User login

Your menopausal patient’s breast biopsy reveals atypical hyperplasia

A new series brought to you by the menopause experts

| Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD Professor and Associate Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville. Dr. Kaunitz is a NAMS Board member and certified menopause practitioner. He also serves on the OBG Management Board of Editors. |

| JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and Director, Division of Midlife Women’s Health, University of Virginia. Dr. Pinkerton is a North American Menopause Society (NAMS) past president and certified menopause practitioner. She also serves on the OBG Management Board of Editors. |

| James A. Simon, MD Clinical Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, George Washington University, and Medical Director, Women’s Health & Research Consultants, Washington, DC. Dr. Simon is a NAMS past president, a certified menopause practitioner, and a certified clinical densitometrist. He also serves on the OBG Management Board of Editors. |

Disclosures

Dr. Kaunitz reports that his institution receives grant or research support from Agile, Bayer, Endoceutics, Teva, Medical Diagnostic Laboratories, and Noven, and that he is a consultant to Bayer, Merck, and Teva.

Dr. Pinkerton reports that her institution receives consulting fees from Pfizer, DepoMed, Shionogi, and Noven and multicenter research fees from DepoMed, Endoceutics, and Bionova.

Dr. Simon reports being a consultant to or on the advisory boards of Abbott Laboratories, Agile Therapeutics, Amgen, Ascend Therapeutics, BioSante, Depomed, Lelo, MD Therapeutics, Meda Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Noven, Novo Nordisk, Novogyne, Pfizer, Shionogi, Shippan Point Advisors LLC, Slate Pharmaceuticals, Sprout Pharmaceuticals, Teva, Warner Chilcott, and Watson. He also reports receiving (currently or in the past year) grant/research support from BioSante, EndoCeutics, Novo Nordisk, Novogyne, Palatin Technologies, Teva, and Warner Chilcott. He reports serving on the speakers bureaus of Amgen, Merck, Novartis, Noven, Novo Nordisk, Novogyne, Teva, and Warner Chilcott. Dr. Simon is currently the Chief Medical Officer for Sprout Pharmaceuticals.

CASE: Atypical ductal hyperplasia

Your 56-year-old, married, white patient has been on hormone therapy (HT) since age 52 for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms. She is taking a low-dose oral estrogen and micronized progesterone combination as she has an intact uterus. Her family history is positive for breast cancer, as her mother was diagnosed at age 68.

Her most recent annual screening mammogram shows linear calcifications. Because fine, linear, branching or casting calcifications are worrisome for atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) or ductal carcinoma in situ, a biopsy is recommended.

She elects to wean off and discontinue HT during the evaluation of her abnormal mammogram. The mammographic-guided stereotactic biopsy reveals ADH. She undergoes an open excisional biopsy, the results of which reveal extensive ADH with negative margins.

Six weeks after a lumpectomy she returns to your office reporting moderate to severe hot flashes that occur seven to 10 times per day and impair her sleep, leading to fatigue and “brain fog.” In addition, she is noticing vaginal dryness and dyspareunia despite use of lubricants. She requests treatment for her symptoms and wonders if she can restart HT systemically or vaginally.

How do you manage her hot flashes?

What are the alternatives to HT for hot flashes?

Certain lifestyle changes have been reported to provide relief for hot flushes.1 These include:

- use of layered clothing

- maintenance of cool ambient temperature (particularly during sleep)

- consumption of cool foods or beverages

- relaxation techniques (such as deep breathing, or paced respirations, for 20 min three times per day).

Despite sparse data, avoiding triggers such as spicy or hot foods or alcohol may be helpful.

Therapies such as evening primrose oil, dong quai, ginseng, wild yam, magnet therapy, reflexology, and homeopathy have not been found more effective in treating hot flashes than placebo.2

Phytoestrogens (such as equol), acupuncture, yoga, and hypnosis continue to be tested in randomized trials with mixed results.

Off-label drug options offer modest help. There are currently no FDA-approved nonhormonal pharmaceutical options for relief of hot flashes; the gold standard for treatment remains estrogen therapy. For moderate to severe bothersome hot flashes, potentially effective drug therapies used off label include clonidine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and gabapentin (TABLE 1).2,4 In large, randomized, controlled trials, the following agents were modestly more effective than placebo: desvenlafaxine,5 low-dose paroxetine salt,6 escitalopram,7 and gastroretentive gabapentin.8 Participants in these trials included women with both spontaneous and surgically induced menopause.

Although sponsors have applied for approval for three of these agents, the FDA so far has declined to approve these agents for vasomotor treatment due to concerns about risks versus benefits. Benefits of these nonhormonal prescription therapies need to be weighed carefully against side effects, because the reduction in absolute hot flushes is modest.

Many small trials have assessed other medications and complementary and alternative therapies regarding management of menopausal symptoms. Most, however, are limited by small numbers of enrolled participants and shorter study duration (≤12 weeks). In addition, enrolled participants have variable numbers of hot flashes, often less than 14 per week.2,4

TABLE 1

Nonhormonal treatment of vasomotor symptoms

| Treatment | Study Design* | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Complementary/alternative medicines (black cohosh, St. John’s Wort, red clover, acupuncture, exercise) | Duration: 4–52 wk; OL and RPL trials; entry criteria for most trials: >14 hot flashes/wk | Mixed results, mostly with no sustained improvement |

| SSRIs** (paroxetine, fluoxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram) | Duration: 4–36 wk; RPL trials with all agents; N = 20–90 in active arms; entry criteria for most trials: >14 hot flashes/wk | Reduction in vasomotor symptoms (frequency, composite scores): 28%–55% |

| SNRIs** (venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine) | Duration, 12–52 wk; RPL trials with all agents; N = 20–65 in VEN; N = 120–200 in DVS; Entry criteria >14 hot flashes/wk for VEN; >50/wk for DVS | Reduction in VMS (frequency, composite scores): 35%–58% for VEN, 55%–68% for DVS |

| Gabapentin** | Duration: 4–12 wk; RPL trials; N = 20–100; entry criteria for most trials: >14–50 hot flashes/wk | Reduction in vasomotor symptoms (frequency, composite scores): 50%–70% |

| *All studies of menopausal, nondepressed women. **Treatment is off label. Hall E, et al. Drugs. 2011;71:287-304. Reprinted with permission. Pinkerton JV, Shapiro M. The North American Menopause Society. Overview of available treatment options for VMS and VVA. Medscape Education Web site. http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/763413. Published May 24, 2012. Accessed February 23, 2013.19 | ||

Can your patient restart HT? If so, should HT be offered vaginally or systemically?

Non-HT may be enough for vaginal dryness. Benefit has been shown with the use of vaginal moisturizers twice weekly and lubricants as needed for sexual activity.9 Therefore, the local application of daily lubricants, such as olive oil, along with the use of moisturizers with regular sexual intercourse may be enough to maintain vaginal health and function.

In randomized trials, phytoestrogens lack benefit data for vaginal atrophy. Small pilot studies of the effect of oral/ vaginal phytoestrogens on vaginal atrophy do not show any benefit on vaginal pH or vaginal maturation index and mixed improvement in vaginal dryness. In addition, no clear effect of these agents has been seen compared with placebo, except that there may be less progression of vaginal atrophy over time with phytoestrogens.10 It is possible that the benefits of phytoestrogens may take longer to take effect than the 12 weeks required to see an effect with HT.

Vaginal estrogen: limited safety data. No published clinical trials have assessed the impact of topical vaginal estrogen on risk of recurrence in breast cancer survivors, and concern exists because detectable estradiol levels have been reported in women who take aromatase inhibitors and have very atrophic vaginal mucosa.11 NAMS recommends that the discussion about vaginal estrogen be individualized between the patient, her provider, and her oncologist.12

Vaginal estrogen creams and tablets (Vagifem 10 μg per tablet) are often started daily for 2 weeks for a “priming dose” then dosed twice per week. To minimize systemic absorption, creams may be used externally or with smaller doses vaginally. The higher the dose or more frequent the use, the greater the risk of significant systemic absorption, particularly when the vagina is atrophic.13

Another option is the vaginal estradiol ring, which delivers a low dose (7.5 μg per day) for 90 days.14,15

Progestogen therapy is generally not needed when low-dose estrogen is administered locally to treat vaginal atrophy.12

A new oral option. In February 2013, ospemifene, a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM), was approved for pain with intercourse and vaginal dryness.

