User login

In Lecanemab Alzheimer Extension Study, Placebo Roll-Over Group Does Not Catch Up

DENVER — , according to a first report of 6-month OLE data.

Due to the steady disease progression observed after the switch of placebo to active therapy, the message of these data is that “early initiation of lecanemab is important,” according to Michael Irizarry, MD, the senior vice president of clinical research at Eisai Ltd, which markets lecanemab.

The 6-month OLE data along with data from a tau PET substudy were presented by Dr. Irizarry at the 2024 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

From the start of the OLE through the 6-month follow-up, the downward trajectory of cognitive function, as measured with the Clinical Dementia Rating – Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB), has been parallel for the lecanemab-start and switch arms. As a result, the degree of separation between active and placebo groups over the course of the OLE has remained unchanged from the end of the randomized trial.

This does not rule out any benefit in the switch arm, according to Dr. Irizarry. Although there was no discernible change in the trajectory of decline among placebo patients after they were switched to lecanemab, Dr. Irizarry postulated that this might overlook the greater likely decline over time with no treatment.

“There was no placebo group in the OLE to compare with those on active treatment,” he pointed out. He then juxtaposed data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Over the same 6-month timeframe, these data show a hypothetical separation of the curves if no treatment had been received.

The 6-month OLE data provide a preliminary look at outcomes in a planned 4-year follow-up. At the end of the randomized CLARITY trial, the mean decline from the baseline CDR-SB score of 3.2, was 1.21 in the lecanemab group, translating into a 38% decline, and 1.66 in the placebo group, translating into about a 50% decline. Over the 6 months of OLE, there has been a further mean CDR-SB reduction of approximately 0.6 in both arms, suggesting a further 18% decline from baseline.

Additional Data

In the pivotal CLARITY trial, which was published a few months prior to regulatory approval early last year, 1785 patients were randomized to 10 mg/kg lecanemab or placebo infused every 2 weeks. At the end of 18 months, the superiority of lecanemab for the primary endpoint of adverse change in CDR-SB was highly significant (P < .001) as were the differences in key secondary endpoints, such as Alzheimer’s Disease Composite Score (P < .001).

Of those who participated in CLARITY, 1385 patients entered the OLE. Placebo patients were switched to lecanemab which is being maintained in all patients on the trial schedule of 10 mg/kg administered by intravenous infusion every 2 weeks.

In addition to the overall OLE 6-month data, which has not raised any new safety signals, Dr. Irizarry provided a new look at the PET TAU substudy with a focus on patients who entered the study with a low relative tau burden. Of the three classifications, which also included medium and high tau, as measured with positron-emission tomography (PET), the low tau group represented 41.2% of the 342 tau PET substudy participants. With only 2.9% entering the study with a high tau burden, almost all the others fell in the medium stratification.

Due to the potential for a lower therapeutic response, “patients with low Tau are often excluded from trials,” Dr. Irizarry said. But the sizable proportion of low tau patients has permitted an assessment of relative response with lecanemab, which turned out to be substantial.

“Consistent rates of clinical stability or improvements were observed regardless of baseline tau levels with the highest rates of improvements observed for the low tau group after 24 months of follow-up,” Dr. Irizarry reported.

In previously reported results from the tau PET substudy, lecanemab was shown to slow tau spread at least numerically in every section of the brain evaluated, including the frontal, cingulate, parietal, and whole cortical gray matter areas. The reductions reached significance for the medial temporal (P = .0024), meta temporal (P = .012), and temporal (P = .16) portions.

When most recently evaluated in the OLE, the CDR-SB score declined 38% less among those treated with lecanemab than those treated with placebo in the subgroup enrolled in the tau PET substudy.

Relative to those with intermediate or high tau, patients in the low tau had an even greater reduction in cognitive decline than those with higher tau burdens. Although Dr. Irizarry cautioned that greater baseline CDR-SB scores exaggerated the treatment effect in the low tau group, the message is that “a lecanemab treatment effect is seen even when baseline tau levels are low.”

Now, with the recent market withdrawal of aducanumab, another anti-amyloid monoclonal antibody that was previously approved for Alzheimer’s disease, lecanemab is the only therapy currently available for the goal of changing disease progression, not just modifying symptoms.

Looking Long Term

Both sets of data provide important messages for clinicians, according to Marcelo Matiello, MD, a physician investigator at Mass General Hospital and associate professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“Clinicians are really looking for more data because this remains a relatively new drug,” he said. Both sets of findings presented by Dr. Irizarry “look good but the follow-up is still short, so I think everyone is still looking closely at long-term safety and efficacy.”

The need for continuous indefinite therapy is one concern that Dr. Matiello expressed. As moderator of the session in which these data were presented, Dr. Matiello specifically asked Dr. Irizarry if there are plans to explore whether periods without treatment might be a means to reduce the cost and burden of frequent infusions while preserving cognitive gains.

In response, Dr. Irizarry said that earlier studies showed rapid progression when lecanemab was stopped. On this basis, he thinks therapy must be maintained, but he did say that there are plans to look at less frequent dosing, such as once per month. He also said that a subcutaneous formulation in development might also reduce the burden of prolonged treatment.

Dr. Irizarry is an employee of Eisai Ltd., which manufacturers lecanemab. Dr. Matiello reports no potential conflicts of interest.

DENVER — , according to a first report of 6-month OLE data.

Due to the steady disease progression observed after the switch of placebo to active therapy, the message of these data is that “early initiation of lecanemab is important,” according to Michael Irizarry, MD, the senior vice president of clinical research at Eisai Ltd, which markets lecanemab.

The 6-month OLE data along with data from a tau PET substudy were presented by Dr. Irizarry at the 2024 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

From the start of the OLE through the 6-month follow-up, the downward trajectory of cognitive function, as measured with the Clinical Dementia Rating – Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB), has been parallel for the lecanemab-start and switch arms. As a result, the degree of separation between active and placebo groups over the course of the OLE has remained unchanged from the end of the randomized trial.

This does not rule out any benefit in the switch arm, according to Dr. Irizarry. Although there was no discernible change in the trajectory of decline among placebo patients after they were switched to lecanemab, Dr. Irizarry postulated that this might overlook the greater likely decline over time with no treatment.

“There was no placebo group in the OLE to compare with those on active treatment,” he pointed out. He then juxtaposed data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Over the same 6-month timeframe, these data show a hypothetical separation of the curves if no treatment had been received.

The 6-month OLE data provide a preliminary look at outcomes in a planned 4-year follow-up. At the end of the randomized CLARITY trial, the mean decline from the baseline CDR-SB score of 3.2, was 1.21 in the lecanemab group, translating into a 38% decline, and 1.66 in the placebo group, translating into about a 50% decline. Over the 6 months of OLE, there has been a further mean CDR-SB reduction of approximately 0.6 in both arms, suggesting a further 18% decline from baseline.

Additional Data

In the pivotal CLARITY trial, which was published a few months prior to regulatory approval early last year, 1785 patients were randomized to 10 mg/kg lecanemab or placebo infused every 2 weeks. At the end of 18 months, the superiority of lecanemab for the primary endpoint of adverse change in CDR-SB was highly significant (P < .001) as were the differences in key secondary endpoints, such as Alzheimer’s Disease Composite Score (P < .001).

Of those who participated in CLARITY, 1385 patients entered the OLE. Placebo patients were switched to lecanemab which is being maintained in all patients on the trial schedule of 10 mg/kg administered by intravenous infusion every 2 weeks.

In addition to the overall OLE 6-month data, which has not raised any new safety signals, Dr. Irizarry provided a new look at the PET TAU substudy with a focus on patients who entered the study with a low relative tau burden. Of the three classifications, which also included medium and high tau, as measured with positron-emission tomography (PET), the low tau group represented 41.2% of the 342 tau PET substudy participants. With only 2.9% entering the study with a high tau burden, almost all the others fell in the medium stratification.

Due to the potential for a lower therapeutic response, “patients with low Tau are often excluded from trials,” Dr. Irizarry said. But the sizable proportion of low tau patients has permitted an assessment of relative response with lecanemab, which turned out to be substantial.

“Consistent rates of clinical stability or improvements were observed regardless of baseline tau levels with the highest rates of improvements observed for the low tau group after 24 months of follow-up,” Dr. Irizarry reported.

In previously reported results from the tau PET substudy, lecanemab was shown to slow tau spread at least numerically in every section of the brain evaluated, including the frontal, cingulate, parietal, and whole cortical gray matter areas. The reductions reached significance for the medial temporal (P = .0024), meta temporal (P = .012), and temporal (P = .16) portions.

When most recently evaluated in the OLE, the CDR-SB score declined 38% less among those treated with lecanemab than those treated with placebo in the subgroup enrolled in the tau PET substudy.

Relative to those with intermediate or high tau, patients in the low tau had an even greater reduction in cognitive decline than those with higher tau burdens. Although Dr. Irizarry cautioned that greater baseline CDR-SB scores exaggerated the treatment effect in the low tau group, the message is that “a lecanemab treatment effect is seen even when baseline tau levels are low.”

