User login

Women increasingly turn to CBD, with or without doc’s blessing

When 42-year-old Danielle Simone Brand started having hormonal migraines, she first turned to cannabidiol (CBD) oil, eventually adding an occasional pull on a prefilled tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) vape for nighttime use. She was careful to avoid THC during work hours. A parenting and cannabis writer, Ms. Brand had more than a cursory background in cannabinoid medicine and had spent time at her local California dispensary discussing various cannabinoid components that might help alleviate her pain.

A self-professed “do-it-yourselfer,” Ms. Brand continues to use cannabinoids for her monthly headaches, forgoing any other pain medication. “There are times for conventional medicine in partnership with your doctor, but when it comes to health and wellness, women should be empowered to make decisions and self-experiment,” she said in an interview.

Ms. Brand is not alone. Significant numbers of women are replacing or supplementing prescription medications with cannabinoids, often without consulting their primary care physician, ob.gyn., or other specialist. At times, women have tried to have these conversations, only to be met with silence or worse.

Take Linda Fuller, a 58-year-old yoga instructor from Long Island who says that she uses CBD and THC for chronic sacroiliac pain after a car accident and to alleviate stress-triggered eczema flares. “I’ve had doctors turn their backs on me; I’ve had nurse practitioners walk out on me in the middle of a sentence,” she said in an interview.

Ms. Fuller said her conversion to cannabinoid medicine is relatively new; she never used cannabis recreationally before her accident but now considers it a gift. She doesn’t keep aspirin in the house and refused pain medication immediately after she injured her back.

Diana Krach, a 34-year-old writer from Maryland, says she’s encountered roadblocks about her decision to use cannabinoids for endometriosis and for pain from Crohn’s disease. When she tried to discuss her CBD use with a gastroenterologist, he interrupted her: “Whatever pot you’re smoking isn’t going to work, you’re going on biologics.”

Ms. Krach had not been smoking anything but had turned to a CBD tincture for symptom relief after prescription pain medications failed to help.

Ms. Brand, Ms. Fuller, and Ms. Krach are the tip of the iceberg when it comes to women seeking symptom relief outside the medicine cabinet. A recent survey in the Journal of Women’s Health of almost 1,000 women show that 90% (most between the ages of 35 and 44) had used cannabis and would consider using it to treat gynecologic pain. Roughly 80% said they would consider using it for procedure-related pain or other conditions. Additionally, women have reported using cannabinoids for PTSD, sleep disturbances or insomnia, anxiety, and migraine headaches.

Observational survey data have likewise shown that 80% of women with advanced or recurrent gynecologic malignancies who were prescribed cannabis reported that it was equivalent or superior to other medications for relieving pain, neuropathy, nausea, insomnia, decreased appetite, and anxiety.

In another survey, almost half (45%) of women with gynecologic malignancies who used nonprescribed cannabis for the same symptoms reported that they had reduced their use of prescription narcotics after initiating use of cannabis.

The gray zone

There has been a surge in self-reported cannabis use among pregnant women in particular. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health findings for the periods 2002-2003 and 2016-2017 highlight increases in adjusted prevalence rates from 3.4% to 7% in past-month use among pregnant women overall and from 5.7% to 12.1% during the first trimester alone.

“The more that you talk to pregnant women, the more that you realize that a lot are using cannabinoids for something that is basically medicinal, for sleep, for anxiety, or for nausea,” Katrina Mark, MD, an ob.gyn. and associate professor of medicine at the University of Maryland, College Park, said in an interview. “I’m not saying it’s fine to use drugs in pregnancy, but it is a grayer conversation than a lot of colleagues want to believe. Telling women to quit seems foolish since the alternative is to be anxious, don’t sleep, don’t eat, or use a medication that also has risks to it.”

One observational study shows that pregnant women themselves are conflicted. Although the majority believe that cannabis is “natural” and “safe,” compared with prescription drugs, they aren’t entirely in the dark about potential risks. They often express frustration with practitioners’ responses when these topics are broached during office visits. An observational survey among women and practitioners published in 2020 highlights that only half of doctors openly discouraged perinatal cannabis use and that others opted out of the discussion entirely.

This is the experience of many of the women that this news organization spoke with. Ms. Krach pointed out that “there’s a big deficit in listening; the doctor is supposed to be working for our behalf, especially when it comes to reproductive health.”

Dr. Mark believed that a lot of the conversation has been clouded by the illegality of the substance but that cannabinoids deserve as much of a fair chance for discussion and consideration as other medicines, which also carry risks in pregnancy. “There’s literally no evidence that it will work in pregnancy [for these symptoms], but there’s no evidence that it doesn’t, either,” she said in an interview. “When I have this conversation with colleagues who do not share my views, I try to encourage them to look at the actual risks versus the benefits versus the alternatives.”

The ‘entourage effect’

Data supporting cannabinoids have been mostly laboratory based, case based, or observational. However, several well-designed (albeit small) trials have demonstrated efficacy for chronic pain conditions, including neuropathic and headache pain, as well as in Crohn’s disease. Most investigators have concluded that dosage is important and that there is a synergistic interaction between compounds (known as the “entourage effect”) that relates to cannabinoid efficacy or lack thereof, as well as possible adverse effects.

In addition to legality issues, the entourage effect is one of the most important factors related to the medical use of cannabinoids. “There are literally thousands of cultivars of cannabis, each with their own phytocannabinoid and terpenic profiles that may produce distinct therapeutic effects, [so] it is misguided to speak of cannabis in monolithic terms. It is like making broad claims about soup,” wrote coauthor Samoon Ahmad, MD, in Medical Marijuana: A Clinical Handbook.

Additionally, the role that reproductive hormones play is not entirely understood. Reproductive-aged women appear to be more susceptible to a “telescoping” (gender-related progression to dependence) effect in comparison with men. Ziva Cooper, PhD, director of the Cannabis Research Initiative at the University of California, Los Angeles, said in an interview. She explained that research has shown that factors such as the degree of exposure, frequency of use, and menses confound this susceptibility.

It’s the data

Frustration over cannabinoid therapeutics abound, especially when it comes to data, legal issues, and lack of training. “The feedback that I hear from providers is that there isn’t enough information; we just don’t know enough about it,” Dr. Mark said, “but there is information that we do have, and ignoring it is not beneficial.”

Dr. Cooper concurred. Although she readily acknowledges that data from randomized, placebo-controlled trials are mostly lacking, she says, “There are signals in the literature providing evidence for the utility of cannabis and cannabinoids for pain and some other effects.”

Other practitioners said in an interview that some patients admit to using cannabinoids but that they lack the ample information to guide these patients. By and large, many women equate “natural” with “safe,” and some will experiment on their own to see what works.

Those experiments are not without risk, which is why “it’s just as important for physicians to talk to their patients about cannabis use as it is for patients to be forthcoming about that use,” said Dr. Cooper. “It could have implications on their overall health as well as interactions with other drugs that they’re using.”

That balance from a clinical perspective on cannabis is crucial, wrote coauthor Kenneth Hill, MD, in Medical Marijuana: A Clinical Handbook. “Without it,” he wrote, “the window of opportunity for a patient to accept treatment that she needs may not be open very long.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When 42-year-old Danielle Simone Brand started having hormonal migraines, she first turned to cannabidiol (CBD) oil, eventually adding an occasional pull on a prefilled tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) vape for nighttime use. She was careful to avoid THC during work hours. A parenting and cannabis writer, Ms. Brand had more than a cursory background in cannabinoid medicine and had spent time at her local California dispensary discussing various cannabinoid components that might help alleviate her pain.

A self-professed “do-it-yourselfer,” Ms. Brand continues to use cannabinoids for her monthly headaches, forgoing any other pain medication. “There are times for conventional medicine in partnership with your doctor, but when it comes to health and wellness, women should be empowered to make decisions and self-experiment,” she said in an interview.

