User login

Addressing the Shortage of Physician Assistants in Medicine Clerkship Sites

The Federal Bureau of Labor Statistics projects 37% job growth for physician assistants (PAs) from 2016 to 2026, much greater than the average for all other occupations as well as for other medical professions.1 This growth has been accompanied by increased enrollment in medical (doctor of medicine [MD], doctor of osteopathic medicine) and nurse practitioner (NP) schools.2 Clinical teaching sites serve a crucial function in the training of all clinical disciplines. These sites provide hands-on and experiential learning in medical settings, necessary components for learners practicing to become clinicians. Significant PA program expansion has led to increased demand for clinical training, creating competition for sites and a shortage of willing and well-trained preceptors.3

This challenge has been recognized by PA program directors. In the Joint Report of the 2013 Multi-Discipline Clerkship/Clinical Training Site Survey, PA program directors expressed concern about the adequacy of clinical opportunities for students, increased difficulty developing new core sites, and preserving existing core sites. In addition, they noted that a shortage of clinical sites was one of the greatest barriers to the PA programs’ sustained growth and success.4

Program directors also indicated difficulty securing clinical training sites in internal medicine (IM) and high rates of attrition of medicine clinical preceptors for their students.5 The reasons are multifold: increasing clinical demands, time, teaching competence, lack of experience, academic affiliation, lack of reimbursement, or compensation. Moreover, there is a declining number of PAs who work in primary care compared with specialty and subspecialty care, limiting the availability of clinical training preceptors in medicine and primary care.6-8 According to the American Academy of PAs (AAPA) census and salary survey data, the percentage of PAs working in the primary care specialties (ie, family medicine, IM, and general pediatrics) has decreased from > 47% in 1995 to 24% in 2017.9 As such, there is a need to broaden the educational landscape to provide more high-quality training sites in IM.

The postacute health care setting may address this training need. It offers a unique clinical opportunity to expose learners to a broad range of disease complexity and clinical acuity, as the percentage of patients discharged from hospitals to postacute care (PAC) has increased and care shifts from the hospital to the PAC setting.10,11 The longer PAC length of stay also enables learners to follow patients longitudinally over several weeks and experience interprofessional team-based care. In addition, the PAC setting offers learners the ability to acquire the necessary skills for smooth and effective transitions of care. This setting has been extensively used for trainees of nursing, pharmacy, physical therapy (PT) and occupational therapy (OT), speech-language pathology, psychology, and social work (SW), but few programs have used the PAC setting as clerkship sites for IM rotations for PA students. To address this need for IM sites, the VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS), in conjunction with the Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program, developed a novel medicine clinical clerkship site for physician assistants in the PAC unit of the community living center (CLC) at VABHS. This report describes the program structure, curriculum, and participant evaluation results.

Clinical Clerkship Program

VABHS CLC is a 110-bed facility comprising 3 units: a 65-bed PAC unit, a 15-bed closed hospice/palliative care unit, and a 30-bed long-term care unit. The service is staffed continuously with physicians, PAs, and NPs. A majority of patients are admitted from the acute care hospital of VABHS (West Roxbury campus) and other regional VA facilities. The CLC offers dynamic services, including phlebotomy, general radiology, IV diuretics and antibiotics, wound care, and subacute PT, OT, and speech-language pathology rehabilitation. The CLC serves as a venue for transitioning patients from acute inpatient care to home. The patient population is often elderly, with multiple active comorbidities and variable medical literacy, adherence, and follow-up.

The CLC provides a diverse interprofessional learning environment, offering core IM rotations for first-year psychiatry residents, oral and maxillofacial surgery residents, and PA students. The CLC also has expanded as a clinical site both for transitions-in-care IM resident curricula and electives as well as a geriatrics fellowship. In addition, the site offers rotations for NPs, nursing, pharmacy, physical and occupational therapies, speech-language pathology, psychology, and SW.

The Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program was founded in 2015 as a master’s degree program completed over 28 months. The first 12 months are didactic, and the following 16 months are clinical training with 14 months of rotations (2 IM, family medicine, pediatrics, emergency medicine, general surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, psychiatry, neurology, and 5 elective rotations), and 2 months for a thesis. The program has about 30 students per year and 4 clerkship sites for IM.

Program Description

The VABHS medicine clerkship hosts 1 to 2 PA students for 4-week blocks in the PAC unit of the CLC. Each student rotates on both PA and MD teams. Students follow 3 to 4 patients and participate fully in their care from admission to discharge; they prepare daily presentations and participate in medical management, family meetings, chart documentation, and care coordination with the interprofessional team. Students are provided a physical examination checklist and feedback form, and they are expected to track findings and record feedback and goals with their supervising preceptor weekly. They also make formal case presentations and participate in monthly medicine didactic rounds available to all VABHS IM students and trainees via videoconference.

In addition, beginning in July 2017, all PA students in the CLC began to participate in a 4-week Interprofessional Curriculum in Transitional Care. The curriculum includes 14 didactic lectures taught by 16 interprofessional faculty, including medicine, geriatric, and palliative care physicians; PAs; social workers; physical and occupational therapists; pharmacists; and a geriatric psychologist. The didactics include topics on the interprofessional team, the care continuum, teams and teamwork, interdisciplinary coordination of care, components of effective transitions in care, medication reconciliation, approaching difficult conversations, advance care planning, and quality improvement. The goal of the curriculum is to provide learners the knowledge, skills, and dispositions necessary for high-quality transitional care and interprofessional practice as well as specific training for effective and safe transfers of care between clinical settings. Although PA students are the main participants in this curriculum, all other learners in the PAC unit are also invited to attend the lectures.

The unique attributes of this training site include direct interaction with supervising PAs and physicians, rather than experiencing the traditional teaching hierarchy (with interns, residents, fellows); observation of the natural progression of disease of both acute care and primary care issues due to the longer length of stay (2 to 6 weeks, where the typical student will see the same patient 7 to 10 times during their rotation); exposure to a host of medically complex patients offering a multitude of clinical scenarios and abnormal physical exam findings; exposure to a hospice/palliative care ward and end-of-life care; and interaction within an interprofessional training environment of nursing, pharmacy, PT, OT, speech-language pathology, psychology, and SW trainees.

Program Evaluation

At the end of rotations continuously through the year, PA students electronically complete a site evaluation from the Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program. The evaluation consists of 14 questions: 6 about site quality and 8 about instruction quality. The questions are answered on a 5-point Likert scale. Also included are 2 open-ended response questions that ask what they liked about the rotation and what they felt could be improved. Results are anonymous, de-identified and blinded both to the program as well as the clerkship site. Results are aggregated and provided to program sites annually. Responses are converted to a dichotomous variable, where any good or excellent response (4 or 5) is considered positive and any neutral or below (3, 2, 1) is considered a nonpositive response.

Results

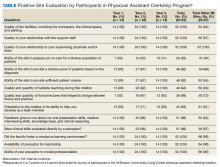

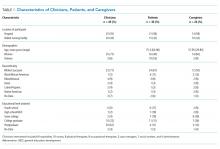

The clerkship site has been operational since June 22, 2015. There have been 59 students who participated in the rotation. A different scale in these evaluations was used between June 22, 2015, and September 13, 2015. Therefore, 7 responses were excluded from the analysis, leaving 52 usable evaluations. The responses were analyzed both in total (for the CLC as well as other IM rotation sites) and by individual clerkship year to look for any trends over time: September 14, 2015, through April 24, 2016; April 25, 2016, through April 28, 2017; and May 1, 2017, through March 1, 2018 (Table).

Site evaluations showed high satisfaction regarding the quality of the physical environment as well as the learning environment. Students endorsed the PAC unit having resources and physical space for them, such as a desk and computer, opportunity for participation in patient care, and parking (100%; n = 52). Site evaluations revealed high satisfaction with the quality of teaching and faculty encouragement and support of their learning (100%; n = 52). The evaluations revealed that bedside teaching was strong (94%; n = 49). The students reported high satisfaction with the volume of patients provided (92%; n = 48) as well as the diversity of diagnoses (92%; n = 48).

