User login

Same-day discharge for elective PCI shown safe in real-world analysis

Based on a large registry, there appears to be no adverse consequences for same-day discharge following an elective percutaneous cardiovascular intervention (PCI), according to an analysis of a nationwide registry.

“Our data suggest there has been no negative impact on patient outcomes as a result of increasing use of same-day discharge,” lead investigator Steven M. Bradley, MD, said in an interview.

The analysis was based on data on 819,091 patients who underwent an elective PCI procedure during July 2009–December 2017 in the National CathPCI Registry. During this period, the proportion of elective PCIs performed with same-day discharge rose from 4.5% to 28.6%, a fivefold gain, according to Dr. Bradley, an associate cardiologist at the Minneapolis Heart Institute, and colleagues.

Within this study, outcomes in 212,369 patients were analyzed through a link to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services data. Despite the growth in same-day discharge PCIs over the study period, there was no change in 30-day mortality rates while the rate of 30-day rehospitalization fell after risk adjustment.

These data are considered to have a message for routine practice, particularly for those hospitals that have been slow to move to same-day discharge for elective PCI when lack of complications makes this appropriate.

However, “this does not mean same-day discharge is safe for all patients,” Dr. Bradley cautioned, but these data suggest “there is a clear opportunity at sites with low rates” to look for strategies that allow patients to recover at home, which is preferred by many patients and lowers costs.

In 2009, the first year in which the data were analyzed, there was relatively little variation in the rate of same day discharge for elective PCI among the 1,716 hospitals that contributed patients to the registry. At that point, almost all hospitals had rates below 10%, according to the report published in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions on Aug 2, 2021 .

From 2011 onward, there were progressive gains at most hospitals, with an even steeper rise beginning in 2014. By 2017, even though some hospitals were still performing almost no same-day discharge PCIs, many were discharging up to 40%, and the outliers were discharging nearly all.

Expressed in interquartiles at the hospital level, the range climbed from 0.0% to 4.7% in 2009 and reached 4.5% to 41.0% by 2017. For 2017, relative to 2009, this produced an odds ratio for same-day discharge that was more than fourfold greater, after adjustment for year and access site.

Access site was an important variable. For those undergoing PCI with radial access, the median same-day discharge rates climbed from 21.8% in 2009 to 58.3% in 2017. Same-day discharge rates for elective PCI performed by femoral access, already lower in 2009, have consistently lagged. By 2017, the median rate of same-day discharge for those undergoing PCI by the femoral route was less than half of that associated with radial access.

Despite the faster rise in same-day discharge and radial access over the course of the study, these were not directly correlated. In 2017, 25% of sites performing PCI by radial access were still discharging fewer than 10% of patients on the same day as their elective PCI.

Several previous studies have also found that same-day discharge can be offered selectively after elective PCI without adversely affecting outcomes, according to multiple citations provided by the authors. The advantage of early discharge includes both convenience for the patient and lower costs, with some of the studies attempting to quantify savings. In one, it was estimated that per-case savings from performing radial-access elective PCI with same-day discharge was nearly $3,700 when compared with transfemoral access and an overnight stay.

Radial access key to same-day success

An accompanying editorial by Deepak Bhatt, MD, and Jonathan G. Sung, MBChB, who are both interventional cardiologists at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, generally agreed with the premise that these data support judicious use of same-day discharge for elective PCI.

They pointed out limitations in the study, including its retrospective design and the inability to look at important outcomes other than mortality and 30-day rehospitalization, such as bleeding, that are relevant to the safety of early discharge, but concluded that same-day discharge, as well as radial access procedures, are underused.

“For uncomplicated elective PCI, we should aim for same-day discharge,” Dr. Bhatt said in an interview. He linked this to radial access.

“Radial access certainly facilitates same-day discharge, though even beyond that aspect, it should be the default route of vascular access whenever possible,” Dr. Bhatt said. Yet he was careful to say that neither same-day discharge nor radial access can be recommended in all patients. While the operator needs “to be comfortable” with a radial access approach, there are multiple factors that might preclude early discharge.

“Of course, if a long procedure, high contrast use, bleeding, a long travel distance to get home, etc. [are considered], then an overnight stay may be warranted,” he said.

Dr. Bradley advised centers planning to increase their same-day discharge rates for elective PCI to use a systematic approach.

“Sites should identify areas for opportunity in the use of same-day discharge and then track the implications on patient outcomes to ensure that the approach being used maintains high-quality care,” he said.

Dr. Bradley reported no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Bhatt has received research funding from a large number of pharmaceutical and device manufacturers, including those that make products relevant to PCI.

Based on a large registry, there appears to be no adverse consequences for same-day discharge following an elective percutaneous cardiovascular intervention (PCI), according to an analysis of a nationwide registry.

“Our data suggest there has been no negative impact on patient outcomes as a result of increasing use of same-day discharge,” lead investigator Steven M. Bradley, MD, said in an interview.

The analysis was based on data on 819,091 patients who underwent an elective PCI procedure during July 2009–December 2017 in the National CathPCI Registry. During this period, the proportion of elective PCIs performed with same-day discharge rose from 4.5% to 28.6%, a fivefold gain, according to Dr. Bradley, an associate cardiologist at the Minneapolis Heart Institute, and colleagues.

Within this study, outcomes in 212,369 patients were analyzed through a link to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services data. Despite the growth in same-day discharge PCIs over the study period, there was no change in 30-day mortality rates while the rate of 30-day rehospitalization fell after risk adjustment.

These data are considered to have a message for routine practice, particularly for those hospitals that have been slow to move to same-day discharge for elective PCI when lack of complications makes this appropriate.

However, “this does not mean same-day discharge is safe for all patients,” Dr. Bradley cautioned, but these data suggest “there is a clear opportunity at sites with low rates” to look for strategies that allow patients to recover at home, which is preferred by many patients and lowers costs.

In 2009, the first year in which the data were analyzed, there was relatively little variation in the rate of same day discharge for elective PCI among the 1,716 hospitals that contributed patients to the registry. At that point, almost all hospitals had rates below 10%, according to the report published in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions on Aug 2, 2021 .

From 2011 onward, there were progressive gains at most hospitals, with an even steeper rise beginning in 2014. By 2017, even though some hospitals were still performing almost no same-day discharge PCIs, many were discharging up to 40%, and the outliers were discharging nearly all.

Expressed in interquartiles at the hospital level, the range climbed from 0.0% to 4.7% in 2009 and reached 4.5% to 41.0% by 2017. For 2017, relative to 2009, this produced an odds ratio for same-day discharge that was more than fourfold greater, after adjustment for year and access site.

Access site was an important variable. For those undergoing PCI with radial access, the median same-day discharge rates climbed from 21.8% in 2009 to 58.3% in 2017. Same-day discharge rates for elective PCI performed by femoral access, already lower in 2009, have consistently lagged. By 2017, the median rate of same-day discharge for those undergoing PCI by the femoral route was less than half of that associated with radial access.

Despite the faster rise in same-day discharge and radial access over the course of the study, these were not directly correlated. In 2017, 25% of sites performing PCI by radial access were still discharging fewer than 10% of patients on the same day as their elective PCI.

Several previous studies have also found that same-day discharge can be offered selectively after elective PCI without adversely affecting outcomes, according to multiple citations provided by the authors. The advantage of early discharge includes both convenience for the patient and lower costs, with some of the studies attempting to quantify savings. In one, it was estimated that per-case savings from performing radial-access elective PCI with same-day discharge was nearly $3,700 when compared with transfemoral access and an overnight stay.

Radial access key to same-day success

An accompanying editorial by Deepak Bhatt, MD, and Jonathan G. Sung, MBChB, who are both interventional cardiologists at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, generally agreed with the premise that these data support judicious use of same-day discharge for elective PCI.

They pointed out limitations in the study, including its retrospective design and the inability to look at important outcomes other than mortality and 30-day rehospitalization, such as bleeding, that are relevant to the safety of early discharge, but concluded that same-day discharge, as well as radial access procedures, are underused.

“For uncomplicated elective PCI, we should aim for same-day discharge,” Dr. Bhatt said in an interview. He linked this to radial access.

“Radial access certainly facilitates same-day discharge, though even beyond that aspect, it should be the default route of vascular access whenever possible,” Dr. Bhatt said. Yet he was careful to say that neither same-day discharge nor radial access can be recommended in all patients. While the operator needs “to be comfortable” with a radial access approach, there are multiple factors that might preclude early discharge.

“Of course, if a long procedure, high contrast use, bleeding, a long travel distance to get home, etc. [are considered], then an overnight stay may be warranted,” he said.

Dr. Bradley advised centers planning to increase their same-day discharge rates for elective PCI to use a systematic approach.

“Sites should identify areas for opportunity in the use of same-day discharge and then track the implications on patient outcomes to ensure that the approach being used maintains high-quality care,” he said.

