User login

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Associated With Midlife Memory, Thinking Problems

TOPLINE:

People with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) may score lower on cognitive tests than people without the condition, a research showed. They also may have worse integrity of brain tissue as evident on an MRI.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers used data from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Women’s Study; individuals were 18-30 years old at the beginning of the study and were followed over 30 years.

- A little over 900 women were included in the study, of which 66 had PCOS, which was defined as having elevated androgen levels or self-reported hirsutism and irregular menstrual cycles more than 32 days apart.

- Study participants completed tests measuring verbal learning and memory, processing speed and executive function, attention and cognitive control, and semantics and attention.

- Researchers analyzed brain white matter integrity for 291 of the individuals, including 25 with PCOS, who underwent MRI.

TAKEAWAY:

- Individuals with PCOS had worse memory, attention, and verbal ability scores than those without the disorder.

- MRI scans showed that those with PCOS had lower white matter integrity, an indicator of cognitive deficits, including poorer decision-making abilities.

- Those in the PCOS group were more likely to be White and have diabetes than those in the control group.

IN PRACTICE:

“This report of midlife cognition in PCOS raises a new concern about another potential comorbidity for individuals with this common disorder; given that up to 10% of women may be affected by PCOS, these results have important implications for public health at large,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

Heather G. Huddleston, MD, director of the PCOS Clinic at the UCSF Health, San Francisco, California, is the lead author of the study published in Neurology.

LIMITATIONS:

PCOS was determined on the basis of serum androgen levels and self-reporting of hirsutism and oligomenorrhea, so some cases may have been misclassified without the official diagnosis of a clinician.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors did not report any relevant financial conflicts. The study was funded by a grant from the University of California, San Francisco, California.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

People with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) may score lower on cognitive tests than people without the condition, a research showed. They also may have worse integrity of brain tissue as evident on an MRI.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers used data from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Women’s Study; individuals were 18-30 years old at the beginning of the study and were followed over 30 years.

- A little over 900 women were included in the study, of which 66 had PCOS, which was defined as having elevated androgen levels or self-reported hirsutism and irregular menstrual cycles more than 32 days apart.

- Study participants completed tests measuring verbal learning and memory, processing speed and executive function, attention and cognitive control, and semantics and attention.

- Researchers analyzed brain white matter integrity for 291 of the individuals, including 25 with PCOS, who underwent MRI.

TAKEAWAY:

- Individuals with PCOS had worse memory, attention, and verbal ability scores than those without the disorder.

- MRI scans showed that those with PCOS had lower white matter integrity, an indicator of cognitive deficits, including poorer decision-making abilities.

- Those in the PCOS group were more likely to be White and have diabetes than those in the control group.

IN PRACTICE:

“This report of midlife cognition in PCOS raises a new concern about another potential comorbidity for individuals with this common disorder; given that up to 10% of women may be affected by PCOS, these results have important implications for public health at large,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

Heather G. Huddleston, MD, director of the PCOS Clinic at the UCSF Health, San Francisco, California, is the lead author of the study published in Neurology.

LIMITATIONS:

PCOS was determined on the basis of serum androgen levels and self-reporting of hirsutism and oligomenorrhea, so some cases may have been misclassified without the official diagnosis of a clinician.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors did not report any relevant financial conflicts. The study was funded by a grant from the University of California, San Francisco, California.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

People with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) may score lower on cognitive tests than people without the condition, a research showed. They also may have worse integrity of brain tissue as evident on an MRI.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers used data from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Women’s Study; individuals were 18-30 years old at the beginning of the study and were followed over 30 years.

- A little over 900 women were included in the study, of which 66 had PCOS, which was defined as having elevated androgen levels or self-reported hirsutism and irregular menstrual cycles more than 32 days apart.

- Study participants completed tests measuring verbal learning and memory, processing speed and executive function, attention and cognitive control, and semantics and attention.

- Researchers analyzed brain white matter integrity for 291 of the individuals, including 25 with PCOS, who underwent MRI.

TAKEAWAY:

- Individuals with PCOS had worse memory, attention, and verbal ability scores than those without the disorder.

- MRI scans showed that those with PCOS had lower white matter integrity, an indicator of cognitive deficits, including poorer decision-making abilities.

- Those in the PCOS group were more likely to be White and have diabetes than those in the control group.

IN PRACTICE:

“This report of midlife cognition in PCOS raises a new concern about another potential comorbidity for individuals with this common disorder; given that up to 10% of women may be affected by PCOS, these results have important implications for public health at large,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

Heather G. Huddleston, MD, director of the PCOS Clinic at the UCSF Health, San Francisco, California, is the lead author of the study published in Neurology.

LIMITATIONS:

PCOS was determined on the basis of serum androgen levels and self-reporting of hirsutism and oligomenorrhea, so some cases may have been misclassified without the official diagnosis of a clinician.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors did not report any relevant financial conflicts. The study was funded by a grant from the University of California, San Francisco, California.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Restricted Abortion Access Tied to Mental Health Harm

, which revoked a woman’s constitutional right to an abortion, new research shows.

This could be due to a variety of factors, investigators led by Benjamin Thornburg, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, noted. These include fear about the imminent risk of being denied an abortion, uncertainty around future limitations on abortion and other related rights such as contraception, worry over the ability to receive lifesaving medical care during pregnancy, and a general sense of violation and powerlessness related to loss of the right to reproductive autonomy.

The study was published online on January 23, 2024, in JAMA.

Mental Health Harm

In June 2022, the US Supreme Court overturned Roe vs Wade, removing federal protections for abortion rights. Thirteen states had “trigger laws” that immediately banned or severely restricted abortion — raising concerns this could negatively affect mental health.

The researchers used data from the Household Pulse Survey to estimate changes in anxiety and depression symptoms after vs before the Dobbs decision in nearly 160,000 adults living in 13 states with trigger laws compared with roughly 559,000 adults living in 37 states without trigger laws.

The mean age of respondents was 48 years, and 51% were women. Anxiety and depression symptoms were measured via the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4).

In trigger states, the mean PHQ-4 score at baseline (before Dobbs) was 3.51 (out of 12) and increased to 3.81 after the Dobbs decision. In nontrigger states, the mean PHQ-4 score at baseline was 3.31 and increased to 3.49 after Dobbs.

Living in a trigger state was associated with a small but statistically significant worsening (0.11-point; P < .001) in anxiety/depression symptoms following the Dobbs decision vs living in a nontrigger state, the investigators report.

Women aged 18-45 years faced greater worsening of anxiety and depression symptoms following Dobbs in trigger vs nontrigger states, whereas men of a similar age experienced minimal or negligible changes.

Implications for Care

In an accompanying editorial, Julie Steinberg, PhD, with University of Maryland in College Park, notes the study results provide “emerging evidence that at an individual level taking away reproductive autonomy (by not having legal access to an abortion) may increase symptoms of anxiety and depression in all people and particularly females of reproductive age.”

These results add to findings from two other studies that examined abortion restrictions and mental health outcomes. Both found that limiting access to abortion was associated with more mental health symptoms among females of reproductive age than among others,” Dr. Steinberg pointed out.

“Together these findings highlight the need for clinicians who practice in states where abortion is banned to be aware that female patients of reproductive age may be experiencing significantly more distress than before the Dobbs decision,” Dr. Steinberg added.

The study received no specific funding. The authors had no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Steinberg reported serving as a paid expert scientist on abortion and mental health in seven cases challenging abortion policies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, which revoked a woman’s constitutional right to an abortion, new research shows.

This could be due to a variety of factors, investigators led by Benjamin Thornburg, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, noted. These include fear about the imminent risk of being denied an abortion, uncertainty around future limitations on abortion and other related rights such as contraception, worry over the ability to receive lifesaving medical care during pregnancy, and a general sense of violation and powerlessness related to loss of the right to reproductive autonomy.

The study was published online on January 23, 2024, in JAMA.

Mental Health Harm

In June 2022, the US Supreme Court overturned Roe vs Wade, removing federal protections for abortion rights. Thirteen states had “trigger laws” that immediately banned or severely restricted abortion — raising concerns this could negatively affect mental health.

The researchers used data from the Household Pulse Survey to estimate changes in anxiety and depression symptoms after vs before the Dobbs decision in nearly 160,000 adults living in 13 states with trigger laws compared with roughly 559,000 adults living in 37 states without trigger laws.

The mean age of respondents was 48 years, and 51% were women. Anxiety and depression symptoms were measured via the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4).

In trigger states, the mean PHQ-4 score at baseline (before Dobbs) was 3.51 (out of 12) and increased to 3.81 after the Dobbs decision. In nontrigger states, the mean PHQ-4 score at baseline was 3.31 and increased to 3.49 after Dobbs.

Living in a trigger state was associated with a small but statistically significant worsening (0.11-point; P < .001) in anxiety/depression symptoms following the Dobbs decision vs living in a nontrigger state, the investigators report.

