User login

Families perceive few benefits from aggressive end-of-life care

Bereaved families were substantially more satisfied with end-of-life cancer care when patients did not die in hospital, received more than 3 days of hospice care, and did not enter the ICU within 30 days of dying, according to a multicenter, prospective study published online Jan. 19 in JAMA.

The analysis is one of the first of its type to assess these end-of-life care indicators, said Dr. Alexi Wright of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her associates. The findings could affect health policy as electronic health records expand under the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act, they said.

End-of-life cancer care has become increasingly aggressive, belying evidence that this approach does not improve patient outcomes, quality of life, or caregiver bereavement. To explore alternatives, the researchers analyzed 1,146 interviews of family members of Medicare patients who died of lung or colorectal cancer by 2011. Their data source was the multiregional, prospective, observational Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) study (JAMA 2016;315:284-92).

Family members described end-of-life care as “excellent” 59% of the time when hospice care lasted more 3 days, but 43% of the time otherwise (95% confidence interval for adjusted difference, 11% to 22%). Notably, 73% of patients who received more than 3 days of hospice care died in their preferred location, compared with 40% of patients who received less or no hospice care. Care was rated as excellent 52% of the time when ICU admission was avoided within 30 days of death, and 57% of the time when patients died outside the hospital, compared with 45% and 42% of the time otherwise.

The results support “advance care planning consistent with the preferences of patients,” said the investigators. They recommended more extensive counseling of cancer patients and families, earlier palliative care referrals, and an audit and feedback system to monitor the use of aggressive end-of-life care.

The National Cancer Institute and the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium funded the study. One coinvestigator reported financial relationships with the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institute on Aging, Retirement Research Retirement Foundation, California Healthcare Foundation, Commonwealth Fund, West Health Institute, University of Wisconsin, and UpToDate.com. Senior author Dr. Mary Landrum, also of Harvard Medical School, reported grant funding from Pfizer and personal fees from McKinsey and Company and Greylock McKinnon Associates. The other authors had no disclosures.

Bereaved families were substantially more satisfied with end-of-life cancer care when patients did not die in hospital, received more than 3 days of hospice care, and did not enter the ICU within 30 days of dying, according to a multicenter, prospective study published online Jan. 19 in JAMA.

The analysis is one of the first of its type to assess these end-of-life care indicators, said Dr. Alexi Wright of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her associates. The findings could affect health policy as electronic health records expand under the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act, they said.

End-of-life cancer care has become increasingly aggressive, belying evidence that this approach does not improve patient outcomes, quality of life, or caregiver bereavement. To explore alternatives, the researchers analyzed 1,146 interviews of family members of Medicare patients who died of lung or colorectal cancer by 2011. Their data source was the multiregional, prospective, observational Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) study (JAMA 2016;315:284-92).

Family members described end-of-life care as “excellent” 59% of the time when hospice care lasted more 3 days, but 43% of the time otherwise (95% confidence interval for adjusted difference, 11% to 22%). Notably, 73% of patients who received more than 3 days of hospice care died in their preferred location, compared with 40% of patients who received less or no hospice care. Care was rated as excellent 52% of the time when ICU admission was avoided within 30 days of death, and 57% of the time when patients died outside the hospital, compared with 45% and 42% of the time otherwise.

The results support “advance care planning consistent with the preferences of patients,” said the investigators. They recommended more extensive counseling of cancer patients and families, earlier palliative care referrals, and an audit and feedback system to monitor the use of aggressive end-of-life care.

The National Cancer Institute and the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium funded the study. One coinvestigator reported financial relationships with the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institute on Aging, Retirement Research Retirement Foundation, California Healthcare Foundation, Commonwealth Fund, West Health Institute, University of Wisconsin, and UpToDate.com. Senior author Dr. Mary Landrum, also of Harvard Medical School, reported grant funding from Pfizer and personal fees from McKinsey and Company and Greylock McKinnon Associates. The other authors had no disclosures.

Bereaved families were substantially more satisfied with end-of-life cancer care when patients did not die in hospital, received more than 3 days of hospice care, and did not enter the ICU within 30 days of dying, according to a multicenter, prospective study published online Jan. 19 in JAMA.

The analysis is one of the first of its type to assess these end-of-life care indicators, said Dr. Alexi Wright of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her associates. The findings could affect health policy as electronic health records expand under the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act, they said.

End-of-life cancer care has become increasingly aggressive, belying evidence that this approach does not improve patient outcomes, quality of life, or caregiver bereavement. To explore alternatives, the researchers analyzed 1,146 interviews of family members of Medicare patients who died of lung or colorectal cancer by 2011. Their data source was the multiregional, prospective, observational Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) study (JAMA 2016;315:284-92).

Family members described end-of-life care as “excellent” 59% of the time when hospice care lasted more 3 days, but 43% of the time otherwise (95% confidence interval for adjusted difference, 11% to 22%). Notably, 73% of patients who received more than 3 days of hospice care died in their preferred location, compared with 40% of patients who received less or no hospice care. Care was rated as excellent 52% of the time when ICU admission was avoided within 30 days of death, and 57% of the time when patients died outside the hospital, compared with 45% and 42% of the time otherwise.

The results support “advance care planning consistent with the preferences of patients,” said the investigators. They recommended more extensive counseling of cancer patients and families, earlier palliative care referrals, and an audit and feedback system to monitor the use of aggressive end-of-life care.

The National Cancer Institute and the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium funded the study. One coinvestigator reported financial relationships with the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institute on Aging, Retirement Research Retirement Foundation, California Healthcare Foundation, Commonwealth Fund, West Health Institute, University of Wisconsin, and UpToDate.com. Senior author Dr. Mary Landrum, also of Harvard Medical School, reported grant funding from Pfizer and personal fees from McKinsey and Company and Greylock McKinnon Associates. The other authors had no disclosures.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Bereaved family members were more satisfied with end-of-life cancer care when patients spent more than 3 days in hospice, died outside the hospital, and were not admitted to the ICU within 30 days of dying.

Major finding: Care was described as “excellent” about 9%-17% more often when these end-of-life quality indicators were met.

Data source: A multicenter, prospective, observational study of 1,146 family members of patients who died of lung or colorectal cancer.

Disclosures: The National Cancer Institute and the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium funded the analysis. One coinvestigator reported financial relationships with the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institute on Aging, Retirement Research Retirement Foundation, California Healthcare Foundation, Commonwealth Fund, West Health Institute, University of Wisconsin, and UpToDate.com. Senior author Dr. Mary Landrum reported grant funding from Pfizer and personal fees from McKinsey and Company and Greylock McKinnon Associates. The other authors had no disclosures.

Significant risk of relapse remains for ER-positive breast cancer patients beyond 10 years

The risk of breast cancer relapse decreases consistently for 10 years, then remains stable through 25 years, with ER-positive disease carrying higher risk than ER-negative disease from years 5 to 25, according to researchers.

At a median follow up of 24 years, the study reported outcomes of 4,105 patients who were diagnosed from 1978 to 1985 and participated in the International Breast Cancer Study Group Trials I to V. During the first 5 years of follow-up, risk of recurrence was lower for ER-positive compared with ER-negative disease: 9.9% vs. 11.5%. Beyond 5 years, risk was higher: 5-10 years, 5.4% vs. 3.3%; 10-15 years, 2.9% vs. 1.3%, 15-20 years, 2.8% vs. 1.2%. At 20-25 years, risk was 1.3% vs. 1.4% (P less than .001).

“We identified a population (ER positive) that maintains a significant risk of relapse even after more than 10 years of follow-up. New targeted treatments and different modes of breast cancer surveillance for preventing late recurrences within this population should be studied,” wrote Dr. Marco Colleoni of the European Institute of Oncology and International Breast Cancer Study Group, and colleagues (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jan 18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.3504).

For the entire patient group, breast cancer recurrence reached a peak at years 1-2 (15.2%), and decreased consistently through year 10 (5-10 years, 4.5%), then remained stable (10-15 years, 2.2%; 15-20, 1.5%; 20-25, 0.7%). Cumulative incidence of distant recurrence for the ER-positive group occurred less frequently than for the ER-negative group during the first 5 years and more frequently from 5 to 25 years: at 5 years, 27.1% vs. 23.4%; at 10 years, 31.9% vs. 31.8%; at 15 years, 35% vs. 33.4%; at 20 years, 37.4% vs. 34.1%; at 25 years, 38.3% vs. 35.3% (P less than .001).

