User login

Betamethasone Dipropionate Spray 0.05% Alleviates Troublesome Symptoms of Plaque Psoriasis

Psoriasis affects approximately 2% to 3% of the US population and is characterized by plaques that are red, scaly, and elevated.1 Cutaneous symptoms of the disease are described by patients as itching, burning, and stinging sensations. Large multinational and US surveys have reported pruritus as patients’ most bothersome symptom, with scaling/flaking reported as the second most bothersome.2,3 Reported incidence rates for itching range from 60.4% to 98.3%, with at least half of these patients reporting daily or constant pruritus.2,4-7 Consequent effects on quality of life include impaired sleep,6 difficulty concentrating, lower sex drive, and depression.7 Despite these findings, pruritus is rarely included in the efficacy assessments of psoriasis treatments. In addition, 2 of the most commonly reported but difficult-to-treat locations for plaques are the outside of the elbows (45%) and the knees (32%),1,2,8 areas where the stratum corneum typically is thicker, less hydrated, and less likely to absorb topical products.9-11 Clinical studies have not focused specifically on these areas when assessing treatments.

Topical corticosteroids have been the mainstay of psoriasis therapy for decades because of their anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative properties.7 One large multinational physician survey indicated that 75% of patients are prescribed topical steroids,12 which are important for first-line treatment and are often maintained as adjunctive therapy in combination with other treatments for patients with extensive disease or recalcitrant lesions.13 Topical corticosteroids are ranked into different classes based on their vasoconstrictor assay (VCA), a measure of skin blanching used as a marker for vasoconstriction. Topical agents with VCA ratings of mid-potency or superpotency are generally recommended for initial therapy, with superpotent agents required for the treatment of thick chronic plaques. However, longer durations of use may contribute to systemic absorption and adverse events.13 The vehicle composition is important for corticosteroid delivery and retention at the site of pathology, contributing to the efficacy of the steroid.13,14 Selecting the appropriate steroid and vehicle is important to maximize efficacy and minimize adverse events.

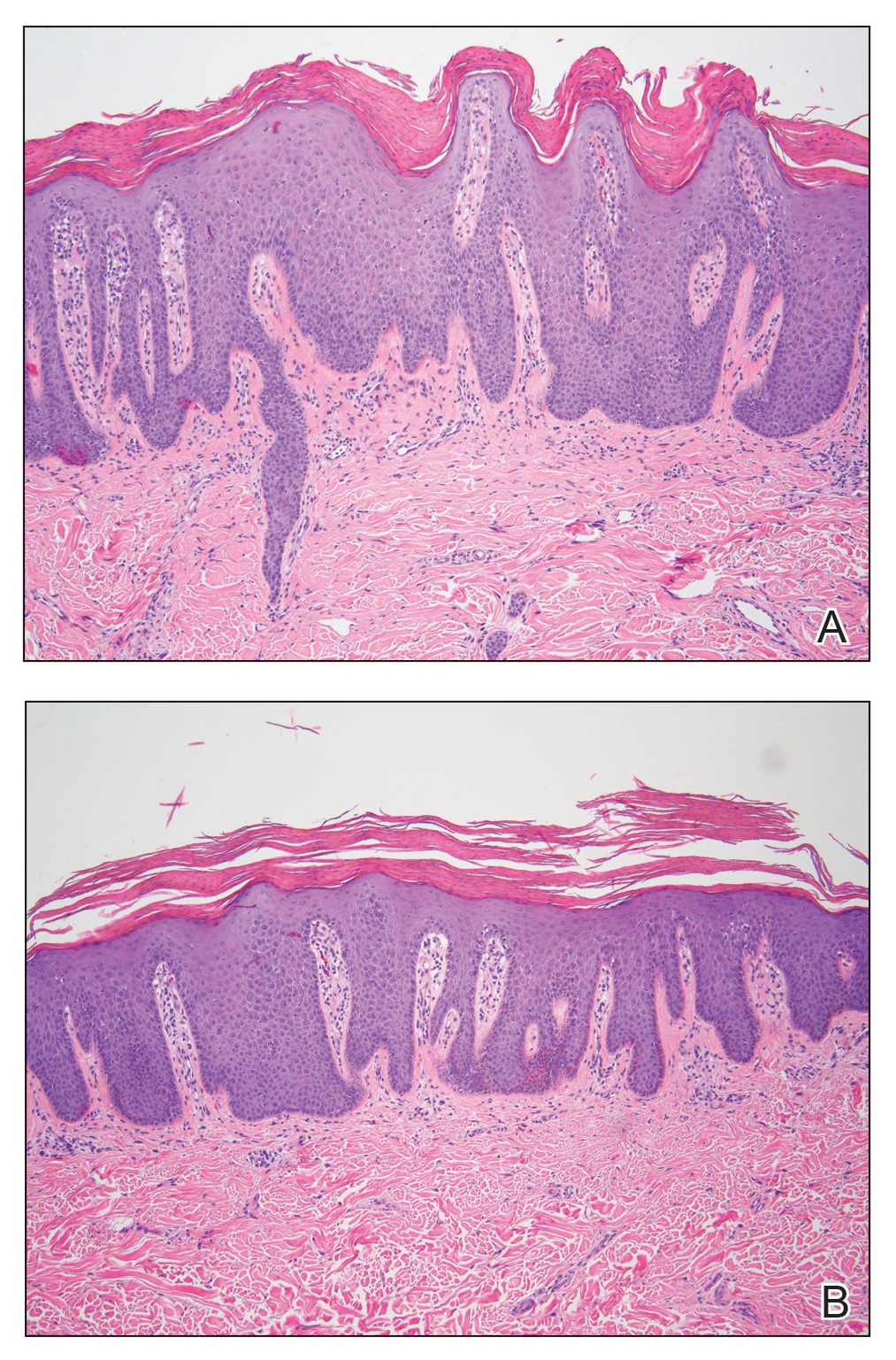

Betamethasone dipropionate (BD) spray 0.05% is an emollient formulation of 0.05% BD that can be sprayed onto psoriatic plaques. The BD spray formulation was designed to penetrate the stratum corneum and be retained within the dermis and epidermis, the site of T-cell activity that drives the psoriatic disease process.14 In 2 phase 3 studies, BD spray demonstrated the ability to reduce the signs of plaque psoriasis with indication of improvement by day 4.15,16 These studies also showed improvement in the local cutaneous symptoms of itching, burning and stinging, and pain. As a mid-potent steroid, BD spray displays less systemic absorption but similar efficacy compared to a superpotent augmented BD (AugBD) lotion in relieving the signs and symptoms of plaque psoriasis.15-17

The objective of the current investigation was to assess the ability of BD spray to relieve itching and to clear plaque psoriasis on the knees and elbows utilizing post hoc analyses of the 2 phase 3 trials. The goal of these analyses was to demonstrate BD spray as effective at relieving the most troublesome signs and symptoms affecting patients with plaque psoriasis.

Methods

Two phase 3 studies were conducted to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of BD spray.15,16 The design of the studies was similar15,16 to allow the data to be pooled for post hoc analyses.

Both were US multicenter, randomized, vehicle-controlled, double-blind, parallel-group studies comparing the safety and efficacy of BD spray 0.05% (Sernivo, Promius Pharma) with its vehicle formulation spray (identical to BD spray, but lacking the active steroid component).15,16 One of the studies also compared BD spray with an AugBD lotion 0.05% (Diprolene,Merck & Co). Adults with moderate plaque psoriasis (investigator global assessment of 3; 10%–20% body surface area) were randomized to apply BD spray, vehicle spray, or AugBD lotion (1 study only) twice daily to all affected areas, excluding the face, scalp, and intertriginous areas for 28 days (BD spray and vehicle) or 14 days (AugBD lotion, per product label).15

Assessments

Two post hoc analyses were conducted on data pooled from the 2 phase 3 trials: (1) incidence of itching, and (2) total sign score (TSS) for lesions located on the knees and elbows.

Itching

Itching was assessed proactively by asking patients if they were experiencing itching (yes/no) at each visit (baseline and days 4, 8, 15, and 29) or had experienced itching since their last visit. As itching could be an adverse event of topical application, application-site pruritus was also recorded.

Total Sign Score

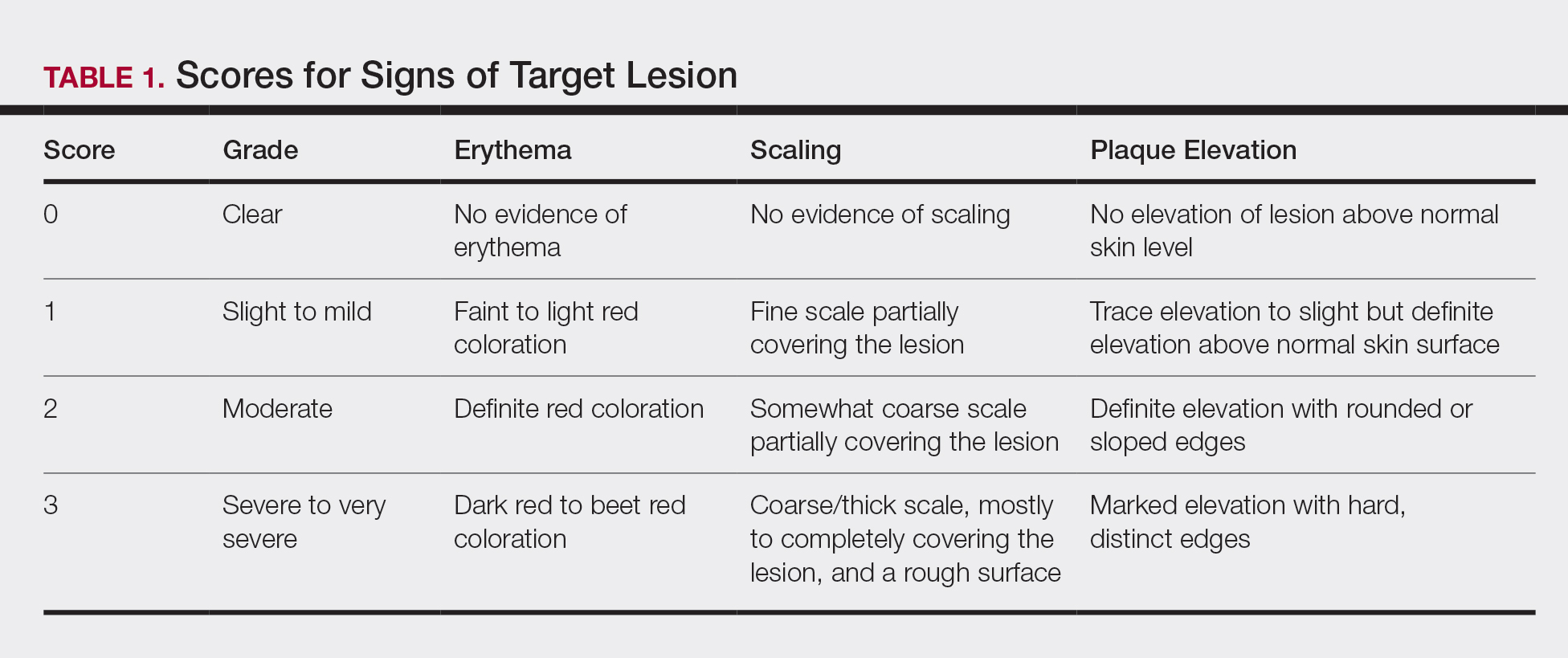

For each patient, a target plaque was selected that was representative of their psoriasis. The plaque was assessed on a 3-point grading scale for each of 3 key signs of plaque psoriasis: erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation (Table 1) at baseline and days 4, 8, 15, and 29. Total sign score was calculated by summing the scores for these 3 signs, resulting in a score ranging from 0 to 9. Treatment success was measured as (1) achieving a score of 0 or 1 (ie, reducing the plaque to clear or slight to mild) for the individual signs of erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation; and (2) achieving a TSS of 0 or 1 for all 3 signs—erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation—for each target lesion. Total sign score was assessed proactively for all patients.15,16 The post hoc analysis reported here examined patients whose target lesion was located on either the knee or the elbow.

