User login

Antimalarials in pregnancy and lactation

According to the World Health Organization, there were about 219 million cases of malaria and an estimated 660,000 deaths in 2010. Although huge, this was a 26% decrease from the rates in 2000. Six countries in Africa account for 47% of malaria cases: Cote d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mozambique, Nigeria, Uganda, and the United Republic of Tanzania. The second-most affected region in the world is Southeast Asia, which includes Myanmar, India, and Indonesia. In comparison, about 1,500 malaria cases and 5 deaths are reported annually in the United States, mostly from returned travelers.

if they will be traveling in any of the above regions. Malaria during pregnancy increases the risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes, including maternal anemia, prematurity, spontaneous abortion, and stillbirth.

As stated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, no antimalarial agent is 100% protective. Therefore, whatever agent is used must be combined with personal protective measures such as wearing insect repellent, long sleeves, and long pants; sleeping in a mosquito-free setting; or using an insecticide-treated bed net.

There are nine antimalarial drugs available in the United States.

Atovaquone/Proguanil Hcl (Malarone and as generic)

This agent is good for last-minute travelers because the drug is started 1-2 days before traveling to areas where malaria transmission occurs. The combination can be classified as compatible in pregnancy. No reports in breastfeeding with atovaquone or the combination have been found. Proguanil is not available in the United States as a single agent.

Chloroquine (generic)

This is the drug of choice to prevent and treat sensitive malaria species during pregnancy. The drug crosses the placenta producing fetal concentrations that are similar to those in the mother. The drug appears to be low risk for embryo-fetal harm.

It is compatible in breastfeeding.

Dapsone (generic)

This agent does not appear to represent a major risk of harm to the fetus. Although it has been used in combination with pyrimethamine (an antiparasitic) or trimethoprim (an antibiotic) to prevent malaria, the efficacy of the combination has not been confirmed.

In breastfeeding, there is one case of mild hemolytic anemia in the mother and her breastfeeding infant that may have been caused by the drug.

Hydroxychloroquine (generic)

This agent is used for the treatment of malaria, systemic erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis. For antimalarial prophylaxis, 400 mg/week appears to be low risk for embryo-fetal harm. Doses used to treat malaria have been 200-400 mg/day.

Because very low concentrations of the drug have been found in breast milk, breastfeeding is probably compatible.

Mefloquine (generic)

This agent is a quinoline-methanol agent that does not appear to cause embryo-fetal harm based on a large number of pregnancy exposures.

There are no reports of its use while breastfeeding.

Primaquine (generic)

This agent is best avoided in pregnancy. There is no human pregnancy data, but it may cause hemolytic anemia in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD). Because the fetus is relatively G6PD deficient, it is best avoided in pregnancy regardless of the mother’s status.

There are no reports describing the use of the drug during lactation. Both the mother and baby should be tested for G6PD deficiency before the drug is used during breastfeeding.

Pyrimethamine (generic)

This agent has been used for the treatment or prophylaxis of malaria. Most studies have found this agent to be relatively safe and effective.

It is excreted into breast milk and has been effective in eliminating malaria parasites from breastfeeding infants.

Quinidine (generic)

Reports linking the use of this agent with congenital defects have not been found. Although the drug has data on its use as an antiarrhythmic, its published use to treat malaria is limited.

The drug is excreted into breast milk, but there are no reports of its during breastfeeding.

Quinine (generic)

This agent has a large amount of human pregnancy data (more than 1,000 exposures) that found no increased risk of birth defects. The drug has been replaced by newer agents but still may be used for chloroquine-resistant malaria.

The drug appears to be compatible during breastfeeding.

Mr. Briggs is clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco, and adjunct professor of pharmacy at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, as well as at Washington State University, Spokane. Mr. Briggs said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

According to the World Health Organization, there were about 219 million cases of malaria and an estimated 660,000 deaths in 2010. Although huge, this was a 26% decrease from the rates in 2000. Six countries in Africa account for 47% of malaria cases: Cote d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mozambique, Nigeria, Uganda, and the United Republic of Tanzania. The second-most affected region in the world is Southeast Asia, which includes Myanmar, India, and Indonesia. In comparison, about 1,500 malaria cases and 5 deaths are reported annually in the United States, mostly from returned travelers.

if they will be traveling in any of the above regions. Malaria during pregnancy increases the risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes, including maternal anemia, prematurity, spontaneous abortion, and stillbirth.

As stated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, no antimalarial agent is 100% protective. Therefore, whatever agent is used must be combined with personal protective measures such as wearing insect repellent, long sleeves, and long pants; sleeping in a mosquito-free setting; or using an insecticide-treated bed net.

There are nine antimalarial drugs available in the United States.

Atovaquone/Proguanil Hcl (Malarone and as generic)

This agent is good for last-minute travelers because the drug is started 1-2 days before traveling to areas where malaria transmission occurs. The combination can be classified as compatible in pregnancy. No reports in breastfeeding with atovaquone or the combination have been found. Proguanil is not available in the United States as a single agent.

Chloroquine (generic)

This is the drug of choice to prevent and treat sensitive malaria species during pregnancy. The drug crosses the placenta producing fetal concentrations that are similar to those in the mother. The drug appears to be low risk for embryo-fetal harm.

It is compatible in breastfeeding.

Dapsone (generic)

This agent does not appear to represent a major risk of harm to the fetus. Although it has been used in combination with pyrimethamine (an antiparasitic) or trimethoprim (an antibiotic) to prevent malaria, the efficacy of the combination has not been confirmed.

In breastfeeding, there is one case of mild hemolytic anemia in the mother and her breastfeeding infant that may have been caused by the drug.

Hydroxychloroquine (generic)

This agent is used for the treatment of malaria, systemic erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis. For antimalarial prophylaxis, 400 mg/week appears to be low risk for embryo-fetal harm. Doses used to treat malaria have been 200-400 mg/day.

Because very low concentrations of the drug have been found in breast milk, breastfeeding is probably compatible.

Mefloquine (generic)

This agent is a quinoline-methanol agent that does not appear to cause embryo-fetal harm based on a large number of pregnancy exposures.

There are no reports of its use while breastfeeding.

Primaquine (generic)

This agent is best avoided in pregnancy. There is no human pregnancy data, but it may cause hemolytic anemia in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD). Because the fetus is relatively G6PD deficient, it is best avoided in pregnancy regardless of the mother’s status.

There are no reports describing the use of the drug during lactation. Both the mother and baby should be tested for G6PD deficiency before the drug is used during breastfeeding.

Pyrimethamine (generic)

This agent has been used for the treatment or prophylaxis of malaria. Most studies have found this agent to be relatively safe and effective.

It is excreted into breast milk and has been effective in eliminating malaria parasites from breastfeeding infants.

Quinidine (generic)

Reports linking the use of this agent with congenital defects have not been found. Although the drug has data on its use as an antiarrhythmic, its published use to treat malaria is limited.

The drug is excreted into breast milk, but there are no reports of its during breastfeeding.

Quinine (generic)

This agent has a large amount of human pregnancy data (more than 1,000 exposures) that found no increased risk of birth defects. The drug has been replaced by newer agents but still may be used for chloroquine-resistant malaria.

The drug appears to be compatible during breastfeeding.

Mr. Briggs is clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco, and adjunct professor of pharmacy at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, as well as at Washington State University, Spokane. Mr. Briggs said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

According to the World Health Organization, there were about 219 million cases of malaria and an estimated 660,000 deaths in 2010. Although huge, this was a 26% decrease from the rates in 2000. Six countries in Africa account for 47% of malaria cases: Cote d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mozambique, Nigeria, Uganda, and the United Republic of Tanzania. The second-most affected region in the world is Southeast Asia, which includes Myanmar, India, and Indonesia. In comparison, about 1,500 malaria cases and 5 deaths are reported annually in the United States, mostly from returned travelers.

if they will be traveling in any of the above regions. Malaria during pregnancy increases the risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes, including maternal anemia, prematurity, spontaneous abortion, and stillbirth.

