User login

Elagolix is effective second-tier treatment for endometriosis-associated dysmenorrhea

PHILADELPHIA – Charles E. Miller, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine.

Although clinicians need prior authorization and evidence of treatment failure before prescribing Elagolix, the drug is a viable option as a second-tier treatment for patients with endometriosis-associated dysmenorrhea, said Dr. Miller, director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital in Park Ridge, Ill. “We have a drug that is very effective, that has a very low adverse event profile, and is tolerated by the vast majority of our patients.”

First-line options

NSAIDs are first-line treatment for endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, with acetaminophen used in cases where NSAIDs are contraindicated or cause side effects such as gastrointestinal issues. Hormonal contraceptives also can be used as first-line treatment, divided into estrogen/progestin and progestin-only options that can be combined. Evidence from the literature has shown oral pills decrease pain, compared with placebo, but the decrease is not dose dependent, said Dr. Miller.

“We also know that if you use it continuously or prolonged, we find that there is going to be greater success with dysmenorrhea, and that ultimately you would use a higher-dose pill because of the greater risk of breakthrough when using a lesser dose in a continuous fashion,” he said. “Obviously if you’re not having menses, you’re not going to have dysmenorrhea.”

Other estrogen/progestin hormonal contraception such as the vaginal ring or transdermal patch also have been shown to decrease dysmenorrhea from endometriosis, with one study showing a reduction from 17% to 6% in moderate to severe dysmenorrhea in patients using the vaginal ring, compared with patients receiving oral contraceptives. In a separate randomized, controlled trial, “dysmenorrhea was more common in patch users, so it doesn’t appear that the patch is quite as effective in terms of reducing dysmenorrhea,” said Dr. Miller (JAMA. 2001 May 9. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2347).

Compared with combination hormone therapy, there has been less research conducted on progestin-only hormone contraceptives on reducing dysmenorrhea from endometriosis. For example, there is little evidence for depot medroxyprogesterone acetate in reducing dysmenorrhea, but rather with it causing amenorrhea; one study showed a 50% amenorrhea rate at 1 year. “The disadvantage, however, in our infertile population is ultimately getting the menses back,” said Dr. Miller.

IUDs using levonorgestrel appear comparable with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists in reducing endometriosis-related pain; in one study, most women treated with either of these had visual analogue scores of less than 3 at 6 months of treatment. Between 68% and 75% of women with dysmenorrhea who receive an implantable contraceptive device with etonogestrel report decreased pain, and one meta-analysis reported 75% of women had “complete resolution of dysmenorrhea.” Concerning progestin-only pills, they can be used for endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, but they are “problematic in that there’s a lot of breakthrough bleeding, and often times that is associated with pain,” said Dr. Miller.

Second-tier options

Injectable GnRH agonists are effective options as second-tier treatments for endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, but patients are at risk of developing postmenopausal symptoms such as hot flashes, insomnia, spotting, and decreased libido. “One advantage to that is, over the years and particularly something that I’ve done with my endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, is to utilize add-back with these patients,” said Dr. Miller, who noted that patients on 2.5 mg of norethindrone acetate and 0.5 mg of ethinyl estradiol“do very well” with that combination of add-back therapy.

Elagolix is the most recent second-tier treatment option for these patients, and was studied in the Elaris EM-I and Elaris EM-II trials in a once-daily dose of 150 mg and a twice-daily dose of 200 mg. In Elaris EM-1, 76% of patients in the 200-mg elagolix group had a clinical response, compared with 46% in the 150-mg group and 20% in the placebo group (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700089). However, patients should not be on elagolix at 200 mg for more than 6 months, while patients receiving elagolix at 150 mg can stay on the treatment for up to 2 years.

Patients taking elagolix also showed postmenopausal symptoms, with 24% in the 150-mg group and 46% in the 200-mg group experiencing hot flashes, compared with 9% of patients in the placebo group. While 6% of patients in the 150-mg group and 10% in the 200-mg group discontinued because of adverse events, 1% and 3% of patients in the 150-mg and 200-mg group discontinued because of hot flashes or night sweats, respectively. “Symptoms are well tolerated, far different than in comparison with leuprolide acetate and GnRH agonists,” said Dr. Miller.

There also is a benefit to how patients recover from bone mineral density (BMD) changes after remaining on elagolix, Dr. Miller noted. In patients who received elagolix for 12 months at doses of 150 mg and 200 mg, there was an increase in lumbar spine BMD recovered 6 months after discontinuation, with patients in the 150-mg group experiencing a recovery close to baseline BMD levels. Among patients who discontinued treatment, there also was a quick resumption in menses for both groups: 87% of patients in the 150 mg group and 88% of patients in the 200-mg group who discontinued treatment after 6 months had resumed menses by 2 months after discontinuation, while 95% of patients in the 150-mg and 91% in the 200-mg group who discontinued after 12 months resumed menses by 2 months after discontinuation.

Dr. Miller reported relationships with AbbVie, Allergan, Blue Seas Med Spa, Espiner Medical, Gynesonics, Halt Medical, Hologic, Karl Storz, Medtronic, and Richard Wolf in the form of consultancies, grants, speakers’ bureau appointments, stock options, royalties, and ownership interests.

PHILADELPHIA – Charles E. Miller, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine.

Although clinicians need prior authorization and evidence of treatment failure before prescribing Elagolix, the drug is a viable option as a second-tier treatment for patients with endometriosis-associated dysmenorrhea, said Dr. Miller, director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital in Park Ridge, Ill. “We have a drug that is very effective, that has a very low adverse event profile, and is tolerated by the vast majority of our patients.”

First-line options

NSAIDs are first-line treatment for endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, with acetaminophen used in cases where NSAIDs are contraindicated or cause side effects such as gastrointestinal issues. Hormonal contraceptives also can be used as first-line treatment, divided into estrogen/progestin and progestin-only options that can be combined. Evidence from the literature has shown oral pills decrease pain, compared with placebo, but the decrease is not dose dependent, said Dr. Miller.

“We also know that if you use it continuously or prolonged, we find that there is going to be greater success with dysmenorrhea, and that ultimately you would use a higher-dose pill because of the greater risk of breakthrough when using a lesser dose in a continuous fashion,” he said. “Obviously if you’re not having menses, you’re not going to have dysmenorrhea.”

Other estrogen/progestin hormonal contraception such as the vaginal ring or transdermal patch also have been shown to decrease dysmenorrhea from endometriosis, with one study showing a reduction from 17% to 6% in moderate to severe dysmenorrhea in patients using the vaginal ring, compared with patients receiving oral contraceptives. In a separate randomized, controlled trial, “dysmenorrhea was more common in patch users, so it doesn’t appear that the patch is quite as effective in terms of reducing dysmenorrhea,” said Dr. Miller (JAMA. 2001 May 9. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2347).

Compared with combination hormone therapy, there has been less research conducted on progestin-only hormone contraceptives on reducing dysmenorrhea from endometriosis. For example, there is little evidence for depot medroxyprogesterone acetate in reducing dysmenorrhea, but rather with it causing amenorrhea; one study showed a 50% amenorrhea rate at 1 year. “The disadvantage, however, in our infertile population is ultimately getting the menses back,” said Dr. Miller.

IUDs using levonorgestrel appear comparable with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists in reducing endometriosis-related pain; in one study, most women treated with either of these had visual analogue scores of less than 3 at 6 months of treatment. Between 68% and 75% of women with dysmenorrhea who receive an implantable contraceptive device with etonogestrel report decreased pain, and one meta-analysis reported 75% of women had “complete resolution of dysmenorrhea.” Concerning progestin-only pills, they can be used for endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, but they are “problematic in that there’s a lot of breakthrough bleeding, and often times that is associated with pain,” said Dr. Miller.

Second-tier options

Injectable GnRH agonists are effective options as second-tier treatments for endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, but patients are at risk of developing postmenopausal symptoms such as hot flashes, insomnia, spotting, and decreased libido. “One advantage to that is, over the years and particularly something that I’ve done with my endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, is to utilize add-back with these patients,” said Dr. Miller, who noted that patients on 2.5 mg of norethindrone acetate and 0.5 mg of ethinyl estradiol“do very well” with that combination of add-back therapy.

Elagolix is the most recent second-tier treatment option for these patients, and was studied in the Elaris EM-I and Elaris EM-II trials in a once-daily dose of 150 mg and a twice-daily dose of 200 mg. In Elaris EM-1, 76% of patients in the 200-mg elagolix group had a clinical response, compared with 46% in the 150-mg group and 20% in the placebo group (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700089). However, patients should not be on elagolix at 200 mg for more than 6 months, while patients receiving elagolix at 150 mg can stay on the treatment for up to 2 years.

Patients taking elagolix also showed postmenopausal symptoms, with 24% in the 150-mg group and 46% in the 200-mg group experiencing hot flashes, compared with 9% of patients in the placebo group. While 6% of patients in the 150-mg group and 10% in the 200-mg group discontinued because of adverse events, 1% and 3% of patients in the 150-mg and 200-mg group discontinued because of hot flashes or night sweats, respectively. “Symptoms are well tolerated, far different than in comparison with leuprolide acetate and GnRH agonists,” said Dr. Miller.

