User login

ObGyn malpractice liability risk: 2020 developments and probabilities

In this second in a series of 3 articles discussing medical malpractice and the ObGyn we look at the reasons for malpractice claims and liability, what happens to malpractice claims, and the direction and future of medical malpractice. The first article dealt with 2 sources of major malpractice damages: the “big verdict” and physicians with multiple malpractice paid claims. Next month we look at the place of apology in medicine, in cases in which error, including negligence, may have caused a patient injury.

CASE 1 Long-term brachial plexus injury

Right upper extremity injury occurs in the neonate at delivery with sequela of long-term brachial plexus injury (which is diagnosed around 6 months of age). Physical therapy and orthopedic assessment are rendered. Despite continued treatment, discrepancy in arm lengths (ie, affected side arm is noticeably shorter than opposite side) remains. The child cannot play basketball with his older brother and is the victim of ridicule, the plaintiff’s attorney emphasizes. He is unable to properly pronate or supinate the affected arm.

The defendant ObGyn maintains that there was “no shoulder dystocia [at delivery] and the shoulder did not get obstructed in the pelvis; shoulder was delivered 15 seconds after delivery of the head.” The nursing staff testifies that if shoulder dystocia had been the problem they would have launched upon a series of procedures to address such, in accord with the delivering obstetrician. The defense expert witness testifies that a brachial plexus injury can happen without shoulder dystocia.

A defense verdict is rendered by the Florida jury.1

CASE 2 Shoulder dystocia

During delivery, the obstetrician notes a shoulder dystocia (“turtle sign”). After initial attempts to release the shoulder were unsuccessful, the physician applies traction several times to the head of the child, and the baby is delivered. There is permanent injury to the right brachial plexus. The defendant ObGyn says that traction was necessary to dislodge the shoulder, and that the injury was the result of the forces of labor (not the traction). The expert witness for the plaintiff testifies that the medical standard of care did not permit traction under these circumstances, and that the traction was the likely cause of the injury.

The Virginia jury awards $2.32 million in damages.2

Note: The above vignettes are drawn from actual cases but are only outlines of those cases and are not complete descriptions of the claims in the cases. Because the information comes from informal sources, not formal court records, the facts may be inaccurate and incomplete. They should be viewed as illustrations only.

The trend in malpractice

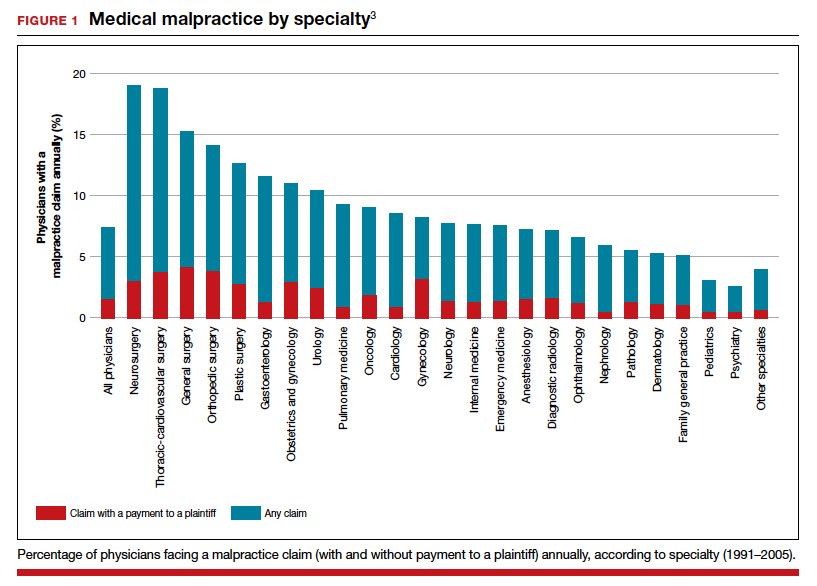

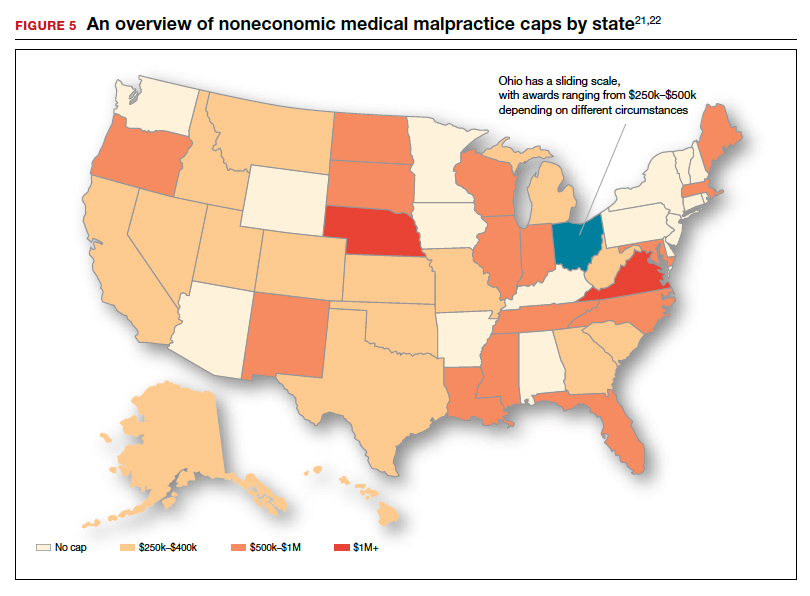

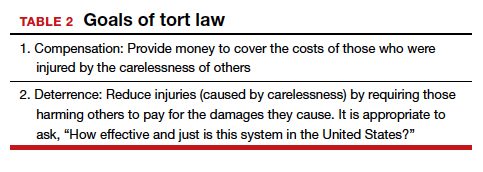

It has been clear for many years that medical malpractice claims are not randomly or evenly distributed among physicians. Notably, the variation among specialties has, and continues to be, substantial (FIGURE 1).3 Recent data suggest that, although paid claims per “1,000 physician-years” averages 14 paid claims per 1,000 physician years, it ranges from 4 or 5 in 1,000 (psychiatry and pediatrics) to 53 and 49 claims per 1,000 (neurology and plastic surgery, respectively). Obstetrics and gynecology has the fourth highest rate at 42.5 paid claims per 1,000 physician years.4 (These data are for the years 1992–2014.)

Continue to: The number of ObGyn paid malpractice claims has decreased over time...

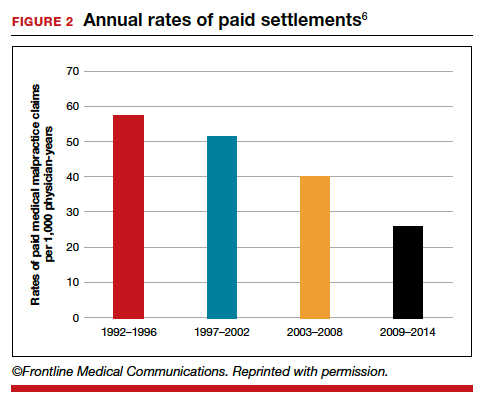

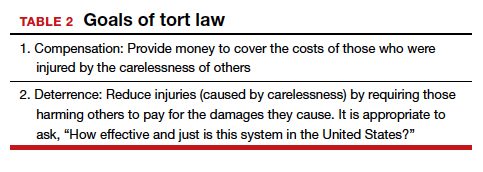

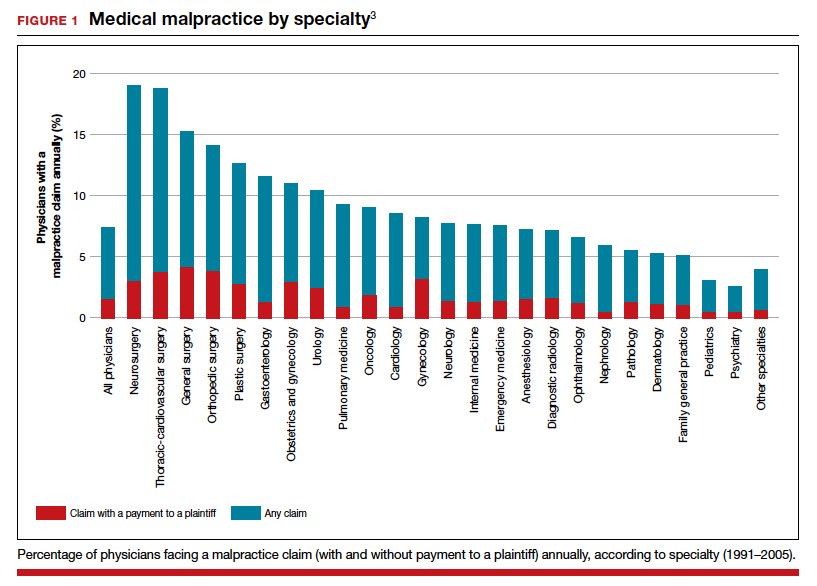

The number of ObGyn paid malpractice claims has decreased over time. Although large verdicts and physicians with multiple paid malpractice claims receive a good deal of attention (as we noted in part 1 of our series), in fact, paid medical malpractice claims have trended downward in recent decades.5 When the data above are disaggregated by 5-year periods, for example, in obstetrics and gynecology, there has been a consistent reduction in paid malpractice claims from 1992 to 2014. Paid claims went from 58 per 1,000 physician-years in 1992–1996 to 25 per 1,000 in 2009–2014 (FIGURE 2).4,6 In short, the rate dropped by half over approximately 20 years.4

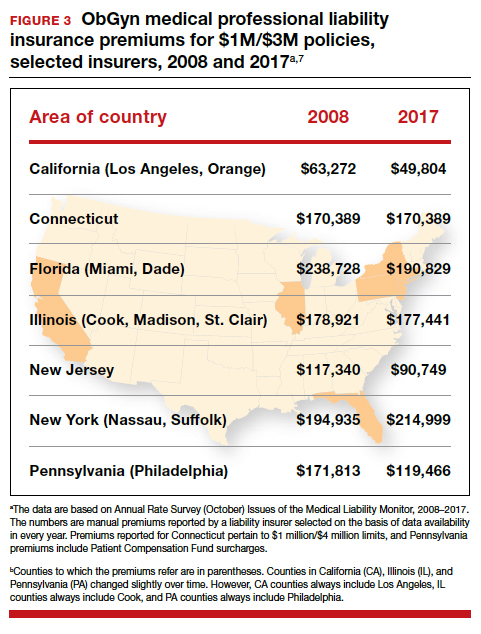

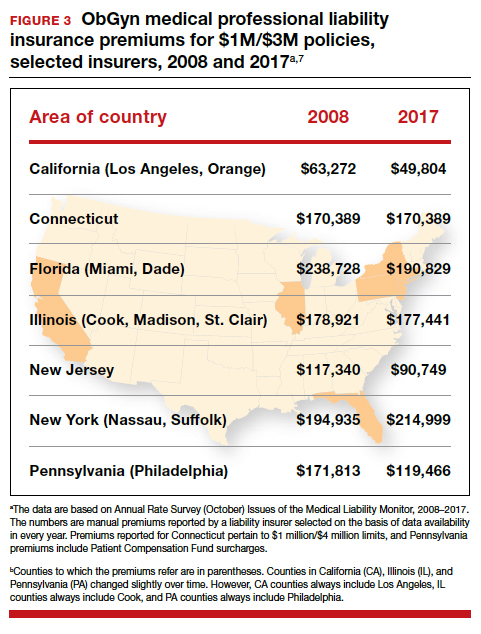

It is reasonable to expect that such a decline in the cost of malpractice insurance premiums would follow. Robert L. Barbieri, MD, who practices in Boston, Massachusetts, in his excellent recent editorial in OBG M

Why have malpractice payouts declined overall?