Ms. Brand is not alone. Significant numbers of women are replacing or supplementing prescription medications with cannabinoids, often without consulting their primary care physician, ob.gyn., or other specialist. At times, women have tried to have these conversations, only to be met with silence or worse.

Take Linda Fuller, a 58-year-old yoga instructor from Long Island who says that she uses CBD and THC for chronic sacroiliac pain after a car accident and to alleviate stress-triggered eczema flares. “I’ve had doctors turn their backs on me; I’ve had nurse practitioners walk out on me in the middle of a sentence,” she said in an interview.

Ms. Fuller said her conversion to cannabinoid medicine is relatively new; she never used cannabis recreationally before her accident but now considers it a gift. She doesn’t keep aspirin in the house and refused pain medication immediately after she injured her back.

Diana Krach, a 34-year-old writer from Maryland, says she’s encountered roadblocks about her decision to use cannabinoids for endometriosis and for pain from Crohn’s disease. When she tried to discuss her CBD use with a gastroenterologist, he interrupted her: “Whatever pot you’re smoking isn’t going to work, you’re going on biologics.”

Ms. Krach had not been smoking anything but had turned to a CBD tincture for symptom relief after prescription pain medications failed to help.

Ms. Brand, Ms. Fuller, and Ms. Krach are the tip of the iceberg when it comes to women seeking symptom relief outside the medicine cabinet. A recent survey in the Journal of Women’s Health of almost 1,000 women show that 90% (most between the ages of 35 and 44) had used cannabis and would consider using it to treat gynecologic pain. Roughly 80% said they would consider using it for procedure-related pain or other conditions. Additionally, women have reported using cannabinoids for PTSD, sleep disturbances or insomnia, anxiety, and migraine headaches.

Observational survey data have likewise shown that 80% of women with advanced or recurrent gynecologic malignancies who were prescribed cannabis reported that it was equivalent or superior to other medications for relieving pain, neuropathy, nausea, insomnia, decreased appetite, and anxiety.

In another survey, almost half (45%) of women with gynecologic malignancies who used nonprescribed cannabis for the same symptoms reported that they had reduced their use of prescription narcotics after initiating use of cannabis.

The gray zone

There has been a surge in self-reported cannabis use among pregnant women in particular. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health findings for the periods 2002-2003 and 2016-2017 highlight increases in adjusted prevalence rates from 3.4% to 7% in past-month use among pregnant women overall and from 5.7% to 12.1% during the first trimester alone.

“The more that you talk to pregnant women, the more that you realize that a lot are using cannabinoids for something that is basically medicinal, for sleep, for anxiety, or for nausea,” Katrina Mark, MD, an ob.gyn. and associate professor of medicine at the University of Maryland, College Park, said in an interview. “I’m not saying it’s fine to use drugs in pregnancy, but it is a grayer conversation than a lot of colleagues want to believe. Telling women to quit seems foolish since the alternative is to be anxious, don’t sleep, don’t eat, or use a medication that also has risks to it.”

One observational study shows that pregnant women themselves are conflicted. Although the majority believe that cannabis is “natural” and “safe,” compared with prescription drugs, they aren’t entirely in the dark about potential risks. They often express frustration with practitioners’ responses when these topics are broached during office visits. An observational survey among women and practitioners published in 2020 highlights that only half of doctors openly discouraged perinatal cannabis use and that others opted out of the discussion entirely.

This is the experience of many of the women that this news organization spoke with. Ms. Krach pointed out that “there’s a big deficit in listening; the doctor is supposed to be working for our behalf, especially when it comes to reproductive health.”

Dr. Mark believed that a lot of the conversation has been clouded by the illegality of the substance but that cannabinoids deserve as much of a fair chance for discussion and consideration as other medicines, which also carry risks in pregnancy. “There’s literally no evidence that it will work in pregnancy [for these symptoms], but there’s no evidence that it doesn’t, either,” she said in an interview. “When I have this conversation with colleagues who do not share my views, I try to encourage them to look at the actual risks versus the benefits versus the alternatives.”

The ‘entourage effect’

Data supporting cannabinoids have been mostly laboratory based, case based, or observational. However, several well-designed (albeit small) trials have demonstrated efficacy for chronic pain conditions, including neuropathic and headache pain, as well as in Crohn’s disease. Most investigators have concluded that dosage is important and that there is a synergistic interaction between compounds (known as the “entourage effect”) that relates to cannabinoid efficacy or lack thereof, as well as possible adverse effects.

In addition to legality issues, the entourage effect is one of the most important factors related to the medical use of cannabinoids. “There are literally thousands of cultivars of cannabis, each with their own phytocannabinoid and terpenic profiles that may produce distinct therapeutic effects, [so] it is misguided to speak of cannabis in monolithic terms. It is like making broad claims about soup,” wrote coauthor Samoon Ahmad, MD, in Medical Marijuana: A Clinical Handbook.

Additionally, the role that reproductive hormones play is not entirely understood. Reproductive-aged women appear to be more susceptible to a “telescoping” (gender-related progression to dependence) effect in comparison with men. Ziva Cooper, PhD, director of the Cannabis Research Initiative at the University of California, Los Angeles, said in an interview. She explained that research has shown that factors such as the degree of exposure, frequency of use, and menses confound this susceptibility.

It’s the data

Frustration over cannabinoid therapeutics abound, especially when it comes to data, legal issues, and lack of training. “The feedback that I hear from providers is that there isn’t enough information; we just don’t know enough about it,” Dr. Mark said, “but there is information that we do have, and ignoring it is not beneficial.”

Dr. Cooper concurred. Although she readily acknowledges that data from randomized, placebo-controlled trials are mostly lacking, she says, “There are signals in the literature providing evidence for the utility of cannabis and cannabinoids for pain and some other effects.”

Other practitioners said in an interview that some patients admit to using cannabinoids but that they lack the ample information to guide these patients. By and large, many women equate “natural” with “safe,” and some will experiment on their own to see what works.

Those experiments are not without risk, which is why “it’s just as important for physicians to talk to their patients about cannabis use as it is for patients to be forthcoming about that use,” said Dr. Cooper. “It could have implications on their overall health as well as interactions with other drugs that they’re using.”

That balance from a clinical perspective on cannabis is crucial, wrote coauthor Kenneth Hill, MD, in Medical Marijuana: A Clinical Handbook. “Without it,” he wrote, “the window of opportunity for a patient to accept treatment that she needs may not be open very long.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When 42-year-old Danielle Simone Brand started having hormonal migraines, she first turned to cannabidiol (CBD) oil, eventually adding an occasional pull on a prefilled tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) vape for nighttime use. She was careful to avoid THC during work hours. A parenting and cannabis writer, Ms. Brand had more than a cursory background in cannabinoid medicine and had spent time at her local California dispensary discussing various cannabinoid components that might help alleviate her pain.

A self-professed “do-it-yourselfer,” Ms. Brand continues to use cannabinoids for her monthly headaches, forgoing any other pain medication. “There are times for conventional medicine in partnership with your doctor, but when it comes to health and wellness, women should be empowered to make decisions and self-experiment,” she said in an interview.

Ms. Brand is not alone. Significant numbers of women are replacing or supplementing prescription medications with cannabinoids, often without consulting their primary care physician, ob.gyn., or other specialist. At times, women have tried to have these conversations, only to be met with silence or worse.

Take Linda Fuller, a 58-year-old yoga instructor from Long Island who says that she uses CBD and THC for chronic sacroiliac pain after a car accident and to alleviate stress-triggered eczema flares. “I’ve had doctors turn their backs on me; I’ve had nurse practitioners walk out on me in the middle of a sentence,” she said in an interview.

Ms. Fuller said her conversion to cannabinoid medicine is relatively new; she never used cannabis recreationally before her accident but now considers it a gift. She doesn’t keep aspirin in the house and refused pain medication immediately after she injured her back.

Diana Krach, a 34-year-old writer from Maryland, says she’s encountered roadblocks about her decision to use cannabinoids for endometriosis and for pain from Crohn’s disease. When she tried to discuss her CBD use with a gastroenterologist, he interrupted her: “Whatever pot you’re smoking isn’t going to work, you’re going on biologics.”

