User login

Joint guidelines favor antibody testing for certain Lyme disease manifestations

New clinical practice guidelines on Lyme disease place a strong emphasis on antibody testing to assess for rheumatologic and neurologic syndromes. “Diagnostically, we recommend testing via antibodies, and an index of antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] versus serum. Importantly, we recommend against using polymerase chain reaction [PCR] in CSF,” Jeffrey A. Rumbaugh, MD, PhD, a coauthor of the guidelines and a member of the American Academy of Neurology, said in an interview.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America, AAN, and the American College of Rheumatology convened a multidisciplinary panel to develop the 43 recommendations, seeking input from 12 additional medical specialties, and patients. The panel conducted a systematic review of available evidence on preventing, diagnosing, and treating Lyme disease, using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation model to evaluate clinical evidence and strength of recommendations. The guidelines were simultaneous published in Clinical Infectious Diseases, Neurology, Arthritis & Rheumatology, and Arthritis Care & Research.

This is the first time these organizations have collaborated on joint Lyme disease guidelines, which focus mainly on neurologic, cardiac, and rheumatologic manifestations.

“We are very excited to provide these updated guidelines to assist clinicians working in numerous medical specialties around the country, and even the world, as they care for patients suffering from Lyme disease,” Dr. Rumbaugh said.

When to use and not to use PCR

Guideline authors called for specific testing regimens depending on presentation of symptoms. Generally, they advised that individuals with a skin rash suggestive of early disease seek a clinical diagnosis instead of laboratory testing.

Recommendations on Lyme arthritis support previous IDSA guidelines published in 2006, Linda K. Bockenstedt, MD, professor of medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and a coauthor of the guidelines, said in an interview.

To evaluate for potential Lyme arthritis, clinicians should choose serum antibody testing over PCR or culture of blood or synovial fluid/tissue. However, if a doctor is assessing a seropositive patient for Lyme arthritis diagnosis but needs more information for treatment decisions, the authors recommended PCR applied to synovial fluid or tissue over Borrelia culture.

“Synovial fluid can be analyzed by PCR, but sensitivity is generally lower than serology,” Dr. Bockenstedt explained. Additionally, culture of joint fluid or synovial tissue for Lyme spirochetes has 0% sensitivity in multiple studies. “For these reasons, we recommend serum antibody testing over PCR of joint fluid or other methods for an initial diagnosis.”

Serum antibody testing over PCR or culture is also recommended for identifying Lyme neuroborreliosis in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) or CNS.

Despite the recent popularity of Lyme PCR testing in hospitals and labs, “with Lyme at least, antibodies are better in the CSF,” Dr. Rumbaugh said. Studies have shown that “most patients with even early neurologic Lyme disease are seropositive by conventional antibody testing at time of initial clinical presentation, and that intrathecal antibody production, as demonstrated by an elevated CSF:serum index, is highly specific for CNS involvement.”

If done correctly, antibody testing is both sensitive and specific for neurologic Lyme disease. “On the other hand, sensitivity of Lyme PCR performed on CSF has been only in the 5%-17% range in studies. Incidentally, Lyme PCR on blood is also not sensitive and therefore not recommended,” Dr. Rumbaugh said.

Guideline authors recommended testing in patients with the following conditions: acute neurologic disorders such as meningitis, painful radiculoneuritis, mononeuropathy multiplex; evidence of spinal cord or brain inflammation; and acute myocarditis/pericarditis of unknown cause in an appropriate epidemiologic setting.

They did not recommend testing in patients with typical amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis; Parkinson’s disease, dementia, or cognitive decline; new-onset seizures; other neurologic syndromes or those lacking clinical or epidemiologic history that would support a diagnosis of Lyme disease; and patients with chronic cardiomyopathy of unknown cause.

The authors also called for judicious use of electrocardiogram to screen for Lyme carditis, recommending it only in patients signs or symptoms of this condition. However, patients at risk for or showing signs of severe cardiac complications of Lyme disease should be hospitalized and monitored via ECG.

Timelines for antibiotics

Most patients with Lyme disease should receive oral antibiotics, although duration times vary depending on the disease state. “We recommend that prophylactic antibiotic therapy be given to adults and children only within 72 hours of removal of an identified high-risk tick bite, but not for bites that are equivocal risk or low risk,” according to the guideline authors.

Specific antibiotic treatment regimens by condition are as follows: 10-14 days for early-stage disease, 14 days for Lyme carditis, 14-21 days for neurologic Lyme disease, and 28 days for late Lyme arthritis.

“Despite arthritis occurring late in the course of infection, treatment with a 28-day course of oral antibiotic is effective, although the rates of complete resolution of joint swelling can vary,” Dr. Bockenstedt said. Clinicians may consider a second 28-day course of oral antibiotics or a 2- to 4-week course of ceftriaxone in patients with persistent swelling, after an initial course of oral antibiotics.

Citing knowledge gaps, the authors made no recommendation on secondary antibiotic treatment for unresolved Lyme arthritis. Rheumatologists can play an important role in the care of this small subset of patients, Dr. Bockenstedt noted. “Studies of patients with ‘postantibiotic Lyme arthritis’ show that they can be treated successfully with intra-articular steroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, biologic response modifiers, and even synovectomy with successful outcomes.” Some of these therapies also work in cases where first courses of oral and intravenous antibiotics are unsuccessful.

“Antibiotic therapy for longer than 8 weeks is not expected to provide additional benefit to patients with persistent arthritis if that treatment has included one course of IV therapy,” the authors clarified.

For patients with Lyme disease–associated meningitis, cranial neuropathy, radiculoneuropathy, or other PNS manifestations, the authors recommended intravenous ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, penicillin G, or oral doxycycline over other antimicrobials.

“For most neurologic presentations, oral doxycycline is just as effective as appropriate IV antibiotics,” Dr. Rumbaugh said. “The exception is the relatively rare situation where the patient is felt to have parenchymal involvement of brain or spinal cord, in which case the guidelines recommend IV antibiotics over oral antibiotics.” In the studies, there was no statistically significant difference between oral or intravenous regimens in response rate or risk of adverse effects.

Patients with nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, pain, or cognitive impairment following treatment should not receive additional antibiotic therapy if there’s no evidence of treatment failure or infection. These two markers “would include objective signs of disease activity, such as arthritis, meningitis, or neuropathy,” the guideline authors wrote in comments accompanying the recommendation.

Clinicians caring for patients with symptomatic bradycardia caused by Lyme carditis should consider temporary pacing measures instead of a permanent pacemaker. For patients hospitalized with Lyme carditis, “we suggest initially using IV ceftriaxone over oral antibiotics until there is evidence of clinical improvement, then switching to oral antibiotics to complete treatment,” they advised. Outpatients with this condition should receive oral antibiotics instead of intravenous antibiotics.

Advice on antibodies testing ‘particularly cogent’

For individuals without expertise in these areas, the recommendations are clear and useful, Daniel E. Furst, MD, professor of medicine (emeritus) at the University of California, Los Angeles, adjunct professor at the University of Washington, Seattle, and research professor at the University of Florence (Italy), said in an interview.

“As a rheumatologist, I would have appreciated literature references for some of the recommendations but, nevertheless, find these useful. I applaud the care with which the evidence was gathered and the general formatting, which tried to review multiple possible scenarios surrounding Lyme arthritis,” said Dr. Furst, offering a third-party perspective.

The advice on using antibodies tests to make a diagnosis of Lyme arthritis “is particularly cogent and more useful than trying to culture these fastidious organisms,” he added.

The IDSA, AAN, and ACR provided support for the guideline. Dr. Bockenstedt reported receiving research funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Gordon and the Llura Gund Foundation and remuneration from L2 Diagnostics for investigator-initiated NIH-sponsored research. Dr. Rumbaugh had no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Furst reported no conflicts of interest in commenting on these guidelines.

