User login

Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist: Diagnosis and Management of Measles

Measles is a highly contagious acute respiratory illness that can cause complications in multiple organ systems. Measles was declared eliminated in the United States in 2000; however, outbreaks still occur, especially in unvaccinated populations. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that as of October 3, 2019, 1,250 cases of measles had been confirmed in 31 states in 2019, which represents the greatest number of cases reported in the US since 1992.1 Although the disease is often self-limited, infected individuals can also develop complications requiring hospitalization, which occurred in 10% of confirmed cases this year.1 In February 2018, the CDC updated their recommendations about measles diagnosis and treatment on their website,2 adding an interim update in July 2019 to include new guidelines about infection control and prevention.3 This highlight reviews those recommendations most relevant to hospitalists, who can play a critical role in the diagnosis and management of patients with suspected and/or confirmed measles.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE HOSPITALIST

Recommendation 1. Healthcare providers should consider measles in patients presenting with febrile rash illness and clinically compatible measles symptoms, especially if the person recently traveled internationally or was exposed to a person with febrile rash illness. Healthcare providers should report suspected measles cases to their local health department within 24 hours.

Measles is an acute febrile illness that begins with a prodrome of fever, followed by one or more of the following three “C’s”: cough, coryza (rhinitis), and conjunctivitis. Koplik spots, a pathognomonic buccal enanthem consisting of white lesions on an erythematous base, can appear shortly thereafter. An erythematous, maculopapular rash develops three to four days after the onset of the fever. The rash starts on the face and then spreads over the next few days to the trunk and extremities. Clinical recovery generally occurs within one week of rash onset in uncomplicated measles. Complications can affect almost any organ system. The most common complications are pneumonia, often caused by secondary viral or bacterial pathogens, diarrhea, otitis media, and laryngotracheobronchitis. Rare but serious complications include acute encephalitis and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Groups at the highest risk for serious disease include children aged <5 years, adults aged >20 years, pregnant women, and immunocompromised individuals.

When encountering patients with a febrile rash and compatible symptoms, clinicians should also have a high index of suspicion for measles in patients who are unvaccinated or undervaccinated, since the majority of measles cases have occurred in the unvaccinated population. Providers should contact their local health department and infectious diseases/infection control team as soon as suspected measles cases are identified. Laboratory confirmation is necessary for all suspected cases and should typically consist of measles IgM antibody testing from serum and real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from respiratory and urine specimens.

Recommendation 2. Adhere to airborne precautions for anyone with known or suspected measles.

Measles is highly contagious, and infectious particles can remain in the air for up to two hours after a person with measles leaves a room. From 2001 to 2014, 6% (78/1,318) of nonimported measles cases in the US were transmitted in healthcare settings.4 Key steps in preventing the spread of measles within hospitals include ensuring that all healthcare personnel have evidence of immunity to measles and rapid identification and isolation of suspect cases. Patients with suspected measles should be given a facemask and moved immediately into a single-patient airborne infection isolation room. Personnel, even those with presumptive evidence of immunity, should use N95 respirators or the equivalent when caring for patients with suspected or confirmed measles. Patients with measles are contagious from four days before to four days after rash onset; therefore, airborne precautions should be continued for four days following the onset of rash in immunocompetent patients. For immunocompromised patients, airborne precautions should be continued for the duration of the illness based on data suggesting prolonged shedding, particularly in the setting of altered T-cell immunity.4

Recommendation 3. People exposed to measles who cannot readily show that they have evidence of immunity against measles should be offered postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) or be excluded from the setting (school, hospital, childcare). To potentially provide protection or modify the clinical course of disease among susceptible persons, either administer a measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine within 72 hours of initial measles exposure or immunoglobulin (IG) within six days of exposure.

MMR vaccine is recommended for vaccine-eligible, exposed individuals aged ≥6 months within 72 hours of measles exposure. IG, which contains measles antibody due to widespread immunization in the US, is recommended for individuals at high risk for serious illness, including infants aged ≤12 months, pregnant women without evidence of measles immunity, and severely immunocompromised patients regardless of vaccination status. For infants aged 6-11 months, MMR vaccine can be given in place of IG if done within 72 hours of exposure. PEP for children during the 2013 New York City outbreak reduced the risk of measles by 83.4% (95% CI: 34.4%-95.8%) in recipients of MMR vaccine and by 100% (95% CI: 56.2%-99.8%) in recipients of IG compared with those without prophylaxis.5 A 2014 Cochrane Review found that IG reduced the risk of measles by 83% (95% CI: 64%-92%).6

Recommendation 4. Severe measles cases among children, such as those who are hospitalized, should be treated with vitamin A. Vitamin A should be administered immediately on diagnosis and repeated the next day.

In children, vitamin A deficiency, even if clinically inapparent, leads to increased measles severity, and randomized controlled trial data suggest that supplementation reduces measles-related morbidity and mortality.4 Even in high-income countries, children with measles have high rates of vitamin A deficiency, which is associated with increased morbidity.7 A Cochrane review found that two-dose regimens of vitamin A reduced the overall mortality (RR 0.21; 95% CI: 0.07-0.66) in children with measles aged <2 years.8 World Health Organization guidelines suggest vitamin A therapy for all children with acute measles infection, and the AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases recommends vitamin A for severe (ie, hospitalized) cases. Vitamin A is given orally once daily for two days at the following doses: 50,000 international units (IU) for infants aged <6 months, 100,000 IU for infants aged 6-11 months, and 200,000 IU for children aged ≥12 months. A third dose can be given two to four weeks later for children with signs and symptoms of vitamin A deficiency (eg, corneal clouding or conjunctival plaques).

CRITIQUE

In outbreak settings, hospitalists may find challenges with having a sufficient number of single negative-pressure rooms for patients with suspected or confirmed measles and providing IG prophylaxis given the recent national shortages of intravenous immunoglobulin. Collaboration with the infection control team, pharmacy, and the local public health department is essential to appropriately address these challenges. With regard to treatment recommendations, randomized studies on the impact of vitamin A treatment in children have been primarily conducted in resource-limited settings.8 However, these data, in combination with observational data from resource-rich settings,7 support its use given the favorable risk-benefit profile. The role of vitamin A therapy in adults with measles infection is considerably less clear, although there are reports of its use in severe cases.

AREAS OF FUTURE STUDY

Much of our knowledge regarding measles complications and treatment outcomes comes from resource-limited settings or from older data before widespread vaccination. Data suggest that prophylactic antibiotics may prevent complications; however, currently available data are insufficient to support routine use.9 Coordination and collaboration between public health, infectious diseases, and hospital medicine would enhance the ability to conduct detailed epidemiologic studies during outbreak situations. Further studies examining treatment and outcomes in hospitalized patients, including the role of prophylactic antibiotics in the prevention of complications, would provide valuable guidance for hospitalists caring for patients with severe measles.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles Cases and Outbreaks. 2019; https://www.cdc.gov/measles/cases-outbreaks.html. Accessed October 14, 2019.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles (Rubeola): For Healthcare Professionals. 2019; https://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/index.html. Accessed October 14, 2019.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Measles in Healthcare Settings. 2019.

4. Fiebelkorn AP, Redd SB, Kuhar DT. Measles in healthcare facilities in the United States during the postelimination era, 2001-2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(4):615-618. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ387.

5. Arciuolo RJ, Jablonski RR, Zucker JR, Rosen JB. Effectiveness of measles vaccination and immune globulin post-exposure prophylaxis in an outbreak setting-New York City, 2013. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(11):1843-1847. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix639.

6. Young MK, Nimmo GR, Cripps AW, Jones MA. Post-exposure passive immunisation for preventing measles. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(4):Cd010056. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010056.pub2.

7. Frieden TR, Sowell AL, Henning KJ, Huff DL, Gunn RA. Vitamin A levels and severity of measles. New York City. Am J Dis Child. 1992;146(2):182-186. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1992.02160140048019.

8. Huiming Y, Chaomin W, Meng M. Vitamin A for treating measles in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005(4):Cd001479. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001479.pub3.

