User login

Trichodysplasia Spinulosa in the Setting of Colon Cancer

Case Report

An 82-year-old woman presented to the clinic with a rash on the face that had been present for a few months. She denied any treatment or prior occurrence. Her medical history was remarkable for non-Hodgkin lymphoma that had been successfully treated with chemotherapy 4 years prior. Additionally, she recently had been diagnosed with stage IV colon cancer. She reported that surgery had been scheduled and she would start adjuvant chemotherapy soon after.

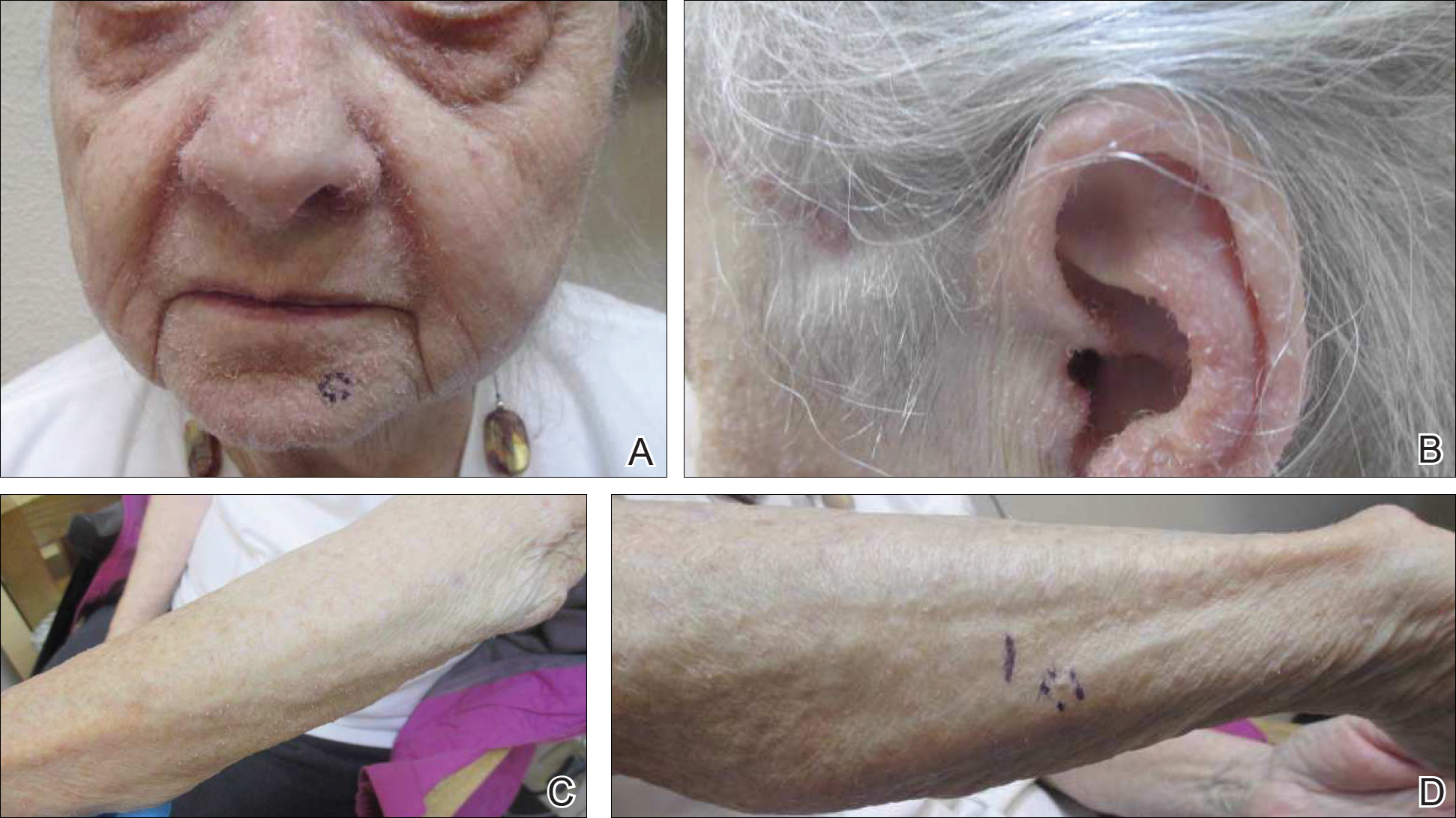

On physical examination she exhibited perioral and perinasal erythematous papules with sparing of the vermilion border. A diagnosis of perioral dermatitis was made, and she was started on topical metronidazole. At 1-month follow-up, her condition had slightly worsened and she was subsequently started on doxycycline. When she returned to the clinic again the following month, physical examination revealed agminated folliculocentric papules with central spicules on the face, nose, ears, upper extremities (Figure 1), and trunk. The differential diagnosis included multiple minute digitate hyperkeratosis, spiculosis of multiple myeloma, and trichodysplasia spinulosa (TS).

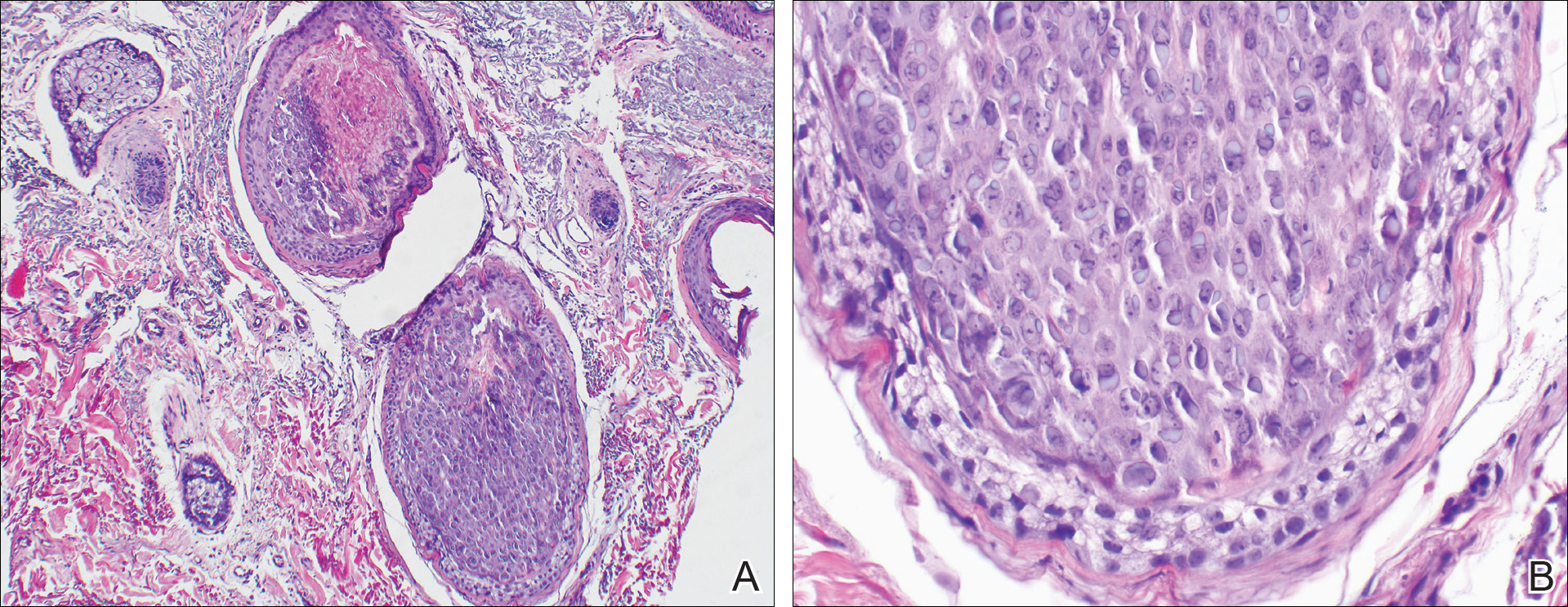

A punch biopsy of 2 separate papules on the face and upper extremity revealed dilated follicles with enlarged trichohyalin granules and dyskeratosis (Figure 2), consistent with TS. Additional testing such as electron microscopy or polymerase chain reaction was not performed to keep the patient’s medical costs down; also, the strong clinical and histopathologic evidence did not warrant further testing.

The plan was to start split-face treatment with topical acyclovir and a topical retinoid to see which agent was more effective, but the patient declined until her chemotherapy regimen had concluded. Unfortunately, the patient died 3 months later due to colon cancer.

