User login

Anti-Xa assays: What is their role today in antithrombotic therapy?

Should clinicians abandon the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) for monitoring heparin therapy in favor of tests that measure the activity of the patient’s plasma against activated factor X (anti-Xa assays)?

Although other anticoagulants are now available for preventing and treating arterial and venous thromboembolism, unfractionated heparin—which requires laboratory monitoring of therapy—is still widely used. And this monitoring can be challenging. Despite its wide use, the aPTT lacks standardization, and the role of alternative monitoring assays such as the anti-Xa assay is not well defined.

This article reviews the advantages, limitations, and clinical applicability of anti-Xa assays for monitoring therapy with unfractionated heparin and other anticoagulants.

UNFRACTIONATED HEPARIN AND WARFARIN ARE STILL WIDELY USED

Until the mid-1990s, unfractionated heparin and oral vitamin K antagonists (eg, warfarin) were the only anticoagulants widely available for clinical use. These agents have complex pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties, resulting in highly variable dosing requirements (both between patients and in individual patients) and narrow therapeutic windows, making frequent laboratory monitoring and dose adjustments mandatory.

Over the past 3 decades, other anticoagulants have been approved, including low-molecular-weight heparins, fondaparinux, parenteral direct thrombin inhibitors, and direct oral anticoagulants. While these agents have expanded the options for preventing and treating thromboembolism, unfractionated heparin and warfarin are still the most appropriate choices for many patients, eg, those with stage 4 chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease on dialysis, and those with mechanical heart valves.

In addition, unfractionated heparin remains the anticoagulant of choice during procedures such as hemodialysis, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, and cardiopulmonary bypass, as well as in hospitalized and critically ill patients, who often have acute kidney injury or require frequent interruptions of therapy for invasive procedures. In these scenarios, unfractionated heparin is typically preferred because of its short plasma half-life, complete reversibility by protamine, safety regardless of renal function, and low cost compared with parenteral direct thrombin inhibitors.

As long as unfractionated heparin and warfarin remain important therapies, the need for their laboratory monitoring continues. For warfarin monitoring, the prothrombin time and international normalized ratio are validated and widely reproducible methods. But monitoring unfractionated heparin therapy remains a challenge.

UNFRACTIONATED HEPARIN’S EFFECT IS UNPREDICTABLE

Unfractionated heparin, a negatively charged mucopolysaccharide, inhibits coagulation by binding to antithrombin through the high-affinity pentasaccharide sequence.1–6 Such binding induces a conformational change in the antithrombin molecule, converting it to a rapid inhibitor of several coagulation proteins, especially factors IIa and Xa.2–4

Unfractionated heparin inhibits factors IIa and Xa in a 1:1 ratio, but low-molecular-weight heparins inhibit factor Xa more than factor IIa, with IIa-Xa inhibition ratios ranging from 1:2 to 1:4, owing to their smaller molecular size.7

One of the most important reasons for the unpredictable and highly variable individual responses to unfractionated heparin is that, infused into the blood, the large and negatively charged unfractionated heparin molecules bind nonspecifically to positively charged plasma proteins.7 In patients who are critically ill, have acute infections or inflammatory states, or have undergone major surgery, unfractionated heparin binds to acute-phase proteins that are elevated, particularly factor VIII. This results in fewer free heparin molecules and a variable anticoagulant effect.8

In contrast, low-molecular-weight heparins have longer half-lives and bind less to plasma proteins, resulting in more predictable plasma levels following subcutaneous injection.9

MONITORING UNFRACTIONATED HEPARIN IMPROVES OUTCOMES

In 1960, Barritt and Jordan10 conducted a small but landmark trial that established the clinical importance of unfractionated heparin for treating venous thromboembolism. None of the patients who received unfractionated heparin for acute pulmonary embolism developed a recurrence during the subsequent 2 weeks, while 50% of those who did not receive it had recurrent pulmonary embolism, fatal in half of the cases.

The importance of achieving a specific aPTT therapeutic target was not demonstrated until a 1972 study by Basu et al,11 in which 162 patients with venous thromboembolism were treated with heparin with a target aPTT of 1.5 to 2.5 times the control value. Patients who suffered recurrent events had subtherapeutic aPTT values on 71% of treatment days, while the rest of the patients, with no recurrences, had subtherapeutic aPTT values only 28% of treatment days. The different outcomes could not be explained by the average daily dose of unfractionated heparin, which was similar in the patients regardless of recurrence.

Subsequent studies showed that the best outcomes occur when unfractionated heparin is given in doses high enough to rapidly achieve a therapeutic prolongation of the aPTT,12–14 and that the total daily dose is also important in preventing recurrences.15,16 Failure to achieve a target aPTT within 24 hours of starting unfractionated heparin is associated with increased risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism.13,17

Raschke et al17 found that patients prospectively randomized to weight-based doses of intravenous unfractionated heparin (bolus plus infusion) achieved significantly higher rates of therapeutic aPTT within 6 hours and 24 hours after starting the infusion, and had significantly lower rates of recurrent venous thromboembolism than those randomized to a fixed unfractionated heparin protocol, without an increase in major bleeding.

Smith et al,18 in a study of 400 consecutive patients with acute pulmonary embolism treated with unfractionated heparin, found that patients who achieved a therapeutic aPTT within 24 hours had lower in-hospital and 30-day mortality rates than those who did not achieve the first therapeutic aPTT until more than 24 hours after starting unfractionated heparin infusion.

Such data lend support to the widely accepted practice and current guideline recommendation8 of using laboratory assays to adjust the dose of unfractionated heparin to achieve and maintain a therapeutic target. The use of dosing nomograms significantly reduces the time to achieve a therapeutic aPTT while minimizing subtherapeutic and supratherapeutic unfractionated heparin levels.19,20

THE aPTT REFLECTS THROMBIN INHIBITION

The aPTT has a log-linear relationship with plasma concentrations of unfractionated heparin,21 but it was not developed specifically for monitoring unfractionated heparin therapy. Originally described in 1953 as a screening tool for hemophilia,22–24 the aPTT is prolonged in the setting of factor deficiencies (typically with levels < 45%, except for factors VII and XIII), as well as lupus anticoagulants and therapy with parenteral direct thrombin inhibitors.8,25,26

Because thrombin (factor IIa) is 10 times more sensitive than factor Xa to inhibition by the heparin-antithrombin complex,4,7 thrombin inhibition appears to be the most likely mechanism by which unfractionated heparin prolongs the aPTT. In contrast, aPTT is minimally or not at all prolonged by low-molecular-weight heparins, which are predominantly factor Xa inhibitors.7

HEPARIN ASSAYS MEASURE UNFRACTIONATED HEPARIN ACTIVITY

While the aPTT is a surrogate marker of unfractionated heparin activity in plasma, unfractionated heparin activity can be measured more precisely by so-called heparin assays, which are typically not direct measures of the plasma concentration of heparins, but rather functional assays that provide indirect estimates. They include protamine sulfate titration assays and anti-Xa assays.

Protamine sulfate titration assays measure the amount of protamine sulfate required to neutralize heparin: the more protamine required, the greater the estimated concentration of unfractionated heparin in plasma.8,27–29 Protamine titration assays are technically demanding, so they are rarely used clinically.

Anti-Xa assays provide a measure of the functional level of heparins in plasma.29–33 Chromogenic anti-Xa assays are available on automated analyzers with standardized kits29,33,34 and may be faster to perform than the aPTT.35

Experiments in rabbits show that unfractionated heparin inhibits thrombus formation and extension at concentrations of 0.2 to 0.4 U/mL as measured by the protamine titration assay,27 which correlated with an anti-Xa activity of 0.35 to 0.67 U/mL in a randomized controlled trial.32

Assays that directly measure the plasma concentration of heparin exist but are not clinically relevant because they also measure heparin molecules lacking the pentasaccharide sequence, which have no anticoagulant activity.36

ANTI-Xa ASSAY VS THE aPTT

Anti-Xa assays are more expensive than the aPTT and are not available in all hospitals. For these reasons, the aPTT remains the most commonly used laboratory assay for monitoring unfractionated heparin therapy.