Dr. Bradley reported no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Bhatt has received research funding from a large number of pharmaceutical and device manufacturers, including those that make products relevant to PCI.

Based on a large registry, there appears to be no adverse consequences for same-day discharge following an elective percutaneous cardiovascular intervention (PCI), according to an analysis of a nationwide registry.

“Our data suggest there has been no negative impact on patient outcomes as a result of increasing use of same-day discharge,” lead investigator Steven M. Bradley, MD, said in an interview.

The analysis was based on data on 819,091 patients who underwent an elective PCI procedure during July 2009–December 2017 in the National CathPCI Registry. During this period, the proportion of elective PCIs performed with same-day discharge rose from 4.5% to 28.6%, a fivefold gain, according to Dr. Bradley, an associate cardiologist at the Minneapolis Heart Institute, and colleagues.

Within this study, outcomes in 212,369 patients were analyzed through a link to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services data. Despite the growth in same-day discharge PCIs over the study period, there was no change in 30-day mortality rates while the rate of 30-day rehospitalization fell after risk adjustment.

These data are considered to have a message for routine practice, particularly for those hospitals that have been slow to move to same-day discharge for elective PCI when lack of complications makes this appropriate.

However, “this does not mean same-day discharge is safe for all patients,” Dr. Bradley cautioned, but these data suggest “there is a clear opportunity at sites with low rates” to look for strategies that allow patients to recover at home, which is preferred by many patients and lowers costs.

In 2009, the first year in which the data were analyzed, there was relatively little variation in the rate of same day discharge for elective PCI among the 1,716 hospitals that contributed patients to the registry. At that point, almost all hospitals had rates below 10%, according to the report published in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions on Aug 2, 2021 .

From 2011 onward, there were progressive gains at most hospitals, with an even steeper rise beginning in 2014. By 2017, even though some hospitals were still performing almost no same-day discharge PCIs, many were discharging up to 40%, and the outliers were discharging nearly all.

Expressed in interquartiles at the hospital level, the range climbed from 0.0% to 4.7% in 2009 and reached 4.5% to 41.0% by 2017. For 2017, relative to 2009, this produced an odds ratio for same-day discharge that was more than fourfold greater, after adjustment for year and access site.

Access site was an important variable. For those undergoing PCI with radial access, the median same-day discharge rates climbed from 21.8% in 2009 to 58.3% in 2017. Same-day discharge rates for elective PCI performed by femoral access, already lower in 2009, have consistently lagged. By 2017, the median rate of same-day discharge for those undergoing PCI by the femoral route was less than half of that associated with radial access.

Despite the faster rise in same-day discharge and radial access over the course of the study, these were not directly correlated. In 2017, 25% of sites performing PCI by radial access were still discharging fewer than 10% of patients on the same day as their elective PCI.

Several previous studies have also found that same-day discharge can be offered selectively after elective PCI without adversely affecting outcomes, according to multiple citations provided by the authors. The advantage of early discharge includes both convenience for the patient and lower costs, with some of the studies attempting to quantify savings. In one, it was estimated that per-case savings from performing radial-access elective PCI with same-day discharge was nearly $3,700 when compared with transfemoral access and an overnight stay.

Radial access key to same-day success

An accompanying editorial by Deepak Bhatt, MD, and Jonathan G. Sung, MBChB, who are both interventional cardiologists at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, generally agreed with the premise that these data support judicious use of same-day discharge for elective PCI.

They pointed out limitations in the study, including its retrospective design and the inability to look at important outcomes other than mortality and 30-day rehospitalization, such as bleeding, that are relevant to the safety of early discharge, but concluded that same-day discharge, as well as radial access procedures, are underused.

“For uncomplicated elective PCI, we should aim for same-day discharge,” Dr. Bhatt said in an interview. He linked this to radial access.

“Radial access certainly facilitates same-day discharge, though even beyond that aspect, it should be the default route of vascular access whenever possible,” Dr. Bhatt said. Yet he was careful to say that neither same-day discharge nor radial access can be recommended in all patients. While the operator needs “to be comfortable” with a radial access approach, there are multiple factors that might preclude early discharge.

“Of course, if a long procedure, high contrast use, bleeding, a long travel distance to get home, etc. [are considered], then an overnight stay may be warranted,” he said.

Dr. Bradley advised centers planning to increase their same-day discharge rates for elective PCI to use a systematic approach.

“Sites should identify areas for opportunity in the use of same-day discharge and then track the implications on patient outcomes to ensure that the approach being used maintains high-quality care,” he said.

Dr. Bradley reported no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Bhatt has received research funding from a large number of pharmaceutical and device manufacturers, including those that make products relevant to PCI.

FROM JACC: CARDIOVASCULAR INTERVENTIONS

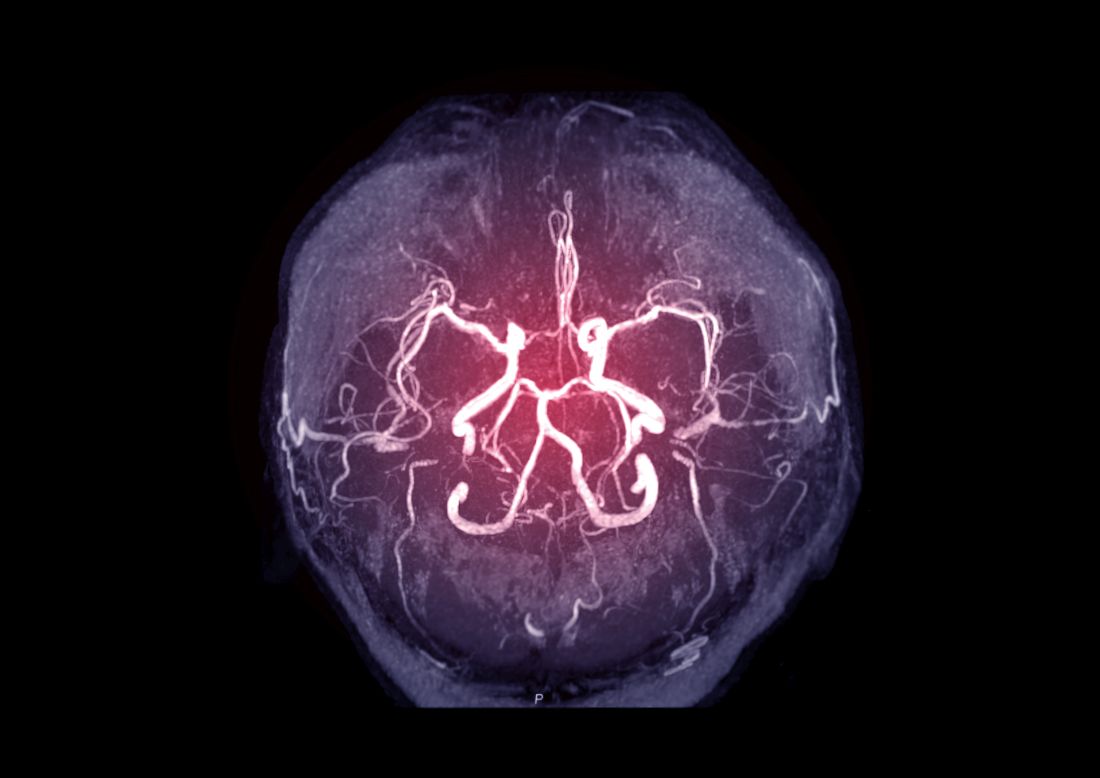

Intracranial atherosclerosis finding on MRA linked to stroke

An incidental diagnosis of intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis in stroke-free individuals should trigger a thorough assessment of vascular health, according to the authors of a study identifying risk factors and vascular event risk in asymptomatic ICAS.

That conclusion emerged from data collected on more than 1,000 stroke-free participants in NOMAS (Northern Manhattan Study), a trial that prospectively followed participants who underwent a brain magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) during 2003-2008.

In ICAS patients with stenosis of at least 70%, even with aggressive medical therapy, the annual stroke recurrence rate is 10%-20% in those with occlusions and at least three or more vascular risk factors. This high rate of recurrent vascular events in patients with stroke caused by ICAS warrants greater focus on primary prevention and targeted interventions for stroke-free individuals at highest risk for ICAS-related events, the investigators concluded.

Identify high-risk ICAS

Using NOMAS data, the investigators, led by Jose Gutierrez, MD, MPH, tested the hypothesis that stroke-free subjects at high risk of stroke and vascular events could be identified through the presence of asymptomatic ICAS. NOMAS is an ongoing, population-based epidemiologic study among randomly selected people with home telephones living in northern Manhattan.

During 2003-2008, investigators invited participants who were at least 50 years old, stroke free, and without contraindications to undergo brain MRA. The 1,211 study members were followed annually via telephone and in-person adjudication of events. A control group of 79 patients with no MRA was also identified with similar rates of hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia and current smoking.

