User login

Osteoporosis drugs may extend life after fracture

Long-term osteoporosis medications are associated with a reduced mortality risk following a fracture, new data suggest.

The findings, from nearly 50,000 individuals in a nationwide Taiwanese database from 2009 until 2018, suggest that alendronate/risedronate, denosumab, and zoledronic acid all result in a significantly lower mortality risk post fracture of 17%-22%, compared with raloxifene and bazedoxifene.

“Treatment for osteoporosis has the potential to minimize mortality risk in people of all ages and sexes for any type of fracture. The longer-acting treatments could lower mortality risk,” wrote Chih-Hsing Wu, MD, of the Institute of Gerontology at National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan, and colleagues.

The findings have been published online in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

Robert A. Adler, MD, who is chief of endocrinology at the Central Virginia Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Richmond, told this news organization that he hopes these new findings from a “really good database ... may be helpful in talking to a patient about the pros and cons of taking these drugs.”

“Patients have been made very fearful of the unusual side effects, particularly of the antiresorptive drugs,” which he notes include the rare adverse effects of jaw necrosis and atypical femoral fracture, which occur in about 1 per 10,000 patient-years.

“And because of that we have a hard time convincing people to want to take the drug in the first place or to stay on the drug once they start,” said Dr. Adler, who stressed that his viewpoints are his own and not representative of the VA.

“These data should help reinforce the advice already given in professional guidelines that their benefit outweighs any risks,” he stresses.

Dr. Adler also pointed out that both bisphosphonates included in the study, alendronate and zoledronic acid, are now available as generics and therefore inexpensive, but the latter can be subject to facility fees depending on where the infusion is delivered.

He added that hip fracture, in particular, triples the overall 1-year mortality risk in women aged 75-84 years and quadruples the risk in men. The study’s findings suggest that bisphosphonates, in particular, have pleiotropic effects beyond the bone; however, the underlying mechanisms are hard to determine.

“We don’t know all the reasons why people die after a fracture. These are older people who often have multiple medical problems, so it’s hard to dissect that out,” he said.

But whatever the mechanism for the salutary effect of the drugs, Dr. Adler said: “This is one other factor that might change people’s minds. You’re less likely to die. Well, that’s pretty good.”

‘Denosumab is a more potent antiresorptive than bisphosphonates’

Dr. Wu and colleagues analyzed data for individuals from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database. Between 2009 and 2017, 219,461 individuals had been newly diagnosed with an osteoporotic fracture. Of those, 46,729 were aged 40 and older and had been prescribed at least one anti-osteoporosis medication.

Participants were a mean age of 74.5 years, were 80% women, and 32% died during a mean follow-up of 4.7 years. The most commonly used anti-osteoporosis medications were the bisphosphonates alendronate or risedronate, followed by denosumab and the selective estrogen-receptor modulators (SERMs) daily oral raloxifene or bazedoxifene.

Patients treated with SERMs were used as the reference group because those drugs have been shown to have a neutral effect on mortality.

After adjustments, all but one of the medications had significantly lower mortality risks during follow-up, compared with raloxifene and bazedoxifene.

Compared with SERMs, at all fracture sites, the hazard ratios for mortality were 0.83 for alendronate/risedronate, 0.86 for denosumab, and 0.78 for zoledronic acid. Only ibandronate did not show the same protective effect.

Similar results were found for hip and vertebral fractures analyzed individually.

Women had a lower mortality risk than men.

Dr. Adler wrote an accompanying editorial for the article by Dr. Wu and colleagues.

Regarding the finding of benefit for denosumab, Dr. Adler notes: “I don’t know of another study that found denosumab leads to lower mortality. On the other hand, denosumab is a more potent antiresorptive than bisphosphonates.”

The study was funded by research grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, partially supported by a research grant from the Taiwanese Osteoporosis Association and grants from National Cheng Kung University Hospital, Taiwan. Dr. Wu has reported receiving honoraria for lectures, attending meetings, and/or travel from Eli Lilly, Roche, Amgen, Merck, Servier, GE Lunar, Harvester, TCM Biotech, and Alvogen/Lotus. Dr. Adler has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Long-term osteoporosis medications are associated with a reduced mortality risk following a fracture, new data suggest.

The findings, from nearly 50,000 individuals in a nationwide Taiwanese database from 2009 until 2018, suggest that alendronate/risedronate, denosumab, and zoledronic acid all result in a significantly lower mortality risk post fracture of 17%-22%, compared with raloxifene and bazedoxifene.

“Treatment for osteoporosis has the potential to minimize mortality risk in people of all ages and sexes for any type of fracture. The longer-acting treatments could lower mortality risk,” wrote Chih-Hsing Wu, MD, of the Institute of Gerontology at National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan, and colleagues.

The findings have been published online in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

Robert A. Adler, MD, who is chief of endocrinology at the Central Virginia Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Richmond, told this news organization that he hopes these new findings from a “really good database ... may be helpful in talking to a patient about the pros and cons of taking these drugs.”

“Patients have been made very fearful of the unusual side effects, particularly of the antiresorptive drugs,” which he notes include the rare adverse effects of jaw necrosis and atypical femoral fracture, which occur in about 1 per 10,000 patient-years.

“And because of that we have a hard time convincing people to want to take the drug in the first place or to stay on the drug once they start,” said Dr. Adler, who stressed that his viewpoints are his own and not representative of the VA.

“These data should help reinforce the advice already given in professional guidelines that their benefit outweighs any risks,” he stresses.

Dr. Adler also pointed out that both bisphosphonates included in the study, alendronate and zoledronic acid, are now available as generics and therefore inexpensive, but the latter can be subject to facility fees depending on where the infusion is delivered.

He added that hip fracture, in particular, triples the overall 1-year mortality risk in women aged 75-84 years and quadruples the risk in men. The study’s findings suggest that bisphosphonates, in particular, have pleiotropic effects beyond the bone; however, the underlying mechanisms are hard to determine.

“We don’t know all the reasons why people die after a fracture. These are older people who often have multiple medical problems, so it’s hard to dissect that out,” he said.

But whatever the mechanism for the salutary effect of the drugs, Dr. Adler said: “This is one other factor that might change people’s minds. You’re less likely to die. Well, that’s pretty good.”

‘Denosumab is a more potent antiresorptive than bisphosphonates’

Dr. Wu and colleagues analyzed data for individuals from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database. Between 2009 and 2017, 219,461 individuals had been newly diagnosed with an osteoporotic fracture. Of those, 46,729 were aged 40 and older and had been prescribed at least one anti-osteoporosis medication.

Participants were a mean age of 74.5 years, were 80% women, and 32% died during a mean follow-up of 4.7 years. The most commonly used anti-osteoporosis medications were the bisphosphonates alendronate or risedronate, followed by denosumab and the selective estrogen-receptor modulators (SERMs) daily oral raloxifene or bazedoxifene.

Patients treated with SERMs were used as the reference group because those drugs have been shown to have a neutral effect on mortality.

After adjustments, all but one of the medications had significantly lower mortality risks during follow-up, compared with raloxifene and bazedoxifene.

Compared with SERMs, at all fracture sites, the hazard ratios for mortality were 0.83 for alendronate/risedronate, 0.86 for denosumab, and 0.78 for zoledronic acid. Only ibandronate did not show the same protective effect.

Similar results were found for hip and vertebral fractures analyzed individually.

Women had a lower mortality risk than men.

Dr. Adler wrote an accompanying editorial for the article by Dr. Wu and colleagues.

Regarding the finding of benefit for denosumab, Dr. Adler notes: “I don’t know of another study that found denosumab leads to lower mortality. On the other hand, denosumab is a more potent antiresorptive than bisphosphonates.”

The study was funded by research grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, partially supported by a research grant from the Taiwanese Osteoporosis Association and grants from National Cheng Kung University Hospital, Taiwan. Dr. Wu has reported receiving honoraria for lectures, attending meetings, and/or travel from Eli Lilly, Roche, Amgen, Merck, Servier, GE Lunar, Harvester, TCM Biotech, and Alvogen/Lotus. Dr. Adler has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Long-term osteoporosis medications are associated with a reduced mortality risk following a fracture, new data suggest.

The findings, from nearly 50,000 individuals in a nationwide Taiwanese database from 2009 until 2018, suggest that alendronate/risedronate, denosumab, and zoledronic acid all result in a significantly lower mortality risk post fracture of 17%-22%, compared with raloxifene and bazedoxifene.

“Treatment for osteoporosis has the potential to minimize mortality risk in people of all ages and sexes for any type of fracture. The longer-acting treatments could lower mortality risk,” wrote Chih-Hsing Wu, MD, of the Institute of Gerontology at National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan, and colleagues.

The findings have been published online in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

Robert A. Adler, MD, who is chief of endocrinology at the Central Virginia Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Richmond, told this news organization that he hopes these new findings from a “really good database ... may be helpful in talking to a patient about the pros and cons of taking these drugs.”

“Patients have been made very fearful of the unusual side effects, particularly of the antiresorptive drugs,” which he notes include the rare adverse effects of jaw necrosis and atypical femoral fracture, which occur in about 1 per 10,000 patient-years.

“And because of that we have a hard time convincing people to want to take the drug in the first place or to stay on the drug once they start,” said Dr. Adler, who stressed that his viewpoints are his own and not representative of the VA.

“These data should help reinforce the advice already given in professional guidelines that their benefit outweighs any risks,” he stresses.

Dr. Adler also pointed out that both bisphosphonates included in the study, alendronate and zoledronic acid, are now available as generics and therefore inexpensive, but the latter can be subject to facility fees depending on where the infusion is delivered.

He added that hip fracture, in particular, triples the overall 1-year mortality risk in women aged 75-84 years and quadruples the risk in men. The study’s findings suggest that bisphosphonates, in particular, have pleiotropic effects beyond the bone; however, the underlying mechanisms are hard to determine.

“We don’t know all the reasons why people die after a fracture. These are older people who often have multiple medical problems, so it’s hard to dissect that out,” he said.

But whatever the mechanism for the salutary effect of the drugs, Dr. Adler said: “This is one other factor that might change people’s minds. You’re less likely to die. Well, that’s pretty good.”

‘Denosumab is a more potent antiresorptive than bisphosphonates’

Dr. Wu and colleagues analyzed data for individuals from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database. Between 2009 and 2017, 219,461 individuals had been newly diagnosed with an osteoporotic fracture. Of those, 46,729 were aged 40 and older and had been prescribed at least one anti-osteoporosis medication.

