), calcific tendonitis, radiographic evidence of os acromiale, cervical radiculopathy, Spurling sign, neck pain, radiating arm pain or numbness, sensory deficits, or neck and upper extremity motor dysfunction. Also excluded were patients with full-thickness rotator cuff tear, weakness on arm elevation, positive "drop arm sign," or high-riding humerus on standing shoulder radiograph. Patients who had work-related injuries or who were involved in worker compensation were excluded as well.

Enrolled patients were randomly assigned (with use of a computer-based random number generator) to receive either anterior CSI or posterior CSI.

Injection Procedures

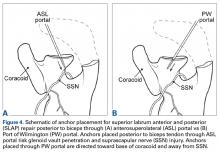

All patients were administered 5 mL of lidocaine 1% (without epinephrine) and 2 mL (80 mg) of triamcinolone by 2 board-certified orthopedic surgeons using a 22-gauge 1½-inch needle. For patients who received their subacromial CSI by the anterior route, the arm was held in 0° of abduction and 20° of external rotation. The needle was inserted medial to the humeral head, lateral to the coracoid process, beginning 1 cm inferior to the clavicle with the needle directed posteriorly and laterally toward the acromion.10 For patients who received their CSI by the posterior route, the arm was held in 0° of abduction, the posterolateral corner of the acromion was identified by palpation, and the needle was inserted 1 cm inferior and medial to this point with the needle directed anteriorly and laterally toward the acromion.10,12 In both groups, the subacromial space was identified when a drop in pressure was felt during needle insertion. Accuracy was assessed post hoc by asking patients to grade their response to the injection on a visual analog scale (VAS); VAS score was used as a surrogate for improvement. All patients had a positive Neer test: Pain decreased with impingement maneuvers immediately after injection.

All patients were referred for PT provided according to an evidence-based rehabilitation protocol.14 This program emphasized range of motion with shoulder shrugs, scapular retraction, and pendulum exercises; flexibility with stretching exercises targeting the anterior and posterior aspects of the shoulder and cane stretching for forward elevation and external rotation; and strength with strengthening exercises involving the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers.

Outcome Measures

Pain was measured with VAS scores and function with Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation (SANE) scores. The VAS is a validated outcome measure of pain intensity. A numeric version of the VAS was used: Patients selected the whole number, from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain), that best reflected their pain intensity. On SANE, another validated outcome measure, patients rated their shoulder function as a percentage of normal, from 0% (no function possible) to 100% (perfect).15 Before injection, all patients were administered the VAS and SANE questionnaires to establish their baseline pain level and opinion of shoulder function. These measures were repeated 1, 3, and 6 months after injection. Telephone interviews were conducted at 1 month and 6 months. Patients were asked to return to clinic 3 months after injection as part of the standard of care. At 3 months, 47 (86%) of the 55 patients returned for follow-up and were administered the VAS and SANE questionnaires; the other 8 completed the questionnaires by telephone. At each time point, patients were asked to report on their participation in PT and/or adherence to their home exercise program.

Statistical Analysis

Power analysis performed with Student t test and a 2-sided level of P = .05 compared VAS pain scores between the anterior and posterior injection routes and found a mean (SD) difference of 1.4 (1.7).16 Power calculations made with nQuery Advisor Version 7.0 (Statistical Solutions) indicated a total sample size of 60 patients (30/group) would provide 80% power for detecting a significant difference assuming a 20% dropout rate.

Two-way mixed-model analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the anterior and posterior routes for statistical differences in both VAS pain scores and SANE function scores at baseline and 1, 3, and 6 months after injection. Likewise, time at baseline (just before injection)was compared with follow-up (1, 3, 6 months) with 2-way mixed-model ANOVA adjusting for anterior or posterior route. Multivariate analysis was performed to evaluate differences between baseline and 6-month follow-up with respect to anterior and posterior injection routes, controlling for age, sex, and body mass index (BMI) for VAS and SANE scores. Parametric testing methods were used for statistical analysis, which was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics Version 21.0 (IBM Corp). Significance was set at P < .05.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Of the 55 patients enrolled, 25 (46%) received anterior subacromial CSI and 30 (54%) received posterior CSI. All enrolled patients had a positive Neer impingement test immediately after injection. Mean (SD) age was 48 (9.3) years for anterior group patients and 48 (9.0) years for posterior group patients. There was no significant difference in age or BMI between the 2 groups (Table).

Five patients (9%) were excluded from the study after randomization and CSI: 2 for a full-thickness rotator cuff tear, 1 for a Bankart lesion, 1 for adhesive capsulitis, and 1 for a worker compensation claim.

One month after injection, 41 patients (75%) reported having engaged in PT as prescribed. Of the 47 patients (86%) who returned for the 3-month follow-up, 25 (46%) reported having engaged in PT between 1 month and 3 months after injection. Fourteen patients (26%) reported attending PT between 3 and 6 months post-injection.

Outcome Measures

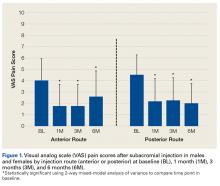

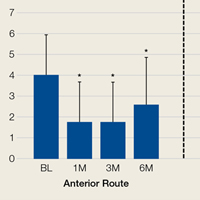

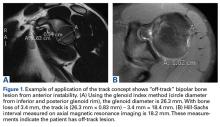

Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with age, sex, and BMI included as covariates revealed no significant differences in VAS scores between the anterior and posterior groups at any time point (P = .45). Both groups had highly significant pain reductions (anterior, F = 9.71, P < .001; posterior, F = 13.46, P < .001). Figure 1 shows mean VAS scores and significant reductions in pain 1, 3, and 6 months after injection (see asterisks for anterior and posterior groups; P < .001 for all). The groups had parallel rates of pain reduction over time, as indicated by a nonsignificant (P = .50) difference in slopes. These pain score reductions were significant for both injection routes and were independent of age, sex, and BMI (P > .05 for all).

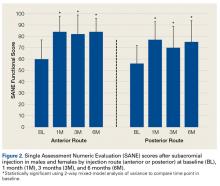

Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with age, sex, and BMI included as covariates revealed no significant differences in SANE scores between the anterior and posterior groups, except for a higher mean score in the anterior group at 3 months

(P = .02). There were no other group differences (P > .10 for all). Both groups had highly significant improvements in function (anterior, F = 17.34,

P < .001; posterior, F = 13.57, P < .001). Figure 2 shows mean SANE scores and significant improvement at 1, 3, and 6 months (see asterisks for anterior and posterior groups; P < .001 for all). The groups had parallel rates of improved function over time, as indicated by a nonsignificant (P = .51) difference in slopes. These function score improvements were significant for both injection routes and were independent of age, sex, and BMI (P > .05 for all).

From the results of this prospective randomized study, we concluded subacromial CSI significantly reduces pain and improves function regardless of route used. In addition, age, sex, and BMI do not significantly affect the efficacy of either anterior CSI or posterior CSI.

Discussion

In patients with SIS, anterior CSI and posterior CSI provided significant improvements in pain and function 1, 3, and 6 months after injection. These effects were independent of age, sex, BMI, and PT participation. There were no significant differences in outcomes between injection routes.

When conservative treatments for SIS do not resolve symptoms, inflammation and pain can be reduced with use of subacromial CSI.4-8 Although clinical outcomes are inconsistent, CSI can be used to address SIS symptoms in appropriate patients. Specifically, Blair and colleagues6 found that, CSI consisting of 4 mL of lidocaine 1% (without epinephrine) and 2 mL (80 mg) of triamcinolone was effective in alleviating shoulder pain and improving shoulder range of motion. Other authors have similarly reported improved outcomes after subacromial injection and short-term follow-up with PT.4,7,8 Our findings are consistent with these reports: CSI coupled with a structured rehabilitation program is effective in alleviating symptoms associated with acute or subacute SIS.

Numerous studies have found improved clinical outcomes after anterior CSI and after posterior CSI,6-8 but no study has directly compared the clinical impact of anterior CSI with that of posterior CSI—which suggests injection route may not affect ultimate clinical outcomes.

CSI accuracy has been studied extensively.10-12,17-20 Although 2 studies found similar accuracy for anterior and posterior routes,10,11 there may be a sex difference: In women, a posterior route may be less accurate than an anterior or a lateral route.12 Collectively, these studies expose the inherent difficulty in treating shoulder pain with localized subacromial injection. Therapy may fail because of errant needle positioning. Two prospective studies found improved clinical outcomes with successful delivery of medication into the subacromial space.17,18 Poor clinical outcomes may result from inaccurate CSI.

