User login

Things We Do For No Reason: Electrolyte Testing in Pediatric Acute Gastroenteritis

The “Things We Do for No Reason” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but that may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

Acute gastroenteritis (AGE) remains a substantial cause of childhood illness and is 1 of the top 10 reasons for pediatric hospitalization nationwide. In the United States, AGE is responsible for 10% of hospital admissions and approximately 300 deaths annually.1 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and other organizations have emphasized supportive care in the management of AGE. Routine diagnostic testing has been discouraged in national guidelines except in cases of severe dehydration or an otherwise complicated course. Despite AGE guidelines, diagnostic laboratory tests are still widely used even though they have been shown to be poor predictors of dehydration. Studies have shown that high test utilization in various pediatric disease processes often influences the decision for hospitalization without improvement in patient outcome. In children with AGE, the initial and follow-up laboratory tests may not only be something that we do for no reason, but something that is associated with more risk than benefit.

An 18-month-old healthy male is brought to the emergency department (ED) with a chief complaint of 2 days of nonbloody, nonbilious emesis and watery diarrhea. He has decreased energy but smiles and plays for a few minutes. He has had decreased wet diapers. His exam is notable for mild tachycardia, mildly dry lips, and capillary refill of 3 seconds. A serum electrolyte panel is normal except for a sodium of 134 mEq/L, a bicarbonate of 16 mEq/L, and an anion gap of 18, which are flagged as abnormal by the electronic medical record. These results prompt intravenous (IV) access, a normal saline bolus, and admission on maintenance fluids overnight. The next morning, his electrolyte panel is repeated, and his sodium is 140 mEq/L and bicarbonate is 15 mEq/L. He is now drinking well with no further episodes of emesis, so he is discharged home.

WHY PHYSICIANS MIGHT THINK ELECTROLYTE TESTING IS HELPFUL

Many physicians across the United States continue to order electrolytes in AGE as a way to avoid missing severe dehydration, severe electrolyte abnormalities, or rare diagnoses, such as adrenal insufficiency or new-onset diabetes, in a child. Previous studies have revealed that bicarbonate and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) may be helpful predictors of severe dehydration. A retrospective study of 168 patients by Yilmaz et al.2 showed that BUN and bicarbonate strongly correlated with dehydration severity (P < 0.00001 and P = 0.01, respectively). A 97-patient prospective study by Vega and Avner3 showed that bicarbonate <17 can help in predicting percent body weight loss (PBWL) (sensitivity of 77% for PBWL 6-10 and 94% for PBWL >10).

In AGE, obtaining laboratory data is often considered to be the more conservative approach. Some attribute this to the medical education and legal system rewarding the uncovering of rare diagnoses,4 while others believe physicians obtain laboratory data to avoid missing severe electrolyte disorders. One author notes, “physicians who are anxious about a patient’s problem may be tempted to do something—anything—decisive in order to diminish their own anxiety.”5 Severe electrolyte derangements are common in developing countries6 but less so in the United States. A prospective pediatric dehydration study over 1 year in the United States demonstrated rates of 6% and 3% of hypo- and hypernatremia, respectively (n = 182). Only 1 patient had a sodium level >160, and this patient had an underlying genetic syndrome, and none had hyponatremia <130. Hypoglycemia was the most common electrolyte abnormality, which was present in 9.8% of patients. Electrolyte results changed management in 10.4% of patients.7

WHY ELECTROLYTE TESTING IS GENERALLY NOT HELPFUL

In AGE with or without dehydration, guidelines from the AAP and other international organizations emphasize supportive care in the management of AGE and discourage routine diagnostic testing.8-10 Yet, there continues to be wide variation in AGE management.11-13 Most AGE cases presenting to an outpatient setting or ED are uncomplicated: age >6 months, nontoxic appearance, no comorbidities, no hematochezia, diarrhea <7 days, and mild-to-moderate dehydration.

Steiner et al.14 performed a systematic meta-analysis of the precision and accuracy of symptoms, signs, and laboratory tests for evaluating dehydration in children. They concluded that a standardized clinical assessment based on physical exam (PE) findings more accurately classifies the degree of dehydration than laboratory testing. Steiner et al14 specifically analyzed the works by Yilmaz et al.2 and Vega and Avner,3 and determined that the positive likelihood ratios for >5% dehydration resulting from a BUN >45 or bicarbonate <17 were too small or had confidence intervals that were too wide to be clinically helpful alone. Therefore, Steiner et al.14 recommended that laboratory testing should not be considered definitive for dehydration.

Vega and Avner3 found that electrolyte testing is less helpful in distinguishing between <5% (mild) and 5% to 10% (moderate) dehydration compared to PBWL. Because both mild and moderate dehydration respond equally well to oral rehydration therapy (ORT),8 electrolyte testing is not helpful in managing these categories. Many studies have excluded children with hypernatremia, but generally, severe hypernatremia is uncommon in healthy patients with AGE. In most cases of mild hypernatremia, ORT is the preferred resuscitation method and is possibly safer than IV rehydration because ORT may induce less rapid shifts in intracellular water.15

Tieder et al.16 demonstrated that better hospital adherence to national recommendations to avoid diagnostic testing in children with AGE resulted in lower charges and equivalent outcomes. In this large, multicenter study among 27 children’s hospitals in the Pediatric Hospital Information System (PHIS) database, only 70% of the 188,000 patients received guideline-adherent care. Nonrecommended laboratory testing was common, especially in the admitted population. Electrolytes were measured in 22.1% of the ED and observation patients compared with 85% of admitted patients. Hospitals that were most guideline adherent in the ED demonstrated 50% lower charges. The authors estimate that standardizing AGE care and eliminating nonrecommended laboratory testing would decrease admissions by 45% and save more than $1 billion per year in direct medical costs.16 In a similar PHIS study, laboratory testing was strongly correlated with the percentage of children hospitalized for AGE at each hospital (r = 0.73, P < 0.001). Results were unchanged when excluding children <1 year of age (r = 0.75, P < 0.001). In contrast, the mean testing count was not correlated with return visits within 3 days for children discharged from the ED (r = 0.21, P = 0.235), nor was it correlated with hospital length of stay (r = −0.04, P = 0.804) or return visits within 7 days (r = 0.03, P = 0.862) for hospitalized children.12 In addition, Freedman et al.17 revealed that the clinical dehydration score is independently associated with successful ED discharge without revisits, and laboratory testing does not prevent missed cases of severe dehydration.

Nonrecommended and often unnecessary laboratory testing in AGE results in IV procedures that are sometimes repeated because of abnormal values. “Shotgun testing,” or ordering a panel of labs, can result in abnormal laboratory values in healthy patients. Deyo et al.

WHY ELECTROLYTE TESTING MIGHT BE HELPFUL

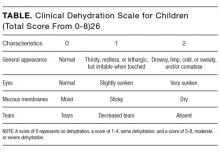

Electrolyte panels may be useful in assessing children with severe dehydration (scores of 5-8 on the Clinical Dehydration Scale (CDS) or more than 10% weight loss) or in complicated cases of AGE (those that do not meet the criteria of age >6 months, nontoxic appearance, no comorbidities, no hematochezia, and diarrhea <7 days) to guide IV fluid management and correct markedly abnormal electrolytes.14

Electrolyte panels may also rarely uncover disease processes, such as new-onset diabetes, hemolytic uremic syndrome, adrenal insufficiency, or inborn errors of metabolism, allowing for early diagnosis and preventing adverse outcomes. Suspicion to investigate such entities should arise during a thorough history and PE instead of routinely screening all children with symptoms of AGE. One should also have a higher level of concern for other disease processes when clinical recovery does not occur within the expected amount of time; symptoms usually resolve within 2 to 3 days but sometimes will last up to a week.

WHAT WE SHOULD DO INSTEAD

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Perform a thorough history and PE to diagnose AGE.8

- Clinical assessment of dehydration should be performed upon initial presentation and repeatedly with vital signs throughout the stay using a validated CDS to classify the patient’s initial dehydration severity and monitor improvement. Obtain a current patient weight and compare with previously recorded weights, if available.25,26

- Laboratory testing in patients with AGE should not be performed unless a patient is classified as severely dehydrated, is toxic appearing, has a comorbidity that increases the likelihood of complications, or is not improving as expected.

