User login

Link between pediatric hepatitis and adenovirus 41 still unclear

While two new studies reiterate a possible relationship between adenovirus 41 and acute hepatitis of unknown cause in children, whether these infections are significant or merely bystanders remains unclear.

In both studies – one conducted in Alabama and the other conducted in the United Kingdom – researchers found that 90% of children with acute hepatitis of unknown cause tested positive for adenovirus 41. The virus subtype is not an uncommon infection, but it usually causes gastroenteritis in children.

“Across the world, adenovirus continues to be a common signal” in these pediatric hepatitis cases, said Helena Gutierrez, MD, the medical director of the Pediatric Liver Transplant Program at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, in an interview. She led one of the studies. More data are necessary to understand what role this virus may play in these cases, she said.

In November, the Alabama Department of Public Health and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention began investigating a cluster of severe pediatric hepatitis cases at the Children’s of Alabama hospital in Birmingham. These children also tested positive for adenovirus. In April, the United Kingdom announced they were investigating similar cases, and the CDC expanded their search nationally. As of July 8, 1,010 cases in 35 countries have been reported to the World Health Organization. There are 263 confirmed cases in the United Kingdom and 332 cases under investigation by the CDC in the United States, according to the most recent counts.

The two studies, both published in the New England Journal of Medicine, provide additional clinical data on a number of these mysterious hepatitis cases. Dr. Gutierrez’s study looked at nine children admitted for hepatitis of unknown origin between October 1 and February 28. Patients had a median age of 2 years 11 months and two required liver transplants, and there were no deaths.

Eight out of nine patients (89%) tested positive for adenovirus, and all five of the samples that were of sufficient quality for gene sequencing tested positive for adenovirus 41. None of the six liver biopsies performed found signs of adenovirus infection, but the liver tissue samples of three patients tested positive for adenovirus via PCR.

The second study involved 44 children referred to a liver transplantation center in the United Kingdom between January 1 and April 11, 2022. The median age for patients was 4 years. Six children required liver transplants, and there were no deaths. Of the 30 patients who underwent molecular adenovirus testing, 27 (90%) were positive for adenovirus 41. Liver samples of nine children (3 from biopsies and 6 from explanted livers) all tested negative for adenovirus antibodies.

In both studies, however, the median adenovirus viral load of patients needing a transplant was much higher than the viral loads in children who did not require liver transplants.

Although most of the clinical features and test results of these cases suggest that adenovirus may be involved, the negative results in histology are “intriguing,” Chayarani Kelgeri, MD, a consultant pediatric hepatologist at the Birmingham Women’s and Children’s Hospital, U.K., said in an email. She is the lead author of the U.K. study. “Whether this is because the liver injury we see is an aftermath of the viral infection, the mechanism of injury is immune mediated, and if other cofactors are involved is being explored,” she added. “Further investigations being undertaken by UK Health Security Agency will add to our understanding of this illness.”

Although there is a high adenovirus positivity rate amongst these cases, there is not enough evidence yet to say adenovirus 41 is a new cause of pediatric hepatitis in previously healthy children, said Saul Karpen, MD, PhD, the division chief of pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta. He wrote an editorial accompanying the two NEJM studies.

The CDC has not yet found an increase in pediatric hepatitis cases, according to a recent analysis, though the United Kingdom has found an uptick in cases this year, he told this news organization. Also, the cases highlighted in both articles showed no histological evidence of adenovirus in liver biopsies. “That’s completely opposite of what we generally see in adenoviral hepatitis that can be quite severe,” he said, adding that in general, there are detectable viral particles and antigens in affected livers.

“These two important reports indicate to those inside and outside the field of pediatric hepatology that registries and clinical studies of acute hepatitis in children are sorely needed,” Dr. Karpen writes in the editorial; “It is likely that with greater attention to collecting data on cases and biospecimens from children with acute hepatitis, we will be able to determine whether this one virus, human adenovirus 41, is of relevance to this important and serious condition in children.”

Dr. Gutierrez, Dr. Kelgeri, and Dr. Karpen report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While two new studies reiterate a possible relationship between adenovirus 41 and acute hepatitis of unknown cause in children, whether these infections are significant or merely bystanders remains unclear.

In both studies – one conducted in Alabama and the other conducted in the United Kingdom – researchers found that 90% of children with acute hepatitis of unknown cause tested positive for adenovirus 41. The virus subtype is not an uncommon infection, but it usually causes gastroenteritis in children.

“Across the world, adenovirus continues to be a common signal” in these pediatric hepatitis cases, said Helena Gutierrez, MD, the medical director of the Pediatric Liver Transplant Program at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, in an interview. She led one of the studies. More data are necessary to understand what role this virus may play in these cases, she said.

In November, the Alabama Department of Public Health and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention began investigating a cluster of severe pediatric hepatitis cases at the Children’s of Alabama hospital in Birmingham. These children also tested positive for adenovirus. In April, the United Kingdom announced they were investigating similar cases, and the CDC expanded their search nationally. As of July 8, 1,010 cases in 35 countries have been reported to the World Health Organization. There are 263 confirmed cases in the United Kingdom and 332 cases under investigation by the CDC in the United States, according to the most recent counts.

The two studies, both published in the New England Journal of Medicine, provide additional clinical data on a number of these mysterious hepatitis cases. Dr. Gutierrez’s study looked at nine children admitted for hepatitis of unknown origin between October 1 and February 28. Patients had a median age of 2 years 11 months and two required liver transplants, and there were no deaths.

Eight out of nine patients (89%) tested positive for adenovirus, and all five of the samples that were of sufficient quality for gene sequencing tested positive for adenovirus 41. None of the six liver biopsies performed found signs of adenovirus infection, but the liver tissue samples of three patients tested positive for adenovirus via PCR.

The second study involved 44 children referred to a liver transplantation center in the United Kingdom between January 1 and April 11, 2022. The median age for patients was 4 years. Six children required liver transplants, and there were no deaths. Of the 30 patients who underwent molecular adenovirus testing, 27 (90%) were positive for adenovirus 41. Liver samples of nine children (3 from biopsies and 6 from explanted livers) all tested negative for adenovirus antibodies.

In both studies, however, the median adenovirus viral load of patients needing a transplant was much higher than the viral loads in children who did not require liver transplants.

Although most of the clinical features and test results of these cases suggest that adenovirus may be involved, the negative results in histology are “intriguing,” Chayarani Kelgeri, MD, a consultant pediatric hepatologist at the Birmingham Women’s and Children’s Hospital, U.K., said in an email. She is the lead author of the U.K. study. “Whether this is because the liver injury we see is an aftermath of the viral infection, the mechanism of injury is immune mediated, and if other cofactors are involved is being explored,” she added. “Further investigations being undertaken by UK Health Security Agency will add to our understanding of this illness.”

Although there is a high adenovirus positivity rate amongst these cases, there is not enough evidence yet to say adenovirus 41 is a new cause of pediatric hepatitis in previously healthy children, said Saul Karpen, MD, PhD, the division chief of pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta. He wrote an editorial accompanying the two NEJM studies.

The CDC has not yet found an increase in pediatric hepatitis cases, according to a recent analysis, though the United Kingdom has found an uptick in cases this year, he told this news organization. Also, the cases highlighted in both articles showed no histological evidence of adenovirus in liver biopsies. “That’s completely opposite of what we generally see in adenoviral hepatitis that can be quite severe,” he said, adding that in general, there are detectable viral particles and antigens in affected livers.

“These two important reports indicate to those inside and outside the field of pediatric hepatology that registries and clinical studies of acute hepatitis in children are sorely needed,” Dr. Karpen writes in the editorial; “It is likely that with greater attention to collecting data on cases and biospecimens from children with acute hepatitis, we will be able to determine whether this one virus, human adenovirus 41, is of relevance to this important and serious condition in children.”

Dr. Gutierrez, Dr. Kelgeri, and Dr. Karpen report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While two new studies reiterate a possible relationship between adenovirus 41 and acute hepatitis of unknown cause in children, whether these infections are significant or merely bystanders remains unclear.

In both studies – one conducted in Alabama and the other conducted in the United Kingdom – researchers found that 90% of children with acute hepatitis of unknown cause tested positive for adenovirus 41. The virus subtype is not an uncommon infection, but it usually causes gastroenteritis in children.

“Across the world, adenovirus continues to be a common signal” in these pediatric hepatitis cases, said Helena Gutierrez, MD, the medical director of the Pediatric Liver Transplant Program at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, in an interview. She led one of the studies. More data are necessary to understand what role this virus may play in these cases, she said.