Statistical Analyses

Because both study protocols were identical, data were pooled from the 2 phase 3 trials. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS Institute). Two-sided hypothesis testing was conducted for all analyses using a significance level of P=.05. Post hoc analyses used Fisher exact test. No imputations were made for missing data.

Statistical analyses of itching compared the incidence of itching at each assessment time point (baseline and days 4, 8, 15, and 29) between BD spray and vehicle and between BD spray and AugBD lotion. Additional analysis included a statistical test on the incidence of itching in the subgroup of patients who reported itching at baseline.

Statistical analyses for the knees and elbows included only patients with their target lesion located on either the knee or the elbow. Analyses compared BD spray with vehicle and BD spray with AugBD lotion at days 4, 8, 15, and 29. Comparison with AugBD lotion treatment was up to day 14 only, consistent with application time limits in the AugBD lotion product label.18

Results

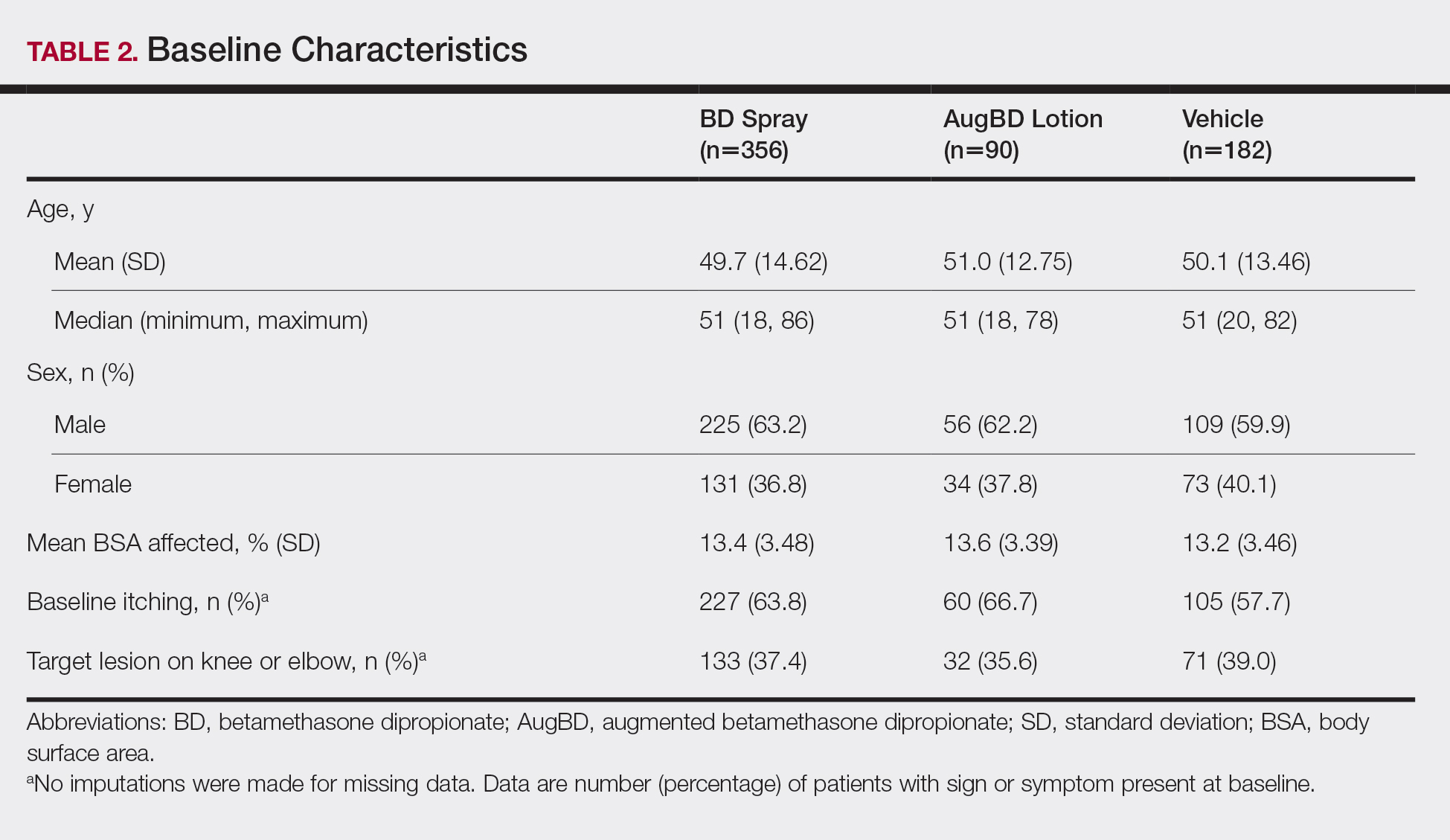

These analyses included data from the 628 patients enrolled in the 2 phase 3 trials. Patients had similar baseline characteristics across treatment groups (Table 2). Itching was the most common cutaneous symptom at baseline, reported by almost two-thirds (n=392, 62.4%) of patients. Of the 628 patients, 236 (37.6%) had a target lesion located on the elbow or knee selected for assessment. The mean baseline body surface area was 13% to 14% across groups.

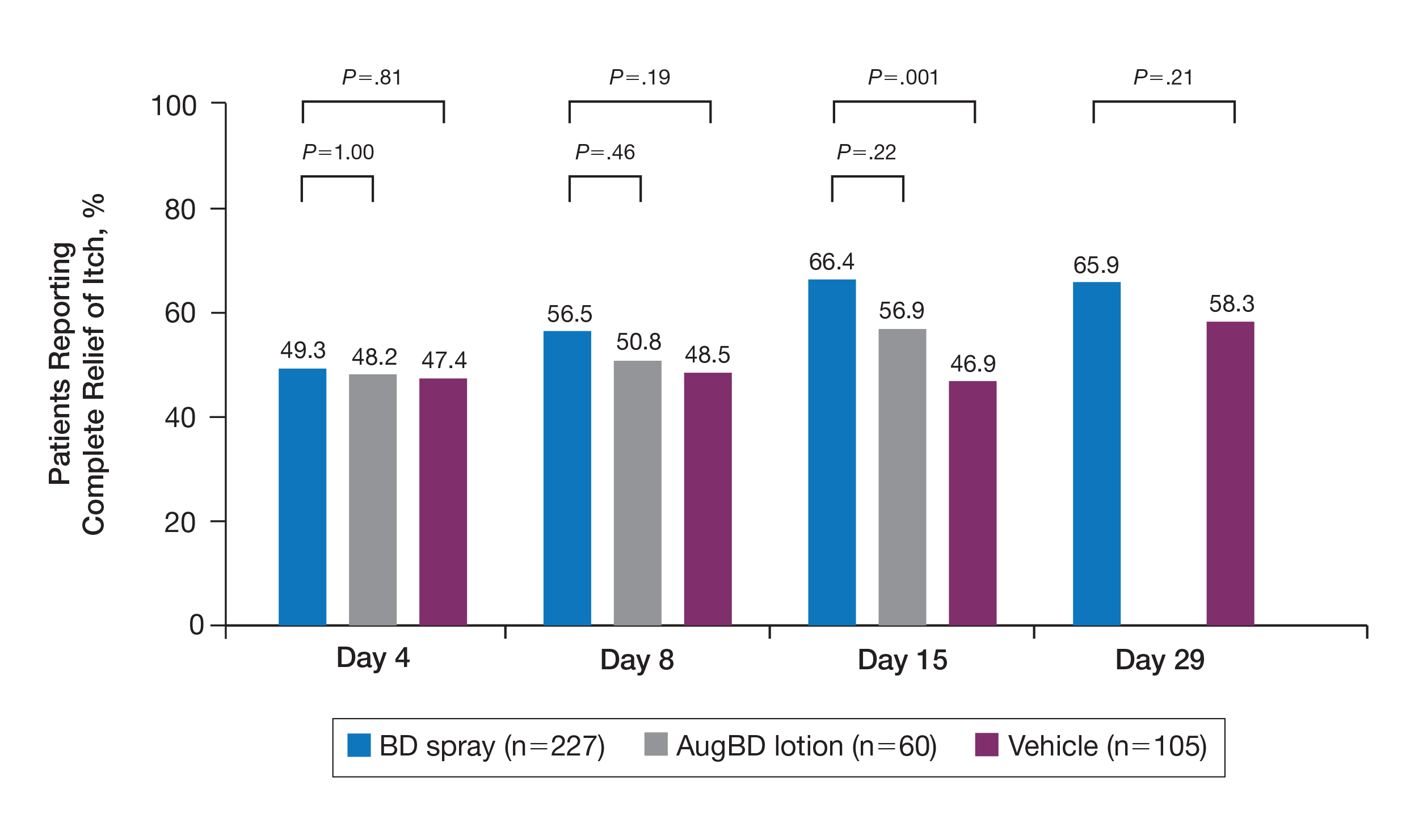

A post hoc analysis was performed on the subgroup of patients who reported itching at baseline (N=392)(eFigure 1). For these patients, almost half were itch free by day 4 across all groups (49.3% BD spray, 48.2% AugBD lotion, and 47.4% vehicle). By the end of treatment, 65.9% of patients using BD spray and 58.3% of patients using vehicle were itch free at day 29, with 56.9% of AugBD lotion patients itch free at day 15.

Application-site pruritus recorded as a treatment-emergent adverse event was seen in low numbers and was similar in proportion between the 2 steroid treatments (7.7% BD spray, 6.7% AugBD lotion, and 14.4% vehicle).