Participants were a mean age of 74.5 years, were 80% women, and 32% died during a mean follow-up of 4.7 years. The most commonly used anti-osteoporosis medications were the bisphosphonates alendronate or risedronate, followed by denosumab and the selective estrogen-receptor modulators (SERMs) daily oral raloxifene or bazedoxifene.

Patients treated with SERMs were used as the reference group because those drugs have been shown to have a neutral effect on mortality.

After adjustments, all but one of the medications had significantly lower mortality risks during follow-up, compared with raloxifene and bazedoxifene.

Compared with SERMs, at all fracture sites, the hazard ratios for mortality were 0.83 for alendronate/risedronate, 0.86 for denosumab, and 0.78 for zoledronic acid. Only ibandronate did not show the same protective effect.

Similar results were found for hip and vertebral fractures analyzed individually.

Women had a lower mortality risk than men.

Dr. Adler wrote an accompanying editorial for the article by Dr. Wu and colleagues.

Regarding the finding of benefit for denosumab, Dr. Adler notes: “I don’t know of another study that found denosumab leads to lower mortality. On the other hand, denosumab is a more potent antiresorptive than bisphosphonates.”

The study was funded by research grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, partially supported by a research grant from the Taiwanese Osteoporosis Association and grants from National Cheng Kung University Hospital, Taiwan. Dr. Wu has reported receiving honoraria for lectures, attending meetings, and/or travel from Eli Lilly, Roche, Amgen, Merck, Servier, GE Lunar, Harvester, TCM Biotech, and Alvogen/Lotus. Dr. Adler has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Meet the JCOM Author with Dr. Barkoudah: Residence Characteristics and Nursing Home Compare Quality Measures

Relationships Between Residence Characteristics and Nursing Home Compare Database Quality Measures

From the University of Nebraska, Lincoln (Mr. Puckett and Dr. Ryherd), University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha (Dr. Manley), and the University of Nebraska, Omaha (Dr. Ryan).

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study evaluated relationships between physical characteristics of nursing home residences and quality-of-care measures.

Design: This was a cross-sectional ecologic study. The dependent variables were 5 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Nursing Home Compare database long-stay quality measures (QMs) during 2019: percentage of residents who displayed depressive symptoms, percentage of residents who were physically restrained, percentage of residents who experienced 1 or more falls resulting in injury, percentage of residents who received antipsychotic medication, and percentage of residents who received anti-anxiety medication. The independent variables were 4 residence characteristics: ownership type, size, occupancy, and region within the United States. We explored how different types of each residence characteristic compare for each QM.

Setting, participants, and measurements: Quality measure values from 15,420 CMS-supported nursing homes across the United States averaged over the 4 quarters of 2019 reporting were used. Welch’s analysis of variance was performed to examine whether the mean QM values for groups within each residential characteristic were statistically different.

Results: Publicly owned and low-occupancy residences had the highest mean QM values, indicating the poorest performance. Nonprofit and high-occupancy residences generally had the lowest (ie, best) mean QM values. There were significant differences in mean QM values among nursing home sizes and regions.

Conclusion: This study suggests that residence characteristics are related to 5 nursing home QMs. Results suggest that physical characteristics may be related to overall quality of life in nursing homes.

Keywords: quality of care, quality measures, residence characteristics, Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

More than 55 million people worldwide are living with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD).1 With the aging of the Baby Boomer population, this number is expected to rise to more than 78 million worldwide by 2030.1 Given the growing number of cognitively impaired older adults, there is an increased need for residences designed for the specialized care of this population. Although there are dozens of living options for the elderly, and although most specialized establishments have the resources to meet the immediate needs of their residents, many facilities lack universal design features that support a high quality of life for someone with ADRD or mild cognitive impairment. Previous research has shown relationships between behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) and environmental characteristics such as acoustics, lighting, and indoor air temperature.2,3 Physical behaviors of BPSD, including aggression and wandering, and psychological symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, and delusions, put residents at risk of injury.4 Additionally, BPSD is correlated with caregiver burden and stress.5-8 Patients with dementia may also experience a lower stress threshold, changes in perception of space, and decreased short-term memory, creating environmental difficulties for those with ADRD9 that lead them to exhibit BPSD due to poor environmental design. Thus, there is a need to learn more about design features that minimize BPSD and promote a high quality of life for those with ADRD.10

Although research has shown relationships between physical environmental characteristics and BPSD, in this work we study relationships between possible BPSD indicators and 4 residence-level characteristics: ownership type, size, occupancy, and region in the United States (determined by location of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS] regional offices). We analyzed data from the CMS Nursing Home Compare database for the year 2019.11 This database publishes quarterly data and star ratings for quality-of-care measures (QMs), staffing levels, and health inspections for every nursing home supported by CMS. Previous research has investigated the accuracy of QM reporting for resident falls, the impact of residential characteristics on administration of antipsychotic medication, the influence of profit status on resident outcomes and quality of care, and the effect of nursing home size on quality of life.12-16 Additionally, research suggests that residential characteristics such as size and location could be associated with infection control in nursing homes.17

Certain QMs, such as psychotropic drug administration, resident falls, and physical restraint, provide indicators of agitation, disorientation, or aggression, which are often signals of BPSD episodes. We hypothesized that residence types are associated with different QM scores, which could indicate different occurrences of BPSD. We selected 5 QMs for long-stay residents that could potentially be used as indicators of BPSD. Short-stay resident data were not included in this work to control for BPSD that could be a result of sheer unfamiliarity with the environment and confusion from being in a new home.

Methods

Design and Data Collection

This was a cross-sectional ecologic study aimed at exploring relationships between aggregate residential characteristics and QMs. Data were retrieved from the 2019 annual archives found in the CMS provider data catalog on nursing homes, including rehabilitation services.11 The dataset provides general residence information, such as ownership, number of beds, number of residents, and location, as well as residence quality metrics, such as QMs, staffing data, and inspection data. Residence characteristics and 4-quarter averages of QMs were retrieved and used as cross-sectional data. The data used are from 15,420 residences across the United States. Nursing homes located in Guam, the US Pacific Territories, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands, while supported by CMS and included in the dataset, were excluded from the study due to a severe absence of QM data.

Dependent Variables

We investigated 5 QMs that were averaged across the 4 quarters of 2019. The QMs used as dependent variables were percentage of residents who displayed depressive symptoms (depression), percentage of residents who were physically restrained (restraint), percentage of residents who experienced 1 or more falls resulting in a major injury (falls), percentage of residents who received antipsychotic medication (antipsychotic medication), and percentage of residents who received anti-anxiety or hypnotic medication (anti-anxiety medication).

A total of 2471 QM values were unreported across the 5 QM analyzed: 501 residences did not report depression data; 479 did not report restraint data; 477 did not report falls data; 508 did not report antipsychotic medication data; and 506 did not report anti-anxiety medication data. A residence with a missing QM value was excluded from that respective analysis.

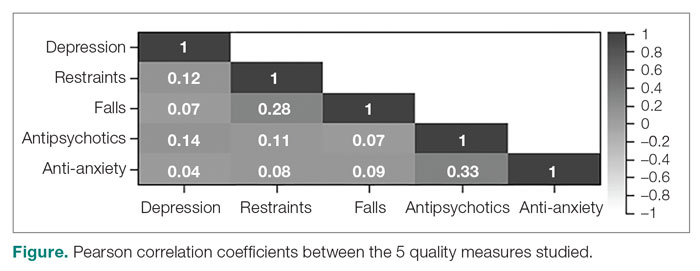

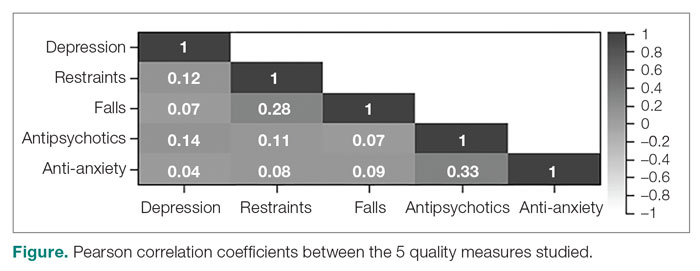

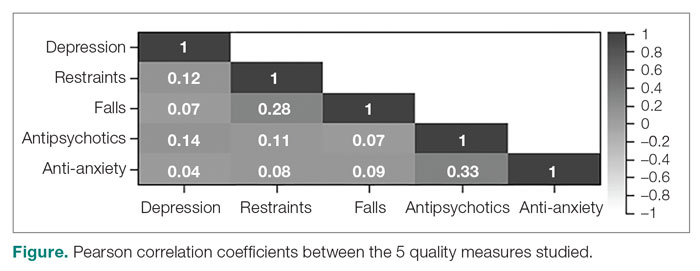

To assess the relationships among the different QMs, a Pearson correlation coefficient r was computed for each unique pair of QMs (Figure). All QMs studied were found to be very weakly or weakly correlated with one another using the Evans classification for very weak and weak correlations (r < 0.20 and 0.20 < r < 0.39, respectively).18

Independent Variables

A total of 15,420 residences were included in the study. Seventy-nine residences did not report occupancy data, however, so those residences were excluded from the occupancy analyses. We categorized the ownership of each nursing home as for-profit, nonprofit, or public. We categorized nursing home size, based on quartiles of the size distribution, as large (> 127 beds), medium (64 to 126 beds), and small (< 64 beds). This method for categorizing the residential characteristics was similar to that used in previous work.19 Similarly, we categorized nursing home occupancy as high (> 92% occupancy), medium (73% to 91% occupancy), and low (< 73% occupancy) based on quartiles of the occupancy distribution. For the regional analysis, we grouped states together based on the CMS regional offices: Atlanta, Georgia; Boston, Massachusetts; Chicago, Illinois; Dallas, Texas; Denver, Colorado; Kansas City, Missouri; New York, New York; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; San Francisco, California; and Seattle, Washington.20

Analyses

We used Levene’s test to determine whether variances among the residential groups were equal for each QM, using an a priori α = 0.05. For all 20 tests conducted (4 residential characteristics for all 5 QMs), the resulting F-statistics were significant, indicating that the assumption of homogeneity of variance was not met.

