User login

Doc never met patient who died from insect bite, but negligence suit moves forward; more

On-call specialist incurred a clear ‘duty of care,’ court rules

a state appeals court ruled late in January.

The appeals decision is the result of a case involving the late Dennis Blagden.

On July 26, 2017, Mr. Blagden arrived at the Graham Hospital ED, in Canton, Ill., complaining of neck pain and an insect bite that had resulted in a swollen elbow. His ED doctor, Matthew McMillin, MD, who worked for Coleman Medical Associates, ordered tests and prescribed an anti-inflammatory pain medication and a muscle relaxant.

Dr. McMillin consulted via telephone with Kenneth Krock, MD, an internal medicine specialist and pediatrician, who was on call that day and who enjoyed admitting privileges at Graham. (Krock was also an employee of Coleman Medical Associates, which provided clinical staffing for the hospital.)

Dr. Krock had final admitting authority in this instance. Court records show that Dr. McMillin and he agreed that the patient could be discharged from the ED, despite Krock’s differential diagnosis indicating a possible infection.

Three days later, now with “hypercapnic respiratory failure, sepsis, and an altered mental state,” Mr. Blagden was again seen at the Graham Hospital ED. Mr. Blagden underwent intubation by Dr. McMillin, his original ED doctor, and was airlifted to Methodist Medical Center, in Peoria, 30 miles away. There, an MRI showed that he’d developed a spinal epidural abscess. On Aug. 7, 2017, a little over a week after his admission to Methodist, Mr. Blagden died from complications of his infection.

In January 2019, Mr. Blagden’s wife, Judy, filed a suit against Dr. McMillin, his practice, and Graham Hospital, which is a part of Graham Health System. Her suit alleged medical negligence in the death of her husband.

About 6 months later, Mr.s Blagden amended her original complaint, adding a second count of medical negligence against Dr. Krock; his practice and employer, Coleman Medical Associates; and Graham Hospital. In her amended complaint, Mrs. Blagden alleged that although Krock hadn’t actually seen her husband Dennis, his consultation with Dr. McMillin was sufficient to establish a doctor-patient relationship and thus a legal duty of care. That duty, Mrs. Blagden further alleged, was breached when Dr. Krock failed both to rule out her husband’s “infectious process” and to admit him for proper follow-up monitoring.

In July 2021, after the case had been transferred from Peoria County to Fulton County, Dr. Krock cried foul. In a motion to the court for summary judgment – that is, a ruling prior to an actual trial – he and his practice put forth the following argument: As a mere on-call consultant that day in 2017, he had neither seen the patient nor established a relationship with him, thereby precluding his legal duty of care.

The trial court judge agreed and granted both Dr. Krock and Dr. Coleman the summary judgment they had sought.

Mrs. Blagden then appealed to the Appellate Court of Illinois, Fourth District, which is located in Springfield.

In its unanimous decision, the three-judge panel reversed the lower court’s ruling. Taking direct aim at Dr. Krock’s earlier motion, Justice Eugene Doherty, who wrote the panel’s opinion, said that state law had long established that “the special relationship giving rise to a duty of care may exist even in the absence of any meeting between the physician and the patient where the physician performs specific services for the benefit of the patient.”

As Justice Doherty explained, Dr. Krock’s status that day as both the on-call doctor and the one with final admitting authority undermined his argument for summary judgment. Also undermining it, Justice Doherty added, was the fact that the conversation between the two doctors that day in 2017 was a formal exchange “contemplated by hospital bylaws.”

“While public policy should encourage informal consultations between physicians,” the justice continued, “it must not ignore actual physician involvement in decisions that directly affect a patient’s care.”

Following the Fourth District decision, the suit against Dr. McMillin, Dr. Krock, and the other defendants has now been tossed back to the trial court for further proceedings. At press time, no trial date had been set.

Will this proposed damages cap help retain more physicians?

Fear of a doctor shortage, triggered in part by a recent history of large payouts, has prompted Iowa lawmakers to push for new state caps on medical malpractice awards, as a story in the Des Moines Register reports.

Currently, Iowa caps most noneconomic damages – including those for pain and suffering – at $250,000, which is among the lowest such caps in the nation.

Under existing Iowa law, however, the limit doesn’t apply in extraordinary cases – that is, those involving “substantial or permanent loss of body function, substantial disfigurement, or death.” It also isn’t applicable in cases in which a jury decides that a defendant acted with intentional malice.

Lawmakers and Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds would like to change this.

Under a Senate bill that has now passed out of committee and is awaiting debate on the Senate floor, even plaintiffs involved in extreme cases would receive no more than $1 million to compensate for their pain, suffering, or emotional distress. (The bill also includes a 2.1% annual hike to compensate for inflation. A similar bill, which adds “loss of pregnancy” to the list of extreme cases, has advanced to the House floor.)

Supporters say the proposed cap would help to limit mega awards. In Johnson County in March 2022, for instance, a jury awarded $97.4 million to the parents of a young boy who sustained severe brain injuries during his delivery, causing the clinic that had been involved in the case to file for bankruptcy. This award was nearly three times the total payouts ($35 million) in the entire state of Iowa in all of 2021, a year in which there were 192 closed claims, including at least a dozen that resulted in payouts of $1 million or more.

Supporters also think the proposed cap will mitigate what they see as a looming doctor shortage, especially among ob.gyns. in eastern Iowa. “I just cannot overstate how much this is affecting our workforce, and that turns into effects for the women and the children, the babies, in our state,” Shannon Leveridge, MD, an obstetrician in Davenport said. “In order to keep these women and their babies safe, we need doctors.”

But critics of the bill, including some lawmakers and the trial bar, say it overreaches, even in the case of the $97.4 million award.

“They don’t want to talk about the actual damages that are caused by medical negligence,” explained a spokesman for the trial lawyers. “So, you don’t hear about the fact that, of the $50 million of economic damages ... most of that is going to go to the 24/7 care for this child for the rest of his life.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On-call specialist incurred a clear ‘duty of care,’ court rules

a state appeals court ruled late in January.

The appeals decision is the result of a case involving the late Dennis Blagden.

On July 26, 2017, Mr. Blagden arrived at the Graham Hospital ED, in Canton, Ill., complaining of neck pain and an insect bite that had resulted in a swollen elbow. His ED doctor, Matthew McMillin, MD, who worked for Coleman Medical Associates, ordered tests and prescribed an anti-inflammatory pain medication and a muscle relaxant.

Dr. McMillin consulted via telephone with Kenneth Krock, MD, an internal medicine specialist and pediatrician, who was on call that day and who enjoyed admitting privileges at Graham. (Krock was also an employee of Coleman Medical Associates, which provided clinical staffing for the hospital.)

Dr. Krock had final admitting authority in this instance. Court records show that Dr. McMillin and he agreed that the patient could be discharged from the ED, despite Krock’s differential diagnosis indicating a possible infection.

Three days later, now with “hypercapnic respiratory failure, sepsis, and an altered mental state,” Mr. Blagden was again seen at the Graham Hospital ED. Mr. Blagden underwent intubation by Dr. McMillin, his original ED doctor, and was airlifted to Methodist Medical Center, in Peoria, 30 miles away. There, an MRI showed that he’d developed a spinal epidural abscess. On Aug. 7, 2017, a little over a week after his admission to Methodist, Mr. Blagden died from complications of his infection.

In January 2019, Mr. Blagden’s wife, Judy, filed a suit against Dr. McMillin, his practice, and Graham Hospital, which is a part of Graham Health System. Her suit alleged medical negligence in the death of her husband.

About 6 months later, Mr.s Blagden amended her original complaint, adding a second count of medical negligence against Dr. Krock; his practice and employer, Coleman Medical Associates; and Graham Hospital. In her amended complaint, Mrs. Blagden alleged that although Krock hadn’t actually seen her husband Dennis, his consultation with Dr. McMillin was sufficient to establish a doctor-patient relationship and thus a legal duty of care. That duty, Mrs. Blagden further alleged, was breached when Dr. Krock failed both to rule out her husband’s “infectious process” and to admit him for proper follow-up monitoring.

In July 2021, after the case had been transferred from Peoria County to Fulton County, Dr. Krock cried foul. In a motion to the court for summary judgment – that is, a ruling prior to an actual trial – he and his practice put forth the following argument: As a mere on-call consultant that day in 2017, he had neither seen the patient nor established a relationship with him, thereby precluding his legal duty of care.

The trial court judge agreed and granted both Dr. Krock and Dr. Coleman the summary judgment they had sought.

Mrs. Blagden then appealed to the Appellate Court of Illinois, Fourth District, which is located in Springfield.

In its unanimous decision, the three-judge panel reversed the lower court’s ruling. Taking direct aim at Dr. Krock’s earlier motion, Justice Eugene Doherty, who wrote the panel’s opinion, said that state law had long established that “the special relationship giving rise to a duty of care may exist even in the absence of any meeting between the physician and the patient where the physician performs specific services for the benefit of the patient.”