However, the aPTT correlates poorly with the activity level of unfractionated heparin in plasma. In one study, an anti-Xa level of 0.3 U/mL corresponded to aPTT results ranging from 47 to 108 seconds.31 Furthermore, in studies that used a heparin therapeutic target based on an aPTT ratio 1.5 to 2.5 times the control aPTT value, the lower end of that target range was often associated with subtherapeutic plasma unfractionated heparin activity measured by anti-Xa and protamine titration assays.28,31

Because of these limitations, individual laboratories should determine their own aPTT therapeutic target ranges for unfractionated heparin based on the response curves obtained with the reagent and coagulometer used. The optimal therapeutic aPTT range for treating acute venous thromboembolism should be defined as the aPTT range (in seconds) that correlates with a plasma activity level of unfractionated heparin of 0.3 to 0.7 U/mL based on a chromogenic anti-Xa assay, or 0.2 to 0.4 U/mL based on a protamine titration assay.32,34–36

Nevertheless, the anticoagulant effect of unfractionated heparin as measured by the aPTT can be unpredictable and can vary widely among individuals and in the same patient.7 This wide variability can be explained by a number of technical and biologic variables. Different commercial aPTT reagents, different lots of the same reagent, and different reagent and instrument combinations have different sensitivities to unfractionated heparin, which can lead to variable aPTT results.37 Moreover, high plasma levels of acute-phase proteins, low plasma antithrombin levels, consumptive coagulopathies, liver failure, and lupus anticoagulants may also affect the aPTT.7,25,32,36–41 These variables account for the poor correlation—ranging from 25% to 66%—reported between aPTT and anti-Xa assays.32,42–48

Such discrepancies may have serious clinical implications: if a patient’s aPTT is low (subtherapeutic) or high (supratherapeutic) but the anti-Xa assay result is within the therapeutic range (0.3–0.7 units/mL), changing the dose of unfractionated heparin (guided by an aPTT nomogram) may increase the risk of bleeding or of recurrent thromboembolism.

CLINICAL APPLICABILITY OF THE ANTI-Xa ASSAY

Neither anti-Xa nor protamine titration assays are standardized across reference laboratories, but chromogenic anti-Xa assays have better interlaboratory correlation than the aPTT49,50 and can be calibrated specifically for unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparins.29,33

Although reagent costs are higher for chromogenic anti-Xa assays than for the aPTT, some technical variables (described below) may partially offset the cost difference.29,33,41 In addition, unlike the aPTT, anti-Xa assays do not need local calibration; the therapeutic range for unfractionated heparin is the same (0.3–0.7 U/mL) regardless of instrument or reagent.33,41

Most important, studies have found that patients monitored by anti-Xa assay achieve significantly higher rates of therapeutic anticoagulation within 24 and 48 hours after starting unfractionated heparin infusion than those monitored by the aPTT. Fewer dose adjustments and repeat tests are required, which may also result in lower cost.32,51–55

While these studies found chromogenic anti-Xa assays better for achieving laboratory end points, data regarding relevant clinical outcomes are more limited. In a retrospective, observational cohort study,51 the rate of venous thromboembolism or bleeding-related death was 2% in patients receiving unfractionated heparin therapy monitored by anti-Xa assay and 6% in patients monitored by aPTT (P = .62). Rates of major hemorrhage were also not significantly different.

In a randomized controlled trial32 in 131 patients with acute venous thromboembolism and heparin resistance, rates of recurrent venous thromboembolism were 4.6% and 6.1% in the groups randomized to anti-Xa and aPTT monitoring, respectively, whereas overall bleeding rates were 1.5% and 6.1%, respectively. Again, the differences were not statistically significant.

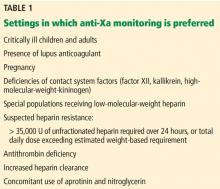

Heparin resistance. Some patients require unusually high doses of unfractionated heparin to achieve a therapeutic aPTT: typically, more than 35,000 U over 24 hours,7,8,32 or total daily doses that exceed their estimated weight-based requirements. Heparin resistance has been observed in various clinical settings.7,8,32,37–40,59–61 Patients with heparin resistance monitored by anti-Xa had similar rates of recurrent venous thromboembolism while receiving significantly lower doses of unfractionated heparin than those monitored by the aPTT.32

Lupus anticoagulant. Patients with the specific antiphospholipid antibody known as lupus anticoagulant frequently have a prolonged baseline aPTT,25 making it an unreliable marker of anticoagulant effect for intravenous unfractionated heparin therapy.

Critically ill infants and children. Arachchillage et al35 found that infants (< 1 year old) treated with intravenous unfractionated heparin in an intensive care department had only a 32.4% correlation between aPTT and anti-Xa levels, which was lower than that found in children ages 1 to 15 (66%) and adults (52%). In two-thirds of cases of discordant aPTT and anti-Xa levels, the aPTT was elevated (supratherapeutic) while the anti-Xa assay was within the therapeutic range (0.3–0.7 U/mL). Despite the lack of data on clinical outcomes (eg, rates of thrombosis and bleeding) with the use of an anti-Xa assay, it has been considered the method of choice for unfractionated heparin monitoring in critically ill children, and especially in those under age 1.41,44,62–64

While anti-Xa assays may also be better for unfractionated heparin monitoring in critically ill adults, the lack of clinical outcome data from large-scale randomized trials has precluded evidence-based recommendations favoring them over the aPTT.8,34

LIMITATIONS OF ANTI-Xa ASSAYS

Anti-Xa assays are hampered by some technical limitations:

Samples must be processed within 1 hour to avoid heparin neutralization.34

Samples must be clear. Hemolyzed or opaque samples (eg, due to bilirubin levels > 6.6 mg/dL or triglyceride levels > 360 mg/dL) cannot be processed, as they can cause falsely low levels.

Exposure to other anticoagulants can interfere with the results. The anti-Xa assay may be unreliable for unfractionated heparin monitoring in patients who are transitioned from low-molecular-weight heparins, fondaparinux, or an oral factor Xa inhibitor (apixaban, betrixaban, edoxaban, rivaroxaban) to intravenous unfractionated heparin, eg, due to hospitalization or acute kidney injury.65,66 Different reports have found that anti-Xa assays may be elevated for as long as 63 to 96 hours after the last dose of oral Xa inhibitors,67–69 potentially resulting in underdosing of unfractionated heparin. In such settings, unfractionated heparin therapy should be monitored by the aPTT.

ANTI-Xa ASSAYS AND LOW-MOLECULAR-WEIGHT HEPARINS

Most patients receiving low-molecular-weight heparins do not need laboratory monitoring.8 Alhenc-Gelas et al70 randomized patients to receive dalteparin in doses either based on weight or guided by anti-Xa assay results, and found that dose adjustments were rare and lacked clinical benefit.

The suggested therapeutic anti-Xa levels for low-molecular-weight heparins are:

- 0.5–1.2 U/mL for twice-daily enoxaparin

- 1.0–2.0 U/mL for once-daily enoxaparin or dalteparin.

Levels should be measured at peak plasma level (ie, 3–4 hours after subcutaneous injection, except during pregnancy, when it is 4–6 hours), and only after at least 3 doses of low-molecular-weight heparin.8,71 Unlike the anti-Xa therapeutic range recommended for unfractionated heparin therapy, these ranges are not based on prospective data, and if the assay result is outside the suggested therapeutic target range, current guidelines offer no advice on safely adjusting the dose.8,71

Measuring anti-Xa activity is particularly important for pregnant women with a mechanical prosthetic heart valve who are treated with low-molecular-weight heparins. In this setting, valve thrombosis and cardioembolic events have been reported in patients with peak low-molecular-weight heparin anti-Xa assay levels below or even at the lower end of the therapeutic range, and increased bleeding risk has been reported with elevated anti-Xa levels.71–74 Measuring trough low-molecular-weight heparin anti-Xa levels has been suggested to guide dose adjustments during pregnancy.75

Clearance of low-molecular-weight heparins as measured by the anti-Xa assay is highly correlated with creatinine clearance.76,77 A strong linear correlation has been demonstrated between creatine clearance and anti-Xa levels of enoxaparin after multiple therapeutic doses, and low-molecular-weight heparins accumulate in the plasma, especially in patients with creatine clearance less than 30 mL/min.78 The risk of major bleeding is significantly increased in patients with severe renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min) not on dialysis who are treated with either prophylactic or therapeutic doses of low-molecular-weight heparin.79–81 In a meta-analysis, the risk of bleeding with therapeutic-intensity doses of enoxaparin was 4 times higher than with prophylactic-intensity doses.79 Although bleeding risk appears to be reduced when the enoxaparin dose is reduced by 50%,8 the efficacy and safety of this strategy has not been determined by prospective trials.

ANTI-Xa ASSAYS IN PATIENTS RECEIVING DIRECT ORAL ANTICOAGULANTS

Direct oral factor Xa inhibitors cannot be measured accurately by heparin anti-Xa assays. Nevertheless, such assays may be useful to assess whether clinically relevant plasma levels are present in cases of major bleeding, suspected anticoagulant failure, or patient noncompliance.82

Intense research has focused on developing drug-specific chromogenic anti-Xa assays using calibrators and standards for apixaban, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban,82,83 and good linear correlation has been shown with some assays.82,84 In patients treated with oral factor Xa inhibitors who need to undergo an urgent invasive procedure associated with high bleeding risk, use of a specific reversal agent may be considered with drug concentrations more than 30 ng/mL measured by a drug-specific anti-Xa assay. A similar suggestion has been made for drug concentrations more than 50 ng/mL in the setting of major bleeding.85 Unfortunately, such assays are not widely available at this time.82,86

While drug-specific anti-Xa assays could become clinically important to guide reversal strategies, their relevance for drug monitoring remains uncertain. This is because no therapeutic target ranges have been established for any of the direct oral anticoagulants, which were approved on the basis of favorable clinical trial outcomes that neither measured nor were correlated with specific drug levels in plasma. Therefore, a specific anti-Xa level cannot yet be used as a marker of clinical efficacy for any specific oral direct Xa inhibitor.