Psoriasis Individual Sign Scores for Knee and Elbow Plaques

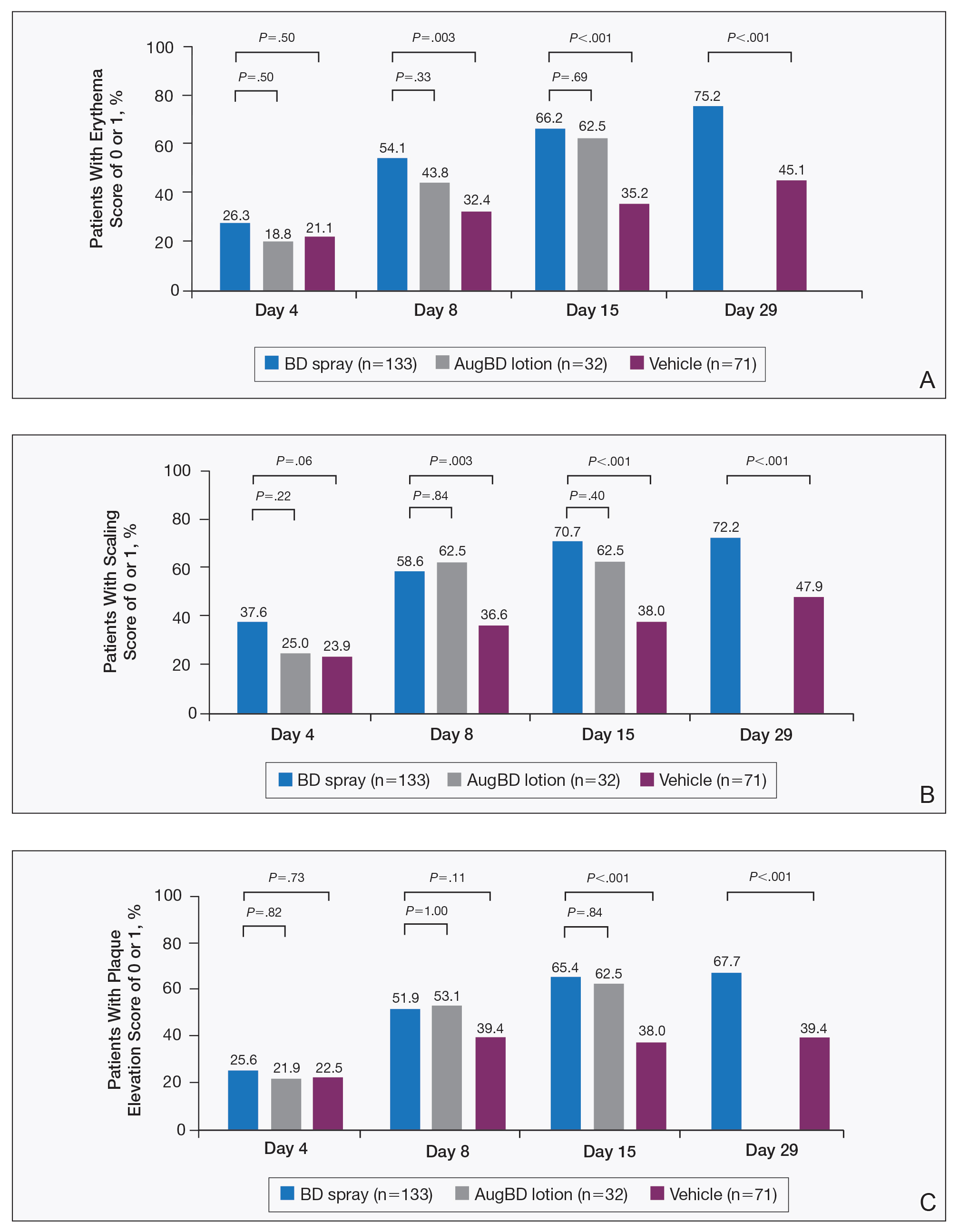

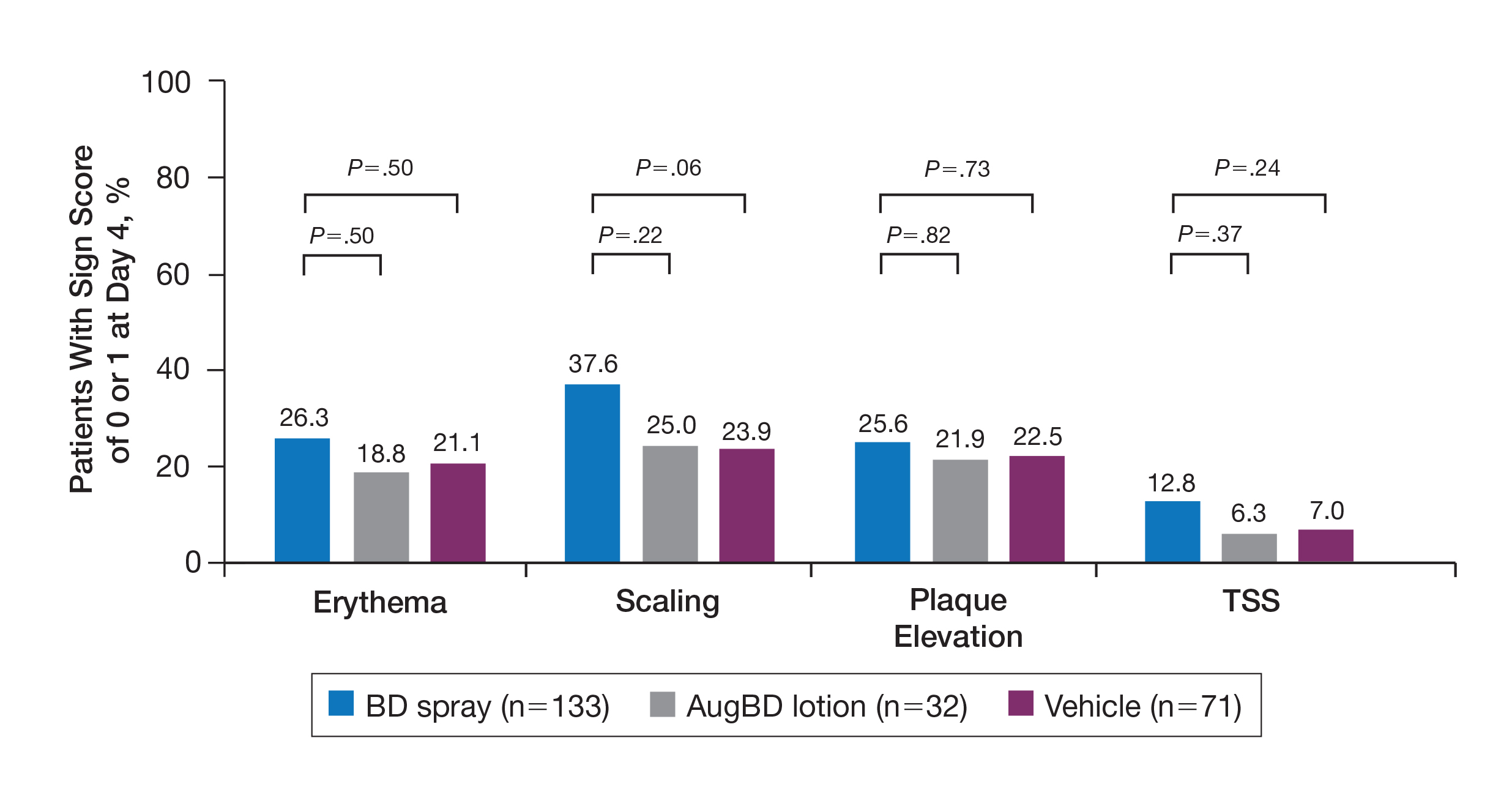

Target lesions located on the knee or elbow represented 37.6% of all target lesions assessed. Efficacy analysis of the pooled data on knee and elbow lesions revealed that BD spray was similar to AugBD lotion in reducing sign scores to 0 or 1 (Figures 1 and 2).

The percentage of patients reporting improvements in erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation scores at day 4

The proportion of patients achieving treatment success (defined as a score of 0 or 1) was comparable for the2 products on day 15 for erythema (66.2% BD spray vs 62.5% AugBD lotion), scaling (70.7% BD spray vs 62.5% AugBD lotion), and plaque elevation (65.4% BD spray vs 62.5% AugBD lotion)(Figure 1). From day 8, BD spray reduced erythema and scaling in significantly more patients than vehicle (P=.003 for both), and BD spray reduced erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation in more patients than vehicle from day 15 (P<.001 for all). No statistically significant difference was found between BD spray and AugBD lotion on erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation scores.

Total Sign Score

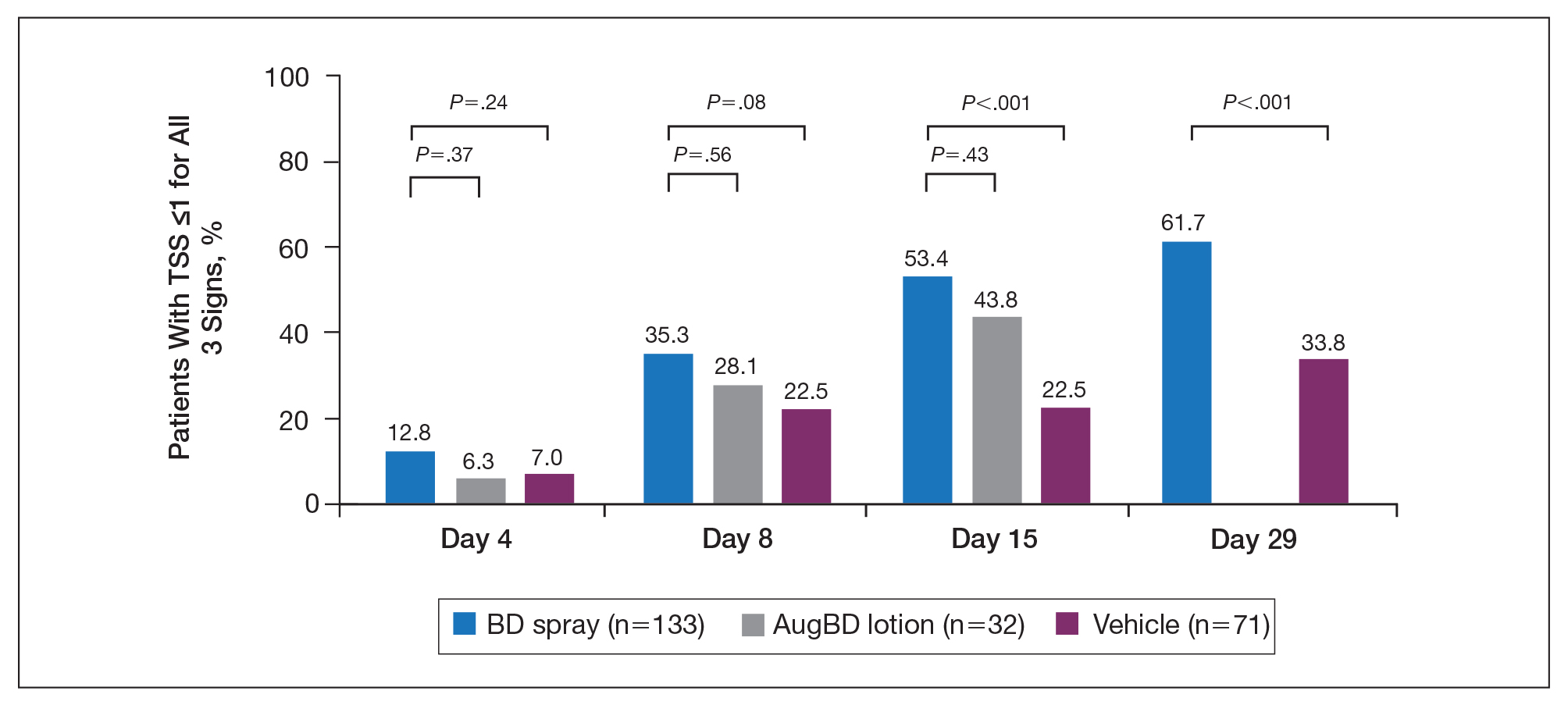

Total sign score results showed that the mean percentage of patients achieving a TSS of 0 or 1 for all signs for lesions located on the knees or elbows was numerically higher for BD spray vs AugBD lotion at day 4, but this difference was not statistically significant (Figure 2). Day 15 outcomes for TSS also showed a numerically greater success rate for BD spray, but again this difference was not statistically significant (53.4% BD spray vs 43.8% AugBD lotion). At days 15 and 29, significantly more patients treated with BD spray achieved TSS of 0 or 1 for all 3 signs compared to those treated with vehicle (P<.001). Improvement in TSS with BD spray continued through to day 29 of the study.

