User login

Age-Friendly Health Systems and Meeting the Principles of High Reliability Organizations in the VHA

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest integrated health care system in the US, providing care to more than 9 million enrolled veterans at 1298 facilities.1 In February 2019, the VHA identified key action steps to become a high reliability organization (HRO), transforming how employees think about patient safety and care quality.2 The VHA is also working toward becoming the largest age-friendly health system in the US to be recognized by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) for its commitment to providing care guided by the 4Ms (what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility), causing no harm, and aligning care with what matters to older veterans.3 In this article, we describe how the Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS) movement supports the culture shift observed in HROs.

Age-Friendly Veteran Care

By 2060, the US population of adults aged ≥ 65 years is projected to increase to about 95 million.3 In the VHA, nearly half of veteran enrollees are aged ≥ 65 years, necessitating evidence-based models of care, such as the 4Ms, to meet their complex care needs.3 Historically, the VHA has been a leader in caring for older adults, recognizing the value of age-friendly care for veterans.4 In 1975, the VHA established the Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Centers (GRECCs) to serve as catalysts for developing, implementing, and refining enduring models of geriatric care.4 For 5 decades, GRECCs have driven innovations related to the 4Ms.

The VHA is well positioned to be a leader in the AFHS movement, building on decades of GRECC innovations and geriatric programs that align with the 4Ms and providing specialized geriatric training for health care professionals to expand age-friendly care to new settings and health systems.4 The AFHS movement organizes the 4Ms into a simple framework for frontline staff, and the VHA has recently begun tracking 4Ms care in the electronic health record (EHR) to facilitate evaluation and continuous improvement.

AFHS use the 4Ms as a framework to be implemented in every care setting, from the emergency department to inpatient units, outpatient settings, and postacute and long-term care. By assessing and acting on each M and practicing the 4Ms collectively, all members of the care team work to improve health outcomes and prevent avoidable harm.5

The 4Ms

What matters, is the driver of this person-centered approach. Any member of the care team may initiate a what matters conversation with the older adult to understand their personal values, health goals, and care preferences. When compared with usual care, care aligned with the older adult’s health priorities has been shown to decrease the use of high-risk medications and reduce treatment burden.6 The VHA has adopted Whole Health principles of care and the Patient Priorities Care approach to identify and support what matters to veterans.7,8

Addressing polypharmacy and identifying and deprescribing potentially inappropriate medications are essential in preventing adverse drug events, drug-drug interactions, and medication nonadherence.9 In the VHA, VIONE (Vital, Important, Optional, Not indicated, Every medication has an indication) is a rapidly expanding medication deprescribing program that exemplifies HRO principles.9 VIONE provides medication management that supports shared decision making, reducing risk and improving patient safety and quality of life.9 As of June 2023, > 600,000 unique veterans have benefited from VIONE, with an average of 2.2 medications deprescribed per patient with an annual cost avoidance of > $100 million.10

Assessing and acting on mentation includes preventing, identifying, and managing depression and dementia in outpatient settings and delirium in hospital and long-term care settings.5 There are many tools and clinical reminders available in the EHR so that interdisciplinary teams can document changes to mentation and identify opportunities for continuous improvement.

Closely aligned with mentation is mobility, with evidence suggesting that regular physical activity reduces the risk of falls (preventing associated complications), maintains physical functioning, and lowers the risk of cognitive impairment and depression.5 Ensuring early, frequent, and safe mobility helps patients achieve better health outcomes and prevent injury.5 Mobility programs within the VHA include the STRIDE program for the inpatient setting and Gerofit for outpatient settings.11,12

HRO Principles

An HRO is a complex environment of care that experiences fewer than anticipated accidents or adverse events by (1) establishing trust among leaders and staff by balancing individual accountability with systems thinking; (2) empowering staff to lead continuous process improvements; and (3) creating an environment where employees feel safe to report harm or near misses, focusing on the reasons errors occur.13 The work of AFHS incorporates HRO principles with an emphasis on 3 elements. First, it involves interactive systems and processes needed to support 4Ms care across care settings. Second, AFHS acknowledge the complexity of age-friendly work and deference to the expertise of interdisciplinary team members. Finally, AFHS are committed to resilience by overcoming failures and challenges to implementation and long-term sustainment as a standard of practice.

Case study

The names and details in this case have been modified to protect patient privacy. It is representative of many Community Living Centers (CLCs) involved in AFHS that work to create a safe, person-centered environment for veterans.

In a CLC team workroom, 2 nurses were discussing a long-term care resident. The nurses approached the attending physician and explained that they were worried about Sgt Johnson, who seemed depressed and sometimes combative. They had noticed a change in his behavior when they helped him clean up after an episode of incontinence and were concerned that he would try to get out of bed on his own and fall. The attending physician thanked them for sharing their concerns. Sgt Johnson was a retired Army veteran who had a long, decorated military career. His chronic health conditions had led to muscle weakness, and he fell and broke a hip before this admission. He had an uneventful hip replacement but was showing signs of depression due to his limited mobility, loss of independence, and inability to live at home without additional support.

The attending physician knocked on the door of his room, sat down next to the bed, and asked, “How are you feeling today?” Sgt Johnson tersely replied, “About the same.” The physician asked, “Sgt Johnson, what matters most to you related to your recovery? What is important to you?” Sgt Johnson responded, “Feeling like a man!” The doctor replied, “So what makes you feel ‘not like a man’?” The Sgt replied, “Having to be cleaned up by the nurses and not being able to use the toilet on my own.” The physician surmised that his decline in physical functioning had a connection to his worsening depression and combativeness and said to the Sgt, “Let’s get the team together and work out a plan to get you strong enough to use a bedside commode by yourself. Let’s make that the first goal in our plan to get you back to using the toilet independently. Can you work with us on that?” He smiled and said, “Sir, yes Sir!”

At the weekly interdisciplinary team meeting, the team discussed Sgt Johnson’s wishes and the nurses’ safety concerns. The physician reported to the team what mattered to the veteran. The nurses arranged for a bedside commode and supplies to be placed in his room, encouraged and assisted him, and provided a privacy screen. The physical therapist continued to support his mobility needs, concentrating on transfers, small steps like standing and turning with a walker to get in position to use the bedside commode, and later the bathroom toilet. The psychologist addressed what matters to Sgt Johnson and his mentation, health goals, and coping strategies. The social worker provided support and counseling for the veteran and his family. The pharmacist checked his medications to be sure that none were affecting his gastrointestinal tract and his ability to move safely and do what matters to him. Knowing what mattered to Sgt Johnson was the driver of the interdisciplinary care plan to provide 4Ms care.

The team worked collaboratively with the veteran to develop and set attainable goals around toileting and regaining his dignity. This improved his overall recovery. As Sgt Johnson became more independent, his mood gradually improved and he began to participate in other activities and interact with other residents on the unit, and he did not experience any falls. By addressing the 4Ms, the interdisciplinary team coordinated efforts to provide high-quality, person-centered care. They built trust with the veteran, shared accountability, and followed HRO principles to keep the veteran safe.

Becoming an Age-Friendly HRO

Becoming an HRO is a dynamic, ever-changing process to maintain high standards, improve care quality, and cause no harm. There are 3 pillars and 5 principles that guide an HRO. The pillars are critical areas of focus and include leadership commitment, culture of safety, and continuous process improvement.14 The first of 5 HRO principles is sensitivity to operations. This is defined as an awareness of how processes and systems impact the entire organization, the downstream impact.15 Focusing on the 4Ms helps develop the capability of frontline staff to provide high-quality care for older adults while ensuring that processes are in place to support the work. The 4Ms provide an efficient way to organize interdisciplinary team meetings, provide warm handoffs using Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation, and standardize documentation. Involvement in the AFHS movement improves communication, care quality, and patient and staff satisfaction to meet this HRO principle.15

The second HRO principle, reluctance to simplify, ensures that direct care staff and leaders delve further into issues to find solutions.15 AFHS use the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle to put the 4Ms into practice; this cycle helps teams test small increments of change, study their performance, and act to ensure that all 4Ms are being practiced as a set. AFHS teams are encouraged to review at least 3 months of data after implementation of the 4Ms, working to find solutions if there are gaps or issues identified.

