User login

Medicaid Expansion and Veterans’ Reliance on the VA for Depression Care

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the largest integrated health care system in the United States, providing care for more than 9 million veterans.1 With veterans experiencing mental health conditions like posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance use disorders, and other serious mental illnesses (SMI) at higher rates compared with the general population, the VA plays an important role in the provision of mental health services.2-5 Since the implementation of its Mental Health Strategic Plan in 2004, the VA has overseen the development of a wide array of mental health programs geared toward the complex needs of veterans. Research has demonstrated VA care outperforming Medicaid-reimbursed services in terms of the percentage of veterans filling antidepressants for at least 12 weeks after initiation of treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD), as well as posthospitalization follow-up.6

Eligible veterans enrolled in the VA often also seek non-VA care. Medicaid covers nearly 10% of all nonelderly veterans, and of these veterans, 39% rely solely on Medicaid for health care access.7 Today, Medicaid is the largest payer for mental health services in the US, providing coverage for approximately 27% of Americans who have SMI and helping fulfill unmet mental health needs.8,9 Understanding which of these systems veterans choose to use, and under which circumstances, is essential in guiding the allocation of limited health care resources.10

Beyond Medicaid, alternatives to VA care may include TRICARE, Medicare, Indian Health Services, and employer-based or self-purchased private insurance. While these options potentially increase convenience, choice, and access to health care practitioners (HCPs) and services not available at local VA systems, cross-system utilization with poor integration may cause care coordination and continuity problems, such as medication mismanagement and opioid overdose, unnecessary duplicate utilization, and possible increased mortality.11-15 As recent national legislative changes, such as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act, and the VA MISSION Act, continue to shift the health care landscape for veterans, questions surrounding how veterans are changing their health care use become significant.16,17

Here, we approach the impacts of Medicaid expansion on veterans’ reliance on the VA for mental health services with a unique lens. We leverage a difference-in-difference design to study 2 historical Medicaid expansions in Arizona (AZ) and New York (NY), which extended eligibility to childless adults in 2001. Prior Medicaid dual-eligible mental health research investigated reliance shifts during the immediate postenrollment year in a subset of veterans newly enrolled in Medicaid.18 However, this study took place in a period of relative policy stability. In contrast, we investigate the potential effects of a broad policy shift by analyzing state-level changes in veterans’ reliance over 6 years after a statewide Medicaid expansion. We match expansion states with demographically similar nonexpansion states to account for unobserved trends and confounding effects. Prior studies have used this method to evaluate post-Medicaid expansion mortality changes and changes in veteran dual enrollment and hospitalizations.10,19 While a study of ACA Medicaid expansion states would be ideal, Medicaid data from most states were only available through 2014 at the time of this analysis. Our study offers a quasi-experimental framework leveraging longitudinal data that can be applied as more post-ACA data become available.

Given the rising incidence of suicide among veterans, understanding care-seeking behaviors for depression among veterans is important as it is the most common psychiatric condition found in those who died by suicide.20,21 Furthermore, depression may be useful as a clinical proxy for mental health policy impacts, given that the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) screening tool is well validated and increasingly research accessible, and it is a chronic condition responsive to both well-managed pharmacologic treatment and psychotherapeutic interventions.22,23

In this study, we quantify the change in care-seeking behavior for depression among veterans after Medicaid expansion, using a quasi-experimental design. We hypothesize that new access to Medicaid would be associated with a shift away from using VA services for depression. Given the income-dependent eligibility requirements of Medicaid, we also hypothesize that veterans who qualified for VA coverage due to low income, determined by a regional means test (Priority group 5, “income-eligible”), would be more likely to shift care compared with those whose serviced-connected conditions related to their military service (Priority groups 1-4, “service-connected”) provide VA access.

Methods

To investigate the relative changes in veterans’ reliance on the VA for depression care after the 2001 NY and AZ Medicaid expansions We used a retrospective, difference-in-difference analysis. Our comparison pairings, based on prior demographic analyses were as follows: NY with Pennsylvania(PA); AZ with New Mexico and Nevada (NM/NV).19 The time frame of our analysis was 1999 to 2006, with pre- and postexpansion periods defined as 1999 to 2000 and 2001 to 2006, respectively.

Data

We included veterans aged 18 to 64 years, seeking care for depression from 1999 to 2006, who were also VA-enrolled and residing in our states of interest. We counted veterans as enrolled in Medicaid if they were enrolled at least 1 month in a given year.

Using similar methods like those used in prior studies, we selected patients with encounters documenting depression as the primary outpatient or inpatient diagnosis using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes: 296.2x for a single episode of major depressive disorder, 296.3x for a recurrent episode of MDD, 300.4 for dysthymia, and 311.0 for depression not otherwise specified.18,24 We used data from the Medicaid Analytic eXtract files (MAX) for Medicaid data and the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) for VA data. We chose 1999 as the first study year because it was the earliest year MAX data were available.

Our final sample included 1833 person-years pre-expansion and 7157 postexpansion in our inpatient analysis, as well as 31,767 person-years pre-expansion and 130,382 postexpansion in our outpatient analysis.

Outcomes and Variables

Our primary outcomes were comparative shifts in VA reliance between expansion and nonexpansion states after Medicaid expansion for both inpatient and outpatient depression care. For each year of study, we calculated a veteran’s VA reliance by aggregating the number of days with depression-related encounters at the VA and dividing by the total number of days with a VA or Medicaid depression-related encounters for the year. To provide context to these shifts in VA reliance, we further analyzed the changes in the proportion of annual VA-Medicaid dual users and annual per capita utilization of depression care across the VA and Medicaid.

We conducted subanalyses by income-eligible and service-connected veterans and adjusted our models for age, non-White race, sex, distances to the nearest inpatient and outpatient VA facilities, and VA Relative Risk Score, which is a measure of disease burden and clinical complexity validated specifically for veterans.25

Statistical Analysis

We used fractional logistic regression to model the adjusted effect of Medicaid expansion on VA reliance for depression care. In parallel, we leveraged ordered logit regression and negative binomial regression models to examine the proportion of VA-Medicaid dual users and the per capita utilization of Medicaid and VA depression care, respectively. To estimate the difference-in-difference effects, we used the interaction term of 2 categorical variables—expansion vs nonexpansion states and pre- vs postexpansion status—as the independent variable. We then calculated the average marginal effects with 95% CIs to estimate the differences in outcomes between expansion and nonexpansion states from pre- to postexpansion periods, as well as year-by-year shifts as a robustness check. We conducted these analyses using Stata MP, version 15.

Results

Baseline and postexpansion characteristics

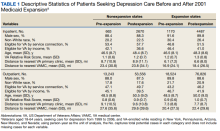

VA Reliance

Overall, we observed postexpansion decreases in VA reliance for depression care

At the state level, reliance on the VA for inpatient depression care in NY decreased by 13.53 pp (95% CI, -22.58 to -4.49) for income-eligible veterans and 16.67 pp (95% CI, -24.53 to -8.80) for service-connected veterans. No relative differences were observed in the outpatient comparisons for both income-eligible (-0.58 pp; 95% CI, -2.13 to 0.98) and service-connected (0.05 pp; 95% CI, -1.00 to 1.10) veterans. In AZ, Medicaid expansion was associated with decreased VA reliance for outpatient depression care among income-eligible veterans (-8.60 pp; 95% CI, -10.60 to -6.61), greater than that for service-connected veterans (-2.89 pp; 95% CI, -4.02 to -1.77). This decrease in VA reliance was significant in the inpatient context only for service-connected veterans (-4.55 pp; 95% CI, -8.14 to -0.97), not income-eligible veterans (-8.38 pp; 95% CI, -17.91 to 1.16).

By applying the aggregate pp changes toward the postexpansion number of visits across both expansion and nonexpansion states, we found that expansion of Medicaid across all our study states would have resulted in 996 fewer hospitalizations and 10,109 fewer outpatient visits for depression at VA in the postexpansion period vs if no states had chosen to expand Medicaid.