We therefore used Welch’s analysis of variance (ANOVA) to evaluate whether the groups within each residential characteristic were the same on their QM means. For example, we tested whether for-profit, nonprofit, and public residences had significantly different mean depression rates. For statistically significant differences, a Games-Howell post-hoc test was conducted to test the difference between all unique pairwise comparisons. An a priori α = 0.05 was used for both Welch’s ANOVA and post-hoc testing. All analyses were conducted in RStudio Version 1.2.5033 (Posit Software, PBC).

Results

Mean Differences

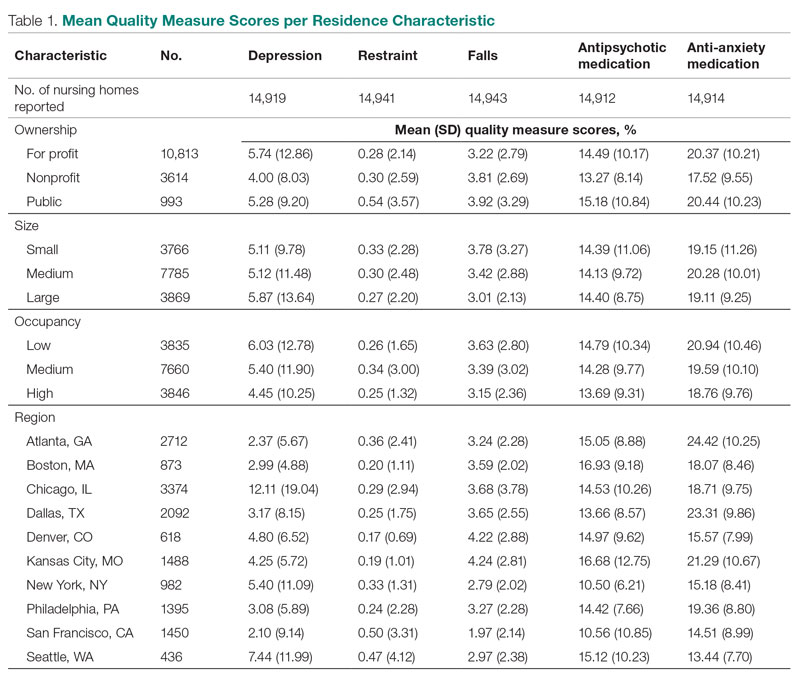

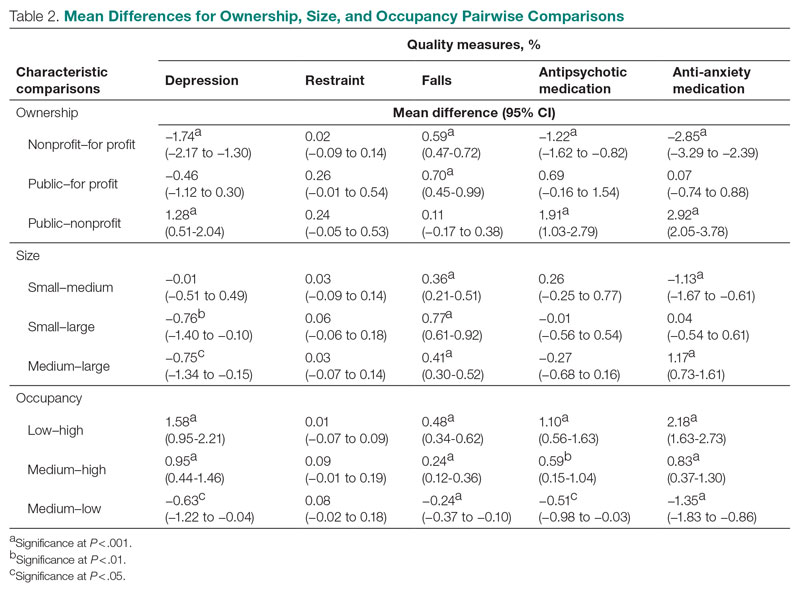

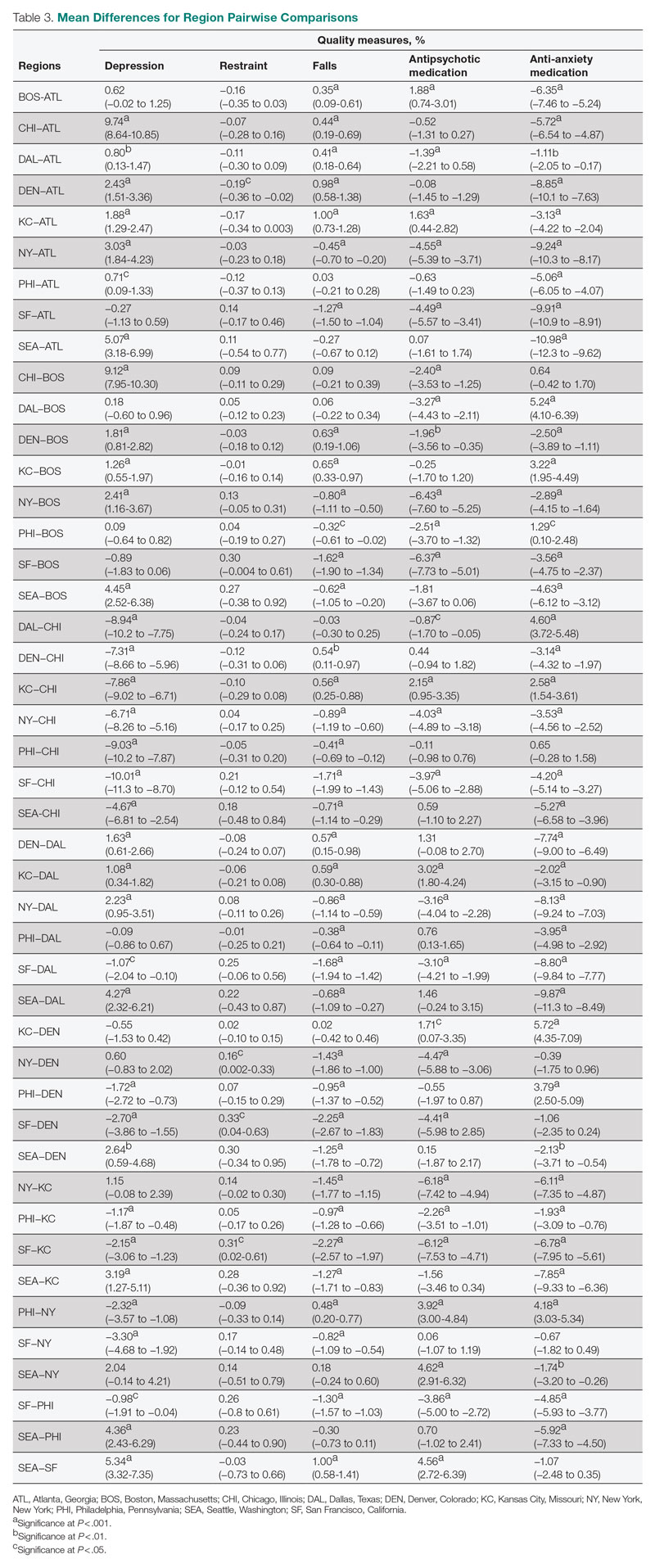

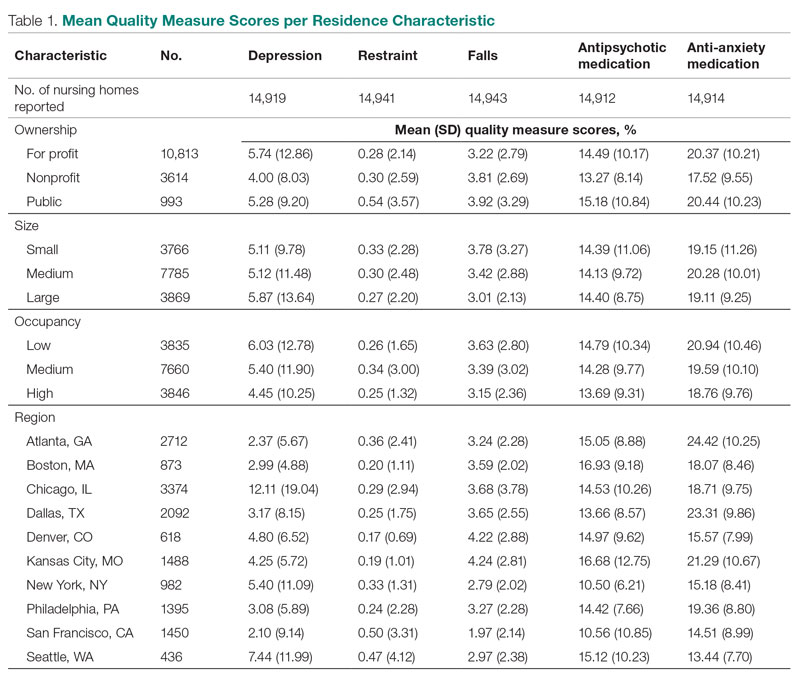

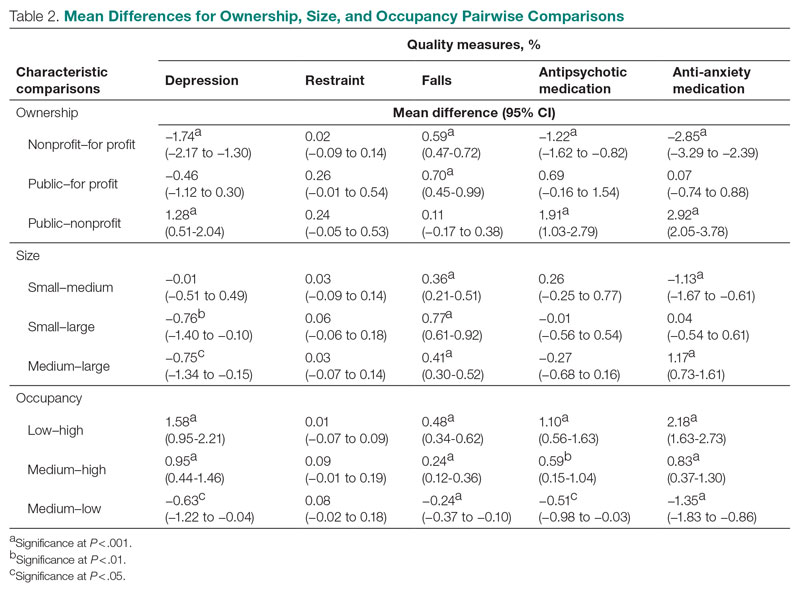