There were fewer positive responses in the first 2 years of the rotation with regard to formal lectures (50% and 67%; 7/14 and 16/24, respectively). In the third year of the rotation, students had a much higher satisfaction rate (93%; 13/14). This increased satisfaction was associated with the development and incorporation of the Interprofessional Curriculum in Transitional Care in 2017.

Discussion

Access to high-quality PA student clerkship sites has become a pressing issue in recent years because of increased competition for sites and a shortage of willing and well-trained preceptors. There has been marked growth in schools and enrollment across all medical professions. The Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the PA (ARC-PA) reported that the total number of accredited entry-level PA programs in 2018 was 246, with 58 new accredited programs projected by 2022.12 The Joint Report of the 2013 Multi-Discipline Clerkship/Clinical Training Site Survey reported a 66% increase in first-year enrollment in PA programs from 2002 to 2012.5 Programs must implement alternative strategies to attract clinical sites (eg, academic appointments, increased clinical resources to training sites) or face continued challenges with recruiting training sites for their students. Postacute care may be a natural extension to expand the footprint for clinical sites for these programs, augmenting acute inpatient and outpatient rotations. This implementation would increase the pool of clinical training sites and preceptors.

The experience with this novel training site, based on PA student feedback and evaluations, has been positive, and the postacute setting can provide students with high-quality IM clinical experiences. Students report adequate patient volume and diversity. In addition, evaluations are comparable with that of other IM site rotations the students experience. Qualitative feedback has emphasized the value of following patients over longer periods; eg, weeks vs days (as in acute care) enabling students to build relationships with patients as well as observe a richer clinical spectrum of disease over a less compressed period. “Patients have complex issues, so from a medical standpoint it challenges you to think of new ways to manage their care,” commented a representative student. “It is really beneficial that you can follow them over time.”

Furthermore, in response to student feedback on didactics, an interprofessional curriculum was developed to add formal structure as well as to create a curriculum in care transitions. This curriculum provided a unique opportunity for PA students to receive formal instruction on areas of particular relevance for transitional care (eg, care continuum, end of life issues, and care transitions). The curriculum also allows the interprofessional faculty a unique and enjoyable opportunity for interprofessional collaboration.

The 1 month PAC rotation is augmented with inpatient IM and outpatient family medicine rotations, consequently giving exposure to the full continuum of care. The PAC setting provides learners multifaceted benefits: the opportunity to strengthen and develop the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary for IM; increased understanding of other professions by observing and interacting as a team caring for a patient over a longer period as opposed to the acute care setting; the ability to perform effective, efficient, and safe transfer between clinical settings; and broad exposure to transitional care. As a result, the PAC rotation enhances but does not replace the necessary and essential rotations of inpatient and outpatient medicine.

Moreover, this rotation provides unique and core IM training for PA students. Our site focuses on interprofessional collaboration, emphasizing the importance of team-based care, an essential concept in modern day medicine. Formal exposure to other care specialties, such as PT and OT, SW, and mental health, is essential for students to appreciate clinical medicine and a patient’s physical and mental experience over the course of a disease and clinical state. In addition, the physical exam checklist ensures that students are exposed to the full spectrum of IM examination findings during their rotation. Finally, weekly feedback forms require students to ask and receive concrete feedback from their supervising providers.

Limitations

The generalizability of this model requires careful consideration. VABHS is a tertiary care integrated health care system, enabling students to learn from patients moving through multiple care transitions in a single health care system. In addition, other settings may not have the staffing or clinical volume to sustain such a model. All PAC clinical faculty teach voluntarily, and local leadership has set expectations for all clinicians to participate in teaching of trainees and PA students. Evaluations also note less diversity in the patient population, a challenge that some VA facilities face. This issue could be addressed by ensuring that students also have IM rotations at other inpatient medical facilities. A more balanced experience, where students reap the positive benefits of PAC but do not lose exposure to a diverse patient pool, could result. Furthermore, some of the perceived positive impacts also may be related to professional and personal attributes of the teaching clinicians rather than to the PAC setting.

Conclusion

PAC settings can be effective training sites for medicine clerkships for PA students and can provide high-quality training in IM as PA programs continue to expand. This setting offers students exposure to interprofessional, team-based care and the opportunity to care for patients with a broad range of disease complexity. Learning is further enhanced by the ability to follow patients longitudinally over their disease course as well as to work directly with teaching faculty and other interprofessional health care professionals. Evaluations of this novel clerkship experience have shown high levels of student satisfaction in knowledge growth, clinical skills, bedside teaching, and mentorship.

Acknowledgments

We thank Juman Hijab for her critical role in establishing and maintaining the clerkship. We thank Steven Simon, Matt Russell, and Thomas Parrino for their leadership and guidance in establishing and maintaining the clerkship. We thank the Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program Director Mary Warner for her support and guidance in creating and supporting the clerkship. In addition, we thank the interprofessional education faculty for their dedicated involvement in teaching, including Stephanie Saunders, Lindsay Lefers, Jessica Rawlins, Lindsay Brennan, Angela Viani, Eric Charette, Nicole O’Neil, Susan Nathan, Jordana Meyerson, Shivani Jindal, Wei Shen, Amy Hanson, Gilda Cain, and Kate Hinrichs.

1. US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational outlook handbook: physician assistants. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physician-assistants.htm. Updated June 18, 2019. Accessed August 13, 2019.

2. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2019 update: the complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2017 to 2032. https://aamc-black.global.ssl.fastly.net/production/media/filer_public/31/13/3113ee5c-a038-4c16-89af-294a69826650/2019_update_-_the_complexities_of_physician_supply_and_demand_-_projections_from_2017-2032.pdf. Published April 2019. Accessed August 15, 2019.

3. Glicken AD, Miller AA. Physician assistants: from pipeline to practice. Acad Med. 2013;88(12):1883-1889.

4. Erikson C, Hamann R, Levitan T, Pankow S, Stanley J, Whatley M. Recruiting and maintaining US clinical training sites: joint report of the 2013 multi-discipline clerkship/clinical training site survey. https://paeaonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Recruiting-and-Maintaining-U.S.-Clinical-Training-Sites.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2019.

5. Physician Assistant Education Association. By the numbers: 30th annual report on physician assistant educational programs. 2015. http://paeaonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/2015-by-the-numbers-program-report-30.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed August 15, 2019.

6. Morgan P, Himmerick KA, Leach B, Dieter P, Everett C. Scarcity of primary care positions may divert physician assistants into specialty practice. Med Care Res Rev. 2017;74(1):109-122.

7. Coplan B, Cawley J, Stoehr J. Physician assistants in primary care: trends and characteristics. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(1):75-79.

8. Morgan P, Leach B, Himmerick K, Everett C. Job openings for PAs by specialty. JAAPA. 2018;31(1):45-47.

9. American Academy of Physician Assistants. 2017 AAPA Salary Report. Alexandria, VA; 2017.

10. Barnett ML, Grabowski DC, Mehrotra A. Home-to-home time—measuring what matters to patients and payers. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):4-6.

11. Werner RM, Konetzka RT. Trends in post-acute care use among Medicare beneficiaries: 2000 to 2015. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1616-1617.

12. Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the Physician Assistant. http://www.arc-pa.org/accreditation/accredited-programs. Accessed May 10, 2019.

The Federal Bureau of Labor Statistics projects 37% job growth for physician assistants (PAs) from 2016 to 2026, much greater than the average for all other occupations as well as for other medical professions.1 This growth has been accompanied by increased enrollment in medical (doctor of medicine [MD], doctor of osteopathic medicine) and nurse practitioner (NP) schools.2 Clinical teaching sites serve a crucial function in the training of all clinical disciplines. These sites provide hands-on and experiential learning in medical settings, necessary components for learners practicing to become clinicians. Significant PA program expansion has led to increased demand for clinical training, creating competition for sites and a shortage of willing and well-trained preceptors.3

This challenge has been recognized by PA program directors. In the Joint Report of the 2013 Multi-Discipline Clerkship/Clinical Training Site Survey, PA program directors expressed concern about the adequacy of clinical opportunities for students, increased difficulty developing new core sites, and preserving existing core sites. In addition, they noted that a shortage of clinical sites was one of the greatest barriers to the PA programs’ sustained growth and success.4

Program directors also indicated difficulty securing clinical training sites in internal medicine (IM) and high rates of attrition of medicine clinical preceptors for their students.5 The reasons are multifold: increasing clinical demands, time, teaching competence, lack of experience, academic affiliation, lack of reimbursement, or compensation. Moreover, there is a declining number of PAs who work in primary care compared with specialty and subspecialty care, limiting the availability of clinical training preceptors in medicine and primary care.6-8 According to the American Academy of PAs (AAPA) census and salary survey data, the percentage of PAs working in the primary care specialties (ie, family medicine, IM, and general pediatrics) has decreased from > 47% in 1995 to 24% in 2017.9 As such, there is a need to broaden the educational landscape to provide more high-quality training sites in IM.

