User login

PCPC: Avoid these traps when prescribing medical marijuana

ORLANDO – Good data suggest that marijuana has legitimate medical indications, but smoking the drug is not the appropriate method of delivery, and clinicians without experience with marijuana should consider its many liabilities before issuing a prescription, according to an expert who said he is not antimarijuana and has prescribed this therapy himself.

“Dried cannabis is not a medication in any traditional sense of the word. That does not mean cannabinoids have no legitimate indication as therapeutic agents, but smoking anything for your health is something of an oxymoron,” Dr. Douglas L. Gourlay of the departments of anesthesiology and psychiatry at the University of Toronto said at the Pain Care for Primary Care meeting.

Cannabis, distinct from cannabinoids, is defined as the dried leaves of the marijuana plant. According to Dr. Gourlay, who spoke at the meeting, which was cosponsored by the Journal of Family Practice, the plant has more than 400 compounds, including more than 60 cannabinoids, which are chemicals that act on cannabinoid receptors, primarily in the central nervous system. For physicians wishing to deliver cannabinoids for a medical indication, the problem posed by cannabis is quality control.

“You are being asked to prescribe something for which you have no practical means of titrating the dose,” Dr. Gourlay said. Even ignoring the potential risks of exposing the lungs to a variety of oxidized chemicals with no known therapeutic benefit, the absence of quality control will be problematic if the patient or family members subsequently claim iatrogenic harm.

For recreational use of cannabis, the focus has been on the concentration of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which is the cannabinoid most closely associated with euphoric effects. However, the potential medical benefits of marijuana, such as relief of glaucoma symptoms, reduction of chemotherapy-induced nausea, or control of neuropathic pain, are not necessarily related to THC. Well-designed clinical studies aimed at determining which other cannabinoids and at which doses are most relevant for medical use have yet to be performed, Dr. Gourlay said.

For the clinician, legalization of medical marijuana in the absence of reliable data on best practice creates some potential risks. According to Dr. Gourlay, patients who harm themselves or others in an accident attributed to impaired judgment from medical marijuana might pursue legal action against the prescribing physician. The relative absence of standards regarding marijuana use would complicate the defense.

“Unless you can competently discuss the pros and cons of herbal cannabis, including indications and contraindications that are relevant to informed consent, you would be wise to consider carefully any decision to prescribe,” Dr. Gourlay suggested.

The problem for many clinicians, according to Dr. Gourlay, is that patients often are already using marijuana and employ a variety of strategies to induce the physician to provide a prescription to legitimize this activity. He outlined several familiar traps that he urged physicians to avoid. These include claims by patients that a prescription would protect them from legal problems for a drug they will be using in any event or that clinicians can provide a dosing regimen that can be the basis for a plan to eventually taper use.

“Once you start down this road, it will be very difficult to change course,” said Dr. Gourlay, noting that even a discussion of marijuana should be well documented so that there are no misinterpretations regarding instructions about use or avoiding use. In situations in which patients are insistent about their need for marijuana, “consider having a third party in the room,” he suggested.

In areas where cannabinoids are available in well-defined concentrations for oral delivery, a stronger case can be made for medicinal applications, but clinical studies still remain limited, Dr. Gourlay said. He said he hopes trials will eventually be conducted to gauge the benefit-to-risk ratio for specific indications.

“I am not anticannabinoids, but I have never prescribed cannabis to smoke,” Dr. Gourlay reported. Even though recent legislation now permits recreational use of marijuana in several states, Dr. Gourlay urged clinicians to employ a conservative approach to clinical use until more data clarify both the drug’s benefits and safety.

The Journal of Family Practice and this news organization are owned by the same company.

The meeting was held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education. Global Academy and this news organization are owned the same company.

This post has been updated 8/5/2015.

ORLANDO – Good data suggest that marijuana has legitimate medical indications, but smoking the drug is not the appropriate method of delivery, and clinicians without experience with marijuana should consider its many liabilities before issuing a prescription, according to an expert who said he is not antimarijuana and has prescribed this therapy himself.

“Dried cannabis is not a medication in any traditional sense of the word. That does not mean cannabinoids have no legitimate indication as therapeutic agents, but smoking anything for your health is something of an oxymoron,” Dr. Douglas L. Gourlay of the departments of anesthesiology and psychiatry at the University of Toronto said at the Pain Care for Primary Care meeting.

Cannabis, distinct from cannabinoids, is defined as the dried leaves of the marijuana plant. According to Dr. Gourlay, who spoke at the meeting, which was cosponsored by the Journal of Family Practice, the plant has more than 400 compounds, including more than 60 cannabinoids, which are chemicals that act on cannabinoid receptors, primarily in the central nervous system. For physicians wishing to deliver cannabinoids for a medical indication, the problem posed by cannabis is quality control.

“You are being asked to prescribe something for which you have no practical means of titrating the dose,” Dr. Gourlay said. Even ignoring the potential risks of exposing the lungs to a variety of oxidized chemicals with no known therapeutic benefit, the absence of quality control will be problematic if the patient or family members subsequently claim iatrogenic harm.

For recreational use of cannabis, the focus has been on the concentration of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which is the cannabinoid most closely associated with euphoric effects. However, the potential medical benefits of marijuana, such as relief of glaucoma symptoms, reduction of chemotherapy-induced nausea, or control of neuropathic pain, are not necessarily related to THC. Well-designed clinical studies aimed at determining which other cannabinoids and at which doses are most relevant for medical use have yet to be performed, Dr. Gourlay said.

For the clinician, legalization of medical marijuana in the absence of reliable data on best practice creates some potential risks. According to Dr. Gourlay, patients who harm themselves or others in an accident attributed to impaired judgment from medical marijuana might pursue legal action against the prescribing physician. The relative absence of standards regarding marijuana use would complicate the defense.

“Unless you can competently discuss the pros and cons of herbal cannabis, including indications and contraindications that are relevant to informed consent, you would be wise to consider carefully any decision to prescribe,” Dr. Gourlay suggested.

The problem for many clinicians, according to Dr. Gourlay, is that patients often are already using marijuana and employ a variety of strategies to induce the physician to provide a prescription to legitimize this activity. He outlined several familiar traps that he urged physicians to avoid. These include claims by patients that a prescription would protect them from legal problems for a drug they will be using in any event or that clinicians can provide a dosing regimen that can be the basis for a plan to eventually taper use.

“Once you start down this road, it will be very difficult to change course,” said Dr. Gourlay, noting that even a discussion of marijuana should be well documented so that there are no misinterpretations regarding instructions about use or avoiding use. In situations in which patients are insistent about their need for marijuana, “consider having a third party in the room,” he suggested.

In areas where cannabinoids are available in well-defined concentrations for oral delivery, a stronger case can be made for medicinal applications, but clinical studies still remain limited, Dr. Gourlay said. He said he hopes trials will eventually be conducted to gauge the benefit-to-risk ratio for specific indications.

“I am not anticannabinoids, but I have never prescribed cannabis to smoke,” Dr. Gourlay reported. Even though recent legislation now permits recreational use of marijuana in several states, Dr. Gourlay urged clinicians to employ a conservative approach to clinical use until more data clarify both the drug’s benefits and safety.

The Journal of Family Practice and this news organization are owned by the same company.

The meeting was held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education. Global Academy and this news organization are owned the same company.

This post has been updated 8/5/2015.

ORLANDO – Good data suggest that marijuana has legitimate medical indications, but smoking the drug is not the appropriate method of delivery, and clinicians without experience with marijuana should consider its many liabilities before issuing a prescription, according to an expert who said he is not antimarijuana and has prescribed this therapy himself.

