User login

Association Between Psoriasis and Obesity Among US Adults in the 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated dermatologic condition that is associated with various comorbidities, including obesity.1 The underlying pathophysiology of psoriasis has been extensively studied, and recent research has discussed the role of obesity in IL-17 secretion.2 The relationship between being overweight/obese and having psoriasis has been documented in the literature.1,2 However, this association in a recent population is lacking. We sought to investigate the association between psoriasis and obesity utilizing a representative US population of adults—the 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data,3 which contains the most recent psoriasis data.

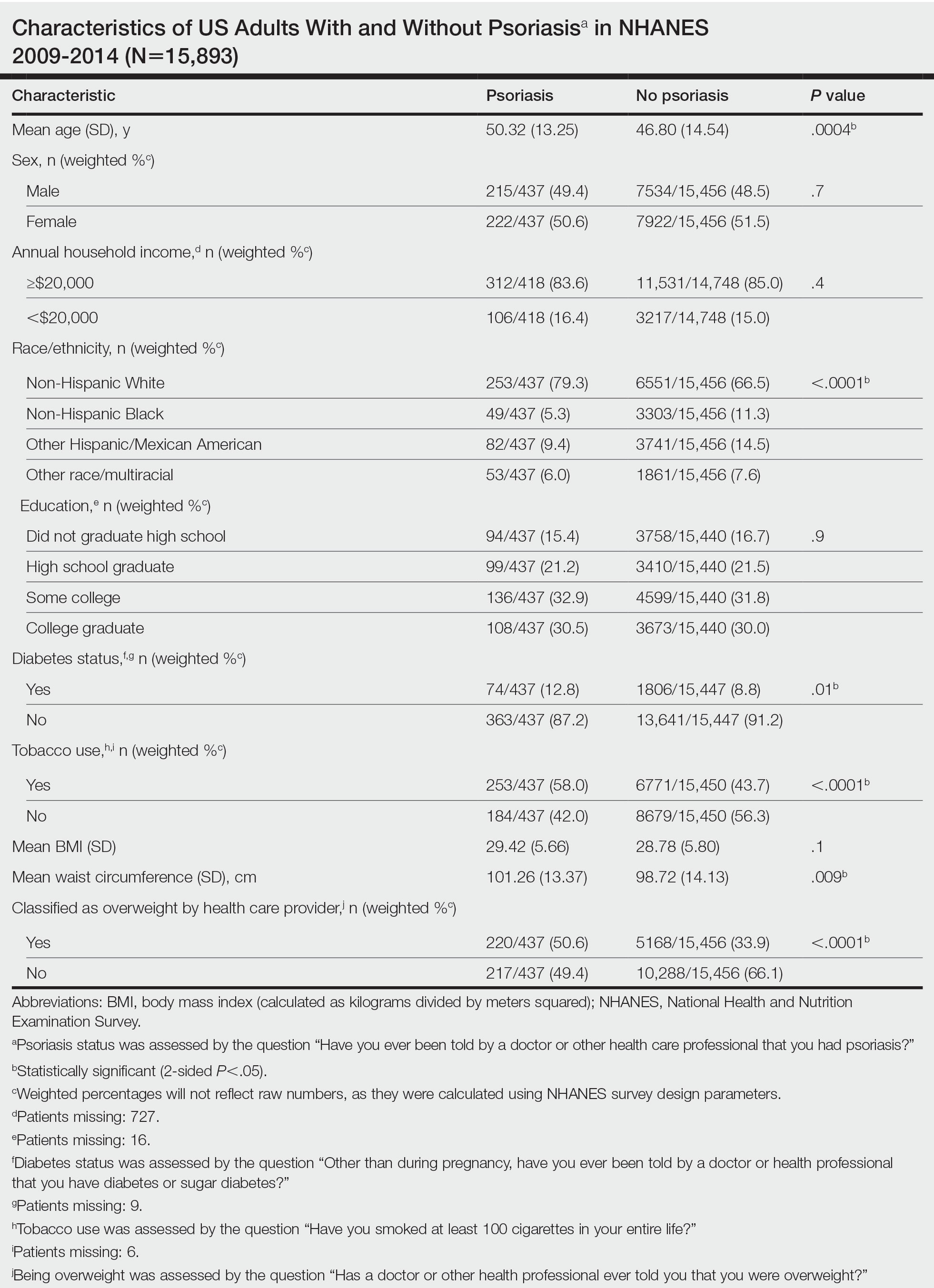

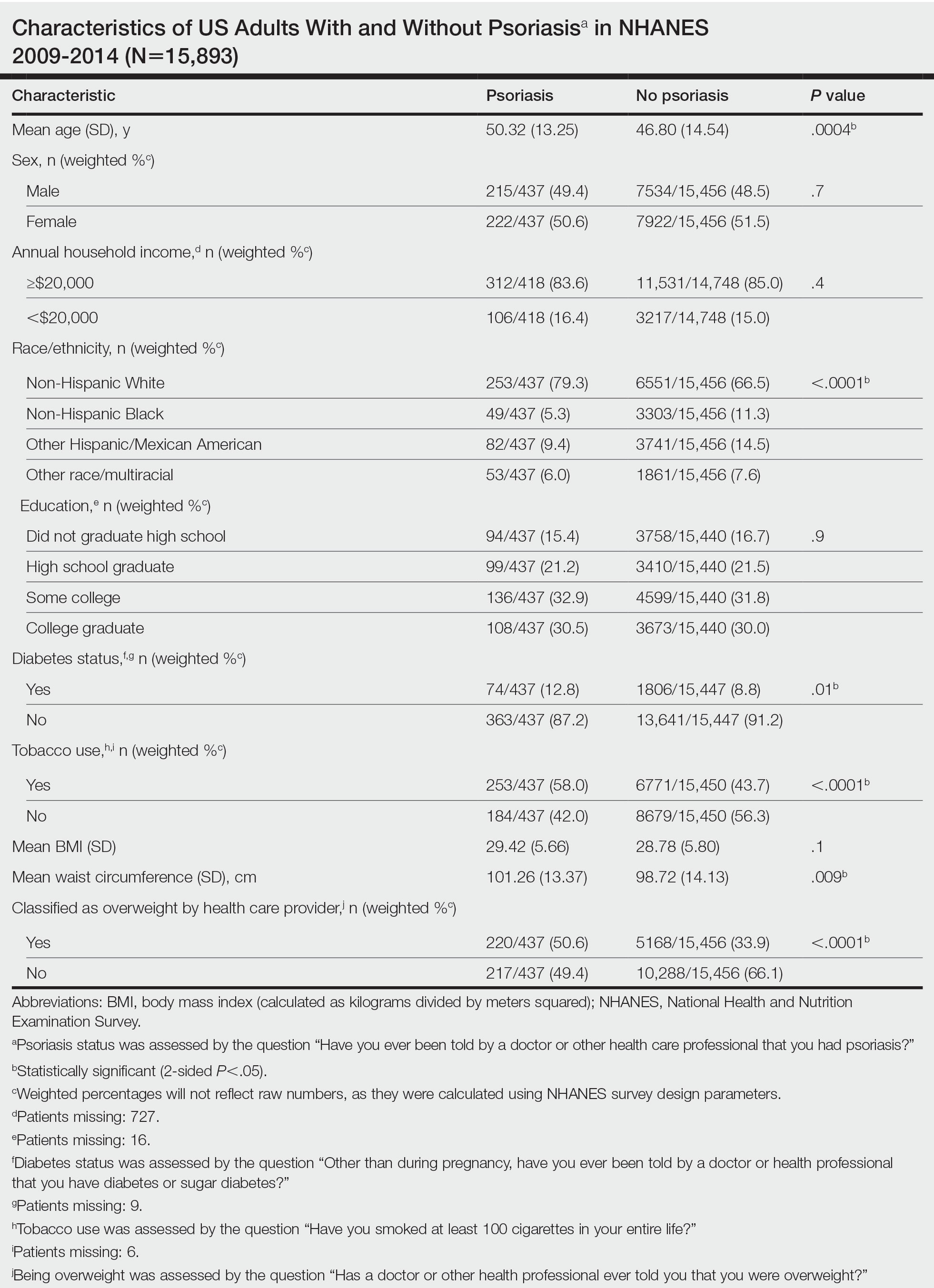

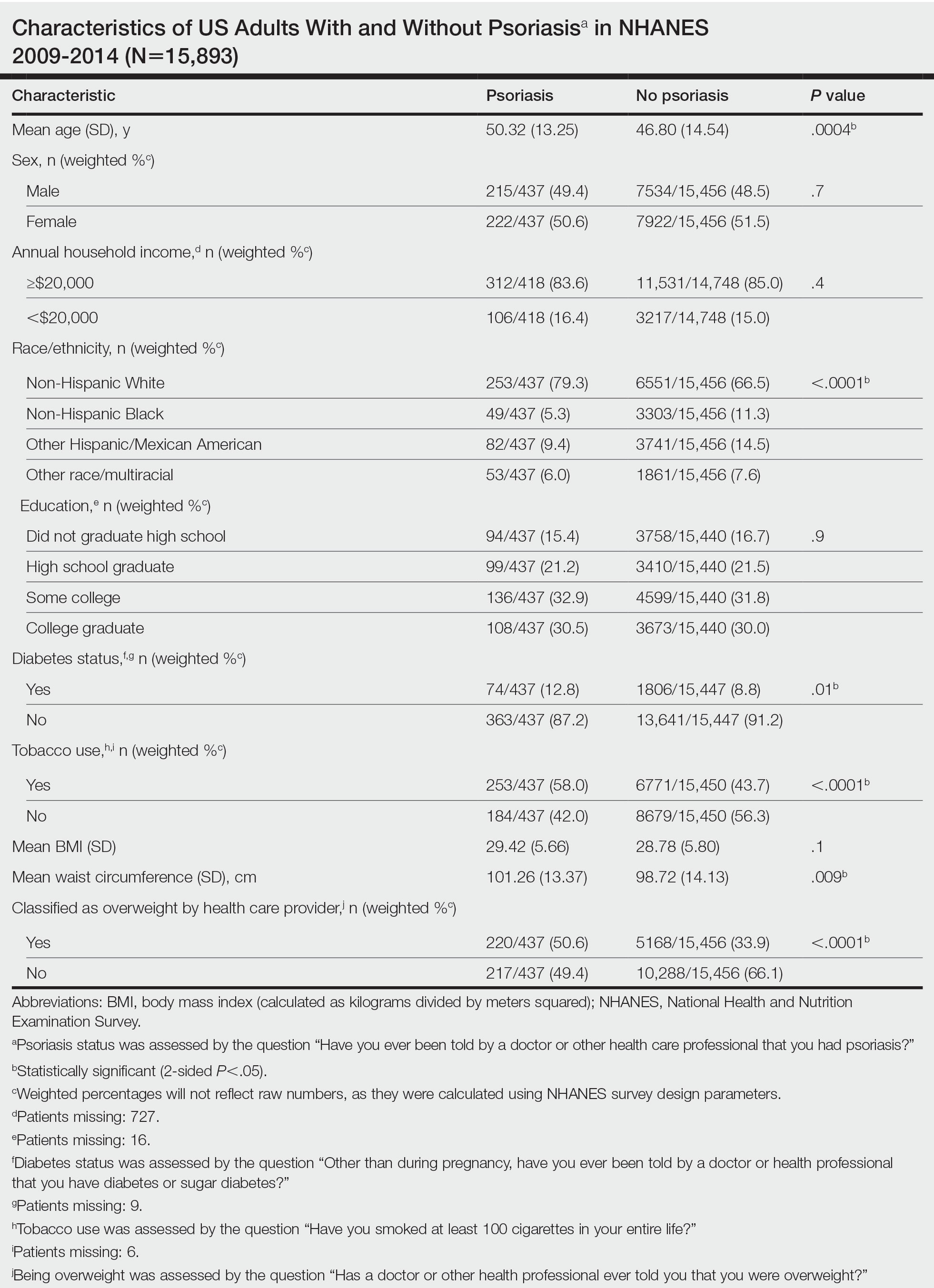

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database. Three 2-year cycles of NHANES data were combined to create our 2009 to 2014 dataset. In the Table, numerous variables including age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, education, diabetes status, tobacco use, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and being called overweight by a health care provider were analyzed using χ2 or t test analyses to evaluate for differences among those with and without psoriasis. Diabetes status was assessed by the question “Other than during pregnancy, have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?” Tobacco use was assessed by the question “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” Psoriasis status was assessed by a self-reported response to the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health care professional that you had psoriasis?” Three different outcome variables were used to determine if patients were overweight or obese: BMI, waist circumference, and response to the question “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?” Obesity was defined as having a BMI of 30 or higher or waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females.4 Being overweight was defined as having a BMI of 25 to 29.99 or response of Yes to “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?”