9. Kabra SK, Lodha R. Antibiotics for preventing complications in children with measles. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(8):Cd001477. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001477.pub3.

Measles is a highly contagious acute respiratory illness that can cause complications in multiple organ systems. Measles was declared eliminated in the United States in 2000; however, outbreaks still occur, especially in unvaccinated populations. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that as of October 3, 2019, 1,250 cases of measles had been confirmed in 31 states in 2019, which represents the greatest number of cases reported in the US since 1992.1 Although the disease is often self-limited, infected individuals can also develop complications requiring hospitalization, which occurred in 10% of confirmed cases this year.1 In February 2018, the CDC updated their recommendations about measles diagnosis and treatment on their website,2 adding an interim update in July 2019 to include new guidelines about infection control and prevention.3 This highlight reviews those recommendations most relevant to hospitalists, who can play a critical role in the diagnosis and management of patients with suspected and/or confirmed measles.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE HOSPITALIST

Recommendation 1. Healthcare providers should consider measles in patients presenting with febrile rash illness and clinically compatible measles symptoms, especially if the person recently traveled internationally or was exposed to a person with febrile rash illness. Healthcare providers should report suspected measles cases to their local health department within 24 hours.

Measles is an acute febrile illness that begins with a prodrome of fever, followed by one or more of the following three “C’s”: cough, coryza (rhinitis), and conjunctivitis. Koplik spots, a pathognomonic buccal enanthem consisting of white lesions on an erythematous base, can appear shortly thereafter. An erythematous, maculopapular rash develops three to four days after the onset of the fever. The rash starts on the face and then spreads over the next few days to the trunk and extremities. Clinical recovery generally occurs within one week of rash onset in uncomplicated measles. Complications can affect almost any organ system. The most common complications are pneumonia, often caused by secondary viral or bacterial pathogens, diarrhea, otitis media, and laryngotracheobronchitis. Rare but serious complications include acute encephalitis and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Groups at the highest risk for serious disease include children aged <5 years, adults aged >20 years, pregnant women, and immunocompromised individuals.

When encountering patients with a febrile rash and compatible symptoms, clinicians should also have a high index of suspicion for measles in patients who are unvaccinated or undervaccinated, since the majority of measles cases have occurred in the unvaccinated population. Providers should contact their local health department and infectious diseases/infection control team as soon as suspected measles cases are identified. Laboratory confirmation is necessary for all suspected cases and should typically consist of measles IgM antibody testing from serum and real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from respiratory and urine specimens.

Recommendation 2. Adhere to airborne precautions for anyone with known or suspected measles.

Measles is highly contagious, and infectious particles can remain in the air for up to two hours after a person with measles leaves a room. From 2001 to 2014, 6% (78/1,318) of nonimported measles cases in the US were transmitted in healthcare settings.4 Key steps in preventing the spread of measles within hospitals include ensuring that all healthcare personnel have evidence of immunity to measles and rapid identification and isolation of suspect cases. Patients with suspected measles should be given a facemask and moved immediately into a single-patient airborne infection isolation room. Personnel, even those with presumptive evidence of immunity, should use N95 respirators or the equivalent when caring for patients with suspected or confirmed measles. Patients with measles are contagious from four days before to four days after rash onset; therefore, airborne precautions should be continued for four days following the onset of rash in immunocompetent patients. For immunocompromised patients, airborne precautions should be continued for the duration of the illness based on data suggesting prolonged shedding, particularly in the setting of altered T-cell immunity.4

Recommendation 3. People exposed to measles who cannot readily show that they have evidence of immunity against measles should be offered postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) or be excluded from the setting (school, hospital, childcare). To potentially provide protection or modify the clinical course of disease among susceptible persons, either administer a measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine within 72 hours of initial measles exposure or immunoglobulin (IG) within six days of exposure.

MMR vaccine is recommended for vaccine-eligible, exposed individuals aged ≥6 months within 72 hours of measles exposure. IG, which contains measles antibody due to widespread immunization in the US, is recommended for individuals at high risk for serious illness, including infants aged ≤12 months, pregnant women without evidence of measles immunity, and severely immunocompromised patients regardless of vaccination status. For infants aged 6-11 months, MMR vaccine can be given in place of IG if done within 72 hours of exposure. PEP for children during the 2013 New York City outbreak reduced the risk of measles by 83.4% (95% CI: 34.4%-95.8%) in recipients of MMR vaccine and by 100% (95% CI: 56.2%-99.8%) in recipients of IG compared with those without prophylaxis.5 A 2014 Cochrane Review found that IG reduced the risk of measles by 83% (95% CI: 64%-92%).6

Recommendation 4. Severe measles cases among children, such as those who are hospitalized, should be treated with vitamin A. Vitamin A should be administered immediately on diagnosis and repeated the next day.

In children, vitamin A deficiency, even if clinically inapparent, leads to increased measles severity, and randomized controlled trial data suggest that supplementation reduces measles-related morbidity and mortality.4 Even in high-income countries, children with measles have high rates of vitamin A deficiency, which is associated with increased morbidity.7 A Cochrane review found that two-dose regimens of vitamin A reduced the overall mortality (RR 0.21; 95% CI: 0.07-0.66) in children with measles aged <2 years.8 World Health Organization guidelines suggest vitamin A therapy for all children with acute measles infection, and the AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases recommends vitamin A for severe (ie, hospitalized) cases. Vitamin A is given orally once daily for two days at the following doses: 50,000 international units (IU) for infants aged <6 months, 100,000 IU for infants aged 6-11 months, and 200,000 IU for children aged ≥12 months. A third dose can be given two to four weeks later for children with signs and symptoms of vitamin A deficiency (eg, corneal clouding or conjunctival plaques).

CRITIQUE

In outbreak settings, hospitalists may find challenges with having a sufficient number of single negative-pressure rooms for patients with suspected or confirmed measles and providing IG prophylaxis given the recent national shortages of intravenous immunoglobulin. Collaboration with the infection control team, pharmacy, and the local public health department is essential to appropriately address these challenges. With regard to treatment recommendations, randomized studies on the impact of vitamin A treatment in children have been primarily conducted in resource-limited settings.8 However, these data, in combination with observational data from resource-rich settings,7 support its use given the favorable risk-benefit profile. The role of vitamin A therapy in adults with measles infection is considerably less clear, although there are reports of its use in severe cases.

AREAS OF FUTURE STUDY

Much of our knowledge regarding measles complications and treatment outcomes comes from resource-limited settings or from older data before widespread vaccination. Data suggest that prophylactic antibiotics may prevent complications; however, currently available data are insufficient to support routine use.9 Coordination and collaboration between public health, infectious diseases, and hospital medicine would enhance the ability to conduct detailed epidemiologic studies during outbreak situations. Further studies examining treatment and outcomes in hospitalized patients, including the role of prophylactic antibiotics in the prevention of complications, would provide valuable guidance for hospitalists caring for patients with severe measles.

Measles is a highly contagious acute respiratory illness that can cause complications in multiple organ systems. Measles was declared eliminated in the United States in 2000; however, outbreaks still occur, especially in unvaccinated populations. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that as of October 3, 2019, 1,250 cases of measles had been confirmed in 31 states in 2019, which represents the greatest number of cases reported in the US since 1992.1 Although the disease is often self-limited, infected individuals can also develop complications requiring hospitalization, which occurred in 10% of confirmed cases this year.1 In February 2018, the CDC updated their recommendations about measles diagnosis and treatment on their website,2 adding an interim update in July 2019 to include new guidelines about infection control and prevention.3 This highlight reviews those recommendations most relevant to hospitalists, who can play a critical role in the diagnosis and management of patients with suspected and/or confirmed measles.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE HOSPITALIST

Recommendation 1. Healthcare providers should consider measles in patients presenting with febrile rash illness and clinically compatible measles symptoms, especially if the person recently traveled internationally or was exposed to a person with febrile rash illness. Healthcare providers should report suspected measles cases to their local health department within 24 hours.

