User login

Use of opioids, SSRIs linked to increased fracture risk in RA

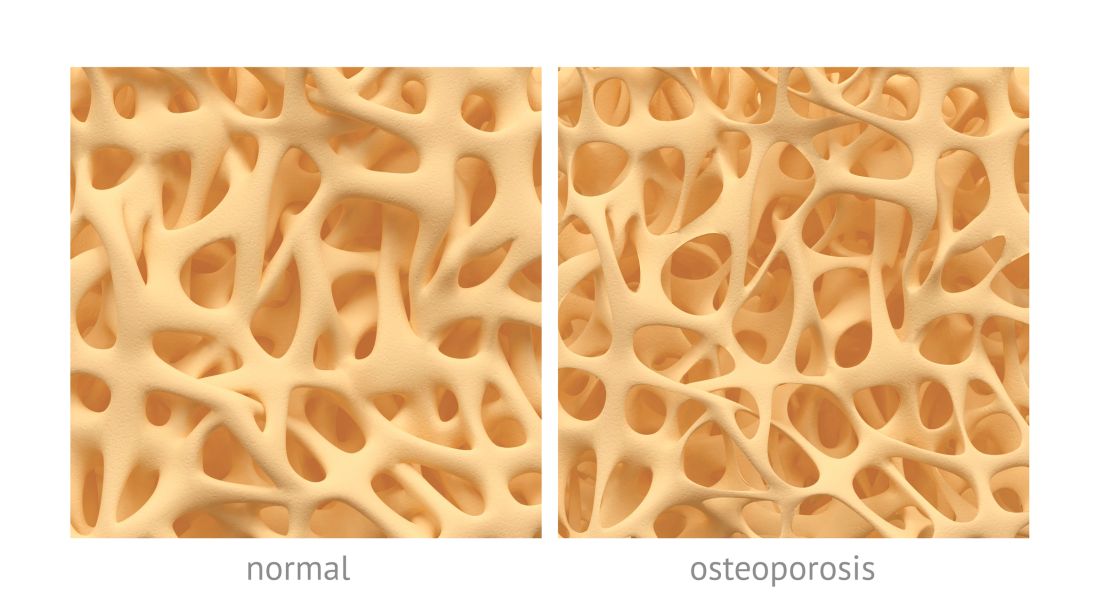

SAN DIEGO – The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and opioids was associated with an increased osteoporotic fracture risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, results from an analysis of national data showed.

“Osteoporotic fractures are one of the important causes of disability, health-related costs, and mortality in RA, with substantially higher complication and mortality rates than the general population,” study author Gulsen Ozen, MD, said in an interview prior to the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “Given the burden of osteoporotic fractures and the suboptimal osteoporosis care, identifying the factors associated with fracture risk in RA patients is of paramount importance.”

During a median follow-up of nearly 6 years, 863 patients (7.8%) sustained osteoporotic fractures. Compared with patients who did not develop fractures, those who did were significantly older, had higher disease duration and activity, glucocorticoid use, comorbidity and FRAX, a fracture risk assessment tool, scores at baseline. After adjusting for sociodemographics, comorbidities, body mass index, fracture risk by FRAX, and RA severity measures, the researchers found a significant risk of osteoporotic fractures with use of opioids of any strength (weak agents, hazard ratio, 1.45; strong agents, HR, 1.79; P less than .001 for both), SSRI use (HR, 1.35; P = .003), and glucocorticoid use of 3 months or longer at a dose of at least 7.5 mg per day (HR, 1.74; P less than .05). Osteoporotic fracture risk increase started even after 1-30 days of opioid use (HR, 1.96; P less than .001), whereas SSRI-associated risk increase started after 3 months of use (HR, 1.42; P = .054). No significant association with fracture risk was observed with the use of other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, statins, antidepressants, proton pump inhibitors, NSAIDs, anticonvulsants, and antipsychotics.

“One of the first surprising findings was that almost 40% of the RA patients older than 40 years of age were at least once exposed to opioid analgesics,” said Dr. Ozen, who is a research fellow in the division of immunology and rheumatology at the medical center. “Another surprising finding was that even very short-term (1-30 days) use of opioids was associated with increased fracture risk.” She went on to note that careful and regular reviewing of patient medications “is an essential part of the RA patient care, as the use of medications not indicated anymore brings harm rather than a benefit. The most well-known example for this is glucocorticoid use. This is valid for all medications, too. Therefore, we hope that our findings provide more awareness about osteoporotic fractures and associated risk factors in RA patients.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its observational design. “Additionally, fracture and the level of the trauma in our cohort were reported by patients,” she said. “Therefore, there might be some misclassification of fractures as osteoporotic fractures. Lastly, we did not have detailed data regarding fall risk, which might explain the associations we observed with opioids and potentially, SSRIs.”

Dr. Ozen reported having no disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and opioids was associated with an increased osteoporotic fracture risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, results from an analysis of national data showed.

“Osteoporotic fractures are one of the important causes of disability, health-related costs, and mortality in RA, with substantially higher complication and mortality rates than the general population,” study author Gulsen Ozen, MD, said in an interview prior to the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “Given the burden of osteoporotic fractures and the suboptimal osteoporosis care, identifying the factors associated with fracture risk in RA patients is of paramount importance.”

During a median follow-up of nearly 6 years, 863 patients (7.8%) sustained osteoporotic fractures. Compared with patients who did not develop fractures, those who did were significantly older, had higher disease duration and activity, glucocorticoid use, comorbidity and FRAX, a fracture risk assessment tool, scores at baseline. After adjusting for sociodemographics, comorbidities, body mass index, fracture risk by FRAX, and RA severity measures, the researchers found a significant risk of osteoporotic fractures with use of opioids of any strength (weak agents, hazard ratio, 1.45; strong agents, HR, 1.79; P less than .001 for both), SSRI use (HR, 1.35; P = .003), and glucocorticoid use of 3 months or longer at a dose of at least 7.5 mg per day (HR, 1.74; P less than .05). Osteoporotic fracture risk increase started even after 1-30 days of opioid use (HR, 1.96; P less than .001), whereas SSRI-associated risk increase started after 3 months of use (HR, 1.42; P = .054). No significant association with fracture risk was observed with the use of other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, statins, antidepressants, proton pump inhibitors, NSAIDs, anticonvulsants, and antipsychotics.

“One of the first surprising findings was that almost 40% of the RA patients older than 40 years of age were at least once exposed to opioid analgesics,” said Dr. Ozen, who is a research fellow in the division of immunology and rheumatology at the medical center. “Another surprising finding was that even very short-term (1-30 days) use of opioids was associated with increased fracture risk.” She went on to note that careful and regular reviewing of patient medications “is an essential part of the RA patient care, as the use of medications not indicated anymore brings harm rather than a benefit. The most well-known example for this is glucocorticoid use. This is valid for all medications, too. Therefore, we hope that our findings provide more awareness about osteoporotic fractures and associated risk factors in RA patients.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its observational design. “Additionally, fracture and the level of the trauma in our cohort were reported by patients,” she said. “Therefore, there might be some misclassification of fractures as osteoporotic fractures. Lastly, we did not have detailed data regarding fall risk, which might explain the associations we observed with opioids and potentially, SSRIs.”

Dr. Ozen reported having no disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and opioids was associated with an increased osteoporotic fracture risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, results from an analysis of national data showed.

“Osteoporotic fractures are one of the important causes of disability, health-related costs, and mortality in RA, with substantially higher complication and mortality rates than the general population,” study author Gulsen Ozen, MD, said in an interview prior to the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “Given the burden of osteoporotic fractures and the suboptimal osteoporosis care, identifying the factors associated with fracture risk in RA patients is of paramount importance.”