Dual Use/Per Capita Utilization

Overall, Medicaid expansion was associated with greater dual use for inpatient depression care—a 0.97-pp (95% CI, 0.46 to 1.48) increase among service-connected veterans and a 0.64-pp (95% CI, 0.35 to 0.94) increase among income-eligible veterans.

At the state level, NY similarly showed increases in dual use among both service-connected (1.48 pp; 95% CI, 0.80 to 2.16) and income-eligible veterans (0.73 pp; 95% CI, 0.39 to 1.07) after Medicaid expansion. However, dual use in AZ increased significantly only among service-connected veterans (0.70 pp; 95% CI, 0.03 to 1.38), not income-eligible veterans (0.31 pp; 95% CI, -0.17 to 0.78).

Among outpatient visits, Medicaid expansion was associated with increased dual use only for income-eligible veterans (0.16 pp; 95% CI, 0.03-0.29), and not service-connected veterans (0.09 pp; 95% CI, -0.04 to 0.21). State-level analyses showed that Medicaid expansion in NY was not associated with changes in dual use for either service-connected (0.01 pp; 95% CI, -0.16 to 0.17) or income-eligible veterans (0.03 pp; 95% CI, -0.12 to 0.18), while expansion in AZ was associated with increases in dual use among both service-connected (0.42 pp; 95% CI, 0.23 to 0.61) and income-eligible veterans (0.83 pp; 95% CI, 0.59 to 1.07).

Concerning per capita utilization of depression care after Medicaid expansion, analyses showed no detectable changes for either inpatient or outpatient services, among both service-connected and income-eligible veterans. However, while this pattern held at the state level among hospitalizations, outpatient visit results showed divergent trends between AZ and NY. In NY, Medicaid expansion was associated with decreased per capita utilization of outpatient depression care among both service-connected (-0.25 visits annually; 95% CI, -0.48 to -0.01) and income-eligible veterans (-0.64 visits annually; 95% CI, -0.93 to -0.35). In AZ, Medicaid expansion was associated with increased per capita utilization of outpatient depression care among both service-connected (0.62 visits annually; 95% CI, 0.32-0.91) and income-eligible veterans (2.32 visits annually; 95% CI, 1.99-2.65).

Discussion

Our study quantified changes in depression-related health care utilization after Medicaid expansions in NY and AZ in 2001. Overall, the balance of evidence indicated that Medicaid expansion was associated with decreased reliance on the VA for depression-related services. There was an exception: income-eligible veterans in AZ did not shift their hospital care away from the VA in a statistically discernible way, although the point estimate was lower. More broadly, these findings concerning veterans’ reliance varied not only in inpatient vs outpatient services and income- vs service-connected eligibility, but also in the state-level contexts of veteran dual users and per capita utilization.

Given that the overall per capita utilization of depression care was unchanged from pre- to postexpansion periods, one might interpret the decreases in VA reliance and increases in Medicaid-VA dual users as a substitution effect from VA care to non-VA care. This could be plausible for hospitalizations where state-level analyses showed similarly stable levels of per capita utilization. However, state-level trends in our outpatient utilization analysis, especially with a substantial 2.32 pp increase in annual per capita visits among income-eligible veterans in AZ, leave open the possibility that in some cases veterans may be complementing VA care with Medicaid-reimbursed services.

The causes underlying these differences in reliance shifts between NY and AZ are likely also influenced by the policy contexts of their respective Medicaid expansions. For example, in 1999, NY passed Kendra’s Law, which established a procedure for obtaining court orders for assisted outpatient mental health treatment for individuals deemed unlikely to survive safely in the community.26 A reasonable inference is that there was less unfulfilled outpatient mental health need in NY under the existing accessibility provisioned by Kendra’s Law. In addition, while both states extended coverage to childless adults under 100% of the Federal Poverty level (FPL), the AZ Medicaid expansion was via a voters’ initiative and extended family coverage to 200% FPL vs 150% FPL for families in NY. Given that the AZ Medicaid expansion enjoyed both broader public participation and generosity in terms of eligibility, its uptake and therefore effect size may have been larger than in NY for nonacute outpatient care.

Our findings contribute to the growing body of literature surrounding the changes in health care utilization after Medicaid expansion, specifically for a newly dual-eligible population of veterans seeking mental health services for depression. While prior research concerning Medicare dual-enrolled veterans has shown high reliance on the VA for both mental health diagnoses and services, scholars have established the association of Medicaid enrollment with decreased VA reliance.27-29 Our analysis is the first to investigate state-level effects of Medicaid expansion on VA reliance for a single mental health condition using a natural experimental framework. We focus on a population that includes a large portion of veterans who are newly Medicaid-eligible due to a sweeping policy change and use demographically matched nonexpansion states to draw comparisons in VA reliance for depression care. Our findings of Medicaid expansion–associated decreases in VA reliance for depression care complement prior literature that describe Medicaid enrollment–associated decreases in VA reliance for overall mental health care.

Implications

From a systems-level perspective, the implications of shifting services away from the VA are complex and incompletely understood. The VA lacks interoperability with the electronic health records (EHRs) used by Medicaid clinicians. Consequently, significant issues of service duplication and incomplete clinical data exist for veterans seeking treatment outside of the VA system, posing health care quality and safety concerns.30 On one hand, Medicaid access is associated with increased health care utilization attributed to filling unmet needs for Medicare dual enrollees, as well as increased prescription filling for psychiatric medications.31,32 Furthermore, the only randomized control trial of Medicaid expansion to date was associated with a 9-pp decrease in positive screening rates for depression among those who received access at around 2 years postexpansion.33 On the other hand, the VA has developed a mental health system tailored to the particular needs of veterans, and health care practitioners at the VA have significantly greater rates of military cultural competency compared to those in nonmilitary settings (70% vs 24% in the TRICARE network and 8% among those with no military or TRICARE affiliation).34 Compared to individuals seeking mental health services with private insurance plans, veterans were about twice as likely to receive appropriate treatment for schizophrenia and depression at the VA.35 These documented strengths of VA mental health care may together help explain the small absolute number of visits that were associated with shifts away from VA overall after Medicaid expansion.

Finally, it is worth considering extrinsic factors that influence utilization among newly dual-eligible veterans. For example, hospitalizations are less likely to be planned than outpatient services, translating to a greater importance of proximity to a nearby medical facility than a veteran’s preference of where to seek care. In the same vein, major VA medical centers are fewer and more distant on average than VA outpatient clinics, therefore reducing the advantage of a Medicaid-reimbursed outpatient clinic in terms of distance.36 These realities may partially explain the proportionally larger shifts away from the VA for hospitalizations compared to outpatient care for depression.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our results should be interpreted within methodological and data limitations. With only 2 states in our sample, NY demonstrably skewed overall results, contributing 1.7 to 3 times more observations than AZ across subanalyses—a challenge also cited by Sommers and colleagues.19 Our veteran groupings were also unable to distinguish those veterans classified as service-connected who may also have qualified by income-eligible criteria (which would tend to understate the size of results) and those veterans who gained and then lost Medicaid coverage in a given year. Our study also faces limitations in generalizability and establishing causality. First, we included only 2 historical state Medicaid expansions, compared with the 38 states and Washington, DC, that have now expanded Medicaid to date under the ACA. Just in the 2 states from our study, we noted significant heterogeneity in the shifts associated with Medicaid expansion, which makes extrapolating specific trends difficult. Differences in underlying health care resources, legislation, and other external factors may limit the applicability of Medicaid expansion in the era of the ACA, as well as the Veterans Choice and MISSION acts. Second, while we leveraged a difference-in-difference analysis using demographically matched, neighboring comparison states, our findings are nevertheless drawn from observational data obviating causality. VA data for other sources of coverage such as private insurance are limited and not included in our study, and MAX datasets vary by quality across states, translating to potential gaps in our study cohort.28

Moving forward, our study demonstrates the potential for applying a natural experimental approach to studying dual-eligible veterans at the interface of Medicaid expansion. We focused on changes in VA reliance for the specific condition of depression and, in doing so, invite further inquiry into the impact of state mental health policy on outcomes more proximate to veterans’ outcomes. Clinical indicators, such as rates of antidepressant filling, utilization and duration of psychotherapy, and PHQ-9 scores, can similarly be investigated by natural experimental design. While current limits of administrative data and the siloing of EHRs may pose barriers to some of these avenues of research, multidisciplinary methodologies and data querying innovations such as natural language processing algorithms for clinical notes hold exciting opportunities to bridge the gap between policy and clinical efficacy.