Comment

History and Presentation

Trichodysplasia spinulosa was first recognized as hairlike hyperkeratosis.1 The name by which it is currently known was later championed by Haycox et al.2 They reported a case of a 44-year-old man who underwent a combined renal-pancreas transplant and while taking immunosuppressive medication developed erythematous papules with follicular spinous processes and progressive alopecia.2 Other synonymous terms used for this condition include pilomatrix dysplasia, cyclosporine-induced folliculodystrophy, virus-associated trichodysplasia,3 and follicular dystrophy of immunosuppression.4 Trichodysplasia spinulosa can affect both adult and pediatric immunocompromised patients, including organ transplant recipients on immunosuppressants and cancer patients on chemotherapy.3 The condition also has been reported to precede the recurrence of lymphoma.5

Etiology

The connection of TS with a viral etiology was first demonstrated in 1999, and subsequently it was confirmed to be a polyomavirus.2 The family name of Polyomaviridae possesses a Greek derivation with poly- meaning many and -oma meaning cancer.3 This name was given after the polyomavirus induced multiple tumors in mice.3,6 This viral family consists of multiple naked viruses with a surrounding icosahedral capsid containing 3 structural proteins known as VP1, VP2, and VP3. Their life cycle is characterized by early and late phases with respective early and late protein formation.3

Polyomavirus infections maintain an asymptomatic and latent course in immunocompetent patients.7 The prevalence and manifestation of these viruses change when the host’s immune system is altered. The first identified JC virus and BK virus of the same family have been found at increased frequencies in blood and lymphoid tissue during host immunosuppression.6 Moreover, the Merkel cell polyomavirus detected in Merkel cell carcinoma is well documented in the dermatologic literature.6,8

A specific polyomavirus has been implicated in the majority of TS cases and has subsequently received the name of TS polyomavirus.9 As a polyomavirus, it similarly produces capsid antigens and large/small T antigens. Among the viral protein antigens produced, the large tumor or LT antigen represents one of the most potent viral proteins. It has been postulated to inhibit the retinoblastoma family of proteins, leading to increased inner root sheath cells that allow for further viral replication.9,10

The disease presents with folliculocentric papules localized mainly on the central face and ears, which grow central keratin spines or spicules that can become 1 to 3 mm in length. Coinciding alopecia and madarosis also may be present.9

Diagnosis

Histologic examination reveals abnormal follicular maturation and distension. Additionally, increased proliferation and amount of trichohyalin is seen within the inner root sheath cells. Further testing via viral culture, polymerase chain reaction, electron microscopy, or immunohistochemical stains can confirm the diagnosis. Such testing may not be warranted in all cases given that classic clinical findings coupled with routine histopathology staining can provide enough evidence.10,11

Management

Currently, a universal successful treatment for TS does not exist. There have been anecdotal successes reported with topical medications such as cidofovir ointment 1%, acyclovir combined with 2-deoxy-D-glucose and epigallocatechin, corticosteroids, topical tacrolimus, topical retinoids, and imiquimod. Additionally, success has been seen with oral minocycline, oral retinoids, valacyclovir, and valganciclovir, with the latter showing the best results. Patients also have shown improvement after modifying their immunosuppressive treatment regimen.10,12

Conclusion

Given the previously published case of TS preceding the recurrence of lymphoma,5 we notified our patient’s oncologist of this potential risk. Her history of lymphoma and immunosuppressive treatment 4 years prior may represent the etiology of the cutaneous presentation; however, the TS with concurrent colon cancer presented prior to starting immunosuppressive therapy, suggesting that it also may have been a paraneoplastic process and not just a sign of immunosuppression. Therefore, we recommend that patients who present with TS should be evaluated for underlying malignancy if not already diagnosed.

- Linke M, Geraud C, Sauer C, et al. Follicular erythematous papules with keratotic spicules. Acta Derm Venereol . 2014;94:493-494.

- Haycox CL, Kim S, Fleckman P, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa—a newly described folliculocentric viral infection in an immunocompromised host. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:268-271.

- Moens U, Ludvigsen M, Van Ghelue M. Human polyomaviruses in skin diseases [published online September 12, 2011]. Patholog Res Int. 2011;2011:123491.

- Matthews MR, Wang RC, Reddick RL, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia spinulosa: a case with electron microscopic and molecular detection of the trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated human polyomavirus. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:420-431.

- Osswald SS, Kulick KB, Tomaszewski MM, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia in a patient with lymphoma: a case report and review. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:721-725.

- Dalianis T, Hirsch HH. Human polyomavirus in disease and cancer. Virology. 2013;437:63-72.

- Tsuzuki S, Fukumoto H, Mine S, et al. Detection of trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated polyomavirus in a fatal case of myocarditis in a seven-month-old girl. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:5308-5312.

- Sadeghi M, Aronen M, Chen T, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus and trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated polyomavirus DNAs and antibodies in blood among the elderly. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:383.

- Van der Meijden E, Kazem S, Burgers MM, et al. Seroprevalence of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1355-1363.

- Krichhof MG, Shojania K, Hull MW, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: rare presentation of polyomavirus infection in immunocompromised patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18:430-435.

- Rianthavorn P, Posuwan N, Payungporn S, et al. Polyomavirus reactivation in pediatric patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2012;228:197-204.

- Wanat KA, Holler PD, Dentchev T, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia: characterization of a novel polyomavirus infection with therapeutic insights. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:219-223.

Case Report

An 82-year-old woman presented to the clinic with a rash on the face that had been present for a few months. She denied any treatment or prior occurrence. Her medical history was remarkable for non-Hodgkin lymphoma that had been successfully treated with chemotherapy 4 years prior. Additionally, she recently had been diagnosed with stage IV colon cancer. She reported that surgery had been scheduled and she would start adjuvant chemotherapy soon after.

On physical examination she exhibited perioral and perinasal erythematous papules with sparing of the vermilion border. A diagnosis of perioral dermatitis was made, and she was started on topical metronidazole. At 1-month follow-up, her condition had slightly worsened and she was subsequently started on doxycycline. When she returned to the clinic again the following month, physical examination revealed agminated folliculocentric papules with central spicules on the face, nose, ears, upper extremities (Figure 1), and trunk. The differential diagnosis included multiple minute digitate hyperkeratosis, spiculosis of multiple myeloma, and trichodysplasia spinulosa (TS).

A punch biopsy of 2 separate papules on the face and upper extremity revealed dilated follicles with enlarged trichohyalin granules and dyskeratosis (Figure 2), consistent with TS. Additional testing such as electron microscopy or polymerase chain reaction was not performed to keep the patient’s medical costs down; also, the strong clinical and histopathologic evidence did not warrant further testing.

The plan was to start split-face treatment with topical acyclovir and a topical retinoid to see which agent was more effective, but the patient declined until her chemotherapy regimen had concluded. Unfortunately, the patient died 3 months later due to colon cancer.

Comment

History and Presentation

Trichodysplasia spinulosa was first recognized as hairlike hyperkeratosis.1 The name by which it is currently known was later championed by Haycox et al.2 They reported a case of a 44-year-old man who underwent a combined renal-pancreas transplant and while taking immunosuppressive medication developed erythematous papules with follicular spinous processes and progressive alopecia.2 Other synonymous terms used for this condition include pilomatrix dysplasia, cyclosporine-induced folliculodystrophy, virus-associated trichodysplasia,3 and follicular dystrophy of immunosuppression.4 Trichodysplasia spinulosa can affect both adult and pediatric immunocompromised patients, including organ transplant recipients on immunosuppressants and cancer patients on chemotherapy.3 The condition also has been reported to precede the recurrence of lymphoma.5

Etiology

The connection of TS with a viral etiology was first demonstrated in 1999, and subsequently it was confirmed to be a polyomavirus.2 The family name of Polyomaviridae possesses a Greek derivation with poly- meaning many and -oma meaning cancer.3 This name was given after the polyomavirus induced multiple tumors in mice.3,6 This viral family consists of multiple naked viruses with a surrounding icosahedral capsid containing 3 structural proteins known as VP1, VP2, and VP3. Their life cycle is characterized by early and late phases with respective early and late protein formation.3

Polyomavirus infections maintain an asymptomatic and latent course in immunocompetent patients.7 The prevalence and manifestation of these viruses change when the host’s immune system is altered. The first identified JC virus and BK virus of the same family have been found at increased frequencies in blood and lymphoid tissue during host immunosuppression.6 Moreover, the Merkel cell polyomavirus detected in Merkel cell carcinoma is well documented in the dermatologic literature.6,8

A specific polyomavirus has been implicated in the majority of TS cases and has subsequently received the name of TS polyomavirus.9 As a polyomavirus, it similarly produces capsid antigens and large/small T antigens. Among the viral protein antigens produced, the large tumor or LT antigen represents one of the most potent viral proteins. It has been postulated to inhibit the retinoblastoma family of proteins, leading to increased inner root sheath cells that allow for further viral replication.9,10

The disease presents with folliculocentric papules localized mainly on the central face and ears, which grow central keratin spines or spicules that can become 1 to 3 mm in length. Coinciding alopecia and madarosis also may be present.9

Diagnosis

Histologic examination reveals abnormal follicular maturation and distension. Additionally, increased proliferation and amount of trichohyalin is seen within the inner root sheath cells. Further testing via viral culture, polymerase chain reaction, electron microscopy, or immunohistochemical stains can confirm the diagnosis. Such testing may not be warranted in all cases given that classic clinical findings coupled with routine histopathology staining can provide enough evidence.10,11

Management

Currently, a universal successful treatment for TS does not exist. There have been anecdotal successes reported with topical medications such as cidofovir ointment 1%, acyclovir combined with 2-deoxy-D-glucose and epigallocatechin, corticosteroids, topical tacrolimus, topical retinoids, and imiquimod. Additionally, success has been seen with oral minocycline, oral retinoids, valacyclovir, and valganciclovir, with the latter showing the best results. Patients also have shown improvement after modifying their immunosuppressive treatment regimen.10,12

Conclusion

Given the previously published case of TS preceding the recurrence of lymphoma,5 we notified our patient’s oncologist of this potential risk. Her history of lymphoma and immunosuppressive treatment 4 years prior may represent the etiology of the cutaneous presentation; however, the TS with concurrent colon cancer presented prior to starting immunosuppressive therapy, suggesting that it also may have been a paraneoplastic process and not just a sign of immunosuppression. Therefore, we recommend that patients who present with TS should be evaluated for underlying malignancy if not already diagnosed.

