User login

For MD-IQ on Family Practice News, but a regular topic for Rheumatology News

Long-term follow-up results of ongoing trials highlighted at ACR 2018

A 5-year follow-up study comparing methods of meniscal tear management in patients with osteoarthritis kicks off the second Plenary Session on Monday, Oct. 22, at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Jeffrey N. Katz, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and his colleagues conducted a long-term follow-up of patients from the METEOR study, the early results of which were presented at OARSI in 2017. Dr. Katz and his colleagues randomized patients with knee pain, meniscal tears, and OA changes on x-ray or MRI to physical therapy vs. physical therapy plus arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. After 5 years, pain relief was similar across treatment groups, supporting the short-term conclusion that these patients experience relief over time, irrespective of initial treatment. Overall, 25% of the patients had total knee replacement surgery during the follow-up period.

The session also includes a new presentation by Kenneth G. Saag, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham of 2-year outcomes from a phase 3 trial of denosumab versus risedronate for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis that was first presented at EULAR this year.

At 2 years, denosumab proved superior for increasing spine and hip bone mineral density in osteoporosis patients, compared with risedronate, and demonstrated a similar safety profile.

In addition, attendees will hear updated long-term results from the SCOT trial of myeloablative autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for scleroderma patients. Keith M. Sullivan, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and his colleagues found that the benefits of the treatment endured after 6-11 years, supporting results presented at ACR 2016.

A 5-year follow-up study comparing methods of meniscal tear management in patients with osteoarthritis kicks off the second Plenary Session on Monday, Oct. 22, at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Jeffrey N. Katz, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and his colleagues conducted a long-term follow-up of patients from the METEOR study, the early results of which were presented at OARSI in 2017. Dr. Katz and his colleagues randomized patients with knee pain, meniscal tears, and OA changes on x-ray or MRI to physical therapy vs. physical therapy plus arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. After 5 years, pain relief was similar across treatment groups, supporting the short-term conclusion that these patients experience relief over time, irrespective of initial treatment. Overall, 25% of the patients had total knee replacement surgery during the follow-up period.

The session also includes a new presentation by Kenneth G. Saag, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham of 2-year outcomes from a phase 3 trial of denosumab versus risedronate for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis that was first presented at EULAR this year.

At 2 years, denosumab proved superior for increasing spine and hip bone mineral density in osteoporosis patients, compared with risedronate, and demonstrated a similar safety profile.

In addition, attendees will hear updated long-term results from the SCOT trial of myeloablative autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for scleroderma patients. Keith M. Sullivan, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and his colleagues found that the benefits of the treatment endured after 6-11 years, supporting results presented at ACR 2016.

A 5-year follow-up study comparing methods of meniscal tear management in patients with osteoarthritis kicks off the second Plenary Session on Monday, Oct. 22, at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Jeffrey N. Katz, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and his colleagues conducted a long-term follow-up of patients from the METEOR study, the early results of which were presented at OARSI in 2017. Dr. Katz and his colleagues randomized patients with knee pain, meniscal tears, and OA changes on x-ray or MRI to physical therapy vs. physical therapy plus arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. After 5 years, pain relief was similar across treatment groups, supporting the short-term conclusion that these patients experience relief over time, irrespective of initial treatment. Overall, 25% of the patients had total knee replacement surgery during the follow-up period.

The session also includes a new presentation by Kenneth G. Saag, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham of 2-year outcomes from a phase 3 trial of denosumab versus risedronate for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis that was first presented at EULAR this year.

At 2 years, denosumab proved superior for increasing spine and hip bone mineral density in osteoporosis patients, compared with risedronate, and demonstrated a similar safety profile.

In addition, attendees will hear updated long-term results from the SCOT trial of myeloablative autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for scleroderma patients. Keith M. Sullivan, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and his colleagues found that the benefits of the treatment endured after 6-11 years, supporting results presented at ACR 2016.

REPORTING FROM THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

Anxiety and depression widespread among arthritis patients

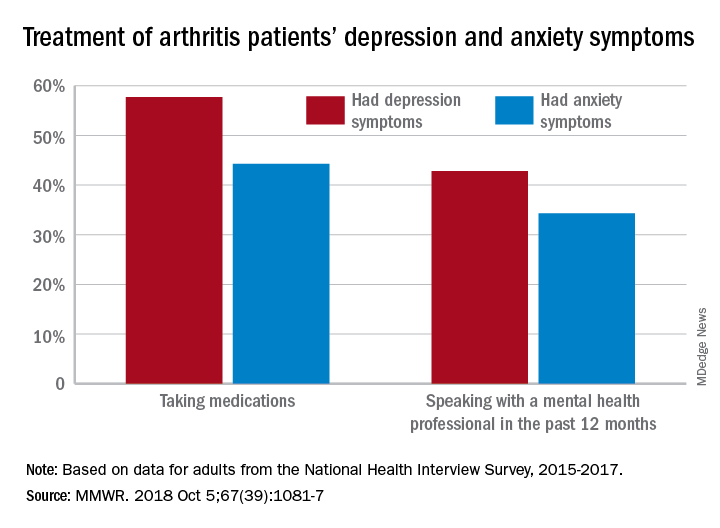

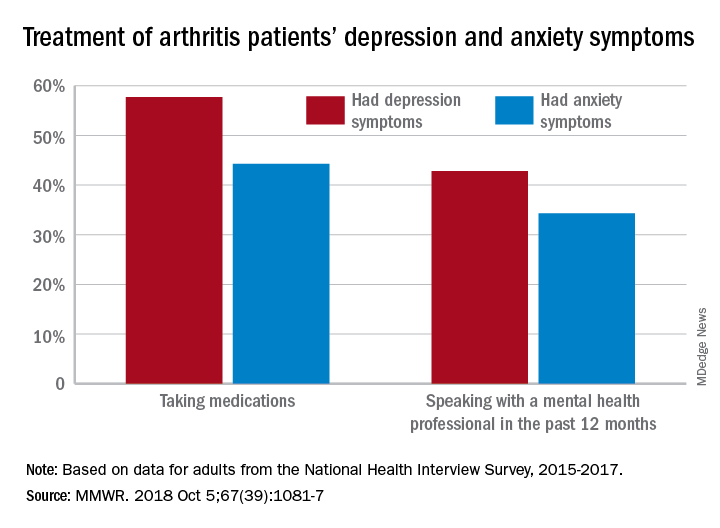

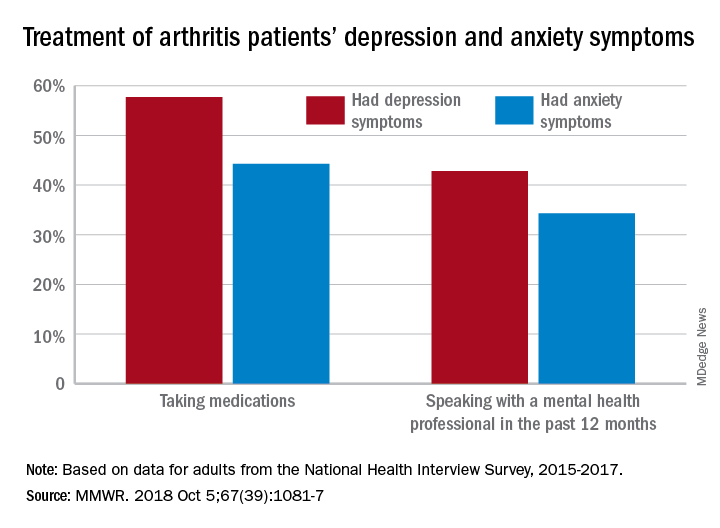

Adults with arthritis are almost twice as likely to have symptoms of anxiety than depression, but the depressed patients are more likely to receive treatment, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

During 2015-2017, the prevalence of anxiety symptoms was 22.5% in adults with arthritis, compared with 12.1% for depression symptoms. Treatment of those symptoms, however, was another story: 57.7% of arthritis patients with depression symptoms were taking medications, versus 44.3% of those with anxiety symptoms, and 42.8% of those with symptoms of depression reported seeing a mental health professional the past 12 months, compared with 34.3% of adults with anxiety, Dana Guglielmo, MPH, of the CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Atlanta, and her associates reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Prevalences of anxiety and depression symptoms varied considerably by sociodemographic characteristic during 2015-2017. Anxiety and depression were both more common in those aged 18-44 years (28.3% and 13.7%, respectively) than in those aged over 65 (9.7% and 6.2%), and women with arthritis were more likely than were men to experience symptoms of anxiety (26.9% vs. 16%) and depression (14% vs. 9.2%), the investigators said, based on data from the National Health Interview Survey.

