User login

Mesothelioma trials: Moving toward improved survival

Although mesothelioma continues to be a very difficult disease to treat and one with a poor prognosis, new and emerging therapeutic developments hold the promise of extending survival for appropriately selected patients.

Following years of little to no movement, encouraging advances in treatment have been seen on the immunotherapy front. Immune checkpoint inhibitors have demonstrated acceptable safety and promising efficacy in the treatment of unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM), including an overall survival advantage over standard-of-care first-line chemotherapy. Beyond systemic therapy, the development of new radiation techniques to complement current, more conservative surgical approaches is likewise encouraging, though further randomized clinical trial data is awaited to determine the potential impact on survival.

Longer survival would be good news for the estimated 3,000 individuals diagnosed with MPM each year in the United States. Overall, the outlook for patients with this rare cancer remains unfavorable, with a 5-year survival rate of about 11%, according to data from the U.S. Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program.

One factor underlying that grim survival statistic is a relative lack of investment in the development of drugs specific to rare cancers, as compared to more common malignancies, said Anne S. Tsao, MD, professor and director of the mesothelioma program at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

On the plus side, the wave of research for more common cancers has yielded a number of agents, including the immune checkpoint inhibitors such as nivolumab, ipilimumab, pembrolizumab, and durvalumab, that hold promise in rare tumor types as well.

“I think that mesothelioma has benefited from that, because these all are agents that have been developed for other solid tumors that are then brought into mesothelioma,” Dr. Tsao said in an interview. “So there’s always a lag time, but nevertheless, of course we are thrilled that we have additional treatment options for these patients.”

Checkpoint inhibitors

Multiple checkpoint inhibitors have received Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) over the past few years. Because many mesothelioma doctors also treat NSCLC, bringing those agents into the mesothelioma sphere was not a very difficult jump, Dr. Tsao said.

Checkpoint inhibitors got a foothold in mesothelioma, much like in NSCLC, by demonstrating clear benefit in the salvage setting, according to Dr. Tsao.

Pembrolizumab, nivolumab, and avelumab were evaluated in phase 1b/2 clinical trials and real-world cohorts that demonstrated response rates of around 20%, median progression-free survival of 4 months, and median overall survival (OS) around 12 months in patients with previously treated MPM.

Although results of those early-stage studies had to be interpreted with caution, they nonetheless suggested a slight edge for these checkpoint inhibitors over historical data, according to the authors of a recent article in Cancer Treatment Reviews.1 On the basis of phase 1 and 2 data, current clinical practice guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network2 list pembrolizumab and the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab as options for MPM patients who have received previous therapy. Phase 3 trials have also been launched, including PROMISE-meso, which is comparing pembrolizumab to single-agent chemotherapy in advanced, pretreated MPM3, and CONFIRM, which pits nivolumab against placebo in relapsed MPM.4

On the front lines

Encouraging results in previously treated MPM led to the evaluation of checkpoint inhibitors as first-line therapy. Notably, the FDA approved nivolumab given with ipilimumab for the treatment of patients with unresectable MPM in October 2020, making that combination the first immunotherapy regimen to receive an indication in this disease.

The FDA approval was based on prespecified interim analysis of CheckMate 743, a phase 3 study that included 605 patients randomly allocated to nivolumab plus ipilimumab or to placebo.

At the interim analysis, median OS was 18.1 months for nivolumab plus ipilimumab, versus just 14.1 months for placebo (hazard ratio, 0.74; 96.6% confidence interval, 0.60-0.91; P = 0.0020), according to results of the study published in the Lancet.5 The 2-year OS rate was 41% for the immunotherapy combination and 27% for placebo. Grade 3-4 treatment-related adverse events were seen in 30% of the immunotherapy-treated patients and 32% of the chemotherapy-treated patients.

The magnitude of nivolumab-ipilimumab benefit appeared to be largest among patients with non-epithelioid MPM subtypes (sarcomatoid and biphasic), owing to the inferior impact of chemotherapy in these patients, with a median OS of just 8.8 months, according to investigators.

That’s not to say that immunotherapy didn’t work for patients with epithelioid histology. The benefit of nivolumab-ipilimumab was consistent for non-epithelioid and epithelioid patient subsets, with median OS of 18.1 and 18.7 months, respectively, results of subgroup analysis showed.

According to Dr. Tsao, those results reflect the extremely poor prognosis and pressing need for effective therapy early in the course of treatment for patients with non-epithelioid histology.

“You have to get the most effective therapy into these patients as quickly as you can,” she explained. “If you can get the more effective treatment and early, then you’ll see a longer-term benefit for them.”

Role of the PD-L1 biomarker

Despite this progress, one key hurdle has been determining the role of the PD-L1 biomarker in mesothelioma. In NSCLC, PD-L1 is often used to determine which patients will benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors. In mesothelioma, the correlations have been more elusive.

Among patients in the CheckMate 743 study treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab, OS was not significantly different for those with PD-L1 expression levels of less than 1% and those with 1% or greater, investigators said. Moreover, PD-L1 expression wasn’t a stratification factor in the study.

“When looking at all of the studies, it appears that the checkpoint inhibitors can truly benefit a certain percentage of mesothelioma patients, but we can’t pick them out just yet,” Dr. Tsao said.

“So our recommendation is to offer [checkpoint inhibitor therapy] at some point in their treatment, whether it’s first, second, or third line,” she continued. “They can get some benefit, and even in those if you don’t get a great response, you can still get disease stabilization, which in and of itself can be highly beneficial.”

Future directions

Immune checkpoint inhibitor–based combination regimens and cellular therapy represent promising directions forward in MPM research. There are several notable phase 3 trials of checkpoint inhibitors plus chemotherapy and targeted therapy going forward, plus intriguing data emerging on the potential role of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy in this setting.

One phase 3 trial to watch is IND277, which is comparing pembrolizumab plus cisplatin/pemetrexed chemotherapy to cisplatin/pemetrexed alone; that trial has enrolled 520 participants and has an estimated primary completion date in July 2022, according to the ClinicalTrials.gov website. Another is BEAT-Meso, a comparison of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and chemotherapy against bevacizumab and chemotherapy, which has an estimated enrollment of 400 participants and primary completion date of January 2024. A third trial of interest is DREAM3R, which compares durvalumab plus chemotherapy followed by durvalumab maintenance to standard chemotherapy followed by observation. That study should enroll 480 participants and has an estimated primary completion date of April 2025.

CAR T-cell therapy, while best known for its emerging role in the treatment of hematologic malignancies, may also have a place in mesothelioma therapy one day. In a recently published report, investigators described a first-in-human phase I study of a mesothelin-targeted CAR T-cell therapy given in combination with pembrolizumab. Among 18 MPM patients who received pembrolizumab safely, median OS from time of CAR T-cell infusion was 23.9 months and 1-year OS was 83%, according to investigators.6An OS of nearly 24 months is “very encouraging” and compares favorably with historical results with systemic therapy in this difficult-to-treat disease, said Jacques P. Fontaine, MD, a thoracic surgeon and section head of mesothelioma research and treatment center at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Fla.

“It’s huge, but you have to take into account that this [OS] is still less than 2 years,” Dr. Fontaine said in an interview. “There’s still a lot of work to be done.”

Radiotherapy making an IMPRINT

Meanwhile, new developments in the multimodality treatment of resectable MPM are progressing and have the potential to extend survival among patients who undergo lung-sparing surgery.

Less aggressive intervention is increasingly the preferred approach to surgery in this patient population. That shift is supported by studies showing that lung-sparing pleurectomy-decortication (P/D) resulted in less morbidity and potentially better survival outcomes than extrapleural pneumonectomy (EPP), according to Andreas Rimner, MD, associate attending physician and director of thoracic radiation oncology research at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

However, it is more challenging to deliver radiotherapy safely in patients who have undergone P/D as compared with patients who have undergone EPP, according to Dr. Rimner.

“When there’s no lung in place [as in EPP], it’s pretty simple – you just treat the entire empty chest to kill any microscopic cells that may still be left behind,” he said in an interview. “But now we have a situation where both lungs are still in place, and they are very radiation sensitive, so that’s not an easy feat.”

Driven by the limitations of conventional radiation, Dr. Rimner and colleagues developed a novel technique known as hemithoracic intensity-modulated pleural radiation therapy (IMPRINT) that allows more precise application of radiotherapy.

In a phase 2 study published in 2016, IMPRINT was found to be safe, with an acceptable rate of radiation pneumonitis (30% grade 2 or 3), according to investigators.7

Subsequent studies have demonstrated encouraging clinical outcomes, including a 20.2-month median OS for IMPRINT versus 12.3 months for conventional adjuvant radiotherapy in a retrospective study of 209 patients who underwent P/D between 1975 and 2015.8 Those findings led to the development of a phase 3 trial known as NRG-LU006 that is evaluating P/D plus chemotherapy with or without adjuvant IMPRINT in an estimated 150 patients. The study has a primary endpoint of OS, and an estimated primary completion date in July 2025, according to ClinicalTrials.gov.

Dr. Rimner said he’s optimistic about the prospects of this study, particularly with recently published results of a phase 3 study in which Italian investigators demonstrated an OS benefit of IMPRINT over palliative radiation in patients with nonmetastatic MPM.9

“That’s more data and rationale that shows there is good reason to believe that we are adding something here with this radiation technique,” said Dr. Rimner.

Dr. Fontaine, the thoracic surgeon and mesothelioma research head at Moffitt Cancer Center, said he’s hoping to see a substantial impact of IMPRINT on disease-free survival (DFS) once results of NRG-LU006 are available.

“I think DFS plays a role that we’ve underestimated over the last few years for sure,” he said.

For a patient with MPM, a short DFS can be anxiety provoking and may have negative impacts on quality of life, even despite a long OS, he explained.

“In terms of your outlook on life, how many times you have to go see a doctor, and how you enjoy life, there’s a big difference between the two,” he said.

Dr. Tsao provided disclosures related to Ariad, AstraZeneca, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono, Epizyme, Genentech, Huron, Merck, Millennium, Novartis, Polaris, Roche, Seattle Genetics, SELLAS Life Sciences Group, and Takeda. Dr. Fontaine reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Rimner reported disclosures related to Bristol-Myers Squibb, GE Healthcare, Varian Medical Systems, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

References

1. Parikh K et al. Cancer Treat Rev. 2021 Sept 1;99:102250.

2. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines. Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Version 2.2021, published 2021 Feb 16. Accessed 2021 Aug 30. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/mpm.pdf

3. Popat S et al. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(12):1734-45.

4. Fennell D et al. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2021 Mar 1;16(3):S62.

5. Baas P et al. [published correction appears in Lancet. 2021 Feb 20;397(10275):670]. Lancet. 2021 Jan 30;397(10272):375-86.

6. Adusumilli PS et al. Cancer Discov. 2021 Jul 15;candisc.0407.2021.

7. Rimner A et al. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(23):2761-8.

8. Shaikh F et al. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(6):993-1000.

9. Trovo M et al. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021;109(5):1368-76.

Although mesothelioma continues to be a very difficult disease to treat and one with a poor prognosis, new and emerging therapeutic developments hold the promise of extending survival for appropriately selected patients.

Following years of little to no movement, encouraging advances in treatment have been seen on the immunotherapy front. Immune checkpoint inhibitors have demonstrated acceptable safety and promising efficacy in the treatment of unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM), including an overall survival advantage over standard-of-care first-line chemotherapy. Beyond systemic therapy, the development of new radiation techniques to complement current, more conservative surgical approaches is likewise encouraging, though further randomized clinical trial data is awaited to determine the potential impact on survival.

Longer survival would be good news for the estimated 3,000 individuals diagnosed with MPM each year in the United States. Overall, the outlook for patients with this rare cancer remains unfavorable, with a 5-year survival rate of about 11%, according to data from the U.S. Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program.

