User login

Rhymin’ pediatric dermatologist provides Demodex tips

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – Pediatric dermatologist Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, has composed a whimsical couplet to help physicians broaden their differential diagnosis for acneiform rashes in children.

Pustules on noses: Think demodicosis!

The classic teaching has been that Demodex carriage and its pathologic clinical expression, demodicosis, are rare in children. Not so, Dr. Zaenglein asserted at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

“One of the things that we never used to see in kids but now I see all the time, probably because I’m looking for it, is Demodex. You’re not born with Demodex. Your carriage rate will increase over the years and by the time you’re elderly, 95% of us will have it – but not me. I just decided I’m not having these. I’m not looking for them, and I don’t want to know if they’re there,” she quipped, referring to the creepiness factor surrounding these facial parasitic mites invisible to the naked eye.

The mites live in pilosebaceous units. In animals, the disease is called mange. In humans, demodicosis is caused by two species of mites: Demodex folliculorum and D. brevis. The diagnosis is made by microscopic examination of mineral oil skin scrapings.

Primary demodicosis can take the form of pityriasis folliculorum, also known as spinulate demodicosis, papulopustular perioral, periauricular, or periorbital demodicosis, or a nodulocystic/conglobate version.

More commonly, however, .

“Demodicosis can be associated with immunosuppression. Kids with Langerhans cell histiocytosis seem to be prone to it. But you can see it in kids who don’t have any underlying immunosuppression, and I think there are more and more cases of that as we go looking for it,” said Dr. Zaenglein, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at Penn State University, Hershey, and immediate past president of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

Look for Demodex in children with somewhat atypical versions of common acneiform eruptions: for example, the ‘pustules on noses’ variant.

“Finding Demodex can alter your treatment and make it easier in these cases,” she said.

Metronidazole and ivermectin are the systemic treatment options for pediatric demodicosis.

“I tend to use topical permethrin, just because it’s easy to get. I’ll treat them once a week for 3 weeks in a row. But also make sure to treat the underlying primary inflammatory disorder,” the pediatric dermatologist advised.

Other topical options include ivermectin cream, crotamiton cream, metronidazole gel, and salicylic acid cream.

Dr. Zaenglein reported having financial relationships with Sun Pharmaceuticals, Allergan, and Ortho Dermatologics.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – Pediatric dermatologist Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, has composed a whimsical couplet to help physicians broaden their differential diagnosis for acneiform rashes in children.

Pustules on noses: Think demodicosis!

The classic teaching has been that Demodex carriage and its pathologic clinical expression, demodicosis, are rare in children. Not so, Dr. Zaenglein asserted at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

“One of the things that we never used to see in kids but now I see all the time, probably because I’m looking for it, is Demodex. You’re not born with Demodex. Your carriage rate will increase over the years and by the time you’re elderly, 95% of us will have it – but not me. I just decided I’m not having these. I’m not looking for them, and I don’t want to know if they’re there,” she quipped, referring to the creepiness factor surrounding these facial parasitic mites invisible to the naked eye.

The mites live in pilosebaceous units. In animals, the disease is called mange. In humans, demodicosis is caused by two species of mites: Demodex folliculorum and D. brevis. The diagnosis is made by microscopic examination of mineral oil skin scrapings.

Primary demodicosis can take the form of pityriasis folliculorum, also known as spinulate demodicosis, papulopustular perioral, periauricular, or periorbital demodicosis, or a nodulocystic/conglobate version.

More commonly, however, .

“Demodicosis can be associated with immunosuppression. Kids with Langerhans cell histiocytosis seem to be prone to it. But you can see it in kids who don’t have any underlying immunosuppression, and I think there are more and more cases of that as we go looking for it,” said Dr. Zaenglein, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at Penn State University, Hershey, and immediate past president of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

Look for Demodex in children with somewhat atypical versions of common acneiform eruptions: for example, the ‘pustules on noses’ variant.

“Finding Demodex can alter your treatment and make it easier in these cases,” she said.

Metronidazole and ivermectin are the systemic treatment options for pediatric demodicosis.

“I tend to use topical permethrin, just because it’s easy to get. I’ll treat them once a week for 3 weeks in a row. But also make sure to treat the underlying primary inflammatory disorder,” the pediatric dermatologist advised.

Other topical options include ivermectin cream, crotamiton cream, metronidazole gel, and salicylic acid cream.

Dr. Zaenglein reported having financial relationships with Sun Pharmaceuticals, Allergan, and Ortho Dermatologics.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – Pediatric dermatologist Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, has composed a whimsical couplet to help physicians broaden their differential diagnosis for acneiform rashes in children.

Pustules on noses: Think demodicosis!

The classic teaching has been that Demodex carriage and its pathologic clinical expression, demodicosis, are rare in children. Not so, Dr. Zaenglein asserted at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

“One of the things that we never used to see in kids but now I see all the time, probably because I’m looking for it, is Demodex. You’re not born with Demodex. Your carriage rate will increase over the years and by the time you’re elderly, 95% of us will have it – but not me. I just decided I’m not having these. I’m not looking for them, and I don’t want to know if they’re there,” she quipped, referring to the creepiness factor surrounding these facial parasitic mites invisible to the naked eye.

The mites live in pilosebaceous units. In animals, the disease is called mange. In humans, demodicosis is caused by two species of mites: Demodex folliculorum and D. brevis. The diagnosis is made by microscopic examination of mineral oil skin scrapings.

Primary demodicosis can take the form of pityriasis folliculorum, also known as spinulate demodicosis, papulopustular perioral, periauricular, or periorbital demodicosis, or a nodulocystic/conglobate version.

More commonly, however, .

“Demodicosis can be associated with immunosuppression. Kids with Langerhans cell histiocytosis seem to be prone to it. But you can see it in kids who don’t have any underlying immunosuppression, and I think there are more and more cases of that as we go looking for it,” said Dr. Zaenglein, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at Penn State University, Hershey, and immediate past president of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

Look for Demodex in children with somewhat atypical versions of common acneiform eruptions: for example, the ‘pustules on noses’ variant.

“Finding Demodex can alter your treatment and make it easier in these cases,” she said.

Metronidazole and ivermectin are the systemic treatment options for pediatric demodicosis.

“I tend to use topical permethrin, just because it’s easy to get. I’ll treat them once a week for 3 weeks in a row. But also make sure to treat the underlying primary inflammatory disorder,” the pediatric dermatologist advised.

Other topical options include ivermectin cream, crotamiton cream, metronidazole gel, and salicylic acid cream.

Dr. Zaenglein reported having financial relationships with Sun Pharmaceuticals, Allergan, and Ortho Dermatologics.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

REPORTING FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

How to surf the rosacea treatment algorithm

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – according to Linda Stein Gold, MD, director of dermatology research at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit.

Papules and pustules need an oral or topical anti-inflammatory drug. Background erythema requires an alpha adrenergic agonist. Telangiectasia is best handled by a laser device, and if a patient has a phyma, “you’ve got to use a surgical approach,” she said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation. It sounds simple, but there are decisions to be made about what drugs and formulations to use, and when, and when to combine them.

In an interview, Dr. Stein Gold shared her approach to treatment, along with the latest on using ivermectin and brimonidine together, plus her thoughts on new medications under development and the role of the Demodex mite in rosacea.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – according to Linda Stein Gold, MD, director of dermatology research at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit.

Papules and pustules need an oral or topical anti-inflammatory drug. Background erythema requires an alpha adrenergic agonist. Telangiectasia is best handled by a laser device, and if a patient has a phyma, “you’ve got to use a surgical approach,” she said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation. It sounds simple, but there are decisions to be made about what drugs and formulations to use, and when, and when to combine them.

In an interview, Dr. Stein Gold shared her approach to treatment, along with the latest on using ivermectin and brimonidine together, plus her thoughts on new medications under development and the role of the Demodex mite in rosacea.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – according to Linda Stein Gold, MD, director of dermatology research at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit.

Papules and pustules need an oral or topical anti-inflammatory drug. Background erythema requires an alpha adrenergic agonist. Telangiectasia is best handled by a laser device, and if a patient has a phyma, “you’ve got to use a surgical approach,” she said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation. It sounds simple, but there are decisions to be made about what drugs and formulations to use, and when, and when to combine them.