SOURCE: Rumbaugh JA et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Nov 30. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1215.

New clinical practice guidelines on Lyme disease place a strong emphasis on antibody testing to assess for rheumatologic and neurologic syndromes. “Diagnostically, we recommend testing via antibodies, and an index of antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] versus serum. Importantly, we recommend against using polymerase chain reaction [PCR] in CSF,” Jeffrey A. Rumbaugh, MD, PhD, a coauthor of the guidelines and a member of the American Academy of Neurology, said in an interview.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America, AAN, and the American College of Rheumatology convened a multidisciplinary panel to develop the 43 recommendations, seeking input from 12 additional medical specialties, and patients. The panel conducted a systematic review of available evidence on preventing, diagnosing, and treating Lyme disease, using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation model to evaluate clinical evidence and strength of recommendations. The guidelines were simultaneous published in Clinical Infectious Diseases, Neurology, Arthritis & Rheumatology, and Arthritis Care & Research.

This is the first time these organizations have collaborated on joint Lyme disease guidelines, which focus mainly on neurologic, cardiac, and rheumatologic manifestations.

“We are very excited to provide these updated guidelines to assist clinicians working in numerous medical specialties around the country, and even the world, as they care for patients suffering from Lyme disease,” Dr. Rumbaugh said.

When to use and not to use PCR

Guideline authors called for specific testing regimens depending on presentation of symptoms. Generally, they advised that individuals with a skin rash suggestive of early disease seek a clinical diagnosis instead of laboratory testing.

Recommendations on Lyme arthritis support previous IDSA guidelines published in 2006, Linda K. Bockenstedt, MD, professor of medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and a coauthor of the guidelines, said in an interview.

To evaluate for potential Lyme arthritis, clinicians should choose serum antibody testing over PCR or culture of blood or synovial fluid/tissue. However, if a doctor is assessing a seropositive patient for Lyme arthritis diagnosis but needs more information for treatment decisions, the authors recommended PCR applied to synovial fluid or tissue over Borrelia culture.

“Synovial fluid can be analyzed by PCR, but sensitivity is generally lower than serology,” Dr. Bockenstedt explained. Additionally, culture of joint fluid or synovial tissue for Lyme spirochetes has 0% sensitivity in multiple studies. “For these reasons, we recommend serum antibody testing over PCR of joint fluid or other methods for an initial diagnosis.”

Serum antibody testing over PCR or culture is also recommended for identifying Lyme neuroborreliosis in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) or CNS.

Despite the recent popularity of Lyme PCR testing in hospitals and labs, “with Lyme at least, antibodies are better in the CSF,” Dr. Rumbaugh said. Studies have shown that “most patients with even early neurologic Lyme disease are seropositive by conventional antibody testing at time of initial clinical presentation, and that intrathecal antibody production, as demonstrated by an elevated CSF:serum index, is highly specific for CNS involvement.”

If done correctly, antibody testing is both sensitive and specific for neurologic Lyme disease. “On the other hand, sensitivity of Lyme PCR performed on CSF has been only in the 5%-17% range in studies. Incidentally, Lyme PCR on blood is also not sensitive and therefore not recommended,” Dr. Rumbaugh said.

Guideline authors recommended testing in patients with the following conditions: acute neurologic disorders such as meningitis, painful radiculoneuritis, mononeuropathy multiplex; evidence of spinal cord or brain inflammation; and acute myocarditis/pericarditis of unknown cause in an appropriate epidemiologic setting.

They did not recommend testing in patients with typical amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis; Parkinson’s disease, dementia, or cognitive decline; new-onset seizures; other neurologic syndromes or those lacking clinical or epidemiologic history that would support a diagnosis of Lyme disease; and patients with chronic cardiomyopathy of unknown cause.

The authors also called for judicious use of electrocardiogram to screen for Lyme carditis, recommending it only in patients signs or symptoms of this condition. However, patients at risk for or showing signs of severe cardiac complications of Lyme disease should be hospitalized and monitored via ECG.

Timelines for antibiotics

Most patients with Lyme disease should receive oral antibiotics, although duration times vary depending on the disease state. “We recommend that prophylactic antibiotic therapy be given to adults and children only within 72 hours of removal of an identified high-risk tick bite, but not for bites that are equivocal risk or low risk,” according to the guideline authors.

Specific antibiotic treatment regimens by condition are as follows: 10-14 days for early-stage disease, 14 days for Lyme carditis, 14-21 days for neurologic Lyme disease, and 28 days for late Lyme arthritis.

“Despite arthritis occurring late in the course of infection, treatment with a 28-day course of oral antibiotic is effective, although the rates of complete resolution of joint swelling can vary,” Dr. Bockenstedt said. Clinicians may consider a second 28-day course of oral antibiotics or a 2- to 4-week course of ceftriaxone in patients with persistent swelling, after an initial course of oral antibiotics.

Citing knowledge gaps, the authors made no recommendation on secondary antibiotic treatment for unresolved Lyme arthritis. Rheumatologists can play an important role in the care of this small subset of patients, Dr. Bockenstedt noted. “Studies of patients with ‘postantibiotic Lyme arthritis’ show that they can be treated successfully with intra-articular steroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, biologic response modifiers, and even synovectomy with successful outcomes.” Some of these therapies also work in cases where first courses of oral and intravenous antibiotics are unsuccessful.

“Antibiotic therapy for longer than 8 weeks is not expected to provide additional benefit to patients with persistent arthritis if that treatment has included one course of IV therapy,” the authors clarified.

For patients with Lyme disease–associated meningitis, cranial neuropathy, radiculoneuropathy, or other PNS manifestations, the authors recommended intravenous ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, penicillin G, or oral doxycycline over other antimicrobials.

“For most neurologic presentations, oral doxycycline is just as effective as appropriate IV antibiotics,” Dr. Rumbaugh said. “The exception is the relatively rare situation where the patient is felt to have parenchymal involvement of brain or spinal cord, in which case the guidelines recommend IV antibiotics over oral antibiotics.” In the studies, there was no statistically significant difference between oral or intravenous regimens in response rate or risk of adverse effects.

Patients with nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, pain, or cognitive impairment following treatment should not receive additional antibiotic therapy if there’s no evidence of treatment failure or infection. These two markers “would include objective signs of disease activity, such as arthritis, meningitis, or neuropathy,” the guideline authors wrote in comments accompanying the recommendation.

Clinicians caring for patients with symptomatic bradycardia caused by Lyme carditis should consider temporary pacing measures instead of a permanent pacemaker. For patients hospitalized with Lyme carditis, “we suggest initially using IV ceftriaxone over oral antibiotics until there is evidence of clinical improvement, then switching to oral antibiotics to complete treatment,” they advised. Outpatients with this condition should receive oral antibiotics instead of intravenous antibiotics.

Advice on antibodies testing ‘particularly cogent’

For individuals without expertise in these areas, the recommendations are clear and useful, Daniel E. Furst, MD, professor of medicine (emeritus) at the University of California, Los Angeles, adjunct professor at the University of Washington, Seattle, and research professor at the University of Florence (Italy), said in an interview.

“As a rheumatologist, I would have appreciated literature references for some of the recommendations but, nevertheless, find these useful. I applaud the care with which the evidence was gathered and the general formatting, which tried to review multiple possible scenarios surrounding Lyme arthritis,” said Dr. Furst, offering a third-party perspective.

The advice on using antibodies tests to make a diagnosis of Lyme arthritis “is particularly cogent and more useful than trying to culture these fastidious organisms,” he added.

The IDSA, AAN, and ACR provided support for the guideline. Dr. Bockenstedt reported receiving research funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Gordon and the Llura Gund Foundation and remuneration from L2 Diagnostics for investigator-initiated NIH-sponsored research. Dr. Rumbaugh had no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Furst reported no conflicts of interest in commenting on these guidelines.