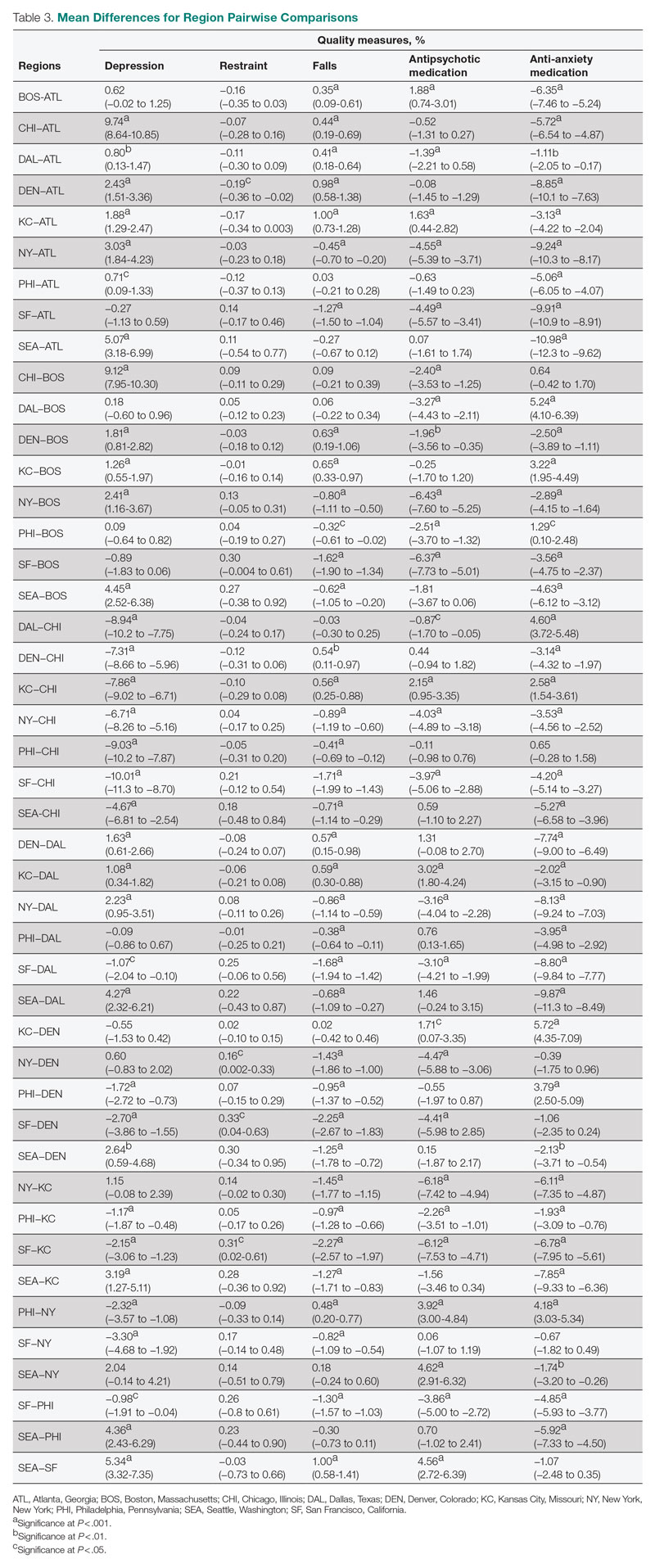

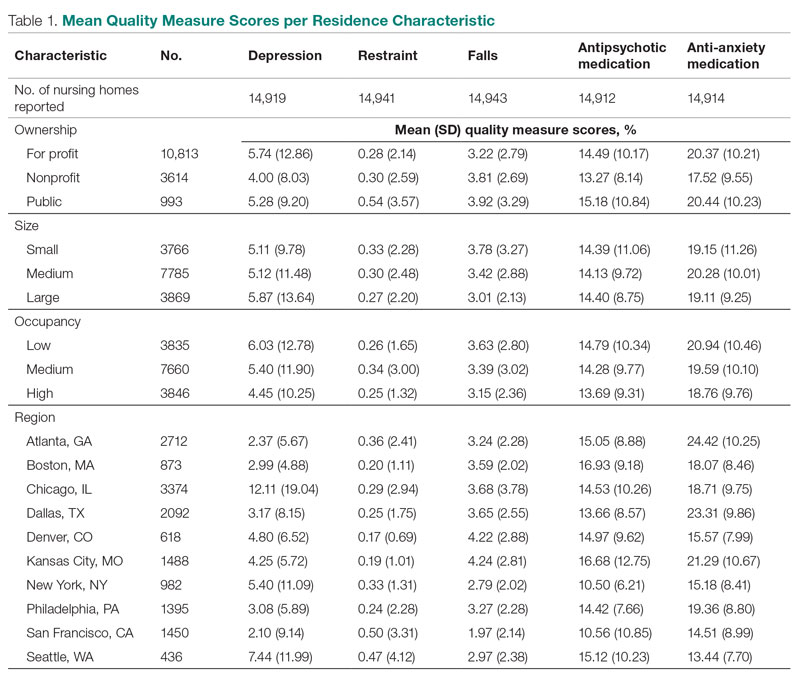

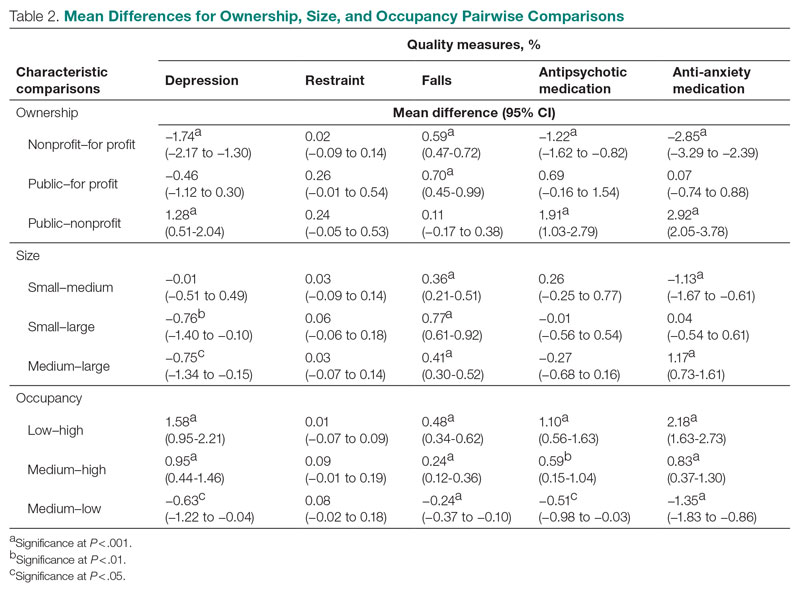

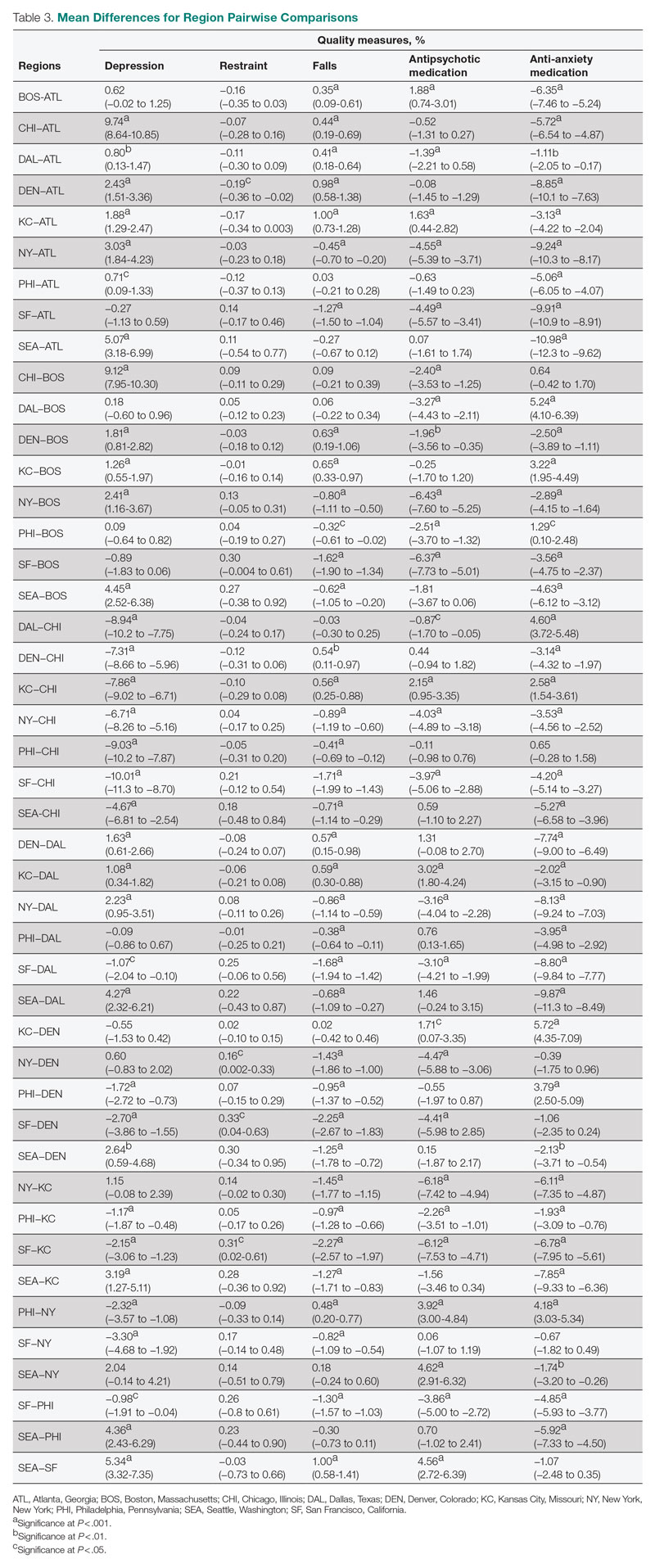

Mean QM scores for the 5 QMs investigated, grouped by residential characteristic for the 2019 year of reporting, are shown in Table 1. It should be noted that the number of residences that reported occupancy data (n = 15,341) does not equal the total number of residences included in the study (N = 15,420) because 79 residences did not report occupancy data. For all QMs reported in Table 1, lower scores are better. Table 2 and Table 3 show results from pairwise comparisons of mean differences for the different residential characteristic and QM groupings. Mean differences and 95% CI are presented along with an indication of statistical significance (when applicable).