In November, the Alabama Department of Public Health and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention began investigating a cluster of severe pediatric hepatitis cases at the Children’s of Alabama hospital in Birmingham. These children also tested positive for adenovirus. In April, the United Kingdom announced they were investigating similar cases, and the CDC expanded their search nationally. As of July 8, 1,010 cases in 35 countries have been reported to the World Health Organization. There are 263 confirmed cases in the United Kingdom and 332 cases under investigation by the CDC in the United States, according to the most recent counts.

The two studies, both published in the New England Journal of Medicine, provide additional clinical data on a number of these mysterious hepatitis cases. Dr. Gutierrez’s study looked at nine children admitted for hepatitis of unknown origin between October 1 and February 28. Patients had a median age of 2 years 11 months and two required liver transplants, and there were no deaths.

Eight out of nine patients (89%) tested positive for adenovirus, and all five of the samples that were of sufficient quality for gene sequencing tested positive for adenovirus 41. None of the six liver biopsies performed found signs of adenovirus infection, but the liver tissue samples of three patients tested positive for adenovirus via PCR.

The second study involved 44 children referred to a liver transplantation center in the United Kingdom between January 1 and April 11, 2022. The median age for patients was 4 years. Six children required liver transplants, and there were no deaths. Of the 30 patients who underwent molecular adenovirus testing, 27 (90%) were positive for adenovirus 41. Liver samples of nine children (3 from biopsies and 6 from explanted livers) all tested negative for adenovirus antibodies.

In both studies, however, the median adenovirus viral load of patients needing a transplant was much higher than the viral loads in children who did not require liver transplants.

Although most of the clinical features and test results of these cases suggest that adenovirus may be involved, the negative results in histology are “intriguing,” Chayarani Kelgeri, MD, a consultant pediatric hepatologist at the Birmingham Women’s and Children’s Hospital, U.K., said in an email. She is the lead author of the U.K. study. “Whether this is because the liver injury we see is an aftermath of the viral infection, the mechanism of injury is immune mediated, and if other cofactors are involved is being explored,” she added. “Further investigations being undertaken by UK Health Security Agency will add to our understanding of this illness.”

Although there is a high adenovirus positivity rate amongst these cases, there is not enough evidence yet to say adenovirus 41 is a new cause of pediatric hepatitis in previously healthy children, said Saul Karpen, MD, PhD, the division chief of pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta. He wrote an editorial accompanying the two NEJM studies.

The CDC has not yet found an increase in pediatric hepatitis cases, according to a recent analysis, though the United Kingdom has found an uptick in cases this year, he told this news organization. Also, the cases highlighted in both articles showed no histological evidence of adenovirus in liver biopsies. “That’s completely opposite of what we generally see in adenoviral hepatitis that can be quite severe,” he said, adding that in general, there are detectable viral particles and antigens in affected livers.

“These two important reports indicate to those inside and outside the field of pediatric hepatology that registries and clinical studies of acute hepatitis in children are sorely needed,” Dr. Karpen writes in the editorial; “It is likely that with greater attention to collecting data on cases and biospecimens from children with acute hepatitis, we will be able to determine whether this one virus, human adenovirus 41, is of relevance to this important and serious condition in children.”

Dr. Gutierrez, Dr. Kelgeri, and Dr. Karpen report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New insights into worldwide biliary tract cancer incidence, mortality

Incidence and mortality for biliary tract cancer (BTC) are both on the rise worldwide, according to a new analysis of data from the International Agency for Research on Cancer and the World Health Organization.

This diverse group of hepatic and perihepatic cancers include gallbladder cancer (GBC), intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC and ECC), and ampulla of Vater cancer. Although BTC is considered rare, incidence of its subtypes can vary significantly by geographic region. Because BTC is typically asymptomatic in its early stage, diagnosis is often made after tumors have spread, when there are few therapeutic options available. In the United States and Europe, 5-year survival is less than 20%.

Although previous studies have examined worldwide BTC incidence, few looked at multiple global regions or at all subtypes. Instead, subtypes may be grouped together and reported as composites, or BTC is lumped together with primary liver cancer. “To our knowledge, this is the first report combining data on worldwide incidence and mortality of all BTC subtypes per the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision,” the authors wrote in the study, published online in Gastro Hep Advances.

The researchers pointed out that classification coding systems have improved at defining BTC subtypes, so that studies using older coding subtypes could cause misinterpretation of incidence rates.

BTC subtypes also have unique sets of risk factors and different prognoses and treatment outcomes. “Thus, there is a need to define accurate epidemiologic trends that will allow specific risk factors to be identified, guiding experts in implementing policies to improve diagnosis and survival,” the authors wrote.

The study included data from 22 countries. BTC incidence ranged from 1.12 cases per 100,000 person-years in Vietnam to 12.42 in Chile. As expected, incidence rates were higher in the Asia-Pacific region (1.12-9.00) and South America (2.73-12.42), compared with Europe (2.00-3.59) and North America (2.33-2.35). Within the United States, Asian Americans had a higher BTC incidence than the general population (2.99 vs. 2.33).

In most countries, new cases were dominated by GBC, while ICC was the most common cause of death.

In each country, older patients were 5-10 times more likely to die than BTC patients generally. The sixth and seventh decades of life are the most common time of diagnosis, and treatment options may be limited in older patients.

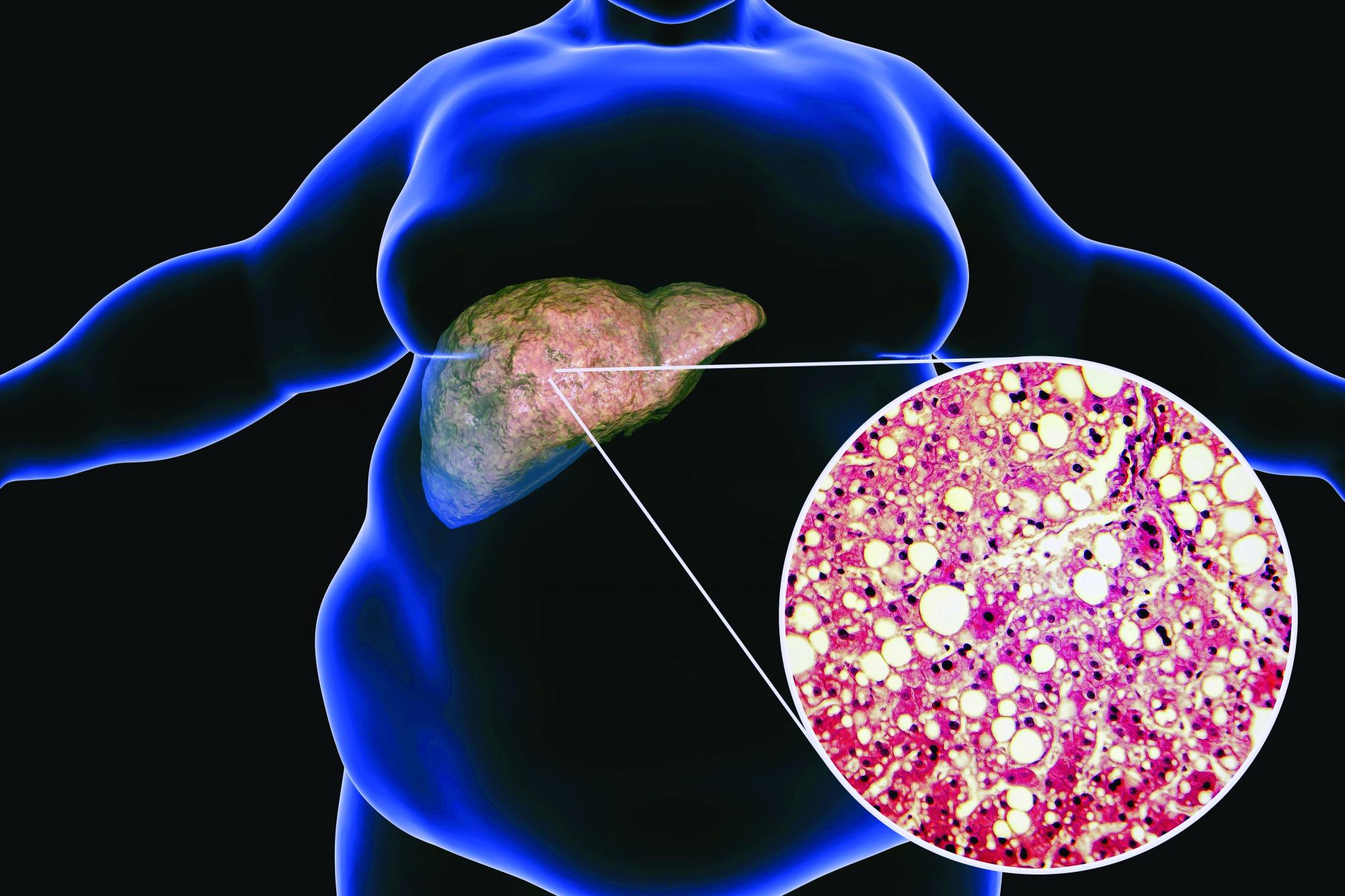

Risk factors for BTC may include common comorbidities like obesity, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and diabetes. Each is increasing individually, which may in turn contribute to rising BTC incidence. Observational analyses suggest that obesity may contribute to risk of ECC and gallbladder cancer, while diabetes and obesity may raise the risk of ICC. Smoking is associated with increased risk of all BTC subtypes except GBC, and alcohol consumption is associated with ICC.

