User login

Unmasking gastric cancer

A 50-year-old male Japanese immigrant with a history of smoking and occasional untreated heartburn presented with the recent onset of flank pain, weight loss, headache, syncope, and blurred vision.

Previously healthy, he began feeling moderate pain in his left flank 1 month ago; it was diagnosed as kidney stones and was treated conservatively. Two weeks later he had an episode of syncope and soon after developed blurred vision, mainly in his left eye, along with severe bifrontal headache. An eye examination and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain indicated optic neuritis, for which he was given glucocorticoids intravenously for 3 days, with moderate improvement.

As his symptoms continued over the next 2 weeks, he lost 20 lb (9.1 kg) due to the pain, loss of appetite, nausea, and occasional vomiting.

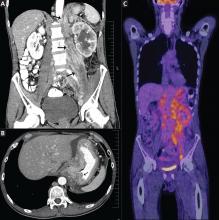

Positron emission tomography showed the retroperitoneal infiltrative process and the thickened gastric cardia to be hypermetabolic (Figure 1C).

The area of retroperitoneal infiltration was biopsied under CT guidance, and pathologic study showed poorly differentiated carcinoma with signet-ring cells, a feature of gastric cancer.

The patient underwent lumbar puncture. His cerebrospinal fluid had 206 white blood cells/μL (reference range 0–5) and large numbers of poorly differentiated malignant cells, most consistent with adenocarcinoma on cytologic study.

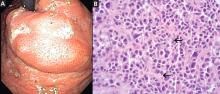

duodenoscopy (EGD) revealed a large, ulcerated, submucosal, nodular mass in the cardia of the stomach extending to the gastroesophageal junction (Figure 2A). Biopsy of the mass again revealed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with scattered signet-ring cells undermining the gastric mucosa, favoring a gastric origin (Figure 2B).

THREE SUBTYPES OF GASTRIC CANCER

Worldwide, gastric cancer is the third most common type of cancer and the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths.1 In the United States, blacks and people of Asian ancestry have almost twice the risk of death, with the highest incidence and mortality rates.2,3

Most cases of gastric adenocarcinoma can be categorized as either intestinal or diffuse, but a new proximal subtype is emerging.4

Intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinoma is the most common subtype and accounts for almost all the ethnic and geographic variation in incidence.2 The lesions are often ulcerative and distal; the pathogenesis is stepwise and is initiated by chronic inflammation. Risk factors include old age, Helicobacter pylori infection, tobacco smoking, family history, and high salt intake, with an observed risk-reduction with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and with a high intake of fruits and vegetables.3

Diffuse gastric adenocarcinoma, on the other hand, has a uniform distribution worldwide, and its incidence is increasing. It typically carries a poor prognosis. Evidence thus far has shown its pathogenesis to be independent of chronic inflammation, but it has a strong tendency to be hereditary.3

Proximal gastric adenocarcinoma is observed in the gastric cardia and near the gastroesophageal junction. It is often grouped with the distal esophageal adenocarcinomas and has similar risk factors, including reflux disease, obesity, alcohol abuse, and tobacco smoking. Interestingly, however, H pylori infection does not contribute to the pathogenesis of this type, and it may even have a protective role.3

DIFFICULT TO DETECT EARLY

Gastric cancer is difficult to detect early enough in its course to be cured. Understanding its risk factors, recognizing its common symptoms, and regarding its uncommon symptoms with suspicion may lead to earlier diagnosis and more effective treatment.

Our patient’s proximal gastric cancer was diagnosed late even though he had several risk factors for it (he was Japanese, he was a smoker, and he had gastroesophageal reflux disease) because of a late and atypical presentation with misleading paraneoplastic symptoms.

Early diagnosis is difficult because most patients have no symptoms in the early stage; weight loss and abdominal pain are often late signs of tumor progression.

Screening may be justified in high-risk groups in the United States, although the issue is debatable. Diagnostic imaging is the only effective method for screening,5 with EGD considered the first-line targeted evaluation should there be suspicion of gastric cancer either from the clinical presentation or from barium swallow.6 Candidates for screening may include elderly patients with atrophic gastritis or pernicious anemia, immigrants from countries with high rates of gastric carcinoma, and people with a family history of gastrointestinal cancer.7

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 2005; 55:74–108.

- Crew KD, Neugut AI. Epidemiology of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12:354–362.

- Shah MA, Kelsen DP. Gastric cancer: a primer on the epidemiology and biology of the disease and an overview of the medical management of advanced disease. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2010; 8:437–447.

- Fine G, Chan K. Alimentary tract. In:Kissane JM, editor. Anderson’s Pathology. 8th ed. Saint Louis, MO: Mosby; 1985:1055–1095.

- Kunisaki C, Ishino J, Nakajima S, et al. Outcomes of mass screening for gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2006; 13:221–228.

- Cappell MS, Friedel D. The role of esophagogastroduodenoscopy in the diagnosis and management of upper gastrointestinal disorders. Med Clin North Am 2002; 86:1165–1216.

- Hisamuchi S, Fukao P, Sugawara N, et al. Evaluation of mass screening programme for stomach cancer in Japan. In:Miller AB, Chamberlain J, Day NE, et al, editors. Cancer Screening. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1991:357–372.

A 50-year-old male Japanese immigrant with a history of smoking and occasional untreated heartburn presented with the recent onset of flank pain, weight loss, headache, syncope, and blurred vision.

Previously healthy, he began feeling moderate pain in his left flank 1 month ago; it was diagnosed as kidney stones and was treated conservatively. Two weeks later he had an episode of syncope and soon after developed blurred vision, mainly in his left eye, along with severe bifrontal headache. An eye examination and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain indicated optic neuritis, for which he was given glucocorticoids intravenously for 3 days, with moderate improvement.

As his symptoms continued over the next 2 weeks, he lost 20 lb (9.1 kg) due to the pain, loss of appetite, nausea, and occasional vomiting.

Positron emission tomography showed the retroperitoneal infiltrative process and the thickened gastric cardia to be hypermetabolic (Figure 1C).

The area of retroperitoneal infiltration was biopsied under CT guidance, and pathologic study showed poorly differentiated carcinoma with signet-ring cells, a feature of gastric cancer.

The patient underwent lumbar puncture. His cerebrospinal fluid had 206 white blood cells/μL (reference range 0–5) and large numbers of poorly differentiated malignant cells, most consistent with adenocarcinoma on cytologic study.

duodenoscopy (EGD) revealed a large, ulcerated, submucosal, nodular mass in the cardia of the stomach extending to the gastroesophageal junction (Figure 2A). Biopsy of the mass again revealed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with scattered signet-ring cells undermining the gastric mucosa, favoring a gastric origin (Figure 2B).