Ownership

Nonprofit residences had significantly lower (ie, better) mean scores than for-profit and public residences for 3 QMs: resident depression, antipsychotic medication use, and anti-anxiety medication use. For-profit and public residences did not significantly differ in their mean values for these QMs. For-profit residences had a significantly lower mean score for resident falls than both nonprofit and public residences, but no significant difference existed between scores for nonprofit and public residence falls. There were no statistically significant differences between mean restraint scores among the ownership types.

Size

Large (ie, high-capacity) residences had a significantly higher mean depression score than both medium and small residences, but there was not a significant difference between medium and small residences. Large residences had the significantly lowest mean score for resident falls, and medium residences scored significantly lower than small residences. Medium residences had a significantly higher mean score for anti-anxiety medication use than both small and large residences, but there was no significant difference between small and large residences. There were no statistically significant differences between mean scores for restraint and antipsychotic medication use among the nursing home sizes.

Occupancy

The mean scores for 4 out of the 5 QMs exhibited similar relationships with occupancy rates: resident depression, falls, and antipsychotic and anti-anxiety medication use. Low-occupancy residences consistently scored significantly higher than both medium- and high-occupancy residences, and medium-occupancy residences consistently scored significantly higher than high-occupancy residences. On average, high-occupancy (≥ 92%) residences reported better QM scores than low-occupancy (< 73%) and medium-occupancy (73% to 91%) residences for all the QMs studied except physical restraint, which yielded no significant results. These findings indicate a possible inverse relationship between building occupancy rate and these 4 QMs.

Region

Pairwise comparisons of mean QM scores by region are shown in Table 3. The Chicago region had a significantly higher mean depression score than all other regions, while the San Francisco region’s score was significantly lower than all other regions, except Atlanta and Boston. The Kansas City region had a significantly higher mean score for resident falls than all other regions, with the exception of Denver, and the San Francisco region scored significantly lower than all other regions in falls. The Boston region had a significantly higher mean score for administering antipsychotic medication than all other regions, except for Kansas City and Seattle, and the New York and San Francisco regions both had significantly lower scores than all other regions except for each other. The Atlanta region reported a significantly higher mean score for administering antianxiety medication than all other regions, and the Seattle region’s score for anti-anxiety medication use was significantly lower than all other regions except for San Francisco.

Discussion

This study presented mean percentages for 5 QMs reported in the Nursing Home Compare database for the year 2019: depression, restraint, falls, antipsychotic medication use, and anti-anxiety medication use. We investigated these scores by 4 residential characteristics: ownership type, size, occupancy, and region. In general, publicly owned and low-occupancy residences had the highest scores, and thus the poorest performances, for the 5 chosen QMs during 2019. Nonprofit and high-occupancy residences generally had the lowest (ie, better) scores, and this result agrees with previous findings on long-stay nursing home residents.21 One possible explanation for better performance by high-occupancy buildings could be that increased social interaction is beneficial to nursing home residents as compared with low-occupancy buildings, where less social interaction is probable. It is difficult to draw conclusions regarding nursing home size and region; however, there are significant differences among sizes for 3 out of the 5 QMs and significant differences among regions for all 5 QMs. The analyses suggest that residence-level characteristics are related to QM scores. Although reported QMs are not a direct representation of resident quality of life, this work agrees with previous research that residential characteristics have some impact on the lives of nursing home residents.13-17 Improvements in QM reporting and changes in quality improvement goals since the formation of Nursing Home Compare exist, suggesting that nursing homes’ awareness of their reporting duties may impact quality of care or reporting tendencies.21,22 Future research should consider investigating the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality-reporting trends and QM scores.

Other physical characteristics of nursing homes, such as noise, lighting levels, and air quality, may also have an impact on QMs and possibly nursing home residents themselves. This type of data exploration could be included in future research. Additionally, future research could include a similar analysis over a longer period, rather than the 1-year period examined here, to investigate which types of residences consistently have high or low scores or how different types of residences have evolved over the years, particularly considering the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Information such as staffing levels, building renovations, and inspection data could be accounted for in future studies. Different QMs could also be investigated to better understand the influence of residential characteristics on quality of care.

Conclusion

This study suggests that residence-level characteristics are related to 5 reported nursing home QMs. Overall, nonprofit and high-occupancy residences had the lowest QM scores, indicating the highest performance. Although the results do not necessarily suggest that residence-level characteristics impact individual nursing home residents’ quality of life, they suggest that physical characteristics affect overall quality of life in nursing homes. Future research is needed to determine the specific physical characteristics of these residences that affect QM scores.

Corresponding author: Brian J. Puckett, [email protected].

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Gauthier S, Rosa-Neto P, Morais JA, et al. World Alzheimer report 2021: journey through the diagnosis of dementia. Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2021.

2. Garre-Olmo J, López-Pousa S, Turon-Estrada A, et al. Environmental determinants of quality of life in nursing home residents with severe dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(7):1230-1236. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04040.x

3. Zeisel J, Silverstein N, Hyde J, et al. Environmental correlates to behavioral health outcomes in Alzheimer’s special care units. Gerontologist. 2003;43(5):697-711. doi:10.1093/geront/43.5.697

4. Brawley E. Environmental design for Alzheimer’s disease: a quality of life issue. Aging Ment Health. 2001;5(1):S79-S83. doi:10.1080/13607860120044846

5. Joosse L. Do sound levels and space contribute to agitation in nursing home residents with dementia? Research Gerontol Nurs. 2012;5(3):174-184. doi:10.3928/19404921-20120605-02

6. Dowling G, Graf C, Hubbard E, et al. Light treatment for neuropsychiatric behaviors in Alzheimer’s disease. Western J Nurs Res. 2007;29(8):961-975. doi:10.1177/0193945907303083

7. Tartarini F, Cooper P, Fleming R, et al. Indoor air temperature and agitation of nursing home residents with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2017;32(5):272-281. doi:10.1177/1533317517704898

8. Miyamoto Y, Tachimori H, Ito H. Formal caregiver burden in dementia: impact of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and activities of daily living. Geriatr Nurs. 2010;31(4):246-253. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2010.01.002

9. Dementia care and the built environment: position paper 3. Alzheimer’s Australia; 2004.

10. Cloak N, Al Khalili Y. Behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia. Updated July 21, 2022. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

11. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Nursing homes including rehab services data archive. 2019 annual files. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://data.cms.gov/provider-data/archived-data/nursing-homes

12. Sanghavi P, Pan S, Caudry D. Assessment of nursing home reporting of major injury falls for quality measurement on Nursing Home Compare. Health Serv Res. 2020;55(2):201-210. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13247

13. Hughes C, Lapane K, Mor V. Influence of facility characteristics on use of antipsychotic medications in nursing homes. Med Care. 2000;38(12):1164-1173. doi:10.1097/00005650-200012000-00003

14. Aaronson W, Zinn J, Rosko M. Do for-profit and not-for-profit nursing homes behave differently? Gerontologist. 1994;34(6):775-786. doi:10.1093/geront/34.6.775

15. O’Neill C, Harrington C, Kitchener M, et al. Quality of care in nursing homes: an analysis of relationships among profit, quality, and ownership. Med Care. 2003;41(12):1318-1330. doi:10.1097/01.MLR.0000100586.33970.58

16. Allen PD, Klein WC, Gruman C. Correlates of complaints made to the Connecticut Long-Term Care Ombudsman program: the role of organizational and structural factors. Res Aging. 2003;25(6):631-654. doi:10.1177/0164027503256691

17. Abrams H, Loomer L, Gandhi A, et al. Characteristics of U.S. nursing homes with COVID-19 cases. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(8):1653-1656. doi:10.1111/jgs.16661

18. Evans JD. Straightforward Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. Thomson Brooks/Cole Publishing Co; 1996.

19. Zinn J, Spector W, Hsieh L, et al. Do trends in the reporting of quality measures on the Nursing Home Compare web site differ by nursing home characteristics? Gerontologist. 2005;45(6):720-730.

20. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS Regional Offices. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/ICD10/CMS-Regional-Offices

21. Mukamel DB, Weimer DL, Spector WD, et al. Publication of quality report cards and trends in reported quality measures in nursing homes. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(4):1244-1262. doi:10.1093/geront/45.6.720

22. Harris Y, Clauser SB. Achieving improvement through nursing home quality measurement. Health Care Financ Rev. 2002;23(4):5-18.

From the University of Nebraska, Lincoln (Mr. Puckett and Dr. Ryherd), University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha (Dr. Manley), and the University of Nebraska, Omaha (Dr. Ryan).

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study evaluated relationships between physical characteristics of nursing home residences and quality-of-care measures.

Design: This was a cross-sectional ecologic study. The dependent variables were 5 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Nursing Home Compare database long-stay quality measures (QMs) during 2019: percentage of residents who displayed depressive symptoms, percentage of residents who were physically restrained, percentage of residents who experienced 1 or more falls resulting in injury, percentage of residents who received antipsychotic medication, and percentage of residents who received anti-anxiety medication. The independent variables were 4 residence characteristics: ownership type, size, occupancy, and region within the United States. We explored how different types of each residence characteristic compare for each QM.

Setting, participants, and measurements: Quality measure values from 15,420 CMS-supported nursing homes across the United States averaged over the 4 quarters of 2019 reporting were used. Welch’s analysis of variance was performed to examine whether the mean QM values for groups within each residential characteristic were statistically different.

Results: Publicly owned and low-occupancy residences had the highest mean QM values, indicating the poorest performance. Nonprofit and high-occupancy residences generally had the lowest (ie, best) mean QM values. There were significant differences in mean QM values among nursing home sizes and regions.

Conclusion: This study suggests that residence characteristics are related to 5 nursing home QMs. Results suggest that physical characteristics may be related to overall quality of life in nursing homes.