Now, with the recent market withdrawal of aducanumab, another anti-amyloid monoclonal antibody that was previously approved for Alzheimer’s disease, lecanemab is the only therapy currently available for the goal of changing disease progression, not just modifying symptoms.

Looking Long Term

Both sets of data provide important messages for clinicians, according to Marcelo Matiello, MD, a physician investigator at Mass General Hospital and associate professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“Clinicians are really looking for more data because this remains a relatively new drug,” he said. Both sets of findings presented by Dr. Irizarry “look good but the follow-up is still short, so I think everyone is still looking closely at long-term safety and efficacy.”

The need for continuous indefinite therapy is one concern that Dr. Matiello expressed. As moderator of the session in which these data were presented, Dr. Matiello specifically asked Dr. Irizarry if there are plans to explore whether periods without treatment might be a means to reduce the cost and burden of frequent infusions while preserving cognitive gains.

In response, Dr. Irizarry said that earlier studies showed rapid progression when lecanemab was stopped. On this basis, he thinks therapy must be maintained, but he did say that there are plans to look at less frequent dosing, such as once per month. He also said that a subcutaneous formulation in development might also reduce the burden of prolonged treatment.

Dr. Irizarry is an employee of Eisai Ltd., which manufacturers lecanemab. Dr. Matiello reports no potential conflicts of interest.

DENVER — , according to a first report of 6-month OLE data.

Due to the steady disease progression observed after the switch of placebo to active therapy, the message of these data is that “early initiation of lecanemab is important,” according to Michael Irizarry, MD, the senior vice president of clinical research at Eisai Ltd, which markets lecanemab.

The 6-month OLE data along with data from a tau PET substudy were presented by Dr. Irizarry at the 2024 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

From the start of the OLE through the 6-month follow-up, the downward trajectory of cognitive function, as measured with the Clinical Dementia Rating – Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB), has been parallel for the lecanemab-start and switch arms. As a result, the degree of separation between active and placebo groups over the course of the OLE has remained unchanged from the end of the randomized trial.

This does not rule out any benefit in the switch arm, according to Dr. Irizarry. Although there was no discernible change in the trajectory of decline among placebo patients after they were switched to lecanemab, Dr. Irizarry postulated that this might overlook the greater likely decline over time with no treatment.

“There was no placebo group in the OLE to compare with those on active treatment,” he pointed out. He then juxtaposed data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Over the same 6-month timeframe, these data show a hypothetical separation of the curves if no treatment had been received.

The 6-month OLE data provide a preliminary look at outcomes in a planned 4-year follow-up. At the end of the randomized CLARITY trial, the mean decline from the baseline CDR-SB score of 3.2, was 1.21 in the lecanemab group, translating into a 38% decline, and 1.66 in the placebo group, translating into about a 50% decline. Over the 6 months of OLE, there has been a further mean CDR-SB reduction of approximately 0.6 in both arms, suggesting a further 18% decline from baseline.

Additional Data

In the pivotal CLARITY trial, which was published a few months prior to regulatory approval early last year, 1785 patients were randomized to 10 mg/kg lecanemab or placebo infused every 2 weeks. At the end of 18 months, the superiority of lecanemab for the primary endpoint of adverse change in CDR-SB was highly significant (P < .001) as were the differences in key secondary endpoints, such as Alzheimer’s Disease Composite Score (P < .001).

Of those who participated in CLARITY, 1385 patients entered the OLE. Placebo patients were switched to lecanemab which is being maintained in all patients on the trial schedule of 10 mg/kg administered by intravenous infusion every 2 weeks.

In addition to the overall OLE 6-month data, which has not raised any new safety signals, Dr. Irizarry provided a new look at the PET TAU substudy with a focus on patients who entered the study with a low relative tau burden. Of the three classifications, which also included medium and high tau, as measured with positron-emission tomography (PET), the low tau group represented 41.2% of the 342 tau PET substudy participants. With only 2.9% entering the study with a high tau burden, almost all the others fell in the medium stratification.

Due to the potential for a lower therapeutic response, “patients with low Tau are often excluded from trials,” Dr. Irizarry said. But the sizable proportion of low tau patients has permitted an assessment of relative response with lecanemab, which turned out to be substantial.

“Consistent rates of clinical stability or improvements were observed regardless of baseline tau levels with the highest rates of improvements observed for the low tau group after 24 months of follow-up,” Dr. Irizarry reported.

In previously reported results from the tau PET substudy, lecanemab was shown to slow tau spread at least numerically in every section of the brain evaluated, including the frontal, cingulate, parietal, and whole cortical gray matter areas. The reductions reached significance for the medial temporal (P = .0024), meta temporal (P = .012), and temporal (P = .16) portions.

When most recently evaluated in the OLE, the CDR-SB score declined 38% less among those treated with lecanemab than those treated with placebo in the subgroup enrolled in the tau PET substudy.

Relative to those with intermediate or high tau, patients in the low tau had an even greater reduction in cognitive decline than those with higher tau burdens. Although Dr. Irizarry cautioned that greater baseline CDR-SB scores exaggerated the treatment effect in the low tau group, the message is that “a lecanemab treatment effect is seen even when baseline tau levels are low.”

Now, with the recent market withdrawal of aducanumab, another anti-amyloid monoclonal antibody that was previously approved for Alzheimer’s disease, lecanemab is the only therapy currently available for the goal of changing disease progression, not just modifying symptoms.

Looking Long Term

Both sets of data provide important messages for clinicians, according to Marcelo Matiello, MD, a physician investigator at Mass General Hospital and associate professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“Clinicians are really looking for more data because this remains a relatively new drug,” he said. Both sets of findings presented by Dr. Irizarry “look good but the follow-up is still short, so I think everyone is still looking closely at long-term safety and efficacy.”

The need for continuous indefinite therapy is one concern that Dr. Matiello expressed. As moderator of the session in which these data were presented, Dr. Matiello specifically asked Dr. Irizarry if there are plans to explore whether periods without treatment might be a means to reduce the cost and burden of frequent infusions while preserving cognitive gains.

In response, Dr. Irizarry said that earlier studies showed rapid progression when lecanemab was stopped. On this basis, he thinks therapy must be maintained, but he did say that there are plans to look at less frequent dosing, such as once per month. He also said that a subcutaneous formulation in development might also reduce the burden of prolonged treatment.

Dr. Irizarry is an employee of Eisai Ltd., which manufacturers lecanemab. Dr. Matiello reports no potential conflicts of interest.

FROM AAN 2024

Salt Substitutes May Cut All-Cause And Cardiovascular Mortality

Large-scale salt substitution holds promise for reducing mortality with no elevated risk of serious harms, especially for older people at increased cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, a systematic review and meta-analysis by Australian researchers suggested.

The study, published in Annals of Internal Medicine, adds more evidence that broad adoption of potassium-rich salt substitutes for food preparation could have a significant effect on population health.