“Dried cannabis is not a medication in any traditional sense of the word. That does not mean cannabinoids have no legitimate indication as therapeutic agents, but smoking anything for your health is something of an oxymoron,” Dr. Douglas L. Gourlay of the departments of anesthesiology and psychiatry at the University of Toronto said at the Pain Care for Primary Care meeting.

Cannabis, distinct from cannabinoids, is defined as the dried leaves of the marijuana plant. According to Dr. Gourlay, who spoke at the meeting, which was cosponsored by the Journal of Family Practice, the plant has more than 400 compounds, including more than 60 cannabinoids, which are chemicals that act on cannabinoid receptors, primarily in the central nervous system. For physicians wishing to deliver cannabinoids for a medical indication, the problem posed by cannabis is quality control.

“You are being asked to prescribe something for which you have no practical means of titrating the dose,” Dr. Gourlay said. Even ignoring the potential risks of exposing the lungs to a variety of oxidized chemicals with no known therapeutic benefit, the absence of quality control will be problematic if the patient or family members subsequently claim iatrogenic harm.

For recreational use of cannabis, the focus has been on the concentration of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which is the cannabinoid most closely associated with euphoric effects. However, the potential medical benefits of marijuana, such as relief of glaucoma symptoms, reduction of chemotherapy-induced nausea, or control of neuropathic pain, are not necessarily related to THC. Well-designed clinical studies aimed at determining which other cannabinoids and at which doses are most relevant for medical use have yet to be performed, Dr. Gourlay said.

For the clinician, legalization of medical marijuana in the absence of reliable data on best practice creates some potential risks. According to Dr. Gourlay, patients who harm themselves or others in an accident attributed to impaired judgment from medical marijuana might pursue legal action against the prescribing physician. The relative absence of standards regarding marijuana use would complicate the defense.

“Unless you can competently discuss the pros and cons of herbal cannabis, including indications and contraindications that are relevant to informed consent, you would be wise to consider carefully any decision to prescribe,” Dr. Gourlay suggested.

The problem for many clinicians, according to Dr. Gourlay, is that patients often are already using marijuana and employ a variety of strategies to induce the physician to provide a prescription to legitimize this activity. He outlined several familiar traps that he urged physicians to avoid. These include claims by patients that a prescription would protect them from legal problems for a drug they will be using in any event or that clinicians can provide a dosing regimen that can be the basis for a plan to eventually taper use.

“Once you start down this road, it will be very difficult to change course,” said Dr. Gourlay, noting that even a discussion of marijuana should be well documented so that there are no misinterpretations regarding instructions about use or avoiding use. In situations in which patients are insistent about their need for marijuana, “consider having a third party in the room,” he suggested.

In areas where cannabinoids are available in well-defined concentrations for oral delivery, a stronger case can be made for medicinal applications, but clinical studies still remain limited, Dr. Gourlay said. He said he hopes trials will eventually be conducted to gauge the benefit-to-risk ratio for specific indications.

“I am not anticannabinoids, but I have never prescribed cannabis to smoke,” Dr. Gourlay reported. Even though recent legislation now permits recreational use of marijuana in several states, Dr. Gourlay urged clinicians to employ a conservative approach to clinical use until more data clarify both the drug’s benefits and safety.

The Journal of Family Practice and this news organization are owned by the same company.

The meeting was held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education. Global Academy and this news organization are owned the same company.

This post has been updated 8/5/2015.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT THE PAIN CARE FOR PRIMARY CARE MEETING

Anticoagulant therapy not contraindicated in brain metastases

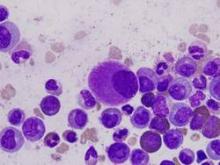

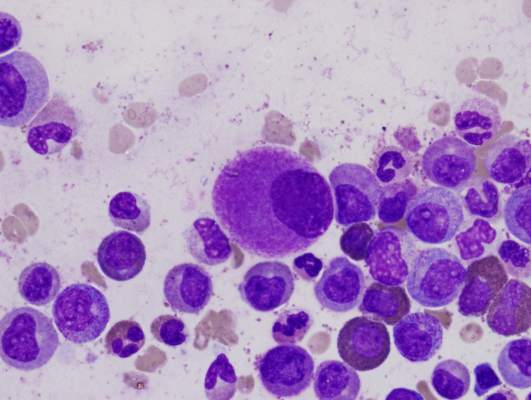

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is common in cancer patients with brain metastases but therapeutic anticoagulation does not increase the risk for intracranial hemorrhage, according to new data.

In a matched, retrospective cohort study of 293 cancer patients with brain metastases (104 treated with therapeutic enoxaparin and 189 controls), there were no differences at 1 year between the two groups for measurable (19% vs 21%; Gray test, P = .97; hazard ratio, 1.02; 90% confidence interval [CI], 0.66-1.59), significant (21% vs 22%; P = .87), and total (44% vs 37%; P = .13) intracranial hemorrhages.

“Reassuringly, the cumulative incidence of intracranial hemorrhage was not significantly different in those patients who received therapeutic enoxaparin compared with controls for all outcomes including measurable, total, and significant intracranial hemorrhages,” wrote Dr. Jessica Donato of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues (Blood 2015 Jul 23 doi:10.1182/blood-2015-02-626788).

The only covariate that was predictive of hemorrhage in this study was the combined group of renal cell carcinoma and melanoma, as the risk for intracranial hemorrhage was fourfold higher (adjusted hazard ratio, 3.98; 90% CI, 2.41-6.57; P less than .001) in those subgroups.

In an accompanying commentary in the same issue of Blood, Dr. Lisa Baumann Kreuziger of Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, wrote that although the study was well designed, “its retrospective nature creates inherent limitations.”

As an example, besides tumor type, the multivariable analysis did not identify other clinical factors that could guide clinicians when assessing the risk of intracranial hemorrhage, she wrote (Blood 2015 Jul 23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-06-648089]).

But in spite of the limitations, the study “further supports the statement from the 2014 American Society of Clinical Oncology Guidelines that brain metastases are not a contraindication to treatment of VTE with low-molecular-weight heparin,” she concluded.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is common in cancer patients with brain metastases but therapeutic anticoagulation does not increase the risk for intracranial hemorrhage, according to new data.

In a matched, retrospective cohort study of 293 cancer patients with brain metastases (104 treated with therapeutic enoxaparin and 189 controls), there were no differences at 1 year between the two groups for measurable (19% vs 21%; Gray test, P = .97; hazard ratio, 1.02; 90% confidence interval [CI], 0.66-1.59), significant (21% vs 22%; P = .87), and total (44% vs 37%; P = .13) intracranial hemorrhages.

“Reassuringly, the cumulative incidence of intracranial hemorrhage was not significantly different in those patients who received therapeutic enoxaparin compared with controls for all outcomes including measurable, total, and significant intracranial hemorrhages,” wrote Dr. Jessica Donato of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues (Blood 2015 Jul 23 doi:10.1182/blood-2015-02-626788).

The only covariate that was predictive of hemorrhage in this study was the combined group of renal cell carcinoma and melanoma, as the risk for intracranial hemorrhage was fourfold higher (adjusted hazard ratio, 3.98; 90% CI, 2.41-6.57; P less than .001) in those subgroups.

In an accompanying commentary in the same issue of Blood, Dr. Lisa Baumann Kreuziger of Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, wrote that although the study was well designed, “its retrospective nature creates inherent limitations.”

As an example, besides tumor type, the multivariable analysis did not identify other clinical factors that could guide clinicians when assessing the risk of intracranial hemorrhage, she wrote (Blood 2015 Jul 23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-06-648089]).

But in spite of the limitations, the study “further supports the statement from the 2014 American Society of Clinical Oncology Guidelines that brain metastases are not a contraindication to treatment of VTE with low-molecular-weight heparin,” she concluded.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is common in cancer patients with brain metastases but therapeutic anticoagulation does not increase the risk for intracranial hemorrhage, according to new data.