The third principle, preoccupation with failure, refers to shared attentiveness—being prepared for the unexpected and learning from mistakes.15 The entire AFHS team shares responsibility for providing 4Ms care, where staff are empowered to report any safety concerns or close calls. The fourth principle of deference to expertise includes listening to staff who have the most knowledge for the task at hand, which aligns with the collaborative interdisciplinary teamwork of age-friendly teams.15

The final HRO principle, commitment to resilience, includes continuous learning, interdisciplinary team training, and sharing of lessons learned.15 Although IHI offers 2 levels of AFHS recognition, teams are continuously learning to improve and sustain care beyond level 2, Committed to Care Excellence recognition.16

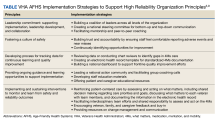

The Table shows the VHA’s AFHS implementation strategies and the HRO principles adapted from the Joint Commission’s High Reliability Health Care Maturity Model and the IHI’s Framework for Safe, Reliable, and Effective Care. The VHA is developing a national dashboard to capture age-friendly processes and health outcome measures that address patient safety and care quality.

Conclusions

AFHS empowers VHA teams to honor veterans’ care preferences and values, supporting their independence, dignity, and quality of life across care settings. The adoption of AFHS brings evidence-based practices to the point of care by addressing common pitfalls in the care of older adults, drawing attention to, and calling for action on inappropriate medication use, physical inactivity, and assessment of the vulnerable brain. The 4Ms also serve as a framework to continuously improve care and cause zero harm, reinforcing HRO pillars and principles across the VHA, and ensuring that older adults reliably receive the evidence-based, high-quality care they deserve.

1. Veterans Health Administration. Providing healthcare for veterans. Updated June 20, 2023. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.va.gov/health

2. Veazie S, Peterson K, Bourne D. Evidence brief: implementation of high reliability organization principles. Washington, DC: Evidence Synthesis Program, Health Services Research and Development Service, Office of Research and Development, Department of Veterans Affairs. VA ESP Project #09-199; 2019. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/high-reliability-org.cfm

3. Church K, Munro S, Shaughnessy M, Clancy C. Age-Friendly Health Systems: improving care for older adults in the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2023;58(suppl 1):5-8. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14110

4. Farrell TW, Volden TA, Butler JM, et al. Age-friendly care in the Veterans Health Administration: past, present, and future. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(1):18-25. doi:10.1111/jgs.18070

5. Mate K, Fulmer T, Pelton L, et al. Evidence for the 4Ms: interactions and outcomes across the care continuum. J Aging Health. 2021;33(7-8):469-481. doi:10.1177/0898264321991658

6. Tinetti ME, Naik AD, Dindo L, et al. Association of patient priorities-aligned decision-making with patient outcomes and ambulatory health care burden among older adults with multiple chronic conditions: A nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12):1688-1697. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4235

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs. What is whole health? Updated: October 31, 2023. November 30, 2023. https://www.va.gov/wholehealth

8. Patient Priorities Care. Updated 2019. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://patientprioritiescare.org

9. Battar S, Watson Dickerson KR, Sedgwick C, Cmelik T. Understanding principles of high reliability organizations through the eyes of VIONE: a clinical program to improve patient safety by deprescribing potentially inappropriate medications and reducing polypharmacy. Fed Pract. 2019;36(12):564-568.

10. VA Diffusion Marketplace. VIONE- medication optimization and polypharmacy reduction initiative. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://marketplace.va.gov/innovations/vione

11. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. STRIDE program to keep hospitalized veterans mobile. Updated November 6, 2018. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.research.va.gov/research_in_action/STRIDE-program-to-keep-hospitalized-Veterans-mobile.cfm

12. US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Geriatrics and Extended Care. Gerofit: a program promoting exercise and health for older veterans. Updated August 2, 2023. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.va.gov/GERIATRICS/pages/gerofit_Home.asp

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development. VHA’s vision for a high reliability organization. Updated August 14, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/forum/summer20/default.cfm?ForumMenu=summer20-1

14. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development. Three HRO evaluation priorities. Updated August 14, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/forum/summer20/default.cfm?ForumMenu=summer20-2

15. Oster CA, Deakins S. Practical application of high-reliability principles in healthcare to optimize quality and safety outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2018;48(1):50-55. doi:10.1097/NNA.0000000000000570

16. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Age-Friendly Health Systems recognitions. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/Recognition.aspx

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest integrated health care system in the US, providing care to more than 9 million enrolled veterans at 1298 facilities.1 In February 2019, the VHA identified key action steps to become a high reliability organization (HRO), transforming how employees think about patient safety and care quality.2 The VHA is also working toward becoming the largest age-friendly health system in the US to be recognized by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) for its commitment to providing care guided by the 4Ms (what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility), causing no harm, and aligning care with what matters to older veterans.3 In this article, we describe how the Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS) movement supports the culture shift observed in HROs.

Age-Friendly Veteran Care

By 2060, the US population of adults aged ≥ 65 years is projected to increase to about 95 million.3 In the VHA, nearly half of veteran enrollees are aged ≥ 65 years, necessitating evidence-based models of care, such as the 4Ms, to meet their complex care needs.3 Historically, the VHA has been a leader in caring for older adults, recognizing the value of age-friendly care for veterans.4 In 1975, the VHA established the Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Centers (GRECCs) to serve as catalysts for developing, implementing, and refining enduring models of geriatric care.4 For 5 decades, GRECCs have driven innovations related to the 4Ms.

The VHA is well positioned to be a leader in the AFHS movement, building on decades of GRECC innovations and geriatric programs that align with the 4Ms and providing specialized geriatric training for health care professionals to expand age-friendly care to new settings and health systems.4 The AFHS movement organizes the 4Ms into a simple framework for frontline staff, and the VHA has recently begun tracking 4Ms care in the electronic health record (EHR) to facilitate evaluation and continuous improvement.

AFHS use the 4Ms as a framework to be implemented in every care setting, from the emergency department to inpatient units, outpatient settings, and postacute and long-term care. By assessing and acting on each M and practicing the 4Ms collectively, all members of the care team work to improve health outcomes and prevent avoidable harm.5

The 4Ms

What matters, is the driver of this person-centered approach. Any member of the care team may initiate a what matters conversation with the older adult to understand their personal values, health goals, and care preferences. When compared with usual care, care aligned with the older adult’s health priorities has been shown to decrease the use of high-risk medications and reduce treatment burden.6 The VHA has adopted Whole Health principles of care and the Patient Priorities Care approach to identify and support what matters to veterans.7,8

Addressing polypharmacy and identifying and deprescribing potentially inappropriate medications are essential in preventing adverse drug events, drug-drug interactions, and medication nonadherence.9 In the VHA, VIONE (Vital, Important, Optional, Not indicated, Every medication has an indication) is a rapidly expanding medication deprescribing program that exemplifies HRO principles.9 VIONE provides medication management that supports shared decision making, reducing risk and improving patient safety and quality of life.9 As of June 2023, > 600,000 unique veterans have benefited from VIONE, with an average of 2.2 medications deprescribed per patient with an annual cost avoidance of > $100 million.10

Assessing and acting on mentation includes preventing, identifying, and managing depression and dementia in outpatient settings and delirium in hospital and long-term care settings.5 There are many tools and clinical reminders available in the EHR so that interdisciplinary teams can document changes to mentation and identify opportunities for continuous improvement.