Measles is an acute febrile illness that begins with a prodrome of fever, followed by one or more of the following three “C’s”: cough, coryza (rhinitis), and conjunctivitis. Koplik spots, a pathognomonic buccal enanthem consisting of white lesions on an erythematous base, can appear shortly thereafter. An erythematous, maculopapular rash develops three to four days after the onset of the fever. The rash starts on the face and then spreads over the next few days to the trunk and extremities. Clinical recovery generally occurs within one week of rash onset in uncomplicated measles. Complications can affect almost any organ system. The most common complications are pneumonia, often caused by secondary viral or bacterial pathogens, diarrhea, otitis media, and laryngotracheobronchitis. Rare but serious complications include acute encephalitis and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Groups at the highest risk for serious disease include children aged <5 years, adults aged >20 years, pregnant women, and immunocompromised individuals.

When encountering patients with a febrile rash and compatible symptoms, clinicians should also have a high index of suspicion for measles in patients who are unvaccinated or undervaccinated, since the majority of measles cases have occurred in the unvaccinated population. Providers should contact their local health department and infectious diseases/infection control team as soon as suspected measles cases are identified. Laboratory confirmation is necessary for all suspected cases and should typically consist of measles IgM antibody testing from serum and real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from respiratory and urine specimens.

Recommendation 2. Adhere to airborne precautions for anyone with known or suspected measles.

Measles is highly contagious, and infectious particles can remain in the air for up to two hours after a person with measles leaves a room. From 2001 to 2014, 6% (78/1,318) of nonimported measles cases in the US were transmitted in healthcare settings.4 Key steps in preventing the spread of measles within hospitals include ensuring that all healthcare personnel have evidence of immunity to measles and rapid identification and isolation of suspect cases. Patients with suspected measles should be given a facemask and moved immediately into a single-patient airborne infection isolation room. Personnel, even those with presumptive evidence of immunity, should use N95 respirators or the equivalent when caring for patients with suspected or confirmed measles. Patients with measles are contagious from four days before to four days after rash onset; therefore, airborne precautions should be continued for four days following the onset of rash in immunocompetent patients. For immunocompromised patients, airborne precautions should be continued for the duration of the illness based on data suggesting prolonged shedding, particularly in the setting of altered T-cell immunity.4

Recommendation 3. People exposed to measles who cannot readily show that they have evidence of immunity against measles should be offered postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) or be excluded from the setting (school, hospital, childcare). To potentially provide protection or modify the clinical course of disease among susceptible persons, either administer a measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine within 72 hours of initial measles exposure or immunoglobulin (IG) within six days of exposure.

MMR vaccine is recommended for vaccine-eligible, exposed individuals aged ≥6 months within 72 hours of measles exposure. IG, which contains measles antibody due to widespread immunization in the US, is recommended for individuals at high risk for serious illness, including infants aged ≤12 months, pregnant women without evidence of measles immunity, and severely immunocompromised patients regardless of vaccination status. For infants aged 6-11 months, MMR vaccine can be given in place of IG if done within 72 hours of exposure. PEP for children during the 2013 New York City outbreak reduced the risk of measles by 83.4% (95% CI: 34.4%-95.8%) in recipients of MMR vaccine and by 100% (95% CI: 56.2%-99.8%) in recipients of IG compared with those without prophylaxis.5 A 2014 Cochrane Review found that IG reduced the risk of measles by 83% (95% CI: 64%-92%).6

Recommendation 4. Severe measles cases among children, such as those who are hospitalized, should be treated with vitamin A. Vitamin A should be administered immediately on diagnosis and repeated the next day.

In children, vitamin A deficiency, even if clinically inapparent, leads to increased measles severity, and randomized controlled trial data suggest that supplementation reduces measles-related morbidity and mortality.4 Even in high-income countries, children with measles have high rates of vitamin A deficiency, which is associated with increased morbidity.7 A Cochrane review found that two-dose regimens of vitamin A reduced the overall mortality (RR 0.21; 95% CI: 0.07-0.66) in children with measles aged <2 years.8 World Health Organization guidelines suggest vitamin A therapy for all children with acute measles infection, and the AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases recommends vitamin A for severe (ie, hospitalized) cases. Vitamin A is given orally once daily for two days at the following doses: 50,000 international units (IU) for infants aged <6 months, 100,000 IU for infants aged 6-11 months, and 200,000 IU for children aged ≥12 months. A third dose can be given two to four weeks later for children with signs and symptoms of vitamin A deficiency (eg, corneal clouding or conjunctival plaques).

CRITIQUE

In outbreak settings, hospitalists may find challenges with having a sufficient number of single negative-pressure rooms for patients with suspected or confirmed measles and providing IG prophylaxis given the recent national shortages of intravenous immunoglobulin. Collaboration with the infection control team, pharmacy, and the local public health department is essential to appropriately address these challenges. With regard to treatment recommendations, randomized studies on the impact of vitamin A treatment in children have been primarily conducted in resource-limited settings.8 However, these data, in combination with observational data from resource-rich settings,7 support its use given the favorable risk-benefit profile. The role of vitamin A therapy in adults with measles infection is considerably less clear, although there are reports of its use in severe cases.

AREAS OF FUTURE STUDY

Much of our knowledge regarding measles complications and treatment outcomes comes from resource-limited settings or from older data before widespread vaccination. Data suggest that prophylactic antibiotics may prevent complications; however, currently available data are insufficient to support routine use.9 Coordination and collaboration between public health, infectious diseases, and hospital medicine would enhance the ability to conduct detailed epidemiologic studies during outbreak situations. Further studies examining treatment and outcomes in hospitalized patients, including the role of prophylactic antibiotics in the prevention of complications, would provide valuable guidance for hospitalists caring for patients with severe measles.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles Cases and Outbreaks. 2019; https://www.cdc.gov/measles/cases-outbreaks.html. Accessed October 14, 2019.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles (Rubeola): For Healthcare Professionals. 2019; https://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/index.html. Accessed October 14, 2019.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Measles in Healthcare Settings. 2019.

4. Fiebelkorn AP, Redd SB, Kuhar DT. Measles in healthcare facilities in the United States during the postelimination era, 2001-2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(4):615-618. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ387.

5. Arciuolo RJ, Jablonski RR, Zucker JR, Rosen JB. Effectiveness of measles vaccination and immune globulin post-exposure prophylaxis in an outbreak setting-New York City, 2013. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(11):1843-1847. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix639.

6. Young MK, Nimmo GR, Cripps AW, Jones MA. Post-exposure passive immunisation for preventing measles. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(4):Cd010056. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010056.pub2.

7. Frieden TR, Sowell AL, Henning KJ, Huff DL, Gunn RA. Vitamin A levels and severity of measles. New York City. Am J Dis Child. 1992;146(2):182-186. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1992.02160140048019.

8. Huiming Y, Chaomin W, Meng M. Vitamin A for treating measles in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005(4):Cd001479. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001479.pub3.

9. Kabra SK, Lodha R. Antibiotics for preventing complications in children with measles. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(8):Cd001477. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001477.pub3.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles Cases and Outbreaks. 2019; https://www.cdc.gov/measles/cases-outbreaks.html. Accessed October 14, 2019.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles (Rubeola): For Healthcare Professionals. 2019; https://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/index.html. Accessed October 14, 2019.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Measles in Healthcare Settings. 2019.

4. Fiebelkorn AP, Redd SB, Kuhar DT. Measles in healthcare facilities in the United States during the postelimination era, 2001-2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(4):615-618. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ387.

5. Arciuolo RJ, Jablonski RR, Zucker JR, Rosen JB. Effectiveness of measles vaccination and immune globulin post-exposure prophylaxis in an outbreak setting-New York City, 2013. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(11):1843-1847. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix639.

6. Young MK, Nimmo GR, Cripps AW, Jones MA. Post-exposure passive immunisation for preventing measles. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(4):Cd010056. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010056.pub2.

7. Frieden TR, Sowell AL, Henning KJ, Huff DL, Gunn RA. Vitamin A levels and severity of measles. New York City. Am J Dis Child. 1992;146(2):182-186. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1992.02160140048019.

8. Huiming Y, Chaomin W, Meng M. Vitamin A for treating measles in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005(4):Cd001479. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001479.pub3.