- Abildgaard U. Highly purified antithrombin 3 with heparin cofactor activity prepared by disc electrophoresis. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1968; 21(1):89–91. pmid:5637480

- Rosenberg RD, Lam L. Correlation between structure and function of heparin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1979; 76(3):1218–1222. pmid:286307

- Lindahl U, Bäckström G, Höök M, Thunberg L, Fransson LA, Linker A. Structure of the antithrombin-binding site of heparin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1979; 76(7):3198–3202. pmid:226960

- Rosenberg RD, Rosenberg JS. Natural anticoagulant mechanisms. J Clin Invest 1984; 74(1):1–6. doi:10.1172/JCI111389

- Casu B, Oreste P, Torri G, et al. The structure of heparin oligosaccharide fragments with high anti-(factor Xa) activity containing the minimal antithrombin III-binding sequence. Chemical and 13C nuclear-magnetic-resonance studies. Biochem J 1981; 197(3):599–609. pmid:7325974

- Choay J, Lormeau JC, Petitou M, Sinaÿ P, Fareed J. Structural studies on a biologically active hexasaccharide obtained from heparin. Ann NY Acad Sci 1981; 370: 644–649. pmid:6943974

- Hirsh J, Warkentin TE, Shaughnessy SG, et al. Heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin: mechanisms of action, pharmacokinetics, dosing, monitoring, efficacy, and safety. Chest 2001; 119(suppl 1):64S–94S. pmid:11157643

- Garcia DA, Baglin TP, Weitz JI, Samama MM. Parenteral anticoagulants: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012; 141(suppl 2):e24S–e43S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2291

- Hirsh J, Levine M. Low-molecular weight heparin. Blood 1992; 79(1):1–17. pmid:1309422

- Barritt DW, Jordan SC. Anticoagulant drugs in the treatment of pulmonary embolism. A controlled trial. Lancet 1960; 1(7138):1309–1312. pmid:13797091

- Basu D, Gallus A, Hirsh J, Cade J. A prospective study of the value of monitoring heparin treatment with the activated partial thromboplastin time. N Engl J Med 1972; 287(7):324–327. doi:10.1056/NEJM197208172870703

- Hull RD, Raskob GE, Hirsh J, et al. Continuous intravenous heparin compared with intermittent subcutaneous heparin in the initial treatment of proximal-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med 1986; 315(18):1109–1114. doi:10.1056/NEJM198610303151801

- Hull RD, Raskob GE, Brant RF, Pineo GF, Valentine KA. Relation between the time to achieve the lower limit of the APTT therapeutic range and recurrent venous thromboembolism during heparin treatment for deep vein thrombosis. Arch Intern Med 1997; 157(22):2562–2568. pmid:9531224

- Hull RD, Raskob GE, Brant RF, Pineo GF, Valentine KA. The importance of initial heparin treatment on long-term clinical outcomes of antithrombotic therapy. The emerging theme of delayed recurrence. Arch Intern Med 1997; 157(20):2317–2321. pmid:9361572

- Anand S, Ginsberg JS, Kearon C, Gent M, Hirsh J. The relation between the activated partial thromboplastin time response and recurrence in patients with venous thrombosis treated with continuous intravenous heparin. Arch Intern Med 1996; 156(15):1677–1681. pmid:8694666

- Anand SS, Bates S, Ginsberg JS, et al. Recurrent venous thrombosis and heparin therapy: an evaluation of the importance of early activated partial thromboplastin times. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159(17):2029–2032. pmid:10510988

- Raschke RA, Reilly BM, Guidry JR, Fontana JR, Srinivas S. The weight-based heparin dosing nomogram compared with a “standard care” nomogram. A randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1993; 119(9):874–881. pmid:8214998

- Smith SB, Geske JB, Maguire JM, Zane NA, Carter RE, Morgenthaler TI. Early anticoagulation is associated with reduced mortality for acute pulmonary embolism. Chest 2010; 137(6):1382–1390. doi:10.1378/chest.09-0959

- Cruickshank MK, Levine MN, Hirsh J, Roberts R, Siguenza M. A standard heparin nomogram for the management of heparin therapy. Arch Intern Med 1991; 151(2):333–337. pmid:1789820

- Raschke RA, Gollihare B, Peirce J. The effectiveness of implementing the weight-based heparin nomogram as a practice guideline. Arch Intern Med 1996; 156(15):1645–1649. pmid:8694662

- Simko RJ, Tsung FF, Stanek EJ. Activated clotting time versus activated partial thromboplastin time for therapeutic monitoring of heparin. Ann Pharmacother 1995; 29(10):1015–1021. doi:10.1177/106002809502901012

- Langdell RD, Wagner RH, Brinkhous KM. Effect of antihemophilic factor on one-stage clotting tests; a presumptive test for hemophilia and a simple one-stage antihemophilic factor assy procedure. J Lab Clin Med 1953; 41(4):637–647.

- White GC 2nd. The partial thromboplastin time: defining an era in coagulation. J Thromb Haemost 2003; 1(11):2267–2270. pmid:14629454

- Proctor RR, Rapaport SI. The partial thromboplastin time with kaolin. A simple screening test for first stage plasma clotting factor deficiencies. Am J Clin Pathol 1961; 36:212–219. pmid:13738153

- Brandt JT, Triplett DA, Rock WA, Bovill EG, Arkin CF. Effect of lupus anticoagulants on the activated partial thromboplastin time. Results of the College of American Pathologists survey program. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1991; 115(2):109–114. pmid:1899555

- Tripodi A, Mannucci PM. Activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT). New indications for an old test? J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4(4):750–751. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01857.x

- Chiu HM, Hirsh J, Yung WL, Regoeczi E, Gent M. Relationship between the anticoagulant and antithrombotic effects of heparin in experimental venous thrombosis. Blood 1977; 49(2):171–184. pmid:831872

- Brill-Edwards P, Ginsberg JS, Johnston M, Hirsh J. Establishing a therapeutic range for heparin therapy. Ann Intern Med 1993; 119(2):104–109. pmid:8512158

- Vandiver JW, Vondracek TG. Antifactor Xa levels versus activated partial thromboplastin time for monitoring unfractionated heparin. Pharmacotherapy 2012; 32(6):546–558. doi:10.1002/j.1875-9114.2011.01049.x

- Newall F. Anti-factor Xa (anti-Xa). In: Monagle P, ed. Haemostasis: Methods and Protocols. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2013.

- Bates SM, Weitz JI, Johnston M, Hirsh J, Ginsberg JS. Use of a fixed activated partial thromboplastin time ratio to establish a therapeutic range for unfractionated heparin. Arch Intern Med 2001; 161(3):385–391. pmid:11176764

- Levine MN, Hirsh J, Gent M, et al. A randomized trial comparing activated thromboplastin time with heparin assay in patients with acute venous thromboembolism requiring large doses of heparin. Arch Intern Med 1994; 154(1):49–56. pmid:8267489

- Wool GD, Lu CM; Education Committee of the Academy of Clinical Laboratory Physicians and Scientists. Pathology consultation on anticoagulation monitoring: factor X-related assays. Am J Clin Pathol 2013; 140(5):623–634. doi:10.1309/AJCPR3JTOK7NKDBJ

- Lehman CM, Frank EL. Laboratory monitoring of heparin therapy: partial thromboplastin time or anti-Xa assay? Lab Med 2009; 40(1):47–51. doi:10.1309/LM9NJGW2ZIOLPHY6

- Arachchillage DR, Kamani F, Deplano S, Banya W, Laffan M. Should we abandon the aPTT for monitoring unfractionated heparin? Thromb Res 2017; 157:157–161. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2017.07.006

- Olson JD, Arkin CA, Brandt JT, et al. College of American Pathologists Conference XXXI on Laboratory Monitoring of Anticoagulant Therapy: laboratory monitoring of unfractionated heparin therapy. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1998; 122(9):782–798. pmid:9740136

- Eikelboom JW, Hirsh J. Monitoring unfractionated heparin with the aPTT: time for a fresh look. Thromb Haemost 2006; 96(5):547–552. pmid:17080209

- Young E, Prins M, Levine MN, Hirsh J. Heparin binding to plasma proteins, an important mechanism of heparin resistance. Thromb Haemost 1992; 67(6):639–643. pmid:1509402

- Edson JR, Krivit W, White JG. Kaolin partial thromboplastin time: high levels of procoagulants producing short clotting times or masking deficiencies of other procoagulants or low concentrations of anticoagulants. J Lab Clin Med 1967; 70(3):463–470. pmid:6072020

- Whitfield LR, Lele AS, Levy G. Effect of pregnancy on the relationship between concentration and anticoagulant action of heparin. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1983; 34(1):23–28. pmid:6861435

- Marci CD, Prager D. A review of the clinical indications for the plasma heparin assay. Am J Clin Pathol 1993; 99(5):546–550.

