User login

Thyroid Hormone Balance Crucial for Liver Fat Reduction

TOPLINE:

Greater availability of peripheral tri-iodothyronine (T3), indicated by higher concentrations of free T3, T3, and T3/thyroxine (T4) ratio, is associated with increased liver fat content at baseline and a greater liver fat reduction following a dietary intervention known to reduce liver fat.

METHODOLOGY:

- Systemic hypothyroidism and subclinical hypothyroidism are proposed as independent risk factors for steatotic liver disease, but there are conflicting results in euthyroid individuals with normal thyroid function.

- Researchers investigated the association between thyroid function and intrahepatic lipids in 332 euthyroid individuals aged 50-80 years who reported limited alcohol consumption and had at least one condition for unhealthy aging (eg, cardiovascular disease).

- The analysis drew on a sub-cohort from the NutriAct trial, in which participants were randomly assigned to either an intervention group (diet rich in unsaturated fatty acids, plant protein, and fiber) or a control group (following the German Nutrition Society recommendations).

- The relationship between changes in intrahepatic lipid content and thyroid hormone parameters was evaluated in 243 individuals with data available at 12 months.

TAKEAWAY:

- Higher levels of free T3 and T3/T4 ratio were associated with increased liver fat content at baseline (P = .03 and P = .01, respectively).

- After 12 months, both the intervention and control groups showed reductions in liver fat content, along with similar reductions in free T3, total T3, T3/T4 ratio, and free T3/free T4 ratio (all P < .01).

- Thyroid stimulating hormone, T4, and free T4 levels remained stable in either group during the intervention.

- Participants who maintained higher T3 levels during the dietary intervention experienced a greater reduction in liver fat content over 12 months (Rho = −0.133; P = .039).

IN PRACTICE:

“A higher peripheral concentration of active THs [thyroid hormones] might reflect a compensatory mechanism in subjects with mildly increased IHL [intrahepatic lipid] content and early stages of MASLD [metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease],” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Miriam Sommer-Ballarini, Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany. It was published online in the European Journal of Endocrinology.

LIMITATIONS:

Participants younger than 50 years of age and with severe hepatic disease, severe substance abuse, or active cancer were excluded, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Because the study cohort had only mildly elevated median intrahepatic lipid content at baseline, it may not be suited to address the advanced stages of metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease. The study’s findings are based on a specific dietary intervention, which may not be applicable to other dietary patterns or populations.

DISCLOSURES:

The Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and German Federal Ministry for Education and Research funded this study. Some authors declared receiving funding, serving as consultants, or being employed by relevant private companies.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Greater availability of peripheral tri-iodothyronine (T3), indicated by higher concentrations of free T3, T3, and T3/thyroxine (T4) ratio, is associated with increased liver fat content at baseline and a greater liver fat reduction following a dietary intervention known to reduce liver fat.

METHODOLOGY:

- Systemic hypothyroidism and subclinical hypothyroidism are proposed as independent risk factors for steatotic liver disease, but there are conflicting results in euthyroid individuals with normal thyroid function.

- Researchers investigated the association between thyroid function and intrahepatic lipids in 332 euthyroid individuals aged 50-80 years who reported limited alcohol consumption and had at least one condition for unhealthy aging (eg, cardiovascular disease).

- The analysis drew on a sub-cohort from the NutriAct trial, in which participants were randomly assigned to either an intervention group (diet rich in unsaturated fatty acids, plant protein, and fiber) or a control group (following the German Nutrition Society recommendations).

- The relationship between changes in intrahepatic lipid content and thyroid hormone parameters was evaluated in 243 individuals with data available at 12 months.

TAKEAWAY:

- Higher levels of free T3 and T3/T4 ratio were associated with increased liver fat content at baseline (P = .03 and P = .01, respectively).

- After 12 months, both the intervention and control groups showed reductions in liver fat content, along with similar reductions in free T3, total T3, T3/T4 ratio, and free T3/free T4 ratio (all P < .01).

- Thyroid stimulating hormone, T4, and free T4 levels remained stable in either group during the intervention.

- Participants who maintained higher T3 levels during the dietary intervention experienced a greater reduction in liver fat content over 12 months (Rho = −0.133; P = .039).

IN PRACTICE:

“A higher peripheral concentration of active THs [thyroid hormones] might reflect a compensatory mechanism in subjects with mildly increased IHL [intrahepatic lipid] content and early stages of MASLD [metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease],” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Miriam Sommer-Ballarini, Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany. It was published online in the European Journal of Endocrinology.

LIMITATIONS:

Participants younger than 50 years of age and with severe hepatic disease, severe substance abuse, or active cancer were excluded, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Because the study cohort had only mildly elevated median intrahepatic lipid content at baseline, it may not be suited to address the advanced stages of metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease. The study’s findings are based on a specific dietary intervention, which may not be applicable to other dietary patterns or populations.

DISCLOSURES:

The Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and German Federal Ministry for Education and Research funded this study. Some authors declared receiving funding, serving as consultants, or being employed by relevant private companies.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Greater availability of peripheral tri-iodothyronine (T3), indicated by higher concentrations of free T3, T3, and T3/thyroxine (T4) ratio, is associated with increased liver fat content at baseline and a greater liver fat reduction following a dietary intervention known to reduce liver fat.

METHODOLOGY:

- Systemic hypothyroidism and subclinical hypothyroidism are proposed as independent risk factors for steatotic liver disease, but there are conflicting results in euthyroid individuals with normal thyroid function.

- Researchers investigated the association between thyroid function and intrahepatic lipids in 332 euthyroid individuals aged 50-80 years who reported limited alcohol consumption and had at least one condition for unhealthy aging (eg, cardiovascular disease).

- The analysis drew on a sub-cohort from the NutriAct trial, in which participants were randomly assigned to either an intervention group (diet rich in unsaturated fatty acids, plant protein, and fiber) or a control group (following the German Nutrition Society recommendations).

- The relationship between changes in intrahepatic lipid content and thyroid hormone parameters was evaluated in 243 individuals with data available at 12 months.

TAKEAWAY:

- Higher levels of free T3 and T3/T4 ratio were associated with increased liver fat content at baseline (P = .03 and P = .01, respectively).

- After 12 months, both the intervention and control groups showed reductions in liver fat content, along with similar reductions in free T3, total T3, T3/T4 ratio, and free T3/free T4 ratio (all P < .01).

- Thyroid stimulating hormone, T4, and free T4 levels remained stable in either group during the intervention.

- Participants who maintained higher T3 levels during the dietary intervention experienced a greater reduction in liver fat content over 12 months (Rho = −0.133; P = .039).

IN PRACTICE:

“A higher peripheral concentration of active THs [thyroid hormones] might reflect a compensatory mechanism in subjects with mildly increased IHL [intrahepatic lipid] content and early stages of MASLD [metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease],” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Miriam Sommer-Ballarini, Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany. It was published online in the European Journal of Endocrinology.

LIMITATIONS:

Participants younger than 50 years of age and with severe hepatic disease, severe substance abuse, or active cancer were excluded, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Because the study cohort had only mildly elevated median intrahepatic lipid content at baseline, it may not be suited to address the advanced stages of metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease. The study’s findings are based on a specific dietary intervention, which may not be applicable to other dietary patterns or populations.

DISCLOSURES:

The Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and German Federal Ministry for Education and Research funded this study. Some authors declared receiving funding, serving as consultants, or being employed by relevant private companies.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Weight gain despite dieting

Binge-eating disorder is more prevalent in women than men and has one of the strongest associations with obesity; among patients with obesity, lifetime prevalence of binge eating is approximately 5.5%. Large population studies suggest that binge-eating disorder may be present in 2%-4% of adolescents, with a mean age of onset of 12-13 years. This patient probably had milder binge-eating disorder as an adolescent and young adult, which was exacerbated by the pandemic.