“This study highlights how each subtype may be vulnerable to specific risk factors and emphasizes the value of separating epidemiologic data by subtype in order to better understand disease etiology,” the researchers wrote.

Risk factors associated with incidence and mortality from BTC aren’t limited to clinical characteristics. Genetic susceptibility may also play a role in incidence and mortality of different subtypes. There is also a relationship between gallstones and BTC risk. In Chile, about 50% of women have gallstones versus 17% of women in the United States. The cancer incidence is 27 per 100,000 person-years in Chile and 2 per 100,000 person-years in the United States. BTC is also the leading cause of cancer death among women in Chile.

The authors also highlighted the high rates of gallbladder cancer in India, despite a low prevalence of gallstones. Incidences can vary with geography along the flow of the Ganges River, which might reflect varying risks from contamination caused by agricultural runoff or industrial or human waste.

Worldwide BTC incidence and mortality was generally higher among women than men, with the exception of ampulla of Vater cancer, which was more common in men.

The study is limited by quality of data, which varied significantly between countries. Mortality data was missing from some countries know to have high BTC incidence. The databases had little survival data, which could have provided insights into treatment efficacy.

The study was funded by AstraZeneca. The authors have extensive financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

Biliary tract cancers (BTCs) are understudied malignancies with poor prognoses. A major impediment to a deeper understanding of BTC epidemiology is that the term BTC encompasses a heterogeneous group of cancers including cholangiocarcinoma (both intrahepatic and extrahepatic), as well as ampullary and gallbladder cancer. Studies have often lumped all BTC subgroups together despite differences in their geographic distribution, risk factors, and underlying pathogenesis. Furthermore, epidemiological reporting has often grouped “intrahepatic liver and bile duct cancers” which include hepatocellular carcinoma, a biologically different entity requiring a separate management strategy.

The study highlights the importance of future policy work to address the risk factors for BTCs that vary by region and that will likely evolve over time. It also stresses the urgent need for both early diagnostic strategies and improved biomarker-driven medical therapy, areas of ongoing research requiring accelerated development.

Irun Bhan, MD, is a transplant hepatologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and instructor at Harvard Medical School, Boston. He has no relevant conflicts.

Biliary tract cancers (BTCs) are understudied malignancies with poor prognoses. A major impediment to a deeper understanding of BTC epidemiology is that the term BTC encompasses a heterogeneous group of cancers including cholangiocarcinoma (both intrahepatic and extrahepatic), as well as ampullary and gallbladder cancer. Studies have often lumped all BTC subgroups together despite differences in their geographic distribution, risk factors, and underlying pathogenesis. Furthermore, epidemiological reporting has often grouped “intrahepatic liver and bile duct cancers” which include hepatocellular carcinoma, a biologically different entity requiring a separate management strategy.

The study highlights the importance of future policy work to address the risk factors for BTCs that vary by region and that will likely evolve over time. It also stresses the urgent need for both early diagnostic strategies and improved biomarker-driven medical therapy, areas of ongoing research requiring accelerated development.

Irun Bhan, MD, is a transplant hepatologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and instructor at Harvard Medical School, Boston. He has no relevant conflicts.

Biliary tract cancers (BTCs) are understudied malignancies with poor prognoses. A major impediment to a deeper understanding of BTC epidemiology is that the term BTC encompasses a heterogeneous group of cancers including cholangiocarcinoma (both intrahepatic and extrahepatic), as well as ampullary and gallbladder cancer. Studies have often lumped all BTC subgroups together despite differences in their geographic distribution, risk factors, and underlying pathogenesis. Furthermore, epidemiological reporting has often grouped “intrahepatic liver and bile duct cancers” which include hepatocellular carcinoma, a biologically different entity requiring a separate management strategy.

The study highlights the importance of future policy work to address the risk factors for BTCs that vary by region and that will likely evolve over time. It also stresses the urgent need for both early diagnostic strategies and improved biomarker-driven medical therapy, areas of ongoing research requiring accelerated development.

Irun Bhan, MD, is a transplant hepatologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and instructor at Harvard Medical School, Boston. He has no relevant conflicts.

Incidence and mortality for biliary tract cancer (BTC) are both on the rise worldwide, according to a new analysis of data from the International Agency for Research on Cancer and the World Health Organization.

This diverse group of hepatic and perihepatic cancers include gallbladder cancer (GBC), intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC and ECC), and ampulla of Vater cancer. Although BTC is considered rare, incidence of its subtypes can vary significantly by geographic region. Because BTC is typically asymptomatic in its early stage, diagnosis is often made after tumors have spread, when there are few therapeutic options available. In the United States and Europe, 5-year survival is less than 20%.

Although previous studies have examined worldwide BTC incidence, few looked at multiple global regions or at all subtypes. Instead, subtypes may be grouped together and reported as composites, or BTC is lumped together with primary liver cancer. “To our knowledge, this is the first report combining data on worldwide incidence and mortality of all BTC subtypes per the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision,” the authors wrote in the study, published online in Gastro Hep Advances.

The researchers pointed out that classification coding systems have improved at defining BTC subtypes, so that studies using older coding subtypes could cause misinterpretation of incidence rates.

BTC subtypes also have unique sets of risk factors and different prognoses and treatment outcomes. “Thus, there is a need to define accurate epidemiologic trends that will allow specific risk factors to be identified, guiding experts in implementing policies to improve diagnosis and survival,” the authors wrote.

The study included data from 22 countries. BTC incidence ranged from 1.12 cases per 100,000 person-years in Vietnam to 12.42 in Chile. As expected, incidence rates were higher in the Asia-Pacific region (1.12-9.00) and South America (2.73-12.42), compared with Europe (2.00-3.59) and North America (2.33-2.35). Within the United States, Asian Americans had a higher BTC incidence than the general population (2.99 vs. 2.33).

In most countries, new cases were dominated by GBC, while ICC was the most common cause of death.

In each country, older patients were 5-10 times more likely to die than BTC patients generally. The sixth and seventh decades of life are the most common time of diagnosis, and treatment options may be limited in older patients.

Risk factors for BTC may include common comorbidities like obesity, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and diabetes. Each is increasing individually, which may in turn contribute to rising BTC incidence. Observational analyses suggest that obesity may contribute to risk of ECC and gallbladder cancer, while diabetes and obesity may raise the risk of ICC. Smoking is associated with increased risk of all BTC subtypes except GBC, and alcohol consumption is associated with ICC.

“This study highlights how each subtype may be vulnerable to specific risk factors and emphasizes the value of separating epidemiologic data by subtype in order to better understand disease etiology,” the researchers wrote.

Risk factors associated with incidence and mortality from BTC aren’t limited to clinical characteristics. Genetic susceptibility may also play a role in incidence and mortality of different subtypes. There is also a relationship between gallstones and BTC risk. In Chile, about 50% of women have gallstones versus 17% of women in the United States. The cancer incidence is 27 per 100,000 person-years in Chile and 2 per 100,000 person-years in the United States. BTC is also the leading cause of cancer death among women in Chile.

The authors also highlighted the high rates of gallbladder cancer in India, despite a low prevalence of gallstones. Incidences can vary with geography along the flow of the Ganges River, which might reflect varying risks from contamination caused by agricultural runoff or industrial or human waste.

Worldwide BTC incidence and mortality was generally higher among women than men, with the exception of ampulla of Vater cancer, which was more common in men.