In contrast to other clinical studies, our study found that injection route was not associated with differences in clinical response. In a prospective randomized clinical trial in which 75 patients received a subacromial injection, Marder and colleagues12 found anterior routes 84% accurate and posterior routes 56% accurate; they concluded acromion anatomy and subacromial bursa anatomy make posterior injections more difficult. As theorized by Gruson and colleagues,13 with use of an anterior route, the needle enters inferior to the concavity of the acromion and provides easier access to the subacromial space. This idea is in line with Marder and colleagues’12 conclusion that subacromial bursa anatomy provides a favorable environment for accurate CSI.

If accuracy is positively correlated with clinical improvement and anterior routes are more accurate, there should be a difference in response to posterior injections. Our results provide evidence that clinical response to CSI may not depend on injection accuracy. Perhaps merely placing the corticosteroid near the bursa is adequate for improving symptoms or perhaps some of the clinical improvement is due to the systemic effect of corticosteroids. These possibilities require further analysis.

Establishing the efficacy of CSI in SIS is difficult. The literature includes various study designs, different CSI indications and medication formulations, and varying emphasis on the role of organized PT. Rehabilitation has been found to alleviate joint pain by reducing inflammation,14 but data do not universally support this finding.21,22 Nevertheless, use of PT might explain the divergence in clinical outcomes reported by Marder and colleagues,12 who found anterior CSI more accurate than posterior CSI. In our practice, PT is recommended for all SIS patients, not only those who have CSI. Thus, our findings are framed within the context of successful CSI but may include patients who improved with PT alone. This issue raises the question of whether subacromial CSI should be guided by ultrasound. Ultrasound guidance can improve CSI accuracy and clinical outcomes,23-25 though the value of this benefit is debated.26

This study had several limitations. First, pain relief was patient reported. Second, the treatment plan involved CSI with PT but did not control for CSI used alone. PT, which is part of the standard of care for patients with SIS, added another degree of complexity to the study. Third, there may have been some variability in SIS severity (stage 1, 2, or 3). Fourth, although the study design controlled for various shoulder pathologies, advanced imaging, which could have provided diagnosis confirmation, was not available for all patients. Therefore, concurrent conditions may have confounded results. However, randomization was used to try to minimize this effect. Fifth, although injection routes were randomly assigned, the trial was not blinded. Sixth, the study was underpowered by 1 patient, as there was an estimated 20% dropout rate over 3 and 6 months of follow-up. However, we do not think our results were significantly affected.

Although more research is needed to fully describe the role of subacromial CSI in SIS, our study findings suggested that CSI using either an anterior or a posterior route creates a window of symptomatic relief in which patients may be able to engage in PT.

Conclusion

Both anterior CSI and posterior CSI significantly improved pain and function for up to 6 months. No differences were found between anterior and posterior CSIs. In the context of this study, CSI combined with structured PT produced significant improvement in pain and function in patients with SIS, regardless of injection route used. Clinicians should rely on their clinical acumen when selecting injection routes, as anterior and posterior are both beneficial.

1. Buchbinder R, Green S, Youd JM. Corticosteroid injections for shoulder pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(1):CD004016.

2. Bell AD, Conaway D. Corticosteroid injections for painful shoulders. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59(10):1178-1186.

3. Michener LA, McClure PW, Karduna AR. Anatomical and biomechanical mechanisms of subacromial impingement syndrome. Clin Biomech. 2003;18(5):369-379.

4. Akgün K, Birtane M, Akarirmak U. Is local subacromial corticosteroid injection beneficial in subacromial impingement syndrome? Clin Rheumatol. 2004;23(6):496-500.

5. Bhagra A, Syed H, Reed DA, et al. Efficacy of musculoskeletal injections by primary care providers in the office: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Gen Med. 2013;6:237-243.

6. Blair B, Rokito AS, Cuomo F, Jarolem K, Zuckerman JD. Efficacy of injections of corticosteroids for subacromial impingement syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(11):1685-1689.

7. Cummins CA, Sasso LM, Nicholson D. Impingement syndrome: temporal outcomes of nonoperative treatment.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(2):172-177.

8. Yu C, Chen CH, Liu HT, Dai MH, Wang IC, Wang KC. Subacromial injections of corticosteroids and Xylocaine for painful subacromial impingement syndrome. Chang Gung Med J. 2006;29(5):474-478.

9. Codsi MJ. The painful shoulder: when to inject and when to refer. Cleve Clin J Med. 2007;74(7):473-474, 477-478, 480-482 passim.

10. Henkus HE, Cobben LP, Coerkamp EG, Nelissen RG, van Arkel ER. The accuracy of subacromial injections: a prospective randomized magnetic resonance imaging study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(3):277-282.

11. Kang MN, Rizio L, Prybicien M, Middlemas DA, Blacksin MF. The accuracy of subacromial corticosteroid injections: a comparison of multiple methods. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(15):61S-66S.

12. Marder RA, Kim SH, Labson JD, Hunter JC. Injection of the subacromial bursa in patients with rotator cuff syndrome: a prospective, randomized study comparing the effectiveness of different routes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(16):

1442-1447.

13. Gruson, KI, Ruchelsman DE, Zuckerman JD. Subacromial corticosteroid injections. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(1 suppl):118S-130S.

14. Kuhn JE. Exercise in the treatment of rotator cuff impingement: a systematic review and a synthesized evidence-based rehabilitation protocol. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(1):138-160.

15. Williams GN, Gangel TJ, Arciero RA, Uhorchak JM, Taylor DC. Comparison of the Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation method and two shoulder rating scales. Outcomes measures after shoulder surgery. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27(2):214-221.

16. Tashjian RZ, Deloach J, Porucznik CA, Powell AP. Minimal clinically important differences (MCID) and patient acceptable symptomatic state (PASS) for visual analog scales (VAS) measuring pain in patients treated for rotator cuff disease.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;88(6):927-932.

17. Eustace JA, Brophy DP, Gibney RP, Bresnihan B, FitzGerald O. Comparison of the accuracy of steroid placement with clinical outcome in patients with shoulder symptoms. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56(1):59-63.

18. Esenyel CZ, Esenyel M, Yeiltepe R, et al. The correlation between the accuracy of steroid injections and subsequent shoulder pain and function in subacromial impingement

syndrome [in Turkish]. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2003;37(1):

41-45.

19. Powell SE, Davis SM, Lee EH, et al. Accuracy of palpation-directed intra-articular glenohumeral injection confirmed by magnetic resonance arthrography. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(2):205-208.

20. Rutten MJ, Maresch BJ, Jager GJ, de Waal Malefijt MC. Injection of the subacromial-subdeltoid bursa: blind or ultrasound-guided? Acta Orthop. 2007;78(2):254-257.

21. Desmeules F, Côté CH, Frémont P. Therapeutic exercise and orthopedic manual therapy for impingement syndrome: a systematic review. Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13(3):176-182.

22. Winters JC, Sobel JS, Groenier KH, Arendzen HJ, Meyboom-de Jong B. Comparison of physiotherapy, manipulation, and corticosteroid injection for treating shoulder complaints in general practice: randomised, single blind study. BMJ. 1997;314(7090):1320-1325.

23. Chen MJ, Lew HL, Hsu TC, et al. Ultrasound-guided shoulder injections in the treatment of subacromial bursitis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85(1):31-35.

24. Hsieh LF, Hsu WC, Lin YJ, Wu SH, Chang KC, Chang HL. Is ultrasound-guided injection more effective in chronic subacromial bursitis? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(12):

2205-2213.

25. Naredo E, Cabero F, Beneyto P, et al. A randomized comparative study of short term response to blind injection versus sonographic-guided injection of local corticosteroids in patients with painful shoulder. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(2):308-314.

26. Hall S, Buchbinder R. Do imaging methods that guide needle placement improve outcome? Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(9):1007-1008.

Take-Home Points

When conservative treatments for SIS do not resolve symptoms, inflammation and pain can be reduced with use of subacromial CSI.

Both anterior CSI and posterior CSI significantly improved pain and function for up to 6 months

CSI combined with structured PT produced significant improvement in pain and function in patients with SIS, regardless of injection route used.

