User login

Massive rise in drug overdose deaths driven by opioids

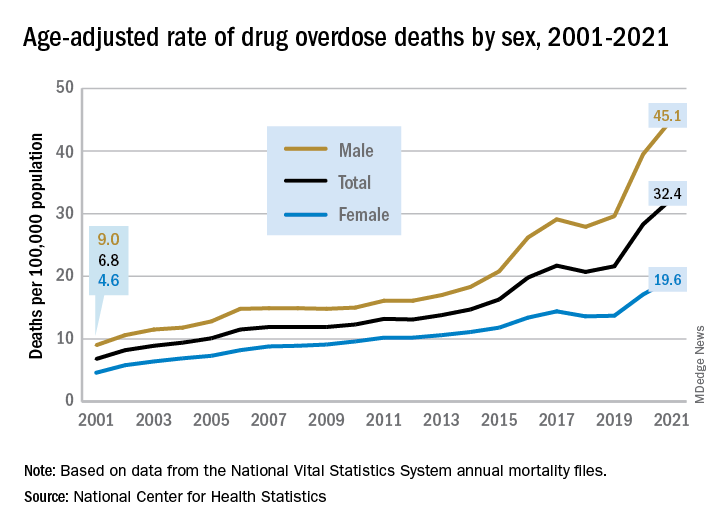

The 376% represents the change in age-adjusted overdose deaths per 100,000 population, which went from 6.9 in 2001 to 32.4 in 2021, as the total number of deaths rose from 19,394 to 106,699 (450%) over that time period, the NCHS said in a recent data brief. That total made 2021 the first year ever with more than 100,000 overdose deaths.

Since the age-adjusted rate stood at 21.6 per 100,000 in 2019, that means 42% of the total increase over 20 years actually occurred in 2020 and 2021. The number of deaths increased by about 36,000 over those 2 years, accounting for 41% of the total annual increase from 2001 to 2021, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System mortality files.

The overdose death rate was significantly higher for males than females for all of the years from 2001 to 2021, with males seeing an increase from 9.0 to 45.1 per 100,000 and females going from 4.6 to 19.6 deaths per 100,000. In the single year from 2020 to 2021, the age-adjusted rate was up by 14% for males and 15% for females, the mortality-file data show.

Analysis by age showed an even larger effect in some groups from 2020 to 2021. Drug overdose deaths jumped 28% among adults aged 65 years and older, more than any other group, and by 21% in those aged 55-64 years, according to the NCHS.

The only age group for which deaths didn’t increase significantly from 2020 to 2021 was 15- to 24-year-olds, whose rate rose by just 3%. The age group with the highest rate in both 2020 and 2021, however, was the 35- to 44-year-olds: 53.9 and 62.0 overdose deaths per 100,000, respectively, for an increase of 15%, the NCHS said in the report.

The drugs now involved in overdose deaths are most often opioids, a change from 2001. That year, opioids were involved in 49% of all overdose deaths, but by 2021 that share had increased to 75%. The trend for opioid-related deaths almost matches that of overall deaths over the 20-year span, and the significantly increasing trend that began for all overdose deaths in 2013 closely follows that of synthetic opioids such as fentanyl and tramadol, the report shows.

Overdose deaths involving cocaine and psychostimulants such as methamphetamine, amphetamine, and methylphenidate also show similar increases. The cocaine-related death rate rose 22% from 2020 to 2021 and is up by 421% since 2012, while the corresponding increases for psychostimulant deaths were 33% and 2,400%, the NCHS said.

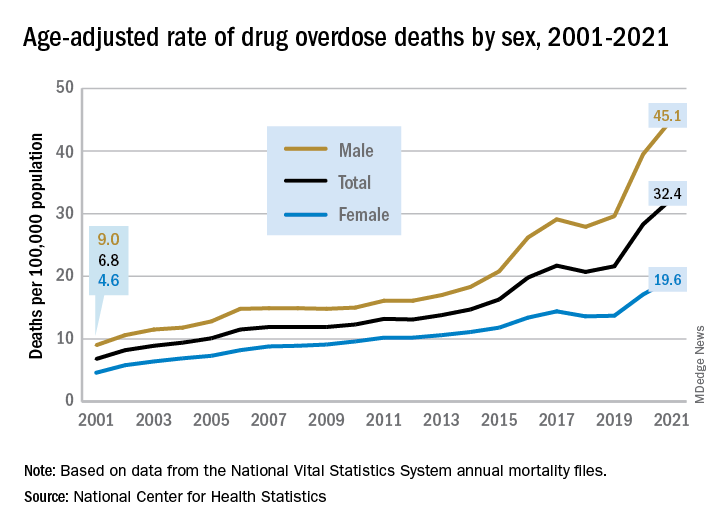

The 376% represents the change in age-adjusted overdose deaths per 100,000 population, which went from 6.9 in 2001 to 32.4 in 2021, as the total number of deaths rose from 19,394 to 106,699 (450%) over that time period, the NCHS said in a recent data brief. That total made 2021 the first year ever with more than 100,000 overdose deaths.

Since the age-adjusted rate stood at 21.6 per 100,000 in 2019, that means 42% of the total increase over 20 years actually occurred in 2020 and 2021. The number of deaths increased by about 36,000 over those 2 years, accounting for 41% of the total annual increase from 2001 to 2021, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System mortality files.

The overdose death rate was significantly higher for males than females for all of the years from 2001 to 2021, with males seeing an increase from 9.0 to 45.1 per 100,000 and females going from 4.6 to 19.6 deaths per 100,000. In the single year from 2020 to 2021, the age-adjusted rate was up by 14% for males and 15% for females, the mortality-file data show.

Analysis by age showed an even larger effect in some groups from 2020 to 2021. Drug overdose deaths jumped 28% among adults aged 65 years and older, more than any other group, and by 21% in those aged 55-64 years, according to the NCHS.

The only age group for which deaths didn’t increase significantly from 2020 to 2021 was 15- to 24-year-olds, whose rate rose by just 3%. The age group with the highest rate in both 2020 and 2021, however, was the 35- to 44-year-olds: 53.9 and 62.0 overdose deaths per 100,000, respectively, for an increase of 15%, the NCHS said in the report.

The drugs now involved in overdose deaths are most often opioids, a change from 2001. That year, opioids were involved in 49% of all overdose deaths, but by 2021 that share had increased to 75%. The trend for opioid-related deaths almost matches that of overall deaths over the 20-year span, and the significantly increasing trend that began for all overdose deaths in 2013 closely follows that of synthetic opioids such as fentanyl and tramadol, the report shows.

Overdose deaths involving cocaine and psychostimulants such as methamphetamine, amphetamine, and methylphenidate also show similar increases. The cocaine-related death rate rose 22% from 2020 to 2021 and is up by 421% since 2012, while the corresponding increases for psychostimulant deaths were 33% and 2,400%, the NCHS said.

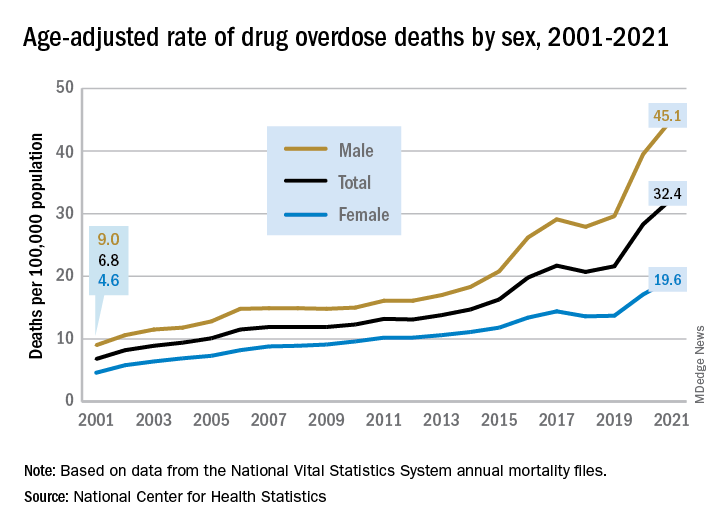

The 376% represents the change in age-adjusted overdose deaths per 100,000 population, which went from 6.9 in 2001 to 32.4 in 2021, as the total number of deaths rose from 19,394 to 106,699 (450%) over that time period, the NCHS said in a recent data brief. That total made 2021 the first year ever with more than 100,000 overdose deaths.

Since the age-adjusted rate stood at 21.6 per 100,000 in 2019, that means 42% of the total increase over 20 years actually occurred in 2020 and 2021. The number of deaths increased by about 36,000 over those 2 years, accounting for 41% of the total annual increase from 2001 to 2021, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System mortality files.

