User login

Implementing shared decision making in labor and delivery: TeamBirth is a model for person-centered birthing care

CASE The TeamBirth experience: Making a difference

“At a community hospital in Washington where we had implemented TeamBirth (a labor and delivery shared decision making model), a patient, her partner, a labor and delivery nurse, and myself (an ObGyn) were making a plan for the patient’s induction of labor admission. I asked the patient, a 29-year-old (G2P1001), how we could improve her care in relation to her first birth. Her answer was simple: I want to be treated with respect. Her partner went on to describe their past experience in which the provider was inappropriately texting while in between the patient’s knees during delivery. Our team had the opportunity to undo some of the trauma from her first birth. That’s what I like about TeamBirth. It gives every patient the opportunity, regardless of their background, to define safety and participate in their care experience.”

–Angela Chien, MD, Obstetrician and Quality Improvement leader, Washington

Unfortunately, disrespect and mistreatment are far from an anomaly in the obstetrics setting. In a systematic review of respectful maternity care, the World Health Organization delineated 7 dimensions of maternal mistreatment: physical abuse, sexual abuse, verbal abuse, stigma and discrimination, failure to meet professional standards of care, poor rapport between women and providers, and poor conditions and constraints presented by the health system.1 In 2019, the Giving Voice to Mothers study showed that 17% of birthing people in the United States reported experiencing 1 or more types of maternal mistreatment.2 Rates of mistreatment were disproportionately greater in populations of color, hospital-based births, and among those with social, economic, or health challenges.2 It is well known that Black and African American and American Indian and Alaska Native populations experience the rare events of severe maternal morbidity and mortality more frequently than their White counterparts; the disproportionate burden of mistreatment is lesser known and far more common.

Overlooking the longitudinal harm of a negative birth experience has cascading impact. While an empowering perinatal experience can foster preventive screening and management of chronic disease, a poor experience conversely can seed mistrust at an individual, generational, and community level.

The patient quality enterprise is beginning to shift attention toward maternal experience with the development of PREMs (patient-reported experience measures), PROMs (patient-reported outcome measures), and novel validated scales that assess autonomy and trust.3 Development of a maternal Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) survey on childbirth is forthcoming.4 Of course, continuing to prioritize physical safety through initiatives on blood pressure monitoring and severe maternal morbidity and mortality remains paramount. Yet emotional and psychological safety also must be recognized as essential pillars of patient safety. Transgressions related to autonomy and dignity, as well as racism, sexism, classicism, and ableism, should be treated as “adverse and never events.”5

How the TeamBirth model works

Shared decision making (SDM) is cited in medical pedagogy as the solution to respectfullyrecognizing social context, integrating subjective experience, and honoring patient autonomy.6 The onus has always been on individual clinicians to exercise SDM. A new practice model, TeamBirth, embeds SDM into the culture and workflow. It offers a behavioral framework to mitigate implicit bias and operationalizes SDM tools, such that every patient is an empowered participant in their care.

TeamBirth was created through Ariadne Labs’ Delivery Decisions Initiative, a research and social impact program that designs, tests, and scales transformative, systems-level solutions that promote quality, equity, and dignity in childbirth. By the end of 2023, TeamBirth will be implemented in more than 100 hospitals across the United States, cumulatively touching over 200,000 lives. (For more information on the TeamBirth model, view the “Why TeamBirth” video at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EoVrSaGk7gc.)

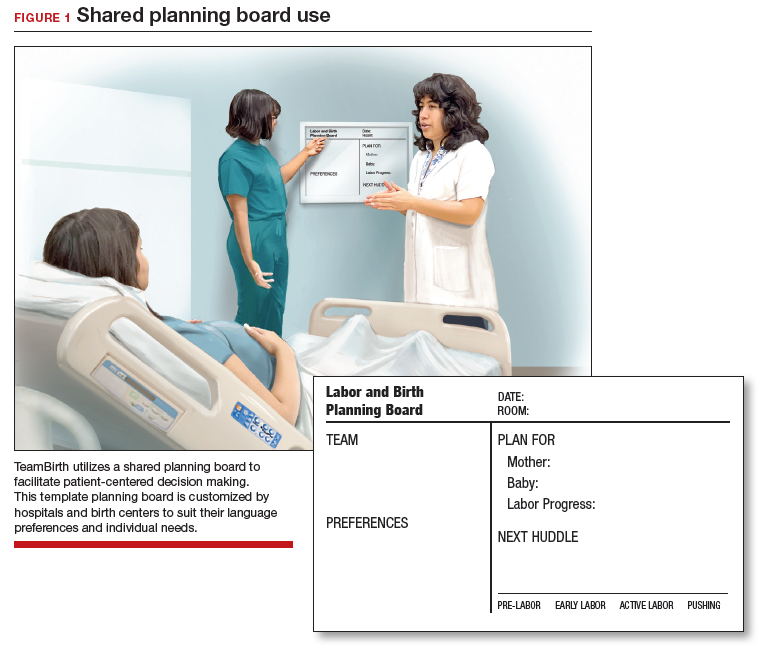

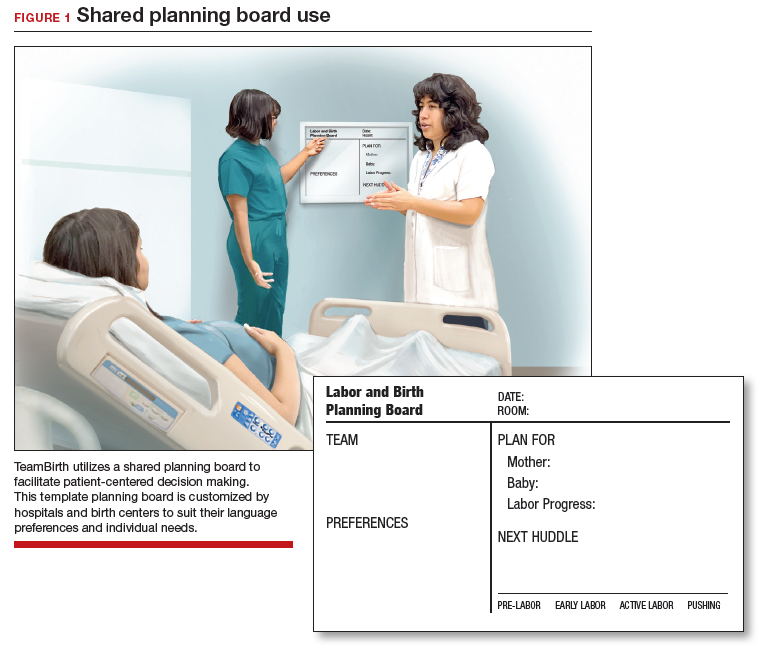

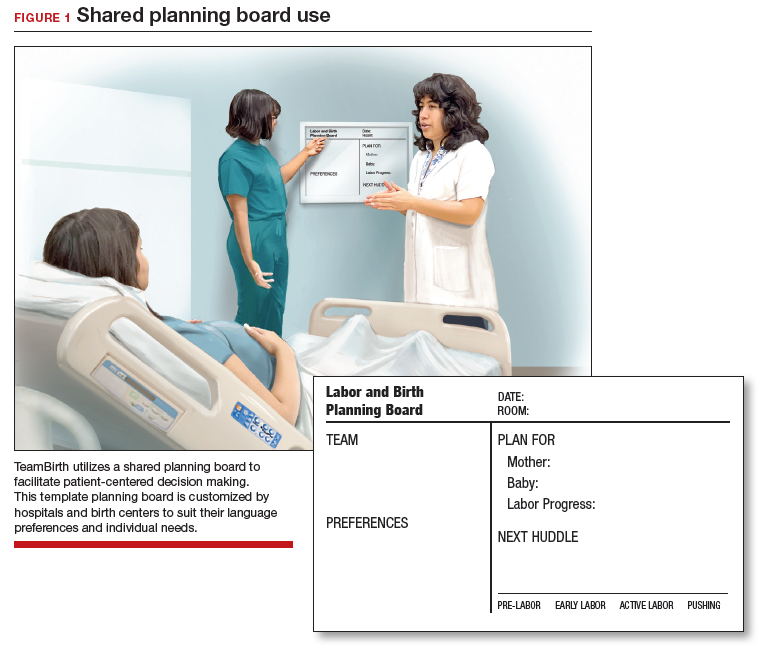

The tenets of TeamBirth are enacted through a patient-facing, shared whiteboard or dry-erase planning board in the labor room (FIGURE 1). Research has demonstrated how dry-erase boards in clinical settings can support safety and dignity in care, especially to improve patient-provider communication, teamwork, and patient satisfaction.7,8 The planning board is initially filled out by a clinical team member and is updated during team “huddles” throughout labor.

Huddles are care plan discussions with the full care team (the patient, nurse, doula and/or other support person(s), delivering provider, and interpreter or social worker as needed). At a minimum, huddles occur on admission, with changes to the clinical course and care plan, and at the request of any team member. Huddles can transpire through in-person, virtual, or phone communication.9 The concept builds on interdisciplinary and patient-centered rounding and establishes a communication system that is suited to the dynamic environment and amplified patient autonomy unique to labor and delivery. Dr. Bob Barbieri, a steadfast leader and champion of TeamBirth implementation at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston (and the Editor in Chief of OBG M

Continue to: Patient response to TeamBirth is positive...