Related article: “New treatment option for vulvar and vaginal atrophy,” by Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (May 2013)

There is concern with systemic estrogen use

If her hot flashes remain persistent and bothersome, low-dose estrogen could be considered. However, data from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium9 showed that as postmenopausal HT use decreased (from 35% to 11% between 1999 and 2005), rates of ADH decreased from a peak of 5.5 per 10,000 mammograms in 1999 to 2.4 per 10,000 mammograms in 2005. Similarly, rates of invasive cancer with ADH decreased from a peak of 4.3 per 10,000 mammograms in 2003 to 3.3 per 10,000 mammograms in 2005. This finding—that rates of ADH and invasive breast cancer were significantly linked to postmenopausal use of HT—raises concern about using HT in women with prior ADH. Of note, the cancers linked with ADH were of lower grade and stage and more estrogen receptor–positive than cancers not linked with ADH.17

How do you manage your patient’s increased risk of breast cancer?

In examining the answer to this management point, we need to first ask and answer, “How does ADH develop?” and “What is her risk of developing breast cancer?”

The development of invasive breast cancer is believed to involve a complex, multistep process. Initially, there is disruption of normal cell development and growth, with overproduction of normal-looking cells (hyperplasia). These excess cells stack up and/or become abnormal. Then, there is continued change in appearance and multiplication, becoming ductal carcinoma in situ (noninvasive). If left untreated, the cells may develop into invasive cancer.18 See TABLE 2 for the relative risk of a patient with ADH developing breast cancer.10

Now, we can address, “How do you manage this patient’s increased risk of breast cancer?”

TABLE 2. Relative risk of developing breast cancer

| Risk | Relative Risk |

|---|---|

| Atypical ductal hyperplasia | 4-5 |

| Atypical ductal hyperplasia and positive family history | 6-8 |

More frequent breast screening!

- Clinical breast exams twice per year

- Screening mammograms annually

- Screening tomosynthesis (These are additional digital screening views which provide almost a 3D view.)

- Screening breast ultrasound

- Screening breast MRI — if she has a 20% lifetime risk of breast cancer (family history or genetic predisposition) (TABLE 3).

TABLE 3. ACS guidelines for screening breast MRI

| Risk | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| <15% lifetime risk | MRI not recommended |

| 15% to 20% lifetime risk | Talk about benefits and limitations of MRI screening |

| >20% lifetime risk | Annual mammogram and annual MRI alternating every 6 months |

Careful consideration of medications

Since it is possible that estrogen may fuel the growth of some breast cancers, avoiding systemic menopausal HT may be safest.

Counsel her about strategies to reduce breast cancer risk

These include:

- Lifestyle changes, including weight loss, exercise, and avoiding excess alcohol intake.

- Preventive medications. Tamoxifen or raloxifene (Evista) can be used for 5 years. These medications block estrogen from binding to the breast estrogen receptors. Another option is an aromatase inhibitor, which decreases estrogen production.

- Risk-reducing (prophylactic) mastectomy.

Management approach for this patient

This patient has had her ADH surgically excised. She will remain at higher risk for breast cancer and should consider strategies to decrease her risk, including lifestyle changes and the possible initiation of medications such as tamoxifen or raloxifene. New screening modalities, such as tomosynthesis or breast ultrasound, may be used to screen for breast cancer, and she may be a candidate for alternating mammograms and MRIs at 6-month intervals.

For her vaginal dryness, over-the-counter lubricants and moisturizers may be helpful. If not, topical or vaginal estrogen is available (as creams, tablets, or a ring) and provides primarily local benefit with limited systemic absorption.

For her bothersome hot flashes, if lifestyle changes don’t work, nonhormonal therapies can be offered off label, such as effexor, desvenlafaxine, gabapentin, or any of the SSRIs—including those tested in large, randomized, controlled trials, such as escitalopram and low-dose paroxetine salt, at low doses.

If she is taking tamoxifen, however, SSRIs such as paroxetine should be avoided due to P450 interaction.

If her hot flashes remain persistent and bothersome, low-dose estrogen could be considered, with education about the potential risks, as she is already at higher risk for breast cancer.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD, for his forward thinking in helping to establish this new series on menopause.

Suggest it to our expert panel. They may address your management dilemma in a future issue!

Email us at [email protected] or send a Letter to the Editor to [email protected]

1. North American Menopause Society. Treatment of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms: position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2004;11(1):11-33.

2. Pinkerton JV, Stovall DW, Kightlinger RS. Advances in the treatment of menopausal symptoms. Womens Health (Lond Engl). 2009;5(4):361-384.

3. Ghaleiha A, Jahangard L, Sherafat Z, et al. Oxybutynin reduces sweating in depressed patients treated with sertraline: a double-blink, placebo-controlled, clinical study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2012;8:407-412.

4. Hall E, Frey BN, Soares CN. Non-hormonal treatment strategies for vasomotor symptoms: a critical review. Drugs. 2011;71(3):287-304.

5. Pinkerton JV, Archer DF, Guico-Pabia CJ, Hwang E, Cheng RF. Maintenance of the efficacy of desvenlafaxine in menopausal vasomotor symptoms: a 1-year randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2013;20(1):38-46.

6. Simon JA, Sanacora G, Bhaskar S, Lippman J. Safety and efficacy of low-dose mesylate salt of paroxetine (LDMP) for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms (VMS) associated with menopause: a 24-week randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Menopause. 2012;19(12):1371.-

7. Freeman EW, Guthrie KA, Caan B, et al. Efficacy of escitalopram for hot flashes in healthy menopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305(3):267-274.

8. Pinkerton JV, Kagan R, Portman D, Sathyanarayan RK, Sweeney M. Efficacy of gabapentin extended release in the treatment of menopausal hot flashes: results of the Breeze 3 study. Menopause. 2012;19(12):1377.-

9. MacBride MB, Rhodes DJ, Shuster LT. Vulvovaginal atrophy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(1):87-94.

10. Bedell S, Nachtigall M, Naftolin F. The pros and cons of plant estrogens for menopause [published online ahead of print December 25 2012]. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2012.12.004.

11. Moegele M, Buchholz S, Seitz S, Ortmann O. Vaginal estrogen therapy in postmenopausal breast cancer patients treated with aromatase inhibitors. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285(5):1397-402.

12. North American Menopause Society. The role of local vaginal estrogen for treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: 2007 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2007;14(3 Pt 1):355-371.

13. Archer DF. Efficacy and tolerability of local estrogen therapy for urogenital atrophy. Menopause. 2010;17(1):194-203.

14. Simon JA. Vulvovaginal atrophy: new and upcoming approaches. Menopause. 2009;16(1):5-7.

15. Kaunitz AM. Transdermal and vaginal estradiol for the treatment of menopausal symptoms: the nuts and bolts. Menopause. 2012;19(6):602-603.

16. Pruthi S, Simon JA, Early AP. Current overview of the management of urogenital atrophy in women with breast cancer. Breast J. 2011;17(4):403-408.

17. Menes TS, Kerlikowske K, Jaffer S, Seger D, Miglioretti D. Rates of atypical ductal hyperplasia declined with less use of postmenopausal hormone treatment: findings from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(11):2822-2828.

18. Santen RJ, Mansel R. Benign breast disorders. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(3):275-285.

19. Pinkerton JV, Shapiro M. The North American Menopause Society. Overview of available treatment options for VMS and VVA. Medscape Education Web site. http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/763413. Published May 24 2012. Accessed February 23, 2013.

A new series brought to you by the menopause experts

| Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD Professor and Associate Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville. Dr. Kaunitz is a NAMS Board member and certified menopause practitioner. He also serves on the OBG Management Board of Editors. |

| JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and Director, Division of Midlife Women’s Health, University of Virginia. Dr. Pinkerton is a North American Menopause Society (NAMS) past president and certified menopause practitioner. She also serves on the OBG Management Board of Editors. |

| James A. Simon, MD Clinical Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, George Washington University, and Medical Director, Women’s Health & Research Consultants, Washington, DC. Dr. Simon is a NAMS past president, a certified menopause practitioner, and a certified clinical densitometrist. He also serves on the OBG Management Board of Editors. |

Disclosures

Dr. Kaunitz reports that his institution receives grant or research support from Agile, Bayer, Endoceutics, Teva, Medical Diagnostic Laboratories, and Noven, and that he is a consultant to Bayer, Merck, and Teva.