In a matched, retrospective cohort study of 293 cancer patients with brain metastases (104 treated with therapeutic enoxaparin and 189 controls), there were no differences at 1 year between the two groups for measurable (19% vs 21%; Gray test, P = .97; hazard ratio, 1.02; 90% confidence interval [CI], 0.66-1.59), significant (21% vs 22%; P = .87), and total (44% vs 37%; P = .13) intracranial hemorrhages.

“Reassuringly, the cumulative incidence of intracranial hemorrhage was not significantly different in those patients who received therapeutic enoxaparin compared with controls for all outcomes including measurable, total, and significant intracranial hemorrhages,” wrote Dr. Jessica Donato of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues (Blood 2015 Jul 23 doi:10.1182/blood-2015-02-626788).

The only covariate that was predictive of hemorrhage in this study was the combined group of renal cell carcinoma and melanoma, as the risk for intracranial hemorrhage was fourfold higher (adjusted hazard ratio, 3.98; 90% CI, 2.41-6.57; P less than .001) in those subgroups.

In an accompanying commentary in the same issue of Blood, Dr. Lisa Baumann Kreuziger of Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, wrote that although the study was well designed, “its retrospective nature creates inherent limitations.”

As an example, besides tumor type, the multivariable analysis did not identify other clinical factors that could guide clinicians when assessing the risk of intracranial hemorrhage, she wrote (Blood 2015 Jul 23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-06-648089]).

But in spite of the limitations, the study “further supports the statement from the 2014 American Society of Clinical Oncology Guidelines that brain metastases are not a contraindication to treatment of VTE with low-molecular-weight heparin,” she concluded.

FROM BLOOD

Key clinical point: Therapeutic anticoagulation does not increase the risk for intracranial hemorrhage in patients with brain metastases.

Major finding: There were no differences in the cumulative incidence of intracranial hemorrhage at 1 year in the enoxaparin and control cohorts for total (44% vs 37%; P = .13) intracranial hemorrhages.

Data source: A matched, retrospective cohort study of 293 cancer patients with brain metastases.

Disclosures: The Harvard Catalyst/The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center and a Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Core Grant supported the study. Dr. Zwicker received prior research funding from Sanofi, serves on advisory committees for Portola Pharmaceuticals and Merck, and receives consulting fees from Parexel. The remaining authors declared no financial conflicts.

Fertility preservation more likely for young male cancer patients

Young male cancer patients are significantly more likely than female cancer patients to be involved in discussions around fertility preservation and more than four times as likely to make arrangements for fertility preservation, a study has found.

The survey of 459 adolescent and young adult cancer patients revealed that 80% of males and 74% of females had been told that their cancer therapy might affect their fertility, with more than half the male patients and around 17% of female patients classified as being at intermediate or high risk for fertility effects from treatment.

According to the paper published online July 27 in Cancer, having a medical oncologist increased the likelihood that fertility effects were discussed but males with children or who were diagnosed with lymphoma, acute lymphocytic leukemia, or sarcoma were less likely to have fertility issues raised.

In female patients, those who were younger at diagnosis, were Hispanic or non-Hispanic black, or who had less than a college degree or government insurance were also less likely to be told that their treatment might impact their fertility.

Overall, 71% of males and 44 % of females discussed fertility preservation, and 31% of males and 6.8% of females made arrangements for fertility preservation (Cancer 2015 July 27 [doi:10.1002/cncr.29328]).

“The access-related and health-related reasons for not making arrangements for fertility preservation reported by participants in the current study further highlight the need for decreased cost, improved insurance coverage, and partnerships between cancer health care providers and fertility experts to develop strategies that increase awareness of fertility preservation options and decrease delays in cancer therapy as fertility preservation for adolescent and young adult patients with cancer improves,” wrote Dr. Margarett Shnorhavorian, from the Seattle Children’s Hospital, and coauthors.

The study was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institutes of Health. Two authors declared National Cancer Institute grants but there were no other conflicts of interest declared.

Young male cancer patients are significantly more likely than female cancer patients to be involved in discussions around fertility preservation and more than four times as likely to make arrangements for fertility preservation, a study has found.

The survey of 459 adolescent and young adult cancer patients revealed that 80% of males and 74% of females had been told that their cancer therapy might affect their fertility, with more than half the male patients and around 17% of female patients classified as being at intermediate or high risk for fertility effects from treatment.

According to the paper published online July 27 in Cancer, having a medical oncologist increased the likelihood that fertility effects were discussed but males with children or who were diagnosed with lymphoma, acute lymphocytic leukemia, or sarcoma were less likely to have fertility issues raised.

In female patients, those who were younger at diagnosis, were Hispanic or non-Hispanic black, or who had less than a college degree or government insurance were also less likely to be told that their treatment might impact their fertility.

Overall, 71% of males and 44 % of females discussed fertility preservation, and 31% of males and 6.8% of females made arrangements for fertility preservation (Cancer 2015 July 27 [doi:10.1002/cncr.29328]).

“The access-related and health-related reasons for not making arrangements for fertility preservation reported by participants in the current study further highlight the need for decreased cost, improved insurance coverage, and partnerships between cancer health care providers and fertility experts to develop strategies that increase awareness of fertility preservation options and decrease delays in cancer therapy as fertility preservation for adolescent and young adult patients with cancer improves,” wrote Dr. Margarett Shnorhavorian, from the Seattle Children’s Hospital, and coauthors.

The study was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institutes of Health. Two authors declared National Cancer Institute grants but there were no other conflicts of interest declared.

Young male cancer patients are significantly more likely than female cancer patients to be involved in discussions around fertility preservation and more than four times as likely to make arrangements for fertility preservation, a study has found.

The survey of 459 adolescent and young adult cancer patients revealed that 80% of males and 74% of females had been told that their cancer therapy might affect their fertility, with more than half the male patients and around 17% of female patients classified as being at intermediate or high risk for fertility effects from treatment.

According to the paper published online July 27 in Cancer, having a medical oncologist increased the likelihood that fertility effects were discussed but males with children or who were diagnosed with lymphoma, acute lymphocytic leukemia, or sarcoma were less likely to have fertility issues raised.

In female patients, those who were younger at diagnosis, were Hispanic or non-Hispanic black, or who had less than a college degree or government insurance were also less likely to be told that their treatment might impact their fertility.

Overall, 71% of males and 44 % of females discussed fertility preservation, and 31% of males and 6.8% of females made arrangements for fertility preservation (Cancer 2015 July 27 [doi:10.1002/cncr.29328]).

“The access-related and health-related reasons for not making arrangements for fertility preservation reported by participants in the current study further highlight the need for decreased cost, improved insurance coverage, and partnerships between cancer health care providers and fertility experts to develop strategies that increase awareness of fertility preservation options and decrease delays in cancer therapy as fertility preservation for adolescent and young adult patients with cancer improves,” wrote Dr. Margarett Shnorhavorian, from the Seattle Children’s Hospital, and coauthors.

The study was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institutes of Health. Two authors declared National Cancer Institute grants but there were no other conflicts of interest declared.

FROM CANCER

Key clinical point: Young male cancer patients are significantly more likely than female cancer patients to discuss fertility preservation with their provider.

Major finding: Overall, 71% of males and 44 % of females discussed fertility preservation, and 31% of males and 6.8% of females made arrangements for fertility preservation.

Data source: A population-based questionnaire study of 459 adolescent and young adult cancer patients.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institutes of Health. Two authors declared National Cancer Institute grants but there were no other conflicts of interest declared.

