User login

Acute cardiorenal syndrome: Mechanisms and clinical implications

As the heart goes, so go the kidneys—and vice versa. Cardiac and renal function are intricately interdependent, and failure of either organ causes injury to the other in a vicious circle of worsening function.1

Here, we discuss acute cardiorenal syndrome, ie, acute exacerbation of heart failure leading to acute kidney injury, a common cause of hospitalization and admission to the intensive care unit. We examine its clinical definition, pathophysiology, hemodynamic derangements, clues that help in diagnosing it, and its treatment.

A GROUP OF LINKED DISORDERS

Two types of acute cardiac dysfunction

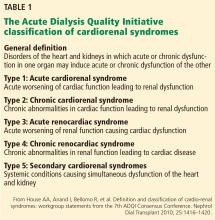

Although these definitions offer a good general description, further clarification of the nature of organ dysfunction is needed. Acute renal dysfunction can be unambiguously defined using the AKIN (Acute Kidney Injury Network) and RIFLE (risk, injury, failure, loss of kidney function, and end-stage kidney disease) classifications.3 Acute cardiac dysfunction, on the other hand, is an ambiguous term that encompasses 2 clinically and pathophysiologically distinct conditions: cardiogenic shock and acute heart failure.

Cardiogenic shock is characterized by a catastrophic compromise of cardiac pump function leading to global hypoperfusion severe enough to cause systemic organ damage.4 The cardiac index at which organs start to fail varies in different cases, but a value of less than 1.8 L/min/m2 is typically used to define cardiogenic shock.4

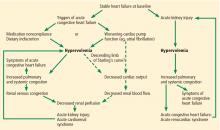

Acute heart failure, on the other hand, is defined as gradually or rapidly worsening signs and symptoms of congestive heart failure due to worsening pulmonary or systemic congestion.5 Hypervolemia is the hallmark of acute heart failure, whereas patients with cardiogenic shock may be hypervolemic, normovolemic, or hypovolemic. Although cardiac output may be mildly reduced in some cases of acute heart failure, systemic perfusion is enough to maintain organ function.

These two conditions cause renal injury by distinct mechanisms and have entirely different therapeutic implications. As we discuss later, reduced renal perfusion due to renal venous congestion is now believed to be the major hemodynamic mechanism of renal injury in acute heart failure. On the other hand, in cardiogenic shock, renal perfusion is reduced due to a critical decline of cardiac pump function.

The ideal definition of acute cardiorenal syndrome should describe a distinct pathophysiology of the syndrome and offer distinct therapeutic options that counteract it. Hence, we propose that renal injury from cardiogenic shock should not be included in its definition, an approach that has been adopted in some of the recent reviews as well.6 Our discussion of acute cardiorenal syndrome is restricted to renal injury caused by acute heart failure.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF ACUTE CARDIORENAL SYNDROME

Multiple mechanisms have been implicated in the pathophysiology of cardiorenal syndrome.7,8

Sympathetic hyperactivity is a compensatory mechanism in heart failure and may be aggravated if cardiac output is further reduced. Its effects include constriction of afferent and efferent arterioles, causing reduced renal perfusion and increased tubular sodium and water reabsorption.7

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system is activated in patients with stable congestive heart failure and may be further stimulated in a state of reduced renal perfusion, which is a hallmark of acute cardiorenal syndrome. Its activation can cause further salt and water retention.

However, direct hemodynamic mechanisms likely play the most important role and have obvious diagnostic and therapeutic implications.

Elevated venous pressure, not reduced cardiac output, drives kidney injury

The classic view was that renal dysfunction in acute heart failure is caused by reduced renal blood flow due to failing cardiac pump function. Cardiac output may be reduced in acute heart failure for various reasons, such as atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, or other processes, but reduced cardiac output has a minimal role, if any, in the pathogenesis of renal injury in acute heart failure.

As evidence of this, acute heart failure is not always associated with reduced cardiac output.5 Even if the cardiac index (cardiac output divided by body surface area) is mildly reduced, renal blood flow is largely unaffected, thanks to effective renal autoregulatory mechanisms. Not until the mean arterial pressure falls below 70 mm Hg do these mechanisms fail and renal blood flow starts to drop.9 Hence, unless cardiac performance is compromised enough to cause cardiogenic shock, renal blood flow usually does not change significantly with mild reduction in cardiac output.

Hanberg et al10 performed a post hoc analysis of the Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheter Effectiveness (ESCAPE) trial, in which 525 patients with advanced heart failure underwent pulmonary artery catheterization to measure their cardiac index. The authors found no association between the cardiac index and renal function in these patients.

How venous congestion impairs the kidney

In view of the current clinical evidence, the focus has shifted to renal venous congestion. According to Poiseuille’s law, blood flow through the kidneys depends on the pressure gradient—high pressure on the arterial side, low pressure on the venous side.8 Increased renal venous pressure causes reduced renal perfusion pressure, thereby affecting renal perfusion. This is now recognized as an important hemodynamic mechanism of acute cardiorenal syndrome.

Renal congestion can also affect renal function through indirect mechanisms. For example, it can cause renal interstitial edema that may then increase the intratubular pressure, thereby reducing the transglomerular pressure gradient.11

Firth et al,14 in experiments in animals, found that increasing the renal venous pressure above 18.75 mm Hg significantly reduced the glomerular filtration rate, which completely resolved when renal venous pressure was restored to basal levels.

Mullens et al,15 in a study of 145 patients admitted with acute heart failure, reported that 58 (40%) developed acute kidney injury. Pulmonary artery catheterization revealed that elevated central venous pressure, rather than reduced cardiac index, was the primary hemodynamic factor driving renal dysfunction.

DIAGNOSIS AND CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

Patients with acute cardiorenal syndrome present with clinical features of pulmonary or systemic congestion (or both) and acute kidney injury.

Elevated left-sided pressures are usually but not always associated with elevated right-sided pressures. In a study of 1,000 patients with advanced heart failure, a pulmonary capillary wedge pressure of 22 mm Hg or higher had a positive predictive value of 88% for a right atrial pressure of 10 mm Hg or higher.16 Hence, the clinical presentation may vary depending on the location (pulmonary, systemic, or both) and degree of congestion.

Symptoms of pulmonary congestion include worsening exertional dyspnea and orthopnea; bilateral crackles may be heard on physical examination if pulmonary edema is present.

Systemic congestion can cause significant peripheral edema and weight gain. Jugular venous distention may be noted. Oliguria may be present due to renal dysfunction; patients on maintenance diuretic therapy often note its lack of efficacy.

Signs of acute heart failure

Wang et al,17 in a meta-analysis of 22 studies, concluded that the features that most strongly suggested acute heart failure were:

- History of paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea

- A third heart sound

- Evidence of pulmonary venous congestion on chest radiography.

Features that most strongly suggested the patient did not have acute heart failure were:

- Absence of exertional dyspnea

- Absence of rales

- Absence of radiographic evidence of cardiomegaly.

Patients may present without some of these classic clinical features, and the diagnosis of acute heart failure may be challenging. For example, even if left-sided pressures are very high, pulmonary edema may be absent because of pulmonary vascular remodeling in chronic heart failure.18 Pulmonary artery catheterization reveals elevated cardiac filling pressures and can be used to guide therapy, but clinical evidence argues against its routine use.19

Urine electrolytes (fractional excretion of sodium < 1% and fractional excretion of urea < 35%) often suggest a prerenal form of acute kidney injury, since the hemodynamic derangements in acute cardiorenal syndrome reduce renal perfusion.

Biomarkers of cell-cycle arrest such as urine insulinlike growth factor-binding protein 7 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 2 have recently been shown to identify patients with acute heart failure at risk of developing acute cardiorenal syndrome.20

Acute cardiorenal syndrome vs renal injury due to hypovolemia

The major alternative in the differential diagnosis of acute cardiorenal syndrome is renal injury due to hypovolemia. Patients with stable heart failure usually have mild hypervolemia at baseline, but they can become hypovolemic due to overaggressive diuretic therapy, severe diarrhea, or other causes.

Although the fluid status of patients in these 2 conditions is opposite, they can be difficult to distinguish. In both conditions, urine electrolytes suggest a prerenal acute kidney injury. A history of recent fluid losses or diuretic overuse may help identify hypovolemia. If available, analysis of the recent trend in weight can be vital in making the right diagnosis.

Misdiagnosis of acute cardiorenal syndrome as hypovolemia-induced acute kidney injury can be catastrophic. If volume depletion is erroneously judged to be the cause of acute kidney injury, fluid administration can further worsen both cardiac and renal function. This can perpetuate the vicious circle that is already in play. Lack of renal recovery may invite further fluid administration.