THREE SUBTYPES OF GASTRIC CANCER

Worldwide, gastric cancer is the third most common type of cancer and the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths.1 In the United States, blacks and people of Asian ancestry have almost twice the risk of death, with the highest incidence and mortality rates.2,3

Most cases of gastric adenocarcinoma can be categorized as either intestinal or diffuse, but a new proximal subtype is emerging.4

Intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinoma is the most common subtype and accounts for almost all the ethnic and geographic variation in incidence.2 The lesions are often ulcerative and distal; the pathogenesis is stepwise and is initiated by chronic inflammation. Risk factors include old age, Helicobacter pylori infection, tobacco smoking, family history, and high salt intake, with an observed risk-reduction with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and with a high intake of fruits and vegetables.3

Diffuse gastric adenocarcinoma, on the other hand, has a uniform distribution worldwide, and its incidence is increasing. It typically carries a poor prognosis. Evidence thus far has shown its pathogenesis to be independent of chronic inflammation, but it has a strong tendency to be hereditary.3

Proximal gastric adenocarcinoma is observed in the gastric cardia and near the gastroesophageal junction. It is often grouped with the distal esophageal adenocarcinomas and has similar risk factors, including reflux disease, obesity, alcohol abuse, and tobacco smoking. Interestingly, however, H pylori infection does not contribute to the pathogenesis of this type, and it may even have a protective role.3

DIFFICULT TO DETECT EARLY

Gastric cancer is difficult to detect early enough in its course to be cured. Understanding its risk factors, recognizing its common symptoms, and regarding its uncommon symptoms with suspicion may lead to earlier diagnosis and more effective treatment.

Our patient’s proximal gastric cancer was diagnosed late even though he had several risk factors for it (he was Japanese, he was a smoker, and he had gastroesophageal reflux disease) because of a late and atypical presentation with misleading paraneoplastic symptoms.

Early diagnosis is difficult because most patients have no symptoms in the early stage; weight loss and abdominal pain are often late signs of tumor progression.

Screening may be justified in high-risk groups in the United States, although the issue is debatable. Diagnostic imaging is the only effective method for screening,5 with EGD considered the first-line targeted evaluation should there be suspicion of gastric cancer either from the clinical presentation or from barium swallow.6 Candidates for screening may include elderly patients with atrophic gastritis or pernicious anemia, immigrants from countries with high rates of gastric carcinoma, and people with a family history of gastrointestinal cancer.7

A 50-year-old male Japanese immigrant with a history of smoking and occasional untreated heartburn presented with the recent onset of flank pain, weight loss, headache, syncope, and blurred vision.

Previously healthy, he began feeling moderate pain in his left flank 1 month ago; it was diagnosed as kidney stones and was treated conservatively. Two weeks later he had an episode of syncope and soon after developed blurred vision, mainly in his left eye, along with severe bifrontal headache. An eye examination and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain indicated optic neuritis, for which he was given glucocorticoids intravenously for 3 days, with moderate improvement.

As his symptoms continued over the next 2 weeks, he lost 20 lb (9.1 kg) due to the pain, loss of appetite, nausea, and occasional vomiting.

Positron emission tomography showed the retroperitoneal infiltrative process and the thickened gastric cardia to be hypermetabolic (Figure 1C).

The area of retroperitoneal infiltration was biopsied under CT guidance, and pathologic study showed poorly differentiated carcinoma with signet-ring cells, a feature of gastric cancer.

The patient underwent lumbar puncture. His cerebrospinal fluid had 206 white blood cells/μL (reference range 0–5) and large numbers of poorly differentiated malignant cells, most consistent with adenocarcinoma on cytologic study.

duodenoscopy (EGD) revealed a large, ulcerated, submucosal, nodular mass in the cardia of the stomach extending to the gastroesophageal junction (Figure 2A). Biopsy of the mass again revealed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with scattered signet-ring cells undermining the gastric mucosa, favoring a gastric origin (Figure 2B).

THREE SUBTYPES OF GASTRIC CANCER

Worldwide, gastric cancer is the third most common type of cancer and the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths.1 In the United States, blacks and people of Asian ancestry have almost twice the risk of death, with the highest incidence and mortality rates.2,3

Most cases of gastric adenocarcinoma can be categorized as either intestinal or diffuse, but a new proximal subtype is emerging.4

Intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinoma is the most common subtype and accounts for almost all the ethnic and geographic variation in incidence.2 The lesions are often ulcerative and distal; the pathogenesis is stepwise and is initiated by chronic inflammation. Risk factors include old age, Helicobacter pylori infection, tobacco smoking, family history, and high salt intake, with an observed risk-reduction with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and with a high intake of fruits and vegetables.3

Diffuse gastric adenocarcinoma, on the other hand, has a uniform distribution worldwide, and its incidence is increasing. It typically carries a poor prognosis. Evidence thus far has shown its pathogenesis to be independent of chronic inflammation, but it has a strong tendency to be hereditary.3

Proximal gastric adenocarcinoma is observed in the gastric cardia and near the gastroesophageal junction. It is often grouped with the distal esophageal adenocarcinomas and has similar risk factors, including reflux disease, obesity, alcohol abuse, and tobacco smoking. Interestingly, however, H pylori infection does not contribute to the pathogenesis of this type, and it may even have a protective role.3

DIFFICULT TO DETECT EARLY

Gastric cancer is difficult to detect early enough in its course to be cured. Understanding its risk factors, recognizing its common symptoms, and regarding its uncommon symptoms with suspicion may lead to earlier diagnosis and more effective treatment.

Our patient’s proximal gastric cancer was diagnosed late even though he had several risk factors for it (he was Japanese, he was a smoker, and he had gastroesophageal reflux disease) because of a late and atypical presentation with misleading paraneoplastic symptoms.

Early diagnosis is difficult because most patients have no symptoms in the early stage; weight loss and abdominal pain are often late signs of tumor progression.

Screening may be justified in high-risk groups in the United States, although the issue is debatable. Diagnostic imaging is the only effective method for screening,5 with EGD considered the first-line targeted evaluation should there be suspicion of gastric cancer either from the clinical presentation or from barium swallow.6 Candidates for screening may include elderly patients with atrophic gastritis or pernicious anemia, immigrants from countries with high rates of gastric carcinoma, and people with a family history of gastrointestinal cancer.7

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 2005; 55:74–108.

- Crew KD, Neugut AI. Epidemiology of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12:354–362.

- Shah MA, Kelsen DP. Gastric cancer: a primer on the epidemiology and biology of the disease and an overview of the medical management of advanced disease. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2010; 8:437–447.

- Fine G, Chan K. Alimentary tract. In:Kissane JM, editor. Anderson’s Pathology. 8th ed. Saint Louis, MO: Mosby; 1985:1055–1095.

- Kunisaki C, Ishino J, Nakajima S, et al. Outcomes of mass screening for gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2006; 13:221–228.

- Cappell MS, Friedel D. The role of esophagogastroduodenoscopy in the diagnosis and management of upper gastrointestinal disorders. Med Clin North Am 2002; 86:1165–1216.

- Hisamuchi S, Fukao P, Sugawara N, et al. Evaluation of mass screening programme for stomach cancer in Japan. In:Miller AB, Chamberlain J, Day NE, et al, editors. Cancer Screening. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1991:357–372.

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 2005; 55:74–108.

- Crew KD, Neugut AI. Epidemiology of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12:354–362.

- Shah MA, Kelsen DP. Gastric cancer: a primer on the epidemiology and biology of the disease and an overview of the medical management of advanced disease. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2010; 8:437–447.