In an interview, Dr. Stein Gold shared her approach to treatment, along with the latest on using ivermectin and brimonidine together, plus her thoughts on new medications under development and the role of the Demodex mite in rosacea.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Antibiotic use in dermatology declining, with one exception

Dermatologists are prescribing fewer antibiotics for acne and rosacea, but prescribing after dermatologic surgery has increased in the past decade.

In a study published online Jan. 16 in JAMA Dermatology, researchers report the results of a cross-sectional analysis of antibiotic prescribing by 11,986 dermatologists between 2008 and 2016, using commercial claims data.

The analysis showed that, over this period of time, the overall rate of antibiotic prescribing by dermatologists decreased by 36.6%, from 3.36 courses per 100 dermatologist visits to 2.13 courses. In particular, antibiotic prescribing for acne decreased by 28.1%, from 11.76 courses per 100 visits to 8.45 courses, and for rosacea it decreased by 18.1%, from 10.89 courses per 100 visits to 8.92 courses.

John S. Barbieri, MD, of the department of dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, and his coauthors described the overall decline in antibiotic prescribing as “encouraging,” considering that in 2013 dermatologists were identified as the “most frequent prescribers of oral antibiotics per clinician.” The decline resulted in an estimated 480,000 fewer antibiotic courses a year, they noted.

“Much of the decrease in extended courses of antibiotic therapy is associated with visits for acne and rosacea,” they wrote. “Although recent guidelines suggest limiting the duration of therapy in this patient population, course duration has remained stable over time, suggesting that this decrease may be due to fewer patients being treated with antibiotics rather than patients being treated for a shorter duration.”

However, the rate of oral antibiotic prescriptions associated with surgical visits increased by 69.6%, from 3.92 courses per 100 visits to 6.65. This increase was concerning, given the risk of surgical-site infections was low, the authors pointed out. “In addition, a 2008 advisory statement on antibiotic prophylaxis recommends single-dose perioperative antibiotics for patients at increased risk of surgical-site infection,” they added.

The study also noted a 35.3% increase in antibiotic prescribing for cysts and a 3.2% increase for hidradenitis suppurativa.

Over the entire study period, nearly 1 million courses of oral antibiotics were prescribed. Doxycycline hyclate accounted for around one quarter of prescriptions, as did minocycline, while 19.9% of prescriptions were for cephalexin.

“Given the low rate of infectious complications, even for Mohs surgery, and the lack of evidence to support the use of prolonged rather than single-dose perioperative regimens, the postoperative courses of antibiotics identified in this study may increase risks to patients without substantial benefits,” they added.

The study was partly supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Skin Diseases. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Barbieri J et al. JAMA Dermatology. 2019 Jan 16. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4944.

Reducing antibiotic prescribing in dermatology – as in so many other areas of medical practice – is a challenge, but there are a number of strategies that can help.

The first is to take a wait-and-see approach, which has been shown to be effective for childhood otitis media. Communication training for physicians can also help them to manage patient requests for antibiotics by working out the patient’s level of understanding of their condition and treatment options, and their expectations, and getting them to agree to keep antibiotics as a contingency plan. There are clinical decision support tools available to help physicians identify high-risk surgical patients who may require postoperative antibiotics.

It will help to have alternative treatment options for conditions such as acne and rosacea, such as better topical therapies, and an increase in clinical trials for these therapies will hopefully provide more options for patients.

Joslyn S. Kirby, MD, and Jordan S. Lim, MB, are in the department of dermatology, Penn State University, Hershey. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Dermatology. 2019 Jan 16. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4877). They had no disclosures.

Reducing antibiotic prescribing in dermatology – as in so many other areas of medical practice – is a challenge, but there are a number of strategies that can help.

The first is to take a wait-and-see approach, which has been shown to be effective for childhood otitis media. Communication training for physicians can also help them to manage patient requests for antibiotics by working out the patient’s level of understanding of their condition and treatment options, and their expectations, and getting them to agree to keep antibiotics as a contingency plan. There are clinical decision support tools available to help physicians identify high-risk surgical patients who may require postoperative antibiotics.

It will help to have alternative treatment options for conditions such as acne and rosacea, such as better topical therapies, and an increase in clinical trials for these therapies will hopefully provide more options for patients.

Joslyn S. Kirby, MD, and Jordan S. Lim, MB, are in the department of dermatology, Penn State University, Hershey. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Dermatology. 2019 Jan 16. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4877). They had no disclosures.

Reducing antibiotic prescribing in dermatology – as in so many other areas of medical practice – is a challenge, but there are a number of strategies that can help.

The first is to take a wait-and-see approach, which has been shown to be effective for childhood otitis media. Communication training for physicians can also help them to manage patient requests for antibiotics by working out the patient’s level of understanding of their condition and treatment options, and their expectations, and getting them to agree to keep antibiotics as a contingency plan. There are clinical decision support tools available to help physicians identify high-risk surgical patients who may require postoperative antibiotics.

It will help to have alternative treatment options for conditions such as acne and rosacea, such as better topical therapies, and an increase in clinical trials for these therapies will hopefully provide more options for patients.

Joslyn S. Kirby, MD, and Jordan S. Lim, MB, are in the department of dermatology, Penn State University, Hershey. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Dermatology. 2019 Jan 16. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4877). They had no disclosures.

Dermatologists are prescribing fewer antibiotics for acne and rosacea, but prescribing after dermatologic surgery has increased in the past decade.

In a study published online Jan. 16 in JAMA Dermatology, researchers report the results of a cross-sectional analysis of antibiotic prescribing by 11,986 dermatologists between 2008 and 2016, using commercial claims data.

The analysis showed that, over this period of time, the overall rate of antibiotic prescribing by dermatologists decreased by 36.6%, from 3.36 courses per 100 dermatologist visits to 2.13 courses. In particular, antibiotic prescribing for acne decreased by 28.1%, from 11.76 courses per 100 visits to 8.45 courses, and for rosacea it decreased by 18.1%, from 10.89 courses per 100 visits to 8.92 courses.

John S. Barbieri, MD, of the department of dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, and his coauthors described the overall decline in antibiotic prescribing as “encouraging,” considering that in 2013 dermatologists were identified as the “most frequent prescribers of oral antibiotics per clinician.” The decline resulted in an estimated 480,000 fewer antibiotic courses a year, they noted.

“Much of the decrease in extended courses of antibiotic therapy is associated with visits for acne and rosacea,” they wrote. “Although recent guidelines suggest limiting the duration of therapy in this patient population, course duration has remained stable over time, suggesting that this decrease may be due to fewer patients being treated with antibiotics rather than patients being treated for a shorter duration.”

However, the rate of oral antibiotic prescriptions associated with surgical visits increased by 69.6%, from 3.92 courses per 100 visits to 6.65. This increase was concerning, given the risk of surgical-site infections was low, the authors pointed out. “In addition, a 2008 advisory statement on antibiotic prophylaxis recommends single-dose perioperative antibiotics for patients at increased risk of surgical-site infection,” they added.

The study also noted a 35.3% increase in antibiotic prescribing for cysts and a 3.2% increase for hidradenitis suppurativa.

Over the entire study period, nearly 1 million courses of oral antibiotics were prescribed. Doxycycline hyclate accounted for around one quarter of prescriptions, as did minocycline, while 19.9% of prescriptions were for cephalexin.

“Given the low rate of infectious complications, even for Mohs surgery, and the lack of evidence to support the use of prolonged rather than single-dose perioperative regimens, the postoperative courses of antibiotics identified in this study may increase risks to patients without substantial benefits,” they added.

The study was partly supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Skin Diseases. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Barbieri J et al. JAMA Dermatology. 2019 Jan 16. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4944.

Dermatologists are prescribing fewer antibiotics for acne and rosacea, but prescribing after dermatologic surgery has increased in the past decade.

In a study published online Jan. 16 in JAMA Dermatology, researchers report the results of a cross-sectional analysis of antibiotic prescribing by 11,986 dermatologists between 2008 and 2016, using commercial claims data.