TREATMENT

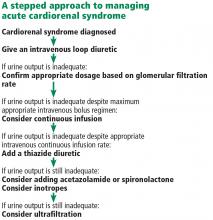

Fluid removal with diuresis or ultrafiltration is the cornerstone of treatment. Other treatments such as inotropes are reserved for patients with resistant disease.

Diuretics

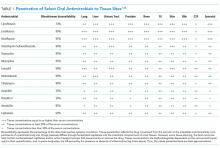

The goal of therapy in acute cardiorenal syndrome is to achieve aggressive diuresis, typically using intravenous diuretics. Loop diuretics are the most potent class of diuretics and are the first-line drugs for this purpose. Other classes of diuretics can be used in conjunction with loop diuretics; however, using them by themselves is neither effective nor recommended.

Resistance to diuretics at usual doses is common in patients with acute cardiorenal syndrome. Several mechanisms contribute to diuretic resistance in these patients.21

Oral bioavailability of diuretics may be reduced due to intestinal edema.

Diuretic pharmacokinetics are significantly deranged in cardiorenal syndrome. All diuretics except mineralocorticoid antagonists (ie, spironolactone and eplerenone) act on targets on the luminal side of renal tubules, but are highly protein-bound and are hence not filtered at the glomerulus. Loop diuretics, thiazides, and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors are secreted in the proximal convoluted tubule via the organic anion transporter,22 whereas epithelial sodium channel inhibitors (amiloride and triamterene) are secreted via the organic cation transporter 2.23 In renal dysfunction, various uremic toxins accumulate in the body and compete with diuretics for secretion into the proximal convoluted tubule via these transporters.24

Finally, activation of the sympathetic nervous system and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system leads to increased tubular sodium and water retention, thereby also blunting the diuretic response.

Diuretic dosage. In patients whose creatinine clearance is less than 15 mL/min, only 10% to 20% as much loop diuretic is secreted into the renal tubule as in normal individuals.25 This effect warrants dose adjustment of diuretics during uremia.

Continuous infusion or bolus? Continuous infusion of loop diuretics is another strategy to optimize drug delivery. Compared with bolus therapy, continuous infusion provides more sustained and uniform drug delivery and prevents postdiuretic sodium retention.

The Diuretic Optimization Strategies Evaluation (DOSE) trial compared the efficacy and safety of continuous vs bolus furosemide therapy in 308 patients admitted with acute decompensated heart failure.26 There was no difference in symptom control or net fluid loss at 72 hours in either group. Other studies have shown more diuresis with continuous infusion than with a similarly dosed bolus regimen.27 However, definitive clinical evidence is lacking at this point to support routine use of continuous loop diuretic therapy.

Combination diuretic therapy. Sequential nephron blockade with combination diuretic therapy is an important therapeutic strategy against diuretic resistance. Notably, urine output-guided diuretic therapy has been shown to be superior to standard diuretic therapy.28 Such therapeutic protocols may employ combination diuretic therapy as a next step when the desired diuretic response is not obtained with high doses of loop diuretic monotherapy.

The desired diuretic response depends on the clinical situation. For example, in patients with severe congestion, we would like the net fluid output to be at least 2 to 3 L more than the fluid intake after the first 24 hours. Sometimes, patients in the intensive care unit are on several essential drug infusions, so that their net intake amounts to 1 to 2 L. In these patients, the desired urine output would be even more than in patients not on these drug infusions.

Loop diuretics block sodium reabsorption at the thick ascending loop of Henle. This disrupts the countercurrent exchange mechanism and reduces renal medullary interstitial osmolarity; these effects prevent water reabsorption. However, the unresorbed sodium can be taken up by the sodium-chloride cotransporter and the epithelial sodium channel in the distal nephron, thereby blunting the diuretic effect. This is the rationale for combining loop diuretics with thiazides or potassium-sparing diuretics.

Similarly, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (eg, acetazolamide) reduce sodium reabsorption from the proximal convoluted tubule, but most of this sodium is then reabsorbed distally. Hence, the combination of a loop diuretic and acetazolamide can also have a synergistic diuretic effect.

The most popular combination is a loop diuretic plus a thiazide, although no large-scale placebo-controlled trials have been performed.29 Metolazone (a thiazidelike diuretic) is typically used due to its low cost and availability.30 Metolazone has also been shown to block sodium reabsorption at the proximal tubule, which may contribute to its synergistic effect. Chlorothiazide is available in an intravenous formulation and has a faster onset of action than metolazone. However, studies have failed to detect any benefit of one over the other.31

The potential benefit of combining a loop diuretic with acetazolamide is a lower tendency to develop metabolic alkalosis, a potential side effect of loop diuretics and thiazides. Although data are limited, a recent study showed that adding acetazolamide to bumetanide led to significantly increased natriuresis.32

In the Aldosterone Targeted Neurohormonal Combined With Natriuresis Therapy in Heart Failure (ATHENA-HF) trial, adding spironolactone in high doses to usual therapy was not found to cause any significant change in N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide level or net urine output.33

Ultrafiltration

Venovenous ultrafiltration (or aquapheresis) employs an extracorporeal circuit, similar to the one used in hemodialysis, which removes iso-osmolar fluid at a fixed rate.34 Newer ultrafiltration systems are more portable, can be used with peripheral venous access, and require minimal nursing supervision.35

Although ultrafiltration seems an attractive alternative to diuresis in acute heart failure, studies have been inconclusive. The Cardiorenal Rescue Study in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure (CARRESS-HF) trial compared ultrafiltration and diuresis in 188 patients with acute heart failure and acute cardiorenal syndrome.36 Diuresis, performed according to an algorithm, was found to be superior to ultrafiltration in terms of a bivariate end point of change in weight and change in serum creatinine level at 96 hours. However, the level of cystatin C is thought to be a more accurate indicator of renal function, and the change in cystatin C level from baseline did not differ between the two treatment groups. Also, the ultrafiltration rate was 200 mL per hour, which, some argue, may have been excessive and may have caused intravascular depletion.

Although the ideal rate of fluid removal is unknown, it should be individualized and adjusted based on the patient’s renal function, volume status, and hemodynamic status. The initial rate should be based on the degree of fluid overload and the anticipated plasma refill rate from the interstitial fluid.37 For example, a malnourished patient may have low serum oncotic pressure and hence have low plasma refill upon ultrafiltration. Disturbance of this delicate balance between the rates of ultrafiltration and plasma refill may lead to intravascular volume contraction.

In summary, although ultrafiltration is a valuable alternative to diuretics in resistant cases, its use as a primary decongestive therapy cannot be endorsed in view of the current data.

Inotropes

Inotropes such as dobutamine and milrinone are typically used in cases of cardiogenic shock to maintain organ perfusion. There is a physiologic rationale to using inotropes in acute cardiorenal syndrome as well, especially when the aforementioned strategies fail to overcome diuretic resistance.7

Inotropes increase cardiac output, improve renal blood flow, improve right ventricular output, and thereby relieve systemic congestion. These hemodynamic effects may improve renal perfusion and response to diuretics. However, clinical evidence to support this is lacking.

The Renal Optimization Strategies Evaluation (ROSE) trial enrolled 360 patients with acute heart failure and renal dysfunction. Adding dopamine in a low dose (2 μg/kg/min) to diuretic therapy had no significant effect on 72-hour cumulative urine output or renal function as measured by cystatin C levels.38 However, acute kidney injury was not identified in this trial, and the renal function of many of these patients may have been at its baseline when they were admitted. In other words, this trial did not necessarily include patients with acute kidney injury along with acute heart failure. Hence, it did not necessarily include patients with acute cardiorenal syndrome.

Vasodilators

Vasodilators such as nitroglycerin, sodium nitroprusside, and hydralazine are commonly used in patients with acute heart failure, although the clinical evidence supporting their use is weak.

Physiologically, arterial dilation reduces afterload and can help relieve pulmonary congestion, and venodilation increases capacitance and reduces preload. In theory, venodilators such as nitroglycerin can relieve renal venous congestion in patients with acute cardiorenal syndrome, thereby improving renal perfusion.

However, the use of vasodilators is often limited by their adverse effects, the most important being hypotension. This is especially relevant in light of recent data identifying reduction in blood pressure during treatment of acute heart failure as an independent risk factor for worsening renal function.39,40 It is important to note that in these studies, changes in cardiac index did not affect the propensity for developing worsening renal function. The precise mechanism of this finding is unclear but it is plausible that systemic vasodilation redistributes the cardiac output to nonrenal tissues, thereby overriding the renal autoregulatory mechanisms that are normally employed in low output states.