Conclusions

This study applied a difference-in-difference analysis and found that Medicaid expansion is associated with decreases in VA reliance for both inpatient and outpatient services for depression. As additional data are generated from the Medicaid expansions of the ACA, similarly robust methods should be applied to further explore the impacts associated with such policy shifts and open the door to a better understanding of implications at the clinical level.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the efforts of Janine Wong, who proofread and formatted the manuscript.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. About VA. 2019. Updated September 27, 2022. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.va.gov/health/

2. Richardson LK, Frueh BC, Acierno R. Prevalence estimates of combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder: critical review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(1):4-19. doi:10.3109/00048670903393597

3. Lan CW, Fiellin DA, Barry DT, et al. The epidemiology of substance use disorders in US veterans: a systematic review and analysis of assessment methods. Am J Addict. 2016;25(1):7-24. doi:10.1111/ajad.12319

4. Grant BF, Saha TD, June Ruan W, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 drug use disorder results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions-III. JAMA Psychiat. 2016;73(1):39-47. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.015.2132

5. Pemberton MR, Forman-Hoffman VL, Lipari RN, Ashley OS, Heller DC, Williams MR. Prevalence of past year substance use and mental illness by veteran status in a nationally representative sample. CBHSQ Data Review. Published November 9, 2016. Accessed October 6, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/prevalence-past-year-substance-use-and-mental-illness-veteran-status-nationally

6. Watkins KE, Pincus HA, Smith B, et al. Veterans Health Administration Mental Health Program Evaluation: Capstone Report. 2011. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR956.html

7. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid’s role in covering veterans. June 29, 2017. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.kff.org/infographic/medicaids-role-in-covering-veterans

8. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: detailed tables. September 7, 2017. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2016/NSDUH-DetTabs-2016.pdf

9. Wen H, Druss BG, Cummings JR. Effect of Medicaid expansions on health insurance coverage and access to care among low-income adults with behavioral health conditions. Health Serv Res. 2015;50:1787-1809. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12411

10. O’Mahen PN, Petersen LA. Effects of state-level Medicaid expansion on Veterans Health Administration dual enrollment and utilization: potential implications for future coverage expansions. Med Care. 2020;58(6):526-533. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001327

11. Ono SS, Dziak KM, Wittrock SM, et al. Treating dual-use patients across two health care systems: a qualitative study. Fed Pract. 2015;32(8):32-37.

12. Weeks WB, Mahar PJ, Wright SM. Utilization of VA and Medicare services by Medicare-eligible veterans: the impact of additional access points in a rural setting. J Healthc Manag. 2005;50(2):95-106.

13. Gellad WF, Thorpe JM, Zhao X, et al. Impact of dual use of Department of Veterans Affairs and Medicare part d drug benefits on potentially unsafe opioid use. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(2):248-255. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.304174

14. Coughlin SS, Young L. A review of dual health care system use by veterans with cardiometabolic disease. J Hosp Manag Health Policy. 2018;2:39. doi:10.21037/jhmhp.2018.07.05

15. Radomski TR, Zhao X, Thorpe CT, et al. The impact of medication-based risk adjustment on the association between veteran health outcomes and dual health system use. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(9):967-973. doi:10.1007/s11606-017-4064-4

16. Kullgren JT, Fagerlin A, Kerr EA. Completing the MISSION: a blueprint for helping veterans make the most of new choices. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(5):1567-1570. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05404-w

17. VA MISSION Act of 2018, 38 USC §101 (2018). https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2018-title38/USCODE-2018-title38-partI-chap1-sec101

18. Vanneman ME, Phibbs CS, Dally SK, Trivedi AN, Yoon J. The impact of Medicaid enrollment on Veterans Health Administration enrollees’ behavioral health services use. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(suppl 3):5238-5259. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13062

19. Sommers BD, Baicker K, Epstein AM. Mortality and access to care among adults after state Medicaid expansions. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(11):1025-1034. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1202099

20. US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Mental Health. 2019 national veteran suicide prevention annual report. 2019. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2019/2019_National_Veteran_Suicide_Prevention_Annual_Report_508.pdf

21. Hawton K, Casañas I Comabella C, Haw C, Saunders K. Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2013;147(1-3):17-28. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.004

22. Adekkanattu P, Sholle ET, DeFerio J, Pathak J, Johnson SB, Campion TR Jr. Ascertaining depression severity by extracting Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scores from clinical notes. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2018;2018:147-156.

23. DeRubeis RJ, Siegle GJ, Hollon SD. Cognitive therapy versus medication for depression: treatment outcomes and neural mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(10):788-796. doi:10.1038/nrn2345

24. Cully JA, Zimmer M, Khan MM, Petersen LA. Quality of depression care and its impact on health service use and mortality among veterans. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(12):1399-1405. doi:10.1176/ps.2008.59.12.1399

25. Byrne MM, Kuebeler M, Pietz K, Petersen LA. Effect of using information from only one system for dually eligible health care users. Med Care. 2006;44(8):768-773. doi:10.1097/01.mlr.0000218786.44722.14

26. Watkins KE, Smith B, Akincigil A, et al. The quality of medication treatment for mental disorders in the Department of Veterans Affairs and in private-sector plans. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(4):391-396. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201400537

27. Petersen LA, Byrne MM, Daw CN, Hasche J, Reis B, Pietz K. Relationship between clinical conditions and use of Veterans Affairs health care among Medicare-enrolled veterans. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(3):762-791. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01107.x

28. Yoon J, Vanneman ME, Dally SK, Trivedi AN, Phibbs Ciaran S. Use of Veterans Affairs and Medicaid services for dually enrolled veterans. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(3):1539-1561. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12727

29. Yoon J, Vanneman ME, Dally SK, Trivedi AN, Phibbs Ciaran S. Veterans’ reliance on VA care by type of service and distance to VA for nonelderly VA-Medicaid dual enrollees. Med Care. 2019;57(3):225-229. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001066

30. Gaglioti A, Cozad A, Wittrock S, et al. Non-VA primary care providers’ perspectives on comanagement for rural veterans. Mil Med. 2014;179(11):1236-1243. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00342

31. Moon S, Shin J. Health care utilization among Medicare-Medicaid dual eligibles: a count data analysis. BMC Public Health. 2006;6(1):88. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-6-88

32. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Facilitating access to mental health services: a look at Medicaid, private insurance, and the uninsured. November 27, 2017. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/facilitating-access-to-mental-health-services-a-look-at-medicaid-private-insurance-and-the-uninsured

33. Baicker K, Taubman SL, Allen HL, et al. The Oregon experiment - effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(18):1713-1722. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1212321

34. Tanielian T, Farris C, Batka C, et al. Ready to serve: community-based provider capacity to deliver culturally competent, quality mental health care to veterans and their families. 2014. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR800/RR806/RAND_RR806.pdf

35. Kizer KW, Dudley RA. Extreme makeover: transformation of the Veterans Health Care System. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30(1):313-339. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090940

36. Brennan KJ. Kendra’s Law: final report on the status of assisted outpatient treatment, appendix 2. 2002. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://omh.ny.gov/omhweb/kendra_web/finalreport/appendix2.htm

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the largest integrated health care system in the United States, providing care for more than 9 million veterans.1 With veterans experiencing mental health conditions like posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance use disorders, and other serious mental illnesses (SMI) at higher rates compared with the general population, the VA plays an important role in the provision of mental health services.2-5 Since the implementation of its Mental Health Strategic Plan in 2004, the VA has overseen the development of a wide array of mental health programs geared toward the complex needs of veterans. Research has demonstrated VA care outperforming Medicaid-reimbursed services in terms of the percentage of veterans filling antidepressants for at least 12 weeks after initiation of treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD), as well as posthospitalization follow-up.6

