User login

‘How could he?’

The headline in a Portland, Maine, newspaper read, “Standish man sentenced to serve 15 years in prison for death of his 3-month-old son” (Edward Murphy, May 23, 2017). I suspect that many of the folks who read the story under the headline feel that the sentence was too light. Others are asking themselves how a 21-year-old man could beat a fragile 5-pound infant to death. What kind of evil monster is this guy?

However, even with the snatches of information provided in the 500-word newspaper story, the unfortunate scenario makes sense, and the child’s death is a tragic culmination of a series of events that shouldn’t surprise any pediatrician. It turns out the infant was a twin who, with his sister, had been born at 30 weeks’ gestation. He had spent a month or more in the hospital, and his sister was still in neonatal ICU at the time of his death. While it is unclear from the newspaper article whether the twins’ parents were married, they were living in a house with eight other adults and some other children. The mother was out of the home working while the father was left to care for his son.

I am sure that the neonatologists and social workers at the hospital where the twins were born were aware of at least some of the red flags that waved over this unfortunate family. I also am confident that they did what they could to assure this infant a safe home environment when it was time for his discharge from the NICU. However, risks factors may have been missed that now seem obvious in retrospect. We should all realize by now from our experience with domestic terrorism that simply appearing on someone’s radar doesn’t mean that preemptive action can or will be taken. Short of keeping the parents of high-risk neonates under constant surveillance for a year or 2, there are few other workable options to prevent every tragedy like this one.

This case is another example of the erosive power of a baby’s cry. Most pediatricians have developed a filtering mechanism that allows us to function in a cacophonous environment dominated by a screaming infant. However, even adults without this young father’s deprived background crack under the stress when they are confined in a space with a crying child. The risk of decompensation is compounded when the adult also feels some responsibility for the child’s welfare. I don’t think we can condone what the father did in this tragic scenario, but we can certainly understand how the dominoes fell.

We are all potential child abusers. When faced with the right, or I guess the wrong, set of circumstances we might lash out to stop the crying. Luckily, most of us are several body lengths from the end of that rope.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

The headline in a Portland, Maine, newspaper read, “Standish man sentenced to serve 15 years in prison for death of his 3-month-old son” (Edward Murphy, May 23, 2017). I suspect that many of the folks who read the story under the headline feel that the sentence was too light. Others are asking themselves how a 21-year-old man could beat a fragile 5-pound infant to death. What kind of evil monster is this guy?

However, even with the snatches of information provided in the 500-word newspaper story, the unfortunate scenario makes sense, and the child’s death is a tragic culmination of a series of events that shouldn’t surprise any pediatrician. It turns out the infant was a twin who, with his sister, had been born at 30 weeks’ gestation. He had spent a month or more in the hospital, and his sister was still in neonatal ICU at the time of his death. While it is unclear from the newspaper article whether the twins’ parents were married, they were living in a house with eight other adults and some other children. The mother was out of the home working while the father was left to care for his son.

I am sure that the neonatologists and social workers at the hospital where the twins were born were aware of at least some of the red flags that waved over this unfortunate family. I also am confident that they did what they could to assure this infant a safe home environment when it was time for his discharge from the NICU. However, risks factors may have been missed that now seem obvious in retrospect. We should all realize by now from our experience with domestic terrorism that simply appearing on someone’s radar doesn’t mean that preemptive action can or will be taken. Short of keeping the parents of high-risk neonates under constant surveillance for a year or 2, there are few other workable options to prevent every tragedy like this one.

This case is another example of the erosive power of a baby’s cry. Most pediatricians have developed a filtering mechanism that allows us to function in a cacophonous environment dominated by a screaming infant. However, even adults without this young father’s deprived background crack under the stress when they are confined in a space with a crying child. The risk of decompensation is compounded when the adult also feels some responsibility for the child’s welfare. I don’t think we can condone what the father did in this tragic scenario, but we can certainly understand how the dominoes fell.

We are all potential child abusers. When faced with the right, or I guess the wrong, set of circumstances we might lash out to stop the crying. Luckily, most of us are several body lengths from the end of that rope.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

The headline in a Portland, Maine, newspaper read, “Standish man sentenced to serve 15 years in prison for death of his 3-month-old son” (Edward Murphy, May 23, 2017). I suspect that many of the folks who read the story under the headline feel that the sentence was too light. Others are asking themselves how a 21-year-old man could beat a fragile 5-pound infant to death. What kind of evil monster is this guy?

However, even with the snatches of information provided in the 500-word newspaper story, the unfortunate scenario makes sense, and the child’s death is a tragic culmination of a series of events that shouldn’t surprise any pediatrician. It turns out the infant was a twin who, with his sister, had been born at 30 weeks’ gestation. He had spent a month or more in the hospital, and his sister was still in neonatal ICU at the time of his death. While it is unclear from the newspaper article whether the twins’ parents were married, they were living in a house with eight other adults and some other children. The mother was out of the home working while the father was left to care for his son.

I am sure that the neonatologists and social workers at the hospital where the twins were born were aware of at least some of the red flags that waved over this unfortunate family. I also am confident that they did what they could to assure this infant a safe home environment when it was time for his discharge from the NICU. However, risks factors may have been missed that now seem obvious in retrospect. We should all realize by now from our experience with domestic terrorism that simply appearing on someone’s radar doesn’t mean that preemptive action can or will be taken. Short of keeping the parents of high-risk neonates under constant surveillance for a year or 2, there are few other workable options to prevent every tragedy like this one.

This case is another example of the erosive power of a baby’s cry. Most pediatricians have developed a filtering mechanism that allows us to function in a cacophonous environment dominated by a screaming infant. However, even adults without this young father’s deprived background crack under the stress when they are confined in a space with a crying child. The risk of decompensation is compounded when the adult also feels some responsibility for the child’s welfare. I don’t think we can condone what the father did in this tragic scenario, but we can certainly understand how the dominoes fell.

We are all potential child abusers. When faced with the right, or I guess the wrong, set of circumstances we might lash out to stop the crying. Luckily, most of us are several body lengths from the end of that rope.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Not better late ...

You all know the statistics or at least have a sense of the scope of the problem. While 85% of mothers in this country intend to breastfeed their infants exclusively for at least 3 months, only slightly more than 30% achieve this goal. Among the dozens of reasons for this unfortunate shortfall is what some experts view as inadequate support by primary care physicians and their offices. In the May 2017 Pediatrics, two members of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding offer a clinical report that hopes to remedy this situation (“The Breastfeeding-Friendly Pediatric Office Practice.” Pediatrics. 2017 May. 139[5]:e20170647). It is a document that begins with an excellent review of the background and epidemiology of breastfeeding in the United States and a survey of the current initiatives targeted at improving our dismal performance. What follows is an extensive set of 19 evidence-based recommendations for the pediatric outpatient practice that hopes to “meet or exceed the AAP recommendations.”

A large part of the problem is the failure of the point person in the office, usually the receptionist, to realize that a tearful call from a new mother who is struggling with breastfeeding is an emergency, one that demands a response in minutes … not hours. Even when the call is eventually routed to someone with a compassionate voice who will call back with the right answers, if that process takes just an hour or two, that is enough time for a mother with a screaming and hungry newborn to reach for a bottle of formula.

I urge you to read this exhaustive clinical report in Pediatrics because it is very likely you will come across some things that you can include in your office practice to make it more breastfeeding friendly. However, Even if you and your staff have the right advice, this is not a situation of “better late than never.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

You all know the statistics or at least have a sense of the scope of the problem. While 85% of mothers in this country intend to breastfeed their infants exclusively for at least 3 months, only slightly more than 30% achieve this goal. Among the dozens of reasons for this unfortunate shortfall is what some experts view as inadequate support by primary care physicians and their offices. In the May 2017 Pediatrics, two members of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding offer a clinical report that hopes to remedy this situation (“The Breastfeeding-Friendly Pediatric Office Practice.” Pediatrics. 2017 May. 139[5]:e20170647). It is a document that begins with an excellent review of the background and epidemiology of breastfeeding in the United States and a survey of the current initiatives targeted at improving our dismal performance. What follows is an extensive set of 19 evidence-based recommendations for the pediatric outpatient practice that hopes to “meet or exceed the AAP recommendations.”

