User login

3-D TEE More Accurate Than 2-D in Aortic Annulus Measurement

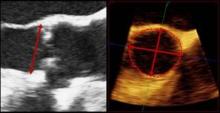

NATIONAL HARBOR – Measurements of aortic annular geometry, valve calcification, and final device position with two- and three-dimensional echocardiography are predictive of increased risk of leakage after transcatheter valve implantation, according to a retrospective study.

The study also showed that 3-D transesophageal echocardiography (3-D TEE) does a better job of measuring the aortic annulus, compared with 2-D TEE, according to a retrospective study.

The annular measurement is critical for optimal valve sizing and prevention of paravalvular aortic regurgitation in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR).

Paravalvular aortic regurgitation (PAR), is a known complication of TAVR, and according to 2-year analysis of the PARTNER trial, PAR after TAVR was associated with increased late mortality (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:1686-95).

TAVR is in its infancy in the United States, compared with Europe, and experts are studying how and which imaging techniques could yield the best results before, during, and after TAVR (also called TAVI).

"Every center has their preference," said Dr. Praveen Mehrotra, a noninvasive cardiologist and the lead author of the study at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. "Some centers use CT and 2-D TEE. At Mass General, we integrate information obtained from 2-D and 3-D TEE."

Meanwhile, the role of 3-D TEE in TAVR hasn’t been adequately explored, added Dr. Mehrotra, who presented his poster at the annual meeting of the American Society of Echocardiography.

Dr. Mehrotra and his colleagues set out to retrospectively identify 2-D and 3-D TEE parameters that could predict significant PAR after TAVR.

They analyzed 2-D and 3-D TEE images from 94 patients undergoing TAVR between June 2008 and December 2011. The images were used to assess three parameters: annulus geometry, aortic valve apparatus calcification, and final device position.

Twenty one of the patients (22%) showed significant PAR after TAVR, but before postdilation.

In 2-D TEE, the annulus geometry was assessed by measuring the largest anteroposterior annulus dimension at the aortic valve hinge points in mid-systole, the authors wrote. Using 3-D TEE, researchers measured or calculated four parameters for the aortic annulus geometry: minor axis, major axis, eccentricity index, and annular area.

The annular dimension measured by 2-D TEE was similar in the PAR (22.8 mm) and No PAR (22.4 mm) groups. But, the 3-D TEE measurements were significantly larger in the PAR group than in the No PAR group, as measured by annular minor axis (23.8 mm vs. 22.7 mm), major axis (27.0 mm vs. 25.3 mm), eccentricity index (0.88 vs. 0.90), and annular area (5.19 cm2 vs. 4.52 cm2), the researchers reported.

The annular-prosthesis incongruence (API) index was also significantly higher in patients with PAR (1.07% vs. 0.93%), "indicating valve undersizing in this group," the authors wrote.

Using 3-D TEE, the researchers identified and graded significant areas of calcification in the aortic valve apparatus, which is also very important before TAVR, said Mehrotra.

The final device position was assessed using 2-D TEE images.

The results showed that higher API index, Aortic Valve Apparatus Calcification score, and final position of the device were predictors of significant PAR after TAVR, with odds ratios of 9.4, 3.6, and 1.2, respectively, the authors reported.

"Our study highlights the ability of 2-D and 3-D TEE for accurate annular sizing and optimal valve positioning during TAVR," they wrote.

The takeaway message, said Dr. Mehrotra in an interview, is that "the role of echo is essential before, during, and after TAVR.

He added that 3-D echocardiography has an emerging role in annular sizing. In particular, annular area by 3-D TEE may be more important than the anteroposterior dimension by 2-D TEE for accurate valve sizing, said Dr. Mehrotra. "Technologies like 3-D TEE and cardiac CT can help with preprocedural planning, but they should be used by people who understand how to use them."

While his study focused on 2-D and 3-D TEE, Dr. Mehrotra said he expected more studies begin comparing cardiac CT and 3-D TEE, which is more like, "comparing apples to apples."

In a discussion on TAVR imaging, Dr. Rebecca T. Hahn, director of interventional echocardiography at Columbia University, New York, said that cardiac CT and echocardiography are complementary. However, CT is less user-dependent, compared with 3-D TEE.

Dr. Mehrotra and Dr. Hahn had no relevant financial disclosures.

NATIONAL HARBOR – Measurements of aortic annular geometry, valve calcification, and final device position with two- and three-dimensional echocardiography are predictive of increased risk of leakage after transcatheter valve implantation, according to a retrospective study.

The study also showed that 3-D transesophageal echocardiography (3-D TEE) does a better job of measuring the aortic annulus, compared with 2-D TEE, according to a retrospective study.

The annular measurement is critical for optimal valve sizing and prevention of paravalvular aortic regurgitation in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR).

Paravalvular aortic regurgitation (PAR), is a known complication of TAVR, and according to 2-year analysis of the PARTNER trial, PAR after TAVR was associated with increased late mortality (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:1686-95).

TAVR is in its infancy in the United States, compared with Europe, and experts are studying how and which imaging techniques could yield the best results before, during, and after TAVR (also called TAVI).

"Every center has their preference," said Dr. Praveen Mehrotra, a noninvasive cardiologist and the lead author of the study at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. "Some centers use CT and 2-D TEE. At Mass General, we integrate information obtained from 2-D and 3-D TEE."

Meanwhile, the role of 3-D TEE in TAVR hasn’t been adequately explored, added Dr. Mehrotra, who presented his poster at the annual meeting of the American Society of Echocardiography.

Dr. Mehrotra and his colleagues set out to retrospectively identify 2-D and 3-D TEE parameters that could predict significant PAR after TAVR.

They analyzed 2-D and 3-D TEE images from 94 patients undergoing TAVR between June 2008 and December 2011. The images were used to assess three parameters: annulus geometry, aortic valve apparatus calcification, and final device position.

Twenty one of the patients (22%) showed significant PAR after TAVR, but before postdilation.

In 2-D TEE, the annulus geometry was assessed by measuring the largest anteroposterior annulus dimension at the aortic valve hinge points in mid-systole, the authors wrote. Using 3-D TEE, researchers measured or calculated four parameters for the aortic annulus geometry: minor axis, major axis, eccentricity index, and annular area.

The annular dimension measured by 2-D TEE was similar in the PAR (22.8 mm) and No PAR (22.4 mm) groups. But, the 3-D TEE measurements were significantly larger in the PAR group than in the No PAR group, as measured by annular minor axis (23.8 mm vs. 22.7 mm), major axis (27.0 mm vs. 25.3 mm), eccentricity index (0.88 vs. 0.90), and annular area (5.19 cm2 vs. 4.52 cm2), the researchers reported.

The annular-prosthesis incongruence (API) index was also significantly higher in patients with PAR (1.07% vs. 0.93%), "indicating valve undersizing in this group," the authors wrote.

Using 3-D TEE, the researchers identified and graded significant areas of calcification in the aortic valve apparatus, which is also very important before TAVR, said Mehrotra.

The final device position was assessed using 2-D TEE images.

The results showed that higher API index, Aortic Valve Apparatus Calcification score, and final position of the device were predictors of significant PAR after TAVR, with odds ratios of 9.4, 3.6, and 1.2, respectively, the authors reported.

"Our study highlights the ability of 2-D and 3-D TEE for accurate annular sizing and optimal valve positioning during TAVR," they wrote.

The takeaway message, said Dr. Mehrotra in an interview, is that "the role of echo is essential before, during, and after TAVR.

He added that 3-D echocardiography has an emerging role in annular sizing. In particular, annular area by 3-D TEE may be more important than the anteroposterior dimension by 2-D TEE for accurate valve sizing, said Dr. Mehrotra. "Technologies like 3-D TEE and cardiac CT can help with preprocedural planning, but they should be used by people who understand how to use them."

While his study focused on 2-D and 3-D TEE, Dr. Mehrotra said he expected more studies begin comparing cardiac CT and 3-D TEE, which is more like, "comparing apples to apples."

In a discussion on TAVR imaging, Dr. Rebecca T. Hahn, director of interventional echocardiography at Columbia University, New York, said that cardiac CT and echocardiography are complementary. However, CT is less user-dependent, compared with 3-D TEE.