There also is a benefit to how patients recover from bone mineral density (BMD) changes after remaining on elagolix, Dr. Miller noted. In patients who received elagolix for 12 months at doses of 150 mg and 200 mg, there was an increase in lumbar spine BMD recovered 6 months after discontinuation, with patients in the 150-mg group experiencing a recovery close to baseline BMD levels. Among patients who discontinued treatment, there also was a quick resumption in menses for both groups: 87% of patients in the 150 mg group and 88% of patients in the 200-mg group who discontinued treatment after 6 months had resumed menses by 2 months after discontinuation, while 95% of patients in the 150-mg and 91% in the 200-mg group who discontinued after 12 months resumed menses by 2 months after discontinuation.

Dr. Miller reported relationships with AbbVie, Allergan, Blue Seas Med Spa, Espiner Medical, Gynesonics, Halt Medical, Hologic, Karl Storz, Medtronic, and Richard Wolf in the form of consultancies, grants, speakers’ bureau appointments, stock options, royalties, and ownership interests.

PHILADELPHIA – Charles E. Miller, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine.

Although clinicians need prior authorization and evidence of treatment failure before prescribing Elagolix, the drug is a viable option as a second-tier treatment for patients with endometriosis-associated dysmenorrhea, said Dr. Miller, director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital in Park Ridge, Ill. “We have a drug that is very effective, that has a very low adverse event profile, and is tolerated by the vast majority of our patients.”

First-line options

NSAIDs are first-line treatment for endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, with acetaminophen used in cases where NSAIDs are contraindicated or cause side effects such as gastrointestinal issues. Hormonal contraceptives also can be used as first-line treatment, divided into estrogen/progestin and progestin-only options that can be combined. Evidence from the literature has shown oral pills decrease pain, compared with placebo, but the decrease is not dose dependent, said Dr. Miller.

“We also know that if you use it continuously or prolonged, we find that there is going to be greater success with dysmenorrhea, and that ultimately you would use a higher-dose pill because of the greater risk of breakthrough when using a lesser dose in a continuous fashion,” he said. “Obviously if you’re not having menses, you’re not going to have dysmenorrhea.”

Other estrogen/progestin hormonal contraception such as the vaginal ring or transdermal patch also have been shown to decrease dysmenorrhea from endometriosis, with one study showing a reduction from 17% to 6% in moderate to severe dysmenorrhea in patients using the vaginal ring, compared with patients receiving oral contraceptives. In a separate randomized, controlled trial, “dysmenorrhea was more common in patch users, so it doesn’t appear that the patch is quite as effective in terms of reducing dysmenorrhea,” said Dr. Miller (JAMA. 2001 May 9. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2347).

Compared with combination hormone therapy, there has been less research conducted on progestin-only hormone contraceptives on reducing dysmenorrhea from endometriosis. For example, there is little evidence for depot medroxyprogesterone acetate in reducing dysmenorrhea, but rather with it causing amenorrhea; one study showed a 50% amenorrhea rate at 1 year. “The disadvantage, however, in our infertile population is ultimately getting the menses back,” said Dr. Miller.

IUDs using levonorgestrel appear comparable with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists in reducing endometriosis-related pain; in one study, most women treated with either of these had visual analogue scores of less than 3 at 6 months of treatment. Between 68% and 75% of women with dysmenorrhea who receive an implantable contraceptive device with etonogestrel report decreased pain, and one meta-analysis reported 75% of women had “complete resolution of dysmenorrhea.” Concerning progestin-only pills, they can be used for endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, but they are “problematic in that there’s a lot of breakthrough bleeding, and often times that is associated with pain,” said Dr. Miller.

Second-tier options

Injectable GnRH agonists are effective options as second-tier treatments for endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, but patients are at risk of developing postmenopausal symptoms such as hot flashes, insomnia, spotting, and decreased libido. “One advantage to that is, over the years and particularly something that I’ve done with my endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, is to utilize add-back with these patients,” said Dr. Miller, who noted that patients on 2.5 mg of norethindrone acetate and 0.5 mg of ethinyl estradiol“do very well” with that combination of add-back therapy.

Elagolix is the most recent second-tier treatment option for these patients, and was studied in the Elaris EM-I and Elaris EM-II trials in a once-daily dose of 150 mg and a twice-daily dose of 200 mg. In Elaris EM-1, 76% of patients in the 200-mg elagolix group had a clinical response, compared with 46% in the 150-mg group and 20% in the placebo group (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700089). However, patients should not be on elagolix at 200 mg for more than 6 months, while patients receiving elagolix at 150 mg can stay on the treatment for up to 2 years.

Patients taking elagolix also showed postmenopausal symptoms, with 24% in the 150-mg group and 46% in the 200-mg group experiencing hot flashes, compared with 9% of patients in the placebo group. While 6% of patients in the 150-mg group and 10% in the 200-mg group discontinued because of adverse events, 1% and 3% of patients in the 150-mg and 200-mg group discontinued because of hot flashes or night sweats, respectively. “Symptoms are well tolerated, far different than in comparison with leuprolide acetate and GnRH agonists,” said Dr. Miller.

There also is a benefit to how patients recover from bone mineral density (BMD) changes after remaining on elagolix, Dr. Miller noted. In patients who received elagolix for 12 months at doses of 150 mg and 200 mg, there was an increase in lumbar spine BMD recovered 6 months after discontinuation, with patients in the 150-mg group experiencing a recovery close to baseline BMD levels. Among patients who discontinued treatment, there also was a quick resumption in menses for both groups: 87% of patients in the 150 mg group and 88% of patients in the 200-mg group who discontinued treatment after 6 months had resumed menses by 2 months after discontinuation, while 95% of patients in the 150-mg and 91% in the 200-mg group who discontinued after 12 months resumed menses by 2 months after discontinuation.

Dr. Miller reported relationships with AbbVie, Allergan, Blue Seas Med Spa, Espiner Medical, Gynesonics, Halt Medical, Hologic, Karl Storz, Medtronic, and Richard Wolf in the form of consultancies, grants, speakers’ bureau appointments, stock options, royalties, and ownership interests.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ASRM 2019

Chronic pain more common in women with ADHD or ASD

Women with ADHD, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), or both report higher rates of chronic pain, which should be accounted for in the treatment received, new research shows.

In some cases, treating the ADHD might lower the pain, reported Karin Asztély of the Sahlgrenska Academy Institute of Neuroscience, Göteborg, Sweden, and associates. The study was published in the Journal of Pain Research.

The research included 77 Swedish women with ADHD, ASD, or both from a larger prospective longitudinal study. From 2015 to 2018, when the women were aged 19-37 years, they were contacted by mail and phone, and interviewed about symptoms of pain. This included chronic widespread or regional symptoms of pain; widespread pain was pain that lasted more than 3 months and was described both above and below the waist, on both sides of the body, and in the axial skeleton. Any pain that lasted more than 3 months but did not meet those other requirements was listed as chronic regional pain.

Chronic pain of any kind was reported by 59 participants (76.6%). Chronic widespread pain was reported by 25 participants (32.5%), and chronic regional pain was reported by 34 (44.2%), both of which were higher than those seen in a cross-sectional survey, which showed prevalences of 11.9% and 23.9% of Swedish participants, respectively (J Rheumatol. 2001 Jun;28[6]:1369-77).

Among the limitations of the latest study is the small sample size and the absence of healthy controls; however, the researchers thought this was compensated for by the comparisons with previous research.

“ and possible unrecognized ASD and/or ADHD in women with chronic pain,” they concluded.

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Asztély et al. J Pain Res. 2019 Oct 18;12:2925-32.

Women with ADHD, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), or both report higher rates of chronic pain, which should be accounted for in the treatment received, new research shows.

In some cases, treating the ADHD might lower the pain, reported Karin Asztély of the Sahlgrenska Academy Institute of Neuroscience, Göteborg, Sweden, and associates. The study was published in the Journal of Pain Research.

The research included 77 Swedish women with ADHD, ASD, or both from a larger prospective longitudinal study. From 2015 to 2018, when the women were aged 19-37 years, they were contacted by mail and phone, and interviewed about symptoms of pain. This included chronic widespread or regional symptoms of pain; widespread pain was pain that lasted more than 3 months and was described both above and below the waist, on both sides of the body, and in the axial skeleton. Any pain that lasted more than 3 months but did not meet those other requirements was listed as chronic regional pain.

Chronic pain of any kind was reported by 59 participants (76.6%). Chronic widespread pain was reported by 25 participants (32.5%), and chronic regional pain was reported by 34 (44.2%), both of which were higher than those seen in a cross-sectional survey, which showed prevalences of 11.9% and 23.9% of Swedish participants, respectively (J Rheumatol. 2001 Jun;28[6]:1369-77).

Among the limitations of the latest study is the small sample size and the absence of healthy controls; however, the researchers thought this was compensated for by the comparisons with previous research.

“ and possible unrecognized ASD and/or ADHD in women with chronic pain,” they concluded.

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Asztély et al. J Pain Res. 2019 Oct 18;12:2925-32.

Women with ADHD, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), or both report higher rates of chronic pain, which should be accounted for in the treatment received, new research shows.

In some cases, treating the ADHD might lower the pain, reported Karin Asztély of the Sahlgrenska Academy Institute of Neuroscience, Göteborg, Sweden, and associates. The study was published in the Journal of Pain Research.

The research included 77 Swedish women with ADHD, ASD, or both from a larger prospective longitudinal study. From 2015 to 2018, when the women were aged 19-37 years, they were contacted by mail and phone, and interviewed about symptoms of pain. This included chronic widespread or regional symptoms of pain; widespread pain was pain that lasted more than 3 months and was described both above and below the waist, on both sides of the body, and in the axial skeleton. Any pain that lasted more than 3 months but did not meet those other requirements was listed as chronic regional pain.

