User login

Novel strategy could improve heart transplant allocation

Prediction models that incorporate more than just treatment status could rank order heart transplant candidates by urgency more effectively than the current system, a modeling study suggests.

Since 2018, the U.S. heart transplant allocation system has ranked heart candidates according to six treatment-based “statuses” (up from three used previously), ignoring many objective patient characteristics, the authors write.

Their study showed no significant difference in survival between statuses four and six, and status five had lower survival than status four.

“We expected multivariable prediction models to outperform the six-status system when it comes to rank ordering patients by how likely they are to die on the wait list (medical urgency),” William F. Parker, MD, MS, PhD, of the University of Chicago, told this news organization.

“However, we were surprised to see that the statuses were out of order,” he said. “Status five patients are more urgent than status three or status four patients,” mainly because most are in renal failure and listed for multiorgan transplantation with a kidney.

Objective physiologic measurements, such as glomerular filtration rate (GFR), had high variable importance, offering a minimally invasive measurement with predictive power in assessing medical urgency. Therefore, including GFR and other variables such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) could improve the accuracy of the allocation system in identifying the most medically urgent candidates, Dr. Parker and colleagues suggest.

The study was published online in JACC: Heart Failure.

‘Moderate ability’ to rank order

The investigators assessed the effectiveness of the standard six-status ranking system and several novel prediction models in identifying the most urgent heart transplant candidates. The primary outcome was death before receipt of a heart transplant.

The final data set contained 32,294 candidates (mean age, 53 years; 74%, men); 27,200 made up the prepolicy training set and 5,094 were included in the postpolicy test set.

The team evaluated the accuracy of the six-status system using Harrell’s C-index and log-rank tests of Kaplan-Meier estimated survival by status for candidates listed after the policy change (November 2018 to March 2020) in the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients data set.

They then developed Cox proportional hazards models and random survival forest models using prepolicy data (2010-2017). Predictor variables included age, diagnosis, laboratory measurements, hemodynamics, and supportive treatment at the time of listing.

They found that the six-status ranking at listing has had “moderate ability” to rank order candidates.

As Dr. Parker indicated, statuses four and six had no significant difference in survival, and status five had lower survival than status four.

The investigators’ multivariable prediction models derived with prepolicy data ranked candidates correctly more often than the six-status rankings. Objective physiologic measurements, such as GFR and ECMO, were identified as having significant importance with regard to ranking by urgency.

“The novel prediction models we developed … could be implemented by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) as allocation policy and would be better than the status quo,” Dr. Parker said. “However, I think we could do even better using the newer data collected after 2018.”

Modifications underway

The OPTN Heart Transplantation Committee is currently working on developing a new framework for allocating deceased donor hearts called Continuous Distribution.

“The six-tiered system works well, and it better stratifies the most medically urgent candidates than the previous allocation framework,” the leadership of the United Network for Organ Sharing Heart Transplantation Committee, including Chair Richard C. Daly, MD, Mayo Clinic; Vice-Chair Jondavid Menteer, MD, University of Southern California, Los Angeles; and former Chair Shelley Hall, MD, Baylor University Medical Center, told this news organization.

“That said, it is always appropriate to review and adjust variables that affect the medical urgency attribute for heart allocation.”

The new framework will change how patients are prioritized, they said. “Continuous distribution will consider all patient factors, including medical urgency, together to determine the order of an organ offer, and no single factor will decide an organ match.

“The goal is to increase fairness by moving to a points-based allocation framework that allows candidates to be compared using a single score composed of multiple factors.

“Furthermore,” they added, “continuous distribution provides a framework that will allow modifications of the criteria defining medical urgency (and other attributes of allocation) to a finer degree than the current policy. … Once continuous distribution is in place and the OPTN has policy monitoring data, the committee may consider and model different ways of defining medical urgency.”

Kiran K. Khush, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University School of Medicine, coauthor of a related commentary, elaborated. “The composite allocation score (CAS) will consist of a ‘points-based system,’ in which candidates will be assigned points based on (1) medical urgency, (2) anticipated posttransplant survival, (3) candidate biology (eg., special characteristics that may result in higher prioritization, such as blood type O and allosensitization), (4) access (eg., prior living donor, pediatric patient), and (5) placement efficacy (travel, proximity).”

Candidates will be assigned points based on these categories, and will be rank ordered for each donor offer.

Dr. Khush and colleagues propose that a multivariable model – such as the ones described in the study – would be the best way to assign points for medical urgency.

“This system will be more equitable than the current system,” Dr. Khush said, “because it will better prioritize the sickest candidates while improving access for patients who are currently at a disadvantage [for example, blood O, highly sensitized patients], and will also remove artificial geographic boundaries [for example, the current 500-mile rule for heart allocation].”

Going further

Jesse D. Schold, PhD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, raises concerns about other aspects of the heart allocation system in another related commentary.

“One big issue with our data in transplantation … is that, while it is very comprehensive for capturing transplant candidates and recipients, there is no data collection for patients and processes of care for patients prior to wait list placement,” he told this news organization. This phase of care is subject to wide variation in practice, he said, “and is likely as important as any to patients – the ability to be referred, evaluated, and placed on a waiting list.”

Report cards that measure quality of care after wait list placement ignore key phases prior to wait list placement, he said. “This may have the unintended consequences of limiting access to care and to the waiting list for patients perceived to be at higher risk, or the use of higher-risk donors, despite their potential survival advantage.

“In contrast,” he said, “quality report cards that incentivize treatment for all patients who may benefit would likely have a greater beneficial impact on patients with end-organ disease.”

There is also significant risk of underlying differences in patient populations between centers, despite the use of multivariable models, he added. This heterogeneity “may not be reflected accurately in the report cards [which] have significant impact for regulatory review, private payer contracting, and center reputation.”

Some of these concerns may be addressed in the new OPTN Modernization Initiative, according to David Bowman, a public affairs specialist at the Health Resources and Services Administration. One of the goals of the initiative “is to ensure that the OPTN Board of Directors is high functioning, has greater independence, and represents the diversity of communities served by the OPTN,” he told this news organization. “Strengthened governance will lead to effective policy development and implementation, and enhanced transparency and accountability of the process.”

Addressing another concern about the system, Savitri Fedson, MD, of the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, wonders in a related editorial whether organ donors and recipients should know more about each other, and if so, could that reverse the ongoing downward trend in organ acceptance?

Although some organizations are in favor of sharing more information, Dr. Fedson notes that “less information may have the greater benefit.” She writes, “We might realize that the simplest approach is often the best: a fulsome thank you for the donor’s gift that is willingly given to a stranger without expectation of payment, and on the recipient side, the knowledge that an organ is of good quality.

“The transplant patient can be comforted with the understanding that the risk of disease transmission, while not zero, is low, and that their survival following acceptance of an organ is better than languishing on a waiting list.”

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Parker, Dr. Khush, Dr. Schold, and Dr. Fedson report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Prediction models that incorporate more than just treatment status could rank order heart transplant candidates by urgency more effectively than the current system, a modeling study suggests.

Since 2018, the U.S. heart transplant allocation system has ranked heart candidates according to six treatment-based “statuses” (up from three used previously), ignoring many objective patient characteristics, the authors write.

Their study showed no significant difference in survival between statuses four and six, and status five had lower survival than status four.

“We expected multivariable prediction models to outperform the six-status system when it comes to rank ordering patients by how likely they are to die on the wait list (medical urgency),” William F. Parker, MD, MS, PhD, of the University of Chicago, told this news organization.