The overdose death rate was significantly higher for males than females for all of the years from 2001 to 2021, with males seeing an increase from 9.0 to 45.1 per 100,000 and females going from 4.6 to 19.6 deaths per 100,000. In the single year from 2020 to 2021, the age-adjusted rate was up by 14% for males and 15% for females, the mortality-file data show.

Analysis by age showed an even larger effect in some groups from 2020 to 2021. Drug overdose deaths jumped 28% among adults aged 65 years and older, more than any other group, and by 21% in those aged 55-64 years, according to the NCHS.

The only age group for which deaths didn’t increase significantly from 2020 to 2021 was 15- to 24-year-olds, whose rate rose by just 3%. The age group with the highest rate in both 2020 and 2021, however, was the 35- to 44-year-olds: 53.9 and 62.0 overdose deaths per 100,000, respectively, for an increase of 15%, the NCHS said in the report.

The drugs now involved in overdose deaths are most often opioids, a change from 2001. That year, opioids were involved in 49% of all overdose deaths, but by 2021 that share had increased to 75%. The trend for opioid-related deaths almost matches that of overall deaths over the 20-year span, and the significantly increasing trend that began for all overdose deaths in 2013 closely follows that of synthetic opioids such as fentanyl and tramadol, the report shows.

Overdose deaths involving cocaine and psychostimulants such as methamphetamine, amphetamine, and methylphenidate also show similar increases. The cocaine-related death rate rose 22% from 2020 to 2021 and is up by 421% since 2012, while the corresponding increases for psychostimulant deaths were 33% and 2,400%, the NCHS said.

Lipid signature may flag schizophrenia

Although such a test remains a long way off, investigators said, the identification of the unique lipid signature is a critical first step. However, one expert noted that the lipid signature not accurately differentiating patients with schizophrenia from those with bipolar disorder (BD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) limits the findings’ applicability.

The profile includes 77 lipids identified from a large analysis of many different classes of lipid species. Lipids such as cholesterol and triglycerides made up only a small fraction of the classes assessed.

The investigators noted that some of the lipids in the profile associated with schizophrenia are involved in determining cell membrane structure and fluidity or cell-to-cell messaging, which could be important to synaptic function.

“These 77 lipids jointly constitute a lipidomic profile that discriminated between individuals with schizophrenia and individuals without a mental health diagnosis with very high accuracy,” investigator Eva C. Schulte, MD, PhD, of the Institute of Psychiatric Phenomics and Genomics (IPPG) and the department of psychiatry and psychotherapy at University Hospital of Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich, told this news organization.

“Of note, we did not see large profile differences between patients with a first psychotic episode who had only been treated for a few days and individuals on long-term antipsychotic therapy,” Dr. Schulte said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Detailed analysis

Lipid profiles in patients with psychiatric diagnoses have been reported previously, but those studies were small and did not identify a reliable signature independent of demographic and environmental factors.

For the current study, researchers analyzed blood plasma lipid levels from 980 individuals with severe psychiatric illness and 572 people without mental illness from three cohorts in China, Germany, Austria, and Russia.

The study sample included patients with schizophrenia (n = 478), BD (n = 184), and MDD (n = 256), as well as 104 patients with a first psychotic episode who had no long-term psychopharmacology use.

Results showed 77 lipids in 14 classes were significantly altered between participants with schizophrenia and the healthy control in all three cohorts.

The most prominent alterations at the lipid class level included increases in ceramide, triacylglyceride, and phosphatidylcholine and decreases in acylcarnitine and phosphatidylcholine plasmalogen (P < .05 for each cohort).

Schizophrenia-associated lipid differences were similar between patients with high and low symptom severity (P < .001), suggesting that the lipid alterations might represent a trait of the psychiatric disorder.

No medication effect

Most patients in the study received long-term antipsychotic medication, which has been shown previously to affect some plasma lipid compounds.

So, to assess a possible effect of medication, the investigators evaluated 13 patients with schizophrenia who were not medicated for at least 6 months prior to blood sample collection and the cohort of patients with a first psychotic episode who had been medicated for less than 1 week.

Comparison of the lipid intensity differences between the healthy controls group and either participants receiving medication or those who were not medicated revealed highly correlated alterations in both patient groups (P < .001).

“Taken together, these results indicate that the identified schizophrenia-associated alterations cannot be attributed to medication effects,” the investigators wrote.

Lipidome alterations in BPD and MDD, assessed in 184 and 256 individuals, respectively, were similar to those of schizophrenia but not identical.

Researchers isolated 97 lipids altered in the MDD cohorts and 47 in the BPD cohorts – with 30 and 28, respectively, overlapping with the schizophrenia-associated features and seven of the lipids found among all three disorders.

Although this was significantly more than expected by chance (P < .001), it was not strong enough to demonstrate a clear association, the investigators wrote.

“The profiles were very successful at differentiating individuals with severe mental health conditions from individuals without a diagnosed mental health condition, but much less so at differentiating between the different diagnostic entities,” coinvestigator Thomas G. Schulze, MD, director of IPPG, said in an interview.

“An important caveat, however, is that the available sample sizes for bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder were smaller than those for schizophrenia, which makes a direct comparison between these difficult,” added Dr. Schulze, clinical professor in psychiatry and behavioral sciences at State University of New York, Syracuse.

More work remains

Although the study is thought to be the largest to date to examine lipid profiles associated with serious psychiatric illness, much work remains, Dr. Schulze noted.

“At this time, based on these first results, no clinical diagnostic test can be derived from these results,” he said.

He added that the development of reliable biomarkers based on lipidomic profiles would require large prospective randomized trials, complemented by observational studies assessing full lipidomic profiles across the lifespan.

Researchers also need to better understand the exact mechanism by which lipid alterations are associated with schizophrenia and other illnesses.

Physiologically, the investigated lipids have many additional functions, such as determining cell membrane structure and fluidity or cell-to-cell messaging.

Dr. Schulte noted that several lipid species may be involved in determining mechanisms important to synaptic function, such as cell membrane fluidity and vesicle release.

“As is commonly known, alterations in synaptic function underly many severe psychiatric disorders,” she said. “Changes in lipid species could theoretically be related to these synaptic alterations.”

A better marker needed

In a comment, Stephen Strakowski, MD, professor and vice chair of research in the department of psychiatry, Indiana University, Indianapolis and Evansville, noted that while the findings are interesting, they don’t really offer the kind of information clinicians who treat patients with serious mental illness need most.

“Do we need a marker to tell us if someone’s got a major mental illness compared to a healthy person?” asked Dr. Strakowski, who was not part of the study. “The answer to that is no. We already know how to do that.”

A truly useful marker would help clinicians differentiate between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression, or another serious mental illness, he said.

“That’s the marker that would be most helpful,” he added. “This can’t address that, but perhaps it could be a step to start designing a test for that.”

Dr. Strakowksi noted that the findings do not clarify whether the lipid profile found in patients with schizophrenia predates diagnosis or whether it is a result of the mental illness, an unrelated illness, or another factor that could be critical in treating patients.

However, he was quick to point out the limitations don’t diminish the importance of the study.

“It’s a large dataset that’s cross-national, cross-diagnostic that says there appears to be a signal here that there’s something about lipid profiles that may be independent of treatment that could be worth understanding,” Dr. Strakowksi said.

“It allows us to think about developing different models based on lipid profiles, and that’s important,” he added.

The study was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China, National One Thousand Foreign Experts Plan, Moscow Center for Innovative Technologies in Healthcare, European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme, NARSAD Young Investigator Grant, German Research Foundation, German Ministry for Education and Research, the Dr. Lisa Oehler Foundation, and the Munich Clinician Scientist Program. Dr. Schulze and Dr. Schulte reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although such a test remains a long way off, investigators said, the identification of the unique lipid signature is a critical first step. However, one expert noted that the lipid signature not accurately differentiating patients with schizophrenia from those with bipolar disorder (BD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) limits the findings’ applicability.

The profile includes 77 lipids identified from a large analysis of many different classes of lipid species. Lipids such as cholesterol and triglycerides made up only a small fraction of the classes assessed.

The investigators noted that some of the lipids in the profile associated with schizophrenia are involved in determining cell membrane structure and fluidity or cell-to-cell messaging, which could be important to synaptic function.

“These 77 lipids jointly constitute a lipidomic profile that discriminated between individuals with schizophrenia and individuals without a mental health diagnosis with very high accuracy,” investigator Eva C. Schulte, MD, PhD, of the Institute of Psychiatric Phenomics and Genomics (IPPG) and the department of psychiatry and psychotherapy at University Hospital of Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich, told this news organization.

