User login

MS bears no effect on certain pregnancy complications, stillbirth, or congenital deformation

, according to a new study published online Feb. 3 in Neurology Clinical Practice. While pregnancy and childbirth are not regarded as conditions that engender high-risk pregnancy in the MS population, previous studies evaluating the effects of MS on pregnancy and parturition have yet to fully elucidate some outcomes for pregnant women and their babies in multiple sclerosis.

“Women with multiple sclerosis may be understandably concerned about the risk of pregnancy,” said Melinda Magyari, MD, PhD, a consultant at the University of Copenhagen. “While previous research has shown there is no higher risk of birth defect for babies born to women with MS, we wanted to find out if women with MS are at risk for a variety of pregnancy complications.”

MS is regarded as a progressive, neurological disease mediated by the immune system that demands careful consideration of numerous situations and life changes including family planning. The MS population is overwhelmingly female, as women account for three out of every four cases of MS. The majority of these women range from 20 to 40 years of age at the time of being diagnosed with MS. Despite the unknown risks of pregnancy-related complications and various perinatal complications in this patient population, women who have MS are not discouraged from conceiving.

Assessing pregnancy outcomes

This nationwide, population-based, cross-sectional study evaluated the pregnancies of 2,930 women with MS between Jan. 1, 1997, and Dec. 31, 2016, registered in the Danish Multiple Sclerosis Registry. The researchers compared pregnancy-related and prenatal outcomes to a 5% random sample of 56,958 randomly-selected pregnant women from Denmark’s general population who did not have MS. They found no differences in the risks associated with several pregnancy-related complications (e.g., preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, or placental complications), emergency Cesarean section (C-section), instrumental delivery, stillbirth, preterm birth, or congenital malformation. Apgar scores were low in both groups. A composite of various biometrics in newborns such as reflexes, muscle tone, and heart rate immediately following birth, the Apgar score is used to help assess the neonatal health, with a value of less than 7 considered low. Here, preterm birth is defined as delivery occurring before 37 weeks of gestation, and stillbirth describes a fetus born dead after 22 weeks of gestation.

Women in the MS cohort were more likely to have elective C-sections (odds ratio, 2.89 [95% confidence interval, 1.65-2.16]), induced labor (OR, 1.15 [95%CI, 1.01-1.31]) and have babies with low birth weight based on their gestational age (OR, 1.29 [95% CI, 1.04-1.60]). Nearly 30% of babies born in the cohort (n = 851) were born to mothers who had received disease-modifying therapy (DMT). Neonates exposed to DMT weighed an average of 116 g less than babies born to mothers who had not received DMT (3,378 g vs. 3,494 g) with a slightly lower gestational age (39 weeks as opposed to 40 weeks). However, babies born to mothers with MS were less likely to show signs of asphyxia (OR, 0.87 [95% CI, 0.78-0.97]) than the comparison cohort.

“We found overall, their pregnancies were just as healthy as those of the moms without MS,” Dr. Magyari said.

Comprehensive data

Denmark’s health care system has two key features that make it an attractive setting in which to conduct such a study – the first being its universal health care. The second advantage is that the country enacted several health registries in the 1970s and 1980s that enable the collection of more comprehensive data. For example, the Danish National Patient Register is a population-based registry that spans the entire nation, facilitating epidemiological research with what the study’s authors describe as “high generalizability.” Providing additional insights regarding the patient story helps add context to pregnancy and outcomes. Among the data collected on the women studied were demographics, contact information, and abortions, both spontaneous and medically induced. The country uses other databases and registries to capture additional data. For example, the Register of Legally Induced Abortions provides data regarding the context of medically induced abortions. In contrast, the Danish Medical Birth Registry provides context regarding specified variables regarding women’s pregnancies, delivery, and perinatal outcomes. Finally, the population’s education register offers information regarding patients’ educational history.

A key strength of this study is that the long duration of follow-up data from the Danish Medical Birth Registry, along with its comprehensive data collection, eliminates recall bias. Universal access to health care also improves the generalizability of data. A limitation of the study is its lack of data on maternal smoking and its effects on low gestational weights. The study also has some data gaps, including body mass index information missing from a large portion of the cohort. Finally, the sample size of newborns born to mothers who had received DMT therapy within the last 6 months of gestation was too underpowered to stratify based on first on first-line or second-line treatment.

Dr. Magyari served on scientific advisory boards for Biogen, Sanofi, Teva, Roche, Novartis, and Merck. She has also received honoraria for lecturing from Biogen, Merck, Novartis, Sanofi, Genzyme, and has received research support and support for congress participation from Biogen, Genzyme, Teva, Roche, Merck, and Novartis. Coauthors disclosed various fees received from Merck, Novartis, Biogen, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, and Teva.

, according to a new study published online Feb. 3 in Neurology Clinical Practice. While pregnancy and childbirth are not regarded as conditions that engender high-risk pregnancy in the MS population, previous studies evaluating the effects of MS on pregnancy and parturition have yet to fully elucidate some outcomes for pregnant women and their babies in multiple sclerosis.

“Women with multiple sclerosis may be understandably concerned about the risk of pregnancy,” said Melinda Magyari, MD, PhD, a consultant at the University of Copenhagen. “While previous research has shown there is no higher risk of birth defect for babies born to women with MS, we wanted to find out if women with MS are at risk for a variety of pregnancy complications.”

MS is regarded as a progressive, neurological disease mediated by the immune system that demands careful consideration of numerous situations and life changes including family planning. The MS population is overwhelmingly female, as women account for three out of every four cases of MS. The majority of these women range from 20 to 40 years of age at the time of being diagnosed with MS. Despite the unknown risks of pregnancy-related complications and various perinatal complications in this patient population, women who have MS are not discouraged from conceiving.

Assessing pregnancy outcomes

This nationwide, population-based, cross-sectional study evaluated the pregnancies of 2,930 women with MS between Jan. 1, 1997, and Dec. 31, 2016, registered in the Danish Multiple Sclerosis Registry. The researchers compared pregnancy-related and prenatal outcomes to a 5% random sample of 56,958 randomly-selected pregnant women from Denmark’s general population who did not have MS. They found no differences in the risks associated with several pregnancy-related complications (e.g., preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, or placental complications), emergency Cesarean section (C-section), instrumental delivery, stillbirth, preterm birth, or congenital malformation. Apgar scores were low in both groups. A composite of various biometrics in newborns such as reflexes, muscle tone, and heart rate immediately following birth, the Apgar score is used to help assess the neonatal health, with a value of less than 7 considered low. Here, preterm birth is defined as delivery occurring before 37 weeks of gestation, and stillbirth describes a fetus born dead after 22 weeks of gestation.

Women in the MS cohort were more likely to have elective C-sections (odds ratio, 2.89 [95% confidence interval, 1.65-2.16]), induced labor (OR, 1.15 [95%CI, 1.01-1.31]) and have babies with low birth weight based on their gestational age (OR, 1.29 [95% CI, 1.04-1.60]). Nearly 30% of babies born in the cohort (n = 851) were born to mothers who had received disease-modifying therapy (DMT). Neonates exposed to DMT weighed an average of 116 g less than babies born to mothers who had not received DMT (3,378 g vs. 3,494 g) with a slightly lower gestational age (39 weeks as opposed to 40 weeks). However, babies born to mothers with MS were less likely to show signs of asphyxia (OR, 0.87 [95% CI, 0.78-0.97]) than the comparison cohort.

“We found overall, their pregnancies were just as healthy as those of the moms without MS,” Dr. Magyari said.

Comprehensive data

Denmark’s health care system has two key features that make it an attractive setting in which to conduct such a study – the first being its universal health care. The second advantage is that the country enacted several health registries in the 1970s and 1980s that enable the collection of more comprehensive data. For example, the Danish National Patient Register is a population-based registry that spans the entire nation, facilitating epidemiological research with what the study’s authors describe as “high generalizability.” Providing additional insights regarding the patient story helps add context to pregnancy and outcomes. Among the data collected on the women studied were demographics, contact information, and abortions, both spontaneous and medically induced. The country uses other databases and registries to capture additional data. For example, the Register of Legally Induced Abortions provides data regarding the context of medically induced abortions. In contrast, the Danish Medical Birth Registry provides context regarding specified variables regarding women’s pregnancies, delivery, and perinatal outcomes. Finally, the population’s education register offers information regarding patients’ educational history.

A key strength of this study is that the long duration of follow-up data from the Danish Medical Birth Registry, along with its comprehensive data collection, eliminates recall bias. Universal access to health care also improves the generalizability of data. A limitation of the study is its lack of data on maternal smoking and its effects on low gestational weights. The study also has some data gaps, including body mass index information missing from a large portion of the cohort. Finally, the sample size of newborns born to mothers who had received DMT therapy within the last 6 months of gestation was too underpowered to stratify based on first on first-line or second-line treatment.

Dr. Magyari served on scientific advisory boards for Biogen, Sanofi, Teva, Roche, Novartis, and Merck. She has also received honoraria for lecturing from Biogen, Merck, Novartis, Sanofi, Genzyme, and has received research support and support for congress participation from Biogen, Genzyme, Teva, Roche, Merck, and Novartis. Coauthors disclosed various fees received from Merck, Novartis, Biogen, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, and Teva.

, according to a new study published online Feb. 3 in Neurology Clinical Practice. While pregnancy and childbirth are not regarded as conditions that engender high-risk pregnancy in the MS population, previous studies evaluating the effects of MS on pregnancy and parturition have yet to fully elucidate some outcomes for pregnant women and their babies in multiple sclerosis.

“Women with multiple sclerosis may be understandably concerned about the risk of pregnancy,” said Melinda Magyari, MD, PhD, a consultant at the University of Copenhagen. “While previous research has shown there is no higher risk of birth defect for babies born to women with MS, we wanted to find out if women with MS are at risk for a variety of pregnancy complications.”

MS is regarded as a progressive, neurological disease mediated by the immune system that demands careful consideration of numerous situations and life changes including family planning. The MS population is overwhelmingly female, as women account for three out of every four cases of MS. The majority of these women range from 20 to 40 years of age at the time of being diagnosed with MS. Despite the unknown risks of pregnancy-related complications and various perinatal complications in this patient population, women who have MS are not discouraged from conceiving.