All patients in the trials had undergone mastectomy and axillary clearance with at least eight nodes removed, with no locoregional radiotherapy, as was standard at the time.

Within the ER-positive group, patients who had zero to three positive nodes had had a stable risk of recurrence beyond 10 years, whereas for patients with four or more involved nodes, risk decreased gradually from 10 to 24 years.

Recent studies have shown that 10 years of adjuvant tamoxifen further improves breast cancer survival compared with 5 years of adjuvant therapy, albeit at a cost of 0.4% due to mortality resulting from endometrial carcinoma or pulmonary embolism. The studies underline the critical importance of sufficiently large patient populations and longer follow-up to provide accurate outcome data.

The report by Colleoni et al. describes clinical trial results from a median 24-year follow up. Patients with ER-positive disease require long-term follow up, which should be fundamentally different from those with ER-negative and/or human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive disease, who require shorter follow-up. Given these differences, adjuvant clinical studies with shorter follow-up periods will underreport events for ER-positive patients.

The study also reports a secondary malignancy rate of 4.9%, a figure likely to be underreported in studies with shorter follow-up schedules.

Limitations of the study arise from the time period in which it began. Regimens used in the study (different schedules of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil, and 1 year of tamoxifen with or without prednisone) have been shown to be inferior to newer regimens. None of the patients received postoperative radiotherapy, in accordance with data available at the time. Today, women with node-positive disease receive locoregional radiotherapy to reduce the risk of locoregional recurrence.

Studies with long-term follow up periods offer insights into both efficacy and safety; however, such studies require extensive resources. The entities that decide which types of cancer care are made available, such as insurance companies, governments, and regional health care funders, must shoulder the responsibility to ensure the required long-term evaluation of these treatments is conducted. Joint projects between pharmaceutical companies and health care providers could identify long-term benefits and adverse effects. The process may be more readily implemented in countries with population-based cancer registries.

Dr. Jonas Bergh is professor in the department of oncology-pathology at Karolinska Institutet and University Hospital, Stockholm. Dr. Kathleen Pritchard is a medical oncologist at Sunnybrook Odette Cancer Centre and professor at the University of Toronto. Dr. David Cameron is clinical director and chair of oncology at the University of Edinburgh Cancer Research Centre, Scotland. These remarks were part of an editorial accompanying the report by Colleoni et al. (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jan 18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.2255). Dr. Bergh reported financial ties to Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Pfizer, Roche, and Sanofi. Dr. Pritchard reported ties to AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Roche, Amgen, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, and Eisai. Dr. Cameron reported ties to Novartis.

Recent studies have shown that 10 years of adjuvant tamoxifen further improves breast cancer survival compared with 5 years of adjuvant therapy, albeit at a cost of 0.4% due to mortality resulting from endometrial carcinoma or pulmonary embolism. The studies underline the critical importance of sufficiently large patient populations and longer follow-up to provide accurate outcome data.

The report by Colleoni et al. describes clinical trial results from a median 24-year follow up. Patients with ER-positive disease require long-term follow up, which should be fundamentally different from those with ER-negative and/or human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive disease, who require shorter follow-up. Given these differences, adjuvant clinical studies with shorter follow-up periods will underreport events for ER-positive patients.

The study also reports a secondary malignancy rate of 4.9%, a figure likely to be underreported in studies with shorter follow-up schedules.

Limitations of the study arise from the time period in which it began. Regimens used in the study (different schedules of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil, and 1 year of tamoxifen with or without prednisone) have been shown to be inferior to newer regimens. None of the patients received postoperative radiotherapy, in accordance with data available at the time. Today, women with node-positive disease receive locoregional radiotherapy to reduce the risk of locoregional recurrence.

Studies with long-term follow up periods offer insights into both efficacy and safety; however, such studies require extensive resources. The entities that decide which types of cancer care are made available, such as insurance companies, governments, and regional health care funders, must shoulder the responsibility to ensure the required long-term evaluation of these treatments is conducted. Joint projects between pharmaceutical companies and health care providers could identify long-term benefits and adverse effects. The process may be more readily implemented in countries with population-based cancer registries.

Dr. Jonas Bergh is professor in the department of oncology-pathology at Karolinska Institutet and University Hospital, Stockholm. Dr. Kathleen Pritchard is a medical oncologist at Sunnybrook Odette Cancer Centre and professor at the University of Toronto. Dr. David Cameron is clinical director and chair of oncology at the University of Edinburgh Cancer Research Centre, Scotland. These remarks were part of an editorial accompanying the report by Colleoni et al. (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jan 18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.2255). Dr. Bergh reported financial ties to Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Pfizer, Roche, and Sanofi. Dr. Pritchard reported ties to AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Roche, Amgen, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, and Eisai. Dr. Cameron reported ties to Novartis.

Recent studies have shown that 10 years of adjuvant tamoxifen further improves breast cancer survival compared with 5 years of adjuvant therapy, albeit at a cost of 0.4% due to mortality resulting from endometrial carcinoma or pulmonary embolism. The studies underline the critical importance of sufficiently large patient populations and longer follow-up to provide accurate outcome data.

The report by Colleoni et al. describes clinical trial results from a median 24-year follow up. Patients with ER-positive disease require long-term follow up, which should be fundamentally different from those with ER-negative and/or human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive disease, who require shorter follow-up. Given these differences, adjuvant clinical studies with shorter follow-up periods will underreport events for ER-positive patients.

The study also reports a secondary malignancy rate of 4.9%, a figure likely to be underreported in studies with shorter follow-up schedules.

Limitations of the study arise from the time period in which it began. Regimens used in the study (different schedules of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil, and 1 year of tamoxifen with or without prednisone) have been shown to be inferior to newer regimens. None of the patients received postoperative radiotherapy, in accordance with data available at the time. Today, women with node-positive disease receive locoregional radiotherapy to reduce the risk of locoregional recurrence.

Studies with long-term follow up periods offer insights into both efficacy and safety; however, such studies require extensive resources. The entities that decide which types of cancer care are made available, such as insurance companies, governments, and regional health care funders, must shoulder the responsibility to ensure the required long-term evaluation of these treatments is conducted. Joint projects between pharmaceutical companies and health care providers could identify long-term benefits and adverse effects. The process may be more readily implemented in countries with population-based cancer registries.

Dr. Jonas Bergh is professor in the department of oncology-pathology at Karolinska Institutet and University Hospital, Stockholm. Dr. Kathleen Pritchard is a medical oncologist at Sunnybrook Odette Cancer Centre and professor at the University of Toronto. Dr. David Cameron is clinical director and chair of oncology at the University of Edinburgh Cancer Research Centre, Scotland. These remarks were part of an editorial accompanying the report by Colleoni et al. (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jan 18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.2255). Dr. Bergh reported financial ties to Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Pfizer, Roche, and Sanofi. Dr. Pritchard reported ties to AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Roche, Amgen, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, and Eisai. Dr. Cameron reported ties to Novartis.

The risk of breast cancer relapse decreases consistently for 10 years, then remains stable through 25 years, with ER-positive disease carrying higher risk than ER-negative disease from years 5 to 25, according to researchers.

At a median follow up of 24 years, the study reported outcomes of 4,105 patients who were diagnosed from 1978 to 1985 and participated in the International Breast Cancer Study Group Trials I to V. During the first 5 years of follow-up, risk of recurrence was lower for ER-positive compared with ER-negative disease: 9.9% vs. 11.5%. Beyond 5 years, risk was higher: 5-10 years, 5.4% vs. 3.3%; 10-15 years, 2.9% vs. 1.3%, 15-20 years, 2.8% vs. 1.2%. At 20-25 years, risk was 1.3% vs. 1.4% (P less than .001).

“We identified a population (ER positive) that maintains a significant risk of relapse even after more than 10 years of follow-up. New targeted treatments and different modes of breast cancer surveillance for preventing late recurrences within this population should be studied,” wrote Dr. Marco Colleoni of the European Institute of Oncology and International Breast Cancer Study Group, and colleagues (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jan 18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.3504).

