User login

For MD-IQ use only

Cancer Drug Shortages Continue in the US, Survey Finds

Nearly 90% of the 28 NCCN member centers who responded to the survey, conducted between May 28 and June 11, said they were experiencing a shortage of at least one drug.

“Many drugs that are currently in shortage form the backbones of effective multiagent regimens across both curative and palliative treatment settings,” NCCN’s CEO Crystal S. Denlinger, MD, said in an interview.

The good news is that carboplatin and cisplatin shortages have fallen dramatically since 2023. At the peak of the shortage in 2023, 93% of centers surveyed reported experiencing a shortage of carboplatin and 70% were experiencing a shortage of cisplatin, whereas in 2024, only 11% reported a carboplatin shortage and 7% reported a cisplatin shortage.

“Thankfully, the shortages for carboplatin and cisplatin are mostly resolved at this time,” Dr. Denlinger said.

However, all three NCCN surveys conducted in the past year, including the most recent one, have found shortages of various chemotherapies and supportive care medications, which suggests this is an ongoing issue affecting a significant spectrum of generic drugs.

“The acute crisis associated with the shortage of carboplatin and cisplatin was a singular event that brought the issue into the national spotlight,” but it’s “important to note that the current broad drug shortages found on this survey are not new,” said Dr. Denlinger.

In the latest survey, 89% of NCCN centers continue to report shortages of one or more drugs, and 75% said they are experiencing shortages of two or more drugs.

Overall, 57% of centers are short on vinblastine, 46% are short on etoposide, and 43% are short on topotecan. Other common chemotherapy and supportive care agents in short supply include dacarbazine (18% of centers) as well as 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and methotrexate (14% of centers).

In 2023, however, shortages of methotrexate and 5-FU were worse, with 67% of centers reporting shortages of methotrexate and 26% of 5-FU.

In the current survey, 75% of NCCN centers also noted they were aware of drug shortages within community practices in their area, and more than one in four centers reported treatment delays requiring additional prior authorization.

Cancer drug shortages impact not only routine treatments but also clinical trials. The recent survey found that 43% of respondents said drug shortages disrupted clinical trials at their center. The biggest issues centers flagged included greater administrative burdens, lower patient enrollment, and fewer open trials.

How are centers dealing with ongoing supply issues?

Top mitigation strategies include reducing waste, limiting use of current stock, and adjusting the timing and dosage within evidence-based ranges.

“The current situation underscores the need for sustainable, long-term solutions that ensure a stable supply of high-quality cancer medications,” Alyssa Schatz, MSW, NCCN senior director of policy and advocacy, said in a news release.

Three-quarters (75%) of survey respondents said they would like to see economic incentives put in place to encourage the high-quality manufacturing of medications, especially generic versions that are often in short supply. Nearly two-thirds (64%) cited a need for a broader buffer stock payment, and the same percentage would like to see more information on user experiences with various generic suppliers to help hospitals contract with those engaging in high-quality practices.

The NCCN also continues to work with federal regulators, agencies, and lawmakers to implement long-term solutions to cancer drug shortages.

“The federal government has a key role to play in addressing this issue,” Ms. Schatz said. “Establishing economic incentives, such as tax breaks or manufacturing grants for generic drugmakers, will help support a robust and resilient supply chain — ultimately safeguarding care for people with cancer across the country.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Nearly 90% of the 28 NCCN member centers who responded to the survey, conducted between May 28 and June 11, said they were experiencing a shortage of at least one drug.

“Many drugs that are currently in shortage form the backbones of effective multiagent regimens across both curative and palliative treatment settings,” NCCN’s CEO Crystal S. Denlinger, MD, said in an interview.

The good news is that carboplatin and cisplatin shortages have fallen dramatically since 2023. At the peak of the shortage in 2023, 93% of centers surveyed reported experiencing a shortage of carboplatin and 70% were experiencing a shortage of cisplatin, whereas in 2024, only 11% reported a carboplatin shortage and 7% reported a cisplatin shortage.

“Thankfully, the shortages for carboplatin and cisplatin are mostly resolved at this time,” Dr. Denlinger said.

However, all three NCCN surveys conducted in the past year, including the most recent one, have found shortages of various chemotherapies and supportive care medications, which suggests this is an ongoing issue affecting a significant spectrum of generic drugs.

“The acute crisis associated with the shortage of carboplatin and cisplatin was a singular event that brought the issue into the national spotlight,” but it’s “important to note that the current broad drug shortages found on this survey are not new,” said Dr. Denlinger.

In the latest survey, 89% of NCCN centers continue to report shortages of one or more drugs, and 75% said they are experiencing shortages of two or more drugs.

Overall, 57% of centers are short on vinblastine, 46% are short on etoposide, and 43% are short on topotecan. Other common chemotherapy and supportive care agents in short supply include dacarbazine (18% of centers) as well as 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and methotrexate (14% of centers).

In 2023, however, shortages of methotrexate and 5-FU were worse, with 67% of centers reporting shortages of methotrexate and 26% of 5-FU.

In the current survey, 75% of NCCN centers also noted they were aware of drug shortages within community practices in their area, and more than one in four centers reported treatment delays requiring additional prior authorization.

Cancer drug shortages impact not only routine treatments but also clinical trials. The recent survey found that 43% of respondents said drug shortages disrupted clinical trials at their center. The biggest issues centers flagged included greater administrative burdens, lower patient enrollment, and fewer open trials.

How are centers dealing with ongoing supply issues?

Top mitigation strategies include reducing waste, limiting use of current stock, and adjusting the timing and dosage within evidence-based ranges.

“The current situation underscores the need for sustainable, long-term solutions that ensure a stable supply of high-quality cancer medications,” Alyssa Schatz, MSW, NCCN senior director of policy and advocacy, said in a news release.

Three-quarters (75%) of survey respondents said they would like to see economic incentives put in place to encourage the high-quality manufacturing of medications, especially generic versions that are often in short supply. Nearly two-thirds (64%) cited a need for a broader buffer stock payment, and the same percentage would like to see more information on user experiences with various generic suppliers to help hospitals contract with those engaging in high-quality practices.

The NCCN also continues to work with federal regulators, agencies, and lawmakers to implement long-term solutions to cancer drug shortages.

“The federal government has a key role to play in addressing this issue,” Ms. Schatz said. “Establishing economic incentives, such as tax breaks or manufacturing grants for generic drugmakers, will help support a robust and resilient supply chain — ultimately safeguarding care for people with cancer across the country.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Nearly 90% of the 28 NCCN member centers who responded to the survey, conducted between May 28 and June 11, said they were experiencing a shortage of at least one drug.

“Many drugs that are currently in shortage form the backbones of effective multiagent regimens across both curative and palliative treatment settings,” NCCN’s CEO Crystal S. Denlinger, MD, said in an interview.

The good news is that carboplatin and cisplatin shortages have fallen dramatically since 2023. At the peak of the shortage in 2023, 93% of centers surveyed reported experiencing a shortage of carboplatin and 70% were experiencing a shortage of cisplatin, whereas in 2024, only 11% reported a carboplatin shortage and 7% reported a cisplatin shortage.

“Thankfully, the shortages for carboplatin and cisplatin are mostly resolved at this time,” Dr. Denlinger said.

However, all three NCCN surveys conducted in the past year, including the most recent one, have found shortages of various chemotherapies and supportive care medications, which suggests this is an ongoing issue affecting a significant spectrum of generic drugs.

“The acute crisis associated with the shortage of carboplatin and cisplatin was a singular event that brought the issue into the national spotlight,” but it’s “important to note that the current broad drug shortages found on this survey are not new,” said Dr. Denlinger.

In the latest survey, 89% of NCCN centers continue to report shortages of one or more drugs, and 75% said they are experiencing shortages of two or more drugs.

Overall, 57% of centers are short on vinblastine, 46% are short on etoposide, and 43% are short on topotecan. Other common chemotherapy and supportive care agents in short supply include dacarbazine (18% of centers) as well as 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and methotrexate (14% of centers).

In 2023, however, shortages of methotrexate and 5-FU were worse, with 67% of centers reporting shortages of methotrexate and 26% of 5-FU.

In the current survey, 75% of NCCN centers also noted they were aware of drug shortages within community practices in their area, and more than one in four centers reported treatment delays requiring additional prior authorization.

Cancer drug shortages impact not only routine treatments but also clinical trials. The recent survey found that 43% of respondents said drug shortages disrupted clinical trials at their center. The biggest issues centers flagged included greater administrative burdens, lower patient enrollment, and fewer open trials.

How are centers dealing with ongoing supply issues?

Top mitigation strategies include reducing waste, limiting use of current stock, and adjusting the timing and dosage within evidence-based ranges.

“The current situation underscores the need for sustainable, long-term solutions that ensure a stable supply of high-quality cancer medications,” Alyssa Schatz, MSW, NCCN senior director of policy and advocacy, said in a news release.

Three-quarters (75%) of survey respondents said they would like to see economic incentives put in place to encourage the high-quality manufacturing of medications, especially generic versions that are often in short supply. Nearly two-thirds (64%) cited a need for a broader buffer stock payment, and the same percentage would like to see more information on user experiences with various generic suppliers to help hospitals contract with those engaging in high-quality practices.

The NCCN also continues to work with federal regulators, agencies, and lawmakers to implement long-term solutions to cancer drug shortages.

“The federal government has a key role to play in addressing this issue,” Ms. Schatz said. “Establishing economic incentives, such as tax breaks or manufacturing grants for generic drugmakers, will help support a robust and resilient supply chain — ultimately safeguarding care for people with cancer across the country.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Diagnostic yield reporting of bronchoscopic peripheral pulmonary nodule biopsies: A call for standardization

THORACIC ONCOLOGY AND CHEST PROCEDURES NETWORK

Interventional Procedures Section

More than 1.5 million Americans are diagnosed with an incidental CT scan-detected lung nodule annually. Advanced bronchoscopy, as a diagnostic tool for evaluation of these nodules, has evolved rapidly, incorporating a range of techniques and tools beyond CT scan-guided biopsies to assess peripheral lesions. The primary goal is to provide patients with accurate benign or malignant diagnoses. However, accurately determining the effectiveness of innovative technologies in providing a diagnosis remains challenging, in part due to limitations in study design and outcome reporting, along with the scarcity of comparative and randomized controlled studies.1,2 Current literature shows significant variability in diagnostic yield definition, lacking generalizability.

To address this issue, an official research statement by the American Thoracic Society and CHEST defines the diagnostic yield as “the proportion of all individuals undergoing the diagnostic procedure under evaluation in whom a specific malignant or benign diagnosis is established.”3 To achieve this measure, the numerator includes all patients with lung nodules in whom the result of a diagnostic procedure establishes a specific benign or malignant diagnosis that is readily sufficient to inform patient care without additional diagnostic workup, and the denominator should include all patients in whom the procedure was attempted or performed. This standardized definition is crucial for ensuring consistency across studies, allowing for comparison or pooling of results, enhancing the reliability of diagnostic yield data, and informing clinical decisions.