- Takemoto CM, Streiff MB, Shermock KM, et al. Activated partial thromboplastin time and anti-Xa measurements in heparin monitoring: biochemical basis of discordance. Am J Clin Pathol 2013; 139(4):450–456. doi:10.1309/AJCPS6OW6DYNOGNH

- Adatya S, Uriel N, Yarmohammadi H, et al. Anti-factor Xa and activated partial thromboplastin time measurements for heparin monitoring in mechanical circulatory support. JACC Heart Fail 2015; 3(4):314–322. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2014.11.009

- Kuhle S, Eulmesekian P, Kavanagh B, et al. Lack of correlation between heparin dose and standard clinical monitoring tests in treatment with unfractionated heparin in critically ill children. Haematologica 2007; 92(4):554–557. pmid:17488668

- Price EA, Jin J, Nguyen HM, Krishnan G, Bowen R, Zehnder JL. Discordant aPTT and anti-Xa values and outcomes in hospitalized patients treated with intravenous unfractionated heparin. Ann Pharmacother 2013; 47(2):151–158. doi:10.1345/aph.1R635

- Baker BA, Adelman MD, Smith PA, Osborn JC. Inability of the activated partial thromboplastin time to predict heparin levels. Arch Intern Med 1997; 157(21):2475–2479. pmid:9385299

- Koerber JM, Smythe MA, Begle RL, Mattson JC, Kershaw BP, Westley SJ. Correlation of activated clotting time and activated partial thromboplastin time to plasma heparin concentration. Pharmacotherapy 1999; 19(8):922–931. pmid:10453963

- Smythe MA, Mattson JC, Koerber JM. The heparin anti-Xa therapeutic range: are we there yet? Chest 2002; 121(1):303–304. pmid:11796474

- Cuker A, Ptashkin B, Konkle A, et al. Interlaboratory agreement in the monitoring of unfractionated heparin using the anti-factor Xa-correlated activated partial thromboplastin time. J Thromb Haemost 2009; 7(1):80–86. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03224.x

- Taylor CT, Petros WP, Ortel TL. Two instruments to determine activated partial thromboplastin time: implications for heparin monitoring. Pharmacotherapy 1999; 19(4):383–387. pmid:10212007

- Guervil DJ, Rosenberg AF, Winterstein AG, Harris NS, Johns TE, Zumberg MS. Activated partial thromboplastin time versus antifactor Xa heparin assay in monitoring unfractionated heparin by continuous intravenous infusion. Ann Pharmacother 2011; 45(7–8):861–868. doi:10.1345/aph.1Q161

- Fruge KS, Lee YR. Comparison of unfractionated heparin protocols using antifactor Xa monitoring or activated partial thrombin time monitoring. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2015; 72(17 suppl 2):S90–S97. doi:10.2146/sp150016

- Rosborough TK. Monitoring unfractionated heparin therapy with antifactor Xa activity results in fewer monitoring tests and dosage changes than monitoring with activated partial thromboplastin time. Pharmacotherapy 1999; 19(6):760–766. pmid:10391423

- Rosborough TK, Shepherd MF. Achieving target antifactor Xa activity with a heparin protocol based on sex, age, height, and weight. Pharmacotherapy 2004; 24(6):713–719. doi:10.1592/phco.24.8.713.36067

- Smith ML, Wheeler KE. Weight-based heparin protocol using antifactor Xa monitoring. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2010; 67(5):371–374. doi:10.2146/ajhp090123

- Bartholomew JR, Kottke-Marchant K. Monitoring anticoagulation therapy in patients with the lupus anticoagulant. J Clin Rheumatol 1998; 4(6):307–312. pmid:19078327

- Wool GD, Lu CM; Education Committee of the Academy of Clinical Laboratory Physicians and Scientists. Pathology consultation on anticoagulation monitoring: factor X-related assays. Am J Clin Pathol 2013; 140(5):623–634. doi:10.1309/AJCPR3JTOK7NKDBJ

- Mehta TP, Smythe MA, Mattson JC. Strategies for managing heparin therapy in patients with antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. Pharmacotherapy 2011; 31(12):1221–1231. doi:10.1592/phco.31.12.1221

- Levine SP, Sorenson RR, Harris MA, Knieriem LK. The effect of platelet factor 4 (PF4) on assays of plasma heparin. Br J Haematol 1984; 57(4):585–596. pmid:6743573

- Fisher AR, Bailey CR, Shannon CN, Wielogorski AK. Heparin resistance after aprotinin. Lancet 1992; 340(8829):1230–1231. pmid:1279335

- Becker RC, Corrao JM, Bovill EG, et al. Intravenous nitroglycerin-induced heparin resistance: a qualitative antithrombin III abnormality. Am Heart J 1990; 119(6):1254–1261. pmid:2112878

- Monagle P, Chan AK, Goldenberg NA, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in neonates and children: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012; 141(suppl 2):e737S–e801S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2308

- Long E, Pitfield AF, Kissoon N. Anticoagulation therapy: indications, monitoring, and complications. Pediatr Emerg Care 2011; 27(1):55–61. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e31820461b1

- Andrew M, Schmidt B. Use of heparin in newborn infants. Semin Thromb Hemost 1988; 14(1):28–32. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1002752

- Teien AN, Lie M, Abildgaard U. Assay of heparin in plasma using a chromogenic substrate for activated factor X. Thromb Res 1976; 8(3):413–416. pmid:1265712

- Vera-Aguillera J, Yousef H, Beltran-Melgarejo D, et al. Clinical scenarios for discordant anti-Xa. Adv Hematol 2016; 2016:4054806. doi:10.1155/2016/4054806

- Macedo KA, Tatarian P, Eugenio KR. Influence of direct oral anticoagulants on anti-factor Xa measurements utilized for monitoring heparin. Ann Pharmacother 2018; 52(2):154–159. doi:10.1177/1060028017729481

- Wendte J, Voss G, Van Overschelde B. Influence of apixaban on antifactor Xa levels in a patient with acute kidney injury. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2016; 73(8):563–567. doi:10.2146/ajhp150360

- Faust AC, Kanyer D, Wittkowsky AK. Managing transitions from oral factor Xa inhibitors to unfractionated heparin infusions. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2016; 73(24):2037–2041. doi:10.2146/ajhp150596

- Alhenc-Gelas M, Jestin-Le Guernic C, Vitoux JF, Kher A, Aiach M, Fiessinger JN. Adjusted versus fixed doses of the low-molecular-weight heparin fragmin in the treatment of deep vein thrombosis. Fragmin-Study Group. Thromb Haemost 1994; 71(6):698–702. pmid:7974334

- Bates SM, Greer IA, Middeldorp S, Veenstra DL, Prabulos AM, Vandvik PO. VTE, thrombophilia, antithrombotic therapy, and pregnancy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012; 141(suppl 2):e691S–e736S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2300

- Bara L, Leizorovicz A, Picolet H, Samama M. Correlation between anti-Xa and occurrence of thrombosis and haemorrhage in post-surgical patients treated with either Logiparin (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin. Post-surgery Logiparin Study Group. Thromb Res 1992; 65(4–5):641–650. pmid:1319619

- Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Büller HR, et al. Comparison of subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin with intravenous standard heparin in proximal deep-vein thrombosis. Lancet 1992; 339(8791):441–445. pmid:1346817

- Walenga JM, Hoppensteadt D, Fareed J. Laboratory monitoring of the clinical effects of low molecular weight heparins. Thromb Res Suppl 1991;14:49–62. pmid:1658970

- Elkayam U. Anticoagulation therapy for pregnant women with mechanical prosthetic heart valves: how to improve safety? J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(22):2692–2695. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.034

- Brophy DF, Wazny LD, Gehr TW, Comstock TJ, Venitz J. The pharmacokinetics of subcutaneous enoxaparin in end-stage renal disease. Pharmacotherapy 2001; 21(2):169–174. pmid:11213853

- Becker RC, Spencer FA, Gibson M, et al; TIMI 11A Investigators. Influence of patient characteristics and renal function on factor Xa inhibition pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics after enoxaparin administration in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J 2002; 143(5):753–759. pmid:12040334

- Chow SL, Zammit K, West K, Dannenhoffer M, Lopez-Candales A. Correlation of antifactor Xa concentrations with renal function in patients on enoxaparin. J Clin Pharmacol 2003; 43(6):586–590. pmid:12817521

- Lim W, Dentali F, Eikelboom JW, Crowther MA. Meta-analysis: low-molecular-weight heparin and bleeding in patients with severe renal insufficiency. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144(9):673–684. pmid:16670137

- Spinler SA, Inverso SM, Cohen M, Goodman SG, Stringer KA, Antman EM; ESSENCE and TIMI 11B Investigators. Safety and efficacy of unfractionated heparin versus enoxaparin in patients who are obese and patients with severe renal impairment: analysis from the ESSENCE and TIMI 11B studies. Am Heart J 2003; 146(1):33–41. doi:10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00121-2

- Cestac P, Bagheri H, Lapeyre-Mestre M, et al. Utilisation and safety of low molecular weight heparins: prospective observational study in medical inpatients. Drug Saf 2003; 26(3):197–207. doi:10.2165/00002018-200326030-00005

- Douxfils J, Ageno W, Samama CM, et al. Laboratory testing in patients treated with direct oral anticoagulants: a practical guide for clinicians. J Thromb Haemost 2018; 16(2):209–219. doi:10.1111/jth.13912

- Samuelson BT, Cuker A, Siegal DM, Crowther M, Garcia DA. Laboratory assessment of the anticoagulant activity of direct oral anticoagulants: a systematic review. Chest 2017; 151(1):127–138. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2016.08.1462

- Gosselin RC, Francart SJ, Hawes EM, Moll S, Dager WE, Adcock DM. Heparin-calibrated chromogenic anti-Xa activity measurements in patients receiving rivaroxaban: can this test be used to quantify drug level? Ann Pharmacother 2015; 49(7):777–783. doi:10.1177/1060028015578451

- Levy JH, Ageno W, Chan NC, Crowther M, Verhamme P, Weitz JI; Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation. When and how to use antidotes for the reversal of direct oral anticoagulants: guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost 2016; 14(3):623–627. doi:10.1111/jth.13227

- Cuker A, Siegal D. Monitoring and reversal of direct oral anticoagulants. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2015; 2015:117–124. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2015.1.117

Should clinicians abandon the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) for monitoring heparin therapy in favor of tests that measure the activity of the patient’s plasma against activated factor X (anti-Xa assays)?