Chronic pain of any kind was reported by 59 participants (76.6%). Chronic widespread pain was reported by 25 participants (32.5%), and chronic regional pain was reported by 34 (44.2%), both of which were higher than those seen in a cross-sectional survey, which showed prevalences of 11.9% and 23.9% of Swedish participants, respectively (J Rheumatol. 2001 Jun;28[6]:1369-77).

Among the limitations of the latest study is the small sample size and the absence of healthy controls; however, the researchers thought this was compensated for by the comparisons with previous research.

“ and possible unrecognized ASD and/or ADHD in women with chronic pain,” they concluded.

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Asztély et al. J Pain Res. 2019 Oct 18;12:2925-32.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PAIN RESEARCH

Cannabis frequently is used for endometriosis pain

VANCOUVER, B.C. – with over a third reporting either current or past use, according to a new survey.

The finding comes as more and more companies are marketing CBD-containing products to women, with unsubstantiated claims about efficacy, according to Anna Reinert, MD, who presented the research at a meeting sponsored by AAGL.

Women self-reported that marijuana use was moderately effective, while the median value for CBD corresponded to “slightly effective.”

To investigate use patterns, Dr. Reinert and colleagues created a questionnaire with 55-75 questions, which followed a branching logic tree. Topics included pain history, demographics, and experience with marijuana and CBD for the purpose of controlling pelvic pain. The survey was sent to two populations: an endometriosis association mailing list, and patients at a chronic pain center in Phoenix.

About 24,500 surveys were sent out; 366 were received and analyzed. The response rate was much different between the two populations, at 1% in the endometriosis association and 16% of the clinic population. Dr. Reinert attributed the low response rate in the association sample to the continuing stigma surrounding marijuana use, citing much higher response rates to other surveys sent out by the association around the same time.

Overall, 63% of respondents said they had never used marijuana; 37% reported past or present use; 65% said they had never used CBD; and 35% reported past or present use. About 45% of marijuana users reported that its use was very effective, and 25% said it was moderately effective. About 22% of CBD users said it was very effective, and about 33% said it was moderately effective. The median values lay in the moderately effective range for marijuana, and in the slightly effective range for CBD.

The findings suggest a need for more research into the potential benefit and limitations of cannabis for pelvic pain from endometriosis, said Dr. Reinert, an obstetrician/gynecologist the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

Until this study, evidence of efficacy of marijuana for this indication has been sparse. A report from the National Academy of Sciences showed that there is evidence that cannabis and cannabinoids have a therapeutic effect on chronic pain in adults (National Academies Press (US) 2017 Jan 12), but the report made no mention of gynecological applications. Despite this lack of evidence, surveys have shown that women of reproductive age use marijuana, and an analysis by the Ameritox Laboratory in a pain management population found that 13% of women and 19% of men tested positive for marijuana in their urine.

Still, “there is not research looking at marijuana for women with chronic health pain,” Dr. Reinert said at the meeting.

But that doesn’t stop companies from developing CBD vaginal suppositories and marketing them for menstrual pelvic discomfort, pain during sex, and other issues. Lay press articles often boost these claims, although some skeptical takes address the lack of evidence. Still, “there’s a lot on the more positive side,” she said.

That leads to a lot of interest among patients in using marijuana or CBD for symptom relief, which is part of the reason that Dr. Reinert’s team decided to examine its use and perceived efficacy. Another reason is that there is some biological basis to believe that cannabis could be helpful. There is some evidence that women with endometriosis have changes in their endocannabinoid system (Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2017;2:72-80), and there are clinical trials examining the impact of non-CBD, non-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) endocannabinoid ligands.

Dr. Reinert has no financial disclosures.

VANCOUVER, B.C. – with over a third reporting either current or past use, according to a new survey.

The finding comes as more and more companies are marketing CBD-containing products to women, with unsubstantiated claims about efficacy, according to Anna Reinert, MD, who presented the research at a meeting sponsored by AAGL.

Women self-reported that marijuana use was moderately effective, while the median value for CBD corresponded to “slightly effective.”

To investigate use patterns, Dr. Reinert and colleagues created a questionnaire with 55-75 questions, which followed a branching logic tree. Topics included pain history, demographics, and experience with marijuana and CBD for the purpose of controlling pelvic pain. The survey was sent to two populations: an endometriosis association mailing list, and patients at a chronic pain center in Phoenix.

About 24,500 surveys were sent out; 366 were received and analyzed. The response rate was much different between the two populations, at 1% in the endometriosis association and 16% of the clinic population. Dr. Reinert attributed the low response rate in the association sample to the continuing stigma surrounding marijuana use, citing much higher response rates to other surveys sent out by the association around the same time.

Overall, 63% of respondents said they had never used marijuana; 37% reported past or present use; 65% said they had never used CBD; and 35% reported past or present use. About 45% of marijuana users reported that its use was very effective, and 25% said it was moderately effective. About 22% of CBD users said it was very effective, and about 33% said it was moderately effective. The median values lay in the moderately effective range for marijuana, and in the slightly effective range for CBD.

The findings suggest a need for more research into the potential benefit and limitations of cannabis for pelvic pain from endometriosis, said Dr. Reinert, an obstetrician/gynecologist the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

Until this study, evidence of efficacy of marijuana for this indication has been sparse. A report from the National Academy of Sciences showed that there is evidence that cannabis and cannabinoids have a therapeutic effect on chronic pain in adults (National Academies Press (US) 2017 Jan 12), but the report made no mention of gynecological applications. Despite this lack of evidence, surveys have shown that women of reproductive age use marijuana, and an analysis by the Ameritox Laboratory in a pain management population found that 13% of women and 19% of men tested positive for marijuana in their urine.

Still, “there is not research looking at marijuana for women with chronic health pain,” Dr. Reinert said at the meeting.

But that doesn’t stop companies from developing CBD vaginal suppositories and marketing them for menstrual pelvic discomfort, pain during sex, and other issues. Lay press articles often boost these claims, although some skeptical takes address the lack of evidence. Still, “there’s a lot on the more positive side,” she said.

That leads to a lot of interest among patients in using marijuana or CBD for symptom relief, which is part of the reason that Dr. Reinert’s team decided to examine its use and perceived efficacy. Another reason is that there is some biological basis to believe that cannabis could be helpful. There is some evidence that women with endometriosis have changes in their endocannabinoid system (Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2017;2:72-80), and there are clinical trials examining the impact of non-CBD, non-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) endocannabinoid ligands.

Dr. Reinert has no financial disclosures.

VANCOUVER, B.C. – with over a third reporting either current or past use, according to a new survey.

The finding comes as more and more companies are marketing CBD-containing products to women, with unsubstantiated claims about efficacy, according to Anna Reinert, MD, who presented the research at a meeting sponsored by AAGL.

Women self-reported that marijuana use was moderately effective, while the median value for CBD corresponded to “slightly effective.”

To investigate use patterns, Dr. Reinert and colleagues created a questionnaire with 55-75 questions, which followed a branching logic tree. Topics included pain history, demographics, and experience with marijuana and CBD for the purpose of controlling pelvic pain. The survey was sent to two populations: an endometriosis association mailing list, and patients at a chronic pain center in Phoenix.

About 24,500 surveys were sent out; 366 were received and analyzed. The response rate was much different between the two populations, at 1% in the endometriosis association and 16% of the clinic population. Dr. Reinert attributed the low response rate in the association sample to the continuing stigma surrounding marijuana use, citing much higher response rates to other surveys sent out by the association around the same time.

Overall, 63% of respondents said they had never used marijuana; 37% reported past or present use; 65% said they had never used CBD; and 35% reported past or present use. About 45% of marijuana users reported that its use was very effective, and 25% said it was moderately effective. About 22% of CBD users said it was very effective, and about 33% said it was moderately effective. The median values lay in the moderately effective range for marijuana, and in the slightly effective range for CBD.

The findings suggest a need for more research into the potential benefit and limitations of cannabis for pelvic pain from endometriosis, said Dr. Reinert, an obstetrician/gynecologist the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

Until this study, evidence of efficacy of marijuana for this indication has been sparse. A report from the National Academy of Sciences showed that there is evidence that cannabis and cannabinoids have a therapeutic effect on chronic pain in adults (National Academies Press (US) 2017 Jan 12), but the report made no mention of gynecological applications. Despite this lack of evidence, surveys have shown that women of reproductive age use marijuana, and an analysis by the Ameritox Laboratory in a pain management population found that 13% of women and 19% of men tested positive for marijuana in their urine.

Still, “there is not research looking at marijuana for women with chronic health pain,” Dr. Reinert said at the meeting.

But that doesn’t stop companies from developing CBD vaginal suppositories and marketing them for menstrual pelvic discomfort, pain during sex, and other issues. Lay press articles often boost these claims, although some skeptical takes address the lack of evidence. Still, “there’s a lot on the more positive side,” she said.

That leads to a lot of interest among patients in using marijuana or CBD for symptom relief, which is part of the reason that Dr. Reinert’s team decided to examine its use and perceived efficacy. Another reason is that there is some biological basis to believe that cannabis could be helpful. There is some evidence that women with endometriosis have changes in their endocannabinoid system (Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2017;2:72-80), and there are clinical trials examining the impact of non-CBD, non-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) endocannabinoid ligands.

