User login

Pain in a Man Who Had Childhood Spine Surgery

A Man Who Is Dyspneic

Using the 320-Multidetector Computed Tomography Scanner for Four-Dimensional Functional Assessment of the Elbow Joint

Fulminant Spread of a Femur Anaerobic Osteomyelitis to Abdomen in a 17-Year-Old Boy

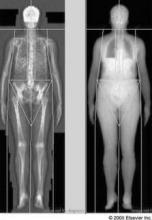

Evidence Suggests Optimal Intervals for Osteoporosis Screening

Based on available evidence, osteoporosis screening should take place at 15-year intervals for postmenopausal women who have normal bone density or mild osteopenia at their first assessment, at 5-year intervals for those who have moderate osteopenia, and at 1-year intervals for those who have advanced osteopenia, according to a report in the Jan. 19 New England Journal of Medicine.

Screening at shorter intervals is unlikely to improve prediction of the transition to osteoporosis, and thus won’t help clinicians judge when to start osteoporosis therapy so as to avert hip or vertebral fractures, said Dr. Margaret L. Gourlay of the department of family medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and her associates in the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures research group.

Current guidelines do not specify how long to wait between bone mineral density screening with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), and no U.S. study to date "has addressed this clinical uncertainty," they noted.

"To determine how the BMD testing interval relates to the timing of the transition from normal [bone mineral density] or osteopenia to the development of osteoporosis before a hip or clinical vertebral fracture occurs, we conducted competing-risk analyses of data from 4,957 women, 67 years of age or older, who did not have osteoporosis at baseline and who were followed longitudinally for up to 15 years in the [Study of Osteoporotic Fractures]," the investigators said.

The appropriate screening interval was defined as the estimated time for 10% of the study subjects in each category of osteopenia severity to make the transition from normal BMD or osteopenia to osteoporosis before fractures occurred and before treatment for osteoporosis was initiated. The three categories of severity were normal BMD/mild osteopenia (T score of greater than -1.50) at the initial assessment, moderate osteopenia (T score of -1.50 to -1.99), and advanced osteopenia (T score of -2.00 to -2.49).

This interval was found to be 15 years for normal BMD/mild osteopenia, 5 years for moderate osteopenia, and 1 year for advanced osteopenia, Dr. Gourlay and her colleagues said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:225-33).

"Recent controversy over the harms of excessive screening for other chronic diseases reinforces the importance of developing a rational screening program for osteoporosis that is based on the best available evidence rather than on health care marketing, advocacy, and public beliefs that have encouraged overtesting and overtreatment in the U.S.," they noted.

"Our estimates for BMD testing proved to be robust after adjustment for major clinical risk factors" such as fracture history, smoking status, use of estrogen, and use of glucocorticoids. "However, clinicians may choose to reevaluate patients before our estimated screening intervals if there is evidence of decreased activity or mobility, weight loss, or other risk factors not considered in our analyses," they said.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. No potential conflicts of interest were reported.

Based on available evidence, osteoporosis screening should take place at 15-year intervals for postmenopausal women who have normal bone density or mild osteopenia at their first assessment, at 5-year intervals for those who have moderate osteopenia, and at 1-year intervals for those who have advanced osteopenia, according to a report in the Jan. 19 New England Journal of Medicine.

Screening at shorter intervals is unlikely to improve prediction of the transition to osteoporosis, and thus won’t help clinicians judge when to start osteoporosis therapy so as to avert hip or vertebral fractures, said Dr. Margaret L. Gourlay of the department of family medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and her associates in the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures research group.

Current guidelines do not specify how long to wait between bone mineral density screening with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), and no U.S. study to date "has addressed this clinical uncertainty," they noted.

"To determine how the BMD testing interval relates to the timing of the transition from normal [bone mineral density] or osteopenia to the development of osteoporosis before a hip or clinical vertebral fracture occurs, we conducted competing-risk analyses of data from 4,957 women, 67 years of age or older, who did not have osteoporosis at baseline and who were followed longitudinally for up to 15 years in the [Study of Osteoporotic Fractures]," the investigators said.