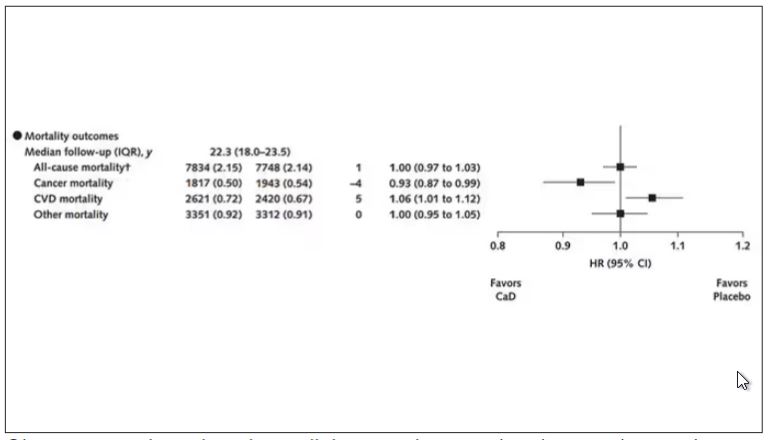

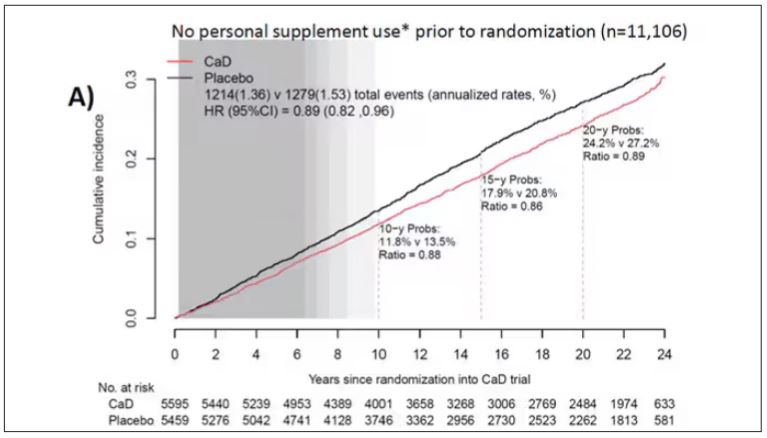

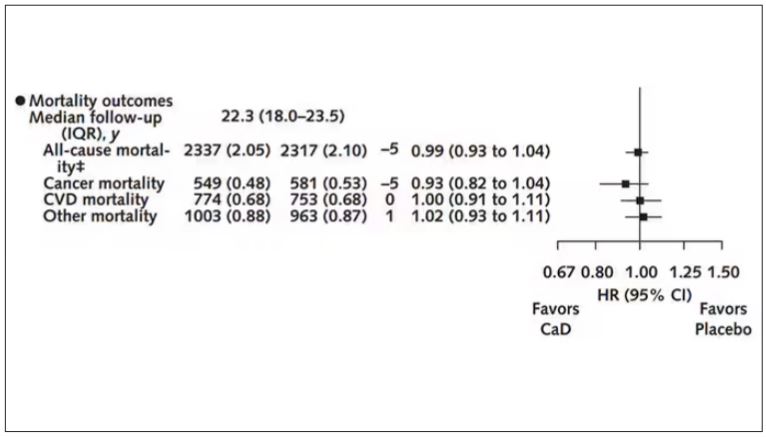

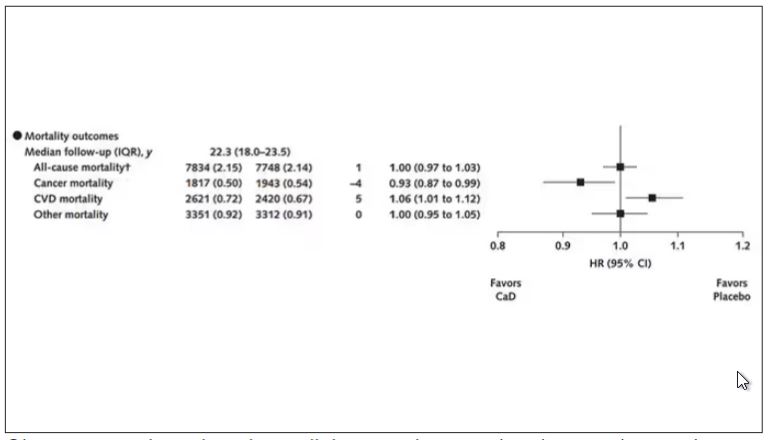

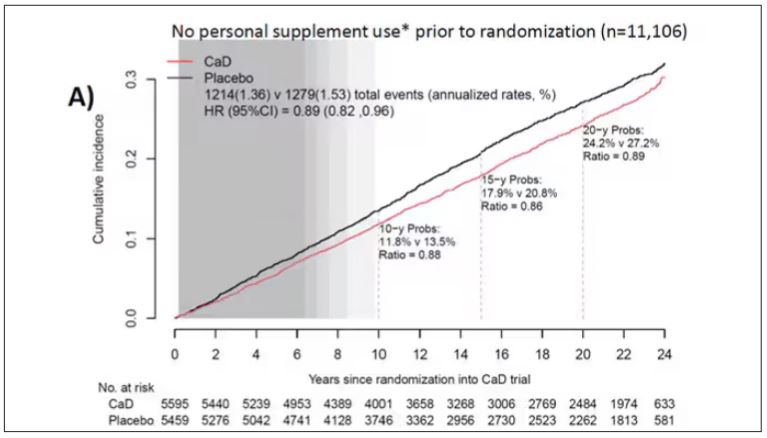

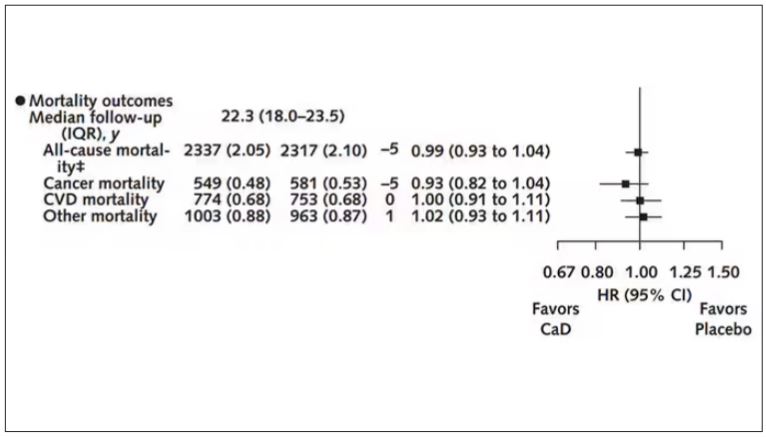

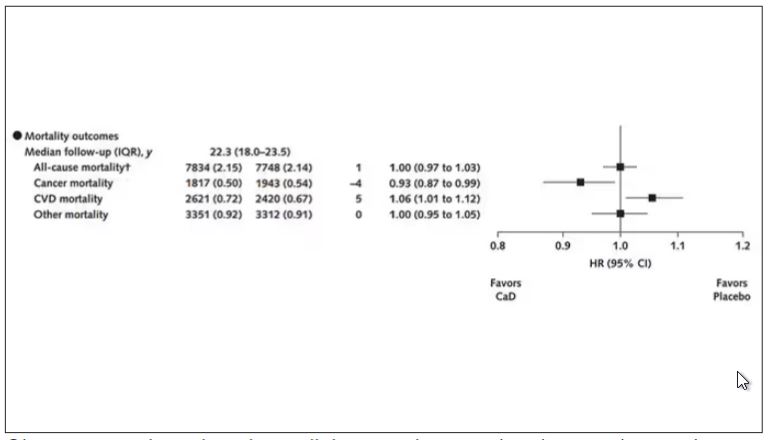

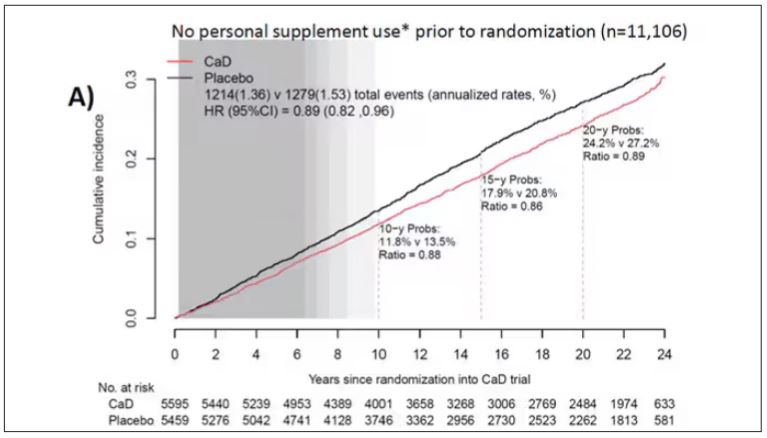

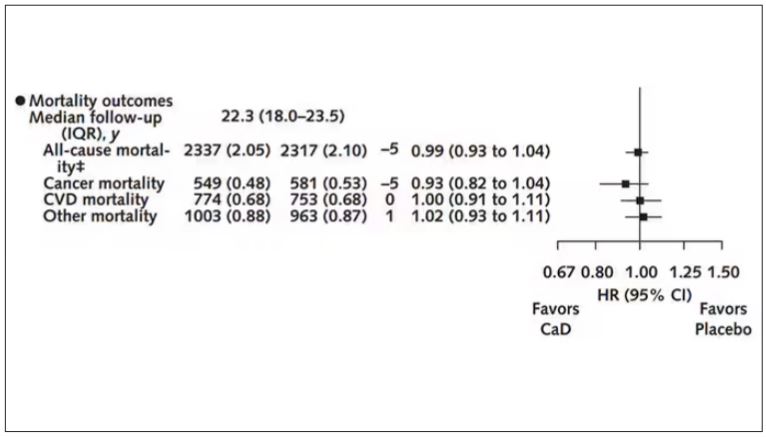

Although the supporting evidence was of low certainty, the analysis of 16 international randomized controlled trials of various interventions with 35,321 participants found salt substitution to be associated with an absolute reduction of 5 in 1000 in all-cause mortality (confidence interval, –3 to –7) and 3 in 1000 in CVD mortality (CI, –1 to –5).

Led by Hannah Greenwood, BPsychSc, a cardiovascular researcher at the Institute for Evidence-Based Healthcare at Bond University in Gold Coast, Queensland, the investigators also found very low certainty evidence of an absolute reduction of 8 in 1000 in major adverse cardiovascular events (CI, 0 to –15), with a 1 in 1000 decrease in more serious adverse events (CI, 4 to –2) in the same population.

Seven of the 16 studies were conducted in China and Taiwan and seven were conducted in populations of older age (mean age 62 years) and/or at higher cardiovascular risk.

With most of the data deriving from populations of older age at higher-than-average CV risk and/or eating an Asian diet, the findings’ generalizability to populations following a Western diet and/or at average CVD risk is limited, the researchers acknowledged.