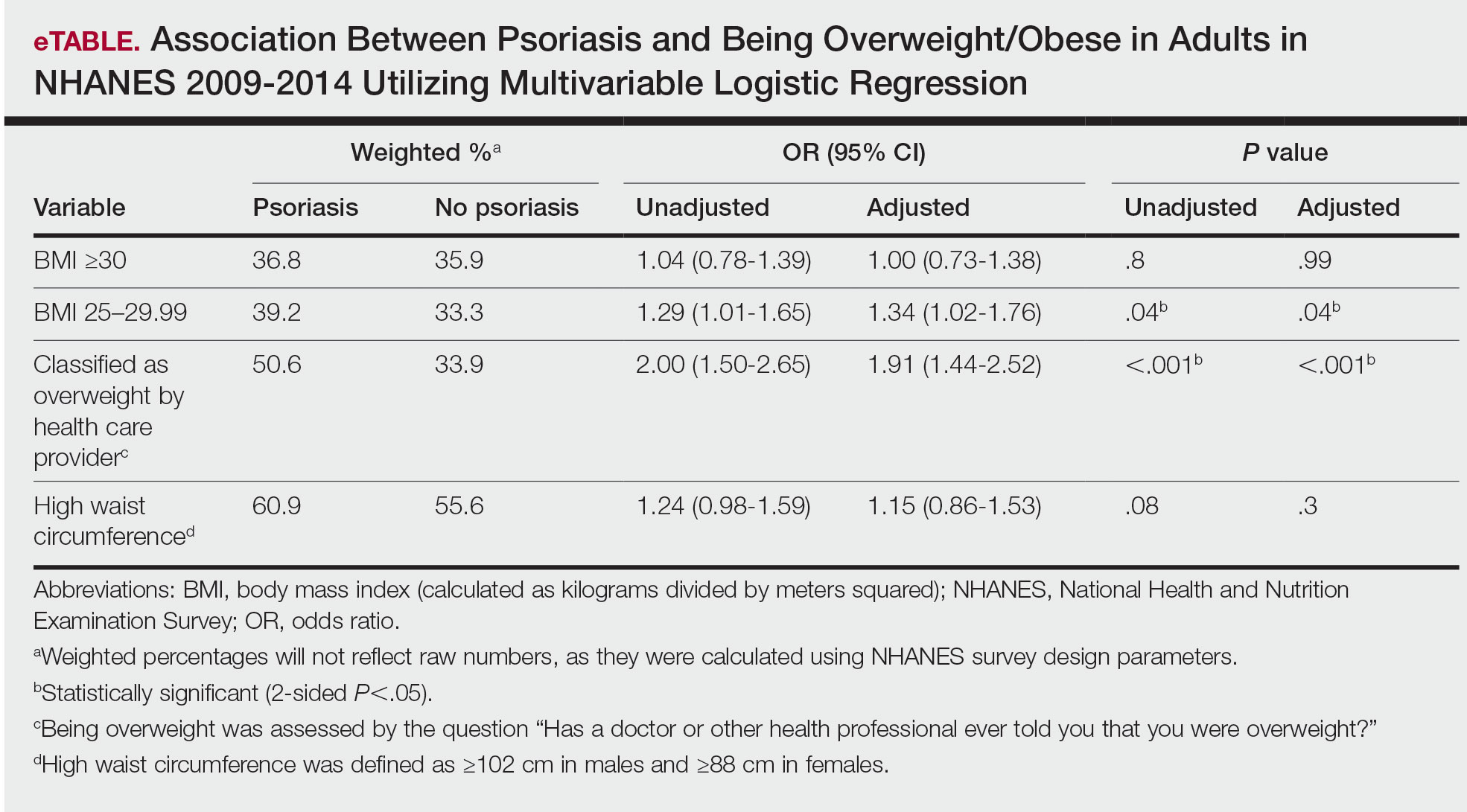

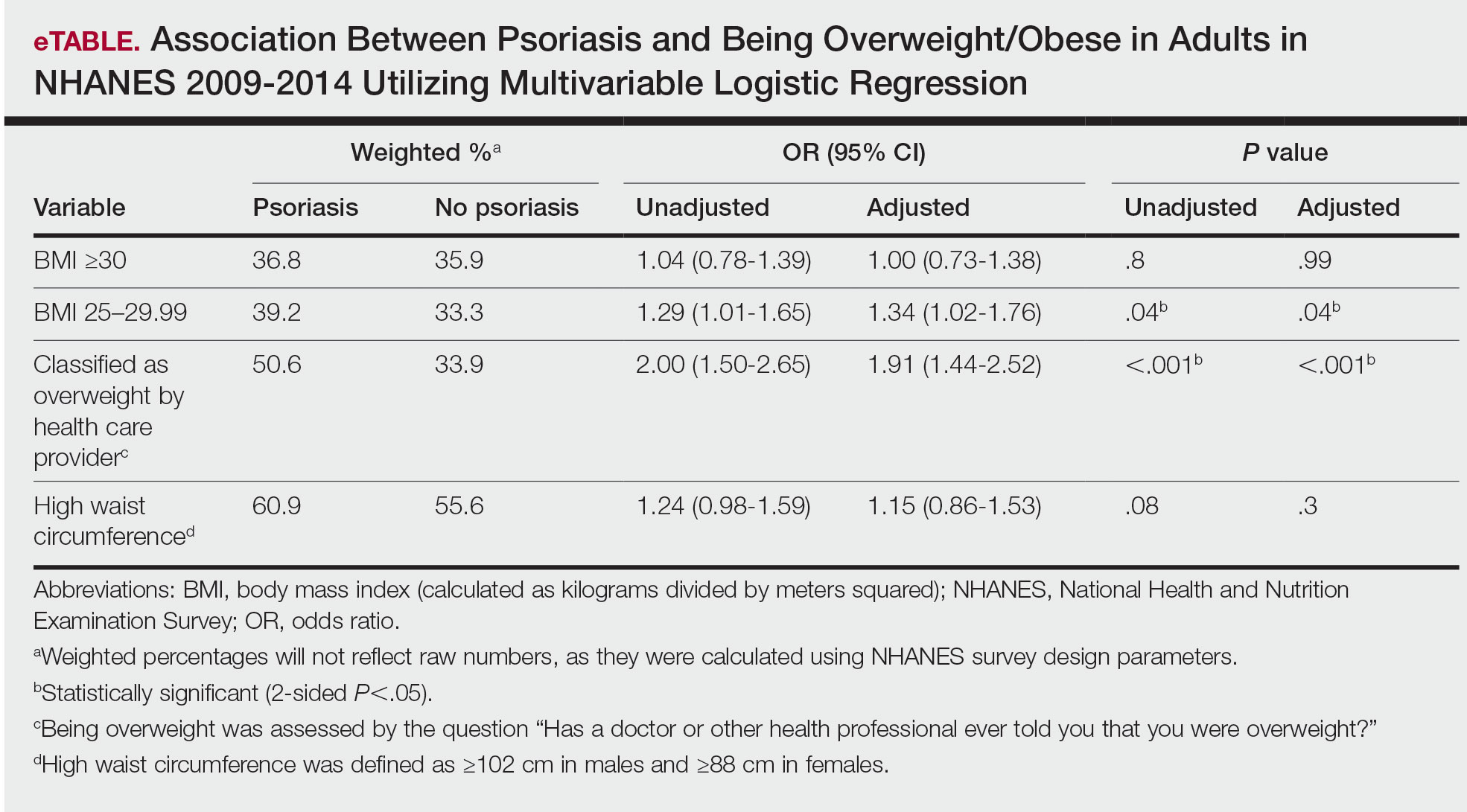

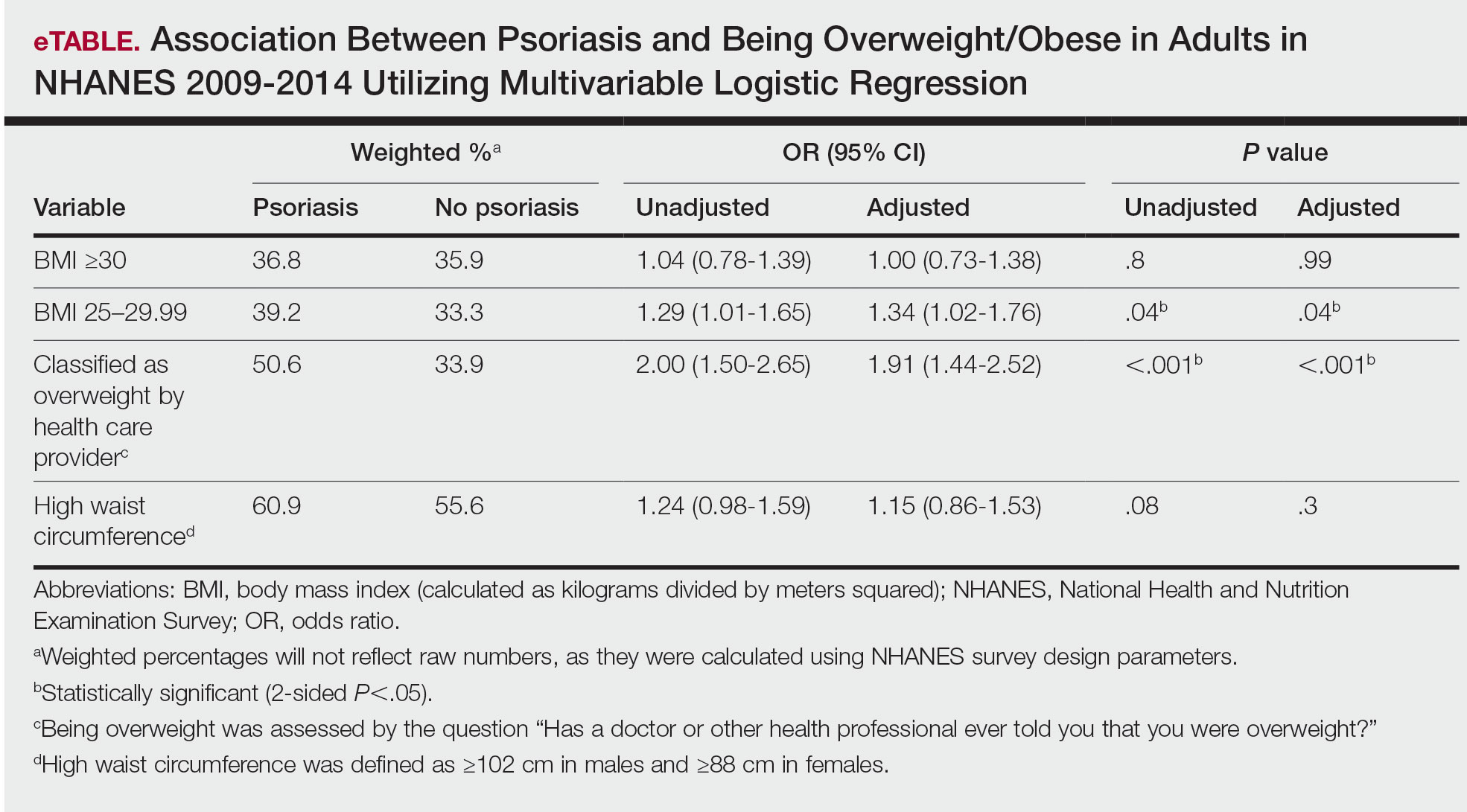

Initially, there were 17,547 participants 20 years and older from 2009 to 2014, but 1654 participants were excluded because of missing data for obesity or psoriasis; therefore, 15,893 patients were included in our analysis. Multivariable logistic regressions were utilized to examine the association between psoriasis and being overweight/obese (eTable). Additionally, the models were adjusted based on age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, diabetes status, and tobacco use. All data processing and analysis were performed in Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

The Table shows characteristics of US adults with and without psoriasis in NHANES 2009-2014. We found that the variables of interest evaluating body weight that were significantly different on analysis between patients with and without psoriasis included waist circumference—patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher waist circumference (P=.009)—and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (P<.0001), which supports the findings by Love et al,5 who reported abdominal obesity was the most common feature of metabolic syndrome exhibited among patients with psoriasis.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis (eTable) revealed that there was a significant association between psoriasis and BMI of 25 to 29.99 (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.34; 95% CI, 1.02-1.76; P=.04) and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (AOR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.44-2.52; P<.001). After adjusting for confounding variables, there was no significant association between psoriasis and a BMI of 30 or higher (AOR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.73-1.38; P=.99) or a waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females (AOR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.86-1.53; P=.3).

Our findings suggest that a few variables indicative of being overweight or obese are associated with psoriasis. This relationship most likely is due to increased adipokine, including resistin, levels in overweight individuals, resulting in a proinflammatory state.6 It has been suggested that BMI alone is not a definitive marker for measuring fat storage levels in individuals. People can have a normal or slightly elevated BMI but possess excessive adiposity, resulting in chronic inflammation.6 Therefore, our findings of a significant association between psoriasis and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight might be a stronger measurement for possessing excessive fat, as this is likely due to clinical judgment rather than BMI measurement.