The adoption of standardized outcome definitions is essential to critically evaluate modern, minimally invasive procedures for peripheral lung nodules diagnosis and to guide patient-centered care while minimizing the downstream effects of nondiagnostic biopsies. Clear, transparent, and consistent reporting will enable physicians to choose the most appropriate diagnostic tools, improve patient outcomes by reducing unnecessary procedures, and expedite accurate diagnoses. This initiative is a crucial first step toward creating high-quality studies that can inform technology implementation decisions and promote equitable health care.

References

1. Tanner NT, Yarmus L, Chen A, et al. Standard bronchoscopy with fluoroscopy vs thin bronchoscopy and radial endobronchial ultrasound for biopsy of pulmonary lesions: a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial. Chest. 2018;154(5):1035-1043.

2. Ost DE, Ernst A, Lei X, et al. Diagnostic yield and complications of bronchoscopy for peripheral lung lesions. Results of the AQuIRE Registry. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2016;193(1):68-77.

3. Gonzalez AV, Silvestri GA, Korevaar DA, et al. Assessment of advanced diagnostic bronchoscopy outcomes for peripheral lung lesions: a Delphi consensus definition of diagnostic yield and recommendations for patient-centered study designs. An official American Thoracic Society/American College of Chest Physicians research statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2024;209(6):634-646.

THORACIC ONCOLOGY AND CHEST PROCEDURES NETWORK

Interventional Procedures Section

More than 1.5 million Americans are diagnosed with an incidental CT scan-detected lung nodule annually. Advanced bronchoscopy, as a diagnostic tool for evaluation of these nodules, has evolved rapidly, incorporating a range of techniques and tools beyond CT scan-guided biopsies to assess peripheral lesions. The primary goal is to provide patients with accurate benign or malignant diagnoses. However, accurately determining the effectiveness of innovative technologies in providing a diagnosis remains challenging, in part due to limitations in study design and outcome reporting, along with the scarcity of comparative and randomized controlled studies.1,2 Current literature shows significant variability in diagnostic yield definition, lacking generalizability.

To address this issue, an official research statement by the American Thoracic Society and CHEST defines the diagnostic yield as “the proportion of all individuals undergoing the diagnostic procedure under evaluation in whom a specific malignant or benign diagnosis is established.”3 To achieve this measure, the numerator includes all patients with lung nodules in whom the result of a diagnostic procedure establishes a specific benign or malignant diagnosis that is readily sufficient to inform patient care without additional diagnostic workup, and the denominator should include all patients in whom the procedure was attempted or performed. This standardized definition is crucial for ensuring consistency across studies, allowing for comparison or pooling of results, enhancing the reliability of diagnostic yield data, and informing clinical decisions.

The adoption of standardized outcome definitions is essential to critically evaluate modern, minimally invasive procedures for peripheral lung nodules diagnosis and to guide patient-centered care while minimizing the downstream effects of nondiagnostic biopsies. Clear, transparent, and consistent reporting will enable physicians to choose the most appropriate diagnostic tools, improve patient outcomes by reducing unnecessary procedures, and expedite accurate diagnoses. This initiative is a crucial first step toward creating high-quality studies that can inform technology implementation decisions and promote equitable health care.

References

1. Tanner NT, Yarmus L, Chen A, et al. Standard bronchoscopy with fluoroscopy vs thin bronchoscopy and radial endobronchial ultrasound for biopsy of pulmonary lesions: a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial. Chest. 2018;154(5):1035-1043.

2. Ost DE, Ernst A, Lei X, et al. Diagnostic yield and complications of bronchoscopy for peripheral lung lesions. Results of the AQuIRE Registry. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2016;193(1):68-77.

3. Gonzalez AV, Silvestri GA, Korevaar DA, et al. Assessment of advanced diagnostic bronchoscopy outcomes for peripheral lung lesions: a Delphi consensus definition of diagnostic yield and recommendations for patient-centered study designs. An official American Thoracic Society/American College of Chest Physicians research statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2024;209(6):634-646.

THORACIC ONCOLOGY AND CHEST PROCEDURES NETWORK

Interventional Procedures Section

More than 1.5 million Americans are diagnosed with an incidental CT scan-detected lung nodule annually. Advanced bronchoscopy, as a diagnostic tool for evaluation of these nodules, has evolved rapidly, incorporating a range of techniques and tools beyond CT scan-guided biopsies to assess peripheral lesions. The primary goal is to provide patients with accurate benign or malignant diagnoses. However, accurately determining the effectiveness of innovative technologies in providing a diagnosis remains challenging, in part due to limitations in study design and outcome reporting, along with the scarcity of comparative and randomized controlled studies.1,2 Current literature shows significant variability in diagnostic yield definition, lacking generalizability.

To address this issue, an official research statement by the American Thoracic Society and CHEST defines the diagnostic yield as “the proportion of all individuals undergoing the diagnostic procedure under evaluation in whom a specific malignant or benign diagnosis is established.”3 To achieve this measure, the numerator includes all patients with lung nodules in whom the result of a diagnostic procedure establishes a specific benign or malignant diagnosis that is readily sufficient to inform patient care without additional diagnostic workup, and the denominator should include all patients in whom the procedure was attempted or performed. This standardized definition is crucial for ensuring consistency across studies, allowing for comparison or pooling of results, enhancing the reliability of diagnostic yield data, and informing clinical decisions.

The adoption of standardized outcome definitions is essential to critically evaluate modern, minimally invasive procedures for peripheral lung nodules diagnosis and to guide patient-centered care while minimizing the downstream effects of nondiagnostic biopsies. Clear, transparent, and consistent reporting will enable physicians to choose the most appropriate diagnostic tools, improve patient outcomes by reducing unnecessary procedures, and expedite accurate diagnoses. This initiative is a crucial first step toward creating high-quality studies that can inform technology implementation decisions and promote equitable health care.

References

1. Tanner NT, Yarmus L, Chen A, et al. Standard bronchoscopy with fluoroscopy vs thin bronchoscopy and radial endobronchial ultrasound for biopsy of pulmonary lesions: a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial. Chest. 2018;154(5):1035-1043.

2. Ost DE, Ernst A, Lei X, et al. Diagnostic yield and complications of bronchoscopy for peripheral lung lesions. Results of the AQuIRE Registry. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2016;193(1):68-77.

3. Gonzalez AV, Silvestri GA, Korevaar DA, et al. Assessment of advanced diagnostic bronchoscopy outcomes for peripheral lung lesions: a Delphi consensus definition of diagnostic yield and recommendations for patient-centered study designs. An official American Thoracic Society/American College of Chest Physicians research statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2024;209(6):634-646.

Short telomere length and immunosuppression: Updates in nonidiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, interstitial lung disease

DIFFUSE LUNG DISEASE AND LUNG TRANSPLANT NETWORK

Interstitial Lung Disease Section

Interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) are a diverse group of relentlessly progressive fibroinflammatory disorders. Pharmacotherapy includes antifibrotics and immunosuppressants as foundational strategies to mitigate loss of lung function. There has been a growing interest in telomere length and its response to immunosuppression in the ILD community.

Telomeres are repetitive nucleotide sequences that “cap” chromosomes and protect against chromosomal shortening during cell replication. Genetic and environmental factors can lead to premature shortening of telomeres. Once a critical length is reached, the cell enters senescence. Short telomere length has been linked to rapid progression, worse outcomes, and poor response to immunosuppressants in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

Data in patients with non-IPF ILD (which is arguably more difficult to diagnose and manage) were lacking until a recent retrospective cohort study of patients from five centers across the US demonstrated that immunosuppressant exposure in patients with age-adjusted telomere length <10th percentile was associated with a reduced 2-year transplant-free survival in fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis and unclassifiable ILD subgroups.1 This study was underpowered to detect associations in the connective tissue disease-ILD group. Interestingly, authors noted that immunosuppressant exposure was not associated with lung function decline in the short telomere group, suggesting that worse outcomes may be attributable to unmasking extrapulmonary manifestations of short telomeres, such as bone marrow failure and impaired adaptive immunity. Studies like these are essential to guide decision-making in the age of personalized medicine and underscore the necessity for prospective studies to validate these findings.

References

1. Zhang D, Adegunsoye A, Oldham JM, et al. Telomere length and immunosuppression in non-idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir J. 2023;62(5):2300441.

DIFFUSE LUNG DISEASE AND LUNG TRANSPLANT NETWORK

Interstitial Lung Disease Section

Interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) are a diverse group of relentlessly progressive fibroinflammatory disorders. Pharmacotherapy includes antifibrotics and immunosuppressants as foundational strategies to mitigate loss of lung function. There has been a growing interest in telomere length and its response to immunosuppression in the ILD community.

Telomeres are repetitive nucleotide sequences that “cap” chromosomes and protect against chromosomal shortening during cell replication. Genetic and environmental factors can lead to premature shortening of telomeres. Once a critical length is reached, the cell enters senescence. Short telomere length has been linked to rapid progression, worse outcomes, and poor response to immunosuppressants in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

Data in patients with non-IPF ILD (which is arguably more difficult to diagnose and manage) were lacking until a recent retrospective cohort study of patients from five centers across the US demonstrated that immunosuppressant exposure in patients with age-adjusted telomere length <10th percentile was associated with a reduced 2-year transplant-free survival in fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis and unclassifiable ILD subgroups.1 This study was underpowered to detect associations in the connective tissue disease-ILD group. Interestingly, authors noted that immunosuppressant exposure was not associated with lung function decline in the short telomere group, suggesting that worse outcomes may be attributable to unmasking extrapulmonary manifestations of short telomeres, such as bone marrow failure and impaired adaptive immunity. Studies like these are essential to guide decision-making in the age of personalized medicine and underscore the necessity for prospective studies to validate these findings.

References

1. Zhang D, Adegunsoye A, Oldham JM, et al. Telomere length and immunosuppression in non-idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir J. 2023;62(5):2300441.

DIFFUSE LUNG DISEASE AND LUNG TRANSPLANT NETWORK

Interstitial Lung Disease Section

Interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) are a diverse group of relentlessly progressive fibroinflammatory disorders. Pharmacotherapy includes antifibrotics and immunosuppressants as foundational strategies to mitigate loss of lung function. There has been a growing interest in telomere length and its response to immunosuppression in the ILD community.

Telomeres are repetitive nucleotide sequences that “cap” chromosomes and protect against chromosomal shortening during cell replication. Genetic and environmental factors can lead to premature shortening of telomeres. Once a critical length is reached, the cell enters senescence. Short telomere length has been linked to rapid progression, worse outcomes, and poor response to immunosuppressants in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

Data in patients with non-IPF ILD (which is arguably more difficult to diagnose and manage) were lacking until a recent retrospective cohort study of patients from five centers across the US demonstrated that immunosuppressant exposure in patients with age-adjusted telomere length <10th percentile was associated with a reduced 2-year transplant-free survival in fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis and unclassifiable ILD subgroups.1 This study was underpowered to detect associations in the connective tissue disease-ILD group. Interestingly, authors noted that immunosuppressant exposure was not associated with lung function decline in the short telomere group, suggesting that worse outcomes may be attributable to unmasking extrapulmonary manifestations of short telomeres, such as bone marrow failure and impaired adaptive immunity. Studies like these are essential to guide decision-making in the age of personalized medicine and underscore the necessity for prospective studies to validate these findings.