Although other anticoagulants are now available for preventing and treating arterial and venous thromboembolism, unfractionated heparin—which requires laboratory monitoring of therapy—is still widely used. And this monitoring can be challenging. Despite its wide use, the aPTT lacks standardization, and the role of alternative monitoring assays such as the anti-Xa assay is not well defined.

This article reviews the advantages, limitations, and clinical applicability of anti-Xa assays for monitoring therapy with unfractionated heparin and other anticoagulants.

UNFRACTIONATED HEPARIN AND WARFARIN ARE STILL WIDELY USED

Until the mid-1990s, unfractionated heparin and oral vitamin K antagonists (eg, warfarin) were the only anticoagulants widely available for clinical use. These agents have complex pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties, resulting in highly variable dosing requirements (both between patients and in individual patients) and narrow therapeutic windows, making frequent laboratory monitoring and dose adjustments mandatory.

Over the past 3 decades, other anticoagulants have been approved, including low-molecular-weight heparins, fondaparinux, parenteral direct thrombin inhibitors, and direct oral anticoagulants. While these agents have expanded the options for preventing and treating thromboembolism, unfractionated heparin and warfarin are still the most appropriate choices for many patients, eg, those with stage 4 chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease on dialysis, and those with mechanical heart valves.

In addition, unfractionated heparin remains the anticoagulant of choice during procedures such as hemodialysis, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, and cardiopulmonary bypass, as well as in hospitalized and critically ill patients, who often have acute kidney injury or require frequent interruptions of therapy for invasive procedures. In these scenarios, unfractionated heparin is typically preferred because of its short plasma half-life, complete reversibility by protamine, safety regardless of renal function, and low cost compared with parenteral direct thrombin inhibitors.

As long as unfractionated heparin and warfarin remain important therapies, the need for their laboratory monitoring continues. For warfarin monitoring, the prothrombin time and international normalized ratio are validated and widely reproducible methods. But monitoring unfractionated heparin therapy remains a challenge.

UNFRACTIONATED HEPARIN’S EFFECT IS UNPREDICTABLE

Unfractionated heparin, a negatively charged mucopolysaccharide, inhibits coagulation by binding to antithrombin through the high-affinity pentasaccharide sequence.1–6 Such binding induces a conformational change in the antithrombin molecule, converting it to a rapid inhibitor of several coagulation proteins, especially factors IIa and Xa.2–4

Unfractionated heparin inhibits factors IIa and Xa in a 1:1 ratio, but low-molecular-weight heparins inhibit factor Xa more than factor IIa, with IIa-Xa inhibition ratios ranging from 1:2 to 1:4, owing to their smaller molecular size.7

One of the most important reasons for the unpredictable and highly variable individual responses to unfractionated heparin is that, infused into the blood, the large and negatively charged unfractionated heparin molecules bind nonspecifically to positively charged plasma proteins.7 In patients who are critically ill, have acute infections or inflammatory states, or have undergone major surgery, unfractionated heparin binds to acute-phase proteins that are elevated, particularly factor VIII. This results in fewer free heparin molecules and a variable anticoagulant effect.8

In contrast, low-molecular-weight heparins have longer half-lives and bind less to plasma proteins, resulting in more predictable plasma levels following subcutaneous injection.9

MONITORING UNFRACTIONATED HEPARIN IMPROVES OUTCOMES

In 1960, Barritt and Jordan10 conducted a small but landmark trial that established the clinical importance of unfractionated heparin for treating venous thromboembolism. None of the patients who received unfractionated heparin for acute pulmonary embolism developed a recurrence during the subsequent 2 weeks, while 50% of those who did not receive it had recurrent pulmonary embolism, fatal in half of the cases.

The importance of achieving a specific aPTT therapeutic target was not demonstrated until a 1972 study by Basu et al,11 in which 162 patients with venous thromboembolism were treated with heparin with a target aPTT of 1.5 to 2.5 times the control value. Patients who suffered recurrent events had subtherapeutic aPTT values on 71% of treatment days, while the rest of the patients, with no recurrences, had subtherapeutic aPTT values only 28% of treatment days. The different outcomes could not be explained by the average daily dose of unfractionated heparin, which was similar in the patients regardless of recurrence.

Subsequent studies showed that the best outcomes occur when unfractionated heparin is given in doses high enough to rapidly achieve a therapeutic prolongation of the aPTT,12–14 and that the total daily dose is also important in preventing recurrences.15,16 Failure to achieve a target aPTT within 24 hours of starting unfractionated heparin is associated with increased risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism.13,17

Raschke et al17 found that patients prospectively randomized to weight-based doses of intravenous unfractionated heparin (bolus plus infusion) achieved significantly higher rates of therapeutic aPTT within 6 hours and 24 hours after starting the infusion, and had significantly lower rates of recurrent venous thromboembolism than those randomized to a fixed unfractionated heparin protocol, without an increase in major bleeding.

Smith et al,18 in a study of 400 consecutive patients with acute pulmonary embolism treated with unfractionated heparin, found that patients who achieved a therapeutic aPTT within 24 hours had lower in-hospital and 30-day mortality rates than those who did not achieve the first therapeutic aPTT until more than 24 hours after starting unfractionated heparin infusion.

Such data lend support to the widely accepted practice and current guideline recommendation8 of using laboratory assays to adjust the dose of unfractionated heparin to achieve and maintain a therapeutic target. The use of dosing nomograms significantly reduces the time to achieve a therapeutic aPTT while minimizing subtherapeutic and supratherapeutic unfractionated heparin levels.19,20

THE aPTT REFLECTS THROMBIN INHIBITION

The aPTT has a log-linear relationship with plasma concentrations of unfractionated heparin,21 but it was not developed specifically for monitoring unfractionated heparin therapy. Originally described in 1953 as a screening tool for hemophilia,22–24 the aPTT is prolonged in the setting of factor deficiencies (typically with levels < 45%, except for factors VII and XIII), as well as lupus anticoagulants and therapy with parenteral direct thrombin inhibitors.8,25,26

Because thrombin (factor IIa) is 10 times more sensitive than factor Xa to inhibition by the heparin-antithrombin complex,4,7 thrombin inhibition appears to be the most likely mechanism by which unfractionated heparin prolongs the aPTT. In contrast, aPTT is minimally or not at all prolonged by low-molecular-weight heparins, which are predominantly factor Xa inhibitors.7

HEPARIN ASSAYS MEASURE UNFRACTIONATED HEPARIN ACTIVITY

While the aPTT is a surrogate marker of unfractionated heparin activity in plasma, unfractionated heparin activity can be measured more precisely by so-called heparin assays, which are typically not direct measures of the plasma concentration of heparins, but rather functional assays that provide indirect estimates. They include protamine sulfate titration assays and anti-Xa assays.

Protamine sulfate titration assays measure the amount of protamine sulfate required to neutralize heparin: the more protamine required, the greater the estimated concentration of unfractionated heparin in plasma.8,27–29 Protamine titration assays are technically demanding, so they are rarely used clinically.

Anti-Xa assays provide a measure of the functional level of heparins in plasma.29–33 Chromogenic anti-Xa assays are available on automated analyzers with standardized kits29,33,34 and may be faster to perform than the aPTT.35

Experiments in rabbits show that unfractionated heparin inhibits thrombus formation and extension at concentrations of 0.2 to 0.4 U/mL as measured by the protamine titration assay,27 which correlated with an anti-Xa activity of 0.35 to 0.67 U/mL in a randomized controlled trial.32

Assays that directly measure the plasma concentration of heparin exist but are not clinically relevant because they also measure heparin molecules lacking the pentasaccharide sequence, which have no anticoagulant activity.36

ANTI-Xa ASSAY VS THE aPTT

Anti-Xa assays are more expensive than the aPTT and are not available in all hospitals. For these reasons, the aPTT remains the most commonly used laboratory assay for monitoring unfractionated heparin therapy.