One factor underlying that grim survival statistic is a relative lack of investment in the development of drugs specific to rare cancers, as compared to more common malignancies, said Anne S. Tsao, MD, professor and director of the mesothelioma program at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

On the plus side, the wave of research for more common cancers has yielded a number of agents, including the immune checkpoint inhibitors such as nivolumab, ipilimumab, pembrolizumab, and durvalumab, that hold promise in rare tumor types as well.

“I think that mesothelioma has benefited from that, because these all are agents that have been developed for other solid tumors that are then brought into mesothelioma,” Dr. Tsao said in an interview. “So there’s always a lag time, but nevertheless, of course we are thrilled that we have additional treatment options for these patients.”

Checkpoint inhibitors

Multiple checkpoint inhibitors have received Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) over the past few years. Because many mesothelioma doctors also treat NSCLC, bringing those agents into the mesothelioma sphere was not a very difficult jump, Dr. Tsao said.

Checkpoint inhibitors got a foothold in mesothelioma, much like in NSCLC, by demonstrating clear benefit in the salvage setting, according to Dr. Tsao.

Pembrolizumab, nivolumab, and avelumab were evaluated in phase 1b/2 clinical trials and real-world cohorts that demonstrated response rates of around 20%, median progression-free survival of 4 months, and median overall survival (OS) around 12 months in patients with previously treated MPM.

Although results of those early-stage studies had to be interpreted with caution, they nonetheless suggested a slight edge for these checkpoint inhibitors over historical data, according to the authors of a recent article in Cancer Treatment Reviews.1 On the basis of phase 1 and 2 data, current clinical practice guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network2 list pembrolizumab and the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab as options for MPM patients who have received previous therapy. Phase 3 trials have also been launched, including PROMISE-meso, which is comparing pembrolizumab to single-agent chemotherapy in advanced, pretreated MPM3, and CONFIRM, which pits nivolumab against placebo in relapsed MPM.4

On the front lines

Encouraging results in previously treated MPM led to the evaluation of checkpoint inhibitors as first-line therapy. Notably, the FDA approved nivolumab given with ipilimumab for the treatment of patients with unresectable MPM in October 2020, making that combination the first immunotherapy regimen to receive an indication in this disease.

The FDA approval was based on prespecified interim analysis of CheckMate 743, a phase 3 study that included 605 patients randomly allocated to nivolumab plus ipilimumab or to placebo.

At the interim analysis, median OS was 18.1 months for nivolumab plus ipilimumab, versus just 14.1 months for placebo (hazard ratio, 0.74; 96.6% confidence interval, 0.60-0.91; P = 0.0020), according to results of the study published in the Lancet.5 The 2-year OS rate was 41% for the immunotherapy combination and 27% for placebo. Grade 3-4 treatment-related adverse events were seen in 30% of the immunotherapy-treated patients and 32% of the chemotherapy-treated patients.

The magnitude of nivolumab-ipilimumab benefit appeared to be largest among patients with non-epithelioid MPM subtypes (sarcomatoid and biphasic), owing to the inferior impact of chemotherapy in these patients, with a median OS of just 8.8 months, according to investigators.

That’s not to say that immunotherapy didn’t work for patients with epithelioid histology. The benefit of nivolumab-ipilimumab was consistent for non-epithelioid and epithelioid patient subsets, with median OS of 18.1 and 18.7 months, respectively, results of subgroup analysis showed.

According to Dr. Tsao, those results reflect the extremely poor prognosis and pressing need for effective therapy early in the course of treatment for patients with non-epithelioid histology.

“You have to get the most effective therapy into these patients as quickly as you can,” she explained. “If you can get the more effective treatment and early, then you’ll see a longer-term benefit for them.”

Role of the PD-L1 biomarker

Despite this progress, one key hurdle has been determining the role of the PD-L1 biomarker in mesothelioma. In NSCLC, PD-L1 is often used to determine which patients will benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors. In mesothelioma, the correlations have been more elusive.

Among patients in the CheckMate 743 study treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab, OS was not significantly different for those with PD-L1 expression levels of less than 1% and those with 1% or greater, investigators said. Moreover, PD-L1 expression wasn’t a stratification factor in the study.

“When looking at all of the studies, it appears that the checkpoint inhibitors can truly benefit a certain percentage of mesothelioma patients, but we can’t pick them out just yet,” Dr. Tsao said.

“So our recommendation is to offer [checkpoint inhibitor therapy] at some point in their treatment, whether it’s first, second, or third line,” she continued. “They can get some benefit, and even in those if you don’t get a great response, you can still get disease stabilization, which in and of itself can be highly beneficial.”

Future directions

Immune checkpoint inhibitor–based combination regimens and cellular therapy represent promising directions forward in MPM research. There are several notable phase 3 trials of checkpoint inhibitors plus chemotherapy and targeted therapy going forward, plus intriguing data emerging on the potential role of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy in this setting.

One phase 3 trial to watch is IND277, which is comparing pembrolizumab plus cisplatin/pemetrexed chemotherapy to cisplatin/pemetrexed alone; that trial has enrolled 520 participants and has an estimated primary completion date in July 2022, according to the ClinicalTrials.gov website. Another is BEAT-Meso, a comparison of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and chemotherapy against bevacizumab and chemotherapy, which has an estimated enrollment of 400 participants and primary completion date of January 2024. A third trial of interest is DREAM3R, which compares durvalumab plus chemotherapy followed by durvalumab maintenance to standard chemotherapy followed by observation. That study should enroll 480 participants and has an estimated primary completion date of April 2025.

CAR T-cell therapy, while best known for its emerging role in the treatment of hematologic malignancies, may also have a place in mesothelioma therapy one day. In a recently published report, investigators described a first-in-human phase I study of a mesothelin-targeted CAR T-cell therapy given in combination with pembrolizumab. Among 18 MPM patients who received pembrolizumab safely, median OS from time of CAR T-cell infusion was 23.9 months and 1-year OS was 83%, according to investigators.6An OS of nearly 24 months is “very encouraging” and compares favorably with historical results with systemic therapy in this difficult-to-treat disease, said Jacques P. Fontaine, MD, a thoracic surgeon and section head of mesothelioma research and treatment center at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Fla.

“It’s huge, but you have to take into account that this [OS] is still less than 2 years,” Dr. Fontaine said in an interview. “There’s still a lot of work to be done.”

Radiotherapy making an IMPRINT

Meanwhile, new developments in the multimodality treatment of resectable MPM are progressing and have the potential to extend survival among patients who undergo lung-sparing surgery.

Less aggressive intervention is increasingly the preferred approach to surgery in this patient population. That shift is supported by studies showing that lung-sparing pleurectomy-decortication (P/D) resulted in less morbidity and potentially better survival outcomes than extrapleural pneumonectomy (EPP), according to Andreas Rimner, MD, associate attending physician and director of thoracic radiation oncology research at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

However, it is more challenging to deliver radiotherapy safely in patients who have undergone P/D as compared with patients who have undergone EPP, according to Dr. Rimner.

“When there’s no lung in place [as in EPP], it’s pretty simple – you just treat the entire empty chest to kill any microscopic cells that may still be left behind,” he said in an interview. “But now we have a situation where both lungs are still in place, and they are very radiation sensitive, so that’s not an easy feat.”

Driven by the limitations of conventional radiation, Dr. Rimner and colleagues developed a novel technique known as hemithoracic intensity-modulated pleural radiation therapy (IMPRINT) that allows more precise application of radiotherapy.

In a phase 2 study published in 2016, IMPRINT was found to be safe, with an acceptable rate of radiation pneumonitis (30% grade 2 or 3), according to investigators.7

Subsequent studies have demonstrated encouraging clinical outcomes, including a 20.2-month median OS for IMPRINT versus 12.3 months for conventional adjuvant radiotherapy in a retrospective study of 209 patients who underwent P/D between 1975 and 2015.8 Those findings led to the development of a phase 3 trial known as NRG-LU006 that is evaluating P/D plus chemotherapy with or without adjuvant IMPRINT in an estimated 150 patients. The study has a primary endpoint of OS, and an estimated primary completion date in July 2025, according to ClinicalTrials.gov.

Dr. Rimner said he’s optimistic about the prospects of this study, particularly with recently published results of a phase 3 study in which Italian investigators demonstrated an OS benefit of IMPRINT over palliative radiation in patients with nonmetastatic MPM.9

“That’s more data and rationale that shows there is good reason to believe that we are adding something here with this radiation technique,” said Dr. Rimner.

Dr. Fontaine, the thoracic surgeon and mesothelioma research head at Moffitt Cancer Center, said he’s hoping to see a substantial impact of IMPRINT on disease-free survival (DFS) once results of NRG-LU006 are available.

“I think DFS plays a role that we’ve underestimated over the last few years for sure,” he said.

For a patient with MPM, a short DFS can be anxiety provoking and may have negative impacts on quality of life, even despite a long OS, he explained.

“In terms of your outlook on life, how many times you have to go see a doctor, and how you enjoy life, there’s a big difference between the two,” he said.

Dr. Tsao provided disclosures related to Ariad, AstraZeneca, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono, Epizyme, Genentech, Huron, Merck, Millennium, Novartis, Polaris, Roche, Seattle Genetics, SELLAS Life Sciences Group, and Takeda. Dr. Fontaine reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Rimner reported disclosures related to Bristol-Myers Squibb, GE Healthcare, Varian Medical Systems, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

References

1. Parikh K et al. Cancer Treat Rev. 2021 Sept 1;99:102250.

2. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines. Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Version 2.2021, published 2021 Feb 16. Accessed 2021 Aug 30. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/mpm.pdf

3. Popat S et al. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(12):1734-45.

4. Fennell D et al. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2021 Mar 1;16(3):S62.

5. Baas P et al. [published correction appears in Lancet. 2021 Feb 20;397(10275):670]. Lancet. 2021 Jan 30;397(10272):375-86.

6. Adusumilli PS et al. Cancer Discov. 2021 Jul 15;candisc.0407.2021.

7. Rimner A et al. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(23):2761-8.

8. Shaikh F et al. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(6):993-1000.

9. Trovo M et al. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021;109(5):1368-76.

Although mesothelioma continues to be a very difficult disease to treat and one with a poor prognosis, new and emerging therapeutic developments hold the promise of extending survival for appropriately selected patients.

Following years of little to no movement, encouraging advances in treatment have been seen on the immunotherapy front. Immune checkpoint inhibitors have demonstrated acceptable safety and promising efficacy in the treatment of unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM), including an overall survival advantage over standard-of-care first-line chemotherapy. Beyond systemic therapy, the development of new radiation techniques to complement current, more conservative surgical approaches is likewise encouraging, though further randomized clinical trial data is awaited to determine the potential impact on survival.

Longer survival would be good news for the estimated 3,000 individuals diagnosed with MPM each year in the United States. Overall, the outlook for patients with this rare cancer remains unfavorable, with a 5-year survival rate of about 11%, according to data from the U.S. Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program.

One factor underlying that grim survival statistic is a relative lack of investment in the development of drugs specific to rare cancers, as compared to more common malignancies, said Anne S. Tsao, MD, professor and director of the mesothelioma program at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

On the plus side, the wave of research for more common cancers has yielded a number of agents, including the immune checkpoint inhibitors such as nivolumab, ipilimumab, pembrolizumab, and durvalumab, that hold promise in rare tumor types as well.

“I think that mesothelioma has benefited from that, because these all are agents that have been developed for other solid tumors that are then brought into mesothelioma,” Dr. Tsao said in an interview. “So there’s always a lag time, but nevertheless, of course we are thrilled that we have additional treatment options for these patients.”