Both new diagnoses and reports of clinical worsening in patients with preexisting diagnoses of binge-eating disorder during the pandemic have been documented. Food insecurity has been associated with binge eating, consistent with this patient's anxiety over food and grocery availability during the pandemic. The definition of binge-eating disorder includes recurrent specific episodes of overeating that are not consistent with the patient's usual behavior, eating to the point of being uncomfortably full, eating more quickly or when not hungry, and having feelings of loss of control during episodes and of guilt or disgust afterward.

Obesity and eating disorders share some common risk factors and approaches to management. Binge eating has been associated with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, asthma, sleep disorders, and menstrual disorders, all of which are also affected by obesity. The presence of both conditions increases the adverse outcomes associated with each, including negative impacts on cardiometabolic and psychological health. Workup of patients presenting with binge eating and obesity should always include complete blood/metabolic panels and cardiovascular and renal health, as well as assessments of nutrition status, electrolyte imbalances, gastrointestinal reflux disease, and chronic pain.

In general, where binge-eating disorder and obesity are concurrent, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for binge-eating disorder should be the first priority, with obesity management (medication or surgery) to follow. CBT has the strongest evidence of benefit for patients with binge-eating disorder and is the recommended treatment approach. Other psychotherapeutic interventions that may be of benefit include dialectical behavioral therapy (to reduce binge-eating frequency), technology-based options, and family-based therapy when symptoms are recognized in children or adolescents. Structured behavioral weight management strategies for management of obesity and overweight do not increase symptoms of eating disorders and may instead relieve some symptoms. An emerging approach to binge eating in patients with obesity is CBT that integrates therapeutic approaches to both issues.

Medications to treat binge-eating disorder are limited and should not be used without concurrent psychotherapy; lisdexamfetamine has demonstrated benefit, is recommended by the American Psychiatric Association, and is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration specifically to treat adults with binge-eating disorder.

The success of psychological interventions and lifestyle modifications for obesity is heavily dependent on the individual's ability and motivation to comply with recommended interventions. The American Gastroenterological Association and other organizations recommend treatment with antiobesity medications along with lifestyle modifications for patients with obesity (BMI ≥ 30) and weight-related complications (BMI > 27). Recommended medications include phentermine-topiramate and bupropion-naltrexone (which may benefit those with binge-eating disorder), as well as injectable glucagon-like peptide receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) at the approved dosage for obesity management (semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly or liraglutide 3.0 mg daily). Orlistat is not recommended. Ongoing research on the potential benefit of GLP-1 RAs in management of binge eating offers additional support for a role in patients, like this one, with binge-eating disorder and obesity.

Carolyn Newberry, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of GI Nutrition, Innovative Center for Health and Nutrition in Gastroenterology (ICHANGE), Division of Gastroenterology, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY.

Disclosure: Carolyn Newberry, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Baster International; InBody.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Binge-eating disorder is more prevalent in women than men and has one of the strongest associations with obesity; among patients with obesity, lifetime prevalence of binge eating is approximately 5.5%. Large population studies suggest that binge-eating disorder may be present in 2%-4% of adolescents, with a mean age of onset of 12-13 years. This patient probably had milder binge-eating disorder as an adolescent and young adult, which was exacerbated by the pandemic.

Both new diagnoses and reports of clinical worsening in patients with preexisting diagnoses of binge-eating disorder during the pandemic have been documented. Food insecurity has been associated with binge eating, consistent with this patient's anxiety over food and grocery availability during the pandemic. The definition of binge-eating disorder includes recurrent specific episodes of overeating that are not consistent with the patient's usual behavior, eating to the point of being uncomfortably full, eating more quickly or when not hungry, and having feelings of loss of control during episodes and of guilt or disgust afterward.

Obesity and eating disorders share some common risk factors and approaches to management. Binge eating has been associated with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, asthma, sleep disorders, and menstrual disorders, all of which are also affected by obesity. The presence of both conditions increases the adverse outcomes associated with each, including negative impacts on cardiometabolic and psychological health. Workup of patients presenting with binge eating and obesity should always include complete blood/metabolic panels and cardiovascular and renal health, as well as assessments of nutrition status, electrolyte imbalances, gastrointestinal reflux disease, and chronic pain.

In general, where binge-eating disorder and obesity are concurrent, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for binge-eating disorder should be the first priority, with obesity management (medication or surgery) to follow. CBT has the strongest evidence of benefit for patients with binge-eating disorder and is the recommended treatment approach. Other psychotherapeutic interventions that may be of benefit include dialectical behavioral therapy (to reduce binge-eating frequency), technology-based options, and family-based therapy when symptoms are recognized in children or adolescents. Structured behavioral weight management strategies for management of obesity and overweight do not increase symptoms of eating disorders and may instead relieve some symptoms. An emerging approach to binge eating in patients with obesity is CBT that integrates therapeutic approaches to both issues.

Medications to treat binge-eating disorder are limited and should not be used without concurrent psychotherapy; lisdexamfetamine has demonstrated benefit, is recommended by the American Psychiatric Association, and is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration specifically to treat adults with binge-eating disorder.

The success of psychological interventions and lifestyle modifications for obesity is heavily dependent on the individual's ability and motivation to comply with recommended interventions. The American Gastroenterological Association and other organizations recommend treatment with antiobesity medications along with lifestyle modifications for patients with obesity (BMI ≥ 30) and weight-related complications (BMI > 27). Recommended medications include phentermine-topiramate and bupropion-naltrexone (which may benefit those with binge-eating disorder), as well as injectable glucagon-like peptide receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) at the approved dosage for obesity management (semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly or liraglutide 3.0 mg daily). Orlistat is not recommended. Ongoing research on the potential benefit of GLP-1 RAs in management of binge eating offers additional support for a role in patients, like this one, with binge-eating disorder and obesity.

Carolyn Newberry, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of GI Nutrition, Innovative Center for Health and Nutrition in Gastroenterology (ICHANGE), Division of Gastroenterology, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY.

Disclosure: Carolyn Newberry, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Baster International; InBody.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Binge-eating disorder is more prevalent in women than men and has one of the strongest associations with obesity; among patients with obesity, lifetime prevalence of binge eating is approximately 5.5%. Large population studies suggest that binge-eating disorder may be present in 2%-4% of adolescents, with a mean age of onset of 12-13 years. This patient probably had milder binge-eating disorder as an adolescent and young adult, which was exacerbated by the pandemic.

Both new diagnoses and reports of clinical worsening in patients with preexisting diagnoses of binge-eating disorder during the pandemic have been documented. Food insecurity has been associated with binge eating, consistent with this patient's anxiety over food and grocery availability during the pandemic. The definition of binge-eating disorder includes recurrent specific episodes of overeating that are not consistent with the patient's usual behavior, eating to the point of being uncomfortably full, eating more quickly or when not hungry, and having feelings of loss of control during episodes and of guilt or disgust afterward.

Obesity and eating disorders share some common risk factors and approaches to management. Binge eating has been associated with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, asthma, sleep disorders, and menstrual disorders, all of which are also affected by obesity. The presence of both conditions increases the adverse outcomes associated with each, including negative impacts on cardiometabolic and psychological health. Workup of patients presenting with binge eating and obesity should always include complete blood/metabolic panels and cardiovascular and renal health, as well as assessments of nutrition status, electrolyte imbalances, gastrointestinal reflux disease, and chronic pain.