Ms. Krach had not been smoking anything but had turned to a CBD tincture for symptom relief after prescription pain medications failed to help.

Ms. Brand, Ms. Fuller, and Ms. Krach are the tip of the iceberg when it comes to women seeking symptom relief outside the medicine cabinet. A recent survey in the Journal of Women’s Health of almost 1,000 women show that 90% (most between the ages of 35 and 44) had used cannabis and would consider using it to treat gynecologic pain. Roughly 80% said they would consider using it for procedure-related pain or other conditions. Additionally, women have reported using cannabinoids for PTSD, sleep disturbances or insomnia, anxiety, and migraine headaches.

Observational survey data have likewise shown that 80% of women with advanced or recurrent gynecologic malignancies who were prescribed cannabis reported that it was equivalent or superior to other medications for relieving pain, neuropathy, nausea, insomnia, decreased appetite, and anxiety.

In another survey, almost half (45%) of women with gynecologic malignancies who used nonprescribed cannabis for the same symptoms reported that they had reduced their use of prescription narcotics after initiating use of cannabis.

The gray zone

There has been a surge in self-reported cannabis use among pregnant women in particular. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health findings for the periods 2002-2003 and 2016-2017 highlight increases in adjusted prevalence rates from 3.4% to 7% in past-month use among pregnant women overall and from 5.7% to 12.1% during the first trimester alone.

“The more that you talk to pregnant women, the more that you realize that a lot are using cannabinoids for something that is basically medicinal, for sleep, for anxiety, or for nausea,” Katrina Mark, MD, an ob.gyn. and associate professor of medicine at the University of Maryland, College Park, said in an interview. “I’m not saying it’s fine to use drugs in pregnancy, but it is a grayer conversation than a lot of colleagues want to believe. Telling women to quit seems foolish since the alternative is to be anxious, don’t sleep, don’t eat, or use a medication that also has risks to it.”

One observational study shows that pregnant women themselves are conflicted. Although the majority believe that cannabis is “natural” and “safe,” compared with prescription drugs, they aren’t entirely in the dark about potential risks. They often express frustration with practitioners’ responses when these topics are broached during office visits. An observational survey among women and practitioners published in 2020 highlights that only half of doctors openly discouraged perinatal cannabis use and that others opted out of the discussion entirely.

This is the experience of many of the women that this news organization spoke with. Ms. Krach pointed out that “there’s a big deficit in listening; the doctor is supposed to be working for our behalf, especially when it comes to reproductive health.”

Dr. Mark believed that a lot of the conversation has been clouded by the illegality of the substance but that cannabinoids deserve as much of a fair chance for discussion and consideration as other medicines, which also carry risks in pregnancy. “There’s literally no evidence that it will work in pregnancy [for these symptoms], but there’s no evidence that it doesn’t, either,” she said in an interview. “When I have this conversation with colleagues who do not share my views, I try to encourage them to look at the actual risks versus the benefits versus the alternatives.”

The ‘entourage effect’

Data supporting cannabinoids have been mostly laboratory based, case based, or observational. However, several well-designed (albeit small) trials have demonstrated efficacy for chronic pain conditions, including neuropathic and headache pain, as well as in Crohn’s disease. Most investigators have concluded that dosage is important and that there is a synergistic interaction between compounds (known as the “entourage effect”) that relates to cannabinoid efficacy or lack thereof, as well as possible adverse effects.

In addition to legality issues, the entourage effect is one of the most important factors related to the medical use of cannabinoids. “There are literally thousands of cultivars of cannabis, each with their own phytocannabinoid and terpenic profiles that may produce distinct therapeutic effects, [so] it is misguided to speak of cannabis in monolithic terms. It is like making broad claims about soup,” wrote coauthor Samoon Ahmad, MD, in Medical Marijuana: A Clinical Handbook.

Additionally, the role that reproductive hormones play is not entirely understood. Reproductive-aged women appear to be more susceptible to a “telescoping” (gender-related progression to dependence) effect in comparison with men. Ziva Cooper, PhD, director of the Cannabis Research Initiative at the University of California, Los Angeles, said in an interview. She explained that research has shown that factors such as the degree of exposure, frequency of use, and menses confound this susceptibility.

It’s the data

Frustration over cannabinoid therapeutics abound, especially when it comes to data, legal issues, and lack of training. “The feedback that I hear from providers is that there isn’t enough information; we just don’t know enough about it,” Dr. Mark said, “but there is information that we do have, and ignoring it is not beneficial.”

Dr. Cooper concurred. Although she readily acknowledges that data from randomized, placebo-controlled trials are mostly lacking, she says, “There are signals in the literature providing evidence for the utility of cannabis and cannabinoids for pain and some other effects.”

Other practitioners said in an interview that some patients admit to using cannabinoids but that they lack the ample information to guide these patients. By and large, many women equate “natural” with “safe,” and some will experiment on their own to see what works.

Those experiments are not without risk, which is why “it’s just as important for physicians to talk to their patients about cannabis use as it is for patients to be forthcoming about that use,” said Dr. Cooper. “It could have implications on their overall health as well as interactions with other drugs that they’re using.”

That balance from a clinical perspective on cannabis is crucial, wrote coauthor Kenneth Hill, MD, in Medical Marijuana: A Clinical Handbook. “Without it,” he wrote, “the window of opportunity for a patient to accept treatment that she needs may not be open very long.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Minimizing Opioids After Joint Operation: Protocol to Decrease Postoperative Opioid Use After Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty

For decades, opioids have been a mainstay in the management of pain after total joint arthroplasty. In the past 10 years, however, opioid prescribing has come under increased scrutiny due to a rise in rates of opioid abuse, pill diversion, and opioid-related deaths.1,2 Opioids are associated with adverse effects, including nausea, vomiting, constipation, apathy, and respiratory depression, all of which influence arthroplasty outcomes and affect the patient experience. Although primary care groups account for nearly half of prescriptions written, orthopedic surgeons have the third highest per capita rate of opioid prescribing of all medical specialties.3,4 This puts orthopedic surgeons, particularly those who perform routine procedures, in an opportune but challenging position to confront this problem through novel pain management strategies.

Approximately 1 million total knee arthroplasties (TKAs) are performed in the US every year, and the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health system performs about 10,000 hip and knee joint replacements.5,6 There is no standardization of opioid prescribing in the postoperative period following these procedures, and studies have reported a wide variation in prescribing habits even within a single institution for a specific surgery.7 Patients who undergo TKA are at particularly high risk of long-term opioid use if they are on continuous opioids at the time of surgery; this is problematic in a VA patient population in which at least 16% of patients are prescribed opioids in a given year.8 Furthermore, veterans are twice as likely as nonveterans to die of an accidental overdose.9 Despite these risks, opioids remain a cornerstone of postoperative pain management both within and outside of the VA.10

In 2018, to limit unnecessary prescribing of opioid pain medication, the total joint service at the VA Portland Health Care System (VAPHCS) in Oregon implemented the Minimizing Opioids after Joint Operation (MOJO) postoperative pain protocol. The goal of the protocol was to reduce opioid use following TKA. The objectives were to provide safe, appropriate analgesia while allowing early mobilization and discharge without a concomitant increase in readmissions or emergency department (ED) visits. The purpose of this retrospective chart review was to compare the efficacy of the MOJO protocol with our historical experience and report our preliminary results.

Methods

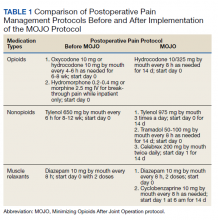

Institutional review board approval was obtained to retrospectively review the medical records of patients who had undergone TKA surgery during 2018 at VAPHCS. The MOJO protocol was composed of several simultaneous changes. The centerpiece of the new protocol was a drastic decrease in routine prescription of postoperative opioids (Table 1). Other changes included instructing patients to reduce the use of preoperative opioid pain medication 6 weeks before surgery with a goal of no opioid consumption, perform daily sets of preoperative exercises, and attend a preoperative consultation/education session with a nurse coordinator to emphasize early recovery and discharge. In patients with chronic use of opioid pain medication (particularly those for whom the medication had been prescribed for other sources of pain, such as lumbar back pain), the goal was daily opioid use of ≤ 30 morphine equivalent doses (MEDs). During the inpatient stay, we stopped prescribing prophylactic pain medication prior to physical therapy (PT).