Checkpoint inhibitors

Multiple checkpoint inhibitors have received Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) over the past few years. Because many mesothelioma doctors also treat NSCLC, bringing those agents into the mesothelioma sphere was not a very difficult jump, Dr. Tsao said.

Checkpoint inhibitors got a foothold in mesothelioma, much like in NSCLC, by demonstrating clear benefit in the salvage setting, according to Dr. Tsao.

Pembrolizumab, nivolumab, and avelumab were evaluated in phase 1b/2 clinical trials and real-world cohorts that demonstrated response rates of around 20%, median progression-free survival of 4 months, and median overall survival (OS) around 12 months in patients with previously treated MPM.

Although results of those early-stage studies had to be interpreted with caution, they nonetheless suggested a slight edge for these checkpoint inhibitors over historical data, according to the authors of a recent article in Cancer Treatment Reviews.1 On the basis of phase 1 and 2 data, current clinical practice guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network2 list pembrolizumab and the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab as options for MPM patients who have received previous therapy. Phase 3 trials have also been launched, including PROMISE-meso, which is comparing pembrolizumab to single-agent chemotherapy in advanced, pretreated MPM3, and CONFIRM, which pits nivolumab against placebo in relapsed MPM.4

On the front lines

Encouraging results in previously treated MPM led to the evaluation of checkpoint inhibitors as first-line therapy. Notably, the FDA approved nivolumab given with ipilimumab for the treatment of patients with unresectable MPM in October 2020, making that combination the first immunotherapy regimen to receive an indication in this disease.

The FDA approval was based on prespecified interim analysis of CheckMate 743, a phase 3 study that included 605 patients randomly allocated to nivolumab plus ipilimumab or to placebo.

At the interim analysis, median OS was 18.1 months for nivolumab plus ipilimumab, versus just 14.1 months for placebo (hazard ratio, 0.74; 96.6% confidence interval, 0.60-0.91; P = 0.0020), according to results of the study published in the Lancet.5 The 2-year OS rate was 41% for the immunotherapy combination and 27% for placebo. Grade 3-4 treatment-related adverse events were seen in 30% of the immunotherapy-treated patients and 32% of the chemotherapy-treated patients.

The magnitude of nivolumab-ipilimumab benefit appeared to be largest among patients with non-epithelioid MPM subtypes (sarcomatoid and biphasic), owing to the inferior impact of chemotherapy in these patients, with a median OS of just 8.8 months, according to investigators.

That’s not to say that immunotherapy didn’t work for patients with epithelioid histology. The benefit of nivolumab-ipilimumab was consistent for non-epithelioid and epithelioid patient subsets, with median OS of 18.1 and 18.7 months, respectively, results of subgroup analysis showed.

According to Dr. Tsao, those results reflect the extremely poor prognosis and pressing need for effective therapy early in the course of treatment for patients with non-epithelioid histology.

“You have to get the most effective therapy into these patients as quickly as you can,” she explained. “If you can get the more effective treatment and early, then you’ll see a longer-term benefit for them.”

Role of the PD-L1 biomarker

Despite this progress, one key hurdle has been determining the role of the PD-L1 biomarker in mesothelioma. In NSCLC, PD-L1 is often used to determine which patients will benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors. In mesothelioma, the correlations have been more elusive.

Among patients in the CheckMate 743 study treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab, OS was not significantly different for those with PD-L1 expression levels of less than 1% and those with 1% or greater, investigators said. Moreover, PD-L1 expression wasn’t a stratification factor in the study.

“When looking at all of the studies, it appears that the checkpoint inhibitors can truly benefit a certain percentage of mesothelioma patients, but we can’t pick them out just yet,” Dr. Tsao said.

“So our recommendation is to offer [checkpoint inhibitor therapy] at some point in their treatment, whether it’s first, second, or third line,” she continued. “They can get some benefit, and even in those if you don’t get a great response, you can still get disease stabilization, which in and of itself can be highly beneficial.”

Future directions

Immune checkpoint inhibitor–based combination regimens and cellular therapy represent promising directions forward in MPM research. There are several notable phase 3 trials of checkpoint inhibitors plus chemotherapy and targeted therapy going forward, plus intriguing data emerging on the potential role of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy in this setting.

One phase 3 trial to watch is IND277, which is comparing pembrolizumab plus cisplatin/pemetrexed chemotherapy to cisplatin/pemetrexed alone; that trial has enrolled 520 participants and has an estimated primary completion date in July 2022, according to the ClinicalTrials.gov website. Another is BEAT-Meso, a comparison of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and chemotherapy against bevacizumab and chemotherapy, which has an estimated enrollment of 400 participants and primary completion date of January 2024. A third trial of interest is DREAM3R, which compares durvalumab plus chemotherapy followed by durvalumab maintenance to standard chemotherapy followed by observation. That study should enroll 480 participants and has an estimated primary completion date of April 2025.

CAR T-cell therapy, while best known for its emerging role in the treatment of hematologic malignancies, may also have a place in mesothelioma therapy one day. In a recently published report, investigators described a first-in-human phase I study of a mesothelin-targeted CAR T-cell therapy given in combination with pembrolizumab. Among 18 MPM patients who received pembrolizumab safely, median OS from time of CAR T-cell infusion was 23.9 months and 1-year OS was 83%, according to investigators.6An OS of nearly 24 months is “very encouraging” and compares favorably with historical results with systemic therapy in this difficult-to-treat disease, said Jacques P. Fontaine, MD, a thoracic surgeon and section head of mesothelioma research and treatment center at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Fla.

“It’s huge, but you have to take into account that this [OS] is still less than 2 years,” Dr. Fontaine said in an interview. “There’s still a lot of work to be done.”

Radiotherapy making an IMPRINT

Meanwhile, new developments in the multimodality treatment of resectable MPM are progressing and have the potential to extend survival among patients who undergo lung-sparing surgery.

Less aggressive intervention is increasingly the preferred approach to surgery in this patient population. That shift is supported by studies showing that lung-sparing pleurectomy-decortication (P/D) resulted in less morbidity and potentially better survival outcomes than extrapleural pneumonectomy (EPP), according to Andreas Rimner, MD, associate attending physician and director of thoracic radiation oncology research at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

However, it is more challenging to deliver radiotherapy safely in patients who have undergone P/D as compared with patients who have undergone EPP, according to Dr. Rimner.

“When there’s no lung in place [as in EPP], it’s pretty simple – you just treat the entire empty chest to kill any microscopic cells that may still be left behind,” he said in an interview. “But now we have a situation where both lungs are still in place, and they are very radiation sensitive, so that’s not an easy feat.”

Driven by the limitations of conventional radiation, Dr. Rimner and colleagues developed a novel technique known as hemithoracic intensity-modulated pleural radiation therapy (IMPRINT) that allows more precise application of radiotherapy.

In a phase 2 study published in 2016, IMPRINT was found to be safe, with an acceptable rate of radiation pneumonitis (30% grade 2 or 3), according to investigators.7

Subsequent studies have demonstrated encouraging clinical outcomes, including a 20.2-month median OS for IMPRINT versus 12.3 months for conventional adjuvant radiotherapy in a retrospective study of 209 patients who underwent P/D between 1975 and 2015.8 Those findings led to the development of a phase 3 trial known as NRG-LU006 that is evaluating P/D plus chemotherapy with or without adjuvant IMPRINT in an estimated 150 patients. The study has a primary endpoint of OS, and an estimated primary completion date in July 2025, according to ClinicalTrials.gov.

Dr. Rimner said he’s optimistic about the prospects of this study, particularly with recently published results of a phase 3 study in which Italian investigators demonstrated an OS benefit of IMPRINT over palliative radiation in patients with nonmetastatic MPM.9

“That’s more data and rationale that shows there is good reason to believe that we are adding something here with this radiation technique,” said Dr. Rimner.

Dr. Fontaine, the thoracic surgeon and mesothelioma research head at Moffitt Cancer Center, said he’s hoping to see a substantial impact of IMPRINT on disease-free survival (DFS) once results of NRG-LU006 are available.

“I think DFS plays a role that we’ve underestimated over the last few years for sure,” he said.

For a patient with MPM, a short DFS can be anxiety provoking and may have negative impacts on quality of life, even despite a long OS, he explained.

“In terms of your outlook on life, how many times you have to go see a doctor, and how you enjoy life, there’s a big difference between the two,” he said.

Dr. Tsao provided disclosures related to Ariad, AstraZeneca, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono, Epizyme, Genentech, Huron, Merck, Millennium, Novartis, Polaris, Roche, Seattle Genetics, SELLAS Life Sciences Group, and Takeda. Dr. Fontaine reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Rimner reported disclosures related to Bristol-Myers Squibb, GE Healthcare, Varian Medical Systems, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

References

1. Parikh K et al. Cancer Treat Rev. 2021 Sept 1;99:102250.

2. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines. Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Version 2.2021, published 2021 Feb 16. Accessed 2021 Aug 30. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/mpm.pdf

3. Popat S et al. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(12):1734-45.

4. Fennell D et al. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2021 Mar 1;16(3):S62.

5. Baas P et al. [published correction appears in Lancet. 2021 Feb 20;397(10275):670]. Lancet. 2021 Jan 30;397(10272):375-86.

6. Adusumilli PS et al. Cancer Discov. 2021 Jul 15;candisc.0407.2021.

7. Rimner A et al. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(23):2761-8.

8. Shaikh F et al. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(6):993-1000.

9. Trovo M et al. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021;109(5):1368-76.

A Fatal Case of Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis Secondary to Anti-MDA5–Positive Dermatomyositis

To the Editor:

Dermatomyositis (DM) is an idiopathic inflammatory myopathy characterized by bilateral, symmetrical, proximal muscle weakness and classic cutaneous manifestations.1 Patients with antibodies directed against melanoma differentiation–associated gene 5, MDA5, have a distinct presentation due to vasculopathy with more severe cutaneous ulcerations, palmar papules, alopecia, and an elevated risk of rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease.2 A ferritin level greater than 1600 ng/mL portends an increased risk for pulmonary disease and therefore can be of prognostic value.3 Further, patients with anti-MDA5 DM are at a lower risk of malignancy and are more likely to test negative for antinuclear antibodies in comparison to other patients with DM.2,4

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), also known as hemophagocytic syndrome, is a potentially lethal condition whereby uncontrolled activation of histiocytes in the reticuloendothelial system causes hemophagocytosis and a hyperinflammatory state. Patients present with fever, splenomegaly, cytopenia, and hyperferritinemia.5 Autoimmune‐associated hemophagocytic syndrome (AAHS) describes HLH that develops in association with autoimmune conditions, most commonly systemic lupus erythematosus and adult-onset Still disease. Cases reported in association with DM exist but are few in number, and there is no standard-of-care treatment.6 We report a case of a woman with anti-MDA5 DM complicated by HLH and DM-associated liver injury.

A 50-year-old woman presented as a direct admit from the rheumatology clinic for diffuse muscle weakness of 8 months’ duration, 40-pound unintentional weight loss, pruritic rash, bilateral joint pains, dry eyes, dry mouth, and altered mental status. Four months prior, she presented to an outside hospital and was given a diagnosis of probable Sjögren syndrome and autoimmune hepatitis vs drug-induced liver injury. At that time, a workup was notable for antibodies against Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A, anti–smooth muscle antibodies, and transaminitis. Ultrasonography of the right upper quadrant revealed hepatic steatosis. The patient was started on oral prednisone and pilocarpine but had been off all medications for 1 month when she presented to our hospital.