Dr. Mehrotra and Dr. Hahn had no relevant financial disclosures.

NATIONAL HARBOR – Measurements of aortic annular geometry, valve calcification, and final device position with two- and three-dimensional echocardiography are predictive of increased risk of leakage after transcatheter valve implantation, according to a retrospective study.

The study also showed that 3-D transesophageal echocardiography (3-D TEE) does a better job of measuring the aortic annulus, compared with 2-D TEE, according to a retrospective study.

The annular measurement is critical for optimal valve sizing and prevention of paravalvular aortic regurgitation in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR).

Paravalvular aortic regurgitation (PAR), is a known complication of TAVR, and according to 2-year analysis of the PARTNER trial, PAR after TAVR was associated with increased late mortality (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:1686-95).

TAVR is in its infancy in the United States, compared with Europe, and experts are studying how and which imaging techniques could yield the best results before, during, and after TAVR (also called TAVI).

"Every center has their preference," said Dr. Praveen Mehrotra, a noninvasive cardiologist and the lead author of the study at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. "Some centers use CT and 2-D TEE. At Mass General, we integrate information obtained from 2-D and 3-D TEE."

Meanwhile, the role of 3-D TEE in TAVR hasn’t been adequately explored, added Dr. Mehrotra, who presented his poster at the annual meeting of the American Society of Echocardiography.

Dr. Mehrotra and his colleagues set out to retrospectively identify 2-D and 3-D TEE parameters that could predict significant PAR after TAVR.

They analyzed 2-D and 3-D TEE images from 94 patients undergoing TAVR between June 2008 and December 2011. The images were used to assess three parameters: annulus geometry, aortic valve apparatus calcification, and final device position.

Twenty one of the patients (22%) showed significant PAR after TAVR, but before postdilation.

In 2-D TEE, the annulus geometry was assessed by measuring the largest anteroposterior annulus dimension at the aortic valve hinge points in mid-systole, the authors wrote. Using 3-D TEE, researchers measured or calculated four parameters for the aortic annulus geometry: minor axis, major axis, eccentricity index, and annular area.

The annular dimension measured by 2-D TEE was similar in the PAR (22.8 mm) and No PAR (22.4 mm) groups. But, the 3-D TEE measurements were significantly larger in the PAR group than in the No PAR group, as measured by annular minor axis (23.8 mm vs. 22.7 mm), major axis (27.0 mm vs. 25.3 mm), eccentricity index (0.88 vs. 0.90), and annular area (5.19 cm2 vs. 4.52 cm2), the researchers reported.

The annular-prosthesis incongruence (API) index was also significantly higher in patients with PAR (1.07% vs. 0.93%), "indicating valve undersizing in this group," the authors wrote.

Using 3-D TEE, the researchers identified and graded significant areas of calcification in the aortic valve apparatus, which is also very important before TAVR, said Mehrotra.

The final device position was assessed using 2-D TEE images.

The results showed that higher API index, Aortic Valve Apparatus Calcification score, and final position of the device were predictors of significant PAR after TAVR, with odds ratios of 9.4, 3.6, and 1.2, respectively, the authors reported.

"Our study highlights the ability of 2-D and 3-D TEE for accurate annular sizing and optimal valve positioning during TAVR," they wrote.

The takeaway message, said Dr. Mehrotra in an interview, is that "the role of echo is essential before, during, and after TAVR.

He added that 3-D echocardiography has an emerging role in annular sizing. In particular, annular area by 3-D TEE may be more important than the anteroposterior dimension by 2-D TEE for accurate valve sizing, said Dr. Mehrotra. "Technologies like 3-D TEE and cardiac CT can help with preprocedural planning, but they should be used by people who understand how to use them."

While his study focused on 2-D and 3-D TEE, Dr. Mehrotra said he expected more studies begin comparing cardiac CT and 3-D TEE, which is more like, "comparing apples to apples."

In a discussion on TAVR imaging, Dr. Rebecca T. Hahn, director of interventional echocardiography at Columbia University, New York, said that cardiac CT and echocardiography are complementary. However, CT is less user-dependent, compared with 3-D TEE.

Dr. Mehrotra and Dr. Hahn had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY

Major Finding: Higher API index, Aortic Valve Apparatus Calcification score, and final position of the replacement valve as measured by 3-D and 2-D transesophageal echocardiography were predictors of significant PAR after TAVR, with odds ratios of 9.4, 3.6, and 1.2, respectively.

Data Source: Retrospective analysis of 2-D and 3-D TEE images from 94 patients undergoing TAVR between June 2008 and December 2011.

Disclosures: Dr. Mehrotra and Dr. Hahn had no relevant financial disclosures.

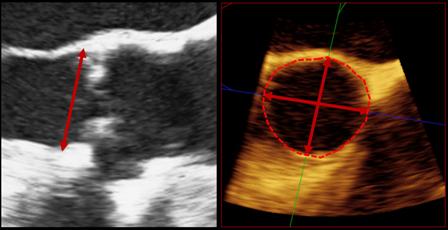

2-D Echo Is Inadequate Cardiomyopathy Screen in Childhood Cancer Survivors

Transthoracic two-dimensional echocardiography appears to be inadequate for identifying cardiomyopathy in adults who survive childhood cancer, according to a cross-sectional study published online July 16 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Compared with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI), which is considered the reference standard to which other cardiac imaging techniques are compared, 2-D echocardiography had a sensitivity of only 25% and a false-negative rate of 75% in identifying cardiomyopathy in a study of 134 adult survivors of childhood cancer, said Dr. Gregory T. Armstrong of the department of epidemiology and cancer control at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, and his associates.

In these relatively young and apparently healthy study subjects who had never been diagnosed as having any cardiac abnormality, nearly half (48%) were found to have the reduced cardiac mass indicative of cancer therapy–related injury. And fully 11% of subjects who were judged to have a normal ejection fraction (EF) on 2-D echocardiography were actually proved to have an EF of less than 50% on CMRI, the researchers noted.

That number easily could have been higher, but there happened to be a low absolute number of patients (16) with this degree of EF impairment in the small cohort, they pointed out.

Adults who survive childhood cancer are at risk for cardiomyopathy because of their exposure to chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Current guidelines recommend screening such adults by transthoracic 2-D echocardiography because it is noninvasive, widely available, and less expensive than other techniques.

However, the quality of the acoustic windows obtained on 2-D echo varies widely, and the method depends on geometric assumptions that may not be valid in patients who have dilated or remodeled ventricles. Three-dimensional echocardiography yields somewhat more accurate results but is not as widely available. CMRI is the most accurate noninvasive imaging technique, but is more expensive and is even less widely available, Dr. Armstrong and his colleagues explained.

They assessed the accuracy of 2-D and 3-D echocardiography against CMRI as a screen for cardiomyopathy in a longitudinal cohort of 134 adults who had been treated at St. Jude’s for childhood cancer 18-38 years earlier. All had received chest-directed radiotherapy and/or anthracycline chemotherapy, both of which are known to impair cardiac function during treatment and to raise the risk of reduced left ventricular function later in life.

The most common pediatric malignancies were acute lymphoblastic leukemia (44 subjects) and Hodgkin’s lymphoma (37 subjects).

The median age at echocardiographic screening in adulthood was 39 years (range, 22-53 years).

Of the study subjects, 20 were unable to complete CMRI for a variety of reasons. Future studies that compare imaging techniques should take into consideration this relatively high noncompletion rate (15%) for CMRI, especially in cost-benefit analyses, Dr. Armstrong and his colleagues said (J. Clin. Oncol. 2012 July 16 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.40.3584]).

In the remaining 114 subjects, 2-D echocardiography consistently overestimated left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and underestimated both end-systolic and end-diastolic ventricular volumes.

In all, 16 subjects were identified as having markedly decreased LVEF (50% or more) by CMRI, but only 4 of them were so identified by 2-D echocardiography and only 11 of them by 3-D echocardiography.

Compared with CMRI, the sensitivity of 2-D echocardiography was only 25%; that of 3-D echo was better but still inadequate, at only 53%. And false-negative rates were high with both 2-D echocardiography (75%) and 3-D echocardiography (47%).