Dr. Reinert has no financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM THE AAGL GLOBAL CONGRESS

Depression linked to persistent opioid use after hysterectomy

VANCOUVER –

Women with depression had an 8% increased risk of perioperative opioid use but a 43% increased risk of persistent use, defined as at least one perioperative prescription followed by at least one prescription 90 days or longer after surgery.

Opioid prescriptions after surgery have been on the rise in recent years, and this has led to a focus on how chronic pain disorders are managed. But studies have shown that patients undergoing general surgery, both minor and major, are at increased risk of persistent opioid use, even after a single surgery, according to Erin Carey, MD, director of the division of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who presented the research at the meeting sponsored by AAGL.

“We also know that preoperative depression has been linked to adverse outcomes after hysterectomy, both acute postoperative pain in the first 2 days after surgery, and increasing the risk of chronic postoperative pain,” Dr. Carey said.

That prompted her and her team to look at whether preoperative depression might influence the risk of new persistent opioid use after hysterectomy. They analyzed data from the IBM Watson/Truven Health Analytics MarketScan database of claims-based data, which collects information from a variety of sources, including electronic medical records and workplace records such as absences, disability, and long-term disability.

“So it does allow for long-term tracking, which makes it optimal for this type of study,” said Dr. Carey.

The study included 382,078 hysterectomies performed between 2001 and 2015 on women who had continuous prescription plans 180 days before to 180 days after the procedure, excluding anyone who had an opioid prescription in the previous 180 days; 60% of the procedures were minimally invasive. About 20% of women were considered to have depression before the procedure, based on a diagnosis (55%), an antidepressant prescription (22%), or both (23%).

There were some differences at baseline between the two populations: Women with preoperative depression were more likely to have a comorbid pain disorder, compared with patients without depression (20% vs. 14%), another psychiatric disorder (2% vs. less than 1%), and a Charlson comorbidity (12% vs. 9%). They also were less likely to undergo a minimally invasive procedure than women without depression (66% vs. 79%). There was an increase in the prevalence of depression over time, from 16% to 23%.

Overall, 74% of women were prescribed an opioid during the perioperative period; 17% were filled before the hysterectomy was performed. Preoperative fills also increased over time, from 4% in 2001 to 21% in 2015.

Women with preoperative depression were at a slightly greater risk for perioperative opioid use (risk ratio, 1.08), but a greater risk for persistent postoperative opioid use (11% vs. 8%; RR, 1.43). The heightened risk for opioid use was similar whether the surgery was performed on an outpatient or inpatient basis.

The presence of other comorbidities in women with diagnosed depression or prescribed antidepressants complicates the findings, according to Dr. Carey. “There may be additional chronic pain factors that are confounding this data, but it is consistent with other data that de novo postoperative opioid dependence may be a higher risk for these patients, so it’s important for us to look at that critically.”

Dr. Carey has been a consultant for Teleflex Medical and a speaker for Med-IQ.

VANCOUVER –

Women with depression had an 8% increased risk of perioperative opioid use but a 43% increased risk of persistent use, defined as at least one perioperative prescription followed by at least one prescription 90 days or longer after surgery.

Opioid prescriptions after surgery have been on the rise in recent years, and this has led to a focus on how chronic pain disorders are managed. But studies have shown that patients undergoing general surgery, both minor and major, are at increased risk of persistent opioid use, even after a single surgery, according to Erin Carey, MD, director of the division of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who presented the research at the meeting sponsored by AAGL.

“We also know that preoperative depression has been linked to adverse outcomes after hysterectomy, both acute postoperative pain in the first 2 days after surgery, and increasing the risk of chronic postoperative pain,” Dr. Carey said.

That prompted her and her team to look at whether preoperative depression might influence the risk of new persistent opioid use after hysterectomy. They analyzed data from the IBM Watson/Truven Health Analytics MarketScan database of claims-based data, which collects information from a variety of sources, including electronic medical records and workplace records such as absences, disability, and long-term disability.

“So it does allow for long-term tracking, which makes it optimal for this type of study,” said Dr. Carey.

The study included 382,078 hysterectomies performed between 2001 and 2015 on women who had continuous prescription plans 180 days before to 180 days after the procedure, excluding anyone who had an opioid prescription in the previous 180 days; 60% of the procedures were minimally invasive. About 20% of women were considered to have depression before the procedure, based on a diagnosis (55%), an antidepressant prescription (22%), or both (23%).

There were some differences at baseline between the two populations: Women with preoperative depression were more likely to have a comorbid pain disorder, compared with patients without depression (20% vs. 14%), another psychiatric disorder (2% vs. less than 1%), and a Charlson comorbidity (12% vs. 9%). They also were less likely to undergo a minimally invasive procedure than women without depression (66% vs. 79%). There was an increase in the prevalence of depression over time, from 16% to 23%.

Overall, 74% of women were prescribed an opioid during the perioperative period; 17% were filled before the hysterectomy was performed. Preoperative fills also increased over time, from 4% in 2001 to 21% in 2015.

Women with preoperative depression were at a slightly greater risk for perioperative opioid use (risk ratio, 1.08), but a greater risk for persistent postoperative opioid use (11% vs. 8%; RR, 1.43). The heightened risk for opioid use was similar whether the surgery was performed on an outpatient or inpatient basis.

The presence of other comorbidities in women with diagnosed depression or prescribed antidepressants complicates the findings, according to Dr. Carey. “There may be additional chronic pain factors that are confounding this data, but it is consistent with other data that de novo postoperative opioid dependence may be a higher risk for these patients, so it’s important for us to look at that critically.”

Dr. Carey has been a consultant for Teleflex Medical and a speaker for Med-IQ.

VANCOUVER –

Women with depression had an 8% increased risk of perioperative opioid use but a 43% increased risk of persistent use, defined as at least one perioperative prescription followed by at least one prescription 90 days or longer after surgery.

Opioid prescriptions after surgery have been on the rise in recent years, and this has led to a focus on how chronic pain disorders are managed. But studies have shown that patients undergoing general surgery, both minor and major, are at increased risk of persistent opioid use, even after a single surgery, according to Erin Carey, MD, director of the division of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who presented the research at the meeting sponsored by AAGL.

“We also know that preoperative depression has been linked to adverse outcomes after hysterectomy, both acute postoperative pain in the first 2 days after surgery, and increasing the risk of chronic postoperative pain,” Dr. Carey said.

That prompted her and her team to look at whether preoperative depression might influence the risk of new persistent opioid use after hysterectomy. They analyzed data from the IBM Watson/Truven Health Analytics MarketScan database of claims-based data, which collects information from a variety of sources, including electronic medical records and workplace records such as absences, disability, and long-term disability.

“So it does allow for long-term tracking, which makes it optimal for this type of study,” said Dr. Carey.

The study included 382,078 hysterectomies performed between 2001 and 2015 on women who had continuous prescription plans 180 days before to 180 days after the procedure, excluding anyone who had an opioid prescription in the previous 180 days; 60% of the procedures were minimally invasive. About 20% of women were considered to have depression before the procedure, based on a diagnosis (55%), an antidepressant prescription (22%), or both (23%).

There were some differences at baseline between the two populations: Women with preoperative depression were more likely to have a comorbid pain disorder, compared with patients without depression (20% vs. 14%), another psychiatric disorder (2% vs. less than 1%), and a Charlson comorbidity (12% vs. 9%). They also were less likely to undergo a minimally invasive procedure than women without depression (66% vs. 79%). There was an increase in the prevalence of depression over time, from 16% to 23%.

Overall, 74% of women were prescribed an opioid during the perioperative period; 17% were filled before the hysterectomy was performed. Preoperative fills also increased over time, from 4% in 2001 to 21% in 2015.

Women with preoperative depression were at a slightly greater risk for perioperative opioid use (risk ratio, 1.08), but a greater risk for persistent postoperative opioid use (11% vs. 8%; RR, 1.43). The heightened risk for opioid use was similar whether the surgery was performed on an outpatient or inpatient basis.

The presence of other comorbidities in women with diagnosed depression or prescribed antidepressants complicates the findings, according to Dr. Carey. “There may be additional chronic pain factors that are confounding this data, but it is consistent with other data that de novo postoperative opioid dependence may be a higher risk for these patients, so it’s important for us to look at that critically.”

Dr. Carey has been a consultant for Teleflex Medical and a speaker for Med-IQ.

REPORTING FROM THE AAGL GLOBAL CONGRESS

Children may develop prolonged headache after concussion

CHARLOTTE, N.C. – , according to research presented at the annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society. The headache may be migraine, chronic daily headache, tension-type headache, or a combination of these headaches.

“We strongly recommend that individuals who develop persistent headache after a concussion be evaluated and treated by a neurologist with experience in administering treatment for headache,” said Marcus Barissi, Weller Scholar at the Cleveland Clinic, and colleagues. “Using this approach, we hope that their prolonged headaches will be lessened.”

Few studies have examined prolonged pediatric postconcussion headache

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that between 1.6 million and 3.8 million concussions occur annually during athletic and recreational activities in the United States. About 90% of concussions affect children or adolescents. The symptom most often reported after concussion is headache.

Few studies have focused on new persistent postconcussion headache (NPPCH) in children. Mr. Barissi and colleagues did not find any previous study that had examined prolonged headache following concussion in patients without prior chronic headache. They sought to ascertain the prognosis of patients with NPPCH and no history of prior headache, to describe this clinical entity, and to identify beneficial treatment methods.