Closely aligned with mentation is mobility, with evidence suggesting that regular physical activity reduces the risk of falls (preventing associated complications), maintains physical functioning, and lowers the risk of cognitive impairment and depression.5 Ensuring early, frequent, and safe mobility helps patients achieve better health outcomes and prevent injury.5 Mobility programs within the VHA include the STRIDE program for the inpatient setting and Gerofit for outpatient settings.11,12

HRO Principles

An HRO is a complex environment of care that experiences fewer than anticipated accidents or adverse events by (1) establishing trust among leaders and staff by balancing individual accountability with systems thinking; (2) empowering staff to lead continuous process improvements; and (3) creating an environment where employees feel safe to report harm or near misses, focusing on the reasons errors occur.13 The work of AFHS incorporates HRO principles with an emphasis on 3 elements. First, it involves interactive systems and processes needed to support 4Ms care across care settings. Second, AFHS acknowledge the complexity of age-friendly work and deference to the expertise of interdisciplinary team members. Finally, AFHS are committed to resilience by overcoming failures and challenges to implementation and long-term sustainment as a standard of practice.

Case study

The names and details in this case have been modified to protect patient privacy. It is representative of many Community Living Centers (CLCs) involved in AFHS that work to create a safe, person-centered environment for veterans.

In a CLC team workroom, 2 nurses were discussing a long-term care resident. The nurses approached the attending physician and explained that they were worried about Sgt Johnson, who seemed depressed and sometimes combative. They had noticed a change in his behavior when they helped him clean up after an episode of incontinence and were concerned that he would try to get out of bed on his own and fall. The attending physician thanked them for sharing their concerns. Sgt Johnson was a retired Army veteran who had a long, decorated military career. His chronic health conditions had led to muscle weakness, and he fell and broke a hip before this admission. He had an uneventful hip replacement but was showing signs of depression due to his limited mobility, loss of independence, and inability to live at home without additional support.

The attending physician knocked on the door of his room, sat down next to the bed, and asked, “How are you feeling today?” Sgt Johnson tersely replied, “About the same.” The physician asked, “Sgt Johnson, what matters most to you related to your recovery? What is important to you?” Sgt Johnson responded, “Feeling like a man!” The doctor replied, “So what makes you feel ‘not like a man’?” The Sgt replied, “Having to be cleaned up by the nurses and not being able to use the toilet on my own.” The physician surmised that his decline in physical functioning had a connection to his worsening depression and combativeness and said to the Sgt, “Let’s get the team together and work out a plan to get you strong enough to use a bedside commode by yourself. Let’s make that the first goal in our plan to get you back to using the toilet independently. Can you work with us on that?” He smiled and said, “Sir, yes Sir!”

At the weekly interdisciplinary team meeting, the team discussed Sgt Johnson’s wishes and the nurses’ safety concerns. The physician reported to the team what mattered to the veteran. The nurses arranged for a bedside commode and supplies to be placed in his room, encouraged and assisted him, and provided a privacy screen. The physical therapist continued to support his mobility needs, concentrating on transfers, small steps like standing and turning with a walker to get in position to use the bedside commode, and later the bathroom toilet. The psychologist addressed what matters to Sgt Johnson and his mentation, health goals, and coping strategies. The social worker provided support and counseling for the veteran and his family. The pharmacist checked his medications to be sure that none were affecting his gastrointestinal tract and his ability to move safely and do what matters to him. Knowing what mattered to Sgt Johnson was the driver of the interdisciplinary care plan to provide 4Ms care.

The team worked collaboratively with the veteran to develop and set attainable goals around toileting and regaining his dignity. This improved his overall recovery. As Sgt Johnson became more independent, his mood gradually improved and he began to participate in other activities and interact with other residents on the unit, and he did not experience any falls. By addressing the 4Ms, the interdisciplinary team coordinated efforts to provide high-quality, person-centered care. They built trust with the veteran, shared accountability, and followed HRO principles to keep the veteran safe.

Becoming an Age-Friendly HRO

Becoming an HRO is a dynamic, ever-changing process to maintain high standards, improve care quality, and cause no harm. There are 3 pillars and 5 principles that guide an HRO. The pillars are critical areas of focus and include leadership commitment, culture of safety, and continuous process improvement.14 The first of 5 HRO principles is sensitivity to operations. This is defined as an awareness of how processes and systems impact the entire organization, the downstream impact.15 Focusing on the 4Ms helps develop the capability of frontline staff to provide high-quality care for older adults while ensuring that processes are in place to support the work. The 4Ms provide an efficient way to organize interdisciplinary team meetings, provide warm handoffs using Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation, and standardize documentation. Involvement in the AFHS movement improves communication, care quality, and patient and staff satisfaction to meet this HRO principle.15

The second HRO principle, reluctance to simplify, ensures that direct care staff and leaders delve further into issues to find solutions.15 AFHS use the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle to put the 4Ms into practice; this cycle helps teams test small increments of change, study their performance, and act to ensure that all 4Ms are being practiced as a set. AFHS teams are encouraged to review at least 3 months of data after implementation of the 4Ms, working to find solutions if there are gaps or issues identified.

The third principle, preoccupation with failure, refers to shared attentiveness—being prepared for the unexpected and learning from mistakes.15 The entire AFHS team shares responsibility for providing 4Ms care, where staff are empowered to report any safety concerns or close calls. The fourth principle of deference to expertise includes listening to staff who have the most knowledge for the task at hand, which aligns with the collaborative interdisciplinary teamwork of age-friendly teams.15

The final HRO principle, commitment to resilience, includes continuous learning, interdisciplinary team training, and sharing of lessons learned.15 Although IHI offers 2 levels of AFHS recognition, teams are continuously learning to improve and sustain care beyond level 2, Committed to Care Excellence recognition.16

The Table shows the VHA’s AFHS implementation strategies and the HRO principles adapted from the Joint Commission’s High Reliability Health Care Maturity Model and the IHI’s Framework for Safe, Reliable, and Effective Care. The VHA is developing a national dashboard to capture age-friendly processes and health outcome measures that address patient safety and care quality.

Conclusions

AFHS empowers VHA teams to honor veterans’ care preferences and values, supporting their independence, dignity, and quality of life across care settings. The adoption of AFHS brings evidence-based practices to the point of care by addressing common pitfalls in the care of older adults, drawing attention to, and calling for action on inappropriate medication use, physical inactivity, and assessment of the vulnerable brain. The 4Ms also serve as a framework to continuously improve care and cause zero harm, reinforcing HRO pillars and principles across the VHA, and ensuring that older adults reliably receive the evidence-based, high-quality care they deserve.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest integrated health care system in the US, providing care to more than 9 million enrolled veterans at 1298 facilities.1 In February 2019, the VHA identified key action steps to become a high reliability organization (HRO), transforming how employees think about patient safety and care quality.2 The VHA is also working toward becoming the largest age-friendly health system in the US to be recognized by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) for its commitment to providing care guided by the 4Ms (what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility), causing no harm, and aligning care with what matters to older veterans.3 In this article, we describe how the Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS) movement supports the culture shift observed in HROs.