- Rehydration via ORT is preferred to an IV in mild and moderate dehydration.15

- If initial testing is performed and indicates an expected value indicative of dehydration, do not repeat testing to demonstrate normalization as long as the child is clinically improving as expected.

CONCLUSION

Children presenting with mild-to-moderate dehydration should be treated with supportive measures in accordance with current guidelines. Electrolyte panels very rarely provide clinical information that cannot be garnered through a thorough history and PE. As in our clinical scenario, the laboratory values obtained may have led to potential harm, including overdiagnosis, painful procedures, and psychological distress. Without testing, the patient likely could have been appropriately treated with ORT and discharged from the ED.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason?” Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by emailing [email protected].

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Elliott EJ. Acute gastroenteritis in children. BMJ. 2007;334(7583):35-40. PubMed

2. Yilmaz K, Karabocuoglu M, Citak A, Uzel N. Evaluation of laboratory tests in dehydrated children with acute gastroenteritis. J Paediatr Child Health. 2002;38(3):226-228. PubMed

3. Vega RM, Avner JR. A prospective study of the usefulness of clinical and laboratory parameters for predicting percentage of dehydration in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1997;13(3):179-182. PubMed

4. Jha S. Stop hunting for zebras in Texas: end the diagnostic culture of “rule-out”. BMJ. 2014;348:g2625. PubMed

5. Mold JW, Stein HF. The cascade effect in the clinical care of patients. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(8):512-514. PubMed

6. Shahrin L, Chisti MJ, Huq S, et al. Clinical Manifestations of Hyponatremia and Hypernatremia in Under-Five Diarrheal Children in a Diarrhea Hospital. J Trop Pediatr. 2016;62(3):206-212. PubMed

7. Wathen JE, MacKenzie T, Bothner JP. Usefulness of the serum electrolyte panel in the management of pediatric dehydration treated with intravenously administered fluids. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1227-1234. PubMed

8. Practice parameter: the management of acute gastroenteritis in young children. American Academy of Pediatrics, Provisional Committee on Quality Improvement, Subcommittee on Acute Gastroenteritis. Pediatrics. 1996;97(3):424-435. PubMed

9. National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. Diarrhoea and Vomiting Caused by Gastroenteritis: Diagnosis, Assessment and Management in Children Younger than 5 Years. London: RCOG Press; 2009. PubMed

10. Guarino A, Ashkenazi S, Gendrel D, et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition/European Society for Pediatric Infectious Diseases evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute gastroenteritis in children in Europe: Update 2014. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;59(1):132-152. PubMed

11. Freedman SB, Gouin S, Bhatt M, et al. Prospective assessment of practice pattern variations in the treatment of pediatric gastroenteritis. Pediatrics. 2011;127(2):e287-e295. PubMed

12. Lind CH, Hall M, Arnold DH, et al. Variation in Diagnostic Testing and Hospitalization Rates in Children With Acute Gastroenteritis. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(12):714-721. PubMed

13. Powell EC, Hampers LC. Physician variation in test ordering in the management of gastroenteritis in children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(10):978-983. PubMed

14. Steiner MJ, DeWalt DA, Byerley JS. Is this child dehydrated? JAMA. 2004;291(22):2746-2754. PubMed

15. Sandhu BK, European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology H, Nutrition Working Group on Acute D. Practical guidelines for the management of gastroenteritis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;33(suppl 2):S36-S39.

16. Tieder JS, Robertson A, Garrison MM. Pediatric hospital adherence to the standard of care for acute gastroenteritis. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):e1081-e1087. PubMed

17. Freedman SB, DeGroot JM, Parkin PC. Successful discharge of children with gastroenteritis requiring intravenous rehydration. J Emerg Med. 2014;46(1):9-20. PubMed

18. Deyo RA. Cascade effects of medical technology. Annu Rev Public Health. 2002;23:23-44. PubMed

19. Coon ER, Quinonez RA, Moyer VA, Schroeder AR. Overdiagnosis: how our compulsion for diagnosis may be harming children. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):1013-1023. PubMed

20. Florin TA, French B, Zorc JJ, Alpern ER, Shah SS. Variation in emergency department diagnostic testing and disposition outcomes in pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2013;132(2):237-244. PubMed

21. Newman TB, Bernzweig JA, Takayama JI, Finch SA, Wasserman RC, Pantell RH. Urine testing and urinary tract infections in febrile infants seen in office settings: the Pediatric Research in Office Settings’ Febrile Infant Study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(1):44-54. PubMed

22. McMurtry CM, Noel M, Chambers CT, McGrath PJ. Children’s fear during procedural pain: preliminary investigation of the Children’s Fear Scale. Health Psychol. 2011;30(6):780-788. PubMed

23. von Baeyer CL, Marche TA, Rocha EM, Salmon K. Children’s memory for pain: overview and implications for practice. J Pain. 2004;5(5):241-249. PubMed

24. American Academy of Pediatrics. Section on Hospital Medicine. Rauch DA, Gershel JC. Caring for the hospitalized child: a handbook of inpatient pediatrics. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2013.

25. Bailey B, Gravel J, Goldman RD, Friedman JN, Parkin PC. External validation of the clinical dehydration scale for children with acute gastroenteritis. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(6):583-588. PubMed

26. Friedman JN, Goldman RD, Srivastava R, Parkin PC. Development of a clinical dehydration scale for use in children between 1 and 36 months of age. J Pediatr. 2004;145(2):201-207. PubMed

The “Things We Do for No Reason” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but that may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

Acute gastroenteritis (AGE) remains a substantial cause of childhood illness and is 1 of the top 10 reasons for pediatric hospitalization nationwide. In the United States, AGE is responsible for 10% of hospital admissions and approximately 300 deaths annually.1 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and other organizations have emphasized supportive care in the management of AGE. Routine diagnostic testing has been discouraged in national guidelines except in cases of severe dehydration or an otherwise complicated course. Despite AGE guidelines, diagnostic laboratory tests are still widely used even though they have been shown to be poor predictors of dehydration. Studies have shown that high test utilization in various pediatric disease processes often influences the decision for hospitalization without improvement in patient outcome. In children with AGE, the initial and follow-up laboratory tests may not only be something that we do for no reason, but something that is associated with more risk than benefit.

An 18-month-old healthy male is brought to the emergency department (ED) with a chief complaint of 2 days of nonbloody, nonbilious emesis and watery diarrhea. He has decreased energy but smiles and plays for a few minutes. He has had decreased wet diapers. His exam is notable for mild tachycardia, mildly dry lips, and capillary refill of 3 seconds. A serum electrolyte panel is normal except for a sodium of 134 mEq/L, a bicarbonate of 16 mEq/L, and an anion gap of 18, which are flagged as abnormal by the electronic medical record. These results prompt intravenous (IV) access, a normal saline bolus, and admission on maintenance fluids overnight. The next morning, his electrolyte panel is repeated, and his sodium is 140 mEq/L and bicarbonate is 15 mEq/L. He is now drinking well with no further episodes of emesis, so he is discharged home.

WHY PHYSICIANS MIGHT THINK ELECTROLYTE TESTING IS HELPFUL

Many physicians across the United States continue to order electrolytes in AGE as a way to avoid missing severe dehydration, severe electrolyte abnormalities, or rare diagnoses, such as adrenal insufficiency or new-onset diabetes, in a child. Previous studies have revealed that bicarbonate and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) may be helpful predictors of severe dehydration. A retrospective study of 168 patients by Yilmaz et al.2 showed that BUN and bicarbonate strongly correlated with dehydration severity (P < 0.00001 and P = 0.01, respectively). A 97-patient prospective study by Vega and Avner3 showed that bicarbonate <17 can help in predicting percent body weight loss (PBWL) (sensitivity of 77% for PBWL 6-10 and 94% for PBWL >10).