Case Report

An 82-year-old woman presented to the clinic with a rash on the face that had been present for a few months. She denied any treatment or prior occurrence. Her medical history was remarkable for non-Hodgkin lymphoma that had been successfully treated with chemotherapy 4 years prior. Additionally, she recently had been diagnosed with stage IV colon cancer. She reported that surgery had been scheduled and she would start adjuvant chemotherapy soon after.

On physical examination she exhibited perioral and perinasal erythematous papules with sparing of the vermilion border. A diagnosis of perioral dermatitis was made, and she was started on topical metronidazole. At 1-month follow-up, her condition had slightly worsened and she was subsequently started on doxycycline. When she returned to the clinic again the following month, physical examination revealed agminated folliculocentric papules with central spicules on the face, nose, ears, upper extremities (Figure 1), and trunk. The differential diagnosis included multiple minute digitate hyperkeratosis, spiculosis of multiple myeloma, and trichodysplasia spinulosa (TS).

A punch biopsy of 2 separate papules on the face and upper extremity revealed dilated follicles with enlarged trichohyalin granules and dyskeratosis (Figure 2), consistent with TS. Additional testing such as electron microscopy or polymerase chain reaction was not performed to keep the patient’s medical costs down; also, the strong clinical and histopathologic evidence did not warrant further testing.

The plan was to start split-face treatment with topical acyclovir and a topical retinoid to see which agent was more effective, but the patient declined until her chemotherapy regimen had concluded. Unfortunately, the patient died 3 months later due to colon cancer.

Comment

History and Presentation

Trichodysplasia spinulosa was first recognized as hairlike hyperkeratosis.1 The name by which it is currently known was later championed by Haycox et al.2 They reported a case of a 44-year-old man who underwent a combined renal-pancreas transplant and while taking immunosuppressive medication developed erythematous papules with follicular spinous processes and progressive alopecia.2 Other synonymous terms used for this condition include pilomatrix dysplasia, cyclosporine-induced folliculodystrophy, virus-associated trichodysplasia,3 and follicular dystrophy of immunosuppression.4 Trichodysplasia spinulosa can affect both adult and pediatric immunocompromised patients, including organ transplant recipients on immunosuppressants and cancer patients on chemotherapy.3 The condition also has been reported to precede the recurrence of lymphoma.5

Etiology

The connection of TS with a viral etiology was first demonstrated in 1999, and subsequently it was confirmed to be a polyomavirus.2 The family name of Polyomaviridae possesses a Greek derivation with poly- meaning many and -oma meaning cancer.3 This name was given after the polyomavirus induced multiple tumors in mice.3,6 This viral family consists of multiple naked viruses with a surrounding icosahedral capsid containing 3 structural proteins known as VP1, VP2, and VP3. Their life cycle is characterized by early and late phases with respective early and late protein formation.3

Polyomavirus infections maintain an asymptomatic and latent course in immunocompetent patients.7 The prevalence and manifestation of these viruses change when the host’s immune system is altered. The first identified JC virus and BK virus of the same family have been found at increased frequencies in blood and lymphoid tissue during host immunosuppression.6 Moreover, the Merkel cell polyomavirus detected in Merkel cell carcinoma is well documented in the dermatologic literature.6,8

A specific polyomavirus has been implicated in the majority of TS cases and has subsequently received the name of TS polyomavirus.9 As a polyomavirus, it similarly produces capsid antigens and large/small T antigens. Among the viral protein antigens produced, the large tumor or LT antigen represents one of the most potent viral proteins. It has been postulated to inhibit the retinoblastoma family of proteins, leading to increased inner root sheath cells that allow for further viral replication.9,10

The disease presents with folliculocentric papules localized mainly on the central face and ears, which grow central keratin spines or spicules that can become 1 to 3 mm in length. Coinciding alopecia and madarosis also may be present.9

Diagnosis

Histologic examination reveals abnormal follicular maturation and distension. Additionally, increased proliferation and amount of trichohyalin is seen within the inner root sheath cells. Further testing via viral culture, polymerase chain reaction, electron microscopy, or immunohistochemical stains can confirm the diagnosis. Such testing may not be warranted in all cases given that classic clinical findings coupled with routine histopathology staining can provide enough evidence.10,11

Management

Currently, a universal successful treatment for TS does not exist. There have been anecdotal successes reported with topical medications such as cidofovir ointment 1%, acyclovir combined with 2-deoxy-D-glucose and epigallocatechin, corticosteroids, topical tacrolimus, topical retinoids, and imiquimod. Additionally, success has been seen with oral minocycline, oral retinoids, valacyclovir, and valganciclovir, with the latter showing the best results. Patients also have shown improvement after modifying their immunosuppressive treatment regimen.10,12

Conclusion

Given the previously published case of TS preceding the recurrence of lymphoma,5 we notified our patient’s oncologist of this potential risk. Her history of lymphoma and immunosuppressive treatment 4 years prior may represent the etiology of the cutaneous presentation; however, the TS with concurrent colon cancer presented prior to starting immunosuppressive therapy, suggesting that it also may have been a paraneoplastic process and not just a sign of immunosuppression. Therefore, we recommend that patients who present with TS should be evaluated for underlying malignancy if not already diagnosed.

- Linke M, Geraud C, Sauer C, et al. Follicular erythematous papules with keratotic spicules. Acta Derm Venereol . 2014;94:493-494.

- Haycox CL, Kim S, Fleckman P, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa—a newly described folliculocentric viral infection in an immunocompromised host. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:268-271.

- Moens U, Ludvigsen M, Van Ghelue M. Human polyomaviruses in skin diseases [published online September 12, 2011]. Patholog Res Int. 2011;2011:123491.

- Matthews MR, Wang RC, Reddick RL, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia spinulosa: a case with electron microscopic and molecular detection of the trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated human polyomavirus. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:420-431.

- Osswald SS, Kulick KB, Tomaszewski MM, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia in a patient with lymphoma: a case report and review. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:721-725.

- Dalianis T, Hirsch HH. Human polyomavirus in disease and cancer. Virology. 2013;437:63-72.

- Tsuzuki S, Fukumoto H, Mine S, et al. Detection of trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated polyomavirus in a fatal case of myocarditis in a seven-month-old girl. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:5308-5312.

- Sadeghi M, Aronen M, Chen T, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus and trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated polyomavirus DNAs and antibodies in blood among the elderly. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:383.

- Van der Meijden E, Kazem S, Burgers MM, et al. Seroprevalence of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1355-1363.

- Krichhof MG, Shojania K, Hull MW, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: rare presentation of polyomavirus infection in immunocompromised patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18:430-435.

- Rianthavorn P, Posuwan N, Payungporn S, et al. Polyomavirus reactivation in pediatric patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2012;228:197-204.

- Wanat KA, Holler PD, Dentchev T, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia: characterization of a novel polyomavirus infection with therapeutic insights. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:219-223.

- Linke M, Geraud C, Sauer C, et al. Follicular erythematous papules with keratotic spicules. Acta Derm Venereol . 2014;94:493-494.

- Haycox CL, Kim S, Fleckman P, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa—a newly described folliculocentric viral infection in an immunocompromised host. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:268-271.

- Moens U, Ludvigsen M, Van Ghelue M. Human polyomaviruses in skin diseases [published online September 12, 2011]. Patholog Res Int. 2011;2011:123491.

- Matthews MR, Wang RC, Reddick RL, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia spinulosa: a case with electron microscopic and molecular detection of the trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated human polyomavirus. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:420-431.

- Osswald SS, Kulick KB, Tomaszewski MM, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia in a patient with lymphoma: a case report and review. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:721-725.

- Dalianis T, Hirsch HH. Human polyomavirus in disease and cancer. Virology. 2013;437:63-72.

- Tsuzuki S, Fukumoto H, Mine S, et al. Detection of trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated polyomavirus in a fatal case of myocarditis in a seven-month-old girl. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:5308-5312.

- Sadeghi M, Aronen M, Chen T, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus and trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated polyomavirus DNAs and antibodies in blood among the elderly. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:383.