The analysis showed that, over this period of time, the overall rate of antibiotic prescribing by dermatologists decreased by 36.6%, from 3.36 courses per 100 dermatologist visits to 2.13 courses. In particular, antibiotic prescribing for acne decreased by 28.1%, from 11.76 courses per 100 visits to 8.45 courses, and for rosacea it decreased by 18.1%, from 10.89 courses per 100 visits to 8.92 courses.

John S. Barbieri, MD, of the department of dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, and his coauthors described the overall decline in antibiotic prescribing as “encouraging,” considering that in 2013 dermatologists were identified as the “most frequent prescribers of oral antibiotics per clinician.” The decline resulted in an estimated 480,000 fewer antibiotic courses a year, they noted.

“Much of the decrease in extended courses of antibiotic therapy is associated with visits for acne and rosacea,” they wrote. “Although recent guidelines suggest limiting the duration of therapy in this patient population, course duration has remained stable over time, suggesting that this decrease may be due to fewer patients being treated with antibiotics rather than patients being treated for a shorter duration.”

However, the rate of oral antibiotic prescriptions associated with surgical visits increased by 69.6%, from 3.92 courses per 100 visits to 6.65. This increase was concerning, given the risk of surgical-site infections was low, the authors pointed out. “In addition, a 2008 advisory statement on antibiotic prophylaxis recommends single-dose perioperative antibiotics for patients at increased risk of surgical-site infection,” they added.

The study also noted a 35.3% increase in antibiotic prescribing for cysts and a 3.2% increase for hidradenitis suppurativa.

Over the entire study period, nearly 1 million courses of oral antibiotics were prescribed. Doxycycline hyclate accounted for around one quarter of prescriptions, as did minocycline, while 19.9% of prescriptions were for cephalexin.

“Given the low rate of infectious complications, even for Mohs surgery, and the lack of evidence to support the use of prolonged rather than single-dose perioperative regimens, the postoperative courses of antibiotics identified in this study may increase risks to patients without substantial benefits,” they added.

The study was partly supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Skin Diseases. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Barbieri J et al. JAMA Dermatology. 2019 Jan 16. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4944.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Antibiotic prescriptions by dermatologists have decreased since 2008.

Major finding: Between 2008 and 2016, antibiotic prescriptions by dermatologists dropped by 36.6%.

Study details: Cross-sectional analysis of antibiotic prescribing by 11,986 dermatologists from 2008 to 2016.

Disclosures: The study was partly supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Skin Diseases. The authors had no disclosures.

Source: Barbieri J et al. JAMA Dermatology. 2019 Jan 16. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4944.

A theory of relativity for rosacea patients

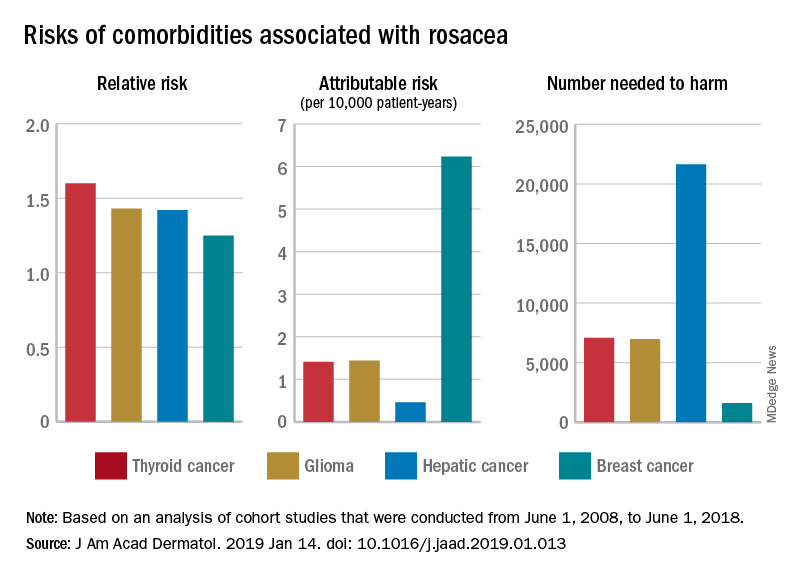

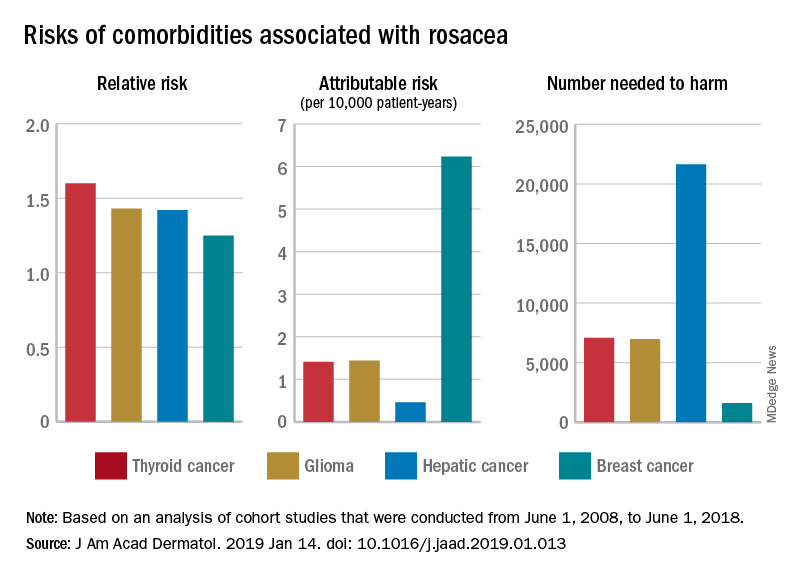

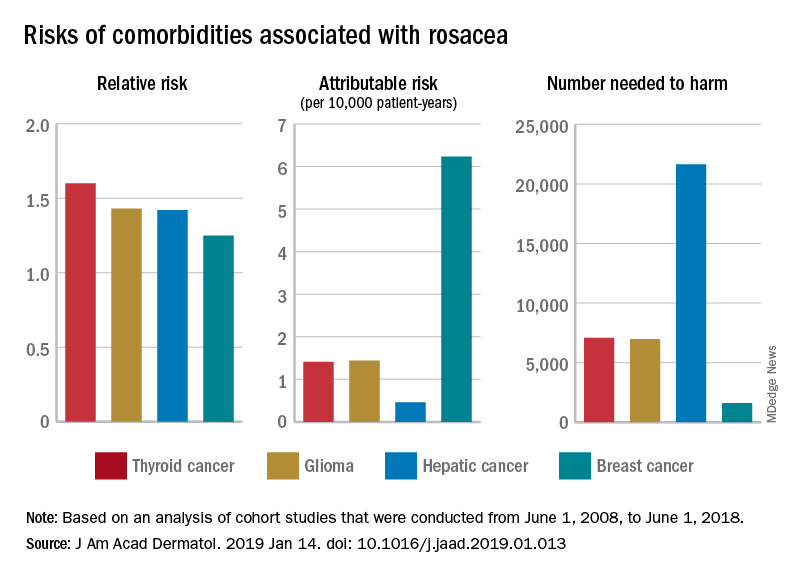

Rosacea has several known comorbidities, but the widespread use of their relative, rather than absolute, risks “may result in overestimation of the clinical importance of exposures,” Leonardo A. Tjahjono and his associates wrote.

For a patient with rosacea, the relative risk of hepatic cancer is 1.42, but the attributable risk and the number needed to harm (NNH), which provide “a clearer, absolute picture regarding the association” with rosacea, are 0.46 per 10,000 patient-years and 21,645, respectively. The relative risk of comorbid breast cancer is 1.25, compared with an attributable risk of 6.23 per 10,000 patient-years and an NNH of 1,606, Mr. Tjahjono of Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C., and his associates reported in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Physician misconceptions based on patients’ relative risks of comorbidities may lead to increased cancer screenings, which “can provide great benefit in a proper context; however, they are not without consequences. For example, 0.7 % of liver biopsies result in severe intraperitoneal hematoma,” the investigators said.

The absolute risks – calculated by the investigators using cohort studies that were conducted from June 1, 2008, to June 1, 2018 – present “a better understanding regarding rosacea’s impact on public health and clinical settings, “ they wrote.

SOURCE: Tjahjono LA et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.01.013.