Moreover, it should be noted that the potential reason for the lack of association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis in our analysis may be a result of BMI serving as a poor measurement for adiposity. Additionally, Armstrong and colleagues7 discussed that the association between BMI and psoriasis was stronger for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Our study consisted of NHANES data for self-reported psoriasis diagnoses without a psoriasis severity index, making it difficult to extrapolate which individuals had mild or moderate to severe psoriasis, which may have contributed to our finding of no association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis.

The self-reported nature of the survey questions and lack of questions regarding psoriasis severity serve as limitations to the study. Both obesity and psoriasis can have various systemic consequences, such as cardiovascular disease, due to the development of an inflammatory state.8 Future studies may explore other body measurements that indicate being overweight or obese and the potential synergistic relationship of obesity and psoriasis severity, optimizing the development of effective treatment plans.

- Jensen P, Skov L. Psoriasis and obesity. Dermatology. 2016;232:633-639.

- Xu C, Ji J, Su T, et al. The association of psoriasis and obesity: focusing on IL-17A-related immunological mechanisms. Int J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;4:116-121.

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.govnchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Ross R, Neeland IJ, Yamashita S, et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:177-189.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- Paroutoglou K, Papadavid E, Christodoulatos GS, et al. Deciphering the association between psoriasis and obesity: current evidence and treatment considerations. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9:165-178.

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. The association between psoriasis and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Diabetes. 2012;2:E54.

- Hamminga EA, van der Lely AJ, Neumann HAM, et al. Chronic inflammation in psoriasis and obesity: implications for therapy. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:768-773.

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated dermatologic condition that is associated with various comorbidities, including obesity.1 The underlying pathophysiology of psoriasis has been extensively studied, and recent research has discussed the role of obesity in IL-17 secretion.2 The relationship between being overweight/obese and having psoriasis has been documented in the literature.1,2 However, this association in a recent population is lacking. We sought to investigate the association between psoriasis and obesity utilizing a representative US population of adults—the 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data,3 which contains the most recent psoriasis data.

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database. Three 2-year cycles of NHANES data were combined to create our 2009 to 2014 dataset. In the Table, numerous variables including age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, education, diabetes status, tobacco use, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and being called overweight by a health care provider were analyzed using χ2 or t test analyses to evaluate for differences among those with and without psoriasis. Diabetes status was assessed by the question “Other than during pregnancy, have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?” Tobacco use was assessed by the question “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” Psoriasis status was assessed by a self-reported response to the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health care professional that you had psoriasis?” Three different outcome variables were used to determine if patients were overweight or obese: BMI, waist circumference, and response to the question “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?” Obesity was defined as having a BMI of 30 or higher or waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females.4 Being overweight was defined as having a BMI of 25 to 29.99 or response of Yes to “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?”

Initially, there were 17,547 participants 20 years and older from 2009 to 2014, but 1654 participants were excluded because of missing data for obesity or psoriasis; therefore, 15,893 patients were included in our analysis. Multivariable logistic regressions were utilized to examine the association between psoriasis and being overweight/obese (eTable). Additionally, the models were adjusted based on age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, diabetes status, and tobacco use. All data processing and analysis were performed in Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

The Table shows characteristics of US adults with and without psoriasis in NHANES 2009-2014. We found that the variables of interest evaluating body weight that were significantly different on analysis between patients with and without psoriasis included waist circumference—patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher waist circumference (P=.009)—and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (P<.0001), which supports the findings by Love et al,5 who reported abdominal obesity was the most common feature of metabolic syndrome exhibited among patients with psoriasis.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis (eTable) revealed that there was a significant association between psoriasis and BMI of 25 to 29.99 (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.34; 95% CI, 1.02-1.76; P=.04) and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (AOR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.44-2.52; P<.001). After adjusting for confounding variables, there was no significant association between psoriasis and a BMI of 30 or higher (AOR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.73-1.38; P=.99) or a waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females (AOR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.86-1.53; P=.3).

Our findings suggest that a few variables indicative of being overweight or obese are associated with psoriasis. This relationship most likely is due to increased adipokine, including resistin, levels in overweight individuals, resulting in a proinflammatory state.6 It has been suggested that BMI alone is not a definitive marker for measuring fat storage levels in individuals. People can have a normal or slightly elevated BMI but possess excessive adiposity, resulting in chronic inflammation.6 Therefore, our findings of a significant association between psoriasis and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight might be a stronger measurement for possessing excessive fat, as this is likely due to clinical judgment rather than BMI measurement.

Moreover, it should be noted that the potential reason for the lack of association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis in our analysis may be a result of BMI serving as a poor measurement for adiposity. Additionally, Armstrong and colleagues7 discussed that the association between BMI and psoriasis was stronger for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Our study consisted of NHANES data for self-reported psoriasis diagnoses without a psoriasis severity index, making it difficult to extrapolate which individuals had mild or moderate to severe psoriasis, which may have contributed to our finding of no association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis.

The self-reported nature of the survey questions and lack of questions regarding psoriasis severity serve as limitations to the study. Both obesity and psoriasis can have various systemic consequences, such as cardiovascular disease, due to the development of an inflammatory state.8 Future studies may explore other body measurements that indicate being overweight or obese and the potential synergistic relationship of obesity and psoriasis severity, optimizing the development of effective treatment plans.

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated dermatologic condition that is associated with various comorbidities, including obesity.1 The underlying pathophysiology of psoriasis has been extensively studied, and recent research has discussed the role of obesity in IL-17 secretion.2 The relationship between being overweight/obese and having psoriasis has been documented in the literature.1,2 However, this association in a recent population is lacking. We sought to investigate the association between psoriasis and obesity utilizing a representative US population of adults—the 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data,3 which contains the most recent psoriasis data.

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database. Three 2-year cycles of NHANES data were combined to create our 2009 to 2014 dataset. In the Table, numerous variables including age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, education, diabetes status, tobacco use, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and being called overweight by a health care provider were analyzed using χ2 or t test analyses to evaluate for differences among those with and without psoriasis. Diabetes status was assessed by the question “Other than during pregnancy, have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?” Tobacco use was assessed by the question “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” Psoriasis status was assessed by a self-reported response to the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health care professional that you had psoriasis?” Three different outcome variables were used to determine if patients were overweight or obese: BMI, waist circumference, and response to the question “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?” Obesity was defined as having a BMI of 30 or higher or waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females.4 Being overweight was defined as having a BMI of 25 to 29.99 or response of Yes to “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?”

Initially, there were 17,547 participants 20 years and older from 2009 to 2014, but 1654 participants were excluded because of missing data for obesity or psoriasis; therefore, 15,893 patients were included in our analysis. Multivariable logistic regressions were utilized to examine the association between psoriasis and being overweight/obese (eTable). Additionally, the models were adjusted based on age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, diabetes status, and tobacco use. All data processing and analysis were performed in Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

The Table shows characteristics of US adults with and without psoriasis in NHANES 2009-2014. We found that the variables of interest evaluating body weight that were significantly different on analysis between patients with and without psoriasis included waist circumference—patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher waist circumference (P=.009)—and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (P<.0001), which supports the findings by Love et al,5 who reported abdominal obesity was the most common feature of metabolic syndrome exhibited among patients with psoriasis.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis (eTable) revealed that there was a significant association between psoriasis and BMI of 25 to 29.99 (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.34; 95% CI, 1.02-1.76; P=.04) and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (AOR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.44-2.52; P<.001). After adjusting for confounding variables, there was no significant association between psoriasis and a BMI of 30 or higher (AOR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.73-1.38; P=.99) or a waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females (AOR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.86-1.53; P=.3).

Our findings suggest that a few variables indicative of being overweight or obese are associated with psoriasis. This relationship most likely is due to increased adipokine, including resistin, levels in overweight individuals, resulting in a proinflammatory state.6 It has been suggested that BMI alone is not a definitive marker for measuring fat storage levels in individuals. People can have a normal or slightly elevated BMI but possess excessive adiposity, resulting in chronic inflammation.6 Therefore, our findings of a significant association between psoriasis and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight might be a stronger measurement for possessing excessive fat, as this is likely due to clinical judgment rather than BMI measurement.

Moreover, it should be noted that the potential reason for the lack of association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis in our analysis may be a result of BMI serving as a poor measurement for adiposity. Additionally, Armstrong and colleagues7 discussed that the association between BMI and psoriasis was stronger for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Our study consisted of NHANES data for self-reported psoriasis diagnoses without a psoriasis severity index, making it difficult to extrapolate which individuals had mild or moderate to severe psoriasis, which may have contributed to our finding of no association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis.

The self-reported nature of the survey questions and lack of questions regarding psoriasis severity serve as limitations to the study. Both obesity and psoriasis can have various systemic consequences, such as cardiovascular disease, due to the development of an inflammatory state.8 Future studies may explore other body measurements that indicate being overweight or obese and the potential synergistic relationship of obesity and psoriasis severity, optimizing the development of effective treatment plans.

- Jensen P, Skov L. Psoriasis and obesity. Dermatology. 2016;232:633-639.

- Xu C, Ji J, Su T, et al. The association of psoriasis and obesity: focusing on IL-17A-related immunological mechanisms. Int J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;4:116-121.

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.govnchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Ross R, Neeland IJ, Yamashita S, et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:177-189.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- Paroutoglou K, Papadavid E, Christodoulatos GS, et al. Deciphering the association between psoriasis and obesity: current evidence and treatment considerations. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9:165-178.

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. The association between psoriasis and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Diabetes. 2012;2:E54.

- Hamminga EA, van der Lely AJ, Neumann HAM, et al. Chronic inflammation in psoriasis and obesity: implications for therapy. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:768-773.

- Jensen P, Skov L. Psoriasis and obesity. Dermatology. 2016;232:633-639.

- Xu C, Ji J, Su T, et al. The association of psoriasis and obesity: focusing on IL-17A-related immunological mechanisms. Int J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;4:116-121.

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.govnchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Ross R, Neeland IJ, Yamashita S, et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:177-189.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- Paroutoglou K, Papadavid E, Christodoulatos GS, et al. Deciphering the association between psoriasis and obesity: current evidence and treatment considerations. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9:165-178.

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. The association between psoriasis and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Diabetes. 2012;2:E54.

- Hamminga EA, van der Lely AJ, Neumann HAM, et al. Chronic inflammation in psoriasis and obesity: implications for therapy. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:768-773.

Practice Points

- There are many comorbidities that are associated with psoriasis, making it crucial to evaluate for these diseases in patients with psoriasis.

- Obesity may be a contributing factor to psoriasis development due to the role of IL-17 secretion.

Palliative Care: Utilization Patterns in Inpatient Dermatology

Palliative care (PC) is a field of medicine that focuses on improving quality of life by managing physical symptoms as well as mental and spiritual well-being in patients with severe illnesses.1,2 Despite cases of severe dermatologic disease, the use of PC in the field of dermatology is limited, often leaving patients with a range of unmet needs.2,3 In one study that explored PC in patients with melanoma, only one-third of patients with advanced melanoma had a PC consultation.4 Reasons behind the lack of utilization of PC in dermatology include time constraints and limited training in addressing the complex psychosocial needs of patients with severe dermatologic illnesses.1 We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional, single-institution study of specific inpatient dermatology consultations over a 5-year period to describe PC utilization among patients who were hospitalized with select severe dermatologic diseases.

Methods

A retrospective, cross-sectional study of inpatient dermatology consultations over a 5-year period (October 2016 to October 2021) was performed at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (Winston-Salem, North Carolina). Patients’ medical records were reviewed if they had one of the following diseases: bullous pemphigoid, calciphylaxis, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, erythrodermic psoriasis, graft-vs-host disease, pemphigus vulgaris (PV), purpura fulminans, pyoderma gangrenosum, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. These diseases were selected for inclusion because they have been associated with a documented increase in inpatient mortality and have been described in the published literature on PC in dermatology.2 This study was reviewed and approved by the Wake Forest University institutional review board.

Use of PC consultative services along with other associated consultative care (ie, recreation therapy [RT], acute pain management, pastoral care) was assessed for each patient. Recreation therapy included specific interventions such as music therapy, arts/craft therapy, pet therapy, and other services with the goal of improving patient cognitive, emotional, and social function. For patients with a completed PC consultation, goals for PC intervention were recorded.