For the entire patient group, breast cancer recurrence reached a peak at years 1-2 (15.2%), and decreased consistently through year 10 (5-10 years, 4.5%), then remained stable (10-15 years, 2.2%; 15-20, 1.5%; 20-25, 0.7%). Cumulative incidence of distant recurrence for the ER-positive group occurred less frequently than for the ER-negative group during the first 5 years and more frequently from 5 to 25 years: at 5 years, 27.1% vs. 23.4%; at 10 years, 31.9% vs. 31.8%; at 15 years, 35% vs. 33.4%; at 20 years, 37.4% vs. 34.1%; at 25 years, 38.3% vs. 35.3% (P less than .001).

All patients in the trials had undergone mastectomy and axillary clearance with at least eight nodes removed, with no locoregional radiotherapy, as was standard at the time.

Within the ER-positive group, patients who had zero to three positive nodes had had a stable risk of recurrence beyond 10 years, whereas for patients with four or more involved nodes, risk decreased gradually from 10 to 24 years.

The risk of breast cancer relapse decreases consistently for 10 years, then remains stable through 25 years, with ER-positive disease carrying higher risk than ER-negative disease from years 5 to 25, according to researchers.

At a median follow up of 24 years, the study reported outcomes of 4,105 patients who were diagnosed from 1978 to 1985 and participated in the International Breast Cancer Study Group Trials I to V. During the first 5 years of follow-up, risk of recurrence was lower for ER-positive compared with ER-negative disease: 9.9% vs. 11.5%. Beyond 5 years, risk was higher: 5-10 years, 5.4% vs. 3.3%; 10-15 years, 2.9% vs. 1.3%, 15-20 years, 2.8% vs. 1.2%. At 20-25 years, risk was 1.3% vs. 1.4% (P less than .001).

“We identified a population (ER positive) that maintains a significant risk of relapse even after more than 10 years of follow-up. New targeted treatments and different modes of breast cancer surveillance for preventing late recurrences within this population should be studied,” wrote Dr. Marco Colleoni of the European Institute of Oncology and International Breast Cancer Study Group, and colleagues (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jan 18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.3504).

For the entire patient group, breast cancer recurrence reached a peak at years 1-2 (15.2%), and decreased consistently through year 10 (5-10 years, 4.5%), then remained stable (10-15 years, 2.2%; 15-20, 1.5%; 20-25, 0.7%). Cumulative incidence of distant recurrence for the ER-positive group occurred less frequently than for the ER-negative group during the first 5 years and more frequently from 5 to 25 years: at 5 years, 27.1% vs. 23.4%; at 10 years, 31.9% vs. 31.8%; at 15 years, 35% vs. 33.4%; at 20 years, 37.4% vs. 34.1%; at 25 years, 38.3% vs. 35.3% (P less than .001).

All patients in the trials had undergone mastectomy and axillary clearance with at least eight nodes removed, with no locoregional radiotherapy, as was standard at the time.

Within the ER-positive group, patients who had zero to three positive nodes had had a stable risk of recurrence beyond 10 years, whereas for patients with four or more involved nodes, risk decreased gradually from 10 to 24 years.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: The risk of breast cancer recurrence continues through 24 years after primary treatments, especially for estrogen receptor–positive disease.

Major finding: During the first 5 years, risk of recurrence was lower for ER-positive disease than for ER-negative disease (9.9% vs. 11.5%). Risk was higher 5-10 years later (5.4% vs. 3.3%), at 10-15 years (2.9% vs. 1.3%), and at 15-20 years (2.8% vs. 1.2%). From 20 to 25 years on, the risk was 1.3% vs. 1.4% (P less than .001).

Data sources: The International Breast Cancer Study Group Trials I to V, comprising 4,105 patients with breast cancer diagnosed from 1978 to 1985.

Disclosures: Dr. Colleoni reported financial ties to Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Taiho Pharmaceutical, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Pierre Fabre, and Pfizer. Several of his coauthors reported ties to industry.

SABCS: Longer overnight fasting may reduce breast cancer recurrence risk

SAN ANTONIO – Breast cancer survivors who typically didn’t eat for at least 13 hours overnight had a 36% reduction in the risk of breast cancer recurrence compared to those with a shorter duration of overnight fasting in a secondary analysis of the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living Study presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

“Prolonging the length of the nighttime fasting interval may be a simple nonpharmacologic strategy for reducing the risk of breast cancer recurrence as well as other chronic conditions with etiologic ties to breast cancer, like type 2 diabetes,” concluded to Catherine R. Marinac, a doctoral candidate in public health at the University of California, San Diego.

“A lot of dietary recommendations for cancer prevention really focus on what to eat in order to prevent or recover from breast cancer. For a lot of people that can be a really complicated recommendation, like ‘count your carbs, count your fat, don’t eat this/don’t eat that.’ We think timing of food intake in order to prolong the length of the nightly fasting interval can be a simple strategy most women can understand and adopt and that may reduce their risk of breast cancer,” she added.

The new results from the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) study are encouragingly consistent with the findings of earlier rodent studies demonstrating that intermittent fasting regimens aligned with the sleep cycle bring better glycemic control and protection against carcinogenesis, Ms. Marinac noted.

She presented an analysis of 2,413 nondiabetic breast cancer survivors who participated in the multicenter WHEL study and for whom multiple detailed 24-hour dietary recall records were obtained at baseline and 4 years of followup.

“The diets were very well characterized. We analyzed roughly 30,000 time-stamped dietary recalls,” she said in an interview.

During 7.3 years of follow-up, 390 women experienced recurrent breast cancer. Those in the top tertile for duration of overnight fasting, at 13 hours or longer, were 36% less likely to have a recurrence, according to a Cox proportionate hazard analysis and a multivariate linear regression analysis controlling for patient demographics; calorie consumption and other dietary variables; breast cancer stage, grade, and treatment; body mass index; comorbid conditions; and sleep duration.

During 11.4 years of follow-up, 329 subjects died of their breast cancer. All-cause mortality occurred in 420. Women with an overnight fasting duration of 13 hours or greater were 21% less likely to experience breast cancer mortality and 22% less likely to die of any cause. Neither trend achieved statistical significance.

Looking for potential mechanisms to explain the observed relationship between overnight fasting duration and breast cancer recurrence, Ms. Marinac and coinvestigators considered as evaluable possibilities systemic inflammation, glucoregulation, adiposity, and sleep duration.

C-reactive protein levels and body mass index proved to be unrelated to recurrence risk. However, glucoregulation and sleep duration were. Women with an overnight fasting length of at least 13 hours had a significantly lower glycated hemoglobin level and slept longer than those with a shorter overnight fast. The lower HbA1c seen in women who fasted for longer at night mimics an intriguing finding from the classic mouse studies that showed fasting is related to better glycemic control, she observed.

The WHEL study is sponsored by the National Cancer Institute, the University of California at San Diego, and a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award. Ms. Marinac reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Breast cancer survivors who typically didn’t eat for at least 13 hours overnight had a 36% reduction in the risk of breast cancer recurrence compared to those with a shorter duration of overnight fasting in a secondary analysis of the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living Study presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

“Prolonging the length of the nighttime fasting interval may be a simple nonpharmacologic strategy for reducing the risk of breast cancer recurrence as well as other chronic conditions with etiologic ties to breast cancer, like type 2 diabetes,” concluded to Catherine R. Marinac, a doctoral candidate in public health at the University of California, San Diego.

“A lot of dietary recommendations for cancer prevention really focus on what to eat in order to prevent or recover from breast cancer. For a lot of people that can be a really complicated recommendation, like ‘count your carbs, count your fat, don’t eat this/don’t eat that.’ We think timing of food intake in order to prolong the length of the nightly fasting interval can be a simple strategy most women can understand and adopt and that may reduce their risk of breast cancer,” she added.

The new results from the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) study are encouragingly consistent with the findings of earlier rodent studies demonstrating that intermittent fasting regimens aligned with the sleep cycle bring better glycemic control and protection against carcinogenesis, Ms. Marinac noted.