Have medical errors declined?

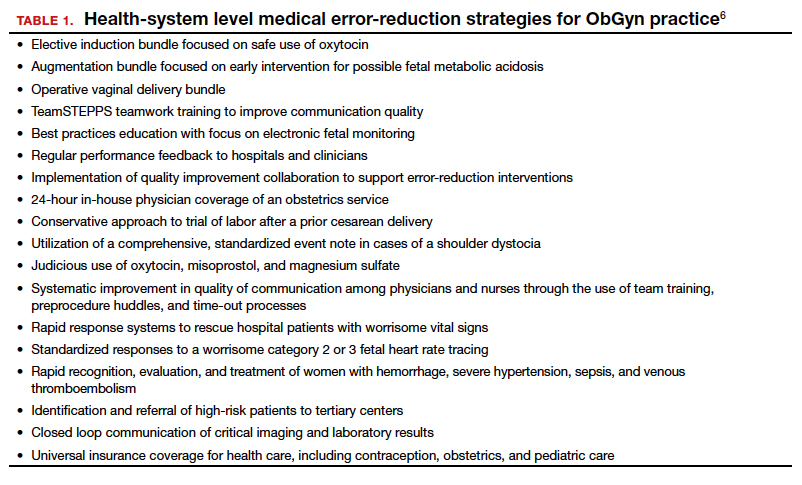

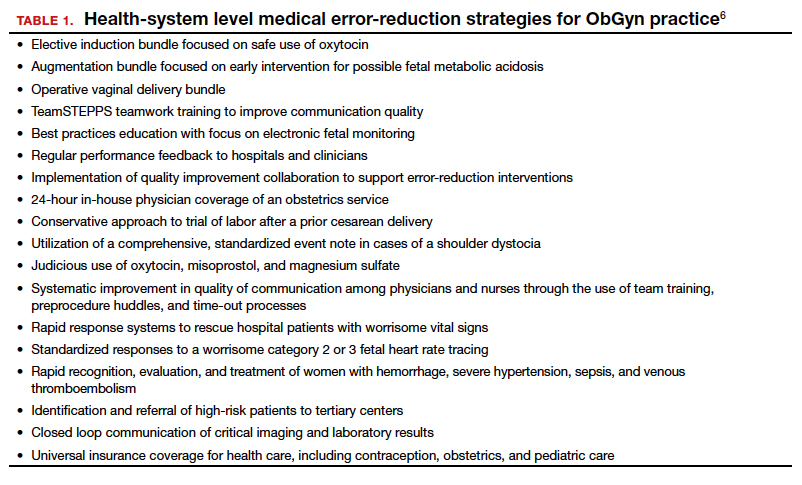

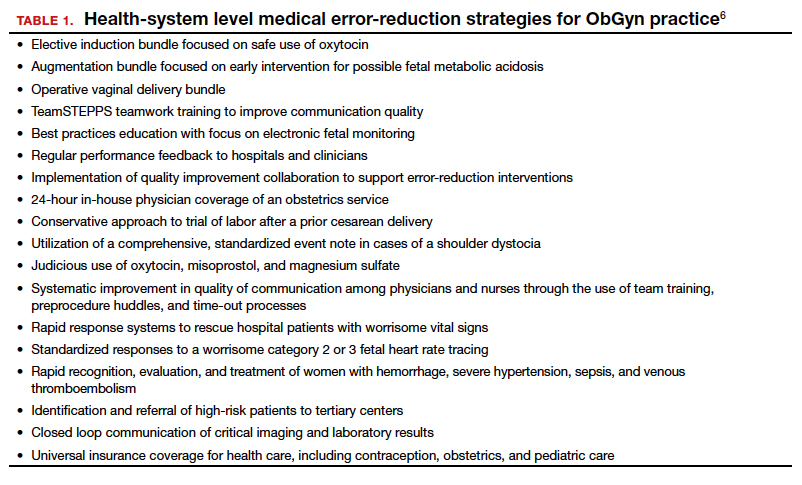

It would be wonderful if the reduction in malpractice claims represented a significant decrease in medical errors. Attention to medical errors was driven by the first widely noticed study of medical error deaths. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) study in 2000, put the number of deaths annually at 44,000 to 98,000.8 There have been many efforts to reduce such errors, and it is possible that those efforts have indeed reduced errors somewhat.4 Barbieri provided a helpful digest of many of the error-reduction suggestions for ObGyn practice (TABLE 1).6 But the number of medical errors remains high. More recent studies have suggested that the IOM’s reported number of injuries may have been low.9 In 2013, one study suggested that 210,000 deaths annually were “associated with preventable harm” in hospitals. Because of how the data were gathered the authors estimated that the actual number of preventable deaths was closer to 400,000 annually. Serious harm to patients was estimated at 10 to 20 times the IOM rate.9

Therefore, a dramatic reduction in preventable medical errors does not appear to explain the reduction in malpractice claims. Some portion of it may be explained by malpractice reforms—see "The medical reform factor" section below.

The collective accountability factor

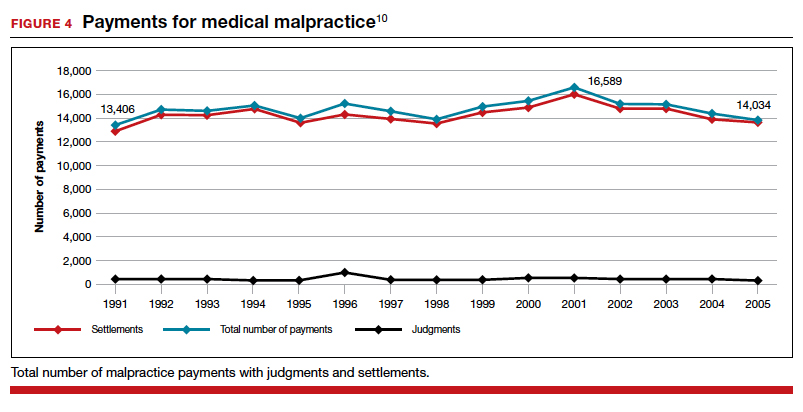

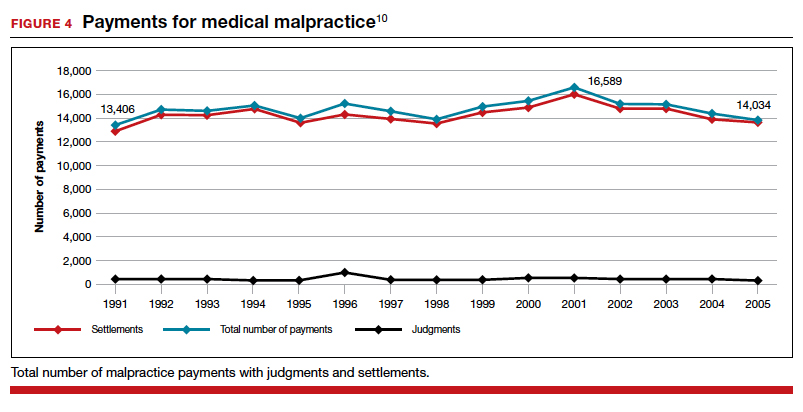

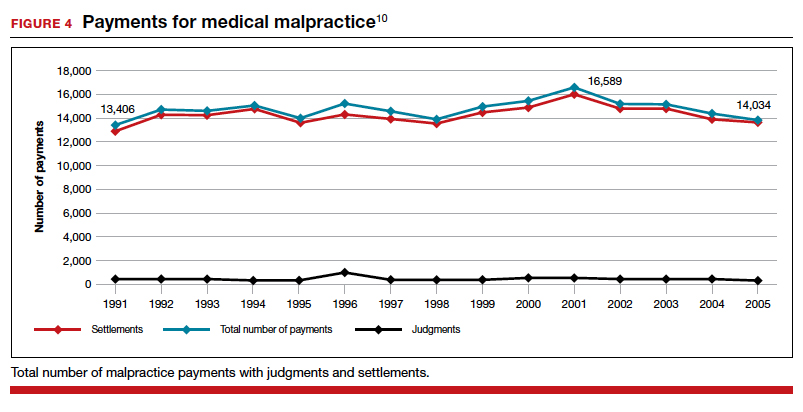

The way malpractice claims are paid (FIGURE 4),10 reported, and handled may explain some of the apparent reduction in overall paid claims. Perhaps the advent of “collective accountability,” in which patient care is rendered by teams and responsibility accepted at a team level, can alleviate a significant amount of individual physician medical malpractice claims.11 This “enterprise liability” may shift the burden of medical error from physicians to health care organizations.12 Collective accountability may, therefore, focus on institutional responsibility rather than individual physician negligence.11,13 Institutions frequently hire multiple specialists and cover their medical malpractice costs as well as stand to be named in suits.

Continue to: The institutional involvement in malpractice cases also may affect...

The institutional involvement in malpractice cases also may affect apparent malpractice rates in another way. The National Practitioner Data Bank, which is the source of information for many malpractice studies, only requires reporting about individual physicians, not institutions.14 If, therefore, claims are settled on behalf of an institution, without implicating the physician, the number of physician malpractice cases may appear to decline without any real change in malpractice rates.14 In addition, institutions have taken the lead in informal resolution of injuries that occur in the institution, and these programs may reduce the direct malpractice claims against physicians. (These “disclosure, apology, and offer,” and similar programs, are discussed in the upcoming third part of this series.)