Mean age was about 71 years (59% female, 65% Hispanic, 45% any stenosis). At the time of MRA, 78% had hypertension, 25% had diabetes, 81% had hypercholesterolemia, and 11% were current smokers.

Researchers rated stenoses in 11 brain arteries as 0, with no stenosis; 1, with less than 50% stenosis or luminal irregularities; 2, 50%-69% stenosis; and 3, at least 70% stenosis or flow gap. Outcomes included vascular death, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, cardioembolic stroke, intracranial artery disease stroke (which combined intracranial small and large artery disease strokes), and any vascular events (defined as a composite of vascular death, any stroke, or MI).

Greater stenosis denotes higher risk

Analysis found ICAS to be associated with older age (odds ratio, 1.02 per year; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.04), hypertension duration (OR, 1.01 per year; 95% CI, 1.00-1.02), higher number of glucose-lowering drugs (OR, 1.64 per each medication; 95% CI, 1.24-2.15), and HDL cholesterol(OR, 0.96 per mg/dL; 95% CI, 0.92-0.99). Event risk was greater among participants with ICAS of at least 70% (5.5% annual risk of vascular events; HR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.4-3.2; compared with those with no ICAS), the investigators reported in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Furthermore, 80% of incident strokes initially classified as small artery disease occurred among individuals with evidence of any degree of ICAS at their baseline MRI, the investigators noted. They found also that individuals with ICAS who had a primary care physician at the time of their initial MRI had a lower risk of events. Frequent primary care visits, they observed, might imply greater control of risk factors and other unmeasured confounders, such as health literacy, health care trust, access, and availability.

Incidental ICAS should trigger vascular assessment

An incidental diagnosis of ICAS in stroke-free subjects should trigger a thorough assessment of vascular health, the investigators concluded. They commented also that prophylaxis of first-ever stroke at this asymptomatic stage “may magnify the societal benefits of vascular prevention and decrease stroke-related disability and vascular death in our communities.”

“The big gap in our knowledge,” Tanya N. Turan, MD, professor of neurology at Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, wrote in an accompanying editorial “is understanding the pathophysiological triggers for an asymptomatic stenosis to become a high-risk symptomatic stenosis. Until that question is answered, screening for asymptomatic ICAS is unlikely to change management among patients with known vascular risk factors.” In an interview, she observed further that “MRI plaque imaging could be a useful research tool to see if certain plaque features in an asymptomatic lesion are high risk for causing stroke. If that were proven, then it would make more sense to screen for ICAS and develop specific therapeutic strategies targeting high-risk asymptomatic plaque.”

Focus on recurrent stroke misplaced

Dr. Gutierrez said in an interview: “In the stroke world, most of what we do focuses on preventing recurrent stroke. Nonetheless, three-fourths of strokes in this country are new strokes, so to me it doesn’t make much sense to spend most of our efforts and attention to prevent the smallest fractions of strokes that occur in our society.”

He stressed that “the first immediate application of our results is that if people having a brain MRA for other reasons are found to have incidental, and therefore asymptomatic, ICAS, then they should be aggressively treated for vascular risk factors.” Secondly, “we hope to identify the patients at the highest risk of prevalent ICAS before they have a stroke. Among them, a brain MRI/MRA evaluating the phenotype would determine how aggressively to treat LDL.”

Dr. Gutierrez, professor of neurology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, noted that educating patients of their underlying high risk of events may have the effect of engaging them more in their own care. “There is evidence that actually showing people scans increases compliance and health literacy. It’s not yet standard of care, but we hope our future projects will help advance the field in the primary prevention direction,” he said.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported that they had no relevant financial disclosures.

An incidental diagnosis of intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis in stroke-free individuals should trigger a thorough assessment of vascular health, according to the authors of a study identifying risk factors and vascular event risk in asymptomatic ICAS.

That conclusion emerged from data collected on more than 1,000 stroke-free participants in NOMAS (Northern Manhattan Study), a trial that prospectively followed participants who underwent a brain magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) during 2003-2008.

In ICAS patients with stenosis of at least 70%, even with aggressive medical therapy, the annual stroke recurrence rate is 10%-20% in those with occlusions and at least three or more vascular risk factors. This high rate of recurrent vascular events in patients with stroke caused by ICAS warrants greater focus on primary prevention and targeted interventions for stroke-free individuals at highest risk for ICAS-related events, the investigators concluded.

Identify high-risk ICAS

Using NOMAS data, the investigators, led by Jose Gutierrez, MD, MPH, tested the hypothesis that stroke-free subjects at high risk of stroke and vascular events could be identified through the presence of asymptomatic ICAS. NOMAS is an ongoing, population-based epidemiologic study among randomly selected people with home telephones living in northern Manhattan.

During 2003-2008, investigators invited participants who were at least 50 years old, stroke free, and without contraindications to undergo brain MRA. The 1,211 study members were followed annually via telephone and in-person adjudication of events. A control group of 79 patients with no MRA was also identified with similar rates of hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia and current smoking.

Mean age was about 71 years (59% female, 65% Hispanic, 45% any stenosis). At the time of MRA, 78% had hypertension, 25% had diabetes, 81% had hypercholesterolemia, and 11% were current smokers.

Researchers rated stenoses in 11 brain arteries as 0, with no stenosis; 1, with less than 50% stenosis or luminal irregularities; 2, 50%-69% stenosis; and 3, at least 70% stenosis or flow gap. Outcomes included vascular death, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, cardioembolic stroke, intracranial artery disease stroke (which combined intracranial small and large artery disease strokes), and any vascular events (defined as a composite of vascular death, any stroke, or MI).

Greater stenosis denotes higher risk

Analysis found ICAS to be associated with older age (odds ratio, 1.02 per year; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.04), hypertension duration (OR, 1.01 per year; 95% CI, 1.00-1.02), higher number of glucose-lowering drugs (OR, 1.64 per each medication; 95% CI, 1.24-2.15), and HDL cholesterol(OR, 0.96 per mg/dL; 95% CI, 0.92-0.99). Event risk was greater among participants with ICAS of at least 70% (5.5% annual risk of vascular events; HR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.4-3.2; compared with those with no ICAS), the investigators reported in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Furthermore, 80% of incident strokes initially classified as small artery disease occurred among individuals with evidence of any degree of ICAS at their baseline MRI, the investigators noted. They found also that individuals with ICAS who had a primary care physician at the time of their initial MRI had a lower risk of events. Frequent primary care visits, they observed, might imply greater control of risk factors and other unmeasured confounders, such as health literacy, health care trust, access, and availability.

Incidental ICAS should trigger vascular assessment

An incidental diagnosis of ICAS in stroke-free subjects should trigger a thorough assessment of vascular health, the investigators concluded. They commented also that prophylaxis of first-ever stroke at this asymptomatic stage “may magnify the societal benefits of vascular prevention and decrease stroke-related disability and vascular death in our communities.”

“The big gap in our knowledge,” Tanya N. Turan, MD, professor of neurology at Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, wrote in an accompanying editorial “is understanding the pathophysiological triggers for an asymptomatic stenosis to become a high-risk symptomatic stenosis. Until that question is answered, screening for asymptomatic ICAS is unlikely to change management among patients with known vascular risk factors.” In an interview, she observed further that “MRI plaque imaging could be a useful research tool to see if certain plaque features in an asymptomatic lesion are high risk for causing stroke. If that were proven, then it would make more sense to screen for ICAS and develop specific therapeutic strategies targeting high-risk asymptomatic plaque.”

Focus on recurrent stroke misplaced

Dr. Gutierrez said in an interview: “In the stroke world, most of what we do focuses on preventing recurrent stroke. Nonetheless, three-fourths of strokes in this country are new strokes, so to me it doesn’t make much sense to spend most of our efforts and attention to prevent the smallest fractions of strokes that occur in our society.”

He stressed that “the first immediate application of our results is that if people having a brain MRA for other reasons are found to have incidental, and therefore asymptomatic, ICAS, then they should be aggressively treated for vascular risk factors.” Secondly, “we hope to identify the patients at the highest risk of prevalent ICAS before they have a stroke. Among them, a brain MRI/MRA evaluating the phenotype would determine how aggressively to treat LDL.”

Dr. Gutierrez, professor of neurology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, noted that educating patients of their underlying high risk of events may have the effect of engaging them more in their own care. “There is evidence that actually showing people scans increases compliance and health literacy. It’s not yet standard of care, but we hope our future projects will help advance the field in the primary prevention direction,” he said.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported that they had no relevant financial disclosures.

An incidental diagnosis of intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis in stroke-free individuals should trigger a thorough assessment of vascular health, according to the authors of a study identifying risk factors and vascular event risk in asymptomatic ICAS.