During a median follow-up of nearly 6 years, 863 patients (7.8%) sustained osteoporotic fractures. Compared with patients who did not develop fractures, those who did were significantly older, had higher disease duration and activity, glucocorticoid use, comorbidity and FRAX, a fracture risk assessment tool, scores at baseline. After adjusting for sociodemographics, comorbidities, body mass index, fracture risk by FRAX, and RA severity measures, the researchers found a significant risk of osteoporotic fractures with use of opioids of any strength (weak agents, hazard ratio, 1.45; strong agents, HR, 1.79; P less than .001 for both), SSRI use (HR, 1.35; P = .003), and glucocorticoid use of 3 months or longer at a dose of at least 7.5 mg per day (HR, 1.74; P less than .05). Osteoporotic fracture risk increase started even after 1-30 days of opioid use (HR, 1.96; P less than .001), whereas SSRI-associated risk increase started after 3 months of use (HR, 1.42; P = .054). No significant association with fracture risk was observed with the use of other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, statins, antidepressants, proton pump inhibitors, NSAIDs, anticonvulsants, and antipsychotics.

“One of the first surprising findings was that almost 40% of the RA patients older than 40 years of age were at least once exposed to opioid analgesics,” said Dr. Ozen, who is a research fellow in the division of immunology and rheumatology at the medical center. “Another surprising finding was that even very short-term (1-30 days) use of opioids was associated with increased fracture risk.” She went on to note that careful and regular reviewing of patient medications “is an essential part of the RA patient care, as the use of medications not indicated anymore brings harm rather than a benefit. The most well-known example for this is glucocorticoid use. This is valid for all medications, too. Therefore, we hope that our findings provide more awareness about osteoporotic fractures and associated risk factors in RA patients.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its observational design. “Additionally, fracture and the level of the trauma in our cohort were reported by patients,” she said. “Therefore, there might be some misclassification of fractures as osteoporotic fractures. Lastly, we did not have detailed data regarding fall risk, which might explain the associations we observed with opioids and potentially, SSRIs.”

Dr. Ozen reported having no disclosures.

AT ACR 2017

Key clinical point: When managing with opioids, even in the short-term, clinicians should be aware of the fracture risk.

Major finding: In patients with RA, concomitant use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors was associated with an increased risk of osteoporotic fracture (HR, 1.35; P = .003), as was opioid use (HR, 1.45 and HR, 1.79) for weak and strong agents, respectively; P less than .001 for both).

Study details: An observational study of 11,049 patients from the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases.

Disclosures: Dr. Ozen reported having no disclosures.

VIDEO: Dr. Andrew Kaunitz’s top lessons from NAMS 2017

PHILADELPHIA – Andrew Kaunitz, MD, the chair of the 2017 scientific program committee for the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society, shared his top take-home messages from the meeting.

New anabolic medications that increase bone mineral density and dramatically reduce fracture risk are in the pipeline, Dr. Kaunitz, a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Florida, Jacksonville, said in a video interview.

Another finding from the meeting is that type 2 diabetes, despite being associated with an increased body mass index, actually elevates a woman’s risk for fracture. “That was something new for me, and I think it was something new for a lot of the practitioners attending the NAMS meeting,” Dr. Kaunitz said.

The meeting also offered tips for managing polycystic ovarian syndrome in women who are in midlife, including the importance of screening for diabetes and assessing for lipid disorders. Additionally, attendees learned about the management of migraines in menopausal women and older reproductive-age women.

A well-attended session on breast imaging explored how breast tomosynthesis can reduce false positives and recalls, as well as how new technology can reduce the radiation exposure associated with tomosynthesis. The session also featured evidence that screening mammography has lower-than-reported sensitivity, but offered a hopeful note on the promise of improved sensitivity through molecular breast imaging.

Dr. Kaunitz reported consultant/advisory board work for Allergan, Amag Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Mithra Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Shionogi. He has received grant/research support from Bayer, Radius Health, TherapeuticsMD, and Millendo Therapeutics.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

PHILADELPHIA – Andrew Kaunitz, MD, the chair of the 2017 scientific program committee for the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society, shared his top take-home messages from the meeting.

New anabolic medications that increase bone mineral density and dramatically reduce fracture risk are in the pipeline, Dr. Kaunitz, a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Florida, Jacksonville, said in a video interview.

Another finding from the meeting is that type 2 diabetes, despite being associated with an increased body mass index, actually elevates a woman’s risk for fracture. “That was something new for me, and I think it was something new for a lot of the practitioners attending the NAMS meeting,” Dr. Kaunitz said.

The meeting also offered tips for managing polycystic ovarian syndrome in women who are in midlife, including the importance of screening for diabetes and assessing for lipid disorders. Additionally, attendees learned about the management of migraines in menopausal women and older reproductive-age women.

A well-attended session on breast imaging explored how breast tomosynthesis can reduce false positives and recalls, as well as how new technology can reduce the radiation exposure associated with tomosynthesis. The session also featured evidence that screening mammography has lower-than-reported sensitivity, but offered a hopeful note on the promise of improved sensitivity through molecular breast imaging.

Dr. Kaunitz reported consultant/advisory board work for Allergan, Amag Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Mithra Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Shionogi. He has received grant/research support from Bayer, Radius Health, TherapeuticsMD, and Millendo Therapeutics.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

PHILADELPHIA – Andrew Kaunitz, MD, the chair of the 2017 scientific program committee for the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society, shared his top take-home messages from the meeting.

New anabolic medications that increase bone mineral density and dramatically reduce fracture risk are in the pipeline, Dr. Kaunitz, a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Florida, Jacksonville, said in a video interview.

Another finding from the meeting is that type 2 diabetes, despite being associated with an increased body mass index, actually elevates a woman’s risk for fracture. “That was something new for me, and I think it was something new for a lot of the practitioners attending the NAMS meeting,” Dr. Kaunitz said.

The meeting also offered tips for managing polycystic ovarian syndrome in women who are in midlife, including the importance of screening for diabetes and assessing for lipid disorders. Additionally, attendees learned about the management of migraines in menopausal women and older reproductive-age women.

A well-attended session on breast imaging explored how breast tomosynthesis can reduce false positives and recalls, as well as how new technology can reduce the radiation exposure associated with tomosynthesis. The session also featured evidence that screening mammography has lower-than-reported sensitivity, but offered a hopeful note on the promise of improved sensitivity through molecular breast imaging.

Dr. Kaunitz reported consultant/advisory board work for Allergan, Amag Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Mithra Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Shionogi. He has received grant/research support from Bayer, Radius Health, TherapeuticsMD, and Millendo Therapeutics.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM NAMS 2017

Time to take the fear out of the hormone therapy conversation

PHILADELPHIA – It’s time to be clear about the benefits of hormone therapy for many women in midlife, JoAnn Pinkerton, MD, executive director of the North American Menopause Society, said during the keynote address at the group’s annual meeting.

“I want to take fear out of the conversation. Hormone therapy remains the most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms and the genitourinary syndrome of menopause and has been shown to prevent bone loss and fracture,” said Dr. Pinkerton, who also chaired the advisory panel that penned the 2017 NAMS position statement on hormone therapy.

Hormone therapy is currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration as first-line therapy to relieve vasomotor symptoms (VMS). Low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy is also a first-line treatment for the genitourinary syndrome of menopause, since it can directly address vulvovaginal atrophy.

An additional approved indication for systemic hormone therapy (HT) is the prevention of bone loss and fracture reduction in postmenopausal women who have increased risk of osteoporosis or fractures. It’s also FDA approved for women who had hypogonadism, primary ovarian insufficiency, or premature surgical menopause, who may use HT until the average age of menopause – about 52 years.

Unopposed systemic estrogen should not be used as HT in women with an intact uterus because of the elevated risk of endometrial cancer, and all indications assume there are no contraindications to HT use.

The position statement was developed by an expert panel, and has been endorsed by a number of international menopause societies, other American women’s health societies, and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

Cardiovascular risks

Early analysis of cardiovascular health data from the large, prospective Women’s Health Initiative trial raised significant concerns about increased risk. But further study of data from the Women’s Health Initiative, as well as meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials, have yielded a more nuanced view of the relationship between HT and cardiovascular disease, she said.

“Age matters,” Dr. Pinkerton said. “Data show that there is reduced heart disease in women who start [hormone replacement] early.” There is increasing data, she said, to support the “timing hypothesis.”