In AGE, obtaining laboratory data is often considered to be the more conservative approach. Some attribute this to the medical education and legal system rewarding the uncovering of rare diagnoses,4 while others believe physicians obtain laboratory data to avoid missing severe electrolyte disorders. One author notes, “physicians who are anxious about a patient’s problem may be tempted to do something—anything—decisive in order to diminish their own anxiety.”5 Severe electrolyte derangements are common in developing countries6 but less so in the United States. A prospective pediatric dehydration study over 1 year in the United States demonstrated rates of 6% and 3% of hypo- and hypernatremia, respectively (n = 182). Only 1 patient had a sodium level >160, and this patient had an underlying genetic syndrome, and none had hyponatremia <130. Hypoglycemia was the most common electrolyte abnormality, which was present in 9.8% of patients. Electrolyte results changed management in 10.4% of patients.7

WHY ELECTROLYTE TESTING IS GENERALLY NOT HELPFUL

In AGE with or without dehydration, guidelines from the AAP and other international organizations emphasize supportive care in the management of AGE and discourage routine diagnostic testing.8-10 Yet, there continues to be wide variation in AGE management.11-13 Most AGE cases presenting to an outpatient setting or ED are uncomplicated: age >6 months, nontoxic appearance, no comorbidities, no hematochezia, diarrhea <7 days, and mild-to-moderate dehydration.

Steiner et al.14 performed a systematic meta-analysis of the precision and accuracy of symptoms, signs, and laboratory tests for evaluating dehydration in children. They concluded that a standardized clinical assessment based on physical exam (PE) findings more accurately classifies the degree of dehydration than laboratory testing. Steiner et al14 specifically analyzed the works by Yilmaz et al.2 and Vega and Avner,3 and determined that the positive likelihood ratios for >5% dehydration resulting from a BUN >45 or bicarbonate <17 were too small or had confidence intervals that were too wide to be clinically helpful alone. Therefore, Steiner et al.14 recommended that laboratory testing should not be considered definitive for dehydration.

Vega and Avner3 found that electrolyte testing is less helpful in distinguishing between <5% (mild) and 5% to 10% (moderate) dehydration compared to PBWL. Because both mild and moderate dehydration respond equally well to oral rehydration therapy (ORT),8 electrolyte testing is not helpful in managing these categories. Many studies have excluded children with hypernatremia, but generally, severe hypernatremia is uncommon in healthy patients with AGE. In most cases of mild hypernatremia, ORT is the preferred resuscitation method and is possibly safer than IV rehydration because ORT may induce less rapid shifts in intracellular water.15

Tieder et al.16 demonstrated that better hospital adherence to national recommendations to avoid diagnostic testing in children with AGE resulted in lower charges and equivalent outcomes. In this large, multicenter study among 27 children’s hospitals in the Pediatric Hospital Information System (PHIS) database, only 70% of the 188,000 patients received guideline-adherent care. Nonrecommended laboratory testing was common, especially in the admitted population. Electrolytes were measured in 22.1% of the ED and observation patients compared with 85% of admitted patients. Hospitals that were most guideline adherent in the ED demonstrated 50% lower charges. The authors estimate that standardizing AGE care and eliminating nonrecommended laboratory testing would decrease admissions by 45% and save more than $1 billion per year in direct medical costs.16 In a similar PHIS study, laboratory testing was strongly correlated with the percentage of children hospitalized for AGE at each hospital (r = 0.73, P < 0.001). Results were unchanged when excluding children <1 year of age (r = 0.75, P < 0.001). In contrast, the mean testing count was not correlated with return visits within 3 days for children discharged from the ED (r = 0.21, P = 0.235), nor was it correlated with hospital length of stay (r = −0.04, P = 0.804) or return visits within 7 days (r = 0.03, P = 0.862) for hospitalized children.12 In addition, Freedman et al.17 revealed that the clinical dehydration score is independently associated with successful ED discharge without revisits, and laboratory testing does not prevent missed cases of severe dehydration.

Nonrecommended and often unnecessary laboratory testing in AGE results in IV procedures that are sometimes repeated because of abnormal values. “Shotgun testing,” or ordering a panel of labs, can result in abnormal laboratory values in healthy patients. Deyo et al.

WHY ELECTROLYTE TESTING MIGHT BE HELPFUL

Electrolyte panels may be useful in assessing children with severe dehydration (scores of 5-8 on the Clinical Dehydration Scale (CDS) or more than 10% weight loss) or in complicated cases of AGE (those that do not meet the criteria of age >6 months, nontoxic appearance, no comorbidities, no hematochezia, and diarrhea <7 days) to guide IV fluid management and correct markedly abnormal electrolytes.14

Electrolyte panels may also rarely uncover disease processes, such as new-onset diabetes, hemolytic uremic syndrome, adrenal insufficiency, or inborn errors of metabolism, allowing for early diagnosis and preventing adverse outcomes. Suspicion to investigate such entities should arise during a thorough history and PE instead of routinely screening all children with symptoms of AGE. One should also have a higher level of concern for other disease processes when clinical recovery does not occur within the expected amount of time; symptoms usually resolve within 2 to 3 days but sometimes will last up to a week.

WHAT WE SHOULD DO INSTEAD

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Perform a thorough history and PE to diagnose AGE.8

- Clinical assessment of dehydration should be performed upon initial presentation and repeatedly with vital signs throughout the stay using a validated CDS to classify the patient’s initial dehydration severity and monitor improvement. Obtain a current patient weight and compare with previously recorded weights, if available.25,26

- Laboratory testing in patients with AGE should not be performed unless a patient is classified as severely dehydrated, is toxic appearing, has a comorbidity that increases the likelihood of complications, or is not improving as expected.

- Rehydration via ORT is preferred to an IV in mild and moderate dehydration.15

- If initial testing is performed and indicates an expected value indicative of dehydration, do not repeat testing to demonstrate normalization as long as the child is clinically improving as expected.

CONCLUSION

Children presenting with mild-to-moderate dehydration should be treated with supportive measures in accordance with current guidelines. Electrolyte panels very rarely provide clinical information that cannot be garnered through a thorough history and PE. As in our clinical scenario, the laboratory values obtained may have led to potential harm, including overdiagnosis, painful procedures, and psychological distress. Without testing, the patient likely could have been appropriately treated with ORT and discharged from the ED.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason?” Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by emailing [email protected].

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

The “Things We Do for No Reason” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but that may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

Acute gastroenteritis (AGE) remains a substantial cause of childhood illness and is 1 of the top 10 reasons for pediatric hospitalization nationwide. In the United States, AGE is responsible for 10% of hospital admissions and approximately 300 deaths annually.1 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and other organizations have emphasized supportive care in the management of AGE. Routine diagnostic testing has been discouraged in national guidelines except in cases of severe dehydration or an otherwise complicated course. Despite AGE guidelines, diagnostic laboratory tests are still widely used even though they have been shown to be poor predictors of dehydration. Studies have shown that high test utilization in various pediatric disease processes often influences the decision for hospitalization without improvement in patient outcome. In children with AGE, the initial and follow-up laboratory tests may not only be something that we do for no reason, but something that is associated with more risk than benefit.

An 18-month-old healthy male is brought to the emergency department (ED) with a chief complaint of 2 days of nonbloody, nonbilious emesis and watery diarrhea. He has decreased energy but smiles and plays for a few minutes. He has had decreased wet diapers. His exam is notable for mild tachycardia, mildly dry lips, and capillary refill of 3 seconds. A serum electrolyte panel is normal except for a sodium of 134 mEq/L, a bicarbonate of 16 mEq/L, and an anion gap of 18, which are flagged as abnormal by the electronic medical record. These results prompt intravenous (IV) access, a normal saline bolus, and admission on maintenance fluids overnight. The next morning, his electrolyte panel is repeated, and his sodium is 140 mEq/L and bicarbonate is 15 mEq/L. He is now drinking well with no further episodes of emesis, so he is discharged home.

WHY PHYSICIANS MIGHT THINK ELECTROLYTE TESTING IS HELPFUL

Many physicians across the United States continue to order electrolytes in AGE as a way to avoid missing severe dehydration, severe electrolyte abnormalities, or rare diagnoses, such as adrenal insufficiency or new-onset diabetes, in a child. Previous studies have revealed that bicarbonate and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) may be helpful predictors of severe dehydration. A retrospective study of 168 patients by Yilmaz et al.2 showed that BUN and bicarbonate strongly correlated with dehydration severity (P < 0.00001 and P = 0.01, respectively). A 97-patient prospective study by Vega and Avner3 showed that bicarbonate <17 can help in predicting percent body weight loss (PBWL) (sensitivity of 77% for PBWL 6-10 and 94% for PBWL >10).