Patient response to TeamBirth is positive

Patients and providers alike have endorsed TeamBirth. In initial pilot testing across 4 sites, 99% of all patients surveyed “definitely” or “somewhat” had the role they wanted in making decisions about their labor.9

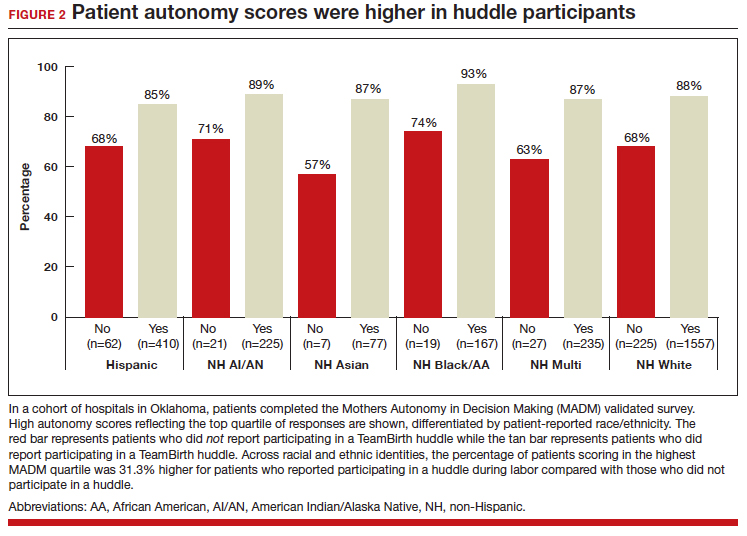

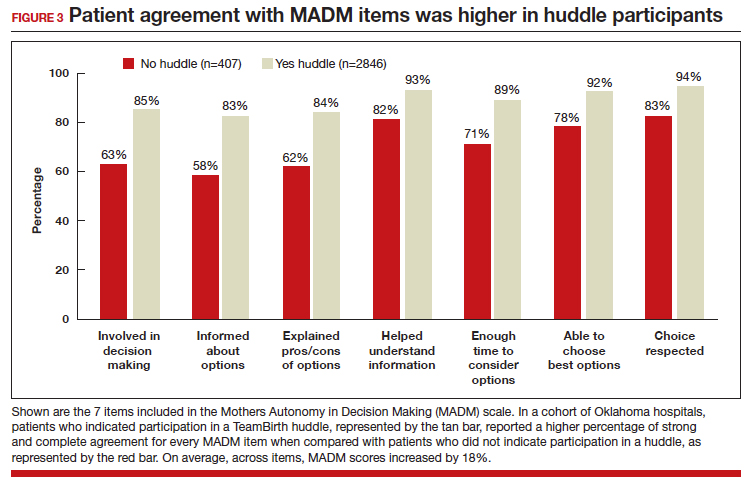

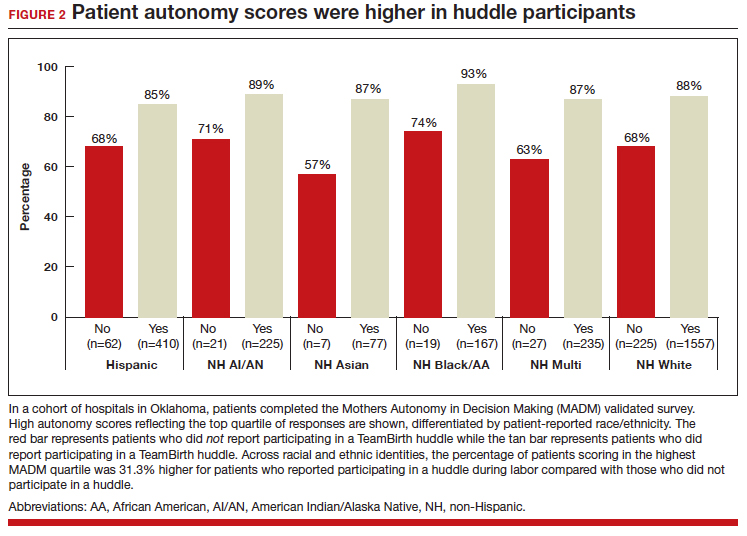

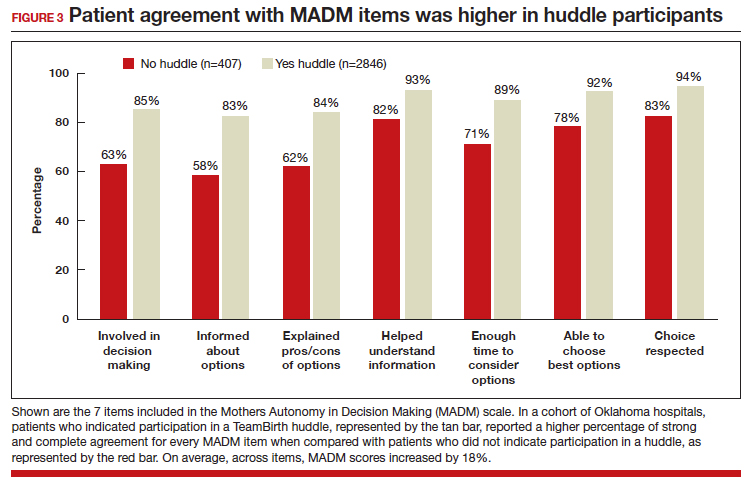

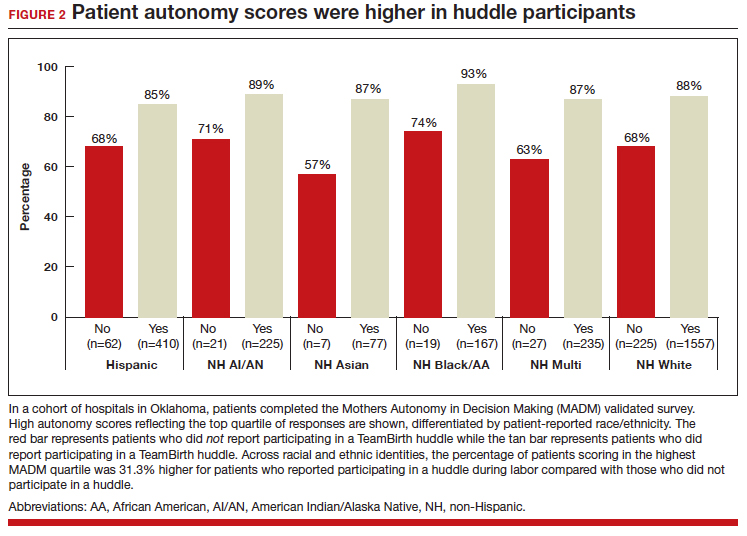

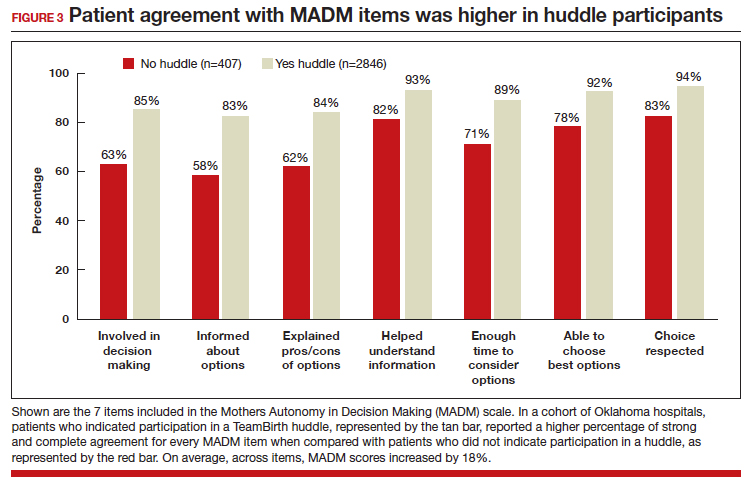

In partnership with the Oklahoma Perinatal Quality Improvement Collaborative (OPQIC), the impact of TeamBirth was assessed in a statewide patient cohort (n = 3,121) using the validated Mothers Autonomy in Decision Making (MADM) scale created by the Birth Place Lab at the University of British Columbia. The percentage of patients who scored in the highest MADM quartile was 31.3% higher for patients who indicated participation in a huddle during labor compared with those who did not participate in a huddle. This trend held across all racial and ethnic groups: For example, 93% of non-Hispanic Black/African American patients who had a TeamBirth huddle reported high autonomy, a nearly 20 percentage point increase from those without a huddle (FIGURE 2). Similarly, a higher percentage of agreement was observed across all 7 items in the MADM scale for patients who reported a TeamBirth huddle (FIGURE 3). TeamBirth’s effect has been observed across surveys and multiple validated metrics.

Data collection related to TeamBirth continues to be ongoing, with reported values retrieved on July 14, 2023. Rigorous review of patient-reported outcomes is forthcoming, and assessing impact on clinical outcomes, such as NTSV (nulliparous, term, singleton vertex) cesarean delivery rates and severe maternal morbidity, is on the horizon.