Dr. Pinkerton reports that her institution receives consulting fees from Pfizer, DepoMed, Shionogi, and Noven and multicenter research fees from DepoMed, Endoceutics, and Bionova.

Dr. Simon reports being a consultant to or on the advisory boards of Abbott Laboratories, Agile Therapeutics, Amgen, Ascend Therapeutics, BioSante, Depomed, Lelo, MD Therapeutics, Meda Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Noven, Novo Nordisk, Novogyne, Pfizer, Shionogi, Shippan Point Advisors LLC, Slate Pharmaceuticals, Sprout Pharmaceuticals, Teva, Warner Chilcott, and Watson. He also reports receiving (currently or in the past year) grant/research support from BioSante, EndoCeutics, Novo Nordisk, Novogyne, Palatin Technologies, Teva, and Warner Chilcott. He reports serving on the speakers bureaus of Amgen, Merck, Novartis, Noven, Novo Nordisk, Novogyne, Teva, and Warner Chilcott. Dr. Simon is currently the Chief Medical Officer for Sprout Pharmaceuticals.

CASE: Atypical ductal hyperplasia

Your 56-year-old, married, white patient has been on hormone therapy (HT) since age 52 for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms. She is taking a low-dose oral estrogen and micronized progesterone combination as she has an intact uterus. Her family history is positive for breast cancer, as her mother was diagnosed at age 68.

Her most recent annual screening mammogram shows linear calcifications. Because fine, linear, branching or casting calcifications are worrisome for atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) or ductal carcinoma in situ, a biopsy is recommended.

She elects to wean off and discontinue HT during the evaluation of her abnormal mammogram. The mammographic-guided stereotactic biopsy reveals ADH. She undergoes an open excisional biopsy, the results of which reveal extensive ADH with negative margins.

Six weeks after a lumpectomy she returns to your office reporting moderate to severe hot flashes that occur seven to 10 times per day and impair her sleep, leading to fatigue and “brain fog.” In addition, she is noticing vaginal dryness and dyspareunia despite use of lubricants. She requests treatment for her symptoms and wonders if she can restart HT systemically or vaginally.

How do you manage her hot flashes?

What are the alternatives to HT for hot flashes?

Certain lifestyle changes have been reported to provide relief for hot flushes.1 These include:

- use of layered clothing

- maintenance of cool ambient temperature (particularly during sleep)

- consumption of cool foods or beverages

- relaxation techniques (such as deep breathing, or paced respirations, for 20 min three times per day).

Despite sparse data, avoiding triggers such as spicy or hot foods or alcohol may be helpful.

Therapies such as evening primrose oil, dong quai, ginseng, wild yam, magnet therapy, reflexology, and homeopathy have not been found more effective in treating hot flashes than placebo.2

Phytoestrogens (such as equol), acupuncture, yoga, and hypnosis continue to be tested in randomized trials with mixed results.

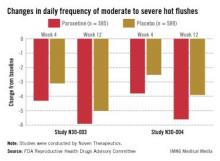

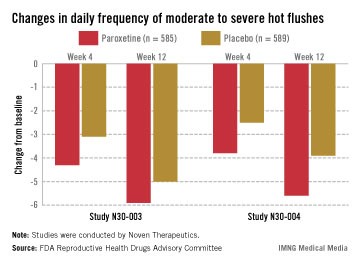

Off-label drug options offer modest help. There are currently no FDA-approved nonhormonal pharmaceutical options for relief of hot flashes; the gold standard for treatment remains estrogen therapy. For moderate to severe bothersome hot flashes, potentially effective drug therapies used off label include clonidine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and gabapentin (TABLE 1).2,4 In large, randomized, controlled trials, the following agents were modestly more effective than placebo: desvenlafaxine,5 low-dose paroxetine salt,6 escitalopram,7 and gastroretentive gabapentin.8 Participants in these trials included women with both spontaneous and surgically induced menopause.

Although sponsors have applied for approval for three of these agents, the FDA so far has declined to approve these agents for vasomotor treatment due to concerns about risks versus benefits. Benefits of these nonhormonal prescription therapies need to be weighed carefully against side effects, because the reduction in absolute hot flushes is modest.

Many small trials have assessed other medications and complementary and alternative therapies regarding management of menopausal symptoms. Most, however, are limited by small numbers of enrolled participants and shorter study duration (≤12 weeks). In addition, enrolled participants have variable numbers of hot flashes, often less than 14 per week.2,4

TABLE 1

Nonhormonal treatment of vasomotor symptoms

| Treatment | Study Design* | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Complementary/alternative medicines (black cohosh, St. John’s Wort, red clover, acupuncture, exercise) | Duration: 4–52 wk; OL and RPL trials; entry criteria for most trials: >14 hot flashes/wk | Mixed results, mostly with no sustained improvement |

| SSRIs** (paroxetine, fluoxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram) | Duration: 4–36 wk; RPL trials with all agents; N = 20–90 in active arms; entry criteria for most trials: >14 hot flashes/wk | Reduction in vasomotor symptoms (frequency, composite scores): 28%–55% |

| SNRIs** (venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine) | Duration, 12–52 wk; RPL trials with all agents; N = 20–65 in VEN; N = 120–200 in DVS; Entry criteria >14 hot flashes/wk for VEN; >50/wk for DVS | Reduction in VMS (frequency, composite scores): 35%–58% for VEN, 55%–68% for DVS |

| Gabapentin** | Duration: 4–12 wk; RPL trials; N = 20–100; entry criteria for most trials: >14–50 hot flashes/wk | Reduction in vasomotor symptoms (frequency, composite scores): 50%–70% |

| *All studies of menopausal, nondepressed women. **Treatment is off label. Hall E, et al. Drugs. 2011;71:287-304. Reprinted with permission. Pinkerton JV, Shapiro M. The North American Menopause Society. Overview of available treatment options for VMS and VVA. Medscape Education Web site. http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/763413. Published May 24, 2012. Accessed February 23, 2013.19 | ||

Can your patient restart HT? If so, should HT be offered vaginally or systemically?

Non-HT may be enough for vaginal dryness. Benefit has been shown with the use of vaginal moisturizers twice weekly and lubricants as needed for sexual activity.9 Therefore, the local application of daily lubricants, such as olive oil, along with the use of moisturizers with regular sexual intercourse may be enough to maintain vaginal health and function.

In randomized trials, phytoestrogens lack benefit data for vaginal atrophy. Small pilot studies of the effect of oral/ vaginal phytoestrogens on vaginal atrophy do not show any benefit on vaginal pH or vaginal maturation index and mixed improvement in vaginal dryness. In addition, no clear effect of these agents has been seen compared with placebo, except that there may be less progression of vaginal atrophy over time with phytoestrogens.10 It is possible that the benefits of phytoestrogens may take longer to take effect than the 12 weeks required to see an effect with HT.

Vaginal estrogen: limited safety data. No published clinical trials have assessed the impact of topical vaginal estrogen on risk of recurrence in breast cancer survivors, and concern exists because detectable estradiol levels have been reported in women who take aromatase inhibitors and have very atrophic vaginal mucosa.11 NAMS recommends that the discussion about vaginal estrogen be individualized between the patient, her provider, and her oncologist.12

Vaginal estrogen creams and tablets (Vagifem 10 μg per tablet) are often started daily for 2 weeks for a “priming dose” then dosed twice per week. To minimize systemic absorption, creams may be used externally or with smaller doses vaginally. The higher the dose or more frequent the use, the greater the risk of significant systemic absorption, particularly when the vagina is atrophic.13

Another option is the vaginal estradiol ring, which delivers a low dose (7.5 μg per day) for 90 days.14,15

Progestogen therapy is generally not needed when low-dose estrogen is administered locally to treat vaginal atrophy.12

A new oral option. In February 2013, ospemifene, a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM), was approved for pain with intercourse and vaginal dryness.

Related article: “New treatment option for vulvar and vaginal atrophy,” by Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (May 2013)

There is concern with systemic estrogen use

If her hot flashes remain persistent and bothersome, low-dose estrogen could be considered. However, data from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium9 showed that as postmenopausal HT use decreased (from 35% to 11% between 1999 and 2005), rates of ADH decreased from a peak of 5.5 per 10,000 mammograms in 1999 to 2.4 per 10,000 mammograms in 2005. Similarly, rates of invasive cancer with ADH decreased from a peak of 4.3 per 10,000 mammograms in 2003 to 3.3 per 10,000 mammograms in 2005. This finding—that rates of ADH and invasive breast cancer were significantly linked to postmenopausal use of HT—raises concern about using HT in women with prior ADH. Of note, the cancers linked with ADH were of lower grade and stage and more estrogen receptor–positive than cancers not linked with ADH.17

How do you manage your patient’s increased risk of breast cancer?