Rosacea has several known comorbidities, but the widespread use of their relative, rather than absolute, risks “may result in overestimation of the clinical importance of exposures,” Leonardo A. Tjahjono and his associates wrote.

For a patient with rosacea, the relative risk of hepatic cancer is 1.42, but the attributable risk and the number needed to harm (NNH), which provide “a clearer, absolute picture regarding the association” with rosacea, are 0.46 per 10,000 patient-years and 21,645, respectively. The relative risk of comorbid breast cancer is 1.25, compared with an attributable risk of 6.23 per 10,000 patient-years and an NNH of 1,606, Mr. Tjahjono of Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C., and his associates reported in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Physician misconceptions based on patients’ relative risks of comorbidities may lead to increased cancer screenings, which “can provide great benefit in a proper context; however, they are not without consequences. For example, 0.7 % of liver biopsies result in severe intraperitoneal hematoma,” the investigators said.

The absolute risks – calculated by the investigators using cohort studies that were conducted from June 1, 2008, to June 1, 2018 – present “a better understanding regarding rosacea’s impact on public health and clinical settings, “ they wrote.

SOURCE: Tjahjono LA et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.01.013.

Rosacea has several known comorbidities, but the widespread use of their relative, rather than absolute, risks “may result in overestimation of the clinical importance of exposures,” Leonardo A. Tjahjono and his associates wrote.

For a patient with rosacea, the relative risk of hepatic cancer is 1.42, but the attributable risk and the number needed to harm (NNH), which provide “a clearer, absolute picture regarding the association” with rosacea, are 0.46 per 10,000 patient-years and 21,645, respectively. The relative risk of comorbid breast cancer is 1.25, compared with an attributable risk of 6.23 per 10,000 patient-years and an NNH of 1,606, Mr. Tjahjono of Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C., and his associates reported in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Physician misconceptions based on patients’ relative risks of comorbidities may lead to increased cancer screenings, which “can provide great benefit in a proper context; however, they are not without consequences. For example, 0.7 % of liver biopsies result in severe intraperitoneal hematoma,” the investigators said.

The absolute risks – calculated by the investigators using cohort studies that were conducted from June 1, 2008, to June 1, 2018 – present “a better understanding regarding rosacea’s impact on public health and clinical settings, “ they wrote.

SOURCE: Tjahjono LA et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.01.013.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Annual cost of branded topical rosacea therapy is twice that of generics

according to a retrospective analysis of claims data published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“We found the mean annual cost of topical therapy for branded medications per person was nearly twice the cost of generics, despite the rise in generic drug costs,” Hadar Lev-Tov, MD, from the department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery at the University of Miami and his colleagues wrote in their study, published as a letter to the editor. “Thus, there is an opportunity to save healthcare costs, nearly $7.5 million annually, for this cohort.”

Dr. Lev-Tov and his colleagues performed an analysis of the MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database to determine real-world costs and usage of rosacea medication and identified 72,173 adults with two or more claims for rosacea who visited a primary care provider, dermatologist, or ophthalmologist over 18 months, from January 2005 through December 2014. The majority of these patients – 62,074 (86%) – received topical medication therapy, while 4,463 (6%) of patients received oral therapy only. Of the patients who received topical therapy, 47,035 (75.8%) received single agent topical therapy and 15,039 (24.2%) patients used combination topical therapy. Metronidazole and azelaic acid were the most common combination used.

The researchers noted that this was “an important proportion” of patients who used combination topical therapy, despite it not being discussed in most guidelines. In addition, they added, “these medications are thought to work by similar mechanisms (anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and KLK5 modulation) and to our knowledge have not been studied together.”

More patients were treated with branded topical medications (50,334) than with generics (39,621). With regard to price (calculated as the sum of insurance payments, copay, and deductible for each medication over 1 year), the mean annual cost of the branded topical medication was $308.02, compared with $160.37 for generic medications (P less than .0001). The researchers noted switching to a generic medication for treatment of rosacea would potentially save $147.65 per patient a year. (Costs were reported in 2015 US dollars.)

The researchers said their study was limited by lack of Medicare and Medicaid claims data, the retrospective study design, and dependence on an ICD-9 code only for diagnosis of rosacea, but they noted that 92% of patients received a diagnosis from a dermatologist. In addition, they recommended more studies be conducted on the cost-effectiveness of rosacea therapy when comparing systemic medications and topical therapies.

This study was funded in part by a grant from the American Acne and Rosacea Society. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Lev-Tov H et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.039.

according to a retrospective analysis of claims data published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“We found the mean annual cost of topical therapy for branded medications per person was nearly twice the cost of generics, despite the rise in generic drug costs,” Hadar Lev-Tov, MD, from the department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery at the University of Miami and his colleagues wrote in their study, published as a letter to the editor. “Thus, there is an opportunity to save healthcare costs, nearly $7.5 million annually, for this cohort.”

Dr. Lev-Tov and his colleagues performed an analysis of the MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database to determine real-world costs and usage of rosacea medication and identified 72,173 adults with two or more claims for rosacea who visited a primary care provider, dermatologist, or ophthalmologist over 18 months, from January 2005 through December 2014. The majority of these patients – 62,074 (86%) – received topical medication therapy, while 4,463 (6%) of patients received oral therapy only. Of the patients who received topical therapy, 47,035 (75.8%) received single agent topical therapy and 15,039 (24.2%) patients used combination topical therapy. Metronidazole and azelaic acid were the most common combination used.

The researchers noted that this was “an important proportion” of patients who used combination topical therapy, despite it not being discussed in most guidelines. In addition, they added, “these medications are thought to work by similar mechanisms (anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and KLK5 modulation) and to our knowledge have not been studied together.”

More patients were treated with branded topical medications (50,334) than with generics (39,621). With regard to price (calculated as the sum of insurance payments, copay, and deductible for each medication over 1 year), the mean annual cost of the branded topical medication was $308.02, compared with $160.37 for generic medications (P less than .0001). The researchers noted switching to a generic medication for treatment of rosacea would potentially save $147.65 per patient a year. (Costs were reported in 2015 US dollars.)

The researchers said their study was limited by lack of Medicare and Medicaid claims data, the retrospective study design, and dependence on an ICD-9 code only for diagnosis of rosacea, but they noted that 92% of patients received a diagnosis from a dermatologist. In addition, they recommended more studies be conducted on the cost-effectiveness of rosacea therapy when comparing systemic medications and topical therapies.

This study was funded in part by a grant from the American Acne and Rosacea Society. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Lev-Tov H et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.039.

according to a retrospective analysis of claims data published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“We found the mean annual cost of topical therapy for branded medications per person was nearly twice the cost of generics, despite the rise in generic drug costs,” Hadar Lev-Tov, MD, from the department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery at the University of Miami and his colleagues wrote in their study, published as a letter to the editor. “Thus, there is an opportunity to save healthcare costs, nearly $7.5 million annually, for this cohort.”

Dr. Lev-Tov and his colleagues performed an analysis of the MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database to determine real-world costs and usage of rosacea medication and identified 72,173 adults with two or more claims for rosacea who visited a primary care provider, dermatologist, or ophthalmologist over 18 months, from January 2005 through December 2014. The majority of these patients – 62,074 (86%) – received topical medication therapy, while 4,463 (6%) of patients received oral therapy only. Of the patients who received topical therapy, 47,035 (75.8%) received single agent topical therapy and 15,039 (24.2%) patients used combination topical therapy. Metronidazole and azelaic acid were the most common combination used.

The researchers noted that this was “an important proportion” of patients who used combination topical therapy, despite it not being discussed in most guidelines. In addition, they added, “these medications are thought to work by similar mechanisms (anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and KLK5 modulation) and to our knowledge have not been studied together.”

More patients were treated with branded topical medications (50,334) than with generics (39,621). With regard to price (calculated as the sum of insurance payments, copay, and deductible for each medication over 1 year), the mean annual cost of the branded topical medication was $308.02, compared with $160.37 for generic medications (P less than .0001). The researchers noted switching to a generic medication for treatment of rosacea would potentially save $147.65 per patient a year. (Costs were reported in 2015 US dollars.)