SOURCE: Rumbaugh JA et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Nov 30. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1215.

New clinical practice guidelines on Lyme disease place a strong emphasis on antibody testing to assess for rheumatologic and neurologic syndromes. “Diagnostically, we recommend testing via antibodies, and an index of antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] versus serum. Importantly, we recommend against using polymerase chain reaction [PCR] in CSF,” Jeffrey A. Rumbaugh, MD, PhD, a coauthor of the guidelines and a member of the American Academy of Neurology, said in an interview.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America, AAN, and the American College of Rheumatology convened a multidisciplinary panel to develop the 43 recommendations, seeking input from 12 additional medical specialties, and patients. The panel conducted a systematic review of available evidence on preventing, diagnosing, and treating Lyme disease, using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation model to evaluate clinical evidence and strength of recommendations. The guidelines were simultaneous published in Clinical Infectious Diseases, Neurology, Arthritis & Rheumatology, and Arthritis Care & Research.

This is the first time these organizations have collaborated on joint Lyme disease guidelines, which focus mainly on neurologic, cardiac, and rheumatologic manifestations.

“We are very excited to provide these updated guidelines to assist clinicians working in numerous medical specialties around the country, and even the world, as they care for patients suffering from Lyme disease,” Dr. Rumbaugh said.

When to use and not to use PCR

Guideline authors called for specific testing regimens depending on presentation of symptoms. Generally, they advised that individuals with a skin rash suggestive of early disease seek a clinical diagnosis instead of laboratory testing.

Recommendations on Lyme arthritis support previous IDSA guidelines published in 2006, Linda K. Bockenstedt, MD, professor of medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and a coauthor of the guidelines, said in an interview.

To evaluate for potential Lyme arthritis, clinicians should choose serum antibody testing over PCR or culture of blood or synovial fluid/tissue. However, if a doctor is assessing a seropositive patient for Lyme arthritis diagnosis but needs more information for treatment decisions, the authors recommended PCR applied to synovial fluid or tissue over Borrelia culture.

“Synovial fluid can be analyzed by PCR, but sensitivity is generally lower than serology,” Dr. Bockenstedt explained. Additionally, culture of joint fluid or synovial tissue for Lyme spirochetes has 0% sensitivity in multiple studies. “For these reasons, we recommend serum antibody testing over PCR of joint fluid or other methods for an initial diagnosis.”

Serum antibody testing over PCR or culture is also recommended for identifying Lyme neuroborreliosis in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) or CNS.

Despite the recent popularity of Lyme PCR testing in hospitals and labs, “with Lyme at least, antibodies are better in the CSF,” Dr. Rumbaugh said. Studies have shown that “most patients with even early neurologic Lyme disease are seropositive by conventional antibody testing at time of initial clinical presentation, and that intrathecal antibody production, as demonstrated by an elevated CSF:serum index, is highly specific for CNS involvement.”

If done correctly, antibody testing is both sensitive and specific for neurologic Lyme disease. “On the other hand, sensitivity of Lyme PCR performed on CSF has been only in the 5%-17% range in studies. Incidentally, Lyme PCR on blood is also not sensitive and therefore not recommended,” Dr. Rumbaugh said.

Guideline authors recommended testing in patients with the following conditions: acute neurologic disorders such as meningitis, painful radiculoneuritis, mononeuropathy multiplex; evidence of spinal cord or brain inflammation; and acute myocarditis/pericarditis of unknown cause in an appropriate epidemiologic setting.

They did not recommend testing in patients with typical amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis; Parkinson’s disease, dementia, or cognitive decline; new-onset seizures; other neurologic syndromes or those lacking clinical or epidemiologic history that would support a diagnosis of Lyme disease; and patients with chronic cardiomyopathy of unknown cause.

The authors also called for judicious use of electrocardiogram to screen for Lyme carditis, recommending it only in patients signs or symptoms of this condition. However, patients at risk for or showing signs of severe cardiac complications of Lyme disease should be hospitalized and monitored via ECG.

Timelines for antibiotics

Most patients with Lyme disease should receive oral antibiotics, although duration times vary depending on the disease state. “We recommend that prophylactic antibiotic therapy be given to adults and children only within 72 hours of removal of an identified high-risk tick bite, but not for bites that are equivocal risk or low risk,” according to the guideline authors.

Specific antibiotic treatment regimens by condition are as follows: 10-14 days for early-stage disease, 14 days for Lyme carditis, 14-21 days for neurologic Lyme disease, and 28 days for late Lyme arthritis.

“Despite arthritis occurring late in the course of infection, treatment with a 28-day course of oral antibiotic is effective, although the rates of complete resolution of joint swelling can vary,” Dr. Bockenstedt said. Clinicians may consider a second 28-day course of oral antibiotics or a 2- to 4-week course of ceftriaxone in patients with persistent swelling, after an initial course of oral antibiotics.

Citing knowledge gaps, the authors made no recommendation on secondary antibiotic treatment for unresolved Lyme arthritis. Rheumatologists can play an important role in the care of this small subset of patients, Dr. Bockenstedt noted. “Studies of patients with ‘postantibiotic Lyme arthritis’ show that they can be treated successfully with intra-articular steroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, biologic response modifiers, and even synovectomy with successful outcomes.” Some of these therapies also work in cases where first courses of oral and intravenous antibiotics are unsuccessful.

“Antibiotic therapy for longer than 8 weeks is not expected to provide additional benefit to patients with persistent arthritis if that treatment has included one course of IV therapy,” the authors clarified.

For patients with Lyme disease–associated meningitis, cranial neuropathy, radiculoneuropathy, or other PNS manifestations, the authors recommended intravenous ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, penicillin G, or oral doxycycline over other antimicrobials.

“For most neurologic presentations, oral doxycycline is just as effective as appropriate IV antibiotics,” Dr. Rumbaugh said. “The exception is the relatively rare situation where the patient is felt to have parenchymal involvement of brain or spinal cord, in which case the guidelines recommend IV antibiotics over oral antibiotics.” In the studies, there was no statistically significant difference between oral or intravenous regimens in response rate or risk of adverse effects.

Patients with nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, pain, or cognitive impairment following treatment should not receive additional antibiotic therapy if there’s no evidence of treatment failure or infection. These two markers “would include objective signs of disease activity, such as arthritis, meningitis, or neuropathy,” the guideline authors wrote in comments accompanying the recommendation.

Clinicians caring for patients with symptomatic bradycardia caused by Lyme carditis should consider temporary pacing measures instead of a permanent pacemaker. For patients hospitalized with Lyme carditis, “we suggest initially using IV ceftriaxone over oral antibiotics until there is evidence of clinical improvement, then switching to oral antibiotics to complete treatment,” they advised. Outpatients with this condition should receive oral antibiotics instead of intravenous antibiotics.

Advice on antibodies testing ‘particularly cogent’

For individuals without expertise in these areas, the recommendations are clear and useful, Daniel E. Furst, MD, professor of medicine (emeritus) at the University of California, Los Angeles, adjunct professor at the University of Washington, Seattle, and research professor at the University of Florence (Italy), said in an interview.

“As a rheumatologist, I would have appreciated literature references for some of the recommendations but, nevertheless, find these useful. I applaud the care with which the evidence was gathered and the general formatting, which tried to review multiple possible scenarios surrounding Lyme arthritis,” said Dr. Furst, offering a third-party perspective.

The advice on using antibodies tests to make a diagnosis of Lyme arthritis “is particularly cogent and more useful than trying to culture these fastidious organisms,” he added.