A large part of the problem is the failure of the point person in the office, usually the receptionist, to realize that a tearful call from a new mother who is struggling with breastfeeding is an emergency, one that demands a response in minutes … not hours. Even when the call is eventually routed to someone with a compassionate voice who will call back with the right answers, if that process takes just an hour or two, that is enough time for a mother with a screaming and hungry newborn to reach for a bottle of formula.

I urge you to read this exhaustive clinical report in Pediatrics because it is very likely you will come across some things that you can include in your office practice to make it more breastfeeding friendly. However, Even if you and your staff have the right advice, this is not a situation of “better late than never.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

You all know the statistics or at least have a sense of the scope of the problem. While 85% of mothers in this country intend to breastfeed their infants exclusively for at least 3 months, only slightly more than 30% achieve this goal. Among the dozens of reasons for this unfortunate shortfall is what some experts view as inadequate support by primary care physicians and their offices. In the May 2017 Pediatrics, two members of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding offer a clinical report that hopes to remedy this situation (“The Breastfeeding-Friendly Pediatric Office Practice.” Pediatrics. 2017 May. 139[5]:e20170647). It is a document that begins with an excellent review of the background and epidemiology of breastfeeding in the United States and a survey of the current initiatives targeted at improving our dismal performance. What follows is an extensive set of 19 evidence-based recommendations for the pediatric outpatient practice that hopes to “meet or exceed the AAP recommendations.”

A large part of the problem is the failure of the point person in the office, usually the receptionist, to realize that a tearful call from a new mother who is struggling with breastfeeding is an emergency, one that demands a response in minutes … not hours. Even when the call is eventually routed to someone with a compassionate voice who will call back with the right answers, if that process takes just an hour or two, that is enough time for a mother with a screaming and hungry newborn to reach for a bottle of formula.

I urge you to read this exhaustive clinical report in Pediatrics because it is very likely you will come across some things that you can include in your office practice to make it more breastfeeding friendly. However, Even if you and your staff have the right advice, this is not a situation of “better late than never.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

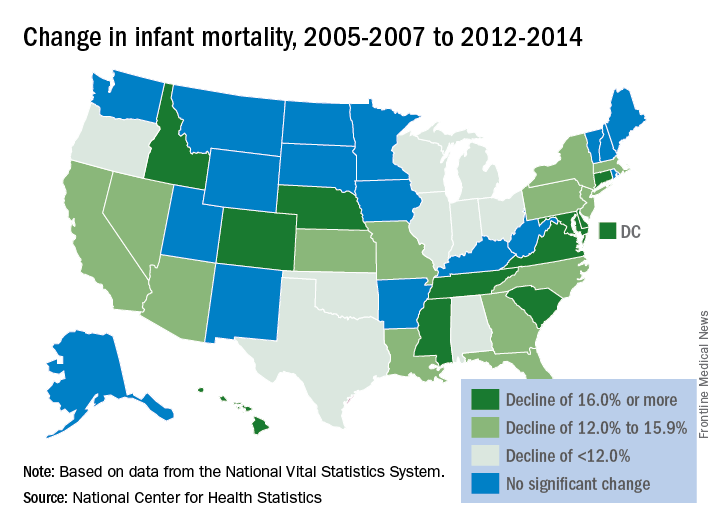

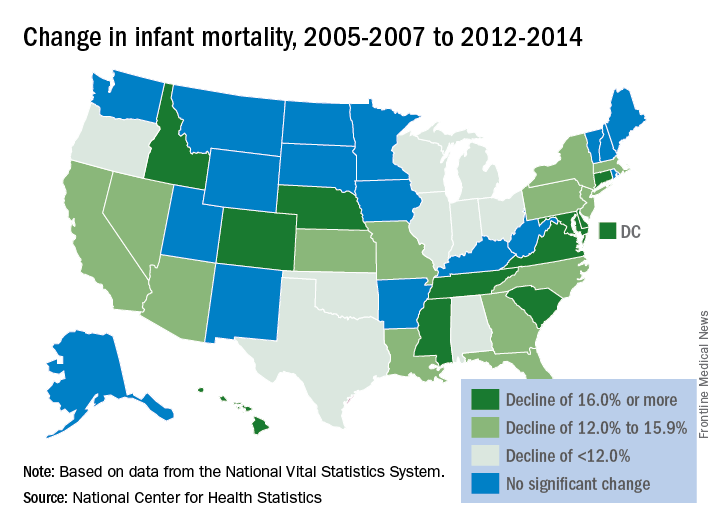

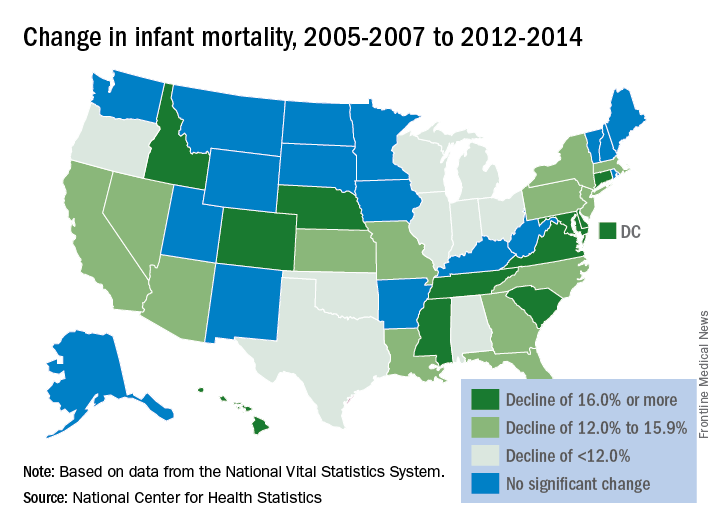

Infant mortality down in most states

Infant mortality in the United States was down by 15% from 2005 to 2014, with 33 states reporting significant declines, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

The overall rate for 2014 was 5.82 infant deaths per 1,000 live births, compared with 6.84 per 1,000 in 2005. The data for individual states were grouped into 3-year periods, so between the periods of 2005-2007 and 2012-2014, there were 33 states (and the District of Columbia) with a significant decline and 17 states with no significant change. Three states – Maine, South Dakota, and Utah – had increased infant mortality, but the changes did not reach significance, the NCHS reported, using data from the National Vital Statistics System.

Infant mortality in the United States was down by 15% from 2005 to 2014, with 33 states reporting significant declines, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

The overall rate for 2014 was 5.82 infant deaths per 1,000 live births, compared with 6.84 per 1,000 in 2005. The data for individual states were grouped into 3-year periods, so between the periods of 2005-2007 and 2012-2014, there were 33 states (and the District of Columbia) with a significant decline and 17 states with no significant change. Three states – Maine, South Dakota, and Utah – had increased infant mortality, but the changes did not reach significance, the NCHS reported, using data from the National Vital Statistics System.

Infant mortality in the United States was down by 15% from 2005 to 2014, with 33 states reporting significant declines, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

The overall rate for 2014 was 5.82 infant deaths per 1,000 live births, compared with 6.84 per 1,000 in 2005. The data for individual states were grouped into 3-year periods, so between the periods of 2005-2007 and 2012-2014, there were 33 states (and the District of Columbia) with a significant decline and 17 states with no significant change. Three states – Maine, South Dakota, and Utah – had increased infant mortality, but the changes did not reach significance, the NCHS reported, using data from the National Vital Statistics System.

Management of asymptomatic chorioamnionitis-exposed neonates needs revamping

Clinical observation and laboratory evaluation without immediate antibiotic use in asymptomatic chorioamnionitis-exposed neonates prevented neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission in two-thirds of these infants, Amanda I. Jan, MD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and her associates reported in a study.

Since maternal intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis was introduced, neonatal early-onset sepsis (EOS) rates have dropped considerably, and rates remain low even in chorioamnionitis-exposed infants. Despite these low risks, current American Academy of Pediatrics and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations still call for a limited laboratory evaluation and immediate empirical antibiotic therapy in all infants exposed to chorioamnionitis, often necessitating NICU admission for IV antibiotics, the researchers noted.