References

1. Zhang D, Adegunsoye A, Oldham JM, et al. Telomere length and immunosuppression in non-idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir J. 2023;62(5):2300441.

Expanding recommendations for RSV vaccination

AIRWAYS DISORDERS NETWORK

Asthma and COPD Section

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) has been increasingly recognized as a prevalent cause of lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) among adults in the United States. The risk of hospitalization and mortality from RSV-associated respiratory failure is higher in those with chronic lung disease. In adults aged 65 years or older, RSV has shown to cause up to 160,000 hospitalizations and 10,000 deaths annually.

RSV has been well established as a major cause of LRTI and morbidity among infants. Maternal vaccination with RSVPreF in patients who are pregnant is suggested between 32 0/7 and 36 6/7 weeks of gestation if the date of delivery falls during RSV season to prevent severe illness in young infants in their first months of life. At present, there are no data supporting vaccine administration to patients who are pregnant delivering outside of the RSV season.

What about the rest of the patients? A phase 3b clinical trial to assess the safety and immunogenicity of the RSVPreF3 vaccine in individuals 18 to 49 years of age at increased risk for RSV LRTI, including those with chronic respiratory diseases, is currently underway with projected completion in April 2025 (clinical trials.gov; ID NCT06389487). Additional studies examining safety and immunogenicity combining RSV vaccines with PCV20, influenza, COVID, or Tdap vaccines are also underway. These outcomes will be significant for future recommendations to further lower the risk of developing LRTI, hospitalization, and death among patients less than the age of 60 with chronic lung diseases.

Resources

1. Melgar M, Britton A, Roper LE, et al. Use of respiratory syncytial virus vaccines in older adults: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices - United States, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(29):793-801.

2. Healthcare Providers: RSV Vaccination for Adults 60 Years of Age and Over. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated March 1, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/rsv/hcp/older-adults.html

3. Ault KA, Hughes BL, Riley LE. Maternal Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccination. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Updated December 11, 2023. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2023/09/maternal-respiratory-syncytial-virus-vaccination

AIRWAYS DISORDERS NETWORK

Asthma and COPD Section

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) has been increasingly recognized as a prevalent cause of lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) among adults in the United States. The risk of hospitalization and mortality from RSV-associated respiratory failure is higher in those with chronic lung disease. In adults aged 65 years or older, RSV has shown to cause up to 160,000 hospitalizations and 10,000 deaths annually.

RSV has been well established as a major cause of LRTI and morbidity among infants. Maternal vaccination with RSVPreF in patients who are pregnant is suggested between 32 0/7 and 36 6/7 weeks of gestation if the date of delivery falls during RSV season to prevent severe illness in young infants in their first months of life. At present, there are no data supporting vaccine administration to patients who are pregnant delivering outside of the RSV season.

What about the rest of the patients? A phase 3b clinical trial to assess the safety and immunogenicity of the RSVPreF3 vaccine in individuals 18 to 49 years of age at increased risk for RSV LRTI, including those with chronic respiratory diseases, is currently underway with projected completion in April 2025 (clinical trials.gov; ID NCT06389487). Additional studies examining safety and immunogenicity combining RSV vaccines with PCV20, influenza, COVID, or Tdap vaccines are also underway. These outcomes will be significant for future recommendations to further lower the risk of developing LRTI, hospitalization, and death among patients less than the age of 60 with chronic lung diseases.

Resources

1. Melgar M, Britton A, Roper LE, et al. Use of respiratory syncytial virus vaccines in older adults: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices - United States, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(29):793-801.

2. Healthcare Providers: RSV Vaccination for Adults 60 Years of Age and Over. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated March 1, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/rsv/hcp/older-adults.html

3. Ault KA, Hughes BL, Riley LE. Maternal Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccination. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Updated December 11, 2023. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2023/09/maternal-respiratory-syncytial-virus-vaccination

AIRWAYS DISORDERS NETWORK

Asthma and COPD Section

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) has been increasingly recognized as a prevalent cause of lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) among adults in the United States. The risk of hospitalization and mortality from RSV-associated respiratory failure is higher in those with chronic lung disease. In adults aged 65 years or older, RSV has shown to cause up to 160,000 hospitalizations and 10,000 deaths annually.

RSV has been well established as a major cause of LRTI and morbidity among infants. Maternal vaccination with RSVPreF in patients who are pregnant is suggested between 32 0/7 and 36 6/7 weeks of gestation if the date of delivery falls during RSV season to prevent severe illness in young infants in their first months of life. At present, there are no data supporting vaccine administration to patients who are pregnant delivering outside of the RSV season.

What about the rest of the patients? A phase 3b clinical trial to assess the safety and immunogenicity of the RSVPreF3 vaccine in individuals 18 to 49 years of age at increased risk for RSV LRTI, including those with chronic respiratory diseases, is currently underway with projected completion in April 2025 (clinical trials.gov; ID NCT06389487). Additional studies examining safety and immunogenicity combining RSV vaccines with PCV20, influenza, COVID, or Tdap vaccines are also underway. These outcomes will be significant for future recommendations to further lower the risk of developing LRTI, hospitalization, and death among patients less than the age of 60 with chronic lung diseases.

Resources

1. Melgar M, Britton A, Roper LE, et al. Use of respiratory syncytial virus vaccines in older adults: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices - United States, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(29):793-801.

2. Healthcare Providers: RSV Vaccination for Adults 60 Years of Age and Over. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated March 1, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/rsv/hcp/older-adults.html

3. Ault KA, Hughes BL, Riley LE. Maternal Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccination. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Updated December 11, 2023. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2023/09/maternal-respiratory-syncytial-virus-vaccination

Dubious Medicine

Interest in and knowledge of the gut microbiome, and its role in health and disease, has increased exponentially in the past decade. Billions of dollars have been invested in gut microbiome research since release of the NIH Human Microbiome Project’s reference database in 2012, aimed not only at better understanding pathology and disease mechanisms, but also promoting development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. However, it is fair to say that gut microbiome research is still in its infancy, and there is still much to be learned.

Despite this, a global, and largely unregulated, industry of direct-to-consumer (DTC) microbiome tests has emerged. These (often costly) tests are now widely available to our patients via retail outlets and online — in exchange for a stool sample, consumers receive a detailed report comparing their microbiome to a “healthy” reference patient and recommending various interventions such as follow-up testing, special diets, or nutritional supplements. By now, we likely all have been handed one of these reports in clinic identifying a patient’s “abnormal” microbiome and asked to weigh in on its dubious results. A special feature article in this month’s issue outlines the controversies surrounding these DTC microbiome tests, which currently lack analytic and clinical validity, and highlights recent calls for increased regulation in this space.

Also We invite you to learn more about the exceptional Dr. Maria Abreu of the University of Miami, who recently assumed her new role as AGA President. Our quarterly Perspectives column tackles the issue of GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) in GI endoscopy — gastroenterologist Dr. Jana Hashash and anesthesiologists Dr. Thomas Hickey and Dr. Ryan Pouliot offer contrasting perspectives on this topic drawn from AGA and American Society of Anesthesiologists guidance. Finally, our July Member Spotlight features Dr. Lisa Mathew of South Denver Gastroenterology who shares her perspectives on hosting a GI podcast, why private practice is a fantastic laboratory for clinical innovation, and how she found her “tribe” in the field of gastroenterology.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

Interest in and knowledge of the gut microbiome, and its role in health and disease, has increased exponentially in the past decade. Billions of dollars have been invested in gut microbiome research since release of the NIH Human Microbiome Project’s reference database in 2012, aimed not only at better understanding pathology and disease mechanisms, but also promoting development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. However, it is fair to say that gut microbiome research is still in its infancy, and there is still much to be learned.

Despite this, a global, and largely unregulated, industry of direct-to-consumer (DTC) microbiome tests has emerged. These (often costly) tests are now widely available to our patients via retail outlets and online — in exchange for a stool sample, consumers receive a detailed report comparing their microbiome to a “healthy” reference patient and recommending various interventions such as follow-up testing, special diets, or nutritional supplements. By now, we likely all have been handed one of these reports in clinic identifying a patient’s “abnormal” microbiome and asked to weigh in on its dubious results. A special feature article in this month’s issue outlines the controversies surrounding these DTC microbiome tests, which currently lack analytic and clinical validity, and highlights recent calls for increased regulation in this space.

Also We invite you to learn more about the exceptional Dr. Maria Abreu of the University of Miami, who recently assumed her new role as AGA President. Our quarterly Perspectives column tackles the issue of GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) in GI endoscopy — gastroenterologist Dr. Jana Hashash and anesthesiologists Dr. Thomas Hickey and Dr. Ryan Pouliot offer contrasting perspectives on this topic drawn from AGA and American Society of Anesthesiologists guidance. Finally, our July Member Spotlight features Dr. Lisa Mathew of South Denver Gastroenterology who shares her perspectives on hosting a GI podcast, why private practice is a fantastic laboratory for clinical innovation, and how she found her “tribe” in the field of gastroenterology.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

Interest in and knowledge of the gut microbiome, and its role in health and disease, has increased exponentially in the past decade. Billions of dollars have been invested in gut microbiome research since release of the NIH Human Microbiome Project’s reference database in 2012, aimed not only at better understanding pathology and disease mechanisms, but also promoting development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. However, it is fair to say that gut microbiome research is still in its infancy, and there is still much to be learned.

Despite this, a global, and largely unregulated, industry of direct-to-consumer (DTC) microbiome tests has emerged. These (often costly) tests are now widely available to our patients via retail outlets and online — in exchange for a stool sample, consumers receive a detailed report comparing their microbiome to a “healthy” reference patient and recommending various interventions such as follow-up testing, special diets, or nutritional supplements. By now, we likely all have been handed one of these reports in clinic identifying a patient’s “abnormal” microbiome and asked to weigh in on its dubious results. A special feature article in this month’s issue outlines the controversies surrounding these DTC microbiome tests, which currently lack analytic and clinical validity, and highlights recent calls for increased regulation in this space.

Also We invite you to learn more about the exceptional Dr. Maria Abreu of the University of Miami, who recently assumed her new role as AGA President. Our quarterly Perspectives column tackles the issue of GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) in GI endoscopy — gastroenterologist Dr. Jana Hashash and anesthesiologists Dr. Thomas Hickey and Dr. Ryan Pouliot offer contrasting perspectives on this topic drawn from AGA and American Society of Anesthesiologists guidance. Finally, our July Member Spotlight features Dr. Lisa Mathew of South Denver Gastroenterology who shares her perspectives on hosting a GI podcast, why private practice is a fantastic laboratory for clinical innovation, and how she found her “tribe” in the field of gastroenterology.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

FDA Proposes that Interchangeability Status for Biosimilars Doesn’t Need Switching Studies

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued new draft guidance that does not require additional switching studies for biosimilars seeking interchangeability. These studies were previously recommended to demonstrate that switching between the biosimilar and its reference product showed no greater risk than using the reference product alone.