“Women who start HT before the age of 60 years, or within 10 years of menopause, may have a reduced risk of coronary heart disease,” Dr. Pinkerton said. “There is concern of increased risk of [coronary heart disease] in women who initiate hormone therapy more than 10 or 20 years from menopause.”

Use of HT is associated with a significantly increased risk of venous thromboembolism, a risk that increases with time, as does the risk of stroke and pulmonary embolism. Using lower doses or transdermal HT may reduce this risk, but “the lack of comparative randomized controlled trial data limit recommendations,” she said.

Transdermal therapy can also be considered for women with metabolic syndrome, hypertriglyceridemia, and fatty liver, since this route avoids first-pass hepatic metabolism.

Breast cancer

“The effect of hormone therapy on breast cancer risk is complex and conflicting,” said Dr Pinkerton, noting that breast cancer risk from HT may depend on many factors, including whether progestins are added to estrogen, the dose and duration of HT use, and how HT is administered.

Regarding the use of vaginal estrogen for women who have had breast cancer, Dr. Pinkerton said, “It’s a data-free zone.” Systemic absorption of vaginally-dosed estrogen is minimal, but the decision to use vaginal estrogen for a breast cancer survivor who is experiencing genitourinary syndrome of menopause symptoms should always be made in consultation with the woman’s oncologist and in shared decision-making with the patient herself, Dr. Pinkerton added.

Bioidentical HT

“Unique concerns about safety surround the use of compounded bioidentical hormone therapy,” Dr. Pinkerton said.

The lack of regulation and monitoring, together with lax labeling requirements, are areas of concern. Accurate dosing may not be occurring, and data are lacking to support safety and efficacy of compounded bioidentical products, she said. Neither is there evidence to support routine testing of serum or salivary hormone levels, she added.

Symptom relief

For isolated symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause, low-dose vaginal preparations are safe and effective, Dr. Pinkerton said. For women who are symptomatic, use of either low-dose vaginal estrogen or systemic HT increases sexual function scores; however, she said, “hormone therapy is not recommended as the sole treatment of other sexual function problems,” such as diminished libido, though it can be a useful adjunct.

“Hormone therapy is the most effective treatment for hot flashes,” said Dr. Pinkerton, and using HT improves sleep quality and duration in women with bothersome nighttime hot flashes.

Fracture prevention

Data from the Women’s Health Initiative showed a highly significant 33% reduction in hip fractures for women using both estrogen alone and estrogen with progestogen. “That seems to get forgotten,” Dr. Pinkerton said. Though HT’s osteoporosis and fracture prevention effects stop when HT is discontinued, there’s no evidence of elevated fracture risk above baseline in women who have used HT and then stopped.

“Younger women may need higher doses to protect bone, but make sure you get adequate endometrial protection if you do that,” said Dr. Pinkerton, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Virginia.

Unapproved uses

“Hormone therapy is not recommended at any age to prevent or treat cognition or dementia,” said Dr. Pinkerton, citing a lack of data to support its use for these reasons. Observational data may show some reduction in risk of Alzheimer’s disease in women who use HT at younger ages or soon after menopause, she said.

Though HT users have a reduced risk of developing type 2 diabetes, diabetes prevention is not a Food and Drug Administration–approved indication for HT. Abdominal fat accumulation and weight gain may be reduced by HT as well, Dr. Pinkerton said.

Similarly, there are no data to support the use of HT for the treatment of clinical depression. Perimenopausal – but not postmenopausal – women may see some benefit from estrogen therapy; progestins may actually contribute to mood disturbance, she said.

Special populations

“Systemic hormone therapy is not recommended for survivors of breast cancer,” Dr. Pinkerton said. Any consideration for systemic HT in this population should include the oncologist, and only be entertained after other nonhormonal options have been tried, she said.

Women with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer, or with the BRCA mutation, do not appear to have their risk increased by the use of HT, though the ovarian cancer data are limited and observational, Dr. Pinkerton said.

The NAMS position statement also addresses the use of HT in other special populations, including survivors of other cancers and women who have primary ovarian insufficiency or early menopause, BRCA-positive women who have undergone oophorectomy, and those over age 65 years.

“The recommendation to routinely discontinue systemic hormone therapy after age 65 is not supported by data,” Dr. Pinkerton said. “I would tell you that there’s a lack of good data about prolonged duration. What I tell patients is, we really are in another data-free zone.” She recommends an individualized approach that balances benefits and risks and includes ongoing surveillance.

New message

“So what do I want us to do? I want us to change the message,” she said. Rather than advocating for HT to be used in “the lowest dose, for the shortest period of time,” she said the new message should be for women to use “appropriate hormone therapy to meet their treatment goals.”

The bottom line? After accounting for women who should avoid HT for specific contraindications, “benefits are likely to outweigh risks for symptomatic women who initiate hormone therapy when aged younger than 60 years and within 10 years of menopause,” Dr. Pinkerton said.

Dr. Pinkerton reported that she has received grant or research support from TherapeuticsMD.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

PHILADELPHIA – It’s time to be clear about the benefits of hormone therapy for many women in midlife, JoAnn Pinkerton, MD, executive director of the North American Menopause Society, said during the keynote address at the group’s annual meeting.

“I want to take fear out of the conversation. Hormone therapy remains the most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms and the genitourinary syndrome of menopause and has been shown to prevent bone loss and fracture,” said Dr. Pinkerton, who also chaired the advisory panel that penned the 2017 NAMS position statement on hormone therapy.

Hormone therapy is currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration as first-line therapy to relieve vasomotor symptoms (VMS). Low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy is also a first-line treatment for the genitourinary syndrome of menopause, since it can directly address vulvovaginal atrophy.

An additional approved indication for systemic hormone therapy (HT) is the prevention of bone loss and fracture reduction in postmenopausal women who have increased risk of osteoporosis or fractures. It’s also FDA approved for women who had hypogonadism, primary ovarian insufficiency, or premature surgical menopause, who may use HT until the average age of menopause – about 52 years.

Unopposed systemic estrogen should not be used as HT in women with an intact uterus because of the elevated risk of endometrial cancer, and all indications assume there are no contraindications to HT use.

The position statement was developed by an expert panel, and has been endorsed by a number of international menopause societies, other American women’s health societies, and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

Cardiovascular risks

Early analysis of cardiovascular health data from the large, prospective Women’s Health Initiative trial raised significant concerns about increased risk. But further study of data from the Women’s Health Initiative, as well as meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials, have yielded a more nuanced view of the relationship between HT and cardiovascular disease, she said.

“Age matters,” Dr. Pinkerton said. “Data show that there is reduced heart disease in women who start [hormone replacement] early.” There is increasing data, she said, to support the “timing hypothesis.”

“Women who start HT before the age of 60 years, or within 10 years of menopause, may have a reduced risk of coronary heart disease,” Dr. Pinkerton said. “There is concern of increased risk of [coronary heart disease] in women who initiate hormone therapy more than 10 or 20 years from menopause.”

Use of HT is associated with a significantly increased risk of venous thromboembolism, a risk that increases with time, as does the risk of stroke and pulmonary embolism. Using lower doses or transdermal HT may reduce this risk, but “the lack of comparative randomized controlled trial data limit recommendations,” she said.

Transdermal therapy can also be considered for women with metabolic syndrome, hypertriglyceridemia, and fatty liver, since this route avoids first-pass hepatic metabolism.

Breast cancer

“The effect of hormone therapy on breast cancer risk is complex and conflicting,” said Dr Pinkerton, noting that breast cancer risk from HT may depend on many factors, including whether progestins are added to estrogen, the dose and duration of HT use, and how HT is administered.

Regarding the use of vaginal estrogen for women who have had breast cancer, Dr. Pinkerton said, “It’s a data-free zone.” Systemic absorption of vaginally-dosed estrogen is minimal, but the decision to use vaginal estrogen for a breast cancer survivor who is experiencing genitourinary syndrome of menopause symptoms should always be made in consultation with the woman’s oncologist and in shared decision-making with the patient herself, Dr. Pinkerton added.