That conclusion emerged from data collected on more than 1,000 stroke-free participants in NOMAS (Northern Manhattan Study), a trial that prospectively followed participants who underwent a brain magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) during 2003-2008.

In ICAS patients with stenosis of at least 70%, even with aggressive medical therapy, the annual stroke recurrence rate is 10%-20% in those with occlusions and at least three or more vascular risk factors. This high rate of recurrent vascular events in patients with stroke caused by ICAS warrants greater focus on primary prevention and targeted interventions for stroke-free individuals at highest risk for ICAS-related events, the investigators concluded.

Identify high-risk ICAS

Using NOMAS data, the investigators, led by Jose Gutierrez, MD, MPH, tested the hypothesis that stroke-free subjects at high risk of stroke and vascular events could be identified through the presence of asymptomatic ICAS. NOMAS is an ongoing, population-based epidemiologic study among randomly selected people with home telephones living in northern Manhattan.

During 2003-2008, investigators invited participants who were at least 50 years old, stroke free, and without contraindications to undergo brain MRA. The 1,211 study members were followed annually via telephone and in-person adjudication of events. A control group of 79 patients with no MRA was also identified with similar rates of hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia and current smoking.

Mean age was about 71 years (59% female, 65% Hispanic, 45% any stenosis). At the time of MRA, 78% had hypertension, 25% had diabetes, 81% had hypercholesterolemia, and 11% were current smokers.

Researchers rated stenoses in 11 brain arteries as 0, with no stenosis; 1, with less than 50% stenosis or luminal irregularities; 2, 50%-69% stenosis; and 3, at least 70% stenosis or flow gap. Outcomes included vascular death, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, cardioembolic stroke, intracranial artery disease stroke (which combined intracranial small and large artery disease strokes), and any vascular events (defined as a composite of vascular death, any stroke, or MI).

Greater stenosis denotes higher risk

Analysis found ICAS to be associated with older age (odds ratio, 1.02 per year; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.04), hypertension duration (OR, 1.01 per year; 95% CI, 1.00-1.02), higher number of glucose-lowering drugs (OR, 1.64 per each medication; 95% CI, 1.24-2.15), and HDL cholesterol(OR, 0.96 per mg/dL; 95% CI, 0.92-0.99). Event risk was greater among participants with ICAS of at least 70% (5.5% annual risk of vascular events; HR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.4-3.2; compared with those with no ICAS), the investigators reported in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Furthermore, 80% of incident strokes initially classified as small artery disease occurred among individuals with evidence of any degree of ICAS at their baseline MRI, the investigators noted. They found also that individuals with ICAS who had a primary care physician at the time of their initial MRI had a lower risk of events. Frequent primary care visits, they observed, might imply greater control of risk factors and other unmeasured confounders, such as health literacy, health care trust, access, and availability.

Incidental ICAS should trigger vascular assessment

An incidental diagnosis of ICAS in stroke-free subjects should trigger a thorough assessment of vascular health, the investigators concluded. They commented also that prophylaxis of first-ever stroke at this asymptomatic stage “may magnify the societal benefits of vascular prevention and decrease stroke-related disability and vascular death in our communities.”

“The big gap in our knowledge,” Tanya N. Turan, MD, professor of neurology at Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, wrote in an accompanying editorial “is understanding the pathophysiological triggers for an asymptomatic stenosis to become a high-risk symptomatic stenosis. Until that question is answered, screening for asymptomatic ICAS is unlikely to change management among patients with known vascular risk factors.” In an interview, she observed further that “MRI plaque imaging could be a useful research tool to see if certain plaque features in an asymptomatic lesion are high risk for causing stroke. If that were proven, then it would make more sense to screen for ICAS and develop specific therapeutic strategies targeting high-risk asymptomatic plaque.”

Focus on recurrent stroke misplaced

Dr. Gutierrez said in an interview: “In the stroke world, most of what we do focuses on preventing recurrent stroke. Nonetheless, three-fourths of strokes in this country are new strokes, so to me it doesn’t make much sense to spend most of our efforts and attention to prevent the smallest fractions of strokes that occur in our society.”

He stressed that “the first immediate application of our results is that if people having a brain MRA for other reasons are found to have incidental, and therefore asymptomatic, ICAS, then they should be aggressively treated for vascular risk factors.” Secondly, “we hope to identify the patients at the highest risk of prevalent ICAS before they have a stroke. Among them, a brain MRI/MRA evaluating the phenotype would determine how aggressively to treat LDL.”

Dr. Gutierrez, professor of neurology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, noted that educating patients of their underlying high risk of events may have the effect of engaging them more in their own care. “There is evidence that actually showing people scans increases compliance and health literacy. It’s not yet standard of care, but we hope our future projects will help advance the field in the primary prevention direction,” he said.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported that they had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

DOACs best aspirin after ventricular ablation: STROKE-VT

Catheter ablation has been around a lot longer for ventricular arrhythmia than for atrial fibrillation, but far less is settled about what antithrombotic therapy should follow ventricular ablations, as there have been no big, randomized trials for guidance.

But the evidence base grew stronger this week, and it favors postprocedure treatment with a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) over antiplatelet therapy with aspirin for patients undergoing radiofrequency (RF) ablation to treat left ventricular (LV) arrhythmias.

The 30-day risk for ischemic stroke or transient ischemia attack (TIA) was sharply higher for patients who took daily aspirin after RF ablation for ventricular tachycardia (VT) or premature ventricular contractions (PVC) in a multicenter randomized trial.

Those of its 246 patients who received aspirin were also far more likely to show asymptomatic lesions on cerebral MRI scans performed both 24 hours and 30 days after the procedure.

The findings show the importance of DOAC therapy after ventricular ablation procedures, a setting for which there are no evidence-based guidelines, “to mitigate the risk of systemic thromboembolic events,” said Dhanunjaya Lakkireddy, MD, Kansas City Heart Rhythm Institute, Overland Park. He spoke at a media presentation on the trial, called STROKE-VT, during the Heart Rhythm Society 2021 Scientific Sessions, held virtually and on-site in Boston.

The risk for stroke and TIA went up in association with several procedural issues, including some that operators might be able to change in order to reach for better outcomes, Dr. Lakkireddy observed.

“Prolonged radiofrequency ablation times, especially in those with low left ventricle ejection fractions, are definitely higher risk,” as are procedures that involved the retrograde transaortic approach for advancing the ablation catheter, rather than a trans-septal approach.

The retrograde transaortic approach should be avoided in such procedures, “whenever it can be avoided,” said Dr. Lakkireddy, who formally presented STROKE-VT at the HRS sessions and is lead author on its report published about the same time in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

The trial has limitations, but “it’s a very important study, and I think that this could become our standard of care for managing anticoagulation after VT and PVC left-sided ablations,” Mina K. Chung, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said as an invited discussant after Dr. Lakkireddy’s presentation.

How patients are treated with antithrombotics after ventricular ablations can vary widely, sometimes based on the operator’s “subjective feeling of how extensive the ablation is,” Christine M. Albert, MD, MPH, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, not involved in the study, said during the STROKE-VT media briefing.

That’s consistent with the guidelines, which propose oral anticoagulation therapy after more extensive ventricular ablations and antiplatelets when the ablation is more limited – based more on consensus than firm evidence – as described by Jeffrey R. Winterfield, MD, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, and Usha Tedrow, MD, MSc, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, in an accompanying editorial.

“This is really the first randomized trial data, that I know of, that we have on this. So I do think it will be guideline-influencing,” Dr. Albert said.

“This should change practice,” agreed Jonathan P. Piccini, MD, MHS, Duke University, Durham, N.C., also not part of STROKE-VT. “A lot of evidence in the trial is consistent and provides a compelling story, not to mention that, in my opinion, the study probably underestimates the value of DOACs,” he told this news organization.

That’s because patients assigned to DOACs had far longer ablation times, “so their risk was even greater than in the aspirin arm,” Dr. Piccini said. Ablation times averaged 2,095 seconds in the DOAC group, compared with only 1,708 seconds in the aspirin group, probably because the preponderance of VT over PVC ablations for those getting a DOAC was even greater in the aspirin group.

Of the 246 patients assigned to either aspirin or a DOAC, usually a factor Xa inhibitor, 75% had undergone VT ablation and the remainder ablation for PVCs. Their mean age was 60 years and only 18% were women. None had experienced a cerebrovascular event in the previous 3 months.

The 30-day odds ratio for TIA or ischemic stroke in patients who received aspirin, compared with a DOAC, was 12.6 (95% confidence interval, 4.10-39.11; P < .001).

The corresponding OR for asymptomatic cerebral lesions by MRI at 24 hours was 2.15 (95% CI, 1.02-4.54; P = .04) and at 30 days was 3.48 (95% CI, 1.38-8.80; P = .008).