- Van der Meijden E, Kazem S, Burgers MM, et al. Seroprevalence of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1355-1363.

- Krichhof MG, Shojania K, Hull MW, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: rare presentation of polyomavirus infection in immunocompromised patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18:430-435.

- Rianthavorn P, Posuwan N, Payungporn S, et al. Polyomavirus reactivation in pediatric patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2012;228:197-204.

- Wanat KA, Holler PD, Dentchev T, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia: characterization of a novel polyomavirus infection with therapeutic insights. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:219-223.

Practice Points

- Rashes have a life span and can evolve with time.

- If apparent straightforward conditions do not appear to respond to standard therapy, start to think outside the box for underlying potential causes.

Identifying and Treating CNS Vasculitis

Often difficult to diagnose, CNS vasculitis is a serious condition that can be treated effectively if addressed early.

HILTON HEAD, SC—Vasculitis is a general term for a group of uncommon diseases involving inflammation of blood vessels, which can lead to the occlusion or destruction of the vessels and to ischemia of the tissues supplied by those vessels. CNS vasculitis can be a primary disease or occur secondary to infections or as part of a systemic vasculitis or systemic inflammatory (eg, rheumatologic) disease. Without prompt diagnosis and treatment, patients are at high risk of permanent neurologic disability or death, according to a presentation at the 41st Annual Contemporary Clinical Neurology Symposium.

If diagnosed and treated early, CNS vasculitis has a good prognosis, but delayed intervention can result in severe morbidity or mortality, said Siddharama Pawate, MD, Associate Professor of Neurology at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville. “You have to do extensive workups sometimes before you can make a diagnosis,” he said, citing the need for neurology, rheumatology, and infectious disease input. “Investigations include serologic testing, CSF analysis, MRI, and brain biopsy.”

Rare But With a High Risk of Morbidity

The 2012 International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference on the Nomenclature of Vasculitis adopted an extensive list of names for the numerous manifestations of vasculitis. These include the following:

• Large-vessel vasculitis (eg, giant cell arteritis [GCA])

• Medium-vessel vasculitis (eg, polyarteritis nodosa)

• Small-vessel vasculitis (eg, microscopic polyangiitis and granulomatosis with polyangiitis [Wegener’s granulomatosis])

• Variable-vessel vasculitis (eg, Behçet’s disease)

• Single-organ vasculitis (eg, primary CNS vasculitis)

• Vasculitis associated with systemic disease (eg, rheumatoid vasculitis)

• Vasculitis associated with probable etiology (eg, hepatitis B virus-associated or cancer-associated vasculitis).

CNS vasculitis may be grouped into two larger categories—infectious CNS vasculitis and immune-mediated CNS vasculitis. Dr. Pawate provided a brief overview of infectious causes of vasculitis including bacteria, mycobacteria, varicella-zoster, fungi, and neurocysticercosis, but devoted the main part of his presentation to the latter of the two categories, including a focus on primary CNS vasculitis (PCNSV), which is also known as primary angiitis of the CNS (PACNS). Dr. Pawate offered an analysis of what is entailed in the recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of CNS vasculitis in general and its immune-mediated variants more specifically.

CNS vasculitis may occur as part of a broader systemic vasculitis. GCA is a medical emergency that can cause permanent visual loss if not diagnosed and treated early. Vision loss occurs most often due to anterior ischemic optic neuropathy but also central retinal artery occlusion and posterior ischemic optic neuropathy. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for GCA diagnosis include three of the five following core features: age 50 or older at onset, new-onset headaches, temporal artery abnormality, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of at least 50 mm/h, and abnormal temporal artery biopsy. High-dose steroids should be started if there is suspicion, without waiting for biopsy results. Recently, the anti-IL6 monoclonal antibody tocilizumab was approved by the FDA as a treatment for GCA. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis most often causes peripheral neuropathy, but can cause a small or medium vessel CNS vasculitis. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss syndrome) is characterized by the triad of asthma, hypereosinophilia, and necrotizing vasculitis, usually in that order. CNS involvement is common as part of the vasculitis. CNS vasculitis may also be seen in Behçet’s disease manifesting as dural sinus thrombosis and arterial occlusion or aneurysm.

In systemic lupus erythematosus, vasculitis has a prevalence ranging between 11% and 36%, but CNS involvement is much less common. Case reports of CNS vasculitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis are rare.

Primary CNS Vasculitis

Primary CNS vasculitis causes inflammation of mostly small- to medium-sized leptomeningeal and parenchymal arterial vessels. It is rare—a 2007 retrospective analysis by Salvarani et al of 101 cases estimated the average annual incidence to be 2.4 cases per one million person-years. Onset tends to occur in middle age, with a median age at diagnosis of 50 and a similar frequency in males and females.

Clinical presentation of PCNSV can be acute, subacute, chronic, or recurrent. Depending on the area of the brain or spinal cord that is affected, patients can present with a wide variety of neurologic complaints. Headache is the most common symptom—found in 50% to 78% of patients—followed by altered cognition and persistent neurologic deficits. Stroke and transient ischemic attack involving multiple vascular areas occur in 30% to 50% of patients.

The diagnostic gold standard for PCNSV is brain parenchymal/leptomeningeal biopsy. The most common diagnoses are granulomatous angiitis of the CNS (58%), lymphocytic PACNS (28%), and necrotizing vasculitis (14%). More than 90% of patients have abnormalities on MRI, and the most common imaging findings are cortical and subcortical infarcts, leptomeningeal enhancement, intracranial hemorrhage, and areas of increased signal on FLAIR and T2-weighted sequences. It has been increasingly recognized that differential diagnosis for PCNSV should include reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS), which is characterized by reversible multifocal narrowing of the cerebral arteries—typically preceded by sudden, severe thunderclap headaches with or without associated neurologic deficits. RCVS typically resolves in approximately 12 weeks.

Regarding treatment for PCNSV, Dr. Pawate recommended starting with high-dose steroids—eg, IV methylprednisolone, 1,000 mg daily for five days, with a prolonged oral prednisone taper starting at 1 mg/kg/day—and six to nine months of IV cyclophosphamide pulse therapy, 500–750 mg/m2 every two to four weeks for more severe cases. Case studies have shown rituximab and mycophenolate to be effective. “I had one patient initially on cyclophosphamide for six months who we [then] maintained on mycophenolate for five years and then stopped immunosuppression,” Dr. Pawate said. “She did quite well.”

—Fred Balzac

Suggested Reading

Abdel Razek AA, Alvarez H, Bagg S, et al. Imaging spectrum of CNS vasculitis. Radiographics. 2014;34(4):873-894.

Chow FC, Marra CM, Cho TA. Cerebrovascular disease in central nervous system infections. Semin Neurol. 2011;31(3):286-306.

Hajj-Ali RA, Calabrese LH. Diagnosis and classification of central nervous system vasculitis. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:149-152.

Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(1):1-11.

Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Calamia KT, et al. Primary central nervous system vasculitis: analysis of 101 patients. Ann Neurol. 2007;62(5):442-451.

Scolding NJ. Central nervous system vasculitis. Semin Immunopathol. 2009;31(4):527-536.

Often difficult to diagnose, CNS vasculitis is a serious condition that can be treated effectively if addressed early.

Often difficult to diagnose, CNS vasculitis is a serious condition that can be treated effectively if addressed early.

HILTON HEAD, SC—Vasculitis is a general term for a group of uncommon diseases involving inflammation of blood vessels, which can lead to the occlusion or destruction of the vessels and to ischemia of the tissues supplied by those vessels. CNS vasculitis can be a primary disease or occur secondary to infections or as part of a systemic vasculitis or systemic inflammatory (eg, rheumatologic) disease. Without prompt diagnosis and treatment, patients are at high risk of permanent neurologic disability or death, according to a presentation at the 41st Annual Contemporary Clinical Neurology Symposium.

If diagnosed and treated early, CNS vasculitis has a good prognosis, but delayed intervention can result in severe morbidity or mortality, said Siddharama Pawate, MD, Associate Professor of Neurology at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville. “You have to do extensive workups sometimes before you can make a diagnosis,” he said, citing the need for neurology, rheumatology, and infectious disease input. “Investigations include serologic testing, CSF analysis, MRI, and brain biopsy.”

Rare But With a High Risk of Morbidity

The 2012 International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference on the Nomenclature of Vasculitis adopted an extensive list of names for the numerous manifestations of vasculitis. These include the following:

• Large-vessel vasculitis (eg, giant cell arteritis [GCA])

• Medium-vessel vasculitis (eg, polyarteritis nodosa)

• Small-vessel vasculitis (eg, microscopic polyangiitis and granulomatosis with polyangiitis [Wegener’s granulomatosis])

• Variable-vessel vasculitis (eg, Behçet’s disease)

• Single-organ vasculitis (eg, primary CNS vasculitis)

• Vasculitis associated with systemic disease (eg, rheumatoid vasculitis)

• Vasculitis associated with probable etiology (eg, hepatitis B virus-associated or cancer-associated vasculitis).