She presented an analysis of 2,413 nondiabetic breast cancer survivors who participated in the multicenter WHEL study and for whom multiple detailed 24-hour dietary recall records were obtained at baseline and 4 years of followup.

“The diets were very well characterized. We analyzed roughly 30,000 time-stamped dietary recalls,” she said in an interview.

During 7.3 years of follow-up, 390 women experienced recurrent breast cancer. Those in the top tertile for duration of overnight fasting, at 13 hours or longer, were 36% less likely to have a recurrence, according to a Cox proportionate hazard analysis and a multivariate linear regression analysis controlling for patient demographics; calorie consumption and other dietary variables; breast cancer stage, grade, and treatment; body mass index; comorbid conditions; and sleep duration.

During 11.4 years of follow-up, 329 subjects died of their breast cancer. All-cause mortality occurred in 420. Women with an overnight fasting duration of 13 hours or greater were 21% less likely to experience breast cancer mortality and 22% less likely to die of any cause. Neither trend achieved statistical significance.

Looking for potential mechanisms to explain the observed relationship between overnight fasting duration and breast cancer recurrence, Ms. Marinac and coinvestigators considered as evaluable possibilities systemic inflammation, glucoregulation, adiposity, and sleep duration.

C-reactive protein levels and body mass index proved to be unrelated to recurrence risk. However, glucoregulation and sleep duration were. Women with an overnight fasting length of at least 13 hours had a significantly lower glycated hemoglobin level and slept longer than those with a shorter overnight fast. The lower HbA1c seen in women who fasted for longer at night mimics an intriguing finding from the classic mouse studies that showed fasting is related to better glycemic control, she observed.

The WHEL study is sponsored by the National Cancer Institute, the University of California at San Diego, and a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award. Ms. Marinac reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Breast cancer survivors who typically didn’t eat for at least 13 hours overnight had a 36% reduction in the risk of breast cancer recurrence compared to those with a shorter duration of overnight fasting in a secondary analysis of the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living Study presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

“Prolonging the length of the nighttime fasting interval may be a simple nonpharmacologic strategy for reducing the risk of breast cancer recurrence as well as other chronic conditions with etiologic ties to breast cancer, like type 2 diabetes,” concluded to Catherine R. Marinac, a doctoral candidate in public health at the University of California, San Diego.

“A lot of dietary recommendations for cancer prevention really focus on what to eat in order to prevent or recover from breast cancer. For a lot of people that can be a really complicated recommendation, like ‘count your carbs, count your fat, don’t eat this/don’t eat that.’ We think timing of food intake in order to prolong the length of the nightly fasting interval can be a simple strategy most women can understand and adopt and that may reduce their risk of breast cancer,” she added.

The new results from the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) study are encouragingly consistent with the findings of earlier rodent studies demonstrating that intermittent fasting regimens aligned with the sleep cycle bring better glycemic control and protection against carcinogenesis, Ms. Marinac noted.

She presented an analysis of 2,413 nondiabetic breast cancer survivors who participated in the multicenter WHEL study and for whom multiple detailed 24-hour dietary recall records were obtained at baseline and 4 years of followup.

“The diets were very well characterized. We analyzed roughly 30,000 time-stamped dietary recalls,” she said in an interview.

During 7.3 years of follow-up, 390 women experienced recurrent breast cancer. Those in the top tertile for duration of overnight fasting, at 13 hours or longer, were 36% less likely to have a recurrence, according to a Cox proportionate hazard analysis and a multivariate linear regression analysis controlling for patient demographics; calorie consumption and other dietary variables; breast cancer stage, grade, and treatment; body mass index; comorbid conditions; and sleep duration.

During 11.4 years of follow-up, 329 subjects died of their breast cancer. All-cause mortality occurred in 420. Women with an overnight fasting duration of 13 hours or greater were 21% less likely to experience breast cancer mortality and 22% less likely to die of any cause. Neither trend achieved statistical significance.

Looking for potential mechanisms to explain the observed relationship between overnight fasting duration and breast cancer recurrence, Ms. Marinac and coinvestigators considered as evaluable possibilities systemic inflammation, glucoregulation, adiposity, and sleep duration.

C-reactive protein levels and body mass index proved to be unrelated to recurrence risk. However, glucoregulation and sleep duration were. Women with an overnight fasting length of at least 13 hours had a significantly lower glycated hemoglobin level and slept longer than those with a shorter overnight fast. The lower HbA1c seen in women who fasted for longer at night mimics an intriguing finding from the classic mouse studies that showed fasting is related to better glycemic control, she observed.

The WHEL study is sponsored by the National Cancer Institute, the University of California at San Diego, and a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award. Ms. Marinac reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AT SABCS 2015

Key clinical point: Lengthening the overnight fasting interval to at least 13 hours may be a novel, easily adoptable strategy to reduce breast cancer risk.

Major finding: Breast cancer survivors who typically went without eating for at least 13 hours overnight were 36% less likely to experience recurrent breast cancer than those with a shorter overnight fast.

Data source: This was a secondary analysis of a long-term prospective dietary study in 2,413 nondiabetic breast cancer survivors.

Disclosures: The WHEL study is sponsored by the National Cancer Institute, the University of California at San Diego, and a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Death from late effects of childhood cancer on decline

The rate of death from treatment-related late effects such as subsequent cancers and cardiopulmonary conditions has decreased among childhood cancer survivors, according to researchers.

At 15 years post diagnosis, the cumulative incidence of death from any cause for survivors diagnosed in the 1970s was 10.7%, 7.9% for those diagnosed in the 1980s, and 5.8% for those diagnosed in the 1990s (P less than .001). The cumulative incidence of death due to health-related causes, which include late effects of cancer therapy, were 3.1%, 2.4%, and 1.9%, respectively (P less than .001).

Results indicate that “the strategy of reducing treatment exposures in order to decrease the frequency of late effects is translating into a significant reduction in observed late mortality and an extension of the life span of children and adolescents who are successfully treated for cancer,” wrote Dr. Gregory Armstrong of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, Tenn., and colleagues (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jan 13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510795).

A multivariate model showed that more recent treatment eras were associated with a reduced rate of death. The adjusted relative rate per every 5 years for death due to subsequent neoplasms was 0.83 (95% CI, 0.78-0.88), for cardiac causes, 0.77 (0.68-0.86), and for pulmonary causes, 0.77 (0.66-0.89).

Reductions across treatment eras in the rate of death from health-related causes were observed among survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (3.2% in the early 1970s to 2.1% in the 1990s, P less than .001), Hodgkin lymphoma (5.3% to 2.6%, P = .006), Wilms tumor (2.6% to 0.4%, P = .005), and astrocytoma (4.7% to 1.8%, P = .02).

Temporal reductions in exposure to radiotherapy and anthracyclines occurred in treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Hodgkin lymphoma, Wilms tumor, and astrocytoma. Health-related mortality reductions were observed concurrently with reduced therapeutic exposures for acute lymphoblastic leukemia and Wilms tumor. For Hodgkin lymphoma and astrocytoma, other factors such as improved screening for late effects of cancer treatment appear to account for reductions in late health-related mortality.

For certain cancers, primarily neuroblastoma, late mortality has increased in recent decades. Increased therapeutic intensity has improved 5-year survival but increased the risk of late effects.

The reduced rate of death from recurrence or progression of primary cancers is the main driver to reductions in all-cause mortality, consistent with results from previous studies.

The retrospective Childhood Cancer Survivor Study evaluated 34,033 patients diagnosed at 31 hospitals in the United States and Canada from 1970 through 1999. In total, 3,958 deaths occurred, 2,002 due to primary cancer and 1,618 due to health-related causes: 746 subsequent neoplasms, 241 cardiac causes, 137 pulmonary causes, and 494 from other causes.

The rate of death from treatment-related late effects such as subsequent cancers and cardiopulmonary conditions has decreased among childhood cancer survivors, according to researchers.

At 15 years post diagnosis, the cumulative incidence of death from any cause for survivors diagnosed in the 1970s was 10.7%, 7.9% for those diagnosed in the 1980s, and 5.8% for those diagnosed in the 1990s (P less than .001). The cumulative incidence of death due to health-related causes, which include late effects of cancer therapy, were 3.1%, 2.4%, and 1.9%, respectively (P less than .001).