Among racial/ethnic groups, the prevalence of anxiety was highest for whites (23.9%) and lowest for Asians (10.6%), who also had lowest depression symptom prevalence at 3.3%, with American Indians/Alaska Natives highest at 15.4%. Adults categorized as other/multiple race, however, were highest in both cases at 32.3% for anxiety and 17.4% for depression, Ms. Guglielmo and her associates said.

The overall prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms in patients with arthritis was much higher than in those without arthritis – 10.7% for anxiety and 4.7% for depression – which “suggests that all adults with arthritis would benefit from mental health screening,” they noted.

, and encouraging physical activity, which is an effective nonpharmacologic strategy that can help reduce the symptoms of anxiety and depression, improve arthritis symptoms, and promote better quality of life,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Guglielmo D et al. MMWR. 2018 Oct 5;67(39):1081-7.

Adults with arthritis are almost twice as likely to have symptoms of anxiety than depression, but the depressed patients are more likely to receive treatment, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

During 2015-2017, the prevalence of anxiety symptoms was 22.5% in adults with arthritis, compared with 12.1% for depression symptoms. Treatment of those symptoms, however, was another story: 57.7% of arthritis patients with depression symptoms were taking medications, versus 44.3% of those with anxiety symptoms, and 42.8% of those with symptoms of depression reported seeing a mental health professional the past 12 months, compared with 34.3% of adults with anxiety, Dana Guglielmo, MPH, of the CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Atlanta, and her associates reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Prevalences of anxiety and depression symptoms varied considerably by sociodemographic characteristic during 2015-2017. Anxiety and depression were both more common in those aged 18-44 years (28.3% and 13.7%, respectively) than in those aged over 65 (9.7% and 6.2%), and women with arthritis were more likely than were men to experience symptoms of anxiety (26.9% vs. 16%) and depression (14% vs. 9.2%), the investigators said, based on data from the National Health Interview Survey.

Among racial/ethnic groups, the prevalence of anxiety was highest for whites (23.9%) and lowest for Asians (10.6%), who also had lowest depression symptom prevalence at 3.3%, with American Indians/Alaska Natives highest at 15.4%. Adults categorized as other/multiple race, however, were highest in both cases at 32.3% for anxiety and 17.4% for depression, Ms. Guglielmo and her associates said.

The overall prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms in patients with arthritis was much higher than in those without arthritis – 10.7% for anxiety and 4.7% for depression – which “suggests that all adults with arthritis would benefit from mental health screening,” they noted.

, and encouraging physical activity, which is an effective nonpharmacologic strategy that can help reduce the symptoms of anxiety and depression, improve arthritis symptoms, and promote better quality of life,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Guglielmo D et al. MMWR. 2018 Oct 5;67(39):1081-7.

Adults with arthritis are almost twice as likely to have symptoms of anxiety than depression, but the depressed patients are more likely to receive treatment, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

During 2015-2017, the prevalence of anxiety symptoms was 22.5% in adults with arthritis, compared with 12.1% for depression symptoms. Treatment of those symptoms, however, was another story: 57.7% of arthritis patients with depression symptoms were taking medications, versus 44.3% of those with anxiety symptoms, and 42.8% of those with symptoms of depression reported seeing a mental health professional the past 12 months, compared with 34.3% of adults with anxiety, Dana Guglielmo, MPH, of the CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Atlanta, and her associates reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Prevalences of anxiety and depression symptoms varied considerably by sociodemographic characteristic during 2015-2017. Anxiety and depression were both more common in those aged 18-44 years (28.3% and 13.7%, respectively) than in those aged over 65 (9.7% and 6.2%), and women with arthritis were more likely than were men to experience symptoms of anxiety (26.9% vs. 16%) and depression (14% vs. 9.2%), the investigators said, based on data from the National Health Interview Survey.

Among racial/ethnic groups, the prevalence of anxiety was highest for whites (23.9%) and lowest for Asians (10.6%), who also had lowest depression symptom prevalence at 3.3%, with American Indians/Alaska Natives highest at 15.4%. Adults categorized as other/multiple race, however, were highest in both cases at 32.3% for anxiety and 17.4% for depression, Ms. Guglielmo and her associates said.

The overall prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms in patients with arthritis was much higher than in those without arthritis – 10.7% for anxiety and 4.7% for depression – which “suggests that all adults with arthritis would benefit from mental health screening,” they noted.

, and encouraging physical activity, which is an effective nonpharmacologic strategy that can help reduce the symptoms of anxiety and depression, improve arthritis symptoms, and promote better quality of life,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Guglielmo D et al. MMWR. 2018 Oct 5;67(39):1081-7.

FROM MMWR

Opioid use in OA may mean more activity-limiting pain

LAS VEGAS – Patients with OA pain who used opioids persistently were more likely to report worse pain interference with daily activities and more functional limitations than nonopioid users in a nationally representative survey, Drishti Shah and her colleagues reported at the annual PAINWeek.

“These findings suggest an unmet need and calls for better patient management, including consideration of alternative treatment strategies,” said Ms. Shah, a graduate student at West Virginia University, Morgantown.

The authors examined data from 4,172 adults with OA aged 18 years and older who took part in the nationally representative Medical Expenditure Panel Survey during 2010-2015.

Each respondent was followed for up to 2 years, with five rounds of surveys. The primary outcomes were longitudinal changes in pain interference with daily activities (PIA) as measured by the bodily pain item of the Short Form Health Survey scale and functional limitations in social, physical, work, and cognitive activities.

Opioid use was considered persistent when reported in at least two consecutive rounds and intermittent use was opioid use reported in any one or alternative rounds of the panel. Multivariate regression analyses were conducted, controlling for baseline sociodemographics, clinical characteristics, and prescription NSAID use.

Most of the patients were female (66%), and the mean age was 62 years. The majority (83%) were aged 50 years or older. About 45% were employed at baseline.

About one-third of patients reported opioid use in each round, and 25% reported prescription NSAID use. About 15% of patients reported persistent opioid use and 19% disclosed intermittent use.

At the end of follow-up, persistent opioid users were nearly three times more likely to report extreme or severe PIA when compared with nonopioid users (odds ratio, 2.91) and twice as likely to report moderate PIA (OR, 2.04). No significant differences were observed for intermittent opioid users.

Regardless of baseline functional status, persistent opioid users had a significantly higher likelihood of reporting functional limitation at end of follow-up when compared against nonopioid users. Similar results were observed for intermittent opioid users who reported no functional limitations at baseline. However, intermittent opioid users who reported functional limitation at baseline were less likely to report social and cognitive limitations at end of follow-up than were nonopioid users.

Regeneron and Teva Pharmaceuticals supported the study. Ms. Shah was a paid consultant for both companies and has no other personal financial relationships with either company.

LAS VEGAS – Patients with OA pain who used opioids persistently were more likely to report worse pain interference with daily activities and more functional limitations than nonopioid users in a nationally representative survey, Drishti Shah and her colleagues reported at the annual PAINWeek.

“These findings suggest an unmet need and calls for better patient management, including consideration of alternative treatment strategies,” said Ms. Shah, a graduate student at West Virginia University, Morgantown.

The authors examined data from 4,172 adults with OA aged 18 years and older who took part in the nationally representative Medical Expenditure Panel Survey during 2010-2015.

Each respondent was followed for up to 2 years, with five rounds of surveys. The primary outcomes were longitudinal changes in pain interference with daily activities (PIA) as measured by the bodily pain item of the Short Form Health Survey scale and functional limitations in social, physical, work, and cognitive activities.