As stated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, no antimalarial agent is 100% protective. Therefore, whatever agent is used must be combined with personal protective measures such as wearing insect repellent, long sleeves, and long pants; sleeping in a mosquito-free setting; or using an insecticide-treated bed net.

There are nine antimalarial drugs available in the United States.

Atovaquone/Proguanil Hcl (Malarone and as generic)

This agent is good for last-minute travelers because the drug is started 1-2 days before traveling to areas where malaria transmission occurs. The combination can be classified as compatible in pregnancy. No reports in breastfeeding with atovaquone or the combination have been found. Proguanil is not available in the United States as a single agent.

Chloroquine (generic)

This is the drug of choice to prevent and treat sensitive malaria species during pregnancy. The drug crosses the placenta producing fetal concentrations that are similar to those in the mother. The drug appears to be low risk for embryo-fetal harm.

It is compatible in breastfeeding.

Dapsone (generic)

This agent does not appear to represent a major risk of harm to the fetus. Although it has been used in combination with pyrimethamine (an antiparasitic) or trimethoprim (an antibiotic) to prevent malaria, the efficacy of the combination has not been confirmed.

In breastfeeding, there is one case of mild hemolytic anemia in the mother and her breastfeeding infant that may have been caused by the drug.

Hydroxychloroquine (generic)

This agent is used for the treatment of malaria, systemic erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis. For antimalarial prophylaxis, 400 mg/week appears to be low risk for embryo-fetal harm. Doses used to treat malaria have been 200-400 mg/day.

Because very low concentrations of the drug have been found in breast milk, breastfeeding is probably compatible.

Mefloquine (generic)

This agent is a quinoline-methanol agent that does not appear to cause embryo-fetal harm based on a large number of pregnancy exposures.

There are no reports of its use while breastfeeding.

Primaquine (generic)

This agent is best avoided in pregnancy. There is no human pregnancy data, but it may cause hemolytic anemia in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD). Because the fetus is relatively G6PD deficient, it is best avoided in pregnancy regardless of the mother’s status.

There are no reports describing the use of the drug during lactation. Both the mother and baby should be tested for G6PD deficiency before the drug is used during breastfeeding.

Pyrimethamine (generic)

This agent has been used for the treatment or prophylaxis of malaria. Most studies have found this agent to be relatively safe and effective.

It is excreted into breast milk and has been effective in eliminating malaria parasites from breastfeeding infants.

Quinidine (generic)

Reports linking the use of this agent with congenital defects have not been found. Although the drug has data on its use as an antiarrhythmic, its published use to treat malaria is limited.

The drug is excreted into breast milk, but there are no reports of its during breastfeeding.

Quinine (generic)

This agent has a large amount of human pregnancy data (more than 1,000 exposures) that found no increased risk of birth defects. The drug has been replaced by newer agents but still may be used for chloroquine-resistant malaria.

The drug appears to be compatible during breastfeeding.

Mr. Briggs is clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco, and adjunct professor of pharmacy at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, as well as at Washington State University, Spokane. Mr. Briggs said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

Louisiana House passes 6-week abortion ban

about the time a heartbeat is usually detectable.

The legislation, which does not include an exception for rape or incest cases, passed by a 79-23 vote on May 29 in the Louisiana House. The bill does allow exceptions if the woman’s life is in danger, if the pregnancy poses risk of serious impairment to a woman’s body, of if the pregnancy is deemed medically futile. Democratic Gov. John Bel Edwards said he plans to sign the measure when it hits his desk.

“In 2015, I ran for governor as a pro-life candidate after serving as a pro-life legislator for 8 years,” Gov. Edwards said in a May 29 statement. “As governor, I have been true to my word and my beliefs on this issue. As I prepare to sign this bill, I call on the overwhelming bipartisan majority of legislators who voted for it to join me in continuing to build a better Louisiana that cares for the least among us and provides more opportunity for everyone.”

Six other states have enacted similar abortion bans: Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, and Ohio. While most of the laws bar abortions after a heartbeat is detected, Alabama’s measure prohibits abortion at every pregnancy stage and penalizes physicians with a Class A felony for performing an abortion and a Class C felony for attempting to perform an abortion. Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey (R) signed the bill into law on May 15.

A number of lawsuits have been filed against the bans, including a May 24 legal challenge against Alabama’s law by Planned Parenthood Federation of America and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and a May 15 legal challenge against Ohio’s law by the ACLU and Planned Parenthood of Greater Ohio.

The U.S. Supreme Court on May 28 upheld part of an Indiana law that requires burial or cremation of fetal remains after an abortion, but the justices declined to address the measure’s prohibition on abortions sought because of race, sex, or disability of the fetus.

Court analysts say it’s only a matter of time before the Supreme Court takes up one of the abortion ban cases, most likely the legal challenge against Alabama’s law. Abortion critics have been encouraged by the Supreme Court appointment of right-leaning Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh, and hope the Alabama measure will drive the Supreme Court to reconsider its central holding in Roe v. Wade, court watchers said.

about the time a heartbeat is usually detectable.

The legislation, which does not include an exception for rape or incest cases, passed by a 79-23 vote on May 29 in the Louisiana House. The bill does allow exceptions if the woman’s life is in danger, if the pregnancy poses risk of serious impairment to a woman’s body, of if the pregnancy is deemed medically futile. Democratic Gov. John Bel Edwards said he plans to sign the measure when it hits his desk.

“In 2015, I ran for governor as a pro-life candidate after serving as a pro-life legislator for 8 years,” Gov. Edwards said in a May 29 statement. “As governor, I have been true to my word and my beliefs on this issue. As I prepare to sign this bill, I call on the overwhelming bipartisan majority of legislators who voted for it to join me in continuing to build a better Louisiana that cares for the least among us and provides more opportunity for everyone.”

Six other states have enacted similar abortion bans: Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, and Ohio. While most of the laws bar abortions after a heartbeat is detected, Alabama’s measure prohibits abortion at every pregnancy stage and penalizes physicians with a Class A felony for performing an abortion and a Class C felony for attempting to perform an abortion. Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey (R) signed the bill into law on May 15.

A number of lawsuits have been filed against the bans, including a May 24 legal challenge against Alabama’s law by Planned Parenthood Federation of America and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and a May 15 legal challenge against Ohio’s law by the ACLU and Planned Parenthood of Greater Ohio.

The U.S. Supreme Court on May 28 upheld part of an Indiana law that requires burial or cremation of fetal remains after an abortion, but the justices declined to address the measure’s prohibition on abortions sought because of race, sex, or disability of the fetus.

Court analysts say it’s only a matter of time before the Supreme Court takes up one of the abortion ban cases, most likely the legal challenge against Alabama’s law. Abortion critics have been encouraged by the Supreme Court appointment of right-leaning Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh, and hope the Alabama measure will drive the Supreme Court to reconsider its central holding in Roe v. Wade, court watchers said.

about the time a heartbeat is usually detectable.

The legislation, which does not include an exception for rape or incest cases, passed by a 79-23 vote on May 29 in the Louisiana House. The bill does allow exceptions if the woman’s life is in danger, if the pregnancy poses risk of serious impairment to a woman’s body, of if the pregnancy is deemed medically futile. Democratic Gov. John Bel Edwards said he plans to sign the measure when it hits his desk.

“In 2015, I ran for governor as a pro-life candidate after serving as a pro-life legislator for 8 years,” Gov. Edwards said in a May 29 statement. “As governor, I have been true to my word and my beliefs on this issue. As I prepare to sign this bill, I call on the overwhelming bipartisan majority of legislators who voted for it to join me in continuing to build a better Louisiana that cares for the least among us and provides more opportunity for everyone.”