Results

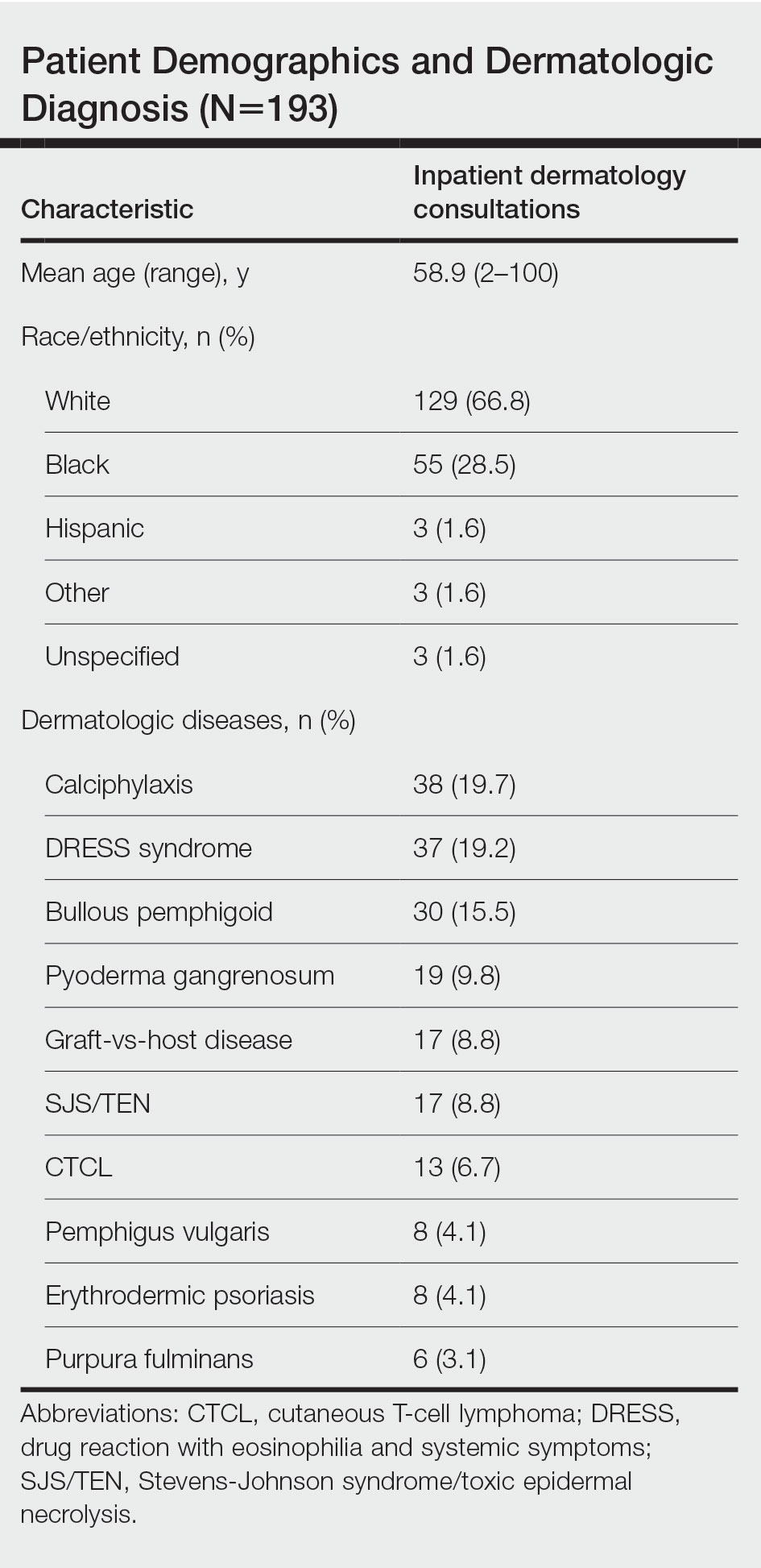

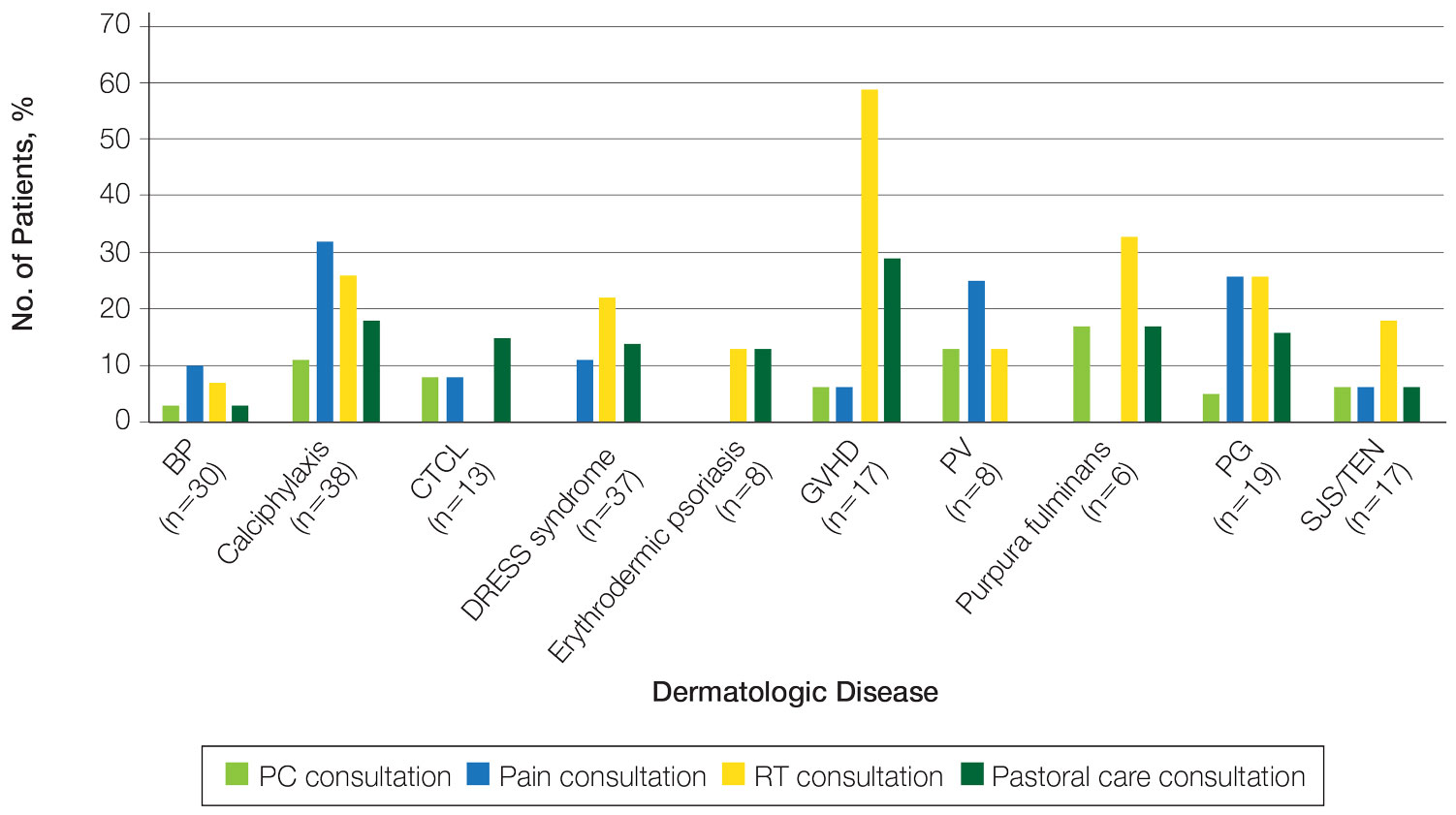

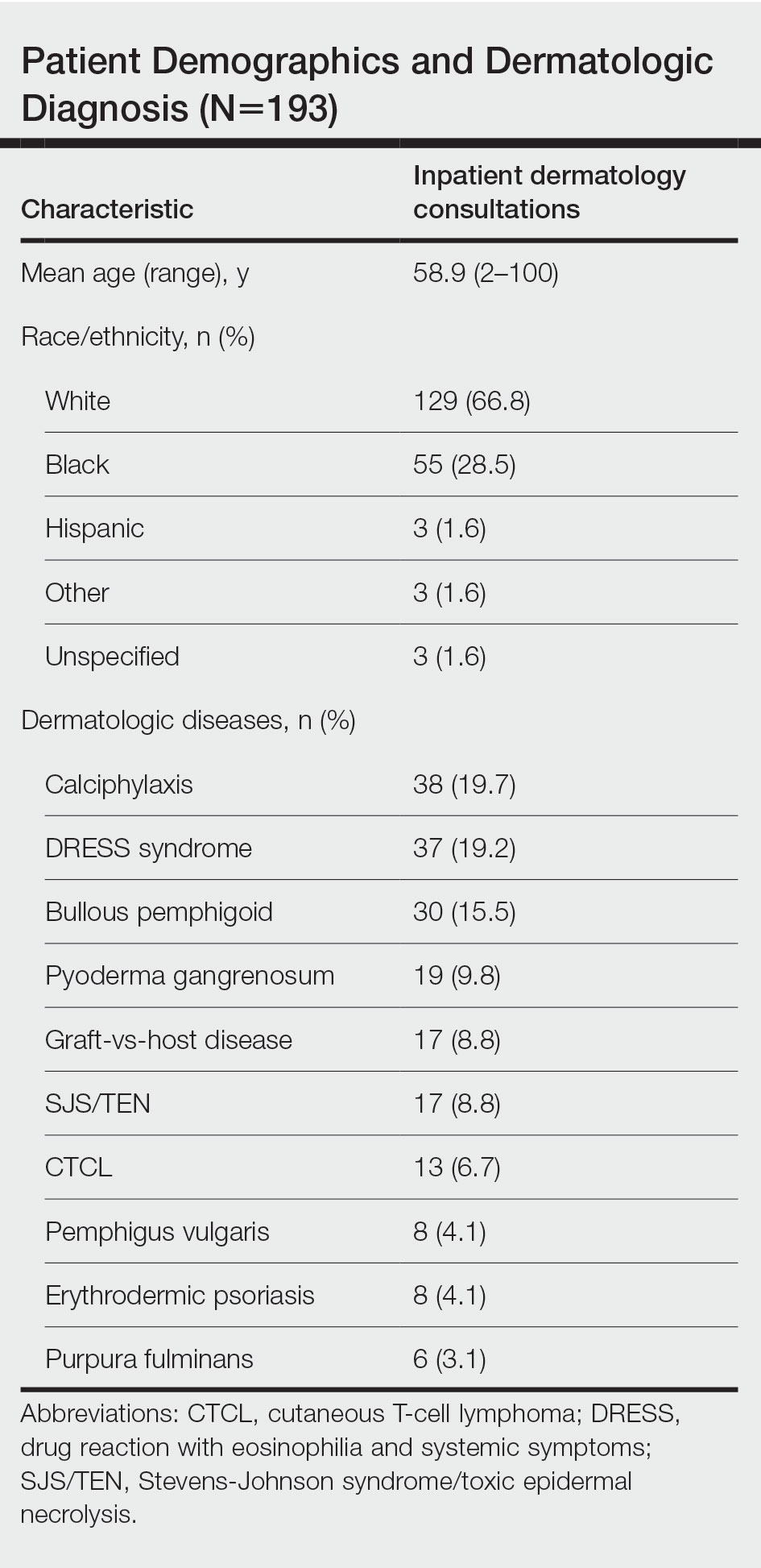

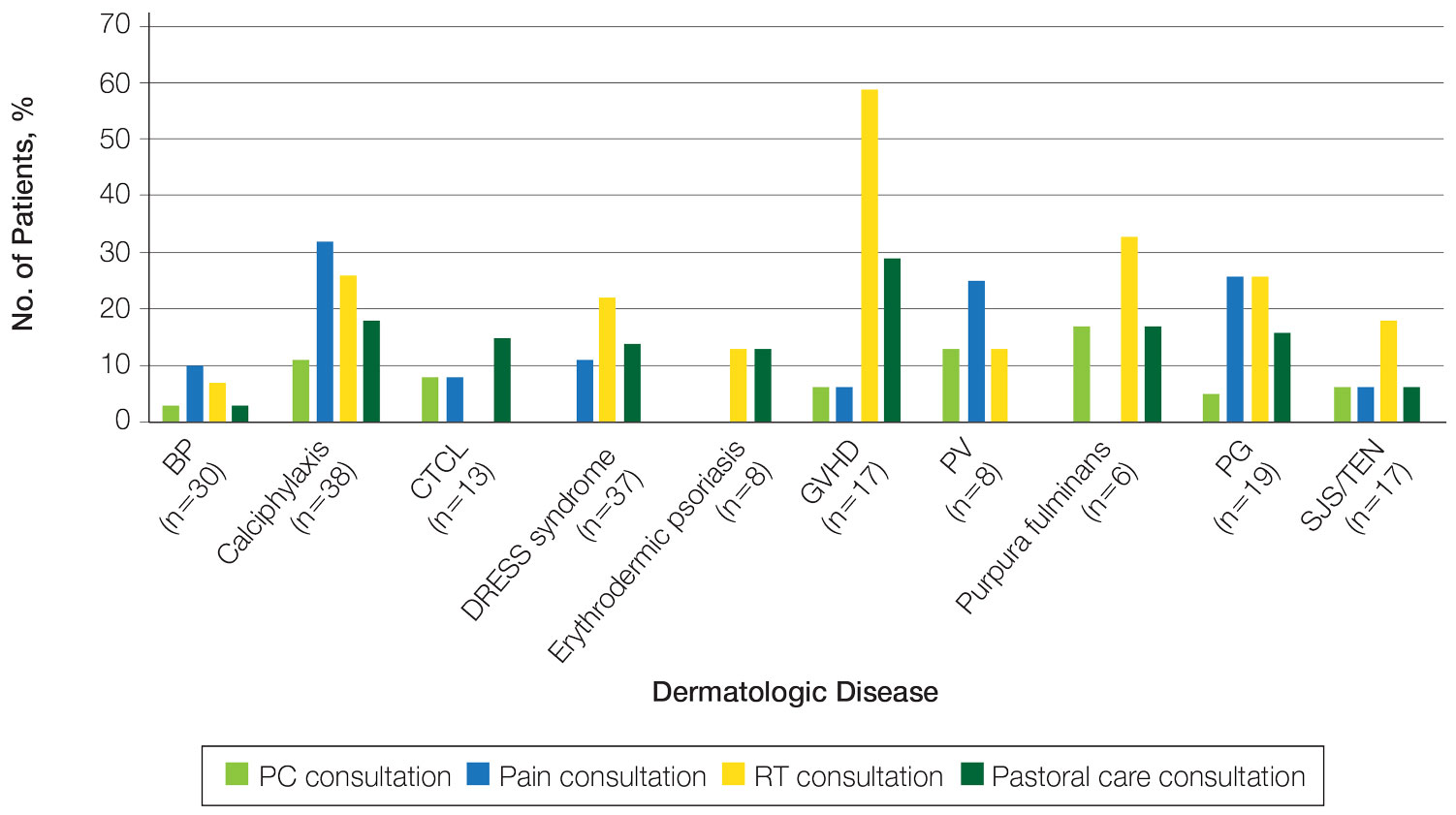

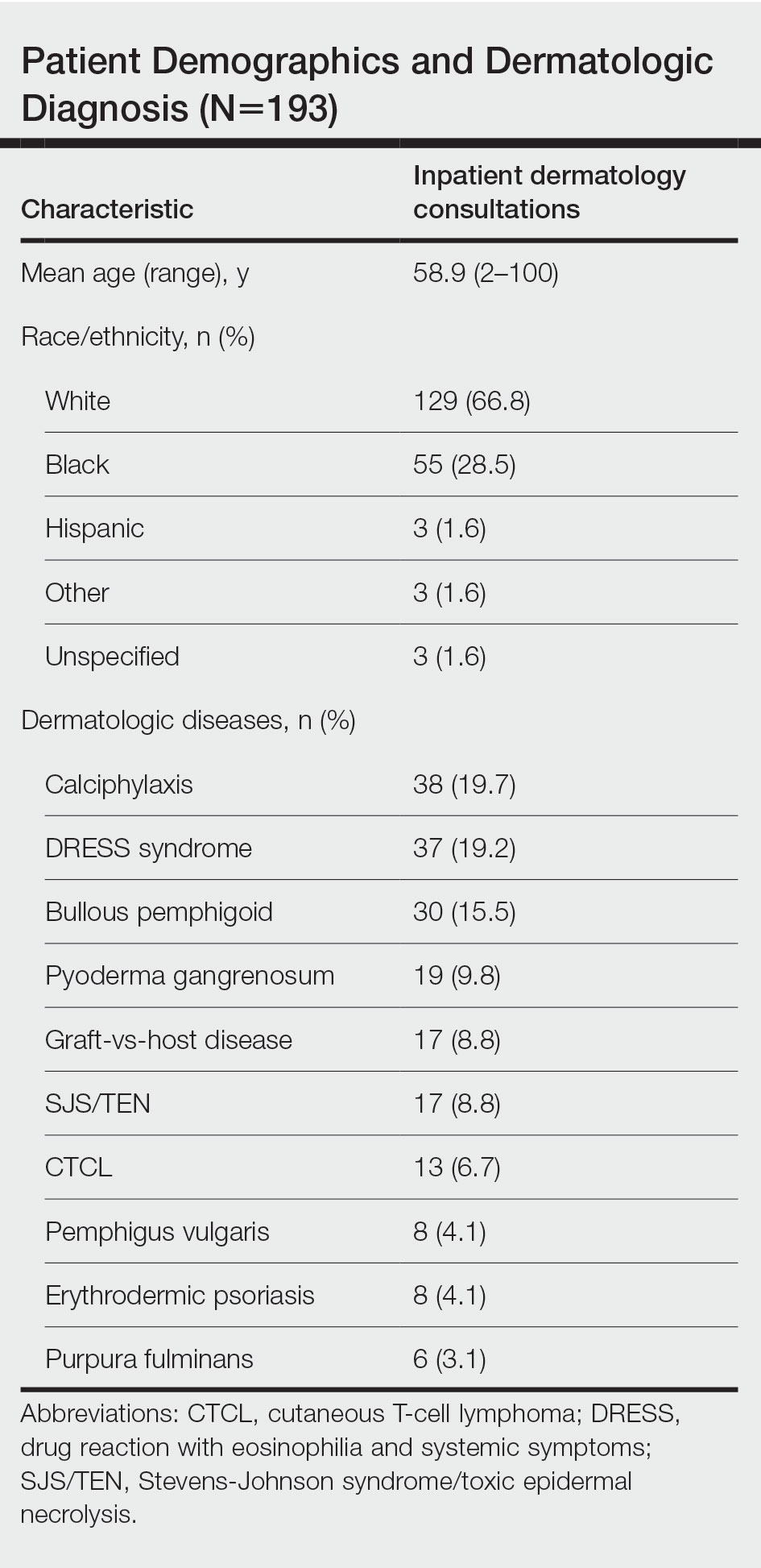

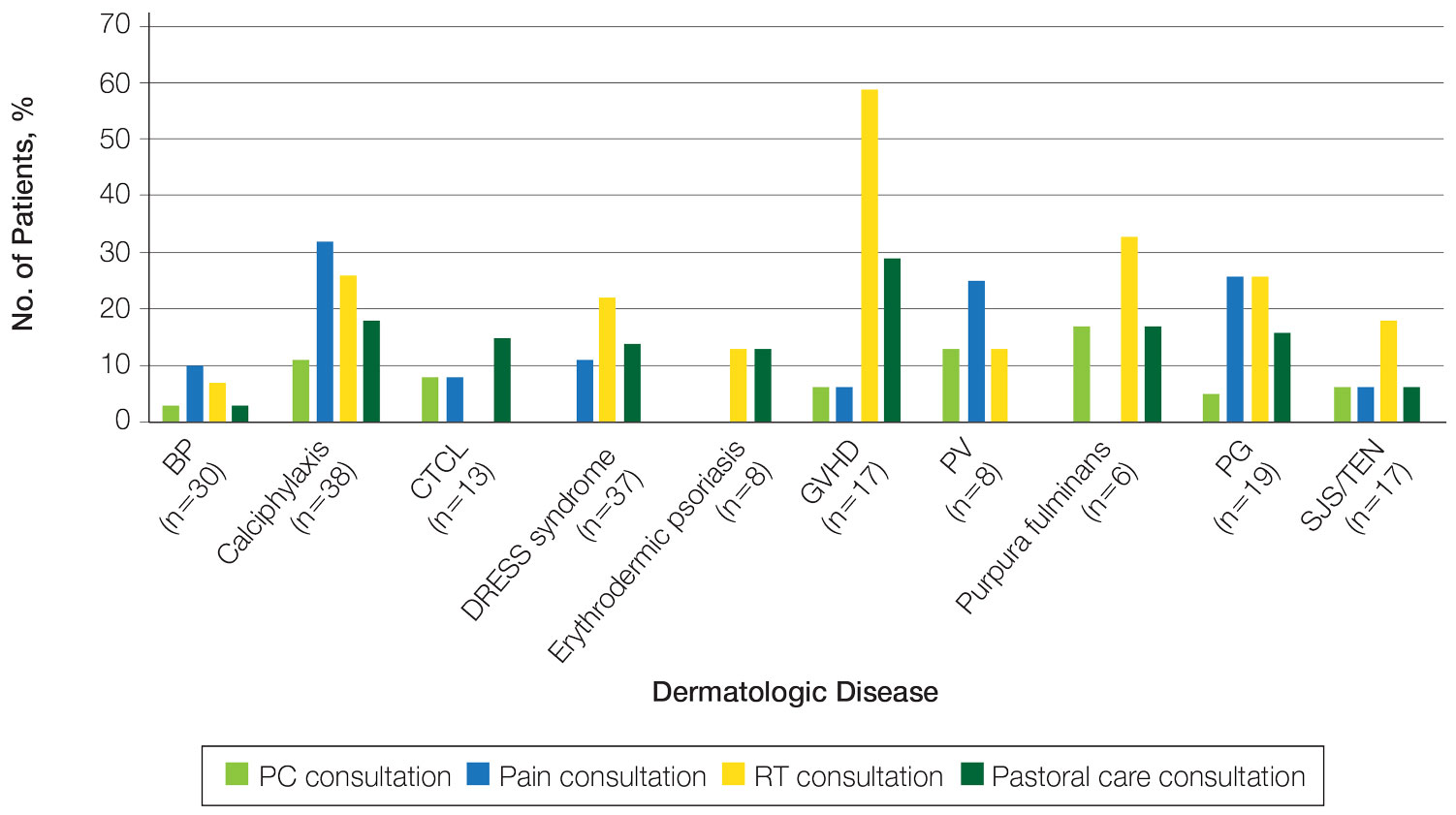

The total study sample included 193 inpatient dermatology consultations. The mean age of the patients was 58.9 years (range, 2–100 years); 66.8% (129/193) were White and 28.5% (55/193) were Black (Table). Palliative care was consulted in 5.7% of cases, with consultations being requested by the primary care team. Reasons for PC consultation included assessment of the patient’s goals of care (4.1% [8/193]), pain management (3.6% [7/193]), non–pain symptom management (2.6% [5/193]), psychosocial support (1.6% [3/193]), and transitions of care (1.0% [2/193]). The average length of patients’ hospital stay prior to PC consultation was 11.5 days(range, 1–32 days). Acute pain management was the reason for consultation in 15.0% of cases (29/193), RT in 21.8% (42/193), and pastoral care in 13.5% (26/193) of cases. Patients with calciphylaxis received the most PC and pain consultations, but fewer than half received these services. Patients with calciphylaxis, PV, purpura fulminans, and CTCL received a higher percentage of PC consultations than the overall cohort, while patients with calciphylaxis, DRESS syndrome, PV, and pyoderma gangrenosum received relatively more pain consultations than the overall cohort (Figure).

Comment

Clinical practice guidelines for quality PC stress the importance of specialists being familiar with these services and the ability to involve PC as part of the treatment plan to achieve better care for patients with serious illnesses.5 Our results demonstrated low rates of PC consultation services for dermatology patients, which supports the existing literature and suggests that PC may be highly underutilized in inpatient settings for patients with serious skin diseases. Use of PC was infrequent and was initiated relatively late in the course of hospital admission, which can negatively impact a patient’s well-being and care experience and can increase the care burden on their caregivers and families.2