The appropriate screening interval was defined as the estimated time for 10% of the study subjects in each category of osteopenia severity to make the transition from normal BMD or osteopenia to osteoporosis before fractures occurred and before treatment for osteoporosis was initiated. The three categories of severity were normal BMD/mild osteopenia (T score of greater than -1.50) at the initial assessment, moderate osteopenia (T score of -1.50 to -1.99), and advanced osteopenia (T score of -2.00 to -2.49).

This interval was found to be 15 years for normal BMD/mild osteopenia, 5 years for moderate osteopenia, and 1 year for advanced osteopenia, Dr. Gourlay and her colleagues said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:225-33).

"Recent controversy over the harms of excessive screening for other chronic diseases reinforces the importance of developing a rational screening program for osteoporosis that is based on the best available evidence rather than on health care marketing, advocacy, and public beliefs that have encouraged overtesting and overtreatment in the U.S.," they noted.

"Our estimates for BMD testing proved to be robust after adjustment for major clinical risk factors" such as fracture history, smoking status, use of estrogen, and use of glucocorticoids. "However, clinicians may choose to reevaluate patients before our estimated screening intervals if there is evidence of decreased activity or mobility, weight loss, or other risk factors not considered in our analyses," they said.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. No potential conflicts of interest were reported.

Based on available evidence, osteoporosis screening should take place at 15-year intervals for postmenopausal women who have normal bone density or mild osteopenia at their first assessment, at 5-year intervals for those who have moderate osteopenia, and at 1-year intervals for those who have advanced osteopenia, according to a report in the Jan. 19 New England Journal of Medicine.

Screening at shorter intervals is unlikely to improve prediction of the transition to osteoporosis, and thus won’t help clinicians judge when to start osteoporosis therapy so as to avert hip or vertebral fractures, said Dr. Margaret L. Gourlay of the department of family medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and her associates in the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures research group.

Current guidelines do not specify how long to wait between bone mineral density screening with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), and no U.S. study to date "has addressed this clinical uncertainty," they noted.

"To determine how the BMD testing interval relates to the timing of the transition from normal [bone mineral density] or osteopenia to the development of osteoporosis before a hip or clinical vertebral fracture occurs, we conducted competing-risk analyses of data from 4,957 women, 67 years of age or older, who did not have osteoporosis at baseline and who were followed longitudinally for up to 15 years in the [Study of Osteoporotic Fractures]," the investigators said.

The appropriate screening interval was defined as the estimated time for 10% of the study subjects in each category of osteopenia severity to make the transition from normal BMD or osteopenia to osteoporosis before fractures occurred and before treatment for osteoporosis was initiated. The three categories of severity were normal BMD/mild osteopenia (T score of greater than -1.50) at the initial assessment, moderate osteopenia (T score of -1.50 to -1.99), and advanced osteopenia (T score of -2.00 to -2.49).

This interval was found to be 15 years for normal BMD/mild osteopenia, 5 years for moderate osteopenia, and 1 year for advanced osteopenia, Dr. Gourlay and her colleagues said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:225-33).

"Recent controversy over the harms of excessive screening for other chronic diseases reinforces the importance of developing a rational screening program for osteoporosis that is based on the best available evidence rather than on health care marketing, advocacy, and public beliefs that have encouraged overtesting and overtreatment in the U.S.," they noted.

"Our estimates for BMD testing proved to be robust after adjustment for major clinical risk factors" such as fracture history, smoking status, use of estrogen, and use of glucocorticoids. "However, clinicians may choose to reevaluate patients before our estimated screening intervals if there is evidence of decreased activity or mobility, weight loss, or other risk factors not considered in our analyses," they said.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. No potential conflicts of interest were reported.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Major Finding: DEXA screening for osteoporosis should be done at 15-year intervals for women with normal BMD or mild osteopenia (T score of greater than -1.50) at their initial screen, at 5-year intervals for those who have moderate osteopenia (T score of -1.50 to -1.99), and at 1-year intervals for those who have advanced osteopenia (T score of -2.00 to -2.49).