Six other states have enacted similar abortion bans: Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, and Ohio. While most of the laws bar abortions after a heartbeat is detected, Alabama’s measure prohibits abortion at every pregnancy stage and penalizes physicians with a Class A felony for performing an abortion and a Class C felony for attempting to perform an abortion. Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey (R) signed the bill into law on May 15.

A number of lawsuits have been filed against the bans, including a May 24 legal challenge against Alabama’s law by Planned Parenthood Federation of America and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and a May 15 legal challenge against Ohio’s law by the ACLU and Planned Parenthood of Greater Ohio.

The U.S. Supreme Court on May 28 upheld part of an Indiana law that requires burial or cremation of fetal remains after an abortion, but the justices declined to address the measure’s prohibition on abortions sought because of race, sex, or disability of the fetus.

Court analysts say it’s only a matter of time before the Supreme Court takes up one of the abortion ban cases, most likely the legal challenge against Alabama’s law. Abortion critics have been encouraged by the Supreme Court appointment of right-leaning Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh, and hope the Alabama measure will drive the Supreme Court to reconsider its central holding in Roe v. Wade, court watchers said.

FIGO outlines global standards for preeclampsia screening

as a one-step procedure, according to new recommendations from The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO).

FIGO “encourages all countries and its member associations to adopt and promote strategies to ensure [universal screening],” Liona C. Poon, MD, of Prince of Wales Hospital, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, and colleagues wrote in a guide published in the International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics.

“The best combined test is one that includes maternal risk factors, measurements of mean arterial pressure (MAP), serum placental growth factor (PLGF), and uterine artery pulsatility index (UTPI),” the authors said, noting that the baseline screening test plus a combination of maternal risk factors with MAP is an alternative when PLGF and/or UTPI can’t be measured.

The FIGO recommendations are the culmination of an initiative on PE, which involved a group of international experts convened to discuss and evaluate current knowledge on PE and to “develop a document to frame the issues and suggest key actions to address the health burden posed by PE.” Among the group’s objectives are raising awareness of the links between PE and poor outcomes, and demanding a “clearly defined global health agenda” to address the issue because preeclampsia affects 2%-5% of all pregnant women and is a leading cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality.

The recommendations represent a consensus document that provides guidance for the first trimester screening and prevention of preterm PE.

“Based on high‐quality evidence, the document outlines current global standards for the first‐trimester screening and prevention of preterm PE, which is in line with FIGO good clinical practice advice on first trimester screening and prevention of preeclampsia in singleton pregnancy,” the authors said, explaining that “[it] provides both the best and the most pragmatic recommendations according to the level of acceptability, feasibility, and ease of implementation that have the potential to produce the most significant impact in different resource settings” (Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2019;145[Suppl. 1]:1-33).

Specific suggestions are made based on region and resources, and research priorities are outlined to “bridge the current knowledge and evidence gap.”

In addition to universal first trimester screening for PE, the guide stresses a need for improved public health focus, and contingent screening approaches in areas with limited resources (including routine screening for preterm PE by maternal factors and MAP in most cases, with PLGF and UTPI measurement reserved for higher-risk women). It also recommends that women at high risk should receive prophylactic measures such as aspirin therapy beginning at 11–14+6 weeks of gestation at a dose of about 150 mg to be taken every night until 36 weeks of gestation, when delivery occurs, or when PE is diagnosed.

Mary E. D’Alton, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist who is chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology and the Willard C. Rappleye Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology at Columbia University, New York, was asked to comment on Dr. Sibai’s concerns about the guidelines. “I would simply say that ACOG and SMFM are the organizations in the United States [that] provide educational guidelines about practice in the United States.” Dr. D’Alton assisted Dr. Poon and her associates on the guidelines as an expert on preeclampsia.

Dr. Poon, given a chance to comment on the concern that the FIGO guidelines diverged from those of ACOG and SMFM, responded in an interview, “FIGO, being the global voice for women’s health, likes to ensure that our recommendations are resource appropriate. The objective of these guidelines is to provide a best practice approach, and also offers other pragmatic options for lower resource settings to ensure that preeclampsia testing can be implemented globally. We urge the broader membership of FIGO to adapt these guidelines to their local contexts.”*

She also emphasized that “PerkinElmer’s sponsorship was an unrestricted grant. The company had no involvement in writing the guideline.”*

This work was funded by an unrestricted grant from PerkinElmer, which markets an assay used for first trimester preeclampsia screening. Dr. Poon and her associates reported having no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

*This article was updated 5/31/2019.

The recommendations regarding screening and management of first trimester preeclampsia as issued by FIGO are largely inconsistent with those from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and from the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), according to Baha M. Sibai, MD.

The FIGO recommendation for first trimester screening and use of low-dose aspirin at 150 mg daily starting at 13 weeks also contradicts the ACOG and SMFM recommendations, he said, noting that a 2019 ACOG practice bulletin on preeclampsia recommends 81 mg of aspirin daily initiated between 12 and 28 weeks of gestation (optimally before 16 weeks of gestation) and continuing until delivery; this is for women with any of the high risk factors for preeclampsia and for women with more than one of the moderate risk factors. Under that recommendation, more women would be eligible based on clinical risk factors. The FIGO approach is not cost effective and will miss many cases of preeclampsia, compared with the ACOG recommendations, he said.

It also should be noted that the FIGO document is funded by a grant from PerkinElmer, which markets a test for PE, he said, stressing that there are “no data suggesting that this test is valid in U.S. pregnancies.”

Dr. Sibai is a maternal-fetal medicine specialist with UT Physicians Maternal-Fetal Medicine Center–Texas Medical Center, and a professor in the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston. He was asked to comment on the article by Poon et al. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

The recommendations regarding screening and management of first trimester preeclampsia as issued by FIGO are largely inconsistent with those from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and from the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), according to Baha M. Sibai, MD.

The FIGO recommendation for first trimester screening and use of low-dose aspirin at 150 mg daily starting at 13 weeks also contradicts the ACOG and SMFM recommendations, he said, noting that a 2019 ACOG practice bulletin on preeclampsia recommends 81 mg of aspirin daily initiated between 12 and 28 weeks of gestation (optimally before 16 weeks of gestation) and continuing until delivery; this is for women with any of the high risk factors for preeclampsia and for women with more than one of the moderate risk factors. Under that recommendation, more women would be eligible based on clinical risk factors. The FIGO approach is not cost effective and will miss many cases of preeclampsia, compared with the ACOG recommendations, he said.

It also should be noted that the FIGO document is funded by a grant from PerkinElmer, which markets a test for PE, he said, stressing that there are “no data suggesting that this test is valid in U.S. pregnancies.”

Dr. Sibai is a maternal-fetal medicine specialist with UT Physicians Maternal-Fetal Medicine Center–Texas Medical Center, and a professor in the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston. He was asked to comment on the article by Poon et al. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

The recommendations regarding screening and management of first trimester preeclampsia as issued by FIGO are largely inconsistent with those from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and from the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), according to Baha M. Sibai, MD.

The FIGO recommendation for first trimester screening and use of low-dose aspirin at 150 mg daily starting at 13 weeks also contradicts the ACOG and SMFM recommendations, he said, noting that a 2019 ACOG practice bulletin on preeclampsia recommends 81 mg of aspirin daily initiated between 12 and 28 weeks of gestation (optimally before 16 weeks of gestation) and continuing until delivery; this is for women with any of the high risk factors for preeclampsia and for women with more than one of the moderate risk factors. Under that recommendation, more women would be eligible based on clinical risk factors. The FIGO approach is not cost effective and will miss many cases of preeclampsia, compared with the ACOG recommendations, he said.

It also should be noted that the FIGO document is funded by a grant from PerkinElmer, which markets a test for PE, he said, stressing that there are “no data suggesting that this test is valid in U.S. pregnancies.”