Results indicate that “the strategy of reducing treatment exposures in order to decrease the frequency of late effects is translating into a significant reduction in observed late mortality and an extension of the life span of children and adolescents who are successfully treated for cancer,” wrote Dr. Gregory Armstrong of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, Tenn., and colleagues (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jan 13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510795).

A multivariate model showed that more recent treatment eras were associated with a reduced rate of death. The adjusted relative rate per every 5 years for death due to subsequent neoplasms was 0.83 (95% CI, 0.78-0.88), for cardiac causes, 0.77 (0.68-0.86), and for pulmonary causes, 0.77 (0.66-0.89).

Reductions across treatment eras in the rate of death from health-related causes were observed among survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (3.2% in the early 1970s to 2.1% in the 1990s, P less than .001), Hodgkin lymphoma (5.3% to 2.6%, P = .006), Wilms tumor (2.6% to 0.4%, P = .005), and astrocytoma (4.7% to 1.8%, P = .02).

Temporal reductions in exposure to radiotherapy and anthracyclines occurred in treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Hodgkin lymphoma, Wilms tumor, and astrocytoma. Health-related mortality reductions were observed concurrently with reduced therapeutic exposures for acute lymphoblastic leukemia and Wilms tumor. For Hodgkin lymphoma and astrocytoma, other factors such as improved screening for late effects of cancer treatment appear to account for reductions in late health-related mortality.

For certain cancers, primarily neuroblastoma, late mortality has increased in recent decades. Increased therapeutic intensity has improved 5-year survival but increased the risk of late effects.

The reduced rate of death from recurrence or progression of primary cancers is the main driver to reductions in all-cause mortality, consistent with results from previous studies.

The retrospective Childhood Cancer Survivor Study evaluated 34,033 patients diagnosed at 31 hospitals in the United States and Canada from 1970 through 1999. In total, 3,958 deaths occurred, 2,002 due to primary cancer and 1,618 due to health-related causes: 746 subsequent neoplasms, 241 cardiac causes, 137 pulmonary causes, and 494 from other causes.

The rate of death from treatment-related late effects such as subsequent cancers and cardiopulmonary conditions has decreased among childhood cancer survivors, according to researchers.

At 15 years post diagnosis, the cumulative incidence of death from any cause for survivors diagnosed in the 1970s was 10.7%, 7.9% for those diagnosed in the 1980s, and 5.8% for those diagnosed in the 1990s (P less than .001). The cumulative incidence of death due to health-related causes, which include late effects of cancer therapy, were 3.1%, 2.4%, and 1.9%, respectively (P less than .001).

Results indicate that “the strategy of reducing treatment exposures in order to decrease the frequency of late effects is translating into a significant reduction in observed late mortality and an extension of the life span of children and adolescents who are successfully treated for cancer,” wrote Dr. Gregory Armstrong of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, Tenn., and colleagues (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jan 13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510795).

A multivariate model showed that more recent treatment eras were associated with a reduced rate of death. The adjusted relative rate per every 5 years for death due to subsequent neoplasms was 0.83 (95% CI, 0.78-0.88), for cardiac causes, 0.77 (0.68-0.86), and for pulmonary causes, 0.77 (0.66-0.89).

Reductions across treatment eras in the rate of death from health-related causes were observed among survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (3.2% in the early 1970s to 2.1% in the 1990s, P less than .001), Hodgkin lymphoma (5.3% to 2.6%, P = .006), Wilms tumor (2.6% to 0.4%, P = .005), and astrocytoma (4.7% to 1.8%, P = .02).

Temporal reductions in exposure to radiotherapy and anthracyclines occurred in treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Hodgkin lymphoma, Wilms tumor, and astrocytoma. Health-related mortality reductions were observed concurrently with reduced therapeutic exposures for acute lymphoblastic leukemia and Wilms tumor. For Hodgkin lymphoma and astrocytoma, other factors such as improved screening for late effects of cancer treatment appear to account for reductions in late health-related mortality.

For certain cancers, primarily neuroblastoma, late mortality has increased in recent decades. Increased therapeutic intensity has improved 5-year survival but increased the risk of late effects.

The reduced rate of death from recurrence or progression of primary cancers is the main driver to reductions in all-cause mortality, consistent with results from previous studies.

The retrospective Childhood Cancer Survivor Study evaluated 34,033 patients diagnosed at 31 hospitals in the United States and Canada from 1970 through 1999. In total, 3,958 deaths occurred, 2,002 due to primary cancer and 1,618 due to health-related causes: 746 subsequent neoplasms, 241 cardiac causes, 137 pulmonary causes, and 494 from other causes.

Key clinical point: Five-year survivors of childhood cancers have increased lifespans due in part to reduced rates of treatment-related late effects.

Major finding: At 15 years post diagnosis, the cumulative incidence of death from any cause for survivors diagnosed in the 1970s was 10.7%; in the 1980s, 7.9%; and in the 1990s, 5.8% (P less than .001). The cumulative incidence of death due to health-related causes, which include late effects of cancer therapy, were 3.1%, 2.4%, and 1.9%, respectively (P less than .001).

Data source: The retrospective Childhood Cancer Survivor Study, evaluating 34,033 patients diagnosed at 31 hospitals in the United States and Canada from 1970 through 1999; 3,958 deaths occurred.

Disclosures: Dr. Armstrong and coauthors reported having no disclosures.

Hong Kong zygomycosis deaths pinned to dirty hospital laundry

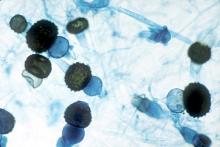

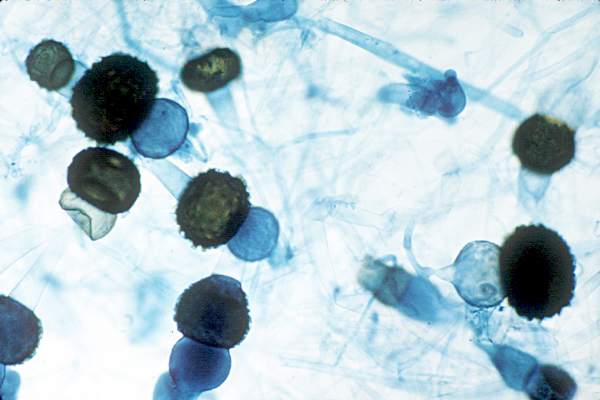

Contaminated laundry led to an outbreak of cutaneous and pulmonary zygomycosis that killed three immunocompromised patients and sickened three others at Queen Mary Hospital in Hong Kong.

The contamination was traced to a contract laundry service that was, in short, a microbe Disneyland. It was hot and humid, with sealed windows, dim lights, and a thick layer of dust on just about everything. Washers weren’t hot enough to kill spores; washed items were packed while warm and moist; and dirty linens rich with organic material were transported with clean ones (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Dec 13. doi:10.1093/cid/civ1006).

Of 195 environmental samples, 119 (61%) were positive for Zygomycetes, as well as 100% of air samples. Freshly laundered items – including clothes and bedding – had bacteria counts of 1,028 colony forming units (CFU)/100 cm2, far exceeding the “hygienically clean” standard of 20 CFU/100 cm2 set by U.S. healthcare textile certification requirements.

Queen Mary didn’t regularly audit its linens for cleanliness and microbe counts. “Our findings [suggest] that such standards should be adopted to prevent similar outbreaks,” said the investigators, led by Dr. Vincent Cheng, an infection control officer at Queen Mary, one of Hong Kong’s largest hospitals and a teaching hospital for the University of Hong Kong.

It has since switched to a new laundry service.

The outbreak ran from June 2 to July 18, 2015, during Hong Kong’s hot and humid season, which didn’t help matters.

The six patients were 42-74 years old; one had interstitial lung disease and the rest were either cancer or transplant patients. Infection was due to the spore-forming mold Rhizopus microsporus. Two pulmonary and one cutaneous infection patient died.

Length of stay was the most significant risk factor for infection; the mean interval from admission to diagnosis was more than 2 months.

