User login

For MD-IQ use only

Aaron Rodgers’s Panchakarma ‘cleanse’ is a dangerous play

Green Bay Packers quarterback Aaron Rodgers recently made headlines when he said he finished a 12-day detoxification process that is said to cleanse the body from within.

Registered dietitians who spoke to this news organizastion about the Panchakarma cleanse were quick to debunk it.

“There is no scientific evidence that supports a cleanse,” says Jessica DeGore, a registered dietitian and owner of Pittsburgh-based Dietitian Jess. “Our kidneys, GI systems, and liver all work to keep us healthy and rid us of toxins.”

The Panchakarma cleanse has roots in the ancient Indian alternative medicine approach known as ayurveda. Its 12-day approach includes such actions as self-induced vomiting; enemas; “nasya,” which means eliminating toxins through the nose; and even bloodletting in an effort to “detoxify” the blood.

All of it is misguided, says Alyssa Pike, a registered dietitian and senior manager of nutrition communications at the International Food Information Council.

“Certainly, there are medical procedures that require a fast of some kind for an extended period, and some choose to engage in a fast for religious or spiritual reasons,” she says, “but those are both very different from doing a voluntary ‘cleanse’ or ‘detox’ diet for purported health benefits.”

In fact, the idea that our bodies are full of “toxins” is simply incorrect.

“There isn’t a real medical definition of the word ‘toxins,’” says Ms. DeGore. “If you really had toxins in your body, you’d need emergency medical care, not a cleanse.”

Harmful advice

The entire notion of cleansing, whether Mr. Rodgers’s favored method or another, has gathered steam in the past few decades as celebrities like Gwyneth Paltrow peddle their favored methods for health.

“It’s easy for people to buy into these ideas when they see beautiful celebrities touting their methods for taking care of themselves,” says Ms. DeGore. “But behind the scenes, they receive support we can’t see or access to keep them well.”

Fans of Mr. Rodgers, Ms. Paltrow, and the like easily forget that these public figures have no medical credentials to support what they are pushing. And the celebrities often profit from their claims in the form of books and products related to them, leaving them anything but an unbiased resource.

In the case of Mr. Rodgers’s Panchakarma cleanse, there are real health risks in following its principles, says registered dietitian nutritionist Tiffany Godwin, director of nutrition and wellness at Connections Wellness Group.

“From a medical standpoint, engaging in activities such as induced vomiting, forced diarrhea, and enema use pose a high risk of extreme dehydration,” she says. “Dehydration can lead to fatigue, headaches, and dizziness at best. At worst, it can lead to seizures, kidney failure, coma, and death.”

Also, a cleanse that is designed to rid your body of toxins may introduce them to your body if you are using herbal medicines.

“Some of the products used in ayurvedic medicine contain herbs, metals, minerals, or other materials that may be harmful if used improperly,” Ms. Pike explains. “Ayurvedic medicines are regulated as dietary supplements rather than as drugs in the United States, so they are not required to meet the safety and efficacy standards for conventional medicines.”

When it comes to ayurveda, which is based on ancient writings that rely on a “natural” or holistic approach to physical and mental health, there is scant research or clinical trials in Western medical journals to support the approach. So people interested in following the practices should always consult with a doctor before trying them.

Mr. Rodgers’s approach includes a “nasal herbal remedy,” for instance.

“Tread very lightly with herbs and supplements,” advises Ms. DeGore. “We have the FDA to put drugs through a rigorous process before they approve them. These supplements are unregulated and don’t go through the same processes.”

Another danger is that when “cleansing,” you are starving your body of the nutrients it needs.

“When we vomit, or have diarrhea, we are not simply losing a mass amount of fluid from our bodies, but we are also losing essential electrolytes and minerals,” says Ms. Godwin.

Instead, say the registered dietitians, you can help your body by feeding it what it really needs.

“Eating plenty of fiber-rich foods such as fruits, veggies, beans, legumes, and whole grains, for example, keeps our GI tract moving and grooving, creating an ideal environment for our gut to use the useful things, and get rid of the not so useful,” says Ms. Godwin. “These systems can be compromised in different disease states, such as liver disease, kidney disease, and other GI disorders like Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis. With these disease states, however, cleanses can be even more harmful.”

Cleansing practices can also be a very slippery slope for people struggling with disordered eating.

“When celebrities promote these cleanses, they often bring in impressionable people,” says Ms. DeGore. “These approaches are stripping your body of nutritional needs and inducing disruptive behaviors. Ironically, they will slow down your metabolism, eventually leading to weight gain when you return to normal eating.”

With the Panchakarma cleanse, the 12-day length of cleansing is particularly alarming, says Ms. DeGore.

“Even after 5 days, you cannot think clearly and will have nasty side effects,” she says.

At the end of the day, whether it’s Mr. Rodgers, Ms. Paltrow, or another celebrity, all of the dietitians recommend steering clear of their advice when it comes to health and nutrition.

“Be wary of celebrities, influencers, or anyone who tries to persuade you to try an extreme cleanse or ‘too good to be true’ diet,” says Ms. Pike. “These can be dangerous for your health, physically and mentally.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Green Bay Packers quarterback Aaron Rodgers recently made headlines when he said he finished a 12-day detoxification process that is said to cleanse the body from within.

Registered dietitians who spoke to this news organizastion about the Panchakarma cleanse were quick to debunk it.

“There is no scientific evidence that supports a cleanse,” says Jessica DeGore, a registered dietitian and owner of Pittsburgh-based Dietitian Jess. “Our kidneys, GI systems, and liver all work to keep us healthy and rid us of toxins.”

The Panchakarma cleanse has roots in the ancient Indian alternative medicine approach known as ayurveda. Its 12-day approach includes such actions as self-induced vomiting; enemas; “nasya,” which means eliminating toxins through the nose; and even bloodletting in an effort to “detoxify” the blood.

All of it is misguided, says Alyssa Pike, a registered dietitian and senior manager of nutrition communications at the International Food Information Council.

“Certainly, there are medical procedures that require a fast of some kind for an extended period, and some choose to engage in a fast for religious or spiritual reasons,” she says, “but those are both very different from doing a voluntary ‘cleanse’ or ‘detox’ diet for purported health benefits.”

In fact, the idea that our bodies are full of “toxins” is simply incorrect.

“There isn’t a real medical definition of the word ‘toxins,’” says Ms. DeGore. “If you really had toxins in your body, you’d need emergency medical care, not a cleanse.”

Harmful advice

The entire notion of cleansing, whether Mr. Rodgers’s favored method or another, has gathered steam in the past few decades as celebrities like Gwyneth Paltrow peddle their favored methods for health.

“It’s easy for people to buy into these ideas when they see beautiful celebrities touting their methods for taking care of themselves,” says Ms. DeGore. “But behind the scenes, they receive support we can’t see or access to keep them well.”

Fans of Mr. Rodgers, Ms. Paltrow, and the like easily forget that these public figures have no medical credentials to support what they are pushing. And the celebrities often profit from their claims in the form of books and products related to them, leaving them anything but an unbiased resource.

In the case of Mr. Rodgers’s Panchakarma cleanse, there are real health risks in following its principles, says registered dietitian nutritionist Tiffany Godwin, director of nutrition and wellness at Connections Wellness Group.

“From a medical standpoint, engaging in activities such as induced vomiting, forced diarrhea, and enema use pose a high risk of extreme dehydration,” she says. “Dehydration can lead to fatigue, headaches, and dizziness at best. At worst, it can lead to seizures, kidney failure, coma, and death.”

Also, a cleanse that is designed to rid your body of toxins may introduce them to your body if you are using herbal medicines.

“Some of the products used in ayurvedic medicine contain herbs, metals, minerals, or other materials that may be harmful if used improperly,” Ms. Pike explains. “Ayurvedic medicines are regulated as dietary supplements rather than as drugs in the United States, so they are not required to meet the safety and efficacy standards for conventional medicines.”

When it comes to ayurveda, which is based on ancient writings that rely on a “natural” or holistic approach to physical and mental health, there is scant research or clinical trials in Western medical journals to support the approach. So people interested in following the practices should always consult with a doctor before trying them.

Mr. Rodgers’s approach includes a “nasal herbal remedy,” for instance.

“Tread very lightly with herbs and supplements,” advises Ms. DeGore. “We have the FDA to put drugs through a rigorous process before they approve them. These supplements are unregulated and don’t go through the same processes.”

Another danger is that when “cleansing,” you are starving your body of the nutrients it needs.

“When we vomit, or have diarrhea, we are not simply losing a mass amount of fluid from our bodies, but we are also losing essential electrolytes and minerals,” says Ms. Godwin.

Instead, say the registered dietitians, you can help your body by feeding it what it really needs.

“Eating plenty of fiber-rich foods such as fruits, veggies, beans, legumes, and whole grains, for example, keeps our GI tract moving and grooving, creating an ideal environment for our gut to use the useful things, and get rid of the not so useful,” says Ms. Godwin. “These systems can be compromised in different disease states, such as liver disease, kidney disease, and other GI disorders like Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis. With these disease states, however, cleanses can be even more harmful.”

Cleansing practices can also be a very slippery slope for people struggling with disordered eating.

“When celebrities promote these cleanses, they often bring in impressionable people,” says Ms. DeGore. “These approaches are stripping your body of nutritional needs and inducing disruptive behaviors. Ironically, they will slow down your metabolism, eventually leading to weight gain when you return to normal eating.”

With the Panchakarma cleanse, the 12-day length of cleansing is particularly alarming, says Ms. DeGore.

“Even after 5 days, you cannot think clearly and will have nasty side effects,” she says.

At the end of the day, whether it’s Mr. Rodgers, Ms. Paltrow, or another celebrity, all of the dietitians recommend steering clear of their advice when it comes to health and nutrition.