Data Source: Analysis of data from the longitudinal Study of Osteoporotic Fractures involving 4,957 postmenopausal women aged 67 years and older at baseline who were followed for 15 years.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. No potential conflicts of interest were reported.

DXA Reimbursement Slated to Plummet March 1

Medicare payments for the use of dual energy x-ray absorptiometry are set to drop on March 1 unless Congress acts to extend the current payment rates for the screening procedure.

Physicians performing dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) testing currently are reimbursed at around $100 per test on average, but those payments are scheduled to drop to about $50 without congressional intervention. Physicians also are concerned that the steep cut could force more office-based physicians to stop offering bone density screening, thereby limiting access for patients.

"We will definitely be changing the way that we do business when it comes to DXA," said Dr. Christopher R. Shuhart, a family physician and medical director for bone health and osteoporosis at Swedish Medical Group in Seattle.

The large multispecialty group is considering a range of options, including whether to limit the number of sites where they offer DXA testing, in part because of the potential Medicare fee cut. They had already been considering changes to their DXA practice for other reasons, Dr. Shuhart said, but the financial pressure that would come with a cut to $50 per test is a significant factor.

"DXA is both clinically valuable and cost effective."

Dr. Shuhart, who also is cochair for facility accreditation at the International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD), said that Swedish Medical Group is in a better position to absorb the DXA cuts than most small private practices because they are part of a large health care system, which allows them to benefit from higher private insurance contract rates that help to offset cuts in Medicare payments.

Congress first cut DXA payments in 2007, when it slashed Medicare payments for imaging services as part of the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005. Although DXA wasn’t one of the high-cost imaging modalities lawmakers had in their crosshairs, it still was included in the law.

Physicians took another payment hit when the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services reduced payments for physician work involved in interpreting the results of a DXA test. The cuts were phased in over time, but by the beginning of 2010, the average Medicare payment for DXA had dropped from a high of about $140 to about $62.

Under the Affordable Care Act, DXA payments were restored to 70% of the 2006 level, bringing them back up to nearly $100. But that increase was only for 2 years. At the end of last year, the increase was scheduled to expire, when Congress granted a 2-month reprieve by including DXA in the Temporary Payroll Tax Cut Continuation Act of 2011, which also extended the 2011 Medicare physician fee schedule rates, the payroll tax holiday, and federal unemployment benefits temporarily.

What will happen next with DXA payment is uncertain and depends in large part on the fate of the larger legislative package currently under consideration in Congress.

"It looks like the [Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate formula], DXA, and payroll taxes are wrapped up together for at least the immediate future," said Dr. Jonathan D. Leffert, an endocrinologist in Dallas and chair of the Legislative and Regulatory Committee for the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

Dr. Leffert said that a permanent stabilization of DXA payment rates is not likely right now and that an extension of the current payment rates could range anywhere from 2 months to 22 months. "At this point, it’s pretty much not about the policy, but about the money," he said. Specifically, lawmakers are struggling to find ways to pay for not only the increased DXA payments to physicians but a temporary fix for the 27% Medicare physician fee cut that is also slated to take effect on March 1.

But just getting lawmakers to include DXA in the Temporary Payroll Tax Cut Continuation Act was a big step, said Dr. Andrew J. Laster, a rheumatologist in private practice in Charlotte, N.C., and chair of the public policy committee for the ISCD. There were only about a dozen health provisions that made it into that bill, so it shows that Congress recognizes the value of identifying people with osteoporosis and treating them. "Now at least we are in the room and acknowledged," he said.