Clinical response to CSI may not depend on injection accuracy.

Clinicians should rely on their clinical acumen when selecting injection routes, as anterior and posterior are both beneficial.

Shoulder pain, a common clinical problem, occurs in 7% to 34% of the general population and in 21% of people older than 70 years.1Subacromial impingement refers to shoulder pain resulting from mechanical impingement of the rotator cuff underneath the coracoacromial arch between the acromion and the humeral head.2,3 Subacromial impingement syndrome (SIS) is the most common cause of shoulder pain, resulting in significant functional deficits and disability.3

Treatment options for SIS include conservative modalities such as use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, physical therapy (PT), and subacromial corticosteroid injections (CSIs). Studies have found short- and long-term improvement in pain, function, and range of motion after CSI.4-8 Subacromial CSI can be administered through an anterior or a posterior route.4,9 There have been several studies of the accuracy of anterior and posterior CSIs,10-12 with 2 studies finding similar accuracy for these routes.10,11 However, there may be a sex difference: In women, a posterior route may be less accurate than an anterior or a lateral route.12

Although the accuracy of anterior and posterior routes has been studied, their effect on clinical outcomes has not. We conducted a study to understand the effects of anterior and posterior CSIs on SIS. As one of the accuracy studies suggested anterior CSI is more accurate—the anterior route was theorized to provide easier access to the subacromial space12—we hypothesized patients treated with anterior CSI would have superior clinical outcomes 6 months after injection.12,13

Materials and Methods

Study Participants and Randomization

After this study received Institutional Review Board approval, patients with shoulder pain of more than 3 months’ duration and consistent with SIS were screened for inclusion. Eligible patients had pain in the anterior biceps and over the top of the shoulder with overhead activities as well as one or more clinical findings on physical examination: Hawkins-Kennedy sign, Neer sign, painful arc, and infraspinatus pain (pain with external rotation).

Patients were excluded if their history included prior subacromial CSI, adhesive capsulitis (inability to passively abduct shoulder to 90° with scapular stabilization), calcific tendonitis, radiographic evidence of os acromiale, cervical radiculopathy, Spurling sign, neck pain, radiating arm pain or numbness, sensory deficits, or neck and upper extremity motor dysfunction. Also excluded were patients with full-thickness rotator cuff tear, weakness on arm elevation, positive "drop arm sign," or high-riding humerus on standing shoulder radiograph. Patients who had work-related injuries or who were involved in worker compensation were excluded as well.

Enrolled patients were randomly assigned (with use of a computer-based random number generator) to receive either anterior CSI or posterior CSI.

Injection Procedures

All patients were administered 5 mL of lidocaine 1% (without epinephrine) and 2 mL (80 mg) of triamcinolone by 2 board-certified orthopedic surgeons using a 22-gauge 1½-inch needle. For patients who received their subacromial CSI by the anterior route, the arm was held in 0° of abduction and 20° of external rotation. The needle was inserted medial to the humeral head, lateral to the coracoid process, beginning 1 cm inferior to the clavicle with the needle directed posteriorly and laterally toward the acromion.10 For patients who received their CSI by the posterior route, the arm was held in 0° of abduction, the posterolateral corner of the acromion was identified by palpation, and the needle was inserted 1 cm inferior and medial to this point with the needle directed anteriorly and laterally toward the acromion.10,12 In both groups, the subacromial space was identified when a drop in pressure was felt during needle insertion. Accuracy was assessed post hoc by asking patients to grade their response to the injection on a visual analog scale (VAS); VAS score was used as a surrogate for improvement. All patients had a positive Neer test: Pain decreased with impingement maneuvers immediately after injection.

All patients were referred for PT provided according to an evidence-based rehabilitation protocol.14 This program emphasized range of motion with shoulder shrugs, scapular retraction, and pendulum exercises; flexibility with stretching exercises targeting the anterior and posterior aspects of the shoulder and cane stretching for forward elevation and external rotation; and strength with strengthening exercises involving the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers.

Outcome Measures

Pain was measured with VAS scores and function with Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation (SANE) scores. The VAS is a validated outcome measure of pain intensity. A numeric version of the VAS was used: Patients selected the whole number, from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain), that best reflected their pain intensity. On SANE, another validated outcome measure, patients rated their shoulder function as a percentage of normal, from 0% (no function possible) to 100% (perfect).15 Before injection, all patients were administered the VAS and SANE questionnaires to establish their baseline pain level and opinion of shoulder function. These measures were repeated 1, 3, and 6 months after injection. Telephone interviews were conducted at 1 month and 6 months. Patients were asked to return to clinic 3 months after injection as part of the standard of care. At 3 months, 47 (86%) of the 55 patients returned for follow-up and were administered the VAS and SANE questionnaires; the other 8 completed the questionnaires by telephone. At each time point, patients were asked to report on their participation in PT and/or adherence to their home exercise program.

Statistical Analysis

Power analysis performed with Student t test and a 2-sided level of P = .05 compared VAS pain scores between the anterior and posterior injection routes and found a mean (SD) difference of 1.4 (1.7).16 Power calculations made with nQuery Advisor Version 7.0 (Statistical Solutions) indicated a total sample size of 60 patients (30/group) would provide 80% power for detecting a significant difference assuming a 20% dropout rate.

Two-way mixed-model analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the anterior and posterior routes for statistical differences in both VAS pain scores and SANE function scores at baseline and 1, 3, and 6 months after injection. Likewise, time at baseline (just before injection)was compared with follow-up (1, 3, 6 months) with 2-way mixed-model ANOVA adjusting for anterior or posterior route. Multivariate analysis was performed to evaluate differences between baseline and 6-month follow-up with respect to anterior and posterior injection routes, controlling for age, sex, and body mass index (BMI) for VAS and SANE scores. Parametric testing methods were used for statistical analysis, which was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics Version 21.0 (IBM Corp). Significance was set at P < .05.

Results

Patient Characteristics

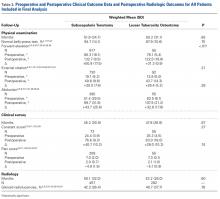

Of the 55 patients enrolled, 25 (46%) received anterior subacromial CSI and 30 (54%) received posterior CSI. All enrolled patients had a positive Neer impingement test immediately after injection. Mean (SD) age was 48 (9.3) years for anterior group patients and 48 (9.0) years for posterior group patients. There was no significant difference in age or BMI between the 2 groups (Table).

Five patients (9%) were excluded from the study after randomization and CSI: 2 for a full-thickness rotator cuff tear, 1 for a Bankart lesion, 1 for adhesive capsulitis, and 1 for a worker compensation claim.

One month after injection, 41 patients (75%) reported having engaged in PT as prescribed. Of the 47 patients (86%) who returned for the 3-month follow-up, 25 (46%) reported having engaged in PT between 1 month and 3 months after injection. Fourteen patients (26%) reported attending PT between 3 and 6 months post-injection.

Outcome Measures

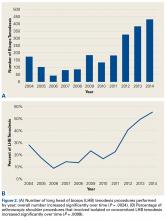

Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with age, sex, and BMI included as covariates revealed no significant differences in VAS scores between the anterior and posterior groups at any time point (P = .45). Both groups had highly significant pain reductions (anterior, F = 9.71, P < .001; posterior, F = 13.46, P < .001). Figure 1 shows mean VAS scores and significant reductions in pain 1, 3, and 6 months after injection (see asterisks for anterior and posterior groups; P < .001 for all). The groups had parallel rates of pain reduction over time, as indicated by a nonsignificant (P = .50) difference in slopes. These pain score reductions were significant for both injection routes and were independent of age, sex, and BMI (P > .05 for all).

Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with age, sex, and BMI included as covariates revealed no significant differences in SANE scores between the anterior and posterior groups, except for a higher mean score in the anterior group at 3 months

(P = .02). There were no other group differences (P > .10 for all). Both groups had highly significant improvements in function (anterior, F = 17.34,

P < .001; posterior, F = 13.57, P < .001). Figure 2 shows mean SANE scores and significant improvement at 1, 3, and 6 months (see asterisks for anterior and posterior groups; P < .001 for all). The groups had parallel rates of improved function over time, as indicated by a nonsignificant (P = .51) difference in slopes. These function score improvements were significant for both injection routes and were independent of age, sex, and BMI (P > .05 for all).