Qualitative survey responses reinforce how patients value TeamBirth and appreciate huddles and whiteboards.

Continue to: Patient testimonials...

Patient testimonials

The following testimonials were obtained from a TeamBirth survey that patients in participating Massachusetts hospitals completed in the postpartum unit prior to discharge.

According to one patient, “TeamBirth is great, feels like all obstacles are covered by multiple people with many talents, expertise. Feels like mom is part of the process, much different than my delivery 2 years ago when I felt like things were decided for me/I was ‘told’ what we were doing and questioned if I felt uneasy about it…. We felt safe and like all things were covered no matter what may happen.”

Another patient, also at a Massachusetts hospital, offered these comments about TeamBirth: “The entire staff was very genuine and my experience the best it could be. They deserve updated whiteboards in every room. I found them to be very useful.”

The clinician perspective

To be certain, clinician workflow must be a consideration for any practice change. The feasibility, acceptability, and safety of the TeamBirth model to clinicians was validated through a study at 4 community hospitals across the United States in which TeamBirth had been implemented in the 8 months prior.9

The clinician response rate was an impressive 78%. Ninety percent of clinicians, including physicians, midwives, and nurses, indicated that they would “definitely” (68%) or “probably” (22%) recommend TeamBirth for use in other labor and delivery units. None of the clinicians surveyed (n = 375) reported that TeamBirth negatively impacted care delivery.9

Obstetricians also provided qualitative commentary, noting that, while at times huddling infringed on efficiency, it also enhanced staff fulfillment. An obstetrician at a Massachusetts hospital observed, “Overall I think [TeamBirth is] helpful in slowing us down a little bit to really make sure that we’re providing the human part of the care, like the communication, and not just the medical care. And I think most providers value the human part and the communication. You know, we all think most providers value good communication with the patients, but when you’re in the middle of running around doing a bunch of stuff, you don’t always remember to prioritize it. And I think that at the end of the day…when you know you’ve communicated well with your patients, you end up feeling better about what you’re doing.”

As with most cross-sectional survey studies, selection bias remains an important caveat; patients and providers may decide to complete or not complete voluntary surveys based on particularly positive or negative experiences.

Metrics aside, obstetricians have an ethical duty to provide dignified and safe care, both physically and psychologically. Collectively, as a specialty, we share the responsibility to mitigate maternal mistreatment. As individuals, we can prevent perpetuation of birth trauma and foster healing and empowerment, one patient at a time, by employing tenets of TeamBirth.

To connect with Delivery Decisions Initiative, visit our website: https://www.ariadnelabs.org/deliverydecisions-initiative/ or contact: deliverydecisions@ ariadnelabs.org

Steps for implementing the TeamBirth model

To incorporate TeamBirth into your practice:

- Make patients the “team captain” and center them as the primary decision maker.

- Elicit patient preferences and subjective experiences to develop a collaborative plan on admission and when changes occur in clinical status.

- Round with and utilize the expertise of the full care team—nurse and midwife or obstetrician, as well as support person(s) and/or doula, learners, interpreter, and social worker as applicable.

- Ensure that the patient knows the names and roles of the care team members and provide updates at shift change.

- If your birthing rooms have a whiteboard, use it to keep the patient and team informed of the plan.

- Delineate status updates by maternal condition, fetal condition, and labor progress.

- Provide explicit permission for patients to call for a team huddle at any time and encourage support from their support people and/or doula. ●

This project is supported by:

- The Oklahoma Department of Health as part of the State Maternal Health Innovation Program Grant, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services.

- The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of an award to the Oklahoma State Department of Health. The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS, or the U.S. Government. For more information, please visit HRSA.gov.

- The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant T76MC00001 and entitled Training Grant in Maternal and Child Health.

- Point32 Health’s Clinical Innovation Fund.

Data included in this article was collected and analyzed in partnership with the Oklahoma Perinatal Quality Improvement Collaborative, Department of OB/GYN, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City.

- Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, et al. The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: a mixedmethods systematic review. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e100184. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001847

- Vedam S, Stoll K, Taiwo TK, et al. The Giving Voice to Mothers study: inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reprod Health. 2019;16. doi:10.1186/s12978-019-0729-2

- Kemmerer A, Alteras T. Evolving the maternal health quality measurement enterprise to support the communitybased maternity model. Maternal Health Hub. April 25, 2023. Accessed September 13, 2023. https:/www .maternalhealthhub.org

- Potential CAHPS survey to assess patients’ prenatal and childbirth care experiences. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. March 2023. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://www.ahrq.gov/news/cahps-comments-sought.html

- Lyndon A, Davis DA, Sharma AE, et al. Emotional safety is patient safety. BMJ Qual Saf. 2023;32:369-372. doi:10.1136 /bmjqs-2022-015573

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 819. Informed consent and shared decision making in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e34-e41. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance /committee-opinion/articles/2021/02/informed -consent-and-shared-decision-making-in-obstetrics-and -gynecology

- Goyal AA, Tur K, Mann J, et al. Do bedside visual tools improve patient and caregiver satisfaction? A systematic review of the literature. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:930-936. doi:10.12788 /jhm.2871

- Sehgal NL, Green A, Vidyarthi AR, et al. Patient whiteboards as a communication tool in the hospital setting: a survey of practices and recommendations. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:234-239. doi:10.1002/jhm.638

- Weiseth A, Plough A, Aggarwal R, et al. Improving communication and teamwork during labor: a feasibility, acceptability, and safety study. Birth. 2022:49:637-647. doi:10.1111/birt.12630

CASE The TeamBirth experience: Making a difference

“At a community hospital in Washington where we had implemented TeamBirth (a labor and delivery shared decision making model), a patient, her partner, a labor and delivery nurse, and myself (an ObGyn) were making a plan for the patient’s induction of labor admission. I asked the patient, a 29-year-old (G2P1001), how we could improve her care in relation to her first birth. Her answer was simple: I want to be treated with respect. Her partner went on to describe their past experience in which the provider was inappropriately texting while in between the patient’s knees during delivery. Our team had the opportunity to undo some of the trauma from her first birth. That’s what I like about TeamBirth. It gives every patient the opportunity, regardless of their background, to define safety and participate in their care experience.”

–Angela Chien, MD, Obstetrician and Quality Improvement leader, Washington

Unfortunately, disrespect and mistreatment are far from an anomaly in the obstetrics setting. In a systematic review of respectful maternity care, the World Health Organization delineated 7 dimensions of maternal mistreatment: physical abuse, sexual abuse, verbal abuse, stigma and discrimination, failure to meet professional standards of care, poor rapport between women and providers, and poor conditions and constraints presented by the health system.1 In 2019, the Giving Voice to Mothers study showed that 17% of birthing people in the United States reported experiencing 1 or more types of maternal mistreatment.2 Rates of mistreatment were disproportionately greater in populations of color, hospital-based births, and among those with social, economic, or health challenges.2 It is well known that Black and African American and American Indian and Alaska Native populations experience the rare events of severe maternal morbidity and mortality more frequently than their White counterparts; the disproportionate burden of mistreatment is lesser known and far more common.

Overlooking the longitudinal harm of a negative birth experience has cascading impact. While an empowering perinatal experience can foster preventive screening and management of chronic disease, a poor experience conversely can seed mistrust at an individual, generational, and community level.

The patient quality enterprise is beginning to shift attention toward maternal experience with the development of PREMs (patient-reported experience measures), PROMs (patient-reported outcome measures), and novel validated scales that assess autonomy and trust.3 Development of a maternal Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) survey on childbirth is forthcoming.4 Of course, continuing to prioritize physical safety through initiatives on blood pressure monitoring and severe maternal morbidity and mortality remains paramount. Yet emotional and psychological safety also must be recognized as essential pillars of patient safety. Transgressions related to autonomy and dignity, as well as racism, sexism, classicism, and ableism, should be treated as “adverse and never events.”5

How the TeamBirth model works

Shared decision making (SDM) is cited in medical pedagogy as the solution to respectfullyrecognizing social context, integrating subjective experience, and honoring patient autonomy.6 The onus has always been on individual clinicians to exercise SDM. A new practice model, TeamBirth, embeds SDM into the culture and workflow. It offers a behavioral framework to mitigate implicit bias and operationalizes SDM tools, such that every patient is an empowered participant in their care.

TeamBirth was created through Ariadne Labs’ Delivery Decisions Initiative, a research and social impact program that designs, tests, and scales transformative, systems-level solutions that promote quality, equity, and dignity in childbirth. By the end of 2023, TeamBirth will be implemented in more than 100 hospitals across the United States, cumulatively touching over 200,000 lives. (For more information on the TeamBirth model, view the “Why TeamBirth” video at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EoVrSaGk7gc.)

The tenets of TeamBirth are enacted through a patient-facing, shared whiteboard or dry-erase planning board in the labor room (FIGURE 1). Research has demonstrated how dry-erase boards in clinical settings can support safety and dignity in care, especially to improve patient-provider communication, teamwork, and patient satisfaction.7,8 The planning board is initially filled out by a clinical team member and is updated during team “huddles” throughout labor.