“However, we were surprised to see that the statuses were out of order,” he said. “Status five patients are more urgent than status three or status four patients,” mainly because most are in renal failure and listed for multiorgan transplantation with a kidney.

Objective physiologic measurements, such as glomerular filtration rate (GFR), had high variable importance, offering a minimally invasive measurement with predictive power in assessing medical urgency. Therefore, including GFR and other variables such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) could improve the accuracy of the allocation system in identifying the most medically urgent candidates, Dr. Parker and colleagues suggest.

The study was published online in JACC: Heart Failure.

‘Moderate ability’ to rank order

The investigators assessed the effectiveness of the standard six-status ranking system and several novel prediction models in identifying the most urgent heart transplant candidates. The primary outcome was death before receipt of a heart transplant.

The final data set contained 32,294 candidates (mean age, 53 years; 74%, men); 27,200 made up the prepolicy training set and 5,094 were included in the postpolicy test set.

The team evaluated the accuracy of the six-status system using Harrell’s C-index and log-rank tests of Kaplan-Meier estimated survival by status for candidates listed after the policy change (November 2018 to March 2020) in the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients data set.

They then developed Cox proportional hazards models and random survival forest models using prepolicy data (2010-2017). Predictor variables included age, diagnosis, laboratory measurements, hemodynamics, and supportive treatment at the time of listing.

They found that the six-status ranking at listing has had “moderate ability” to rank order candidates.

As Dr. Parker indicated, statuses four and six had no significant difference in survival, and status five had lower survival than status four.

The investigators’ multivariable prediction models derived with prepolicy data ranked candidates correctly more often than the six-status rankings. Objective physiologic measurements, such as GFR and ECMO, were identified as having significant importance with regard to ranking by urgency.

“The novel prediction models we developed … could be implemented by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) as allocation policy and would be better than the status quo,” Dr. Parker said. “However, I think we could do even better using the newer data collected after 2018.”

Modifications underway

The OPTN Heart Transplantation Committee is currently working on developing a new framework for allocating deceased donor hearts called Continuous Distribution.

“The six-tiered system works well, and it better stratifies the most medically urgent candidates than the previous allocation framework,” the leadership of the United Network for Organ Sharing Heart Transplantation Committee, including Chair Richard C. Daly, MD, Mayo Clinic; Vice-Chair Jondavid Menteer, MD, University of Southern California, Los Angeles; and former Chair Shelley Hall, MD, Baylor University Medical Center, told this news organization.

“That said, it is always appropriate to review and adjust variables that affect the medical urgency attribute for heart allocation.”

The new framework will change how patients are prioritized, they said. “Continuous distribution will consider all patient factors, including medical urgency, together to determine the order of an organ offer, and no single factor will decide an organ match.

“The goal is to increase fairness by moving to a points-based allocation framework that allows candidates to be compared using a single score composed of multiple factors.

“Furthermore,” they added, “continuous distribution provides a framework that will allow modifications of the criteria defining medical urgency (and other attributes of allocation) to a finer degree than the current policy. … Once continuous distribution is in place and the OPTN has policy monitoring data, the committee may consider and model different ways of defining medical urgency.”

Kiran K. Khush, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University School of Medicine, coauthor of a related commentary, elaborated. “The composite allocation score (CAS) will consist of a ‘points-based system,’ in which candidates will be assigned points based on (1) medical urgency, (2) anticipated posttransplant survival, (3) candidate biology (eg., special characteristics that may result in higher prioritization, such as blood type O and allosensitization), (4) access (eg., prior living donor, pediatric patient), and (5) placement efficacy (travel, proximity).”

Candidates will be assigned points based on these categories, and will be rank ordered for each donor offer.

Dr. Khush and colleagues propose that a multivariable model – such as the ones described in the study – would be the best way to assign points for medical urgency.

“This system will be more equitable than the current system,” Dr. Khush said, “because it will better prioritize the sickest candidates while improving access for patients who are currently at a disadvantage [for example, blood O, highly sensitized patients], and will also remove artificial geographic boundaries [for example, the current 500-mile rule for heart allocation].”

Going further

Jesse D. Schold, PhD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, raises concerns about other aspects of the heart allocation system in another related commentary.

“One big issue with our data in transplantation … is that, while it is very comprehensive for capturing transplant candidates and recipients, there is no data collection for patients and processes of care for patients prior to wait list placement,” he told this news organization. This phase of care is subject to wide variation in practice, he said, “and is likely as important as any to patients – the ability to be referred, evaluated, and placed on a waiting list.”

Report cards that measure quality of care after wait list placement ignore key phases prior to wait list placement, he said. “This may have the unintended consequences of limiting access to care and to the waiting list for patients perceived to be at higher risk, or the use of higher-risk donors, despite their potential survival advantage.

“In contrast,” he said, “quality report cards that incentivize treatment for all patients who may benefit would likely have a greater beneficial impact on patients with end-organ disease.”

There is also significant risk of underlying differences in patient populations between centers, despite the use of multivariable models, he added. This heterogeneity “may not be reflected accurately in the report cards [which] have significant impact for regulatory review, private payer contracting, and center reputation.”

Some of these concerns may be addressed in the new OPTN Modernization Initiative, according to David Bowman, a public affairs specialist at the Health Resources and Services Administration. One of the goals of the initiative “is to ensure that the OPTN Board of Directors is high functioning, has greater independence, and represents the diversity of communities served by the OPTN,” he told this news organization. “Strengthened governance will lead to effective policy development and implementation, and enhanced transparency and accountability of the process.”

Addressing another concern about the system, Savitri Fedson, MD, of the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, wonders in a related editorial whether organ donors and recipients should know more about each other, and if so, could that reverse the ongoing downward trend in organ acceptance?

Although some organizations are in favor of sharing more information, Dr. Fedson notes that “less information may have the greater benefit.” She writes, “We might realize that the simplest approach is often the best: a fulsome thank you for the donor’s gift that is willingly given to a stranger without expectation of payment, and on the recipient side, the knowledge that an organ is of good quality.

“The transplant patient can be comforted with the understanding that the risk of disease transmission, while not zero, is low, and that their survival following acceptance of an organ is better than languishing on a waiting list.”

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Parker, Dr. Khush, Dr. Schold, and Dr. Fedson report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Prediction models that incorporate more than just treatment status could rank order heart transplant candidates by urgency more effectively than the current system, a modeling study suggests.

Since 2018, the U.S. heart transplant allocation system has ranked heart candidates according to six treatment-based “statuses” (up from three used previously), ignoring many objective patient characteristics, the authors write.

Their study showed no significant difference in survival between statuses four and six, and status five had lower survival than status four.

“We expected multivariable prediction models to outperform the six-status system when it comes to rank ordering patients by how likely they are to die on the wait list (medical urgency),” William F. Parker, MD, MS, PhD, of the University of Chicago, told this news organization.

“However, we were surprised to see that the statuses were out of order,” he said. “Status five patients are more urgent than status three or status four patients,” mainly because most are in renal failure and listed for multiorgan transplantation with a kidney.

Objective physiologic measurements, such as glomerular filtration rate (GFR), had high variable importance, offering a minimally invasive measurement with predictive power in assessing medical urgency. Therefore, including GFR and other variables such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) could improve the accuracy of the allocation system in identifying the most medically urgent candidates, Dr. Parker and colleagues suggest.

The study was published online in JACC: Heart Failure.

‘Moderate ability’ to rank order

The investigators assessed the effectiveness of the standard six-status ranking system and several novel prediction models in identifying the most urgent heart transplant candidates. The primary outcome was death before receipt of a heart transplant.