Eligible veterans enrolled in the VA often also seek non-VA care. Medicaid covers nearly 10% of all nonelderly veterans, and of these veterans, 39% rely solely on Medicaid for health care access.7 Today, Medicaid is the largest payer for mental health services in the US, providing coverage for approximately 27% of Americans who have SMI and helping fulfill unmet mental health needs.8,9 Understanding which of these systems veterans choose to use, and under which circumstances, is essential in guiding the allocation of limited health care resources.10

Beyond Medicaid, alternatives to VA care may include TRICARE, Medicare, Indian Health Services, and employer-based or self-purchased private insurance. While these options potentially increase convenience, choice, and access to health care practitioners (HCPs) and services not available at local VA systems, cross-system utilization with poor integration may cause care coordination and continuity problems, such as medication mismanagement and opioid overdose, unnecessary duplicate utilization, and possible increased mortality.11-15 As recent national legislative changes, such as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act, and the VA MISSION Act, continue to shift the health care landscape for veterans, questions surrounding how veterans are changing their health care use become significant.16,17

Here, we approach the impacts of Medicaid expansion on veterans’ reliance on the VA for mental health services with a unique lens. We leverage a difference-in-difference design to study 2 historical Medicaid expansions in Arizona (AZ) and New York (NY), which extended eligibility to childless adults in 2001. Prior Medicaid dual-eligible mental health research investigated reliance shifts during the immediate postenrollment year in a subset of veterans newly enrolled in Medicaid.18 However, this study took place in a period of relative policy stability. In contrast, we investigate the potential effects of a broad policy shift by analyzing state-level changes in veterans’ reliance over 6 years after a statewide Medicaid expansion. We match expansion states with demographically similar nonexpansion states to account for unobserved trends and confounding effects. Prior studies have used this method to evaluate post-Medicaid expansion mortality changes and changes in veteran dual enrollment and hospitalizations.10,19 While a study of ACA Medicaid expansion states would be ideal, Medicaid data from most states were only available through 2014 at the time of this analysis. Our study offers a quasi-experimental framework leveraging longitudinal data that can be applied as more post-ACA data become available.

Given the rising incidence of suicide among veterans, understanding care-seeking behaviors for depression among veterans is important as it is the most common psychiatric condition found in those who died by suicide.20,21 Furthermore, depression may be useful as a clinical proxy for mental health policy impacts, given that the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) screening tool is well validated and increasingly research accessible, and it is a chronic condition responsive to both well-managed pharmacologic treatment and psychotherapeutic interventions.22,23

In this study, we quantify the change in care-seeking behavior for depression among veterans after Medicaid expansion, using a quasi-experimental design. We hypothesize that new access to Medicaid would be associated with a shift away from using VA services for depression. Given the income-dependent eligibility requirements of Medicaid, we also hypothesize that veterans who qualified for VA coverage due to low income, determined by a regional means test (Priority group 5, “income-eligible”), would be more likely to shift care compared with those whose serviced-connected conditions related to their military service (Priority groups 1-4, “service-connected”) provide VA access.

Methods

To investigate the relative changes in veterans’ reliance on the VA for depression care after the 2001 NY and AZ Medicaid expansions We used a retrospective, difference-in-difference analysis. Our comparison pairings, based on prior demographic analyses were as follows: NY with Pennsylvania(PA); AZ with New Mexico and Nevada (NM/NV).19 The time frame of our analysis was 1999 to 2006, with pre- and postexpansion periods defined as 1999 to 2000 and 2001 to 2006, respectively.

Data

We included veterans aged 18 to 64 years, seeking care for depression from 1999 to 2006, who were also VA-enrolled and residing in our states of interest. We counted veterans as enrolled in Medicaid if they were enrolled at least 1 month in a given year.

Using similar methods like those used in prior studies, we selected patients with encounters documenting depression as the primary outpatient or inpatient diagnosis using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes: 296.2x for a single episode of major depressive disorder, 296.3x for a recurrent episode of MDD, 300.4 for dysthymia, and 311.0 for depression not otherwise specified.18,24 We used data from the Medicaid Analytic eXtract files (MAX) for Medicaid data and the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) for VA data. We chose 1999 as the first study year because it was the earliest year MAX data were available.

Our final sample included 1833 person-years pre-expansion and 7157 postexpansion in our inpatient analysis, as well as 31,767 person-years pre-expansion and 130,382 postexpansion in our outpatient analysis.

Outcomes and Variables

Our primary outcomes were comparative shifts in VA reliance between expansion and nonexpansion states after Medicaid expansion for both inpatient and outpatient depression care. For each year of study, we calculated a veteran’s VA reliance by aggregating the number of days with depression-related encounters at the VA and dividing by the total number of days with a VA or Medicaid depression-related encounters for the year. To provide context to these shifts in VA reliance, we further analyzed the changes in the proportion of annual VA-Medicaid dual users and annual per capita utilization of depression care across the VA and Medicaid.

We conducted subanalyses by income-eligible and service-connected veterans and adjusted our models for age, non-White race, sex, distances to the nearest inpatient and outpatient VA facilities, and VA Relative Risk Score, which is a measure of disease burden and clinical complexity validated specifically for veterans.25

Statistical Analysis

We used fractional logistic regression to model the adjusted effect of Medicaid expansion on VA reliance for depression care. In parallel, we leveraged ordered logit regression and negative binomial regression models to examine the proportion of VA-Medicaid dual users and the per capita utilization of Medicaid and VA depression care, respectively. To estimate the difference-in-difference effects, we used the interaction term of 2 categorical variables—expansion vs nonexpansion states and pre- vs postexpansion status—as the independent variable. We then calculated the average marginal effects with 95% CIs to estimate the differences in outcomes between expansion and nonexpansion states from pre- to postexpansion periods, as well as year-by-year shifts as a robustness check. We conducted these analyses using Stata MP, version 15.

Results

Baseline and postexpansion characteristics

VA Reliance

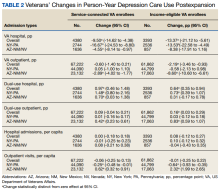

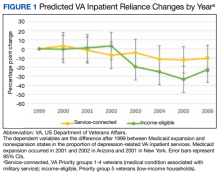

Overall, we observed postexpansion decreases in VA reliance for depression care

At the state level, reliance on the VA for inpatient depression care in NY decreased by 13.53 pp (95% CI, -22.58 to -4.49) for income-eligible veterans and 16.67 pp (95% CI, -24.53 to -8.80) for service-connected veterans. No relative differences were observed in the outpatient comparisons for both income-eligible (-0.58 pp; 95% CI, -2.13 to 0.98) and service-connected (0.05 pp; 95% CI, -1.00 to 1.10) veterans. In AZ, Medicaid expansion was associated with decreased VA reliance for outpatient depression care among income-eligible veterans (-8.60 pp; 95% CI, -10.60 to -6.61), greater than that for service-connected veterans (-2.89 pp; 95% CI, -4.02 to -1.77). This decrease in VA reliance was significant in the inpatient context only for service-connected veterans (-4.55 pp; 95% CI, -8.14 to -0.97), not income-eligible veterans (-8.38 pp; 95% CI, -17.91 to 1.16).

By applying the aggregate pp changes toward the postexpansion number of visits across both expansion and nonexpansion states, we found that expansion of Medicaid across all our study states would have resulted in 996 fewer hospitalizations and 10,109 fewer outpatient visits for depression at VA in the postexpansion period vs if no states had chosen to expand Medicaid.

Dual Use/Per Capita Utilization

Overall, Medicaid expansion was associated with greater dual use for inpatient depression care—a 0.97-pp (95% CI, 0.46 to 1.48) increase among service-connected veterans and a 0.64-pp (95% CI, 0.35 to 0.94) increase among income-eligible veterans.