From the results of this prospective randomized study, we concluded subacromial CSI significantly reduces pain and improves function regardless of route used. In addition, age, sex, and BMI do not significantly affect the efficacy of either anterior CSI or posterior CSI.

Discussion

In patients with SIS, anterior CSI and posterior CSI provided significant improvements in pain and function 1, 3, and 6 months after injection. These effects were independent of age, sex, BMI, and PT participation. There were no significant differences in outcomes between injection routes.

When conservative treatments for SIS do not resolve symptoms, inflammation and pain can be reduced with use of subacromial CSI.4-8 Although clinical outcomes are inconsistent, CSI can be used to address SIS symptoms in appropriate patients. Specifically, Blair and colleagues6 found that, CSI consisting of 4 mL of lidocaine 1% (without epinephrine) and 2 mL (80 mg) of triamcinolone was effective in alleviating shoulder pain and improving shoulder range of motion. Other authors have similarly reported improved outcomes after subacromial injection and short-term follow-up with PT.4,7,8 Our findings are consistent with these reports: CSI coupled with a structured rehabilitation program is effective in alleviating symptoms associated with acute or subacute SIS.

Numerous studies have found improved clinical outcomes after anterior CSI and after posterior CSI,6-8 but no study has directly compared the clinical impact of anterior CSI with that of posterior CSI—which suggests injection route may not affect ultimate clinical outcomes.

CSI accuracy has been studied extensively.10-12,17-20 Although 2 studies found similar accuracy for anterior and posterior routes,10,11 there may be a sex difference: In women, a posterior route may be less accurate than an anterior or a lateral route.12 Collectively, these studies expose the inherent difficulty in treating shoulder pain with localized subacromial injection. Therapy may fail because of errant needle positioning. Two prospective studies found improved clinical outcomes with successful delivery of medication into the subacromial space.17,18 Poor clinical outcomes may result from inaccurate CSI.

In contrast to other clinical studies, our study found that injection route was not associated with differences in clinical response. In a prospective randomized clinical trial in which 75 patients received a subacromial injection, Marder and colleagues12 found anterior routes 84% accurate and posterior routes 56% accurate; they concluded acromion anatomy and subacromial bursa anatomy make posterior injections more difficult. As theorized by Gruson and colleagues,13 with use of an anterior route, the needle enters inferior to the concavity of the acromion and provides easier access to the subacromial space. This idea is in line with Marder and colleagues’12 conclusion that subacromial bursa anatomy provides a favorable environment for accurate CSI.

If accuracy is positively correlated with clinical improvement and anterior routes are more accurate, there should be a difference in response to posterior injections. Our results provide evidence that clinical response to CSI may not depend on injection accuracy. Perhaps merely placing the corticosteroid near the bursa is adequate for improving symptoms or perhaps some of the clinical improvement is due to the systemic effect of corticosteroids. These possibilities require further analysis.

Establishing the efficacy of CSI in SIS is difficult. The literature includes various study designs, different CSI indications and medication formulations, and varying emphasis on the role of organized PT. Rehabilitation has been found to alleviate joint pain by reducing inflammation,14 but data do not universally support this finding.21,22 Nevertheless, use of PT might explain the divergence in clinical outcomes reported by Marder and colleagues,12 who found anterior CSI more accurate than posterior CSI. In our practice, PT is recommended for all SIS patients, not only those who have CSI. Thus, our findings are framed within the context of successful CSI but may include patients who improved with PT alone. This issue raises the question of whether subacromial CSI should be guided by ultrasound. Ultrasound guidance can improve CSI accuracy and clinical outcomes,23-25 though the value of this benefit is debated.26

This study had several limitations. First, pain relief was patient reported. Second, the treatment plan involved CSI with PT but did not control for CSI used alone. PT, which is part of the standard of care for patients with SIS, added another degree of complexity to the study. Third, there may have been some variability in SIS severity (stage 1, 2, or 3). Fourth, although the study design controlled for various shoulder pathologies, advanced imaging, which could have provided diagnosis confirmation, was not available for all patients. Therefore, concurrent conditions may have confounded results. However, randomization was used to try to minimize this effect. Fifth, although injection routes were randomly assigned, the trial was not blinded. Sixth, the study was underpowered by 1 patient, as there was an estimated 20% dropout rate over 3 and 6 months of follow-up. However, we do not think our results were significantly affected.

Although more research is needed to fully describe the role of subacromial CSI in SIS, our study findings suggested that CSI using either an anterior or a posterior route creates a window of symptomatic relief in which patients may be able to engage in PT.

Conclusion

Both anterior CSI and posterior CSI significantly improved pain and function for up to 6 months. No differences were found between anterior and posterior CSIs. In the context of this study, CSI combined with structured PT produced significant improvement in pain and function in patients with SIS, regardless of injection route used. Clinicians should rely on their clinical acumen when selecting injection routes, as anterior and posterior are both beneficial.

Take-Home Points

When conservative treatments for SIS do not resolve symptoms, inflammation and pain can be reduced with use of subacromial CSI.

Both anterior CSI and posterior CSI significantly improved pain and function for up to 6 months

CSI combined with structured PT produced significant improvement in pain and function in patients with SIS, regardless of injection route used.

Clinical response to CSI may not depend on injection accuracy.

Clinicians should rely on their clinical acumen when selecting injection routes, as anterior and posterior are both beneficial.

Shoulder pain, a common clinical problem, occurs in 7% to 34% of the general population and in 21% of people older than 70 years.1Subacromial impingement refers to shoulder pain resulting from mechanical impingement of the rotator cuff underneath the coracoacromial arch between the acromion and the humeral head.2,3 Subacromial impingement syndrome (SIS) is the most common cause of shoulder pain, resulting in significant functional deficits and disability.3

Treatment options for SIS include conservative modalities such as use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, physical therapy (PT), and subacromial corticosteroid injections (CSIs). Studies have found short- and long-term improvement in pain, function, and range of motion after CSI.4-8 Subacromial CSI can be administered through an anterior or a posterior route.4,9 There have been several studies of the accuracy of anterior and posterior CSIs,10-12 with 2 studies finding similar accuracy for these routes.10,11 However, there may be a sex difference: In women, a posterior route may be less accurate than an anterior or a lateral route.12

Although the accuracy of anterior and posterior routes has been studied, their effect on clinical outcomes has not. We conducted a study to understand the effects of anterior and posterior CSIs on SIS. As one of the accuracy studies suggested anterior CSI is more accurate—the anterior route was theorized to provide easier access to the subacromial space12—we hypothesized patients treated with anterior CSI would have superior clinical outcomes 6 months after injection.12,13

Materials and Methods

Study Participants and Randomization

After this study received Institutional Review Board approval, patients with shoulder pain of more than 3 months’ duration and consistent with SIS were screened for inclusion. Eligible patients had pain in the anterior biceps and over the top of the shoulder with overhead activities as well as one or more clinical findings on physical examination: Hawkins-Kennedy sign, Neer sign, painful arc, and infraspinatus pain (pain with external rotation).

Patients were excluded if their history included prior subacromial CSI, adhesive capsulitis (inability to passively abduct shoulder to 90° with scapular stabilization), calcific tendonitis, radiographic evidence of os acromiale, cervical radiculopathy, Spurling sign, neck pain, radiating arm pain or numbness, sensory deficits, or neck and upper extremity motor dysfunction. Also excluded were patients with full-thickness rotator cuff tear, weakness on arm elevation, positive "drop arm sign," or high-riding humerus on standing shoulder radiograph. Patients who had work-related injuries or who were involved in worker compensation were excluded as well.

Enrolled patients were randomly assigned (with use of a computer-based random number generator) to receive either anterior CSI or posterior CSI.

Injection Procedures

All patients were administered 5 mL of lidocaine 1% (without epinephrine) and 2 mL (80 mg) of triamcinolone by 2 board-certified orthopedic surgeons using a 22-gauge 1½-inch needle. For patients who received their subacromial CSI by the anterior route, the arm was held in 0° of abduction and 20° of external rotation. The needle was inserted medial to the humeral head, lateral to the coracoid process, beginning 1 cm inferior to the clavicle with the needle directed posteriorly and laterally toward the acromion.10 For patients who received their CSI by the posterior route, the arm was held in 0° of abduction, the posterolateral corner of the acromion was identified by palpation, and the needle was inserted 1 cm inferior and medial to this point with the needle directed anteriorly and laterally toward the acromion.10,12 In both groups, the subacromial space was identified when a drop in pressure was felt during needle insertion. Accuracy was assessed post hoc by asking patients to grade their response to the injection on a visual analog scale (VAS); VAS score was used as a surrogate for improvement. All patients had a positive Neer test: Pain decreased with impingement maneuvers immediately after injection.