"We will definitely be changing the way that we do business when it comes to DXA."

Dr. Laster added that he’s also encouraged by a recent study published in the journal Health Affairs that helps bolster the case for increasing payments for bone density testing (Health Aff. 2011;30:2362-70). Looking at a large population of Medicare beneficiaries, researchers found that as payments for DXA dropped, Medicare claims for the test plateaued. For instance, from 1996 through 2006, before the payment cuts went into effect, DXA testing was growing at a rate of about 6.5%. From 2007 through 2009, however, about 800,000 fewer tests were administered to Medicare beneficiaries than would have been expected based on the earlier growth rate.

The study also showed that DXA testing was linked to fewer fractures. The researchers found that, over a 3-year period, fracture rates were nearly 20% lower in elderly women who had received a DXA test, compared with those who did not.

Alison King, Ph.D., one of the coauthors of the study and a health care consultant, said the results make a strong case for averting the scheduled payment cut for DXA both to improve public health and to save money in the long term. "There are many valuable medical interventions that do not save money," she said. "DXA is both clinically valuable and cost effective."

Dr. Charles King, a rheumatologist in Tupelo, Miss., and chair of the American College of Rheumatology’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care, said that he thinks lawmakers are starting to hear the message about the cost effectiveness of DXA. "We are getting the word out," he said. The problem, he noted, is that Congress has been reticent to provide legislative carve-outs for certain diseases or treatments.

Dr. King advised physicians that if they want to continue to offer DXA they need to view it as a loss leader, but he urged rheumatologists to keep performing it. Rheumatologists must continue to read and interpret these studies because they inadvertently contribute to the development of osteoporosis through the use of corticosteroids and other treatments for rheumatic conditions. "We have to retain ownership of this disease," he said.

Medicare payments for the use of dual energy x-ray absorptiometry are set to drop on March 1 unless Congress acts to extend the current payment rates for the screening procedure.

Physicians performing dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) testing currently are reimbursed at around $100 per test on average, but those payments are scheduled to drop to about $50 without congressional intervention. Physicians also are concerned that the steep cut could force more office-based physicians to stop offering bone density screening, thereby limiting access for patients.

"We will definitely be changing the way that we do business when it comes to DXA," said Dr. Christopher R. Shuhart, a family physician and medical director for bone health and osteoporosis at Swedish Medical Group in Seattle.

The large multispecialty group is considering a range of options, including whether to limit the number of sites where they offer DXA testing, in part because of the potential Medicare fee cut. They had already been considering changes to their DXA practice for other reasons, Dr. Shuhart said, but the financial pressure that would come with a cut to $50 per test is a significant factor.

"DXA is both clinically valuable and cost effective."

Dr. Shuhart, who also is cochair for facility accreditation at the International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD), said that Swedish Medical Group is in a better position to absorb the DXA cuts than most small private practices because they are part of a large health care system, which allows them to benefit from higher private insurance contract rates that help to offset cuts in Medicare payments.

Congress first cut DXA payments in 2007, when it slashed Medicare payments for imaging services as part of the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005. Although DXA wasn’t one of the high-cost imaging modalities lawmakers had in their crosshairs, it still was included in the law.

Physicians took another payment hit when the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services reduced payments for physician work involved in interpreting the results of a DXA test. The cuts were phased in over time, but by the beginning of 2010, the average Medicare payment for DXA had dropped from a high of about $140 to about $62.

Under the Affordable Care Act, DXA payments were restored to 70% of the 2006 level, bringing them back up to nearly $100. But that increase was only for 2 years. At the end of last year, the increase was scheduled to expire, when Congress granted a 2-month reprieve by including DXA in the Temporary Payroll Tax Cut Continuation Act of 2011, which also extended the 2011 Medicare physician fee schedule rates, the payroll tax holiday, and federal unemployment benefits temporarily.

What will happen next with DXA payment is uncertain and depends in large part on the fate of the larger legislative package currently under consideration in Congress.