Opioid use was considered persistent when reported in at least two consecutive rounds and intermittent use was opioid use reported in any one or alternative rounds of the panel. Multivariate regression analyses were conducted, controlling for baseline sociodemographics, clinical characteristics, and prescription NSAID use.

Most of the patients were female (66%), and the mean age was 62 years. The majority (83%) were aged 50 years or older. About 45% were employed at baseline.

About one-third of patients reported opioid use in each round, and 25% reported prescription NSAID use. About 15% of patients reported persistent opioid use and 19% disclosed intermittent use.

At the end of follow-up, persistent opioid users were nearly three times more likely to report extreme or severe PIA when compared with nonopioid users (odds ratio, 2.91) and twice as likely to report moderate PIA (OR, 2.04). No significant differences were observed for intermittent opioid users.

Regardless of baseline functional status, persistent opioid users had a significantly higher likelihood of reporting functional limitation at end of follow-up when compared against nonopioid users. Similar results were observed for intermittent opioid users who reported no functional limitations at baseline. However, intermittent opioid users who reported functional limitation at baseline were less likely to report social and cognitive limitations at end of follow-up than were nonopioid users.

Regeneron and Teva Pharmaceuticals supported the study. Ms. Shah was a paid consultant for both companies and has no other personal financial relationships with either company.

LAS VEGAS – Patients with OA pain who used opioids persistently were more likely to report worse pain interference with daily activities and more functional limitations than nonopioid users in a nationally representative survey, Drishti Shah and her colleagues reported at the annual PAINWeek.

“These findings suggest an unmet need and calls for better patient management, including consideration of alternative treatment strategies,” said Ms. Shah, a graduate student at West Virginia University, Morgantown.

The authors examined data from 4,172 adults with OA aged 18 years and older who took part in the nationally representative Medical Expenditure Panel Survey during 2010-2015.

Each respondent was followed for up to 2 years, with five rounds of surveys. The primary outcomes were longitudinal changes in pain interference with daily activities (PIA) as measured by the bodily pain item of the Short Form Health Survey scale and functional limitations in social, physical, work, and cognitive activities.

Opioid use was considered persistent when reported in at least two consecutive rounds and intermittent use was opioid use reported in any one or alternative rounds of the panel. Multivariate regression analyses were conducted, controlling for baseline sociodemographics, clinical characteristics, and prescription NSAID use.

Most of the patients were female (66%), and the mean age was 62 years. The majority (83%) were aged 50 years or older. About 45% were employed at baseline.

About one-third of patients reported opioid use in each round, and 25% reported prescription NSAID use. About 15% of patients reported persistent opioid use and 19% disclosed intermittent use.

At the end of follow-up, persistent opioid users were nearly three times more likely to report extreme or severe PIA when compared with nonopioid users (odds ratio, 2.91) and twice as likely to report moderate PIA (OR, 2.04). No significant differences were observed for intermittent opioid users.

Regardless of baseline functional status, persistent opioid users had a significantly higher likelihood of reporting functional limitation at end of follow-up when compared against nonopioid users. Similar results were observed for intermittent opioid users who reported no functional limitations at baseline. However, intermittent opioid users who reported functional limitation at baseline were less likely to report social and cognitive limitations at end of follow-up than were nonopioid users.

Regeneron and Teva Pharmaceuticals supported the study. Ms. Shah was a paid consultant for both companies and has no other personal financial relationships with either company.

REPORTING FROM PAINWEEK 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Compared with intermittent opioid users, persistent opioid users were three times more likely to report extreme or severe pain interfering with daily activities.

Study details: A group of 4,172 adults with OA from the 2010-2015 Medical Expenditure Panel Surveys

Disclosures: Regeneron and Teva Pharmaceuticals supported the study. Ms. Shah was a paid consultant for both companies and has no other personal financial relationships with either company.

Arthritis prevalent in older adults with any degree of depression

Arthritis is highly prevalent in older adults with any degree of depression, results of a recent study suggest.

Doctor-diagnosed arthritis was reported by more than 50% of older adults with mild depression, according to results of the study, which was based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

The prevalence of arthritis exceeded 60% in participants with moderate depression, and approached 70% for those with severe depression, according to the study, published in the International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.

Based on those findings, arthritis and depression need to be viewed as frequently co-occurring physical and psychosocial issues, reported Jessica M. Brooks, PhD, of the department of psychiatry at Dartmouth College, Lebanon, N.H., and her coauthors.

“It may be critical for mental health care providers to provide regular arthritis-related pain assessments and evidence‐based treatments for co‐occurring arthritis in older adults with or at risk for depression,” Dr. Brooks and her colleagues said in their report.

Their analysis was based on 2,483 women and 2,309 men aged 50 years and older (mean age, 64.5 years) who had participated in the NHANES survey between 2011 and 2014. Out of that sample, 2,094 participants (43.7%) said they had been told by a doctor that they had arthritis, the researchers said.

The rate of arthritis was 38.2% for participants with no depressive symptoms as indicated by a 0-4 score on the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). By comparison, rates of arthritis were 55.0%, 62.9%, and 67.8% for those with mild, moderate, or severe depression by PHQ-9.

Individuals with arthritis had a significantly higher mean PHQ-9 score, at 4.6, compared with 2.6 for those without arthritis (P less than .001), the investigators said.

that controlled for age, gender, comorbid conditions, and other factors such as smoking history.

Establishing prevalence rates of arthritis in older adults with depression is an “important step” toward informing mental health professionals on the need to identify and treat arthritis-related pain, Dr. Brooks and her coauthors said.

“Addressing arthritis in mental health treatment and behavioral medicine may also help to reduce the overlapping cognitive, behavioral, and somatic symptoms in older adults with depressive symptoms and arthritis, which may be difficult for providers to disentangle through brief screening procedures and treat through conventional depression care,” they wrote.

The investigators cited several limitations. For example, the cross-sectional nature of the study makes it difficult to draw conclusions about causality. In addition, Dr. Brooks and her colleagues did not distinguish between different types of arthritis.

The researchers declared no conflicts of interest. The study was supported by several U.S. institutes, including the National Institute of Mental Health, and by numerous entities related to Dartmouth, including the Dartmouth Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research Center. The Howard and Phyllis Schwartz Philanthropic Fund also provided funding.

SOURCE: Brooks JM et al. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018 Sep 19. doi: 10.1022/gps.4971.

Arthritis is highly prevalent in older adults with any degree of depression, results of a recent study suggest.

Doctor-diagnosed arthritis was reported by more than 50% of older adults with mild depression, according to results of the study, which was based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

The prevalence of arthritis exceeded 60% in participants with moderate depression, and approached 70% for those with severe depression, according to the study, published in the International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.

Based on those findings, arthritis and depression need to be viewed as frequently co-occurring physical and psychosocial issues, reported Jessica M. Brooks, PhD, of the department of psychiatry at Dartmouth College, Lebanon, N.H., and her coauthors.

“It may be critical for mental health care providers to provide regular arthritis-related pain assessments and evidence‐based treatments for co‐occurring arthritis in older adults with or at risk for depression,” Dr. Brooks and her colleagues said in their report.

Their analysis was based on 2,483 women and 2,309 men aged 50 years and older (mean age, 64.5 years) who had participated in the NHANES survey between 2011 and 2014. Out of that sample, 2,094 participants (43.7%) said they had been told by a doctor that they had arthritis, the researchers said.

The rate of arthritis was 38.2% for participants with no depressive symptoms as indicated by a 0-4 score on the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). By comparison, rates of arthritis were 55.0%, 62.9%, and 67.8% for those with mild, moderate, or severe depression by PHQ-9.

Individuals with arthritis had a significantly higher mean PHQ-9 score, at 4.6, compared with 2.6 for those without arthritis (P less than .001), the investigators said.

that controlled for age, gender, comorbid conditions, and other factors such as smoking history.

Establishing prevalence rates of arthritis in older adults with depression is an “important step” toward informing mental health professionals on the need to identify and treat arthritis-related pain, Dr. Brooks and her coauthors said.