As Justice Doherty explained, Dr. Krock’s status that day as both the on-call doctor and the one with final admitting authority undermined his argument for summary judgment. Also undermining it, Justice Doherty added, was the fact that the conversation between the two doctors that day in 2017 was a formal exchange “contemplated by hospital bylaws.”

“While public policy should encourage informal consultations between physicians,” the justice continued, “it must not ignore actual physician involvement in decisions that directly affect a patient’s care.”

Following the Fourth District decision, the suit against Dr. McMillin, Dr. Krock, and the other defendants has now been tossed back to the trial court for further proceedings. At press time, no trial date had been set.

Will this proposed damages cap help retain more physicians?

Fear of a doctor shortage, triggered in part by a recent history of large payouts, has prompted Iowa lawmakers to push for new state caps on medical malpractice awards, as a story in the Des Moines Register reports.

Currently, Iowa caps most noneconomic damages – including those for pain and suffering – at $250,000, which is among the lowest such caps in the nation.

Under existing Iowa law, however, the limit doesn’t apply in extraordinary cases – that is, those involving “substantial or permanent loss of body function, substantial disfigurement, or death.” It also isn’t applicable in cases in which a jury decides that a defendant acted with intentional malice.

Lawmakers and Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds would like to change this.

Under a Senate bill that has now passed out of committee and is awaiting debate on the Senate floor, even plaintiffs involved in extreme cases would receive no more than $1 million to compensate for their pain, suffering, or emotional distress. (The bill also includes a 2.1% annual hike to compensate for inflation. A similar bill, which adds “loss of pregnancy” to the list of extreme cases, has advanced to the House floor.)

Supporters say the proposed cap would help to limit mega awards. In Johnson County in March 2022, for instance, a jury awarded $97.4 million to the parents of a young boy who sustained severe brain injuries during his delivery, causing the clinic that had been involved in the case to file for bankruptcy. This award was nearly three times the total payouts ($35 million) in the entire state of Iowa in all of 2021, a year in which there were 192 closed claims, including at least a dozen that resulted in payouts of $1 million or more.

Supporters also think the proposed cap will mitigate what they see as a looming doctor shortage, especially among ob.gyns. in eastern Iowa. “I just cannot overstate how much this is affecting our workforce, and that turns into effects for the women and the children, the babies, in our state,” Shannon Leveridge, MD, an obstetrician in Davenport said. “In order to keep these women and their babies safe, we need doctors.”

But critics of the bill, including some lawmakers and the trial bar, say it overreaches, even in the case of the $97.4 million award.

“They don’t want to talk about the actual damages that are caused by medical negligence,” explained a spokesman for the trial lawyers. “So, you don’t hear about the fact that, of the $50 million of economic damages ... most of that is going to go to the 24/7 care for this child for the rest of his life.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On-call specialist incurred a clear ‘duty of care,’ court rules

a state appeals court ruled late in January.

The appeals decision is the result of a case involving the late Dennis Blagden.

On July 26, 2017, Mr. Blagden arrived at the Graham Hospital ED, in Canton, Ill., complaining of neck pain and an insect bite that had resulted in a swollen elbow. His ED doctor, Matthew McMillin, MD, who worked for Coleman Medical Associates, ordered tests and prescribed an anti-inflammatory pain medication and a muscle relaxant.

Dr. McMillin consulted via telephone with Kenneth Krock, MD, an internal medicine specialist and pediatrician, who was on call that day and who enjoyed admitting privileges at Graham. (Krock was also an employee of Coleman Medical Associates, which provided clinical staffing for the hospital.)

Dr. Krock had final admitting authority in this instance. Court records show that Dr. McMillin and he agreed that the patient could be discharged from the ED, despite Krock’s differential diagnosis indicating a possible infection.

Three days later, now with “hypercapnic respiratory failure, sepsis, and an altered mental state,” Mr. Blagden was again seen at the Graham Hospital ED. Mr. Blagden underwent intubation by Dr. McMillin, his original ED doctor, and was airlifted to Methodist Medical Center, in Peoria, 30 miles away. There, an MRI showed that he’d developed a spinal epidural abscess. On Aug. 7, 2017, a little over a week after his admission to Methodist, Mr. Blagden died from complications of his infection.

In January 2019, Mr. Blagden’s wife, Judy, filed a suit against Dr. McMillin, his practice, and Graham Hospital, which is a part of Graham Health System. Her suit alleged medical negligence in the death of her husband.

About 6 months later, Mr.s Blagden amended her original complaint, adding a second count of medical negligence against Dr. Krock; his practice and employer, Coleman Medical Associates; and Graham Hospital. In her amended complaint, Mrs. Blagden alleged that although Krock hadn’t actually seen her husband Dennis, his consultation with Dr. McMillin was sufficient to establish a doctor-patient relationship and thus a legal duty of care. That duty, Mrs. Blagden further alleged, was breached when Dr. Krock failed both to rule out her husband’s “infectious process” and to admit him for proper follow-up monitoring.

In July 2021, after the case had been transferred from Peoria County to Fulton County, Dr. Krock cried foul. In a motion to the court for summary judgment – that is, a ruling prior to an actual trial – he and his practice put forth the following argument: As a mere on-call consultant that day in 2017, he had neither seen the patient nor established a relationship with him, thereby precluding his legal duty of care.

The trial court judge agreed and granted both Dr. Krock and Dr. Coleman the summary judgment they had sought.

Mrs. Blagden then appealed to the Appellate Court of Illinois, Fourth District, which is located in Springfield.

In its unanimous decision, the three-judge panel reversed the lower court’s ruling. Taking direct aim at Dr. Krock’s earlier motion, Justice Eugene Doherty, who wrote the panel’s opinion, said that state law had long established that “the special relationship giving rise to a duty of care may exist even in the absence of any meeting between the physician and the patient where the physician performs specific services for the benefit of the patient.”

As Justice Doherty explained, Dr. Krock’s status that day as both the on-call doctor and the one with final admitting authority undermined his argument for summary judgment. Also undermining it, Justice Doherty added, was the fact that the conversation between the two doctors that day in 2017 was a formal exchange “contemplated by hospital bylaws.”

“While public policy should encourage informal consultations between physicians,” the justice continued, “it must not ignore actual physician involvement in decisions that directly affect a patient’s care.”

Following the Fourth District decision, the suit against Dr. McMillin, Dr. Krock, and the other defendants has now been tossed back to the trial court for further proceedings. At press time, no trial date had been set.

Will this proposed damages cap help retain more physicians?

Fear of a doctor shortage, triggered in part by a recent history of large payouts, has prompted Iowa lawmakers to push for new state caps on medical malpractice awards, as a story in the Des Moines Register reports.

Currently, Iowa caps most noneconomic damages – including those for pain and suffering – at $250,000, which is among the lowest such caps in the nation.

Under existing Iowa law, however, the limit doesn’t apply in extraordinary cases – that is, those involving “substantial or permanent loss of body function, substantial disfigurement, or death.” It also isn’t applicable in cases in which a jury decides that a defendant acted with intentional malice.

Lawmakers and Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds would like to change this.

Under a Senate bill that has now passed out of committee and is awaiting debate on the Senate floor, even plaintiffs involved in extreme cases would receive no more than $1 million to compensate for their pain, suffering, or emotional distress. (The bill also includes a 2.1% annual hike to compensate for inflation. A similar bill, which adds “loss of pregnancy” to the list of extreme cases, has advanced to the House floor.)

Supporters say the proposed cap would help to limit mega awards. In Johnson County in March 2022, for instance, a jury awarded $97.4 million to the parents of a young boy who sustained severe brain injuries during his delivery, causing the clinic that had been involved in the case to file for bankruptcy. This award was nearly three times the total payouts ($35 million) in the entire state of Iowa in all of 2021, a year in which there were 192 closed claims, including at least a dozen that resulted in payouts of $1 million or more.

Supporters also think the proposed cap will mitigate what they see as a looming doctor shortage, especially among ob.gyns. in eastern Iowa. “I just cannot overstate how much this is affecting our workforce, and that turns into effects for the women and the children, the babies, in our state,” Shannon Leveridge, MD, an obstetrician in Davenport said. “In order to keep these women and their babies safe, we need doctors.”

But critics of the bill, including some lawmakers and the trial bar, say it overreaches, even in the case of the $97.4 million award.

“They don’t want to talk about the actual damages that are caused by medical negligence,” explained a spokesman for the trial lawyers. “So, you don’t hear about the fact that, of the $50 million of economic damages ... most of that is going to go to the 24/7 care for this child for the rest of his life.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Remote electrical neuromodulation device helps reduce migraine days

, according to recent research published in the journal Headache.

The prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial showed that remote electrical neuromodulation (REN) with Nerivio (Theranica Bio-Electronics Ltd.; Bridgewater, N.J.) found a mean reduction/decrease in the number of migraine days by an average of 4.0 days per month, according to Stewart J. Tepper MD, of the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth in Hanover, N.H., and colleagues.*

“The statistically significant results were maintained in separate subanalyses of the chronic and episodic subsamples, as well as in the separate subanalyses of participants who used and did not use migraine prophylaxis,” Dr. Tepper and colleagues wrote.

A nonpharmacological alternative

Researchers randomized 248 participants into active and placebo groups, with 95 participants in the active group and 84 participants in the placebo group meeting the criteria for a modified intention-to-treat (mITT) analysis. Most of the participants in the ITT dataset were women (85.9%) with an average age of 41.7 years, and a baseline average of 12.2 migraine days and 15.6 headache days. Overall, 52.4% of participants in the ITT dataset had chronic migraine, 25.0% had migraine with aura, and 41.1% were taking preventative medication.

Dr. Tepper and colleagues followed participants for 4 weeks at baseline for observation followed by 8 weeks of participants using the REN device every other day for 45 minutes, or a placebo device that “produces electrical pulses of the same maximum intensity (34 mA) and overall energy, but with different pulse durations and much lower frequencies compared with the active device.” Participants completed a daily diary where they recorded their symptoms.

Researchers assessed the mean change in number of migraine days per month as a primary outcome, and evaluated participants who experienced episodic and chronic migraines separately in subgroup analyses. Secondary outcome measures included mean change in number of moderate or severe headache days, 50% reduction in mean number of headache days compared with baseline, Headache Impact Test short form (HIT-6) and Migraine Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (MSQ) Role Function Domain total score mean change at 12 weeks compared with week 1, and reduction in mean number of days taking acute headache or migraine medication.

Participants receiving REN treatment had a significant reduction in mean migraine days per month compared with the placebo group (4.0 days vs. 1.3 days; 95% confidence interval, –3.9 days to –1.5 days; P < .001). In subgroup analyses, a significant reduction in migraine days was seen in participants receiving REN treatment with episodic migraine (3.2 days vs. 1.0 days; P = .003) and chronic migraine (4.7 days vs. 1.6 days; P = .001) compared with placebo.

Dr. Tepper and colleagues found a significant reduction in moderate and/or severe headache days among participants receiving REN treatment compared with placebo (3.8 days vs. 2.2 days; P = .005), a significant reduction in headache days overall compared with placebo (4.5 days vs. 1.8 days; P < .001), a significant percentage of patients who experienced 50% reduction in moderate and/or severe headache days compared with placebo (51.6% vs. 35.7%; P = .033), and a significant reduction in acute medication days compared with placebo (3.5 days vs. 1.4 days; P = .001). Dr. Tepper and colleagues found no serious device-related adverse events in either group.

The researchers noted that REN therapy is a “much-needed nonpharmacological alternative” to other preventive and acute treatments for migraine. “Given the previously well-established clinical efficacy and high safety profile in acute treatment of migraine, REN can cover the entire treatment spectrum of migraine, including both acute and preventive treatments,” they said.

‘A good place to start’

Commenting on the study, Alan M. Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at University of California, Los Angeles; past president of the International Headache Society; and editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews, said the study was well designed, but acknowledged the 8-week follow-up time for participants as one potential area where he would have wanted to see more data.

As a medical device cleared for use by the Food and Drug Administration for acute treatment of migraine, the REM device also appears to be effective as a migraine preventative based on the results of the study with “virtually no adverse events,” he noted.

“I think this is a great treatment. I think it’s a good place to start,” Dr. Rapoport said. Given the low adverse event rate, he said he would be willing to offer the device to patients as a first option for preventing migraine and either switch to another preventative option or add an additional medication in combination based on how the patient responds. However, at the moment, he noted that this device is not covered by insurance.

Now that a REN device has been shown to work in the acute setting and as a preventative, Dr. Rapoport said he is interested in seeing other devices that have been cleared by the FDA as migraine treatments evaluated in migraine prevention. “I think we need more patients tried on the devices so we get an idea of which ones work acutely, which ones work preventively,” he said.

The authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of advisory board positions, consultancies, grants, research principal investigator roles, royalties, speakers bureau positions, and stockholders for a variety of pharmaceutical companies, agencies, and other organizations. Several authors disclosed ties with Theranica, the manufacturer of the REN device used in the study. Dr. Rapoport is editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews and a consultant for Theranica, but was not involved in studies associated with the REN device.

Correction, 2/10/23: An earlier version of this article misstated the reduction in number of migraine days.

, according to recent research published in the journal Headache.

The prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial showed that remote electrical neuromodulation (REN) with Nerivio (Theranica Bio-Electronics Ltd.; Bridgewater, N.J.) found a mean reduction/decrease in the number of migraine days by an average of 4.0 days per month, according to Stewart J. Tepper MD, of the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth in Hanover, N.H., and colleagues.*

“The statistically significant results were maintained in separate subanalyses of the chronic and episodic subsamples, as well as in the separate subanalyses of participants who used and did not use migraine prophylaxis,” Dr. Tepper and colleagues wrote.

A nonpharmacological alternative

Researchers randomized 248 participants into active and placebo groups, with 95 participants in the active group and 84 participants in the placebo group meeting the criteria for a modified intention-to-treat (mITT) analysis. Most of the participants in the ITT dataset were women (85.9%) with an average age of 41.7 years, and a baseline average of 12.2 migraine days and 15.6 headache days. Overall, 52.4% of participants in the ITT dataset had chronic migraine, 25.0% had migraine with aura, and 41.1% were taking preventative medication.

Dr. Tepper and colleagues followed participants for 4 weeks at baseline for observation followed by 8 weeks of participants using the REN device every other day for 45 minutes, or a placebo device that “produces electrical pulses of the same maximum intensity (34 mA) and overall energy, but with different pulse durations and much lower frequencies compared with the active device.” Participants completed a daily diary where they recorded their symptoms.

Researchers assessed the mean change in number of migraine days per month as a primary outcome, and evaluated participants who experienced episodic and chronic migraines separately in subgroup analyses. Secondary outcome measures included mean change in number of moderate or severe headache days, 50% reduction in mean number of headache days compared with baseline, Headache Impact Test short form (HIT-6) and Migraine Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (MSQ) Role Function Domain total score mean change at 12 weeks compared with week 1, and reduction in mean number of days taking acute headache or migraine medication.

Participants receiving REN treatment had a significant reduction in mean migraine days per month compared with the placebo group (4.0 days vs. 1.3 days; 95% confidence interval, –3.9 days to –1.5 days; P < .001). In subgroup analyses, a significant reduction in migraine days was seen in participants receiving REN treatment with episodic migraine (3.2 days vs. 1.0 days; P = .003) and chronic migraine (4.7 days vs. 1.6 days; P = .001) compared with placebo.

Dr. Tepper and colleagues found a significant reduction in moderate and/or severe headache days among participants receiving REN treatment compared with placebo (3.8 days vs. 2.2 days; P = .005), a significant reduction in headache days overall compared with placebo (4.5 days vs. 1.8 days; P < .001), a significant percentage of patients who experienced 50% reduction in moderate and/or severe headache days compared with placebo (51.6% vs. 35.7%; P = .033), and a significant reduction in acute medication days compared with placebo (3.5 days vs. 1.4 days; P = .001). Dr. Tepper and colleagues found no serious device-related adverse events in either group.

The researchers noted that REN therapy is a “much-needed nonpharmacological alternative” to other preventive and acute treatments for migraine. “Given the previously well-established clinical efficacy and high safety profile in acute treatment of migraine, REN can cover the entire treatment spectrum of migraine, including both acute and preventive treatments,” they said.

‘A good place to start’

Commenting on the study, Alan M. Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at University of California, Los Angeles; past president of the International Headache Society; and editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews, said the study was well designed, but acknowledged the 8-week follow-up time for participants as one potential area where he would have wanted to see more data.

As a medical device cleared for use by the Food and Drug Administration for acute treatment of migraine, the REM device also appears to be effective as a migraine preventative based on the results of the study with “virtually no adverse events,” he noted.

“I think this is a great treatment. I think it’s a good place to start,” Dr. Rapoport said. Given the low adverse event rate, he said he would be willing to offer the device to patients as a first option for preventing migraine and either switch to another preventative option or add an additional medication in combination based on how the patient responds. However, at the moment, he noted that this device is not covered by insurance.

Now that a REN device has been shown to work in the acute setting and as a preventative, Dr. Rapoport said he is interested in seeing other devices that have been cleared by the FDA as migraine treatments evaluated in migraine prevention. “I think we need more patients tried on the devices so we get an idea of which ones work acutely, which ones work preventively,” he said.

The authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of advisory board positions, consultancies, grants, research principal investigator roles, royalties, speakers bureau positions, and stockholders for a variety of pharmaceutical companies, agencies, and other organizations. Several authors disclosed ties with Theranica, the manufacturer of the REN device used in the study. Dr. Rapoport is editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews and a consultant for Theranica, but was not involved in studies associated with the REN device.