“Be wary of celebrities, influencers, or anyone who tries to persuade you to try an extreme cleanse or ‘too good to be true’ diet,” says Ms. Pike. “These can be dangerous for your health, physically and mentally.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Green Bay Packers quarterback Aaron Rodgers recently made headlines when he said he finished a 12-day detoxification process that is said to cleanse the body from within.

Registered dietitians who spoke to this news organizastion about the Panchakarma cleanse were quick to debunk it.

“There is no scientific evidence that supports a cleanse,” says Jessica DeGore, a registered dietitian and owner of Pittsburgh-based Dietitian Jess. “Our kidneys, GI systems, and liver all work to keep us healthy and rid us of toxins.”

The Panchakarma cleanse has roots in the ancient Indian alternative medicine approach known as ayurveda. Its 12-day approach includes such actions as self-induced vomiting; enemas; “nasya,” which means eliminating toxins through the nose; and even bloodletting in an effort to “detoxify” the blood.

All of it is misguided, says Alyssa Pike, a registered dietitian and senior manager of nutrition communications at the International Food Information Council.

“Certainly, there are medical procedures that require a fast of some kind for an extended period, and some choose to engage in a fast for religious or spiritual reasons,” she says, “but those are both very different from doing a voluntary ‘cleanse’ or ‘detox’ diet for purported health benefits.”

In fact, the idea that our bodies are full of “toxins” is simply incorrect.

“There isn’t a real medical definition of the word ‘toxins,’” says Ms. DeGore. “If you really had toxins in your body, you’d need emergency medical care, not a cleanse.”

Harmful advice

The entire notion of cleansing, whether Mr. Rodgers’s favored method or another, has gathered steam in the past few decades as celebrities like Gwyneth Paltrow peddle their favored methods for health.

“It’s easy for people to buy into these ideas when they see beautiful celebrities touting their methods for taking care of themselves,” says Ms. DeGore. “But behind the scenes, they receive support we can’t see or access to keep them well.”

Fans of Mr. Rodgers, Ms. Paltrow, and the like easily forget that these public figures have no medical credentials to support what they are pushing. And the celebrities often profit from their claims in the form of books and products related to them, leaving them anything but an unbiased resource.

In the case of Mr. Rodgers’s Panchakarma cleanse, there are real health risks in following its principles, says registered dietitian nutritionist Tiffany Godwin, director of nutrition and wellness at Connections Wellness Group.

“From a medical standpoint, engaging in activities such as induced vomiting, forced diarrhea, and enema use pose a high risk of extreme dehydration,” she says. “Dehydration can lead to fatigue, headaches, and dizziness at best. At worst, it can lead to seizures, kidney failure, coma, and death.”

Also, a cleanse that is designed to rid your body of toxins may introduce them to your body if you are using herbal medicines.

“Some of the products used in ayurvedic medicine contain herbs, metals, minerals, or other materials that may be harmful if used improperly,” Ms. Pike explains. “Ayurvedic medicines are regulated as dietary supplements rather than as drugs in the United States, so they are not required to meet the safety and efficacy standards for conventional medicines.”

When it comes to ayurveda, which is based on ancient writings that rely on a “natural” or holistic approach to physical and mental health, there is scant research or clinical trials in Western medical journals to support the approach. So people interested in following the practices should always consult with a doctor before trying them.

Mr. Rodgers’s approach includes a “nasal herbal remedy,” for instance.

“Tread very lightly with herbs and supplements,” advises Ms. DeGore. “We have the FDA to put drugs through a rigorous process before they approve them. These supplements are unregulated and don’t go through the same processes.”

Another danger is that when “cleansing,” you are starving your body of the nutrients it needs.

“When we vomit, or have diarrhea, we are not simply losing a mass amount of fluid from our bodies, but we are also losing essential electrolytes and minerals,” says Ms. Godwin.

Instead, say the registered dietitians, you can help your body by feeding it what it really needs.

“Eating plenty of fiber-rich foods such as fruits, veggies, beans, legumes, and whole grains, for example, keeps our GI tract moving and grooving, creating an ideal environment for our gut to use the useful things, and get rid of the not so useful,” says Ms. Godwin. “These systems can be compromised in different disease states, such as liver disease, kidney disease, and other GI disorders like Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis. With these disease states, however, cleanses can be even more harmful.”

Cleansing practices can also be a very slippery slope for people struggling with disordered eating.

“When celebrities promote these cleanses, they often bring in impressionable people,” says Ms. DeGore. “These approaches are stripping your body of nutritional needs and inducing disruptive behaviors. Ironically, they will slow down your metabolism, eventually leading to weight gain when you return to normal eating.”

With the Panchakarma cleanse, the 12-day length of cleansing is particularly alarming, says Ms. DeGore.

“Even after 5 days, you cannot think clearly and will have nasty side effects,” she says.

At the end of the day, whether it’s Mr. Rodgers, Ms. Paltrow, or another celebrity, all of the dietitians recommend steering clear of their advice when it comes to health and nutrition.

“Be wary of celebrities, influencers, or anyone who tries to persuade you to try an extreme cleanse or ‘too good to be true’ diet,” says Ms. Pike. “These can be dangerous for your health, physically and mentally.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Can liquid biopsy predict oropharyngeal cancer recurrence?

PHOENIX – A liquid biopsy test may accurately predict recurrence of human papillomavirus (HPV)–driven oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) earlier than standard clinical and imaging assessments, a new analysis indicates.

Of 80 patients who tested positive for circulating tumor tissue–modified viral (TTMV)-HPV DNA during surveillance, 74% (n = 59) had no other evidence of disease or had indeterminate disease status.

And of those patients, 93% (n = 55) “later had proven recurrent, metastatic disease on imaging and/or biopsy,” according to Glenn Hanna, MD, from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, who presented the results Feb. 24 at the 2022 Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Cancers Symposium.

“This is the first study to demonstrate broad clinical utility and validity of the biomarker in HPV-driven oropharyngeal cancer,” Dr. Hanna said in a press release.

Although patients with HPV-driven OPSCC generally have favorable outcomes, up to 25% will experience recurrence after treatment.

Post-treatment surveillance currently relies on physical examinations and imaging, but Dr. Hanna and colleagues wanted to determine whether a routine circulating cell-free TTMV-HPV DNA test could detect occult recurrence sooner.

Dr. Hanna and colleagues analyzed the records of 1,076 patients with HPV-driven OPSCC at 118 sites in the U.S. who had completed therapy more than 3 months previously and undergone an TTMV-HPV DNA test (NavDx, Naveris) between June 2020 and November 2021.

The results of the test, which used ultrasensitive digital droplet PCR to identify HPV subtypes 16, 18, 31, 33, and 35, were compared with subsequent clinical evidence of OPSCC via nasopharyngolaryngoscopy, radiologic evaluations, or tissue biopsy.

Approximately 7% of the patients tested positive (n = 80) for circulating TTMV-HPV DNA. Of those, 26.2% (n = 21) had known clinical recurrence, while 73.8% (n = 59) had no other evidence of disease or an intermediate disease status.

Among those with no clinical evidence of recurrence, 93.2% (n = 55) had their recurrence subsequently confirmed using imaging or biopsy. Of the 4 remaining patients, 2 had clinically suspicious lesions, and 2 had no other evidence of disease.

Overall, the data indicate that the biomarker test demonstrated a 95% positive predictive value (76 of 80 patients) for recurrence or persistence of HPV-driven OPSCC.

According to Dr. Hanna, a positive TTMV-HPV DNA test was the first indicator of recurrence for 72% of patients, and almost half of recurrences were detected more than 12 months after completing therapy.

“Incorporating a test for TTMV-HPV DNA into routine post-treatment follow-up can enable physicians to detect recurrent cancers earlier and allow us to start recommended interventions more quickly to improve outcomes,” Dr. Hanna said in the release.

The study was supported by Naveris, which developed the TTMV-HPV DNA test studied. Dr. Hanna declares relationships with Actuate Therapeutics, Altor BioScience, Bicara, BMS, GSK, Merck, Regeneron, Sanofi/Genzyme, and others.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

PHOENIX – A liquid biopsy test may accurately predict recurrence of human papillomavirus (HPV)–driven oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) earlier than standard clinical and imaging assessments, a new analysis indicates.

Of 80 patients who tested positive for circulating tumor tissue–modified viral (TTMV)-HPV DNA during surveillance, 74% (n = 59) had no other evidence of disease or had indeterminate disease status.

And of those patients, 93% (n = 55) “later had proven recurrent, metastatic disease on imaging and/or biopsy,” according to Glenn Hanna, MD, from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, who presented the results Feb. 24 at the 2022 Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Cancers Symposium.

“This is the first study to demonstrate broad clinical utility and validity of the biomarker in HPV-driven oropharyngeal cancer,” Dr. Hanna said in a press release.

Although patients with HPV-driven OPSCC generally have favorable outcomes, up to 25% will experience recurrence after treatment.

Post-treatment surveillance currently relies on physical examinations and imaging, but Dr. Hanna and colleagues wanted to determine whether a routine circulating cell-free TTMV-HPV DNA test could detect occult recurrence sooner.

Dr. Hanna and colleagues analyzed the records of 1,076 patients with HPV-driven OPSCC at 118 sites in the U.S. who had completed therapy more than 3 months previously and undergone an TTMV-HPV DNA test (NavDx, Naveris) between June 2020 and November 2021.

The results of the test, which used ultrasensitive digital droplet PCR to identify HPV subtypes 16, 18, 31, 33, and 35, were compared with subsequent clinical evidence of OPSCC via nasopharyngolaryngoscopy, radiologic evaluations, or tissue biopsy.

Approximately 7% of the patients tested positive (n = 80) for circulating TTMV-HPV DNA. Of those, 26.2% (n = 21) had known clinical recurrence, while 73.8% (n = 59) had no other evidence of disease or an intermediate disease status.

Among those with no clinical evidence of recurrence, 93.2% (n = 55) had their recurrence subsequently confirmed using imaging or biopsy. Of the 4 remaining patients, 2 had clinically suspicious lesions, and 2 had no other evidence of disease.