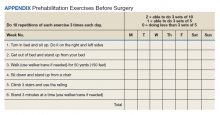

We encouraged preoperative optimization of muscle strength by giving instructions for 4 to 8 weeks of daily exercises (Appendix). We introduced perioperative adductor canal blocks (at the discretion of the anesthesia team) and transitioned to surgery without a tourniquet. Patients in both groups received intraoperative antibiotics and IV tranexamic acid (TXA); the MOJO group also received topical TXA.

Further patient care optimization included providing patients with a team-based approach, which consisted of nurse coordinators, physician assistants and nurse practitioners, residents, and the attending surgeon. Our team reviews the planned pain management protocol, perioperative expectations, criteria for discharge, and anticipated surgical outcomes with the patient during their preoperative visits. On postoperative day 1, these members round as a team to encourage patients in their immediate postoperative recovery and rehabilitation. During rounds, the team assesses whether the patient meets the criteria for discharge, adjusting the pain management protocol if necessary.

Changes in surgical technique included arthrotomy with electrocautery, minimizing traumatic dissection or resection of the synovial tissue, and intra-articular injection of a cocktail of ropivacaine 5 mg/mL 40 mL, epinephrine 1:1,000 0.5 mL, and methylprednisolone sodium 40 mg diluted with normal saline to a total volume of 120 mL.

The new routine was gradually implemented beginning January 2017 and fully implemented by July 2018. This study compared the first 20 consecutive patients undergoing primary TKA after July 2018 to the last 20 consecutive patients undergoing primary TKA prior to January 2017. Exclusion criteria included bilateral TKA, death before 90 days, and revision as the indication for surgery. The senior attending surgeon performed all surgeries using a standard midline approach. The majority of surgeries were performed using a cemented Vanguard total knee system (Zimmer Biomet); 4 patients in the historical group had a NexGen knee system, cementless monoblock tibial components (Zimmer Biomet); and 1 patient had a Logic knee system (Exactech). Surgical selection criteria for patients did not differ between groups.

Electronic health records were reviewed and data were abstracted. The data included demographic information (age, gender, body mass index [BMI], diagnosis, and procedure), surgical factors (American Society of Anesthesiologists score, Risk Assessment and Predictive Tool score, operative time, tourniquet time, estimated blood loss), hospital factors (length of stay [LOS], discharge location), postoperative pain scores (measured on postoperative day 1 and on day of discharge), and postdischarge events (90-day complications, telephone calls reporting pain, reoperations, returns to the ED, 90-day readmissions).

The primary outcome was the mean postoperative daily MED during the inpatient stay. Secondary outcomes included pain on postoperative day 1, pain at the time of discharge, LOS, hospital readmissions, and ED visits within 90 days of surgery. Because different opioid pain medications were used by patients postoperatively, all opioids were converted to MED prior to the final analysis. Collected patient data were de-identified prior to analysis.

Power analysis was conducted to determine whether the study had sufficient population size to reject the null hypothesis for the primary outcome measure. Because practitioners controlled postoperative opioid use, a Cohen’s d of 1.0 was used so that a very large effect size was needed to reach clinical significance. Statistical significance was set to 0.05, and patient groups were set at 20 patients each. This yielded an appropriate power of 0.87. Population characteristics were compared between groups using t tests and χ2 tests as appropriate. To analyze the primary outcome, comparisons were made between the 2 cohorts using 2-tailed t tests. Secondary outcomes were compared between groups using t tests or χ2 tests. All statistics were performed using R version 3.5.2. Power analysis was conducted using the package pwr.11 Statistical significance was set at

Results

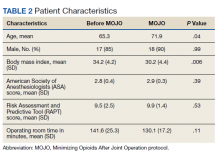

Forty patients met the inclusion criteria, evenly divided between those undergoing TKA before and after instituting the MOJO protocol (Table 2). A single patient in the MOJO group died and was excluded. A patient who underwent bilateral TKA also was excluded. Both groups reflected the male predominance of the VA patient population. MOJO patients tended to have lower BMIs (34 vs 30, P < .01). All patients indicated for surgery with preoperative opioid use were able to titrate down to their preoperative goal as verified by prescriptions filled at VA pharmacies. Twelve of the patients in the MOJO group received adductor canal blocks.

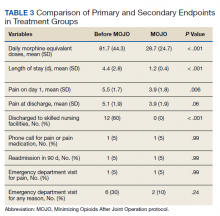

Results of t tests and χ2 tests comparing primary and secondary endpoints are listed in Table 3. Differences between the daily MEDs given in the historical and MOJO groups are shown. There were significant differences between the pre-MOJO and MOJO groups with regard to daily inpatient MEDs (82 mg vs 29 mg, P < .01) and total inpatient MEDs (306 mg vs 32 mg, P < .01). There was less self-reported pain on postoperative day 1 in the MOJO group (5.5 vs 3.9, P < .01), decreased LOS (4.4 days vs 1.2 days, P < .01), a trend toward fewer total ED visits (6 vs 2, P = .24), and fewer discharges to skilled nursing facilities (12 vs 0, P < .01). There were no blood transfusions in either group.

There were no readmissions due to uncontrolled pain. There was 1 readmission for shortness of breath in the MOJO group. The patient was discharged home the following day after ruling out thromboembolic and cardiovascular events. One patient from the control group was readmitted after missing a step on a staircase and falling. The patient sustained a quadriceps tendon rupture and underwent primary suture repair.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that a multimodal approach to significantly reduce postoperative opioid use in patients with TKA is possible without increasing readmissions or ED visits for pain control. The patients in the MOJO group had a faster recovery, earlier discharge, and less use of postoperative opioid medication. Our approach to postoperative pain management was divided into 2 main categories: patient optimization and surgical optimization.

Patient Selection

Besides the standard evaluation and optimization of patients’ medical conditions, identifying and optimizing at-risk patients before surgery was a critical component of our protocol. Managing postoperative pain in patients with prior opioid use is an intractable challenge in orthopedic surgery. Patients with a history of chronic pain and preoperative use of opioid medications remain at higher risk of postoperative chronic pain and persistent use of opioid medication despite no obvious surgical complications.8 In a sample of > 6,000 veterans who underwent TKA at VA hospitals in 2014, 57% of the patients with daily use of opioids in the 90 days before surgery remained on opioids 1 year after surgery (vs 2 % in patients not on long-term opioids).8 This relationship between pre- and postoperative opioid use also was dose dependent.12

Furthermore, those with high preoperative use may experience worse outcomes relative to the opioid naive population as measured by arthritis-specific pain indices.13 In a well-powered retrospective study of patients who underwent elective orthopedic procedures, preoperative opioid abuse or dependence (determined by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision diagnosis) increased inpatient mortality, aggregate morbidity, surgical site infection, myocardial infarction, and LOS.14 Preoperative opioid use also has been associated with increased risk of ED visits, readmission, infection, stiffness, and aseptic revision.15 In patients with TKA in the VA specifically, preoperative opioid use (> 3 months in the prior year) was associated with increased revision rates that were even higher than those for patients with diabetes mellitus.16

Patient Education

Based on this evidence, we instruct patients to reduce their preoperative opioid dosing to zero (for patients with joint pain) or < 30 MED (for patients using opioids for other reasons). Although preoperative reduction of opioid use has been shown to improve outcomes after TKA, pain subspecialty recommendations for patients with chronic opioid use recommend considering adjunctive therapies, including transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, cognitive behavioral therapy, gabapentin, or ketamine.17,18 Through patient education our team has been successful in decreasing preoperative opioid use without adding other drugs or modalities.