“We are less certain about the effects in Western, younger, and healthy population groups,” corresponding author Loai Albarqouni, MD, MSc, PhD, assistant professor at the Institute for Evidence-Based Healthcare, said in an interview. “While we saw small, clinically meaningful reductions in cardiovascular deaths and events, effectiveness should be better established before salt substitutes are recommended more broadly, though they are promising.”

In addition, he said, since the longest follow-up of substitute use was 10 years, “we can’t speak to benefits or harms beyond this time frame.”

Still, recommending salt substitutes may be an effective way for physicians to help patients reduce CVD risk, especially those hesitant to start medication, he said. “But physicians should take into account individual circumstances and other factors like kidney disease before recommending salt substitutes. Other non-drug methods of reducing cardiovascular risk, such as diet or exercise, may also be considered.”

Dr. Albarqouni stressed that sodium intake is not the only driver of CVD and reducing intake is just one piece of the puzzle. He cautioned that substitutes themselves can contain high levels of sodium, “so if people are using them in large volumes, they may still present similar risks to the sodium in regular salt.”

While the substitutes appear safe as evidenced by low incidence of hyperkalemia or renal dysfunction, the evidence is scarce, heterogeneous, and weak, the authors stressed.

“They can pose a health risk among people who have kidney disease, diabetes, and heart failure or who take certain medications, including ACE inhibitors and potassium-sparing diuretics,” said Emma Laing, PhD, RDN, director of dietetics at the University of Georgia in Athens. And while their salty flavor makes these a reasonable alternate to sodium chloride, “the downsides include a higher cost and bitter or metallic taste in high amounts. These salt substitutes tend to be better accepted by patients if they contain less than 30% potassium chloride.”

She noted that flavorful salt-free spices, herbs, lemon and lime juices, and vinegars can be effective in lowering dietary sodium when used in lieu of cooking salt.

In similar findings, a recent Chinese study of elderly normotensive people in residential care facilities observed a decrease in the incidence of hypertension with salt substitution.

Approximately one-third of otherwise health individuals are salt-sensitive, rising to more than 50% those with hypertension, and excessive salt intake is estimated to be responsible for nearly 5 million deaths per year globally.

How much impact could household food preparation with salt substitutes really have in North America where sodium consumption is largely driven by processed and takeout food? “While someone may make the switch to a salt substitute for home cooking, their sodium intake might still be very high if a lot of processed or takeaway foods are eaten,” Dr. Albarqouni said. “To see large population impacts, we will likely need policy and institutional-level change as to how sodium is used in food processing, alongside individuals’ switching from regular salt to salt substitutes.”

In agreement, an accompanying editorial by researchers from the universities of Sydney, New South Wales, and California, San Diego, noted the failure of governments and industry to address the World Health Organization’s call for a 30% reduction in global sodium consumption by 2025. With hypertension a major global health burden, the editorialists, led by J. Jaime Miranda, MD, MSc, PhD, of the Sydney School of Public Health at the University of Sydney, believe salt substitutes could be an accessible path toward that goal for food production companies.

“Although the benefits of reducing salt intake have been known for decades, little progress has been made in the quest to lower salt intake on the industry and commercial fronts with existing regulatory tools,” they wrote. “Consequently, we must turn our attention to effective evidence-based alternatives, such as the use of potassium-enriched salts.”

Given the high rates of nonadherence to antihypertensive medication, nonpharmacologic measures to improve blood pressure control are required, they added. “Expanding the routine use of potassium-enriched salts across households and the food industry would benefit not only persons with existing hypertension but all members of the household and communities. An entire shift of the population’s blood pressure curve is possible.”

The study authors called for research to determine the cost-effectiveness of salt substitution in older Asian populations and its efficacy in groups at average cardiovascular risk or following a Western diet.

This research was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. Coauthor Dr. Lauren Ball disclosed support from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Ms. Hannah Greenwood received support from the Australian government and Bond University. Dr. Miranda disclosed numerous consulting, advisory, and research-funding relationships with government, academic, philanthropic, and nonprofit organizations. Editorial commentator Dr. Kathy Trieu reported research support from multiple government and non-profit research-funding organizations. Dr. Cheryl Anderson disclosed ties to Weight Watchers and the McCormick Science Institute, as well support from numerous government, academic, and nonprofit research-funding agencies.

Large-scale salt substitution holds promise for reducing mortality with no elevated risk of serious harms, especially for older people at increased cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, a systematic review and meta-analysis by Australian researchers suggested.

The study, published in Annals of Internal Medicine, adds more evidence that broad adoption of potassium-rich salt substitutes for food preparation could have a significant effect on population health.

Although the supporting evidence was of low certainty, the analysis of 16 international randomized controlled trials of various interventions with 35,321 participants found salt substitution to be associated with an absolute reduction of 5 in 1000 in all-cause mortality (confidence interval, –3 to –7) and 3 in 1000 in CVD mortality (CI, –1 to –5).

Led by Hannah Greenwood, BPsychSc, a cardiovascular researcher at the Institute for Evidence-Based Healthcare at Bond University in Gold Coast, Queensland, the investigators also found very low certainty evidence of an absolute reduction of 8 in 1000 in major adverse cardiovascular events (CI, 0 to –15), with a 1 in 1000 decrease in more serious adverse events (CI, 4 to –2) in the same population.

Seven of the 16 studies were conducted in China and Taiwan and seven were conducted in populations of older age (mean age 62 years) and/or at higher cardiovascular risk.

With most of the data deriving from populations of older age at higher-than-average CV risk and/or eating an Asian diet, the findings’ generalizability to populations following a Western diet and/or at average CVD risk is limited, the researchers acknowledged.

“We are less certain about the effects in Western, younger, and healthy population groups,” corresponding author Loai Albarqouni, MD, MSc, PhD, assistant professor at the Institute for Evidence-Based Healthcare, said in an interview. “While we saw small, clinically meaningful reductions in cardiovascular deaths and events, effectiveness should be better established before salt substitutes are recommended more broadly, though they are promising.”

In addition, he said, since the longest follow-up of substitute use was 10 years, “we can’t speak to benefits or harms beyond this time frame.”

Still, recommending salt substitutes may be an effective way for physicians to help patients reduce CVD risk, especially those hesitant to start medication, he said. “But physicians should take into account individual circumstances and other factors like kidney disease before recommending salt substitutes. Other non-drug methods of reducing cardiovascular risk, such as diet or exercise, may also be considered.”

Dr. Albarqouni stressed that sodium intake is not the only driver of CVD and reducing intake is just one piece of the puzzle. He cautioned that substitutes themselves can contain high levels of sodium, “so if people are using them in large volumes, they may still present similar risks to the sodium in regular salt.”

While the substitutes appear safe as evidenced by low incidence of hyperkalemia or renal dysfunction, the evidence is scarce, heterogeneous, and weak, the authors stressed.

“They can pose a health risk among people who have kidney disease, diabetes, and heart failure or who take certain medications, including ACE inhibitors and potassium-sparing diuretics,” said Emma Laing, PhD, RDN, director of dietetics at the University of Georgia in Athens. And while their salty flavor makes these a reasonable alternate to sodium chloride, “the downsides include a higher cost and bitter or metallic taste in high amounts. These salt substitutes tend to be better accepted by patients if they contain less than 30% potassium chloride.”

She noted that flavorful salt-free spices, herbs, lemon and lime juices, and vinegars can be effective in lowering dietary sodium when used in lieu of cooking salt.

In similar findings, a recent Chinese study of elderly normotensive people in residential care facilities observed a decrease in the incidence of hypertension with salt substitution.

Approximately one-third of otherwise health individuals are salt-sensitive, rising to more than 50% those with hypertension, and excessive salt intake is estimated to be responsible for nearly 5 million deaths per year globally.

How much impact could household food preparation with salt substitutes really have in North America where sodium consumption is largely driven by processed and takeout food? “While someone may make the switch to a salt substitute for home cooking, their sodium intake might still be very high if a lot of processed or takeaway foods are eaten,” Dr. Albarqouni said. “To see large population impacts, we will likely need policy and institutional-level change as to how sodium is used in food processing, alongside individuals’ switching from regular salt to salt substitutes.”

In agreement, an accompanying editorial by researchers from the universities of Sydney, New South Wales, and California, San Diego, noted the failure of governments and industry to address the World Health Organization’s call for a 30% reduction in global sodium consumption by 2025. With hypertension a major global health burden, the editorialists, led by J. Jaime Miranda, MD, MSc, PhD, of the Sydney School of Public Health at the University of Sydney, believe salt substitutes could be an accessible path toward that goal for food production companies.

“Although the benefits of reducing salt intake have been known for decades, little progress has been made in the quest to lower salt intake on the industry and commercial fronts with existing regulatory tools,” they wrote. “Consequently, we must turn our attention to effective evidence-based alternatives, such as the use of potassium-enriched salts.”

Given the high rates of nonadherence to antihypertensive medication, nonpharmacologic measures to improve blood pressure control are required, they added. “Expanding the routine use of potassium-enriched salts across households and the food industry would benefit not only persons with existing hypertension but all members of the household and communities. An entire shift of the population’s blood pressure curve is possible.”