The IDSA, AAN, and ACR provided support for the guideline. Dr. Bockenstedt reported receiving research funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Gordon and the Llura Gund Foundation and remuneration from L2 Diagnostics for investigator-initiated NIH-sponsored research. Dr. Rumbaugh had no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Furst reported no conflicts of interest in commenting on these guidelines.

SOURCE: Rumbaugh JA et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Nov 30. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1215.

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

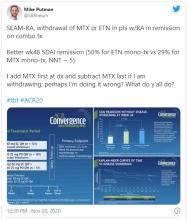

How Twitter amplifies my doctor and human voice

When I graduated from residency in 2007, Facebook had just become “a thing,” and my cohort decided to use it to keep in touch. These days, Twitter seems to be the social media platform of choice for health care professionals.

When I started on Twitter a few years ago, it was in reaction to the current political climate. I wanted to keep track of what my favorite thinkers were writing. I was anonymous and tweeted about politics mostly. My husband was my only follower for a while.

I deanonymized when, at last year’s American College of Rheumatology meeting, I presented a poster and wanted to reach a wider audience. I could have created two different personas on Twitter, like many doctors apparently do. Initially, I resisted doing that because I am frankly too lazy to keep track of two different social media profiles, but now I resist because I see my profession as an extension of my political self, and have no problem with using my (very low) profile to amplify both my doctor voice and my human voice.

Professionally, Twitter is rewarding. It is a space for networking and for promoting one’s work. It is a fantastic learning format, as evidenced by the popularity of tweetorials. The international consortium that has worked to collect information on rheumatology patients with COVID started as an idea on Twitter. The fact that ACR Convergence 2020 abstracts are now available? I only know because of the #ACRambassadors that I follow.

But I find that I cannot separate who I am from what I do. As a rheumatologist, I build long-term relationships with patients. I cannot care for their medical conditions in isolation without also concerning myself with their nonmedical circumstances. For that reason, I have opinions that one might call humanist, and I suspect that I am not alone among rheumatologists.

I can think of three areas, broadly construed but with huge overlaps, that concern me a great deal.

First, there are things that affect all physicians: race and gender discrimination in the workplace; advancement of women in science, technology, engineering, or math; Medicare reimbursement; COVID-19 preparedness; immigration issues (an issue near and dear to me, as I am an immigrant and a foreign medical graduate); and federal funding (including funding for training programs and community health centers, funding for the National Institutes of Health, and funding for stem cell research).

Then there are the things that affect rheumatologists in particular. Access to medications and procedures is one thing. (I did say these categories hugely overlap.) If you›ve ever tried to prescribe even a drug as old as oral cyclophosphamide, you’ll have experienced the difficulty of getting it for Medicare patients. Patients who need biologics are limited by insurance contracts with pharmaceutical companies, but also by requirements such as step therapy. I am all varieties of annoyed, incredulous, and apologetic that when a patient asks me how much a treatment will cost him/her, I do not have an answer.

Speaking of pricing, don’t even get me started on pharmaceutical company price gouging. Yes, the H.P. Acthar gel may be the most egregious offender among rheumatology medications, but it’s easy to not prescribe a drug that costs $80,000 a vial and which does not do much more than prednisone does. On the other hand, I remember a time when colchicine cost $0.10 cents a pill and patients did not have to jump through hoops to get it.

And what of reproductive freedom? Our patients rely on us for advice about their childbearing options, including birth control, in vitro fertilization, and pregnancy termination.

Finally, and most important, the things that affect me most are the issues that affect patients. The lowest-hanging fruit here is the abject incompetence of the federal response to the ongoing pandemic. How many of our patients’ lives have been lost or adversely affected? And what of coverage for preexisting conditions for the vast majority of our patients, whose illnesses are chronic?

While we’re at it, the fact of health insurance being tied to employment, something that seemingly no other country in the developed world does, makes living with chronic conditions outright scary, doesn’t it? It isn’t quite so easy to remain employed when one cannot get the right medications for RA.

I could go on. Gun violence and health care disparities, vaccine denialism, coverage for mental health issues, LGBTQ rights, refugee rights, police brutality … there is a seemingly endless list of things to care about. It’s exhausting.

While I do use my Twitter account to learn from colleagues and to promote work that interests me, my primary aim is to participate in civil society as a person. Critics will use “stay in your lane” as shorthand to say x professionals should stick to x (actors to acting, musicians to music, athletes to sports). If only I could. But my humanity won’t let me. Aristotle said man is a political animal; even the venerable New England Journal of Medicine has found it impossible to keep silent.

Karmela Kim Chan, MD, is an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and an attending physician at the Hospital for Special Surgery and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, both in New York. Before moving to New York City, she spent 7 years in private practice in Rhode Island and was a past columnist for MDedge Rheumatology, writing about the challenges of starting life as a full-fledged rheumatologist in a private practice.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

When I graduated from residency in 2007, Facebook had just become “a thing,” and my cohort decided to use it to keep in touch. These days, Twitter seems to be the social media platform of choice for health care professionals.

When I started on Twitter a few years ago, it was in reaction to the current political climate. I wanted to keep track of what my favorite thinkers were writing. I was anonymous and tweeted about politics mostly. My husband was my only follower for a while.

I deanonymized when, at last year’s American College of Rheumatology meeting, I presented a poster and wanted to reach a wider audience. I could have created two different personas on Twitter, like many doctors apparently do. Initially, I resisted doing that because I am frankly too lazy to keep track of two different social media profiles, but now I resist because I see my profession as an extension of my political self, and have no problem with using my (very low) profile to amplify both my doctor voice and my human voice.

Professionally, Twitter is rewarding. It is a space for networking and for promoting one’s work. It is a fantastic learning format, as evidenced by the popularity of tweetorials. The international consortium that has worked to collect information on rheumatology patients with COVID started as an idea on Twitter. The fact that ACR Convergence 2020 abstracts are now available? I only know because of the #ACRambassadors that I follow.

But I find that I cannot separate who I am from what I do. As a rheumatologist, I build long-term relationships with patients. I cannot care for their medical conditions in isolation without also concerning myself with their nonmedical circumstances. For that reason, I have opinions that one might call humanist, and I suspect that I am not alone among rheumatologists.

I can think of three areas, broadly construed but with huge overlaps, that concern me a great deal.

First, there are things that affect all physicians: race and gender discrimination in the workplace; advancement of women in science, technology, engineering, or math; Medicare reimbursement; COVID-19 preparedness; immigration issues (an issue near and dear to me, as I am an immigrant and a foreign medical graduate); and federal funding (including funding for training programs and community health centers, funding for the National Institutes of Health, and funding for stem cell research).

Then there are the things that affect rheumatologists in particular. Access to medications and procedures is one thing. (I did say these categories hugely overlap.) If you›ve ever tried to prescribe even a drug as old as oral cyclophosphamide, you’ll have experienced the difficulty of getting it for Medicare patients. Patients who need biologics are limited by insurance contracts with pharmaceutical companies, but also by requirements such as step therapy. I am all varieties of annoyed, incredulous, and apologetic that when a patient asks me how much a treatment will cost him/her, I do not have an answer.

Speaking of pricing, don’t even get me started on pharmaceutical company price gouging. Yes, the H.P. Acthar gel may be the most egregious offender among rheumatology medications, but it’s easy to not prescribe a drug that costs $80,000 a vial and which does not do much more than prednisone does. On the other hand, I remember a time when colchicine cost $0.10 cents a pill and patients did not have to jump through hoops to get it.

And what of reproductive freedom? Our patients rely on us for advice about their childbearing options, including birth control, in vitro fertilization, and pregnancy termination.

Finally, and most important, the things that affect me most are the issues that affect patients. The lowest-hanging fruit here is the abject incompetence of the federal response to the ongoing pandemic. How many of our patients’ lives have been lost or adversely affected? And what of coverage for preexisting conditions for the vast majority of our patients, whose illnesses are chronic?