However, the aPTT correlates poorly with the activity level of unfractionated heparin in plasma. In one study, an anti-Xa level of 0.3 U/mL corresponded to aPTT results ranging from 47 to 108 seconds.31 Furthermore, in studies that used a heparin therapeutic target based on an aPTT ratio 1.5 to 2.5 times the control aPTT value, the lower end of that target range was often associated with subtherapeutic plasma unfractionated heparin activity measured by anti-Xa and protamine titration assays.28,31

Because of these limitations, individual laboratories should determine their own aPTT therapeutic target ranges for unfractionated heparin based on the response curves obtained with the reagent and coagulometer used. The optimal therapeutic aPTT range for treating acute venous thromboembolism should be defined as the aPTT range (in seconds) that correlates with a plasma activity level of unfractionated heparin of 0.3 to 0.7 U/mL based on a chromogenic anti-Xa assay, or 0.2 to 0.4 U/mL based on a protamine titration assay.32,34–36

Nevertheless, the anticoagulant effect of unfractionated heparin as measured by the aPTT can be unpredictable and can vary widely among individuals and in the same patient.7 This wide variability can be explained by a number of technical and biologic variables. Different commercial aPTT reagents, different lots of the same reagent, and different reagent and instrument combinations have different sensitivities to unfractionated heparin, which can lead to variable aPTT results.37 Moreover, high plasma levels of acute-phase proteins, low plasma antithrombin levels, consumptive coagulopathies, liver failure, and lupus anticoagulants may also affect the aPTT.7,25,32,36–41 These variables account for the poor correlation—ranging from 25% to 66%—reported between aPTT and anti-Xa assays.32,42–48

Such discrepancies may have serious clinical implications: if a patient’s aPTT is low (subtherapeutic) or high (supratherapeutic) but the anti-Xa assay result is within the therapeutic range (0.3–0.7 units/mL), changing the dose of unfractionated heparin (guided by an aPTT nomogram) may increase the risk of bleeding or of recurrent thromboembolism.

CLINICAL APPLICABILITY OF THE ANTI-Xa ASSAY

Neither anti-Xa nor protamine titration assays are standardized across reference laboratories, but chromogenic anti-Xa assays have better interlaboratory correlation than the aPTT49,50 and can be calibrated specifically for unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparins.29,33

Although reagent costs are higher for chromogenic anti-Xa assays than for the aPTT, some technical variables (described below) may partially offset the cost difference.29,33,41 In addition, unlike the aPTT, anti-Xa assays do not need local calibration; the therapeutic range for unfractionated heparin is the same (0.3–0.7 U/mL) regardless of instrument or reagent.33,41

Most important, studies have found that patients monitored by anti-Xa assay achieve significantly higher rates of therapeutic anticoagulation within 24 and 48 hours after starting unfractionated heparin infusion than those monitored by the aPTT. Fewer dose adjustments and repeat tests are required, which may also result in lower cost.32,51–55

While these studies found chromogenic anti-Xa assays better for achieving laboratory end points, data regarding relevant clinical outcomes are more limited. In a retrospective, observational cohort study,51 the rate of venous thromboembolism or bleeding-related death was 2% in patients receiving unfractionated heparin therapy monitored by anti-Xa assay and 6% in patients monitored by aPTT (P = .62). Rates of major hemorrhage were also not significantly different.

In a randomized controlled trial32 in 131 patients with acute venous thromboembolism and heparin resistance, rates of recurrent venous thromboembolism were 4.6% and 6.1% in the groups randomized to anti-Xa and aPTT monitoring, respectively, whereas overall bleeding rates were 1.5% and 6.1%, respectively. Again, the differences were not statistically significant.

Heparin resistance. Some patients require unusually high doses of unfractionated heparin to achieve a therapeutic aPTT: typically, more than 35,000 U over 24 hours,7,8,32 or total daily doses that exceed their estimated weight-based requirements. Heparin resistance has been observed in various clinical settings.7,8,32,37–40,59–61 Patients with heparin resistance monitored by anti-Xa had similar rates of recurrent venous thromboembolism while receiving significantly lower doses of unfractionated heparin than those monitored by the aPTT.32

Lupus anticoagulant. Patients with the specific antiphospholipid antibody known as lupus anticoagulant frequently have a prolonged baseline aPTT,25 making it an unreliable marker of anticoagulant effect for intravenous unfractionated heparin therapy.

Critically ill infants and children. Arachchillage et al35 found that infants (< 1 year old) treated with intravenous unfractionated heparin in an intensive care department had only a 32.4% correlation between aPTT and anti-Xa levels, which was lower than that found in children ages 1 to 15 (66%) and adults (52%). In two-thirds of cases of discordant aPTT and anti-Xa levels, the aPTT was elevated (supratherapeutic) while the anti-Xa assay was within the therapeutic range (0.3–0.7 U/mL). Despite the lack of data on clinical outcomes (eg, rates of thrombosis and bleeding) with the use of an anti-Xa assay, it has been considered the method of choice for unfractionated heparin monitoring in critically ill children, and especially in those under age 1.41,44,62–64

While anti-Xa assays may also be better for unfractionated heparin monitoring in critically ill adults, the lack of clinical outcome data from large-scale randomized trials has precluded evidence-based recommendations favoring them over the aPTT.8,34

LIMITATIONS OF ANTI-Xa ASSAYS

Anti-Xa assays are hampered by some technical limitations:

Samples must be processed within 1 hour to avoid heparin neutralization.34

Samples must be clear. Hemolyzed or opaque samples (eg, due to bilirubin levels > 6.6 mg/dL or triglyceride levels > 360 mg/dL) cannot be processed, as they can cause falsely low levels.

Exposure to other anticoagulants can interfere with the results. The anti-Xa assay may be unreliable for unfractionated heparin monitoring in patients who are transitioned from low-molecular-weight heparins, fondaparinux, or an oral factor Xa inhibitor (apixaban, betrixaban, edoxaban, rivaroxaban) to intravenous unfractionated heparin, eg, due to hospitalization or acute kidney injury.65,66 Different reports have found that anti-Xa assays may be elevated for as long as 63 to 96 hours after the last dose of oral Xa inhibitors,67–69 potentially resulting in underdosing of unfractionated heparin. In such settings, unfractionated heparin therapy should be monitored by the aPTT.

ANTI-Xa ASSAYS AND LOW-MOLECULAR-WEIGHT HEPARINS

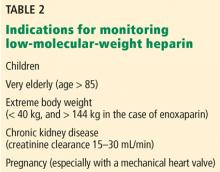

Most patients receiving low-molecular-weight heparins do not need laboratory monitoring.8 Alhenc-Gelas et al70 randomized patients to receive dalteparin in doses either based on weight or guided by anti-Xa assay results, and found that dose adjustments were rare and lacked clinical benefit.

The suggested therapeutic anti-Xa levels for low-molecular-weight heparins are:

- 0.5–1.2 U/mL for twice-daily enoxaparin

- 1.0–2.0 U/mL for once-daily enoxaparin or dalteparin.

Levels should be measured at peak plasma level (ie, 3–4 hours after subcutaneous injection, except during pregnancy, when it is 4–6 hours), and only after at least 3 doses of low-molecular-weight heparin.8,71 Unlike the anti-Xa therapeutic range recommended for unfractionated heparin therapy, these ranges are not based on prospective data, and if the assay result is outside the suggested therapeutic target range, current guidelines offer no advice on safely adjusting the dose.8,71

Measuring anti-Xa activity is particularly important for pregnant women with a mechanical prosthetic heart valve who are treated with low-molecular-weight heparins. In this setting, valve thrombosis and cardioembolic events have been reported in patients with peak low-molecular-weight heparin anti-Xa assay levels below or even at the lower end of the therapeutic range, and increased bleeding risk has been reported with elevated anti-Xa levels.71–74 Measuring trough low-molecular-weight heparin anti-Xa levels has been suggested to guide dose adjustments during pregnancy.75

Clearance of low-molecular-weight heparins as measured by the anti-Xa assay is highly correlated with creatinine clearance.76,77 A strong linear correlation has been demonstrated between creatine clearance and anti-Xa levels of enoxaparin after multiple therapeutic doses, and low-molecular-weight heparins accumulate in the plasma, especially in patients with creatine clearance less than 30 mL/min.78 The risk of major bleeding is significantly increased in patients with severe renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min) not on dialysis who are treated with either prophylactic or therapeutic doses of low-molecular-weight heparin.79–81 In a meta-analysis, the risk of bleeding with therapeutic-intensity doses of enoxaparin was 4 times higher than with prophylactic-intensity doses.79 Although bleeding risk appears to be reduced when the enoxaparin dose is reduced by 50%,8 the efficacy and safety of this strategy has not been determined by prospective trials.