“The recommendations in today’s draft guidance, when finalized, will provide clarity and transparency about the FDA’s thinking and align the review and approval process with existing and emerging science,” said Sarah Yim, MD, director of the FDA’s Office of Therapeutic Biologics and Biosimilars in a statement on June 20. “We have gained valuable experience reviewing both biosimilar and interchangeable biosimilar medications over the past 10 years. Both biosimilars and interchangeable biosimilars meet the same high standard of biosimilarity for FDA approval and both are as safe and effective as the reference product.”

An interchangeable status allows a biosimilar product to be swapped with the reference product without involvement from the prescribing provider, depending on state law.

While switching studies were not required under previous FDA guidance, the 2019 document did state that the agency “expects that applications generally will include data from a switching study or studies in one or more appropriate conditions of use.”

However, of the 13 biosimilars that received interchangeability status, 9 did not include switching study data.

“Experience has shown that, for the products approved as biosimilars to date, the risk in terms of safety or diminished efficacy is insignificant following single or multiple switches between a reference product and a biosimilar product,” the FDA stated. The agency’s investigators also conducted a systematic review of switching studies, which found no differences in risk for death, serious adverse events, and treatment discontinuations in participants switched between biosimilars and reference products and those that remained on reference products.

“Additionally, today’s analytical tools can accurately evaluate the structure and effects [of] biologic products, both in the lab (in vitro) and in living organisms (in vivo) with more precision and sensitivity than switching studies,” the agency noted.

The FDA is now calling for commentary on these draft recommendations to be submitted by Aug. 20, 2024.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued new draft guidance that does not require additional switching studies for biosimilars seeking interchangeability. These studies were previously recommended to demonstrate that switching between the biosimilar and its reference product showed no greater risk than using the reference product alone.

“The recommendations in today’s draft guidance, when finalized, will provide clarity and transparency about the FDA’s thinking and align the review and approval process with existing and emerging science,” said Sarah Yim, MD, director of the FDA’s Office of Therapeutic Biologics and Biosimilars in a statement on June 20. “We have gained valuable experience reviewing both biosimilar and interchangeable biosimilar medications over the past 10 years. Both biosimilars and interchangeable biosimilars meet the same high standard of biosimilarity for FDA approval and both are as safe and effective as the reference product.”

An interchangeable status allows a biosimilar product to be swapped with the reference product without involvement from the prescribing provider, depending on state law.

While switching studies were not required under previous FDA guidance, the 2019 document did state that the agency “expects that applications generally will include data from a switching study or studies in one or more appropriate conditions of use.”

However, of the 13 biosimilars that received interchangeability status, 9 did not include switching study data.

“Experience has shown that, for the products approved as biosimilars to date, the risk in terms of safety or diminished efficacy is insignificant following single or multiple switches between a reference product and a biosimilar product,” the FDA stated. The agency’s investigators also conducted a systematic review of switching studies, which found no differences in risk for death, serious adverse events, and treatment discontinuations in participants switched between biosimilars and reference products and those that remained on reference products.

“Additionally, today’s analytical tools can accurately evaluate the structure and effects [of] biologic products, both in the lab (in vitro) and in living organisms (in vivo) with more precision and sensitivity than switching studies,” the agency noted.

The FDA is now calling for commentary on these draft recommendations to be submitted by Aug. 20, 2024.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued new draft guidance that does not require additional switching studies for biosimilars seeking interchangeability. These studies were previously recommended to demonstrate that switching between the biosimilar and its reference product showed no greater risk than using the reference product alone.

“The recommendations in today’s draft guidance, when finalized, will provide clarity and transparency about the FDA’s thinking and align the review and approval process with existing and emerging science,” said Sarah Yim, MD, director of the FDA’s Office of Therapeutic Biologics and Biosimilars in a statement on June 20. “We have gained valuable experience reviewing both biosimilar and interchangeable biosimilar medications over the past 10 years. Both biosimilars and interchangeable biosimilars meet the same high standard of biosimilarity for FDA approval and both are as safe and effective as the reference product.”

An interchangeable status allows a biosimilar product to be swapped with the reference product without involvement from the prescribing provider, depending on state law.

While switching studies were not required under previous FDA guidance, the 2019 document did state that the agency “expects that applications generally will include data from a switching study or studies in one or more appropriate conditions of use.”

However, of the 13 biosimilars that received interchangeability status, 9 did not include switching study data.

“Experience has shown that, for the products approved as biosimilars to date, the risk in terms of safety or diminished efficacy is insignificant following single or multiple switches between a reference product and a biosimilar product,” the FDA stated. The agency’s investigators also conducted a systematic review of switching studies, which found no differences in risk for death, serious adverse events, and treatment discontinuations in participants switched between biosimilars and reference products and those that remained on reference products.

“Additionally, today’s analytical tools can accurately evaluate the structure and effects [of] biologic products, both in the lab (in vitro) and in living organisms (in vivo) with more precision and sensitivity than switching studies,” the agency noted.

The FDA is now calling for commentary on these draft recommendations to be submitted by Aug. 20, 2024.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Neurofilament Light Chain Detects Early Chemotherapy-Related Neurotoxicity

Investigators found Nfl levels increased in cancer patients following a first infusion of the medication paclitaxel and corresponded to neuropathy severity 6-12 months post-treatment, suggesting the blood protein may provide an early CIPN biomarker.

“Nfl after a single cycle could detect axonal degeneration,” said lead investigator Masarra Joda, a researcher and PhD candidate at the University of Sydney in Australia. She added that “quantification of Nfl may provide a clinically useful marker of emerging neurotoxicity in patients vulnerable to CIPN.”

The findings were presented at the Peripheral Nerve Society (PNS) 2024 annual meeting.

Common, Burdensome Side Effect

A common side effect of chemotherapy, CIPN manifests as sensory neuropathy and causes degeneration of the peripheral axons. A protein biomarker of axonal degeneration, Nfl has previously been investigated as a way of identifying patients at risk of CIPN.

The goal of the current study was to identify the potential link between Nfl with neurophysiological markers of axon degeneration in patients receiving the neurotoxin chemotherapy paclitaxel.

The study included 93 cancer patients. All were assessed at the beginning, middle, and end of treatment. CIPN was assessed using blood samples of Nfl and the Total Neuropathy Score (TNS), the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) neuropathy scale, and patient-reported measures using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire–Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy Module (EORTC-CIPN20).

Axonal degeneration was measured with neurophysiological tests including sural nerve compound sensory action potential (CSAP) for the lower limbs, and sensory median nerve CSAP, as well as stimulus threshold testing, for the upper limbs.

Almost all of study participants (97%) were female. The majority (66%) had breast cancer and 30% had gynecological cancer. Most (73%) were receiving a weekly regimen of paclitaxel, and the remainder were treated with taxanes plus platinum once every 3 weeks. By the end of treatment, 82% of the patients had developed CIPN, which was mild in 44% and moderate/severe in 38%.

Nfl levels increased significantly from baseline to after the first dose of chemotherapy (P < .001), “highlighting that nerve damage occurs from the very beginning of treatment,” senior investigator Susanna Park, PhD, told this news organization.

In addition, “patients with higher Nfl levels after a single paclitaxel treatment had greater neuropathy at the end of treatment (higher EORTC scores [P ≤ .026], and higher TNS scores [P ≤ .00]),” added Dr. Park, who is associate professor at the University of Sydney.

“Importantly, we also looked at long-term outcomes beyond the end of chemotherapy, because chronic neuropathy produces a significant burden in cancer survivors,” said Dr. Park.

“Among a total of 44 patients who completed the 6- to 12-month post-treatment follow-up, NfL levels after a single treatment were linked to severity of nerve damage quantified with neurophysiological tests, and greater Nfl levels at mid-treatment were correlated with worse patient and neurologically graded neuropathy at 6-12 months.”

Dr. Park said the results suggest that NfL may provide a biomarker of long-term axon damage and that Nfl assays “may enable clinicians to evaluate the risk of long-term toxicity early during paclitaxel treatment to hopefully provide clinically significant information to guide better treatment titration.”

Currently, she said, CIPN is a prominent cause of dose reduction and early chemotherapy cessation.

“For example, in early breast cancer around 25% of patients experience a dose reduction due to the severity of neuropathy symptoms.” But, she said, “there is no standardized way of identifying which patients are at risk of long-term neuropathy and therefore, may benefit more from dose reduction. In this setting, a biomarker such as Nfl could provide oncologists with more information about the risk of long-term toxicity and take that into account in dose decision-making.”

For some cancers, she added, there are multiple potential therapy options.

“A biomarker such as NfL could assist in determining risk-benefit profile in terms of switching to alternate therapies. However, further studies will be needed to fully define the utility of NfL as a biomarker of paclitaxel neuropathy.”

Promising Research

Commenting on the research for this news organization, Maryam Lustberg, MD, associate professor, director of the Center for Breast Cancer at Smilow Cancer Hospital and Yale Cancer Center, and chief of Breast Medical Oncology at Yale Cancer Center, in New Haven, Connecticut, said the study “builds on a body of work previously reported by others showing that neurofilament light chains as detected in the blood can be associated with early signs of neurotoxic injury.”

She added that the research “is promising, since existing clinical and patient-reported measures tend to under-detect chemotherapy-induced neuropathy until more permanent injury might have occurred.”

Dr. Lustberg, who is immediate past president of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, said future studies are needed before Nfl testing can be implemented in routine practice, but that “early detection will allow earlier initiation of supportive care strategies such as physical therapy and exercise, as well as dose modifications, which may be helpful for preventing permanent damage and improving quality of life.”

The investigators and Dr. Lustberg report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found Nfl levels increased in cancer patients following a first infusion of the medication paclitaxel and corresponded to neuropathy severity 6-12 months post-treatment, suggesting the blood protein may provide an early CIPN biomarker.

“Nfl after a single cycle could detect axonal degeneration,” said lead investigator Masarra Joda, a researcher and PhD candidate at the University of Sydney in Australia. She added that “quantification of Nfl may provide a clinically useful marker of emerging neurotoxicity in patients vulnerable to CIPN.”

The findings were presented at the Peripheral Nerve Society (PNS) 2024 annual meeting.

Common, Burdensome Side Effect

A common side effect of chemotherapy, CIPN manifests as sensory neuropathy and causes degeneration of the peripheral axons. A protein biomarker of axonal degeneration, Nfl has previously been investigated as a way of identifying patients at risk of CIPN.

The goal of the current study was to identify the potential link between Nfl with neurophysiological markers of axon degeneration in patients receiving the neurotoxin chemotherapy paclitaxel.

The study included 93 cancer patients. All were assessed at the beginning, middle, and end of treatment. CIPN was assessed using blood samples of Nfl and the Total Neuropathy Score (TNS), the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) neuropathy scale, and patient-reported measures using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire–Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy Module (EORTC-CIPN20).

Axonal degeneration was measured with neurophysiological tests including sural nerve compound sensory action potential (CSAP) for the lower limbs, and sensory median nerve CSAP, as well as stimulus threshold testing, for the upper limbs.