All patients were referred for PT provided according to an evidence-based rehabilitation protocol.14 This program emphasized range of motion with shoulder shrugs, scapular retraction, and pendulum exercises; flexibility with stretching exercises targeting the anterior and posterior aspects of the shoulder and cane stretching for forward elevation and external rotation; and strength with strengthening exercises involving the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers.

Outcome Measures

Pain was measured with VAS scores and function with Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation (SANE) scores. The VAS is a validated outcome measure of pain intensity. A numeric version of the VAS was used: Patients selected the whole number, from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain), that best reflected their pain intensity. On SANE, another validated outcome measure, patients rated their shoulder function as a percentage of normal, from 0% (no function possible) to 100% (perfect).15 Before injection, all patients were administered the VAS and SANE questionnaires to establish their baseline pain level and opinion of shoulder function. These measures were repeated 1, 3, and 6 months after injection. Telephone interviews were conducted at 1 month and 6 months. Patients were asked to return to clinic 3 months after injection as part of the standard of care. At 3 months, 47 (86%) of the 55 patients returned for follow-up and were administered the VAS and SANE questionnaires; the other 8 completed the questionnaires by telephone. At each time point, patients were asked to report on their participation in PT and/or adherence to their home exercise program.

Statistical Analysis

Power analysis performed with Student t test and a 2-sided level of P = .05 compared VAS pain scores between the anterior and posterior injection routes and found a mean (SD) difference of 1.4 (1.7).16 Power calculations made with nQuery Advisor Version 7.0 (Statistical Solutions) indicated a total sample size of 60 patients (30/group) would provide 80% power for detecting a significant difference assuming a 20% dropout rate.

Two-way mixed-model analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the anterior and posterior routes for statistical differences in both VAS pain scores and SANE function scores at baseline and 1, 3, and 6 months after injection. Likewise, time at baseline (just before injection)was compared with follow-up (1, 3, 6 months) with 2-way mixed-model ANOVA adjusting for anterior or posterior route. Multivariate analysis was performed to evaluate differences between baseline and 6-month follow-up with respect to anterior and posterior injection routes, controlling for age, sex, and body mass index (BMI) for VAS and SANE scores. Parametric testing methods were used for statistical analysis, which was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics Version 21.0 (IBM Corp). Significance was set at P < .05.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Of the 55 patients enrolled, 25 (46%) received anterior subacromial CSI and 30 (54%) received posterior CSI. All enrolled patients had a positive Neer impingement test immediately after injection. Mean (SD) age was 48 (9.3) years for anterior group patients and 48 (9.0) years for posterior group patients. There was no significant difference in age or BMI between the 2 groups (Table).

Five patients (9%) were excluded from the study after randomization and CSI: 2 for a full-thickness rotator cuff tear, 1 for a Bankart lesion, 1 for adhesive capsulitis, and 1 for a worker compensation claim.

One month after injection, 41 patients (75%) reported having engaged in PT as prescribed. Of the 47 patients (86%) who returned for the 3-month follow-up, 25 (46%) reported having engaged in PT between 1 month and 3 months after injection. Fourteen patients (26%) reported attending PT between 3 and 6 months post-injection.

Outcome Measures

Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with age, sex, and BMI included as covariates revealed no significant differences in VAS scores between the anterior and posterior groups at any time point (P = .45). Both groups had highly significant pain reductions (anterior, F = 9.71, P < .001; posterior, F = 13.46, P < .001). Figure 1 shows mean VAS scores and significant reductions in pain 1, 3, and 6 months after injection (see asterisks for anterior and posterior groups; P < .001 for all). The groups had parallel rates of pain reduction over time, as indicated by a nonsignificant (P = .50) difference in slopes. These pain score reductions were significant for both injection routes and were independent of age, sex, and BMI (P > .05 for all).

Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with age, sex, and BMI included as covariates revealed no significant differences in SANE scores between the anterior and posterior groups, except for a higher mean score in the anterior group at 3 months

(P = .02). There were no other group differences (P > .10 for all). Both groups had highly significant improvements in function (anterior, F = 17.34,

P < .001; posterior, F = 13.57, P < .001). Figure 2 shows mean SANE scores and significant improvement at 1, 3, and 6 months (see asterisks for anterior and posterior groups; P < .001 for all). The groups had parallel rates of improved function over time, as indicated by a nonsignificant (P = .51) difference in slopes. These function score improvements were significant for both injection routes and were independent of age, sex, and BMI (P > .05 for all).

From the results of this prospective randomized study, we concluded subacromial CSI significantly reduces pain and improves function regardless of route used. In addition, age, sex, and BMI do not significantly affect the efficacy of either anterior CSI or posterior CSI.

Discussion

In patients with SIS, anterior CSI and posterior CSI provided significant improvements in pain and function 1, 3, and 6 months after injection. These effects were independent of age, sex, BMI, and PT participation. There were no significant differences in outcomes between injection routes.

When conservative treatments for SIS do not resolve symptoms, inflammation and pain can be reduced with use of subacromial CSI.4-8 Although clinical outcomes are inconsistent, CSI can be used to address SIS symptoms in appropriate patients. Specifically, Blair and colleagues6 found that, CSI consisting of 4 mL of lidocaine 1% (without epinephrine) and 2 mL (80 mg) of triamcinolone was effective in alleviating shoulder pain and improving shoulder range of motion. Other authors have similarly reported improved outcomes after subacromial injection and short-term follow-up with PT.4,7,8 Our findings are consistent with these reports: CSI coupled with a structured rehabilitation program is effective in alleviating symptoms associated with acute or subacute SIS.

Numerous studies have found improved clinical outcomes after anterior CSI and after posterior CSI,6-8 but no study has directly compared the clinical impact of anterior CSI with that of posterior CSI—which suggests injection route may not affect ultimate clinical outcomes.

CSI accuracy has been studied extensively.10-12,17-20 Although 2 studies found similar accuracy for anterior and posterior routes,10,11 there may be a sex difference: In women, a posterior route may be less accurate than an anterior or a lateral route.12 Collectively, these studies expose the inherent difficulty in treating shoulder pain with localized subacromial injection. Therapy may fail because of errant needle positioning. Two prospective studies found improved clinical outcomes with successful delivery of medication into the subacromial space.17,18 Poor clinical outcomes may result from inaccurate CSI.

In contrast to other clinical studies, our study found that injection route was not associated with differences in clinical response. In a prospective randomized clinical trial in which 75 patients received a subacromial injection, Marder and colleagues12 found anterior routes 84% accurate and posterior routes 56% accurate; they concluded acromion anatomy and subacromial bursa anatomy make posterior injections more difficult. As theorized by Gruson and colleagues,13 with use of an anterior route, the needle enters inferior to the concavity of the acromion and provides easier access to the subacromial space. This idea is in line with Marder and colleagues’12 conclusion that subacromial bursa anatomy provides a favorable environment for accurate CSI.

If accuracy is positively correlated with clinical improvement and anterior routes are more accurate, there should be a difference in response to posterior injections. Our results provide evidence that clinical response to CSI may not depend on injection accuracy. Perhaps merely placing the corticosteroid near the bursa is adequate for improving symptoms or perhaps some of the clinical improvement is due to the systemic effect of corticosteroids. These possibilities require further analysis.