The researchers said their study was limited by lack of Medicare and Medicaid claims data, the retrospective study design, and dependence on an ICD-9 code only for diagnosis of rosacea, but they noted that 92% of patients received a diagnosis from a dermatologist. In addition, they recommended more studies be conducted on the cost-effectiveness of rosacea therapy when comparing systemic medications and topical therapies.

This study was funded in part by a grant from the American Acne and Rosacea Society. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Lev-Tov H et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.039.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Patients used branded topical medications more often than generic medications for treatment of rosacea.

Major finding: About 50,000 patients were treated with branded topical medications than with generics (almost 40,000), at a mean annual cost of $308.02 and $160.37, respectively.

Study details: A retrospective cohort analysis of 72,173 adults with rosacea treated with topical or oral therapy from a commercial claims database between January 2005 and 2014.

Disclosures: This study was funded in part by a grant from the American Acne and Rosacea Society. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Lev-Tov H et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.039.

Caffeinated coffee intake linked to lower rosacea risk

Caffeinated coffee intake is linked to a decreased incidence of rosacea, results of a large, observational study suggest.

Increased levels of caffeinated coffee consumption were associated with progressively lower levels of incident rosacea in a study of more than 82,000 participants representing more than 1.1 million person-years of follow-up.

By contrast, caffeine from other foods was not associated with rosacea incidence, reported Wen-Qing Li, PhD, of the department of dermatology at Brown University, Providence, R.I., and his coinvestigators. Those findings may have implications for the “causes and clinical approach” to rosacea.

“Our findings do not support limiting caffeine intake as a preventive strategy for rosacea,” they concluded in the study, published in JAMA Dermatology.

This is not the first study looking for potential links between rosacea and caffeine or coffee intake. However, previous studies didn’t distinguish between caffeinated coffee versus other beverages, and only one previous study made a distinction between the amounts of caffeine and coffee consumed, according to the authors.

Their research was based on data from the Nurses’ Health Study II, a prospective cohort study started in 1989. They looked specifically at 82,737 women who, in 2005, responded to the question about whether they had been diagnosed with rosacea. They identified 4,945 incident rosacea cases over the 1,120,051 person-years of follow-up.

A significant inverse association was found between caffeinated coffee intake and rosacea: Individuals who consumed four or more servings a day had a significantly lower risk of rosacea, compared with those who consumed one or fewer servings per month (hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.69-0.87; P less than .001). They also found a dose-dependent effect, with the absolute risk of rosacea decreased by 131 per 100,000 person-years with at least four daily servings of caffeinated coffee, compared with under one serving a month.

By contrast, decaffeinated coffee was not associated with a reduced risk of rosacea, and in further analysis, the investigators found that there was no significant inverse association when they looked just at caffeine intake from sources other than coffee, such as chocolate, tea, and soda.

Caffeine could influence rosacea incidence by one of several mechanisms, including its effect on vascular contractility, the investigators hypothesized. “Increased caffeine intake may decrease vasodilation and consequently lead to diminution of rosacea symptoms.”

However, caffeine also has documented immunosuppressant effects that could possibly decrease rosacea-associated inflammation and has been shown to modulate hormone levels. “Hormonal factors have been implicated in the development of rosacea, and caffeine can modulate hormone levels,” they wrote.

Two study authors reported disclosures related to AbbVie, Amgen, Astellas Pharma, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer, among others. Funding for the study came from several sources, including National Institutes of Health grants for the Nurses’ Health Study II.

SOURCE: Li W-Q et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Oct 17. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3301.

This study shows an inverse association between caffeine intake and incidence rosacea, which suggests that patients with rosacea need not avoid coffee, according to Mackenzie R. Wehner, MD, and Eleni Linos, MD, MPH.

For everyone else, the findings offer yet another reason to keep indulging in one of “life’s habitual pleasures,” they wrote. “We will raise an insulated travel mug to that.”

This latest study fits in with numerous studies suggesting coffee may be protective against a number of maladies, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and Parkinson’s disease, they wrote in their editorial published in JAMA Dermatology.

However, this is an observational study, not a rigorous, randomized trial that could more conclusively prove coffee actually provides an antirosacea benefit that cannot be explained by other factors, such as systematic differences between people who do and do not drink coffee. Enrollment of all women, mostly white, in the Nurses’ Health Study II is another limitation, they added.

Nevertheless, studies like this are the “next-best option” in lieu of randomized, controlled trials to evaluate these relationships, they wrote. “Importantly, the strength of the protective effect noted and the dose-response relationship with increasing coffee and caffeine intake are convincing.”

Dr. Wehner , is with the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Linos is with the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Wehner reported support from a National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases/National Institutes of Health Dermatology Research Training grant. Dr. Linos reported support from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Aging.

This study shows an inverse association between caffeine intake and incidence rosacea, which suggests that patients with rosacea need not avoid coffee, according to Mackenzie R. Wehner, MD, and Eleni Linos, MD, MPH.

For everyone else, the findings offer yet another reason to keep indulging in one of “life’s habitual pleasures,” they wrote. “We will raise an insulated travel mug to that.”

This latest study fits in with numerous studies suggesting coffee may be protective against a number of maladies, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and Parkinson’s disease, they wrote in their editorial published in JAMA Dermatology.

However, this is an observational study, not a rigorous, randomized trial that could more conclusively prove coffee actually provides an antirosacea benefit that cannot be explained by other factors, such as systematic differences between people who do and do not drink coffee. Enrollment of all women, mostly white, in the Nurses’ Health Study II is another limitation, they added.

Nevertheless, studies like this are the “next-best option” in lieu of randomized, controlled trials to evaluate these relationships, they wrote. “Importantly, the strength of the protective effect noted and the dose-response relationship with increasing coffee and caffeine intake are convincing.”

Dr. Wehner , is with the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Linos is with the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Wehner reported support from a National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases/National Institutes of Health Dermatology Research Training grant. Dr. Linos reported support from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Aging.

This study shows an inverse association between caffeine intake and incidence rosacea, which suggests that patients with rosacea need not avoid coffee, according to Mackenzie R. Wehner, MD, and Eleni Linos, MD, MPH.

For everyone else, the findings offer yet another reason to keep indulging in one of “life’s habitual pleasures,” they wrote. “We will raise an insulated travel mug to that.”

This latest study fits in with numerous studies suggesting coffee may be protective against a number of maladies, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and Parkinson’s disease, they wrote in their editorial published in JAMA Dermatology.

However, this is an observational study, not a rigorous, randomized trial that could more conclusively prove coffee actually provides an antirosacea benefit that cannot be explained by other factors, such as systematic differences between people who do and do not drink coffee. Enrollment of all women, mostly white, in the Nurses’ Health Study II is another limitation, they added.

Nevertheless, studies like this are the “next-best option” in lieu of randomized, controlled trials to evaluate these relationships, they wrote. “Importantly, the strength of the protective effect noted and the dose-response relationship with increasing coffee and caffeine intake are convincing.”

Dr. Wehner , is with the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Linos is with the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Wehner reported support from a National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases/National Institutes of Health Dermatology Research Training grant. Dr. Linos reported support from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Aging.

Caffeinated coffee intake is linked to a decreased incidence of rosacea, results of a large, observational study suggest.

Increased levels of caffeinated coffee consumption were associated with progressively lower levels of incident rosacea in a study of more than 82,000 participants representing more than 1.1 million person-years of follow-up.

By contrast, caffeine from other foods was not associated with rosacea incidence, reported Wen-Qing Li, PhD, of the department of dermatology at Brown University, Providence, R.I., and his coinvestigators. Those findings may have implications for the “causes and clinical approach” to rosacea.

“Our findings do not support limiting caffeine intake as a preventive strategy for rosacea,” they concluded in the study, published in JAMA Dermatology.

This is not the first study looking for potential links between rosacea and caffeine or coffee intake. However, previous studies didn’t distinguish between caffeinated coffee versus other beverages, and only one previous study made a distinction between the amounts of caffeine and coffee consumed, according to the authors.

Their research was based on data from the Nurses’ Health Study II, a prospective cohort study started in 1989. They looked specifically at 82,737 women who, in 2005, responded to the question about whether they had been diagnosed with rosacea. They identified 4,945 incident rosacea cases over the 1,120,051 person-years of follow-up.