Bioidentical HT

“Unique concerns about safety surround the use of compounded bioidentical hormone therapy,” Dr. Pinkerton said.

The lack of regulation and monitoring, together with lax labeling requirements, are areas of concern. Accurate dosing may not be occurring, and data are lacking to support safety and efficacy of compounded bioidentical products, she said. Neither is there evidence to support routine testing of serum or salivary hormone levels, she added.

Symptom relief

For isolated symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause, low-dose vaginal preparations are safe and effective, Dr. Pinkerton said. For women who are symptomatic, use of either low-dose vaginal estrogen or systemic HT increases sexual function scores; however, she said, “hormone therapy is not recommended as the sole treatment of other sexual function problems,” such as diminished libido, though it can be a useful adjunct.

“Hormone therapy is the most effective treatment for hot flashes,” said Dr. Pinkerton, and using HT improves sleep quality and duration in women with bothersome nighttime hot flashes.

Fracture prevention

Data from the Women’s Health Initiative showed a highly significant 33% reduction in hip fractures for women using both estrogen alone and estrogen with progestogen. “That seems to get forgotten,” Dr. Pinkerton said. Though HT’s osteoporosis and fracture prevention effects stop when HT is discontinued, there’s no evidence of elevated fracture risk above baseline in women who have used HT and then stopped.

“Younger women may need higher doses to protect bone, but make sure you get adequate endometrial protection if you do that,” said Dr. Pinkerton, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Virginia.

Unapproved uses

“Hormone therapy is not recommended at any age to prevent or treat cognition or dementia,” said Dr. Pinkerton, citing a lack of data to support its use for these reasons. Observational data may show some reduction in risk of Alzheimer’s disease in women who use HT at younger ages or soon after menopause, she said.

Though HT users have a reduced risk of developing type 2 diabetes, diabetes prevention is not a Food and Drug Administration–approved indication for HT. Abdominal fat accumulation and weight gain may be reduced by HT as well, Dr. Pinkerton said.

Similarly, there are no data to support the use of HT for the treatment of clinical depression. Perimenopausal – but not postmenopausal – women may see some benefit from estrogen therapy; progestins may actually contribute to mood disturbance, she said.

Special populations

“Systemic hormone therapy is not recommended for survivors of breast cancer,” Dr. Pinkerton said. Any consideration for systemic HT in this population should include the oncologist, and only be entertained after other nonhormonal options have been tried, she said.

Women with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer, or with the BRCA mutation, do not appear to have their risk increased by the use of HT, though the ovarian cancer data are limited and observational, Dr. Pinkerton said.

The NAMS position statement also addresses the use of HT in other special populations, including survivors of other cancers and women who have primary ovarian insufficiency or early menopause, BRCA-positive women who have undergone oophorectomy, and those over age 65 years.

“The recommendation to routinely discontinue systemic hormone therapy after age 65 is not supported by data,” Dr. Pinkerton said. “I would tell you that there’s a lack of good data about prolonged duration. What I tell patients is, we really are in another data-free zone.” She recommends an individualized approach that balances benefits and risks and includes ongoing surveillance.

New message

“So what do I want us to do? I want us to change the message,” she said. Rather than advocating for HT to be used in “the lowest dose, for the shortest period of time,” she said the new message should be for women to use “appropriate hormone therapy to meet their treatment goals.”

The bottom line? After accounting for women who should avoid HT for specific contraindications, “benefits are likely to outweigh risks for symptomatic women who initiate hormone therapy when aged younger than 60 years and within 10 years of menopause,” Dr. Pinkerton said.

Dr. Pinkerton reported that she has received grant or research support from TherapeuticsMD.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

PHILADELPHIA – It’s time to be clear about the benefits of hormone therapy for many women in midlife, JoAnn Pinkerton, MD, executive director of the North American Menopause Society, said during the keynote address at the group’s annual meeting.

“I want to take fear out of the conversation. Hormone therapy remains the most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms and the genitourinary syndrome of menopause and has been shown to prevent bone loss and fracture,” said Dr. Pinkerton, who also chaired the advisory panel that penned the 2017 NAMS position statement on hormone therapy.

Hormone therapy is currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration as first-line therapy to relieve vasomotor symptoms (VMS). Low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy is also a first-line treatment for the genitourinary syndrome of menopause, since it can directly address vulvovaginal atrophy.

An additional approved indication for systemic hormone therapy (HT) is the prevention of bone loss and fracture reduction in postmenopausal women who have increased risk of osteoporosis or fractures. It’s also FDA approved for women who had hypogonadism, primary ovarian insufficiency, or premature surgical menopause, who may use HT until the average age of menopause – about 52 years.

Unopposed systemic estrogen should not be used as HT in women with an intact uterus because of the elevated risk of endometrial cancer, and all indications assume there are no contraindications to HT use.

The position statement was developed by an expert panel, and has been endorsed by a number of international menopause societies, other American women’s health societies, and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

Cardiovascular risks

Early analysis of cardiovascular health data from the large, prospective Women’s Health Initiative trial raised significant concerns about increased risk. But further study of data from the Women’s Health Initiative, as well as meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials, have yielded a more nuanced view of the relationship between HT and cardiovascular disease, she said.

“Age matters,” Dr. Pinkerton said. “Data show that there is reduced heart disease in women who start [hormone replacement] early.” There is increasing data, she said, to support the “timing hypothesis.”

“Women who start HT before the age of 60 years, or within 10 years of menopause, may have a reduced risk of coronary heart disease,” Dr. Pinkerton said. “There is concern of increased risk of [coronary heart disease] in women who initiate hormone therapy more than 10 or 20 years from menopause.”

Use of HT is associated with a significantly increased risk of venous thromboembolism, a risk that increases with time, as does the risk of stroke and pulmonary embolism. Using lower doses or transdermal HT may reduce this risk, but “the lack of comparative randomized controlled trial data limit recommendations,” she said.

Transdermal therapy can also be considered for women with metabolic syndrome, hypertriglyceridemia, and fatty liver, since this route avoids first-pass hepatic metabolism.

Breast cancer

“The effect of hormone therapy on breast cancer risk is complex and conflicting,” said Dr Pinkerton, noting that breast cancer risk from HT may depend on many factors, including whether progestins are added to estrogen, the dose and duration of HT use, and how HT is administered.

Regarding the use of vaginal estrogen for women who have had breast cancer, Dr. Pinkerton said, “It’s a data-free zone.” Systemic absorption of vaginally-dosed estrogen is minimal, but the decision to use vaginal estrogen for a breast cancer survivor who is experiencing genitourinary syndrome of menopause symptoms should always be made in consultation with the woman’s oncologist and in shared decision-making with the patient herself, Dr. Pinkerton added.

Bioidentical HT

“Unique concerns about safety surround the use of compounded bioidentical hormone therapy,” Dr. Pinkerton said.

The lack of regulation and monitoring, together with lax labeling requirements, are areas of concern. Accurate dosing may not be occurring, and data are lacking to support safety and efficacy of compounded bioidentical products, she said. Neither is there evidence to support routine testing of serum or salivary hormone levels, she added.

Symptom relief

For isolated symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause, low-dose vaginal preparations are safe and effective, Dr. Pinkerton said. For women who are symptomatic, use of either low-dose vaginal estrogen or systemic HT increases sexual function scores; however, she said, “hormone therapy is not recommended as the sole treatment of other sexual function problems,” such as diminished libido, though it can be a useful adjunct.

“Hormone therapy is the most effective treatment for hot flashes,” said Dr. Pinkerton, and using HT improves sleep quality and duration in women with bothersome nighttime hot flashes.

Fracture prevention

Data from the Women’s Health Initiative showed a highly significant 33% reduction in hip fractures for women using both estrogen alone and estrogen with progestogen. “That seems to get forgotten,” Dr. Pinkerton said. Though HT’s osteoporosis and fracture prevention effects stop when HT is discontinued, there’s no evidence of elevated fracture risk above baseline in women who have used HT and then stopped.