Overall, the data indicate that the biomarker test demonstrated a 95% positive predictive value (76 of 80 patients) for recurrence or persistence of HPV-driven OPSCC.

According to Dr. Hanna, a positive TTMV-HPV DNA test was the first indicator of recurrence for 72% of patients, and almost half of recurrences were detected more than 12 months after completing therapy.

“Incorporating a test for TTMV-HPV DNA into routine post-treatment follow-up can enable physicians to detect recurrent cancers earlier and allow us to start recommended interventions more quickly to improve outcomes,” Dr. Hanna said in the release.

The study was supported by Naveris, which developed the TTMV-HPV DNA test studied. Dr. Hanna declares relationships with Actuate Therapeutics, Altor BioScience, Bicara, BMS, GSK, Merck, Regeneron, Sanofi/Genzyme, and others.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

PHOENIX – A liquid biopsy test may accurately predict recurrence of human papillomavirus (HPV)–driven oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) earlier than standard clinical and imaging assessments, a new analysis indicates.

Of 80 patients who tested positive for circulating tumor tissue–modified viral (TTMV)-HPV DNA during surveillance, 74% (n = 59) had no other evidence of disease or had indeterminate disease status.

And of those patients, 93% (n = 55) “later had proven recurrent, metastatic disease on imaging and/or biopsy,” according to Glenn Hanna, MD, from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, who presented the results Feb. 24 at the 2022 Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Cancers Symposium.

“This is the first study to demonstrate broad clinical utility and validity of the biomarker in HPV-driven oropharyngeal cancer,” Dr. Hanna said in a press release.

Although patients with HPV-driven OPSCC generally have favorable outcomes, up to 25% will experience recurrence after treatment.

Post-treatment surveillance currently relies on physical examinations and imaging, but Dr. Hanna and colleagues wanted to determine whether a routine circulating cell-free TTMV-HPV DNA test could detect occult recurrence sooner.

Dr. Hanna and colleagues analyzed the records of 1,076 patients with HPV-driven OPSCC at 118 sites in the U.S. who had completed therapy more than 3 months previously and undergone an TTMV-HPV DNA test (NavDx, Naveris) between June 2020 and November 2021.

The results of the test, which used ultrasensitive digital droplet PCR to identify HPV subtypes 16, 18, 31, 33, and 35, were compared with subsequent clinical evidence of OPSCC via nasopharyngolaryngoscopy, radiologic evaluations, or tissue biopsy.

Approximately 7% of the patients tested positive (n = 80) for circulating TTMV-HPV DNA. Of those, 26.2% (n = 21) had known clinical recurrence, while 73.8% (n = 59) had no other evidence of disease or an intermediate disease status.

Among those with no clinical evidence of recurrence, 93.2% (n = 55) had their recurrence subsequently confirmed using imaging or biopsy. Of the 4 remaining patients, 2 had clinically suspicious lesions, and 2 had no other evidence of disease.

Overall, the data indicate that the biomarker test demonstrated a 95% positive predictive value (76 of 80 patients) for recurrence or persistence of HPV-driven OPSCC.

According to Dr. Hanna, a positive TTMV-HPV DNA test was the first indicator of recurrence for 72% of patients, and almost half of recurrences were detected more than 12 months after completing therapy.

“Incorporating a test for TTMV-HPV DNA into routine post-treatment follow-up can enable physicians to detect recurrent cancers earlier and allow us to start recommended interventions more quickly to improve outcomes,” Dr. Hanna said in the release.

The study was supported by Naveris, which developed the TTMV-HPV DNA test studied. Dr. Hanna declares relationships with Actuate Therapeutics, Altor BioScience, Bicara, BMS, GSK, Merck, Regeneron, Sanofi/Genzyme, and others.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Tastier chocolate may be healthier chocolate

Chocolate: Now part of a well-balanced diet

Asking if someone loves chocolate is like asking if they love breathing. It’s really not a question that needs to be asked. The thing with chocolate, however, is that most people who love chocolate actually love sugar, since your typical milk chocolate contains only about 30% cacao. The rest, of course, is sugar.

Now, dark chocolate is actually kind of good for you since it contains beneficial flavonoids and less sugar. But that healthiness comes at a cost: Dark chocolate is quite bitter, and gets more so as the cacao content rises, to the point where 100% cacao chocolate is very nearly inedible. That’s the chocolate conundrum, the healthier it is, the worse it tastes. But what if there’s another way? What if you can have tasty chocolate that’s good for you?

That’s the question a group of researchers from Penn State University dared to ask. The secret, they discovered, is to subject the cacao beans to extra-intense roasting. We’re not sure how screaming insults at a bunch of beans will help, but if science says so ... YOU USELESS LUMP OF BARELY EDIBLE FOOD! HOW DARE YOU EXIST!

Oh, not that kind of roasting. Oops.

For their study, the researchers made 27 unsweetened chocolates, prepared using various cacao bean roasting times and temperatures, and served them to volunteers. Those volunteers reported that chocolates made with cacao beans roasted more intensely (such as 20 minutes at 340° F, 80 min at 275° F, and 54 min at 304° F) were far more acceptable than were chocolates prepared with raw or lightly roasted cacao beans.

The implications of healthy yet tasty chocolate are obvious: Master the chocolate and you’ll make millions. Imagine a future where parents say to their kids: “Don’t forget to eat your chocolate.” So, we’re off to do some cooking. Don’t want Hershey to make all the money off of this revelation.

The villain hiding in dairy for some MS patients

For some of us, lactose can be a real heartbreaker when it comes to dairy consumption, but for people with multiple sclerosis (MS) there’s another villain they may also have to face that can make their symptoms worse.

Physicians at the Institute of Anatomy at University Hospital Bonn (Germany) were getting so many complaints from patients with MS about how much worse they felt about after having cheese, yogurt, and milk that they decided to get to the bottom of it. The culprit, it seems, is casein, a protein specifically found in cow’s milk.

The researchers injected mice with various proteins found in cow’s milk and found perforated myelin sheaths in those given casein. In MS, the patient’s own immune system destroys that sheath, which leads to paresthesia, vision problems, and movement disorders.

“The body’s defenses actually attack the casein, but in the process they also destroy proteins involved in the formation of myelin, “ said Rittika Chunder, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Bonn. How? Apparently it’s all a big misunderstanding.

While looking at molecules needed for myelin production, the researchers came across MAG, which is very similar to casein, which is a problem when patients with MS are allergic to casein. After they have dairy products, the B-cell squad gets called in to clean up the evil twin, casein, but can’t differentiate it from the good twin, MAG, so it all gets a wash and the myelin sheath suffers.

Since this happens only to patients with MS who have a casein allergy, the researchers advise them to stay away from milk, yogurt, or cottage cheese while they work on a self-test to check if patients carry the antibodies.

A small price to pay, perhaps, to stop a villainous evil twin.

You would even say it glows

If you’re anything like us – and we think you are since you’re reading this – you’ve been asking yourself: Are there any common medications in my house that will make good radiation sensors?

Not that anyone needs to worry about excess radiation or anything. Far from it. We were just wondering.

It just so happens that Anna Mrozik and Paweł Bilski, both of the Institute of Nuclear Physics Polish Academy of Sciences (IFJ PAN) in Kraków, Poland, were wondering the same thing: “During an uncontrolled release of radiation, it is highly unlikely that members of the public will be equipped with personal radiation dose monitors.”

People would need to use something they had lying around the house. A smartphone would work, the investigators explained in a statement from the IFJ PAN, but the process of converting one to radiation-sensor duty, which involves dismantling it and breaking the display glass, “is laborious and time-consuming [and] the destruction of a valuable and useful device does not seem to be the optimal solution.”

Naturally, they turned to drugs. The key, in this case, is optically stimulated luminescence. They needed to find materials that would glow with greater intensity as the radiation dose increased. Turns out that ibuprofen- and paracetamol-based painkillers fit the bill quite nicely, although aspirin also works.

It’s not known exactly which substance is causing the luminescence, but rest assured, the “physicists from the IFJ PAN intend to identify it.”

This is why you don’t interrupt someone using headphones

There’s nothing like taking a nice relaxing walk with your headphones. Whether you’re listening to a podcast or a song or talking on the phone, it’s an escape from reality that makes you feel like you’re completely in tune with what you’re listening to.

According to a new study, headphones, as opposed to speakers, make people feel more connected to what they are listening to. Data collected from more than 4,000 people showed that listening with headphones makes more of an impact than listening to speakers.

“Headphones produce a phenomenon called in-head localization, which makes the speaker sound as if they’re inside your head,” study coauthor On Amir of the University of California, San Diego, said in a statement. Because of this, people feel like the speakers are close to them and there’s more of a sense of empathy for the speakers and the listener is more likely to be swayed toward the ideas of the speaker.

These findings could lead to more efficient training programs, online work, and advertising, the investigators suggested.

We now finally understand why people get so mad when they have to take out their headphones to answer or talk to us. We ruined a satisfying moment going on in their brains.

Chocolate: Now part of a well-balanced diet

Asking if someone loves chocolate is like asking if they love breathing. It’s really not a question that needs to be asked. The thing with chocolate, however, is that most people who love chocolate actually love sugar, since your typical milk chocolate contains only about 30% cacao. The rest, of course, is sugar.

Now, dark chocolate is actually kind of good for you since it contains beneficial flavonoids and less sugar. But that healthiness comes at a cost: Dark chocolate is quite bitter, and gets more so as the cacao content rises, to the point where 100% cacao chocolate is very nearly inedible. That’s the chocolate conundrum, the healthier it is, the worse it tastes. But what if there’s another way? What if you can have tasty chocolate that’s good for you?

That’s the question a group of researchers from Penn State University dared to ask. The secret, they discovered, is to subject the cacao beans to extra-intense roasting. We’re not sure how screaming insults at a bunch of beans will help, but if science says so ... YOU USELESS LUMP OF BARELY EDIBLE FOOD! HOW DARE YOU EXIST!