In AGE, obtaining laboratory data is often considered to be the more conservative approach. Some attribute this to the medical education and legal system rewarding the uncovering of rare diagnoses,4 while others believe physicians obtain laboratory data to avoid missing severe electrolyte disorders. One author notes, “physicians who are anxious about a patient’s problem may be tempted to do something—anything—decisive in order to diminish their own anxiety.”5 Severe electrolyte derangements are common in developing countries6 but less so in the United States. A prospective pediatric dehydration study over 1 year in the United States demonstrated rates of 6% and 3% of hypo- and hypernatremia, respectively (n = 182). Only 1 patient had a sodium level >160, and this patient had an underlying genetic syndrome, and none had hyponatremia <130. Hypoglycemia was the most common electrolyte abnormality, which was present in 9.8% of patients. Electrolyte results changed management in 10.4% of patients.7

WHY ELECTROLYTE TESTING IS GENERALLY NOT HELPFUL

In AGE with or without dehydration, guidelines from the AAP and other international organizations emphasize supportive care in the management of AGE and discourage routine diagnostic testing.8-10 Yet, there continues to be wide variation in AGE management.11-13 Most AGE cases presenting to an outpatient setting or ED are uncomplicated: age >6 months, nontoxic appearance, no comorbidities, no hematochezia, diarrhea <7 days, and mild-to-moderate dehydration.

Steiner et al.14 performed a systematic meta-analysis of the precision and accuracy of symptoms, signs, and laboratory tests for evaluating dehydration in children. They concluded that a standardized clinical assessment based on physical exam (PE) findings more accurately classifies the degree of dehydration than laboratory testing. Steiner et al14 specifically analyzed the works by Yilmaz et al.2 and Vega and Avner,3 and determined that the positive likelihood ratios for >5% dehydration resulting from a BUN >45 or bicarbonate <17 were too small or had confidence intervals that were too wide to be clinically helpful alone. Therefore, Steiner et al.14 recommended that laboratory testing should not be considered definitive for dehydration.

Vega and Avner3 found that electrolyte testing is less helpful in distinguishing between <5% (mild) and 5% to 10% (moderate) dehydration compared to PBWL. Because both mild and moderate dehydration respond equally well to oral rehydration therapy (ORT),8 electrolyte testing is not helpful in managing these categories. Many studies have excluded children with hypernatremia, but generally, severe hypernatremia is uncommon in healthy patients with AGE. In most cases of mild hypernatremia, ORT is the preferred resuscitation method and is possibly safer than IV rehydration because ORT may induce less rapid shifts in intracellular water.15

Tieder et al.16 demonstrated that better hospital adherence to national recommendations to avoid diagnostic testing in children with AGE resulted in lower charges and equivalent outcomes. In this large, multicenter study among 27 children’s hospitals in the Pediatric Hospital Information System (PHIS) database, only 70% of the 188,000 patients received guideline-adherent care. Nonrecommended laboratory testing was common, especially in the admitted population. Electrolytes were measured in 22.1% of the ED and observation patients compared with 85% of admitted patients. Hospitals that were most guideline adherent in the ED demonstrated 50% lower charges. The authors estimate that standardizing AGE care and eliminating nonrecommended laboratory testing would decrease admissions by 45% and save more than $1 billion per year in direct medical costs.16 In a similar PHIS study, laboratory testing was strongly correlated with the percentage of children hospitalized for AGE at each hospital (r = 0.73, P < 0.001). Results were unchanged when excluding children <1 year of age (r = 0.75, P < 0.001). In contrast, the mean testing count was not correlated with return visits within 3 days for children discharged from the ED (r = 0.21, P = 0.235), nor was it correlated with hospital length of stay (r = −0.04, P = 0.804) or return visits within 7 days (r = 0.03, P = 0.862) for hospitalized children.12 In addition, Freedman et al.17 revealed that the clinical dehydration score is independently associated with successful ED discharge without revisits, and laboratory testing does not prevent missed cases of severe dehydration.

Nonrecommended and often unnecessary laboratory testing in AGE results in IV procedures that are sometimes repeated because of abnormal values. “Shotgun testing,” or ordering a panel of labs, can result in abnormal laboratory values in healthy patients. Deyo et al.

WHY ELECTROLYTE TESTING MIGHT BE HELPFUL

Electrolyte panels may be useful in assessing children with severe dehydration (scores of 5-8 on the Clinical Dehydration Scale (CDS) or more than 10% weight loss) or in complicated cases of AGE (those that do not meet the criteria of age >6 months, nontoxic appearance, no comorbidities, no hematochezia, and diarrhea <7 days) to guide IV fluid management and correct markedly abnormal electrolytes.14

Electrolyte panels may also rarely uncover disease processes, such as new-onset diabetes, hemolytic uremic syndrome, adrenal insufficiency, or inborn errors of metabolism, allowing for early diagnosis and preventing adverse outcomes. Suspicion to investigate such entities should arise during a thorough history and PE instead of routinely screening all children with symptoms of AGE. One should also have a higher level of concern for other disease processes when clinical recovery does not occur within the expected amount of time; symptoms usually resolve within 2 to 3 days but sometimes will last up to a week.

WHAT WE SHOULD DO INSTEAD

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Perform a thorough history and PE to diagnose AGE.8

- Clinical assessment of dehydration should be performed upon initial presentation and repeatedly with vital signs throughout the stay using a validated CDS to classify the patient’s initial dehydration severity and monitor improvement. Obtain a current patient weight and compare with previously recorded weights, if available.25,26

- Laboratory testing in patients with AGE should not be performed unless a patient is classified as severely dehydrated, is toxic appearing, has a comorbidity that increases the likelihood of complications, or is not improving as expected.

- Rehydration via ORT is preferred to an IV in mild and moderate dehydration.15

- If initial testing is performed and indicates an expected value indicative of dehydration, do not repeat testing to demonstrate normalization as long as the child is clinically improving as expected.

CONCLUSION

Children presenting with mild-to-moderate dehydration should be treated with supportive measures in accordance with current guidelines. Electrolyte panels very rarely provide clinical information that cannot be garnered through a thorough history and PE. As in our clinical scenario, the laboratory values obtained may have led to potential harm, including overdiagnosis, painful procedures, and psychological distress. Without testing, the patient likely could have been appropriately treated with ORT and discharged from the ED.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason?” Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by emailing [email protected].

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Elliott EJ. Acute gastroenteritis in children. BMJ. 2007;334(7583):35-40. PubMed

2. Yilmaz K, Karabocuoglu M, Citak A, Uzel N. Evaluation of laboratory tests in dehydrated children with acute gastroenteritis. J Paediatr Child Health. 2002;38(3):226-228. PubMed

3. Vega RM, Avner JR. A prospective study of the usefulness of clinical and laboratory parameters for predicting percentage of dehydration in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1997;13(3):179-182. PubMed

4. Jha S. Stop hunting for zebras in Texas: end the diagnostic culture of “rule-out”. BMJ. 2014;348:g2625. PubMed

5. Mold JW, Stein HF. The cascade effect in the clinical care of patients. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(8):512-514. PubMed

6. Shahrin L, Chisti MJ, Huq S, et al. Clinical Manifestations of Hyponatremia and Hypernatremia in Under-Five Diarrheal Children in a Diarrhea Hospital. J Trop Pediatr. 2016;62(3):206-212. PubMed

7. Wathen JE, MacKenzie T, Bothner JP. Usefulness of the serum electrolyte panel in the management of pediatric dehydration treated with intravenously administered fluids. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1227-1234. PubMed

8. Practice parameter: the management of acute gastroenteritis in young children. American Academy of Pediatrics, Provisional Committee on Quality Improvement, Subcommittee on Acute Gastroenteritis. Pediatrics. 1996;97(3):424-435. PubMed

9. National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. Diarrhoea and Vomiting Caused by Gastroenteritis: Diagnosis, Assessment and Management in Children Younger than 5 Years. London: RCOG Press; 2009. PubMed

10. Guarino A, Ashkenazi S, Gendrel D, et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition/European Society for Pediatric Infectious Diseases evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute gastroenteritis in children in Europe: Update 2014. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;59(1):132-152. PubMed

11. Freedman SB, Gouin S, Bhatt M, et al. Prospective assessment of practice pattern variations in the treatment of pediatric gastroenteritis. Pediatrics. 2011;127(2):e287-e295. PubMed

12. Lind CH, Hall M, Arnold DH, et al. Variation in Diagnostic Testing and Hospitalization Rates in Children With Acute Gastroenteritis. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(12):714-721. PubMed

13. Powell EC, Hampers LC. Physician variation in test ordering in the management of gastroenteritis in children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(10):978-983. PubMed

14. Steiner MJ, DeWalt DA, Byerley JS. Is this child dehydrated? JAMA. 2004;291(22):2746-2754. PubMed

15. Sandhu BK, European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology H, Nutrition Working Group on Acute D. Practical guidelines for the management of gastroenteritis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;33(suppl 2):S36-S39.