“Pulmonary zygomycosis due to contaminated hospital linens has never been reported.” Clinicians need to “maintain a high index of suspicion for early diagnosis and treatment of zygomycosis in immunosuppressed patients,” the investigators said.

The U.S. recently had a cutaneous outbreak in Louisiana; hospital linens contaminated with Rhizopus species killed five immunocompromised children there in 2015.

“Invasive zygomycosis is an emerging infection that is increasingly reported in immunosuppressed hosts;” previously reported sources include adhesive bandages, wooden tongue depressors, ostomy bags, damaged water circuitry, adjacent building construction activity, and, as Queen Mary reported previously, contaminated allopurinol tablets.

Detecting the problem isn’t easy. None of the Replicate Organism Detection and Counting contact plates at Queen Mary recovered zygomycetes from the contaminated linen items. It took sponge swapping to find it; “without the use of sponge swab and selective culture medium, the causative agents in this outbreak would have been overlooked,” the investigators said.

Hong Kong government services helped support the work. The authors did not have any financial conflicts of interest.

Contaminated laundry led to an outbreak of cutaneous and pulmonary zygomycosis that killed three immunocompromised patients and sickened three others at Queen Mary Hospital in Hong Kong.

The contamination was traced to a contract laundry service that was, in short, a microbe Disneyland. It was hot and humid, with sealed windows, dim lights, and a thick layer of dust on just about everything. Washers weren’t hot enough to kill spores; washed items were packed while warm and moist; and dirty linens rich with organic material were transported with clean ones (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Dec 13. doi:10.1093/cid/civ1006).

Of 195 environmental samples, 119 (61%) were positive for Zygomycetes, as well as 100% of air samples. Freshly laundered items – including clothes and bedding – had bacteria counts of 1,028 colony forming units (CFU)/100 cm2, far exceeding the “hygienically clean” standard of 20 CFU/100 cm2 set by U.S. healthcare textile certification requirements.

Queen Mary didn’t regularly audit its linens for cleanliness and microbe counts. “Our findings [suggest] that such standards should be adopted to prevent similar outbreaks,” said the investigators, led by Dr. Vincent Cheng, an infection control officer at Queen Mary, one of Hong Kong’s largest hospitals and a teaching hospital for the University of Hong Kong.

It has since switched to a new laundry service.

The outbreak ran from June 2 to July 18, 2015, during Hong Kong’s hot and humid season, which didn’t help matters.

The six patients were 42-74 years old; one had interstitial lung disease and the rest were either cancer or transplant patients. Infection was due to the spore-forming mold Rhizopus microsporus. Two pulmonary and one cutaneous infection patient died.

Length of stay was the most significant risk factor for infection; the mean interval from admission to diagnosis was more than 2 months.

“Pulmonary zygomycosis due to contaminated hospital linens has never been reported.” Clinicians need to “maintain a high index of suspicion for early diagnosis and treatment of zygomycosis in immunosuppressed patients,” the investigators said.

The U.S. recently had a cutaneous outbreak in Louisiana; hospital linens contaminated with Rhizopus species killed five immunocompromised children there in 2015.

“Invasive zygomycosis is an emerging infection that is increasingly reported in immunosuppressed hosts;” previously reported sources include adhesive bandages, wooden tongue depressors, ostomy bags, damaged water circuitry, adjacent building construction activity, and, as Queen Mary reported previously, contaminated allopurinol tablets.

Detecting the problem isn’t easy. None of the Replicate Organism Detection and Counting contact plates at Queen Mary recovered zygomycetes from the contaminated linen items. It took sponge swapping to find it; “without the use of sponge swab and selective culture medium, the causative agents in this outbreak would have been overlooked,” the investigators said.

Hong Kong government services helped support the work. The authors did not have any financial conflicts of interest.

Contaminated laundry led to an outbreak of cutaneous and pulmonary zygomycosis that killed three immunocompromised patients and sickened three others at Queen Mary Hospital in Hong Kong.

The contamination was traced to a contract laundry service that was, in short, a microbe Disneyland. It was hot and humid, with sealed windows, dim lights, and a thick layer of dust on just about everything. Washers weren’t hot enough to kill spores; washed items were packed while warm and moist; and dirty linens rich with organic material were transported with clean ones (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Dec 13. doi:10.1093/cid/civ1006).

Of 195 environmental samples, 119 (61%) were positive for Zygomycetes, as well as 100% of air samples. Freshly laundered items – including clothes and bedding – had bacteria counts of 1,028 colony forming units (CFU)/100 cm2, far exceeding the “hygienically clean” standard of 20 CFU/100 cm2 set by U.S. healthcare textile certification requirements.

Queen Mary didn’t regularly audit its linens for cleanliness and microbe counts. “Our findings [suggest] that such standards should be adopted to prevent similar outbreaks,” said the investigators, led by Dr. Vincent Cheng, an infection control officer at Queen Mary, one of Hong Kong’s largest hospitals and a teaching hospital for the University of Hong Kong.

It has since switched to a new laundry service.

The outbreak ran from June 2 to July 18, 2015, during Hong Kong’s hot and humid season, which didn’t help matters.

The six patients were 42-74 years old; one had interstitial lung disease and the rest were either cancer or transplant patients. Infection was due to the spore-forming mold Rhizopus microsporus. Two pulmonary and one cutaneous infection patient died.

Length of stay was the most significant risk factor for infection; the mean interval from admission to diagnosis was more than 2 months.

“Pulmonary zygomycosis due to contaminated hospital linens has never been reported.” Clinicians need to “maintain a high index of suspicion for early diagnosis and treatment of zygomycosis in immunosuppressed patients,” the investigators said.

The U.S. recently had a cutaneous outbreak in Louisiana; hospital linens contaminated with Rhizopus species killed five immunocompromised children there in 2015.

“Invasive zygomycosis is an emerging infection that is increasingly reported in immunosuppressed hosts;” previously reported sources include adhesive bandages, wooden tongue depressors, ostomy bags, damaged water circuitry, adjacent building construction activity, and, as Queen Mary reported previously, contaminated allopurinol tablets.

Detecting the problem isn’t easy. None of the Replicate Organism Detection and Counting contact plates at Queen Mary recovered zygomycetes from the contaminated linen items. It took sponge swapping to find it; “without the use of sponge swab and selective culture medium, the causative agents in this outbreak would have been overlooked,” the investigators said.

Hong Kong government services helped support the work. The authors did not have any financial conflicts of interest.

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point: Clinicians need to maintain a high index of suspicion for early diagnosis and treatment of zygomycosis in immunosuppressed patients,

Major finding: Of 195 environmental samples at the contaminated laundry, 119 (61%) were positive for Zygomycetes, as well as 100% of air samples.

Data source: Epidemiological study in Hong Kong.

Disclosures: Hong Kong government services helped support the work. The authors do not have any financial conflicts of interest.

Neurosurgery at the End of Life

The juxtaposition between my first 2 days of neurosurgery could not have been more profound. On my first day as a third-year medical student, the attending and chief resident let me take the lead on the first case: a straightforward brain biopsy. I got to make the incision, drill the burr hole, and perform the needle biopsy. I still remember the thrill of the technical challenge, the controlled violence of drilling into the skull, and the finesse of accessing the tumor core.

The buzz was so strong that I barely registered the diagnosis that was called back from the pathologist: glioblastoma. It was not until I saw the face of the disease the next morning that I understood the reality of a GBM diagnosis. That face belonged to a 47-year-old man who hadn’t slept all night, wide eyed with apprehension at what news I might bring. He beseeched me with questions, and though his aphasia left him stammering to get the words out, I knew exactly what he was asking: Would he live or die? It was a question I was in no position to answer. Instead, I reassured him that we were waiting on the final pathology, all the while trying to forget the fact that the frozen section suggested an aggressive subtype, surely heralding a poor prognosis.