Oh, not that kind of roasting. Oops.

For their study, the researchers made 27 unsweetened chocolates, prepared using various cacao bean roasting times and temperatures, and served them to volunteers. Those volunteers reported that chocolates made with cacao beans roasted more intensely (such as 20 minutes at 340° F, 80 min at 275° F, and 54 min at 304° F) were far more acceptable than were chocolates prepared with raw or lightly roasted cacao beans.

The implications of healthy yet tasty chocolate are obvious: Master the chocolate and you’ll make millions. Imagine a future where parents say to their kids: “Don’t forget to eat your chocolate.” So, we’re off to do some cooking. Don’t want Hershey to make all the money off of this revelation.

The villain hiding in dairy for some MS patients

For some of us, lactose can be a real heartbreaker when it comes to dairy consumption, but for people with multiple sclerosis (MS) there’s another villain they may also have to face that can make their symptoms worse.

Physicians at the Institute of Anatomy at University Hospital Bonn (Germany) were getting so many complaints from patients with MS about how much worse they felt about after having cheese, yogurt, and milk that they decided to get to the bottom of it. The culprit, it seems, is casein, a protein specifically found in cow’s milk.

The researchers injected mice with various proteins found in cow’s milk and found perforated myelin sheaths in those given casein. In MS, the patient’s own immune system destroys that sheath, which leads to paresthesia, vision problems, and movement disorders.

“The body’s defenses actually attack the casein, but in the process they also destroy proteins involved in the formation of myelin, “ said Rittika Chunder, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Bonn. How? Apparently it’s all a big misunderstanding.

While looking at molecules needed for myelin production, the researchers came across MAG, which is very similar to casein, which is a problem when patients with MS are allergic to casein. After they have dairy products, the B-cell squad gets called in to clean up the evil twin, casein, but can’t differentiate it from the good twin, MAG, so it all gets a wash and the myelin sheath suffers.

Since this happens only to patients with MS who have a casein allergy, the researchers advise them to stay away from milk, yogurt, or cottage cheese while they work on a self-test to check if patients carry the antibodies.

A small price to pay, perhaps, to stop a villainous evil twin.

You would even say it glows

If you’re anything like us – and we think you are since you’re reading this – you’ve been asking yourself: Are there any common medications in my house that will make good radiation sensors?

Not that anyone needs to worry about excess radiation or anything. Far from it. We were just wondering.

It just so happens that Anna Mrozik and Paweł Bilski, both of the Institute of Nuclear Physics Polish Academy of Sciences (IFJ PAN) in Kraków, Poland, were wondering the same thing: “During an uncontrolled release of radiation, it is highly unlikely that members of the public will be equipped with personal radiation dose monitors.”

People would need to use something they had lying around the house. A smartphone would work, the investigators explained in a statement from the IFJ PAN, but the process of converting one to radiation-sensor duty, which involves dismantling it and breaking the display glass, “is laborious and time-consuming [and] the destruction of a valuable and useful device does not seem to be the optimal solution.”

Naturally, they turned to drugs. The key, in this case, is optically stimulated luminescence. They needed to find materials that would glow with greater intensity as the radiation dose increased. Turns out that ibuprofen- and paracetamol-based painkillers fit the bill quite nicely, although aspirin also works.

It’s not known exactly which substance is causing the luminescence, but rest assured, the “physicists from the IFJ PAN intend to identify it.”

This is why you don’t interrupt someone using headphones

There’s nothing like taking a nice relaxing walk with your headphones. Whether you’re listening to a podcast or a song or talking on the phone, it’s an escape from reality that makes you feel like you’re completely in tune with what you’re listening to.

According to a new study, headphones, as opposed to speakers, make people feel more connected to what they are listening to. Data collected from more than 4,000 people showed that listening with headphones makes more of an impact than listening to speakers.

“Headphones produce a phenomenon called in-head localization, which makes the speaker sound as if they’re inside your head,” study coauthor On Amir of the University of California, San Diego, said in a statement. Because of this, people feel like the speakers are close to them and there’s more of a sense of empathy for the speakers and the listener is more likely to be swayed toward the ideas of the speaker.

These findings could lead to more efficient training programs, online work, and advertising, the investigators suggested.

We now finally understand why people get so mad when they have to take out their headphones to answer or talk to us. We ruined a satisfying moment going on in their brains.

Chocolate: Now part of a well-balanced diet

Asking if someone loves chocolate is like asking if they love breathing. It’s really not a question that needs to be asked. The thing with chocolate, however, is that most people who love chocolate actually love sugar, since your typical milk chocolate contains only about 30% cacao. The rest, of course, is sugar.

Now, dark chocolate is actually kind of good for you since it contains beneficial flavonoids and less sugar. But that healthiness comes at a cost: Dark chocolate is quite bitter, and gets more so as the cacao content rises, to the point where 100% cacao chocolate is very nearly inedible. That’s the chocolate conundrum, the healthier it is, the worse it tastes. But what if there’s another way? What if you can have tasty chocolate that’s good for you?

That’s the question a group of researchers from Penn State University dared to ask. The secret, they discovered, is to subject the cacao beans to extra-intense roasting. We’re not sure how screaming insults at a bunch of beans will help, but if science says so ... YOU USELESS LUMP OF BARELY EDIBLE FOOD! HOW DARE YOU EXIST!

Oh, not that kind of roasting. Oops.

For their study, the researchers made 27 unsweetened chocolates, prepared using various cacao bean roasting times and temperatures, and served them to volunteers. Those volunteers reported that chocolates made with cacao beans roasted more intensely (such as 20 minutes at 340° F, 80 min at 275° F, and 54 min at 304° F) were far more acceptable than were chocolates prepared with raw or lightly roasted cacao beans.

The implications of healthy yet tasty chocolate are obvious: Master the chocolate and you’ll make millions. Imagine a future where parents say to their kids: “Don’t forget to eat your chocolate.” So, we’re off to do some cooking. Don’t want Hershey to make all the money off of this revelation.

The villain hiding in dairy for some MS patients

For some of us, lactose can be a real heartbreaker when it comes to dairy consumption, but for people with multiple sclerosis (MS) there’s another villain they may also have to face that can make their symptoms worse.

Physicians at the Institute of Anatomy at University Hospital Bonn (Germany) were getting so many complaints from patients with MS about how much worse they felt about after having cheese, yogurt, and milk that they decided to get to the bottom of it. The culprit, it seems, is casein, a protein specifically found in cow’s milk.

The researchers injected mice with various proteins found in cow’s milk and found perforated myelin sheaths in those given casein. In MS, the patient’s own immune system destroys that sheath, which leads to paresthesia, vision problems, and movement disorders.

“The body’s defenses actually attack the casein, but in the process they also destroy proteins involved in the formation of myelin, “ said Rittika Chunder, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Bonn. How? Apparently it’s all a big misunderstanding.

While looking at molecules needed for myelin production, the researchers came across MAG, which is very similar to casein, which is a problem when patients with MS are allergic to casein. After they have dairy products, the B-cell squad gets called in to clean up the evil twin, casein, but can’t differentiate it from the good twin, MAG, so it all gets a wash and the myelin sheath suffers.

Since this happens only to patients with MS who have a casein allergy, the researchers advise them to stay away from milk, yogurt, or cottage cheese while they work on a self-test to check if patients carry the antibodies.

A small price to pay, perhaps, to stop a villainous evil twin.

You would even say it glows

If you’re anything like us – and we think you are since you’re reading this – you’ve been asking yourself: Are there any common medications in my house that will make good radiation sensors?

Not that anyone needs to worry about excess radiation or anything. Far from it. We were just wondering.

It just so happens that Anna Mrozik and Paweł Bilski, both of the Institute of Nuclear Physics Polish Academy of Sciences (IFJ PAN) in Kraków, Poland, were wondering the same thing: “During an uncontrolled release of radiation, it is highly unlikely that members of the public will be equipped with personal radiation dose monitors.”

People would need to use something they had lying around the house. A smartphone would work, the investigators explained in a statement from the IFJ PAN, but the process of converting one to radiation-sensor duty, which involves dismantling it and breaking the display glass, “is laborious and time-consuming [and] the destruction of a valuable and useful device does not seem to be the optimal solution.”

Naturally, they turned to drugs. The key, in this case, is optically stimulated luminescence. They needed to find materials that would glow with greater intensity as the radiation dose increased. Turns out that ibuprofen- and paracetamol-based painkillers fit the bill quite nicely, although aspirin also works.

It’s not known exactly which substance is causing the luminescence, but rest assured, the “physicists from the IFJ PAN intend to identify it.”

This is why you don’t interrupt someone using headphones

There’s nothing like taking a nice relaxing walk with your headphones. Whether you’re listening to a podcast or a song or talking on the phone, it’s an escape from reality that makes you feel like you’re completely in tune with what you’re listening to.

According to a new study, headphones, as opposed to speakers, make people feel more connected to what they are listening to. Data collected from more than 4,000 people showed that listening with headphones makes more of an impact than listening to speakers.

“Headphones produce a phenomenon called in-head localization, which makes the speaker sound as if they’re inside your head,” study coauthor On Amir of the University of California, San Diego, said in a statement. Because of this, people feel like the speakers are close to them and there’s more of a sense of empathy for the speakers and the listener is more likely to be swayed toward the ideas of the speaker.

These findings could lead to more efficient training programs, online work, and advertising, the investigators suggested.

We now finally understand why people get so mad when they have to take out their headphones to answer or talk to us. We ruined a satisfying moment going on in their brains.

Practicing across state lines: A challenge for telemental health

I was taught to think clinically first and legally second. There are moments when following every regulation is clearly detrimental to the well-being of both the patient and the medical community at large, and these challenges have been highlighted by issues with telemental health during the pandemic.