“Addressing arthritis in mental health treatment and behavioral medicine may also help to reduce the overlapping cognitive, behavioral, and somatic symptoms in older adults with depressive symptoms and arthritis, which may be difficult for providers to disentangle through brief screening procedures and treat through conventional depression care,” they wrote.

The investigators cited several limitations. For example, the cross-sectional nature of the study makes it difficult to draw conclusions about causality. In addition, Dr. Brooks and her colleagues did not distinguish between different types of arthritis.

The researchers declared no conflicts of interest. The study was supported by several U.S. institutes, including the National Institute of Mental Health, and by numerous entities related to Dartmouth, including the Dartmouth Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research Center. The Howard and Phyllis Schwartz Philanthropic Fund also provided funding.

SOURCE: Brooks JM et al. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018 Sep 19. doi: 10.1022/gps.4971.

Arthritis is highly prevalent in older adults with any degree of depression, results of a recent study suggest.

Doctor-diagnosed arthritis was reported by more than 50% of older adults with mild depression, according to results of the study, which was based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

The prevalence of arthritis exceeded 60% in participants with moderate depression, and approached 70% for those with severe depression, according to the study, published in the International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.

Based on those findings, arthritis and depression need to be viewed as frequently co-occurring physical and psychosocial issues, reported Jessica M. Brooks, PhD, of the department of psychiatry at Dartmouth College, Lebanon, N.H., and her coauthors.

“It may be critical for mental health care providers to provide regular arthritis-related pain assessments and evidence‐based treatments for co‐occurring arthritis in older adults with or at risk for depression,” Dr. Brooks and her colleagues said in their report.

Their analysis was based on 2,483 women and 2,309 men aged 50 years and older (mean age, 64.5 years) who had participated in the NHANES survey between 2011 and 2014. Out of that sample, 2,094 participants (43.7%) said they had been told by a doctor that they had arthritis, the researchers said.

The rate of arthritis was 38.2% for participants with no depressive symptoms as indicated by a 0-4 score on the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). By comparison, rates of arthritis were 55.0%, 62.9%, and 67.8% for those with mild, moderate, or severe depression by PHQ-9.

Individuals with arthritis had a significantly higher mean PHQ-9 score, at 4.6, compared with 2.6 for those without arthritis (P less than .001), the investigators said.

that controlled for age, gender, comorbid conditions, and other factors such as smoking history.

Establishing prevalence rates of arthritis in older adults with depression is an “important step” toward informing mental health professionals on the need to identify and treat arthritis-related pain, Dr. Brooks and her coauthors said.

“Addressing arthritis in mental health treatment and behavioral medicine may also help to reduce the overlapping cognitive, behavioral, and somatic symptoms in older adults with depressive symptoms and arthritis, which may be difficult for providers to disentangle through brief screening procedures and treat through conventional depression care,” they wrote.

The investigators cited several limitations. For example, the cross-sectional nature of the study makes it difficult to draw conclusions about causality. In addition, Dr. Brooks and her colleagues did not distinguish between different types of arthritis.

The researchers declared no conflicts of interest. The study was supported by several U.S. institutes, including the National Institute of Mental Health, and by numerous entities related to Dartmouth, including the Dartmouth Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research Center. The Howard and Phyllis Schwartz Philanthropic Fund also provided funding.

SOURCE: Brooks JM et al. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018 Sep 19. doi: 10.1022/gps.4971.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF GERIATRIC PSYCHIATRY

Key clinical point: “It may be critical for mental health care providers to provide regular arthritis-related pain assessments” for older adults with or at risk for depression.

Major finding: Rates of arthritis were 55.0%, 62.9%, and 67.8% for those with mild, moderate, or severe depression, respectively, according to the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores.

Study details: Findings on 2,483 women and 2,309 men aged 50 years and older who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Disclosures: Dr. Brooks and her coauthors declared no conflicts of interest. The study was supported by several U.S. institutes, including the National Institute of Mental Health, and by numerous entities related to Dartmouth, including the Dartmouth Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research Center. The Howard and Phyllis Schwartz Philanthropic Fund also provided funding.

Source: Brooks JM et al. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018 Sep 19. doi: 10.1002/gps.4971.

Updates to EULAR hand OA management recommendations reflect current evidence

Updated EULAR recommendations on the management of hand osteoarthritis include five overarching principles as well as two new recommendations that reflect new research in the field.

The task force, led by Margreet Kloppenburg, MD, PhD, of the department of rheumatology at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, noted that a decade had passed since the first recommendations were published in 2007.

“It was timely to update the recommendations, as many new studies had emerged during this period. In light of this new evidence, many of the 2007 recommendations were modified and new recommendations were added,” wrote Dr. Kloppenburg and her colleagues. The recommendations were published online in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

They noted that the recommendations were targeted to all health professionals across primary and secondary care but also aimed to inform patients about their disease to “support shared decision making.”

In line with other EULAR sets of management recommendations, the update included five overarching principles that cover treatment goals, information and education for patients, individualization of treatment, shared decision making between clinicians and patients, and the need to take into consideration a multidisciplinary and multimodal (pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic) treatment approach.

The authors noted that for a long time hand OA was a “forgotten disease” and this was reflected by the paucity of clinical trials in the area. As a direct consequence, previous recommendations were based on expert opinion rather than evidence.

However, new data allowed the task force to recommend not to treat patients with hand OA with conventional synthetic or biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). The recommendation achieved the strongest level of evidence and a high level of agreement from the 19-member expert panel, which included 2 patient research partners. The authors said the recommendation was based on newer studies that demonstrated a lack of efficacy of csDMARDs and bDMARDs.

The authors also advised adapting the long-term follow-up of patients with hand OA to individual needs, although they noted this was based on expert opinion alone and that in the absence of a disease-modifying treatment, the goal of follow-up differs from that of many other rheumatic diseases. Individual needs will dictate the degree of follow-up required, based on the severity of symptoms, presence of erosive disease, reevaluation of the use of pharmacologic therapy, and a patient’s wishes and expectations. They also noted that “for most patients, standard radiographic follow-up is not useful at this moment” and that “follow-up does not necessarily have to be performed by a rheumatologist.

“Follow-up will likely increase adherence to nonpharmacological therapies like exercise or orthoses, and provides an opportunity for reevaluation of treatment,” they wrote.

The recommendations advise offering education and training in ergonomic principles and exercises to patients to improve function and muscle strength, as well as considering the use of orthoses in some patients.

Treatment recommendations suggested preferring topical treatments over systemic treatments and that oral analgesics, particularly NSAIDs, should be considered for a limited duration. The authors advised that chondroitin sulfate may be used in patients for pain relief and improvement in functioning and that intra-articular glucocorticoids should not generally be used but may be considered in patients with painful interphalangeal joints. Surgery should be considered for patients with structural abnormalities when other treatment modalities have not been sufficiently effective in relieving pain.

The recommendations were funded by EULAR. Several of the authors reported receiving consultancy fees and/or honoraria as well as research funding from industry.

SOURCE: Kloppenburg M et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Aug 28. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213826.

EULAR has updated its 2007 guidelines for the management of hand osteoarthritis. I find the recommendations helpful, and I have no disagreements.

The authors performed a systematic literature review that was more complete than the original guidelines. In addition, the methodology in developing the guidelines was updated utilizing the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) system to guide the expert opinion. The manuscript presents recommendations that are carefully supported in the text. To understand guidelines, one really needs to read the text.

The update lists a set of research questions, similar to the 2007 recommendations.

The authors group their therapeutic recommendations according to nonpharmacologic, pharmacologic, and surgical approaches, as well as about the need for follow-up. The three nonpharmacologic recommendations include education and training, exercise and muscle strengthening, and the use of orthoses. The pharmacologic approach includes topical therapy as a first-line, oral NSAIDs and analgesics, chondroitin sulfate, and intra-articular injections. There is a negative recommendation for the use of biologics. The surgical recommendation is directed at the relief of pain. The last recommendation emphasizes the need for follow-up and individual care.