Comment

In these post hoc analyses, mid-potency BD spray demonstrated early relief of itching and early efficacy in the treatment of psoriasis plaques on the elbows and knees with minimal systemic absorption and a low rate of adverse events.

Betamethasone dipropionate spray and its vehicle formulation relieved psoriatic itching with similar efficacy to the superpotent AugBD steroid lotion. Notably, relief was rapid, with approximately half of responding patients reporting relief of itching by day 4. The results seen with vehicle suggest that the emollient formulation of BD spray is responsible for hydrating dry skin, contributing to the relief of this cutaneous symptom. Dry skin can exacerbate itching, and emollients are recognized as being able to alleviate itching by hydrating and soothing the skin.7

The second set of post hoc analyses reported here demonstrated that BD spray was efficacious in clearing the signs of psoriatic lesions on the difficult-to-treat areas of the knees and elbows. Efficacy with BD spray was similar to the superpotent steroid AugBD lotion, with no statistical difference between the 2 products at any time point. Betamethasone dipropionate spray was significantly more effective than its vehicle in reducing the signs of erythema and scaling from day 8 and plaque elevation from day 15.

Rapid relief of symptoms is important for patient comfort and to improve treatment adherence. These analyses showed that by day 4, BD spray resulted in numerically higher percentages of patients achieving a score of 0 or 1 for the individual signs of erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation compared to AugBD lotion. Of particular note, 37.6% of patients treated with BD spray had scaling scores of clear or almost clear by day 4 compared to 25.0% of patients treated with AugBD lotion. Scaling has been consistently reported as the second most bothersome symptom experienced by patients2,3 and has been shown to be associated with decreased quality of life and work productivity.19

Betamethasone dipropionate spray has a rationally designed vehicle, with the formulation selected specifically to maximize penetration of the product through the stratum corneum and retention of BD steroid in the epidermis and upper dermis while reducing absorption into the systemic circulation.14 The reduced absorption into the systemic circulation leads to less vasoconstriction; fewer adverse events; and a “medium potent” VCA designation compared to the “superpotent” designation of the AugBD formulation, despite containing the same active ingredient.

These analyses demonstrate that BD spray is effective at addressing 2 symptoms that patients with psoriasis consider most bothersome: itching and scaling. Notably, BD spray was able to achieve these results rapidly, with many patients experiencing improvements in 4 days. In these analyses, mid-potent BD spray demonstrated similar efficacy to AugBD lotion, a superpotent steroid formulation.

This analysis is limited by being post hoc. Although the statistical methodology is valid, the AugBD lotion arm of the analyses was relatively small compared with the BD spray and vehicle arms, as it was only included in 1 of 2 studies pooled.

Conclusion

Mid-potency BD spray effectively improved the symptom of itching and cleared hard-to-treat lesions on knees and elbows with efficacy similar to a superpotent AugBD formulation but with less systemic absorption. Improvements were seen in erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation. Reductions in psoriatic signs were observed as early as day 4, with continued improvement seen throughout the study period. These findings provide evidence that BD spray can rapidly relieve 2 of the most troublesome symptoms affecting patients with psoriasis (itching and scaling), potentially improving quality of life.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Alix Bennett, PhD, formerly of Promius Pharma, a subsidiary of Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Inc (Princeton, New Jersey), and Jodie Macoun, PhD, of CUBE Information (Katonah, New York), for their review and assistance with the preparation of this manuscript. Manuscript preparation was supported by Promius Pharma (Princeton, New Jersey)(DRL #866).

- About psoriasis. National Psoriasis Foundation website. https://www.psoriasis.org/about-psoriasis. Accessed October 1, 2019.

- Lebwohl MG, Bachelez H, Barker J, et al. Patient perspectives in the management of psoriasis: results from the population-based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis Survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:871-881.e1-30.

- Pariser D, Schenkel B, Carter C, et al; Psoriasis Patient Interview Study Group. A multicenter, non-interventional study to evaluate patient-reported experiences of living with psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:19-26.

- Dickison P, Swain G, Peek JJ, et al. Itching for answers: prevalence and severity of pruritus in psoriasis. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:206-209.

- Bahali AG, Onsun N, Su O, et al. The relationship between pruritus and clinical variables in patients with psoriasis. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:470-473.

- Prignano F, Ricceri F, Pescitelli L, et al. Itch in psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical aspects and treatment options. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2009;2:9-13.

- Dawn A, Yosipovitch G. Treating itch in psoriasis. Dermatol Nurs. 2006;18:227-233.

- Queille-Roussel C, Rosen M, Clonier F, et al. Efficacy and safety of calcipotriol plus betamethasone dipropionate aerosol foam compared with betamethasone 17-valerate-medicated plaster for the treatment of psoriasis. Clin Drug Investig. 2017;37:355-361.

- Betesil [package insert]. Lodi, Italy: IBSA Pharmaceutici Italia S.r.I; 2013.

- Cannavò SP, Guarneri F, Giuffrida R, et al. Evaluation of cutaneous surface parameters in psoriatic patients. Skin Res Technol. 2017;23:41-47.

- Egawa M, Arimoto H, Hirao T, et al. Regional difference of water content in human skin studied by diffuse-reflectance near-infrared spectroscopy: consideration of measurement depth. Appl Spectrosc. 2006;60:24-28.

- van de Kerkhof PC, Reich K, Kavanaugh A, et al. Physician perspectives in the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: results from the population-based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2002-2010.

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al; American Academy of Dermatology. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. section 3. guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:643-659.

- Kircik L, Okumu F, Kandavilli S, et al. Rational vehicle design ensures targeted cutaneous steroid delivery. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10:12-19.

- Fowler JF Jr, Herbert AA, Sugarman J. DFD-01, a novel medium potency betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% emollient spray, demonstrates similar efficacy to augmented betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% lotion for the treatment of moderate plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:154-162.

- Stein Gold L, Jackson JM, Knuckles ML, et al. Improvement in extensive moderate plaque psoriasis with a novel emollient spray formulation of betamethasone dipropionate 0.05. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:334-342.

- Sidgiddi S, Pakunlu RI, Allenby K. Efficacy, safety, and potency of betamethasone dipropionate spray 0.05%: a treatment for adults with mild-to-moderate plaque psoriasis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:14-22.

- Diprolene Lotion (augmented betamethasone dipropionate 0.05%) [package insert]. Kenilworth, NJ: Schering Corporation; 1999.

- Korman NJ, Zhao Y, Pike J, et al. Increased severity of itching, pain, and scaling in psoriasis patients is associated with increased disease severity, reduced quality of life, and reduced work productivity. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21. pii:13030/qt1x16v3dg.

Psoriasis affects approximately 2% to 3% of the US population and is characterized by plaques that are red, scaly, and elevated.1 Cutaneous symptoms of the disease are described by patients as itching, burning, and stinging sensations. Large multinational and US surveys have reported pruritus as patients’ most bothersome symptom, with scaling/flaking reported as the second most bothersome.2,3 Reported incidence rates for itching range from 60.4% to 98.3%, with at least half of these patients reporting daily or constant pruritus.2,4-7 Consequent effects on quality of life include impaired sleep,6 difficulty concentrating, lower sex drive, and depression.7 Despite these findings, pruritus is rarely included in the efficacy assessments of psoriasis treatments. In addition, 2 of the most commonly reported but difficult-to-treat locations for plaques are the outside of the elbows (45%) and the knees (32%),1,2,8 areas where the stratum corneum typically is thicker, less hydrated, and less likely to absorb topical products.9-11 Clinical studies have not focused specifically on these areas when assessing treatments.

Topical corticosteroids have been the mainstay of psoriasis therapy for decades because of their anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative properties.7 One large multinational physician survey indicated that 75% of patients are prescribed topical steroids,12 which are important for first-line treatment and are often maintained as adjunctive therapy in combination with other treatments for patients with extensive disease or recalcitrant lesions.13 Topical corticosteroids are ranked into different classes based on their vasoconstrictor assay (VCA), a measure of skin blanching used as a marker for vasoconstriction. Topical agents with VCA ratings of mid-potency or superpotency are generally recommended for initial therapy, with superpotent agents required for the treatment of thick chronic plaques. However, longer durations of use may contribute to systemic absorption and adverse events.13 The vehicle composition is important for corticosteroid delivery and retention at the site of pathology, contributing to the efficacy of the steroid.13,14 Selecting the appropriate steroid and vehicle is important to maximize efficacy and minimize adverse events.

Betamethasone dipropionate (BD) spray 0.05% is an emollient formulation of 0.05% BD that can be sprayed onto psoriatic plaques. The BD spray formulation was designed to penetrate the stratum corneum and be retained within the dermis and epidermis, the site of T-cell activity that drives the psoriatic disease process.14 In 2 phase 3 studies, BD spray demonstrated the ability to reduce the signs of plaque psoriasis with indication of improvement by day 4.15,16 These studies also showed improvement in the local cutaneous symptoms of itching, burning and stinging, and pain. As a mid-potent steroid, BD spray displays less systemic absorption but similar efficacy compared to a superpotent augmented BD (AugBD) lotion in relieving the signs and symptoms of plaque psoriasis.15-17

The objective of the current investigation was to assess the ability of BD spray to relieve itching and to clear plaque psoriasis on the knees and elbows utilizing post hoc analyses of the 2 phase 3 trials. The goal of these analyses was to demonstrate BD spray as effective at relieving the most troublesome signs and symptoms affecting patients with plaque psoriasis.

Methods

Two phase 3 studies were conducted to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of BD spray.15,16 The design of the studies was similar15,16 to allow the data to be pooled for post hoc analyses.

Both were US multicenter, randomized, vehicle-controlled, double-blind, parallel-group studies comparing the safety and efficacy of BD spray 0.05% (Sernivo, Promius Pharma) with its vehicle formulation spray (identical to BD spray, but lacking the active steroid component).15,16 One of the studies also compared BD spray with an AugBD lotion 0.05% (Diprolene,Merck & Co). Adults with moderate plaque psoriasis (investigator global assessment of 3; 10%–20% body surface area) were randomized to apply BD spray, vehicle spray, or AugBD lotion (1 study only) twice daily to all affected areas, excluding the face, scalp, and intertriginous areas for 28 days (BD spray and vehicle) or 14 days (AugBD lotion, per product label).15

Assessments

Two post hoc analyses were conducted on data pooled from the 2 phase 3 trials: (1) incidence of itching, and (2) total sign score (TSS) for lesions located on the knees and elbows.

Itching

Itching was assessed proactively by asking patients if they were experiencing itching (yes/no) at each visit (baseline and days 4, 8, 15, and 29) or had experienced itching since their last visit. As itching could be an adverse event of topical application, application-site pruritus was also recorded.

Total Sign Score

For each patient, a target plaque was selected that was representative of their psoriasis. The plaque was assessed on a 3-point grading scale for each of 3 key signs of plaque psoriasis: erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation (Table 1) at baseline and days 4, 8, 15, and 29. Total sign score was calculated by summing the scores for these 3 signs, resulting in a score ranging from 0 to 9. Treatment success was measured as (1) achieving a score of 0 or 1 (ie, reducing the plaque to clear or slight to mild) for the individual signs of erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation; and (2) achieving a TSS of 0 or 1 for all 3 signs—erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation—for each target lesion. Total sign score was assessed proactively for all patients.15,16 The post hoc analysis reported here examined patients whose target lesion was located on either the knee or the elbow.