“Of note, we did not see large profile differences between patients with a first psychotic episode who had only been treated for a few days and individuals on long-term antipsychotic therapy,” Dr. Schulte said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Detailed analysis

Lipid profiles in patients with psychiatric diagnoses have been reported previously, but those studies were small and did not identify a reliable signature independent of demographic and environmental factors.

For the current study, researchers analyzed blood plasma lipid levels from 980 individuals with severe psychiatric illness and 572 people without mental illness from three cohorts in China, Germany, Austria, and Russia.

The study sample included patients with schizophrenia (n = 478), BD (n = 184), and MDD (n = 256), as well as 104 patients with a first psychotic episode who had no long-term psychopharmacology use.

Results showed 77 lipids in 14 classes were significantly altered between participants with schizophrenia and the healthy control in all three cohorts.

The most prominent alterations at the lipid class level included increases in ceramide, triacylglyceride, and phosphatidylcholine and decreases in acylcarnitine and phosphatidylcholine plasmalogen (P < .05 for each cohort).

Schizophrenia-associated lipid differences were similar between patients with high and low symptom severity (P < .001), suggesting that the lipid alterations might represent a trait of the psychiatric disorder.

No medication effect

Most patients in the study received long-term antipsychotic medication, which has been shown previously to affect some plasma lipid compounds.

So, to assess a possible effect of medication, the investigators evaluated 13 patients with schizophrenia who were not medicated for at least 6 months prior to blood sample collection and the cohort of patients with a first psychotic episode who had been medicated for less than 1 week.

Comparison of the lipid intensity differences between the healthy controls group and either participants receiving medication or those who were not medicated revealed highly correlated alterations in both patient groups (P < .001).

“Taken together, these results indicate that the identified schizophrenia-associated alterations cannot be attributed to medication effects,” the investigators wrote.

Lipidome alterations in BPD and MDD, assessed in 184 and 256 individuals, respectively, were similar to those of schizophrenia but not identical.

Researchers isolated 97 lipids altered in the MDD cohorts and 47 in the BPD cohorts – with 30 and 28, respectively, overlapping with the schizophrenia-associated features and seven of the lipids found among all three disorders.

Although this was significantly more than expected by chance (P < .001), it was not strong enough to demonstrate a clear association, the investigators wrote.

“The profiles were very successful at differentiating individuals with severe mental health conditions from individuals without a diagnosed mental health condition, but much less so at differentiating between the different diagnostic entities,” coinvestigator Thomas G. Schulze, MD, director of IPPG, said in an interview.

“An important caveat, however, is that the available sample sizes for bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder were smaller than those for schizophrenia, which makes a direct comparison between these difficult,” added Dr. Schulze, clinical professor in psychiatry and behavioral sciences at State University of New York, Syracuse.

More work remains

Although the study is thought to be the largest to date to examine lipid profiles associated with serious psychiatric illness, much work remains, Dr. Schulze noted.

“At this time, based on these first results, no clinical diagnostic test can be derived from these results,” he said.

He added that the development of reliable biomarkers based on lipidomic profiles would require large prospective randomized trials, complemented by observational studies assessing full lipidomic profiles across the lifespan.

Researchers also need to better understand the exact mechanism by which lipid alterations are associated with schizophrenia and other illnesses.

Physiologically, the investigated lipids have many additional functions, such as determining cell membrane structure and fluidity or cell-to-cell messaging.

Dr. Schulte noted that several lipid species may be involved in determining mechanisms important to synaptic function, such as cell membrane fluidity and vesicle release.

“As is commonly known, alterations in synaptic function underly many severe psychiatric disorders,” she said. “Changes in lipid species could theoretically be related to these synaptic alterations.”

A better marker needed

In a comment, Stephen Strakowski, MD, professor and vice chair of research in the department of psychiatry, Indiana University, Indianapolis and Evansville, noted that while the findings are interesting, they don’t really offer the kind of information clinicians who treat patients with serious mental illness need most.

“Do we need a marker to tell us if someone’s got a major mental illness compared to a healthy person?” asked Dr. Strakowski, who was not part of the study. “The answer to that is no. We already know how to do that.”

A truly useful marker would help clinicians differentiate between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression, or another serious mental illness, he said.

“That’s the marker that would be most helpful,” he added. “This can’t address that, but perhaps it could be a step to start designing a test for that.”

Dr. Strakowksi noted that the findings do not clarify whether the lipid profile found in patients with schizophrenia predates diagnosis or whether it is a result of the mental illness, an unrelated illness, or another factor that could be critical in treating patients.

However, he was quick to point out the limitations don’t diminish the importance of the study.

“It’s a large dataset that’s cross-national, cross-diagnostic that says there appears to be a signal here that there’s something about lipid profiles that may be independent of treatment that could be worth understanding,” Dr. Strakowksi said.

“It allows us to think about developing different models based on lipid profiles, and that’s important,” he added.

The study was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China, National One Thousand Foreign Experts Plan, Moscow Center for Innovative Technologies in Healthcare, European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme, NARSAD Young Investigator Grant, German Research Foundation, German Ministry for Education and Research, the Dr. Lisa Oehler Foundation, and the Munich Clinician Scientist Program. Dr. Schulze and Dr. Schulte reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although such a test remains a long way off, investigators said, the identification of the unique lipid signature is a critical first step. However, one expert noted that the lipid signature not accurately differentiating patients with schizophrenia from those with bipolar disorder (BD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) limits the findings’ applicability.

The profile includes 77 lipids identified from a large analysis of many different classes of lipid species. Lipids such as cholesterol and triglycerides made up only a small fraction of the classes assessed.

The investigators noted that some of the lipids in the profile associated with schizophrenia are involved in determining cell membrane structure and fluidity or cell-to-cell messaging, which could be important to synaptic function.

“These 77 lipids jointly constitute a lipidomic profile that discriminated between individuals with schizophrenia and individuals without a mental health diagnosis with very high accuracy,” investigator Eva C. Schulte, MD, PhD, of the Institute of Psychiatric Phenomics and Genomics (IPPG) and the department of psychiatry and psychotherapy at University Hospital of Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich, told this news organization.

“Of note, we did not see large profile differences between patients with a first psychotic episode who had only been treated for a few days and individuals on long-term antipsychotic therapy,” Dr. Schulte said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Detailed analysis

Lipid profiles in patients with psychiatric diagnoses have been reported previously, but those studies were small and did not identify a reliable signature independent of demographic and environmental factors.

For the current study, researchers analyzed blood plasma lipid levels from 980 individuals with severe psychiatric illness and 572 people without mental illness from three cohorts in China, Germany, Austria, and Russia.

The study sample included patients with schizophrenia (n = 478), BD (n = 184), and MDD (n = 256), as well as 104 patients with a first psychotic episode who had no long-term psychopharmacology use.

Results showed 77 lipids in 14 classes were significantly altered between participants with schizophrenia and the healthy control in all three cohorts.

The most prominent alterations at the lipid class level included increases in ceramide, triacylglyceride, and phosphatidylcholine and decreases in acylcarnitine and phosphatidylcholine plasmalogen (P < .05 for each cohort).

Schizophrenia-associated lipid differences were similar between patients with high and low symptom severity (P < .001), suggesting that the lipid alterations might represent a trait of the psychiatric disorder.

No medication effect

Most patients in the study received long-term antipsychotic medication, which has been shown previously to affect some plasma lipid compounds.

So, to assess a possible effect of medication, the investigators evaluated 13 patients with schizophrenia who were not medicated for at least 6 months prior to blood sample collection and the cohort of patients with a first psychotic episode who had been medicated for less than 1 week.

Comparison of the lipid intensity differences between the healthy controls group and either participants receiving medication or those who were not medicated revealed highly correlated alterations in both patient groups (P < .001).

“Taken together, these results indicate that the identified schizophrenia-associated alterations cannot be attributed to medication effects,” the investigators wrote.

Lipidome alterations in BPD and MDD, assessed in 184 and 256 individuals, respectively, were similar to those of schizophrenia but not identical.

Researchers isolated 97 lipids altered in the MDD cohorts and 47 in the BPD cohorts – with 30 and 28, respectively, overlapping with the schizophrenia-associated features and seven of the lipids found among all three disorders.

Although this was significantly more than expected by chance (P < .001), it was not strong enough to demonstrate a clear association, the investigators wrote.

“The profiles were very successful at differentiating individuals with severe mental health conditions from individuals without a diagnosed mental health condition, but much less so at differentiating between the different diagnostic entities,” coinvestigator Thomas G. Schulze, MD, director of IPPG, said in an interview.

“An important caveat, however, is that the available sample sizes for bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder were smaller than those for schizophrenia, which makes a direct comparison between these difficult,” added Dr. Schulze, clinical professor in psychiatry and behavioral sciences at State University of New York, Syracuse.