Women aged 18-45 years faced greater worsening of anxiety and depression symptoms following Dobbs in trigger vs nontrigger states, whereas men of a similar age experienced minimal or negligible changes.

Implications for Care

In an accompanying editorial, Julie Steinberg, PhD, with University of Maryland in College Park, notes the study results provide “emerging evidence that at an individual level taking away reproductive autonomy (by not having legal access to an abortion) may increase symptoms of anxiety and depression in all people and particularly females of reproductive age.”

These results add to findings from two other studies that examined abortion restrictions and mental health outcomes. Both found that limiting access to abortion was associated with more mental health symptoms among females of reproductive age than among others,” Dr. Steinberg pointed out.

“Together these findings highlight the need for clinicians who practice in states where abortion is banned to be aware that female patients of reproductive age may be experiencing significantly more distress than before the Dobbs decision,” Dr. Steinberg added.

The study received no specific funding. The authors had no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Steinberg reported serving as a paid expert scientist on abortion and mental health in seven cases challenging abortion policies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, which revoked a woman’s constitutional right to an abortion, new research shows.

This could be due to a variety of factors, investigators led by Benjamin Thornburg, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, noted. These include fear about the imminent risk of being denied an abortion, uncertainty around future limitations on abortion and other related rights such as contraception, worry over the ability to receive lifesaving medical care during pregnancy, and a general sense of violation and powerlessness related to loss of the right to reproductive autonomy.

The study was published online on January 23, 2024, in JAMA.

Mental Health Harm

In June 2022, the US Supreme Court overturned Roe vs Wade, removing federal protections for abortion rights. Thirteen states had “trigger laws” that immediately banned or severely restricted abortion — raising concerns this could negatively affect mental health.

The researchers used data from the Household Pulse Survey to estimate changes in anxiety and depression symptoms after vs before the Dobbs decision in nearly 160,000 adults living in 13 states with trigger laws compared with roughly 559,000 adults living in 37 states without trigger laws.

The mean age of respondents was 48 years, and 51% were women. Anxiety and depression symptoms were measured via the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4).

In trigger states, the mean PHQ-4 score at baseline (before Dobbs) was 3.51 (out of 12) and increased to 3.81 after the Dobbs decision. In nontrigger states, the mean PHQ-4 score at baseline was 3.31 and increased to 3.49 after Dobbs.

Living in a trigger state was associated with a small but statistically significant worsening (0.11-point; P < .001) in anxiety/depression symptoms following the Dobbs decision vs living in a nontrigger state, the investigators report.

Women aged 18-45 years faced greater worsening of anxiety and depression symptoms following Dobbs in trigger vs nontrigger states, whereas men of a similar age experienced minimal or negligible changes.

Implications for Care

In an accompanying editorial, Julie Steinberg, PhD, with University of Maryland in College Park, notes the study results provide “emerging evidence that at an individual level taking away reproductive autonomy (by not having legal access to an abortion) may increase symptoms of anxiety and depression in all people and particularly females of reproductive age.”

These results add to findings from two other studies that examined abortion restrictions and mental health outcomes. Both found that limiting access to abortion was associated with more mental health symptoms among females of reproductive age than among others,” Dr. Steinberg pointed out.

“Together these findings highlight the need for clinicians who practice in states where abortion is banned to be aware that female patients of reproductive age may be experiencing significantly more distress than before the Dobbs decision,” Dr. Steinberg added.

The study received no specific funding. The authors had no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Steinberg reported serving as a paid expert scientist on abortion and mental health in seven cases challenging abortion policies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA

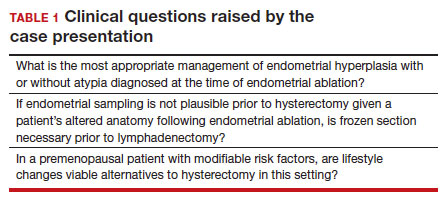

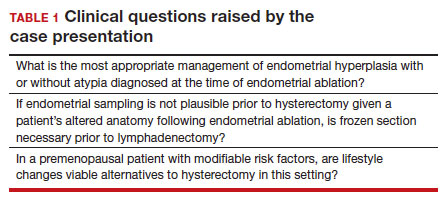

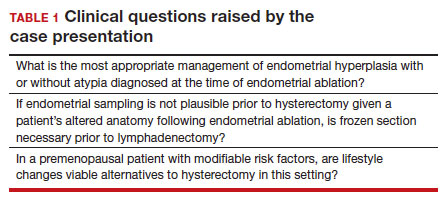

Time to rethink endometrial ablation: A gyn oncology perspective on the sequelae of an overused procedure

CASE New patient presents with a history of endometrial hyperplasia

A 51-year-old patient (G2P2002) presents to a new gynecologist’s office after moving from a different state. In her medical history, the gynecologist notes that 5 years ago she underwent dilation and curettage and endometrial ablation procedures for heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB). Ultrasonography performed prior to those procedures showed a slightly enlarged uterus, a simple left ovarian cyst, and a non ̶ visualized right ovary. The patient had declined a 2-step procedure due to concerns with anesthesia, and surgical pathology at the time of ablation revealed hyperplasia without atypia. The patient’s medical history was otherwise notable for prediabetes (recent hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c] measurement, 6.0%) and obesity (body mass index, 43 kg/m2). Pertinent family history included her mother’s diagnosis of endometrial cancer at age 36. Given the patient’s diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia, she was referred to gynecologic oncology, but she ultimately declined hysterectomy, stating that she was happy with the resolution of her abnormal bleeding. At the time of her initial gynecologic oncology consultation, the consultant suggested lifestyle changes to combat prediabetes and obesity to reduce the risk of endometrial cancer, as future signs of cancer, namely bleeding, may be masked by the endometrial ablation. The patient was prescribed metformin given these medical comorbidities.

At today’s appointment, the patient notes continued resolution of bleeding since the procedure. She does, however, note a 6-month history of vasomotor symptoms and one episode of spotting 3 months ago. Three years ago she was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus, and her current HbA1c is 6.9%. She has gained 10 lb since being diagnosed with endometrial cancer 5 years ago, and she has continued to take metformin.

An in-office endometrial biopsy is unsuccessful due to cervical stenosis. The treating gynecologist orders a transvaginal ultrasound, which reveals a small left ovarian cyst and a thickened endometrium (measuring 10 mm). Concerned that these findings could represent endometrial cancer, the gynecologist refers the patient to gynecologic oncology for further evaluation.

Sequelae and complications following endometrial ablation are often managed by a gynecologic oncologist. Indeed, a 2018 poll of Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) members revealed that 93.8% of respondents had received such a referral, and almost 20% of respondents were managing more than 20 patients with post-ablation complications in their practices.1 These complications, including hematometra, post-ablation tubal sterilization syndrome, other pain syndromes associated with retrograde menstruation, and thickened endometrium with scarring leading to an inability to sample the endometrium to investigate post-ablation bleeding are symptoms and findings that often lead to further surgery, including hysterectomy.2 General gynecologists faced with these complications may refer patients to gynecologic oncology given an inability to sample the post-ablation endometrium or anticipated difficulties with hysterectomy. A recent meta-analysis revealed a 12.4% hysterectomy rate 5 years after endometrial ablation. Among these patients, the incidence of endometrial cancer ranged from 0% to 1.6%.3

In 2023, endometrial cancer incidence continues to increase, as does the incidence of obesity in women of all ages. Endometrial cancer mortality rates are also increasing, and these trends disproportionately affects non-Hispanic Black women.4 As providers and advocates work to narrow these disparities, gynecologic oncologists are simultaneously noting increased referrals for very likely benign conditions.5 Patients referred for post-ablation bleeding are a subset of these, as most patients who undergo endometrial ablation will not develop cancer. Considering the potential bottlenecks created en route to a gynecologic oncology evaluation, it seems prudent to minimize practices, like endometrial ablation, that may directly or indirectly prevent timely referral of patients with cancer to a gynecologic oncologist.

In this review we focus on the current use of endometrial ablation, associated complications, the incidence of treatment failure, and patient selection. Considering these issues in the context of the current endometrial cancer landscape, we posit best practices aimed at optimizing patient outcomes, and empowering general gynecologists to practice cancer prevention and to triage their surgical patients.

- Before performing endometrial ablation, consider whether alternatives such as hysterectomy or insertion of a progestin-containing IUD would be appropriate.

- Clinical management of patients with abnormal bleeding with indications for endometrial ablation should be guidelinedriven.

- Post-ablation bleeding or pain does not inherently require referral to oncology.

- General gynecologists can perform hysterectomy in this setting if appropriate.

- Patients with endometrial hyperplasia at endometrial ablation should be promptly offered hysterectomy. If atypia is not present, this hysterectomy, too, can be performed by a general gynecologist if appropriate, as the chance for malignancy is minimal.

Continue to: Current use of endometrial ablation in the US...