Aromatase inhibitors, bisphosphonates cut postmenopausal breast cancer recurrence

Aromatase inhibitors and bisphosphonates can improve survival in postmenopausal early-stage breast cancer, and combining the two drug classes can help negate their individual adverse effects, according to two studies published online in The Lancet.

The research offers “the best evidence yet for the effects of aromatase inhibitors and bisphosphonates on postmenopausal women with early breast cancer,” according to a news release by The Lancet that accompanied the reports.

Breast cancer typically occurs after menopause and is usually detected early enough to be operable, but can metastasize years later in bone or other sites if dormant malignant cells become activated, noted researchers from the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group, which conducted both meta-analyses.

For the aromatase inhibitor (AI) study, researchers analyzed data from almost 32,000 postmenopausal women with estrogen receptor–positive (ER-positive) early breast cancer who had participated in nine randomized, multiyear trials comparing AIs with standard tamoxifen-based endocrine therapy. Compared with tamoxifen, AI therapy cut the chances of breast cancer recurrence by about 30% during years 0-1 and 2-4 (P less than .001), they reported. “However, in the 2014 ASCO guidelines on endocrine treatment of postmenopausal women with ER-positive early breast cancer, three of the four recommended options start with tamoxifen; a review seems appropriate,” the investigators noted (Lancet 2015 July 24 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61074-1]). Treatment with AIs also appeared to cut 10-year breast cancer mortality by about 15% compared with tamoxifen, and to lower the risk of dying of breast cancer by about 40% compared with no endocrine therapy, the researchers reported. “The impact of AIs is particularly remarkable given how specific these drugs are – removing only the tiny amount of estrogen that remains in the circulation of women after the menopause – and given the extraordinary molecular differences between ER-positive tumors,” Dr. Mitch Dowsett, the lead author, said in a statement.

“But AI treatment is not free of side effects, and it’s important to ensure that women with significant side effects are supported to try to continue to take treatment and fully benefit from it,” added Dr. Dowsett of The Royal Marsden and The Institute of Cancer Research, both in London.

Because AIs can increase fracture risk, clinicians need to monitor treated patients’ bone health and should consider using bisphosphonates when indicated, Dr. Dowsett and his associates added. The study also linked AIs to a slightly lower rate of endometrial cancer compared with tamoxifen therapy, helping offset the increased fracture risk, they said.

For the second study, investigators analyzed data from more than 18,700 women who had participated in 26 randomized controlled trials of bisphosphonates that assessed breast cancer recurrence, distant metastasis, and mortality. Bisphosphonate treatment did not seem to affect outcomes in premenopausal women, they found. But in postmenopausal patients, treatment led to “highly significant reductions” in local recurrence (risk ratio, 0.86, 95% confidence interval, 0.78 to 0.94; P = .002), distant recurrence (P = .0003), bone recurrence (P = .0002) and breast cancer mortality (P = .002), they reported (Lancet 2015 July 24 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60908-4]).

Use of bisphosphonates also was tied to a small drop in fracture rates, which was probably real based on studies of other groups of patients, they noted. While bisphosphonates have been used primarily to help prevent bone loss and fractures in postmenopausal women with ER-positive disease who are receiving AIs, the findings show an additional oncological benefit “and suggest that adjuvant bisphosphonates should be considered in a broader range of postmenopausal women,” the researchers concluded. They were unable to assess rates of osteonecrosis of the jaw, but past reports point to rates of about 1% of patients on clodronate, ibandronate, or 6-monthly zoledronic acid therapy, and about 2% of those receiving more intensive zoledronic acid treatment, they noted.

Cancer Research UK and the UK Medical Research Council funded both studies. Ten authors from the AI study and eight authors from the bisphosphonate study reported financial relationships with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

Aromatase inhibitors and bisphosphonates can improve survival in postmenopausal early-stage breast cancer, and combining the two drug classes can help negate their individual adverse effects, according to two studies published online in The Lancet.

The research offers “the best evidence yet for the effects of aromatase inhibitors and bisphosphonates on postmenopausal women with early breast cancer,” according to a news release by The Lancet that accompanied the reports.

Breast cancer typically occurs after menopause and is usually detected early enough to be operable, but can metastasize years later in bone or other sites if dormant malignant cells become activated, noted researchers from the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group, which conducted both meta-analyses.

For the aromatase inhibitor (AI) study, researchers analyzed data from almost 32,000 postmenopausal women with estrogen receptor–positive (ER-positive) early breast cancer who had participated in nine randomized, multiyear trials comparing AIs with standard tamoxifen-based endocrine therapy. Compared with tamoxifen, AI therapy cut the chances of breast cancer recurrence by about 30% during years 0-1 and 2-4 (P less than .001), they reported. “However, in the 2014 ASCO guidelines on endocrine treatment of postmenopausal women with ER-positive early breast cancer, three of the four recommended options start with tamoxifen; a review seems appropriate,” the investigators noted (Lancet 2015 July 24 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61074-1]). Treatment with AIs also appeared to cut 10-year breast cancer mortality by about 15% compared with tamoxifen, and to lower the risk of dying of breast cancer by about 40% compared with no endocrine therapy, the researchers reported. “The impact of AIs is particularly remarkable given how specific these drugs are – removing only the tiny amount of estrogen that remains in the circulation of women after the menopause – and given the extraordinary molecular differences between ER-positive tumors,” Dr. Mitch Dowsett, the lead author, said in a statement.

“But AI treatment is not free of side effects, and it’s important to ensure that women with significant side effects are supported to try to continue to take treatment and fully benefit from it,” added Dr. Dowsett of The Royal Marsden and The Institute of Cancer Research, both in London.

Because AIs can increase fracture risk, clinicians need to monitor treated patients’ bone health and should consider using bisphosphonates when indicated, Dr. Dowsett and his associates added. The study also linked AIs to a slightly lower rate of endometrial cancer compared with tamoxifen therapy, helping offset the increased fracture risk, they said.

For the second study, investigators analyzed data from more than 18,700 women who had participated in 26 randomized controlled trials of bisphosphonates that assessed breast cancer recurrence, distant metastasis, and mortality. Bisphosphonate treatment did not seem to affect outcomes in premenopausal women, they found. But in postmenopausal patients, treatment led to “highly significant reductions” in local recurrence (risk ratio, 0.86, 95% confidence interval, 0.78 to 0.94; P = .002), distant recurrence (P = .0003), bone recurrence (P = .0002) and breast cancer mortality (P = .002), they reported (Lancet 2015 July 24 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60908-4]).

Use of bisphosphonates also was tied to a small drop in fracture rates, which was probably real based on studies of other groups of patients, they noted. While bisphosphonates have been used primarily to help prevent bone loss and fractures in postmenopausal women with ER-positive disease who are receiving AIs, the findings show an additional oncological benefit “and suggest that adjuvant bisphosphonates should be considered in a broader range of postmenopausal women,” the researchers concluded. They were unable to assess rates of osteonecrosis of the jaw, but past reports point to rates of about 1% of patients on clodronate, ibandronate, or 6-monthly zoledronic acid therapy, and about 2% of those receiving more intensive zoledronic acid treatment, they noted.

Cancer Research UK and the UK Medical Research Council funded both studies. Ten authors from the AI study and eight authors from the bisphosphonate study reported financial relationships with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

Aromatase inhibitors and bisphosphonates can improve survival in postmenopausal early-stage breast cancer, and combining the two drug classes can help negate their individual adverse effects, according to two studies published online in The Lancet.

The research offers “the best evidence yet for the effects of aromatase inhibitors and bisphosphonates on postmenopausal women with early breast cancer,” according to a news release by The Lancet that accompanied the reports.

Breast cancer typically occurs after menopause and is usually detected early enough to be operable, but can metastasize years later in bone or other sites if dormant malignant cells become activated, noted researchers from the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group, which conducted both meta-analyses.