More work remains

Although the study is thought to be the largest to date to examine lipid profiles associated with serious psychiatric illness, much work remains, Dr. Schulze noted.

“At this time, based on these first results, no clinical diagnostic test can be derived from these results,” he said.

He added that the development of reliable biomarkers based on lipidomic profiles would require large prospective randomized trials, complemented by observational studies assessing full lipidomic profiles across the lifespan.

Researchers also need to better understand the exact mechanism by which lipid alterations are associated with schizophrenia and other illnesses.

Physiologically, the investigated lipids have many additional functions, such as determining cell membrane structure and fluidity or cell-to-cell messaging.

Dr. Schulte noted that several lipid species may be involved in determining mechanisms important to synaptic function, such as cell membrane fluidity and vesicle release.

“As is commonly known, alterations in synaptic function underly many severe psychiatric disorders,” she said. “Changes in lipid species could theoretically be related to these synaptic alterations.”

A better marker needed

In a comment, Stephen Strakowski, MD, professor and vice chair of research in the department of psychiatry, Indiana University, Indianapolis and Evansville, noted that while the findings are interesting, they don’t really offer the kind of information clinicians who treat patients with serious mental illness need most.

“Do we need a marker to tell us if someone’s got a major mental illness compared to a healthy person?” asked Dr. Strakowski, who was not part of the study. “The answer to that is no. We already know how to do that.”

A truly useful marker would help clinicians differentiate between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression, or another serious mental illness, he said.

“That’s the marker that would be most helpful,” he added. “This can’t address that, but perhaps it could be a step to start designing a test for that.”

Dr. Strakowksi noted that the findings do not clarify whether the lipid profile found in patients with schizophrenia predates diagnosis or whether it is a result of the mental illness, an unrelated illness, or another factor that could be critical in treating patients.

However, he was quick to point out the limitations don’t diminish the importance of the study.

“It’s a large dataset that’s cross-national, cross-diagnostic that says there appears to be a signal here that there’s something about lipid profiles that may be independent of treatment that could be worth understanding,” Dr. Strakowksi said.

“It allows us to think about developing different models based on lipid profiles, and that’s important,” he added.

The study was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China, National One Thousand Foreign Experts Plan, Moscow Center for Innovative Technologies in Healthcare, European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme, NARSAD Young Investigator Grant, German Research Foundation, German Ministry for Education and Research, the Dr. Lisa Oehler Foundation, and the Munich Clinician Scientist Program. Dr. Schulze and Dr. Schulte reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

Similar brain atrophy in obesity and Alzheimer’s disease

Comparisons of MRI scans for more than 1,000 participants indicate correlations between the two conditions, especially in areas of gray matter thinning, suggesting that managing excess weight might slow cognitive decline and lower the risk for AD, according to the researchers.

However, brain maps of obesity did not correlate with maps of amyloid or tau protein accumulation.

“The fact that obesity-related brain atrophy did not correlate with the distribution of amyloid and tau proteins in AD was not what we expected,” study author Filip Morys, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview. “But it might just show that the specific mechanisms underpinning obesity- and Alzheimer’s disease–related neurodegeneration are different. This remains to be confirmed.”

The study was published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Cortical Thinning

The current study was prompted by the team’s earlier study, which showed that obesity-related neurodegeneration patterns were visually similar to those of AD, said Dr. Morys. “It was known previously that obesity is a risk factor for AD, but we wanted to directly compare brain atrophy patterns in both, which is what we did in this new study.”

The researchers analyzed data from a pooled sample of more than 1,300 participants. From the ADNI database, the researchers selected participants with AD and age- and sex-matched cognitively healthy controls. From the UK Biobank, the researchers drew a sample of lean, overweight, and obese participants without neurologic disease.

To determine how the weight status of patients with AD affects the correspondence between AD and obesity maps, they categorized participants with AD and healthy controls from the ADNI database into lean, overweight, and obese subgroups.

Then, to investigate mechanisms that might drive the similarities between obesity-related brain atrophy and AD-related amyloid-beta accumulation, they looked for overlapping areas in PET brain maps between patients with these outcomes.

The investigations showed that obesity maps were highly correlated with AD maps, but not with amyloid-beta or tau protein maps. The researchers also found significant correlations between obesity and the lean individuals with AD.

Brain regions with the highest similarities between obesity and AD were located mainly in the left temporal and bilateral prefrontal cortices.

“Our research confirms that obesity-related gray matter atrophy resembles that of AD,” the authors concluded. “Excess weight management could lead to improved health outcomes, slow down cognitive decline in aging, and lower the risk for AD.”

Upcoming research “will focus on investigating how weight loss can affect the risk for AD, other dementias, and cognitive decline in general,” said Dr. Morys. “At this point, our study suggests that obesity prevention, weight loss, but also decreasing other metabolic risk factors related to obesity, such as type-2 diabetes or hypertension, might reduce the risk for AD and have beneficial effects on cognition.”

Lifestyle habits

Commenting on the findings, Claire Sexton, DPhil, vice president of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, cautioned that a single cross-sectional study isn’t conclusive. “Previous studies have illustrated that the relationship between obesity and dementia is complex. Growing evidence indicates that people can reduce their risk of cognitive decline by adopting key lifestyle habits, like regular exercise, a heart-healthy diet and staying socially and cognitively engaged.”

The Alzheimer’s Association is leading a 2-year clinical trial, U.S. Pointer, to study how targeting these risk factors in combination may reduce risk for cognitive decline in older adults.

The work was supported by a Foundation Scheme award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Morys received a postdoctoral fellowship from Fonds de Recherche du Quebec – Santé. Data collection and sharing were funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and multiple pharmaceutical companies and other private sector organizations. Dr. Morys and Dr. Sexton reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Comparisons of MRI scans for more than 1,000 participants indicate correlations between the two conditions, especially in areas of gray matter thinning, suggesting that managing excess weight might slow cognitive decline and lower the risk for AD, according to the researchers.

However, brain maps of obesity did not correlate with maps of amyloid or tau protein accumulation.

“The fact that obesity-related brain atrophy did not correlate with the distribution of amyloid and tau proteins in AD was not what we expected,” study author Filip Morys, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview. “But it might just show that the specific mechanisms underpinning obesity- and Alzheimer’s disease–related neurodegeneration are different. This remains to be confirmed.”

The study was published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Cortical Thinning

The current study was prompted by the team’s earlier study, which showed that obesity-related neurodegeneration patterns were visually similar to those of AD, said Dr. Morys. “It was known previously that obesity is a risk factor for AD, but we wanted to directly compare brain atrophy patterns in both, which is what we did in this new study.”

The researchers analyzed data from a pooled sample of more than 1,300 participants. From the ADNI database, the researchers selected participants with AD and age- and sex-matched cognitively healthy controls. From the UK Biobank, the researchers drew a sample of lean, overweight, and obese participants without neurologic disease.

To determine how the weight status of patients with AD affects the correspondence between AD and obesity maps, they categorized participants with AD and healthy controls from the ADNI database into lean, overweight, and obese subgroups.

Then, to investigate mechanisms that might drive the similarities between obesity-related brain atrophy and AD-related amyloid-beta accumulation, they looked for overlapping areas in PET brain maps between patients with these outcomes.

The investigations showed that obesity maps were highly correlated with AD maps, but not with amyloid-beta or tau protein maps. The researchers also found significant correlations between obesity and the lean individuals with AD.

Brain regions with the highest similarities between obesity and AD were located mainly in the left temporal and bilateral prefrontal cortices.

“Our research confirms that obesity-related gray matter atrophy resembles that of AD,” the authors concluded. “Excess weight management could lead to improved health outcomes, slow down cognitive decline in aging, and lower the risk for AD.”

Upcoming research “will focus on investigating how weight loss can affect the risk for AD, other dementias, and cognitive decline in general,” said Dr. Morys. “At this point, our study suggests that obesity prevention, weight loss, but also decreasing other metabolic risk factors related to obesity, such as type-2 diabetes or hypertension, might reduce the risk for AD and have beneficial effects on cognition.”

Lifestyle habits

Commenting on the findings, Claire Sexton, DPhil, vice president of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, cautioned that a single cross-sectional study isn’t conclusive. “Previous studies have illustrated that the relationship between obesity and dementia is complex. Growing evidence indicates that people can reduce their risk of cognitive decline by adopting key lifestyle habits, like regular exercise, a heart-healthy diet and staying socially and cognitively engaged.”

The Alzheimer’s Association is leading a 2-year clinical trial, U.S. Pointer, to study how targeting these risk factors in combination may reduce risk for cognitive decline in older adults.