The postacute health care setting may address this training need. It offers a unique clinical opportunity to expose learners to a broad range of disease complexity and clinical acuity, as the percentage of patients discharged from hospitals to postacute care (PAC) has increased and care shifts from the hospital to the PAC setting.10,11 The longer PAC length of stay also enables learners to follow patients longitudinally over several weeks and experience interprofessional team-based care. In addition, the PAC setting offers learners the ability to acquire the necessary skills for smooth and effective transitions of care. This setting has been extensively used for trainees of nursing, pharmacy, physical therapy (PT) and occupational therapy (OT), speech-language pathology, psychology, and social work (SW), but few programs have used the PAC setting as clerkship sites for IM rotations for PA students. To address this need for IM sites, the VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS), in conjunction with the Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program, developed a novel medicine clinical clerkship site for physician assistants in the PAC unit of the community living center (CLC) at VABHS. This report describes the program structure, curriculum, and participant evaluation results.

Clinical Clerkship Program

VABHS CLC is a 110-bed facility comprising 3 units: a 65-bed PAC unit, a 15-bed closed hospice/palliative care unit, and a 30-bed long-term care unit. The service is staffed continuously with physicians, PAs, and NPs. A majority of patients are admitted from the acute care hospital of VABHS (West Roxbury campus) and other regional VA facilities. The CLC offers dynamic services, including phlebotomy, general radiology, IV diuretics and antibiotics, wound care, and subacute PT, OT, and speech-language pathology rehabilitation. The CLC serves as a venue for transitioning patients from acute inpatient care to home. The patient population is often elderly, with multiple active comorbidities and variable medical literacy, adherence, and follow-up.

The CLC provides a diverse interprofessional learning environment, offering core IM rotations for first-year psychiatry residents, oral and maxillofacial surgery residents, and PA students. The CLC also has expanded as a clinical site both for transitions-in-care IM resident curricula and electives as well as a geriatrics fellowship. In addition, the site offers rotations for NPs, nursing, pharmacy, physical and occupational therapies, speech-language pathology, psychology, and SW.

The Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program was founded in 2015 as a master’s degree program completed over 28 months. The first 12 months are didactic, and the following 16 months are clinical training with 14 months of rotations (2 IM, family medicine, pediatrics, emergency medicine, general surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, psychiatry, neurology, and 5 elective rotations), and 2 months for a thesis. The program has about 30 students per year and 4 clerkship sites for IM.

Program Description

The VABHS medicine clerkship hosts 1 to 2 PA students for 4-week blocks in the PAC unit of the CLC. Each student rotates on both PA and MD teams. Students follow 3 to 4 patients and participate fully in their care from admission to discharge; they prepare daily presentations and participate in medical management, family meetings, chart documentation, and care coordination with the interprofessional team. Students are provided a physical examination checklist and feedback form, and they are expected to track findings and record feedback and goals with their supervising preceptor weekly. They also make formal case presentations and participate in monthly medicine didactic rounds available to all VABHS IM students and trainees via videoconference.

In addition, beginning in July 2017, all PA students in the CLC began to participate in a 4-week Interprofessional Curriculum in Transitional Care. The curriculum includes 14 didactic lectures taught by 16 interprofessional faculty, including medicine, geriatric, and palliative care physicians; PAs; social workers; physical and occupational therapists; pharmacists; and a geriatric psychologist. The didactics include topics on the interprofessional team, the care continuum, teams and teamwork, interdisciplinary coordination of care, components of effective transitions in care, medication reconciliation, approaching difficult conversations, advance care planning, and quality improvement. The goal of the curriculum is to provide learners the knowledge, skills, and dispositions necessary for high-quality transitional care and interprofessional practice as well as specific training for effective and safe transfers of care between clinical settings. Although PA students are the main participants in this curriculum, all other learners in the PAC unit are also invited to attend the lectures.

The unique attributes of this training site include direct interaction with supervising PAs and physicians, rather than experiencing the traditional teaching hierarchy (with interns, residents, fellows); observation of the natural progression of disease of both acute care and primary care issues due to the longer length of stay (2 to 6 weeks, where the typical student will see the same patient 7 to 10 times during their rotation); exposure to a host of medically complex patients offering a multitude of clinical scenarios and abnormal physical exam findings; exposure to a hospice/palliative care ward and end-of-life care; and interaction within an interprofessional training environment of nursing, pharmacy, PT, OT, speech-language pathology, psychology, and SW trainees.

Program Evaluation

At the end of rotations continuously through the year, PA students electronically complete a site evaluation from the Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program. The evaluation consists of 14 questions: 6 about site quality and 8 about instruction quality. The questions are answered on a 5-point Likert scale. Also included are 2 open-ended response questions that ask what they liked about the rotation and what they felt could be improved. Results are anonymous, de-identified and blinded both to the program as well as the clerkship site. Results are aggregated and provided to program sites annually. Responses are converted to a dichotomous variable, where any good or excellent response (4 or 5) is considered positive and any neutral or below (3, 2, 1) is considered a nonpositive response.

Results

The clerkship site has been operational since June 22, 2015. There have been 59 students who participated in the rotation. A different scale in these evaluations was used between June 22, 2015, and September 13, 2015. Therefore, 7 responses were excluded from the analysis, leaving 52 usable evaluations. The responses were analyzed both in total (for the CLC as well as other IM rotation sites) and by individual clerkship year to look for any trends over time: September 14, 2015, through April 24, 2016; April 25, 2016, through April 28, 2017; and May 1, 2017, through March 1, 2018 (Table).

Site evaluations showed high satisfaction regarding the quality of the physical environment as well as the learning environment. Students endorsed the PAC unit having resources and physical space for them, such as a desk and computer, opportunity for participation in patient care, and parking (100%; n = 52). Site evaluations revealed high satisfaction with the quality of teaching and faculty encouragement and support of their learning (100%; n = 52). The evaluations revealed that bedside teaching was strong (94%; n = 49). The students reported high satisfaction with the volume of patients provided (92%; n = 48) as well as the diversity of diagnoses (92%; n = 48).

There were fewer positive responses in the first 2 years of the rotation with regard to formal lectures (50% and 67%; 7/14 and 16/24, respectively). In the third year of the rotation, students had a much higher satisfaction rate (93%; 13/14). This increased satisfaction was associated with the development and incorporation of the Interprofessional Curriculum in Transitional Care in 2017.

Discussion

Access to high-quality PA student clerkship sites has become a pressing issue in recent years because of increased competition for sites and a shortage of willing and well-trained preceptors. There has been marked growth in schools and enrollment across all medical professions. The Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the PA (ARC-PA) reported that the total number of accredited entry-level PA programs in 2018 was 246, with 58 new accredited programs projected by 2022.12 The Joint Report of the 2013 Multi-Discipline Clerkship/Clinical Training Site Survey reported a 66% increase in first-year enrollment in PA programs from 2002 to 2012.5 Programs must implement alternative strategies to attract clinical sites (eg, academic appointments, increased clinical resources to training sites) or face continued challenges with recruiting training sites for their students. Postacute care may be a natural extension to expand the footprint for clinical sites for these programs, augmenting acute inpatient and outpatient rotations. This implementation would increase the pool of clinical training sites and preceptors.