Of particular concern was the finding that on CMRI, 32% of the study subjects had an LVEF that was well below normal. The rate in the subgroup of patients who had received both chest irradiation and anthracycline during childhood cancer treatment was even higher, at 42%.

A total of 48% of the study subjects had a cardiac mass that was at least 2 standard deviations below normal for their age and sex, a clear sign of cardiotoxicity from their childhood cancer treatment. "Notably, even patients who received less than 150 mg/m2 of anthracyclines had a high prevalence of reduced EF (27%), stroke volume (29%), or cardiac mass (56%)," the investigators said.

Estimates derived from Medicare data suggest that at roughly $449 each, CMRI examinations cost about $217 more than does echocardiography ($232 each). Given the high rate of cardiomyopathy discovered in this cohort, and the poor sensitivity of echocardiography as a screening tool, this cost difference may be small enough to warrant a switch in the current screening recommendations from echocardiography to CMRI.

The additional cost of a CMRI-only screening strategy per case of cardiotoxicity correctly identified would be only $1,973, they noted.

The study findings suggest that in this high-risk patient population that was exposed to cardiotoxic therapy during childhood, "consideration should be given to referring survivors with an EF of 50%-59% on [2-D echocardiography] for comprehensive cardiology assessment that includes cardiac history, symptom index, and examination; biomarker assessment; consideration of [CMRI]; functional assessment by treadmill testing; and possibly medical therapy to prevent progression of disease," Dr. Armstrong and his associates said.

This study was supported by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the American Lebanese-Syrian Associated Charities. Dr. Armstrong’s associates reported ties to General Electric and Philips Healthcare.

Transthoracic two-dimensional echocardiography appears to be inadequate for identifying cardiomyopathy in adults who survive childhood cancer, according to a cross-sectional study published online July 16 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Compared with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI), which is considered the reference standard to which other cardiac imaging techniques are compared, 2-D echocardiography had a sensitivity of only 25% and a false-negative rate of 75% in identifying cardiomyopathy in a study of 134 adult survivors of childhood cancer, said Dr. Gregory T. Armstrong of the department of epidemiology and cancer control at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, and his associates.

In these relatively young and apparently healthy study subjects who had never been diagnosed as having any cardiac abnormality, nearly half (48%) were found to have the reduced cardiac mass indicative of cancer therapy–related injury. And fully 11% of subjects who were judged to have a normal ejection fraction (EF) on 2-D echocardiography were actually proved to have an EF of less than 50% on CMRI, the researchers noted.

That number easily could have been higher, but there happened to be a low absolute number of patients (16) with this degree of EF impairment in the small cohort, they pointed out.

Adults who survive childhood cancer are at risk for cardiomyopathy because of their exposure to chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Current guidelines recommend screening such adults by transthoracic 2-D echocardiography because it is noninvasive, widely available, and less expensive than other techniques.

However, the quality of the acoustic windows obtained on 2-D echo varies widely, and the method depends on geometric assumptions that may not be valid in patients who have dilated or remodeled ventricles. Three-dimensional echocardiography yields somewhat more accurate results but is not as widely available. CMRI is the most accurate noninvasive imaging technique, but is more expensive and is even less widely available, Dr. Armstrong and his colleagues explained.

They assessed the accuracy of 2-D and 3-D echocardiography against CMRI as a screen for cardiomyopathy in a longitudinal cohort of 134 adults who had been treated at St. Jude’s for childhood cancer 18-38 years earlier. All had received chest-directed radiotherapy and/or anthracycline chemotherapy, both of which are known to impair cardiac function during treatment and to raise the risk of reduced left ventricular function later in life.

The most common pediatric malignancies were acute lymphoblastic leukemia (44 subjects) and Hodgkin’s lymphoma (37 subjects).

The median age at echocardiographic screening in adulthood was 39 years (range, 22-53 years).

Of the study subjects, 20 were unable to complete CMRI for a variety of reasons. Future studies that compare imaging techniques should take into consideration this relatively high noncompletion rate (15%) for CMRI, especially in cost-benefit analyses, Dr. Armstrong and his colleagues said (J. Clin. Oncol. 2012 July 16 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.40.3584]).

In the remaining 114 subjects, 2-D echocardiography consistently overestimated left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and underestimated both end-systolic and end-diastolic ventricular volumes.

In all, 16 subjects were identified as having markedly decreased LVEF (50% or more) by CMRI, but only 4 of them were so identified by 2-D echocardiography and only 11 of them by 3-D echocardiography.

Compared with CMRI, the sensitivity of 2-D echocardiography was only 25%; that of 3-D echo was better but still inadequate, at only 53%. And false-negative rates were high with both 2-D echocardiography (75%) and 3-D echocardiography (47%).

Of particular concern was the finding that on CMRI, 32% of the study subjects had an LVEF that was well below normal. The rate in the subgroup of patients who had received both chest irradiation and anthracycline during childhood cancer treatment was even higher, at 42%.

A total of 48% of the study subjects had a cardiac mass that was at least 2 standard deviations below normal for their age and sex, a clear sign of cardiotoxicity from their childhood cancer treatment. "Notably, even patients who received less than 150 mg/m2 of anthracyclines had a high prevalence of reduced EF (27%), stroke volume (29%), or cardiac mass (56%)," the investigators said.

Estimates derived from Medicare data suggest that at roughly $449 each, CMRI examinations cost about $217 more than does echocardiography ($232 each). Given the high rate of cardiomyopathy discovered in this cohort, and the poor sensitivity of echocardiography as a screening tool, this cost difference may be small enough to warrant a switch in the current screening recommendations from echocardiography to CMRI.

The additional cost of a CMRI-only screening strategy per case of cardiotoxicity correctly identified would be only $1,973, they noted.

The study findings suggest that in this high-risk patient population that was exposed to cardiotoxic therapy during childhood, "consideration should be given to referring survivors with an EF of 50%-59% on [2-D echocardiography] for comprehensive cardiology assessment that includes cardiac history, symptom index, and examination; biomarker assessment; consideration of [CMRI]; functional assessment by treadmill testing; and possibly medical therapy to prevent progression of disease," Dr. Armstrong and his associates said.

This study was supported by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the American Lebanese-Syrian Associated Charities. Dr. Armstrong’s associates reported ties to General Electric and Philips Healthcare.

Transthoracic two-dimensional echocardiography appears to be inadequate for identifying cardiomyopathy in adults who survive childhood cancer, according to a cross-sectional study published online July 16 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Compared with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI), which is considered the reference standard to which other cardiac imaging techniques are compared, 2-D echocardiography had a sensitivity of only 25% and a false-negative rate of 75% in identifying cardiomyopathy in a study of 134 adult survivors of childhood cancer, said Dr. Gregory T. Armstrong of the department of epidemiology and cancer control at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, and his associates.

In these relatively young and apparently healthy study subjects who had never been diagnosed as having any cardiac abnormality, nearly half (48%) were found to have the reduced cardiac mass indicative of cancer therapy–related injury. And fully 11% of subjects who were judged to have a normal ejection fraction (EF) on 2-D echocardiography were actually proved to have an EF of less than 50% on CMRI, the researchers noted.

That number easily could have been higher, but there happened to be a low absolute number of patients (16) with this degree of EF impairment in the small cohort, they pointed out.

Adults who survive childhood cancer are at risk for cardiomyopathy because of their exposure to chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Current guidelines recommend screening such adults by transthoracic 2-D echocardiography because it is noninvasive, widely available, and less expensive than other techniques.

However, the quality of the acoustic windows obtained on 2-D echo varies widely, and the method depends on geometric assumptions that may not be valid in patients who have dilated or remodeled ventricles. Three-dimensional echocardiography yields somewhat more accurate results but is not as widely available. CMRI is the most accurate noninvasive imaging technique, but is more expensive and is even less widely available, Dr. Armstrong and his colleagues explained.