CNS vasculitis may be grouped into two larger categories—infectious CNS vasculitis and immune-mediated CNS vasculitis. Dr. Pawate provided a brief overview of infectious causes of vasculitis including bacteria, mycobacteria, varicella-zoster, fungi, and neurocysticercosis, but devoted the main part of his presentation to the latter of the two categories, including a focus on primary CNS vasculitis (PCNSV), which is also known as primary angiitis of the CNS (PACNS). Dr. Pawate offered an analysis of what is entailed in the recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of CNS vasculitis in general and its immune-mediated variants more specifically.

CNS vasculitis may occur as part of a broader systemic vasculitis. GCA is a medical emergency that can cause permanent visual loss if not diagnosed and treated early. Vision loss occurs most often due to anterior ischemic optic neuropathy but also central retinal artery occlusion and posterior ischemic optic neuropathy. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for GCA diagnosis include three of the five following core features: age 50 or older at onset, new-onset headaches, temporal artery abnormality, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of at least 50 mm/h, and abnormal temporal artery biopsy. High-dose steroids should be started if there is suspicion, without waiting for biopsy results. Recently, the anti-IL6 monoclonal antibody tocilizumab was approved by the FDA as a treatment for GCA. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis most often causes peripheral neuropathy, but can cause a small or medium vessel CNS vasculitis. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss syndrome) is characterized by the triad of asthma, hypereosinophilia, and necrotizing vasculitis, usually in that order. CNS involvement is common as part of the vasculitis. CNS vasculitis may also be seen in Behçet’s disease manifesting as dural sinus thrombosis and arterial occlusion or aneurysm.

In systemic lupus erythematosus, vasculitis has a prevalence ranging between 11% and 36%, but CNS involvement is much less common. Case reports of CNS vasculitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis are rare.

Primary CNS Vasculitis

Primary CNS vasculitis causes inflammation of mostly small- to medium-sized leptomeningeal and parenchymal arterial vessels. It is rare—a 2007 retrospective analysis by Salvarani et al of 101 cases estimated the average annual incidence to be 2.4 cases per one million person-years. Onset tends to occur in middle age, with a median age at diagnosis of 50 and a similar frequency in males and females.

Clinical presentation of PCNSV can be acute, subacute, chronic, or recurrent. Depending on the area of the brain or spinal cord that is affected, patients can present with a wide variety of neurologic complaints. Headache is the most common symptom—found in 50% to 78% of patients—followed by altered cognition and persistent neurologic deficits. Stroke and transient ischemic attack involving multiple vascular areas occur in 30% to 50% of patients.

The diagnostic gold standard for PCNSV is brain parenchymal/leptomeningeal biopsy. The most common diagnoses are granulomatous angiitis of the CNS (58%), lymphocytic PACNS (28%), and necrotizing vasculitis (14%). More than 90% of patients have abnormalities on MRI, and the most common imaging findings are cortical and subcortical infarcts, leptomeningeal enhancement, intracranial hemorrhage, and areas of increased signal on FLAIR and T2-weighted sequences. It has been increasingly recognized that differential diagnosis for PCNSV should include reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS), which is characterized by reversible multifocal narrowing of the cerebral arteries—typically preceded by sudden, severe thunderclap headaches with or without associated neurologic deficits. RCVS typically resolves in approximately 12 weeks.

Regarding treatment for PCNSV, Dr. Pawate recommended starting with high-dose steroids—eg, IV methylprednisolone, 1,000 mg daily for five days, with a prolonged oral prednisone taper starting at 1 mg/kg/day—and six to nine months of IV cyclophosphamide pulse therapy, 500–750 mg/m2 every two to four weeks for more severe cases. Case studies have shown rituximab and mycophenolate to be effective. “I had one patient initially on cyclophosphamide for six months who we [then] maintained on mycophenolate for five years and then stopped immunosuppression,” Dr. Pawate said. “She did quite well.”

—Fred Balzac

Suggested Reading

Abdel Razek AA, Alvarez H, Bagg S, et al. Imaging spectrum of CNS vasculitis. Radiographics. 2014;34(4):873-894.

Chow FC, Marra CM, Cho TA. Cerebrovascular disease in central nervous system infections. Semin Neurol. 2011;31(3):286-306.

Hajj-Ali RA, Calabrese LH. Diagnosis and classification of central nervous system vasculitis. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:149-152.

Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(1):1-11.

Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Calamia KT, et al. Primary central nervous system vasculitis: analysis of 101 patients. Ann Neurol. 2007;62(5):442-451.

Scolding NJ. Central nervous system vasculitis. Semin Immunopathol. 2009;31(4):527-536.

HILTON HEAD, SC—Vasculitis is a general term for a group of uncommon diseases involving inflammation of blood vessels, which can lead to the occlusion or destruction of the vessels and to ischemia of the tissues supplied by those vessels. CNS vasculitis can be a primary disease or occur secondary to infections or as part of a systemic vasculitis or systemic inflammatory (eg, rheumatologic) disease. Without prompt diagnosis and treatment, patients are at high risk of permanent neurologic disability or death, according to a presentation at the 41st Annual Contemporary Clinical Neurology Symposium.

If diagnosed and treated early, CNS vasculitis has a good prognosis, but delayed intervention can result in severe morbidity or mortality, said Siddharama Pawate, MD, Associate Professor of Neurology at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville. “You have to do extensive workups sometimes before you can make a diagnosis,” he said, citing the need for neurology, rheumatology, and infectious disease input. “Investigations include serologic testing, CSF analysis, MRI, and brain biopsy.”

Rare But With a High Risk of Morbidity

The 2012 International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference on the Nomenclature of Vasculitis adopted an extensive list of names for the numerous manifestations of vasculitis. These include the following:

• Large-vessel vasculitis (eg, giant cell arteritis [GCA])

• Medium-vessel vasculitis (eg, polyarteritis nodosa)

• Small-vessel vasculitis (eg, microscopic polyangiitis and granulomatosis with polyangiitis [Wegener’s granulomatosis])

• Variable-vessel vasculitis (eg, Behçet’s disease)

• Single-organ vasculitis (eg, primary CNS vasculitis)

• Vasculitis associated with systemic disease (eg, rheumatoid vasculitis)

• Vasculitis associated with probable etiology (eg, hepatitis B virus-associated or cancer-associated vasculitis).

CNS vasculitis may be grouped into two larger categories—infectious CNS vasculitis and immune-mediated CNS vasculitis. Dr. Pawate provided a brief overview of infectious causes of vasculitis including bacteria, mycobacteria, varicella-zoster, fungi, and neurocysticercosis, but devoted the main part of his presentation to the latter of the two categories, including a focus on primary CNS vasculitis (PCNSV), which is also known as primary angiitis of the CNS (PACNS). Dr. Pawate offered an analysis of what is entailed in the recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of CNS vasculitis in general and its immune-mediated variants more specifically.

CNS vasculitis may occur as part of a broader systemic vasculitis. GCA is a medical emergency that can cause permanent visual loss if not diagnosed and treated early. Vision loss occurs most often due to anterior ischemic optic neuropathy but also central retinal artery occlusion and posterior ischemic optic neuropathy. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for GCA diagnosis include three of the five following core features: age 50 or older at onset, new-onset headaches, temporal artery abnormality, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of at least 50 mm/h, and abnormal temporal artery biopsy. High-dose steroids should be started if there is suspicion, without waiting for biopsy results. Recently, the anti-IL6 monoclonal antibody tocilizumab was approved by the FDA as a treatment for GCA. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis most often causes peripheral neuropathy, but can cause a small or medium vessel CNS vasculitis. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss syndrome) is characterized by the triad of asthma, hypereosinophilia, and necrotizing vasculitis, usually in that order. CNS involvement is common as part of the vasculitis. CNS vasculitis may also be seen in Behçet’s disease manifesting as dural sinus thrombosis and arterial occlusion or aneurysm.

In systemic lupus erythematosus, vasculitis has a prevalence ranging between 11% and 36%, but CNS involvement is much less common. Case reports of CNS vasculitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis are rare.

Primary CNS Vasculitis

Primary CNS vasculitis causes inflammation of mostly small- to medium-sized leptomeningeal and parenchymal arterial vessels. It is rare—a 2007 retrospective analysis by Salvarani et al of 101 cases estimated the average annual incidence to be 2.4 cases per one million person-years. Onset tends to occur in middle age, with a median age at diagnosis of 50 and a similar frequency in males and females.

Clinical presentation of PCNSV can be acute, subacute, chronic, or recurrent. Depending on the area of the brain or spinal cord that is affected, patients can present with a wide variety of neurologic complaints. Headache is the most common symptom—found in 50% to 78% of patients—followed by altered cognition and persistent neurologic deficits. Stroke and transient ischemic attack involving multiple vascular areas occur in 30% to 50% of patients.