The experience with this novel training site, based on PA student feedback and evaluations, has been positive, and the postacute setting can provide students with high-quality IM clinical experiences. Students report adequate patient volume and diversity. In addition, evaluations are comparable with that of other IM site rotations the students experience. Qualitative feedback has emphasized the value of following patients over longer periods; eg, weeks vs days (as in acute care) enabling students to build relationships with patients as well as observe a richer clinical spectrum of disease over a less compressed period. “Patients have complex issues, so from a medical standpoint it challenges you to think of new ways to manage their care,” commented a representative student. “It is really beneficial that you can follow them over time.”

Furthermore, in response to student feedback on didactics, an interprofessional curriculum was developed to add formal structure as well as to create a curriculum in care transitions. This curriculum provided a unique opportunity for PA students to receive formal instruction on areas of particular relevance for transitional care (eg, care continuum, end of life issues, and care transitions). The curriculum also allows the interprofessional faculty a unique and enjoyable opportunity for interprofessional collaboration.

The 1 month PAC rotation is augmented with inpatient IM and outpatient family medicine rotations, consequently giving exposure to the full continuum of care. The PAC setting provides learners multifaceted benefits: the opportunity to strengthen and develop the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary for IM; increased understanding of other professions by observing and interacting as a team caring for a patient over a longer period as opposed to the acute care setting; the ability to perform effective, efficient, and safe transfer between clinical settings; and broad exposure to transitional care. As a result, the PAC rotation enhances but does not replace the necessary and essential rotations of inpatient and outpatient medicine.

Moreover, this rotation provides unique and core IM training for PA students. Our site focuses on interprofessional collaboration, emphasizing the importance of team-based care, an essential concept in modern day medicine. Formal exposure to other care specialties, such as PT and OT, SW, and mental health, is essential for students to appreciate clinical medicine and a patient’s physical and mental experience over the course of a disease and clinical state. In addition, the physical exam checklist ensures that students are exposed to the full spectrum of IM examination findings during their rotation. Finally, weekly feedback forms require students to ask and receive concrete feedback from their supervising providers.

Limitations

The generalizability of this model requires careful consideration. VABHS is a tertiary care integrated health care system, enabling students to learn from patients moving through multiple care transitions in a single health care system. In addition, other settings may not have the staffing or clinical volume to sustain such a model. All PAC clinical faculty teach voluntarily, and local leadership has set expectations for all clinicians to participate in teaching of trainees and PA students. Evaluations also note less diversity in the patient population, a challenge that some VA facilities face. This issue could be addressed by ensuring that students also have IM rotations at other inpatient medical facilities. A more balanced experience, where students reap the positive benefits of PAC but do not lose exposure to a diverse patient pool, could result. Furthermore, some of the perceived positive impacts also may be related to professional and personal attributes of the teaching clinicians rather than to the PAC setting.

Conclusion

PAC settings can be effective training sites for medicine clerkships for PA students and can provide high-quality training in IM as PA programs continue to expand. This setting offers students exposure to interprofessional, team-based care and the opportunity to care for patients with a broad range of disease complexity. Learning is further enhanced by the ability to follow patients longitudinally over their disease course as well as to work directly with teaching faculty and other interprofessional health care professionals. Evaluations of this novel clerkship experience have shown high levels of student satisfaction in knowledge growth, clinical skills, bedside teaching, and mentorship.

Acknowledgments

We thank Juman Hijab for her critical role in establishing and maintaining the clerkship. We thank Steven Simon, Matt Russell, and Thomas Parrino for their leadership and guidance in establishing and maintaining the clerkship. We thank the Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program Director Mary Warner for her support and guidance in creating and supporting the clerkship. In addition, we thank the interprofessional education faculty for their dedicated involvement in teaching, including Stephanie Saunders, Lindsay Lefers, Jessica Rawlins, Lindsay Brennan, Angela Viani, Eric Charette, Nicole O’Neil, Susan Nathan, Jordana Meyerson, Shivani Jindal, Wei Shen, Amy Hanson, Gilda Cain, and Kate Hinrichs.

The Federal Bureau of Labor Statistics projects 37% job growth for physician assistants (PAs) from 2016 to 2026, much greater than the average for all other occupations as well as for other medical professions.1 This growth has been accompanied by increased enrollment in medical (doctor of medicine [MD], doctor of osteopathic medicine) and nurse practitioner (NP) schools.2 Clinical teaching sites serve a crucial function in the training of all clinical disciplines. These sites provide hands-on and experiential learning in medical settings, necessary components for learners practicing to become clinicians. Significant PA program expansion has led to increased demand for clinical training, creating competition for sites and a shortage of willing and well-trained preceptors.3

This challenge has been recognized by PA program directors. In the Joint Report of the 2013 Multi-Discipline Clerkship/Clinical Training Site Survey, PA program directors expressed concern about the adequacy of clinical opportunities for students, increased difficulty developing new core sites, and preserving existing core sites. In addition, they noted that a shortage of clinical sites was one of the greatest barriers to the PA programs’ sustained growth and success.4

Program directors also indicated difficulty securing clinical training sites in internal medicine (IM) and high rates of attrition of medicine clinical preceptors for their students.5 The reasons are multifold: increasing clinical demands, time, teaching competence, lack of experience, academic affiliation, lack of reimbursement, or compensation. Moreover, there is a declining number of PAs who work in primary care compared with specialty and subspecialty care, limiting the availability of clinical training preceptors in medicine and primary care.6-8 According to the American Academy of PAs (AAPA) census and salary survey data, the percentage of PAs working in the primary care specialties (ie, family medicine, IM, and general pediatrics) has decreased from > 47% in 1995 to 24% in 2017.9 As such, there is a need to broaden the educational landscape to provide more high-quality training sites in IM.

The postacute health care setting may address this training need. It offers a unique clinical opportunity to expose learners to a broad range of disease complexity and clinical acuity, as the percentage of patients discharged from hospitals to postacute care (PAC) has increased and care shifts from the hospital to the PAC setting.10,11 The longer PAC length of stay also enables learners to follow patients longitudinally over several weeks and experience interprofessional team-based care. In addition, the PAC setting offers learners the ability to acquire the necessary skills for smooth and effective transitions of care. This setting has been extensively used for trainees of nursing, pharmacy, physical therapy (PT) and occupational therapy (OT), speech-language pathology, psychology, and social work (SW), but few programs have used the PAC setting as clerkship sites for IM rotations for PA students. To address this need for IM sites, the VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS), in conjunction with the Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program, developed a novel medicine clinical clerkship site for physician assistants in the PAC unit of the community living center (CLC) at VABHS. This report describes the program structure, curriculum, and participant evaluation results.

Clinical Clerkship Program

VABHS CLC is a 110-bed facility comprising 3 units: a 65-bed PAC unit, a 15-bed closed hospice/palliative care unit, and a 30-bed long-term care unit. The service is staffed continuously with physicians, PAs, and NPs. A majority of patients are admitted from the acute care hospital of VABHS (West Roxbury campus) and other regional VA facilities. The CLC offers dynamic services, including phlebotomy, general radiology, IV diuretics and antibiotics, wound care, and subacute PT, OT, and speech-language pathology rehabilitation. The CLC serves as a venue for transitioning patients from acute inpatient care to home. The patient population is often elderly, with multiple active comorbidities and variable medical literacy, adherence, and follow-up.

The CLC provides a diverse interprofessional learning environment, offering core IM rotations for first-year psychiatry residents, oral and maxillofacial surgery residents, and PA students. The CLC also has expanded as a clinical site both for transitions-in-care IM resident curricula and electives as well as a geriatrics fellowship. In addition, the site offers rotations for NPs, nursing, pharmacy, physical and occupational therapies, speech-language pathology, psychology, and SW.

The Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program was founded in 2015 as a master’s degree program completed over 28 months. The first 12 months are didactic, and the following 16 months are clinical training with 14 months of rotations (2 IM, family medicine, pediatrics, emergency medicine, general surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, psychiatry, neurology, and 5 elective rotations), and 2 months for a thesis. The program has about 30 students per year and 4 clerkship sites for IM.