In examining the answer to this management point, we need to first ask and answer, “How does ADH develop?” and “What is her risk of developing breast cancer?”

The development of invasive breast cancer is believed to involve a complex, multistep process. Initially, there is disruption of normal cell development and growth, with overproduction of normal-looking cells (hyperplasia). These excess cells stack up and/or become abnormal. Then, there is continued change in appearance and multiplication, becoming ductal carcinoma in situ (noninvasive). If left untreated, the cells may develop into invasive cancer.18 See TABLE 2 for the relative risk of a patient with ADH developing breast cancer.10

Now, we can address, “How do you manage this patient’s increased risk of breast cancer?”

TABLE 2. Relative risk of developing breast cancer

| Risk | Relative Risk |

|---|---|

| Atypical ductal hyperplasia | 4-5 |

| Atypical ductal hyperplasia and positive family history | 6-8 |

More frequent breast screening!

- Clinical breast exams twice per year

- Screening mammograms annually

- Screening tomosynthesis (These are additional digital screening views which provide almost a 3D view.)

- Screening breast ultrasound

- Screening breast MRI — if she has a 20% lifetime risk of breast cancer (family history or genetic predisposition) (TABLE 3).

TABLE 3. ACS guidelines for screening breast MRI

| Risk | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| <15% lifetime risk | MRI not recommended |

| 15% to 20% lifetime risk | Talk about benefits and limitations of MRI screening |

| >20% lifetime risk | Annual mammogram and annual MRI alternating every 6 months |

Careful consideration of medications

Since it is possible that estrogen may fuel the growth of some breast cancers, avoiding systemic menopausal HT may be safest.

Counsel her about strategies to reduce breast cancer risk

These include:

- Lifestyle changes, including weight loss, exercise, and avoiding excess alcohol intake.

- Preventive medications. Tamoxifen or raloxifene (Evista) can be used for 5 years. These medications block estrogen from binding to the breast estrogen receptors. Another option is an aromatase inhibitor, which decreases estrogen production.

- Risk-reducing (prophylactic) mastectomy.

Management approach for this patient

This patient has had her ADH surgically excised. She will remain at higher risk for breast cancer and should consider strategies to decrease her risk, including lifestyle changes and the possible initiation of medications such as tamoxifen or raloxifene. New screening modalities, such as tomosynthesis or breast ultrasound, may be used to screen for breast cancer, and she may be a candidate for alternating mammograms and MRIs at 6-month intervals.

For her vaginal dryness, over-the-counter lubricants and moisturizers may be helpful. If not, topical or vaginal estrogen is available (as creams, tablets, or a ring) and provides primarily local benefit with limited systemic absorption.

For her bothersome hot flashes, if lifestyle changes don’t work, nonhormonal therapies can be offered off label, such as effexor, desvenlafaxine, gabapentin, or any of the SSRIs—including those tested in large, randomized, controlled trials, such as escitalopram and low-dose paroxetine salt, at low doses.

If she is taking tamoxifen, however, SSRIs such as paroxetine should be avoided due to P450 interaction.

If her hot flashes remain persistent and bothersome, low-dose estrogen could be considered, with education about the potential risks, as she is already at higher risk for breast cancer.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD, for his forward thinking in helping to establish this new series on menopause.

Suggest it to our expert panel. They may address your management dilemma in a future issue!

Email us at [email protected] or send a Letter to the Editor to [email protected]

A new series brought to you by the menopause experts

| Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD Professor and Associate Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville. Dr. Kaunitz is a NAMS Board member and certified menopause practitioner. He also serves on the OBG Management Board of Editors. |

| JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and Director, Division of Midlife Women’s Health, University of Virginia. Dr. Pinkerton is a North American Menopause Society (NAMS) past president and certified menopause practitioner. She also serves on the OBG Management Board of Editors. |

| James A. Simon, MD Clinical Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, George Washington University, and Medical Director, Women’s Health & Research Consultants, Washington, DC. Dr. Simon is a NAMS past president, a certified menopause practitioner, and a certified clinical densitometrist. He also serves on the OBG Management Board of Editors. |

Disclosures

Dr. Kaunitz reports that his institution receives grant or research support from Agile, Bayer, Endoceutics, Teva, Medical Diagnostic Laboratories, and Noven, and that he is a consultant to Bayer, Merck, and Teva.

Dr. Pinkerton reports that her institution receives consulting fees from Pfizer, DepoMed, Shionogi, and Noven and multicenter research fees from DepoMed, Endoceutics, and Bionova.

Dr. Simon reports being a consultant to or on the advisory boards of Abbott Laboratories, Agile Therapeutics, Amgen, Ascend Therapeutics, BioSante, Depomed, Lelo, MD Therapeutics, Meda Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Noven, Novo Nordisk, Novogyne, Pfizer, Shionogi, Shippan Point Advisors LLC, Slate Pharmaceuticals, Sprout Pharmaceuticals, Teva, Warner Chilcott, and Watson. He also reports receiving (currently or in the past year) grant/research support from BioSante, EndoCeutics, Novo Nordisk, Novogyne, Palatin Technologies, Teva, and Warner Chilcott. He reports serving on the speakers bureaus of Amgen, Merck, Novartis, Noven, Novo Nordisk, Novogyne, Teva, and Warner Chilcott. Dr. Simon is currently the Chief Medical Officer for Sprout Pharmaceuticals.

CASE: Atypical ductal hyperplasia

Your 56-year-old, married, white patient has been on hormone therapy (HT) since age 52 for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms. She is taking a low-dose oral estrogen and micronized progesterone combination as she has an intact uterus. Her family history is positive for breast cancer, as her mother was diagnosed at age 68.

Her most recent annual screening mammogram shows linear calcifications. Because fine, linear, branching or casting calcifications are worrisome for atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) or ductal carcinoma in situ, a biopsy is recommended.

She elects to wean off and discontinue HT during the evaluation of her abnormal mammogram. The mammographic-guided stereotactic biopsy reveals ADH. She undergoes an open excisional biopsy, the results of which reveal extensive ADH with negative margins.

Six weeks after a lumpectomy she returns to your office reporting moderate to severe hot flashes that occur seven to 10 times per day and impair her sleep, leading to fatigue and “brain fog.” In addition, she is noticing vaginal dryness and dyspareunia despite use of lubricants. She requests treatment for her symptoms and wonders if she can restart HT systemically or vaginally.

How do you manage her hot flashes?

What are the alternatives to HT for hot flashes?

Certain lifestyle changes have been reported to provide relief for hot flushes.1 These include:

- use of layered clothing

- maintenance of cool ambient temperature (particularly during sleep)

- consumption of cool foods or beverages

- relaxation techniques (such as deep breathing, or paced respirations, for 20 min three times per day).

Despite sparse data, avoiding triggers such as spicy or hot foods or alcohol may be helpful.

Therapies such as evening primrose oil, dong quai, ginseng, wild yam, magnet therapy, reflexology, and homeopathy have not been found more effective in treating hot flashes than placebo.2

Phytoestrogens (such as equol), acupuncture, yoga, and hypnosis continue to be tested in randomized trials with mixed results.

Off-label drug options offer modest help. There are currently no FDA-approved nonhormonal pharmaceutical options for relief of hot flashes; the gold standard for treatment remains estrogen therapy. For moderate to severe bothersome hot flashes, potentially effective drug therapies used off label include clonidine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and gabapentin (TABLE 1).2,4 In large, randomized, controlled trials, the following agents were modestly more effective than placebo: desvenlafaxine,5 low-dose paroxetine salt,6 escitalopram,7 and gastroretentive gabapentin.8 Participants in these trials included women with both spontaneous and surgically induced menopause.

Although sponsors have applied for approval for three of these agents, the FDA so far has declined to approve these agents for vasomotor treatment due to concerns about risks versus benefits. Benefits of these nonhormonal prescription therapies need to be weighed carefully against side effects, because the reduction in absolute hot flushes is modest.