The study authors called for research to determine the cost-effectiveness of salt substitution in older Asian populations and its efficacy in groups at average cardiovascular risk or following a Western diet.

This research was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. Coauthor Dr. Lauren Ball disclosed support from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Ms. Hannah Greenwood received support from the Australian government and Bond University. Dr. Miranda disclosed numerous consulting, advisory, and research-funding relationships with government, academic, philanthropic, and nonprofit organizations. Editorial commentator Dr. Kathy Trieu reported research support from multiple government and non-profit research-funding organizations. Dr. Cheryl Anderson disclosed ties to Weight Watchers and the McCormick Science Institute, as well support from numerous government, academic, and nonprofit research-funding agencies.

Large-scale salt substitution holds promise for reducing mortality with no elevated risk of serious harms, especially for older people at increased cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, a systematic review and meta-analysis by Australian researchers suggested.

The study, published in Annals of Internal Medicine, adds more evidence that broad adoption of potassium-rich salt substitutes for food preparation could have a significant effect on population health.

Although the supporting evidence was of low certainty, the analysis of 16 international randomized controlled trials of various interventions with 35,321 participants found salt substitution to be associated with an absolute reduction of 5 in 1000 in all-cause mortality (confidence interval, –3 to –7) and 3 in 1000 in CVD mortality (CI, –1 to –5).

Led by Hannah Greenwood, BPsychSc, a cardiovascular researcher at the Institute for Evidence-Based Healthcare at Bond University in Gold Coast, Queensland, the investigators also found very low certainty evidence of an absolute reduction of 8 in 1000 in major adverse cardiovascular events (CI, 0 to –15), with a 1 in 1000 decrease in more serious adverse events (CI, 4 to –2) in the same population.

Seven of the 16 studies were conducted in China and Taiwan and seven were conducted in populations of older age (mean age 62 years) and/or at higher cardiovascular risk.

With most of the data deriving from populations of older age at higher-than-average CV risk and/or eating an Asian diet, the findings’ generalizability to populations following a Western diet and/or at average CVD risk is limited, the researchers acknowledged.

“We are less certain about the effects in Western, younger, and healthy population groups,” corresponding author Loai Albarqouni, MD, MSc, PhD, assistant professor at the Institute for Evidence-Based Healthcare, said in an interview. “While we saw small, clinically meaningful reductions in cardiovascular deaths and events, effectiveness should be better established before salt substitutes are recommended more broadly, though they are promising.”

In addition, he said, since the longest follow-up of substitute use was 10 years, “we can’t speak to benefits or harms beyond this time frame.”

Still, recommending salt substitutes may be an effective way for physicians to help patients reduce CVD risk, especially those hesitant to start medication, he said. “But physicians should take into account individual circumstances and other factors like kidney disease before recommending salt substitutes. Other non-drug methods of reducing cardiovascular risk, such as diet or exercise, may also be considered.”

Dr. Albarqouni stressed that sodium intake is not the only driver of CVD and reducing intake is just one piece of the puzzle. He cautioned that substitutes themselves can contain high levels of sodium, “so if people are using them in large volumes, they may still present similar risks to the sodium in regular salt.”

While the substitutes appear safe as evidenced by low incidence of hyperkalemia or renal dysfunction, the evidence is scarce, heterogeneous, and weak, the authors stressed.

“They can pose a health risk among people who have kidney disease, diabetes, and heart failure or who take certain medications, including ACE inhibitors and potassium-sparing diuretics,” said Emma Laing, PhD, RDN, director of dietetics at the University of Georgia in Athens. And while their salty flavor makes these a reasonable alternate to sodium chloride, “the downsides include a higher cost and bitter or metallic taste in high amounts. These salt substitutes tend to be better accepted by patients if they contain less than 30% potassium chloride.”

She noted that flavorful salt-free spices, herbs, lemon and lime juices, and vinegars can be effective in lowering dietary sodium when used in lieu of cooking salt.

In similar findings, a recent Chinese study of elderly normotensive people in residential care facilities observed a decrease in the incidence of hypertension with salt substitution.

Approximately one-third of otherwise health individuals are salt-sensitive, rising to more than 50% those with hypertension, and excessive salt intake is estimated to be responsible for nearly 5 million deaths per year globally.

How much impact could household food preparation with salt substitutes really have in North America where sodium consumption is largely driven by processed and takeout food? “While someone may make the switch to a salt substitute for home cooking, their sodium intake might still be very high if a lot of processed or takeaway foods are eaten,” Dr. Albarqouni said. “To see large population impacts, we will likely need policy and institutional-level change as to how sodium is used in food processing, alongside individuals’ switching from regular salt to salt substitutes.”

In agreement, an accompanying editorial by researchers from the universities of Sydney, New South Wales, and California, San Diego, noted the failure of governments and industry to address the World Health Organization’s call for a 30% reduction in global sodium consumption by 2025. With hypertension a major global health burden, the editorialists, led by J. Jaime Miranda, MD, MSc, PhD, of the Sydney School of Public Health at the University of Sydney, believe salt substitutes could be an accessible path toward that goal for food production companies.

“Although the benefits of reducing salt intake have been known for decades, little progress has been made in the quest to lower salt intake on the industry and commercial fronts with existing regulatory tools,” they wrote. “Consequently, we must turn our attention to effective evidence-based alternatives, such as the use of potassium-enriched salts.”

Given the high rates of nonadherence to antihypertensive medication, nonpharmacologic measures to improve blood pressure control are required, they added. “Expanding the routine use of potassium-enriched salts across households and the food industry would benefit not only persons with existing hypertension but all members of the household and communities. An entire shift of the population’s blood pressure curve is possible.”

The study authors called for research to determine the cost-effectiveness of salt substitution in older Asian populations and its efficacy in groups at average cardiovascular risk or following a Western diet.

This research was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. Coauthor Dr. Lauren Ball disclosed support from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Ms. Hannah Greenwood received support from the Australian government and Bond University. Dr. Miranda disclosed numerous consulting, advisory, and research-funding relationships with government, academic, philanthropic, and nonprofit organizations. Editorial commentator Dr. Kathy Trieu reported research support from multiple government and non-profit research-funding organizations. Dr. Cheryl Anderson disclosed ties to Weight Watchers and the McCormick Science Institute, as well support from numerous government, academic, and nonprofit research-funding agencies.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Hormone Therapy After 65 a Good Option for Most Women

Hormone Therapy (HT) is a good option for most women over age 65, despite entrenched fears about HT safety, according to findings from a new study published in Menopause.

The study, led by Seo H. Baik, PhD, of Lister Hill National Center for Biomedical Communications, National Library of Medicine, in Bethesda, Maryland, and colleagues is based on the health records of 10 million senior women on Medicare from 2007 to 2020. It concludes there are important health benefits with HT beyond age 65 and the effects of using HT after age 65 vary by type of therapy, route of administration, and dose.

Controversial Since Women’s Health Initiative

Use of HT after age 65 has been controversial in light of the findings of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study in 2002. Since that study, many women have decided against HT, especially after age 65, because of fears of increased risks for cancers and heart disease.

Baik et al. concluded that, compared with never using or stopping use of HT before the age of 65 years, the use of estrogen alone beyond age 65 years was associated with the following significant risk reductions: mortality (19%); breast cancer (16%); lung cancer (13%); colorectal cancer (12%); congestive heart failure (5%); venous thromboembolism (5%); atrial fibrillation (4%); acute myocardial infarction (11%); and dementia (2%).

The authors further found that estrogen plus progestin was associated with significant risk reductions in endometrial cancer (45%); ovarian cancer (21%); ischemic heart disease (5%); congestive heart failure (5%); and venous thromboembolism (5%).

Estrogen plus progesterone, however, was linked with risk reduction only in congestive heart failure (4%).

Reassuring Results

“These results should provide additional reassurance to women about hormone therapy,” said Lisa C, Larkin, MD, president of The Menopause Society. “This data is largely consistent with the WHI data as we understand it today — that for the majority of women with symptoms transitioning through menopause, hormone therapy is the most effective treatment and has benefits that outweigh risks.”

There may be some exceptions, she noted, particularly in older women with high risk for cardiovascular disease and stroke. Among those women, she explained, the risks of HT may outweigh the benefits and it may be appropriate to stop hormone therapy.

“In these older women with specific risk factors, the discussion of continuing or stopping HT is nuanced and complex and must involve shared decision-making,” she said.

Elevated Breast Cancer Risk Can be Mitigated

With a therapy combining estrogen and progestogen, both estrogen plus progestin and estrogen plus progesterone were associated with a 10%-19% increased risk of breast cancer, but the authors say that risk can be mitigated using low doses of transdermal or vaginal estrogen plus progestin.

“In general, risk reductions appear to be greater with low rather than medium or high doses, vaginal or transdermal rather than oral preparations, and with E2 (estradiol) rather than conjugated estrogen,” the authors write.