Almost all of study participants (97%) were female. The majority (66%) had breast cancer and 30% had gynecological cancer. Most (73%) were receiving a weekly regimen of paclitaxel, and the remainder were treated with taxanes plus platinum once every 3 weeks. By the end of treatment, 82% of the patients had developed CIPN, which was mild in 44% and moderate/severe in 38%.

Nfl levels increased significantly from baseline to after the first dose of chemotherapy (P < .001), “highlighting that nerve damage occurs from the very beginning of treatment,” senior investigator Susanna Park, PhD, told this news organization.

In addition, “patients with higher Nfl levels after a single paclitaxel treatment had greater neuropathy at the end of treatment (higher EORTC scores [P ≤ .026], and higher TNS scores [P ≤ .00]),” added Dr. Park, who is associate professor at the University of Sydney.

“Importantly, we also looked at long-term outcomes beyond the end of chemotherapy, because chronic neuropathy produces a significant burden in cancer survivors,” said Dr. Park.

“Among a total of 44 patients who completed the 6- to 12-month post-treatment follow-up, NfL levels after a single treatment were linked to severity of nerve damage quantified with neurophysiological tests, and greater Nfl levels at mid-treatment were correlated with worse patient and neurologically graded neuropathy at 6-12 months.”

Dr. Park said the results suggest that NfL may provide a biomarker of long-term axon damage and that Nfl assays “may enable clinicians to evaluate the risk of long-term toxicity early during paclitaxel treatment to hopefully provide clinically significant information to guide better treatment titration.”

Currently, she said, CIPN is a prominent cause of dose reduction and early chemotherapy cessation.

“For example, in early breast cancer around 25% of patients experience a dose reduction due to the severity of neuropathy symptoms.” But, she said, “there is no standardized way of identifying which patients are at risk of long-term neuropathy and therefore, may benefit more from dose reduction. In this setting, a biomarker such as Nfl could provide oncologists with more information about the risk of long-term toxicity and take that into account in dose decision-making.”

For some cancers, she added, there are multiple potential therapy options.

“A biomarker such as NfL could assist in determining risk-benefit profile in terms of switching to alternate therapies. However, further studies will be needed to fully define the utility of NfL as a biomarker of paclitaxel neuropathy.”

Promising Research

Commenting on the research for this news organization, Maryam Lustberg, MD, associate professor, director of the Center for Breast Cancer at Smilow Cancer Hospital and Yale Cancer Center, and chief of Breast Medical Oncology at Yale Cancer Center, in New Haven, Connecticut, said the study “builds on a body of work previously reported by others showing that neurofilament light chains as detected in the blood can be associated with early signs of neurotoxic injury.”

She added that the research “is promising, since existing clinical and patient-reported measures tend to under-detect chemotherapy-induced neuropathy until more permanent injury might have occurred.”

Dr. Lustberg, who is immediate past president of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, said future studies are needed before Nfl testing can be implemented in routine practice, but that “early detection will allow earlier initiation of supportive care strategies such as physical therapy and exercise, as well as dose modifications, which may be helpful for preventing permanent damage and improving quality of life.”

The investigators and Dr. Lustberg report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found Nfl levels increased in cancer patients following a first infusion of the medication paclitaxel and corresponded to neuropathy severity 6-12 months post-treatment, suggesting the blood protein may provide an early CIPN biomarker.

“Nfl after a single cycle could detect axonal degeneration,” said lead investigator Masarra Joda, a researcher and PhD candidate at the University of Sydney in Australia. She added that “quantification of Nfl may provide a clinically useful marker of emerging neurotoxicity in patients vulnerable to CIPN.”

The findings were presented at the Peripheral Nerve Society (PNS) 2024 annual meeting.

Common, Burdensome Side Effect

A common side effect of chemotherapy, CIPN manifests as sensory neuropathy and causes degeneration of the peripheral axons. A protein biomarker of axonal degeneration, Nfl has previously been investigated as a way of identifying patients at risk of CIPN.

The goal of the current study was to identify the potential link between Nfl with neurophysiological markers of axon degeneration in patients receiving the neurotoxin chemotherapy paclitaxel.

The study included 93 cancer patients. All were assessed at the beginning, middle, and end of treatment. CIPN was assessed using blood samples of Nfl and the Total Neuropathy Score (TNS), the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) neuropathy scale, and patient-reported measures using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire–Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy Module (EORTC-CIPN20).

Axonal degeneration was measured with neurophysiological tests including sural nerve compound sensory action potential (CSAP) for the lower limbs, and sensory median nerve CSAP, as well as stimulus threshold testing, for the upper limbs.

Almost all of study participants (97%) were female. The majority (66%) had breast cancer and 30% had gynecological cancer. Most (73%) were receiving a weekly regimen of paclitaxel, and the remainder were treated with taxanes plus platinum once every 3 weeks. By the end of treatment, 82% of the patients had developed CIPN, which was mild in 44% and moderate/severe in 38%.

Nfl levels increased significantly from baseline to after the first dose of chemotherapy (P < .001), “highlighting that nerve damage occurs from the very beginning of treatment,” senior investigator Susanna Park, PhD, told this news organization.

In addition, “patients with higher Nfl levels after a single paclitaxel treatment had greater neuropathy at the end of treatment (higher EORTC scores [P ≤ .026], and higher TNS scores [P ≤ .00]),” added Dr. Park, who is associate professor at the University of Sydney.

“Importantly, we also looked at long-term outcomes beyond the end of chemotherapy, because chronic neuropathy produces a significant burden in cancer survivors,” said Dr. Park.

“Among a total of 44 patients who completed the 6- to 12-month post-treatment follow-up, NfL levels after a single treatment were linked to severity of nerve damage quantified with neurophysiological tests, and greater Nfl levels at mid-treatment were correlated with worse patient and neurologically graded neuropathy at 6-12 months.”

Dr. Park said the results suggest that NfL may provide a biomarker of long-term axon damage and that Nfl assays “may enable clinicians to evaluate the risk of long-term toxicity early during paclitaxel treatment to hopefully provide clinically significant information to guide better treatment titration.”

Currently, she said, CIPN is a prominent cause of dose reduction and early chemotherapy cessation.

“For example, in early breast cancer around 25% of patients experience a dose reduction due to the severity of neuropathy symptoms.” But, she said, “there is no standardized way of identifying which patients are at risk of long-term neuropathy and therefore, may benefit more from dose reduction. In this setting, a biomarker such as Nfl could provide oncologists with more information about the risk of long-term toxicity and take that into account in dose decision-making.”

For some cancers, she added, there are multiple potential therapy options.

“A biomarker such as NfL could assist in determining risk-benefit profile in terms of switching to alternate therapies. However, further studies will be needed to fully define the utility of NfL as a biomarker of paclitaxel neuropathy.”

Promising Research

Commenting on the research for this news organization, Maryam Lustberg, MD, associate professor, director of the Center for Breast Cancer at Smilow Cancer Hospital and Yale Cancer Center, and chief of Breast Medical Oncology at Yale Cancer Center, in New Haven, Connecticut, said the study “builds on a body of work previously reported by others showing that neurofilament light chains as detected in the blood can be associated with early signs of neurotoxic injury.”

She added that the research “is promising, since existing clinical and patient-reported measures tend to under-detect chemotherapy-induced neuropathy until more permanent injury might have occurred.”

Dr. Lustberg, who is immediate past president of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, said future studies are needed before Nfl testing can be implemented in routine practice, but that “early detection will allow earlier initiation of supportive care strategies such as physical therapy and exercise, as well as dose modifications, which may be helpful for preventing permanent damage and improving quality of life.”

The investigators and Dr. Lustberg report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

AT PNS 2024

Teaching Tips for Dermatology Residents

Dermatology residents interact with trainees of various levels throughout the workday—from undergraduate or even high school students to postgraduate fellows. Depending on the institution’s training program, residents may have responsibilities to teach through lecture series such as Grand Rounds and didactics. Therefore, it is an integral part of resident training to become educators in addition to being learners; however, formal pedagogy education is rare in dermatology programs. 1,2 Herein, I discuss several techniques that residents can apply to their practice to cultivate ideal learning environments and outcomes for trainees.