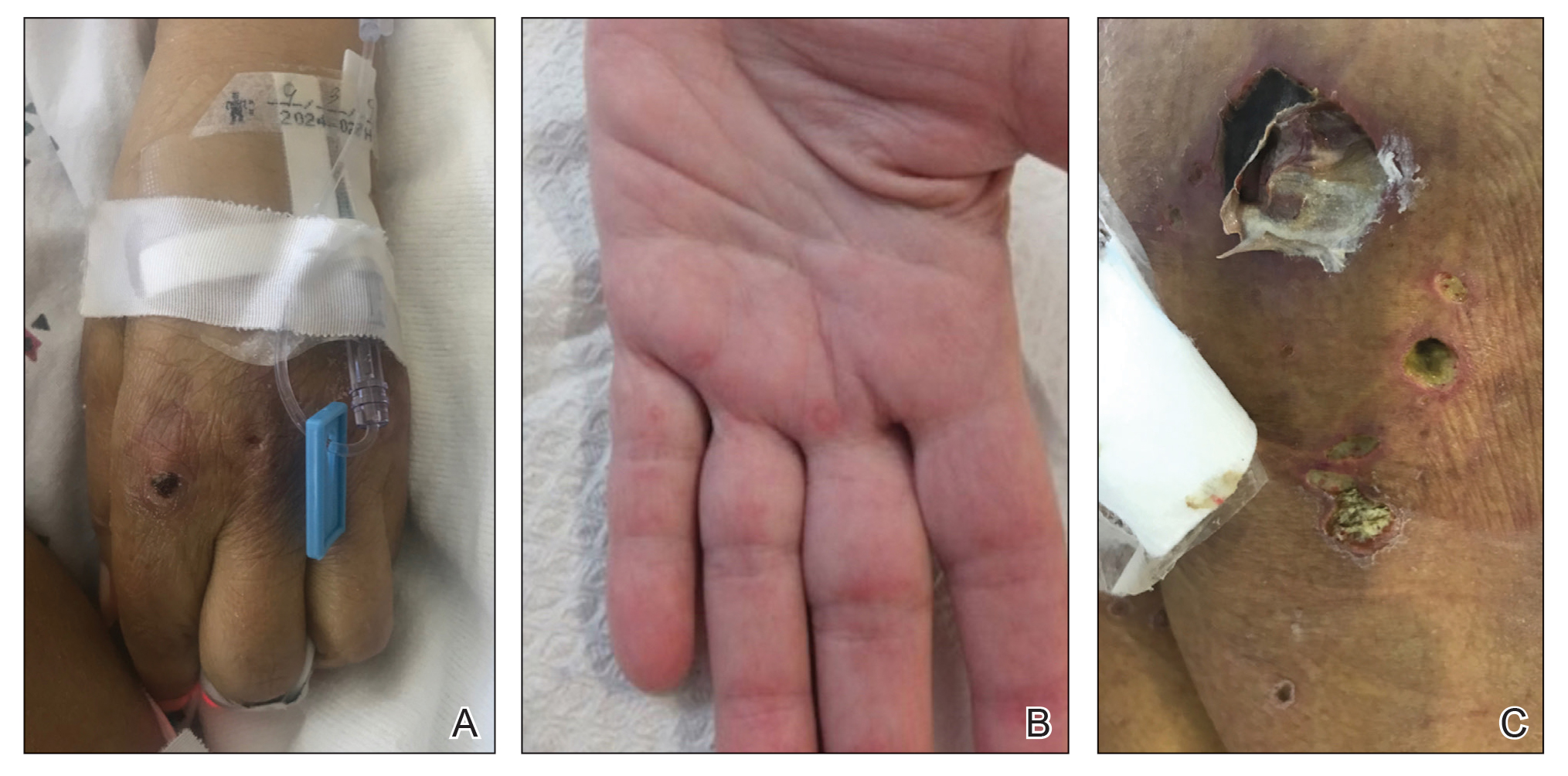

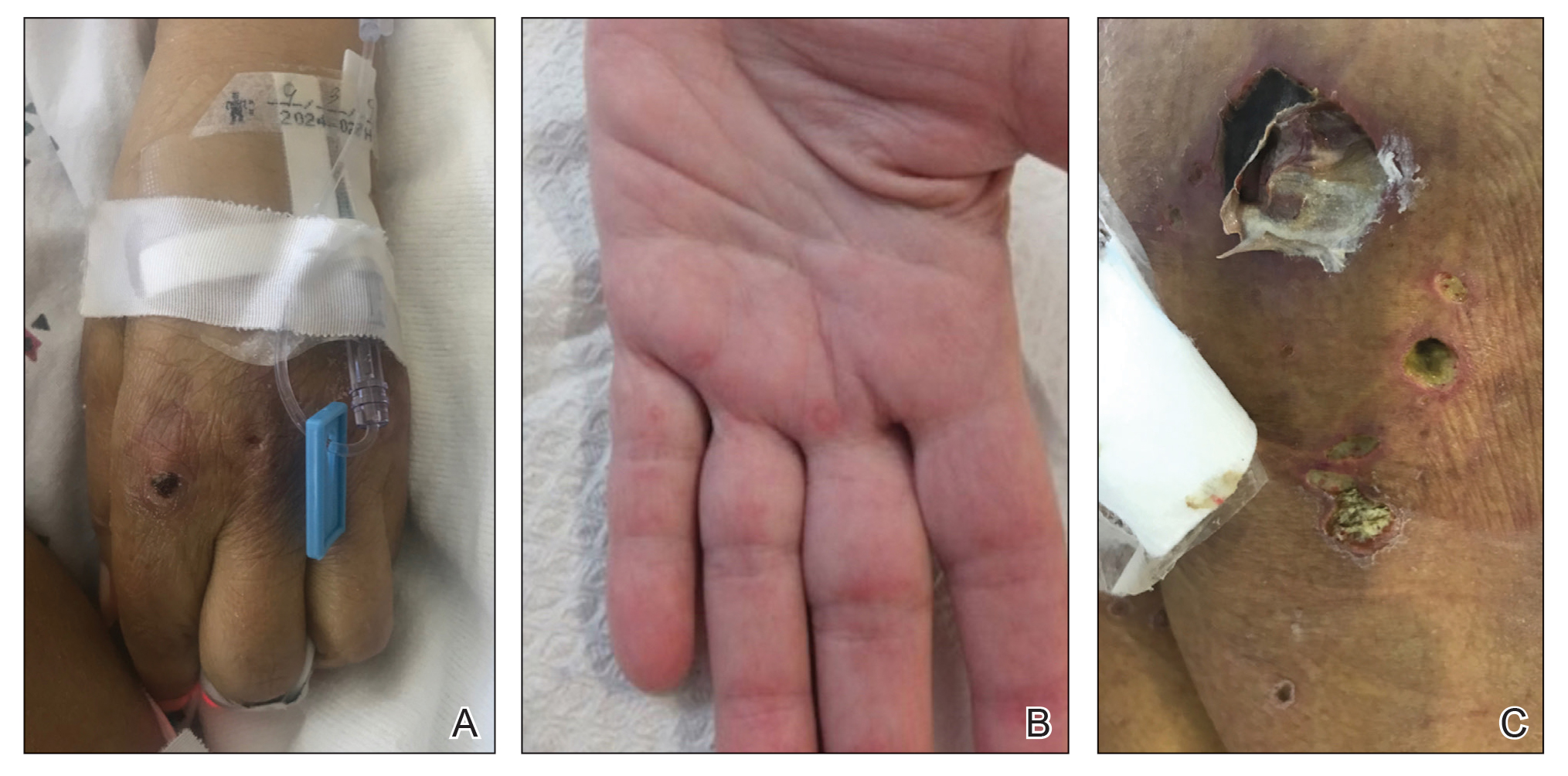

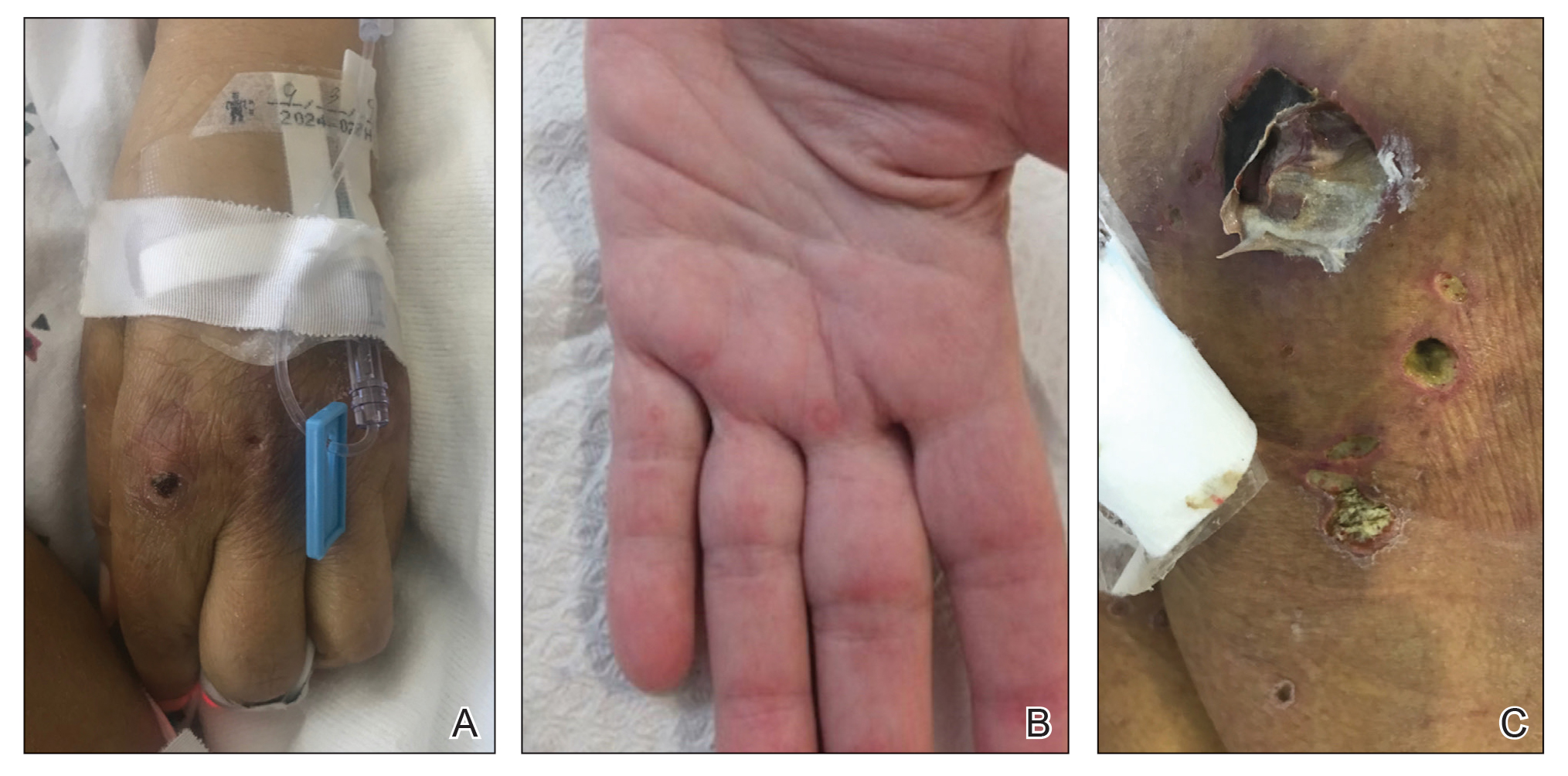

On hospital admission, physical examination revealed a violaceous heliotrope rash; a v-sign on the chest; shawl sign; palmar papules with pits at the fingertips; and periungual erythema and ulcerations along the metacarpophalangeal joints, elbows, lateral feet, and upper eyelids (Figure 1). Laboratory workup showed the following results: white blood cell count, 4100/μL (reference range, 4000–11,000/μL); hemoglobin, 11.6 g/dL (reference range, 12–16 g/dL); platelet count, 100,000/μL (reference range, 150,000–450,000/μL); lactate dehydrogenase, 510 U/L (reference range, 80–225 U/L); alkaline phosphatase (ALP), 766 U/L (reference range, 30–120 U/L); alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 88 U/L (reference range, 10–40 U/L); aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 544 U/L (reference range, 10–40 U/L); total bilirubin, 4.2 mg/dL (reference range, 0.3–1.0 mg/dL); direct bilirubin, 3.7 mg/dL (reference range, 0.1–0.3 mg/dL); aldolase, 20.2 U/L (reference range, 1–7.5 U/L), creatine kinase, 180 U/L (reference range, 30–135 U/L); γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT), 2743 U/L (reference range, 8–40 U/L); high sensitivity C-reactive protein, 122.9 mg/L (low-risk reference range, <1.0 mg/L); triglycerides, 534 mg/dL (reference range, <150 mg/dL); ferritin, 3784 ng/mL (reference range, 24–307 ng/mL); antinuclear antibody, negative titer; antimitochondrial antibody, negative titer; soluble IL-2 receptor (CD25), 7000 U/mL (reference range, 189–846 U/mL); anti-Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A antibody, positive.