Establishing the efficacy of CSI in SIS is difficult. The literature includes various study designs, different CSI indications and medication formulations, and varying emphasis on the role of organized PT. Rehabilitation has been found to alleviate joint pain by reducing inflammation,14 but data do not universally support this finding.21,22 Nevertheless, use of PT might explain the divergence in clinical outcomes reported by Marder and colleagues,12 who found anterior CSI more accurate than posterior CSI. In our practice, PT is recommended for all SIS patients, not only those who have CSI. Thus, our findings are framed within the context of successful CSI but may include patients who improved with PT alone. This issue raises the question of whether subacromial CSI should be guided by ultrasound. Ultrasound guidance can improve CSI accuracy and clinical outcomes,23-25 though the value of this benefit is debated.26

This study had several limitations. First, pain relief was patient reported. Second, the treatment plan involved CSI with PT but did not control for CSI used alone. PT, which is part of the standard of care for patients with SIS, added another degree of complexity to the study. Third, there may have been some variability in SIS severity (stage 1, 2, or 3). Fourth, although the study design controlled for various shoulder pathologies, advanced imaging, which could have provided diagnosis confirmation, was not available for all patients. Therefore, concurrent conditions may have confounded results. However, randomization was used to try to minimize this effect. Fifth, although injection routes were randomly assigned, the trial was not blinded. Sixth, the study was underpowered by 1 patient, as there was an estimated 20% dropout rate over 3 and 6 months of follow-up. However, we do not think our results were significantly affected.

Although more research is needed to fully describe the role of subacromial CSI in SIS, our study findings suggested that CSI using either an anterior or a posterior route creates a window of symptomatic relief in which patients may be able to engage in PT.

Conclusion

Both anterior CSI and posterior CSI significantly improved pain and function for up to 6 months. No differences were found between anterior and posterior CSIs. In the context of this study, CSI combined with structured PT produced significant improvement in pain and function in patients with SIS, regardless of injection route used. Clinicians should rely on their clinical acumen when selecting injection routes, as anterior and posterior are both beneficial.

1. Buchbinder R, Green S, Youd JM. Corticosteroid injections for shoulder pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(1):CD004016.

2. Bell AD, Conaway D. Corticosteroid injections for painful shoulders. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59(10):1178-1186.

3. Michener LA, McClure PW, Karduna AR. Anatomical and biomechanical mechanisms of subacromial impingement syndrome. Clin Biomech. 2003;18(5):369-379.

4. Akgün K, Birtane M, Akarirmak U. Is local subacromial corticosteroid injection beneficial in subacromial impingement syndrome? Clin Rheumatol. 2004;23(6):496-500.

5. Bhagra A, Syed H, Reed DA, et al. Efficacy of musculoskeletal injections by primary care providers in the office: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Gen Med. 2013;6:237-243.

6. Blair B, Rokito AS, Cuomo F, Jarolem K, Zuckerman JD. Efficacy of injections of corticosteroids for subacromial impingement syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(11):1685-1689.

7. Cummins CA, Sasso LM, Nicholson D. Impingement syndrome: temporal outcomes of nonoperative treatment.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(2):172-177.

8. Yu C, Chen CH, Liu HT, Dai MH, Wang IC, Wang KC. Subacromial injections of corticosteroids and Xylocaine for painful subacromial impingement syndrome. Chang Gung Med J. 2006;29(5):474-478.

9. Codsi MJ. The painful shoulder: when to inject and when to refer. Cleve Clin J Med. 2007;74(7):473-474, 477-478, 480-482 passim.

10. Henkus HE, Cobben LP, Coerkamp EG, Nelissen RG, van Arkel ER. The accuracy of subacromial injections: a prospective randomized magnetic resonance imaging study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(3):277-282.

11. Kang MN, Rizio L, Prybicien M, Middlemas DA, Blacksin MF. The accuracy of subacromial corticosteroid injections: a comparison of multiple methods. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(15):61S-66S.

12. Marder RA, Kim SH, Labson JD, Hunter JC. Injection of the subacromial bursa in patients with rotator cuff syndrome: a prospective, randomized study comparing the effectiveness of different routes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(16):

1442-1447.

13. Gruson, KI, Ruchelsman DE, Zuckerman JD. Subacromial corticosteroid injections. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(1 suppl):118S-130S.

14. Kuhn JE. Exercise in the treatment of rotator cuff impingement: a systematic review and a synthesized evidence-based rehabilitation protocol. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(1):138-160.

15. Williams GN, Gangel TJ, Arciero RA, Uhorchak JM, Taylor DC. Comparison of the Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation method and two shoulder rating scales. Outcomes measures after shoulder surgery. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27(2):214-221.

16. Tashjian RZ, Deloach J, Porucznik CA, Powell AP. Minimal clinically important differences (MCID) and patient acceptable symptomatic state (PASS) for visual analog scales (VAS) measuring pain in patients treated for rotator cuff disease.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;88(6):927-932.

17. Eustace JA, Brophy DP, Gibney RP, Bresnihan B, FitzGerald O. Comparison of the accuracy of steroid placement with clinical outcome in patients with shoulder symptoms. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56(1):59-63.

18. Esenyel CZ, Esenyel M, Yeiltepe R, et al. The correlation between the accuracy of steroid injections and subsequent shoulder pain and function in subacromial impingement

syndrome [in Turkish]. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2003;37(1):

41-45.

19. Powell SE, Davis SM, Lee EH, et al. Accuracy of palpation-directed intra-articular glenohumeral injection confirmed by magnetic resonance arthrography. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(2):205-208.

20. Rutten MJ, Maresch BJ, Jager GJ, de Waal Malefijt MC. Injection of the subacromial-subdeltoid bursa: blind or ultrasound-guided? Acta Orthop. 2007;78(2):254-257.

21. Desmeules F, Côté CH, Frémont P. Therapeutic exercise and orthopedic manual therapy for impingement syndrome: a systematic review. Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13(3):176-182.

22. Winters JC, Sobel JS, Groenier KH, Arendzen HJ, Meyboom-de Jong B. Comparison of physiotherapy, manipulation, and corticosteroid injection for treating shoulder complaints in general practice: randomised, single blind study. BMJ. 1997;314(7090):1320-1325.

23. Chen MJ, Lew HL, Hsu TC, et al. Ultrasound-guided shoulder injections in the treatment of subacromial bursitis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85(1):31-35.

24. Hsieh LF, Hsu WC, Lin YJ, Wu SH, Chang KC, Chang HL. Is ultrasound-guided injection more effective in chronic subacromial bursitis? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(12):

2205-2213.

25. Naredo E, Cabero F, Beneyto P, et al. A randomized comparative study of short term response to blind injection versus sonographic-guided injection of local corticosteroids in patients with painful shoulder. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(2):308-314.

26. Hall S, Buchbinder R. Do imaging methods that guide needle placement improve outcome? Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(9):1007-1008.

1. Buchbinder R, Green S, Youd JM. Corticosteroid injections for shoulder pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(1):CD004016.

2. Bell AD, Conaway D. Corticosteroid injections for painful shoulders. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59(10):1178-1186.

3. Michener LA, McClure PW, Karduna AR. Anatomical and biomechanical mechanisms of subacromial impingement syndrome. Clin Biomech. 2003;18(5):369-379.

4. Akgün K, Birtane M, Akarirmak U. Is local subacromial corticosteroid injection beneficial in subacromial impingement syndrome? Clin Rheumatol. 2004;23(6):496-500.

5. Bhagra A, Syed H, Reed DA, et al. Efficacy of musculoskeletal injections by primary care providers in the office: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Gen Med. 2013;6:237-243.

6. Blair B, Rokito AS, Cuomo F, Jarolem K, Zuckerman JD. Efficacy of injections of corticosteroids for subacromial impingement syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(11):1685-1689.

7. Cummins CA, Sasso LM, Nicholson D. Impingement syndrome: temporal outcomes of nonoperative treatment.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(2):172-177.

8. Yu C, Chen CH, Liu HT, Dai MH, Wang IC, Wang KC. Subacromial injections of corticosteroids and Xylocaine for painful subacromial impingement syndrome. Chang Gung Med J. 2006;29(5):474-478.

9. Codsi MJ. The painful shoulder: when to inject and when to refer. Cleve Clin J Med. 2007;74(7):473-474, 477-478, 480-482 passim.

10. Henkus HE, Cobben LP, Coerkamp EG, Nelissen RG, van Arkel ER. The accuracy of subacromial injections: a prospective randomized magnetic resonance imaging study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(3):277-282.

11. Kang MN, Rizio L, Prybicien M, Middlemas DA, Blacksin MF. The accuracy of subacromial corticosteroid injections: a comparison of multiple methods. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(15):61S-66S.

12. Marder RA, Kim SH, Labson JD, Hunter JC. Injection of the subacromial bursa in patients with rotator cuff syndrome: a prospective, randomized study comparing the effectiveness of different routes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(16):

1442-1447.