Dr. Sibai is a maternal-fetal medicine specialist with UT Physicians Maternal-Fetal Medicine Center–Texas Medical Center, and a professor in the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston. He was asked to comment on the article by Poon et al. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

as a one-step procedure, according to new recommendations from The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO).

FIGO “encourages all countries and its member associations to adopt and promote strategies to ensure [universal screening],” Liona C. Poon, MD, of Prince of Wales Hospital, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, and colleagues wrote in a guide published in the International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics.

“The best combined test is one that includes maternal risk factors, measurements of mean arterial pressure (MAP), serum placental growth factor (PLGF), and uterine artery pulsatility index (UTPI),” the authors said, noting that the baseline screening test plus a combination of maternal risk factors with MAP is an alternative when PLGF and/or UTPI can’t be measured.

The FIGO recommendations are the culmination of an initiative on PE, which involved a group of international experts convened to discuss and evaluate current knowledge on PE and to “develop a document to frame the issues and suggest key actions to address the health burden posed by PE.” Among the group’s objectives are raising awareness of the links between PE and poor outcomes, and demanding a “clearly defined global health agenda” to address the issue because preeclampsia affects 2%-5% of all pregnant women and is a leading cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality.

The recommendations represent a consensus document that provides guidance for the first trimester screening and prevention of preterm PE.

“Based on high‐quality evidence, the document outlines current global standards for the first‐trimester screening and prevention of preterm PE, which is in line with FIGO good clinical practice advice on first trimester screening and prevention of preeclampsia in singleton pregnancy,” the authors said, explaining that “[it] provides both the best and the most pragmatic recommendations according to the level of acceptability, feasibility, and ease of implementation that have the potential to produce the most significant impact in different resource settings” (Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2019;145[Suppl. 1]:1-33).

Specific suggestions are made based on region and resources, and research priorities are outlined to “bridge the current knowledge and evidence gap.”

In addition to universal first trimester screening for PE, the guide stresses a need for improved public health focus, and contingent screening approaches in areas with limited resources (including routine screening for preterm PE by maternal factors and MAP in most cases, with PLGF and UTPI measurement reserved for higher-risk women). It also recommends that women at high risk should receive prophylactic measures such as aspirin therapy beginning at 11–14+6 weeks of gestation at a dose of about 150 mg to be taken every night until 36 weeks of gestation, when delivery occurs, or when PE is diagnosed.

Mary E. D’Alton, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist who is chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology and the Willard C. Rappleye Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology at Columbia University, New York, was asked to comment on Dr. Sibai’s concerns about the guidelines. “I would simply say that ACOG and SMFM are the organizations in the United States [that] provide educational guidelines about practice in the United States.” Dr. D’Alton assisted Dr. Poon and her associates on the guidelines as an expert on preeclampsia.

Dr. Poon, given a chance to comment on the concern that the FIGO guidelines diverged from those of ACOG and SMFM, responded in an interview, “FIGO, being the global voice for women’s health, likes to ensure that our recommendations are resource appropriate. The objective of these guidelines is to provide a best practice approach, and also offers other pragmatic options for lower resource settings to ensure that preeclampsia testing can be implemented globally. We urge the broader membership of FIGO to adapt these guidelines to their local contexts.”*

She also emphasized that “PerkinElmer’s sponsorship was an unrestricted grant. The company had no involvement in writing the guideline.”*

This work was funded by an unrestricted grant from PerkinElmer, which markets an assay used for first trimester preeclampsia screening. Dr. Poon and her associates reported having no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

*This article was updated 5/31/2019.

as a one-step procedure, according to new recommendations from The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO).

FIGO “encourages all countries and its member associations to adopt and promote strategies to ensure [universal screening],” Liona C. Poon, MD, of Prince of Wales Hospital, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, and colleagues wrote in a guide published in the International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics.

“The best combined test is one that includes maternal risk factors, measurements of mean arterial pressure (MAP), serum placental growth factor (PLGF), and uterine artery pulsatility index (UTPI),” the authors said, noting that the baseline screening test plus a combination of maternal risk factors with MAP is an alternative when PLGF and/or UTPI can’t be measured.

The FIGO recommendations are the culmination of an initiative on PE, which involved a group of international experts convened to discuss and evaluate current knowledge on PE and to “develop a document to frame the issues and suggest key actions to address the health burden posed by PE.” Among the group’s objectives are raising awareness of the links between PE and poor outcomes, and demanding a “clearly defined global health agenda” to address the issue because preeclampsia affects 2%-5% of all pregnant women and is a leading cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality.

The recommendations represent a consensus document that provides guidance for the first trimester screening and prevention of preterm PE.

“Based on high‐quality evidence, the document outlines current global standards for the first‐trimester screening and prevention of preterm PE, which is in line with FIGO good clinical practice advice on first trimester screening and prevention of preeclampsia in singleton pregnancy,” the authors said, explaining that “[it] provides both the best and the most pragmatic recommendations according to the level of acceptability, feasibility, and ease of implementation that have the potential to produce the most significant impact in different resource settings” (Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2019;145[Suppl. 1]:1-33).

Specific suggestions are made based on region and resources, and research priorities are outlined to “bridge the current knowledge and evidence gap.”

In addition to universal first trimester screening for PE, the guide stresses a need for improved public health focus, and contingent screening approaches in areas with limited resources (including routine screening for preterm PE by maternal factors and MAP in most cases, with PLGF and UTPI measurement reserved for higher-risk women). It also recommends that women at high risk should receive prophylactic measures such as aspirin therapy beginning at 11–14+6 weeks of gestation at a dose of about 150 mg to be taken every night until 36 weeks of gestation, when delivery occurs, or when PE is diagnosed.

Mary E. D’Alton, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist who is chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology and the Willard C. Rappleye Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology at Columbia University, New York, was asked to comment on Dr. Sibai’s concerns about the guidelines. “I would simply say that ACOG and SMFM are the organizations in the United States [that] provide educational guidelines about practice in the United States.” Dr. D’Alton assisted Dr. Poon and her associates on the guidelines as an expert on preeclampsia.

Dr. Poon, given a chance to comment on the concern that the FIGO guidelines diverged from those of ACOG and SMFM, responded in an interview, “FIGO, being the global voice for women’s health, likes to ensure that our recommendations are resource appropriate. The objective of these guidelines is to provide a best practice approach, and also offers other pragmatic options for lower resource settings to ensure that preeclampsia testing can be implemented globally. We urge the broader membership of FIGO to adapt these guidelines to their local contexts.”*

She also emphasized that “PerkinElmer’s sponsorship was an unrestricted grant. The company had no involvement in writing the guideline.”*

This work was funded by an unrestricted grant from PerkinElmer, which markets an assay used for first trimester preeclampsia screening. Dr. Poon and her associates reported having no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

*This article was updated 5/31/2019.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF GYNECOLOGY & OBSTETRICS