The study is limited by quality of data, which varied significantly between countries. Mortality data was missing from some countries know to have high BTC incidence. The databases had little survival data, which could have provided insights into treatment efficacy.

The study was funded by AstraZeneca. The authors have extensive financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

Incidence and mortality for biliary tract cancer (BTC) are both on the rise worldwide, according to a new analysis of data from the International Agency for Research on Cancer and the World Health Organization.

This diverse group of hepatic and perihepatic cancers include gallbladder cancer (GBC), intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC and ECC), and ampulla of Vater cancer. Although BTC is considered rare, incidence of its subtypes can vary significantly by geographic region. Because BTC is typically asymptomatic in its early stage, diagnosis is often made after tumors have spread, when there are few therapeutic options available. In the United States and Europe, 5-year survival is less than 20%.

Although previous studies have examined worldwide BTC incidence, few looked at multiple global regions or at all subtypes. Instead, subtypes may be grouped together and reported as composites, or BTC is lumped together with primary liver cancer. “To our knowledge, this is the first report combining data on worldwide incidence and mortality of all BTC subtypes per the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision,” the authors wrote in the study, published online in Gastro Hep Advances.

The researchers pointed out that classification coding systems have improved at defining BTC subtypes, so that studies using older coding subtypes could cause misinterpretation of incidence rates.

BTC subtypes also have unique sets of risk factors and different prognoses and treatment outcomes. “Thus, there is a need to define accurate epidemiologic trends that will allow specific risk factors to be identified, guiding experts in implementing policies to improve diagnosis and survival,” the authors wrote.

The study included data from 22 countries. BTC incidence ranged from 1.12 cases per 100,000 person-years in Vietnam to 12.42 in Chile. As expected, incidence rates were higher in the Asia-Pacific region (1.12-9.00) and South America (2.73-12.42), compared with Europe (2.00-3.59) and North America (2.33-2.35). Within the United States, Asian Americans had a higher BTC incidence than the general population (2.99 vs. 2.33).

In most countries, new cases were dominated by GBC, while ICC was the most common cause of death.

In each country, older patients were 5-10 times more likely to die than BTC patients generally. The sixth and seventh decades of life are the most common time of diagnosis, and treatment options may be limited in older patients.

Risk factors for BTC may include common comorbidities like obesity, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and diabetes. Each is increasing individually, which may in turn contribute to rising BTC incidence. Observational analyses suggest that obesity may contribute to risk of ECC and gallbladder cancer, while diabetes and obesity may raise the risk of ICC. Smoking is associated with increased risk of all BTC subtypes except GBC, and alcohol consumption is associated with ICC.

“This study highlights how each subtype may be vulnerable to specific risk factors and emphasizes the value of separating epidemiologic data by subtype in order to better understand disease etiology,” the researchers wrote.

Risk factors associated with incidence and mortality from BTC aren’t limited to clinical characteristics. Genetic susceptibility may also play a role in incidence and mortality of different subtypes. There is also a relationship between gallstones and BTC risk. In Chile, about 50% of women have gallstones versus 17% of women in the United States. The cancer incidence is 27 per 100,000 person-years in Chile and 2 per 100,000 person-years in the United States. BTC is also the leading cause of cancer death among women in Chile.

The authors also highlighted the high rates of gallbladder cancer in India, despite a low prevalence of gallstones. Incidences can vary with geography along the flow of the Ganges River, which might reflect varying risks from contamination caused by agricultural runoff or industrial or human waste.

Worldwide BTC incidence and mortality was generally higher among women than men, with the exception of ampulla of Vater cancer, which was more common in men.

The study is limited by quality of data, which varied significantly between countries. Mortality data was missing from some countries know to have high BTC incidence. The databases had little survival data, which could have provided insights into treatment efficacy.

The study was funded by AstraZeneca. The authors have extensive financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

FROM GASTRO HEP ADVANCES

Bulevirtide reduces hepatitis D viral load in difficult-to-treat patients

Bulevirtide (Hepcludex) monotherapy significantly reduces the load of hepatitis delta virus (HDV) and is safe in difficult-to-treat patients with compensated cirrhosis and clinically significant portal hypertension, according to the results of an ongoing 1-year study.

In presenting a poster with these findings at the annual International Liver Congress, sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver, lead author Elisabetta Degasperi, MD, from the Grand Hospital Maggiore Policlinico in Milan, said that they were important “because they confirm the safety of this drug in real life.”

Dr. Degasperi and colleagues showed that bulevirtide leads to a significant viral response in 78% of patients by week 48, which was measured using the outcome of greater than 2 log decline in HDV RNA from baseline.

Dr. Degasperi added that the research still needed to assess the longer-term benefits, but

Addressing an immense, unmet therapeutic need

HDV requires the presence of hepatitis B virus to replicate. Bulevirtide blocks the entry of HDV and hepatitis B virus into hepatocytes.

In July 2020, it was conditionally approved in the European Economic Area for use to treat chronic HDV infection in adults with compensated liver disease upon confirmation of HDV RNA in the blood. It currently remains an investigational agent in the United States, as well as outside of the EEA.

The ongoing trial led by Dr. Degasperi is specifically conducted in patients with compensated cirrhosis who also have clinically significant portal hypertension, where safety and efficacy are unknown.

Dr. Degasperi said in an interview that, although HDV was rare, there is nonetheless an “immense” need for effective therapies against it, especially in young patients with advanced liver disease.

“We have a lot of patients with hepatitis D who have not responded to other antiviral treatment. Right now, the only other available treatment is pegylated interferon,” she said. “Unfortunately, rates of sustained viral response to pegylated interferon are extremely low at around 30% of patients.”

Chronic HDV is the most severe form of viral hepatitis and can have mortality rates as high as 50% within 5 years in patients with cirrhosis.

The management of hepatitis D is also complicated by the fact that patients with advanced cirrhosis and clinically significant portal hypertension cannot be treated with pegylated interferon owing to lack of efficacy and safety reasons, including a high risk for decompensation and liver-related complications. Pegylated interferon is contraindicated in these patients.

Bulevirtide at 48 weeks: A closer look at the findings

Eighteen patients with HDV, compensated cirrhosis, and clinically significant portal hypertension were consecutively enrolled in this single-center, longitudinal study.

All received bulevirtide monotherapy at 2 mg/day and underwent monitoring every 2 months. They were also treated with nucleotide analogs for their hepatitis B virus, which was suppressed when they began bulevirtide.

Clinical and virologic characteristics were collected at baseline, at weeks 4 and 8, and then every 8 weeks thereafter.

Bulevirtide led to a significant viral response such that by week 48, HDV RNA declined by 3.1 log IU/mL (range, 0.2-4.6 log IU/mL), was undetectable in six patients (33%), and was less than 100 IU/L in 50% of patients. Two patients were nonresponders. In addition, 78% of patients achieved at least an HDV RNA 2 log decline from baseline.

There was also a normalization of biochemical response in the majority of patients.

Alanine aminotransferase normalization was seen in 89% of patients and declined by a median of 34 U/L (range, 15-76 U/L) over 48 weeks. Aspartate aminotransferase declined to 39 U/L (range, 21-92 U/L). A combined response was seen in 72% of patients, reported Dr. Degasperi.

“Previously, we only had results from a phase 2 study, so we had no idea of the results over such a long treatment period,” said Dr. Degasperi. “It is also the first time we have been able to treat these patients with such advanced disease that is so difficult to manage.”

“Real-world results are typically inferior to those from clinical trials, but the viral decline is comparable to phase 2 trials, and the first report of the phase 3 trial,” said Dr. Degasperi.

Gamma-glutamyltransferase, alpha-fetoprotein, immunoglobulin G, and gamma-globulin levels also improved, whereas hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B virus RNA, hepatitis B core-related antigen, platelet, and bilirubin values did not significantly change.

“All patients were Child-Pugh score A, so well-compensated [disease]. However, they increased a little bit in liver function by week 48,” Dr. Degasperi said. “This was important for this very advanced disease population.”

She added that the safety profile was very favorable, with no adverse events, including no injection-site reactions.

There was an asymptomatic increase in serum bile acids. “No patients complained about itching or pruritus,” Dr. Degasperi said.

What’s ahead for bulevirtide?

In a comment, Marc Bourlière, MD, from Saint Joseph Hospital in Marseilles, France, welcomed the decrease in viral load.