Preventive strategies

Various strategies can be used to prevent acute cardiorenal syndrome. An optimal outpatient diuretic regimen to avoid hypervolemia is essential. Patients with advanced congestive heart failure should be followed up closely in dedicated heart failure clinics until their diuretic regimen is optimized. Patients should be advised to check their weight on a regular basis and seek medical advice if they notice an increase in their weight or a reduction in their urine output.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- A robust clinical definition of cardiorenal syndrome is lacking. Hence, recognition of this condition can be challenging.

- Volume overload is central to its pathogenesis, and accurate assessment of volume status is critical.

- Renal venous congestion is the major mechanism of type 1 cardiorenal syndrome.

- Misdiagnosis can have devastating consequences, as it may lead to an opposite therapeutic approach.

- Fluid removal by various strategies is the mainstay of treatment.

- Temporary inotropic support should be saved for the last resort.

- Geisberg C, Butler J. Addressing the challenges of cardiorenal syndrome. Cleve Clin J Med 2006; 73:485–491.

- House AA, Anand I, Bellomo R, et al. Definition and classification of cardio-renal syndromes: workgroup statements from the 7th ADQI Consensus Conference. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010; 25:1416–1420.

- Chang CH, Lin CY, Tian YC, et al. Acute kidney injury classification: comparison of AKIN and RIFLE criteria. Shock 2010; 33:247-252.

- Reynolds HR, Hochman JS. Cardiogenic shock: current concepts and improving outcomes. Circulation 2008; 117:686–697.

- Gheorghiade M, Pang PS. Acute heart failure syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53:557–573.

- ter Maaten JM, Valente MA, Damman K, et al. Diuretic response in acute heart failure—pathophysiology, evaluation, and therapy. Nat Rev Cardiol 2015; 12:184–192.

- Hatamizadeh P, Fonarow GC, Budoff MJ, Darabian S, Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Cardiorenal syndrome: pathophysiology and potential targets for clinical management. Nat Rev Nephrol 2013; 9:99–111.

- Bock JS, Gottlieb SS. Cardiorenal syndrome: new perspectives. Circulation 2010; 121:2592–2600.

- Burke M, Pabbidi MR, Farley J, et al. Molecular mechanisms of renal blood flow autoregulation. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2014; 12:845–858.

- Hanberg JS, Sury K, Wilson FP, et al. Reduced cardiac index is not the dominant driver of renal dysfunction in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 67:2199–2208.

- Afsar B, Ortiz A, Covic A, et al. Focus on renal congestion in heart failure. Clin Kidney J 2016; 9:39–47.

- Verbrugge FH, Dupont M, Steels P, et al. Abdominal contributions to cardiorenal dysfunction in congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62:485–495.

- Mullens W, Abrahams Z, Skouri HN, et al. Elevated intra-abdominal pressure in acute decompensated heart failure: a potential contributor to worsening renal function? J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 51:300–306.

- Firth JD, Raine AE, Ledingham JG. Raised venous pressure: a direct cause of renal sodium retention in oedema? Lancet 1988; 1:1033–1035.

- Mullens W, Abrahams Z, Francis GS, et al. Importance of venous congestion for worsening of renal function in advanced decompensated heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53:589–596.

- Drazner MH, Hamilton MA, Fonarow G, et al. Relationship between right and left-sided filling pressures in 1000 patients with advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant 1999; 18:1126–1132.

- Wang CS, FitzGerald JM, Schulzer M, et al. Does this dyspneic patient in the emergency department have congestive heart failure? JAMA 2005; 294:1944–1956.

- Gehlbach BK, Geppert E. The pulmonary manifestations of left heart failure. Chest 2004; 125:669–682.

- Binanay C, Califf RM, Hasselblad V, et al. Evaluation study of congestive heart failure and pulmonary artery catheterization effectiveness: the ESCAPE trial. JAMA 2005; 294:1625–1633.

- Schanz M, Shi J , Wasser C , Alscher MD, Kimmel M. Urinary [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] for risk prediction of acute kidney injury in decompensated heart failure. Clin Cardiol 2017; doi.org/10.1002/clc.22683.

- Bowman BN, Nawarskas JJ, Anderson JR. Treating diuretic resistance: an overview. Cardiol Rev 2016; 24:256–260.

- Uwai Y, Saito H, Hashimoto Y, Inui KI. Interaction and transport of thiazide diuretics, loop diuretics, and acetazolamide via rat renal organic anion transporter rOAT1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2000; 295:261–265.

- Hacker K, Maas R, Kornhuber J, et al. Substrate-dependent inhibition of the human organic cation transporter OCT2: a comparison of metformin with experimental substrates. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0136451.

- Schophuizen CM, Wilmer MJ, Jansen J, et al. Cationic uremic toxins affect human renal proximal tubule cell functioning through interaction with the organic cation transporter. Pflugers Arch 2013; 465:1701–1714.

- Brater DC. Diuretic therapy. N Engl J Med 1998; 339:387–395.

- Felker GM, Lee KL, Bull DA, et al. Diuretic strategies in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:797–805.

- Thomson MR, Nappi JM, Dunn SP, Hollis IB, Rodgers JE, Van Bakel AB. Continuous versus intermittent infusion of furosemide in acute decompensated heart failure. J Card Fail 2010; 16:188–193.

- Grodin JL, Stevens SR, de Las Fuentes L, et al. Intensification of medication therapy for cardiorenal syndrome in acute decompensated heart failure. J Card Fail 2016; 22:26–32.

- Ng TM, Konopka E, Hyderi AF, et al. Comparison of bumetanide- and metolazone-based diuretic regimens to furosemide in acute heart failure. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 2013; 18:345–353.

- Sica DA. Metolazone and its role in edema management. Congest Heart Fail 2003; 9:100–105.

- Moranville MP, Choi S, Hogg J, Anderson AS, Rich JD. Comparison of metolazone versus chlorothiazide in acute decompensated heart failure with diuretic resistance. Cardiovasc Ther 2015; 33:42–49.

- Verbrugge FH, Dupont M, Bertrand PB, et al. Determinants and impact of the natriuretic response to diuretic therapy in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and volume overload. Acta Cardiol 2015; 70:265–373.

- Butler J, Anstrom KJ, Felker GM, et al. Efficacy and safety of spironolactone in acute heart failure: the ATHENA-HF randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol 2017 Jul 12. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.2198. [Epub ahead of print]

- Pourafshar N, Karimi A, Kazory A. Extracorporeal ultrafiltration therapy for acute decompensated heart failure. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2016; 14:5–13.

- Jaski BE, Ha J, Denys BG, et al. Peripherally inserted veno-venous ultrafiltration for rapid treatment of volume overloaded patients. J Card Fail 2003; 9:227–231.

- Jaski BE, Ha J, Denys BG, Lamba S, Trupp RJ, Abraham WT. Ultrafiltration in decompensated heart failure with cardiorenal syndrome. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:2296–2304.

- Kazory A. Cardiorenal syndrome: ultrafiltration therapy for heart failure—trials and tribulations. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2013; 8:1816–1828.

- Chen HH, Anstrom KJ, Givertz MM, et al. Low-dose dopamine or low-dose nesiritide in acute heart failure with renal dysfunction: the ROSE acute heart failure randomized trial. JAMA 2013; 310:2533–2543.

- Testani JM, Coca SG, McCauley BD, et al. Impact of changes in blood pressure during the treatment of acute decompensated heart failure on renal and clinical outcomes. Eur J Heart Fail 2011; 13:877–884.

- Dupont M, Mullens W, Finucan M, et al. Determinants of dynamic changes in serum creatinine in acute decompensated heart failure: the importance of blood pressure reduction during treatment. Eur J Heart Fail 2013; 15:433–440.

As the heart goes, so go the kidneys—and vice versa. Cardiac and renal function are intricately interdependent, and failure of either organ causes injury to the other in a vicious circle of worsening function.1

Here, we discuss acute cardiorenal syndrome, ie, acute exacerbation of heart failure leading to acute kidney injury, a common cause of hospitalization and admission to the intensive care unit. We examine its clinical definition, pathophysiology, hemodynamic derangements, clues that help in diagnosing it, and its treatment.

A GROUP OF LINKED DISORDERS

Two types of acute cardiac dysfunction

Although these definitions offer a good general description, further clarification of the nature of organ dysfunction is needed. Acute renal dysfunction can be unambiguously defined using the AKIN (Acute Kidney Injury Network) and RIFLE (risk, injury, failure, loss of kidney function, and end-stage kidney disease) classifications.3 Acute cardiac dysfunction, on the other hand, is an ambiguous term that encompasses 2 clinically and pathophysiologically distinct conditions: cardiogenic shock and acute heart failure.