Correction, 2/10/23: An earlier version of this article misstated the reduction in number of migraine days.

, according to recent research published in the journal Headache.

The prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial showed that remote electrical neuromodulation (REN) with Nerivio (Theranica Bio-Electronics Ltd.; Bridgewater, N.J.) found a mean reduction/decrease in the number of migraine days by an average of 4.0 days per month, according to Stewart J. Tepper MD, of the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth in Hanover, N.H., and colleagues.*

“The statistically significant results were maintained in separate subanalyses of the chronic and episodic subsamples, as well as in the separate subanalyses of participants who used and did not use migraine prophylaxis,” Dr. Tepper and colleagues wrote.

A nonpharmacological alternative

Researchers randomized 248 participants into active and placebo groups, with 95 participants in the active group and 84 participants in the placebo group meeting the criteria for a modified intention-to-treat (mITT) analysis. Most of the participants in the ITT dataset were women (85.9%) with an average age of 41.7 years, and a baseline average of 12.2 migraine days and 15.6 headache days. Overall, 52.4% of participants in the ITT dataset had chronic migraine, 25.0% had migraine with aura, and 41.1% were taking preventative medication.

Dr. Tepper and colleagues followed participants for 4 weeks at baseline for observation followed by 8 weeks of participants using the REN device every other day for 45 minutes, or a placebo device that “produces electrical pulses of the same maximum intensity (34 mA) and overall energy, but with different pulse durations and much lower frequencies compared with the active device.” Participants completed a daily diary where they recorded their symptoms.

Researchers assessed the mean change in number of migraine days per month as a primary outcome, and evaluated participants who experienced episodic and chronic migraines separately in subgroup analyses. Secondary outcome measures included mean change in number of moderate or severe headache days, 50% reduction in mean number of headache days compared with baseline, Headache Impact Test short form (HIT-6) and Migraine Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (MSQ) Role Function Domain total score mean change at 12 weeks compared with week 1, and reduction in mean number of days taking acute headache or migraine medication.

Participants receiving REN treatment had a significant reduction in mean migraine days per month compared with the placebo group (4.0 days vs. 1.3 days; 95% confidence interval, –3.9 days to –1.5 days; P < .001). In subgroup analyses, a significant reduction in migraine days was seen in participants receiving REN treatment with episodic migraine (3.2 days vs. 1.0 days; P = .003) and chronic migraine (4.7 days vs. 1.6 days; P = .001) compared with placebo.

Dr. Tepper and colleagues found a significant reduction in moderate and/or severe headache days among participants receiving REN treatment compared with placebo (3.8 days vs. 2.2 days; P = .005), a significant reduction in headache days overall compared with placebo (4.5 days vs. 1.8 days; P < .001), a significant percentage of patients who experienced 50% reduction in moderate and/or severe headache days compared with placebo (51.6% vs. 35.7%; P = .033), and a significant reduction in acute medication days compared with placebo (3.5 days vs. 1.4 days; P = .001). Dr. Tepper and colleagues found no serious device-related adverse events in either group.

The researchers noted that REN therapy is a “much-needed nonpharmacological alternative” to other preventive and acute treatments for migraine. “Given the previously well-established clinical efficacy and high safety profile in acute treatment of migraine, REN can cover the entire treatment spectrum of migraine, including both acute and preventive treatments,” they said.

‘A good place to start’

Commenting on the study, Alan M. Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at University of California, Los Angeles; past president of the International Headache Society; and editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews, said the study was well designed, but acknowledged the 8-week follow-up time for participants as one potential area where he would have wanted to see more data.

As a medical device cleared for use by the Food and Drug Administration for acute treatment of migraine, the REM device also appears to be effective as a migraine preventative based on the results of the study with “virtually no adverse events,” he noted.

“I think this is a great treatment. I think it’s a good place to start,” Dr. Rapoport said. Given the low adverse event rate, he said he would be willing to offer the device to patients as a first option for preventing migraine and either switch to another preventative option or add an additional medication in combination based on how the patient responds. However, at the moment, he noted that this device is not covered by insurance.

Now that a REN device has been shown to work in the acute setting and as a preventative, Dr. Rapoport said he is interested in seeing other devices that have been cleared by the FDA as migraine treatments evaluated in migraine prevention. “I think we need more patients tried on the devices so we get an idea of which ones work acutely, which ones work preventively,” he said.

The authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of advisory board positions, consultancies, grants, research principal investigator roles, royalties, speakers bureau positions, and stockholders for a variety of pharmaceutical companies, agencies, and other organizations. Several authors disclosed ties with Theranica, the manufacturer of the REN device used in the study. Dr. Rapoport is editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews and a consultant for Theranica, but was not involved in studies associated with the REN device.

Correction, 2/10/23: An earlier version of this article misstated the reduction in number of migraine days.

FROM HEADACHE

Black patients less likely to receive opioids for advanced cancer

Opioids are widely regarded as a linchpin in the treatment of moderate to severe cancer-related pain and end-of-life symptoms; however, a new study suggests.

Black patients were more likely to undergo urine drug screening (UDS) despite being less likely to receive any opioids for pain management and receiving lower daily doses of opioids in comparison with White patients, the study found.

The inequities were particularly stark for Black men. “We found that Black men were far less likely to be prescribed reasonable doses than White men were,” said the study’s senior author, Alexi Wright, MD, MPH, a gynecologic oncologist and a researcher in the division of population sciences at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston. “And Black men were less likely to receive long-acting opioids, which are essential for many patients dying of cancer. Our findings are startling because everyone should agree that cancer patients should have equal access to pain relief at the end of life.”

The study was published on in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The researchers gathered data on 318,549 Medicare beneficiaries older than 65 years with poor-prognosis cancers who died between 2007 and 2019. During this time frame, for all groups, access to opioids declined and urine drug testing expanded, owing to the overall opioid epidemic in the United States. Overall, the proportion of patients near end of life (EOL) who received any opioid or long-acting opioids decreased from 42.2% to 32.7% and from 17.9% to 9.4%, respectively.

The investigators used National Drug Codes to identify all Medicare Part D claims for outpatient opioid prescriptions, excluding addiction treatments, cough suppressants, and parenteral opioids. They focused on prescriptions that were filled at least 30 days before death or hospice enrollment.

Among the study participants, the majority (85.5%) of patients were White, 29,555 patients (9.3%) were Black, and 16,636 patients (5.2%) were Hispanic.

Black and Hispanic patients were statistically less likely than White patients to receive opioid prescriptions near EOL (Black, –4.3 percentage points; Hispanic, –3.6 percentage points). They were also less likely to receive long-acting opioid prescriptions (Black, –3.1 percentage points; Hispanic, –2.2 percentage points).

“It’s not just that patients of color are less likely to get opioids, but when they do get them, they get lower doses, and they also are less likely to get long-acting opioids, which a lot of people view as sort of more potential for addiction, which isn’t necessarily true but kind of viewed with heightened concern or suspicion,” the study’s lead author, Andrea Enzinger, MD, a gastrointestinal oncologist and a researcher in Dana-Farber’s division of population sciences, said in an interview.

Dr. Enzinger added that she believes systemic racism and preconceived biases toward minorities and drug addiction may be contributing to these trends.

When Black patients did receive at least one opioid prescription, they received daily doses that were 10.5 morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs) lower than doses given to White patients. Compared with the total opioid dose filled per White decedent near EOL, the total dose filled per Black decedent was 210 MMEs lower.

“We all need to be worried about the potential for misuse or addiction, but this is the one setting that is very low on my priority list when somebody is dying. I mean, we’re looking at the last month of life, so nobody has the potential to become addicted,” Dr. Enzinger commented.

The team also evaluated rates or urine drug screening (UDS), but as these rates were relatively low, they expanded the time frame to 180 days before death or hospice. They found that disparities in UDS disproportionately affected Black men.

From 2007 to 2019, the proportion of patients who underwent UDS increased from 0.6% to 6.7% in the 180 days before death or hospice; however, Black decedents were tested more often than White or Hispanic decedents.

Black decedents were 0.5 percentage points more likely than White decedents to undergo UDS near EOL.

“The disparities in urine drug screening are modest but important, because they hint at underlying systematic racism in recommending patients for screening,” Dr. Wright said. “Screening needs to either be applied uniformly or not at all for patients in this situation.”

The researchers acknowledged that their findings likely do not represent the full spectrum of prescribing disparities and believe that the work should be expanded among younger populations. Nevertheless, the investigators believe the work highlights the persistent racial and ethnic disparities in opioid access.

The study was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Policy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Opioids are widely regarded as a linchpin in the treatment of moderate to severe cancer-related pain and end-of-life symptoms; however, a new study suggests.

Black patients were more likely to undergo urine drug screening (UDS) despite being less likely to receive any opioids for pain management and receiving lower daily doses of opioids in comparison with White patients, the study found.