The final data set contained 32,294 candidates (mean age, 53 years; 74%, men); 27,200 made up the prepolicy training set and 5,094 were included in the postpolicy test set.

The team evaluated the accuracy of the six-status system using Harrell’s C-index and log-rank tests of Kaplan-Meier estimated survival by status for candidates listed after the policy change (November 2018 to March 2020) in the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients data set.

They then developed Cox proportional hazards models and random survival forest models using prepolicy data (2010-2017). Predictor variables included age, diagnosis, laboratory measurements, hemodynamics, and supportive treatment at the time of listing.

They found that the six-status ranking at listing has had “moderate ability” to rank order candidates.

As Dr. Parker indicated, statuses four and six had no significant difference in survival, and status five had lower survival than status four.

The investigators’ multivariable prediction models derived with prepolicy data ranked candidates correctly more often than the six-status rankings. Objective physiologic measurements, such as GFR and ECMO, were identified as having significant importance with regard to ranking by urgency.

“The novel prediction models we developed … could be implemented by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) as allocation policy and would be better than the status quo,” Dr. Parker said. “However, I think we could do even better using the newer data collected after 2018.”

Modifications underway

The OPTN Heart Transplantation Committee is currently working on developing a new framework for allocating deceased donor hearts called Continuous Distribution.

“The six-tiered system works well, and it better stratifies the most medically urgent candidates than the previous allocation framework,” the leadership of the United Network for Organ Sharing Heart Transplantation Committee, including Chair Richard C. Daly, MD, Mayo Clinic; Vice-Chair Jondavid Menteer, MD, University of Southern California, Los Angeles; and former Chair Shelley Hall, MD, Baylor University Medical Center, told this news organization.

“That said, it is always appropriate to review and adjust variables that affect the medical urgency attribute for heart allocation.”

The new framework will change how patients are prioritized, they said. “Continuous distribution will consider all patient factors, including medical urgency, together to determine the order of an organ offer, and no single factor will decide an organ match.

“The goal is to increase fairness by moving to a points-based allocation framework that allows candidates to be compared using a single score composed of multiple factors.

“Furthermore,” they added, “continuous distribution provides a framework that will allow modifications of the criteria defining medical urgency (and other attributes of allocation) to a finer degree than the current policy. … Once continuous distribution is in place and the OPTN has policy monitoring data, the committee may consider and model different ways of defining medical urgency.”

Kiran K. Khush, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University School of Medicine, coauthor of a related commentary, elaborated. “The composite allocation score (CAS) will consist of a ‘points-based system,’ in which candidates will be assigned points based on (1) medical urgency, (2) anticipated posttransplant survival, (3) candidate biology (eg., special characteristics that may result in higher prioritization, such as blood type O and allosensitization), (4) access (eg., prior living donor, pediatric patient), and (5) placement efficacy (travel, proximity).”

Candidates will be assigned points based on these categories, and will be rank ordered for each donor offer.

Dr. Khush and colleagues propose that a multivariable model – such as the ones described in the study – would be the best way to assign points for medical urgency.

“This system will be more equitable than the current system,” Dr. Khush said, “because it will better prioritize the sickest candidates while improving access for patients who are currently at a disadvantage [for example, blood O, highly sensitized patients], and will also remove artificial geographic boundaries [for example, the current 500-mile rule for heart allocation].”

Going further

Jesse D. Schold, PhD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, raises concerns about other aspects of the heart allocation system in another related commentary.

“One big issue with our data in transplantation … is that, while it is very comprehensive for capturing transplant candidates and recipients, there is no data collection for patients and processes of care for patients prior to wait list placement,” he told this news organization. This phase of care is subject to wide variation in practice, he said, “and is likely as important as any to patients – the ability to be referred, evaluated, and placed on a waiting list.”

Report cards that measure quality of care after wait list placement ignore key phases prior to wait list placement, he said. “This may have the unintended consequences of limiting access to care and to the waiting list for patients perceived to be at higher risk, or the use of higher-risk donors, despite their potential survival advantage.

“In contrast,” he said, “quality report cards that incentivize treatment for all patients who may benefit would likely have a greater beneficial impact on patients with end-organ disease.”

There is also significant risk of underlying differences in patient populations between centers, despite the use of multivariable models, he added. This heterogeneity “may not be reflected accurately in the report cards [which] have significant impact for regulatory review, private payer contracting, and center reputation.”

Some of these concerns may be addressed in the new OPTN Modernization Initiative, according to David Bowman, a public affairs specialist at the Health Resources and Services Administration. One of the goals of the initiative “is to ensure that the OPTN Board of Directors is high functioning, has greater independence, and represents the diversity of communities served by the OPTN,” he told this news organization. “Strengthened governance will lead to effective policy development and implementation, and enhanced transparency and accountability of the process.”

Addressing another concern about the system, Savitri Fedson, MD, of the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, wonders in a related editorial whether organ donors and recipients should know more about each other, and if so, could that reverse the ongoing downward trend in organ acceptance?

Although some organizations are in favor of sharing more information, Dr. Fedson notes that “less information may have the greater benefit.” She writes, “We might realize that the simplest approach is often the best: a fulsome thank you for the donor’s gift that is willingly given to a stranger without expectation of payment, and on the recipient side, the knowledge that an organ is of good quality.

“The transplant patient can be comforted with the understanding that the risk of disease transmission, while not zero, is low, and that their survival following acceptance of an organ is better than languishing on a waiting list.”

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Parker, Dr. Khush, Dr. Schold, and Dr. Fedson report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JACC: HEART FAILURE

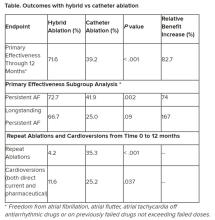

Hybrid ablation superior for persistent AFib: CEASE-AF

BARCELONA – Staged hybrid ablation provided superior freedom from atrial arrhythmias compared with endocardial catheter ablation alone, including the need for repeat ablations in patients with advanced atrial fibrillation (AF), new data show.

“We have seen that hybrid ablation resulted in 32.4% absolute benefit increase in effectiveness and 83% relative benefit increase, so this is a huge difference,” concluded cardiac surgeon Nicholas Doll, MD, PhD, Schüchtermann Clinic, Bad Rothenfelde, Germany.

Dr. Doll presented the 12-month follow up results of the Combined Endoscopic Epicardial and Percutaneous Endocardial Ablation Versus Repeated Catheter Ablation in Persistent and Longstanding Persistent Atrial Fibrillation (CEASE-AF) trial at the European Heart Rhythm Association 2023 Congress, held recently in Barcelona and virtually.

He said CEASE-AF is the largest multicenter randomized clinical trial comparing these two approaches for control of atrial arrhythmias.

Safety outcomes were numerically higher in the hybrid ablation (HA) group of the trial but not statistically different from the catheter ablation (CA) group.

Unstable wavefront

As background, Dr. Doll explained that in advanced AF, there is a high degree of endocardial-epicardial dissociation with unstable wavefront propagation transitioning between the endocardial and epicardial surfaces. Endocardial mapping and ablation alone may be insufficient to address the mechanism of AF.

“So, the hypothesis of the CEASE-AF study was a minimally invasive hybrid ablation approach which combines endocardial and epicardial ablation to achieve superior effectiveness when compared to endocardial catheter ablation alone,” he said.

This prospective clinical trial randomized patients 2:1 at nine sites in five countries to HA (n = 102) or CA (n = 52). All had left atrial diameter of 4 cm to 6 cm and persistent AF for up to 1 year or longstanding persistent AF for greater than 1 year up to 10 years.