The work was supported by a Foundation Scheme award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Morys received a postdoctoral fellowship from Fonds de Recherche du Quebec – Santé. Data collection and sharing were funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and multiple pharmaceutical companies and other private sector organizations. Dr. Morys and Dr. Sexton reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Comparisons of MRI scans for more than 1,000 participants indicate correlations between the two conditions, especially in areas of gray matter thinning, suggesting that managing excess weight might slow cognitive decline and lower the risk for AD, according to the researchers.

However, brain maps of obesity did not correlate with maps of amyloid or tau protein accumulation.

“The fact that obesity-related brain atrophy did not correlate with the distribution of amyloid and tau proteins in AD was not what we expected,” study author Filip Morys, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview. “But it might just show that the specific mechanisms underpinning obesity- and Alzheimer’s disease–related neurodegeneration are different. This remains to be confirmed.”

The study was published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Cortical Thinning

The current study was prompted by the team’s earlier study, which showed that obesity-related neurodegeneration patterns were visually similar to those of AD, said Dr. Morys. “It was known previously that obesity is a risk factor for AD, but we wanted to directly compare brain atrophy patterns in both, which is what we did in this new study.”

The researchers analyzed data from a pooled sample of more than 1,300 participants. From the ADNI database, the researchers selected participants with AD and age- and sex-matched cognitively healthy controls. From the UK Biobank, the researchers drew a sample of lean, overweight, and obese participants without neurologic disease.

To determine how the weight status of patients with AD affects the correspondence between AD and obesity maps, they categorized participants with AD and healthy controls from the ADNI database into lean, overweight, and obese subgroups.

Then, to investigate mechanisms that might drive the similarities between obesity-related brain atrophy and AD-related amyloid-beta accumulation, they looked for overlapping areas in PET brain maps between patients with these outcomes.

The investigations showed that obesity maps were highly correlated with AD maps, but not with amyloid-beta or tau protein maps. The researchers also found significant correlations between obesity and the lean individuals with AD.

Brain regions with the highest similarities between obesity and AD were located mainly in the left temporal and bilateral prefrontal cortices.

“Our research confirms that obesity-related gray matter atrophy resembles that of AD,” the authors concluded. “Excess weight management could lead to improved health outcomes, slow down cognitive decline in aging, and lower the risk for AD.”

Upcoming research “will focus on investigating how weight loss can affect the risk for AD, other dementias, and cognitive decline in general,” said Dr. Morys. “At this point, our study suggests that obesity prevention, weight loss, but also decreasing other metabolic risk factors related to obesity, such as type-2 diabetes or hypertension, might reduce the risk for AD and have beneficial effects on cognition.”

Lifestyle habits

Commenting on the findings, Claire Sexton, DPhil, vice president of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, cautioned that a single cross-sectional study isn’t conclusive. “Previous studies have illustrated that the relationship between obesity and dementia is complex. Growing evidence indicates that people can reduce their risk of cognitive decline by adopting key lifestyle habits, like regular exercise, a heart-healthy diet and staying socially and cognitively engaged.”

The Alzheimer’s Association is leading a 2-year clinical trial, U.S. Pointer, to study how targeting these risk factors in combination may reduce risk for cognitive decline in older adults.

The work was supported by a Foundation Scheme award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Morys received a postdoctoral fellowship from Fonds de Recherche du Quebec – Santé. Data collection and sharing were funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and multiple pharmaceutical companies and other private sector organizations. Dr. Morys and Dr. Sexton reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Psychiatric illnesses share common brain network

Investigators used coordinate and lesion network mapping to assess whether there was a shared brain network common to multiple psychiatric disorders. In a meta-analysis of almost 200 studies encompassing more than 15,000 individuals, they found that atrophy coordinates across these six psychiatric conditions all mapped to a common brain network.

Moreover, lesion damage to this network in patients with penetrating head trauma correlated with the number of psychiatric illnesses that the patients were diagnosed with post trauma.

The findings have “bigger-picture potential implications,” lead author Joseph Taylor, MD, PhD, medical director of transcranial magnetic stimulation at Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Center for Brain Circuit Therapeutics, Boston, told this news organization.

“In psychiatry, we talk about symptoms and define our disorders based on symptom checklists, which are fairly reliable but don’t have neurobiological underpinnings,” said Dr. Taylor, who is also an associate psychiatrist in Brigham’s department of psychiatry.

By contrast, “in neurology, we ask: ‘Where is the lesion?’ Studying brain networks could potentially help us diagnose and treat people with psychiatric illness more effectively, just as we treat neurological disorders,” he added.

The findings were published online in Nature Human Behavior.

Beyond symptom checklists

Dr. Taylor noted that, in the field of psychiatry, “we often study disorders in isolation,” such as generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder.

“But what see clinically is that half of patients meet the criteria for more than one psychiatric disorder,” he said. “It can be difficult to diagnose and treat these patients, and there are worse treatment outcomes.”

There is also a “discrepancy” between how these disorders are studied (one at a time) and how patients are treated in clinic, Dr. Taylor noted. And there is increasing evidence that psychiatric disorders may share a common neurobiology.

This “highlights the possibility of potentially developing transdiagnostic treatments based on common neurobiology, not just symptom checklists,” Dr. Taylor said.

Prior work “has attempted to map abnormalities to common brain regions rather than to a common brain network,” the investigators wrote. Moreover, “prior studies have rarely tested specificity by comparing psychiatric disorders to other brain disorders.”

In the current study, the researchers used “morphometric brain lesion datasets coupled with a wiring diagram of the human brain to derive a convergent brain network for psychiatric illness.”

They analyzed four large published datasets. Dataset 1 was sourced from an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis (ALE) of whole-brain voxel-based studies that compared patients with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, BD, depression, addiction, OCD, and anxiety to healthy controls (n = 193 studies; 15,892 individuals in total).

Dataset 2 was drawn from published neuroimaging studies involving patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative conditions (n = 72 studies). They reported coordinates regarding which patients with these disorders had more atrophy compared with control persons.

Dataset 3 was sourced from the Vietnam Head Injury study, which followed veterans with and those without penetrating head injuries (n = 194 veterans with injuries). Dataset 4 was sourced from published neurosurgical ablation coordinates for depression.

Shared neurobiology

Upon analyzing dataset 1, the researchers found decreased gray matter in the bilateral anterior insula, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, thalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, and parietal operculum – findings that are “consistent with prior work.”

However, fewer than 35% of the studies contributed to any single cluster; and no cluster was specific to psychiatric versus neurodegenerative coordinates (drawn from dataset 2).

On the other hand, coordinate network mapping yielded “more statistically robust” (P < .001) results, which were found in 85% of the studies. “Psychiatric atrophy coordinates were functionally connected to the same network of brain regions,” the researchers reported.

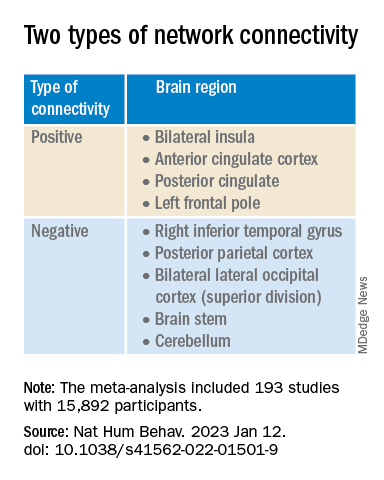

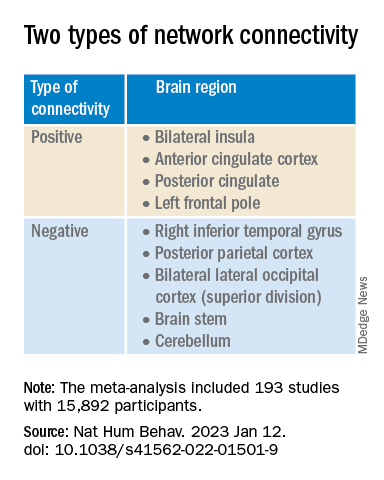

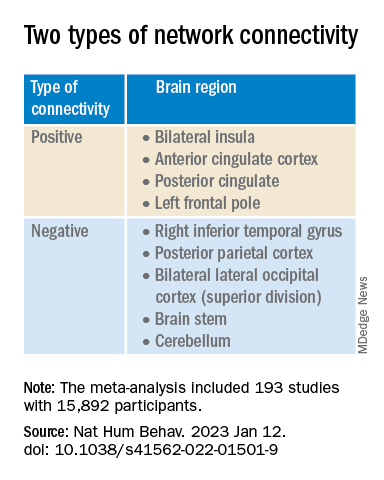

This network was defined by two types of connectivity, positive and negative.

“The topography of this transdiagnostic network was independent of the statistical threshold and specific to psychiatric (vs. neurodegenerative) disorders, with the strongest peak occurring in the posterior parietal cortex (Brodmann Area 7) near the intraparietal sulcus,” the investigators wrote.