A significant inverse association was found between caffeinated coffee intake and rosacea: Individuals who consumed four or more servings a day had a significantly lower risk of rosacea, compared with those who consumed one or fewer servings per month (hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.69-0.87; P less than .001). They also found a dose-dependent effect, with the absolute risk of rosacea decreased by 131 per 100,000 person-years with at least four daily servings of caffeinated coffee, compared with under one serving a month.

By contrast, decaffeinated coffee was not associated with a reduced risk of rosacea, and in further analysis, the investigators found that there was no significant inverse association when they looked just at caffeine intake from sources other than coffee, such as chocolate, tea, and soda.

Caffeine could influence rosacea incidence by one of several mechanisms, including its effect on vascular contractility, the investigators hypothesized. “Increased caffeine intake may decrease vasodilation and consequently lead to diminution of rosacea symptoms.”

However, caffeine also has documented immunosuppressant effects that could possibly decrease rosacea-associated inflammation and has been shown to modulate hormone levels. “Hormonal factors have been implicated in the development of rosacea, and caffeine can modulate hormone levels,” they wrote.

Two study authors reported disclosures related to AbbVie, Amgen, Astellas Pharma, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer, among others. Funding for the study came from several sources, including National Institutes of Health grants for the Nurses’ Health Study II.

SOURCE: Li W-Q et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Oct 17. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3301.

Caffeinated coffee intake is linked to a decreased incidence of rosacea, results of a large, observational study suggest.

Increased levels of caffeinated coffee consumption were associated with progressively lower levels of incident rosacea in a study of more than 82,000 participants representing more than 1.1 million person-years of follow-up.

By contrast, caffeine from other foods was not associated with rosacea incidence, reported Wen-Qing Li, PhD, of the department of dermatology at Brown University, Providence, R.I., and his coinvestigators. Those findings may have implications for the “causes and clinical approach” to rosacea.

“Our findings do not support limiting caffeine intake as a preventive strategy for rosacea,” they concluded in the study, published in JAMA Dermatology.

This is not the first study looking for potential links between rosacea and caffeine or coffee intake. However, previous studies didn’t distinguish between caffeinated coffee versus other beverages, and only one previous study made a distinction between the amounts of caffeine and coffee consumed, according to the authors.

Their research was based on data from the Nurses’ Health Study II, a prospective cohort study started in 1989. They looked specifically at 82,737 women who, in 2005, responded to the question about whether they had been diagnosed with rosacea. They identified 4,945 incident rosacea cases over the 1,120,051 person-years of follow-up.

A significant inverse association was found between caffeinated coffee intake and rosacea: Individuals who consumed four or more servings a day had a significantly lower risk of rosacea, compared with those who consumed one or fewer servings per month (hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.69-0.87; P less than .001). They also found a dose-dependent effect, with the absolute risk of rosacea decreased by 131 per 100,000 person-years with at least four daily servings of caffeinated coffee, compared with under one serving a month.

By contrast, decaffeinated coffee was not associated with a reduced risk of rosacea, and in further analysis, the investigators found that there was no significant inverse association when they looked just at caffeine intake from sources other than coffee, such as chocolate, tea, and soda.

Caffeine could influence rosacea incidence by one of several mechanisms, including its effect on vascular contractility, the investigators hypothesized. “Increased caffeine intake may decrease vasodilation and consequently lead to diminution of rosacea symptoms.”

However, caffeine also has documented immunosuppressant effects that could possibly decrease rosacea-associated inflammation and has been shown to modulate hormone levels. “Hormonal factors have been implicated in the development of rosacea, and caffeine can modulate hormone levels,” they wrote.

Two study authors reported disclosures related to AbbVie, Amgen, Astellas Pharma, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer, among others. Funding for the study came from several sources, including National Institutes of Health grants for the Nurses’ Health Study II.

SOURCE: Li W-Q et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Oct 17. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3301.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Caffeinated coffee intake was linked to decreased incidence of rosacea, while decaffeinated coffee and noncoffee sources of caffeine had no such effect.

Major finding: Consuming four or more servings of caffeinated coffee was associated with lower risk of rosacea versus one or fewer servings per month (hazard ratio, 0.77; P less than .001).

Study details: An analysis based on 82,737 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study II who responded to a question about rosacea.

Disclosures: Two study authors reported disclosures related to AbbVie, Amgen, Astellas Pharma, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer, among others. Funding for the study came from National Institutes of Health grants for the Nurses’ Health Study II and other sources.

Source: Li W-Q et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Oct 17. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3301.

Q and A with Dr. Julie Harper: Treating acne and rosacea

MONTEREY, CALIF. – Julie C. Harper, MD, likes to warn her patients with acne about an unexpected possible side effect of treatment with isotretinoin. “You may become a dermatologist.”

After all, that’s exactly how Dr. Harper herself was inspired to pursue a career in dermatology. As a teenager, she had acne and was treated with isotretinoin three times. The experience was so influential that she went into dermatology with a specific goal of treating acne.

“I love all of it, and in my practice I treat everything,” said Dr. Harper, “but I have a special interest in helping people with acne be as clear as they can be.” Indeed, she helped found the American Acne and Rosacea Society, which she now serves as president.

Dr. Harper, who practices in Birmingham, Ala., spoke about her approach to acne and rosacea in an interview following one of her presentations at the annual Coastal Dermatology Symposium.

DERMATOLOGY NEWS: What drew you to focus on rosacea in addition to acne?

Dr. Harper: But they’re very distinct diagnoses, and their pathogenesis is completely different. My interest in treating rosacea was secondary to acne, but I love to treat them both.

DN: Are they both equally challenging to treat?

Dr. Harper: In some ways, rosacea is more challenging to treat.

With acne, we have a pretty good algorithm for how we treat it. We can end with isotretinoin, which for many people is a cure. But we really don’t have that last step in rosacea.

DN: What are you doing differently with rosacea than you might not have done a few years ago?

Dr. Harper: More combination therapy. The trend is more toward a comprehensive combination approach to treat everything we see in rosacea: Hit this as hard as you can. Hit everything you see. Part of that is because we have some newer drugs like the alpha-adrenergic agonists that work differently than anything we’ve had before.

We have a couple of good combination studies. One study examined ivermectin plus brimonidine (J Drugs Dermatol. 2017 Sep 1;16[9]:909-16). Those two worked better together if you did not delay the brimonidine for 4 weeks and only used it with the ivermectin for part of the study.

There are also the newer studies that look at doxycycline plus ivermectin and compare it with ivermectin plus placebo. The combination works better, and it works faster (Adv Ther. 2016;33[9]:1481-1501; unpublished clinical trial data on file with Galderma, NCT03075891).

On top of those treatments, we may need to add laser for background redness, or an oral beta-blocker for flushing if the patient still complains of the symptoms.

DN: What’s most challenging to treat in rosacea?

Dr. Harper: The redness and phymatous changes are the hardest. Once you get phymatous changes, you have to do a physical modality.

Most of us think that if we treat rosacea aggressively up front, maybe we can prevent the phymatous changes. Prevention is key, just like prevention of acne scarring is easier than getting rid of scars once you have it.

Other than phyma, it’s the redness. Even the Food and Drug Administration–approved products we have for redness don’t work for flushing. Patients stand up to give up a presentation and “Oh no, here comes a red face.” That’s the hardest part to manage.

DN: How do beta-blockers fare at treating flushing?

Dr. Harper: They can help, but I don’t know that they can knock it out completely.

And we should remember that there are no FDA-approved beta-blockers to treat this. Most of the data we have are small case reports or case series. We don’t have a lot of data.

DN: Is there anything that’s used too much in rosacea?

Dr. Harper: Probably metronidazole. I understand why it’s used. It’s not a bad drug. But we have better drugs now.

I think we use metronidazole whenever things aren’t covered by insurance. And we use it to do too many things. Don’t try to make metronidazole do everything.

Metronidazole is FDA-approved for papules and pustules. It wasn’t ever intended to help with flushing and background erythema, and you’ll need to use something else with it.

DN: What’s coming down the line for rosacea?

Dr. Harper: We’ve got a couple new antibiotics: a new topical antibiotic and another oral antibiotic.