Our results suggest a discrepancy in the frequency of formal PC and other palliative consultative services used for dermatologic diseases, with non-PC services including RT, acute pain management, and pastoral care more likely to be utilized. Impacting this finding may be that RT, pastoral care, and acute pain management are provided by nonphysician providers at our institution, not attending faculty staffing PC services. Patients with calciphylaxis were more likely to have PC consultations, potentially due to medicine providers’ familiarity with its morbidity and mortality, as it is commonly associated with end-stage renal disease. Similarly, internal medicine providers may be more familiar with pain classically associated with PG and PV and may be more likely to engage pain experts. Some diseases with notable morbidity and potential mortality were underrepresented including SJS/TEN, erythrodermic psoriasis, CTCL, and GVHD.

Limitations of our study included examination of data from a single institution, as well as the small sample sizes in specific subgroups, which prevented us from making comparisons between diseases. The cross-sectional design also limited our ability to control for confounding variables.

Conclusion

We urge dermatology consultation services to advocate for patients with serious skin diseases andinclude PC consultation as part of their recommendations to primary care teams. Further research should characterize the specific needs of patients that may be addressed by PC services and explore ways dermatologists and others can identify and provide specialty care to hospitalized patients.

- Kelley AS, Morrison RS. Palliative care for the seriously ill. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:747-755.

- Thompson LL, Chen ST, Lawton A, et al. Palliative care in dermatology: a clinical primer, review of the literature, and needs assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:708-717. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.029

- Yang CS, Quan VL, Charrow A. The power of a palliative perspective in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:609-610. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.1298

- Osagiede O, Colibaseanu DT, Spaulding AC, et al. Palliative care use among patients with solid cancer tumors. J Palliat Care. 2018;33:149-158.

- Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 4th ed. National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care; 2018. Accessed June 21, 2023. https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/NCHPC-NCPGuidelines_4thED_web_FINAL.pdf

Palliative care (PC) is a field of medicine that focuses on improving quality of life by managing physical symptoms as well as mental and spiritual well-being in patients with severe illnesses.1,2 Despite cases of severe dermatologic disease, the use of PC in the field of dermatology is limited, often leaving patients with a range of unmet needs.2,3 In one study that explored PC in patients with melanoma, only one-third of patients with advanced melanoma had a PC consultation.4 Reasons behind the lack of utilization of PC in dermatology include time constraints and limited training in addressing the complex psychosocial needs of patients with severe dermatologic illnesses.1 We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional, single-institution study of specific inpatient dermatology consultations over a 5-year period to describe PC utilization among patients who were hospitalized with select severe dermatologic diseases.

Methods

A retrospective, cross-sectional study of inpatient dermatology consultations over a 5-year period (October 2016 to October 2021) was performed at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (Winston-Salem, North Carolina). Patients’ medical records were reviewed if they had one of the following diseases: bullous pemphigoid, calciphylaxis, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, erythrodermic psoriasis, graft-vs-host disease, pemphigus vulgaris (PV), purpura fulminans, pyoderma gangrenosum, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. These diseases were selected for inclusion because they have been associated with a documented increase in inpatient mortality and have been described in the published literature on PC in dermatology.2 This study was reviewed and approved by the Wake Forest University institutional review board.

Use of PC consultative services along with other associated consultative care (ie, recreation therapy [RT], acute pain management, pastoral care) was assessed for each patient. Recreation therapy included specific interventions such as music therapy, arts/craft therapy, pet therapy, and other services with the goal of improving patient cognitive, emotional, and social function. For patients with a completed PC consultation, goals for PC intervention were recorded.

Results

The total study sample included 193 inpatient dermatology consultations. The mean age of the patients was 58.9 years (range, 2–100 years); 66.8% (129/193) were White and 28.5% (55/193) were Black (Table). Palliative care was consulted in 5.7% of cases, with consultations being requested by the primary care team. Reasons for PC consultation included assessment of the patient’s goals of care (4.1% [8/193]), pain management (3.6% [7/193]), non–pain symptom management (2.6% [5/193]), psychosocial support (1.6% [3/193]), and transitions of care (1.0% [2/193]). The average length of patients’ hospital stay prior to PC consultation was 11.5 days(range, 1–32 days). Acute pain management was the reason for consultation in 15.0% of cases (29/193), RT in 21.8% (42/193), and pastoral care in 13.5% (26/193) of cases. Patients with calciphylaxis received the most PC and pain consultations, but fewer than half received these services. Patients with calciphylaxis, PV, purpura fulminans, and CTCL received a higher percentage of PC consultations than the overall cohort, while patients with calciphylaxis, DRESS syndrome, PV, and pyoderma gangrenosum received relatively more pain consultations than the overall cohort (Figure).

Comment

Clinical practice guidelines for quality PC stress the importance of specialists being familiar with these services and the ability to involve PC as part of the treatment plan to achieve better care for patients with serious illnesses.5 Our results demonstrated low rates of PC consultation services for dermatology patients, which supports the existing literature and suggests that PC may be highly underutilized in inpatient settings for patients with serious skin diseases. Use of PC was infrequent and was initiated relatively late in the course of hospital admission, which can negatively impact a patient’s well-being and care experience and can increase the care burden on their caregivers and families.2

Our results suggest a discrepancy in the frequency of formal PC and other palliative consultative services used for dermatologic diseases, with non-PC services including RT, acute pain management, and pastoral care more likely to be utilized. Impacting this finding may be that RT, pastoral care, and acute pain management are provided by nonphysician providers at our institution, not attending faculty staffing PC services. Patients with calciphylaxis were more likely to have PC consultations, potentially due to medicine providers’ familiarity with its morbidity and mortality, as it is commonly associated with end-stage renal disease. Similarly, internal medicine providers may be more familiar with pain classically associated with PG and PV and may be more likely to engage pain experts. Some diseases with notable morbidity and potential mortality were underrepresented including SJS/TEN, erythrodermic psoriasis, CTCL, and GVHD.

Limitations of our study included examination of data from a single institution, as well as the small sample sizes in specific subgroups, which prevented us from making comparisons between diseases. The cross-sectional design also limited our ability to control for confounding variables.

Conclusion

We urge dermatology consultation services to advocate for patients with serious skin diseases andinclude PC consultation as part of their recommendations to primary care teams. Further research should characterize the specific needs of patients that may be addressed by PC services and explore ways dermatologists and others can identify and provide specialty care to hospitalized patients.

Palliative care (PC) is a field of medicine that focuses on improving quality of life by managing physical symptoms as well as mental and spiritual well-being in patients with severe illnesses.1,2 Despite cases of severe dermatologic disease, the use of PC in the field of dermatology is limited, often leaving patients with a range of unmet needs.2,3 In one study that explored PC in patients with melanoma, only one-third of patients with advanced melanoma had a PC consultation.4 Reasons behind the lack of utilization of PC in dermatology include time constraints and limited training in addressing the complex psychosocial needs of patients with severe dermatologic illnesses.1 We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional, single-institution study of specific inpatient dermatology consultations over a 5-year period to describe PC utilization among patients who were hospitalized with select severe dermatologic diseases.

Methods

A retrospective, cross-sectional study of inpatient dermatology consultations over a 5-year period (October 2016 to October 2021) was performed at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (Winston-Salem, North Carolina). Patients’ medical records were reviewed if they had one of the following diseases: bullous pemphigoid, calciphylaxis, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, erythrodermic psoriasis, graft-vs-host disease, pemphigus vulgaris (PV), purpura fulminans, pyoderma gangrenosum, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. These diseases were selected for inclusion because they have been associated with a documented increase in inpatient mortality and have been described in the published literature on PC in dermatology.2 This study was reviewed and approved by the Wake Forest University institutional review board.

Use of PC consultative services along with other associated consultative care (ie, recreation therapy [RT], acute pain management, pastoral care) was assessed for each patient. Recreation therapy included specific interventions such as music therapy, arts/craft therapy, pet therapy, and other services with the goal of improving patient cognitive, emotional, and social function. For patients with a completed PC consultation, goals for PC intervention were recorded.

Results

The total study sample included 193 inpatient dermatology consultations. The mean age of the patients was 58.9 years (range, 2–100 years); 66.8% (129/193) were White and 28.5% (55/193) were Black (Table). Palliative care was consulted in 5.7% of cases, with consultations being requested by the primary care team. Reasons for PC consultation included assessment of the patient’s goals of care (4.1% [8/193]), pain management (3.6% [7/193]), non–pain symptom management (2.6% [5/193]), psychosocial support (1.6% [3/193]), and transitions of care (1.0% [2/193]). The average length of patients’ hospital stay prior to PC consultation was 11.5 days(range, 1–32 days). Acute pain management was the reason for consultation in 15.0% of cases (29/193), RT in 21.8% (42/193), and pastoral care in 13.5% (26/193) of cases. Patients with calciphylaxis received the most PC and pain consultations, but fewer than half received these services. Patients with calciphylaxis, PV, purpura fulminans, and CTCL received a higher percentage of PC consultations than the overall cohort, while patients with calciphylaxis, DRESS syndrome, PV, and pyoderma gangrenosum received relatively more pain consultations than the overall cohort (Figure).

Comment

Clinical practice guidelines for quality PC stress the importance of specialists being familiar with these services and the ability to involve PC as part of the treatment plan to achieve better care for patients with serious illnesses.5 Our results demonstrated low rates of PC consultation services for dermatology patients, which supports the existing literature and suggests that PC may be highly underutilized in inpatient settings for patients with serious skin diseases. Use of PC was infrequent and was initiated relatively late in the course of hospital admission, which can negatively impact a patient’s well-being and care experience and can increase the care burden on their caregivers and families.2

Our results suggest a discrepancy in the frequency of formal PC and other palliative consultative services used for dermatologic diseases, with non-PC services including RT, acute pain management, and pastoral care more likely to be utilized. Impacting this finding may be that RT, pastoral care, and acute pain management are provided by nonphysician providers at our institution, not attending faculty staffing PC services. Patients with calciphylaxis were more likely to have PC consultations, potentially due to medicine providers’ familiarity with its morbidity and mortality, as it is commonly associated with end-stage renal disease. Similarly, internal medicine providers may be more familiar with pain classically associated with PG and PV and may be more likely to engage pain experts. Some diseases with notable morbidity and potential mortality were underrepresented including SJS/TEN, erythrodermic psoriasis, CTCL, and GVHD.

Limitations of our study included examination of data from a single institution, as well as the small sample sizes in specific subgroups, which prevented us from making comparisons between diseases. The cross-sectional design also limited our ability to control for confounding variables.

Conclusion

We urge dermatology consultation services to advocate for patients with serious skin diseases andinclude PC consultation as part of their recommendations to primary care teams. Further research should characterize the specific needs of patients that may be addressed by PC services and explore ways dermatologists and others can identify and provide specialty care to hospitalized patients.

- Kelley AS, Morrison RS. Palliative care for the seriously ill. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:747-755.

- Thompson LL, Chen ST, Lawton A, et al. Palliative care in dermatology: a clinical primer, review of the literature, and needs assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:708-717. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.029

- Yang CS, Quan VL, Charrow A. The power of a palliative perspective in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:609-610. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.1298

- Osagiede O, Colibaseanu DT, Spaulding AC, et al. Palliative care use among patients with solid cancer tumors. J Palliat Care. 2018;33:149-158.

- Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 4th ed. National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care; 2018. Accessed June 21, 2023. https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/NCHPC-NCPGuidelines_4thED_web_FINAL.pdf

- Kelley AS, Morrison RS. Palliative care for the seriously ill. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:747-755.

- Thompson LL, Chen ST, Lawton A, et al. Palliative care in dermatology: a clinical primer, review of the literature, and needs assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:708-717. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.029

- Yang CS, Quan VL, Charrow A. The power of a palliative perspective in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:609-610. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.1298

- Osagiede O, Colibaseanu DT, Spaulding AC, et al. Palliative care use among patients with solid cancer tumors. J Palliat Care. 2018;33:149-158.

- Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 4th ed. National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care; 2018. Accessed June 21, 2023. https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/NCHPC-NCPGuidelines_4thED_web_FINAL.pdf

Practice Points

- Although severe dermatologic disease negatively impacts patients’ quality of life, palliative care may be underutilized in this population.

- Palliative care should be an integral part of caring for patients who are admitted to the hospital with serious dermatologic illnesses.

New guidelines for MTX use in pediatric inflammatory skin disease unveiled

While the typical dose of methotrexate (MTX) for inflammatory disease in pediatric patients varies in published studies, the maximum dose is considered to be 1 mg/kg and not to exceed 25 mg/week. In addition, test doses are not necessary for pediatric patients starting low dose (1 mg/kg or less) MTX for inflammatory skin disease, and the onset of efficacy with MTX may take 8-16 weeks.

and published online in Pediatric Dermatology.

“Methotrexate is a cost-effective, readily accessible, well-tolerated, useful, and time-honored option for children with a spectrum of inflammatory skin diseases,” project cochair Elaine C. Siegfried, MD, professor of pediatrics and dermatology at Saint Louis University, told this news organization. “Although considered an ‘immune suppressant’ by some, it is more accurately classified as an immune modulator and has been widely used for more than 50 years, and remains the standard of care when administered at very high doses and intrathecally in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia – a practice that supports safety. But many details that support optimized treatment are not widely appreciated.”

In their guidelines document, Dr. Siegfried and her 22 coauthors noted that Food and Drug Administration labeling does not include approved indications for the use of MTX for many inflammatory skin diseases in pediatric patients, including morphea, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and alopecia areata. “Furthermore, some clinicians may be unfamiliar or uncomfortable prescribing medications off label for pediatric patients, causing delayed initiation, premature drug discontinuation, or use of less advantageous alternatives,” they wrote.

To address this unmet need, Dr. Siegfried and the other committee members used a modified Delphi process to reach agreement on recommendations related to five key topic areas: indications and contraindications, dosing, interactions with immunizations and medications, potential for and management of adverse effects, and monitoring needs. Consensus was predefined as at least 70% of participants rating a statement as 7-9 on the Likert scale. The effort to develop 46 recommendations has been a work in progress for almost 5 years, “somewhat delayed by the pandemic,” Dr. Siegfried, past president and director of the American Board of Dermatology, said in an interview. “But it remains relevant, despite the emergence of biologics and JAK inhibitors for treating inflammatory skin conditions in children. Although the mechanism-of-action of low-dose MTX is not clear, it may overlap with the newer small molecules.”

The guidelines contain several pearls to guide optimal dosing, including the following key points:

- MTX can be discontinued abruptly without adverse effects, other than the risk of disease worsening.