Maternal mortality: Critical next steps in addressing the crisis

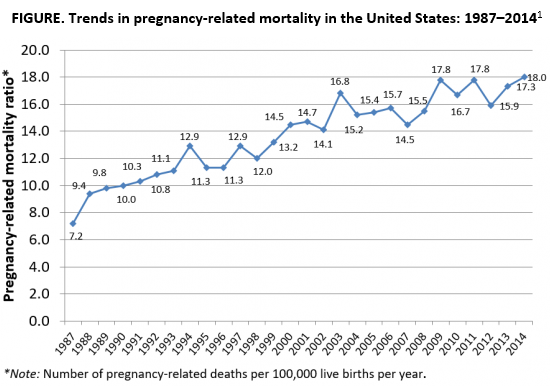

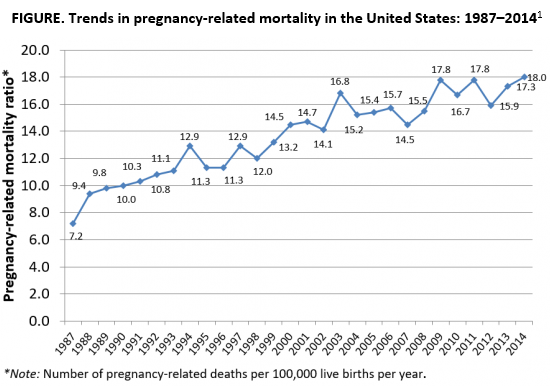

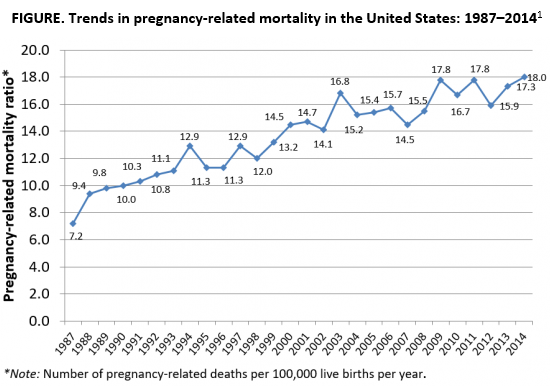

As the rest of the industrialized world has seen a decline in maternal mortality, the United States has seen a substantial rise over the last 30 years (FIGURE).1 It is estimated that more than 60% of these pregnancy-related deaths are preventable. Additionally, substantial disparities exist, with African-American women 3 to 4 times more likely to die of pregnancy-related complications than white women.1

A good first step

The Preventing Maternal Deaths Act was passed by the 115th Congress and signed into law December 2018 in an effort to support and expand maternal mortality review committees (MMRCs) on a state level while allowing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to further study disparities within maternal mortality. Although these efforts are a good first step to help reduce maternal mortality, more needs to be done to quell this growing epidemic.

We must now improve care access

One strategy to aid in decreasing maternal morbidity and mortality is to improve affordable access to medical care. Medicaid is the largest single payer of maternity care in the United States, covering 42.6% of births. Currently, in many states, Medicaid coverage only lasts until a woman is 60 days postpartum.2 Although 31 states, including the District of Columbia, have adopted Medicaid expansion programs to allow women to extend coverage beyond those 60 days, offering these programs is not a federal law. In the 19 remaining states with no extension options, the vast majority of women will lose their Medicaid coverage just after they are 2 months postpartum and will have no alternative health insurance coverage.2

Why does this coverage cutoff matter? Pregnancy-related deaths are defined as up to 12 months postpartum. A report reviewing 9 MMRCs found that 38% of pregnancy-related deaths occurred while a woman was pregnant, 45% of deaths occurred within 42 days of delivery, and 18% from 43 days to 1 year after delivery.3 Additionally, nearly half of women with Medicaid do not come to their 6-week postpartum visit (for a variety of reasons), missing a critical opportunity to address health concerns.2 Of the deaths that occurred in this later postpartum period, leading causes were cardiomyopathy (32%), mental health conditions (16%), and embolism (11%).3 Prevention and management of these conditions require regular follow-up with an ObGyn, as well as potentially from subspecialists in cardiology, psychiatry, hematology, and other subspecialties. Women not having access to affordable health care during the critical postpartum period greatly increases their risk of death or severe morbidity.

An important next step beyond the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act is to extend Medicaid coverage to 12 months postpartum for all women everywhere. MMRCs have concluded that extending coverage would ensure that “medical and behavioral health conditions [could be] managed and treated before becoming progressively severe.”3 This would presumably help decrease the risk of pregnancy-related death and address worsening morbidity. Additionally, the postpartum period is a well-established time of increased stress and can be an overwhelming and emotional time for many new mothers, especially for those with limited resources for childcare, transportation, stable housing, etc.6 Providing and ensuring ongoing medical care would substantially improve the lives and health of women and the health of their families.

We, as a country, need to make changes

Every step of the way, a woman faces challenges to safely and affordably access health care. Providing access to insurance coverage for 12 months postpartum can help to decrease our country’s rising maternal mortality and morbidity rates.

Take action

Congresswoman Robin Kelly (D-IL) and Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL) have introduced the MOMMA Act (H.R. 1897/S. 916) to help address the rising maternal mortality rate.

This Act would:

- Expand Medicaid coverage to 1 year postpartum.

- Work with the CDC to uniformly collect data to accurately assess maternal mortality and morbidity.

- Ensure the sharing of best practices of care across hospital systems.

- Focus on culturally-competent care to address implicit bias among health care workers.

- Support and expand the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM)—a data-driven initiative to implement safety protocols in hospitals across the country.

To call or contact your representative to co-sponsor this bill, click here. To review if your Congressperson is a co-sponsor, click here. To review if your Senator is a co-sponsor, click here.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System, Trends in Pregnancy-Related Deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- Stuebe A, Moore JE, Mittal P, et al. Extending medicaid coverage for postpartum moms. May 6, 2019. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190501.254675/full/. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- Building U.S. Capacity to Review and Prevent Maternal Deaths. Report from nine maternal mortality review committees. 2018. Color/Word_R17_G85_B204http://reviewtoaction.org/Report_from_Nine_MMRCs. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- MacDorman MF, Declercq E, Cabral H, et al. Recent increases in the U.S. maternal mortality rate: disentangling trends from measurement issues. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:447-455.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, et al. Births: final data for 2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67:1-55.

- Vestal C. For addicted women, the year after childbirth is the deadliest. August 14, 2018. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2018/08/14/for-addicted-women-the-year-after-childbirth-is-the-deadliest. Accessed May 29, 2019.

As the rest of the industrialized world has seen a decline in maternal mortality, the United States has seen a substantial rise over the last 30 years (FIGURE).1 It is estimated that more than 60% of these pregnancy-related deaths are preventable. Additionally, substantial disparities exist, with African-American women 3 to 4 times more likely to die of pregnancy-related complications than white women.1

A good first step

The Preventing Maternal Deaths Act was passed by the 115th Congress and signed into law December 2018 in an effort to support and expand maternal mortality review committees (MMRCs) on a state level while allowing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to further study disparities within maternal mortality. Although these efforts are a good first step to help reduce maternal mortality, more needs to be done to quell this growing epidemic.

We must now improve care access

One strategy to aid in decreasing maternal morbidity and mortality is to improve affordable access to medical care. Medicaid is the largest single payer of maternity care in the United States, covering 42.6% of births. Currently, in many states, Medicaid coverage only lasts until a woman is 60 days postpartum.2 Although 31 states, including the District of Columbia, have adopted Medicaid expansion programs to allow women to extend coverage beyond those 60 days, offering these programs is not a federal law. In the 19 remaining states with no extension options, the vast majority of women will lose their Medicaid coverage just after they are 2 months postpartum and will have no alternative health insurance coverage.2

Why does this coverage cutoff matter? Pregnancy-related deaths are defined as up to 12 months postpartum. A report reviewing 9 MMRCs found that 38% of pregnancy-related deaths occurred while a woman was pregnant, 45% of deaths occurred within 42 days of delivery, and 18% from 43 days to 1 year after delivery.3 Additionally, nearly half of women with Medicaid do not come to their 6-week postpartum visit (for a variety of reasons), missing a critical opportunity to address health concerns.2 Of the deaths that occurred in this later postpartum period, leading causes were cardiomyopathy (32%), mental health conditions (16%), and embolism (11%).3 Prevention and management of these conditions require regular follow-up with an ObGyn, as well as potentially from subspecialists in cardiology, psychiatry, hematology, and other subspecialties. Women not having access to affordable health care during the critical postpartum period greatly increases their risk of death or severe morbidity.