ANTI-Xa ASSAYS IN PATIENTS RECEIVING DIRECT ORAL ANTICOAGULANTS

Direct oral factor Xa inhibitors cannot be measured accurately by heparin anti-Xa assays. Nevertheless, such assays may be useful to assess whether clinically relevant plasma levels are present in cases of major bleeding, suspected anticoagulant failure, or patient noncompliance.82

Intense research has focused on developing drug-specific chromogenic anti-Xa assays using calibrators and standards for apixaban, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban,82,83 and good linear correlation has been shown with some assays.82,84 In patients treated with oral factor Xa inhibitors who need to undergo an urgent invasive procedure associated with high bleeding risk, use of a specific reversal agent may be considered with drug concentrations more than 30 ng/mL measured by a drug-specific anti-Xa assay. A similar suggestion has been made for drug concentrations more than 50 ng/mL in the setting of major bleeding.85 Unfortunately, such assays are not widely available at this time.82,86

While drug-specific anti-Xa assays could become clinically important to guide reversal strategies, their relevance for drug monitoring remains uncertain. This is because no therapeutic target ranges have been established for any of the direct oral anticoagulants, which were approved on the basis of favorable clinical trial outcomes that neither measured nor were correlated with specific drug levels in plasma. Therefore, a specific anti-Xa level cannot yet be used as a marker of clinical efficacy for any specific oral direct Xa inhibitor.

Should clinicians abandon the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) for monitoring heparin therapy in favor of tests that measure the activity of the patient’s plasma against activated factor X (anti-Xa assays)?

Although other anticoagulants are now available for preventing and treating arterial and venous thromboembolism, unfractionated heparin—which requires laboratory monitoring of therapy—is still widely used. And this monitoring can be challenging. Despite its wide use, the aPTT lacks standardization, and the role of alternative monitoring assays such as the anti-Xa assay is not well defined.

This article reviews the advantages, limitations, and clinical applicability of anti-Xa assays for monitoring therapy with unfractionated heparin and other anticoagulants.

UNFRACTIONATED HEPARIN AND WARFARIN ARE STILL WIDELY USED

Until the mid-1990s, unfractionated heparin and oral vitamin K antagonists (eg, warfarin) were the only anticoagulants widely available for clinical use. These agents have complex pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties, resulting in highly variable dosing requirements (both between patients and in individual patients) and narrow therapeutic windows, making frequent laboratory monitoring and dose adjustments mandatory.

Over the past 3 decades, other anticoagulants have been approved, including low-molecular-weight heparins, fondaparinux, parenteral direct thrombin inhibitors, and direct oral anticoagulants. While these agents have expanded the options for preventing and treating thromboembolism, unfractionated heparin and warfarin are still the most appropriate choices for many patients, eg, those with stage 4 chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease on dialysis, and those with mechanical heart valves.

In addition, unfractionated heparin remains the anticoagulant of choice during procedures such as hemodialysis, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, and cardiopulmonary bypass, as well as in hospitalized and critically ill patients, who often have acute kidney injury or require frequent interruptions of therapy for invasive procedures. In these scenarios, unfractionated heparin is typically preferred because of its short plasma half-life, complete reversibility by protamine, safety regardless of renal function, and low cost compared with parenteral direct thrombin inhibitors.

As long as unfractionated heparin and warfarin remain important therapies, the need for their laboratory monitoring continues. For warfarin monitoring, the prothrombin time and international normalized ratio are validated and widely reproducible methods. But monitoring unfractionated heparin therapy remains a challenge.

UNFRACTIONATED HEPARIN’S EFFECT IS UNPREDICTABLE

Unfractionated heparin, a negatively charged mucopolysaccharide, inhibits coagulation by binding to antithrombin through the high-affinity pentasaccharide sequence.1–6 Such binding induces a conformational change in the antithrombin molecule, converting it to a rapid inhibitor of several coagulation proteins, especially factors IIa and Xa.2–4

Unfractionated heparin inhibits factors IIa and Xa in a 1:1 ratio, but low-molecular-weight heparins inhibit factor Xa more than factor IIa, with IIa-Xa inhibition ratios ranging from 1:2 to 1:4, owing to their smaller molecular size.7

One of the most important reasons for the unpredictable and highly variable individual responses to unfractionated heparin is that, infused into the blood, the large and negatively charged unfractionated heparin molecules bind nonspecifically to positively charged plasma proteins.7 In patients who are critically ill, have acute infections or inflammatory states, or have undergone major surgery, unfractionated heparin binds to acute-phase proteins that are elevated, particularly factor VIII. This results in fewer free heparin molecules and a variable anticoagulant effect.8

In contrast, low-molecular-weight heparins have longer half-lives and bind less to plasma proteins, resulting in more predictable plasma levels following subcutaneous injection.9

MONITORING UNFRACTIONATED HEPARIN IMPROVES OUTCOMES

In 1960, Barritt and Jordan10 conducted a small but landmark trial that established the clinical importance of unfractionated heparin for treating venous thromboembolism. None of the patients who received unfractionated heparin for acute pulmonary embolism developed a recurrence during the subsequent 2 weeks, while 50% of those who did not receive it had recurrent pulmonary embolism, fatal in half of the cases.

The importance of achieving a specific aPTT therapeutic target was not demonstrated until a 1972 study by Basu et al,11 in which 162 patients with venous thromboembolism were treated with heparin with a target aPTT of 1.5 to 2.5 times the control value. Patients who suffered recurrent events had subtherapeutic aPTT values on 71% of treatment days, while the rest of the patients, with no recurrences, had subtherapeutic aPTT values only 28% of treatment days. The different outcomes could not be explained by the average daily dose of unfractionated heparin, which was similar in the patients regardless of recurrence.

Subsequent studies showed that the best outcomes occur when unfractionated heparin is given in doses high enough to rapidly achieve a therapeutic prolongation of the aPTT,12–14 and that the total daily dose is also important in preventing recurrences.15,16 Failure to achieve a target aPTT within 24 hours of starting unfractionated heparin is associated with increased risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism.13,17

Raschke et al17 found that patients prospectively randomized to weight-based doses of intravenous unfractionated heparin (bolus plus infusion) achieved significantly higher rates of therapeutic aPTT within 6 hours and 24 hours after starting the infusion, and had significantly lower rates of recurrent venous thromboembolism than those randomized to a fixed unfractionated heparin protocol, without an increase in major bleeding.

Smith et al,18 in a study of 400 consecutive patients with acute pulmonary embolism treated with unfractionated heparin, found that patients who achieved a therapeutic aPTT within 24 hours had lower in-hospital and 30-day mortality rates than those who did not achieve the first therapeutic aPTT until more than 24 hours after starting unfractionated heparin infusion.

Such data lend support to the widely accepted practice and current guideline recommendation8 of using laboratory assays to adjust the dose of unfractionated heparin to achieve and maintain a therapeutic target. The use of dosing nomograms significantly reduces the time to achieve a therapeutic aPTT while minimizing subtherapeutic and supratherapeutic unfractionated heparin levels.19,20

THE aPTT REFLECTS THROMBIN INHIBITION

The aPTT has a log-linear relationship with plasma concentrations of unfractionated heparin,21 but it was not developed specifically for monitoring unfractionated heparin therapy. Originally described in 1953 as a screening tool for hemophilia,22–24 the aPTT is prolonged in the setting of factor deficiencies (typically with levels < 45%, except for factors VII and XIII), as well as lupus anticoagulants and therapy with parenteral direct thrombin inhibitors.8,25,26

Because thrombin (factor IIa) is 10 times more sensitive than factor Xa to inhibition by the heparin-antithrombin complex,4,7 thrombin inhibition appears to be the most likely mechanism by which unfractionated heparin prolongs the aPTT. In contrast, aPTT is minimally or not at all prolonged by low-molecular-weight heparins, which are predominantly factor Xa inhibitors.7

HEPARIN ASSAYS MEASURE UNFRACTIONATED HEPARIN ACTIVITY

While the aPTT is a surrogate marker of unfractionated heparin activity in plasma, unfractionated heparin activity can be measured more precisely by so-called heparin assays, which are typically not direct measures of the plasma concentration of heparins, but rather functional assays that provide indirect estimates. They include protamine sulfate titration assays and anti-Xa assays.

Protamine sulfate titration assays measure the amount of protamine sulfate required to neutralize heparin: the more protamine required, the greater the estimated concentration of unfractionated heparin in plasma.8,27–29 Protamine titration assays are technically demanding, so they are rarely used clinically.

Anti-Xa assays provide a measure of the functional level of heparins in plasma.29–33 Chromogenic anti-Xa assays are available on automated analyzers with standardized kits29,33,34 and may be faster to perform than the aPTT.35

Experiments in rabbits show that unfractionated heparin inhibits thrombus formation and extension at concentrations of 0.2 to 0.4 U/mL as measured by the protamine titration assay,27 which correlated with an anti-Xa activity of 0.35 to 0.67 U/mL in a randomized controlled trial.32

Assays that directly measure the plasma concentration of heparin exist but are not clinically relevant because they also measure heparin molecules lacking the pentasaccharide sequence, which have no anticoagulant activity.36

ANTI-Xa ASSAY VS THE aPTT

Anti-Xa assays are more expensive than the aPTT and are not available in all hospitals. For these reasons, the aPTT remains the most commonly used laboratory assay for monitoring unfractionated heparin therapy.