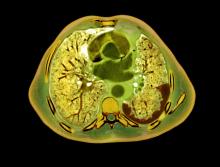

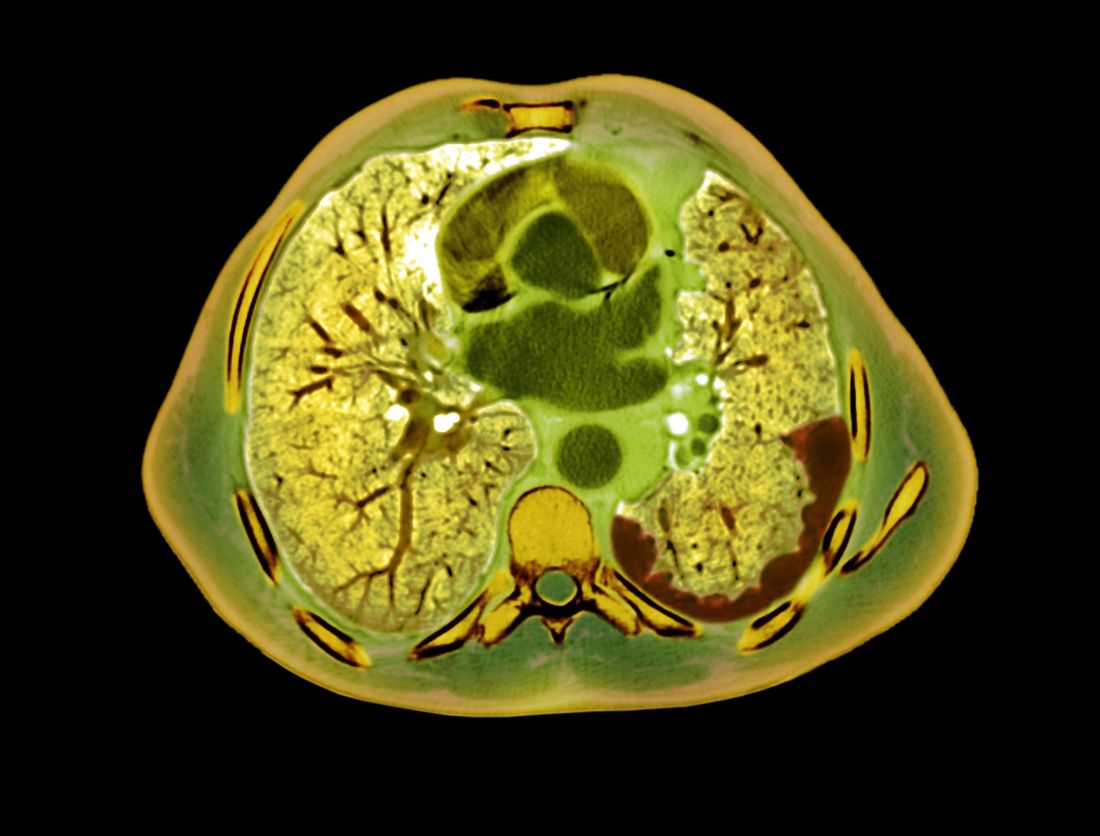

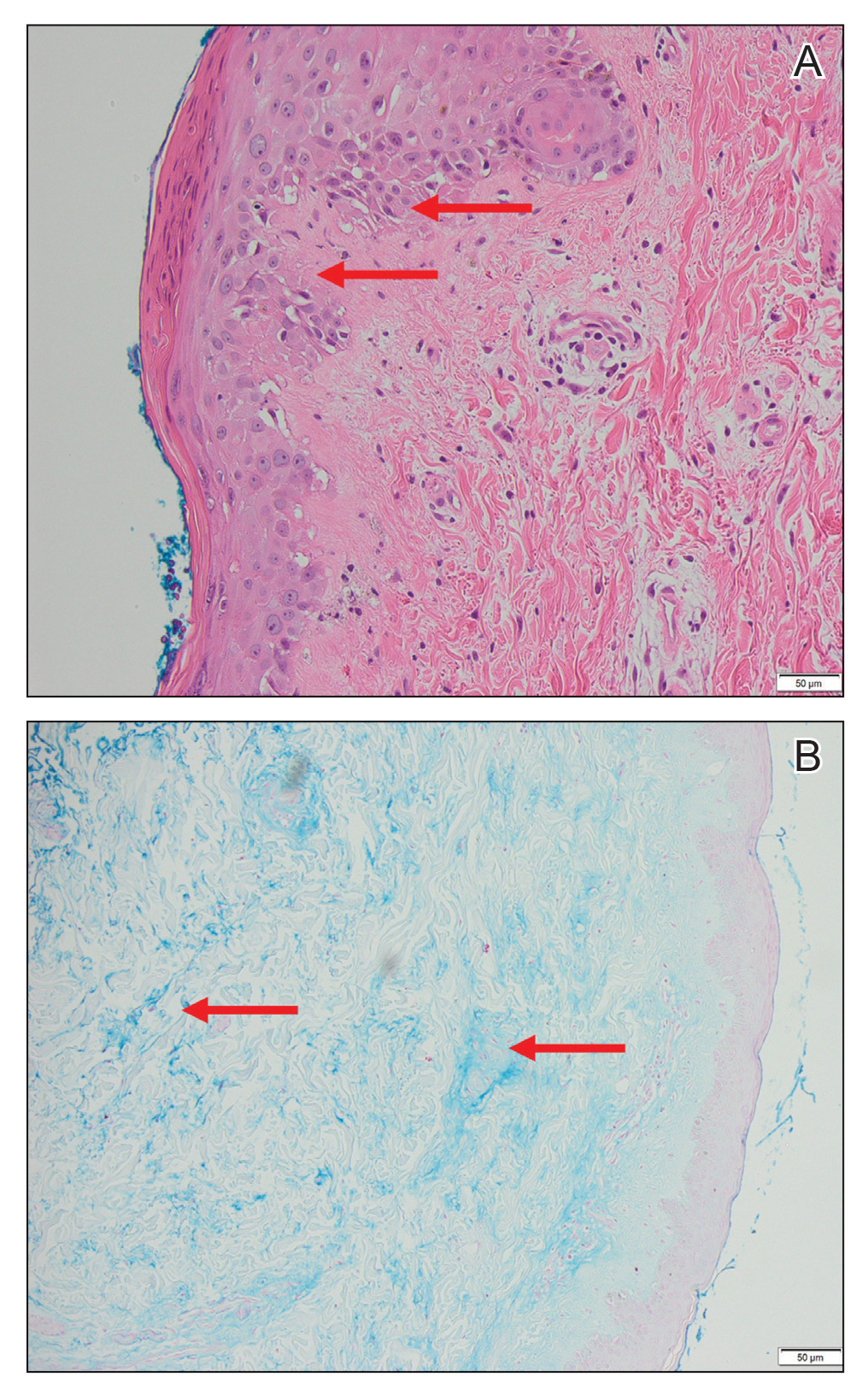

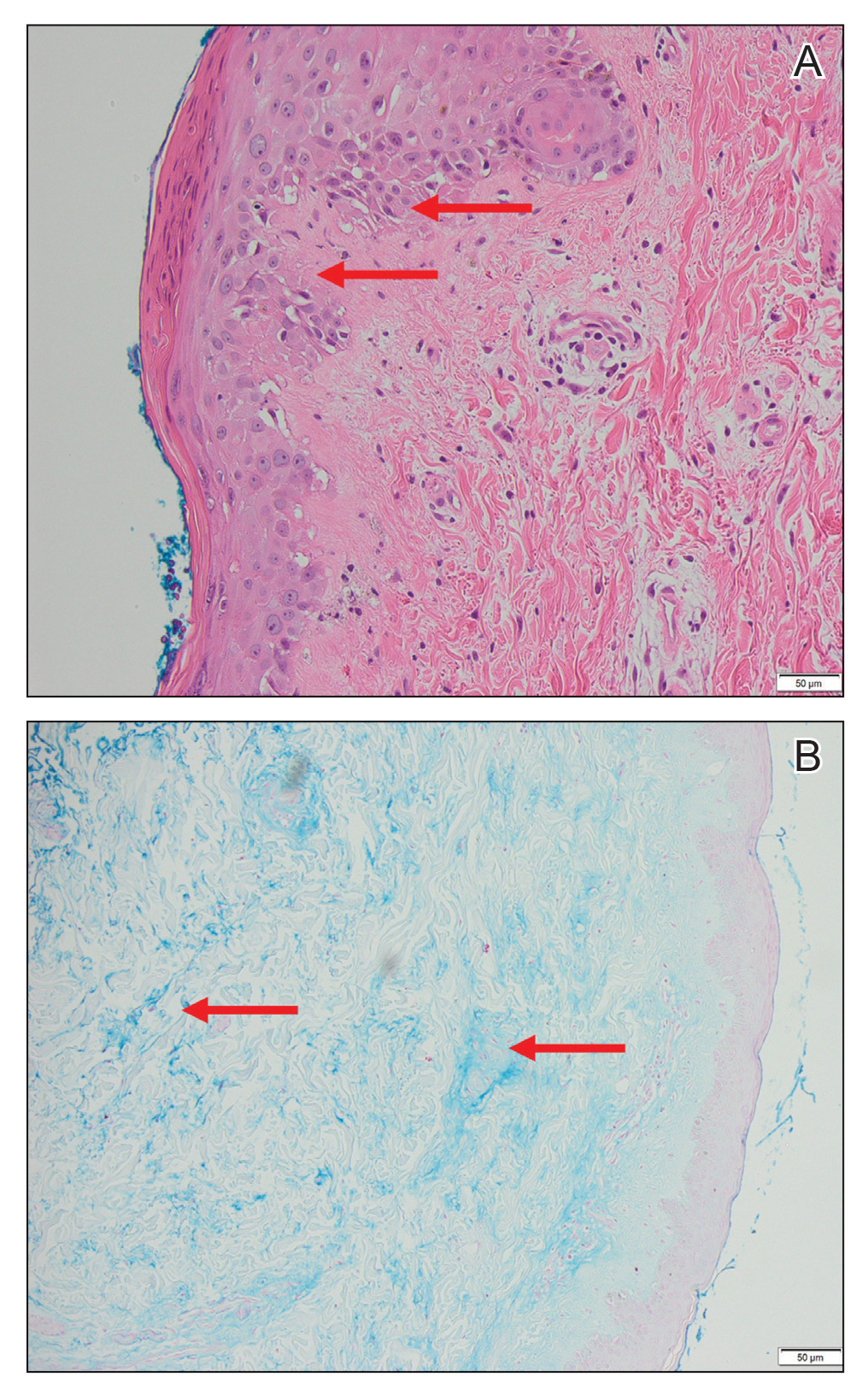

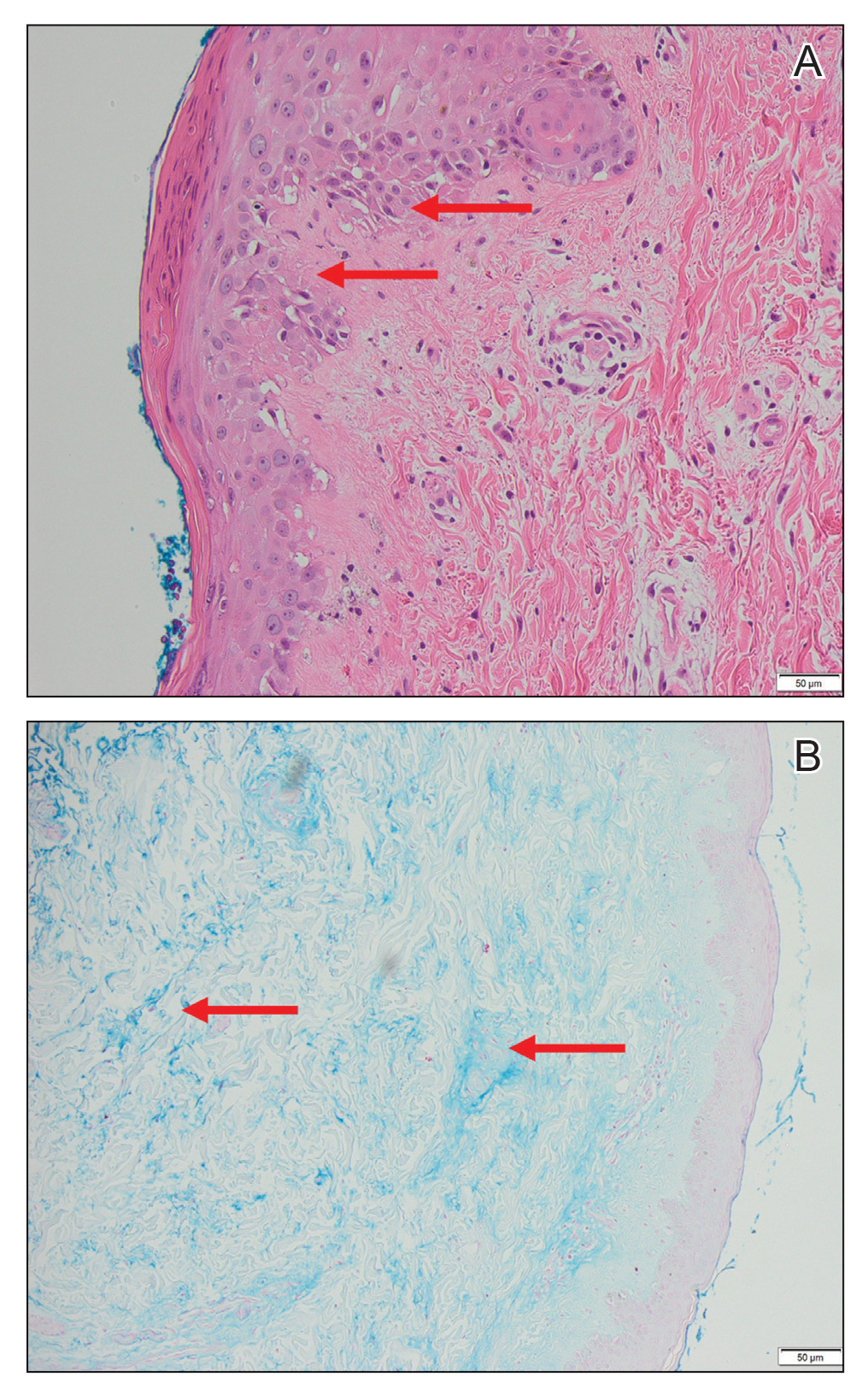

Magnetic resonance imaging of the shoulders showed diffuse soft-tissue edema. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest demonstrated parabronchial thickening and parenchymal bands suggestive of DM. An age-appropriate malignancy workup was negative, and results from a liver biopsy showed diffuse steatosis with no histologic evidence of autoimmune hepatitis. Punch biopsy results from a plaque on the left knee revealed vacuolar interface dermatitis with increased dermal mucin on colloidal iron staining, indicative of connective tissue disease (Figure 2). The patient was treated with intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone 250 mg twice daily for 2 days followed by oral prednisone 50 mg daily with IV immunoglobulin (IVIG) 0.4 mg/kg daily for 5 days. The patient’s symptoms improved, and she was discharged on oral prednisone 50 mg and mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg twice daily with a plan for outpatient IVIG.

Two days after discharge, the patient was re-admitted for worsening muscle weakness; recalcitrant rash; new-onset hypophonia, dysphagia, and odynophagia; and intermittent fevers. Myositis panel results were positive for MDA5. Additionally, workup for HLH, which was initiated during the first hospital admission, revealed that she met 6 of 8 diagnostic criteria: intermittent fevers (maximum temperature, 38.2 °C), splenomegaly (12.6 cm on CT scan of abdomen), cytopenia in 2 cell lines (anemia, thrombocytopenia), hypertriglyceridemia, hyperferritinemia, and elevated IL-2 receptor (CD25). Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with anti-MDA5 DM associated with HLH.

The patient was started on IV methylprednisolone 1000 mg daily and received 1 rituximab infusion. Two days later, she experienced worsening fever with tachycardia, and a chest radiograph showed bibasilar infiltrates concerning for aspiration pneumonia, with sputum cultures growing Staphylococcus aureus. Due to the infection, the dosage of methylprednisolone was decreased to 16 mg 3 times daily and rituximab was stopped. The hematology department was consulted for the patient’s HLH, and due to her profound weakness and sepsis, the decision was made to hold initiation of etoposide, which, in addition to glucocorticoids, is considered first-line therapy for HLH. She subsequently experienced worsening hypoxia requiring intubation and received a second course of IVIG. Two days later, CT of the chest revealed progressive ground-glass opacities in the lower lobes of the lungs. The patient was then started on plasmapheresis every other day, hydroxychloroquine 200 mg daily, and IV methylprednisolone 1000 mg daily. Over the subsequent 6 days, she developed worsening renal failure, liver dysfunction, profound thrombocytopenia (13/μL), and acidemia. After extensive discussion with her family, the patient was transitioned to comfort care, and she died 33 days after the initial admission to our hospital.

Our case is a collection of several rare presentations: anti-MDA5 DM, with HLH and AAHS as complications of anti-MDA5 DM, and DM-associated liver injury. Anti-MDA5 DM is frequently refractory to conventional therapy, including high-dose glucocorticoids, cyclophosphamide, oral tacrolimus, and cyclosporine, and there currently is no single treatment algorithm.2 Lake and colleagues7 highlighted the importance of personalizing treatment of anti-MDA5 DM, as it can be one of the most aggressive rheumatologic diseases. We initially chose to treat our patient with high-dose methylprednisolone, IVIG, and rituximab. Kampylafka et al8 performed a retrospective analysis of the use of IVIG for DM as compared to standard therapy and demonstrated improved muscle and cutaneous involvement from a collection of 50 patients. Case reports have specifically revealed efficacy for the use of IVIG in patients with anti-MDA5 DM.9,10 Additionally, rituximab—an anti–B lymphocyte therapy—has been shown to be an effective supplemental therapy for cases of aggressive anti-MDA5 DM with associated interstitial lung disease, especially when conventional therapy has failed.11,12 Our patient’s sepsis secondary to S aureus pneumonia limited her to only receiving 1 dose of rituximab.