The diagnostic gold standard for PCNSV is brain parenchymal/leptomeningeal biopsy. The most common diagnoses are granulomatous angiitis of the CNS (58%), lymphocytic PACNS (28%), and necrotizing vasculitis (14%). More than 90% of patients have abnormalities on MRI, and the most common imaging findings are cortical and subcortical infarcts, leptomeningeal enhancement, intracranial hemorrhage, and areas of increased signal on FLAIR and T2-weighted sequences. It has been increasingly recognized that differential diagnosis for PCNSV should include reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS), which is characterized by reversible multifocal narrowing of the cerebral arteries—typically preceded by sudden, severe thunderclap headaches with or without associated neurologic deficits. RCVS typically resolves in approximately 12 weeks.

Regarding treatment for PCNSV, Dr. Pawate recommended starting with high-dose steroids—eg, IV methylprednisolone, 1,000 mg daily for five days, with a prolonged oral prednisone taper starting at 1 mg/kg/day—and six to nine months of IV cyclophosphamide pulse therapy, 500–750 mg/m2 every two to four weeks for more severe cases. Case studies have shown rituximab and mycophenolate to be effective. “I had one patient initially on cyclophosphamide for six months who we [then] maintained on mycophenolate for five years and then stopped immunosuppression,” Dr. Pawate said. “She did quite well.”

—Fred Balzac

Suggested Reading

Abdel Razek AA, Alvarez H, Bagg S, et al. Imaging spectrum of CNS vasculitis. Radiographics. 2014;34(4):873-894.

Chow FC, Marra CM, Cho TA. Cerebrovascular disease in central nervous system infections. Semin Neurol. 2011;31(3):286-306.

Hajj-Ali RA, Calabrese LH. Diagnosis and classification of central nervous system vasculitis. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:149-152.

Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(1):1-11.

Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Calamia KT, et al. Primary central nervous system vasculitis: analysis of 101 patients. Ann Neurol. 2007;62(5):442-451.

Scolding NJ. Central nervous system vasculitis. Semin Immunopathol. 2009;31(4):527-536.

Diagnosis, Pathology, and Treatment of bvFTD Pose Challenges

Certain clinical features may indicate bvFTD, and off-label treatments may provide benefits.

HILTON HEAD, SC—Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), a clinically and pathologically heterogenous condition, can be difficult to distinguish from other forms of dementia or frontotemporal disease. “Although clinical symptoms vary based on which part of the brain is affected, there is a significant amount of overlap, with different pathologies causing the same type of syndrome,” said Richard Ryan Darby, MD, Assistant Professor of Neurology at Vanderbilt University Medical School in Nashville. “In a large proportion of patients, behavioral changes can lead to criminal behavior.” Future research examining brain lesion networks may shed light on this condition, said Dr. Darby at the 41st Annual Contemporary Clinical Neurology Symposium.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

The incidence of bvFTD is equal to that of Alzheimer’s disease. However, patients with bvFTD tend to be younger: between the ages of 45 and 65. “Social and behavioral features predominate,” said Dr. Darby. “If a patient in this age range with no previous psychiatric history presents to you with a new psychiatric diagnosis such as schizophrenia or bipolar disease, this should raise your suspicion of bvFTD.” These psychiatric problems often cause considerable disruptions in patients’ lives. They often have problems at work and lose their source of income. “Patients often have no insight about their symptoms,” said Dr. Darby.

A differential diagnosis of bvFTD is possible in patients with three or more of the following six clinical features: socially inappropriate behavior (eg, eating from the trash or walking around naked at inappropriate times); lack of empathy; apathy; stereotyped or repetitive behavior (eg, saying things repeatedly, pacing); hyperorality (eg, eating uncontrollably, particularly sweet foods); and executive dysfunction, especially when memory is preserved.

“When you talk to caregivers, they often say, ‘This is not the person I married,’ or, ‘This is not my father. He seems like a different person,’” said Dr. Darby. An MRI or a PET scan showing changes in the frontotemporal lobes is a firm basis for a diagnosis of bvFTD, said Dr. Darby. Genetic testing for autosomal dominant mutation or pathology or an autopsy provides a definite diagnosis.

Pathology

Between 40% and 50% of patients with bvFTD have tau pathology, said Dr. Darby. This pathology includes the classic Pick body form of tau, tufted astrocytes (which are associated with clinical symptoms of progressive supranuclear palsy), and astrocytic plaques (which are associated with symptoms of corticobasal degeneration). Similarly, between 40% and 50% of patients with bvFTD have a TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) pathology. TDP-43 Type A pathology is associated with perirolandic seizures, Type B is associated with

Mutations in C9orf72 occur in 13% to 50% of patients with bvFTD who have genetic mutations. ALS and parkinsonism are common clinical presentations in patients with this genetic mutation. MAPT and GRN mutations are present in 5% to 20% of cases, and each can present clinically as parkinsonism.

Treatment

SSRIs, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, and stimulants have been used to treat apathy, disinhibition, compulsive behaviors, agitation, and inappropriate behavior in patients with bvFTD. “There are no FDA-approved treatments for bvFTD, and the evidence for [these agents] has been mostly reported in case studies and small clinical trials,” said Dr. Darby. Among the SSRIs, paroxetine improved repetitive behavior in open-label trials, but not in a randomized controlled trial. Sertraline and citalopram have been studied in open-label trials, and trazodone was examined in a randomized controlled crossover trial involving 26 patients.

The FDA issued a black box warning against the use of atypical antipsychotics in patients with dementia because they entail a risk of cardiac- and infection-related mortality. “For patients with bvFTD tau pathology in particular, there is a risk of extrapyramidal adverse effects,” said Dr. Darby. A series of case reports of risperidone and aripiprazole provided evidence of symptom improvement, as did an open label study of olanzapine. Quetiapine improved agitation in a case series but failed to show benefit in a double-blind crossover trial of eight patients with FTD.

Case series have shown evidence that antiepileptic drugs (eg, valproic acid, topiramate, and carbamazepine) have a stabilizing effect. “Stimulants are tried in some patients, but should be used with caution,” said Dr. Darby.

Criminality

Between 37% and 57% of patients with bvFTD engage in criminal behavior. “Approximately 10% to 15% of the time, a patient’s getting in trouble with the law is the reason for the initial presentation,” said Dr. Darby. The types of crimes described in case reports include pedophilia, public masturbation, hit and run, traffic violations, and theft.

“Murder and violent crimes occur but are rare. Crimes committed by patients with bvFTD are usually reactive,” said Dr. Darby. “When asked, they can tell you whether a specific act is right or wrong; however, they don’t show remorse for criminal behavior.” It is not clear whether executive dysfunction and the inability to reason, social perception and the inability to empathize, or differences in moral decision making are the reasons for changes in patients’ behavior, he said.

“One idea is that a network of brain regions, not just one part of the brain, is responsible for formulating the complex concept of morality.” In 2017, Dr. Darby and colleagues systematically mapped brain lesions with a documented temporal association with criminal behavior in 17 patients who were identified through a literature search. Criminal behavior included white collar crimes, and 12 of 17 patients had committed violent crimes. Fifteen cases had no history of criminal behavior before the lesion, and the behavior resolved following treatment of the lesion in two cases.

No single brain region had been damaged in all cases. Because lesion-induced symptoms can arise from sites connected to the lesion location, the investigators identified these sites in the cases. The network of these sites included regions involved in morality, value-based decision making, and theory of mind, but not regions involved in cognitive control or empathy. Darby and colleagues replicated these results in a separate cohort of 23 cases in which a temporal relationship between brain lesions and criminal behavior was plausible, but not definite.

Prior research suggests that the areas associated with criminal behavior in patients with brain lesions closely resemble the areas typically affected in patients with bvFTD. Prospective studies are needed to further elucidate these results, Dr. Darby concluded.

—Adriene Marshall

Suggested Reading

Darby RR, Horn A, Cushman F, Fox MD. Lesion network localization of criminal behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(3):601-606.

Perry DC, Brown JA, Possin KL, et al. Clinicopathological correlations in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2017;140(12):3329-3345.

Certain clinical features may indicate bvFTD, and off-label treatments may provide benefits.

Certain clinical features may indicate bvFTD, and off-label treatments may provide benefits.

HILTON HEAD, SC—Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), a clinically and pathologically heterogenous condition, can be difficult to distinguish from other forms of dementia or frontotemporal disease. “Although clinical symptoms vary based on which part of the brain is affected, there is a significant amount of overlap, with different pathologies causing the same type of syndrome,” said Richard Ryan Darby, MD, Assistant Professor of Neurology at Vanderbilt University Medical School in Nashville. “In a large proportion of patients, behavioral changes can lead to criminal behavior.” Future research examining brain lesion networks may shed light on this condition, said Dr. Darby at the 41st Annual Contemporary Clinical Neurology Symposium.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

The incidence of bvFTD is equal to that of Alzheimer’s disease. However, patients with bvFTD tend to be younger: between the ages of 45 and 65. “Social and behavioral features predominate,” said Dr. Darby. “If a patient in this age range with no previous psychiatric history presents to you with a new psychiatric diagnosis such as schizophrenia or bipolar disease, this should raise your suspicion of bvFTD.” These psychiatric problems often cause considerable disruptions in patients’ lives. They often have problems at work and lose their source of income. “Patients often have no insight about their symptoms,” said Dr. Darby.