Cardiogenic shock is characterized by a catastrophic compromise of cardiac pump function leading to global hypoperfusion severe enough to cause systemic organ damage.4 The cardiac index at which organs start to fail varies in different cases, but a value of less than 1.8 L/min/m2 is typically used to define cardiogenic shock.4

Acute heart failure, on the other hand, is defined as gradually or rapidly worsening signs and symptoms of congestive heart failure due to worsening pulmonary or systemic congestion.5 Hypervolemia is the hallmark of acute heart failure, whereas patients with cardiogenic shock may be hypervolemic, normovolemic, or hypovolemic. Although cardiac output may be mildly reduced in some cases of acute heart failure, systemic perfusion is enough to maintain organ function.

These two conditions cause renal injury by distinct mechanisms and have entirely different therapeutic implications. As we discuss later, reduced renal perfusion due to renal venous congestion is now believed to be the major hemodynamic mechanism of renal injury in acute heart failure. On the other hand, in cardiogenic shock, renal perfusion is reduced due to a critical decline of cardiac pump function.

The ideal definition of acute cardiorenal syndrome should describe a distinct pathophysiology of the syndrome and offer distinct therapeutic options that counteract it. Hence, we propose that renal injury from cardiogenic shock should not be included in its definition, an approach that has been adopted in some of the recent reviews as well.6 Our discussion of acute cardiorenal syndrome is restricted to renal injury caused by acute heart failure.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF ACUTE CARDIORENAL SYNDROME

Multiple mechanisms have been implicated in the pathophysiology of cardiorenal syndrome.7,8

Sympathetic hyperactivity is a compensatory mechanism in heart failure and may be aggravated if cardiac output is further reduced. Its effects include constriction of afferent and efferent arterioles, causing reduced renal perfusion and increased tubular sodium and water reabsorption.7

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system is activated in patients with stable congestive heart failure and may be further stimulated in a state of reduced renal perfusion, which is a hallmark of acute cardiorenal syndrome. Its activation can cause further salt and water retention.

However, direct hemodynamic mechanisms likely play the most important role and have obvious diagnostic and therapeutic implications.

Elevated venous pressure, not reduced cardiac output, drives kidney injury

The classic view was that renal dysfunction in acute heart failure is caused by reduced renal blood flow due to failing cardiac pump function. Cardiac output may be reduced in acute heart failure for various reasons, such as atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, or other processes, but reduced cardiac output has a minimal role, if any, in the pathogenesis of renal injury in acute heart failure.

As evidence of this, acute heart failure is not always associated with reduced cardiac output.5 Even if the cardiac index (cardiac output divided by body surface area) is mildly reduced, renal blood flow is largely unaffected, thanks to effective renal autoregulatory mechanisms. Not until the mean arterial pressure falls below 70 mm Hg do these mechanisms fail and renal blood flow starts to drop.9 Hence, unless cardiac performance is compromised enough to cause cardiogenic shock, renal blood flow usually does not change significantly with mild reduction in cardiac output.

Hanberg et al10 performed a post hoc analysis of the Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheter Effectiveness (ESCAPE) trial, in which 525 patients with advanced heart failure underwent pulmonary artery catheterization to measure their cardiac index. The authors found no association between the cardiac index and renal function in these patients.

How venous congestion impairs the kidney

In view of the current clinical evidence, the focus has shifted to renal venous congestion. According to Poiseuille’s law, blood flow through the kidneys depends on the pressure gradient—high pressure on the arterial side, low pressure on the venous side.8 Increased renal venous pressure causes reduced renal perfusion pressure, thereby affecting renal perfusion. This is now recognized as an important hemodynamic mechanism of acute cardiorenal syndrome.

Renal congestion can also affect renal function through indirect mechanisms. For example, it can cause renal interstitial edema that may then increase the intratubular pressure, thereby reducing the transglomerular pressure gradient.11

Firth et al,14 in experiments in animals, found that increasing the renal venous pressure above 18.75 mm Hg significantly reduced the glomerular filtration rate, which completely resolved when renal venous pressure was restored to basal levels.

Mullens et al,15 in a study of 145 patients admitted with acute heart failure, reported that 58 (40%) developed acute kidney injury. Pulmonary artery catheterization revealed that elevated central venous pressure, rather than reduced cardiac index, was the primary hemodynamic factor driving renal dysfunction.

DIAGNOSIS AND CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

Patients with acute cardiorenal syndrome present with clinical features of pulmonary or systemic congestion (or both) and acute kidney injury.

Elevated left-sided pressures are usually but not always associated with elevated right-sided pressures. In a study of 1,000 patients with advanced heart failure, a pulmonary capillary wedge pressure of 22 mm Hg or higher had a positive predictive value of 88% for a right atrial pressure of 10 mm Hg or higher.16 Hence, the clinical presentation may vary depending on the location (pulmonary, systemic, or both) and degree of congestion.

Symptoms of pulmonary congestion include worsening exertional dyspnea and orthopnea; bilateral crackles may be heard on physical examination if pulmonary edema is present.

Systemic congestion can cause significant peripheral edema and weight gain. Jugular venous distention may be noted. Oliguria may be present due to renal dysfunction; patients on maintenance diuretic therapy often note its lack of efficacy.

Signs of acute heart failure

Wang et al,17 in a meta-analysis of 22 studies, concluded that the features that most strongly suggested acute heart failure were:

- History of paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea

- A third heart sound

- Evidence of pulmonary venous congestion on chest radiography.

Features that most strongly suggested the patient did not have acute heart failure were:

- Absence of exertional dyspnea

- Absence of rales

- Absence of radiographic evidence of cardiomegaly.

Patients may present without some of these classic clinical features, and the diagnosis of acute heart failure may be challenging. For example, even if left-sided pressures are very high, pulmonary edema may be absent because of pulmonary vascular remodeling in chronic heart failure.18 Pulmonary artery catheterization reveals elevated cardiac filling pressures and can be used to guide therapy, but clinical evidence argues against its routine use.19

Urine electrolytes (fractional excretion of sodium < 1% and fractional excretion of urea < 35%) often suggest a prerenal form of acute kidney injury, since the hemodynamic derangements in acute cardiorenal syndrome reduce renal perfusion.

Biomarkers of cell-cycle arrest such as urine insulinlike growth factor-binding protein 7 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 2 have recently been shown to identify patients with acute heart failure at risk of developing acute cardiorenal syndrome.20

Acute cardiorenal syndrome vs renal injury due to hypovolemia

The major alternative in the differential diagnosis of acute cardiorenal syndrome is renal injury due to hypovolemia. Patients with stable heart failure usually have mild hypervolemia at baseline, but they can become hypovolemic due to overaggressive diuretic therapy, severe diarrhea, or other causes.

Although the fluid status of patients in these 2 conditions is opposite, they can be difficult to distinguish. In both conditions, urine electrolytes suggest a prerenal acute kidney injury. A history of recent fluid losses or diuretic overuse may help identify hypovolemia. If available, analysis of the recent trend in weight can be vital in making the right diagnosis.

Misdiagnosis of acute cardiorenal syndrome as hypovolemia-induced acute kidney injury can be catastrophic. If volume depletion is erroneously judged to be the cause of acute kidney injury, fluid administration can further worsen both cardiac and renal function. This can perpetuate the vicious circle that is already in play. Lack of renal recovery may invite further fluid administration.

TREATMENT

Fluid removal with diuresis or ultrafiltration is the cornerstone of treatment. Other treatments such as inotropes are reserved for patients with resistant disease.

Diuretics

The goal of therapy in acute cardiorenal syndrome is to achieve aggressive diuresis, typically using intravenous diuretics. Loop diuretics are the most potent class of diuretics and are the first-line drugs for this purpose. Other classes of diuretics can be used in conjunction with loop diuretics; however, using them by themselves is neither effective nor recommended.

Resistance to diuretics at usual doses is common in patients with acute cardiorenal syndrome. Several mechanisms contribute to diuretic resistance in these patients.21

Oral bioavailability of diuretics may be reduced due to intestinal edema.