When lesions from dataset 3 were overlaid onto the ALE map and the transdiagnostic network in order to evaluate whether damage to either map correlated with number of post-lesion psychiatric diagnosis, results showed no evidence of a correlation between psychiatric comorbidity and damage on the ALE map (Pearson r, 0.02; P = .766).

However, when the same approach was applied to the transdiagnostic network, a statistically significant correlation was found between psychiatric comorbidity and lesion damage (Pearson r, –0.21; P = .01). A multiple regression model showed that the transdiagnostic, but not the ALE, network “independently predicted the number of post-lesion psychiatric diagnoses” (P = .003 vs. P = .1), the investigators reported.

All four neurosurgical ablative targets for psychiatric disorders found on analysis of dataset 4 “intersected” and aligned with the transdiagnostic network.

“The study does not immediately impact clinical practice, but it would be helpful for practicing clinicians to know that psychiatric disorders commonly co-occur and might share common neurobiology and a convergent brain network,” Dr. Taylor said.

“Future work based on our findings could potentially influence clinical trials and clinical practice, especially in the area of brain stimulation,” he added.

‘Exciting new targets’

In a comment, Desmond Oathes, PhD, associate director, Center for Neuromodulation and Stress, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the “next step in the science is to combine individual brain imaging, aka, ‘individualized connectomes,’ with these promising group maps to determine something meaningful at the individual patient level.”

Dr. Oathes, who is also a faculty clinician at the Center for the Treatment and Study of Anxiety and was not involved with the study, noted that an open question is whether the brain volume abnormalities/atrophy “can be changed with treatment and in what direction.”

A “strong take-home message from this paper is that brain volume measures from single coordinates are noisy as measures of psychiatric abnormality, whereas network effects seem to be especially sensitive for capturing these effects,” Dr. Oathes said.

The “abnormal networks across these disorders do not fit easily into well-known networks from healthy participants. However, they map well onto other databases relevant to psychiatric disorders and offer exciting new potential targets for prospective treatment studies,” he added.

The investigators received no specific funding for this work. Dr. Taylor reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Oathes reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators used coordinate and lesion network mapping to assess whether there was a shared brain network common to multiple psychiatric disorders. In a meta-analysis of almost 200 studies encompassing more than 15,000 individuals, they found that atrophy coordinates across these six psychiatric conditions all mapped to a common brain network.

Moreover, lesion damage to this network in patients with penetrating head trauma correlated with the number of psychiatric illnesses that the patients were diagnosed with post trauma.

The findings have “bigger-picture potential implications,” lead author Joseph Taylor, MD, PhD, medical director of transcranial magnetic stimulation at Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Center for Brain Circuit Therapeutics, Boston, told this news organization.

“In psychiatry, we talk about symptoms and define our disorders based on symptom checklists, which are fairly reliable but don’t have neurobiological underpinnings,” said Dr. Taylor, who is also an associate psychiatrist in Brigham’s department of psychiatry.

By contrast, “in neurology, we ask: ‘Where is the lesion?’ Studying brain networks could potentially help us diagnose and treat people with psychiatric illness more effectively, just as we treat neurological disorders,” he added.

The findings were published online in Nature Human Behavior.

Beyond symptom checklists

Dr. Taylor noted that, in the field of psychiatry, “we often study disorders in isolation,” such as generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder.

“But what see clinically is that half of patients meet the criteria for more than one psychiatric disorder,” he said. “It can be difficult to diagnose and treat these patients, and there are worse treatment outcomes.”

There is also a “discrepancy” between how these disorders are studied (one at a time) and how patients are treated in clinic, Dr. Taylor noted. And there is increasing evidence that psychiatric disorders may share a common neurobiology.

This “highlights the possibility of potentially developing transdiagnostic treatments based on common neurobiology, not just symptom checklists,” Dr. Taylor said.

Prior work “has attempted to map abnormalities to common brain regions rather than to a common brain network,” the investigators wrote. Moreover, “prior studies have rarely tested specificity by comparing psychiatric disorders to other brain disorders.”

In the current study, the researchers used “morphometric brain lesion datasets coupled with a wiring diagram of the human brain to derive a convergent brain network for psychiatric illness.”

They analyzed four large published datasets. Dataset 1 was sourced from an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis (ALE) of whole-brain voxel-based studies that compared patients with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, BD, depression, addiction, OCD, and anxiety to healthy controls (n = 193 studies; 15,892 individuals in total).

Dataset 2 was drawn from published neuroimaging studies involving patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative conditions (n = 72 studies). They reported coordinates regarding which patients with these disorders had more atrophy compared with control persons.

Dataset 3 was sourced from the Vietnam Head Injury study, which followed veterans with and those without penetrating head injuries (n = 194 veterans with injuries). Dataset 4 was sourced from published neurosurgical ablation coordinates for depression.

Shared neurobiology

Upon analyzing dataset 1, the researchers found decreased gray matter in the bilateral anterior insula, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, thalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, and parietal operculum – findings that are “consistent with prior work.”

However, fewer than 35% of the studies contributed to any single cluster; and no cluster was specific to psychiatric versus neurodegenerative coordinates (drawn from dataset 2).

On the other hand, coordinate network mapping yielded “more statistically robust” (P < .001) results, which were found in 85% of the studies. “Psychiatric atrophy coordinates were functionally connected to the same network of brain regions,” the researchers reported.

This network was defined by two types of connectivity, positive and negative.

“The topography of this transdiagnostic network was independent of the statistical threshold and specific to psychiatric (vs. neurodegenerative) disorders, with the strongest peak occurring in the posterior parietal cortex (Brodmann Area 7) near the intraparietal sulcus,” the investigators wrote.

When lesions from dataset 3 were overlaid onto the ALE map and the transdiagnostic network in order to evaluate whether damage to either map correlated with number of post-lesion psychiatric diagnosis, results showed no evidence of a correlation between psychiatric comorbidity and damage on the ALE map (Pearson r, 0.02; P = .766).

However, when the same approach was applied to the transdiagnostic network, a statistically significant correlation was found between psychiatric comorbidity and lesion damage (Pearson r, –0.21; P = .01). A multiple regression model showed that the transdiagnostic, but not the ALE, network “independently predicted the number of post-lesion psychiatric diagnoses” (P = .003 vs. P = .1), the investigators reported.

All four neurosurgical ablative targets for psychiatric disorders found on analysis of dataset 4 “intersected” and aligned with the transdiagnostic network.

“The study does not immediately impact clinical practice, but it would be helpful for practicing clinicians to know that psychiatric disorders commonly co-occur and might share common neurobiology and a convergent brain network,” Dr. Taylor said.

“Future work based on our findings could potentially influence clinical trials and clinical practice, especially in the area of brain stimulation,” he added.

‘Exciting new targets’

In a comment, Desmond Oathes, PhD, associate director, Center for Neuromodulation and Stress, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the “next step in the science is to combine individual brain imaging, aka, ‘individualized connectomes,’ with these promising group maps to determine something meaningful at the individual patient level.”

Dr. Oathes, who is also a faculty clinician at the Center for the Treatment and Study of Anxiety and was not involved with the study, noted that an open question is whether the brain volume abnormalities/atrophy “can be changed with treatment and in what direction.”

A “strong take-home message from this paper is that brain volume measures from single coordinates are noisy as measures of psychiatric abnormality, whereas network effects seem to be especially sensitive for capturing these effects,” Dr. Oathes said.

The “abnormal networks across these disorders do not fit easily into well-known networks from healthy participants. However, they map well onto other databases relevant to psychiatric disorders and offer exciting new potential targets for prospective treatment studies,” he added.

The investigators received no specific funding for this work. Dr. Taylor reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Oathes reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators used coordinate and lesion network mapping to assess whether there was a shared brain network common to multiple psychiatric disorders. In a meta-analysis of almost 200 studies encompassing more than 15,000 individuals, they found that atrophy coordinates across these six psychiatric conditions all mapped to a common brain network.

Moreover, lesion damage to this network in patients with penetrating head trauma correlated with the number of psychiatric illnesses that the patients were diagnosed with post trauma.

The findings have “bigger-picture potential implications,” lead author Joseph Taylor, MD, PhD, medical director of transcranial magnetic stimulation at Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Center for Brain Circuit Therapeutics, Boston, told this news organization.

“In psychiatry, we talk about symptoms and define our disorders based on symptom checklists, which are fairly reliable but don’t have neurobiological underpinnings,” said Dr. Taylor, who is also an associate psychiatrist in Brigham’s department of psychiatry.

By contrast, “in neurology, we ask: ‘Where is the lesion?’ Studying brain networks could potentially help us diagnose and treat people with psychiatric illness more effectively, just as we treat neurological disorders,” he added.