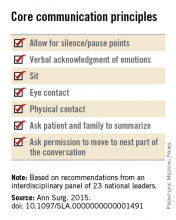

In his poignant memoir, “Do No Harm: Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery” (New York: Thomas Dunne Book, 2015), Dr. Henry Marsh writes beautifully about how difficult it can be to find the balance between optimism and realism. In one memorable passage, Dr. Marsh shows a house officer a scan of a highly malignant brain tumor and asks him what he would say to the patient. The trainee reflexively hides behind jargon, skirting around what he knew to be the truth: This tumor would kill her. Marsh presses him to admit that he’s lying, before lamenting at how hard it is to improve these critical communication skills: “When I have had to break bad news I never know whether I have done it well or not. The patients aren’t going to ring me up afterward and say, ‘Mr. Marsh, I really liked the way you told me that I was going to die,’ or ‘Mr. Marsh, you were crap.’ You can only hope that you haven’t made too much of a mess of it.”

I could certainly relate to Dr. Marsh’s house officer as I walked away from my own patient. I felt almost deceitful withholding diagnostic information from him, even if I did the “right” thing. It made me wonder, why did I want to become a neurosurgeon? Surely to help people through some of the most difficult moments of their lives. But is it possible to be a source of comfort when you are required so often to be a harbinger of death? The answer depends on whether one can envision a role for the neurosurgeon beyond the mandate of “life at all costs.”

While the field has become known for its life-saving procedures, neurosurgeons are called just as often to preside over the end of their patient’s lives – work that requires just as much skill as any technical procedure. Dr. Marsh recognized the tremendous human cost of neglecting that work. For cases that appear “hopeless,” he writes, “We often end up operating because it’s easier than being honest, and it means that we can avoid a painful conversation.”

We are only beginning to understand the many issues that neurosurgical patients face at the end of life, but so far it is clear that neurosurgical trainees require substantive training in prognostication, communication, and palliation (Crit Care Med. 2015 Sep;43[9]:1964-77 1,2; J Neurooncol. 2009 Jan;91[1]:39-43). Is there room in the current training paradigm for more formal education in these domains? As we move further into the 21st century, we must embrace the need for masterful clinicians outside of the operating room if we are to ever challenge the axiom set forth by the renowned French surgeon, René Leriche, some 65 years ago: “Every surgeon carries within himself a small cemetery, where from time to time he goes to pray – a place of bitterness and regret, where he must look for an explanation for his failures.” Let us look forward to the day when this is no longer the case.

Stephen Miranda is a medical student from the University of Rochester, who is now working as a research fellow at Ariadne Labs, a joint center for health systems innovation at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, both in Boston.

The juxtaposition between my first 2 days of neurosurgery could not have been more profound. On my first day as a third-year medical student, the attending and chief resident let me take the lead on the first case: a straightforward brain biopsy. I got to make the incision, drill the burr hole, and perform the needle biopsy. I still remember the thrill of the technical challenge, the controlled violence of drilling into the skull, and the finesse of accessing the tumor core.

The buzz was so strong that I barely registered the diagnosis that was called back from the pathologist: glioblastoma. It was not until I saw the face of the disease the next morning that I understood the reality of a GBM diagnosis. That face belonged to a 47-year-old man who hadn’t slept all night, wide eyed with apprehension at what news I might bring. He beseeched me with questions, and though his aphasia left him stammering to get the words out, I knew exactly what he was asking: Would he live or die? It was a question I was in no position to answer. Instead, I reassured him that we were waiting on the final pathology, all the while trying to forget the fact that the frozen section suggested an aggressive subtype, surely heralding a poor prognosis.

In his poignant memoir, “Do No Harm: Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery” (New York: Thomas Dunne Book, 2015), Dr. Henry Marsh writes beautifully about how difficult it can be to find the balance between optimism and realism. In one memorable passage, Dr. Marsh shows a house officer a scan of a highly malignant brain tumor and asks him what he would say to the patient. The trainee reflexively hides behind jargon, skirting around what he knew to be the truth: This tumor would kill her. Marsh presses him to admit that he’s lying, before lamenting at how hard it is to improve these critical communication skills: “When I have had to break bad news I never know whether I have done it well or not. The patients aren’t going to ring me up afterward and say, ‘Mr. Marsh, I really liked the way you told me that I was going to die,’ or ‘Mr. Marsh, you were crap.’ You can only hope that you haven’t made too much of a mess of it.”

I could certainly relate to Dr. Marsh’s house officer as I walked away from my own patient. I felt almost deceitful withholding diagnostic information from him, even if I did the “right” thing. It made me wonder, why did I want to become a neurosurgeon? Surely to help people through some of the most difficult moments of their lives. But is it possible to be a source of comfort when you are required so often to be a harbinger of death? The answer depends on whether one can envision a role for the neurosurgeon beyond the mandate of “life at all costs.”

While the field has become known for its life-saving procedures, neurosurgeons are called just as often to preside over the end of their patient’s lives – work that requires just as much skill as any technical procedure. Dr. Marsh recognized the tremendous human cost of neglecting that work. For cases that appear “hopeless,” he writes, “We often end up operating because it’s easier than being honest, and it means that we can avoid a painful conversation.”

We are only beginning to understand the many issues that neurosurgical patients face at the end of life, but so far it is clear that neurosurgical trainees require substantive training in prognostication, communication, and palliation (Crit Care Med. 2015 Sep;43[9]:1964-77 1,2; J Neurooncol. 2009 Jan;91[1]:39-43). Is there room in the current training paradigm for more formal education in these domains? As we move further into the 21st century, we must embrace the need for masterful clinicians outside of the operating room if we are to ever challenge the axiom set forth by the renowned French surgeon, René Leriche, some 65 years ago: “Every surgeon carries within himself a small cemetery, where from time to time he goes to pray – a place of bitterness and regret, where he must look for an explanation for his failures.” Let us look forward to the day when this is no longer the case.

Stephen Miranda is a medical student from the University of Rochester, who is now working as a research fellow at Ariadne Labs, a joint center for health systems innovation at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, both in Boston.

The juxtaposition between my first 2 days of neurosurgery could not have been more profound. On my first day as a third-year medical student, the attending and chief resident let me take the lead on the first case: a straightforward brain biopsy. I got to make the incision, drill the burr hole, and perform the needle biopsy. I still remember the thrill of the technical challenge, the controlled violence of drilling into the skull, and the finesse of accessing the tumor core.

The buzz was so strong that I barely registered the diagnosis that was called back from the pathologist: glioblastoma. It was not until I saw the face of the disease the next morning that I understood the reality of a GBM diagnosis. That face belonged to a 47-year-old man who hadn’t slept all night, wide eyed with apprehension at what news I might bring. He beseeched me with questions, and though his aphasia left him stammering to get the words out, I knew exactly what he was asking: Would he live or die? It was a question I was in no position to answer. Instead, I reassured him that we were waiting on the final pathology, all the while trying to forget the fact that the frozen section suggested an aggressive subtype, surely heralding a poor prognosis.

In his poignant memoir, “Do No Harm: Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery” (New York: Thomas Dunne Book, 2015), Dr. Henry Marsh writes beautifully about how difficult it can be to find the balance between optimism and realism. In one memorable passage, Dr. Marsh shows a house officer a scan of a highly malignant brain tumor and asks him what he would say to the patient. The trainee reflexively hides behind jargon, skirting around what he knew to be the truth: This tumor would kill her. Marsh presses him to admit that he’s lying, before lamenting at how hard it is to improve these critical communication skills: “When I have had to break bad news I never know whether I have done it well or not. The patients aren’t going to ring me up afterward and say, ‘Mr. Marsh, I really liked the way you told me that I was going to die,’ or ‘Mr. Marsh, you were crap.’ You can only hope that you haven’t made too much of a mess of it.”

I could certainly relate to Dr. Marsh’s house officer as I walked away from my own patient. I felt almost deceitful withholding diagnostic information from him, even if I did the “right” thing. It made me wonder, why did I want to become a neurosurgeon? Surely to help people through some of the most difficult moments of their lives. But is it possible to be a source of comfort when you are required so often to be a harbinger of death? The answer depends on whether one can envision a role for the neurosurgeon beyond the mandate of “life at all costs.”

While the field has become known for its life-saving procedures, neurosurgeons are called just as often to preside over the end of their patient’s lives – work that requires just as much skill as any technical procedure. Dr. Marsh recognized the tremendous human cost of neglecting that work. For cases that appear “hopeless,” he writes, “We often end up operating because it’s easier than being honest, and it means that we can avoid a painful conversation.”