13. Gruson, KI, Ruchelsman DE, Zuckerman JD. Subacromial corticosteroid injections. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(1 suppl):118S-130S.

14. Kuhn JE. Exercise in the treatment of rotator cuff impingement: a systematic review and a synthesized evidence-based rehabilitation protocol. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(1):138-160.

15. Williams GN, Gangel TJ, Arciero RA, Uhorchak JM, Taylor DC. Comparison of the Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation method and two shoulder rating scales. Outcomes measures after shoulder surgery. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27(2):214-221.

16. Tashjian RZ, Deloach J, Porucznik CA, Powell AP. Minimal clinically important differences (MCID) and patient acceptable symptomatic state (PASS) for visual analog scales (VAS) measuring pain in patients treated for rotator cuff disease.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;88(6):927-932.

17. Eustace JA, Brophy DP, Gibney RP, Bresnihan B, FitzGerald O. Comparison of the accuracy of steroid placement with clinical outcome in patients with shoulder symptoms. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56(1):59-63.

18. Esenyel CZ, Esenyel M, Yeiltepe R, et al. The correlation between the accuracy of steroid injections and subsequent shoulder pain and function in subacromial impingement

syndrome [in Turkish]. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2003;37(1):

41-45.

19. Powell SE, Davis SM, Lee EH, et al. Accuracy of palpation-directed intra-articular glenohumeral injection confirmed by magnetic resonance arthrography. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(2):205-208.

20. Rutten MJ, Maresch BJ, Jager GJ, de Waal Malefijt MC. Injection of the subacromial-subdeltoid bursa: blind or ultrasound-guided? Acta Orthop. 2007;78(2):254-257.

21. Desmeules F, Côté CH, Frémont P. Therapeutic exercise and orthopedic manual therapy for impingement syndrome: a systematic review. Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13(3):176-182.

22. Winters JC, Sobel JS, Groenier KH, Arendzen HJ, Meyboom-de Jong B. Comparison of physiotherapy, manipulation, and corticosteroid injection for treating shoulder complaints in general practice: randomised, single blind study. BMJ. 1997;314(7090):1320-1325.

23. Chen MJ, Lew HL, Hsu TC, et al. Ultrasound-guided shoulder injections in the treatment of subacromial bursitis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85(1):31-35.

24. Hsieh LF, Hsu WC, Lin YJ, Wu SH, Chang KC, Chang HL. Is ultrasound-guided injection more effective in chronic subacromial bursitis? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(12):

2205-2213.

25. Naredo E, Cabero F, Beneyto P, et al. A randomized comparative study of short term response to blind injection versus sonographic-guided injection of local corticosteroids in patients with painful shoulder. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(2):308-314.

26. Hall S, Buchbinder R. Do imaging methods that guide needle placement improve outcome? Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(9):1007-1008.

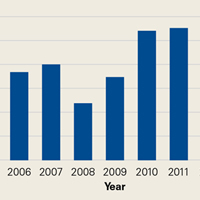

Biceps Tenodesis: An Evolution of Treatment

Take-Home Points

- The LHB tendon has been shown to be a significant pain generator in the shoulder.

- At our institution, the number of LHB tenodeses significantly increased from 2004 to 2014.

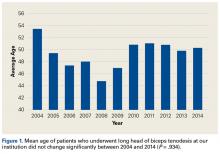

- The age of patients who underwent a LHB tenodesis did not change significantly over the study period.

- Furthermore, the percentage of shoulder procedures that involved a LHB tenodesis significantly increased over the study period.

- Biceps tenodesis has become a more common procedure to treat shoulder pathology.

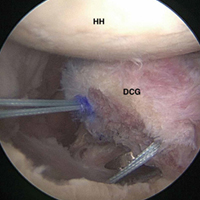

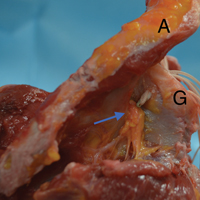

Although the exact function of the long head of the biceps (LHB) tendon is not completely understood, it is accepted that the LHB tendon can be a significant source of pain within the shoulder.1-4 Patients with symptoms related to biceps pathology often present with anterior shoulder pain that worsens with flexion and supination of the affected elbow and wrist.5 Although the sensitivity and specificity of physical examination maneuvers have been called into question, special tests have been developed to aid in the diagnosis of tendonitis of the LHB. These tests include the Speed, Yergason, bear hug, and uppercut tests as well as the O’Brien test (cross-body adduction).6,7 Recent studies have found LHB pathology in 45% of patients who undergo rotator cuff repair and in 63% of patients with a subscapularis tear.8,9

Pathology of the LHB tendon, including superior labrum anterior to posterior (SLAP) tears, can be treated in many ways.5,10,11 Options include SLAP repair, biceps tenodesis, débridement, and biceps tenotomy.11,12 Results of SLAP repairs have been less than optimal, but biceps tenodesis has been effective, and avoids the issue of cramping as can be seen with biceps tenotomy and débridement.10,12,13 Surgical methods for biceps tenodesis include open subpectoral and all-arthroscopic.11,12 Both methods have had good, reliable outcomes, but the all-arthroscopic technique is relatively new.11,12,14We conducted a study to determine LHB tenodesis trends, including patient age at time of surgery. We used surgical data from fellowship-trained sports or shoulder/elbow orthopedic surgeons at a busy subspecialty-based shoulder orthopedic practice. We hypothesized that the rate of LHB tenodesis would increase significantly over time and that there would be no significant change in the age of patients who underwent LHB tenodesis.

Methods

Our Institutional Review Board exempted this study. To determine the number of LHB tenodesis procedures performed at our institution, overall and in comparison with other common arthroscopic shoulder procedures, we queried the surgical database of 4 fellowship-trained orthopedic surgeons (shoulder/elbow, Drs. Nicholson and Cole; sports, Drs. Romeo and Verma) for the period January 1, 2004 to December 31, 2014. We used Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 23430 to determine the number of LHB tenodesis cases, as the surgeons primarily perform an open subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Patient age at time of surgery and the date of surgery were recorded. All patients who underwent LHB tenodesis between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2014 were included. Number of procedures performed each year by each surgeon was recorded, as were concomitant procedures performed at the same time as the LHB tenodesis. To get the denominator (and reference point) for the number of arthroscopic shoulder surgeries performed by these 4 surgeons during the study period, and thereby determine the rate of LHB tenodesis, we selected the most common shoulder arthroscopy CPT codes used in our practice: 23430, 29806, 29807, 29822, 29823, 29825, 29826, and 29827. For a patient who underwent multiple procedures on the same day (multiple CPT codes entered on the same day), only one code was counted for that day. If 23430 was among the codes, it was included, and the case was placed in the numerator; if 23430 was not among the codes, the case was placed in the denominator.

The Arthroscopy Association of North America provides descriptions for the CPT codes: 23430 (tenodesis of long tendon of biceps), 29806 (arthroscopy, shoulder, surgical; capsulorrhaphy), 29807 (arthroscopy, shoulder, surgical; repair of SLAP lesion), 29822 (arthroscopy, shoulder, surgical; débridement, limited), 29823 (arthroscopy, shoulder, surgical; débridement, extensive), 29825 (arthroscopy, shoulder, surgical; with lysis and resection of adhesions, with or without manipulation), 29826 (arthroscopy, shoulder, surgical; decompression of subacromial space with partial acromioplasty, with or without coracoacromial release), and 29827 (arthroscopy, shoulder, surgical; with rotator cuff repair).

For analysis, we divided the data into total number of arthroscopic shoulder procedures performed by each surgeon each year and number of LHB tenodesis procedures performed by each surgeon each year. Total number of patients who had an arthroscopic procedure was used to create a denominator, and number of LHB tenodesis procedures showed the percentage of arthroscopic shoulder surgery patients who underwent LHB tenodesis. (All patients who undergo biceps tenodesis also have, at the least, diagnostic shoulder arthroscopy with or without tenotomy; if the tendon is ruptured, tenotomy is unnecessary.)

Descriptive statistics were calculated as means (SDs) for continuous variables and as frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. Linear regression analysis was used to determine whether the number of LHB tenodesis procedures changed during the study period and whether patient age changed over time. Significance was set at P < .05.

Results

Of the 7640 patients who underwent arthroscopic shoulder procedures between 2004 and 2014, 2125 had LHB tenodesis (CPT code 23430).