Statistical Analyses

Because both study protocols were identical, data were pooled from the 2 phase 3 trials. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS Institute). Two-sided hypothesis testing was conducted for all analyses using a significance level of P=.05. Post hoc analyses used Fisher exact test. No imputations were made for missing data.

Statistical analyses of itching compared the incidence of itching at each assessment time point (baseline and days 4, 8, 15, and 29) between BD spray and vehicle and between BD spray and AugBD lotion. Additional analysis included a statistical test on the incidence of itching in the subgroup of patients who reported itching at baseline.

Statistical analyses for the knees and elbows included only patients with their target lesion located on either the knee or the elbow. Analyses compared BD spray with vehicle and BD spray with AugBD lotion at days 4, 8, 15, and 29. Comparison with AugBD lotion treatment was up to day 14 only, consistent with application time limits in the AugBD lotion product label.18

Results

These analyses included data from the 628 patients enrolled in the 2 phase 3 trials. Patients had similar baseline characteristics across treatment groups (Table 2). Itching was the most common cutaneous symptom at baseline, reported by almost two-thirds (n=392, 62.4%) of patients. Of the 628 patients, 236 (37.6%) had a target lesion located on the elbow or knee selected for assessment. The mean baseline body surface area was 13% to 14% across groups.

A post hoc analysis was performed on the subgroup of patients who reported itching at baseline (N=392)(eFigure 1). For these patients, almost half were itch free by day 4 across all groups (49.3% BD spray, 48.2% AugBD lotion, and 47.4% vehicle). By the end of treatment, 65.9% of patients using BD spray and 58.3% of patients using vehicle were itch free at day 29, with 56.9% of AugBD lotion patients itch free at day 15.

Application-site pruritus recorded as a treatment-emergent adverse event was seen in low numbers and was similar in proportion between the 2 steroid treatments (7.7% BD spray, 6.7% AugBD lotion, and 14.4% vehicle).

Psoriasis Individual Sign Scores for Knee and Elbow Plaques

Target lesions located on the knee or elbow represented 37.6% of all target lesions assessed. Efficacy analysis of the pooled data on knee and elbow lesions revealed that BD spray was similar to AugBD lotion in reducing sign scores to 0 or 1 (Figures 1 and 2).

The percentage of patients reporting improvements in erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation scores at day 4

The proportion of patients achieving treatment success (defined as a score of 0 or 1) was comparable for the2 products on day 15 for erythema (66.2% BD spray vs 62.5% AugBD lotion), scaling (70.7% BD spray vs 62.5% AugBD lotion), and plaque elevation (65.4% BD spray vs 62.5% AugBD lotion)(Figure 1). From day 8, BD spray reduced erythema and scaling in significantly more patients than vehicle (P=.003 for both), and BD spray reduced erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation in more patients than vehicle from day 15 (P<.001 for all). No statistically significant difference was found between BD spray and AugBD lotion on erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation scores.

Total Sign Score

Total sign score results showed that the mean percentage of patients achieving a TSS of 0 or 1 for all signs for lesions located on the knees or elbows was numerically higher for BD spray vs AugBD lotion at day 4, but this difference was not statistically significant (Figure 2). Day 15 outcomes for TSS also showed a numerically greater success rate for BD spray, but again this difference was not statistically significant (53.4% BD spray vs 43.8% AugBD lotion). At days 15 and 29, significantly more patients treated with BD spray achieved TSS of 0 or 1 for all 3 signs compared to those treated with vehicle (P<.001). Improvement in TSS with BD spray continued through to day 29 of the study.

Comment

In these post hoc analyses, mid-potency BD spray demonstrated early relief of itching and early efficacy in the treatment of psoriasis plaques on the elbows and knees with minimal systemic absorption and a low rate of adverse events.

Betamethasone dipropionate spray and its vehicle formulation relieved psoriatic itching with similar efficacy to the superpotent AugBD steroid lotion. Notably, relief was rapid, with approximately half of responding patients reporting relief of itching by day 4. The results seen with vehicle suggest that the emollient formulation of BD spray is responsible for hydrating dry skin, contributing to the relief of this cutaneous symptom. Dry skin can exacerbate itching, and emollients are recognized as being able to alleviate itching by hydrating and soothing the skin.7

The second set of post hoc analyses reported here demonstrated that BD spray was efficacious in clearing the signs of psoriatic lesions on the difficult-to-treat areas of the knees and elbows. Efficacy with BD spray was similar to the superpotent steroid AugBD lotion, with no statistical difference between the 2 products at any time point. Betamethasone dipropionate spray was significantly more effective than its vehicle in reducing the signs of erythema and scaling from day 8 and plaque elevation from day 15.

Rapid relief of symptoms is important for patient comfort and to improve treatment adherence. These analyses showed that by day 4, BD spray resulted in numerically higher percentages of patients achieving a score of 0 or 1 for the individual signs of erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation compared to AugBD lotion. Of particular note, 37.6% of patients treated with BD spray had scaling scores of clear or almost clear by day 4 compared to 25.0% of patients treated with AugBD lotion. Scaling has been consistently reported as the second most bothersome symptom experienced by patients2,3 and has been shown to be associated with decreased quality of life and work productivity.19

Betamethasone dipropionate spray has a rationally designed vehicle, with the formulation selected specifically to maximize penetration of the product through the stratum corneum and retention of BD steroid in the epidermis and upper dermis while reducing absorption into the systemic circulation.14 The reduced absorption into the systemic circulation leads to less vasoconstriction; fewer adverse events; and a “medium potent” VCA designation compared to the “superpotent” designation of the AugBD formulation, despite containing the same active ingredient.

These analyses demonstrate that BD spray is effective at addressing 2 symptoms that patients with psoriasis consider most bothersome: itching and scaling. Notably, BD spray was able to achieve these results rapidly, with many patients experiencing improvements in 4 days. In these analyses, mid-potent BD spray demonstrated similar efficacy to AugBD lotion, a superpotent steroid formulation.

This analysis is limited by being post hoc. Although the statistical methodology is valid, the AugBD lotion arm of the analyses was relatively small compared with the BD spray and vehicle arms, as it was only included in 1 of 2 studies pooled.

Conclusion

Mid-potency BD spray effectively improved the symptom of itching and cleared hard-to-treat lesions on knees and elbows with efficacy similar to a superpotent AugBD formulation but with less systemic absorption. Improvements were seen in erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation. Reductions in psoriatic signs were observed as early as day 4, with continued improvement seen throughout the study period. These findings provide evidence that BD spray can rapidly relieve 2 of the most troublesome symptoms affecting patients with psoriasis (itching and scaling), potentially improving quality of life.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Alix Bennett, PhD, formerly of Promius Pharma, a subsidiary of Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Inc (Princeton, New Jersey), and Jodie Macoun, PhD, of CUBE Information (Katonah, New York), for their review and assistance with the preparation of this manuscript. Manuscript preparation was supported by Promius Pharma (Princeton, New Jersey)(DRL #866).

Psoriasis affects approximately 2% to 3% of the US population and is characterized by plaques that are red, scaly, and elevated.1 Cutaneous symptoms of the disease are described by patients as itching, burning, and stinging sensations. Large multinational and US surveys have reported pruritus as patients’ most bothersome symptom, with scaling/flaking reported as the second most bothersome.2,3 Reported incidence rates for itching range from 60.4% to 98.3%, with at least half of these patients reporting daily or constant pruritus.2,4-7 Consequent effects on quality of life include impaired sleep,6 difficulty concentrating, lower sex drive, and depression.7 Despite these findings, pruritus is rarely included in the efficacy assessments of psoriasis treatments. In addition, 2 of the most commonly reported but difficult-to-treat locations for plaques are the outside of the elbows (45%) and the knees (32%),1,2,8 areas where the stratum corneum typically is thicker, less hydrated, and less likely to absorb topical products.9-11 Clinical studies have not focused specifically on these areas when assessing treatments.

Topical corticosteroids have been the mainstay of psoriasis therapy for decades because of their anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative properties.7 One large multinational physician survey indicated that 75% of patients are prescribed topical steroids,12 which are important for first-line treatment and are often maintained as adjunctive therapy in combination with other treatments for patients with extensive disease or recalcitrant lesions.13 Topical corticosteroids are ranked into different classes based on their vasoconstrictor assay (VCA), a measure of skin blanching used as a marker for vasoconstriction. Topical agents with VCA ratings of mid-potency or superpotency are generally recommended for initial therapy, with superpotent agents required for the treatment of thick chronic plaques. However, longer durations of use may contribute to systemic absorption and adverse events.13 The vehicle composition is important for corticosteroid delivery and retention at the site of pathology, contributing to the efficacy of the steroid.13,14 Selecting the appropriate steroid and vehicle is important to maximize efficacy and minimize adverse events.

Betamethasone dipropionate (BD) spray 0.05% is an emollient formulation of 0.05% BD that can be sprayed onto psoriatic plaques. The BD spray formulation was designed to penetrate the stratum corneum and be retained within the dermis and epidermis, the site of T-cell activity that drives the psoriatic disease process.14 In 2 phase 3 studies, BD spray demonstrated the ability to reduce the signs of plaque psoriasis with indication of improvement by day 4.15,16 These studies also showed improvement in the local cutaneous symptoms of itching, burning and stinging, and pain. As a mid-potent steroid, BD spray displays less systemic absorption but similar efficacy compared to a superpotent augmented BD (AugBD) lotion in relieving the signs and symptoms of plaque psoriasis.15-17

The objective of the current investigation was to assess the ability of BD spray to relieve itching and to clear plaque psoriasis on the knees and elbows utilizing post hoc analyses of the 2 phase 3 trials. The goal of these analyses was to demonstrate BD spray as effective at relieving the most troublesome signs and symptoms affecting patients with plaque psoriasis.

Methods

Two phase 3 studies were conducted to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of BD spray.15,16 The design of the studies was similar15,16 to allow the data to be pooled for post hoc analyses.

Both were US multicenter, randomized, vehicle-controlled, double-blind, parallel-group studies comparing the safety and efficacy of BD spray 0.05% (Sernivo, Promius Pharma) with its vehicle formulation spray (identical to BD spray, but lacking the active steroid component).15,16 One of the studies also compared BD spray with an AugBD lotion 0.05% (Diprolene,Merck & Co). Adults with moderate plaque psoriasis (investigator global assessment of 3; 10%–20% body surface area) were randomized to apply BD spray, vehicle spray, or AugBD lotion (1 study only) twice daily to all affected areas, excluding the face, scalp, and intertriginous areas for 28 days (BD spray and vehicle) or 14 days (AugBD lotion, per product label).15

Assessments

Two post hoc analyses were conducted on data pooled from the 2 phase 3 trials: (1) incidence of itching, and (2) total sign score (TSS) for lesions located on the knees and elbows.

Itching

Itching was assessed proactively by asking patients if they were experiencing itching (yes/no) at each visit (baseline and days 4, 8, 15, and 29) or had experienced itching since their last visit. As itching could be an adverse event of topical application, application-site pruritus was also recorded.

Total Sign Score

For each patient, a target plaque was selected that was representative of their psoriasis. The plaque was assessed on a 3-point grading scale for each of 3 key signs of plaque psoriasis: erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation (Table 1) at baseline and days 4, 8, 15, and 29. Total sign score was calculated by summing the scores for these 3 signs, resulting in a score ranging from 0 to 9. Treatment success was measured as (1) achieving a score of 0 or 1 (ie, reducing the plaque to clear or slight to mild) for the individual signs of erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation; and (2) achieving a TSS of 0 or 1 for all 3 signs—erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation—for each target lesion. Total sign score was assessed proactively for all patients.15,16 The post hoc analysis reported here examined patients whose target lesion was located on either the knee or the elbow.