9. Kabra SK, Lodha R. Antibiotics for preventing complications in children with measles. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(8):Cd001477. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001477.pub3.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

A Plea to Reconsider the Diagnosis

An eight-month-old unvaccinated boy presented to an emergency department (ED) with fever, neck pain, and lethargy. Examination of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) demonstrated hazy fluid with a white blood cell count of 3,906 cells/uL (90% polymorphonuclear cells, 6% lymphocytes, and 4% monocytes), 0 red blood cells/uL, protein of 40 mg/dL, and glucose of 56 mg/dL. No organisms were seen on Gram stain. Ceftriaxone and vancomycin were administered. CSF, blood, and urine cultures remained sterile; arbovirus serology was nonreactive, and polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) for enterovirus, Herpes simplex virus (HSV), Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Haemophilus influenza were negative. His irritability improved, but his fevers continued. The antibiotics were stopped after 10 days of empiric treatment, and his fever resolved within 36 hours of cessation of antibiotics. He was diagnosed with aseptic meningitis and possible drug fever, attributed to either ceftriaxone or vancomycin.

There are many possibilities to consider in an unimmunized child with signs and symptoms of meningitis. The vaccine-preventable infections are ruled out in the setting of negative cultures and PCRs. While the most common etiology of aseptic meningitis is secondary to viral infections, the considerations of drug fever and aseptic meningitis deserve more attention. A thorough medication history should be taken as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are relatively commonly linked to aseptic meningitis. Evaluation should focus on family history, medications, and exposures.

There was no family history of meningitis nor known exposures to mosquitos or ticks. The patient did not have a history of atypical or severe infections. He had one episode of acute otitis media that resolved without antibiotics. He had a history of delayed speech and was more irritable than his siblings.

Sixteen months later, at two years of age, he presented to his primary care physician in Wisconsin for evaluation of one day of fever and fussiness without rhinorrhea or cough. Examination showed enlarged tonsils without exudate or pharyngeal erythema. His tympanic membranes were normal, and the lung fields were clear. Two of his older siblings and his father had been diagnosed with streptococcal pharyngitis and were receiving antibiotic treatment. A rapid streptococcal antigen test was positive, and amoxicillin started.

Group A streptococcal (GAS) pharyngitis is an acute infection of the oropharynx or nasopharynx caused by Streptococcus pyogenes and is most common in school-aged children. GAS pharyngitis is less common at age two years unless there is definite exposure. The most frequent presentations in this age group (<3 years of age) include protracted nasal symptoms (congestion and rhinorrhea) and cough instead of a well-localized episode of pharyngitis.

The amoxicillin was continued for four days without improvement in fever or fussiness. His oral intake decreased, and he developed nonbilious, nonbloody emesis without diarrhea. He followed up with his pediatrician for the presumed streptococcal pharyngitis. Because of the previous concern for drug fever related to his ceftriaxone exposure, the amoxicillin was discontinued. Supportive care was recommended.

While viral infections remain the most likely etiology, noninfectious etiologies, such as vasculitis, should be considered. Kawasaki disease should be considered in any child with prolonged fever. Kawasaki disease can also cause aseptic meningitis that could provide an explanation for his original episode at eight months of age; nevertheless, it is rare for Kawasaki disease to recur.

Over the next three days, his temperature was as high as 38.8°C (101.8°F), he became more irritable, and his vomiting worsened; his family believed he had a headache. He was again seen by his pediatrician, now with eight days of fever. On examination, his oropharynx was mildly erythematous with palatal petechiae and 2+ tonsillar enlargement; shotty anterior cervical lymphadenopathy was present. Concern for incompletely treated streptococcal pharyngitis prompted prescription of azithromycin for five days.

This information does not change the differential diagnosis significantly. Azithromycin is as effective as beta lactams for the treatment of GAS pharyngitis if the GAS is susceptible to macrolides. Macrolide resistance rates vary between communities and have been as high as 15% in Wisconsin; knowledge of local resistance patterns is important.1

Despite the azithromycin, his symptoms worsened, and he became lethargic. The family believed the symptoms were similar to those during his previous episode of meningitis. They presented to an ED where he was febrile to 39.4°C (102.9°F) with a heart rate of 159 beats per minute and blood pressure of 113/84 mm Hg. His head circumference was 50.5 cm (97th percentile) compared with his weight of 10.8 kg (23.81 lbs; 22nd percentile). He was listless when undisturbed and irritable during the examination; his neck was supple and strong, and reflexes were normal. The remainder of his examination, including joints and skin, was normal. His white blood cell count was 18.6 K/uL, hemoglobin 11.8 g/dL, and platelets 401 K/uL. A chest radiograph was normal.

The patient is presenting on the 10th day of fever—a long time for any patient to remain febrile. Although most typically due to infectious etiologies, rheumatologic and oncologic diseases must be considered. It is important to characterize the pattern of fevers during the past 10 days and whether the patient has had similar febrile illnesses in the past. In this case, his past medical history substantially alters the differential diagnosis. The positive rapid strep test and history of recent strep pharyngitis are of uncertain importance, and the patient’s nonresponsiveness to antibiotics should raise concern for a second disease process (other than streptococcal infection) causing the fever. His unimmunized status changes the pretest probability of serious conditions such as bacterial meningitis caused by S. pneumoniae. A lumbar puncture should be performed, including an opening pressure; if the CSF again shows pleocytosis, but no infectious etiology is identified, then imaging of the brain (magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] or magnetic resonance angiogram) should be performed to evaluate for anatomic abnormalities.

CSF examination revealed 9,327 white blood cells/uL (82% polymorphonuclear cells, 1% lymphocytes, and 17% monocytes), 114 red blood cells/uL, protein of 87 mg/dL, and glucose of 63 mg/dL. Gram stain revealed no organisms. Ceftriaxone, vancomycin, and acyclovir were started, and he was transferred to a children’s hospital.

This history must be viewed through two alternate lenses: that the two episodes of meningitis are related or that they are unrelated. The finding of a neutrophil predominance in the CSF in the setting of aseptic (or nonbacterial) meningitis is less common than a lymphocytic predominance. Most commonly, aseptic meningitis is due to viral infection and is typically associated with a lymphocyte predominance, although a moderate neutrophil predominance can be seen in patients with enterovirus meningitis. Neutrophil-predominant aseptic meningitis can also accompany genetic auto-inflammatory syndromes (eg, familial Mediterranean fever and cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome). This finding can also be seen in other noninfectious conditions such as neurosarcoidosis, Behçet’s disease, Cogan syndrome, and other vasculitides. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis can also cause neutrophil predominance. Additionally, the apparent neutrophil predominance could be explained if the patient had lymphopenia associated with primary or acquired immunodeficiency; therefore, the peripheral leukocyte differential obtained at the same time as the CSF should be evaluated. However, immunodeficiency is less likely given the patient’s lack of history of recurrent infections.

The main objective information added here is that the patient now has his second episode of likely aseptic meningitis with neutrophilic predominance, although it is possible that antibiotic therapy may have led to a false-negative CSF culture. However, this possible partial treatment was not a consideration in the first episode of meningitis. Having two similar episodes increases the likelihood that the patient has an underlying inflammatory/immune disorder, likely genetic (now termed “inborn errors of immunity”), or that there is a common exposure not yet revealed in the history (eg, drug-induced meningitis). Primary immunodeficiency is less likely than an autoinflammatory disease, considering the patient’s course of recovery with the first episode.

Further evaluation of the CSF did not reveal a pathogen. Bacterial CSF culture was sterile, and PCRs for HSV and enterovirus were negative.

The differential diagnosis is narrowing to include causes of recurrent, aseptic, neutrophilic meningitis. The incongruous head circumference and weight could be due to a relatively large head, a relatively low weight, or both. To interpret these data properly, one also needs to know the patient’s length, the trajectory of his growth parameters over time, and the parents’ heights and head circumferences. One possible scenario, considering the rest of the history, is that the patient has a chronic inflammatory condition of the central nervous system (CNS), leading to hydrocephalus and macrocephaly. It is possible that systemic inflammation could also lead to poor weight gain.