Patient Optimization

Preoperative patient optimization included 4 to 8 weeks of daily sets of physical activity instructions (prehab) to improve the musculoskeletal function. These instructions are given to patients 4 to 8 weeks before surgery and aim to improve the patient’s balance, mobility, and functional ability (Appendix). Meta-analysis has shown that patients who undergo preoperative PT have a small but statistically significant decrease in postoperative pain at 4 weeks, though this does not persist beyond that period.19

We did note a lower BMI in patients in the MOJO group. Though this has the potential to be a confounder, a study of BMI in > 4,000 patients who underwent joint replacement surgery has shown that BMI is not associated with differences in postoperative pain.20

Surgeon and Surgical-Related Variables

Patients in the MOJO group had increased use of adductor canal blocks. A 2017 meta-analysis of 12,530 patients comparing analgesic modalities found that peripheral nerve blocks targeting multiple nerves (eg, femoral/sciatic) decreased pain at rest, decreased opioid consumption, and improved range of motion postoperatively.21 Also, these were found to be superior to single nerve blocks, periarticular infiltration, and epidural blocks.21 However, major nerve and epidural blocks affecting the lower extremity may increase the risk of falls and prolong LOS.22,23 The preferred peripheral block at VAPHCS is a single shot ultrasound-guided adductor canal block before the induction of general or spinal anesthesia. A randomized controlled trial has demonstrated superiority of this block to the femoral nerve block with regard to postoperative quadriceps strength, conferring the theoretical advantage of decreased fall risk and ability to participate in immediate PT.24 Although we are unable to confirm an association between anesthetic modalities and opioid burden, our clinical impression is that blocks were effective at reducing immediate postoperative pain. However, among MOJO patients there were no differences in patients with and without blocks for either pain (4.2 vs 3.8, P = .69) or opioid consumption (28.8 vs 33.0, P = .72) after surgery, though our study was not powered to detect a difference in this restricted subgroup.

Patients who frequently had reported postoperative thigh pain prompted us to make changes in our surgical technique, performing TKA without use of a tourniquet. Tourniquet use has been associated with an increased risk of thigh pain after TKA by multiple authors.25,26 Postoperative thigh pain also is pressure dependent.27 In addition, its use may be associated with a slightly increased risk of thromboembolic events and delayed functional recovery.28,29

Because postoperative hemarthrosis is associated with more pain and reduced joint recovery function, we used topical TXA to reduce postoperative surgical site and joint hematoma. TXA (either oral, IV, or topical) during TKA is used to control postoperative bleeding primarily and decrease the need for transfusion without concomitant increase in thromboembolic events.30,31 Topical TXA may be more effective than IV, particularly in the immediate postoperative period.32 Although pain typically is not an endpoint in studies of TXA, a prospective study of 48 patients showed evidence that its use may be associated with decreased postoperative pain in the first 24 hours after surgery (though not after).33 Finally, the use of intra-articular injection has evolved in our clinical practice, but literature is lacking with regard to its efficacy; more studies are needed to determine its effect relative to no injection. We have not seen any benefits to using

Limitations

This is a nonrandomized retrospective single-institution study. Our study population is composed of mostly males with military experience and is not necessarily a representative sample of the general population eligible for joint arthroplasty. Our primary endpoint (reduction of opioid use postoperatively) also was a cornerstone of our intervention. To account for this, we set a very large effect size in our power analysis and evaluated multiple secondary endpoints to determine whether postoperative pain remained well controlled and complications/readmission minimized with our interventions. Because our intervention was multimodal, our study cannot make conclusions about the effect of a particular component of our treatment strategy. We did not measure or compare functional outcomes between both groups, which offers an opportunity for further research.

These limitations are balanced by several strengths. Our cohort was well controlled with respect to the dose and type of drug used. There is staff dedicated to postoperative telephone follow-up after discharge, and veterans are apt to seek care within the VA health care system, which improves case finding for complications and ED visits. No patients were lost to follow-up. Moreover, our drastic reduction in opioid use is promising enough to warrant reporting, while the broader orthopedic literature explores the relative impact of each variable.

Conclusions

The MOJO protocol has been effective for reducing postoperative opioid use after TKA without compromising effective pain management. The drastic reduction in the postoperative use of opioid pain medications and LOS have contributed to a cultural shift within our department, comprehensive team approach, multimodal pain management, and preoperative patient optimization. Further investigations are required to assess the impact of each intervention on observed outcomes. However, the framework and routines are applicable to other institutions and surgical specialties.

Acknowledgments

The authors recognize Derek Bond, MD, for his help in creating the MOJO acronym.

1. Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2017. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief No. 329. Published November 2018. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db329-h.pdf

2. Hedegaard H, Warner M, Miniño AM. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2016. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics NCHS data brief No. 294. Published December 2017. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db294.pdf

3. Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in opioid analgesic–prescribing rates by specialty, U.S., 2007-2012. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(3):409-413. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.020

4. Guy GP, Zhang K. Opioid prescribing by specialty and volume in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(5):e153-155. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.06.008

5. Kremers HM, Larson DR, Crowson CS, et al. Prevalence of total hip and knee replacement in the United States. J Bone Joint Surgery Am. 2015;17:1386-1397. doi:10.2106/JBJS.N.01141

6. Giori NJ, Amanatullah DF, Gupta S, Bowe T, Harris AHS. Risk reduction compared with access to care: quantifying the trade-off of enforcing a body mass index eligibility criterion for joint replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018; 4(100):539-545. doi:10.2106/JBJS.17.00120

7. Sabatino MJ, Kunkel ST, Ramkumar DB, Keeney BJ, Jevsevar DS. Excess opioid medication and variation in prescribing patterns following common orthopaedic procedures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(3):180-188. doi:10.2106/JBJS.17.00672

8. Hadlandsmyth K, Vander Weg MW, McCoy KD, Mosher HJ, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS, Lund BC. Risk for prolonged opioid use following total knee arthroplasty in veterans. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(1):119-123. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2017.08.022

9. Bohnert ASB, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1315-1321. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.370

10. Hall MJ, Schwartzman A, Zhang J, Liu X. Ambulatory surgery data from hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers: United States, 2010. Natl Health Stat Report. 2017(102):1-15.

11. Champely S. pwr: basic functions for power analysis. R package version 1.2-2; 2018. Accessed January 13, 2021. https://rdrr.io/cran/pwr/

12. Goesling J, Moser SE, Zaidi B, et al. Trends and predictors of opioid use after total knee and total hip arthroplasty. Pain. 2016;157(6):1259-1265. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000516

13. Smith SR, Bido J, Collins JE, Yang H, Katz JN, Losina E. Impact of preoperative opioid use on total knee arthroplasty outcomes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(10):803-808. doi:10.2106/JBJS.16.01200

14. Menendez ME, Ring D, Bateman BT. Preoperative opioid misuse is associated with increased morbidity and mortality after elective orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(7):2402-412. doi:10.1007/s11999-015-4173-5

15. Cancienne JM, Patel KJ, Browne JA, Werner BC. Narcotic use and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(1):113-118. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2017.08.006

16. Ben-Ari A, Chansky H, Rozet I. Preoperative opioid use is associated with early revision after total knee arthroplasty: a study of male patients treated in the Veterans Affairs System. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(1):1-9. doi:10.2106/JBJS.16.00167

17. Nguyen L-CL, Sing DC, Bozic KJ. Preoperative reduction of opioid use before total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(suppl 9):282-287. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2016.01.068

18. Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131-157. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008

19. Wang L, Lee M, Zhang Z, Moodie J, Cheng D, Martin J. Does preoperative rehabilitation for patients planning to undergo joint replacement surgery improve outcomes? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e009857. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009857

20. Li W, Ayers DC, Lewis CG, Bowen TR, Allison JJ, Franklin PD. Functional gain and pain relief after total joint replacement according to obesity status. J Bone Joint Surg. 2017;99(14):1183-1189. doi:10.2106/JBJS.16.00960