An important next step beyond the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act is to extend Medicaid coverage to 12 months postpartum for all women everywhere. MMRCs have concluded that extending coverage would ensure that “medical and behavioral health conditions [could be] managed and treated before becoming progressively severe.”3 This would presumably help decrease the risk of pregnancy-related death and address worsening morbidity. Additionally, the postpartum period is a well-established time of increased stress and can be an overwhelming and emotional time for many new mothers, especially for those with limited resources for childcare, transportation, stable housing, etc.6 Providing and ensuring ongoing medical care would substantially improve the lives and health of women and the health of their families.

We, as a country, need to make changes

Every step of the way, a woman faces challenges to safely and affordably access health care. Providing access to insurance coverage for 12 months postpartum can help to decrease our country’s rising maternal mortality and morbidity rates.

Take action

Congresswoman Robin Kelly (D-IL) and Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL) have introduced the MOMMA Act (H.R. 1897/S. 916) to help address the rising maternal mortality rate.

This Act would:

- Expand Medicaid coverage to 1 year postpartum.

- Work with the CDC to uniformly collect data to accurately assess maternal mortality and morbidity.

- Ensure the sharing of best practices of care across hospital systems.

- Focus on culturally-competent care to address implicit bias among health care workers.

- Support and expand the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM)—a data-driven initiative to implement safety protocols in hospitals across the country.

To call or contact your representative to co-sponsor this bill, click here. To review if your Congressperson is a co-sponsor, click here. To review if your Senator is a co-sponsor, click here.

As the rest of the industrialized world has seen a decline in maternal mortality, the United States has seen a substantial rise over the last 30 years (FIGURE).1 It is estimated that more than 60% of these pregnancy-related deaths are preventable. Additionally, substantial disparities exist, with African-American women 3 to 4 times more likely to die of pregnancy-related complications than white women.1

A good first step

The Preventing Maternal Deaths Act was passed by the 115th Congress and signed into law December 2018 in an effort to support and expand maternal mortality review committees (MMRCs) on a state level while allowing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to further study disparities within maternal mortality. Although these efforts are a good first step to help reduce maternal mortality, more needs to be done to quell this growing epidemic.

We must now improve care access

One strategy to aid in decreasing maternal morbidity and mortality is to improve affordable access to medical care. Medicaid is the largest single payer of maternity care in the United States, covering 42.6% of births. Currently, in many states, Medicaid coverage only lasts until a woman is 60 days postpartum.2 Although 31 states, including the District of Columbia, have adopted Medicaid expansion programs to allow women to extend coverage beyond those 60 days, offering these programs is not a federal law. In the 19 remaining states with no extension options, the vast majority of women will lose their Medicaid coverage just after they are 2 months postpartum and will have no alternative health insurance coverage.2

Why does this coverage cutoff matter? Pregnancy-related deaths are defined as up to 12 months postpartum. A report reviewing 9 MMRCs found that 38% of pregnancy-related deaths occurred while a woman was pregnant, 45% of deaths occurred within 42 days of delivery, and 18% from 43 days to 1 year after delivery.3 Additionally, nearly half of women with Medicaid do not come to their 6-week postpartum visit (for a variety of reasons), missing a critical opportunity to address health concerns.2 Of the deaths that occurred in this later postpartum period, leading causes were cardiomyopathy (32%), mental health conditions (16%), and embolism (11%).3 Prevention and management of these conditions require regular follow-up with an ObGyn, as well as potentially from subspecialists in cardiology, psychiatry, hematology, and other subspecialties. Women not having access to affordable health care during the critical postpartum period greatly increases their risk of death or severe morbidity.

An important next step beyond the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act is to extend Medicaid coverage to 12 months postpartum for all women everywhere. MMRCs have concluded that extending coverage would ensure that “medical and behavioral health conditions [could be] managed and treated before becoming progressively severe.”3 This would presumably help decrease the risk of pregnancy-related death and address worsening morbidity. Additionally, the postpartum period is a well-established time of increased stress and can be an overwhelming and emotional time for many new mothers, especially for those with limited resources for childcare, transportation, stable housing, etc.6 Providing and ensuring ongoing medical care would substantially improve the lives and health of women and the health of their families.

We, as a country, need to make changes

Every step of the way, a woman faces challenges to safely and affordably access health care. Providing access to insurance coverage for 12 months postpartum can help to decrease our country’s rising maternal mortality and morbidity rates.

Take action

Congresswoman Robin Kelly (D-IL) and Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL) have introduced the MOMMA Act (H.R. 1897/S. 916) to help address the rising maternal mortality rate.

This Act would:

- Expand Medicaid coverage to 1 year postpartum.

- Work with the CDC to uniformly collect data to accurately assess maternal mortality and morbidity.

- Ensure the sharing of best practices of care across hospital systems.

- Focus on culturally-competent care to address implicit bias among health care workers.

- Support and expand the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM)—a data-driven initiative to implement safety protocols in hospitals across the country.

To call or contact your representative to co-sponsor this bill, click here. To review if your Congressperson is a co-sponsor, click here. To review if your Senator is a co-sponsor, click here.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System, Trends in Pregnancy-Related Deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- Stuebe A, Moore JE, Mittal P, et al. Extending medicaid coverage for postpartum moms. May 6, 2019. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190501.254675/full/. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- Building U.S. Capacity to Review and Prevent Maternal Deaths. Report from nine maternal mortality review committees. 2018. Color/Word_R17_G85_B204http://reviewtoaction.org/Report_from_Nine_MMRCs. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- MacDorman MF, Declercq E, Cabral H, et al. Recent increases in the U.S. maternal mortality rate: disentangling trends from measurement issues. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:447-455.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, et al. Births: final data for 2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67:1-55.

- Vestal C. For addicted women, the year after childbirth is the deadliest. August 14, 2018. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2018/08/14/for-addicted-women-the-year-after-childbirth-is-the-deadliest. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System, Trends in Pregnancy-Related Deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- Stuebe A, Moore JE, Mittal P, et al. Extending medicaid coverage for postpartum moms. May 6, 2019. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190501.254675/full/. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- Building U.S. Capacity to Review and Prevent Maternal Deaths. Report from nine maternal mortality review committees. 2018. Color/Word_R17_G85_B204http://reviewtoaction.org/Report_from_Nine_MMRCs. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- MacDorman MF, Declercq E, Cabral H, et al. Recent increases in the U.S. maternal mortality rate: disentangling trends from measurement issues. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:447-455.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, et al. Births: final data for 2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67:1-55.

- Vestal C. For addicted women, the year after childbirth is the deadliest. August 14, 2018. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2018/08/14/for-addicted-women-the-year-after-childbirth-is-the-deadliest. Accessed May 29, 2019.

What closing Missouri’s last abortion clinic will mean for neighboring states

ST. LOUIS – As the last abortion clinic in Missouri warned that it will have to stop providing the procedure as soon as May 31, abortion providers in surrounding states said they are anticipating an uptick of even more Missouri patients.

At Hope Clinic in Granite City, Ill., just 10 minutes from downtown St. Louis, Deputy Director Alison Dreith said on May 28 that her clinic was preparing for more patients as news about Missouri spread.

“We’re really scrambling today about the need for increased staff and how fast can we hire and train,” Dreith said.

And at a Trust Women clinic in Wichita, Kan., that already has to fly in doctors, the staff didn’t know what it would mean for their overloaded patient schedule.

“God forbid we see that people can’t get services in Missouri,” said Julie Burkhart, Trust Women founder and CEO. “What is that going to mean on our limited physician days?”

If St. Louis’ Planned Parenthood clinic is unable to offer abortions, the group said, Missouri would be the only state in the country to not have an operating abortion clinic. Five other states – Kentucky, Mississippi, North Dakota, South Dakota and West Virginia – reportedly have only one abortion clinic. And 90% of U.S. counties didn’t have an abortion clinic as of 2014, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a reproductive rights research and advocacy group.