Creating Effective Teaching and Learning Experiences

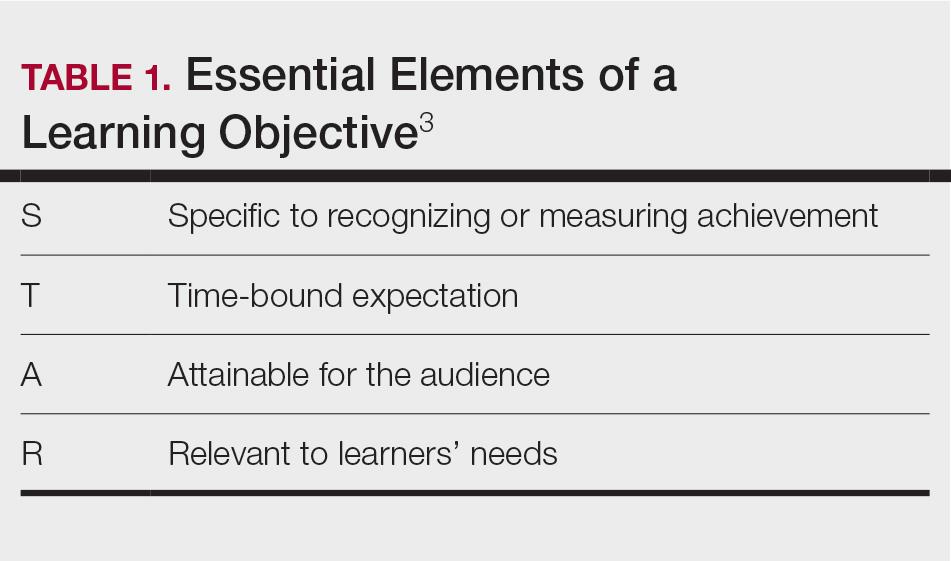

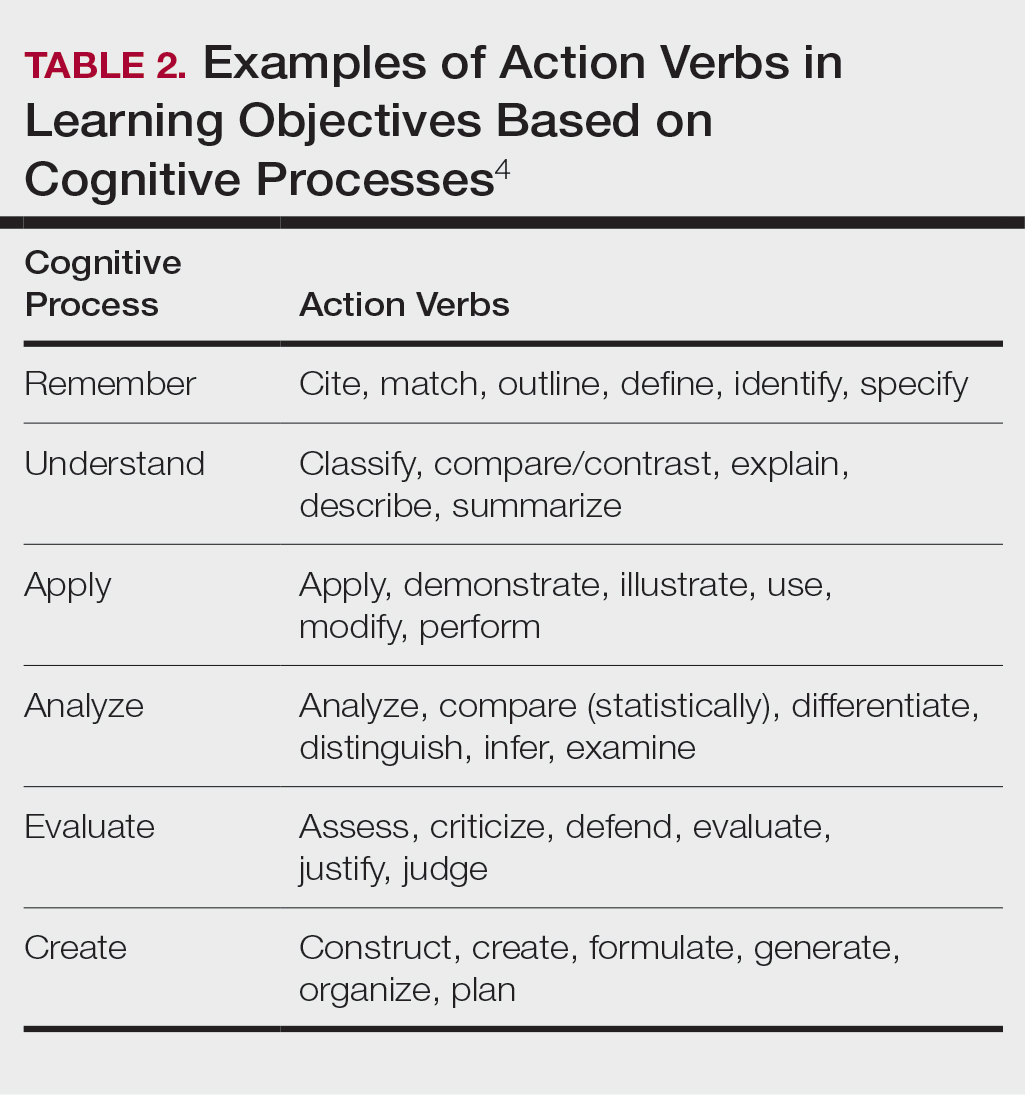

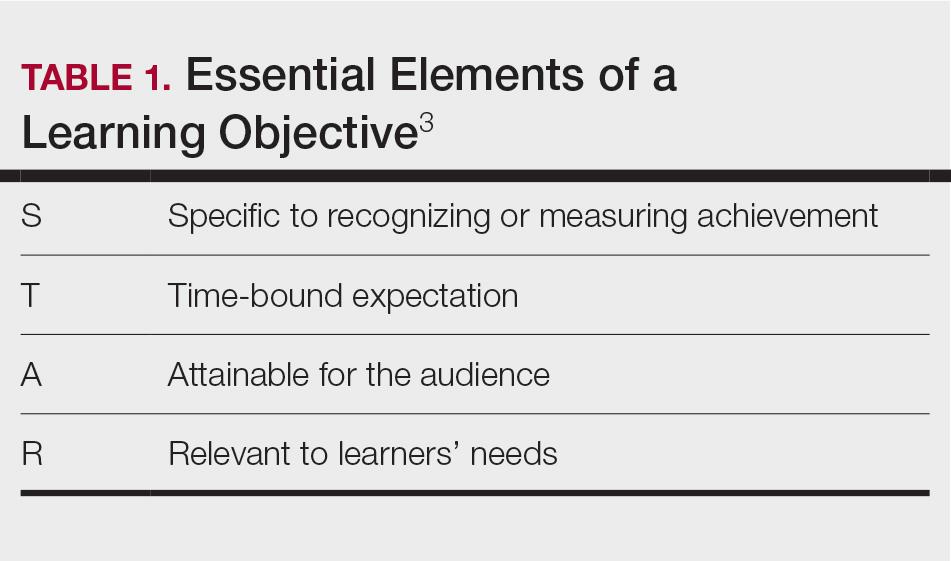

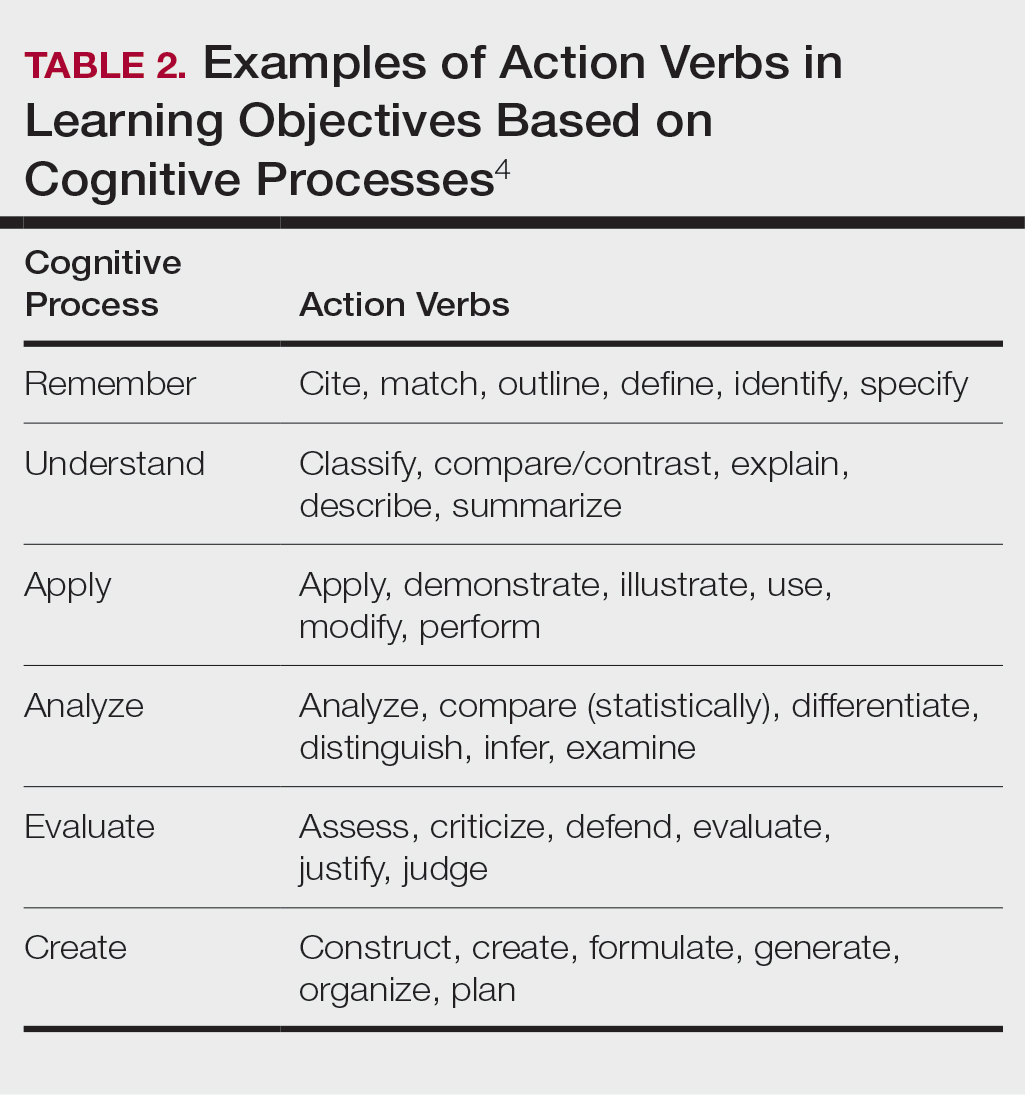

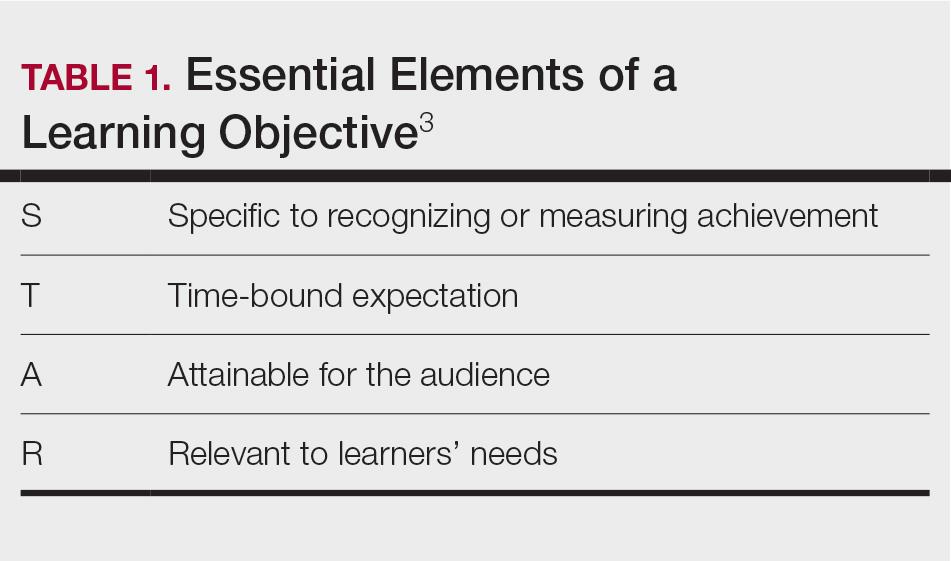

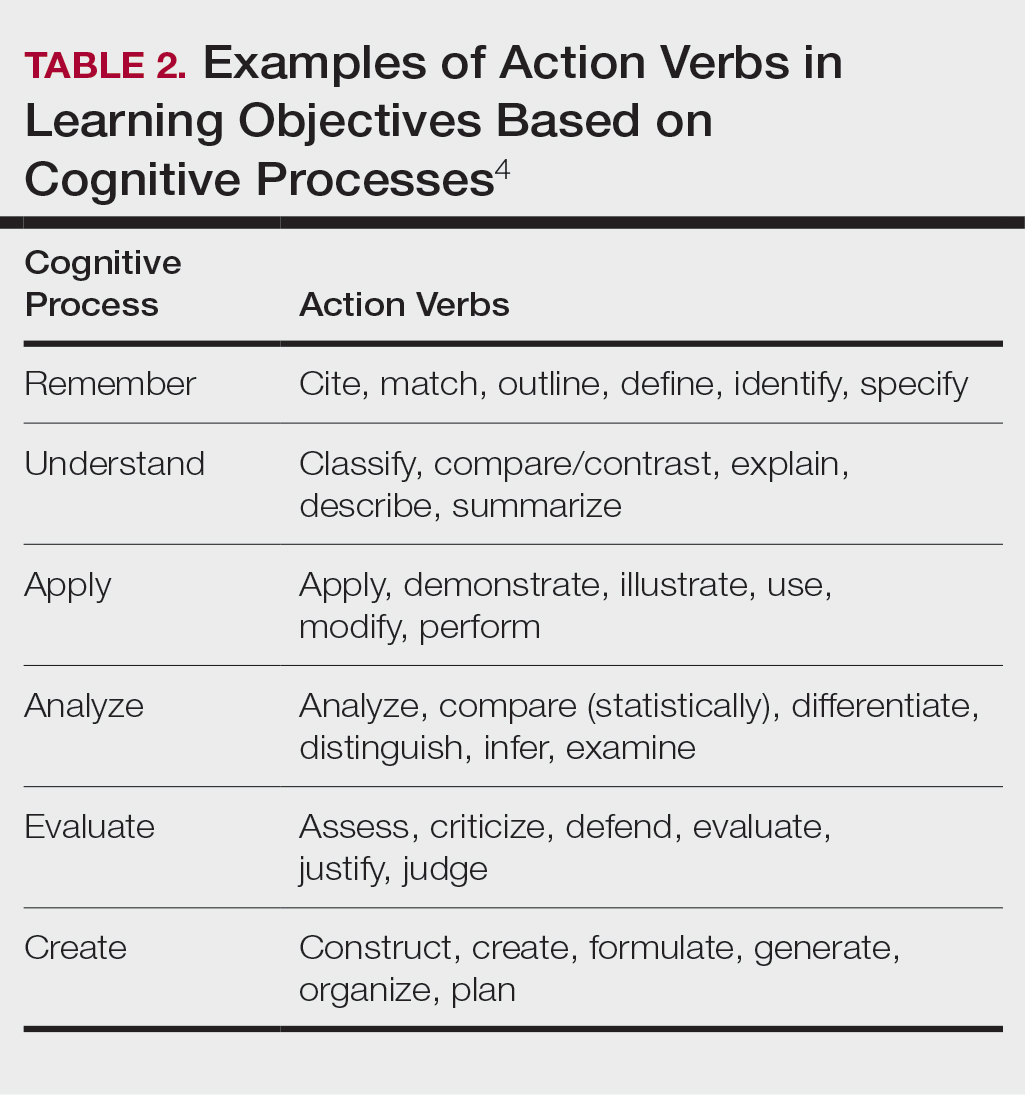

Planning to teach can be as important as teaching itself. Developing learning objectives can help to create effective teaching and learning experiences. Learning objectives should be specific, time bound, attainable, and learner centered (Table 1). It is recommended that residents aim for no more than 4 objectives per hour of learning.3 By creating clear learning objectives, residents can make connections between the content and any assessments. Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive learning objectives gives guidance on action verbs to use in writing learning objectives depending on the cognitive process being tested (Table 2).4