Of the 78 infants admitted to the NICU and put on antibiotics, 76% were treated with antibiotics for more than 72 hours, with a median 7 days of treatment, compared with a median 2 days for nonadmitted infants (P less than .001). Only 85% of admitted infants received any breast milk, compared with 94% of infants in the mother-infant unit (P = .032), and none of the admitted infants were exclusively breastfed.

“When the overall risks of EOS are low, exposure of large numbers of well-appearing infants to even short courses of antibiotics is no longer justified,” Dr. Jan and her associates stated. “The [difference in] cost of a stay in the mother-infant unit for 2 days, compared with a NICU stay, which averaged a week, is substantial. The charge for our NICU is $12,612 per day in contrast to $5,300 per day in the mother-infant unit. The cost savings for the 162 infants who were cared for 2 days in the mother-infant unit, compared with an EOS evaluation and antibiotic therapy in the NICU, totals $2,369,088, or $359,861 per year.

“There were no deaths or morbidities identified in any infant during the study period,” they reported. No infant was readmitted to the study hospital for sepsis after discharge.

Dr. Jan and her associates recommend their alternative management of asymptomatic chorioamnionitis-exposed neonates involving lab evaluations and close clinical observation without immediate antibiotic administration in a mother-infant unit. They believe this prevents unnecessary antibiotic exposure, unnecessarily high hospitalization costs, and disruption of maternal-neonatal bonding and breastfeeding. Additional studies are needed to determine the safety of this approach.

This study received no external funding, and Dr. Jan and her associates reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Jan and her associates have taken steps in the right direction in altering management of asymptomatic term and near-term newborns with a maternal history of chorioamnionitis to avoid administering empirical antibiotics to all these babies, which is sorely needed as the current American Academy of Pediatrics and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines are outdated.

However, their alternative plan needs some tweaking. The positive predictive value of abnormal complete blood count or C-reactive protein results is too low to be of use in diagnosing sepsis. “We believe a better approach would be to forgo routine laboratory evaluations among this population altogether and manage them using clinical signs alone.”

They said it was important to state two key caveats. “First, in the immediate postpartum period, mild respiratory distress among term or near-term newborns may be attributable to the physiologic transition, which occurs in all newborn infants. It is not necessary to draw laboratories or start antibiotics on these patients as long as their symptoms improve and resolve within the first 6 hours of life. Second, if newborns with a maternal history of chorioamnionitis are to be monitored for signs of sepsis outside the NICU setting, observations must be frequent (at least hourly for the first 6 hours of life and then every 3 hours for the next 18 hours) and performed by adequately trained medical staff. In the absence of frequent, reliable observation, there is a possibility that the early signs of sepsis will be missed and go untreated with potentially severe consequences.”

This approach, as with any other, needs additional study.

Thomas A. Hooven, MD, and Richard A. Polin, MD, pediatricians at the Columbia University, New York, discussed the study by Jan et al. in a commentary, which is summarized here (Pediatrics. 2017;140[1]:e20171155). They reported that they received no external funding and had no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Jan and her associates have taken steps in the right direction in altering management of asymptomatic term and near-term newborns with a maternal history of chorioamnionitis to avoid administering empirical antibiotics to all these babies, which is sorely needed as the current American Academy of Pediatrics and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines are outdated.

However, their alternative plan needs some tweaking. The positive predictive value of abnormal complete blood count or C-reactive protein results is too low to be of use in diagnosing sepsis. “We believe a better approach would be to forgo routine laboratory evaluations among this population altogether and manage them using clinical signs alone.”

They said it was important to state two key caveats. “First, in the immediate postpartum period, mild respiratory distress among term or near-term newborns may be attributable to the physiologic transition, which occurs in all newborn infants. It is not necessary to draw laboratories or start antibiotics on these patients as long as their symptoms improve and resolve within the first 6 hours of life. Second, if newborns with a maternal history of chorioamnionitis are to be monitored for signs of sepsis outside the NICU setting, observations must be frequent (at least hourly for the first 6 hours of life and then every 3 hours for the next 18 hours) and performed by adequately trained medical staff. In the absence of frequent, reliable observation, there is a possibility that the early signs of sepsis will be missed and go untreated with potentially severe consequences.”

This approach, as with any other, needs additional study.

Thomas A. Hooven, MD, and Richard A. Polin, MD, pediatricians at the Columbia University, New York, discussed the study by Jan et al. in a commentary, which is summarized here (Pediatrics. 2017;140[1]:e20171155). They reported that they received no external funding and had no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Jan and her associates have taken steps in the right direction in altering management of asymptomatic term and near-term newborns with a maternal history of chorioamnionitis to avoid administering empirical antibiotics to all these babies, which is sorely needed as the current American Academy of Pediatrics and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines are outdated.

However, their alternative plan needs some tweaking. The positive predictive value of abnormal complete blood count or C-reactive protein results is too low to be of use in diagnosing sepsis. “We believe a better approach would be to forgo routine laboratory evaluations among this population altogether and manage them using clinical signs alone.”

They said it was important to state two key caveats. “First, in the immediate postpartum period, mild respiratory distress among term or near-term newborns may be attributable to the physiologic transition, which occurs in all newborn infants. It is not necessary to draw laboratories or start antibiotics on these patients as long as their symptoms improve and resolve within the first 6 hours of life. Second, if newborns with a maternal history of chorioamnionitis are to be monitored for signs of sepsis outside the NICU setting, observations must be frequent (at least hourly for the first 6 hours of life and then every 3 hours for the next 18 hours) and performed by adequately trained medical staff. In the absence of frequent, reliable observation, there is a possibility that the early signs of sepsis will be missed and go untreated with potentially severe consequences.”

This approach, as with any other, needs additional study.

Thomas A. Hooven, MD, and Richard A. Polin, MD, pediatricians at the Columbia University, New York, discussed the study by Jan et al. in a commentary, which is summarized here (Pediatrics. 2017;140[1]:e20171155). They reported that they received no external funding and had no relevant financial disclosures.

Clinical observation and laboratory evaluation without immediate antibiotic use in asymptomatic chorioamnionitis-exposed neonates prevented neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission in two-thirds of these infants, Amanda I. Jan, MD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and her associates reported in a study.

Since maternal intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis was introduced, neonatal early-onset sepsis (EOS) rates have dropped considerably, and rates remain low even in chorioamnionitis-exposed infants. Despite these low risks, current American Academy of Pediatrics and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations still call for a limited laboratory evaluation and immediate empirical antibiotic therapy in all infants exposed to chorioamnionitis, often necessitating NICU admission for IV antibiotics, the researchers noted.

Of the 78 infants admitted to the NICU and put on antibiotics, 76% were treated with antibiotics for more than 72 hours, with a median 7 days of treatment, compared with a median 2 days for nonadmitted infants (P less than .001). Only 85% of admitted infants received any breast milk, compared with 94% of infants in the mother-infant unit (P = .032), and none of the admitted infants were exclusively breastfed.

“When the overall risks of EOS are low, exposure of large numbers of well-appearing infants to even short courses of antibiotics is no longer justified,” Dr. Jan and her associates stated. “The [difference in] cost of a stay in the mother-infant unit for 2 days, compared with a NICU stay, which averaged a week, is substantial. The charge for our NICU is $12,612 per day in contrast to $5,300 per day in the mother-infant unit. The cost savings for the 162 infants who were cared for 2 days in the mother-infant unit, compared with an EOS evaluation and antibiotic therapy in the NICU, totals $2,369,088, or $359,861 per year.

“There were no deaths or morbidities identified in any infant during the study period,” they reported. No infant was readmitted to the study hospital for sepsis after discharge.

Dr. Jan and her associates recommend their alternative management of asymptomatic chorioamnionitis-exposed neonates involving lab evaluations and close clinical observation without immediate antibiotic administration in a mother-infant unit. They believe this prevents unnecessary antibiotic exposure, unnecessarily high hospitalization costs, and disruption of maternal-neonatal bonding and breastfeeding. Additional studies are needed to determine the safety of this approach.

This study received no external funding, and Dr. Jan and her associates reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Clinical observation and laboratory evaluation without immediate antibiotic use in asymptomatic chorioamnionitis-exposed neonates prevented neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission in two-thirds of these infants, Amanda I. Jan, MD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and her associates reported in a study.