For some, this echoes back to the days before abortion was legalized nationwide in 1973 with the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision, when patients who could afford to travel would go to more liberal states like California or New York where abortion was legal.

But providers in Kansas and Illinois say this influx from Missouri isn’t new. About half of their clients already come from the Show Me State. To the south, in neighboring Arkansas, where a 72-hour waiting period will go into effect in July, the vast majority of its patients still live within the state.

Over the past 10 years, four Missouri abortion clinics have closed because of increased regulations, including a mandatory 72-hour waiting period after receiving counseling on abortion, thus requiring two trips to a facility; requirements that physicians have hospital admitting privileges within 15 minutes of their clinics; and a rule requiring two-parent notification for minors and one-parent notarized consent. All those limits left one clinic in downtown St. Louis to serve the whole state.

Now Planned Parenthood, which operates that final abortion clinic, said on May 28 that it will be forced to end its abortion services altogether by May 31 if the state suspends its license. The closure is not related to new anti-abortion laws that Missouri Gov. Mike Parson, a Republican, signed on May 24 to ban most abortions after 8 weeks of pregnancy. The new laws don’t take effect until August.

Already the number of patients in Missouri seeking an abortion at the clinic from April 2018 until this April had dropped by 50% compared with the same period the previous year. Planned Parenthood spokesman Jesse Lawder attributes two-thirds of the decrease to the clinic’s refusal to do pelvic exams for abortions performed through medication – recently required by the state – thus forcing all such abortions to be performed out of state.

For Dreith, while she expects the Missouri numbers to continue to grow at her Illinois clinic across the Mississippi River, it’s not the only state sending patients her way.

“Patients were literally coming to us from the last remaining clinics in Kentucky ... so that they wouldn’t get past 24 weeks,” Dreith said. “We don’t want these patients in surrounding states traveling [to] New York [or] California like they once had to.”

That’s how it was prior to the Roe v. Wade ruling, according to Mary Ziegler, a professor at Florida State University College of Law who is writing her third book on the history of the legal battle around abortion access. She anticipates the pattern of privilege will repeat itself.

“You would still expect women with resources to be able to travel as far as they needed,” she said. “And you would expect women without resources to not be able to travel. ... The more the court retreats from protecting abortion rights, the more stark those differences will become.”

For Dreith, the historical comparison to the pre-Roe era rings true, albeit with improved medical practices.

There are safer, easier, and more effective ways to perform abortions now than the “horror stories that we saw pre-Roe,” said Dreith. “But I think the travel will be one of the huge throwbacks and the scariest part will be the criminalization.”

States such as Missouri could feel pressure to start arresting women who perform their own abortions with pills at home or travel out of state, Ziegler said. But, she said, “punishing women isn’t something that’s thought to be very popular.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

ST. LOUIS – As the last abortion clinic in Missouri warned that it will have to stop providing the procedure as soon as May 31, abortion providers in surrounding states said they are anticipating an uptick of even more Missouri patients.

At Hope Clinic in Granite City, Ill., just 10 minutes from downtown St. Louis, Deputy Director Alison Dreith said on May 28 that her clinic was preparing for more patients as news about Missouri spread.

“We’re really scrambling today about the need for increased staff and how fast can we hire and train,” Dreith said.

And at a Trust Women clinic in Wichita, Kan., that already has to fly in doctors, the staff didn’t know what it would mean for their overloaded patient schedule.

“God forbid we see that people can’t get services in Missouri,” said Julie Burkhart, Trust Women founder and CEO. “What is that going to mean on our limited physician days?”

If St. Louis’ Planned Parenthood clinic is unable to offer abortions, the group said, Missouri would be the only state in the country to not have an operating abortion clinic. Five other states – Kentucky, Mississippi, North Dakota, South Dakota and West Virginia – reportedly have only one abortion clinic. And 90% of U.S. counties didn’t have an abortion clinic as of 2014, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a reproductive rights research and advocacy group.

For some, this echoes back to the days before abortion was legalized nationwide in 1973 with the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision, when patients who could afford to travel would go to more liberal states like California or New York where abortion was legal.

But providers in Kansas and Illinois say this influx from Missouri isn’t new. About half of their clients already come from the Show Me State. To the south, in neighboring Arkansas, where a 72-hour waiting period will go into effect in July, the vast majority of its patients still live within the state.

Over the past 10 years, four Missouri abortion clinics have closed because of increased regulations, including a mandatory 72-hour waiting period after receiving counseling on abortion, thus requiring two trips to a facility; requirements that physicians have hospital admitting privileges within 15 minutes of their clinics; and a rule requiring two-parent notification for minors and one-parent notarized consent. All those limits left one clinic in downtown St. Louis to serve the whole state.

Now Planned Parenthood, which operates that final abortion clinic, said on May 28 that it will be forced to end its abortion services altogether by May 31 if the state suspends its license. The closure is not related to new anti-abortion laws that Missouri Gov. Mike Parson, a Republican, signed on May 24 to ban most abortions after 8 weeks of pregnancy. The new laws don’t take effect until August.

Already the number of patients in Missouri seeking an abortion at the clinic from April 2018 until this April had dropped by 50% compared with the same period the previous year. Planned Parenthood spokesman Jesse Lawder attributes two-thirds of the decrease to the clinic’s refusal to do pelvic exams for abortions performed through medication – recently required by the state – thus forcing all such abortions to be performed out of state.

For Dreith, while she expects the Missouri numbers to continue to grow at her Illinois clinic across the Mississippi River, it’s not the only state sending patients her way.

“Patients were literally coming to us from the last remaining clinics in Kentucky ... so that they wouldn’t get past 24 weeks,” Dreith said. “We don’t want these patients in surrounding states traveling [to] New York [or] California like they once had to.”

That’s how it was prior to the Roe v. Wade ruling, according to Mary Ziegler, a professor at Florida State University College of Law who is writing her third book on the history of the legal battle around abortion access. She anticipates the pattern of privilege will repeat itself.

“You would still expect women with resources to be able to travel as far as they needed,” she said. “And you would expect women without resources to not be able to travel. ... The more the court retreats from protecting abortion rights, the more stark those differences will become.”

For Dreith, the historical comparison to the pre-Roe era rings true, albeit with improved medical practices.

There are safer, easier, and more effective ways to perform abortions now than the “horror stories that we saw pre-Roe,” said Dreith. “But I think the travel will be one of the huge throwbacks and the scariest part will be the criminalization.”

States such as Missouri could feel pressure to start arresting women who perform their own abortions with pills at home or travel out of state, Ziegler said. But, she said, “punishing women isn’t something that’s thought to be very popular.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

ST. LOUIS – As the last abortion clinic in Missouri warned that it will have to stop providing the procedure as soon as May 31, abortion providers in surrounding states said they are anticipating an uptick of even more Missouri patients.

At Hope Clinic in Granite City, Ill., just 10 minutes from downtown St. Louis, Deputy Director Alison Dreith said on May 28 that her clinic was preparing for more patients as news about Missouri spread.

“We’re really scrambling today about the need for increased staff and how fast can we hire and train,” Dreith said.

And at a Trust Women clinic in Wichita, Kan., that already has to fly in doctors, the staff didn’t know what it would mean for their overloaded patient schedule.

“God forbid we see that people can’t get services in Missouri,” said Julie Burkhart, Trust Women founder and CEO. “What is that going to mean on our limited physician days?”

If St. Louis’ Planned Parenthood clinic is unable to offer abortions, the group said, Missouri would be the only state in the country to not have an operating abortion clinic. Five other states – Kentucky, Mississippi, North Dakota, South Dakota and West Virginia – reportedly have only one abortion clinic. And 90% of U.S. counties didn’t have an abortion clinic as of 2014, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a reproductive rights research and advocacy group.