The medical reform factor

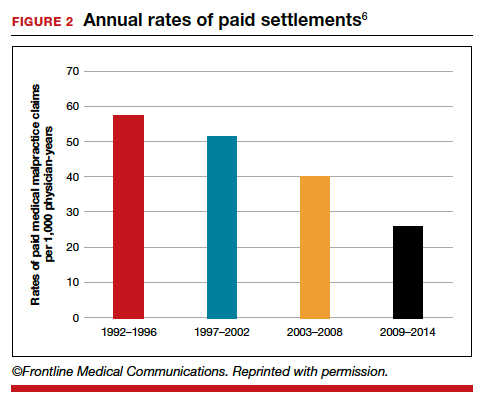

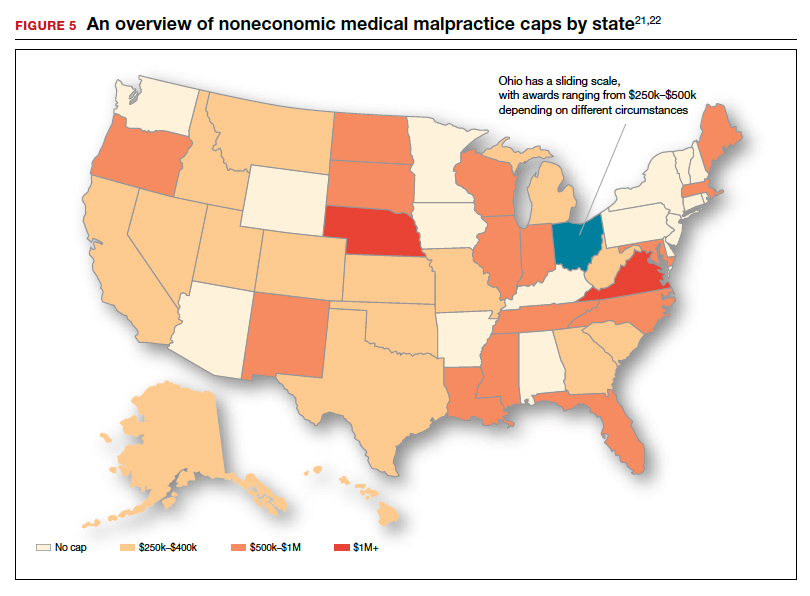

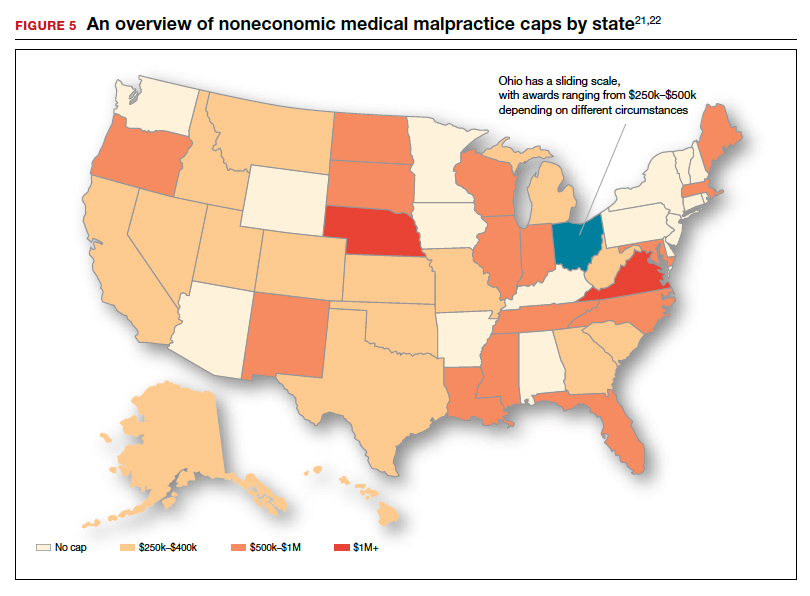

As noted, annual rates paid for medical malpractice in our specialty are trending downward. Many commentators look to malpractice reforms as the reason for the drop in malpractice rates.15-17 Because medical malpractice is essentially a matter of state law, the medical malpractice reform has occurred primarily at the state level.18 There have been many different reforms tried—limits on expert witnesses, review panels, and a variety of procedural limitations.19 Perhaps the most effective reform has been caps being placed on noneconomic damages (generally pain and suffering).20 These caps vary by state (FIGURE 5)21,22 and, of course, affect the “big verdict” cases. (As we saw in the second case scenario above, Virginia is an example of a state with a cap on malpractice awards.) They also have the secondary effect of reducing the number of malpractice cases. They make malpractice cases less attractive to some attorneys because they reduce the opportunity of large contingency fees from large verdicts. (Virtually all medical malpractice cases in the United States are tried on a contingency-fee basis, meaning that the plaintiff does not pay the attorney handling the case but rather the attorney takes a percentage of any recovery—typically in the neighborhood of 35%.) The reform process continues, although, presently, there is less pressure to act on the malpractice crisis.

Medical malpractice cases are emotional and costly

Another reason for the relatively low rate of paid claims is that medical malpractice cases are difficult, emotionally challenging, time consuming, and expensive to pursue.23 They typically drag on for years, require extensive and expensive expert consultants as well as witnesses, and face stiff defense (compared with many other torts). The settlement of medical malpractice cases, for example, is less likely than other kinds of personal injury cases.

The contingency-fee basis does mean that injured patients do not have to pay attorney fees up front; however, plaintiffs may have to pay substantial costs along the way. The other side of this coin is that lawyers can be reluctant to take malpractice cases in which the damages are likely to be small, or where the legal uncertainty reduces the odds of achieving any damages. Thus, many potential malpractice cases are never filed.

A word of caution

The news of a reduction in malpractice paid claims may not be permanent. The numbers can conceivably be cyclical, and political reforms achieved can be changed. In addition, new technology will likely bring new kinds of malpractice claims. That appears to be the case, for example, with electronic health records (EHRs). One insurer reports that EHR malpractice claims have increased over the last 8 years.24 The most common injury in these claims was death (25%), as well as a magnitude of less serious injuries. EHR-related claims result from system failures, copy-paste inaccuracies, faulty drop-down menu use, and uncorrected “auto-populated” fields. Obstetrics is tied for fifth on the list of 14 specialties with claims related to EHRs, and gynecology is tied for eighth place.24

Continue to: A federal court ruled that a hospital that changed from...

A federal court ruled that a hospital that changed from paper records to EHRs for test results had a duty to “‘implement a reasonable procedure during the transition phase’ to ensure the timely delivery of test results” to health care providers.25 We will address this in a future “What’s the Verdict?”.

Rates of harm, malpractice cases, and the disposition of cases

There are many surprises when looking at medical malpractice claims data generally. The first surprise is how few claims are filed relative to the number of error-related injuries. Given the estimate of 210,000 to 400,000 deaths “associated with preventable harm” in hospitals, plus 10 to 20 times that number of serious injuries, it would be reasonable to expect claims of many hundreds of thousands per year. Compare the probability of a malpractice claim from an error-related injury, for example, with the probability of other personal injuries—eg, of traffic deaths associated with preventable harm.

The second key observation is how many of the claims filed are not successful—even when there was evidence in the record of errors associated with the injury. Studies slice the data in different ways but collectively suggest that only a small proportion of malpractice claims filed (a claim is generally regarded as some written demand for compensation for injuries) result in payments, either through settlement or by trial. A 2006 study by Studdert and colleagues determined that 63% of formal malpractice claims filed did involve injuries resulting from errors.26 The study found that in 16% of the claims (not injuries) there was no payment even though there was error. In 10% of the claims there was payment, even in the absence of error.

Overall, in this study, 56% of the claims received some compensation.26 That is higher than a more recent study by Jena and others, which found only 22% of claims resulted in compensation.3

How malpractice claims are decided is also interesting. Jena and colleagues found that only 55% of claims resulted in litigation.27 Presumably, the other 45% may have resulted in the plaintiff dropping the case, or in some form of settlement. Of the claims that were litigated, 54% were dismissed by the court, and another 35% were settled before a trial verdict. The cases that went to trial (about 10%), overwhelmingly (80%) resulted in verdicts for the defense.3,27 A different study found that only 9% of cases went to trial, and 87% were a defense verdict.28 The high level of defense verdicts may suggest that malpractice defense lawyers, and their client physicians, do a good job of assessing cases they are likely to lose, and settling them before trial.

ObGyns generally have larger numbers of claims and among the largest payment amounts when there is payment. Fewer of their cases are dismissed by the courts, so more go to trial. At trial, however, ObGyns prevail at a remarkably high rate.27 As for the probability of payment of a malpractice claim for ObGyns, one study suggested that there is approximately a 16% annual probability of a claim being filed, but only a 3% annual probability of a payment being made (suggesting about a 20% probability of payment per claim).3

Continue to: The purposes and effects of the medical malpractice system...

The purposes and effects of the medical malpractice system

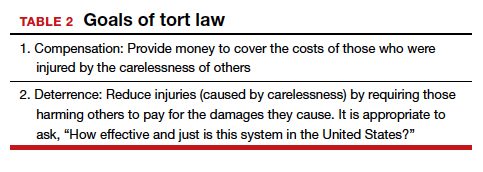

The essential goals of tort law (including medical malpractice) include compensation for those who are injured and deterrence of future injuries (TABLE 2). What are the overall effects to the medical malpractice system? Unfortunately, the answer is that the law delivers disappointing results at best. It has a fairly high error rate. Many people who deserve some compensation for their injuries never seek compensation, and many deserving injured patients fail in efforts to receive compensation. At the same time, a few of the injured receive huge recoveries (even windfalls), and at least a small fraction receive compensation when there was no medical error. In addition to the high error rate, the system is inefficient and very expensive. Both defendants (through their insurance carriers) and plaintiffs spend a lot of money, years of time, and untold emotional pain dealing with these cases. The system also exacts high emotional and personal costs on plaintiffs and defendants.

Malpractice reform has not really addressed these issues—it has generally been focused on ways to reduce the cost of malpractice insurance. The most effective reform in reducing rates—caps—has had the effect of compensating the most seriously injured as though they were more modestly injured, and dissuading attorneys from taking the cases of those less seriously injured.

The medical and legal professions exist to help patients (the public). It does not seem that we have arrived at a system that does that very fairly or efficiently when a patient is injured because of preventable medical error.