The rate of stroke or TIA was similar in patients who underwent ablation for VT and for PVCs (14% vs. 16%, respectively; P = .70). There were fewer asymptomatic cerebrovascular events by MRI at 24 hours for those undergoing VT ablations (14.7% and 25.8%, respectively; P = .046); but difference between rates attenuated by 30 days (11.4% and 14.5%, respectively; P = .52).

The OR for TIA or stroke associated with the retrograde transaortic approach, performed in about 40% of the patients, compared with the trans-septal approach in the remainder was 2.60 (95% CI, 1.06-6.37; P = .04).

“The study tells us it’s safe and indeed preferable to anticoagulate after an ablation procedure. But the more important finding, perhaps, wasn’t the one related to the core hypothesis. And that was the effect of retrograde access,” Paul A. Friedman, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said as an invited discussant after Dr. Lakkireddy’s formal presentation of the trial.

Whether a ventricular ablation is performed using the retrograde transaortic or trans-septal approach often depends on the location of the ablation targets in the left ventricle. But in some cases it’s a matter of operator preference, Dr. Piccini observed.

“There are some situations where, really, it is better to do retrograde aortic, and there are some cases that are better to do trans-septal. But now there’s going to be a higher burden of proof,” he said. Given the findings of STROKE-VT, operators may need to consider that a ventricular ablation procedure that can be done by the trans-septal route perhaps ought to be consistently done that way.

Dr. Lakkireddy discloses financial relationships with Boston Scientific, Biosense Webster, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and more. Dr. Chung had “nothing relevant to disclose.” Dr. Piccini discloses receiving honoraria or speaking or consulting fees from Sanofi, Abbott, ARCA Biopharma, Medtronic, Philips, Biotronik, Allergan, LivaNova, and Myokardia; and research in conjunction with Bayer Healthcare, Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Philips. Dr. Friedman discloses conducting research in conjunction with Medtronic and Abbott; holding intellectual property rights with AliveCor, Inference, Medicool, Eko, and Anumana; and receiving honoraria or speaking or consulting fees from Boston Scientific. Dr. Winterfield and Dr. Tedrow had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Catheter ablation has been around a lot longer for ventricular arrhythmia than for atrial fibrillation, but far less is settled about what antithrombotic therapy should follow ventricular ablations, as there have been no big, randomized trials for guidance.

But the evidence base grew stronger this week, and it favors postprocedure treatment with a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) over antiplatelet therapy with aspirin for patients undergoing radiofrequency (RF) ablation to treat left ventricular (LV) arrhythmias.

The 30-day risk for ischemic stroke or transient ischemia attack (TIA) was sharply higher for patients who took daily aspirin after RF ablation for ventricular tachycardia (VT) or premature ventricular contractions (PVC) in a multicenter randomized trial.

Those of its 246 patients who received aspirin were also far more likely to show asymptomatic lesions on cerebral MRI scans performed both 24 hours and 30 days after the procedure.

The findings show the importance of DOAC therapy after ventricular ablation procedures, a setting for which there are no evidence-based guidelines, “to mitigate the risk of systemic thromboembolic events,” said Dhanunjaya Lakkireddy, MD, Kansas City Heart Rhythm Institute, Overland Park. He spoke at a media presentation on the trial, called STROKE-VT, during the Heart Rhythm Society 2021 Scientific Sessions, held virtually and on-site in Boston.

The risk for stroke and TIA went up in association with several procedural issues, including some that operators might be able to change in order to reach for better outcomes, Dr. Lakkireddy observed.

“Prolonged radiofrequency ablation times, especially in those with low left ventricle ejection fractions, are definitely higher risk,” as are procedures that involved the retrograde transaortic approach for advancing the ablation catheter, rather than a trans-septal approach.

The retrograde transaortic approach should be avoided in such procedures, “whenever it can be avoided,” said Dr. Lakkireddy, who formally presented STROKE-VT at the HRS sessions and is lead author on its report published about the same time in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

The trial has limitations, but “it’s a very important study, and I think that this could become our standard of care for managing anticoagulation after VT and PVC left-sided ablations,” Mina K. Chung, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said as an invited discussant after Dr. Lakkireddy’s presentation.

How patients are treated with antithrombotics after ventricular ablations can vary widely, sometimes based on the operator’s “subjective feeling of how extensive the ablation is,” Christine M. Albert, MD, MPH, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, not involved in the study, said during the STROKE-VT media briefing.

That’s consistent with the guidelines, which propose oral anticoagulation therapy after more extensive ventricular ablations and antiplatelets when the ablation is more limited – based more on consensus than firm evidence – as described by Jeffrey R. Winterfield, MD, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, and Usha Tedrow, MD, MSc, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, in an accompanying editorial.

“This is really the first randomized trial data, that I know of, that we have on this. So I do think it will be guideline-influencing,” Dr. Albert said.

“This should change practice,” agreed Jonathan P. Piccini, MD, MHS, Duke University, Durham, N.C., also not part of STROKE-VT. “A lot of evidence in the trial is consistent and provides a compelling story, not to mention that, in my opinion, the study probably underestimates the value of DOACs,” he told this news organization.

That’s because patients assigned to DOACs had far longer ablation times, “so their risk was even greater than in the aspirin arm,” Dr. Piccini said. Ablation times averaged 2,095 seconds in the DOAC group, compared with only 1,708 seconds in the aspirin group, probably because the preponderance of VT over PVC ablations for those getting a DOAC was even greater in the aspirin group.

Of the 246 patients assigned to either aspirin or a DOAC, usually a factor Xa inhibitor, 75% had undergone VT ablation and the remainder ablation for PVCs. Their mean age was 60 years and only 18% were women. None had experienced a cerebrovascular event in the previous 3 months.

The 30-day odds ratio for TIA or ischemic stroke in patients who received aspirin, compared with a DOAC, was 12.6 (95% confidence interval, 4.10-39.11; P < .001).

The corresponding OR for asymptomatic cerebral lesions by MRI at 24 hours was 2.15 (95% CI, 1.02-4.54; P = .04) and at 30 days was 3.48 (95% CI, 1.38-8.80; P = .008).

The rate of stroke or TIA was similar in patients who underwent ablation for VT and for PVCs (14% vs. 16%, respectively; P = .70). There were fewer asymptomatic cerebrovascular events by MRI at 24 hours for those undergoing VT ablations (14.7% and 25.8%, respectively; P = .046); but difference between rates attenuated by 30 days (11.4% and 14.5%, respectively; P = .52).

The OR for TIA or stroke associated with the retrograde transaortic approach, performed in about 40% of the patients, compared with the trans-septal approach in the remainder was 2.60 (95% CI, 1.06-6.37; P = .04).

“The study tells us it’s safe and indeed preferable to anticoagulate after an ablation procedure. But the more important finding, perhaps, wasn’t the one related to the core hypothesis. And that was the effect of retrograde access,” Paul A. Friedman, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said as an invited discussant after Dr. Lakkireddy’s formal presentation of the trial.

Whether a ventricular ablation is performed using the retrograde transaortic or trans-septal approach often depends on the location of the ablation targets in the left ventricle. But in some cases it’s a matter of operator preference, Dr. Piccini observed.

“There are some situations where, really, it is better to do retrograde aortic, and there are some cases that are better to do trans-septal. But now there’s going to be a higher burden of proof,” he said. Given the findings of STROKE-VT, operators may need to consider that a ventricular ablation procedure that can be done by the trans-septal route perhaps ought to be consistently done that way.

Dr. Lakkireddy discloses financial relationships with Boston Scientific, Biosense Webster, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and more. Dr. Chung had “nothing relevant to disclose.” Dr. Piccini discloses receiving honoraria or speaking or consulting fees from Sanofi, Abbott, ARCA Biopharma, Medtronic, Philips, Biotronik, Allergan, LivaNova, and Myokardia; and research in conjunction with Bayer Healthcare, Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Philips. Dr. Friedman discloses conducting research in conjunction with Medtronic and Abbott; holding intellectual property rights with AliveCor, Inference, Medicool, Eko, and Anumana; and receiving honoraria or speaking or consulting fees from Boston Scientific. Dr. Winterfield and Dr. Tedrow had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Catheter ablation has been around a lot longer for ventricular arrhythmia than for atrial fibrillation, but far less is settled about what antithrombotic therapy should follow ventricular ablations, as there have been no big, randomized trials for guidance.

But the evidence base grew stronger this week, and it favors postprocedure treatment with a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) over antiplatelet therapy with aspirin for patients undergoing radiofrequency (RF) ablation to treat left ventricular (LV) arrhythmias.

The 30-day risk for ischemic stroke or transient ischemia attack (TIA) was sharply higher for patients who took daily aspirin after RF ablation for ventricular tachycardia (VT) or premature ventricular contractions (PVC) in a multicenter randomized trial.