Program Description

The VABHS medicine clerkship hosts 1 to 2 PA students for 4-week blocks in the PAC unit of the CLC. Each student rotates on both PA and MD teams. Students follow 3 to 4 patients and participate fully in their care from admission to discharge; they prepare daily presentations and participate in medical management, family meetings, chart documentation, and care coordination with the interprofessional team. Students are provided a physical examination checklist and feedback form, and they are expected to track findings and record feedback and goals with their supervising preceptor weekly. They also make formal case presentations and participate in monthly medicine didactic rounds available to all VABHS IM students and trainees via videoconference.

In addition, beginning in July 2017, all PA students in the CLC began to participate in a 4-week Interprofessional Curriculum in Transitional Care. The curriculum includes 14 didactic lectures taught by 16 interprofessional faculty, including medicine, geriatric, and palliative care physicians; PAs; social workers; physical and occupational therapists; pharmacists; and a geriatric psychologist. The didactics include topics on the interprofessional team, the care continuum, teams and teamwork, interdisciplinary coordination of care, components of effective transitions in care, medication reconciliation, approaching difficult conversations, advance care planning, and quality improvement. The goal of the curriculum is to provide learners the knowledge, skills, and dispositions necessary for high-quality transitional care and interprofessional practice as well as specific training for effective and safe transfers of care between clinical settings. Although PA students are the main participants in this curriculum, all other learners in the PAC unit are also invited to attend the lectures.

The unique attributes of this training site include direct interaction with supervising PAs and physicians, rather than experiencing the traditional teaching hierarchy (with interns, residents, fellows); observation of the natural progression of disease of both acute care and primary care issues due to the longer length of stay (2 to 6 weeks, where the typical student will see the same patient 7 to 10 times during their rotation); exposure to a host of medically complex patients offering a multitude of clinical scenarios and abnormal physical exam findings; exposure to a hospice/palliative care ward and end-of-life care; and interaction within an interprofessional training environment of nursing, pharmacy, PT, OT, speech-language pathology, psychology, and SW trainees.

Program Evaluation

At the end of rotations continuously through the year, PA students electronically complete a site evaluation from the Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program. The evaluation consists of 14 questions: 6 about site quality and 8 about instruction quality. The questions are answered on a 5-point Likert scale. Also included are 2 open-ended response questions that ask what they liked about the rotation and what they felt could be improved. Results are anonymous, de-identified and blinded both to the program as well as the clerkship site. Results are aggregated and provided to program sites annually. Responses are converted to a dichotomous variable, where any good or excellent response (4 or 5) is considered positive and any neutral or below (3, 2, 1) is considered a nonpositive response.

Results

The clerkship site has been operational since June 22, 2015. There have been 59 students who participated in the rotation. A different scale in these evaluations was used between June 22, 2015, and September 13, 2015. Therefore, 7 responses were excluded from the analysis, leaving 52 usable evaluations. The responses were analyzed both in total (for the CLC as well as other IM rotation sites) and by individual clerkship year to look for any trends over time: September 14, 2015, through April 24, 2016; April 25, 2016, through April 28, 2017; and May 1, 2017, through March 1, 2018 (Table).

Site evaluations showed high satisfaction regarding the quality of the physical environment as well as the learning environment. Students endorsed the PAC unit having resources and physical space for them, such as a desk and computer, opportunity for participation in patient care, and parking (100%; n = 52). Site evaluations revealed high satisfaction with the quality of teaching and faculty encouragement and support of their learning (100%; n = 52). The evaluations revealed that bedside teaching was strong (94%; n = 49). The students reported high satisfaction with the volume of patients provided (92%; n = 48) as well as the diversity of diagnoses (92%; n = 48).

There were fewer positive responses in the first 2 years of the rotation with regard to formal lectures (50% and 67%; 7/14 and 16/24, respectively). In the third year of the rotation, students had a much higher satisfaction rate (93%; 13/14). This increased satisfaction was associated with the development and incorporation of the Interprofessional Curriculum in Transitional Care in 2017.

Discussion

Access to high-quality PA student clerkship sites has become a pressing issue in recent years because of increased competition for sites and a shortage of willing and well-trained preceptors. There has been marked growth in schools and enrollment across all medical professions. The Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the PA (ARC-PA) reported that the total number of accredited entry-level PA programs in 2018 was 246, with 58 new accredited programs projected by 2022.12 The Joint Report of the 2013 Multi-Discipline Clerkship/Clinical Training Site Survey reported a 66% increase in first-year enrollment in PA programs from 2002 to 2012.5 Programs must implement alternative strategies to attract clinical sites (eg, academic appointments, increased clinical resources to training sites) or face continued challenges with recruiting training sites for their students. Postacute care may be a natural extension to expand the footprint for clinical sites for these programs, augmenting acute inpatient and outpatient rotations. This implementation would increase the pool of clinical training sites and preceptors.

The experience with this novel training site, based on PA student feedback and evaluations, has been positive, and the postacute setting can provide students with high-quality IM clinical experiences. Students report adequate patient volume and diversity. In addition, evaluations are comparable with that of other IM site rotations the students experience. Qualitative feedback has emphasized the value of following patients over longer periods; eg, weeks vs days (as in acute care) enabling students to build relationships with patients as well as observe a richer clinical spectrum of disease over a less compressed period. “Patients have complex issues, so from a medical standpoint it challenges you to think of new ways to manage their care,” commented a representative student. “It is really beneficial that you can follow them over time.”

Furthermore, in response to student feedback on didactics, an interprofessional curriculum was developed to add formal structure as well as to create a curriculum in care transitions. This curriculum provided a unique opportunity for PA students to receive formal instruction on areas of particular relevance for transitional care (eg, care continuum, end of life issues, and care transitions). The curriculum also allows the interprofessional faculty a unique and enjoyable opportunity for interprofessional collaboration.

The 1 month PAC rotation is augmented with inpatient IM and outpatient family medicine rotations, consequently giving exposure to the full continuum of care. The PAC setting provides learners multifaceted benefits: the opportunity to strengthen and develop the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary for IM; increased understanding of other professions by observing and interacting as a team caring for a patient over a longer period as opposed to the acute care setting; the ability to perform effective, efficient, and safe transfer between clinical settings; and broad exposure to transitional care. As a result, the PAC rotation enhances but does not replace the necessary and essential rotations of inpatient and outpatient medicine.

Moreover, this rotation provides unique and core IM training for PA students. Our site focuses on interprofessional collaboration, emphasizing the importance of team-based care, an essential concept in modern day medicine. Formal exposure to other care specialties, such as PT and OT, SW, and mental health, is essential for students to appreciate clinical medicine and a patient’s physical and mental experience over the course of a disease and clinical state. In addition, the physical exam checklist ensures that students are exposed to the full spectrum of IM examination findings during their rotation. Finally, weekly feedback forms require students to ask and receive concrete feedback from their supervising providers.

Limitations

The generalizability of this model requires careful consideration. VABHS is a tertiary care integrated health care system, enabling students to learn from patients moving through multiple care transitions in a single health care system. In addition, other settings may not have the staffing or clinical volume to sustain such a model. All PAC clinical faculty teach voluntarily, and local leadership has set expectations for all clinicians to participate in teaching of trainees and PA students. Evaluations also note less diversity in the patient population, a challenge that some VA facilities face. This issue could be addressed by ensuring that students also have IM rotations at other inpatient medical facilities. A more balanced experience, where students reap the positive benefits of PAC but do not lose exposure to a diverse patient pool, could result. Furthermore, some of the perceived positive impacts also may be related to professional and personal attributes of the teaching clinicians rather than to the PAC setting.

Conclusion

PAC settings can be effective training sites for medicine clerkships for PA students and can provide high-quality training in IM as PA programs continue to expand. This setting offers students exposure to interprofessional, team-based care and the opportunity to care for patients with a broad range of disease complexity. Learning is further enhanced by the ability to follow patients longitudinally over their disease course as well as to work directly with teaching faculty and other interprofessional health care professionals. Evaluations of this novel clerkship experience have shown high levels of student satisfaction in knowledge growth, clinical skills, bedside teaching, and mentorship.