The two vignettes described at the beginning, with similar injuries (shoulder dystocia), had disparate outcomes. In one there was a defense verdict and in the other a verdict for the plaintiffs of more than $2 million. The differences explain a number of important elements related to malpractice claims. (We have only very abbreviated and incomplete descriptions of the cases, so this discussion necessarily assumes facts and jumps to conclusions that may not be entirely consistent with the actual cases.)

These vignettes are unusual in that they went to trial. As we have noted, only a small percentage of malpractice cases are tried. And the verdict for the plaintiff-patient (in the second case) is unusual among those cases that go to trial, where plaintiffs seldom prevail.

From the facts we have, one significant difference in the 2 cases is that the plaintiff’s expert witness specifically testified in the second case that the “medical standard of care did not permit traction under these circumstances.” That is an essential element of a successful plaintiff’s malpractice case. In this case, the expert could also draw a connection between that breach of standard of care and harm to the child. In the case without liability, the nursing staff was able to testify that there was no shoulder dystocia because if there had been such an injury, they would have immediately launched into special action, which did not happen. By contrast, in the liability case, there seemed to be critical gaps in the medical record.

It is also important to remember that these cases were tried in different states, with different laws. The juries and judges in the 2 cases were different. Finally, the quality of the attorneys representing the plaintiffs and defendants were different. We mention these factors to point out that medical malpractice is not an exact science. It depends on many human elements that make the outcome of cases somewhat unpredictable. This unpredictability is one reason why parties and attorneys like to settle cases.

Watch for the third and final article in this series next month, as we are going to look at “apology in medicine and a proactive response” to communication regarding a complication.

- Shoulder dystocia—Florida defense verdict. Medical Malpractice: Verdicts, Settlements & Experts. 2019;35(1):18.

- Shoulder dystocia improperly managed--$2.320 million Virginia verdict. Medical Malpractice: Verdicts, Settlements & Experts. 2019;35(2):13.

- Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D, et al. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:629-636.

- Schaffer AC, Jena AB, Seabury SA, et al. Rates and characteristics of paid malpractice claims among US physicians by specialty, 1992-2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:710-718.

- Lowes R. Malpractice premiums trail inflation for some physicians. Medscape. December 16, 2016. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/873422. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Barbieri RL. Good news for ObGyns: medical liability claims resulting in payment are decreasing! OBG Manag. 2019;31:10-13.

- Guardado JR. Medical professional liability insurance premiums: an overview of the market from 2008 to 2017. AMA Policy Research Perspectives, 2018. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/ama-assn.org/files/corp/media-browser/public/government/advocacy/policy-research-perspective-liability-insurance-premiums.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality Health Care in America; Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000.

- James JT. A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care. J Patient Saf. 2013;9:122-128. https://journals.lww.com/journalpatientsafety/Fulltext/

2013/09000/A_New,_Evidence_based_Estimate_of_Patient_

Harms.2.aspx. Accessed January 10, 2020. - Public Citizen Congress Watch. The great medical malpractice hoax: NPDB data continue to show medical liability system produces rational outcomes. January 2007. https://www.citizen.org/wp-content/uploads/npdb_report_

final.pdf. Accessed January 23, 2020. - Bell SK, Delbanco T, Anderson-Shaw L, et al. Accountability for medical error: moving beyond blame to advocacy. Chest. 2011;140:519-526.

- Ramanathan T. Legal mechanisms supporting accountable care principles. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:2048-2051.

- Kachalia A, Kaufman SR, Boothman R, et al. Liability claims and costs before and after implementation of a medical error disclosure program. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:213-221.

- National Practitioner Data Bank web site. What you must report to the NPDB. https://www.npdb.hrsa.gov/hcorg/whatYouMustReport

ToTheDataBank.jsp. Accessed January 10, 2020. - Bovbjerg RR. Malpractice crisis and reform. Clin Perinatol. 2005;32:203-233, viii-ix.

- Viscusi WK. Medical malpractice reform: what works and what doesn't. Denver Law Rev. 2019;96:775-791. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5cb79f7efd6793296c0eb738 /t/5d5f4ffabd6c5400011a12f6/1566527483118/Vol96_Issue4_Viscusi_

FINAL.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2020. - National Conference of State Legislatures. Medical malpractice reform. Health Cost Containment and Efficiencies: NCSL Briefs for State Legislators. 2011;(16). http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/medical-malpractice-reform-health-cost-brief.aspx. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Kass JS, Rose RV. Medical malpractice reform: historical approaches, alternative models, and communication and resolution programs. AMA J Ethics. 2016;18:299-310.

- Boehm G. Debunking medical malpractice myths: unraveling the false premises behind "tort reform". Yale J Health Policy Law Ethics. 2005;5:357-369.

- Hellinger FJ, Encinosa WE. The impact of state laws limiting malpractice damage awards on health care expenditures. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1375-1381.

- Perry G. Medical malpractice caps by state [infographic]. January 3, 2013. https://www.business2community.com/infographics/medical-malpractice-caps-by-state-infographic-0368345. Accessed January 23, 2020.

- Goguen D. State-by-state medical malpractice damages caps. An in-depth look at state laws limiting compensation for medical malpractice plaintiffs. https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/state-state-medical-malpractice-damages-caps.html. Accessed January 23, 2020.

- Berlin L. Medical errors, malpractice, and defensive medicine: an ill-fated triad. Diagnosis (Berl). 2017;4:133-139.

- Ranum D. Electronic health records continue to lead to medical malpractice suits. The Doctors Company. August 2019. https://www.thedoctors.com/articles/electronic-health-records-continue-to-lead-to-medical-malpractice-suits/. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Mangalmurti SS, Murtagh L, Mello MM. Medical malpractice liability in the age of electronic health records. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2060-2067.

- Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(19):2024-2033.

- Jena AB, Chandra A, Lakdawalla D, et al. Outcomes of medical malpractice litigation against US physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:892-894.

- Glaser LM, Alvi FA, Milad MP. Trends in malpractice claims for obstetric and gynecologic procedures, 2005 through 2014. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:340.e1-340.e6.

In this second in a series of 3 articles discussing medical malpractice and the ObGyn we look at the reasons for malpractice claims and liability, what happens to malpractice claims, and the direction and future of medical malpractice. The first article dealt with 2 sources of major malpractice damages: the “big verdict” and physicians with multiple malpractice paid claims. Next month we look at the place of apology in medicine, in cases in which error, including negligence, may have caused a patient injury.

CASE 1 Long-term brachial plexus injury

Right upper extremity injury occurs in the neonate at delivery with sequela of long-term brachial plexus injury (which is diagnosed around 6 months of age). Physical therapy and orthopedic assessment are rendered. Despite continued treatment, discrepancy in arm lengths (ie, affected side arm is noticeably shorter than opposite side) remains. The child cannot play basketball with his older brother and is the victim of ridicule, the plaintiff’s attorney emphasizes. He is unable to properly pronate or supinate the affected arm.

The defendant ObGyn maintains that there was “no shoulder dystocia [at delivery] and the shoulder did not get obstructed in the pelvis; shoulder was delivered 15 seconds after delivery of the head.” The nursing staff testifies that if shoulder dystocia had been the problem they would have launched upon a series of procedures to address such, in accord with the delivering obstetrician. The defense expert witness testifies that a brachial plexus injury can happen without shoulder dystocia.

A defense verdict is rendered by the Florida jury.1

CASE 2 Shoulder dystocia

During delivery, the obstetrician notes a shoulder dystocia (“turtle sign”). After initial attempts to release the shoulder were unsuccessful, the physician applies traction several times to the head of the child, and the baby is delivered. There is permanent injury to the right brachial plexus. The defendant ObGyn says that traction was necessary to dislodge the shoulder, and that the injury was the result of the forces of labor (not the traction). The expert witness for the plaintiff testifies that the medical standard of care did not permit traction under these circumstances, and that the traction was the likely cause of the injury.

The Virginia jury awards $2.32 million in damages.2

Note: The above vignettes are drawn from actual cases but are only outlines of those cases and are not complete descriptions of the claims in the cases. Because the information comes from informal sources, not formal court records, the facts may be inaccurate and incomplete. They should be viewed as illustrations only.

The trend in malpractice

It has been clear for many years that medical malpractice claims are not randomly or evenly distributed among physicians. Notably, the variation among specialties has, and continues to be, substantial (FIGURE 1).3 Recent data suggest that, although paid claims per “1,000 physician-years” averages 14 paid claims per 1,000 physician years, it ranges from 4 or 5 in 1,000 (psychiatry and pediatrics) to 53 and 49 claims per 1,000 (neurology and plastic surgery, respectively). Obstetrics and gynecology has the fourth highest rate at 42.5 paid claims per 1,000 physician years.4 (These data are for the years 1992–2014.)

Continue to: The number of ObGyn paid malpractice claims has decreased over time...

The number of ObGyn paid malpractice claims has decreased over time. Although large verdicts and physicians with multiple paid malpractice claims receive a good deal of attention (as we noted in part 1 of our series), in fact, paid medical malpractice claims have trended downward in recent decades.5 When the data above are disaggregated by 5-year periods, for example, in obstetrics and gynecology, there has been a consistent reduction in paid malpractice claims from 1992 to 2014. Paid claims went from 58 per 1,000 physician-years in 1992–1996 to 25 per 1,000 in 2009–2014 (FIGURE 2).4,6 In short, the rate dropped by half over approximately 20 years.4

It is reasonable to expect that such a decline in the cost of malpractice insurance premiums would follow. Robert L. Barbieri, MD, who practices in Boston, Massachusetts, in his excellent recent editorial in OBG M

Why have malpractice payouts declined overall?

Have medical errors declined?

It would be wonderful if the reduction in malpractice claims represented a significant decrease in medical errors. Attention to medical errors was driven by the first widely noticed study of medical error deaths. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) study in 2000, put the number of deaths annually at 44,000 to 98,000.8 There have been many efforts to reduce such errors, and it is possible that those efforts have indeed reduced errors somewhat.4 Barbieri provided a helpful digest of many of the error-reduction suggestions for ObGyn practice (TABLE 1).6 But the number of medical errors remains high. More recent studies have suggested that the IOM’s reported number of injuries may have been low.9 In 2013, one study suggested that 210,000 deaths annually were “associated with preventable harm” in hospitals. Because of how the data were gathered the authors estimated that the actual number of preventable deaths was closer to 400,000 annually. Serious harm to patients was estimated at 10 to 20 times the IOM rate.9

Therefore, a dramatic reduction in preventable medical errors does not appear to explain the reduction in malpractice claims. Some portion of it may be explained by malpractice reforms—see "The medical reform factor" section below.