Current use of endometrial ablation in the US

In 2015, more than 500,000 endometrial ablations were performed in the United States.Given the ability to perform in-office ablation, this number is growing and potentially underestimated each year.6 In 2022, the global endometrial ablation market was valued at $3.4 billion, a figure projected to double in 10 years.7 The procedure has evolved as different devices and approaches have developed, offering patients different means to manage bleeding without hysterectomy. The minimally invasive procedure, performed in premenopausal patients with heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) due to benign causes who have completed childbearing, has been associated with faster recovery times and fewer short-term complications compared with more invasive surgery.8 There are several non-resectoscope ablative devices approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and each work to destroy the endometrial lining via thermal or cryoablation. Endometrial ablation can be performed in premenopausal patients with HMB due to benign causes who have completed childbearing.

Recently, promotional literature has begun to report on so-called overuse of hysterectomy, despite decreasing overall hysterectomy rates. This reporting proposes and applies “appropriateness criteria,” accounting for the rate of preoperative counseling regarding alternatives to hysterectomy, as well as the rate of “unsupportive” final pathology.9 The adoption of endometrial ablation and increasing market value of such vendors suggest that this campaign is having its desired effect. From the oncology perspective, we are concerned the pendulum could swing too far away from hysterectomy, a procedure that definitively cures abnormal uterine bleeding, toward endometrial ablation without explicit acknowledgement of the trade-offs involved.

Endometrial ablation complications: Late-onset procedure failure

A number of post-ablation syndromes may present at least 1 month following the procedure. Collectively known as late-onset endometrial ablation failure (LOEAF), these syndromes are characterized by recurrent vaginal bleeding, and/or new cyclic pelvic pain.10 It is difficult to measure the true incidence of LOEAF. Thomassee and colleagues examined a Canadian retrospective cohort of 437 patients who underwent endometrial ablation; 20.8% reported post-ablation pelvic pain after a median 301 days.11 The subsequent need for surgical intervention, often hysterectomy, is a surrogate for LOEAF.

It should be noted that LOEAF is distinct from post-ablation tubal sterilization syndrome (PATSS), which describes cornual menstrual bleeding impeded by the ligated proximal fallopian tube.12 Increased awareness of PATSS, along with the discontinuation of Essure (a permanent hysteroscopic sterilization device) in 2018, has led some surgeons to advocate for concomitant salpingectomy at the time of endometrial ablation.13 The role of opportunistic salpingectomy in primary prevention of epithelial ovarian cancer is well described, and while we strongly support this practice at the time of endometrial ablation, we do not feel that it effectively prevents LOEAF.14

The post-ablation inability to adequately sample the endometrium is also considered a LOEAF. A prospective study of 57 women who underwent endometrial ablation assessed post-ablation sampling feasibility via transvaginal ultrasonography, saline infusion sonohysterography (SIS), and in-office endometrial biopsies. In 23% of the cohort, endometrial sampling failed, and the authors noted decreased reliability of pathologic assessment.15 One systematic review, in which authors examined the incidence of endometrial cancer following endometrial ablation, characterized 38 cases of endometrial cancer and reported a post-ablation endometrial sampling success rate of 89%. This figure was based on a self-selected sample of 18 patients; cases in which endometrial sampling was thought to be impossible were excluded. The study also had a 30% missing data rate and several other biases.16

In the previously mentioned poll of SGO members,1 84% of the surveyed gynecologic oncologists managing post-ablation patients reported that endometrial sampling following endometrial ablation was “moderately” or “extremely” difficult. More than half of the survey respondents believed that hysterectomy was required for accurate diagnosis.1 While we acknowledge the likely sampling bias affecting the survey results, we are not comforted by any data that minimizes this diagnostic challenge.

Appropriate patient selection and contraindications

The ideal candidate for endometrial ablation is a premenopausal patient with HMB who does not desire future fertility. According to the FDA, absolute contraindications include pregnancy or desired fertility, prior ablation, current IUD in place, inadequate preoperative endometrial assessment, known or suspected malignancy, active infection, or unfavorable anatomy.17

What about patients who may be at increased risk for endometrial cancer?

There is a paucity of data regarding the safety of endometrial ablation in patients at increased risk for developing endometrial cancer in the future. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) 2007 practice bulletin on endometrial ablation (no longer accessible online) alludes to this concern and other contraindications,18 but there are no established guidelines. Currently, no ACOG practice bulletin or committee opinion lists relative contraindications to endometrial ablation, long-term complications (except risks associated with future pregnancy), or risk of subsequent hysterectomy. The risk that “it may be harder to detect endometrial cancer after ablation” is noted on ACOG’s web page dedicated to frequently asked questions (FAQs) regarding abnormal uterine bleeding.19 It is not mentioned on their web page dedicated to the FAQs regarding endometrial ablation.20

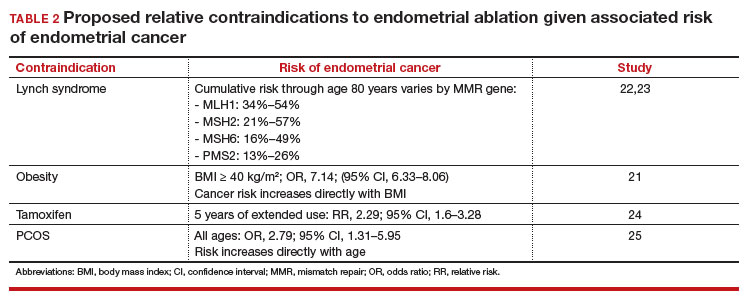

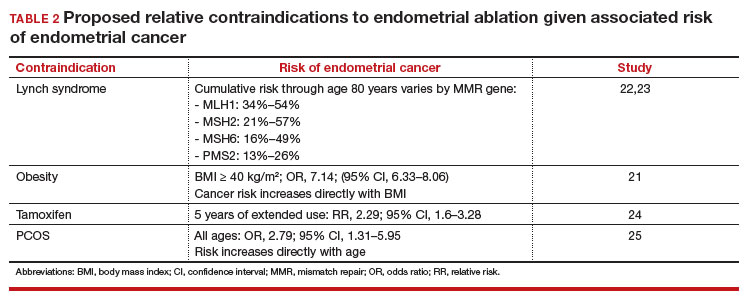

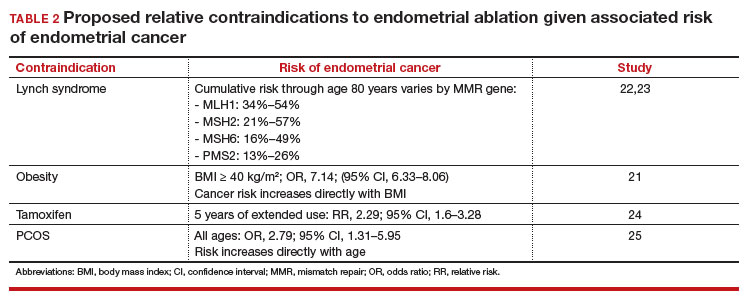

In the absence of high-quality published data on established contraindications for endometrial ablation, we advocate for the increased awareness of possible relative contraindications—namely well-established risk factors for endometrial cancer (TABLE 1).For example, in a pooled analysis of 24 epidemiologic studies, authors found that the odds of developing endometrial cancer was 7 times higher among patients with a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 40 kg/m2, compared with controls (odds ratio [OR], 7.14; 95% confidence interval [CI], 6.33–8.06).21 Additionally, patients with Lynch syndrome, a history of extended tamoxifen use, or those with a history of chronic anovulation or polycystic ovary syndrome are at increased risk for endometrial cancer.22-24 If the presence of one or more of these factors does not dissuade general gynecologists from performing an endometrial ablation (even armed with a negative preoperative endometrial biopsy), we feel they should at least prompt thoughtful guideline-driven pause.

Continue to: Hysterectomy—A disincentivized option...

Hysterectomy—A disincentivized option

The annual number of hysterectomies performed by general gynecologists has declined over time. One study by Cadish and colleagues revealed that recent residency graduates performed only 3 to 4 annually.25 These numbers partly reflect the decreasing number of hysterectomies performed during residency training. Furthermore, other factors—including the increasing rate of placenta accreta spectrum, the focus on risk stratification of adnexal masses via the ovarian-adnexal reporting and data classification system (O-RADs), and the emphasis on minimally invasive approaches often acquired in subspecialty training—have likely contributed to referral patterns to such specialists as minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons and gynecologic oncologists.26 This trend is self-actualizing, as quality metrics funnel patients to high-volume surgeons, and general gynecologists risk losing hysterectomy privileges.

These factors lend themselves to a growing emphasis on endometrial ablation. Endometrial ablations can be performed in several settings, including in the hospital, in outpatient clinics, and more and more commonly, in ambulatory surgery centers. This increased access to endometrial ablation in the ambulatory surgery setting has corresponded with an annual endometrial ablation market value growth rate of 5% to 7%.27 These rates are likely compounded by payer reimbursement policies that promote endometrial ablation and other alternatives to hysterectomy that are cost savings in the short term.28 While the actual payer models are unavailable to review, they may not consider the costs of LOEAFs, including subsequent hysterectomy up to 5 years after initial ablation procedures. Provocatively, they almost certainly do not consider the costs of delayed care of patients with endometrial cancer vying for gynecologic oncology appointment slots occupied by post-ablation patients.