Assessing pregnancy outcomes

This nationwide, population-based, cross-sectional study evaluated the pregnancies of 2,930 women with MS between Jan. 1, 1997, and Dec. 31, 2016, registered in the Danish Multiple Sclerosis Registry. The researchers compared pregnancy-related and prenatal outcomes to a 5% random sample of 56,958 randomly-selected pregnant women from Denmark’s general population who did not have MS. They found no differences in the risks associated with several pregnancy-related complications (e.g., preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, or placental complications), emergency Cesarean section (C-section), instrumental delivery, stillbirth, preterm birth, or congenital malformation. Apgar scores were low in both groups. A composite of various biometrics in newborns such as reflexes, muscle tone, and heart rate immediately following birth, the Apgar score is used to help assess the neonatal health, with a value of less than 7 considered low. Here, preterm birth is defined as delivery occurring before 37 weeks of gestation, and stillbirth describes a fetus born dead after 22 weeks of gestation.

Women in the MS cohort were more likely to have elective C-sections (odds ratio, 2.89 [95% confidence interval, 1.65-2.16]), induced labor (OR, 1.15 [95%CI, 1.01-1.31]) and have babies with low birth weight based on their gestational age (OR, 1.29 [95% CI, 1.04-1.60]). Nearly 30% of babies born in the cohort (n = 851) were born to mothers who had received disease-modifying therapy (DMT). Neonates exposed to DMT weighed an average of 116 g less than babies born to mothers who had not received DMT (3,378 g vs. 3,494 g) with a slightly lower gestational age (39 weeks as opposed to 40 weeks). However, babies born to mothers with MS were less likely to show signs of asphyxia (OR, 0.87 [95% CI, 0.78-0.97]) than the comparison cohort.

“We found overall, their pregnancies were just as healthy as those of the moms without MS,” Dr. Magyari said.

Comprehensive data

Denmark’s health care system has two key features that make it an attractive setting in which to conduct such a study – the first being its universal health care. The second advantage is that the country enacted several health registries in the 1970s and 1980s that enable the collection of more comprehensive data. For example, the Danish National Patient Register is a population-based registry that spans the entire nation, facilitating epidemiological research with what the study’s authors describe as “high generalizability.” Providing additional insights regarding the patient story helps add context to pregnancy and outcomes. Among the data collected on the women studied were demographics, contact information, and abortions, both spontaneous and medically induced. The country uses other databases and registries to capture additional data. For example, the Register of Legally Induced Abortions provides data regarding the context of medically induced abortions. In contrast, the Danish Medical Birth Registry provides context regarding specified variables regarding women’s pregnancies, delivery, and perinatal outcomes. Finally, the population’s education register offers information regarding patients’ educational history.

A key strength of this study is that the long duration of follow-up data from the Danish Medical Birth Registry, along with its comprehensive data collection, eliminates recall bias. Universal access to health care also improves the generalizability of data. A limitation of the study is its lack of data on maternal smoking and its effects on low gestational weights. The study also has some data gaps, including body mass index information missing from a large portion of the cohort. Finally, the sample size of newborns born to mothers who had received DMT therapy within the last 6 months of gestation was too underpowered to stratify based on first on first-line or second-line treatment.

Dr. Magyari served on scientific advisory boards for Biogen, Sanofi, Teva, Roche, Novartis, and Merck. She has also received honoraria for lecturing from Biogen, Merck, Novartis, Sanofi, Genzyme, and has received research support and support for congress participation from Biogen, Genzyme, Teva, Roche, Merck, and Novartis. Coauthors disclosed various fees received from Merck, Novartis, Biogen, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, and Teva.

FROM NEUROLOGY CLINICAL PRACTICE

Survey finds practice gaps in counseling women with hidradenitis suppurativa about pregnancy

that surveyed 59 women with HS.

Previous studies have shown the potential for adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with inflammatory conditions such as systemic vasculitis and lupus, but such data on HS and pregnancy are limited, which makes patient counseling a challenge, Ademide A. Adelekun, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues wrote.

In a research letter published in JAMA Dermatology, they reported their findings from an email survey of female patients at two academic dermatology departments. A total of 59 women responded to the survey; their average age was 32 years, the majority (76%) had Hurley stage II disease, and 29 (49%) reported having ever been pregnant.

Two of the 29 women (7%) were pregnant at the time of the study survey; 20 of the other 27 pregnant women (74%) said they had full-term births, 4 (15%) reported miscarriages, and 3 (11%) had undergone an abortion.

A total of five patients (9%) reported difficulty getting pregnant after 1 year, and seven (12%) reported undergoing fertility treatments.

Nearly three-quarters of the women (73%) reported that HS had a negative impact on their sexual health, and 54% said they wished their doctors provided more counseling on HS and pregnancy.

A total of 14 patients (24%) said they believed HS affected their ability to become pregnant because of either decreased sexual activity or decreased fertility caused by HS medications, and nearly half (49%) said they believed that discontinuing all HS medications during pregnancy was necessary for safety reasons.

Patients also expressed concern about the possible heritability of HS: 80% said that physicians had not counseled them about HS heritability and 68% expressed concern that their child would have HS.

In addition, 83% said they had not received information about the potential impact of HS on pregnancy, and 22%, or 13 women, were concerned that childbirth would be more difficult; 11 of these 13 women (85%) had HS that affected the vulva and groin, and 4 of the 8 women who reported concerns about difficulty breastfeeding had HS that involved the breast.

Of the 59 patients surveyed, 12 (20%) said they believed HS poses risks to the child, including through transmission of HS in 8 (67%) or through an infection during a vaginal delivery in 7 women (58%).

The prevalence of HS patients’ concerns about pregnancy “may have unfavorable implications for family planning and mental health and may play a role in the inadequate treatment of HS in patients who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant,” the authors noted. “Family planning and prenatal counseling are particularly critical for those with HS given that clinicians weigh the risks of medication use against the benefits of disease control, which is associated with improved pregnancy outcomes for those with inflammatory conditions.”

The study findings were limited by several factors including “recall bias, low response rate, use of a nonvalidated survey, and generalizability to nonacademic settings,” the researchers noted. However, the results emphasize the often-underrecognized concerns of women with HS and the need for improvements in pregnancy-related counseling and systematic evaluation of outcomes.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. This study was funded by a FOCUS Medical Student Fellowship in Women’s Health grant.

that surveyed 59 women with HS.

Previous studies have shown the potential for adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with inflammatory conditions such as systemic vasculitis and lupus, but such data on HS and pregnancy are limited, which makes patient counseling a challenge, Ademide A. Adelekun, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues wrote.

In a research letter published in JAMA Dermatology, they reported their findings from an email survey of female patients at two academic dermatology departments. A total of 59 women responded to the survey; their average age was 32 years, the majority (76%) had Hurley stage II disease, and 29 (49%) reported having ever been pregnant.

Two of the 29 women (7%) were pregnant at the time of the study survey; 20 of the other 27 pregnant women (74%) said they had full-term births, 4 (15%) reported miscarriages, and 3 (11%) had undergone an abortion.

A total of five patients (9%) reported difficulty getting pregnant after 1 year, and seven (12%) reported undergoing fertility treatments.

Nearly three-quarters of the women (73%) reported that HS had a negative impact on their sexual health, and 54% said they wished their doctors provided more counseling on HS and pregnancy.

A total of 14 patients (24%) said they believed HS affected their ability to become pregnant because of either decreased sexual activity or decreased fertility caused by HS medications, and nearly half (49%) said they believed that discontinuing all HS medications during pregnancy was necessary for safety reasons.

Patients also expressed concern about the possible heritability of HS: 80% said that physicians had not counseled them about HS heritability and 68% expressed concern that their child would have HS.

In addition, 83% said they had not received information about the potential impact of HS on pregnancy, and 22%, or 13 women, were concerned that childbirth would be more difficult; 11 of these 13 women (85%) had HS that affected the vulva and groin, and 4 of the 8 women who reported concerns about difficulty breastfeeding had HS that involved the breast.

Of the 59 patients surveyed, 12 (20%) said they believed HS poses risks to the child, including through transmission of HS in 8 (67%) or through an infection during a vaginal delivery in 7 women (58%).

The prevalence of HS patients’ concerns about pregnancy “may have unfavorable implications for family planning and mental health and may play a role in the inadequate treatment of HS in patients who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant,” the authors noted. “Family planning and prenatal counseling are particularly critical for those with HS given that clinicians weigh the risks of medication use against the benefits of disease control, which is associated with improved pregnancy outcomes for those with inflammatory conditions.”

The study findings were limited by several factors including “recall bias, low response rate, use of a nonvalidated survey, and generalizability to nonacademic settings,” the researchers noted. However, the results emphasize the often-underrecognized concerns of women with HS and the need for improvements in pregnancy-related counseling and systematic evaluation of outcomes.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. This study was funded by a FOCUS Medical Student Fellowship in Women’s Health grant.

that surveyed 59 women with HS.

Previous studies have shown the potential for adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with inflammatory conditions such as systemic vasculitis and lupus, but such data on HS and pregnancy are limited, which makes patient counseling a challenge, Ademide A. Adelekun, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues wrote.

In a research letter published in JAMA Dermatology, they reported their findings from an email survey of female patients at two academic dermatology departments. A total of 59 women responded to the survey; their average age was 32 years, the majority (76%) had Hurley stage II disease, and 29 (49%) reported having ever been pregnant.

Two of the 29 women (7%) were pregnant at the time of the study survey; 20 of the other 27 pregnant women (74%) said they had full-term births, 4 (15%) reported miscarriages, and 3 (11%) had undergone an abortion.

A total of five patients (9%) reported difficulty getting pregnant after 1 year, and seven (12%) reported undergoing fertility treatments.

Nearly three-quarters of the women (73%) reported that HS had a negative impact on their sexual health, and 54% said they wished their doctors provided more counseling on HS and pregnancy.

A total of 14 patients (24%) said they believed HS affected their ability to become pregnant because of either decreased sexual activity or decreased fertility caused by HS medications, and nearly half (49%) said they believed that discontinuing all HS medications during pregnancy was necessary for safety reasons.

Patients also expressed concern about the possible heritability of HS: 80% said that physicians had not counseled them about HS heritability and 68% expressed concern that their child would have HS.

In addition, 83% said they had not received information about the potential impact of HS on pregnancy, and 22%, or 13 women, were concerned that childbirth would be more difficult; 11 of these 13 women (85%) had HS that affected the vulva and groin, and 4 of the 8 women who reported concerns about difficulty breastfeeding had HS that involved the breast.

Of the 59 patients surveyed, 12 (20%) said they believed HS poses risks to the child, including through transmission of HS in 8 (67%) or through an infection during a vaginal delivery in 7 women (58%).

The prevalence of HS patients’ concerns about pregnancy “may have unfavorable implications for family planning and mental health and may play a role in the inadequate treatment of HS in patients who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant,” the authors noted. “Family planning and prenatal counseling are particularly critical for those with HS given that clinicians weigh the risks of medication use against the benefits of disease control, which is associated with improved pregnancy outcomes for those with inflammatory conditions.”