“This is known to be beneficial in terms of reducing morbidity and mortality in hepatitis D,” he said. “Remember that this disease is very difficult to treat, and until now, we have had no drug available. Pegylated interferon achieves cure in only 30% of patients, and half of these relapse, so actually only 15% have a meaningful response from pegylated interferon.”

“The main issue is its use as a daily subcutaneous injection. In clinical practice, it is a little bit complicated to set up, but once done, it is quite well accepted,” he said.

“I’m impressed with these results to date because there are no other compounds that have, as yet, achieved such results. This is impressive,” he added. “But whether it translates into a long-term response we don’t yet know.”

Dr. Bourlière also noted the meaningful 2-point log decline, noting that “HDV RNA negativity where treatment can be stopped would be really meaningful, but this endpoint is hard to obtain.”

Dr. Bourlière is awaiting results of the current ongoing phase 2/3 study, which would help determine a possible final treatment duration. He is also curious to settle the ongoing debate about whether bulevirtide should be used alone or in combination.

“We need to combine bulevirtide with pegylated interferon in less-advanced patients, because we know it is more potent and active against the HDV RNA,” he said.

Dr. Degasperi has previously declared she was on the advisory board for AbbVie and has spoken and taught for Gilead, MSD, and AbbVie. Dr. Bourlière declared interests with all companies involved in the R&D of liver therapies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Bulevirtide (Hepcludex) monotherapy significantly reduces the load of hepatitis delta virus (HDV) and is safe in difficult-to-treat patients with compensated cirrhosis and clinically significant portal hypertension, according to the results of an ongoing 1-year study.

In presenting a poster with these findings at the annual International Liver Congress, sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver, lead author Elisabetta Degasperi, MD, from the Grand Hospital Maggiore Policlinico in Milan, said that they were important “because they confirm the safety of this drug in real life.”

Dr. Degasperi and colleagues showed that bulevirtide leads to a significant viral response in 78% of patients by week 48, which was measured using the outcome of greater than 2 log decline in HDV RNA from baseline.

Dr. Degasperi added that the research still needed to assess the longer-term benefits, but

Addressing an immense, unmet therapeutic need

HDV requires the presence of hepatitis B virus to replicate. Bulevirtide blocks the entry of HDV and hepatitis B virus into hepatocytes.

In July 2020, it was conditionally approved in the European Economic Area for use to treat chronic HDV infection in adults with compensated liver disease upon confirmation of HDV RNA in the blood. It currently remains an investigational agent in the United States, as well as outside of the EEA.

The ongoing trial led by Dr. Degasperi is specifically conducted in patients with compensated cirrhosis who also have clinically significant portal hypertension, where safety and efficacy are unknown.

Dr. Degasperi said in an interview that, although HDV was rare, there is nonetheless an “immense” need for effective therapies against it, especially in young patients with advanced liver disease.

“We have a lot of patients with hepatitis D who have not responded to other antiviral treatment. Right now, the only other available treatment is pegylated interferon,” she said. “Unfortunately, rates of sustained viral response to pegylated interferon are extremely low at around 30% of patients.”

Chronic HDV is the most severe form of viral hepatitis and can have mortality rates as high as 50% within 5 years in patients with cirrhosis.

The management of hepatitis D is also complicated by the fact that patients with advanced cirrhosis and clinically significant portal hypertension cannot be treated with pegylated interferon owing to lack of efficacy and safety reasons, including a high risk for decompensation and liver-related complications. Pegylated interferon is contraindicated in these patients.

Bulevirtide at 48 weeks: A closer look at the findings

Eighteen patients with HDV, compensated cirrhosis, and clinically significant portal hypertension were consecutively enrolled in this single-center, longitudinal study.

All received bulevirtide monotherapy at 2 mg/day and underwent monitoring every 2 months. They were also treated with nucleotide analogs for their hepatitis B virus, which was suppressed when they began bulevirtide.

Clinical and virologic characteristics were collected at baseline, at weeks 4 and 8, and then every 8 weeks thereafter.

Bulevirtide led to a significant viral response such that by week 48, HDV RNA declined by 3.1 log IU/mL (range, 0.2-4.6 log IU/mL), was undetectable in six patients (33%), and was less than 100 IU/L in 50% of patients. Two patients were nonresponders. In addition, 78% of patients achieved at least an HDV RNA 2 log decline from baseline.

There was also a normalization of biochemical response in the majority of patients.

Alanine aminotransferase normalization was seen in 89% of patients and declined by a median of 34 U/L (range, 15-76 U/L) over 48 weeks. Aspartate aminotransferase declined to 39 U/L (range, 21-92 U/L). A combined response was seen in 72% of patients, reported Dr. Degasperi.

“Previously, we only had results from a phase 2 study, so we had no idea of the results over such a long treatment period,” said Dr. Degasperi. “It is also the first time we have been able to treat these patients with such advanced disease that is so difficult to manage.”

“Real-world results are typically inferior to those from clinical trials, but the viral decline is comparable to phase 2 trials, and the first report of the phase 3 trial,” said Dr. Degasperi.

Gamma-glutamyltransferase, alpha-fetoprotein, immunoglobulin G, and gamma-globulin levels also improved, whereas hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B virus RNA, hepatitis B core-related antigen, platelet, and bilirubin values did not significantly change.

“All patients were Child-Pugh score A, so well-compensated [disease]. However, they increased a little bit in liver function by week 48,” Dr. Degasperi said. “This was important for this very advanced disease population.”

She added that the safety profile was very favorable, with no adverse events, including no injection-site reactions.

There was an asymptomatic increase in serum bile acids. “No patients complained about itching or pruritus,” Dr. Degasperi said.

What’s ahead for bulevirtide?

In a comment, Marc Bourlière, MD, from Saint Joseph Hospital in Marseilles, France, welcomed the decrease in viral load.

“This is known to be beneficial in terms of reducing morbidity and mortality in hepatitis D,” he said. “Remember that this disease is very difficult to treat, and until now, we have had no drug available. Pegylated interferon achieves cure in only 30% of patients, and half of these relapse, so actually only 15% have a meaningful response from pegylated interferon.”

“The main issue is its use as a daily subcutaneous injection. In clinical practice, it is a little bit complicated to set up, but once done, it is quite well accepted,” he said.

“I’m impressed with these results to date because there are no other compounds that have, as yet, achieved such results. This is impressive,” he added. “But whether it translates into a long-term response we don’t yet know.”

Dr. Bourlière also noted the meaningful 2-point log decline, noting that “HDV RNA negativity where treatment can be stopped would be really meaningful, but this endpoint is hard to obtain.”

Dr. Bourlière is awaiting results of the current ongoing phase 2/3 study, which would help determine a possible final treatment duration. He is also curious to settle the ongoing debate about whether bulevirtide should be used alone or in combination.

“We need to combine bulevirtide with pegylated interferon in less-advanced patients, because we know it is more potent and active against the HDV RNA,” he said.

Dr. Degasperi has previously declared she was on the advisory board for AbbVie and has spoken and taught for Gilead, MSD, and AbbVie. Dr. Bourlière declared interests with all companies involved in the R&D of liver therapies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Bulevirtide (Hepcludex) monotherapy significantly reduces the load of hepatitis delta virus (HDV) and is safe in difficult-to-treat patients with compensated cirrhosis and clinically significant portal hypertension, according to the results of an ongoing 1-year study.

In presenting a poster with these findings at the annual International Liver Congress, sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver, lead author Elisabetta Degasperi, MD, from the Grand Hospital Maggiore Policlinico in Milan, said that they were important “because they confirm the safety of this drug in real life.”

Dr. Degasperi and colleagues showed that bulevirtide leads to a significant viral response in 78% of patients by week 48, which was measured using the outcome of greater than 2 log decline in HDV RNA from baseline.

Dr. Degasperi added that the research still needed to assess the longer-term benefits, but

Addressing an immense, unmet therapeutic need

HDV requires the presence of hepatitis B virus to replicate. Bulevirtide blocks the entry of HDV and hepatitis B virus into hepatocytes.

In July 2020, it was conditionally approved in the European Economic Area for use to treat chronic HDV infection in adults with compensated liver disease upon confirmation of HDV RNA in the blood. It currently remains an investigational agent in the United States, as well as outside of the EEA.

The ongoing trial led by Dr. Degasperi is specifically conducted in patients with compensated cirrhosis who also have clinically significant portal hypertension, where safety and efficacy are unknown.

Dr. Degasperi said in an interview that, although HDV was rare, there is nonetheless an “immense” need for effective therapies against it, especially in young patients with advanced liver disease.