The investigators retrospectively reviewed charts for approximately 2,000 patients who presented to the Cleveland Clinic pediatric neurology department between June 2017 and August 2018 for headaches. They identified 259 patients who received a diagnosis of concussion, 69 (27%) of whom had headaches for longer than 2 months after injury.

Mr. Barissi and colleagues emailed these patients, and 33 (48%) of them agreed to complete a questionnaire and participate in a 10-minute phone interview. Thirty-one patients (43%) could not be contacted, and eight (11%) declined to participate. All participants confirmed that they had not had consistent headache before the concussion and that chronic headache had arisen after concussion. To determine participants’ medical outcomes, the researchers compared participants’ initial assessment data with posttreatment data collected during the interview process.

Healthy behaviors increased after concussion

Of the 69 eligible participants, 38 (55%) were female. The population’s median age was 17. Twenty-eight (85%) of the 33 patients who completed the questionnaire considered the information and treatment that they had received to be beneficial. Twenty-five (78%) patients continued to have headache after several months, despite treatment.

Participants had withstood a mean of 1.72 concussions, and the mean age at first injury was 12.49 years. The most common cause of injury was a fall for males (36%) and an automobile accident for females (18%).

Forty-eight patients (70%) reported having two types of headache. Fifty-two patients (75%) had migraines, and 65 (94%) had chronic daily headache or tension-type headache. Forty-eight (70%) participants had a family history of headache.

In all, 64 patients (93%) had used a headache medication. The most common headache medications used were amitriptyline, topiramate, and cyproheptadine. Few patients were still taking these medications at several months after evaluation. The most common nonprescription medications used were Migravent (i.e., magnesium, riboflavin, coenzyme Q10, and butterbur), ondansetron, and melatonin. Furthermore, 61 patients (88%) participated in nonmedicinal therapy such as physical therapy, chiropractic therapy, and acupuncture.

After evaluation, patients engaged in several healthy behaviors (e.g., adequate exercise, proper use of over-the-counter medications, and drinking sufficient water) more frequently, but did not get adequate sleep. Sixty-five participants (94%) had undergone CT or MRI imaging, but the results did not improve understanding of headache etiology or treatment. Many patients missed several days of school, but average attendance improved after months of treatment.

Long-term outcomes

Thirty-one survey respondents (94%) reported that their emotional, cognitive, sleep, and somatic postconcussion symptoms had resolved. Nevertheless, a majority of participants still had headache. “The persistence of postconcussion symptoms is uncommon, but lasting headache is not,” said the researchers. “If patients are not properly educated, conditions may deteriorate, extending the duration of disability.” A longer study with a larger sample size could provide valuable information, said the researchers. Future work should examine objectively the efficacy of various medications used to treat NPPCH and determine the best methods of treatment for this syndrome, which “can cause prolonged pain, suffering, and lack of function,” they concluded.

The investigators did not report any study funding or disclosures.

SOURCE: Barissi M et al. CNS 2019, Abstract 95.

CHARLOTTE, N.C. – , according to research presented at the annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society. The headache may be migraine, chronic daily headache, tension-type headache, or a combination of these headaches.

“We strongly recommend that individuals who develop persistent headache after a concussion be evaluated and treated by a neurologist with experience in administering treatment for headache,” said Marcus Barissi, Weller Scholar at the Cleveland Clinic, and colleagues. “Using this approach, we hope that their prolonged headaches will be lessened.”

Few studies have examined prolonged pediatric postconcussion headache

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that between 1.6 million and 3.8 million concussions occur annually during athletic and recreational activities in the United States. About 90% of concussions affect children or adolescents. The symptom most often reported after concussion is headache.

Few studies have focused on new persistent postconcussion headache (NPPCH) in children. Mr. Barissi and colleagues did not find any previous study that had examined prolonged headache following concussion in patients without prior chronic headache. They sought to ascertain the prognosis of patients with NPPCH and no history of prior headache, to describe this clinical entity, and to identify beneficial treatment methods.

The investigators retrospectively reviewed charts for approximately 2,000 patients who presented to the Cleveland Clinic pediatric neurology department between June 2017 and August 2018 for headaches. They identified 259 patients who received a diagnosis of concussion, 69 (27%) of whom had headaches for longer than 2 months after injury.

Mr. Barissi and colleagues emailed these patients, and 33 (48%) of them agreed to complete a questionnaire and participate in a 10-minute phone interview. Thirty-one patients (43%) could not be contacted, and eight (11%) declined to participate. All participants confirmed that they had not had consistent headache before the concussion and that chronic headache had arisen after concussion. To determine participants’ medical outcomes, the researchers compared participants’ initial assessment data with posttreatment data collected during the interview process.

Healthy behaviors increased after concussion

Of the 69 eligible participants, 38 (55%) were female. The population’s median age was 17. Twenty-eight (85%) of the 33 patients who completed the questionnaire considered the information and treatment that they had received to be beneficial. Twenty-five (78%) patients continued to have headache after several months, despite treatment.

Participants had withstood a mean of 1.72 concussions, and the mean age at first injury was 12.49 years. The most common cause of injury was a fall for males (36%) and an automobile accident for females (18%).

Forty-eight patients (70%) reported having two types of headache. Fifty-two patients (75%) had migraines, and 65 (94%) had chronic daily headache or tension-type headache. Forty-eight (70%) participants had a family history of headache.

In all, 64 patients (93%) had used a headache medication. The most common headache medications used were amitriptyline, topiramate, and cyproheptadine. Few patients were still taking these medications at several months after evaluation. The most common nonprescription medications used were Migravent (i.e., magnesium, riboflavin, coenzyme Q10, and butterbur), ondansetron, and melatonin. Furthermore, 61 patients (88%) participated in nonmedicinal therapy such as physical therapy, chiropractic therapy, and acupuncture.

After evaluation, patients engaged in several healthy behaviors (e.g., adequate exercise, proper use of over-the-counter medications, and drinking sufficient water) more frequently, but did not get adequate sleep. Sixty-five participants (94%) had undergone CT or MRI imaging, but the results did not improve understanding of headache etiology or treatment. Many patients missed several days of school, but average attendance improved after months of treatment.

Long-term outcomes

Thirty-one survey respondents (94%) reported that their emotional, cognitive, sleep, and somatic postconcussion symptoms had resolved. Nevertheless, a majority of participants still had headache. “The persistence of postconcussion symptoms is uncommon, but lasting headache is not,” said the researchers. “If patients are not properly educated, conditions may deteriorate, extending the duration of disability.” A longer study with a larger sample size could provide valuable information, said the researchers. Future work should examine objectively the efficacy of various medications used to treat NPPCH and determine the best methods of treatment for this syndrome, which “can cause prolonged pain, suffering, and lack of function,” they concluded.

The investigators did not report any study funding or disclosures.

SOURCE: Barissi M et al. CNS 2019, Abstract 95.

CHARLOTTE, N.C. – , according to research presented at the annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society. The headache may be migraine, chronic daily headache, tension-type headache, or a combination of these headaches.

“We strongly recommend that individuals who develop persistent headache after a concussion be evaluated and treated by a neurologist with experience in administering treatment for headache,” said Marcus Barissi, Weller Scholar at the Cleveland Clinic, and colleagues. “Using this approach, we hope that their prolonged headaches will be lessened.”

Few studies have examined prolonged pediatric postconcussion headache

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that between 1.6 million and 3.8 million concussions occur annually during athletic and recreational activities in the United States. About 90% of concussions affect children or adolescents. The symptom most often reported after concussion is headache.

Few studies have focused on new persistent postconcussion headache (NPPCH) in children. Mr. Barissi and colleagues did not find any previous study that had examined prolonged headache following concussion in patients without prior chronic headache. They sought to ascertain the prognosis of patients with NPPCH and no history of prior headache, to describe this clinical entity, and to identify beneficial treatment methods.

The investigators retrospectively reviewed charts for approximately 2,000 patients who presented to the Cleveland Clinic pediatric neurology department between June 2017 and August 2018 for headaches. They identified 259 patients who received a diagnosis of concussion, 69 (27%) of whom had headaches for longer than 2 months after injury.

Mr. Barissi and colleagues emailed these patients, and 33 (48%) of them agreed to complete a questionnaire and participate in a 10-minute phone interview. Thirty-one patients (43%) could not be contacted, and eight (11%) declined to participate. All participants confirmed that they had not had consistent headache before the concussion and that chronic headache had arisen after concussion. To determine participants’ medical outcomes, the researchers compared participants’ initial assessment data with posttreatment data collected during the interview process.

Healthy behaviors increased after concussion

Of the 69 eligible participants, 38 (55%) were female. The population’s median age was 17. Twenty-eight (85%) of the 33 patients who completed the questionnaire considered the information and treatment that they had received to be beneficial. Twenty-five (78%) patients continued to have headache after several months, despite treatment.

Participants had withstood a mean of 1.72 concussions, and the mean age at first injury was 12.49 years. The most common cause of injury was a fall for males (36%) and an automobile accident for females (18%).

Forty-eight patients (70%) reported having two types of headache. Fifty-two patients (75%) had migraines, and 65 (94%) had chronic daily headache or tension-type headache. Forty-eight (70%) participants had a family history of headache.