Acknowledgments

We thank Juman Hijab for her critical role in establishing and maintaining the clerkship. We thank Steven Simon, Matt Russell, and Thomas Parrino for their leadership and guidance in establishing and maintaining the clerkship. We thank the Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program Director Mary Warner for her support and guidance in creating and supporting the clerkship. In addition, we thank the interprofessional education faculty for their dedicated involvement in teaching, including Stephanie Saunders, Lindsay Lefers, Jessica Rawlins, Lindsay Brennan, Angela Viani, Eric Charette, Nicole O’Neil, Susan Nathan, Jordana Meyerson, Shivani Jindal, Wei Shen, Amy Hanson, Gilda Cain, and Kate Hinrichs.

1. US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational outlook handbook: physician assistants. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physician-assistants.htm. Updated June 18, 2019. Accessed August 13, 2019.

2. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2019 update: the complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2017 to 2032. https://aamc-black.global.ssl.fastly.net/production/media/filer_public/31/13/3113ee5c-a038-4c16-89af-294a69826650/2019_update_-_the_complexities_of_physician_supply_and_demand_-_projections_from_2017-2032.pdf. Published April 2019. Accessed August 15, 2019.

3. Glicken AD, Miller AA. Physician assistants: from pipeline to practice. Acad Med. 2013;88(12):1883-1889.

4. Erikson C, Hamann R, Levitan T, Pankow S, Stanley J, Whatley M. Recruiting and maintaining US clinical training sites: joint report of the 2013 multi-discipline clerkship/clinical training site survey. https://paeaonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Recruiting-and-Maintaining-U.S.-Clinical-Training-Sites.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2019.

5. Physician Assistant Education Association. By the numbers: 30th annual report on physician assistant educational programs. 2015. http://paeaonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/2015-by-the-numbers-program-report-30.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed August 15, 2019.

6. Morgan P, Himmerick KA, Leach B, Dieter P, Everett C. Scarcity of primary care positions may divert physician assistants into specialty practice. Med Care Res Rev. 2017;74(1):109-122.

7. Coplan B, Cawley J, Stoehr J. Physician assistants in primary care: trends and characteristics. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(1):75-79.

8. Morgan P, Leach B, Himmerick K, Everett C. Job openings for PAs by specialty. JAAPA. 2018;31(1):45-47.

9. American Academy of Physician Assistants. 2017 AAPA Salary Report. Alexandria, VA; 2017.

10. Barnett ML, Grabowski DC, Mehrotra A. Home-to-home time—measuring what matters to patients and payers. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):4-6.

11. Werner RM, Konetzka RT. Trends in post-acute care use among Medicare beneficiaries: 2000 to 2015. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1616-1617.

12. Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the Physician Assistant. http://www.arc-pa.org/accreditation/accredited-programs. Accessed May 10, 2019.

1. US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational outlook handbook: physician assistants. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physician-assistants.htm. Updated June 18, 2019. Accessed August 13, 2019.

2. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2019 update: the complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2017 to 2032. https://aamc-black.global.ssl.fastly.net/production/media/filer_public/31/13/3113ee5c-a038-4c16-89af-294a69826650/2019_update_-_the_complexities_of_physician_supply_and_demand_-_projections_from_2017-2032.pdf. Published April 2019. Accessed August 15, 2019.

3. Glicken AD, Miller AA. Physician assistants: from pipeline to practice. Acad Med. 2013;88(12):1883-1889.

4. Erikson C, Hamann R, Levitan T, Pankow S, Stanley J, Whatley M. Recruiting and maintaining US clinical training sites: joint report of the 2013 multi-discipline clerkship/clinical training site survey. https://paeaonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Recruiting-and-Maintaining-U.S.-Clinical-Training-Sites.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2019.

5. Physician Assistant Education Association. By the numbers: 30th annual report on physician assistant educational programs. 2015. http://paeaonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/2015-by-the-numbers-program-report-30.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed August 15, 2019.

6. Morgan P, Himmerick KA, Leach B, Dieter P, Everett C. Scarcity of primary care positions may divert physician assistants into specialty practice. Med Care Res Rev. 2017;74(1):109-122.

7. Coplan B, Cawley J, Stoehr J. Physician assistants in primary care: trends and characteristics. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(1):75-79.

8. Morgan P, Leach B, Himmerick K, Everett C. Job openings for PAs by specialty. JAAPA. 2018;31(1):45-47.

9. American Academy of Physician Assistants. 2017 AAPA Salary Report. Alexandria, VA; 2017.

10. Barnett ML, Grabowski DC, Mehrotra A. Home-to-home time—measuring what matters to patients and payers. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):4-6.

11. Werner RM, Konetzka RT. Trends in post-acute care use among Medicare beneficiaries: 2000 to 2015. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1616-1617.

12. Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the Physician Assistant. http://www.arc-pa.org/accreditation/accredited-programs. Accessed May 10, 2019.

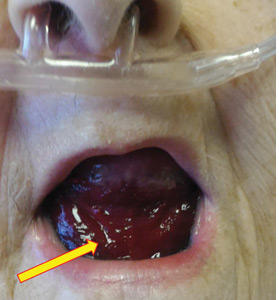

Pseudo-Ludwig angina

An 83-year-old woman with hypertension, hypothyroidism, and a history of depression presented to the emergency department with acute shortness of breath and hypoxia. She was found to have submassive pulmonary embolism, and a heparin infusion was started immediately.

Urgent nasopharyngeal laryngoscopy revealed a hematoma at the base of her tongue that extended into the vallecula, piriform sinuses, and aryepiglottic fold, causing acute airway obstruction. These features combined with the supratherapeutic aPTT led to the diagnosis of pseudo-Ludwig angina.

DANGER OF RAPID AIRWAY COMPROMISE

Pseudo-Ludwig angina is a rare condition in which over-anticoagulation causes sublingual swelling leading to airway obstruction, whereas true Ludwig angina is an infectious regional suppuration of the neck.

Most reported cases of pseudo-Ludwig angina have resulted from overanticogulation with warfarin or warfarin-like substances (rodenticides), or from coagulopathy due to liver disease.1–3 Early recognition is essential to avoid airway compromise.

In our patient, all anticoagulation was discontinued, and she was intubated until the hematoma began to resolve, the aPTT returned to normal, and respiratory compromise improved. At follow-up 2 months later, the sublingual hematoma had completely resolved (Figure 1). And at a 6-month follow-up visit, the pulmonary embolism had resolved, and pulmonary pressures by 2-dimensional echocardiography were normal.

- Lovallo E, Patterson S, Erickson M, Chin C, Blanc P, Durrani TS. When is “pseudo-Ludwig’s angina” associated with coagulopathy also a “pseudo” hemorrhage? J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep 2013; 1(2):2324709613492503. doi:10.1177/2324709613492503

- Smith RG, Parker TJ, Anderson TA. Noninfectious acute upper airway obstruction (pseudo-Ludwig phenomenon): report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1987; 45(8):701–704. pmid:3475442

- Zacharia GS, Kandiyil S, Thomas V. Pseudo-Ludwig's phenomenon: a rare clinical manifestation in liver cirrhosis. ACG Case Rep J 2014; 2(1):53–54. doi:10.14309/crj.2014.83

An 83-year-old woman with hypertension, hypothyroidism, and a history of depression presented to the emergency department with acute shortness of breath and hypoxia. She was found to have submassive pulmonary embolism, and a heparin infusion was started immediately.

Urgent nasopharyngeal laryngoscopy revealed a hematoma at the base of her tongue that extended into the vallecula, piriform sinuses, and aryepiglottic fold, causing acute airway obstruction. These features combined with the supratherapeutic aPTT led to the diagnosis of pseudo-Ludwig angina.

DANGER OF RAPID AIRWAY COMPROMISE

Pseudo-Ludwig angina is a rare condition in which over-anticoagulation causes sublingual swelling leading to airway obstruction, whereas true Ludwig angina is an infectious regional suppuration of the neck.

Most reported cases of pseudo-Ludwig angina have resulted from overanticogulation with warfarin or warfarin-like substances (rodenticides), or from coagulopathy due to liver disease.1–3 Early recognition is essential to avoid airway compromise.