The collective accountability factor

The way malpractice claims are paid (FIGURE 4),10 reported, and handled may explain some of the apparent reduction in overall paid claims. Perhaps the advent of “collective accountability,” in which patient care is rendered by teams and responsibility accepted at a team level, can alleviate a significant amount of individual physician medical malpractice claims.11 This “enterprise liability” may shift the burden of medical error from physicians to health care organizations.12 Collective accountability may, therefore, focus on institutional responsibility rather than individual physician negligence.11,13 Institutions frequently hire multiple specialists and cover their medical malpractice costs as well as stand to be named in suits.

Continue to: The institutional involvement in malpractice cases also may affect...

The institutional involvement in malpractice cases also may affect apparent malpractice rates in another way. The National Practitioner Data Bank, which is the source of information for many malpractice studies, only requires reporting about individual physicians, not institutions.14 If, therefore, claims are settled on behalf of an institution, without implicating the physician, the number of physician malpractice cases may appear to decline without any real change in malpractice rates.14 In addition, institutions have taken the lead in informal resolution of injuries that occur in the institution, and these programs may reduce the direct malpractice claims against physicians. (These “disclosure, apology, and offer,” and similar programs, are discussed in the upcoming third part of this series.)

The medical reform factor

As noted, annual rates paid for medical malpractice in our specialty are trending downward. Many commentators look to malpractice reforms as the reason for the drop in malpractice rates.15-17 Because medical malpractice is essentially a matter of state law, the medical malpractice reform has occurred primarily at the state level.18 There have been many different reforms tried—limits on expert witnesses, review panels, and a variety of procedural limitations.19 Perhaps the most effective reform has been caps being placed on noneconomic damages (generally pain and suffering).20 These caps vary by state (FIGURE 5)21,22 and, of course, affect the “big verdict” cases. (As we saw in the second case scenario above, Virginia is an example of a state with a cap on malpractice awards.) They also have the secondary effect of reducing the number of malpractice cases. They make malpractice cases less attractive to some attorneys because they reduce the opportunity of large contingency fees from large verdicts. (Virtually all medical malpractice cases in the United States are tried on a contingency-fee basis, meaning that the plaintiff does not pay the attorney handling the case but rather the attorney takes a percentage of any recovery—typically in the neighborhood of 35%.) The reform process continues, although, presently, there is less pressure to act on the malpractice crisis.

Medical malpractice cases are emotional and costly

Another reason for the relatively low rate of paid claims is that medical malpractice cases are difficult, emotionally challenging, time consuming, and expensive to pursue.23 They typically drag on for years, require extensive and expensive expert consultants as well as witnesses, and face stiff defense (compared with many other torts). The settlement of medical malpractice cases, for example, is less likely than other kinds of personal injury cases.

The contingency-fee basis does mean that injured patients do not have to pay attorney fees up front; however, plaintiffs may have to pay substantial costs along the way. The other side of this coin is that lawyers can be reluctant to take malpractice cases in which the damages are likely to be small, or where the legal uncertainty reduces the odds of achieving any damages. Thus, many potential malpractice cases are never filed.

A word of caution

The news of a reduction in malpractice paid claims may not be permanent. The numbers can conceivably be cyclical, and political reforms achieved can be changed. In addition, new technology will likely bring new kinds of malpractice claims. That appears to be the case, for example, with electronic health records (EHRs). One insurer reports that EHR malpractice claims have increased over the last 8 years.24 The most common injury in these claims was death (25%), as well as a magnitude of less serious injuries. EHR-related claims result from system failures, copy-paste inaccuracies, faulty drop-down menu use, and uncorrected “auto-populated” fields. Obstetrics is tied for fifth on the list of 14 specialties with claims related to EHRs, and gynecology is tied for eighth place.24

Continue to: A federal court ruled that a hospital that changed from...

A federal court ruled that a hospital that changed from paper records to EHRs for test results had a duty to “‘implement a reasonable procedure during the transition phase’ to ensure the timely delivery of test results” to health care providers.25 We will address this in a future “What’s the Verdict?”.

Rates of harm, malpractice cases, and the disposition of cases

There are many surprises when looking at medical malpractice claims data generally. The first surprise is how few claims are filed relative to the number of error-related injuries. Given the estimate of 210,000 to 400,000 deaths “associated with preventable harm” in hospitals, plus 10 to 20 times that number of serious injuries, it would be reasonable to expect claims of many hundreds of thousands per year. Compare the probability of a malpractice claim from an error-related injury, for example, with the probability of other personal injuries—eg, of traffic deaths associated with preventable harm.

The second key observation is how many of the claims filed are not successful—even when there was evidence in the record of errors associated with the injury. Studies slice the data in different ways but collectively suggest that only a small proportion of malpractice claims filed (a claim is generally regarded as some written demand for compensation for injuries) result in payments, either through settlement or by trial. A 2006 study by Studdert and colleagues determined that 63% of formal malpractice claims filed did involve injuries resulting from errors.26 The study found that in 16% of the claims (not injuries) there was no payment even though there was error. In 10% of the claims there was payment, even in the absence of error.

Overall, in this study, 56% of the claims received some compensation.26 That is higher than a more recent study by Jena and others, which found only 22% of claims resulted in compensation.3

How malpractice claims are decided is also interesting. Jena and colleagues found that only 55% of claims resulted in litigation.27 Presumably, the other 45% may have resulted in the plaintiff dropping the case, or in some form of settlement. Of the claims that were litigated, 54% were dismissed by the court, and another 35% were settled before a trial verdict. The cases that went to trial (about 10%), overwhelmingly (80%) resulted in verdicts for the defense.3,27 A different study found that only 9% of cases went to trial, and 87% were a defense verdict.28 The high level of defense verdicts may suggest that malpractice defense lawyers, and their client physicians, do a good job of assessing cases they are likely to lose, and settling them before trial.

ObGyns generally have larger numbers of claims and among the largest payment amounts when there is payment. Fewer of their cases are dismissed by the courts, so more go to trial. At trial, however, ObGyns prevail at a remarkably high rate.27 As for the probability of payment of a malpractice claim for ObGyns, one study suggested that there is approximately a 16% annual probability of a claim being filed, but only a 3% annual probability of a payment being made (suggesting about a 20% probability of payment per claim).3

Continue to: The purposes and effects of the medical malpractice system...

The purposes and effects of the medical malpractice system

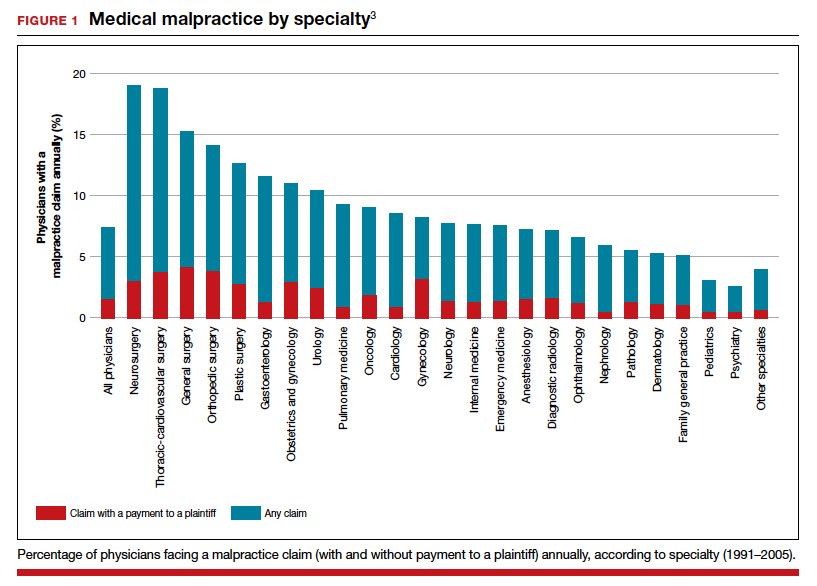

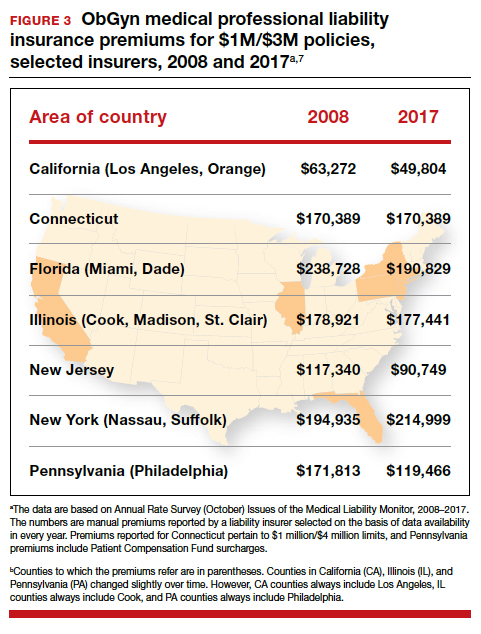

The essential goals of tort law (including medical malpractice) include compensation for those who are injured and deterrence of future injuries (TABLE 2). What are the overall effects to the medical malpractice system? Unfortunately, the answer is that the law delivers disappointing results at best. It has a fairly high error rate. Many people who deserve some compensation for their injuries never seek compensation, and many deserving injured patients fail in efforts to receive compensation. At the same time, a few of the injured receive huge recoveries (even windfalls), and at least a small fraction receive compensation when there was no medical error. In addition to the high error rate, the system is inefficient and very expensive. Both defendants (through their insurance carriers) and plaintiffs spend a lot of money, years of time, and untold emotional pain dealing with these cases. The system also exacts high emotional and personal costs on plaintiffs and defendants.

Malpractice reform has not really addressed these issues—it has generally been focused on ways to reduce the cost of malpractice insurance. The most effective reform in reducing rates—caps—has had the effect of compensating the most seriously injured as though they were more modestly injured, and dissuading attorneys from taking the cases of those less seriously injured.

The medical and legal professions exist to help patients (the public). It does not seem that we have arrived at a system that does that very fairly or efficiently when a patient is injured because of preventable medical error.

The two vignettes described at the beginning, with similar injuries (shoulder dystocia), had disparate outcomes. In one there was a defense verdict and in the other a verdict for the plaintiffs of more than $2 million. The differences explain a number of important elements related to malpractice claims. (We have only very abbreviated and incomplete descriptions of the cases, so this discussion necessarily assumes facts and jumps to conclusions that may not be entirely consistent with the actual cases.)