The findings were published online in Nature Human Behavior.

Beyond symptom checklists

Dr. Taylor noted that, in the field of psychiatry, “we often study disorders in isolation,” such as generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder.

“But what see clinically is that half of patients meet the criteria for more than one psychiatric disorder,” he said. “It can be difficult to diagnose and treat these patients, and there are worse treatment outcomes.”

There is also a “discrepancy” between how these disorders are studied (one at a time) and how patients are treated in clinic, Dr. Taylor noted. And there is increasing evidence that psychiatric disorders may share a common neurobiology.

This “highlights the possibility of potentially developing transdiagnostic treatments based on common neurobiology, not just symptom checklists,” Dr. Taylor said.

Prior work “has attempted to map abnormalities to common brain regions rather than to a common brain network,” the investigators wrote. Moreover, “prior studies have rarely tested specificity by comparing psychiatric disorders to other brain disorders.”

In the current study, the researchers used “morphometric brain lesion datasets coupled with a wiring diagram of the human brain to derive a convergent brain network for psychiatric illness.”

They analyzed four large published datasets. Dataset 1 was sourced from an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis (ALE) of whole-brain voxel-based studies that compared patients with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, BD, depression, addiction, OCD, and anxiety to healthy controls (n = 193 studies; 15,892 individuals in total).

Dataset 2 was drawn from published neuroimaging studies involving patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative conditions (n = 72 studies). They reported coordinates regarding which patients with these disorders had more atrophy compared with control persons.

Dataset 3 was sourced from the Vietnam Head Injury study, which followed veterans with and those without penetrating head injuries (n = 194 veterans with injuries). Dataset 4 was sourced from published neurosurgical ablation coordinates for depression.

Shared neurobiology

Upon analyzing dataset 1, the researchers found decreased gray matter in the bilateral anterior insula, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, thalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, and parietal operculum – findings that are “consistent with prior work.”

However, fewer than 35% of the studies contributed to any single cluster; and no cluster was specific to psychiatric versus neurodegenerative coordinates (drawn from dataset 2).

On the other hand, coordinate network mapping yielded “more statistically robust” (P < .001) results, which were found in 85% of the studies. “Psychiatric atrophy coordinates were functionally connected to the same network of brain regions,” the researchers reported.

This network was defined by two types of connectivity, positive and negative.

“The topography of this transdiagnostic network was independent of the statistical threshold and specific to psychiatric (vs. neurodegenerative) disorders, with the strongest peak occurring in the posterior parietal cortex (Brodmann Area 7) near the intraparietal sulcus,” the investigators wrote.

When lesions from dataset 3 were overlaid onto the ALE map and the transdiagnostic network in order to evaluate whether damage to either map correlated with number of post-lesion psychiatric diagnosis, results showed no evidence of a correlation between psychiatric comorbidity and damage on the ALE map (Pearson r, 0.02; P = .766).

However, when the same approach was applied to the transdiagnostic network, a statistically significant correlation was found between psychiatric comorbidity and lesion damage (Pearson r, –0.21; P = .01). A multiple regression model showed that the transdiagnostic, but not the ALE, network “independently predicted the number of post-lesion psychiatric diagnoses” (P = .003 vs. P = .1), the investigators reported.

All four neurosurgical ablative targets for psychiatric disorders found on analysis of dataset 4 “intersected” and aligned with the transdiagnostic network.

“The study does not immediately impact clinical practice, but it would be helpful for practicing clinicians to know that psychiatric disorders commonly co-occur and might share common neurobiology and a convergent brain network,” Dr. Taylor said.

“Future work based on our findings could potentially influence clinical trials and clinical practice, especially in the area of brain stimulation,” he added.

‘Exciting new targets’

In a comment, Desmond Oathes, PhD, associate director, Center for Neuromodulation and Stress, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the “next step in the science is to combine individual brain imaging, aka, ‘individualized connectomes,’ with these promising group maps to determine something meaningful at the individual patient level.”

Dr. Oathes, who is also a faculty clinician at the Center for the Treatment and Study of Anxiety and was not involved with the study, noted that an open question is whether the brain volume abnormalities/atrophy “can be changed with treatment and in what direction.”

A “strong take-home message from this paper is that brain volume measures from single coordinates are noisy as measures of psychiatric abnormality, whereas network effects seem to be especially sensitive for capturing these effects,” Dr. Oathes said.

The “abnormal networks across these disorders do not fit easily into well-known networks from healthy participants. However, they map well onto other databases relevant to psychiatric disorders and offer exciting new potential targets for prospective treatment studies,” he added.

The investigators received no specific funding for this work. Dr. Taylor reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Oathes reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NATURE HUMAN BEHAVIOR

Six healthy lifestyle habits linked to slowed memory decline

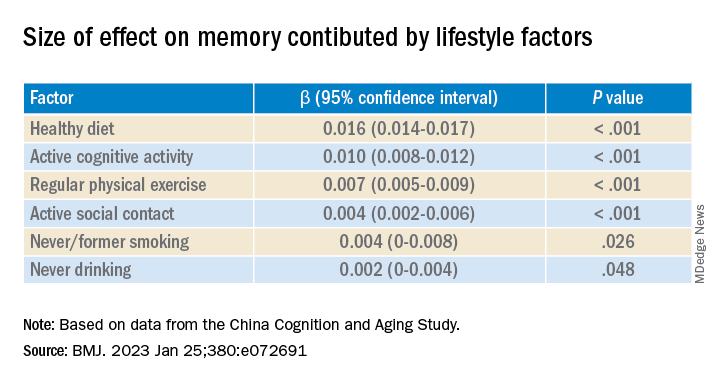

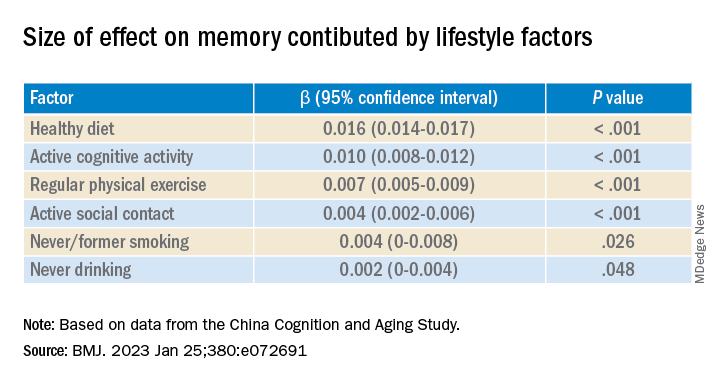

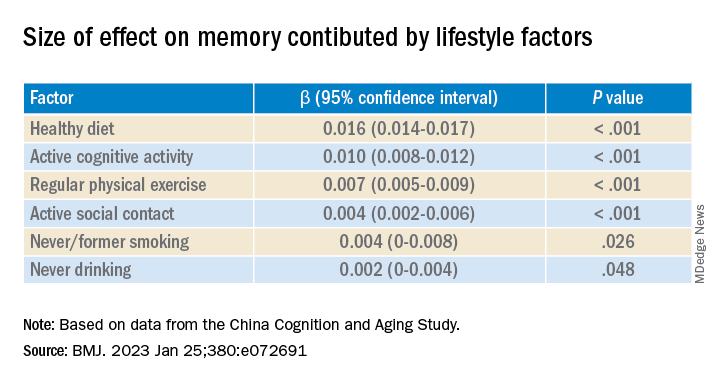

Investigators found that a healthy diet, cognitive activity, regular physical exercise, not smoking, and abstaining from alcohol were significantly linked to slowed cognitive decline irrespective of APOE4 status.

After adjusting for health and socioeconomic factors, investigators found that each individual healthy behavior was associated with a slower-than-average decline in memory over a decade. A healthy diet emerged as the strongest deterrent, followed by cognitive activity and physical exercise.

“A healthy lifestyle is associated with slower memory decline, even in the presence of the APOE4 allele,” study investigators led by Jianping Jia, MD, PhD, of the Innovation Center for Neurological Disorders and the department of neurology, Xuan Wu Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, write.

“This study might offer important information to protect older adults against memory decline,” they add.

The study was published online in the BMJ.

Preventing memory decline

Memory “continuously declines as people age,” but age-related memory decline is not necessarily a prodrome of dementia and can “merely be senescent forgetfulness,” the investigators note. This can be “reversed or [can] become stable,” instead of progressing to a pathologic state.

Factors affecting memory include aging, APOE4 genotype, chronic diseases, and lifestyle patterns, with lifestyle “receiving increasing attention as a modifiable behavior.”

Nevertheless, few studies have focused on the impact of lifestyle on memory, and those that have are mostly cross-sectional and also “did not consider the interaction between a healthy lifestyle and genetic risk,” the researchers note.