- Fine G, Chan K. Alimentary tract. In:Kissane JM, editor. Anderson’s Pathology. 8th ed. Saint Louis, MO: Mosby; 1985:1055–1095.

- Kunisaki C, Ishino J, Nakajima S, et al. Outcomes of mass screening for gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2006; 13:221–228.

- Cappell MS, Friedel D. The role of esophagogastroduodenoscopy in the diagnosis and management of upper gastrointestinal disorders. Med Clin North Am 2002; 86:1165–1216.

- Hisamuchi S, Fukao P, Sugawara N, et al. Evaluation of mass screening programme for stomach cancer in Japan. In:Miller AB, Chamberlain J, Day NE, et al, editors. Cancer Screening. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1991:357–372.

Induration of Arms and Legs

Worsening Abdominal Pain

Bone Edema on MRI Predicts Rheumatoid Arthritis

Magnetic resonance imaging evidence of bone edema in the wrist and metatarsophalangeal joints was an independent predictor of future development of rheumatoid arthritis in a prospective Danish study of patients with early undifferentiated arthritis.

Incorporating MRI bone edema findings, together with clinical and biochemical parameters, yielded a prediction model that showed unprecedented accuracy in identifying which patients would or would not develop rheumatoid arthritis, Dr. Anne Duer-Jensen of Copenhagen University Hospital at Hvidovre and Copenhagen University Hospital at Glostrup, and her associates reported in Arthritis & Rheumatism (2011;63:2192-202).

The study involved 116 patients with early undifferentiated arthritis, 23% of whom went on to meet American College of Rheumatology 1987 criteria for RA during a median 17 months of follow-up. They were matched with 24 healthy controls. The predictive model had a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 82% for progression to RA. Thus, it classified 82% of patients correctly.

That’s a markedly better predictive accuracy than achieved when the investigators applied the published and validated van der Helm-van Mil prediction model to the same study population. The van der Helm-van Mil model (Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:433-40) had a 60% predictive accuracy.

Participants in the Danish study had two or more tender joints and/or two or more swollen joints among the wrist, metatarsophalangeal (MTP), proximal interphalangeal, or metacarpophalangeal joints for more than 6 weeks but less than 2 years. None of the 116 subjects had a specific rheumatologic diagnosis at baseline. Thus, they were typical of the patients often referred to rheumatologists for early undifferentiated arthritis, a condition that can morph into osteoarthritis, RA, persistent arthralgias, or nonprogressive disease.

The investigators developed their predictive model based on the findings of a multivariate logistic regression analysis that encompassed numerous variables. The final prediction model included four independent predictors of RA: serum positivity for rheumatoid factor, the presence of hand arthritis, morning stiffness lasting longer than 1 hour, and the MRI summary score for bone edema in the wrist and MTP joints that grew out of the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology Clinical Trials, or OMERACT (J. Rheumatol. 2003;30:1385-6).

Of note, in the Danish study the presence of rheumatoid factor was an independent predictor of subsequent RA, whereas a positive anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide test was not, unlike in several recent studies. MRI summary scores for bone edema proved to be a significantly more potent predictor of RA than MRI scores for synovitis or erosion.

The formula for the current iteration of the prediction model is cumbersome. A simpler version would be welcome. Toward that end, the investigators tried using MRI bone edema scores for the wrist or MTP joints alone, but they found that it unacceptably weakened the model’s predictive power.

The next step in this project will be to see how the prediction model performs in other cohorts of patients with early undifferentiated arthritis. The goal is to develop a tool that enables physicians to extend the current, highly successful early and aggressive treatment strategy for RA into the pre-RA setting.

This study was funded by the Danish Rheumatism Foundation and other foundation grants. While Dr. Duer-Jensen reported having no financial conflicts of interest, several of her associates did. Those can be found on the full text of the journal article.

Magnetic resonance imaging evidence of bone edema in the wrist and metatarsophalangeal joints was an independent predictor of future development of rheumatoid arthritis in a prospective Danish study of patients with early undifferentiated arthritis.

Incorporating MRI bone edema findings, together with clinical and biochemical parameters, yielded a prediction model that showed unprecedented accuracy in identifying which patients would or would not develop rheumatoid arthritis, Dr. Anne Duer-Jensen of Copenhagen University Hospital at Hvidovre and Copenhagen University Hospital at Glostrup, and her associates reported in Arthritis & Rheumatism (2011;63:2192-202).

The study involved 116 patients with early undifferentiated arthritis, 23% of whom went on to meet American College of Rheumatology 1987 criteria for RA during a median 17 months of follow-up. They were matched with 24 healthy controls. The predictive model had a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 82% for progression to RA. Thus, it classified 82% of patients correctly.

That’s a markedly better predictive accuracy than achieved when the investigators applied the published and validated van der Helm-van Mil prediction model to the same study population. The van der Helm-van Mil model (Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:433-40) had a 60% predictive accuracy.

Participants in the Danish study had two or more tender joints and/or two or more swollen joints among the wrist, metatarsophalangeal (MTP), proximal interphalangeal, or metacarpophalangeal joints for more than 6 weeks but less than 2 years. None of the 116 subjects had a specific rheumatologic diagnosis at baseline. Thus, they were typical of the patients often referred to rheumatologists for early undifferentiated arthritis, a condition that can morph into osteoarthritis, RA, persistent arthralgias, or nonprogressive disease.

The investigators developed their predictive model based on the findings of a multivariate logistic regression analysis that encompassed numerous variables. The final prediction model included four independent predictors of RA: serum positivity for rheumatoid factor, the presence of hand arthritis, morning stiffness lasting longer than 1 hour, and the MRI summary score for bone edema in the wrist and MTP joints that grew out of the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology Clinical Trials, or OMERACT (J. Rheumatol. 2003;30:1385-6).

Of note, in the Danish study the presence of rheumatoid factor was an independent predictor of subsequent RA, whereas a positive anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide test was not, unlike in several recent studies. MRI summary scores for bone edema proved to be a significantly more potent predictor of RA than MRI scores for synovitis or erosion.

The formula for the current iteration of the prediction model is cumbersome. A simpler version would be welcome. Toward that end, the investigators tried using MRI bone edema scores for the wrist or MTP joints alone, but they found that it unacceptably weakened the model’s predictive power.

The next step in this project will be to see how the prediction model performs in other cohorts of patients with early undifferentiated arthritis. The goal is to develop a tool that enables physicians to extend the current, highly successful early and aggressive treatment strategy for RA into the pre-RA setting.

This study was funded by the Danish Rheumatism Foundation and other foundation grants. While Dr. Duer-Jensen reported having no financial conflicts of interest, several of her associates did. Those can be found on the full text of the journal article.

Magnetic resonance imaging evidence of bone edema in the wrist and metatarsophalangeal joints was an independent predictor of future development of rheumatoid arthritis in a prospective Danish study of patients with early undifferentiated arthritis.

Incorporating MRI bone edema findings, together with clinical and biochemical parameters, yielded a prediction model that showed unprecedented accuracy in identifying which patients would or would not develop rheumatoid arthritis, Dr. Anne Duer-Jensen of Copenhagen University Hospital at Hvidovre and Copenhagen University Hospital at Glostrup, and her associates reported in Arthritis & Rheumatism (2011;63:2192-202).