DN: Let’s talk about acne. Do you think isotretinoin is underused?

Dr. Harper: We should be using more of it. Why do we hold this drug hostage from our patients? In many people, it will cure their acne if they take it for just 5-6 months.

Are we worried about inflammatory bowel disease? The most recent studies say that’s not really an association. Are we worried about depression? We’ve had a meta-analysis that suggests if you take all that data, depression – if anything – gets better in people who take isotretinoin (Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Apr;109[4]:563-9; J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jun;76[6]:1068-76.e9).

We need to take [the risk with pregnancy] seriously. But we need to be putting more people on the drug and giving them the opportunity to be clear.

DN: What should be used less in acne?

Dr. Harper: We should use less antibiotics and more of everything else – more hormonal treatments, more isotretinoin, more topical retinoids.

That doesn’t mean no antibiotics. But instead of doing three repetitive courses of antibiotics, do one. If acne recurs, go to isotretinoin. Go to an alternative.

DN: What about spironolactone in acne?

Dr. Harper: It’s a blood pressure medicine, but it’s got an antiandrogenic qualities. It blocks the androgen receptor so it’s like getting the benefits of the birth control pill without the estrogen. It can be very beneficial for acne in women.

Its use increased from 2004 to 2013, and people are getting the hang of it. But when you compare it with the number of antibiotics prescribed, antibiotics are written a whole lot more (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Sep;77[3],456-63.e4).

DN: Is there anything that is especially helpful in treating men?

Dr. Harper: Part of the way that birth control and spironolactone work is by decreasing sebum, and we don’t have anything like that for men. But potentially, there may be a topical antiandrogen product that decreases sebum.

DN: How do you deal with patients who are in a lot of distress because of acne or rosacea?

Dr. Harper: You listen to them and tell them you hear what they’re saying. “I understand that you want to be clear, and I’ll help you do that.”

Listen to why they’re not doing well and why they’re frustrated with what they’ve used. They might say, “I don’t use what you gave me because I don’t like the way it feels.” Or, “the drug that you prescribed is too expensive.”

If they’re really doing everything you said, and they’re not doing well, in both of those conditions it may be time for isotretinoin.

In acne, I’ve never seen it fail. It doesn’t work as predictably in rosacea, but it does pretty well if you do low-dose, intermittent isotretinoin.

DN: Do you ever try treatments that are unexpected for acne and rosacea?

Dr. Harper: If you use the right combination of what we have, and try to target pathogenesis, I don’t think we have to go off the reservation very often. We can get good results with what we have available.

The Coastal Dermatology Symposium is jointly presented by the University of Louisville and Global Academy for Medical Education. This publication and Global Academy for Medical Education are both owned by Frontline Medical Communications. Dr. Harper disclosed speaker/advisor relationships with Allergan, Bayer, BioPharmX, Galderma, La Roche–Posay, and Ortho Pharmaceutical, and has served as an investigator for Bayer.

MONTEREY, CALIF. – Julie C. Harper, MD, likes to warn her patients with acne about an unexpected possible side effect of treatment with isotretinoin. “You may become a dermatologist.”

After all, that’s exactly how Dr. Harper herself was inspired to pursue a career in dermatology. As a teenager, she had acne and was treated with isotretinoin three times. The experience was so influential that she went into dermatology with a specific goal of treating acne.

“I love all of it, and in my practice I treat everything,” said Dr. Harper, “but I have a special interest in helping people with acne be as clear as they can be.” Indeed, she helped found the American Acne and Rosacea Society, which she now serves as president.

Dr. Harper, who practices in Birmingham, Ala., spoke about her approach to acne and rosacea in an interview following one of her presentations at the annual Coastal Dermatology Symposium.

DERMATOLOGY NEWS: What drew you to focus on rosacea in addition to acne?

Dr. Harper: But they’re very distinct diagnoses, and their pathogenesis is completely different. My interest in treating rosacea was secondary to acne, but I love to treat them both.

DN: Are they both equally challenging to treat?

Dr. Harper: In some ways, rosacea is more challenging to treat.

With acne, we have a pretty good algorithm for how we treat it. We can end with isotretinoin, which for many people is a cure. But we really don’t have that last step in rosacea.

DN: What are you doing differently with rosacea than you might not have done a few years ago?

Dr. Harper: More combination therapy. The trend is more toward a comprehensive combination approach to treat everything we see in rosacea: Hit this as hard as you can. Hit everything you see. Part of that is because we have some newer drugs like the alpha-adrenergic agonists that work differently than anything we’ve had before.

We have a couple of good combination studies. One study examined ivermectin plus brimonidine (J Drugs Dermatol. 2017 Sep 1;16[9]:909-16). Those two worked better together if you did not delay the brimonidine for 4 weeks and only used it with the ivermectin for part of the study.

There are also the newer studies that look at doxycycline plus ivermectin and compare it with ivermectin plus placebo. The combination works better, and it works faster (Adv Ther. 2016;33[9]:1481-1501; unpublished clinical trial data on file with Galderma, NCT03075891).

On top of those treatments, we may need to add laser for background redness, or an oral beta-blocker for flushing if the patient still complains of the symptoms.

DN: What’s most challenging to treat in rosacea?

Dr. Harper: The redness and phymatous changes are the hardest. Once you get phymatous changes, you have to do a physical modality.

Most of us think that if we treat rosacea aggressively up front, maybe we can prevent the phymatous changes. Prevention is key, just like prevention of acne scarring is easier than getting rid of scars once you have it.

Other than phyma, it’s the redness. Even the Food and Drug Administration–approved products we have for redness don’t work for flushing. Patients stand up to give up a presentation and “Oh no, here comes a red face.” That’s the hardest part to manage.

DN: How do beta-blockers fare at treating flushing?

Dr. Harper: They can help, but I don’t know that they can knock it out completely.

And we should remember that there are no FDA-approved beta-blockers to treat this. Most of the data we have are small case reports or case series. We don’t have a lot of data.

DN: Is there anything that’s used too much in rosacea?

Dr. Harper: Probably metronidazole. I understand why it’s used. It’s not a bad drug. But we have better drugs now.

I think we use metronidazole whenever things aren’t covered by insurance. And we use it to do too many things. Don’t try to make metronidazole do everything.

Metronidazole is FDA-approved for papules and pustules. It wasn’t ever intended to help with flushing and background erythema, and you’ll need to use something else with it.

DN: What’s coming down the line for rosacea?

Dr. Harper: We’ve got a couple new antibiotics: a new topical antibiotic and another oral antibiotic.

DN: Let’s talk about acne. Do you think isotretinoin is underused?

Dr. Harper: We should be using more of it. Why do we hold this drug hostage from our patients? In many people, it will cure their acne if they take it for just 5-6 months.

Are we worried about inflammatory bowel disease? The most recent studies say that’s not really an association. Are we worried about depression? We’ve had a meta-analysis that suggests if you take all that data, depression – if anything – gets better in people who take isotretinoin (Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Apr;109[4]:563-9; J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jun;76[6]:1068-76.e9).

We need to take [the risk with pregnancy] seriously. But we need to be putting more people on the drug and giving them the opportunity to be clear.

DN: What should be used less in acne?

Dr. Harper: We should use less antibiotics and more of everything else – more hormonal treatments, more isotretinoin, more topical retinoids.

That doesn’t mean no antibiotics. But instead of doing three repetitive courses of antibiotics, do one. If acne recurs, go to isotretinoin. Go to an alternative.

DN: What about spironolactone in acne?

Dr. Harper: It’s a blood pressure medicine, but it’s got an antiandrogenic qualities. It blocks the androgen receptor so it’s like getting the benefits of the birth control pill without the estrogen. It can be very beneficial for acne in women.

Its use increased from 2004 to 2013, and people are getting the hang of it. But when you compare it with the number of antibiotics prescribed, antibiotics are written a whole lot more (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Sep;77[3],456-63.e4).

DN: Is there anything that is especially helpful in treating men?

Dr. Harper: Part of the way that birth control and spironolactone work is by decreasing sebum, and we don’t have anything like that for men. But potentially, there may be a topical antiandrogen product that decreases sebum.

DN: How do you deal with patients who are in a lot of distress because of acne or rosacea?