Keywords: quality of care, quality measures, residence characteristics, Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

More than 55 million people worldwide are living with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD).1 With the aging of the Baby Boomer population, this number is expected to rise to more than 78 million worldwide by 2030.1 Given the growing number of cognitively impaired older adults, there is an increased need for residences designed for the specialized care of this population. Although there are dozens of living options for the elderly, and although most specialized establishments have the resources to meet the immediate needs of their residents, many facilities lack universal design features that support a high quality of life for someone with ADRD or mild cognitive impairment. Previous research has shown relationships between behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) and environmental characteristics such as acoustics, lighting, and indoor air temperature.2,3 Physical behaviors of BPSD, including aggression and wandering, and psychological symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, and delusions, put residents at risk of injury.4 Additionally, BPSD is correlated with caregiver burden and stress.5-8 Patients with dementia may also experience a lower stress threshold, changes in perception of space, and decreased short-term memory, creating environmental difficulties for those with ADRD9 that lead them to exhibit BPSD due to poor environmental design. Thus, there is a need to learn more about design features that minimize BPSD and promote a high quality of life for those with ADRD.10

Although research has shown relationships between physical environmental characteristics and BPSD, in this work we study relationships between possible BPSD indicators and 4 residence-level characteristics: ownership type, size, occupancy, and region in the United States (determined by location of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS] regional offices). We analyzed data from the CMS Nursing Home Compare database for the year 2019.11 This database publishes quarterly data and star ratings for quality-of-care measures (QMs), staffing levels, and health inspections for every nursing home supported by CMS. Previous research has investigated the accuracy of QM reporting for resident falls, the impact of residential characteristics on administration of antipsychotic medication, the influence of profit status on resident outcomes and quality of care, and the effect of nursing home size on quality of life.12-16 Additionally, research suggests that residential characteristics such as size and location could be associated with infection control in nursing homes.17

Certain QMs, such as psychotropic drug administration, resident falls, and physical restraint, provide indicators of agitation, disorientation, or aggression, which are often signals of BPSD episodes. We hypothesized that residence types are associated with different QM scores, which could indicate different occurrences of BPSD. We selected 5 QMs for long-stay residents that could potentially be used as indicators of BPSD. Short-stay resident data were not included in this work to control for BPSD that could be a result of sheer unfamiliarity with the environment and confusion from being in a new home.

Methods

Design and Data Collection

This was a cross-sectional ecologic study aimed at exploring relationships between aggregate residential characteristics and QMs. Data were retrieved from the 2019 annual archives found in the CMS provider data catalog on nursing homes, including rehabilitation services.11 The dataset provides general residence information, such as ownership, number of beds, number of residents, and location, as well as residence quality metrics, such as QMs, staffing data, and inspection data. Residence characteristics and 4-quarter averages of QMs were retrieved and used as cross-sectional data. The data used are from 15,420 residences across the United States. Nursing homes located in Guam, the US Pacific Territories, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands, while supported by CMS and included in the dataset, were excluded from the study due to a severe absence of QM data.

Dependent Variables

We investigated 5 QMs that were averaged across the 4 quarters of 2019. The QMs used as dependent variables were percentage of residents who displayed depressive symptoms (depression), percentage of residents who were physically restrained (restraint), percentage of residents who experienced 1 or more falls resulting in a major injury (falls), percentage of residents who received antipsychotic medication (antipsychotic medication), and percentage of residents who received anti-anxiety or hypnotic medication (anti-anxiety medication).

A total of 2471 QM values were unreported across the 5 QM analyzed: 501 residences did not report depression data; 479 did not report restraint data; 477 did not report falls data; 508 did not report antipsychotic medication data; and 506 did not report anti-anxiety medication data. A residence with a missing QM value was excluded from that respective analysis.

To assess the relationships among the different QMs, a Pearson correlation coefficient r was computed for each unique pair of QMs (Figure). All QMs studied were found to be very weakly or weakly correlated with one another using the Evans classification for very weak and weak correlations (r < 0.20 and 0.20 < r < 0.39, respectively).18

Independent Variables

A total of 15,420 residences were included in the study. Seventy-nine residences did not report occupancy data, however, so those residences were excluded from the occupancy analyses. We categorized the ownership of each nursing home as for-profit, nonprofit, or public. We categorized nursing home size, based on quartiles of the size distribution, as large (> 127 beds), medium (64 to 126 beds), and small (< 64 beds). This method for categorizing the residential characteristics was similar to that used in previous work.19 Similarly, we categorized nursing home occupancy as high (> 92% occupancy), medium (73% to 91% occupancy), and low (< 73% occupancy) based on quartiles of the occupancy distribution. For the regional analysis, we grouped states together based on the CMS regional offices: Atlanta, Georgia; Boston, Massachusetts; Chicago, Illinois; Dallas, Texas; Denver, Colorado; Kansas City, Missouri; New York, New York; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; San Francisco, California; and Seattle, Washington.20

Analyses

We used Levene’s test to determine whether variances among the residential groups were equal for each QM, using an a priori α = 0.05. For all 20 tests conducted (4 residential characteristics for all 5 QMs), the resulting F-statistics were significant, indicating that the assumption of homogeneity of variance was not met.

We therefore used Welch’s analysis of variance (ANOVA) to evaluate whether the groups within each residential characteristic were the same on their QM means. For example, we tested whether for-profit, nonprofit, and public residences had significantly different mean depression rates. For statistically significant differences, a Games-Howell post-hoc test was conducted to test the difference between all unique pairwise comparisons. An a priori α = 0.05 was used for both Welch’s ANOVA and post-hoc testing. All analyses were conducted in RStudio Version 1.2.5033 (Posit Software, PBC).

Results

Mean Differences

Mean QM scores for the 5 QMs investigated, grouped by residential characteristic for the 2019 year of reporting, are shown in Table 1. It should be noted that the number of residences that reported occupancy data (n = 15,341) does not equal the total number of residences included in the study (N = 15,420) because 79 residences did not report occupancy data. For all QMs reported in Table 1, lower scores are better. Table 2 and Table 3 show results from pairwise comparisons of mean differences for the different residential characteristic and QM groupings. Mean differences and 95% CI are presented along with an indication of statistical significance (when applicable).

Ownership

Nonprofit residences had significantly lower (ie, better) mean scores than for-profit and public residences for 3 QMs: resident depression, antipsychotic medication use, and anti-anxiety medication use. For-profit and public residences did not significantly differ in their mean values for these QMs. For-profit residences had a significantly lower mean score for resident falls than both nonprofit and public residences, but no significant difference existed between scores for nonprofit and public residence falls. There were no statistically significant differences between mean restraint scores among the ownership types.

Size

Large (ie, high-capacity) residences had a significantly higher mean depression score than both medium and small residences, but there was not a significant difference between medium and small residences. Large residences had the significantly lowest mean score for resident falls, and medium residences scored significantly lower than small residences. Medium residences had a significantly higher mean score for anti-anxiety medication use than both small and large residences, but there was no significant difference between small and large residences. There were no statistically significant differences between mean scores for restraint and antipsychotic medication use among the nursing home sizes.

Occupancy

The mean scores for 4 out of the 5 QMs exhibited similar relationships with occupancy rates: resident depression, falls, and antipsychotic and anti-anxiety medication use. Low-occupancy residences consistently scored significantly higher than both medium- and high-occupancy residences, and medium-occupancy residences consistently scored significantly higher than high-occupancy residences. On average, high-occupancy (≥ 92%) residences reported better QM scores than low-occupancy (< 73%) and medium-occupancy (73% to 91%) residences for all the QMs studied except physical restraint, which yielded no significant results. These findings indicate a possible inverse relationship between building occupancy rate and these 4 QMs.

Region

Pairwise comparisons of mean QM scores by region are shown in Table 3. The Chicago region had a significantly higher mean depression score than all other regions, while the San Francisco region’s score was significantly lower than all other regions, except Atlanta and Boston. The Kansas City region had a significantly higher mean score for resident falls than all other regions, with the exception of Denver, and the San Francisco region scored significantly lower than all other regions in falls. The Boston region had a significantly higher mean score for administering antipsychotic medication than all other regions, except for Kansas City and Seattle, and the New York and San Francisco regions both had significantly lower scores than all other regions except for each other. The Atlanta region reported a significantly higher mean score for administering antianxiety medication than all other regions, and the Seattle region’s score for anti-anxiety medication use was significantly lower than all other regions except for San Francisco.

Discussion

This study presented mean percentages for 5 QMs reported in the Nursing Home Compare database for the year 2019: depression, restraint, falls, antipsychotic medication use, and anti-anxiety medication use. We investigated these scores by 4 residential characteristics: ownership type, size, occupancy, and region. In general, publicly owned and low-occupancy residences had the highest scores, and thus the poorest performances, for the 5 chosen QMs during 2019. Nonprofit and high-occupancy residences generally had the lowest (ie, better) scores, and this result agrees with previous findings on long-stay nursing home residents.21 One possible explanation for better performance by high-occupancy buildings could be that increased social interaction is beneficial to nursing home residents as compared with low-occupancy buildings, where less social interaction is probable. It is difficult to draw conclusions regarding nursing home size and region; however, there are significant differences among sizes for 3 out of the 5 QMs and significant differences among regions for all 5 QMs. The analyses suggest that residence-level characteristics are related to QM scores. Although reported QMs are not a direct representation of resident quality of life, this work agrees with previous research that residential characteristics have some impact on the lives of nursing home residents.13-17 Improvements in QM reporting and changes in quality improvement goals since the formation of Nursing Home Compare exist, suggesting that nursing homes’ awareness of their reporting duties may impact quality of care or reporting tendencies.21,22 Future research should consider investigating the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality-reporting trends and QM scores.

Other physical characteristics of nursing homes, such as noise, lighting levels, and air quality, may also have an impact on QMs and possibly nursing home residents themselves. This type of data exploration could be included in future research. Additionally, future research could include a similar analysis over a longer period, rather than the 1-year period examined here, to investigate which types of residences consistently have high or low scores or how different types of residences have evolved over the years, particularly considering the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Information such as staffing levels, building renovations, and inspection data could be accounted for in future studies. Different QMs could also be investigated to better understand the influence of residential characteristics on quality of care.

Conclusion

This study suggests that residence-level characteristics are related to 5 reported nursing home QMs. Overall, nonprofit and high-occupancy residences had the lowest QM scores, indicating the highest performance. Although the results do not necessarily suggest that residence-level characteristics impact individual nursing home residents’ quality of life, they suggest that physical characteristics affect overall quality of life in nursing homes. Future research is needed to determine the specific physical characteristics of these residences that affect QM scores.

Corresponding author: Brian J. Puckett, [email protected].

Disclosures: None reported.

From the University of Nebraska, Lincoln (Mr. Puckett and Dr. Ryherd), University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha (Dr. Manley), and the University of Nebraska, Omaha (Dr. Ryan).

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study evaluated relationships between physical characteristics of nursing home residences and quality-of-care measures.