16. Tieder JS, Robertson A, Garrison MM. Pediatric hospital adherence to the standard of care for acute gastroenteritis. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):e1081-e1087. PubMed

17. Freedman SB, DeGroot JM, Parkin PC. Successful discharge of children with gastroenteritis requiring intravenous rehydration. J Emerg Med. 2014;46(1):9-20. PubMed

18. Deyo RA. Cascade effects of medical technology. Annu Rev Public Health. 2002;23:23-44. PubMed

19. Coon ER, Quinonez RA, Moyer VA, Schroeder AR. Overdiagnosis: how our compulsion for diagnosis may be harming children. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):1013-1023. PubMed

20. Florin TA, French B, Zorc JJ, Alpern ER, Shah SS. Variation in emergency department diagnostic testing and disposition outcomes in pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2013;132(2):237-244. PubMed

21. Newman TB, Bernzweig JA, Takayama JI, Finch SA, Wasserman RC, Pantell RH. Urine testing and urinary tract infections in febrile infants seen in office settings: the Pediatric Research in Office Settings’ Febrile Infant Study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(1):44-54. PubMed

22. McMurtry CM, Noel M, Chambers CT, McGrath PJ. Children’s fear during procedural pain: preliminary investigation of the Children’s Fear Scale. Health Psychol. 2011;30(6):780-788. PubMed

23. von Baeyer CL, Marche TA, Rocha EM, Salmon K. Children’s memory for pain: overview and implications for practice. J Pain. 2004;5(5):241-249. PubMed

24. American Academy of Pediatrics. Section on Hospital Medicine. Rauch DA, Gershel JC. Caring for the hospitalized child: a handbook of inpatient pediatrics. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2013.

25. Bailey B, Gravel J, Goldman RD, Friedman JN, Parkin PC. External validation of the clinical dehydration scale for children with acute gastroenteritis. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(6):583-588. PubMed

26. Friedman JN, Goldman RD, Srivastava R, Parkin PC. Development of a clinical dehydration scale for use in children between 1 and 36 months of age. J Pediatr. 2004;145(2):201-207. PubMed

1. Elliott EJ. Acute gastroenteritis in children. BMJ. 2007;334(7583):35-40. PubMed

2. Yilmaz K, Karabocuoglu M, Citak A, Uzel N. Evaluation of laboratory tests in dehydrated children with acute gastroenteritis. J Paediatr Child Health. 2002;38(3):226-228. PubMed

3. Vega RM, Avner JR. A prospective study of the usefulness of clinical and laboratory parameters for predicting percentage of dehydration in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1997;13(3):179-182. PubMed

4. Jha S. Stop hunting for zebras in Texas: end the diagnostic culture of “rule-out”. BMJ. 2014;348:g2625. PubMed

5. Mold JW, Stein HF. The cascade effect in the clinical care of patients. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(8):512-514. PubMed

6. Shahrin L, Chisti MJ, Huq S, et al. Clinical Manifestations of Hyponatremia and Hypernatremia in Under-Five Diarrheal Children in a Diarrhea Hospital. J Trop Pediatr. 2016;62(3):206-212. PubMed

7. Wathen JE, MacKenzie T, Bothner JP. Usefulness of the serum electrolyte panel in the management of pediatric dehydration treated with intravenously administered fluids. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1227-1234. PubMed

8. Practice parameter: the management of acute gastroenteritis in young children. American Academy of Pediatrics, Provisional Committee on Quality Improvement, Subcommittee on Acute Gastroenteritis. Pediatrics. 1996;97(3):424-435. PubMed

9. National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. Diarrhoea and Vomiting Caused by Gastroenteritis: Diagnosis, Assessment and Management in Children Younger than 5 Years. London: RCOG Press; 2009. PubMed

10. Guarino A, Ashkenazi S, Gendrel D, et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition/European Society for Pediatric Infectious Diseases evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute gastroenteritis in children in Europe: Update 2014. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;59(1):132-152. PubMed

11. Freedman SB, Gouin S, Bhatt M, et al. Prospective assessment of practice pattern variations in the treatment of pediatric gastroenteritis. Pediatrics. 2011;127(2):e287-e295. PubMed

12. Lind CH, Hall M, Arnold DH, et al. Variation in Diagnostic Testing and Hospitalization Rates in Children With Acute Gastroenteritis. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(12):714-721. PubMed

13. Powell EC, Hampers LC. Physician variation in test ordering in the management of gastroenteritis in children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(10):978-983. PubMed

14. Steiner MJ, DeWalt DA, Byerley JS. Is this child dehydrated? JAMA. 2004;291(22):2746-2754. PubMed

15. Sandhu BK, European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology H, Nutrition Working Group on Acute D. Practical guidelines for the management of gastroenteritis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;33(suppl 2):S36-S39.

16. Tieder JS, Robertson A, Garrison MM. Pediatric hospital adherence to the standard of care for acute gastroenteritis. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):e1081-e1087. PubMed

17. Freedman SB, DeGroot JM, Parkin PC. Successful discharge of children with gastroenteritis requiring intravenous rehydration. J Emerg Med. 2014;46(1):9-20. PubMed

18. Deyo RA. Cascade effects of medical technology. Annu Rev Public Health. 2002;23:23-44. PubMed

19. Coon ER, Quinonez RA, Moyer VA, Schroeder AR. Overdiagnosis: how our compulsion for diagnosis may be harming children. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):1013-1023. PubMed

20. Florin TA, French B, Zorc JJ, Alpern ER, Shah SS. Variation in emergency department diagnostic testing and disposition outcomes in pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2013;132(2):237-244. PubMed

21. Newman TB, Bernzweig JA, Takayama JI, Finch SA, Wasserman RC, Pantell RH. Urine testing and urinary tract infections in febrile infants seen in office settings: the Pediatric Research in Office Settings’ Febrile Infant Study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(1):44-54. PubMed

22. McMurtry CM, Noel M, Chambers CT, McGrath PJ. Children’s fear during procedural pain: preliminary investigation of the Children’s Fear Scale. Health Psychol. 2011;30(6):780-788. PubMed

23. von Baeyer CL, Marche TA, Rocha EM, Salmon K. Children’s memory for pain: overview and implications for practice. J Pain. 2004;5(5):241-249. PubMed

24. American Academy of Pediatrics. Section on Hospital Medicine. Rauch DA, Gershel JC. Caring for the hospitalized child: a handbook of inpatient pediatrics. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2013.

25. Bailey B, Gravel J, Goldman RD, Friedman JN, Parkin PC. External validation of the clinical dehydration scale for children with acute gastroenteritis. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(6):583-588. PubMed

26. Friedman JN, Goldman RD, Srivastava R, Parkin PC. Development of a clinical dehydration scale for use in children between 1 and 36 months of age. J Pediatr. 2004;145(2):201-207. PubMed

©2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

When Reducing Low-Value Care in Hospital Medicine Saves Money, Who Benefits?