Age-Friendly Veteran Care

By 2060, the US population of adults aged ≥ 65 years is projected to increase to about 95 million.3 In the VHA, nearly half of veteran enrollees are aged ≥ 65 years, necessitating evidence-based models of care, such as the 4Ms, to meet their complex care needs.3 Historically, the VHA has been a leader in caring for older adults, recognizing the value of age-friendly care for veterans.4 In 1975, the VHA established the Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Centers (GRECCs) to serve as catalysts for developing, implementing, and refining enduring models of geriatric care.4 For 5 decades, GRECCs have driven innovations related to the 4Ms.

The VHA is well positioned to be a leader in the AFHS movement, building on decades of GRECC innovations and geriatric programs that align with the 4Ms and providing specialized geriatric training for health care professionals to expand age-friendly care to new settings and health systems.4 The AFHS movement organizes the 4Ms into a simple framework for frontline staff, and the VHA has recently begun tracking 4Ms care in the electronic health record (EHR) to facilitate evaluation and continuous improvement.

AFHS use the 4Ms as a framework to be implemented in every care setting, from the emergency department to inpatient units, outpatient settings, and postacute and long-term care. By assessing and acting on each M and practicing the 4Ms collectively, all members of the care team work to improve health outcomes and prevent avoidable harm.5

The 4Ms

What matters, is the driver of this person-centered approach. Any member of the care team may initiate a what matters conversation with the older adult to understand their personal values, health goals, and care preferences. When compared with usual care, care aligned with the older adult’s health priorities has been shown to decrease the use of high-risk medications and reduce treatment burden.6 The VHA has adopted Whole Health principles of care and the Patient Priorities Care approach to identify and support what matters to veterans.7,8

Addressing polypharmacy and identifying and deprescribing potentially inappropriate medications are essential in preventing adverse drug events, drug-drug interactions, and medication nonadherence.9 In the VHA, VIONE (Vital, Important, Optional, Not indicated, Every medication has an indication) is a rapidly expanding medication deprescribing program that exemplifies HRO principles.9 VIONE provides medication management that supports shared decision making, reducing risk and improving patient safety and quality of life.9 As of June 2023, > 600,000 unique veterans have benefited from VIONE, with an average of 2.2 medications deprescribed per patient with an annual cost avoidance of > $100 million.10

Assessing and acting on mentation includes preventing, identifying, and managing depression and dementia in outpatient settings and delirium in hospital and long-term care settings.5 There are many tools and clinical reminders available in the EHR so that interdisciplinary teams can document changes to mentation and identify opportunities for continuous improvement.

Closely aligned with mentation is mobility, with evidence suggesting that regular physical activity reduces the risk of falls (preventing associated complications), maintains physical functioning, and lowers the risk of cognitive impairment and depression.5 Ensuring early, frequent, and safe mobility helps patients achieve better health outcomes and prevent injury.5 Mobility programs within the VHA include the STRIDE program for the inpatient setting and Gerofit for outpatient settings.11,12

HRO Principles

An HRO is a complex environment of care that experiences fewer than anticipated accidents or adverse events by (1) establishing trust among leaders and staff by balancing individual accountability with systems thinking; (2) empowering staff to lead continuous process improvements; and (3) creating an environment where employees feel safe to report harm or near misses, focusing on the reasons errors occur.13 The work of AFHS incorporates HRO principles with an emphasis on 3 elements. First, it involves interactive systems and processes needed to support 4Ms care across care settings. Second, AFHS acknowledge the complexity of age-friendly work and deference to the expertise of interdisciplinary team members. Finally, AFHS are committed to resilience by overcoming failures and challenges to implementation and long-term sustainment as a standard of practice.

Case study

The names and details in this case have been modified to protect patient privacy. It is representative of many Community Living Centers (CLCs) involved in AFHS that work to create a safe, person-centered environment for veterans.

In a CLC team workroom, 2 nurses were discussing a long-term care resident. The nurses approached the attending physician and explained that they were worried about Sgt Johnson, who seemed depressed and sometimes combative. They had noticed a change in his behavior when they helped him clean up after an episode of incontinence and were concerned that he would try to get out of bed on his own and fall. The attending physician thanked them for sharing their concerns. Sgt Johnson was a retired Army veteran who had a long, decorated military career. His chronic health conditions had led to muscle weakness, and he fell and broke a hip before this admission. He had an uneventful hip replacement but was showing signs of depression due to his limited mobility, loss of independence, and inability to live at home without additional support.

The attending physician knocked on the door of his room, sat down next to the bed, and asked, “How are you feeling today?” Sgt Johnson tersely replied, “About the same.” The physician asked, “Sgt Johnson, what matters most to you related to your recovery? What is important to you?” Sgt Johnson responded, “Feeling like a man!” The doctor replied, “So what makes you feel ‘not like a man’?” The Sgt replied, “Having to be cleaned up by the nurses and not being able to use the toilet on my own.” The physician surmised that his decline in physical functioning had a connection to his worsening depression and combativeness and said to the Sgt, “Let’s get the team together and work out a plan to get you strong enough to use a bedside commode by yourself. Let’s make that the first goal in our plan to get you back to using the toilet independently. Can you work with us on that?” He smiled and said, “Sir, yes Sir!”

At the weekly interdisciplinary team meeting, the team discussed Sgt Johnson’s wishes and the nurses’ safety concerns. The physician reported to the team what mattered to the veteran. The nurses arranged for a bedside commode and supplies to be placed in his room, encouraged and assisted him, and provided a privacy screen. The physical therapist continued to support his mobility needs, concentrating on transfers, small steps like standing and turning with a walker to get in position to use the bedside commode, and later the bathroom toilet. The psychologist addressed what matters to Sgt Johnson and his mentation, health goals, and coping strategies. The social worker provided support and counseling for the veteran and his family. The pharmacist checked his medications to be sure that none were affecting his gastrointestinal tract and his ability to move safely and do what matters to him. Knowing what mattered to Sgt Johnson was the driver of the interdisciplinary care plan to provide 4Ms care.

The team worked collaboratively with the veteran to develop and set attainable goals around toileting and regaining his dignity. This improved his overall recovery. As Sgt Johnson became more independent, his mood gradually improved and he began to participate in other activities and interact with other residents on the unit, and he did not experience any falls. By addressing the 4Ms, the interdisciplinary team coordinated efforts to provide high-quality, person-centered care. They built trust with the veteran, shared accountability, and followed HRO principles to keep the veteran safe.

Becoming an Age-Friendly HRO

Becoming an HRO is a dynamic, ever-changing process to maintain high standards, improve care quality, and cause no harm. There are 3 pillars and 5 principles that guide an HRO. The pillars are critical areas of focus and include leadership commitment, culture of safety, and continuous process improvement.14 The first of 5 HRO principles is sensitivity to operations. This is defined as an awareness of how processes and systems impact the entire organization, the downstream impact.15 Focusing on the 4Ms helps develop the capability of frontline staff to provide high-quality care for older adults while ensuring that processes are in place to support the work. The 4Ms provide an efficient way to organize interdisciplinary team meetings, provide warm handoffs using Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation, and standardize documentation. Involvement in the AFHS movement improves communication, care quality, and patient and staff satisfaction to meet this HRO principle.15

The second HRO principle, reluctance to simplify, ensures that direct care staff and leaders delve further into issues to find solutions.15 AFHS use the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle to put the 4Ms into practice; this cycle helps teams test small increments of change, study their performance, and act to ensure that all 4Ms are being practiced as a set. AFHS teams are encouraged to review at least 3 months of data after implementation of the 4Ms, working to find solutions if there are gaps or issues identified.