Creating a Safe Educational Environment

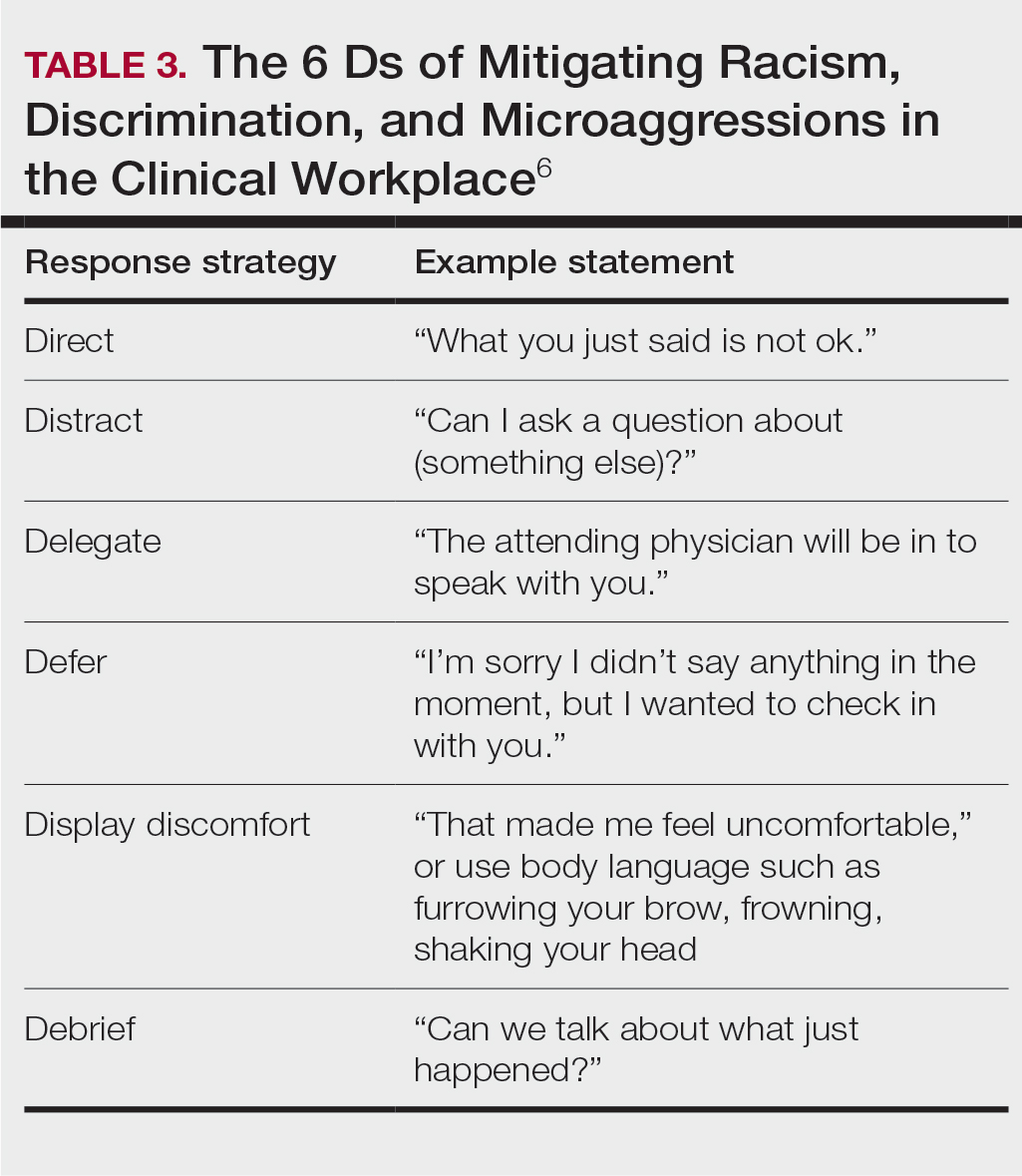

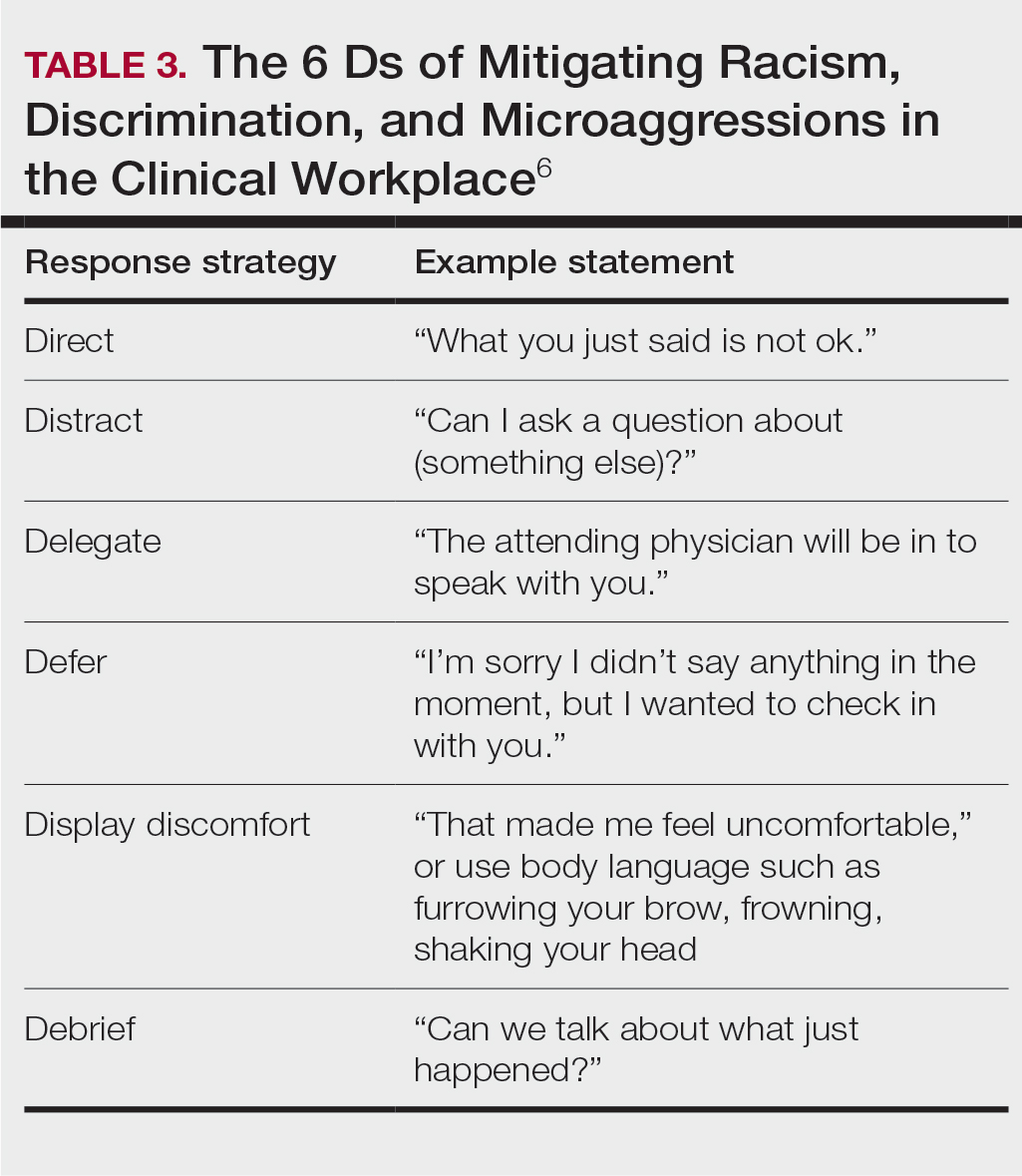

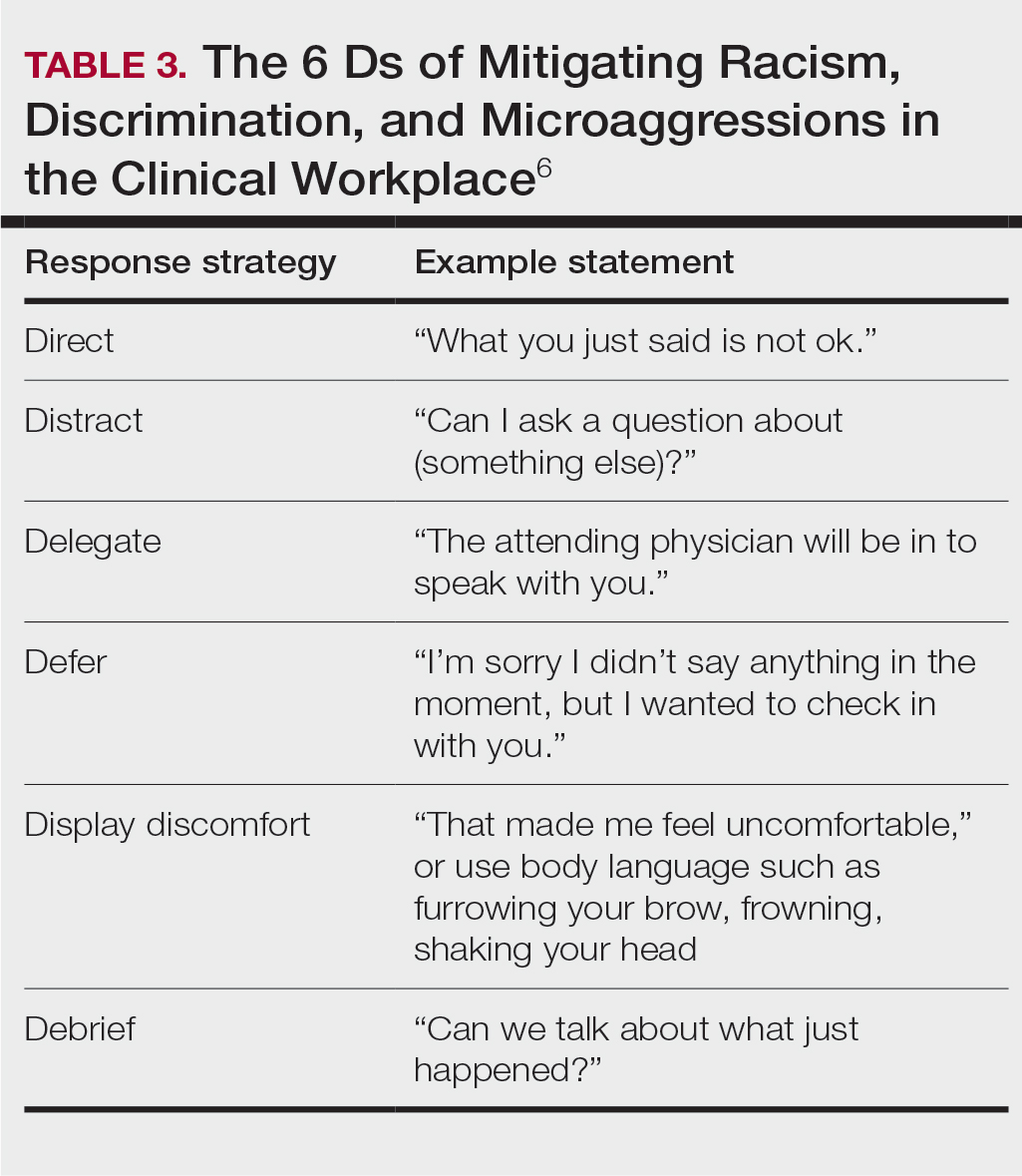

Psychological safety is the belief that a learning environment is a safe place in which to take risks.5 A clinical learning environment that is psychologically safe can support trainee well-being and learning. Cultivating a safe educational environment may include addressing microaggressions and bias in the clinical workplace. Table 3 provides examples of statements using the 6 Ds, which can be used to mitigate these issues.6 The first 4—direct, distract, delegate, and defer—represent ways to respond to racism, microaggressions, and bias, and the last 2—display discomfort and debrief—are responses that may be utilized in any problematic incident. Residents can play an important supportive role in scenarios where learners are faced with an incident that may not be regarded as psychologically safe. This is especially true if the learner is at a lower training level than the dermatology resident. We all play a role in creating a safe workplace for our teams.

Teaching in the Clinic and Hospital

There are multiple challenges to teaching in both inpatient and outpatient environments, including limited space and time; thus, more informal teaching methods are common. For example, in an outpatient dermatology clinic, the patient schedule can become a “table of contents” of potential teaching and learning opportunities. This technique is called the focused half day.3,7 By reviewing the clinic schedule, students can focus on a specific area of interest or theme throughout the course of the day.3

Priming and framing are other focused techniques that work well in both outpatient and inpatient settings.3,8,9 Priming means alerting the trainee to upcoming learning objective(s) and focusing their attention on what to observe or do during a shared visit with a patient. Framing—instructing learners to collect information that is relevant to the diagnosis and treatment—allows trainees to help move patient care forward while the resident attends to other patients.3

Modeling involves describing a thought process out loud for a learner3,10; for example, prior to starting a patient encounter, a dermatology resident may clearly state the goal of a patient conversation to the learner, describe their thought process about the topic, summarize the important points, and ask the learner if they have any questions about what was just said. Using this technique, learners may have a better understanding of why and how to go about conducting a patient encounter after the resident models one for them.

Effectively Integrating Visual Media and Presentations

Research supported by the cognitive load theory and cognitive theory of multimedia learning has led to the assertion-evidence approach for creating presentation slides that are built around messages, not topics, and messages are supported with visuals, not bullets.3,11,12 For example, slides should be constructed with 1- to 2-line assertion statements as titles and relevant illustrations or figures as supporting evidence to enhance visual memory.3

Written text on presentation slides often is redundant with spoken narration and also decreases learning because of cognitive load. Busy background colors and/or designs consume working memory and also can be detrimental to learning. Limiting these common distractors in a presentation makes for more effective delivery and retention of knowledge.3

Final Thoughts

There are multiple avenues for teaching as a resident and not all techniques may be applicable depending on the clinical or academic scenario. This column provides a starting point for residents to augment their pedagogical skills, particularly because formal teaching on pedagogy is lacking in medical education.

- Burgin S, Zhong CS, Rana J. A resident-as-teacher program increases dermatology residents’ knowledge and confidence in teaching techniques: a pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:651-653. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.008

- Burgin S, Homayounfar G, Newman LR, et al. Instruction in teaching and teaching opportunities for residents in US dermatology programs: results of a national survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:703-706. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.043

- UNM School of Medicine Continuous Professional Learning. Residents as Educators. UNM School of Medicine; 2023.

- Bloom BS. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Book 1, Cognitive Domain. Longman; 1979.

- McClintock AH, Fainstad T, Blau K, et al. Psychological safety in medical education: a scoping review and synthesis of the literature. Med Teach. 2023;45:1290-1299. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2023.2216863

- Ackerman-Barger K, Jacobs NN, Orozco R, et al. Addressing microaggressions in academic health: a workshop for inclusiveexcellence. MedEdPORTAL. 2021;17:11103. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11103

- Taylor C, Lipsky MS, Bauer L. Focused teaching: facilitating early clinical experience in an office setting. Fam Med. 1998;30:547-548.

- Pan Z, Kosicki G. Framing analysis: an approach to news discourse. Polit Commun. 1993;10:55-75. doi:10.1080/10584609.1993.9962963