Physicians face growing pressure to reduce their use of “low value” care—services that provide either little to no benefit, little benefit relative to cost, or outsized potential harm compared to benefit. One emerging policy solution for deterring such services is to financially penalize physicians who prescribe them.1,2

Physicians’ willingness to support such policies may depend on who they believe benefits from reductions in low-value care. In previous studies of cancer screening, the more that primary care physicians felt that the money saved from cost-containment efforts went to insurance company profits rather than to patients, the less willing they were to use less expensive cancer screening approaches.3

Similarly, physicians may be more likely to support financial penalty policies if they perceive that the benefits from reducing low-value care accrue to patients (eg, lower out-of-pocket costs) rather than insurers or hospitals (eg, profits and salaries of their leaders). If present, such perceptions could inform incentive design. We explored the hypothesis that support of financial penalties

METHODS

Study Sample

By using a panel of internists maintained by the American College of Physicians, we conducted a randomized, web-based survey among 484 physicians who were either internal medicine residents or internal medicine physicians practicing hospital medicine.

Survey Instrument

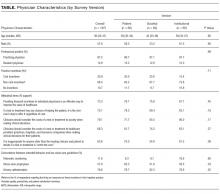

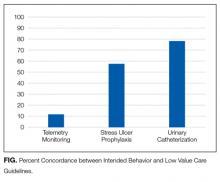

Respondents used a 5-point scale (“strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”) to indicate their agreement with a policy that financially penalizes physicians for prescribing services that provide few benefits to patients. Respondents were asked to simultaneously consider the following hospital medicine services, deemed to be low value based on medical evidence and consensus guidelines4: (1) placing, and leaving in, urinary catheters for urine output monitoring in noncritically ill patients, (2) ordering continuous telemetry monitoring for nonintensive care unit patients without a protocol governing continuation, and (3) prescribing stress ulcer prophylaxis for medical patients not at a high risk for gastrointestinal complications. Policy support was defined as “somewhat” or “strongly” agreeing with the policy. As part of another study of this physician cohort, this question varied in how the harm of low-value services was framed: either as harm to patients, to society, or to hospitals and insurers as institutions. Respondent characteristics were balanced across survey versions, and for the current analysis, we pooled responses across all versions.

All other questions in the survey, described in detail elsewhere,5 were identical for all respondents. For this analysis, we focused on a question that asked physicians to assume that reducing these services saves money without harming the quality of care and to rate on a 4-point scale (“none” to “a lot”) how much of the money saved would ultimately go to the following 6 nonmutually exclusive areas: (a) other healthcare services for patients, (b) reduced charges to patients’ employers or insurers, (c) reduced out-of-pocket costs for patients, (d) salaries and bonuses for physicians, (e) salaries and profits for insurance companies and their leaders, and (f) salaries and profits for hospitals and/or health systems and their leaders.

Based on the positive correlation identified between the first 4 items (a to d) and negative correlation with the other 2 items (e and f), we reverse-coded the latter 2 and summed all 6 into a single-outcome scale, effectively representing the degree to which the money saved from reducing low-value services accrues generally to patients or physicians instead of to hospitals, insurance companies, and their leaders. The Cronbach alpha for the scale was 0.74, indicating acceptable reliability. Based on scale responses, we dichotomized respondents at the median into those who believe that the money saved from reducing low-value services would accrue as benefits to patients or physicians and those who believe benefits accrue to insurance companies or hospitals and/or health systems and their leaders. The protocol was exempted by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Statistical Analysis

We used a χ2 test and multivariable logistic regression analysis to evaluate the association between policy support and physician beliefs about who benefits from reductions in low-value care. A χ2 test and a Kruskal-Wallis test were also used to evaluate the association between other respondent characteristics and beliefs about who benefits from reductions in low-value care. Analyses were performed by using Stata version 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Tests of significance were 2-tailed at an alpha of .05.

RESULTS

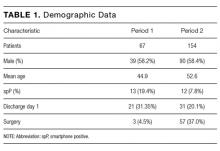

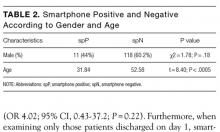

Compared with nonrespondents, the 187 physicians who responded (39% response rate) were more likely to be female (30% vs 26%, P = 0.001), older (mean age 41 vs 36 years old, P < 0.001), and practicing clinicians rather than internal medicine residents (87% vs 69%, P < 0.001). Twenty-one percent reported that their personal compensation was tied to cost incentives.

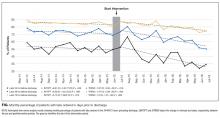

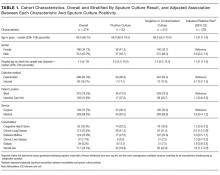

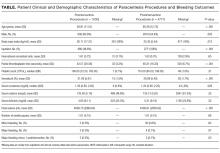

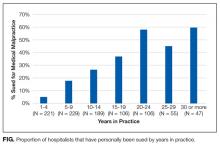

Overall, respondents believed that more of any money saved from reducing low-value services would go to profits and leadership salaries for insurance companies and hospitals and/or health systems rather than to patients (panel A of Figure). Few respondents felt that the money saved would ultimately go toward physician compensation.

Sixty-six percent of physicians who supported penalties believed that benefits from reducing low-value care accrue to patients or physicians, compared to 39% among those not supporting penalties (P < 0.001). In multivariable analyses, policy support was associated with the belief that the money saved from reducing low-value services would accrue as benefits to patients or physicians rather than as salaries and profits for insurance companies or hospitals and/or health systems and their leaders (Table). There were no statistically significant associations between respondent age, gender, or professional status and beliefs about who benefits from reductions in low-value care.

DISCUSSION

Despite ongoing efforts to highlight how reducing low-value care benefits patients, physicians in our sample did not believe that much of the money saved would benefit patients.

This result may reflect that while some care patterns are considered low value because they provide little benefit at a high cost, others yield potential harm, regardless of cost. For example, limiting stress ulcer prophylaxis largely aims to avoid clinical harm (eg, adverse drug effects and nosocomial infections). Limiting telemetric monitoring largely aims to reduce costly care that provides only limited benefit. Therefore, the nature of potential benefit to patients is very different—improved clinical outcomes in the former and potential cost savings in the latter. Future studies could separately assess physician attitudes about these 2 different definitions of low-value services.

Our study also demonstrates that the more physicians believe that much of any money saved goes to the profits and salaries of insurance companies, hospitals and/or health systems, and their leaders rather than to patients, the less likely they are to support policies financially penalizing physicians for prescribing low-value services.

Our study does not address why physicians have the beliefs that they have, but a likely explanation, at least in part, is that financial flows in healthcare are complex and tangled. Indeed, a clear understanding of who actually benefits is so hard to determine that these stated beliefs may really derive from views of power or justice rather than from some understanding of funds flow. Whether or not ideological attitudes underlie these expressed beliefs, policymakers and healthcare institutions might be advised to increase transparency about how cost savings are realized and whom they benefit.

Our analysis has limitations. Although it provides insight into where physicians believe relative amounts of money saved go with respect to 6 common options, the study did not include an exhaustive list of possibilities. The response rate also limits the representativeness of our results. Additionally, the study design prevents conclusions about causality; we cannot determine whether the belief that savings go to insurance companies and their executives is what reduces physicians’ enthusiasm for penalties, whether the causal association is in the opposite direction, or whether the 2 factors are linked in another way.

Nonetheless, our findings are consistent with a sense of healthcare justice in which physicians support penalties imposed on themselves only if the resulting benefits accrue to patients rather than to corporate or organizational interests. Effective physician penalties will likely need to address the belief that insurers and provider organizations stand to gain more than patients when low-value care services are reduced.

Disclosure

Drs. Liao, Schapira, Mitra, and Weissman have no conflicts to disclose. Dr. Navathe serves as advisor to Navvis and Company, Navigant Inc., Lynx Medical, Indegene Inc., and Sutherland Global Services and receives an honorarium from Elsevier Press, none of which have relationship to this manuscript. Dr. Asch is a partner and partial owner of VAL Health, which has no relationship to this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by The Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania, which had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of results.

1. Berwick DM. Avoiding overuse – the next quality frontier. Lancet. 2017;390(10090):102-104. PubMed

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS response to Public Comments on Non-Recommended PSA-Based Screening Measure. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/MMS/Downloads/eCQM-Development-and-Maintenance-for-Eligible-Professionals_CMS_PSA_Response_Public-Comment.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2017.