At the state level, NY similarly showed increases in dual use among both service-connected (1.48 pp; 95% CI, 0.80 to 2.16) and income-eligible veterans (0.73 pp; 95% CI, 0.39 to 1.07) after Medicaid expansion. However, dual use in AZ increased significantly only among service-connected veterans (0.70 pp; 95% CI, 0.03 to 1.38), not income-eligible veterans (0.31 pp; 95% CI, -0.17 to 0.78).

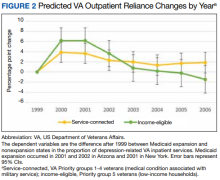

Among outpatient visits, Medicaid expansion was associated with increased dual use only for income-eligible veterans (0.16 pp; 95% CI, 0.03-0.29), and not service-connected veterans (0.09 pp; 95% CI, -0.04 to 0.21). State-level analyses showed that Medicaid expansion in NY was not associated with changes in dual use for either service-connected (0.01 pp; 95% CI, -0.16 to 0.17) or income-eligible veterans (0.03 pp; 95% CI, -0.12 to 0.18), while expansion in AZ was associated with increases in dual use among both service-connected (0.42 pp; 95% CI, 0.23 to 0.61) and income-eligible veterans (0.83 pp; 95% CI, 0.59 to 1.07).

Concerning per capita utilization of depression care after Medicaid expansion, analyses showed no detectable changes for either inpatient or outpatient services, among both service-connected and income-eligible veterans. However, while this pattern held at the state level among hospitalizations, outpatient visit results showed divergent trends between AZ and NY. In NY, Medicaid expansion was associated with decreased per capita utilization of outpatient depression care among both service-connected (-0.25 visits annually; 95% CI, -0.48 to -0.01) and income-eligible veterans (-0.64 visits annually; 95% CI, -0.93 to -0.35). In AZ, Medicaid expansion was associated with increased per capita utilization of outpatient depression care among both service-connected (0.62 visits annually; 95% CI, 0.32-0.91) and income-eligible veterans (2.32 visits annually; 95% CI, 1.99-2.65).

Discussion

Our study quantified changes in depression-related health care utilization after Medicaid expansions in NY and AZ in 2001. Overall, the balance of evidence indicated that Medicaid expansion was associated with decreased reliance on the VA for depression-related services. There was an exception: income-eligible veterans in AZ did not shift their hospital care away from the VA in a statistically discernible way, although the point estimate was lower. More broadly, these findings concerning veterans’ reliance varied not only in inpatient vs outpatient services and income- vs service-connected eligibility, but also in the state-level contexts of veteran dual users and per capita utilization.

Given that the overall per capita utilization of depression care was unchanged from pre- to postexpansion periods, one might interpret the decreases in VA reliance and increases in Medicaid-VA dual users as a substitution effect from VA care to non-VA care. This could be plausible for hospitalizations where state-level analyses showed similarly stable levels of per capita utilization. However, state-level trends in our outpatient utilization analysis, especially with a substantial 2.32 pp increase in annual per capita visits among income-eligible veterans in AZ, leave open the possibility that in some cases veterans may be complementing VA care with Medicaid-reimbursed services.

The causes underlying these differences in reliance shifts between NY and AZ are likely also influenced by the policy contexts of their respective Medicaid expansions. For example, in 1999, NY passed Kendra’s Law, which established a procedure for obtaining court orders for assisted outpatient mental health treatment for individuals deemed unlikely to survive safely in the community.26 A reasonable inference is that there was less unfulfilled outpatient mental health need in NY under the existing accessibility provisioned by Kendra’s Law. In addition, while both states extended coverage to childless adults under 100% of the Federal Poverty level (FPL), the AZ Medicaid expansion was via a voters’ initiative and extended family coverage to 200% FPL vs 150% FPL for families in NY. Given that the AZ Medicaid expansion enjoyed both broader public participation and generosity in terms of eligibility, its uptake and therefore effect size may have been larger than in NY for nonacute outpatient care.

Our findings contribute to the growing body of literature surrounding the changes in health care utilization after Medicaid expansion, specifically for a newly dual-eligible population of veterans seeking mental health services for depression. While prior research concerning Medicare dual-enrolled veterans has shown high reliance on the VA for both mental health diagnoses and services, scholars have established the association of Medicaid enrollment with decreased VA reliance.27-29 Our analysis is the first to investigate state-level effects of Medicaid expansion on VA reliance for a single mental health condition using a natural experimental framework. We focus on a population that includes a large portion of veterans who are newly Medicaid-eligible due to a sweeping policy change and use demographically matched nonexpansion states to draw comparisons in VA reliance for depression care. Our findings of Medicaid expansion–associated decreases in VA reliance for depression care complement prior literature that describe Medicaid enrollment–associated decreases in VA reliance for overall mental health care.

Implications

From a systems-level perspective, the implications of shifting services away from the VA are complex and incompletely understood. The VA lacks interoperability with the electronic health records (EHRs) used by Medicaid clinicians. Consequently, significant issues of service duplication and incomplete clinical data exist for veterans seeking treatment outside of the VA system, posing health care quality and safety concerns.30 On one hand, Medicaid access is associated with increased health care utilization attributed to filling unmet needs for Medicare dual enrollees, as well as increased prescription filling for psychiatric medications.31,32 Furthermore, the only randomized control trial of Medicaid expansion to date was associated with a 9-pp decrease in positive screening rates for depression among those who received access at around 2 years postexpansion.33 On the other hand, the VA has developed a mental health system tailored to the particular needs of veterans, and health care practitioners at the VA have significantly greater rates of military cultural competency compared to those in nonmilitary settings (70% vs 24% in the TRICARE network and 8% among those with no military or TRICARE affiliation).34 Compared to individuals seeking mental health services with private insurance plans, veterans were about twice as likely to receive appropriate treatment for schizophrenia and depression at the VA.35 These documented strengths of VA mental health care may together help explain the small absolute number of visits that were associated with shifts away from VA overall after Medicaid expansion.

Finally, it is worth considering extrinsic factors that influence utilization among newly dual-eligible veterans. For example, hospitalizations are less likely to be planned than outpatient services, translating to a greater importance of proximity to a nearby medical facility than a veteran’s preference of where to seek care. In the same vein, major VA medical centers are fewer and more distant on average than VA outpatient clinics, therefore reducing the advantage of a Medicaid-reimbursed outpatient clinic in terms of distance.36 These realities may partially explain the proportionally larger shifts away from the VA for hospitalizations compared to outpatient care for depression.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our results should be interpreted within methodological and data limitations. With only 2 states in our sample, NY demonstrably skewed overall results, contributing 1.7 to 3 times more observations than AZ across subanalyses—a challenge also cited by Sommers and colleagues.19 Our veteran groupings were also unable to distinguish those veterans classified as service-connected who may also have qualified by income-eligible criteria (which would tend to understate the size of results) and those veterans who gained and then lost Medicaid coverage in a given year. Our study also faces limitations in generalizability and establishing causality. First, we included only 2 historical state Medicaid expansions, compared with the 38 states and Washington, DC, that have now expanded Medicaid to date under the ACA. Just in the 2 states from our study, we noted significant heterogeneity in the shifts associated with Medicaid expansion, which makes extrapolating specific trends difficult. Differences in underlying health care resources, legislation, and other external factors may limit the applicability of Medicaid expansion in the era of the ACA, as well as the Veterans Choice and MISSION acts. Second, while we leveraged a difference-in-difference analysis using demographically matched, neighboring comparison states, our findings are nevertheless drawn from observational data obviating causality. VA data for other sources of coverage such as private insurance are limited and not included in our study, and MAX datasets vary by quality across states, translating to potential gaps in our study cohort.28

Moving forward, our study demonstrates the potential for applying a natural experimental approach to studying dual-eligible veterans at the interface of Medicaid expansion. We focused on changes in VA reliance for the specific condition of depression and, in doing so, invite further inquiry into the impact of state mental health policy on outcomes more proximate to veterans’ outcomes. Clinical indicators, such as rates of antidepressant filling, utilization and duration of psychotherapy, and PHQ-9 scores, can similarly be investigated by natural experimental design. While current limits of administrative data and the siloing of EHRs may pose barriers to some of these avenues of research, multidisciplinary methodologies and data querying innovations such as natural language processing algorithms for clinical notes hold exciting opportunities to bridge the gap between policy and clinical efficacy.