A friend emailed me with a problem: He has a son who is a traveling nurse and is currently in psychotherapy. The therapist has, in accordance with licensing requirements, told his son that she can not see him when assignments take him to any state where she is not licensed. The patient needs to physically be in the same state where the clinician holds a license, technically for every appointment. The nursing assignments last for 3 months and he will be going to a variety of states. Does he really need to get a new therapist every 90 days?

The logistics seem mind-boggling in a time when there is a shortage of mental health professionals, and there are often long wait lists to get care. And even if it was all easy, I’ll point out that working with a therapist is a bit different then going to an urgent care center to have sutures removed or to obtain antibiotics for strep throat: The relationship is not easily interchangeable, and I know of no one who would think it clinically optimal for anyone to change psychotherapists every 3 months. The traveling nurse does not just need to find a “provider” in each state, he needs to find one he is comfortable with and he will have to spend several sessions relaying his history and forming a new therapeutic alliance. And given the ambiguities of psychotherapy, he would optimally see therapists who do not make conflicting interpretations or recommendations. Mind-boggling. And while none of us are irreplaceable, it feels heartless to tell someone who is traveling to provide medical care to others during a pandemic that they can’t have mental health care when our technology would allow for it.

In the “old days” it was simpler: Patients came to the office and both the patient and the clinician were physically located in the same state, even if the patient resided in another state and commuted hours to the appointment. Telemental health was done in select rural areas or in military settings, and most physicians did not consider the option for video visits, much less full video treatment. For the average practitioner, issues of location were not relevant. The exception was for college students who might reside in one state and see a psychiatrist or therapist in another, but typically everyone was comfortable taking a break from therapy when the patient could not meet with the therapist in person. If psychiatrists were having phone or video sessions with out-of-state patients on an occasional basis, it may have been because there was less scrutiny and it was less obvious that this was not permitted.

When the pandemic forced treatment to go online, the issues changed. At the beginning, issues related to state licensing were waived. Now each state has a different requirement with regard to out-of-state physicians; some allow their residents to be seen, while others require the physician to get licensed in their state and the process may or may not be costly or arduous for the provider. The regulations change frequently, and can be quite confusing to follow. Since psychiatry is a shortage field, many psychiatrists are not looking to have more patients from other states and are not motivated to apply for extra licenses.

Life as a practicing psychiatrist has been a moving target: I reopened my practice for some in-person visits for vaccinated patients in June 2021, then closed it when the Omicron surge seemed too risky, and I’ll be reopening soon. Patients, too, have had unpredictable lives.

For the practitioner who is following the rules precisely, the issues can be sticky. It may be fine to have Zoom visits with a patient who lives across the street, but not with the elderly patient who has to drive 90 minutes across a state line, and it’s always fine to have a video session with a patient in Guam. If a patient signs on for a video visit with a doctor licensed in Maine and announces there will be a visit to a brother in Michigan, does the clinician abruptly end the session? Does he charge for the then missed appointment, and don’t we feel this is a waste of the psychiatrist’s time when appointments are limited?

If college students started with therapists in their home states when universities shut down in the spring of 2020, must they now try to get treatment in the states where their college campuses are located? What if the university has a long wait for services, there are no local psychiatrists taking on new patients, or the student feels he is making good progress with the doctor he is working with? And how do we even know for sure where our patients are located? Are we obligated to ask for a precise location at the beginning of each session? What if patients do not offer their locations, or lie about where they are?

Oddly, the issue is with the location of the patient; the doctor can be anywhere as long as the patient’s body is in a state where he or she is licensed. And it has never been a problem to send prescriptions to pharmacies in other states, though this seems to me the essence of practicing across state lines.

In the State of the Union Address on March 1, President Biden had a hefty agenda: The Russian invasion of Ukraine, a global pandemic, spiraling inflation, and for the first time in a SOTU address, our president discussed a strategy to address our National Mental Health Crisis. The fact sheet released by the White House details many long-awaited changes to increase the mental health workforce to address shortages, instituting a “988” crisis line to initiate “someone to call, someone to respond, and somewhere for every American in crisis to go.” The proposals call for a sweeping reform in providing access to services, strengthening parity, and improving community, veterans, and university services – and the Biden administration specifically addresses telemental health. “To maintain continuity of access, the Administration will work with Congress to ensure coverage of tele-behavioral health across health plans, and support appropriate delivery of telemedicine across state lines.”

This is good news, as it’s time we concentrated on allowing for access to care in a consumer-oriented way. It may let us focus on offering good clinical care and not focus on following outdated regulations. Hopefully, those who want help will be able to access it, and perhaps soon a traveling nurse will be permitted to get mental health care with continuity of treatment.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. Dr. Miller has no conflicts of interest.

I was taught to think clinically first and legally second. There are moments when following every regulation is clearly detrimental to the well-being of both the patient and the medical community at large, and these challenges have been highlighted by issues with telemental health during the pandemic.

A friend emailed me with a problem: He has a son who is a traveling nurse and is currently in psychotherapy. The therapist has, in accordance with licensing requirements, told his son that she can not see him when assignments take him to any state where she is not licensed. The patient needs to physically be in the same state where the clinician holds a license, technically for every appointment. The nursing assignments last for 3 months and he will be going to a variety of states. Does he really need to get a new therapist every 90 days?

The logistics seem mind-boggling in a time when there is a shortage of mental health professionals, and there are often long wait lists to get care. And even if it was all easy, I’ll point out that working with a therapist is a bit different then going to an urgent care center to have sutures removed or to obtain antibiotics for strep throat: The relationship is not easily interchangeable, and I know of no one who would think it clinically optimal for anyone to change psychotherapists every 3 months. The traveling nurse does not just need to find a “provider” in each state, he needs to find one he is comfortable with and he will have to spend several sessions relaying his history and forming a new therapeutic alliance. And given the ambiguities of psychotherapy, he would optimally see therapists who do not make conflicting interpretations or recommendations. Mind-boggling. And while none of us are irreplaceable, it feels heartless to tell someone who is traveling to provide medical care to others during a pandemic that they can’t have mental health care when our technology would allow for it.

In the “old days” it was simpler: Patients came to the office and both the patient and the clinician were physically located in the same state, even if the patient resided in another state and commuted hours to the appointment. Telemental health was done in select rural areas or in military settings, and most physicians did not consider the option for video visits, much less full video treatment. For the average practitioner, issues of location were not relevant. The exception was for college students who might reside in one state and see a psychiatrist or therapist in another, but typically everyone was comfortable taking a break from therapy when the patient could not meet with the therapist in person. If psychiatrists were having phone or video sessions with out-of-state patients on an occasional basis, it may have been because there was less scrutiny and it was less obvious that this was not permitted.

When the pandemic forced treatment to go online, the issues changed. At the beginning, issues related to state licensing were waived. Now each state has a different requirement with regard to out-of-state physicians; some allow their residents to be seen, while others require the physician to get licensed in their state and the process may or may not be costly or arduous for the provider. The regulations change frequently, and can be quite confusing to follow. Since psychiatry is a shortage field, many psychiatrists are not looking to have more patients from other states and are not motivated to apply for extra licenses.

Life as a practicing psychiatrist has been a moving target: I reopened my practice for some in-person visits for vaccinated patients in June 2021, then closed it when the Omicron surge seemed too risky, and I’ll be reopening soon. Patients, too, have had unpredictable lives.

For the practitioner who is following the rules precisely, the issues can be sticky. It may be fine to have Zoom visits with a patient who lives across the street, but not with the elderly patient who has to drive 90 minutes across a state line, and it’s always fine to have a video session with a patient in Guam. If a patient signs on for a video visit with a doctor licensed in Maine and announces there will be a visit to a brother in Michigan, does the clinician abruptly end the session? Does he charge for the then missed appointment, and don’t we feel this is a waste of the psychiatrist’s time when appointments are limited?

If college students started with therapists in their home states when universities shut down in the spring of 2020, must they now try to get treatment in the states where their college campuses are located? What if the university has a long wait for services, there are no local psychiatrists taking on new patients, or the student feels he is making good progress with the doctor he is working with? And how do we even know for sure where our patients are located? Are we obligated to ask for a precise location at the beginning of each session? What if patients do not offer their locations, or lie about where they are?

Oddly, the issue is with the location of the patient; the doctor can be anywhere as long as the patient’s body is in a state where he or she is licensed. And it has never been a problem to send prescriptions to pharmacies in other states, though this seems to me the essence of practicing across state lines.

In the State of the Union Address on March 1, President Biden had a hefty agenda: The Russian invasion of Ukraine, a global pandemic, spiraling inflation, and for the first time in a SOTU address, our president discussed a strategy to address our National Mental Health Crisis. The fact sheet released by the White House details many long-awaited changes to increase the mental health workforce to address shortages, instituting a “988” crisis line to initiate “someone to call, someone to respond, and somewhere for every American in crisis to go.” The proposals call for a sweeping reform in providing access to services, strengthening parity, and improving community, veterans, and university services – and the Biden administration specifically addresses telemental health. “To maintain continuity of access, the Administration will work with Congress to ensure coverage of tele-behavioral health across health plans, and support appropriate delivery of telemedicine across state lines.”

This is good news, as it’s time we concentrated on allowing for access to care in a consumer-oriented way. It may let us focus on offering good clinical care and not focus on following outdated regulations. Hopefully, those who want help will be able to access it, and perhaps soon a traveling nurse will be permitted to get mental health care with continuity of treatment.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. Dr. Miller has no conflicts of interest.

I was taught to think clinically first and legally second. There are moments when following every regulation is clearly detrimental to the well-being of both the patient and the medical community at large, and these challenges have been highlighted by issues with telemental health during the pandemic.

A friend emailed me with a problem: He has a son who is a traveling nurse and is currently in psychotherapy. The therapist has, in accordance with licensing requirements, told his son that she can not see him when assignments take him to any state where she is not licensed. The patient needs to physically be in the same state where the clinician holds a license, technically for every appointment. The nursing assignments last for 3 months and he will be going to a variety of states. Does he really need to get a new therapist every 90 days?