The differences between the recommendations include the removal of acetaminophen as a first-line therapy. Indeed, it seems to be barely recommended at all. In addition, there is an emphasis on topical therapy, particularly NSAIDs. The authors are equivocal on the recommendations for intra-articular therapy. Paraffin and local heat are no longer included. The recommendation against biologic therapy is new. They included agents used for rheumatoid arthritis, such as methotrexate, in this negative recommendation.

These new recommendations are an update of guidelines that are over 10 years old. They are practical and helpful. Unfortunately, more research is needed as the present day therapy is often inadequate.

Roy D. Altman, MD, is professor emeritus of medicine in the division of rheumatology and immunology at the University of California, Los Angeles. He is a consultant to Ferring, Flexion, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Olatec, Pfizer, and Sorrento Therapeutics.

EULAR has updated its 2007 guidelines for the management of hand osteoarthritis. I find the recommendations helpful, and I have no disagreements.

The authors performed a systematic literature review that was more complete than the original guidelines. In addition, the methodology in developing the guidelines was updated utilizing the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) system to guide the expert opinion. The manuscript presents recommendations that are carefully supported in the text. To understand guidelines, one really needs to read the text.

The update lists a set of research questions, similar to the 2007 recommendations.

The authors group their therapeutic recommendations according to nonpharmacologic, pharmacologic, and surgical approaches, as well as about the need for follow-up. The three nonpharmacologic recommendations include education and training, exercise and muscle strengthening, and the use of orthoses. The pharmacologic approach includes topical therapy as a first-line, oral NSAIDs and analgesics, chondroitin sulfate, and intra-articular injections. There is a negative recommendation for the use of biologics. The surgical recommendation is directed at the relief of pain. The last recommendation emphasizes the need for follow-up and individual care.

The differences between the recommendations include the removal of acetaminophen as a first-line therapy. Indeed, it seems to be barely recommended at all. In addition, there is an emphasis on topical therapy, particularly NSAIDs. The authors are equivocal on the recommendations for intra-articular therapy. Paraffin and local heat are no longer included. The recommendation against biologic therapy is new. They included agents used for rheumatoid arthritis, such as methotrexate, in this negative recommendation.

These new recommendations are an update of guidelines that are over 10 years old. They are practical and helpful. Unfortunately, more research is needed as the present day therapy is often inadequate.

Roy D. Altman, MD, is professor emeritus of medicine in the division of rheumatology and immunology at the University of California, Los Angeles. He is a consultant to Ferring, Flexion, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Olatec, Pfizer, and Sorrento Therapeutics.

EULAR has updated its 2007 guidelines for the management of hand osteoarthritis. I find the recommendations helpful, and I have no disagreements.

The authors performed a systematic literature review that was more complete than the original guidelines. In addition, the methodology in developing the guidelines was updated utilizing the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) system to guide the expert opinion. The manuscript presents recommendations that are carefully supported in the text. To understand guidelines, one really needs to read the text.

The update lists a set of research questions, similar to the 2007 recommendations.

The authors group their therapeutic recommendations according to nonpharmacologic, pharmacologic, and surgical approaches, as well as about the need for follow-up. The three nonpharmacologic recommendations include education and training, exercise and muscle strengthening, and the use of orthoses. The pharmacologic approach includes topical therapy as a first-line, oral NSAIDs and analgesics, chondroitin sulfate, and intra-articular injections. There is a negative recommendation for the use of biologics. The surgical recommendation is directed at the relief of pain. The last recommendation emphasizes the need for follow-up and individual care.

The differences between the recommendations include the removal of acetaminophen as a first-line therapy. Indeed, it seems to be barely recommended at all. In addition, there is an emphasis on topical therapy, particularly NSAIDs. The authors are equivocal on the recommendations for intra-articular therapy. Paraffin and local heat are no longer included. The recommendation against biologic therapy is new. They included agents used for rheumatoid arthritis, such as methotrexate, in this negative recommendation.

These new recommendations are an update of guidelines that are over 10 years old. They are practical and helpful. Unfortunately, more research is needed as the present day therapy is often inadequate.

Roy D. Altman, MD, is professor emeritus of medicine in the division of rheumatology and immunology at the University of California, Los Angeles. He is a consultant to Ferring, Flexion, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Olatec, Pfizer, and Sorrento Therapeutics.

Updated EULAR recommendations on the management of hand osteoarthritis include five overarching principles as well as two new recommendations that reflect new research in the field.

The task force, led by Margreet Kloppenburg, MD, PhD, of the department of rheumatology at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, noted that a decade had passed since the first recommendations were published in 2007.

“It was timely to update the recommendations, as many new studies had emerged during this period. In light of this new evidence, many of the 2007 recommendations were modified and new recommendations were added,” wrote Dr. Kloppenburg and her colleagues. The recommendations were published online in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

They noted that the recommendations were targeted to all health professionals across primary and secondary care but also aimed to inform patients about their disease to “support shared decision making.”

In line with other EULAR sets of management recommendations, the update included five overarching principles that cover treatment goals, information and education for patients, individualization of treatment, shared decision making between clinicians and patients, and the need to take into consideration a multidisciplinary and multimodal (pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic) treatment approach.

The authors noted that for a long time hand OA was a “forgotten disease” and this was reflected by the paucity of clinical trials in the area. As a direct consequence, previous recommendations were based on expert opinion rather than evidence.

However, new data allowed the task force to recommend not to treat patients with hand OA with conventional synthetic or biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). The recommendation achieved the strongest level of evidence and a high level of agreement from the 19-member expert panel, which included 2 patient research partners. The authors said the recommendation was based on newer studies that demonstrated a lack of efficacy of csDMARDs and bDMARDs.

The authors also advised adapting the long-term follow-up of patients with hand OA to individual needs, although they noted this was based on expert opinion alone and that in the absence of a disease-modifying treatment, the goal of follow-up differs from that of many other rheumatic diseases. Individual needs will dictate the degree of follow-up required, based on the severity of symptoms, presence of erosive disease, reevaluation of the use of pharmacologic therapy, and a patient’s wishes and expectations. They also noted that “for most patients, standard radiographic follow-up is not useful at this moment” and that “follow-up does not necessarily have to be performed by a rheumatologist.

“Follow-up will likely increase adherence to nonpharmacological therapies like exercise or orthoses, and provides an opportunity for reevaluation of treatment,” they wrote.

The recommendations advise offering education and training in ergonomic principles and exercises to patients to improve function and muscle strength, as well as considering the use of orthoses in some patients.

Treatment recommendations suggested preferring topical treatments over systemic treatments and that oral analgesics, particularly NSAIDs, should be considered for a limited duration. The authors advised that chondroitin sulfate may be used in patients for pain relief and improvement in functioning and that intra-articular glucocorticoids should not generally be used but may be considered in patients with painful interphalangeal joints. Surgery should be considered for patients with structural abnormalities when other treatment modalities have not been sufficiently effective in relieving pain.

The recommendations were funded by EULAR. Several of the authors reported receiving consultancy fees and/or honoraria as well as research funding from industry.

SOURCE: Kloppenburg M et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Aug 28. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213826.

Updated EULAR recommendations on the management of hand osteoarthritis include five overarching principles as well as two new recommendations that reflect new research in the field.

The task force, led by Margreet Kloppenburg, MD, PhD, of the department of rheumatology at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, noted that a decade had passed since the first recommendations were published in 2007.

“It was timely to update the recommendations, as many new studies had emerged during this period. In light of this new evidence, many of the 2007 recommendations were modified and new recommendations were added,” wrote Dr. Kloppenburg and her colleagues. The recommendations were published online in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

They noted that the recommendations were targeted to all health professionals across primary and secondary care but also aimed to inform patients about their disease to “support shared decision making.”

In line with other EULAR sets of management recommendations, the update included five overarching principles that cover treatment goals, information and education for patients, individualization of treatment, shared decision making between clinicians and patients, and the need to take into consideration a multidisciplinary and multimodal (pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic) treatment approach.