They assessed the accuracy of 2-D and 3-D echocardiography against CMRI as a screen for cardiomyopathy in a longitudinal cohort of 134 adults who had been treated at St. Jude’s for childhood cancer 18-38 years earlier. All had received chest-directed radiotherapy and/or anthracycline chemotherapy, both of which are known to impair cardiac function during treatment and to raise the risk of reduced left ventricular function later in life.

The most common pediatric malignancies were acute lymphoblastic leukemia (44 subjects) and Hodgkin’s lymphoma (37 subjects).

The median age at echocardiographic screening in adulthood was 39 years (range, 22-53 years).

Of the study subjects, 20 were unable to complete CMRI for a variety of reasons. Future studies that compare imaging techniques should take into consideration this relatively high noncompletion rate (15%) for CMRI, especially in cost-benefit analyses, Dr. Armstrong and his colleagues said (J. Clin. Oncol. 2012 July 16 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.40.3584]).

In the remaining 114 subjects, 2-D echocardiography consistently overestimated left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and underestimated both end-systolic and end-diastolic ventricular volumes.

In all, 16 subjects were identified as having markedly decreased LVEF (50% or more) by CMRI, but only 4 of them were so identified by 2-D echocardiography and only 11 of them by 3-D echocardiography.

Compared with CMRI, the sensitivity of 2-D echocardiography was only 25%; that of 3-D echo was better but still inadequate, at only 53%. And false-negative rates were high with both 2-D echocardiography (75%) and 3-D echocardiography (47%).

Of particular concern was the finding that on CMRI, 32% of the study subjects had an LVEF that was well below normal. The rate in the subgroup of patients who had received both chest irradiation and anthracycline during childhood cancer treatment was even higher, at 42%.

A total of 48% of the study subjects had a cardiac mass that was at least 2 standard deviations below normal for their age and sex, a clear sign of cardiotoxicity from their childhood cancer treatment. "Notably, even patients who received less than 150 mg/m2 of anthracyclines had a high prevalence of reduced EF (27%), stroke volume (29%), or cardiac mass (56%)," the investigators said.

Estimates derived from Medicare data suggest that at roughly $449 each, CMRI examinations cost about $217 more than does echocardiography ($232 each). Given the high rate of cardiomyopathy discovered in this cohort, and the poor sensitivity of echocardiography as a screening tool, this cost difference may be small enough to warrant a switch in the current screening recommendations from echocardiography to CMRI.

The additional cost of a CMRI-only screening strategy per case of cardiotoxicity correctly identified would be only $1,973, they noted.

The study findings suggest that in this high-risk patient population that was exposed to cardiotoxic therapy during childhood, "consideration should be given to referring survivors with an EF of 50%-59% on [2-D echocardiography] for comprehensive cardiology assessment that includes cardiac history, symptom index, and examination; biomarker assessment; consideration of [CMRI]; functional assessment by treadmill testing; and possibly medical therapy to prevent progression of disease," Dr. Armstrong and his associates said.

This study was supported by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the American Lebanese-Syrian Associated Charities. Dr. Armstrong’s associates reported ties to General Electric and Philips Healthcare.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Major Finding: Compared with cardiac MRI, 2-D echocardiography had only a 25% sensitivity at identifying cardiomyopathy and a 75% false-negative rate, whereas 3-D echo had only a 53% sensitivity and a 47% false-negative rate.

Data Source: A cross-sectional study of simultaneous assessment of cardiac structure and function using 2-D echo, 3-D echo, and CMRI in 134 adult survivors of childhood cancer who had no apparent cardiotoxicity from their cancer treatment.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the American Lebanese-Syrian Associated Charities. Dr. Armstrong’s associates reported ties to General Electric and Philips Healthcare.

Was the Correct Imaging Performed After a Motor Vehicle Accident?

A Young Dancer With Thigh Pain

Severe, Diffuse Abdominal Pain

Mazabraud Syndrome

ASE Meeting Focuses on New Directions

Multimodality imaging is among the highlights of this year's American Society of Echocardiography meeting, which starts on June 30 at the National Harbor, Maryland.

The society is pushing forward the concept, looking at different diseases and integrating different kinds of imaging such as echo plus nuclear, cardiac CT, or cardiac MR, in order to get the best diagnoses, said Dr. Melissa Wood, co-director of Massachusetts General Hospital Heart Center Women's Heart Health Program, Boston, and the chair of ASE Public Relations Committee.

"This isn't just about echo, it's also about all the other imaging techniques that are out there and how we can work together and deliver the highest quality of care," said Dr. Wood in an interview. "It's also about what's superfluous, and what we don't need to do."

On the policy front, Accountable Care Organizations will be in the forefront during the meeting. Dr. Wood said that the speakers will address how "ACOs affect those of us who read echos and do them, and how they affect practices."

Echocardiography will also leave this planet for a bit during a symposium. ASE president Dr. James Thomas has long been actively involved in doing research with the space program and helping pick the right echo machine for use up there, said Dr. Wood. "There's substantial interest in microgravity and the heart, and how heart changes its function in space. It's something that's very unique, and there are lessons that can be learned from that, and that experience will be somehow useful in our clinical practices, whether it's specific type of research techniques or specific types of information that are gained in that environment."

Echocardiography is the second most commonly ordered test after ECG, according to Dr. Wood, and with the aging population, the use of the test is likely to increase.

"I see echo take off more because of this concern about heart failure being an epidemic. Echo as a way to diagnose heart failure before it becomes profound," she said. And given the appropriate use criteria, "we're tying to moderate the reasons echos are ordered, so they'll continue to be fairly reimbursed by third parties and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services," said Dr. Wood.

You can find the meeting's program here. And be sure to check our coverage on ecardiologynews.com.

By Naseem S. Miller (@NaseemSMiller)

Multimodality imaging is among the highlights of this year's American Society of Echocardiography meeting, which starts on June 30 at the National Harbor, Maryland.

The society is pushing forward the concept, looking at different diseases and integrating different kinds of imaging such as echo plus nuclear, cardiac CT, or cardiac MR, in order to get the best diagnoses, said Dr. Melissa Wood, co-director of Massachusetts General Hospital Heart Center Women's Heart Health Program, Boston, and the chair of ASE Public Relations Committee.

"This isn't just about echo, it's also about all the other imaging techniques that are out there and how we can work together and deliver the highest quality of care," said Dr. Wood in an interview. "It's also about what's superfluous, and what we don't need to do."

On the policy front, Accountable Care Organizations will be in the forefront during the meeting. Dr. Wood said that the speakers will address how "ACOs affect those of us who read echos and do them, and how they affect practices."

Echocardiography will also leave this planet for a bit during a symposium. ASE president Dr. James Thomas has long been actively involved in doing research with the space program and helping pick the right echo machine for use up there, said Dr. Wood. "There's substantial interest in microgravity and the heart, and how heart changes its function in space. It's something that's very unique, and there are lessons that can be learned from that, and that experience will be somehow useful in our clinical practices, whether it's specific type of research techniques or specific types of information that are gained in that environment."

Echocardiography is the second most commonly ordered test after ECG, according to Dr. Wood, and with the aging population, the use of the test is likely to increase.

"I see echo take off more because of this concern about heart failure being an epidemic. Echo as a way to diagnose heart failure before it becomes profound," she said. And given the appropriate use criteria, "we're tying to moderate the reasons echos are ordered, so they'll continue to be fairly reimbursed by third parties and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services," said Dr. Wood.

You can find the meeting's program here. And be sure to check our coverage on ecardiologynews.com.

By Naseem S. Miller (@NaseemSMiller)

Multimodality imaging is among the highlights of this year's American Society of Echocardiography meeting, which starts on June 30 at the National Harbor, Maryland.

The society is pushing forward the concept, looking at different diseases and integrating different kinds of imaging such as echo plus nuclear, cardiac CT, or cardiac MR, in order to get the best diagnoses, said Dr. Melissa Wood, co-director of Massachusetts General Hospital Heart Center Women's Heart Health Program, Boston, and the chair of ASE Public Relations Committee.

"This isn't just about echo, it's also about all the other imaging techniques that are out there and how we can work together and deliver the highest quality of care," said Dr. Wood in an interview. "It's also about what's superfluous, and what we don't need to do."