Statistical Analyses

Because both study protocols were identical, data were pooled from the 2 phase 3 trials. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS Institute). Two-sided hypothesis testing was conducted for all analyses using a significance level of P=.05. Post hoc analyses used Fisher exact test. No imputations were made for missing data.

Statistical analyses of itching compared the incidence of itching at each assessment time point (baseline and days 4, 8, 15, and 29) between BD spray and vehicle and between BD spray and AugBD lotion. Additional analysis included a statistical test on the incidence of itching in the subgroup of patients who reported itching at baseline.

Statistical analyses for the knees and elbows included only patients with their target lesion located on either the knee or the elbow. Analyses compared BD spray with vehicle and BD spray with AugBD lotion at days 4, 8, 15, and 29. Comparison with AugBD lotion treatment was up to day 14 only, consistent with application time limits in the AugBD lotion product label.18

Results

These analyses included data from the 628 patients enrolled in the 2 phase 3 trials. Patients had similar baseline characteristics across treatment groups (Table 2). Itching was the most common cutaneous symptom at baseline, reported by almost two-thirds (n=392, 62.4%) of patients. Of the 628 patients, 236 (37.6%) had a target lesion located on the elbow or knee selected for assessment. The mean baseline body surface area was 13% to 14% across groups.

A post hoc analysis was performed on the subgroup of patients who reported itching at baseline (N=392)(eFigure 1). For these patients, almost half were itch free by day 4 across all groups (49.3% BD spray, 48.2% AugBD lotion, and 47.4% vehicle). By the end of treatment, 65.9% of patients using BD spray and 58.3% of patients using vehicle were itch free at day 29, with 56.9% of AugBD lotion patients itch free at day 15.

Application-site pruritus recorded as a treatment-emergent adverse event was seen in low numbers and was similar in proportion between the 2 steroid treatments (7.7% BD spray, 6.7% AugBD lotion, and 14.4% vehicle).

Psoriasis Individual Sign Scores for Knee and Elbow Plaques

Target lesions located on the knee or elbow represented 37.6% of all target lesions assessed. Efficacy analysis of the pooled data on knee and elbow lesions revealed that BD spray was similar to AugBD lotion in reducing sign scores to 0 or 1 (Figures 1 and 2).

The percentage of patients reporting improvements in erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation scores at day 4

The proportion of patients achieving treatment success (defined as a score of 0 or 1) was comparable for the2 products on day 15 for erythema (66.2% BD spray vs 62.5% AugBD lotion), scaling (70.7% BD spray vs 62.5% AugBD lotion), and plaque elevation (65.4% BD spray vs 62.5% AugBD lotion)(Figure 1). From day 8, BD spray reduced erythema and scaling in significantly more patients than vehicle (P=.003 for both), and BD spray reduced erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation in more patients than vehicle from day 15 (P<.001 for all). No statistically significant difference was found between BD spray and AugBD lotion on erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation scores.

Total Sign Score

Total sign score results showed that the mean percentage of patients achieving a TSS of 0 or 1 for all signs for lesions located on the knees or elbows was numerically higher for BD spray vs AugBD lotion at day 4, but this difference was not statistically significant (Figure 2). Day 15 outcomes for TSS also showed a numerically greater success rate for BD spray, but again this difference was not statistically significant (53.4% BD spray vs 43.8% AugBD lotion). At days 15 and 29, significantly more patients treated with BD spray achieved TSS of 0 or 1 for all 3 signs compared to those treated with vehicle (P<.001). Improvement in TSS with BD spray continued through to day 29 of the study.

Comment

In these post hoc analyses, mid-potency BD spray demonstrated early relief of itching and early efficacy in the treatment of psoriasis plaques on the elbows and knees with minimal systemic absorption and a low rate of adverse events.

Betamethasone dipropionate spray and its vehicle formulation relieved psoriatic itching with similar efficacy to the superpotent AugBD steroid lotion. Notably, relief was rapid, with approximately half of responding patients reporting relief of itching by day 4. The results seen with vehicle suggest that the emollient formulation of BD spray is responsible for hydrating dry skin, contributing to the relief of this cutaneous symptom. Dry skin can exacerbate itching, and emollients are recognized as being able to alleviate itching by hydrating and soothing the skin.7

The second set of post hoc analyses reported here demonstrated that BD spray was efficacious in clearing the signs of psoriatic lesions on the difficult-to-treat areas of the knees and elbows. Efficacy with BD spray was similar to the superpotent steroid AugBD lotion, with no statistical difference between the 2 products at any time point. Betamethasone dipropionate spray was significantly more effective than its vehicle in reducing the signs of erythema and scaling from day 8 and plaque elevation from day 15.

Rapid relief of symptoms is important for patient comfort and to improve treatment adherence. These analyses showed that by day 4, BD spray resulted in numerically higher percentages of patients achieving a score of 0 or 1 for the individual signs of erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation compared to AugBD lotion. Of particular note, 37.6% of patients treated with BD spray had scaling scores of clear or almost clear by day 4 compared to 25.0% of patients treated with AugBD lotion. Scaling has been consistently reported as the second most bothersome symptom experienced by patients2,3 and has been shown to be associated with decreased quality of life and work productivity.19

Betamethasone dipropionate spray has a rationally designed vehicle, with the formulation selected specifically to maximize penetration of the product through the stratum corneum and retention of BD steroid in the epidermis and upper dermis while reducing absorption into the systemic circulation.14 The reduced absorption into the systemic circulation leads to less vasoconstriction; fewer adverse events; and a “medium potent” VCA designation compared to the “superpotent” designation of the AugBD formulation, despite containing the same active ingredient.

These analyses demonstrate that BD spray is effective at addressing 2 symptoms that patients with psoriasis consider most bothersome: itching and scaling. Notably, BD spray was able to achieve these results rapidly, with many patients experiencing improvements in 4 days. In these analyses, mid-potent BD spray demonstrated similar efficacy to AugBD lotion, a superpotent steroid formulation.

This analysis is limited by being post hoc. Although the statistical methodology is valid, the AugBD lotion arm of the analyses was relatively small compared with the BD spray and vehicle arms, as it was only included in 1 of 2 studies pooled.

Conclusion

Mid-potency BD spray effectively improved the symptom of itching and cleared hard-to-treat lesions on knees and elbows with efficacy similar to a superpotent AugBD formulation but with less systemic absorption. Improvements were seen in erythema, scaling, and plaque elevation. Reductions in psoriatic signs were observed as early as day 4, with continued improvement seen throughout the study period. These findings provide evidence that BD spray can rapidly relieve 2 of the most troublesome symptoms affecting patients with psoriasis (itching and scaling), potentially improving quality of life.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Alix Bennett, PhD, formerly of Promius Pharma, a subsidiary of Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Inc (Princeton, New Jersey), and Jodie Macoun, PhD, of CUBE Information (Katonah, New York), for their review and assistance with the preparation of this manuscript. Manuscript preparation was supported by Promius Pharma (Princeton, New Jersey)(DRL #866).

- About psoriasis. National Psoriasis Foundation website. https://www.psoriasis.org/about-psoriasis. Accessed October 1, 2019.

- Lebwohl MG, Bachelez H, Barker J, et al. Patient perspectives in the management of psoriasis: results from the population-based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis Survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:871-881.e1-30.

- Pariser D, Schenkel B, Carter C, et al; Psoriasis Patient Interview Study Group. A multicenter, non-interventional study to evaluate patient-reported experiences of living with psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:19-26.

- Dickison P, Swain G, Peek JJ, et al. Itching for answers: prevalence and severity of pruritus in psoriasis. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:206-209.

- Bahali AG, Onsun N, Su O, et al. The relationship between pruritus and clinical variables in patients with psoriasis. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:470-473.

- Prignano F, Ricceri F, Pescitelli L, et al. Itch in psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical aspects and treatment options. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2009;2:9-13.

- Dawn A, Yosipovitch G. Treating itch in psoriasis. Dermatol Nurs. 2006;18:227-233.

- Queille-Roussel C, Rosen M, Clonier F, et al. Efficacy and safety of calcipotriol plus betamethasone dipropionate aerosol foam compared with betamethasone 17-valerate-medicated plaster for the treatment of psoriasis. Clin Drug Investig. 2017;37:355-361.

- Betesil [package insert]. Lodi, Italy: IBSA Pharmaceutici Italia S.r.I; 2013.

- Cannavò SP, Guarneri F, Giuffrida R, et al. Evaluation of cutaneous surface parameters in psoriatic patients. Skin Res Technol. 2017;23:41-47.

- Egawa M, Arimoto H, Hirao T, et al. Regional difference of water content in human skin studied by diffuse-reflectance near-infrared spectroscopy: consideration of measurement depth. Appl Spectrosc. 2006;60:24-28.

- van de Kerkhof PC, Reich K, Kavanaugh A, et al. Physician perspectives in the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: results from the population-based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2002-2010.

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al; American Academy of Dermatology. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. section 3. guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:643-659.

- Kircik L, Okumu F, Kandavilli S, et al. Rational vehicle design ensures targeted cutaneous steroid delivery. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10:12-19.

- Fowler JF Jr, Herbert AA, Sugarman J. DFD-01, a novel medium potency betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% emollient spray, demonstrates similar efficacy to augmented betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% lotion for the treatment of moderate plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:154-162.

- Stein Gold L, Jackson JM, Knuckles ML, et al. Improvement in extensive moderate plaque psoriasis with a novel emollient spray formulation of betamethasone dipropionate 0.05. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:334-342.

- Sidgiddi S, Pakunlu RI, Allenby K. Efficacy, safety, and potency of betamethasone dipropionate spray 0.05%: a treatment for adults with mild-to-moderate plaque psoriasis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:14-22.

- Diprolene Lotion (augmented betamethasone dipropionate 0.05%) [package insert]. Kenilworth, NJ: Schering Corporation; 1999.

- Korman NJ, Zhao Y, Pike J, et al. Increased severity of itching, pain, and scaling in psoriasis patients is associated with increased disease severity, reduced quality of life, and reduced work productivity. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21. pii:13030/qt1x16v3dg.

- About psoriasis. National Psoriasis Foundation website. https://www.psoriasis.org/about-psoriasis. Accessed October 1, 2019.

- Lebwohl MG, Bachelez H, Barker J, et al. Patient perspectives in the management of psoriasis: results from the population-based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis Survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:871-881.e1-30.

- Pariser D, Schenkel B, Carter C, et al; Psoriasis Patient Interview Study Group. A multicenter, non-interventional study to evaluate patient-reported experiences of living with psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:19-26.

- Dickison P, Swain G, Peek JJ, et al. Itching for answers: prevalence and severity of pruritus in psoriasis. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:206-209.

- Bahali AG, Onsun N, Su O, et al. The relationship between pruritus and clinical variables in patients with psoriasis. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:470-473.

- Prignano F, Ricceri F, Pescitelli L, et al. Itch in psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical aspects and treatment options. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2009;2:9-13.

- Dawn A, Yosipovitch G. Treating itch in psoriasis. Dermatol Nurs. 2006;18:227-233.