In general, where binge-eating disorder and obesity are concurrent, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for binge-eating disorder should be the first priority, with obesity management (medication or surgery) to follow. CBT has the strongest evidence of benefit for patients with binge-eating disorder and is the recommended treatment approach. Other psychotherapeutic interventions that may be of benefit include dialectical behavioral therapy (to reduce binge-eating frequency), technology-based options, and family-based therapy when symptoms are recognized in children or adolescents. Structured behavioral weight management strategies for management of obesity and overweight do not increase symptoms of eating disorders and may instead relieve some symptoms. An emerging approach to binge eating in patients with obesity is CBT that integrates therapeutic approaches to both issues.

Medications to treat binge-eating disorder are limited and should not be used without concurrent psychotherapy; lisdexamfetamine has demonstrated benefit, is recommended by the American Psychiatric Association, and is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration specifically to treat adults with binge-eating disorder.

The success of psychological interventions and lifestyle modifications for obesity is heavily dependent on the individual's ability and motivation to comply with recommended interventions. The American Gastroenterological Association and other organizations recommend treatment with antiobesity medications along with lifestyle modifications for patients with obesity (BMI ≥ 30) and weight-related complications (BMI > 27). Recommended medications include phentermine-topiramate and bupropion-naltrexone (which may benefit those with binge-eating disorder), as well as injectable glucagon-like peptide receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) at the approved dosage for obesity management (semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly or liraglutide 3.0 mg daily). Orlistat is not recommended. Ongoing research on the potential benefit of GLP-1 RAs in management of binge eating offers additional support for a role in patients, like this one, with binge-eating disorder and obesity.

Carolyn Newberry, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of GI Nutrition, Innovative Center for Health and Nutrition in Gastroenterology (ICHANGE), Division of Gastroenterology, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY.

Disclosure: Carolyn Newberry, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Baster International; InBody.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

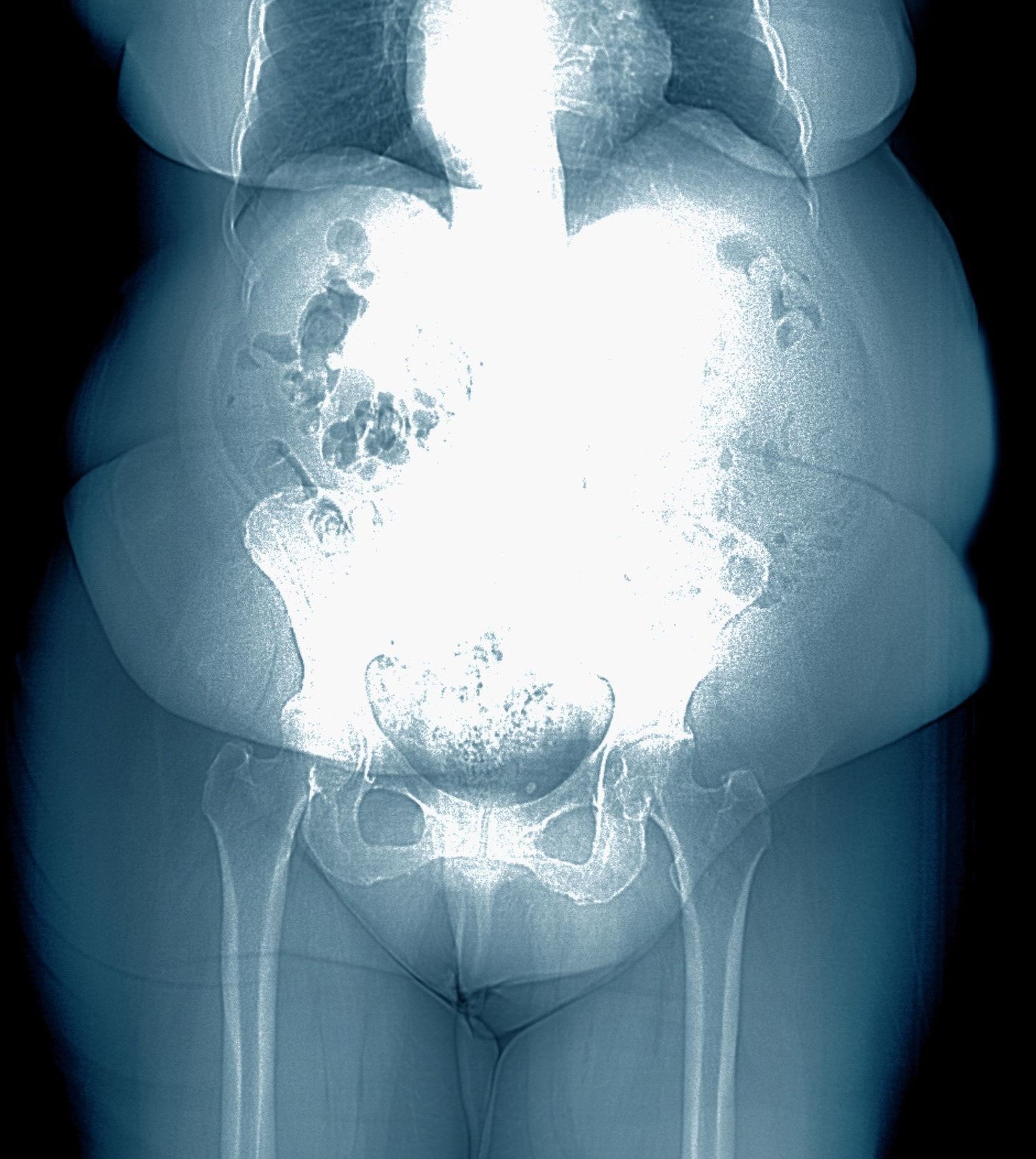

A 28-year-old woman presents with concerns about weight gain despite dieting. She is 5 ft 4 in and weighs 180 lb (BMI 30.9). The patient lives alone and says she often feels isolated and has ongoing anxiety. She states that she has been overweight since her early teen years and had rare episodes of overeating. As an adult, her weight remained relatively stable (BMI ~26) until she began working remotely because of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. She admits to becoming increasingly anxious and worried about food availability and grocery shopping during the early pandemic closures, feelings that have not completely resolved. While working from home, she has had more days where she compulsively overeats, even while trying to diet or use supplements she saw on TV or the internet. She stopped participating in a regular exercise walking group in mid-2020 and has not returned to it.

At presentation, she appears anxious and nervous. Her blood pressure is elevated (140/90 mm Hg), heart rate is 110 beats/min, and respiratory rate is 18 breaths/min. Her results on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder assessment indicate moderate symptoms of anxiety. Lab results indicate A1c = 6.5%, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol = 105 mg/dL, and estimated glomerular filtration rate = 90 mL/min/1.73 m2; all other results are within normal.

How Does ‘Eat Less, Move More’ Promote Obesity Bias?

Experts are debating whether and how to define obesity, but clinicians’ attitudes and behavior toward patients with obesity don’t seem to be undergoing similar scrutiny.

“Despite scientific evidence to the contrary, the prevailing view in society is that obesity is a choice that can be reversed by voluntary decisions to eat less and exercise more,” a multidisciplinary group of 36 international experts wrote in a joint consensus statement for ending the stigma of obesity, published a few years ago in Nature Medicine. “These assumptions mislead public health policies, confuse messages in popular media, undermine access to evidence-based treatments, and compromise advances in research.”

These assumptions also affect how clinicians view and treat their patients.

A systematic review and meta-analysis from Australia using 27 different outcomes to assess weight bias found that “medical doctors, nurses, dietitians, psychologists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech pathologists, podiatrists, and exercise physiologists hold implicit and/or explicit weight-biased attitudes toward people with obesity.”

Another recent systematic review, this one from Brazil, found that obesity bias affected both clinical decision-making and quality of care. Patients with obesity had fewer screening exams for cancer, less-frequent treatment intensification in the management of obesity, and fewer pelvic exams. The authors concluded that their findings “reveal the urgent necessity for reflection and development of strategies to mitigate the adverse impacts” of obesity bias.