For the aromatase inhibitor (AI) study, researchers analyzed data from almost 32,000 postmenopausal women with estrogen receptor–positive (ER-positive) early breast cancer who had participated in nine randomized, multiyear trials comparing AIs with standard tamoxifen-based endocrine therapy. Compared with tamoxifen, AI therapy cut the chances of breast cancer recurrence by about 30% during years 0-1 and 2-4 (P less than .001), they reported. “However, in the 2014 ASCO guidelines on endocrine treatment of postmenopausal women with ER-positive early breast cancer, three of the four recommended options start with tamoxifen; a review seems appropriate,” the investigators noted (Lancet 2015 July 24 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61074-1]). Treatment with AIs also appeared to cut 10-year breast cancer mortality by about 15% compared with tamoxifen, and to lower the risk of dying of breast cancer by about 40% compared with no endocrine therapy, the researchers reported. “The impact of AIs is particularly remarkable given how specific these drugs are – removing only the tiny amount of estrogen that remains in the circulation of women after the menopause – and given the extraordinary molecular differences between ER-positive tumors,” Dr. Mitch Dowsett, the lead author, said in a statement.

“But AI treatment is not free of side effects, and it’s important to ensure that women with significant side effects are supported to try to continue to take treatment and fully benefit from it,” added Dr. Dowsett of The Royal Marsden and The Institute of Cancer Research, both in London.

Because AIs can increase fracture risk, clinicians need to monitor treated patients’ bone health and should consider using bisphosphonates when indicated, Dr. Dowsett and his associates added. The study also linked AIs to a slightly lower rate of endometrial cancer compared with tamoxifen therapy, helping offset the increased fracture risk, they said.

For the second study, investigators analyzed data from more than 18,700 women who had participated in 26 randomized controlled trials of bisphosphonates that assessed breast cancer recurrence, distant metastasis, and mortality. Bisphosphonate treatment did not seem to affect outcomes in premenopausal women, they found. But in postmenopausal patients, treatment led to “highly significant reductions” in local recurrence (risk ratio, 0.86, 95% confidence interval, 0.78 to 0.94; P = .002), distant recurrence (P = .0003), bone recurrence (P = .0002) and breast cancer mortality (P = .002), they reported (Lancet 2015 July 24 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60908-4]).

Use of bisphosphonates also was tied to a small drop in fracture rates, which was probably real based on studies of other groups of patients, they noted. While bisphosphonates have been used primarily to help prevent bone loss and fractures in postmenopausal women with ER-positive disease who are receiving AIs, the findings show an additional oncological benefit “and suggest that adjuvant bisphosphonates should be considered in a broader range of postmenopausal women,” the researchers concluded. They were unable to assess rates of osteonecrosis of the jaw, but past reports point to rates of about 1% of patients on clodronate, ibandronate, or 6-monthly zoledronic acid therapy, and about 2% of those receiving more intensive zoledronic acid treatment, they noted.

Cancer Research UK and the UK Medical Research Council funded both studies. Ten authors from the AI study and eight authors from the bisphosphonate study reported financial relationships with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

FROM THE LANCET

Key clinical point: Aromatase inhibitors (AIs) and bisphosphonates help prevent recurrence of early-stage breast cancer in postmenopausal women.

Major finding: Recurrence of estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer was about 30% lower for AIs compared with tamoxifen during years 0-1 and 2-4 (P less than .0001). Bisphosphonate therapy also significantly cut risk of recurrence (relative risk, 0.86, 95% confidence interval, 0.78 to 0.94; P= .002), distant recurrence (P = .0003), bone recurrence (P = .0002), and breast cancer mortality (P = .002).

Data source: Meta-analyses of nine randomized trials of aromatase inhibitors (comprising 31,920 women with early estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer) and 26 trials of bisphosphonates (comprising 18,766 women with early breast cancer).

Disclosures: Cancer Research UK and the UK Medical Research Council funded both studies. Ten authors from the AI study and eight authors from the bisphosphonate study reported financial relationships with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

Amlodipine reduced vismodegib-induced muscle cramps

The calcium channel blocker amlodipine besylate was effective in reducing the number of muscle cramps caused by vismodegib, a basal cell carcinoma drug, according to a research letter from Dr. Mina Ally and her associates.

Patients who took amlodipine had the number of muscle cramps halved after 2 weeks of treatment, and this level was maintained for the 8-week medication regimen. No significant change in cramp severity, duration, or frequency of nighttime awakenings was seen. Side effects only appeared in too patients, with one reporting mild intermittent dizziness and another reporting grade 1 peripheral edema.

The control group saw a nonsignificant increase in cramp frequency, compared with the significant decrease in the amlodipine group. No change was seen in cramp severity, duration, or number of nighttime awakenings in the control group.

“Amlodipine may be effective in vismodegib-induced muscle cramps because it blocks voltage-gated calcium channels and inhibits the transport of extracellular calcium into muscle that is required for contraction,” the investigators noted.

Find the full research letter in JAMA Dermatology (doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.1937).

The calcium channel blocker amlodipine besylate was effective in reducing the number of muscle cramps caused by vismodegib, a basal cell carcinoma drug, according to a research letter from Dr. Mina Ally and her associates.

Patients who took amlodipine had the number of muscle cramps halved after 2 weeks of treatment, and this level was maintained for the 8-week medication regimen. No significant change in cramp severity, duration, or frequency of nighttime awakenings was seen. Side effects only appeared in too patients, with one reporting mild intermittent dizziness and another reporting grade 1 peripheral edema.

The control group saw a nonsignificant increase in cramp frequency, compared with the significant decrease in the amlodipine group. No change was seen in cramp severity, duration, or number of nighttime awakenings in the control group.

“Amlodipine may be effective in vismodegib-induced muscle cramps because it blocks voltage-gated calcium channels and inhibits the transport of extracellular calcium into muscle that is required for contraction,” the investigators noted.

Find the full research letter in JAMA Dermatology (doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.1937).

The calcium channel blocker amlodipine besylate was effective in reducing the number of muscle cramps caused by vismodegib, a basal cell carcinoma drug, according to a research letter from Dr. Mina Ally and her associates.

Patients who took amlodipine had the number of muscle cramps halved after 2 weeks of treatment, and this level was maintained for the 8-week medication regimen. No significant change in cramp severity, duration, or frequency of nighttime awakenings was seen. Side effects only appeared in too patients, with one reporting mild intermittent dizziness and another reporting grade 1 peripheral edema.

The control group saw a nonsignificant increase in cramp frequency, compared with the significant decrease in the amlodipine group. No change was seen in cramp severity, duration, or number of nighttime awakenings in the control group.

“Amlodipine may be effective in vismodegib-induced muscle cramps because it blocks voltage-gated calcium channels and inhibits the transport of extracellular calcium into muscle that is required for contraction,” the investigators noted.

Find the full research letter in JAMA Dermatology (doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.1937).

Chemo lessens quality of life for end-stage patients with good performance status

Palliative chemotherapy for patients with end-stage cancer who exhibit promising performance scores should be discouraged, as it does not improve the quality of life for these patients and may actively detract from it, according to a study published in JAMA Oncology.

“Despite the lack of evidence to support the practice, chemotherapy is widely used in cancer patients with poor performance status and progression following an initial course of palliative chemotherapy,” wrote Holly G. Prigerson, Ph.D., of Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. “The goal of palliative chemotherapy for patients with incurable cancer is to prolong survival and promote [quality of life] [but] chemotherapy use among patients with metastatic cancer whose cancer has progressed while receiving prior chemotherapy was not significantly related to longer survival [and] was associated with more aggressive medical care in the patient’s final week and heightened risk of dying in an intensive care unit.”