A differential diagnosis of bvFTD is possible in patients with three or more of the following six clinical features: socially inappropriate behavior (eg, eating from the trash or walking around naked at inappropriate times); lack of empathy; apathy; stereotyped or repetitive behavior (eg, saying things repeatedly, pacing); hyperorality (eg, eating uncontrollably, particularly sweet foods); and executive dysfunction, especially when memory is preserved.

“When you talk to caregivers, they often say, ‘This is not the person I married,’ or, ‘This is not my father. He seems like a different person,’” said Dr. Darby. An MRI or a PET scan showing changes in the frontotemporal lobes is a firm basis for a diagnosis of bvFTD, said Dr. Darby. Genetic testing for autosomal dominant mutation or pathology or an autopsy provides a definite diagnosis.

Pathology

Between 40% and 50% of patients with bvFTD have tau pathology, said Dr. Darby. This pathology includes the classic Pick body form of tau, tufted astrocytes (which are associated with clinical symptoms of progressive supranuclear palsy), and astrocytic plaques (which are associated with symptoms of corticobasal degeneration). Similarly, between 40% and 50% of patients with bvFTD have a TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) pathology. TDP-43 Type A pathology is associated with perirolandic seizures, Type B is associated with

Mutations in C9orf72 occur in 13% to 50% of patients with bvFTD who have genetic mutations. ALS and parkinsonism are common clinical presentations in patients with this genetic mutation. MAPT and GRN mutations are present in 5% to 20% of cases, and each can present clinically as parkinsonism.

Treatment

SSRIs, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, and stimulants have been used to treat apathy, disinhibition, compulsive behaviors, agitation, and inappropriate behavior in patients with bvFTD. “There are no FDA-approved treatments for bvFTD, and the evidence for [these agents] has been mostly reported in case studies and small clinical trials,” said Dr. Darby. Among the SSRIs, paroxetine improved repetitive behavior in open-label trials, but not in a randomized controlled trial. Sertraline and citalopram have been studied in open-label trials, and trazodone was examined in a randomized controlled crossover trial involving 26 patients.

The FDA issued a black box warning against the use of atypical antipsychotics in patients with dementia because they entail a risk of cardiac- and infection-related mortality. “For patients with bvFTD tau pathology in particular, there is a risk of extrapyramidal adverse effects,” said Dr. Darby. A series of case reports of risperidone and aripiprazole provided evidence of symptom improvement, as did an open label study of olanzapine. Quetiapine improved agitation in a case series but failed to show benefit in a double-blind crossover trial of eight patients with FTD.

Case series have shown evidence that antiepileptic drugs (eg, valproic acid, topiramate, and carbamazepine) have a stabilizing effect. “Stimulants are tried in some patients, but should be used with caution,” said Dr. Darby.

Criminality

Between 37% and 57% of patients with bvFTD engage in criminal behavior. “Approximately 10% to 15% of the time, a patient’s getting in trouble with the law is the reason for the initial presentation,” said Dr. Darby. The types of crimes described in case reports include pedophilia, public masturbation, hit and run, traffic violations, and theft.

“Murder and violent crimes occur but are rare. Crimes committed by patients with bvFTD are usually reactive,” said Dr. Darby. “When asked, they can tell you whether a specific act is right or wrong; however, they don’t show remorse for criminal behavior.” It is not clear whether executive dysfunction and the inability to reason, social perception and the inability to empathize, or differences in moral decision making are the reasons for changes in patients’ behavior, he said.

“One idea is that a network of brain regions, not just one part of the brain, is responsible for formulating the complex concept of morality.” In 2017, Dr. Darby and colleagues systematically mapped brain lesions with a documented temporal association with criminal behavior in 17 patients who were identified through a literature search. Criminal behavior included white collar crimes, and 12 of 17 patients had committed violent crimes. Fifteen cases had no history of criminal behavior before the lesion, and the behavior resolved following treatment of the lesion in two cases.

No single brain region had been damaged in all cases. Because lesion-induced symptoms can arise from sites connected to the lesion location, the investigators identified these sites in the cases. The network of these sites included regions involved in morality, value-based decision making, and theory of mind, but not regions involved in cognitive control or empathy. Darby and colleagues replicated these results in a separate cohort of 23 cases in which a temporal relationship between brain lesions and criminal behavior was plausible, but not definite.

Prior research suggests that the areas associated with criminal behavior in patients with brain lesions closely resemble the areas typically affected in patients with bvFTD. Prospective studies are needed to further elucidate these results, Dr. Darby concluded.

—Adriene Marshall

Suggested Reading

Darby RR, Horn A, Cushman F, Fox MD. Lesion network localization of criminal behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(3):601-606.

Perry DC, Brown JA, Possin KL, et al. Clinicopathological correlations in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2017;140(12):3329-3345.

HILTON HEAD, SC—Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), a clinically and pathologically heterogenous condition, can be difficult to distinguish from other forms of dementia or frontotemporal disease. “Although clinical symptoms vary based on which part of the brain is affected, there is a significant amount of overlap, with different pathologies causing the same type of syndrome,” said Richard Ryan Darby, MD, Assistant Professor of Neurology at Vanderbilt University Medical School in Nashville. “In a large proportion of patients, behavioral changes can lead to criminal behavior.” Future research examining brain lesion networks may shed light on this condition, said Dr. Darby at the 41st Annual Contemporary Clinical Neurology Symposium.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

The incidence of bvFTD is equal to that of Alzheimer’s disease. However, patients with bvFTD tend to be younger: between the ages of 45 and 65. “Social and behavioral features predominate,” said Dr. Darby. “If a patient in this age range with no previous psychiatric history presents to you with a new psychiatric diagnosis such as schizophrenia or bipolar disease, this should raise your suspicion of bvFTD.” These psychiatric problems often cause considerable disruptions in patients’ lives. They often have problems at work and lose their source of income. “Patients often have no insight about their symptoms,” said Dr. Darby.

A differential diagnosis of bvFTD is possible in patients with three or more of the following six clinical features: socially inappropriate behavior (eg, eating from the trash or walking around naked at inappropriate times); lack of empathy; apathy; stereotyped or repetitive behavior (eg, saying things repeatedly, pacing); hyperorality (eg, eating uncontrollably, particularly sweet foods); and executive dysfunction, especially when memory is preserved.

“When you talk to caregivers, they often say, ‘This is not the person I married,’ or, ‘This is not my father. He seems like a different person,’” said Dr. Darby. An MRI or a PET scan showing changes in the frontotemporal lobes is a firm basis for a diagnosis of bvFTD, said Dr. Darby. Genetic testing for autosomal dominant mutation or pathology or an autopsy provides a definite diagnosis.

Pathology

Between 40% and 50% of patients with bvFTD have tau pathology, said Dr. Darby. This pathology includes the classic Pick body form of tau, tufted astrocytes (which are associated with clinical symptoms of progressive supranuclear palsy), and astrocytic plaques (which are associated with symptoms of corticobasal degeneration). Similarly, between 40% and 50% of patients with bvFTD have a TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) pathology. TDP-43 Type A pathology is associated with perirolandic seizures, Type B is associated with

Mutations in C9orf72 occur in 13% to 50% of patients with bvFTD who have genetic mutations. ALS and parkinsonism are common clinical presentations in patients with this genetic mutation. MAPT and GRN mutations are present in 5% to 20% of cases, and each can present clinically as parkinsonism.

Treatment

SSRIs, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, and stimulants have been used to treat apathy, disinhibition, compulsive behaviors, agitation, and inappropriate behavior in patients with bvFTD. “There are no FDA-approved treatments for bvFTD, and the evidence for [these agents] has been mostly reported in case studies and small clinical trials,” said Dr. Darby. Among the SSRIs, paroxetine improved repetitive behavior in open-label trials, but not in a randomized controlled trial. Sertraline and citalopram have been studied in open-label trials, and trazodone was examined in a randomized controlled crossover trial involving 26 patients.

The FDA issued a black box warning against the use of atypical antipsychotics in patients with dementia because they entail a risk of cardiac- and infection-related mortality. “For patients with bvFTD tau pathology in particular, there is a risk of extrapyramidal adverse effects,” said Dr. Darby. A series of case reports of risperidone and aripiprazole provided evidence of symptom improvement, as did an open label study of olanzapine. Quetiapine improved agitation in a case series but failed to show benefit in a double-blind crossover trial of eight patients with FTD.

Case series have shown evidence that antiepileptic drugs (eg, valproic acid, topiramate, and carbamazepine) have a stabilizing effect. “Stimulants are tried in some patients, but should be used with caution,” said Dr. Darby.

Criminality

Between 37% and 57% of patients with bvFTD engage in criminal behavior. “Approximately 10% to 15% of the time, a patient’s getting in trouble with the law is the reason for the initial presentation,” said Dr. Darby. The types of crimes described in case reports include pedophilia, public masturbation, hit and run, traffic violations, and theft.