Any patient with a previous ablation procedure, BMI greater than 35 kg/m2, or left ventricular ejection fraction less than 30% was excluded.

For HA, stage 1 consisted of epicardial lesions for pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) plus the posterior wall box plus left atrial appendage exclusion using the AtriClip (AtriCure Inc.) left atrial appendage exclusion device. Stage 2 involved endocardial mapping and catheter ablation to address gaps.

For CA, the index procedure involved catheter-mediated PVI plus repeat endocardial ablation as clinically indicated. For both HA and CA, additional ablation techniques and lesions were allowed for nonparoxysmal AF.

The HA timeline was the first stage, index procedure at time 0 (n = 102), a 90-day blanking period, and then the second stage, endocardial procedure at 90 to 180 days from the index procedure (n = 93).

For the CA arm of the trial, endocardial catheter ablation was performed on a minimal endocardial lesion set at time 0. Then after a 90-day blanking period, repeat catheter ablation was performed if clinically indicated (6/52).

Repeat ablations and electrical or pharmaceutical cardioversions were allowed during the 12-month follow-up period from time 0.

The primary efficacy endpoint was freedom from AF, atrial flutter, or atrial tachycardia of greater than 30 seconds through 12 months in the absence of class I/III antiarrhythmic drugs except ones that previously had failed, at doses not exceeding those previously failed doses. The safety endpoint was a composite rate of major complications over the course of the study.

Even with relatively modest cohort sizes, the HA and CA arms of the trial were well matched at baseline for age (approximately 60 years), gender (75.5% and 73.1% male, respectively), BMI (29.7 and 29.8 kg/m2), and persistent AF (79.4% and 82.7%).

The groups had persistent AF for 2.94 ± 3.29 years and 3.34 ± 3.52 years, respectively. The mean left atrial size was 4.7 ± 0.5 cm for the HA group and 4.7 ± 0.4 cm for the CA group.

Outcomes favored hybrid ablation over catheter ablation, the researchers reported. “We never would have expected these huge differences,” Dr. Doll told the congress. “We have seen that hybrid ablation resulted in 32.4% absolute benefit increase in effectiveness and 83% relative benefit increase.”

Subgroup analyses were consistent with the primary endpoint, but he said they would not be published because the trial was not powered for such comparisons.

Still, he noted that “there are only slightly reduced outcomes in the long-standing [persistent AF subgroup] in a really challenging patient arm, and we still have a success rate of 67%.” And the repeat ablations in about one-third of patients in the CA arm and need for cardioversions in about one quarter of them may have implications for reduced quality of life.

The total procedure duration was higher for the hybrid group at 336.4 ± 97 minutes, taking into account the index procedure plus the second stage procedure, vs. endocardial ablation at 251.9 ± 114 minutes, which includes the index procedure plus any repeat ablations (HA vs AF total duration, P < .001). Overall fluoroscopy time was approximately 8 minutes shorter for the HA arm.

Complications were assessed for 30 days post index procedure and 30 days post second stage procedure for the HA arm and for 30 days post index procedure and any repeat ablation for the CA arm.

The HA arm showed a complication rate of 7.8% vs. 5.8% for the CA arm (P = .751). Two patients in the former and three patients in the latter group had more than one major complication. There was one death in the HA group 93 days after the index procedure, and it was adjudicated as unrelated to the procedure.

“If you look back in the past, other studies showed a ... higher complication rate in the hybrid arm, so we feel very comfortable with these complication rates, which [are] very low and almost comparable,” Dr. Doll said.

Limitations of the study included symptom-driven electrocardiogram monitoring performed at unscheduled visits. Also, ablation beyond PVI in the CA arm and PVI/posterior box in the HA arm was not standardized and was performed according to standard practices in the participating countries.

“Success of epicardial-endocardial approach emphasizes the role of the collaborative heart team approach in the treatment of nonparoxysmal atrial fibrillation, and if I sum it up together, we can do it better” together, Dr. Doll advised.

‘Exceptional’ trial

After Dr. Doll’s presentation, appointed discussant Stylianos Tzeis, MD, PhD, head of the cardiology clinic and electrophysiology and pacing department at Mitera Hospital in Athens, congratulated the investigators and called CEASE-AF “an exceptional trial. It was really challenging to enroll patients in such a randomized controlled clinical trial.”

But Dr. Tzeis questioned whether pitting CA against HA was a fair comparison.

“Were the ablation targets similar between the two groups?” he asked. He noted that for the HA group, in the first stage the patients had PVI, posterior wall isolation, exclusion of the left atrial appendage, and additional lesions at the discretion of the operator. Ninety percent proceeded to the second stage, which was endocardial catheter ablation with verification of posterior wall isolation and PVI and additional lesions made if needed.

In the CA group, repeat catheter ablation could be performed after the 90-day blanking period if clinically indicated. “Please take note that only 10% were offered the second ablation. So at least in my perspective, this was a comparison of a two-stage approach versus a single-stage approach with a much more aggressive ablation protocol in the hybrid ablation group as compared to the endocardial group,” he said.

Seeing the higher success rate of the HA group in achieving the primary efficacy endpoint of freedom from all arrhythmias at 12 months, Dr. Tzeis asked, “Does this reflect the superiority of the epi-endo approach, or does it reflect the suboptimal performance of the catheter ablation approach?”

There was a 40% success rate in the CA patient population, a cohort that he deemed “not the most challenging persistent AF population in the world”: those with left atrial diameter of 47 millimeters and with 80% having an AF duration less than 12 months.

He also noted that “the average duration of the catheter ablation for the PVI in the vast majority of cases was 4 hours, which does not reflect what really happens in the everyday practice.”

All those critiques having been advanced, Dr. Tzeis said, “Definitely do not doubt my first comment that the authors should be congratulated, and I strongly believe that the main objective has been achieved to bring electrophysiologist and cardiac surgeons ... closer.”

The study sponsor was AtriCure Inc. with collaboration of Cardialysis BV. Doll has received consulting fees or royalties and/or has ownership or stockholder interest in AtriCure. Tzeis reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

BARCELONA – Staged hybrid ablation provided superior freedom from atrial arrhythmias compared with endocardial catheter ablation alone, including the need for repeat ablations in patients with advanced atrial fibrillation (AF), new data show.

“We have seen that hybrid ablation resulted in 32.4% absolute benefit increase in effectiveness and 83% relative benefit increase, so this is a huge difference,” concluded cardiac surgeon Nicholas Doll, MD, PhD, Schüchtermann Clinic, Bad Rothenfelde, Germany.

Dr. Doll presented the 12-month follow up results of the Combined Endoscopic Epicardial and Percutaneous Endocardial Ablation Versus Repeated Catheter Ablation in Persistent and Longstanding Persistent Atrial Fibrillation (CEASE-AF) trial at the European Heart Rhythm Association 2023 Congress, held recently in Barcelona and virtually.

He said CEASE-AF is the largest multicenter randomized clinical trial comparing these two approaches for control of atrial arrhythmias.

Safety outcomes were numerically higher in the hybrid ablation (HA) group of the trial but not statistically different from the catheter ablation (CA) group.

Unstable wavefront

As background, Dr. Doll explained that in advanced AF, there is a high degree of endocardial-epicardial dissociation with unstable wavefront propagation transitioning between the endocardial and epicardial surfaces. Endocardial mapping and ablation alone may be insufficient to address the mechanism of AF.