3. Asch DA, Jepson C, Hershey JC, Baron J, Ubel PA. When Money is Saved by Reducing Healthcare Costs, Where Do US Primary Care Physicians Think the Money Goes? Am J Manag Care. 2003;9(6):438-442. PubMed

4. Society of Hospital Medicine. Choosing Wisely. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/choosingwisely. Accessed September 18, 2017.

5. Liao JM, Navathe AS, Schapira MS, Weissman A, Mitra N, Asch DAA. Penalizing Physicians for Low Value Care in Hospital Medicine: A Randomized Survey. J Hosp Med. 2017. (In press). PubMed

Physicians face growing pressure to reduce their use of “low value” care—services that provide either little to no benefit, little benefit relative to cost, or outsized potential harm compared to benefit. One emerging policy solution for deterring such services is to financially penalize physicians who prescribe them.1,2

Physicians’ willingness to support such policies may depend on who they believe benefits from reductions in low-value care. In previous studies of cancer screening, the more that primary care physicians felt that the money saved from cost-containment efforts went to insurance company profits rather than to patients, the less willing they were to use less expensive cancer screening approaches.3

Similarly, physicians may be more likely to support financial penalty policies if they perceive that the benefits from reducing low-value care accrue to patients (eg, lower out-of-pocket costs) rather than insurers or hospitals (eg, profits and salaries of their leaders). If present, such perceptions could inform incentive design. We explored the hypothesis that support of financial penalties

METHODS

Study Sample

By using a panel of internists maintained by the American College of Physicians, we conducted a randomized, web-based survey among 484 physicians who were either internal medicine residents or internal medicine physicians practicing hospital medicine.

Survey Instrument

Respondents used a 5-point scale (“strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”) to indicate their agreement with a policy that financially penalizes physicians for prescribing services that provide few benefits to patients. Respondents were asked to simultaneously consider the following hospital medicine services, deemed to be low value based on medical evidence and consensus guidelines4: (1) placing, and leaving in, urinary catheters for urine output monitoring in noncritically ill patients, (2) ordering continuous telemetry monitoring for nonintensive care unit patients without a protocol governing continuation, and (3) prescribing stress ulcer prophylaxis for medical patients not at a high risk for gastrointestinal complications. Policy support was defined as “somewhat” or “strongly” agreeing with the policy. As part of another study of this physician cohort, this question varied in how the harm of low-value services was framed: either as harm to patients, to society, or to hospitals and insurers as institutions. Respondent characteristics were balanced across survey versions, and for the current analysis, we pooled responses across all versions.

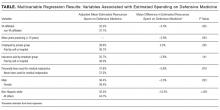

All other questions in the survey, described in detail elsewhere,5 were identical for all respondents. For this analysis, we focused on a question that asked physicians to assume that reducing these services saves money without harming the quality of care and to rate on a 4-point scale (“none” to “a lot”) how much of the money saved would ultimately go to the following 6 nonmutually exclusive areas: (a) other healthcare services for patients, (b) reduced charges to patients’ employers or insurers, (c) reduced out-of-pocket costs for patients, (d) salaries and bonuses for physicians, (e) salaries and profits for insurance companies and their leaders, and (f) salaries and profits for hospitals and/or health systems and their leaders.

Based on the positive correlation identified between the first 4 items (a to d) and negative correlation with the other 2 items (e and f), we reverse-coded the latter 2 and summed all 6 into a single-outcome scale, effectively representing the degree to which the money saved from reducing low-value services accrues generally to patients or physicians instead of to hospitals, insurance companies, and their leaders. The Cronbach alpha for the scale was 0.74, indicating acceptable reliability. Based on scale responses, we dichotomized respondents at the median into those who believe that the money saved from reducing low-value services would accrue as benefits to patients or physicians and those who believe benefits accrue to insurance companies or hospitals and/or health systems and their leaders. The protocol was exempted by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Statistical Analysis

We used a χ2 test and multivariable logistic regression analysis to evaluate the association between policy support and physician beliefs about who benefits from reductions in low-value care. A χ2 test and a Kruskal-Wallis test were also used to evaluate the association between other respondent characteristics and beliefs about who benefits from reductions in low-value care. Analyses were performed by using Stata version 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Tests of significance were 2-tailed at an alpha of .05.

RESULTS

Compared with nonrespondents, the 187 physicians who responded (39% response rate) were more likely to be female (30% vs 26%, P = 0.001), older (mean age 41 vs 36 years old, P < 0.001), and practicing clinicians rather than internal medicine residents (87% vs 69%, P < 0.001). Twenty-one percent reported that their personal compensation was tied to cost incentives.

Overall, respondents believed that more of any money saved from reducing low-value services would go to profits and leadership salaries for insurance companies and hospitals and/or health systems rather than to patients (panel A of Figure). Few respondents felt that the money saved would ultimately go toward physician compensation.

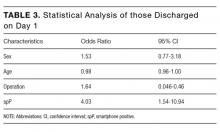

Sixty-six percent of physicians who supported penalties believed that benefits from reducing low-value care accrue to patients or physicians, compared to 39% among those not supporting penalties (P < 0.001). In multivariable analyses, policy support was associated with the belief that the money saved from reducing low-value services would accrue as benefits to patients or physicians rather than as salaries and profits for insurance companies or hospitals and/or health systems and their leaders (Table). There were no statistically significant associations between respondent age, gender, or professional status and beliefs about who benefits from reductions in low-value care.

DISCUSSION

Despite ongoing efforts to highlight how reducing low-value care benefits patients, physicians in our sample did not believe that much of the money saved would benefit patients.

This result may reflect that while some care patterns are considered low value because they provide little benefit at a high cost, others yield potential harm, regardless of cost. For example, limiting stress ulcer prophylaxis largely aims to avoid clinical harm (eg, adverse drug effects and nosocomial infections). Limiting telemetric monitoring largely aims to reduce costly care that provides only limited benefit. Therefore, the nature of potential benefit to patients is very different—improved clinical outcomes in the former and potential cost savings in the latter. Future studies could separately assess physician attitudes about these 2 different definitions of low-value services.

Our study also demonstrates that the more physicians believe that much of any money saved goes to the profits and salaries of insurance companies, hospitals and/or health systems, and their leaders rather than to patients, the less likely they are to support policies financially penalizing physicians for prescribing low-value services.

Our study does not address why physicians have the beliefs that they have, but a likely explanation, at least in part, is that financial flows in healthcare are complex and tangled. Indeed, a clear understanding of who actually benefits is so hard to determine that these stated beliefs may really derive from views of power or justice rather than from some understanding of funds flow. Whether or not ideological attitudes underlie these expressed beliefs, policymakers and healthcare institutions might be advised to increase transparency about how cost savings are realized and whom they benefit.

Our analysis has limitations. Although it provides insight into where physicians believe relative amounts of money saved go with respect to 6 common options, the study did not include an exhaustive list of possibilities. The response rate also limits the representativeness of our results. Additionally, the study design prevents conclusions about causality; we cannot determine whether the belief that savings go to insurance companies and their executives is what reduces physicians’ enthusiasm for penalties, whether the causal association is in the opposite direction, or whether the 2 factors are linked in another way.

Nonetheless, our findings are consistent with a sense of healthcare justice in which physicians support penalties imposed on themselves only if the resulting benefits accrue to patients rather than to corporate or organizational interests. Effective physician penalties will likely need to address the belief that insurers and provider organizations stand to gain more than patients when low-value care services are reduced.

Disclosure

Drs. Liao, Schapira, Mitra, and Weissman have no conflicts to disclose. Dr. Navathe serves as advisor to Navvis and Company, Navigant Inc., Lynx Medical, Indegene Inc., and Sutherland Global Services and receives an honorarium from Elsevier Press, none of which have relationship to this manuscript. Dr. Asch is a partner and partial owner of VAL Health, which has no relationship to this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by The Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania, which had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of results.