Conclusions

This study applied a difference-in-difference analysis and found that Medicaid expansion is associated with decreases in VA reliance for both inpatient and outpatient services for depression. As additional data are generated from the Medicaid expansions of the ACA, similarly robust methods should be applied to further explore the impacts associated with such policy shifts and open the door to a better understanding of implications at the clinical level.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the efforts of Janine Wong, who proofread and formatted the manuscript.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the largest integrated health care system in the United States, providing care for more than 9 million veterans.1 With veterans experiencing mental health conditions like posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance use disorders, and other serious mental illnesses (SMI) at higher rates compared with the general population, the VA plays an important role in the provision of mental health services.2-5 Since the implementation of its Mental Health Strategic Plan in 2004, the VA has overseen the development of a wide array of mental health programs geared toward the complex needs of veterans. Research has demonstrated VA care outperforming Medicaid-reimbursed services in terms of the percentage of veterans filling antidepressants for at least 12 weeks after initiation of treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD), as well as posthospitalization follow-up.6

Eligible veterans enrolled in the VA often also seek non-VA care. Medicaid covers nearly 10% of all nonelderly veterans, and of these veterans, 39% rely solely on Medicaid for health care access.7 Today, Medicaid is the largest payer for mental health services in the US, providing coverage for approximately 27% of Americans who have SMI and helping fulfill unmet mental health needs.8,9 Understanding which of these systems veterans choose to use, and under which circumstances, is essential in guiding the allocation of limited health care resources.10

Beyond Medicaid, alternatives to VA care may include TRICARE, Medicare, Indian Health Services, and employer-based or self-purchased private insurance. While these options potentially increase convenience, choice, and access to health care practitioners (HCPs) and services not available at local VA systems, cross-system utilization with poor integration may cause care coordination and continuity problems, such as medication mismanagement and opioid overdose, unnecessary duplicate utilization, and possible increased mortality.11-15 As recent national legislative changes, such as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act, and the VA MISSION Act, continue to shift the health care landscape for veterans, questions surrounding how veterans are changing their health care use become significant.16,17

Here, we approach the impacts of Medicaid expansion on veterans’ reliance on the VA for mental health services with a unique lens. We leverage a difference-in-difference design to study 2 historical Medicaid expansions in Arizona (AZ) and New York (NY), which extended eligibility to childless adults in 2001. Prior Medicaid dual-eligible mental health research investigated reliance shifts during the immediate postenrollment year in a subset of veterans newly enrolled in Medicaid.18 However, this study took place in a period of relative policy stability. In contrast, we investigate the potential effects of a broad policy shift by analyzing state-level changes in veterans’ reliance over 6 years after a statewide Medicaid expansion. We match expansion states with demographically similar nonexpansion states to account for unobserved trends and confounding effects. Prior studies have used this method to evaluate post-Medicaid expansion mortality changes and changes in veteran dual enrollment and hospitalizations.10,19 While a study of ACA Medicaid expansion states would be ideal, Medicaid data from most states were only available through 2014 at the time of this analysis. Our study offers a quasi-experimental framework leveraging longitudinal data that can be applied as more post-ACA data become available.

Given the rising incidence of suicide among veterans, understanding care-seeking behaviors for depression among veterans is important as it is the most common psychiatric condition found in those who died by suicide.20,21 Furthermore, depression may be useful as a clinical proxy for mental health policy impacts, given that the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) screening tool is well validated and increasingly research accessible, and it is a chronic condition responsive to both well-managed pharmacologic treatment and psychotherapeutic interventions.22,23

In this study, we quantify the change in care-seeking behavior for depression among veterans after Medicaid expansion, using a quasi-experimental design. We hypothesize that new access to Medicaid would be associated with a shift away from using VA services for depression. Given the income-dependent eligibility requirements of Medicaid, we also hypothesize that veterans who qualified for VA coverage due to low income, determined by a regional means test (Priority group 5, “income-eligible”), would be more likely to shift care compared with those whose serviced-connected conditions related to their military service (Priority groups 1-4, “service-connected”) provide VA access.

Methods

To investigate the relative changes in veterans’ reliance on the VA for depression care after the 2001 NY and AZ Medicaid expansions We used a retrospective, difference-in-difference analysis. Our comparison pairings, based on prior demographic analyses were as follows: NY with Pennsylvania(PA); AZ with New Mexico and Nevada (NM/NV).19 The time frame of our analysis was 1999 to 2006, with pre- and postexpansion periods defined as 1999 to 2000 and 2001 to 2006, respectively.

Data

We included veterans aged 18 to 64 years, seeking care for depression from 1999 to 2006, who were also VA-enrolled and residing in our states of interest. We counted veterans as enrolled in Medicaid if they were enrolled at least 1 month in a given year.

Using similar methods like those used in prior studies, we selected patients with encounters documenting depression as the primary outpatient or inpatient diagnosis using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes: 296.2x for a single episode of major depressive disorder, 296.3x for a recurrent episode of MDD, 300.4 for dysthymia, and 311.0 for depression not otherwise specified.18,24 We used data from the Medicaid Analytic eXtract files (MAX) for Medicaid data and the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) for VA data. We chose 1999 as the first study year because it was the earliest year MAX data were available.

Our final sample included 1833 person-years pre-expansion and 7157 postexpansion in our inpatient analysis, as well as 31,767 person-years pre-expansion and 130,382 postexpansion in our outpatient analysis.

Outcomes and Variables

Our primary outcomes were comparative shifts in VA reliance between expansion and nonexpansion states after Medicaid expansion for both inpatient and outpatient depression care. For each year of study, we calculated a veteran’s VA reliance by aggregating the number of days with depression-related encounters at the VA and dividing by the total number of days with a VA or Medicaid depression-related encounters for the year. To provide context to these shifts in VA reliance, we further analyzed the changes in the proportion of annual VA-Medicaid dual users and annual per capita utilization of depression care across the VA and Medicaid.

We conducted subanalyses by income-eligible and service-connected veterans and adjusted our models for age, non-White race, sex, distances to the nearest inpatient and outpatient VA facilities, and VA Relative Risk Score, which is a measure of disease burden and clinical complexity validated specifically for veterans.25

Statistical Analysis

We used fractional logistic regression to model the adjusted effect of Medicaid expansion on VA reliance for depression care. In parallel, we leveraged ordered logit regression and negative binomial regression models to examine the proportion of VA-Medicaid dual users and the per capita utilization of Medicaid and VA depression care, respectively. To estimate the difference-in-difference effects, we used the interaction term of 2 categorical variables—expansion vs nonexpansion states and pre- vs postexpansion status—as the independent variable. We then calculated the average marginal effects with 95% CIs to estimate the differences in outcomes between expansion and nonexpansion states from pre- to postexpansion periods, as well as year-by-year shifts as a robustness check. We conducted these analyses using Stata MP, version 15.

Results

Baseline and postexpansion characteristics

VA Reliance

Overall, we observed postexpansion decreases in VA reliance for depression care

At the state level, reliance on the VA for inpatient depression care in NY decreased by 13.53 pp (95% CI, -22.58 to -4.49) for income-eligible veterans and 16.67 pp (95% CI, -24.53 to -8.80) for service-connected veterans. No relative differences were observed in the outpatient comparisons for both income-eligible (-0.58 pp; 95% CI, -2.13 to 0.98) and service-connected (0.05 pp; 95% CI, -1.00 to 1.10) veterans. In AZ, Medicaid expansion was associated with decreased VA reliance for outpatient depression care among income-eligible veterans (-8.60 pp; 95% CI, -10.60 to -6.61), greater than that for service-connected veterans (-2.89 pp; 95% CI, -4.02 to -1.77). This decrease in VA reliance was significant in the inpatient context only for service-connected veterans (-4.55 pp; 95% CI, -8.14 to -0.97), not income-eligible veterans (-8.38 pp; 95% CI, -17.91 to 1.16).