The third principle, preoccupation with failure, refers to shared attentiveness—being prepared for the unexpected and learning from mistakes.15 The entire AFHS team shares responsibility for providing 4Ms care, where staff are empowered to report any safety concerns or close calls. The fourth principle of deference to expertise includes listening to staff who have the most knowledge for the task at hand, which aligns with the collaborative interdisciplinary teamwork of age-friendly teams.15

The final HRO principle, commitment to resilience, includes continuous learning, interdisciplinary team training, and sharing of lessons learned.15 Although IHI offers 2 levels of AFHS recognition, teams are continuously learning to improve and sustain care beyond level 2, Committed to Care Excellence recognition.16

The Table shows the VHA’s AFHS implementation strategies and the HRO principles adapted from the Joint Commission’s High Reliability Health Care Maturity Model and the IHI’s Framework for Safe, Reliable, and Effective Care. The VHA is developing a national dashboard to capture age-friendly processes and health outcome measures that address patient safety and care quality.

Conclusions

AFHS empowers VHA teams to honor veterans’ care preferences and values, supporting their independence, dignity, and quality of life across care settings. The adoption of AFHS brings evidence-based practices to the point of care by addressing common pitfalls in the care of older adults, drawing attention to, and calling for action on inappropriate medication use, physical inactivity, and assessment of the vulnerable brain. The 4Ms also serve as a framework to continuously improve care and cause zero harm, reinforcing HRO pillars and principles across the VHA, and ensuring that older adults reliably receive the evidence-based, high-quality care they deserve.

1. Veterans Health Administration. Providing healthcare for veterans. Updated June 20, 2023. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.va.gov/health

2. Veazie S, Peterson K, Bourne D. Evidence brief: implementation of high reliability organization principles. Washington, DC: Evidence Synthesis Program, Health Services Research and Development Service, Office of Research and Development, Department of Veterans Affairs. VA ESP Project #09-199; 2019. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/high-reliability-org.cfm

3. Church K, Munro S, Shaughnessy M, Clancy C. Age-Friendly Health Systems: improving care for older adults in the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2023;58(suppl 1):5-8. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14110

4. Farrell TW, Volden TA, Butler JM, et al. Age-friendly care in the Veterans Health Administration: past, present, and future. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(1):18-25. doi:10.1111/jgs.18070

5. Mate K, Fulmer T, Pelton L, et al. Evidence for the 4Ms: interactions and outcomes across the care continuum. J Aging Health. 2021;33(7-8):469-481. doi:10.1177/0898264321991658

6. Tinetti ME, Naik AD, Dindo L, et al. Association of patient priorities-aligned decision-making with patient outcomes and ambulatory health care burden among older adults with multiple chronic conditions: A nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12):1688-1697. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4235

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs. What is whole health? Updated: October 31, 2023. November 30, 2023. https://www.va.gov/wholehealth

8. Patient Priorities Care. Updated 2019. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://patientprioritiescare.org

9. Battar S, Watson Dickerson KR, Sedgwick C, Cmelik T. Understanding principles of high reliability organizations through the eyes of VIONE: a clinical program to improve patient safety by deprescribing potentially inappropriate medications and reducing polypharmacy. Fed Pract. 2019;36(12):564-568.

10. VA Diffusion Marketplace. VIONE- medication optimization and polypharmacy reduction initiative. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://marketplace.va.gov/innovations/vione

11. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. STRIDE program to keep hospitalized veterans mobile. Updated November 6, 2018. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.research.va.gov/research_in_action/STRIDE-program-to-keep-hospitalized-Veterans-mobile.cfm

12. US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Geriatrics and Extended Care. Gerofit: a program promoting exercise and health for older veterans. Updated August 2, 2023. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.va.gov/GERIATRICS/pages/gerofit_Home.asp

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development. VHA’s vision for a high reliability organization. Updated August 14, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/forum/summer20/default.cfm?ForumMenu=summer20-1

14. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development. Three HRO evaluation priorities. Updated August 14, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/forum/summer20/default.cfm?ForumMenu=summer20-2

15. Oster CA, Deakins S. Practical application of high-reliability principles in healthcare to optimize quality and safety outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2018;48(1):50-55. doi:10.1097/NNA.0000000000000570

16. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Age-Friendly Health Systems recognitions. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/Recognition.aspx

1. Veterans Health Administration. Providing healthcare for veterans. Updated June 20, 2023. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.va.gov/health

2. Veazie S, Peterson K, Bourne D. Evidence brief: implementation of high reliability organization principles. Washington, DC: Evidence Synthesis Program, Health Services Research and Development Service, Office of Research and Development, Department of Veterans Affairs. VA ESP Project #09-199; 2019. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/high-reliability-org.cfm

3. Church K, Munro S, Shaughnessy M, Clancy C. Age-Friendly Health Systems: improving care for older adults in the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2023;58(suppl 1):5-8. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14110

4. Farrell TW, Volden TA, Butler JM, et al. Age-friendly care in the Veterans Health Administration: past, present, and future. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(1):18-25. doi:10.1111/jgs.18070

5. Mate K, Fulmer T, Pelton L, et al. Evidence for the 4Ms: interactions and outcomes across the care continuum. J Aging Health. 2021;33(7-8):469-481. doi:10.1177/0898264321991658

6. Tinetti ME, Naik AD, Dindo L, et al. Association of patient priorities-aligned decision-making with patient outcomes and ambulatory health care burden among older adults with multiple chronic conditions: A nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12):1688-1697. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4235

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs. What is whole health? Updated: October 31, 2023. November 30, 2023. https://www.va.gov/wholehealth

8. Patient Priorities Care. Updated 2019. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://patientprioritiescare.org

9. Battar S, Watson Dickerson KR, Sedgwick C, Cmelik T. Understanding principles of high reliability organizations through the eyes of VIONE: a clinical program to improve patient safety by deprescribing potentially inappropriate medications and reducing polypharmacy. Fed Pract. 2019;36(12):564-568.

10. VA Diffusion Marketplace. VIONE- medication optimization and polypharmacy reduction initiative. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://marketplace.va.gov/innovations/vione

11. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. STRIDE program to keep hospitalized veterans mobile. Updated November 6, 2018. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.research.va.gov/research_in_action/STRIDE-program-to-keep-hospitalized-Veterans-mobile.cfm

12. US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Geriatrics and Extended Care. Gerofit: a program promoting exercise and health for older veterans. Updated August 2, 2023. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.va.gov/GERIATRICS/pages/gerofit_Home.asp

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development. VHA’s vision for a high reliability organization. Updated August 14, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/forum/summer20/default.cfm?ForumMenu=summer20-1

14. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development. Three HRO evaluation priorities. Updated August 14, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/forum/summer20/default.cfm?ForumMenu=summer20-2

15. Oster CA, Deakins S. Practical application of high-reliability principles in healthcare to optimize quality and safety outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2018;48(1):50-55. doi:10.1097/NNA.0000000000000570

16. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Age-Friendly Health Systems recognitions. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/Recognition.aspx

JAMA Internal Medicine Editor Recaps 2023’s High-Impact Research

Harvard Medical School’s Sharon K. Inouye, MD, MPH, is editor in chief of JAMA Internal Medicine and a leading voice in American gerontology. We asked her to choose five of the influential journal’s most impactful studies from 2023 and highlight important take-home messages for internists and their colleagues.

Q: One of the studies you chose suggests that the antiviral nirmatrelvir (Paxlovid) can ward off long COVID. Could you recap the findings?

A: Researchers followed a group of more than 280,000 Department of Veterans Affairs patients who were seen in 2022, had a positive COVID test, and had at least one risk factor for severe COVID. They focused on those who survived to 30 days after their COVID infection and compared those who received the drug within the first 5 days of a positive test with an equivalent control group.

They found that 13 long COVID symptoms were all significantly less common (relative risk = 0.74) in those who received nirmatrelvir. This was true no matter whether they’d ever had a COVID vaccination.

Q: How should this research affect clinical practice?