The authors report that over 14 years of follow-up (from 2007 to 2020), the proportion of senior women taking any HT-containing estrogen dropped by half, from 11.4% to 5.5%. E2 has largely replaced conjugated estrogen (CEE); and vaginal administration largely replaced oral.

Controversy Remains

Even with these results, hormone use will remain controversial, Dr. Larkin said, without enormous efforts to educate. Menopausal HT therapy in young 50-year-old women having symptoms is still controversial — despite the large body of evidence supporting safety and benefit in the majority of women, she said.

“For the last 25 years we have completely neglected education of clinicians about menopause and the data on hormone therapy,” she said. “As a result, most of the clinicians practicing do not understand the data and remain very negative about hormones even in younger women. The decades of lack of education of clinicians about menopause is one of the major reasons far too many young, healthy, 50-year-old women with symptoms are not getting the care they need [hormone therapy] at menopause.” Instead, she says, women are told to take supplements because some providers think hormone therapy is too dangerous.

Lauren Streicher, MD, a clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, and founding director of the Northwestern Medical Center for Sexual Medicine and Menopause, both in Chicago, says, “In the WHI, 70% of the women were over the age of 65 when they initiated therapy, which partially accounts for the negative outcomes. In addition, in WHI, everyone was taking oral [HT]. This (current) data is very reassuring — and validating — for women who would like to continue taking HT.”

Dr. Streicher says women who would like to start HT after 65 should be counseled on individual risks and after cardiac health is evaluated. But, she notes, this study did not address that.

‘Best Time to Stop HT is When You Die’

She says in her practice she will counsel women who are on HT and would like to continue after age 65 the way she always has: “If someone is taking HT and has no specific reason to stop, there is no reason to stop at some arbitrary age or time and that if they do, they will lose many of the benefits,” particularly bone, cognitive, cardiovascular, and vulvovaginal benefits, she explained. “The best time to stop HT is when you die,” Dr. Streicher said, “And, given the reduction in mortality in women who take HT, that will be at a much older age than women who don’t take HT.”

So will these new data be convincing?

“It will convince the already convinced — menopause experts who follow the data. It is the rare menopause expert that tells women to stop HT,” Dr. Streicher said.

However, she said, “The overwhelming majority of clinicians in the US currently do not prescribe HT. Sadly, I don’t think this will change much.”

The authors report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Larkin consults for several women’s health companies including Mayne Pharma, Astellas, Johnson & Johnson, Grail, Pfizer, and Solv Wellness. Dr. Streicher reports no relevant financial relationships.

Hormone Therapy (HT) is a good option for most women over age 65, despite entrenched fears about HT safety, according to findings from a new study published in Menopause.

The study, led by Seo H. Baik, PhD, of Lister Hill National Center for Biomedical Communications, National Library of Medicine, in Bethesda, Maryland, and colleagues is based on the health records of 10 million senior women on Medicare from 2007 to 2020. It concludes there are important health benefits with HT beyond age 65 and the effects of using HT after age 65 vary by type of therapy, route of administration, and dose.

Controversial Since Women’s Health Initiative

Use of HT after age 65 has been controversial in light of the findings of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study in 2002. Since that study, many women have decided against HT, especially after age 65, because of fears of increased risks for cancers and heart disease.

Baik et al. concluded that, compared with never using or stopping use of HT before the age of 65 years, the use of estrogen alone beyond age 65 years was associated with the following significant risk reductions: mortality (19%); breast cancer (16%); lung cancer (13%); colorectal cancer (12%); congestive heart failure (5%); venous thromboembolism (5%); atrial fibrillation (4%); acute myocardial infarction (11%); and dementia (2%).

The authors further found that estrogen plus progestin was associated with significant risk reductions in endometrial cancer (45%); ovarian cancer (21%); ischemic heart disease (5%); congestive heart failure (5%); and venous thromboembolism (5%).

Estrogen plus progesterone, however, was linked with risk reduction only in congestive heart failure (4%).

Reassuring Results

“These results should provide additional reassurance to women about hormone therapy,” said Lisa C, Larkin, MD, president of The Menopause Society. “This data is largely consistent with the WHI data as we understand it today — that for the majority of women with symptoms transitioning through menopause, hormone therapy is the most effective treatment and has benefits that outweigh risks.”

There may be some exceptions, she noted, particularly in older women with high risk for cardiovascular disease and stroke. Among those women, she explained, the risks of HT may outweigh the benefits and it may be appropriate to stop hormone therapy.

“In these older women with specific risk factors, the discussion of continuing or stopping HT is nuanced and complex and must involve shared decision-making,” she said.

Elevated Breast Cancer Risk Can be Mitigated

With a therapy combining estrogen and progestogen, both estrogen plus progestin and estrogen plus progesterone were associated with a 10%-19% increased risk of breast cancer, but the authors say that risk can be mitigated using low doses of transdermal or vaginal estrogen plus progestin.

“In general, risk reductions appear to be greater with low rather than medium or high doses, vaginal or transdermal rather than oral preparations, and with E2 (estradiol) rather than conjugated estrogen,” the authors write.

The authors report that over 14 years of follow-up (from 2007 to 2020), the proportion of senior women taking any HT-containing estrogen dropped by half, from 11.4% to 5.5%. E2 has largely replaced conjugated estrogen (CEE); and vaginal administration largely replaced oral.

Controversy Remains

Even with these results, hormone use will remain controversial, Dr. Larkin said, without enormous efforts to educate. Menopausal HT therapy in young 50-year-old women having symptoms is still controversial — despite the large body of evidence supporting safety and benefit in the majority of women, she said.

“For the last 25 years we have completely neglected education of clinicians about menopause and the data on hormone therapy,” she said. “As a result, most of the clinicians practicing do not understand the data and remain very negative about hormones even in younger women. The decades of lack of education of clinicians about menopause is one of the major reasons far too many young, healthy, 50-year-old women with symptoms are not getting the care they need [hormone therapy] at menopause.” Instead, she says, women are told to take supplements because some providers think hormone therapy is too dangerous.

Lauren Streicher, MD, a clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, and founding director of the Northwestern Medical Center for Sexual Medicine and Menopause, both in Chicago, says, “In the WHI, 70% of the women were over the age of 65 when they initiated therapy, which partially accounts for the negative outcomes. In addition, in WHI, everyone was taking oral [HT]. This (current) data is very reassuring — and validating — for women who would like to continue taking HT.”

Dr. Streicher says women who would like to start HT after 65 should be counseled on individual risks and after cardiac health is evaluated. But, she notes, this study did not address that.

‘Best Time to Stop HT is When You Die’

She says in her practice she will counsel women who are on HT and would like to continue after age 65 the way she always has: “If someone is taking HT and has no specific reason to stop, there is no reason to stop at some arbitrary age or time and that if they do, they will lose many of the benefits,” particularly bone, cognitive, cardiovascular, and vulvovaginal benefits, she explained. “The best time to stop HT is when you die,” Dr. Streicher said, “And, given the reduction in mortality in women who take HT, that will be at a much older age than women who don’t take HT.”

So will these new data be convincing?

“It will convince the already convinced — menopause experts who follow the data. It is the rare menopause expert that tells women to stop HT,” Dr. Streicher said.

However, she said, “The overwhelming majority of clinicians in the US currently do not prescribe HT. Sadly, I don’t think this will change much.”

The authors report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Larkin consults for several women’s health companies including Mayne Pharma, Astellas, Johnson & Johnson, Grail, Pfizer, and Solv Wellness. Dr. Streicher reports no relevant financial relationships.

Hormone Therapy (HT) is a good option for most women over age 65, despite entrenched fears about HT safety, according to findings from a new study published in Menopause.

The study, led by Seo H. Baik, PhD, of Lister Hill National Center for Biomedical Communications, National Library of Medicine, in Bethesda, Maryland, and colleagues is based on the health records of 10 million senior women on Medicare from 2007 to 2020. It concludes there are important health benefits with HT beyond age 65 and the effects of using HT after age 65 vary by type of therapy, route of administration, and dose.

Controversial Since Women’s Health Initiative

Use of HT after age 65 has been controversial in light of the findings of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study in 2002. Since that study, many women have decided against HT, especially after age 65, because of fears of increased risks for cancers and heart disease.

Baik et al. concluded that, compared with never using or stopping use of HT before the age of 65 years, the use of estrogen alone beyond age 65 years was associated with the following significant risk reductions: mortality (19%); breast cancer (16%); lung cancer (13%); colorectal cancer (12%); congestive heart failure (5%); venous thromboembolism (5%); atrial fibrillation (4%); acute myocardial infarction (11%); and dementia (2%).

The authors further found that estrogen plus progestin was associated with significant risk reductions in endometrial cancer (45%); ovarian cancer (21%); ischemic heart disease (5%); congestive heart failure (5%); and venous thromboembolism (5%).

Estrogen plus progesterone, however, was linked with risk reduction only in congestive heart failure (4%).