Huddles are care plan discussions with the full care team (the patient, nurse, doula and/or other support person(s), delivering provider, and interpreter or social worker as needed). At a minimum, huddles occur on admission, with changes to the clinical course and care plan, and at the request of any team member. Huddles can transpire through in-person, virtual, or phone communication.9 The concept builds on interdisciplinary and patient-centered rounding and establishes a communication system that is suited to the dynamic environment and amplified patient autonomy unique to labor and delivery. Dr. Bob Barbieri, a steadfast leader and champion of TeamBirth implementation at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston (and the Editor in Chief of OBG M

Continue to: Patient response to TeamBirth is positive...

Patient response to TeamBirth is positive

Patients and providers alike have endorsed TeamBirth. In initial pilot testing across 4 sites, 99% of all patients surveyed “definitely” or “somewhat” had the role they wanted in making decisions about their labor.9

In partnership with the Oklahoma Perinatal Quality Improvement Collaborative (OPQIC), the impact of TeamBirth was assessed in a statewide patient cohort (n = 3,121) using the validated Mothers Autonomy in Decision Making (MADM) scale created by the Birth Place Lab at the University of British Columbia. The percentage of patients who scored in the highest MADM quartile was 31.3% higher for patients who indicated participation in a huddle during labor compared with those who did not participate in a huddle. This trend held across all racial and ethnic groups: For example, 93% of non-Hispanic Black/African American patients who had a TeamBirth huddle reported high autonomy, a nearly 20 percentage point increase from those without a huddle (FIGURE 2). Similarly, a higher percentage of agreement was observed across all 7 items in the MADM scale for patients who reported a TeamBirth huddle (FIGURE 3). TeamBirth’s effect has been observed across surveys and multiple validated metrics.

Data collection related to TeamBirth continues to be ongoing, with reported values retrieved on July 14, 2023. Rigorous review of patient-reported outcomes is forthcoming, and assessing impact on clinical outcomes, such as NTSV (nulliparous, term, singleton vertex) cesarean delivery rates and severe maternal morbidity, is on the horizon.

Qualitative survey responses reinforce how patients value TeamBirth and appreciate huddles and whiteboards.

Continue to: Patient testimonials...

Patient testimonials

The following testimonials were obtained from a TeamBirth survey that patients in participating Massachusetts hospitals completed in the postpartum unit prior to discharge.

According to one patient, “TeamBirth is great, feels like all obstacles are covered by multiple people with many talents, expertise. Feels like mom is part of the process, much different than my delivery 2 years ago when I felt like things were decided for me/I was ‘told’ what we were doing and questioned if I felt uneasy about it…. We felt safe and like all things were covered no matter what may happen.”

Another patient, also at a Massachusetts hospital, offered these comments about TeamBirth: “The entire staff was very genuine and my experience the best it could be. They deserve updated whiteboards in every room. I found them to be very useful.”

The clinician perspective

To be certain, clinician workflow must be a consideration for any practice change. The feasibility, acceptability, and safety of the TeamBirth model to clinicians was validated through a study at 4 community hospitals across the United States in which TeamBirth had been implemented in the 8 months prior.9

The clinician response rate was an impressive 78%. Ninety percent of clinicians, including physicians, midwives, and nurses, indicated that they would “definitely” (68%) or “probably” (22%) recommend TeamBirth for use in other labor and delivery units. None of the clinicians surveyed (n = 375) reported that TeamBirth negatively impacted care delivery.9

Obstetricians also provided qualitative commentary, noting that, while at times huddling infringed on efficiency, it also enhanced staff fulfillment. An obstetrician at a Massachusetts hospital observed, “Overall I think [TeamBirth is] helpful in slowing us down a little bit to really make sure that we’re providing the human part of the care, like the communication, and not just the medical care. And I think most providers value the human part and the communication. You know, we all think most providers value good communication with the patients, but when you’re in the middle of running around doing a bunch of stuff, you don’t always remember to prioritize it. And I think that at the end of the day…when you know you’ve communicated well with your patients, you end up feeling better about what you’re doing.”

As with most cross-sectional survey studies, selection bias remains an important caveat; patients and providers may decide to complete or not complete voluntary surveys based on particularly positive or negative experiences.

Metrics aside, obstetricians have an ethical duty to provide dignified and safe care, both physically and psychologically. Collectively, as a specialty, we share the responsibility to mitigate maternal mistreatment. As individuals, we can prevent perpetuation of birth trauma and foster healing and empowerment, one patient at a time, by employing tenets of TeamBirth.

To connect with Delivery Decisions Initiative, visit our website: https://www.ariadnelabs.org/deliverydecisions-initiative/ or contact: deliverydecisions@ ariadnelabs.org

Steps for implementing the TeamBirth model

To incorporate TeamBirth into your practice:

- Make patients the “team captain” and center them as the primary decision maker.

- Elicit patient preferences and subjective experiences to develop a collaborative plan on admission and when changes occur in clinical status.

- Round with and utilize the expertise of the full care team—nurse and midwife or obstetrician, as well as support person(s) and/or doula, learners, interpreter, and social worker as applicable.

- Ensure that the patient knows the names and roles of the care team members and provide updates at shift change.

- If your birthing rooms have a whiteboard, use it to keep the patient and team informed of the plan.

- Delineate status updates by maternal condition, fetal condition, and labor progress.

- Provide explicit permission for patients to call for a team huddle at any time and encourage support from their support people and/or doula. ●

This project is supported by:

- The Oklahoma Department of Health as part of the State Maternal Health Innovation Program Grant, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services.

- The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of an award to the Oklahoma State Department of Health. The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS, or the U.S. Government. For more information, please visit HRSA.gov.

- The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant T76MC00001 and entitled Training Grant in Maternal and Child Health.

- Point32 Health’s Clinical Innovation Fund.

Data included in this article was collected and analyzed in partnership with the Oklahoma Perinatal Quality Improvement Collaborative, Department of OB/GYN, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City.

CASE The TeamBirth experience: Making a difference

“At a community hospital in Washington where we had implemented TeamBirth (a labor and delivery shared decision making model), a patient, her partner, a labor and delivery nurse, and myself (an ObGyn) were making a plan for the patient’s induction of labor admission. I asked the patient, a 29-year-old (G2P1001), how we could improve her care in relation to her first birth. Her answer was simple: I want to be treated with respect. Her partner went on to describe their past experience in which the provider was inappropriately texting while in between the patient’s knees during delivery. Our team had the opportunity to undo some of the trauma from her first birth. That’s what I like about TeamBirth. It gives every patient the opportunity, regardless of their background, to define safety and participate in their care experience.”

–Angela Chien, MD, Obstetrician and Quality Improvement leader, Washington

Unfortunately, disrespect and mistreatment are far from an anomaly in the obstetrics setting. In a systematic review of respectful maternity care, the World Health Organization delineated 7 dimensions of maternal mistreatment: physical abuse, sexual abuse, verbal abuse, stigma and discrimination, failure to meet professional standards of care, poor rapport between women and providers, and poor conditions and constraints presented by the health system.1 In 2019, the Giving Voice to Mothers study showed that 17% of birthing people in the United States reported experiencing 1 or more types of maternal mistreatment.2 Rates of mistreatment were disproportionately greater in populations of color, hospital-based births, and among those with social, economic, or health challenges.2 It is well known that Black and African American and American Indian and Alaska Native populations experience the rare events of severe maternal morbidity and mortality more frequently than their White counterparts; the disproportionate burden of mistreatment is lesser known and far more common.

Overlooking the longitudinal harm of a negative birth experience has cascading impact. While an empowering perinatal experience can foster preventive screening and management of chronic disease, a poor experience conversely can seed mistrust at an individual, generational, and community level.

The patient quality enterprise is beginning to shift attention toward maternal experience with the development of PREMs (patient-reported experience measures), PROMs (patient-reported outcome measures), and novel validated scales that assess autonomy and trust.3 Development of a maternal Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) survey on childbirth is forthcoming.4 Of course, continuing to prioritize physical safety through initiatives on blood pressure monitoring and severe maternal morbidity and mortality remains paramount. Yet emotional and psychological safety also must be recognized as essential pillars of patient safety. Transgressions related to autonomy and dignity, as well as racism, sexism, classicism, and ableism, should be treated as “adverse and never events.”5

How the TeamBirth model works

Shared decision making (SDM) is cited in medical pedagogy as the solution to respectfullyrecognizing social context, integrating subjective experience, and honoring patient autonomy.6 The onus has always been on individual clinicians to exercise SDM. A new practice model, TeamBirth, embeds SDM into the culture and workflow. It offers a behavioral framework to mitigate implicit bias and operationalizes SDM tools, such that every patient is an empowered participant in their care.

TeamBirth was created through Ariadne Labs’ Delivery Decisions Initiative, a research and social impact program that designs, tests, and scales transformative, systems-level solutions that promote quality, equity, and dignity in childbirth. By the end of 2023, TeamBirth will be implemented in more than 100 hospitals across the United States, cumulatively touching over 200,000 lives. (For more information on the TeamBirth model, view the “Why TeamBirth” video at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EoVrSaGk7gc.)