The authors noted that for a long time hand OA was a “forgotten disease” and this was reflected by the paucity of clinical trials in the area. As a direct consequence, previous recommendations were based on expert opinion rather than evidence.

However, new data allowed the task force to recommend not to treat patients with hand OA with conventional synthetic or biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). The recommendation achieved the strongest level of evidence and a high level of agreement from the 19-member expert panel, which included 2 patient research partners. The authors said the recommendation was based on newer studies that demonstrated a lack of efficacy of csDMARDs and bDMARDs.

The authors also advised adapting the long-term follow-up of patients with hand OA to individual needs, although they noted this was based on expert opinion alone and that in the absence of a disease-modifying treatment, the goal of follow-up differs from that of many other rheumatic diseases. Individual needs will dictate the degree of follow-up required, based on the severity of symptoms, presence of erosive disease, reevaluation of the use of pharmacologic therapy, and a patient’s wishes and expectations. They also noted that “for most patients, standard radiographic follow-up is not useful at this moment” and that “follow-up does not necessarily have to be performed by a rheumatologist.

“Follow-up will likely increase adherence to nonpharmacological therapies like exercise or orthoses, and provides an opportunity for reevaluation of treatment,” they wrote.

The recommendations advise offering education and training in ergonomic principles and exercises to patients to improve function and muscle strength, as well as considering the use of orthoses in some patients.

Treatment recommendations suggested preferring topical treatments over systemic treatments and that oral analgesics, particularly NSAIDs, should be considered for a limited duration. The authors advised that chondroitin sulfate may be used in patients for pain relief and improvement in functioning and that intra-articular glucocorticoids should not generally be used but may be considered in patients with painful interphalangeal joints. Surgery should be considered for patients with structural abnormalities when other treatment modalities have not been sufficiently effective in relieving pain.

The recommendations were funded by EULAR. Several of the authors reported receiving consultancy fees and/or honoraria as well as research funding from industry.

SOURCE: Kloppenburg M et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Aug 28. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213826.

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

Diclofenac’s cardiovascular risk confirmed in novel Nordic study

Those beginning diclofenac had a 50% increased 30-day risk for a composite outcome of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) compared with individuals who didn’t initiate an NSAID or acetaminophen (95% confidence interval for incidence rate ratio, 1.4-1.7).

The risk was still significantly elevated when the study’s first author, Morten Schmidt, MD, and his colleagues compared diclofenac initiation with beginning other NSAIDs or acetaminophen. Compared with those starting ibuprofen or acetaminophen, the MACE risk was elevated 20% in diclofenac initiators (95% CI, 1.1-1.3 for both). Initiating diclofenac was associated with 30% greater risk for MACE compared with initiating naproxen (95% CI, 1.1-1.5).

“Diclofenac is the most frequently used NSAID in low-, middle-, and high-income countries and is available over the counter in most countries; therefore, its cardiovascular risk profile is of major clinical and public health importance,” wrote Dr. Schmidt and his coauthors.

In all, the study included 1,370,832 individuals who initiated diclofenac, 3,878,454 ibuprofen initiators, 291,490 naproxen initiators, and 764,781 acetaminophen initiators. Those starting diclofenac were compared with those starting other medications, and with 1,303,209 individuals who sought health care but did not start one of the medications.

The researchers used the longstanding and complete Danish health registry system to their advantage in designing a cohort trial that was modeled to resemble a clinical trial. For each month, beginning in 1996 and continuing through 2016, Dr. Schmidt and his collaborators assembled propensity-matched cohorts of individuals to compare each study group. The study design achieved many of the aims of a clinical trial while working within the ethical constraints of studying medications now known to elevate cardiovascular risk.

For each 30-day period, the investigators were then able to track and compare cardiovascular outcomes for each group. Each month, data for a new cohort were collected, beginning a new “clinical trial.” Individuals could be included in more than one month’s worth of “trial” data as long as they continued to meet inclusion criteria.

The completeness of Danish health data meant that the researchers were confident in data about comorbidities, other prescription medications, and outcomes.

Dr. Schmidt and his colleagues performed subgroup and sensitivity analyses to look at the extent to which preexisting risks for cardiovascular disease mediated MACE risk on diclofenac initiation. They found that diclofenac initiators in the highest risk group had up to 40 excess cardiovascular events per year – about half of them fatal – that were attributable to starting the medication. Although that group had the highest absolute risk, however, “the relative risks were highest in those with the lowest baseline risk,” wrote the investigators.

In addition to looking at rates of MACE, secondary outcomes for the study included evaluating the association between medication use or non-use and each individual component of the composite primary outcome. These included first-time occurrences of the nonfatal endpoints of atrial fibrillation or flutter, ischemic (but not hemorrhagic) stroke, heart failure, and myocardial infarction. Cardiac death was death from any cardiac cause.

“Supporting use of a combined endpoint, event rates consistently increased for all individual outcomes” for diclofenac initiators compared with those who did not start an NSAID, wrote Dr. Schmidt and his colleagues.

Individuals were excluded if they had known cardiovascular, kidney, liver, or ulcer disease, and if they had malignancy or serious mental health diagnoses such as dementia or schizophrenia. Participants, aged a mean 48-56 years, had to be at least 18 years of age and could not have filled a prescription for an NSAID within the previous 12 months. Men made up 36.6%-46.3% of the cohorts.

Dr. Schmidt, of Aarhus (Denmark) University, and his collaborators said that in comparison with other NSAIDs, the short half-life of diclofenac means that a supratherapeutic plasma concentration of diclofenac soon after initiation achieves not just cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), but also COX-1 inhibition. However, after those high levels fall, patients taking diclofenac spend a substantial period of time with unopposed COX-2 inhibition, a state that is known to be prothrombotic, and also associated with blood pressure elevation, atherogenesis, and worsening of heart failure.

Diclofenac and ibuprofen had similar gastrointestinal bleeding risks, and both medications were associated with a higher risk of bleeding than were ibuprofen, acetaminophen, or no medication.

“Comparing diclofenac initiation with no NSAID initiation, the consistency between our results and those of previous meta-analyses of both trial and observational data provides strong evidence to guide clinical decision making,” said Dr. Schmidt and his coauthors.

“Considering its cardiovascular and gastrointestinal risks, however, there is little justification to initiate diclofenac treatment before other traditional NSAIDs,” noted the investigators. “It is time to acknowledge the potential health risk of diclofenac and to reduce its use.”

The study was funded by the Department of Clinical Epidemiology Research Foundation, University of Aarhus, and by the Program for Clinical Research Infrastructure, funded by the Lundbeck Foundation, Novo Nordisk Foundation, and the Danish Research Council. The authors reported that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schmidt M et al. BMJ 2018;362:k3426

Those beginning diclofenac had a 50% increased 30-day risk for a composite outcome of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) compared with individuals who didn’t initiate an NSAID or acetaminophen (95% confidence interval for incidence rate ratio, 1.4-1.7).

The risk was still significantly elevated when the study’s first author, Morten Schmidt, MD, and his colleagues compared diclofenac initiation with beginning other NSAIDs or acetaminophen. Compared with those starting ibuprofen or acetaminophen, the MACE risk was elevated 20% in diclofenac initiators (95% CI, 1.1-1.3 for both). Initiating diclofenac was associated with 30% greater risk for MACE compared with initiating naproxen (95% CI, 1.1-1.5).

“Diclofenac is the most frequently used NSAID in low-, middle-, and high-income countries and is available over the counter in most countries; therefore, its cardiovascular risk profile is of major clinical and public health importance,” wrote Dr. Schmidt and his coauthors.

In all, the study included 1,370,832 individuals who initiated diclofenac, 3,878,454 ibuprofen initiators, 291,490 naproxen initiators, and 764,781 acetaminophen initiators. Those starting diclofenac were compared with those starting other medications, and with 1,303,209 individuals who sought health care but did not start one of the medications.

The researchers used the longstanding and complete Danish health registry system to their advantage in designing a cohort trial that was modeled to resemble a clinical trial. For each month, beginning in 1996 and continuing through 2016, Dr. Schmidt and his collaborators assembled propensity-matched cohorts of individuals to compare each study group. The study design achieved many of the aims of a clinical trial while working within the ethical constraints of studying medications now known to elevate cardiovascular risk.