- Folic acid supplementation (starting at 1 mg/day, regardless of weight) is an effective approach to minimizing associated gastrointestinal adverse effects.

- Concomitant use of MTX and antibiotics (including trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) and NSAIDS are not contraindicated for most pediatric patients treated for inflammatory skin disease.

- Live virus vaccine boosters such as varicella-zoster virus (VZV) and measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) are not contraindicated in patients taking MTX; there are insufficient data to make recommendations for or against primary immunization with MMR vaccine in patients taking MTX; inactivated vaccines should be given to patients taking MTX.

- Routine surveillance laboratory monitoring (i.e., CBC with differential, alanine transaminase, aspartate aminotransferase, creatinine) is recommended at baseline, after 1 month of treatment, and every 3-4 months thereafter.

- Transient transaminase elevation (≤ 3 upper limit normal for < 3 months) is not uncommon with low-dose MTX and does not usually require interruption of MTX. The most likely causes are concomitant viral infection, MTX dosing within 24 hours prior to phlebotomy, recent administration of other medications (such as acetaminophen), and/or recent alcohol consumption.

- Liver biopsy is not indicated for routine monitoring of pediatric patients taking low-dose MTX.

According to Dr. Siegfried, consensus of the committee members was lowest on the need for a test dose of MTX.

Overall, she said in the interview, helping to craft the guidelines caused her to reflect on how her approach to using MTX has evolved over the past 35 years, after treating “many hundreds” of patients. “I was gratified to confirm similar practice patterns among my colleagues,” she added.

The project’s other cochair was Heather Brandling-Bennett, MD, a dermatologist at Seattle Children’s Hospital. This work was supported by a grant from the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance (PeDRA), with additional funding from the National Eczema Association and the National Psoriasis Foundation. Dr. Siegfried disclosed ties with AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Incyte, LEO Pharma, Novan, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, UCB, and Verrica. She has participated in contracted research for AI Therapeutics, and has served as principal investigator for Janssen. Many of the guideline coauthors disclosed having received grant support and other funding from pharmaceutical companies.

While the typical dose of methotrexate (MTX) for inflammatory disease in pediatric patients varies in published studies, the maximum dose is considered to be 1 mg/kg and not to exceed 25 mg/week. In addition, test doses are not necessary for pediatric patients starting low dose (1 mg/kg or less) MTX for inflammatory skin disease, and the onset of efficacy with MTX may take 8-16 weeks.

and published online in Pediatric Dermatology.

“Methotrexate is a cost-effective, readily accessible, well-tolerated, useful, and time-honored option for children with a spectrum of inflammatory skin diseases,” project cochair Elaine C. Siegfried, MD, professor of pediatrics and dermatology at Saint Louis University, told this news organization. “Although considered an ‘immune suppressant’ by some, it is more accurately classified as an immune modulator and has been widely used for more than 50 years, and remains the standard of care when administered at very high doses and intrathecally in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia – a practice that supports safety. But many details that support optimized treatment are not widely appreciated.”

In their guidelines document, Dr. Siegfried and her 22 coauthors noted that Food and Drug Administration labeling does not include approved indications for the use of MTX for many inflammatory skin diseases in pediatric patients, including morphea, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and alopecia areata. “Furthermore, some clinicians may be unfamiliar or uncomfortable prescribing medications off label for pediatric patients, causing delayed initiation, premature drug discontinuation, or use of less advantageous alternatives,” they wrote.

To address this unmet need, Dr. Siegfried and the other committee members used a modified Delphi process to reach agreement on recommendations related to five key topic areas: indications and contraindications, dosing, interactions with immunizations and medications, potential for and management of adverse effects, and monitoring needs. Consensus was predefined as at least 70% of participants rating a statement as 7-9 on the Likert scale. The effort to develop 46 recommendations has been a work in progress for almost 5 years, “somewhat delayed by the pandemic,” Dr. Siegfried, past president and director of the American Board of Dermatology, said in an interview. “But it remains relevant, despite the emergence of biologics and JAK inhibitors for treating inflammatory skin conditions in children. Although the mechanism-of-action of low-dose MTX is not clear, it may overlap with the newer small molecules.”

The guidelines contain several pearls to guide optimal dosing, including the following key points:

- MTX can be discontinued abruptly without adverse effects, other than the risk of disease worsening.

- Folic acid supplementation (starting at 1 mg/day, regardless of weight) is an effective approach to minimizing associated gastrointestinal adverse effects.

- Concomitant use of MTX and antibiotics (including trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) and NSAIDS are not contraindicated for most pediatric patients treated for inflammatory skin disease.

- Live virus vaccine boosters such as varicella-zoster virus (VZV) and measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) are not contraindicated in patients taking MTX; there are insufficient data to make recommendations for or against primary immunization with MMR vaccine in patients taking MTX; inactivated vaccines should be given to patients taking MTX.

- Routine surveillance laboratory monitoring (i.e., CBC with differential, alanine transaminase, aspartate aminotransferase, creatinine) is recommended at baseline, after 1 month of treatment, and every 3-4 months thereafter.

- Transient transaminase elevation (≤ 3 upper limit normal for < 3 months) is not uncommon with low-dose MTX and does not usually require interruption of MTX. The most likely causes are concomitant viral infection, MTX dosing within 24 hours prior to phlebotomy, recent administration of other medications (such as acetaminophen), and/or recent alcohol consumption.

- Liver biopsy is not indicated for routine monitoring of pediatric patients taking low-dose MTX.

According to Dr. Siegfried, consensus of the committee members was lowest on the need for a test dose of MTX.

Overall, she said in the interview, helping to craft the guidelines caused her to reflect on how her approach to using MTX has evolved over the past 35 years, after treating “many hundreds” of patients. “I was gratified to confirm similar practice patterns among my colleagues,” she added.

The project’s other cochair was Heather Brandling-Bennett, MD, a dermatologist at Seattle Children’s Hospital. This work was supported by a grant from the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance (PeDRA), with additional funding from the National Eczema Association and the National Psoriasis Foundation. Dr. Siegfried disclosed ties with AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Incyte, LEO Pharma, Novan, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, UCB, and Verrica. She has participated in contracted research for AI Therapeutics, and has served as principal investigator for Janssen. Many of the guideline coauthors disclosed having received grant support and other funding from pharmaceutical companies.

While the typical dose of methotrexate (MTX) for inflammatory disease in pediatric patients varies in published studies, the maximum dose is considered to be 1 mg/kg and not to exceed 25 mg/week. In addition, test doses are not necessary for pediatric patients starting low dose (1 mg/kg or less) MTX for inflammatory skin disease, and the onset of efficacy with MTX may take 8-16 weeks.

and published online in Pediatric Dermatology.

“Methotrexate is a cost-effective, readily accessible, well-tolerated, useful, and time-honored option for children with a spectrum of inflammatory skin diseases,” project cochair Elaine C. Siegfried, MD, professor of pediatrics and dermatology at Saint Louis University, told this news organization. “Although considered an ‘immune suppressant’ by some, it is more accurately classified as an immune modulator and has been widely used for more than 50 years, and remains the standard of care when administered at very high doses and intrathecally in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia – a practice that supports safety. But many details that support optimized treatment are not widely appreciated.”

In their guidelines document, Dr. Siegfried and her 22 coauthors noted that Food and Drug Administration labeling does not include approved indications for the use of MTX for many inflammatory skin diseases in pediatric patients, including morphea, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and alopecia areata. “Furthermore, some clinicians may be unfamiliar or uncomfortable prescribing medications off label for pediatric patients, causing delayed initiation, premature drug discontinuation, or use of less advantageous alternatives,” they wrote.

To address this unmet need, Dr. Siegfried and the other committee members used a modified Delphi process to reach agreement on recommendations related to five key topic areas: indications and contraindications, dosing, interactions with immunizations and medications, potential for and management of adverse effects, and monitoring needs. Consensus was predefined as at least 70% of participants rating a statement as 7-9 on the Likert scale. The effort to develop 46 recommendations has been a work in progress for almost 5 years, “somewhat delayed by the pandemic,” Dr. Siegfried, past president and director of the American Board of Dermatology, said in an interview. “But it remains relevant, despite the emergence of biologics and JAK inhibitors for treating inflammatory skin conditions in children. Although the mechanism-of-action of low-dose MTX is not clear, it may overlap with the newer small molecules.”

The guidelines contain several pearls to guide optimal dosing, including the following key points:

- MTX can be discontinued abruptly without adverse effects, other than the risk of disease worsening.

- Folic acid supplementation (starting at 1 mg/day, regardless of weight) is an effective approach to minimizing associated gastrointestinal adverse effects.

- Concomitant use of MTX and antibiotics (including trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) and NSAIDS are not contraindicated for most pediatric patients treated for inflammatory skin disease.

- Live virus vaccine boosters such as varicella-zoster virus (VZV) and measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) are not contraindicated in patients taking MTX; there are insufficient data to make recommendations for or against primary immunization with MMR vaccine in patients taking MTX; inactivated vaccines should be given to patients taking MTX.

- Routine surveillance laboratory monitoring (i.e., CBC with differential, alanine transaminase, aspartate aminotransferase, creatinine) is recommended at baseline, after 1 month of treatment, and every 3-4 months thereafter.

- Transient transaminase elevation (≤ 3 upper limit normal for < 3 months) is not uncommon with low-dose MTX and does not usually require interruption of MTX. The most likely causes are concomitant viral infection, MTX dosing within 24 hours prior to phlebotomy, recent administration of other medications (such as acetaminophen), and/or recent alcohol consumption.

- Liver biopsy is not indicated for routine monitoring of pediatric patients taking low-dose MTX.

According to Dr. Siegfried, consensus of the committee members was lowest on the need for a test dose of MTX.

Overall, she said in the interview, helping to craft the guidelines caused her to reflect on how her approach to using MTX has evolved over the past 35 years, after treating “many hundreds” of patients. “I was gratified to confirm similar practice patterns among my colleagues,” she added.

The project’s other cochair was Heather Brandling-Bennett, MD, a dermatologist at Seattle Children’s Hospital. This work was supported by a grant from the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance (PeDRA), with additional funding from the National Eczema Association and the National Psoriasis Foundation. Dr. Siegfried disclosed ties with AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Incyte, LEO Pharma, Novan, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, UCB, and Verrica. She has participated in contracted research for AI Therapeutics, and has served as principal investigator for Janssen. Many of the guideline coauthors disclosed having received grant support and other funding from pharmaceutical companies.

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

For psoriasis, review finds several biosimilars as safe and effective as biologics

The effectiveness and safety of biosimilars for psoriasis appear to be similar to the originator biologics, reported the authors of a review of studies comparing the two.

“This systematic review found that there was no clinically or statistically significant difference in the efficacy and safety between biosimilars and originators of adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, and ustekinumab for the treatment of psoriasis,” senior study author and clinical lecturer Zenas Z. N. Yiu, MBChB, PhD, and his colleagues at the University of Manchester, England, wrote in JAMA Dermatology.“The biosimilars evaluated in this study could be considered alongside originators for biologic-naive patients to improve the accessibility of biological treatments,” they added. “Switching patients currently on originators to biosimilars could be considered where clinically appropriate to reduce treatment costs.”

Biologics versus biosimilars

In contrast to most chemically synthesized drugs, biologics are created from living organisms, and they have complex structures that can vary slightly from batch to batch, Luigi Naldi, MD, director of the department of dermatology of Ospedale San Bortolo, Vicenza, Italy, and Antonio Addis, PharmD, researcher in the department of epidemiology, Regione Lazio, in Rome, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Once the patent on the “originator” biologic expires, U.S. and European regulators allow other manufacturers to develop similar molecules – biosimilars – through an abbreviated approval process. If the results of a limited number of equivalence or noninferiority clinical trials are acceptable, registration for all the indications of the originator is allowed for its biosimilars. Referring to the expense of biologics, Dr. Naldi and Dr. Addis noted that in the United States, “biologics comprise less than 3% of the volume of drugs on the market, but account for more than one-third of all drug spending.”

Systematic review

Dr. Yiu and his colleagues queried standard medical research databases in August 2022, and included 14 randomized clinical trials (10 adalimumab, 2 etanercept, 1 infliximab, and 1 ustekinumab) and 3 cohort studies (1 adalimumab, 1 etanercept, 1 infliximab and etanercept) in their review.

Twelve trials compared biosimilars vs. originators in originator-naive patients, and 11 trials compared switching from originators to biosimilars vs. continuous treatment with the originator.

The researchers found the following:

At week 16, mean PASI75 (Psoriasis Area and Severity Index) response rates ranges from 60.7% to 90.6% for adalimumab biosimilars, vs. 61.5% to 91.7% for the originator. Mean PASI75 responses for the two etanercept biosimilars were 56.1% and 76.7% vs. 55.5% and 73.4% for the originator. In the ustekinumab study, mean PASI75 responses were 86.1% for the biosimilar vs. 84.0% for the originator.