The inequities were particularly stark for Black men. “We found that Black men were far less likely to be prescribed reasonable doses than White men were,” said the study’s senior author, Alexi Wright, MD, MPH, a gynecologic oncologist and a researcher in the division of population sciences at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston. “And Black men were less likely to receive long-acting opioids, which are essential for many patients dying of cancer. Our findings are startling because everyone should agree that cancer patients should have equal access to pain relief at the end of life.”

The study was published on in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The researchers gathered data on 318,549 Medicare beneficiaries older than 65 years with poor-prognosis cancers who died between 2007 and 2019. During this time frame, for all groups, access to opioids declined and urine drug testing expanded, owing to the overall opioid epidemic in the United States. Overall, the proportion of patients near end of life (EOL) who received any opioid or long-acting opioids decreased from 42.2% to 32.7% and from 17.9% to 9.4%, respectively.

The investigators used National Drug Codes to identify all Medicare Part D claims for outpatient opioid prescriptions, excluding addiction treatments, cough suppressants, and parenteral opioids. They focused on prescriptions that were filled at least 30 days before death or hospice enrollment.

Among the study participants, the majority (85.5%) of patients were White, 29,555 patients (9.3%) were Black, and 16,636 patients (5.2%) were Hispanic.

Black and Hispanic patients were statistically less likely than White patients to receive opioid prescriptions near EOL (Black, –4.3 percentage points; Hispanic, –3.6 percentage points). They were also less likely to receive long-acting opioid prescriptions (Black, –3.1 percentage points; Hispanic, –2.2 percentage points).

“It’s not just that patients of color are less likely to get opioids, but when they do get them, they get lower doses, and they also are less likely to get long-acting opioids, which a lot of people view as sort of more potential for addiction, which isn’t necessarily true but kind of viewed with heightened concern or suspicion,” the study’s lead author, Andrea Enzinger, MD, a gastrointestinal oncologist and a researcher in Dana-Farber’s division of population sciences, said in an interview.

Dr. Enzinger added that she believes systemic racism and preconceived biases toward minorities and drug addiction may be contributing to these trends.

When Black patients did receive at least one opioid prescription, they received daily doses that were 10.5 morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs) lower than doses given to White patients. Compared with the total opioid dose filled per White decedent near EOL, the total dose filled per Black decedent was 210 MMEs lower.

“We all need to be worried about the potential for misuse or addiction, but this is the one setting that is very low on my priority list when somebody is dying. I mean, we’re looking at the last month of life, so nobody has the potential to become addicted,” Dr. Enzinger commented.

The team also evaluated rates or urine drug screening (UDS), but as these rates were relatively low, they expanded the time frame to 180 days before death or hospice. They found that disparities in UDS disproportionately affected Black men.

From 2007 to 2019, the proportion of patients who underwent UDS increased from 0.6% to 6.7% in the 180 days before death or hospice; however, Black decedents were tested more often than White or Hispanic decedents.

Black decedents were 0.5 percentage points more likely than White decedents to undergo UDS near EOL.

“The disparities in urine drug screening are modest but important, because they hint at underlying systematic racism in recommending patients for screening,” Dr. Wright said. “Screening needs to either be applied uniformly or not at all for patients in this situation.”

The researchers acknowledged that their findings likely do not represent the full spectrum of prescribing disparities and believe that the work should be expanded among younger populations. Nevertheless, the investigators believe the work highlights the persistent racial and ethnic disparities in opioid access.

The study was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Policy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Opioids are widely regarded as a linchpin in the treatment of moderate to severe cancer-related pain and end-of-life symptoms; however, a new study suggests.

Black patients were more likely to undergo urine drug screening (UDS) despite being less likely to receive any opioids for pain management and receiving lower daily doses of opioids in comparison with White patients, the study found.

The inequities were particularly stark for Black men. “We found that Black men were far less likely to be prescribed reasonable doses than White men were,” said the study’s senior author, Alexi Wright, MD, MPH, a gynecologic oncologist and a researcher in the division of population sciences at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston. “And Black men were less likely to receive long-acting opioids, which are essential for many patients dying of cancer. Our findings are startling because everyone should agree that cancer patients should have equal access to pain relief at the end of life.”

The study was published on in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The researchers gathered data on 318,549 Medicare beneficiaries older than 65 years with poor-prognosis cancers who died between 2007 and 2019. During this time frame, for all groups, access to opioids declined and urine drug testing expanded, owing to the overall opioid epidemic in the United States. Overall, the proportion of patients near end of life (EOL) who received any opioid or long-acting opioids decreased from 42.2% to 32.7% and from 17.9% to 9.4%, respectively.

The investigators used National Drug Codes to identify all Medicare Part D claims for outpatient opioid prescriptions, excluding addiction treatments, cough suppressants, and parenteral opioids. They focused on prescriptions that were filled at least 30 days before death or hospice enrollment.

Among the study participants, the majority (85.5%) of patients were White, 29,555 patients (9.3%) were Black, and 16,636 patients (5.2%) were Hispanic.

Black and Hispanic patients were statistically less likely than White patients to receive opioid prescriptions near EOL (Black, –4.3 percentage points; Hispanic, –3.6 percentage points). They were also less likely to receive long-acting opioid prescriptions (Black, –3.1 percentage points; Hispanic, –2.2 percentage points).

“It’s not just that patients of color are less likely to get opioids, but when they do get them, they get lower doses, and they also are less likely to get long-acting opioids, which a lot of people view as sort of more potential for addiction, which isn’t necessarily true but kind of viewed with heightened concern or suspicion,” the study’s lead author, Andrea Enzinger, MD, a gastrointestinal oncologist and a researcher in Dana-Farber’s division of population sciences, said in an interview.

Dr. Enzinger added that she believes systemic racism and preconceived biases toward minorities and drug addiction may be contributing to these trends.

When Black patients did receive at least one opioid prescription, they received daily doses that were 10.5 morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs) lower than doses given to White patients. Compared with the total opioid dose filled per White decedent near EOL, the total dose filled per Black decedent was 210 MMEs lower.

“We all need to be worried about the potential for misuse or addiction, but this is the one setting that is very low on my priority list when somebody is dying. I mean, we’re looking at the last month of life, so nobody has the potential to become addicted,” Dr. Enzinger commented.

The team also evaluated rates or urine drug screening (UDS), but as these rates were relatively low, they expanded the time frame to 180 days before death or hospice. They found that disparities in UDS disproportionately affected Black men.

From 2007 to 2019, the proportion of patients who underwent UDS increased from 0.6% to 6.7% in the 180 days before death or hospice; however, Black decedents were tested more often than White or Hispanic decedents.

Black decedents were 0.5 percentage points more likely than White decedents to undergo UDS near EOL.

“The disparities in urine drug screening are modest but important, because they hint at underlying systematic racism in recommending patients for screening,” Dr. Wright said. “Screening needs to either be applied uniformly or not at all for patients in this situation.”

The researchers acknowledged that their findings likely do not represent the full spectrum of prescribing disparities and believe that the work should be expanded among younger populations. Nevertheless, the investigators believe the work highlights the persistent racial and ethnic disparities in opioid access.

The study was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Policy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Is the American Venous Forum consensus statement on lymphedema helpful?

Despite treatments, patients still continue to suffer with symptoms such as pain and leg heaviness, and get only mild improvement. Patients receiving treatments rarely become symptom free.

According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), primary or congenital lymphedema is a rare disorder occurring in 1 out of 100,00 Americans. On the other hand, secondary or acquired lymphedema is seen in 1 out of every 1,000 and is a complication of many cancers. For example, 1 out of every 5 women who survive breast cancer will develop lymphedema.

Given the statistics, primary care doctors will likely be responsible for treating patients with this disorder. It is important to note that the American Venous Forum consensus statement concluded that the diagnosis can be made based on clinical exam alone.

Given this fact, practitioners should be able to distinguish lymphedema from other similar diseases. As primary care doctors, we are likely to be the first ones to evaluate and diagnose this disease and need to be proficient on physical findings. We should also know the risk factors. No tests need to be performed, and this is a positive in this time of rising health care costs.

Another important conclusion of the consensus statement is that patients with chronic venous insufficiency should be treated the same as patients with lymphedema, especially given the fact that it can be a secondary cause of lymphedema. However, those disagreeing with this in the panel that developed the consensus statement endorsed doing a venous ultrasound to establish the cause.

Chronic venous insufficiency and lymphedema are often confused for each other, and the fact that they should be treated the same further establishes the fact that no further testing is needed. It can be argued that if we order a test when we suspect lymphedema, it serves only to drive up the cost and delays the initiation of treatment.

One area in which the panel of experts who developed the consensus statement showed some variability was in their recommendations for the treatment of lymphedema. Regular use of compression stockings to reduce lymphedema progression and manual lymphatic drainage were favored by most of the panel members, while Velcro devices and surgery were not.