The tenets of TeamBirth are enacted through a patient-facing, shared whiteboard or dry-erase planning board in the labor room (FIGURE 1). Research has demonstrated how dry-erase boards in clinical settings can support safety and dignity in care, especially to improve patient-provider communication, teamwork, and patient satisfaction.7,8 The planning board is initially filled out by a clinical team member and is updated during team “huddles” throughout labor.

Huddles are care plan discussions with the full care team (the patient, nurse, doula and/or other support person(s), delivering provider, and interpreter or social worker as needed). At a minimum, huddles occur on admission, with changes to the clinical course and care plan, and at the request of any team member. Huddles can transpire through in-person, virtual, or phone communication.9 The concept builds on interdisciplinary and patient-centered rounding and establishes a communication system that is suited to the dynamic environment and amplified patient autonomy unique to labor and delivery. Dr. Bob Barbieri, a steadfast leader and champion of TeamBirth implementation at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston (and the Editor in Chief of OBG M

Continue to: Patient response to TeamBirth is positive...

Patient response to TeamBirth is positive

Patients and providers alike have endorsed TeamBirth. In initial pilot testing across 4 sites, 99% of all patients surveyed “definitely” or “somewhat” had the role they wanted in making decisions about their labor.9

In partnership with the Oklahoma Perinatal Quality Improvement Collaborative (OPQIC), the impact of TeamBirth was assessed in a statewide patient cohort (n = 3,121) using the validated Mothers Autonomy in Decision Making (MADM) scale created by the Birth Place Lab at the University of British Columbia. The percentage of patients who scored in the highest MADM quartile was 31.3% higher for patients who indicated participation in a huddle during labor compared with those who did not participate in a huddle. This trend held across all racial and ethnic groups: For example, 93% of non-Hispanic Black/African American patients who had a TeamBirth huddle reported high autonomy, a nearly 20 percentage point increase from those without a huddle (FIGURE 2). Similarly, a higher percentage of agreement was observed across all 7 items in the MADM scale for patients who reported a TeamBirth huddle (FIGURE 3). TeamBirth’s effect has been observed across surveys and multiple validated metrics.

Data collection related to TeamBirth continues to be ongoing, with reported values retrieved on July 14, 2023. Rigorous review of patient-reported outcomes is forthcoming, and assessing impact on clinical outcomes, such as NTSV (nulliparous, term, singleton vertex) cesarean delivery rates and severe maternal morbidity, is on the horizon.

Qualitative survey responses reinforce how patients value TeamBirth and appreciate huddles and whiteboards.

Continue to: Patient testimonials...

Patient testimonials

The following testimonials were obtained from a TeamBirth survey that patients in participating Massachusetts hospitals completed in the postpartum unit prior to discharge.

According to one patient, “TeamBirth is great, feels like all obstacles are covered by multiple people with many talents, expertise. Feels like mom is part of the process, much different than my delivery 2 years ago when I felt like things were decided for me/I was ‘told’ what we were doing and questioned if I felt uneasy about it…. We felt safe and like all things were covered no matter what may happen.”

Another patient, also at a Massachusetts hospital, offered these comments about TeamBirth: “The entire staff was very genuine and my experience the best it could be. They deserve updated whiteboards in every room. I found them to be very useful.”

The clinician perspective

To be certain, clinician workflow must be a consideration for any practice change. The feasibility, acceptability, and safety of the TeamBirth model to clinicians was validated through a study at 4 community hospitals across the United States in which TeamBirth had been implemented in the 8 months prior.9

The clinician response rate was an impressive 78%. Ninety percent of clinicians, including physicians, midwives, and nurses, indicated that they would “definitely” (68%) or “probably” (22%) recommend TeamBirth for use in other labor and delivery units. None of the clinicians surveyed (n = 375) reported that TeamBirth negatively impacted care delivery.9

Obstetricians also provided qualitative commentary, noting that, while at times huddling infringed on efficiency, it also enhanced staff fulfillment. An obstetrician at a Massachusetts hospital observed, “Overall I think [TeamBirth is] helpful in slowing us down a little bit to really make sure that we’re providing the human part of the care, like the communication, and not just the medical care. And I think most providers value the human part and the communication. You know, we all think most providers value good communication with the patients, but when you’re in the middle of running around doing a bunch of stuff, you don’t always remember to prioritize it. And I think that at the end of the day…when you know you’ve communicated well with your patients, you end up feeling better about what you’re doing.”

As with most cross-sectional survey studies, selection bias remains an important caveat; patients and providers may decide to complete or not complete voluntary surveys based on particularly positive or negative experiences.

Metrics aside, obstetricians have an ethical duty to provide dignified and safe care, both physically and psychologically. Collectively, as a specialty, we share the responsibility to mitigate maternal mistreatment. As individuals, we can prevent perpetuation of birth trauma and foster healing and empowerment, one patient at a time, by employing tenets of TeamBirth.

To connect with Delivery Decisions Initiative, visit our website: https://www.ariadnelabs.org/deliverydecisions-initiative/ or contact: deliverydecisions@ ariadnelabs.org

Steps for implementing the TeamBirth model

To incorporate TeamBirth into your practice:

- Make patients the “team captain” and center them as the primary decision maker.

- Elicit patient preferences and subjective experiences to develop a collaborative plan on admission and when changes occur in clinical status.

- Round with and utilize the expertise of the full care team—nurse and midwife or obstetrician, as well as support person(s) and/or doula, learners, interpreter, and social worker as applicable.

- Ensure that the patient knows the names and roles of the care team members and provide updates at shift change.

- If your birthing rooms have a whiteboard, use it to keep the patient and team informed of the plan.

- Delineate status updates by maternal condition, fetal condition, and labor progress.

- Provide explicit permission for patients to call for a team huddle at any time and encourage support from their support people and/or doula. ●

This project is supported by:

- The Oklahoma Department of Health as part of the State Maternal Health Innovation Program Grant, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services.

- The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of an award to the Oklahoma State Department of Health. The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS, or the U.S. Government. For more information, please visit HRSA.gov.

- The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant T76MC00001 and entitled Training Grant in Maternal and Child Health.

- Point32 Health’s Clinical Innovation Fund.

Data included in this article was collected and analyzed in partnership with the Oklahoma Perinatal Quality Improvement Collaborative, Department of OB/GYN, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City.

- Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, et al. The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: a mixedmethods systematic review. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e100184. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001847

- Vedam S, Stoll K, Taiwo TK, et al. The Giving Voice to Mothers study: inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reprod Health. 2019;16. doi:10.1186/s12978-019-0729-2

- Kemmerer A, Alteras T. Evolving the maternal health quality measurement enterprise to support the communitybased maternity model. Maternal Health Hub. April 25, 2023. Accessed September 13, 2023. https:/www .maternalhealthhub.org

- Potential CAHPS survey to assess patients’ prenatal and childbirth care experiences. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. March 2023. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://www.ahrq.gov/news/cahps-comments-sought.html

- Lyndon A, Davis DA, Sharma AE, et al. Emotional safety is patient safety. BMJ Qual Saf. 2023;32:369-372. doi:10.1136 /bmjqs-2022-015573

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 819. Informed consent and shared decision making in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e34-e41. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance /committee-opinion/articles/2021/02/informed -consent-and-shared-decision-making-in-obstetrics-and -gynecology

- Goyal AA, Tur K, Mann J, et al. Do bedside visual tools improve patient and caregiver satisfaction? A systematic review of the literature. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:930-936. doi:10.12788 /jhm.2871

- Sehgal NL, Green A, Vidyarthi AR, et al. Patient whiteboards as a communication tool in the hospital setting: a survey of practices and recommendations. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:234-239. doi:10.1002/jhm.638

- Weiseth A, Plough A, Aggarwal R, et al. Improving communication and teamwork during labor: a feasibility, acceptability, and safety study. Birth. 2022:49:637-647. doi:10.1111/birt.12630

- Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, et al. The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: a mixedmethods systematic review. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e100184. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001847

- Vedam S, Stoll K, Taiwo TK, et al. The Giving Voice to Mothers study: inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reprod Health. 2019;16. doi:10.1186/s12978-019-0729-2

- Kemmerer A, Alteras T. Evolving the maternal health quality measurement enterprise to support the communitybased maternity model. Maternal Health Hub. April 25, 2023. Accessed September 13, 2023. https:/www .maternalhealthhub.org

- Potential CAHPS survey to assess patients’ prenatal and childbirth care experiences. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. March 2023. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://www.ahrq.gov/news/cahps-comments-sought.html

- Lyndon A, Davis DA, Sharma AE, et al. Emotional safety is patient safety. BMJ Qual Saf. 2023;32:369-372. doi:10.1136 /bmjqs-2022-015573

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 819. Informed consent and shared decision making in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e34-e41. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance /committee-opinion/articles/2021/02/informed -consent-and-shared-decision-making-in-obstetrics-and -gynecology

- Goyal AA, Tur K, Mann J, et al. Do bedside visual tools improve patient and caregiver satisfaction? A systematic review of the literature. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:930-936. doi:10.12788 /jhm.2871

- Sehgal NL, Green A, Vidyarthi AR, et al. Patient whiteboards as a communication tool in the hospital setting: a survey of practices and recommendations. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:234-239. doi:10.1002/jhm.638

- Weiseth A, Plough A, Aggarwal R, et al. Improving communication and teamwork during labor: a feasibility, acceptability, and safety study. Birth. 2022:49:637-647. doi:10.1111/birt.12630

New RSV vaccine will cut hospitalizations, study shows

, according to research presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“With RSV maternal vaccination that is associated with clinical efficacy of 69% against severe RSV disease at 6 months, we estimated that up to 200,000 cases can be averted, and that is associated with almost $800 million in total,” presenting author Amy W. Law, PharmD, director of global value and evidence at Pfizer, pointed out during a news briefing.