On the policy front, Accountable Care Organizations will be in the forefront during the meeting. Dr. Wood said that the speakers will address how "ACOs affect those of us who read echos and do them, and how they affect practices."

Echocardiography will also leave this planet for a bit during a symposium. ASE president Dr. James Thomas has long been actively involved in doing research with the space program and helping pick the right echo machine for use up there, said Dr. Wood. "There's substantial interest in microgravity and the heart, and how heart changes its function in space. It's something that's very unique, and there are lessons that can be learned from that, and that experience will be somehow useful in our clinical practices, whether it's specific type of research techniques or specific types of information that are gained in that environment."

Echocardiography is the second most commonly ordered test after ECG, according to Dr. Wood, and with the aging population, the use of the test is likely to increase.

"I see echo take off more because of this concern about heart failure being an epidemic. Echo as a way to diagnose heart failure before it becomes profound," she said. And given the appropriate use criteria, "we're tying to moderate the reasons echos are ordered, so they'll continue to be fairly reimbursed by third parties and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services," said Dr. Wood.

You can find the meeting's program here. And be sure to check our coverage on ecardiologynews.com.

By Naseem S. Miller (@NaseemSMiller)

Do We Really Need That CAT Scan?

First, do no harm ... our creed, our command, our imperative. It’s easy to point out those times when a doctor does harm by commission of an act, but what about when we do harm by omission? After all, we get extraordinarily busy sometimes and, out of necessity, sometimes omit things deemed to be "not as important" as other things. If we are honest with ourselves, there are times we fail our patients, and fail miserably.

We are only human, right? How long can we go without sleep, food, or fluid, trying desperately to make it through the "next few patients" before we take a break and tend to our own needs? When we are hungry, thirsty, or just plain grumpy from stress on the job, and life’s events in general, how often do we opt to forgo opportunities to educate and protect our patients?

I think this happens more than any of us want to openly admit. Sometimes it just seems easier to order a test than to spend extra time determining whether there is a better alternative. And then there’s that ever-consuming lawsuit issue. On occasion, most physicians do order tests and procedures to avert a potential lawsuit, even though in our guts we feel the patients don’t really them.

Case in point: the glorious CT scan. Television would have our patients believe that CT scans can diagnose every condition under the sun. No wonder so many ask for them (and sometimes demand them) even for the simplest of symptoms.

Have you ever had a patient who has had 10 or 15 CAT scans in the recent past, all of which were normal, or nearly normal? I have. But after explaining that each scan carries a small but real risk of promoting cancer in the future, that CAT scan that was once so important became rather insignificant. Of course, clinically I did not feel the patient needed yet another scan and after learning about the risks involved, he didn’t either.

Many radiologists – who know the risks better than we do as hospitalists – sometimes feel uncomfortable about the number of CT scans performed. Says Dr. Peter Vandermeer, vice-chair of the department of radiology at Baltimore Washington Medical Center in Glen Burnie, Md.: "We are alternately frustrated and chastened by the fact that we cannot know everything that goes into decision making. It is hard to know if this is the real episode in which a CT will finally help. It will always remain a clinical decision based on immediate circumstances.

"Especially in young patients, we need to be aware that there are small but potentially serious consequences of CT scans. The other side of it is that as radiologists we are always willing to discuss alternate tests, such as ultrasound and MRI, that may be helpful in answering specific, directed questions. CT is great in giving a broad overview of the entire abdomen, but if all you really want to know is if there is hydronephrosis, renal ultrasound may be sufficient."

As a parent, I am particularly concerned about the risk in children. In an article published in The Lancet, researchers reported that 10 years after a first scan for children under the age of 10, there was one excess case of leukemia as well as one additional brain tumor per 10,000 head scans performed (Lancet 2012 June 7 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60815-0]).

While a single CT scan does not seem problematic, for that 1 in 10,000 patients who does develop cancer, it is highly problematic. So let us make sure that each scan we order is truly worth the risk to out patients.

First, do no harm ... our creed, our command, our imperative. It’s easy to point out those times when a doctor does harm by commission of an act, but what about when we do harm by omission? After all, we get extraordinarily busy sometimes and, out of necessity, sometimes omit things deemed to be "not as important" as other things. If we are honest with ourselves, there are times we fail our patients, and fail miserably.

We are only human, right? How long can we go without sleep, food, or fluid, trying desperately to make it through the "next few patients" before we take a break and tend to our own needs? When we are hungry, thirsty, or just plain grumpy from stress on the job, and life’s events in general, how often do we opt to forgo opportunities to educate and protect our patients?

I think this happens more than any of us want to openly admit. Sometimes it just seems easier to order a test than to spend extra time determining whether there is a better alternative. And then there’s that ever-consuming lawsuit issue. On occasion, most physicians do order tests and procedures to avert a potential lawsuit, even though in our guts we feel the patients don’t really them.

Case in point: the glorious CT scan. Television would have our patients believe that CT scans can diagnose every condition under the sun. No wonder so many ask for them (and sometimes demand them) even for the simplest of symptoms.

Have you ever had a patient who has had 10 or 15 CAT scans in the recent past, all of which were normal, or nearly normal? I have. But after explaining that each scan carries a small but real risk of promoting cancer in the future, that CAT scan that was once so important became rather insignificant. Of course, clinically I did not feel the patient needed yet another scan and after learning about the risks involved, he didn’t either.

Many radiologists – who know the risks better than we do as hospitalists – sometimes feel uncomfortable about the number of CT scans performed. Says Dr. Peter Vandermeer, vice-chair of the department of radiology at Baltimore Washington Medical Center in Glen Burnie, Md.: "We are alternately frustrated and chastened by the fact that we cannot know everything that goes into decision making. It is hard to know if this is the real episode in which a CT will finally help. It will always remain a clinical decision based on immediate circumstances.

"Especially in young patients, we need to be aware that there are small but potentially serious consequences of CT scans. The other side of it is that as radiologists we are always willing to discuss alternate tests, such as ultrasound and MRI, that may be helpful in answering specific, directed questions. CT is great in giving a broad overview of the entire abdomen, but if all you really want to know is if there is hydronephrosis, renal ultrasound may be sufficient."

As a parent, I am particularly concerned about the risk in children. In an article published in The Lancet, researchers reported that 10 years after a first scan for children under the age of 10, there was one excess case of leukemia as well as one additional brain tumor per 10,000 head scans performed (Lancet 2012 June 7 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60815-0]).

While a single CT scan does not seem problematic, for that 1 in 10,000 patients who does develop cancer, it is highly problematic. So let us make sure that each scan we order is truly worth the risk to out patients.

First, do no harm ... our creed, our command, our imperative. It’s easy to point out those times when a doctor does harm by commission of an act, but what about when we do harm by omission? After all, we get extraordinarily busy sometimes and, out of necessity, sometimes omit things deemed to be "not as important" as other things. If we are honest with ourselves, there are times we fail our patients, and fail miserably.

We are only human, right? How long can we go without sleep, food, or fluid, trying desperately to make it through the "next few patients" before we take a break and tend to our own needs? When we are hungry, thirsty, or just plain grumpy from stress on the job, and life’s events in general, how often do we opt to forgo opportunities to educate and protect our patients?

I think this happens more than any of us want to openly admit. Sometimes it just seems easier to order a test than to spend extra time determining whether there is a better alternative. And then there’s that ever-consuming lawsuit issue. On occasion, most physicians do order tests and procedures to avert a potential lawsuit, even though in our guts we feel the patients don’t really them.

Case in point: the glorious CT scan. Television would have our patients believe that CT scans can diagnose every condition under the sun. No wonder so many ask for them (and sometimes demand them) even for the simplest of symptoms.

Have you ever had a patient who has had 10 or 15 CAT scans in the recent past, all of which were normal, or nearly normal? I have. But after explaining that each scan carries a small but real risk of promoting cancer in the future, that CAT scan that was once so important became rather insignificant. Of course, clinically I did not feel the patient needed yet another scan and after learning about the risks involved, he didn’t either.