“We have a lot of patients with hepatitis D who have not responded to other antiviral treatment. Right now, the only other available treatment is pegylated interferon,” she said. “Unfortunately, rates of sustained viral response to pegylated interferon are extremely low at around 30% of patients.”

Chronic HDV is the most severe form of viral hepatitis and can have mortality rates as high as 50% within 5 years in patients with cirrhosis.

The management of hepatitis D is also complicated by the fact that patients with advanced cirrhosis and clinically significant portal hypertension cannot be treated with pegylated interferon owing to lack of efficacy and safety reasons, including a high risk for decompensation and liver-related complications. Pegylated interferon is contraindicated in these patients.

Bulevirtide at 48 weeks: A closer look at the findings

Eighteen patients with HDV, compensated cirrhosis, and clinically significant portal hypertension were consecutively enrolled in this single-center, longitudinal study.

All received bulevirtide monotherapy at 2 mg/day and underwent monitoring every 2 months. They were also treated with nucleotide analogs for their hepatitis B virus, which was suppressed when they began bulevirtide.

Clinical and virologic characteristics were collected at baseline, at weeks 4 and 8, and then every 8 weeks thereafter.

Bulevirtide led to a significant viral response such that by week 48, HDV RNA declined by 3.1 log IU/mL (range, 0.2-4.6 log IU/mL), was undetectable in six patients (33%), and was less than 100 IU/L in 50% of patients. Two patients were nonresponders. In addition, 78% of patients achieved at least an HDV RNA 2 log decline from baseline.

There was also a normalization of biochemical response in the majority of patients.

Alanine aminotransferase normalization was seen in 89% of patients and declined by a median of 34 U/L (range, 15-76 U/L) over 48 weeks. Aspartate aminotransferase declined to 39 U/L (range, 21-92 U/L). A combined response was seen in 72% of patients, reported Dr. Degasperi.

“Previously, we only had results from a phase 2 study, so we had no idea of the results over such a long treatment period,” said Dr. Degasperi. “It is also the first time we have been able to treat these patients with such advanced disease that is so difficult to manage.”

“Real-world results are typically inferior to those from clinical trials, but the viral decline is comparable to phase 2 trials, and the first report of the phase 3 trial,” said Dr. Degasperi.

Gamma-glutamyltransferase, alpha-fetoprotein, immunoglobulin G, and gamma-globulin levels also improved, whereas hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B virus RNA, hepatitis B core-related antigen, platelet, and bilirubin values did not significantly change.

“All patients were Child-Pugh score A, so well-compensated [disease]. However, they increased a little bit in liver function by week 48,” Dr. Degasperi said. “This was important for this very advanced disease population.”

She added that the safety profile was very favorable, with no adverse events, including no injection-site reactions.

There was an asymptomatic increase in serum bile acids. “No patients complained about itching or pruritus,” Dr. Degasperi said.

What’s ahead for bulevirtide?

In a comment, Marc Bourlière, MD, from Saint Joseph Hospital in Marseilles, France, welcomed the decrease in viral load.

“This is known to be beneficial in terms of reducing morbidity and mortality in hepatitis D,” he said. “Remember that this disease is very difficult to treat, and until now, we have had no drug available. Pegylated interferon achieves cure in only 30% of patients, and half of these relapse, so actually only 15% have a meaningful response from pegylated interferon.”

“The main issue is its use as a daily subcutaneous injection. In clinical practice, it is a little bit complicated to set up, but once done, it is quite well accepted,” he said.

“I’m impressed with these results to date because there are no other compounds that have, as yet, achieved such results. This is impressive,” he added. “But whether it translates into a long-term response we don’t yet know.”

Dr. Bourlière also noted the meaningful 2-point log decline, noting that “HDV RNA negativity where treatment can be stopped would be really meaningful, but this endpoint is hard to obtain.”

Dr. Bourlière is awaiting results of the current ongoing phase 2/3 study, which would help determine a possible final treatment duration. He is also curious to settle the ongoing debate about whether bulevirtide should be used alone or in combination.

“We need to combine bulevirtide with pegylated interferon in less-advanced patients, because we know it is more potent and active against the HDV RNA,” he said.

Dr. Degasperi has previously declared she was on the advisory board for AbbVie and has spoken and taught for Gilead, MSD, and AbbVie. Dr. Bourlière declared interests with all companies involved in the R&D of liver therapies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ILC 2022

Finding HBV ‘cure’ may mean going ‘back to the drawing board’

LONDON – Achieving a functional cure for hepatitis B virus (HBV) is not going to be easily achieved with the drugs that are currently in development, according to a presentation at the annual International Liver Congress sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

“Intriguing results have been presented at ILC 2022 that must be carefully interpreted,” said Jean-Michel Pawlotsky, MD, PhD, of Henri Mondor Hospital in Créteil, France, during the viral hepatitis highlights session on the closing day of the meeting.

“New HBV drug development looks more complicated than initially expected and its goals and strategies need to be redefined and refocused,” he added

“This is really something that came from the discussions we had during the sessions but also in the corridors,” Dr. Pawlotsky added. “We know it’s going to be difficult; we have to reset, restart – not from zero, but from not much – and revise our strategy,” he suggested.

There are many new drugs under investigation for HBV, Dr. Pawlotsky said, noting that the number of studies being presented at the meeting was reminiscent of the flurry of activity before a functional cure for hepatitis C had been found. “It’s good to see that this is happening again for HBV,” he said.

Indeed, there are many new direct-acting antiviral agents, immunomodulatory, or other approaches being tested, and some of the more advanced studies are “teaching us a few things and probably raising more questions than getting answers,” Dr. Pawlotsky said.

The B-CLEAR study

One these studies is the phase 2b B-CLEAR study presented during the late-breaker session. This study involved bepirovirsen, an antisense oligonucleotide, and tested its efficacy and safety in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection who were either on or off stable nucleos(t)ide analogue (NA/NUC) therapy.

A similar proportion (28% and 29%, respectively) of patients achieved an hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) level below the lower limit of quantification at the end of 24 weeks treatment. However, the effect on HBsAg varied according to the treatment arm, with changes to the dosing or switching to placebo indicating that the effect might wane when the treatment is stopped or if the dose is reduced.

“Interestingly, ALT elevations were observed in association with most HBsAg declines,” Dr. Pawlotsky pointed out. “I think we still have to determine whether this is good flare/bad flare, good sign/bad sign, of what is going to happen afterward.”

The REEF studies

Another approach highlighted was the combination of the silencing or small interfering RNA (siRNA) JNJ-3989 with the capsid assembly modulator (CAM) JNJ-6379 in the phase 2 REEF-1 and REEF-2 studies.

REEF-1, conducted in patients who were either hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positive or negative who were not treated with NA/NUC or were NA/NUC suppressed, showed a dose-dependent, but variable effect among individual patients as might be expected at the end of 48 weeks’ treatment. This was sustained at week 72, which was 24 weeks’ follow-up after stopping treatment.

However, pointed out Dr. Pawlotsky “I think the most important part of this is that if you add a CAM on top of the siRNA, you do not improve the effect on HBsAg levels.”

Then there is the REEF-2 study, testing the same combination but in only patients who were NA suppressed or HBeAg negative alongside standard NA/NUC therapy. As well as being the first novel combination treatment trial to report, this was essentially a stopping trial, Kosh Agarwal, BMedSci (Hons), MBBS, MD, one of the study’s investigators explained separately at a media briefing.

Patients (n = 130) were treated for 48 weeks, then all treatment – including NA/NUC – was discontinued, with 48 weeks of follow-up after discontinuation, said Dr. Agarwal, who is a consultant hepatologist based at the Institute of Liver Studies at King’s College Hospital, London. He presented data from the first 24 week period after treatment had ended.

At the end of treatment, the combination had resulted in a mean reduction in HBsAg of 1.89 log10 IU/mL versus a reduction of 0.06 for the NA/NUC-only group, which acted as the control group in this trial. But “no patient in this study lost their surface antigen, i.e., were cured of their hepatitis B in the active arm or in the control arm,” Dr. Agarwal said.

“We didn’t achieve a cure, but a significant proportion were in a ‘controlled’ viral stage,” said Dr. Agarwal. Indeed, during his presentation of the findings, he showed that HBsAg inhibition was maintained in the majority (72%) of patients after stopping the combination.

While the trial’s primary endpoint wasn’t met, “it’s a really important study,” said Dr. Agarwal. “This [study] was fulfilled and delivered in the COVID era, so a lot of patients were looked after very carefully by sites in Europe,” he observed.