Diuretic pharmacokinetics are significantly deranged in cardiorenal syndrome. All diuretics except mineralocorticoid antagonists (ie, spironolactone and eplerenone) act on targets on the luminal side of renal tubules, but are highly protein-bound and are hence not filtered at the glomerulus. Loop diuretics, thiazides, and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors are secreted in the proximal convoluted tubule via the organic anion transporter,22 whereas epithelial sodium channel inhibitors (amiloride and triamterene) are secreted via the organic cation transporter 2.23 In renal dysfunction, various uremic toxins accumulate in the body and compete with diuretics for secretion into the proximal convoluted tubule via these transporters.24

Finally, activation of the sympathetic nervous system and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system leads to increased tubular sodium and water retention, thereby also blunting the diuretic response.

Diuretic dosage. In patients whose creatinine clearance is less than 15 mL/min, only 10% to 20% as much loop diuretic is secreted into the renal tubule as in normal individuals.25 This effect warrants dose adjustment of diuretics during uremia.

Continuous infusion or bolus? Continuous infusion of loop diuretics is another strategy to optimize drug delivery. Compared with bolus therapy, continuous infusion provides more sustained and uniform drug delivery and prevents postdiuretic sodium retention.

The Diuretic Optimization Strategies Evaluation (DOSE) trial compared the efficacy and safety of continuous vs bolus furosemide therapy in 308 patients admitted with acute decompensated heart failure.26 There was no difference in symptom control or net fluid loss at 72 hours in either group. Other studies have shown more diuresis with continuous infusion than with a similarly dosed bolus regimen.27 However, definitive clinical evidence is lacking at this point to support routine use of continuous loop diuretic therapy.

Combination diuretic therapy. Sequential nephron blockade with combination diuretic therapy is an important therapeutic strategy against diuretic resistance. Notably, urine output-guided diuretic therapy has been shown to be superior to standard diuretic therapy.28 Such therapeutic protocols may employ combination diuretic therapy as a next step when the desired diuretic response is not obtained with high doses of loop diuretic monotherapy.

The desired diuretic response depends on the clinical situation. For example, in patients with severe congestion, we would like the net fluid output to be at least 2 to 3 L more than the fluid intake after the first 24 hours. Sometimes, patients in the intensive care unit are on several essential drug infusions, so that their net intake amounts to 1 to 2 L. In these patients, the desired urine output would be even more than in patients not on these drug infusions.

Loop diuretics block sodium reabsorption at the thick ascending loop of Henle. This disrupts the countercurrent exchange mechanism and reduces renal medullary interstitial osmolarity; these effects prevent water reabsorption. However, the unresorbed sodium can be taken up by the sodium-chloride cotransporter and the epithelial sodium channel in the distal nephron, thereby blunting the diuretic effect. This is the rationale for combining loop diuretics with thiazides or potassium-sparing diuretics.

Similarly, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (eg, acetazolamide) reduce sodium reabsorption from the proximal convoluted tubule, but most of this sodium is then reabsorbed distally. Hence, the combination of a loop diuretic and acetazolamide can also have a synergistic diuretic effect.

The most popular combination is a loop diuretic plus a thiazide, although no large-scale placebo-controlled trials have been performed.29 Metolazone (a thiazidelike diuretic) is typically used due to its low cost and availability.30 Metolazone has also been shown to block sodium reabsorption at the proximal tubule, which may contribute to its synergistic effect. Chlorothiazide is available in an intravenous formulation and has a faster onset of action than metolazone. However, studies have failed to detect any benefit of one over the other.31

The potential benefit of combining a loop diuretic with acetazolamide is a lower tendency to develop metabolic alkalosis, a potential side effect of loop diuretics and thiazides. Although data are limited, a recent study showed that adding acetazolamide to bumetanide led to significantly increased natriuresis.32

In the Aldosterone Targeted Neurohormonal Combined With Natriuresis Therapy in Heart Failure (ATHENA-HF) trial, adding spironolactone in high doses to usual therapy was not found to cause any significant change in N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide level or net urine output.33

Ultrafiltration

Venovenous ultrafiltration (or aquapheresis) employs an extracorporeal circuit, similar to the one used in hemodialysis, which removes iso-osmolar fluid at a fixed rate.34 Newer ultrafiltration systems are more portable, can be used with peripheral venous access, and require minimal nursing supervision.35

Although ultrafiltration seems an attractive alternative to diuresis in acute heart failure, studies have been inconclusive. The Cardiorenal Rescue Study in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure (CARRESS-HF) trial compared ultrafiltration and diuresis in 188 patients with acute heart failure and acute cardiorenal syndrome.36 Diuresis, performed according to an algorithm, was found to be superior to ultrafiltration in terms of a bivariate end point of change in weight and change in serum creatinine level at 96 hours. However, the level of cystatin C is thought to be a more accurate indicator of renal function, and the change in cystatin C level from baseline did not differ between the two treatment groups. Also, the ultrafiltration rate was 200 mL per hour, which, some argue, may have been excessive and may have caused intravascular depletion.

Although the ideal rate of fluid removal is unknown, it should be individualized and adjusted based on the patient’s renal function, volume status, and hemodynamic status. The initial rate should be based on the degree of fluid overload and the anticipated plasma refill rate from the interstitial fluid.37 For example, a malnourished patient may have low serum oncotic pressure and hence have low plasma refill upon ultrafiltration. Disturbance of this delicate balance between the rates of ultrafiltration and plasma refill may lead to intravascular volume contraction.

In summary, although ultrafiltration is a valuable alternative to diuretics in resistant cases, its use as a primary decongestive therapy cannot be endorsed in view of the current data.

Inotropes

Inotropes such as dobutamine and milrinone are typically used in cases of cardiogenic shock to maintain organ perfusion. There is a physiologic rationale to using inotropes in acute cardiorenal syndrome as well, especially when the aforementioned strategies fail to overcome diuretic resistance.7

Inotropes increase cardiac output, improve renal blood flow, improve right ventricular output, and thereby relieve systemic congestion. These hemodynamic effects may improve renal perfusion and response to diuretics. However, clinical evidence to support this is lacking.

The Renal Optimization Strategies Evaluation (ROSE) trial enrolled 360 patients with acute heart failure and renal dysfunction. Adding dopamine in a low dose (2 μg/kg/min) to diuretic therapy had no significant effect on 72-hour cumulative urine output or renal function as measured by cystatin C levels.38 However, acute kidney injury was not identified in this trial, and the renal function of many of these patients may have been at its baseline when they were admitted. In other words, this trial did not necessarily include patients with acute kidney injury along with acute heart failure. Hence, it did not necessarily include patients with acute cardiorenal syndrome.

Vasodilators

Vasodilators such as nitroglycerin, sodium nitroprusside, and hydralazine are commonly used in patients with acute heart failure, although the clinical evidence supporting their use is weak.

Physiologically, arterial dilation reduces afterload and can help relieve pulmonary congestion, and venodilation increases capacitance and reduces preload. In theory, venodilators such as nitroglycerin can relieve renal venous congestion in patients with acute cardiorenal syndrome, thereby improving renal perfusion.

However, the use of vasodilators is often limited by their adverse effects, the most important being hypotension. This is especially relevant in light of recent data identifying reduction in blood pressure during treatment of acute heart failure as an independent risk factor for worsening renal function.39,40 It is important to note that in these studies, changes in cardiac index did not affect the propensity for developing worsening renal function. The precise mechanism of this finding is unclear but it is plausible that systemic vasodilation redistributes the cardiac output to nonrenal tissues, thereby overriding the renal autoregulatory mechanisms that are normally employed in low output states.

Preventive strategies

Various strategies can be used to prevent acute cardiorenal syndrome. An optimal outpatient diuretic regimen to avoid hypervolemia is essential. Patients with advanced congestive heart failure should be followed up closely in dedicated heart failure clinics until their diuretic regimen is optimized. Patients should be advised to check their weight on a regular basis and seek medical advice if they notice an increase in their weight or a reduction in their urine output.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- A robust clinical definition of cardiorenal syndrome is lacking. Hence, recognition of this condition can be challenging.

- Volume overload is central to its pathogenesis, and accurate assessment of volume status is critical.

- Renal venous congestion is the major mechanism of type 1 cardiorenal syndrome.

- Misdiagnosis can have devastating consequences, as it may lead to an opposite therapeutic approach.

- Fluid removal by various strategies is the mainstay of treatment.

- Temporary inotropic support should be saved for the last resort.

As the heart goes, so go the kidneys—and vice versa. Cardiac and renal function are intricately interdependent, and failure of either organ causes injury to the other in a vicious circle of worsening function.1

Here, we discuss acute cardiorenal syndrome, ie, acute exacerbation of heart failure leading to acute kidney injury, a common cause of hospitalization and admission to the intensive care unit. We examine its clinical definition, pathophysiology, hemodynamic derangements, clues that help in diagnosing it, and its treatment.