A: You can’t generalize from this to everyone because, of course, not everyone was included in this study. But it is highly suggestive that this drug is very effective for preventing long COVID.

Nirmatrelvir was touted as being able to shorten duration of illness and prevent hospitalization. But if you were low risk or you were already well into your COVID course, it wasn’t like rush, rush, rush to the doctor to get it.

This changes that equation because we know long COVID is such a huge issue. The vast majority of doctors who work with COVID patients and know this are now being more aggressive about prescribing it.

Q: What about patients whom the CDC considers to be at less risk — people with up-to-date vaccinations who are under 50 with mild-to-moderate COVID and no higher-risk medical conditions? Should they take nirmatrelvir?

A: The evidence is not 100% in yet. A study like this one needs to be repeated and include younger people without any risk factors to see if we see the same thing. So it’s a personal choice, and a personal calculus needs to be done. A lot of people are making that choice [to take the drug], and it can be a rational decision.

Q: You also chose a study that links high thyroid hormone levels to higher rates of dementia. What did it reveal?

A: This study looks at patients who had thyrotoxicosis — a thyroid level that’s too high — from hormone produced endogenously, and exogenously. Researchers tracked almost 66,000 patients aged 65 and older and found that thyrotoxicosis from all causes, whether it was endogenous or exogenous, was linked to an increased risk of dementia in a dose-response relationship (adjusted hazard ratio = 1.39).

Q: Is there a clinical take-home message here?

A: When we start patients on thyroid medication, they don’t always get reassessed on a regular basis. Given this finding, a TSH [thyroid-stimulating hormone] level is indicated during the annual wellness check that patients on Medicare can get every year.

Q: Is TSH measured as part of routine blood tests?

A: No it’s not. It has to be ordered. I think that’s why we’re seeing this problem to begin with — because it’s not something we all have awareness about. I wasn’t aware myself that mildly high levels of thyroid could increase the risk of cognitive impairment. Certainly, I’m going to be much more aware in my practice.

Q: You also picked a study about silicosis in workers who are exposed to dust when they make engineered stone countertops, also known as quartz countertops. What were the findings?

A: Silicosis is a very serious lung condition that develops from exposure to crystalline silica. Essentially, sand gets inhaled into the lungs. Workers can be exposed when they’re making engineered stone countertops, the most popular countertops now in the United States.

This study is based on statewide surveys from 2019 to 2022 that the California Department of Public Health does routinely. They gathered cases of silicosis and found 52 — all men with an average age of 45. All but one were Latino immigrants, and most either had no insurance or very poor insurance.

Q: The study found that “diagnosis was delayed in 58%, with 38% presenting with advanced disease (progressive massive fibrosis), and 19% died.” What does that tell you?

A: It’s a very serious condition. Once it gets to the advanced stage, it will just continue to progress, and the person will die. That’s why it’s so important to know that it’s absolutely preventable.

Q: Is there a message here for internists?

A: If you treat a lot of immigrants or work in an area where there are a lot of industrial workers, you’re going to want to have a very high suspicion about it. If you see an atypical pattern on the chest x-ray or via diffusion scoring, have a low threshold for getting a pulmonary function test.

Doctors need to be aware and diagnose this very quickly. When patients present, you can pull them out of that work environment or put mitigation systems into place.

Q: California regulators were expected to put emergency rules into place in late December to protect workers. Did this study play a role in focusing attention on the problem?

A: This article, along with a commentary and podcast that we put out, really helped with advocacy to improve health and safety for workers at stone-cutting and fabrication shops.

Q: You were impressed by another study about airborne dangers, this one linking air pollution to dementia. What did researchers discover?

A: [This analysis] of more than 27,000 people in the Health and Retirement Study, a respected and rich database, found that exposure to air pollution was associated with greater rates of dementia — an increase of about 8% a year. Exposure to agricultural emissions and wildfire smoke were most robustly associated with a greater risk of dementia.

Q: How are these findings important, especially in light of the unhealthy air spawned by recent wildfires in the United States and Canada?

A: Studies like this will make it even more compelling that we are better prepared for air quality issues.

I grew up in Los Angeles, where smog and pollution were very big issues. I was constantly hearing about various mitigation strategies that were going into place. But after I moved to the East Coast, I almost never heard about prevention.

Now, I’m hoping we can keep this topic in the national conversation.

Q: You also highlighted a systematic review of the use of restraints in the emergency department. Why did you choose this research?

A: At JAMA Internal Medicine, we’re really focused on ways we can address health disparities and raise awareness of potential unconscious bias.

This review looked at 10 studies that included more than 2.5 million patient encounters, including 24,000 incidents of physical restraint use. They found that the overall rate of use of restraints was low at below 1%.

But when they are used, Black patients were 1.3 times more likely to be restrained than White patients.

Q: What’s the message here?

A: This is an important start to recognizing these differences and then changing our behavior. Perhaps restraints don’t need to be used as often in light of evidence, for example, of increased rates of misdiagnosis of psychosis in the Black population.

Q: How should physicians change their approach to restraints?

A: Restraints are not to be used to control disruption — wild behavior or verbal outbursts. They’re for when someone is a danger to themselves or others.

Dr. Inouye has no conflicts of interest.

Harvard Medical School’s Sharon K. Inouye, MD, MPH, is editor in chief of JAMA Internal Medicine and a leading voice in American gerontology. We asked her to choose five of the influential journal’s most impactful studies from 2023 and highlight important take-home messages for internists and their colleagues.

Q: One of the studies you chose suggests that the antiviral nirmatrelvir (Paxlovid) can ward off long COVID. Could you recap the findings?

A: Researchers followed a group of more than 280,000 Department of Veterans Affairs patients who were seen in 2022, had a positive COVID test, and had at least one risk factor for severe COVID. They focused on those who survived to 30 days after their COVID infection and compared those who received the drug within the first 5 days of a positive test with an equivalent control group.

They found that 13 long COVID symptoms were all significantly less common (relative risk = 0.74) in those who received nirmatrelvir. This was true no matter whether they’d ever had a COVID vaccination.

Q: How should this research affect clinical practice?

A: You can’t generalize from this to everyone because, of course, not everyone was included in this study. But it is highly suggestive that this drug is very effective for preventing long COVID.

Nirmatrelvir was touted as being able to shorten duration of illness and prevent hospitalization. But if you were low risk or you were already well into your COVID course, it wasn’t like rush, rush, rush to the doctor to get it.

This changes that equation because we know long COVID is such a huge issue. The vast majority of doctors who work with COVID patients and know this are now being more aggressive about prescribing it.

Q: What about patients whom the CDC considers to be at less risk — people with up-to-date vaccinations who are under 50 with mild-to-moderate COVID and no higher-risk medical conditions? Should they take nirmatrelvir?

A: The evidence is not 100% in yet. A study like this one needs to be repeated and include younger people without any risk factors to see if we see the same thing. So it’s a personal choice, and a personal calculus needs to be done. A lot of people are making that choice [to take the drug], and it can be a rational decision.

Q: You also chose a study that links high thyroid hormone levels to higher rates of dementia. What did it reveal?

A: This study looks at patients who had thyrotoxicosis — a thyroid level that’s too high — from hormone produced endogenously, and exogenously. Researchers tracked almost 66,000 patients aged 65 and older and found that thyrotoxicosis from all causes, whether it was endogenous or exogenous, was linked to an increased risk of dementia in a dose-response relationship (adjusted hazard ratio = 1.39).

Q: Is there a clinical take-home message here?

A: When we start patients on thyroid medication, they don’t always get reassessed on a regular basis. Given this finding, a TSH [thyroid-stimulating hormone] level is indicated during the annual wellness check that patients on Medicare can get every year.