“So, the hypothesis of the CEASE-AF study was a minimally invasive hybrid ablation approach which combines endocardial and epicardial ablation to achieve superior effectiveness when compared to endocardial catheter ablation alone,” he said.

This prospective clinical trial randomized patients 2:1 at nine sites in five countries to HA (n = 102) or CA (n = 52). All had left atrial diameter of 4 cm to 6 cm and persistent AF for up to 1 year or longstanding persistent AF for greater than 1 year up to 10 years.

Any patient with a previous ablation procedure, BMI greater than 35 kg/m2, or left ventricular ejection fraction less than 30% was excluded.

For HA, stage 1 consisted of epicardial lesions for pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) plus the posterior wall box plus left atrial appendage exclusion using the AtriClip (AtriCure Inc.) left atrial appendage exclusion device. Stage 2 involved endocardial mapping and catheter ablation to address gaps.

For CA, the index procedure involved catheter-mediated PVI plus repeat endocardial ablation as clinically indicated. For both HA and CA, additional ablation techniques and lesions were allowed for nonparoxysmal AF.

The HA timeline was the first stage, index procedure at time 0 (n = 102), a 90-day blanking period, and then the second stage, endocardial procedure at 90 to 180 days from the index procedure (n = 93).

For the CA arm of the trial, endocardial catheter ablation was performed on a minimal endocardial lesion set at time 0. Then after a 90-day blanking period, repeat catheter ablation was performed if clinically indicated (6/52).

Repeat ablations and electrical or pharmaceutical cardioversions were allowed during the 12-month follow-up period from time 0.

The primary efficacy endpoint was freedom from AF, atrial flutter, or atrial tachycardia of greater than 30 seconds through 12 months in the absence of class I/III antiarrhythmic drugs except ones that previously had failed, at doses not exceeding those previously failed doses. The safety endpoint was a composite rate of major complications over the course of the study.

Even with relatively modest cohort sizes, the HA and CA arms of the trial were well matched at baseline for age (approximately 60 years), gender (75.5% and 73.1% male, respectively), BMI (29.7 and 29.8 kg/m2), and persistent AF (79.4% and 82.7%).

The groups had persistent AF for 2.94 ± 3.29 years and 3.34 ± 3.52 years, respectively. The mean left atrial size was 4.7 ± 0.5 cm for the HA group and 4.7 ± 0.4 cm for the CA group.

Outcomes favored hybrid ablation over catheter ablation, the researchers reported. “We never would have expected these huge differences,” Dr. Doll told the congress. “We have seen that hybrid ablation resulted in 32.4% absolute benefit increase in effectiveness and 83% relative benefit increase.”

Subgroup analyses were consistent with the primary endpoint, but he said they would not be published because the trial was not powered for such comparisons.

Still, he noted that “there are only slightly reduced outcomes in the long-standing [persistent AF subgroup] in a really challenging patient arm, and we still have a success rate of 67%.” And the repeat ablations in about one-third of patients in the CA arm and need for cardioversions in about one quarter of them may have implications for reduced quality of life.

The total procedure duration was higher for the hybrid group at 336.4 ± 97 minutes, taking into account the index procedure plus the second stage procedure, vs. endocardial ablation at 251.9 ± 114 minutes, which includes the index procedure plus any repeat ablations (HA vs AF total duration, P < .001). Overall fluoroscopy time was approximately 8 minutes shorter for the HA arm.

Complications were assessed for 30 days post index procedure and 30 days post second stage procedure for the HA arm and for 30 days post index procedure and any repeat ablation for the CA arm.

The HA arm showed a complication rate of 7.8% vs. 5.8% for the CA arm (P = .751). Two patients in the former and three patients in the latter group had more than one major complication. There was one death in the HA group 93 days after the index procedure, and it was adjudicated as unrelated to the procedure.

“If you look back in the past, other studies showed a ... higher complication rate in the hybrid arm, so we feel very comfortable with these complication rates, which [are] very low and almost comparable,” Dr. Doll said.

Limitations of the study included symptom-driven electrocardiogram monitoring performed at unscheduled visits. Also, ablation beyond PVI in the CA arm and PVI/posterior box in the HA arm was not standardized and was performed according to standard practices in the participating countries.

“Success of epicardial-endocardial approach emphasizes the role of the collaborative heart team approach in the treatment of nonparoxysmal atrial fibrillation, and if I sum it up together, we can do it better” together, Dr. Doll advised.

‘Exceptional’ trial

After Dr. Doll’s presentation, appointed discussant Stylianos Tzeis, MD, PhD, head of the cardiology clinic and electrophysiology and pacing department at Mitera Hospital in Athens, congratulated the investigators and called CEASE-AF “an exceptional trial. It was really challenging to enroll patients in such a randomized controlled clinical trial.”

But Dr. Tzeis questioned whether pitting CA against HA was a fair comparison.

“Were the ablation targets similar between the two groups?” he asked. He noted that for the HA group, in the first stage the patients had PVI, posterior wall isolation, exclusion of the left atrial appendage, and additional lesions at the discretion of the operator. Ninety percent proceeded to the second stage, which was endocardial catheter ablation with verification of posterior wall isolation and PVI and additional lesions made if needed.

In the CA group, repeat catheter ablation could be performed after the 90-day blanking period if clinically indicated. “Please take note that only 10% were offered the second ablation. So at least in my perspective, this was a comparison of a two-stage approach versus a single-stage approach with a much more aggressive ablation protocol in the hybrid ablation group as compared to the endocardial group,” he said.

Seeing the higher success rate of the HA group in achieving the primary efficacy endpoint of freedom from all arrhythmias at 12 months, Dr. Tzeis asked, “Does this reflect the superiority of the epi-endo approach, or does it reflect the suboptimal performance of the catheter ablation approach?”

There was a 40% success rate in the CA patient population, a cohort that he deemed “not the most challenging persistent AF population in the world”: those with left atrial diameter of 47 millimeters and with 80% having an AF duration less than 12 months.

He also noted that “the average duration of the catheter ablation for the PVI in the vast majority of cases was 4 hours, which does not reflect what really happens in the everyday practice.”

All those critiques having been advanced, Dr. Tzeis said, “Definitely do not doubt my first comment that the authors should be congratulated, and I strongly believe that the main objective has been achieved to bring electrophysiologist and cardiac surgeons ... closer.”

The study sponsor was AtriCure Inc. with collaboration of Cardialysis BV. Doll has received consulting fees or royalties and/or has ownership or stockholder interest in AtriCure. Tzeis reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

BARCELONA – Staged hybrid ablation provided superior freedom from atrial arrhythmias compared with endocardial catheter ablation alone, including the need for repeat ablations in patients with advanced atrial fibrillation (AF), new data show.

“We have seen that hybrid ablation resulted in 32.4% absolute benefit increase in effectiveness and 83% relative benefit increase, so this is a huge difference,” concluded cardiac surgeon Nicholas Doll, MD, PhD, Schüchtermann Clinic, Bad Rothenfelde, Germany.

Dr. Doll presented the 12-month follow up results of the Combined Endoscopic Epicardial and Percutaneous Endocardial Ablation Versus Repeated Catheter Ablation in Persistent and Longstanding Persistent Atrial Fibrillation (CEASE-AF) trial at the European Heart Rhythm Association 2023 Congress, held recently in Barcelona and virtually.

He said CEASE-AF is the largest multicenter randomized clinical trial comparing these two approaches for control of atrial arrhythmias.

Safety outcomes were numerically higher in the hybrid ablation (HA) group of the trial but not statistically different from the catheter ablation (CA) group.