"It looks like the [Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate formula], DXA, and payroll taxes are wrapped up together for at least the immediate future," said Dr. Jonathan D. Leffert, an endocrinologist in Dallas and chair of the Legislative and Regulatory Committee for the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

Dr. Leffert said that a permanent stabilization of DXA payment rates is not likely right now and that an extension of the current payment rates could range anywhere from 2 months to 22 months. "At this point, it’s pretty much not about the policy, but about the money," he said. Specifically, lawmakers are struggling to find ways to pay for not only the increased DXA payments to physicians but a temporary fix for the 27% Medicare physician fee cut that is also slated to take effect on March 1.

But just getting lawmakers to include DXA in the Temporary Payroll Tax Cut Continuation Act was a big step, said Dr. Andrew J. Laster, a rheumatologist in private practice in Charlotte, N.C., and chair of the public policy committee for the ISCD. There were only about a dozen health provisions that made it into that bill, so it shows that Congress recognizes the value of identifying people with osteoporosis and treating them. "Now at least we are in the room and acknowledged," he said.

"We will definitely be changing the way that we do business when it comes to DXA."

Dr. Laster added that he’s also encouraged by a recent study published in the journal Health Affairs that helps bolster the case for increasing payments for bone density testing (Health Aff. 2011;30:2362-70). Looking at a large population of Medicare beneficiaries, researchers found that as payments for DXA dropped, Medicare claims for the test plateaued. For instance, from 1996 through 2006, before the payment cuts went into effect, DXA testing was growing at a rate of about 6.5%. From 2007 through 2009, however, about 800,000 fewer tests were administered to Medicare beneficiaries than would have been expected based on the earlier growth rate.

The study also showed that DXA testing was linked to fewer fractures. The researchers found that, over a 3-year period, fracture rates were nearly 20% lower in elderly women who had received a DXA test, compared with those who did not.

Alison King, Ph.D., one of the coauthors of the study and a health care consultant, said the results make a strong case for averting the scheduled payment cut for DXA both to improve public health and to save money in the long term. "There are many valuable medical interventions that do not save money," she said. "DXA is both clinically valuable and cost effective."

Dr. Charles King, a rheumatologist in Tupelo, Miss., and chair of the American College of Rheumatology’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care, said that he thinks lawmakers are starting to hear the message about the cost effectiveness of DXA. "We are getting the word out," he said. The problem, he noted, is that Congress has been reticent to provide legislative carve-outs for certain diseases or treatments.

Dr. King advised physicians that if they want to continue to offer DXA they need to view it as a loss leader, but he urged rheumatologists to keep performing it. Rheumatologists must continue to read and interpret these studies because they inadvertently contribute to the development of osteoporosis through the use of corticosteroids and other treatments for rheumatic conditions. "We have to retain ownership of this disease," he said.

Medicare payments for the use of dual energy x-ray absorptiometry are set to drop on March 1 unless Congress acts to extend the current payment rates for the screening procedure.

Physicians performing dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) testing currently are reimbursed at around $100 per test on average, but those payments are scheduled to drop to about $50 without congressional intervention. Physicians also are concerned that the steep cut could force more office-based physicians to stop offering bone density screening, thereby limiting access for patients.

"We will definitely be changing the way that we do business when it comes to DXA," said Dr. Christopher R. Shuhart, a family physician and medical director for bone health and osteoporosis at Swedish Medical Group in Seattle.

The large multispecialty group is considering a range of options, including whether to limit the number of sites where they offer DXA testing, in part because of the potential Medicare fee cut. They had already been considering changes to their DXA practice for other reasons, Dr. Shuhart said, but the financial pressure that would come with a cut to $50 per test is a significant factor.

"DXA is both clinically valuable and cost effective."