Many small trials have assessed other medications and complementary and alternative therapies regarding management of menopausal symptoms. Most, however, are limited by small numbers of enrolled participants and shorter study duration (≤12 weeks). In addition, enrolled participants have variable numbers of hot flashes, often less than 14 per week.2,4

TABLE 1

Nonhormonal treatment of vasomotor symptoms

| Treatment | Study Design* | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Complementary/alternative medicines (black cohosh, St. John’s Wort, red clover, acupuncture, exercise) | Duration: 4–52 wk; OL and RPL trials; entry criteria for most trials: >14 hot flashes/wk | Mixed results, mostly with no sustained improvement |

| SSRIs** (paroxetine, fluoxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram) | Duration: 4–36 wk; RPL trials with all agents; N = 20–90 in active arms; entry criteria for most trials: >14 hot flashes/wk | Reduction in vasomotor symptoms (frequency, composite scores): 28%–55% |

| SNRIs** (venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine) | Duration, 12–52 wk; RPL trials with all agents; N = 20–65 in VEN; N = 120–200 in DVS; Entry criteria >14 hot flashes/wk for VEN; >50/wk for DVS | Reduction in VMS (frequency, composite scores): 35%–58% for VEN, 55%–68% for DVS |

| Gabapentin** | Duration: 4–12 wk; RPL trials; N = 20–100; entry criteria for most trials: >14–50 hot flashes/wk | Reduction in vasomotor symptoms (frequency, composite scores): 50%–70% |

| *All studies of menopausal, nondepressed women. **Treatment is off label. Hall E, et al. Drugs. 2011;71:287-304. Reprinted with permission. Pinkerton JV, Shapiro M. The North American Menopause Society. Overview of available treatment options for VMS and VVA. Medscape Education Web site. http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/763413. Published May 24, 2012. Accessed February 23, 2013.19 | ||

Can your patient restart HT? If so, should HT be offered vaginally or systemically?

Non-HT may be enough for vaginal dryness. Benefit has been shown with the use of vaginal moisturizers twice weekly and lubricants as needed for sexual activity.9 Therefore, the local application of daily lubricants, such as olive oil, along with the use of moisturizers with regular sexual intercourse may be enough to maintain vaginal health and function.

In randomized trials, phytoestrogens lack benefit data for vaginal atrophy. Small pilot studies of the effect of oral/ vaginal phytoestrogens on vaginal atrophy do not show any benefit on vaginal pH or vaginal maturation index and mixed improvement in vaginal dryness. In addition, no clear effect of these agents has been seen compared with placebo, except that there may be less progression of vaginal atrophy over time with phytoestrogens.10 It is possible that the benefits of phytoestrogens may take longer to take effect than the 12 weeks required to see an effect with HT.

Vaginal estrogen: limited safety data. No published clinical trials have assessed the impact of topical vaginal estrogen on risk of recurrence in breast cancer survivors, and concern exists because detectable estradiol levels have been reported in women who take aromatase inhibitors and have very atrophic vaginal mucosa.11 NAMS recommends that the discussion about vaginal estrogen be individualized between the patient, her provider, and her oncologist.12

Vaginal estrogen creams and tablets (Vagifem 10 μg per tablet) are often started daily for 2 weeks for a “priming dose” then dosed twice per week. To minimize systemic absorption, creams may be used externally or with smaller doses vaginally. The higher the dose or more frequent the use, the greater the risk of significant systemic absorption, particularly when the vagina is atrophic.13

Another option is the vaginal estradiol ring, which delivers a low dose (7.5 μg per day) for 90 days.14,15

Progestogen therapy is generally not needed when low-dose estrogen is administered locally to treat vaginal atrophy.12

A new oral option. In February 2013, ospemifene, a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM), was approved for pain with intercourse and vaginal dryness.

Related article: “New treatment option for vulvar and vaginal atrophy,” by Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (May 2013)

There is concern with systemic estrogen use

If her hot flashes remain persistent and bothersome, low-dose estrogen could be considered. However, data from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium9 showed that as postmenopausal HT use decreased (from 35% to 11% between 1999 and 2005), rates of ADH decreased from a peak of 5.5 per 10,000 mammograms in 1999 to 2.4 per 10,000 mammograms in 2005. Similarly, rates of invasive cancer with ADH decreased from a peak of 4.3 per 10,000 mammograms in 2003 to 3.3 per 10,000 mammograms in 2005. This finding—that rates of ADH and invasive breast cancer were significantly linked to postmenopausal use of HT—raises concern about using HT in women with prior ADH. Of note, the cancers linked with ADH were of lower grade and stage and more estrogen receptor–positive than cancers not linked with ADH.17

How do you manage your patient’s increased risk of breast cancer?

In examining the answer to this management point, we need to first ask and answer, “How does ADH develop?” and “What is her risk of developing breast cancer?”

The development of invasive breast cancer is believed to involve a complex, multistep process. Initially, there is disruption of normal cell development and growth, with overproduction of normal-looking cells (hyperplasia). These excess cells stack up and/or become abnormal. Then, there is continued change in appearance and multiplication, becoming ductal carcinoma in situ (noninvasive). If left untreated, the cells may develop into invasive cancer.18 See TABLE 2 for the relative risk of a patient with ADH developing breast cancer.10

Now, we can address, “How do you manage this patient’s increased risk of breast cancer?”

TABLE 2. Relative risk of developing breast cancer

| Risk | Relative Risk |

|---|---|

| Atypical ductal hyperplasia | 4-5 |

| Atypical ductal hyperplasia and positive family history | 6-8 |

More frequent breast screening!

- Clinical breast exams twice per year

- Screening mammograms annually

- Screening tomosynthesis (These are additional digital screening views which provide almost a 3D view.)

- Screening breast ultrasound

- Screening breast MRI — if she has a 20% lifetime risk of breast cancer (family history or genetic predisposition) (TABLE 3).

TABLE 3. ACS guidelines for screening breast MRI

| Risk | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| <15% lifetime risk | MRI not recommended |

| 15% to 20% lifetime risk | Talk about benefits and limitations of MRI screening |

| >20% lifetime risk | Annual mammogram and annual MRI alternating every 6 months |

Careful consideration of medications

Since it is possible that estrogen may fuel the growth of some breast cancers, avoiding systemic menopausal HT may be safest.

Counsel her about strategies to reduce breast cancer risk

These include:

- Lifestyle changes, including weight loss, exercise, and avoiding excess alcohol intake.

- Preventive medications. Tamoxifen or raloxifene (Evista) can be used for 5 years. These medications block estrogen from binding to the breast estrogen receptors. Another option is an aromatase inhibitor, which decreases estrogen production.

- Risk-reducing (prophylactic) mastectomy.

Management approach for this patient

This patient has had her ADH surgically excised. She will remain at higher risk for breast cancer and should consider strategies to decrease her risk, including lifestyle changes and the possible initiation of medications such as tamoxifen or raloxifene. New screening modalities, such as tomosynthesis or breast ultrasound, may be used to screen for breast cancer, and she may be a candidate for alternating mammograms and MRIs at 6-month intervals.

For her vaginal dryness, over-the-counter lubricants and moisturizers may be helpful. If not, topical or vaginal estrogen is available (as creams, tablets, or a ring) and provides primarily local benefit with limited systemic absorption.

For her bothersome hot flashes, if lifestyle changes don’t work, nonhormonal therapies can be offered off label, such as effexor, desvenlafaxine, gabapentin, or any of the SSRIs—including those tested in large, randomized, controlled trials, such as escitalopram and low-dose paroxetine salt, at low doses.

If she is taking tamoxifen, however, SSRIs such as paroxetine should be avoided due to P450 interaction.

If her hot flashes remain persistent and bothersome, low-dose estrogen could be considered, with education about the potential risks, as she is already at higher risk for breast cancer.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD, for his forward thinking in helping to establish this new series on menopause.

Suggest it to our expert panel. They may address your management dilemma in a future issue!

Email us at [email protected] or send a Letter to the Editor to [email protected]

1. North American Menopause Society. Treatment of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms: position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2004;11(1):11-33.

2. Pinkerton JV, Stovall DW, Kightlinger RS. Advances in the treatment of menopausal symptoms. Womens Health (Lond Engl). 2009;5(4):361-384.

3. Ghaleiha A, Jahangard L, Sherafat Z, et al. Oxybutynin reduces sweating in depressed patients treated with sertraline: a double-blink, placebo-controlled, clinical study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2012;8:407-412.

4. Hall E, Frey BN, Soares CN. Non-hormonal treatment strategies for vasomotor symptoms: a critical review. Drugs. 2011;71(3):287-304.