- Queille-Roussel C, Rosen M, Clonier F, et al. Efficacy and safety of calcipotriol plus betamethasone dipropionate aerosol foam compared with betamethasone 17-valerate-medicated plaster for the treatment of psoriasis. Clin Drug Investig. 2017;37:355-361.

- Betesil [package insert]. Lodi, Italy: IBSA Pharmaceutici Italia S.r.I; 2013.

- Cannavò SP, Guarneri F, Giuffrida R, et al. Evaluation of cutaneous surface parameters in psoriatic patients. Skin Res Technol. 2017;23:41-47.

- Egawa M, Arimoto H, Hirao T, et al. Regional difference of water content in human skin studied by diffuse-reflectance near-infrared spectroscopy: consideration of measurement depth. Appl Spectrosc. 2006;60:24-28.

- van de Kerkhof PC, Reich K, Kavanaugh A, et al. Physician perspectives in the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: results from the population-based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2002-2010.

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al; American Academy of Dermatology. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. section 3. guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:643-659.

- Kircik L, Okumu F, Kandavilli S, et al. Rational vehicle design ensures targeted cutaneous steroid delivery. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10:12-19.

- Fowler JF Jr, Herbert AA, Sugarman J. DFD-01, a novel medium potency betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% emollient spray, demonstrates similar efficacy to augmented betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% lotion for the treatment of moderate plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:154-162.

- Stein Gold L, Jackson JM, Knuckles ML, et al. Improvement in extensive moderate plaque psoriasis with a novel emollient spray formulation of betamethasone dipropionate 0.05. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:334-342.

- Sidgiddi S, Pakunlu RI, Allenby K. Efficacy, safety, and potency of betamethasone dipropionate spray 0.05%: a treatment for adults with mild-to-moderate plaque psoriasis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:14-22.

- Diprolene Lotion (augmented betamethasone dipropionate 0.05%) [package insert]. Kenilworth, NJ: Schering Corporation; 1999.

- Korman NJ, Zhao Y, Pike J, et al. Increased severity of itching, pain, and scaling in psoriasis patients is associated with increased disease severity, reduced quality of life, and reduced work productivity. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21. pii:13030/qt1x16v3dg.

Practice Points

- Pruritus is one of the most bothersome symptoms of psoriasis; plaques located on the knees and elbows remain hard to treat.

- Topical corticosteroids are the initial form of treatment of localized plaque psoriasis.

- The choice of vehicle can change the penetration of the medication, alter the efficacy, and minimize side effects of the drug.

- Betamethasone dipropionate spray 0.05% is a mid-potent corticosteroid that provides fast symptom relief and early efficacy in clearing plaques, similar to a high-potency topical corticosteroid but with less potential for systemic absorption and adverse events.

Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitors May Reduce Cardiovascular Morbidity in Patients With Psoriasis

The connection between psoriasis and increased major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) has been well studied. 1,2 Although treatment of psoriasis can improve skin and joint symptoms, it is less clear whether therapies may mitigate the increased risk for cardiovascular comorbidities. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors in particular have been studied with great interest given the role of TNF in vascular and metabolic functions. 3 Using a retrospective cohort design, Wu and colleagues 4 examined if treatment with TNF inhibitors in patients with psoriasis would be associated with a lower risk for MACEs compared to phototherapy. Results suggested a significantly lower hazard of MACEs in patients using TNF inhibitors vs patients treated with phototherapy (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.77; P = .046). Moreover, based on these findings, they calculated that treating approximately 161 patients with TNF inhibitors rather than phototherapy would result in 1 less MACE per year overall. 4

Patients with psoriasis have been shown to have a greater noncalcified coronary plaque burden and prevalence of high-risk plaque compared to healthy patients.5 Lerman and colleagues5 measured the coronary plaque burden of 105 patients with psoriasis and 25 healthy volunteers using coronary computed tomography angiography. Although the patients were on average 10 years younger and had lower cardiovascular risk as measured by traditional risk scores, patients with psoriasis were found to have a greater noncalcified coronary plaque burden compared to 100 patients with hyperlipidemia. This burden was associated with an increased prevalence of high-risk plaques. Furthermore, in patients followed for 1 year, improvements in psoriasis severity were associated with reductions in noncalcified coronary plaque burden, though this finding was across all treatment modalities. However, there was no significant difference in calcified coronary plaque burden associated with reduced psoriasis severity.5

Moreover, Pina et al6 conducted a prospective study evaluating the use of the TNF inhibitor adalimumab to improve endothelial function and arterial stiffness in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Among 29 patients, they found a significant improvement in endothelial function as measured by flow-mediated dilatation after 6 months of adalimumab therapy, with a mean increase from 6.19% to 7.46% (P=.008). They also reported decreases in arterial stiffness by pulse wave velocity (P=.03). Despite a small sample size, these findings provide 2 potential mechanisms by which TNF inhibitor therapy may reduce the risk for cardiovascular events.6

A retrospective cohort study evaluating data from the Kaiser Permanente Southern California health plan assessed whether TNF inhibitor therapy was associated with a lower risk for MACE in patients with psoriasis.7 A total of 18,194 patients were included; of these, 1463 received TNF inhibitor therapy for at least 2 months. After controlling for other variables, including age at psoriasis diagnosis, sex, race/ethnicity, and other cardiovascular risk factors (eg, history of smoking or alcohol use; use of clopidogrel, antihypertensive agents, antihyperlipidemics, or anticoagulants), patients in the TNF inhibitor cohort demonstrated a significantly lower MACE hazard ratio compared to patients treated with topicals (hazard ratio, 0.80; 95% confidence interval, 0.66-0.98; P<.05).7

Conversely, a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 107 patients found no difference in vascular inflammation of the ascending aorta and the carotids after 16 weeks of adalimumab treatment vs placebo. In this study, however, most patients had only moderate psoriasis based on a mean psoriasis area and severity index score of 9.8.8 Given studies finding higher risk burden in patients with more severe skin disease,2 it is possible that the effect of TNF inhibitor therapy may not be as pronounced in patients with less skin involvement. There was a significant effect on C-reactive protein levels in patients receiving TNF inhibitor therapy compared to placebo at 16 weeks (P=.012), suggesting TNF does play some role in systemic inflammation, and it is possible it may exert cardiovascular effects through a mechanism other than vascular inflammation.8

A second double-blind, randomized trial reported similar results.9 Among 97 patients randomized to receive adalimumab, placebo, or phototherapy, no significant difference in vascular inflammation was found after 12 weeks of therapy. In contrast, levels of C-reactive protein, IL-6, and glycoprotein acetylation were markedly reduced. The authors also reported adverse effects of adalimumab therapy on lipid metabolism with reduced cholesterol efflux capacity, a marker of ability of high-density-lipoprotein particles to perform reverse cholesterol transport, and high-density-lipoprotein particles, suggesting these effects may counteract some of the anti-inflammatory effects of TNF inhibitors.9

A growing body of data regarding the effect of TNF inhibitors on cardiovascular morbidity in patients with psoriasis is being collected, but no strong conclusions can be made. Given the disconnect of findings across these studies, it is possible that we have yet to elucidate the full mechanism by which TNF inhibitors may affect cardiovascular health. However, there may be additional confounding factors or patient characteristics at play. More large, prospective, randomized, controlled studies are needed to further understand this relationship.

- Ogdie A, Yu Y, Haynes K, et al. Risk of major cardiovascular events in patients with psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:326-332.

- Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, Charlot M, et al. Psoriasis is associated with clinically significant cardiovascular risk: a Danish nationwide cohort study. J Intern Med. 2011;270:147-157.

- Kölliker Frers RA, Bisoendial RJ, Montoya SF, et al. Psoriasis and cardiovascular risk: immune-mediated crosstalk between metabolic, vascular, and autoimmune inflammation. Int J Cardiol Metab Endocr. 2015;6:43-54.

- Wu JJ, Sundaram M, Cloutier M, et al. The risk of cardiovascular events in psoriasis patients treated with tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors versus phototherapy: an observational cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:60-68.

- Lerman JB, Joshi AA, Chaturvedi A, et al. Coronary plaque characterization in psoriasis reveals high-risk features that improve after treatment in a prospective observational study. Circulation. 2017;136:263-276.

- Pina T, Corrales A, Lopez-Mejias R, et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-α therapy improves endothelial function and arterial stiffness in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: a 6 month prospective study. J Dermatol. 2016;43:1267-1272.

- Wu JJ, Joshi AA, Reddy SP, et al. Anti-inflammatory therapy with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors is associated with reduced risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in psoriasis [published online March 24, 2018]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.14951.

- Bissonnette R, Harel F, Krueger JG, et al. TNF-α antagonist and vascular inflammation patients with psoriasis vulgaris: a randomized placebo-controlled study. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:1638-1645 .

- Mehta NN, Shin DB, Joshi AA, et al. Effect of 2 psoriasis treatments on vascular inflammation and novel inflammatory cardiovascular biomarkers: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11:e007394.

The connection between psoriasis and increased major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) has been well studied. 1,2 Although treatment of psoriasis can improve skin and joint symptoms, it is less clear whether therapies may mitigate the increased risk for cardiovascular comorbidities. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors in particular have been studied with great interest given the role of TNF in vascular and metabolic functions. 3 Using a retrospective cohort design, Wu and colleagues 4 examined if treatment with TNF inhibitors in patients with psoriasis would be associated with a lower risk for MACEs compared to phototherapy. Results suggested a significantly lower hazard of MACEs in patients using TNF inhibitors vs patients treated with phototherapy (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.77; P = .046). Moreover, based on these findings, they calculated that treating approximately 161 patients with TNF inhibitors rather than phototherapy would result in 1 less MACE per year overall. 4

Patients with psoriasis have been shown to have a greater noncalcified coronary plaque burden and prevalence of high-risk plaque compared to healthy patients.5 Lerman and colleagues5 measured the coronary plaque burden of 105 patients with psoriasis and 25 healthy volunteers using coronary computed tomography angiography. Although the patients were on average 10 years younger and had lower cardiovascular risk as measured by traditional risk scores, patients with psoriasis were found to have a greater noncalcified coronary plaque burden compared to 100 patients with hyperlipidemia. This burden was associated with an increased prevalence of high-risk plaques. Furthermore, in patients followed for 1 year, improvements in psoriasis severity were associated with reductions in noncalcified coronary plaque burden, though this finding was across all treatment modalities. However, there was no significant difference in calcified coronary plaque burden associated with reduced psoriasis severity.5

Moreover, Pina et al6 conducted a prospective study evaluating the use of the TNF inhibitor adalimumab to improve endothelial function and arterial stiffness in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Among 29 patients, they found a significant improvement in endothelial function as measured by flow-mediated dilatation after 6 months of adalimumab therapy, with a mean increase from 6.19% to 7.46% (P=.008). They also reported decreases in arterial stiffness by pulse wave velocity (P=.03). Despite a small sample size, these findings provide 2 potential mechanisms by which TNF inhibitor therapy may reduce the risk for cardiovascular events.6

A retrospective cohort study evaluating data from the Kaiser Permanente Southern California health plan assessed whether TNF inhibitor therapy was associated with a lower risk for MACE in patients with psoriasis.7 A total of 18,194 patients were included; of these, 1463 received TNF inhibitor therapy for at least 2 months. After controlling for other variables, including age at psoriasis diagnosis, sex, race/ethnicity, and other cardiovascular risk factors (eg, history of smoking or alcohol use; use of clopidogrel, antihypertensive agents, antihyperlipidemics, or anticoagulants), patients in the TNF inhibitor cohort demonstrated a significantly lower MACE hazard ratio compared to patients treated with topicals (hazard ratio, 0.80; 95% confidence interval, 0.66-0.98; P<.05).7