Dr. Shuhart, who also is cochair for facility accreditation at the International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD), said that Swedish Medical Group is in a better position to absorb the DXA cuts than most small private practices because they are part of a large health care system, which allows them to benefit from higher private insurance contract rates that help to offset cuts in Medicare payments.

Congress first cut DXA payments in 2007, when it slashed Medicare payments for imaging services as part of the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005. Although DXA wasn’t one of the high-cost imaging modalities lawmakers had in their crosshairs, it still was included in the law.

Physicians took another payment hit when the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services reduced payments for physician work involved in interpreting the results of a DXA test. The cuts were phased in over time, but by the beginning of 2010, the average Medicare payment for DXA had dropped from a high of about $140 to about $62.

Under the Affordable Care Act, DXA payments were restored to 70% of the 2006 level, bringing them back up to nearly $100. But that increase was only for 2 years. At the end of last year, the increase was scheduled to expire, when Congress granted a 2-month reprieve by including DXA in the Temporary Payroll Tax Cut Continuation Act of 2011, which also extended the 2011 Medicare physician fee schedule rates, the payroll tax holiday, and federal unemployment benefits temporarily.

What will happen next with DXA payment is uncertain and depends in large part on the fate of the larger legislative package currently under consideration in Congress.

"It looks like the [Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate formula], DXA, and payroll taxes are wrapped up together for at least the immediate future," said Dr. Jonathan D. Leffert, an endocrinologist in Dallas and chair of the Legislative and Regulatory Committee for the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

Dr. Leffert said that a permanent stabilization of DXA payment rates is not likely right now and that an extension of the current payment rates could range anywhere from 2 months to 22 months. "At this point, it’s pretty much not about the policy, but about the money," he said. Specifically, lawmakers are struggling to find ways to pay for not only the increased DXA payments to physicians but a temporary fix for the 27% Medicare physician fee cut that is also slated to take effect on March 1.

But just getting lawmakers to include DXA in the Temporary Payroll Tax Cut Continuation Act was a big step, said Dr. Andrew J. Laster, a rheumatologist in private practice in Charlotte, N.C., and chair of the public policy committee for the ISCD. There were only about a dozen health provisions that made it into that bill, so it shows that Congress recognizes the value of identifying people with osteoporosis and treating them. "Now at least we are in the room and acknowledged," he said.

"We will definitely be changing the way that we do business when it comes to DXA."

Dr. Laster added that he’s also encouraged by a recent study published in the journal Health Affairs that helps bolster the case for increasing payments for bone density testing (Health Aff. 2011;30:2362-70). Looking at a large population of Medicare beneficiaries, researchers found that as payments for DXA dropped, Medicare claims for the test plateaued. For instance, from 1996 through 2006, before the payment cuts went into effect, DXA testing was growing at a rate of about 6.5%. From 2007 through 2009, however, about 800,000 fewer tests were administered to Medicare beneficiaries than would have been expected based on the earlier growth rate.

The study also showed that DXA testing was linked to fewer fractures. The researchers found that, over a 3-year period, fracture rates were nearly 20% lower in elderly women who had received a DXA test, compared with those who did not.

Alison King, Ph.D., one of the coauthors of the study and a health care consultant, said the results make a strong case for averting the scheduled payment cut for DXA both to improve public health and to save money in the long term. "There are many valuable medical interventions that do not save money," she said. "DXA is both clinically valuable and cost effective."

Dr. Charles King, a rheumatologist in Tupelo, Miss., and chair of the American College of Rheumatology’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care, said that he thinks lawmakers are starting to hear the message about the cost effectiveness of DXA. "We are getting the word out," he said. The problem, he noted, is that Congress has been reticent to provide legislative carve-outs for certain diseases or treatments.

Dr. King advised physicians that if they want to continue to offer DXA they need to view it as a loss leader, but he urged rheumatologists to keep performing it. Rheumatologists must continue to read and interpret these studies because they inadvertently contribute to the development of osteoporosis through the use of corticosteroids and other treatments for rheumatic conditions. "We have to retain ownership of this disease," he said.