Since maternal intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis was introduced, neonatal early-onset sepsis (EOS) rates have dropped considerably, and rates remain low even in chorioamnionitis-exposed infants. Despite these low risks, current American Academy of Pediatrics and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations still call for a limited laboratory evaluation and immediate empirical antibiotic therapy in all infants exposed to chorioamnionitis, often necessitating NICU admission for IV antibiotics, the researchers noted.

Of the 78 infants admitted to the NICU and put on antibiotics, 76% were treated with antibiotics for more than 72 hours, with a median 7 days of treatment, compared with a median 2 days for nonadmitted infants (P less than .001). Only 85% of admitted infants received any breast milk, compared with 94% of infants in the mother-infant unit (P = .032), and none of the admitted infants were exclusively breastfed.

“When the overall risks of EOS are low, exposure of large numbers of well-appearing infants to even short courses of antibiotics is no longer justified,” Dr. Jan and her associates stated. “The [difference in] cost of a stay in the mother-infant unit for 2 days, compared with a NICU stay, which averaged a week, is substantial. The charge for our NICU is $12,612 per day in contrast to $5,300 per day in the mother-infant unit. The cost savings for the 162 infants who were cared for 2 days in the mother-infant unit, compared with an EOS evaluation and antibiotic therapy in the NICU, totals $2,369,088, or $359,861 per year.

“There were no deaths or morbidities identified in any infant during the study period,” they reported. No infant was readmitted to the study hospital for sepsis after discharge.

Dr. Jan and her associates recommend their alternative management of asymptomatic chorioamnionitis-exposed neonates involving lab evaluations and close clinical observation without immediate antibiotic administration in a mother-infant unit. They believe this prevents unnecessary antibiotic exposure, unnecessarily high hospitalization costs, and disruption of maternal-neonatal bonding and breastfeeding. Additional studies are needed to determine the safety of this approach.

This study received no external funding, and Dr. Jan and her associates reported no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Alternative management of asymptomatic chorioamnionitis-exposed neonates will prevent unnecessary antibiotic exposure, unnecessarily high hospitalization costs, and disruption of maternal-neonatal bonding and breastfeeding.

Major finding: Of the 240 infants, 67.5% remained well with a routine newborn course in the mother-infant unit and 32.5% subsequently were admitted to the NICU because of abnormal laboratory data, a positive blood culture, or the onset of clinical signs of sepsis.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 240 asymptomatic chorioamnionitis-exposed neonates.

Disclosures: This study received no external funding, and Dr. Jan and her associates reported no relevant financial disclosures.

First trimester lithium exposure ups risk of cardiac malformations

Cardiac malformations are three times more likely to occur in infants exposed to lithium during the first trimester of gestation than in unexposed infants.

The increased risk could account for one additional cardiac malformation per 100 live births, Elisabetta Patorno, MD, and her colleagues wrote in the June 8 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine (2017;376:2245-54).

Dr. Patorno’s study is the largest conducted since then. It comprised more than 1.3 million pregnancies included in the U.S. Medicaid Analytic eXtract database during 2000-2010. Of these, 663 had first trimester lithium exposure. These were compared with 1,945 pregnancies with first trimester exposure to lamotrigine, another mood stabilizer, and to the remaining 1.3 million pregnancies unexposed to either drug.

There were 16 cardiac malformations in the lithium group (2.41%); 27 in the lamotrigine group (1.39%); and 15,251 in the unexposed group (1.15%). Lithium conferred a 65% increased risk of cardiac defect, compared with unexposed pregnancies. It more than doubled the risk when compared with lamotrigine-exposed pregnancies (risk ratio, 2.25).

The risk was dose dependent, however, with an 11% increase associated with 600 mg/day or less and a 60% increase associated with 601-900 mg/day. Infants exposed to more than 900 mg per day in the first trimester, however, were more than 300% more likely to have a cardiac malformation (RR, 3.22).

The investigators also examined the association of lithium with cardiac defects consistent with Ebstein’s anomaly. Lithium more than doubled the risk, compared with unexposed infants (RR, 2.66). This risk was also dose dependent; all of the right ventricular outflow defects occurred in infants exposed to more than 600 mg/day.

Dr. Patorno reported grant support from National Institute of Mental Health during the study and grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim and GlaxoSmithKline outside of the study. Other authors reported receiving grants or personal fees from various pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

Cardiac malformations are three times more likely to occur in infants exposed to lithium during the first trimester of gestation than in unexposed infants.

The increased risk could account for one additional cardiac malformation per 100 live births, Elisabetta Patorno, MD, and her colleagues wrote in the June 8 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine (2017;376:2245-54).

Dr. Patorno’s study is the largest conducted since then. It comprised more than 1.3 million pregnancies included in the U.S. Medicaid Analytic eXtract database during 2000-2010. Of these, 663 had first trimester lithium exposure. These were compared with 1,945 pregnancies with first trimester exposure to lamotrigine, another mood stabilizer, and to the remaining 1.3 million pregnancies unexposed to either drug.

There were 16 cardiac malformations in the lithium group (2.41%); 27 in the lamotrigine group (1.39%); and 15,251 in the unexposed group (1.15%). Lithium conferred a 65% increased risk of cardiac defect, compared with unexposed pregnancies. It more than doubled the risk when compared with lamotrigine-exposed pregnancies (risk ratio, 2.25).

The risk was dose dependent, however, with an 11% increase associated with 600 mg/day or less and a 60% increase associated with 601-900 mg/day. Infants exposed to more than 900 mg per day in the first trimester, however, were more than 300% more likely to have a cardiac malformation (RR, 3.22).

The investigators also examined the association of lithium with cardiac defects consistent with Ebstein’s anomaly. Lithium more than doubled the risk, compared with unexposed infants (RR, 2.66). This risk was also dose dependent; all of the right ventricular outflow defects occurred in infants exposed to more than 600 mg/day.

Dr. Patorno reported grant support from National Institute of Mental Health during the study and grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim and GlaxoSmithKline outside of the study. Other authors reported receiving grants or personal fees from various pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

Cardiac malformations are three times more likely to occur in infants exposed to lithium during the first trimester of gestation than in unexposed infants.

The increased risk could account for one additional cardiac malformation per 100 live births, Elisabetta Patorno, MD, and her colleagues wrote in the June 8 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine (2017;376:2245-54).

Dr. Patorno’s study is the largest conducted since then. It comprised more than 1.3 million pregnancies included in the U.S. Medicaid Analytic eXtract database during 2000-2010. Of these, 663 had first trimester lithium exposure. These were compared with 1,945 pregnancies with first trimester exposure to lamotrigine, another mood stabilizer, and to the remaining 1.3 million pregnancies unexposed to either drug.

There were 16 cardiac malformations in the lithium group (2.41%); 27 in the lamotrigine group (1.39%); and 15,251 in the unexposed group (1.15%). Lithium conferred a 65% increased risk of cardiac defect, compared with unexposed pregnancies. It more than doubled the risk when compared with lamotrigine-exposed pregnancies (risk ratio, 2.25).

The risk was dose dependent, however, with an 11% increase associated with 600 mg/day or less and a 60% increase associated with 601-900 mg/day. Infants exposed to more than 900 mg per day in the first trimester, however, were more than 300% more likely to have a cardiac malformation (RR, 3.22).

The investigators also examined the association of lithium with cardiac defects consistent with Ebstein’s anomaly. Lithium more than doubled the risk, compared with unexposed infants (RR, 2.66). This risk was also dose dependent; all of the right ventricular outflow defects occurred in infants exposed to more than 600 mg/day.

Dr. Patorno reported grant support from National Institute of Mental Health during the study and grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim and GlaxoSmithKline outside of the study. Other authors reported receiving grants or personal fees from various pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The dose-dependent increased risks ranged from 11% to more than 300%, compared with unexposed pregnancies.

Data source: The Medicaid database review comprised more than 1.3 million pregnancies.

Disclosures: Dr. Patorno reported grant support from National Institute of Mental Health during the study and grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim and GlaxoSmithKline outside of the study. Other authors reported receiving grants or personal fees from various pharmaceutical companies.