“Younger women may need higher doses to protect bone, but make sure you get adequate endometrial protection if you do that,” said Dr. Pinkerton, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Virginia.

Unapproved uses

“Hormone therapy is not recommended at any age to prevent or treat cognition or dementia,” said Dr. Pinkerton, citing a lack of data to support its use for these reasons. Observational data may show some reduction in risk of Alzheimer’s disease in women who use HT at younger ages or soon after menopause, she said.

Though HT users have a reduced risk of developing type 2 diabetes, diabetes prevention is not a Food and Drug Administration–approved indication for HT. Abdominal fat accumulation and weight gain may be reduced by HT as well, Dr. Pinkerton said.

Similarly, there are no data to support the use of HT for the treatment of clinical depression. Perimenopausal – but not postmenopausal – women may see some benefit from estrogen therapy; progestins may actually contribute to mood disturbance, she said.

Special populations

“Systemic hormone therapy is not recommended for survivors of breast cancer,” Dr. Pinkerton said. Any consideration for systemic HT in this population should include the oncologist, and only be entertained after other nonhormonal options have been tried, she said.

Women with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer, or with the BRCA mutation, do not appear to have their risk increased by the use of HT, though the ovarian cancer data are limited and observational, Dr. Pinkerton said.

The NAMS position statement also addresses the use of HT in other special populations, including survivors of other cancers and women who have primary ovarian insufficiency or early menopause, BRCA-positive women who have undergone oophorectomy, and those over age 65 years.

“The recommendation to routinely discontinue systemic hormone therapy after age 65 is not supported by data,” Dr. Pinkerton said. “I would tell you that there’s a lack of good data about prolonged duration. What I tell patients is, we really are in another data-free zone.” She recommends an individualized approach that balances benefits and risks and includes ongoing surveillance.

New message

“So what do I want us to do? I want us to change the message,” she said. Rather than advocating for HT to be used in “the lowest dose, for the shortest period of time,” she said the new message should be for women to use “appropriate hormone therapy to meet their treatment goals.”

The bottom line? After accounting for women who should avoid HT for specific contraindications, “benefits are likely to outweigh risks for symptomatic women who initiate hormone therapy when aged younger than 60 years and within 10 years of menopause,” Dr. Pinkerton said.

Dr. Pinkerton reported that she has received grant or research support from TherapeuticsMD.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

AT NAMS 2017

PBC linked to low BMD, increased risk of osteoporosis

Patients with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) have lower lumbar spine and hip bone mineral density (BMD) and are at an increased risk of osteoporosis and fracture, according to Junyu Fan, MD, and associates.

In a meta-analysis of 210 potentially relevant articles, only 8 met the study’s criteria. Of those, five studies were pooled and the overall relationship between PBC and osteoporosis risk was assessed. Results found a significant association between PBC (n = 504) and the prevalence of osteoporosis (P = .01), compared with the control group (n = 2,052).

The study additionally examined possible connection between PBC and bone fractures; more fracture events were reported in PBC patients (n = 929) than in controls (n = 8,699; P less than .00001). It is noted that there was no publication bias (P = .476).

“Further clinical management, follow-up, and surveillance issues should be addressed with caution,” researchers concluded. “Given the limited number of studies included, more high-quality studies will be required to determine the mechanisms underpinning the relationship between PBC and osteoporosis risk.”

Find the full study in Clinical Rheumatology (2017. doi: 10.1007/s10067-017-3844-x).

Patients with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) have lower lumbar spine and hip bone mineral density (BMD) and are at an increased risk of osteoporosis and fracture, according to Junyu Fan, MD, and associates.

In a meta-analysis of 210 potentially relevant articles, only 8 met the study’s criteria. Of those, five studies were pooled and the overall relationship between PBC and osteoporosis risk was assessed. Results found a significant association between PBC (n = 504) and the prevalence of osteoporosis (P = .01), compared with the control group (n = 2,052).

The study additionally examined possible connection between PBC and bone fractures; more fracture events were reported in PBC patients (n = 929) than in controls (n = 8,699; P less than .00001). It is noted that there was no publication bias (P = .476).

“Further clinical management, follow-up, and surveillance issues should be addressed with caution,” researchers concluded. “Given the limited number of studies included, more high-quality studies will be required to determine the mechanisms underpinning the relationship between PBC and osteoporosis risk.”

Find the full study in Clinical Rheumatology (2017. doi: 10.1007/s10067-017-3844-x).

Patients with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) have lower lumbar spine and hip bone mineral density (BMD) and are at an increased risk of osteoporosis and fracture, according to Junyu Fan, MD, and associates.

In a meta-analysis of 210 potentially relevant articles, only 8 met the study’s criteria. Of those, five studies were pooled and the overall relationship between PBC and osteoporosis risk was assessed. Results found a significant association between PBC (n = 504) and the prevalence of osteoporosis (P = .01), compared with the control group (n = 2,052).

The study additionally examined possible connection between PBC and bone fractures; more fracture events were reported in PBC patients (n = 929) than in controls (n = 8,699; P less than .00001). It is noted that there was no publication bias (P = .476).

“Further clinical management, follow-up, and surveillance issues should be addressed with caution,” researchers concluded. “Given the limited number of studies included, more high-quality studies will be required to determine the mechanisms underpinning the relationship between PBC and osteoporosis risk.”

Find the full study in Clinical Rheumatology (2017. doi: 10.1007/s10067-017-3844-x).

FROM CLINICAL RHEUMATOLOGY

Gap in osteoporosis diagnosis and treatment stirs concern

DENVER – A recent study of Medicare recipients who experienced a hip fracture found that just 19% of them had been receiving a bone-active osteoporosis treatment before the fracture occurred. That number reveals an alarming trend of underdiagnosis of osteoporosis.

But that number – from a 2016 study in JAMA Internal Medicine – is just the start. After the fracture, the percentage of women receiving treatment barely changed, rising to just 21% (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Oct 1;176[10]:1531-8).

This trend of under-diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis has occurred in spite of the fact that effective therapy exists to reduce future fractures. In fact, a single dose of zoledronic acid has been shown to reduce clinical fractures by 35%, and mortality by 28% over an average 2-year follow-up (N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1799-1809).

“To me, this is really a shame,” Douglas Bauer, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, said at a session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research that was dedicated to the issue.

It remains unclear why the fracture rate declined despite low levels of diagnosis and treatment. Some researchers, such as Bo Abrahamsen, MD, PhD, suggest there is a population effect. At the ASBMR annual meeting, Dr. Abrahamsen of the University of Southern Denmark, Odense, noted that in the western world, women born in the 1930s appear to be less prone to fractures than other birth cohorts, and it could be that this group contributed to the decline in fracture rates. A Danish study, he said, seems to confirm this idea. As other birth cohorts age, the numbers could well get worse.

And that’s worrying, because a gap in treatment and diagnosis of osteoporosis could lead to an epidemic of new fractures. “We need to address this crisis in health care for a very preventable disease,” Meryl LeBoff, MD, director of the skeletal health and osteoporosis center and bone density unit at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

There are several likely causes of declining treatment and diagnosis rates. In 2003, a report surfaced that osteonecrosis of the jaw occurred in cancer patients taking bisphosphonates to prevent metastasis to bone. Those patients received doses that were far higher than the typical osteoporosis patient, but the reports spooked patients. In 2005, researchers pinned another rare side effect on bisphosphonates – atypical femur fractures.

Other factors contributed. In 2007, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services cut the reimbursement rate for bone densitometry (DXA) testing, which has led to a drop in the number of tests, from a peak of 17.9% of women over age 65 years having been tested in 2009 to 14.8% in 2014. That has complicated efforts to diagnose osteoporosis, and may be affecting patients’ willingness to undergo therapy. A patient may go to the hospital for a hip fracture, but without a bone density test to raise concerns, she may write the fracture off as an accident. A DXA test that returns an abnormal value can change that. “If you have low BMD and a fracture, you have a worse prognosis and a higher risk of the next fracture. It’s much easier to convince patients [to begin therapy],” said John Carey, MD, a rheumatologist at Galway (Ireland) University Hospitals and president of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry.