In our patient, all anticoagulation was discontinued, and she was intubated until the hematoma began to resolve, the aPTT returned to normal, and respiratory compromise improved. At follow-up 2 months later, the sublingual hematoma had completely resolved (Figure 1). And at a 6-month follow-up visit, the pulmonary embolism had resolved, and pulmonary pressures by 2-dimensional echocardiography were normal.

An 83-year-old woman with hypertension, hypothyroidism, and a history of depression presented to the emergency department with acute shortness of breath and hypoxia. She was found to have submassive pulmonary embolism, and a heparin infusion was started immediately.

Urgent nasopharyngeal laryngoscopy revealed a hematoma at the base of her tongue that extended into the vallecula, piriform sinuses, and aryepiglottic fold, causing acute airway obstruction. These features combined with the supratherapeutic aPTT led to the diagnosis of pseudo-Ludwig angina.

DANGER OF RAPID AIRWAY COMPROMISE

Pseudo-Ludwig angina is a rare condition in which over-anticoagulation causes sublingual swelling leading to airway obstruction, whereas true Ludwig angina is an infectious regional suppuration of the neck.

Most reported cases of pseudo-Ludwig angina have resulted from overanticogulation with warfarin or warfarin-like substances (rodenticides), or from coagulopathy due to liver disease.1–3 Early recognition is essential to avoid airway compromise.

In our patient, all anticoagulation was discontinued, and she was intubated until the hematoma began to resolve, the aPTT returned to normal, and respiratory compromise improved. At follow-up 2 months later, the sublingual hematoma had completely resolved (Figure 1). And at a 6-month follow-up visit, the pulmonary embolism had resolved, and pulmonary pressures by 2-dimensional echocardiography were normal.

- Lovallo E, Patterson S, Erickson M, Chin C, Blanc P, Durrani TS. When is “pseudo-Ludwig’s angina” associated with coagulopathy also a “pseudo” hemorrhage? J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep 2013; 1(2):2324709613492503. doi:10.1177/2324709613492503

- Smith RG, Parker TJ, Anderson TA. Noninfectious acute upper airway obstruction (pseudo-Ludwig phenomenon): report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1987; 45(8):701–704. pmid:3475442

- Zacharia GS, Kandiyil S, Thomas V. Pseudo-Ludwig's phenomenon: a rare clinical manifestation in liver cirrhosis. ACG Case Rep J 2014; 2(1):53–54. doi:10.14309/crj.2014.83

- Lovallo E, Patterson S, Erickson M, Chin C, Blanc P, Durrani TS. When is “pseudo-Ludwig’s angina” associated with coagulopathy also a “pseudo” hemorrhage? J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep 2013; 1(2):2324709613492503. doi:10.1177/2324709613492503

- Smith RG, Parker TJ, Anderson TA. Noninfectious acute upper airway obstruction (pseudo-Ludwig phenomenon): report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1987; 45(8):701–704. pmid:3475442

- Zacharia GS, Kandiyil S, Thomas V. Pseudo-Ludwig's phenomenon: a rare clinical manifestation in liver cirrhosis. ACG Case Rep J 2014; 2(1):53–54. doi:10.14309/crj.2014.83

Are daily chest radiographs and arterial blood gas tests required in ICU patients on mechanical ventilation?

No, they are not required or needed, but daily radiography and arterial blood gas testing are common practice: eg, 60% of intensive care unit (ICU) patients get daily radiographs,1 even though results provide low diagnostic yield and are unlikely to alter patient management compared with testing only when indicated.

The Choosing Wisely campaign,2 a collaborative effort of a number of professional societies, advises against ordering these diagnostic tests daily because routine testing increases risks to patients and burdens the healthcare system. Instead, testing is recommended only in response to a specific clinical question, or when the test results will affect the patient’s treatment.

CHEST RADIOGRAPHS: DAILY VS CLINICALLY INDICATED

Chest radiographs enable practitioners to monitor the position of endotracheal tubes and central venous catheters, evaluate fluid status, follow up on abnormal findings, detect complications of procedures (such as a pneumothorax), and identify otherwise undetected conditions.

And daily chest radiographs often detect abnormalities. A 1991 study by Hall et al3 of 538 chest radiographs in 74 patients on mechanical ventilation reported that 30% of daily routine chest radiographs disclosed a new but minor finding (eg, a small change in endotracheal tube position or a small infiltrate). The new findings were major in 13 (17.6%) of the 74 patients (95% confidence interval [CI] 9%–26%). These included findings that required an immediate diagnostic or therapeutic intervention (eg, endotracheal tube below the tracheal carina, malposition of a catheter, pneumothorax, large pleural effusion).

But most studies say daily radiographs are not needed. In a large prospective study published in 2006, Graat et al4 evaluated the clinical value of 2,457 routine chest radiographs in 754 patients in a combined surgical and medical ICU. Daily chest radiographs revealed new or unexpected findings in 5.8% of cases, but only 2.2% warranted a change in therapy. No differences were found between the medical and surgical patients. The authors concluded that daily routine radiographs in ICU patients seldom reveal unexpected, clinically relevant abnormalities, and those findings rarely require urgent intervention.

A 2010 meta-analysis of 8 studies (7,078 patients) by Oba and Zaza5 compared on-demand and daily routine strategies of performing chest radiographs. They estimated that eliminating daily routine chest radiographs would not affect death rates in the hospital (odds ratio [OR] 1.02, 95% CI 0.89–1.17, P = .78) or the ICU (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.76–1.11, P = .4). They also found no significant differences in length of stay or duration of mechanical ventilation. This meta-analysis suggests that routine radiographs can be eliminated without adversely affecting outcomes in ICU patients.

A larger meta-analysis (9 trials, 39,358 radiographs, 9,611 patients) published in 2012 by Ganapathy et al6 also found no harm associated with restrictive radiography protocols. These investigators compared a daily chest radiography protocol against a protocol based on clinical indications. The primary outcome was the mortality rate in the ICU; secondary outcomes were the mortality rate in the hospital, the length of stay in the ICU, and duration of mechanical ventilation. They found no differences between routine and restrictive strategies in terms of ICU mortality (risk ratio [RR] 1.04, 95% CI 0.84–1.28, P = .72), hospital mortality (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.68–1.41, P = .91), or other secondary outcomes.

Clinically indicated testing is better

The conclusion from these studies is that routine chest radiographs in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation does not improve patient outcomes, and thus, a clinically indicated protocol is preferred.

Furthermore, routine daily radiographs have adverse effects such as more cumulative radiation exposure to the patient7 and greater risk of accidental removal of devices (eg, catheters, tubes).8 Another concern is a higher risk of hospital-associated infections from bacterial spread from caregivers’ hands.9

Finally, daily radiographs increase the use of healthcare resources and expenditures. In a 2011 study, Gershengorn et al1 estimated that adopting a clinically indicated radiography strategy could save more than $144 million annually in the United States.

The ACR agrees. Appropriateness criteria published by the American College of Radiology (ACR) in 201510 recommend against routine daily chest radiographs in the ICU, in keeping with the findings of the critical care community. The ACR recommends an initial radiograph at admission to the ICU. However, follow-up radiographs should be obtained only for specific clinical indications, including a change in the patient’s clinical condition or to check for proper placement of endotracheal or nasogastric or orogastric tubes, pulmonary arterial catheters, central venous catheters, chest tubes, and other life-support devices.

Ultrasonography as an alternative

Ultrasonography is widely available and provides an alternative to chest radiography for detecting significant abnormalities in patients on mechanical ventilation without exposing them to radiation and using relatively fewer resources.

A 2012 meta-analysis (8 studies, 1,048 patients) found that bedside ultrasonography reliably detects pneumothorax.11 It can also provide a rapid diagnosis of the cause of acute respiratory failure such as pneumonia or pulmonary edema.12 Ultrasonography, with the appropriate expertise, can also confirm the position of an endotracheal tube13 or central venous catheter.14

ARTERIAL BLOOD GAS TESTING: DAILY VS CLINICALLY INDICATED

Arterial blood gas testing has value for managing patients undergoing mechanical ventilation, and it is one of the most commonly performed diagnostic tests in the ICU. It provides reliable information about the patient’s oxygenation and acid-base status. It is commonly requested when changing ventilator settings.