Study contradicts AAP recommendations on infant room-sharing

Infants who slept in their own rooms by age 9 months slept significantly longer and better than those who continued sharing a room with their parents as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics, the authors of a prospective study of 279 mother-infant dyads reported June 5.

The findings “raise questions about the well-intended AAP recommendation that room-sharing should ideally occur for all infants until their first birthday,” wrote Ian M. Paul, MD, of Penn State University, Hershey, and his associates (Pediatrics. 2017 Jun 5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0122). “Perhaps our most troubling finding was that room-sharing was associated with overnight transitions to bed-sharing, which is strongly discouraged by the AAP.”

Insufficient sleep leads to excess weight gain during infancy and sleep problems later in childhood and has negative implications for parents. “The desire to optimize infant sleep duration and consolidation, however, must be balanced with safe infant sleep,” the researchers emphasized. About 3,500 infants die annually of SIDS and other sleep-related deaths, about 90% of which occur before age 6 months. Currently, however, the AAP’s updated 2016 recommendations advise that infants sleep on a separate surface in their parents’ room for at least the first 6 months and ideally for 1 year (Pediatrics. 2016; 138:e20162938).

To examine relationships among where, how well, and how long infants slept, the researchers analyzed Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaires collected from first-time mothers of term singletons as part of the prospective, single-center Intervention Nurses Start Infants Growing on Healthy Trajectories (INSIGHT) study.

For 4-month-olds, average reported sleep duration was similar whether they slept alone or in the parental bedroom. Solo sleepers, however, had better sleep consolidation, averaging 46 more minutes of sleep at the longest stretch, compared with room sharers (P = .02). By age 9 months, infants who had slept alone by age 4 months averaged 40 more minutes of nightly sleep than room-sharers and 26 more minutes than infants who began sleeping alone after 4 months of age (P = .008). Furthermore, the average longest sleep span of early solo sleepers was 100 minutes more than that of room-sharers and 45 minutes more than that of infants who began sleeping alone between ages 4 and 9 months (P = .01).

At age 30 months, infants who had slept alone by age 9 months averaged 45 more minutes of nightly sleep than those who had shared a room (P = .004). Room-sharing at 4 months also was tied to a two-fold greater odds of having pillows, blankets, or other unsafe objects on the sleep surface, the researchers said. Together, the findings support revising the AAP recommendation until evidence conclusively supports it, they concluded.

The study’s funders included Penn State University, Hershey; Penn State Children’s Hospital; the U.S. Department of Agriculture; the Penn State Clinical and Translational Science Institute, and the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

The study by Dr. Paul and his associates is an important contribution to the literature, wrote Rachel Y. Moon, MD, and Fern R. Hauck, MD, in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2017 Jun 5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1323). However, they said, more research is needed.

For example, it is unclear whether sleep consolidation in young infants is preferable from a physiologic perspective. “The ability to arouse is critical physiologically, and a leading hypothesis is that failure to arouse makes an infant vulnerable to SIDS,” they wrote.

Dr. Moon and Dr. Hauck also noted that the AAP’s recommendation on room-sharing without bed-sharing is based on studies conducted in England, New Zealand, and Scotland showing that room-sharing lowers the risk of SIDS, compared with solitary sleeping.

“More recent, unpublished data from the New Zealand Sudden and Unexplained Death in Infancy study show similar protection from room-sharing, with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.36 (95% confidence interval, 0.19-0.71) for room-sharing infants compared with solitary-sleeping infants (E. Mitchell, MBBS, personal communication, 2016),” they wrote. “Because none of these studies stratified the risk by infant age in months, it is difficult to determine the optimal endpoint for room-sharing.

“We strongly support more research, both about the physiology of infant sleep and arousal for room-sharing infants and about the consequences of room-sharing on parental and child sleep.”

Dr. Moon and Dr. Hauck are with the University of Virginia, Charlottesville. They had no relevant disclosures.

The study by Dr. Paul and his associates is an important contribution to the literature, wrote Rachel Y. Moon, MD, and Fern R. Hauck, MD, in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2017 Jun 5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1323). However, they said, more research is needed.

For example, it is unclear whether sleep consolidation in young infants is preferable from a physiologic perspective. “The ability to arouse is critical physiologically, and a leading hypothesis is that failure to arouse makes an infant vulnerable to SIDS,” they wrote.

Dr. Moon and Dr. Hauck also noted that the AAP’s recommendation on room-sharing without bed-sharing is based on studies conducted in England, New Zealand, and Scotland showing that room-sharing lowers the risk of SIDS, compared with solitary sleeping.

“More recent, unpublished data from the New Zealand Sudden and Unexplained Death in Infancy study show similar protection from room-sharing, with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.36 (95% confidence interval, 0.19-0.71) for room-sharing infants compared with solitary-sleeping infants (E. Mitchell, MBBS, personal communication, 2016),” they wrote. “Because none of these studies stratified the risk by infant age in months, it is difficult to determine the optimal endpoint for room-sharing.

“We strongly support more research, both about the physiology of infant sleep and arousal for room-sharing infants and about the consequences of room-sharing on parental and child sleep.”

Dr. Moon and Dr. Hauck are with the University of Virginia, Charlottesville. They had no relevant disclosures.

The study by Dr. Paul and his associates is an important contribution to the literature, wrote Rachel Y. Moon, MD, and Fern R. Hauck, MD, in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2017 Jun 5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1323). However, they said, more research is needed.

For example, it is unclear whether sleep consolidation in young infants is preferable from a physiologic perspective. “The ability to arouse is critical physiologically, and a leading hypothesis is that failure to arouse makes an infant vulnerable to SIDS,” they wrote.

Dr. Moon and Dr. Hauck also noted that the AAP’s recommendation on room-sharing without bed-sharing is based on studies conducted in England, New Zealand, and Scotland showing that room-sharing lowers the risk of SIDS, compared with solitary sleeping.

“More recent, unpublished data from the New Zealand Sudden and Unexplained Death in Infancy study show similar protection from room-sharing, with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.36 (95% confidence interval, 0.19-0.71) for room-sharing infants compared with solitary-sleeping infants (E. Mitchell, MBBS, personal communication, 2016),” they wrote. “Because none of these studies stratified the risk by infant age in months, it is difficult to determine the optimal endpoint for room-sharing.

“We strongly support more research, both about the physiology of infant sleep and arousal for room-sharing infants and about the consequences of room-sharing on parental and child sleep.”

Dr. Moon and Dr. Hauck are with the University of Virginia, Charlottesville. They had no relevant disclosures.

Infants who slept in their own rooms by age 9 months slept significantly longer and better than those who continued sharing a room with their parents as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics, the authors of a prospective study of 279 mother-infant dyads reported June 5.

The findings “raise questions about the well-intended AAP recommendation that room-sharing should ideally occur for all infants until their first birthday,” wrote Ian M. Paul, MD, of Penn State University, Hershey, and his associates (Pediatrics. 2017 Jun 5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0122). “Perhaps our most troubling finding was that room-sharing was associated with overnight transitions to bed-sharing, which is strongly discouraged by the AAP.”

Insufficient sleep leads to excess weight gain during infancy and sleep problems later in childhood and has negative implications for parents. “The desire to optimize infant sleep duration and consolidation, however, must be balanced with safe infant sleep,” the researchers emphasized. About 3,500 infants die annually of SIDS and other sleep-related deaths, about 90% of which occur before age 6 months. Currently, however, the AAP’s updated 2016 recommendations advise that infants sleep on a separate surface in their parents’ room for at least the first 6 months and ideally for 1 year (Pediatrics. 2016; 138:e20162938).

To examine relationships among where, how well, and how long infants slept, the researchers analyzed Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaires collected from first-time mothers of term singletons as part of the prospective, single-center Intervention Nurses Start Infants Growing on Healthy Trajectories (INSIGHT) study.