Design: This was a cross-sectional ecologic study. The dependent variables were 5 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Nursing Home Compare database long-stay quality measures (QMs) during 2019: percentage of residents who displayed depressive symptoms, percentage of residents who were physically restrained, percentage of residents who experienced 1 or more falls resulting in injury, percentage of residents who received antipsychotic medication, and percentage of residents who received anti-anxiety medication. The independent variables were 4 residence characteristics: ownership type, size, occupancy, and region within the United States. We explored how different types of each residence characteristic compare for each QM.

Setting, participants, and measurements: Quality measure values from 15,420 CMS-supported nursing homes across the United States averaged over the 4 quarters of 2019 reporting were used. Welch’s analysis of variance was performed to examine whether the mean QM values for groups within each residential characteristic were statistically different.

Results: Publicly owned and low-occupancy residences had the highest mean QM values, indicating the poorest performance. Nonprofit and high-occupancy residences generally had the lowest (ie, best) mean QM values. There were significant differences in mean QM values among nursing home sizes and regions.

Conclusion: This study suggests that residence characteristics are related to 5 nursing home QMs. Results suggest that physical characteristics may be related to overall quality of life in nursing homes.

Keywords: quality of care, quality measures, residence characteristics, Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

More than 55 million people worldwide are living with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD).1 With the aging of the Baby Boomer population, this number is expected to rise to more than 78 million worldwide by 2030.1 Given the growing number of cognitively impaired older adults, there is an increased need for residences designed for the specialized care of this population. Although there are dozens of living options for the elderly, and although most specialized establishments have the resources to meet the immediate needs of their residents, many facilities lack universal design features that support a high quality of life for someone with ADRD or mild cognitive impairment. Previous research has shown relationships between behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) and environmental characteristics such as acoustics, lighting, and indoor air temperature.2,3 Physical behaviors of BPSD, including aggression and wandering, and psychological symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, and delusions, put residents at risk of injury.4 Additionally, BPSD is correlated with caregiver burden and stress.5-8 Patients with dementia may also experience a lower stress threshold, changes in perception of space, and decreased short-term memory, creating environmental difficulties for those with ADRD9 that lead them to exhibit BPSD due to poor environmental design. Thus, there is a need to learn more about design features that minimize BPSD and promote a high quality of life for those with ADRD.10

Although research has shown relationships between physical environmental characteristics and BPSD, in this work we study relationships between possible BPSD indicators and 4 residence-level characteristics: ownership type, size, occupancy, and region in the United States (determined by location of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS] regional offices). We analyzed data from the CMS Nursing Home Compare database for the year 2019.11 This database publishes quarterly data and star ratings for quality-of-care measures (QMs), staffing levels, and health inspections for every nursing home supported by CMS. Previous research has investigated the accuracy of QM reporting for resident falls, the impact of residential characteristics on administration of antipsychotic medication, the influence of profit status on resident outcomes and quality of care, and the effect of nursing home size on quality of life.12-16 Additionally, research suggests that residential characteristics such as size and location could be associated with infection control in nursing homes.17

Certain QMs, such as psychotropic drug administration, resident falls, and physical restraint, provide indicators of agitation, disorientation, or aggression, which are often signals of BPSD episodes. We hypothesized that residence types are associated with different QM scores, which could indicate different occurrences of BPSD. We selected 5 QMs for long-stay residents that could potentially be used as indicators of BPSD. Short-stay resident data were not included in this work to control for BPSD that could be a result of sheer unfamiliarity with the environment and confusion from being in a new home.

Methods

Design and Data Collection

This was a cross-sectional ecologic study aimed at exploring relationships between aggregate residential characteristics and QMs. Data were retrieved from the 2019 annual archives found in the CMS provider data catalog on nursing homes, including rehabilitation services.11 The dataset provides general residence information, such as ownership, number of beds, number of residents, and location, as well as residence quality metrics, such as QMs, staffing data, and inspection data. Residence characteristics and 4-quarter averages of QMs were retrieved and used as cross-sectional data. The data used are from 15,420 residences across the United States. Nursing homes located in Guam, the US Pacific Territories, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands, while supported by CMS and included in the dataset, were excluded from the study due to a severe absence of QM data.

Dependent Variables

We investigated 5 QMs that were averaged across the 4 quarters of 2019. The QMs used as dependent variables were percentage of residents who displayed depressive symptoms (depression), percentage of residents who were physically restrained (restraint), percentage of residents who experienced 1 or more falls resulting in a major injury (falls), percentage of residents who received antipsychotic medication (antipsychotic medication), and percentage of residents who received anti-anxiety or hypnotic medication (anti-anxiety medication).

A total of 2471 QM values were unreported across the 5 QM analyzed: 501 residences did not report depression data; 479 did not report restraint data; 477 did not report falls data; 508 did not report antipsychotic medication data; and 506 did not report anti-anxiety medication data. A residence with a missing QM value was excluded from that respective analysis.

To assess the relationships among the different QMs, a Pearson correlation coefficient r was computed for each unique pair of QMs (Figure). All QMs studied were found to be very weakly or weakly correlated with one another using the Evans classification for very weak and weak correlations (r < 0.20 and 0.20 < r < 0.39, respectively).18

Independent Variables

A total of 15,420 residences were included in the study. Seventy-nine residences did not report occupancy data, however, so those residences were excluded from the occupancy analyses. We categorized the ownership of each nursing home as for-profit, nonprofit, or public. We categorized nursing home size, based on quartiles of the size distribution, as large (> 127 beds), medium (64 to 126 beds), and small (< 64 beds). This method for categorizing the residential characteristics was similar to that used in previous work.19 Similarly, we categorized nursing home occupancy as high (> 92% occupancy), medium (73% to 91% occupancy), and low (< 73% occupancy) based on quartiles of the occupancy distribution. For the regional analysis, we grouped states together based on the CMS regional offices: Atlanta, Georgia; Boston, Massachusetts; Chicago, Illinois; Dallas, Texas; Denver, Colorado; Kansas City, Missouri; New York, New York; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; San Francisco, California; and Seattle, Washington.20

Analyses

We used Levene’s test to determine whether variances among the residential groups were equal for each QM, using an a priori α = 0.05. For all 20 tests conducted (4 residential characteristics for all 5 QMs), the resulting F-statistics were significant, indicating that the assumption of homogeneity of variance was not met.

We therefore used Welch’s analysis of variance (ANOVA) to evaluate whether the groups within each residential characteristic were the same on their QM means. For example, we tested whether for-profit, nonprofit, and public residences had significantly different mean depression rates. For statistically significant differences, a Games-Howell post-hoc test was conducted to test the difference between all unique pairwise comparisons. An a priori α = 0.05 was used for both Welch’s ANOVA and post-hoc testing. All analyses were conducted in RStudio Version 1.2.5033 (Posit Software, PBC).

Results

Mean Differences

Mean QM scores for the 5 QMs investigated, grouped by residential characteristic for the 2019 year of reporting, are shown in Table 1. It should be noted that the number of residences that reported occupancy data (n = 15,341) does not equal the total number of residences included in the study (N = 15,420) because 79 residences did not report occupancy data. For all QMs reported in Table 1, lower scores are better. Table 2 and Table 3 show results from pairwise comparisons of mean differences for the different residential characteristic and QM groupings. Mean differences and 95% CI are presented along with an indication of statistical significance (when applicable).

Ownership

Nonprofit residences had significantly lower (ie, better) mean scores than for-profit and public residences for 3 QMs: resident depression, antipsychotic medication use, and anti-anxiety medication use. For-profit and public residences did not significantly differ in their mean values for these QMs. For-profit residences had a significantly lower mean score for resident falls than both nonprofit and public residences, but no significant difference existed between scores for nonprofit and public residence falls. There were no statistically significant differences between mean restraint scores among the ownership types.

Size

Large (ie, high-capacity) residences had a significantly higher mean depression score than both medium and small residences, but there was not a significant difference between medium and small residences. Large residences had the significantly lowest mean score for resident falls, and medium residences scored significantly lower than small residences. Medium residences had a significantly higher mean score for anti-anxiety medication use than both small and large residences, but there was no significant difference between small and large residences. There were no statistically significant differences between mean scores for restraint and antipsychotic medication use among the nursing home sizes.

Occupancy

The mean scores for 4 out of the 5 QMs exhibited similar relationships with occupancy rates: resident depression, falls, and antipsychotic and anti-anxiety medication use. Low-occupancy residences consistently scored significantly higher than both medium- and high-occupancy residences, and medium-occupancy residences consistently scored significantly higher than high-occupancy residences. On average, high-occupancy (≥ 92%) residences reported better QM scores than low-occupancy (< 73%) and medium-occupancy (73% to 91%) residences for all the QMs studied except physical restraint, which yielded no significant results. These findings indicate a possible inverse relationship between building occupancy rate and these 4 QMs.

Region

Pairwise comparisons of mean QM scores by region are shown in Table 3. The Chicago region had a significantly higher mean depression score than all other regions, while the San Francisco region’s score was significantly lower than all other regions, except Atlanta and Boston. The Kansas City region had a significantly higher mean score for resident falls than all other regions, with the exception of Denver, and the San Francisco region scored significantly lower than all other regions in falls. The Boston region had a significantly higher mean score for administering antipsychotic medication than all other regions, except for Kansas City and Seattle, and the New York and San Francisco regions both had significantly lower scores than all other regions except for each other. The Atlanta region reported a significantly higher mean score for administering antianxiety medication than all other regions, and the Seattle region’s score for anti-anxiety medication use was significantly lower than all other regions except for San Francisco.

Discussion

This study presented mean percentages for 5 QMs reported in the Nursing Home Compare database for the year 2019: depression, restraint, falls, antipsychotic medication use, and anti-anxiety medication use. We investigated these scores by 4 residential characteristics: ownership type, size, occupancy, and region. In general, publicly owned and low-occupancy residences had the highest scores, and thus the poorest performances, for the 5 chosen QMs during 2019. Nonprofit and high-occupancy residences generally had the lowest (ie, better) scores, and this result agrees with previous findings on long-stay nursing home residents.21 One possible explanation for better performance by high-occupancy buildings could be that increased social interaction is beneficial to nursing home residents as compared with low-occupancy buildings, where less social interaction is probable. It is difficult to draw conclusions regarding nursing home size and region; however, there are significant differences among sizes for 3 out of the 5 QMs and significant differences among regions for all 5 QMs. The analyses suggest that residence-level characteristics are related to QM scores. Although reported QMs are not a direct representation of resident quality of life, this work agrees with previous research that residential characteristics have some impact on the lives of nursing home residents.13-17 Improvements in QM reporting and changes in quality improvement goals since the formation of Nursing Home Compare exist, suggesting that nursing homes’ awareness of their reporting duties may impact quality of care or reporting tendencies.21,22 Future research should consider investigating the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality-reporting trends and QM scores.