Others emphasized the need to get DXA reimbursement raised, at least to a point where physicians can break even on the test. “Unfortunately, what’s happening is that as DXA reimbursement goes down, physicians are investing less in the education of their staff according to current guidelines,” Dr. Lewiecki said. He noted that there is draft legislation in Congress to raise DXA reimbursement (H.R. 1898), although it is currently in committee.

The forces that create the treatment and diagnostic gap aren’t simple, and no single strategy is likely to fix the problem. A number have been proposed.

FLS programs seek to quickly identify and provide treatment and monitoring for individuals who are at high risk for additional fractures. The programs identify patients who have suffered a fragility fracture and place them into a coordinated care model. For example, if a radiologist identified a patient of concern, she can be immediately referred to the FLS for quick follow-up, to include bone density scans and other steps to ensure proper diagnosis and treatment. In the absence of an FLS, it could be months before a patient is seen again, if a radiologist refers her at all. “You lose patients. But if they are tied into a coordination of care model, the patient is brought in immediately and they get the attention and awareness. They’re not just lost,” said Debbie Zeldow, executive director of the National Bone Health Alliance (NBHA).

Despite their effectiveness, FLS programs could be a tough sell for the upfront investment they require. To help organizations determine the cost-effectiveness of an FLS, the National Bone Health Alliance has developed a return on investment calculator.

And in fact, FLS programs are gaining traction, according to Ms. Zeldow. NBHA has posted a variety of resources for establishing an FLS on its website, which contains webinars and other resources, including the text of patient flyers produced by Kaiser Permanente translated into many languages. “There’s been a huge jump in interest in implementation. I’m getting calls on a daily basis from sites that want to implement an FLS. People are being pinged for readmission, and they’re looking for ways for their hospital or practice to improve outcomes. It’s definitely a way for hospitals to differentiate themselves around care,” Ms. Zeldow said in an interview.

FLS programs reduce secondary fractures, but the ultimate goal is to catch osteoporosis earlier and prevent even first-time fractures. That will require better communication with primary care providers, who bear the brunt of osteoporosis diagnosis and care.

“We need to do a better job of reducing barriers for primary care doctors, to try to minimize unnecessary treatment complexity, and address the fact that this is one of the many prevention issues that physicians are asked to manage, and all that in an increasingly time-constrained world,” Dr. Bauer said.

With that goal in mind, the American College of Physicians released new guidelines in May (Ann Intern Med. 2017;166[11]:818-39). They were intended to identify first-line therapies and simplify matters for primary care physicians, but they drew the ire of many endocrinologists for being too general. NBHA has formed an ACP guideline working group that aims to refine those guidelines. The committee is drafting a statement and a document for patients to help clarify the guidelines, particularly with respect to high-risk patients. The committee also seeks to avoid any rancor. “We’ve made a concerted effort to include primary care doctors, to make sure there’s not a disconnect between experts and general practitioners. We want to make sure it’s a useful tool and we’re not just bashing the guidelines,” Ms. Zeldow said.

Another way to help overburdened primary care providers is to provide training for physicians, especially in underserved areas. The National Osteoporosis Foundation’s TeleECHO program is a remote training service that can help interested local providers elevate their knowledge so they can become a local osteoporosis expert. “Patients can get better care, at more convenience and at lower cost, rather than having to travel to a specialist center far away,” Dr. Lewiecki said.

Patient concerns about side effects, the changing health care climate, and the challenges facing primary care providers add up to difficult environment for countering the reductions in diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis, but Dr. Lewiecki is hopeful. “Fracture liaison services combined with better education of health care providers through new educational methods I think have great promise. It’s just a matter of getting those things online,” he said.

Dr. Carey has been a speaker for Roche, Pfizer, and AbbVie. Dr. Lewiecki has consulted for Amgen. Dr. Leder has received funding from Lilly and Amgen, and has been a consultant for Lilly, Amgen, and Radius. Dr. Bauer and Ms. Zeldow reported having no financial disclosures.

DENVER – A recent study of Medicare recipients who experienced a hip fracture found that just 19% of them had been receiving a bone-active osteoporosis treatment before the fracture occurred. That number reveals an alarming trend of underdiagnosis of osteoporosis.

But that number – from a 2016 study in JAMA Internal Medicine – is just the start. After the fracture, the percentage of women receiving treatment barely changed, rising to just 21% (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Oct 1;176[10]:1531-8).

This trend of under-diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis has occurred in spite of the fact that effective therapy exists to reduce future fractures. In fact, a single dose of zoledronic acid has been shown to reduce clinical fractures by 35%, and mortality by 28% over an average 2-year follow-up (N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1799-1809).

“To me, this is really a shame,” Douglas Bauer, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, said at a session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research that was dedicated to the issue.

It remains unclear why the fracture rate declined despite low levels of diagnosis and treatment. Some researchers, such as Bo Abrahamsen, MD, PhD, suggest there is a population effect. At the ASBMR annual meeting, Dr. Abrahamsen of the University of Southern Denmark, Odense, noted that in the western world, women born in the 1930s appear to be less prone to fractures than other birth cohorts, and it could be that this group contributed to the decline in fracture rates. A Danish study, he said, seems to confirm this idea. As other birth cohorts age, the numbers could well get worse.

And that’s worrying, because a gap in treatment and diagnosis of osteoporosis could lead to an epidemic of new fractures. “We need to address this crisis in health care for a very preventable disease,” Meryl LeBoff, MD, director of the skeletal health and osteoporosis center and bone density unit at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

There are several likely causes of declining treatment and diagnosis rates. In 2003, a report surfaced that osteonecrosis of the jaw occurred in cancer patients taking bisphosphonates to prevent metastasis to bone. Those patients received doses that were far higher than the typical osteoporosis patient, but the reports spooked patients. In 2005, researchers pinned another rare side effect on bisphosphonates – atypical femur fractures.

Other factors contributed. In 2007, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services cut the reimbursement rate for bone densitometry (DXA) testing, which has led to a drop in the number of tests, from a peak of 17.9% of women over age 65 years having been tested in 2009 to 14.8% in 2014. That has complicated efforts to diagnose osteoporosis, and may be affecting patients’ willingness to undergo therapy. A patient may go to the hospital for a hip fracture, but without a bone density test to raise concerns, she may write the fracture off as an accident. A DXA test that returns an abnormal value can change that. “If you have low BMD and a fracture, you have a worse prognosis and a higher risk of the next fracture. It’s much easier to convince patients [to begin therapy],” said John Carey, MD, a rheumatologist at Galway (Ireland) University Hospitals and president of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry.

Others emphasized the need to get DXA reimbursement raised, at least to a point where physicians can break even on the test. “Unfortunately, what’s happening is that as DXA reimbursement goes down, physicians are investing less in the education of their staff according to current guidelines,” Dr. Lewiecki said. He noted that there is draft legislation in Congress to raise DXA reimbursement (H.R. 1898), although it is currently in committee.

The forces that create the treatment and diagnostic gap aren’t simple, and no single strategy is likely to fix the problem. A number have been proposed.

FLS programs seek to quickly identify and provide treatment and monitoring for individuals who are at high risk for additional fractures. The programs identify patients who have suffered a fragility fracture and place them into a coordinated care model. For example, if a radiologist identified a patient of concern, she can be immediately referred to the FLS for quick follow-up, to include bone density scans and other steps to ensure proper diagnosis and treatment. In the absence of an FLS, it could be months before a patient is seen again, if a radiologist refers her at all. “You lose patients. But if they are tied into a coordination of care model, the patient is brought in immediately and they get the attention and awareness. They’re not just lost,” said Debbie Zeldow, executive director of the National Bone Health Alliance (NBHA).

Despite their effectiveness, FLS programs could be a tough sell for the upfront investment they require. To help organizations determine the cost-effectiveness of an FLS, the National Bone Health Alliance has developed a return on investment calculator.