The study involved 116 patients with early undifferentiated arthritis, 23% of whom went on to meet American College of Rheumatology 1987 criteria for RA during a median 17 months of follow-up. They were matched with 24 healthy controls. The predictive model had a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 82% for progression to RA. Thus, it classified 82% of patients correctly.

That’s a markedly better predictive accuracy than achieved when the investigators applied the published and validated van der Helm-van Mil prediction model to the same study population. The van der Helm-van Mil model (Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:433-40) had a 60% predictive accuracy.

Participants in the Danish study had two or more tender joints and/or two or more swollen joints among the wrist, metatarsophalangeal (MTP), proximal interphalangeal, or metacarpophalangeal joints for more than 6 weeks but less than 2 years. None of the 116 subjects had a specific rheumatologic diagnosis at baseline. Thus, they were typical of the patients often referred to rheumatologists for early undifferentiated arthritis, a condition that can morph into osteoarthritis, RA, persistent arthralgias, or nonprogressive disease.

The investigators developed their predictive model based on the findings of a multivariate logistic regression analysis that encompassed numerous variables. The final prediction model included four independent predictors of RA: serum positivity for rheumatoid factor, the presence of hand arthritis, morning stiffness lasting longer than 1 hour, and the MRI summary score for bone edema in the wrist and MTP joints that grew out of the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology Clinical Trials, or OMERACT (J. Rheumatol. 2003;30:1385-6).

Of note, in the Danish study the presence of rheumatoid factor was an independent predictor of subsequent RA, whereas a positive anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide test was not, unlike in several recent studies. MRI summary scores for bone edema proved to be a significantly more potent predictor of RA than MRI scores for synovitis or erosion.

The formula for the current iteration of the prediction model is cumbersome. A simpler version would be welcome. Toward that end, the investigators tried using MRI bone edema scores for the wrist or MTP joints alone, but they found that it unacceptably weakened the model’s predictive power.

The next step in this project will be to see how the prediction model performs in other cohorts of patients with early undifferentiated arthritis. The goal is to develop a tool that enables physicians to extend the current, highly successful early and aggressive treatment strategy for RA into the pre-RA setting.

This study was funded by the Danish Rheumatism Foundation and other foundation grants. While Dr. Duer-Jensen reported having no financial conflicts of interest, several of her associates did. Those can be found on the full text of the journal article.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATISM

Major Finding: Incorporating MRI bone edema findings, together with clinical and biochemical parameters, yielded a prediction model that had a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 82% for progression to RA.

Data Source: The study involved 24 healthy controls and 116 patients with early undifferentiated arthritis, 23% of whom went on to meet American College of Rheumatology 1987 criteria for RA during a median 17 months of follow-up.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Danish Rheumatism Foundation and other foundation grants. While Dr. Duer-Jensen reported having no financial conflicts of interest, several of her associates did. Those can be found on the full text of the journal article.

MRI Poised to Boost Early Osteoarthritis Detection

Magnetic resonance imaging has an increasingly important role in the early detection and diagnosis of osteoarthritis, although for now it remains one of several diagnostic tools that also include x-rays, clinical findings, and lab results.

Physicians who treat patients with osteoarthritis (OA) need further research results to better clarify the best use of MRI in early OA detection, said Dr. Philip Conaghan, professor of musculoskeletal medicine at the University of Leeds (England).

In June, Dr. Conaghan and his colleagues on the OA Imaging Working Group for the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) issued 11 propositions on using MRI to define OA – propositions that the group said need formal testing "regarding their diagnostic performance before they are more widely used" (Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011;19:963-9).

The working group clearly endorsed MRI, saying that "MRI may add to the diagnosis of OA and should be incorporated into the [American College of Rheumatology] diagnostic criteria," but in the same proposition, the working group also reiterated the role of x-ray, clinical, and laboratory parameters. Other propositions caution that "no single MRI finding is diagnostic of MRI," and that "certain MRI changes in isolation ... are not diagnostic of osteoarthritis."

The working group’s propositions included two MRI-based definitions of OA, for the tibiofemoral form and for the patellofemoral type.

In a recent talk on MRI and OA, Dr. Conaghan stressed the potential that MRI holds for early OA detection.

"We need to develop an early OA culture," similar to what has emerged for rheumatoid arthritis, he said speaking in May at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology in London. "In OA, we need a culture of early intervention" that would rely on early detection, most likely using MRI.

"Clinical features may suffice at present" for early OA detection, but MRI offers the best individualized option for assessing cartilage, bone features, and possibly the meniscus, he said. Soluble biomarkers may be more feasible than MRI, but biomarkers need more development and for early detection are "not there yet."

The sheer frequency of MRI lesions in OA patients may prove limiting. OA lesions appear more often on MRI than on x-rays. In five different reported series, the prevalence of cartilage defects visible by MRI in OA patients was 85%-98%, and the prevalence of osteophytes was 70%-100%, Dr. Conaghan noted. Often the MRI changes appear with no radiographic change visible. Other MRI changes that look like promising OA markers are bone marrow lesions and bone shape.

The OARSI Working Group defined tibiofemoral OA by MRI as either both items from group A, or one group A item and at least two from group B. The group A diagnostic features are definite osteophyte formation and full-thickness cartilage loss. The group B items are a subchondral bone marrow lesion or cyst that is not associated with meniscal or ligamentous attachments; meniscal subluxation, maceration, or degenerative tear; partial-thickness cartilage loss, and bone attrition.

The working group’s definition of patellofemoral OA requires both a definitive osteophyte and partial- or full-thickness cartilage loss.

Dr. Conaghan said that he had no relevant disclosures.

Magnetic resonance imaging has an increasingly important role in the early detection and diagnosis of osteoarthritis, although for now it remains one of several diagnostic tools that also include x-rays, clinical findings, and lab results.

Physicians who treat patients with osteoarthritis (OA) need further research results to better clarify the best use of MRI in early OA detection, said Dr. Philip Conaghan, professor of musculoskeletal medicine at the University of Leeds (England).

In June, Dr. Conaghan and his colleagues on the OA Imaging Working Group for the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) issued 11 propositions on using MRI to define OA – propositions that the group said need formal testing "regarding their diagnostic performance before they are more widely used" (Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011;19:963-9).

The working group clearly endorsed MRI, saying that "MRI may add to the diagnosis of OA and should be incorporated into the [American College of Rheumatology] diagnostic criteria," but in the same proposition, the working group also reiterated the role of x-ray, clinical, and laboratory parameters. Other propositions caution that "no single MRI finding is diagnostic of MRI," and that "certain MRI changes in isolation ... are not diagnostic of osteoarthritis."

The working group’s propositions included two MRI-based definitions of OA, for the tibiofemoral form and for the patellofemoral type.

In a recent talk on MRI and OA, Dr. Conaghan stressed the potential that MRI holds for early OA detection.

"We need to develop an early OA culture," similar to what has emerged for rheumatoid arthritis, he said speaking in May at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology in London. "In OA, we need a culture of early intervention" that would rely on early detection, most likely using MRI.