“Murder and violent crimes occur but are rare. Crimes committed by patients with bvFTD are usually reactive,” said Dr. Darby. “When asked, they can tell you whether a specific act is right or wrong; however, they don’t show remorse for criminal behavior.” It is not clear whether executive dysfunction and the inability to reason, social perception and the inability to empathize, or differences in moral decision making are the reasons for changes in patients’ behavior, he said.

“One idea is that a network of brain regions, not just one part of the brain, is responsible for formulating the complex concept of morality.” In 2017, Dr. Darby and colleagues systematically mapped brain lesions with a documented temporal association with criminal behavior in 17 patients who were identified through a literature search. Criminal behavior included white collar crimes, and 12 of 17 patients had committed violent crimes. Fifteen cases had no history of criminal behavior before the lesion, and the behavior resolved following treatment of the lesion in two cases.

No single brain region had been damaged in all cases. Because lesion-induced symptoms can arise from sites connected to the lesion location, the investigators identified these sites in the cases. The network of these sites included regions involved in morality, value-based decision making, and theory of mind, but not regions involved in cognitive control or empathy. Darby and colleagues replicated these results in a separate cohort of 23 cases in which a temporal relationship between brain lesions and criminal behavior was plausible, but not definite.

Prior research suggests that the areas associated with criminal behavior in patients with brain lesions closely resemble the areas typically affected in patients with bvFTD. Prospective studies are needed to further elucidate these results, Dr. Darby concluded.

—Adriene Marshall

Suggested Reading

Darby RR, Horn A, Cushman F, Fox MD. Lesion network localization of criminal behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(3):601-606.

Perry DC, Brown JA, Possin KL, et al. Clinicopathological correlations in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2017;140(12):3329-3345.

FDA Grants Fund Rare Disease Research

Twelve FDA grants fund new clinical trials to advance the development of medical products for the treatment of rare diseases.

On September 24, 2018, the FDA announced that it awarded 12 new clinical trial research grants totaling more than $18 million over the next four years to enhance the development of medical products for patients with rare diseases. These new grants were awarded to principal investigators from academia and industry across the country.

“Developing a treatment for a rare disease can be especially challenging. Given the often small number of patients affected by certain very rare diseases, there can be limited markets for new treatments, and as a result fewer resources devoted to researching these opportunities,” said FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD. “The FDA is committed to doing its part to facilitate continued progress toward more treatments, and even potential cures, for patients with rare diseases. New scientific advances offer more opportunities to develop these potential cures. With efficient regulation, proper incentives for product development, and the continued support of patients, providers, and researchers, we have more opportunities to pursue these advances than ever before. For 35 years, the FDA has provided much-needed financial support for clinical trials of potentially life-changing treatments for patients with rare diseases. This funding helps support early-stage development activities targeting rare diseases that do not have effective treatments. By providing seed capital, these FDA-administered grants enable researchers to prove out important concepts. The FDA grants also provide some important recognition to promising development programs that ultimately can help researchers attract additional funding.”

The FDA awarded the grants through the Orphan Products Clinical Trials Grants Program. This program is funded by Congressional appropriations and encourages clinical development of drugs, biologics, medical devices, or medical foods for use in rare diseases. The grants are intended for clinical studies evaluating the safety and effectiveness of products that could either result in, or substantially contribute to, the FDA approval of products targeted to the treatment of rare diseases. Grant applications were reviewed and evaluated for scientific and technical merit by more than 100 rare disease experts, which included representatives from academia, the NIH, and the FDA.

The grant recipients, principal investigators, and approximate funding amounts, listed alphabetically, are:

Alkeus Pharmaceuticals, Inc (Cambridge, Massachusetts), Leonide Saad, phase 2 study of ALK-001 for the treatment of Stargardt disease—$1.75 million over four years

Arizona State University–Tempe Campus (Tempe, Arizona), Keith Lindor, phase 2 study of oral vancomycin for the treatment of primary sclerosing cholangitis—$2 million over four years

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (Los Angeles), Shlomo Melmed, phase 2 study of seliciclib for the treatment of Cushing disease—$2 million over four years

Columbia University (New York), Yvonne Saenger, phase 1 study of talimogene laherparepvec for the treatment for advanced pancreatic cancer—$750,000 over three years

Emory University (Atlanta), Eric Sorscher, phase 1/ 2 study of Ad/PNP fludarabine for the treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma—$1.5 million over three years

Fibrocell Technologies, Inc (Exton, Pennsylvania), John Maslowski, phase 1/2 study of gene-modified ex-vivo autologous fibroblasts for the treatment of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa—$1.5 million over four years

Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore), Amy Dezern, phase 1/2 study of CD8-reduced T cells for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukemia—$750,000 over three years

Oncolmmune, Inc (Rockville, Maryland) Yang Liu, phase 2b study of CD24Fc for the prevention of graft versus host disease—$2 million over four years

Patagonia Pharmaceuticals, LLC (Woodcliff Lake, New Jersey), Zachary Rome, phase 2 study of PAT-001 (isotretinoin) for the treatment of congenital ichthyosis—$1.5 million over three years

The General Hospital Corporation (Boston), Stephanie Seminara, phase 2 study of kisspeptin for the treatment of dopamine agonist intolerant hyperprolactinemia—$1.4 million over four years

University of Minnesota (Minneapolis), Kyriakie Sarafoglou, phase 2a study of subcutaneous hydrocortisone infusion pump for the treatment of congenital adrenal hyperplasia—$1.4 million over three years

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Chapel Hill, North Carolina), Matthew Laughon, phase 2 study of sildenafil for the prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia—$2 million over four years.

“Since its creation in 1983, the Orphan Products Grants Program has provided more than $400 million to fund more than 600 new clinical studies,” said Debra Lewis, OD, Acting Director of the FDA’s Office of Orphan Products Development. “We are encouraged to see so much interest in our grants program and are pleased to support research for a variety of rare diseases that have little, or no, treatment options for patients.”

One-third of the new awards aim to accelerate cancer research by enrolling patients with rare forms of cancer, including advanced pancreatic cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, myelodysplastic syndrome, and acute myeloid leukemia. Another 25% of the new awards fund studies evaluating drug products for rare endocrine disorders, including Cushing disease, dopamine agonist intolerant hyperprolactinemia, and congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Another study addresses an unmet need in primary sclerosing cholangitis, a rare, chronic, and potentially serious bile duct disease.

About 42% of the grants fund studies that enroll children and adolescents, targeting a variety of rare diseases in children such as Stargardt disease, a juvenile genetic eye disorder that causes progressive vision loss; dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, a genetic condition that causes the skin to be fragile resulting in painful blisters; and bronchopulmonary dysplasia, a serious lung condition that affects infants.

To date, the program’s grants have supported research that led to the marketing approval of more than 60 orphan products. Among the recent product approvals which were supported by studies funded by this grants program are a marketing approval for a much-needed treatment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection in adults with multidrug resistant HIV-1 infection and another approval to reduce the acute complications of sickle cell disease in adult and pediatric patients.

The FDA is also currently supporting six natural history studies for rare diseases to further advance the mission of bringing new therapies to market.

Twelve FDA grants fund new clinical trials to advance the development of medical products for the treatment of rare diseases.

Twelve FDA grants fund new clinical trials to advance the development of medical products for the treatment of rare diseases.

On September 24, 2018, the FDA announced that it awarded 12 new clinical trial research grants totaling more than $18 million over the next four years to enhance the development of medical products for patients with rare diseases. These new grants were awarded to principal investigators from academia and industry across the country.

“Developing a treatment for a rare disease can be especially challenging. Given the often small number of patients affected by certain very rare diseases, there can be limited markets for new treatments, and as a result fewer resources devoted to researching these opportunities,” said FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD. “The FDA is committed to doing its part to facilitate continued progress toward more treatments, and even potential cures, for patients with rare diseases. New scientific advances offer more opportunities to develop these potential cures. With efficient regulation, proper incentives for product development, and the continued support of patients, providers, and researchers, we have more opportunities to pursue these advances than ever before. For 35 years, the FDA has provided much-needed financial support for clinical trials of potentially life-changing treatments for patients with rare diseases. This funding helps support early-stage development activities targeting rare diseases that do not have effective treatments. By providing seed capital, these FDA-administered grants enable researchers to prove out important concepts. The FDA grants also provide some important recognition to promising development programs that ultimately can help researchers attract additional funding.”

The FDA awarded the grants through the Orphan Products Clinical Trials Grants Program. This program is funded by Congressional appropriations and encourages clinical development of drugs, biologics, medical devices, or medical foods for use in rare diseases. The grants are intended for clinical studies evaluating the safety and effectiveness of products that could either result in, or substantially contribute to, the FDA approval of products targeted to the treatment of rare diseases. Grant applications were reviewed and evaluated for scientific and technical merit by more than 100 rare disease experts, which included representatives from academia, the NIH, and the FDA.

The grant recipients, principal investigators, and approximate funding amounts, listed alphabetically, are:

Alkeus Pharmaceuticals, Inc (Cambridge, Massachusetts), Leonide Saad, phase 2 study of ALK-001 for the treatment of Stargardt disease—$1.75 million over four years