Dr. Prigerson and her coinvestigators looked at 312 end-stage metastatic cancer patients between September 2002 and February 2008, all of whom were on at least one chemotherapy regimen at one of six outpatient oncology clinics in the United States. They were followed prospectively until death to determine quality of life near death (QOD) as measured by Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status scores of 0 (“fully active, able to carry on all predisease performance without restriction”) through 5 (“dead”).

At enrollment, 158 subjects were on chemotherapy and 154 were not. Of the nine subjects with baseline ECOG score of 0, all of whom continued with chemotherapy, six (66.7%) reported lower QOD following treatment. Of 122 subjects with ECOG score 1, 71 of whom continued with chemotherapy, 40 (56.3%) reported lower QOD compared with 35 of the 51 subjects (68.6%) who reported higher QOD after not undergoing chemotherapy. However, as ECOG scores got higher, chemotherapy did appear to be of some benefit to patients.

ECOG score of 2 was found in 116 patients at baseline, of which 55 did chemotherapy and 67 did not; 28 chemotherapy subjects (50.9%) reported lower QOD than at baseline, and 32 (52.5%) of those without chemotherapy also reported lower QOD. For the 58 subjects with ECOG scores of 3, 12 of the 22 who did chemotherapy (54.5%) reported higher QOD after chemotherapy, compared with 19 of the 36 who did not do chemotherapy (52.8%) reporting lower QOD. Finally, seven subjects had ECOG scores of 4 at baseline, of which one did chemotherapy and reported a higher QOD after treatment; of the six who did not, it was a 50/50 split between those with higher and lower QOD.

“Patients receiving palliative chemotherapy with an ECOG performance status of 0 or 1 had significantly worse QOD than did those who avoided chemotherapy [and] no difference in QOD scores was observed by chemotherapy use among those with ECOG performance status of 2 or 3,” the researchers wrote. “Given no observed survival benefit in the studied patients [and] the observed significant association between chemotherapy use and worse QOL in the final week of life among those with a baseline ECOG score of 1, these results highlight the potential harm of chemotherapy in patients with metastatic cancer toward the end of life, even in patients with good performance status,” the investigators said (JAMA Oncol. 2015 July 23 [doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2378]).

The study had limitations; specifically, Dr. Prigerson and colleagues did not have complete information about the dose and duration of the chemotherapy used for each patient, as well as detailed information on prior chemotherapy use and the exact specifications of chemotherapy treatments given between baseline assessment and death for each patient.

This study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health, National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Minority Heath and Health Disparities, Weill Cornell Medical College, and the Health Services Research and Development Service Career Development Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Prigerson did not report any relevant financial disclosures, but two coinvestigators reported associations with pharmaceutical companies.

These data from Prigerson and associates suggest that equating treatment with hope is inappropriate. Even when oncologists communicate clearly about prognosis and are honest about the limitations of treatment, many patients feel immense pressure to continue treatment. Patients with end-stage cancer are encouraged by friends and family to keep fighting, but the battle analogy itself can portray the dying patient as a loser and should be discouraged.

Costs aside, we feel the last 6 months of life are not best spent in an oncology treatment unit or at home suffering the toxic effects of largely ineffectual therapies for the majority of patients. At this time, it would not be fitting to suggest guidelines must be changed to prohibit chemotherapy for all patients near death without irrefutable data defining who might actually benefit, but if an oncologist suspects the death of a patient in the next 6 months, the default should be no active treatment. Oncologists with a compelling reason to offer chemotherapy in that setting should only do so after documenting a conversation discussing prognosis, goals, fears, and acceptable trade-offs with the patient and family. Let us help patients with metastatic cancer make good decisions at this sad, but often inevitable, stage. Let us not contribute to the suffering that cancer, and often associated therapy, brings, particularly at the end.

Dr. Charles D. Blanke and Dr. Erik K. Fromme are in the division of hematology and medical oncology, Knight Cancer Institute and Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. Neither reported any relevant disclosures. These comments were excerpted from an editorial (JAMA Oncol. 2015 July 23 [doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2379]).

These data from Prigerson and associates suggest that equating treatment with hope is inappropriate. Even when oncologists communicate clearly about prognosis and are honest about the limitations of treatment, many patients feel immense pressure to continue treatment. Patients with end-stage cancer are encouraged by friends and family to keep fighting, but the battle analogy itself can portray the dying patient as a loser and should be discouraged.

Costs aside, we feel the last 6 months of life are not best spent in an oncology treatment unit or at home suffering the toxic effects of largely ineffectual therapies for the majority of patients. At this time, it would not be fitting to suggest guidelines must be changed to prohibit chemotherapy for all patients near death without irrefutable data defining who might actually benefit, but if an oncologist suspects the death of a patient in the next 6 months, the default should be no active treatment. Oncologists with a compelling reason to offer chemotherapy in that setting should only do so after documenting a conversation discussing prognosis, goals, fears, and acceptable trade-offs with the patient and family. Let us help patients with metastatic cancer make good decisions at this sad, but often inevitable, stage. Let us not contribute to the suffering that cancer, and often associated therapy, brings, particularly at the end.

Dr. Charles D. Blanke and Dr. Erik K. Fromme are in the division of hematology and medical oncology, Knight Cancer Institute and Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. Neither reported any relevant disclosures. These comments were excerpted from an editorial (JAMA Oncol. 2015 July 23 [doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2379]).

These data from Prigerson and associates suggest that equating treatment with hope is inappropriate. Even when oncologists communicate clearly about prognosis and are honest about the limitations of treatment, many patients feel immense pressure to continue treatment. Patients with end-stage cancer are encouraged by friends and family to keep fighting, but the battle analogy itself can portray the dying patient as a loser and should be discouraged.

Costs aside, we feel the last 6 months of life are not best spent in an oncology treatment unit or at home suffering the toxic effects of largely ineffectual therapies for the majority of patients. At this time, it would not be fitting to suggest guidelines must be changed to prohibit chemotherapy for all patients near death without irrefutable data defining who might actually benefit, but if an oncologist suspects the death of a patient in the next 6 months, the default should be no active treatment. Oncologists with a compelling reason to offer chemotherapy in that setting should only do so after documenting a conversation discussing prognosis, goals, fears, and acceptable trade-offs with the patient and family. Let us help patients with metastatic cancer make good decisions at this sad, but often inevitable, stage. Let us not contribute to the suffering that cancer, and often associated therapy, brings, particularly at the end.

Dr. Charles D. Blanke and Dr. Erik K. Fromme are in the division of hematology and medical oncology, Knight Cancer Institute and Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. Neither reported any relevant disclosures. These comments were excerpted from an editorial (JAMA Oncol. 2015 July 23 [doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2379]).

Palliative chemotherapy for patients with end-stage cancer who exhibit promising performance scores should be discouraged, as it does not improve the quality of life for these patients and may actively detract from it, according to a study published in JAMA Oncology.

“Despite the lack of evidence to support the practice, chemotherapy is widely used in cancer patients with poor performance status and progression following an initial course of palliative chemotherapy,” wrote Holly G. Prigerson, Ph.D., of Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. “The goal of palliative chemotherapy for patients with incurable cancer is to prolong survival and promote [quality of life] [but] chemotherapy use among patients with metastatic cancer whose cancer has progressed while receiving prior chemotherapy was not significantly related to longer survival [and] was associated with more aggressive medical care in the patient’s final week and heightened risk of dying in an intensive care unit.”

Dr. Prigerson and her coinvestigators looked at 312 end-stage metastatic cancer patients between September 2002 and February 2008, all of whom were on at least one chemotherapy regimen at one of six outpatient oncology clinics in the United States. They were followed prospectively until death to determine quality of life near death (QOD) as measured by Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status scores of 0 (“fully active, able to carry on all predisease performance without restriction”) through 5 (“dead”).