A Man With Back Pain and Fever

A Complex Injury of the Distal Ulnar Physis: A Case Report and Brief Review of the Literature

When Is a Medial Epicondyle Fracture a Medial Condyle Fracture?

Pre-Anthracycline-Based Chemo Cardiac Imaging Questioned

SAN ANTONIO – The guideline-recommended practice of routinely measuring left ventricular ejection fraction before anthracycline-based chemotherapy to screen out patients at increased risk for treatment-induced heart failure has come under fire as unproductive and financially wasteful.

It’s a practice endorsed by the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology, enshrined in Food and Drug Administration labeling, required as part of most U.S. clinical trials, and common in community-based oncology practice.

Yet there are no data to support the utility of this practice as a screening tool aimed at minimizing heart failure induced by anthracycline-based chemotherapy, according to a report at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Dr. Seema M. Policepatil of the Gundersen Lutheran Medical Foundation, La Crosse, Wis., and colleagues presented a retrospective study that suggested routine cardiac ejection fraction screening under these circumstances is without merit. The study included 466 patients with early-stage, HER2-negative invasive breast cancer who were under consideration for anthracycline-based chemotherapy as part of their initial therapy. None had prior heart failure.

Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was measured by echocardiography, nuclear imaging, or MRI prior to chemotherapy in 241 of the patients. This reflects institutional practice: at Gundersen, pretreatment assessment of cardiac pump function is common but not uniform.

One of the 241 patients was found to have asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction, with a screening ejection fraction of 48%, and she therefore didn’t receive anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Thus, modification of the treatment strategy in response to screening of ejection fraction occurred only rarely.

In addition, nine patients – six who had pretreatment cardiac imaging and three who did not – skipped the chemotherapy, either because of physician or patient preference or participation in clinical trials.

During a mean 5 years of follow-up, 3 of the remaining 456 women were diagnosed with heart failure: 2 among those with a pretreatment LVEF measurement, and 1 among those without it. That’s an acceptably low 0.7% event rate, she declared.

Current practice guidelines recommending pretreatment LVEF measurement are based upon expert consensus. It’s time to incorporate the available evidence, which in the case of the Gundersen experience doesn’t support the practice, Dr. Policepatil continued.

Assuming that nationally half of all patients with early-stage HER2-negative breast cancer undergo measurement of their LV ejection fraction before getting chemotherapy, eliminating this routine practice would save $7 million to $17 million annually based upon Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement rates, the physician added.

This study was funded by the Center for Cancer and Blood Disorders at the Gundersen Lutheran Medical Foundation. Dr. Policepatil declared having no financial conflicts.

SAN ANTONIO – The guideline-recommended practice of routinely measuring left ventricular ejection fraction before anthracycline-based chemotherapy to screen out patients at increased risk for treatment-induced heart failure has come under fire as unproductive and financially wasteful.

It’s a practice endorsed by the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology, enshrined in Food and Drug Administration labeling, required as part of most U.S. clinical trials, and common in community-based oncology practice.

Yet there are no data to support the utility of this practice as a screening tool aimed at minimizing heart failure induced by anthracycline-based chemotherapy, according to a report at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Dr. Seema M. Policepatil of the Gundersen Lutheran Medical Foundation, La Crosse, Wis., and colleagues presented a retrospective study that suggested routine cardiac ejection fraction screening under these circumstances is without merit. The study included 466 patients with early-stage, HER2-negative invasive breast cancer who were under consideration for anthracycline-based chemotherapy as part of their initial therapy. None had prior heart failure.

Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was measured by echocardiography, nuclear imaging, or MRI prior to chemotherapy in 241 of the patients. This reflects institutional practice: at Gundersen, pretreatment assessment of cardiac pump function is common but not uniform.