We urge providers, patients, and advocates to question who benefits from the uptake of ablation procedures: Patients? Payors? Providers? And how will the field of gynecology fare if hysterectomy skills and privileges are supplanted by ablation?

Post-ablation bleeding: Management by the gyn oncologist

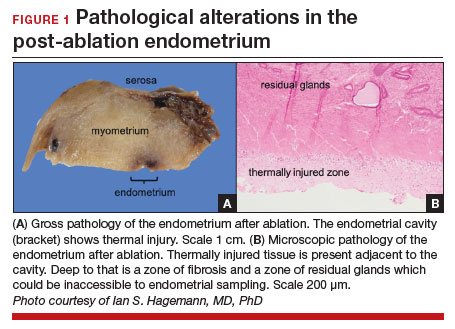

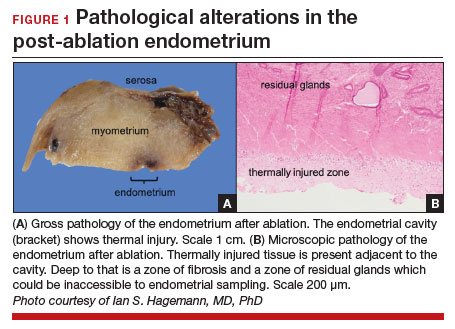

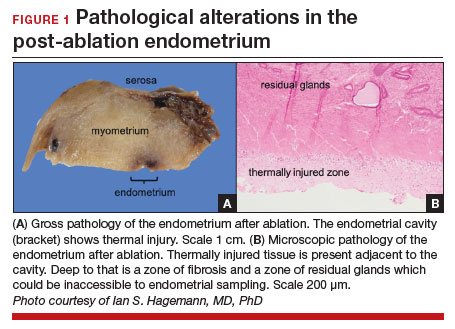

Patients with post-ablation bleeding, either immediately or years later, are sometimes referred to a gynecologic oncologist given the possible risk for cancer and need for surgical staging if cancer is found on the hysterectomy specimen. In practice, assuming normal preoperative ultrasonography and no other clinical or radiologic findings suggestive of malignancy (eg, computed tomography findings concerning for metastases, abnormal cervical cytology, etc.), the presence of cancer is extremely unlikely to be determined at the time of surgery. Frozen section is not generally performed on the endometrium; intraoperative evaluation of even the unablated endometrium is notoriously unreliable; and histologic assessment of the ablated endometrium is limited by artifact (FIGURE 1). The abnormalities caused by ablation further impede selection of a representative focus, obfuscating any actionable result.

Some surgeons routinely bivalve the excised uterus prior to fixation to assess presence of tumor, tumor size, and the degree of myometrial invasion.29 A combination of factors may compel surgeons to perform lymphadenectomy if not already performed, or if sentinel lymph node mapping was unsuccessful. But this practice has not been studied in patients with post-ablation bleeding, and applying these principles relies on a preoperative diagnosis establishing the presence and grade of a cancer. Furthermore, the utility of frozen section and myometrial assessment to decide whether or not to proceed with lymphadenectomy is less relevant in the era of molecular classification guiding adjuvant therapy. In summary, assuming no pathologic or radiologic findings suggestive of cancer, gynecologic oncologists are unlikely to perform lymphadenectomy at the time of hysterectomy in these post-ablation cases, which therefore can safely be performed by general gynecologists.

Our recommendations

Consider the LNG-IUD as an alternative to ablation. A recent randomized controlled trial by Beelen and colleagues compared the effectiveness of LNG-releasing IUDs with endometrial ablation in patients with HMB. While the LNG-IUD was inferior to endometrial ablation, quality-of-life measures were similar up to 2 years.31 Realizing that the hysterectomy rate following endometrial ablation increases significantly beyond that time point (2 years), this narrative may be incomplete. A 5- to 10-year follow-up time-frame may be a more helpful gauge of long-term outcomes. This prolonged time-frame also may allow study of the LNG-IUD’s protective effects on the endometrium in the prevention of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer.

Consider hysterectomy. A 2021 Cochrane review revealed that, compared with endometrial ablation, minimally invasive hysterectomy is associated with higher quality-of-life metrics, higher self-reported patient satisfaction, and similar rates of adverse events.32 While patient autonomy is paramount, the developing step-wise approach from endometrial ablation to hysterectomy, and its potential effects on the health care system at a time when endometrial cancer incidence and mortality rates are rising, is troubling.

Postablation, consider hysterectomy by the general gynecologist. Current trends appear to disincentivize general gynecologists from performing hysterectomy either for HMB or LOEAF. We would offer reassurance that they can safely perform this procedure. Referral to oncology may not be necessary since, in the absence of an established diagnosis of cancer, a lymphadenectomy is not typically required. A shift away from referral for these patients can preserve access to oncology for those women, especially minority women, with an explicit need for oncologic care.

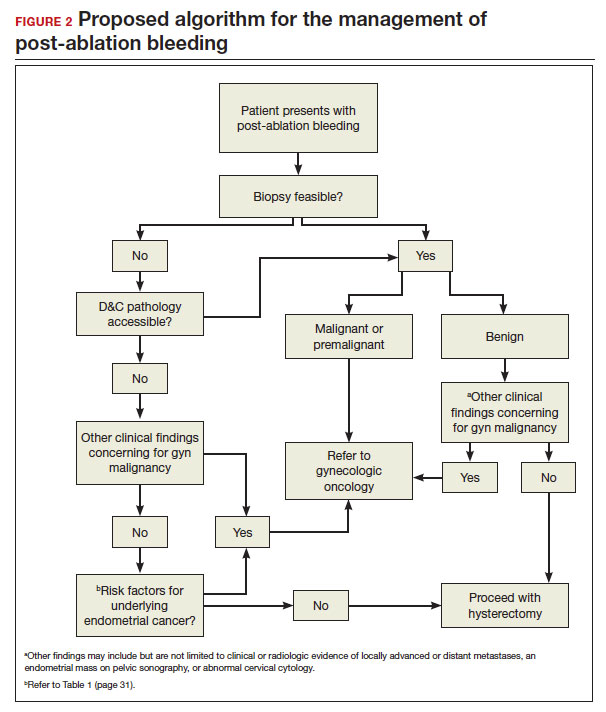

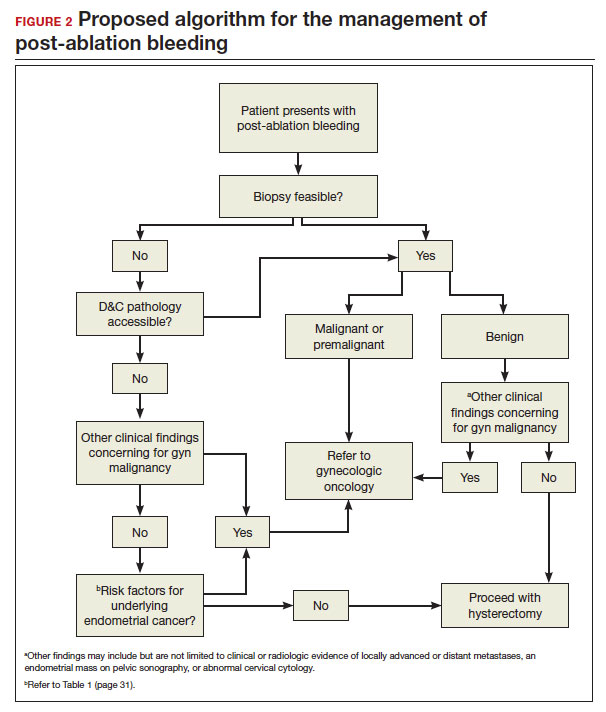

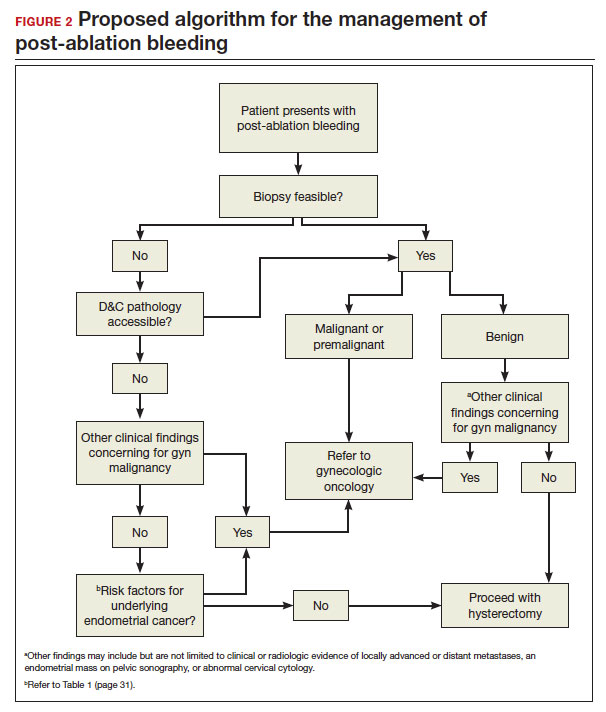

In FIGURE 2, we propose a management algorithm for the patient who presents with post–ablation bleeding. We acknowledge that the evidence base for our management recommendations is limited. Still, we hope providers, ACOG, and other guidelines-issuing organizations consider them as they adapt their own practices and recommendations. We believe this is one of many steps needed to improve outcomes for patients with gynecologic cancer, particularly those in marginalized communities disproportionately impacted by current trends.