By applying the aggregate pp changes toward the postexpansion number of visits across both expansion and nonexpansion states, we found that expansion of Medicaid across all our study states would have resulted in 996 fewer hospitalizations and 10,109 fewer outpatient visits for depression at VA in the postexpansion period vs if no states had chosen to expand Medicaid.

Dual Use/Per Capita Utilization

Overall, Medicaid expansion was associated with greater dual use for inpatient depression care—a 0.97-pp (95% CI, 0.46 to 1.48) increase among service-connected veterans and a 0.64-pp (95% CI, 0.35 to 0.94) increase among income-eligible veterans.

At the state level, NY similarly showed increases in dual use among both service-connected (1.48 pp; 95% CI, 0.80 to 2.16) and income-eligible veterans (0.73 pp; 95% CI, 0.39 to 1.07) after Medicaid expansion. However, dual use in AZ increased significantly only among service-connected veterans (0.70 pp; 95% CI, 0.03 to 1.38), not income-eligible veterans (0.31 pp; 95% CI, -0.17 to 0.78).

Among outpatient visits, Medicaid expansion was associated with increased dual use only for income-eligible veterans (0.16 pp; 95% CI, 0.03-0.29), and not service-connected veterans (0.09 pp; 95% CI, -0.04 to 0.21). State-level analyses showed that Medicaid expansion in NY was not associated with changes in dual use for either service-connected (0.01 pp; 95% CI, -0.16 to 0.17) or income-eligible veterans (0.03 pp; 95% CI, -0.12 to 0.18), while expansion in AZ was associated with increases in dual use among both service-connected (0.42 pp; 95% CI, 0.23 to 0.61) and income-eligible veterans (0.83 pp; 95% CI, 0.59 to 1.07).

Concerning per capita utilization of depression care after Medicaid expansion, analyses showed no detectable changes for either inpatient or outpatient services, among both service-connected and income-eligible veterans. However, while this pattern held at the state level among hospitalizations, outpatient visit results showed divergent trends between AZ and NY. In NY, Medicaid expansion was associated with decreased per capita utilization of outpatient depression care among both service-connected (-0.25 visits annually; 95% CI, -0.48 to -0.01) and income-eligible veterans (-0.64 visits annually; 95% CI, -0.93 to -0.35). In AZ, Medicaid expansion was associated with increased per capita utilization of outpatient depression care among both service-connected (0.62 visits annually; 95% CI, 0.32-0.91) and income-eligible veterans (2.32 visits annually; 95% CI, 1.99-2.65).

Discussion

Our study quantified changes in depression-related health care utilization after Medicaid expansions in NY and AZ in 2001. Overall, the balance of evidence indicated that Medicaid expansion was associated with decreased reliance on the VA for depression-related services. There was an exception: income-eligible veterans in AZ did not shift their hospital care away from the VA in a statistically discernible way, although the point estimate was lower. More broadly, these findings concerning veterans’ reliance varied not only in inpatient vs outpatient services and income- vs service-connected eligibility, but also in the state-level contexts of veteran dual users and per capita utilization.

Given that the overall per capita utilization of depression care was unchanged from pre- to postexpansion periods, one might interpret the decreases in VA reliance and increases in Medicaid-VA dual users as a substitution effect from VA care to non-VA care. This could be plausible for hospitalizations where state-level analyses showed similarly stable levels of per capita utilization. However, state-level trends in our outpatient utilization analysis, especially with a substantial 2.32 pp increase in annual per capita visits among income-eligible veterans in AZ, leave open the possibility that in some cases veterans may be complementing VA care with Medicaid-reimbursed services.

The causes underlying these differences in reliance shifts between NY and AZ are likely also influenced by the policy contexts of their respective Medicaid expansions. For example, in 1999, NY passed Kendra’s Law, which established a procedure for obtaining court orders for assisted outpatient mental health treatment for individuals deemed unlikely to survive safely in the community.26 A reasonable inference is that there was less unfulfilled outpatient mental health need in NY under the existing accessibility provisioned by Kendra’s Law. In addition, while both states extended coverage to childless adults under 100% of the Federal Poverty level (FPL), the AZ Medicaid expansion was via a voters’ initiative and extended family coverage to 200% FPL vs 150% FPL for families in NY. Given that the AZ Medicaid expansion enjoyed both broader public participation and generosity in terms of eligibility, its uptake and therefore effect size may have been larger than in NY for nonacute outpatient care.

Our findings contribute to the growing body of literature surrounding the changes in health care utilization after Medicaid expansion, specifically for a newly dual-eligible population of veterans seeking mental health services for depression. While prior research concerning Medicare dual-enrolled veterans has shown high reliance on the VA for both mental health diagnoses and services, scholars have established the association of Medicaid enrollment with decreased VA reliance.27-29 Our analysis is the first to investigate state-level effects of Medicaid expansion on VA reliance for a single mental health condition using a natural experimental framework. We focus on a population that includes a large portion of veterans who are newly Medicaid-eligible due to a sweeping policy change and use demographically matched nonexpansion states to draw comparisons in VA reliance for depression care. Our findings of Medicaid expansion–associated decreases in VA reliance for depression care complement prior literature that describe Medicaid enrollment–associated decreases in VA reliance for overall mental health care.

Implications

From a systems-level perspective, the implications of shifting services away from the VA are complex and incompletely understood. The VA lacks interoperability with the electronic health records (EHRs) used by Medicaid clinicians. Consequently, significant issues of service duplication and incomplete clinical data exist for veterans seeking treatment outside of the VA system, posing health care quality and safety concerns.30 On one hand, Medicaid access is associated with increased health care utilization attributed to filling unmet needs for Medicare dual enrollees, as well as increased prescription filling for psychiatric medications.31,32 Furthermore, the only randomized control trial of Medicaid expansion to date was associated with a 9-pp decrease in positive screening rates for depression among those who received access at around 2 years postexpansion.33 On the other hand, the VA has developed a mental health system tailored to the particular needs of veterans, and health care practitioners at the VA have significantly greater rates of military cultural competency compared to those in nonmilitary settings (70% vs 24% in the TRICARE network and 8% among those with no military or TRICARE affiliation).34 Compared to individuals seeking mental health services with private insurance plans, veterans were about twice as likely to receive appropriate treatment for schizophrenia and depression at the VA.35 These documented strengths of VA mental health care may together help explain the small absolute number of visits that were associated with shifts away from VA overall after Medicaid expansion.

Finally, it is worth considering extrinsic factors that influence utilization among newly dual-eligible veterans. For example, hospitalizations are less likely to be planned than outpatient services, translating to a greater importance of proximity to a nearby medical facility than a veteran’s preference of where to seek care. In the same vein, major VA medical centers are fewer and more distant on average than VA outpatient clinics, therefore reducing the advantage of a Medicaid-reimbursed outpatient clinic in terms of distance.36 These realities may partially explain the proportionally larger shifts away from the VA for hospitalizations compared to outpatient care for depression.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our results should be interpreted within methodological and data limitations. With only 2 states in our sample, NY demonstrably skewed overall results, contributing 1.7 to 3 times more observations than AZ across subanalyses—a challenge also cited by Sommers and colleagues.19 Our veteran groupings were also unable to distinguish those veterans classified as service-connected who may also have qualified by income-eligible criteria (which would tend to understate the size of results) and those veterans who gained and then lost Medicaid coverage in a given year. Our study also faces limitations in generalizability and establishing causality. First, we included only 2 historical state Medicaid expansions, compared with the 38 states and Washington, DC, that have now expanded Medicaid to date under the ACA. Just in the 2 states from our study, we noted significant heterogeneity in the shifts associated with Medicaid expansion, which makes extrapolating specific trends difficult. Differences in underlying health care resources, legislation, and other external factors may limit the applicability of Medicaid expansion in the era of the ACA, as well as the Veterans Choice and MISSION acts. Second, while we leveraged a difference-in-difference analysis using demographically matched, neighboring comparison states, our findings are nevertheless drawn from observational data obviating causality. VA data for other sources of coverage such as private insurance are limited and not included in our study, and MAX datasets vary by quality across states, translating to potential gaps in our study cohort.28

Moving forward, our study demonstrates the potential for applying a natural experimental approach to studying dual-eligible veterans at the interface of Medicaid expansion. We focused on changes in VA reliance for the specific condition of depression and, in doing so, invite further inquiry into the impact of state mental health policy on outcomes more proximate to veterans’ outcomes. Clinical indicators, such as rates of antidepressant filling, utilization and duration of psychotherapy, and PHQ-9 scores, can similarly be investigated by natural experimental design. While current limits of administrative data and the siloing of EHRs may pose barriers to some of these avenues of research, multidisciplinary methodologies and data querying innovations such as natural language processing algorithms for clinical notes hold exciting opportunities to bridge the gap between policy and clinical efficacy.