While it is worthwhile to note this conclusion, determining how to treat a patient in clinical practice is often much more difficult. For one thing, some of these treatments are hard to get covered by insurance companies. Also, there is no objective data, unlike blood pressure or diabetic readings, to show the efficacy of a therapy for lymphedema. Instead, a diagnosis of lymphedema is based on a patient’s subjective symptoms. Many patients experience no substantial improvement from treatment, and even modest improvements can be considered a failure to them.

Another obstacle to treatment is that many patients find the treatment modalities uncomfortable or unsustainable. Some find the compression devices painful, for example. But often, they are given ones that have not been custom fitted to them, especially in the days of COVID when these are most often shipped to the patients’ homes. Also, manual drainage can be very time-consuming. To be effective, some patients need to do it more than once a day and it can take 30-60 minutes. Patients have jobs to go to and just don’t have the downtime to be able to do it effectively.

While this consensus statement does a good job analyzing current diagnosis and treatment of lymphedema, further research is needed to find new treatments and better education of clinicians needs to be done.

Lymphedema is an often-overlooked diagnosis despite having obvious clinical findings. There is currently no cure for lymphedema and the treatments that we do have available are not going to eliminate symptoms.

Patients are often frustrated by the lack of clinical improvement and there is little left to offer them. If we truly want to make an impact in our lymphedema patients, we need a better treatment. For now, we can offer them what is proven by the best evidence to reduce symptoms and support them in their suffering. Sometimes a listening ear and kind heart can make an even larger impact than just offering a treatment that doesn’t cure their disease.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, N.J., and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. You can contact her at [email protected].

Despite treatments, patients still continue to suffer with symptoms such as pain and leg heaviness, and get only mild improvement. Patients receiving treatments rarely become symptom free.

According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), primary or congenital lymphedema is a rare disorder occurring in 1 out of 100,00 Americans. On the other hand, secondary or acquired lymphedema is seen in 1 out of every 1,000 and is a complication of many cancers. For example, 1 out of every 5 women who survive breast cancer will develop lymphedema.

Given the statistics, primary care doctors will likely be responsible for treating patients with this disorder. It is important to note that the American Venous Forum consensus statement concluded that the diagnosis can be made based on clinical exam alone.

Given this fact, practitioners should be able to distinguish lymphedema from other similar diseases. As primary care doctors, we are likely to be the first ones to evaluate and diagnose this disease and need to be proficient on physical findings. We should also know the risk factors. No tests need to be performed, and this is a positive in this time of rising health care costs.

Another important conclusion of the consensus statement is that patients with chronic venous insufficiency should be treated the same as patients with lymphedema, especially given the fact that it can be a secondary cause of lymphedema. However, those disagreeing with this in the panel that developed the consensus statement endorsed doing a venous ultrasound to establish the cause.

Chronic venous insufficiency and lymphedema are often confused for each other, and the fact that they should be treated the same further establishes the fact that no further testing is needed. It can be argued that if we order a test when we suspect lymphedema, it serves only to drive up the cost and delays the initiation of treatment.

One area in which the panel of experts who developed the consensus statement showed some variability was in their recommendations for the treatment of lymphedema. Regular use of compression stockings to reduce lymphedema progression and manual lymphatic drainage were favored by most of the panel members, while Velcro devices and surgery were not.

While it is worthwhile to note this conclusion, determining how to treat a patient in clinical practice is often much more difficult. For one thing, some of these treatments are hard to get covered by insurance companies. Also, there is no objective data, unlike blood pressure or diabetic readings, to show the efficacy of a therapy for lymphedema. Instead, a diagnosis of lymphedema is based on a patient’s subjective symptoms. Many patients experience no substantial improvement from treatment, and even modest improvements can be considered a failure to them.

Another obstacle to treatment is that many patients find the treatment modalities uncomfortable or unsustainable. Some find the compression devices painful, for example. But often, they are given ones that have not been custom fitted to them, especially in the days of COVID when these are most often shipped to the patients’ homes. Also, manual drainage can be very time-consuming. To be effective, some patients need to do it more than once a day and it can take 30-60 minutes. Patients have jobs to go to and just don’t have the downtime to be able to do it effectively.

While this consensus statement does a good job analyzing current diagnosis and treatment of lymphedema, further research is needed to find new treatments and better education of clinicians needs to be done.

Lymphedema is an often-overlooked diagnosis despite having obvious clinical findings. There is currently no cure for lymphedema and the treatments that we do have available are not going to eliminate symptoms.

Patients are often frustrated by the lack of clinical improvement and there is little left to offer them. If we truly want to make an impact in our lymphedema patients, we need a better treatment. For now, we can offer them what is proven by the best evidence to reduce symptoms and support them in their suffering. Sometimes a listening ear and kind heart can make an even larger impact than just offering a treatment that doesn’t cure their disease.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, N.J., and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. You can contact her at [email protected].

Despite treatments, patients still continue to suffer with symptoms such as pain and leg heaviness, and get only mild improvement. Patients receiving treatments rarely become symptom free.

According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), primary or congenital lymphedema is a rare disorder occurring in 1 out of 100,00 Americans. On the other hand, secondary or acquired lymphedema is seen in 1 out of every 1,000 and is a complication of many cancers. For example, 1 out of every 5 women who survive breast cancer will develop lymphedema.

Given the statistics, primary care doctors will likely be responsible for treating patients with this disorder. It is important to note that the American Venous Forum consensus statement concluded that the diagnosis can be made based on clinical exam alone.

Given this fact, practitioners should be able to distinguish lymphedema from other similar diseases. As primary care doctors, we are likely to be the first ones to evaluate and diagnose this disease and need to be proficient on physical findings. We should also know the risk factors. No tests need to be performed, and this is a positive in this time of rising health care costs.

Another important conclusion of the consensus statement is that patients with chronic venous insufficiency should be treated the same as patients with lymphedema, especially given the fact that it can be a secondary cause of lymphedema. However, those disagreeing with this in the panel that developed the consensus statement endorsed doing a venous ultrasound to establish the cause.

Chronic venous insufficiency and lymphedema are often confused for each other, and the fact that they should be treated the same further establishes the fact that no further testing is needed. It can be argued that if we order a test when we suspect lymphedema, it serves only to drive up the cost and delays the initiation of treatment.

One area in which the panel of experts who developed the consensus statement showed some variability was in their recommendations for the treatment of lymphedema. Regular use of compression stockings to reduce lymphedema progression and manual lymphatic drainage were favored by most of the panel members, while Velcro devices and surgery were not.

While it is worthwhile to note this conclusion, determining how to treat a patient in clinical practice is often much more difficult. For one thing, some of these treatments are hard to get covered by insurance companies. Also, there is no objective data, unlike blood pressure or diabetic readings, to show the efficacy of a therapy for lymphedema. Instead, a diagnosis of lymphedema is based on a patient’s subjective symptoms. Many patients experience no substantial improvement from treatment, and even modest improvements can be considered a failure to them.

Another obstacle to treatment is that many patients find the treatment modalities uncomfortable or unsustainable. Some find the compression devices painful, for example. But often, they are given ones that have not been custom fitted to them, especially in the days of COVID when these are most often shipped to the patients’ homes. Also, manual drainage can be very time-consuming. To be effective, some patients need to do it more than once a day and it can take 30-60 minutes. Patients have jobs to go to and just don’t have the downtime to be able to do it effectively.

While this consensus statement does a good job analyzing current diagnosis and treatment of lymphedema, further research is needed to find new treatments and better education of clinicians needs to be done.

Lymphedema is an often-overlooked diagnosis despite having obvious clinical findings. There is currently no cure for lymphedema and the treatments that we do have available are not going to eliminate symptoms.

Patients are often frustrated by the lack of clinical improvement and there is little left to offer them. If we truly want to make an impact in our lymphedema patients, we need a better treatment. For now, we can offer them what is proven by the best evidence to reduce symptoms and support them in their suffering. Sometimes a listening ear and kind heart can make an even larger impact than just offering a treatment that doesn’t cure their disease.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, N.J., and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. You can contact her at [email protected].

14-year-old boy • aching midsternal pain following a basketball injury • worsening pain with direct pressure and when the patient sneezed • Dx?

THE CASE

A 14-year-old boy sought care at our clinic for persistent chest pain after being hit in the chest with a teammate’s shoulder during a basketball game 3 weeks earlier. He had aching midsternal chest pain that worsened with direct pressure and when he sneezed, twisted, or bent forward. There was no bruising or swelling.

On examination, the patient demonstrated normal perfusion and normal work of breathing. He had focal tenderness with palpation at the manubrium with no noticeable step-off, and mild tenderness at the adjacent costochondral junctions and over his pectoral muscles. His sternal pain along the proximal sternum was reproducible with a weighted wall push-up. Although the patient maintained full range of motion in his upper extremities, he did have sternal pain with flexion, abduction, and external rotation of the bilateral upper extremities against resistance. Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral chest radiographs were unremarkable.