These vignettes are unusual in that they went to trial. As we have noted, only a small percentage of malpractice cases are tried. And the verdict for the plaintiff-patient (in the second case) is unusual among those cases that go to trial, where plaintiffs seldom prevail.

From the facts we have, one significant difference in the 2 cases is that the plaintiff’s expert witness specifically testified in the second case that the “medical standard of care did not permit traction under these circumstances.” That is an essential element of a successful plaintiff’s malpractice case. In this case, the expert could also draw a connection between that breach of standard of care and harm to the child. In the case without liability, the nursing staff was able to testify that there was no shoulder dystocia because if there had been such an injury, they would have immediately launched into special action, which did not happen. By contrast, in the liability case, there seemed to be critical gaps in the medical record.

It is also important to remember that these cases were tried in different states, with different laws. The juries and judges in the 2 cases were different. Finally, the quality of the attorneys representing the plaintiffs and defendants were different. We mention these factors to point out that medical malpractice is not an exact science. It depends on many human elements that make the outcome of cases somewhat unpredictable. This unpredictability is one reason why parties and attorneys like to settle cases.

Watch for the third and final article in this series next month, as we are going to look at “apology in medicine and a proactive response” to communication regarding a complication.

In this second in a series of 3 articles discussing medical malpractice and the ObGyn we look at the reasons for malpractice claims and liability, what happens to malpractice claims, and the direction and future of medical malpractice. The first article dealt with 2 sources of major malpractice damages: the “big verdict” and physicians with multiple malpractice paid claims. Next month we look at the place of apology in medicine, in cases in which error, including negligence, may have caused a patient injury.

CASE 1 Long-term brachial plexus injury

Right upper extremity injury occurs in the neonate at delivery with sequela of long-term brachial plexus injury (which is diagnosed around 6 months of age). Physical therapy and orthopedic assessment are rendered. Despite continued treatment, discrepancy in arm lengths (ie, affected side arm is noticeably shorter than opposite side) remains. The child cannot play basketball with his older brother and is the victim of ridicule, the plaintiff’s attorney emphasizes. He is unable to properly pronate or supinate the affected arm.

The defendant ObGyn maintains that there was “no shoulder dystocia [at delivery] and the shoulder did not get obstructed in the pelvis; shoulder was delivered 15 seconds after delivery of the head.” The nursing staff testifies that if shoulder dystocia had been the problem they would have launched upon a series of procedures to address such, in accord with the delivering obstetrician. The defense expert witness testifies that a brachial plexus injury can happen without shoulder dystocia.

A defense verdict is rendered by the Florida jury.1

CASE 2 Shoulder dystocia

During delivery, the obstetrician notes a shoulder dystocia (“turtle sign”). After initial attempts to release the shoulder were unsuccessful, the physician applies traction several times to the head of the child, and the baby is delivered. There is permanent injury to the right brachial plexus. The defendant ObGyn says that traction was necessary to dislodge the shoulder, and that the injury was the result of the forces of labor (not the traction). The expert witness for the plaintiff testifies that the medical standard of care did not permit traction under these circumstances, and that the traction was the likely cause of the injury.

The Virginia jury awards $2.32 million in damages.2

Note: The above vignettes are drawn from actual cases but are only outlines of those cases and are not complete descriptions of the claims in the cases. Because the information comes from informal sources, not formal court records, the facts may be inaccurate and incomplete. They should be viewed as illustrations only.

The trend in malpractice

It has been clear for many years that medical malpractice claims are not randomly or evenly distributed among physicians. Notably, the variation among specialties has, and continues to be, substantial (FIGURE 1).3 Recent data suggest that, although paid claims per “1,000 physician-years” averages 14 paid claims per 1,000 physician years, it ranges from 4 or 5 in 1,000 (psychiatry and pediatrics) to 53 and 49 claims per 1,000 (neurology and plastic surgery, respectively). Obstetrics and gynecology has the fourth highest rate at 42.5 paid claims per 1,000 physician years.4 (These data are for the years 1992–2014.)

Continue to: The number of ObGyn paid malpractice claims has decreased over time...

The number of ObGyn paid malpractice claims has decreased over time. Although large verdicts and physicians with multiple paid malpractice claims receive a good deal of attention (as we noted in part 1 of our series), in fact, paid medical malpractice claims have trended downward in recent decades.5 When the data above are disaggregated by 5-year periods, for example, in obstetrics and gynecology, there has been a consistent reduction in paid malpractice claims from 1992 to 2014. Paid claims went from 58 per 1,000 physician-years in 1992–1996 to 25 per 1,000 in 2009–2014 (FIGURE 2).4,6 In short, the rate dropped by half over approximately 20 years.4

It is reasonable to expect that such a decline in the cost of malpractice insurance premiums would follow. Robert L. Barbieri, MD, who practices in Boston, Massachusetts, in his excellent recent editorial in OBG M

Why have malpractice payouts declined overall?

Have medical errors declined?

It would be wonderful if the reduction in malpractice claims represented a significant decrease in medical errors. Attention to medical errors was driven by the first widely noticed study of medical error deaths. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) study in 2000, put the number of deaths annually at 44,000 to 98,000.8 There have been many efforts to reduce such errors, and it is possible that those efforts have indeed reduced errors somewhat.4 Barbieri provided a helpful digest of many of the error-reduction suggestions for ObGyn practice (TABLE 1).6 But the number of medical errors remains high. More recent studies have suggested that the IOM’s reported number of injuries may have been low.9 In 2013, one study suggested that 210,000 deaths annually were “associated with preventable harm” in hospitals. Because of how the data were gathered the authors estimated that the actual number of preventable deaths was closer to 400,000 annually. Serious harm to patients was estimated at 10 to 20 times the IOM rate.9

Therefore, a dramatic reduction in preventable medical errors does not appear to explain the reduction in malpractice claims. Some portion of it may be explained by malpractice reforms—see "The medical reform factor" section below.

The collective accountability factor

The way malpractice claims are paid (FIGURE 4),10 reported, and handled may explain some of the apparent reduction in overall paid claims. Perhaps the advent of “collective accountability,” in which patient care is rendered by teams and responsibility accepted at a team level, can alleviate a significant amount of individual physician medical malpractice claims.11 This “enterprise liability” may shift the burden of medical error from physicians to health care organizations.12 Collective accountability may, therefore, focus on institutional responsibility rather than individual physician negligence.11,13 Institutions frequently hire multiple specialists and cover their medical malpractice costs as well as stand to be named in suits.

Continue to: The institutional involvement in malpractice cases also may affect...

The institutional involvement in malpractice cases also may affect apparent malpractice rates in another way. The National Practitioner Data Bank, which is the source of information for many malpractice studies, only requires reporting about individual physicians, not institutions.14 If, therefore, claims are settled on behalf of an institution, without implicating the physician, the number of physician malpractice cases may appear to decline without any real change in malpractice rates.14 In addition, institutions have taken the lead in informal resolution of injuries that occur in the institution, and these programs may reduce the direct malpractice claims against physicians. (These “disclosure, apology, and offer,” and similar programs, are discussed in the upcoming third part of this series.)

The medical reform factor

As noted, annual rates paid for medical malpractice in our specialty are trending downward. Many commentators look to malpractice reforms as the reason for the drop in malpractice rates.15-17 Because medical malpractice is essentially a matter of state law, the medical malpractice reform has occurred primarily at the state level.18 There have been many different reforms tried—limits on expert witnesses, review panels, and a variety of procedural limitations.19 Perhaps the most effective reform has been caps being placed on noneconomic damages (generally pain and suffering).20 These caps vary by state (FIGURE 5)21,22 and, of course, affect the “big verdict” cases. (As we saw in the second case scenario above, Virginia is an example of a state with a cap on malpractice awards.) They also have the secondary effect of reducing the number of malpractice cases. They make malpractice cases less attractive to some attorneys because they reduce the opportunity of large contingency fees from large verdicts. (Virtually all medical malpractice cases in the United States are tried on a contingency-fee basis, meaning that the plaintiff does not pay the attorney handling the case but rather the attorney takes a percentage of any recovery—typically in the neighborhood of 35%.) The reform process continues, although, presently, there is less pressure to act on the malpractice crisis.

Medical malpractice cases are emotional and costly

Another reason for the relatively low rate of paid claims is that medical malpractice cases are difficult, emotionally challenging, time consuming, and expensive to pursue.23 They typically drag on for years, require extensive and expensive expert consultants as well as witnesses, and face stiff defense (compared with many other torts). The settlement of medical malpractice cases, for example, is less likely than other kinds of personal injury cases.

The contingency-fee basis does mean that injured patients do not have to pay attorney fees up front; however, plaintiffs may have to pay substantial costs along the way. The other side of this coin is that lawyers can be reluctant to take malpractice cases in which the damages are likely to be small, or where the legal uncertainty reduces the odds of achieving any damages. Thus, many potential malpractice cases are never filed.

A word of caution

The news of a reduction in malpractice paid claims may not be permanent. The numbers can conceivably be cyclical, and political reforms achieved can be changed. In addition, new technology will likely bring new kinds of malpractice claims. That appears to be the case, for example, with electronic health records (EHRs). One insurer reports that EHR malpractice claims have increased over the last 8 years.24 The most common injury in these claims was death (25%), as well as a magnitude of less serious injuries. EHR-related claims result from system failures, copy-paste inaccuracies, faulty drop-down menu use, and uncorrected “auto-populated” fields. Obstetrics is tied for fifth on the list of 14 specialties with claims related to EHRs, and gynecology is tied for eighth place.24

Continue to: A federal court ruled that a hospital that changed from...

A federal court ruled that a hospital that changed from paper records to EHRs for test results had a duty to “‘implement a reasonable procedure during the transition phase’ to ensure the timely delivery of test results” to health care providers.25 We will address this in a future “What’s the Verdict?”.

Rates of harm, malpractice cases, and the disposition of cases

There are many surprises when looking at medical malpractice claims data generally. The first surprise is how few claims are filed relative to the number of error-related injuries. Given the estimate of 210,000 to 400,000 deaths “associated with preventable harm” in hospitals, plus 10 to 20 times that number of serious injuries, it would be reasonable to expect claims of many hundreds of thousands per year. Compare the probability of a malpractice claim from an error-related injury, for example, with the probability of other personal injuries—eg, of traffic deaths associated with preventable harm.

The second key observation is how many of the claims filed are not successful—even when there was evidence in the record of errors associated with the injury. Studies slice the data in different ways but collectively suggest that only a small proportion of malpractice claims filed (a claim is generally regarded as some written demand for compensation for injuries) result in payments, either through settlement or by trial. A 2006 study by Studdert and colleagues determined that 63% of formal malpractice claims filed did involve injuries resulting from errors.26 The study found that in 16% of the claims (not injuries) there was no payment even though there was error. In 10% of the claims there was payment, even in the absence of error.