When considering chronic causes of aseptic meningitis associated with neutrophil predominance in the CSF, autoinflammatory disorders (cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome, Muckle–Wells syndrome, neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease [NOMID], and chronic infantile neurological cutaneous articular syndrome [CINCA]) should be considered. The patient lacks the typical deforming arthropathy of the most severe NOMID/CINCA phenotype. If the brain imaging does not reveal another etiology, then genetic testing of the patient is indicated.

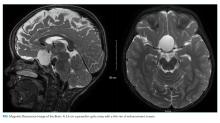

Because of the history of recurrent meningitis with marked neutrophilic pleocytosis, yet no evidence of infection given normal glucose, only mildly elevated protein, and no culture growth, an MRI of the brain was obtained. MRI revealed a sharply circumscribed, homogeneous, nonenhancing 2.6 cm diameter cystic suprasellar mass with a thin rim of capsular enhancement (Figure). The appearance was most consistent with an epidermoid cyst, a dermoid, Rathke’s cleft cyst (RCC), or, less likely, a craniopharyngioma. The recurrent aseptic meningitis was attributed to chemical meningitis secondary to episodic discharging of the tumor. There was no hydrocephalus on imaging, and the enlarged head circumference was attributed to large parental head circumference.

Antibiotics were discontinued and supportive care continued. A CSF cholesterol level of 4 mg/dL was found (normal range 0.6 ± 0.2 mg/dL) on the CSF from admission. Fevers and symptoms ultimately improved with 72 hours of admission. He was discharged with neurosurgical follow-up, and within a year, he developed a third episode of aseptic meningitis. He eventually underwent a craniotomy with near-total resection of the cyst. Histopathological analysis indicated the presence of an underlying RCC, despite initial clinical and radiographic suspicion of an epidermoid cyst. He recovered well with follow-up imaging demonstrating stable resolution of the RCC and no further incidents of aseptic meningitis in the 12 months since the surgery.

DISCUSSION

Aseptic meningitis is defined as meningitis with negative bacterial cultures from CSF and is habitually equated with viral meningitis.2 This erroneous equivalence may curb critical thinking about alternative diagnoses, as aseptic meningitis may also be associated with a wide range of both infectious and noninfectious etiologies (Table). A thorough history and physical examination are the essential first steps in determining the etiology of aseptic meningitis, as many of the listed etiologies can be effectively eliminated through the evaluation of risk factors and exposures. Laboratory evaluation of CSF including cell count with differential, glucose, and protein levels is required. Gram stain and culture should be obtained to evaluate for bacterial meningitis even if suspicion is low. Multiplex and dedicated PCRs to viral agents as well as a serologic test for arboviruses, are widely available. Multiple episodes of aseptic meningitis with HSV, known as Mollaret’s meningitis, or enterovirus, which is more common in males with X-linked agammaglobulinemia, should be considered in patients with recurrent disease. Imaging is not indicated for every patient with aseptic meningitis; however, if anatomic abnormalities or malignancy are suspected, or in the evaluation of recurrent disease, then an MRI of the brain should be considered.

This case highlights how the analysis of CSF pleocytosis is not always predictive of a specific underlying etiology. The classic teaching that viral meningitis is associated with lymphocytic pleocytosis is based on studies of mumps meningitis.3 It is important to recognize that a neutrophilic pleocytosis is also described in viral infections including those caused by an enterovirus, herpes simplex, and arboviruses.4,5 Moreover, while the magnitude of the neutrophilic pleocytosis should always raise suspicion of bacterial meningitis, it should also be associated with hypoglycorrhachia and elevated CSF protein levels. Antibiotic pretreatment of bacterial meningitis can alter CSF chemistries (raise CSF glucose levels and lower CSF protein levels), but chemistries are unlikely to return completely to normal.6 In this case, one clue that hinted toward a noninfectious etiology was the recurrence of relatively normal CSF glucose and protein levels in the setting of such a highly inflammatory pleocytosis on multiple occasions.

There is a wide spectrum of CNS mass lesions known for causing chemical meningitis including epidermoid, dermoid, craniopharyngiomas, and RCCs. While imaging can be suggestive, histological examination is often required to make a specific diagnosis. In this patient, the diagnosis of chemical meningitis secondary to a ruptured brain tumor was confirmed by MRI. CNS tumors that may cause aseptic meningitis are typically slow-growing lesions that cause symptoms due both to local growth and regional neurovascular compression. These masses can rupture and disseminate inflammatory contents into the subarachnoid space giving rise to chemical aseptic meningitis. Their contents may include materials rich in keratin, cholesterol, and lipids, which cause an intense sterile inflammatory reaction when discharged, possibly via cholesterol activation of the inflammasome.7,8 The subsequent inflammatory response produces a neutrophilic pleocytosis, often suggestive of bacterial meningitis, while simultaneously maintaining the near normalcy of the CSF glucose and protein levels. Elevated levels of CSF cholesterol may raise suspicion of the diagnosis. Not all discharging tumors result in purely chemical meningitis, as secondary bacterial meningitis with S. pneumoniae or other respiratory flora can coexist if cysts communicate with the respiratory tract.9

Rathke’s cleft is formed during the development of the pituitary gland by the evagination of oral ectoderm through the precursor of the oral cavity.10 The cleft gives rise to the endocrine cells of the anterior pituitary. It subsequently disconnects from the oral cavity and develops into the pars intermedia between the anterior and posterior pituitary. Cystic enlargement of Rathke’s cleft through epithelial proliferation and secondary secretions leads to the development of an RCC. RCCs are nonneoplastic lesions, and the majority are diagnosed incidentally. Asymptomatic RCCs are common and are detected in 13%-22% of routine autopsies.11 Symptomatic lesions may present with headaches due to mechanical effects on pain-sensitive dura or cranial nerves. Severe acute onset headaches may arise secondary to pituitary hemorrhage. RCCs can also cause ophthalmic or endocrinological impairment due to sellar compression. As in the present case, rarely cystic rupture and subarachnoid extravasation of epithelial-derived contents lead to a chemical aseptic meningitis.12

Surgical resection is indicated for symptomatic RCCs that exert neurologic, ophthalmic, or endocrinological symptoms.13 The surgical goal is the removal of the lesion and complete excision of the capsule unless it is extremely adherent to neurovascular structures. Surgical morbidity is related to the risk of hypopituitarism, visual decline, incomplete resection with lesion regrowth, and aseptic meningitis. Surgical approaches to this region are potentially complicated by proximity to optic nerves, pituitary glands, major arteries, and perforating vessels belonging to the circle of Willis. In addition, potential dehiscence of the skull base floor due to progressive cyst growth can give rise to a delayed risk of CSF leak and complicate surgical recovery. Surgery was indicated for this patient because of the parasellar location of his cyst placing him at risk for visual decline due to compression of the optic chiasm as well as pituitary dysfunction or obstructive hydrocephalus from ventricular compression.

This case is illustrative for learning because, at the outset, there were many possibilities to explore in an unimmunized child with meningitis. This patient’s neutrophilic cell count and partial antibiotic treatment only compounded the certainty of a bacterial etiology. However, further scrutiny of the history and laboratory parameters revealed the true underlying diagnosis of RCC. Ultimately, the plea to reconsider the pleocytosis was heard.

KEY LEARNING POINTS

- The CSF cell count and differential should be used in conjunction with CSF chemistries (glucose and protein) to raise or lower suspicion of bacterial meningitis.

- Aseptic meningitis is a syndrome and not a specific diagnosis. Clinicians should be alert to key aspects of the history and physical examination, which prompt consideration of noninfectious etiologies.

- Aseptic chemical meningitis secondary to discharging CNS tumors, including RCCs, should be considered in episodes of recurrent culture-negative meningitis.

1. DeMuri GP, Sterkel AK, Kubica PA, Duster MN, Reed KD, Wald ER. Macrolide and clindamycin resistance in group a streptococci isolated from children with pharyngitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36(3):342-344. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000001442.

2. Lee BE, Davies HD. Aseptic meningitis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20(3):272-277. https://doi.org/10.1097/QCO.0b013e3280ad4672.