“RSV is associated with a significant burden in the U.S. and this newly approved and recommended maternal RSV vaccine can have substantial impact in easing some of that burden,” Dr. Law explained.

This study is “particularly timely as we head into RSV peak season,” said briefing moderator Natasha Halasa, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics, division of pediatric infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

The challenge, said Dr. Halasa, is that uptake of maternal vaccines and vaccines in general is “not optimal,” making increased awareness of this new maternal RSV vaccine important.

Strong efficacy data

Most children are infected with RSV at least once by the time they reach age 2 years. Very young children are at particular risk of severe complications, such as pneumonia or bronchitis.

As reported previously by this news organization, in the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study, Pfizer’s maternal RSV vaccine had an almost 82% efficacy against severe RSV infection in infants from birth through the first 90 days of life.

The vaccine also had a 69% efficacy against severe disease through the first 6 months of life. As part of the trial, a total of 7,400 women received a single dose of the vaccine in the late second or third trimester of their pregnancy. There were no signs of safety issues for the mothers or infants.

Based on the results, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the vaccine, known as Abrysvo, in August, to be given between weeks 32 and 36 of pregnancy.

New modeling study

Dr. Law and colleagues modeled the potential public health impact – both clinical and economic – of the maternal RSV vaccine among the population of all pregnant women and their infants born during a 12-month period in the United States. The model focused on severe RSV disease in babies that required medical attention.

According to their model, without widespread use of the maternal RSV vaccine, 48,246 hospitalizations, 144,495 emergency department encounters, and 399,313 outpatient clinic visits related to RSV are projected to occur annually among the U.S. birth cohort of 3.7 million infants younger than 12 months.

With widespread use of the vaccine, annual hospitalizations resulting from infant RSV would fall by 51%, emergency department encounters would decline by 32%, and outpatient clinic visits by 32% – corresponding to a decrease in direct medical costs of about $692 million and indirect nonmedical costs of roughly $110 million.

Dr. Law highlighted two important caveats to the data. “The protections are based on the year-round administration of the vaccine to pregnant women at 32 to 36 weeks’ gestational age, and this is also assuming 100% uptake. Of course, in reality, that most likely is not the case,” she told the briefing.

Dr. Halasa noted that the peak age for severe RSV illness is 3 months and it’s tough to identify infants at highest risk for severe RSV.

Nearly 80% of infants with RSV who are hospitalized do not have an underlying medical condition, “so we don’t even know who those high-risk infants are. That’s why having this vaccine is so exciting,” she told the briefing.

Dr. Halasa said it’s also important to note that infants with severe RSV typically make not just one but multiple visits to the clinic or emergency department, leading to missed days of work for the parent, not to mention the “emotional burden of having your otherwise healthy newborn or young infant in the hospital.”

In addition to Pfizer’s maternal RSV vaccine, the FDA in July approved AstraZeneca’s monoclonal antibody nirsevimab (Beyfortus) for the prevention of RSV in neonates and infants entering their first RSV season, and in children up to 24 months who remain vulnerable to severe RSV disease through their second RSV season.

The study was funded by Pfizer. Dr. Law is employed by Pfizer. Dr. Halasa has received grant and research support from Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to research presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“With RSV maternal vaccination that is associated with clinical efficacy of 69% against severe RSV disease at 6 months, we estimated that up to 200,000 cases can be averted, and that is associated with almost $800 million in total,” presenting author Amy W. Law, PharmD, director of global value and evidence at Pfizer, pointed out during a news briefing.

“RSV is associated with a significant burden in the U.S. and this newly approved and recommended maternal RSV vaccine can have substantial impact in easing some of that burden,” Dr. Law explained.

This study is “particularly timely as we head into RSV peak season,” said briefing moderator Natasha Halasa, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics, division of pediatric infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

The challenge, said Dr. Halasa, is that uptake of maternal vaccines and vaccines in general is “not optimal,” making increased awareness of this new maternal RSV vaccine important.

Strong efficacy data

Most children are infected with RSV at least once by the time they reach age 2 years. Very young children are at particular risk of severe complications, such as pneumonia or bronchitis.

As reported previously by this news organization, in the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study, Pfizer’s maternal RSV vaccine had an almost 82% efficacy against severe RSV infection in infants from birth through the first 90 days of life.

The vaccine also had a 69% efficacy against severe disease through the first 6 months of life. As part of the trial, a total of 7,400 women received a single dose of the vaccine in the late second or third trimester of their pregnancy. There were no signs of safety issues for the mothers or infants.

Based on the results, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the vaccine, known as Abrysvo, in August, to be given between weeks 32 and 36 of pregnancy.

New modeling study

Dr. Law and colleagues modeled the potential public health impact – both clinical and economic – of the maternal RSV vaccine among the population of all pregnant women and their infants born during a 12-month period in the United States. The model focused on severe RSV disease in babies that required medical attention.

According to their model, without widespread use of the maternal RSV vaccine, 48,246 hospitalizations, 144,495 emergency department encounters, and 399,313 outpatient clinic visits related to RSV are projected to occur annually among the U.S. birth cohort of 3.7 million infants younger than 12 months.

With widespread use of the vaccine, annual hospitalizations resulting from infant RSV would fall by 51%, emergency department encounters would decline by 32%, and outpatient clinic visits by 32% – corresponding to a decrease in direct medical costs of about $692 million and indirect nonmedical costs of roughly $110 million.

Dr. Law highlighted two important caveats to the data. “The protections are based on the year-round administration of the vaccine to pregnant women at 32 to 36 weeks’ gestational age, and this is also assuming 100% uptake. Of course, in reality, that most likely is not the case,” she told the briefing.

Dr. Halasa noted that the peak age for severe RSV illness is 3 months and it’s tough to identify infants at highest risk for severe RSV.

Nearly 80% of infants with RSV who are hospitalized do not have an underlying medical condition, “so we don’t even know who those high-risk infants are. That’s why having this vaccine is so exciting,” she told the briefing.

Dr. Halasa said it’s also important to note that infants with severe RSV typically make not just one but multiple visits to the clinic or emergency department, leading to missed days of work for the parent, not to mention the “emotional burden of having your otherwise healthy newborn or young infant in the hospital.”

In addition to Pfizer’s maternal RSV vaccine, the FDA in July approved AstraZeneca’s monoclonal antibody nirsevimab (Beyfortus) for the prevention of RSV in neonates and infants entering their first RSV season, and in children up to 24 months who remain vulnerable to severe RSV disease through their second RSV season.

The study was funded by Pfizer. Dr. Law is employed by Pfizer. Dr. Halasa has received grant and research support from Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to research presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“With RSV maternal vaccination that is associated with clinical efficacy of 69% against severe RSV disease at 6 months, we estimated that up to 200,000 cases can be averted, and that is associated with almost $800 million in total,” presenting author Amy W. Law, PharmD, director of global value and evidence at Pfizer, pointed out during a news briefing.

“RSV is associated with a significant burden in the U.S. and this newly approved and recommended maternal RSV vaccine can have substantial impact in easing some of that burden,” Dr. Law explained.

This study is “particularly timely as we head into RSV peak season,” said briefing moderator Natasha Halasa, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics, division of pediatric infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

The challenge, said Dr. Halasa, is that uptake of maternal vaccines and vaccines in general is “not optimal,” making increased awareness of this new maternal RSV vaccine important.

Strong efficacy data

Most children are infected with RSV at least once by the time they reach age 2 years. Very young children are at particular risk of severe complications, such as pneumonia or bronchitis.

As reported previously by this news organization, in the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study, Pfizer’s maternal RSV vaccine had an almost 82% efficacy against severe RSV infection in infants from birth through the first 90 days of life.

The vaccine also had a 69% efficacy against severe disease through the first 6 months of life. As part of the trial, a total of 7,400 women received a single dose of the vaccine in the late second or third trimester of their pregnancy. There were no signs of safety issues for the mothers or infants.

Based on the results, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the vaccine, known as Abrysvo, in August, to be given between weeks 32 and 36 of pregnancy.

New modeling study

Dr. Law and colleagues modeled the potential public health impact – both clinical and economic – of the maternal RSV vaccine among the population of all pregnant women and their infants born during a 12-month period in the United States. The model focused on severe RSV disease in babies that required medical attention.

According to their model, without widespread use of the maternal RSV vaccine, 48,246 hospitalizations, 144,495 emergency department encounters, and 399,313 outpatient clinic visits related to RSV are projected to occur annually among the U.S. birth cohort of 3.7 million infants younger than 12 months.