For some, this echoes back to the days before abortion was legalized nationwide in 1973 with the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision, when patients who could afford to travel would go to more liberal states like California or New York where abortion was legal.

But providers in Kansas and Illinois say this influx from Missouri isn’t new. About half of their clients already come from the Show Me State. To the south, in neighboring Arkansas, where a 72-hour waiting period will go into effect in July, the vast majority of its patients still live within the state.

Over the past 10 years, four Missouri abortion clinics have closed because of increased regulations, including a mandatory 72-hour waiting period after receiving counseling on abortion, thus requiring two trips to a facility; requirements that physicians have hospital admitting privileges within 15 minutes of their clinics; and a rule requiring two-parent notification for minors and one-parent notarized consent. All those limits left one clinic in downtown St. Louis to serve the whole state.

Now Planned Parenthood, which operates that final abortion clinic, said on May 28 that it will be forced to end its abortion services altogether by May 31 if the state suspends its license. The closure is not related to new anti-abortion laws that Missouri Gov. Mike Parson, a Republican, signed on May 24 to ban most abortions after 8 weeks of pregnancy. The new laws don’t take effect until August.

Already the number of patients in Missouri seeking an abortion at the clinic from April 2018 until this April had dropped by 50% compared with the same period the previous year. Planned Parenthood spokesman Jesse Lawder attributes two-thirds of the decrease to the clinic’s refusal to do pelvic exams for abortions performed through medication – recently required by the state – thus forcing all such abortions to be performed out of state.

For Dreith, while she expects the Missouri numbers to continue to grow at her Illinois clinic across the Mississippi River, it’s not the only state sending patients her way.

“Patients were literally coming to us from the last remaining clinics in Kentucky ... so that they wouldn’t get past 24 weeks,” Dreith said. “We don’t want these patients in surrounding states traveling [to] New York [or] California like they once had to.”

That’s how it was prior to the Roe v. Wade ruling, according to Mary Ziegler, a professor at Florida State University College of Law who is writing her third book on the history of the legal battle around abortion access. She anticipates the pattern of privilege will repeat itself.

“You would still expect women with resources to be able to travel as far as they needed,” she said. “And you would expect women without resources to not be able to travel. ... The more the court retreats from protecting abortion rights, the more stark those differences will become.”

For Dreith, the historical comparison to the pre-Roe era rings true, albeit with improved medical practices.

There are safer, easier, and more effective ways to perform abortions now than the “horror stories that we saw pre-Roe,” said Dreith. “But I think the travel will be one of the huge throwbacks and the scariest part will be the criminalization.”

States such as Missouri could feel pressure to start arresting women who perform their own abortions with pills at home or travel out of state, Ziegler said. But, she said, “punishing women isn’t something that’s thought to be very popular.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Syncope during pregnancy increases risk for poor outcomes

a retrospective population-based cohort study finds. Risks appeared highest with first-trimester syncope.

“There are very limited data on the frequency of fainting during pregnancy,” Padma Kaul, Ph.D., senior study author and professor of medicine at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, said in a statement. “In our study, fainting during pregnancy occurred in about 1%, or 10 per 1,000 pregnancies, but appears to be increasing by 5% each year.”

“Fainting during pregnancy has previously been thought to follow a relatively benign course,” Dr. Kaul said. “The findings of our study suggest that timing of fainting during pregnancy may be important. When the faint happens early during pregnancy or multiple times during pregnancy, it may be associated with both short- and long-term health issues for the baby and the mother.”

First authors Safia Chatur, MD, of the University of Calgary (Alta.) and Sunjidatul Islam, MBBS, of the Canadian Vigour Centre, Edmonton, Alta., and associates analyzed 481,930 pregnancies occurring during 2005-2014 in the province.

Study results, reported in the Journal of the American Heart Association, showed that syncope occurred in almost 1% of pregnancies (9.7 episodes per 1,000 pregnancies) overall. Incidence increased by 5% per year during the study period.

Syncope episodes were distributed across the first trimester (32%), second trimester (44%), and third trimester (24%). Eight percent of pregnancies had more than one episode.

Compared with unaffected peers, women who experienced syncope were younger (age younger than 25 years, 35% vs. 21%; P less than .001) and more often primiparous (52% vs. 42%; P less than .001).

The rate of preterm birth was 18%, 16%, and 14% in pregnancies with an initial syncope episode during the first, second, and third trimester, respectively, compared with 15% in pregnancies without syncope (P less than .01 across groups).

With a median follow-up of about 5 years, compared with peers of syncope-free pregnancies, children of pregnancies complicated by syncope had a higher incidence of congenital anomalies (3.1% vs. 2.6%; P = .023). Incidence was highest in pregnancies with multiple episodes of syncope (5% vs. 3%; P less than .01).

In adjusted analyses that accounted for multiple pregnancies in individual women, relative to counterparts with no syncope during pregnancy, women who experienced syncope during the first trimester had higher odds of giving birth preterm (odds ratio, 1.3; P = .001) and of having an infant small for gestational age (OR, 1.2; P = .04) or with congenital anomalies (OR, 1.4; P = .036). Women with multiple syncope episodes versus none were twice as likely to have offspring with congenital anomalies (OR, 2.0; P = .003).

Relative to peers who did not experience syncope in pregnancy, women who did had higher incidences of cardiac arrhythmias (0.8% vs. 0.2%; P less than .01) and syncope episodes (1.4% vs. 0.2%; P less than .01) in the first year after delivery.

“Our data suggest that syncope during pregnancy may not be a benign occurrence,” Dr. Chatur and associates said. “More detailed clinical data are needed to identify potential causes for the observed increase in syncope during pregnancy in our study.“Whether women who experience syncope during pregnancy may benefit from closer monitoring during the obstetric and postpartum periods requires further study,” they concluded.

The investigators disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest. This study was funded by a grant from the Cardiac Arrhythmia Network of Canada.

SOURCE: Chatur S et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011608.

a retrospective population-based cohort study finds. Risks appeared highest with first-trimester syncope.

“There are very limited data on the frequency of fainting during pregnancy,” Padma Kaul, Ph.D., senior study author and professor of medicine at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, said in a statement. “In our study, fainting during pregnancy occurred in about 1%, or 10 per 1,000 pregnancies, but appears to be increasing by 5% each year.”

“Fainting during pregnancy has previously been thought to follow a relatively benign course,” Dr. Kaul said. “The findings of our study suggest that timing of fainting during pregnancy may be important. When the faint happens early during pregnancy or multiple times during pregnancy, it may be associated with both short- and long-term health issues for the baby and the mother.”

First authors Safia Chatur, MD, of the University of Calgary (Alta.) and Sunjidatul Islam, MBBS, of the Canadian Vigour Centre, Edmonton, Alta., and associates analyzed 481,930 pregnancies occurring during 2005-2014 in the province.

Study results, reported in the Journal of the American Heart Association, showed that syncope occurred in almost 1% of pregnancies (9.7 episodes per 1,000 pregnancies) overall. Incidence increased by 5% per year during the study period.

Syncope episodes were distributed across the first trimester (32%), second trimester (44%), and third trimester (24%). Eight percent of pregnancies had more than one episode.

Compared with unaffected peers, women who experienced syncope were younger (age younger than 25 years, 35% vs. 21%; P less than .001) and more often primiparous (52% vs. 42%; P less than .001).

The rate of preterm birth was 18%, 16%, and 14% in pregnancies with an initial syncope episode during the first, second, and third trimester, respectively, compared with 15% in pregnancies without syncope (P less than .01 across groups).

With a median follow-up of about 5 years, compared with peers of syncope-free pregnancies, children of pregnancies complicated by syncope had a higher incidence of congenital anomalies (3.1% vs. 2.6%; P = .023). Incidence was highest in pregnancies with multiple episodes of syncope (5% vs. 3%; P less than .01).