For each 30-day period, the investigators were then able to track and compare cardiovascular outcomes for each group. Each month, data for a new cohort were collected, beginning a new “clinical trial.” Individuals could be included in more than one month’s worth of “trial” data as long as they continued to meet inclusion criteria.

The completeness of Danish health data meant that the researchers were confident in data about comorbidities, other prescription medications, and outcomes.

Dr. Schmidt and his colleagues performed subgroup and sensitivity analyses to look at the extent to which preexisting risks for cardiovascular disease mediated MACE risk on diclofenac initiation. They found that diclofenac initiators in the highest risk group had up to 40 excess cardiovascular events per year – about half of them fatal – that were attributable to starting the medication. Although that group had the highest absolute risk, however, “the relative risks were highest in those with the lowest baseline risk,” wrote the investigators.

In addition to looking at rates of MACE, secondary outcomes for the study included evaluating the association between medication use or non-use and each individual component of the composite primary outcome. These included first-time occurrences of the nonfatal endpoints of atrial fibrillation or flutter, ischemic (but not hemorrhagic) stroke, heart failure, and myocardial infarction. Cardiac death was death from any cardiac cause.

“Supporting use of a combined endpoint, event rates consistently increased for all individual outcomes” for diclofenac initiators compared with those who did not start an NSAID, wrote Dr. Schmidt and his colleagues.

Individuals were excluded if they had known cardiovascular, kidney, liver, or ulcer disease, and if they had malignancy or serious mental health diagnoses such as dementia or schizophrenia. Participants, aged a mean 48-56 years, had to be at least 18 years of age and could not have filled a prescription for an NSAID within the previous 12 months. Men made up 36.6%-46.3% of the cohorts.

Dr. Schmidt, of Aarhus (Denmark) University, and his collaborators said that in comparison with other NSAIDs, the short half-life of diclofenac means that a supratherapeutic plasma concentration of diclofenac soon after initiation achieves not just cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), but also COX-1 inhibition. However, after those high levels fall, patients taking diclofenac spend a substantial period of time with unopposed COX-2 inhibition, a state that is known to be prothrombotic, and also associated with blood pressure elevation, atherogenesis, and worsening of heart failure.

Diclofenac and ibuprofen had similar gastrointestinal bleeding risks, and both medications were associated with a higher risk of bleeding than were ibuprofen, acetaminophen, or no medication.

“Comparing diclofenac initiation with no NSAID initiation, the consistency between our results and those of previous meta-analyses of both trial and observational data provides strong evidence to guide clinical decision making,” said Dr. Schmidt and his coauthors.

“Considering its cardiovascular and gastrointestinal risks, however, there is little justification to initiate diclofenac treatment before other traditional NSAIDs,” noted the investigators. “It is time to acknowledge the potential health risk of diclofenac and to reduce its use.”

The study was funded by the Department of Clinical Epidemiology Research Foundation, University of Aarhus, and by the Program for Clinical Research Infrastructure, funded by the Lundbeck Foundation, Novo Nordisk Foundation, and the Danish Research Council. The authors reported that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schmidt M et al. BMJ 2018;362:k3426

Those beginning diclofenac had a 50% increased 30-day risk for a composite outcome of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) compared with individuals who didn’t initiate an NSAID or acetaminophen (95% confidence interval for incidence rate ratio, 1.4-1.7).

The risk was still significantly elevated when the study’s first author, Morten Schmidt, MD, and his colleagues compared diclofenac initiation with beginning other NSAIDs or acetaminophen. Compared with those starting ibuprofen or acetaminophen, the MACE risk was elevated 20% in diclofenac initiators (95% CI, 1.1-1.3 for both). Initiating diclofenac was associated with 30% greater risk for MACE compared with initiating naproxen (95% CI, 1.1-1.5).

“Diclofenac is the most frequently used NSAID in low-, middle-, and high-income countries and is available over the counter in most countries; therefore, its cardiovascular risk profile is of major clinical and public health importance,” wrote Dr. Schmidt and his coauthors.

In all, the study included 1,370,832 individuals who initiated diclofenac, 3,878,454 ibuprofen initiators, 291,490 naproxen initiators, and 764,781 acetaminophen initiators. Those starting diclofenac were compared with those starting other medications, and with 1,303,209 individuals who sought health care but did not start one of the medications.

The researchers used the longstanding and complete Danish health registry system to their advantage in designing a cohort trial that was modeled to resemble a clinical trial. For each month, beginning in 1996 and continuing through 2016, Dr. Schmidt and his collaborators assembled propensity-matched cohorts of individuals to compare each study group. The study design achieved many of the aims of a clinical trial while working within the ethical constraints of studying medications now known to elevate cardiovascular risk.

For each 30-day period, the investigators were then able to track and compare cardiovascular outcomes for each group. Each month, data for a new cohort were collected, beginning a new “clinical trial.” Individuals could be included in more than one month’s worth of “trial” data as long as they continued to meet inclusion criteria.

The completeness of Danish health data meant that the researchers were confident in data about comorbidities, other prescription medications, and outcomes.

Dr. Schmidt and his colleagues performed subgroup and sensitivity analyses to look at the extent to which preexisting risks for cardiovascular disease mediated MACE risk on diclofenac initiation. They found that diclofenac initiators in the highest risk group had up to 40 excess cardiovascular events per year – about half of them fatal – that were attributable to starting the medication. Although that group had the highest absolute risk, however, “the relative risks were highest in those with the lowest baseline risk,” wrote the investigators.

In addition to looking at rates of MACE, secondary outcomes for the study included evaluating the association between medication use or non-use and each individual component of the composite primary outcome. These included first-time occurrences of the nonfatal endpoints of atrial fibrillation or flutter, ischemic (but not hemorrhagic) stroke, heart failure, and myocardial infarction. Cardiac death was death from any cardiac cause.

“Supporting use of a combined endpoint, event rates consistently increased for all individual outcomes” for diclofenac initiators compared with those who did not start an NSAID, wrote Dr. Schmidt and his colleagues.

Individuals were excluded if they had known cardiovascular, kidney, liver, or ulcer disease, and if they had malignancy or serious mental health diagnoses such as dementia or schizophrenia. Participants, aged a mean 48-56 years, had to be at least 18 years of age and could not have filled a prescription for an NSAID within the previous 12 months. Men made up 36.6%-46.3% of the cohorts.

Dr. Schmidt, of Aarhus (Denmark) University, and his collaborators said that in comparison with other NSAIDs, the short half-life of diclofenac means that a supratherapeutic plasma concentration of diclofenac soon after initiation achieves not just cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), but also COX-1 inhibition. However, after those high levels fall, patients taking diclofenac spend a substantial period of time with unopposed COX-2 inhibition, a state that is known to be prothrombotic, and also associated with blood pressure elevation, atherogenesis, and worsening of heart failure.

Diclofenac and ibuprofen had similar gastrointestinal bleeding risks, and both medications were associated with a higher risk of bleeding than were ibuprofen, acetaminophen, or no medication.

“Comparing diclofenac initiation with no NSAID initiation, the consistency between our results and those of previous meta-analyses of both trial and observational data provides strong evidence to guide clinical decision making,” said Dr. Schmidt and his coauthors.

“Considering its cardiovascular and gastrointestinal risks, however, there is little justification to initiate diclofenac treatment before other traditional NSAIDs,” noted the investigators. “It is time to acknowledge the potential health risk of diclofenac and to reduce its use.”

The study was funded by the Department of Clinical Epidemiology Research Foundation, University of Aarhus, and by the Program for Clinical Research Infrastructure, funded by the Lundbeck Foundation, Novo Nordisk Foundation, and the Danish Research Council. The authors reported that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schmidt M et al. BMJ 2018;362:k3426

FROM BMJ

Key clinical point: Those starting diclofenac had increased risk for cardiovascular events or cardiac death.

Major finding: Risk for major adverse cardiovascular events was increased by 50% compared with noninitiators.