Further follow-up from the trial is expected, and Dr. Agarwal said that the subsequent discussion will “take us back to the drawing board to think about whether we need better antiviral treatments or whether we need to think about different combinations, and whether actually stopping treatment with every treatment is the right strategy to take.”

Both Dr. Agarwal and Dr. Pawlotsky flagged up the case of one patient in the trial who had been in the control arm and had experienced severe HBV reactivation that required a liver transplant.

“This patient is a warning signal,” Dr. Pawlotsky suggested in his talk. “When we think about NUC stopping, we have to think about the potential benefit in terms of HbsAg loss but also the potential risks.”

While Dr. Agarwal had noted that it highlights that “careful design of retreatment criteria is important in studies assessing the NA/NUC-stopping concept”.

Monoclonal antibody shows promise

Other combinations could involve an siRNA and an immunomodulatory agent and, during the poster sessions at the meeting, Dr. Agarwal also presented data from an ongoing phase 1 study with a novel, neutralizing monoclonal antibody called VIR-3434.

This monoclonal antibody is novel because it is thought to have several modes of action, first by binding to HBV and affecting its entry into liver cells, then by presenting the virus to T cells and stimulating a ‘vaccinal’ or immune effect, and then by helping the with the clearance of HBsAg and delivery of the virus to dendritic cells.

In the study, single doses of VIR-3434 were found to be well tolerated and to produce rapid reductions in HBsAg, with the highest dose used (300 mg) producing the greatest and most durable effect up to week 8.

VIR-3434 is also being tested in combination with other drugs in the phase 2 MARCH trial. One of these combinations is VIR-3434 together with an investigational siRNA dubbed VIR-2218. Preclinical work presented at ILC 2022 suggests that this combination appears to be capable of reducing HBsAg to a greater extent than using either agent alone.

Rethinking the strategy to get to a cure

Of course, VIR-3434 is one of several immunomodulatory compounds in development. There are therapeutic vaccines, drugs targeting the innate immune response, other monoclonal antibodies, T-cell receptors, checkpoint inhibitors and PD-L1 inhibitors. Then there are other compounds such as entry inhibitors, apoptosis inducers, and farnesoid X receptor agonists.

“I finish this meeting with more questions than answers,” Dr. Pawlotsky said. “What is the right target to enhance specific anti-HBV immunity? Does in vivo induction of immune responses translate into any beneficial effect on HBV infection? Will therapeutic vaccines every work in a viral infection?”

Moreover, he asked, “how can we avoid the side effect of enhancing multiple and complex nonspecific immune responses? Are treatment-induced flares good flares or bad flares? All of these are questions that are really unanswered and that we’ll have to get answers to in the near future.”

The B-CLEAR study was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline. The REEF-2 study was sponsored by Janssen Research & Development. The VIR-3434 studies were funded by Vir Biotechnology. Dr. Pawlotsky has received grant and research support, acted as a consultant, adviser, or speaker, and participated in advisory boards for multiple pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies. This news organization was unable to verify Dr. Agarwal’s ties to Vir Biotechnology, but he presented one of the posters on VIR-3434 at the meeting and has been involved in the phase 1 study that was reported.

LONDON – Achieving a functional cure for hepatitis B virus (HBV) is not going to be easily achieved with the drugs that are currently in development, according to a presentation at the annual International Liver Congress sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

“Intriguing results have been presented at ILC 2022 that must be carefully interpreted,” said Jean-Michel Pawlotsky, MD, PhD, of Henri Mondor Hospital in Créteil, France, during the viral hepatitis highlights session on the closing day of the meeting.

“New HBV drug development looks more complicated than initially expected and its goals and strategies need to be redefined and refocused,” he added

“This is really something that came from the discussions we had during the sessions but also in the corridors,” Dr. Pawlotsky added. “We know it’s going to be difficult; we have to reset, restart – not from zero, but from not much – and revise our strategy,” he suggested.

There are many new drugs under investigation for HBV, Dr. Pawlotsky said, noting that the number of studies being presented at the meeting was reminiscent of the flurry of activity before a functional cure for hepatitis C had been found. “It’s good to see that this is happening again for HBV,” he said.

Indeed, there are many new direct-acting antiviral agents, immunomodulatory, or other approaches being tested, and some of the more advanced studies are “teaching us a few things and probably raising more questions than getting answers,” Dr. Pawlotsky said.

The B-CLEAR study

One these studies is the phase 2b B-CLEAR study presented during the late-breaker session. This study involved bepirovirsen, an antisense oligonucleotide, and tested its efficacy and safety in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection who were either on or off stable nucleos(t)ide analogue (NA/NUC) therapy.

A similar proportion (28% and 29%, respectively) of patients achieved an hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) level below the lower limit of quantification at the end of 24 weeks treatment. However, the effect on HBsAg varied according to the treatment arm, with changes to the dosing or switching to placebo indicating that the effect might wane when the treatment is stopped or if the dose is reduced.

“Interestingly, ALT elevations were observed in association with most HBsAg declines,” Dr. Pawlotsky pointed out. “I think we still have to determine whether this is good flare/bad flare, good sign/bad sign, of what is going to happen afterward.”

The REEF studies

Another approach highlighted was the combination of the silencing or small interfering RNA (siRNA) JNJ-3989 with the capsid assembly modulator (CAM) JNJ-6379 in the phase 2 REEF-1 and REEF-2 studies.

REEF-1, conducted in patients who were either hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positive or negative who were not treated with NA/NUC or were NA/NUC suppressed, showed a dose-dependent, but variable effect among individual patients as might be expected at the end of 48 weeks’ treatment. This was sustained at week 72, which was 24 weeks’ follow-up after stopping treatment.

However, pointed out Dr. Pawlotsky “I think the most important part of this is that if you add a CAM on top of the siRNA, you do not improve the effect on HBsAg levels.”

Then there is the REEF-2 study, testing the same combination but in only patients who were NA suppressed or HBeAg negative alongside standard NA/NUC therapy. As well as being the first novel combination treatment trial to report, this was essentially a stopping trial, Kosh Agarwal, BMedSci (Hons), MBBS, MD, one of the study’s investigators explained separately at a media briefing.

Patients (n = 130) were treated for 48 weeks, then all treatment – including NA/NUC – was discontinued, with 48 weeks of follow-up after discontinuation, said Dr. Agarwal, who is a consultant hepatologist based at the Institute of Liver Studies at King’s College Hospital, London. He presented data from the first 24 week period after treatment had ended.

At the end of treatment, the combination had resulted in a mean reduction in HBsAg of 1.89 log10 IU/mL versus a reduction of 0.06 for the NA/NUC-only group, which acted as the control group in this trial. But “no patient in this study lost their surface antigen, i.e., were cured of their hepatitis B in the active arm or in the control arm,” Dr. Agarwal said.

“We didn’t achieve a cure, but a significant proportion were in a ‘controlled’ viral stage,” said Dr. Agarwal. Indeed, during his presentation of the findings, he showed that HBsAg inhibition was maintained in the majority (72%) of patients after stopping the combination.

While the trial’s primary endpoint wasn’t met, “it’s a really important study,” said Dr. Agarwal. “This [study] was fulfilled and delivered in the COVID era, so a lot of patients were looked after very carefully by sites in Europe,” he observed.

Further follow-up from the trial is expected, and Dr. Agarwal said that the subsequent discussion will “take us back to the drawing board to think about whether we need better antiviral treatments or whether we need to think about different combinations, and whether actually stopping treatment with every treatment is the right strategy to take.”

Both Dr. Agarwal and Dr. Pawlotsky flagged up the case of one patient in the trial who had been in the control arm and had experienced severe HBV reactivation that required a liver transplant.

“This patient is a warning signal,” Dr. Pawlotsky suggested in his talk. “When we think about NUC stopping, we have to think about the potential benefit in terms of HbsAg loss but also the potential risks.”

While Dr. Agarwal had noted that it highlights that “careful design of retreatment criteria is important in studies assessing the NA/NUC-stopping concept”.

Monoclonal antibody shows promise

Other combinations could involve an siRNA and an immunomodulatory agent and, during the poster sessions at the meeting, Dr. Agarwal also presented data from an ongoing phase 1 study with a novel, neutralizing monoclonal antibody called VIR-3434.

This monoclonal antibody is novel because it is thought to have several modes of action, first by binding to HBV and affecting its entry into liver cells, then by presenting the virus to T cells and stimulating a ‘vaccinal’ or immune effect, and then by helping the with the clearance of HBsAg and delivery of the virus to dendritic cells.