5. Pinkerton JV, Archer DF, Guico-Pabia CJ, Hwang E, Cheng RF. Maintenance of the efficacy of desvenlafaxine in menopausal vasomotor symptoms: a 1-year randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2013;20(1):38-46.

6. Simon JA, Sanacora G, Bhaskar S, Lippman J. Safety and efficacy of low-dose mesylate salt of paroxetine (LDMP) for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms (VMS) associated with menopause: a 24-week randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Menopause. 2012;19(12):1371.-

7. Freeman EW, Guthrie KA, Caan B, et al. Efficacy of escitalopram for hot flashes in healthy menopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305(3):267-274.

8. Pinkerton JV, Kagan R, Portman D, Sathyanarayan RK, Sweeney M. Efficacy of gabapentin extended release in the treatment of menopausal hot flashes: results of the Breeze 3 study. Menopause. 2012;19(12):1377.-

9. MacBride MB, Rhodes DJ, Shuster LT. Vulvovaginal atrophy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(1):87-94.

10. Bedell S, Nachtigall M, Naftolin F. The pros and cons of plant estrogens for menopause [published online ahead of print December 25 2012]. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2012.12.004.

11. Moegele M, Buchholz S, Seitz S, Ortmann O. Vaginal estrogen therapy in postmenopausal breast cancer patients treated with aromatase inhibitors. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285(5):1397-402.

12. North American Menopause Society. The role of local vaginal estrogen for treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: 2007 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2007;14(3 Pt 1):355-371.

13. Archer DF. Efficacy and tolerability of local estrogen therapy for urogenital atrophy. Menopause. 2010;17(1):194-203.

14. Simon JA. Vulvovaginal atrophy: new and upcoming approaches. Menopause. 2009;16(1):5-7.

15. Kaunitz AM. Transdermal and vaginal estradiol for the treatment of menopausal symptoms: the nuts and bolts. Menopause. 2012;19(6):602-603.

16. Pruthi S, Simon JA, Early AP. Current overview of the management of urogenital atrophy in women with breast cancer. Breast J. 2011;17(4):403-408.

17. Menes TS, Kerlikowske K, Jaffer S, Seger D, Miglioretti D. Rates of atypical ductal hyperplasia declined with less use of postmenopausal hormone treatment: findings from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(11):2822-2828.

18. Santen RJ, Mansel R. Benign breast disorders. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(3):275-285.

19. Pinkerton JV, Shapiro M. The North American Menopause Society. Overview of available treatment options for VMS and VVA. Medscape Education Web site. http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/763413. Published May 24 2012. Accessed February 23, 2013.

1. North American Menopause Society. Treatment of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms: position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2004;11(1):11-33.

2. Pinkerton JV, Stovall DW, Kightlinger RS. Advances in the treatment of menopausal symptoms. Womens Health (Lond Engl). 2009;5(4):361-384.

3. Ghaleiha A, Jahangard L, Sherafat Z, et al. Oxybutynin reduces sweating in depressed patients treated with sertraline: a double-blink, placebo-controlled, clinical study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2012;8:407-412.

4. Hall E, Frey BN, Soares CN. Non-hormonal treatment strategies for vasomotor symptoms: a critical review. Drugs. 2011;71(3):287-304.

5. Pinkerton JV, Archer DF, Guico-Pabia CJ, Hwang E, Cheng RF. Maintenance of the efficacy of desvenlafaxine in menopausal vasomotor symptoms: a 1-year randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2013;20(1):38-46.

6. Simon JA, Sanacora G, Bhaskar S, Lippman J. Safety and efficacy of low-dose mesylate salt of paroxetine (LDMP) for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms (VMS) associated with menopause: a 24-week randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Menopause. 2012;19(12):1371.-

7. Freeman EW, Guthrie KA, Caan B, et al. Efficacy of escitalopram for hot flashes in healthy menopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305(3):267-274.

8. Pinkerton JV, Kagan R, Portman D, Sathyanarayan RK, Sweeney M. Efficacy of gabapentin extended release in the treatment of menopausal hot flashes: results of the Breeze 3 study. Menopause. 2012;19(12):1377.-

9. MacBride MB, Rhodes DJ, Shuster LT. Vulvovaginal atrophy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(1):87-94.

10. Bedell S, Nachtigall M, Naftolin F. The pros and cons of plant estrogens for menopause [published online ahead of print December 25 2012]. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2012.12.004.

11. Moegele M, Buchholz S, Seitz S, Ortmann O. Vaginal estrogen therapy in postmenopausal breast cancer patients treated with aromatase inhibitors. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285(5):1397-402.

12. North American Menopause Society. The role of local vaginal estrogen for treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: 2007 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2007;14(3 Pt 1):355-371.

13. Archer DF. Efficacy and tolerability of local estrogen therapy for urogenital atrophy. Menopause. 2010;17(1):194-203.

14. Simon JA. Vulvovaginal atrophy: new and upcoming approaches. Menopause. 2009;16(1):5-7.

15. Kaunitz AM. Transdermal and vaginal estradiol for the treatment of menopausal symptoms: the nuts and bolts. Menopause. 2012;19(6):602-603.

16. Pruthi S, Simon JA, Early AP. Current overview of the management of urogenital atrophy in women with breast cancer. Breast J. 2011;17(4):403-408.

17. Menes TS, Kerlikowske K, Jaffer S, Seger D, Miglioretti D. Rates of atypical ductal hyperplasia declined with less use of postmenopausal hormone treatment: findings from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(11):2822-2828.

18. Santen RJ, Mansel R. Benign breast disorders. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(3):275-285.

19. Pinkerton JV, Shapiro M. The North American Menopause Society. Overview of available treatment options for VMS and VVA. Medscape Education Web site. http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/763413. Published May 24 2012. Accessed February 23, 2013.

Prevention and treatment of osteoporosis

The National Osteoporosis Foundation released new 2013 guidelines for the treatment and management of osteoporosis for postmenopausal women and men over the age of 50 years.

Osteoporosis definition

Osteoporosis is defined by a bone mineral density (BMD) measurement (T score) less than or equal to 2.5 standard deviations (SD) below the mean for a young adult reference population, or the occurrence of a hip or vertebral fracture without preceding major trauma. Osteopenia is established by BMD testing showing a T score between 1.0-2.5 SD below a young adult reference population.

Assess patient’s risk for fracture

All postmenopausal women and men above age 50 years should be evaluated for risk of osteoporosis in order to determine the need for BMD testing and/or vertebral imaging. In addition, all patients should be evaluated for their risk of falling, since the majority of osteoporosis-related fractures occur because of a fall.

The WHO FRAX tool, may be used in order to calculate the 10-year probability of a hip fracture and the 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture (clinical vertebral, hip, forearm or proximal humerus fracture). Risk of fracture can be calculated either with or without availability of BMD. The 10-year probability of fracture can be used to determine the need for pharmacologic treatment.

Diagnosis

Bone mineral density testing

Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) imaging of the hip and spine can diagnose or confirm osteoporosis. Testing should be considered in:

• Women aged 65 years and older and men 70 years of age and older, regardless of clinical risk factors.

• Patients of either sex who are aged between 50-69 years with clinical risk factors.

• Patients with a fracture after age 50 years.

• And patients with conditions (for example, rheumatoid arthritis) or on medications (for example, glucocorticoids) associated with low bone mass or bone loss.

Vertebral imaging

A single vertebral fracture increases the risk of subsequent vertebral and hip fractures, is consistent with the diagnosis of osteoporosis, and is an indication for pharmacologic treatment regardless of BMD. New to these guidelines is a recommendation for a proactive screening effort for vertebral fractures using lateral thoracic and lumbar spine x-ray or by lateral vertebral fracture assessment (VFA). Indications for vertebral imaging are:

• Women aged 65 years and older and men aged 70 years and older if T score is –1.5 or below.

• Women aged 70 years and men age 80 years and older.

• Postmenopausal women and men aged 50 years and older with a low trauma fracture.

• And/or postmenopausal women and men aged 50-69 years if there is height loss of 1.5 inches or more or ongoing long-term glucocorticoid treatment.

Markers of bone turnover

Biochemical markers of bone turnover are divided into two types:

• Markers of bone remodeling – serum C-telopeptide (CTx) and urinary N-telopeptide (NTx)

• Formation markers-serum bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BSAP), osteocalcin (OC), and aminoterminal propeptide of type 1 procollagen (P1NP)]

Markers should be collected as fasting morning specimens and may be helpful in predicting risk of fracture and extend of fracture risk reduction when repeated after 3-6 months of pharmacologic therapy.