For 4-month-olds, average reported sleep duration was similar whether they slept alone or in the parental bedroom. Solo sleepers, however, had better sleep consolidation, averaging 46 more minutes of sleep at the longest stretch, compared with room sharers (P = .02). By age 9 months, infants who had slept alone by age 4 months averaged 40 more minutes of nightly sleep than room-sharers and 26 more minutes than infants who began sleeping alone after 4 months of age (P = .008). Furthermore, the average longest sleep span of early solo sleepers was 100 minutes more than that of room-sharers and 45 minutes more than that of infants who began sleeping alone between ages 4 and 9 months (P = .01).

At age 30 months, infants who had slept alone by age 9 months averaged 45 more minutes of nightly sleep than those who had shared a room (P = .004). Room-sharing at 4 months also was tied to a two-fold greater odds of having pillows, blankets, or other unsafe objects on the sleep surface, the researchers said. Together, the findings support revising the AAP recommendation until evidence conclusively supports it, they concluded.

The study’s funders included Penn State University, Hershey; Penn State Children’s Hospital; the U.S. Department of Agriculture; the Penn State Clinical and Translational Science Institute, and the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

Infants who slept in their own rooms by age 9 months slept significantly longer and better than those who continued sharing a room with their parents as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics, the authors of a prospective study of 279 mother-infant dyads reported June 5.

The findings “raise questions about the well-intended AAP recommendation that room-sharing should ideally occur for all infants until their first birthday,” wrote Ian M. Paul, MD, of Penn State University, Hershey, and his associates (Pediatrics. 2017 Jun 5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0122). “Perhaps our most troubling finding was that room-sharing was associated with overnight transitions to bed-sharing, which is strongly discouraged by the AAP.”

Insufficient sleep leads to excess weight gain during infancy and sleep problems later in childhood and has negative implications for parents. “The desire to optimize infant sleep duration and consolidation, however, must be balanced with safe infant sleep,” the researchers emphasized. About 3,500 infants die annually of SIDS and other sleep-related deaths, about 90% of which occur before age 6 months. Currently, however, the AAP’s updated 2016 recommendations advise that infants sleep on a separate surface in their parents’ room for at least the first 6 months and ideally for 1 year (Pediatrics. 2016; 138:e20162938).

To examine relationships among where, how well, and how long infants slept, the researchers analyzed Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaires collected from first-time mothers of term singletons as part of the prospective, single-center Intervention Nurses Start Infants Growing on Healthy Trajectories (INSIGHT) study.

For 4-month-olds, average reported sleep duration was similar whether they slept alone or in the parental bedroom. Solo sleepers, however, had better sleep consolidation, averaging 46 more minutes of sleep at the longest stretch, compared with room sharers (P = .02). By age 9 months, infants who had slept alone by age 4 months averaged 40 more minutes of nightly sleep than room-sharers and 26 more minutes than infants who began sleeping alone after 4 months of age (P = .008). Furthermore, the average longest sleep span of early solo sleepers was 100 minutes more than that of room-sharers and 45 minutes more than that of infants who began sleeping alone between ages 4 and 9 months (P = .01).

At age 30 months, infants who had slept alone by age 9 months averaged 45 more minutes of nightly sleep than those who had shared a room (P = .004). Room-sharing at 4 months also was tied to a two-fold greater odds of having pillows, blankets, or other unsafe objects on the sleep surface, the researchers said. Together, the findings support revising the AAP recommendation until evidence conclusively supports it, they concluded.

The study’s funders included Penn State University, Hershey; Penn State Children’s Hospital; the U.S. Department of Agriculture; the Penn State Clinical and Translational Science Institute, and the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Infants who slept in their own room by age 4 months slept significantly longer and better than those who continued sharing a room with their parents as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Major finding: By age 9 months, infants who had slept alone by age 4 months averaged 40 more minutes of nightly sleep than room sharers and 26 more minutes than infants who began sleeping alone after 4 months of age (P = .008). Furthermore, the average longest sleep span of early solo sleepers was 100 minutes more than that of room-sharers and 45 minutes more than that of infants who began sleeping alone between ages 4 and 9 months (P = .01).

Data source: Secondary analyses of 279 mother-infant dyads from the single-center, prospective Intervention Nurses Start Infants Growing on Healthy Trajectories (INSIGHT) study.

Disclosures: The study funders included Penn State University, Hershey; Penn State Children’s Hospital; the U.S. Department of Agriculture; the Penn State Clinical and Translational Science Institute, and the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

Caffeine therapy of VLBW neonates reduces later motor impairment

SAN FRANCISCO – The 11-year follow-up results of the Caffeine for Apnea of Prematurity randomized, placebo-controlled trial has established the benefits of methylated xanthine therapy in the form of caffeine for very-low-birth-weight (VLBW) neonates in lessening the risk of motor impairment.

“The latest findings bolster the value of caffeine therapy to address apnea of prematurity in VLBW neonates. The CAP trial has provided compelling evidence for the use of caffeine even before this latest finding of improved motor function at age 11 years,” said presenter and the CAP trial’s principal investigator Barbara Schmidt, MD, of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

At least 5 of every 1,000 live-born babies are very premature with a VLBW. Up of 40% die or survive with lasting disabilities. One cause of mortality or disability is apnea. Apnea can be lessened by treatment with methylxanthines such as caffeine, she noted. However, at the time the CAP trial began, it was unclear whether the therapy posed a danger by worsening the damage caused by lack of oxygen.

“Very few studies have followed more recent cohorts of very preterm infants to middle school age. Therefore, it was difficult to anticipate actual rates of functional impairment, and the possible effect of caffeine on those rates,” said Dr. Schmidt.

As reported about a decade ago, the CAP trial involving VLBW infants randomized to caffeine therapy or placebo established the short-term safety and effectiveness of the therapy in terms of reducing cerebral palsy and cognitive delay (N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1893-902).

Follow-ups at 18 months and 5 years revealed the benefits of caffeine therapy in reducing the rates of bronchopulmonary dysplasia, severe retinopathy, and neurodevelopmental disability. The present follow-up data assessed academic performance, motor function, and behavior in 1,202 children with a median age of 11 years. Of these, 602 had received caffeine therapy and 600 had been randomized to the placebo group. Data at age 11 years was available for 457 and 463 of the children randomized to caffeine therapy or placebo, respectively.

The primary outcome was functional impairment, which was indicated by at least one of poor academic performance (with at least one standard score more than two standard deviations below the mean on the Wide Range Achievement Test, 4th edition), motor impairment (percentile rank of 5 or less on the Movement Assessment Battery for Children, Second Edition), and behavior problems (Total Problem T score more than two standard deviations above the mean on the Child Behavior Checklist).

Functional impairment was evident in 145 the 457 (32%) children who had received caffeine therapy and 174 of the 463 (38%) who had not. The rates of 32% and 38% were statistically similar (P = .07). In the individual functional outcomes, the caffeine and placebo groups also were similar in terms of poor academic performance (14% vs. 13%; P = .58) and behavior (11% vs. 8%, respectively; P = .22).

However, caffeine therapy was associated with a reduced risk of motor impairment at age 11 years, compared with those in the placebo group (20% vs. 28%, respectively; odds ratio [OR], 0.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.48-0.90; P = .009). The number of children needed to treat to lessen motor impairment in one child was 13 (95% CI, 8-42).

“Caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity did not significantly reduce the combined rate of academic, motor, and behavioral impairments at age 11 years. However, caffeine therapy reduced the risk of motor impairment 11 years later,” said Dr. Schmidt. Whether caffeine therapy using higher doses or longer treatment duration is equally risk free is uncertain and further studies, which are not planned, would be needed, she said.

These 11-year follow-up findings of the CAP trial were published online in JAMA Pediatrics (2017, Apr 24. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0238).

The sponsor of study was McMaster University. The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Dr. Schmidt had no relevant financial disclosures to report.

SAN FRANCISCO – The 11-year follow-up results of the Caffeine for Apnea of Prematurity randomized, placebo-controlled trial has established the benefits of methylated xanthine therapy in the form of caffeine for very-low-birth-weight (VLBW) neonates in lessening the risk of motor impairment.