Q: Is TSH measured as part of routine blood tests?

A: No it’s not. It has to be ordered. I think that’s why we’re seeing this problem to begin with — because it’s not something we all have awareness about. I wasn’t aware myself that mildly high levels of thyroid could increase the risk of cognitive impairment. Certainly, I’m going to be much more aware in my practice.

Q: You also picked a study about silicosis in workers who are exposed to dust when they make engineered stone countertops, also known as quartz countertops. What were the findings?

A: Silicosis is a very serious lung condition that develops from exposure to crystalline silica. Essentially, sand gets inhaled into the lungs. Workers can be exposed when they’re making engineered stone countertops, the most popular countertops now in the United States.

This study is based on statewide surveys from 2019 to 2022 that the California Department of Public Health does routinely. They gathered cases of silicosis and found 52 — all men with an average age of 45. All but one were Latino immigrants, and most either had no insurance or very poor insurance.

Q: The study found that “diagnosis was delayed in 58%, with 38% presenting with advanced disease (progressive massive fibrosis), and 19% died.” What does that tell you?

A: It’s a very serious condition. Once it gets to the advanced stage, it will just continue to progress, and the person will die. That’s why it’s so important to know that it’s absolutely preventable.

Q: Is there a message here for internists?

A: If you treat a lot of immigrants or work in an area where there are a lot of industrial workers, you’re going to want to have a very high suspicion about it. If you see an atypical pattern on the chest x-ray or via diffusion scoring, have a low threshold for getting a pulmonary function test.

Doctors need to be aware and diagnose this very quickly. When patients present, you can pull them out of that work environment or put mitigation systems into place.

Q: California regulators were expected to put emergency rules into place in late December to protect workers. Did this study play a role in focusing attention on the problem?

A: This article, along with a commentary and podcast that we put out, really helped with advocacy to improve health and safety for workers at stone-cutting and fabrication shops.

Q: You were impressed by another study about airborne dangers, this one linking air pollution to dementia. What did researchers discover?

A: [This analysis] of more than 27,000 people in the Health and Retirement Study, a respected and rich database, found that exposure to air pollution was associated with greater rates of dementia — an increase of about 8% a year. Exposure to agricultural emissions and wildfire smoke were most robustly associated with a greater risk of dementia.

Q: How are these findings important, especially in light of the unhealthy air spawned by recent wildfires in the United States and Canada?

A: Studies like this will make it even more compelling that we are better prepared for air quality issues.

I grew up in Los Angeles, where smog and pollution were very big issues. I was constantly hearing about various mitigation strategies that were going into place. But after I moved to the East Coast, I almost never heard about prevention.

Now, I’m hoping we can keep this topic in the national conversation.

Q: You also highlighted a systematic review of the use of restraints in the emergency department. Why did you choose this research?

A: At JAMA Internal Medicine, we’re really focused on ways we can address health disparities and raise awareness of potential unconscious bias.

This review looked at 10 studies that included more than 2.5 million patient encounters, including 24,000 incidents of physical restraint use. They found that the overall rate of use of restraints was low at below 1%.

But when they are used, Black patients were 1.3 times more likely to be restrained than White patients.

Q: What’s the message here?

A: This is an important start to recognizing these differences and then changing our behavior. Perhaps restraints don’t need to be used as often in light of evidence, for example, of increased rates of misdiagnosis of psychosis in the Black population.

Q: How should physicians change their approach to restraints?

A: Restraints are not to be used to control disruption — wild behavior or verbal outbursts. They’re for when someone is a danger to themselves or others.

Dr. Inouye has no conflicts of interest.

Harvard Medical School’s Sharon K. Inouye, MD, MPH, is editor in chief of JAMA Internal Medicine and a leading voice in American gerontology. We asked her to choose five of the influential journal’s most impactful studies from 2023 and highlight important take-home messages for internists and their colleagues.

Q: One of the studies you chose suggests that the antiviral nirmatrelvir (Paxlovid) can ward off long COVID. Could you recap the findings?

A: Researchers followed a group of more than 280,000 Department of Veterans Affairs patients who were seen in 2022, had a positive COVID test, and had at least one risk factor for severe COVID. They focused on those who survived to 30 days after their COVID infection and compared those who received the drug within the first 5 days of a positive test with an equivalent control group.

They found that 13 long COVID symptoms were all significantly less common (relative risk = 0.74) in those who received nirmatrelvir. This was true no matter whether they’d ever had a COVID vaccination.

Q: How should this research affect clinical practice?

A: You can’t generalize from this to everyone because, of course, not everyone was included in this study. But it is highly suggestive that this drug is very effective for preventing long COVID.

Nirmatrelvir was touted as being able to shorten duration of illness and prevent hospitalization. But if you were low risk or you were already well into your COVID course, it wasn’t like rush, rush, rush to the doctor to get it.

This changes that equation because we know long COVID is such a huge issue. The vast majority of doctors who work with COVID patients and know this are now being more aggressive about prescribing it.

Q: What about patients whom the CDC considers to be at less risk — people with up-to-date vaccinations who are under 50 with mild-to-moderate COVID and no higher-risk medical conditions? Should they take nirmatrelvir?

A: The evidence is not 100% in yet. A study like this one needs to be repeated and include younger people without any risk factors to see if we see the same thing. So it’s a personal choice, and a personal calculus needs to be done. A lot of people are making that choice [to take the drug], and it can be a rational decision.

Q: You also chose a study that links high thyroid hormone levels to higher rates of dementia. What did it reveal?

A: This study looks at patients who had thyrotoxicosis — a thyroid level that’s too high — from hormone produced endogenously, and exogenously. Researchers tracked almost 66,000 patients aged 65 and older and found that thyrotoxicosis from all causes, whether it was endogenous or exogenous, was linked to an increased risk of dementia in a dose-response relationship (adjusted hazard ratio = 1.39).

Q: Is there a clinical take-home message here?

A: When we start patients on thyroid medication, they don’t always get reassessed on a regular basis. Given this finding, a TSH [thyroid-stimulating hormone] level is indicated during the annual wellness check that patients on Medicare can get every year.

Q: Is TSH measured as part of routine blood tests?

A: No it’s not. It has to be ordered. I think that’s why we’re seeing this problem to begin with — because it’s not something we all have awareness about. I wasn’t aware myself that mildly high levels of thyroid could increase the risk of cognitive impairment. Certainly, I’m going to be much more aware in my practice.

Q: You also picked a study about silicosis in workers who are exposed to dust when they make engineered stone countertops, also known as quartz countertops. What were the findings?

A: Silicosis is a very serious lung condition that develops from exposure to crystalline silica. Essentially, sand gets inhaled into the lungs. Workers can be exposed when they’re making engineered stone countertops, the most popular countertops now in the United States.

This study is based on statewide surveys from 2019 to 2022 that the California Department of Public Health does routinely. They gathered cases of silicosis and found 52 — all men with an average age of 45. All but one were Latino immigrants, and most either had no insurance or very poor insurance.

Q: The study found that “diagnosis was delayed in 58%, with 38% presenting with advanced disease (progressive massive fibrosis), and 19% died.” What does that tell you?

A: It’s a very serious condition. Once it gets to the advanced stage, it will just continue to progress, and the person will die. That’s why it’s so important to know that it’s absolutely preventable.

Q: Is there a message here for internists?

A: If you treat a lot of immigrants or work in an area where there are a lot of industrial workers, you’re going to want to have a very high suspicion about it. If you see an atypical pattern on the chest x-ray or via diffusion scoring, have a low threshold for getting a pulmonary function test.

Doctors need to be aware and diagnose this very quickly. When patients present, you can pull them out of that work environment or put mitigation systems into place.