The study findings were limited by several factors including “recall bias, low response rate, use of a nonvalidated survey, and generalizability to nonacademic settings,” the researchers noted. However, the results emphasize the often-underrecognized concerns of women with HS and the need for improvements in pregnancy-related counseling and systematic evaluation of outcomes.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. This study was funded by a FOCUS Medical Student Fellowship in Women’s Health grant.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Cesarean myomectomy: Safe operation or surgical folly?

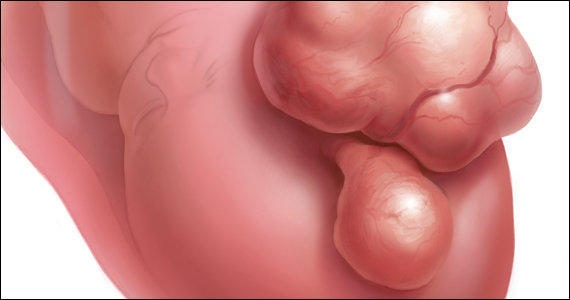

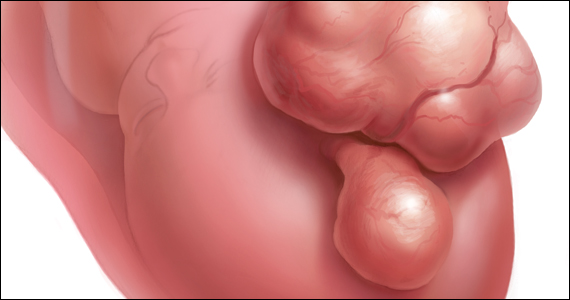

Uterine leiomyomata (fibroids) are the most common pelvic tumor of women. When women are planning to conceive, and their fibroid(s) are clinically significant, causing abnormal uterine bleeding or bulk symptoms, it is often optimal to remove the uterine tumor(s) before conception. Advances in minimally invasive surgery offer women the option of laparoscopic or robot-assisted myomectomy with a low rate of operative complications, including excessive blood loss and hysterectomy, and a low rate of postoperative complications, including major pelvic adhesions and uterine rupture during subsequent pregnancy.1-3 However, many women become pregnant when they have clinically significant fibroids, and at least one-third of these women will have a cesarean birth.

Important clinical issues are the relative benefits and risks of performing a myomectomy at the time of the cesarean birth, so called cesarean myomectomy. Cesarean myomectomy offers carefully selected women the opportunity to have a cesarean birth and myomectomy in one operation, thereby avoiding a second major operation. Over the past 6 decades, most experts in the United States and the United Kingdom have strongly recommended against myomectomy at the time of cesarean delivery because of the risk of excessive blood loss and hysterectomy. Recently, expert opinion has shifted, especially in continental Europe and Asia, and cesarean myomectomy is now viewed as an acceptable surgical option in a limited number of clinical situations, including removal of pedunculated fibroids, excision of large solitary subserosal fibroids, and to achieve optimal management of the hysterotomy incision.

Decades of expert guidance: Avoid cesarean myomectomy at all costs

Dr. K.S.J. Olah succinctly captured the standard teaching that cesarean myomectomy should be avoided in this personal vignette:

Many years ago as a trainee I removed a subserosal fibroid during a cesarean section that was hanging by a thin stalk on the back of the uterus. The berating I received was severe and disproportionate to the crime. The rule was that myomectomy performed at cesarean section was not just frowned upon but expressly forbidden. It has always been considered foolish to consider removing fibroids at cesarean section, mostly because of the associated morbidity and the risk of haemorrhage requiring hysterectomy.4

Dr. Olah quoted guidance from Shaw’s Textbook of Operative Gynaecology,5 “It should be stressed that myomectomy in pregnancy should be avoided at all costs, including at caesarean section.” However, large case series published over the past 10 years report that, in limited clinical situations, cesarean myomectomy is a viable surgical option, where benefit may outweigh risk.6-14 The current literature has many weaknesses, including failure to specifically identify the indication for the cesarean myomectomy and lack of controlled prospective clinical trials. In almost all cases, cesarean myomectomy is performed after delivery of the fetus and placenta.

Continue to: The pedunculated, FIGO type 7 fibroid...