We are only beginning to understand the many issues that neurosurgical patients face at the end of life, but so far it is clear that neurosurgical trainees require substantive training in prognostication, communication, and palliation (Crit Care Med. 2015 Sep;43[9]:1964-77 1,2; J Neurooncol. 2009 Jan;91[1]:39-43). Is there room in the current training paradigm for more formal education in these domains? As we move further into the 21st century, we must embrace the need for masterful clinicians outside of the operating room if we are to ever challenge the axiom set forth by the renowned French surgeon, René Leriche, some 65 years ago: “Every surgeon carries within himself a small cemetery, where from time to time he goes to pray – a place of bitterness and regret, where he must look for an explanation for his failures.” Let us look forward to the day when this is no longer the case.

Stephen Miranda is a medical student from the University of Rochester, who is now working as a research fellow at Ariadne Labs, a joint center for health systems innovation at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, both in Boston.

Late risks of breast cancer RT are higher for smokers

SAN ANTONIO – The late side effects of modern radiation therapy for breast cancer depend in part on a woman’s smoking status, suggests a meta-analysis of data from more than 40,000 women presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

For nonsmokers, radiation therapy had little impact on the absolute risks of lung cancer or cardiac death, the main risks identified, which combined totaled less than 1%, Dr. Carolyn Taylor reported on behalf of the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. But for women who had smoked throughout their adult life and continued to do so during and after treatment, it increased that absolute risk to roughly 2%.

“Smoking status can determine the net long-term effects of breast cancer radiotherapy on mortality. Stopping smoking at the time of radiotherapy may avoid much of the risk, and that’s because most of the risk of lung cancer starts more than 10 years after radiotherapy,” said Dr. Taylor, a radiation oncologist at the University of Oxford (England).

Radiation therapy remains an important tool in treating breast cancer, ultimately reducing the likelihood of death from the disease, she reminded symposium attendees. “The absolute benefit in women treated according to current guidelines is a few percent. Let’s remember the magnitude of that benefit as we think about the risks of radiotherapy.”

Attendee Dr. Steven Vogl of Montefiore Medical Center, New York, asked whether information was available on the location of the lung cancers that occurred in the trials.

“We didn’t have location of lung cancers. We didn’t even know if it was ipsilateral or contralateral to the previous breast cancer in this study,” Dr. Taylor replied. “But we’ve done other studies where we have known the location of the lung cancer, and there were similar findings in those studies.”

“In the last 4 years, we’ve had very good information that annual CT screening substantially and very quickly reduces the mortality from lung cancer,” Dr. Vogl added as a comment. “Any of us who care for patients who have been radiated where, really, any lung has been treated, who continue to smoke, should be screened – and screened and screened and screened again,” he recommended.

The investigators analyzed data from 40,781 women with breast cancer from 75 randomized trials conducted worldwide that compared outcomes with versus without radiation therapy. The median year of trial entry was 1983. On average, women in the trials received 10 Gy to both lungs combined and 6 Gy to the heart.

Comparing women who did and did not receive radiation therapy, the rate ratio for lung cancer was 2.10 at 10 or more years out, and the rate ratio for cardiac mortality was 1.30 overall. Given the mean radiation doses in the trials, the excess risk translated to 12% per Gray for lung cancer and 4% per Gray for cardiac mortality. “These rate ratios are likely to apply today,” Dr. Taylor maintained.

However, she noted, contemporary breast cancer radiation therapy techniques are much better at sparing normal tissues. To derive absolute risk estimates that are relevant today, she and her colleagues reviewed the literature for 2010-2015 and determined that women now receive an average of 5 Gy to both lungs combined and 4 Gy to the heart, with some centers achieving even lower values.

Among nonsmokers, the estimated cumulative 30-year risk of lung cancer was 0.5% for women who did not receive radiation therapy and 0.8% for those who received radiation therapy with a mean dose of 5 Gy to both lungs combined, Dr. Taylor reported. However, among long-term smokers, it was 9.4% without radiation and a substantially higher 13.8% with it.

Similarly, among nonsmokers, the estimated cumulative 30-year risk of ischemic heart disease death was 1.8% for women who did not receive radiation therapy and 2.0% for women who received radiation therapy with a mean dose of 2 Gy to the heart. Among long-term smokers, it was 8.0% without radiation and a slightly higher 8.6% with it.

Additional analyses looking at other late side effects showed no radiation therapy–related excess risk of sarcomas, according to Dr. Taylor. The risk of leukemia was increased with radiation, but actual numbers of cases were very small, she cautioned.

Attendee Dr. Pamela Goodwin, University of Toronto, said, “I’m just wondering whether you considered if it was valid to assume that there was a linear relationship between radiation dose and the risk of lung cancer in the range of radiation doses that you looked at, so, from the higher range in the earlier studies to the much lower dose now.”

Numbers of heart disease events were sufficient to establish a linear relationship, according to Dr. Taylor. Numbers of lung cancers were not, but case-control studies in the literature with adequate numbers have identified a linear relationship there, too. “We use what we can, and we have got now several hundred events, if you combine all of the literature together. And they do suggest the dose-response relationship is linear, but we can’t know that for certain,” she said.

SAN ANTONIO – The late side effects of modern radiation therapy for breast cancer depend in part on a woman’s smoking status, suggests a meta-analysis of data from more than 40,000 women presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

For nonsmokers, radiation therapy had little impact on the absolute risks of lung cancer or cardiac death, the main risks identified, which combined totaled less than 1%, Dr. Carolyn Taylor reported on behalf of the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. But for women who had smoked throughout their adult life and continued to do so during and after treatment, it increased that absolute risk to roughly 2%.

“Smoking status can determine the net long-term effects of breast cancer radiotherapy on mortality. Stopping smoking at the time of radiotherapy may avoid much of the risk, and that’s because most of the risk of lung cancer starts more than 10 years after radiotherapy,” said Dr. Taylor, a radiation oncologist at the University of Oxford (England).

Radiation therapy remains an important tool in treating breast cancer, ultimately reducing the likelihood of death from the disease, she reminded symposium attendees. “The absolute benefit in women treated according to current guidelines is a few percent. Let’s remember the magnitude of that benefit as we think about the risks of radiotherapy.”

Attendee Dr. Steven Vogl of Montefiore Medical Center, New York, asked whether information was available on the location of the lung cancers that occurred in the trials.

“We didn’t have location of lung cancers. We didn’t even know if it was ipsilateral or contralateral to the previous breast cancer in this study,” Dr. Taylor replied. “But we’ve done other studies where we have known the location of the lung cancer, and there were similar findings in those studies.”

“In the last 4 years, we’ve had very good information that annual CT screening substantially and very quickly reduces the mortality from lung cancer,” Dr. Vogl added as a comment. “Any of us who care for patients who have been radiated where, really, any lung has been treated, who continue to smoke, should be screened – and screened and screened and screened again,” he recommended.

The investigators analyzed data from 40,781 women with breast cancer from 75 randomized trials conducted worldwide that compared outcomes with versus without radiation therapy. The median year of trial entry was 1983. On average, women in the trials received 10 Gy to both lungs combined and 6 Gy to the heart.

Comparing women who did and did not receive radiation therapy, the rate ratio for lung cancer was 2.10 at 10 or more years out, and the rate ratio for cardiac mortality was 1.30 overall. Given the mean radiation doses in the trials, the excess risk translated to 12% per Gray for lung cancer and 4% per Gray for cardiac mortality. “These rate ratios are likely to apply today,” Dr. Taylor maintained.

However, she noted, contemporary breast cancer radiation therapy techniques are much better at sparing normal tissues. To derive absolute risk estimates that are relevant today, she and her colleagues reviewed the literature for 2010-2015 and determined that women now receive an average of 5 Gy to both lungs combined and 4 Gy to the heart, with some centers achieving even lower values.

Among nonsmokers, the estimated cumulative 30-year risk of lung cancer was 0.5% for women who did not receive radiation therapy and 0.8% for those who received radiation therapy with a mean dose of 5 Gy to both lungs combined, Dr. Taylor reported. However, among long-term smokers, it was 9.4% without radiation and a substantially higher 13.8% with it.