At enrollment, 158 subjects were on chemotherapy and 154 were not. Of the nine subjects with baseline ECOG score of 0, all of whom continued with chemotherapy, six (66.7%) reported lower QOD following treatment. Of 122 subjects with ECOG score 1, 71 of whom continued with chemotherapy, 40 (56.3%) reported lower QOD compared with 35 of the 51 subjects (68.6%) who reported higher QOD after not undergoing chemotherapy. However, as ECOG scores got higher, chemotherapy did appear to be of some benefit to patients.

ECOG score of 2 was found in 116 patients at baseline, of which 55 did chemotherapy and 67 did not; 28 chemotherapy subjects (50.9%) reported lower QOD than at baseline, and 32 (52.5%) of those without chemotherapy also reported lower QOD. For the 58 subjects with ECOG scores of 3, 12 of the 22 who did chemotherapy (54.5%) reported higher QOD after chemotherapy, compared with 19 of the 36 who did not do chemotherapy (52.8%) reporting lower QOD. Finally, seven subjects had ECOG scores of 4 at baseline, of which one did chemotherapy and reported a higher QOD after treatment; of the six who did not, it was a 50/50 split between those with higher and lower QOD.

“Patients receiving palliative chemotherapy with an ECOG performance status of 0 or 1 had significantly worse QOD than did those who avoided chemotherapy [and] no difference in QOD scores was observed by chemotherapy use among those with ECOG performance status of 2 or 3,” the researchers wrote. “Given no observed survival benefit in the studied patients [and] the observed significant association between chemotherapy use and worse QOL in the final week of life among those with a baseline ECOG score of 1, these results highlight the potential harm of chemotherapy in patients with metastatic cancer toward the end of life, even in patients with good performance status,” the investigators said (JAMA Oncol. 2015 July 23 [doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2378]).

The study had limitations; specifically, Dr. Prigerson and colleagues did not have complete information about the dose and duration of the chemotherapy used for each patient, as well as detailed information on prior chemotherapy use and the exact specifications of chemotherapy treatments given between baseline assessment and death for each patient.

This study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health, National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Minority Heath and Health Disparities, Weill Cornell Medical College, and the Health Services Research and Development Service Career Development Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Prigerson did not report any relevant financial disclosures, but two coinvestigators reported associations with pharmaceutical companies.

Palliative chemotherapy for patients with end-stage cancer who exhibit promising performance scores should be discouraged, as it does not improve the quality of life for these patients and may actively detract from it, according to a study published in JAMA Oncology.

“Despite the lack of evidence to support the practice, chemotherapy is widely used in cancer patients with poor performance status and progression following an initial course of palliative chemotherapy,” wrote Holly G. Prigerson, Ph.D., of Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. “The goal of palliative chemotherapy for patients with incurable cancer is to prolong survival and promote [quality of life] [but] chemotherapy use among patients with metastatic cancer whose cancer has progressed while receiving prior chemotherapy was not significantly related to longer survival [and] was associated with more aggressive medical care in the patient’s final week and heightened risk of dying in an intensive care unit.”

Dr. Prigerson and her coinvestigators looked at 312 end-stage metastatic cancer patients between September 2002 and February 2008, all of whom were on at least one chemotherapy regimen at one of six outpatient oncology clinics in the United States. They were followed prospectively until death to determine quality of life near death (QOD) as measured by Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status scores of 0 (“fully active, able to carry on all predisease performance without restriction”) through 5 (“dead”).

At enrollment, 158 subjects were on chemotherapy and 154 were not. Of the nine subjects with baseline ECOG score of 0, all of whom continued with chemotherapy, six (66.7%) reported lower QOD following treatment. Of 122 subjects with ECOG score 1, 71 of whom continued with chemotherapy, 40 (56.3%) reported lower QOD compared with 35 of the 51 subjects (68.6%) who reported higher QOD after not undergoing chemotherapy. However, as ECOG scores got higher, chemotherapy did appear to be of some benefit to patients.

ECOG score of 2 was found in 116 patients at baseline, of which 55 did chemotherapy and 67 did not; 28 chemotherapy subjects (50.9%) reported lower QOD than at baseline, and 32 (52.5%) of those without chemotherapy also reported lower QOD. For the 58 subjects with ECOG scores of 3, 12 of the 22 who did chemotherapy (54.5%) reported higher QOD after chemotherapy, compared with 19 of the 36 who did not do chemotherapy (52.8%) reporting lower QOD. Finally, seven subjects had ECOG scores of 4 at baseline, of which one did chemotherapy and reported a higher QOD after treatment; of the six who did not, it was a 50/50 split between those with higher and lower QOD.

“Patients receiving palliative chemotherapy with an ECOG performance status of 0 or 1 had significantly worse QOD than did those who avoided chemotherapy [and] no difference in QOD scores was observed by chemotherapy use among those with ECOG performance status of 2 or 3,” the researchers wrote. “Given no observed survival benefit in the studied patients [and] the observed significant association between chemotherapy use and worse QOL in the final week of life among those with a baseline ECOG score of 1, these results highlight the potential harm of chemotherapy in patients with metastatic cancer toward the end of life, even in patients with good performance status,” the investigators said (JAMA Oncol. 2015 July 23 [doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2378]).

The study had limitations; specifically, Dr. Prigerson and colleagues did not have complete information about the dose and duration of the chemotherapy used for each patient, as well as detailed information on prior chemotherapy use and the exact specifications of chemotherapy treatments given between baseline assessment and death for each patient.

This study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health, National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Minority Heath and Health Disparities, Weill Cornell Medical College, and the Health Services Research and Development Service Career Development Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Prigerson did not report any relevant financial disclosures, but two coinvestigators reported associations with pharmaceutical companies.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: End-stage cancer patients should not receive chemotherapy because it does not improve quality of life and, in some cases, can harm it.

Major finding: Among patients with good baseline performance chemotherapy status (ECOG score = 1), patients with chemotherapy use versus those without chemotherapy had worse quality of life near death (QOD) (P = .01).

Data source: A multi-institutional, longitudinal cohort study of 312 patients with progressive metastatic cancer, conducted between September 2002 and February 2008.

Disclosures: Study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health, National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Minority Heath and Health Disparities, Weill Cornell Medical College, and the Health Services Research and Development Service Career Development Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Prigerson did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

A weekly speech and language therapy service for head and neck radiotherapy patients during treatment: maximizing accessibility and efficiency

Background Our hospital did not provide a weekly speech and language therapy (SLT) service for head and neck cancer patients during radiotherapy treatment. SLT is recommended in the international guidelines, but many centers do not offer this service. In the case of our hospital, SLT was not provided because there were no funds to cover the costs of additional staff.

Objectives To create a new service model within a multidisciplinary setting to comply with the international SLT guidelines and without increasing staff. We aimed to measure the accessibility and efficiency of a new model of service delivery at our center both for patients and for the service.

Methods 79 patients were recruited for the study. We followed 1 group of patients (n = 29; observation group) throughout their treatment for 6 weeks to establish if there was a clinical need to offer SLT at the treatment center. A second group of patients (n = 50; intervention group) received a weekly SLT review at the treatment center throughout their radiotherapy. Data collected at the tertiary cancer center for 6 months included: age, gender, tumor site and size, treatment modality, swallowing outcomes, communication outcomes, patient satisfaction, multidisciplinary team feedback, and time efficiency. The observation group did not participate in the intervention group because the data was collected between 2 different groups of participants. However, all participants were referred to their local SLT service at the end of their treatment if that was clinically indicated, regardless of the group they had been in.

Results The proportion of patients accessing SLT services during treatment and the time efficiency of the service were both improved with this model of delivery. The service’s compliance with international guidelines was met. More patients continued with oral intake during their treatment at our center with the new service. Improvements were also reported in communication clarity and communication confidence in the same group.