Reassuring Results

“These results should provide additional reassurance to women about hormone therapy,” said Lisa C, Larkin, MD, president of The Menopause Society. “This data is largely consistent with the WHI data as we understand it today — that for the majority of women with symptoms transitioning through menopause, hormone therapy is the most effective treatment and has benefits that outweigh risks.”

There may be some exceptions, she noted, particularly in older women with high risk for cardiovascular disease and stroke. Among those women, she explained, the risks of HT may outweigh the benefits and it may be appropriate to stop hormone therapy.

“In these older women with specific risk factors, the discussion of continuing or stopping HT is nuanced and complex and must involve shared decision-making,” she said.

Elevated Breast Cancer Risk Can be Mitigated

With a therapy combining estrogen and progestogen, both estrogen plus progestin and estrogen plus progesterone were associated with a 10%-19% increased risk of breast cancer, but the authors say that risk can be mitigated using low doses of transdermal or vaginal estrogen plus progestin.

“In general, risk reductions appear to be greater with low rather than medium or high doses, vaginal or transdermal rather than oral preparations, and with E2 (estradiol) rather than conjugated estrogen,” the authors write.

The authors report that over 14 years of follow-up (from 2007 to 2020), the proportion of senior women taking any HT-containing estrogen dropped by half, from 11.4% to 5.5%. E2 has largely replaced conjugated estrogen (CEE); and vaginal administration largely replaced oral.

Controversy Remains

Even with these results, hormone use will remain controversial, Dr. Larkin said, without enormous efforts to educate. Menopausal HT therapy in young 50-year-old women having symptoms is still controversial — despite the large body of evidence supporting safety and benefit in the majority of women, she said.

“For the last 25 years we have completely neglected education of clinicians about menopause and the data on hormone therapy,” she said. “As a result, most of the clinicians practicing do not understand the data and remain very negative about hormones even in younger women. The decades of lack of education of clinicians about menopause is one of the major reasons far too many young, healthy, 50-year-old women with symptoms are not getting the care they need [hormone therapy] at menopause.” Instead, she says, women are told to take supplements because some providers think hormone therapy is too dangerous.

Lauren Streicher, MD, a clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, and founding director of the Northwestern Medical Center for Sexual Medicine and Menopause, both in Chicago, says, “In the WHI, 70% of the women were over the age of 65 when they initiated therapy, which partially accounts for the negative outcomes. In addition, in WHI, everyone was taking oral [HT]. This (current) data is very reassuring — and validating — for women who would like to continue taking HT.”

Dr. Streicher says women who would like to start HT after 65 should be counseled on individual risks and after cardiac health is evaluated. But, she notes, this study did not address that.

‘Best Time to Stop HT is When You Die’

She says in her practice she will counsel women who are on HT and would like to continue after age 65 the way she always has: “If someone is taking HT and has no specific reason to stop, there is no reason to stop at some arbitrary age or time and that if they do, they will lose many of the benefits,” particularly bone, cognitive, cardiovascular, and vulvovaginal benefits, she explained. “The best time to stop HT is when you die,” Dr. Streicher said, “And, given the reduction in mortality in women who take HT, that will be at a much older age than women who don’t take HT.”

So will these new data be convincing?

“It will convince the already convinced — menopause experts who follow the data. It is the rare menopause expert that tells women to stop HT,” Dr. Streicher said.

However, she said, “The overwhelming majority of clinicians in the US currently do not prescribe HT. Sadly, I don’t think this will change much.”

The authors report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Larkin consults for several women’s health companies including Mayne Pharma, Astellas, Johnson & Johnson, Grail, Pfizer, and Solv Wellness. Dr. Streicher reports no relevant financial relationships.

FROM MENOPAUSE

Higher BMI More CVD Protective in Older Adults With T2D?

Among adults with type 2 diabetes (T2D) older than 65 years, a body mass index (BMI) in the moderate overweight category (26-28) appears to offer better protection from cardiovascular death than does a BMI in the “normal” range, new data suggested.

On the other hand, the study findings also suggest that the “normal” range of 23-25 is optimal for middle-aged adults with T2D.

The findings reflect a previously demonstrated phenomenon called the “obesity paradox,” in which older people with overweight may have better outcomes than leaner people due to factors such as bone loss, frailty, and nutritional deficits, study lead author Shaoyong Xu, of Xiangyang Central Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Hubei University of Arts and Science, Xiangyang, China, told this news organization.

“In this era of population growth and aging, the question arises as to whether obesity or overweight can be beneficial in improving survival rates for older individuals with diabetes. This topic holds significant relevance due to the potential implications it has on weight management strategies for older adults. If overweight does not pose an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality, it may suggest that older individuals are not necessarily required to strive for weight loss to achieve so-called normal values.”

Moreover, Dr. Xu added, “inappropriate weight loss and being underweight could potentially elevate the risk of cardiovascular events, myocardial infarction, cerebral infarction, and all-cause mortality.”

Thus, he said, “while there are general guidelines recommending a BMI below 25, our findings suggest that personalized BMI targets may be more beneficial, particularly for different age groups and individuals with specific health conditions.”

Asked to comment, Ian J. Neeland, MD, director of cardiovascular prevention, University Hospitals Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, pointed out that older people who are underweight or in lower weight categories may be more likely to smoke or have undiagnosed cancer, or that “their BMI is not so much reflective of fat mass as of low muscle mass, or sarcopenia, and that is definitely a risk factor for adverse outcomes and risks. ... And those who have slightly higher BMIs may be maintaining muscle mass, even though they’re older, and therefore they have less risk.”

However, Dr. Neeland disagreed with the authors’ conclusions regarding “optimal” BMI. “Just because you have different risk categories based on BMI doesn’t mean that’s ‘optimal’ BMI. The way I would interpret this paper is that there’s an association of mildly overweight with better outcomes in adults who are over 65 with type 2 diabetes. We need to try to understand the mechanisms underlying that observation.”

Dr. Neeland advised that for an older person with T2D who has low muscle mass and frailty, “I wouldn’t recommend necessarily targeted weight loss in that person. But I would potentially recommend weight loss in addition to resistance training, muscle building, and endurance training, and therefore reducing fat mass. The goal would be not so much weight loss but reduction of body fat and maintaining and improving muscle health.”

U-Shaped Relationship Found Between Age, BMI, and Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) Risk

The data come from the UK Biobank, a population-based prospective cohort study of adults in the United Kingdom. A total of 22,874 participants with baseline T2D were included in the current study. Baseline surveys were conducted between 2006 and 2010, and follow-up was a median of 12.52 years. During that time, 891 people died of CVD.

Hazard ratios were adjusted for baseline variables including age, sex, smoking history, alcohol consumption, level of physical exercise, and history of CVDs.

Compared with people with BMI a < 25 in the group who were aged 65 years or younger, those with a BMI of 25.0-29.9 had a 13% higher risk for cardiovascular death. However, among those older than 65 years, a BMI between 25.0 and 29.9 was associated with an 18% lower risk.

A U-shaped relationship was found between BMI and the risk for cardiovascular death, with an optimal BMI cutoff of 24.0 in the under-65 group and a 27.0 cutoff in the older group. Ranges of 23.0-25.0 in the under-65 group and 26.0-28 in the older group were associated with the lowest cardiovascular risk.

In contrast, there was a linear relationship between both waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio and the risk for cardiovascular death, making those more direct measures of adiposity, Dr. Xu told this news organization.

“For clinicians, our data underscores the importance of considering age when assessing BMI targets for cardiovascular health. Personalized treatment plans that account for age-specific BMI cutoffs and other risk factors may enhance patient outcomes and reduce CVD mortality,” Dr. Xu said.

However, he added, “while these findings suggest an optimal BMI range, it is crucial to acknowledge that these cutoff points may vary based on gender, race, and other factors. Our future studies will validate these findings in different populations and attempt to explain the mechanism by which the optimal nodal values exist in people with diabetes at different ages.”

Dr. Neeland cautioned, “I think more work needs to be done in terms of not just identifying the risk differences but understanding why and how to better risk stratify individuals and do personalized medicine. I think that’s important, but you have to have good data to support the strategies you’re going to use. These data are observational, and they’re a good start, but they wouldn’t directly impact practice at this point.”

The data will be presented at the European Congress on Obesity taking place May 12-15 in Venice, Italy.

The authors declared no competing interests. Study funding came from several sources, including the Young Talents Project of Hubei Provincial Health Commission, China, Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China, the Science and Technology Research Key Project of the Education Department of Hubei Province China, and the Sanuo Diabetes Charity Foundation, China, and the Xiangyang Science and Technology Plan Project, China. Dr. Neeland is a speaker and/or consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, Bayer, and Eli Lilly and Company.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Among adults with type 2 diabetes (T2D) older than 65 years, a body mass index (BMI) in the moderate overweight category (26-28) appears to offer better protection from cardiovascular death than does a BMI in the “normal” range, new data suggested.

On the other hand, the study findings also suggest that the “normal” range of 23-25 is optimal for middle-aged adults with T2D.