Overall, in this study, 56% of the claims received some compensation.26 That is higher than a more recent study by Jena and others, which found only 22% of claims resulted in compensation.3

How malpractice claims are decided is also interesting. Jena and colleagues found that only 55% of claims resulted in litigation.27 Presumably, the other 45% may have resulted in the plaintiff dropping the case, or in some form of settlement. Of the claims that were litigated, 54% were dismissed by the court, and another 35% were settled before a trial verdict. The cases that went to trial (about 10%), overwhelmingly (80%) resulted in verdicts for the defense.3,27 A different study found that only 9% of cases went to trial, and 87% were a defense verdict.28 The high level of defense verdicts may suggest that malpractice defense lawyers, and their client physicians, do a good job of assessing cases they are likely to lose, and settling them before trial.

ObGyns generally have larger numbers of claims and among the largest payment amounts when there is payment. Fewer of their cases are dismissed by the courts, so more go to trial. At trial, however, ObGyns prevail at a remarkably high rate.27 As for the probability of payment of a malpractice claim for ObGyns, one study suggested that there is approximately a 16% annual probability of a claim being filed, but only a 3% annual probability of a payment being made (suggesting about a 20% probability of payment per claim).3

Continue to: The purposes and effects of the medical malpractice system...

The purposes and effects of the medical malpractice system

The essential goals of tort law (including medical malpractice) include compensation for those who are injured and deterrence of future injuries (TABLE 2). What are the overall effects to the medical malpractice system? Unfortunately, the answer is that the law delivers disappointing results at best. It has a fairly high error rate. Many people who deserve some compensation for their injuries never seek compensation, and many deserving injured patients fail in efforts to receive compensation. At the same time, a few of the injured receive huge recoveries (even windfalls), and at least a small fraction receive compensation when there was no medical error. In addition to the high error rate, the system is inefficient and very expensive. Both defendants (through their insurance carriers) and plaintiffs spend a lot of money, years of time, and untold emotional pain dealing with these cases. The system also exacts high emotional and personal costs on plaintiffs and defendants.

Malpractice reform has not really addressed these issues—it has generally been focused on ways to reduce the cost of malpractice insurance. The most effective reform in reducing rates—caps—has had the effect of compensating the most seriously injured as though they were more modestly injured, and dissuading attorneys from taking the cases of those less seriously injured.

The medical and legal professions exist to help patients (the public). It does not seem that we have arrived at a system that does that very fairly or efficiently when a patient is injured because of preventable medical error.

The two vignettes described at the beginning, with similar injuries (shoulder dystocia), had disparate outcomes. In one there was a defense verdict and in the other a verdict for the plaintiffs of more than $2 million. The differences explain a number of important elements related to malpractice claims. (We have only very abbreviated and incomplete descriptions of the cases, so this discussion necessarily assumes facts and jumps to conclusions that may not be entirely consistent with the actual cases.)

These vignettes are unusual in that they went to trial. As we have noted, only a small percentage of malpractice cases are tried. And the verdict for the plaintiff-patient (in the second case) is unusual among those cases that go to trial, where plaintiffs seldom prevail.

From the facts we have, one significant difference in the 2 cases is that the plaintiff’s expert witness specifically testified in the second case that the “medical standard of care did not permit traction under these circumstances.” That is an essential element of a successful plaintiff’s malpractice case. In this case, the expert could also draw a connection between that breach of standard of care and harm to the child. In the case without liability, the nursing staff was able to testify that there was no shoulder dystocia because if there had been such an injury, they would have immediately launched into special action, which did not happen. By contrast, in the liability case, there seemed to be critical gaps in the medical record.

It is also important to remember that these cases were tried in different states, with different laws. The juries and judges in the 2 cases were different. Finally, the quality of the attorneys representing the plaintiffs and defendants were different. We mention these factors to point out that medical malpractice is not an exact science. It depends on many human elements that make the outcome of cases somewhat unpredictable. This unpredictability is one reason why parties and attorneys like to settle cases.

Watch for the third and final article in this series next month, as we are going to look at “apology in medicine and a proactive response” to communication regarding a complication.

- Shoulder dystocia—Florida defense verdict. Medical Malpractice: Verdicts, Settlements & Experts. 2019;35(1):18.

- Shoulder dystocia improperly managed--$2.320 million Virginia verdict. Medical Malpractice: Verdicts, Settlements & Experts. 2019;35(2):13.

- Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D, et al. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:629-636.

- Schaffer AC, Jena AB, Seabury SA, et al. Rates and characteristics of paid malpractice claims among US physicians by specialty, 1992-2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:710-718.

- Lowes R. Malpractice premiums trail inflation for some physicians. Medscape. December 16, 2016. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/873422. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Barbieri RL. Good news for ObGyns: medical liability claims resulting in payment are decreasing! OBG Manag. 2019;31:10-13.

- Guardado JR. Medical professional liability insurance premiums: an overview of the market from 2008 to 2017. AMA Policy Research Perspectives, 2018. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/ama-assn.org/files/corp/media-browser/public/government/advocacy/policy-research-perspective-liability-insurance-premiums.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality Health Care in America; Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000.

- James JT. A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care. J Patient Saf. 2013;9:122-128. https://journals.lww.com/journalpatientsafety/Fulltext/

2013/09000/A_New,_Evidence_based_Estimate_of_Patient_

Harms.2.aspx. Accessed January 10, 2020. - Public Citizen Congress Watch. The great medical malpractice hoax: NPDB data continue to show medical liability system produces rational outcomes. January 2007. https://www.citizen.org/wp-content/uploads/npdb_report_

final.pdf. Accessed January 23, 2020. - Bell SK, Delbanco T, Anderson-Shaw L, et al. Accountability for medical error: moving beyond blame to advocacy. Chest. 2011;140:519-526.

- Ramanathan T. Legal mechanisms supporting accountable care principles. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:2048-2051.

- Kachalia A, Kaufman SR, Boothman R, et al. Liability claims and costs before and after implementation of a medical error disclosure program. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:213-221.

- National Practitioner Data Bank web site. What you must report to the NPDB. https://www.npdb.hrsa.gov/hcorg/whatYouMustReport

ToTheDataBank.jsp. Accessed January 10, 2020. - Bovbjerg RR. Malpractice crisis and reform. Clin Perinatol. 2005;32:203-233, viii-ix.

- Viscusi WK. Medical malpractice reform: what works and what doesn't. Denver Law Rev. 2019;96:775-791. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5cb79f7efd6793296c0eb738 /t/5d5f4ffabd6c5400011a12f6/1566527483118/Vol96_Issue4_Viscusi_

FINAL.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2020. - National Conference of State Legislatures. Medical malpractice reform. Health Cost Containment and Efficiencies: NCSL Briefs for State Legislators. 2011;(16). http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/medical-malpractice-reform-health-cost-brief.aspx. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Kass JS, Rose RV. Medical malpractice reform: historical approaches, alternative models, and communication and resolution programs. AMA J Ethics. 2016;18:299-310.

- Boehm G. Debunking medical malpractice myths: unraveling the false premises behind "tort reform". Yale J Health Policy Law Ethics. 2005;5:357-369.

- Hellinger FJ, Encinosa WE. The impact of state laws limiting malpractice damage awards on health care expenditures. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1375-1381.

- Perry G. Medical malpractice caps by state [infographic]. January 3, 2013. https://www.business2community.com/infographics/medical-malpractice-caps-by-state-infographic-0368345. Accessed January 23, 2020.

- Goguen D. State-by-state medical malpractice damages caps. An in-depth look at state laws limiting compensation for medical malpractice plaintiffs. https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/state-state-medical-malpractice-damages-caps.html. Accessed January 23, 2020.

- Berlin L. Medical errors, malpractice, and defensive medicine: an ill-fated triad. Diagnosis (Berl). 2017;4:133-139.

- Ranum D. Electronic health records continue to lead to medical malpractice suits. The Doctors Company. August 2019. https://www.thedoctors.com/articles/electronic-health-records-continue-to-lead-to-medical-malpractice-suits/. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Mangalmurti SS, Murtagh L, Mello MM. Medical malpractice liability in the age of electronic health records. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2060-2067.

- Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(19):2024-2033.

- Jena AB, Chandra A, Lakdawalla D, et al. Outcomes of medical malpractice litigation against US physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:892-894.

- Glaser LM, Alvi FA, Milad MP. Trends in malpractice claims for obstetric and gynecologic procedures, 2005 through 2014. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:340.e1-340.e6.

- Shoulder dystocia—Florida defense verdict. Medical Malpractice: Verdicts, Settlements & Experts. 2019;35(1):18.

- Shoulder dystocia improperly managed--$2.320 million Virginia verdict. Medical Malpractice: Verdicts, Settlements & Experts. 2019;35(2):13.

- Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D, et al. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:629-636.

- Schaffer AC, Jena AB, Seabury SA, et al. Rates and characteristics of paid malpractice claims among US physicians by specialty, 1992-2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:710-718.

- Lowes R. Malpractice premiums trail inflation for some physicians. Medscape. December 16, 2016. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/873422. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Barbieri RL. Good news for ObGyns: medical liability claims resulting in payment are decreasing! OBG Manag. 2019;31:10-13.

- Guardado JR. Medical professional liability insurance premiums: an overview of the market from 2008 to 2017. AMA Policy Research Perspectives, 2018. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/ama-assn.org/files/corp/media-browser/public/government/advocacy/policy-research-perspective-liability-insurance-premiums.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality Health Care in America; Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000.

- James JT. A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care. J Patient Saf. 2013;9:122-128. https://journals.lww.com/journalpatientsafety/Fulltext/

2013/09000/A_New,_Evidence_based_Estimate_of_Patient_

Harms.2.aspx. Accessed January 10, 2020. - Public Citizen Congress Watch. The great medical malpractice hoax: NPDB data continue to show medical liability system produces rational outcomes. January 2007. https://www.citizen.org/wp-content/uploads/npdb_report_

final.pdf. Accessed January 23, 2020. - Bell SK, Delbanco T, Anderson-Shaw L, et al. Accountability for medical error: moving beyond blame to advocacy. Chest. 2011;140:519-526.

- Ramanathan T. Legal mechanisms supporting accountable care principles. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:2048-2051.

- Kachalia A, Kaufman SR, Boothman R, et al. Liability claims and costs before and after implementation of a medical error disclosure program. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:213-221.