Many radiologists – who know the risks better than we do as hospitalists – sometimes feel uncomfortable about the number of CT scans performed. Says Dr. Peter Vandermeer, vice-chair of the department of radiology at Baltimore Washington Medical Center in Glen Burnie, Md.: "We are alternately frustrated and chastened by the fact that we cannot know everything that goes into decision making. It is hard to know if this is the real episode in which a CT will finally help. It will always remain a clinical decision based on immediate circumstances.

"Especially in young patients, we need to be aware that there are small but potentially serious consequences of CT scans. The other side of it is that as radiologists we are always willing to discuss alternate tests, such as ultrasound and MRI, that may be helpful in answering specific, directed questions. CT is great in giving a broad overview of the entire abdomen, but if all you really want to know is if there is hydronephrosis, renal ultrasound may be sufficient."

As a parent, I am particularly concerned about the risk in children. In an article published in The Lancet, researchers reported that 10 years after a first scan for children under the age of 10, there was one excess case of leukemia as well as one additional brain tumor per 10,000 head scans performed (Lancet 2012 June 7 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60815-0]).

While a single CT scan does not seem problematic, for that 1 in 10,000 patients who does develop cancer, it is highly problematic. So let us make sure that each scan we order is truly worth the risk to out patients.

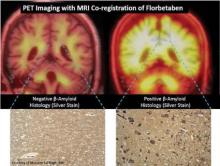

Amyloid Imaging Studies Track Dementia Development

Longitudinal tracking of the deposition of beta-amyloid over a period of 2-3 years with the use of PET imaging radiotracers in patients with mild cognitive impairment can help predict progression to Alzheimer’s disease or reliably rule it out as a diagnosis.

Those results, reported in two studies of the investigational agents 11C-Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) and 18F-florbetaben at the annual meeting of the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging in Miami, showed that the tracers could be used to predict progression to Alzheimer’s in 66%-75% of those with elevated binding of the agents to beta-amyloid plaques in the brains of individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). In cases where an individual tested negative for elevated beta-amyloid binding, fewer than 20% progressed to another type of dementia.

Results such as these show that detecting beta-amyloid burden in the brain "can help lead to diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease when a patient has mild symptoms rather than wait until they have established dementia as is the current clinical practice. This may have important benefits for the patient, for their family, and for society," said Dr. Christopher Rowe, the lead investigator on the PiB study and senior investigator on the florbetaben study.

The PiB study, called the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers, and Lifestyle Flagship Study of Ageing, included 92 patients with MCI. At baseline, Dr. Rowe and his colleagues detected high PiB binding in 65% of MCI patients. After 3 years, 66% of MCI patients who had a positive scan for high beta-amyloid burden at baseline had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, compared with only 7% of MCI patients with a negative scan.

Other studies of PiB out to 6 years of follow-up have shown that patients accrue beta-amyloid at "an incredibly slow" rate of about 2% per year. "If you have a negative scan, you can be reassured that you’re not going to have Alzheimer’s disease for at least the next 10 years," Dr. Rowe said at a press conference at the meeting.

Because the half-life of PiB is only 20 minutes, it is not suitable for clinical use. The 2-hour half-life of florbetaben and other 18F amyloid radiotracers make them much more cost effective for clinical use, noted Dr. Rowe, director of the department of nuclear medicine and the center for PET and a consultant neurologist to the memory disorders clinic at the Austin Hospital in Melbourne, Australia.

The florbetaben study involved 45 patients with MCI who received PET imaging with the compound. At baseline, 53% had a high level of neocortical binding, and binding increased 3% after 2 years in those with already high levels. Overall, 75% of patients with elevated florbetaben binding progressed to Alzheimer’s disease, whereas 19% of those with a low level of binding progressed to other kinds of dementias.

MR imaging in the same individuals indicated that 53% of patients with hippocampal atrophy at baseline had progressed to Alzheimer’s. When the combination of high florbetaben binding and hippocampal atrophy was present, 80% had progressed to Alzheimer’s after 2 years.

"We don’t say that everybody who’s got Alzheimer’s disease should have these scans because I don’t think that would be cost effective. But in selected scenarios, when they’ve seen a memory specialist, I think these can be very useful clinically," Dr. Rowe said.

He said amyloid imaging agents such as florbetaben have two potential uses:

• In patients with established dementia when there is uncertainty about whether the patient has Alzheimer’s disease or frontotemporal dementia. He noted that this has therapeutic implications because some of the medications used to treat Alzheimer’s, such as cholinesterase inhibitors, can make behavioral symptoms worse in frontotemporal dementia.

• In patients with MCI who have seen a specialist who is not sure what the cause of the symptoms might be and wants to see if it might be Alzheimer’s instead of waiting years for dementia to develop. Because about 40% with MCI do not go on to develop dementia, amyloid imaging studies would be reassuring to those patients, Dr. Rowe said.

Guidelines from the Alzheimer’s Association and the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (which recently changed its name from the Society of Nuclear Medicine) will soon be available on the appropriate use of the imaging agents, Dr. Rowe said in an interview.

He disclosed that he has served as an investigator on studies for many of the companies developing amyloid imaging products, including Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Bayer Schering Pharma, GE Healthcare, and AstraZeneca. He has also received payments for consulting for Bayer and GE.

Longitudinal tracking of the deposition of beta-amyloid over a period of 2-3 years with the use of PET imaging radiotracers in patients with mild cognitive impairment can help predict progression to Alzheimer’s disease or reliably rule it out as a diagnosis.

Those results, reported in two studies of the investigational agents 11C-Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) and 18F-florbetaben at the annual meeting of the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging in Miami, showed that the tracers could be used to predict progression to Alzheimer’s in 66%-75% of those with elevated binding of the agents to beta-amyloid plaques in the brains of individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). In cases where an individual tested negative for elevated beta-amyloid binding, fewer than 20% progressed to another type of dementia.

Results such as these show that detecting beta-amyloid burden in the brain "can help lead to diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease when a patient has mild symptoms rather than wait until they have established dementia as is the current clinical practice. This may have important benefits for the patient, for their family, and for society," said Dr. Christopher Rowe, the lead investigator on the PiB study and senior investigator on the florbetaben study.

The PiB study, called the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers, and Lifestyle Flagship Study of Ageing, included 92 patients with MCI. At baseline, Dr. Rowe and his colleagues detected high PiB binding in 65% of MCI patients. After 3 years, 66% of MCI patients who had a positive scan for high beta-amyloid burden at baseline had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, compared with only 7% of MCI patients with a negative scan.

Other studies of PiB out to 6 years of follow-up have shown that patients accrue beta-amyloid at "an incredibly slow" rate of about 2% per year. "If you have a negative scan, you can be reassured that you’re not going to have Alzheimer’s disease for at least the next 10 years," Dr. Rowe said at a press conference at the meeting.

Because the half-life of PiB is only 20 minutes, it is not suitable for clinical use. The 2-hour half-life of florbetaben and other 18F amyloid radiotracers make them much more cost effective for clinical use, noted Dr. Rowe, director of the department of nuclear medicine and the center for PET and a consultant neurologist to the memory disorders clinic at the Austin Hospital in Melbourne, Australia.

The florbetaben study involved 45 patients with MCI who received PET imaging with the compound. At baseline, 53% had a high level of neocortical binding, and binding increased 3% after 2 years in those with already high levels. Overall, 75% of patients with elevated florbetaben binding progressed to Alzheimer’s disease, whereas 19% of those with a low level of binding progressed to other kinds of dementias.

MR imaging in the same individuals indicated that 53% of patients with hippocampal atrophy at baseline had progressed to Alzheimer’s. When the combination of high florbetaben binding and hippocampal atrophy was present, 80% had progressed to Alzheimer’s after 2 years.

"We don’t say that everybody who’s got Alzheimer’s disease should have these scans because I don’t think that would be cost effective. But in selected scenarios, when they’ve seen a memory specialist, I think these can be very useful clinically," Dr. Rowe said.

He said amyloid imaging agents such as florbetaben have two potential uses:

• In patients with established dementia when there is uncertainty about whether the patient has Alzheimer’s disease or frontotemporal dementia. He noted that this has therapeutic implications because some of the medications used to treat Alzheimer’s, such as cholinesterase inhibitors, can make behavioral symptoms worse in frontotemporal dementia.