However, the aPTT correlates poorly with the activity level of unfractionated heparin in plasma. In one study, an anti-Xa level of 0.3 U/mL corresponded to aPTT results ranging from 47 to 108 seconds.31 Furthermore, in studies that used a heparin therapeutic target based on an aPTT ratio 1.5 to 2.5 times the control aPTT value, the lower end of that target range was often associated with subtherapeutic plasma unfractionated heparin activity measured by anti-Xa and protamine titration assays.28,31

Because of these limitations, individual laboratories should determine their own aPTT therapeutic target ranges for unfractionated heparin based on the response curves obtained with the reagent and coagulometer used. The optimal therapeutic aPTT range for treating acute venous thromboembolism should be defined as the aPTT range (in seconds) that correlates with a plasma activity level of unfractionated heparin of 0.3 to 0.7 U/mL based on a chromogenic anti-Xa assay, or 0.2 to 0.4 U/mL based on a protamine titration assay.32,34–36

Nevertheless, the anticoagulant effect of unfractionated heparin as measured by the aPTT can be unpredictable and can vary widely among individuals and in the same patient.7 This wide variability can be explained by a number of technical and biologic variables. Different commercial aPTT reagents, different lots of the same reagent, and different reagent and instrument combinations have different sensitivities to unfractionated heparin, which can lead to variable aPTT results.37 Moreover, high plasma levels of acute-phase proteins, low plasma antithrombin levels, consumptive coagulopathies, liver failure, and lupus anticoagulants may also affect the aPTT.7,25,32,36–41 These variables account for the poor correlation—ranging from 25% to 66%—reported between aPTT and anti-Xa assays.32,42–48

Such discrepancies may have serious clinical implications: if a patient’s aPTT is low (subtherapeutic) or high (supratherapeutic) but the anti-Xa assay result is within the therapeutic range (0.3–0.7 units/mL), changing the dose of unfractionated heparin (guided by an aPTT nomogram) may increase the risk of bleeding or of recurrent thromboembolism.

CLINICAL APPLICABILITY OF THE ANTI-Xa ASSAY

Neither anti-Xa nor protamine titration assays are standardized across reference laboratories, but chromogenic anti-Xa assays have better interlaboratory correlation than the aPTT49,50 and can be calibrated specifically for unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparins.29,33

Although reagent costs are higher for chromogenic anti-Xa assays than for the aPTT, some technical variables (described below) may partially offset the cost difference.29,33,41 In addition, unlike the aPTT, anti-Xa assays do not need local calibration; the therapeutic range for unfractionated heparin is the same (0.3–0.7 U/mL) regardless of instrument or reagent.33,41

Most important, studies have found that patients monitored by anti-Xa assay achieve significantly higher rates of therapeutic anticoagulation within 24 and 48 hours after starting unfractionated heparin infusion than those monitored by the aPTT. Fewer dose adjustments and repeat tests are required, which may also result in lower cost.32,51–55

While these studies found chromogenic anti-Xa assays better for achieving laboratory end points, data regarding relevant clinical outcomes are more limited. In a retrospective, observational cohort study,51 the rate of venous thromboembolism or bleeding-related death was 2% in patients receiving unfractionated heparin therapy monitored by anti-Xa assay and 6% in patients monitored by aPTT (P = .62). Rates of major hemorrhage were also not significantly different.

In a randomized controlled trial32 in 131 patients with acute venous thromboembolism and heparin resistance, rates of recurrent venous thromboembolism were 4.6% and 6.1% in the groups randomized to anti-Xa and aPTT monitoring, respectively, whereas overall bleeding rates were 1.5% and 6.1%, respectively. Again, the differences were not statistically significant.

Heparin resistance. Some patients require unusually high doses of unfractionated heparin to achieve a therapeutic aPTT: typically, more than 35,000 U over 24 hours,7,8,32 or total daily doses that exceed their estimated weight-based requirements. Heparin resistance has been observed in various clinical settings.7,8,32,37–40,59–61 Patients with heparin resistance monitored by anti-Xa had similar rates of recurrent venous thromboembolism while receiving significantly lower doses of unfractionated heparin than those monitored by the aPTT.32

Lupus anticoagulant. Patients with the specific antiphospholipid antibody known as lupus anticoagulant frequently have a prolonged baseline aPTT,25 making it an unreliable marker of anticoagulant effect for intravenous unfractionated heparin therapy.

Critically ill infants and children. Arachchillage et al35 found that infants (< 1 year old) treated with intravenous unfractionated heparin in an intensive care department had only a 32.4% correlation between aPTT and anti-Xa levels, which was lower than that found in children ages 1 to 15 (66%) and adults (52%). In two-thirds of cases of discordant aPTT and anti-Xa levels, the aPTT was elevated (supratherapeutic) while the anti-Xa assay was within the therapeutic range (0.3–0.7 U/mL). Despite the lack of data on clinical outcomes (eg, rates of thrombosis and bleeding) with the use of an anti-Xa assay, it has been considered the method of choice for unfractionated heparin monitoring in critically ill children, and especially in those under age 1.41,44,62–64

While anti-Xa assays may also be better for unfractionated heparin monitoring in critically ill adults, the lack of clinical outcome data from large-scale randomized trials has precluded evidence-based recommendations favoring them over the aPTT.8,34

LIMITATIONS OF ANTI-Xa ASSAYS

Anti-Xa assays are hampered by some technical limitations:

Samples must be processed within 1 hour to avoid heparin neutralization.34

Samples must be clear. Hemolyzed or opaque samples (eg, due to bilirubin levels > 6.6 mg/dL or triglyceride levels > 360 mg/dL) cannot be processed, as they can cause falsely low levels.

Exposure to other anticoagulants can interfere with the results. The anti-Xa assay may be unreliable for unfractionated heparin monitoring in patients who are transitioned from low-molecular-weight heparins, fondaparinux, or an oral factor Xa inhibitor (apixaban, betrixaban, edoxaban, rivaroxaban) to intravenous unfractionated heparin, eg, due to hospitalization or acute kidney injury.65,66 Different reports have found that anti-Xa assays may be elevated for as long as 63 to 96 hours after the last dose of oral Xa inhibitors,67–69 potentially resulting in underdosing of unfractionated heparin. In such settings, unfractionated heparin therapy should be monitored by the aPTT.

ANTI-Xa ASSAYS AND LOW-MOLECULAR-WEIGHT HEPARINS

Most patients receiving low-molecular-weight heparins do not need laboratory monitoring.8 Alhenc-Gelas et al70 randomized patients to receive dalteparin in doses either based on weight or guided by anti-Xa assay results, and found that dose adjustments were rare and lacked clinical benefit.

The suggested therapeutic anti-Xa levels for low-molecular-weight heparins are:

- 0.5–1.2 U/mL for twice-daily enoxaparin

- 1.0–2.0 U/mL for once-daily enoxaparin or dalteparin.

Levels should be measured at peak plasma level (ie, 3–4 hours after subcutaneous injection, except during pregnancy, when it is 4–6 hours), and only after at least 3 doses of low-molecular-weight heparin.8,71 Unlike the anti-Xa therapeutic range recommended for unfractionated heparin therapy, these ranges are not based on prospective data, and if the assay result is outside the suggested therapeutic target range, current guidelines offer no advice on safely adjusting the dose.8,71

Measuring anti-Xa activity is particularly important for pregnant women with a mechanical prosthetic heart valve who are treated with low-molecular-weight heparins. In this setting, valve thrombosis and cardioembolic events have been reported in patients with peak low-molecular-weight heparin anti-Xa assay levels below or even at the lower end of the therapeutic range, and increased bleeding risk has been reported with elevated anti-Xa levels.71–74 Measuring trough low-molecular-weight heparin anti-Xa levels has been suggested to guide dose adjustments during pregnancy.75

Clearance of low-molecular-weight heparins as measured by the anti-Xa assay is highly correlated with creatinine clearance.76,77 A strong linear correlation has been demonstrated between creatine clearance and anti-Xa levels of enoxaparin after multiple therapeutic doses, and low-molecular-weight heparins accumulate in the plasma, especially in patients with creatine clearance less than 30 mL/min.78 The risk of major bleeding is significantly increased in patients with severe renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min) not on dialysis who are treated with either prophylactic or therapeutic doses of low-molecular-weight heparin.79–81 In a meta-analysis, the risk of bleeding with therapeutic-intensity doses of enoxaparin was 4 times higher than with prophylactic-intensity doses.79 Although bleeding risk appears to be reduced when the enoxaparin dose is reduced by 50%,8 the efficacy and safety of this strategy has not been determined by prospective trials.

ANTI-Xa ASSAYS IN PATIENTS RECEIVING DIRECT ORAL ANTICOAGULANTS

Direct oral factor Xa inhibitors cannot be measured accurately by heparin anti-Xa assays. Nevertheless, such assays may be useful to assess whether clinically relevant plasma levels are present in cases of major bleeding, suspected anticoagulant failure, or patient noncompliance.82