"Clinical features may suffice at present" for early OA detection, but MRI offers the best individualized option for assessing cartilage, bone features, and possibly the meniscus, he said. Soluble biomarkers may be more feasible than MRI, but biomarkers need more development and for early detection are "not there yet."

The sheer frequency of MRI lesions in OA patients may prove limiting. OA lesions appear more often on MRI than on x-rays. In five different reported series, the prevalence of cartilage defects visible by MRI in OA patients was 85%-98%, and the prevalence of osteophytes was 70%-100%, Dr. Conaghan noted. Often the MRI changes appear with no radiographic change visible. Other MRI changes that look like promising OA markers are bone marrow lesions and bone shape.

The OARSI Working Group defined tibiofemoral OA by MRI as either both items from group A, or one group A item and at least two from group B. The group A diagnostic features are definite osteophyte formation and full-thickness cartilage loss. The group B items are a subchondral bone marrow lesion or cyst that is not associated with meniscal or ligamentous attachments; meniscal subluxation, maceration, or degenerative tear; partial-thickness cartilage loss, and bone attrition.

The working group’s definition of patellofemoral OA requires both a definitive osteophyte and partial- or full-thickness cartilage loss.

Dr. Conaghan said that he had no relevant disclosures.

Magnetic resonance imaging has an increasingly important role in the early detection and diagnosis of osteoarthritis, although for now it remains one of several diagnostic tools that also include x-rays, clinical findings, and lab results.

Physicians who treat patients with osteoarthritis (OA) need further research results to better clarify the best use of MRI in early OA detection, said Dr. Philip Conaghan, professor of musculoskeletal medicine at the University of Leeds (England).

In June, Dr. Conaghan and his colleagues on the OA Imaging Working Group for the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) issued 11 propositions on using MRI to define OA – propositions that the group said need formal testing "regarding their diagnostic performance before they are more widely used" (Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011;19:963-9).

The working group clearly endorsed MRI, saying that "MRI may add to the diagnosis of OA and should be incorporated into the [American College of Rheumatology] diagnostic criteria," but in the same proposition, the working group also reiterated the role of x-ray, clinical, and laboratory parameters. Other propositions caution that "no single MRI finding is diagnostic of MRI," and that "certain MRI changes in isolation ... are not diagnostic of osteoarthritis."

The working group’s propositions included two MRI-based definitions of OA, for the tibiofemoral form and for the patellofemoral type.

In a recent talk on MRI and OA, Dr. Conaghan stressed the potential that MRI holds for early OA detection.

"We need to develop an early OA culture," similar to what has emerged for rheumatoid arthritis, he said speaking in May at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology in London. "In OA, we need a culture of early intervention" that would rely on early detection, most likely using MRI.

"Clinical features may suffice at present" for early OA detection, but MRI offers the best individualized option for assessing cartilage, bone features, and possibly the meniscus, he said. Soluble biomarkers may be more feasible than MRI, but biomarkers need more development and for early detection are "not there yet."

The sheer frequency of MRI lesions in OA patients may prove limiting. OA lesions appear more often on MRI than on x-rays. In five different reported series, the prevalence of cartilage defects visible by MRI in OA patients was 85%-98%, and the prevalence of osteophytes was 70%-100%, Dr. Conaghan noted. Often the MRI changes appear with no radiographic change visible. Other MRI changes that look like promising OA markers are bone marrow lesions and bone shape.

The OARSI Working Group defined tibiofemoral OA by MRI as either both items from group A, or one group A item and at least two from group B. The group A diagnostic features are definite osteophyte formation and full-thickness cartilage loss. The group B items are a subchondral bone marrow lesion or cyst that is not associated with meniscal or ligamentous attachments; meniscal subluxation, maceration, or degenerative tear; partial-thickness cartilage loss, and bone attrition.

The working group’s definition of patellofemoral OA requires both a definitive osteophyte and partial- or full-thickness cartilage loss.

Dr. Conaghan said that he had no relevant disclosures.

Lower Extremity Pain

Digital Templating: Here to Stay

Accuracy of Digital Templating in Total Hip Arthroplasty

Entheses Seen on Ultrasound Can Accurately Predict Spondyloarthritis

A power Doppler ultrasound examination may provide the most accurate early diagnosis of spondyloarthritis, with a sensitivity of 76% and a specificity of 81% upon the visualization of at least one vascularized enthesis.

The finding may be particularly valuable to rheumatologists because the existing spondyloarthritis diagnostic criteria have, at best, a limited ability to accurately identify the disease in its earliest stages, Dr. Maria Antoinette D’Agostino and her colleagues wrote in the August issue of Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

Although the test itself is a "delicate technique," it is within the reach of most ultrasound technicians. "It can be performed reliably by sonographers with varying levels of experience followed by dedicated training," said Dr. D’Agostino of Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yveline (France) University.

The 2-year prospective cohort study comprised 118 patients with symptoms suggestive of spondyloarthritis. These included inflammatory back pain (48); arthritis or arthralgia (38); enthesitis or dactylitis (12) and HLA B27 plus acute anterior uveitis (20). Their median age was 40 years; the median disease duration at baseline was 2 years.

All patients underwent a standard clinical examination by a rheumatologist who was blinded to the diagnosis of the referring physician. All had provided a pelvic x-ray not more than 6 months old for the scoring of sacroiliitis; if the radiologic findings were equivocal or if there was persistent buttock pain, the patients underwent a pelvic CT scan. Those with past or present inflammatory back pain also underwent MRI.

Every patient had a power Doppler ultrasound examination of peripheral entheses by a sonographer who was blinded to the patients’ data. Areas examined included plantar fascia, Achilles tendon, patellar ligament on the patella apex, quadriceps femoris, gluteus medius tendon, and the common extensor and common flexor tendons on the lateral and medial epicondyle of the elbow.

Important findings included any morphologic or structural abnormalities and vascularization at bony insertion points. The study evaluated three criteria: any vascularized enthesis, the number of abnormal entheses, and the global ultrasound score.

The referring physician’s diagnosis was used as the clinical standard in evaluating ultrasound’s diagnostic capability; after 2 years, the patients were reevaluated for a final diagnosis, which the investigators then compared with the original diagnosis to compute ultrasound’s diagnostic capability. At the end of the follow-up period, patients were reclassified by their referring rheumatologist (51 diagnosed with SpA, 48 not diagnosed as SpA, and 19 unclassified).

In building the prediction model, the investigators examined the ultrasound findings in light of the final diagnoses. Ultrasound found at least one abnormal enthesis in 88 (75%) of the patients; the enthesis was vascularized in 56 of these patients. At least one vascularized enthesis occurred in 76% of those with an SpA diagnosis, 19% of those with a non-SpA diagnosis, and 42% of unclassified patients (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011;70:1433-40).

Ultrasound detected significantly more abnormal and vascularized entheses in SpA patients than in non-SpA patients. Those with a SpA diagnosis also had significantly higher ultrasound global scores than did the other groups.