Conclusions

This study applied a difference-in-difference analysis and found that Medicaid expansion is associated with decreases in VA reliance for both inpatient and outpatient services for depression. As additional data are generated from the Medicaid expansions of the ACA, similarly robust methods should be applied to further explore the impacts associated with such policy shifts and open the door to a better understanding of implications at the clinical level.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the efforts of Janine Wong, who proofread and formatted the manuscript.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. About VA. 2019. Updated September 27, 2022. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.va.gov/health/

2. Richardson LK, Frueh BC, Acierno R. Prevalence estimates of combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder: critical review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(1):4-19. doi:10.3109/00048670903393597

3. Lan CW, Fiellin DA, Barry DT, et al. The epidemiology of substance use disorders in US veterans: a systematic review and analysis of assessment methods. Am J Addict. 2016;25(1):7-24. doi:10.1111/ajad.12319

4. Grant BF, Saha TD, June Ruan W, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 drug use disorder results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions-III. JAMA Psychiat. 2016;73(1):39-47. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.015.2132

5. Pemberton MR, Forman-Hoffman VL, Lipari RN, Ashley OS, Heller DC, Williams MR. Prevalence of past year substance use and mental illness by veteran status in a nationally representative sample. CBHSQ Data Review. Published November 9, 2016. Accessed October 6, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/prevalence-past-year-substance-use-and-mental-illness-veteran-status-nationally

6. Watkins KE, Pincus HA, Smith B, et al. Veterans Health Administration Mental Health Program Evaluation: Capstone Report. 2011. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR956.html

7. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid’s role in covering veterans. June 29, 2017. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.kff.org/infographic/medicaids-role-in-covering-veterans

8. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: detailed tables. September 7, 2017. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2016/NSDUH-DetTabs-2016.pdf

9. Wen H, Druss BG, Cummings JR. Effect of Medicaid expansions on health insurance coverage and access to care among low-income adults with behavioral health conditions. Health Serv Res. 2015;50:1787-1809. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12411

10. O’Mahen PN, Petersen LA. Effects of state-level Medicaid expansion on Veterans Health Administration dual enrollment and utilization: potential implications for future coverage expansions. Med Care. 2020;58(6):526-533. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001327

11. Ono SS, Dziak KM, Wittrock SM, et al. Treating dual-use patients across two health care systems: a qualitative study. Fed Pract. 2015;32(8):32-37.

12. Weeks WB, Mahar PJ, Wright SM. Utilization of VA and Medicare services by Medicare-eligible veterans: the impact of additional access points in a rural setting. J Healthc Manag. 2005;50(2):95-106.

13. Gellad WF, Thorpe JM, Zhao X, et al. Impact of dual use of Department of Veterans Affairs and Medicare part d drug benefits on potentially unsafe opioid use. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(2):248-255. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.304174

14. Coughlin SS, Young L. A review of dual health care system use by veterans with cardiometabolic disease. J Hosp Manag Health Policy. 2018;2:39. doi:10.21037/jhmhp.2018.07.05

15. Radomski TR, Zhao X, Thorpe CT, et al. The impact of medication-based risk adjustment on the association between veteran health outcomes and dual health system use. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(9):967-973. doi:10.1007/s11606-017-4064-4

16. Kullgren JT, Fagerlin A, Kerr EA. Completing the MISSION: a blueprint for helping veterans make the most of new choices. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(5):1567-1570. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05404-w

17. VA MISSION Act of 2018, 38 USC §101 (2018). https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2018-title38/USCODE-2018-title38-partI-chap1-sec101

18. Vanneman ME, Phibbs CS, Dally SK, Trivedi AN, Yoon J. The impact of Medicaid enrollment on Veterans Health Administration enrollees’ behavioral health services use. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(suppl 3):5238-5259. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13062

19. Sommers BD, Baicker K, Epstein AM. Mortality and access to care among adults after state Medicaid expansions. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(11):1025-1034. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1202099

20. US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Mental Health. 2019 national veteran suicide prevention annual report. 2019. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2019/2019_National_Veteran_Suicide_Prevention_Annual_Report_508.pdf

21. Hawton K, Casañas I Comabella C, Haw C, Saunders K. Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2013;147(1-3):17-28. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.004

22. Adekkanattu P, Sholle ET, DeFerio J, Pathak J, Johnson SB, Campion TR Jr. Ascertaining depression severity by extracting Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scores from clinical notes. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2018;2018:147-156.

23. DeRubeis RJ, Siegle GJ, Hollon SD. Cognitive therapy versus medication for depression: treatment outcomes and neural mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(10):788-796. doi:10.1038/nrn2345

24. Cully JA, Zimmer M, Khan MM, Petersen LA. Quality of depression care and its impact on health service use and mortality among veterans. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(12):1399-1405. doi:10.1176/ps.2008.59.12.1399

25. Byrne MM, Kuebeler M, Pietz K, Petersen LA. Effect of using information from only one system for dually eligible health care users. Med Care. 2006;44(8):768-773. doi:10.1097/01.mlr.0000218786.44722.14

26. Watkins KE, Smith B, Akincigil A, et al. The quality of medication treatment for mental disorders in the Department of Veterans Affairs and in private-sector plans. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(4):391-396. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201400537

27. Petersen LA, Byrne MM, Daw CN, Hasche J, Reis B, Pietz K. Relationship between clinical conditions and use of Veterans Affairs health care among Medicare-enrolled veterans. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(3):762-791. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01107.x

28. Yoon J, Vanneman ME, Dally SK, Trivedi AN, Phibbs Ciaran S. Use of Veterans Affairs and Medicaid services for dually enrolled veterans. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(3):1539-1561. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12727

29. Yoon J, Vanneman ME, Dally SK, Trivedi AN, Phibbs Ciaran S. Veterans’ reliance on VA care by type of service and distance to VA for nonelderly VA-Medicaid dual enrollees. Med Care. 2019;57(3):225-229. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001066

30. Gaglioti A, Cozad A, Wittrock S, et al. Non-VA primary care providers’ perspectives on comanagement for rural veterans. Mil Med. 2014;179(11):1236-1243. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00342

31. Moon S, Shin J. Health care utilization among Medicare-Medicaid dual eligibles: a count data analysis. BMC Public Health. 2006;6(1):88. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-6-88

32. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Facilitating access to mental health services: a look at Medicaid, private insurance, and the uninsured. November 27, 2017. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/facilitating-access-to-mental-health-services-a-look-at-medicaid-private-insurance-and-the-uninsured

33. Baicker K, Taubman SL, Allen HL, et al. The Oregon experiment - effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(18):1713-1722. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1212321

34. Tanielian T, Farris C, Batka C, et al. Ready to serve: community-based provider capacity to deliver culturally competent, quality mental health care to veterans and their families. 2014. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR800/RR806/RAND_RR806.pdf

35. Kizer KW, Dudley RA. Extreme makeover: transformation of the Veterans Health Care System. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30(1):313-339. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090940

36. Brennan KJ. Kendra’s Law: final report on the status of assisted outpatient treatment, appendix 2. 2002. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://omh.ny.gov/omhweb/kendra_web/finalreport/appendix2.htm