The logistics seem mind-boggling in a time when there is a shortage of mental health professionals, and there are often long wait lists to get care. And even if it was all easy, I’ll point out that working with a therapist is a bit different then going to an urgent care center to have sutures removed or to obtain antibiotics for strep throat: The relationship is not easily interchangeable, and I know of no one who would think it clinically optimal for anyone to change psychotherapists every 3 months. The traveling nurse does not just need to find a “provider” in each state, he needs to find one he is comfortable with and he will have to spend several sessions relaying his history and forming a new therapeutic alliance. And given the ambiguities of psychotherapy, he would optimally see therapists who do not make conflicting interpretations or recommendations. Mind-boggling. And while none of us are irreplaceable, it feels heartless to tell someone who is traveling to provide medical care to others during a pandemic that they can’t have mental health care when our technology would allow for it.

In the “old days” it was simpler: Patients came to the office and both the patient and the clinician were physically located in the same state, even if the patient resided in another state and commuted hours to the appointment. Telemental health was done in select rural areas or in military settings, and most physicians did not consider the option for video visits, much less full video treatment. For the average practitioner, issues of location were not relevant. The exception was for college students who might reside in one state and see a psychiatrist or therapist in another, but typically everyone was comfortable taking a break from therapy when the patient could not meet with the therapist in person. If psychiatrists were having phone or video sessions with out-of-state patients on an occasional basis, it may have been because there was less scrutiny and it was less obvious that this was not permitted.

When the pandemic forced treatment to go online, the issues changed. At the beginning, issues related to state licensing were waived. Now each state has a different requirement with regard to out-of-state physicians; some allow their residents to be seen, while others require the physician to get licensed in their state and the process may or may not be costly or arduous for the provider. The regulations change frequently, and can be quite confusing to follow. Since psychiatry is a shortage field, many psychiatrists are not looking to have more patients from other states and are not motivated to apply for extra licenses.

Life as a practicing psychiatrist has been a moving target: I reopened my practice for some in-person visits for vaccinated patients in June 2021, then closed it when the Omicron surge seemed too risky, and I’ll be reopening soon. Patients, too, have had unpredictable lives.

For the practitioner who is following the rules precisely, the issues can be sticky. It may be fine to have Zoom visits with a patient who lives across the street, but not with the elderly patient who has to drive 90 minutes across a state line, and it’s always fine to have a video session with a patient in Guam. If a patient signs on for a video visit with a doctor licensed in Maine and announces there will be a visit to a brother in Michigan, does the clinician abruptly end the session? Does he charge for the then missed appointment, and don’t we feel this is a waste of the psychiatrist’s time when appointments are limited?

If college students started with therapists in their home states when universities shut down in the spring of 2020, must they now try to get treatment in the states where their college campuses are located? What if the university has a long wait for services, there are no local psychiatrists taking on new patients, or the student feels he is making good progress with the doctor he is working with? And how do we even know for sure where our patients are located? Are we obligated to ask for a precise location at the beginning of each session? What if patients do not offer their locations, or lie about where they are?

Oddly, the issue is with the location of the patient; the doctor can be anywhere as long as the patient’s body is in a state where he or she is licensed. And it has never been a problem to send prescriptions to pharmacies in other states, though this seems to me the essence of practicing across state lines.

In the State of the Union Address on March 1, President Biden had a hefty agenda: The Russian invasion of Ukraine, a global pandemic, spiraling inflation, and for the first time in a SOTU address, our president discussed a strategy to address our National Mental Health Crisis. The fact sheet released by the White House details many long-awaited changes to increase the mental health workforce to address shortages, instituting a “988” crisis line to initiate “someone to call, someone to respond, and somewhere for every American in crisis to go.” The proposals call for a sweeping reform in providing access to services, strengthening parity, and improving community, veterans, and university services – and the Biden administration specifically addresses telemental health. “To maintain continuity of access, the Administration will work with Congress to ensure coverage of tele-behavioral health across health plans, and support appropriate delivery of telemedicine across state lines.”

This is good news, as it’s time we concentrated on allowing for access to care in a consumer-oriented way. It may let us focus on offering good clinical care and not focus on following outdated regulations. Hopefully, those who want help will be able to access it, and perhaps soon a traveling nurse will be permitted to get mental health care with continuity of treatment.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. Dr. Miller has no conflicts of interest.