Those of its 246 patients who received aspirin were also far more likely to show asymptomatic lesions on cerebral MRI scans performed both 24 hours and 30 days after the procedure.

The findings show the importance of DOAC therapy after ventricular ablation procedures, a setting for which there are no evidence-based guidelines, “to mitigate the risk of systemic thromboembolic events,” said Dhanunjaya Lakkireddy, MD, Kansas City Heart Rhythm Institute, Overland Park. He spoke at a media presentation on the trial, called STROKE-VT, during the Heart Rhythm Society 2021 Scientific Sessions, held virtually and on-site in Boston.

The risk for stroke and TIA went up in association with several procedural issues, including some that operators might be able to change in order to reach for better outcomes, Dr. Lakkireddy observed.

“Prolonged radiofrequency ablation times, especially in those with low left ventricle ejection fractions, are definitely higher risk,” as are procedures that involved the retrograde transaortic approach for advancing the ablation catheter, rather than a trans-septal approach.

The retrograde transaortic approach should be avoided in such procedures, “whenever it can be avoided,” said Dr. Lakkireddy, who formally presented STROKE-VT at the HRS sessions and is lead author on its report published about the same time in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

The trial has limitations, but “it’s a very important study, and I think that this could become our standard of care for managing anticoagulation after VT and PVC left-sided ablations,” Mina K. Chung, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said as an invited discussant after Dr. Lakkireddy’s presentation.

How patients are treated with antithrombotics after ventricular ablations can vary widely, sometimes based on the operator’s “subjective feeling of how extensive the ablation is,” Christine M. Albert, MD, MPH, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, not involved in the study, said during the STROKE-VT media briefing.

That’s consistent with the guidelines, which propose oral anticoagulation therapy after more extensive ventricular ablations and antiplatelets when the ablation is more limited – based more on consensus than firm evidence – as described by Jeffrey R. Winterfield, MD, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, and Usha Tedrow, MD, MSc, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, in an accompanying editorial.

“This is really the first randomized trial data, that I know of, that we have on this. So I do think it will be guideline-influencing,” Dr. Albert said.

“This should change practice,” agreed Jonathan P. Piccini, MD, MHS, Duke University, Durham, N.C., also not part of STROKE-VT. “A lot of evidence in the trial is consistent and provides a compelling story, not to mention that, in my opinion, the study probably underestimates the value of DOACs,” he told this news organization.

That’s because patients assigned to DOACs had far longer ablation times, “so their risk was even greater than in the aspirin arm,” Dr. Piccini said. Ablation times averaged 2,095 seconds in the DOAC group, compared with only 1,708 seconds in the aspirin group, probably because the preponderance of VT over PVC ablations for those getting a DOAC was even greater in the aspirin group.

Of the 246 patients assigned to either aspirin or a DOAC, usually a factor Xa inhibitor, 75% had undergone VT ablation and the remainder ablation for PVCs. Their mean age was 60 years and only 18% were women. None had experienced a cerebrovascular event in the previous 3 months.

The 30-day odds ratio for TIA or ischemic stroke in patients who received aspirin, compared with a DOAC, was 12.6 (95% confidence interval, 4.10-39.11; P < .001).

The corresponding OR for asymptomatic cerebral lesions by MRI at 24 hours was 2.15 (95% CI, 1.02-4.54; P = .04) and at 30 days was 3.48 (95% CI, 1.38-8.80; P = .008).

The rate of stroke or TIA was similar in patients who underwent ablation for VT and for PVCs (14% vs. 16%, respectively; P = .70). There were fewer asymptomatic cerebrovascular events by MRI at 24 hours for those undergoing VT ablations (14.7% and 25.8%, respectively; P = .046); but difference between rates attenuated by 30 days (11.4% and 14.5%, respectively; P = .52).

The OR for TIA or stroke associated with the retrograde transaortic approach, performed in about 40% of the patients, compared with the trans-septal approach in the remainder was 2.60 (95% CI, 1.06-6.37; P = .04).

“The study tells us it’s safe and indeed preferable to anticoagulate after an ablation procedure. But the more important finding, perhaps, wasn’t the one related to the core hypothesis. And that was the effect of retrograde access,” Paul A. Friedman, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said as an invited discussant after Dr. Lakkireddy’s formal presentation of the trial.

Whether a ventricular ablation is performed using the retrograde transaortic or trans-septal approach often depends on the location of the ablation targets in the left ventricle. But in some cases it’s a matter of operator preference, Dr. Piccini observed.

“There are some situations where, really, it is better to do retrograde aortic, and there are some cases that are better to do trans-septal. But now there’s going to be a higher burden of proof,” he said. Given the findings of STROKE-VT, operators may need to consider that a ventricular ablation procedure that can be done by the trans-septal route perhaps ought to be consistently done that way.

Dr. Lakkireddy discloses financial relationships with Boston Scientific, Biosense Webster, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and more. Dr. Chung had “nothing relevant to disclose.” Dr. Piccini discloses receiving honoraria or speaking or consulting fees from Sanofi, Abbott, ARCA Biopharma, Medtronic, Philips, Biotronik, Allergan, LivaNova, and Myokardia; and research in conjunction with Bayer Healthcare, Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Philips. Dr. Friedman discloses conducting research in conjunction with Medtronic and Abbott; holding intellectual property rights with AliveCor, Inference, Medicool, Eko, and Anumana; and receiving honoraria or speaking or consulting fees from Boston Scientific. Dr. Winterfield and Dr. Tedrow had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dissolving pacemaker impressive in early research

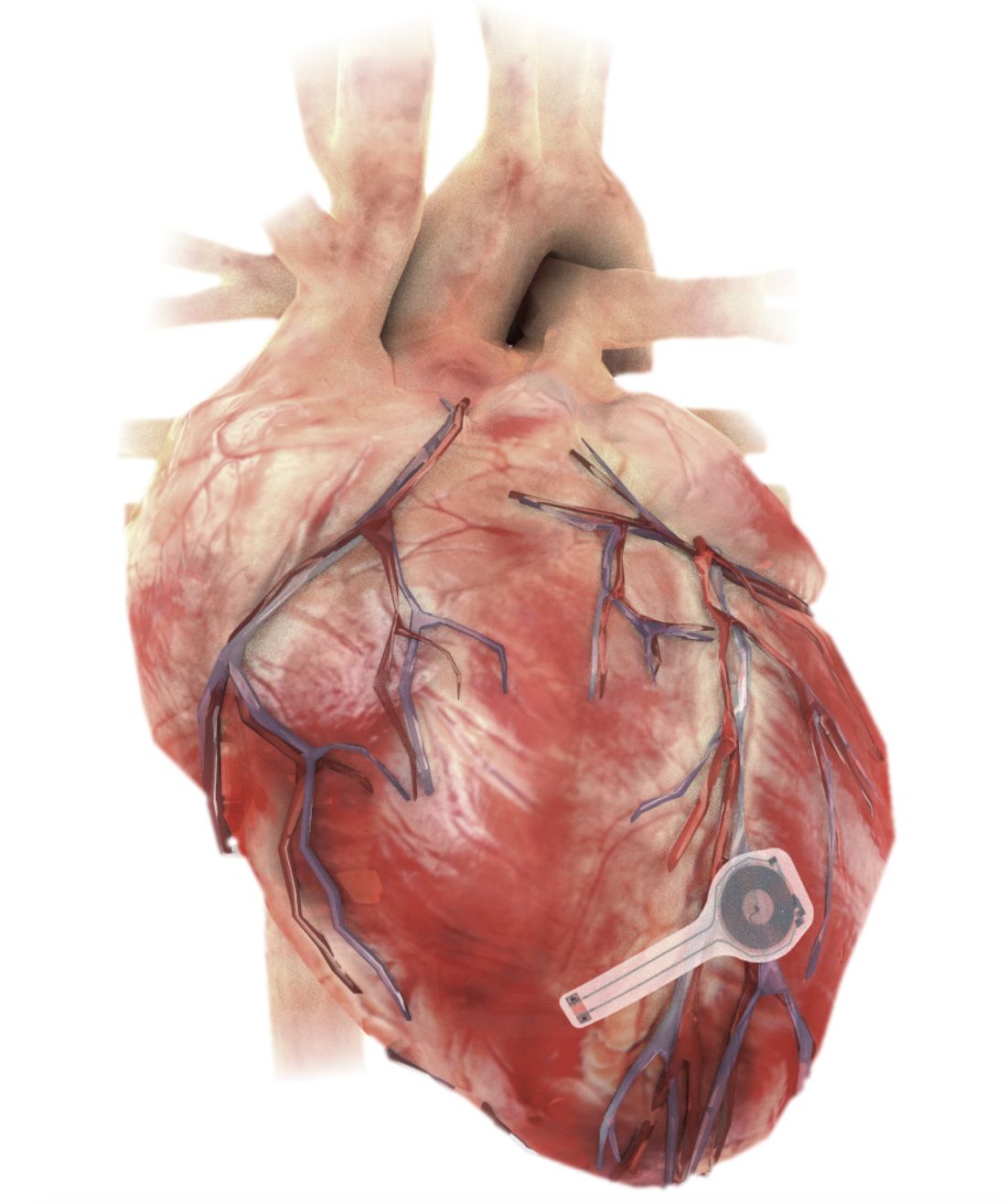

A fully implantable, bioresorbable pacemaker has been developed that’s capable of sustaining heart rhythms in animal and human donor hearts before disappearing over 5-7 weeks.