Other physical characteristics of nursing homes, such as noise, lighting levels, and air quality, may also have an impact on QMs and possibly nursing home residents themselves. This type of data exploration could be included in future research. Additionally, future research could include a similar analysis over a longer period, rather than the 1-year period examined here, to investigate which types of residences consistently have high or low scores or how different types of residences have evolved over the years, particularly considering the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Information such as staffing levels, building renovations, and inspection data could be accounted for in future studies. Different QMs could also be investigated to better understand the influence of residential characteristics on quality of care.

Conclusion

This study suggests that residence-level characteristics are related to 5 reported nursing home QMs. Overall, nonprofit and high-occupancy residences had the lowest QM scores, indicating the highest performance. Although the results do not necessarily suggest that residence-level characteristics impact individual nursing home residents’ quality of life, they suggest that physical characteristics affect overall quality of life in nursing homes. Future research is needed to determine the specific physical characteristics of these residences that affect QM scores.

Corresponding author: Brian J. Puckett, [email protected].

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Gauthier S, Rosa-Neto P, Morais JA, et al. World Alzheimer report 2021: journey through the diagnosis of dementia. Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2021.

2. Garre-Olmo J, López-Pousa S, Turon-Estrada A, et al. Environmental determinants of quality of life in nursing home residents with severe dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(7):1230-1236. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04040.x

3. Zeisel J, Silverstein N, Hyde J, et al. Environmental correlates to behavioral health outcomes in Alzheimer’s special care units. Gerontologist. 2003;43(5):697-711. doi:10.1093/geront/43.5.697

4. Brawley E. Environmental design for Alzheimer’s disease: a quality of life issue. Aging Ment Health. 2001;5(1):S79-S83. doi:10.1080/13607860120044846

5. Joosse L. Do sound levels and space contribute to agitation in nursing home residents with dementia? Research Gerontol Nurs. 2012;5(3):174-184. doi:10.3928/19404921-20120605-02

6. Dowling G, Graf C, Hubbard E, et al. Light treatment for neuropsychiatric behaviors in Alzheimer’s disease. Western J Nurs Res. 2007;29(8):961-975. doi:10.1177/0193945907303083

7. Tartarini F, Cooper P, Fleming R, et al. Indoor air temperature and agitation of nursing home residents with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2017;32(5):272-281. doi:10.1177/1533317517704898

8. Miyamoto Y, Tachimori H, Ito H. Formal caregiver burden in dementia: impact of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and activities of daily living. Geriatr Nurs. 2010;31(4):246-253. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2010.01.002

9. Dementia care and the built environment: position paper 3. Alzheimer’s Australia; 2004.

10. Cloak N, Al Khalili Y. Behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia. Updated July 21, 2022. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

11. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Nursing homes including rehab services data archive. 2019 annual files. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://data.cms.gov/provider-data/archived-data/nursing-homes

12. Sanghavi P, Pan S, Caudry D. Assessment of nursing home reporting of major injury falls for quality measurement on Nursing Home Compare. Health Serv Res. 2020;55(2):201-210. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13247

13. Hughes C, Lapane K, Mor V. Influence of facility characteristics on use of antipsychotic medications in nursing homes. Med Care. 2000;38(12):1164-1173. doi:10.1097/00005650-200012000-00003

14. Aaronson W, Zinn J, Rosko M. Do for-profit and not-for-profit nursing homes behave differently? Gerontologist. 1994;34(6):775-786. doi:10.1093/geront/34.6.775

15. O’Neill C, Harrington C, Kitchener M, et al. Quality of care in nursing homes: an analysis of relationships among profit, quality, and ownership. Med Care. 2003;41(12):1318-1330. doi:10.1097/01.MLR.0000100586.33970.58

16. Allen PD, Klein WC, Gruman C. Correlates of complaints made to the Connecticut Long-Term Care Ombudsman program: the role of organizational and structural factors. Res Aging. 2003;25(6):631-654. doi:10.1177/0164027503256691

17. Abrams H, Loomer L, Gandhi A, et al. Characteristics of U.S. nursing homes with COVID-19 cases. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(8):1653-1656. doi:10.1111/jgs.16661

18. Evans JD. Straightforward Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. Thomson Brooks/Cole Publishing Co; 1996.

19. Zinn J, Spector W, Hsieh L, et al. Do trends in the reporting of quality measures on the Nursing Home Compare web site differ by nursing home characteristics? Gerontologist. 2005;45(6):720-730.

20. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS Regional Offices. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/ICD10/CMS-Regional-Offices

21. Mukamel DB, Weimer DL, Spector WD, et al. Publication of quality report cards and trends in reported quality measures in nursing homes. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(4):1244-1262. doi:10.1093/geront/45.6.720

22. Harris Y, Clauser SB. Achieving improvement through nursing home quality measurement. Health Care Financ Rev. 2002;23(4):5-18.

1. Gauthier S, Rosa-Neto P, Morais JA, et al. World Alzheimer report 2021: journey through the diagnosis of dementia. Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2021.

2. Garre-Olmo J, López-Pousa S, Turon-Estrada A, et al. Environmental determinants of quality of life in nursing home residents with severe dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(7):1230-1236. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04040.x

3. Zeisel J, Silverstein N, Hyde J, et al. Environmental correlates to behavioral health outcomes in Alzheimer’s special care units. Gerontologist. 2003;43(5):697-711. doi:10.1093/geront/43.5.697

4. Brawley E. Environmental design for Alzheimer’s disease: a quality of life issue. Aging Ment Health. 2001;5(1):S79-S83. doi:10.1080/13607860120044846

5. Joosse L. Do sound levels and space contribute to agitation in nursing home residents with dementia? Research Gerontol Nurs. 2012;5(3):174-184. doi:10.3928/19404921-20120605-02

6. Dowling G, Graf C, Hubbard E, et al. Light treatment for neuropsychiatric behaviors in Alzheimer’s disease. Western J Nurs Res. 2007;29(8):961-975. doi:10.1177/0193945907303083

7. Tartarini F, Cooper P, Fleming R, et al. Indoor air temperature and agitation of nursing home residents with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2017;32(5):272-281. doi:10.1177/1533317517704898

8. Miyamoto Y, Tachimori H, Ito H. Formal caregiver burden in dementia: impact of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and activities of daily living. Geriatr Nurs. 2010;31(4):246-253. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2010.01.002

9. Dementia care and the built environment: position paper 3. Alzheimer’s Australia; 2004.

10. Cloak N, Al Khalili Y. Behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia. Updated July 21, 2022. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

11. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Nursing homes including rehab services data archive. 2019 annual files. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://data.cms.gov/provider-data/archived-data/nursing-homes

12. Sanghavi P, Pan S, Caudry D. Assessment of nursing home reporting of major injury falls for quality measurement on Nursing Home Compare. Health Serv Res. 2020;55(2):201-210. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13247

13. Hughes C, Lapane K, Mor V. Influence of facility characteristics on use of antipsychotic medications in nursing homes. Med Care. 2000;38(12):1164-1173. doi:10.1097/00005650-200012000-00003

14. Aaronson W, Zinn J, Rosko M. Do for-profit and not-for-profit nursing homes behave differently? Gerontologist. 1994;34(6):775-786. doi:10.1093/geront/34.6.775

15. O’Neill C, Harrington C, Kitchener M, et al. Quality of care in nursing homes: an analysis of relationships among profit, quality, and ownership. Med Care. 2003;41(12):1318-1330. doi:10.1097/01.MLR.0000100586.33970.58

16. Allen PD, Klein WC, Gruman C. Correlates of complaints made to the Connecticut Long-Term Care Ombudsman program: the role of organizational and structural factors. Res Aging. 2003;25(6):631-654. doi:10.1177/0164027503256691

17. Abrams H, Loomer L, Gandhi A, et al. Characteristics of U.S. nursing homes with COVID-19 cases. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(8):1653-1656. doi:10.1111/jgs.16661

18. Evans JD. Straightforward Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. Thomson Brooks/Cole Publishing Co; 1996.

19. Zinn J, Spector W, Hsieh L, et al. Do trends in the reporting of quality measures on the Nursing Home Compare web site differ by nursing home characteristics? Gerontologist. 2005;45(6):720-730.

20. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS Regional Offices. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/ICD10/CMS-Regional-Offices

21. Mukamel DB, Weimer DL, Spector WD, et al. Publication of quality report cards and trends in reported quality measures in nursing homes. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(4):1244-1262. doi:10.1093/geront/45.6.720

22. Harris Y, Clauser SB. Achieving improvement through nursing home quality measurement. Health Care Financ Rev. 2002;23(4):5-18.

Tooth loss and diabetes together hasten mental decline

most specifically in those 65-74 years of age, new findings suggest.

The data come from a 12-year follow-up of older adults in a nationally representative U.S. survey.

“From a clinical perspective, our study demonstrates the importance of improving access to dental health care and integrating primary dental and medical care. Health care professionals and family caregivers should pay close attention to the cognitive status of diabetic older adults with poor oral health status,” lead author Bei Wu, PhD, of New York University, said in an interview. Dr. Wu is the Dean’s Professor in Global Health and codirector of the NYU Aging Incubator.

Moreover, said Dr. Wu: “For individuals with both poor oral health and diabetes, regular dental visits should be encouraged in addition to adherence to the diabetes self-care protocol.”

Diabetes has long been recognized as a risk factor for cognitive decline, but the findings have been inconsistent for different age groups. Tooth loss has also been linked to cognitive decline and dementia, as well as diabetes.

The mechanisms aren’t entirely clear, but “co-occurring diabetes and poor oral health may increase the risk for dementia, possibly via the potentially interrelated pathways of chronic inflammation and cardiovascular risk factors,” Dr. Wu said.

The new study, published in the Journal of Dental Research, is the first to examine the relationships between all three conditions by age group.

Diabetes, edentulism, and cognitive decline

The data came from a total of 9,948 participants in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) from 2006 to 2018. At baseline, 5,440 participants were aged 65-74 years, 3,300 were aged 75-84, and 1,208 were aged 85 years or older.