Conclusion Offering head and neck cancer patients SLT at the same time and place as their radiotherapy treatment improves patient outcomes and increases SLT efficiencies. As this was not a treatment study, further clinical trials are required with regards to functional outcomes.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background Our hospital did not provide a weekly speech and language therapy (SLT) service for head and neck cancer patients during radiotherapy treatment. SLT is recommended in the international guidelines, but many centers do not offer this service. In the case of our hospital, SLT was not provided because there were no funds to cover the costs of additional staff.

Objectives To create a new service model within a multidisciplinary setting to comply with the international SLT guidelines and without increasing staff. We aimed to measure the accessibility and efficiency of a new model of service delivery at our center both for patients and for the service.

Methods 79 patients were recruited for the study. We followed 1 group of patients (n = 29; observation group) throughout their treatment for 6 weeks to establish if there was a clinical need to offer SLT at the treatment center. A second group of patients (n = 50; intervention group) received a weekly SLT review at the treatment center throughout their radiotherapy. Data collected at the tertiary cancer center for 6 months included: age, gender, tumor site and size, treatment modality, swallowing outcomes, communication outcomes, patient satisfaction, multidisciplinary team feedback, and time efficiency. The observation group did not participate in the intervention group because the data was collected between 2 different groups of participants. However, all participants were referred to their local SLT service at the end of their treatment if that was clinically indicated, regardless of the group they had been in.

Results The proportion of patients accessing SLT services during treatment and the time efficiency of the service were both improved with this model of delivery. The service’s compliance with international guidelines was met. More patients continued with oral intake during their treatment at our center with the new service. Improvements were also reported in communication clarity and communication confidence in the same group.

Conclusion Offering head and neck cancer patients SLT at the same time and place as their radiotherapy treatment improves patient outcomes and increases SLT efficiencies. As this was not a treatment study, further clinical trials are required with regards to functional outcomes.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background Our hospital did not provide a weekly speech and language therapy (SLT) service for head and neck cancer patients during radiotherapy treatment. SLT is recommended in the international guidelines, but many centers do not offer this service. In the case of our hospital, SLT was not provided because there were no funds to cover the costs of additional staff.

Objectives To create a new service model within a multidisciplinary setting to comply with the international SLT guidelines and without increasing staff. We aimed to measure the accessibility and efficiency of a new model of service delivery at our center both for patients and for the service.

Methods 79 patients were recruited for the study. We followed 1 group of patients (n = 29; observation group) throughout their treatment for 6 weeks to establish if there was a clinical need to offer SLT at the treatment center. A second group of patients (n = 50; intervention group) received a weekly SLT review at the treatment center throughout their radiotherapy. Data collected at the tertiary cancer center for 6 months included: age, gender, tumor site and size, treatment modality, swallowing outcomes, communication outcomes, patient satisfaction, multidisciplinary team feedback, and time efficiency. The observation group did not participate in the intervention group because the data was collected between 2 different groups of participants. However, all participants were referred to their local SLT service at the end of their treatment if that was clinically indicated, regardless of the group they had been in.

Results The proportion of patients accessing SLT services during treatment and the time efficiency of the service were both improved with this model of delivery. The service’s compliance with international guidelines was met. More patients continued with oral intake during their treatment at our center with the new service. Improvements were also reported in communication clarity and communication confidence in the same group.

Conclusion Offering head and neck cancer patients SLT at the same time and place as their radiotherapy treatment improves patient outcomes and increases SLT efficiencies. As this was not a treatment study, further clinical trials are required with regards to functional outcomes.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Health care expenditures associated with depression in adults with cancer

Background The rates of depression in adults with cancer have been reported as high as 38%-58%. How depression affects overall health care expenditures in individuals with cancer is an under-researched area.

Objective To estimate excess average total health care expenditures associated with depression in adults with cancer by comparing those with and without depression after controlling for demographic, socioeconomic, access to care, and other health status variables.

Methods Cross-sectional data on 4,766 adult survivors of cancer from 2006-2009 of the nationally representative household survey, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), were used. The patients were older than 21 years. Cancer and depression were identified from the patients’ medical conditions files. Dependent variables consisted of total, inpatient, outpatient, emergency department, prescription drugs, and other expenditures. Ordinary least square (OLS) on logged dollars and generalized linear models with log-link function were performed. All analyses (SAS 9.3 and STATA12) accounted for the complex survey design of the MEPS.

Results Overall, 14% of individuals with cancer reported having depression. In those with cancer and depression, the average annual health care expenditures were $18,401 compared with $12,091 in those without depression. After adjusting for demographic, socioeconomic, access to care, and other health status variables, those with depression had about 31.7% greater total expenditures compared with those without depression. Total, outpatient, and prescription expenditures were higher in individuals with depression than in those without depression. Individuals with cancer and depression were significantly more likely to use emergency departments (adjusted odds ratio, 1.46) compared with their counterparts without depression.

Limitations Cancer patients who died during the reporting year were excluded. The financial burden of depression may have been underestimated because the costs of end-of-life care are high. The burden for each cancer type was not analyzed because of the small sample size.

Conclusion In adults with cancer, those with depression had higher health care utilization and expenditures compared with those without depression.

Funding/sponsorship One author partially supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, U54GM104942.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background The rates of depression in adults with cancer have been reported as high as 38%-58%. How depression affects overall health care expenditures in individuals with cancer is an under-researched area.

Objective To estimate excess average total health care expenditures associated with depression in adults with cancer by comparing those with and without depression after controlling for demographic, socioeconomic, access to care, and other health status variables.

Methods Cross-sectional data on 4,766 adult survivors of cancer from 2006-2009 of the nationally representative household survey, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), were used. The patients were older than 21 years. Cancer and depression were identified from the patients’ medical conditions files. Dependent variables consisted of total, inpatient, outpatient, emergency department, prescription drugs, and other expenditures. Ordinary least square (OLS) on logged dollars and generalized linear models with log-link function were performed. All analyses (SAS 9.3 and STATA12) accounted for the complex survey design of the MEPS.

Results Overall, 14% of individuals with cancer reported having depression. In those with cancer and depression, the average annual health care expenditures were $18,401 compared with $12,091 in those without depression. After adjusting for demographic, socioeconomic, access to care, and other health status variables, those with depression had about 31.7% greater total expenditures compared with those without depression. Total, outpatient, and prescription expenditures were higher in individuals with depression than in those without depression. Individuals with cancer and depression were significantly more likely to use emergency departments (adjusted odds ratio, 1.46) compared with their counterparts without depression.

Limitations Cancer patients who died during the reporting year were excluded. The financial burden of depression may have been underestimated because the costs of end-of-life care are high. The burden for each cancer type was not analyzed because of the small sample size.

Conclusion In adults with cancer, those with depression had higher health care utilization and expenditures compared with those without depression.

Funding/sponsorship One author partially supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, U54GM104942.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background The rates of depression in adults with cancer have been reported as high as 38%-58%. How depression affects overall health care expenditures in individuals with cancer is an under-researched area.

Objective To estimate excess average total health care expenditures associated with depression in adults with cancer by comparing those with and without depression after controlling for demographic, socioeconomic, access to care, and other health status variables.

Methods Cross-sectional data on 4,766 adult survivors of cancer from 2006-2009 of the nationally representative household survey, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), were used. The patients were older than 21 years. Cancer and depression were identified from the patients’ medical conditions files. Dependent variables consisted of total, inpatient, outpatient, emergency department, prescription drugs, and other expenditures. Ordinary least square (OLS) on logged dollars and generalized linear models with log-link function were performed. All analyses (SAS 9.3 and STATA12) accounted for the complex survey design of the MEPS.