3. Ritter BS. Mumps meningoencephalitis in children. J Pediatr. 1958;52(4):424-433. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3476(58)80063-3.

4. Miller SA, Wald ER, Bergman I, DeBiasio R. Enteroviral meningitis in January with marked cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1986;5(6):706-707. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006454-198611000-00024.

5. Jaijakul S, Salazar L, Wootton SH, Aguilera E, Hasbun R. The clinical significance of neutrophilic pleocytosis in cerebrospinal fluid in patients with viral central nervous system infections. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;59:77-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2017.04.010.

6. Nigrovic LE, Malley R, Macias CG, et al. Effect of antibiotic pretreatment on cerebrospinal fluid profiles of children with bacterial meningitis. Pediatrics. 2008;122(4):726-730. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-3275.

7. Cherian A, Baheti NN, Easwar HV, Nair DS, Iype T. Recurrent meningitis due to epidermoid. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2012;7(1):47-48. https://doi.org/10.4103/1817-1745.97624.

8. Grebe A, Latz E. Cholesterol crystals and inflammation. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2013;15(3):313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-012-0313-z.

9. Kriss TC, Kriss VM, Warf BC. Recurrent meningitis: the search for the dermoid or epidermoid tumor. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14(8):697-700.

10. Bresson D, Herman P, Polivka M, Froelich S. Sellar lesions/pathology. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2016;49(1):63-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2015.09.004.

11. Billeci D, Marton E, Tripodi M, Orvieto E, Longatti P. Symptomatic Rathke’s cleft cysts: a radiological, surgical and pathological review. Pituitary. 2004;7(3):131-137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-005-1755-3.

12. Steinberg GK, Koenig GH, Golden JB. Symptomatic Rathke’s cleft cysts. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 1982;56(2):290-295. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1982.56.2.0290.

13. Zada G. Rathke cleft cysts: a review of clinical and surgical management. Neurosurg Focus. 2011;31(1):E1. https://doi.org/10.3171/2011.5.FOCUS1183.

An eight-month-old unvaccinated boy presented to an emergency department (ED) with fever, neck pain, and lethargy. Examination of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) demonstrated hazy fluid with a white blood cell count of 3,906 cells/uL (90% polymorphonuclear cells, 6% lymphocytes, and 4% monocytes), 0 red blood cells/uL, protein of 40 mg/dL, and glucose of 56 mg/dL. No organisms were seen on Gram stain. Ceftriaxone and vancomycin were administered. CSF, blood, and urine cultures remained sterile; arbovirus serology was nonreactive, and polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) for enterovirus, Herpes simplex virus (HSV), Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Haemophilus influenza were negative. His irritability improved, but his fevers continued. The antibiotics were stopped after 10 days of empiric treatment, and his fever resolved within 36 hours of cessation of antibiotics. He was diagnosed with aseptic meningitis and possible drug fever, attributed to either ceftriaxone or vancomycin.

There are many possibilities to consider in an unimmunized child with signs and symptoms of meningitis. The vaccine-preventable infections are ruled out in the setting of negative cultures and PCRs. While the most common etiology of aseptic meningitis is secondary to viral infections, the considerations of drug fever and aseptic meningitis deserve more attention. A thorough medication history should be taken as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are relatively commonly linked to aseptic meningitis. Evaluation should focus on family history, medications, and exposures.

There was no family history of meningitis nor known exposures to mosquitos or ticks. The patient did not have a history of atypical or severe infections. He had one episode of acute otitis media that resolved without antibiotics. He had a history of delayed speech and was more irritable than his siblings.

Sixteen months later, at two years of age, he presented to his primary care physician in Wisconsin for evaluation of one day of fever and fussiness without rhinorrhea or cough. Examination showed enlarged tonsils without exudate or pharyngeal erythema. His tympanic membranes were normal, and the lung fields were clear. Two of his older siblings and his father had been diagnosed with streptococcal pharyngitis and were receiving antibiotic treatment. A rapid streptococcal antigen test was positive, and amoxicillin started.

Group A streptococcal (GAS) pharyngitis is an acute infection of the oropharynx or nasopharynx caused by Streptococcus pyogenes and is most common in school-aged children. GAS pharyngitis is less common at age two years unless there is definite exposure. The most frequent presentations in this age group (<3 years of age) include protracted nasal symptoms (congestion and rhinorrhea) and cough instead of a well-localized episode of pharyngitis.

The amoxicillin was continued for four days without improvement in fever or fussiness. His oral intake decreased, and he developed nonbilious, nonbloody emesis without diarrhea. He followed up with his pediatrician for the presumed streptococcal pharyngitis. Because of the previous concern for drug fever related to his ceftriaxone exposure, the amoxicillin was discontinued. Supportive care was recommended.

While viral infections remain the most likely etiology, noninfectious etiologies, such as vasculitis, should be considered. Kawasaki disease should be considered in any child with prolonged fever. Kawasaki disease can also cause aseptic meningitis that could provide an explanation for his original episode at eight months of age; nevertheless, it is rare for Kawasaki disease to recur.

Over the next three days, his temperature was as high as 38.8°C (101.8°F), he became more irritable, and his vomiting worsened; his family believed he had a headache. He was again seen by his pediatrician, now with eight days of fever. On examination, his oropharynx was mildly erythematous with palatal petechiae and 2+ tonsillar enlargement; shotty anterior cervical lymphadenopathy was present. Concern for incompletely treated streptococcal pharyngitis prompted prescription of azithromycin for five days.

This information does not change the differential diagnosis significantly. Azithromycin is as effective as beta lactams for the treatment of GAS pharyngitis if the GAS is susceptible to macrolides. Macrolide resistance rates vary between communities and have been as high as 15% in Wisconsin; knowledge of local resistance patterns is important.1

Despite the azithromycin, his symptoms worsened, and he became lethargic. The family believed the symptoms were similar to those during his previous episode of meningitis. They presented to an ED where he was febrile to 39.4°C (102.9°F) with a heart rate of 159 beats per minute and blood pressure of 113/84 mm Hg. His head circumference was 50.5 cm (97th percentile) compared with his weight of 10.8 kg (23.81 lbs; 22nd percentile). He was listless when undisturbed and irritable during the examination; his neck was supple and strong, and reflexes were normal. The remainder of his examination, including joints and skin, was normal. His white blood cell count was 18.6 K/uL, hemoglobin 11.8 g/dL, and platelets 401 K/uL. A chest radiograph was normal.

The patient is presenting on the 10th day of fever—a long time for any patient to remain febrile. Although most typically due to infectious etiologies, rheumatologic and oncologic diseases must be considered. It is important to characterize the pattern of fevers during the past 10 days and whether the patient has had similar febrile illnesses in the past. In this case, his past medical history substantially alters the differential diagnosis. The positive rapid strep test and history of recent strep pharyngitis are of uncertain importance, and the patient’s nonresponsiveness to antibiotics should raise concern for a second disease process (other than streptococcal infection) causing the fever. His unimmunized status changes the pretest probability of serious conditions such as bacterial meningitis caused by S. pneumoniae. A lumbar puncture should be performed, including an opening pressure; if the CSF again shows pleocytosis, but no infectious etiology is identified, then imaging of the brain (magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] or magnetic resonance angiogram) should be performed to evaluate for anatomic abnormalities.

CSF examination revealed 9,327 white blood cells/uL (82% polymorphonuclear cells, 1% lymphocytes, and 17% monocytes), 114 red blood cells/uL, protein of 87 mg/dL, and glucose of 63 mg/dL. Gram stain revealed no organisms. Ceftriaxone, vancomycin, and acyclovir were started, and he was transferred to a children’s hospital.