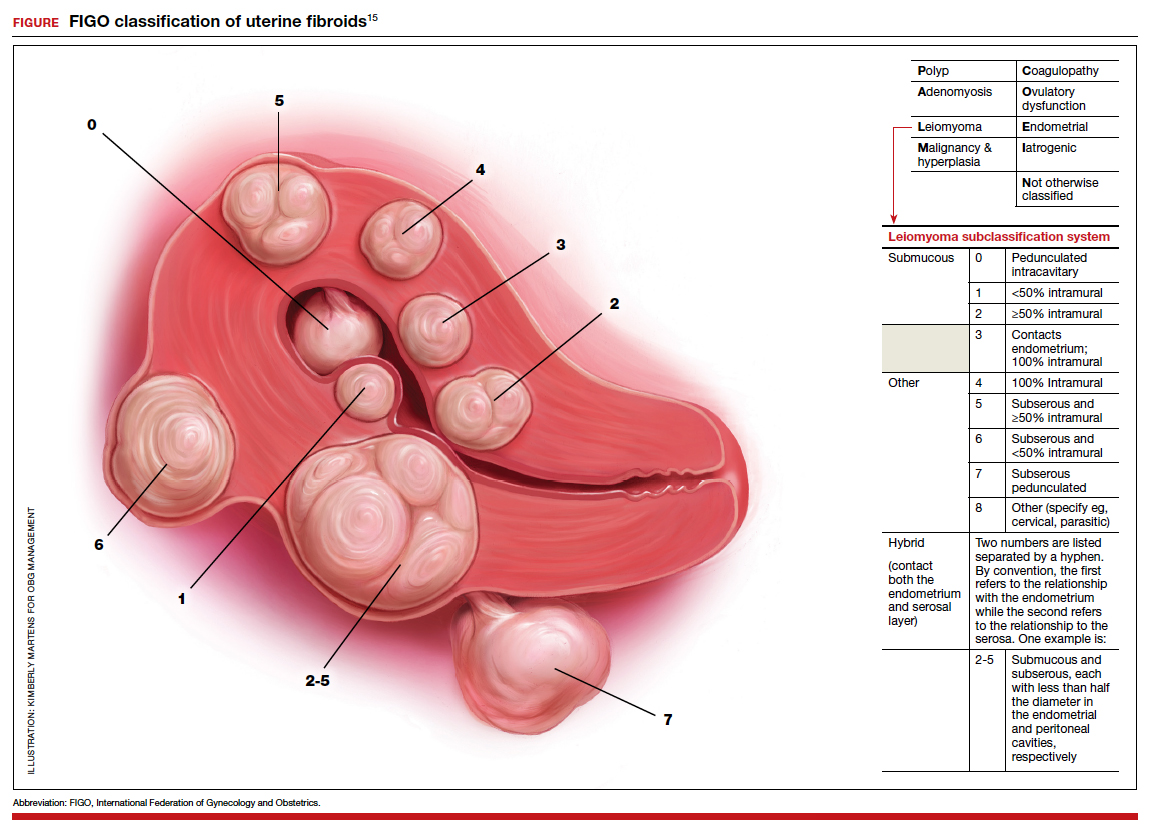

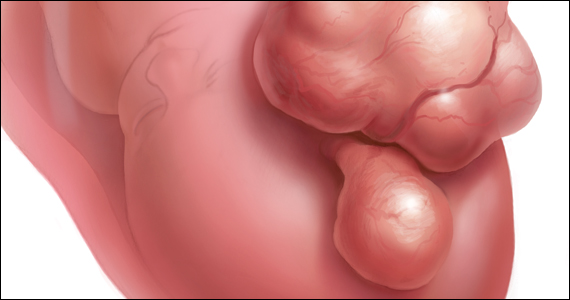

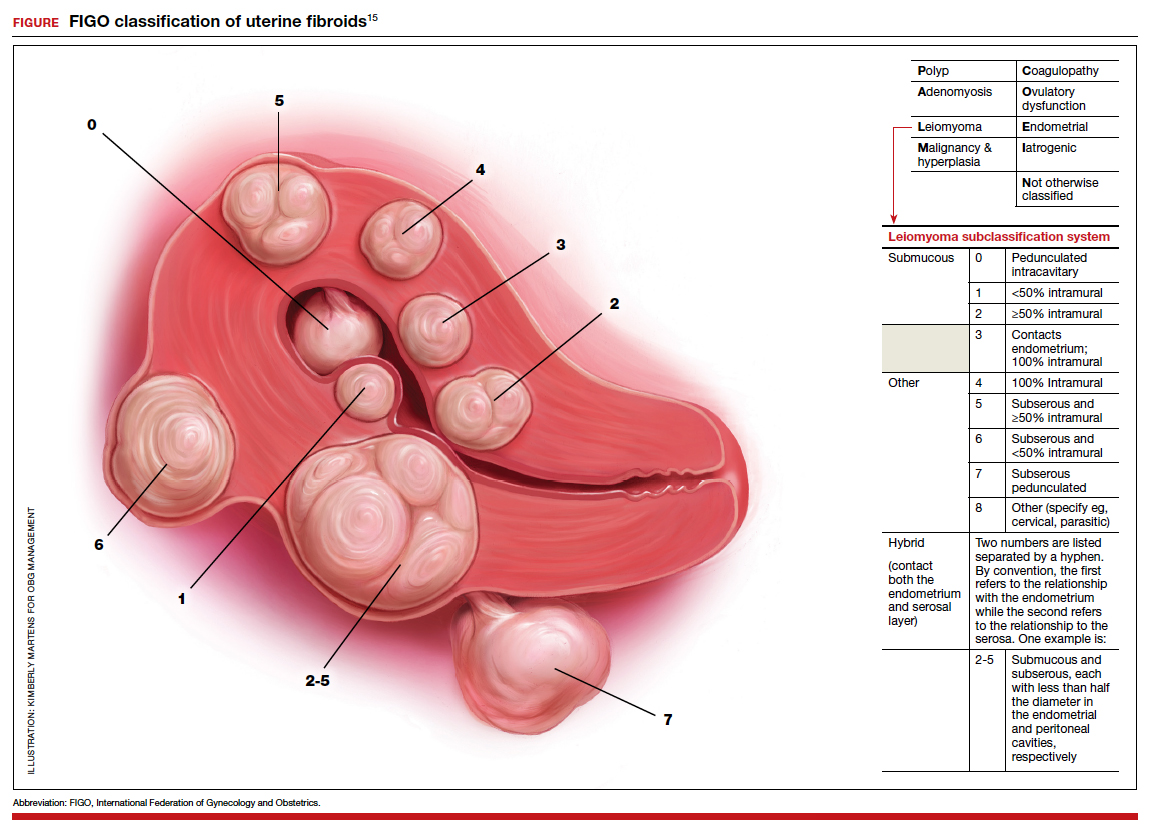

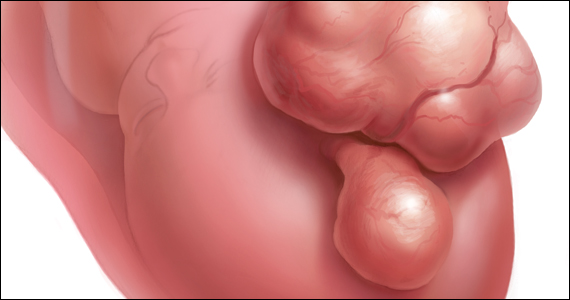

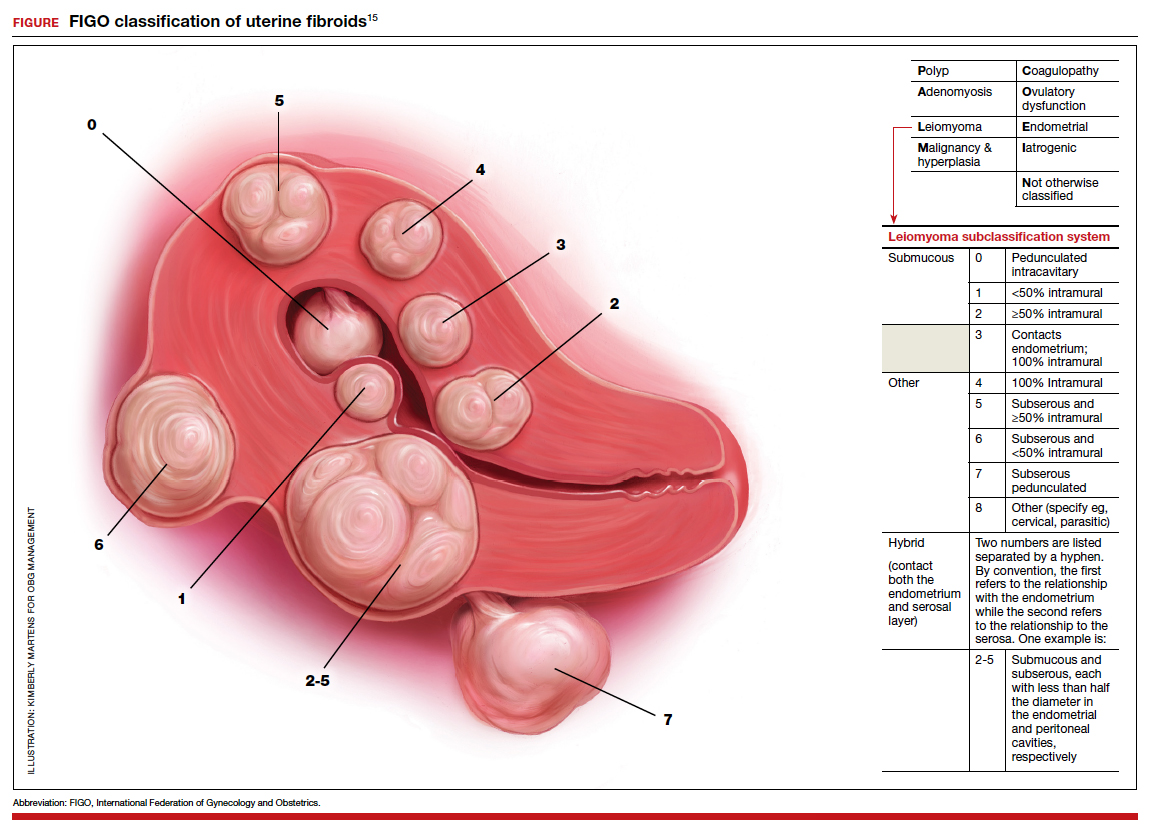

The pedunculated, FIGO type 7 fibroid

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) leiomyoma classification system identifies subserosal pedunculated fibroids as type 7 (FIGURE).15 Pedunculated fibroids are attached to the uterus by a stalk that is ≤10% of the mean of the 3 diameters of the fibroid. When a clinically significant pedunculated fibroid, causing bulk symptoms, is encountered at cesarean birth, I recommend that it be removed. This will save many patients a second major operation to perform a myomectomy. The surgical risk of removing a pedunculated is low.

The solitary FIGO type 6 fibroid

Type 6 fibroids are subserosal fibroids with less than 50% of their mass being subserosal. The type 6 fibroid is relatively easy to enucleate from the uterus. Following removal of a type 6 fibroid, closure of the serosal defect is relatively straightforward. In carefully selected cases, if the type 6 fibroid is causing bulk symptoms, cesarean myomectomy may be indicated with a low risk of operative complications.

The FIGO type 2-5 fibroid

The type 2-5 fibroid is a transmural fibroid with significant mass abutting both the endometrial cavity and serosal surface. Excision of a type 2-5 fibroid is likely to result in a large transmyometrial defect that will be more difficult to close and could be associated with greater blood loss. Although data are limited, I would recommend against cesarean myomectomy for type 2-5 fibroids in most clinical situations.

Myomectomy to achieve optimal management of the cesarean hysterotomy incision

Many surgeons performing a cesarean birth for a woman with clinically significant fibroids will plan the hysterotomy incision to avoid the fibroids. However, following delivery and contraction of the uterus, proper closure of the hysterotomy incision may be very difficult without removing a fibroid that is abutting the hysterotomy incision. Surgeons have reported performing myomectomy on lower uterine segment fibroids before making the hysterotomy incision in order to facilitate the hysterotomy incision and closure.16 Myomectomy prior to delivery of the newborn must be associated with additional risks to the fetus. I would prefer to identify an optimal site to perform a hysterotomy, deliver the newborn and placenta, and then consider myomectomy.

Complications associated with cesarean myomectomy

The evidence concerning the complications of cesarean birth plus myomectomy compared with cesarean birth alone in women with fibroids is limited to case series. There are no reported controlled clinical trials to guide practice. The largest single case series reported on 1,242 women with fibroids who had a cesarean birth plus myomectomy compared with 3 control groups, including 200 women without fibroids who had a cesarean birth, 145 women with fibroids who had a cesarean birth and no myomectomy, and 51 women with fibroids who had a cesarean hysterectomy. The investigators reported no significant differences in preoperative to postoperative hemoglobin change, incidence of postoperative fever, or length of hospital stay among the 4 groups.8 The authors concluded that myomectomy during cesarean birth was a safe and effective procedure.

Continue to: A systematic review and meta-analysis reported...

A systematic review and meta-analysis reported on the results of 17 studies which included 4,702 women who had a cesarean myomectomy and 1,843 women with cesarean birth without myomectomy.17 The authors of the meta-analysis noted that most reported case series had excluded women with a high risk of bleeding, including women with placenta previa, placenta accreta, coagulation disorders, and a history of multiple myomectomy operations. The investigators reported that, compared with the control women, the women undergoing cesarean myomectomy had a statistically significant but clinically insignificant decrease in mean hemoglobin concentration (-0.27 g/dL), a significant increase in mean operative time (+15 minutes) and a significant increase in the length of hospital stay (+0.36 days). There was an increase in the need for blood transfusion (risk ratio, 1.45; 95% confidence interval, 1.05–1.99), but only 3% of women undergoing cesarean myomectomy received a blood transfusion. There was no significant difference between the two groups in the incidence of postoperative fever. The authors concluded that cesarean myomectomy is a safe procedure when performed by experienced surgeons with appropriate hemostatic techniques.

Techniques to reduce blood loss at the time of cesarean myomectomy

A detailed review of all the available techniques to reduce blood loss at the time of cesarean myomectomy is beyond the scope of this editorial. All gynecologists know that control of uterine blood flow through the uterine artery, infundibulopelvic vessels and internal iliac artery can help to reduce bleeding at the time of myomectomy. Tourniquets, vascular clamps, and artery ligation all have been reported to be useful at the time of cesarean myomectomy. In addition, intravenous infusion of oxytocin and tranexamic acid is often used at the time of cesarean myomectomy. Direct injection of uterotonics, including carbetocin, oxytocin, and vasopressin, into the uterus also has been reported. Cell saver blood salvage technology has been utilized in a limited number of cases of cesarean myomectomy.8,18,19

Medicine is not a static field

Discoveries and new data help guide advances in medical practice. After 6 decades of strict adherence to the advice that myomectomy in pregnancy should be avoided at all costs, including at caesarean delivery, new data indicate that in carefully selected cases cesarean myomectomy is an acceptable operation. ●

- Pitter MC, Gargiulo AR, Bonaventura LM, et al. Pregnancy outcomes following robot-assisted myomectomy. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:99-108.

- Pitter MC, Srouji SS, Gargiulo AR, et al. Fertility and symptom relief following robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2015;2015:967568.

- Huberlant S, Lenot J, Neron M, et al. Fertility and obstetric outcomes after robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy. Int J Med Robot. 2020;16:e2059.

- Olah KSJ. Caesarean myomectomy: TE or not TE? BJOG. 2018;125:501.

- Shaw, et al. Textbook of Operative Gynaecology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingston; 1977.

- Burton CA, Grimes DA, March CM. Surgical management of leiomyomata during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;74:707-709.

- Ortac F, Gungor M, Sonmezer M. Myomectomy during cesarean section. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1999;67:189-193.

- Li H, Du J, Jin L, et al. Myomectomy during cesarean section. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica. 2009;88:183-186.

- Kwon DH, Song JE, Yoon KR, et al. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2014;57:367-372.

- Senturk MB, Polat M, Dogan O, et al. Outcome of cesarean myomectomy: is it a safe procedure? Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2017;77:1200-1206.

- Chauhan AR. Cesarean myomectomy: necessity or opportunity? J Obstet Gynecol India. 2018;68:432-436.

- Sparic R, Kadija S, Stefanovic A, et al. Cesarean myomectomy in modern obstetrics: more light and fewer shadows. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43:798-804.

- Ramya T, Sabnis SS, Chitra TV, et al. Cesarean myomectomy: an experience from a tertiary care teaching hospital. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2019;69:426-430.

- Zhao R, Wang X, Zou L, et al. Outcomes of myomectomy at the time of cesarean section among pregnant women with uterine fibroids: a retrospective cohort study. Biomed Res Int. 2019;7576934.

- Munro MG, Critchley HOD, Fraser IS; FIGO Menstrual Disorders Committee. The two FIGO systems for normal and abnormal uterine bleeding symptoms and classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years: 2018 revisions. In J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;143:393.