21. Terkawi AS, Mavridis D, Sessler DI, et al. Pain management modalities after total knee arthroplasty: a network meta-analysis of 170 randomized controlled trials. Anesthesiology. 2017;126(5):923-937. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000001607

22. Ilfeld BM, Duke KB, Donohue MC. The association between lower extremity continuous peripheral nerve blocks and patient falls after knee and hip arthroplasty. Anesth Analg. 2010;111(6):1552-1554. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181fb9507

23. Elkassabany NM, Antosh S, Ahmed M, et al. The risk of falls after total knee arthroplasty with the use of a femoral nerve block versus an adductor canal block. Anest Analg. 2016;122(5):1696-1703. doi:10.1213/ane.0000000000001237

24. Wang D, Yang Y, Li Q, et al. Adductor canal block versus femoral nerve block for total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40721. doi:10.1038/srep40721

25. Liu D, Graham D, Gillies K, Gillies RM. Effects of tourniquet use on quadriceps function and pain in total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2014;26(4):207-213. doi:10.5792/ksrr.2014.26.4.207

26. Abdel-Salam A, Eyres KS. Effects of tourniquet during total knee arthroplasty. A prospective randomised study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77(2):250-253.

27. Worland RL, Arredondo J, Angles F, Lopez-Jimenez F, Jessup DE. Thigh pain following tourniquet application in simultaneous bilateral total knee replacement arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12(8):848-852. doi:10.1016/s0883-5403(97)90153-4

28. Tai T-W, Lin C-J, Jou I-M, Chang C-W, Lai K-A, Yang C-Y. Tourniquet use in total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol, Arthrosc. 2011;19(7):1121-1130. doi:10.1007/s00167-010-1342-7

29. Jiang F-Z, Zhong H-M, Hong Y-C, Zhao G-F. Use of a tourniquet in total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Orthop Sci. 2015;20(21):110-123. doi:10.1007/s00776-014-0664-6

30. Alshryda S, Sarda P, Sukeik M, Nargol A, Blenkinsopp J, Mason JM. Tranexamic acid in total knee replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(12):1577-1585. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.93B12.26989

31. Panteli M, Papakostidis C, Dahabreh Z, Giannoudis PV. Topical tranexamic acid in total knee replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee. 2013;20(5):300-309. doi:10.1016/j.knee.2013.05.014

32. Wang J, Wang Q, Zhang X, Wang Q. Intra-articular application is more effective than intravenous application of tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(11):3385-3389. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2017.06.024

33. Guerreiro JPF, Badaro BS, Balbino JRM, Danieli MV, Queiroz AO, Cataneo DC. Application of tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty – prospective randomized trial. J Open Orthop J. 2017;11:1049-1057. doi:10.2174/1874325001711011049

For decades, opioids have been a mainstay in the management of pain after total joint arthroplasty. In the past 10 years, however, opioid prescribing has come under increased scrutiny due to a rise in rates of opioid abuse, pill diversion, and opioid-related deaths.1,2 Opioids are associated with adverse effects, including nausea, vomiting, constipation, apathy, and respiratory depression, all of which influence arthroplasty outcomes and affect the patient experience. Although primary care groups account for nearly half of prescriptions written, orthopedic surgeons have the third highest per capita rate of opioid prescribing of all medical specialties.3,4 This puts orthopedic surgeons, particularly those who perform routine procedures, in an opportune but challenging position to confront this problem through novel pain management strategies.

Approximately 1 million total knee arthroplasties (TKAs) are performed in the US every year, and the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health system performs about 10,000 hip and knee joint replacements.5,6 There is no standardization of opioid prescribing in the postoperative period following these procedures, and studies have reported a wide variation in prescribing habits even within a single institution for a specific surgery.7 Patients who undergo TKA are at particularly high risk of long-term opioid use if they are on continuous opioids at the time of surgery; this is problematic in a VA patient population in which at least 16% of patients are prescribed opioids in a given year.8 Furthermore, veterans are twice as likely as nonveterans to die of an accidental overdose.9 Despite these risks, opioids remain a cornerstone of postoperative pain management both within and outside of the VA.10

In 2018, to limit unnecessary prescribing of opioid pain medication, the total joint service at the VA Portland Health Care System (VAPHCS) in Oregon implemented the Minimizing Opioids after Joint Operation (MOJO) postoperative pain protocol. The goal of the protocol was to reduce opioid use following TKA. The objectives were to provide safe, appropriate analgesia while allowing early mobilization and discharge without a concomitant increase in readmissions or emergency department (ED) visits. The purpose of this retrospective chart review was to compare the efficacy of the MOJO protocol with our historical experience and report our preliminary results.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained to retrospectively review the medical records of patients who had undergone TKA surgery during 2018 at VAPHCS. The MOJO protocol was composed of several simultaneous changes. The centerpiece of the new protocol was a drastic decrease in routine prescription of postoperative opioids (Table 1). Other changes included instructing patients to reduce the use of preoperative opioid pain medication 6 weeks before surgery with a goal of no opioid consumption, perform daily sets of preoperative exercises, and attend a preoperative consultation/education session with a nurse coordinator to emphasize early recovery and discharge. In patients with chronic use of opioid pain medication (particularly those for whom the medication had been prescribed for other sources of pain, such as lumbar back pain), the goal was daily opioid use of ≤ 30 morphine equivalent doses (MEDs). During the inpatient stay, we stopped prescribing prophylactic pain medication prior to physical therapy (PT).

We encouraged preoperative optimization of muscle strength by giving instructions for 4 to 8 weeks of daily exercises (Appendix). We introduced perioperative adductor canal blocks (at the discretion of the anesthesia team) and transitioned to surgery without a tourniquet. Patients in both groups received intraoperative antibiotics and IV tranexamic acid (TXA); the MOJO group also received topical TXA.

Further patient care optimization included providing patients with a team-based approach, which consisted of nurse coordinators, physician assistants and nurse practitioners, residents, and the attending surgeon. Our team reviews the planned pain management protocol, perioperative expectations, criteria for discharge, and anticipated surgical outcomes with the patient during their preoperative visits. On postoperative day 1, these members round as a team to encourage patients in their immediate postoperative recovery and rehabilitation. During rounds, the team assesses whether the patient meets the criteria for discharge, adjusting the pain management protocol if necessary.

Changes in surgical technique included arthrotomy with electrocautery, minimizing traumatic dissection or resection of the synovial tissue, and intra-articular injection of a cocktail of ropivacaine 5 mg/mL 40 mL, epinephrine 1:1,000 0.5 mL, and methylprednisolone sodium 40 mg diluted with normal saline to a total volume of 120 mL.

The new routine was gradually implemented beginning January 2017 and fully implemented by July 2018. This study compared the first 20 consecutive patients undergoing primary TKA after July 2018 to the last 20 consecutive patients undergoing primary TKA prior to January 2017. Exclusion criteria included bilateral TKA, death before 90 days, and revision as the indication for surgery. The senior attending surgeon performed all surgeries using a standard midline approach. The majority of surgeries were performed using a cemented Vanguard total knee system (Zimmer Biomet); 4 patients in the historical group had a NexGen knee system, cementless monoblock tibial components (Zimmer Biomet); and 1 patient had a Logic knee system (Exactech). Surgical selection criteria for patients did not differ between groups.

Electronic health records were reviewed and data were abstracted. The data included demographic information (age, gender, body mass index [BMI], diagnosis, and procedure), surgical factors (American Society of Anesthesiologists score, Risk Assessment and Predictive Tool score, operative time, tourniquet time, estimated blood loss), hospital factors (length of stay [LOS], discharge location), postoperative pain scores (measured on postoperative day 1 and on day of discharge), and postdischarge events (90-day complications, telephone calls reporting pain, reoperations, returns to the ED, 90-day readmissions).