Temporary pacing devices are frequently used after cardiac surgery but rely on bulky external generators and transcutaneous pacing leads that run the risk of becoming infected or dislodged and can damage the heart when removed if they’re enveloped in fibrotic tissue.

The experimental device is thin, powered without leads or batteries, and made of water-soluble, biocompatible materials, thereby bypassing many of the disadvantages of conventional temporary pacing devices, according to John A. Rogers, PhD, who led the device’s development and directs the Querrey Simpson Institute for Bioelectronics at Northwestern University in Chicago.

“The total material load on the body is very minimal,” he said in an interview. “The amount of silicon and magnesium in a multivitamin tablet is about 3,000 times more than the amount of those materials in our electronics. So you can think of them as a very tiny vitamin pill, in a sense, but configured with electronic functionality.”

Dr. Rogers and his team have a reputation for innovation in bioelectronic medicine, having recently constructed transient wireless devices to accelerate neuroregeneration associated with damaged peripheral nerves, to monitor critically ill neonates, and to detect early signs and symptoms associated with COVID-19.

Shortly after Dr. Rogers joined Northwestern, Rishi Arora, MD, a cardiac electrophysiologist and professor of medicine at Northwestern, reached out to discuss how they could leverage wireless electronics for patients needing temporary pacing.

“It was a natural marriage,” Dr. Arora said in an interview. “Part of the reason to go into the heart was because the cardiology group here at Northwestern, especially on the electrophysiology side, has been very involved in translational research, and John also had a very strong collaboration before he came here with Igor Efimov, [PhD, of George Washington University, Washington], a giant in the field in terms of heart rhythm research.”

Dr. Arora noted that the incidence of temporary pacing after cardiac surgery is at least 10% but can reach 20%. Current devices work well in most patients, but temporary pacing with epicardial wires can cause complications and, typically, work well only for a few days after cardiac surgery. Clinically, though, several patients need postoperative pacing support for 1-2 weeks.

“So if something like this were available where you could tack it onto the surface and forget it for a week or 10 days or 2 weeks, you’d be doing those 20% of patients a huge service,” he said.

Bioresorbable scaffold déjà vu?

The philosophy of “leave nothing behind” is nothing new in cardiology, with bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) gaining initial support as a potential solution to neoatherosclerosis and late-stent thrombosis in permanent metal stents. Failure to show advantages, and safety concerns such as in-scaffold thrombosis, however, led Abbott to stop global sales of the first approved BVS and Boston Scientific to halt its BVS program in 2017.

The wireless pacemaker, however, is an electrical device, not a mechanical one, observed Dr. Rogers. “The fact that it’s not in the bloodstream greatly lowers risks and, as I mentioned before, everything is super thin, low-mass quantities of materials. So, I guess there’s a relationship there, but it’s different in a couple of very important ways.”

As Dr. Rogers, Dr. Arora, Dr. Efimov, and colleagues recently reported in Nature Biotechnology, the electronic part of the pacemaker contains three layers: A loop antenna with a bilayer tungsten-coated magnesium inductive coil, a radiofrequency PIN diode based on a monocrystalline silicon nanomembrane, and a poly (lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) dielectric interlayer.

The electronic components rest between two encapsulation layers of PLGA to isolate the active materials from the surrounding biofluids during implantation, and connect to a pair of flexible extension electrodes that deliver the electrical stimuli to a contact pad sutured onto the heart. The entire system is about 16 mm in width and 15 mm in length, and weighs in at about 0.3 g.

The pacemaker receives power and control commands through a wireless inductive power transfer – the same technology used in implanted medical devices, smartphones, and radio-frequency identification tags – between the receiver coil in the device and a wand-shaped, external transmission coil placed on top of or within a few inches of the heart.

“Right now we’re almost at 15 inches, which I think is a very respectable distance for this particular piece of hardware, and clinically very doable,” observed Dr. Arora.

Competing considerations

Testing thus far shows effective ventricular capture across a range of frequencies in mouse and rabbit hearts and successful pacing and activation of human cardiac tissue.

In vivo tests in dogs also suggest that the system can “achieve the power necessary for operation of bioresorbable pacemakers in adult human patients,” the authors say.

Electrodes placed on the dogs’ legs showed a change in ECG signals from a narrow QRS complex (consistent with a normal rate sinus rhythm of 350-400 bpm) to a widened QRS complex with a shortened R-R interval (consistent with a paced rhythm of 400-450 bpm) – indicating successful ventricular capture.

The device successfully paced the dogs through postoperative day 4 but couldn’t provide enough energy to capture the ventricular myocardium on day 5 and failed to pace the heart on day 6, even when transmitting voltages were increased from 1 Vpp to more than 10 Vpp.

Dr. Rogers pointed out that a transient device of theirs that uses very thin films of silica provides stable intracranial pressure monitoring for traumatic brain injury recovery for 3 weeks before dissolving. The problem with the polymers used as encapsulating layers in the pacemaker is that even if they haven’t completely dissolved, there’s a finite rate of water permeation through the film.

“It turns out that’s what’s become the limiting factor, rather than the chemistry of bioresorption,” he said. “So, what we’re seeing with these devices beginning to degrade electrically in terms of performance around 5-6 days is due to that water permeation.”

Although it is not part of the current study, there’s no reason thin silica layers couldn’t be incorporated into the pacemaker to make it less water permeable, Dr. Rogers said. Still, this will have to be weighed against the competing consideration of stable operating life.

The researchers specifically chose materials that would naturally bioresorb via hydrolysis and metabolic action in the body. PLGA degrades into glycolic and lactic acid, the tungsten-coated magnesium inductive coil into Wox and Mg(OH)2, and the silicon nanomembrane radiofrequency PIN diode into Si(OH)4.

CT imaging in rat models shows the device is enveloped in fibrotic tissue and completely decouples from the heart at 4 weeks, while images of explanted devices suggest the pacemaker largely dissolves within 3 weeks and the remaining residues disappear after 12 weeks.

The researchers have started an investigational device exemption process to allow the device to be used in clinical trials, and they plan to dig deeper into the potential for fragments to form at various stages of resorption, which some imaging suggests may occur.

“Because these devices are made out of pure materials and they’re in a heterogeneous environment, both mechanically and biomechanically, the devices don’t resorb in a perfectly uniform way and, as a result, at the tail end of the process you can end up with small fragments that eventually bioresorb, but before they’re gone, they are potentially mobile within the body cavity,” Dr. Rogers said.

“We feel that because the devices aren’t in the bloodstream, the risk associated with those fragments is probably manageable but at the same time, these are the sorts of details that must be thoroughly addressed before trials in humans,” he said, adding that one solution, if needed, would be to encapsulate the entire device in a thin bioresorbable hydrogel as a containment vehicle.

Dr. Arora said they hope the pacemaker “will make patients’ lives a lot easier in the postoperative setting but, even there, I think one must remember current pacing technology in this setting is actually very good. So there’s a word of caution not to get ahead of ourselves.”

Looking forward, the excitement of this approach is not only in the immediate postop setting but in the transvenous setting, he said. “If we can get to the point where we can actually do this transvenously, that opens up a huge window of opportunity because there we’re talking about post-TAVR [transcatheter aortic valve replacement], post–myocardial infarction, etc.”

Currently, temporary transvenous pacing can be quite unreliable because of a high risk of dislodgement and infection – much higher than for surgical pacing wires, he noted.

“In terms of translatability to larger numbers of patients, the value would be huge. But again, a lot needs to be done before we can get there. But if it can get to that point, then I think you have a real therapy that could potentially be transformative,” Dr. Arora said.

Dr. Rogers reported support from the Leducq Foundation projects RHYTHM and ROI-HL121270. Dr. Arora has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Coauthor disclosures are listed in the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A fully implantable, bioresorbable pacemaker has been developed that’s capable of sustaining heart rhythms in animal and human donor hearts before disappearing over 5-7 weeks.

Temporary pacing devices are frequently used after cardiac surgery but rely on bulky external generators and transcutaneous pacing leads that run the risk of becoming infected or dislodged and can damage the heart when removed if they’re enveloped in fibrotic tissue.