One promising treatment approach for anti-MDA5 DM recently published by Tsuji et al13 involves the use of combination therapy. In this prospective multicenter trial, patients were initially treated with a combination of high-dose glucocorticoids, oral tacrolimus, and IV cyclophosphamide. Plasmapheresis was then started for patients without symptomatic improvement. This method was compared to the more traditional step-up approach of high-dose steroids followed by another immunosuppressant. At 1-year follow-up, the combination therapy group demonstrated an 85% survival rate compared to 33% of historical controls.13

We suspect that our patient developed HLH and AAHS secondary to her underlying anti-MDA5 DM. Kumakura and Murakawa6 reported that among 116 cases of AAHS, 6.9% of cases were associated with DM, most commonly anti-Jo-1 DM. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with anti-MDA5 DM has been described in only a few cases.14-16 The diagnosis of HLH is critical, as the treatments for HLH and DM differ. Both diseases manifest with hyperferritinemia—greater than 500 ng/mL in the case of HLH and 3784 ng/mL in our patient. Therefore, HLH can be easily overlooked. It is possible the rates of HLH associated with anti-MDA5 DM are higher than reported given their similar presentations.

Analogous to our case, Fujita et al15 reported a case of HLH associated with anti-MDA5 DM successfully treated with IV cyclophosphamide pulse therapy and plasmapheresis. The rationale for using plasmapheresis in anti-MDA5 DM is based on its success in patients with other antibody-mediated conditions such as Goodpasture syndrome and granulomatosis with polyangiitis.7 It is thought to expedite response to traditional treatment, and in the case described by Fujita et al,15 the patient received plasmapheresis 6 times total over the course of 9 days. The patient’s clinical symptoms, as well as platelet levels, liver enzymes, and ferritin value, improved.15 Our patient received 3 days of plasmapheresis with no improvement when the decision was made to discontinue plasmapheresis given her worsening clinical state.

Additionally, our patient had elevated hepatic enzymes (ALT, AST, ALP, GGT), and results of a liver biopsy demonstrated diffuse steatosis. We speculate her transaminitis was a complication of anti-MDA5 DM. Hepatocellular damage accompanying DM has been investigated in multiple studies and is most often defined as an elevated ALT.17-20 Improvement in ALT levels has been seen with DM treatment. However, investigators note that creatine kinase (CK) values often do not correlate with the resolution of the transaminitis, suggesting that CK denotes muscle damage whereas ALT represents separate liver damage.18-21

Nagashima et al22 highlighted that among 50 patients with DM without malignancy, only 20% presented with a transaminitis or elevated bilirubin. However, among those with liver injury, all were positive for antibodies against MDA5.22 The patients with anti-MDA5 DM liver dysfunction had higher ALT, ALP, and GGT levels compared to those without liver dysfunction. Similarly, in a retrospective review of 14 patients with anti-MDA5 DM, Gono and colleagues3 found elevated GGT levels and lower CK levels in comparison to patients with anti-aminoacyl-transfer RNA synthetase DM. Although liver enzymes can be elevated in patients with DM secondary to muscle damage, the authors argue that the specificity of GGT to the liver suggests intrinsic liver damage.3

The mechanism behind liver disease in anti-MDA5 DM is unclear, but it is hypothesized to be similar to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.22 Other studies have revealed drug-induced hepatitis, hepatic congestion, nonspecific reactive hepatitis, metastatic liver tumor, primary biliary cholangitis, and autoimmune hepatitis as the etiology behind liver disease in their patients with DM.17-19 Liver biopsy results from patients with anti-MDA5 DM most commonly reveal hepatic steatosis, as seen in our patient, as well as hepatocyte ballooning and increased pigmented macrophages.22

We presented a case of anti-MDA5 DM complicated by HLH. Our patient had a fatal outcome despite aggressive treatment with high-dose methylprednisolone, IVIG, rituximab, and plasmapheresis. It is accepted that anti-MDA5 DM affects the lungs and skin, and our patient’s presentation also suggests liver involvement. In our case, onset of symptoms to fatality was approximately 1 year. It is essential to consider the diagnosis of HLH in all cases of anti-MDA5 DM given clinical disease overlap. Our patient could have benefited from earlier disease recognition and thus earlier aggressive therapy.

1. Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. N Engl J Med. 1975;292:344-347.

2. Kurtzman DJB, Vleugels RA. Anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) dermatomyositis: a concise review with an emphasis on distinctive clinical features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:776-785.

3. Gono T, Kawaguchi Y, Satoh T, et al. Clinical manifestation and prognostic factor in anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody-associated interstitial lung disease as a complication of dermatomyositis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49:1713-1719.

4. Fiorentino D, Chung L, Zwerner J, et al. The mucocutaneous and systemic phenotype of dermatomyositis patients with antibodies to MDA5 (CADM-140): a retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:25-34.

5. Sepulveda FE, de Saint Basile G. Hemophagocytic syndrome: primary forms and predisposing conditions. Curr Opin Immunol. 2017;49:20-26.

6. Kumakura S, Murakawa Y. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes of autoimmune-associated hemophagocytic syndrome in adults. Arthritis Rheum. 2014;66:2297-2307.

7. Lake M, George G, Summer R. Time to personalize the treatment of anti-MDA-5 associated lung disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:E52.

8. Kampylafka EI, Kosmidis ML, Panagiotakos DB, et al. The effect of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) treatment on patients with dermatomyositis: a 4-year follow-up study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30:397-401.

9. Koguchi-Yoshioka H, Okiyama N, Iwamoto K, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin contributes to the control of antimelanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 antibody-associated dermatomyositis with palmar violaceous macules/papules. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:1442-1446.

10. Hamada-Ode K, Taniguchi Y, Kimata T, et al. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for rapidly progressive interstitial pneumonitis accompanied by anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody-positive amyopathic dermatomyositis. Eur J Rheumatol. 2015;2:83-85.

11. So H, Wong VTL, Lao VWN, et al. Rituximab for refractory rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease related to anti-MDA5 antibody-positive amyopathic dermatomyositis. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37:1983-1989.

12. Koichi Y, Aya Y, Megumi U, et al. A case of anti-MDA5-positive rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease in a patient with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis ameliorated by rituximab, in addition to standard immunosuppressive treatment. Mod Rheumatol. 2017;27:536-540.

13. Tsuji H, Nakashima R, Hosono Y, et al. Multicenter prospective study of the efficacy and safety of combined immunosuppressive therapy with high-dose glucocorticoid, tacrolimus, and cyclophosphamide in interstitial lung diseases accompanied by anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5-positive dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72:488-498.

14. Honda M, Moriyama M, Kondo M, et al. Three cases of autoimmune-associated haemophagocytic syndrome in dermatomyositis with anti-MDA5 autoantibody. Scand J Rheumatol. 2020;49:244-246.

15. Fujita Y, Fukui S, Suzuki T, et al. Anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis complicated by autoimmune-associated hemophagocytic syndrome that was successfully treated with immunosuppressive therapy and plasmapheresis. Intern Med. 2018;57:3473-3478.

16. Gono T, Miyake K, Kawaguchi Y, et al. Hyperferritinaemia and macrophage activation in a patient with interstitial lung disease with clinically amyopathic DM. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51:1336-1338.

17. Wada T, Abe G, Kudou, T, et al. Liver damage in patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Kitasato Med Journal. 2016;46:40-46.

18. Takahashi A, Abe K, Yokokawa J, et al. Clinical features of liver dysfunction in collagen diseases. Hepatol Res. 2010;40:1092-1097.

19. Matsumoto T, Kobayashi S, Shimizu H, et al. The liver in collagen diseases: pathologic study of 160 cases with particular reference to hepatic arteritis, primary biliary cirrhosis, autoimmune hepatitis and nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver. Liver. 2000;20:366-373.

20. Shi Q, Niu J, Huang X, et al. Do muscle enzyme changes forecast liver injury in polymyositis/dermatomyositis patients treated with methylprednisolone and methotrexate? Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2016;46:266-269.

21. Noda S, Asano Y, Tamaki Z, et al. A case of dermatomyositis with “liver disease associated with rheumatoid diseases” positive for anti-liver-kidney microsome-1 antibody. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29:941-943.

22. Nagashima T, Kamata Y, Iwamoto M, et al. Liver dysfunction in anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody-positive patients with dermatomyositis. Rheumatol Int. 2019;39:901-909.

To the Editor:

Dermatomyositis (DM) is an idiopathic inflammatory myopathy characterized by bilateral, symmetrical, proximal muscle weakness and classic cutaneous manifestations.1 Patients with antibodies directed against melanoma differentiation–associated gene 5, MDA5, have a distinct presentation due to vasculopathy with more severe cutaneous ulcerations, palmar papules, alopecia, and an elevated risk of rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease.2 A ferritin level greater than 1600 ng/mL portends an increased risk for pulmonary disease and therefore can be of prognostic value.3 Further, patients with anti-MDA5 DM are at a lower risk of malignancy and are more likely to test negative for antinuclear antibodies in comparison to other patients with DM.2,4

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), also known as hemophagocytic syndrome, is a potentially lethal condition whereby uncontrolled activation of histiocytes in the reticuloendothelial system causes hemophagocytosis and a hyperinflammatory state. Patients present with fever, splenomegaly, cytopenia, and hyperferritinemia.5 Autoimmune‐associated hemophagocytic syndrome (AAHS) describes HLH that develops in association with autoimmune conditions, most commonly systemic lupus erythematosus and adult-onset Still disease. Cases reported in association with DM exist but are few in number, and there is no standard-of-care treatment.6 We report a case of a woman with anti-MDA5 DM complicated by HLH and DM-associated liver injury.

A 50-year-old woman presented as a direct admit from the rheumatology clinic for diffuse muscle weakness of 8 months’ duration, 40-pound unintentional weight loss, pruritic rash, bilateral joint pains, dry eyes, dry mouth, and altered mental status. Four months prior, she presented to an outside hospital and was given a diagnosis of probable Sjögren syndrome and autoimmune hepatitis vs drug-induced liver injury. At that time, a workup was notable for antibodies against Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A, anti–smooth muscle antibodies, and transaminitis. Ultrasonography of the right upper quadrant revealed hepatic steatosis. The patient was started on oral prednisone and pilocarpine but had been off all medications for 1 month when she presented to our hospital.

On hospital admission, physical examination revealed a violaceous heliotrope rash; a v-sign on the chest; shawl sign; palmar papules with pits at the fingertips; and periungual erythema and ulcerations along the metacarpophalangeal joints, elbows, lateral feet, and upper eyelids (Figure 1). Laboratory workup showed the following results: white blood cell count, 4100/μL (reference range, 4000–11,000/μL); hemoglobin, 11.6 g/dL (reference range, 12–16 g/dL); platelet count, 100,000/μL (reference range, 150,000–450,000/μL); lactate dehydrogenase, 510 U/L (reference range, 80–225 U/L); alkaline phosphatase (ALP), 766 U/L (reference range, 30–120 U/L); alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 88 U/L (reference range, 10–40 U/L); aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 544 U/L (reference range, 10–40 U/L); total bilirubin, 4.2 mg/dL (reference range, 0.3–1.0 mg/dL); direct bilirubin, 3.7 mg/dL (reference range, 0.1–0.3 mg/dL); aldolase, 20.2 U/L (reference range, 1–7.5 U/L), creatine kinase, 180 U/L (reference range, 30–135 U/L); γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT), 2743 U/L (reference range, 8–40 U/L); high sensitivity C-reactive protein, 122.9 mg/L (low-risk reference range, <1.0 mg/L); triglycerides, 534 mg/dL (reference range, <150 mg/dL); ferritin, 3784 ng/mL (reference range, 24–307 ng/mL); antinuclear antibody, negative titer; antimitochondrial antibody, negative titer; soluble IL-2 receptor (CD25), 7000 U/mL (reference range, 189–846 U/mL); anti-Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A antibody, positive.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the shoulders showed diffuse soft-tissue edema. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest demonstrated parabronchial thickening and parenchymal bands suggestive of DM. An age-appropriate malignancy workup was negative, and results from a liver biopsy showed diffuse steatosis with no histologic evidence of autoimmune hepatitis. Punch biopsy results from a plaque on the left knee revealed vacuolar interface dermatitis with increased dermal mucin on colloidal iron staining, indicative of connective tissue disease (Figure 2). The patient was treated with intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone 250 mg twice daily for 2 days followed by oral prednisone 50 mg daily with IV immunoglobulin (IVIG) 0.4 mg/kg daily for 5 days. The patient’s symptoms improved, and she was discharged on oral prednisone 50 mg and mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg twice daily with a plan for outpatient IVIG.

Two days after discharge, the patient was re-admitted for worsening muscle weakness; recalcitrant rash; new-onset hypophonia, dysphagia, and odynophagia; and intermittent fevers. Myositis panel results were positive for MDA5. Additionally, workup for HLH, which was initiated during the first hospital admission, revealed that she met 6 of 8 diagnostic criteria: intermittent fevers (maximum temperature, 38.2 °C), splenomegaly (12.6 cm on CT scan of abdomen), cytopenia in 2 cell lines (anemia, thrombocytopenia), hypertriglyceridemia, hyperferritinemia, and elevated IL-2 receptor (CD25). Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with anti-MDA5 DM associated with HLH.

The patient was started on IV methylprednisolone 1000 mg daily and received 1 rituximab infusion. Two days later, she experienced worsening fever with tachycardia, and a chest radiograph showed bibasilar infiltrates concerning for aspiration pneumonia, with sputum cultures growing Staphylococcus aureus. Due to the infection, the dosage of methylprednisolone was decreased to 16 mg 3 times daily and rituximab was stopped. The hematology department was consulted for the patient’s HLH, and due to her profound weakness and sepsis, the decision was made to hold initiation of etoposide, which, in addition to glucocorticoids, is considered first-line therapy for HLH. She subsequently experienced worsening hypoxia requiring intubation and received a second course of IVIG. Two days later, CT of the chest revealed progressive ground-glass opacities in the lower lobes of the lungs. The patient was then started on plasmapheresis every other day, hydroxychloroquine 200 mg daily, and IV methylprednisolone 1000 mg daily. Over the subsequent 6 days, she developed worsening renal failure, liver dysfunction, profound thrombocytopenia (13/μL), and acidemia. After extensive discussion with her family, the patient was transitioned to comfort care, and she died 33 days after the initial admission to our hospital.

Our case is a collection of several rare presentations: anti-MDA5 DM, with HLH and AAHS as complications of anti-MDA5 DM, and DM-associated liver injury. Anti-MDA5 DM is frequently refractory to conventional therapy, including high-dose glucocorticoids, cyclophosphamide, oral tacrolimus, and cyclosporine, and there currently is no single treatment algorithm.2 Lake and colleagues7 highlighted the importance of personalizing treatment of anti-MDA5 DM, as it can be one of the most aggressive rheumatologic diseases. We initially chose to treat our patient with high-dose methylprednisolone, IVIG, and rituximab. Kampylafka et al8 performed a retrospective analysis of the use of IVIG for DM as compared to standard therapy and demonstrated improved muscle and cutaneous involvement from a collection of 50 patients. Case reports have specifically revealed efficacy for the use of IVIG in patients with anti-MDA5 DM.9,10 Additionally, rituximab—an anti–B lymphocyte therapy—has been shown to be an effective supplemental therapy for cases of aggressive anti-MDA5 DM with associated interstitial lung disease, especially when conventional therapy has failed.11,12 Our patient’s sepsis secondary to S aureus pneumonia limited her to only receiving 1 dose of rituximab.