While we’re at it, the fact of health insurance being tied to employment, something that seemingly no other country in the developed world does, makes living with chronic conditions outright scary, doesn’t it? It isn’t quite so easy to remain employed when one cannot get the right medications for RA.

I could go on. Gun violence and health care disparities, vaccine denialism, coverage for mental health issues, LGBTQ rights, refugee rights, police brutality … there is a seemingly endless list of things to care about. It’s exhausting.

While I do use my Twitter account to learn from colleagues and to promote work that interests me, my primary aim is to participate in civil society as a person. Critics will use “stay in your lane” as shorthand to say x professionals should stick to x (actors to acting, musicians to music, athletes to sports). If only I could. But my humanity won’t let me. Aristotle said man is a political animal; even the venerable New England Journal of Medicine has found it impossible to keep silent.

Karmela Kim Chan, MD, is an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and an attending physician at the Hospital for Special Surgery and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, both in New York. Before moving to New York City, she spent 7 years in private practice in Rhode Island and was a past columnist for MDedge Rheumatology, writing about the challenges of starting life as a full-fledged rheumatologist in a private practice.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

When I graduated from residency in 2007, Facebook had just become “a thing,” and my cohort decided to use it to keep in touch. These days, Twitter seems to be the social media platform of choice for health care professionals.

When I started on Twitter a few years ago, it was in reaction to the current political climate. I wanted to keep track of what my favorite thinkers were writing. I was anonymous and tweeted about politics mostly. My husband was my only follower for a while.

I deanonymized when, at last year’s American College of Rheumatology meeting, I presented a poster and wanted to reach a wider audience. I could have created two different personas on Twitter, like many doctors apparently do. Initially, I resisted doing that because I am frankly too lazy to keep track of two different social media profiles, but now I resist because I see my profession as an extension of my political self, and have no problem with using my (very low) profile to amplify both my doctor voice and my human voice.

Professionally, Twitter is rewarding. It is a space for networking and for promoting one’s work. It is a fantastic learning format, as evidenced by the popularity of tweetorials. The international consortium that has worked to collect information on rheumatology patients with COVID started as an idea on Twitter. The fact that ACR Convergence 2020 abstracts are now available? I only know because of the #ACRambassadors that I follow.

But I find that I cannot separate who I am from what I do. As a rheumatologist, I build long-term relationships with patients. I cannot care for their medical conditions in isolation without also concerning myself with their nonmedical circumstances. For that reason, I have opinions that one might call humanist, and I suspect that I am not alone among rheumatologists.

I can think of three areas, broadly construed but with huge overlaps, that concern me a great deal.

First, there are things that affect all physicians: race and gender discrimination in the workplace; advancement of women in science, technology, engineering, or math; Medicare reimbursement; COVID-19 preparedness; immigration issues (an issue near and dear to me, as I am an immigrant and a foreign medical graduate); and federal funding (including funding for training programs and community health centers, funding for the National Institutes of Health, and funding for stem cell research).

Then there are the things that affect rheumatologists in particular. Access to medications and procedures is one thing. (I did say these categories hugely overlap.) If you›ve ever tried to prescribe even a drug as old as oral cyclophosphamide, you’ll have experienced the difficulty of getting it for Medicare patients. Patients who need biologics are limited by insurance contracts with pharmaceutical companies, but also by requirements such as step therapy. I am all varieties of annoyed, incredulous, and apologetic that when a patient asks me how much a treatment will cost him/her, I do not have an answer.

Speaking of pricing, don’t even get me started on pharmaceutical company price gouging. Yes, the H.P. Acthar gel may be the most egregious offender among rheumatology medications, but it’s easy to not prescribe a drug that costs $80,000 a vial and which does not do much more than prednisone does. On the other hand, I remember a time when colchicine cost $0.10 cents a pill and patients did not have to jump through hoops to get it.

And what of reproductive freedom? Our patients rely on us for advice about their childbearing options, including birth control, in vitro fertilization, and pregnancy termination.

Finally, and most important, the things that affect me most are the issues that affect patients. The lowest-hanging fruit here is the abject incompetence of the federal response to the ongoing pandemic. How many of our patients’ lives have been lost or adversely affected? And what of coverage for preexisting conditions for the vast majority of our patients, whose illnesses are chronic?

While we’re at it, the fact of health insurance being tied to employment, something that seemingly no other country in the developed world does, makes living with chronic conditions outright scary, doesn’t it? It isn’t quite so easy to remain employed when one cannot get the right medications for RA.

I could go on. Gun violence and health care disparities, vaccine denialism, coverage for mental health issues, LGBTQ rights, refugee rights, police brutality … there is a seemingly endless list of things to care about. It’s exhausting.

While I do use my Twitter account to learn from colleagues and to promote work that interests me, my primary aim is to participate in civil society as a person. Critics will use “stay in your lane” as shorthand to say x professionals should stick to x (actors to acting, musicians to music, athletes to sports). If only I could. But my humanity won’t let me. Aristotle said man is a political animal; even the venerable New England Journal of Medicine has found it impossible to keep silent.

Karmela Kim Chan, MD, is an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and an attending physician at the Hospital for Special Surgery and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, both in New York. Before moving to New York City, she spent 7 years in private practice in Rhode Island and was a past columnist for MDedge Rheumatology, writing about the challenges of starting life as a full-fledged rheumatologist in a private practice.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Colchicine a case study for what’s wrong with U.S. drug pricing

Public spending on colchicine has grown exponentially over the past decade despite generics suggesting an uphill slog for patients seeking access to long-term therapy for gout or cardiac conditions.

Medicaid spending on single-ingredient colchicine jumped 2,833%, from $1.1 million in 2008 to $32.2 million in 2017, new findings show. Medicaid expansion likely played a role in the increase, but 58% was due to price hikes alone.

The centuries-old drug sold for pennies in the United States before increasing 50-fold to about $5 per pill in 2009 after the first FDA-approved colchicine product, Colcrys, was granted 3 years’ market exclusivity for the treatment of acute gout based on a 1-week trial.

If prices had remained at pre-Colcrys levels, Medicaid spending in 2017 would have totaled just $2.1 million rather than $32.2 million according to the analysis, published online Nov. 30 in JAMA Internal Medicine (doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.5017).

The study was motivated by difficulties gout patients have in accessing colchicine, but also last year’s COLCOT trial, which reported fewer ischemic cardiovascular events in patients receiving colchicine after MI, observed Natalie McCormick, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

“They were suggesting it could be a cost-effective way for secondary prevention and it is fairly inexpensive in most countries, but not the U.S.,” she said in an interview. “So there’s really a potential to increase public spending if more and more patients are then taking colchicine for prevention of cardiovascular events and the prices don’t change.”

The current pandemic could potentially further increase demand. Results initially slated for September are expected this month from the COLCORONA trial, which is testing whether the anti-inflammatory agent can prevent hospitalizations, lung complications, and death when given early in the course of COVID-19.

University of Oxford (England) researchers also announced last week that colchicine is being added to the massive RECOVERY trial, which is studying treatments for hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Notably, the Canadian-based COLCOT trial did not use Colcrys, but rather a colchicine product that costs just $0.26 a pill in Canada, roughly the price of most generics available worldwide.

Authorized generics typically drive down drug prices when competing with independent generics, but this competition is missing in the United States, where Colcrys holds patents until 2029, Dr. McCormick and colleagues noted. More than a half-dozen independent generics have FDA approval to date, but only authorized generics with price points set by the brand-name companies are available to treat acute gout, pericarditis, and potentially millions with MI.

“One of the key takeaways is this difference between the brand names and the authorized generics and the independents,” she said. “The authorized [generics] have really not saved money. The list prices were just slightly lower and patients can also have more difficulty in getting those covered.”