- Omar SZ, Sivanesaratnam V, Damodaran P. Large lower segment myoma—myomectomy at lower segment caesarean section—a report of two cases. Singapore Med J. 1999;40:109-110.

- Goyal M, Dawood AS, Elbohoty SB, et al. Cesarean myomectomy in the last ten years; A true shift from contraindication to indication: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;256:145-157.

- Lin JY, Lee WL, Wang PH, et al. Uterine artery occlusion and myomectomy for treatment of pregnant women with uterine leiomyomas who are undergoing caesarean section. J Obstet Gynecol Res. 2010;36:284-290.

- Alfred E, Joy G, Uduak O, et al. Cesarean myomectomy outcome in a Nigerian hospital district hospital. J Basic Clin Reprod Sci. 2013;2:115-118.

Uterine leiomyomata (fibroids) are the most common pelvic tumor of women. When women are planning to conceive, and their fibroid(s) are clinically significant, causing abnormal uterine bleeding or bulk symptoms, it is often optimal to remove the uterine tumor(s) before conception. Advances in minimally invasive surgery offer women the option of laparoscopic or robot-assisted myomectomy with a low rate of operative complications, including excessive blood loss and hysterectomy, and a low rate of postoperative complications, including major pelvic adhesions and uterine rupture during subsequent pregnancy.1-3 However, many women become pregnant when they have clinically significant fibroids, and at least one-third of these women will have a cesarean birth.

Important clinical issues are the relative benefits and risks of performing a myomectomy at the time of the cesarean birth, so called cesarean myomectomy. Cesarean myomectomy offers carefully selected women the opportunity to have a cesarean birth and myomectomy in one operation, thereby avoiding a second major operation. Over the past 6 decades, most experts in the United States and the United Kingdom have strongly recommended against myomectomy at the time of cesarean delivery because of the risk of excessive blood loss and hysterectomy. Recently, expert opinion has shifted, especially in continental Europe and Asia, and cesarean myomectomy is now viewed as an acceptable surgical option in a limited number of clinical situations, including removal of pedunculated fibroids, excision of large solitary subserosal fibroids, and to achieve optimal management of the hysterotomy incision.

Decades of expert guidance: Avoid cesarean myomectomy at all costs

Dr. K.S.J. Olah succinctly captured the standard teaching that cesarean myomectomy should be avoided in this personal vignette:

Many years ago as a trainee I removed a subserosal fibroid during a cesarean section that was hanging by a thin stalk on the back of the uterus. The berating I received was severe and disproportionate to the crime. The rule was that myomectomy performed at cesarean section was not just frowned upon but expressly forbidden. It has always been considered foolish to consider removing fibroids at cesarean section, mostly because of the associated morbidity and the risk of haemorrhage requiring hysterectomy.4

Dr. Olah quoted guidance from Shaw’s Textbook of Operative Gynaecology,5 “It should be stressed that myomectomy in pregnancy should be avoided at all costs, including at caesarean section.” However, large case series published over the past 10 years report that, in limited clinical situations, cesarean myomectomy is a viable surgical option, where benefit may outweigh risk.6-14 The current literature has many weaknesses, including failure to specifically identify the indication for the cesarean myomectomy and lack of controlled prospective clinical trials. In almost all cases, cesarean myomectomy is performed after delivery of the fetus and placenta.

Continue to: The pedunculated, FIGO type 7 fibroid...

The pedunculated, FIGO type 7 fibroid

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) leiomyoma classification system identifies subserosal pedunculated fibroids as type 7 (FIGURE).15 Pedunculated fibroids are attached to the uterus by a stalk that is ≤10% of the mean of the 3 diameters of the fibroid. When a clinically significant pedunculated fibroid, causing bulk symptoms, is encountered at cesarean birth, I recommend that it be removed. This will save many patients a second major operation to perform a myomectomy. The surgical risk of removing a pedunculated is low.

The solitary FIGO type 6 fibroid

Type 6 fibroids are subserosal fibroids with less than 50% of their mass being subserosal. The type 6 fibroid is relatively easy to enucleate from the uterus. Following removal of a type 6 fibroid, closure of the serosal defect is relatively straightforward. In carefully selected cases, if the type 6 fibroid is causing bulk symptoms, cesarean myomectomy may be indicated with a low risk of operative complications.

The FIGO type 2-5 fibroid

The type 2-5 fibroid is a transmural fibroid with significant mass abutting both the endometrial cavity and serosal surface. Excision of a type 2-5 fibroid is likely to result in a large transmyometrial defect that will be more difficult to close and could be associated with greater blood loss. Although data are limited, I would recommend against cesarean myomectomy for type 2-5 fibroids in most clinical situations.

Myomectomy to achieve optimal management of the cesarean hysterotomy incision

Many surgeons performing a cesarean birth for a woman with clinically significant fibroids will plan the hysterotomy incision to avoid the fibroids. However, following delivery and contraction of the uterus, proper closure of the hysterotomy incision may be very difficult without removing a fibroid that is abutting the hysterotomy incision. Surgeons have reported performing myomectomy on lower uterine segment fibroids before making the hysterotomy incision in order to facilitate the hysterotomy incision and closure.16 Myomectomy prior to delivery of the newborn must be associated with additional risks to the fetus. I would prefer to identify an optimal site to perform a hysterotomy, deliver the newborn and placenta, and then consider myomectomy.

Complications associated with cesarean myomectomy

The evidence concerning the complications of cesarean birth plus myomectomy compared with cesarean birth alone in women with fibroids is limited to case series. There are no reported controlled clinical trials to guide practice. The largest single case series reported on 1,242 women with fibroids who had a cesarean birth plus myomectomy compared with 3 control groups, including 200 women without fibroids who had a cesarean birth, 145 women with fibroids who had a cesarean birth and no myomectomy, and 51 women with fibroids who had a cesarean hysterectomy. The investigators reported no significant differences in preoperative to postoperative hemoglobin change, incidence of postoperative fever, or length of hospital stay among the 4 groups.8 The authors concluded that myomectomy during cesarean birth was a safe and effective procedure.

Continue to: A systematic review and meta-analysis reported...

A systematic review and meta-analysis reported on the results of 17 studies which included 4,702 women who had a cesarean myomectomy and 1,843 women with cesarean birth without myomectomy.17 The authors of the meta-analysis noted that most reported case series had excluded women with a high risk of bleeding, including women with placenta previa, placenta accreta, coagulation disorders, and a history of multiple myomectomy operations. The investigators reported that, compared with the control women, the women undergoing cesarean myomectomy had a statistically significant but clinically insignificant decrease in mean hemoglobin concentration (-0.27 g/dL), a significant increase in mean operative time (+15 minutes) and a significant increase in the length of hospital stay (+0.36 days). There was an increase in the need for blood transfusion (risk ratio, 1.45; 95% confidence interval, 1.05–1.99), but only 3% of women undergoing cesarean myomectomy received a blood transfusion. There was no significant difference between the two groups in the incidence of postoperative fever. The authors concluded that cesarean myomectomy is a safe procedure when performed by experienced surgeons with appropriate hemostatic techniques.

Techniques to reduce blood loss at the time of cesarean myomectomy

A detailed review of all the available techniques to reduce blood loss at the time of cesarean myomectomy is beyond the scope of this editorial. All gynecologists know that control of uterine blood flow through the uterine artery, infundibulopelvic vessels and internal iliac artery can help to reduce bleeding at the time of myomectomy. Tourniquets, vascular clamps, and artery ligation all have been reported to be useful at the time of cesarean myomectomy. In addition, intravenous infusion of oxytocin and tranexamic acid is often used at the time of cesarean myomectomy. Direct injection of uterotonics, including carbetocin, oxytocin, and vasopressin, into the uterus also has been reported. Cell saver blood salvage technology has been utilized in a limited number of cases of cesarean myomectomy.8,18,19

Medicine is not a static field

Discoveries and new data help guide advances in medical practice. After 6 decades of strict adherence to the advice that myomectomy in pregnancy should be avoided at all costs, including at caesarean delivery, new data indicate that in carefully selected cases cesarean myomectomy is an acceptable operation. ●

Uterine leiomyomata (fibroids) are the most common pelvic tumor of women. When women are planning to conceive, and their fibroid(s) are clinically significant, causing abnormal uterine bleeding or bulk symptoms, it is often optimal to remove the uterine tumor(s) before conception. Advances in minimally invasive surgery offer women the option of laparoscopic or robot-assisted myomectomy with a low rate of operative complications, including excessive blood loss and hysterectomy, and a low rate of postoperative complications, including major pelvic adhesions and uterine rupture during subsequent pregnancy.1-3 However, many women become pregnant when they have clinically significant fibroids, and at least one-third of these women will have a cesarean birth.

Important clinical issues are the relative benefits and risks of performing a myomectomy at the time of the cesarean birth, so called cesarean myomectomy. Cesarean myomectomy offers carefully selected women the opportunity to have a cesarean birth and myomectomy in one operation, thereby avoiding a second major operation. Over the past 6 decades, most experts in the United States and the United Kingdom have strongly recommended against myomectomy at the time of cesarean delivery because of the risk of excessive blood loss and hysterectomy. Recently, expert opinion has shifted, especially in continental Europe and Asia, and cesarean myomectomy is now viewed as an acceptable surgical option in a limited number of clinical situations, including removal of pedunculated fibroids, excision of large solitary subserosal fibroids, and to achieve optimal management of the hysterotomy incision.

Decades of expert guidance: Avoid cesarean myomectomy at all costs

Dr. K.S.J. Olah succinctly captured the standard teaching that cesarean myomectomy should be avoided in this personal vignette:

Many years ago as a trainee I removed a subserosal fibroid during a cesarean section that was hanging by a thin stalk on the back of the uterus. The berating I received was severe and disproportionate to the crime. The rule was that myomectomy performed at cesarean section was not just frowned upon but expressly forbidden. It has always been considered foolish to consider removing fibroids at cesarean section, mostly because of the associated morbidity and the risk of haemorrhage requiring hysterectomy.4

Dr. Olah quoted guidance from Shaw’s Textbook of Operative Gynaecology,5 “It should be stressed that myomectomy in pregnancy should be avoided at all costs, including at caesarean section.” However, large case series published over the past 10 years report that, in limited clinical situations, cesarean myomectomy is a viable surgical option, where benefit may outweigh risk.6-14 The current literature has many weaknesses, including failure to specifically identify the indication for the cesarean myomectomy and lack of controlled prospective clinical trials. In almost all cases, cesarean myomectomy is performed after delivery of the fetus and placenta.

Continue to: The pedunculated, FIGO type 7 fibroid...