- National Practitioner Data Bank web site. What you must report to the NPDB. https://www.npdb.hrsa.gov/hcorg/whatYouMustReport

ToTheDataBank.jsp. Accessed January 10, 2020. - Bovbjerg RR. Malpractice crisis and reform. Clin Perinatol. 2005;32:203-233, viii-ix.

- Viscusi WK. Medical malpractice reform: what works and what doesn't. Denver Law Rev. 2019;96:775-791. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5cb79f7efd6793296c0eb738 /t/5d5f4ffabd6c5400011a12f6/1566527483118/Vol96_Issue4_Viscusi_

FINAL.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2020. - National Conference of State Legislatures. Medical malpractice reform. Health Cost Containment and Efficiencies: NCSL Briefs for State Legislators. 2011;(16). http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/medical-malpractice-reform-health-cost-brief.aspx. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Kass JS, Rose RV. Medical malpractice reform: historical approaches, alternative models, and communication and resolution programs. AMA J Ethics. 2016;18:299-310.

- Boehm G. Debunking medical malpractice myths: unraveling the false premises behind "tort reform". Yale J Health Policy Law Ethics. 2005;5:357-369.

- Hellinger FJ, Encinosa WE. The impact of state laws limiting malpractice damage awards on health care expenditures. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1375-1381.

- Perry G. Medical malpractice caps by state [infographic]. January 3, 2013. https://www.business2community.com/infographics/medical-malpractice-caps-by-state-infographic-0368345. Accessed January 23, 2020.

- Goguen D. State-by-state medical malpractice damages caps. An in-depth look at state laws limiting compensation for medical malpractice plaintiffs. https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/state-state-medical-malpractice-damages-caps.html. Accessed January 23, 2020.

- Berlin L. Medical errors, malpractice, and defensive medicine: an ill-fated triad. Diagnosis (Berl). 2017;4:133-139.

- Ranum D. Electronic health records continue to lead to medical malpractice suits. The Doctors Company. August 2019. https://www.thedoctors.com/articles/electronic-health-records-continue-to-lead-to-medical-malpractice-suits/. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Mangalmurti SS, Murtagh L, Mello MM. Medical malpractice liability in the age of electronic health records. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2060-2067.

- Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(19):2024-2033.

- Jena AB, Chandra A, Lakdawalla D, et al. Outcomes of medical malpractice litigation against US physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:892-894.

- Glaser LM, Alvi FA, Milad MP. Trends in malpractice claims for obstetric and gynecologic procedures, 2005 through 2014. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:340.e1-340.e6.

Racial disparities persist in preterm birth risk

Education, status are not protective for non-Hispanic black women

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – College education and high socioeconomic status do not erase U.S. racial disparities in birth outcomes, according to a new analysis of all U.S. live births from 2015-2017.

Very early preterm birth – birth before 28 weeks gestational age – was five times more likely to occur in non-Hispanic black women of high socioeconomic status as similarly situated white women, even after statistical adjustment for a host of potentially confounding factors.

Being of non-Hispanic black race was the single strongest predictor of preterm birth (PTB) at less than 28 weeks’ gestation. The adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 4.99 surpassed an interpregnancy interval under 1 year (aOR, 4.47), chronic hypertension (aOR, 2.84), and prior history of preterm birth (aOR, 2.81).

“Even among college-educated women with private insurance who are not receiving (Women, Infants, and Children support), racial disparities in prematurity persist. These results suggest that factors other than sociodemographics are important in the underlying pathogenesis of PTB and in etiologies of racial disparities,” wrote Jasmine Johnson, MD, and her coauthors in the abstract accompanying the presentation at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The analysis that Dr. Johnson and her coinvestigators used, she explained during her plenary session presentation, still found significantly elevated risks for preterm birth for non-Hispanic black women after accounting for marital status, prior history of preterm birth, tobacco use, an interpregnancy interval of fewer than 12 months, and carrying a male fetus.

“Birth certificates do not inform the lived experiences of one’s self-identified race, and how that experience – or possibly just one’s identification with a particular racial group – may positively or negatively affect their clinical risk of preterm birth,” said Dr. Johnson. “In this study, as in others, race is a social construct. It’s a surrogate for social and societal racism that disproportionately affects birth outcomes of women of color.”

Using non-Hispanic white (NHW) women as a reference, women who described themselves as non-Hispanic black (NHB) had increased odds of preterm birth at 34 and 37 weeks gestation as well. Women identifying as both NHB and NHW had numerically elevated odds for preterm birth at all time points as well, but the odds at 37 weeks didn’t reach statistical significance.

The results were based on a retrospective population-based study of a cohort drawn from the National Vital Statistics birth certificate data of all live births in the United States between 2015 and 2017, explained Dr. Johnson, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Drawing from a nationally representative sample and having a population-level design drawn were strengths of the study, she said.

Women with singleton pregnancies without anomalies who identified as NHB, NHW, or as both NHB and NHW were included if they also had high socioeconomic status. Including women who identify as both black and white was another strength of the study, Dr. Johnson added.

She explained that, for the purposes of the study, high socioeconomic status was defined as having 16 or more years of education and private insurance, and not receiving WIC benefits.

In addition to the primary outcome measure of preterm birth at fewer than 37 weeks gestation, secondary outcomes included preterm birth at fewer than 34 and fewer than 28 weeks’ gestation, as well as low birthweight (LBW) and very low birthweight (VLBW).

About 11.8 million live births occurred during the study period, and 11.3 million of those were singleton pregnancies without fetal anomaly. After excluding women who did not meet the racial self-identification or socioeconomic status inclusion criteria, the investigators arrived at the final study population of 2,170,688 individuals.

Of those, 2,017,470, or 92.9%, were non-Hispanic white, while 144,612, or 6.7%, were non-Hispanic black. The remaining 8,604 participants, or 0.4%, identified their race as non-Hispanic black and non-Hispanic white.

The groups identified in the study differed significantly in demographic characteristics, Dr. Johnson said. Women in the NHB and NHB + NHW groups were less likely to be married than NHW women – about 75% of the former two groups were married, compared with 92.5% of NHW women. This difference was statistically significant with a P value of .001, as were all the differences Dr. Johnson reported.

Pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) was highest in NHB women at 27.1 kg/m sq, followed by NHB = NHW women at 25.7 kg/m sq, with NHW women having the lowest BMI at 23.8 kg/m sq.

Prior preterm birth of 37 weeks’ gestation or less was more common in NHB women and NHB + NHW women, as was an interpregnancy interval of fewer than 12 months.

Chronic hypertension was more than twice as common in NHB women than in either NHB = NHW or NHW women, occurring in 3.9%, 1.8%, and 1.4% of participants, respectively.

Pregestational diabetes was about twice as common in NHB women than NHW women, occurring in 1% and 0.52% of those groups, respectively. Prevalence of pregestational diabetes was intermediate in NHB = NHW women, at 0.72%.

Tobacco use was rare overall, and less common in NHB women than NHB + NHW and NHW women.

In terms of pregnancy characteristics, though 85% of NHB women initiated prenatal care in the first trimester, they were less likely to have done so than either of the other two groups. Few women overall had no prenatal care, but 0.7% of NHB women fell into this category, more than the 0.4% and 0.3% reported for NHB + NHW and NHW women, respectively.

During their pregnancies, NHB women were more likely to develop gestational hypertension and/or pre-eclampsia as well as gestational diabetes than either of the other two groups (7.6% compared with 6% for the other two groups). Of the NHB women, 5.9% developed gestational diabetes, compared with 4.8% of NHB + NHW and 4.8% of NHW women.

Delivering a baby with a birthweight less than the 10th percentile was twice as common for NHB, compared with NHW women (7.2% versus 3.4%). The risk for NHB + NHW women was intermediate, at 4.7%.

Dr. Johnson said she and her team performed further analyses, including using initiation of prenatal care in the first trimester of pregnancy as a surrogate for high socioeconomic status; the association of race and risk for preterm birth persisted.

The study had the usual limitations of using National Vital Statistics data, such as the inability to evaluate underlying etiologies for preterm birth.

However, Dr. Johnson highlighted additional limitations that pertain to the experience of race in 21st century America. “Our definition of high socioeconomic status does not guarantee that all women in this analysis have financial stability,” she said, pointing out that the study’s definition of high socioeconomic status was insensitive to wealth accumulation. She also noted that high educational attainment does not necessarily correlate with high income. Hence, the potential burden of economic stressors could not fully be captured.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Johnson reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Johnson J et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan;222(1):S-37-8, Abstract 44.

Education, status are not protective for non-Hispanic black women

Education, status are not protective for non-Hispanic black women

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – College education and high socioeconomic status do not erase U.S. racial disparities in birth outcomes, according to a new analysis of all U.S. live births from 2015-2017.

Very early preterm birth – birth before 28 weeks gestational age – was five times more likely to occur in non-Hispanic black women of high socioeconomic status as similarly situated white women, even after statistical adjustment for a host of potentially confounding factors.

Being of non-Hispanic black race was the single strongest predictor of preterm birth (PTB) at less than 28 weeks’ gestation. The adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 4.99 surpassed an interpregnancy interval under 1 year (aOR, 4.47), chronic hypertension (aOR, 2.84), and prior history of preterm birth (aOR, 2.81).

“Even among college-educated women with private insurance who are not receiving (Women, Infants, and Children support), racial disparities in prematurity persist. These results suggest that factors other than sociodemographics are important in the underlying pathogenesis of PTB and in etiologies of racial disparities,” wrote Jasmine Johnson, MD, and her coauthors in the abstract accompanying the presentation at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The analysis that Dr. Johnson and her coinvestigators used, she explained during her plenary session presentation, still found significantly elevated risks for preterm birth for non-Hispanic black women after accounting for marital status, prior history of preterm birth, tobacco use, an interpregnancy interval of fewer than 12 months, and carrying a male fetus.

“Birth certificates do not inform the lived experiences of one’s self-identified race, and how that experience – or possibly just one’s identification with a particular racial group – may positively or negatively affect their clinical risk of preterm birth,” said Dr. Johnson. “In this study, as in others, race is a social construct. It’s a surrogate for social and societal racism that disproportionately affects birth outcomes of women of color.”

Using non-Hispanic white (NHW) women as a reference, women who described themselves as non-Hispanic black (NHB) had increased odds of preterm birth at 34 and 37 weeks gestation as well. Women identifying as both NHB and NHW had numerically elevated odds for preterm birth at all time points as well, but the odds at 37 weeks didn’t reach statistical significance.