• In patients with MCI who have seen a specialist who is not sure what the cause of the symptoms might be and wants to see if it might be Alzheimer’s instead of waiting years for dementia to develop. Because about 40% with MCI do not go on to develop dementia, amyloid imaging studies would be reassuring to those patients, Dr. Rowe said.

Guidelines from the Alzheimer’s Association and the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (which recently changed its name from the Society of Nuclear Medicine) will soon be available on the appropriate use of the imaging agents, Dr. Rowe said in an interview.

He disclosed that he has served as an investigator on studies for many of the companies developing amyloid imaging products, including Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Bayer Schering Pharma, GE Healthcare, and AstraZeneca. He has also received payments for consulting for Bayer and GE.

Longitudinal tracking of the deposition of beta-amyloid over a period of 2-3 years with the use of PET imaging radiotracers in patients with mild cognitive impairment can help predict progression to Alzheimer’s disease or reliably rule it out as a diagnosis.

Those results, reported in two studies of the investigational agents 11C-Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) and 18F-florbetaben at the annual meeting of the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging in Miami, showed that the tracers could be used to predict progression to Alzheimer’s in 66%-75% of those with elevated binding of the agents to beta-amyloid plaques in the brains of individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). In cases where an individual tested negative for elevated beta-amyloid binding, fewer than 20% progressed to another type of dementia.

Results such as these show that detecting beta-amyloid burden in the brain "can help lead to diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease when a patient has mild symptoms rather than wait until they have established dementia as is the current clinical practice. This may have important benefits for the patient, for their family, and for society," said Dr. Christopher Rowe, the lead investigator on the PiB study and senior investigator on the florbetaben study.

The PiB study, called the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers, and Lifestyle Flagship Study of Ageing, included 92 patients with MCI. At baseline, Dr. Rowe and his colleagues detected high PiB binding in 65% of MCI patients. After 3 years, 66% of MCI patients who had a positive scan for high beta-amyloid burden at baseline had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, compared with only 7% of MCI patients with a negative scan.

Other studies of PiB out to 6 years of follow-up have shown that patients accrue beta-amyloid at "an incredibly slow" rate of about 2% per year. "If you have a negative scan, you can be reassured that you’re not going to have Alzheimer’s disease for at least the next 10 years," Dr. Rowe said at a press conference at the meeting.

Because the half-life of PiB is only 20 minutes, it is not suitable for clinical use. The 2-hour half-life of florbetaben and other 18F amyloid radiotracers make them much more cost effective for clinical use, noted Dr. Rowe, director of the department of nuclear medicine and the center for PET and a consultant neurologist to the memory disorders clinic at the Austin Hospital in Melbourne, Australia.

The florbetaben study involved 45 patients with MCI who received PET imaging with the compound. At baseline, 53% had a high level of neocortical binding, and binding increased 3% after 2 years in those with already high levels. Overall, 75% of patients with elevated florbetaben binding progressed to Alzheimer’s disease, whereas 19% of those with a low level of binding progressed to other kinds of dementias.

MR imaging in the same individuals indicated that 53% of patients with hippocampal atrophy at baseline had progressed to Alzheimer’s. When the combination of high florbetaben binding and hippocampal atrophy was present, 80% had progressed to Alzheimer’s after 2 years.

"We don’t say that everybody who’s got Alzheimer’s disease should have these scans because I don’t think that would be cost effective. But in selected scenarios, when they’ve seen a memory specialist, I think these can be very useful clinically," Dr. Rowe said.

He said amyloid imaging agents such as florbetaben have two potential uses:

• In patients with established dementia when there is uncertainty about whether the patient has Alzheimer’s disease or frontotemporal dementia. He noted that this has therapeutic implications because some of the medications used to treat Alzheimer’s, such as cholinesterase inhibitors, can make behavioral symptoms worse in frontotemporal dementia.

• In patients with MCI who have seen a specialist who is not sure what the cause of the symptoms might be and wants to see if it might be Alzheimer’s instead of waiting years for dementia to develop. Because about 40% with MCI do not go on to develop dementia, amyloid imaging studies would be reassuring to those patients, Dr. Rowe said.

Guidelines from the Alzheimer’s Association and the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (which recently changed its name from the Society of Nuclear Medicine) will soon be available on the appropriate use of the imaging agents, Dr. Rowe said in an interview.

He disclosed that he has served as an investigator on studies for many of the companies developing amyloid imaging products, including Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Bayer Schering Pharma, GE Healthcare, and AstraZeneca. He has also received payments for consulting for Bayer and GE.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOCIETY OF NUCLEAR MEDICINE AND MOLECULAR IMAGING

Major Finding: Longitudinal tracking of the deposition of beta-amyloid over a period of 2-3 years with the use of PET imaging radiotracers in patients with mild cognitive impairment can help predict progression to Alzheimer’s disease or reliably rule it out as a diagnosis.

Data Source: Data were taken from two studies of the investigational agents 11C-Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) and 18F-florbetaben.

Disclosures: Dr. Rowe disclosed that he has served as an investigator on studies for many of the companies developing amyloid imaging products, including Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Bayer Schering Pharma, GE Healthcare, and AstraZeneca. He has also received payments for consulting for Bayer and GE.

Diagnostic Imaging on the Rise Even in 'Accountable' HMOs

Advanced diagnostic imaging, with its much higher radiation doses than conventional radiography, is being used with increased frequency even within integrated health care delivery systems that are "clinically and fiscally accountable for their members’ outcomes" – in other words, even in the absence of financial incentives to overuse technologies, according to a report in the June 13 issue of JAMA.

The burgeoning use of diagnostic imaging has been well documented in Medicare and in fee-for-service insured populations, but until now no large, multicenter study has assessed time trends in imaging procedures within HMOs, which supposedly put greater limitations on questionable procedures, said Dr. Rebecca Smith-Bindman of the departments of radiology and biomedical imaging, epidemiology and biostatistics, and ob.gyn. and reproductive sciences, University of California, San Francisco, and her coinvestigators.

"Understanding imaging utilization and associated radiation exposure in these settings could help us determine how much of the increase in imaging may be independent of direct financial incentives," they noted (JAMA 307:2400-9).

The marked increase in advanced imaging is a concern because the higher radiation exposures have been linked with the development of radiation-induced cancers.

Dr. Smith-Bindman and her colleagues performed a retrospective population-based study of imaging trends between 1996 and 2010 among members of six geographically diverse U.S. health care delivery systems: Group Health Cooperative in Washington state; Kaiser Permanente in Colorado, Georgia, Hawaii, and Oregon; and Marshfield Clinic and Security Health Plan in Wisconsin.

Between 933,897 and 1,998,650 patients were included during each year of the study, and they underwent a total of 30.9 million imaging examinations. This averages out to 1.18 imaging studies per patient per year.

The investigators estimated the effective dose of ionizing radiation for each procedure, a measure that includes both the amount of radiation to which the patient is exposed and the biologic effect of that radiation on the exposed organs. They then used that data to calculate the total radiation dose each HMO member received each year, as well as the collective effective dose to the entire population.

The rates of conventional radiography and angiography/fluoroscopy remained relatively stable over the 15-year study period, rising just over 1% each year.

In marked contrast, the number of CT studies tripled, from 52 per 1,000 patients in 1996 to 149 per 1,000 in 2010. This represents an annual growth of nearly 8%.

The number of MRIs quadrupled, from 17 to 65 per 1,000 patients, an annual growth of 10%.

The number of ultrasound exams approximately doubled, from 134 to 230 per 1,000 patients, for an annual growth of 4%.

The rates of nuclear medicine exams decreased slightly, with one notable exception: During the last half of the study period, the number of PET scans skyrocketed from 0.24 per 1,000 patients in 2004 to 3.6 per 1,000 in 2010. This represents an annual growth of 57%.

Not surprisingly, the mean per capita effective radiation dose also rose significantly during the study period, effectively doubling from 1.2 mSv to 2.3 mSv. Among patients exposed to any radiation from medical imaging, the average effective dose climbed from 4.8 mSv in 1996 to 7.8 in 2010.