One of the 241 patients was found to have asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction, with a screening ejection fraction of 48%, and she therefore didn’t receive anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Thus, modification of the treatment strategy in response to screening of ejection fraction occurred only rarely.

In addition, nine patients – six who had pretreatment cardiac imaging and three who did not – skipped the chemotherapy, either because of physician or patient preference or participation in clinical trials.

During a mean 5 years of follow-up, 3 of the remaining 456 women were diagnosed with heart failure: 2 among those with a pretreatment LVEF measurement, and 1 among those without it. That’s an acceptably low 0.7% event rate, she declared.

Current practice guidelines recommending pretreatment LVEF measurement are based upon expert consensus. It’s time to incorporate the available evidence, which in the case of the Gundersen experience doesn’t support the practice, Dr. Policepatil continued.

Assuming that nationally half of all patients with early-stage HER2-negative breast cancer undergo measurement of their LV ejection fraction before getting chemotherapy, eliminating this routine practice would save $7 million to $17 million annually based upon Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement rates, the physician added.

This study was funded by the Center for Cancer and Blood Disorders at the Gundersen Lutheran Medical Foundation. Dr. Policepatil declared having no financial conflicts.

SAN ANTONIO – The guideline-recommended practice of routinely measuring left ventricular ejection fraction before anthracycline-based chemotherapy to screen out patients at increased risk for treatment-induced heart failure has come under fire as unproductive and financially wasteful.

It’s a practice endorsed by the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology, enshrined in Food and Drug Administration labeling, required as part of most U.S. clinical trials, and common in community-based oncology practice.

Yet there are no data to support the utility of this practice as a screening tool aimed at minimizing heart failure induced by anthracycline-based chemotherapy, according to a report at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Dr. Seema M. Policepatil of the Gundersen Lutheran Medical Foundation, La Crosse, Wis., and colleagues presented a retrospective study that suggested routine cardiac ejection fraction screening under these circumstances is without merit. The study included 466 patients with early-stage, HER2-negative invasive breast cancer who were under consideration for anthracycline-based chemotherapy as part of their initial therapy. None had prior heart failure.

Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was measured by echocardiography, nuclear imaging, or MRI prior to chemotherapy in 241 of the patients. This reflects institutional practice: at Gundersen, pretreatment assessment of cardiac pump function is common but not uniform.

One of the 241 patients was found to have asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction, with a screening ejection fraction of 48%, and she therefore didn’t receive anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Thus, modification of the treatment strategy in response to screening of ejection fraction occurred only rarely.

In addition, nine patients – six who had pretreatment cardiac imaging and three who did not – skipped the chemotherapy, either because of physician or patient preference or participation in clinical trials.

During a mean 5 years of follow-up, 3 of the remaining 456 women were diagnosed with heart failure: 2 among those with a pretreatment LVEF measurement, and 1 among those without it. That’s an acceptably low 0.7% event rate, she declared.

Current practice guidelines recommending pretreatment LVEF measurement are based upon expert consensus. It’s time to incorporate the available evidence, which in the case of the Gundersen experience doesn’t support the practice, Dr. Policepatil continued.

Assuming that nationally half of all patients with early-stage HER2-negative breast cancer undergo measurement of their LV ejection fraction before getting chemotherapy, eliminating this routine practice would save $7 million to $17 million annually based upon Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement rates, the physician added.

This study was funded by the Center for Cancer and Blood Disorders at the Gundersen Lutheran Medical Foundation. Dr. Policepatil declared having no financial conflicts.

FROM THE SAN ANTONIO BREAST CANCER SYMPOSIUM

Major Finding: Heart failure was diagnosed in three women within 5 years of anthracycline-based therapy – for an event rate of 0.7%.

Data Source: A single-center retrospective study of 466 breast cancer patients under consideration for anthracycline-based chemotherapy.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Center for Cancer and Blood Disorders at the Gundersen Lutheran Medical Foundation. Dr. Policepatil declared having no financial conflicts.