At week 52, mean PASI75 responses were between 86.3% and 92.8% for adalimumab biosimilars vs. 84.9% and 93.9% for the originator. In the one comparison of an etanercept biosimilar, mean PAS175 responses were 80.9% for the biosimilar vs. 82.9% for the originator.

In studies involving patients switching from the originator to a biosimilar vs. continuing treatment with the originator, 32-week response rates ranged from 87.0% to 91.3% for adalimumab biosimilars and from 88.2% to 93.2% for the originator. In the one ustekinumab study, the 32-week mean PASI75 response was 92.6% after switching from the originator to a biosimilar vs. 92.9% with continuous treatment with the originator.

At week 52, mean PASI75 responses to adalimumab were between 84.2% and 94.8% for patients who switched to biosimilars and between 88.1% and 93.9% for those who stayed on the originator.

At week 52, in all the randomized trials, the incidence of adverse events and serious adverse events among those who switched to the biosimilar and those who continued with the originator were similar. Two cohort studies showed similar safety outcomes between originators and biosimilars, but one reported more adverse events in patients who switched to adalimumab biosimilars (P = .04).

Three clinical trials showed low risk for bias, 11 had moderate risk, and all cohort studies had moderate to high risk for bias.

Experts weigh in

Asked to comment on the study, Steven R. Feldman, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., told this news organization that he expects that the results will affect patient care.

However, he added, “I believe the decision of whether to use a biosimilar instead of the originator biologic may be more in the hands of the insurers than in the hands of physicians and patients.

“Biologics for psoriasis are so complicated that even the originator products vary from batch to batch. A biosimilar is basically like another batch of the innovative product,” explained Dr. Feldman, who was not involved in the study. “If we’re comfortable with patients being on different batches of the innovator product, we probably should be comfortable with them being on a biosimilar, as we have more evidence for the similarity of the biosimilar than we do for the current batch of the originator product.”

Aída Lugo-Somolinos, MD, professor of dermatology and director of the Contact Dermatitis Clinic at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said that “biologics have become the treatment of choice for moderate to severe psoriasis, and the use of biosimilars may be an alternative to reduce psoriasis treatment costs.

“Unfortunately, this study included a comparison of the existing biosimilars, which are drugs that are not the first line of treatment for psoriasis any longer,” added Dr. Lugo-Somolinos, who was not involved in the study.

Neil J. Korman, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology and codirector of the Skin Study Center at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, said the study was an important systematic review.

“This is a very timely publication because in the United States, several biosimilars are reaching the market in 2023,” he said. “The costs of the originator biologics are extraordinarily high, and the promise of biosimilars is that their costs will be significantly lower.”

Because all the studies were short term, Dr. Korman, who was not involved in the study, joins the study authors in recommending further related research into the long-term safety and efficacy of these agents.

Dr. Feldman, as well as one study author and one editorial author, reported relevant relationships with various pharmaceutical companies, including those that develop biosimilars. The remaining study authors, as well as Dr. Lugo-Somolinos and Dr. Korman, reported no relevant relationships. The study was funded by the Psoriasis Association and supported by the NIHR (National Institute for Health and Care Research) Manchester Biomedical Research Centre. All outside experts commented by email.

The effectiveness and safety of biosimilars for psoriasis appear to be similar to the originator biologics, reported the authors of a review of studies comparing the two.

“This systematic review found that there was no clinically or statistically significant difference in the efficacy and safety between biosimilars and originators of adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, and ustekinumab for the treatment of psoriasis,” senior study author and clinical lecturer Zenas Z. N. Yiu, MBChB, PhD, and his colleagues at the University of Manchester, England, wrote in JAMA Dermatology.“The biosimilars evaluated in this study could be considered alongside originators for biologic-naive patients to improve the accessibility of biological treatments,” they added. “Switching patients currently on originators to biosimilars could be considered where clinically appropriate to reduce treatment costs.”

Biologics versus biosimilars

In contrast to most chemically synthesized drugs, biologics are created from living organisms, and they have complex structures that can vary slightly from batch to batch, Luigi Naldi, MD, director of the department of dermatology of Ospedale San Bortolo, Vicenza, Italy, and Antonio Addis, PharmD, researcher in the department of epidemiology, Regione Lazio, in Rome, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Once the patent on the “originator” biologic expires, U.S. and European regulators allow other manufacturers to develop similar molecules – biosimilars – through an abbreviated approval process. If the results of a limited number of equivalence or noninferiority clinical trials are acceptable, registration for all the indications of the originator is allowed for its biosimilars. Referring to the expense of biologics, Dr. Naldi and Dr. Addis noted that in the United States, “biologics comprise less than 3% of the volume of drugs on the market, but account for more than one-third of all drug spending.”

Systematic review

Dr. Yiu and his colleagues queried standard medical research databases in August 2022, and included 14 randomized clinical trials (10 adalimumab, 2 etanercept, 1 infliximab, and 1 ustekinumab) and 3 cohort studies (1 adalimumab, 1 etanercept, 1 infliximab and etanercept) in their review.

Twelve trials compared biosimilars vs. originators in originator-naive patients, and 11 trials compared switching from originators to biosimilars vs. continuous treatment with the originator.

The researchers found the following:

At week 16, mean PASI75 (Psoriasis Area and Severity Index) response rates ranges from 60.7% to 90.6% for adalimumab biosimilars, vs. 61.5% to 91.7% for the originator. Mean PASI75 responses for the two etanercept biosimilars were 56.1% and 76.7% vs. 55.5% and 73.4% for the originator. In the ustekinumab study, mean PASI75 responses were 86.1% for the biosimilar vs. 84.0% for the originator.

At week 52, mean PASI75 responses were between 86.3% and 92.8% for adalimumab biosimilars vs. 84.9% and 93.9% for the originator. In the one comparison of an etanercept biosimilar, mean PAS175 responses were 80.9% for the biosimilar vs. 82.9% for the originator.

In studies involving patients switching from the originator to a biosimilar vs. continuing treatment with the originator, 32-week response rates ranged from 87.0% to 91.3% for adalimumab biosimilars and from 88.2% to 93.2% for the originator. In the one ustekinumab study, the 32-week mean PASI75 response was 92.6% after switching from the originator to a biosimilar vs. 92.9% with continuous treatment with the originator.

At week 52, mean PASI75 responses to adalimumab were between 84.2% and 94.8% for patients who switched to biosimilars and between 88.1% and 93.9% for those who stayed on the originator.

At week 52, in all the randomized trials, the incidence of adverse events and serious adverse events among those who switched to the biosimilar and those who continued with the originator were similar. Two cohort studies showed similar safety outcomes between originators and biosimilars, but one reported more adverse events in patients who switched to adalimumab biosimilars (P = .04).

Three clinical trials showed low risk for bias, 11 had moderate risk, and all cohort studies had moderate to high risk for bias.

Experts weigh in

Asked to comment on the study, Steven R. Feldman, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., told this news organization that he expects that the results will affect patient care.

However, he added, “I believe the decision of whether to use a biosimilar instead of the originator biologic may be more in the hands of the insurers than in the hands of physicians and patients.

“Biologics for psoriasis are so complicated that even the originator products vary from batch to batch. A biosimilar is basically like another batch of the innovative product,” explained Dr. Feldman, who was not involved in the study. “If we’re comfortable with patients being on different batches of the innovator product, we probably should be comfortable with them being on a biosimilar, as we have more evidence for the similarity of the biosimilar than we do for the current batch of the originator product.”

Aída Lugo-Somolinos, MD, professor of dermatology and director of the Contact Dermatitis Clinic at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said that “biologics have become the treatment of choice for moderate to severe psoriasis, and the use of biosimilars may be an alternative to reduce psoriasis treatment costs.

“Unfortunately, this study included a comparison of the existing biosimilars, which are drugs that are not the first line of treatment for psoriasis any longer,” added Dr. Lugo-Somolinos, who was not involved in the study.

Neil J. Korman, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology and codirector of the Skin Study Center at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, said the study was an important systematic review.

“This is a very timely publication because in the United States, several biosimilars are reaching the market in 2023,” he said. “The costs of the originator biologics are extraordinarily high, and the promise of biosimilars is that their costs will be significantly lower.”

Because all the studies were short term, Dr. Korman, who was not involved in the study, joins the study authors in recommending further related research into the long-term safety and efficacy of these agents.

Dr. Feldman, as well as one study author and one editorial author, reported relevant relationships with various pharmaceutical companies, including those that develop biosimilars. The remaining study authors, as well as Dr. Lugo-Somolinos and Dr. Korman, reported no relevant relationships. The study was funded by the Psoriasis Association and supported by the NIHR (National Institute for Health and Care Research) Manchester Biomedical Research Centre. All outside experts commented by email.

The effectiveness and safety of biosimilars for psoriasis appear to be similar to the originator biologics, reported the authors of a review of studies comparing the two.

“This systematic review found that there was no clinically or statistically significant difference in the efficacy and safety between biosimilars and originators of adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, and ustekinumab for the treatment of psoriasis,” senior study author and clinical lecturer Zenas Z. N. Yiu, MBChB, PhD, and his colleagues at the University of Manchester, England, wrote in JAMA Dermatology.“The biosimilars evaluated in this study could be considered alongside originators for biologic-naive patients to improve the accessibility of biological treatments,” they added. “Switching patients currently on originators to biosimilars could be considered where clinically appropriate to reduce treatment costs.”

Biologics versus biosimilars

In contrast to most chemically synthesized drugs, biologics are created from living organisms, and they have complex structures that can vary slightly from batch to batch, Luigi Naldi, MD, director of the department of dermatology of Ospedale San Bortolo, Vicenza, Italy, and Antonio Addis, PharmD, researcher in the department of epidemiology, Regione Lazio, in Rome, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Once the patent on the “originator” biologic expires, U.S. and European regulators allow other manufacturers to develop similar molecules – biosimilars – through an abbreviated approval process. If the results of a limited number of equivalence or noninferiority clinical trials are acceptable, registration for all the indications of the originator is allowed for its biosimilars. Referring to the expense of biologics, Dr. Naldi and Dr. Addis noted that in the United States, “biologics comprise less than 3% of the volume of drugs on the market, but account for more than one-third of all drug spending.”

Systematic review

Dr. Yiu and his colleagues queried standard medical research databases in August 2022, and included 14 randomized clinical trials (10 adalimumab, 2 etanercept, 1 infliximab, and 1 ustekinumab) and 3 cohort studies (1 adalimumab, 1 etanercept, 1 infliximab and etanercept) in their review.

Twelve trials compared biosimilars vs. originators in originator-naive patients, and 11 trials compared switching from originators to biosimilars vs. continuous treatment with the originator.

The researchers found the following:

At week 16, mean PASI75 (Psoriasis Area and Severity Index) response rates ranges from 60.7% to 90.6% for adalimumab biosimilars, vs. 61.5% to 91.7% for the originator. Mean PASI75 responses for the two etanercept biosimilars were 56.1% and 76.7% vs. 55.5% and 73.4% for the originator. In the ustekinumab study, mean PASI75 responses were 86.1% for the biosimilar vs. 84.0% for the originator.

At week 52, mean PASI75 responses were between 86.3% and 92.8% for adalimumab biosimilars vs. 84.9% and 93.9% for the originator. In the one comparison of an etanercept biosimilar, mean PAS175 responses were 80.9% for the biosimilar vs. 82.9% for the originator.

In studies involving patients switching from the originator to a biosimilar vs. continuing treatment with the originator, 32-week response rates ranged from 87.0% to 91.3% for adalimumab biosimilars and from 88.2% to 93.2% for the originator. In the one ustekinumab study, the 32-week mean PASI75 response was 92.6% after switching from the originator to a biosimilar vs. 92.9% with continuous treatment with the originator.

At week 52, mean PASI75 responses to adalimumab were between 84.2% and 94.8% for patients who switched to biosimilars and between 88.1% and 93.9% for those who stayed on the originator.

At week 52, in all the randomized trials, the incidence of adverse events and serious adverse events among those who switched to the biosimilar and those who continued with the originator were similar. Two cohort studies showed similar safety outcomes between originators and biosimilars, but one reported more adverse events in patients who switched to adalimumab biosimilars (P = .04).

Three clinical trials showed low risk for bias, 11 had moderate risk, and all cohort studies had moderate to high risk for bias.

Experts weigh in

Asked to comment on the study, Steven R. Feldman, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., told this news organization that he expects that the results will affect patient care.

However, he added, “I believe the decision of whether to use a biosimilar instead of the originator biologic may be more in the hands of the insurers than in the hands of physicians and patients.

“Biologics for psoriasis are so complicated that even the originator products vary from batch to batch. A biosimilar is basically like another batch of the innovative product,” explained Dr. Feldman, who was not involved in the study. “If we’re comfortable with patients being on different batches of the innovator product, we probably should be comfortable with them being on a biosimilar, as we have more evidence for the similarity of the biosimilar than we do for the current batch of the originator product.”