THE DIAGNOSIS

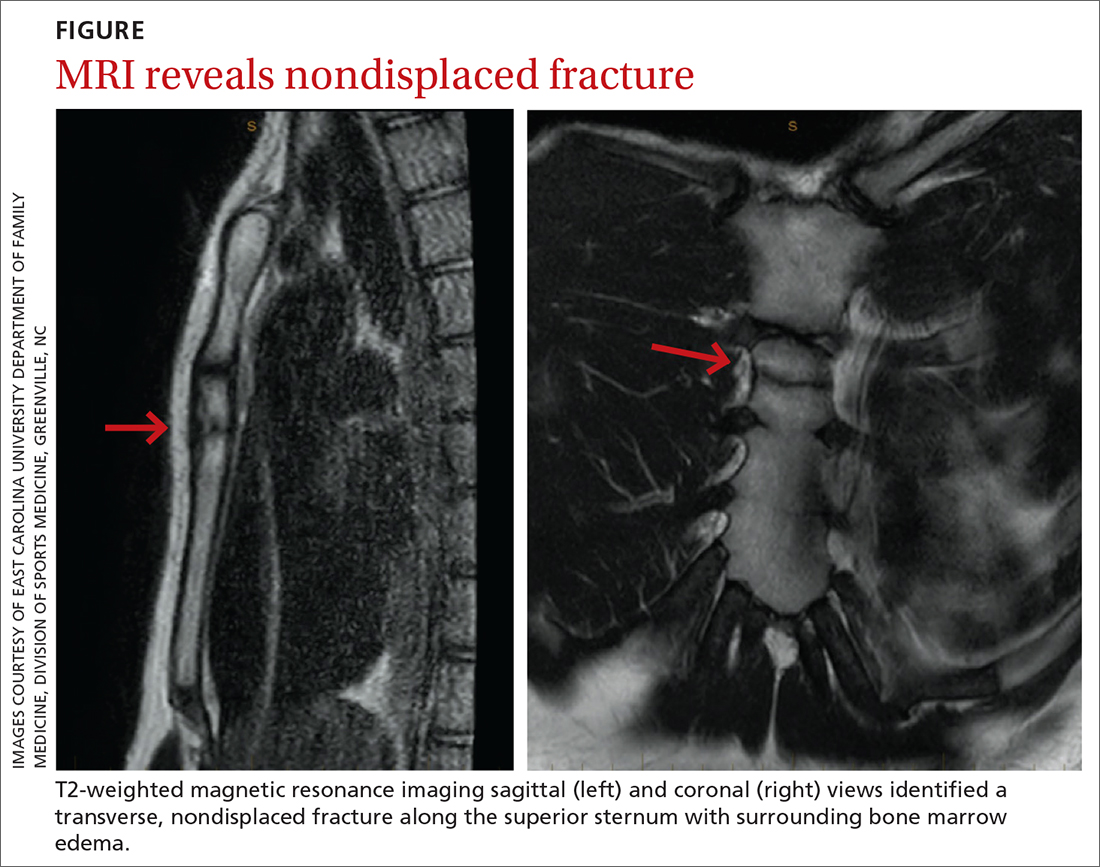

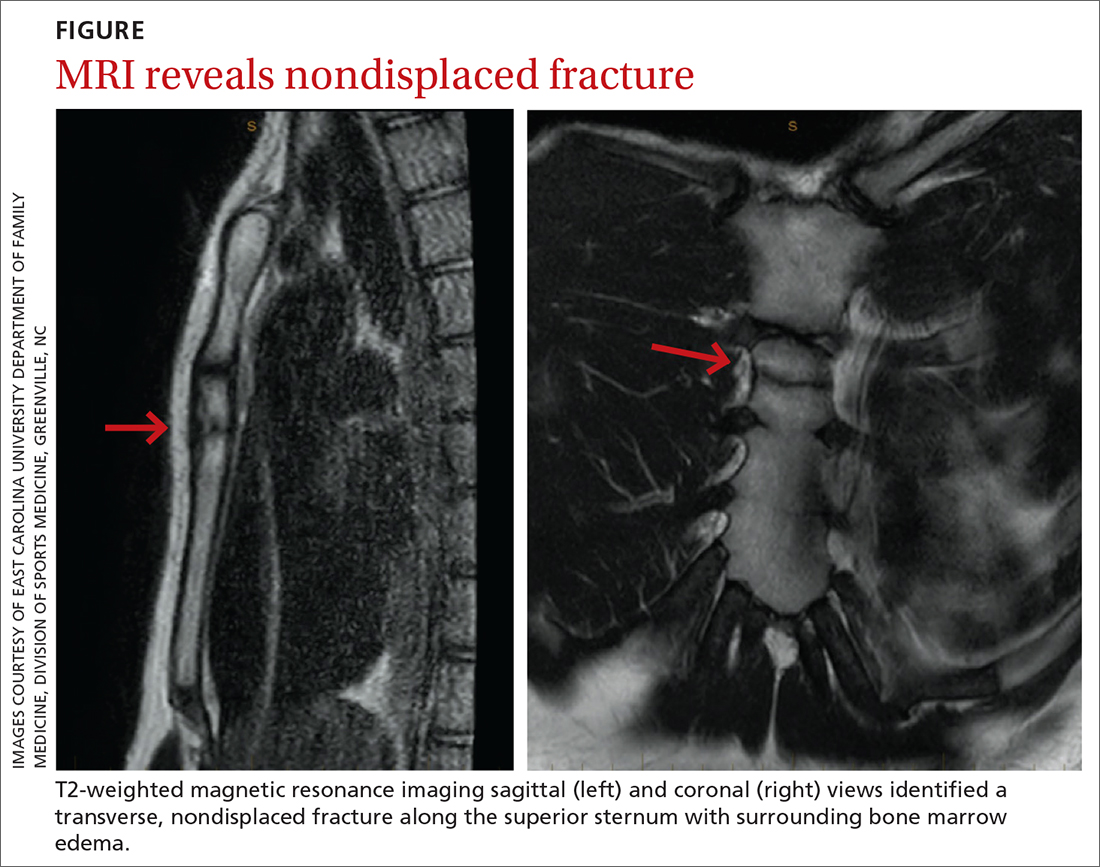

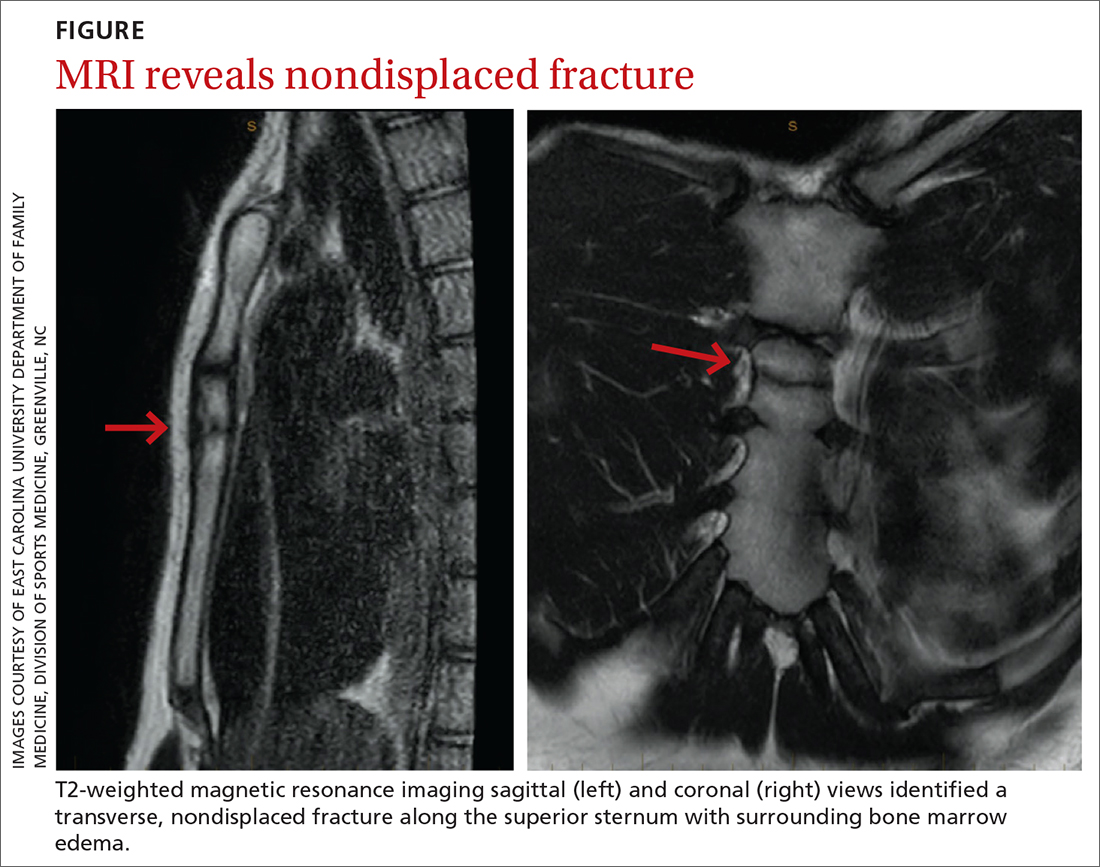

The unremarkable chest radiographs prompted further investigation with a diagnostic ultrasound, which revealed a small cortical defect with overlying anechoic fluid collection in the area of focal tenderness. T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the chest was performed; it revealed a transverse, nondisplaced fracture of the superior body of the sternum with surrounding bone marrow edema (FIGURE).