In all, 64 patients (93%) had used a headache medication. The most common headache medications used were amitriptyline, topiramate, and cyproheptadine. Few patients were still taking these medications at several months after evaluation. The most common nonprescription medications used were Migravent (i.e., magnesium, riboflavin, coenzyme Q10, and butterbur), ondansetron, and melatonin. Furthermore, 61 patients (88%) participated in nonmedicinal therapy such as physical therapy, chiropractic therapy, and acupuncture.

After evaluation, patients engaged in several healthy behaviors (e.g., adequate exercise, proper use of over-the-counter medications, and drinking sufficient water) more frequently, but did not get adequate sleep. Sixty-five participants (94%) had undergone CT or MRI imaging, but the results did not improve understanding of headache etiology or treatment. Many patients missed several days of school, but average attendance improved after months of treatment.

Long-term outcomes

Thirty-one survey respondents (94%) reported that their emotional, cognitive, sleep, and somatic postconcussion symptoms had resolved. Nevertheless, a majority of participants still had headache. “The persistence of postconcussion symptoms is uncommon, but lasting headache is not,” said the researchers. “If patients are not properly educated, conditions may deteriorate, extending the duration of disability.” A longer study with a larger sample size could provide valuable information, said the researchers. Future work should examine objectively the efficacy of various medications used to treat NPPCH and determine the best methods of treatment for this syndrome, which “can cause prolonged pain, suffering, and lack of function,” they concluded.

The investigators did not report any study funding or disclosures.

SOURCE: Barissi M et al. CNS 2019, Abstract 95.

REPORTING FROM CNS 2019

FDA announces approval of fifth adalimumab biosimilar, Abrilada

The Food and Drug Administration has cleared adalimumab-afzb (Abrilada) as the fifth approved Humira biosimilar and the 25th approved biosimilar drug overall, the agency said in a Nov. 15 announcement.

According to a press release from Pfizer, approval for Abrilada was based on review of a comprehensive data package demonstrating biosimilarity of the drug to the reference product. This included data from a clinical comparative study, which found no clinically meaningful difference between Abrilada and the reference in terms of efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA). In addition to RA, Abrilada is indicated for juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and plaque psoriasis.

Common adverse events in adalimumab clinical trials included infection, injection-site reactions, headache, and rash.

Pfizer said that it “is working to make Abrilada available to U.S. patients as soon as feasible based on the terms of our agreement with AbbVie [the manufacturer of Humira]. Our current plans are to launch in 2023.”

The Food and Drug Administration has cleared adalimumab-afzb (Abrilada) as the fifth approved Humira biosimilar and the 25th approved biosimilar drug overall, the agency said in a Nov. 15 announcement.

According to a press release from Pfizer, approval for Abrilada was based on review of a comprehensive data package demonstrating biosimilarity of the drug to the reference product. This included data from a clinical comparative study, which found no clinically meaningful difference between Abrilada and the reference in terms of efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA). In addition to RA, Abrilada is indicated for juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and plaque psoriasis.

Common adverse events in adalimumab clinical trials included infection, injection-site reactions, headache, and rash.

Pfizer said that it “is working to make Abrilada available to U.S. patients as soon as feasible based on the terms of our agreement with AbbVie [the manufacturer of Humira]. Our current plans are to launch in 2023.”

The Food and Drug Administration has cleared adalimumab-afzb (Abrilada) as the fifth approved Humira biosimilar and the 25th approved biosimilar drug overall, the agency said in a Nov. 15 announcement.

According to a press release from Pfizer, approval for Abrilada was based on review of a comprehensive data package demonstrating biosimilarity of the drug to the reference product. This included data from a clinical comparative study, which found no clinically meaningful difference between Abrilada and the reference in terms of efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA). In addition to RA, Abrilada is indicated for juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and plaque psoriasis.

Common adverse events in adalimumab clinical trials included infection, injection-site reactions, headache, and rash.

Pfizer said that it “is working to make Abrilada available to U.S. patients as soon as feasible based on the terms of our agreement with AbbVie [the manufacturer of Humira]. Our current plans are to launch in 2023.”

Female Runner, 47, with Inguinal Lump

A 47-year-old woman was referred to the gynecology office by her primary care NP for surgical excision of an enlarging nodule on the right side of her mons pubis. Onset occurred about 6 months earlier. The patient reported that symptoms waxed and waned but had worsened progressively over the past 2 to 3 months, adding that the nodule hurt only occasionally. She noted that symptoms were exacerbated by exercise, specifically running. Further questioning prompted the observation that her symptoms were more noticeable at the time of menses.

The patient’s medical history was unremarkable, with no chronic conditions; her surgical history consisted of a wisdom tooth extraction. She had no known drug allergies. Her family history included cerebrovascular accident, hypertension, and arthritis. Reproductive history revealed that she was G1 P1, with a 38-week uncomplicated vaginal delivery. She experienced menarche at age 14, and her menses was regular at every 28 days. For the past 5 days, there had been no dysmenorrhea. The patient was married, exercised regularly, and did not use tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs.

On examination, the patient’s blood pressure was 123/73 mm Hg; heart rate, 77 beats/min; respiratory rate, 12 breaths/min; weight, 128 lb; height, 5 ft 7 in; O2 saturation, 99% on room air; and BMI, 20. The patient was alert and oriented to person, place, and time. She was thin, appeared physically fit, and exhibited no signs of distress. Her physical exam was unremarkable, apart from a firm, minimally tender, well-circumscribed, 3.5 × 3.5–cm nodule right of midline on the mons pubis.

The patient was scheduled for outpatient surgical excision of a benign skin lesion (excluding skin tags) of the genitalia, 3.1 to 3.5 cm (CPT code 11424). During this procedure, it became evident that this was not a lipoma. The lesion was exceptionally hard, and it was difficult to discern if it was incorporated into the rectus abdominis near the point of attachment to the pubic symphysis. The lesion was unintentionally disrupted, revealing black powdery material within the capsule. The tissue was sent for a fast, frozen section that showed “soft tissue with extensive involvement by endometriosis.” The pathology report noted “[m]any endometrial glands in a background of stromal tissue. Necrosis was not a feature. No evidence of atypia.” The patient’s postoperative diagnosis was endometriosis.

DISCUSSION

Endometriosis occurs when endometrial or “endometrial-like” tissue is displaced to sites other than within the uterus. It is most frequently found on tissues close to the uterus, such as the ovaries or pelvic peritoneum. Estrogen is the driving force that feeds the endometrium, causing it to proliferate, whether inside or outside the uterus. Given this dependence on hormones, endometriosis occurs most often during a woman’s fertile years, although it can occur after menopause. Endometriosis is common, affecting at least 10% of premenopausal women; moreover, it is identified as the cause in 70% of all female chronic pelvic pain cases.1-4

Endometriosis has certain identifiable features, such as chronic pain, dyspareunia, infertility, and menstrual and gastrointestinal symptoms. However, it is seldom diagnosed quickly; studies indicate that diagnosis can be delayed by 5 to 10 years after a patient has first sought treatment for symptoms.2,4 Multiple factors contribute to a lag in diagnosis: Presentation is not always straightforward. There are no definitive lab values or biomarkers. Symptoms vary from patient to patient, as do clinical skills from one diagnostician to another.1

Unlike pelvic endometriosis, inguinal endometriosis is not common; disease in this location encompasses only 0.3% to 0.6% of all diagnosed cases.3,5-7 Since the discovery of the first known case of round ligament endometriosis in 1896, there have been only 70 cases reported in the medical literature.6,7

If the more common form of endometriosis is frequently missed, this rarely seen variant presents an even greater diagnostic challenge. The typical presentation of inguinal endometriosis includes a firm nodule in the groin, accompanied by tenderness and swelling. A careful history will allude to pain that occurs cyclically with menses.

Cause

Among several theories about the etiology of endometriosis, the most popular has been retrograde menstruation.1,4,5 According to this hypothesis, the flow of menstrual blood moves backward through the fallopian tubes, spilling into the pelvic cavity and carrying endometrial tissue with it. One theory purports that endometrial tissue is transplanted from the uterus to other areas of the body via the bloodstream or the lymphatics, much like a metastatic disease.1,4 Another theory states that cells outside the uterus, which line the peritoneum, transform into endometrial cells through metaplasia.4,5 Endometrial tissue can also be transplanted iatrogenically during surgery—for example, when endometrial tissue is displaced during a cesarean delivery, resulting in implants above the fascia and below the subcutaneous layers. Several other hypotheses concern stem-cell involvement, hormonal factors, immune system dysfunction, and genetics.4,5 Currently, there are no definitive answers.