The pedunculated, FIGO type 7 fibroid

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) leiomyoma classification system identifies subserosal pedunculated fibroids as type 7 (FIGURE).15 Pedunculated fibroids are attached to the uterus by a stalk that is ≤10% of the mean of the 3 diameters of the fibroid. When a clinically significant pedunculated fibroid, causing bulk symptoms, is encountered at cesarean birth, I recommend that it be removed. This will save many patients a second major operation to perform a myomectomy. The surgical risk of removing a pedunculated is low.

The solitary FIGO type 6 fibroid

Type 6 fibroids are subserosal fibroids with less than 50% of their mass being subserosal. The type 6 fibroid is relatively easy to enucleate from the uterus. Following removal of a type 6 fibroid, closure of the serosal defect is relatively straightforward. In carefully selected cases, if the type 6 fibroid is causing bulk symptoms, cesarean myomectomy may be indicated with a low risk of operative complications.

The FIGO type 2-5 fibroid

The type 2-5 fibroid is a transmural fibroid with significant mass abutting both the endometrial cavity and serosal surface. Excision of a type 2-5 fibroid is likely to result in a large transmyometrial defect that will be more difficult to close and could be associated with greater blood loss. Although data are limited, I would recommend against cesarean myomectomy for type 2-5 fibroids in most clinical situations.

Myomectomy to achieve optimal management of the cesarean hysterotomy incision

Many surgeons performing a cesarean birth for a woman with clinically significant fibroids will plan the hysterotomy incision to avoid the fibroids. However, following delivery and contraction of the uterus, proper closure of the hysterotomy incision may be very difficult without removing a fibroid that is abutting the hysterotomy incision. Surgeons have reported performing myomectomy on lower uterine segment fibroids before making the hysterotomy incision in order to facilitate the hysterotomy incision and closure.16 Myomectomy prior to delivery of the newborn must be associated with additional risks to the fetus. I would prefer to identify an optimal site to perform a hysterotomy, deliver the newborn and placenta, and then consider myomectomy.

Complications associated with cesarean myomectomy

The evidence concerning the complications of cesarean birth plus myomectomy compared with cesarean birth alone in women with fibroids is limited to case series. There are no reported controlled clinical trials to guide practice. The largest single case series reported on 1,242 women with fibroids who had a cesarean birth plus myomectomy compared with 3 control groups, including 200 women without fibroids who had a cesarean birth, 145 women with fibroids who had a cesarean birth and no myomectomy, and 51 women with fibroids who had a cesarean hysterectomy. The investigators reported no significant differences in preoperative to postoperative hemoglobin change, incidence of postoperative fever, or length of hospital stay among the 4 groups.8 The authors concluded that myomectomy during cesarean birth was a safe and effective procedure.

Continue to: A systematic review and meta-analysis reported...

A systematic review and meta-analysis reported on the results of 17 studies which included 4,702 women who had a cesarean myomectomy and 1,843 women with cesarean birth without myomectomy.17 The authors of the meta-analysis noted that most reported case series had excluded women with a high risk of bleeding, including women with placenta previa, placenta accreta, coagulation disorders, and a history of multiple myomectomy operations. The investigators reported that, compared with the control women, the women undergoing cesarean myomectomy had a statistically significant but clinically insignificant decrease in mean hemoglobin concentration (-0.27 g/dL), a significant increase in mean operative time (+15 minutes) and a significant increase in the length of hospital stay (+0.36 days). There was an increase in the need for blood transfusion (risk ratio, 1.45; 95% confidence interval, 1.05–1.99), but only 3% of women undergoing cesarean myomectomy received a blood transfusion. There was no significant difference between the two groups in the incidence of postoperative fever. The authors concluded that cesarean myomectomy is a safe procedure when performed by experienced surgeons with appropriate hemostatic techniques.

Techniques to reduce blood loss at the time of cesarean myomectomy

A detailed review of all the available techniques to reduce blood loss at the time of cesarean myomectomy is beyond the scope of this editorial. All gynecologists know that control of uterine blood flow through the uterine artery, infundibulopelvic vessels and internal iliac artery can help to reduce bleeding at the time of myomectomy. Tourniquets, vascular clamps, and artery ligation all have been reported to be useful at the time of cesarean myomectomy. In addition, intravenous infusion of oxytocin and tranexamic acid is often used at the time of cesarean myomectomy. Direct injection of uterotonics, including carbetocin, oxytocin, and vasopressin, into the uterus also has been reported. Cell saver blood salvage technology has been utilized in a limited number of cases of cesarean myomectomy.8,18,19

Medicine is not a static field

Discoveries and new data help guide advances in medical practice. After 6 decades of strict adherence to the advice that myomectomy in pregnancy should be avoided at all costs, including at caesarean delivery, new data indicate that in carefully selected cases cesarean myomectomy is an acceptable operation. ●

- Pitter MC, Gargiulo AR, Bonaventura LM, et al. Pregnancy outcomes following robot-assisted myomectomy. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:99-108.

- Pitter MC, Srouji SS, Gargiulo AR, et al. Fertility and symptom relief following robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2015;2015:967568.

- Huberlant S, Lenot J, Neron M, et al. Fertility and obstetric outcomes after robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy. Int J Med Robot. 2020;16:e2059.

- Olah KSJ. Caesarean myomectomy: TE or not TE? BJOG. 2018;125:501.

- Shaw, et al. Textbook of Operative Gynaecology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingston; 1977.

- Burton CA, Grimes DA, March CM. Surgical management of leiomyomata during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;74:707-709.

- Ortac F, Gungor M, Sonmezer M. Myomectomy during cesarean section. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1999;67:189-193.

- Li H, Du J, Jin L, et al. Myomectomy during cesarean section. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica. 2009;88:183-186.

- Kwon DH, Song JE, Yoon KR, et al. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2014;57:367-372.

- Senturk MB, Polat M, Dogan O, et al. Outcome of cesarean myomectomy: is it a safe procedure? Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2017;77:1200-1206.

- Chauhan AR. Cesarean myomectomy: necessity or opportunity? J Obstet Gynecol India. 2018;68:432-436.

- Sparic R, Kadija S, Stefanovic A, et al. Cesarean myomectomy in modern obstetrics: more light and fewer shadows. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43:798-804.

- Ramya T, Sabnis SS, Chitra TV, et al. Cesarean myomectomy: an experience from a tertiary care teaching hospital. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2019;69:426-430.

- Zhao R, Wang X, Zou L, et al. Outcomes of myomectomy at the time of cesarean section among pregnant women with uterine fibroids: a retrospective cohort study. Biomed Res Int. 2019;7576934.

- Munro MG, Critchley HOD, Fraser IS; FIGO Menstrual Disorders Committee. The two FIGO systems for normal and abnormal uterine bleeding symptoms and classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years: 2018 revisions. In J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;143:393.

- Omar SZ, Sivanesaratnam V, Damodaran P. Large lower segment myoma—myomectomy at lower segment caesarean section—a report of two cases. Singapore Med J. 1999;40:109-110.

- Goyal M, Dawood AS, Elbohoty SB, et al. Cesarean myomectomy in the last ten years; A true shift from contraindication to indication: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;256:145-157.

- Lin JY, Lee WL, Wang PH, et al. Uterine artery occlusion and myomectomy for treatment of pregnant women with uterine leiomyomas who are undergoing caesarean section. J Obstet Gynecol Res. 2010;36:284-290.

- Alfred E, Joy G, Uduak O, et al. Cesarean myomectomy outcome in a Nigerian hospital district hospital. J Basic Clin Reprod Sci. 2013;2:115-118.

- Pitter MC, Gargiulo AR, Bonaventura LM, et al. Pregnancy outcomes following robot-assisted myomectomy. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:99-108.

- Pitter MC, Srouji SS, Gargiulo AR, et al. Fertility and symptom relief following robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2015;2015:967568.

- Huberlant S, Lenot J, Neron M, et al. Fertility and obstetric outcomes after robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy. Int J Med Robot. 2020;16:e2059.

- Olah KSJ. Caesarean myomectomy: TE or not TE? BJOG. 2018;125:501.

- Shaw, et al. Textbook of Operative Gynaecology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingston; 1977.

- Burton CA, Grimes DA, March CM. Surgical management of leiomyomata during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;74:707-709.

- Ortac F, Gungor M, Sonmezer M. Myomectomy during cesarean section. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1999;67:189-193.

- Li H, Du J, Jin L, et al. Myomectomy during cesarean section. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica. 2009;88:183-186.

- Kwon DH, Song JE, Yoon KR, et al. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2014;57:367-372.

- Senturk MB, Polat M, Dogan O, et al. Outcome of cesarean myomectomy: is it a safe procedure? Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2017;77:1200-1206.

- Chauhan AR. Cesarean myomectomy: necessity or opportunity? J Obstet Gynecol India. 2018;68:432-436.

- Sparic R, Kadija S, Stefanovic A, et al. Cesarean myomectomy in modern obstetrics: more light and fewer shadows. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43:798-804.

- Ramya T, Sabnis SS, Chitra TV, et al. Cesarean myomectomy: an experience from a tertiary care teaching hospital. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2019;69:426-430.

- Zhao R, Wang X, Zou L, et al. Outcomes of myomectomy at the time of cesarean section among pregnant women with uterine fibroids: a retrospective cohort study. Biomed Res Int. 2019;7576934.

- Munro MG, Critchley HOD, Fraser IS; FIGO Menstrual Disorders Committee. The two FIGO systems for normal and abnormal uterine bleeding symptoms and classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years: 2018 revisions. In J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;143:393.

- Omar SZ, Sivanesaratnam V, Damodaran P. Large lower segment myoma—myomectomy at lower segment caesarean section—a report of two cases. Singapore Med J. 1999;40:109-110.

- Goyal M, Dawood AS, Elbohoty SB, et al. Cesarean myomectomy in the last ten years; A true shift from contraindication to indication: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;256:145-157.

- Lin JY, Lee WL, Wang PH, et al. Uterine artery occlusion and myomectomy for treatment of pregnant women with uterine leiomyomas who are undergoing caesarean section. J Obstet Gynecol Res. 2010;36:284-290.

- Alfred E, Joy G, Uduak O, et al. Cesarean myomectomy outcome in a Nigerian hospital district hospital. J Basic Clin Reprod Sci. 2013;2:115-118.

A case of BV during pregnancy: Best management approach

CASE Pregnant woman with abnormal vaginal discharge

A 26-year-old woman (G2P1001) at 24 weeks of gestation requests evaluation for increased frothy, whitish-gray vaginal discharge with a fishy odor. She notes that her underclothes constantly feel damp. The vaginal pH is 4.5, and the amine test is positive.

- What is the most likely diagnosis?