“Weight is one of those things that gets judged because it can be seen,” Obesity Society Spokesperson Peminda Cabandugama, MD, of Cleveland Clinic, told this news organization. “People just look at someone with overweight and say, ‘That person needs to eat less and exercise more.’ ”

How Obesity Bias Manifests

The Obesity Action Coalition (OAC), a partner organization to the consensus statement, defines weight bias as “negative attitudes, beliefs, judgments, stereotypes, and discriminatory acts aimed at individuals simply because of their weight. It can be overt or subtle and occur in any setting, including employment, healthcare, education, mass media, and relationships with family and friends.”

The organization notes that weight bias takes many forms, including verbal, written, media, and online.

The consensus statement authors offer these definitions, which encompass the manifestations of obesity bias: Weight stigma refers to “social devaluation and denigration of individuals because of their excess body weight and can lead to negative attitudes, stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination.”

Weight discrimination refers to “overt forms of weight-based prejudice and unfair treatment (biased behaviors) toward individuals with overweight or obesity.” The authors noted that some public health efforts “openly embrace stigmatization of individuals with obesity based on the assumption that shame will motivate them to change behavior and achieve weight loss through a self-directed diet and increased physical exercise.”

The result: “Individuals with obesity face not only increased risk of serious medical complications but also a pervasive, resilient form of social stigma. Often perceived (without evidence) as lazy, gluttonous, lacking will power and self-discipline, individuals with overweight or obesity are vulnerable to stigma and discrimination in the workplace, education, healthcare settings, and society in general.”

“Obesity bias is so pervasive that the most common thing I hear when I ask a patient why they’re referred to me is ‘my doctor wants me to lose weight,’” Dr. Cabandugama said. “And the first thing I ask them is ‘what do you want to do?’ They come in because they’ve already been judged, and more often than not, in ways that come across as derogatory or punitive — like it’s their fault.”

Why It Persists

Experts say a big part of the problem is the lack of obesity education in medical school. A recent survey study found that medical schools are not prioritizing obesity in their curricula. Among 40 medical schools responding to the survey, only 10% said they believed their students were “very prepared” to manage patients with obesity, and one third had no obesity education program in place with no plans to develop one.

“Most healthcare providers do not get much meaningful education on obesity during medical school or postgraduate training, and many of their opinions may be influenced by the pervasive weight bias that exists in society,” affirmed Jaime Almandoz, MD, medical director of Weight Wellness Program and associate professor of internal medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. “We need to prioritize updating education and certification curricula to reflect the current science.”

Small wonder that a recent comparison of explicit weight bias among US resident physicians from 49 medical schools across 16 clinical specialties found “problematic levels” of weight bias — eg, anti-fat blame, anti-fat dislike, and other negative attitudes toward patients — in all specialties.

What to Do

To counteract the stigma, when working with patients who have overweight, “We need to be respectful of them, their bodies, and their health wishes,” Dr. Almandoz told this news organization. “Clinicians should always ask for permission to discuss their weight and frame weight or BMI in the context of health, not just an arbitrary number or goal.”

“Many people with obesity have had traumatic and stigmatizing experiences with well-intentioned healthcare providers,” he noted. “This can lead to the avoidance of routine healthcare and screenings and potential exacerbations and maladaptive health behaviors.”

“Be mindful of the environment that you and your office create for people with obesity,” he advised. “Consider getting additional education and information about weight bias.”

The OAC has resources on obesity bias, including steps clinicians can take to reduce the impact. These include, among others: Encouraging patients to share their experiences of stigma to help them feel less isolated in these experiences; helping them identify ways to effectively cope with stigma, such as using positive “self-talk” and obtaining social support from others; and encouraging participation in activities that they may have restricted due to feelings of shame about their weight.

Clinicians can also improve the physical and social environment of their practice by having bathrooms that are easily negotiated by heavier individuals, sturdy armless chairs in waiting rooms, offices with large exam tables, gowns and blood pressure cuffs in appropriate sizes, and “weight-friendly” reading materials rather than fashion magazines with thin supermodels.

Importantly, clinicians need to address the issue of weight bias within themselves, their medical staff, and colleagues, according to the OAC. To be effective and empathic with individuals affected by obesity “requires honest self-examination of one’s own attitudes and weight bias.”

Dr. Almandoz reported being a consultant/advisory board member for Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Eli Lilly and Company. Dr. Cabandugama reported no competing interests.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Experts are debating whether and how to define obesity, but clinicians’ attitudes and behavior toward patients with obesity don’t seem to be undergoing similar scrutiny.

“Despite scientific evidence to the contrary, the prevailing view in society is that obesity is a choice that can be reversed by voluntary decisions to eat less and exercise more,” a multidisciplinary group of 36 international experts wrote in a joint consensus statement for ending the stigma of obesity, published a few years ago in Nature Medicine. “These assumptions mislead public health policies, confuse messages in popular media, undermine access to evidence-based treatments, and compromise advances in research.”

These assumptions also affect how clinicians view and treat their patients.

A systematic review and meta-analysis from Australia using 27 different outcomes to assess weight bias found that “medical doctors, nurses, dietitians, psychologists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech pathologists, podiatrists, and exercise physiologists hold implicit and/or explicit weight-biased attitudes toward people with obesity.”

Another recent systematic review, this one from Brazil, found that obesity bias affected both clinical decision-making and quality of care. Patients with obesity had fewer screening exams for cancer, less-frequent treatment intensification in the management of obesity, and fewer pelvic exams. The authors concluded that their findings “reveal the urgent necessity for reflection and development of strategies to mitigate the adverse impacts” of obesity bias.

“Weight is one of those things that gets judged because it can be seen,” Obesity Society Spokesperson Peminda Cabandugama, MD, of Cleveland Clinic, told this news organization. “People just look at someone with overweight and say, ‘That person needs to eat less and exercise more.’ ”

How Obesity Bias Manifests

The Obesity Action Coalition (OAC), a partner organization to the consensus statement, defines weight bias as “negative attitudes, beliefs, judgments, stereotypes, and discriminatory acts aimed at individuals simply because of their weight. It can be overt or subtle and occur in any setting, including employment, healthcare, education, mass media, and relationships with family and friends.”

The organization notes that weight bias takes many forms, including verbal, written, media, and online.

The consensus statement authors offer these definitions, which encompass the manifestations of obesity bias: Weight stigma refers to “social devaluation and denigration of individuals because of their excess body weight and can lead to negative attitudes, stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination.”

Weight discrimination refers to “overt forms of weight-based prejudice and unfair treatment (biased behaviors) toward individuals with overweight or obesity.” The authors noted that some public health efforts “openly embrace stigmatization of individuals with obesity based on the assumption that shame will motivate them to change behavior and achieve weight loss through a self-directed diet and increased physical exercise.”

The result: “Individuals with obesity face not only increased risk of serious medical complications but also a pervasive, resilient form of social stigma. Often perceived (without evidence) as lazy, gluttonous, lacking will power and self-discipline, individuals with overweight or obesity are vulnerable to stigma and discrimination in the workplace, education, healthcare settings, and society in general.”

“Obesity bias is so pervasive that the most common thing I hear when I ask a patient why they’re referred to me is ‘my doctor wants me to lose weight,’” Dr. Cabandugama said. “And the first thing I ask them is ‘what do you want to do?’ They come in because they’ve already been judged, and more often than not, in ways that come across as derogatory or punitive — like it’s their fault.”