Physicians face growing pressure to reduce their use of “low value” care—services that provide either little to no benefit, little benefit relative to cost, or outsized potential harm compared to benefit. One emerging policy solution for deterring such services is to financially penalize physicians who prescribe them.1,2

Physicians’ willingness to support such policies may depend on who they believe benefits from reductions in low-value care. In previous studies of cancer screening, the more that primary care physicians felt that the money saved from cost-containment efforts went to insurance company profits rather than to patients, the less willing they were to use less expensive cancer screening approaches.3

Similarly, physicians may be more likely to support financial penalty policies if they perceive that the benefits from reducing low-value care accrue to patients (eg, lower out-of-pocket costs) rather than insurers or hospitals (eg, profits and salaries of their leaders). If present, such perceptions could inform incentive design. We explored the hypothesis that support of financial penalties

METHODS

Study Sample

By using a panel of internists maintained by the American College of Physicians, we conducted a randomized, web-based survey among 484 physicians who were either internal medicine residents or internal medicine physicians practicing hospital medicine.

Survey Instrument

Respondents used a 5-point scale (“strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”) to indicate their agreement with a policy that financially penalizes physicians for prescribing services that provide few benefits to patients. Respondents were asked to simultaneously consider the following hospital medicine services, deemed to be low value based on medical evidence and consensus guidelines4: (1) placing, and leaving in, urinary catheters for urine output monitoring in noncritically ill patients, (2) ordering continuous telemetry monitoring for nonintensive care unit patients without a protocol governing continuation, and (3) prescribing stress ulcer prophylaxis for medical patients not at a high risk for gastrointestinal complications. Policy support was defined as “somewhat” or “strongly” agreeing with the policy. As part of another study of this physician cohort, this question varied in how the harm of low-value services was framed: either as harm to patients, to society, or to hospitals and insurers as institutions. Respondent characteristics were balanced across survey versions, and for the current analysis, we pooled responses across all versions.

All other questions in the survey, described in detail elsewhere,5 were identical for all respondents. For this analysis, we focused on a question that asked physicians to assume that reducing these services saves money without harming the quality of care and to rate on a 4-point scale (“none” to “a lot”) how much of the money saved would ultimately go to the following 6 nonmutually exclusive areas: (a) other healthcare services for patients, (b) reduced charges to patients’ employers or insurers, (c) reduced out-of-pocket costs for patients, (d) salaries and bonuses for physicians, (e) salaries and profits for insurance companies and their leaders, and (f) salaries and profits for hospitals and/or health systems and their leaders.

Based on the positive correlation identified between the first 4 items (a to d) and negative correlation with the other 2 items (e and f), we reverse-coded the latter 2 and summed all 6 into a single-outcome scale, effectively representing the degree to which the money saved from reducing low-value services accrues generally to patients or physicians instead of to hospitals, insurance companies, and their leaders. The Cronbach alpha for the scale was 0.74, indicating acceptable reliability. Based on scale responses, we dichotomized respondents at the median into those who believe that the money saved from reducing low-value services would accrue as benefits to patients or physicians and those who believe benefits accrue to insurance companies or hospitals and/or health systems and their leaders. The protocol was exempted by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Statistical Analysis

We used a χ2 test and multivariable logistic regression analysis to evaluate the association between policy support and physician beliefs about who benefits from reductions in low-value care. A χ2 test and a Kruskal-Wallis test were also used to evaluate the association between other respondent characteristics and beliefs about who benefits from reductions in low-value care. Analyses were performed by using Stata version 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Tests of significance were 2-tailed at an alpha of .05.

RESULTS

Compared with nonrespondents, the 187 physicians who responded (39% response rate) were more likely to be female (30% vs 26%, P = 0.001), older (mean age 41 vs 36 years old, P < 0.001), and practicing clinicians rather than internal medicine residents (87% vs 69%, P < 0.001). Twenty-one percent reported that their personal compensation was tied to cost incentives.

Overall, respondents believed that more of any money saved from reducing low-value services would go to profits and leadership salaries for insurance companies and hospitals and/or health systems rather than to patients (panel A of Figure). Few respondents felt that the money saved would ultimately go toward physician compensation.

Sixty-six percent of physicians who supported penalties believed that benefits from reducing low-value care accrue to patients or physicians, compared to 39% among those not supporting penalties (P < 0.001). In multivariable analyses, policy support was associated with the belief that the money saved from reducing low-value services would accrue as benefits to patients or physicians rather than as salaries and profits for insurance companies or hospitals and/or health systems and their leaders (Table). There were no statistically significant associations between respondent age, gender, or professional status and beliefs about who benefits from reductions in low-value care.

DISCUSSION

Despite ongoing efforts to highlight how reducing low-value care benefits patients, physicians in our sample did not believe that much of the money saved would benefit patients.

This result may reflect that while some care patterns are considered low value because they provide little benefit at a high cost, others yield potential harm, regardless of cost. For example, limiting stress ulcer prophylaxis largely aims to avoid clinical harm (eg, adverse drug effects and nosocomial infections). Limiting telemetric monitoring largely aims to reduce costly care that provides only limited benefit. Therefore, the nature of potential benefit to patients is very different—improved clinical outcomes in the former and potential cost savings in the latter. Future studies could separately assess physician attitudes about these 2 different definitions of low-value services.

Our study also demonstrates that the more physicians believe that much of any money saved goes to the profits and salaries of insurance companies, hospitals and/or health systems, and their leaders rather than to patients, the less likely they are to support policies financially penalizing physicians for prescribing low-value services.

Our study does not address why physicians have the beliefs that they have, but a likely explanation, at least in part, is that financial flows in healthcare are complex and tangled. Indeed, a clear understanding of who actually benefits is so hard to determine that these stated beliefs may really derive from views of power or justice rather than from some understanding of funds flow. Whether or not ideological attitudes underlie these expressed beliefs, policymakers and healthcare institutions might be advised to increase transparency about how cost savings are realized and whom they benefit.

Our analysis has limitations. Although it provides insight into where physicians believe relative amounts of money saved go with respect to 6 common options, the study did not include an exhaustive list of possibilities. The response rate also limits the representativeness of our results. Additionally, the study design prevents conclusions about causality; we cannot determine whether the belief that savings go to insurance companies and their executives is what reduces physicians’ enthusiasm for penalties, whether the causal association is in the opposite direction, or whether the 2 factors are linked in another way.

Nonetheless, our findings are consistent with a sense of healthcare justice in which physicians support penalties imposed on themselves only if the resulting benefits accrue to patients rather than to corporate or organizational interests. Effective physician penalties will likely need to address the belief that insurers and provider organizations stand to gain more than patients when low-value care services are reduced.

Disclosure

Drs. Liao, Schapira, Mitra, and Weissman have no conflicts to disclose. Dr. Navathe serves as advisor to Navvis and Company, Navigant Inc., Lynx Medical, Indegene Inc., and Sutherland Global Services and receives an honorarium from Elsevier Press, none of which have relationship to this manuscript. Dr. Asch is a partner and partial owner of VAL Health, which has no relationship to this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by The Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania, which had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of results.

1. Berwick DM. Avoiding overuse – the next quality frontier. Lancet. 2017;390(10090):102-104. PubMed

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS response to Public Comments on Non-Recommended PSA-Based Screening Measure. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/MMS/Downloads/eCQM-Development-and-Maintenance-for-Eligible-Professionals_CMS_PSA_Response_Public-Comment.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2017.

3. Asch DA, Jepson C, Hershey JC, Baron J, Ubel PA. When Money is Saved by Reducing Healthcare Costs, Where Do US Primary Care Physicians Think the Money Goes? Am J Manag Care. 2003;9(6):438-442. PubMed

4. Society of Hospital Medicine. Choosing Wisely. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/choosingwisely. Accessed September 18, 2017.

5. Liao JM, Navathe AS, Schapira MS, Weissman A, Mitra N, Asch DAA. Penalizing Physicians for Low Value Care in Hospital Medicine: A Randomized Survey. J Hosp Med. 2017. (In press). PubMed

1. Berwick DM. Avoiding overuse – the next quality frontier. Lancet. 2017;390(10090):102-104. PubMed

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS response to Public Comments on Non-Recommended PSA-Based Screening Measure. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/MMS/Downloads/eCQM-Development-and-Maintenance-for-Eligible-Professionals_CMS_PSA_Response_Public-Comment.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2017.