- What obstetrical complications may be associated with this condition?

- How should her condition be treated?

Meet our perpetrator

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is one of the most common conditions associated with vaginal discharge among women of reproductive age. It is characterized by a polymicrobial alteration of the vaginal microbiome, and most distinctly, a relative absence of vaginal lactobacilli. This review discusses the microbiology, epidemiology, specific obstetric and gynecologic complications, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of BV.

The role of vaginal flora

Estrogen has a fundamental role in regulating the normal state of the vagina. In a woman’s reproductive years, estrogen increases glycogen in the vaginal epithelial cells, and the increased glycogen concentration promotes colonization by lactobacilli. The lack of estrogen in pre- and postmenopausal women inhibits the growth of the vaginal lactobacilli, leading to a high vaginal pH, which facilitates the growth of bacteria, particularly anaerobes, that can cause BV.

The vaginal microbiome is polymicrobial and has been classified into at least 5 community state types (CSTs). Four CSTs are dominated by lactobacilli. A fifth CST is characterized by the absence of lactobacilli and high concentrations of obligate or facultative anaerobes.1 The hydrogen peroxide–producing lactobacilli predominate in normal vaginal flora and make up 70% to 90% of the total microbiome. These hydrogen peroxide–producing lactobacilli are associated with reduced vaginal proinflammatory cytokines and a highly acidic vaginal pH. Both factors defend against sexually transmitted infections (STIs).2

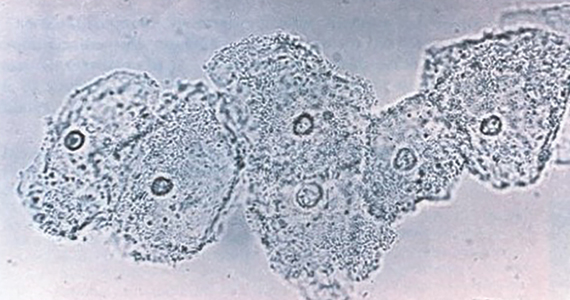

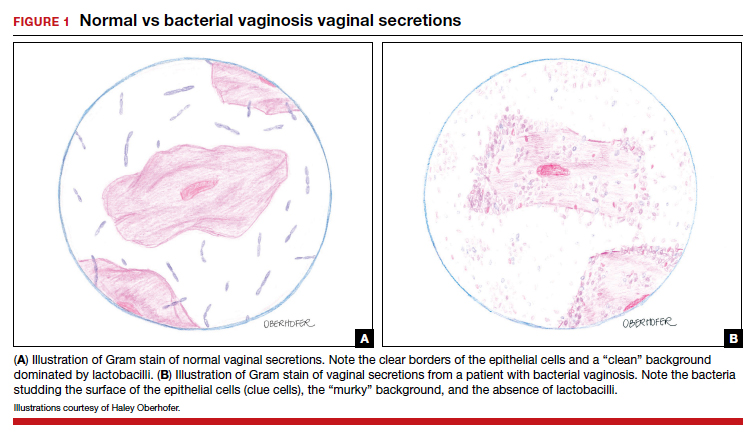

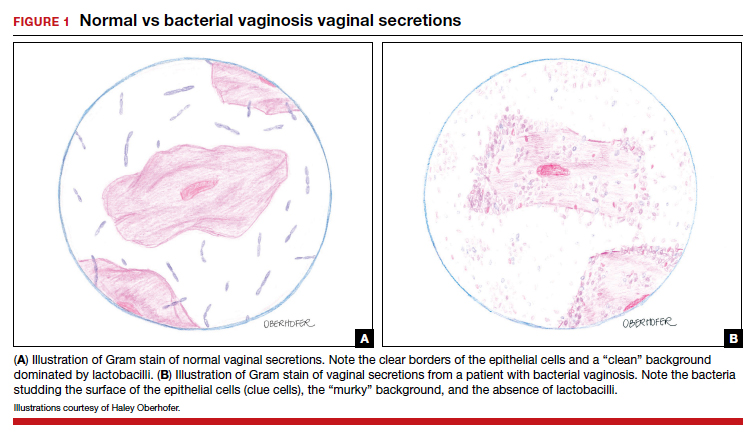

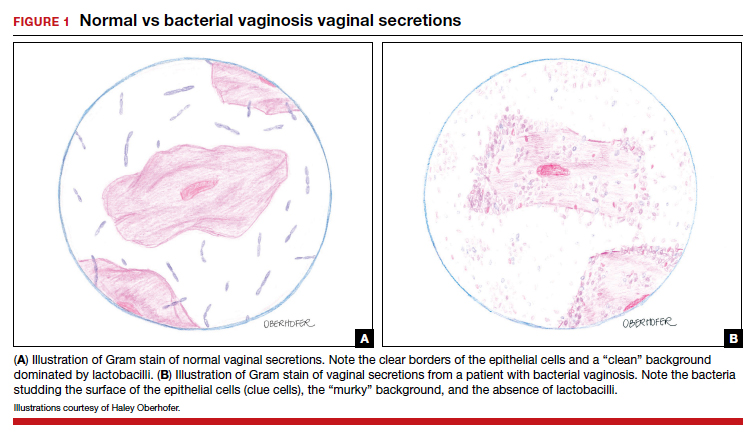

BV is a polymicrobial disorder marked by the significant reduction in the number of vaginal lactobacilli (FIGURE 1). A recent study showed that BV is associated first with a decrease in Lactobacillus crispatus, followed by increase in Prevotella bivia, Gardnerella vaginalis, Atopobium vaginae, and Megasphaera type 1.3 The polymicrobial load is increased by a factor of up to 1,000, compared with normal vaginal flora.4 BV should be considered a biofilm infection caused by adherence of G vaginalis to the vaginal epithelium.5 This biofilm creates a favorable environment for the overgrowth of obligate anaerobic bacteria.

BMI factors into epidemiology

BV is the leading cause of vaginal discharge in reproductive-age women. In the United States, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey estimated a prevalence of 29% in the general population and 50% in Black women aged 14 to 49 years.6 In 2013, Kenyon and colleagues performed a systematic review to assess the worldwide epidemiology of BV, and the prevalence varied by country. Within the US population, rates were highest among non-Hispanic, Black women.7 Brookheart and colleagues demonstrated that, even after controlling for race, overweight and obese women had a higher frequency of BV compared with leaner women. In this investigation, the overall prevalence of BV was 28.1%. When categorized by body mass index (BMI), the prevalence was 21.3% in lean women, 30.4% in overweight women, and 34.5% in obese women (P<.001). The authors also found that Black women had a higher prevalence, independent of BMI, compared with White women.8

Complications may occur. BV is notable for having several serious sequelae in both pregnant and nonpregnant women. For obstetric patients, these sequelae include an increased risk of preterm birth; first trimester spontaneous abortion, particularly in the setting of in vitro fertilization; intra-amniotic infection; and endometritis.9,10 The risk of preterm birth increases by a factor of 2 in infected women; however, most women with BV do not deliver preterm.4 The risk of endometritis is increased 6-fold in women with BV.11 Nonpregnant women with BV are at increased risk for pelvic inflammatory disease, postoperative infections, and an increased susceptibility to STIs such as chlamydia, gonorrhea, herpes simplex virus, and HIV.12-15 The risk for vaginal-cuff cellulitis and abscess after hysterectomy is increased 6-fold in the setting of BV.16

Continue to: Clinical manifestations...

Clinical manifestations

BV is characterized by a milky, homogenous, and malodorous vaginal discharge accompanied by vulvovaginal discomfort and vulvar irritation. Vaginal inflammation typically is absent. The associated odor is fishy, and this odor is accentuated when potassium hydroxide (KOH) is added to the vaginal discharge (amine or “whiff” test) or after the patient has coitus. The distinctive odor is due to the release of organic acids and polyamines that are byproducts of anaerobic bacterial metabolism of putrescine and cadaverine. This release is enhanced by exposure of vaginal secretions to alkaline substances such as KOH or semen.

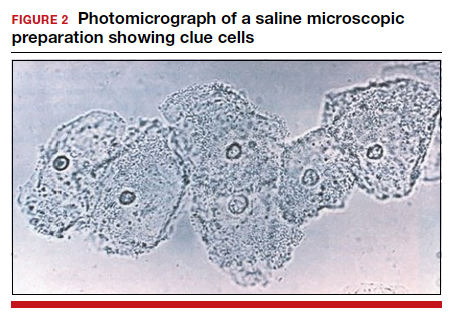

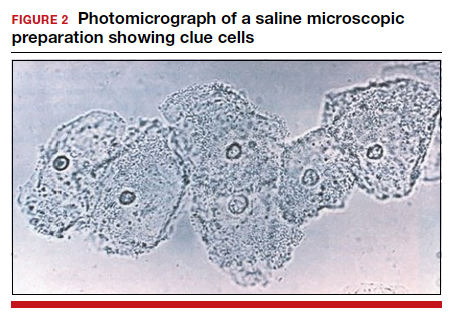

Diagnostic tests and criteria. The diagnosis of BV is made using Amsel criteria or Gram stain with Nugent scoring; bacterial culture is not recommended. Amsel criteria include:

- homogenous, thin, white-gray discharge

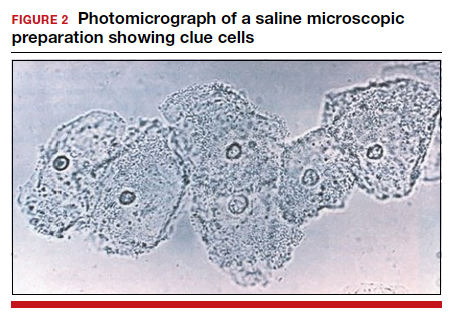

- >20% clue cells on saline microscopy (FIGURE 2)

- a pH >4.5 of vaginal fluid

- positive KOH whiff test.