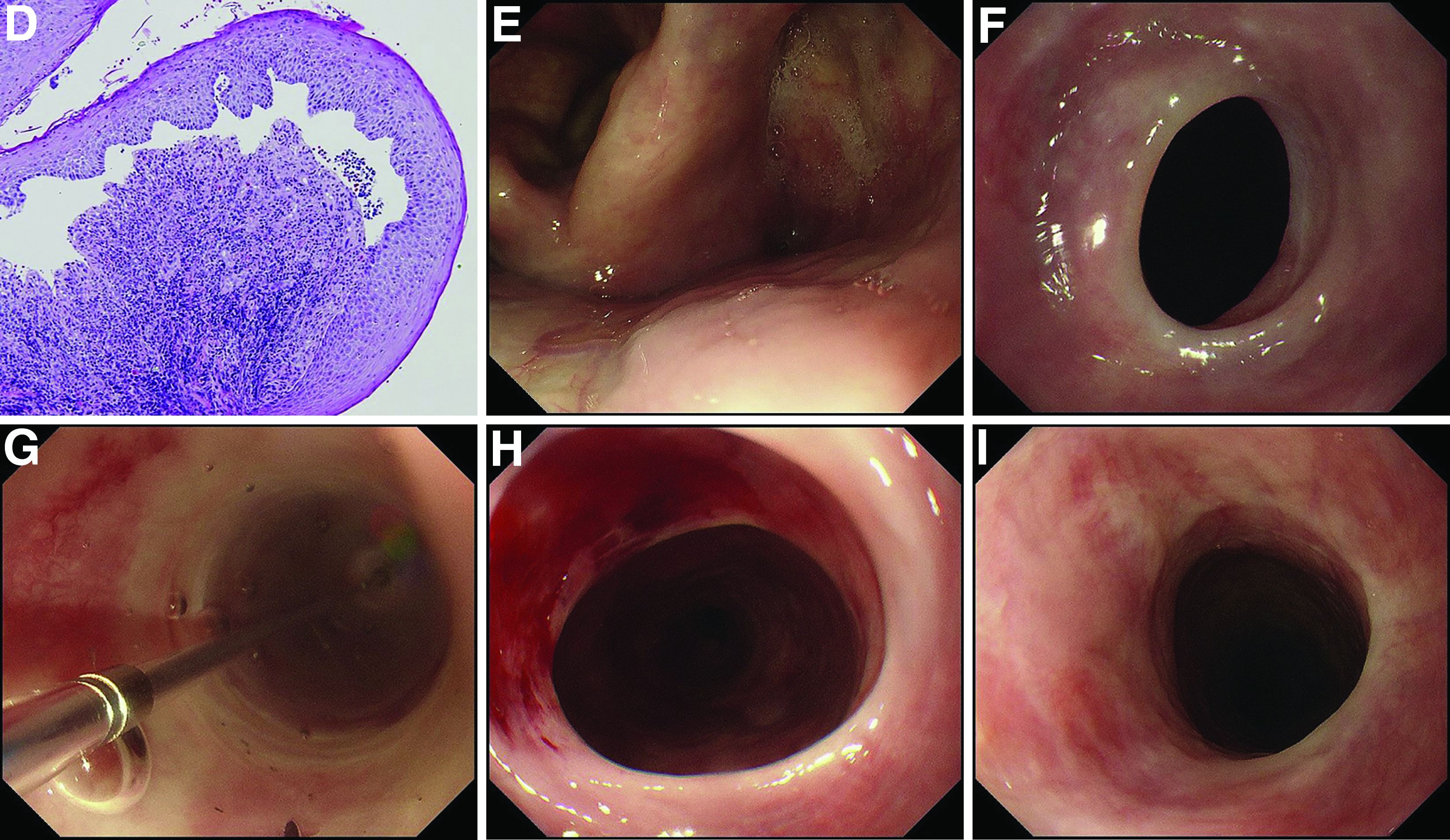

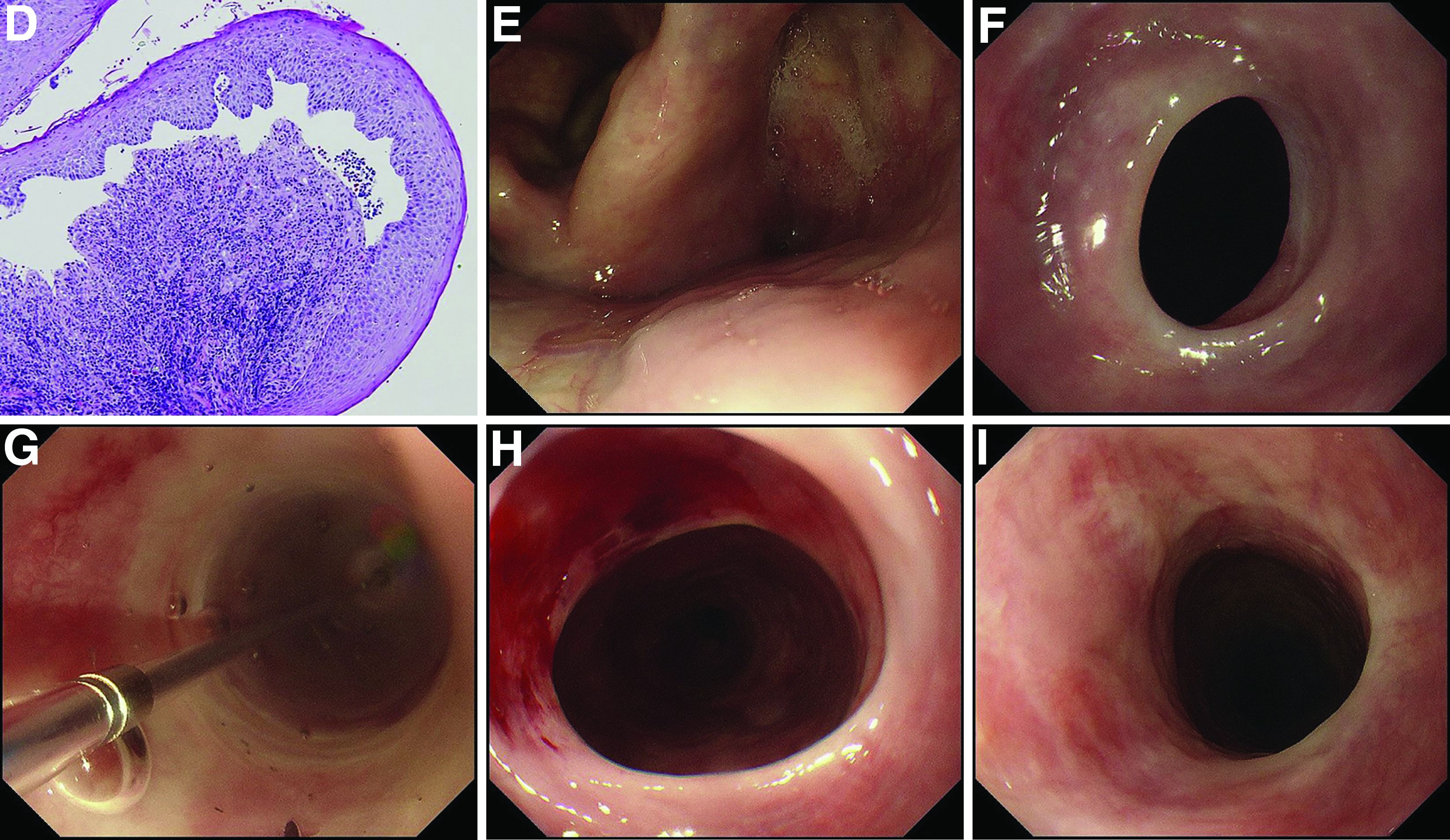

Dressing in blue

On the first Friday in March, it has become an annual tradition to dress in blue to promote colorectal cancer awareness. Twitter feeds are filled with photos of members of our gastroenterology community (sometimes entire endoscopy units!) swathed in various shades of blue. This tradition was started in the mid-2000’s by a patient diagnosed with early-onset colorectal cancer who planned a fund raiser at her daughter’s elementary school where students were encouraged to wear a blue outfit and make a $1 donation to support awareness of this deadly but preventable cancer. What was once a local effort has now grown into a national phenomenon, and a powerful opportunity for the medical community to educate patients, friends, and family regarding risk factors for colorectal cancer and the importance of timely and effective screening. But while raising awareness is vital, it is only an initial step in the complex process of optimizing delivery of screening services and improving cancer outcomes through prevention and early detection.

In this month’s issue of GIHN, we report on a study from Cancer demonstrating the effectiveness of Spanish-speaking patient navigators in boosting colorectal cancer screening rates among Hispanic patients. We also highlight a quality improvement initiative at a large academic medical center demonstrating the impact of an electronic “primer” message delivered through the patient portal on screening completion rates in a mailed fecal immunochemical test outreach program. Finally, in this month’s Practice Management Toolbox column, Dr. Brill and Dr. Lieberman advise us on how to prepare for upcoming coverage changes impacting screening colonoscopy – a result of AGA’s tireless efforts to eliminate financial barriers impeding access to colorectal cancer screening.

As always, thank you for being a dedicated reader and please stay safe out there. Better days are ahead.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

On the first Friday in March, it has become an annual tradition to dress in blue to promote colorectal cancer awareness. Twitter feeds are filled with photos of members of our gastroenterology community (sometimes entire endoscopy units!) swathed in various shades of blue. This tradition was started in the mid-2000’s by a patient diagnosed with early-onset colorectal cancer who planned a fund raiser at her daughter’s elementary school where students were encouraged to wear a blue outfit and make a $1 donation to support awareness of this deadly but preventable cancer. What was once a local effort has now grown into a national phenomenon, and a powerful opportunity for the medical community to educate patients, friends, and family regarding risk factors for colorectal cancer and the importance of timely and effective screening. But while raising awareness is vital, it is only an initial step in the complex process of optimizing delivery of screening services and improving cancer outcomes through prevention and early detection.

In this month’s issue of GIHN, we report on a study from Cancer demonstrating the effectiveness of Spanish-speaking patient navigators in boosting colorectal cancer screening rates among Hispanic patients. We also highlight a quality improvement initiative at a large academic medical center demonstrating the impact of an electronic “primer” message delivered through the patient portal on screening completion rates in a mailed fecal immunochemical test outreach program. Finally, in this month’s Practice Management Toolbox column, Dr. Brill and Dr. Lieberman advise us on how to prepare for upcoming coverage changes impacting screening colonoscopy – a result of AGA’s tireless efforts to eliminate financial barriers impeding access to colorectal cancer screening.

As always, thank you for being a dedicated reader and please stay safe out there. Better days are ahead.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

On the first Friday in March, it has become an annual tradition to dress in blue to promote colorectal cancer awareness. Twitter feeds are filled with photos of members of our gastroenterology community (sometimes entire endoscopy units!) swathed in various shades of blue. This tradition was started in the mid-2000’s by a patient diagnosed with early-onset colorectal cancer who planned a fund raiser at her daughter’s elementary school where students were encouraged to wear a blue outfit and make a $1 donation to support awareness of this deadly but preventable cancer. What was once a local effort has now grown into a national phenomenon, and a powerful opportunity for the medical community to educate patients, friends, and family regarding risk factors for colorectal cancer and the importance of timely and effective screening. But while raising awareness is vital, it is only an initial step in the complex process of optimizing delivery of screening services and improving cancer outcomes through prevention and early detection.

In this month’s issue of GIHN, we report on a study from Cancer demonstrating the effectiveness of Spanish-speaking patient navigators in boosting colorectal cancer screening rates among Hispanic patients. We also highlight a quality improvement initiative at a large academic medical center demonstrating the impact of an electronic “primer” message delivered through the patient portal on screening completion rates in a mailed fecal immunochemical test outreach program. Finally, in this month’s Practice Management Toolbox column, Dr. Brill and Dr. Lieberman advise us on how to prepare for upcoming coverage changes impacting screening colonoscopy – a result of AGA’s tireless efforts to eliminate financial barriers impeding access to colorectal cancer screening.

As always, thank you for being a dedicated reader and please stay safe out there. Better days are ahead.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

Autism spectrum disorder: Keys to early detection and accurate diagnosis

FIRST OF 2 PARTS

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex, heterogenous neurodevelopmental disorder with genetic and environmental underpinnings, and an onset early in life.1-9 It affects social communication, cognition, and sensory-motor domains, and manifests as deficits in social reciprocity, repetitive behavior, restricted range of interests, and sensory sensitivities.6,10-14 In recent years, the prevalence of ASD has been increasing.3,6,10 A large percentage of individuals with ASD experience significant social deficits in adulthood,10 which often leads to isolation, depressive symptoms, and poor occupational and relationship functioning.15,16 Interventions in early childhood can result in significant and lasting changes in outcome and in functioning of individuals with ASD.

This article provides an update on various aspects of ASD diagnosis, with the goal of equipping clinicians with knowledge to help make an accurate ASD diagnosis at an early stage. Part 1 focuses on early detection and diagnosis, while Part 2 will describe treatment strategies.

Benefits of early detection

Substantial research has established that early intervention confers substantial benefits for outcomes among children with ASD.2,3,5,6,9,13,14,16-22 Earlier age of intervention correlates with greater developmental gain and symptom reduction.21,23 The atypical neural development responsible for ASD likely occurs much earlier than the behavioral manifestations of this disorder, which implies that there is a crucial period to intervene before behavioral features emerge.1 This necessitates early recognition of ASD,9,17 and the need for further research to find novel ways to detect ASD earlier.

In the United States, children with ASD are diagnosed with the disorder on average between age 3 and 4 years.6,24 However, evidence suggests there may be a prodromal phase for ASD during the first several months of life, wherein infants and toddlers exhibit developmentally inadequate communication and social skills and/or unusual behaviors.18 Behavioral signs suggestive of ASD may be evident as early as infancy, and commonly earlier than age 18 months.1,17,19 Problems with sleeping and eating may be evident in early childhood.19 Deficits in joint attention may be evident as early as age 6 months to 8 months. Research suggests that a diagnosis of ASD by trained, expert professionals is likely to be accurate at the age of 2, and even as early as 18 months.6,24

In a prospective study, Anderson et al25 found that 9% of children who were diagnosed with ASD at age 2 no longer met the diagnostic criteria for ASD by adulthood.6 Those who no longer met ASD criteria were more likely to have received early intervention, had a verbal IQ ≥70, and had experienced a larger decrease in repetitive behaviors between ages 2 and 3, compared with other youth in this study who had a verbal IQ ≥70. One of the limitations of this study was a small sample size (85 participants); larger, randomized studies are needed to replicate these findings.25

Continue to: Characteristics of ASD...