And in fact, FLS programs are gaining traction, according to Ms. Zeldow. NBHA has posted a variety of resources for establishing an FLS on its website, which contains webinars and other resources, including the text of patient flyers produced by Kaiser Permanente translated into many languages. “There’s been a huge jump in interest in implementation. I’m getting calls on a daily basis from sites that want to implement an FLS. People are being pinged for readmission, and they’re looking for ways for their hospital or practice to improve outcomes. It’s definitely a way for hospitals to differentiate themselves around care,” Ms. Zeldow said in an interview.

FLS programs reduce secondary fractures, but the ultimate goal is to catch osteoporosis earlier and prevent even first-time fractures. That will require better communication with primary care providers, who bear the brunt of osteoporosis diagnosis and care.

“We need to do a better job of reducing barriers for primary care doctors, to try to minimize unnecessary treatment complexity, and address the fact that this is one of the many prevention issues that physicians are asked to manage, and all that in an increasingly time-constrained world,” Dr. Bauer said.

With that goal in mind, the American College of Physicians released new guidelines in May (Ann Intern Med. 2017;166[11]:818-39). They were intended to identify first-line therapies and simplify matters for primary care physicians, but they drew the ire of many endocrinologists for being too general. NBHA has formed an ACP guideline working group that aims to refine those guidelines. The committee is drafting a statement and a document for patients to help clarify the guidelines, particularly with respect to high-risk patients. The committee also seeks to avoid any rancor. “We’ve made a concerted effort to include primary care doctors, to make sure there’s not a disconnect between experts and general practitioners. We want to make sure it’s a useful tool and we’re not just bashing the guidelines,” Ms. Zeldow said.

Another way to help overburdened primary care providers is to provide training for physicians, especially in underserved areas. The National Osteoporosis Foundation’s TeleECHO program is a remote training service that can help interested local providers elevate their knowledge so they can become a local osteoporosis expert. “Patients can get better care, at more convenience and at lower cost, rather than having to travel to a specialist center far away,” Dr. Lewiecki said.

Patient concerns about side effects, the changing health care climate, and the challenges facing primary care providers add up to difficult environment for countering the reductions in diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis, but Dr. Lewiecki is hopeful. “Fracture liaison services combined with better education of health care providers through new educational methods I think have great promise. It’s just a matter of getting those things online,” he said.

Dr. Carey has been a speaker for Roche, Pfizer, and AbbVie. Dr. Lewiecki has consulted for Amgen. Dr. Leder has received funding from Lilly and Amgen, and has been a consultant for Lilly, Amgen, and Radius. Dr. Bauer and Ms. Zeldow reported having no financial disclosures.

DENVER – A recent study of Medicare recipients who experienced a hip fracture found that just 19% of them had been receiving a bone-active osteoporosis treatment before the fracture occurred. That number reveals an alarming trend of underdiagnosis of osteoporosis.

But that number – from a 2016 study in JAMA Internal Medicine – is just the start. After the fracture, the percentage of women receiving treatment barely changed, rising to just 21% (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Oct 1;176[10]:1531-8).

This trend of under-diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis has occurred in spite of the fact that effective therapy exists to reduce future fractures. In fact, a single dose of zoledronic acid has been shown to reduce clinical fractures by 35%, and mortality by 28% over an average 2-year follow-up (N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1799-1809).

“To me, this is really a shame,” Douglas Bauer, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, said at a session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research that was dedicated to the issue.

It remains unclear why the fracture rate declined despite low levels of diagnosis and treatment. Some researchers, such as Bo Abrahamsen, MD, PhD, suggest there is a population effect. At the ASBMR annual meeting, Dr. Abrahamsen of the University of Southern Denmark, Odense, noted that in the western world, women born in the 1930s appear to be less prone to fractures than other birth cohorts, and it could be that this group contributed to the decline in fracture rates. A Danish study, he said, seems to confirm this idea. As other birth cohorts age, the numbers could well get worse.

And that’s worrying, because a gap in treatment and diagnosis of osteoporosis could lead to an epidemic of new fractures. “We need to address this crisis in health care for a very preventable disease,” Meryl LeBoff, MD, director of the skeletal health and osteoporosis center and bone density unit at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

There are several likely causes of declining treatment and diagnosis rates. In 2003, a report surfaced that osteonecrosis of the jaw occurred in cancer patients taking bisphosphonates to prevent metastasis to bone. Those patients received doses that were far higher than the typical osteoporosis patient, but the reports spooked patients. In 2005, researchers pinned another rare side effect on bisphosphonates – atypical femur fractures.

Other factors contributed. In 2007, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services cut the reimbursement rate for bone densitometry (DXA) testing, which has led to a drop in the number of tests, from a peak of 17.9% of women over age 65 years having been tested in 2009 to 14.8% in 2014. That has complicated efforts to diagnose osteoporosis, and may be affecting patients’ willingness to undergo therapy. A patient may go to the hospital for a hip fracture, but without a bone density test to raise concerns, she may write the fracture off as an accident. A DXA test that returns an abnormal value can change that. “If you have low BMD and a fracture, you have a worse prognosis and a higher risk of the next fracture. It’s much easier to convince patients [to begin therapy],” said John Carey, MD, a rheumatologist at Galway (Ireland) University Hospitals and president of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry.

Others emphasized the need to get DXA reimbursement raised, at least to a point where physicians can break even on the test. “Unfortunately, what’s happening is that as DXA reimbursement goes down, physicians are investing less in the education of their staff according to current guidelines,” Dr. Lewiecki said. He noted that there is draft legislation in Congress to raise DXA reimbursement (H.R. 1898), although it is currently in committee.

The forces that create the treatment and diagnostic gap aren’t simple, and no single strategy is likely to fix the problem. A number have been proposed.

FLS programs seek to quickly identify and provide treatment and monitoring for individuals who are at high risk for additional fractures. The programs identify patients who have suffered a fragility fracture and place them into a coordinated care model. For example, if a radiologist identified a patient of concern, she can be immediately referred to the FLS for quick follow-up, to include bone density scans and other steps to ensure proper diagnosis and treatment. In the absence of an FLS, it could be months before a patient is seen again, if a radiologist refers her at all. “You lose patients. But if they are tied into a coordination of care model, the patient is brought in immediately and they get the attention and awareness. They’re not just lost,” said Debbie Zeldow, executive director of the National Bone Health Alliance (NBHA).

Despite their effectiveness, FLS programs could be a tough sell for the upfront investment they require. To help organizations determine the cost-effectiveness of an FLS, the National Bone Health Alliance has developed a return on investment calculator.

And in fact, FLS programs are gaining traction, according to Ms. Zeldow. NBHA has posted a variety of resources for establishing an FLS on its website, which contains webinars and other resources, including the text of patient flyers produced by Kaiser Permanente translated into many languages. “There’s been a huge jump in interest in implementation. I’m getting calls on a daily basis from sites that want to implement an FLS. People are being pinged for readmission, and they’re looking for ways for their hospital or practice to improve outcomes. It’s definitely a way for hospitals to differentiate themselves around care,” Ms. Zeldow said in an interview.

FLS programs reduce secondary fractures, but the ultimate goal is to catch osteoporosis earlier and prevent even first-time fractures. That will require better communication with primary care providers, who bear the brunt of osteoporosis diagnosis and care.

“We need to do a better job of reducing barriers for primary care doctors, to try to minimize unnecessary treatment complexity, and address the fact that this is one of the many prevention issues that physicians are asked to manage, and all that in an increasingly time-constrained world,” Dr. Bauer said.

With that goal in mind, the American College of Physicians released new guidelines in May (Ann Intern Med. 2017;166[11]:818-39). They were intended to identify first-line therapies and simplify matters for primary care physicians, but they drew the ire of many endocrinologists for being too general. NBHA has formed an ACP guideline working group that aims to refine those guidelines. The committee is drafting a statement and a document for patients to help clarify the guidelines, particularly with respect to high-risk patients. The committee also seeks to avoid any rancor. “We’ve made a concerted effort to include primary care doctors, to make sure there’s not a disconnect between experts and general practitioners. We want to make sure it’s a useful tool and we’re not just bashing the guidelines,” Ms. Zeldow said.