In the study, single doses of VIR-3434 were found to be well tolerated and to produce rapid reductions in HBsAg, with the highest dose used (300 mg) producing the greatest and most durable effect up to week 8.

VIR-3434 is also being tested in combination with other drugs in the phase 2 MARCH trial. One of these combinations is VIR-3434 together with an investigational siRNA dubbed VIR-2218. Preclinical work presented at ILC 2022 suggests that this combination appears to be capable of reducing HBsAg to a greater extent than using either agent alone.

Rethinking the strategy to get to a cure

Of course, VIR-3434 is one of several immunomodulatory compounds in development. There are therapeutic vaccines, drugs targeting the innate immune response, other monoclonal antibodies, T-cell receptors, checkpoint inhibitors and PD-L1 inhibitors. Then there are other compounds such as entry inhibitors, apoptosis inducers, and farnesoid X receptor agonists.

“I finish this meeting with more questions than answers,” Dr. Pawlotsky said. “What is the right target to enhance specific anti-HBV immunity? Does in vivo induction of immune responses translate into any beneficial effect on HBV infection? Will therapeutic vaccines every work in a viral infection?”

Moreover, he asked, “how can we avoid the side effect of enhancing multiple and complex nonspecific immune responses? Are treatment-induced flares good flares or bad flares? All of these are questions that are really unanswered and that we’ll have to get answers to in the near future.”

The B-CLEAR study was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline. The REEF-2 study was sponsored by Janssen Research & Development. The VIR-3434 studies were funded by Vir Biotechnology. Dr. Pawlotsky has received grant and research support, acted as a consultant, adviser, or speaker, and participated in advisory boards for multiple pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies. This news organization was unable to verify Dr. Agarwal’s ties to Vir Biotechnology, but he presented one of the posters on VIR-3434 at the meeting and has been involved in the phase 1 study that was reported.

LONDON – Achieving a functional cure for hepatitis B virus (HBV) is not going to be easily achieved with the drugs that are currently in development, according to a presentation at the annual International Liver Congress sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

“Intriguing results have been presented at ILC 2022 that must be carefully interpreted,” said Jean-Michel Pawlotsky, MD, PhD, of Henri Mondor Hospital in Créteil, France, during the viral hepatitis highlights session on the closing day of the meeting.

“New HBV drug development looks more complicated than initially expected and its goals and strategies need to be redefined and refocused,” he added

“This is really something that came from the discussions we had during the sessions but also in the corridors,” Dr. Pawlotsky added. “We know it’s going to be difficult; we have to reset, restart – not from zero, but from not much – and revise our strategy,” he suggested.

There are many new drugs under investigation for HBV, Dr. Pawlotsky said, noting that the number of studies being presented at the meeting was reminiscent of the flurry of activity before a functional cure for hepatitis C had been found. “It’s good to see that this is happening again for HBV,” he said.

Indeed, there are many new direct-acting antiviral agents, immunomodulatory, or other approaches being tested, and some of the more advanced studies are “teaching us a few things and probably raising more questions than getting answers,” Dr. Pawlotsky said.

The B-CLEAR study

One these studies is the phase 2b B-CLEAR study presented during the late-breaker session. This study involved bepirovirsen, an antisense oligonucleotide, and tested its efficacy and safety in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection who were either on or off stable nucleos(t)ide analogue (NA/NUC) therapy.

A similar proportion (28% and 29%, respectively) of patients achieved an hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) level below the lower limit of quantification at the end of 24 weeks treatment. However, the effect on HBsAg varied according to the treatment arm, with changes to the dosing or switching to placebo indicating that the effect might wane when the treatment is stopped or if the dose is reduced.

“Interestingly, ALT elevations were observed in association with most HBsAg declines,” Dr. Pawlotsky pointed out. “I think we still have to determine whether this is good flare/bad flare, good sign/bad sign, of what is going to happen afterward.”

The REEF studies

Another approach highlighted was the combination of the silencing or small interfering RNA (siRNA) JNJ-3989 with the capsid assembly modulator (CAM) JNJ-6379 in the phase 2 REEF-1 and REEF-2 studies.

REEF-1, conducted in patients who were either hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positive or negative who were not treated with NA/NUC or were NA/NUC suppressed, showed a dose-dependent, but variable effect among individual patients as might be expected at the end of 48 weeks’ treatment. This was sustained at week 72, which was 24 weeks’ follow-up after stopping treatment.

However, pointed out Dr. Pawlotsky “I think the most important part of this is that if you add a CAM on top of the siRNA, you do not improve the effect on HBsAg levels.”

Then there is the REEF-2 study, testing the same combination but in only patients who were NA suppressed or HBeAg negative alongside standard NA/NUC therapy. As well as being the first novel combination treatment trial to report, this was essentially a stopping trial, Kosh Agarwal, BMedSci (Hons), MBBS, MD, one of the study’s investigators explained separately at a media briefing.

Patients (n = 130) were treated for 48 weeks, then all treatment – including NA/NUC – was discontinued, with 48 weeks of follow-up after discontinuation, said Dr. Agarwal, who is a consultant hepatologist based at the Institute of Liver Studies at King’s College Hospital, London. He presented data from the first 24 week period after treatment had ended.

At the end of treatment, the combination had resulted in a mean reduction in HBsAg of 1.89 log10 IU/mL versus a reduction of 0.06 for the NA/NUC-only group, which acted as the control group in this trial. But “no patient in this study lost their surface antigen, i.e., were cured of their hepatitis B in the active arm or in the control arm,” Dr. Agarwal said.

“We didn’t achieve a cure, but a significant proportion were in a ‘controlled’ viral stage,” said Dr. Agarwal. Indeed, during his presentation of the findings, he showed that HBsAg inhibition was maintained in the majority (72%) of patients after stopping the combination.

While the trial’s primary endpoint wasn’t met, “it’s a really important study,” said Dr. Agarwal. “This [study] was fulfilled and delivered in the COVID era, so a lot of patients were looked after very carefully by sites in Europe,” he observed.

Further follow-up from the trial is expected, and Dr. Agarwal said that the subsequent discussion will “take us back to the drawing board to think about whether we need better antiviral treatments or whether we need to think about different combinations, and whether actually stopping treatment with every treatment is the right strategy to take.”

Both Dr. Agarwal and Dr. Pawlotsky flagged up the case of one patient in the trial who had been in the control arm and had experienced severe HBV reactivation that required a liver transplant.

“This patient is a warning signal,” Dr. Pawlotsky suggested in his talk. “When we think about NUC stopping, we have to think about the potential benefit in terms of HbsAg loss but also the potential risks.”

While Dr. Agarwal had noted that it highlights that “careful design of retreatment criteria is important in studies assessing the NA/NUC-stopping concept”.

Monoclonal antibody shows promise

Other combinations could involve an siRNA and an immunomodulatory agent and, during the poster sessions at the meeting, Dr. Agarwal also presented data from an ongoing phase 1 study with a novel, neutralizing monoclonal antibody called VIR-3434.

This monoclonal antibody is novel because it is thought to have several modes of action, first by binding to HBV and affecting its entry into liver cells, then by presenting the virus to T cells and stimulating a ‘vaccinal’ or immune effect, and then by helping the with the clearance of HBsAg and delivery of the virus to dendritic cells.

In the study, single doses of VIR-3434 were found to be well tolerated and to produce rapid reductions in HBsAg, with the highest dose used (300 mg) producing the greatest and most durable effect up to week 8.

VIR-3434 is also being tested in combination with other drugs in the phase 2 MARCH trial. One of these combinations is VIR-3434 together with an investigational siRNA dubbed VIR-2218. Preclinical work presented at ILC 2022 suggests that this combination appears to be capable of reducing HBsAg to a greater extent than using either agent alone.

Rethinking the strategy to get to a cure

Of course, VIR-3434 is one of several immunomodulatory compounds in development. There are therapeutic vaccines, drugs targeting the innate immune response, other monoclonal antibodies, T-cell receptors, checkpoint inhibitors and PD-L1 inhibitors. Then there are other compounds such as entry inhibitors, apoptosis inducers, and farnesoid X receptor agonists.

“I finish this meeting with more questions than answers,” Dr. Pawlotsky said. “What is the right target to enhance specific anti-HBV immunity? Does in vivo induction of immune responses translate into any beneficial effect on HBV infection? Will therapeutic vaccines every work in a viral infection?”