“The latest findings bolster the value of caffeine therapy to address apnea of prematurity in VLBW neonates. The CAP trial has provided compelling evidence for the use of caffeine even before this latest finding of improved motor function at age 11 years,” said presenter and the CAP trial’s principal investigator Barbara Schmidt, MD, of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

At least 5 of every 1,000 live-born babies are very premature with a VLBW. Up of 40% die or survive with lasting disabilities. One cause of mortality or disability is apnea. Apnea can be lessened by treatment with methylxanthines such as caffeine, she noted. However, at the time the CAP trial began, it was unclear whether the therapy posed a danger by worsening the damage caused by lack of oxygen.

“Very few studies have followed more recent cohorts of very preterm infants to middle school age. Therefore, it was difficult to anticipate actual rates of functional impairment, and the possible effect of caffeine on those rates,” said Dr. Schmidt.

As reported about a decade ago, the CAP trial involving VLBW infants randomized to caffeine therapy or placebo established the short-term safety and effectiveness of the therapy in terms of reducing cerebral palsy and cognitive delay (N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1893-902).

Follow-ups at 18 months and 5 years revealed the benefits of caffeine therapy in reducing the rates of bronchopulmonary dysplasia, severe retinopathy, and neurodevelopmental disability. The present follow-up data assessed academic performance, motor function, and behavior in 1,202 children with a median age of 11 years. Of these, 602 had received caffeine therapy and 600 had been randomized to the placebo group. Data at age 11 years was available for 457 and 463 of the children randomized to caffeine therapy or placebo, respectively.

The primary outcome was functional impairment, which was indicated by at least one of poor academic performance (with at least one standard score more than two standard deviations below the mean on the Wide Range Achievement Test, 4th edition), motor impairment (percentile rank of 5 or less on the Movement Assessment Battery for Children, Second Edition), and behavior problems (Total Problem T score more than two standard deviations above the mean on the Child Behavior Checklist).

Functional impairment was evident in 145 the 457 (32%) children who had received caffeine therapy and 174 of the 463 (38%) who had not. The rates of 32% and 38% were statistically similar (P = .07). In the individual functional outcomes, the caffeine and placebo groups also were similar in terms of poor academic performance (14% vs. 13%; P = .58) and behavior (11% vs. 8%, respectively; P = .22).

However, caffeine therapy was associated with a reduced risk of motor impairment at age 11 years, compared with those in the placebo group (20% vs. 28%, respectively; odds ratio [OR], 0.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.48-0.90; P = .009). The number of children needed to treat to lessen motor impairment in one child was 13 (95% CI, 8-42).

“Caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity did not significantly reduce the combined rate of academic, motor, and behavioral impairments at age 11 years. However, caffeine therapy reduced the risk of motor impairment 11 years later,” said Dr. Schmidt. Whether caffeine therapy using higher doses or longer treatment duration is equally risk free is uncertain and further studies, which are not planned, would be needed, she said.

These 11-year follow-up findings of the CAP trial were published online in JAMA Pediatrics (2017, Apr 24. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0238).

The sponsor of study was McMaster University. The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Dr. Schmidt had no relevant financial disclosures to report.

SAN FRANCISCO – The 11-year follow-up results of the Caffeine for Apnea of Prematurity randomized, placebo-controlled trial has established the benefits of methylated xanthine therapy in the form of caffeine for very-low-birth-weight (VLBW) neonates in lessening the risk of motor impairment.

“The latest findings bolster the value of caffeine therapy to address apnea of prematurity in VLBW neonates. The CAP trial has provided compelling evidence for the use of caffeine even before this latest finding of improved motor function at age 11 years,” said presenter and the CAP trial’s principal investigator Barbara Schmidt, MD, of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

At least 5 of every 1,000 live-born babies are very premature with a VLBW. Up of 40% die or survive with lasting disabilities. One cause of mortality or disability is apnea. Apnea can be lessened by treatment with methylxanthines such as caffeine, she noted. However, at the time the CAP trial began, it was unclear whether the therapy posed a danger by worsening the damage caused by lack of oxygen.

“Very few studies have followed more recent cohorts of very preterm infants to middle school age. Therefore, it was difficult to anticipate actual rates of functional impairment, and the possible effect of caffeine on those rates,” said Dr. Schmidt.

As reported about a decade ago, the CAP trial involving VLBW infants randomized to caffeine therapy or placebo established the short-term safety and effectiveness of the therapy in terms of reducing cerebral palsy and cognitive delay (N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1893-902).

Follow-ups at 18 months and 5 years revealed the benefits of caffeine therapy in reducing the rates of bronchopulmonary dysplasia, severe retinopathy, and neurodevelopmental disability. The present follow-up data assessed academic performance, motor function, and behavior in 1,202 children with a median age of 11 years. Of these, 602 had received caffeine therapy and 600 had been randomized to the placebo group. Data at age 11 years was available for 457 and 463 of the children randomized to caffeine therapy or placebo, respectively.

The primary outcome was functional impairment, which was indicated by at least one of poor academic performance (with at least one standard score more than two standard deviations below the mean on the Wide Range Achievement Test, 4th edition), motor impairment (percentile rank of 5 or less on the Movement Assessment Battery for Children, Second Edition), and behavior problems (Total Problem T score more than two standard deviations above the mean on the Child Behavior Checklist).

Functional impairment was evident in 145 the 457 (32%) children who had received caffeine therapy and 174 of the 463 (38%) who had not. The rates of 32% and 38% were statistically similar (P = .07). In the individual functional outcomes, the caffeine and placebo groups also were similar in terms of poor academic performance (14% vs. 13%; P = .58) and behavior (11% vs. 8%, respectively; P = .22).

However, caffeine therapy was associated with a reduced risk of motor impairment at age 11 years, compared with those in the placebo group (20% vs. 28%, respectively; odds ratio [OR], 0.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.48-0.90; P = .009). The number of children needed to treat to lessen motor impairment in one child was 13 (95% CI, 8-42).

“Caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity did not significantly reduce the combined rate of academic, motor, and behavioral impairments at age 11 years. However, caffeine therapy reduced the risk of motor impairment 11 years later,” said Dr. Schmidt. Whether caffeine therapy using higher doses or longer treatment duration is equally risk free is uncertain and further studies, which are not planned, would be needed, she said.

These 11-year follow-up findings of the CAP trial were published online in JAMA Pediatrics (2017, Apr 24. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0238).

The sponsor of study was McMaster University. The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Dr. Schmidt had no relevant financial disclosures to report.

AT PAS 17

Key clinical point:

Major finding: At the 11-year follow-up, motor impairment was identified in 20% of those who received caffeine therapy versus 28% of those in the placebo group (P = .009).

Data source: Multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (NCT00182312).

Disclosures: The sponsor of study was McMaster University. The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Dr. Schmidt had no relevant financial disclosures to report.

Drainage, irrigation, and fibrinolytic therapy held safe, effective for PHVD

SAN FRANCISCO – The 10-year follow-up of neonates treated for posthemorrhagic ventricular dilatation (PHVD) has demonstrated the long-term success of drainage, irrigation, and fibrinolytic therapy (DRIFT), with a cognitive advantage in the now school-age children evident, compared with those neonates who had not received the therapy.

“Children in the DRIFT group had a 23-point cognitive quotient advantage and were nine times more likely to be alive without severe cognitive disability at 10 years,” presenter and DRIFT investigator Karen Luyt, MBChB, PhD, of the University of Bristol and St. Michael’s Hospital, Bristol, England, said at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting.

PHVD carries a high risk of disabilities in cognition and movement. DRIFT was developed as a way to wash out the ventricles in the brain to clear the effects of bleeding, with the goal of reducing neurodevelopmental disability. In the technique, catheters are inserted into the affected ventricles and are used to deliver an anti-clotting agent (alteplase) and to drain the bloody fluid. The catheters remain in place for a time as a conduit for artificial cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) containing antibiotics.

In the DRIFT trial, 77 preterm infants were randomized to DRIFT (n = 39) or the standard treatment of siphoning off cerebrospinal fluid to restrict brain expansion (n = 38). At 2 years, the DRIFT group displayed fewer cases of severe disability and cognitive disability, and death (Pediatrics. 2010 Apr;125[4]:e852-8).

Dr. Luyt summarized the final 10-year data from 52 school-age children (28 treated using DRIFT and 24 treated in the standard manner). The primary outcomes in the school-age children were cognitive quotient (CQ) and survival without severe cognitive disability. Secondary outcomes included visual function, sensory and motor disabilities, and emotional or behavior problems.