Why It Persists

Experts say a big part of the problem is the lack of obesity education in medical school. A recent survey study found that medical schools are not prioritizing obesity in their curricula. Among 40 medical schools responding to the survey, only 10% said they believed their students were “very prepared” to manage patients with obesity, and one third had no obesity education program in place with no plans to develop one.

“Most healthcare providers do not get much meaningful education on obesity during medical school or postgraduate training, and many of their opinions may be influenced by the pervasive weight bias that exists in society,” affirmed Jaime Almandoz, MD, medical director of Weight Wellness Program and associate professor of internal medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. “We need to prioritize updating education and certification curricula to reflect the current science.”

Small wonder that a recent comparison of explicit weight bias among US resident physicians from 49 medical schools across 16 clinical specialties found “problematic levels” of weight bias — eg, anti-fat blame, anti-fat dislike, and other negative attitudes toward patients — in all specialties.

What to Do

To counteract the stigma, when working with patients who have overweight, “We need to be respectful of them, their bodies, and their health wishes,” Dr. Almandoz told this news organization. “Clinicians should always ask for permission to discuss their weight and frame weight or BMI in the context of health, not just an arbitrary number or goal.”

“Many people with obesity have had traumatic and stigmatizing experiences with well-intentioned healthcare providers,” he noted. “This can lead to the avoidance of routine healthcare and screenings and potential exacerbations and maladaptive health behaviors.”

“Be mindful of the environment that you and your office create for people with obesity,” he advised. “Consider getting additional education and information about weight bias.”

The OAC has resources on obesity bias, including steps clinicians can take to reduce the impact. These include, among others: Encouraging patients to share their experiences of stigma to help them feel less isolated in these experiences; helping them identify ways to effectively cope with stigma, such as using positive “self-talk” and obtaining social support from others; and encouraging participation in activities that they may have restricted due to feelings of shame about their weight.

Clinicians can also improve the physical and social environment of their practice by having bathrooms that are easily negotiated by heavier individuals, sturdy armless chairs in waiting rooms, offices with large exam tables, gowns and blood pressure cuffs in appropriate sizes, and “weight-friendly” reading materials rather than fashion magazines with thin supermodels.

Importantly, clinicians need to address the issue of weight bias within themselves, their medical staff, and colleagues, according to the OAC. To be effective and empathic with individuals affected by obesity “requires honest self-examination of one’s own attitudes and weight bias.”

Dr. Almandoz reported being a consultant/advisory board member for Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Eli Lilly and Company. Dr. Cabandugama reported no competing interests.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Experts are debating whether and how to define obesity, but clinicians’ attitudes and behavior toward patients with obesity don’t seem to be undergoing similar scrutiny.

“Despite scientific evidence to the contrary, the prevailing view in society is that obesity is a choice that can be reversed by voluntary decisions to eat less and exercise more,” a multidisciplinary group of 36 international experts wrote in a joint consensus statement for ending the stigma of obesity, published a few years ago in Nature Medicine. “These assumptions mislead public health policies, confuse messages in popular media, undermine access to evidence-based treatments, and compromise advances in research.”

These assumptions also affect how clinicians view and treat their patients.

A systematic review and meta-analysis from Australia using 27 different outcomes to assess weight bias found that “medical doctors, nurses, dietitians, psychologists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech pathologists, podiatrists, and exercise physiologists hold implicit and/or explicit weight-biased attitudes toward people with obesity.”

Another recent systematic review, this one from Brazil, found that obesity bias affected both clinical decision-making and quality of care. Patients with obesity had fewer screening exams for cancer, less-frequent treatment intensification in the management of obesity, and fewer pelvic exams. The authors concluded that their findings “reveal the urgent necessity for reflection and development of strategies to mitigate the adverse impacts” of obesity bias.

“Weight is one of those things that gets judged because it can be seen,” Obesity Society Spokesperson Peminda Cabandugama, MD, of Cleveland Clinic, told this news organization. “People just look at someone with overweight and say, ‘That person needs to eat less and exercise more.’ ”

How Obesity Bias Manifests

The Obesity Action Coalition (OAC), a partner organization to the consensus statement, defines weight bias as “negative attitudes, beliefs, judgments, stereotypes, and discriminatory acts aimed at individuals simply because of their weight. It can be overt or subtle and occur in any setting, including employment, healthcare, education, mass media, and relationships with family and friends.”

The organization notes that weight bias takes many forms, including verbal, written, media, and online.

The consensus statement authors offer these definitions, which encompass the manifestations of obesity bias: Weight stigma refers to “social devaluation and denigration of individuals because of their excess body weight and can lead to negative attitudes, stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination.”

Weight discrimination refers to “overt forms of weight-based prejudice and unfair treatment (biased behaviors) toward individuals with overweight or obesity.” The authors noted that some public health efforts “openly embrace stigmatization of individuals with obesity based on the assumption that shame will motivate them to change behavior and achieve weight loss through a self-directed diet and increased physical exercise.”

The result: “Individuals with obesity face not only increased risk of serious medical complications but also a pervasive, resilient form of social stigma. Often perceived (without evidence) as lazy, gluttonous, lacking will power and self-discipline, individuals with overweight or obesity are vulnerable to stigma and discrimination in the workplace, education, healthcare settings, and society in general.”

“Obesity bias is so pervasive that the most common thing I hear when I ask a patient why they’re referred to me is ‘my doctor wants me to lose weight,’” Dr. Cabandugama said. “And the first thing I ask them is ‘what do you want to do?’ They come in because they’ve already been judged, and more often than not, in ways that come across as derogatory or punitive — like it’s their fault.”

Why It Persists

Experts say a big part of the problem is the lack of obesity education in medical school. A recent survey study found that medical schools are not prioritizing obesity in their curricula. Among 40 medical schools responding to the survey, only 10% said they believed their students were “very prepared” to manage patients with obesity, and one third had no obesity education program in place with no plans to develop one.

“Most healthcare providers do not get much meaningful education on obesity during medical school or postgraduate training, and many of their opinions may be influenced by the pervasive weight bias that exists in society,” affirmed Jaime Almandoz, MD, medical director of Weight Wellness Program and associate professor of internal medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. “We need to prioritize updating education and certification curricula to reflect the current science.”

Small wonder that a recent comparison of explicit weight bias among US resident physicians from 49 medical schools across 16 clinical specialties found “problematic levels” of weight bias — eg, anti-fat blame, anti-fat dislike, and other negative attitudes toward patients — in all specialties.

What to Do

To counteract the stigma, when working with patients who have overweight, “We need to be respectful of them, their bodies, and their health wishes,” Dr. Almandoz told this news organization. “Clinicians should always ask for permission to discuss their weight and frame weight or BMI in the context of health, not just an arbitrary number or goal.”

“Many people with obesity have had traumatic and stigmatizing experiences with well-intentioned healthcare providers,” he noted. “This can lead to the avoidance of routine healthcare and screenings and potential exacerbations and maladaptive health behaviors.”

“Be mindful of the environment that you and your office create for people with obesity,” he advised. “Consider getting additional education and information about weight bias.”

The OAC has resources on obesity bias, including steps clinicians can take to reduce the impact. These include, among others: Encouraging patients to share their experiences of stigma to help them feel less isolated in these experiences; helping them identify ways to effectively cope with stigma, such as using positive “self-talk” and obtaining social support from others; and encouraging participation in activities that they may have restricted due to feelings of shame about their weight.

Clinicians can also improve the physical and social environment of their practice by having bathrooms that are easily negotiated by heavier individuals, sturdy armless chairs in waiting rooms, offices with large exam tables, gowns and blood pressure cuffs in appropriate sizes, and “weight-friendly” reading materials rather than fashion magazines with thin supermodels.