A GROUP OF LINKED DISORDERS

Two types of acute cardiac dysfunction

Although these definitions offer a good general description, further clarification of the nature of organ dysfunction is needed. Acute renal dysfunction can be unambiguously defined using the AKIN (Acute Kidney Injury Network) and RIFLE (risk, injury, failure, loss of kidney function, and end-stage kidney disease) classifications.3 Acute cardiac dysfunction, on the other hand, is an ambiguous term that encompasses 2 clinically and pathophysiologically distinct conditions: cardiogenic shock and acute heart failure.

Cardiogenic shock is characterized by a catastrophic compromise of cardiac pump function leading to global hypoperfusion severe enough to cause systemic organ damage.4 The cardiac index at which organs start to fail varies in different cases, but a value of less than 1.8 L/min/m2 is typically used to define cardiogenic shock.4

Acute heart failure, on the other hand, is defined as gradually or rapidly worsening signs and symptoms of congestive heart failure due to worsening pulmonary or systemic congestion.5 Hypervolemia is the hallmark of acute heart failure, whereas patients with cardiogenic shock may be hypervolemic, normovolemic, or hypovolemic. Although cardiac output may be mildly reduced in some cases of acute heart failure, systemic perfusion is enough to maintain organ function.

These two conditions cause renal injury by distinct mechanisms and have entirely different therapeutic implications. As we discuss later, reduced renal perfusion due to renal venous congestion is now believed to be the major hemodynamic mechanism of renal injury in acute heart failure. On the other hand, in cardiogenic shock, renal perfusion is reduced due to a critical decline of cardiac pump function.

The ideal definition of acute cardiorenal syndrome should describe a distinct pathophysiology of the syndrome and offer distinct therapeutic options that counteract it. Hence, we propose that renal injury from cardiogenic shock should not be included in its definition, an approach that has been adopted in some of the recent reviews as well.6 Our discussion of acute cardiorenal syndrome is restricted to renal injury caused by acute heart failure.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF ACUTE CARDIORENAL SYNDROME

Multiple mechanisms have been implicated in the pathophysiology of cardiorenal syndrome.7,8

Sympathetic hyperactivity is a compensatory mechanism in heart failure and may be aggravated if cardiac output is further reduced. Its effects include constriction of afferent and efferent arterioles, causing reduced renal perfusion and increased tubular sodium and water reabsorption.7

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system is activated in patients with stable congestive heart failure and may be further stimulated in a state of reduced renal perfusion, which is a hallmark of acute cardiorenal syndrome. Its activation can cause further salt and water retention.

However, direct hemodynamic mechanisms likely play the most important role and have obvious diagnostic and therapeutic implications.

Elevated venous pressure, not reduced cardiac output, drives kidney injury

The classic view was that renal dysfunction in acute heart failure is caused by reduced renal blood flow due to failing cardiac pump function. Cardiac output may be reduced in acute heart failure for various reasons, such as atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, or other processes, but reduced cardiac output has a minimal role, if any, in the pathogenesis of renal injury in acute heart failure.

As evidence of this, acute heart failure is not always associated with reduced cardiac output.5 Even if the cardiac index (cardiac output divided by body surface area) is mildly reduced, renal blood flow is largely unaffected, thanks to effective renal autoregulatory mechanisms. Not until the mean arterial pressure falls below 70 mm Hg do these mechanisms fail and renal blood flow starts to drop.9 Hence, unless cardiac performance is compromised enough to cause cardiogenic shock, renal blood flow usually does not change significantly with mild reduction in cardiac output.

Hanberg et al10 performed a post hoc analysis of the Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheter Effectiveness (ESCAPE) trial, in which 525 patients with advanced heart failure underwent pulmonary artery catheterization to measure their cardiac index. The authors found no association between the cardiac index and renal function in these patients.

How venous congestion impairs the kidney

In view of the current clinical evidence, the focus has shifted to renal venous congestion. According to Poiseuille’s law, blood flow through the kidneys depends on the pressure gradient—high pressure on the arterial side, low pressure on the venous side.8 Increased renal venous pressure causes reduced renal perfusion pressure, thereby affecting renal perfusion. This is now recognized as an important hemodynamic mechanism of acute cardiorenal syndrome.

Renal congestion can also affect renal function through indirect mechanisms. For example, it can cause renal interstitial edema that may then increase the intratubular pressure, thereby reducing the transglomerular pressure gradient.11

Firth et al,14 in experiments in animals, found that increasing the renal venous pressure above 18.75 mm Hg significantly reduced the glomerular filtration rate, which completely resolved when renal venous pressure was restored to basal levels.

Mullens et al,15 in a study of 145 patients admitted with acute heart failure, reported that 58 (40%) developed acute kidney injury. Pulmonary artery catheterization revealed that elevated central venous pressure, rather than reduced cardiac index, was the primary hemodynamic factor driving renal dysfunction.

DIAGNOSIS AND CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

Patients with acute cardiorenal syndrome present with clinical features of pulmonary or systemic congestion (or both) and acute kidney injury.

Elevated left-sided pressures are usually but not always associated with elevated right-sided pressures. In a study of 1,000 patients with advanced heart failure, a pulmonary capillary wedge pressure of 22 mm Hg or higher had a positive predictive value of 88% for a right atrial pressure of 10 mm Hg or higher.16 Hence, the clinical presentation may vary depending on the location (pulmonary, systemic, or both) and degree of congestion.

Symptoms of pulmonary congestion include worsening exertional dyspnea and orthopnea; bilateral crackles may be heard on physical examination if pulmonary edema is present.

Systemic congestion can cause significant peripheral edema and weight gain. Jugular venous distention may be noted. Oliguria may be present due to renal dysfunction; patients on maintenance diuretic therapy often note its lack of efficacy.

Signs of acute heart failure

Wang et al,17 in a meta-analysis of 22 studies, concluded that the features that most strongly suggested acute heart failure were:

- History of paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea

- A third heart sound

- Evidence of pulmonary venous congestion on chest radiography.

Features that most strongly suggested the patient did not have acute heart failure were:

- Absence of exertional dyspnea

- Absence of rales

- Absence of radiographic evidence of cardiomegaly.

Patients may present without some of these classic clinical features, and the diagnosis of acute heart failure may be challenging. For example, even if left-sided pressures are very high, pulmonary edema may be absent because of pulmonary vascular remodeling in chronic heart failure.18 Pulmonary artery catheterization reveals elevated cardiac filling pressures and can be used to guide therapy, but clinical evidence argues against its routine use.19

Urine electrolytes (fractional excretion of sodium < 1% and fractional excretion of urea < 35%) often suggest a prerenal form of acute kidney injury, since the hemodynamic derangements in acute cardiorenal syndrome reduce renal perfusion.

Biomarkers of cell-cycle arrest such as urine insulinlike growth factor-binding protein 7 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 2 have recently been shown to identify patients with acute heart failure at risk of developing acute cardiorenal syndrome.20

Acute cardiorenal syndrome vs renal injury due to hypovolemia

The major alternative in the differential diagnosis of acute cardiorenal syndrome is renal injury due to hypovolemia. Patients with stable heart failure usually have mild hypervolemia at baseline, but they can become hypovolemic due to overaggressive diuretic therapy, severe diarrhea, or other causes.

Although the fluid status of patients in these 2 conditions is opposite, they can be difficult to distinguish. In both conditions, urine electrolytes suggest a prerenal acute kidney injury. A history of recent fluid losses or diuretic overuse may help identify hypovolemia. If available, analysis of the recent trend in weight can be vital in making the right diagnosis.

Misdiagnosis of acute cardiorenal syndrome as hypovolemia-induced acute kidney injury can be catastrophic. If volume depletion is erroneously judged to be the cause of acute kidney injury, fluid administration can further worsen both cardiac and renal function. This can perpetuate the vicious circle that is already in play. Lack of renal recovery may invite further fluid administration.

TREATMENT

Fluid removal with diuresis or ultrafiltration is the cornerstone of treatment. Other treatments such as inotropes are reserved for patients with resistant disease.

Diuretics

The goal of therapy in acute cardiorenal syndrome is to achieve aggressive diuresis, typically using intravenous diuretics. Loop diuretics are the most potent class of diuretics and are the first-line drugs for this purpose. Other classes of diuretics can be used in conjunction with loop diuretics; however, using them by themselves is neither effective nor recommended.

Resistance to diuretics at usual doses is common in patients with acute cardiorenal syndrome. Several mechanisms contribute to diuretic resistance in these patients.21

Oral bioavailability of diuretics may be reduced due to intestinal edema.