For diagnosis, 3 of the 4 Amsel criteria must be present.17 Gram stain with Nugent score typically is used for research purposes. Nugent scoring assigns a value to different bacterial morphotypes on Gram stain of vaginal secretions. A score of 7 to 10 is consistent with BV.18

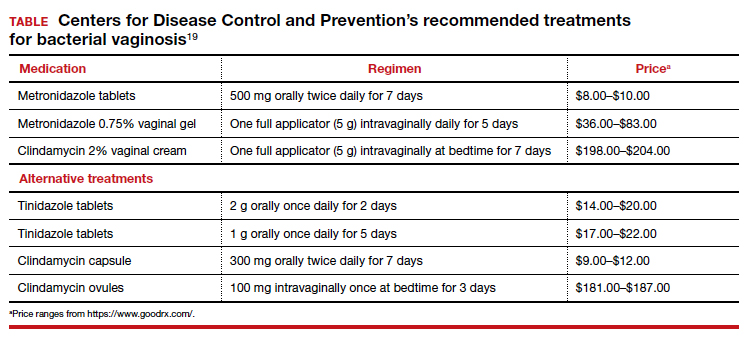

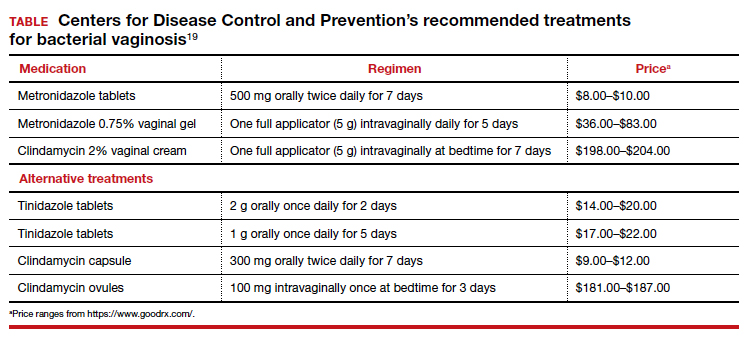

Oral and topical treatments

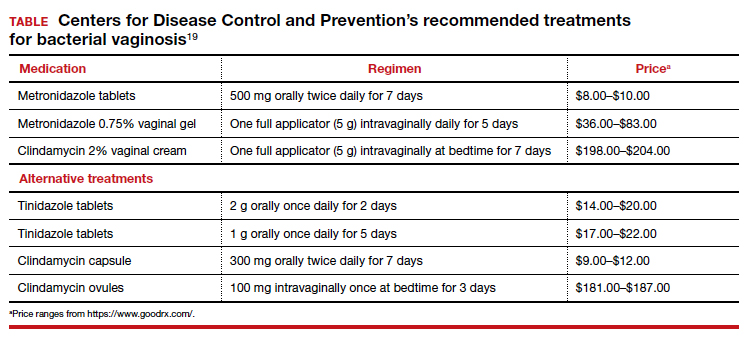

Treatment is recommended for symptomatic patients. Treatment may reduce the risk of transmission and acquisition of other STIs. The TABLE summarizes Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for BV treatment,19 with options including both oral and topical regimens. Oral and topical metronidazole and oral and topical clindamycin are equally effective at eradicating the local source of infection20; however, only oral metronidazole and oral clindamycin are effective in preventing the systemic complications of BV. Oral metronidazole has more adverse effects than oral clindamycin—including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and a disulfiram-like reaction (characterized by flushing, dizziness, throbbing headache, chest and abdominal discomfort, and a distinct hangover effect in addition to nausea and vomiting). However, oral clindamycin can cause antibiotic-associated colitis and is more expensive than metronidazole.

Currently, there are no single-dose regimens for the treatment of BV readily available in the United States. Secnidazole, a 5-nitroimidazole with a longer half-life than metronidazole, (17 vs 8 hours) has been used as therapy in Europe and Asia but is not yet available commercially in the United States.21 Hiller and colleagues found that 1 g and 2 g secnidazole oral granules were superior to placebo in treating BV.22 A larger randomized trial comparing this regimen to standard treatment is necessary before this therapy is adopted as the standard of care.

Continue to: Managing recurrent disease...

Managing recurrent disease, a common problem. Bradshaw and colleagues noted that, although the initial treatment of BV is effective in approximately 80% of women, up to 50% have a recurrence within 12 months.23 Data are limited regarding optimal treatment for recurrent infections; however, most regimens consist of some form of suppressive therapy. One regimen includes one full applicator of metronidazole vaginal gel 0.75% twice weekly for 6 months.24 A second regimen consists of vaginal boric acid capsules 600 mg once daily at bedtime for 21 days. Upon completion of boric acid therapy, metronidazole vaginal gel 0.75% should be administered twice weekly for 6 months.25 A third option is oral metronidazole 2 g and fluconazole 250 mg once every month.26 Of note, boric acid can be fatal if consumed orally and is not recommended during pregnancy.

Most recently, a randomized trial evaluated the ability of L crispatus to prevent BV recurrence. After completion of standard treatment therapy with metronidazole, women were randomly assigned to receive vaginally administered L crispatus (152 patients) or placebo (76 patients) for 11 weeks. In the intention-to-treat population, recurrent BV occurred in 30% of patients in the L crispatus group and 45% of patients in the placebo group. The use of L crispatus significantly reduced recurrence of BV by one-third (P = .01; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.44–0.87).27 These findings are encouraging; however, confirmatory studies are needed before adopting this as standard of care.

Should sexual partners be treated as well? BV has not traditionally been considered an STI, and the CDC does not currently recommend treatment of partners of women who have BV. However, in women who have sex with women, the rate of BV concordance is high, and in women who have sex with men, coitus can clearly influence disease activity. Therefore, in patients with refractory BV, we recommend treatment of the sexual partner(s) with metronidazole 500 mg orally twice daily for 7 days. For women having sex with men, we also recommend consistent use of condoms, at least until the patient’s infection is better controlled.28

CASE Resolved

The patient’s clinical findings are indicative of BV. This condition is associated with an increased risk of preterm delivery and intrapartum and postpartum infection. To reduce the risk of these systemic complications, she was treated with oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 7 days. Within 1 week of completing treatment, she noted complete resolution of the malodorous discharge. ●

- Smith SB, Ravel J. The vaginal microbiota, host defence and reproductive physiology. J Physiol. 2017;595:451-463.

- Mitchell C, Fredricks D, Agnew K, et al. Hydrogen peroxide-producing lactobacilli are associated with lower levels of vaginal interleukin-1β, independent of bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Infect. 2015;42:358-363.

- Munzy CA, Blanchard E, Taylor CM, et al. Identification of key bacteria involved in the induction of incident bacterial vaginosis: a prospective study. J Infect. 2018;218:966-978.

- Paavonen J, Brunham RC. Bacterial vaginosis and desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:2246-2254.

- Hardy L, Jespers V, Dahchour N, et al. Unravelling the bacterial vaginosis-associated biofilm: a multiplex Gardnerella vaginalis and Atopobium vaginae fluorescence in situ hybridization assay using peptide nucleic acid probes. PloS One. 2015;10:E0136658.

- Allswoth JE, Peipert JF. Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis: 2001-2004 national health and nutrition examination survey data. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:114-120.

- Kenyon C, Colebunders R, Crucitti T. The global epidemiology of bacterial vaginosis: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:505-523.

- Brookheart RT, Lewis WG, Peipert JF, et al. Association between obesity and bacterial vaginosis as assessed by Nugent score. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:476.e1-476.e11.

- Onderdonk AB, Delaney ML, Fichorova RN. The human microbiome during bacterial vaginosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2016;29:223-238.

- Brown RG, Marchesi JR, Lee YS, et al. Vaginal dysbiosis increases risk of preterm fetal membrane rupture, neonatal sepsis and is exacerbated by erythromycin. BMC Med. 2018;16:9.

- Watts DH, Eschenbach DA, Kenny GE. Early postpartum endometritis: the role of bacteria, genital mycoplasmas, and chlamydia trachomatis. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:52-60.

- Balkus JE, Richardson BA, Rabe LK, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and the risk of Trichomonas vaginalis acquisition among HIV1-negative women. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41:123-128.

- Cherpes TL, Meyn LA, Krohn MA, et al. Association between acquisition of herpes simplex virus type 2 in women and bacterial vaginosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:319-325.

- Wiesenfeld HC, Hillier SL, Krohn MA, et al. Bacterial vaginosis is a strong predictor of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:663-668.

- Myer L, Denny L, Telerant R, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and susceptibility to HIV infection in South African women: a nested case-control study. J Infect. 2005;192:1372-1380.

- Soper DE, Bump RC, Hurt WG. Bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis vaginitis are risk factors for cuff cellulitis after abdominal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:1061-1121.

- Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, et al. Nonspecific vaginitis. diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med. 1983;74:14-22.

- Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:297-301.

- Bacterial vaginosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Updated June 4, 2015. Accessed December 9, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/bv.htm.

- Oduyebo OO, Anorlu RI, Ogunsola FT. The effects of antimicrobial therapy on bacterial vaginosis in non-pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD006055.

- Videau D, Niel G, Siboulet A, et al. Secnidazole. a 5-nitroimidazole derivative with a long half-life. Br J Vener Dis. 1978;54:77-80.

- Hillier SL, Nyirjesy P, Waldbaum AS, et al. Secnidazole treatment of bacterial vaginosis: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:379-386.

- Bradshaw CS, Morton AN, Hocking J, et al. High recurrence rates of bacterial vaginosis over the course of 12 months after oral metronidazole therapy and factors associated with recurrence. J Infect. 2006;193:1478-1486.

- Sobel JD, Ferris D, Schwebke J, et al. Suppressive antibacterial therapy with 0.75% metronidazole vaginal gel to prevent recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1283-1289.

- Reichman O, Akins R, Sobel JD. Boric acid addition to suppressive antimicrobial therapy for recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:732-734.

- McClelland RS, Richardson BA, Hassan WM, et al. Improvement of vaginal health for Kenyan women at risk for acquisition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: results of a randomized trial. J Infect. 2008;197:1361-1368.

- Cohen CR, Wierzbicki MR, French AL, et al. Randomized trial of lactin-v to prevent recurrence of bacterial vaginosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:906-915.

- Barbieri RL. Effective treatment of recurrent bacterial vaginosis. OBG Manag. 2017;29:7-12.

CASE Pregnant woman with abnormal vaginal discharge

A 26-year-old woman (G2P1001) at 24 weeks of gestation requests evaluation for increased frothy, whitish-gray vaginal discharge with a fishy odor. She notes that her underclothes constantly feel damp. The vaginal pH is 4.5, and the amine test is positive.

- What is the most likely diagnosis?

- What obstetrical complications may be associated with this condition?

- How should her condition be treated?

Meet our perpetrator

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is one of the most common conditions associated with vaginal discharge among women of reproductive age. It is characterized by a polymicrobial alteration of the vaginal microbiome, and most distinctly, a relative absence of vaginal lactobacilli. This review discusses the microbiology, epidemiology, specific obstetric and gynecologic complications, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of BV.

The role of vaginal flora

Estrogen has a fundamental role in regulating the normal state of the vagina. In a woman’s reproductive years, estrogen increases glycogen in the vaginal epithelial cells, and the increased glycogen concentration promotes colonization by lactobacilli. The lack of estrogen in pre- and postmenopausal women inhibits the growth of the vaginal lactobacilli, leading to a high vaginal pH, which facilitates the growth of bacteria, particularly anaerobes, that can cause BV.