The age at the time of treatment randomization was 19 days in the DRIFT group and 19 days in the standard group. The DRIFT group was composed of more males (79% vs. 63%) and newborns with lower birth weight (336 vs. 535 grams). The gestational age and the prevalence of grade 4 intraventricular hemorrhage were similar between the groups.

DRIFT increased cognitive ability at 10 years (P = .096). Adjustment for gender, birth weight, and grade of intraventricular hemorrhage strengthened this association, with the DRIFT group having an average advantage in CQ score of 23.5 points (P = .009), which translated to a 2.5-year advantage in cognitive ability. When the data was further adjusted by ruling out the three children (two in the DRIFT group and one in the standard treatment group) who died between the 2- and 10-year follow-ups, the CQ score advantage remained (20 points; P = .029).

The other primary outcome of survival without severe cognitive disability also favored DRIFT, with an unadjusted odds ratio (OR) of 3.3 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1-10.4 (P = .037) and adjusted (as above) OR of 8.9 (95% CI, 1.9-42.3; P = .006). Fewer children in the DRIFT group were attending schools with an expertise in special needs (OR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.07-1.05; P = .059). No differences between the groups were evident for the secondary outcomes.

The number needed to treat to prevent death or severe cognitive disability was four.

Dr. Luyt’s recommendation that DRIFT become the standard of care for neonatal intraventricular hemorrhage comes with the caveat of increased secondary bleeding, which caused the trial to be halted after a planned external safety monitoring review. Children who already had been treated were followed up, with no further recruitment. In her response to a question from the audience regarding her endorsement of DRIFT despite the trial’s halt, Dr. Luyt pointed to the comparable safety profiles of the two groups, the superior outcomes in the DRIFT group, and the knowledge that modifications made to the technique in the intervening years have reduced the possibility of secondary bleeds.

The sponsor of study was Dr. Birgit Whitman of the University of Bristol. The study was funded by the National Institute of Health’s Health Technology Assessment Programme. Dr. Luyt disclosed the off-label use of alteplase.

SAN FRANCISCO – The 10-year follow-up of neonates treated for posthemorrhagic ventricular dilatation (PHVD) has demonstrated the long-term success of drainage, irrigation, and fibrinolytic therapy (DRIFT), with a cognitive advantage in the now school-age children evident, compared with those neonates who had not received the therapy.

“Children in the DRIFT group had a 23-point cognitive quotient advantage and were nine times more likely to be alive without severe cognitive disability at 10 years,” presenter and DRIFT investigator Karen Luyt, MBChB, PhD, of the University of Bristol and St. Michael’s Hospital, Bristol, England, said at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting.

PHVD carries a high risk of disabilities in cognition and movement. DRIFT was developed as a way to wash out the ventricles in the brain to clear the effects of bleeding, with the goal of reducing neurodevelopmental disability. In the technique, catheters are inserted into the affected ventricles and are used to deliver an anti-clotting agent (alteplase) and to drain the bloody fluid. The catheters remain in place for a time as a conduit for artificial cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) containing antibiotics.

In the DRIFT trial, 77 preterm infants were randomized to DRIFT (n = 39) or the standard treatment of siphoning off cerebrospinal fluid to restrict brain expansion (n = 38). At 2 years, the DRIFT group displayed fewer cases of severe disability and cognitive disability, and death (Pediatrics. 2010 Apr;125[4]:e852-8).

Dr. Luyt summarized the final 10-year data from 52 school-age children (28 treated using DRIFT and 24 treated in the standard manner). The primary outcomes in the school-age children were cognitive quotient (CQ) and survival without severe cognitive disability. Secondary outcomes included visual function, sensory and motor disabilities, and emotional or behavior problems.

The age at the time of treatment randomization was 19 days in the DRIFT group and 19 days in the standard group. The DRIFT group was composed of more males (79% vs. 63%) and newborns with lower birth weight (336 vs. 535 grams). The gestational age and the prevalence of grade 4 intraventricular hemorrhage were similar between the groups.

DRIFT increased cognitive ability at 10 years (P = .096). Adjustment for gender, birth weight, and grade of intraventricular hemorrhage strengthened this association, with the DRIFT group having an average advantage in CQ score of 23.5 points (P = .009), which translated to a 2.5-year advantage in cognitive ability. When the data was further adjusted by ruling out the three children (two in the DRIFT group and one in the standard treatment group) who died between the 2- and 10-year follow-ups, the CQ score advantage remained (20 points; P = .029).

The other primary outcome of survival without severe cognitive disability also favored DRIFT, with an unadjusted odds ratio (OR) of 3.3 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1-10.4 (P = .037) and adjusted (as above) OR of 8.9 (95% CI, 1.9-42.3; P = .006). Fewer children in the DRIFT group were attending schools with an expertise in special needs (OR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.07-1.05; P = .059). No differences between the groups were evident for the secondary outcomes.

The number needed to treat to prevent death or severe cognitive disability was four.

Dr. Luyt’s recommendation that DRIFT become the standard of care for neonatal intraventricular hemorrhage comes with the caveat of increased secondary bleeding, which caused the trial to be halted after a planned external safety monitoring review. Children who already had been treated were followed up, with no further recruitment. In her response to a question from the audience regarding her endorsement of DRIFT despite the trial’s halt, Dr. Luyt pointed to the comparable safety profiles of the two groups, the superior outcomes in the DRIFT group, and the knowledge that modifications made to the technique in the intervening years have reduced the possibility of secondary bleeds.

The sponsor of study was Dr. Birgit Whitman of the University of Bristol. The study was funded by the National Institute of Health’s Health Technology Assessment Programme. Dr. Luyt disclosed the off-label use of alteplase.

SAN FRANCISCO – The 10-year follow-up of neonates treated for posthemorrhagic ventricular dilatation (PHVD) has demonstrated the long-term success of drainage, irrigation, and fibrinolytic therapy (DRIFT), with a cognitive advantage in the now school-age children evident, compared with those neonates who had not received the therapy.

“Children in the DRIFT group had a 23-point cognitive quotient advantage and were nine times more likely to be alive without severe cognitive disability at 10 years,” presenter and DRIFT investigator Karen Luyt, MBChB, PhD, of the University of Bristol and St. Michael’s Hospital, Bristol, England, said at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting.

PHVD carries a high risk of disabilities in cognition and movement. DRIFT was developed as a way to wash out the ventricles in the brain to clear the effects of bleeding, with the goal of reducing neurodevelopmental disability. In the technique, catheters are inserted into the affected ventricles and are used to deliver an anti-clotting agent (alteplase) and to drain the bloody fluid. The catheters remain in place for a time as a conduit for artificial cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) containing antibiotics.

In the DRIFT trial, 77 preterm infants were randomized to DRIFT (n = 39) or the standard treatment of siphoning off cerebrospinal fluid to restrict brain expansion (n = 38). At 2 years, the DRIFT group displayed fewer cases of severe disability and cognitive disability, and death (Pediatrics. 2010 Apr;125[4]:e852-8).

Dr. Luyt summarized the final 10-year data from 52 school-age children (28 treated using DRIFT and 24 treated in the standard manner). The primary outcomes in the school-age children were cognitive quotient (CQ) and survival without severe cognitive disability. Secondary outcomes included visual function, sensory and motor disabilities, and emotional or behavior problems.

The age at the time of treatment randomization was 19 days in the DRIFT group and 19 days in the standard group. The DRIFT group was composed of more males (79% vs. 63%) and newborns with lower birth weight (336 vs. 535 grams). The gestational age and the prevalence of grade 4 intraventricular hemorrhage were similar between the groups.

DRIFT increased cognitive ability at 10 years (P = .096). Adjustment for gender, birth weight, and grade of intraventricular hemorrhage strengthened this association, with the DRIFT group having an average advantage in CQ score of 23.5 points (P = .009), which translated to a 2.5-year advantage in cognitive ability. When the data was further adjusted by ruling out the three children (two in the DRIFT group and one in the standard treatment group) who died between the 2- and 10-year follow-ups, the CQ score advantage remained (20 points; P = .029).