This history must be viewed through two alternate lenses: that the two episodes of meningitis are related or that they are unrelated. The finding of a neutrophil predominance in the CSF in the setting of aseptic (or nonbacterial) meningitis is less common than a lymphocytic predominance. Most commonly, aseptic meningitis is due to viral infection and is typically associated with a lymphocyte predominance, although a moderate neutrophil predominance can be seen in patients with enterovirus meningitis. Neutrophil-predominant aseptic meningitis can also accompany genetic auto-inflammatory syndromes (eg, familial Mediterranean fever and cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome). This finding can also be seen in other noninfectious conditions such as neurosarcoidosis, Behçet’s disease, Cogan syndrome, and other vasculitides. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis can also cause neutrophil predominance. Additionally, the apparent neutrophil predominance could be explained if the patient had lymphopenia associated with primary or acquired immunodeficiency; therefore, the peripheral leukocyte differential obtained at the same time as the CSF should be evaluated. However, immunodeficiency is less likely given the patient’s lack of history of recurrent infections.

The main objective information added here is that the patient now has his second episode of likely aseptic meningitis with neutrophilic predominance, although it is possible that antibiotic therapy may have led to a false-negative CSF culture. However, this possible partial treatment was not a consideration in the first episode of meningitis. Having two similar episodes increases the likelihood that the patient has an underlying inflammatory/immune disorder, likely genetic (now termed “inborn errors of immunity”), or that there is a common exposure not yet revealed in the history (eg, drug-induced meningitis). Primary immunodeficiency is less likely than an autoinflammatory disease, considering the patient’s course of recovery with the first episode.

Further evaluation of the CSF did not reveal a pathogen. Bacterial CSF culture was sterile, and PCRs for HSV and enterovirus were negative.

The differential diagnosis is narrowing to include causes of recurrent, aseptic, neutrophilic meningitis. The incongruous head circumference and weight could be due to a relatively large head, a relatively low weight, or both. To interpret these data properly, one also needs to know the patient’s length, the trajectory of his growth parameters over time, and the parents’ heights and head circumferences. One possible scenario, considering the rest of the history, is that the patient has a chronic inflammatory condition of the central nervous system (CNS), leading to hydrocephalus and macrocephaly. It is possible that systemic inflammation could also lead to poor weight gain.

When considering chronic causes of aseptic meningitis associated with neutrophil predominance in the CSF, autoinflammatory disorders (cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome, Muckle–Wells syndrome, neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease [NOMID], and chronic infantile neurological cutaneous articular syndrome [CINCA]) should be considered. The patient lacks the typical deforming arthropathy of the most severe NOMID/CINCA phenotype. If the brain imaging does not reveal another etiology, then genetic testing of the patient is indicated.

Because of the history of recurrent meningitis with marked neutrophilic pleocytosis, yet no evidence of infection given normal glucose, only mildly elevated protein, and no culture growth, an MRI of the brain was obtained. MRI revealed a sharply circumscribed, homogeneous, nonenhancing 2.6 cm diameter cystic suprasellar mass with a thin rim of capsular enhancement (Figure). The appearance was most consistent with an epidermoid cyst, a dermoid, Rathke’s cleft cyst (RCC), or, less likely, a craniopharyngioma. The recurrent aseptic meningitis was attributed to chemical meningitis secondary to episodic discharging of the tumor. There was no hydrocephalus on imaging, and the enlarged head circumference was attributed to large parental head circumference.

Antibiotics were discontinued and supportive care continued. A CSF cholesterol level of 4 mg/dL was found (normal range 0.6 ± 0.2 mg/dL) on the CSF from admission. Fevers and symptoms ultimately improved with 72 hours of admission. He was discharged with neurosurgical follow-up, and within a year, he developed a third episode of aseptic meningitis. He eventually underwent a craniotomy with near-total resection of the cyst. Histopathological analysis indicated the presence of an underlying RCC, despite initial clinical and radiographic suspicion of an epidermoid cyst. He recovered well with follow-up imaging demonstrating stable resolution of the RCC and no further incidents of aseptic meningitis in the 12 months since the surgery.

DISCUSSION

Aseptic meningitis is defined as meningitis with negative bacterial cultures from CSF and is habitually equated with viral meningitis.2 This erroneous equivalence may curb critical thinking about alternative diagnoses, as aseptic meningitis may also be associated with a wide range of both infectious and noninfectious etiologies (Table). A thorough history and physical examination are the essential first steps in determining the etiology of aseptic meningitis, as many of the listed etiologies can be effectively eliminated through the evaluation of risk factors and exposures. Laboratory evaluation of CSF including cell count with differential, glucose, and protein levels is required. Gram stain and culture should be obtained to evaluate for bacterial meningitis even if suspicion is low. Multiplex and dedicated PCRs to viral agents as well as a serologic test for arboviruses, are widely available. Multiple episodes of aseptic meningitis with HSV, known as Mollaret’s meningitis, or enterovirus, which is more common in males with X-linked agammaglobulinemia, should be considered in patients with recurrent disease. Imaging is not indicated for every patient with aseptic meningitis; however, if anatomic abnormalities or malignancy are suspected, or in the evaluation of recurrent disease, then an MRI of the brain should be considered.

This case highlights how the analysis of CSF pleocytosis is not always predictive of a specific underlying etiology. The classic teaching that viral meningitis is associated with lymphocytic pleocytosis is based on studies of mumps meningitis.3 It is important to recognize that a neutrophilic pleocytosis is also described in viral infections including those caused by an enterovirus, herpes simplex, and arboviruses.4,5 Moreover, while the magnitude of the neutrophilic pleocytosis should always raise suspicion of bacterial meningitis, it should also be associated with hypoglycorrhachia and elevated CSF protein levels. Antibiotic pretreatment of bacterial meningitis can alter CSF chemistries (raise CSF glucose levels and lower CSF protein levels), but chemistries are unlikely to return completely to normal.6 In this case, one clue that hinted toward a noninfectious etiology was the recurrence of relatively normal CSF glucose and protein levels in the setting of such a highly inflammatory pleocytosis on multiple occasions.

There is a wide spectrum of CNS mass lesions known for causing chemical meningitis including epidermoid, dermoid, craniopharyngiomas, and RCCs. While imaging can be suggestive, histological examination is often required to make a specific diagnosis. In this patient, the diagnosis of chemical meningitis secondary to a ruptured brain tumor was confirmed by MRI. CNS tumors that may cause aseptic meningitis are typically slow-growing lesions that cause symptoms due both to local growth and regional neurovascular compression. These masses can rupture and disseminate inflammatory contents into the subarachnoid space giving rise to chemical aseptic meningitis. Their contents may include materials rich in keratin, cholesterol, and lipids, which cause an intense sterile inflammatory reaction when discharged, possibly via cholesterol activation of the inflammasome.7,8 The subsequent inflammatory response produces a neutrophilic pleocytosis, often suggestive of bacterial meningitis, while simultaneously maintaining the near normalcy of the CSF glucose and protein levels. Elevated levels of CSF cholesterol may raise suspicion of the diagnosis. Not all discharging tumors result in purely chemical meningitis, as secondary bacterial meningitis with S. pneumoniae or other respiratory flora can coexist if cysts communicate with the respiratory tract.9

Rathke’s cleft is formed during the development of the pituitary gland by the evagination of oral ectoderm through the precursor of the oral cavity.10 The cleft gives rise to the endocrine cells of the anterior pituitary. It subsequently disconnects from the oral cavity and develops into the pars intermedia between the anterior and posterior pituitary. Cystic enlargement of Rathke’s cleft through epithelial proliferation and secondary secretions leads to the development of an RCC. RCCs are nonneoplastic lesions, and the majority are diagnosed incidentally. Asymptomatic RCCs are common and are detected in 13%-22% of routine autopsies.11 Symptomatic lesions may present with headaches due to mechanical effects on pain-sensitive dura or cranial nerves. Severe acute onset headaches may arise secondary to pituitary hemorrhage. RCCs can also cause ophthalmic or endocrinological impairment due to sellar compression. As in the present case, rarely cystic rupture and subarachnoid extravasation of epithelial-derived contents lead to a chemical aseptic meningitis.12

Surgical resection is indicated for symptomatic RCCs that exert neurologic, ophthalmic, or endocrinological symptoms.13 The surgical goal is the removal of the lesion and complete excision of the capsule unless it is extremely adherent to neurovascular structures. Surgical morbidity is related to the risk of hypopituitarism, visual decline, incomplete resection with lesion regrowth, and aseptic meningitis. Surgical approaches to this region are potentially complicated by proximity to optic nerves, pituitary glands, major arteries, and perforating vessels belonging to the circle of Willis. In addition, potential dehiscence of the skull base floor due to progressive cyst growth can give rise to a delayed risk of CSF leak and complicate surgical recovery. Surgery was indicated for this patient because of the parasellar location of his cyst placing him at risk for visual decline due to compression of the optic chiasm as well as pituitary dysfunction or obstructive hydrocephalus from ventricular compression.