Conversely, a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 107 patients found no difference in vascular inflammation of the ascending aorta and the carotids after 16 weeks of adalimumab treatment vs placebo. In this study, however, most patients had only moderate psoriasis based on a mean psoriasis area and severity index score of 9.8.8 Given studies finding higher risk burden in patients with more severe skin disease,2 it is possible that the effect of TNF inhibitor therapy may not be as pronounced in patients with less skin involvement. There was a significant effect on C-reactive protein levels in patients receiving TNF inhibitor therapy compared to placebo at 16 weeks (P=.012), suggesting TNF does play some role in systemic inflammation, and it is possible it may exert cardiovascular effects through a mechanism other than vascular inflammation.8

A second double-blind, randomized trial reported similar results.9 Among 97 patients randomized to receive adalimumab, placebo, or phototherapy, no significant difference in vascular inflammation was found after 12 weeks of therapy. In contrast, levels of C-reactive protein, IL-6, and glycoprotein acetylation were markedly reduced. The authors also reported adverse effects of adalimumab therapy on lipid metabolism with reduced cholesterol efflux capacity, a marker of ability of high-density-lipoprotein particles to perform reverse cholesterol transport, and high-density-lipoprotein particles, suggesting these effects may counteract some of the anti-inflammatory effects of TNF inhibitors.9

A growing body of data regarding the effect of TNF inhibitors on cardiovascular morbidity in patients with psoriasis is being collected, but no strong conclusions can be made. Given the disconnect of findings across these studies, it is possible that we have yet to elucidate the full mechanism by which TNF inhibitors may affect cardiovascular health. However, there may be additional confounding factors or patient characteristics at play. More large, prospective, randomized, controlled studies are needed to further understand this relationship.

The connection between psoriasis and increased major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) has been well studied. 1,2 Although treatment of psoriasis can improve skin and joint symptoms, it is less clear whether therapies may mitigate the increased risk for cardiovascular comorbidities. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors in particular have been studied with great interest given the role of TNF in vascular and metabolic functions. 3 Using a retrospective cohort design, Wu and colleagues 4 examined if treatment with TNF inhibitors in patients with psoriasis would be associated with a lower risk for MACEs compared to phototherapy. Results suggested a significantly lower hazard of MACEs in patients using TNF inhibitors vs patients treated with phototherapy (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.77; P = .046). Moreover, based on these findings, they calculated that treating approximately 161 patients with TNF inhibitors rather than phototherapy would result in 1 less MACE per year overall. 4

Patients with psoriasis have been shown to have a greater noncalcified coronary plaque burden and prevalence of high-risk plaque compared to healthy patients.5 Lerman and colleagues5 measured the coronary plaque burden of 105 patients with psoriasis and 25 healthy volunteers using coronary computed tomography angiography. Although the patients were on average 10 years younger and had lower cardiovascular risk as measured by traditional risk scores, patients with psoriasis were found to have a greater noncalcified coronary plaque burden compared to 100 patients with hyperlipidemia. This burden was associated with an increased prevalence of high-risk plaques. Furthermore, in patients followed for 1 year, improvements in psoriasis severity were associated with reductions in noncalcified coronary plaque burden, though this finding was across all treatment modalities. However, there was no significant difference in calcified coronary plaque burden associated with reduced psoriasis severity.5

Moreover, Pina et al6 conducted a prospective study evaluating the use of the TNF inhibitor adalimumab to improve endothelial function and arterial stiffness in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Among 29 patients, they found a significant improvement in endothelial function as measured by flow-mediated dilatation after 6 months of adalimumab therapy, with a mean increase from 6.19% to 7.46% (P=.008). They also reported decreases in arterial stiffness by pulse wave velocity (P=.03). Despite a small sample size, these findings provide 2 potential mechanisms by which TNF inhibitor therapy may reduce the risk for cardiovascular events.6

A retrospective cohort study evaluating data from the Kaiser Permanente Southern California health plan assessed whether TNF inhibitor therapy was associated with a lower risk for MACE in patients with psoriasis.7 A total of 18,194 patients were included; of these, 1463 received TNF inhibitor therapy for at least 2 months. After controlling for other variables, including age at psoriasis diagnosis, sex, race/ethnicity, and other cardiovascular risk factors (eg, history of smoking or alcohol use; use of clopidogrel, antihypertensive agents, antihyperlipidemics, or anticoagulants), patients in the TNF inhibitor cohort demonstrated a significantly lower MACE hazard ratio compared to patients treated with topicals (hazard ratio, 0.80; 95% confidence interval, 0.66-0.98; P<.05).7

Conversely, a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 107 patients found no difference in vascular inflammation of the ascending aorta and the carotids after 16 weeks of adalimumab treatment vs placebo. In this study, however, most patients had only moderate psoriasis based on a mean psoriasis area and severity index score of 9.8.8 Given studies finding higher risk burden in patients with more severe skin disease,2 it is possible that the effect of TNF inhibitor therapy may not be as pronounced in patients with less skin involvement. There was a significant effect on C-reactive protein levels in patients receiving TNF inhibitor therapy compared to placebo at 16 weeks (P=.012), suggesting TNF does play some role in systemic inflammation, and it is possible it may exert cardiovascular effects through a mechanism other than vascular inflammation.8

A second double-blind, randomized trial reported similar results.9 Among 97 patients randomized to receive adalimumab, placebo, or phototherapy, no significant difference in vascular inflammation was found after 12 weeks of therapy. In contrast, levels of C-reactive protein, IL-6, and glycoprotein acetylation were markedly reduced. The authors also reported adverse effects of adalimumab therapy on lipid metabolism with reduced cholesterol efflux capacity, a marker of ability of high-density-lipoprotein particles to perform reverse cholesterol transport, and high-density-lipoprotein particles, suggesting these effects may counteract some of the anti-inflammatory effects of TNF inhibitors.9

A growing body of data regarding the effect of TNF inhibitors on cardiovascular morbidity in patients with psoriasis is being collected, but no strong conclusions can be made. Given the disconnect of findings across these studies, it is possible that we have yet to elucidate the full mechanism by which TNF inhibitors may affect cardiovascular health. However, there may be additional confounding factors or patient characteristics at play. More large, prospective, randomized, controlled studies are needed to further understand this relationship.

- Ogdie A, Yu Y, Haynes K, et al. Risk of major cardiovascular events in patients with psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:326-332.

- Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, Charlot M, et al. Psoriasis is associated with clinically significant cardiovascular risk: a Danish nationwide cohort study. J Intern Med. 2011;270:147-157.

- Kölliker Frers RA, Bisoendial RJ, Montoya SF, et al. Psoriasis and cardiovascular risk: immune-mediated crosstalk between metabolic, vascular, and autoimmune inflammation. Int J Cardiol Metab Endocr. 2015;6:43-54.

- Wu JJ, Sundaram M, Cloutier M, et al. The risk of cardiovascular events in psoriasis patients treated with tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors versus phototherapy: an observational cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:60-68.

- Lerman JB, Joshi AA, Chaturvedi A, et al. Coronary plaque characterization in psoriasis reveals high-risk features that improve after treatment in a prospective observational study. Circulation. 2017;136:263-276.

- Pina T, Corrales A, Lopez-Mejias R, et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-α therapy improves endothelial function and arterial stiffness in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: a 6 month prospective study. J Dermatol. 2016;43:1267-1272.

- Wu JJ, Joshi AA, Reddy SP, et al. Anti-inflammatory therapy with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors is associated with reduced risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in psoriasis [published online March 24, 2018]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.14951.

- Bissonnette R, Harel F, Krueger JG, et al. TNF-α antagonist and vascular inflammation patients with psoriasis vulgaris: a randomized placebo-controlled study. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:1638-1645 .

- Mehta NN, Shin DB, Joshi AA, et al. Effect of 2 psoriasis treatments on vascular inflammation and novel inflammatory cardiovascular biomarkers: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11:e007394.

- Ogdie A, Yu Y, Haynes K, et al. Risk of major cardiovascular events in patients with psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:326-332.

- Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, Charlot M, et al. Psoriasis is associated with clinically significant cardiovascular risk: a Danish nationwide cohort study. J Intern Med. 2011;270:147-157.

- Kölliker Frers RA, Bisoendial RJ, Montoya SF, et al. Psoriasis and cardiovascular risk: immune-mediated crosstalk between metabolic, vascular, and autoimmune inflammation. Int J Cardiol Metab Endocr. 2015;6:43-54.

- Wu JJ, Sundaram M, Cloutier M, et al. The risk of cardiovascular events in psoriasis patients treated with tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors versus phototherapy: an observational cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:60-68.

- Lerman JB, Joshi AA, Chaturvedi A, et al. Coronary plaque characterization in psoriasis reveals high-risk features that improve after treatment in a prospective observational study. Circulation. 2017;136:263-276.

- Pina T, Corrales A, Lopez-Mejias R, et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-α therapy improves endothelial function and arterial stiffness in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: a 6 month prospective study. J Dermatol. 2016;43:1267-1272.

- Wu JJ, Joshi AA, Reddy SP, et al. Anti-inflammatory therapy with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors is associated with reduced risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in psoriasis [published online March 24, 2018]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.14951.

- Bissonnette R, Harel F, Krueger JG, et al. TNF-α antagonist and vascular inflammation patients with psoriasis vulgaris: a randomized placebo-controlled study. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:1638-1645 .

- Mehta NN, Shin DB, Joshi AA, et al. Effect of 2 psoriasis treatments on vascular inflammation and novel inflammatory cardiovascular biomarkers: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11:e007394.

Psoriasis: A look back over the past 50 years, and forward to next steps

Imagine a patient suffering with horrible psoriasis for decades having failed “every available treatment.” Imagine him living all that time with “flaking, cracking, painful, itchy skin,” only to develop cirrhosis after exposure to toxic therapies.

Then imagine the experience for that patient when, 2 weeks after initiating treatment with a new interleukin-17 inhibitor, his skin clears completely.

“Two weeks later it’s all gone – it was a moment to behold,” said Joel M. Gelfand, MD, professor of dermatology and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, who had cared for the man for many years before a psoriasis treatment revolution of sorts took the field of dermatology by storm.

“The progress has been breathtaking – there’s no other way to describe it – and it feels like a miracle every time I see a new patient who has tough disease and I have all these things to offer them,” he continued. “For most patients, I can really help them and make a major difference in their life.”

said Mark Lebwohl, MD, Waldman professor of dermatology and chair of the Kimberly and Eric J. Waldman department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Dr. Lebwohl recounted some of his own experiences with psoriasis patients before the advent of treatments – particularly biologics – that have transformed practice.

There was a time when psoriasis patients had little more to turn to than the effective – but “disgusting” – Goeckerman Regimen involving cycles of UVB light exposure and topical crude coal tar application. Initially, the regimen, which was introduced in the 1920s, was used around the clock on an inpatient basis until the skin cleared, Dr. Lebwohl said.

In the 1970s, the immunosuppressive chemotherapy drug methotrexate became the first oral systemic therapy approved for severe psoriasis. For those with disabling disease, it offered some hope for relief, but only about 40% of patients achieved at least a 75% reduction in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score (PASI 75), he said, adding that they did so at the expense of the liver and bone marrow. “But it was the only thing we had for severe psoriasis other than light treatments.”