Diuretic pharmacokinetics are significantly deranged in cardiorenal syndrome. All diuretics except mineralocorticoid antagonists (ie, spironolactone and eplerenone) act on targets on the luminal side of renal tubules, but are highly protein-bound and are hence not filtered at the glomerulus. Loop diuretics, thiazides, and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors are secreted in the proximal convoluted tubule via the organic anion transporter,22 whereas epithelial sodium channel inhibitors (amiloride and triamterene) are secreted via the organic cation transporter 2.23 In renal dysfunction, various uremic toxins accumulate in the body and compete with diuretics for secretion into the proximal convoluted tubule via these transporters.24

Finally, activation of the sympathetic nervous system and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system leads to increased tubular sodium and water retention, thereby also blunting the diuretic response.

Diuretic dosage. In patients whose creatinine clearance is less than 15 mL/min, only 10% to 20% as much loop diuretic is secreted into the renal tubule as in normal individuals.25 This effect warrants dose adjustment of diuretics during uremia.

Continuous infusion or bolus? Continuous infusion of loop diuretics is another strategy to optimize drug delivery. Compared with bolus therapy, continuous infusion provides more sustained and uniform drug delivery and prevents postdiuretic sodium retention.

The Diuretic Optimization Strategies Evaluation (DOSE) trial compared the efficacy and safety of continuous vs bolus furosemide therapy in 308 patients admitted with acute decompensated heart failure.26 There was no difference in symptom control or net fluid loss at 72 hours in either group. Other studies have shown more diuresis with continuous infusion than with a similarly dosed bolus regimen.27 However, definitive clinical evidence is lacking at this point to support routine use of continuous loop diuretic therapy.

Combination diuretic therapy. Sequential nephron blockade with combination diuretic therapy is an important therapeutic strategy against diuretic resistance. Notably, urine output-guided diuretic therapy has been shown to be superior to standard diuretic therapy.28 Such therapeutic protocols may employ combination diuretic therapy as a next step when the desired diuretic response is not obtained with high doses of loop diuretic monotherapy.

The desired diuretic response depends on the clinical situation. For example, in patients with severe congestion, we would like the net fluid output to be at least 2 to 3 L more than the fluid intake after the first 24 hours. Sometimes, patients in the intensive care unit are on several essential drug infusions, so that their net intake amounts to 1 to 2 L. In these patients, the desired urine output would be even more than in patients not on these drug infusions.

Loop diuretics block sodium reabsorption at the thick ascending loop of Henle. This disrupts the countercurrent exchange mechanism and reduces renal medullary interstitial osmolarity; these effects prevent water reabsorption. However, the unresorbed sodium can be taken up by the sodium-chloride cotransporter and the epithelial sodium channel in the distal nephron, thereby blunting the diuretic effect. This is the rationale for combining loop diuretics with thiazides or potassium-sparing diuretics.

Similarly, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (eg, acetazolamide) reduce sodium reabsorption from the proximal convoluted tubule, but most of this sodium is then reabsorbed distally. Hence, the combination of a loop diuretic and acetazolamide can also have a synergistic diuretic effect.

The most popular combination is a loop diuretic plus a thiazide, although no large-scale placebo-controlled trials have been performed.29 Metolazone (a thiazidelike diuretic) is typically used due to its low cost and availability.30 Metolazone has also been shown to block sodium reabsorption at the proximal tubule, which may contribute to its synergistic effect. Chlorothiazide is available in an intravenous formulation and has a faster onset of action than metolazone. However, studies have failed to detect any benefit of one over the other.31

The potential benefit of combining a loop diuretic with acetazolamide is a lower tendency to develop metabolic alkalosis, a potential side effect of loop diuretics and thiazides. Although data are limited, a recent study showed that adding acetazolamide to bumetanide led to significantly increased natriuresis.32

In the Aldosterone Targeted Neurohormonal Combined With Natriuresis Therapy in Heart Failure (ATHENA-HF) trial, adding spironolactone in high doses to usual therapy was not found to cause any significant change in N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide level or net urine output.33

Ultrafiltration

Venovenous ultrafiltration (or aquapheresis) employs an extracorporeal circuit, similar to the one used in hemodialysis, which removes iso-osmolar fluid at a fixed rate.34 Newer ultrafiltration systems are more portable, can be used with peripheral venous access, and require minimal nursing supervision.35

Although ultrafiltration seems an attractive alternative to diuresis in acute heart failure, studies have been inconclusive. The Cardiorenal Rescue Study in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure (CARRESS-HF) trial compared ultrafiltration and diuresis in 188 patients with acute heart failure and acute cardiorenal syndrome.36 Diuresis, performed according to an algorithm, was found to be superior to ultrafiltration in terms of a bivariate end point of change in weight and change in serum creatinine level at 96 hours. However, the level of cystatin C is thought to be a more accurate indicator of renal function, and the change in cystatin C level from baseline did not differ between the two treatment groups. Also, the ultrafiltration rate was 200 mL per hour, which, some argue, may have been excessive and may have caused intravascular depletion.

Although the ideal rate of fluid removal is unknown, it should be individualized and adjusted based on the patient’s renal function, volume status, and hemodynamic status. The initial rate should be based on the degree of fluid overload and the anticipated plasma refill rate from the interstitial fluid.37 For example, a malnourished patient may have low serum oncotic pressure and hence have low plasma refill upon ultrafiltration. Disturbance of this delicate balance between the rates of ultrafiltration and plasma refill may lead to intravascular volume contraction.

In summary, although ultrafiltration is a valuable alternative to diuretics in resistant cases, its use as a primary decongestive therapy cannot be endorsed in view of the current data.

Inotropes

Inotropes such as dobutamine and milrinone are typically used in cases of cardiogenic shock to maintain organ perfusion. There is a physiologic rationale to using inotropes in acute cardiorenal syndrome as well, especially when the aforementioned strategies fail to overcome diuretic resistance.7

Inotropes increase cardiac output, improve renal blood flow, improve right ventricular output, and thereby relieve systemic congestion. These hemodynamic effects may improve renal perfusion and response to diuretics. However, clinical evidence to support this is lacking.

The Renal Optimization Strategies Evaluation (ROSE) trial enrolled 360 patients with acute heart failure and renal dysfunction. Adding dopamine in a low dose (2 μg/kg/min) to diuretic therapy had no significant effect on 72-hour cumulative urine output or renal function as measured by cystatin C levels.38 However, acute kidney injury was not identified in this trial, and the renal function of many of these patients may have been at its baseline when they were admitted. In other words, this trial did not necessarily include patients with acute kidney injury along with acute heart failure. Hence, it did not necessarily include patients with acute cardiorenal syndrome.

Vasodilators

Vasodilators such as nitroglycerin, sodium nitroprusside, and hydralazine are commonly used in patients with acute heart failure, although the clinical evidence supporting their use is weak.

Physiologically, arterial dilation reduces afterload and can help relieve pulmonary congestion, and venodilation increases capacitance and reduces preload. In theory, venodilators such as nitroglycerin can relieve renal venous congestion in patients with acute cardiorenal syndrome, thereby improving renal perfusion.

However, the use of vasodilators is often limited by their adverse effects, the most important being hypotension. This is especially relevant in light of recent data identifying reduction in blood pressure during treatment of acute heart failure as an independent risk factor for worsening renal function.39,40 It is important to note that in these studies, changes in cardiac index did not affect the propensity for developing worsening renal function. The precise mechanism of this finding is unclear but it is plausible that systemic vasodilation redistributes the cardiac output to nonrenal tissues, thereby overriding the renal autoregulatory mechanisms that are normally employed in low output states.

Preventive strategies

Various strategies can be used to prevent acute cardiorenal syndrome. An optimal outpatient diuretic regimen to avoid hypervolemia is essential. Patients with advanced congestive heart failure should be followed up closely in dedicated heart failure clinics until their diuretic regimen is optimized. Patients should be advised to check their weight on a regular basis and seek medical advice if they notice an increase in their weight or a reduction in their urine output.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- A robust clinical definition of cardiorenal syndrome is lacking. Hence, recognition of this condition can be challenging.

- Volume overload is central to its pathogenesis, and accurate assessment of volume status is critical.

- Renal venous congestion is the major mechanism of type 1 cardiorenal syndrome.

- Misdiagnosis can have devastating consequences, as it may lead to an opposite therapeutic approach.

- Fluid removal by various strategies is the mainstay of treatment.

- Temporary inotropic support should be saved for the last resort.

- Geisberg C, Butler J. Addressing the challenges of cardiorenal syndrome. Cleve Clin J Med 2006; 73:485–491.