Importantly, clinicians need to address the issue of weight bias within themselves, their medical staff, and colleagues, according to the OAC. To be effective and empathic with individuals affected by obesity “requires honest self-examination of one’s own attitudes and weight bias.”

Dr. Almandoz reported being a consultant/advisory board member for Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Eli Lilly and Company. Dr. Cabandugama reported no competing interests.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Weight Loss in Obesity May Create ‘Positive’ Hormone Changes

TOPLINE:

In middle-aged patients with severe obesity, changes in endogenous sex hormones may be proportional to the amount of weight loss after bariatric surgery and dietary intervention, leading to an improved hormonal balance, with more pronounced androgen changes in women.

METHODOLOGY:

- Obesity-related hormonal imbalances are common among those seeking weight loss treatment.

- This prospective observational study evaluated the incremental effect of weight loss by three bariatric procedures and a dietary intervention on endogenous sex hormones in men and women over 3 years.

- The study included 61 adults (median age, 50.9 years; baseline mean body mass index, 40.2; 72% women) from obesity clinics and private bariatric services in Sydney, Australia, between 2009 and 2012, who underwent bariatric surgery or received dietary interventions based on their probability of diabetes remission.

- The researchers evaluated weight loss and hormone levels at baseline and at 6, 12, 24, and 36 months.

- Changes in hormones were also compared among patients who received dietary intervention and those who underwent bariatric procedures such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and laparoscopic gastric banding.

TAKEAWAY:

- In women, testosterone levels decreased and sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG) levels increased at 6 months; these changes were maintained at 24 and 36 months and remained statistically significant when controlled for age and menopausal status.

- In men, testosterone levels were significantly higher at 12, 24, and 36 months, and SHBG levels increased at 12 and 24 months. There were no differences in the estradiol levels among men and women.

- Women who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery experienced the greatest weight loss and the largest reduction (54%) in testosterone levels (P = .004), and sleeve gastrectomy led to an increase of 51% in SHBG levels (P = .0001), all compared with dietary interventions. In men, there were no differences in testosterone and SHBG levels between the diet and surgical groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Ongoing monitoring of hormone levels and metabolic parameters is crucial for patients undergoing bariatric procedures to ensure long-term optimal health outcomes,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Malgorzata M. Brzozowska, MD, PhD, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, Australia, and was published online in the International Journal of Obesity.

LIMITATIONS:

The main limitations were a small sample size, lack of randomization, and absence of data on clinical outcomes related to hormone changes. Additionally, the researchers did not evaluate women for polycystic ovary syndrome or menstrual irregularities, and the clinical significance of testosterone reductions within the normal range remains unknown.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council. Some authors have received honoraria and consulting and research support from various pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

In middle-aged patients with severe obesity, changes in endogenous sex hormones may be proportional to the amount of weight loss after bariatric surgery and dietary intervention, leading to an improved hormonal balance, with more pronounced androgen changes in women.

METHODOLOGY:

- Obesity-related hormonal imbalances are common among those seeking weight loss treatment.

- This prospective observational study evaluated the incremental effect of weight loss by three bariatric procedures and a dietary intervention on endogenous sex hormones in men and women over 3 years.

- The study included 61 adults (median age, 50.9 years; baseline mean body mass index, 40.2; 72% women) from obesity clinics and private bariatric services in Sydney, Australia, between 2009 and 2012, who underwent bariatric surgery or received dietary interventions based on their probability of diabetes remission.

- The researchers evaluated weight loss and hormone levels at baseline and at 6, 12, 24, and 36 months.

- Changes in hormones were also compared among patients who received dietary intervention and those who underwent bariatric procedures such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and laparoscopic gastric banding.

TAKEAWAY:

- In women, testosterone levels decreased and sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG) levels increased at 6 months; these changes were maintained at 24 and 36 months and remained statistically significant when controlled for age and menopausal status.

- In men, testosterone levels were significantly higher at 12, 24, and 36 months, and SHBG levels increased at 12 and 24 months. There were no differences in the estradiol levels among men and women.

- Women who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery experienced the greatest weight loss and the largest reduction (54%) in testosterone levels (P = .004), and sleeve gastrectomy led to an increase of 51% in SHBG levels (P = .0001), all compared with dietary interventions. In men, there were no differences in testosterone and SHBG levels between the diet and surgical groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Ongoing monitoring of hormone levels and metabolic parameters is crucial for patients undergoing bariatric procedures to ensure long-term optimal health outcomes,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Malgorzata M. Brzozowska, MD, PhD, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, Australia, and was published online in the International Journal of Obesity.

LIMITATIONS:

The main limitations were a small sample size, lack of randomization, and absence of data on clinical outcomes related to hormone changes. Additionally, the researchers did not evaluate women for polycystic ovary syndrome or menstrual irregularities, and the clinical significance of testosterone reductions within the normal range remains unknown.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council. Some authors have received honoraria and consulting and research support from various pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

In middle-aged patients with severe obesity, changes in endogenous sex hormones may be proportional to the amount of weight loss after bariatric surgery and dietary intervention, leading to an improved hormonal balance, with more pronounced androgen changes in women.

METHODOLOGY:

- Obesity-related hormonal imbalances are common among those seeking weight loss treatment.

- This prospective observational study evaluated the incremental effect of weight loss by three bariatric procedures and a dietary intervention on endogenous sex hormones in men and women over 3 years.

- The study included 61 adults (median age, 50.9 years; baseline mean body mass index, 40.2; 72% women) from obesity clinics and private bariatric services in Sydney, Australia, between 2009 and 2012, who underwent bariatric surgery or received dietary interventions based on their probability of diabetes remission.

- The researchers evaluated weight loss and hormone levels at baseline and at 6, 12, 24, and 36 months.

- Changes in hormones were also compared among patients who received dietary intervention and those who underwent bariatric procedures such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and laparoscopic gastric banding.

TAKEAWAY:

- In women, testosterone levels decreased and sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG) levels increased at 6 months; these changes were maintained at 24 and 36 months and remained statistically significant when controlled for age and menopausal status.

- In men, testosterone levels were significantly higher at 12, 24, and 36 months, and SHBG levels increased at 12 and 24 months. There were no differences in the estradiol levels among men and women.

- Women who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery experienced the greatest weight loss and the largest reduction (54%) in testosterone levels (P = .004), and sleeve gastrectomy led to an increase of 51% in SHBG levels (P = .0001), all compared with dietary interventions. In men, there were no differences in testosterone and SHBG levels between the diet and surgical groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Ongoing monitoring of hormone levels and metabolic parameters is crucial for patients undergoing bariatric procedures to ensure long-term optimal health outcomes,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Malgorzata M. Brzozowska, MD, PhD, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, Australia, and was published online in the International Journal of Obesity.

LIMITATIONS:

The main limitations were a small sample size, lack of randomization, and absence of data on clinical outcomes related to hormone changes. Additionally, the researchers did not evaluate women for polycystic ovary syndrome or menstrual irregularities, and the clinical significance of testosterone reductions within the normal range remains unknown.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council. Some authors have received honoraria and consulting and research support from various pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Gut Microbiota Tied to Food Addiction Vulnerability

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Food addiction, characterized by a loss of control over food intake, may promote obesity and alter gut microbiota composition.

- Researchers used the Yale Food Addiction Scale 2.0 criteria to classify extreme food addiction and nonaddiction in mouse models and humans.

- The gut microbiota between addicted and nonaddicted mice were compared to identify factors related to food addiction in the murine model. Researchers subsequently gave mice drinking water with the prebiotics lactulose or rhamnose and the bacterium Blautia wexlerae, which has been associated with a reduced risk for obesity and diabetes.

- Gut microbiota signatures were also analyzed in 15 individuals with food addiction and 13 matched controls.