Characteristics of ASD

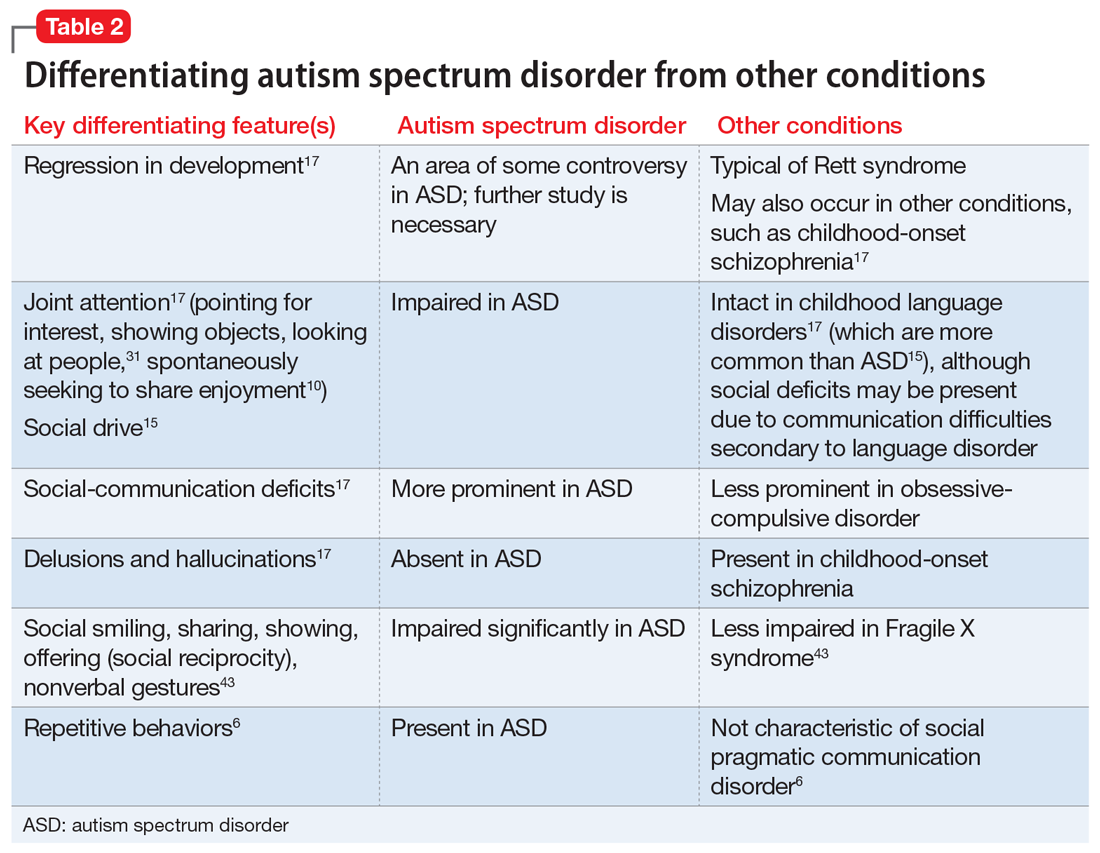

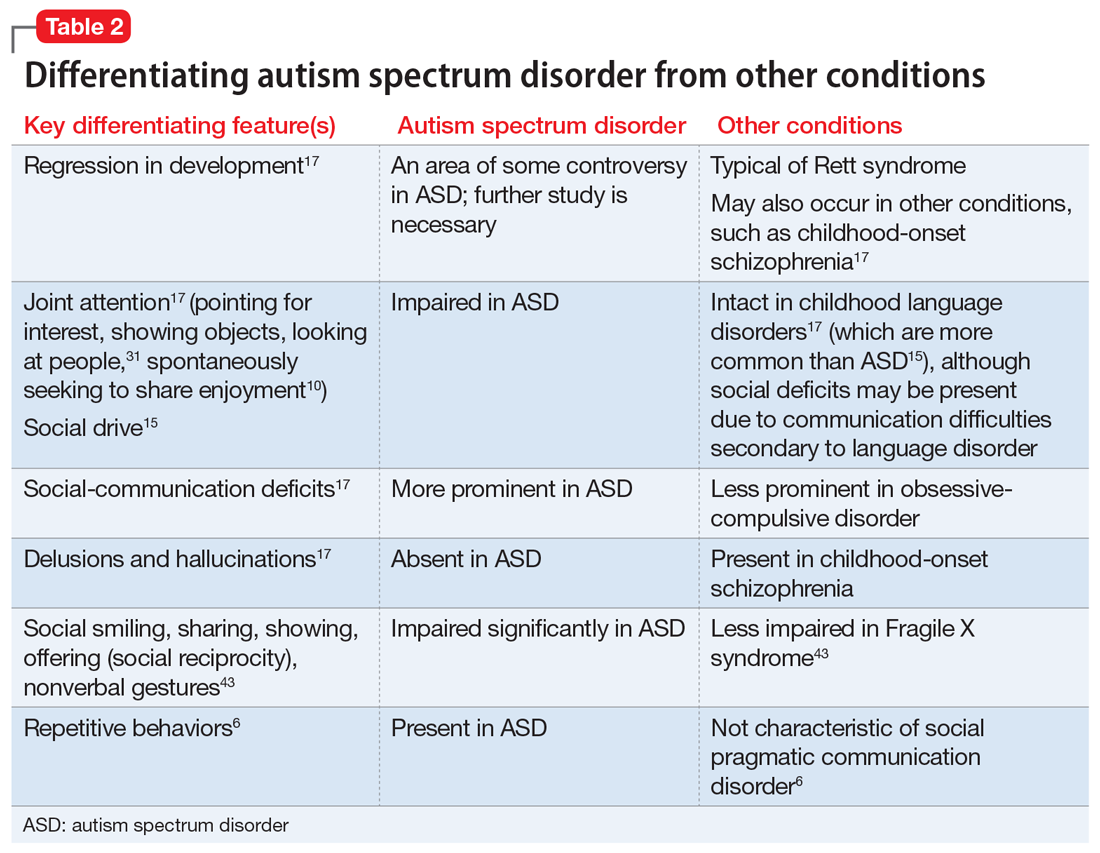

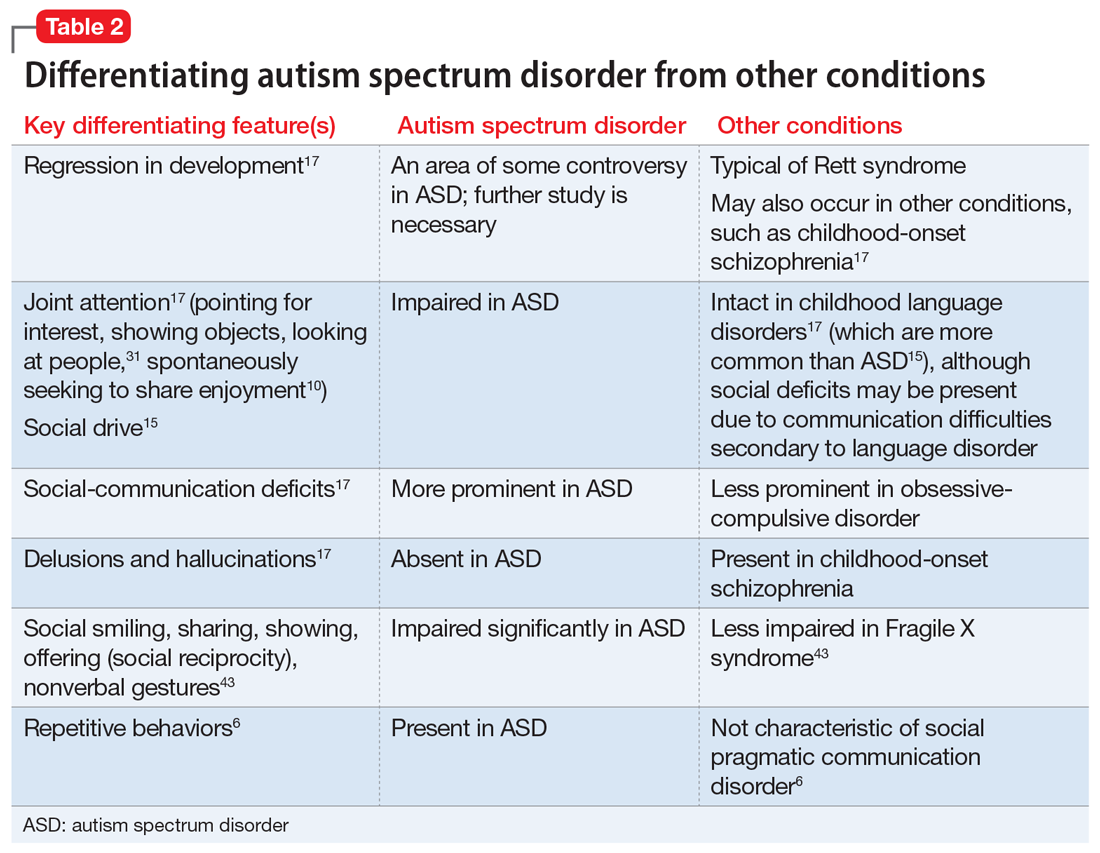

Table 16,8,10,13,15,26-29 outlines various characteristics of ASD, which may manifest in varying degrees among children with the condition.

Speech/language. Speech helps to facilitate bonding between parents and an infant by offering a soothing, pleasurable, and reinforcing experience.30 More than 50% of children with ASD have language delays or deficits that persist throughout adulthood.13 The extent of these language deficits varies; in general, the more severe the speech/language deficits, the more severe the long-term symptoms.13 Language deficits in young children with ASD tend to be of both the expressive and receptive type, with onset in infancy, which suggests that neural processes predate the emergence of behavioral symptoms of ASD, and also that early language deficits/delays could be a marker for or indicator of future risk of ASD.13 Individuals with ASD also have been noted to have limitations in orienting or attending to human voices.13,30

Facial recognition. Evidence has linked ASD with deficits in facial recognition that emerge in the first few months of life.2 Earlier studies have found that lack of attention to others’ faces was the strongest distinguishing factor between 1-year-olds with ASD and typically developing 1-year-olds.2,31 A recent study that used EEG to compare facial emotion recognition in boys with ASD vs typically developing boys found that boys with ASD exhibited significantly lower sensitivity to angry and fearful faces.27