With widespread use of the vaccine, annual hospitalizations resulting from infant RSV would fall by 51%, emergency department encounters would decline by 32%, and outpatient clinic visits by 32% – corresponding to a decrease in direct medical costs of about $692 million and indirect nonmedical costs of roughly $110 million.

Dr. Law highlighted two important caveats to the data. “The protections are based on the year-round administration of the vaccine to pregnant women at 32 to 36 weeks’ gestational age, and this is also assuming 100% uptake. Of course, in reality, that most likely is not the case,” she told the briefing.

Dr. Halasa noted that the peak age for severe RSV illness is 3 months and it’s tough to identify infants at highest risk for severe RSV.

Nearly 80% of infants with RSV who are hospitalized do not have an underlying medical condition, “so we don’t even know who those high-risk infants are. That’s why having this vaccine is so exciting,” she told the briefing.

Dr. Halasa said it’s also important to note that infants with severe RSV typically make not just one but multiple visits to the clinic or emergency department, leading to missed days of work for the parent, not to mention the “emotional burden of having your otherwise healthy newborn or young infant in the hospital.”

In addition to Pfizer’s maternal RSV vaccine, the FDA in July approved AstraZeneca’s monoclonal antibody nirsevimab (Beyfortus) for the prevention of RSV in neonates and infants entering their first RSV season, and in children up to 24 months who remain vulnerable to severe RSV disease through their second RSV season.

The study was funded by Pfizer. Dr. Law is employed by Pfizer. Dr. Halasa has received grant and research support from Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM IDWEEK 2023

Can a novel, rapid-acting oral treatment effectively manage PPD?

Deligiannidis KM, Meltzer-Brody S, Maximos B, et al. Zuranolone for the treatment of postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2023;180:668-675. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.20220785.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Postpartum depression affects approximately 17.2% of patients in the peripartum period.1 Typical pharmacologic treatment of PPD includes selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which may take up to 12 weeks to take effect. Postpartum depression is thought to be secondary to maladaptation to hormonal fluctuations in the peripartum period, including allopregnanolone, a positive allosteric modulator of GABAA (γ-aminobutyric acid type A)receptors and a metabolite of progesterone, levels of which increase in pregnancy and abruptly decrease following delivery.1 In 2019, the GABAA receptor modulator brexanalone was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat PPD through continuous intravenous infusion over 60 hours in the hospital setting.

Zuranolone, an allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors, also has been studied as an investigational medication for rapid treatment of PPD. Prior studies demonstrated the efficacy of oral zuranolone 30 mg daily for the treatment of PPD2 and 50 mg for the treatment of major depression in nonpregnant patients.3 Deligiannidis and colleagues conducted a trial to investigate the 50-mg dose of zuranolone for the treatment of PPD. (Notably, in August 2023, the FDA approved oral zuranolone once daily for 14 days for the treatment of PPD.) Following the FDA approval, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) released a Practice Advisory recommending consideration of zuranolone for PPD that takes into account balancing the benefits and risks, including known sedative effects, potential need for decreasing the dose due to adverse effects, lack of safety data in lactation, and unknown long-term efficacy.4

Details of the study

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study included 196 patients with an episode of major depression, characterized as a baseline score of 26 or greater on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) beginning in the third trimester or within the first 4 weeks postpartum. Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive zuranolone 50 mg daily or placebo, with stratification by stable concurrent antidepressant use. Treatment duration was for 14 days, with follow-up through day 45.

The study’s primary outcome was a change in the baseline HAM-D score at day 15. Changes in HAM-D score also were recorded at days 3, 28, and 45.

The 2 study groups were well balanced by demographic and baseline characteristics. In both groups, the majority of patients experienced the onset of their major depressive episodes within the first 4 weeks postpartum. Completion rates of the 14-day treatment course and 45-day follow-up were high and similar in both groups; 170 patients completed the study. The rate of concurrent psychiatric medications taken, most of which were SSRIs, was similar between the 2 groups at approximately 15% of patients.

Results. A statistically significant improvement in the primary outcome (the change in HAM-D score) at day 15 occurred in patients who received zuranolone versus placebo (P = .001). Additionally, there were statistically significant improvements in the secondary outcomes HAM-D scores at days 3, 28, and 45. Initial response, as measured by changes in HAM-D scores, occurred at a median duration of 9 days in the zuranolone group and 43 days in the placebo group. More patients in the zuranolone group achieved a reduction in HAM-D score at 15 days (57.0% vs 38.9%; P = .02). Zuranolone was associated with a higher rate of HAM-D remission at day 45 (44.0% vs 29.4%; P = .02).

With regard to safety, 16.3% of patients (17) in the zuranolone group (vs 1% in the placebo group) experienced an adverse event, most commonly somnolence, dizziness, and sedation, which led to a dose reduction. However, 15 of these 17 patients still completed the study, and there were no serious adverse events.

Study strengths and limitations

This study’s strengths include the double-blinded design that was continued throughout the duration of the follow-up. Additionally, the study population was heterogeneous andreflective of patients from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. Lastly, only minor and moderate adverse events were reported and, despite this, nearly all patients who experienced adverse events completed the study.

Limitations of the study include the lack of generalizability, as patients with bipolar disorder and mild or moderate PPD were excluded. Additionally, the majority of patients had depressive episodes within the first 4 weeks postpartum, thereby excluding patients with depressive episodes at other time points in the peripartum period. Further, as breastfeeding was prohibited, safety in lactating patients using zuranolone is unknown. Lastly, the study follow-up period was 45 days; therefore, the long-term efficacy of zuranolone treatment is unclear. ●

Zuranolone, a GABAA allosteric modulator, shows promise as an alternative to existing pharmacologic treatments for severe PPD that is orally administered and rapidly acting. While it is reasonable to consider its use in the specific patient population that benefited in this study, further studies are needed to determine its efficacy in other populations, the lowest effective dose for clinical improvement, and its interaction with other medications and breastfeeding. Additionally, the long-term remission rates of depressive symptoms in patients treated with zuranolone are unknown and warrant further study.

JAIMEY M. PAULI, MD; KENDALL CUNNINGHAM, MD

- Deligiannidis KM, Meltzer-Brody S, Maximos B, et al. Zuranolone for the treatment of postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2023;180:668-675. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp .20220785

- Deligiannidis KM, Meltzer-Brody S, Gunduz-Bruce H, et al. Effect of zuranolone vs placebo in postpartum depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:951-959. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1559

- Clayton AH, Lasser R, Parikh SV, et al. Zuranolone for the treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2023;180:676-684. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.20220459

- Zuranolone for the treatment of postpartum depression. Practice Advisory. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. August 2023. Accessed September 18, 2023. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice -advisory/articles/2023/08/zuranolone-for-the-treatment-of -postpartum-depression

Deligiannidis KM, Meltzer-Brody S, Maximos B, et al. Zuranolone for the treatment of postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2023;180:668-675. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.20220785.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Postpartum depression affects approximately 17.2% of patients in the peripartum period.1 Typical pharmacologic treatment of PPD includes selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which may take up to 12 weeks to take effect. Postpartum depression is thought to be secondary to maladaptation to hormonal fluctuations in the peripartum period, including allopregnanolone, a positive allosteric modulator of GABAA (γ-aminobutyric acid type A)receptors and a metabolite of progesterone, levels of which increase in pregnancy and abruptly decrease following delivery.1 In 2019, the GABAA receptor modulator brexanalone was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat PPD through continuous intravenous infusion over 60 hours in the hospital setting.

Zuranolone, an allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors, also has been studied as an investigational medication for rapid treatment of PPD. Prior studies demonstrated the efficacy of oral zuranolone 30 mg daily for the treatment of PPD2 and 50 mg for the treatment of major depression in nonpregnant patients.3 Deligiannidis and colleagues conducted a trial to investigate the 50-mg dose of zuranolone for the treatment of PPD. (Notably, in August 2023, the FDA approved oral zuranolone once daily for 14 days for the treatment of PPD.) Following the FDA approval, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) released a Practice Advisory recommending consideration of zuranolone for PPD that takes into account balancing the benefits and risks, including known sedative effects, potential need for decreasing the dose due to adverse effects, lack of safety data in lactation, and unknown long-term efficacy.4

Details of the study

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study included 196 patients with an episode of major depression, characterized as a baseline score of 26 or greater on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) beginning in the third trimester or within the first 4 weeks postpartum. Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive zuranolone 50 mg daily or placebo, with stratification by stable concurrent antidepressant use. Treatment duration was for 14 days, with follow-up through day 45.

The study’s primary outcome was a change in the baseline HAM-D score at day 15. Changes in HAM-D score also were recorded at days 3, 28, and 45.

The 2 study groups were well balanced by demographic and baseline characteristics. In both groups, the majority of patients experienced the onset of their major depressive episodes within the first 4 weeks postpartum. Completion rates of the 14-day treatment course and 45-day follow-up were high and similar in both groups; 170 patients completed the study. The rate of concurrent psychiatric medications taken, most of which were SSRIs, was similar between the 2 groups at approximately 15% of patients.