Overall, two factors independently predicted a final diagnosis of SpA: Patients who had at least one vascularized enthesis on ultrasound were 12 times more likely to have a final diagnosis of SpA, and patients with an Amor criteria score of 6 or greater were nearly nine times more likely to have SpA than patients with a lower score.

Increasing the number of vascularized entheses to more than one did not improve the prediction model, nor did other diagnostic criteria, including the Berlin criteria and ASAS (Assessment of Spondyloarthritis Society) classification and diagnostic criteria.

Further analysis confirmed that the baseline presence of at least one vascularized enthesis predicted SpA at 2 years with a 76.5% sensitivity and an 81% specificity. If there were no vascularized entheses at baseline, SpA could still be predicted with a combination of ultrasound and positive Amor criteria score, the authors said; this method yielded a sensitivity of 90% for SpA and a specificity of 77%.

The study points out the diagnostic importance of enthesis vascularization in early SpA, the authors noted: "Strikingly, we confirmed that vascularization of the enthesis insertion by [ultrasound] is a landmark feature for SpA, even in suspected cases ... One vascularized enthesis was sufficient to predict a diagnosis of SpA, independent of the localization and the frequency of involvement."h

The study was supported by a grant from the French Society of Rheumatology. None of the authors had any financial disclosures.

A power Doppler ultrasound examination may provide the most accurate early diagnosis of spondyloarthritis, with a sensitivity of 76% and a specificity of 81% upon the visualization of at least one vascularized enthesis.

The finding may be particularly valuable to rheumatologists because the existing spondyloarthritis diagnostic criteria have, at best, a limited ability to accurately identify the disease in its earliest stages, Dr. Maria Antoinette D’Agostino and her colleagues wrote in the August issue of Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

Although the test itself is a "delicate technique," it is within the reach of most ultrasound technicians. "It can be performed reliably by sonographers with varying levels of experience followed by dedicated training," said Dr. D’Agostino of Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yveline (France) University.

The 2-year prospective cohort study comprised 118 patients with symptoms suggestive of spondyloarthritis. These included inflammatory back pain (48); arthritis or arthralgia (38); enthesitis or dactylitis (12) and HLA B27 plus acute anterior uveitis (20). Their median age was 40 years; the median disease duration at baseline was 2 years.

All patients underwent a standard clinical examination by a rheumatologist who was blinded to the diagnosis of the referring physician. All had provided a pelvic x-ray not more than 6 months old for the scoring of sacroiliitis; if the radiologic findings were equivocal or if there was persistent buttock pain, the patients underwent a pelvic CT scan. Those with past or present inflammatory back pain also underwent MRI.

Every patient had a power Doppler ultrasound examination of peripheral entheses by a sonographer who was blinded to the patients’ data. Areas examined included plantar fascia, Achilles tendon, patellar ligament on the patella apex, quadriceps femoris, gluteus medius tendon, and the common extensor and common flexor tendons on the lateral and medial epicondyle of the elbow.

Important findings included any morphologic or structural abnormalities and vascularization at bony insertion points. The study evaluated three criteria: any vascularized enthesis, the number of abnormal entheses, and the global ultrasound score.

The referring physician’s diagnosis was used as the clinical standard in evaluating ultrasound’s diagnostic capability; after 2 years, the patients were reevaluated for a final diagnosis, which the investigators then compared with the original diagnosis to compute ultrasound’s diagnostic capability. At the end of the follow-up period, patients were reclassified by their referring rheumatologist (51 diagnosed with SpA, 48 not diagnosed as SpA, and 19 unclassified).

In building the prediction model, the investigators examined the ultrasound findings in light of the final diagnoses. Ultrasound found at least one abnormal enthesis in 88 (75%) of the patients; the enthesis was vascularized in 56 of these patients. At least one vascularized enthesis occurred in 76% of those with an SpA diagnosis, 19% of those with a non-SpA diagnosis, and 42% of unclassified patients (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011;70:1433-40).

Ultrasound detected significantly more abnormal and vascularized entheses in SpA patients than in non-SpA patients. Those with a SpA diagnosis also had significantly higher ultrasound global scores than did the other groups.

Overall, two factors independently predicted a final diagnosis of SpA: Patients who had at least one vascularized enthesis on ultrasound were 12 times more likely to have a final diagnosis of SpA, and patients with an Amor criteria score of 6 or greater were nearly nine times more likely to have SpA than patients with a lower score.

Increasing the number of vascularized entheses to more than one did not improve the prediction model, nor did other diagnostic criteria, including the Berlin criteria and ASAS (Assessment of Spondyloarthritis Society) classification and diagnostic criteria.

Further analysis confirmed that the baseline presence of at least one vascularized enthesis predicted SpA at 2 years with a 76.5% sensitivity and an 81% specificity. If there were no vascularized entheses at baseline, SpA could still be predicted with a combination of ultrasound and positive Amor criteria score, the authors said; this method yielded a sensitivity of 90% for SpA and a specificity of 77%.

The study points out the diagnostic importance of enthesis vascularization in early SpA, the authors noted: "Strikingly, we confirmed that vascularization of the enthesis insertion by [ultrasound] is a landmark feature for SpA, even in suspected cases ... One vascularized enthesis was sufficient to predict a diagnosis of SpA, independent of the localization and the frequency of involvement."h

The study was supported by a grant from the French Society of Rheumatology. None of the authors had any financial disclosures.

A power Doppler ultrasound examination may provide the most accurate early diagnosis of spondyloarthritis, with a sensitivity of 76% and a specificity of 81% upon the visualization of at least one vascularized enthesis.

The finding may be particularly valuable to rheumatologists because the existing spondyloarthritis diagnostic criteria have, at best, a limited ability to accurately identify the disease in its earliest stages, Dr. Maria Antoinette D’Agostino and her colleagues wrote in the August issue of Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

Although the test itself is a "delicate technique," it is within the reach of most ultrasound technicians. "It can be performed reliably by sonographers with varying levels of experience followed by dedicated training," said Dr. D’Agostino of Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yveline (France) University.

The 2-year prospective cohort study comprised 118 patients with symptoms suggestive of spondyloarthritis. These included inflammatory back pain (48); arthritis or arthralgia (38); enthesitis or dactylitis (12) and HLA B27 plus acute anterior uveitis (20). Their median age was 40 years; the median disease duration at baseline was 2 years.

All patients underwent a standard clinical examination by a rheumatologist who was blinded to the diagnosis of the referring physician. All had provided a pelvic x-ray not more than 6 months old for the scoring of sacroiliitis; if the radiologic findings were equivocal or if there was persistent buttock pain, the patients underwent a pelvic CT scan. Those with past or present inflammatory back pain also underwent MRI.

Every patient had a power Doppler ultrasound examination of peripheral entheses by a sonographer who was blinded to the patients’ data. Areas examined included plantar fascia, Achilles tendon, patellar ligament on the patella apex, quadriceps femoris, gluteus medius tendon, and the common extensor and common flexor tendons on the lateral and medial epicondyle of the elbow.

Important findings included any morphologic or structural abnormalities and vascularization at bony insertion points. The study evaluated three criteria: any vascularized enthesis, the number of abnormal entheses, and the global ultrasound score.