The experimental device is thin, powered without leads or batteries, and made of water-soluble, biocompatible materials, thereby bypassing many of the disadvantages of conventional temporary pacing devices, according to John A. Rogers, PhD, who led the device’s development and directs the Querrey Simpson Institute for Bioelectronics at Northwestern University in Chicago.

“The total material load on the body is very minimal,” he said in an interview. “The amount of silicon and magnesium in a multivitamin tablet is about 3,000 times more than the amount of those materials in our electronics. So you can think of them as a very tiny vitamin pill, in a sense, but configured with electronic functionality.”

Dr. Rogers and his team have a reputation for innovation in bioelectronic medicine, having recently constructed transient wireless devices to accelerate neuroregeneration associated with damaged peripheral nerves, to monitor critically ill neonates, and to detect early signs and symptoms associated with COVID-19.

Shortly after Dr. Rogers joined Northwestern, Rishi Arora, MD, a cardiac electrophysiologist and professor of medicine at Northwestern, reached out to discuss how they could leverage wireless electronics for patients needing temporary pacing.

“It was a natural marriage,” Dr. Arora said in an interview. “Part of the reason to go into the heart was because the cardiology group here at Northwestern, especially on the electrophysiology side, has been very involved in translational research, and John also had a very strong collaboration before he came here with Igor Efimov, [PhD, of George Washington University, Washington], a giant in the field in terms of heart rhythm research.”

Dr. Arora noted that the incidence of temporary pacing after cardiac surgery is at least 10% but can reach 20%. Current devices work well in most patients, but temporary pacing with epicardial wires can cause complications and, typically, work well only for a few days after cardiac surgery. Clinically, though, several patients need postoperative pacing support for 1-2 weeks.

“So if something like this were available where you could tack it onto the surface and forget it for a week or 10 days or 2 weeks, you’d be doing those 20% of patients a huge service,” he said.

Bioresorbable scaffold déjà vu?

The philosophy of “leave nothing behind” is nothing new in cardiology, with bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) gaining initial support as a potential solution to neoatherosclerosis and late-stent thrombosis in permanent metal stents. Failure to show advantages, and safety concerns such as in-scaffold thrombosis, however, led Abbott to stop global sales of the first approved BVS and Boston Scientific to halt its BVS program in 2017.

The wireless pacemaker, however, is an electrical device, not a mechanical one, observed Dr. Rogers. “The fact that it’s not in the bloodstream greatly lowers risks and, as I mentioned before, everything is super thin, low-mass quantities of materials. So, I guess there’s a relationship there, but it’s different in a couple of very important ways.”

As Dr. Rogers, Dr. Arora, Dr. Efimov, and colleagues recently reported in Nature Biotechnology, the electronic part of the pacemaker contains three layers: A loop antenna with a bilayer tungsten-coated magnesium inductive coil, a radiofrequency PIN diode based on a monocrystalline silicon nanomembrane, and a poly (lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) dielectric interlayer.

The electronic components rest between two encapsulation layers of PLGA to isolate the active materials from the surrounding biofluids during implantation, and connect to a pair of flexible extension electrodes that deliver the electrical stimuli to a contact pad sutured onto the heart. The entire system is about 16 mm in width and 15 mm in length, and weighs in at about 0.3 g.

The pacemaker receives power and control commands through a wireless inductive power transfer – the same technology used in implanted medical devices, smartphones, and radio-frequency identification tags – between the receiver coil in the device and a wand-shaped, external transmission coil placed on top of or within a few inches of the heart.

“Right now we’re almost at 15 inches, which I think is a very respectable distance for this particular piece of hardware, and clinically very doable,” observed Dr. Arora.

Competing considerations

Testing thus far shows effective ventricular capture across a range of frequencies in mouse and rabbit hearts and successful pacing and activation of human cardiac tissue.

In vivo tests in dogs also suggest that the system can “achieve the power necessary for operation of bioresorbable pacemakers in adult human patients,” the authors say.

Electrodes placed on the dogs’ legs showed a change in ECG signals from a narrow QRS complex (consistent with a normal rate sinus rhythm of 350-400 bpm) to a widened QRS complex with a shortened R-R interval (consistent with a paced rhythm of 400-450 bpm) – indicating successful ventricular capture.

The device successfully paced the dogs through postoperative day 4 but couldn’t provide enough energy to capture the ventricular myocardium on day 5 and failed to pace the heart on day 6, even when transmitting voltages were increased from 1 Vpp to more than 10 Vpp.

Dr. Rogers pointed out that a transient device of theirs that uses very thin films of silica provides stable intracranial pressure monitoring for traumatic brain injury recovery for 3 weeks before dissolving. The problem with the polymers used as encapsulating layers in the pacemaker is that even if they haven’t completely dissolved, there’s a finite rate of water permeation through the film.

“It turns out that’s what’s become the limiting factor, rather than the chemistry of bioresorption,” he said. “So, what we’re seeing with these devices beginning to degrade electrically in terms of performance around 5-6 days is due to that water permeation.”

Although it is not part of the current study, there’s no reason thin silica layers couldn’t be incorporated into the pacemaker to make it less water permeable, Dr. Rogers said. Still, this will have to be weighed against the competing consideration of stable operating life.

The researchers specifically chose materials that would naturally bioresorb via hydrolysis and metabolic action in the body. PLGA degrades into glycolic and lactic acid, the tungsten-coated magnesium inductive coil into Wox and Mg(OH)2, and the silicon nanomembrane radiofrequency PIN diode into Si(OH)4.

CT imaging in rat models shows the device is enveloped in fibrotic tissue and completely decouples from the heart at 4 weeks, while images of explanted devices suggest the pacemaker largely dissolves within 3 weeks and the remaining residues disappear after 12 weeks.

The researchers have started an investigational device exemption process to allow the device to be used in clinical trials, and they plan to dig deeper into the potential for fragments to form at various stages of resorption, which some imaging suggests may occur.

“Because these devices are made out of pure materials and they’re in a heterogeneous environment, both mechanically and biomechanically, the devices don’t resorb in a perfectly uniform way and, as a result, at the tail end of the process you can end up with small fragments that eventually bioresorb, but before they’re gone, they are potentially mobile within the body cavity,” Dr. Rogers said.

“We feel that because the devices aren’t in the bloodstream, the risk associated with those fragments is probably manageable but at the same time, these are the sorts of details that must be thoroughly addressed before trials in humans,” he said, adding that one solution, if needed, would be to encapsulate the entire device in a thin bioresorbable hydrogel as a containment vehicle.

Dr. Arora said they hope the pacemaker “will make patients’ lives a lot easier in the postoperative setting but, even there, I think one must remember current pacing technology in this setting is actually very good. So there’s a word of caution not to get ahead of ourselves.”

Looking forward, the excitement of this approach is not only in the immediate postop setting but in the transvenous setting, he said. “If we can get to the point where we can actually do this transvenously, that opens up a huge window of opportunity because there we’re talking about post-TAVR [transcatheter aortic valve replacement], post–myocardial infarction, etc.”

Currently, temporary transvenous pacing can be quite unreliable because of a high risk of dislodgement and infection – much higher than for surgical pacing wires, he noted.

“In terms of translatability to larger numbers of patients, the value would be huge. But again, a lot needs to be done before we can get there. But if it can get to that point, then I think you have a real therapy that could potentially be transformative,” Dr. Arora said.

Dr. Rogers reported support from the Leducq Foundation projects RHYTHM and ROI-HL121270. Dr. Arora has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Coauthor disclosures are listed in the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A fully implantable, bioresorbable pacemaker has been developed that’s capable of sustaining heart rhythms in animal and human donor hearts before disappearing over 5-7 weeks.

Temporary pacing devices are frequently used after cardiac surgery but rely on bulky external generators and transcutaneous pacing leads that run the risk of becoming infected or dislodged and can damage the heart when removed if they’re enveloped in fibrotic tissue.

The experimental device is thin, powered without leads or batteries, and made of water-soluble, biocompatible materials, thereby bypassing many of the disadvantages of conventional temporary pacing devices, according to John A. Rogers, PhD, who led the device’s development and directs the Querrey Simpson Institute for Bioelectronics at Northwestern University in Chicago.

“The total material load on the body is very minimal,” he said in an interview. “The amount of silicon and magnesium in a multivitamin tablet is about 3,000 times more than the amount of those materials in our electronics. So you can think of them as a very tiny vitamin pill, in a sense, but configured with electronic functionality.”

Dr. Rogers and his team have a reputation for innovation in bioelectronic medicine, having recently constructed transient wireless devices to accelerate neuroregeneration associated with damaged peripheral nerves, to monitor critically ill neonates, and to detect early signs and symptoms associated with COVID-19.

Shortly after Dr. Rogers joined Northwestern, Rishi Arora, MD, a cardiac electrophysiologist and professor of medicine at Northwestern, reached out to discuss how they could leverage wireless electronics for patients needing temporary pacing.