Of particular concern was the finding that the percentage of patients who received high (over 20-50 mSv) or very high (over 50 mSv) radiation exposure during a given year also approximately doubled. "By 2010, 2.5% of enrollees received a high annual dose of greater than 20-50 mSv, and 1.4% received a very high annual dose of greater than 50 mSv," the investigators wrote (JAMA 2012;307:2400-9).

Putting this exposure level in context, "the National Academy of Sciences’ National Research Council concluded, after a comprehensive review of the published literature, that patients who receive radiation exposures in the same range as a single CT – 10mSv – may be at increased risk for developing cancer," they said.

"The number of patients exposed to such levels highlights the need to consider this potential harm when ordering imaging tests and to track radiation exposures for individual patients so that this information is available to physicians who are ordering tests," Dr. Smith-Bindman and her associates said.

Older patients are at particular risk. The use of imaging, particularly of CT and nuclear medicine exams, increased steeply with patient age. "Among enrollees 45 years and older who underwent imaging, nearly 20% received high or very high radiation exposure annually," the researchers said.

Since the potential harm from such exposure may also increase with patient age, "it is particularly important to quantify the benefits of imaging in these patients," they noted.

The increase in the use of CT scanning accounted for much of the overall rise in radiation exposure. In 1996, 30% of patients’ exposure to ionizing radiation was attributed to CT studies; by 2010, 68% of exposure was attributed to CT studies.

"The increase in use of advanced diagnostic imaging has almost certainly contributed to both improved patient care processes and outcomes, but there are remarkably few data to quantify the benefits of imaging. Given the high costs of imaging – estimated at $100 billion annually – and the potential risks of cancer and other harms, these benefits should be quantified, and evidence-based guidelines for using imaging should be developed that clearly balance benefits against financial costs and health risk," Dr. Smith-Bindman and her colleagues said.

This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute and the National Institutes of Health. No financial conflicts of interest were reported by Dr. Smith-Bindman and her coinvestigators.

The findings of Dr. Smith-Bindman and his colleagues suggest that when ordering diagnostic tests, physicians must consider, and discuss with patients, the risks of radiation, said Dr. George T. O’Connor and Dr. Hiroto Hatabu.

The number of people who receive high or very high annual exposure to ionizing radiation from imaging studies is not trivial. It may even be appropriate for clinicians to consider the cumulative radiation exposure a given patient has received in recent months or years, they added.

Dr. O’Connor is with the pulmonary center at Boston University and is a contributing editor at JAMA. Dr. Hatabu is in the department of radiology and the center for pulmonary functional imaging at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. O’Connor reported no relevant financial disclosures, and Dr. Hatabu reported receiving grant support from Toshiba Medical, Canon, and AZE. These remarks were taken from their editorial comments accompanying Dr. Smith-Bindman’s report (JAMA 2012;307:2434-5).

The findings of Dr. Smith-Bindman and his colleagues suggest that when ordering diagnostic tests, physicians must consider, and discuss with patients, the risks of radiation, said Dr. George T. O’Connor and Dr. Hiroto Hatabu.

The number of people who receive high or very high annual exposure to ionizing radiation from imaging studies is not trivial. It may even be appropriate for clinicians to consider the cumulative radiation exposure a given patient has received in recent months or years, they added.

Dr. O’Connor is with the pulmonary center at Boston University and is a contributing editor at JAMA. Dr. Hatabu is in the department of radiology and the center for pulmonary functional imaging at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. O’Connor reported no relevant financial disclosures, and Dr. Hatabu reported receiving grant support from Toshiba Medical, Canon, and AZE. These remarks were taken from their editorial comments accompanying Dr. Smith-Bindman’s report (JAMA 2012;307:2434-5).

The findings of Dr. Smith-Bindman and his colleagues suggest that when ordering diagnostic tests, physicians must consider, and discuss with patients, the risks of radiation, said Dr. George T. O’Connor and Dr. Hiroto Hatabu.

The number of people who receive high or very high annual exposure to ionizing radiation from imaging studies is not trivial. It may even be appropriate for clinicians to consider the cumulative radiation exposure a given patient has received in recent months or years, they added.

Dr. O’Connor is with the pulmonary center at Boston University and is a contributing editor at JAMA. Dr. Hatabu is in the department of radiology and the center for pulmonary functional imaging at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. O’Connor reported no relevant financial disclosures, and Dr. Hatabu reported receiving grant support from Toshiba Medical, Canon, and AZE. These remarks were taken from their editorial comments accompanying Dr. Smith-Bindman’s report (JAMA 2012;307:2434-5).

Advanced diagnostic imaging, with its much higher radiation doses than conventional radiography, is being used with increased frequency even within integrated health care delivery systems that are "clinically and fiscally accountable for their members’ outcomes" – in other words, even in the absence of financial incentives to overuse technologies, according to a report in the June 13 issue of JAMA.

The burgeoning use of diagnostic imaging has been well documented in Medicare and in fee-for-service insured populations, but until now no large, multicenter study has assessed time trends in imaging procedures within HMOs, which supposedly put greater limitations on questionable procedures, said Dr. Rebecca Smith-Bindman of the departments of radiology and biomedical imaging, epidemiology and biostatistics, and ob.gyn. and reproductive sciences, University of California, San Francisco, and her coinvestigators.

"Understanding imaging utilization and associated radiation exposure in these settings could help us determine how much of the increase in imaging may be independent of direct financial incentives," they noted (JAMA 307:2400-9).

The marked increase in advanced imaging is a concern because the higher radiation exposures have been linked with the development of radiation-induced cancers.

Dr. Smith-Bindman and her colleagues performed a retrospective population-based study of imaging trends between 1996 and 2010 among members of six geographically diverse U.S. health care delivery systems: Group Health Cooperative in Washington state; Kaiser Permanente in Colorado, Georgia, Hawaii, and Oregon; and Marshfield Clinic and Security Health Plan in Wisconsin.

Between 933,897 and 1,998,650 patients were included during each year of the study, and they underwent a total of 30.9 million imaging examinations. This averages out to 1.18 imaging studies per patient per year.

The investigators estimated the effective dose of ionizing radiation for each procedure, a measure that includes both the amount of radiation to which the patient is exposed and the biologic effect of that radiation on the exposed organs. They then used that data to calculate the total radiation dose each HMO member received each year, as well as the collective effective dose to the entire population.

The rates of conventional radiography and angiography/fluoroscopy remained relatively stable over the 15-year study period, rising just over 1% each year.

In marked contrast, the number of CT studies tripled, from 52 per 1,000 patients in 1996 to 149 per 1,000 in 2010. This represents an annual growth of nearly 8%.

The number of MRIs quadrupled, from 17 to 65 per 1,000 patients, an annual growth of 10%.

The number of ultrasound exams approximately doubled, from 134 to 230 per 1,000 patients, for an annual growth of 4%.

The rates of nuclear medicine exams decreased slightly, with one notable exception: During the last half of the study period, the number of PET scans skyrocketed from 0.24 per 1,000 patients in 2004 to 3.6 per 1,000 in 2010. This represents an annual growth of 57%.

Not surprisingly, the mean per capita effective radiation dose also rose significantly during the study period, effectively doubling from 1.2 mSv to 2.3 mSv. Among patients exposed to any radiation from medical imaging, the average effective dose climbed from 4.8 mSv in 1996 to 7.8 in 2010.

Of particular concern was the finding that the percentage of patients who received high (over 20-50 mSv) or very high (over 50 mSv) radiation exposure during a given year also approximately doubled. "By 2010, 2.5% of enrollees received a high annual dose of greater than 20-50 mSv, and 1.4% received a very high annual dose of greater than 50 mSv," the investigators wrote (JAMA 2012;307:2400-9).

Putting this exposure level in context, "the National Academy of Sciences’ National Research Council concluded, after a comprehensive review of the published literature, that patients who receive radiation exposures in the same range as a single CT – 10mSv – may be at increased risk for developing cancer," they said.

"The number of patients exposed to such levels highlights the need to consider this potential harm when ordering imaging tests and to track radiation exposures for individual patients so that this information is available to physicians who are ordering tests," Dr. Smith-Bindman and her associates said.