The primary outcome was the mean postoperative daily MED during the inpatient stay. Secondary outcomes included pain on postoperative day 1, pain at the time of discharge, LOS, hospital readmissions, and ED visits within 90 days of surgery. Because different opioid pain medications were used by patients postoperatively, all opioids were converted to MED prior to the final analysis. Collected patient data were de-identified prior to analysis.

Power analysis was conducted to determine whether the study had sufficient population size to reject the null hypothesis for the primary outcome measure. Because practitioners controlled postoperative opioid use, a Cohen’s d of 1.0 was used so that a very large effect size was needed to reach clinical significance. Statistical significance was set to 0.05, and patient groups were set at 20 patients each. This yielded an appropriate power of 0.87. Population characteristics were compared between groups using t tests and χ2 tests as appropriate. To analyze the primary outcome, comparisons were made between the 2 cohorts using 2-tailed t tests. Secondary outcomes were compared between groups using t tests or χ2 tests. All statistics were performed using R version 3.5.2. Power analysis was conducted using the package pwr.11 Statistical significance was set at

Results

Forty patients met the inclusion criteria, evenly divided between those undergoing TKA before and after instituting the MOJO protocol (Table 2). A single patient in the MOJO group died and was excluded. A patient who underwent bilateral TKA also was excluded. Both groups reflected the male predominance of the VA patient population. MOJO patients tended to have lower BMIs (34 vs 30, P < .01). All patients indicated for surgery with preoperative opioid use were able to titrate down to their preoperative goal as verified by prescriptions filled at VA pharmacies. Twelve of the patients in the MOJO group received adductor canal blocks.

Results of t tests and χ2 tests comparing primary and secondary endpoints are listed in Table 3. Differences between the daily MEDs given in the historical and MOJO groups are shown. There were significant differences between the pre-MOJO and MOJO groups with regard to daily inpatient MEDs (82 mg vs 29 mg, P < .01) and total inpatient MEDs (306 mg vs 32 mg, P < .01). There was less self-reported pain on postoperative day 1 in the MOJO group (5.5 vs 3.9, P < .01), decreased LOS (4.4 days vs 1.2 days, P < .01), a trend toward fewer total ED visits (6 vs 2, P = .24), and fewer discharges to skilled nursing facilities (12 vs 0, P < .01). There were no blood transfusions in either group.

There were no readmissions due to uncontrolled pain. There was 1 readmission for shortness of breath in the MOJO group. The patient was discharged home the following day after ruling out thromboembolic and cardiovascular events. One patient from the control group was readmitted after missing a step on a staircase and falling. The patient sustained a quadriceps tendon rupture and underwent primary suture repair.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that a multimodal approach to significantly reduce postoperative opioid use in patients with TKA is possible without increasing readmissions or ED visits for pain control. The patients in the MOJO group had a faster recovery, earlier discharge, and less use of postoperative opioid medication. Our approach to postoperative pain management was divided into 2 main categories: patient optimization and surgical optimization.

Patient Selection

Besides the standard evaluation and optimization of patients’ medical conditions, identifying and optimizing at-risk patients before surgery was a critical component of our protocol. Managing postoperative pain in patients with prior opioid use is an intractable challenge in orthopedic surgery. Patients with a history of chronic pain and preoperative use of opioid medications remain at higher risk of postoperative chronic pain and persistent use of opioid medication despite no obvious surgical complications.8 In a sample of > 6,000 veterans who underwent TKA at VA hospitals in 2014, 57% of the patients with daily use of opioids in the 90 days before surgery remained on opioids 1 year after surgery (vs 2 % in patients not on long-term opioids).8 This relationship between pre- and postoperative opioid use also was dose dependent.12

Furthermore, those with high preoperative use may experience worse outcomes relative to the opioid naive population as measured by arthritis-specific pain indices.13 In a well-powered retrospective study of patients who underwent elective orthopedic procedures, preoperative opioid abuse or dependence (determined by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision diagnosis) increased inpatient mortality, aggregate morbidity, surgical site infection, myocardial infarction, and LOS.14 Preoperative opioid use also has been associated with increased risk of ED visits, readmission, infection, stiffness, and aseptic revision.15 In patients with TKA in the VA specifically, preoperative opioid use (> 3 months in the prior year) was associated with increased revision rates that were even higher than those for patients with diabetes mellitus.16

Patient Education

Based on this evidence, we instruct patients to reduce their preoperative opioid dosing to zero (for patients with joint pain) or < 30 MED (for patients using opioids for other reasons). Although preoperative reduction of opioid use has been shown to improve outcomes after TKA, pain subspecialty recommendations for patients with chronic opioid use recommend considering adjunctive therapies, including transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, cognitive behavioral therapy, gabapentin, or ketamine.17,18 Through patient education our team has been successful in decreasing preoperative opioid use without adding other drugs or modalities.

Patient Optimization

Preoperative patient optimization included 4 to 8 weeks of daily sets of physical activity instructions (prehab) to improve the musculoskeletal function. These instructions are given to patients 4 to 8 weeks before surgery and aim to improve the patient’s balance, mobility, and functional ability (Appendix). Meta-analysis has shown that patients who undergo preoperative PT have a small but statistically significant decrease in postoperative pain at 4 weeks, though this does not persist beyond that period.19

We did note a lower BMI in patients in the MOJO group. Though this has the potential to be a confounder, a study of BMI in > 4,000 patients who underwent joint replacement surgery has shown that BMI is not associated with differences in postoperative pain.20

Surgeon and Surgical-Related Variables

Patients in the MOJO group had increased use of adductor canal blocks. A 2017 meta-analysis of 12,530 patients comparing analgesic modalities found that peripheral nerve blocks targeting multiple nerves (eg, femoral/sciatic) decreased pain at rest, decreased opioid consumption, and improved range of motion postoperatively.21 Also, these were found to be superior to single nerve blocks, periarticular infiltration, and epidural blocks.21 However, major nerve and epidural blocks affecting the lower extremity may increase the risk of falls and prolong LOS.22,23 The preferred peripheral block at VAPHCS is a single shot ultrasound-guided adductor canal block before the induction of general or spinal anesthesia. A randomized controlled trial has demonstrated superiority of this block to the femoral nerve block with regard to postoperative quadriceps strength, conferring the theoretical advantage of decreased fall risk and ability to participate in immediate PT.24 Although we are unable to confirm an association between anesthetic modalities and opioid burden, our clinical impression is that blocks were effective at reducing immediate postoperative pain. However, among MOJO patients there were no differences in patients with and without blocks for either pain (4.2 vs 3.8, P = .69) or opioid consumption (28.8 vs 33.0, P = .72) after surgery, though our study was not powered to detect a difference in this restricted subgroup.

Patients who frequently had reported postoperative thigh pain prompted us to make changes in our surgical technique, performing TKA without use of a tourniquet. Tourniquet use has been associated with an increased risk of thigh pain after TKA by multiple authors.25,26 Postoperative thigh pain also is pressure dependent.27 In addition, its use may be associated with a slightly increased risk of thromboembolic events and delayed functional recovery.28,29

Because postoperative hemarthrosis is associated with more pain and reduced joint recovery function, we used topical TXA to reduce postoperative surgical site and joint hematoma. TXA (either oral, IV, or topical) during TKA is used to control postoperative bleeding primarily and decrease the need for transfusion without concomitant increase in thromboembolic events.30,31 Topical TXA may be more effective than IV, particularly in the immediate postoperative period.32 Although pain typically is not an endpoint in studies of TXA, a prospective study of 48 patients showed evidence that its use may be associated with decreased postoperative pain in the first 24 hours after surgery (though not after).33 Finally, the use of intra-articular injection has evolved in our clinical practice, but literature is lacking with regard to its efficacy; more studies are needed to determine its effect relative to no injection. We have not seen any benefits to using

Limitations

This is a nonrandomized retrospective single-institution study. Our study population is composed of mostly males with military experience and is not necessarily a representative sample of the general population eligible for joint arthroplasty. Our primary endpoint (reduction of opioid use postoperatively) also was a cornerstone of our intervention. To account for this, we set a very large effect size in our power analysis and evaluated multiple secondary endpoints to determine whether postoperative pain remained well controlled and complications/readmission minimized with our interventions. Because our intervention was multimodal, our study cannot make conclusions about the effect of a particular component of our treatment strategy. We did not measure or compare functional outcomes between both groups, which offers an opportunity for further research.