Unstable wavefront

As background, Dr. Doll explained that in advanced AF, there is a high degree of endocardial-epicardial dissociation with unstable wavefront propagation transitioning between the endocardial and epicardial surfaces. Endocardial mapping and ablation alone may be insufficient to address the mechanism of AF.

“So, the hypothesis of the CEASE-AF study was a minimally invasive hybrid ablation approach which combines endocardial and epicardial ablation to achieve superior effectiveness when compared to endocardial catheter ablation alone,” he said.

This prospective clinical trial randomized patients 2:1 at nine sites in five countries to HA (n = 102) or CA (n = 52). All had left atrial diameter of 4 cm to 6 cm and persistent AF for up to 1 year or longstanding persistent AF for greater than 1 year up to 10 years.

Any patient with a previous ablation procedure, BMI greater than 35 kg/m2, or left ventricular ejection fraction less than 30% was excluded.

For HA, stage 1 consisted of epicardial lesions for pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) plus the posterior wall box plus left atrial appendage exclusion using the AtriClip (AtriCure Inc.) left atrial appendage exclusion device. Stage 2 involved endocardial mapping and catheter ablation to address gaps.

For CA, the index procedure involved catheter-mediated PVI plus repeat endocardial ablation as clinically indicated. For both HA and CA, additional ablation techniques and lesions were allowed for nonparoxysmal AF.

The HA timeline was the first stage, index procedure at time 0 (n = 102), a 90-day blanking period, and then the second stage, endocardial procedure at 90 to 180 days from the index procedure (n = 93).

For the CA arm of the trial, endocardial catheter ablation was performed on a minimal endocardial lesion set at time 0. Then after a 90-day blanking period, repeat catheter ablation was performed if clinically indicated (6/52).

Repeat ablations and electrical or pharmaceutical cardioversions were allowed during the 12-month follow-up period from time 0.

The primary efficacy endpoint was freedom from AF, atrial flutter, or atrial tachycardia of greater than 30 seconds through 12 months in the absence of class I/III antiarrhythmic drugs except ones that previously had failed, at doses not exceeding those previously failed doses. The safety endpoint was a composite rate of major complications over the course of the study.

Even with relatively modest cohort sizes, the HA and CA arms of the trial were well matched at baseline for age (approximately 60 years), gender (75.5% and 73.1% male, respectively), BMI (29.7 and 29.8 kg/m2), and persistent AF (79.4% and 82.7%).

The groups had persistent AF for 2.94 ± 3.29 years and 3.34 ± 3.52 years, respectively. The mean left atrial size was 4.7 ± 0.5 cm for the HA group and 4.7 ± 0.4 cm for the CA group.

Outcomes favored hybrid ablation over catheter ablation, the researchers reported. “We never would have expected these huge differences,” Dr. Doll told the congress. “We have seen that hybrid ablation resulted in 32.4% absolute benefit increase in effectiveness and 83% relative benefit increase.”

Subgroup analyses were consistent with the primary endpoint, but he said they would not be published because the trial was not powered for such comparisons.

Still, he noted that “there are only slightly reduced outcomes in the long-standing [persistent AF subgroup] in a really challenging patient arm, and we still have a success rate of 67%.” And the repeat ablations in about one-third of patients in the CA arm and need for cardioversions in about one quarter of them may have implications for reduced quality of life.

The total procedure duration was higher for the hybrid group at 336.4 ± 97 minutes, taking into account the index procedure plus the second stage procedure, vs. endocardial ablation at 251.9 ± 114 minutes, which includes the index procedure plus any repeat ablations (HA vs AF total duration, P < .001). Overall fluoroscopy time was approximately 8 minutes shorter for the HA arm.

Complications were assessed for 30 days post index procedure and 30 days post second stage procedure for the HA arm and for 30 days post index procedure and any repeat ablation for the CA arm.

The HA arm showed a complication rate of 7.8% vs. 5.8% for the CA arm (P = .751). Two patients in the former and three patients in the latter group had more than one major complication. There was one death in the HA group 93 days after the index procedure, and it was adjudicated as unrelated to the procedure.

“If you look back in the past, other studies showed a ... higher complication rate in the hybrid arm, so we feel very comfortable with these complication rates, which [are] very low and almost comparable,” Dr. Doll said.

Limitations of the study included symptom-driven electrocardiogram monitoring performed at unscheduled visits. Also, ablation beyond PVI in the CA arm and PVI/posterior box in the HA arm was not standardized and was performed according to standard practices in the participating countries.

“Success of epicardial-endocardial approach emphasizes the role of the collaborative heart team approach in the treatment of nonparoxysmal atrial fibrillation, and if I sum it up together, we can do it better” together, Dr. Doll advised.

‘Exceptional’ trial

After Dr. Doll’s presentation, appointed discussant Stylianos Tzeis, MD, PhD, head of the cardiology clinic and electrophysiology and pacing department at Mitera Hospital in Athens, congratulated the investigators and called CEASE-AF “an exceptional trial. It was really challenging to enroll patients in such a randomized controlled clinical trial.”

But Dr. Tzeis questioned whether pitting CA against HA was a fair comparison.

“Were the ablation targets similar between the two groups?” he asked. He noted that for the HA group, in the first stage the patients had PVI, posterior wall isolation, exclusion of the left atrial appendage, and additional lesions at the discretion of the operator. Ninety percent proceeded to the second stage, which was endocardial catheter ablation with verification of posterior wall isolation and PVI and additional lesions made if needed.

In the CA group, repeat catheter ablation could be performed after the 90-day blanking period if clinically indicated. “Please take note that only 10% were offered the second ablation. So at least in my perspective, this was a comparison of a two-stage approach versus a single-stage approach with a much more aggressive ablation protocol in the hybrid ablation group as compared to the endocardial group,” he said.

Seeing the higher success rate of the HA group in achieving the primary efficacy endpoint of freedom from all arrhythmias at 12 months, Dr. Tzeis asked, “Does this reflect the superiority of the epi-endo approach, or does it reflect the suboptimal performance of the catheter ablation approach?”

There was a 40% success rate in the CA patient population, a cohort that he deemed “not the most challenging persistent AF population in the world”: those with left atrial diameter of 47 millimeters and with 80% having an AF duration less than 12 months.

He also noted that “the average duration of the catheter ablation for the PVI in the vast majority of cases was 4 hours, which does not reflect what really happens in the everyday practice.”

All those critiques having been advanced, Dr. Tzeis said, “Definitely do not doubt my first comment that the authors should be congratulated, and I strongly believe that the main objective has been achieved to bring electrophysiologist and cardiac surgeons ... closer.”

The study sponsor was AtriCure Inc. with collaboration of Cardialysis BV. Doll has received consulting fees or royalties and/or has ownership or stockholder interest in AtriCure. Tzeis reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

AT EHRA 2023

AHA statement targets nuance in CVD risk assessment of women

In a new scientific statement, the American Heart Association highlighted the importance of incorporating nonbiological risk factors and social determinants of health in cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk assessment for women, particularly women from different racial and ethnic backgrounds.

CVD risk assessment in women is multifaceted and goes well beyond traditional risk factors to include sex-specific biological risk factors, as well as social, behavioral, and environmental factors, the writing group noted.

They said a greater focus on addressing all CVD risk factors among women from underrepresented races and ethnicities is warranted to avert future CVD.

The scientific statement was published online in Circulation.

Look beyond traditional risk factors

“Risk assessment is the first step in preventing heart disease, yet there are many limitations to traditional risk factors and their ability to comprehensively estimate a woman’s risk for cardiovascular disease,” Jennifer H. Mieres, MD, vice chair of the writing group and professor of cardiology at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., said in a news release.