CASE Resolution

After reviewing the relevant documentation and examining the patient, the gynecologic oncology consultant contacts the referring gynecologist. They review the low utility of frozen section and the overall low risk of cancer on the final hysterectomy specimen if the patient were to undergo hysterectomy. The consultant clarifies that there is no other concern for surgical complexity beyond the skill of the referring provider, and they discuss the possibility of referral to a minimally invasive specialist for the surgery.

Ultimately, the patient undergoes uncomplicated laparoscopic hysterectomy performed by the original referring gynecologist. Final pathology reveals inactive endometrium with ablative changes and cornual focus of endometrial hyperplasia without atypia. ●

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge Ian Hagemann, MD, PhD, for his review of the manuscript.

- Chen H, Saiz AM, McCausland AM, et al. Experience of gynecologic oncologists regarding endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:e17566-e.

- McCausland AM, McCausland VM. Long-term complications of endometrial ablation: cause, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:399-406.

- Oderkerk TJ, Beelen P, Bukkems ALA, et al. Risk of hysterectomy after endometrial ablation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;142:51-60.

- Clarke MA, Devesa SS, Hammer A, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in hysterectomy-corrected uterine corpus cancer mortality by stage and histologic subtype. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8:895-903.

- Barber EL, Rossi EC, Alexander A, et al. Benign hysterectomy performed by gynecologic oncologists: is selection bias altering our ability to measure surgical quality? Gynecol Oncol. 2018;151:141-144.

- Wortman M. Late-onset endometrial ablation failure. Case Rep Womens Health. 2017;15:11-28.

- Insights FM. Endometrial Ablation Market Outlook.Accessed July 26, 2023. https://www.futuremarketinsights.com/reports/endometrial-ablation -market

- Famuyide A. Endometrial ablation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:299-307.

- Corona LE, Swenson CW, Sheetz KH, et al. Use of other treatments before hysterectomy for benign conditions in a statewide hospital collaborative. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:304.e1-e7.

- Wortman M, Cholkeri A, McCausland AM, et al. Late-onset endometrial ablation failure—etiology, treatment, and prevention. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:323-331.

- Thomassee MS, Curlin H, Yunker A, et al. Predicting pelvic pain after endometrial ablation: which preoperative patient characteristics are associated? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20:642-647.

- Townsend DE, McCausland V, McCausland A, et al. Post-ablation-tubal sterilization syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82:422-424.

- Greer Polite F, DeAgostino-Kelly M, Marchand GJ. Combination of laparoscopic salpingectomy and endometrial ablation: a potentially underused procedure. J Gynecol Surg. 2021;37:89-91.

- Hanley GE, Pearce CL, Talhouk A, et al. Outcomes from opportunistic salpingectomy for ovarian cancer prevention. JAMA Network Open. 2022;5:e2147343-e.

- Ahonkallio SJ, Liakka AK, Martikainen HK, et al. Feasibility of endometrial assessment after thermal ablation. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;147:69-71.

- Tamara JO, Mileen RDvdK, Karlijn MCC, et al. Endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation: a systematic review. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2022;32:1555.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Endometrial ablation for heavy menstrual bleeding.Accessed July 26, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices /surgery-devices/endometrial-ablation-heavy-menstrual-bleeding

- ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetriciangynecologists. Number 81, May 2007. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:1233-1248.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Abnormal uterine bleeding frequently asked questions. Accessed July 26, 2023. https://www.acog .org/womens-health/faqs/abnormal-uterine-bleeding

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Endometrial ablation frequently asked questions. Accessed November 28, 2023. https://www.acog. org/womens-health/faqs/endometrial-ablation#:~:text=Can%20I%20still%20 get%20pregnant,should%20not%20have%20this%20procedure

- Setiawan VW, Yang HP, Pike MC, et al. Type I and II endometrial cancers: have they different risk factors? J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2607-2618.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Lynch Syndrome (Version 2.2023). Accessed November 15, 2023. https://www.nccn.org/professionals /physician_gls/pdf/genetics_colon.pdf

- Bonadona V, Bonaïti B, Olschwang S, et al. Cancer risks associated with germline mutations in MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6 genes in Lynch syndrome. JAMA. 2011;305: 2304-2310.

- Fleming CA, Heneghan HM, O’Brien D, et al. Meta-analysis of the cumulative risk of endometrial malignancy and systematic review of endometrial surveillance in extended tamoxifen therapy. Br J Surg. 2018;105:1098-1106.

- Barry JA, Azizia MM, Hardiman PJ. Risk of endometrial, ovarian and breast cancer in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20:748-758.

- Cadish LA, Kropat G, Muffly TM. Hysterectomy volume among recent obstetrics and gynecology residency graduates. Urogynecology. 2021;27.

- Blank SV, Huh WK, Bell M, et al. Doubling down on the future of gynecologic oncology: the SGO future of the profession summit report. Gynecol Oncol. 2023;171:76-82.

- Reports MI. Global endometrial ablation market growth, trends and forecast 2023 to 2028 by types, by application, by regions and by key players like Boston Scientific, Hologic, Olympus, Minerva Surgical. Accessed July 30, 2023. https://www.marketinsightsreports.com/single-report/061612632440/global -endometrial-ablation-market-growth-trends-and-forecast-2023-to-2028-by -types-by-application-by-regions-and-by-key-players-like-boston-scientific -hologic-olympus-minerva-surgical

- London R, Holzman M, Rubin D, et al. Payer cost savings with endometrial ablation therapy. Am J Manag Care. 1999;5:889-897.

- Mariani A, Dowdy SC, Cliby WA, et al. Prospective assessment of lymphatic dissemination in endometrial cancer: a paradigm shift in surgical staging. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109:11-18.

- Beelen P, van den Brink MJ, Herman MC, et al. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system versus endometrial ablation for heavy menstrual bleeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:187.e1-e10.

- Bofill Rodriguez M, Lethaby A, Fergusson RJ. Endometrial resection and ablation versus hysterectomy for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;2:Cd000329.

CASE New patient presents with a history of endometrial hyperplasia

A 51-year-old patient (G2P2002) presents to a new gynecologist’s office after moving from a different state. In her medical history, the gynecologist notes that 5 years ago she underwent dilation and curettage and endometrial ablation procedures for heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB). Ultrasonography performed prior to those procedures showed a slightly enlarged uterus, a simple left ovarian cyst, and a non ̶ visualized right ovary. The patient had declined a 2-step procedure due to concerns with anesthesia, and surgical pathology at the time of ablation revealed hyperplasia without atypia. The patient’s medical history was otherwise notable for prediabetes (recent hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c] measurement, 6.0%) and obesity (body mass index, 43 kg/m2). Pertinent family history included her mother’s diagnosis of endometrial cancer at age 36. Given the patient’s diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia, she was referred to gynecologic oncology, but she ultimately declined hysterectomy, stating that she was happy with the resolution of her abnormal bleeding. At the time of her initial gynecologic oncology consultation, the consultant suggested lifestyle changes to combat prediabetes and obesity to reduce the risk of endometrial cancer, as future signs of cancer, namely bleeding, may be masked by the endometrial ablation. The patient was prescribed metformin given these medical comorbidities.

At today’s appointment, the patient notes continued resolution of bleeding since the procedure. She does, however, note a 6-month history of vasomotor symptoms and one episode of spotting 3 months ago. Three years ago she was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus, and her current HbA1c is 6.9%. She has gained 10 lb since being diagnosed with endometrial cancer 5 years ago, and she has continued to take metformin.

An in-office endometrial biopsy is unsuccessful due to cervical stenosis. The treating gynecologist orders a transvaginal ultrasound, which reveals a small left ovarian cyst and a thickened endometrium (measuring 10 mm). Concerned that these findings could represent endometrial cancer, the gynecologist refers the patient to gynecologic oncology for further evaluation.