The referring physician’s diagnosis was used as the clinical standard in evaluating ultrasound’s diagnostic capability; after 2 years, the patients were reevaluated for a final diagnosis, which the investigators then compared with the original diagnosis to compute ultrasound’s diagnostic capability. At the end of the follow-up period, patients were reclassified by their referring rheumatologist (51 diagnosed with SpA, 48 not diagnosed as SpA, and 19 unclassified).

In building the prediction model, the investigators examined the ultrasound findings in light of the final diagnoses. Ultrasound found at least one abnormal enthesis in 88 (75%) of the patients; the enthesis was vascularized in 56 of these patients. At least one vascularized enthesis occurred in 76% of those with an SpA diagnosis, 19% of those with a non-SpA diagnosis, and 42% of unclassified patients (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011;70:1433-40).

Ultrasound detected significantly more abnormal and vascularized entheses in SpA patients than in non-SpA patients. Those with a SpA diagnosis also had significantly higher ultrasound global scores than did the other groups.

Overall, two factors independently predicted a final diagnosis of SpA: Patients who had at least one vascularized enthesis on ultrasound were 12 times more likely to have a final diagnosis of SpA, and patients with an Amor criteria score of 6 or greater were nearly nine times more likely to have SpA than patients with a lower score.

Increasing the number of vascularized entheses to more than one did not improve the prediction model, nor did other diagnostic criteria, including the Berlin criteria and ASAS (Assessment of Spondyloarthritis Society) classification and diagnostic criteria.

Further analysis confirmed that the baseline presence of at least one vascularized enthesis predicted SpA at 2 years with a 76.5% sensitivity and an 81% specificity. If there were no vascularized entheses at baseline, SpA could still be predicted with a combination of ultrasound and positive Amor criteria score, the authors said; this method yielded a sensitivity of 90% for SpA and a specificity of 77%.

The study points out the diagnostic importance of enthesis vascularization in early SpA, the authors noted: "Strikingly, we confirmed that vascularization of the enthesis insertion by [ultrasound] is a landmark feature for SpA, even in suspected cases ... One vascularized enthesis was sufficient to predict a diagnosis of SpA, independent of the localization and the frequency of involvement."h

The study was supported by a grant from the French Society of Rheumatology. None of the authors had any financial disclosures.

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

Major Finding: One vascularized enthesis seen on ultrasound predicted SpA within 2 years with a sensitivity of 76% and a specificity of 81%. An ultrasound finding of a nonvascularized enthesis, combined with positive Amor criteria, predicted the disorder at 2 years with a sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 77%.

Data Source: A prospective cohort study of 118 patients with symptoms suggestive of spondyloarthritis.

Disclosures: The study was supported by a grant from the French Society of Rheumatology. None of the authors had any financial disclosures.

Editorial: Angiography in Asymptomatic Patients

They came for a second opinion. They were both in their 50s; she a lawyer, the husband a stockbroker. He had insulin dependent diabetes for 20 years but was otherwise well. She was concerned that her husband would die suddenly just as his father had at age 70. He was without symptoms but had a nuclear exercise stress test at the behest of his local medical doctor because of his diabetes. The test was said to be abnormal, but three subsequent in-house readers found the results normal. He was advised to have an angiogram by another cardiologist. "What should we do?" I told her that an angiogram or a stent would not prevent him from dying suddenly. I outlined all the pros and cons and advised against it. The wife was very anxious and wanted an angiogram so that her husband wouldn’t die suddenly. They both left my office, never to be seen again.

A recent report by Dr. William B. Borden and colleagues (JAMA 2011;305:1882-9) examined the change in clinical practice in regard to percutaneous coronary intervention before and after the report of the COURAGE trial 4 years ago (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;356:1503-16), which indicated that there was no mortality or morbidity benefit in patients with stable angina who received PCI when compared to optimal medical therapy (OMT).

Dr. Borden and colleagues presumed that the results of the COURAGE trial would transform clinical practice, and that most of the 293,795 patients in their study who went on to PCI in the COURAGE-like population would receive OMT before PCI. In fact, OMT (defined as therapy with aspirin, a beta-blocker, an ACE inhibitor, and a statin) was used in 43.4% of the patients before COURAGE and in 45.0% after the COURAGE report. In COURAGE, 32% had diabetes, 12% of the patients were asymptomatic, and 30% had class I angina. In the most recent analysis by Dr. Borden, one-third of patients (more than 70,000) had no angina prior to PCI. One must wonder what the perceived patient benefit was that led to the performance of a PCI in those patients.

The other cardiologist advised angiography for my patient partly because of a concern for the early identification of ischemic heart disease in diabetic patients. Indeed, this concern had led the American Diabetes Association to recommend that in addition to standard secondary prevention therapy for both diabetes and coronary artery disease, patients with two or more risk factors for coronary artery disease undergo early screening (Diabetes Care 1998;13:1551-9). These recommendations, however, were not evidence based, but made on the recommendation of an expert panel. The DIAD (Detection of Ischemia in Asymptomatic Diabetics) trial has since provided further insight into the issue of screening asymptomatic diabetic patients (JAMA 2009; 301:1547-55), an issue that remains controversial. Although not a randomized trial, DIAD indicates that the event rate in asymptomatic diabetic patients in general is low, and that a positive myocardial perfusion stress test did not identify patients who were at an increase risk of ischemic events. Of the 522 asymptomatic patients screened, 409 (78%) had normal results, 50 (10%) had a small perfusion defect, and 33 (6%) had moderate or large perfusion defects. Although there was no significantly increased risk of cardiac events in patients with small defects when they were compared with those who had no perfusion defect, there was a sixfold increase risk in patients with moderate to large defects on MPI (myocardial perfusion imaging). Only 4.4% of patients went on to angiography, a decision driven by the clinical judgment of the patient’s physician.

Of course, in my example, the greatest pressure for angiography came from the patient’s wife, who was convinced that on the basis of conventional wisdom, MPI-guided PCI would identify a critical lesion that, when treated with PCI, would prolong her husband’s life. And as a matter of fact, in order to prove the absence of coronary artery disease based on the normal MPI, I agreed to arrange an angiogram should they need reassurance that the MPI was normal. What would have eventuated should we have found a lesion remains for your conjecture. But it is clear that there is an overabundance of angiograms being performed in asymptomatic patients, which more than likely leads to the performance of unnecessary PCIs in asymptomatic patients. Angiography has become the "carpenter’s hammer," with the little regard for its benefit. A more reasonable and effective approach to diabetic patients (as well as other asymptomatic patients) is the institution of adequate primary prevention, which has been shown to have both morbidity and mortality benefits.

Dr. Goldstein is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

They came for a second opinion. They were both in their 50s; she a lawyer, the husband a stockbroker. He had insulin dependent diabetes for 20 years but was otherwise well. She was concerned that her husband would die suddenly just as his father had at age 70. He was without symptoms but had a nuclear exercise stress test at the behest of his local medical doctor because of his diabetes. The test was said to be abnormal, but three subsequent in-house readers found the results normal. He was advised to have an angiogram by another cardiologist. "What should we do?" I told her that an angiogram or a stent would not prevent him from dying suddenly. I outlined all the pros and cons and advised against it. The wife was very anxious and wanted an angiogram so that her husband wouldn’t die suddenly. They both left my office, never to be seen again.