General recommendations

Vitamin D and calcium: A diet rich in vitamin D and calcium is an inexpensive way to prevent bone mineral density loss. Fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy, and sunlight are great sources. If dietary supplementation is required, men aged 50-70 years should consume 1,000 mg of calcium/day and women over 51 years old should have 1,200 mg of calcium daily. Both men and women over 50 years should have 800-1,000 IU of vitamin D daily.

Treat vitamin D deficiencies: Supplementation should be adequate to achieve serum levels of 30ng/mL (75nmol/L).

Decreased alcohol use, smoking cessation, exercise, and fall prevention: Smoking cessation should be strongly advised. Moderate alcohol intake does not adversely affect bone and may be associated with lower fracture risk, though consuming more than three drinks daily may have an adverse effect on bone health and increases the risk of falling. Weight-bearing and muscle-strengthening exercise improves bone health and decreases the risk of falls. Home assessment for fall prevention for the elderly may decrease the risk of fracture.

Pharmacologic treatments

Treatment should be considered in postmenopausal women and men over 50 years with a hip or vertebral fracture; T score less than or equal to –2.5 at femoral neck, total hip or lumbar spine; low bone mass (T score between –1.0 and –2.5) and a 10-year probability of hip fracture greater than or equal to 3% or 10 year probability of major osteoporosis-related fracture greater than or equal to 20%. The antifracture benefits of medications have been studied primarily in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Pharmacologic therapy should not be considered life-long and that treatment decisions should be individualized. After 3-5 years of treatment a comprehensive risk assessment should be performed.

The bottom line

Identify risk factors for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and men over the age of 50 years. Bone mineral density screening is an important part of fracture prevention, and vertebral imaging should now be considered as a part of osteoporosis screening. Pharmacologic treatment can be considered when a nontraumatic fracture is apparent; if the T score is less than or equal to –2.5; or for individuals with an elevated 10-year fracture risk based on WHO model.

• Source: Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Washington, DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation; 2013.

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia. Dr. Charles is a second year resident in the Family Medicine Residency Program at Abington Memorial Hospital.

The National Osteoporosis Foundation released new 2013 guidelines for the treatment and management of osteoporosis for postmenopausal women and men over the age of 50 years.

Osteoporosis definition

Osteoporosis is defined by a bone mineral density (BMD) measurement (T score) less than or equal to 2.5 standard deviations (SD) below the mean for a young adult reference population, or the occurrence of a hip or vertebral fracture without preceding major trauma. Osteopenia is established by BMD testing showing a T score between 1.0-2.5 SD below a young adult reference population.

Assess patient’s risk for fracture

All postmenopausal women and men above age 50 years should be evaluated for risk of osteoporosis in order to determine the need for BMD testing and/or vertebral imaging. In addition, all patients should be evaluated for their risk of falling, since the majority of osteoporosis-related fractures occur because of a fall.

The WHO FRAX tool, may be used in order to calculate the 10-year probability of a hip fracture and the 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture (clinical vertebral, hip, forearm or proximal humerus fracture). Risk of fracture can be calculated either with or without availability of BMD. The 10-year probability of fracture can be used to determine the need for pharmacologic treatment.

Diagnosis

Bone mineral density testing

Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) imaging of the hip and spine can diagnose or confirm osteoporosis. Testing should be considered in:

• Women aged 65 years and older and men 70 years of age and older, regardless of clinical risk factors.

• Patients of either sex who are aged between 50-69 years with clinical risk factors.

• Patients with a fracture after age 50 years.

• And patients with conditions (for example, rheumatoid arthritis) or on medications (for example, glucocorticoids) associated with low bone mass or bone loss.

Vertebral imaging

A single vertebral fracture increases the risk of subsequent vertebral and hip fractures, is consistent with the diagnosis of osteoporosis, and is an indication for pharmacologic treatment regardless of BMD. New to these guidelines is a recommendation for a proactive screening effort for vertebral fractures using lateral thoracic and lumbar spine x-ray or by lateral vertebral fracture assessment (VFA). Indications for vertebral imaging are:

• Women aged 65 years and older and men aged 70 years and older if T score is –1.5 or below.

• Women aged 70 years and men age 80 years and older.

• Postmenopausal women and men aged 50 years and older with a low trauma fracture.

• And/or postmenopausal women and men aged 50-69 years if there is height loss of 1.5 inches or more or ongoing long-term glucocorticoid treatment.

Markers of bone turnover

Biochemical markers of bone turnover are divided into two types:

• Markers of bone remodeling – serum C-telopeptide (CTx) and urinary N-telopeptide (NTx)

• Formation markers-serum bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BSAP), osteocalcin (OC), and aminoterminal propeptide of type 1 procollagen (P1NP)]

Markers should be collected as fasting morning specimens and may be helpful in predicting risk of fracture and extend of fracture risk reduction when repeated after 3-6 months of pharmacologic therapy.

General recommendations

Vitamin D and calcium: A diet rich in vitamin D and calcium is an inexpensive way to prevent bone mineral density loss. Fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy, and sunlight are great sources. If dietary supplementation is required, men aged 50-70 years should consume 1,000 mg of calcium/day and women over 51 years old should have 1,200 mg of calcium daily. Both men and women over 50 years should have 800-1,000 IU of vitamin D daily.

Treat vitamin D deficiencies: Supplementation should be adequate to achieve serum levels of 30ng/mL (75nmol/L).

Decreased alcohol use, smoking cessation, exercise, and fall prevention: Smoking cessation should be strongly advised. Moderate alcohol intake does not adversely affect bone and may be associated with lower fracture risk, though consuming more than three drinks daily may have an adverse effect on bone health and increases the risk of falling. Weight-bearing and muscle-strengthening exercise improves bone health and decreases the risk of falls. Home assessment for fall prevention for the elderly may decrease the risk of fracture.

Pharmacologic treatments

Treatment should be considered in postmenopausal women and men over 50 years with a hip or vertebral fracture; T score less than or equal to –2.5 at femoral neck, total hip or lumbar spine; low bone mass (T score between –1.0 and –2.5) and a 10-year probability of hip fracture greater than or equal to 3% or 10 year probability of major osteoporosis-related fracture greater than or equal to 20%. The antifracture benefits of medications have been studied primarily in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Pharmacologic therapy should not be considered life-long and that treatment decisions should be individualized. After 3-5 years of treatment a comprehensive risk assessment should be performed.

The bottom line

Identify risk factors for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and men over the age of 50 years. Bone mineral density screening is an important part of fracture prevention, and vertebral imaging should now be considered as a part of osteoporosis screening. Pharmacologic treatment can be considered when a nontraumatic fracture is apparent; if the T score is less than or equal to –2.5; or for individuals with an elevated 10-year fracture risk based on WHO model.

• Source: Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Washington, DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation; 2013.

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia. Dr. Charles is a second year resident in the Family Medicine Residency Program at Abington Memorial Hospital.

The National Osteoporosis Foundation released new 2013 guidelines for the treatment and management of osteoporosis for postmenopausal women and men over the age of 50 years.

Osteoporosis definition

Osteoporosis is defined by a bone mineral density (BMD) measurement (T score) less than or equal to 2.5 standard deviations (SD) below the mean for a young adult reference population, or the occurrence of a hip or vertebral fracture without preceding major trauma. Osteopenia is established by BMD testing showing a T score between 1.0-2.5 SD below a young adult reference population.

Assess patient’s risk for fracture

All postmenopausal women and men above age 50 years should be evaluated for risk of osteoporosis in order to determine the need for BMD testing and/or vertebral imaging. In addition, all patients should be evaluated for their risk of falling, since the majority of osteoporosis-related fractures occur because of a fall.

The WHO FRAX tool, may be used in order to calculate the 10-year probability of a hip fracture and the 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture (clinical vertebral, hip, forearm or proximal humerus fracture). Risk of fracture can be calculated either with or without availability of BMD. The 10-year probability of fracture can be used to determine the need for pharmacologic treatment.

Diagnosis

Bone mineral density testing

Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) imaging of the hip and spine can diagnose or confirm osteoporosis. Testing should be considered in:

• Women aged 65 years and older and men 70 years of age and older, regardless of clinical risk factors.

• Patients of either sex who are aged between 50-69 years with clinical risk factors.