DISCUSSION

Fractures of the sternum comprise < 1% of traumatic fractures and have a low mortality rate (0.7%).1,2 The rarity of these fractures is attributed to the ribs’ elastic recoil, which protects the chest wall from anterior forces.1,3 These fractures are even more unusual in children due to the increased elasticity of their chest walls.4-6 Thus, it takes a significant amount of force for a child’s sternum to fracture.

While isolated sternum fractures can occur, two-thirds of sternum fractures are nonisolated and are associated with injuries to surrounding structures (including the heart, lungs, and vasculature) or fractures of the ribs and spine.2,3 Most often, these injuries are caused by significant blunt trauma to the anterior chest, rapid deceleration, or flexion-compression injury.2,3 They are typically transverse and localized, with 70% of fractures occurring in the mid-body and 17.6% at the manubriosternal joint.1,3,6

Athletes with a sternal fracture typically present as our patient did, with a history of blunt force trauma to the chest and with pain and tenderness over the anterior midline of the chest that increases with respiration or movement.1 A physical examination that includes chest palpation and auscultation of the heart and lungs must be performed to rule out damage to intrathoracic structures and assess the patient’s cardiac and pulmonary stability. An electrocardiogram should be performed to confirm that there are no cardiovascular complications.3,4

Initial imaging should include AP and lateral chest radiographs because any displacement will occur in the sagittal plane.1,2,4-6 If the radiograph shows no clear pathology, follow up with computed tomography, ultrasound, MRI, or technetium bone scans to gain additional information.1 Diagnosis of sternal fractures is especially difficult in children due to the presence of ossification centers for bone growth, which may be misinterpreted as a sternal fracture in the absence of a proper understanding of sternal development.5,6 On ultrasound, sternal fractures appear as a sharp step-off in the cortex, whereas in the absence of fracture, there is no cortical step-off and the cartilaginous plate between ossification centers appears in line with the cortex.7

Continue to: A self-limiting injury that requires proper pain control

A self-limiting injury that requires proper pain control

Isolated sternal fractures are typically self-limiting with a good prognosis.2 These injuries are managed supportively with rest, ice, and analgesics1; proper pain control is crucial to prevent respiratory compromise.8

Complete recovery for most patients occurs in 10 to 12 weeks.9 Recovery periods longer than 12 weeks are associated with nonisolated sternal fractures that are complicated by soft-tissue injury, injuries to the chest wall (such as sternoclavicular joint dislocation, usually from a fall on the shoulder), or fracture nonunion.1,2,5

Anterior sternoclavicular joint dislocations and stable posterior dislocations are managed with closed reduction and immobilization in a figure-of-eight brace.1 Operative management is reserved for patients with displaced fractures, sternal deformity, chest wall instability, respiratory insufficiency, uncontrolled pain, or fracture nonunion.1,3,8

A return-to-play protocol can begin once the patient is asymptomatic.1 The timeframe for a full return to play can vary from 6 weeks to 6 months, depending on the severity of the fracture.1 This process is guided by how quickly the symptoms resolve and by radiographic stability.9

Our patient was followed every 3 to 4 weeks and started physical therapy 6 weeks after his injury occurred. He was held from play for 10 weeks and gradually returned to play; he returned to full-contact activity after tolerating a practice without pain.

THE TAKEAWAY

Children typically have greater chest wall elasticity, and thus, it is unusual for them to sustain a sternal fracture. Diagnosis in children is complicated by the presence of ossification centers for bone growth on imaging. In this case, the fracture was first noticed on ultrasound and confirmed with MRI. Since these fractures can be associated with damage to surrounding structures, additional injuries should be considered when evaluating a patient with a sternum fracture.

CORRESPONDENCE

Catherine Romaine, East Carolina University, Brody School of Medicine, 600 Moye Boulevard, Greenville, NC 27834; [email protected]

1. Alent J, Narducci DM, Moran B, et al. Sternal injuries in sport: a review of the literature. Sports Med. 2018;48:2715-2724. doi: 10.1007/s40279-018-0990-5

2. Khoriati A-A, Rajakulasingam R, Shah R. Sternal fractures and their management. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2013;6:113-116. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.110763

3. Athanassiadi K, Gerazounis M, Moustardas M, et al. Sternal fractures: retrospective analysis of 100 cases. World J Surg. 2002;26:1243-1246. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6511-5

4. Ferguson LP, Wilkinson AG, Beattie TF. Fracture of the sternum in children. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:518-520. doi: 10.1136/emj.20.6.518

5. Ramgopal S, Shaffiey SA, Conti KA. Pediatric sternal fractures from a Level 1 trauma center. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54:1628-1631. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.08.040

6. Sesia SB, Prüfer F, Mayr J. Sternal fracture in children: diagnosis by ultrasonography. European J Pediatr Surg Rep. 2017;5:e39-e42. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1606197

7. Nickson C, Rippey J. Ultrasonography of sternal fractures. Australas J Ultrasound Med. 2011;14:6-11. doi: 10.1002/j.2205-0140.2011.tb00131.x

8. Bauman ZM, Yanala U, Waibel BH, et al. Sternal fixation for isolated traumatic sternal fractures improves pain and upper extremity range of motion. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2022;48:225-230. doi: 10.1007/s00068-020-01568-x

9. Culp B, Hurbanek JG, Novak J, et al. Acute traumatic sternum fracture in a female college hockey player. Orthopedics. 2010;33:683. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20100722-17

THE CASE

A 14-year-old boy sought care at our clinic for persistent chest pain after being hit in the chest with a teammate’s shoulder during a basketball game 3 weeks earlier. He had aching midsternal chest pain that worsened with direct pressure and when he sneezed, twisted, or bent forward. There was no bruising or swelling.

On examination, the patient demonstrated normal perfusion and normal work of breathing. He had focal tenderness with palpation at the manubrium with no noticeable step-off, and mild tenderness at the adjacent costochondral junctions and over his pectoral muscles. His sternal pain along the proximal sternum was reproducible with a weighted wall push-up. Although the patient maintained full range of motion in his upper extremities, he did have sternal pain with flexion, abduction, and external rotation of the bilateral upper extremities against resistance. Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral chest radiographs were unremarkable.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The unremarkable chest radiographs prompted further investigation with a diagnostic ultrasound, which revealed a small cortical defect with overlying anechoic fluid collection in the area of focal tenderness. T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the chest was performed; it revealed a transverse, nondisplaced fracture of the superior body of the sternum with surrounding bone marrow edema (FIGURE).

DISCUSSION

Fractures of the sternum comprise < 1% of traumatic fractures and have a low mortality rate (0.7%).1,2 The rarity of these fractures is attributed to the ribs’ elastic recoil, which protects the chest wall from anterior forces.1,3 These fractures are even more unusual in children due to the increased elasticity of their chest walls.4-6 Thus, it takes a significant amount of force for a child’s sternum to fracture.

While isolated sternum fractures can occur, two-thirds of sternum fractures are nonisolated and are associated with injuries to surrounding structures (including the heart, lungs, and vasculature) or fractures of the ribs and spine.2,3 Most often, these injuries are caused by significant blunt trauma to the anterior chest, rapid deceleration, or flexion-compression injury.2,3 They are typically transverse and localized, with 70% of fractures occurring in the mid-body and 17.6% at the manubriosternal joint.1,3,6

Athletes with a sternal fracture typically present as our patient did, with a history of blunt force trauma to the chest and with pain and tenderness over the anterior midline of the chest that increases with respiration or movement.1 A physical examination that includes chest palpation and auscultation of the heart and lungs must be performed to rule out damage to intrathoracic structures and assess the patient’s cardiac and pulmonary stability. An electrocardiogram should be performed to confirm that there are no cardiovascular complications.3,4

Initial imaging should include AP and lateral chest radiographs because any displacement will occur in the sagittal plane.1,2,4-6 If the radiograph shows no clear pathology, follow up with computed tomography, ultrasound, MRI, or technetium bone scans to gain additional information.1 Diagnosis of sternal fractures is especially difficult in children due to the presence of ossification centers for bone growth, which may be misinterpreted as a sternal fracture in the absence of a proper understanding of sternal development.5,6 On ultrasound, sternal fractures appear as a sharp step-off in the cortex, whereas in the absence of fracture, there is no cortical step-off and the cartilaginous plate between ossification centers appears in line with the cortex.7

Continue to: A self-limiting injury that requires proper pain control

A self-limiting injury that requires proper pain control