A recent report by Dr. William B. Borden and colleagues (JAMA 2011;305:1882-9) examined the change in clinical practice in regard to percutaneous coronary intervention before and after the report of the COURAGE trial 4 years ago (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;356:1503-16), which indicated that there was no mortality or morbidity benefit in patients with stable angina who received PCI when compared to optimal medical therapy (OMT).

Dr. Borden and colleagues presumed that the results of the COURAGE trial would transform clinical practice, and that most of the 293,795 patients in their study who went on to PCI in the COURAGE-like population would receive OMT before PCI. In fact, OMT (defined as therapy with aspirin, a beta-blocker, an ACE inhibitor, and a statin) was used in 43.4% of the patients before COURAGE and in 45.0% after the COURAGE report. In COURAGE, 32% had diabetes, 12% of the patients were asymptomatic, and 30% had class I angina. In the most recent analysis by Dr. Borden, one-third of patients (more than 70,000) had no angina prior to PCI. One must wonder what the perceived patient benefit was that led to the performance of a PCI in those patients.

The other cardiologist advised angiography for my patient partly because of a concern for the early identification of ischemic heart disease in diabetic patients. Indeed, this concern had led the American Diabetes Association to recommend that in addition to standard secondary prevention therapy for both diabetes and coronary artery disease, patients with two or more risk factors for coronary artery disease undergo early screening (Diabetes Care 1998;13:1551-9). These recommendations, however, were not evidence based, but made on the recommendation of an expert panel. The DIAD (Detection of Ischemia in Asymptomatic Diabetics) trial has since provided further insight into the issue of screening asymptomatic diabetic patients (JAMA 2009; 301:1547-55), an issue that remains controversial. Although not a randomized trial, DIAD indicates that the event rate in asymptomatic diabetic patients in general is low, and that a positive myocardial perfusion stress test did not identify patients who were at an increase risk of ischemic events. Of the 522 asymptomatic patients screened, 409 (78%) had normal results, 50 (10%) had a small perfusion defect, and 33 (6%) had moderate or large perfusion defects. Although there was no significantly increased risk of cardiac events in patients with small defects when they were compared with those who had no perfusion defect, there was a sixfold increase risk in patients with moderate to large defects on MPI (myocardial perfusion imaging). Only 4.4% of patients went on to angiography, a decision driven by the clinical judgment of the patient’s physician.

Of course, in my example, the greatest pressure for angiography came from the patient’s wife, who was convinced that on the basis of conventional wisdom, MPI-guided PCI would identify a critical lesion that, when treated with PCI, would prolong her husband’s life. And as a matter of fact, in order to prove the absence of coronary artery disease based on the normal MPI, I agreed to arrange an angiogram should they need reassurance that the MPI was normal. What would have eventuated should we have found a lesion remains for your conjecture. But it is clear that there is an overabundance of angiograms being performed in asymptomatic patients, which more than likely leads to the performance of unnecessary PCIs in asymptomatic patients. Angiography has become the "carpenter’s hammer," with the little regard for its benefit. A more reasonable and effective approach to diabetic patients (as well as other asymptomatic patients) is the institution of adequate primary prevention, which has been shown to have both morbidity and mortality benefits.

Dr. Goldstein is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

They came for a second opinion. They were both in their 50s; she a lawyer, the husband a stockbroker. He had insulin dependent diabetes for 20 years but was otherwise well. She was concerned that her husband would die suddenly just as his father had at age 70. He was without symptoms but had a nuclear exercise stress test at the behest of his local medical doctor because of his diabetes. The test was said to be abnormal, but three subsequent in-house readers found the results normal. He was advised to have an angiogram by another cardiologist. "What should we do?" I told her that an angiogram or a stent would not prevent him from dying suddenly. I outlined all the pros and cons and advised against it. The wife was very anxious and wanted an angiogram so that her husband wouldn’t die suddenly. They both left my office, never to be seen again.

A recent report by Dr. William B. Borden and colleagues (JAMA 2011;305:1882-9) examined the change in clinical practice in regard to percutaneous coronary intervention before and after the report of the COURAGE trial 4 years ago (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;356:1503-16), which indicated that there was no mortality or morbidity benefit in patients with stable angina who received PCI when compared to optimal medical therapy (OMT).

Dr. Borden and colleagues presumed that the results of the COURAGE trial would transform clinical practice, and that most of the 293,795 patients in their study who went on to PCI in the COURAGE-like population would receive OMT before PCI. In fact, OMT (defined as therapy with aspirin, a beta-blocker, an ACE inhibitor, and a statin) was used in 43.4% of the patients before COURAGE and in 45.0% after the COURAGE report. In COURAGE, 32% had diabetes, 12% of the patients were asymptomatic, and 30% had class I angina. In the most recent analysis by Dr. Borden, one-third of patients (more than 70,000) had no angina prior to PCI. One must wonder what the perceived patient benefit was that led to the performance of a PCI in those patients.

The other cardiologist advised angiography for my patient partly because of a concern for the early identification of ischemic heart disease in diabetic patients. Indeed, this concern had led the American Diabetes Association to recommend that in addition to standard secondary prevention therapy for both diabetes and coronary artery disease, patients with two or more risk factors for coronary artery disease undergo early screening (Diabetes Care 1998;13:1551-9). These recommendations, however, were not evidence based, but made on the recommendation of an expert panel. The DIAD (Detection of Ischemia in Asymptomatic Diabetics) trial has since provided further insight into the issue of screening asymptomatic diabetic patients (JAMA 2009; 301:1547-55), an issue that remains controversial. Although not a randomized trial, DIAD indicates that the event rate in asymptomatic diabetic patients in general is low, and that a positive myocardial perfusion stress test did not identify patients who were at an increase risk of ischemic events. Of the 522 asymptomatic patients screened, 409 (78%) had normal results, 50 (10%) had a small perfusion defect, and 33 (6%) had moderate or large perfusion defects. Although there was no significantly increased risk of cardiac events in patients with small defects when they were compared with those who had no perfusion defect, there was a sixfold increase risk in patients with moderate to large defects on MPI (myocardial perfusion imaging). Only 4.4% of patients went on to angiography, a decision driven by the clinical judgment of the patient’s physician.

Of course, in my example, the greatest pressure for angiography came from the patient’s wife, who was convinced that on the basis of conventional wisdom, MPI-guided PCI would identify a critical lesion that, when treated with PCI, would prolong her husband’s life. And as a matter of fact, in order to prove the absence of coronary artery disease based on the normal MPI, I agreed to arrange an angiogram should they need reassurance that the MPI was normal. What would have eventuated should we have found a lesion remains for your conjecture. But it is clear that there is an overabundance of angiograms being performed in asymptomatic patients, which more than likely leads to the performance of unnecessary PCIs in asymptomatic patients. Angiography has become the "carpenter’s hammer," with the little regard for its benefit. A more reasonable and effective approach to diabetic patients (as well as other asymptomatic patients) is the institution of adequate primary prevention, which has been shown to have both morbidity and mortality benefits.

Dr. Goldstein is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.