Study details: Retrospective propensity-matched cohort study using national databases and registries.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Department of Clinical Epidemiology Research Foundation of the University of Aarhus, Denmark, and by the Program for Clinical Research Infrastructure, funded by the Lundbeck Foundation, Novo Nordisk Foundation, and the Danish Research Council. The authors reported that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Schmidt M et al. BMJ 2018;362:k3426.

Antibody cleared amyloid plaques, slowed cognitive decline

Can meteorology predict migraines? Why closing a patent foramen ovale is the right approach to prevent recurring ischemic stroke. And claims that cannabis relieves noncancer pain go up in smoke.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News for today’s top news.

Can meteorology predict migraines? Why closing a patent foramen ovale is the right approach to prevent recurring ischemic stroke. And claims that cannabis relieves noncancer pain go up in smoke.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News for today’s top news.

Can meteorology predict migraines? Why closing a patent foramen ovale is the right approach to prevent recurring ischemic stroke. And claims that cannabis relieves noncancer pain go up in smoke.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News for today’s top news.

Nerve growth factor inhibitor shows phase 3 efficacy in osteoarthritis

Two subcutaneous dosages of the nerve growth factor–inhibitor tanezumab showed significant benefits in patients with osteoarthritic joint pain in a multicenter, randomized, phase 3 trial of 698 patients run primarily at U.S. centers.

The 16-week responses to two subcutaneous injections with tanezumab spaced 8 weeks apart showed statistically significant improvements in pain, physical function, and patient global self assessment, compared with placebo, the primary endpoints for the study, Pfizer and Lilly jointly reported. The two companies together are developing tanezumab for an indication for osteoarthritic pain, as well as for chronic lower back pain and pain from cancer metastases.

The company announcement said that patients showed good tolerance to the tanezumab treatments, with no new safety signals and no osteonecrosis seen. About 1% of patients on tanezumab stopped treatment because of an adverse effect, and less than 1.5% of patients on the drug had progressive osteoarthritis during treatment, compared with no patients in the placebo group.

The study enrolled patients at any one of 98 centers in the United States, Puerto Rico, or Canada with confirmed moderate or severe osteoarthritis of the knee or hip that either produced pain refractory to conventional pain medications or involved patients unable to take these medications. The researchers randomized patients to receive two 2.5-mg doses of tanezumab, a 2.5-mg dose followed 8 weeks later by a 5-mg dose, or two placebo doses. The primary outcomes were changes from baseline when measured 16 weeks after the start of treatment in the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain subscale, the WOMAC physical function subscale, and patient’s global assessment of osteoarthritis. Both of the tested tanezumab regimens produced statistically significant improvements in each of the three measures, compared with the placebo control patients, the companies reported.

Tanezumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to and inhibits nerve growth factor. This inhibition may prevent pain signals from reaching the spinal cord and brain, according to the companies’ report. In June 2017, the two companies announced that development of tanezumab had received “Fast Track” designation from the Food and Drug Administration for the indications of treating chronic osteoarthritic pain and chronic lower back pain.

Two subcutaneous dosages of the nerve growth factor–inhibitor tanezumab showed significant benefits in patients with osteoarthritic joint pain in a multicenter, randomized, phase 3 trial of 698 patients run primarily at U.S. centers.

The 16-week responses to two subcutaneous injections with tanezumab spaced 8 weeks apart showed statistically significant improvements in pain, physical function, and patient global self assessment, compared with placebo, the primary endpoints for the study, Pfizer and Lilly jointly reported. The two companies together are developing tanezumab for an indication for osteoarthritic pain, as well as for chronic lower back pain and pain from cancer metastases.

The company announcement said that patients showed good tolerance to the tanezumab treatments, with no new safety signals and no osteonecrosis seen. About 1% of patients on tanezumab stopped treatment because of an adverse effect, and less than 1.5% of patients on the drug had progressive osteoarthritis during treatment, compared with no patients in the placebo group.

The study enrolled patients at any one of 98 centers in the United States, Puerto Rico, or Canada with confirmed moderate or severe osteoarthritis of the knee or hip that either produced pain refractory to conventional pain medications or involved patients unable to take these medications. The researchers randomized patients to receive two 2.5-mg doses of tanezumab, a 2.5-mg dose followed 8 weeks later by a 5-mg dose, or two placebo doses. The primary outcomes were changes from baseline when measured 16 weeks after the start of treatment in the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain subscale, the WOMAC physical function subscale, and patient’s global assessment of osteoarthritis. Both of the tested tanezumab regimens produced statistically significant improvements in each of the three measures, compared with the placebo control patients, the companies reported.

Tanezumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to and inhibits nerve growth factor. This inhibition may prevent pain signals from reaching the spinal cord and brain, according to the companies’ report. In June 2017, the two companies announced that development of tanezumab had received “Fast Track” designation from the Food and Drug Administration for the indications of treating chronic osteoarthritic pain and chronic lower back pain.

Two subcutaneous dosages of the nerve growth factor–inhibitor tanezumab showed significant benefits in patients with osteoarthritic joint pain in a multicenter, randomized, phase 3 trial of 698 patients run primarily at U.S. centers.

The 16-week responses to two subcutaneous injections with tanezumab spaced 8 weeks apart showed statistically significant improvements in pain, physical function, and patient global self assessment, compared with placebo, the primary endpoints for the study, Pfizer and Lilly jointly reported. The two companies together are developing tanezumab for an indication for osteoarthritic pain, as well as for chronic lower back pain and pain from cancer metastases.

The company announcement said that patients showed good tolerance to the tanezumab treatments, with no new safety signals and no osteonecrosis seen. About 1% of patients on tanezumab stopped treatment because of an adverse effect, and less than 1.5% of patients on the drug had progressive osteoarthritis during treatment, compared with no patients in the placebo group.

The study enrolled patients at any one of 98 centers in the United States, Puerto Rico, or Canada with confirmed moderate or severe osteoarthritis of the knee or hip that either produced pain refractory to conventional pain medications or involved patients unable to take these medications. The researchers randomized patients to receive two 2.5-mg doses of tanezumab, a 2.5-mg dose followed 8 weeks later by a 5-mg dose, or two placebo doses. The primary outcomes were changes from baseline when measured 16 weeks after the start of treatment in the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain subscale, the WOMAC physical function subscale, and patient’s global assessment of osteoarthritis. Both of the tested tanezumab regimens produced statistically significant improvements in each of the three measures, compared with the placebo control patients, the companies reported.

Tanezumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to and inhibits nerve growth factor. This inhibition may prevent pain signals from reaching the spinal cord and brain, according to the companies’ report. In June 2017, the two companies announced that development of tanezumab had received “Fast Track” designation from the Food and Drug Administration for the indications of treating chronic osteoarthritic pain and chronic lower back pain.

Severe OA sparks depression, surgery “ameliorates” depression in RA

AMSTERDAM – Structural severity in OA is related to the onset of depressive symptoms while surgery “ameliorates” depression in RA, according to the results of two separate studies presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

Using data on more than 1,600 individuals with knee OA from the Osteoarthritis Initiative, Alan Rathbun, PhD, and his associates looked at the components of disease severity and how they might individually contribute to the development of depression. They found that the odds of having depression more than doubled as joint space width increased (odds ratio, 2.25) and gait speed decreased (OR, 2.08), and rose 60% as pain became more severe (OR, 1.60).

Worsening knee OA could set off depression

“Studies have consistently shown that depressive symptoms are associated with worse osteoarthritis disease severity, however, there is a lack of research focused on identifying the specific components that contribute to the onset of depressive symptoms in nondepressed OA patients,” said Dr. Rathbun in an interview ahead of his presentation.

Dr. Rathbun, a research associate in the departments of epidemiology and of public health and medicine at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, also said that while OA guidelines do advise on treating depression, there is no standardized way to manage comorbid depression in routine clinical practice.

“If OA disease severity contributes to the development and worsening of depressive symptoms, it may be necessary to intervene on both conditions simultaneously in order to successfully manage them,” he suggested.