TAKEAWAY:

- In both humans and mice, gut microbiome signatures suggested possible nonbeneficial effects of bacteria in the Proteobacteria phylum and potential protective effects of Actinobacteria against the development of food addiction.

- In correlational analyses, decreased relative abundance of the species B wexlerae was observed in addicted humans and of the Blautia genus in addicted mice.

- Administration of the nondigestible carbohydrates lactulose and rhamnose, known to favor Blautia growth, led to increased relative abundance of Blautia in mouse feces, as well as “dramatic improvements” in food addiction.

- In functional validation experiments, oral administration of B wexlerae in mice led to similar improvement.

IN PRACTICE:

“This novel understanding of the role of gut microbiota in the development of food addiction may open new approaches for developing biomarkers and innovative therapies for food addiction and related eating disorders,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Solveiga Samulėnaitė, a doctoral student at Vilnius University, Vilnius, Lithuania, was published online in Gut.

LIMITATIONS:

Further research is needed to elucidate the exact mechanisms underlying the potential use of gut microbiota for treating food addiction and to test the safety and efficacy in humans.

DISCLOSURES:

This work was supported by La Caixa Health and numerous grants from Spanish ministries and institutions and the European Union. No competing interests were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Food addiction, characterized by a loss of control over food intake, may promote obesity and alter gut microbiota composition.

- Researchers used the Yale Food Addiction Scale 2.0 criteria to classify extreme food addiction and nonaddiction in mouse models and humans.

- The gut microbiota between addicted and nonaddicted mice were compared to identify factors related to food addiction in the murine model. Researchers subsequently gave mice drinking water with the prebiotics lactulose or rhamnose and the bacterium Blautia wexlerae, which has been associated with a reduced risk for obesity and diabetes.

- Gut microbiota signatures were also analyzed in 15 individuals with food addiction and 13 matched controls.

TAKEAWAY:

- In both humans and mice, gut microbiome signatures suggested possible nonbeneficial effects of bacteria in the Proteobacteria phylum and potential protective effects of Actinobacteria against the development of food addiction.

- In correlational analyses, decreased relative abundance of the species B wexlerae was observed in addicted humans and of the Blautia genus in addicted mice.

- Administration of the nondigestible carbohydrates lactulose and rhamnose, known to favor Blautia growth, led to increased relative abundance of Blautia in mouse feces, as well as “dramatic improvements” in food addiction.

- In functional validation experiments, oral administration of B wexlerae in mice led to similar improvement.

IN PRACTICE:

“This novel understanding of the role of gut microbiota in the development of food addiction may open new approaches for developing biomarkers and innovative therapies for food addiction and related eating disorders,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Solveiga Samulėnaitė, a doctoral student at Vilnius University, Vilnius, Lithuania, was published online in Gut.

LIMITATIONS:

Further research is needed to elucidate the exact mechanisms underlying the potential use of gut microbiota for treating food addiction and to test the safety and efficacy in humans.

DISCLOSURES:

This work was supported by La Caixa Health and numerous grants from Spanish ministries and institutions and the European Union. No competing interests were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Food addiction, characterized by a loss of control over food intake, may promote obesity and alter gut microbiota composition.

- Researchers used the Yale Food Addiction Scale 2.0 criteria to classify extreme food addiction and nonaddiction in mouse models and humans.

- The gut microbiota between addicted and nonaddicted mice were compared to identify factors related to food addiction in the murine model. Researchers subsequently gave mice drinking water with the prebiotics lactulose or rhamnose and the bacterium Blautia wexlerae, which has been associated with a reduced risk for obesity and diabetes.

- Gut microbiota signatures were also analyzed in 15 individuals with food addiction and 13 matched controls.

TAKEAWAY:

- In both humans and mice, gut microbiome signatures suggested possible nonbeneficial effects of bacteria in the Proteobacteria phylum and potential protective effects of Actinobacteria against the development of food addiction.

- In correlational analyses, decreased relative abundance of the species B wexlerae was observed in addicted humans and of the Blautia genus in addicted mice.

- Administration of the nondigestible carbohydrates lactulose and rhamnose, known to favor Blautia growth, led to increased relative abundance of Blautia in mouse feces, as well as “dramatic improvements” in food addiction.

- In functional validation experiments, oral administration of B wexlerae in mice led to similar improvement.

IN PRACTICE:

“This novel understanding of the role of gut microbiota in the development of food addiction may open new approaches for developing biomarkers and innovative therapies for food addiction and related eating disorders,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Solveiga Samulėnaitė, a doctoral student at Vilnius University, Vilnius, Lithuania, was published online in Gut.

LIMITATIONS:

Further research is needed to elucidate the exact mechanisms underlying the potential use of gut microbiota for treating food addiction and to test the safety and efficacy in humans.

DISCLOSURES:

This work was supported by La Caixa Health and numerous grants from Spanish ministries and institutions and the European Union. No competing interests were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Obesity: The Basics

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Non-Prescription Semaglutide Purchased Online Poses Risks

Semaglutide products sold online without a prescription may pose multiple risks to consumers, new research found.

Of six test purchases of semaglutide products offered online without a prescription, only three were actually received. The other three vendors demanded additional payment. Of the three delivered, one was potentially contaminated, and all three contained higher concentrations of semaglutide than indicated on the label, potentially resulting in an overdose.

“Semaglutide products are actively being sold without prescription by illegal online pharmacies, with vendors shipping unregistered and falsified products,” wrote Amir Reza Ashraf, PharmD, of the University of Pécs, Hungary, and colleagues in their paper, published online on August 2, 2024, in JAMA Network Open.

The study was conducted in July 2023, but its publication comes a week after the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an alert about dosing errors in compounded semaglutide, which typically does require a prescription.

Study coauthor Tim K. Mackey, PhD, told this news organization, “Compounding pharmacies are another element of this risk that has become more prominent now but arguably have more controls if prescribed appropriately, while the traditional ‘no-prescription’ online market still exists and will continue to evolve.”

Overall, said Dr. Mackey, professor of global health at the University of California San Diego and director of the Global Health Policy and Data Institute,

He advises clinicians to actively discuss with their patients the risks associated with semaglutide and, specifically, the dangers of buying it online. “Clinicians can act as a primary information source for patient safety information by letting their patients know about these risks ... and also asking where patients get their medications in case they are concerned about reports of adverse events or other patient safety issues.”

Buyer Beware: Online Semaglutide Purchases Not as They Seem

The investigators began by searching online for websites advertising semaglutide without a prescription. They ordered products from six online vendors that showed up prominently in the searches. Of those, three offered prefilled 0.25 mg/dose semaglutide injection pens, while the other three sold vials of lyophilized semaglutide powder to be reconstituted to solution for injection. Prices for the smallest dose and quantity ranged from $113 to $360.

Only three of the ordered products — all vials — actually showed up. The advertised prefilled pens were all nondelivery scams, with requests for an extra payment of $650-$1200 purportedly to clear customs. This was confirmed as fraudulent by customs agencies, the authors noted.

The three vial products were received and assessed physically, of both the packaging and the actual product, by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry to determine purity and peptide concentration, and microbiologically, to examine sterility.

Using a checklist from the International Pharmaceutical Federation, Dr. Ashraf and colleagues found “clear discrepancies in regulatory registration information, accurate labeling, and evidence products were likely unregistered or unlicensed.”

Quality testing showed that one sample had an elevated presence of endotoxin suggesting possible contamination. While all three actually did contain semaglutide, the measured content exceeded the labeled amount by 29%-39%, posing a risk that users could receive up to 39% more than intended per injection, “particularly concerning if a consumer has to reconstitute and self-inject,” Dr. Mackey noted.

At least one of these sites in this study, “semaspace.com,” was subsequently sent a warning letter by the FDA for unauthorized semaglutide sale, Mackey noted.