Another way to help overburdened primary care providers is to provide training for physicians, especially in underserved areas. The National Osteoporosis Foundation’s TeleECHO program is a remote training service that can help interested local providers elevate their knowledge so they can become a local osteoporosis expert. “Patients can get better care, at more convenience and at lower cost, rather than having to travel to a specialist center far away,” Dr. Lewiecki said.

Patient concerns about side effects, the changing health care climate, and the challenges facing primary care providers add up to difficult environment for countering the reductions in diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis, but Dr. Lewiecki is hopeful. “Fracture liaison services combined with better education of health care providers through new educational methods I think have great promise. It’s just a matter of getting those things online,” he said.

Dr. Carey has been a speaker for Roche, Pfizer, and AbbVie. Dr. Lewiecki has consulted for Amgen. Dr. Leder has received funding from Lilly and Amgen, and has been a consultant for Lilly, Amgen, and Radius. Dr. Bauer and Ms. Zeldow reported having no financial disclosures.

AT ASBMR

Biologic may bring relief for children and adults with XLH syndrome

DENVER – Two studies provide hope for a new treatment of X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH), a genetic disorder that leads to low phosphorus levels, which can cause rickets in children and a host of bone and other problems in adulthood.

The studies evaluated the use of burosumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23). FGF23 is a hormone that reduces serum levels of phosphorus and vitamin D through its effects on the kidney.

“For the first time, this establishes the efficacy of any treatment in adults with XLH,” said Karl L. Insogna, MD, professor of medicine (endocrinology), at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., who presented the phase III study results during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. “Even in adults who have a lot of underlying disease burden, which is not likely to be completely reversed by this drug, you can address the underlying pathophysiology of the disease and show not only symptomatic improvement but also healing of fractures and pseudofractures,” he added.

XLH patients may be treated with calcitriol and phosphate, but this requires dosing 3-5 times a day, with side effects that can be onerous. “If you were dealing with a shot, you’d have 100% compliance and (fewer) side effects. It’s going to be a whole lot better,” he noted.

In the phase 3 adult trial, 134 patients were randomized to subcutaneous burosumab (at a dose of 1 mg/kg) or placebo every 4 weeks for 24 weeks. Among those treated with burosumab, 94.1% achieved serum phosphatase levels in the normal range, compared with 7.6% of those on placebo. Among patients taking burosumab, 36.9% of fractures and pseudofractures present at baseline had healed by the end of the study, compared with 9.9% of the fractures and pseudofractures in the placebo group (odds ratio, 7.76; P =.0001).

The two groups had similar safety profiles, with no differences in serum or urine calcium, serum intact parathyroid hormone, or nephrocalcinosis severity score.

In the phase 2 pediatric trial, 52 patients aged 5-12 years received subcutaneous burosumab every other week or once a month for 64 weeks. Although the patients had received vitamin D/phosphate therapy for an average of 7 years before enrollment, rickets was present at baseline (mean Thatcher Rickets Severity Score, 1.8). The dose of burosumab was titrated (maximum dose 2 mg/kg) to achieve age-appropriate fasting serum phosphate. All of the subjects achieved normal fasting serum phosphatase levels, but the values were more stable in the dose treated every other week.

The Thatcher RSS improved overall (–0.92; P less than .0001) in the group dosed every other week (–1.00; P less than .0001) and the group dosed monthly (–0.84; P less than .0001). These changes were more notable in patients with more severe rickets at baseline (RSS, 1.5 or higher), which had a change of –1.44 (P less than .0001).

Similar improvements were seen with the Radiographic Global Impression of Change (RGI-C). Among children with an RSS value of 1.5 or higher, substantial healing (an increase in RGI-C equal to or greater that 2) occurred in the group dosed every other week (82.4%) and the group dosed monthly (70.6%).

There was no evidence of hyperphosphatemia or hypercalcemia, and there were no clinically meaningful changes in urine calcium or serum intact parathyroid hormone levels.

The studies were funded by Ultragenyx and Kyowa Kirin International. Dr. Insogna reported having no financial disclosures.

DENVER – Two studies provide hope for a new treatment of X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH), a genetic disorder that leads to low phosphorus levels, which can cause rickets in children and a host of bone and other problems in adulthood.

The studies evaluated the use of burosumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23). FGF23 is a hormone that reduces serum levels of phosphorus and vitamin D through its effects on the kidney.

“For the first time, this establishes the efficacy of any treatment in adults with XLH,” said Karl L. Insogna, MD, professor of medicine (endocrinology), at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., who presented the phase III study results during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. “Even in adults who have a lot of underlying disease burden, which is not likely to be completely reversed by this drug, you can address the underlying pathophysiology of the disease and show not only symptomatic improvement but also healing of fractures and pseudofractures,” he added.

XLH patients may be treated with calcitriol and phosphate, but this requires dosing 3-5 times a day, with side effects that can be onerous. “If you were dealing with a shot, you’d have 100% compliance and (fewer) side effects. It’s going to be a whole lot better,” he noted.

In the phase 3 adult trial, 134 patients were randomized to subcutaneous burosumab (at a dose of 1 mg/kg) or placebo every 4 weeks for 24 weeks. Among those treated with burosumab, 94.1% achieved serum phosphatase levels in the normal range, compared with 7.6% of those on placebo. Among patients taking burosumab, 36.9% of fractures and pseudofractures present at baseline had healed by the end of the study, compared with 9.9% of the fractures and pseudofractures in the placebo group (odds ratio, 7.76; P =.0001).

The two groups had similar safety profiles, with no differences in serum or urine calcium, serum intact parathyroid hormone, or nephrocalcinosis severity score.

In the phase 2 pediatric trial, 52 patients aged 5-12 years received subcutaneous burosumab every other week or once a month for 64 weeks. Although the patients had received vitamin D/phosphate therapy for an average of 7 years before enrollment, rickets was present at baseline (mean Thatcher Rickets Severity Score, 1.8). The dose of burosumab was titrated (maximum dose 2 mg/kg) to achieve age-appropriate fasting serum phosphate. All of the subjects achieved normal fasting serum phosphatase levels, but the values were more stable in the dose treated every other week.

The Thatcher RSS improved overall (–0.92; P less than .0001) in the group dosed every other week (–1.00; P less than .0001) and the group dosed monthly (–0.84; P less than .0001). These changes were more notable in patients with more severe rickets at baseline (RSS, 1.5 or higher), which had a change of –1.44 (P less than .0001).

Similar improvements were seen with the Radiographic Global Impression of Change (RGI-C). Among children with an RSS value of 1.5 or higher, substantial healing (an increase in RGI-C equal to or greater that 2) occurred in the group dosed every other week (82.4%) and the group dosed monthly (70.6%).

There was no evidence of hyperphosphatemia or hypercalcemia, and there were no clinically meaningful changes in urine calcium or serum intact parathyroid hormone levels.

The studies were funded by Ultragenyx and Kyowa Kirin International. Dr. Insogna reported having no financial disclosures.

DENVER – Two studies provide hope for a new treatment of X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH), a genetic disorder that leads to low phosphorus levels, which can cause rickets in children and a host of bone and other problems in adulthood.

The studies evaluated the use of burosumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23). FGF23 is a hormone that reduces serum levels of phosphorus and vitamin D through its effects on the kidney.

“For the first time, this establishes the efficacy of any treatment in adults with XLH,” said Karl L. Insogna, MD, professor of medicine (endocrinology), at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., who presented the phase III study results during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. “Even in adults who have a lot of underlying disease burden, which is not likely to be completely reversed by this drug, you can address the underlying pathophysiology of the disease and show not only symptomatic improvement but also healing of fractures and pseudofractures,” he added.

XLH patients may be treated with calcitriol and phosphate, but this requires dosing 3-5 times a day, with side effects that can be onerous. “If you were dealing with a shot, you’d have 100% compliance and (fewer) side effects. It’s going to be a whole lot better,” he noted.