The findings reflect a previously demonstrated phenomenon called the “obesity paradox,” in which older people with overweight may have better outcomes than leaner people due to factors such as bone loss, frailty, and nutritional deficits, study lead author Shaoyong Xu, of Xiangyang Central Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Hubei University of Arts and Science, Xiangyang, China, told this news organization.

“In this era of population growth and aging, the question arises as to whether obesity or overweight can be beneficial in improving survival rates for older individuals with diabetes. This topic holds significant relevance due to the potential implications it has on weight management strategies for older adults. If overweight does not pose an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality, it may suggest that older individuals are not necessarily required to strive for weight loss to achieve so-called normal values.”

Moreover, Dr. Xu added, “inappropriate weight loss and being underweight could potentially elevate the risk of cardiovascular events, myocardial infarction, cerebral infarction, and all-cause mortality.”

Thus, he said, “while there are general guidelines recommending a BMI below 25, our findings suggest that personalized BMI targets may be more beneficial, particularly for different age groups and individuals with specific health conditions.”

Asked to comment, Ian J. Neeland, MD, director of cardiovascular prevention, University Hospitals Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, pointed out that older people who are underweight or in lower weight categories may be more likely to smoke or have undiagnosed cancer, or that “their BMI is not so much reflective of fat mass as of low muscle mass, or sarcopenia, and that is definitely a risk factor for adverse outcomes and risks. ... And those who have slightly higher BMIs may be maintaining muscle mass, even though they’re older, and therefore they have less risk.”

However, Dr. Neeland disagreed with the authors’ conclusions regarding “optimal” BMI. “Just because you have different risk categories based on BMI doesn’t mean that’s ‘optimal’ BMI. The way I would interpret this paper is that there’s an association of mildly overweight with better outcomes in adults who are over 65 with type 2 diabetes. We need to try to understand the mechanisms underlying that observation.”

Dr. Neeland advised that for an older person with T2D who has low muscle mass and frailty, “I wouldn’t recommend necessarily targeted weight loss in that person. But I would potentially recommend weight loss in addition to resistance training, muscle building, and endurance training, and therefore reducing fat mass. The goal would be not so much weight loss but reduction of body fat and maintaining and improving muscle health.”

U-Shaped Relationship Found Between Age, BMI, and Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) Risk

The data come from the UK Biobank, a population-based prospective cohort study of adults in the United Kingdom. A total of 22,874 participants with baseline T2D were included in the current study. Baseline surveys were conducted between 2006 and 2010, and follow-up was a median of 12.52 years. During that time, 891 people died of CVD.

Hazard ratios were adjusted for baseline variables including age, sex, smoking history, alcohol consumption, level of physical exercise, and history of CVDs.

Compared with people with BMI a < 25 in the group who were aged 65 years or younger, those with a BMI of 25.0-29.9 had a 13% higher risk for cardiovascular death. However, among those older than 65 years, a BMI between 25.0 and 29.9 was associated with an 18% lower risk.

A U-shaped relationship was found between BMI and the risk for cardiovascular death, with an optimal BMI cutoff of 24.0 in the under-65 group and a 27.0 cutoff in the older group. Ranges of 23.0-25.0 in the under-65 group and 26.0-28 in the older group were associated with the lowest cardiovascular risk.

In contrast, there was a linear relationship between both waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio and the risk for cardiovascular death, making those more direct measures of adiposity, Dr. Xu told this news organization.

“For clinicians, our data underscores the importance of considering age when assessing BMI targets for cardiovascular health. Personalized treatment plans that account for age-specific BMI cutoffs and other risk factors may enhance patient outcomes and reduce CVD mortality,” Dr. Xu said.

However, he added, “while these findings suggest an optimal BMI range, it is crucial to acknowledge that these cutoff points may vary based on gender, race, and other factors. Our future studies will validate these findings in different populations and attempt to explain the mechanism by which the optimal nodal values exist in people with diabetes at different ages.”

Dr. Neeland cautioned, “I think more work needs to be done in terms of not just identifying the risk differences but understanding why and how to better risk stratify individuals and do personalized medicine. I think that’s important, but you have to have good data to support the strategies you’re going to use. These data are observational, and they’re a good start, but they wouldn’t directly impact practice at this point.”

The data will be presented at the European Congress on Obesity taking place May 12-15 in Venice, Italy.

The authors declared no competing interests. Study funding came from several sources, including the Young Talents Project of Hubei Provincial Health Commission, China, Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China, the Science and Technology Research Key Project of the Education Department of Hubei Province China, and the Sanuo Diabetes Charity Foundation, China, and the Xiangyang Science and Technology Plan Project, China. Dr. Neeland is a speaker and/or consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, Bayer, and Eli Lilly and Company.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Among adults with type 2 diabetes (T2D) older than 65 years, a body mass index (BMI) in the moderate overweight category (26-28) appears to offer better protection from cardiovascular death than does a BMI in the “normal” range, new data suggested.

On the other hand, the study findings also suggest that the “normal” range of 23-25 is optimal for middle-aged adults with T2D.

The findings reflect a previously demonstrated phenomenon called the “obesity paradox,” in which older people with overweight may have better outcomes than leaner people due to factors such as bone loss, frailty, and nutritional deficits, study lead author Shaoyong Xu, of Xiangyang Central Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Hubei University of Arts and Science, Xiangyang, China, told this news organization.

“In this era of population growth and aging, the question arises as to whether obesity or overweight can be beneficial in improving survival rates for older individuals with diabetes. This topic holds significant relevance due to the potential implications it has on weight management strategies for older adults. If overweight does not pose an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality, it may suggest that older individuals are not necessarily required to strive for weight loss to achieve so-called normal values.”

Moreover, Dr. Xu added, “inappropriate weight loss and being underweight could potentially elevate the risk of cardiovascular events, myocardial infarction, cerebral infarction, and all-cause mortality.”

Thus, he said, “while there are general guidelines recommending a BMI below 25, our findings suggest that personalized BMI targets may be more beneficial, particularly for different age groups and individuals with specific health conditions.”

Asked to comment, Ian J. Neeland, MD, director of cardiovascular prevention, University Hospitals Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, pointed out that older people who are underweight or in lower weight categories may be more likely to smoke or have undiagnosed cancer, or that “their BMI is not so much reflective of fat mass as of low muscle mass, or sarcopenia, and that is definitely a risk factor for adverse outcomes and risks. ... And those who have slightly higher BMIs may be maintaining muscle mass, even though they’re older, and therefore they have less risk.”

However, Dr. Neeland disagreed with the authors’ conclusions regarding “optimal” BMI. “Just because you have different risk categories based on BMI doesn’t mean that’s ‘optimal’ BMI. The way I would interpret this paper is that there’s an association of mildly overweight with better outcomes in adults who are over 65 with type 2 diabetes. We need to try to understand the mechanisms underlying that observation.”

Dr. Neeland advised that for an older person with T2D who has low muscle mass and frailty, “I wouldn’t recommend necessarily targeted weight loss in that person. But I would potentially recommend weight loss in addition to resistance training, muscle building, and endurance training, and therefore reducing fat mass. The goal would be not so much weight loss but reduction of body fat and maintaining and improving muscle health.”

U-Shaped Relationship Found Between Age, BMI, and Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) Risk

The data come from the UK Biobank, a population-based prospective cohort study of adults in the United Kingdom. A total of 22,874 participants with baseline T2D were included in the current study. Baseline surveys were conducted between 2006 and 2010, and follow-up was a median of 12.52 years. During that time, 891 people died of CVD.

Hazard ratios were adjusted for baseline variables including age, sex, smoking history, alcohol consumption, level of physical exercise, and history of CVDs.

Compared with people with BMI a < 25 in the group who were aged 65 years or younger, those with a BMI of 25.0-29.9 had a 13% higher risk for cardiovascular death. However, among those older than 65 years, a BMI between 25.0 and 29.9 was associated with an 18% lower risk.

A U-shaped relationship was found between BMI and the risk for cardiovascular death, with an optimal BMI cutoff of 24.0 in the under-65 group and a 27.0 cutoff in the older group. Ranges of 23.0-25.0 in the under-65 group and 26.0-28 in the older group were associated with the lowest cardiovascular risk.

In contrast, there was a linear relationship between both waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio and the risk for cardiovascular death, making those more direct measures of adiposity, Dr. Xu told this news organization.

“For clinicians, our data underscores the importance of considering age when assessing BMI targets for cardiovascular health. Personalized treatment plans that account for age-specific BMI cutoffs and other risk factors may enhance patient outcomes and reduce CVD mortality,” Dr. Xu said.

However, he added, “while these findings suggest an optimal BMI range, it is crucial to acknowledge that these cutoff points may vary based on gender, race, and other factors. Our future studies will validate these findings in different populations and attempt to explain the mechanism by which the optimal nodal values exist in people with diabetes at different ages.”

Dr. Neeland cautioned, “I think more work needs to be done in terms of not just identifying the risk differences but understanding why and how to better risk stratify individuals and do personalized medicine. I think that’s important, but you have to have good data to support the strategies you’re going to use. These data are observational, and they’re a good start, but they wouldn’t directly impact practice at this point.”