To investigate, the researchers conducted a longitudinal study, known as the China Cognition and Aging Study, that considered genetic risk as well as lifestyle factors.

The study began in 2009 and concluded in 2019. Participants were evaluated and underwent neuropsychological testing in 2012, 2014, 2016, and at the study’s conclusion.

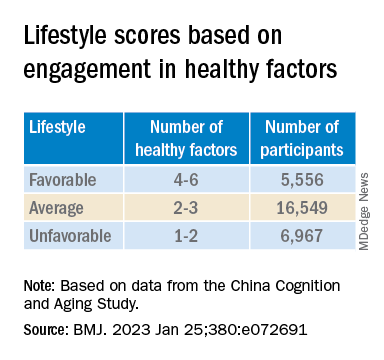

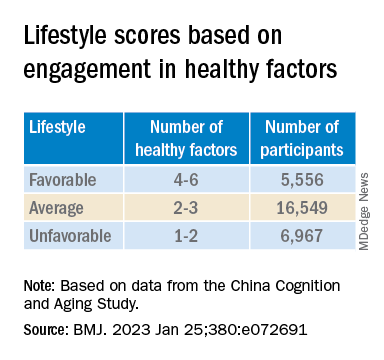

Participants (n = 29,072; mean [SD] age, 72.23 [6.61] years; 48.54% women; 20.43% APOE4 carriers) were required to have normal cognitive function at baseline. Data on those whose condition progressed to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia during the follow-up period were excluded after their diagnosis.

The Mini–Mental State Examination was used to assess global cognitive function. Memory function was assessed using the World Health Organization/University of California, Los Angeles Auditory Verbal Learning Test.

“Lifestyle” consisted of six modifiable factors: physical exercise (weekly frequency and total time), smoking (current, former, or never-smokers), alcohol consumption (never drank, drank occasionally, low to excess drinking, and heavy drinking), diet (daily intake of 12 food items: fruits, vegetables, fish, meat, dairy products, salt, oil, eggs, cereals, legumes, nuts, tea), cognitive activity (writing, reading, playing cards, mahjong, other games), and social contact (participating in meetings, attending parties, visiting friends/relatives, traveling, chatting online).

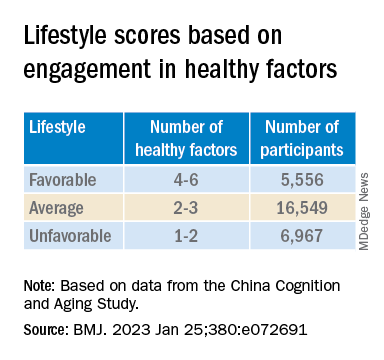

Participants’ lifestyles were scored on the basis of the number of healthy factors they engaged in.

Participants were also stratified by APOE genotype into APOE4 carriers and noncarriers.

Demographic and other items of health information, including the presence of medical illness, were used as covariates. The researchers also included the “learning effect of each participant as a covariate, due to repeated cognitive assessments.”

Important for public health

During the 10-year period, 7,164 participants died, and 3,567 stopped participating.

Participants in the favorable and average groups showed slower memory decline per increased year of age (0.007 [0.005-0.009], P < .001; and 0.002 [0 .000-0.003], P = .033 points higher, respectively), compared with those in the unfavorable group.

Healthy diet had the strongest protective effect on memory.

Memory decline occurred faster in APOE4 vesus non-APOE4 carriers (0.002 points/year [95% confidence interval, 0.001-0.003]; P = .007).

But APOE4 carriers with favorable and average lifestyles showed slower memory decline (0.027 [0.023-0.031] and 0.014 [0.010-0.019], respectively), compared with those with unfavorable lifestyles. Similar findings were obtained in non-APOE4 carriers.

Those with favorable or average lifestyle were respectively almost 90% and 30% less likely to develop dementia or MCI, compared with those with an unfavorable lifestyle.

The authors acknowledge the study’s limitations, including its observational design and the potential for measurement errors, owing to self-reporting of lifestyle factors. Additionally, some participants did not return for follow-up evaluations, leading to potential selection bias.

Nevertheless, the findings “might offer important information for public health to protect older [people] against memory decline,” they note – especially since the study “provides evidence that these effects also include individuals with the APOE4 allele.”

‘Important, encouraging’ research

In a comment, Severine Sabia, PhD, a senior researcher at the Université Paris Cité, INSERM Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Medicalé, France, called the findings “important and encouraging.”

However, said Dr. Sabia, who was not involved with the study, “there remain important research questions that need to be investigated in order to identify key behaviors: which combination, the cutoff of risk, and when to intervene.”

Future research on prevention “should examine a wider range of possible risk factors” and should also “identify specific exposures associated with the greatest risk, while also considering the risk threshold and age at exposure for each one.”

In an accompanying editorial, Dr. Sabia and co-author Archana Singh-Manoux, PhD, note that the risk of cognitive decline and dementia are probably determined by multiple factors.

They liken it to the “multifactorial risk paradigm introduced by the Framingham study,” which has “led to a substantial reduction in cardiovascular disease.” A similar approach could be used with dementia prevention, they suggest.

The authors received support from the Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University for the submitted work. One of the authors received a grant from the French National Research Agency. The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sabia received grant funding from the French National Research Agency. Dr. Singh-Manoux received grants from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found that a healthy diet, cognitive activity, regular physical exercise, not smoking, and abstaining from alcohol were significantly linked to slowed cognitive decline irrespective of APOE4 status.

After adjusting for health and socioeconomic factors, investigators found that each individual healthy behavior was associated with a slower-than-average decline in memory over a decade. A healthy diet emerged as the strongest deterrent, followed by cognitive activity and physical exercise.

“A healthy lifestyle is associated with slower memory decline, even in the presence of the APOE4 allele,” study investigators led by Jianping Jia, MD, PhD, of the Innovation Center for Neurological Disorders and the department of neurology, Xuan Wu Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, write.

“This study might offer important information to protect older adults against memory decline,” they add.

The study was published online in the BMJ.

Preventing memory decline

Memory “continuously declines as people age,” but age-related memory decline is not necessarily a prodrome of dementia and can “merely be senescent forgetfulness,” the investigators note. This can be “reversed or [can] become stable,” instead of progressing to a pathologic state.

Factors affecting memory include aging, APOE4 genotype, chronic diseases, and lifestyle patterns, with lifestyle “receiving increasing attention as a modifiable behavior.”

Nevertheless, few studies have focused on the impact of lifestyle on memory, and those that have are mostly cross-sectional and also “did not consider the interaction between a healthy lifestyle and genetic risk,” the researchers note.

To investigate, the researchers conducted a longitudinal study, known as the China Cognition and Aging Study, that considered genetic risk as well as lifestyle factors.

The study began in 2009 and concluded in 2019. Participants were evaluated and underwent neuropsychological testing in 2012, 2014, 2016, and at the study’s conclusion.

Participants (n = 29,072; mean [SD] age, 72.23 [6.61] years; 48.54% women; 20.43% APOE4 carriers) were required to have normal cognitive function at baseline. Data on those whose condition progressed to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia during the follow-up period were excluded after their diagnosis.

The Mini–Mental State Examination was used to assess global cognitive function. Memory function was assessed using the World Health Organization/University of California, Los Angeles Auditory Verbal Learning Test.

“Lifestyle” consisted of six modifiable factors: physical exercise (weekly frequency and total time), smoking (current, former, or never-smokers), alcohol consumption (never drank, drank occasionally, low to excess drinking, and heavy drinking), diet (daily intake of 12 food items: fruits, vegetables, fish, meat, dairy products, salt, oil, eggs, cereals, legumes, nuts, tea), cognitive activity (writing, reading, playing cards, mahjong, other games), and social contact (participating in meetings, attending parties, visiting friends/relatives, traveling, chatting online).

Participants’ lifestyles were scored on the basis of the number of healthy factors they engaged in.

Participants were also stratified by APOE genotype into APOE4 carriers and noncarriers.

Demographic and other items of health information, including the presence of medical illness, were used as covariates. The researchers also included the “learning effect of each participant as a covariate, due to repeated cognitive assessments.”

Important for public health

During the 10-year period, 7,164 participants died, and 3,567 stopped participating.

Participants in the favorable and average groups showed slower memory decline per increased year of age (0.007 [0.005-0.009], P < .001; and 0.002 [0 .000-0.003], P = .033 points higher, respectively), compared with those in the unfavorable group.

Healthy diet had the strongest protective effect on memory.

Memory decline occurred faster in APOE4 vesus non-APOE4 carriers (0.002 points/year [95% confidence interval, 0.001-0.003]; P = .007).