“The delivery of equitable cardiovascular health care for women depends on improving the knowledge and awareness of all members of the healthcare team about the full spectrum of cardiovascular risk factors for women, including female-specific and female-predominant risk factors,” Dr. Mieres added.

Female-specific factors that should be included in CVD risk assessment include pregnancy-related conditions such as preeclampsia, preterm delivery, and gestational diabetes, the writing group said.

Other factors include menstrual cycle history; types of birth control and/or hormone replacement therapy used; polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), which affects 10% of women of reproductive age and is associated with increased CVD risk; and autoimmune disorders, depression, and PTSD, all of which are more common in women and are also associated with higher risk for CVD.

The statement also highlights the key role that social determinants of health (SDOH) play in the development of CVD in women, particularly women from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. SDOH include education level, economic stability, neighborhood safety, working conditions, environmental hazards, and access to quality health care.

“It is critical that risk assessment be expanded to include [SDOH] as risk factors if we are to improve health outcomes in all women,” Laxmi Mehta, MD, chair of the writing group and director of preventative cardiology and women’s cardiovascular health at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, said in the news release.

“It is also important for the health care team to consider [SDOH] when working with women on shared decisions about cardiovascular disease prevention and treatment,” Dr. Mehta noted.

No one-size-fits-all approach

The statement highlighted significant differences in CVD risk among women of different racial and ethnic backgrounds and provides detailed CV risk factor profiles for non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic/Latinx, Asian and American Indian/Alaska Native women.

It noted that language barriers, discrimination, acculturation, and health care access disproportionately affect women of underrepresented racial and ethnic groups. These factors result in a higher prevalence of CVD and significant challenges in CVD diagnosis and treatment.

“When customizing CVD prevention and treatment strategies to improve cardiovascular health for women, a one-size-fits-all approach is unlikely to be successful,” Dr. Mieres said.

“We must be cognizant of the complex interplay of sex, race and ethnicity, as well as social determinants of health, and how they impact the risk of cardiovascular disease and adverse outcomes in order to avert future CVD morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Mieres added.

Looking ahead, the writing group said future CVD prevention guidelines could be strengthened by including culturally-specific lifestyle recommendations.

They also said community-based approaches, faith-based community partnerships, and peer support to encourage a healthy lifestyle could play a key role in preventing CVD among all women.

This scientific statement was prepared by the volunteer writing group on behalf of the AHA’s Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke in Women and Underrepresented Populations Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, the Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, the Council on Hypertension, the Council on Lifelong Congenital Heart Disease and Heart Health in the Young, the Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health, the Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease, and the Stroke Council.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a new scientific statement, the American Heart Association highlighted the importance of incorporating nonbiological risk factors and social determinants of health in cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk assessment for women, particularly women from different racial and ethnic backgrounds.

CVD risk assessment in women is multifaceted and goes well beyond traditional risk factors to include sex-specific biological risk factors, as well as social, behavioral, and environmental factors, the writing group noted.

They said a greater focus on addressing all CVD risk factors among women from underrepresented races and ethnicities is warranted to avert future CVD.

The scientific statement was published online in Circulation.

Look beyond traditional risk factors

“Risk assessment is the first step in preventing heart disease, yet there are many limitations to traditional risk factors and their ability to comprehensively estimate a woman’s risk for cardiovascular disease,” Jennifer H. Mieres, MD, vice chair of the writing group and professor of cardiology at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., said in a news release.

“The delivery of equitable cardiovascular health care for women depends on improving the knowledge and awareness of all members of the healthcare team about the full spectrum of cardiovascular risk factors for women, including female-specific and female-predominant risk factors,” Dr. Mieres added.

Female-specific factors that should be included in CVD risk assessment include pregnancy-related conditions such as preeclampsia, preterm delivery, and gestational diabetes, the writing group said.

Other factors include menstrual cycle history; types of birth control and/or hormone replacement therapy used; polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), which affects 10% of women of reproductive age and is associated with increased CVD risk; and autoimmune disorders, depression, and PTSD, all of which are more common in women and are also associated with higher risk for CVD.

The statement also highlights the key role that social determinants of health (SDOH) play in the development of CVD in women, particularly women from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. SDOH include education level, economic stability, neighborhood safety, working conditions, environmental hazards, and access to quality health care.

“It is critical that risk assessment be expanded to include [SDOH] as risk factors if we are to improve health outcomes in all women,” Laxmi Mehta, MD, chair of the writing group and director of preventative cardiology and women’s cardiovascular health at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, said in the news release.

“It is also important for the health care team to consider [SDOH] when working with women on shared decisions about cardiovascular disease prevention and treatment,” Dr. Mehta noted.

No one-size-fits-all approach

The statement highlighted significant differences in CVD risk among women of different racial and ethnic backgrounds and provides detailed CV risk factor profiles for non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic/Latinx, Asian and American Indian/Alaska Native women.

It noted that language barriers, discrimination, acculturation, and health care access disproportionately affect women of underrepresented racial and ethnic groups. These factors result in a higher prevalence of CVD and significant challenges in CVD diagnosis and treatment.

“When customizing CVD prevention and treatment strategies to improve cardiovascular health for women, a one-size-fits-all approach is unlikely to be successful,” Dr. Mieres said.

“We must be cognizant of the complex interplay of sex, race and ethnicity, as well as social determinants of health, and how they impact the risk of cardiovascular disease and adverse outcomes in order to avert future CVD morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Mieres added.

Looking ahead, the writing group said future CVD prevention guidelines could be strengthened by including culturally-specific lifestyle recommendations.

They also said community-based approaches, faith-based community partnerships, and peer support to encourage a healthy lifestyle could play a key role in preventing CVD among all women.

This scientific statement was prepared by the volunteer writing group on behalf of the AHA’s Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke in Women and Underrepresented Populations Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, the Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, the Council on Hypertension, the Council on Lifelong Congenital Heart Disease and Heart Health in the Young, the Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health, the Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease, and the Stroke Council.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a new scientific statement, the American Heart Association highlighted the importance of incorporating nonbiological risk factors and social determinants of health in cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk assessment for women, particularly women from different racial and ethnic backgrounds.

CVD risk assessment in women is multifaceted and goes well beyond traditional risk factors to include sex-specific biological risk factors, as well as social, behavioral, and environmental factors, the writing group noted.

They said a greater focus on addressing all CVD risk factors among women from underrepresented races and ethnicities is warranted to avert future CVD.

The scientific statement was published online in Circulation.

Look beyond traditional risk factors

“Risk assessment is the first step in preventing heart disease, yet there are many limitations to traditional risk factors and their ability to comprehensively estimate a woman’s risk for cardiovascular disease,” Jennifer H. Mieres, MD, vice chair of the writing group and professor of cardiology at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., said in a news release.

“The delivery of equitable cardiovascular health care for women depends on improving the knowledge and awareness of all members of the healthcare team about the full spectrum of cardiovascular risk factors for women, including female-specific and female-predominant risk factors,” Dr. Mieres added.

Female-specific factors that should be included in CVD risk assessment include pregnancy-related conditions such as preeclampsia, preterm delivery, and gestational diabetes, the writing group said.

Other factors include menstrual cycle history; types of birth control and/or hormone replacement therapy used; polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), which affects 10% of women of reproductive age and is associated with increased CVD risk; and autoimmune disorders, depression, and PTSD, all of which are more common in women and are also associated with higher risk for CVD.