For this analysis, the investigators used Medicaid and Medicare data to examine prices for all available forms of colchicine from 2008 to 2017, including unregulated/unapproved colchicine (2008-2010), generic combination probenecid-colchicine (2008-2017), Colcrys (2009-2017), brand-name single-ingredient colchicine Mitigare (approved in late 2014 but not marketed until 2015), and their authorized generics (2015-2017). Medicare trends from 2012 to 2017 were analyzed separately because pre-Colcrys Medicare data were not available.

Based on the results, combined spending on Medicare and Medicaid claims for single-ingredient colchicine exceeded $340 million in 2017.

Inflation- and rebate-adjusted Medicaid unit prices rose from $0.24 a pill in 2008, when unapproved formulations were still available, to $4.20 a pill in 2011 (Colcrys only), and peaked at $4.66 a pill in 2015 (Colcrys plus authorized generics).

Prescribing of lower-priced probenecid-colchicine ($0.66/pill in 2017) remained stable throughout. Medicaid rebate-adjusted prices in 2017 were $3.99/pill for all single-ingredient colchicine products, $5.13/pill for Colcrys, $4.49/pill for Mitigare, and $3.88/pill for authorized generics.

Medicare rebate-adjusted 2017 per-pill prices were $5.81 for all single-ingredient colchicine products, $6.78 for Colcrys, $5.68 for Mitigare, $5.16 for authorized generics, and $0.70 for probenecid-colchicine.

“Authorized generics have still driven high spending,” Dr. McCormick said. “We really need to encourage more competition in order to improve access.”

In an accompanying commentary, B. Joseph Guglielmo, PharmD, University of California, San Francisco, pointed out that the estimated median research and development cost to bring a drug to market is between $985 million and $1,335 million, which inevitably translates into a high selling price for the drug. Such investment and its resultant cost, however, should be associated with potential worth to society.

“Only a fraction of an investment was required for Colcrys, a product that has provided no increased value and an unnecessary, long-term cost burden to the health care system,” he wrote. “The current study findings illustrate that we can never allow such an egregious case to take place again.”

Dr. McCormick reported grants from Canadian Institutes of Health Research during the conduct of the study. Dr. Guglielmo reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Public spending on colchicine has grown exponentially over the past decade despite generics suggesting an uphill slog for patients seeking access to long-term therapy for gout or cardiac conditions.

Medicaid spending on single-ingredient colchicine jumped 2,833%, from $1.1 million in 2008 to $32.2 million in 2017, new findings show. Medicaid expansion likely played a role in the increase, but 58% was due to price hikes alone.

The centuries-old drug sold for pennies in the United States before increasing 50-fold to about $5 per pill in 2009 after the first FDA-approved colchicine product, Colcrys, was granted 3 years’ market exclusivity for the treatment of acute gout based on a 1-week trial.

If prices had remained at pre-Colcrys levels, Medicaid spending in 2017 would have totaled just $2.1 million rather than $32.2 million according to the analysis, published online Nov. 30 in JAMA Internal Medicine (doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.5017).

The study was motivated by difficulties gout patients have in accessing colchicine, but also last year’s COLCOT trial, which reported fewer ischemic cardiovascular events in patients receiving colchicine after MI, observed Natalie McCormick, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

“They were suggesting it could be a cost-effective way for secondary prevention and it is fairly inexpensive in most countries, but not the U.S.,” she said in an interview. “So there’s really a potential to increase public spending if more and more patients are then taking colchicine for prevention of cardiovascular events and the prices don’t change.”

The current pandemic could potentially further increase demand. Results initially slated for September are expected this month from the COLCORONA trial, which is testing whether the anti-inflammatory agent can prevent hospitalizations, lung complications, and death when given early in the course of COVID-19.

University of Oxford (England) researchers also announced last week that colchicine is being added to the massive RECOVERY trial, which is studying treatments for hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Notably, the Canadian-based COLCOT trial did not use Colcrys, but rather a colchicine product that costs just $0.26 a pill in Canada, roughly the price of most generics available worldwide.

Authorized generics typically drive down drug prices when competing with independent generics, but this competition is missing in the United States, where Colcrys holds patents until 2029, Dr. McCormick and colleagues noted. More than a half-dozen independent generics have FDA approval to date, but only authorized generics with price points set by the brand-name companies are available to treat acute gout, pericarditis, and potentially millions with MI.

“One of the key takeaways is this difference between the brand names and the authorized generics and the independents,” she said. “The authorized [generics] have really not saved money. The list prices were just slightly lower and patients can also have more difficulty in getting those covered.”

For this analysis, the investigators used Medicaid and Medicare data to examine prices for all available forms of colchicine from 2008 to 2017, including unregulated/unapproved colchicine (2008-2010), generic combination probenecid-colchicine (2008-2017), Colcrys (2009-2017), brand-name single-ingredient colchicine Mitigare (approved in late 2014 but not marketed until 2015), and their authorized generics (2015-2017). Medicare trends from 2012 to 2017 were analyzed separately because pre-Colcrys Medicare data were not available.

Based on the results, combined spending on Medicare and Medicaid claims for single-ingredient colchicine exceeded $340 million in 2017.

Inflation- and rebate-adjusted Medicaid unit prices rose from $0.24 a pill in 2008, when unapproved formulations were still available, to $4.20 a pill in 2011 (Colcrys only), and peaked at $4.66 a pill in 2015 (Colcrys plus authorized generics).

Prescribing of lower-priced probenecid-colchicine ($0.66/pill in 2017) remained stable throughout. Medicaid rebate-adjusted prices in 2017 were $3.99/pill for all single-ingredient colchicine products, $5.13/pill for Colcrys, $4.49/pill for Mitigare, and $3.88/pill for authorized generics.

Medicare rebate-adjusted 2017 per-pill prices were $5.81 for all single-ingredient colchicine products, $6.78 for Colcrys, $5.68 for Mitigare, $5.16 for authorized generics, and $0.70 for probenecid-colchicine.

“Authorized generics have still driven high spending,” Dr. McCormick said. “We really need to encourage more competition in order to improve access.”

In an accompanying commentary, B. Joseph Guglielmo, PharmD, University of California, San Francisco, pointed out that the estimated median research and development cost to bring a drug to market is between $985 million and $1,335 million, which inevitably translates into a high selling price for the drug. Such investment and its resultant cost, however, should be associated with potential worth to society.

“Only a fraction of an investment was required for Colcrys, a product that has provided no increased value and an unnecessary, long-term cost burden to the health care system,” he wrote. “The current study findings illustrate that we can never allow such an egregious case to take place again.”

Dr. McCormick reported grants from Canadian Institutes of Health Research during the conduct of the study. Dr. Guglielmo reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Public spending on colchicine has grown exponentially over the past decade despite generics suggesting an uphill slog for patients seeking access to long-term therapy for gout or cardiac conditions.

Medicaid spending on single-ingredient colchicine jumped 2,833%, from $1.1 million in 2008 to $32.2 million in 2017, new findings show. Medicaid expansion likely played a role in the increase, but 58% was due to price hikes alone.

The centuries-old drug sold for pennies in the United States before increasing 50-fold to about $5 per pill in 2009 after the first FDA-approved colchicine product, Colcrys, was granted 3 years’ market exclusivity for the treatment of acute gout based on a 1-week trial.

If prices had remained at pre-Colcrys levels, Medicaid spending in 2017 would have totaled just $2.1 million rather than $32.2 million according to the analysis, published online Nov. 30 in JAMA Internal Medicine (doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.5017).