These limitations are balanced by several strengths. Our cohort was well controlled with respect to the dose and type of drug used. There is staff dedicated to postoperative telephone follow-up after discharge, and veterans are apt to seek care within the VA health care system, which improves case finding for complications and ED visits. No patients were lost to follow-up. Moreover, our drastic reduction in opioid use is promising enough to warrant reporting, while the broader orthopedic literature explores the relative impact of each variable.

Conclusions

The MOJO protocol has been effective for reducing postoperative opioid use after TKA without compromising effective pain management. The drastic reduction in the postoperative use of opioid pain medications and LOS have contributed to a cultural shift within our department, comprehensive team approach, multimodal pain management, and preoperative patient optimization. Further investigations are required to assess the impact of each intervention on observed outcomes. However, the framework and routines are applicable to other institutions and surgical specialties.

Acknowledgments

The authors recognize Derek Bond, MD, for his help in creating the MOJO acronym.

For decades, opioids have been a mainstay in the management of pain after total joint arthroplasty. In the past 10 years, however, opioid prescribing has come under increased scrutiny due to a rise in rates of opioid abuse, pill diversion, and opioid-related deaths.1,2 Opioids are associated with adverse effects, including nausea, vomiting, constipation, apathy, and respiratory depression, all of which influence arthroplasty outcomes and affect the patient experience. Although primary care groups account for nearly half of prescriptions written, orthopedic surgeons have the third highest per capita rate of opioid prescribing of all medical specialties.3,4 This puts orthopedic surgeons, particularly those who perform routine procedures, in an opportune but challenging position to confront this problem through novel pain management strategies.

Approximately 1 million total knee arthroplasties (TKAs) are performed in the US every year, and the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health system performs about 10,000 hip and knee joint replacements.5,6 There is no standardization of opioid prescribing in the postoperative period following these procedures, and studies have reported a wide variation in prescribing habits even within a single institution for a specific surgery.7 Patients who undergo TKA are at particularly high risk of long-term opioid use if they are on continuous opioids at the time of surgery; this is problematic in a VA patient population in which at least 16% of patients are prescribed opioids in a given year.8 Furthermore, veterans are twice as likely as nonveterans to die of an accidental overdose.9 Despite these risks, opioids remain a cornerstone of postoperative pain management both within and outside of the VA.10

In 2018, to limit unnecessary prescribing of opioid pain medication, the total joint service at the VA Portland Health Care System (VAPHCS) in Oregon implemented the Minimizing Opioids after Joint Operation (MOJO) postoperative pain protocol. The goal of the protocol was to reduce opioid use following TKA. The objectives were to provide safe, appropriate analgesia while allowing early mobilization and discharge without a concomitant increase in readmissions or emergency department (ED) visits. The purpose of this retrospective chart review was to compare the efficacy of the MOJO protocol with our historical experience and report our preliminary results.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained to retrospectively review the medical records of patients who had undergone TKA surgery during 2018 at VAPHCS. The MOJO protocol was composed of several simultaneous changes. The centerpiece of the new protocol was a drastic decrease in routine prescription of postoperative opioids (Table 1). Other changes included instructing patients to reduce the use of preoperative opioid pain medication 6 weeks before surgery with a goal of no opioid consumption, perform daily sets of preoperative exercises, and attend a preoperative consultation/education session with a nurse coordinator to emphasize early recovery and discharge. In patients with chronic use of opioid pain medication (particularly those for whom the medication had been prescribed for other sources of pain, such as lumbar back pain), the goal was daily opioid use of ≤ 30 morphine equivalent doses (MEDs). During the inpatient stay, we stopped prescribing prophylactic pain medication prior to physical therapy (PT).

We encouraged preoperative optimization of muscle strength by giving instructions for 4 to 8 weeks of daily exercises (Appendix). We introduced perioperative adductor canal blocks (at the discretion of the anesthesia team) and transitioned to surgery without a tourniquet. Patients in both groups received intraoperative antibiotics and IV tranexamic acid (TXA); the MOJO group also received topical TXA.

Further patient care optimization included providing patients with a team-based approach, which consisted of nurse coordinators, physician assistants and nurse practitioners, residents, and the attending surgeon. Our team reviews the planned pain management protocol, perioperative expectations, criteria for discharge, and anticipated surgical outcomes with the patient during their preoperative visits. On postoperative day 1, these members round as a team to encourage patients in their immediate postoperative recovery and rehabilitation. During rounds, the team assesses whether the patient meets the criteria for discharge, adjusting the pain management protocol if necessary.

Changes in surgical technique included arthrotomy with electrocautery, minimizing traumatic dissection or resection of the synovial tissue, and intra-articular injection of a cocktail of ropivacaine 5 mg/mL 40 mL, epinephrine 1:1,000 0.5 mL, and methylprednisolone sodium 40 mg diluted with normal saline to a total volume of 120 mL.

The new routine was gradually implemented beginning January 2017 and fully implemented by July 2018. This study compared the first 20 consecutive patients undergoing primary TKA after July 2018 to the last 20 consecutive patients undergoing primary TKA prior to January 2017. Exclusion criteria included bilateral TKA, death before 90 days, and revision as the indication for surgery. The senior attending surgeon performed all surgeries using a standard midline approach. The majority of surgeries were performed using a cemented Vanguard total knee system (Zimmer Biomet); 4 patients in the historical group had a NexGen knee system, cementless monoblock tibial components (Zimmer Biomet); and 1 patient had a Logic knee system (Exactech). Surgical selection criteria for patients did not differ between groups.

Electronic health records were reviewed and data were abstracted. The data included demographic information (age, gender, body mass index [BMI], diagnosis, and procedure), surgical factors (American Society of Anesthesiologists score, Risk Assessment and Predictive Tool score, operative time, tourniquet time, estimated blood loss), hospital factors (length of stay [LOS], discharge location), postoperative pain scores (measured on postoperative day 1 and on day of discharge), and postdischarge events (90-day complications, telephone calls reporting pain, reoperations, returns to the ED, 90-day readmissions).

The primary outcome was the mean postoperative daily MED during the inpatient stay. Secondary outcomes included pain on postoperative day 1, pain at the time of discharge, LOS, hospital readmissions, and ED visits within 90 days of surgery. Because different opioid pain medications were used by patients postoperatively, all opioids were converted to MED prior to the final analysis. Collected patient data were de-identified prior to analysis.

Power analysis was conducted to determine whether the study had sufficient population size to reject the null hypothesis for the primary outcome measure. Because practitioners controlled postoperative opioid use, a Cohen’s d of 1.0 was used so that a very large effect size was needed to reach clinical significance. Statistical significance was set to 0.05, and patient groups were set at 20 patients each. This yielded an appropriate power of 0.87. Population characteristics were compared between groups using t tests and χ2 tests as appropriate. To analyze the primary outcome, comparisons were made between the 2 cohorts using 2-tailed t tests. Secondary outcomes were compared between groups using t tests or χ2 tests. All statistics were performed using R version 3.5.2. Power analysis was conducted using the package pwr.11 Statistical significance was set at

Results

Forty patients met the inclusion criteria, evenly divided between those undergoing TKA before and after instituting the MOJO protocol (Table 2). A single patient in the MOJO group died and was excluded. A patient who underwent bilateral TKA also was excluded. Both groups reflected the male predominance of the VA patient population. MOJO patients tended to have lower BMIs (34 vs 30, P < .01). All patients indicated for surgery with preoperative opioid use were able to titrate down to their preoperative goal as verified by prescriptions filled at VA pharmacies. Twelve of the patients in the MOJO group received adductor canal blocks.