- Price V, Tewksbury D, Powers E. Switching trains of thought: the impact of news frames on readers’ cognitive responses. Commun Res. 1997;24:481-506. doi:10.1177/009365097024005002

- Haston W. Teacher modeling as an effective teaching strategy. Music Educators J. 2007;93:26. doi:10.2307/4127130

- Alley M. Build your scientific talk on messages, not topics. Vimeo website. January 18, 2020. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://vimeo.com/385725653

- Alley M. Support your presentation messages with visual evidence, not bullet lists. Vimeo website. January 18, 2020. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://vimeo.com/385729603

Dermatology residents interact with trainees of various levels throughout the workday—from undergraduate or even high school students to postgraduate fellows. Depending on the institution’s training program, residents may have responsibilities to teach through lecture series such as Grand Rounds and didactics. Therefore, it is an integral part of resident training to become educators in addition to being learners; however, formal pedagogy education is rare in dermatology programs. 1,2 Herein, I discuss several techniques that residents can apply to their practice to cultivate ideal learning environments and outcomes for trainees.

Creating Effective Teaching and Learning Experiences

Planning to teach can be as important as teaching itself. Developing learning objectives can help to create effective teaching and learning experiences. Learning objectives should be specific, time bound, attainable, and learner centered (Table 1). It is recommended that residents aim for no more than 4 objectives per hour of learning.3 By creating clear learning objectives, residents can make connections between the content and any assessments. Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive learning objectives gives guidance on action verbs to use in writing learning objectives depending on the cognitive process being tested (Table 2).4

Creating a Safe Educational Environment

Psychological safety is the belief that a learning environment is a safe place in which to take risks.5 A clinical learning environment that is psychologically safe can support trainee well-being and learning. Cultivating a safe educational environment may include addressing microaggressions and bias in the clinical workplace. Table 3 provides examples of statements using the 6 Ds, which can be used to mitigate these issues.6 The first 4—direct, distract, delegate, and defer—represent ways to respond to racism, microaggressions, and bias, and the last 2—display discomfort and debrief—are responses that may be utilized in any problematic incident. Residents can play an important supportive role in scenarios where learners are faced with an incident that may not be regarded as psychologically safe. This is especially true if the learner is at a lower training level than the dermatology resident. We all play a role in creating a safe workplace for our teams.

Teaching in the Clinic and Hospital

There are multiple challenges to teaching in both inpatient and outpatient environments, including limited space and time; thus, more informal teaching methods are common. For example, in an outpatient dermatology clinic, the patient schedule can become a “table of contents” of potential teaching and learning opportunities. This technique is called the focused half day.3,7 By reviewing the clinic schedule, students can focus on a specific area of interest or theme throughout the course of the day.3

Priming and framing are other focused techniques that work well in both outpatient and inpatient settings.3,8,9 Priming means alerting the trainee to upcoming learning objective(s) and focusing their attention on what to observe or do during a shared visit with a patient. Framing—instructing learners to collect information that is relevant to the diagnosis and treatment—allows trainees to help move patient care forward while the resident attends to other patients.3

Modeling involves describing a thought process out loud for a learner3,10; for example, prior to starting a patient encounter, a dermatology resident may clearly state the goal of a patient conversation to the learner, describe their thought process about the topic, summarize the important points, and ask the learner if they have any questions about what was just said. Using this technique, learners may have a better understanding of why and how to go about conducting a patient encounter after the resident models one for them.

Effectively Integrating Visual Media and Presentations

Research supported by the cognitive load theory and cognitive theory of multimedia learning has led to the assertion-evidence approach for creating presentation slides that are built around messages, not topics, and messages are supported with visuals, not bullets.3,11,12 For example, slides should be constructed with 1- to 2-line assertion statements as titles and relevant illustrations or figures as supporting evidence to enhance visual memory.3

Written text on presentation slides often is redundant with spoken narration and also decreases learning because of cognitive load. Busy background colors and/or designs consume working memory and also can be detrimental to learning. Limiting these common distractors in a presentation makes for more effective delivery and retention of knowledge.3

Final Thoughts