This case is illustrative for learning because, at the outset, there were many possibilities to explore in an unimmunized child with meningitis. This patient’s neutrophilic cell count and partial antibiotic treatment only compounded the certainty of a bacterial etiology. However, further scrutiny of the history and laboratory parameters revealed the true underlying diagnosis of RCC. Ultimately, the plea to reconsider the pleocytosis was heard.

KEY LEARNING POINTS

- The CSF cell count and differential should be used in conjunction with CSF chemistries (glucose and protein) to raise or lower suspicion of bacterial meningitis.

- Aseptic meningitis is a syndrome and not a specific diagnosis. Clinicians should be alert to key aspects of the history and physical examination, which prompt consideration of noninfectious etiologies.

- Aseptic chemical meningitis secondary to discharging CNS tumors, including RCCs, should be considered in episodes of recurrent culture-negative meningitis.

An eight-month-old unvaccinated boy presented to an emergency department (ED) with fever, neck pain, and lethargy. Examination of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) demonstrated hazy fluid with a white blood cell count of 3,906 cells/uL (90% polymorphonuclear cells, 6% lymphocytes, and 4% monocytes), 0 red blood cells/uL, protein of 40 mg/dL, and glucose of 56 mg/dL. No organisms were seen on Gram stain. Ceftriaxone and vancomycin were administered. CSF, blood, and urine cultures remained sterile; arbovirus serology was nonreactive, and polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) for enterovirus, Herpes simplex virus (HSV), Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Haemophilus influenza were negative. His irritability improved, but his fevers continued. The antibiotics were stopped after 10 days of empiric treatment, and his fever resolved within 36 hours of cessation of antibiotics. He was diagnosed with aseptic meningitis and possible drug fever, attributed to either ceftriaxone or vancomycin.

There are many possibilities to consider in an unimmunized child with signs and symptoms of meningitis. The vaccine-preventable infections are ruled out in the setting of negative cultures and PCRs. While the most common etiology of aseptic meningitis is secondary to viral infections, the considerations of drug fever and aseptic meningitis deserve more attention. A thorough medication history should be taken as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are relatively commonly linked to aseptic meningitis. Evaluation should focus on family history, medications, and exposures.

There was no family history of meningitis nor known exposures to mosquitos or ticks. The patient did not have a history of atypical or severe infections. He had one episode of acute otitis media that resolved without antibiotics. He had a history of delayed speech and was more irritable than his siblings.

Sixteen months later, at two years of age, he presented to his primary care physician in Wisconsin for evaluation of one day of fever and fussiness without rhinorrhea or cough. Examination showed enlarged tonsils without exudate or pharyngeal erythema. His tympanic membranes were normal, and the lung fields were clear. Two of his older siblings and his father had been diagnosed with streptococcal pharyngitis and were receiving antibiotic treatment. A rapid streptococcal antigen test was positive, and amoxicillin started.

Group A streptococcal (GAS) pharyngitis is an acute infection of the oropharynx or nasopharynx caused by Streptococcus pyogenes and is most common in school-aged children. GAS pharyngitis is less common at age two years unless there is definite exposure. The most frequent presentations in this age group (<3 years of age) include protracted nasal symptoms (congestion and rhinorrhea) and cough instead of a well-localized episode of pharyngitis.

The amoxicillin was continued for four days without improvement in fever or fussiness. His oral intake decreased, and he developed nonbilious, nonbloody emesis without diarrhea. He followed up with his pediatrician for the presumed streptococcal pharyngitis. Because of the previous concern for drug fever related to his ceftriaxone exposure, the amoxicillin was discontinued. Supportive care was recommended.

While viral infections remain the most likely etiology, noninfectious etiologies, such as vasculitis, should be considered. Kawasaki disease should be considered in any child with prolonged fever. Kawasaki disease can also cause aseptic meningitis that could provide an explanation for his original episode at eight months of age; nevertheless, it is rare for Kawasaki disease to recur.

Over the next three days, his temperature was as high as 38.8°C (101.8°F), he became more irritable, and his vomiting worsened; his family believed he had a headache. He was again seen by his pediatrician, now with eight days of fever. On examination, his oropharynx was mildly erythematous with palatal petechiae and 2+ tonsillar enlargement; shotty anterior cervical lymphadenopathy was present. Concern for incompletely treated streptococcal pharyngitis prompted prescription of azithromycin for five days.

This information does not change the differential diagnosis significantly. Azithromycin is as effective as beta lactams for the treatment of GAS pharyngitis if the GAS is susceptible to macrolides. Macrolide resistance rates vary between communities and have been as high as 15% in Wisconsin; knowledge of local resistance patterns is important.1

Despite the azithromycin, his symptoms worsened, and he became lethargic. The family believed the symptoms were similar to those during his previous episode of meningitis. They presented to an ED where he was febrile to 39.4°C (102.9°F) with a heart rate of 159 beats per minute and blood pressure of 113/84 mm Hg. His head circumference was 50.5 cm (97th percentile) compared with his weight of 10.8 kg (23.81 lbs; 22nd percentile). He was listless when undisturbed and irritable during the examination; his neck was supple and strong, and reflexes were normal. The remainder of his examination, including joints and skin, was normal. His white blood cell count was 18.6 K/uL, hemoglobin 11.8 g/dL, and platelets 401 K/uL. A chest radiograph was normal.

The patient is presenting on the 10th day of fever—a long time for any patient to remain febrile. Although most typically due to infectious etiologies, rheumatologic and oncologic diseases must be considered. It is important to characterize the pattern of fevers during the past 10 days and whether the patient has had similar febrile illnesses in the past. In this case, his past medical history substantially alters the differential diagnosis. The positive rapid strep test and history of recent strep pharyngitis are of uncertain importance, and the patient’s nonresponsiveness to antibiotics should raise concern for a second disease process (other than streptococcal infection) causing the fever. His unimmunized status changes the pretest probability of serious conditions such as bacterial meningitis caused by S. pneumoniae. A lumbar puncture should be performed, including an opening pressure; if the CSF again shows pleocytosis, but no infectious etiology is identified, then imaging of the brain (magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] or magnetic resonance angiogram) should be performed to evaluate for anatomic abnormalities.

CSF examination revealed 9,327 white blood cells/uL (82% polymorphonuclear cells, 1% lymphocytes, and 17% monocytes), 114 red blood cells/uL, protein of 87 mg/dL, and glucose of 63 mg/dL. Gram stain revealed no organisms. Ceftriaxone, vancomycin, and acyclovir were started, and he was transferred to a children’s hospital.

This history must be viewed through two alternate lenses: that the two episodes of meningitis are related or that they are unrelated. The finding of a neutrophil predominance in the CSF in the setting of aseptic (or nonbacterial) meningitis is less common than a lymphocytic predominance. Most commonly, aseptic meningitis is due to viral infection and is typically associated with a lymphocyte predominance, although a moderate neutrophil predominance can be seen in patients with enterovirus meningitis. Neutrophil-predominant aseptic meningitis can also accompany genetic auto-inflammatory syndromes (eg, familial Mediterranean fever and cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome). This finding can also be seen in other noninfectious conditions such as neurosarcoidosis, Behçet’s disease, Cogan syndrome, and other vasculitides. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis can also cause neutrophil predominance. Additionally, the apparent neutrophil predominance could be explained if the patient had lymphopenia associated with primary or acquired immunodeficiency; therefore, the peripheral leukocyte differential obtained at the same time as the CSF should be evaluated. However, immunodeficiency is less likely given the patient’s lack of history of recurrent infections.