Sequelae and complications following endometrial ablation are often managed by a gynecologic oncologist. Indeed, a 2018 poll of Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) members revealed that 93.8% of respondents had received such a referral, and almost 20% of respondents were managing more than 20 patients with post-ablation complications in their practices.1 These complications, including hematometra, post-ablation tubal sterilization syndrome, other pain syndromes associated with retrograde menstruation, and thickened endometrium with scarring leading to an inability to sample the endometrium to investigate post-ablation bleeding are symptoms and findings that often lead to further surgery, including hysterectomy.2 General gynecologists faced with these complications may refer patients to gynecologic oncology given an inability to sample the post-ablation endometrium or anticipated difficulties with hysterectomy. A recent meta-analysis revealed a 12.4% hysterectomy rate 5 years after endometrial ablation. Among these patients, the incidence of endometrial cancer ranged from 0% to 1.6%.3

In 2023, endometrial cancer incidence continues to increase, as does the incidence of obesity in women of all ages. Endometrial cancer mortality rates are also increasing, and these trends disproportionately affects non-Hispanic Black women.4 As providers and advocates work to narrow these disparities, gynecologic oncologists are simultaneously noting increased referrals for very likely benign conditions.5 Patients referred for post-ablation bleeding are a subset of these, as most patients who undergo endometrial ablation will not develop cancer. Considering the potential bottlenecks created en route to a gynecologic oncology evaluation, it seems prudent to minimize practices, like endometrial ablation, that may directly or indirectly prevent timely referral of patients with cancer to a gynecologic oncologist.

In this review we focus on the current use of endometrial ablation, associated complications, the incidence of treatment failure, and patient selection. Considering these issues in the context of the current endometrial cancer landscape, we posit best practices aimed at optimizing patient outcomes, and empowering general gynecologists to practice cancer prevention and to triage their surgical patients.

- Before performing endometrial ablation, consider whether alternatives such as hysterectomy or insertion of a progestin-containing IUD would be appropriate.

- Clinical management of patients with abnormal bleeding with indications for endometrial ablation should be guidelinedriven.

- Post-ablation bleeding or pain does not inherently require referral to oncology.

- General gynecologists can perform hysterectomy in this setting if appropriate.

- Patients with endometrial hyperplasia at endometrial ablation should be promptly offered hysterectomy. If atypia is not present, this hysterectomy, too, can be performed by a general gynecologist if appropriate, as the chance for malignancy is minimal.

Continue to: Current use of endometrial ablation in the US...

Current use of endometrial ablation in the US

In 2015, more than 500,000 endometrial ablations were performed in the United States.Given the ability to perform in-office ablation, this number is growing and potentially underestimated each year.6 In 2022, the global endometrial ablation market was valued at $3.4 billion, a figure projected to double in 10 years.7 The procedure has evolved as different devices and approaches have developed, offering patients different means to manage bleeding without hysterectomy. The minimally invasive procedure, performed in premenopausal patients with heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) due to benign causes who have completed childbearing, has been associated with faster recovery times and fewer short-term complications compared with more invasive surgery.8 There are several non-resectoscope ablative devices approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and each work to destroy the endometrial lining via thermal or cryoablation. Endometrial ablation can be performed in premenopausal patients with HMB due to benign causes who have completed childbearing.

Recently, promotional literature has begun to report on so-called overuse of hysterectomy, despite decreasing overall hysterectomy rates. This reporting proposes and applies “appropriateness criteria,” accounting for the rate of preoperative counseling regarding alternatives to hysterectomy, as well as the rate of “unsupportive” final pathology.9 The adoption of endometrial ablation and increasing market value of such vendors suggest that this campaign is having its desired effect. From the oncology perspective, we are concerned the pendulum could swing too far away from hysterectomy, a procedure that definitively cures abnormal uterine bleeding, toward endometrial ablation without explicit acknowledgement of the trade-offs involved.

Endometrial ablation complications: Late-onset procedure failure

A number of post-ablation syndromes may present at least 1 month following the procedure. Collectively known as late-onset endometrial ablation failure (LOEAF), these syndromes are characterized by recurrent vaginal bleeding, and/or new cyclic pelvic pain.10 It is difficult to measure the true incidence of LOEAF. Thomassee and colleagues examined a Canadian retrospective cohort of 437 patients who underwent endometrial ablation; 20.8% reported post-ablation pelvic pain after a median 301 days.11 The subsequent need for surgical intervention, often hysterectomy, is a surrogate for LOEAF.

It should be noted that LOEAF is distinct from post-ablation tubal sterilization syndrome (PATSS), which describes cornual menstrual bleeding impeded by the ligated proximal fallopian tube.12 Increased awareness of PATSS, along with the discontinuation of Essure (a permanent hysteroscopic sterilization device) in 2018, has led some surgeons to advocate for concomitant salpingectomy at the time of endometrial ablation.13 The role of opportunistic salpingectomy in primary prevention of epithelial ovarian cancer is well described, and while we strongly support this practice at the time of endometrial ablation, we do not feel that it effectively prevents LOEAF.14

The post-ablation inability to adequately sample the endometrium is also considered a LOEAF. A prospective study of 57 women who underwent endometrial ablation assessed post-ablation sampling feasibility via transvaginal ultrasonography, saline infusion sonohysterography (SIS), and in-office endometrial biopsies. In 23% of the cohort, endometrial sampling failed, and the authors noted decreased reliability of pathologic assessment.15 One systematic review, in which authors examined the incidence of endometrial cancer following endometrial ablation, characterized 38 cases of endometrial cancer and reported a post-ablation endometrial sampling success rate of 89%. This figure was based on a self-selected sample of 18 patients; cases in which endometrial sampling was thought to be impossible were excluded. The study also had a 30% missing data rate and several other biases.16

In the previously mentioned poll of SGO members,1 84% of the surveyed gynecologic oncologists managing post-ablation patients reported that endometrial sampling following endometrial ablation was “moderately” or “extremely” difficult. More than half of the survey respondents believed that hysterectomy was required for accurate diagnosis.1 While we acknowledge the likely sampling bias affecting the survey results, we are not comforted by any data that minimizes this diagnostic challenge.

Appropriate patient selection and contraindications

The ideal candidate for endometrial ablation is a premenopausal patient with HMB who does not desire future fertility. According to the FDA, absolute contraindications include pregnancy or desired fertility, prior ablation, current IUD in place, inadequate preoperative endometrial assessment, known or suspected malignancy, active infection, or unfavorable anatomy.17

What about patients who may be at increased risk for endometrial cancer?

There is a paucity of data regarding the safety of endometrial ablation in patients at increased risk for developing endometrial cancer in the future. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) 2007 practice bulletin on endometrial ablation (no longer accessible online) alludes to this concern and other contraindications,18 but there are no established guidelines. Currently, no ACOG practice bulletin or committee opinion lists relative contraindications to endometrial ablation, long-term complications (except risks associated with future pregnancy), or risk of subsequent hysterectomy. The risk that “it may be harder to detect endometrial cancer after ablation” is noted on ACOG’s web page dedicated to frequently asked questions (FAQs) regarding abnormal uterine bleeding.19 It is not mentioned on their web page dedicated to the FAQs regarding endometrial ablation.20

In the absence of high-quality published data on established contraindications for endometrial ablation, we advocate for the increased awareness of possible relative contraindications—namely well-established risk factors for endometrial cancer (TABLE 1).For example, in a pooled analysis of 24 epidemiologic studies, authors found that the odds of developing endometrial cancer was 7 times higher among patients with a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 40 kg/m2, compared with controls (odds ratio [OR], 7.14; 95% confidence interval [CI], 6.33–8.06).21 Additionally, patients with Lynch syndrome, a history of extended tamoxifen use, or those with a history of chronic anovulation or polycystic ovary syndrome are at increased risk for endometrial cancer.22-24 If the presence of one or more of these factors does not dissuade general gynecologists from performing an endometrial ablation (even armed with a negative preoperative endometrial biopsy), we feel they should at least prompt thoughtful guideline-driven pause.

Continue to: Hysterectomy—A disincentivized option...

Hysterectomy—A disincentivized option

The annual number of hysterectomies performed by general gynecologists has declined over time. One study by Cadish and colleagues revealed that recent residency graduates performed only 3 to 4 annually.25 These numbers partly reflect the decreasing number of hysterectomies performed during residency training. Furthermore, other factors—including the increasing rate of placenta accreta spectrum, the focus on risk stratification of adnexal masses via the ovarian-adnexal reporting and data classification system (O-RADs), and the emphasis on minimally invasive approaches often acquired in subspecialty training—have likely contributed to referral patterns to such specialists as minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons and gynecologic oncologists.26 This trend is self-actualizing, as quality metrics funnel patients to high-volume surgeons, and general gynecologists risk losing hysterectomy privileges.

These factors lend themselves to a growing emphasis on endometrial ablation. Endometrial ablations can be performed in several settings, including in the hospital, in outpatient clinics, and more and more commonly, in ambulatory surgery centers. This increased access to endometrial ablation in the ambulatory surgery setting has corresponded with an annual endometrial ablation market value growth rate of 5% to 7%.27 These rates are likely compounded by payer reimbursement policies that promote endometrial ablation and other alternatives to hysterectomy that are cost savings in the short term.28 While the actual payer models are unavailable to review, they may not consider the costs of LOEAFs, including subsequent hysterectomy up to 5 years after initial ablation procedures. Provocatively, they almost certainly do not consider the costs of delayed care of patients with endometrial cancer vying for gynecologic oncology appointment slots occupied by post-ablation patients.