Location

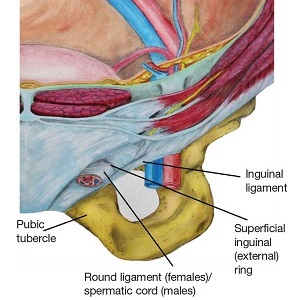

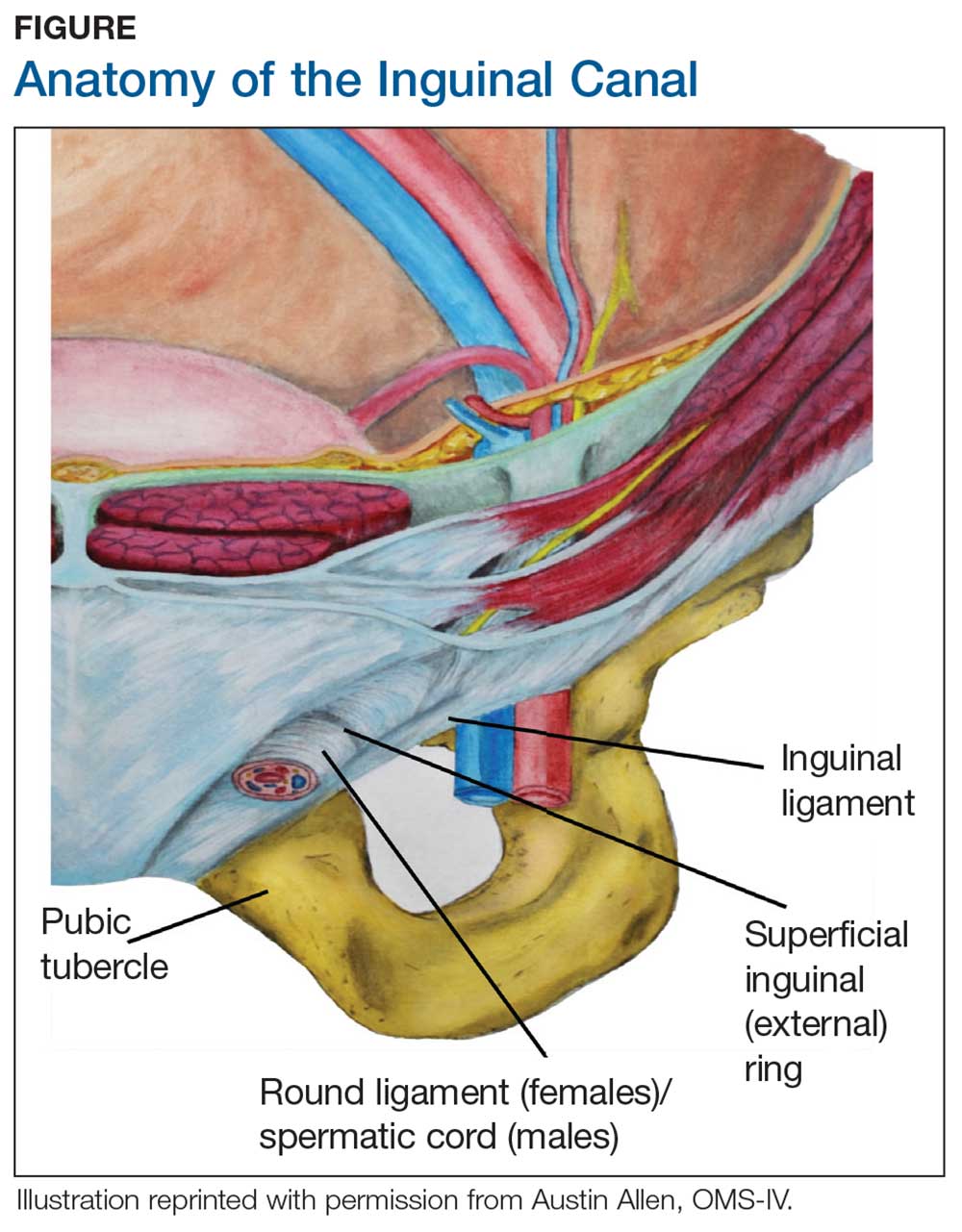

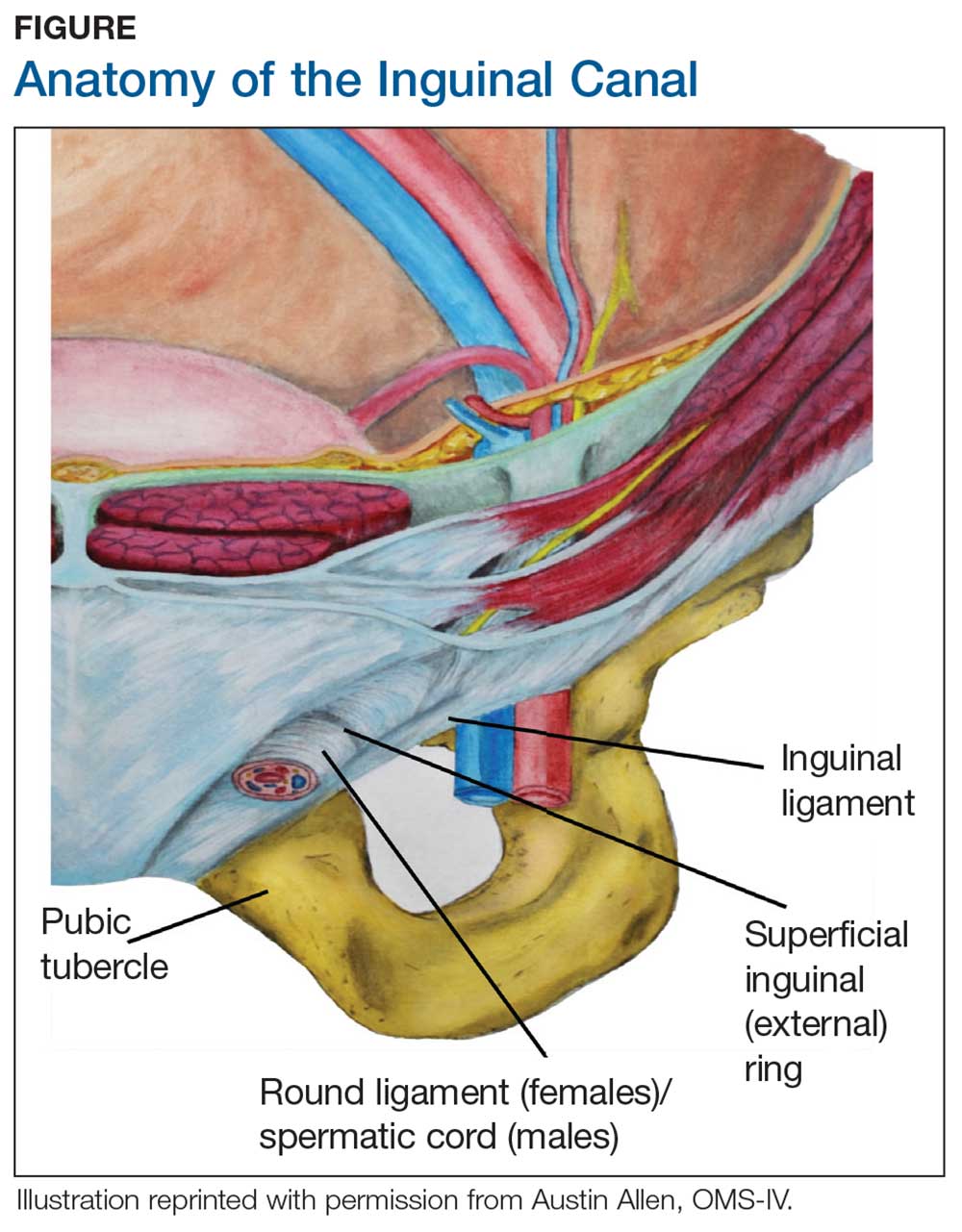

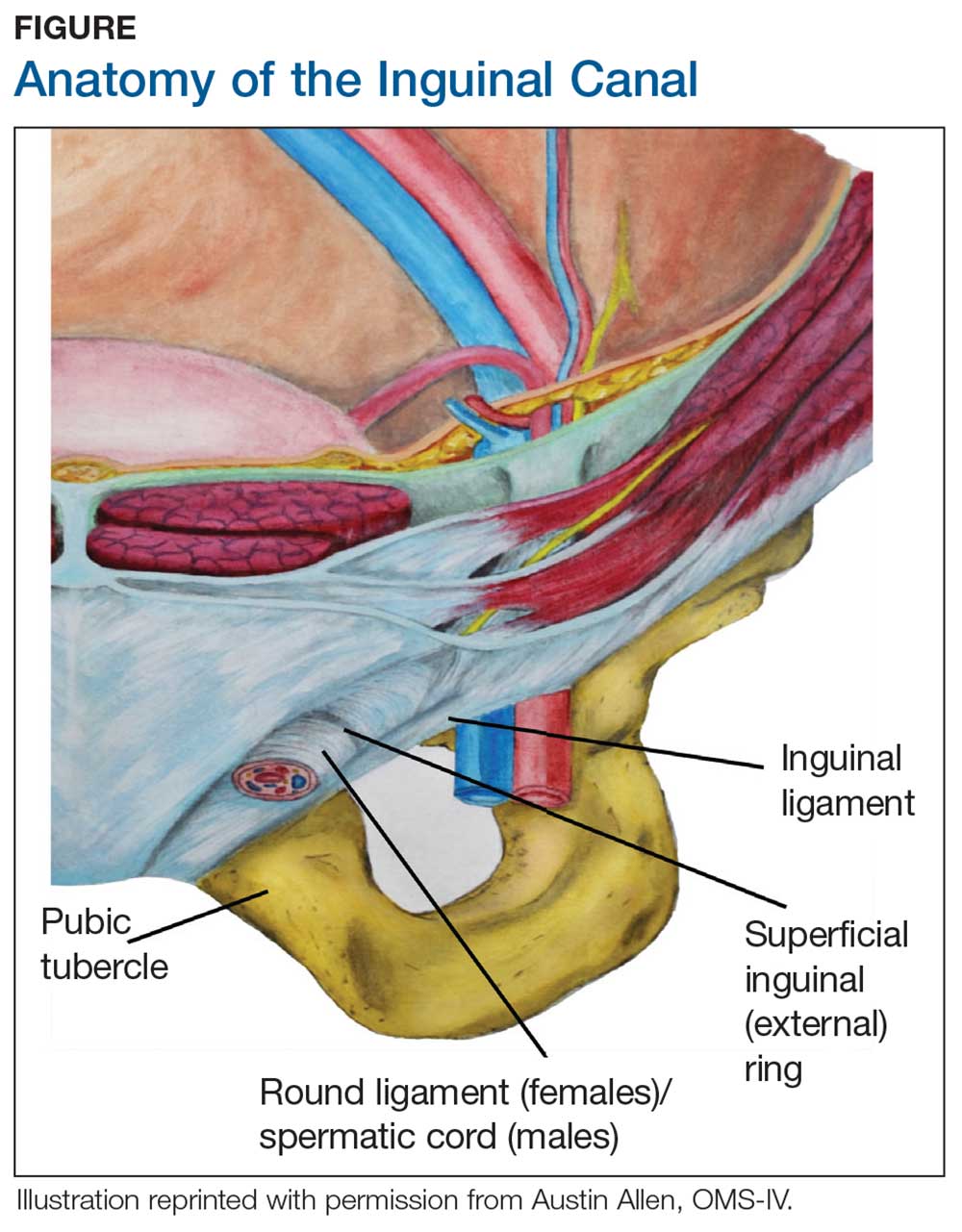

During maturation, the parietal peritoneum develops a pouch called the processus vaginalis, which serves as a passageway for the gubernaculum to transport the round ligament running from the uterus, through the inguinal canal, and ending at the labia. After these structures reach their destination, in normal development, the processus vaginalis degenerates, closing the inguinal canal. Occasionally the processus vaginalis fails to close, allowing for a communication pathway between the peritoneal cavity and the inguinal canal. This leaves the canal vulnerable to the contents of the pelvic cavity, such as a hernia or hydrocele, and provides a clear path for endometriosis.5-7 The implant found in the case patient was at the point where the external ring lies, just above the right pubic tubercle (see Figure 1).

Endometriosis implants can occur anywhere along the round ligament in either the intrapelvic or extrapelvic segments. Implants have also been found in the wall of a hernia sac, the wall of a Nuck canal hydrocele, or even in the subcutaneous tissue surrounding the inguinal canal.3 Interestingly, inguinal endometriosis occurs more often in the right side (up to 94% of cases) than in the left side, as was the case with our patient.5-7 The reason for this predominance has not been established, although there are several theories, including one that suggests the left side is afforded protection by the sigmoid colon.5-7

Laboratory diagnosis

Imaging, such as ultrasound and MRI, offers some diagnostic benefit, although its usefulness is most often realized in the pelvis. Pelvic ultrasound can be used to identify ovarian endometriomas.1 MRI can help rule out, locate, or sometimes determine the degree of deep infiltrating endometriosis, which is an indispensable tool for surgical planning.5,7 Unfortunately, the diagnostic accuracy for extra-pelvic lesions is variable; neither modality is particularly useful in identifying superficial lesions, which comprises most cases.

Ultrasound of the groin can be employed to evaluate for hernia; if a hernia has been excluded, histologic confirmation can be obtained via fine-needle aspiration of nodule contents.5,7 One caveat is that these tests are helpful only if the clinician suspects the diagnosis and orders them. The definitive diagnostic test remains direct visualization, which requires laparoscopy.1,5

Differential diagnosis

Lipoma was a favored diagnosis in this case because of the palpable, well-circumscribed borders, nontender on exam; intermittent, minimal tenderness; and no evidence of erythema or color change. A second possibility was an enlarged lymph node, which was less likely due to the location, large size, and sudden onset without any accompanying symptoms of infection or chronic illness. Finally, an inguinal hernia was least likely, again because of well-defined borders, no history of a lump in the area, a nodule that was not reducible, only minimal tenderness, and no color changes on the skin.

Management

Definitive treatment for inguinal endometriosis entails complete surgical excision.5-7 The provider should be prepared to repair a defect after the excision; there is potential for a substantial defect that might require mesh. Additionally, a herniorrhaphy may be indicated if there is a coexisting hernia.5 The risk for recurrent disease in the inguinal canal after treatment is uncommon, unless the excision was not complete.3

There is an association between inguinal and pelvic endometriosis but not a direct correlation. Data on concomitant pelvic and inguinal endometriosis have been variable. In one case series of 9 patients diagnosed with inguinal endometriosis, none had a history of pelvic endometriosis, and only 1 was subsequently diagnosed with pelvic endometriosis.7 An increased association was noted for patients with implants found on the proximal segment of the round ligament.7 However, implants on the extrapelvic segment were not likely to represent pelvic disease but rather isolated lesions in the canal.7 For those with pelvic endometriosis, complications and recurrence are likely, resulting in the need for long-term treatment.

There is some debate in the literature whether to proceed with laparoscopy once inguinal endometriosis has been identified. Diagnostic laparoscopy to evaluate the pelvis is indicated for symptomatic patients or for cases in which an indirect inguinal hernia is suspected.5 Laparoscopy can offer the benefit of both a diagnostic tool and a mechanism for treatment. However, this is an invasive procedure that also incurs risks. The medical provider, in discussion with the patient, must weigh the risks against the benefits of an invasive procedure before determining how to proceed.