• Patients with a fracture after age 50 years.

• And patients with conditions (for example, rheumatoid arthritis) or on medications (for example, glucocorticoids) associated with low bone mass or bone loss.

Vertebral imaging

A single vertebral fracture increases the risk of subsequent vertebral and hip fractures, is consistent with the diagnosis of osteoporosis, and is an indication for pharmacologic treatment regardless of BMD. New to these guidelines is a recommendation for a proactive screening effort for vertebral fractures using lateral thoracic and lumbar spine x-ray or by lateral vertebral fracture assessment (VFA). Indications for vertebral imaging are:

• Women aged 65 years and older and men aged 70 years and older if T score is –1.5 or below.

• Women aged 70 years and men age 80 years and older.

• Postmenopausal women and men aged 50 years and older with a low trauma fracture.

• And/or postmenopausal women and men aged 50-69 years if there is height loss of 1.5 inches or more or ongoing long-term glucocorticoid treatment.

Markers of bone turnover

Biochemical markers of bone turnover are divided into two types:

• Markers of bone remodeling – serum C-telopeptide (CTx) and urinary N-telopeptide (NTx)

• Formation markers-serum bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BSAP), osteocalcin (OC), and aminoterminal propeptide of type 1 procollagen (P1NP)]

Markers should be collected as fasting morning specimens and may be helpful in predicting risk of fracture and extend of fracture risk reduction when repeated after 3-6 months of pharmacologic therapy.

General recommendations

Vitamin D and calcium: A diet rich in vitamin D and calcium is an inexpensive way to prevent bone mineral density loss. Fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy, and sunlight are great sources. If dietary supplementation is required, men aged 50-70 years should consume 1,000 mg of calcium/day and women over 51 years old should have 1,200 mg of calcium daily. Both men and women over 50 years should have 800-1,000 IU of vitamin D daily.

Treat vitamin D deficiencies: Supplementation should be adequate to achieve serum levels of 30ng/mL (75nmol/L).

Decreased alcohol use, smoking cessation, exercise, and fall prevention: Smoking cessation should be strongly advised. Moderate alcohol intake does not adversely affect bone and may be associated with lower fracture risk, though consuming more than three drinks daily may have an adverse effect on bone health and increases the risk of falling. Weight-bearing and muscle-strengthening exercise improves bone health and decreases the risk of falls. Home assessment for fall prevention for the elderly may decrease the risk of fracture.

Pharmacologic treatments

Treatment should be considered in postmenopausal women and men over 50 years with a hip or vertebral fracture; T score less than or equal to –2.5 at femoral neck, total hip or lumbar spine; low bone mass (T score between –1.0 and –2.5) and a 10-year probability of hip fracture greater than or equal to 3% or 10 year probability of major osteoporosis-related fracture greater than or equal to 20%. The antifracture benefits of medications have been studied primarily in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Pharmacologic therapy should not be considered life-long and that treatment decisions should be individualized. After 3-5 years of treatment a comprehensive risk assessment should be performed.

The bottom line

Identify risk factors for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and men over the age of 50 years. Bone mineral density screening is an important part of fracture prevention, and vertebral imaging should now be considered as a part of osteoporosis screening. Pharmacologic treatment can be considered when a nontraumatic fracture is apparent; if the T score is less than or equal to –2.5; or for individuals with an elevated 10-year fracture risk based on WHO model.

• Source: Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Washington, DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation; 2013.

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia. Dr. Charles is a second year resident in the Family Medicine Residency Program at Abington Memorial Hospital.

Abdominal, thoracic CT scans reliably detect incidental low lumbar BMD

Abdominal and thoracic CT scans obtained for a variety of reasons, such as to assess pain, GI symptoms, or urinary tract complaints, also can be used "opportunistically" to examine lumbar bone mineral density and screen for occult osteoporosis, according to a report in the April 16 issue of the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Abdominal and thoracic CT scans done in routine practice happen to include imaging of the L1 level, which can easily be identified because it is the first non–rib-bearing vertebra. Such scans readily yield data on lumbar bone mineral density (BMD), which is a clinically useful way to diagnose or rule out osteoporosis, said Dr. Perry J. Pickhardt of the department of radiology and his associates at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

It is important not to confuse this standard CT scanning with quantitative CT (QCT) scanning. QCT "is more labor-intensive; requires an imaging phantom or angle-corrected [region-of-interest] measurement of bone, muscle, and fat at multiple levels; and involves additional money, time, and radiation exposure," they explained.

Unlike dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) screening or QCT assessment, "the method that we used requires a negligible amount of training and time; could be applied prospectively by the interpreting radiologist or retrospectively by a radiologist or even nonradiologist; adds no cost; and requires no additional patient time, equipment, software, or radiation exposure," the investigators wrote.

Such incidental CT scans can be assessed retrospectively because they are almost always stored indefinitely in electronic medical records, they noted.

Dr. Pickhardt and his colleagues evaluated CT-derived BMD assessment and compared it against DXA scanning of the hips and spine by identifying 1,867 adults who had undergone the two types of scanning within a 6-month period during the 10-year study interval. They retrieved and reviewed the images, paying particular attention to obvious moderate or severe compression deformities on the CT images, rather than to milder ones, "to avoid ambiguity related to more subjective borderline or mild compression deformities."

The study subjects had a total of 2,063 pairs of CT and DXA assessments that had been performed a median of 67 days apart. A total of 81% of these subjects were women, and the mean age was 59 years.

These patients had undergone abdominal or thoracic CT for a variety of clinical indications, most often for a suspected mass or an oncologic work-up (414 subjects), genitourinary problems (402 subjects), gastrointestinal symptoms (398 subjects), and/or unexplained abdominal pain or symptoms (374 subjects).

Approximately 55% of the CT scans involved intravenous contrast. The use of contrast had no effect on the interpretation of lumbar data on the scans.

The DXA screening identified 22.9% of the study subjects as osteoporotic, 44.8% as osteopenic, and 32.3% as having normal BMD. The CT scans were significantly more sensitive than DXA at distinguishing these three states.

In particular, CT scans identified 119 patients as having osteoporosis, with readily identifiable moderate or severe vertebral fractures, when DXA had classified 62 of these patients as having normal BMD (12 subjects) or only osteopenia (50 subjects).

"Our observations are consistent with prior studies documenting that many patients without osteoporosis diagnosed by DXA will sustain fragility fractures, and suggest that CT attenuation may be a more accurate risk predictor," Dr. Pickhardt and his associates wrote (Ann. Intern. Med. 2013:158:588-95).

If their findings are confirmed in other studies, it may become routine for all abdominal and thoracic CT scans performed for any reason to be used for lumbar BMD assessment as well. "In the future, it may even be possible to incorporate CT ... data into fracture risk assessment tools," they added.

This should result in substantial savings in health care costs since osteoporosis will be diagnosed and treated earlier, before fractures occur, and since it also will reduce the number of costly DXA studies performed.

More than 80 million CT scans were performed in the United States in 2011, "most of which carry potentially useful information about BMD," the researchers noted.

The investigators are now turning their attention to using pelvic CT scans that were obtained for various clinical indications to assess hip BMD. "We are currently investigating the potential for deriving a DXA-equivalent T-score for the hips from standard pelvic CT scans by using a dedicated software tool," Dr. Pickhardt and his associates said.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. None of the investigators reported having any financial conflicts of interest.

Dr. Pickhardt and his associates "have laid all the groundwork needed to justify using conventional CT imaging to detect incidental osteoporosis," said Dr. Sumit R. Majumdar and Dr. William D. Leslie.

Given the large number of such CT scans performed every year, "the idea of extracting more information from imaging data collected for other purposes holds merit," they said.

"It is now up to the rest of us to safely and cost-effectively translate this new knowledge into everyday clinical practice," Dr. Majumdar and Dr. Leslie said.

Dr. Majumdar is with the University of Alberta, Edmonton. Dr. Leslie is with the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg. Neither reported any financial conflicts of interest. These remarks were taken from their editorial, which accompanied Dr. Pickhardt’s report (Ann. Intern. Med. 2013;158:630-1).

Dr. Pickhardt and his associates "have laid all the groundwork needed to justify using conventional CT imaging to detect incidental osteoporosis," said Dr. Sumit R. Majumdar and Dr. William D. Leslie.

Given the large number of such CT scans performed every year, "the idea of extracting more information from imaging data collected for other purposes holds merit," they said.