One promising treatment approach for anti-MDA5 DM recently published by Tsuji et al13 involves the use of combination therapy. In this prospective multicenter trial, patients were initially treated with a combination of high-dose glucocorticoids, oral tacrolimus, and IV cyclophosphamide. Plasmapheresis was then started for patients without symptomatic improvement. This method was compared to the more traditional step-up approach of high-dose steroids followed by another immunosuppressant. At 1-year follow-up, the combination therapy group demonstrated an 85% survival rate compared to 33% of historical controls.13

We suspect that our patient developed HLH and AAHS secondary to her underlying anti-MDA5 DM. Kumakura and Murakawa6 reported that among 116 cases of AAHS, 6.9% of cases were associated with DM, most commonly anti-Jo-1 DM. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with anti-MDA5 DM has been described in only a few cases.14-16 The diagnosis of HLH is critical, as the treatments for HLH and DM differ. Both diseases manifest with hyperferritinemia—greater than 500 ng/mL in the case of HLH and 3784 ng/mL in our patient. Therefore, HLH can be easily overlooked. It is possible the rates of HLH associated with anti-MDA5 DM are higher than reported given their similar presentations.

Analogous to our case, Fujita et al15 reported a case of HLH associated with anti-MDA5 DM successfully treated with IV cyclophosphamide pulse therapy and plasmapheresis. The rationale for using plasmapheresis in anti-MDA5 DM is based on its success in patients with other antibody-mediated conditions such as Goodpasture syndrome and granulomatosis with polyangiitis.7 It is thought to expedite response to traditional treatment, and in the case described by Fujita et al,15 the patient received plasmapheresis 6 times total over the course of 9 days. The patient’s clinical symptoms, as well as platelet levels, liver enzymes, and ferritin value, improved.15 Our patient received 3 days of plasmapheresis with no improvement when the decision was made to discontinue plasmapheresis given her worsening clinical state.

Additionally, our patient had elevated hepatic enzymes (ALT, AST, ALP, GGT), and results of a liver biopsy demonstrated diffuse steatosis. We speculate her transaminitis was a complication of anti-MDA5 DM. Hepatocellular damage accompanying DM has been investigated in multiple studies and is most often defined as an elevated ALT.17-20 Improvement in ALT levels has been seen with DM treatment. However, investigators note that creatine kinase (CK) values often do not correlate with the resolution of the transaminitis, suggesting that CK denotes muscle damage whereas ALT represents separate liver damage.18-21

Nagashima et al22 highlighted that among 50 patients with DM without malignancy, only 20% presented with a transaminitis or elevated bilirubin. However, among those with liver injury, all were positive for antibodies against MDA5.22 The patients with anti-MDA5 DM liver dysfunction had higher ALT, ALP, and GGT levels compared to those without liver dysfunction. Similarly, in a retrospective review of 14 patients with anti-MDA5 DM, Gono and colleagues3 found elevated GGT levels and lower CK levels in comparison to patients with anti-aminoacyl-transfer RNA synthetase DM. Although liver enzymes can be elevated in patients with DM secondary to muscle damage, the authors argue that the specificity of GGT to the liver suggests intrinsic liver damage.3

The mechanism behind liver disease in anti-MDA5 DM is unclear, but it is hypothesized to be similar to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.22 Other studies have revealed drug-induced hepatitis, hepatic congestion, nonspecific reactive hepatitis, metastatic liver tumor, primary biliary cholangitis, and autoimmune hepatitis as the etiology behind liver disease in their patients with DM.17-19 Liver biopsy results from patients with anti-MDA5 DM most commonly reveal hepatic steatosis, as seen in our patient, as well as hepatocyte ballooning and increased pigmented macrophages.22

We presented a case of anti-MDA5 DM complicated by HLH. Our patient had a fatal outcome despite aggressive treatment with high-dose methylprednisolone, IVIG, rituximab, and plasmapheresis. It is accepted that anti-MDA5 DM affects the lungs and skin, and our patient’s presentation also suggests liver involvement. In our case, onset of symptoms to fatality was approximately 1 year. It is essential to consider the diagnosis of HLH in all cases of anti-MDA5 DM given clinical disease overlap. Our patient could have benefited from earlier disease recognition and thus earlier aggressive therapy.

To the Editor:

Dermatomyositis (DM) is an idiopathic inflammatory myopathy characterized by bilateral, symmetrical, proximal muscle weakness and classic cutaneous manifestations.1 Patients with antibodies directed against melanoma differentiation–associated gene 5, MDA5, have a distinct presentation due to vasculopathy with more severe cutaneous ulcerations, palmar papules, alopecia, and an elevated risk of rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease.2 A ferritin level greater than 1600 ng/mL portends an increased risk for pulmonary disease and therefore can be of prognostic value.3 Further, patients with anti-MDA5 DM are at a lower risk of malignancy and are more likely to test negative for antinuclear antibodies in comparison to other patients with DM.2,4

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), also known as hemophagocytic syndrome, is a potentially lethal condition whereby uncontrolled activation of histiocytes in the reticuloendothelial system causes hemophagocytosis and a hyperinflammatory state. Patients present with fever, splenomegaly, cytopenia, and hyperferritinemia.5 Autoimmune‐associated hemophagocytic syndrome (AAHS) describes HLH that develops in association with autoimmune conditions, most commonly systemic lupus erythematosus and adult-onset Still disease. Cases reported in association with DM exist but are few in number, and there is no standard-of-care treatment.6 We report a case of a woman with anti-MDA5 DM complicated by HLH and DM-associated liver injury.

A 50-year-old woman presented as a direct admit from the rheumatology clinic for diffuse muscle weakness of 8 months’ duration, 40-pound unintentional weight loss, pruritic rash, bilateral joint pains, dry eyes, dry mouth, and altered mental status. Four months prior, she presented to an outside hospital and was given a diagnosis of probable Sjögren syndrome and autoimmune hepatitis vs drug-induced liver injury. At that time, a workup was notable for antibodies against Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A, anti–smooth muscle antibodies, and transaminitis. Ultrasonography of the right upper quadrant revealed hepatic steatosis. The patient was started on oral prednisone and pilocarpine but had been off all medications for 1 month when she presented to our hospital.

On hospital admission, physical examination revealed a violaceous heliotrope rash; a v-sign on the chest; shawl sign; palmar papules with pits at the fingertips; and periungual erythema and ulcerations along the metacarpophalangeal joints, elbows, lateral feet, and upper eyelids (Figure 1). Laboratory workup showed the following results: white blood cell count, 4100/μL (reference range, 4000–11,000/μL); hemoglobin, 11.6 g/dL (reference range, 12–16 g/dL); platelet count, 100,000/μL (reference range, 150,000–450,000/μL); lactate dehydrogenase, 510 U/L (reference range, 80–225 U/L); alkaline phosphatase (ALP), 766 U/L (reference range, 30–120 U/L); alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 88 U/L (reference range, 10–40 U/L); aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 544 U/L (reference range, 10–40 U/L); total bilirubin, 4.2 mg/dL (reference range, 0.3–1.0 mg/dL); direct bilirubin, 3.7 mg/dL (reference range, 0.1–0.3 mg/dL); aldolase, 20.2 U/L (reference range, 1–7.5 U/L), creatine kinase, 180 U/L (reference range, 30–135 U/L); γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT), 2743 U/L (reference range, 8–40 U/L); high sensitivity C-reactive protein, 122.9 mg/L (low-risk reference range, <1.0 mg/L); triglycerides, 534 mg/dL (reference range, <150 mg/dL); ferritin, 3784 ng/mL (reference range, 24–307 ng/mL); antinuclear antibody, negative titer; antimitochondrial antibody, negative titer; soluble IL-2 receptor (CD25), 7000 U/mL (reference range, 189–846 U/mL); anti-Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A antibody, positive.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the shoulders showed diffuse soft-tissue edema. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest demonstrated parabronchial thickening and parenchymal bands suggestive of DM. An age-appropriate malignancy workup was negative, and results from a liver biopsy showed diffuse steatosis with no histologic evidence of autoimmune hepatitis. Punch biopsy results from a plaque on the left knee revealed vacuolar interface dermatitis with increased dermal mucin on colloidal iron staining, indicative of connective tissue disease (Figure 2). The patient was treated with intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone 250 mg twice daily for 2 days followed by oral prednisone 50 mg daily with IV immunoglobulin (IVIG) 0.4 mg/kg daily for 5 days. The patient’s symptoms improved, and she was discharged on oral prednisone 50 mg and mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg twice daily with a plan for outpatient IVIG.

Two days after discharge, the patient was re-admitted for worsening muscle weakness; recalcitrant rash; new-onset hypophonia, dysphagia, and odynophagia; and intermittent fevers. Myositis panel results were positive for MDA5. Additionally, workup for HLH, which was initiated during the first hospital admission, revealed that she met 6 of 8 diagnostic criteria: intermittent fevers (maximum temperature, 38.2 °C), splenomegaly (12.6 cm on CT scan of abdomen), cytopenia in 2 cell lines (anemia, thrombocytopenia), hypertriglyceridemia, hyperferritinemia, and elevated IL-2 receptor (CD25). Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with anti-MDA5 DM associated with HLH.

The patient was started on IV methylprednisolone 1000 mg daily and received 1 rituximab infusion. Two days later, she experienced worsening fever with tachycardia, and a chest radiograph showed bibasilar infiltrates concerning for aspiration pneumonia, with sputum cultures growing Staphylococcus aureus. Due to the infection, the dosage of methylprednisolone was decreased to 16 mg 3 times daily and rituximab was stopped. The hematology department was consulted for the patient’s HLH, and due to her profound weakness and sepsis, the decision was made to hold initiation of etoposide, which, in addition to glucocorticoids, is considered first-line therapy for HLH. She subsequently experienced worsening hypoxia requiring intubation and received a second course of IVIG. Two days later, CT of the chest revealed progressive ground-glass opacities in the lower lobes of the lungs. The patient was then started on plasmapheresis every other day, hydroxychloroquine 200 mg daily, and IV methylprednisolone 1000 mg daily. Over the subsequent 6 days, she developed worsening renal failure, liver dysfunction, profound thrombocytopenia (13/μL), and acidemia. After extensive discussion with her family, the patient was transitioned to comfort care, and she died 33 days after the initial admission to our hospital.

Our case is a collection of several rare presentations: anti-MDA5 DM, with HLH and AAHS as complications of anti-MDA5 DM, and DM-associated liver injury. Anti-MDA5 DM is frequently refractory to conventional therapy, including high-dose glucocorticoids, cyclophosphamide, oral tacrolimus, and cyclosporine, and there currently is no single treatment algorithm.2 Lake and colleagues7 highlighted the importance of personalizing treatment of anti-MDA5 DM, as it can be one of the most aggressive rheumatologic diseases. We initially chose to treat our patient with high-dose methylprednisolone, IVIG, and rituximab. Kampylafka et al8 performed a retrospective analysis of the use of IVIG for DM as compared to standard therapy and demonstrated improved muscle and cutaneous involvement from a collection of 50 patients. Case reports have specifically revealed efficacy for the use of IVIG in patients with anti-MDA5 DM.9,10 Additionally, rituximab—an anti–B lymphocyte therapy—has been shown to be an effective supplemental therapy for cases of aggressive anti-MDA5 DM with associated interstitial lung disease, especially when conventional therapy has failed.11,12 Our patient’s sepsis secondary to S aureus pneumonia limited her to only receiving 1 dose of rituximab.

One promising treatment approach for anti-MDA5 DM recently published by Tsuji et al13 involves the use of combination therapy. In this prospective multicenter trial, patients were initially treated with a combination of high-dose glucocorticoids, oral tacrolimus, and IV cyclophosphamide. Plasmapheresis was then started for patients without symptomatic improvement. This method was compared to the more traditional step-up approach of high-dose steroids followed by another immunosuppressant. At 1-year follow-up, the combination therapy group demonstrated an 85% survival rate compared to 33% of historical controls.13