Downsides. Arterial blood gas measurements account for 10% to 20% of the cost incurred during ICU stay.15 In addition, they require an arterial puncture—an invasive procedure associated with potentially serious complications such as occlusion of the artery, digital embolization leading to digital ischemia, local infection, pseudoaneurysm, hematoma, bleeding, and skin necrosis.

Is daily testing needed?

Guidelines say no. The 2013 American Association for Respiratory Care16 guidelines suggest that arterial blood gas testing should be based on the clinical assessment of the patient. They recommend blood gas analysis to evaluate the patient’s ventilatory status (reflected by the partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide [PaCO2], acid-base status (reflected by pH), arterial oxygenation (partial pressure of arterial oxygen [PaO2] and oxyhemoglobin saturation), oxygen-carrying capacity, and whether the patient likely has an intrapulmonary shunt. They state that testing is useful to quantify the response to therapeutic or diagnostic interventions such as cardiopulmonary exercise testing, to monitor severity and progression of documented disease, and to assess the adequacy of circulatory response.

Studies agree

The ACR recommendation to test “as clinically indicated” is supported by studies showing that patient outcomes are not inferior for arterial blood gas testing when clinically indicated instead of daily, and that this practice is associated with fewer complications, less resource use, and reduced overall patient care costs.

A 2015 study compared the efficacy and safety of obtaining arterial blood gases based on clinical assessment vs daily in 300 critically ill patients.17 Overall, fewer samples were obtained per patient in the clinical assessment group than in the daily group (all patients 3.7 vs 5.5; ventilated patients 2.03 vs 6.12; P < .001 for both). In ventilated patients, there was a 60% decrease in arterial blood gas orders without affecting patient outcomes and safety, including a lower risk of complications and overall cost of care.

In another study, Martinez-Balzano et al18 evaluated the effect of guidelines they developed to optimize the use of arterial blood gas testing in their ICUs. These guidelines encouraged testing of arterial blood gases after an acute respiratory event or for a rational clinical concern, and discouraged testing for routine surveillance, after planned changes of positive end-expiratory pressure or inspired oxygen fraction on mechanical ventilation, for spontaneous breathing trials, or when a disorder was not suspected.

Compared with data collected before implementation, these guidelines reduced the number of arterial blood gas tests by 821.5 per month (41.5%), or approximately 1 test per patient per mechanical-ventilation day for each month (43.1%; P < .001). Appropriately indicated testing rose to 83.4% from a baseline of 67.5% (P = .002). Additionally, this approach was associated with saving 49 liters of blood, reducing ICU costs by $39,432, and freeing up 1,643 staff work hours for other tasks. There were no significant differences in days on mechanical ventilation, severity of illness, or mortality between the 2 periods.18

Extubation effects. Routine arterial blood gas testing has not been shown to affect extubation decisions in patients on mechanical ventilation. In a study of 83 patients who completed a spontaneous breathing trial (total of 100 trials), Salam et al19 found arterial blood gas values obtained during the trial did not change the extubation decision in 93% of the cases.

In a study of 54 extubations in 52 patients,20 65% of the extubations were performed without obtaining an arterial blood gas test after the patient completed a trial of spontaneous breathing. The extubation success rate was 94% for the entire group, and it was the same regardless of whether testing was done (94.7% vs 94.3%, respectively).

Alternatives to arterial blood gases

There are less-invasive means to obtain the information that comes from an arterial blood gas test.

Pulse oximetry is a rapid noninvasive tool that provides continuous assessment of peripheral arterial oxygen saturation as a surrogate marker for tissue arterial oxygenation. However, it cannot measure PaO2 or PaCO2.21

Transcutaneous carbon dioxide (PTCO2) monitoring is another continuous noninvasive alternative. The newer PTCO2 devices are useful in patients with acute respiratory failure and in critically ill patients on vasopressors or vasodilators. Studies have shown good correlation between PTCO2 and PaCO2.22,23

End-tidal carbon dioxide (PetCO2) is another alternative to estimate PaCO2. It can also be used to confirm endotracheal tube placement, during transportation, during procedures in which the patient is under conscious sedation, and to monitor the effectiveness of cardiopulmonary resuscitation and return of circulation after cardiac arrest. PetCO2 measurements are not as accurate as arterial blood gas testing owing to a difference of approximately 2 to 5 mm Hg between PaCO2 and PetCO2 in normal lungs due to alveolar dead space. This difference may be much higher depending on the clinical condition and the degree of alveolar dead space.21,24,25

Venous blood gases, which can be obtained from a peripheral or central venous catheter, are adequate to assess pH and partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2) in hemodynamically stable patients. Walkey et al26 found that the accuracy of venous blood gas measurement to predict arterial blood gases was 90%. They recommended adjusting the venous pH up by 0.05 and the PCO2 down by 5 mm Hg to account for the positive bias of venous blood gases. A limitation of this method is that the values are not reliable in patients who are in shock.

These alternatives can be used as a substitute for daily arterial blood gases. However, in certain clinical scenarios, arterial blood gas measurement remains a necessary and useful clinical tool.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

Most scientific evidence suggests that chest radiographs and arterial blood gas measurement in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation—and critically ill, in general—are best done when clinically indicated rather than routinely on a daily basis. This will reduce cost and harm to patients that may result from these unnecessary tests and not adversely affect outcomes.

- Gershengorn HB, Wunsch H, Scales DC, Rubenfeld GD. Trends in use of daily chest radiographs among US adults receiving mechanical ventilation. JAMA Netw Open 2018; 1(4):e181119. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.1119

- American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. Choosing Wisely. http://www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/critical-care-societies-collaborative-regular-diagnostic-tests. Accessed August 18, 2019.

- Hall JB, White SR, Karrison T. Efficacy of daily routine chest radiographs in intubated, mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med 1991; 19(5):689–693. pmid:2026031

- Graat ME, Choi G, Wolthuis EK, et al. The clinical value of daily routine chest radiographs in a mixed medical-surgical intensive care unit is low. Crit Care 2006; 10(1):R11. doi:10.1186/cc3955

- Oba Y, Zaza T. Abandoning daily routine chest radiography in the intensive care unit: meta-analysis. Radiology 2010; 255(2):386–395. doi:10.1148/radiol.10090946

- Ganapathy A, Adhikari NK, Spiegelman J, Scales DC. Routine chest x-rays in intensive care units: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 2012; 16(2):R68. doi:10.1186/cc11321

- Krishnan S, Moghekar A, Duggal A, et al. Radiation exposure in the medical ICU: predictors and characteristics. Chest 2018; 153(5):1160–1168. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2018.01.019

- Hejblum G, Chalumeau-Lemoine L, Ioos V, et al. Comparison of routine and on-demand prescription of chest radiographs in mechanically ventilated adults: a multicentre, cluster-randomised, two-period crossover study. Lancet 2009; 374(9702):1687–1693. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61459-8

- Levin PD, Shatz O, Sviri S, et al. Contamination of portable radiograph equipment with resistant bacteria in the ICU. Chest 2009; 136(2):426–432. doi:10.1378/chest.09-0049

- Suh RD, Genshaft SJ, Kirsch J, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Intensive Care Unit Patients. J Thorac Imaging 2015; 30(6):W63–W65. doi:10.1097/RTI.0000000000000174

- Alrajhi K, Woo MY, Vaillancourt C. Test characteristics of ultrasonography for the detection of pneumothorax: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest 2012; 141(3):703–708. doi:10.1378/chest.11-0131

- Lichetenstein DA, Meziere GA. Relevance of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute respiratory failure: the BLUE protocol. Chest 2008; 134(1):117–125. doi:10.1378/chest.07-2800

- Das SK, Choupoo NS, Haldar R, Lahkar A. Transtracheal ultrasound for verification of endotracheal tube placement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth 2015; 62(4):413–423. doi:10.1007/s12630-014-0301-z