Dr. Harper: You listen to them and tell them you hear what they’re saying. “I understand that you want to be clear, and I’ll help you do that.”

Listen to why they’re not doing well and why they’re frustrated with what they’ve used. They might say, “I don’t use what you gave me because I don’t like the way it feels.” Or, “the drug that you prescribed is too expensive.”

If they’re really doing everything you said, and they’re not doing well, in both of those conditions it may be time for isotretinoin.

In acne, I’ve never seen it fail. It doesn’t work as predictably in rosacea, but it does pretty well if you do low-dose, intermittent isotretinoin.

DN: Do you ever try treatments that are unexpected for acne and rosacea?

Dr. Harper: If you use the right combination of what we have, and try to target pathogenesis, I don’t think we have to go off the reservation very often. We can get good results with what we have available.

The Coastal Dermatology Symposium is jointly presented by the University of Louisville and Global Academy for Medical Education. This publication and Global Academy for Medical Education are both owned by Frontline Medical Communications. Dr. Harper disclosed speaker/advisor relationships with Allergan, Bayer, BioPharmX, Galderma, La Roche–Posay, and Ortho Pharmaceutical, and has served as an investigator for Bayer.

MONTEREY, CALIF. – Julie C. Harper, MD, likes to warn her patients with acne about an unexpected possible side effect of treatment with isotretinoin. “You may become a dermatologist.”

After all, that’s exactly how Dr. Harper herself was inspired to pursue a career in dermatology. As a teenager, she had acne and was treated with isotretinoin three times. The experience was so influential that she went into dermatology with a specific goal of treating acne.

“I love all of it, and in my practice I treat everything,” said Dr. Harper, “but I have a special interest in helping people with acne be as clear as they can be.” Indeed, she helped found the American Acne and Rosacea Society, which she now serves as president.

Dr. Harper, who practices in Birmingham, Ala., spoke about her approach to acne and rosacea in an interview following one of her presentations at the annual Coastal Dermatology Symposium.

DERMATOLOGY NEWS: What drew you to focus on rosacea in addition to acne?

Dr. Harper: But they’re very distinct diagnoses, and their pathogenesis is completely different. My interest in treating rosacea was secondary to acne, but I love to treat them both.

DN: Are they both equally challenging to treat?

Dr. Harper: In some ways, rosacea is more challenging to treat.

With acne, we have a pretty good algorithm for how we treat it. We can end with isotretinoin, which for many people is a cure. But we really don’t have that last step in rosacea.

DN: What are you doing differently with rosacea than you might not have done a few years ago?

Dr. Harper: More combination therapy. The trend is more toward a comprehensive combination approach to treat everything we see in rosacea: Hit this as hard as you can. Hit everything you see. Part of that is because we have some newer drugs like the alpha-adrenergic agonists that work differently than anything we’ve had before.

We have a couple of good combination studies. One study examined ivermectin plus brimonidine (J Drugs Dermatol. 2017 Sep 1;16[9]:909-16). Those two worked better together if you did not delay the brimonidine for 4 weeks and only used it with the ivermectin for part of the study.

There are also the newer studies that look at doxycycline plus ivermectin and compare it with ivermectin plus placebo. The combination works better, and it works faster (Adv Ther. 2016;33[9]:1481-1501; unpublished clinical trial data on file with Galderma, NCT03075891).

On top of those treatments, we may need to add laser for background redness, or an oral beta-blocker for flushing if the patient still complains of the symptoms.

DN: What’s most challenging to treat in rosacea?

Dr. Harper: The redness and phymatous changes are the hardest. Once you get phymatous changes, you have to do a physical modality.

Most of us think that if we treat rosacea aggressively up front, maybe we can prevent the phymatous changes. Prevention is key, just like prevention of acne scarring is easier than getting rid of scars once you have it.

Other than phyma, it’s the redness. Even the Food and Drug Administration–approved products we have for redness don’t work for flushing. Patients stand up to give up a presentation and “Oh no, here comes a red face.” That’s the hardest part to manage.

DN: How do beta-blockers fare at treating flushing?

Dr. Harper: They can help, but I don’t know that they can knock it out completely.

And we should remember that there are no FDA-approved beta-blockers to treat this. Most of the data we have are small case reports or case series. We don’t have a lot of data.

DN: Is there anything that’s used too much in rosacea?

Dr. Harper: Probably metronidazole. I understand why it’s used. It’s not a bad drug. But we have better drugs now.

I think we use metronidazole whenever things aren’t covered by insurance. And we use it to do too many things. Don’t try to make metronidazole do everything.

Metronidazole is FDA-approved for papules and pustules. It wasn’t ever intended to help with flushing and background erythema, and you’ll need to use something else with it.

DN: What’s coming down the line for rosacea?

Dr. Harper: We’ve got a couple new antibiotics: a new topical antibiotic and another oral antibiotic.

DN: Let’s talk about acne. Do you think isotretinoin is underused?

Dr. Harper: We should be using more of it. Why do we hold this drug hostage from our patients? In many people, it will cure their acne if they take it for just 5-6 months.

Are we worried about inflammatory bowel disease? The most recent studies say that’s not really an association. Are we worried about depression? We’ve had a meta-analysis that suggests if you take all that data, depression – if anything – gets better in people who take isotretinoin (Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Apr;109[4]:563-9; J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jun;76[6]:1068-76.e9).

We need to take [the risk with pregnancy] seriously. But we need to be putting more people on the drug and giving them the opportunity to be clear.

DN: What should be used less in acne?

Dr. Harper: We should use less antibiotics and more of everything else – more hormonal treatments, more isotretinoin, more topical retinoids.

That doesn’t mean no antibiotics. But instead of doing three repetitive courses of antibiotics, do one. If acne recurs, go to isotretinoin. Go to an alternative.

DN: What about spironolactone in acne?

Dr. Harper: It’s a blood pressure medicine, but it’s got an antiandrogenic qualities. It blocks the androgen receptor so it’s like getting the benefits of the birth control pill without the estrogen. It can be very beneficial for acne in women.

Its use increased from 2004 to 2013, and people are getting the hang of it. But when you compare it with the number of antibiotics prescribed, antibiotics are written a whole lot more (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Sep;77[3],456-63.e4).

DN: Is there anything that is especially helpful in treating men?

Dr. Harper: Part of the way that birth control and spironolactone work is by decreasing sebum, and we don’t have anything like that for men. But potentially, there may be a topical antiandrogen product that decreases sebum.

DN: How do you deal with patients who are in a lot of distress because of acne or rosacea?

Dr. Harper: You listen to them and tell them you hear what they’re saying. “I understand that you want to be clear, and I’ll help you do that.”

Listen to why they’re not doing well and why they’re frustrated with what they’ve used. They might say, “I don’t use what you gave me because I don’t like the way it feels.” Or, “the drug that you prescribed is too expensive.”

If they’re really doing everything you said, and they’re not doing well, in both of those conditions it may be time for isotretinoin.

In acne, I’ve never seen it fail. It doesn’t work as predictably in rosacea, but it does pretty well if you do low-dose, intermittent isotretinoin.

DN: Do you ever try treatments that are unexpected for acne and rosacea?

Dr. Harper: If you use the right combination of what we have, and try to target pathogenesis, I don’t think we have to go off the reservation very often. We can get good results with what we have available.

The Coastal Dermatology Symposium is jointly presented by the University of Louisville and Global Academy for Medical Education. This publication and Global Academy for Medical Education are both owned by Frontline Medical Communications. Dr. Harper disclosed speaker/advisor relationships with Allergan, Bayer, BioPharmX, Galderma, La Roche–Posay, and Ortho Pharmaceutical, and has served as an investigator for Bayer.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM COASTAL DERMATOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

Rosacea likely underdiagnosed, suboptimally treated in skin of color

in this population, according to the authors of a clinical review article on the topic.

“Current reports of rosacea in patients with skin of color may point to a large pool of undiagnosed patients,” said Andrew F. Alexis, MD, chairman of the department of dermatology, Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and Mount Sinai West, New York, and his coauthors.

Increased awareness of rosacea in these patients may reduce disparities in disease management, they wrote in the review, published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, which outlines strategies for timely diagnosis and effective treatment of rosacea in skin of color.