The statement also highlights the key role that social determinants of health (SDOH) play in the development of CVD in women, particularly women from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. SDOH include education level, economic stability, neighborhood safety, working conditions, environmental hazards, and access to quality health care.

“It is critical that risk assessment be expanded to include [SDOH] as risk factors if we are to improve health outcomes in all women,” Laxmi Mehta, MD, chair of the writing group and director of preventative cardiology and women’s cardiovascular health at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, said in the news release.

“It is also important for the health care team to consider [SDOH] when working with women on shared decisions about cardiovascular disease prevention and treatment,” Dr. Mehta noted.

No one-size-fits-all approach

The statement highlighted significant differences in CVD risk among women of different racial and ethnic backgrounds and provides detailed CV risk factor profiles for non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic/Latinx, Asian and American Indian/Alaska Native women.

It noted that language barriers, discrimination, acculturation, and health care access disproportionately affect women of underrepresented racial and ethnic groups. These factors result in a higher prevalence of CVD and significant challenges in CVD diagnosis and treatment.

“When customizing CVD prevention and treatment strategies to improve cardiovascular health for women, a one-size-fits-all approach is unlikely to be successful,” Dr. Mieres said.

“We must be cognizant of the complex interplay of sex, race and ethnicity, as well as social determinants of health, and how they impact the risk of cardiovascular disease and adverse outcomes in order to avert future CVD morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Mieres added.

Looking ahead, the writing group said future CVD prevention guidelines could be strengthened by including culturally-specific lifestyle recommendations.

They also said community-based approaches, faith-based community partnerships, and peer support to encourage a healthy lifestyle could play a key role in preventing CVD among all women.

This scientific statement was prepared by the volunteer writing group on behalf of the AHA’s Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke in Women and Underrepresented Populations Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, the Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, the Council on Hypertension, the Council on Lifelong Congenital Heart Disease and Heart Health in the Young, the Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health, the Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease, and the Stroke Council.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CIRCULATION

New ASE guideline on interventional echocardiography training

The American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) has issued guidance on all critical aspects of training for cardiology and anesthesiology trainees and postgraduate echocardiographers who plan to specialize in interventional echocardiography (IE).

The guideline outlines requirements of the training institution, the duration and core competencies of training, minimal procedural volume for competency in IE, and knowledge of specific structural health disease (SHD) procedures.

The 16-page guideline was published online in the Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography.

Specific skill set

IE is the primary imaging modality used to support and guide SHD interventions, such as heart valve replacements and other cardiac catheterization procedures, the writing group notes.

They say the “emerging specialty” of IE requires a specific set of skills to support an array of transcatheter therapies, with successful outcomes highly dependent on the skill of the echocardiography team.

“IE techniques are unique since imaging is performed in real-time, it is highly dependent on 3D and non-standard views, and it has immediate and profound implications for patient management,” Stephen H. Little, MD, ASE president and co-chair of the guideline writing group, says in a news release.

“Additionally, IE requires candid, accurate, and timely communication with other members of the multidisciplinary SHD team,” Dr. Little adds.

The new ASE guideline expands on the 2019 statement on echocardiography training put forward by the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and ASE, by focusing specifically on interventional echocardiographers.

It outlines core competencies common to all transcatheter therapies, as well as specific transcatheter procedures. It provides consensus recommendations for specific knowledge, experience, and skills to be learned and demonstrated within an IE training program or during postgraduate training.

A “core principle” in the guideline states that the length of IE training or achieved number of procedures performed are less important than the demonstration of procedure-specific competencies within the milestone domains of knowledge, skill, and communication.

“Transcatheter therapies for SHD continue to grow at a rapid pace, which means that the demand for skilled interventional echocardiographers has steadily increased,” Vera H. Rigolin, MD, co-chair of the guideline writing, says in the release.

“Training standards are needed to ensure that interventional echocardiographers have the necessary expertise to provide fast, accurate, and high-quality image acquisition and interpretation in real-time,” Dr. Rigolin adds.

In addition, the guidelines states that use of simulation training has a role in IE training.

Virtual and simulation training could shorten the learning curve for trainees and, when combined with remote learning, could permit societies to standardize a teaching curriculum and allow the trainee to complete training in a reasonable timeframe. Simulator training may also improve access to training and thus promote diversity and inclusivity, the writing group says.

The guideline has been endorsed by 21 ASE international partners.

Writing group co-chairs Little and Rigolin have declared no conflicts of interest. A complete list of disclosures for the writing group is available with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) has issued guidance on all critical aspects of training for cardiology and anesthesiology trainees and postgraduate echocardiographers who plan to specialize in interventional echocardiography (IE).

The guideline outlines requirements of the training institution, the duration and core competencies of training, minimal procedural volume for competency in IE, and knowledge of specific structural health disease (SHD) procedures.

The 16-page guideline was published online in the Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography.

Specific skill set

IE is the primary imaging modality used to support and guide SHD interventions, such as heart valve replacements and other cardiac catheterization procedures, the writing group notes.

They say the “emerging specialty” of IE requires a specific set of skills to support an array of transcatheter therapies, with successful outcomes highly dependent on the skill of the echocardiography team.

“IE techniques are unique since imaging is performed in real-time, it is highly dependent on 3D and non-standard views, and it has immediate and profound implications for patient management,” Stephen H. Little, MD, ASE president and co-chair of the guideline writing group, says in a news release.

“Additionally, IE requires candid, accurate, and timely communication with other members of the multidisciplinary SHD team,” Dr. Little adds.

The new ASE guideline expands on the 2019 statement on echocardiography training put forward by the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and ASE, by focusing specifically on interventional echocardiographers.

It outlines core competencies common to all transcatheter therapies, as well as specific transcatheter procedures. It provides consensus recommendations for specific knowledge, experience, and skills to be learned and demonstrated within an IE training program or during postgraduate training.

A “core principle” in the guideline states that the length of IE training or achieved number of procedures performed are less important than the demonstration of procedure-specific competencies within the milestone domains of knowledge, skill, and communication.

“Transcatheter therapies for SHD continue to grow at a rapid pace, which means that the demand for skilled interventional echocardiographers has steadily increased,” Vera H. Rigolin, MD, co-chair of the guideline writing, says in the release.

“Training standards are needed to ensure that interventional echocardiographers have the necessary expertise to provide fast, accurate, and high-quality image acquisition and interpretation in real-time,” Dr. Rigolin adds.

In addition, the guidelines states that use of simulation training has a role in IE training.

Virtual and simulation training could shorten the learning curve for trainees and, when combined with remote learning, could permit societies to standardize a teaching curriculum and allow the trainee to complete training in a reasonable timeframe. Simulator training may also improve access to training and thus promote diversity and inclusivity, the writing group says.

The guideline has been endorsed by 21 ASE international partners.

Writing group co-chairs Little and Rigolin have declared no conflicts of interest. A complete list of disclosures for the writing group is available with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) has issued guidance on all critical aspects of training for cardiology and anesthesiology trainees and postgraduate echocardiographers who plan to specialize in interventional echocardiography (IE).

The guideline outlines requirements of the training institution, the duration and core competencies of training, minimal procedural volume for competency in IE, and knowledge of specific structural health disease (SHD) procedures.

The 16-page guideline was published online in the Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography.

Specific skill set

IE is the primary imaging modality used to support and guide SHD interventions, such as heart valve replacements and other cardiac catheterization procedures, the writing group notes.

They say the “emerging specialty” of IE requires a specific set of skills to support an array of transcatheter therapies, with successful outcomes highly dependent on the skill of the echocardiography team.