- House AA, Anand I, Bellomo R, et al. Definition and classification of cardio-renal syndromes: workgroup statements from the 7th ADQI Consensus Conference. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010; 25:1416–1420.

- Chang CH, Lin CY, Tian YC, et al. Acute kidney injury classification: comparison of AKIN and RIFLE criteria. Shock 2010; 33:247-252.

- Reynolds HR, Hochman JS. Cardiogenic shock: current concepts and improving outcomes. Circulation 2008; 117:686–697.

- Gheorghiade M, Pang PS. Acute heart failure syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53:557–573.

- ter Maaten JM, Valente MA, Damman K, et al. Diuretic response in acute heart failure—pathophysiology, evaluation, and therapy. Nat Rev Cardiol 2015; 12:184–192.

- Hatamizadeh P, Fonarow GC, Budoff MJ, Darabian S, Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Cardiorenal syndrome: pathophysiology and potential targets for clinical management. Nat Rev Nephrol 2013; 9:99–111.

- Bock JS, Gottlieb SS. Cardiorenal syndrome: new perspectives. Circulation 2010; 121:2592–2600.

- Burke M, Pabbidi MR, Farley J, et al. Molecular mechanisms of renal blood flow autoregulation. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2014; 12:845–858.

- Hanberg JS, Sury K, Wilson FP, et al. Reduced cardiac index is not the dominant driver of renal dysfunction in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 67:2199–2208.

- Afsar B, Ortiz A, Covic A, et al. Focus on renal congestion in heart failure. Clin Kidney J 2016; 9:39–47.

- Verbrugge FH, Dupont M, Steels P, et al. Abdominal contributions to cardiorenal dysfunction in congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62:485–495.

- Mullens W, Abrahams Z, Skouri HN, et al. Elevated intra-abdominal pressure in acute decompensated heart failure: a potential contributor to worsening renal function? J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 51:300–306.

- Firth JD, Raine AE, Ledingham JG. Raised venous pressure: a direct cause of renal sodium retention in oedema? Lancet 1988; 1:1033–1035.

- Mullens W, Abrahams Z, Francis GS, et al. Importance of venous congestion for worsening of renal function in advanced decompensated heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53:589–596.

- Drazner MH, Hamilton MA, Fonarow G, et al. Relationship between right and left-sided filling pressures in 1000 patients with advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant 1999; 18:1126–1132.

- Wang CS, FitzGerald JM, Schulzer M, et al. Does this dyspneic patient in the emergency department have congestive heart failure? JAMA 2005; 294:1944–1956.

- Gehlbach BK, Geppert E. The pulmonary manifestations of left heart failure. Chest 2004; 125:669–682.

- Binanay C, Califf RM, Hasselblad V, et al. Evaluation study of congestive heart failure and pulmonary artery catheterization effectiveness: the ESCAPE trial. JAMA 2005; 294:1625–1633.

- Schanz M, Shi J , Wasser C , Alscher MD, Kimmel M. Urinary [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] for risk prediction of acute kidney injury in decompensated heart failure. Clin Cardiol 2017; doi.org/10.1002/clc.22683.

- Bowman BN, Nawarskas JJ, Anderson JR. Treating diuretic resistance: an overview. Cardiol Rev 2016; 24:256–260.

- Uwai Y, Saito H, Hashimoto Y, Inui KI. Interaction and transport of thiazide diuretics, loop diuretics, and acetazolamide via rat renal organic anion transporter rOAT1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2000; 295:261–265.

- Hacker K, Maas R, Kornhuber J, et al. Substrate-dependent inhibition of the human organic cation transporter OCT2: a comparison of metformin with experimental substrates. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0136451.

- Schophuizen CM, Wilmer MJ, Jansen J, et al. Cationic uremic toxins affect human renal proximal tubule cell functioning through interaction with the organic cation transporter. Pflugers Arch 2013; 465:1701–1714.

- Brater DC. Diuretic therapy. N Engl J Med 1998; 339:387–395.

- Felker GM, Lee KL, Bull DA, et al. Diuretic strategies in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:797–805.

- Thomson MR, Nappi JM, Dunn SP, Hollis IB, Rodgers JE, Van Bakel AB. Continuous versus intermittent infusion of furosemide in acute decompensated heart failure. J Card Fail 2010; 16:188–193.

- Grodin JL, Stevens SR, de Las Fuentes L, et al. Intensification of medication therapy for cardiorenal syndrome in acute decompensated heart failure. J Card Fail 2016; 22:26–32.

- Ng TM, Konopka E, Hyderi AF, et al. Comparison of bumetanide- and metolazone-based diuretic regimens to furosemide in acute heart failure. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 2013; 18:345–353.

- Sica DA. Metolazone and its role in edema management. Congest Heart Fail 2003; 9:100–105.

- Moranville MP, Choi S, Hogg J, Anderson AS, Rich JD. Comparison of metolazone versus chlorothiazide in acute decompensated heart failure with diuretic resistance. Cardiovasc Ther 2015; 33:42–49.

- Verbrugge FH, Dupont M, Bertrand PB, et al. Determinants and impact of the natriuretic response to diuretic therapy in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and volume overload. Acta Cardiol 2015; 70:265–373.

- Butler J, Anstrom KJ, Felker GM, et al. Efficacy and safety of spironolactone in acute heart failure: the ATHENA-HF randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol 2017 Jul 12. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.2198. [Epub ahead of print]

- Pourafshar N, Karimi A, Kazory A. Extracorporeal ultrafiltration therapy for acute decompensated heart failure. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2016; 14:5–13.

- Jaski BE, Ha J, Denys BG, et al. Peripherally inserted veno-venous ultrafiltration for rapid treatment of volume overloaded patients. J Card Fail 2003; 9:227–231.

- Jaski BE, Ha J, Denys BG, Lamba S, Trupp RJ, Abraham WT. Ultrafiltration in decompensated heart failure with cardiorenal syndrome. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:2296–2304.

- Kazory A. Cardiorenal syndrome: ultrafiltration therapy for heart failure—trials and tribulations. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2013; 8:1816–1828.

- Chen HH, Anstrom KJ, Givertz MM, et al. Low-dose dopamine or low-dose nesiritide in acute heart failure with renal dysfunction: the ROSE acute heart failure randomized trial. JAMA 2013; 310:2533–2543.

- Testani JM, Coca SG, McCauley BD, et al. Impact of changes in blood pressure during the treatment of acute decompensated heart failure on renal and clinical outcomes. Eur J Heart Fail 2011; 13:877–884.

- Dupont M, Mullens W, Finucan M, et al. Determinants of dynamic changes in serum creatinine in acute decompensated heart failure: the importance of blood pressure reduction during treatment. Eur J Heart Fail 2013; 15:433–440.

- Geisberg C, Butler J. Addressing the challenges of cardiorenal syndrome. Cleve Clin J Med 2006; 73:485–491.

- House AA, Anand I, Bellomo R, et al. Definition and classification of cardio-renal syndromes: workgroup statements from the 7th ADQI Consensus Conference. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010; 25:1416–1420.

- Chang CH, Lin CY, Tian YC, et al. Acute kidney injury classification: comparison of AKIN and RIFLE criteria. Shock 2010; 33:247-252.

- Reynolds HR, Hochman JS. Cardiogenic shock: current concepts and improving outcomes. Circulation 2008; 117:686–697.

- Gheorghiade M, Pang PS. Acute heart failure syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53:557–573.

- ter Maaten JM, Valente MA, Damman K, et al. Diuretic response in acute heart failure—pathophysiology, evaluation, and therapy. Nat Rev Cardiol 2015; 12:184–192.

- Hatamizadeh P, Fonarow GC, Budoff MJ, Darabian S, Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Cardiorenal syndrome: pathophysiology and potential targets for clinical management. Nat Rev Nephrol 2013; 9:99–111.

- Bock JS, Gottlieb SS. Cardiorenal syndrome: new perspectives. Circulation 2010; 121:2592–2600.

- Burke M, Pabbidi MR, Farley J, et al. Molecular mechanisms of renal blood flow autoregulation. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2014; 12:845–858.

- Hanberg JS, Sury K, Wilson FP, et al. Reduced cardiac index is not the dominant driver of renal dysfunction in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 67:2199–2208.

- Afsar B, Ortiz A, Covic A, et al. Focus on renal congestion in heart failure. Clin Kidney J 2016; 9:39–47.

- Verbrugge FH, Dupont M, Steels P, et al. Abdominal contributions to cardiorenal dysfunction in congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62:485–495.