We urge providers, patients, and advocates to question who benefits from the uptake of ablation procedures: Patients? Payors? Providers? And how will the field of gynecology fare if hysterectomy skills and privileges are supplanted by ablation?

Post-ablation bleeding: Management by the gyn oncologist

Patients with post-ablation bleeding, either immediately or years later, are sometimes referred to a gynecologic oncologist given the possible risk for cancer and need for surgical staging if cancer is found on the hysterectomy specimen. In practice, assuming normal preoperative ultrasonography and no other clinical or radiologic findings suggestive of malignancy (eg, computed tomography findings concerning for metastases, abnormal cervical cytology, etc.), the presence of cancer is extremely unlikely to be determined at the time of surgery. Frozen section is not generally performed on the endometrium; intraoperative evaluation of even the unablated endometrium is notoriously unreliable; and histologic assessment of the ablated endometrium is limited by artifact (FIGURE 1). The abnormalities caused by ablation further impede selection of a representative focus, obfuscating any actionable result.

Some surgeons routinely bivalve the excised uterus prior to fixation to assess presence of tumor, tumor size, and the degree of myometrial invasion.29 A combination of factors may compel surgeons to perform lymphadenectomy if not already performed, or if sentinel lymph node mapping was unsuccessful. But this practice has not been studied in patients with post-ablation bleeding, and applying these principles relies on a preoperative diagnosis establishing the presence and grade of a cancer. Furthermore, the utility of frozen section and myometrial assessment to decide whether or not to proceed with lymphadenectomy is less relevant in the era of molecular classification guiding adjuvant therapy. In summary, assuming no pathologic or radiologic findings suggestive of cancer, gynecologic oncologists are unlikely to perform lymphadenectomy at the time of hysterectomy in these post-ablation cases, which therefore can safely be performed by general gynecologists.

Our recommendations

Consider the LNG-IUD as an alternative to ablation. A recent randomized controlled trial by Beelen and colleagues compared the effectiveness of LNG-releasing IUDs with endometrial ablation in patients with HMB. While the LNG-IUD was inferior to endometrial ablation, quality-of-life measures were similar up to 2 years.31 Realizing that the hysterectomy rate following endometrial ablation increases significantly beyond that time point (2 years), this narrative may be incomplete. A 5- to 10-year follow-up time-frame may be a more helpful gauge of long-term outcomes. This prolonged time-frame also may allow study of the LNG-IUD’s protective effects on the endometrium in the prevention of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer.

Consider hysterectomy. A 2021 Cochrane review revealed that, compared with endometrial ablation, minimally invasive hysterectomy is associated with higher quality-of-life metrics, higher self-reported patient satisfaction, and similar rates of adverse events.32 While patient autonomy is paramount, the developing step-wise approach from endometrial ablation to hysterectomy, and its potential effects on the health care system at a time when endometrial cancer incidence and mortality rates are rising, is troubling.

Postablation, consider hysterectomy by the general gynecologist. Current trends appear to disincentivize general gynecologists from performing hysterectomy either for HMB or LOEAF. We would offer reassurance that they can safely perform this procedure. Referral to oncology may not be necessary since, in the absence of an established diagnosis of cancer, a lymphadenectomy is not typically required. A shift away from referral for these patients can preserve access to oncology for those women, especially minority women, with an explicit need for oncologic care.

In FIGURE 2, we propose a management algorithm for the patient who presents with post–ablation bleeding. We acknowledge that the evidence base for our management recommendations is limited. Still, we hope providers, ACOG, and other guidelines-issuing organizations consider them as they adapt their own practices and recommendations. We believe this is one of many steps needed to improve outcomes for patients with gynecologic cancer, particularly those in marginalized communities disproportionately impacted by current trends.

CASE Resolution

After reviewing the relevant documentation and examining the patient, the gynecologic oncology consultant contacts the referring gynecologist. They review the low utility of frozen section and the overall low risk of cancer on the final hysterectomy specimen if the patient were to undergo hysterectomy. The consultant clarifies that there is no other concern for surgical complexity beyond the skill of the referring provider, and they discuss the possibility of referral to a minimally invasive specialist for the surgery.

Ultimately, the patient undergoes uncomplicated laparoscopic hysterectomy performed by the original referring gynecologist. Final pathology reveals inactive endometrium with ablative changes and cornual focus of endometrial hyperplasia without atypia. ●

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge Ian Hagemann, MD, PhD, for his review of the manuscript.

CASE New patient presents with a history of endometrial hyperplasia

A 51-year-old patient (G2P2002) presents to a new gynecologist’s office after moving from a different state. In her medical history, the gynecologist notes that 5 years ago she underwent dilation and curettage and endometrial ablation procedures for heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB). Ultrasonography performed prior to those procedures showed a slightly enlarged uterus, a simple left ovarian cyst, and a non ̶ visualized right ovary. The patient had declined a 2-step procedure due to concerns with anesthesia, and surgical pathology at the time of ablation revealed hyperplasia without atypia. The patient’s medical history was otherwise notable for prediabetes (recent hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c] measurement, 6.0%) and obesity (body mass index, 43 kg/m2). Pertinent family history included her mother’s diagnosis of endometrial cancer at age 36. Given the patient’s diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia, she was referred to gynecologic oncology, but she ultimately declined hysterectomy, stating that she was happy with the resolution of her abnormal bleeding. At the time of her initial gynecologic oncology consultation, the consultant suggested lifestyle changes to combat prediabetes and obesity to reduce the risk of endometrial cancer, as future signs of cancer, namely bleeding, may be masked by the endometrial ablation. The patient was prescribed metformin given these medical comorbidities.

At today’s appointment, the patient notes continued resolution of bleeding since the procedure. She does, however, note a 6-month history of vasomotor symptoms and one episode of spotting 3 months ago. Three years ago she was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus, and her current HbA1c is 6.9%. She has gained 10 lb since being diagnosed with endometrial cancer 5 years ago, and she has continued to take metformin.

An in-office endometrial biopsy is unsuccessful due to cervical stenosis. The treating gynecologist orders a transvaginal ultrasound, which reveals a small left ovarian cyst and a thickened endometrium (measuring 10 mm). Concerned that these findings could represent endometrial cancer, the gynecologist refers the patient to gynecologic oncology for further evaluation.

Sequelae and complications following endometrial ablation are often managed by a gynecologic oncologist. Indeed, a 2018 poll of Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) members revealed that 93.8% of respondents had received such a referral, and almost 20% of respondents were managing more than 20 patients with post-ablation complications in their practices.1 These complications, including hematometra, post-ablation tubal sterilization syndrome, other pain syndromes associated with retrograde menstruation, and thickened endometrium with scarring leading to an inability to sample the endometrium to investigate post-ablation bleeding are symptoms and findings that often lead to further surgery, including hysterectomy.2 General gynecologists faced with these complications may refer patients to gynecologic oncology given an inability to sample the post-ablation endometrium or anticipated difficulties with hysterectomy. A recent meta-analysis revealed a 12.4% hysterectomy rate 5 years after endometrial ablation. Among these patients, the incidence of endometrial cancer ranged from 0% to 1.6%.3

In 2023, endometrial cancer incidence continues to increase, as does the incidence of obesity in women of all ages. Endometrial cancer mortality rates are also increasing, and these trends disproportionately affects non-Hispanic Black women.4 As providers and advocates work to narrow these disparities, gynecologic oncologists are simultaneously noting increased referrals for very likely benign conditions.5 Patients referred for post-ablation bleeding are a subset of these, as most patients who undergo endometrial ablation will not develop cancer. Considering the potential bottlenecks created en route to a gynecologic oncology evaluation, it seems prudent to minimize practices, like endometrial ablation, that may directly or indirectly prevent timely referral of patients with cancer to a gynecologic oncologist.

In this review we focus on the current use of endometrial ablation, associated complications, the incidence of treatment failure, and patient selection. Considering these issues in the context of the current endometrial cancer landscape, we posit best practices aimed at optimizing patient outcomes, and empowering general gynecologists to practice cancer prevention and to triage their surgical patients.

- Before performing endometrial ablation, consider whether alternatives such as hysterectomy or insertion of a progestin-containing IUD would be appropriate.

- Clinical management of patients with abnormal bleeding with indications for endometrial ablation should be guidelinedriven.

- Post-ablation bleeding or pain does not inherently require referral to oncology.

- General gynecologists can perform hysterectomy in this setting if appropriate.

- Patients with endometrial hyperplasia at endometrial ablation should be promptly offered hysterectomy. If atypia is not present, this hysterectomy, too, can be performed by a general gynecologist if appropriate, as the chance for malignancy is minimal.

Continue to: Current use of endometrial ablation in the US...