Discussion

Tenodesis has become a common treatment option for several pathologic shoulder conditions involving the LHB tendon.5 We set out to determine trends in LHB tenodesis at a subspecialty-focused shoulder orthopedic practice and hypothesized that the rate of LHB tenodesis would increase significantly over time and that there would be no significant change in the age of patients who underwent LHB tenodesis. Our hypotheses were confirmed: The number of LHB tenodesis cases increased significantly without a significant change in patient age.

Treatment options for LHB pathology and SLAP tears include simple tenotomy, débridement, open biceps tenodesis, and arthroscopic tenodesis.11,12,15

Recent evidence has called into question the results of SLAP repairs and suggested biceps tenodesis may be a better treatment option for SLAP tears.10,13,21 Studies have found excellent outcomes with open subpectoral biceps tenodesis in the treatment of SLAP tears, and others have found better restoration of pitchers’ thoracic rotation with open subpectoral biceps tenodesis than with SLAP repair.13,14 Similarly, comparison studies have largely favored biceps tenodesis over SLAP repair, particularly in patients older than 35 years to 40 years.22 Given these results, it is not surprising that, querying the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgeons (ABOS) part II database for isolated SLAP lesions treated between 2002 and 2011, Patterson and colleagues23 found the percentage of SLAP repairs decreased from 69.3% to 44.8% (P < .0001), whereas the percentage of biceps tenodesis procedures increased from 1.9% to 18.8% (P < .0001), indicating the realization of improved outcomes with LHB tenodesis in the treatment of SLAP tears. On the other hand, in the ABOS part II database for the period 2003 to 2008, Weber and colleagues24 found that, despite a decrease in the percentage of SLAP repairs, total number of SLAP repairs increased from 9.4% to 10.1% (P = .0163). According to our study results, the number of SLAP repairs is decreasing over time, whereas the number of LHB tenodesis procedures is continuing to rise. The practice patterns seen in our study correlate with those in previous studies of the treatment of SLAP tears: good results in tenodesis groups and poor results in SLAP repair groups.10,13Werner and colleagues25 recently used the large PearlDiver database, which includes information from both private payers and Medicare, to determine overall LHB tenodesis trends in the United States for the period 2008 to 2011. Over those years, the incidence of LHB tenodesis increased 1.7-fold, and the rate of arthroscopic LHB tenodesis increased significantly more than the rate of open LHB tenodesis. These results are similar to ours in that the number of LHB tenodesis cases increased significantly over time. However, as the overwhelming majority of patients in our practice undergo open biceps tenodesis, the faster rate of growth in the arthroscopic cohort relative to the open cohort cannot be assessed. Additional randomized studies comparing biceps tenodesis, both open and arthroscopic, with SLAP repair are needed to properly determine the superiority of LHB tenodesis over SLAP repair.

One strength of this database study was the number of patients: more than 7000, 2125 of whom underwent biceps tenodesis performed by 1 of 4 fellowship-trained orthopedic surgeons. There were several study limitations. First, because the original diagnoses were not recorded, it was unclear exactly which pathologies were treated with tenodesis, limiting our ability to make recommendations regarding treatment trends for specific pathologies. Similarly, we did not assess outcome variables, which would have allowed us to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of the biceps tenodesis procedures. Furthermore, some procedures may have been coded incorrectly, and therefore some patients may have been erroneously included or excluded. In addition, using data from only one institution may have introduced bias into our conclusions, though the results are consistent with national trends. Finally, there was some variability among the 4 surgeons in the number of LHB tenodesis procedures performed, and this variability may have confounded results, though these surgeons treat biceps pathology in similar ways.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(4):E219-E223. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Denard PJ, Dai X, Hanypsiak BT, Burkhart SS. Anatomy of the biceps tendon: implications for restoring physiological length–tension relation during biceps tenodesis with interference screw fixation. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(10):1352-1358.

2. Ejnisman B, Monteiro GC, Andreoli CV, de Castro Pochini A. Disorder of the long head of the biceps tendon. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44(5):347-354.

3. Mellano CR, Shin JJ, Yanke AB, Verma NN. Disorders of the long head of the biceps tendon. Instr Course Lect. 2015;64:567-576.

4. Szabo I, Boileau P, Walch G. The proximal biceps as a pain generator and results of tenotomy. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2008;16(3):180-186.

5. Harwin SF, Birns ME, Mbabuike JJ, Porter DA, Galano GJ. Arthroscopic tenodesis of the long head of the biceps. Orthopedics. 2014;37(11):743-747.

6. Holtby R, Razmjou H. Accuracy of the Speed’s and Yergason’s tests in detecting biceps pathology and SLAP lesions: comparison with arthroscopic findings. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(3):231-236.

7. Ben Kibler W, Sciascia AD, Hester P, Dome D, Jacobs C. Clinical utility of traditional and new tests in the diagnosis of biceps tendon injuries and superior labrum anterior and posterior lesions in the shoulder. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(9):1840-1847.

8. Lafosse L, Reiland Y, Baier GP, Toussaint B, Jost B. Anterior and posterior instability of the long head of the biceps tendon in rotator cuff tears: a new classification based on arthroscopic observations. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(1):73-80.

9. Adams CR, Schoolfield JD, Burkhart SS. The results of arthroscopic subscapularis tendon repairs. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(12):1381-1389.

10. Provencher MT, McCormick F, Dewing C, McIntire S, Solomon D. A prospective analysis of 179 type 2 superior labrum anterior and posterior repairs: outcomes and factors associated with success and failure. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(4):880-886.

11. Gombera MM, Kahlenberg CA, Nair R, Saltzman MD, Terry MA. All-arthroscopic suprapectoral versus open subpectoral tenodesis of the long head of the biceps brachii. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(5):1077-1083.

12. Delle Rose G, Borroni M, Silvestro A, et al. The long head of biceps as a source of pain in active population: tenotomy or tenodesis? A comparison of 2 case series with isolated lesions. Musculoskelet Surg. 2012;96(suppl 1):S47-S52.

13. Chalmers PN, Trombley R, Cip J, et al. Postoperative restoration of upper extremity motion and neuromuscular control during the overhand pitch: evaluation of tenodesis and repair for superior labral anterior-posterior tears. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(12):2825-2836.

14. Gupta AK, Chalmers PN, Klosterman EL, et al. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis for bicipital tendonitis with SLAP tear. Orthopedics. 2015;38(1):e48-e53.

15. Ge H, Zhang Q, Sun Y, Li J, Sun L, Cheng B. Tenotomy or tenodesis for the long head of biceps lesions in shoulders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0121286.

16. Kaback LA, Gowda AL, Paller D, Green A, Blaine T. Long head biceps tenodesis with a knotless cinch suture anchor: a biomechanical analysis. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(5):831-835.

17. Kany J, Guinand R, Amaravathi RS, Alassaf I. The keyhole technique for arthroscopic tenodesis of the long head of the biceps tendon. In vivo prospective study with a radio-opaque marker. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015;101(1):31-34.

18. Mazzocca AD, Cote MP, Arciero CL, Romeo AA, Arciero RA. Clinical outcomes after subpectoral biceps tenodesis with an interference screw. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(10):1922-1929.

19. Provencher MT, LeClere LE, Romeo AA. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2008;16(3):170-176.

20. Erickson BJ, Jain A, Abrams GD, et al. SLAP lesions: trends in treatment. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(6):976-981.

21. Erickson J, Lavery K, Monica J, Gatt C, Dhawan A. Surgical treatment of symptomatic superior labrum anterior-posterior tears in patients older than 40 years: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(5):1274-1282.

22. Denard PJ, Ladermann A, Parsley BK, Burkhart SS. Arthroscopic biceps tenodesis compared with repair of isolated type II SLAP lesions in patients older than 35 years. Orthopedics. 2014;37(3):e292-e297.

23. Patterson BM, Creighton RA, Spang JT, Roberson JR, Kamath GV. Surgical trends in the treatment of superior labrum anterior and posterior lesions of the shoulder: analysis of data from the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery certification examination database. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(8):1904-1910.

24. Weber SC, Martin DF, Seiler JG 3rd, Harrast JJ. Superior labrum anterior and posterior lesions of the shoulder: incidence rates, complications, and outcomes as reported by American Board of Orthopedic Surgery. Part II candidates. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(7):1538-1543.