The study was motivated by difficulties gout patients have in accessing colchicine, but also last year’s COLCOT trial, which reported fewer ischemic cardiovascular events in patients receiving colchicine after MI, observed Natalie McCormick, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

“They were suggesting it could be a cost-effective way for secondary prevention and it is fairly inexpensive in most countries, but not the U.S.,” she said in an interview. “So there’s really a potential to increase public spending if more and more patients are then taking colchicine for prevention of cardiovascular events and the prices don’t change.”

The current pandemic could potentially further increase demand. Results initially slated for September are expected this month from the COLCORONA trial, which is testing whether the anti-inflammatory agent can prevent hospitalizations, lung complications, and death when given early in the course of COVID-19.

University of Oxford (England) researchers also announced last week that colchicine is being added to the massive RECOVERY trial, which is studying treatments for hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Notably, the Canadian-based COLCOT trial did not use Colcrys, but rather a colchicine product that costs just $0.26 a pill in Canada, roughly the price of most generics available worldwide.

Authorized generics typically drive down drug prices when competing with independent generics, but this competition is missing in the United States, where Colcrys holds patents until 2029, Dr. McCormick and colleagues noted. More than a half-dozen independent generics have FDA approval to date, but only authorized generics with price points set by the brand-name companies are available to treat acute gout, pericarditis, and potentially millions with MI.

“One of the key takeaways is this difference between the brand names and the authorized generics and the independents,” she said. “The authorized [generics] have really not saved money. The list prices were just slightly lower and patients can also have more difficulty in getting those covered.”

For this analysis, the investigators used Medicaid and Medicare data to examine prices for all available forms of colchicine from 2008 to 2017, including unregulated/unapproved colchicine (2008-2010), generic combination probenecid-colchicine (2008-2017), Colcrys (2009-2017), brand-name single-ingredient colchicine Mitigare (approved in late 2014 but not marketed until 2015), and their authorized generics (2015-2017). Medicare trends from 2012 to 2017 were analyzed separately because pre-Colcrys Medicare data were not available.

Based on the results, combined spending on Medicare and Medicaid claims for single-ingredient colchicine exceeded $340 million in 2017.

Inflation- and rebate-adjusted Medicaid unit prices rose from $0.24 a pill in 2008, when unapproved formulations were still available, to $4.20 a pill in 2011 (Colcrys only), and peaked at $4.66 a pill in 2015 (Colcrys plus authorized generics).

Prescribing of lower-priced probenecid-colchicine ($0.66/pill in 2017) remained stable throughout. Medicaid rebate-adjusted prices in 2017 were $3.99/pill for all single-ingredient colchicine products, $5.13/pill for Colcrys, $4.49/pill for Mitigare, and $3.88/pill for authorized generics.

Medicare rebate-adjusted 2017 per-pill prices were $5.81 for all single-ingredient colchicine products, $6.78 for Colcrys, $5.68 for Mitigare, $5.16 for authorized generics, and $0.70 for probenecid-colchicine.

“Authorized generics have still driven high spending,” Dr. McCormick said. “We really need to encourage more competition in order to improve access.”

In an accompanying commentary, B. Joseph Guglielmo, PharmD, University of California, San Francisco, pointed out that the estimated median research and development cost to bring a drug to market is between $985 million and $1,335 million, which inevitably translates into a high selling price for the drug. Such investment and its resultant cost, however, should be associated with potential worth to society.

“Only a fraction of an investment was required for Colcrys, a product that has provided no increased value and an unnecessary, long-term cost burden to the health care system,” he wrote. “The current study findings illustrate that we can never allow such an egregious case to take place again.”

Dr. McCormick reported grants from Canadian Institutes of Health Research during the conduct of the study. Dr. Guglielmo reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Real acupuncture beat sham for osteoarthritis knee pain

Electro-acupuncture resulted in significant improvement in pain and function, compared with sham acupuncture, in a randomized trial of more than 400 adults with knee OA.

The socioeconomic burden of knee OA (KOA) remains high, and will likely increase with the aging population and rising rates of obesity, wrote first author Jian-Feng Tu, MD, PhD, of Beijing University of Chinese Medicine and colleagues. “Since no disease-modifying pharmaceutical agents have been approved, current KOA treatments are mainly symptomatic,” and identifying new therapies in addition to pharmacological agents or surgery is a research priority, they added. The research on acupuncture as a treatment for KOA has increased, but remains controversial as researchers attempt to determine the number of sessions needed for effectiveness.

In a study published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, the researchers recruited 480 adults aged 45-75 years with confirmed KOA who reported knee pain for longer than 6 months. Participants were randomized to three groups: electroacupuncture (EA), manual acupuncture (MA), or sham acupuncture (SA). Each group received three treatment sessions per week. In all groups, electrodes were attached to selected acupuncture needles, but the current was turned on only in the EA treatment group.

The primary outcome was the response rate after 8 weeks of treatment, defined as patients who achieved the minimal clinically important improvement (MCII) on both the Numeric Rating Scale and the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index function subscale.

Overall, response rates at 8 weeks were 60.3%, 58.6%, and 47.3% for the EA, MA, and SA groups, respectively.

Between-group differences were statistically significant for EA versus SA (13%, P = .0234) but not for MA versus SA (11.3%, P = .0507) at 8 weeks; however, both EA and MA groups showed significantly higher response rates, compared with the SA group at 16 and 26 weeks. “Although a clinically meaningful response rate for KOA is not available in the literature, the difference of 11.3%, which indicates the number needed to treat of 9, is acceptable in clinical practices,” the researchers noted.

Adverse events occurred in 11.5% of the EA group, 14.2% of the MA group, and 10.8% of the SA group, and included subcutaneous hematoma, post-needling pain, and pantalgia. All adverse events related to acupuncture resolved within a week and none were serious, the researchers wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the potential burden on patients of three sessions per week, the limited study population of patients with radiologic grades of II or III only, the use of self-reports, and the lack of blinding for outcome assessors, the researchers noted.

However, the results show persistent effects in reducing pain and improving function with EA or MA, compared with SA, the researchers wrote. The findings were strengthened by “adequate dosage of acupuncture, the use of the primary outcome at an individual level, and the rigorous methodology.” The use of the MCII in the primary outcome “can provide patients and policy makers with more straightforward information to decide whether a treatment should be used.”

Optimal dosing questions remain

Current options for managing KOA are limited by factors that include low efficacy and unwanted side effects, while joint replacements increase the burden on health care systems, wrote David J. Hunter, MBBS, PhD, of the University of Sydney, and Richard E. Harris, PhD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, in an accompanying editorial. “In this context, development of new treatments or identification of efficacy of existing therapies to address the huge unmet need of pain are strongly desired.” Acupuncture continues to gain popularity in North and South America, but its efficacy for pain and KOA remain controversial.

The question of dose is challenging when assessing acupuncture because the optimal dose and how to classify it remains unknown. “In this study, the authors used three treatments a week, which is more frequent than typical studies done in the West and potentially may not be feasible in some health care settings. A recent systematic review suggests that treatment frequency matters and a dose of three sessions per week may be superior to less frequent treatment,” they emphasized. Acupuncture is generally considered to be safe, but many health systems do not reimburse for it. Patients may have large out-of-pocket expenses because of the number of visits required, which may be a barrier to further implementation in practice.

“Acupuncture is already widely practiced and readily available in many countries and health care systems,” the editorialists said. However, “more research is needed in the areas of dose-response relationships, effects of blinding the acupuncturist, feasibility of three times weekly regimens, and clarifying the mechanism of effect, particularly given the persistence of benefit.”

The study was funded by Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission and Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Hunter disclosed support from a National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant and providing consulting advice for Merck Serono, TLC Bio, Tissuegene, Lilly, and Pfizer.

SOURCE: Tu J-F et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Nov 10. doi: 10.1002/art.41584.

Electro-acupuncture resulted in significant improvement in pain and function, compared with sham acupuncture, in a randomized trial of more than 400 adults with knee OA.