Current use of endometrial ablation in the US

In 2015, more than 500,000 endometrial ablations were performed in the United States.Given the ability to perform in-office ablation, this number is growing and potentially underestimated each year.6 In 2022, the global endometrial ablation market was valued at $3.4 billion, a figure projected to double in 10 years.7 The procedure has evolved as different devices and approaches have developed, offering patients different means to manage bleeding without hysterectomy. The minimally invasive procedure, performed in premenopausal patients with heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) due to benign causes who have completed childbearing, has been associated with faster recovery times and fewer short-term complications compared with more invasive surgery.8 There are several non-resectoscope ablative devices approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and each work to destroy the endometrial lining via thermal or cryoablation. Endometrial ablation can be performed in premenopausal patients with HMB due to benign causes who have completed childbearing.

Recently, promotional literature has begun to report on so-called overuse of hysterectomy, despite decreasing overall hysterectomy rates. This reporting proposes and applies “appropriateness criteria,” accounting for the rate of preoperative counseling regarding alternatives to hysterectomy, as well as the rate of “unsupportive” final pathology.9 The adoption of endometrial ablation and increasing market value of such vendors suggest that this campaign is having its desired effect. From the oncology perspective, we are concerned the pendulum could swing too far away from hysterectomy, a procedure that definitively cures abnormal uterine bleeding, toward endometrial ablation without explicit acknowledgement of the trade-offs involved.

Endometrial ablation complications: Late-onset procedure failure

A number of post-ablation syndromes may present at least 1 month following the procedure. Collectively known as late-onset endometrial ablation failure (LOEAF), these syndromes are characterized by recurrent vaginal bleeding, and/or new cyclic pelvic pain.10 It is difficult to measure the true incidence of LOEAF. Thomassee and colleagues examined a Canadian retrospective cohort of 437 patients who underwent endometrial ablation; 20.8% reported post-ablation pelvic pain after a median 301 days.11 The subsequent need for surgical intervention, often hysterectomy, is a surrogate for LOEAF.

It should be noted that LOEAF is distinct from post-ablation tubal sterilization syndrome (PATSS), which describes cornual menstrual bleeding impeded by the ligated proximal fallopian tube.12 Increased awareness of PATSS, along with the discontinuation of Essure (a permanent hysteroscopic sterilization device) in 2018, has led some surgeons to advocate for concomitant salpingectomy at the time of endometrial ablation.13 The role of opportunistic salpingectomy in primary prevention of epithelial ovarian cancer is well described, and while we strongly support this practice at the time of endometrial ablation, we do not feel that it effectively prevents LOEAF.14

The post-ablation inability to adequately sample the endometrium is also considered a LOEAF. A prospective study of 57 women who underwent endometrial ablation assessed post-ablation sampling feasibility via transvaginal ultrasonography, saline infusion sonohysterography (SIS), and in-office endometrial biopsies. In 23% of the cohort, endometrial sampling failed, and the authors noted decreased reliability of pathologic assessment.15 One systematic review, in which authors examined the incidence of endometrial cancer following endometrial ablation, characterized 38 cases of endometrial cancer and reported a post-ablation endometrial sampling success rate of 89%. This figure was based on a self-selected sample of 18 patients; cases in which endometrial sampling was thought to be impossible were excluded. The study also had a 30% missing data rate and several other biases.16

In the previously mentioned poll of SGO members,1 84% of the surveyed gynecologic oncologists managing post-ablation patients reported that endometrial sampling following endometrial ablation was “moderately” or “extremely” difficult. More than half of the survey respondents believed that hysterectomy was required for accurate diagnosis.1 While we acknowledge the likely sampling bias affecting the survey results, we are not comforted by any data that minimizes this diagnostic challenge.

Appropriate patient selection and contraindications

The ideal candidate for endometrial ablation is a premenopausal patient with HMB who does not desire future fertility. According to the FDA, absolute contraindications include pregnancy or desired fertility, prior ablation, current IUD in place, inadequate preoperative endometrial assessment, known or suspected malignancy, active infection, or unfavorable anatomy.17

What about patients who may be at increased risk for endometrial cancer?

There is a paucity of data regarding the safety of endometrial ablation in patients at increased risk for developing endometrial cancer in the future. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) 2007 practice bulletin on endometrial ablation (no longer accessible online) alludes to this concern and other contraindications,18 but there are no established guidelines. Currently, no ACOG practice bulletin or committee opinion lists relative contraindications to endometrial ablation, long-term complications (except risks associated with future pregnancy), or risk of subsequent hysterectomy. The risk that “it may be harder to detect endometrial cancer after ablation” is noted on ACOG’s web page dedicated to frequently asked questions (FAQs) regarding abnormal uterine bleeding.19 It is not mentioned on their web page dedicated to the FAQs regarding endometrial ablation.20

In the absence of high-quality published data on established contraindications for endometrial ablation, we advocate for the increased awareness of possible relative contraindications—namely well-established risk factors for endometrial cancer (TABLE 1).For example, in a pooled analysis of 24 epidemiologic studies, authors found that the odds of developing endometrial cancer was 7 times higher among patients with a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 40 kg/m2, compared with controls (odds ratio [OR], 7.14; 95% confidence interval [CI], 6.33–8.06).21 Additionally, patients with Lynch syndrome, a history of extended tamoxifen use, or those with a history of chronic anovulation or polycystic ovary syndrome are at increased risk for endometrial cancer.22-24 If the presence of one or more of these factors does not dissuade general gynecologists from performing an endometrial ablation (even armed with a negative preoperative endometrial biopsy), we feel they should at least prompt thoughtful guideline-driven pause.

Continue to: Hysterectomy—A disincentivized option...

Hysterectomy—A disincentivized option

The annual number of hysterectomies performed by general gynecologists has declined over time. One study by Cadish and colleagues revealed that recent residency graduates performed only 3 to 4 annually.25 These numbers partly reflect the decreasing number of hysterectomies performed during residency training. Furthermore, other factors—including the increasing rate of placenta accreta spectrum, the focus on risk stratification of adnexal masses via the ovarian-adnexal reporting and data classification system (O-RADs), and the emphasis on minimally invasive approaches often acquired in subspecialty training—have likely contributed to referral patterns to such specialists as minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons and gynecologic oncologists.26 This trend is self-actualizing, as quality metrics funnel patients to high-volume surgeons, and general gynecologists risk losing hysterectomy privileges.

These factors lend themselves to a growing emphasis on endometrial ablation. Endometrial ablations can be performed in several settings, including in the hospital, in outpatient clinics, and more and more commonly, in ambulatory surgery centers. This increased access to endometrial ablation in the ambulatory surgery setting has corresponded with an annual endometrial ablation market value growth rate of 5% to 7%.27 These rates are likely compounded by payer reimbursement policies that promote endometrial ablation and other alternatives to hysterectomy that are cost savings in the short term.28 While the actual payer models are unavailable to review, they may not consider the costs of LOEAFs, including subsequent hysterectomy up to 5 years after initial ablation procedures. Provocatively, they almost certainly do not consider the costs of delayed care of patients with endometrial cancer vying for gynecologic oncology appointment slots occupied by post-ablation patients.

We urge providers, patients, and advocates to question who benefits from the uptake of ablation procedures: Patients? Payors? Providers? And how will the field of gynecology fare if hysterectomy skills and privileges are supplanted by ablation?

Post-ablation bleeding: Management by the gyn oncologist

Patients with post-ablation bleeding, either immediately or years later, are sometimes referred to a gynecologic oncologist given the possible risk for cancer and need for surgical staging if cancer is found on the hysterectomy specimen. In practice, assuming normal preoperative ultrasonography and no other clinical or radiologic findings suggestive of malignancy (eg, computed tomography findings concerning for metastases, abnormal cervical cytology, etc.), the presence of cancer is extremely unlikely to be determined at the time of surgery. Frozen section is not generally performed on the endometrium; intraoperative evaluation of even the unablated endometrium is notoriously unreliable; and histologic assessment of the ablated endometrium is limited by artifact (FIGURE 1). The abnormalities caused by ablation further impede selection of a representative focus, obfuscating any actionable result.

Some surgeons routinely bivalve the excised uterus prior to fixation to assess presence of tumor, tumor size, and the degree of myometrial invasion.29 A combination of factors may compel surgeons to perform lymphadenectomy if not already performed, or if sentinel lymph node mapping was unsuccessful. But this practice has not been studied in patients with post-ablation bleeding, and applying these principles relies on a preoperative diagnosis establishing the presence and grade of a cancer. Furthermore, the utility of frozen section and myometrial assessment to decide whether or not to proceed with lymphadenectomy is less relevant in the era of molecular classification guiding adjuvant therapy. In summary, assuming no pathologic or radiologic findings suggestive of cancer, gynecologic oncologists are unlikely to perform lymphadenectomy at the time of hysterectomy in these post-ablation cases, which therefore can safely be performed by general gynecologists.

Our recommendations