Results. A statistically significant improvement in the primary outcome (the change in HAM-D score) at day 15 occurred in patients who received zuranolone versus placebo (P = .001). Additionally, there were statistically significant improvements in the secondary outcomes HAM-D scores at days 3, 28, and 45. Initial response, as measured by changes in HAM-D scores, occurred at a median duration of 9 days in the zuranolone group and 43 days in the placebo group. More patients in the zuranolone group achieved a reduction in HAM-D score at 15 days (57.0% vs 38.9%; P = .02). Zuranolone was associated with a higher rate of HAM-D remission at day 45 (44.0% vs 29.4%; P = .02).

With regard to safety, 16.3% of patients (17) in the zuranolone group (vs 1% in the placebo group) experienced an adverse event, most commonly somnolence, dizziness, and sedation, which led to a dose reduction. However, 15 of these 17 patients still completed the study, and there were no serious adverse events.

Study strengths and limitations

This study’s strengths include the double-blinded design that was continued throughout the duration of the follow-up. Additionally, the study population was heterogeneous andreflective of patients from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. Lastly, only minor and moderate adverse events were reported and, despite this, nearly all patients who experienced adverse events completed the study.

Limitations of the study include the lack of generalizability, as patients with bipolar disorder and mild or moderate PPD were excluded. Additionally, the majority of patients had depressive episodes within the first 4 weeks postpartum, thereby excluding patients with depressive episodes at other time points in the peripartum period. Further, as breastfeeding was prohibited, safety in lactating patients using zuranolone is unknown. Lastly, the study follow-up period was 45 days; therefore, the long-term efficacy of zuranolone treatment is unclear. ●

Zuranolone, a GABAA allosteric modulator, shows promise as an alternative to existing pharmacologic treatments for severe PPD that is orally administered and rapidly acting. While it is reasonable to consider its use in the specific patient population that benefited in this study, further studies are needed to determine its efficacy in other populations, the lowest effective dose for clinical improvement, and its interaction with other medications and breastfeeding. Additionally, the long-term remission rates of depressive symptoms in patients treated with zuranolone are unknown and warrant further study.

JAIMEY M. PAULI, MD; KENDALL CUNNINGHAM, MD

Deligiannidis KM, Meltzer-Brody S, Maximos B, et al. Zuranolone for the treatment of postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2023;180:668-675. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.20220785.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Postpartum depression affects approximately 17.2% of patients in the peripartum period.1 Typical pharmacologic treatment of PPD includes selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which may take up to 12 weeks to take effect. Postpartum depression is thought to be secondary to maladaptation to hormonal fluctuations in the peripartum period, including allopregnanolone, a positive allosteric modulator of GABAA (γ-aminobutyric acid type A)receptors and a metabolite of progesterone, levels of which increase in pregnancy and abruptly decrease following delivery.1 In 2019, the GABAA receptor modulator brexanalone was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat PPD through continuous intravenous infusion over 60 hours in the hospital setting.

Zuranolone, an allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors, also has been studied as an investigational medication for rapid treatment of PPD. Prior studies demonstrated the efficacy of oral zuranolone 30 mg daily for the treatment of PPD2 and 50 mg for the treatment of major depression in nonpregnant patients.3 Deligiannidis and colleagues conducted a trial to investigate the 50-mg dose of zuranolone for the treatment of PPD. (Notably, in August 2023, the FDA approved oral zuranolone once daily for 14 days for the treatment of PPD.) Following the FDA approval, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) released a Practice Advisory recommending consideration of zuranolone for PPD that takes into account balancing the benefits and risks, including known sedative effects, potential need for decreasing the dose due to adverse effects, lack of safety data in lactation, and unknown long-term efficacy.4

Details of the study

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study included 196 patients with an episode of major depression, characterized as a baseline score of 26 or greater on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) beginning in the third trimester or within the first 4 weeks postpartum. Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive zuranolone 50 mg daily or placebo, with stratification by stable concurrent antidepressant use. Treatment duration was for 14 days, with follow-up through day 45.

The study’s primary outcome was a change in the baseline HAM-D score at day 15. Changes in HAM-D score also were recorded at days 3, 28, and 45.

The 2 study groups were well balanced by demographic and baseline characteristics. In both groups, the majority of patients experienced the onset of their major depressive episodes within the first 4 weeks postpartum. Completion rates of the 14-day treatment course and 45-day follow-up were high and similar in both groups; 170 patients completed the study. The rate of concurrent psychiatric medications taken, most of which were SSRIs, was similar between the 2 groups at approximately 15% of patients.

Results. A statistically significant improvement in the primary outcome (the change in HAM-D score) at day 15 occurred in patients who received zuranolone versus placebo (P = .001). Additionally, there were statistically significant improvements in the secondary outcomes HAM-D scores at days 3, 28, and 45. Initial response, as measured by changes in HAM-D scores, occurred at a median duration of 9 days in the zuranolone group and 43 days in the placebo group. More patients in the zuranolone group achieved a reduction in HAM-D score at 15 days (57.0% vs 38.9%; P = .02). Zuranolone was associated with a higher rate of HAM-D remission at day 45 (44.0% vs 29.4%; P = .02).

With regard to safety, 16.3% of patients (17) in the zuranolone group (vs 1% in the placebo group) experienced an adverse event, most commonly somnolence, dizziness, and sedation, which led to a dose reduction. However, 15 of these 17 patients still completed the study, and there were no serious adverse events.

Study strengths and limitations

This study’s strengths include the double-blinded design that was continued throughout the duration of the follow-up. Additionally, the study population was heterogeneous andreflective of patients from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. Lastly, only minor and moderate adverse events were reported and, despite this, nearly all patients who experienced adverse events completed the study.

Limitations of the study include the lack of generalizability, as patients with bipolar disorder and mild or moderate PPD were excluded. Additionally, the majority of patients had depressive episodes within the first 4 weeks postpartum, thereby excluding patients with depressive episodes at other time points in the peripartum period. Further, as breastfeeding was prohibited, safety in lactating patients using zuranolone is unknown. Lastly, the study follow-up period was 45 days; therefore, the long-term efficacy of zuranolone treatment is unclear. ●

Zuranolone, a GABAA allosteric modulator, shows promise as an alternative to existing pharmacologic treatments for severe PPD that is orally administered and rapidly acting. While it is reasonable to consider its use in the specific patient population that benefited in this study, further studies are needed to determine its efficacy in other populations, the lowest effective dose for clinical improvement, and its interaction with other medications and breastfeeding. Additionally, the long-term remission rates of depressive symptoms in patients treated with zuranolone are unknown and warrant further study.

JAIMEY M. PAULI, MD; KENDALL CUNNINGHAM, MD

- Deligiannidis KM, Meltzer-Brody S, Maximos B, et al. Zuranolone for the treatment of postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2023;180:668-675. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp .20220785

- Deligiannidis KM, Meltzer-Brody S, Gunduz-Bruce H, et al. Effect of zuranolone vs placebo in postpartum depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:951-959. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1559

- Clayton AH, Lasser R, Parikh SV, et al. Zuranolone for the treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2023;180:676-684. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.20220459

- Zuranolone for the treatment of postpartum depression. Practice Advisory. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. August 2023. Accessed September 18, 2023. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice -advisory/articles/2023/08/zuranolone-for-the-treatment-of -postpartum-depression

- Deligiannidis KM, Meltzer-Brody S, Maximos B, et al. Zuranolone for the treatment of postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2023;180:668-675. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp .20220785

- Deligiannidis KM, Meltzer-Brody S, Gunduz-Bruce H, et al. Effect of zuranolone vs placebo in postpartum depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:951-959. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1559

- Clayton AH, Lasser R, Parikh SV, et al. Zuranolone for the treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2023;180:676-684. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.20220459

- Zuranolone for the treatment of postpartum depression. Practice Advisory. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. August 2023. Accessed September 18, 2023. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice -advisory/articles/2023/08/zuranolone-for-the-treatment-of -postpartum-depression

Zuranolone: FAQs for clinicians and patients

The Food and Drug Administration approval of zuranolone for postpartum depression in August 2023 has raised many important questions (and opinions) about its future use in clinical practice.

At the UNC-Chapel Hill Center for Women’s Mood Disorders, we treat women and pregnant people throughout hormonal transitions, including pregnancy and the postpartum, and have been part of development, research, and now delivery of both brexanolone and zuranolone. While we are excited about new tools in the arsenal for alleviating maternal mental health, we also want to be clear that our work is far from complete and continued efforts to care for pregnant people and their families are imperative.

What is zuranolone?

Zuranolone (brand name Zurzuvae) is an oral medication developed by Sage Therapeutics and Biogen. It is a positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor, the brain’s major inhibitory system. As a positive allosteric modulator, it increases the sensitivity of the GABAA receptor to GABA.

Zuranolone is very similar to brexanolone, a synthetic form of allopregnanolone, a neurosteroid byproduct of progesterone (see below). However, zuranolone is not an oral form of brexanolone – it was slightly modified to ensure good oral stability and bioavailability. It is metabolized by the hepatic enzyme CYP3A4 and has a half-life of 16-23 hours. Zurzuvae is currently produced in capsule form.

What does zuranolone treat?