The socioeconomic burden of knee OA (KOA) remains high, and will likely increase with the aging population and rising rates of obesity, wrote first author Jian-Feng Tu, MD, PhD, of Beijing University of Chinese Medicine and colleagues. “Since no disease-modifying pharmaceutical agents have been approved, current KOA treatments are mainly symptomatic,” and identifying new therapies in addition to pharmacological agents or surgery is a research priority, they added. The research on acupuncture as a treatment for KOA has increased, but remains controversial as researchers attempt to determine the number of sessions needed for effectiveness.

In a study published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, the researchers recruited 480 adults aged 45-75 years with confirmed KOA who reported knee pain for longer than 6 months. Participants were randomized to three groups: electroacupuncture (EA), manual acupuncture (MA), or sham acupuncture (SA). Each group received three treatment sessions per week. In all groups, electrodes were attached to selected acupuncture needles, but the current was turned on only in the EA treatment group.

The primary outcome was the response rate after 8 weeks of treatment, defined as patients who achieved the minimal clinically important improvement (MCII) on both the Numeric Rating Scale and the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index function subscale.

Overall, response rates at 8 weeks were 60.3%, 58.6%, and 47.3% for the EA, MA, and SA groups, respectively.

Between-group differences were statistically significant for EA versus SA (13%, P = .0234) but not for MA versus SA (11.3%, P = .0507) at 8 weeks; however, both EA and MA groups showed significantly higher response rates, compared with the SA group at 16 and 26 weeks. “Although a clinically meaningful response rate for KOA is not available in the literature, the difference of 11.3%, which indicates the number needed to treat of 9, is acceptable in clinical practices,” the researchers noted.

Adverse events occurred in 11.5% of the EA group, 14.2% of the MA group, and 10.8% of the SA group, and included subcutaneous hematoma, post-needling pain, and pantalgia. All adverse events related to acupuncture resolved within a week and none were serious, the researchers wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the potential burden on patients of three sessions per week, the limited study population of patients with radiologic grades of II or III only, the use of self-reports, and the lack of blinding for outcome assessors, the researchers noted.

However, the results show persistent effects in reducing pain and improving function with EA or MA, compared with SA, the researchers wrote. The findings were strengthened by “adequate dosage of acupuncture, the use of the primary outcome at an individual level, and the rigorous methodology.” The use of the MCII in the primary outcome “can provide patients and policy makers with more straightforward information to decide whether a treatment should be used.”

Optimal dosing questions remain

Current options for managing KOA are limited by factors that include low efficacy and unwanted side effects, while joint replacements increase the burden on health care systems, wrote David J. Hunter, MBBS, PhD, of the University of Sydney, and Richard E. Harris, PhD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, in an accompanying editorial. “In this context, development of new treatments or identification of efficacy of existing therapies to address the huge unmet need of pain are strongly desired.” Acupuncture continues to gain popularity in North and South America, but its efficacy for pain and KOA remain controversial.

The question of dose is challenging when assessing acupuncture because the optimal dose and how to classify it remains unknown. “In this study, the authors used three treatments a week, which is more frequent than typical studies done in the West and potentially may not be feasible in some health care settings. A recent systematic review suggests that treatment frequency matters and a dose of three sessions per week may be superior to less frequent treatment,” they emphasized. Acupuncture is generally considered to be safe, but many health systems do not reimburse for it. Patients may have large out-of-pocket expenses because of the number of visits required, which may be a barrier to further implementation in practice.

“Acupuncture is already widely practiced and readily available in many countries and health care systems,” the editorialists said. However, “more research is needed in the areas of dose-response relationships, effects of blinding the acupuncturist, feasibility of three times weekly regimens, and clarifying the mechanism of effect, particularly given the persistence of benefit.”

The study was funded by Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission and Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Hunter disclosed support from a National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant and providing consulting advice for Merck Serono, TLC Bio, Tissuegene, Lilly, and Pfizer.

SOURCE: Tu J-F et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Nov 10. doi: 10.1002/art.41584.

Electro-acupuncture resulted in significant improvement in pain and function, compared with sham acupuncture, in a randomized trial of more than 400 adults with knee OA.

The socioeconomic burden of knee OA (KOA) remains high, and will likely increase with the aging population and rising rates of obesity, wrote first author Jian-Feng Tu, MD, PhD, of Beijing University of Chinese Medicine and colleagues. “Since no disease-modifying pharmaceutical agents have been approved, current KOA treatments are mainly symptomatic,” and identifying new therapies in addition to pharmacological agents or surgery is a research priority, they added. The research on acupuncture as a treatment for KOA has increased, but remains controversial as researchers attempt to determine the number of sessions needed for effectiveness.

In a study published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, the researchers recruited 480 adults aged 45-75 years with confirmed KOA who reported knee pain for longer than 6 months. Participants were randomized to three groups: electroacupuncture (EA), manual acupuncture (MA), or sham acupuncture (SA). Each group received three treatment sessions per week. In all groups, electrodes were attached to selected acupuncture needles, but the current was turned on only in the EA treatment group.

The primary outcome was the response rate after 8 weeks of treatment, defined as patients who achieved the minimal clinically important improvement (MCII) on both the Numeric Rating Scale and the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index function subscale.

Overall, response rates at 8 weeks were 60.3%, 58.6%, and 47.3% for the EA, MA, and SA groups, respectively.

Between-group differences were statistically significant for EA versus SA (13%, P = .0234) but not for MA versus SA (11.3%, P = .0507) at 8 weeks; however, both EA and MA groups showed significantly higher response rates, compared with the SA group at 16 and 26 weeks. “Although a clinically meaningful response rate for KOA is not available in the literature, the difference of 11.3%, which indicates the number needed to treat of 9, is acceptable in clinical practices,” the researchers noted.

Adverse events occurred in 11.5% of the EA group, 14.2% of the MA group, and 10.8% of the SA group, and included subcutaneous hematoma, post-needling pain, and pantalgia. All adverse events related to acupuncture resolved within a week and none were serious, the researchers wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the potential burden on patients of three sessions per week, the limited study population of patients with radiologic grades of II or III only, the use of self-reports, and the lack of blinding for outcome assessors, the researchers noted.

However, the results show persistent effects in reducing pain and improving function with EA or MA, compared with SA, the researchers wrote. The findings were strengthened by “adequate dosage of acupuncture, the use of the primary outcome at an individual level, and the rigorous methodology.” The use of the MCII in the primary outcome “can provide patients and policy makers with more straightforward information to decide whether a treatment should be used.”

Optimal dosing questions remain

Current options for managing KOA are limited by factors that include low efficacy and unwanted side effects, while joint replacements increase the burden on health care systems, wrote David J. Hunter, MBBS, PhD, of the University of Sydney, and Richard E. Harris, PhD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, in an accompanying editorial. “In this context, development of new treatments or identification of efficacy of existing therapies to address the huge unmet need of pain are strongly desired.” Acupuncture continues to gain popularity in North and South America, but its efficacy for pain and KOA remain controversial.

The question of dose is challenging when assessing acupuncture because the optimal dose and how to classify it remains unknown. “In this study, the authors used three treatments a week, which is more frequent than typical studies done in the West and potentially may not be feasible in some health care settings. A recent systematic review suggests that treatment frequency matters and a dose of three sessions per week may be superior to less frequent treatment,” they emphasized. Acupuncture is generally considered to be safe, but many health systems do not reimburse for it. Patients may have large out-of-pocket expenses because of the number of visits required, which may be a barrier to further implementation in practice.

“Acupuncture is already widely practiced and readily available in many countries and health care systems,” the editorialists said. However, “more research is needed in the areas of dose-response relationships, effects of blinding the acupuncturist, feasibility of three times weekly regimens, and clarifying the mechanism of effect, particularly given the persistence of benefit.”