Unfortunately, he told this news organization, these dangers are likely to persist. “There is a strong market opportunity to introduce counterfeit and unauthorized versions of semaglutide. Counterfeiters will continue to innovate with where they sell products, what products they offer, and how they mislead consumers about the safety and legality of what they are offering online. We are likely just at the beginning of counterfeiting of semaglutide, and it is likely that these false products will become endemic in our supply chain.”

The research was supported by the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund. The authors had no further disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Semaglutide products sold online without a prescription may pose multiple risks to consumers, new research found.

Of six test purchases of semaglutide products offered online without a prescription, only three were actually received. The other three vendors demanded additional payment. Of the three delivered, one was potentially contaminated, and all three contained higher concentrations of semaglutide than indicated on the label, potentially resulting in an overdose.

“Semaglutide products are actively being sold without prescription by illegal online pharmacies, with vendors shipping unregistered and falsified products,” wrote Amir Reza Ashraf, PharmD, of the University of Pécs, Hungary, and colleagues in their paper, published online on August 2, 2024, in JAMA Network Open.

The study was conducted in July 2023, but its publication comes a week after the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an alert about dosing errors in compounded semaglutide, which typically does require a prescription.

Study coauthor Tim K. Mackey, PhD, told this news organization, “Compounding pharmacies are another element of this risk that has become more prominent now but arguably have more controls if prescribed appropriately, while the traditional ‘no-prescription’ online market still exists and will continue to evolve.”

Overall, said Dr. Mackey, professor of global health at the University of California San Diego and director of the Global Health Policy and Data Institute,

He advises clinicians to actively discuss with their patients the risks associated with semaglutide and, specifically, the dangers of buying it online. “Clinicians can act as a primary information source for patient safety information by letting their patients know about these risks ... and also asking where patients get their medications in case they are concerned about reports of adverse events or other patient safety issues.”

Buyer Beware: Online Semaglutide Purchases Not as They Seem

The investigators began by searching online for websites advertising semaglutide without a prescription. They ordered products from six online vendors that showed up prominently in the searches. Of those, three offered prefilled 0.25 mg/dose semaglutide injection pens, while the other three sold vials of lyophilized semaglutide powder to be reconstituted to solution for injection. Prices for the smallest dose and quantity ranged from $113 to $360.

Only three of the ordered products — all vials — actually showed up. The advertised prefilled pens were all nondelivery scams, with requests for an extra payment of $650-$1200 purportedly to clear customs. This was confirmed as fraudulent by customs agencies, the authors noted.

The three vial products were received and assessed physically, of both the packaging and the actual product, by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry to determine purity and peptide concentration, and microbiologically, to examine sterility.

Using a checklist from the International Pharmaceutical Federation, Dr. Ashraf and colleagues found “clear discrepancies in regulatory registration information, accurate labeling, and evidence products were likely unregistered or unlicensed.”

Quality testing showed that one sample had an elevated presence of endotoxin suggesting possible contamination. While all three actually did contain semaglutide, the measured content exceeded the labeled amount by 29%-39%, posing a risk that users could receive up to 39% more than intended per injection, “particularly concerning if a consumer has to reconstitute and self-inject,” Dr. Mackey noted.

At least one of these sites in this study, “semaspace.com,” was subsequently sent a warning letter by the FDA for unauthorized semaglutide sale, Mackey noted.

Unfortunately, he told this news organization, these dangers are likely to persist. “There is a strong market opportunity to introduce counterfeit and unauthorized versions of semaglutide. Counterfeiters will continue to innovate with where they sell products, what products they offer, and how they mislead consumers about the safety and legality of what they are offering online. We are likely just at the beginning of counterfeiting of semaglutide, and it is likely that these false products will become endemic in our supply chain.”

The research was supported by the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund. The authors had no further disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Semaglutide products sold online without a prescription may pose multiple risks to consumers, new research found.

Of six test purchases of semaglutide products offered online without a prescription, only three were actually received. The other three vendors demanded additional payment. Of the three delivered, one was potentially contaminated, and all three contained higher concentrations of semaglutide than indicated on the label, potentially resulting in an overdose.

“Semaglutide products are actively being sold without prescription by illegal online pharmacies, with vendors shipping unregistered and falsified products,” wrote Amir Reza Ashraf, PharmD, of the University of Pécs, Hungary, and colleagues in their paper, published online on August 2, 2024, in JAMA Network Open.

The study was conducted in July 2023, but its publication comes a week after the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an alert about dosing errors in compounded semaglutide, which typically does require a prescription.

Study coauthor Tim K. Mackey, PhD, told this news organization, “Compounding pharmacies are another element of this risk that has become more prominent now but arguably have more controls if prescribed appropriately, while the traditional ‘no-prescription’ online market still exists and will continue to evolve.”

Overall, said Dr. Mackey, professor of global health at the University of California San Diego and director of the Global Health Policy and Data Institute,

He advises clinicians to actively discuss with their patients the risks associated with semaglutide and, specifically, the dangers of buying it online. “Clinicians can act as a primary information source for patient safety information by letting their patients know about these risks ... and also asking where patients get their medications in case they are concerned about reports of adverse events or other patient safety issues.”

Buyer Beware: Online Semaglutide Purchases Not as They Seem

The investigators began by searching online for websites advertising semaglutide without a prescription. They ordered products from six online vendors that showed up prominently in the searches. Of those, three offered prefilled 0.25 mg/dose semaglutide injection pens, while the other three sold vials of lyophilized semaglutide powder to be reconstituted to solution for injection. Prices for the smallest dose and quantity ranged from $113 to $360.

Only three of the ordered products — all vials — actually showed up. The advertised prefilled pens were all nondelivery scams, with requests for an extra payment of $650-$1200 purportedly to clear customs. This was confirmed as fraudulent by customs agencies, the authors noted.

The three vial products were received and assessed physically, of both the packaging and the actual product, by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry to determine purity and peptide concentration, and microbiologically, to examine sterility.

Using a checklist from the International Pharmaceutical Federation, Dr. Ashraf and colleagues found “clear discrepancies in regulatory registration information, accurate labeling, and evidence products were likely unregistered or unlicensed.”

Quality testing showed that one sample had an elevated presence of endotoxin suggesting possible contamination. While all three actually did contain semaglutide, the measured content exceeded the labeled amount by 29%-39%, posing a risk that users could receive up to 39% more than intended per injection, “particularly concerning if a consumer has to reconstitute and self-inject,” Dr. Mackey noted.

At least one of these sites in this study, “semaspace.com,” was subsequently sent a warning letter by the FDA for unauthorized semaglutide sale, Mackey noted.

Unfortunately, he told this news organization, these dangers are likely to persist. “There is a strong market opportunity to introduce counterfeit and unauthorized versions of semaglutide. Counterfeiters will continue to innovate with where they sell products, what products they offer, and how they mislead consumers about the safety and legality of what they are offering online. We are likely just at the beginning of counterfeiting of semaglutide, and it is likely that these false products will become endemic in our supply chain.”

The research was supported by the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund. The authors had no further disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Ozempic Curbs Hunger – And Not Just for Food

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

If you’ve been paying attention only to the headlines, when you think of “Ozempic” you’ll think of a few things: a blockbuster weight loss drug or the tip of the spear of a completely new industry — why not? A drug so popular that the people it was invented for (those with diabetes) can’t even get it.

Ozempic and other GLP-1 receptor agonists are undeniable game changers. Insofar as obesity is the number-one public health risk in the United States, antiobesity drugs hold immense promise even if all they do is reduce obesity.

In 2023, an article in Scientific Reports presented data suggesting that people on Ozempic might be reducing their alcohol intake, not just their total calories.