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

The lesion was excised completely. Since the patient had been entirely asymptomatic until age 47, and the risks of a potentially unnecessary surgery outweighed the theoretical benefits, the decision was made not to perform a diagnostic laparoscopy to investigate for pelvic endometriosis. The patient made a complete and uneventful recovery. No further treatment was initiated. She continues to be asymptomatic, denying any menstrual complaints, dyspareunia, or further problems with the groin.

CONCLUSION

This case describes a satellite lesion of endometrial tissue found in an unusual location, in a patient with no history, no risk factors, and no symptoms. The final diagnosis had been omitted from the differential—perhaps because the patient initially associated her symptoms with exercise and mentioned the correlation to her menstrual cycle as an afterthought. Fortunately, the correct diagnosis was made and the appropriate treatment provided.

There are numerous presentations of endometriosis; extrapelvic lesions can have very different, often vague, presentations when compared to the familiar symptoms of pelvic disease. Unfortunately, diagnosis is often delayed. Obscure presentations, in unusual sites, can further impede both speed and accuracy of diagnosis. To date, there are no lab tests or biomarkers to aid diagnosis; imaging studies are inconsistent. Until more accurate diagnostic tools become available, the diagnosis remains dependent on history taking, physical exam, and the clinical judgment of the provider. The astute clinician will recognize the catamenial pattern and consider endometriosis as part of the differential.

1. Parasar P, Ozcan P, Terry KL. Endometriosis: epidemiology, diagnosis and clinical management. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep. 2017;6(1):34-41.

2. Soliman AM, Fuldeore M, Snabes MC. Factors associated with time to endometriosis diagnosis in the United States. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2017;26(7):788-797.

3. Niitsu H, Tsumura H, Kanehiro T, et al. Clinical characteristics and surgical treatment for inguinal endometriosis in young women of reproductive age. Dig Surg. 2019;36(2):166-172.

4. Mehedintu C, Plotogea MN, Ionescu S, Antonovici M. Endometriosis still a challenge. J Med Life. 2014;7(3):349-357.

5. Wolfhagen N, Simons NE, de Jong KH, et al. Inguinal endometriosis, a rare entity of which surgeons should be aware: clinical aspects and long-term follow-up of nine cases. Hernia. 2018;22(5):881-886.

6. Prabhu R, Krishna S, Shenoy R, Thangavelu S. Endometriosis of extra-pelvic round ligament, a diagnostic dilemma for physicians. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013.

7. Pandey D, Coondoo A, Shetty J, Mathew S. Jack in the box: inguinal endometriosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015.

A 47-year-old woman was referred to the gynecology office by her primary care NP for surgical excision of an enlarging nodule on the right side of her mons pubis. Onset occurred about 6 months earlier. The patient reported that symptoms waxed and waned but had worsened progressively over the past 2 to 3 months, adding that the nodule hurt only occasionally. She noted that symptoms were exacerbated by exercise, specifically running. Further questioning prompted the observation that her symptoms were more noticeable at the time of menses.

The patient’s medical history was unremarkable, with no chronic conditions; her surgical history consisted of a wisdom tooth extraction. She had no known drug allergies. Her family history included cerebrovascular accident, hypertension, and arthritis. Reproductive history revealed that she was G1 P1, with a 38-week uncomplicated vaginal delivery. She experienced menarche at age 14, and her menses was regular at every 28 days. For the past 5 days, there had been no dysmenorrhea. The patient was married, exercised regularly, and did not use tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs.

On examination, the patient’s blood pressure was 123/73 mm Hg; heart rate, 77 beats/min; respiratory rate, 12 breaths/min; weight, 128 lb; height, 5 ft 7 in; O2 saturation, 99% on room air; and BMI, 20. The patient was alert and oriented to person, place, and time. She was thin, appeared physically fit, and exhibited no signs of distress. Her physical exam was unremarkable, apart from a firm, minimally tender, well-circumscribed, 3.5 × 3.5–cm nodule right of midline on the mons pubis.