Q: California regulators were expected to put emergency rules into place in late December to protect workers. Did this study play a role in focusing attention on the problem?

A: This article, along with a commentary and podcast that we put out, really helped with advocacy to improve health and safety for workers at stone-cutting and fabrication shops.

Q: You were impressed by another study about airborne dangers, this one linking air pollution to dementia. What did researchers discover?

A: [This analysis] of more than 27,000 people in the Health and Retirement Study, a respected and rich database, found that exposure to air pollution was associated with greater rates of dementia — an increase of about 8% a year. Exposure to agricultural emissions and wildfire smoke were most robustly associated with a greater risk of dementia.

Q: How are these findings important, especially in light of the unhealthy air spawned by recent wildfires in the United States and Canada?

A: Studies like this will make it even more compelling that we are better prepared for air quality issues.

I grew up in Los Angeles, where smog and pollution were very big issues. I was constantly hearing about various mitigation strategies that were going into place. But after I moved to the East Coast, I almost never heard about prevention.

Now, I’m hoping we can keep this topic in the national conversation.

Q: You also highlighted a systematic review of the use of restraints in the emergency department. Why did you choose this research?

A: At JAMA Internal Medicine, we’re really focused on ways we can address health disparities and raise awareness of potential unconscious bias.

This review looked at 10 studies that included more than 2.5 million patient encounters, including 24,000 incidents of physical restraint use. They found that the overall rate of use of restraints was low at below 1%.

But when they are used, Black patients were 1.3 times more likely to be restrained than White patients.

Q: What’s the message here?

A: This is an important start to recognizing these differences and then changing our behavior. Perhaps restraints don’t need to be used as often in light of evidence, for example, of increased rates of misdiagnosis of psychosis in the Black population.

Q: How should physicians change their approach to restraints?

A: Restraints are not to be used to control disruption — wild behavior or verbal outbursts. They’re for when someone is a danger to themselves or others.

Dr. Inouye has no conflicts of interest.

Older Adults Want Medicare, Insurance to Cover Obesity Drugs

Weight-loss drugs should be covered by Medicare and by other health insurance, according to a poll of US adults aged 50-80 years.

Among more than 2600 polled, 83% say that health insurance should cover prescription weight-loss drugs that have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and 76% say Medicare should cover such drugs. However, only 30% would be willing to pay higher Medicare premiums to have these medications covered.

Among the 27% of respondents who say they are overweight, 63% are interested in taking such medications, as are 45% of those with diabetes, regardless of weight.

The University of Michigan (U-M) National Poll on Healthy Aging was published online on December 13, 2023.

High Awareness

The findings come at a time when injectable glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), such as Ozempic, Wegovy, Zepbound, and Mounjaro, are receiving a lot of public attention, the university noted.

Overall, 64% of survey respondents had heard of at least one prescription medication used for weight management.

By brand name, 61% had heard of Ozempic, approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes but prescribed off label for weight loss; 18% had heard of Wegovy; and 13% had heard of the anorexiant drug phentermine .

Very few respondents (3% for each) had heard of the GLP-1 RA Saxenda, Qsymia (phentermine plus the anticonvulsant topiramate ), and the opiate antagonist Contrave.

Zepbound, the obesity -specific form of the diabetes drug Mounjaro, received FDA approval after the poll was taken and was not included in survey questions.

Among respondents who had heard of at least one prescription medication used for weight management, 58% had heard about them through the news (eg, TV, magazines, newspapers) and 53% had heard about them from an advertisement on TV, the Internet, or radio. Only 11% heard about them from their healthcare providers.

Respondents more likely to be interested in taking a prescription medication for weight management included women, those aged 50-64 years, Black persons, Hispanic persons, those with household incomes of less than $60,000 annually, those with lower levels of education, those in fair or poor physical or mental health, and those with a health problem or disability limiting their daily activities.

Spotty Coverage

The GLP-1 RAs can cost more than $12,000 a year for people who pay out of pocket, the university noted.

A Medicare Part D law passed in 2003 prohibits Medicare from covering medications for weight loss, although currently it can cover such drugs to help people with type 2 diabetes manage their weight.

Medicaid covers the cost of antiobesity drugs in some states.

Most private plans and the Veterans Health Administration cover them, but with restrictions due to high monthly costs for the newer medications.

The American Medical Association recently called on insurers to cover evidence-based weight-loss medications.

The strong demand for these medications, including for off-label purposes by people willing to pay full price, has created major shortages, the university noted.

“As these medications grow in awareness and use, and insurers make decisions about coverage, it’s crucial for patients who have obesity or diabetes, or who are overweight with other health problems, to talk with their healthcare providers about their options,” said poll director Jeffrey Kullgren, MD, MPH, MS, a primary care physician at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System and associate professor of internal medicine at U-M.

Other weight-management strategies that respondents think should be covered by health insurance include sessions with a registered dietitian or nutritionist (85%); weight-loss surgery (73%); gym or fitness facility memberships (65%); apps or online programs to track diet, exercise, and/or behavior change (58%); and sessions with a personal trainer (53%).

The randomly selected nationally representative household survey of 2657 adults was conducted from July 17 to August 7, 2023, by NORC at the University of Chicago for the U-M Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation. The sample was subsequently weighted to reflect population figures from the US Census Bureau. The completion rate was 50% among those contacted to participate. The margin of error is ±1 to 5 percentage points for questions asked of the full sample and higher among subgroups.

The poll is based at the U-M Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation and supported by AARP and Michigan Medicine, the University of Michigan’s academic medical center.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Weight-loss drugs should be covered by Medicare and by other health insurance, according to a poll of US adults aged 50-80 years.

Among more than 2600 polled, 83% say that health insurance should cover prescription weight-loss drugs that have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and 76% say Medicare should cover such drugs. However, only 30% would be willing to pay higher Medicare premiums to have these medications covered.

Among the 27% of respondents who say they are overweight, 63% are interested in taking such medications, as are 45% of those with diabetes, regardless of weight.

The University of Michigan (U-M) National Poll on Healthy Aging was published online on December 13, 2023.

High Awareness

The findings come at a time when injectable glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), such as Ozempic, Wegovy, Zepbound, and Mounjaro, are receiving a lot of public attention, the university noted.

Overall, 64% of survey respondents had heard of at least one prescription medication used for weight management.

By brand name, 61% had heard of Ozempic, approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes but prescribed off label for weight loss; 18% had heard of Wegovy; and 13% had heard of the anorexiant drug phentermine .

Very few respondents (3% for each) had heard of the GLP-1 RA Saxenda, Qsymia (phentermine plus the anticonvulsant topiramate ), and the opiate antagonist Contrave.

Zepbound, the obesity -specific form of the diabetes drug Mounjaro, received FDA approval after the poll was taken and was not included in survey questions.

Among respondents who had heard of at least one prescription medication used for weight management, 58% had heard about them through the news (eg, TV, magazines, newspapers) and 53% had heard about them from an advertisement on TV, the Internet, or radio. Only 11% heard about them from their healthcare providers.

Respondents more likely to be interested in taking a prescription medication for weight management included women, those aged 50-64 years, Black persons, Hispanic persons, those with household incomes of less than $60,000 annually, those with lower levels of education, those in fair or poor physical or mental health, and those with a health problem or disability limiting their daily activities.

Spotty Coverage

The GLP-1 RAs can cost more than $12,000 a year for people who pay out of pocket, the university noted.

A Medicare Part D law passed in 2003 prohibits Medicare from covering medications for weight loss, although currently it can cover such drugs to help people with type 2 diabetes manage their weight.

Medicaid covers the cost of antiobesity drugs in some states.